Great Bones in Highland Little Pentagon The Pre-Raphaelites: A Series of Encounters As Many Hats As Pleases The Maker Giving Grace to the Fry Cook Red Meat That Bird is Dead Ran Through

Nonfiction

Great Bones in Highland Will Leggat 1st prize

Little Pentagon

Diego Del Aguila 2nd prize

The Pre-Raphaelites: A Series of Encounters

Allie Gruber 3rd prize

As Many Hats as Pleases the Maker

Etai Smotrich-Barr

Honorable mention

Giving Grace to the Fry Cook

Cameron Nye

Honorable mention

Fiction

Red Meat

Everett Yum 1st prize joint winner

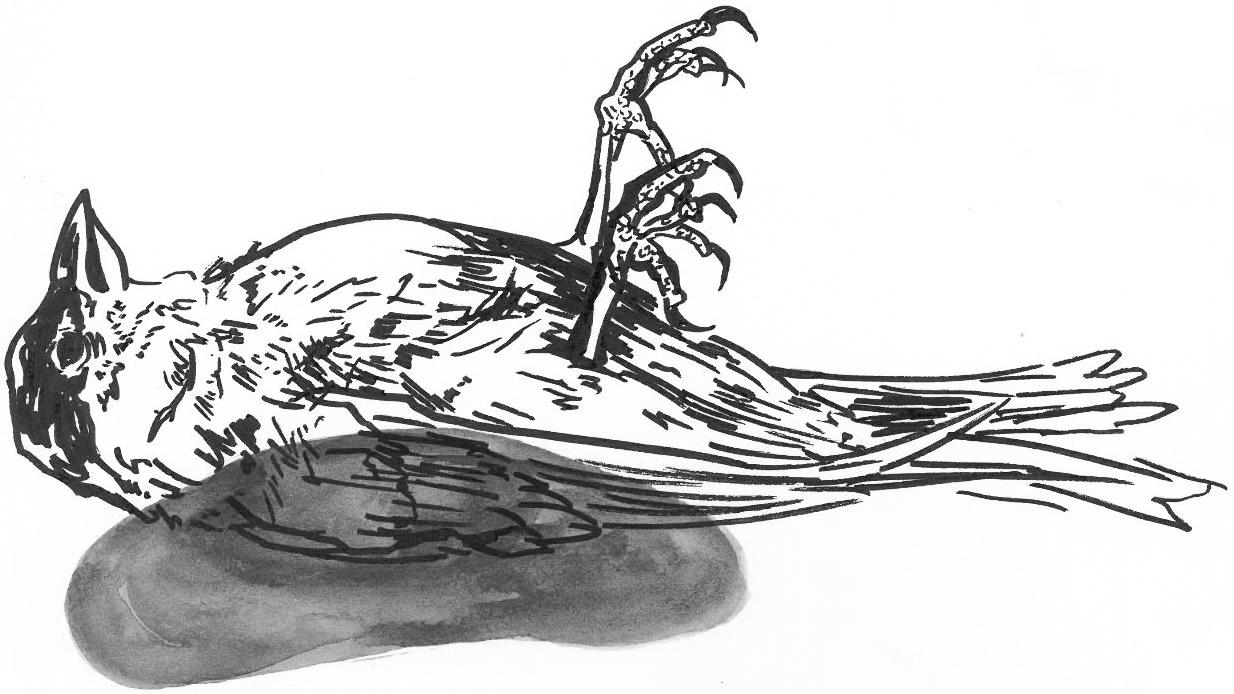

That Bird is Dead

Bluebelle Carroll 1st prize joint winner

Ran Through Eli Osei

Runner up

In memory of Peter J. Wallace ’64, a former member of the Yale Daily News editorial board, the Wallace Prize recognizes exceptional works of fiction and nonfiction written by Yale University undergraduates. It is the most prestigious independently awarded undergraduate writing prize at Yale.

This past spring, the Yale Daily News Magazine’s previous Editors in Chief, Kinnia Cheuk and Harper Love, assembled an independent jury of judges, which consisted of professionals from academia, journalism, and fiction. By April, the jury selected eight winning pieces, which are published in the following pages.

As the Magazine’s new Editors in Chief, we are thrilled to begin this academic year with the release of the 2025 Wallace Prize Issue. Our predecessors, Kinnia and Harper, have blessed us by setting Mag on a meteoric path and cursed us by setting such a high bar. We’re honored to undertake this incredible journalistic and literary project.

In this issue, Will Leggat recounts the two years he lived in “The Barn,” a house in constant repair and disrepair, as well as the animals he lived alongside. Bluebelle Carroll writes a story about two sisters who chase a fox and face the end of the world. Diego Del Aguila reflects on “El Pentagonito,” a lively public park in Lima with a brutalist military complex at its center. Allie Gruber imagines the reality of a Pre-Raphaelite model across several of her paintings.

Mag is just getting started. While you enjoy these Wallace Prize winners, stay tuned for more.

Blessed reading, Ashley and Everett

I am nine years old walking across the living room with the patience and care of a monk stepping over hot coals. My concentration is unbreakable. The floor is my enemy. The floor is defeat. The floor is, well, unfinished. A sharp mess of nails bleeds through the plywood outline of what is to remain, over the two years that I will live at The Barn, just that: an outline. Like the rest of the house, the living in it is beside the point.

My stepdad William is a carpenter. He grew up bouncing around the extra beds his family in Georgia could o!er to give him space from a mother too busy with her own problems to look after his. When he was old enough, he moved to upstate New York with his girlfriend at the time and took up the kind of construction work that paid well—the jobs with foremen who didn’t mind much if you couldn’t read a blueprint if you were willing to put

your fingers, instead of theirs, on the rip saw line. By the time they split up, he had just about enough saved to buy the bones of a house in the farmland on the outer exurbs of Poughkeepsie. Above a tattoo of an ouroboros, the remaining half of his left thumb is a scarred stump: a down payment and, in his mind, a small price to pay for the first place that was ever truly his own.

Every minute he had o! work he put into the place, siphoning from his sites the misfit planks and surplus fasteners that his clients wouldn’t miss. When he had money, it went into The Barn. When he didn’t, he borrowed it. Loan after loan gave the place a foundation, a floor, a roof, the ceilings growing taller and taller as the hole his debt was drilling threatened to swallow the place up from under him. None of this, of course, he mentioned to my mother, who only learned what the place was costing after he declared bankruptcy in their name. And none of this, of course, mattered to William. The day she got the letter from the bank, he came in the front door with his boxer-mutt Red carrying a ladder and walked right past her outstretched arms. With a carpenter’s pencil, he started marking up the dimensions of a spiral staircase he wanted to put straight in the middle of the un-paneled living room floor.

§The first time I saw the place, I didn’t. Without streetlights, it was dark enough out that I couldn’t tell at first what it was I was looking at. I rubbed my eyes, shaking o! the two-hour drive from the city. Mom put her hands on my shoulders, saying that I don’t have to call it home, but I do have to get used to it.

Two sheets of corrugated aluminum roll along a sliding rail on the side of the house to form the door that faces the highway. In the wind, they whack against each other, letting out a sound like cowbell windchimes. On either side, the wood is rotting, brown planks peeling away like they’re trying to run somewhere. Exposed drywall on

the second floor bears the marks of the wet and humid summers; the mold growing just below the surface forms deep grey veins that you can trace along from one side to the other. The façade is cramped by the surrounding foliage, which is so overgrown that it seems to be swelling out from under the roof. Roots and shoots poke out from the cracks in the foundation. Moss grows so thick over the wall of timber stacked in the driveway that drivers might think from a glance that we have a hedge. Everything here looks like it’s in the process of being reclaimed, of being drawn back down into the earth. The walls give slightly, inching back and forth in heavy winds.

It’s cold in the country, and the nights get darker than I’m used to. I’m thankful for the stars, at first, but eventually it’s clear how little of the sky they take up, how huge the rest of the blackness is. The place is right o! I-87, and my bedroom window is close enough to the road that headlights dance across my ceiling as I fall asleep, enough to make me feel—for a second—that I haven’t left Brooklyn.

The Barn is always aspiring, it seems, to be something more. When William wakes up, he grabs his pencil and his tool belt, and by the time he goes to sleep the place is as likely to have lost a wall as it is to have one finished. I never feel quite sure that I could picture the whole building, if I tried. All around is sawdust and the clang of hammers pushing uncertain nails into the surfaces they will just as soon be pulled from. Rooms come and go; corridors emerge or disappear or expand into so many turns you’d need a compass to make it through them. Everywhere there are the marks of his first, second, third drafts: a phantom joist runs across the ceiling of a dead-end hallway in the basement where a door frame used to be. The walls are all half-repainted or covered with small square samples of the next color—the one that, surely, finally, will make the room.

It became clear to William, shortly after he moved in, that he was the only person for miles without a farm to keep or animals to tend. In the backyard, past the plastic-lined hole we call a pool, past the wild grass left untrimmed for years, and just before the decaying cobble wall that divides us from the swamp—whose existence neither I nor he ever venture far enough to confirm, made certain enough by the necessity of the mosquito nets around our beds—stands the small chain-link enclosure that was his answer to the implicit challenge he seemed to read in that fact.

Inside lives a goat just about hungry enough to eat your clothes o! you, a pig—“Sweet Pea”—too fat to walk without leaving a wake in the dirt, and a horde of chickens so desperate for a fight they’ll peck the eyes out of your shoelaces. William continually adds to this collection: a peacock named Vishnu; an exotic Japanese rooster with long black and white feathers. Like those in the house, this expense is always justified the same way. My mother holds a receipt for feed in her hand and shouts at him across the living room, kept at a distance by the no-man’s land of the nails between them. He is standing by the window—etches of inches for its next iteration already sprawling across the pale spruce frame—and staring out at the guinea hens. Over and over, he holds two fingers to his left thumb, tracing laps around his tattoo and saying nothing. This is his home. These are his animals.

It doesn’t take long to notice, however, that despite his best e!orts, the menagerie is dwindling. Claw marks carve around the perimeter of the fence, and blood and feathers are smeared on the henhouse door like some gruesome kindergarten collage. I wake up one day to find William standing over me, shouting at me to get my boots on. He hasn’t seen Red all morning and wants me to go check on the chickens. The rain is coming down so hard it seems to be threatening to burst through the window, but I drag myself out of bed and grab my coat. As I walk through the gate to the enclosure, I pass the guinea hens cowering in the corner. Their heads follow me towards the

henhouse, the normal vigor in their chirping dampened by the rain. Before I make it there, I hear branches cracking behind me and look to the bushes just beyond the chain-link. Red looks back at me, his glazed eyes staring right through me. The chicken is limp between his jaws, swaying more like a doll than like something that once had life in it. He is wringing the neck so hard I think he might shake his own head o!. Blood drips down his chin. His tail is wagging.

I glance back up towards The Barn, where sheets of rain are falling without a rhythm from the mismatched tiles that spread like a patchwork quilt across the roof. The gutters are running over, under the stretches of tin where there are gutters to fill. In the window below stands a silhouette, and I cannot tell if it is staring back at me, or if I am simply part of its survey, or if it is just waiting, waiting for the rain to break.

Then, suddenly, he stops and turns back towards me. He takes a step forward, the body rolling back and forth as his jaws tighten. The rain is coming down hard, beating against the sheet metal roof of the henhouse. Sludge rivers pool and ooze around my feet. Through the clattering torrent, I hear him whimper. He waits there, looking at me, fur soaked through and matted with rain and mulch and blood, deep claw marks scattered across his face and chest. I don’t know whether I should be afraid of him, or for him, or both. He lets out another whimper, and suddenly it looks to me like he had just caught hold of something he didn’t know how to let go of.

You are a child in Lima, Peru, and like any child, your attention is drawn to peculiar sounds. One of them is a word, “Pentagonito,” and you attend to it not just because it sounds funny but because you’ve heard it repeatedly—mom, dad, grandma, and everyone you know pronounces its rhythmic five-syllable sound. You don’t know exactly what it is, but you know it’s important—part of the yet inaccessible world of adulthood—and so, perhaps unintendedly, you decide to store it in your memory.

One Saturday morning, a few years later, when you are perhaps eight years old or seven or maybe even only six, your mother wakes you early enough for you to hear the mourning doves: we have to go; your father is running a marathon, and we must cheer him at the finish line. You hear that word again, “Pentagonito,” and you remember it. You understand now, without hesitation, that it refers

to a place—El Pentagonito is our destination. And so, invaded by curiosity and love, perhaps unaware of the distinction between the two, you hop into the backseat of the car. Through the car window, you observe the familiar streets and houses slowly turn into something yet unknown. Suddenly, you find yourself under the shadows cast by an endless landscape of trees. You notice all the di!erent sizes and shades of green, all the species you cannot yet name—eucalyptus, ficus, guayabo—and when you step out of the car, you witness something unlike anything you’ve seen. The immensity of the park, which you can see extending towards the horizon, has been taken over by a sea of people gathering around what seems to be a running course. Many of them cheer and jump in excitement when moving bodies approach the finish line, and so when you realize your father is one of those bodies, you also cheer and jump and roar under the sun. Invaded by joy, you think to yourself: this is a nice place; this is where people come to run.

In the years that follow, already familiar with this landscape of trees and river of runners, through the car window on your way to school, new sounds and shapes refine your impression of El Pentagonito. You start noticing bikes, scooters, skateboards, and neighbors enjoying morning walks. You see a playground, an activities center—which plays the role of a pilates club, a dance club, and a hub for martial arts—and an outdoor gym. You see a pond with a small bridge crossing through it, the perfect place for newlyweds and quinceañeras to encapsulate their memories with a photograph. There is a di!erent couple and a di!erent quinceañera every time; the photographers, however, are often the same.

Some days, you see your father running on your way to school. Neither you, nor him, nor your sister, nor your mother care about how much attention you’re drawing from other runners as you wave at him and scream “Papááá Papááá” in that high-pitched childish voice. Shame is not yet a thing.

One Sunday, your family decides to spend the day

at El Pentagonito— “We’re going to take rollerblading classes!”—and you finally get to walk around the place. The landscape of trees, the scent of eucalyptus, the playground, the pond, and the newlyweds—they’re all still there. There is, however, something new. Something you haven’t noticed before but had been there all along, in the background of your field of perception, yet at the core of the place.

In the distance, looming over the park, a tall and wide brutalist building. Its sharp angles and gray facade grant it an eerie, mysterious aura. You can see it from everywhere in the park, towering over the trees and the pond, watching over the space like a silent sentinel. As you walk around the park, you become aware of a fence separating you from the building. You had noticed it before—thick concrete slabs with openings in between, wide enough for a small dog to go through. But you couldn’t think of it as a fence. Why would there be one? Why would something need to be protected or set apart from this peaceful, lively, and familiar atmosphere?

Your curiosity brings you to peek through the fence, and you catch glimpses of a vast green lawn, small administrative buildings, parked cars, and the imposing tower at the center of it all. And then you see them: men in camouflage suits, carrying shotguns, patrolling the grounds. They stand like statues, unmoving and watchful, guarding the space. You now understand—El Pentagonito, the place where people come to run, is also a military headquarters. But perhaps you’re too young for this to be a surprise. It seems like another part of the landscape, another layer of the place you’re coming to know. Every country needs a military, you think, and this is simply where ours happens to be. And that is exactly where it has been all along, way before you even existed.

It was January 1971 when, under the military dictatorship of Juan Velasco Alvarado, Major Ernesto Montagne, the Commander General of the Army and Minister of War, announced the decision to build new premises for the Peruvian Military Headquarters. The premises, to

be erected in an unpopulated 95-hectare area located in what back then was the Santiago de Surco district, would respond to the need to centralize all organizations of the War Sector, which at the time found themselves dispersed. Architects Juan Gunther and Martin Tanaka were selected to create a building complex that corresponded with the institutional, monumental, and formalist image, as well as the sense of hierarchy and authority that the military government was attempting to establish. They couldn’t anticipate, however, when the project was initially sketched out, that the place would someday turn into what it is today. The area, now belonging to the district of San Borja, went through a period of radical urbanization, as well as through multiple projects of reforestation, which have all resulted in the place where you now stand—the coexistence of military life with the epitome of familial and healthful civilian living. The forest-like atmosphere, the little pond, the running course, and the amenities center were not part of the initial plan. It all gradually came to be, more out of municipal initiatives than by military design.

Originally intended as a symbol of military strength, the sense of hierarchy and authority has now been neutralized, and the original symbolic meaning of the place has been superseded. You witness this as you grow older and get permission to bike around the city on your own. Your friends message you saying, “Vamos al Pentagonito! Vamos al Penta!” and you know that neither you nor them have in mind the military headquarters. Instead, you think of the running course, the pond, and the endless landscape of trees—instead, you think of the thrill of youth and the comfort of friendship. §

To get to El Pentagonito from home, you exit your neighborhood and turn right, into Caminos del Inca Ave. You then get to Angamos Ave., which separates the residential district of Santiago de Surco from the district of

San Borja, a few blocks away from El Pentagonito. Despite the closeness, you can barely see any runners or bikers. Instead, you see chaos: unregulated combi vans, children selling frugelés, jugglers asking for money after putting on a show, unworking tra c lights, and people violently pacing the streets, going where they have to be. You are also going where you have to be: El Pentagonito.

Once you cross the avenue, you are back to the calmness, to the stillness of being in a park, with the brutalist tower always watching over you. You think of how strange the place is and how it has attained some form of a symbiotic relationship. The location of the Military Headquarters in the middle of the district of San Borja has given place to one of the safest and calmest areas in the entire city; however—and you begin to understand this as you move past the bliss of youth—it is also through the image of familial living propitiated by the surrounding parks that the violence and brutality of military life gets to be concealed.

A few years later, you finally understand where the name of the place comes from. El Pentagonito translates to Little Pentagon, alluding, without any logical reason beyond mere fanatism, to the headquarters building of the United States Department of Defense. You tell your friends about this on your way there, and they all seem surprised. “That is so obvious,” they claim, and yet none of them had ever realized. It was right there, in front of us, all along. Once there, you see the newlyweds, the quinceañeras, and the kids approaching the thick concrete slabs. You spend the afternoon biking in circles around El Pentagonito, and you laugh at the irony: the park named after a pentagon has no corners at all.

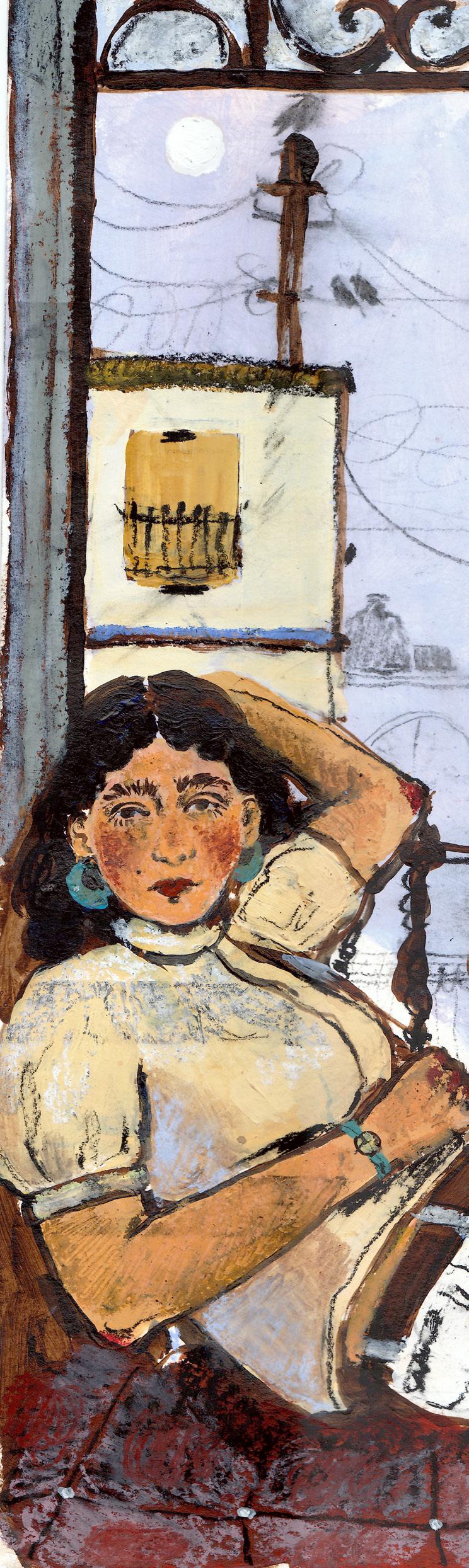

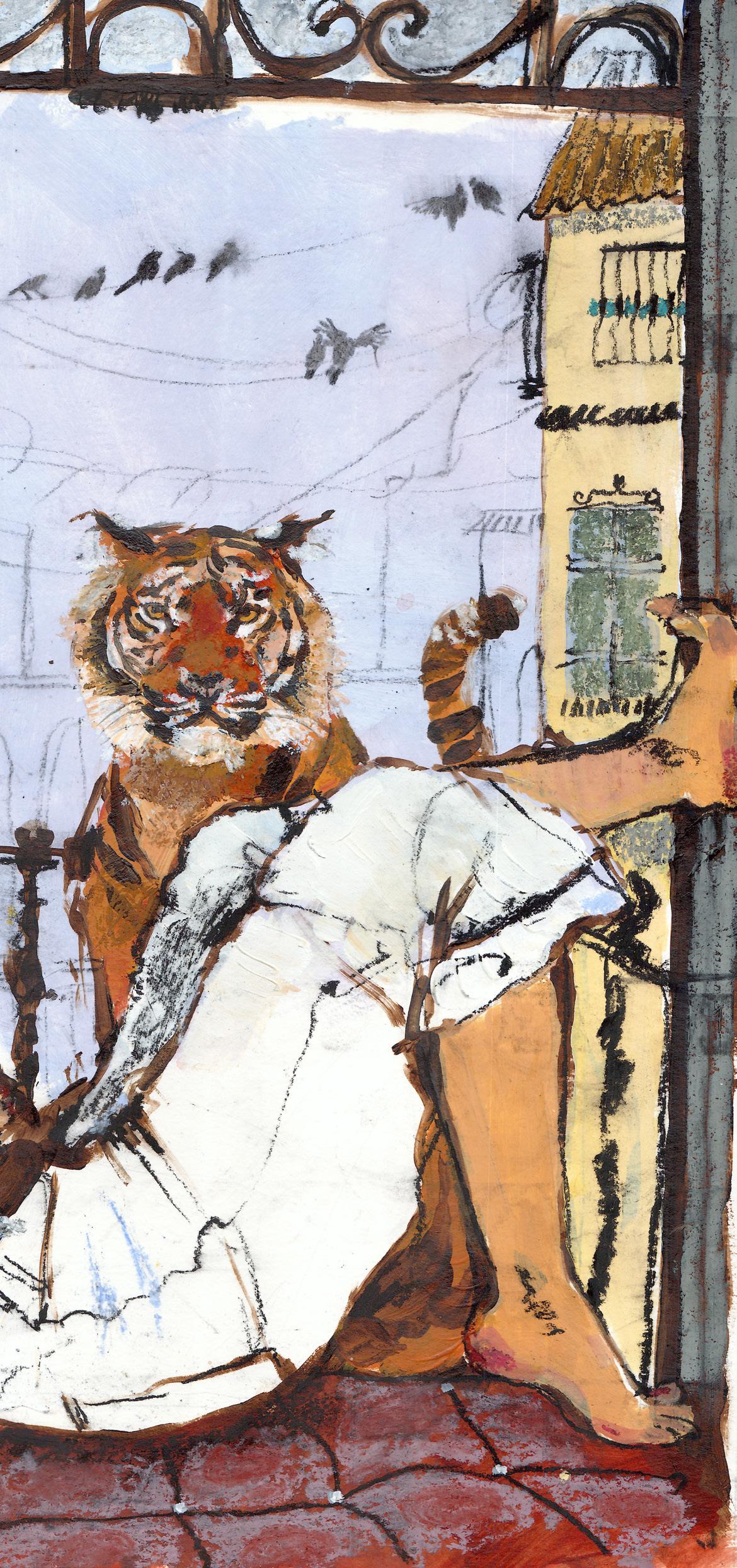

The Pre-Raphaelites: A Series of Encounters

When I was nineteen it was my simple pleasure to walk every morning from class on York Street to my small room overlooking the oak tree in Pierson College. There wasn’t much of interest on those walks: just the usual array of backpacks to admire and sneakers to covet. On days when I felt especially glorious I wore my mother’s brown-leather ankle boots which made a confident click-clack click-clack on the stone slabs. My mood was always joyful on these mornings, and it was then, while the hot sun shone and the trees were in full bloom, that I first saw her.

The first thing I noticed was her orange-red hair. It seemed like hair from a di!erent century. It wasn’t an artificial red, although you’d be hard-pressed to find another person whose locks were as rich in color without synthetic assistance. I say ‘rich’ because the red in her hair was darker than the hair on most redheads. It was at

once glaring and matte, wild and restrained. She looked as though she’d endured much pain, like the tragic heroines I read about as a child. Phaedra. Ophelia. Tess. And now here she was, gliding through the hustle and throb of New Haven streets and then fading into a vision in the distance, a red glint, a ghostly fancy.

I passed her every morning. I came to recognize the way she walked, the way she pushed the red strands of hair from her face on windy days. She seemed to be gazing unconsciously beyond things—beyond the New Haven streets and the rush of cars, beyond the real, even, into some distant abyss. I became so accustomed to our brief encounters that I began to look up when I heard her boots and felt her presence, felt the cloud of pervasive melancholy that seemed to surround her. Sometimes I fancied that we knew one another, and that in our brief intimate instances of crossing, obscure messages were exchanged and cryptic signals acknowledged.

She looked out of place on the streets of New Haven. There was something so ghostly about her, so reminiscent of a bygone era. I began to doubt my senses. Did I really see her, or was she a figment of my imagination? A recurring dream? A nightmare? And then one day I realized I’d seen her before, many times, in the paintings of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais. This mysterious woman looked exactly like the Pre-Raphaelite model Elizabeth Siddal. The same thick red hair, the same pale complexion. But it was the forlorn eyes that struck me. There was something timeless about her, as there also was about Siddal. And yet she seemed trapped in time, a phantom of the 1850s. She had the kind of beauty one associates with poetry. §

In Room 7 of the Tate Britain hangs a marvelous painting by William Holman Hunt. It’s called The Awakening Conscience. A woman looks out the window at the trees beyond. Rising from the arms of her lover, she

experiences a moral revelation. Light filtering through the window suggests the possibility of transcendence. The woman is striking because of the fervor in her eyes. Her eyes blaze with emotional intensity—so inspired, so elevated, so flushed with hope, so keenly striving. Hunt captures her in the most important moment of her life. She looks as though she’s about to cross some crucial boundary, from oppression to freedom, from the earthly to the unearthly. Hunt’s painting reminds me of a passage in William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Blake resists the widely-held belief that body and soul are separate entities. “Man has no body distinct from his soul,” he writes. “Energy is Eternal Delight.” Blake’s words point to something essential within Hunt’s painting. As we gaze into the woman’s blazing eyes, we feel as though we’re rising beyond the limits of her body into a higher, transcendental realm. At once we seem to be gazing at and beyond this extravagant beauty. The models in Pre-Raphaelite paintings are often placed on a pedestal. But not in Hunt’s painting. We seem to look directly into the model’s inner life. We peer through her—past the beauty, past the body, past the material—into the all-consuming brightness of her soul.

What was it about the woman’s eyes that so arrested me? What caused me to stare at the painting for ten, fifteen, twenty minutes? The mahogany piano, the gilded frame, the sumptuous red rug, the ornate wallpaper—every detail evokes a distant era, an age far removed from the present day. It’s almost impossible to imagine how di!erent customs were in 1850s England. But as I stared at the woman in the painting, I wondered—aren’t there deeper di!erences between our worlds, ones that don’t depend on changing laws or moral codes or aesthetic preferences? What would it take to transform me into a product of a di!erent historical era? If you dressed me in 19th-century garb and told me what to say and how to say it, would I be convincing?

Come with me, reader, to the 1850s. Here we are— Piccadilly Circus. I’m wearing a blue skirt and bodice, and

a red shawl is swathed tightly around my shoulders. It’s November. London at this time of year is full of life and energy. Horses and carts bustle in every direction; flower ladies sell violets to young women calling on elderly relatives in Mayfair; workmen load boxes into carts and shout gru!, unintelligible orders. Everywhere the clatter of hooves, everywhere the din of voices and wheels and bells. Newsboys hand out printed copies of The Times and Lloyd’s Weekly News. Streetlights cast an artificial glow over the street. A little beggar boy with wide eyes and a snub nose gapes pleadingly at people passing by. In the center of the roundabout, delicately poised in an arabesque, is the statue of Eros. I can’t help noticing his stillness. He alone is steady; he alone is calm. I step forward and join the throng. Now I too am part of the community, part of the flurry and bustle.

I make my way to Mrs. Tozer’s hat shop on Cranbourne Street. I’ve never seen so many bonnets: brown bonnets and white bonnets, bonnets with pink ribbons and bonnets with blue ribbons, cover-the-ear bonnets and expose-the-ear bonnets. The mannequin beside me is flaunting the most stylish headdress of the season: the leghorn straw hat. It’s all the hats in one, decked with lace and ribbons and flowers. In the back of the shop a group of assistants huddle around a sewing machine. They’re animated in conversation, too absorbed to notice me. “But surely the ribbon ought to be green!” one says. “What about making it longer in the back?” asks another. “The longer the hat, the longer the face,” a third declares with an air of finality. One of these women catches my eye. She has rich coppery-gold hair, but it’s the texture I find outrageous. Her hair billows. It curves and curves again in layered waves of red and gold. Like me, she wears a shawl. Hers is delicate and sheer, but mine feels thick and unseemly. With a pang of recognition I realize: that woman is Elizabeth Siddal.

Here she is, before me. There she was, too, when the pre-Raphaelite painter Walter Deverell discovered her in this very shop. In his restless, boyish mood his eyes fixed

upon one woman who looked di!erent from the other assistants. Her hair was flaming red, her eyes alight with passion. It was something in her air, in the way her thick head of hair rested so delicately on her neck. “A neck like a tower,” Dante Gabriel Rossetti would later write. Deverell instantly wanted to paint her. He wanted to allegorize her, to relocate her in a world of mythological fantasies. And he did. Siddal appears as Viola (or Cesario) in his 1850 painting Twelfth Night. She looks into the world beyond the frame, pensive.

As I gaze at Elizabeth Siddal by the sewing machine, I begin to wonder. Why was Deverall so drawn to her? Was it just the fullness of her hair, the slender neck that rose so delicately? Why was she so easy to idealize? I squint again at the figure by the sewing machine. In paintings she’s always at some sort of threshold: between the sexual and the spiritual, the earthly and the transcendental, the true and the false. But as I watch her holding a ribbon to the light, I feel startled. She looks so human. Striking, yes, but human. Suddenly a bell rings; another customer enters the shop. Siddal looks up. We exchange glances. For a single moment, a single blink of time, she sees me. No longer the tragic heroine, no longer the divine Beata Beatrice. A woman as real as any other.

The moment passes. Elizabeth walks over to the customer and clears her throat. Suddenly I realize: I have no idea how she will sound. What does someone from the 1850s sound like? Is her voice high or low? The earliest voices I’ve heard belong to old Hollywood stars, like Helene Costello and May McAvoy. How would someone who lived eighty years before them speak? Would her voice fit or clash with her appearance? The 1920s actress Norma Talmadge was beloved for her silent films, but her popularity plummeted when her first “talkie” was released. Her accent was too “Brooklyn,” her diction too déclassé. As I watch Siddal handing ribbons to a customer, I wonder— would Siddal have su!ered the same fate? Like Talmadge, Siddal comes from a working-class background. Her father sells silverware. She lives with her family in Southwark, a

neighborhood known for its pickpockets, prostitutes and prisons. Surely, this working-class milieu influences the way she talks. Once the question arises, I can’t unthink it: Does Siddal have a cockney accent?

I watch her helping an old lady try on straw bonnets. From this angle I see that she has a large overbite, and her upper lip protrudes over the bottom lip. As I stare at her, the ethereal beauty begins to slip away. On her cheeks there are several patchy blotches that suggest past encounters with smallpox. She’s not as tall as I expected. When Deverell met her, he told Dante Gabriel Rossetti she was “like a queen, magnificently tall.” I pictured a steeple-like woman gliding majestically like a phantom on water. But the average height in the 1850s is 5’2”. Siddal’s only about my height, 5’5”. Her weight is concentrated unevenly on her right hip. When she walks the weight is redistributed, and she rises like a marionette pulled by an invisible string on her head. I picture myself sitting with her over a glass of whiskey or a game of checkers. When a large bonnet falls o! the lady’s head, she laughs. Her laugh is loud and high-pitched. It rattles like a loose screw. We tend to admire Pre-Raphaelite paintings for the beauty of the models, their distinctiveness, for the purity of their image and the remoteness of the model’s expression. I’ve never stopped to think about Siddal’s voice, or her scent, or any quality other than her appearance. I don’t know how long her steps are, how loudly she speaks, how quickly she walks. I don’t know if she has a sweet tooth, if she likes fish, if she’s ever eaten pork chops. How does she smell? In 1850s England water had to be heated manually, and even the wealthy only bathed once a week. Does Siddal smell of sweat and body odor? Or does she compensate for the smell with strong-scented perfume? And how does she drink her tea? Do her gulps resound through the room—or does she take quiet, dainty sips while her pinky points to the sky? As I watch Siddal wrapping the bonnet in brown paper and tinsel, I realize just how much I don’t know about her. By focusing on her red hair and wistful eyes, I’ve neglected to think about

all the tiny, commonplace habits that make her—and every one of us—human.

My next encounter with Siddal is in the Surrey countryside. It’s a crisp autumn day, one of those delightful few when the leaves crunch underfoot and the sun casts spidery shadows on the woodland floor. The woods are vibrant, full of red and brown and gold. The sky is scarcely visible between the leaves, but it’s as vivid as the bright foliage below: a bold, assertive blue. Here is where William Holman Hunt will paint Valentine Rescuing Sylvia from Proteus. In an opening between the trees, the models cluster together in medieval garb. Three men and Lizzie. I watch them from behind a group of Hunt’s assistants. The fabrics are brightly-colored and expensive: rich velvets, sumptuous silks, plush satin. Siddal’s hair seems one with the autumn leaves and the red velvet of the costumes. She stands as she did in the milliner’s shop: slumped shoulders, weight resting on her right hip. One of the men mutters something, and she laughs. It’s that same rickety laugh— high-pitched, nasal, nervous.

All at once, a man with a long brown beard approaches me. “Who are you?” he asks. His beard hangs down to his belly, which bulges over his belt. His beard is like Siddal’s hair: bushy and billowing, thick like wool. A few gray hairs make him seem older than he is. “Observing,” I say, feigning nonchalance. It’s not a direct answer, but the man doesn’t seem to notice. “Hmph”—he snorts like a boar struggling to heave itself onto its feet—“Well, make yourself useful.” The man’s voice is hoarse, husky, like the crunch of shoes on gravel. As he speaks, several specks of saliva spray from his lips and land on my chin. He’s about my height, but he has an air of authority that makes him seem taller. He leans over me like a cli!. “Thank you, sir. I will.” Another snort, and o! he walks toward the models. But as he draws near, the general murmur of voices subsides. An assistant brings him an easel. Another carries a stool, and several more set paint and brushes on the table beside him. He runs his hand through his beard and clears his throat. He dips his paintbrush into red paint and makes

several broad brush strokes on the side of his canvas. And only then do I realize: that man is William Holman Hunt. When I think of Hunt, I think of his artwork: vibrant colors, biblical symbolism, rustic countryside. His paintings are cheerful and bright, lively and emotional. I’ve never thought about the man behind the paintings. I’ve never separated the art from the creator, the output from the input. The art spoke for him. But the Hunt before me is nothing like what I expected. He’s almost cartoonish: Karl Marx meets Santa Claus. He spits when he talks; his belt doesn’t fit; he walks as though moving requires great e!ort. It’s extraordinary how ordinary he is.

“Painting shall begin!” Hunt cries, and the models scurry into position. Siddal stands in the center, flanked by men on either side. The painting depicts one of the most dramatic scenes in Shakespeare’s play, The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Just before Proteus rapes Sylvia, (“I’ll force thee yield to my desire,”) he’s interrupted by his best friend, Valentine. It’s the usual trope: the damsel in distress is saved by the gentleman she loves, and Proteus is punished. Siddal models for Sylvia. She stares blankly into the distance, her weight concentrated at her hip. Hunt clears his throat. “Miss Siddal,” he says, his voice grating like sandpaper. “You’re too tall. You mustn’t be taller than Valentine.” Veins bulge in his temples as he squints at Siddal. She stands slanted like a dandelion. “On your knees.” She kneels, slouching into herself.

Hunt strokes his beard, squinting. “No, Miss Siddal, you must be closer to Proteus. Lean into him.” Siddal looks weary as she shu#es closer to the man in the center. “Now clasp his hand.” She clasps his hand. “Lower your gaze.” She lowers her gaze. More orders follow. Order; assent. Order; assent. With every command Hunt gives, Siddal’s eyes become more and more blank. She seems disconnected from the world, removed from the forms before her. John Ruskin would later criticize Hunt’s painting for the “commonness” of the faces. In his letter to The Times, Ruskin deplores “the unfortunate type chosen for the face of Sylvia. Certainly this cannot be she whose lover was ‘As

rich in having such a jewel, / As twenty seas, if all their sands were pearl.’” Yet perhaps there’s a reason for this “commonness.” As I watch Siddal kneeling on the woodland floor, I feel a sting of discomfort. She looks lifeless, worn down by the constant scrutiny of painters and critics. After a few minutes my unease subsides: all that remains is an overwhelming feeling of pity, deep and fierce, for this fellow human.

As Many Hats as Pleases the Maker

On a Saturday this fall, Catherine Cazes-Wiley took the train south to Manhattan to check on the status of her proposal to become resident artisan at Angelina Jolie’s NoHo fashion house, Atelier Jolie. As evidence of her talents, she brought with her two handmade hats. The first was a low, flat, radially-symmetrical bolero, made of buckram wrapped in gray fabric, and adorned with a cut of bright yellow mesh from a bag of garlic. The second hat was a yellow cap which also used the garlic-bag mesh as well as some lemon-bag mesh and a tiny plastic lemon. Catherine created both in her New Haven studio, Tinaliah Designs, where she also repairs hats, teaches hatmaking, teaches sewing, tailors suits, alters dresses, and restores and resells vintage handbags.

Catherine is small and broad-shouldered. She wears her gray hair in a bob with curtain bangs, and her large

pink cat-eye glasses are always threatening to slip o! the edge of her nose. She is warm, soft-spoken, prone to making sound e!ects, and unafraid to tell someone that she has forgotten their name or to describe a fashion trend as “fetishist.” Forty years in the United States have neither dulled her French accent, nor tempered her delightfully unusual diction. She is rarely wearing something that she herself has not patched, adorned, or sewn from scratch.

On her visit to Atelier Jolie, Catherine wore a patterned, red and tan floor-length overcoat, which she had sewn from a blanket. This was her third visit. It did not go as planned. Her usual contact was absent and the man, wearing all black, with whom she spoke told her briskly that they were not accepting new designers. She waited patiently for a fuller explanation, which did not come. Eventually, she left. She bought a book on the fallacy of capitalism, and was settling herself on a bench outside a boxing gym when a young couple complimented her coat. They were part-time fashion models, recently on a runway wearing vegan stylings. (They were also part-time musicians and the woman was at the gym to apply for a parttime job.) They agreed to stay in touch. Catherine told me this story because she was certain something would come of the encounter.

§

Tinaliah Designs, on Chapel Street across from the New Haven Green, is a mid-sized room on the second floor of a small commercial building, advertised on the street level via a dry-erase easel with the instructions “Buzz #205.” The front half of the room is composed of a mirrored fitting salon and a crowded, jubilant corner where Catherine displays her hats and handbags, made in every material and color. The back half of the room begins at a small register and contains two long gray tables; three wall-mounted thread racks for spools of every shade; a collection of machines for sewing, steaming, and stretching; a work lamp with an attached bendy-arm magnifying

glass; a wicker basket with formal and improvised hat-making tools; a plastic bin for cloth scraps; more bins with more things; an old-fashioned sewing table; three glorious floor-to-ceiling windows; a chain hanging from the ceiling to which Catherine has attached a fake bird, sideways; and a shelf, stretching from register to windows, atop which sits Catherine’s extensive collection of wooden hat blocks, each one unique, carved into the interior shape of a bolero or bowler or cowboy or pillbox or some dozen other styles that I cannot name, each one waiting patiently for Catherine to take it down and press warm felt overtop its curves and contours. Above the neat hodgepodge hangs a wordart canvas: “JESUS let me count the ways I love you.”

Catherine opened Tinaliah Designs in 2021. Previously, she operated the nonprofit Tinaliah Co-op with her husband John, teaching sewing skills to vulnerable New Haveners and helping them sell their wares. The nonprofit is now on hiatus due to lack of grant funding. (Catherine received the name Tinaliah from God, with whom she has a close, spiritual connection. Tinaliah, she told me, means “to persevere.”)

When she has time and inspiration, Catherine designs a new hat. Her latest set of creations are molded on a hat block she calls “the Ei!el.” The Ei!el is a tapered cylinder, disrupted by the occasional sharp twisting ridge, and absurdly tall—nearly a foot from brim to crown. It is also surprisingly robust, as heroic as its namesake, and more than a little elfin. On my first visit to the studio, three Ei!els in blue, red, and green were arranged on the sales rack. Catherine had priced the green one—adorned with curly-fry- shaped spirals in striped multicolor fabric—at $385. My personal hat collection consists of a gray beanie and five baseball caps. As Catherine talked me through hers, noting when a hat included artificial horsehair or banana byproduct, I tried to decide what my beanie was made of. Cotton?

Catherine had recently been commissioned to create a custom hat, a navy blue fedora. It was a project of about twenty hours, for which Catherine was to receive $350.

Before my arrival, she had already “blocked” the wool felt into form, constructed an intricate golden laurel to encircle the crown in lieu of a hat band, and sewed cotton millinery wire around the circumference of the brim to keep it from flipping upward. The next step was to cover the wire with a thin strip of fabric, like an edge protector.

From tiptoes on a wooden stool, Catherine stretched for a plastic drawer on the shelf. (Later, when the stool was elsewhere, I would see her accomplish this same task by balancing her right foot on the radiator and her left foot on a side table.) The drawer was filled with rolls of what I would call ribbon. “No, ribbon is di!erent,” Catherine explained, and pointed out the woven ribs running perpendicular to the length. “Ribbon is slick and has no ridges. This is grosgrain.” I practiced the new word: “Groh-graw.”

“Groh-greh,” Catherine corrected.

Most modern grosgrain is made of polyester, “useless for millinery,” Catherine said, because it cannot be curved into shape by heat. Her box contained only vintage grosgrain, made of rayon or acetate or rayon-acetate blend or occasionally cotton, and purchased from specialty stores in New York or salvaged from old hats. After some digging, she retrieved the only potential contender for this project, a roll of medium blue, and displayed it, displeased, against the fedora.

Catherine picked up her phone. “Hi Ben, are you at the store? Ben it’s 2:30, are you there? This is Catherine. I was going to stop by. I need a narrow navy blue grosgrain. Okay, give me a call. Thanks!”

Then, without waiting for Ben to give her a call, Catherine said “Well why don’t we go anyway, no?” She pulled on her red and tan overcoat, patterned with geometric trees and flowers and horn-like symbols and multicolor zigzags. I put on my black jacket. We walked seven minutes east to DelMonico Hatter, made sincere, if disjointed, small talk with third-generation hat salesman Ben DelMonico, and then pushed through the sales floor into the musty backroom to rifle through boxes of grosgrain.

Catherine freelances as DelMonico’s hat repairwoman, a role she earned in 2018 by wandering into DelMonico, learning that their longtime repairman had died, and o!ering herself as his replacement. She was new to hat-making then, having just completed a year and a half of training at the Australian Hat Academy, which she attended asynchronously online.

In the backroom with me, Catherine located a bin, dug around for a second, and then let out a vibrato, UFO-abduction-style “AaAaAaAaAaAaAaAaA.” Her hand emerged with a roll of navy grosgrain. After a few more minutes of digging, she brought three contenders into the sunlight to examine their undertones and eliminated a roll that suddenly appeared startlingly green. The other two seemed more suitable. “I have to borrow these two?” she said to Ben. “Whatever you need,” he responded, and the two struck up conversation again about Ben’s recent birthday, the high stress of managing the store, and his recently hired assistant.

“I had a dream that somebody was coming to help me too,” Catherine said.

“I’m still sending people over your way.”

“Thank you.”

“You accepting the work?”

“Yeah.”

“You accept everything, yeah?”

“Yeah, I take everything. We need everything. And we still do alteration. We have to. And we’re still holding on to the nonprofit, because we believe, we believe...”

Catherine glanced at the table behind him. “You know what, I need a foam ring too,” she said, and she took one.

“Happy Birthday!” Catherine called as we made our way out of the store. “Jubilé, Jubilé! It’s your year!” she sang. “Believe, believe! You’ll see.”

§

John Thomson’s 1868 A Treatise on Hat-Making attributes the invention of felt to the monk Saint Clem-

ent, who, on a pilgrimage sometime in the first centuries, stu!ed wool between his sores and his sandals. Felt, I learned, is the catch-all word for the divine material that emerges from compressing fibers: sheep’s wool, but also rabbit hair, beaver fur, synthetics, anything. It is malleable when heated and then holds its new form when cool. A hat can be made from a new piece of felt, sure, but with a bit of steam, a hatmaker can melt down an old hat and rechristen it. The same piece of felt, over a lifetime, can become as many hats as pleases the maker.

Thomson finds the first solid evidence of felted wool hatmakers in France and Germany in the late 14th century, in London by 1510, and in the American colonies by 1732 when the British Crown passed the Hat Act, which limited colonial hat-making apprenticeships. Revolution followed, eventually. That hat-making was the subject of trade protections is a reflection of the booming value of the industry in that era, primarily as a wartime economy. The leading hats of the day were the “cocked hats”: the bicorne (think Napoleon Crossing the Alps) and the tricorne (think Washington Crossing the Delaware).

Over the 19th century, hats civilianized but the habit of wearing them stuck. By the turn of the 20th century, according to Esquire’s Encyclopedia of 20th Century Men’s Fashions, “only a man very low on the social ladder would appear in public hatless.” Menswear trends rotated through the bowler, the fedora, the porkpie (low and flat topped), and the homburg (high with a central gutter), but in some style or another, the felt hat remained a staple until the mid-century, when it promptly disappeared. A variety of theories explain the extinction: post-war malaise, counter-culture, chic hairstyles, the automobile, the trendsetting President Kennedy. Regardless, hat-wearing went from a routine to a statement, and hat-making from an industry to a rarity.

The process of blocking a felt hat, however, has not changed since its invention, a fact that Catherine told me repeatedly and with delight. The hat block illustrated in Thomson’s 1868 treatise looks identical to the blocks on

Catherine’s shelf. There are very few block-makers these days, and most of Catherine’s blocks came vintage from flea markets, eBay, or DelMonico.

A hatmaker’s block collection determines their range of products: each block dictates not just style but size. For the custom fedora, Catherine did not have a block large enough for the client’s head. She had to adapt one with an undisclosed DIY technique (“trade secret”). His head wasn’t unusually large, she explained, but her fedora block was from the ’50s and heads have gotten bigger since then. I asked how that could possibly be true. “Maybe because of the hormones?” she o!ered. §

“Sometime I think people run from their call, you know?” Catherine said, unprompted, as I watched her cut and sew a piece of iridescent lilac satin for the fedora’s interior liner.

Catherine was called to hats late. She was raised in Cameroon and New Hebrides, before her family returned to France. Her father was an administrator in the Gendarmerie Nationale. Her mother painted, sewed, knit, embroidered, cooked, canned, gardened, and drew up the architectural plans for the family home, but she did not make hats. Catherine wanted to go to art school, but alas. “My father told me I can’t be an artist, I’d be starving,” she said. “So he sent me to become aviation. Pilot.”

Catherine pulled the satin lining o! her sewing machine and examined it.

“When did you start learning to be a pilot?” I asked, bewildered.

“I was in a car accident. And then I went to heaven,” she said by way of response, and we did not return to the flying for some while.

A friend had been driving her and some others to a party, too fast. They hit a telephone pole. One passenger died. The driver went into a coma. Catherine fractured her spine.

“I went to heaven,” she said. “And then I met Jesus, and he said, ‘you have to go back.’ And between the time I started in the tunnel of light to the time I met him, I had all these experiences with light... It took me twenty years... to figure out the whole experience, and understand my call in regards to what he wanted me to do.”

She restarted the sewing machine. “And so the money from the car accident sent me to America,” she said. She finished the edge of the liner with a zigzag stitch, and carefully tucked it underneath the leather sweat band.

Catherine earned her commercial pilot’s license from a program in South Carolina, moved to Florida to pursue a certificate in flight instruction, got hit by a truck and missed her instuctor’s exam, “got a job in Africa, in Chad, during the war,” moved to California, got certified as an airplane mechanic, had a son, prototyped leather bags until an earthquake knocked the ceiling of her studio in, and, moved by God’s spirit, became a nomad, wandering from state to state for five years. Eventually, she ended up in New York. Then she got another message from God.

“He said, ‘Get up the map.’ And I lay my hand on it. And, ‘you go there.’ So I went there. And it was Greenwich.”

“After I spent an hour or so I was going back to the Bronx. But then I stopped for a cup of tea, because I’m an addict. So then I got there, and this man was sitting there. He said, ‘Where have you been? You’re late.’ Just like that. Said ‘You’re late. I’ve been waiting two hours for you.’ I said, ‘I was walking around.’”

The man, Catherine says, connected her to a local church, which found her housing first in Bridgeport and then in New Haven. She became a sewing instructor at Village of Power, a social support organization, and began making bags again. She met John, founded the Co-op, attended the Hat Academy, and joined DelMonico. When a longtime seamstress closed down her Chapel Street studio, Catherine bought her equipment and took over the lease. “She left everything,” Catherine said. “Every needle, every thread, everything. She took a pair of scissors and a radio.

That’s it.”

“Everybody has a di!erent plan for their life,” she told me a few days later. “This is my plan. But first, you have to know what it is. If you don’t know God, and if you don’t get close to God, you miss your mission. You miss your destiny because you don’t know what you’re supposed to do, which is what a lot of what people are doing right now. They’re just afraid. So they sit on their talent and they become computer engineer. Or landscaper. Dentist. But they don’t like it. But they don’t consult in their soul, in the spirit: what is it that they supposed to be or do?”

“So it took me a long time to be fine and not be afraid... God is with you, and he’s going to come through no matter what it is. He restore. He repair. He does what I do.”

On one of my last visits to the studio, Catherine o!ered to block a hat with me. She was wearing an Ei!el I had not seen before, black and covered in dark feathers, and she told me that a man who plays bucket drums at Trinity’s service for the disadvantaged had asked her for a cream-colored cap. She did not know his name; she called him “Little Big Man.”

We perused the hat blocks on the shelf and selected a smooth cylinder with a flat crown. It was an odd one, Catherine explained, a “puzzle block”; because our cap had a slight taper from the crown to the rim, we needed the ability to disassemble the block, like a puzzle, so as not to stretch the felt. She pointed to a hook in the corner where our raw material hung—a dainty, floppy beret with an elastic chin-strap attached to a grosgrain sweat band— and handed me a seam ripper.

My mother trained me to be a competent hand-sewer and anyone who has learned to sew has, dissatisfied with his first attempt, learned to seam-rip. Or so I thought. Catherine set me on removing the sweat band and I started picking at the thread, diving in and out like an épée.

Gently, she took the seam-ripper, turned it parallel to the stitch line, and with one smooth motion carved the band away from the felt. She rubbed the grosgrain to confirm that it was the good kind, and tucked it away.

To block a piece of wool felt, you must first get it hot. A Treatise on Hat-Making recommends immersing the felt in boiling water, which Catherine did when she was just getting started. Now, she has two machines for the job. The first, the steamer, is essentially an electric kettle, the size and general shape of a classroom microscope. When Catherine switched it on, a musty bubbling fog formed quickly above the nozzle. The second machine, the boiler, is the heavy-duty older brother. It is a shiny metal cube, the size of a large toaster oven; from its side emerges two insulated tubes, which are braided together and suspended a foot above the machine by a fishing-rod-like apparatus before descending to meet a hand iron.

Catherine dropped the disassembled beret onto the nozzle of the steamer. “So now we’re really going for it,” she warned me. With one hand, she spun the hat around the nozzle like a pizza boy throwing dough. Then she whisked the hat o! the steamer, placed it overtop the block, and began stretching the edges down toward a thin cut-in channel marking the bottom of the hat. “Evenly,” she said. Miraculously, the felt grew. In total, maybe a centimeter.

She lifted the whole block up to the steamer, steamed patiently, and this time, pushed felt out from the middle of the crown, where it was still gathered in a beret-like pu!. When she got one particularly droopy segment down near the perimeter, she picked up her hammer, took a T-pin from the pile in front of us, and hammered the felt into place.

Then it was my turn. “Evenly, evenly,” she cautioned. The felt was less supple than I expected. I pinched it tight and leaned in with my body weight. Everything shifted toward me. Not even. “You’re doing good. You’re doing good,” Catherine reassured.

We switched to the boiler, then back to the steamer,

then to the boiler again. We pushed from the top and pulled from the bottom. We frowned at the result, disassembled the puzzle block, repositioned the felt, and tried again. Steam, pull, hammer. Steam, pull, hammer. Slowly, unevenly, we willed the felt into the neat cylindrical shape of the block. Catherine got out a thin rope and tightened it around the the channel. She tugged at a naughty edge that had risen up, and tightened some more.

“Ok,” Catherine said. “I think we’re done.” In front of us, where twenty minutes earlier lay a floppy mess of wool, was a hat. A sharp, gallant kufi.

Whenever anyone gets hired at McDonald’s, they’re usually told that “1 in every 8 Americans are employed by McDonald’s at some point in their life.” It feels oddly plausible. After all, no matter where you live, you’re likely within a fifteen-minute drive from your very own fluorescent-lit greasy haven. Working for the golden arches isn’t a bad gig. Plenty of celebrities and Fortune 500 magnates once donned the ketchup-stained uniform and attempted to fix the perpetually broken ice cream machine. Rachel McAdams, before becoming the quintessential mean girl, took orders for three years. Je! Bezos was put on Saturday morning egg duty before becoming one of the richest men on Earth. Even Luke Skywalker was known to flip a few burgers before wielding a lightsaber. As for me, I consider myself lucky to be among the select few who have had the pleasure of dealing with boiling grease splatters, exploding

ketchup bags, and the occasional health-code violation. My nearly four-year “McCareer” began in the winter of 2021.

I was sixteen and had finally passed my driver’s test. I had been dreaming of the escapades my hand-me-down BMW would take me on for months now. I was quick to learn a hard lesson that most American teens do: gas is expensive. With my savings account dwindling, I began the job search. My options were limited. Small towns in Pennsylvania aren’t known for their diverse job markets. I already had to drive fifteen minutes to find any viable options. I began searching in the nearby town of Ephrata, a borough in Lancaster County known for rolling farmland and Amish horse-and-buggies. After rejections from Goodwills and Walmarts, McDonald’s seemed to be my last hope. I was not a chef by any means. My culinary expertise did not extend past toast with the occasional scrambled egg. Luckily, McDonald’s is not known for requiring Michelin-star talent, so I was in the clear. Besides, this particular McDonald’s had already burned down once before, so the chances of a second blaze were statistically low.

The restaurant was located within the historic Ephrata Cloister, a small plot of land where the Seventh Day Dunkers had set up shop sometime in the 1780s. The German sect was known for their pious and rigid lifestyle, keeping watch every night from midnight to 2am for the second coming of Christ. Nowadays, the remains of their settlement mainly serve as Instagram backdrops for local highschoolers’ prom photos. Set atop the hill, the McDonald’s overlooked the preserved stone barracks and beautiful greenery. I rolled into the parking lot ready to embrace my destiny. After handing in my application and doing a swift five-minute interview, I was hired on the spot. I like to think it was my confident stature and the smile that said, “I will dedicate my life to this restaurant,” but I think it was more so the fact that they were desperately understa!ed.

I started out working the grill, dropping patties like a

madman during the rushes and making sure all the fridges were stocked. I ran quality controls on the chicken McNuggets and cradled McRibs in a pit of coagulated barbeque sauce. I slowly worked my way up to “table person” which meant I made all the sandwiches. Not to toot my own horn, but I was pretty damn good at it. I could make and wrap a cheeseburger in under 12 seconds. Yet even as I mastered the art of assembly-line sandwich creation, I dreaded my least favorite assignment: the front counter. Here, the worst of humanity often reared its ugly, entitled head.

The McDonald’s uniform, although rather unassuming, seems to function as an invitation to hostility. To a disgruntled customer, the tattered red apron and mustard colored-shirt morphs employees into targets that are just begging to be verbally accosted. Every shift would have at least one scorned patron who would scream at us like we had set their house ablaze simply because there was too much lettuce on their McChicken. My coworkers have been told to kill themselves over a misplaced pickle. I’ve seen parents launch into full-fledged tantrums over flat sodas, their children oblivious behind the glow of their iPads.

Among these moments of madness, one interaction sticks with me to this day. I was a senior in high school, riding high after my college acceptance was finalized and rejoicing that my days at this establishment were numbered. It was a typical, busy afternoon when she arrived. She was your textbook “Karen,” the queen of entitlement who was never happy but always ready to tell you why. Clutching a crumpled bag and visibly shaking, she unleashed a verbal onslaught that would only be allowed to be replicated in an NC-17 movie. She roared how she had wasted her entire day waiting on a Big Mac that had turned out ice cold. I was confused. She had only placed her order six minutes ago (I checked) and I had watched them make it with a fresh tray of patties. I apologized and asked if it was the meat or the bun that was the problem. She spat back that the bottom of the bag wasn’t hot,

which meant that her food was ruined. It turned out that she hadn’t even taken a bite of the sandwich. For those of you who don’t know, the transfer of heat between two objects by direct contact is called conduction. Even at its freshest, a Big Mac will not retain enough heat to pass through the cardboard box to warm the bottom of the bag. I assured her that if she checked the sandwich itself, she would see it was hot. She stared in disbelief as she accused me of disrespecting her intelligence and how corporate would be hearing about this unacceptable behavior.

By this point, the entire restaurant had grinded to a halt to watch this show. Families stopped eating, teenagers put down their phones, and the world stood still as this volcano of a woman continued to erupt, spewing molten insults at the workers who tried to intervene. My manager made her way to the counter and took over, assuring her that we would make this right and that there is no need to call corporate (besides, we are a franchise store so calling corporate is essentially useless). We remade her Big Mac and, through clenched teeth, apologized for such an egregious error. She grabbed the new sandwich and felt the bag to make sure it was hot (my manager had thrown the new bag into the microwave for a few seconds to ensure this). She left, leaving behind an audience of bewildered onlookers and exhausted crew members who were just happy it was over.

I collected myself and began to resume my position of taking orders, praying to God that there weren’t any more crazy people on the way to the restaurant. 15 minutes went by, and a woman with two young kids came up to the counter. I started the whole “Welcome to McDonald’s” script when she interrupted me with an “I’m sorry.” She explained that she had seen the whole debacle unfold and she couldn’t fathom how grown adults could act so ridiculous. She recounted her own tales of customer vulgarity, the countless “Karens” she had dealt with during her stint as a Wendy’s employee back in the 90s. She told me that if people gave each other more “grace” then everyone would be nicer to each other and the world would be a

better place.

Her words lingered. What does it mean to give someone grace? Is it forgiveness and empathy? Or, is it simply pausing before reacting. I’ve come to see grace as something quiet but radical — a refusal to dehumanize, even when it’s easy. It’s the pause before the eye-roll, the softening of your voice when you could raise it. It’s choosing to see the person behind the uniform, behind the mistake, behind the moment.

Grace is a misleadingly simple concept. I struggle with it to this day. I still feel a twinge of rage every time I get stuck behind a slow driver or must endure being placed on hold with my bank. In moments like these, grace is a deep breath or a kind word. It’s not always about excusing mistakes, but rather recognizing the person on the other side is trying. Give grace to the fry cook who has been on their feet all day. Give grace to the cashier struggling to keep up during a rush. Give grace to the frantic teenager fumbling your order. Grace is not just a gift for them, it’s a gift for us, a reminder to act with kindness even when rage begins to fester. And in this day and age, grace isn’t just important. It’s essential.

We live in a time of constant friction. It’s easier than ever to be cruel from a distance. Behind a screen, one can get away with intense cruelty behind the shroud of anonymity. Outrage spreads faster than understanding. Everyone’s on edge. Everyone’s tired. Everyone feels as if they’d just worked the dinner rush. Misinformation, polarization, economic pressure — it all adds up to a world where empathy feels in short supply. But grace interrupts that cycle. It’s a choice to de-escalate. To connect. To remind someone, “I see you. I know this is hard.”

Grace doesn’t solve everything. It won’t stop injustice or fix a broken system. But it can build a bridge, however small, between two people who might otherwise only see each other as obstacles. It’s a seed you plant, in a restaurant, in a conversation, in a moment of tension, and hope it grows into something kinder.

I clocked out of the Ephrata McDonald’s for the last

time on March 21st, 2024. Like a soldier going home from war, I took o! my apron, scrubbed the grease from my hands, and put in my customary post-shift order: a chocolate shake and an order of small fries. As if on cue, the ice cream machine broke (like it always does), and my lactose dreams melted away in front of me. I took a deep breath, smiled, and walked out of the lobby with fries in hand.

Pale steam floated up through the grate onto the sidewalk. Peter, clad in carefully tailored white tie, vaulted down from a black SUV and took a few steps towards the Metropolitan Club’s iron gate, its curved spears gilded at the tips. Grace Murphy, following Peter, lifted the skirt of her snow-white dress, almost tripping on her way down. Mr. and Mrs. Murphy came out after her. Grace flashed Peter a dopey look, smiling at him with slightly crooked teeth. He was to escort her into womanhood.

“By the way, a bunch of us are hosting an afterparty.”

Grace was referring to herself and some of her friends from high school, who were also debutantes. “You should come. We rented out a bar a few blocks away.”

The two were only vaguely friends, and Peter had been surprised when Grace invited him a few months ago. At first, he had wanted to refuse. Grace wasn’t all that pretty,

and he couldn’t imagine making conversation with her for an entire night. But, after a girl and three frats rejected him in late October, he reconsidered it. Grace deserves a chance, he thought, and he didn’t have anything else planned for winter break. He texted her back: “So sorry I didn’t see this / I would love to come.”

He resented the hassle the whole a!air had turned out to be. Only a week before, he had learned that his prom tuxedo wasn’t appropriate for the debutante ball; he needed white tie, not black tie. He sheepishly asked his parents to buy him a set, and they shamed him into thinking that shelling out $1,500 at a moment’s notice was a burden for them. (It was not.) There was a practice reception, practice dinner, and information session all the night before, and then, the next day, drinks with Grace’s family, a photo session, and then, finally, the ball.

They passed through the gate and into the courtyard, where parents, debutantes, and escorts were gathering in a throng. The club’s pallid marble facade framed a pair of dark mahogany doors. Inside, a staircase rolled down like a tongue, flanked by red-velvet wallpaper, artificial shrubs, and metal handrails. Grace exchanged hellos with former classmates, reciting obscenely cheery “How are you settling in”s and “You look so gorgeous”s and “I’m unbelievably thrilled to see you”s. Watching her, Peter writhed in contempt at her high-pitched voice and flattering gesticulations. Could anyone actually be this excited to see someone else? He glanced around at unfamiliar faces with pasty, sunken cheeks, laughing and babbling, and a heat wave radiated along his skin. His shoulders tensed. Even though nobody was bothering to look at him, he still felt foreign eyes all over his body.

“What’s the bar?” asked Peter, just to stave o! their silence.

“It’s called Joe’s,” Grace answered. Peter didn’t have a follow-up. Grace glanced at her “Mother and Father,” as she sarcastically referred to her parents. “I’m not into this ritual,” she admitted. “Don’t you think it’s so sexist? My parents said if I didn’t debut, they wouldn’t take me to

Paris.”

“Poor you.”

“You’re right. I want to go to Paris,” Grace conceded. “But I could do chores or babysit. I cannot imagine why they care about this so much.”

“I’m getting hungry.”

“Dinner’s in an hour.”

“Do you know everybody here?” Peter asked.

“Most of them. I’m not friends with everyone.” Grace spoke casually, not at all comforting Peter.

The two made it to the staircase, and Peter extended his hand, palm up. He trembled, just a little. She took his hand, grasped his white cotton glove with hers, and they climbed the steps together.

The Great Hall was a square. Sloping down on opposite sides, marble staircases lined the walls and converged at a landing near the bottom. Sapphire stained-glass windows loomed above, backlit and coating the room in royal blue light. A solitary lantern, brilliant and caged in gold ribs, was suspended from an ornately carved dark-wood ceiling. A live band drummed out jazz. A scent of whiskey and lavender wafted through the air.

Grace bolted in pursuit of a gin and tonic, and Peter lost her in the crowd. As he searched for Grace, someone else caught his eye. He stared at another debutante, clad in frosting-white silk, her eyes flitting like a doe’s. Her figure was thin, a matchstick dipped in milk, and her neck, long and smooth, curved up like a swan’s. Her golden hair was tied up into what looked like a choux-pastry pu!, perched on the top of her head. Standing still, he tracked her around the room with his eyes for a few minutes, having forgotten about Grace. The chattering of the crowd had faded out of his ears. These girls really are getting debuted into womanhood, aren’t they? Peter thought. How perfect. As if drawn by the gravitational pull of a celestial body, he sauntered in her direction.

“I got you champagne.” Grace stopped him and held out a bubbling flute while clutching a stubbier glass in her own hand. Peter kept staring at the girl with the swan

neck until Grace nudged him with the flute. “I think you look very cute in your garb.”

“Who’s that?” Peter gestured across the room.

“Priss Carrington. A WASP straight from the nest. Her ancestors are dukes. Her dad’s a big private equity guy. Mom graduated from Harvard and now runs Spence’s parent’s association.” Grace sco!ed.

Peter didn’t absorb what she was trying to convey, and the image of Priss only became holier.

“Thanks.” Peter grabbed the flute.

“I just saw my middle school enemy. I heard she was in rehab.”

“Okay.”

“I said hi to her. I felt bad. Her parents were never around.”

“Sure.”

“I felt bad. Are you enjoying yourself?”

Peter was burning. Every moment spent with Grace was one not spent with Priss—one where Priss spoke with another man. His fingers spasmed, and he was bulging out of his white-tie tails, which were crimping his neck and binding his wrists. A drop of sweat dripped into his champagne.

“Yeah. Hey, I see someone I recognize. Be right back.”

“Who is it—”

But Peter was gone. Finally escaping Grace, he locked in on Priss like a missile, barreling through the crowd between them. But, just twenty feet shy of his goal, he felt a hearty blow to his right shoulder. Peter stumbled a little, turned, and recognized the person who had punched him: Daniel. He stood about half a foot taller than Peter, the same as in high school.

“I didn’t know you’d be here,” said Daniel, bringing Peter in for a brief bear hug. “I’m with Grace.”

“I’m escorting Emily.”

How’d Daniel swing that? Peter wondered.

“Dude, we look so gay,” he remarked. He glanced over Daniel’s shoulder and spotted Priss walking away

from where she had been standing. Who was that guy she was just talking to?

“It’s so nice to see everyone back,” Daniel said.

“I love it when people dress up.”

“I know nobody,” Peter replied.

He had felt an initial relief that Daniel was here, someone he knew. His lie to Grace ended up partially true. But that relief had quickly dissipated. He was worried that Priss would suddenly see him, approach him, talk to him, and for some reason he couldn’t muster that kind of strength right now. Thinking for a moment, Peter figured that Daniel was making him nervous. He always seemed small next to Daniel, physically speaking, and it didn’t help that Daniel’s facade always looked so placid and confident.

“D’you rush a frat?” Daniel asked.

“Nah. I wasn’t into it. Did you?”

“K-Sig. I love it, man. Great group of guys, super fun parties. Feel like I’m at home there.”

Peter swallowed a thick glob of spit. There was no way Daniel could be enjoying college this much, he thought. Who could find “home” in a semester?

“Hey, I’m not sure if you know about, um…”

“About what?”

“Uhh—well, I’m sure it’s fine that I’m telling you this.” Peter took a long sip of champagne, drawing out the pause. “There’s an afterparty, if you didn’t know. Everyone’s coming. I’m sure you can sneak in.”

“Really? I’ll ask Emily about it.”

Peter smirked. He thought Daniel looked like an ox. Disgusting and uncouth. His white tie was clearly rented.

“Take a look at that girl. To your left.” Peter pointed to the corner of the hall where Priss was standing.

“Yeah?”

“Isn’t she hot?” asked Peter.

“She’s pretty.”

“A fine, fine thing.”

Daniel didn’t respond.

“How’s Emily?” Peter added, eager to revive the conversation.

“Good. Sorry, I see someone I know o! there. It’s good seeing you, man.” Daniel delivered a parting pat on the shoulder and walked o!. Finally, the path to Priss was clear. Knowing people was such a burden, Peter thought. It was labor. He remembered the first time he met Daniel, the first day of high school. For what felt like minutes, they played one-on-one basketball for an uninterrupted hour. Their friendship formed so naturally. They spent every minute of freshman year together.

What happened to them two? Daniel made varsity basketball, while Peter didn’t and ended up dropping the sport—in Peter’s mind, that definitely changed things. But, most of all, Daniel ultimately resented Peter for being rich. He never said that, but Peter knew it. What control did he have over his wealth? Or Daniel’s lack thereof? In fact, he felt poor among their peers at Riverdale, whose families had second and third houses in the Hamptons and Aspen and “summered” in Europe. There existed far better targets for Daniel’s communist antipathy than him. Peter believed that the specific circumstances of his own birth caused him great misfortune.

Darting towards Priss, her back facing him, Peter began scheming what he’d say to her. “Do we know each other?” or maybe “Have we met?” Something to set the stage. “Are you Priss Carrington by chance?” No, too bold. The approach was to be delicate. “What’s your name?” Something as simple as that? “You beautiful goddess, how might I brighten your night?” Probably not.

“Excuse me, all debutantes and fathers, please come to the back,” said a matronly voice over the speakers. The music had stopped. The debutantes and their fathers started scrambling. Priss ended the conversation she was having and went o! with a few girls. She passed right by Peter, her dress grazing his shin. She didn’t look at him. Peter’s chest pounded like a bell.

The mothers, escorts, and guests all faced the stairs in anticipation. About fifteen minutes after the announcement, the lights dimmed, and the same matronly voice introduced the ceremony, gave thanks to sponsors, and

finally started the debuts. Girls and fathers, arm in arm, began descending the stairs. At the landing where the staircases converged, each girl-father pair paused, illuminated by a bright spotlight, and waited for the voice to announce their names. Then, the girls parted from their fathers and lined up on the left-hand side of the staircase. Grace and her father descended in the middle of the order. Her father, who looked like a melting marshmallow, smiled ear to ear. While they were in the spotlight, he whispered something to Grace, and she chuckled. She didn’t look bad, Peter thought. Her charcoal hair sat neatly on her shoulders. Her smile was nice.

Priss walked down the stairs with her father, a gaunt, placid man. They didn’t look at each other. Only at that moment did Peter get an unobstructed view of Priss. Large and buggy, her eyes motionlessly gazed into some vanishing point. Her cheekbones, jutting out, cast shadows on her emaciated face. Her skin was so smooth that Peter imagined if he poked a needle into it, it would crinkle like taut saran wrap.

The ceremony lasted ten minutes. There: these nineteen-year-old girls were now society women on the marriage market. Dinner was called.

Peter found Grace and her family in the dining room, already sitting down. A row of thin arched windows, draped with blood-red curtains, looked out onto the street. Above, the ceiling featured three neoclassical frescoes painted in long ovals, heavenly depictions of white angels, flu!y clouds, and bronze harps.

“So, Peter, where are you from?” Grace’s mother asked. They were making their way through the appetizer: a luscious tru#e risotto, sprinkled with verdant parsley and creamy to the fork touch.

“I grew up here in New York.”

“I mean your parents.”

“They immigrated when they were young.” Peter was used to these questions.

“Inspiring! It seems they did well for themselves. Raised an excellent son. You know, our family isn’t so

far removed, either. Maybe two generations from Derry. Scott?”

“Yes, I think that’s right—two,” Grace’s dad confirmed. The conversation wandered to another topic.

“I’m sorry,” Grace whispered to Peter.

“I don’t mind.”

The risotto was taken away; cuts of seared filet mignon on a buttery pomme-purée mound were delivered shortly after.

“Just wondering, do you know if Priss is coming to the afterparty?” asked Peter.

“I’m sure we invited her. Why?”

“I’m just wondering.”

“Okay,” Grace replied, in a tone that indicated she knew Peter wasn’t just wondering. She slumped back into her chair and sipped her Negroni, which was her fifth drink of the night. They continued eating.

“I’m not going to finish my filet, if you want it,” Grace o!ered. Peter gladly took the plate with two-thirds of the meal left and stacked it on top of his own finished plate. “I love men,” said Grace. “Their stomachs are black holes.”

“You’re the hungriest after you’ve just eaten.” Peter also had the magical sense that if he ate quickly enough, they all would go to the afterparty faster, and he could access Priss sooner.

As he was forking up his second helping of red meat, Peter peered through a rift in the curtain, which exposed a slim rectangle of the darkened sidewalk. A man, wearing a beanie and smothered in old, stained coats, walked by in a shiver. He descended into a subway stop, entering the pool of decrepit yellow light emanating from underground. Peter watched the man until he went out of view. He turned away from the window, eating the filet even faster than before.