ALTERNATIVE HOUSING SUPPLEMENT

Vencomatic Group o ers a full range of innovative equipment for poultry farms accross North America. We are proud to be a global leader in cage-free solutions that are exible, practical and high-performing.

Our poultry experts provide expert advice on barn layout, bird management, climate management and egg handling.

More information: www.vencomaticgroup.com or please contact your local dealer.

BLR Solutions

QC - T: +1 450 772 2929 jfbourbeau@blrsolutions.ca

Jonkman Equipment Ltd.

BC - T: +1 604 857 2000 info@jonkmanequipment.com

Penner Farm Services

AB - T: +1 403 782 0675

MB - T: +1 204 326 3781 info@pennerfarmservices.com

Pols Enterprises Ltd.

ON - T: +1 905 708 5568 sales@polsltd.ca

Western Ag Systems

SK - T: +1 306 222 4881 wayne@westernagsystems.com

Bolegg

JONKMAN

11 ALTERNATIVE HOUSING PITFALLS TO AVOID

BY TREENA HEIN

There are very few egg farmers in Canada or beyond for whom the road to implementing a new housing system has no bumps or wrong turns. To assist egg producers from coast to coast as they continue to transition their housing from conventional cages to alternative housing, we’ve contacted experts at several companies as well as two producers for their advice. They’ve kindly provided their thoughts on how to avoid the most common pitfalls when converting to enriched or cage-free housing, and how to otherwise make the transition as smooth as possible.

1: EGGS LAID OUTSIDE THE NEST

Leo Apperloo, co-owner of United Agri and Central Agri (western Canadian distributors

for Valli, Jansen and Choretime), notes that whether enriched or cage-free housing, the focus must be on having eggs laid in the nest. Nest-laid eggs are obviously cleaner and the chance of cracks is greatly reduced. As soon as they are placed in the barn, hens will search out a nest, Apperloo says, “and if that nest is not comfortable, has the wrong nest pad, etc., they will choose a more comfortable place to lay.”

Lighting is also critical for high rates of nest lay. Muneer Gilani, managing director at Westlock Eggs and Country Hills Egg Farm in Alberta, explains that in their enriched systems, “We went with hanging tubes in the aisles [versus string lighting in the cages], as we felt like we had more control. The key is to make sure they are mounted away from the nest box to give the bird a dimmer

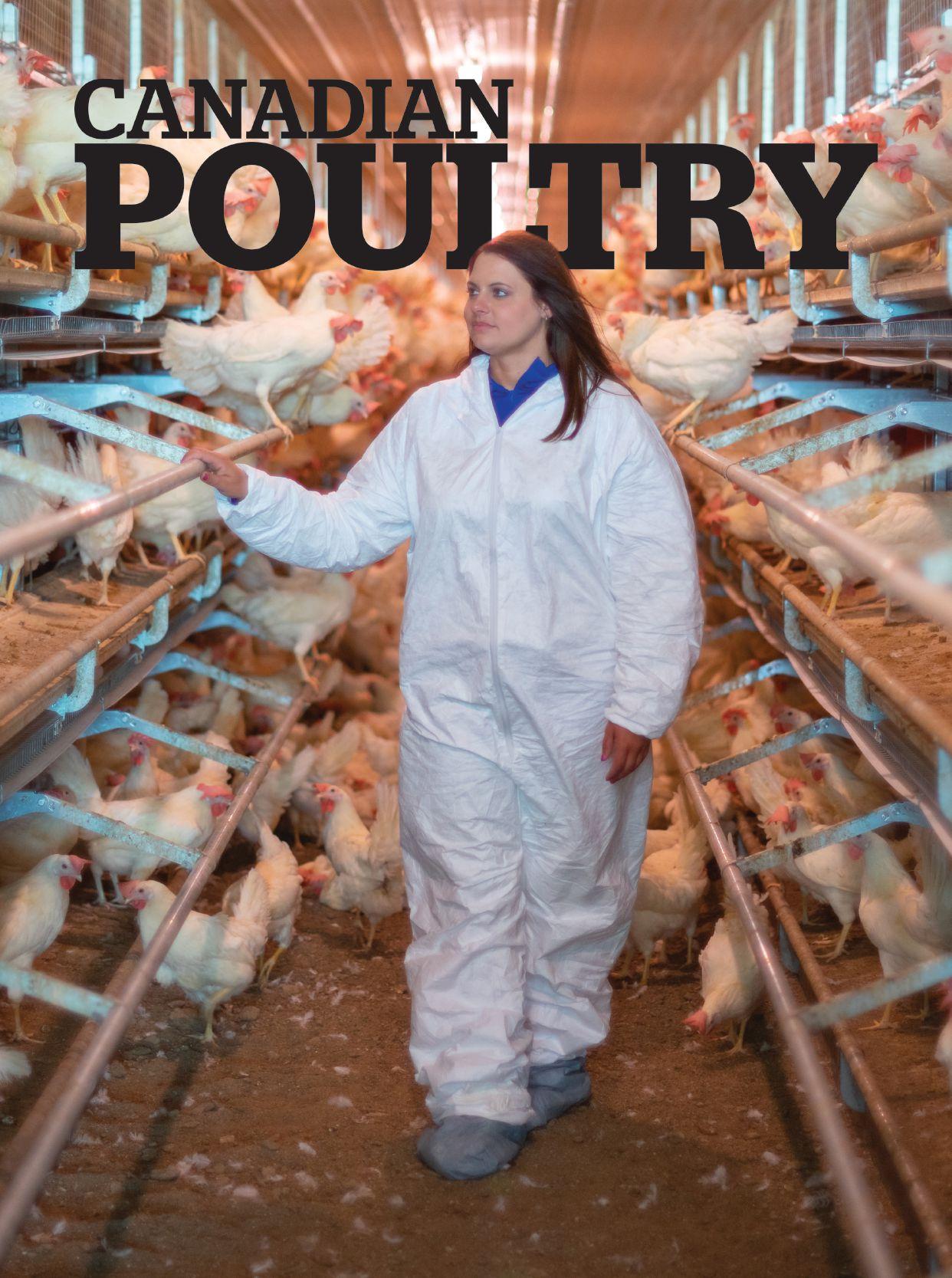

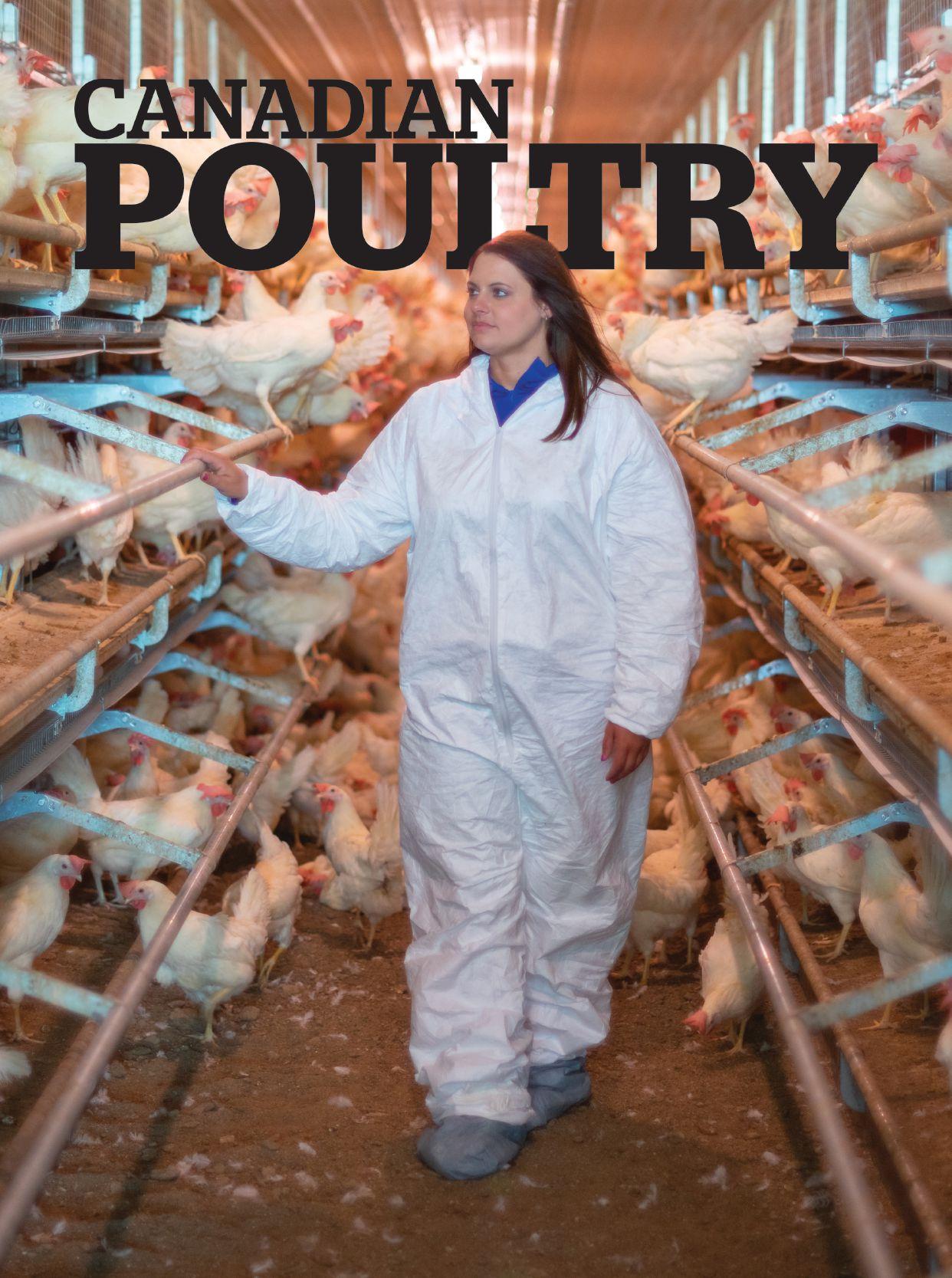

Tylor Van Kessel and Robyn Sitlington Van Kessel in Arkona, Ont., placed their first flock in their new organic aviary barn this summer.

nest box than the rest of the cage, even though we have curtains. With the string lighting, it’s difficult to dim in the nest box.” He adds that nest boxes and scratch pads must be located with care to ensure a high rate of nest lay.

Bradley Mandryk, president of Clark Ag Systems, sees things differently. “Some producers will use both aisle and in-system lighting programs when setting up a new enriched housing system while the birds are in production,” he says. “We have seen no benefit to utilizing both lighting systems simultaneously. In fact, when using in-system lighting only, production was enhanced and energy consumption was reduced.”

2: FAILURE TO ENSURE ELECTRICAL CAPACITY (ENRICHED)

Since in many cases enriched

cage systems need a large power requirement, Mandryk says you should consult your electrical supplier to ensure adequate service. He provides a couple of examples. “Our first barn conversion required a larger pole transformer and our second barn required a conversion to three-phase service at the road. Depending on where and if three-phase power is available, this can be a costly and large upgrade that needs to be considered in the very early barn planning and budgeting stages.”

3: NO PULLET TRAINING

Manage pullets by thinking about what their needs will be in the layer barn, notes Ian Rubinoff, Hy-Line’s director of global technical services. “Train them to jump, adapt them to the same kinds of materials (slats vs. wire) and ideally match the systems.” He believes that although chickens can be unpredictable, there are certain behaviours that should be predictable and teaching them to jump, perch, go to the nest and eat/drink “are all areas that with a good proactive approach can make everyone’s life easier.”

4: NOT MEETING SETBACK REQUIREMENTS

“Again, during the planning stages, and if a larger footprint barn is required (which is very often the case), the farmer needs to ensure that the new facility will meet all the minimum

setbacks required by provincial and county regulations,” Mandryk says. “This can have an impact on how large your new barn will be, which will directly affect your bird population numbers. These planning regulations may make a farmer look at a multi-tier cage configuration in a smaller footprint building in order to keep their bird populations equal to their former conventional housing.”

flicker can lead to much bigger challenges. The quicker something small is fixed, the better your flock will respond.”

Tylor Van Kessel and Robyn Sitlington Van Kessel agree. They started their own free-run farm in Arkona, Ont., a few years ago. And in August, they had their first flock in their new organic aviary. They explain that you have to be willing to slow down and really observe your flock and watch the birds go to bed and wake up, especially the first few nights. “Since they’re constantly on the move, it can be difficult to see problems,” Robyn says. “The flock is adaptive and will take cues from you and an almost-synchronicity occurs. Achieving that is worth the effort and will pay you dividends.”

She and Tylor also value each other’s observations. “For us, that means Tylor has a mechanical skill set as a licensed millwright, whereas I tend to focus more on the behaviour of the birds. Marrying these two skill sets together has led to our ideal outcomes, but it can make for some interesting table talk when we don’t agree.”

6: INADEQUATE MANURE MANAGEMENT (ENRICHED)

Absolutely nothing replaces being in the barn with the

5: NOT MONITORING CLOSELY, OR ACTING QUICKLY

“Absolutely nothing replaces being in the barn with the chickens,” Rubinoff says. “This helps the chicks get used to humans during rearing and helps the hens go to the nest after transfer.” He adds that in conventional systems, small challenges can go unnoticed or may resolve themselves, but “in cage-free systems, there can be a snowball effect where a small problem such as wet litter or light

Mandryk notes that the manure belts in enriched housing are much wider and longer than traditional conventional systems and need to be cleaned and scraped much more frequently. “Since manure can build up fast and heavy on the wider belts, the risk that a belt snapping or stretching becomes magnified with excessive manure build-up,” he explains. “We recommend that belts are scraped a minimum of two times per week to ensure good belt health. On the other hand, over-scraping manure can lead to inefficient scraper performance and excessive energy usage, so find that happy medium.”

7: INADEQUATE VENTILATION (ENRICHED)

Ventilation will very likely be much different in enriched barns compared to traditional barns, Mandryk notes, with dryer manure and better air quality, especially in the winter

Westlock Eggs farm manager David and his wife Treena.

chickens.

months. He advises making sure ventilation programs are set properly to minimize over-ventilation, keep humidity levels correct and minimize energy costs. Gilani adds that it’s worth having a little more ventilation than you think you may need.

8: FAILURE TO GET HELP

Rubinoff strongly advises using the experts available to you. “Something always goes a bit sideways,” he says, “and using the expertise of other farmers, salespeople and technicians can be really helpful as you work through the first flocks.”

Sitlington Van Kessel adds, “Don’t leave any question unasked because usually it’s the ones that go unanswered that will cause you the most strife down the line…I think it’s crucial to stay humble and accept that you as an egg farmer won’t have all the answers but be willing to put in the effort to find them.”

9: INCORRECT PARTITION POSITIONING (ENRICHED)

It’s critical to place partitions in larger-format enriched housing systems, Mandryk says, because if you don’t in certain systems, there will be too much bird migration to one side of the cage, overloading nests and reducing egg production. Having partitions also makes it easier for catching crews at end-of-lay.

10: EGG BACK-UP (ENRICHED)

Eggs can build up in the nest in the morning as a large percentage of the birds want to use the nest at same time. To reduce this issue, Mandryk advises installing a shunt timer on egg belts and egg collection elevators to move the eggs along away from the belt. Apperloo adds that belt advance and egg-saver frequency should be monitored and possibly changed throughout the flock as egg laying times change.

11: IMPROPER FEED MANAGEMENT (ENRICHED)

Feed consumption is slightly higher in enriched housing, as bird activity is higher, Mandryk explains. So, your feed program, bird nutrition and potential areas for feed wastage inside and outside the system must be managed closely.

A FEW OTHER TIPS

Gilani adds that producers should transition to alternative housing with expansion plans in mind, and to design new barns so that they are suitable for a variety of housing systems (you take more time to decide as the barn is built). “Also, consider how flocks will be depleted,” he says. “We use whole barn gassing so we want carts and aisles that can accommodate movement of chickens and room for equipment. It also means having a space for the gas lines and an access point for trucks.”

MATCH FROM HATCH

Studying aviary housing for pullets and layers.

BY ERIN ROSS

Over the last half century, the vast majority of laying hens in Canada have been housed in conventional cages. While this style of housing is financially economical, environmentally friendly and presents a low risk for injury and disease, it comes at the price of compromised animal welfare.

Conventional cages lack the features necessary for hens to exercise and assume typical body postures, while also limiting their capacity to perform motivated behaviours including perching, foraging and laying in a nest box. As consumers have become increasingly concerned about these welfare issues, demand for cage-free eggs has also increased.

While cage-free housing meets more of the behavioural needs of the birds, the added complexity and three-dimensional space offered by cage-free housing systems makes them more physically and cognitively challenging for birds to navigate.

Particularly problematic in aviary housing, the most complex form of alternative housing environments, these challenges contribute to the increased risk of painful bone fractures, emaciation and dehydration. From a production standpoint, floor eggs become an additional concern, as birds may not lay in nest boxes. This directly results in financial loss for producers.

As the Canadian egg industry moves forward in its transition to enriched and cage-free housing for laying hens, use of

A 16-week-old laying hen pullet attempting to navigate a testing arena designed to assess the birds’ physical capabilities.

aviary housing will continue to increase. It is vital that the industry identifies practical strategies for helping hens better adapt to life in adult aviary systems.

PREPARING HENS FOR AVIARIES

Recent research indicates that when a hen is raised in an environment that resembles the one she will inhabit as an adult, she is better able to navigate that adult housing environment. Through exposure to complex and physically demanding housing elements such as multi-tier structures, ramps and raised platforms in early life, birds develop the cognitive, behavioural and physical attributes needed to successfully negotiate the same features in adult housing systems.

Commercial laying aviaries are often several metres tall and feature essential resources (e.g., food, water, and nest boxes) on multiple levels. Thus, it is paramount for both hen welfare and financial feasibility that birds destined for life in these systems develop the skills to navigate them effectively.

Birds raised in rearing aviaries have been shown to better develop these necessary skills, as open-concept rearing supports the development of traits hens needs to adapt to life in adult aviary housing.

While rearing aviaries are readily available to Canadian egg farmers, they vary widely in design. The available units differ most substantially within the smaller compartments where chicks are brooded before the entire aviary system with multiple levels, perches,

PHOTO CREDIT: ERIN ROSS

ramps, and litter is made accessible.

While some such compartments are furnished with perches and raised platforms and offer space for birds to run and fly, others are more barren and offer limited space to move. As a result, the level of load bearing activity available to the birds during their first weeks of life vary greatly between rearing aviary models. These differences in early life experience may have a significant impact on cognitive, behavioural, and physical traits that persist throughout the rearing period and into adulthood.

DIFFERENT AVIARY STYLES

As a master’s student under the supervision of Tina Widowski in the Department of Animal Biosciences at the University of Guelph, I am investigating how three different styles of commercially available rearing aviaries affect the bones, muscles, body composition and physical capabilities of brown and white pullets.

The characteristics of the brooding compartments within these three aviary styles range widely. Style one is similarly enclosed to a conventional cage and features only a perch. Style two features larger compartments outfitted with an additional raised platform. Lastly, style three spans the length of the barn and offers perches and raised platforms from one day of age.

Each aviary style offers similar complexity and opportunities for load bearing movement after the brooding compartments are opened; however, I hypothesize that the differences in these characteristics in the first several weeks of life will impact the development of the pullets’ physical traits and capabilities. I predict that birds performing both the greatest amount and diversity of weight-bearing activity will develop the best musculoskeletal traits.

Recent work from our research group identified differences in the types of locomotion used and the strength of bones in pullets housed in these different styles of aviaries on commercial farms. Differences in the same traits were also found between brown and white feathered birds.

My project takes a closer look at the effects of load bearing exercise during early life within these rearing aviary systems on bones, muscles and behaviour.

It uses a multidisciplinary approach incorporating elements of anatomy and physiology, bone biology and ethology. With this method, my work will offer a holistic evaluation of how varying levels of environmental enrichment and physical activity during early life impact a pullet’s strength and ability to perform physical tasks and how that may impact their success in an aviary system.

As the Canadian egg industry continues with its nationwide transition to alternative housing for laying hens over the next 16 years, producers are charged with selecting and implementing new housing systems to replace existing conventional cages. With so many manufacturers and styles of alternative rearing housing systems to choose from, it is essential that producers understand how the different options available to them will affect their birds.

By identifying rearing aviaries that allow pullets to

Chicks housed in the most open concept and complex rearing aviary (style three), which spans the length of the barn and features perches and a raised platform from one day of age.

develop strong, healthy and functional bones and muscles, the results of my research will directly inform egg farmers. It will enable them to select a system that will produce birds physically equipped to thrive in adult aviary systems. This research was funded by Egg Farmers of Canada, Egg Farmers of Alberta, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada and Canadian Agricultural Partnership.

Erin Ross is a master’s student in the Department of Animal Biosciences at University of Guelph focusing on laying hen musculoskeletal health and welfare.

DREAM. GROW. THRIVE.

5 TIPS FOR OPERATING AN ENRICHED SYSTEM

Management practices to get the most out of furnished cages.

BY RON WARDROP

As the regulations quickly change – the layer industry is mandated to move towards alternative style housing – it’s important to understand that there are many differences between these newer systems and conventional housing. Some of these offer advantages, such as being a safe and humane replacement for conventional housing environments. Take enriched cages, for example. Although similar to the conventional cages, they give birds more space to express natural behaviours and encourage them to lay their eggs in a nest area. However, these traits can also present management challenges. Producers need to overcome these obstacles to maximize egg quality by using management practices specific to the enriched housing.

1. NEST PLACEMENT

ABOVE: Controlling the movement of the eggs in the system and on the collection belts will help with egg quality.

The placement of the cage enrichments is very important to the long-term success of the operation. The most important of these being the nest area, which should be at the front of the cage closest to the egg belt and be kept dark and placed in a calm area (like a corner). This will ensure the eggs don’t have to roll through a high traffic area to get onto

the egg belt where they could get pecked, stepped on or become dirty, making them unsaleable.

As well, the nest curtains should be close to the floor to control the light entering the nest. Darkness will increase nest acceptance and decrease mis-laid eggs. The scratch pad should be placed away from the nest, as it will excite the hens and disturb the laying process.

2. LIGHTING

Enriched cages are a package system with the enhancements working together to achieve an overall positive experience for the hens. A big part of the functionality is the lighting of the cages. The best results come from the lighting being inside the system for direct control of the intensity and consistency in every cage. Direct control also allows the nest area to remain dark, which increases nest acceptance and, as a result, improves egg quality.

3. NEST PAD MAINTENANCE

Nest pads are an important enhancement to the enriched system for hen comfort. However, they do require regular maintenance. Inspecting the nest pads on a weekly basis and removing excess debris build up will cut down on dirty

eggs. In extreme cases, these build ups can stop eggs from reaching the egg belt and increasing the chance of damage.

4. FEEDING

Having a feeding program becomes part of the management of the alternative layer system. Feeding shouldn’t interrupt the egg laying process. This will increase eggs being laid in the nests.

Running the feed system during the egg laying time will disturb the hens and draw the birds out of the nest, which leads to mislaid eggs.

Experts suggest that feed run when the lights are first turned on and then not again until after the peak laying period is over and equally through the rest of the day. This schedule will lead to the birds laying more eggs in the nest, experts say.

As well, ensure that any feed and water sources that can be reached from the nest area is blocked because

you don’t want birds encouraged to stay in the nest area.

5. EGG CONTROL

Controlling the movement of the eggs in the system and on the collection belts will help with egg quality. Most enriched systems have built in programming of the egg belt movement, allowing it to run on a schedule. By moving the egg belts frequently, the length of the nest area, you will keep eggs from overcrowding on the egg belt and crashing into each other, causing damage. This program can be set in your control system and is vital to stopping cracked and checked eggs. Another tool in the control of egg belt density is the use of the egg saver wire. This will help cushion the eggs before they roll onto the egg belt, lessening the impact into other eggs. Also important is ensuring that equal numbers of birds have access to each side of the collection system. This is done by adding a center divider in

the cage so you ensure that equal eggs are deposited on each side’s egg belts. Doing this will prevent belt overcrowding, as sometimes birds prefer a nest side and can overwhelm the collection system on that side. Adding the divider ensures that equal numbers use the collection systems.

If you adopt these simple ideas, you’ll successfully adapt to an enriched system. I know there are many more things that make a successful layer farm. But these, I feel, are the simple items that will help move toward success.

Some equipment manufacturers have bird behavioural specialists on staff to help with the startup and operation of enriched equipment for the novice user. I encourage you to use them to ease the transition and make the conversion experience a success from the very first flock.

Ron Wardrop is regional sale manager, Canada, with Big Dutchman.

WORKING SMARTER

How multi-tier aviaries can help solve labor issues.

BY FRANK LUTTELS

As the cage-free egg trend continues to grow in North American markets, the amount of skilled and consistent labor required to maintain operations has not followed. One of the top barriers to efficient, profitable cage-free egg barns is finding reliable people who can and will work in these facilities.

For years, egg producers have struggled to find — and keep — a talented workforce. And, unfortunately, it does not appear that this trend will be reversing any time soon, as the type of work involved appeals to fewer people. In this environment, facility owners need to be savvy about their equipment — reducing labor needs and improving the work environment — to make their cagefree egg collection worthwhile.

Multi-tier aviaries, also known as open or European-style aviaries, are becoming an increasingly popular solution to this issue. These systems decrease labor costs and offer a better environment for workers, when compared with other popular cage-free systems, while also offering better-producing birds and higher-quality eggs. Owners who establish more efficient systems now will have the infrastructure ready as cage-free chickens continue their trend toward becoming the standard in North America.

THE MULTI-TIER AVIARY

Multi-tier aviaries include different levels. They start at the floor level, where birds can display their natural behaviours like scratching, dust bathing and ground-oriented pecking. Going up, other levels include living areas with feed and a nest level where watering systems are placed in front of nests, allowing birds to easily find their routes. The top of these systems always includes a perching area, where hens prefer to sleep, similar to nature where birds tend to sleep on tree branches.

The design of these systems is based on the animals’ natural behaviours. Intentional aspects of each level “nudge” birds to participate in particular activities in the desired location. Most of these systems are outfitted with wire mesh and manure belts at each level to preserve a sanitary and healthy environment. Overall, multi-tier aviaries aim to eliminate manual labor and self-sustain as much maintenance as possible.

Features such as nipple drinkers and auger-driven feeders are often found with today’s aviary systems. Nipple drinkers automate watering and minimize spilling, while auger-style feeders rapidly distribute and remix feed for a uniform ration across the entire length of the system, so birds cannot select and consume only choice

morsels of feed. These features combined free up time for a smaller labor force to take care of the few remaining manual tasks.

Other cage-free options, including combination and floor systems, require significant manual labor for everyday tasks. Experts estimate that floor systems require two to three times the amount of labour, while combination systems can require up to five times as much, especially with a poor house design. Workers in these systems will also need to be highly skilled in handling and wrangling birds. Any money saved from the initial equipment and installation investments is soon lost to overhead costs.

Industry leaders are switching to multi-tier systems to reduce labor requirements for their cage-free chicken rearing, breeding and egg production facilities. Here are some of the processes that multi-tier aviaries either improve or eliminate the need for entirely:

• Manual hen placement and dispersion.

• Hen organization and access.

• Egg sorting and sanitation.

REDUCED NEED FOR MANUAL HEN PLACEMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Hens naturally tend to sleep at the top of their housing. In other cage-free

Multi-tier aviaries aim to eliminate manual labor and self-sustain as much maintenance as possible.

systems, too many birds sometimes congregate together, creating hot spots and overcrowding. These can lead to unsanitary conditions, unnecessary stress on the animals and even the deaths of otherwise healthy hens. To counter such issues, other types of cage-free systems need much more overall house management. They also tend to require an overabundance of nests. This, in turn, can decrease the quality of the eggs and overtax the egg belts in egg collection facilities.

Because multi-tiered aviaries are built to influence hen behaviour, manual bird management is virtually eliminated. Birds enjoy the different levels at different times, allowing for a more even spread of hens throughout the system. In perching areas, hens naturally spread out, allowing for improved ventilation without manual intervention. In rearing facilities, pullets can build muscle by moving around in open space and jumping between different levels.

Additionally, the labor learning curve for multi-tier aviaries is much lower than other options. Because hen behaviour is more consistent and predictable, workers need less training and can be found more readily.

EASIER ACCESS AND ORGANIZATION OF HENS

Accessing and discovering where certain birds are located consumes a large portion of the workday for most cage-free systems. Because birds are not easily contained, chickens intermingle and are harder to manage. Along with requiring more time from workers, this task is frustrating and requires skilled farmhands. Between a lower enjoyment of the work and a higher threshold of skill, this can lead to more labour costs and less worker retention.

In aviary rearing systems, birds are well distributed, and the use of vertical space allows for easy access and organization. Birds can be separated by breed, and pullets can be secured away from more mature birds for protection.

Ease of access cuts labor time and improves the working experience. Furthermore, many systems include access doors to allow workers easy entry into and out of the system. Time spent on manual processes, like vaccinating hens or maintaining equipment, is cut significantly.

AUTOMATING EGG COLLECTION

In egg collection facilities, multi-tier aviaries can automate much of the manual labor required for egg quality control and collection. Because hens prefer to lay their eggs in dark, sheltered places, the LED lights at the bottom level dissuade hens from laying floor eggs and encourage them to seek out the nests on the second level.

In other systems, workers need to go in the house and individually collect eggs laid in the wrong place. Besides the lost time collecting these eggs, broken floor eggs can cause messes that need to be cleaned up, further increasing required labor.

In multi-tier aviaries, a gentle collection system on the second level minimizes cracking and automates the task. This means more high-quality eggs with less work. To prevent hens from spending too much time in the nesting area at the end of the day, defecating and sullying eggs, there are available automated mechanical technologies that slowly push the hens out of the nests over time. This reduces time spent cleaning the eggs and manually moving hens.

THE FUTURE OF CAGE-FREE LAYER HOUSING

Higher demand for cage-free eggs means greater opportunity for producers. However, demand cannot be met without the appropriate labor. The solution, it seems, is a system that practically manages itself. Multi-tier aviaries come close to doing just that.

Frank Luttels is the layer product manager for Chore-Time.

FEATHER DAMAGE IN ALTERNATIVE LAYER HOUSING

New research provides insight into why it happens and how to improve its management.

BY TREENA HEIN

As more Canadian egg producers continue to adopt enriched and cage-free layer housing, how farmers can optimize welfare of hens in these systems is coming into the spotlight.

Postdoctoral researcher Nienke van Staaveren and associate professor Alexandra Harlander in the department of Animal Biosciences at the University of Guelph have published landmark initial studies on what factors affect the extent of feather damage (FD) from feather pecking in these housing systems. The work was part of a project funded by the Egg Farmers of Canada.

The scientists note that while more research is required, some insights for producers can be gleaned from these studies in terms of how FD can be minimized.

Loss of feather cover is a serious welfare matter that can eventually progress to injuries and mortality. Reduced feather cover also makes it harder for birds to maintain their body temperature and balance. Additionally, FD increases production costs due to increased mortality, reduced egg production and more.

Experts generally believe that feather pecking is a redirected foraging/feeding behaviour caused by the stress of living in a barren environment. But

Loss of feather cover is a serious welfare matter that can eventually progress to injuries and mortality.

nutrition, genetic and barn management factors can all play a role in its extent. “The climate, feeding and other management practices in alternative housing systems here in North America can also differ from those in Europe,” van Staaveren adds. “Though numerous studies have been conducted in Europe, we believe our studies are the first large-scale ones in North America.”

Notably, the flocks surveyed in this study had been placed on-farm between October 2016 and December 2017, a period where Canadian egg farms were undergoing many changes relating to a new code of practice.

Postdoctoral researcher Nienke van Staaveren (pictured here) and associate professor Alexandra Harlander worked on landmark studies examining feather pecking in alternative layer housing.

CAGE-FREE SYSTEMS

Scientists have established in previous studies that feather pecking behaviour is initiated by a small percentage of birds in any flock and then the behaviour spreads. In the large flocks housed in cage-free systems, FD can therefore be very extensive.

In their cage-free housing study, van Staaveren and Harlander received completed surveys from 39 farms with cage-free systems (having sent out surveys to many more) – 17 single-tier systems and 22 multi-tier aviaries. To fill out the survey, farmers visually assessed 50 birds in a flock for FD using a simple scoring scale and answered questions related to housing and management.

On average, about a quarter of the observed cage-free birds exhibited some form of FD, either moderate or severe, but van Staaveren says this is likely an underestimation of the prevalence of FD typically exhibited on egg farms in Canada. “It’s because some of the surveyed flocks were relatively young, and research has consistently shown that FD increases as birds age. We found similar results where FD increased by about one per cent for each week that the flock aged, which can impact a large number of birds.”

Flock age aside, van Staaveren and Harlander found two other factors strongly associated with FD in cagefree housing: Floor type and frequency of manure removal. This is no surprise. Feather pecking stems from stress, and birds with more forage/litter substrate on the floor and better air quality are likely to be less stressed. Specifically, more FD was found in flocks that have all-wire or all-slatted floors. But van Staaveren and Harlander note that these floors were installed before the most recent version of The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pullets and Laying Hens came out, which requires part of the floor to be litter (at least 15 per cent in single-tier systems and 33 per cent in multi-tier). “So, all-wire or all-slatted floors are being phased out,” Harlander says. “It is necessary from a welfare perspective to provide litter substrate for natural foraging behaviour to be expressed, which is the vast majority of natural hen activity each day.”

Researchers haven’t investigated manure removal as a

Premium+® laying nest

The Premium+® laying nest is the number one selling nest worldwide. Its high nest acceptance, minimal amount of floor eggs and use of high quality materials are reasons why many farmers worldwide favour the Premium+® laying nest.

Maximum number of first class hatching eggs

Highest possible nest acceptance

Reduces the amount of floor eggs to a minimum

For more info contact our local dealers:

Avipor | Meller Poultry Equipment | United Agri Central Agri Systems | LBJ Farm Equipment

Follow us on:

Optimal hygienic conditions www.jpe.org

factor in FD much, van Staaveren notes. “In single-tier housing with all wire or slatted floors, manure removal is only possible in between flocks, but in multi-tier aviaries (and enriched cages), manure belts make it possible to have more frequent manure removal,” she explains. “More research is needed, but these results may encourage farmers in general to think about the impact of better air quality and cleanliness on bird behaviour.”

It’s important to monitor feather damage, no matter what housing system is used.

ENRICHED HOUSING SYSTEMS

In the study on FD in enriched housing, similarly to the cage-free results, about 22 per cent of birds in enriched housing exhibited either moderate or severe of FD. Also, similarly to the cage-free results, this is likely an underestimation of what is actually found on Canadian farms.

Van Staaveren and Harlander originally wanted to see if there were differences in FD among layer strains. However, in the survey results, there was no uniform strain representation. Nor was there enough flocks of several strains to allow for a good comparison.

“We, therefore, divided it into white and brown-feathered birds and found that FD was higher in brown-feathered flocks,” van Staaveren explains. “This follows results of other studies. We know that birds tend to be attracted to peck further where there is a contrast between brown feathers and areas of white feathers where brown feathers have already been removed.”

In addition to flock age and feather colour, the researchers found midnight feeding and lack of a scratch area were associated with increased FD in enriched housing systems.

Regarding scratch areas, section 2.5.4 of

the code of practice requires that after April 1, 2017, “Hens must be provided with a minimum of 612.9 cm2 for each 25 birds.” Again, the flocks surveyed in this study were placed between October 2016 and December 2017, and some producers were still in the process of meeting the code. However, the result from this study of finding more FD in flocks without a scratch area does support the requirement in the code for scratch areas.

Regarding midnight feeding practices, where the lights are turned on and rest is disturbed, Harlander notes that this practice has also been shown to induce stress in rodents. She adds that “if we ourselves are woken up in the middle of the night with the lights turned on, we are generally grumpy the next day. It would seem that hens that have undisturbed nightly rest may be less likely to peck at other birds because they are less stressed and more rested. All kinds of frustrations lead to feather pecking. We think the value of undisturbed rest for hens should not be underestimated and should be studied further.”

Midnight feeding may also contribute to FD in another way, van Staaveren and Harlander note. The practice creates an environment where there is a mix of resting and active birds, and likely increases the chance of resting birds becoming victims of the feather pecking of active birds during that time.

Other research also has determined that the use of dark brooders reduces feather pecking during rearing and into lay. These curtained, box-like heated structures simulate the conditions chicks experience with their brooding hen mother. Experts believe that they are effective in separating active and inactive chicks, allowing resting chicks to avoid pecking from active ones.

Overall, van Staaveren and Harlander found a large amount of FD variation among flocks in both alternative housing systems. While further research is needed, they believe this result indicates that management really matters.

“It’s important to monitor FD, no matter what housing system is used,” van Staaveren says. “Farmers can try different things such as ceasing midnight feedings and see how much FD is reduced compared to previous flocks, for example.”

KEY TAKEAWAYS ON FEATHER DAMAGE IN ENRICHED AND CAGEFREE HOUSING

Feather pecking is a multifactorial issue that likely stems from stress, and can happen in all housing systems.

No matter the housing system:

• Older flocks have more feather damage (FD) and monitoring it can help identify the issue earlier.

• Providing birds with access to foraging opportunities (e.g., litter in cage-free systems, scratch areas in enriched cages) can help reduce FD.

Novel factors found to be associated with FD included frequency of manure removal in cage-free systems and midnight feeding in enriched systems. Both of these factors will require further research but could point toward the importance of good barn climate/air quality and undisturbed sleep.