BY KADE GAJDUSEK STAFF REPORTER

An estimated 2,000 people marched Thursday afternoon from the New Haven Green to the School of Medicine in a show of support for Yale unions renegotiating contracts with the University.

The rally, organized by the union advocacy group New Haven Rising, was centered on UNITE HERE Local 34 and Local 35, unions of Yale’s clerical and technical and its service and maintenance workers. Members of other unions and Students Unite Now, an undergraduate group allied with UNITE HERE, also attended the event.

The rally began on the northern corner of the Green at 5 p.m., then headed down College Street

towards the medical school, where some of the union members are employed.

Many different chants cascaded through the large parade of people, often harmonizing into a unanimous “Who’s got the power? We got the power!”

On the side of the road, pick-up trucks filled with Local 35 members were handing out high fives and sharing compliments.

“We are standing here in the heart of the medical school,” Barbara Vereen, chief steward of Local 34, said, gesturing at the building.

“We need to send a message to Yale Medicine, to the dean of medicine and to the seat of the chief operating officer of Yale Medicine. We need to send them a message that says, ‘Respect our work.’”

BY JAEHA JANG STAFF REPORTER

Yale could pay more than $20 million to hire tenure-track faculty through the H-1B visa program if it continues to sponsor a similar number of visas as it has in recent years.

On last Friday, President Donald Trump moved to require a $100,000 payment from employers for every H-1B visa application they sponsor. The H-1B program allows employers to petition for temporary visas for highly educated foreign professionals. Between 2018 and 2024, Yale sponsored 200 or more H-1B visas each fiscal year, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’s H-1B Employer Data Hub.

For Yale to continue sponsoring 200 or more H-1B visas each year, it would have to pay more than $20 million in application fees, under the order.

Karen Peart, a University spokesperson, did not answer the News’ questions about whether Yale would sponsor fewer H-1B visas in the future or how the University would pay the new fees. Instead, she referred to a Sept. 20 announcement from Yale’s Office of International Students and Scholars, which clarifies that petitions submitted before Sept. 21 are unaffected by the new fees.

“The proclamation applies only prospectively to H-1B peti -

Speakers brought up a host of issues they want to see addressed in contract negotiations — including job security commitments, child care provisions and wage increases to match inflation. The word “respect” was ubiquitous, mentioned in almost every speech.

In the crowd, many people held signs reading “We can’t keep up” and “One job should be enough,” alluding to increases in the cost of living.

“Our members are getting priced out of New Haven because rents have gone up 300, 500, 800 dollars, and our wages have not kept up,”

Raven Turquoise-Moon, a senior administrative assistant at the Yale School of Medicine’s development

BY OLIVIA WOO AND JERRY GAO STAFF REPORTERS

Two trustees of the Yale Corporation, Fred Krupp ’75 GRD ’22 and Neal Wolin ’83 LAW ’88, held events with students Thursday afternoon ahead of the corporation’s first meeting of the academic year, which is set for Saturday.

The corporation, Yale’s primary governing body, has long valued secrecy, citing the necessity of “candor” for its meetings. Its meeting agendas are kept secret, and the minutes are sealed for 50 years. The board is made up of 10 successor trustees, who are appointed by Corporation members to serve up to two six-year terms, and six alumni trustees, who are elected by Yale alumni to serve one sixyear term each. In April, the Yale Corporation adopted a Yale College Council initiative demanding more transparency from the body. The YCC, along with the Graduate Student Assembly and the Graduate and Professional Student Senate, said in a letter that they would hold college teas and other events to encourage connection between students and trustees.

It is unclear whether Thursday’s events with trustees were the result of the corporation’s adoption of the YCC proposal. Neither event was hosted by the YCC, the Graduate Student Assembly or the Graduate and SEE TRUSTEES PAGE 5

BY REETI MALHOTRA AND ADELE HAEG STAFF REPORTERS

The American Civil Liberties Union’s Connecticut chapter is backing local progressive activists who allege that state police infringed on First Amendment rights in their response to peaceful protests on highway overpasses in the state.

Early last Friday morning, protesters with the Connecticut Visibility Brigade gathered outside the New Haven County Courthouse to object to the arraignment of one of their leaders after she was arrested twice over the summer.

protesting on overpasses along Interstate 95.

At her arraignment, Hinds pleaded not guilty to the charges. Outside the courthouse, Brigade members held banners that read “Free Speech is in Danger” and “Hate Will Not Make America Great.”

“This is happening in Connecticut, and, you know, Connecticut’s a Democratic state,” Lisa Leib, the organizer of last Friday’s protest, said, referring to Hinds’ arrests.

“We tend to enjoy a lot of rights here. It’s not like some of the other states, where their rights are being abridged. So we’re really concerned that this is happening here.”

Tim Tai

packed Toad's

for a pop-up Foo Fighters concert on Monday. PAGE 8

New Havener Katherine Hinds, 71, was arrested on July 19 and again on Aug. 8. She was charged with second-degree criminal trespassing, second-degree breach of peace and “unauthorized signs on a highway” for

On Monday, U.S. District Judge Stefan Underhill ordered the officials to file a response justifying the state’s restrictions on the overpass protests.

Ronnell Higgins, the commissioner for the Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection and one of two named defendants in the ACLU complaint, wrote in a statement to the News that he had spoken with elected officials, law enforcement officers, prosecutors and citizens about how to protect First Amendment rights while maintaining highway safety. Higgins, a former Yale Police chief, added that state troopers will

It is a misdemeanor under Connecticut law to affix a sign to the fence of a highway overpass. The ACLU last Tuesday filed a lawsuit in federal court on behalf of two other Visibility Brigade members against two state officials, arguing that holding signs rather than affixing them to fences is protected under the First Amendment.

September 26, 1996 / Tame Tap Night for singers

By Kevin O’Connell

On this day in 1996, students across campus awoke after a tame Tap Night for acapella groups. The administration took steps to manage the festivities, following instances of flying furniture and urine balloons the year before. Tap Night began earlier in the evening, with other preventative measures including an increased police presence and prohibition of thrown objects, water and obstacles.

By Adele Haeg and Reeti Malhotra

Last Friday, while en route to a press conference by city officials on legislation allowing for seized ATVs to be crushed, we happened upon a protest occurring at the New Haven courthouse on Elm St. About 20 protesters were shouting at cars, chanting “Free Speech, Free Speech” and waving banners that read “Free Speech is in Danger” and “Words Matter Join Us!” After the press conference, we looped back around to speak to protestors, who said they were part of a national protesting movement known as the “Visibility Brigade.” They were there to voice their discontent that their leader Katherine Hinds, a New Haven resident, had been arraigned and charged for protesting on Connecticut overpasses. We then learned that the ACLU had filed a lawsuit against two state officials, alleging they had curbed free speech in their response to the protest. We meticulously parsed through legal documents about the case against Hinds and the lawsuit filed on her behalf. Hinds is now awaiting trial for her charges for breach of peace, criminal trespass and “unauthorised signs on the highway,” and we’re continuing to follow the story closely.

Read “Overpass protest crackdown curbed speech, activists say” on PAGE 1.

By Kade Gajdusek

I encountered a man at Thursday’s union protest who’d come all the way from Portland. “Portland?” I asked. “You jumped on a flight just for this?” He nodded with a confidence I couldn’t deny. The commitment felt real. While fact-checking my article after the rally, I found out that he was actually from Portland, Conn. — a thirty-minute drive from New Haven.

Read “Yale unions rally for higher pay” on PAGE 1.

ABBY NISSLEY

“So sorry, I’m running five minutes late.” I send the text, frantically gather my purse, and race out of class.

I am late to dinner with one of my best friends, who I have been accidentally neglecting in my schedule. And our dinner is already truncated because I am simultaneously late for another meeting. I end this day exhausted, setting my alarm for an irreligious hour the next morning to finish the assignments I abandoned earlier as I tried to make it to every dinner and debate and meeting.

This panic of busyness is not constrained to one hectic day. I live my life bounded by arbitrary and desperate timelines. I know that I am not alone. Time is our currency at Yale, dolled out unbiasedly to every person, but I fear we are not spending it wisely, despite the depressing number of students increasingly interested in “finance.” For most students, Yale is a golden ticket in life, but the unique opportunities we have at Yale create a culture of chaotic hurry where what matters most in life is often entirely neglected.

“Be there in five!” has become my mantra for breakfast plans, sent like a timer as I only begin to peel myself out of my blankets. Recently, I am late simply because I was lying in bed drifting in and out of consciousness while ignoring my problem set on the desk. My social guilt for being late is so dulled only one month into school, I show up late to everything.

“I just don’t have time.” WRONG. We always have time.

Let’s reframe the statement without the underlying panic of scarcity. Every single day gifts us, equally, 1,440 minutes. In one day, every heart will beat approximately 100,000 times. However, something has been flipped upside down in our economy of time at Yale. Priorities are rare and far between. We cram our Google Calendars so full because we believe, somewhere buried in our Pavlovian-trained brains which crave the sound of activity, that the true exchange rate between productivity and busyness is 1:1.

Going to church or sitting with friends when they are going through a hard day are not activities that are color coded in our calendars. They are inconveniences that have no apparent value in our Yale economy. Friends will always be there and church has no barrier to entry, so these important aspects of life are shoved to the end of our priority list for “when we are less busy.” We will worry about the scary questions of vulnerability and life later.

So, we are left with wandering, wondering and high-achieving students at Yale, whose eyes dance around the dining hall in the middle of conversation. We create students at Yale who are flaky and hold their priorities like juggling balls, never fully grasping them

long enough to examine their core beliefs and values. Juggling does not allow a respite.

It’s too terrifying to admit: busyness does not equal productivity. Somehow these variables have become entirely, fallaciously, correlated. Not only is this a conflation of variables, such a mistake is an unproductive way to live life.

We weren’t designed to be constantly moving and striving.

In John Mark Comer’s book, “The Ruthless Elimination of Hurry,” he writes about a study on how Seventh-day Adventists have a life expectancy 10 years above the average. Their secret? Sabbath. They stop the frantic pace of life one day every week.

If we do the math, taking one day off every week adds up to almost exactly 10 years of rest over a lifetime. Mathematically, this study proves that our bodies give us back, roughly, the time that we take for Sabbath in the long run.

In Christianity, the concept of Sabbath comes from the book of Genesis, when an omnipotent God rested after creating the universe. Why would a religion allude to a seeming weakness in a powerful God? Because, perhaps, rest is not weakness.

I am not arguing that students should not be striving to immerse themselves in novel activities at Yale, and I certainly am not in favor of complacency. A compelling solution? Joining one of the student groups designed to wrestle with faith. Yet, ironically, these are the same groups that lack urgency and an external appeal because they are not competitive.

I wonder how many Yalies traverse campus with contemplative purpose despite the shakiness of college life.

I wonder instead how many students are floating from finance club to debate group because their older friend’s cousin told them to join. I wonder how many students come to Yale with no inherent vision for life, not seeking to discover it even through their hyperactivity here.

We bury the fears lurking at the back of our minds and decide instead to spend the afternoon stressing over our outfit for the night. We are scared to stop and look into ourselves. We are petrified of pausing in the middle of our frantic schedule because we fear having to reevaluate commitments or to ponder the larger questions of life. We are burnt out and hyperactive, but we do not want to reevaluate the investments of our time.

Stop. Think for five minutes before you resume your day. But certainly don’t be late for dinner with your best friend.

ABBY NISSLEY is a sophomore in Ezra Stiles College studying Global Affairs and Philosophy. She can be reached at abby.nissley@yale.edu .

GUEST COLUMNIST

ZACHARY CLIFTON

On Thursday, a story spread like wildfire. Hundreds shared and more than 3,400 liked an Instagram post by the Yale Endowment Justice Collective. In bold, firetruckred letters, the post declared: “Yale gave $1,000,000 to the Friends of the IDF.” Beneath, the post displayed a black-andwhite page from Yale’s federal tax filing — Form 990, Schedule I, which discloses grants and assistance to U.S. organizations.

The image didn’t show the section explaining the purpose of the grant: that it was a donoradvised fund, otherwise known as DAF, distribution.

The Yale Endowment Justice Collective’s examination isn’t exactly unusual. It scrutinizes Yale’s endowment, probing how money flows into and out of the University’s $41-billion fund. But the Instagram post struck a nerve because of its simple yet damning claim: Yale funded the Friends of the Israel Defense Forces.

The Friends of the Israel Defense Forces is explicit about its mission: to provide for the welfare of Israeli soldiers and veterans. That means funding education, housing, and care for active duty troops. Its supporters call this humanitarian; its critics call it militarism dressed in nonprofit clothing. It is inseparable from the ongoing war in Gaza — a war in which tens of thousands of Palestinians have been killed.

The truth, as always, is more complicated than the Yale Endowment Justice Collective’s initial claim — but not necessarily less troubling. Yale claims to educate, to pursue light and truth. Yet there is no light shed or truth told by channeling a million dollars to support foreign soldiers.

The University might argue its hands are tied. Once a donor establishes a DAF, Yale must honor the donor’s intent. To reject a donor’s recommended distribution could expose the University to legal risk or jeopardize future gifts.

But universities are not mere pass-throughs. They are moral institutions that shape their legacies not only through the students they educate but through the values they embody. Yale chose to create and advertise its donor-advised fund program. Yale chooses to operate it each year. Yale assumes responsibility for where the money flows.

The technical answer to whether Yale “gave” money to the FIDF is no: a donor did. The accurate answer is more complicated: Yale distributed the funds, put its name on the tax filing, and became part of the story.

DAFs are like charitable bank accounts. Individuals give money to a sponsoring organization — here, Yale — then they receive an immediate tax deduction and “advise” how the money should be distributed. The Internal Revenue Service makes clear that once a donation is made, the sponsoring institution has legal control, though the donor retains advisory privileges. On its website, Yale invites donors to route their philanthropy through these channels, calling the university “grateful for grants that come from Donor-Advised Funds.” It acts as a middleman, receiving money from a donor, then disbursing it at the donor’s request. Typically, Yale’s donoradvised fund distributions are less remarkable — others include a smaller distribution to the Alliance for Middle East Peace, a group of over a hundred nongovernmental organizations working to build reconciliation between Israelis and Palestinians; another to the Wonderland Educational Estate, which funds a private preschool in Houston, Tx.; a larger one to the Yale New Haven Hospital, which received about $1.3 million.

The Friends of the Israel Defense Forces is a benefactor. But its beneficiaries are not Houston preschoolers or Yale New Haven Hospital patients. They are combat military personnel.

Last year’s $1 million transfer to the Friends of the Israel Defense Forces stands apart. According to hundreds of pages of Yale’s public tax filings I combed through, it appears to be the largest single largest donor-advised distribution the University has made to an organization other than Yale New Haven Hospital since it began disclosing them in 2001.

The Friends of the Israel Defense Forces is not a small neighborhood nonprofit. It is a well-connected organization that raised $282 million last year, headed by a former Israel Defense Forces general. In the wake of Hamas’s Oct. 7 attack on Israel, its annual revenue quadrupled as American donors rushed to show support.

So when Yale’s name appears on a tax filing, next to a $1 million transfer to the Friends of the Israel Defense Forces, it creates more than accounting confusion. It creates moral entanglement.

Partly about the morality of institutions becoming conduits for militarized power, American president Dwight Eisenhower’s speech on the Military Industrial Complex seemed to warn about this kind of thing happening. “The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist,” he said.

Universities cannot forever plead neutrality while their financial machinery bankrolls causes with profound human consequences. Yale may not have chosen this particular war. But by approving the transaction, it chose to be complicit. There is a million-dollar question. No Instagram post or financial footnote can obscure its answer. Yale did not give its own money to the Friends of the Israel Defense Forces, but it did give someone else’s.

ZACHARY CLIFTON is a sophomore in Benjamin Franklin College studying political science. He can be reached at zachary.clifton@yale.edu .

Driving into New Haven this August, I met the northeast in half a dozen unmuffled and shiny BMWs. Each in turn roared down the on-ramp and merged with a jerking motion; they began to weave haphazardly between all three lanes of traffic, brakechecking semi-trucks and terrorizing all the sleepy Saturday-evening-roadtrippers they could find.

To call it a culture shock would be an understatement. My home is Ann Arbor, Mich., a college town much like New Haven, only midwestern, around half as big, and essentially without violent crime or sadistically reckless motorists.

Above all else, Ann Arbor is quiet. I’ve lived on a campus there before, sleeping in a dorm room with the window open, and it’s eminently possible to go weeks without waking at 4 am to the sound of a tricked-out, entirely-unoiled Dodge Challenger tearing through downtown.

There’s a special joy one can only feel in the silent suburban night: that of staying up for hours listening to a lone woodpecker pecking wood somewhere out in the night; of falling asleep to the uninterrupted, rhythmic pitter-patter of rain on roof.

This kind of joy is not to be found in New Haven.

Every night, my Elm Street–facing window in the corner of Durfee Hall rattles nearly out of its frame to the sound of joyriders whooshing by. When my mom called to wish me a happy birthday earlier this week, I had to step out into the common room to hear her over the roar — and even then, a couple of particularly loud ne’er-dowells managed to interrupt our short ten-minute chat.

To most Yalies, the sound is nothing more than an idle irritation — especially to those with childhood big-city bona fides. They shrug their shoulders and say, “Jesus Christ, Ari, you’ve been complaining about this

non-stop for four weeks, please get over it already.”

But we who know the pleasures of quiet suburbia can see New Haven’s sound problem for what it is: a quality of life concern; a heart health hazard; a threat to the constant and uncountable conversations and discourses which make Yale the humming factory of knowledge, innovation, and discovery that it is — a slap in the face of all which is good, peaceful, and pleasant. I tend to be pretty allergic to the misuse of state power; as offended by the overpolicing of minor, victimless crimes as anyone — but noisiness is far from victimless. Really, I can think of few clearer examples in which one individual’s low-cost act — driving around with a large and unmuffled engine — can so totally and forcibly pollute the shared environment.

“Burning coal,” “peeing in the reservoir,” end of list. Noisemaking is cheap to do, but it imposes large external costs.

Economists have a prescription for such issues: We internalize the externalities! Levy a tax on the act in proportion to its burden on the rest of society, and redistribute the proceeds to those affected.

These taxes are called “Pigouvian” and they Pareto-efficiently — that is, perfectly and magically — deter harmful acts, while justly compensating anyone still harmed.

For our sake, the same purpose can be served by a noise ordinance carrying heavy fines for violators.

New Haven does have such an ordinance, with, as of recently, appropriately severe penalties. Section 18-79 (c) of Title III of the New Haven Code of Ordinances prohibits any sound emitted from a motor vehicle “which is plainly audible at a distance of one hundred (100) feet from such vehicles by a person of normal hearing.”

And Section 18-82 (b) assesses fines of up to $2,000 for repeat offenses.

This is wonderful! But as any student of criminal law enforcement will tell you, the deterrent effect of a punishment’s severity is vanishingly small in comparison to that of its enforcement rate.

And, usually, by the time a loud and speeding car’s been reported to New Haven authorities, it’s already loudly sped away. A 2024 article in the News reports that while the New Haven Police Department received more than 2,600 noise complaints that year, few violators received citations.

I don’t expect this to change much. Though the Connecticut legislature passed a law just last year permitting cities to enforce their ordinances with noise-detecting cameras, New Haven’s been hesitant to install them. And besides, for violations caught on camera, the legislature limited maximum penalties to about a tenth the size of those found on New Haven’s books. As it stands, the only realistic way to quiet the New Haven night is to step up nuisance-policing. But as the NHPD struggles to hire cops and focuses its resources on more serious crimes, we find ourselves facing the depressing reality that a couple dozen unapologetic sadists can, with total impunity, degrade the lives of hundreds, even thousands, of lawabiding New Haveners and Yalies. Someday soon, though, the hiring shortages will resolve. And on that day, there will be a reckoning for the noisemakers.

When finally the noise ordinances are enforced, it will be as if a holy declaration has rung out: That beauty and civilization must and will prevail; that, here in New Haven, we must and will act well to one another.

ARI SHTEIN is a first year in Saybrook College. He can be reached at ari.shtein@yale.edu .

office, said. “I feel I should be able to continue to do the work that I've done for 19 years to uphold Yale's mission, a mission that I believe in, and buy a home here.”

Ensuring wages keep up with inflation is a top priority for the unions, according to Ian Dunn, a spokesperson for Local 34 and Local 35, who said the crowd was 2,000 strong.

“This is a time for us to take control of inflation from the past six years,” Dunn said.

Dunn said the unions hoped to emphasize the positivity and solidarity of the unions and the negotiations.

The speakers were joined on stage by the Rev. Scott Marks, the head of New Haven Rising, and Alder Brian Wingate, the vice president of Local 35. Alder Jeanette Morrison and Elias Theodore ’27, the Democratic nominee for Ward 1 alder, were also in the crowd.

As more people took the mic, the focus shifted from the specific contract negotiations to broader testimonies to the strength of unions and collective advocacy.

“We’re fighting for a city where students do not have to live in fear for a future,” Brandon Daley, a junior at Metropolitan Business

Academy, said. “We've won before. We will win again. We've demanded local hiring, and we've won revenue increases for New Haven. This is our city.”

Adam Waters GRD ’26 — the president of Local 33, Yale’s graduate student union — spoke in front of the crowd, reflecting on the sustained relationship between graduate students and other Yale workers.

Norah Laughter ’26, the head of activist group Students Unite Now, who lost the Democratic primary for Ward 1 alder earlier this month, guessed that over 100 Yale undergraduate students showed up to the rally.

The director of organizing for the International Union of Painters and Allied Trades, John LaChapelle, came from Portland, Conn., for the event, standing with the painters and tradespeople who worked inside Yale.

“Push the union, baby. It's all about the union, man,” LaChapelle said between puffs of his cigar.

The current contracts for Local 34 and Local 35 will expire in January 2027.

Contact KADE GAJDUSEK at kade.gajdusek@yale.edu .

BY ABDEL ABDU CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Dozens protested outside a local news station Thursday afternoon in response to its parent company’s refusal to air comedian Jimmy Kimmel’s recently reinstated show.

The Connecticut Citizen Action Group, an advocacy group headquartered in Hartford, organized the protest at WTNH’s station in downtown New Haven after Nexstar Media Group, which owns WTNH, announced it would keep “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” off air even after the show was reinstated Tuesday by ABC. Disney, ABC’s parent company, suspended Kimmel’s show last week after the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission suggested his agency may take action against ABC for Kimmel’s comments about the assassination of Charlie Kirk.

“The fact that they will not have Jimmy Kimmel on is just a symptom of the problem,” Christine McGregor, a resident of West Haven, said. “But the disease is censorship.”

McGregor was among dozens of protesters gathered in front of the WTNH 8 News building at the intersection of Elm and State Streets.

“I would like people to start watching WTNH News with a very discriminating view,” McGregor said. “We don't know now whether Nexstar is also affecting what the local reporting is on WTNH.”

According to their website, Nexstar Media Group is the largest media company in the nation, with over 200 local television stations nationwide, including more than 30 ABC affiliates.

“We have been advised to decline comment,” WTNH’s managing editor Joseph Wenzel wrote in an email to the New Haven Independent on Thursday.

Other protestors shared McGregor’s view that the protest was about more than just the refusal to air “Jimmy Kimmel Live!”

“History is repeating itself with this administration,” Bethany resident James Stirling said, comparing the targeting of shows like “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” by the Trump administration to the censorship experienced in the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany and China.

Stirling echoed other protestors’ concerns that the government was preventing stations like WTNH from airing what actual residents wanted.

Stirling said that he hoped that local stations and private companies would exercise their right to broadcast in response to public opinion, not pressure from the government.

Alongside the local residents who attended the protest, also several local officials who shared their own concerns about the decision to keep “Jimmy Kimmel Live!” off the air. Among them were Middletown state Sen. Matt Lesser, Stratford state Rep. Kaitlyn Shake and Ward 7 Alder Eli Sabin ’22 LAW ’26.

“No administration has fired someone because they don’t like what they’re saying,” Sen. Lesser told the crowd, referring to Kimmel. “What is the next issue they’ll sell us out on?”

Shake and Sabin echoed protestors’ concerns about how the federal government was exerting pressure on both journalists and media companies.

“They try to get unfriendly reporters off the air. They try to sue outlets,” Sabin told protestors, criticizing the pressure the Trump administration has placed on media organizations as censorship. Comments from the three pol -

iticians were met with applause from protestors, while cars driving by on State Street honked their horns in support of the protest. Protestors also carried signs with a variety of free speech messages including, “Censorship is un-American!” and “STOP Media Censorship Nexstar!”

The signs and statements shared by both speakers and protestors reflect the organization’s goal to condemn government censorship, CCAG associate director Liz Dupont-Diehl told the protestors.

The fact that the protest so quickly gained attention despite

being organized the day before reveals just how much people care about the issue of free speech, Dupont-Diehl said.

But protestors are concerned about more than Kimmel’s cancellation, she said.

“Jimmy Kimmel’s okay, but we don’t need corporations bowing to the federal government,” she told the crowd.

Jimmy Kimmel Live! Was suspended by ABC on Sept. 17 and reinstated on Sept. 22.

Contact ABDEL ABDU at abdel.abdu@yale.edu .

TRUSTEES FROM PAGE 1

Professional Student Senate.

Krupp, who was elected to be an alumni fellow in 2022, spoke at a Pierson College tea to about 20 attendees. An environmental advocacy nonprofit executive, Krupp was the first alumni trustee elected after the Corporation controversially eliminated the petition process to appear on its election ballots. Now, prospective alumni trustees must receive nominations from a University nominating body to become candidates.

The same afternoon, Wolin, a successor trustee and former deputy secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, spoke at a small seminar-style event hosted by Yale’s political science honor society, Pi Sigma Alpha. Approximately 12 people attended the conversation, which occurred under Chatham House rules,

under which participants cannot attribute quotes or information to speakers or participants.

“We invited Mr. Wolin to speak because of his distinguished career in public service and the private sector, as well as his record of service to Yale University,” Pi Sigma Alpha treasurer Matthew Quintos ’26 wrote to the News after the event. Wolin declined to answer the News’ questions about matters related to the Yale Corporation. He has been on the corporation since 2023 and serves on six of its 12 committees. During the Pierson tea, Krupp talked about his work as the leader of the Environmental Defense Fund, or EDF. Krupp has led the EDF since 1984.

Many attendees told the News that Krupp’s talk was the first college tea they’d ever attended.

Roxanne Shaviro ’26, a senior, said she was surprised by the accessibility of the trustee.

“I saw the flyer and I was sure there’s going to be people coming here to torment him. That was not my plan, but I thought there would be more people,” Shaviro said in an interview. “I think having the connection of Yale alum status breaks the ice a little bit, and I felt like I kind of want to go to more college teas now.”

When asked during the event about future plans for campus sustainability as the Yale Sustainability Plan nears its end this year, Krupp said that he has not yet gotten the final report on the plan but expressed enthusiasm for Yale to continue pursuing sustainability.

“Every university, including Yale, should be planning for the future and be ambitious,” Krupp said in an interview after the event. “I came directly from climate week this afternoon, where I was at the Yale Club, and was proud to see Julie Zimmerman, our vice provost in charge of plan-

etary solutions, leading the way.” Krupp also declined to answer the News’ questions about the upcoming corporation meeting. Crystal Feimster, head of Pierson College, said she has been wanting to invite Krupp since she became the head of college two years ago, but “just couldn’t work it out” before the Thursday tea. “Oftentimes, when people are in these positions, they’re the expert in the building, even though they’ve learned from lots of people,” Feimster said. “So I love that he was able to point to other experts.”

Pierce Nguyen ’29, a first-year student, asked Krupp during the event whether majoring in engineering would be useful for solving environmental issues. In an interview with the News, Nguyen spoke positively about Krupp, who said that people from multiple disciplines are needed in environmental work.

The Corporation has previously been criticized by student activists for Yale’s investments in the fossil fuel industry. In 2023, the Yale Endowment Justice Coalition, or EJC, organized a teach-in calling for the Yale Corporation to divest from fossil fuels and advocated for stricter rules and greater transparency regarding fossil-fuel related investment.

A Yale spokesperson wrote to the News at the time that the University already has binding rules against companies that act in ways that are “antithetical to a transition to a carbon-free economy.”

University President Maurie McInnis sits on the Yale Corporation.

Contact OLIVIA WOO at olivia.woo@yale.edu and JERRY GAO at jerry.gao.jg2988@yale.edu .

VISAS FROM PAGE 1

tions that have not yet been filed,” the announcement reads. “We still advise caution to those H-1B visa holders currently in the U.S. regarding international travel, as this situation is rapidly evolving.”

Between October 2024 and June 2025 –– the first three quarters of the 2025 financial year — Yale sponsored 157 H-1B visas, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services database. Steven Wilkinson, the dean of faculty of arts and sciences, did not immediately respond to a request for comment on possible changes in faculty hiring in light of the new fees associated with H-1B visa applications.

At Yale, H-1B visas are “generally reserved for tenure-track faculty appointments,” while the J-1 visa typically sponsors nontenure-track faculty and postdoctoral research training positions, an OISS webpage says.

The H-1B visa is initially granted for a maximum period of three years and can be extended to a maximum total period of six years. The OISS’s Saturday announcement noted that Trump’s recent proclamation “does not appear to impact” these extension petitions for individuals already in the United States.

According to a frequently asked questions page on H-1B visas released by the U.S. Citizenship

and Immigration Services on Sept. 21, the $100,000 fee is a one-timeonly payment for new H-1B visa applicants, regardless of duration.

Since the H-1B visa is contingent upon employer and position-specific status, employees on H-1B visas are only authorized to perform the duties detailed in their approved application, the OISS webpage on H-1B visas also notes. If their role changes, they are required to file an amendment, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

OISS’s Saturday announcement said the office has “less clarity regarding an initial H-1B petition requesting a change of status for the beneficiary from a non-immigrant category to H-1B, or an H-1B amendment.”

In a November 2024 webinar, Ozan Say, the director of the OISS, said that if the H-1B visa becomes “not possible,” then individuals could consider applying for O-1 visas instead.

The O-1 visa sponsors an individual who possesses an “extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics, or who has a demonstrated record of extraordinary achievement in the motion picture or television industry and has been recognized nationally or internationally for those achievements,” according to the immigration services website.

“O-1 is a very, actually, even a more subjective visa category than

so it’s usually kind of our last resort,” Say said. The federal government caps H-1B visa issuances at 85,000 per year,

receive “more detailed First Amendment training” and that all body camera footage and 911 calls related to highway protestors would now be published online.

Two arrests and an alleged ‘vendetta’ Hinds became involved with the Visibility Brigade in February, according to Leib. The Visibility Brigade is a nationwide protest movement that began in New Jersey in 2020 and aims to mobilize Americans by “providing physical messaging” in order “to demonstrate that resistance is possible,” according to the organization’s website.

Connecticut State Trooper First Class Joshua Jackson, who filed Hinds’ August arrest warrant, wrote in an affidavit at the time that Hinds had displayed banners and was “engaging in criminal activity related to unlawful protesting” on various overpasses along I-95 on on at least six dates from Feb. 14 to July 19. He identified her activities through posts on her Facebook page, according to the affidavit.

On three of those occasions, Jackson approached Hinds, ordering her and other protestors to take down their signs and leave the area. He cited the state law that prohibits protestors from attaching signs on overpasses and argued that displaying signs was also unlawful,

as it creates a “distraction” for incoming highway motorists.

Hinds ultimately complied with Jackson’s requests in each of the three encounters, and Jackson gave a verbal warning each time, Jackson wrote in the affidavit.

In body camera footage of one such incident — released Monday afternoon by a spokesperson for the Connecticut Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection — Jackson asks protesters to take affixed signs down because the bridge is a “political neutral area.”

Hinds was first arrested on July 19 by a separate group of state troopers for allegedly displaying a banner at the Stevens Avenue overpass in West Haven without proper permits. The troopers claimed that traffic volume had increased as a result, according to Jackson’s affidavit. The Connecticut law that prohibits affixing signs to highway overpasses forbids displaying signs that could interfere with traffic.

“Traffic on the I-95 was created by the sign — if you have spent any time in Connecticut, that alone should be a laugh line,” Dan Barrett, an attorney at the ACLU of Connecticut, said.

On Aug. 8, Hinds was arrested a second time, this time by Jackson.

Jackson arrived at Hinds’ home at 6 a.m. and arrested her on new charges after “loudly pounding on her front door” according to an Aug. 13 letter from Hinds’ attorneys to the Office of the State’s Attorney. In the letter, Hinds’ attor-

neys claim that Jackson is “pursuing a personal vendetta against Ms. Hinds and her protected First Amendment activities.”

The letter also states that Hinds had filed a misconduct complaint against Jackson in April for “his continued harassment” of the protestors. Jackson’s affidavit did not mention this allegation.

Rick Green — the spokesperson for the Connecticut Department of Emergency Services and Public Protection, which oversees the state police — wrote in an email to the News that Jackson was unavailable for comment.

In an Aug. 19 letter Higgins wrote to state lawmakers, he wrote that protests “may be subject to reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions, particularly in areas adjacent to high-speed travel lanes or critical infrastructure, when necessary to ensure public safety and security.” Higgins alluded to an ongoing internal affairs investigation prompted by a citizen complaint. Higgins further refuted “any assertion that Troopers are unfairly targeting certain overpass protestors based upon any perceived political or social affiliations.”

Lawsuit alleges new overpass crackdown According to the ACLU lawsuit, “loosely affiliated groups of Connecticut residents committed to expressing dissent with current federal government

policies and actions” have been peacefully holding signs on state overpasses since President Donald Trump won the November 2024 election. After the president’s inauguration in January, they increased their activities. However, in February 2025, state police began to intervene in the overpass protests, according to the lawsuit.

Erin Quinn, 46, and Robert Marra, 70, are the two named plaintiffs in the ACLU’s lawsuit, which names Higgins and Garrett Eucalitto, the commissioner of Connecticut’s Department of Transportation, as defendants.

According to the complaint, the New Haveners both joined the Visibility Brigade earlier this year and have attended a combined total of approximately 50 sign-holding protests mainly in New Haven, West Haven and Branford.

After continued intervention by state police, Quinn and Marra were left “shaken” and, with members of their organization, began to limit their overpass protests. According to Barrett, at least seven individuals were prosecuted by summons in Fairfield for protesting on an overpass above the Merritt Parkway in August.

Hinds was the first member of the group to be arrested at the protests — and activists’ “last straw,” according to the ACLU complaint.

“Ms. Quinn feels she can no longer tolerate the risk of being harassed or potentially arrested by

police for her protest activities,” the complaint states. “Mr. Marra similarly feels that the variability of the police response to the demonstrations, and reasoning given, means anything could happen.”

The ACLU’s complaint also claimed that the state agencies have taken a “hands-off approach” to other demonstrations on overpasses in the past.

The complaint cites 2013 protests against then-President Barack Obama, during which protestors attached signs to fencing on the overpass and waved to passing motorists, as well as a 2021 assembly of firefighters on overpasses to honor a public employee who died at work. Both protests took place without incident, the complaint notes. Barrett said that citizens should be “tremendously suspicious” of government authorities deciding “that signs involving speech about what's going on right this second in the country are a problem when, in the past, signs on the same topic were not. That should raise everybody's alarm bells.” Underhill, the U.S. district judge, set an Oct. 2 deadline for Higgins and Eucalitto to respond to the activists’ lawsuit.

Contact REETI MALHOTRA at reeti.malhotra@yale.edu and ADELE HAEG at adele.haeg@yale.edu .

“But I set fire to the rain, watched it pour as I touched your face” SET FIRE TO THE RAIN BY ADELE

BY OLIVIA CYRUS AND JOLYNDA WANG STAFF REPORTER AND CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Yale rescinded the admission of a Davenport College first year after administrators concluded that she included falsehoods in her college application, according to a Yale College spokesperson.

The student was escorted out of Lanman-Wright Hall by a Yale Police Department officer and Davenport Head of College Anjelica Gonzalez on Friday afternoon, one of her suitemates told the News.

The Yale College spokesperson, Paul McKinley, wrote in statements to the News that the student “submitted falsified information” and “misrepresented themselves” in their application.

“Yale receives thousands of admissions applications each year and the process relies on the honesty of the applicants,” McKinley wrote.

He did not elaborate or respond to the News’ question about how the University discovered the misrepresentations more than a month after first years arrived on campus. The nature of the removed student’s misrepresentations were unknown.

Davenport Dean Adam Ployd called the student Katherina

Lynn in an email to her remaining suitemates obtained by the News.

On move-in day last month,

Lynn arrived unaccompanied with only one suitcase, according to Sara Bashker ’29, a suitemate who was present at the time.

“She seemed a bit quiet and reserved at the beginning,” Bashker said.

Lynn initially said she was from North Dakota. On the Yale Face Book, where Lynn remained listed on Sunday night, her address corresponds to that of a hotel in the small town of Tioga, N.D.

Bashker said that at different points during her time at Yale, Lynn also mentioned residing in California, China and Canada. Bashker recounted returning from orientation programs and gathering with the rest of her suitemates to discuss their first-year experiences so far. While Bashker and her other suitemates talked about their crushes and romantic interests, Lynn said she had a boyfriend in his 30s who lived in the San Francisco Bay Area, Bashker said.

Bashker recalled that Lynn said she was in a “BDSM relationship” in which she played a dominant role over the man. Bashker estimated that Lynn was on the phone with her partner for three

to four hours a day at Yale.

Reached by phone, Lynn declined to comment for this article. The other two suitemates declined to be interviewed.

Lynn told Bashker that she simultaneously sought out other potential sexual partners through the website FetLife. She told the group that she was going to bring a middle-aged man she met on the website to the suite, Bashker said.

To Bashker’s knowledge, Lynn never brought to the suite a man with whom she had sexual relations.

Bashker said she was in the middle of folding her laundry on Friday afternoon when the police officer and Gonzalez, the head of college, came to the suite. The two told Lynn to pack her belongings, Bashker said, and the officer watched Lynn pack.

Gonzalez, before exiting, asked Bashker and her roommate if they were all right and offered Yale College Community Care, or YC3, mental health resources.

Later on Friday, Ployd, the Davenport dean, wrote to the remaining members of the suite that Lynn “withdrew from Yale College” and “will not be returning.”

Gonzalez and Ployd did not respond to the News’ requests for comment. Yale Police Chief

Anthony Campbell ‘95 DIV ‘09 declined to comment and referred the News to McKinley’s statement. Abdel Abdu ’29, who also lives in Lanman-Wright, or L-Dub, said he watched from outside the residential building as Lynn was escorted out.

Marco Getchell ’29, a member of the same FroCo group as Lynn, recounted Lynn seeming relatively nice, quiet, and reserved in their conversation together.

“This was shocking to me,” Getchell said. “From an outsider’s view, this was completely unexpected.”

This school year, Lanman-Wright Hall houses first years in Grace Hopper College as well as Davenport.

Contact OLIVIA CYRUS at olivia.cyrus@yale.edu and JOLYNDA WANG at jolynda.wang@yale.edu .

BY ORION KIM STAFF REPORTER

The Yale Endowment Justice Collective alleged on Instagram Thursday morning that Yale donated $1 million to an organization backing the Israeli military through a donor-advised fund.

Tina Posterli, a Yale spokesperson, confirmed the “distribution” to Friends of the Israel Defense Forces was made in November 2023, one month after Israel became a subject of campus controversy following Hamas’ Oct. 7, 2023 attack on Israel and the subsequent launch of Israel’s war in Gaza.

In its Instagram post, which has received more than 3,400 likes, the Endowment Justice Collective criticized Yale’s apparent role in financially supporting Israel’s war in Gaza.

Yale’s distribution of funds to Friends of the Israel Defense Forces was made through a donor-advised fund, which allows donors to make initial tax-deductible contributions directly to Yale that are then invested and managed by the Yale Investments Office. The donor may recommend that their funds be distributed among specific areas of Yale or other charitable organizations.

“Part of the funds remain at Yale and part of the funds may go to one

BY OLIVIA WOO STAFF REPORTER

or more other charitable organizations,” Posterli said about the donor-advised funds.

Karen Peart, another Yale spokesperson, wrote to the News that a donor-advised fund is one of many donation options for a small subset of donors. Yale reviews the donors’ recommendations for where their donations go and “approves distribution of funds to qualified charitable organizations.”

The charities are approved if they are U.S.-based 501(c)(3) organizations, a type of nonprofit organization recognized by the Internal Revenue Service as exempt from federal income tax, Posterli said.

At least half of the funds donated through donor-advised funds and any appreciation or income attributed to those amounts must be designated for use at Yale, according to documents posted on University webpages. Furthermore, a webpage on Yale’s For Humanity campaign website says that the minimum initial gift for a donor-advised fund is $5 million dollars.

Friends of the Israel Defense Forces, a New York City-based 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization, collects charitable donations on behalf of the soldiers of Israel’s military, according to its website.

The Thursday Instagram post from the Endowment Justice Collective, which advocates

for Yale to divest “from fossil fuels, distressed debt, military weapons, and other extractive and exploitative industries,” pointed to Yale’s tax filings from the fiscal year ending in June 2024, using its 990 Form Schedule I, which is publicly available online.

On the tax form, Yale is listed as making the donation to Friends of the Israel Defense Forces. The source of the donor-advised fund was not named, and the News was unable to identify the original donor.

Yale’s 990 Form shows that it made three other donor-advised fund disbursements in the 2024 fiscal year — $10,000 to the Alliance for Middle East Peace, $500,000 to the Wonderland Educational Estate Association and $1,294,284 to Yale New Haven Hospital.

According to Mitchell Kane, a professor of taxation at New York University School of Law, donor-advised fund sponsors like Yale “almost never” decline to follow a donor’s recommended disbursement.

“This will inevitably result in the university making transfers out of the endowment to 501c3 organizations that act in politically charged ways—this at a time when the historic need for universities as institutions to remain agnostic on political stances is greater than ever,” Kane wrote to the News.

However, Yale does have veto power over donors’ preferences for how their donor-advised funds are distributed, former Vice President for Development Charles Pagnam wrote to the News in 2001. Pagnam added that “it is unlikely the University and the donor will disagree about how the money will be used.”

Previously, a landing page on Yale’s Office of Planned Giving’s website included a document with information about making donations through donor-advised funds, according to Diego Loustaunau ’27, an organizer with the Endowment Justice Collective, who shared the old document with the News.

Loustaunau said the landing page was taken down on Thursday and reuploaded on Saturday without the donor-advised fund informational document. The News could not confirm when the website was edited.

According to Peart, the Office of Development, which is responsible for University fundraising, uses a third party to manage the Planned Giving microsite, and it takes several days for updates to take effect.

“We have recently changed vendors, and the entire site is under review as we prepare for the conclusion of the campaign and relaunch of Development sites in June 2026,” Peart wrote.

A new document explaining donor-advised funds, which Peart shared, is “in queue” to be loaded onto the Planned Giving site, the spokesperson wrote. Several changes were made to the updated document. The updated version was revised to explain that Yale donor-advised funds offer the tax advantages of giving to a “public charity” — which is Yale — rather than to a “non-profit organization.” The last line of the old document, which says donors can make charitable distributions from a donor-advised fund anonymously, is removed from the updated document.

According to Loustaunau, the Endowment Justice Collective regularly studies Yale’s financial documents as part of its mission to hold the University accountable to its students and its stated values. In its Instagram post about Yale’s distribution of funds to Friends of the Israel Defense Forces, the Endowment Justice Collective also asked viewers to donate to a mutual aid fund for Palestinian families in Gaza.

The Endowment Justice Collective was previously known as the Endowment Justice Coalition.

Contact ORION KIM at orion.kim@yale.edu .

The hiring pause implemented by Yale in June is nearing its end. For Yale College, the freeze has resulted in a small decrease in the number of employees after three months without new searches to fill staff vacancies.

“There’s some number of people who might have been hired over the summer who weren’t hired over the summer,” Yale College Dean Pericles Lewis said in a Monday interview. “And so we’re maybe 3 or 4 percent smaller than we otherwise would have been, and that’s a very rough estimate.”

The Yale College Dean’s Office oversees the hiring of staff members in admissions and financial aid, student affairs, student engagement, undergraduate education and career services.

The hiring pause was an anticipatory response to federal legislation that ultimately increased the tax on the University’s endowment gains from 1.4 percent to 8 percent.

Lewis said the hiring freeze, originally billed as a 90-day policy, would end on Tuesday, Sept. 30 — 92 days after it went into effect.

“It is my expectation that we’re probably going to be able to let it expire at the end of the month,” University President Maurie McInnis said of the hiring pause in a Friday interview with the News.

The June 30 letter announcing the pause — which was signed by Provost Scott Strobel, Senior Vice President for Operations Jack Callahan Jr. and Chief Financial Officer Stephen Murphy — clarified that even after the pause began, faculty hiring processes would be allowed to continue under the supervision of the provost and academic deans.

Lewis said student jobs are funded through non-salary expenses, which will be reduced across the University by 5 percent starting this year. Hiring for student jobs was not affected by the pause this summer, he said.

According to Lewis, a number of positions in Yale College that became vacant as early as two months before the pause was announced have remained empty.

Once the pause is lifted, however, the Yale College Dean’s Office may not immediately choose to hire for all roles that had once been filled.

“They’re down a couple of people in admissions, and we’re going to see how they do,” Lewis said.

“They work very hard, and I’m sure they’re going to do a good job, but the admission staff is a little smaller than it was a year ago.”

The Dean’s Office will be able to begin hiring for vacant roles on Wednesday, Lewis said.

“For each of the people managing different parts of Yale College, I’ve asked them to have a sustainable plan for how they’re going to pay for the level of staff that they expect to have over the next few years,” Lewis said. “So if they don’t have such a plan, we won’t hire in that area, and they can’t just hire on their own.”

Students have already expressed concerns about the hiring pause affecting undergraduate life. The pottery studio general manager position was left vacant this summer, leaving the five residential college pottery studios unable to host open hours for students.

The June letter announcing the 90-day pause clarified that clinical positions in the School of Medicine and grantfunded roles across the University would not be affected by the freeze. Faculty hiring processes remained under the discretion of Strobel and academic deans.

According to Lewis, most faculty hiring occurs in accordance with a

regular annual timeline, with professorship advertisements posted in the fall and final hiring decisions made the following July. Because the pause occurred between July and September, it did not overlap with this typical timeline for hiring new faculty.

“There’s a separate process to carefully review professorship applications, which tend to take a lot longer than staff applications, and to make sure that the units can afford them,” Lewis said. Yale College staff hiring requires a fraction of the time.

Lewis said that if a staff position that was left empty due to a pause needed to be urgently filled, the hiring process for that role could conclude only a few months after the freeze was lifted.

The 8 percent endowment tax increase will take effect for taxable years beginning after Dec. 31. Isobel McClure contributed reporting.

Contact OLIVIA WOO at olivia.woo@yale.edu .

“Now that it’s raining more than ever, know that we’ll still have each other, you can stand under my umbrella”

UMBRELLA BY RIHANNA

BY REETI MALHOTRA AND SARAH MUKKUZHI STAFF REPORTER AND CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Around 50 members of the Yale community and over a dozen dogs, including Harvard’s police dog, gathered to celebrate the retirement of Yale’s public safety dog, Heidi, on Monday afternoon.

The six-year-old yellow lab arrived at Yale in early September 2020, according to her biography.

Originally brought to the University to improve relations between Yale police officers and the broader community, she quickly became a fixture in mental health and legal support services for Yale students and community members.

“To the wide majority of people, she’s kind of just feel-good, niceto-have,” Margaret Kuo SOM ’25 said. “She shows up at large events and just spreads smiles. But Heidi does incredible work individually that a lot of people don’t see because it is so vulnerable and it’s so private.”

Heidi was trained by Puppies Behind Bars, a Manhattanbased organization that “trains incarcerated individuals to raise service dogs for wounded war veterans and first responders, facility dogs for police departments, and explosive-detection canines for law enforcement,” according to the organization’s website.

She was reared in prison by incarcerated workers from the time she was eight weeks old, the organization’s founder Gloria Gilbert Stoga said. The process, according to the organization, costs about $50,000 per dog.

Following her arrival to campus, Heidi became a public personality, currently boasting over 15,000 followers on Instagram and often being sighted as a frequent companion of Handsome Dan, the University’s mascot.

“Heidi was his first friend,” Kassandra Haro ’18, Handsome Dan’s handler, said at the event. “That’s the first dog he met.” She also became a valuable resource and a source of support in a bogged-down mental health support landscape, according to community members.

Ella King ’28 is a student in Silliman College who struggles

with somatic post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, which involves the physical manifestation of emotional distress, she said. During her first year, she began to meet with Heidi on a weekly basis.

“I found a little bit of difficulty working with Yale’s mental health services,” King said. “Getting weekly therapy, for whatever reason, wasn’t available to me in my first year. But it was available with Team Heidi, which was awesome.”

King described Heidi as a valuable mental wellness resource, pointing to both the dog’s training with deescalation for those struggling with PTSD and the willingness of Officer Rich Simons — Heidi’s handler and owner — to make on-call visits.

Kuo added that Heidi, along with Simons, would meet with medical students after the anatomy lab — an exercise when medical students practice skills on cadavers — and sexual assault victims testifying against their perpetrators in court. Kuo, who met Heidi after a particularly difficult midterm, credited Heidi’s “calming” presence with bringing community members together during adverse circumstances.

Stoga lauded Simons’ personality and close relationship with Heidi as instrumental factors in the pair’s success.

“They’re a perfect team because Rich’s whole persona is just to make somebody’s day better,” Stoga said in an interview at the event. “People

in crisis’ lives have been changed because of that dog. She’s a rockstar at Yale.”

Simons declined to speak to the News, citing concerns about facing discipline for speaking to the press amid ongoing contract negotiations between the University and the Yale Police union.

His wife, Michelle Eligio, highlighted the 27 years Simons spent convincing the department to hire Heidi and the dog’s subsequent success.

“He’s taken the program very far from its inception,” Eligio said. “It’s a credit not only to him but also to the dog, Heidi. Out of all the dogs, she’s very unique. She’s very friendly, happy and loves to greet everybody.”

According to King, Heidi is set to continue her service with Simons at New Haven schools after her retirement. The University has not announced any arrangements to replace Heidi or adopt a similar public safety dog.

Heidi has received several accolades during her tenure as Yale’s public safety dog, including the Linda Lorimer Award for Distinguished Service. The award was presented to both Heidi — its first canine recipient — and Simons in 2022.

Contact REETI MALHOTRA at reeti.malhotra@yale.edu and SARAH MUKKUZHI at sarah.mukkuzhi@yale.edu .

BY ASHER BOISKIN STAFF REPORTER

The Yale College Council Senate approved its $1.2 million budget Sunday after more than 90 minutes of debate, resolving a two-week standoff over how much money to allocate for Spring Fling, the annual end-of-year concert that accounts for more than a third of YCC spending.

Senators voted on Sunday to allocate $440,000 to the event, but attached conditions to $20,000 of the funds. Under the plan, Spring Fling will only receive that final tranche in October if it provides monthly updates, shares information about its artist selection process and demonstrates financial need for the funding.

“If Spring Fling upholds these stipulations, then they’ll receive the $20,000,” YCC Speaker Alex William Chen ’28 said in the meeting.

The vote capped two weeks of debate over the concert budget. Last week, senators approved an amendment to the YCC budget by Joseph Elsayyid ’26 that reduced the allocation from $440,116 to $420,000, matching what University administrators had described as the minimum cost for the event.

The remaining $20,000 became the focal point of Sunday’s debate, and senators split over whether to release the money to Spring Fling immediately or to withhold it as leverage.

Spring Fling organizers — Talent Chair Mateo Félix ’27, Hospitality and Operations Chair Lelah Shapiro ’27, Production Chair Jalen Freeman ’27 and Creative Chair Sophie Peetz ’28 — began Sunday’s meeting with a presentation justifying the increased request.

“Our main goal is planning a free festival that all Yale students can enjoy,” Shapiro said. “Spring Fling is free not only for students, but also their guests.” Freeman told the chamber that “production and security are the biggest non-negotiables,” while Félix pointed to rising prices.

“Inflation is happening,” Félix said. “It’s very pronounced in the entertainment industry.”

Last year, the YCC budgeted around $350,000 for Spring Fling — a third of their budget of roughly $930,000.

In the 90 minutes of debate, some senators favored releasing the additional $20,000 to Spring Fling immediately.

Chen’s amendment, which Timothy Dwight senators Cyrus Sadeghi ’27 and Alexander Medel ’27 helped write, proposed holding the $20,000 in reserve to ensure transparency from Spring Fling organizers. But Elsayyid and Kingson Wills ’26, the YCC events director, countered with a rival amendment that would have restored the full amount to Spring

Fling immediately, arguing that delays would weaken organizers’ ability to book performers.

“Since transparency can be secured regardless, it is more effective to release the funds now, allowing Spring Fling to negotiate earlier and secure better pricing,” Elsayyid wrote to the News.

The chamber split sharply.

“We wasted an entire week of debate and discourse that could have been spent on other elements of the YCC, including other proposals that could have directly benefited FGLI students,” Saybrook Senator Brendan Kaminski ’28 said, referring to first-generation or low-income students. “It feels kind of artificial that we’re all of a sudden bumping it up to $440,000.”

Others defended the drawnout process.

Elsayyid noted that this extended debate was part of the job of a YCC senator.

“It’s the most engaged process in actual democratic deliberations that I’ve seen in all four of my years,” he said.

Over the past two weeks, Elsayyid has held meetings for senators to discuss the YCC budget.

“We’ve got an incredibly active group that doesn’t just rubber stamp proposals, but is more than willing to get into the weeds and scrutinize every aspect of them,” YCC President Andrew Boanoh ’27 wrote in a statement to the News.

Senators also discussed whether the conditions attached to the extra $20,000 would actually increase accountability. Wills and Elsayyid argued that the Senate could use existing constitutional measures for oversight of the Spring Fling budget.

Ultimately, Chen’s amendment prevailed. The Senate rejected the Wills-Elsayyid proposal by a 12-8 vote and then approved the overall budget as amended by a 21-2 vote.

“This budget does an excellent job of balancing needs within the YCC while also giving the general student body a look into operations they’ve

historically had no view into,” Boanoh wrote.

Boanoh highlighted that this finalized proposal includes the largest allocations in history, alongside increased transparency, for the Spring Fling committee.

“As Spring Fling Chairs, we are very happy with the outcome of this Senate meeting and the budget that was passed this morning,” Shapiro wrote in a statement to the News.

The chamber postponed votes on delegate approvals and Adobe software funding until its next meeting.

Contact ASHER BOISKIN at asher.boiskin@yale.edu .

BY KAMALA GURURAJA CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Students gathered Sunday to ring in the Ethiopian and Eritrean New Year at Beinecke Plaza.

The event was organized by the Yale Ethiopian and Eritrean Students Association, or YEESA, an organization of students with Ethiopian and Eritrean roots. The celebration was open to all and included a performance by Desta, Yale’s Ethiopian-Eritrean Dance Team.

“It’s definitely been a labor of love. It has been a lot of behind the scenes work but also something that we are all so passionate and excited to pour into” Seline Mesfin ’27, one of the event’s organizers, said.

This year, they celebrated the start of 2018, which officially began on Sept. 11. The Ethiopian and Eritrean calendars, which are the same and based on the Coptic calendar, are around seven to eight years behind the Gregorian calendar.

Many attendees donned traditional Ethiopian and Eritrean clothing and YEESA also served traditional

Ethiopian and Eritrean food, such as injera — a pancake-like flatbread.

Hilldana Tibebu ’27, YEESA president, noted the importance of the New Year celebration for students looking to celebrate their home culture with their Yale community.

Though Tibebu described YEESA as a “more recent” organization, the New Year celebration was also held last year. Tibebu added that the main goal of YEESA is to “give a home to students” at Yale while also connecting to their culture back home.

“Structurally it is very similar in the sense that we are coming to celebrate one another and our cultures with a lot of shared elements like food, music, dance,” Mesfin said. “We do want to try and spin things a little bit to keep people on their toes and keep people interested.”

Many attendees noted the importance of being a part of an Ethiopian community at Yale, while others highlighted the importance of opening the event to the public.

“We are bringing together a wide range of people,” Meron Tegegne ’27, who also helped organize the event,

said. “In the past, people have just been walking by, seen the vibe and the music and just joined. We’re totally open to all of that.”

YEESA has around 70 to 80 regular event attendees, Tegegne said. The group is affiliated with the Afro-American Cultural Center and is advised by Teferi Adem, a research anthropologist and member of the MacMillan Center’s Council on African Studies.

Sosna Biniam ’26 highlighted the importance of the community, describing her culture as “unique.” She said it can feel isolating being one of few members of the Eastern Orthodox Church — a smaller religious community that celebrates holidays at different times from other Chrsitian denominations.

For Saron Tefera ’26, YEESA provides a community different from her home in Cincinnati, Ohio. She said it meant a lot to her to see the YEESA community grow over the years.

“It’s been really nice to see people that look like me with the same cultural background come to this university and share all of our cultural

experiences together,” Tefera said.

In February, YEESA will be hosting the EESA Feast, an annual conference for Ethiopian and Eritrean Students Associations from universities across the country. Mesfin said the conference will be a celebration “for the diaspora and by the diaspora,” and invites will extend across the country.

“It’s supposed to be a really powerful way to unite us, celebrate our culture, but also talk about the things that matter to us and make progress towards our future,” Mesfin said. This is the first time Yale will host the EESA conference.

Contact KAMALA GURURAJA at kamala.gururaja@yale.edu .

“If

BY MADISON AGUILAR AND ADRIAN TURKEDJIEV CONTRIBUTING REPORTERS

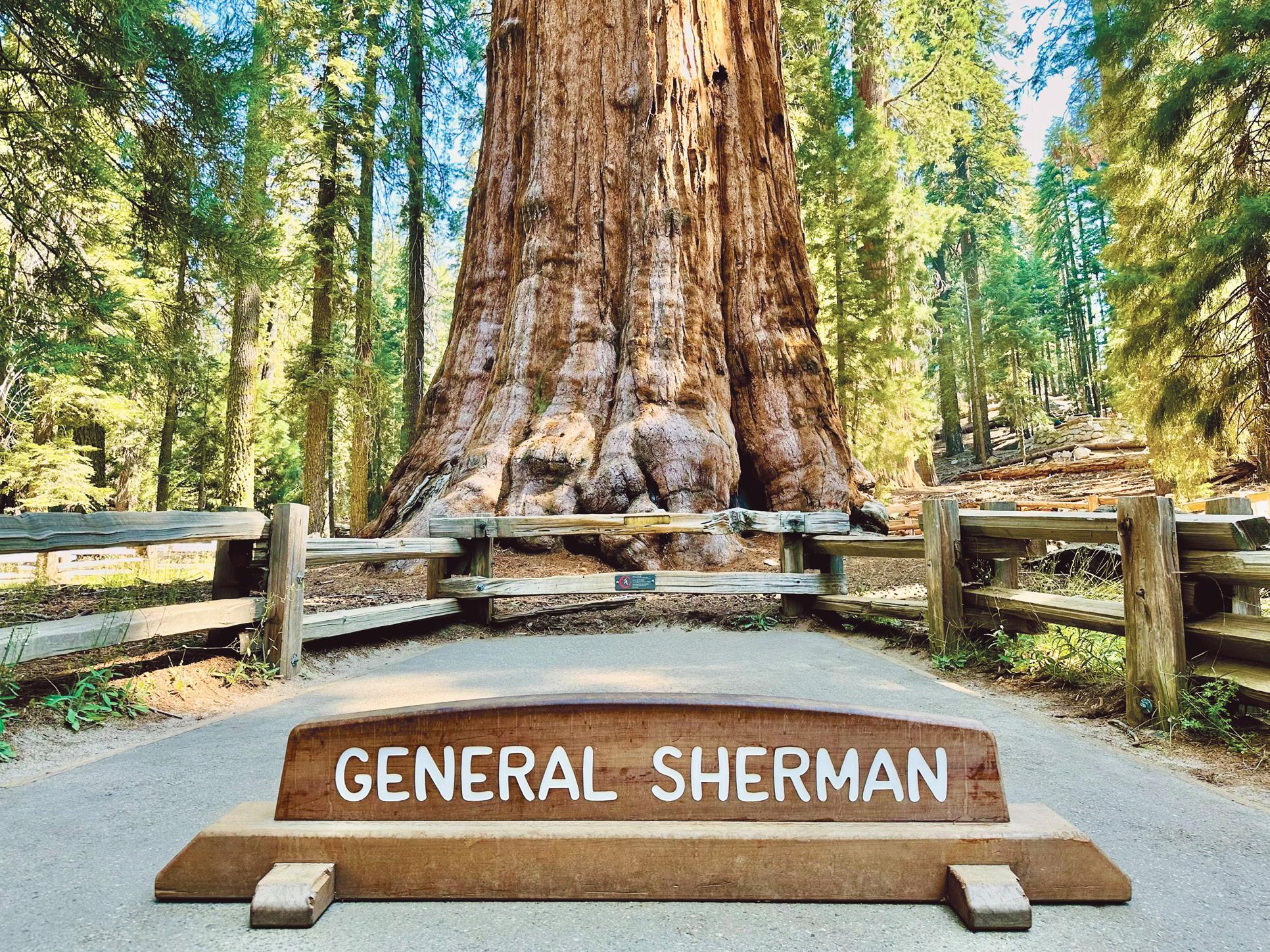

“What’s up, Toad’s?” was a question — accentuated with an expletive — that no one would have expected to hear from Dave Grohl before Monday.

That afternoon, the Foo Fighters announced they would perform a pop-up show at Toad’s Place, on the heels of a Sunday pop-up show in Washington, D.C. The announcement that one of the best-known rock bands, which has won 15 Grammy Awards and sold out stadiums around the world, was playing a 1,000-person venue drew hundreds of fans within hours.

Tickets were sold in person at Toad’s Place, starting at 4 p.m. on Monday. Hundreds of people gathered in line to buy them for $30 each, winding around Yale’s Humanities Quadrangle and Ezra Stiles and Morse Colleges before 5 p.m.

Doors for the concert opened at 6 p.m. Tuesday, after some fans camped out in front of the venue overnight in hopes of getting as close to the stage as possible.

Michael and Suzy Redgate were among the fans who stood in line for two and a half hours on Monday when ticket sales were announced. Michael Redgate said he heard about the surprise show from a friend’s Facebook post.

It prompted him to drive from Trumbull, Connecticut, to wait in line for the tickets. Michael was ecstatic over the “old-school” ticket system — reminiscent of the 1980s, “when you used to sleep out for tickets,” he said.

Redgate said he preferred in-person ticketing to online sales.

“It’s the bots, it’s the computers — they trick the system and they’re all scalpers trying to resell tickets,” he said.

Ed Dingus, the manager of Toad’s Place, said the Foo Fighters wanted to prioritize a small show for the “real fans.” Dingus explained that he knew about the show for about three weeks but kept it under wraps, even from Toad’s employees, who did not find out about the performance until Saturday.

Even fans without tickets were determined to see the band perform on Tuesday.

University of New Haven students Nick Paradise and Nate Swercewski waited in line without tickets. When asked about their game plan, Paradise said, “The plan is we don’t have a plan and we’re going to figure it out at the front door.”

BY NORAH M c PARTLAND

CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Trumbull College recently renovated its once-dormant darkroom, and is now offering a darkroom photography class for students interested in using the space.

Swercewski added: “Who else is stupid enough to wait in line without a ticket, besides us?”

In fact, there were many others with the exact same plan.

Among those hoping for a lucky ticket was 55-year-old Joanne Lamstein. Lamstein and her friends zealously followed the series of teasers the Foo Fighters had posted throughout the week and deduced that the surprise concert would be at Toad’s. They traveled from New York with the small hope they would buy tickets.

Her six friends were able to secure tickets on Monday. Lamstein, who arrived a bit later than her group, was unable to secure a ticket. She camped out at Toad’s overnight.

“It’s a great opportunity to let younger people who don’t have the means come and meet a new band,” Lamstein said, “to bring rock and roll back.”

For the original generation of Foo Fighters fans who were around for the band’s creation, the vintage experience of box office ticketing and camping out for the best view was a blast from the past. For the newer generation of listeners, there was a sense of inherited nostalgia that the Foo Fighters show revitalized.

Lamstein held a poster that said “Be my hero, let me be your +1,” with the hope of finding someone with an extra ticket. However, with the minutes inching closer towards showtime, her luck seemed to be running out.

Around 7:45 p.m., a Toad’s Place worker came out with unmarked blue wristbands and proceeded to hand them to a few people he appeared to have handpicked — among them Lamstein, Swercewski and Paradise.

The Toad’s worker suggested the wristbands would likely get them in. After waiting anxiously, all three made it just as the show was about to start.

The band performed a set lasting roughly two and a half hours.

The setlist featured several fan favorites, including their “Everlong,” “The Pretender” and “Best of You,” as well as early hits such as “Stacked Actors” and “Along + Easy Target.”

It was the Foo Fighters’ 1,573rd show, according to merchandise made specially for this performance.

Toad’s Place opened in 1975.

Contact MADISON AGUILAR at madison.aguilar@yale.edu and ADRIAN TURKEDJIEV at adrian.turkedjiev@yale.edu.

The ideas for the photography class and refurbishment of the darkroom were conceptualized by Samuel Ostrove ’25 and Amartya De ART ’22. The pair met at Yale’s Center for Collaborative Arts and Media towards the end of Ostrove’s first year at Yale College and De’s

final year at the School of Art.

“We’re both kind of gearheads,” Ostrove said. “He got me into a place where I wanted to try my hand at medium format film.”

Ostrove used to send all his film to an offsite lab before he realized there was a darkroom in

Trumbull, his residential college.

“I started asking around, first to our operation manager Deborah Bellmore, and then to our Head of College Fahmeed Hyder,” he said.

Ostrove was informed that although the darkroom had basic equipment, it was out of use and needed renovation.

Trumbull College funded the renovation of the darkroom, which now has three enlargers — devices used to produce large photographic prints from film negatives — instead of one. It also has new equipment and infrastructure, including tables and a sink tray for rinsing the film.

De, an associate fellow of Trumbull College, now instructs the darkroom photography class. Students will learn the technical basics of analog camera operations, film development and darkroom printing. They will have access to roughly a year’s supply of film at no cost and will be able to use the darkroom through the spring semester.

“We had facilities come and work on the lights and redirect our whole water system,” Bellmore said. “Amartya and I just really put our heads together to determine what was needed to make this as cutting edge as we can. And I think that’s what we accomplished, I really do.”

According to Bellmore, “the thought of this happening has been almost a couple years” in the making, adding that Hyder was “really, really responsive” to students’ interest in the darkroom.

“We’re the only college that has this darkroom, and it was really his goal to bring it back to life and to bring somebody like Amartya in,”

Bellmore said.

The first project conducted in the rehabilitated darkroom was a series of photos Ostrove took of the Trumbull dining hall staff. According to Ostrove, the dining hall project was helpful in garnering the interest of other students.