BY EMILY AKBAR AND SULLIVAN HO CONTRIBUTING REPORTERS

At 9:34 p.m. on Tuesday night, AP News declared that Zohran Mamdani — a democratic socialist state lawmaker from Queens — will be the next mayor of New York.

Defeating former New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, who ran as an independent candidate, and underdog Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa, Mamdani’s campaign focused on mobilizing voters through social media and reducing costs of living.

For 10 students interviewed by the News, Mamdani’s win represents a powerful shift away from the political status quo, for better or for worse.

“I voted for Zohran Mamdani, who is the only major political candidate in my lifetime who seems to acknowledge genuine issues and be looking for solutions to them. It’s the first time I felt like I voted for someone with genuine values who will try to improve things instead of maintaining a failing status quo,” Dash Beber-Turkel ’26 wrote in an email.

BY ETAI SMOTRICH-BARR

CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

The University office that responds to reports of harassment and discrimination published an expanded set of procedures in August, explaining how the office responds to reports of misconduct, investigates complaints and issues findings.

In an Aug. 1 email to the Yale community, Elizabeth Conklin, the associate vice president for institutional equity and accessibility, wrote that the revised procedures for the O ce of Institutional Equity and Accessibility, or OIEA, would “o er greater clarity on investigation processes, timelines, alternative resolutions, supportive measures, and confidentiality.”

A confidentiality policy included in the new procedures enables Yale to discipline sta , students or faculty

who share documents related to their engagement with the OIEA, raising questions about how the o ce and University leaders can be held accountable if they fail to adequately address complaints.

In a statement to the News, OIEA Interim Director Nancy Myers stressed that the confidentiality policy applies only to OIEA documents and does not prohibit speaking about interactions with the o ce.

The revised OIEA procedures come after an investigation by the News last October revealed that a senior director of Yale Hospitality remained employed by Yale even after multiple complaints to the OIEA and a finding by the o ce that the director had committed “severe” sexual misconduct.

“It’s so disappointing,” said Vanesa Suarez, a former Yale Hos-

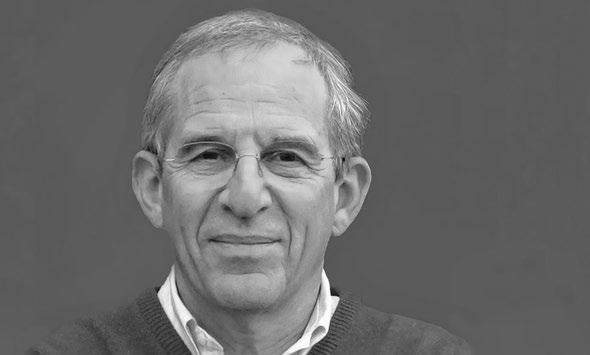

Alum and current White House

advisor Daniel Wasaserman

BY ELIJAH HUREWITZ-RAVITCH STAFF REPORTER

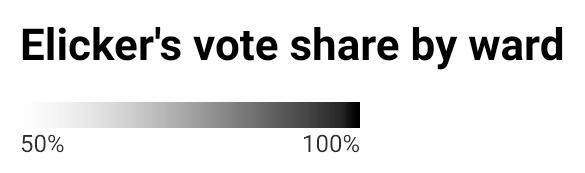

In a resounding victory, Mayor Justin Elicker won reelection to his fourth term, while his fellow Democrats swept every one of New Haven’s municipal elections Tuesday night.

“I feel great,” Elicker said in an interview at his campaign’s Tuesday night celebration. “It was the overwhelming support across the city, and that’s not easy in a city like New Haven, where we have a lot of challenges.”

Elicker won 12,002 votes, or 84.5 percent of the votes cast for mayor, according to election night returns aggregated by the New Haven Independent, which do not include absentee ballots. Elicker’s challenger, Republican candidate Steve Orosco, won 2,185 votes. In 2023, Elicker’s Republican opponent, Tom Goldenberg, won 2,322 votes.

Orosco said in a phone interview that he was “very surprised” and called the decrease in the Republican vote share relative to the 2023 election “disheartening.”

“I always said, going into this election, the chances of winning are very slim,” Orosco said. He added that if he had received around 5,000 votes, roughly half of Elicker’s 2023 total, “that’s definitely a good indicator to fight again in 2027.”

“To me, if the needle wasn’t moved even a little bit, something is o ,” he added. Elicker faced Orosco in this election. But in his victory speech, the only Republican he mentioned was President Donald Trump.

Speaking to a crowd of dozens gathered at Da Legna at Nolo for his victory party, Elicker was exuberant. He attributed the wide margin

SEE ELICKER PAGE 4

BY ELIJAH HUREWITZ-RAVITCH STAFF REPORTER

New Haven’s fledgling Independent Party backed five candidates in alder races across the city this election.

Despite their e orts to disrupt the status quo, all five lost. Come 2026, the Board of Alders will be composed exclusively of Democrats, as it has been since 2012.

“I thought this was a year of change because I thought we had a shot,” Anthony Acri, who ran on the Independent and Republican lines for

alder in East Shore’s Ward 18, said in a phone interview.

Jason Bartlett, a longtime local political organizer and the Independent Party’s founder and executive director, said he was unsurprised by Tuesday’s results.

“I didn’t have a high expectation that we were going to win,” he said in a phone interview. “It’s a new party and part of the strategy is just to start.” Independent candidates around the Elm City performed unevenly at the polls.

BY BRODY GILKISON AND WALTER ROYAL STAFF REPORTERS

After winning two consecutive Ivy League championships and earning bids to March Madness in back-toback seasons, the Yale men’s basketball team will be looking for new players to step up this year. A season ago, Mbeng was named the Ivy League Player of the Year. Townsend, who, while averaging 15 points per game and seven rebounds per game while shooting nearly 50 percent from downtown, made a late run of his own to be in the conversa-

tion for winning player of the year.

While he did not win the award, he was named First Team All-Ivy and is a preseason favorite to win player of the year this season. Additionally, Townsend has been named to several watchlists as one of the best mid-major players of the season.

“Like a lot of the past years, there are a lot of new pieces after we lost some really good ones,” Townsend told CT Insider. “It’s been fun to try to figure out what our potential could be. I feel like this program has done

BY JERRY GAO AND HENRY LIU STAFF REPORTERS

President Maurie McInnis took the stage Wednesday evening in Charleston, S.C. for a talk hosted by the Gibbes Museum of Art.

According to the event’s description, McInnis’ 6 p.m. talk is part of the 14th annual Gibbes Museum of Art Distinguished Lecture Series and explored how her background in art history prepared her for university leadership.

McInnis is regarded by many art history professors as a distinguished art historian. Her work has often involved the American South. In 2005, she published “The Politics of Taste in Antebellum Charleston,” which, according to the book’s description on Amazon.com, “explores the social, political, and material culture of the city to learn how – and at what human cost –Charleston came to be regarded as one of the most refined cities in antebellum America.”

McInnis has consistently referenced artworks in her formal addresses to students.

For the class of 2028’s opening assembly, McInnis referenced Edward Hopper’s “Sunlight in a Cafeteria,” which she said captures the subjects’ “sense of isolation and loneliness.” McInnis pointed to John Trumbull’s painting “The Battle of Bunker’s Hill” as a depiction of “an unexpected demonstration of com-

November 7, 2000 / Yale professor to predict election results for NBC

On this day in 2000, the News reported that professor John Lapinski would predict that evening the winner of the presidential race between Texas Gov. George W. Bush ’68 and Vice President Al Gore. Lapinski, a teacher in American government and political science statistics, was hired by NBC as a member of an eight-person team to predict the winners of over 450 national election races. He emphasized the race’s closeness, telling the News: “It’s so close, I may not be going to bed tonight.”

By Etai Smotrich-Barr

When I received the Aug. 1 email announcing that Yale had revised its misconduct procedures, I was cautiously optimistic. By then I knew more than most about Yale’s anti-harassment o ce, the OIEA, and what I knew was that going to the OIEA for help could be confusing, slow, and ultimately disappointing. Last fall, I published a story in the News saying as much.

Back then, the OIEA’s website contained astonishingly little about how the o ce worked. To learn even the most basic facts, I talked to people who had tried their luck with the OIEA, knocked without warning on the o ce doors of OIEA administrators, and asked around for internal OIEA documents.

Now, the OIEA’s procedures are laid out in semiclear terms on the o ce’s website. But despite my optimism, they seem to bear a striking resemblance to the old. I’ve found only one major revision.

In the coming days, plenty of pundits will o !er their takes on what Tuesday’s election results mean — for the midterms next year, for the presidential race in 2028, and for the country generally. Your columnist’s beat happens to be national politics, so I thought I’d give my two cents.

As regular readers will recall, I’m a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat. And I do have to say: it feels damn good to win again.

Here in New Haven, Mayor Justin Elicker was re-elected in a landslide, and Democrats won six out of the seven contested seats on the board of alders. In Virginia, Abigail Spanberger, a former congresswoman, trounced Winsome Earle-Sears, the state’s Republican lieutenant governor, by 15 points — the largest margin for a Democrat since 1961. Her coattails were long enough to deliver Democrats a thumping majority in the state legislature and to put Jay Jones, the embattled Democratic candidate for Virginia attorney general, over the top. Mikie Sherill won the New Jersey gubernatorial race by 13 points; most polls had the race much closer.

And, of course, Zohran Mamdani was elected mayor of New York City, winning just over 50 percent of the vote against Curtis Sliwa, who was shot several times by the mafia in the back of a yellow cab in the ’90s; and Andrew Cuomo, the former governor, who resigned after he was accused of sexually harassing several women.

I don’t agree with Mamdani on everything — I’m a liberal, not a socialist — but if I lived in New York, I would’ve voted for him in the primary and the general. Mamdani represents something new. He ran an inspiring, hopeful campaign, laser-focused on the cost of living. He delivered on Bernie Sanders’s promise to remake the electorate by bringing record numbers of young people to the polls.

Some people argue that “authenticity” in politics is basically fake. To some extent, it is; a candidate is deemed as “authentic” in part by having their supporters say that they are again and again online during primaries. But you can’t manufacture an aura of authenticity or charisma without the raw material. No amount of “brat” memes could make Kamala Harris seem authentic or charismatic because she isn’t. Zohran “bhai” has the juice. Cuomo, on the other hand, embodies everything wrong and rotten with the Democratic Party. He’s old, he’s corrupt, he’s out of touch. He acted like the mayoralty was owed to him as compensation for being forced to resign from the governorship in 2021 and ran a lazy, uninspired, AI-slop campaign. He deserved to lose, and I’m very glad that he did.

Mamdani’s ads and his social media content were relentlessly focused on one thing — freezing the rent — according to a post-election analysis

from the Searchlight Institute.

Searchlight’s polling found that New Yorkers’ top priorities were a!ordable housing and a!ordable prices. Voters thought Mamdani shared their priorities; they thought Cuomo’s top issues were crime and Israel.

There’s a lesson here for other Democrats. Meet people where they are. Show them that you care about the things that they say matter most. Don’t crowd out your strongest issue by talking about a bunch of other stuff; stay focused, no distractions and grind.

As I said, I really like Zohran Mamdani. I’m rooting for him to be a successful and popular mayor. And I think there are real and valuable lessons to take from his campaign.

But not everything about Mamdani’s success will translate outside of New York City. Not every candidate has either his unique virtues or the good fortune of running against opponents as flawed as Cuomo and Eric Adams.

There are 283 precincts in New York City that voted for Biden in 2020 and Trump in 2024. Andrew Cuomo carried those precincts by 18 points.

The Trump-Mamdani voter appears to be a pretty rare species.

For decades, Democrats have benefitted from higher turnout because we used to have what’s called a “lower-propensity” coalition — our voters often showed up for presidential races but sat out midterms and o!-year races. That’s not true anymore. If everyone had voted in 2024, Trump would’ve won the popular vote by more.

The implication is that while Spanberger and Sherill both ran far ahead of Harris in their respective states, at least some of their overperformance has to be chalked up to Democrats turning out and Republicans staying home. Exactly how much of their victories are owed to turnout differentials and how much is owed to persuasion is something that election analysts will tease out in the coming weeks, but probably not before the post-election narratives have been set.

That’s all to say that while celebration is warranted, those of us on the left of center shouldn’t count our chickens just yet. Depending on how much gerrymandering in red and blue states cancel each other out, Democrats have a good shot at winning the House next year. We might even get lucky and beat Susan Collins in Maine.

Part of that will be due to popular backlash to Trump’s actions. But part of it will be because many of the people who voted for Trump in 2024 will stay home in 2026. In 2028, they won’t.

MILAN SINGH is a senior in Pierson College studying economics and a former Opinion editor for the News. He is also the director of the Yale Youth Poll. His column, “All politics is national,” runs fortnightly. Contact him at milan.singh@yale.edu.

GUEST COLUMNIST

JOHN FOMECHE

Last summer, a young man walked into our clinic determined to stop his methadone. He had been stable for months, working, reconnecting with family, until a viral video convinced him that methadone was “poison,” part of a government plot to keep people addicted. He told me, “Doc, I think I’m ready to do this on my own.” Two weeks later, he overdosed.

At the Yale School of Medicine, we’re trained to interpret data, not defend it. Yet in 2025, defending the truth has become part of the job.

Across the country, medicine faces a new epidemic: misinformation. From vaccines to addiction treatment, science itself has become politicized. Earlier this year, the National Institutes of Health paused a major study on health misinformation after political pushback, raising concerns about interference in public health research. The NIH has proposed cutting university research overhead, a move that would drain resources from community programs.The ground under evidence keeps shifting.

Here at Yale, those national tremors become local realities.

At the Yale Program in Addiction Medicine, we meet people every week whose lives are threatened not only by fentanyl but by falsehoods. Misinformation can turn a lifesaving medication into a moral battleground. Patients fear that buprenorphine is “replacing one addiction with another” or that naloxone, the overdose-reversal medication, “causes overdoses.” These myths spread faster than methadone can stabilize.

Yale’s Community Health Care Van, a mobile harm-reduction unit that travels through New Haven, o!ers clean syringes, HIV testing and linkage to care. Yet its sta! often spend hours countering online rumors instead of treating patients. In August, Connecticut addiction advocates released a short film, “The Truth About Fentanyl

Exposure,” to debunk claims that merely touching fentanyl can cause an overdose, a myth still believed by many in our own community. This isn’t abstract misinformation; it’s misinformation that kills. The erosion of trust also affects how care is delivered. A 2022 survey by the Yale Global Health Justice Partnership found that nearly one-third of Connecticut respondents viewed misinformation about fentanyl exposure and treatment as a major problem in local media coverage. Yale researchers recently reported in JAMA Network Open that racial and ethnic disparities persist in those who receive addiction treatment after an emergency department visit, disparities that deepen when misinformation discourages people from seeking help. When institutions lose credibility, science loses reach. Meanwhile, the policy environment grows murkier. Federal scrutiny of addiction-research grants has made universities cautious. The CDC’s evolving recommendations on opioids have left both patients and providers uncertain about what “safe prescribing” even means. For a patient deciding whether to trust a medication, or a physician deciding whether to initiate it, ambiguity feels like betrayal. Yale stands at the intersection of these tensions. The University partners with the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and helps guide the state’s opioid response Initiative, which deploys settlement funds for prevention and harm reduction. But the success of those programs depends on public confidence. When misinformation spreads faster than outreach, even well-funded interventions lose their footing. The challenge now isn’t data; it’s delivery. Medical education still treats communication as a “soft skill” when it should be a survival

GUEST COLUMNIST

EYTAN

ISRAEL

skill. We need to train physicians to engage publicly with humility, to translate complexity without dilution and to counter falsehoods without arrogance.

Yale is uniquely positioned to lead that change. Its programs, from the Global Health Justice Partnership to the Community Health Care Van, already bridge research and community. The next step is institutional: valuing public communication as seriously as publication. That means supporting physicians who write, speak and post responsibly in public spaces and protecting them from the backlash that often follows.

The next frontier of medicine isn’t technological. It’s relational. It’s about rebuilding credibility in an age when anyone with a smartphone can drown out an epidemiologist. If we don’t equip future physicians to meet people where they are — their feeds, their fears, their forums — we’ll keep winning scientific battles while losing public trust.

The path forward begins in how we teach. Medical training should prepare students not only to diagnose disease but to recognize and respond to the spread of misinformation , an epidemic of its own. Integrating media literacy and science-communication skills into medical curricula is not an academic luxury; it’s a public-health necessity.

Yale’s motto is a promise as much as a legacy. Lux et Veritas can’t remain carved in stone; it must be lived out loud in classrooms, clinics and communities. Because if institutions built on truth don’t defend it, someone else, less qualified, less honest and far more viral will. The stethoscope and the pen once defined the physician. Today, it may also be the microphone.

JOHN FOMECHE is an Addiction Medicine Fellow at the Yale School of Medicine. He can be reached at john.fomeche@yale.edu.

Imagine this hypothetical:

A student councilman at the University of Moral Certainty — who happens to be a leader of Students for Fetal Life — pounds his gavel. “Honorable senators,” he declares, “We have learned that our institution once passed on a donor-advised gift to Planned Parenthood. This is morally outrageous! We must condemn all donations to organizations that perform abortions.”

Another senator raises a hand. “But, didn’t this vote not pass last week?”

“Ah, but progress requires persistence,” the first senator replies. “We can call it double jeopardy for justice. We will keep voting until righteousness wins out, or until the dissenters drop the debate.”

What might sound like an absurd spectacle became reality at Yale over the weekend. This week, two weeks after a very similar proposal failed, the Yale College Council voted to condemn Yale’s donor-advised gift to the Friends of the Israeli Defense Forces — a U.S.-registered 501(c)(3) nonprofit that provides education, housing, therapy and family support to Israeli soldiers and their children. By condemning a lawful charity because it o !ends certain political sensibilities, the YCC has gone down a slippery slope. If we normalize moral gatekeeping over philanthropy, what’s to stop another campus from banning donations to Planned Parenthood or the American Civil Liberties Union? The logic works both ways.

And, by voting again on almost the same failed measure until it passed, the YCC modeled activism — not democracy. A YCC senator

showed me several harassing messages he received in the two weeks between the votes, shaming him for voting “no.” Those messages might have been enough to make the average person vote “yes” in the double jeopardy trial. That’s not moral leadership; it’s moral coercion.

If supporters of the resolution point to last year’s referendum as proof of student will, let’s be clear: the undergraduate referendum addressed Yale’s “investments” in “weapons manufacturers.” Investments and donations are fundamentally di!erent. When Yale invests, it does so for its own financial gain, using university-controlled funds. Donoradvised gifts, by contrast, come from individuals who contribute to Yale with the understanding that their money will be passed on to other registered nonprofits of their choosing.

FIDF is not a weapons manufacturer, nor does it supply arms or even defensive vests or helmets. The organization itself acknowledges that American nonprofits are prohibited from donating military equipment of any kind. Instead, it’s a nonprofit that supports soldiers’ education and well-being within U.S. law. Blocking Yale from passing on the donation would also likely not prevent the money from being given; the individual who wished to make the donation through Yale might simply put it through another donor-advised fund, or donate directly, accomplishing nothing but hurting Yale’s credibility and our culture of open debate. Furthermore, as one senator noted, condemning this donation implies that every future gift not condemned is tacitly approved. Though, predictably,

only those involving Israel seem to invite debate.

To Yale’s international students: I sincerely hope the YCC’s actions do not lead to federal attention that threatens your visa status. To everyone on financial aid: I pray that this motion will not lead the federal government to withhold more funding and lead Yale to cut back on providing vital aid.

Let’s return to our fictional “University of Moral Certainty.” The motion passes easily this retrial, 19-7 — perhaps all the abstentions of senators who had run for o ce to plan Spring Fling turned to yeses to get over with the debate. Applause erupts. The senators congratulate themselves on standing for human life, truth and selective compassion. The chamber adjourns until the next week when they move from condemning Planned Parenthood to condemning climate change prevention charities, global human rights groups and more. If it doesn’t pass the following week, they can and will try again and again. Soon, ‘justice’ is achieved. What began as moral conviction ends as moral control. What began as conscience ends as censorship. And in the silence that follows, diversity of opinion disappears. Student government should make life better for students, not play foreign-policy referee. When it forgets that, we come outstandingly close to the “University of Moral Certainty.”

EYTAN ISRAEL is a senior in Saybrook College studying Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. He can be reached at eytan.israel@yale.edu.

ELICKER FROM PAGE 1

of his win to his administration’s focus on crime, a ordable housing and the climate crisis, but added that “it is also because when Donald Trump attacks our community, we fight back.”

He mentioned all four of the lawsuits New Haven has joined against the Trump administration since the president’s January inauguration. Just last Thursday, the city joined a national lawsuit over anticipated cuts to Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP. After a federal judge filed a temporary restraining order against the White House, it announced it would send partial payments this month.

And Elicker said in an interview that the antagonistic posture he has taken toward Trump may have helped cement his win.

“At a poll, I said to one woman, ‘Thanks for coming and voting,’ and she said, ‘Thanks for fighting Trump,’” he said. “And that kind of message I heard from many voters across the city that feel deeply concerned about what’s going on in our nation.”

Elicker added that he saw much of the president in his challenger.

“Technically, Orosco was my opponent, and Orosco was somewhat Trumpish in his campaign, that wasn’t always accurate, was unbelievably negative, didn’t really have anything positive to say, any real solutions,” he said.

Orosco, for his part, said that he was counting on support from Trump voters that never materialized.

“If Trump got 7,000 votes in New Haven,” he said, “and I only had 2,000, that number doesn’t add up to me, because those 7,000 people should definitely be motivated to vote again this year.”

But entrenched one-party rule has drained energy from the city’s democratic life and kept voter turnout low, per several political observers.

Elicker himself acknowledged that “in New Haven, it’s hard for a Republican to win.”

Referring to Orosco, he added that “I appreciate him throwing his hat in the ring. I think that it’s not easy to run a campaign.”

“The stars don't look bigger, but they do look brighter.”

Democrats sweep alder races Down the ballot, in six of the seven contested alder races, the Democratic candidates won handily.

In Wooster Square’s Ward 8, Democrat Amanda Martinelli, who was endorsed by outgoing alder Ellen Cupo, beat Republican Andrea Zola by around 74 points.

Martinelli said she felt “good” in an interview at Elicker’s victory party.

“I really worked hard to get out and meet as many neighbors as I possibly could” — and that, Martinelli said, is why she won.

In Quinnipiac Meadows’ Ward 12, one-term incumbent Theresa Morant beat Robert Vitello, who ran on the Independent and Republican lines, by around 50 points.

Meanwhile, in Fair Haven Heights’ Ward 13, Democrat Mildred Melendez won 417 votes to Green candidate Paul Garlinghouse’s 71 and Independent Luis Jimenez’s 32.

At Elicker’s party, Melendez said she felt “fantastic, fabulous, super excited. Paul Garlinghouse was a perfect opponent. He was kind. He’s smart. I truly respect him. He ran a great race. It was a good day together — great example of democracy.”

In Fair Haven’s Ward 16, Democrat Magda Natal trumped Independent Rafael Fuentes by around 63 points.

Natal said that she “expected” to win.

“There was no doubt,” the alderelect said. “I was hoping to see higher numbers, just because I’ve been out for so many months.” Natal had won 154 votes as of Tuesday evening. She added that she felt “overwhelmed” thinking about the work that lies ahead.

Over in East Shore’s Ward 18, Democrat Leland Moore received 692 votes, while Anthony Acri, who is running on the Republican and Independent lines, won 395 and petitioning candidate Zelema Harris 37.

“It feels good,” Moore said in an interview inside the ward’s polling place. “I’ll take a little break tomorrow and once sworn in, we’ll get to work.”

Acri lamented the challenge of running as a Republican or Independent candidate.

“We’re fighting against the Democratic machine in this city — but we did pretty well and

maybe some people will listen.” He added that he will “still be involved in the community — politics, I don’t know.”

In West Rock’s Ward 30, threeterm incumbent Honda Smith crushed Republican challenger Perry Flowers by 86 points.

New Haven’s only competitive race took place in the Hill’s Ward 3. In that contest — marred by allegations of misconduct at its eleventh hour — half-term incumbent Angel Hubbard, a Democrat, emerged victorious over challenger Miguel Pittman, winning 347 votes to his

303. Pittman, who ran on the Independent and Republican lines, also lost to Hubbard in this year’s Democratic primary and in a 2024 special election.

For Elicker, it’s straight back to work Wednesday morning.

“I could pull out my schedule, but it’s jam packed with meetings,” he said.

Orosco, meanwhile, is not sure what lies ahead. He lost one race for alder and two for state senator in previous years; last month, he speculated he might one day run for governor. And he has not ruled out running

for mayor again in 2027.

“You know what it is?” Orosco said. “I love to fight. I just do. I can’t help myself.”

This was New Haven’s first municipal general election with early voting, and as of Tuesday night, before all ballots had been counted, turnout was up from 2023 by more than 1,100 votes.

Eric Song, Chantal Eulenstein and Nellie Kenney contributed reporting.

Contact ELIJAH HUREWITZ-RAVITCH at elijah.hurewitz-ravitch@yale.edu.

Most successful was businessman Miguel Pittman, who challenged half-term incumbent Angel Hubbard, a Democrat, for the Hill’s Ward 3 alder seat. He previously lost to Hubbard in a tight 2024 special election and in this year’s Democratic primary. This cycle, running on the Independent and Republican lines in a race marred by allegations of misconduct, he won 303 votes to Hubbard’s 347, according to data from New Haven’s Registrar of Voters.

Pittman led by a wide margin in early voting, however. Bartlett speculated that once it became clear Ward 3’s race would be the most competitive, “the machine — I mean the Democratic Party, the alders, New Haven Rising and UNITE HERE” put its resources behind Hubbard.

Acri, who has previously run as a Republican twice for city clerk and twice for state representative, also nabbed a significant share of the vote in the Ward 18 race, winning 37 percent.

“We did not get the Republicans to turn out as I had hoped that they would,” Acri said. “I did not get the number of Independent votes that I expected either.” Ward 18 saw a higher share of its residents vote for President Donald Trump last fall than any other ward.

Still, Acri fared better than some of his fellow Independents.

In Quinnipiac Meadows’ Ward 12, Robert Vitello, who also ran on the Republican line, won just over 25 percent of the vote.

In Fair Haven’s Ward 16, Rafael Fuentes won 16.7 percent of the vote.

And in Fair Haven Heights’ Ward 13, Luis Jimenez won 6.3 percent.

“Quite frankly,” Bartlett said, some of the candidates “didn’t put in a hundred percent.”

Indeed, Vitello said that he only decided to run for alder because he had heard, mistakenly, that one-term incumbent Teresa Morant was not seeking reelection.

“I would have never went against her,” he said, adding that they became friends while standing outside of the ward’s polling location Tuesday.

Fuentes, meanwhile, said that he only ran to unseat 10-term incumbent Jose Crespo. But when Crespo dropped out of the Democratic primary in August, Fuentes’ name was already on the ballot. He ended up squaring off against teacher Madga Natal, whom he referred to as “a good woman.”

“I didn’t do all that crazy legwork,” Fuentes said, adding that he did not particularly want to win. “I didn’t go knocking door to door. I didn’t call people at their house.”

He said that immediately after the results of his race were called, he congratulated Natal and then drove in his RV from the polls to Maryland to participate in the Haltech World Cup Finals, a drag racing competition. Many of the Independent candidates who ran this cycle have colorful histories.

Acri was sentenced in 2016 to five years in prison for conspiracy to commit wire fraud, while Vitello was once a mob enforcer, he told the News, and was arrested in 2000 for kidnapping. Fuentes has been accused of organizing drag races by

Crespo, the incumbent alder, allegations he denies.

In Bartlett’s eyes, the only way for the Independent Party to gain a foothold on the Board of Alders is to run a larger slate of competitive candidates, which would prevent the Democratic party from concentrating its resources on a single race.

“We understand what it’s going to take,” Bartlett said. “Now that I have a party, I can start recruiting today, tomorrow, and we can build, and we can fundraise and actually have the financial capacity and the infrastructure to actually help people across the finish line.”

Bartlett is now focused on finding “more Miguels — more candidates that truly want to win and serve and make a di erence in the community,” he said, referring to Pittman.

Ultimately, Bartlett places some of the blame for his candidates’ losses on factors far beyond New Haven.

Voters, he said, “weren’t thinking local issues. They were like, ‘Okay, we got to go in there and show that we’re not for Trump. We’re for the Democrats.’ And they just voted straight Democrat.”

Bartlett said that local races in Connecticut became part of “a

national referendum” on the Trump administration.

Indeed, Democrats flipped open seats and ousted Republican incumbents in cities and towns across the state, with Sen. Chris Murphy calling the shift “seismic” and “possibly unprecedented” in a Tuesday night X post.

Anti-Trump sentiment made it “a lot tougher than it should have been” for non-Democrats to win in New Haven, Bartlett said.

He added that the apparent unpopularity of Steve Orosco — who ran against incumbent Mayor Justin Elicker on the Republican and Independent lines and won a smaller vote share than Elicker’s 2023 challenger, Tom Goldenberg, did — might have also discouraged New Haveners from voting for Independents down the ballot.

“Politics in New Haven have gotten too comfortable,” Jimenez said. “I think that people might be scared of change.” Elicker won reelection by around 69 points.

Contact ELIJAH HUREWITZ-RAVITCH at elijah.hurewitz-ravitch@yale.edu.

FROM PAGE 1

passion amidst chaos” for the class of 2025’s baccalaureate and, at this year’s opening assembly, compared the “inherent ambiguity” of Winslow Homer’s “Old Mill” to the uncertainty the class of 2029 may feel.

In an interview with The Post and Courier, a Charleston newspaper, published Oct. 27, McInnis further detailed her connection to the South, specifically South Carolina — adding that she lived in Charleston for three years while writing a dissertation on its architectural history.

“And as a Southerner whose grandfather was himself a South Carolinian, I can hardly resist an opportunity to enjoy some Lowcountry cooking,” McInnis told The Post and Courier.

According to University spokesperson Karen Peart, McInnis was in Charleston mainly for the event and will return to New Haven on Thursday.

“She was invited by Gibbes in June 2024 to participate in its Distinguished Lecture Series, and she plans to discuss the unique skills and perspectives that her background as an art historian brings to her leadership,” Karen Peart, a university spokesperson, wrote in an email to the News on Wednesday afternoon before the event.

Charleston Music Hall and the Gibbes Museum of Art did not immediately respond to the News’ emailed requests for comment.

In 2023, Sarah Lewis GRD ’15, a former art critic at Yale School of Art, was the first art historian to speak at the annual lecture series.

Contact JERRY GAO at jerry.gao.jg2988@yale.eduand HENRY LIU at henry.liu.hal52@yale.edu.

pitality employee whose report of harassment was dismissed by the OIEA. Suarez told the News that she had hoped revisions to OIEA policy would focus on empowering the o ce to take a more active role in preventing misconduct.

“The only thing you could come up with is confidentiality?” Suarez said.

New clarity Before this update, the webpage explaining OIEA procedures contained only eight paragraphs and provided few details on what the o ce did after receiving a report of harassment or discrimination.

“The updated OIEA procedures aim to provide a clear and structured roadmap for individuals engaging with the o ce,” Myers wrote in an email to the News.

According to the revised procedures, someone who reports misconduct to the OIEA can seek non-disciplinary “informal” or “alternative” resolutions, or they can choose to bring a “formal complaint.” A formal complaint requests that the OIEA initiate an investigation against the accused party, who is referred to as the “respondent.”

In an investigation, the OIEA interviews the complainant, respondent and relevant witnesses and then produces an investigative report, which includes a determination of whether or not the respondent has violated Yale’s policy against discrimination and harassment, according to the revised procedures. If the OIEA finds that the respondent violated Yale’s policy, other personnel processes outside of the o ce determine any potential disciplinary action.

The revised procedures publicly describe this process in detail for the first time. Myers wrote that the process is “consistent with the internal investigation practices first developed by the o ce in 2021, which have been regularly reviewed and refined since that time.”

Confidentiality policy

The revised procedures also include new language that restricts the sharing of documents prepared by the OIEA in response to a formal complaint.

Under the new procedures, the OIEA now informs both the complainant and the respondent in an investigation that they “must keep all documents, including any investigative report, prepared specifically for the investigation strictly confidential.” Parties to an investigation cannot share the documents with anyone

except “their support person, family, legal counsel, union representative, or appropriate government agencies.”

“Alleged violations of the confidentiality provision are reported to the appropriate disciplinary body, depending on individual’s affiliation with the University (i.e., student, faculty member, or staff member),” Myers wrote to the News. “OIEA informs both complainants and respondents that violating this confidentiality provision may result in disciplinary action.”

Yale’s status as a private institution means that “they can set disciplinary policies with a great amount of leeway, without much worry of regulation,” according to civil rights attorney Alex Taubes LAW ’15.

The contracts between Yale and UNITE HERE Locals 34 and 35 — the unions that together represent Yale’s clerical, technical, maintenance and service workers — allow the unions to intervene on behalf of their members in any instance where Yale pursues disciplinary action.

“But if it’s a non-unionized employee,” Taubes said, Yale “could discipline them all the way up to firing, if they chose.”

The confidentiality clause permits sharing OIEA documents with some government agencies, such as the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. What the policy seeks to prevent, Taubes said, is “going public.”

Losing a tool for accountability

Last October, an investigation by the News found that dining staff felt neither the OIEA nor University leaders had properly addressed complaints of sexual misconduct by a former senior director of Yale Hospitality, Robert Sullivan. When reached by the News last year, Sullivan broadly denied the accusations without addressing them specifically.

The News’ investigation relied on OIEA documents to show how the office and University leaders responded to the alleged conduct. Those documents would now be subject to the University’s confidentiality policy.

In July 2019, the OIEA reached out to Vanesa Suarez after the o ce was made aware of a letter she wrote alleging that Robert Sullivan, then a senior director of Yale Hospitality, had sexually harassed her.

Yet less than three weeks after the initial outreach and without the OIEA ever meeting with Suarez, the then-director of the office wrote in a document — obtained by the News

and included in the October 2024 article — that she had completed an investigation and “found no evidence to support” Suarez’s account. The OIEA never notified Suarez that her allegations had been dismissed. Suarez, waiting for a meeting that would never come, gave up.

In 2023, the OIEA investigated a new complaint against Sullivan and found — according to another document obtained by the News — that Sullivan had committed “severe” sexual misconduct. Despite the OIEA’s finding, Sullivan was issued a new role as a “consultant” and remained listed as an employee until the News began reaching out to University leaders about Sullivan’s conduct.

Both Suarez and the other complainant, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said they shared their stories with the News because they felt that the OIEA and University leaders had failed to address Sullivan’s behavior. They said they felt particularly betrayed by Sullivan’s continued employment, despite OIEA documents that proved University leaders were aware of his conduct.

Myers wrote that “the confidentiality provisions do not prevent individuals from speaking about their experiences, but it does require that they maintain the confidentiality of documents prepared in the course of an investigation. This protects the privacy of all involved in an OIEA investigation, including witnesses who may otherwise be hesitant to participate.”

Without being able to share OIEA documents, Suarez wondered what mechanisms were left to hold University leaders accountable for their response to misconduct.

The confidentiality policy, Suarez said, means that “Yale is basically telling you, ‘You’re done after us. If we fail you, you can’t go air this out to the rest of the world — not just what happened to you, but the fact that we failed you.’”

Between January 2022 and December 2024, the OIEA received 545 reports of discrimination and harassment, according to the o ce’s data dashboard, resulting in 90 formal investigations.

In 10 of those investigations, the OIEA found that a respondent violated the University’s policy on discrimination and harassment.

Contact ETAI SMOTRICH-BARR at etai.smotrich-barr@yale.edu.

According to exit polling from CNN, Mamdani won 78 percent of votes from New Yorkers aged 18-29. Critics, however, cited inexperience and unfeasible policy proposals as reasons why they were hesitant to support Mamdani’s run. Manu Anpalagan ’26, the president and founder of the Yale College Republicans, wrote in an email that he felt “disappointed by the false promises” Mamdani made “to voters about what he can accomplish.” Anpalagan, who is not from New York City, characterized Mamdani’s messaging as “ingenuine and dishonest.”

Avi Rao ’27, who is from New York but did not vote for Mamdani, said in an interview that he has doubts about many of Mamdani’s policy proposals, since they hinge on increasing tax revenue, which would be dependent on approval from the New York State Assembly.

Ahead of Election Day, a dozen members of Yale College Democrats, or Yale Dems, canvassed for Zohran Mamdani over the weekend. Maryam Abbas ’29, who does not live in New York but canvassed with Yale Dems, observed how many voters expressed their excitement about Mamdani’s policies, citing his plans to make the city affordable. Abbas also mentioned critics she encountered who had less faith in the campaign’s promises. “There were some people who said, ‘I would never vote for that man, God forbid,’” Abbas noted. “There was one person, for example, who I was talking to, and she said that she likes Zohran’s policies, but she feels like it’s hard to attain his policies.”

Mamdani’s win on the national stage

Many students viewed Mamdani’s win as a promising shift in the overall national Democratic strategy. Brooklyn resident Maya Evans ’27 wrote in an email that she hoped his win would be “a big wake up call to the Democratic Party to get o their ass and do something.”

Yale voters also cited the city’s relationship with President Donald Trump as a factor influencing their vote. New Yorker Manu Bosteels ’28, who is an opinion columnist for the News, wrote in an email that “Cuomo has shown himself to be unwilling to stand up to Trump and indeed takes money and cues from the same people.”

“It’s felt really hard to be living in Trump’s America over the last several months,” Sonja Aibel ’28, who is from Brooklyn and is a copy editor for the News, said in an interview. Aibel said she valued the idea of “local gov-

ernment being a place where the values of that city can be upheld despite what is going on on the national level,” and hoped Mamdani could be a step towards that vision.

Rao, however, expressed concern that Mamdani’s election could bring too much federal focus to the city. Rao described Mamdani’s relationship with Trump as “overly combative.”

“You don’t want to be a collaborator necessarily, but being able to deflect federal pressure and run the city well enough that there isn’t this sort of eye on it, I think that’s the most important,” Rao said.

The future of New York

After Mamdani’s win, voters reflected on the direction New York is now headed. Bosteels praised Mamdani’s campaign strategy as a model for Democrats nationwide, specifically by “using social media e ectively and clearly, and being willing to deviate from the stale monotony of mainstream Democratic politics when it matters most.”

Beber-Turkel wrote that Mamdani’s win can signify to the entire country that there is room for more leftist policies within the Democratic party.

“I think his election would signify to the US as a whole that there is a place for real leftism and that the enthusiasm shown for candidates like Mamdani will not automatically transfer to the least o ensive elderly, milquetoast neoliberal selected by the DNC,” Beber-Turkel wrote. Abbas reflected on her enthusiasm at being able to identify with Mamdani, New York’s first Muslim mayor.

“There’s so much excitement, especially as a Muslim, like seeing the Muslim community being really excited about the first Muslim mayor. It’s just so incredible,” she said.

Regarding New York’s relationship with the federal government, Aibel said that she is optimistic about Mamdani’s plans to fight back against pressure from the Trump administration, especially in what she claimed should be a “sanctuary city” for immigrants.

“I am excited about the idea that New York is picking someone who will really stand up to what’s going on outside of New York and will defend the things that make our city special,” Aibel said.

Andrew Bard Epstein GRD ’17, the communications coordinator behind Mamdani’s social media campaigning, graduated from Yale with a doctorate in history.

Contact EMILY AKBAR at emily.akbar@yale.edu and SULLIVAN HO at sullivan.ho@yale.edu.

a really good job of having someone ready to step up every year. There’s something really special about that.”

In addition to Townsend’s preseason spotlight, national media also picked Yale as the unanimous favorite to claim the Ivy League’s March Madness bid in the league’s preseason poll. Harvard and Cornell came in second and third, respectively. Preseason KenPom rankings also favor the Bulldogs. KenPom, short for Ken Pomeroy, is an independent NCAA men’s basketball database whose rankings are widely regarded as one of the more accurate predictions of seasonal performance.

Many of the traditional Ivy basketball powerhouses are reeling following a messy offseason. Princeton’s superstar guard Xavian Lee earned $6 million in NIL and roster deals via a transfer to the reigning champion Florida Gators during the o season, On3, a sports news site, reported. Cornell, last year’s Ivy runner-ups, graduated their leading scorer, Nazir Williams, and their leading rebounder, Guy Ragland Jr. Harvard, who returns unanimous Ivy Rookie of the Year Robert Hinton, also graduated two starters. Nonetheless, the Ivy conference-play season is notoriously unpredictable. Before then, however, Yale will face a challenging non-conference schedule. Highlighted by preseason AP No. 15 Alabama (1-0), the Bulldogs will have a chance to sharpen their teeth against multiple NCAA tournament-level opponents.

big plays of Aletan’s career came in the final seconds of Yale’s victory over Auburn in the first round

of the NCAA Tournament, when he swatted two shots to clinch the win for the Bulldogs. Since then, he has emerged as one of the better defensive players in the Ivy League, making a name for himself on both defense and the o ensive side with his rim-rattling dunks.

“This summer I worked really hard in the weight room because I want to enhance my physicality around the rim on both ends of the floor,” Aletan wrote in a text message. “On the court, my coaches have been great working with me to build confidence handling the ball and improve my touch in the paint.”

With the increased physicality and refined skills on the court, Aletan could become a force for the Bulldogs as they aim to repeat their past success.

“Having seen some of the past guys go through the program and have a lot of success, we’ve been given a great blueprint on how to succeed as a basketball team,” Trevor Mullin ’27 said. “Even though we have a lot of new faces on the court, I’m excited to see how we will work together to accomplish our goals.”

On Friday, the Yale men’s basketball team will open up its 2025-26 season against Navy at 8:30 p.m. in the Veterans Classic in Annapolis, Maryland. The game will be televised on CBS Sports Network.

Contact BRODY GILKISON at brody.gilkison@yale.edu and WALTER ROYAL at walter.royal@yale.edu.

“If the Sun and Moon should ever doubt, they’d immediately go out.”

WILLIAM BLAKE ENGLISH POET

BY ISOBEL MCCLURE AND ASHER BOISKIN STAFF REPORTERS

University President Maurie McInnis traveled to Washington, D.C., last week to attend a Tuesday For Humanity event, as the fundraising campaign enters its final stretch.

Her visits to Washington, now monthly, come as the University increases its lobbying presence amid increased political scrutiny of elite colleges. The For Humanity event featured remarks from Jackson School lecturer Jimmy Hatch ’24 and was attended by a group of Naval Reserve Officer Training Corp, or ROTC, students. During the trip, Hatch and the students visited “a number” of lawmakers on the Hill, McInnis said in a Friday interview.

“We should probably do more of that,” McInnis said, referencing the students’ meetings with lawmakers. She noted that “there is no doubt that they can tell Yale stories in ways that I

think are more personal and perhaps even more meaningful.”

Federal filings released on Oct. 20 show that Yale spent $370,000 on lobbying between July and September, surpassing every other Ivy League university. The filings list the University’s priorities as student aid, endowment taxation and federal research funding.

McInnis described the students’ meetings as a way for lawmakers to “get to know Yale in a di erent way from meeting with” herself or a representative from Yale’s O ce of Federal and State Relations.

During her trip to the capital, McInnis attended the biannual Association of American Universities’ meeting of presidents.

McInnis, who serves on the organization’s board, said that the AAU meets with U.S. Secretaries of Education and Energy and others “who are doing the policy work that relates to higher education.”

“We like to have an opportunity for both us to hear from

them and for them to hear our questions, and then we talk about other things that you know are issues in common for higher education,” McInnis said. She did not specify who gave remarks at the recent AAU meeting.

In June, the University provided financial support to students that organized a rally in the capital against the Republican-backed “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which raised the endowment tax on wealthy universities like Yale from 1.4 to 8 percent. During the spring, the University solicited statements from Yale students about their Yale experience to use in its lobbying efforts.

Asked whether lobbying efforts align with the University’s year-old policy on institutional voice, McInnis said she sees no contradiction between the two. The policy, adopted last fall, advises Yale leaders to avoid commenting publicly on political or social issues except in rare cases.

When lobbying, McInnis said she aims to “defend and speak to Yale’s mission” with lawmakers whose decisions directly affect higher education funding and policy.

“What I believe I am doing is opening up a conversation about the impact that through our education, research and clinical care missions, the impact that we are having on all Americans and the importance of preserving that partnership for the good of the United States,” McInnis said.

Legislation about indirect research costs remains a “very alive and unsettled issue,” she said when asked about this lobbying area. Alongside other universities, Yale has advocated for the Federally Allocated Indirect Rate, or FAIR model — a proposal to reform how the government reimburses institutions for indirect research costs like lab maintenance and equipment.

McInnis said the reform would make the system “more transparent” and “understandable to the public.”

Universities and agencies are “building a lot of support” among lawmakers for the reform, McInnis added. According to McInnis, final decisions could be incorporated into Congress’ upcoming appropriations process, which has been delayed by the ongoing government shutdown.

When asked about the government shutdown, McInnis said that “for now, there have not been major impacts,” although noting that fewer lawmakers are currently in Washington.

“In past government shutdowns, if there have been any gaps in funding, it’s always been later restored,” McInnis said.

“We have always just covered any places there are gaps.”

McInnis was inaugurated as the president of Yale on April 6.

Contact ISOBEL MCCLURE at isobel.mcclure@yale.edu and ASHER BOISKIN at asher.boiskin@yale.edu .

BY SASHA CABRAL STAFF REPORTER

The Yale Center for Civic Thought on Monday hosted recent Yale alum and current White House policy advisor Daniel Wasserman ’19 for an off-therecord discussion about the compact sent by President Donald Trump to various universities and the role presidents should play in reforming universities.

Bryan Garsten, the faculty director and founder of the center, said that the Center for Civic Thought strives to facilitate “a more thoughtful public sphere” along with “a more responsible intellectual life.” Garsten also said that President Donald Trump’s recent pressure on universities makes the views of a young graduate employed at the White House “interesting.”

“He was chosen because he’s a pretty recent Yale alum who finds himself in the position of being

close to the White House working on university issues,” Garsten said in an interview. “He and I have spoken once or twice, and I thought it would be provocative and useful for him to come to campus and he agreed.”

Garsten added in an email to the News that Wasserman spoke on his personal views and was not acting as a representative of the Trump administration.

The 25 attendees in the audience consisted of students, faculty and sta , according to Garsten and Anna Stroinski, the center’s program manager. Attendees leaving the event declined the News’ requests for comment.

“Some people were sympathetic to some of the recent criticisms of universities but skeptical of the administration’s methods and proposed solutions; some approved of the administration’s approach to universities; others rejected the administration’s diagnoses alto-

gether,” Garsten wrote in an email after the event.

“Some participants shared concerns about intellectual diversity and violations of civil rights law. Some raised questions about the administration’s approach, including why research funding was an appropriate response to violations in other parts of the university,” he added.

Wasserman declined the News’ request for comment about the event.

Wasserman, who was in Davenport College as an undergraduate, graduated from Harvard Law School and studied political thought and intellectual history at the University of Cambridge.

At Yale, he wrote a News opinion article arguing for the necessity of “civil” and “concrete” arguments.

In June, the New York Times reported that Wasserman served as a “cooperating witness” in a Justice Department investigation

into alleged claims of discrimination against white men at the student-run Harvard Law Review. In letters to Harvard sent in May, the Times reported, the department disclosed that Wasserman had provided information about the publication and accused the Law Review of retaliating against Wasserman and asking him to destroy evidence.

Wasserman began working for the White House on May 22, the Times reported.

In a confirmation email to the Monday event attendees, Stroinski provided copies of the Trump administration’s “Compact for Academic Excellence in Higher Education,” a Wall Street Journal article regarding the compact being sent to universities and Harvard’s response to the Students for Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College ruling.

“We gently encourage you to read the attached pieces in

advance of the seminar to help prime the discussion. Please note that the event is structured as a small seminar, so it is designed to be an engaged, conversational session for all participants,” Stroinski wrote in the email.

Referring to the future of the Center for Civic Thought, Garsten elaborated on the center’s immediate goals for growth and inclusion of a diversity of people that are “different parts of Yale.”

“Although we’ve been doing similar work for years, we’re brand new as a center,” Garsten said. “So we still want to find our way into more and more parts of the university.” Wasserman’s undergraduate senior essay on political theory won the Philo Sherman Bennett Prize, according to the webpage advertising the Monday discussion.

Contact SASHA CABRAL at sasha.cabral@yale.edu.

‘Olympics’ between opposed groups seen as sign of Law School civility

BY HENRY LIU STAFF REPORTER

Members of Yale Law School’s conservative Federalist Society and liberal American Constitution Society put aside their ideological differences last month for an afternoon of friendly competition at Wilbur Cross High School in East Rock.

The groups came together in early October for the inaugural “FedSoc-ACS Olympics,” consisting of seven athletic competitions held between the two groups. Student organizers characterized the event as a fun opportunity to meet classmates outside their usual circles and to build connections across political and legal divides.

“We’re delighted to see our students taking the initiative to cross ideological lines, have some fun, and build relationships. Such connections foster the respectful dialogue that sharpens legal reasoning and deepens mutual understanding,” the Law School’s interim dean, Yair Listokin LAW ’05, wrote in a statement to the News.

The Federalist Society is a conservative-leaning legal organization, while the American Constitutional Society is a progressive legal organization that has been described as a “counterweight” to the older Federalist Society.

Listokin linked the Olympics to the Ronnie F. Heyman LAW ’72 Crossing Divides Program, which encourages dialogue and cooperation among students of differing viewpoints.

Tobias Johnson LAW ’27 — in email obtained by the News that was sent to the Window, an internal email list server for the Law School — highlighted the event’s significance in light of past tensions at the Law School.

“It’s not lost on any of us that such an event may not have been

possible in years past at YLS, and it’s a tradition we hope continues for years to come,” Johnson wrote in the email.

Colin Dunkley LAW ’26, who participated in the Olympics, told the News that while relations between liberal and conservative students broadly have been positive during his time as a student, he has heard that that relationship was “far more fraught” before he arrived, when there would be a “really intense social ostracization” of Federalist Society members.

“I do not think that if you were going to Yale Law School, let’s say six years ago, and if you were a liberal, I don’t think it would be common or even especially acceptable to have a friend who was in FedSoc,” Dunkley said.

Hannah Terrapin LAW ’26 also described the “leftist vs FedSoc divide” as “a lot less contentious” than previous years. Terrapin attributed that shift to tighter policies the Law School has adopted regarding campus free demonstrations.

Terrapin added that while she thinks some Federalist Society members hold views she finds “abhorrent,” there is a diversity of viewpoints in the Federalist Society and it would be a mistake to not engage with its members.

Ilani Nurick LAW ’27, who is the vice president of community engagement for ACS and was an organizer for the event, spoke to the News about the value of the Olympics for him.

“It’s important to do things that aren’t political and are fun, and humanize each other,” Nurick said. “In many instances, we live in these bubbles where you don’t necessarily get these kinds of interactions and it’s really easy to demonize people or not understand those people when you’re in these kinds of isolated situations.

This is just a very low stakes way of at least giving people the opportunity to chat.” Johnson ended his email about the Olympics by referring to the Crossing Divides program.

“To (actually, for the first time since the inception of the program) crossing divides and to many more FedSoc victories,” Johnson wrote At the Olympics, according to Johnson’s email, the two groups competed in seven events: capture the flag, flag football, kickball, basketball, dodgeball, relay race and tug of war.

While ACS won in basketball and tied in tug of war, the Federal-

ist Society won all five other events, taking home the “Byron White Award for Supreme Excellence.”

“Even though ACS recruited from 90% of the law school’s population, FedSoc posted a dominant showing, winning 5 of the day’s 7 events and tying in another,” Johnson wrote.

David Haungs LAW ’26, the president of the Yale Federalist Society, wrote in a statement that he was proud of the Federalist Society’s win.

“Based on the strong performance of the Federalist Society 1Ls and our ongoing recruiting e orts, I expect that trophy to remain in conservative hands for years to

come,” Haungs wrote, referring to first-year law students.

Organizers said they hoped the event would mark the beginning of renewed cooperation between the two groups, who have co-sponsored Constitution Day events for two years in a row.

“I super hope so,” Nurick said when asked if the event would foster a better relationship between the Federalist Society and ACS.

The Federalist Society was founded in 1982 at Yale, while ACS was founded in 2001 at Georgetown University.

Contact HENRY LIU at henry.liu.hal52@yale.edu .

“I’m sick of the sun. It burns everyone.”

BY KELLY KONG AND SOPHIA LE CONTRIBUTING REPORTERS

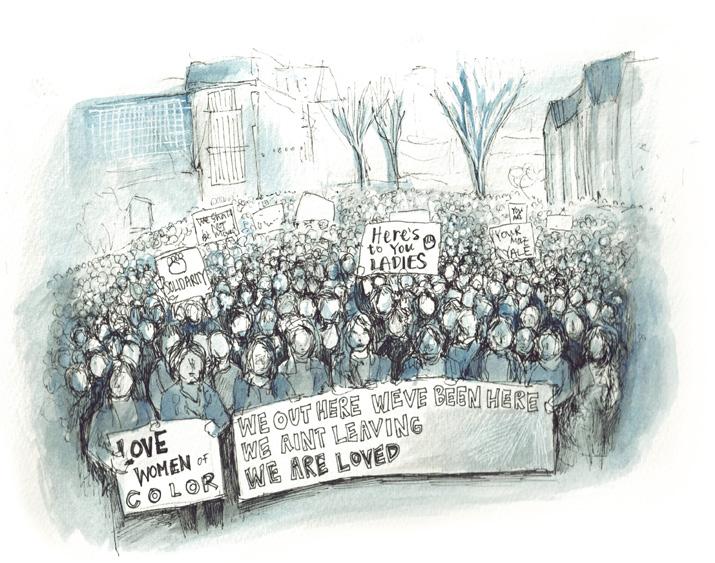

Unidad Latina en Acción hosted its 15th annual Día de los Muertos celebration on Saturday at Bregamos Community Theater, followed by a parade through Fair Haven.

The parade was dedicated to the 20 migrants who, according to NPR, have died in U.S. Immigration Customs Enforcement’s custody in 2025.

“Everybody’s afraid. There are a lot of issues convincing people to be on the streets,” John Lugo, the co-founder and community organizing director of ULA, said. “People should know that we’re here, we’re going to stay, and we’re not going to stop bringing the good stu that we bring to the community of New Haven.”

Originating in pre-Columbian Mexico, Día de los Muertos celebrates and honors deceased loved ones by welcoming their spirits back for a brief reunion. Saturday’s festivities included face painting, Latin fare, music and dance, as well as a community “ofrenda” — an altar honoring departed friends and family members — dedicated to people who died in ICE custody.

According to ICE’s official website, “any death that occurs in ICE custody is a significant cause for concern. ICE prioritizes the health, safety and well-being of all aliens in its custody.” ICE also “employs a multilayered, interagency approach when a detained alien passes away in ICE custody,” the website reads.

In light of the federal government’s increased deportation e orts since President Donald Trump took o ce, Mayor Justin Elicker joined the hundred participants in the parade to demonstrate his support for the local

immigrant community, he said.

“The Trump administration is very actively attacking the immigrant community, particularly residents that are undocumented,” Elicker said. “That is not reflective of New Haven’s values, and we’ve done a lot to fight back on that.”

State Senator Gary Winfield, who represents parts of New Haven and West Haven, said that it is especially important for elected officials to show up for their constituents in person this year.

“A day of celebration, I think, is needed when you’re dealing with all of those terrible things,” Winfield said. “To have a period of time of celebration and release can go a long way towards helping people to continue fighting.”

Because immigrant communities are facing increased surveillance and the threat of deportation, Lugo said that ULA conducted heavier recruitment among American citizens and local politicians for the festival.

“That way, we create some kind of safety net,” Lugo said. “It’s important for the community to see that we’re getting the support, and not everybody’s a Trump supporter.”

Kay McAuliffe, a member of Connecticut Civil Liberties Defense Committee, showed up with fellow members of her organization, hoping to make the event feel larger in scale and less vulnerable, she said.

“It’s a scary time to have a cultural celebration,” McAuli e said. “We’ve lost community members, and we have to fight for the people who are still here and fight so that this doesn’t keep happening.”

During the parade, several attendees wore costumes and makeup to celebrate both the living and the dead.

“I made my skirt with the things

that are from myself, like you see the eagle? It’s my freedom,” attendee

Antonia Agular said.

Agular has been participating in the parade for the past seven years since immigrating from Puebla, Mexico, she said. This year, she also embroidered spiders, scorpions, and dragon flies onto her dress.

“They say when this dragon flies around it is because their spirits that are dead are around or an angel is present,” Agular said.

“That’s why I carry them.”

Participants wore costumes not only to honor loved ones, but also to address

their frustration with the Trump administration’s immigration policy. At the head of the parade, the leader of the crowd wore a dress with a long train embellished with flowers, skeletons and skulls. A poster extending from the top of her dress displayed, “Ni El Presidente Trump se salva de la MUERTE (Not even President Trump is safe from death).” Briam Timko, a volunteer coordinator for ULA, said that every one of ULA’s public parades is also a protest.

“We’re saying, ‘We’re here. We exist. We’re not going anywhere,’” he said. “Right now, honestly, being a migrant openly is more or less a protest in this country because they’ve criminalized it.”

More than 100 people marched in the parade starting from Blatchley Street up to Lombard Street, down to Woolsey Street and back to Bregamos Theater.

Contact KELLY KONG at kelly.kong@yale.edu and SOPHIA LE at sophia.le@yale.edu

BY NICK CIMINIELLO STAFF REPORTER

New Haven Restaurant Week, organized by Market New Haven, has expanded to two weeks this year — lasting from Sunday, Nov. 2, to Saturday, Nov. 15.

The event features a variety of cuisines, including American, Belgian, Spanish, Italian, Peruvian and Mexican. Most of the restaurants featured are in the city’s downtown area, but restaurants in other neighborhoods such as Wooster Square, Long Wharf, Westville and East Rock are included as well. For the two weeks, participating restaurants have special menus at set prices for lunch or dinner.

“Each year, New Haven Restaurant Week showcases the talent and creativity of our chefs and restaurateurs,” Bruno Baggetta, the chief marketing officer of Market

New Haven, said in a news release.

“Expanding to two weeks gives both restaurants and guests more opportunities to enjoy everything New Haven’s dining scene has to o er.”

New Haven’s was the first organized restaurant week program in Connecticut, having been in operation for 18 years, according to Market New Haven. Initially focused on the downtown dining scene, it has expanded to involve restaurants throughout the city.

In order to deal with the increased traffic, The Shops at Yale will offer free two-hour parking with a receipt for $50 or more from any participating restaurant. During lunch, Park New Haven will also o er a flat $6 parking rate in its Crown Street and Temple Street garages.

Some restaurants will o er both a two-course lunch and three-course dinner at set prices, while others will

only o er dinner. The restaurants o ering dinner for $55 per person are 80 Proof American Kitchen & Bar, Jack’s Bar and Steakhouse, John Davenport’s, Melting Pot, Olea and Zinc.

Those offering dinner for $45 are Barcelona Wine Bar, Camacho Garage, Encore by Goodfellas, L’Orcio and Tre Scalini. Eight restaurants will o er both lunch for $25 and dinner for $45: Ca e Bravo, Casanova, Chacra Pisco Bar, Geronimo Tequila Bar & Southwest Grill, Il Gabbiano, Pacifico, South Bay and Villa Lulu. Finally, those o ering lunch for $25 and dinner for $55 are Atelier Florian, BLDG at Hotel Marcel, Harvest Wine Bar and Heirloom. Market New Haven partners with the city to promote local tourism.

Contact NICK CIMINIELLO at nicolas.ciminiello@yale.edu.

BY ESMERALDA VASQUEZ-FERNANDEZ

CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Trending travel destinations worldwide for next year include far-flung locations like Limón, Costa Rica, Madeira, Portugal — and New Haven.

A report by Skyscanner, a British search aggregator, found that online searches for New Haven spiked by 39 percent this year — from January through June compared to the same period last year — earning the Elm City a spot on its list of 10 top travel destinations. City and state officials and a local pizza expert attributed this increased interest in New Haven to its thriving pizza industry.

“People from all over the world — England, Russia, Canada, Australia, South Africa and all of the states — come for New Haven pizza,” Colin Caplan, creator of culinary entertainment company Taste of New Haven and an organizer of September’s Guinness World Record-breaking Apizza Feast, said.

Caplan noted that although New Haven has been informally known as the “Pizza Capital of the United States” for years, the city officially received this title from its own U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro in a congressional statement on May 22, 2024.

In September, Caplan spearheaded New Haven’s 10th annual Apizza Feast, a downtown celebration of the city’s iconic style of pizza. The event broke the Guinness World Record for the largest pizza party, with 4,525 participants. The event generated attention from news outlets across the country, drawing more attention to the city.

Anthony Anthony, Connecticut’s chief marketing officer, works with a team of 16 employees to promote the state’s brand and, among other goals, promote travel to Connecticut. Anthony said Connecticut’s budget for pushing tourism is 4.5 million dollars. Last fall, the state updated highway signs to read “Welcome to Connecticut, Home of the Pizza Capital of the United States.” Connecticut launched pizza license plates in the spring to promote travel to New Haven.

Anthony described his team’s work to promote travel to Connecticut as a “labor of love.”

“We care deeply about the small businesses,” he said. “Connecticut has the biggest number of independent restaurants.97percent ofthemareownedindividually. So that is one thing that makes Connecticut so great, the village of Connecticut — we still have that small intimacy and sense of belonging.”

Michael Piscitelli, New Haven’s

economic development administrator, cited the city’s pizza industry and other attractions as increasing interest in the city.

“Globally significant museums and the meaningful nature of innovation here in the city is driving New

“That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

BY GILLIAN PEIHE FENG CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

The Yale Artists Cabaret, an undergraduate performance group, will perform in the O Broadway Theater this Friday.

“On the Verge,” will feature sixteen songs, spanning a diverse range of genre and style across the musical theater canon. Performance forms include solos, group numbers and one opening song with a full ensemble.

“The theater space of YAC has truly been so welcoming and has taught me so much about the art of performance,” performer Catinca Balasov ’29 wrote in an email.

The show is produced by executive director of the Yale Artists Cabaret Abby Asmuth ’26 and co-directed by Benjamin Jimenez ’27 and Nneka Moweta ’27.

In an email to the News, Moweta discussed the meaning of the show’s title “On the Verge.”

“Our theme this year is all about the crash out musical theater numbers and the Act 1 ending songs,” Moweta wrote.

“Iconic crash out numbers have been making a comeback lately in the musical theater world like ‘With One Look’ or ‘Sunset Boulevard’ from the musical Sunset Blvd. or ‘Rose’s Turn’ from Gypsy. It only feels right to do this theme now.”

Moweta’s interpretation was echoed by performer Angel Wilson ’29, who will be singing “Dust & Ashes” from “Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812,” a musical written by Dave Malloy and based on Leo Tolstoy’s novel “War and Peace.”

According to Wilson, the show explores breaking points and the ways people interact with pres -

sure, elements that prompted the psychological transformation of the character he will be portraying in his song.

“While on the verge, he’s forced to evolve in a truly remarkable way,” Wilson wrote.

Balasov will be performing in the show’s opening ensemble, which she refused to spoil. She will also be singing “Dead Mom” from “Beetlejuice,” a musical by Eddie Perfect.

“Some of the greatest songs in musical theater come from points of emotional and mental breakdown — from being ‘on the verge,’” Balasov wrote. “Without spoiling too much, in my own performance, I interpret this as an unravelling of built-up tension in my character, and the song is a chance to channel that ‘snap.’”

Melany Perez ’26, the graphic designer for “On the Verge,” reflected on arranging visual elements for a cabaret show, confessing that she initially had di culty finding visual elements that fit into the show’s exploration of mental breakdown.

“Honestly it was a struggle to figure out what visual element to use that wasn’t too o -putting,” Perez wrote. Perez added that the final visual designs “focused more on not exactly depicting anger or sadness but more of a blurred emotion, an in-between.”

According to Motewa, the show’s lighting and costumes will follow a red and black color scheme, creating a dark-noirlike aesthetic. Also working as the show’s choreographer, Motewa discussed the role of dance in the production.

Experienced in choreographing for performances of a larger

‘Marseille’ explores friendship, nostalgia

BY LENA KATIR CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Written and directed by Charlie Nevins ’25 and produced by his younger brother Jesse Nevins ’28, “Marseille” follows a group of recent college graduates as they navigate romantic tension, nostalgia and the uneasy transition into adulthood.

Charlie Nevins, a senior in Davenport College, first wrote the play for a class last year. The inspiration, he explained, grew in part from his own anxieties about life after Yale.

“It’s about people our age, played by people our age,” he said. “I hope the audience can recognize parts of themselves in it — the worry about growing up and leaving.”

Marseille captures the liminal moment between student life and adulthood, when everything feels both familiar and unsteady. The production will run from Nov. 6 to Nov. 8 in the Saybrook Underbrook, inviting audiences into a world that feels, as Nevins describes it, “a little too close to home.”

That sense of vulnerability guided the production. Jesse Nevins, who oversaw the production and set design, wanted every visual detail to deepen the sense of authenticity. An self-described interior-design enthusiast, Nevins described building the set as one of his favorite parts of the process.

“We wanted the audience to feel like they are with the characters,”

he said. “Everything — down to the choice of posters, plates, carpets and alcohol — was carefully picked.”

For stage manager Nava Feder ’27, what sets “Marseille” apart from other student theater experiences is its intimacy.

“It’s written by a Yale student who’s about to graduate and really speaks to the minds of people our age,” Feder said. “At its core, the audience will feel the vulnerability and stress the characters are going through in this stage of life.”

Beyond the visual design, “Marseille” is the product of what cast and crew members described as a deeply collaborative process. The Nevins brothers emphasized that the play evolved through conversation and active feedback, which collectively sharpened the dynamic that unfolds on stage.