Anna Font Difference and Nuance

Architecture is a conditioned practice. Through the study of its production and evolution over time, it is therefore possible to identify traces of geopolitical movements, energetic crises and ideological turns as their effects are manifested by shifts in the material assemblages, languages of description and forms of representation that prevail within the discipline at any given moment. Hence, architecture conditions the world in return. In recent years, however, its impact as a material practice has been increasingly deemed problematic. Not represented by a single event but by a rise in forms of scepticism regarding architecture as an operative discipline, the second decade of the new millennium saw a consolidation of the critical voices that emerged in synchrony with the global economic crisis of 2008. This reaction had the effect of interrupting the process by which architectural production was allegedly becoming ever more frictionless as built form flowed smoothly from an inexorable drive for growth, resulting in an erosion of the agendas that mobilised its capacities in the name of experimentation. As this critical discursive apparatus continued to unfold, it not only stymied the developing design processes of its time, but also cut such forms of intelligence off from a context that has powerful resonances with the world today. And so, while a critical reaction to the excesses of architecture pre-2008 was therefore warranted, contemporary processes of design suffer from a lack of referentiality to the material intelligence that was being developed at the time and has since been rejected out of hand.

One very specific example of this can be seen in the widespread contemporary drive to elaborate novel and efficient cycles of reuse in relation to the construction and maintenance of the built environment, for which the design process is contingent on the assessment and organisation of non-standard stock. Salvaged pieces are inevitably of different sizes and states, and so their capacities for functional reuse vary widely. To articulate these materials into new assemblages thus involves the completion of tailored assessments of their performative potential and the invention of one-off relationships that can add value through their reactivation as architectural elements. In doing so, a balance between automation and manual making must therefore be struck, as well as an equilibrium between redundancy and efficacy, acknowledging that recycled and used elements have different and fundamentally non-linear metrics. The possibility to think with agility, quality and novelty about this scenario today is grounded in the knowledge developed in the 1990s by early practices of computation in architecture.

Engaged with an understanding of the world that was ecosystemic and complex, architectural thinking at the time was in need of a philosophy and science that could construct a new conceptual framework for design: one that was both relevant and robust enough to articulate a postfragmentary, post-representational and post-ideological mentality. Similarly, today, although with a tone of urgency

rather than one of transgression, there is a symmetrical quest for a spatial model of progressive thought that uncompromisingly engages with the material world as a complex system of relationships, and within which human inhabitation is one of many considerations. Explorations at both ends of this connective thread, though grounded in the realities of the social and industrial logics of their respective times, were and still are being developed in schools of architecture. This is not surprising, given the role that academia has played in unpacking naturalised conventions and reconstructing complex procedures free from the servitude to either professional interests or particular theoretical agendas. Nevertheless, its effects tend to be mediated by time, and 20-year jumps are common episodes of synchrony between the ideas formulated in the academic realm and their visible effects on the built environment. The influence of the speculative is eventually manifested in the pragmatic, but with a lag in time. In this case, the rupture of the 2008 financial crisis has severed contemporary discourse from the systems of knowledge that preceded it.

Reconnecting these threads requires first a construction of new relationships. Here four central architectural topics and common sources of disciplinary friction will be used to do so: form, typology, complexity and procedure. The aim of tackling them directly (as unfashionable as it is these days to invoke form or procedure), is manifold. On the one hand, to open them is to reveal how their meanings remain present (albeit often hidden) in new forms of speech; only the jargon around them has really changed. On the other, to simply pay attention to them is to reveal a field of nuances within which subtle but structural distinctions between the apparently common traits of different projects can be discerned. By engaging with the conflicts contained within each term, the possibility of a new outlook emerges, one that aims to overcome crystalised assumptions about their typical use in favour of a fresh contemporary debate. With this framework in mind, each topic will be contextualised by its predominant critique, which has often had the effect of flattening its meaning and resulted in the construction of conceptual oppositions. At the same time, a description of the architectural capacity of the area of work that the term activates will be unfolded. By exemplifying the nuances framed by the lineages of practice that operate within the realms of each, the aim is to present an understanding of these concepts as fields of internal difference that speak to the evolution of architectural thought from the 1990s to the first decade of the new millennium. The construction of this double context is an exercise in de-territorialising four key conceptual frameworks and their overlaps in order to ultimately inform contemporary reflections on matters that tendentiously flirt with similar problems to those of the recent past, but currently remain disconnected from their precedent forms of disciplinary intelligence.

The conceptual root of the term ‘form’, whose etymology derives from the Latin forma, can be traced back to two Greek concepts: eidos (abstract form) and morphè (visible form). In the architectural design process, the two coexist and are dependent upon one another. Nevertheless, they are often somewhat questionably split apart. Over the course of the past two decades, this tendency has been especially prevalent as morphè, in isolation, has increasingly been taken to represent the opposite of an essential economy of means. This reaction to form has, paradoxically, contributed to a culture today that privileges the visual, the pictorial and the representational over structural organisation.

Reconfiguring the contemporary discussion on form will therefore involve recognising the spectrum that is framed by the organisational and the formal as operative extremes. To this end, early computational culture, which saw the emergence of formfulness (structured organisation) on the one hand and formlessness (un-structured shape) on the other, offers some insight. Practices that were oriented towards the former placed emphasis on multiplicity in their integration of diverse systems, materials and hierarchies.1 In so doing, their aim was to achieve spatial synthesis by means of material organisation. Within practices that strove for the latter, however, expression came first and was defined by the intentional incorporation of particular characteristics and attributes that are typically generative of formal complexity. Such projects therefore tended to embrace heterogeneity while strongly rejecting hierarchy in the hope of finding new forms of order and novel figurations. For a field of nuance within this spectrum to open again, discussions on form will need to become more explicit and organisational processes in architecture will need to be recovered from the discipline’s current emphasis on representation. Form, at present, is seen as iconographic and symbolic.2

typology

The rise of the symbolic over the organisational, the visible over the abstract, incurs an elevation of the ideological over the procedural. As a consequence, design-oriented practices have recently been experiencing a return to the study of typology as ‘fixed’ type – a regressive loop, considering that this idea was already investigated during the 1990s. At that time, the result was the unfolding of a series of broad spatial explorations that maintain the potential to advance ‘provisional’ typological notions today which could transgress both modern tropes and the instrumentalisation of historical fragments.3 If we are to pick up this conceptual thread from where it was cut, taking type as something provisional implies the consideration of any given typological organisation as

dynamic and ever-changing, shaped by both internal and external forces that shift in relative significance over time. As a consequence, the architectural tendency towards immaterial forms of absolute order is dismantled, as is the prevalent notion that fixed, immutable concepts feed the architectural imaginary. The consideration that types mutate by the intensification of their characteristics thus unlocks new forms of critical operativity. From this perspective, a field of work can be identified in the realm of the provisional between trans-typological and a-typological positions. Trans-typological practices pursue typological invention as a process of problematisation, rather than one of theorisation, through the construction of novel understandings that supersede established conditions and conventions, including architectural categories as ingrained and naturalised as interior and exterior, or public and private. A-typological practices, on the other hand, operate at the margins of standard typological referencing systems in architecture, and often involve the incorporation of rules that are informed by other disciplinary fields, such as biology, geology, ecology or physics. Since these discussions were initiated in the 1990s, the awareness of the complexity of collective patterns and forms of living (as well as their diversity and fragility) has only increased, and thus a critique of fixed precepts in the highly regulated built environment that we live in today is conditional on architectural novelty.

complexity

Embedded in the current necessity to revise the material cycles that move architectural production lies something much greater than mere operative action. While growth and de-growth feed back into one another as reversible processes that extend from a common intelligence, the association of the former to neoliberal progress (and its consequences) has nullified any meaningful discussion on complexity that the latter needs in equal measure to evolve. Unfortunately, de-legitimising complexity has also reinforced the encapsulation of material policies and processes within ‘black-box’ tool sets that limit the impact and influence of architectural knowledge on the world.

As an extension of the philosophical and materialist foundation upon which computational practices were grounded in the 1990s, spatial projects began to incorporate their contexts through the construction of complex relationships.

A structural split within this line of experimentation, however, was riven between the central ideas of consistency and coherence. Practices of coherence embraced softer interpretations of site, and therefore resulted in designs driven by curvilinearity, as well as actions of material deformation and merging – material interventions viscously blended with and embedded themselves within their settings with minimal resistance. By contrast, the practices of consistency were

distinctly non-viscous. Bonds between their parts resulted from the active construction of relationships within which their organisational forces remained implicit. This involved harnessing understandings of the city that included conflict. Interruption and bypass, for example, were thought of as essential to the capacity of such processes to ideate solutions across scales, which in turn necessarily enabled them to transgress known categories such as use, programme and stability in their integration of complexity through material synthesis. In this sense, the design of the pre-architecture of a given project (in any context, built or discursive, and regardless of its size) is the construction of its thesis, which is necessarily complex. It is perhaps more imperative here than in any other discussion to reconnect with what complexity means, 4 not as a heroic act of design capacity but as a structural commitment to the recognition and construction of architectural problems.

procedure

The management of a project’s complexity goes hand in hand with the design of methodologies to articulate it. These kinds of procedures, unlike others, generate organisational scenarios within which analysis becomes a projective medium. Re-describing and testing here substitute the deployment of configurations that are known a priori, and working with degrees of variation enables the problematisation of existing conventions and the achievement of differences in kind. The rapid development of digital tools in architecture, however, has seen the evolution of variation into seriality, a catalogue of options, accelerating the crisis of ‘process’ and ushering in a period of conceptual austerity. In early computational thinking, variation and, by extension, differentiation, were considered the means through which a project could develop its own unique spatial modalities while striving for both finesse and singularity. In design processes of this kind, non-standard solutions were not celebrated as outcomes per se. In fact, by the end of the early computational era there was growing interest in the development of mechanisms that would enable the deployment of discrete parts using flexible, rather than prescriptive, catalogues, and explicit investigations in this direction were gathering steam. The grouping together of families of objects using fields of variation (primarily determined by the attributes of a primitive artefact or form) laid the ground from which practices of customisation could then grow in turn. While variation in design was driven by the generation of conflicts as a source of novelty in contingent relationships, customisation explored the essential malleability of objects and their components. The results of the latter approach therefore often transgressed notions of familiarity, figuration and resemblance, and ultimately gave rise to the emergence of new aesthetic categories and ontologies.

We are arguably witnessing and operating within a comparable scenario today, whereby the singular, the contingent and the unfamiliar (such as scraps and loose parts) are seen as starting points for the design of new material assemblages in a process of variation in reverse.

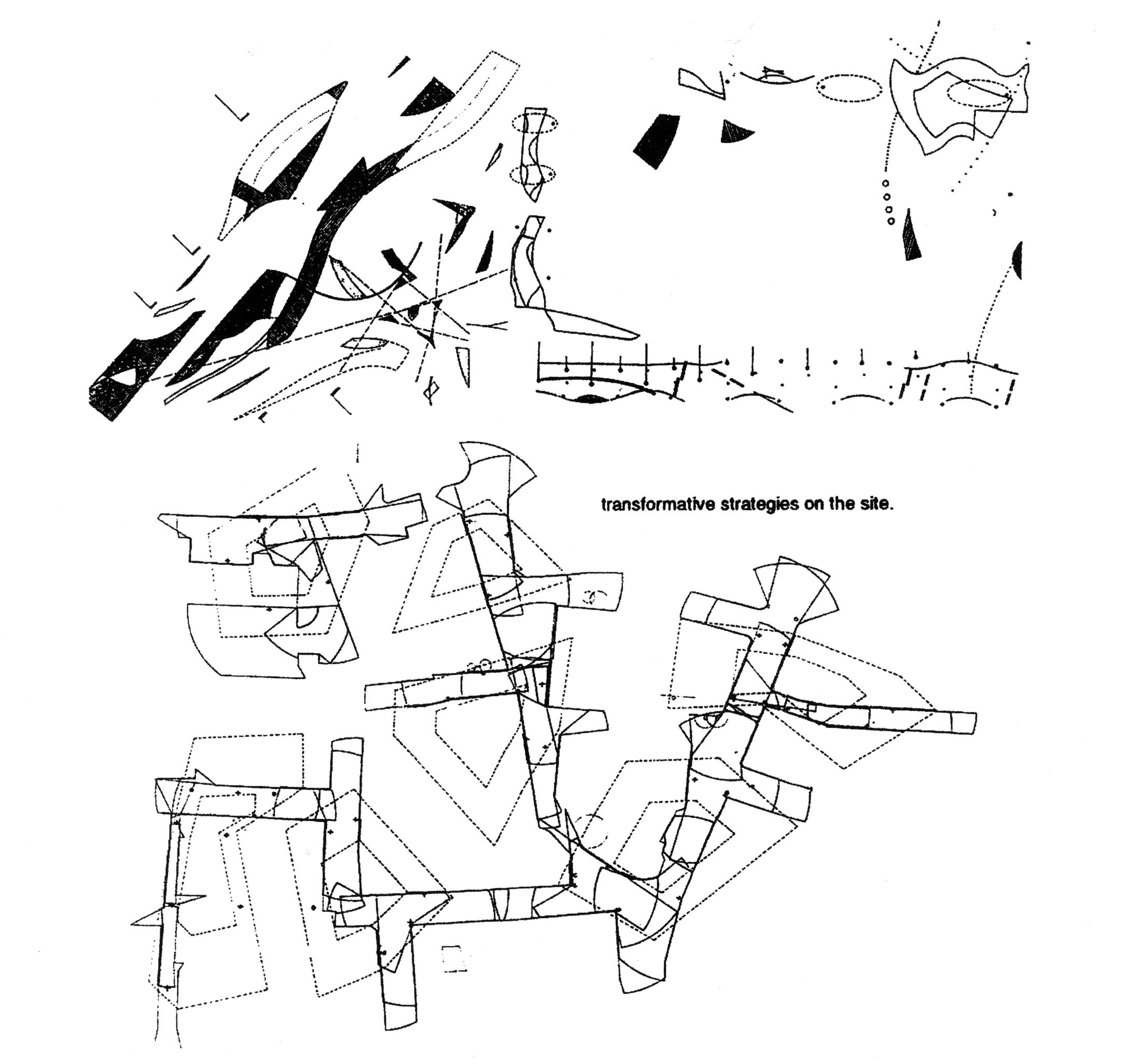

While the recuperation of a discussion in these four areas is an extension of a 20-year disciplinary arch and the critique that punctuated it, the non-oppositions framed by each (formfulness and formlessness, trans-typological and a-typological, consistency and coherence, variation and customisation) offer the key means through which to unpack a period of time that in general has been theorised in very homogeneous, uniform terms. The chronological proximity of the 1990s makes its historicisation as a decade somewhat difficult, particularly if we are interested in an account that can cover the granularity of positions that characterised it. In presenting a set of nuanced internal gradients, the descriptive exercise undertaken here is thus an attempt at an account that seeks to overcome the reductive label that typically encapsulates all such experimentation under the rubric of ‘the digital’. In this sense, these early tendencies of practice are not intended to be interpreted as models to be ‘replicated’, but as precedents in nuanced form. In other words, these reflections aspire to activate questions directed at the present, more than to crystalise affirmations of the past. Complementarily, the two illustrations that accompany the text speak of the research materials upon which this argument is based. Focusing on the context of the Architectural Association between 1992 and 2003, the diagram approximates a map of affinities, mutual influences and fine-grained discrepancies at the school, considering the ‘design unit’ as base measure of content.6 Organised primarily along three lines, it is possible to see how the work of a young and unconsolidated ensemble of tutors evolved into the first programmes of the graduate school. To the left of the diagram (Diploma 5) can be seen the lineage of briefs that appropriated Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the machinic. These agendas foregrounded the study of material relationships in searching for novel systems of architectural organisation, which involved the design of tailored techniques of mapping and acknowledged that the intelligence of a given project resulted from a process of differentiation (de-territorialisation and re-territorialisation). Machinic assemblages of this kind consciously avoided formal composition and expression as modes of evaluation,7 and thus this side of the diagram tends towards formfulness, trans-typological solutions, consistency and variation. To the right (Diploma 4), however, Deleuze’s influence is still felt but emerges more from his ideas of the fold.8 Here, the observation of behaviour in nature and its systems and the measurement of emerging phenomena in matter influenced a particular integration of architectural systems that catalysed the design of complex parametric models. Relationships, in this case, were framed by an interest in the calibration of their

effects, and optimisation and fabrication informed processes of prototyping and manufacturing. In parallel with these two tendencies, Diploma 11’s work on cybernetics as a science of systems comes as a vector from the previous decade, and it therefore takes its place on the diagram as a transversal influence.

Taking this drawing as a plane of work, it is possible to see how the global transformations of the last three decades have also had an effect on academia at large. The emphasis on specialisation and the commodification of distinct niches of work has given way to an atomisation of critical debate and thus resulted in a constellation of oppositions. But convergent contemporary crises have generated a pressure for us to once again reconstruct the ways in which architecture can condition both the global status quo and that of the discipline itself. This must go beyond the instrumentalisation of apparently technical solutions or the accumulation of commentaries that respond to generalised narratives. Instead, it calls for practices that can operate at the fringes of fixed discursive apparatuses; that can integrate and syncretise myriad aspects of the manifold critical landscape of today. In this sense, reflecting on the mirror of the 1990s is a way to relate to a similar moment of complex liminality in architectural thinking. The fundamentally uncynical tone of that time can be a soothing balm with which to restore a creative way of thinking about the possibilities of today.

Images: First Diagram of trends in the Units at the Architectural Association (1992-2003). Source: The Architectural Trait, Anna Font. Second: Machinic Transformation. The drawing ‘is produced through the analysis of the material qualities-scale, density, pattern, distribution, continuity, centrality- ... to introduce a transformation -intensifying, equalising, differentiating- of the existing regime towards a desired condition.’ Diploma Unit 5, Tutors: Farshid Moussavi, Alejandro Zaera-Polo. Students: Urs Britschgi, Michael Cosmas, Oliver Domeisen, Franklin Lee, Laurence Liaw, Gordon Osborne, Christian Oescheer, Anna Pla, Bhaven Raval, Fumika Takemura, Garry Thomas, Alexia Vassallo. Projects Review 1992-1995 Architectural Association School of Architecture, 1995, p 152.

1 The concept of multiplicity is that through which Gilles Deleuze sees all others.

2 Symbolism here is derived in reference to a literary movement that aimed to represent ideas and emotions through the use of indirect suggestion, rather than direct expression.

3 Reflections on fixed type can be found variously in the work of Rudolf Wittkower and Colin Rowe. The provisional type was discussed by D’Arcy Wentworth Thomson in On Growth and Form Cambridge University Press, 1917.

4 ‘[For Deleuze] the concept of complexity is freed from the logic of contradiction and opposition and connected instead to a logic of intervals: it becomes a matter of a “free” differentiation (not subordinated to fixed analogies or categorical identities) and a “complex” repetition (not restricted to the imitation of a pre-given model, origin or end).’ John Rajchman, ‘Out of the Fold’, in Folding in Architecture Academy Editions, 1993, p 78.

5 ‘We are intrigued by the idea that projects could exhibit regularity at the macro and micro scales, while incorporating high capacities of differentiation and variability at the middle scales…The intention of this return to regularity is two-fold: construction still depends on mass-produced elements, but mostly, because regularity is a primary architectural issue. The variety of crude typologies explored in the previous years (mat, strip, tower, pile, etc) can be flexibly deployed.’ Abstract for Studio VI at Columbia University, led by Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto, 1998–1999, in Abstract 98-99 Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, 1999, p 63.

6 Each unit at the AA engendered an intellectual alliance between students and tutors, a concise manifesto about contemporary architecture and its production, and a proposal for a relevant mode of practice that had yet to be explored.

7 ‘But the principle behind all technology is to demonstrate that a technical element remains abstract, entirely undetermined, as long as one does not relate it to an assemblage it presupposes. It is the machine that is primary in relation to the technical element: not the technical machine, itself a collection of elements, but the social or collective machine, the machinic assemblage that determines what is a technical element at a given moment, what is its usage, extension, comprehension, etc.’ Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, ‘1227: Treatise on Nomadology’, in A Thousand Plateaus translated by Brian Massumi, University of Minnesota Press, 1987, pp 397.

8 Gilles Deleuze, ‘The Fold, Leibniz and the Baroque. The Pleats of Matter’, translated by Tom Conley, in Folding in Architecture, op cit, pp 33.

Ahmed Belkhodja is an architect. After graduating from ETH Zurich in 2013, he established fala in Porto, which he leads together with Ana Luisa Soares, Filipe Magalhães and Lera Samovich. He earned his PhD from the University of Porto, and currently teaches at ENSA Paris-Est, HEAD-Genève and EPFL Lausanne.

Anna Font is an architect. She holds a PhD in Design from the AA, and graduated from ETSALS and Harvard GSD. Currently, she is the Head of Learning at the AA, Course Master for the Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities) and an Environmental and Technical Studies Course Tutor. Prior to joining the AA, she was visiting professor at Universidad Torcuato Di Tella.

Anooradha Iyer Siddiqi is an architectural historian and assistant professor at Barnard College, Columbia University, and author of Architecture of Migration: The Dadaab Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Settlement (Duke University Press). Her book manuscript Ecologies of the Past: The Inhabitations and Designs of Anil and Minnette de Silva draws from her book, Minnette De Silva: Intersections (Mack Books).

Boris Hamzeian is an architectural historian specialising in ‘technomorphic’ architecture and experimental pedagogies of the 1960s. He is a researcher in the architecture department of the Centre Pompidou. He is also a lecturer at the École Nationale Superieure d’Architecture de SaintÉtienne, a member of the scientific committee of the Fondazione Renzo Piano and founder of False Mirror Office. He has published monographs on the Centre Pompidou and UFO group, and currently holds a grant from the Italian Ministry of Culture.

George Jepson is a writer and researcher. An SAHGB funded doctoral scholar at the AA, he has held fellowships at the Canadian Centre for Architecture and the British School at Rome. He has taught at the AA, the Royal College of Art and the University of Edinburgh, and is currently tutor in Architectural Humanities at the Manchester School of Architecture.

Huma Gupta is Assistant Professor in the Department of Architecture at MIT in the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. She is an urban and architectural historian affiliated with the History, Theory and Criticism of Architecture and Art group and the Leventhal Center for Advanced Urbanism.

Giaime Meloni is a photographer and researcher living between two islands: the Île-de-France and Sardinia. A senior lecturer at ENSA Paris-Est, his work blends a documentary and a poetic approach to investigate spatial ambiguities. His photographic projects are regularly exhibited internationally.

Sabrina Puddu is a Sardinian-Italian architect and researcher. She teaches design and the history and theory of architecture at the University of Cambridge and the AA. Her work explores the role of major public institutions across the divide between the urban and rural conditions, and her on-going research project entitled ‘Territories of Incarceration’ concerns the architecture of confinement and the territorial logics of prisons and penal colonies.

Sony Devabhaktuni’s research considers the overlapping of economic, social and political intensities with imaginations of space. His writing has appeared in the Architectural Theory Review, Public Culture, Global Performance Studies, Platform, Places and the CCA web-journal. His book Curb-scale Hong Kong: Infrastructures of the Street (2023) describes the social and material relations that articulate the street as a shared public home. He is an Assistant Professor in the Art Program at Swarthmore College.

María Páez González is an architect, researcher and educator from the Venezuelan Andes, currently based between London, Vienna and the Canary Islands. She is a Postdoctoral Researcher at TU Wien and Programme Director for Professional Practice in Architecture at The Bartlett School of Architecture. Her research and practice explore Big Tech as an emerging form of social power and its intersection with historical models of subjectivity, architecture and the architect’s role in society.

Octave Perrault is an architect based in Paris. He is the founder of Zeroth, a design studio focused on energy and climate control in architecture. In 2022–2023 the company received venture funding from Silicon Valley to develop a novel thermal energy system for buildings that resulted in a patent and a functional prototype built in Princeton, USA. Octave Perrault graduated from the AA in 2013.

Olivia Neves Marra is an architect from Rio de Janeiro based in London. She teaches at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL and the AA. Olivia earned her PhD from the AA in 2020 with a thesis on the relationship between ideological enclosures, ownership and urban form. Her recent research traces the history of social movements in Brazil through spatial paradigms of resistance.

• The Lived Grid • Difference and Nuance •

• Technomorphic Architecture on Trial • Warcraft • Demystifying Automation •

• The Library of Missing Metadata • Penitentiair Landbouwcentrum •

• Still-Time at Amaravati • On Architecture in the Age of Renewable Electricity •

• A Commanding Type? • Two Mothers •