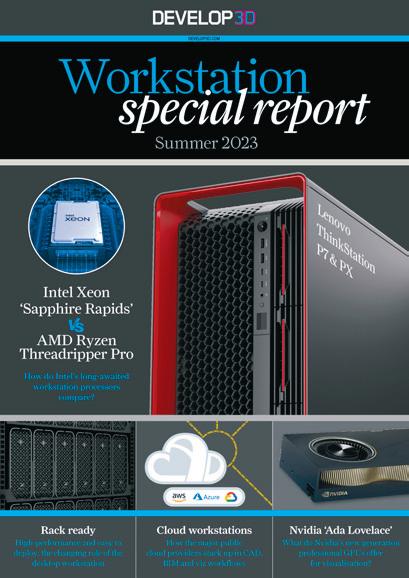

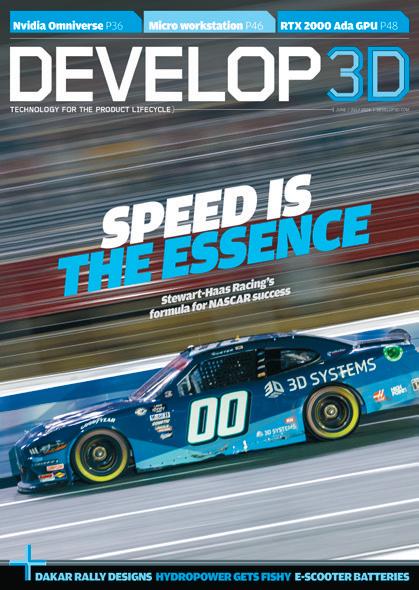

Workstation special report

Winter 2026

From dedicated blade workstations to micro desktops adapted for the datacentre we explore the rise of the 1:1 remote workstation

Workstation GPUs

Why GPU memory matters, plus in-depth Nvidia Blackwell and Intel Arc Pro reviews

Our pick of the best enterpriseclass mobile workstations for CAD, viz, and simulation on the go

Micro machines

Can compact workstations handle big BIM, CAD, and viz? Plus in-depth reviews

memory

shortages

and rising

prices are reshaping workstation buying. Greg Corke explores how architecture, engineering, design, and manufacturing firms can adapt without panicking

If you’ve priced a new workstation recently, one thing is clear: memory now takes up a much larger slice of the quote than it did just a few months ago. There’s no need to panic quite yet, but this significant change in the IT sector cannot be ignored.

Since October, DDR5 prices have climbed sharply, and for architecture, engineering, design, and manufacturing firms that rely on memoryheavy workstations, this has become a planning and purchasing challenge that demands careful thought.

So why has this happened?

‘‘ Treat memory like you did toilet roll in Spring 2020: buy wisely, stay calm, and you’ll get through the crunch unscathed ’’

The short answer: the AI boom broke the memory market. Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron have shifted large portions of production to high-bandwidth memory for AI accelerators and datacentres, leaving DDR5 supply for PCs and workstations starved. For some, what used to be a routine workstation purchase now feels more like hunting for toilet roll in the early days of Covid.

Unfortunately, the disruption isn’t temporary. Analysts expect this shortage, and sky-high prices, to continue through mid 2026, with some warning it may extend into 2027 before supply stabilises.

Rising memory costs are already impacting the price of workstations. In just a few months, DDR5 prices have surged — in some cases tripling or quadrupling. A 96 GB kit that cost £200 in July can now command £800, while a 256 GB ECC kit that sold for £1,500 in August may now push £4,000, if it can be sourced at all. Prices remain volatile, dramatically shifting week to week, even overnight.

The memory crunch is also spilling over into other components. SSDs have climbed in price too — not as sharply as DDR5, but enough to notice — because some of their components are made in the

same fabs. Then there are pro GPUs, which demand far more memory than their consumer cousins. Business Insider reports that a 24 GB Nvidia RTX Pro 5000 Blackwell GPU in a Dell mobile workstation now carries a $530 premium.

All of this leaves firms asking a simple question: how do you make sensible workstation purchasing decisions when the market is so unpredictable?

The most obvious tactic is to shop around, though don’t presume prices will stay still for long. Lenovo has been kicking the proverbial DDR5 can down the road by stockpiling memory, but how long will that last? Unfortunately, boutique integrators don’t have the same buying power, and some have even been forced to ration stock.

Consider buying pre-configured workstation SKUs (Stock Keeping Units) already in the channel. You may also find more pricing stability in systems where memory is soldered onto the mainboard. For example, a top-end HP Z2 Mini G1a with 128 GB of memory that cost £2,280 in August 2025 now goes for just £50 more (see review on page WS24)

Another approach is to extend the life of what you already have. If your workflows have evolved from pure CAD/BIM to visualisation, upgrading the GPU — for instance, to the Nvidia RTX Pro 2000 Blackwell (see review on page WS44) — can breathe new energy into your workstation. Furthermore, if you’re maxing out the system memory in your current machine and you still have spare DIMM slots, adding a bit more RAM is cheaper than replacing all of your memory modules.

If you must buy new systems, planning for future upgrades is more important than ever. Look for platforms with four or more DIMM slots so you can start with a baseline configuration and add more

memory later when prices come down. Don’t splurge on top-tier modules today — leave some room to grow. This way, you meet your immediate needs without blowing the budget, and you’ll be ready to expand when the market stabilises.

Software and workflow strategies can also stretch existing resources. Optimising projects to reduce memory footprint, closing unnecessary applications, or offloading demanding tasks to the cloud, such as rendering, simulation and reality modelling, can all help ease memory pressure.

Renting cloud workstations is another option. With a 1:1 remote workstation (see page WS6), you get the performance you need without tying up capital in potentially overpriced hardware. Some workstation-as-a-service providers, such as Computle (see page WS10), have even locked in prices across their contracts.

The memory crunch isn’t going anywhere fast, so buying a workstation now requires more thought than usual. Preconfigured SKUs, squeezing more life out of your existing machines, and careful planning upgrades for later all help stretch your budget. Cloud processing and remote workstation subscriptions can also ease some pressure. The market is unpredictable, but firms that mix foresight with flexibility can keep design and engineering teams productive without overpaying. In other words, treat memory like you did toilet roll in Spring 2020: buy wisely, stay calm, and you’ll get through the crunch unscathed.

To help shape our 2026 Workstation Special Report, we surveyed over 200 design professionals on real-world workstation use. Thanks to everyone who took part. Here are some of the results, but how does your setup compare?

What type of workstation do you primarily use?

Desktop towers remain the most widely used form factor, reflecting ongoing demand for maximum performance and expandability. Mobile workstations account for over a third of use, underlining the continued shift toward flexible and hybrid working. Small form factor desktops represent a niche but notable segment, suggesting interest in space-efficient systems. Meanwhile, remote and cloud-based workstations remain a small minority, indicating that they have yet to reach mainstream adoption

Nvidia RTX leads, reflecting its dominance in professional workstations and broad OEM availability. GeForce, primarily a consumer GPU, also has a strong showing, offering good price/performance for visualisation, mainly in specialist systems. It’s not surprising to see Intel integrated’s tiny slice, while for AMD integrated we’ve yet to see the impact of its impressive new ‘Zen 5’ chips, including the Ryzen AI Max Pro, which is currently offered by only a few OEMs, mainly HP

Intel Core continues to dominate, but this is not surprising considering it offers the best performance for CAD. Intel Xeon still plays a role in more enterprisefocused workstations, though its share is relatively small. AMD shows a strong overall presence, with Ryzen accounting for a fifth of systems, despite very limited availability from the major OEMs. Higherend AMD Threadripper (Pro) systems remain niche but important, serving users with extreme compute, memory, and I/O requirements that go beyond mainstream workstation needs

How many CPU cores do you have?

Most respondents use mid-to-high core count CPUs, reflecting the dominance of Intel Core. However, buyers may not be choosing these chips specifically for their cores, as they also deliver the highest clock frequencies, which is critical for CAD. Systems with 6–16 cores remain popular, balancing performance and cost. Very low core counts are rare, likely indicative of ageing workstations, while ultra-high core counts point to specialised use cases such as high-end visualisation and simulation

Dual-monitor setups dominate, supporting workflows like modelling on one screen and reference apps or visualisation on the other. Single-monitor setups remain common, used by nearly a quarter of respondents, while three or more screens indicate more complex or immersive workflows. Very few rely solely on a laptop, showing most professionals prefer larger, dedicated displays for detailed design work

Slow model loading, often dictated by single-threaded CPU performance, is the most common performance bottleneck, affecting over half of respondents. Viewport lag and long rendering times affect around a third and a quarter of users, while network and cloud sync issues impact more than a quarter. Crashes, slow simulations, and storage limitations are less common. Only a small fraction report no issues. Notable “others” include single-core-limited applications, drawing production, and poor interface design

What resolution is your primary monitor?

Monitor resolutions are fairly evenly distributed, with 4K leading slightly, reflecting demand for detailed visualisation and design work. A smaller segment uses resolutions above 4K, likely for specialised workflows requiring extreme detail. Overall, most professionals prioritise clarity and workspace efficiency, though FHD, still common in many laptops, remains widespread

How much system memory do you have?

Most workstations feature 64 GB of RAM, reflecting the growing demands of CAD, visualisation, and simulation workflows. 128 GB or more is used by a surprisingly large minority for highly complex tasks. 16 GB is rare, probably indicative of ageing systems that may well benefit from a RAM upgrade. Our heart goes out to the two respondents who suffer with 8 GB, which is barely enough to load Windows, let alone run CAD. Overall, the data shows design professionals prioritise ample memory to support performance and multitasking

From compact ‘desktops’ to purposebuilt blades, a new wave of dedicated 1:1 datacentre-ready workstations are redefining CAD, BIM, and visualisation workflows — combining the benefits of centralisation with the performance of a dedicated desktop, writes Greg Corke

For more than a decade, Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) and cloud workstations have promised flexible, centrally managed workstation resources for design and engineering teams that use CAD, BIM and other 3D software. But a parallel trend is now gathering serious momentum: the rise of the 1:1 remote workstation.

In a 1:1 model, each user gets remote access to a dedicated physical workstation with its own CPU, GPU, memory and storage. There is no resource sharing, no slicing of processors, and no contention with other users. In many ways, it combines the performance predictability of a local desktop workstation with many of the management, security and centralised data benefits traditionally associated with VDI.

This shift is being driven by performance demands, changing IT priorities, and the growing maturity of remote access technologies. And it is appearing in several distinct forms.

What is a 1:1 remote workstation?

Unlike VDI or public cloud environments like AWS or Microsoft Azure, where

multiple users typically share CPUs and GPUs through virtualisation, a 1:1 remote workstation assigns an entire machine to a single user. That machine typically sits in racks in a dedicated server room or datacentre, either on-premise or hosted by a third-party service provider. However, it could also sit under a desk, or in the corner of an office.

The user accesses the workstation remotely using high-performance display protocols such as Mechdyne TGX, PCoIP (HP Anyware), NICE DCV (now Amazon DCV), Parsec or Citrix HDX. However, from a compute perspective, it behaves exactly like a local workstation.

How the trend is emerging

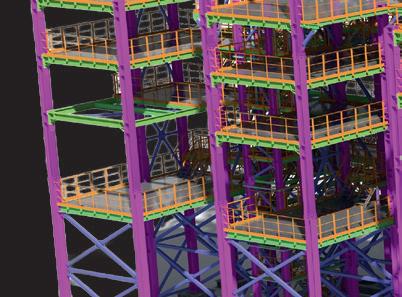

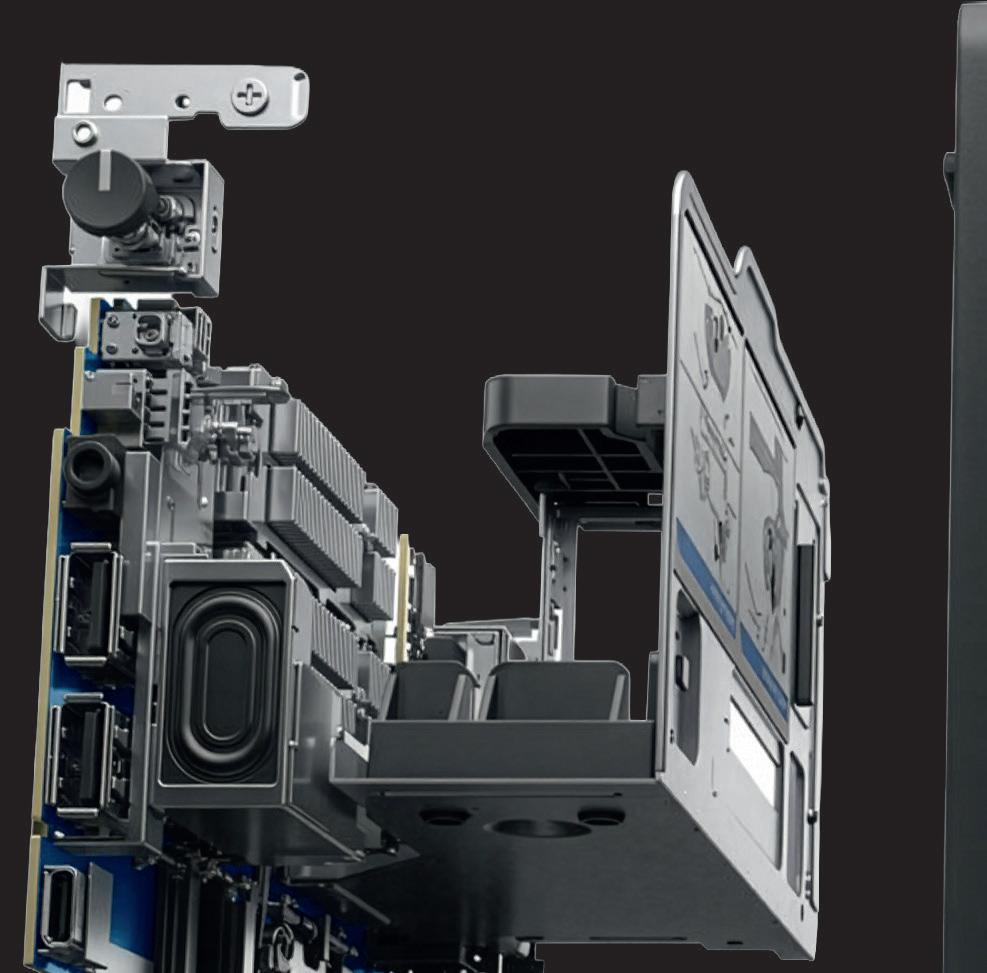

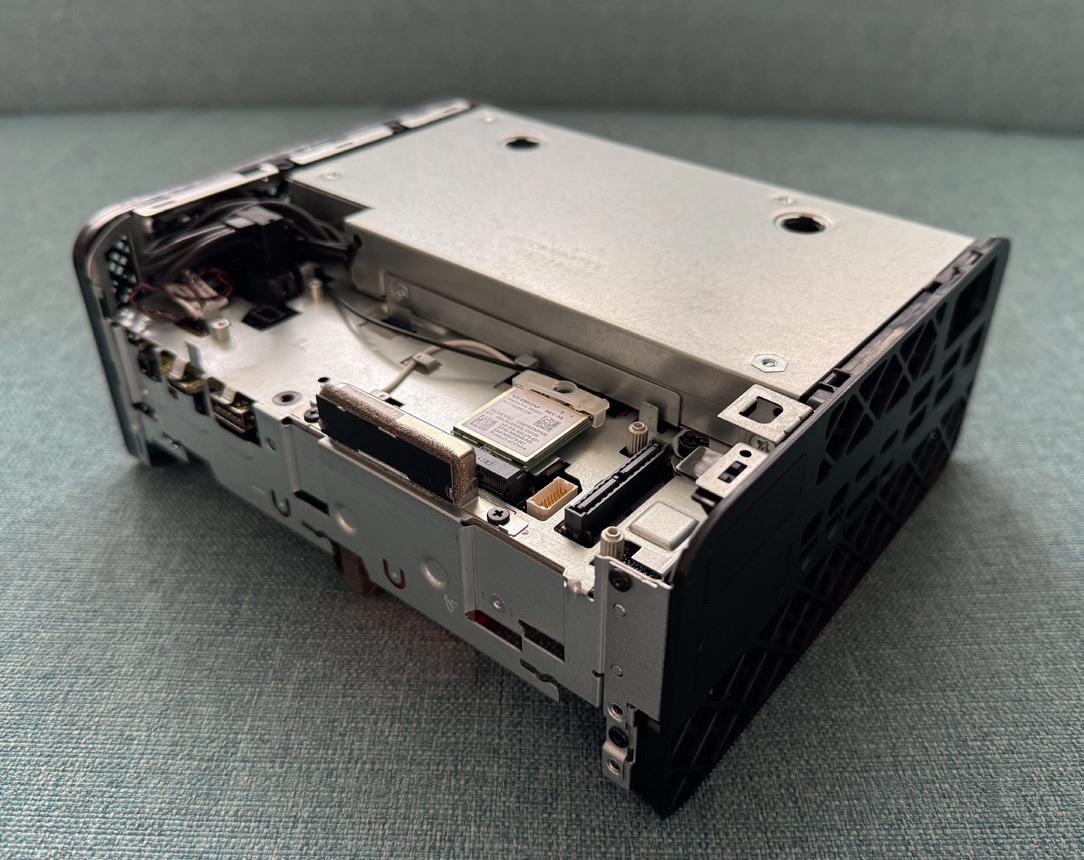

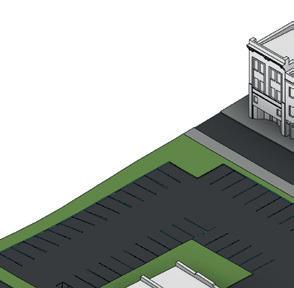

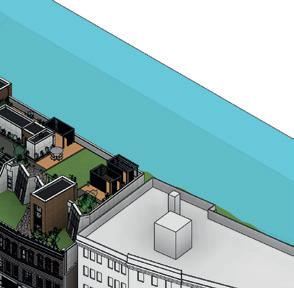

1) Compact desktop workstations in the datacentre

One of the most visible indicators of the 1:1 trend, especially for design and engineering teams that use CAD and BIM software, is the relocation of compact desktop workstations into the datacentre.

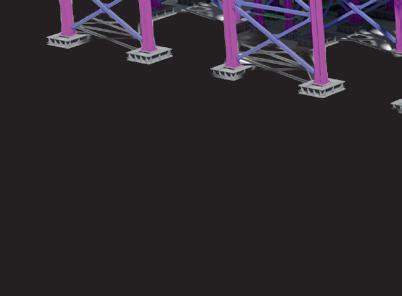

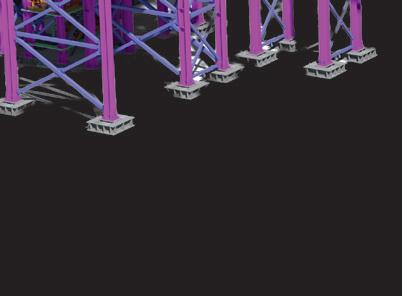

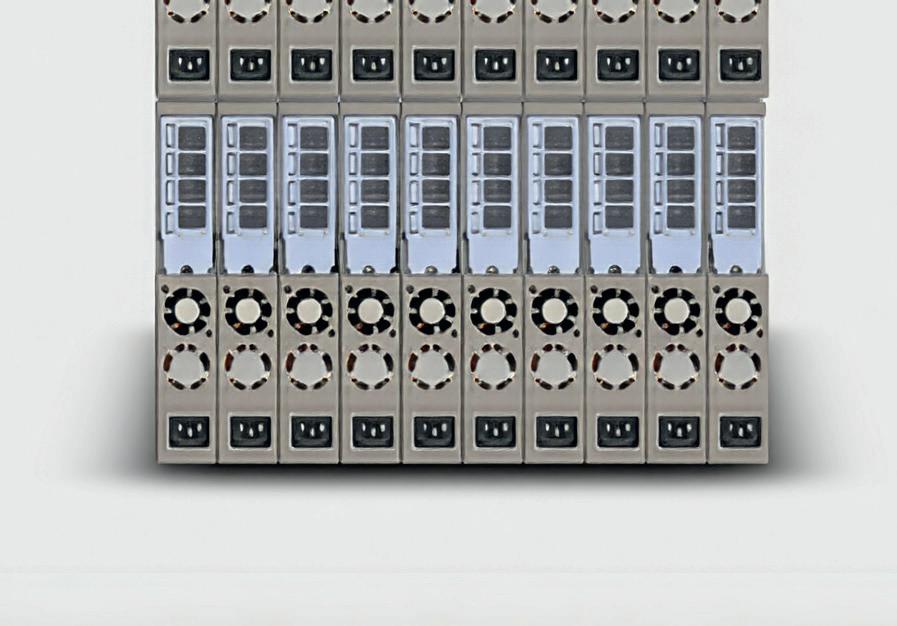

Machines such as the HP Z2 Mini and Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF are increasingly being mounted in racks rather than sitting on desks. Thanks to their small form factors, these systems offer impressive density. With the ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF, for example, seven individual workstations can be housed in a 5U chassis.

Density matters for several reasons. Higher density reduces rack space requirements, lowers hosting costs, and

HP’s 1:1 remote workstation spotlight falls on the HP Z2 Mini, a tiny powerhouse that comes in two flavours.

The HP Z2 Mini G1i packs highfrequency Intel Core Ultra CPUs with discrete Nvidia GPUs up to the powerful RTX 4000 SFF, while the HP Z2 Mini G1a runs on the AMD Ryzen AI Max Pro processor with integrated Radeon graphics (see review on page WS24)

Thanks to its smaller processor package and integrated PSU, the G1a offers a slight advantage in terms of rack density, fitting five units in 4U, compared with six G1i units in 5U.

■ www.hp.com

improves energy efficiency per user.

Crucially, these are still true desktop workstations. Users get the same CPU frequencies, GPU options and application performance they would expect from a machine under their desk. Remote management and access capabilities are typically added via specialist add-in cards, enabling IT teams to control and maintain systems centrally.

Compact desktop workstations do have their limitations. While they can offer the highest-frequency CPUs — capable of boosting into Turbo for excellent performance in single-threaded CAD and BIM applications such as Solidworks and Autodesk Revit — they are typically restricted to low-profile GPUs or integrated graphics.

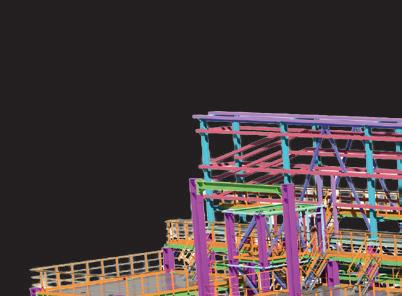

In the past, this confined them largely to traditional CAD and BIM workflows. However, the latest compact models are surprisingly capable, with models including the Nvidia RTX 4000 SFF Ada and Nvidia RTX Pro 4000 Blackwell SFF, having enough graphics horsepower and GPU memory to comfortably handle mainstream visualisation workflows in applications such as Enscape, Twinmotion, KeyShot and Solidworks Visualize.

For more demanding users, high-end desktop tower workstations with high core count CPUs, lots of memory, and one or more exceedingly powerful full height professional GPUs, can also be racked, extending the adapted desktop model

Lenovo’s 1:1 workstation offering centres on the ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF, a compact system with a BMC card for ‘servergrade’ remote management.

Configurable with Intel Core Ultra (Series 2) CPUs and Nvidia RTX GPUs up to the RTX 4000 SFF, it packs a punch for CAD and viz workflows while delivering good density with up to seven units in a 5U rack space. For even higher density, the ThinkStation P3 Tiny delivers twelve systems in 5U. However, the micro workstation is limited to CAD and BIM workflows, with a narrow range of GPUs up to the Nvidia RTX A1000.

■ www.lenovo.com

to advanced visualisation, simulation and AI workflows. However, achievable density is massively reduced.

The major workstation players – Dell, HP and Lenovo – design most of their tower systems to be rack mountable, as does Boxx. However, that’s not the case for all systems, especially custom manufacturers that often use consumer gaming chassis.

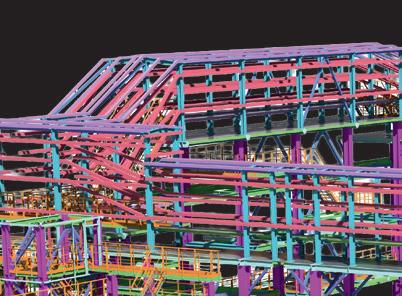

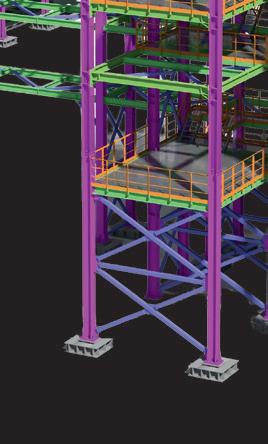

2) Dedicated rack workstations – blades

Another strand of the trend is the resurgence of the purpose-built workstation blade, a form factor first pioneered by HP in the early 2000s. Each blade is a slender, self-contained 1:1 workstation

with its own CPU, GPU, memory, and storage, engineered specifically for deployment in the datacentre.

In 2025, new systems have arrived from Amulet Hotkey, while Computle has gone one step further, launching a workstationas-a-service offering built around its own dedicated blade hardware. Established players such as Boxx and ClearCube also continue to offer blade-based workstation platforms.

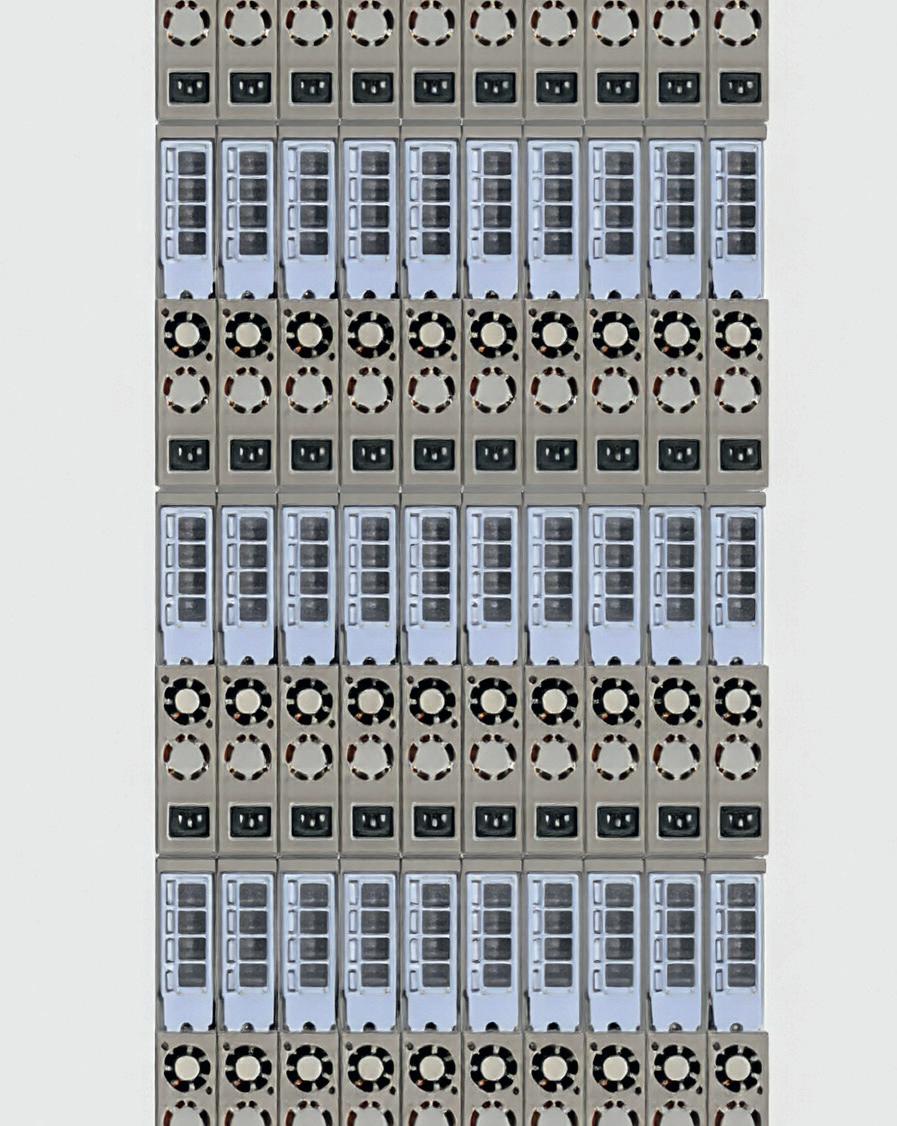

Blades provide a clean, highly modular approach to workstation deployment. The density is impressive with typically around 10 blades slotting into 5U or 6U chassis. Blades also integrate neatly into existing datacentre infrastructure,

Compared with HP and Lenovo, Dell is much less vocal about its 1:1 remote workstation offering, which centres on the Dell Pro Max Micro desktop, which packs seven units into a 5U rack. Unlike the HP Z2 Mini G1i and Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF, which can be configured with 125W Intel Core Ultra 9 285K CPUs, the Dell Pro Max Micro is limited to the 65W Intel Core Ultra 9 285. However, this is unlikely to impact performance in single-threaded CAD and BIM workflows. GPU options include the Nvidia RTX A1000 for CAD and the RTX 4000 SFF Ada for visualisation workloads.

■ www.dell.com

‘‘

The strongest argument for 1:1 remote workstations is performance. Each user gets dedicated CPU, GPU, memory and storage. There is no noisy neighbour effect, no unexpected slowdowns because another user happens to be rendering or running a simulation ’’

relying on centralised and redundant power, which simplifies cabling and makes them inherently well suited to remote-access scenarios.

From a performance perspective, blades are ideal for CAD and BIM workflows, commonly featuring high frequency CPUs and single slot pro GPUs. However, some blades can also support full height, dual slot GPUs, which can push graphics performance into the realms of high-end visualisation, beyond that of the compact desktop workstation.

For organisations standardising on remote-first workflows, blades represent a highly engineered interpretation of the 1:1 workstation concept.

Amulet Hotkey’s CoreStation HX is built for the datacentre combining redundant power and cooling with ‘full remote system management’ via a 5U enclosure that can accommodate up to 12 workstation nodes. The CoreStation HX2000 is built around laptop processors, up to the Intel Core Ultra 9 285H and MXM GPUs up to the CAD-focused Nvidia RTX 2000 Ada. For more demanding workflows, the upcoming CoreStation HX3000 will feature desktop processors up to the Intel Core Ultra 9 285K, paired with low-profile Nvidia RTX and Intel Arc Pro GPUs.

■ www.corestation.com

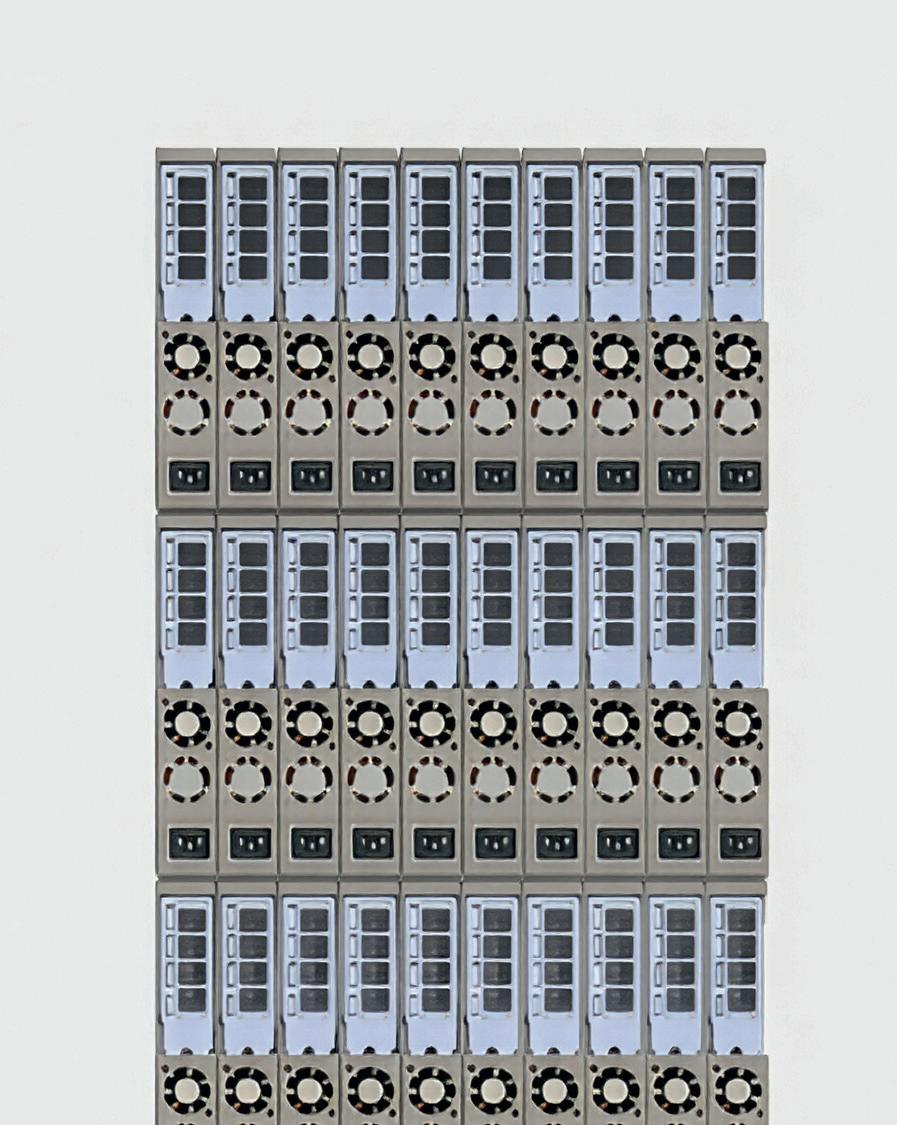

3) Dedicated rack workstations

– 1U and 2U “pizza boxes”

Sitting alongside blades are 1U, 2U, and 4U rack-mounted workstations, purposebuilt, single-user workstations designed specifically for racks. The ultra-slim 1U systems are sometimes called “pizza boxes”.

Rack workstations appeal to organisations seeking maximum performance, full-size professional GPUs, and good integration with existing server infrastructure — without the need for a blade chassis. Like other 1:1 approaches, they deliver predictable, dedicated performance while avoiding the complexity of heavy virtualisation.

The downside of rack workstations is their low density—particularly for CAD and BIM workflows, where the most suitable graphics cards are often small, entry-level models, leaving much of the large internal space unused.

There’s a tonne of firms that offer dedicated rack workstations, including Armari, PC Specialists, Novatech, BOXX G2 Digital, Exxact, Titan, ACnodes, Puget Systems, and Supermicro. HP and Dell also have rack systems but these are now several years old and, presumably, being phased out in favour of small form factor workstations.

Performance predictability

The strongest argument for 1:1 remote workstations is performance.

Each user gets dedicated CPU, GPU, memory and storage. There is no noisy neighbour effect, no unexpected slowdowns because another user happens to be rendering or running a simulation.

CPUs are typically Intel Core processors, which deliver very high clock frequencies and aggressive Turbo behaviour. This is especially important for CAD and BIM applications, which often rely on single-threaded or lightly threaded performance.

In contrast, VDI and cloud workstations rely on virtualised CPUs, where users receive a fraction of a processor. These virtualised environments often use server-class CPUs such as Intel Xeon or AMD Epyc, which prioritise core count over frequency. Even specialist CADfocused VDI platforms based on AMD Ryzen Threadripper Pro involve CPU virtualisation and typically do not allow the processor to go into Turbo.

And frequency really matters for performance. Even simple tasks, such as opening a model or “syncing to central”, are significantly impacted by low CPU frequency. When working with huge models, this can create a major bottleneck, potentially taking hours of out of the working week.

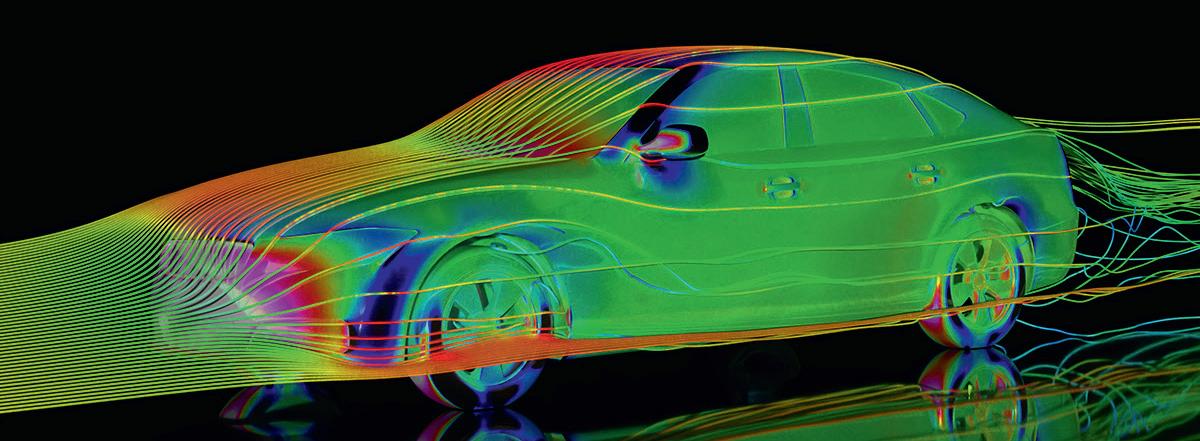

On the GPU side, 1:1 systems avoid contention entirely. While GPU sharing is rarely a major issue for day-to-day CAD and BIM work, it becomes critical for visualisation and rendering workflows, where the GPU may be driven at 100% utilisation for extended periods. A dedicated GPU ensures consistent, predictable performance.

There’s also the matter of GPU memory to consider. A typical entry-level pro GPU for design viz, such as the Nvidia RTX 2000 Pro Blackwell, comes with 20 GB of memory. To get this amount in a VDI setup would be very expensive. And if you don’t have enough GPU memory to load or render a scene, performance can drop dramatically, or software can even crash.

On-premise or fully managed services

As with VDI, organisations can choose where and how their 1:1 workstations are hosted.

Some firms deploy systems onpremise, purchasing hardware from vendors such as HP, Lenovo, Amulet Hotkey, ClearCube and Boxx. Lenovo,

Computle is a workstationas-a-service offering powered by its own 1:1 custom blade workstations, which are purpose-built for the datacentre. Customers can choose from four standard configurations centred on the Intel Core i714700, with GPU options up to the Nvidia ‘Blackwell’ RTX 5090. For more flexibility, components can be mixed and matched, including the Intel Core i9-14900, AMD Ryzen 9 9950X, or Threadripper Pro processors. Professional GPU options include the CAD-focused Nvidia RTX A2000 and high-end RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell (96 GB).

■ www.computle.com

in particular, is working to simplify deployment through its Lenovo Access Blueprints, which provide reference architectures and guidance.

Others opt for fully managed services, hosting dedicated workstations in third-party datacentres. Providers such as IMSCAD, Computle and Creative ITC deliver managed 1:1 workstation platforms, combining dedicated hardware with subscription-based services.

Interestingly, neither HP nor Lenovo has gone so far as to offer their own workstation-as-a-service platforms directly. Instead, they prefer to work through specialist partners, allowing customers to choose between ownership and service-based consumption models.

VDI’s greatest strength has always been flexibility: the ability to resize virtual machines and dynamically allocate CPU, GPU and memory resources.

A 1:1 workstation is inherently more fixed. You cannot simply dial up more cores or memory on demand. However, organisations can still achieve flexibility by deploying a mixed portfolio of workstation configurations tailored to different user profiles.

Many firms are also adopting hybrid strategies, combining VDI for lighter or more variable workloads with 1:1 remote workstations for power users who demand guaranteed performance.

Not all solutions fit neatly into either camp. Service providers like Inevidesk occupy a middle ground: its vdesk solution virtualises a Threadripper Pro CPU shared among seven users, but each user receives a dedicated GPU.

This approach sacrifices some CPU predictability and frequency but ensures

ClearCube stands out for its extremely broad portfolio of 1:1 workstations that are purpose built for the datacentre. At the heart of its range is the CAD Pro, a rack-dense system that fits ten blades in a 6U chassis. The CAD Pro can be configured with a choice of Intel Core CPUs and single-slot Nvidia GPUs, up to the viz-capable RTX Pro 4000 Blackwell, which is more powerful than the SFF variant found in compact 1:1 desktops. For higherend workloads, the CAD Elite line offers dedicated 1U and 2U rack workstations with GPUs up to the RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell Max-Q.

■ www.clearcube.com

‘‘

While GPU sharing is rarely a major issue for day-to-day CAD and BIM work, it becomes critical for visualisation and rendering workflows, where the GPU may be driven at 100% utilisation for extended periods

consistent GPU performance, making it attractive for demanding visualisation tools where GPU contention is the primary concern.

Inevidesk’s approach also offers good flexibility, with the option to quickly reallocate CPU and memory resources to different VMs or pool GPU resources at night for compute intensive workflows such as rendering or AI training.

Energy efficiency is often promoted as a key advantage of VDI, with vendors claiming it has a smaller carbon footprint than maintaining multiple 1:1 workstations. The logic is straightforward: instead of powering and cooling multiple processors, graphics cards, and power supplies, a single shared infrastructure can support many users.

If reducing energy consumption is a priority, it pays to examine the details. Some past carbon comparisons we’ve seen don’t hold up under closer scrutiny, based on maximum power draw rather than typical usage. However, a recent report commissioned by Inevidesk comparing its vdesk platform to a hosted 1:1 desktop workstation, takes a more measured approach and demonstrates tangible energy savings in practice.

That said, 1:1 workstation vendors are also taking energy consumption seriously. Amulet Hotkey, for example, offers lower-

energy laptop processors, HP has machines with the energy-efficient AMD Ryzen AI Max Pro processor with integrated graphics, and Computle is exploring ways to reduce energy use in its blade systems.

1:1 workstations can also offer cost savings, but there are several factors to consider.

On the hardware side, multiple entry-level GPUs — such as the Nvidia RTX A1000 — are often less expensive than a single high-end datacentre GPU used for VDI, like the Nvidia L40, though this depends on how many virtual machines you intend to support. This principle extends to more powerful GPUs as well: some vendors, such as Computle, provide gaming-focused GeForce GPUs instead of the more costly, passively cooled datacentre variants. On the other hand, 1:1 workstations require more individual components, including multiple motherboards, power supplies, fans, and in the case of adapted desktops, aesthetically-pleasing chassis that never see the light of day.

The software stack for 1:1 workstations is also more simple. There is no need for virtualisation software, and GPU licensing is straightforward. For example, slicing a GPU for VDI requires an Nvidia RTX Virtual Workstation (vWS) software license, whereas standard free Nvidia RTX drivers are sufficient for a 1:1 workstation.

There are many compelling reasons why design and engineering firms may favour 1:1 workstations over VDI, with performance chief among them. Time and again, we’ve heard of VDI proof-of-concept projects that fail due to user pushback, particularly when performance falls short of what designers and engineers expect from a CAD workstation. In some organisations, this has become a hard line: firms such as HOK, for example, have stated they will not consider cloud workstations / virtualised server CPUs because of the performance penalties associated with single-threaded workflows. By contrast, 1:1 remote workstations preserve the familiar performance characteristics of a physical desktop. As long as the remote access infrastructure is robust, the transition can be largely transparent to users — delivering high clock speeds, predictable GPU performance, and a consistent experience for demanding CAD, BIM and viz workloads.

That’s not to say VDI doesn’t have its place. Its strengths lie in flexibility, centralised management, and, in the case of public cloud offerings, global availability at scale. But for organisations where performance, user satisfaction, and workflow continuity are paramount, 1:1 remote workstations remain a highly compelling choice for those making the move from desktop to datacentre.

Boxx Flexx is a datacentre–ready 1:1 workstation system, that can support up to ten 1G modules or five 2G modules (or all configurations in between) in a standard 5U rack enclosure.

Boxx Flexx offers an enviable combination of density and performance, with the 1G modules offering liquid-cooled Intel Core Ultra (Series 2) CPUs and one double-width Nvidia GPU, while the 2G modules support two double-width GPUs.

Boxx also offers BoxxCloud, a workstation-as-a-service solution where Flexx workstations are hosted in regional datacentres. ■ www.boxx.com

Inevidesk offers a VDI solution that has some characteristics of a 1:1 remote workstation. Each rack-mounted server or ‘pod’ can host up to seven GPUaccelerated virtual desktops called vdesks.

The Threadripper Pro CPU and memory is virtualised, but each vdesk gets a dedicated GPU, such as the Nvidia RTX 4000 Ada, for predictable graphics performance. Virtual processors and memory can be adjusted, while multiple GPUs can be assigned to a single vdesk to boost performance in GPU rendering or AI workflows.

■ www.inevidesk.com

Blending high-performance 1:1 hardware with streamlined software deployment and smarter energy use, this workstation-as-a-service startup is hard to ignore, writes

In the world of CAD workstations, ‘the cloud’ often comes with compromises: shared virtual GPUs, lower-frequency CPUs, complex licensing, and unpredictable performance. Meanwhile, energy use is hard to understand, let alone control.

Computle is taking a fundamentally different approach. Instead of pooling resources and slicing them up virtually, the UK startup delivers dedicated one-to-one workstations in a fully managed datacentre, built on consumer-grade hardware but delivered as a subscription-based service.

The result, Computle argues, is better performance, lower costs, and a clearer path to energy and cost optimisation — especially for architecture, engineering and construction firms.

Computle’s approach is both economic and technical. On the economics side, there are fewer software licensing costs, which can be significant in traditional virtualised environments.

“If you were taking a traditional graphics card and carving it up, you have to then pay Nvidia virtual workstation licences, whereas because we have dedicated (1:1) graphics cards, there’s no licensing costs associated to that,” explains CEO and founder Jake Elsley.

By leaning on open-source technology, Computle also saves money on the platform side, “Because we can move away from commercial solutions such as VMware, we can essentially use hypervisors built into our free, open-source software stack, so we can get the same performance without all the sort of overhead and costs associated with that, and no noticeable performance impact for the user,” he says.

The net effect is that, instead of each user having a slice of a larger machine, they each get their own dedicated workstation housed in a fully managed datacentre, with monthly billing typically spread over a three-year term.

And because the core components are pretty much the same as those found in a custom desktop workstation, for architecture and engineering firms used to physical machines under desks, this maps neatly to existing expectations.

The hardware setup

Instead of using a high-end server or workstation CPU (such as AMD Epyc or AMD Ryzen Threadripper Pro) and subdividing

its resources through virtualisation, Computle offers individual workstations, each dedicated to a single user.

These custom blades, which slot into a rack, are purpose-built for the datacentre, and come with their own dedicated CPU, GPU, RAM and NVMe SSD storage. Computle primarily uses consumer-grade processors, such as Intel Core, which can reach the high frequencies that CAD workflows demand.

Customers can choose from four standard configurations, each built around the Intel Core i7-14700 CPU (up to 5.4 GHz Turbo), 64 GB RAM, and a 2 TB SSD. GPU options range from the new Nvidia ‘Blackwell’ RTX 5050 (8 GB) up to the RTX 5090 (36 GB). Pricing is aggressive, starting at £123 per month for a 3-year term.

For more flexibility, a full online configurator lets customers mix and match components, including the Intel Core i914900, AMD Ryzen 9 9950X and a choice of AMD Threadripper Pro processors up to the 96-core 7995WX. There’s also a large choice of professional GPUs, such as the CAD-focused Nvidia RTX A2000 or super high-end Nvidia RTX Pro 6000 Blackwell (96 GB), along with options for more memory and expanded storage.

With fixed hardware in each blade, Computle may not offer the same flexibility as a fully virtualised solution, but with the right planning, IT teams can still maintain a good level of adaptability.

Each user can be mapped to one or more specific machines, and organisations can create pools of differently specced workstations for different workflows — say, lighter CAD/BIM-only boxes alongside heavier visualisation rigs.

“We have users that have, for example, a set of [Nvidia RTX] 5090s and then a set of 5080s and a set of 5070s,” says Elsley. “We also have some customers who have a majority of low-end machines, and then a few high specs, so you can fully customise it across each location as required.”

available for Windows and macOS, which wraps and simplifies access to the underlying pixel streaming protocols.

“There’s two options for the customer,” says Elsley. “We have Nice DCV, which is a protocol owned by Amazon, and then we have Mechdyne TGX, which is suitable for dual 5K [monitors], so it comes down to what the customer wants.

“Rather than having the user install multiple applications and set up VPNs, etc., we fully streamlined it [the client application].

“It’s custom coded from the ground up to integrate natively with those two protocols, giving them a much easier connection experience.”

While most remote users connect via their laptops or desktops using Computle’s client software, the company also offers its own thin client devices, preloaded and ready to go.

Meanwhile, for firms with historic investments in platforms like VMware Horizon, Computle can still slot into those environments — but Elsley notes there is a clear trend away from these older stacks towards their native client and DCV/ TGX-based delivery.

He then goes on to reveal that Computle is also developing its own streaming protocol, built to support multiple 5K monitors and multiple connection devices, such as iPads and tablets.

Close to compute, multi-site by design Computle is more than just ‘a workstation in the cloud.’ The company offers a range of storage solutions from enterprise-grade file servers to intelligent caching systems from the likes of LucidLink, Panzura, and Egnyte.

Storage is charged at a flat fee and resides in the same datacentre as the

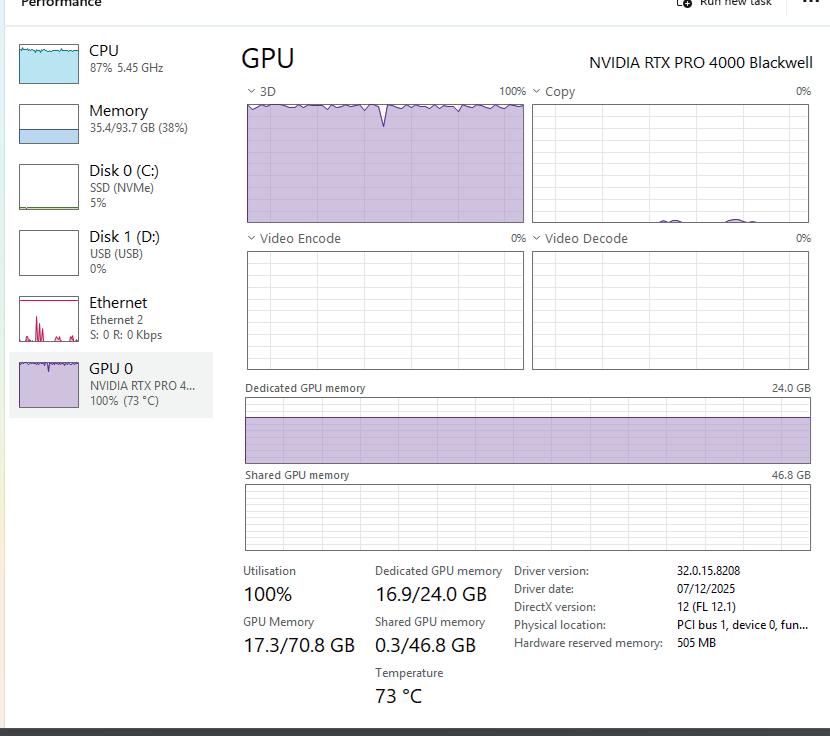

We took one of Computle’s most powerful cloud workstations for a test drive, connecting from our London office to a datacentre in the North of England using Computle’s Windows-based client and the Nice DCV protocol.

Machine specs

• AMD Ryzen 9950X CPU

• Nvidia RTX 5090 GPU

• 128GB DDR5 RAM

• 2TB NVMe SSD

Running Revit and Twinmotion at 4K, the viewport felt just as responsive as a local desktop. Single-threaded CAD benchmarks matched our fastest liquid-cooled Ryzen 9950X desktop, while multi-threaded performance lagged slightly — 7% slower in V-Ray and 13% slower in Cinebench.

The RTX 5090 topped our charts for GPU rendering in Twinmotion and V-Ray. Overall, a cloud workstation experience that felt every bit as capable as a top-end local rig.

constantly syncing down. Panzura caching nodes can be placed in the same rack as the workstations. “There’s no hidden charges, no bandwidth costs. It’s all just based on the storage consumption,” says Elsley.

For some customers, Computle also serves as an introduction to these technologies. “We recently had a client that had no understanding of cloud storage solutions. We were able to bring in some partner firms to get LucidLink set up for them and then deploy Computle across three locations.” says Elsley.

‘‘ With dedicated 1:1 hardware, featuring highfrequency CPUs and the latest Nvidia Blackwell GPUs, Computle promises cloud workstations that feel just like desktops under the desk

Crucially, Computle also bakes in redundancy at the workstation level, as Elsley explains. “[On request] we provide hot spares, so, if there’s any issues connecting to a machine, you have access to two or three extra devices.”

At the heart of Computle’s user experience is its own custom coded client application,

workstations for fast access. “We offer two tiers — all flash based on NVMe drives, and then a slower archiving tier,” says Elsley. “And what we tend to find is that customers will engage us to do an all-flash setup, one per location.”

Computle deploys its hardware in datacentres across the world. For customers with multiple offices and regions, Computle works with LucidLink and Panzura to offload backend data to AWS or Google Cloud, with data

One of the most distinctive aspects of Computle’s roadmap is its plan to rethink how customers are billed. Today, most cloud workstation providers bundle power costs into a flat monthly fee, based on assumed average usage. Computle aims to change this.

“What we’re planning for next year to really upend the market even further is a move towards consumption-based billing on the electricity side,” says Elsley. “So, moving towards two costs. You have a hardware cost, which is a fixed cost every month, and then a cost based on actual data centre charges.”

In its current model, Computle typically bills for 12 hours of usage a day, but as Elsley explains, for firms that might only be actively working on machines 9-to-5, the

‘‘

[For energy reporting] we’ll be able to give you a graph per user, what they’re doing, etc., and we can really drill down, because that’s what drives decisions Computle CEO and founder Jake Elsley ’’

new model could cut costs substantially.

“For the typical architect, they’ll be able to lower their costs probably by 20 to 30%. So, if you have 100 machines with that, that’s going to be a good cost saving.”

Underpinning this is granular control of power states, implemented at the software stack level. For example, Computle can detect when GPU-heavy applications are no longer in focus and drop machines into energy-saving modes or enforce scheduled power throttling overnight. “You have full control of the entire software stack,” says Elsley. “But it’s about giving people choice because some customers like to use it as a render farm overnight.”

Beyond billing, Computle is also looking at energy analytics, so customers can see exactly where power is being consumed and why.

“They’ll be able to see the real time data. We’ll be able to give them a report of how many kilowatts they’re using. We’ll also be able to give them trends. So, we can say ‘OK, you’re using this much overnight, have you considered using our new way to standby your machines overnight?’ So, lots of ways we can help them reduce that down.”

Computle is also exploring energy reporting at a more granular level. “We’re looking at some hardware and software options that give us that per machine level of information,” says Elsley. “So we’ll be able to give you a graph per user, what

they’re doing, etc., and we can really drill down and give that data, because that’s what drives decisions.”

For firms under pressure to reduce reported energy use and emissions — while simultaneously ramping up GPUheavy tasks like real-time visualisation and AI — this kind of visibility could be very important.

Computle is also exploring other ways to bring down costs. In 2026 it will introduce Computle Flex, offering customers the opportunity to save 50% on their idle workstations, as Computle’s Hannah Newbury explains, “A company can reduce their footprint costs by sleeping or suspending their machines during quieter times,” she says. “Credit is then applied to the bill at the end of the term. For example if you have a 50 person firm, you could be spending £7K monthly. If you suspended 50% of them in monthly blocks you would get £1,750 off.”

Estate management: beyond imaging Another area where Computle is investing heavily is in streamlining application deployment and workstation management.

Global footprint, aggressive ambitions

While Computle is still heavily UK-focused, it also operates out of datacentres in New York, Dubai, Hong Kong, and Sydney.

UK capacity is currently in a wholesale datacentre in the North of England, but change is on the horizon.

“We plan to build our own facility, probably in the next one to two years, so we can then get even greater savings for our customers, with the view that this will then get us to our 100 million workstation goal.”

That goal, which Elsley later confirms as 100 million workstations in just ten years, seems overly ambitious, even for a tierone OEM, let alone a startup — especially considering that market research firm IDC (www.idc.com) forecasts total global sales of desktop and mobile workstations will only exceed 8 million by 2026. Even so, Elsley’s bold vision is impossible to ignore.

“One of the things that our customers have struggled with historically is looking after their estate,” says Elsley. “The historical way of doing services would be image-based deployments.

“If you have a 200 person architects they will spend, typically a week or so, updating an image and building it, and then within a month, that image will be out of date.”

Instead of constantly rebuilding and rolling out full images, Computle has plans to introduce its own version of Microsoft Intune, allowing admins to orchestrate CAD application deployment at scale.

With dedicated 1:1 hardware, featuring high-frequency CPUs and the latest Nvidia Blackwell GPUs, Computle promises cloud workstations that feel just like desktops under the desk. But its approach isn’t just about outperforming virtualised machines — the company also deserves much credit for addressing other key challenges, such as smarter energy use and streamlined software deployment

— all combined with aggressive pricing.

While its growth targets are ambitious to say the least, there’s no question that this UK startup is emerging as a credible challenger to established cloud and VDI workstation providers, certainly making it one

time down from many hours to minutes is

Admins upload installers for common CAD, BIM or viz applications once to a central portal, then provision each machine on the fly. “Taking that admin time down from many hours to minutes is our vision, and that’s going to be a free add on for all of our customers,” says Elsley.

“The way it works is, there’s the software

“The way it works is, there’s the software catalogue, where the end user can pick from a curated list of applications, for example, Revit, and then there’s a back end for the admin so they can say, OK, when this machine is built, these are the applications I want to get installed.”

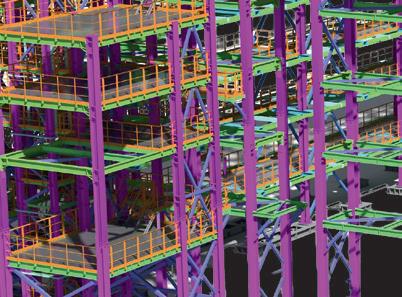

Think remote workstations are complicated? Lenovo begs to differ.

With its new ThinkStation P-Series-based ‘solution blueprints’, the workstation giant is looking to take the mystery — and the headaches — out of deployment, writes Greg Corke

Lenovo workstations have been centralised for years, but a dependable remote workstation solution involves much more than simply putting machines in a server room or datacentre. Traditionally, centralising workstations has been left to experts, given the layers of hardware and software involved to ensure predictable performance and manageability. Lenovo Access aims to change that, providing a framework that makes the deployment of remote workstation environments easier and more accessible to a wider range of IT teams.

Instead of carving up shared servers, Lenovo Access centralises one to one physical desktop workstations – the ThinkStation P series – in racks, then layers on management, monitoring, brokering and remoting protocols. The result is a suite of remote workstation solutions that, to the end user, feel like a powerful local workstation, but behave like a managed solution.

clock, it’s all about instructions per clock, as that’s how you get the performance.”

That’s exactly what you get with Lenovo Access, especially with the ThinkStation P3 Series, which features Intel Core processors with Turbo frequencies of up to 5.8 GHz, significantly more than you get with a typical processor used for Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) or cloud.

Access didn’t emerge in a vacuum. Lenovo has been iterating this approach in public at NXT BLD, Autodesk University, and Dassault Systèmes 3DExperience World for several years.

‘‘

In many ways, Access serves as a subtle rebuke of traditional VDI for design workloads. Rather than virtualising a graphics server to behave like multiple CAD boxes, it starts with actual workstations and exposes them remotely.

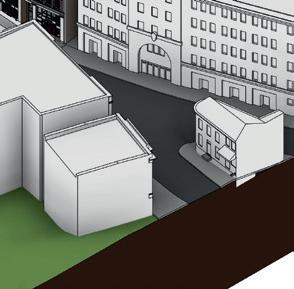

The Access story begins with the ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF, where up to seven of the small form factor workstations are housed in a 5U ‘HyperShelf’, a custom tray developed by RackSolutions. That concept has now expanded with the ThinkStation P3 Tiny, which offers even greater density — up to twelve ultracompact workstations in the same 5U space.

Rather than virtualising a graphics server to behave like multiple CAD boxes, Lenovo Access starts with actual workstations and exposes them remotely

But customer priorities shifted sharply during and, especially, after the pandemic.

At its core is a big emphasis on user experience, and performance, something that’s incredibly important to architecture, engineering or construction firms. As Mark Hirst, Lenovo’s worldwide workstation solutions manager — remote and hybrid, puts it, when you look at typical AECO applications, “It’s all about hitting that turbo

According to Chris Ruffo, worldwide segment lead for AEC and product development in the Lenovo workstations group, the moment came when firms realised remote work wasn’t a short term exception but the new baseline. Many customers, he recalls, said they needed “to deliver a consistent compute experience, a consistent BIM / CAD experience, no matter where they work — at home, in the office, on the job site, in the boardroom.”

The ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF has some clear technical benefits over the ThinkStation P3 Tiny, including a choice of more powerful GPUs up to the Nvidia RTX 4000 SFF Ada Generation, and support for a dedicated Baseboard Management Controller (BMC) PCIe card for out of band management. The Tiny lacks a PCIe slot for that, instead relying on Intel vPro and tools such as Lenovo Device Orchestration.

IT admins don’t get the same level of hardware level control, acknowledges Hirst, but you gain higher density and lower cost. Many customers, he says, “just

want the basic functionality” and already “have ways of managing their devices.”

The mechanical design of the HyperShelf itself has evolved too. The original design simply let the external power supplies hang lose to the side, but in the case of maintenance or failure, customers found it too easy to pull out the wrong cable. A new Gen 2 release makes cable management simpler, and each PSU now sits vertically in a cradle and clearly corresponds to a specific workstation.

Given the density — seven Ultras or twelve Tinys per 5U shelf — thermal behaviour is critical. Hirst stresses that Lenovo and RackSolutions “put it through some pretty rigorous tests to make sure that we’re not going to throttle performance” The shelf relies on front to back airflow with an exhaust fan at the rear.

From a purchasing standpoint, customers can still treat this as a standard Lenovo order. The shelf and supporting parts are available through Lenovo, and as an extension of that, through Lenovo partners.

Lenovo Access isn’t limited to the CAD-focused ThinkStation P3 Series — it also extends to Lenovo’s large tower workstations: the Threadripper Pro-based P8 and Intel Xeon-based P7 and PX. This gives customers a choice of multi-core, multi-GPU, high-memory powerhouses capable of handling the most demanding workflows, albeit at a much lower density.

Of course, there’s also a hard headed economic side. Hirst is very explicit that

Access has to be financially competitive: “If it doesn’t come in less expensive than the competition, than the cloud or VDI, then nobody’s going to adopt it.” He argues that the current Access model “checked all those boxes” — strong user experience, manageable administration at scale, and “saving the customer money as well.”

Then there’s the certification angle. Some software developers, such as Dassault Systèmes and Catia, still certify hardware at the workstation level. “Where that workstation sits, is not critical,” says Hirst, , meaning Lenovo can draw on the same rigorous testing and certification process it has relied on for its desktops for decades.

Blueprints: modular “cookbooks”

Access is not a single appliance or rigid reference design. Lenovo describes it as a set of Blueprints: validated combinations of hardware, remote protocols like Mechdyne TGX or Microsoft RDP, connection brokers like LeoStream, and management tools that partners and customers can adapt.

Specialist partners such as IMSCAD and Creative ITC already have mature stacks of their own. In that context, Lenovo’s job is to evaluate and document what works well on ThinkStation, not dictate a single stack.

Each blueprint comes with a bill of materials and installation guide. For example, the P3 Ultra + TGX + LeoStream

design includes step by step instructions for installing each module. Hirst frames it quite literally as following a recipe.

Collaboration beyond screen sharing Lenovo’s preferred remoting protocol in many Access Blueprints is Mechdyne TGX. It’s chosen partly for efficiency at high resolutions, but perhaps more importantly for how it handles collaboration.

For design teams, high definition, multi monitor setups are becoming standard. Hirst notes that “everyone seems like they’ve got 4K displays on their desks nowadays. The more pixels you send, the harder it is”. TGX, he says, is “very efficient in what it does,” and “very good at matching to whatever your local configuration is” – whether that’s two displays mirrored from the remote workstation while keeping a third display local, or other layouts.

Where it really stands out, though, is multi user sessions. TGX allows multiple collaborators to connect to the same remote workstation, and any user can be handed control. That makes it ideal for design reviews or training: one user can drive Revit or a visualisation tool while a senior architect or engineer “connect[s] to that same session at the same time, sharing keyboard and mouse control.”

Unlike typical meeting tools, Hirst notes that TGX avoids dropping to the “lowest common denominator” connection. Many protocols, he says, will “dumb

‘‘

Instead

of carving up shared servers, Lenovo Access centralises one to one physical desktop workstations – the ThinkStation P series – in racks, then layers on management, monitoring, brokering and remoting protocols

’’

everything down to the lowest network configuration,” giving everyone the worst experience. TGX instead maintains “a separate stream for each collaborator,” so each participant gets a “super high, responsive, interactive experience, full fidelity, full colour.”

Audio and video conference tools still have their place — collaborators typically use it alongside Microsoft Teams, keeping voice and video there while TGX handles the heavy graphics. Under the hood, TGX offloads encoding to Nvidia NVENC on the workstation GPU — “you need to have an Nvidia GPU on the sender at a minimum” for the best experience, notes Hirst — and can decode efficiently on the client using Nvidia or Intel integrated graphics. The Intel decode path, Hirst notes, has improved to the point where “the difference is pretty minimal,” enabling much lighter, cheaper client devices than before.

Proof before commitment

To make these concepts tangible, Lenovo has built a Centre of Excellence for Access. Initially set up in Lenovo’s HQ in Raleigh, North Carolina, it now extends via environments hosted by partners such as IMSCAD and Creative ITC in London, with a new deployment underway at Lenovo’s Milan headquarters and plans for Asia Pacific.

The idea is straightforward: customers can test real workloads on real Access Blueprints without touching their own firewall or infrastructure. They can “just come and access our environment” to see how a P3 Ultra plus TGX plus LeoStream behaves with their tools and data.

And yes, that’s what our customers are trying to do.”

Now that the centre is mature, it doubles as an adoption engine. The conversion rate from VDI/cloud to one to one workstations is striking: he estimates that “eight out of ten” organisations that try the Centre of Excellence and compare it with their existing setups end up “converting,” because “there’s a noticeable difference.”

Access is also reshaping Lenovo’s relationships with partners. Some of the companies now building Accessbased offerings were originally VDI specialists. Hirst notes that customers frustrated with VDI performance are starting to look to private cloud and as a service offerings anchored on one to one workstations instead.

Hirst points out that for standard resellers, competition “really comes down to price,” with “margins… squeezed” and “no way to differentiate” beyond discounting. Solutions like Access let them “talk about solutions in different ways,” focusing on solving customer problems — remote user experience, manageability, data locality and cost — instead of battling solely on unit price.

As remote and hybrid work starts to become the default, the choice for design centric firms is no longer between “old school” desk side workstations and virtualised cloud desktops. Lenovo Access argues for a third path: keep physical, ISV-certified workstations close to your data, manage them like a shared service, and deliver them securely to any location — with high frequency CPU clocks and dedicated GPUs still working exactly as the applications expect. ■ www.lenovoworkstations.com/ar/lenovoaccess/

Hirst notes that this originated as an internal initiative at Lenovo: “We’ve gone from proof of concept to deployment.

Hirst sees strong interest in this route, especially from firms wary of putting IP entirely in public clouds: organisations are “shifting more towards that private environment,” keeping some workflows in the public domain but moving “confidential IP… in a private environment”. For many, the answer is not to run their own datacentre but to work with partners like Creative ITC or IMSCAD “in order to manage that as a

Turn to page WS30 for a full review of the Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF, plus details

not to run their own datacentre but to

IMSCAD “in order to manage that as a service for them.”

At the same time, large generalist

about how design and engineering firms are deploying P3 Ultra-based rack solutions

resellers such as CDW are looking for ways to move beyond pure box shifting.

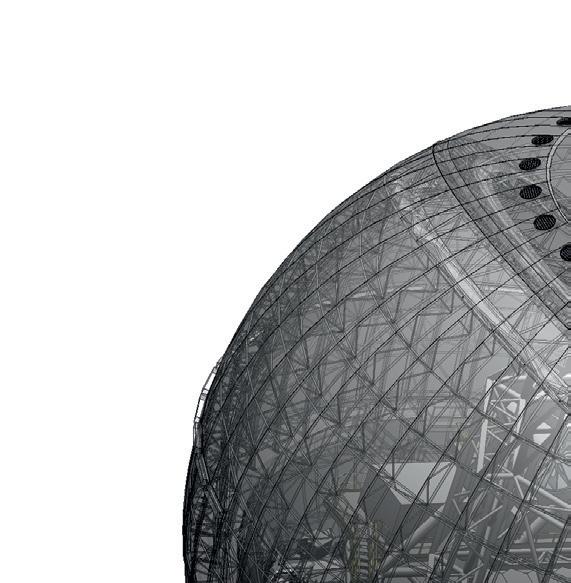

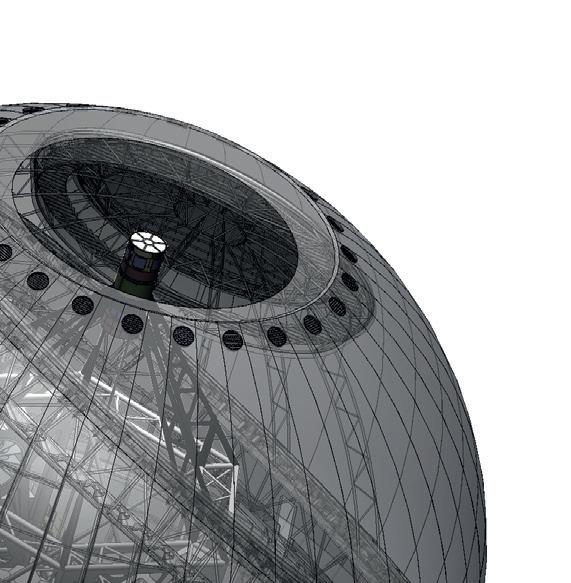

Performance of a dedicated workstation with the features of a data center platform

CoreStation HX provides a bare-metal alternative to virtualization, ensuring your power users can access the resources they need from any location. Housing 12 workstations in just 5U, complete with redundant power and out-of-band management, it is engineered with Intel® Core™ Ultra processors and optional NVIDIA® RTX series GPUs to provide the performance you need to ensure the best possible user experience.

Discover the Bare-Metal Advantage at corestation.com/aec

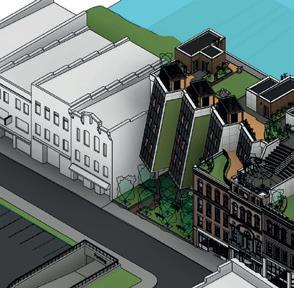

This London-based firm is now taking a hybrid approach to remote workstations blending virtualisation with 1:1 access, giving AEC firms flexible desktops that balance cost, performance, and global access, writes Greg Corke

Creative ITC has earned its reputation by focusing deeply on the complex needs of the AEC sector — something that many IT providers only claim to do. Its founders know these challenges well, having spent large parts of their careers at global engineering and design consultancy Arup.

That key sector focus has helped shape Creative ITC’s evolution from value added reseller into a leading provider of high-performance Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) solutions – installed on-premise or delivered as a fully managed cloud service through a global network of Equinix data centres.

Over the past 18 months in particular, the company has doubled down on its desktop as a service (DaaS) strategy, refining its established VDIPod platform and, crucially in Autumn 2025, adding VCDPod, a complementary layer of dedicated one-to-one remote workstations for the most challenging workloads.

VCDPod was born out of the demands of high-end practices like Zaha Hadid Architects and Foster + Partners, where huge models, intensive visualisation, and increasingly complex workflows exposed the limits of a purely virtualised workstation strategy.

Far from it, it simply adds choice.

In a large engineering firm where single-threaded bottlenecks aren’t a major concern, “Your use case absolutely would be VDI, 100% across the board,” says Dawson. “There would be no real need to have any VCD.”

At the opposite extreme, for a high-end architectural practice, “Where you are battering every application and product, you’re probably a pure VCD play,” he adds.

Most AEC organisations fall somewhere in between. In this “middle ground” for practices such as Populous, WilkinsonEyre, or Scott Brownrigg, Dawson envisions “a little bit of both,” with an “80/20 rule” applying in many architectural and construction firms. One 500-seat customer, he notes, is buying just 20–30 VCDPods alongside 470 VDI desktops.

A single portal

While Creative now offers two distinct technology platforms, for customers that straddle both, the user experience remains consistent. “The ability to log into the

‘‘

exact same physical workstations typically found on desktops. Creative ITC has chosen the Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF as its current VCDPod workhorse, which speaks to the balancing act between performance, density and manageability.

“We can put seven [P3 Ultras] in a 5U space in a rack,” says Adamson. “We found with some of the competitors we could maybe get six. By the time you scale that into hundreds across the datacentre footprint, that’s [a saving] worth having.”

Equally important is the quality of Lenovo’s out of band management. “What Lenovo have done really well is deliver a desktop form factor PC with almost a kind of server grade management tool in their BMC [card],” says Adamson.

“Essentially, they’ve taken their Xclarity platform, which is what they use for their server management, and produced an appropriately cut down version for desktop, which works really well in our experience.”

Creative ITC’s goal is not to position VDI or physical 1:1 remote workstations as inherently “right” or “wrong,” but to align each workload, user group, and region with the most appropriate mix at any given time

Creative ITC found that while VDI can offer high-performance GPUs for graphics-intensive workloads, the cost escalates quickly. “When you breach the top end of our [vGPU] profiling, it becomes very expensive,” admits Creative ITC’s John Dawson.

However, delivering better price–performance on GPUs is not the only appeal. As more customers learned of VCDPod, it quickly attracted a second audience: those running single-threaded applications such as Autodesk Revit, where high CPU clock speeds are critical to performance.

The introduction of VCDPod does not signal the end of VDIPod at Creative ITC.

same system, access data, applications in a consistent way, that was a major goal for us,” says Creative ITC’s Dave Adamson.

In practice, that means users continue to launch via the Omnissa Horizon client. On login, “They’ll just see the eligible types of desktop experience that they can access, which could be one or multiple flavours of VDI and indeed, VCD,” he says.

A BIM generalist might see only a standard VDI desktop; a senior visualiser could see both a VDI desktop for everyday work and a VCDPod for heavy Enscape sessions or end of project crunch.

Flexibility through choice

For the launch of VCDPod, Creative ITC has partnered with Lenovo, using the

Crucially, though, Creative ITC is not committing itself to one chassis or provider in the long term. The VCDPod platform has been architected for flexibility, as Adamson explains. “Should we choose to bring in another form factor in the future, be it a larger PC, be it a 1U pizza box server type approach, we’ll just be able to drop it in.”

Where workstations live

All of this sits against a backdrop of where AEC firms want to locate their workstations. Dawson sees some trends emerging. “The middle ground or lower tier enterprises are quite happy to get out of their datacentres and move away”, he says. By contrast, other organisations “have made large investments and [are] quite happy on prem.”

A common pattern is hybrid. For UK firms, infrastructure stays on prem, while offices in the Far East, North America or elsewhere come into Creative ITC’s hosted environment.

From the end user’s point of view, location is irrelevant. A machine could be on prem in London or in an Equinix cage in Amsterdam; the user simply sees a desktop in Horizon and can request or be assigned either on prem or hosted capacity as the business requires.

For multi site deployments across continents, however, fully hosted often wins out. With Panzura backed ‘file as a service’ and virtual desktops co located in Equinix, Creative ITC can better guarantee datacentre to datacentre bandwidth, place data close to users and avoid the challenges that often surround office-to-office links.

Security is another differentiator. Creative ITC holds multiple ISO certifications and a high level Cloud Controls Matrix (CCM) accreditation that Dawson says places the company “four tiers above” what most of its customers could realistically achieve internally. That really matters in an industry where IT departments are often under funded and overstretched.

“There are some customers we see that scare the living hell out of me, that do it themselves,” admits Dawson. “They are unfortunately ripe for cyber breaches and cyber attacks.”

From a commercial standpoint, Creative mirrors the reservation based economics of the hyperscalers. Customers can opt for pay as you go or commit to one , three or five year terms. “I would be honest, the majority are three years, because to get the TCO and the value,” Dawson says. Many mix commitments, reserving a core

of seats on three year terms while placing additional users on one year or pay-asyou-go contracts to cover project peaks.

Creative ITC is still finalising the details for VCDPod, but it expects the platform to be somewhat more rigid at launch. “I think it will start as standard three years, with the option of a fourth year,” notes Dawson, with more flexibility likely as the installed base grows. Underpinning that stance is confidence that the current generation of VCDPod hardware will remain fit for purpose for at least three to four years in most AEC environments.

It is encouraging to see Creative ITC, a long-time proponent of VDI, expand its workstation portfolio in response to evolving AEC workloads. The goal is not to position VDI or physical 1:1 remote workstations as inherently “right” or “wrong,” but to align each workload, user group, and region with the most appropriate mix at any given time, while maintaining a consistent user experience as those balances evolve.

Viewed through that lens, the combination of VDIPod and VCDPod, unified through a single portal, feels like a coherent strategy for the next phase of remote workstations for AEC: continue to virtualise where it makes sense; deploy dedicated GPU and high-frequency CPU capacity where it doesn’t; and abstract that complexity behind a single, clouddelivered, fully managed service.

■ www.creative-itc.com

For our testing Creative ITC provisioned a pair of VDIPod virtual machines (VMs), based on a virtualised “Zen 3” AMD Ryzen Threadripper Pro 5965WX CPU and a virtualised “Ada Generation” Nvidia L40 GPU. The systems were accessed via the Omnissa Horizon client using the Horizon Blast protocol, with both the client and datacentre located in the London area. Each VM was configured with a different vGPU profile. Creative ITC recommends the Nvidia L40 8Q profile for CAD and BIM workflows, and in our testing the viewport was perfectly responsive, delivering a desktop-like experience in Autodesk Revit. By contrast, the Nvidia L40 24Q profile which is better suited to visualisation, offered a fluid experience in Twinmotion with performance broadly comparable to a desktop Nvidia RTX 5000 or RTX 6000 Ada Generation GPU.

Basic lightly threaded CPU tests showed both VMs to be around 42% slower when opening a Revit file and 65% slower when exporting a PDF compared with one of the fastest liquid-cooled desktop workstations we’ve tested, based on a “Zen 5” AMD Ryzen 9950X processor. However, given the two-generation gap between the CPUs and the fact that the Threadripper Pro does not boost into turbo, this is to be expected.

For customers where single-threaded workflows represent a significant bottleneck, Creative ITC recommends VCDPod, where the latest Intel Core processors in the Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF boast superior Instructions Per Clock (IPC) and can sustain high turbo clock speeds.

Our top picks for enterprise-class mobile workstations — from lightweight 14-inch models to take CAD and BIM on the road to 18-inch powerhouses to power the most demanding, visualisation, simulation, reality modelling and AI workloads

18-inch

HP’s top-end mobile workstation, the 18-inch ZBook Fury G1i, is unapologetically focused on performance. The specs may look familiar — Intel Core Ultra 200HX series processors and Nvidia laptop GPUs up to the RTX Pro 5000 Blackwell (24 GB) — but with a 200W TDP, it extracts more sustained performance from those components than any other major OEM.

While that’s a key differentiator, it may still lag behind some gaming-inspired laptops, where combined CPU/GPU power can reach as high as 270W. Yet the ZBook Fury G1i is a true enterpriseclass machine, designed with fleet management in mind and carefully balancing performance, thermals, acoustics, and reliability. HP’s new hybrid turbo-bladed triple-fan cooling system helps maintain that equilibrium.

The 18-inch display is limited to WQXGA (2,560 x 1,600) LED, but delivers 500 nits, 100% DCI-P3, and a superfast 165 Hz refresh rate. The HP Lumen RGB Z Keyboard also takes a professional-focused approach, with per-key LED backlighting that can highlight only the keys relevant to specific tasks, preloaded with default lighting profiles for applications such as Solidworks, AutoCAD, and Photoshop.

Overall, the HP ZBook Fury G1i is unparalleled in performance, but it’s important to remember that it’s not meant for long stretches away from the desk. Its size and power draw make it best suited to designers, engineers, and visualisers who simply need to move work between office and home, while battery life and portability take a back seat. ■ www.hp.com

14-inch

The HP ZBook Ultra G1a represents a major breakthrough in mobile workstations, redefining what can be achieved with a 14-inch laptop. Powered by the “Strix Halo” AMD Ryzen AI Max+ Pro 395 processor with 16 highperformance ‘Zen 5’ cores and a remarkably powerful integrated Radeon 8060S GPU, it delivers performance typically expected only from larger laptops — making it a genuine powerhouse in a truly portable form factor.

A standout feature is the unified memory architecture. Unlike traditional discrete GPUs with fixed VRAM, the ZBook Ultra can allocate up to 96 GB of high-speed system memory to the integrated Radeon GPU, dramatically boosting its ability to handle large datasets. While it can’t match the computational power of a high-end Nvidia GPU, this innovative approach eliminates the memory bottlenecks that can slow or crash lesser machines, in some cases setting a new benchmark for memory-intensive visualisation and AI workflows. Beyond raw performance, the ZBook Ultra G1a impresses with its slim, lightweight chassis (1.57 kg, 18.1 mm), excellent build quality, and premium display options, including a 2.8K OLED touchscreen. Meanwhile, its advanced cooling system keeps temperatures in check even under heavy loads.

For architects, engineers, and designers seeking desktop-class capabilities in an ultra-compact laptop, the ZBook Ultra G1a is a stand out example. Software support is still catching up compared to workstations with Nvidia GPUs, but with viz tools like V-Ray, KeyShot, and Solidworks Visualize recently adding AMD support, this gap is rapidly closing. Read our in-depth review - www.tinyurl.com/UltraG1a

■ www.hp.com

The Lenovo ThinkPad P14s Gen6 is available in both AMD and Intel variants, but it’s the model powered by the “Strix Point” AMD Ryzen AI processor that really stands out, making this compact 14-inch workstation an excellent choice for CAD and BIM on the go.

In multi-threaded CPU and GPU-intensive operations, the ThinkPad P14s Gen 6 AMD might lag behind the “Strix Halo” HP ZBook Ultra G1a. However, for CAD and BIM workloads, the di erence is negligible — both machines will handle typical assemblies and models with ease.

The ThinkPad’s “Strix Point” AMD Ryzen AI 9 HX 370 processor can match the ZBook’s “Strix Halo” Ryzen AI Max+ Pro 395 processor single-core boost frequencies, while the integrated Radeon 890M GPU delivers more than enough performance to smoothly navigate all but the most demanding CAD and BIM models.

Unlike the Dell Pro Max 14, which uses the same chassis for both AMD and Intel variants, the ThinkPad P14s Gen 6 has separate designs. As there is no need to accommodate a discrete Nvidia GPU, this allows the AMD version to be smaller and lighter, starting at just 1.39 kg. The trade-o is a single-fan cooling system, but this is unlikely to impact most CAD and BIM workloads, which rarely push the CPU and GPU to their limits.

Overall, the ThinkPad P14s Gen 6 AMD is a compelling, highly portable mobile workstation that also earns a special mention for its serviceability, as the entire device can be disassembled and reassembled with basic tools. Finally, for those seeking a bit more screen space, the 16-inch ThinkPad P16s o ers identical specs and starts at 1.71 kg. ■ www.lenovo.com/workstations

16-inch

For the latest incarnation of its flagship mobile workstation, Lenovo has completely redesigned the chassis. The ThinkPad P16 Gen 3 is thinner, lighter, and more power-e cient than its Gen 2 predecessor, making it more of a true day-to-day laptop without compromising its workstation capabilities. It packs the latest ‘Arrow Lake’ Intel Core Ultra 200HX series processors (up to 24 cores and 5.5 GHz), a choice of Nvidia laptop GPUs up to the RTX Pro 5000 Blackwell (24 GB), and supports up to 192 GB of RAM.

While these are top-end specs, the smaller 180 W power supply — down from 230 W in the previous generation — suggests that some peak performance may be left on the table. This is particularly relevant when configured with the RTX Pro 5000 Blackwell GPU, which alone can draw up to 175 W. That said, since all processors and GPUs show diminishing returns at higher power levels, the impact on real-world performance might be relatively modest.

Ultimately, the ThinkPad P16 Gen 3 is all about balancing performance and portability. With practical features such as USB-C charging and a compact versatile chassis, it’s an excellent choice for professionals on the move, capable of handling a wide range of workflows — from CAD and BIM to visualisation, simulation, and reality modelling — without being tethered to a desk.

■ www.lenovo.com/workstations

Last year, Dell retired its long-standing Precision workstation brand in favour of Dell Pro Max. One of the standout models is the Dell Pro Max 16 Premium, which replaces the Precision 5690 as Dell’s thinnest, lightest and most stylish 16-inch mobile workstation. While the Dell Pro Max 16 Premium gives you faster processors, you get less choice over GPUs. It tops out at Nvidia’s 3000 class, whereas the 5690 offered up to the 5000 class. This could be seen as a step backward, but given the thermal/power constraints of the slender 20mm laptop and its 64 GB memory limit, pairing it with the 12 GB Nvidia RTX Pro 3000 Blackwell feels like a more realistic and balanced choice than trying to shoehorn in the 24 GB RTX Pro 5000 Blackwell. Plus, it’s still one class above rival machines like the HP ZBook X G1i and Lenovo ThinkStation P1 Gen 8.

To get the most from the Pro Max 16 Premium, it should be fully configured: a 45 W Intel Core Ultra 9 285H vPro processor, 64 GB of RAM, and the 12 GB Nvidia RTX Pro 3000 Blackwell. This setup puts it squarely in the category of entry-level design visualisation, where the extra 4 GB over the 8 GB RTX Pro 2000 Blackwell is money well spent. For more demanding workloads, the Dell Pro Max 16 Plus is the far better, but heftier, option — supporting 55W Intel Core Ultra 200HX CPUs, Nvidia RTX Pro 5000 Blackwell GPU, and up to 256 GB of memory.

Overall, the Dell Pro Max 16 Premium is an extremely well built pro laptop that delivers a strong balance of performance and portability. Finally, for those still mourning the death of Precision, Dell has confirmed the brand will return later this year as Dell Pro Precision. ■ www.dell.com

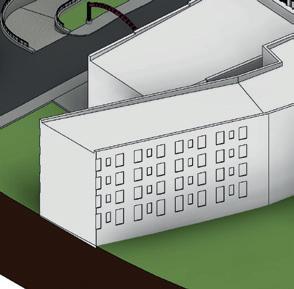

Choosing between a tower and a compact workstation can be confusing, especially when they share the same components. Greg Corke explores where small systems shine, where their limitations lie, and when a traditional tower still makes more sense

Compact workstations are big news right now. And not just because they free up valuable desk space.

Machines such as the HP Z2 Mini and Lenovo ThinkStation P3 Ultra SFF are increasingly finding themselves at the heart of modern workstation strategies, including centralised rack deployments where density matters just as much as performance.

But shrinking down a workstation to the size of a lunchbox does not come without compromise. When you cram high-performance CPUs, GPUs, memory and storage into a very small chassis, you quickly run up against the same fundamental constraints that mobile workstations have wrestled with for years: power delivery, cooling and sustained performance.

So the real question is not whether compact workstations are capable — they clearly are — but where their strengths lie, and where a traditional tower workstation still makes far more sense. Let’s break it down by component.

a level playing field. In practice, however, the realities of power delivery quickly create an imbalance. While the processor has a base power of 125W and can boost up to 250W under Turbo, the P3 Ultra SFF is constrained by its thermals and a 330W power supply. Meanwhile, the more spacious P3 Tower has bigger fans, better airflow and can be equipped with a 1,100W PSU. All of this can have a profound impact on sustained CPU performance.

But there’s no sign of imbalance under single or lightly threaded workloads, which describes the vast majority of CAD and BIM tasks. When modelling in Revit or Solidworks the difference between the two machines is negligible. Most workflows within these applications engage one or

simply cannot dissipate that amount of heat and CPU power will likely peak at around 125W. The result is much lower all-core frequencies and, inevitably, lower performance in sustained multi-threaded workloads.

Meanwhile, Dell provides much more obvious boundaries between its different Dell Pro Max desktop workstations. The super compact “Micro” model only supports 65W CPUs, up to the Intel Core Ultra 9 285, but claims to run this up to 85W. Meanwhile, it’s only the larger “SFF” and “Tower” models that come with the 125W Intel Core Ultra 9 285K.

Graphics is one area where compact workstations have traditionally been seen as compromised — but that perception is increasingly outdated

two CPU cores, allowing the processor to boost to its highest Turbo frequencies. In this scenario, both the compact P3 Ultra SFF and the P3 Tower will deliver very similar performance.

CPU: peak vs sustained performance

Arguably the biggest challenge for any modern compact workstation is the CPU, which can consume a lot of power. But when you look at the specs things can get confusing. Lenovo’s ThinkStation P3 Gen 2 range illustrates this perfectly. Both the P3 Ultra SFF (read our review on page WS30) and the larger P3 Tower can be configured with the same top-end processor, the Intel Core Ultra 9 285K. On paper, that suggests

The picture changes dramatically when all 24 cores are brought into play. In heavily multi-threaded workflows such as CPU rendering or simulation, sustained power becomes critical. The P3 Tower has the thermal and electrical headroom to feed the CPU closer to its 250 W Turbo limit, keeping all cores running at significantly higher frequencies for extended periods.

By contrast, the compact P3 Ultra SFF

GPU: smaller doesn’t mean weak Graphics is another area where compact workstations have traditionally been seen as compromised — but that perception is increasingly outdated. In a compact workstation, you are usually limited to low-profile GPUs with a max Thermal Design Power (TDP) of around 70W. The latest options include the Nvidia RTX Pro 2000 Blackwell and RTX Pro 4000 SFF Blackwell. Meanwhile, in a tower — even an entry level tower — you can step all the way up to a 300W GPU, such as the Nvidia RTX Pro 5000 or 6000 Blackwell which come with a whopping 48 GB and 96 GB of GPU memory respectively.