BY ASHER BOISKIN STAFF REPORTER

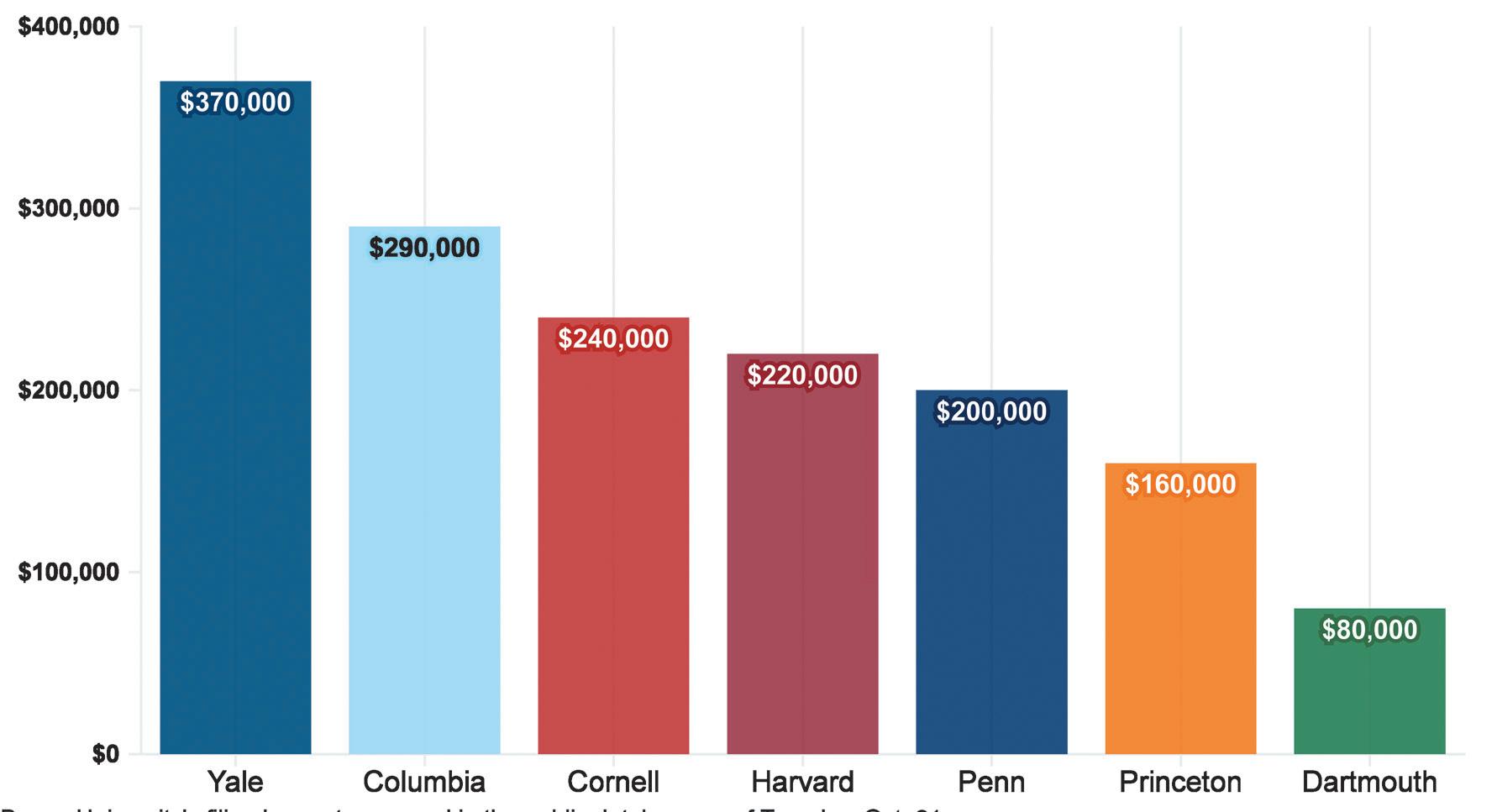

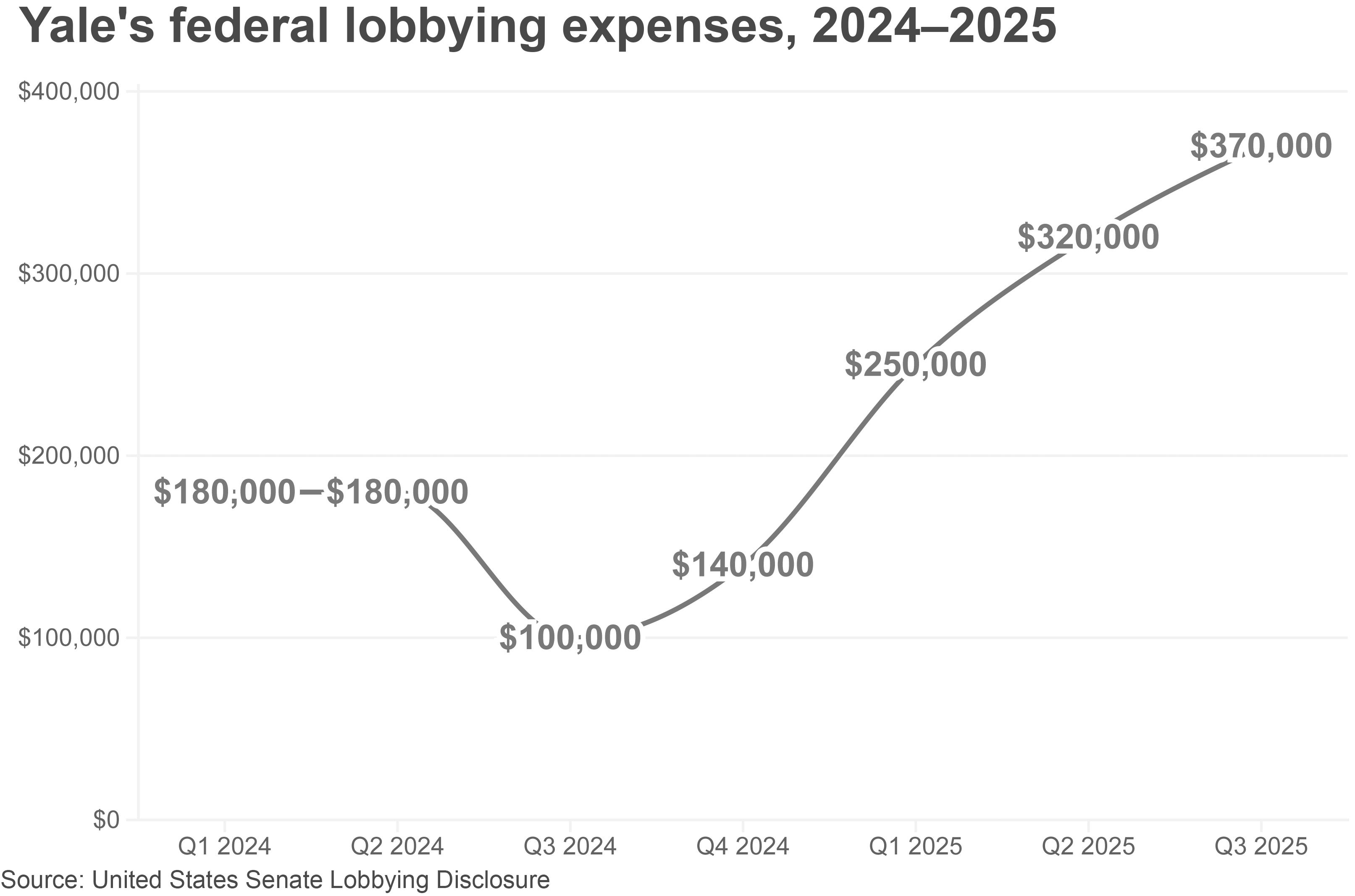

Yale spent $370,000 on lobbying the federal government during the third quarter of 2025 — its highest quarterly total this year and an increase from the $320,000 it reported over the summer — according to new federal disclosures filed Monday.

That brings the University’s total lobbying expenditures for 2025 to $890,000, extending an upward trend as Yale expands its engagement in Washington amid threats to its endowment and research funding. Yale also spent more this quarter than the six other Ivy League universities whose lobbying disclosures were available — all but Brown University.

“The university works to communicate higher education’s

BY LEO NYBERG CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

The committee of professors assembled by University President Maurie McInnis to examine declining trust in universities kicked off a series of listening sessions Wednesday to hear commentary from students and staff.

The Committee on Trust in Higher Education, whose formation McInnis announced in April, plans to publish a report at the end of the academic year with findings and recommendations. In an interview with the News last November, McInnis said that declining trust in universities was one of her top concerns.

“Our mandate is a little bit more the external trust question,” committee co-chair and history professor Beverly Gage ’94 said in an interview. “But it seems pretty intimately tied to the campus climate and people’s own bonds of trust with each other here.”

The committee has not yet decided what to focus on, Gage said, but the group — which consists entirely of tenured faculty — will consider suggestions from the listening sessions to determine its focus.

According to Gage, participants brought up issues of internal trust

impact and Yale’s mission and priorities to legislators on both sides of the aisle,” Richard Jacob, the associate vice president for federal and state relations, wrote in a statement to the News. “We are also sharing the ways in which Yale is addressing problems across American society.”

The University spent $250,000 in the first quarter of 2025 and $320,000 in the second.

Yale ranks at the top of the pack among Ivy League institutions for lobbying expenditures in quarter three. Columbia reported $290,000, followed by Cornell with $240,000, Harvard with $220,000, Penn with $200,000 and Princeton with $160,000. Dartmouth spent $80,000. Brown’s filing had not yet appeared in the public database as of Tuesday.

Dartmouth and Yale are the only Ivy League universities not yet hit with direct funding cuts by the Trump administration.

Yale’s latest report shows that the University’s lobbying targeted legislation related to taxes, student financial aid and federal research funding. That includes the Republican-backed “One Big Beautiful Bill,” which raised the tax on endowment investment returns from 1.4 to 8 percent for Yale and other similarly wealthy universities.

“Since last year, the university has increased its engagement with government officials – opening an office in Washington, D.C., and adding more in-person meetings for the president with government officials in Washington, D.C,” Jacob wrote.

BY REETI MALHOTRA STAFF REPORTER

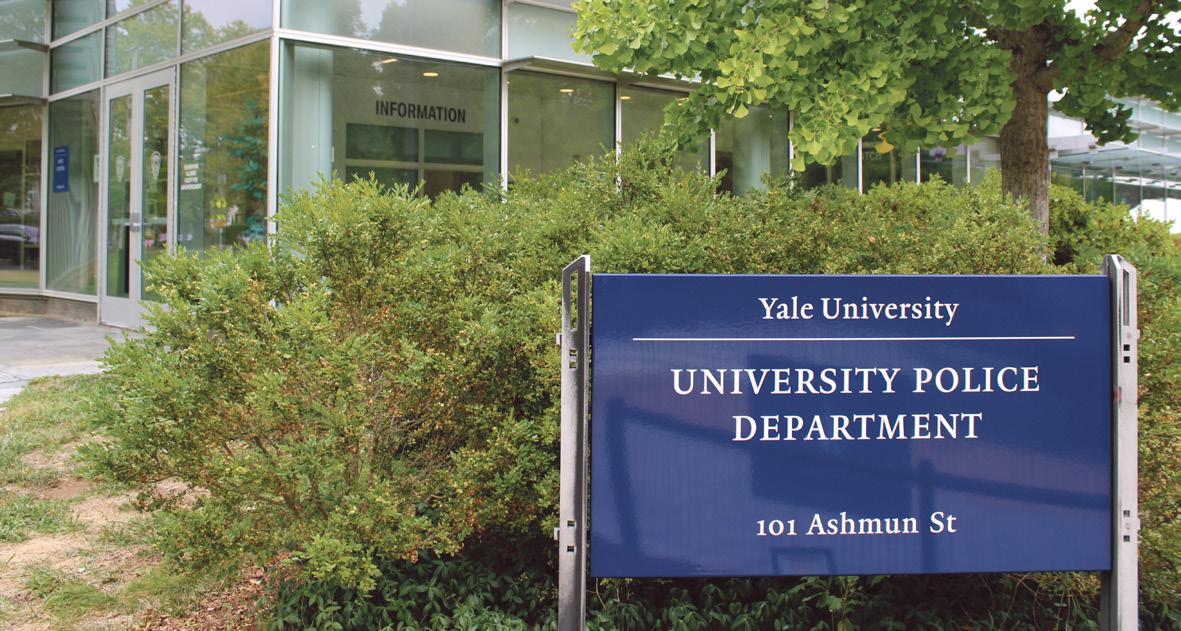

The Yale Police union ratified a new contract agreement with the University last week, ending over two years of tense negotiations.

Yale has not had a contract with its police union since June 2023, when the previous one expired. The new contract will be in effect until June 30, 2028. It marks a major breakthrough after years of fraught back-andforth between the Yale Police Benevolent Association, or YPBA, and Yale negotiators.

The two parties had been at an impasse since November 2024, when the University presented its “Last, Best and Final Offer” and rejected the union’s counterproposal a month later.

Yale negotiators’ refusal to schedule continued negotiations in May prompted the union’s members to vote unanimously to authorize a strike in June. Though

no such strike occurred, the authorization marked a low in the collective bargaining process.

“I am pleased to announce that Yale University and the Yale Police Benevolent Association have reached a new contract agreement that continues to promote the safety and security of the Yale campus,” Joe Sarno, Yale’s head of union management relations, wrote in a statement on Tuesday afternoon.

Union leaders were ambivalent about the latest offer from Yale, Mike Hall, the police union’s president, wrote in a Tuesday email to the News, but members voted to ratify the contract last Wednesday, Oct. 15.

“Unfortunately, the collective bargaining process was contentious from the start, with Yale playing hardball and employing union-busting tactics,” Hall wrote.

In particular, Hall expressed concern that the pay increases in

BY ELIJAH HUREWITZ-RAVITCH STAFF REPORTER

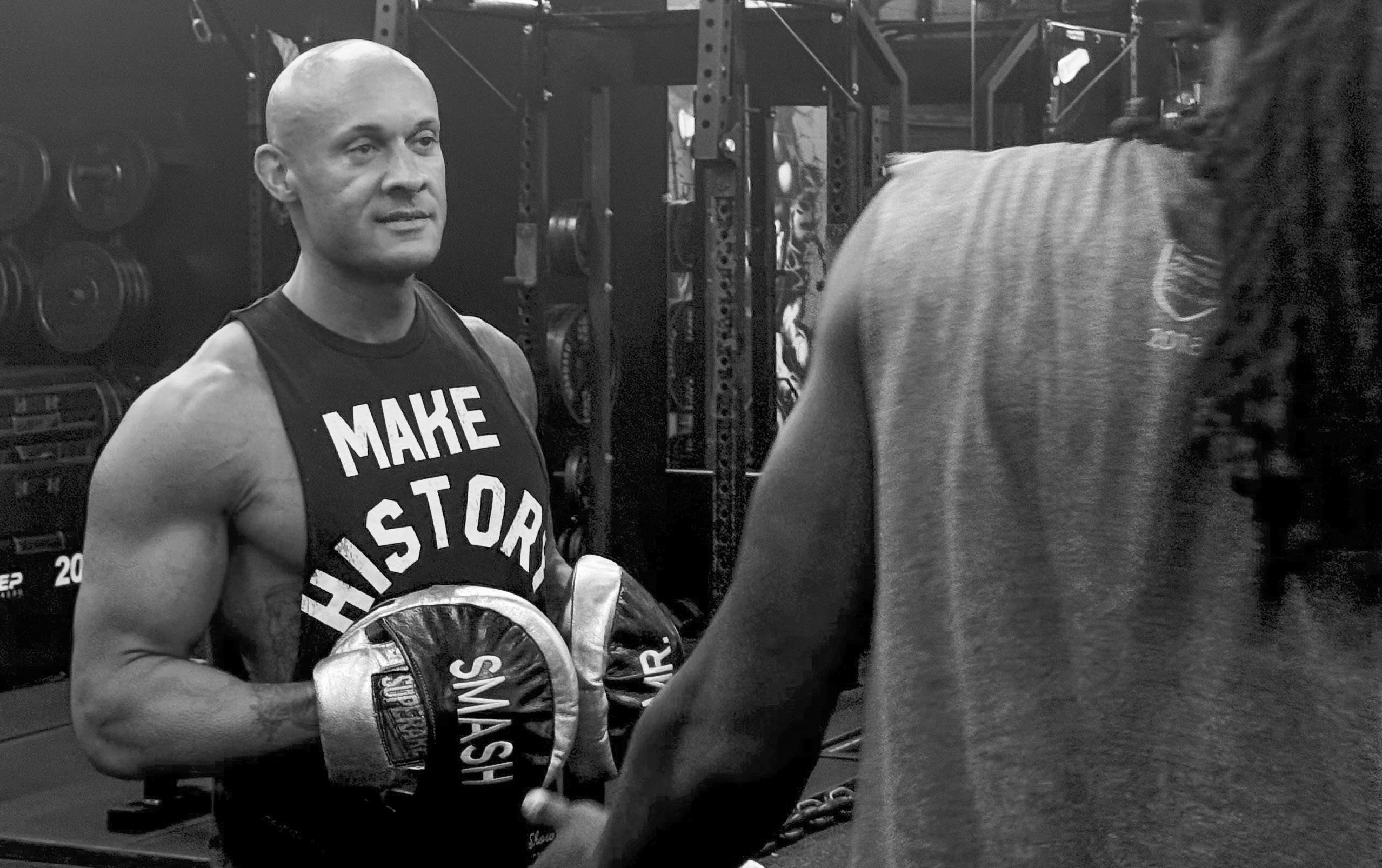

Steve Orosco likes being the “black sheep.”

On a sunny Friday afternoon recently, the 44-year-old businessman, ex–mixed martial arts fighter and Republican candidate for mayor of New Haven, laid out a hypothetical scenario to illustrate his point.

“There’s two rooms with a bunch of venture capitalists in both rooms,” he said. “Room A has one hundred African Americans.

Room B has one hundred white people. I’m walking in the white room every single time, because I’m gonna be the one person that’s different. And everyone in that

room is gonna say, ‘Yo, who is this guy, and why is he in here?’”

After three failed runs for state or local office, Orosco is used to hearing that question. He faces an uphill battle as the Republican challenging the incumbent Democratic mayor, Justin Elicker, in a deep-blue city.

Early voting in the election began on Monday. In interviews with the News and at a mayoral debate last month, Elicker has criticized Orosco for a lack of active engagement in New Haven’s civic life and defended his own record on education, affordable housing and public safety.

But Orosco is undaunted, fueled by an unrelenting desire to win.

“Going into the Democratic machine,” he said, “people are like,

‘You’re crazy.’ That’s all right. I like being David versus Goliath.” Orosco comes from a mixed-race household. His mother, who is white, was raised in what he described as an upper-middle-class family in Taunton, Massachusetts. Her parents “disowned” her when she decided to marry Orosco’s father, an immigrant from Trinidad, and for several years did not allow him in their house, Orosco said. He was raised in Newport, Rhode Island, where his mother worked as a nurse and his father as a bouncer and salesman.

At age 8, Orosco began wrestling — the pursuit that “made me the man I am today,” he said.

BY JAEHA JANG AND OLIVIA WOO STAFF REPORTERS

Directed Studies, Yale’s yearlong Great Books program for firstyear undergraduates, could expand by as much as 25 percent next year, Yale College Dean Pericles Lewis said in an interview.

On Wednesday, Lewis said Yale intends to offer as many as 10 discussion sections instead of the current eight, which would expand the total program size from 120 students to approximately 150. Lewis attributed the expansion of Directed Studies, often referred to as DS, to the program’s popularity, which reached new heights this year with the highest waitlist in known records.

“I hope to expand the number of slots in DS because DS is popular — and rightly popular,” Lewis said. “We’re in the process of hiring the faculty for next year to make that possible.”

The proposed plan drew generally positive responses from the Directed Studies community, though faculty members emphasized that the small seminar sizes are part of the program’s essence. The program provides a survey of the Western canon through three courses each semester on historical and political thought, literature and philosophy.

This year, more than 110 first years were waitlisted for the program. Waitlisted students previously told the News that upperclassmen told

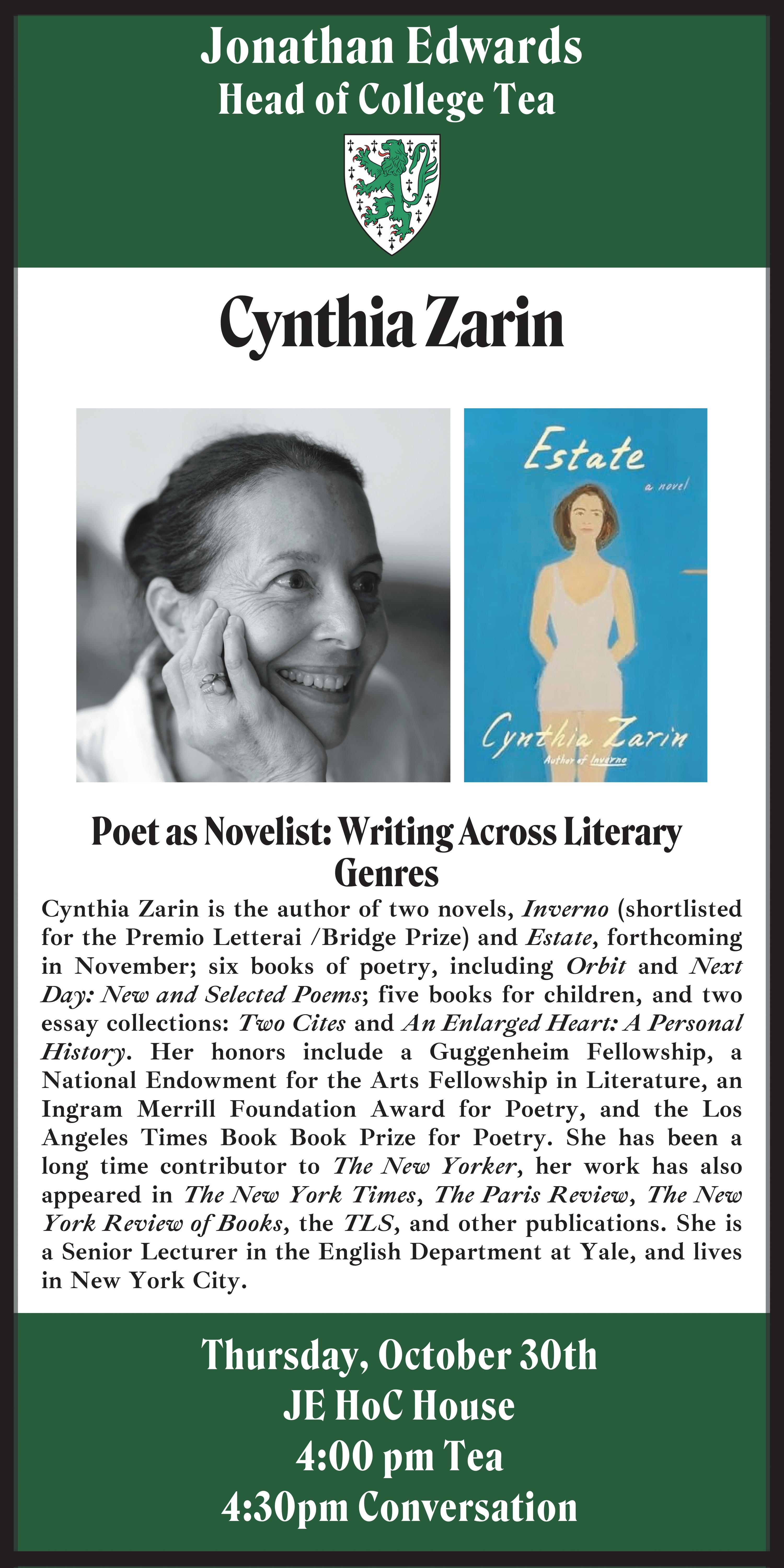

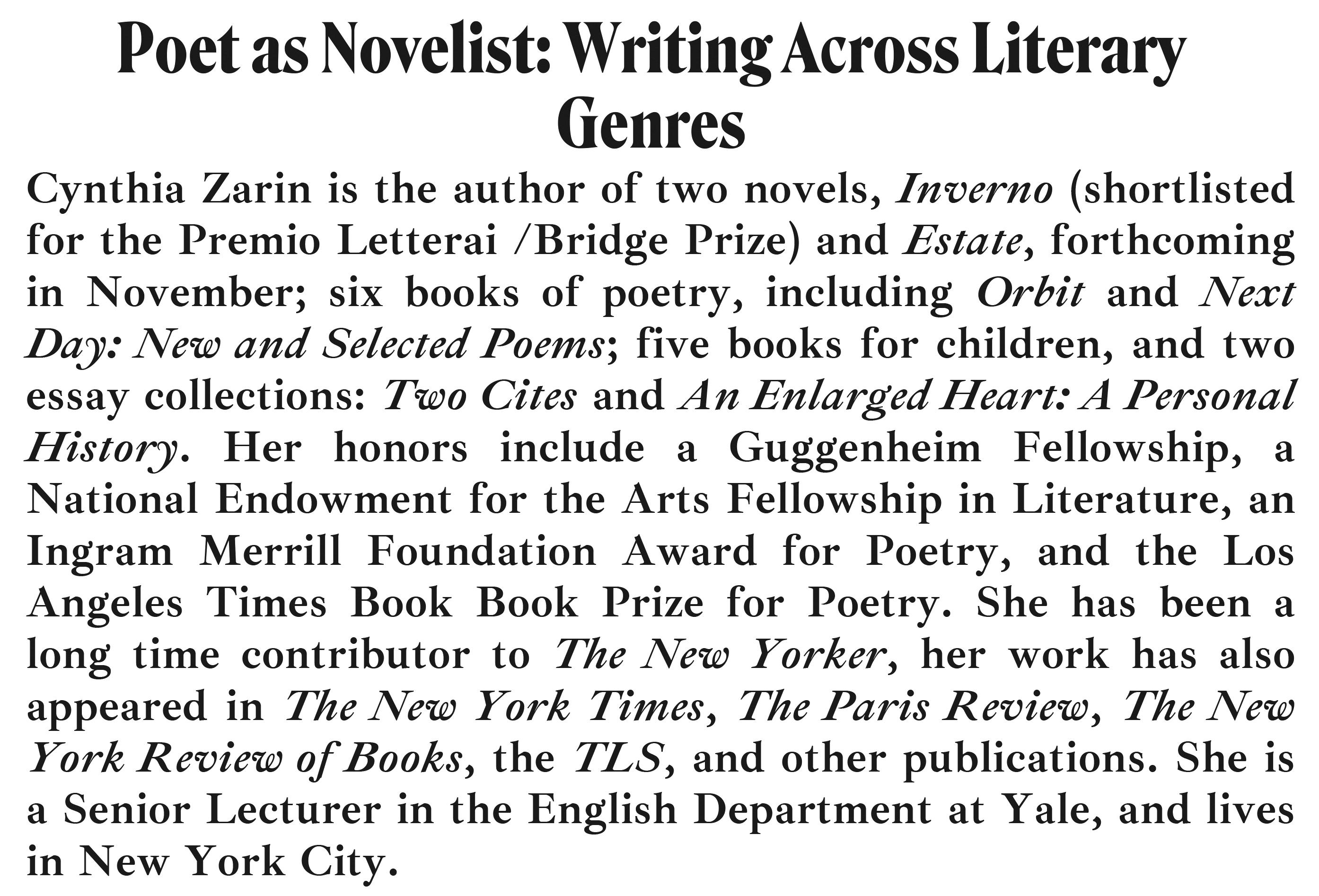

October 24, 2016 / Student Teams Up with Two-Star Michelin Chef for Exclusive Dining Experience

Abdel Morsy ‘17 partnered with Shin Takagi, head chef of the two-star Michelin restaurant Zeniya in Kanazawa, Japan, to host an eight-course Japanese dinner for 12 guests in New Haven. The event celebrated Morsy’s collaboration with Takagi and marked the one year anniversary of Stickershop, Morsy’s art-focused dinner series featuring musicians, chefs and designers.

Morsy first met Takagi while working at Zeniya the previous summer and invited him to co-host the event, where dishes ranged from deep-fried sesame tofu to raw seafood and handmade soy ice cream. Yale musicians performed live, and attendees received custom-designed stickers for the occasion. One guest described the night as “hands-down amazing,” blending culinary artistry with New Haven’s creative community.

By Elijah Hurewitz-Ravitch

I met Steve Orosco for lunch on a sunny afternoon at P&M Deli, where he ordered a chicken pesto sandwich and mentioned to me that he was an intermittent fasting adherent. Although we were in East Rock, which Orosco called “enemy territory,” several people approached him to offer words of support. Eventually, after Orosco and I had discussed MMA, Black conservatism, and segregation in New Haven — among many other topics — we drove to Westville Manor, a dilapidated public housing development on the northwest edge of the Elm City. As Orosco walked its grounds with Perry Flowers, the Republican candidate for Ward 30 alder, curious heads popped out of concrete homes to say hello. But Orosco was on a tight schedule: he had to be at the Milford gym he co-owns to train a twelve-year-old future fighter. Orosco is fond of saying that getting into the cage is “human chess” — not so different, perhaps, from running a city.

American universities are in trouble, and there is much pressure from the outside to change. Unless you are so conservative as to believe that things are fine as they are and no change is needed, then why not consider changing from within rather than from without? The time has come to radically rethink the curriculum and structure of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, whose mission, according to a statement adopted in 2020 by the FAS Senate, “is to preserve, advance, and transmit knowledge through inspiring research, teaching, and art.”

Let me put forth a strong thesis: Yale ought to reassess its curriculum and the departmental structure that organizes the transmission of knowledge along the lines of a global core that would put us at the forefront of American universities and address many of the issues that currently inhibit us from being all we can be.

Such a curriculum would work across departmental lines and even schools, and would be structured by multiple perspectives upon important issues that prepare students for life in the twenty-first century — such as family, religion, community, justice, ethics, politics, the good and bad uses of technology, among other topics. Such a project would encourage civil discourse among faculty who would be encouraged to consider what and how they teach and how their teaching intersects with other areas of inquiry.

The shared nature of a certain number of core required courses

for students in their first two years would work towards the making of community via intellectual means rather than through class, religion, gender, race or ethnicity, which have served to weaken rather than strengthen a sense of shared belonging.

There are certain moments at which universities are called upon to think about purpose: what they do and how they do it. This was the case during the Interwar years when a few institutions — Columbia, the University of Chicago, St. Johns — established a core curriculum. It was again the case after World War II when the research university took a quantum leap forward and when colleges thought about the shape and methods of undergraduate education.

Harvard took the lead with its celebrated General Education in a Free Society, also known as the Harvard Redbook, beginning in 1945. My own alma mater, Amherst College, followed with a radical rethinking of the goals of a liberal education along with the means of achieving those goals. Yale in 1946 took a small but significant step in the direction of curricular reform with Directed Studies, which originally offered about 10 percent of firstand second- year students a curated constellation of courses thought to be necessary for future leaders of the free world. All of these programs along with many others placed the rethinking of curriculum at the center

of evolving institutional identity. It is time for Yale again to take the lead among American universities and to rethink in full the shape

IT IS TIME FOR YALE AGAIN TO TAKE THE LEAD AMONG AMERICAN UNIVERSITIES AND TO RETHINK IN FULL THE SHAPE AND CONTENTS OF ITS UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION.

and contents of its undergraduate education. This is a golden opportunity to assess what belongs in the curriculum and what does not, as well as to reorganize how a university like Yale is structured.

The college is currently governed by a departmental system, which is thought to be a good way in which to manage university resources. Each department has its budgetary allocation and is responsible for staying within budget.

Yet, this organizational model has become unfair and outmoded. Some departments have developed private resources not available to others. Current departmental structure does not best articulate what an education is or should be today or will be tomorrow. Departments are defined by disciplines, and disciplines have changed over time. Foreign literature departments grouped along national lines once corresponded to the colonial empires of the late nineteenth century, while the literatures of every area of the globe have more in common than the particular languages that separate them by department. Almost every department in the humanities teaches some version of history, uses the visuals of art history and has adapted to the demands of digital media and artificial intelligence. Departments are not agile bodies. They are ruled by a certain selfreproducing defensive inertia that leads them to respond neither to developments within the field they originally designated nor to changing relations between fields.

New areas of inquiry have emerged such as Film and Media Studies, which are not so hidebound by nationalist interests. The Humanities Program has consolidated disciplinary differences in a way that also reflects student interest in studying across departmental lines. Nor is the Humanities Program unique. Yale has spawned major programs and certificates — Mathematics and Philosophy, Ethics, Politics and

Economics, Human Rights Studies, Translation Studies. These stretch departmental bounds and correspond to educational pairings within a world of disciplines changing internally and in relation to each other.

We are in some ways unique, given our strengths in the humanities, social sciences, and natural and physical sciences. The consequences of avoiding self-examination are clear: from my observations, science departments which did not reorganize some three or four decades ago to reflect the revolutionary change in the relation between biology and chemistry, and even physics, did not do well.

A response to the current crisis that begins with the matter of education and not government funding, free speech, institutional neutrality, or international diversity offers a chance for those involved in the enterprise of education — faculty with some student input — to seize the initiative in redefining ourselves instead of simply reacting to attacks from without. It is something that should have been undertaken decades ago. It is not too late for Yale to do something radical that might also, by taking charge of the thing we know and do best, do more than anything else I can imagine to restore public trust in higher education.

HOWARD BLOCH is Sterling Professor of French and Humanities. He can be reached at howard.bloch@yale.edu.

Earlier this month, a colleague sent me a story from Campus Reform, a right-wing website I know well. As someone who studies the strategies and politics of the contemporary right, I am familiar with its usual fare: breathless “exposés” of campus decadence, liberal overreach and the alleged persecution of conservatives. The formula is predictable. But this particular story stopped me cold. It claimed to cover a recent meeting of our American Association of University Professors chapter at Yale, in which faculty from several other universities joined us over Zoom to discuss the settlements that the Trump administration had sought to impose on their institutions. A core tenet of academic freedom is protection from unlawful government coercion, a principle that faculty across the political spectrum hold dear. The meeting was widely publicized and open

to all, with nearly 70 professors in attendance on Zoom and in person. Yet the Campus Reform story presented the meeting as a clandestine

Y ET THE CAMPUS REFORM STORY PRESENTED THE MEETING AS A CLANDESTINE EVENT WITH A SINISTER AGENDA.

event with a sinister agenda. The headline read, “Yale AAUP leads panel to prepare for a Trump admin-led Title VI investigation.”

That description was entirely false. There was no discussion of preparing for a Title VI investigation.

But the real surprise came from the accompanying image. The site appeared to have taken a photograph originally published by the News, where I was shown standing at a podium introducing the discussion, and replaced it with an altered, possibly AI-generated version.

In this fabricated scene, the room was dimly lit and on the projection screen appeared several AI-created graphics, including an image of Donald Trump and a slide that displayed the fabricated title text from the headline. Nothing in the picture was real.

Much of the article mirrored the News’ story and included quotations invented, mischaracterized or taken out of context, as well as false claims. There was no mention that the image was AI-generated. Readers are left to believe that Campus Reform had been present at the meeting and conducted original reporting.

That alone would have been strange enough. But what truly caught my attention was the byline. The author is a recent Yale graduate who wrote for the News, won a major prize from the English Department and interned for several prominent journals. By every measure, she had the beginnings of a serious literary career.

So how does someone like that end up attaching her name to a distorted, AI-padded article on a right-wing propaganda site?

When I attend conservative conferences for my research, I often ask participants what drew them to these movements. Their stories are usually about experience and belief. But this case felt different and far more transactional. It reveals how wealthy outside groups on the right are reshaping the political terrain of higher education.

The literary, news and media worlds are contracting. For young writers, breaking in often means years of unpaid internships, endless pitching and uncertain prospects. Campus Reform, by contrast, offers something more immediate. The website

is a project of the Leadership Institute, founded in 1979 by right-wing political operatives, which now brings in nearly $45 million annually from deeppocketed conservative donors. Campus Reform’s business model appears simple: scrape stories from student newspapers and university press releases, attach modified images with menacing faces and darkened rooms and repackage them as evidence of “liberal bias.” Writers are not expected to report or investigate. Campus Reform will pay them and give them a byline simply for feeding the machine.

To be sure, there is a long tradition of conservatives who came of age at Yale, including many prominent figures in the current administration.

WHAT LOOKS LIKE A SILLY LITTLE CAMPUS SIDESHOW OF STUDENTS CHURNING OUT MANUFACTURED STORIES FOR CLICKS AND DONOR DOLLARS IS ACTUALLY A MICROCOSM OF A BROADER RIGHTWING PROJECT.

Historically, conservative students might have gravitated to a right-leaning journal, a legislative office, or a think tank, hoping to develop an intellectual foundation for their ideas. That is not the legacy in which Campus Reform operates. Conservative strategists seem to understand that their agenda on higher education,

including defunding universities, intimidating international students and privatizing loans, has little public support.

What remains for them is spectacle. They rely on the invention of enemies, the creation of crises and the fabrication of offenses that can be used to mobilize outrage. It is fair to call it a grift, not only because it exploits young writers but because it deceives the movement’s own donors and audience, feeding them falsehoods and generating illusions as if they were news.

Attaching such stories to a byline associated with a lauded Yale English major provides a credibility such an article would otherwise lack.

I laughed at the AI version of myself standing in a darkened room before a fake slide with a fake headline. But the laughter stops quickly. That same week, a professor at Rutgers was reportedly fleeing the country with his family after receiving death threats following a smear campaign by the local Turning Point USA chapter.

The grift is not harmless. What looks like a silly little campus sideshow of students churning out manufactured stories for clicks and donor dollars is actually a microcosm of a broader right-wing project. It is a politics that has abandoned ideas altogether and replaced them with simulation.

And for one Yale graduate, that is apparently where a writing career now begins.

DANIEL MARTINEZ

HOSANG is Professor of American Studies and President of the Yale Chapter of the American Association of University Professors. He can be reached at daniel.hosang@yale.edu.

“I must be crazy now. Maybe I dream too much.”

Yale retained Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld during quarter three, which lobbied on “issues related to endowment tax and free speech” and engaged with the U.S. House of Representatives, Senate and White House.

Akin Gump policy advisor Zach Deatherage — who served as legislative director for New York Rep. Elise Stefanik, a Republican, from 2023 to 2025 — lobbied for Yale this quarter. In 2024, after Yale police arrested 47 pro-Palestinian student protesters for trespassing on Beinecke Plaza, Stefanik posted on X that the University’s “failure to protect students is outrageous and unacceptable.”

Akin Gump consultant Lamar Smith ’69, a former Republican congressman from Texas, continued advocating for the University this quarter.

Yale retained Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck in quarter three, which lobbied for “issues related to higher education,” according to its filing. As in quarter two, Brownstein employed lobbyists Evan Corcoran, a former personal defense attorney for Trump, and Marc Lampkin, whom the firm describes as a “veteran Republican lobbyist,” to advocate for Yale.

Yale’s lobbying touched on eight bills besides the “One Big Beautiful Bill.” Seven of the bills — including the “National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2026” — have implications for university research funding, according to the filing.

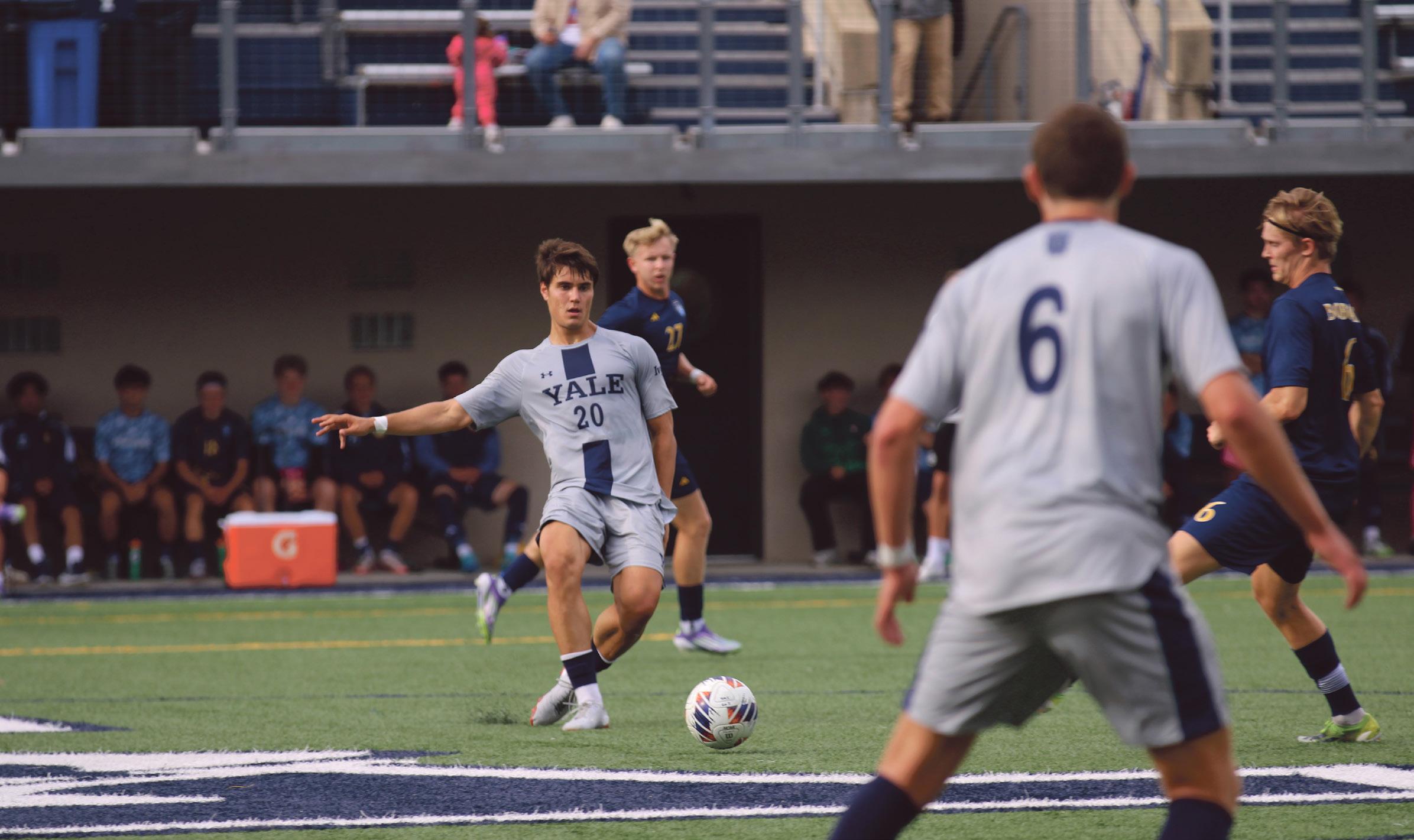

During quarter three, Yale also engaged with the “Student Compensation and Opportunity through Rights and Endorsements (SCORE) Act,” which, according to the filing, contains

“provisions related to name, image, and likeness rights of student athletes in college athletics.”

“Yale has not taken a position on the SCORE Act,” Jacob wrote in his statement. “The univer -

the new contract failed to make up for recent years’ inflation.

“The YPBA brought the proposed Collective Bargaining Agreement to its membership without a recommendation on whether or not to ratify,” Hall wrote. “It believed the wages offered by the University were inadequate to compensate for the record-level inflation which occurred during 2021 and 2022. Inflation reached a forty-year high, with soaring grocery and housing costs.”

The wage increases in the new contract are “generous,” Sarno wrote.

“Since the police union’s last contract expired, Yale has worked diligently to come to this new agreement, which provides generous pay — among the best in the state — along with outstanding and enhanced benefits,” Sarno wrote in his statement.

Sarno insisted that the University had negotiated in good faith.

“The agreement is the result of extensive and thoughtful negotia-

tions by all involved and reflects a fair balance of interests while also achieving long-term sustainability for the university,” he wrote.

“From the outset, the university’s priority has been protecting the safety and well-being of our students, faculty, staff, and visitors.

This contract achieves that.”

In September, the YPBA and University reported that relations between the two organizations were improving after the strike authorization over the summer.

But over parents’ weekend this month, a truck displaying the Yale police badge and signs that read “Yale is a union buster employee” and “Yale doesn’t negotiate. Yale dictates” was seen driving around campus.

In a phone call on Oct. 8, Hall declined to comment on the surge in the union’s advocacy and whether it marked a downturn in negotiations.

The truck’s signage continued a pattern of YPBA advocacy during high-visibility events to drive support for their contract demands. During Bulldog Days this past spring,

more than 30 union members handed leaflets to parents and students outside the Schwarzman Center, imploring them to support a fair contract for “the people protecting you.”

The union had been noticeably quiet during this year’s freshman move-in — a day leveraged by the union for the two consecutive prior years to put public pressure on the University.

Hall wrote on Tuesday that despite the contract ratification, the YPBA’s “experience with the University in this round of bargaining” has prompted the union to “reevaluate its negotiation strategy going forward.”

The union had continued to work under a contract extension agreement after the previous contract’s expiration. However, Hall stated that the union may have to “abandon that practice.”

The YPBA’s previous contract with the University came into effect in 2018.

Contact REETI MALHOTRA at reeti.malhotra@yale.edu.

sity took the introduction of the SCORE as an opportunity to explain Yale’s approach to college athletics.” Yale’s fourth-quarter report, covering lobbying activities

from Oct. 1 through Dec. 31, is due Jan. 20, 2026. Contact ASHER BOISKIN at asher.boiskin@yale.edu.

at Yale, especially as budget constraints cause cutbacks across campus. Around 10 students, faculty and staff attended Wednesday’s private listening session.

“I think it’s really important to include in this report how Yale’s affordability affects how we are perceived on a national scale,” Riley Avelar ’27, one of three undergraduates who participated in the session, said.

The sessions are intended to be small-group discussions about trust in higher education, according to the invitation. Gage pointed to political diversity, cost of education and admissions as issues the committee might address.

In an email to the News, sociology professor and committee co-chair Julia Adams described gathering feedback from Yale students, faculty and staff as “vital for the committee’s work.”

McInnis allowed the committee to choose how they would like to present their findings to the University and the public. According to Gage, the committee has decided to write a report to outline the problem of trust in higher education and propose a set of ways for Yale to chip away at internal and external mistrust.

“Our assumption is that the report is going to be one node

of what we do,” Gage said. “But then once the report comes out, there’s a lot more conversation to facilitate.”

The committee is also set to teach HIST 3127: “Trust et Veritas: The Public Legitimacy of Universities” next semester. According to Gage, the class will engage with primary sources in Yale’s archives to unpack the ways in which American universities have lost public trust.

The committee has previously been criticized for having a faculty-only membership. Gage said the solution to mistrust in higher education has to come from universities, not outside commentators.

“We need to face some of the critiques and problems that we’ve encountered quite seriously and then think about solutions that align with our values, our priorities,” Gage said.

The committee is accepting comments on its website, and they are actively soliciting concerns from outside groups and alumni, according to Adams. Neither Gage nor Adams specified which outside groups have been influential in the committee’s deliberation.

The next listening sessions will be on Oct. 23, Oct. 28 and Oct. 29. Contact LEO NYBERG at leo.nyberg@yale.edu.

“You're

them that it would be easy to get off the waitlist, but that was not the case this year.

Katja Lindskog, the program’s director of undergraduate studies, clarified in an email that the proposed expansion is “very much just an idea that has been suggested to us.”

“We would love for more students to participate if possible,” she wrote, “but we also want to make sure in that case that we get the resources we need to preserve part of what makes DS special, which are the small section sizes and making sure we have enough qualified and passionate faculty teaching to ensure all students can feel as supported, challenged, and inspired as possible.”

Lindskog added that the recent increase in interest in the program is “great news for the humanities in higher education.”

Ruth Yeazell GRD ’69 ’71, who teaches Directed Studies literature and enrolled as a student in the program in 2020, praised the expansion plan.

“I think the increased interest in DS is exciting, and I’m delighted that the College is responding by adding more sections,” she wrote in an email to the News.

Yeazell added that it’s important to preserve the 15-student cap for sections and that she doesn’t expect each student’s experience to change significantly from adding two sections worth of students, “as long as

we can all fit into the HQ lecture hall.”

The program’s weekly lectures are held for the entire cohort in the Humanities Quadrangle’s room L02, which accommodates 187 people, according to a University webpage.

While Paul Freedman, who teaches historical and political thought for the program, wrote in an email to the News that lectures are “already crowded,” he added that he doesn’t think expanding the program would “undermine the overall experience.”

Daniel Schillinger, who teaches historical and political thought for the program, called the proposed expansion a “great idea” — as long as seminar sizes remain small.

“If the students are eager and deserving, why not allow them to join?” he wrote in an email to the News. “The more humanities nerds, the merrier.”

Schillinger also wrote that students’ and faculty’s enthusiasm “fuels” the program, adding that what makes Directed Studies unique from Great Books programs at peer institutions, such as Columbia University’s core curriculum, is its voluntary nature.

Lewis echoed this remark, noting that a required undergraduate core curriculum can limit students’ abilities to explore course offerings.

“For Chicago and Columbia, it’s a big part of their identity, and I always hear from alumni of Columbia and Chicago about what a great experience they had,” Lewis said. “I think having optional cores

like DS works better at a large university with a very diverse set of student interests.”

Anthony Dominguez ’28, a Directed Studies alum and current peer tutor for the program, said that he thinks it is important to make the curriculum more accessible.

“A big problem of this notion of studying the Western canon and being at an institution like Yale is just the inherent tinge of elitism, so if there’s any way to accom -

modate, to democratize, then we should absolutely be doing that,” Dominguez said in an interview.

Dominguez said that opening up the course to additional students is “in line” with making the curriculum more accessible.

Eugenie Kim ’29, who did not get off the program’s waitlist earlier this year, called the proposed expansion “exciting,” although she noted that she is “extremely happy” with her current courses.

“As someone who really wanted to do DS, I think it’s great that more people are able to delve into the literature and enjoy the awesome academic experience,” she wrote in a text message to the News.

The Directed Studies program began in 1947.

Contact JAEHA JANG at jaeha.jang@yale.edu and OLIVIA WOO at olivia.woo@yale.edu.

For a while, though, Orosco planned to fight his way to Wall Street. He went to Pace University and eventually moved to New Haven to work at the Shelton-based Barnum Financial Group and pursue a dual degree at Albertus Magnus College.

But Orosco could not resist the allure of mixed martial arts, or MMA.

In 2009, he moved to San Diego — MMA’s “mecca” — to pursue a career in the sport. He fought professionally until 2015, when he moved to Los Angeles to establish SMASH MMA, a league and events production company. In 2019, he moved back to New Haven’s Morris Cove neighborhood, where his wife had grown up.

Two years later, Anthony Acri, a businessman who is running for Ward 18 alder this year, asked Orosco to run for that seat.

He won just under 40 percent of the vote in the 2021 general election.

In 2022, Orosco decided to challenge then-15-term incumbent Martin Looney for state senator. In that race, and again when he ran last year, Orosco lost by about 55 percentage points.

“You’re not a loser until you quit,” Orosco said. “At some point, you’re not gonna be able to deny me.”

Orosco is upset, he said, by Democrats’ longstanding dominance in New Haven.

“You can’t vote Democrat in New Haven anymore, just like you can’t vote Republican in these places that are in the Deep South,” he said. “When one party reigns for too long, anywhere on the planet, they always fail, always, because they don’t have to earn your vote anymore.”

The biggest hurdle running as a Republican in New Haven — where there are more than 10 registered Democrats for every registered Republican, according to data from the city’s Registrar of Voters office — is finding enough volunteers, Orosco said.

At present, Orosco said that he has four people on his campaign staff. As of Sept. 30, his campaign has raised $21,150. Orosco said that money came mostly from donors outside of New Haven.

With early voting already underway, the race is now entering its final stages.

In interviews with the News and at a mayoral debate late last month, Elicker has voiced his disapproval of Orosco’s social media rhetoric and for what Elicker sees as a lack of sincere engagement in New Haven. And Elicker has defended his record on education, affordable housing and public safety.

For now, Orosco is most focused on mobilizing voters. Tom Goldenberg, the Republican who challenged Elicker in 2023, won 2,322 votes to the mayor’s 10,064. But there are 4,149

registered Republicans in New Haven — and 6,626 residents who voted for Donald Trump in 2024. In the 2021 and 2023 mayoral elections, 12,980 and 13,058 total votes were cast, respectively.

“If you look at that number, somewhere around the 6,500 mark seems to be a magic number,” Connecticut Republican Party Chairman Ben Proto said in a telephone interview.

He said he discussed that target with Orosco over the summer.

“In the past, there’s been a lot of voter apathy,” John Carlson, the chair of New Haven’s Republican Town Committee, said in a telephone interview. “Steve is getting people in his campaign to notice what’s going on, and now they’re more cognizant of the issues. And I think there’s a lot more interest in his mayoral campaign than there’s been in the past.”

If he loses next month, Orosco said he plans to run for mayor again in 2027. But he is confident that “no one’s gonna have moved the needle as much as I have in this election.”

“For the first time in a long time, I’ve seen so many Democrats that are actually nervous,” said Oliver Augustin, vice chair of New Haven’s Republican Town Committee. Augustin clarified in a telephone interview that he was not referring to anyone in particular but “more of a general vibe.” He added that he has noticed that some Newhallville and Westville residents who normally

“would tune out of local politics are taking notice of Steve.”

Orosco traces his “conservative nature” back to the values instilled in him by his father’s parents — “marriage, church, education.”

“Before the Civil Rights Movement, Black America was at its peak,” Orosco said. “That’s when everyone went to church on Sunday. Two-parent home was everything. Mother stayed home, fathers went to work. We wanted education so bad, we risked our lives to go to white schools. We spent all our money within our own community.”

Orosco said he once identified as a conservative Democrat and voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, but he registered as a Republican in 2020.

To be sure, Orosco — who is also running on the Independent Party line — is not a traditional member of the GOP. He said he dislikes the two-party system, is “pro-choice” in regards to abortion and believes in “what a lot of progressives say with ‘tax the rich.’”

The mayoral hopeful wants to be a change agent — to “disrupt the system” — and likened himself to younger Republicans such as the Ohio gubernatorial candidate and former presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy.

As he runs for mayor, Orosco said he has two core priorities: “fully funding the police, and then fully funding education.”

But, he added, “you can’t fund all that stuff unless you audit the city, uncover money.”

He aims to bring a business-minded approach to what he sees as a bloated municipal government.

“We waste money here,” he said. “We’re so central office-heavy and bloated, it’s almost ridiculous.”

He pointed to New Haven having spent over $43,000 on fans a week and a half before the end of the past school year to alleviate high temperatures in buildings without working air conditioning.

A spokesperson for New Haven Public Schools did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Orosco is also determined not to raise taxes — which he said requires building up the local economy. For Orosco, that means development. To begin with, he wants Long Wharf built out.

“I see water taxis going up and down the coast and through Mill River District,” he said. “I see our New Haven Beach, beautiful, having a boardwalk, having restaurants so people can actually use it and create revenue for our city. I see the airport continuing to grow.” Projects like these will create jobs and generate revenue, Orosco said, adding that he would give tax breaks to firms that hired New Haveners below the poverty line.

Orosco wants New Haven to be a place that drivers passing on I-91 and I-95 want to visit.

“We’re more than just pizza,” he added. Although campaigning keeps him busy, Orosco still makes time to train kids to fight at the Milford gym he co-owns.

“There’s nothing like training a kid and pushing them and watching them succeed and win,” he said. He wants to do the same for New Haven.

Despite his three campaigns, Orosco has few ties with the dominant forces in New Haven’s politics. He said that he has not yet spoken with any Yale administrator and that he does not have a relationship with any of its politically powerful unions.

“It’s clearly a tough row to hoe, no doubt about it,” Proto said.

“It’s a heavily Democrat city. But you know, we’ve seen stranger things happen.”

Orosco, for his part, may not want to stop at City Hall.

“I want to be the mayor of New Haven until New Haven is fixed and really moving slow, then maybe I’d be governor,” Orosco said.

The Elm City’s last Republican mayor left office in 1953. Contact

“You’ve been dreaming of the fate of Ophelia” “THE FATE OF OPHELIA” BY TAYLOR SWIFT

BY ISOBEL MCCLURE, JERRY GAO AND ASHER BOISKIN STAFF REPORTERS

Yale is hiring an ombudsperson to provide confidential support to faculty, staff and graduate and professional students regarding concerns about the University environment, President Maurie McInnis announced last Tuesday.

The announcement came in a message addressed to those groups and posted to the president’s office’s website. The ombudsperson will act independently of the University’s existing “procedures and administrative offices,” McInnis wrote.

The role of the ombudsperson, according to McInnis’ message, will be to serve as an impartial actor who informs faculty and staff, as well as graduate and professional students, of their rights under the law and university regulations.

The ombudsperson will report directly to McInnis and will not serve undergraduates, according to the announcement.

“I am prioritizing this role— even during our period of restrained spending—because of the comments and suggestions I have received from all of you,” McInnis wrote. She

cited the community feedback she received during her first year as president, including on “administrative and conflict resolution processes.”

The University is expected to lose $280 million next fiscal year to an elevated endowment tax of 8 percent, signed into law on July 4 by President Donald Trump. On Sept. 30, Provost Scott Strobel, Senior Vice President for Operations Jack Callahan Jr. ’80 and Chief Financial Officer Stephen Murphy ’87 released plans for reduced budget targets and a retirement incentive program for managerial and professional staff.

The establishment of the ombudsperson position comes after years of advocacy from faculty as well as graduate and professional students.

In the spring of 2023, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and School of Engineering and Applied Science Senate, or FASSEAS Senate, convened a committee geared towards advocating for the creation of an ombuds office. Around the same time, the Graduate Student Assembly and Graduate and Professional Student Senate passed a resolution “calling for a University ombuds office.”

Yale has stood apart from peer institutions in its lack of

an ombuds office. The News reported in 2013 that Yale and Dartmouth were the only two Ivy League schools without an ombudsperson. Dartmouth appointed its first ombudsperson in 2022.

Nathan Suri GRD ’25 ’28, the chair of the Graduate Student Assembly, wrote in an email to the News that the group’s executive board applauded the establishment of the position.

“This role will provide graduate students and other members of Yale’s academic populace with direct access to critical resolutions that will improve the academic environment,” Suri wrote.

Saman Haddad LAW ’26, the president of the Graduate and Professional Student Senate, said in a phone interview, that the University’s current conflict resolution system is “very decentralized.”

“An ombudsperson helps you navigate that system, which is otherwise very unclear,” he said.

But he expressed concern about the title “ombudsperson,” noting that students might be unfamiliar with it. While he expects the office may see “limited uptake” at first, he believes that choosing a more accessible name and hiring a “high quality candidate” could help overcome that challenge.

Yale has several University-wide offices and centers intended to address misconduct, discrimination and complaints, including the Office of Institutional Equity and Accessibility, or OIEA, the Title IX Office and Sexual Harassment and Assault Response and Education Center, or SHARE.

Students and staff who have contacted the OIEA have criticized the office for slow responses, opaque processes and disappointing results.

In 2019, the office dismissed a Yale Hospitality employee’s allegations against a former hospitality director without meeting with the employee, a News investigation last year found. The office found that the former administrator had committed “severe” sexual misconduct in another incident in 2023, and he left Yale last year.

Prior to her role as Yale’s president, McInnis served as president of Stony Brook University, as well as in administrative positions at the University of Texas at Austin and the University of Virginia. All three other universities had an ombudsperson role during her time there.

“The ombudsperson will serve as a neutral advocate for fair treatment and processes, operating under strict confidentiality and helping faculty, staff, and G&P students understand their rights and options based on all laws and university policies and procedures,” McInnis wrote in the announcement last week, referring to graduate and professional students.

She added that the official will also “provide informal dispute resolution services” and “offer referrals” to related resources.

Merle Waxman, who was the ombudsperson for the School of Medicine for over 30 years, endorsed the change in an email to the News.

“I am delighted to hear that Yale is moving forward on this important initiative,” Waxman wrote. “Yale is an incredibly wonderful institution, but even the best institutions can benefit from the Ombudsman concept.” McInnis wrote last Tuesday that she has established a search advisory committee for the position. The committee is chaired by Elizabeth Conklin, the Uni -

versity’s associate vice president for equity and accessibility and its Title IX coordinator, and David Post, an ecology and evolutionary biology professor.

Conklin and Post wrote in a joint statement to the News that the committee planned to meet this week to discuss the qualities it will seek in candidates, emphasizing skills in active listening, mediation and negotiation, as well as the ability to remain impartial, independent and credible.

“In her first year at Yale, President McInnis heard many faculty, students, and staff speak of the need for a university-wide ombudsperson, and she recognized the value of an ombudsperson for the Yale community,” Conklin and Post wrote.

Conklin and Post noted that candidates for the role must have certification through the International Ombuds Association or “eligibility to obtain certification.”

Other members of the search committee include doctoral candidate Alex Rich GRD ’27, psychiatry professor Robert Rohrbaugh MED ’82, and Vice Provost for Health Affairs Stephanie Spangler. McInnis noted in her message that the committee would be soliciting comments from community members and linked a webform for people to submit feedback.

McInnis also noted that she would be establishing a “new council to review Yale’s faculty and staff employment policies and procedures.” The group will consider these practices and their support of Yale’s mission, “academic excellence,” the University’s compliance with laws and support for faculty and staff.

McInnis listed the eight members of the council — four professors and four University administrators. She wrote that their work will be completed “by the end of the spring semester” and that she would provide an update on both of the initiatives she announced “by the end of the academic year.”

The word “ombuds” comes from the Swedish word “ombudsman,” meaning “representative.”

Contact ISOBEL MCCLURE, at isobel.mcclure@yale.edu.

JERRY GAO at jerry.gao.jg2988@yale.edu. AND ASHER BOISKIN at asher.boiskin@yale.edu.

BY SARAH MUKKUZHI AND ANNA KOONTZ CONTRIBUTING REPORTERS

Last Wednesday, 41 Yale undergraduates met on Cross Campus and began walking to New York City. Four days and many blisters later, 13 students from the original group arrived at Grand Central Station, hollering and singing in celebration.

Many participants, regardless of whether they completed the journey, considered it a rewarding and transformative experience. Some students, like Bryce Falkoff ’29, signed up without knowing who else would be on the walk. At the end of completing the full trip, Falkoff said he had found a community.

“It was a once-in-a-lifetime adventure. It’s one of those things that you tell your kids, and something that you don’t ever forget,” Falkoff said. “It had to have been one of the most supportive groups I have ever been a part of.”

The idea for the trip started as a joke between four friends — Freeman Irabaruta ’26, Joshua Li ’26, Brian Moore ’26 and Michael Zhao ’26 — but became a reality after they dedicated many late-night hours to preparing routes, researching lodging and planning a budget.

After compiling a seven-page-long planning document and color-coded map, the organizers extended an open invitation for anyone in the student body to participate in the walk.

Their route roughly followed the Metro-North railroad along the Connecticut coastline, allowing an alternative mode of transportation for those who could not complete the entire trip.

“Every Yalie has the experience of taking the Metro-North from New Haven to New York,” Zhao said. “But to say you walked from New Haven to New York is crazy.

It’s such a trip of perseverance and patience.”

The group took brief rest stops about every three to four miles and shared group meals for breakfast, lunch and dinner. The group planned to stay in hotels along the route each night. Along the way, the group encouraged unexpected hospitality. Dunkin’ Donuts donated extra food, a Chinese restaurant in Stamford offered significant discounts and a bakery in Greenwich gave them free baguettes and eclairs, Zhao said.

The group also received free lodging on the final night of the trip. They originally planned to stay in a hotel in New Rochelle, N.Y., but every hotel was fully booked or not affordable, Moore said.

The organizers frantically reached out to student groups, fraternities and Yalies in the area, Moore added, and, finally, one junior agreed to host the group in her family home, accommodating 15.

That night, the walkers also threw a surprise celebration for Kear O’Malley ’28, who turned 20 during the trip. O’Malley said that he had quickly forged strong friendships with the group, despite only having known one participant — his roommate — initially.

“I was exhausted and that was one of the hardest days because my feet were really hurting that day, and when they brought out the birthday cake I was just really overwhelmed,” O’Malley said.

Despite the physically taxing journey, the group persevered by finding joy in small moments. In addition to the birthday party, students celebrated major road signs and borders marking their progress.

“It’s really funny because the city line between the suburbs of New York and New York City was like in between an IHOP and a Wendy’s,” Moore said. “We were in the middle of nowhere, and then we crossed it and we were like ayyyy!”

Eliana Peyton ’26 was one of three female students who finished

to New York City. “We were very vastly outnumbered, but it was never ‘the men are leading the pack, and the women are following behind.’ I was in front a lot of the time,” Peyton said. “We’re all very attached now that we’ve been through an intense experience together.” Li reflected about how the trip changed for the better when it evolved from the four senior organizers to a larger group of students.

“I really don’t think that us four could have done it without the rest of the entire group,” Li said. “The vibes would not have been there. The mutual support. We did not expect so many new friendships, so many new memories and the energy of the entire group.” Driving from New Haven to New York City takes around 2 hours. Along the route, the group encountered numerous instances of hospitality – from a Trumbull junior spontaneously hosting the walkers to free baguettes and eclairs in Greenwich, Connecticut.

OF JOSHUA

and unexpected mishaps.

At the start of the trip, the Yalies walked side by side in two columns that extended a city block. As they walked, students joked, sang sea shanties and shouted compliments to passersby. Irabaruta was nicknamed “CEO of Vlogs and Vibes” and helped foster a welcoming, energetic atmosphere through games and silly conversations. Contact SARAH MUKKUZHI at sarah.mukkuzhi@yale.edu. AND ANNA KOONTZ at anna.koontz@yale.edu.

“At night the fog was thick and full of light, and sometimes voices.”

BY ELIJAH HUREWITZ-RAVITCH STAFF REPORTER

New Haven joined eight other American cities and counties on Monday in suing the Trump administration for alleged “unlawful conditions” included in the Department of Homeland Security’s recently updated terms for receiving federal grants.

Chicago, the suit’s lead plaintiff, along with Baltimore, Boston, Denver, Minneapolis, New York City, Ramsey County, Minn., Saint Paul and New Haven, claimed in the lawsuit that the “Executive Branch has now determined to use this critical federal funding as a cudgel, threatening to hamstring local governments’ emergency-management functions unless they acquiesce to unrelated Executive domestic policy goals.”

The nine cities and counties take issue with sections of the DHS’s updated terms and conditions that require grant recipients to agree not to “operate any programs that advance or promote DEI, DEIA, or discriminatory equity ideology” and to agree to comply with all past and future executive orders.

A DHS spokesperson wrote in an email to the News that the lawsuit obstructs the president’s agenda. Recipients of federal funds, the spokesperson added, are required to follow anti-discrimination laws and cannot use funds for climate activism or for diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives. FEMA has put in place new controls to ensure that all grant program activity follows the law, the spokesperson wrote.

At issue in New Haven is $93,597 awarded by the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s port security grant program, which would fund maintenance, upgrades and expansions to the camera systems around the city’s port, according to Mayor Justin Elicker. Those cameras are used to respond to incidents within the port — the busiest between New York and Boston — per Rebecca Bombero, a city administrator.

At a Monday press conference, Elicker said that the new grant stipulations “are ones that the City of New Haven cannot abide by, both because it does not align with our values, but also because it is just not practical for

any municipality to be able to agree to such requirements.”

Michael Bowler, an assistant counsel for New Haven, said on Monday that the DHS’s new terms and conditions will apply to federal grants from all agencies.

“We’ll be continually applying for federal grants, like the city always does,” Bowler said, “but the standard terms and conditions now have these troubling terms with them, which we have to decide whether we will accept.”

The mayor described the new guidelines, along with President Donald Trump’s executive orders, as “intentionally vague.” The DHS did not immediately respond to the News’ request for comment about the new guidelines.

The city submitted an application in mid-August for over $2 million in grants to fund various port-related projects, according to Kayla Bland, the city’s emergency operations director. In September, New Haven was offered funding for just one project — the camera upgrades.

Bland said that she thought that the grant was approved because it “fit within” the Trump administra-

tion’s “priorities of cyber security and physical security.”

The deadline to sign the grant is Nov. 27. Elicker said he hopes that a federal judge will grant the plaintiffs a preliminary injunction before then, which would prevent the federal government from halting funding.

But if New Haven does not receive the money, Elicker said, “we’ll have to make a decision on whether we want to keep this infrastructure there — keep old, dilapidated infrastructure that may break — fund it in another way, increase taxes to fund these things.”

Monday’s lawsuit, filed in a Chicago federal court, is the third that New Haven has joined against the Trump administration. In February, along with San Francisco, Portland and King County, Washington, New Haven sued the federal government for allegedly targeting sanctuary city jurisdictions, and in March, it joined five other cities and eleven nonprofits in suing the government over funding freezes to environmental and climate projects.

A federal court granted two preliminary injunctions in the sanctuary cities case.

As in both of those suits, the Public Rights Project, a progressive, California-based legal advocacy nonprofit, is helping represent New Haven and covering many of its legal costs, according to Elicker.

The mayor said that despite the aggressive posture he has taken toward the Trump administration, he is not worried about drawing more attention to New Haven than it otherwise might receive.

“I hear from some of my mayoral colleagues out there that they don’t want to make their cities a target,” Elicker said.

“Now is a time that we should not be hiding. Now is a time that we should be standing up and fighting for the values of our community, both because at some point we’re all going to be a target anyway, but more importantly, because this is the right thing to do.”

Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem is the lead defendant in the case.

Contact ELIJAH HUREWITZRAVITCH at elijah.hurewitz-ravitch@yale.edu.

BY MAYA CHATTERJEE

CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

New signs at 290 York Street signal the opening of “Glaze and Grind” in the storefront formerly occupied by Donut Crazy, which closed in the spring after its license was suspended for violating sales tax regulations.

The Donut Crazy storefront in New Haven was opened in 2016 by owner Jason Wojnarowski and shuttered this past March by the Connecticut Department of Revenue Services. The company has also closed its four other locations across Connecticut after a series of evictions.

Despite similarities between Donut Crazy and the new company, Glaze and Grind — including two shared locations and similar menus — managers at Glaze and Grind stressed that the new shop is an entirely separate venture. Donut Crazy owner Wojnarowski was present at the location, helping set up Glaze and Grind, on at least two days last week.

Jimmy Lyons, one of Glaze and Grind’s main operators, described the company as a newly established Connecticutbased business created by a team of six professionals in the restaurant industry.

“We’re pretty much just joining forces, putting a team of Avengers together in the industry and trying to come up with something interesting and unique,” Lyons said. “It’s a totally new company comprised of existing owners and operators of other companies.”

Lyons and several of his partners, including Mauro Tropeano, Marc Goldberg, Jason Garelick, Joe Grosso and Howard Saffan, each bring experience from their respective business ventures. Lyons is the owner of North Fork Doughnut Company on Long Island and co-founded Grounds Donut House in Danbury with Tropeano. After the closure of Donut Crazy, Lyons and Tropeano saw the vacated storefronts as well-suited for Glaze and Grind.

“We saw the opportunity with the old Donut Crazy spaces and we thought this would be a perfect fit for us to launch our brand where we wouldn’t have too much overhead,” Lyons said. Lyons emphasized that there would be no crossover between the Donut Crazy and Glaze and Grind staff. Yet some of the current staff have connections to the previous business.

“As far as any sort of leadership that was at the helm of Donut Crazy, there’s no throughline there whatsoever,” he said. “Anybody that’s in an equity or ownership or partnership position in Glaze and Grind has nothing to do with Donut Crazy.”

Saffan, one of the operators of Glaze and Grind, also owns the Hartford HealthCare Amphitheater, which has partnered with and promoted Donut Crazy. Additionally, Saffan’s real estate company, Bishop Development III, LLC, served as the landlord for Donut Crazy’s Shelton, Conn., location. A 2025 lawsuit filed by Bishop against Donut Crazy owner Wojnarowski alleges the tenant’s failure to pay rent.

Grosso, one of the owners of Glaze and Grind who oversees construction, told the News that he joined the project through Saffan.

The News spoke with Wojnarowski at the York Street site last week. He identified himself as “Jason Wojo,” and said he was assisting Glaze and Grind with construction and design. Wojnarowski added that no one working at Glaze and Grind had worked for Donut Crazy in the past. He did not comment on the closure of Donut Crazy.

“We are just starting to put the finishing touches on. We kept the layout, but it’s all new art and paint,” Wojnarowski said of the construction process.

Both Grosso and Lyons said Wojnarowski’s involvement would be limited to transitional and consulting responsibilities.

“Jason has no equity or stake or partnership in the new company at all,” Lyons said. “It was more just involvement on the end of taking over the leases and transitioning us into the new spaces. He helped with a little bit of design because he had a creative background.”

Lyons added that Glaze and Grind has taken some of Wojnarowski’s guidance during the process.

“We took a couple pages from his book on what worked for Donut Crazy and what we think

would work moving forward.” Lyons emphasized that Glaze and Grind is beginning with a clean slate.

“We’re just excited to bring something new and unique to New Haven and to Shelton,” Lyons said. “We’re really excited to be part of the community.”

Glaze and Grind will begin staff training on Wednesday and intends to open at the end of this week, according to Lyons.

Adele Haeg contributed reporting.

Contact MAYA CHATTERJEE at maya.chatterjee@yale.edu.

BY SABRINA THALER STAFF REPORTER

New Haven Public Schools

released a more detailed version of its 2025-26 fiscal year budget Monday night, the culmination of a months-long process to meet union members’ calls for increased financial transparency.

At a virtual meeting of the Board of Education’s Finance and Operations Committee on Monday, the school district’s chief financial officer, Amilcar Hernandez, presented a spreadsheet that included the district’s budget allocations for more than 100 line items, including salaries, electricity and transportation.

“Whereas earlier documents showed only the general funds budget, we now are showing special funds and interdistrict funds, as well, and tracking projected expenditures across these three categories,” NHPS spokesperson Justin Harmon wrote in an email. “We believe this change will give people a far better understanding of where our funding comes from and where it goes.”

The district’s total budget is over $331 million, more than a third of which comes from special funds — 16 external grants, mostly from the state and federal governments — and state-administered interdistrict funds, according to the line-item budget spreadsheet.

Members of the city’s teachers’ union, the New Haven Federation of Teachers, have demanded that the district release a more detailed lineitem budget as a measure of transparency. Over 40 teachers and union members gathered at a Board of Education meeting in late September, some toting signs that urged NHPS to “show us the money.”

Board of Education Vice President Matthew Wilcox, who also serves as the chair of the finance and operations committee, said the newly released document reflects updated data from previous drafts, including up-to-date personnel expenditures and the precise dollar amounts NHPS received from grants.

When the school district released the initial draft of its 2025-26 fiscal year budget in the spring, it pro-

jected a budget deficit of more than $23.2 million, according to a press release published in the New Haven Independent. The district conducted a series of mitigation efforts, including the elimination of 76 vacant staff positions, the closure of one school and the merging of two schools.

After the Board of Alders voted to set aside $3 million in surplus state funding to a reserve for education earlier this month, NHPS narrowed its projected budget deficit to under $1 million, a step which Wilcox told the News would help the district prevent layoffs during the current school year.

At Monday’s meeting, Hernandez noted the significance of outside grants, labeled as special funds in the budget, in covering some of the district’s major costs, including teacher salaries. This year, the district will receive roughly $81 million in special funds.

Last fiscal year, the district received $107 million in grants, according to a separate presentation Hernandez gave at Monday’s meeting. He said that next fiscal

year, the district’s supply of special funds could decline to the low $70 million range, bringing the total budget further from the $350 million he said it would need to meet the school district’s needs.

“If we cannot sustain this level of special funding, there’s no other funding for us to use to replace whatever those costs are,” Hernandez told the committee, referring to pandemic-era federal grants that have run out. “If we are able to receive more special funds, or we’re able to receive more general funds through the state, then we’re able to alleviate the pressure that special funds have to cover some of the items that normally could be covered by general funds.”

NHFT President Leslie Blatteau said in a phone interview that the new document is a “step in the right direction,” but that she would like to see more detail added to certain line items, including the “Other Contractual Services” item, which comprises seven percent of the budget.

A tab in the spreadsheet entitled “Line Item Descriptions”

includes details about 23 of the budget items. “Other Contractual Services” comprises “contracts for cleaning, professional and technical development of school district personnel including instructional, administrative and service employees,” according to the document. Hernandez said that he would continue to field questions and update the document as community members request more details. “I think that in the future, that will be the theme of our budget process: transparency, and making sure that there’s a trust relationship between us and the community, that they understand how we’re using the funding, how we’re allocating the funding, how we’re implementing equity across all these pieces,” Hernandez said to the committee.

The school district’s 2025-26 fiscal year began on July 1. Contact SABRINA THALER at sabrina.thaler@yale.edu.

BY GILLIAN PEIHE FENG CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

“The Shape of Things,” a play written by Neil LaBute and directed by Emiliano Caceres Manzano ’26, will premiere on Thursday in the Saybrook Underbrook.

“The Shape of Things” examines the lives of students in a Midwestern college town, illustrating themes of love, art and the concept of “change.” The play premiered in London in 2001 and was adapted into a 2003 film that starred Paul Rudd and Rachel Weisz.

“I love ‘The Shape of Things’ because I found it particularly quick and quite witty while still exploring themes of art, its meaning, and the limits of creativity,” Isabella Panico ’26, one of the show’s producers, wrote in an email to the News. “To someone who has never heard of it, I’d just ask them,‘do you think self improvement is a voluntary experience?’”

Other members of the cast and crew said the play’s nuanced exploration of art and love as attracting them to the project.

“I was drawn to The Shape of Things because it is a play that is unafraid to explore difficult questions,” Dorothy Ha ’28, the show’s sound designer, wrote in an email. “How far should we go for art? How far are we willing to go for art?”

“The Shape of Things” unfolds as socially-awkward Adam meets Evelyn, a charismatic art student. Evelyn’s arrival causes every aspect of Adam’s life — from appearance to living habits — to change. Most significantly, Evelyn’s presence alters the dynamic between Adam, his friend Phillip and Phillip’s fianceé Jenny.

Evelyn is played by Isabella Walther-Meade ’26, who is also one of the producers of the show. Walther-Meade wrote in an email that she is drawn to Evelyn’s moral complexity and sees her as multifaceted despite being the sort of woman

“who people think are wrong.”

“Say what you will about Evelyn, but she is very aware of her ability to influence other people, and her self-perception as an artist lets her take that further than we expect,” Walther-Meade wrote.

“She is a deeply passionate person who is willing to do whatever it takes to prove a point that she believes in more than anything, and I can relate to that, but it took me a while to get there.”

Walther-Meade further noted that playing Evelyn has had an impact on the way she approaches art and how she portrays a character on stage.

“The time I have spent preparing for Evelyn has changed the way I think about art, for better or worse,” Walther-Meade wrote. “I hope she does the same for the audience.”

Leila Hyder ’28, who plays Jenny, spoke in a voice memo about the challenges and rewards of playing a character very different to herself.

“I feel like Jenny is very different from me and I guess that’s part of the challenge in a sense, but that’s also what I love about playing her,” Hyder said. She added that she is “excited” to portray her character’s development arc on stage.

According to Hyder, the cast spend a lot of time building backstories to navigate the complex relationships between the characters. Hyder said that improvisational acting has been an important part of the process. To prepare for her character, Hyder said she keeps a notebook to sketch out Jenny’s backstory and track her daily life according to the timeline of the play.

“I think Jenny comes off as a very sweet, very kind of simple girl, very level-headed, which isn’t a bad thing, but I just think there’s more to her than just that,” Hyder said. “By the end of the day, I think I really enjoy seeing who she becomes by the end of the play.”

The complex characters are

backed by an experimental, relatively minimalist scenic design.

According to Panico, the production is “quite stripped down,” focusing mainly on the main character Adam’s external and internal transformations.

Alexa Druyanoff ’26, the scenic artist in the production, emphasized the close relationship between the show’s visual elements and the character’s development.

“The set is composed of painted boxes that are rotated and reconfigured by the actors throughout the show,” Druyanoff wrote in an email. “Their transitions mirror the progres -

sion of the scenes and the lovers, so they create a fluctuating atmosphere that is directly connected to the characters.”

Druyanoff added that the scenic designs for the production were influenced by pop art, with a focus on “abstracting the human body and classical figure.”

When discussing the production’s sound design, Ha highlighted the ties between character development and the production’s aesthetic designs.

“I was aiming for an unsettling vibe,” Ha wrote. “The music becomes more and more distorted as the play goes on,

until the original song is virtually unrecognizable, to mimic the storyline of the play.”

Hyder said the costumes for the play are styled after “a 2000s Midwestern college town kind of vibe.”

“This is a story for everyone who has ever said ‘I can change him,’” Panico wrote. “I hope that it makes audiences equally joyous and uncomfortable.”

“The Shape of Things” will run for four performances between Thursday and Saturday.

Contact GILLIAN PEIHE FENG at peihe.feng@yale.edu .

BY ANGEL HU STAFF REPORTER

Daniel Mendelsohn, a human-

ities professor at Bard College, gave a lecture Monday about his experience translating Homer’s epic poem, “The Odyssey.”

Mendelsohn’s translation of “The Odyssey” was published by University of Chicago Press in April, joining the list of the 29 English translations of “The Odyssey” that have been released since the end of World War II.

In an email to the News, Megan O’Donnell, an associate communications director at the Whitney Humanities Center, which hosted Mendelsohn, praised the way his translation “offers future translators a model of how close attention to form, linguistic precision and cul-

tural nuance can reinvigorate even the most familiar classical texts.”

Mendelsohn’s talk was a part of the Humanities Now lecture series, a new initiative created by the Whitney Humanities Center which “examines questions at the heart of the human condition and invites us to cross boundaries of geographies and disciplines,” Cajetan Iheka, a professor of English and the director of the Whitney Humanities Center said. Chris Kraus, a Latin professor, introduced Mendelsohn to the audience. Kraus recounted that she first met Mendelsohn in 1994 when he was a graduate student at Princeton and said that he has since “turned a nascent academic life into a thriving freelance writing career.”

Mendelsohn has been teaching “The Odyssey” and its many trans-

lations since 1989 — “all of which have something to offer,” he said.

Mendelsohn had not planned on undertaking his own translation of “The Odyssey” until he had published a memoir titled “An Odyssey: A Father, a Son, and an Epic” in 2017. The memoir delves into the spring semester of 2011, when Mendelsohn’s then 81-year-old father decided to enroll in his firstyear seminar on “The Odyssey.”

Through this experience, Mendelsohn described “getting to know his father as a student through ‘The Odyssey’” and hearing his “grumpy reactions” to the book. After the class was over, Mendelsohn and his father discovered and boarded “a cruise that recreates the voyages of Odysseus.”

“Then, my dad fell ill and died not long after we got back, so

the book was sort of an account of what turned out to be the last year of his life as weirdly prismed through ‘The Odyssey,’” Mendelsohn said.

Mendelsohn included snippets of his own translations of “The Odyssey” in the memoir. A few months later, he said he received a phone call from an editor from the University of Chicago Press who read the memoir, liked the snippets of translation that he did and asked him if he wanted to translate “The Odyssey” in its entirety.

“When you love a text, you have a sense of what it is in your head, and I wanted to bring that sense across to English readers who don’t know Greek,” Mendelsohn said.

Mendelsohn described some of his choices and challenges

when attending to the meter, syntax, language and form of the original work — demonstrating how his work differed from previous translations.

For instance, Mendelsohn opted to spell Calypso’s — the nymph who held Odysseus captive on her island — name as Kalypso in order to reflect the original Greek name spelled with the letter kappa.

“I think it’s very important for us to experience these names in a way that slightly estranges them from what we think we know,” Mendelsohn said. Mendelsohn explained the challenges in translating the Greek word for “a meal to which many people contribute.” While previous translators have opted for the word “picnic” or “potluck supper,” Mendelsohn believed that those words are “stoppers” that “pull the reader out of thinking about what’s going on in the text.”

Mendelsohn eventually decided on the translation “neighborly feast” — a choice he attributed to his former professor Jenny Clay. Additionally, Mendelsohn discussed his process of translating Homeric epithets, descriptive phrases that characterize a person or place in Homer’s epic poems. Seeking to “peel away the varnish” of previous translations, Mendelsohn said he took a different approach to translating epithets like “grey-eyed Athena.” Mendelsohn expanded upon previous translations that emphasized the “gleaming” quality of Athena’s eyes by drawing upon the Greek word for owl — which is related to the Greek word for gleaming — to come up with “she of the bright owl eyes.”

“A brilliant translation reignites interest in a text, no matter how many times it’s been translated before,” O’Donnell wrote, reflecting on the role of translation across generations. “To me, that renewed excitement is the first step in connecting readers to a different period and culture.”

The Humanities Now lecture series was founded in 2023. Contact ANGEL HU at angel.hu@yale.edu.

Sweet dreams are made of this, Who am I to disagree?

BY EMMA QIAO CONTRIBUTING REPORTER

Happy, sad, mad, glad. We all know what these emotions feel like, but do we know how to deal with them?

Last month, Marc Brackett, the founding director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and professor in the Child Study Center, released his second book, “Dealing with Feeling,” which aims to share a set of skills and strategies to assist with understanding and responding to your emotions.

“It was, for me, very important to write a whole book just on one skill, which was to help people learn how to regulate their own emotions, but also importantly, how to engage in healthy co-regulation,” Brackett said. “Meaning, how do you help people to help other people manage their feelings?”

Brackett’s first book, “Permission to Feel,” which was published in 2019, revolved around understanding what emotions are and the value of learning emotional intelligence. It has been widely read around the world, and Brackett said readers then wanted to know how to manage such emotions. In response, Brackett began writing “Dealing with Feeling.”

To begin the book, Brackett said he applied his background in emotional intelligence research toward answering the questions of what

people were hoping to learn and what they had not learned before.