6 minute read

I was lost in the desert for nine and a half days and sustained myself with raw bats and urine

by Alloranews

says. He promptly peed into his canteen. “It was clear like water.” He was sure he wouldn’t need it. The organisers would find him soon.

The next morning, Prosperi continued to run. He kept faith in the race, the sense that he was still a competitor. He did not know that the organisers had yet to begin a search - and that to survive, he would need to effect his own rescue. When he heard a helicopter, he assumed it had come for him. It flew low. He saw the pilot’s white helmet. But the pilot did not see Prosperi. The runners had been issued with flares, small and thin like a ballpoint pen.

Advertisement

Prosperi shot his into the sky, waved the Italian flag from his backpack, and lost all self-control. “I ran after him. I shouted at him. I called him Paolo, Giovanni” - every random name that sprang to mind. But the noise of the engine faded to a hum, then there was silence.

In 1994, Mauro Prosperi was running an ultramarathon through the Sahara when he was blown off course by a sandstorm.

Alone and dangerously dehydrated, he found nourishment in unexpected places

by Paula Cocozza

Mauro Prosperi’s run through the Sahara desert was going well. The Marathon des Sables is a notorious foot race - 250km in extreme heat across terrain that ranges from dunes three storeys high to stony outcrops.

Prosperi, a former Olympian, was among the fastest competitors. But, as he began to pass through a section of the race that was dominated by small dunes, the sand around him started to lift and swirl. “Small dunes, unlike large ones, walk,” he says. The swirling resembled a dance, rhythmic and mesmerising at first, but the rhythm became in- sistent and before he knew what was happening, Prosperi faced a yellow wall. “I couldn’t see anything. The wind blew so violently, the sand hurt.”

At the start, the organisers had given a talk and advised runners to take shelter in the event of a sandstorm. If lost, they should walk towards the clouds that gather at sunset. But, as Prosperi says, “There aren’t many shelters in the desert. In the middle of the dunes, it’s hard to find a place that will defend you.”

So he kept moving. He tried to shelter several times, but the sand always covered him up. He moved again, sheltered again. The storm took seven hours to pass. When it had gone, there was absolutely nothing left to point his compass at. “The sandstorm took away every point of reference,” he says. “The landscape was completely transformed.”

Prosperi’s first instinct was to run. He had lost a lot of time and his thoughts were on finishing the race. “I hoped to at least get in the medals,” he says. Still, it struck him as strange that he hadn’t seen anyone. This was 1994, and the event was little known. Prosperi ran mostly alone. But why hadn’t he passed the walkers, who set off early from the checkpoint? Or seen any race markers? He climbed a dune, but saw no one. “I knew that something was wrong,” he says. Still, he would have a story to tell his friend Giovanni Manzo, who was mostly walking the course. And an off-schedule night alone in the Sahara desert brought its own magic. “It was immediately fascinating,” he says. “You have this sky that is white with stars that almost suffocates you.”

Prosperi, who will be 68 this month, says that he had had a fatalistic understanding of death all his life. “I was convinced that the end is already written when you are born.” As a child in Rome, he listened to his grandfather’s stories of the first world war, and perhaps it was a sense of embattlement that brought them to mind now. “He told me that when there was no water, he and other soldiers had drunk their own urine to survive,” Prosperi

Prosperi slowed down to a walk. He was in a different contest, with an unplotted route, a finishing line of his own devising and adversaries that were only beginning to make themselves known. He carried mostly dehydrated food, and no water. And yet for the nine and a half days that he was lost - and this was the moment when he really understood that he was lost - Prosperi says he felt no fear. Instead he experienced a deep, consuming serenity pocked with moments of riveting anger.

The resilience, strength and stamina that he had accrued during years of elite sport must have helped him. But these qualities also honed instincts that he now had to overthrow. He had been a modern pentathlete since the age of seven, when he bumped into one of his father’s friends, who was a coach at the local sports centre in Rome. Prosperi began to excel. He joined the state police from school and was picked up by the Fiamme Oro sports section that is run by the force. In 1984, he represented Italy at the Los Angeles Olympics, and the world championships the year after that. But a profes- sional, single-minded focus was at odds with what he needed now - an aliveness to the world outside the parameters of the race.

“When you are going all out to win, you don’t notice anything. I won Olympics and World Cups. But, I didn’t look around me. As a professional, you have to do the race, full stop. You have to win, full stop,” Prosperi says. “In the desert, I learned that it is really important to look around you, to see what is happening, to know the being next to you.”

In Prosperi’s case, the beings next to him were sometimes a family of dromedary camels, or a tree that interrupted the endless sand whose branches felt like home, almost like kin, the sand on Prosperi’s skin a kind of bark. Climbing one on his second day lost, Prosperi spotted a disturbance to the view. “I was convinced it was somebody’s home or a holy man’s shrine.” But the shrine, or marabout, was empty. The only holy man was in a sarcophagus.

“At least I had a roof over my head,” Prosperi says. Securing his Italian flag to the turret, he heard a squeaking noise, like small birds chirping.

Clusters of tiny bats clung to the walls. He grabbed a handful, squeezed them dead. He cut off their heads, stirred up their insides with his little knife, and sucked them out. He repeated this with about 20 bats. “This way, I ate and drank at the same time,” he says. Did he make a practical decision to catch the bats, or were his instincts in charge? “I saw them. I thought, I’ll eat them raw. Then I won’t need water,” he says. It is fair to say that Prosperi emphasises practicality over emotions. While his friend Giovanni was given to reflection and hoped through the ultra marathon “to know himself better”, Prosperi says, “I don’t really do that.” I’m curious about whether he had to overrule disgust to eat the bats, but he seems nonplussed by the question.

“I ate and that was it. The only thing was they stank a bit.” continued next week

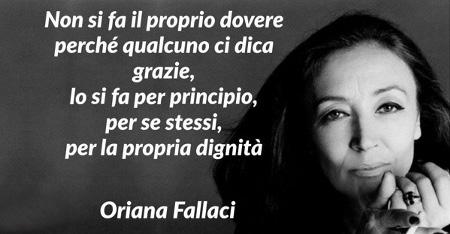

Oriana Fallaci, una figura iconica del giornalismo, ha lasciato un'impronta indelebile nella storia come una donna coraggiosa, incisiva e tenace.

Nata il 29 giugno 1929 a Firenze, in Italia, Fallaci ha intrapreso una carriera giornalistica che l'ha portata a coprire alcuni degli eventi più significativi del XX secolo.

Fin dai primi anni della sua carriera, Oriana Fallaci ha dimostrato un coraggio e una determinazione straordinari nel suo lavoro.

Ha lavorato come inviata di guerra in molte zone di conflitto, tra cui il Vietnam, il Medio Oriente e l'America Latina.

Fallaci ha rischiato la sua vita per portare la verità ai lettori, spesso intervistando leader politici, ribelli e vittime di guerra con una franchezza senza compromessi. La sua voce intrepida si è alzata contro l'ingiustizia e l'oppressione, facendo di lei una figura ammirata da molti.

Oltre al suo lavoro come giornalista, Oriana Fallaci è stata anche una scrittrice di talento. Ha pubblicato diversi libri di successo, tra cui "Lettera a un bambino mai nato" e "Intervista con la storia".

Le sue opere sono caratterizzate da uno stile narrativo coinvolgente e penetrante, in cui Fallaci esamina le profonde contraddizioni dell'umanità e pone domande difficili sui temi sociali e politici del suo tempo.

I suoi libri sono diventati bestseller internazionali e hanno contribuito a consolidare il suo status di figura di spicco nella letteratura e nel giornalismo. Oriana Fallaci ha lasciato un'impronta duratura nel campo del giornalismo.

La sua incisiva capacità di fare domande penetranti e di andare oltre la superficie delle questioni le ha permesso di portare alla luce aspetti spesso trascurati o ignorati.

Fallaci non temeva di sfidare l'autorità o di mettere in discussione le convenzioni, dimostrando che il giornalismo può esse-