Navy and small shipyards eye procurement revamp.

your ship repair process:

Located in northeast Florida — two nautical miles from the Atlantic Ocean — BAE Systems Jacksonville Ship Repair applies competence, efficiency and integrity to its projects. With the opening of our 25,000-ton shiplift, we have expanded our capacity and capabilities, enabling us to enhance our maritime operations and reinforce our position as a trusted leader in the industry. Contact us today to discuss how we can support your goals.

baesystems.com/commercialshiprepair

14 Vessel Report: Undercurrents

Electric ROVs promise offshore efficiency gains.

26 Cover Story: Building Blocks

New ship procurement model could benefit the Navy and small shipbuilders.

32 In Business: Electric Boat

Behind the gates at the US submarine powerhouse.

34 In Business: E-Crane International

Crane builder targets bulk handling and dredging.

20 On the Ways

• California ferry offers diesel power without soot • Maryland fire department adds Metal Shark pair • Yard tug converted to batterypower • Washington ferry returns to service as hybrid-electric • Catalina Express orders new ferry • Second US-built SOV goes to work

• ACL christens first Patriot-class ship • New RIB for Rhode Island police department • Bollinger tapped for rocket barge conversion • First US-built rock-dumper launched • Gladding-Hearn bags another pilot boat order • FMT delivers towboat to Maritime Partners • Blue and Gold adds new tour boats • Crescent Towing orders new tug.

36 Bright Ideas

Compliance with regs, rugged dependability drive lighting innovation.

6 DHS cancels 'wasteful' OPC shipbuilding contract

6 Chevron finalizes Hess deal after legal dispute

6 Marad awards $8.75 million for small shipyards.

6 Investment firm acquires Diversified Marine

8 On the Water: Let’s talk about the weather

8 Insurance Watch: The Li-ion threat.

9 Energy Level: Oil prices and the missing barrels.

9 Legal Talk: What is a ‘bailment’ under maritime law?

10 Capital Corridors: It’s time to prepare for autonomy.

12 Captain’s Table: Drill, baby, drill — for safety’s sake.

USA, Mobile, Ala.,

12 Health, Safety, and Environment: Short-sea shipping, longstanding challenges.

The United States’ commercial shipbuilding industry has been in the limelight in recent years amid ongoing efforts to strengthen the nation’s ability to meet government shipbuilding and repair demands — needs that are critical to national security and defense.

The prevailing view is that a robust commercial maritime sector, including shipbuilding, supports a stronger naval industrial base by sustaining a skilled workforce, shared infrastructure, and supplier networks essential to both commercial and military vessel production.

So, what are the overriding challenges facing this sector, and how can they be addressed? To nd out, the Government Accountability Of ce (GAO), under direction from the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, launched a study of the issue.

For many readers of this publication — long-tenured members of the workboat industry — the ndings come as no surprise: the maritime sector faces stiff competition from other transportation modes, while shipyards struggle with aging infrastructure and workforce instability. These challenges are not new, but they’ve become more pressing as global competitors, particularly China, invest heavily in maritime and naval capabilities.

Also unsurprising are the GAO’s recommendations to expand domestic river and coastal transport, increase funding for shipyards through grants and foreign investment, and stabilize work ow through larger, more consis-

Eric Haun, Executive Editor ehaun@divcom.com

tent federal vessel orders. Again, none of this is new.

Who needs to step up to help drive action? Several parties — but one of them is the Maritime Administration (Marad).

The GAO’s key takeaway is that Marad’s administrator should set measurable goals for its nancial assistance programs — including the Federal Ship Financing Program, Construction Reserve Fund, Capital Construction Fund, and Small Shipyard Grant Program — and put in place a process to track and regularly assess progress.

First, though, we’ll need the Senate to con rm a Marad administrator to see this through.

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Eric Haun / ehaun@divcom.com

SENIOR EDITOR Ken Hocke / khocke@divcom.com

SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Benjamin Hayden / bhayden@divcom.com

SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Kirk Moore / kmoore@divcom.com

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Tim Akpinar • Jonathan Barnes • Capt. Alan Bernstein • Stephen Blakely Dan Bookham • G. Allen Brooks • Bruce Buls • Capt. Eric Colby • Casey Conley

Michael Crowley • Jerry Fraser • Nate Gilman • Pamela Glass • Capt. Arnie Hammerman Craig Hooper • Joel Milton • Richard Paine Jr. • Chris Richmond

DIGITAL PROJECT MANAGER / ART DIRECTOR Doug Stewart / dstewart@divcom.com

ADVERTISING ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE S

Mike Cohen 207-842-5439 / mcohen@divcom.com

Kristin Luke 207-842-5635 / kluke@divcom.com

Krista Randall 207-842-5657 / krandall@divcom.com

Danielle Walters 207-842-5634 / dwalters@divcom.com

ADVERTISING COORDINATOR

Wendy Jalbert 207-842-5616 / wjalbert@divcom.com

Producers of The International WorkBoat Show and Pacific Marine Expo www.workboatshow.com • www.pacificmarineexpo.com

PRESIDENT & CEO Theodore Wirth / twirth@divcom.com

VICE PRESIDENT Wes Doane / wdoane@divcom.com

PUBLISHING OFFICES Main Office 121 Free St., P.O. Box 7438, Portland, ME 04112-7438 207-842-5608 • Fax: 207-842-5609

David Clark Company is proud to be a part of “Project Perfect Storm ” - selected as the boat crew communications provider for the new 11.5-meter, high-tech RHIB Offshore Interceptor from Ocean Craft Marine.

David Clark Marine Headset Systems are transforming the way crews communicate on board high speed patrol boats and interceptors. Noise attenuating headsets and system components provide outstanding reliability and comfort, while reducing crew fatigue from prolonged exposure to wind and engine noise. Call 800-900-3434 (508-751-5800 Outside the USA) to arrange a system demo or visit www.davidclark.com for more information.

“ The {David Clark} wireless headset system has been a game-changer... enhancing crew coordination and overall communication capabilities, while increasing crew situational awareness and effectiveness, making it a must-have for professional boat operations.“

Todd

Salus, VP of Operations, Ocean Craft Marine

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem partially terminated a shipbuilding contract with Eastern Shipbuilding Group Inc. (ESG), Panama City, Fla., due to delays and rising costs in producing Heritage-class offshore patrol cutters (OPC) — also known by the designation WMSM, for maritime security cutter, medium — for the Coast Guard.

The decision comes amid a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) review of Coast Guard contracts that have failed to meet delivery terms. “ESG has been slow to deliver four OPCs, harming the U.S.’s defense capabilities and wasting Americans’ hard-earned money,” the DHS said in a press release on July 11. “In light of that, Secretary Noem partially canceled ESG’s contract for two out of the four OPCs … because it was not an effective use of taxpayer money.”

In 2016, ESG was contracted to build up to nine 360'x54'x17' OPCs, but the Coast Guard later reduced the order to four ships following multiple setbacks, including Hurricane Michael’s 2018 direct hit on ESG’s shipyard.

ESG was scheduled to deliver the lead ship, USCGC Argus (WMSM915), in June 2023, but the timeline has slipped to at least the end of 2026. The company also missed its April 2024 delivery target for the second OPC, USCGC Chase (WMSM-916). Earlier this year, ESG told the Coast Guard that it could not ful ll the remaining two ships in the contract — USCGC Ingham (WMSM-917) and USCGC Rush (WMSM-918) — without unsustainable losses, leading the Coast Guard to halt further work on those ships.

“We share a common goal with the U.S. Coast Guard — to deliver the offshore patrol cutters as quickly and ef ciently as possible,” Joey D’Isernia, ESG CEO, said in a statement following the stop work order.

According to a 2023 report from the Government Accountability Of ce, the OPC program’s estimated acquisition cost has risen from $12.5 billion in 2012 to $17.6 billion due to factors such as contract restructuring and recompetition following Hurricane Michael, as well as higher infrastructure costs.

The Coast Guard maintains its target to procure a eet of 25 OPCs “as fast as possible,” according to the DHS. In 2022, another shipbuilder, Austal USA, Mobile, Ala., was selected to build up to 11 OPCs. — Eric Haun

Chevron Corp., Houston, has fi nalized its $55 billion acquisition of Hess Corp., New York, following a favorable arbitration ruling. The deal, one of the largest in the energy sector in recent years, gives Chevron a 30% stake in Guyana’s Stabroek Block, estimated to hold over 11 billion barrels of recoverable oil equivalent.

Announced in October 2023, the acquisition was delayed by arbitration claims from ExxonMobil Corp., Spring, Texas, and China National Off shore Oil Corp., Beijing — Hess’s partners in the venture — who argued they held a preemptive right to purchase Hess’s stake. The Federal Trade Commission lifted its restrictions on July 17, clearing the way for the acquisition.

The Maritime Administration has awarded $8.75 million in grants to 17 shipyards across 12 states through the 2025 Small Shipyard Grant program, Transportation Secretary Sean P. Duff y announced on July 21. While matching last year’s total, the funding remains well below the roughly $20 million allocated annually from 2017 to 2023.

builder Diversifi ed Marine Inc., Portland, Ore., has been acquired by private equity fi rm Bochi Investments LLC, Lake Oswego, Ore., in a deal that closed on July 3. Financial terms were not disclosed. Under the new ownership structure, the shipyard's previous president and COO, Frank Manning, will become CEO and partner. Kurt Redd, founder and former CEO of Diversifi ed Marine, will spin off the company’s services division to continue running its tug, barge, and marine construction off ering.

talk about

BY JOEL MILTON

Joel Milton works on towing vessels. He can be reached at joelmilton@yahoo.com.

Should we talk about the weather? Should we talk about the government?” sang R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe on “Pop Song 89,” a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the superficiality of modern social interactions, released back in 1988.

America’s sociopolitical culture has gradually evolved into a strange and unpredictable place, where seemingly nothing is allowed to simply be a neutral, generally accepted truth, observation, or pursuit. Almost everything now carries nonnegotiable tribal political baggage and leads to conflict with the greatest of ease. Facts either don’t matter, or their interpretation must be bent to fit a particular ideology.

It’sBY DAN BOOKHAM

Dan Bookham is a vice president with Allen Insurance & Financial. He specializes in longshore, offshore and shipyard risk. He can be reached at 1-800-236-4311 or dbookham@allenif.com.

almost hard to imagine life before lithium-ion batteries.

From electric vehicles to hand tools to our ubiquitous mobile phones, they are everywhere, every day. But while this technology offers numerous benefits, it also poses several significant hazards that vessel operators, industrial facilities, and boatyards must address proactively.

It’s no surprise that Li-ion batteries pose multiple hazards, including thermal runaway — the most serious — as well as electrical, chemical, and physical risks. Whether on land or on the water, operators must prepare for a range of potential “what-if” scenarios.

As with other hazardous materials on board or in the yard, clear standard operating procedures and ongoing training are essential for effective risk mitigation. Best practices include conducting thorough risk assessments to identify where Li-ion batteries are used, stored, charged, and disposed of; evaluating hazards at each stage; designating charging and storage areas away from flammable materials, high-traffic zones, and sensitive equipment; and regularly inspecting batteries and devices for damage, including swelling, leaks,

Which brings us to the once-harmless territory of daily weather, which Stipe so slyly referenced. Long a “safe harbor” for conversation, it can now quickly turn into a squall of disagreement. Why? Because weather and climate, while distinct, are related. Given how politically charged climate change has become, it was inevitable that the controversy would spill over into discussions about weather.

It’s a shame, because recognizing the importance and progress of meteorology — and giving it the priority it deserves — is something everyone should support. The nonpartisan benefits should be obvious, as weather touches everyone and affects every form of human endeavor. Its centrality in daily life is difficult to overstate.

There’s good reason for the National Weather Service’s placement — along with its parent agency, NOAA — in the Department of Commerce. Commerce depends entirely on transportation, and no form of transportation is unaffected by the weather. Hence, no form of commerce is unaffected by the weather. Duh.

So why would any sane person knowingly harm our national capabilities for weather forecasting? It defies all common sense — which is, sadly, unsurprising.

cracks, or unusual odors. Damaged batteries should be immediately taken out of service and quarantined for disposal.

Develop a plan for safely disposing and recycling batteries in accordance with local regulations, and emphasize that damaged or end-of-life batteries must be handled as hazardous waste. Perhaps most importantly, follow proper charging guidelines — the user manual and manufacturer’s instructions are your friends here — and never leave chargers plugged in and unattended overnight. A simple outlet or power strip timer that shuts off at the end of a shift or set time can literally be a lifesaver.

The marine environment can be especially hard on Li-ion batteries. Water, salt, and rugged conditions can cuase damage during routine operations. Onboard battery installations should be done by qualified professionals and comply with marine-specific safety standards and regulations. Store batteries safely during maintenance or offseason, accounting for temperature fluctuations and potential damage. Establish strict onboard charging protocols: ensure proper ventilation, use approved chargers, and avoid unattended charging — especially overnight.

Finally, be aware of employee, crew, and guest devices. We narrowly avoided a significant claim on a vessel resulting from a crewmember’s rechargeable vape pen overheating — thanks to a captain’s vigilance.

By implementing comprehensive mitigation strategies, you can significantly reduce the risks associated with lithium-ion batteries and ensure a safer working environment, a much lower risk of a potentially business-ending incident, and protect the health and lives of your team. You’ll look like a star in the eyes of your insurance company, too.

BY G. ALLEN BROOKS

G. Allen Brooks is an energy analyst. In his over-50year career in energy and investment he has served as an energy security analyst, oil service company manager, and a member of the board of directors for several oilfield service companies.

Everyone in the energy business spends some time thinking about future oil prices. Up. Down. Flat. Regardless of the direction, price changes impact oilfield spending and activity. Given the long-term nature of oilfield projects, there’s little that can be done about short-term fluctuations, except being ready to shut down activities if oil prices crash. Therefore, planning should focus on longer-term trends.

Recently, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasted low oil demand growth for this year. It predicts the world will consume just 700,000 barrels per day (bpd) more in 2025 than in 2024. Moreover, the IEA projects demand growth of only 720,000 bpd in 2026. The IEA expects global oil consumption to peak in 2029, with China’s demand topping out in 2027. The message: get ready for a radically different world in less than five years.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration is slightly more optimistic, forecasting an 800,000 bpd demand increase this year and 1.1 million bpd more next year. The most bullish forecaster, unsurprisingly, is OPEC, projecting demand growth of 1.3 million bpd in both 2025 and 2026. So how do we reconcile these widely differing views?

All forecasts rest on assumptions — in this case, the impact of switching from fossil fuels to green energy. Governments in developed countries are pushing to electrify industrial processes, power grids, and heating and cooling systems using renewables like wind, solar, and batteries.

The IEA believes green energy will rapidly erode oil demand. OPEC disagrees, expecting transportation demand to rise despite electric vehicle adoption. Current EV market trends suggest the IEA’s optimism may be premature. OPEC also assumes developing economies will continue relying on fossil fuels to drive growth and raise living standards.

Depending on whether one relies on the IEA’s or OPEC’s outlook leads to very different futures. When global oil supply and demand data don’t align, the gap is known as “missing barrels.” The IEA accounts for them in its short-term balance, but they often result in historical demand revisions. Few track the accuracy of past forecasts — at their peril.

In May, the IEA revised past global demand estimates, adding 260,000 bpd to 2022, 330,000 bpd to 2023, and 350,000 bpd to 2024. These seemingly minor changes highlight the difficulty of evaluating forecast accuracy. To make sound decisions about the future, scrutinize the assumptions behind every estimate.

MBY TIM AKPINAR

Tim Akpinar is a Little Neck, N.Y.-based maritime attorney and former marine engineer. He can be reached at 718-224-9824 or t.akpinar@verizon.net.

ost readers are familiar with the popular reality show “Pawn Stars,” which follows the daily dealings of a family-run pawn shop in Las Vegas. In each episode, people walk into the store hoping to sell or pawn items ranging from vintage Stratocaster guitars to rare baseball cards, aiming to get top dollar for what they belive are valuable collectibles.

Interestingly, pawn shops share a legal connection with the maritime industry. Both apply the legal concept of bailments, the legal relationship that arises when we leave our valuable property in the temporary custody of another.

This business of bailments was highlighted in a recent decision from the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals involving the sinking of a barge at dockside. A marine transportation company had delivered a barge to a loading facility. Legally, this created a bailment. Unfortunately, the barge sank at dockside. The loading facility hired a salvor to raise the barge, then sued the barge owner in a salvage claim — a demand for money after saving a vessel.

Prior to delivery, the owner had the barge cleaned and inspected, and no leaks were reported. After arrival at the facility, an employee there also inspected the barge. After examining the knuckles and void tanks, he noted no water or sunlight in the void tanks, which would have evidenced a fracture.

After the barge was raised, surveyors found a fracture 12" long and three-quarters of an inch wide on the port bow rake knuckle, which covered the void tank. The court dismissed the salvage claim because the bailment created a preexisting duty on the part of the loading facility to exercise ordinary care toward the barge. The court concluded that the loading facility lacked sufficient evidence to prove that the damage occurred before the barge’s arrival.

What can we learn from bailments? Whether you’re the “bailor” (vessel owner) or the “bailee” (facility owner), know the condition of a vessel when it arrives. A shipyard superintendent probably isn’t going to get into petty arguments over who is to blame for paint dings or oily footprints tracked through a towboat’s pilothouse with the towboat company’s fleet manager, who sends over $5 million a year in diesel repair contracts. But both sides being straightforward about the condition of a vessel at the time a bailment is created can prevent misunderstandings and help preserve longstanding relationships.

BY CRAIG HOOPER

Dr. Craig Hooper is the founder and CEO of the Themistocles Advisory Group, a consulting firm specializing in maritime and national security strategy. He has been a keen observer of navies and coast guards for over two decades.

The U.S. Navy is mulling a dramatic — if not unprecedented — build-up of autonomous platforms. It is great to see the Navy consider sailing high-tech robotic warships alongside conventional warships, but these visions must come with a caution. Unless the Navy starts experimenting at scale soon, the U.S. waterfront will be unready to accommodate wide-ranging fleets of autonomous watercraft.

Without operational preparation, port stakeholders at the state, local, and federal levels will put this new fleet at risk. Right now, as Pentagon bureaucrats trade PowerPoint slides, a fleet of armed, 150' autonomous surface vessels (ASV) looks like a massive manufacturing “win” for hungry shipbuilders. It is a great vision, but, once these robots start showing up, needing maintenance — or even just basic things like, say, mooring spots — this enormous shipbuilding initiative will collapse.

The risks are real. Just accommodating this new fleet will be a management challenge. In America’s aging, decaying, and deindustrialized waterfront, the thousands of robotic craft currently on the drawing board will struggle to tie up.

Traffic is another issue. Key ports are near capacity, and, in busy waterways, seasoned Coast Guard port captains are already warning that traffic is too intense. Integrating roving battle swarms into crowded harbor traffic isn’t something to take lightly. Basic maintenance, security — even simple line handling protocols — are unresolved for robotic fleets. The intricacies of autonomous harbor traffic with degraded sensors, in bad weather — or both — has yet to be fully addressed outside of simulations.

Without serious leadership and tests at scale, the prospect of waterfront chaos looms.

As the Pentagon explores unconventional ways to boost operational readiness, it is best to start planning now. The waterfront knows that ASVs are the not-so-distant future. Builders are already racing to add capacity. And, with the numbers that are being bandied about, states and local ports that get about doing the hard work of preparing and coordinating for this massive fleet may win big.

Of course, the federal government still has work to do in understanding the macro challenges of managing autonomous combat fleets. Naval leaders are wasting time bickering over tactical-level platform requirements, pushing production later and later. That is unnecessary. If the Navy’s maritime industrial base was engaged, America could quickly start

pumping out numbers of simple, easily-upgraded — or even easily-discarded — autonomous prototypes to test at scale.

Getting operational experience at scale is critical. Once we have a fleet out there, America’s waterfront stakeholders can really start working through the basics. Operational grinding has got to be done; the waterfront does not know what it doesn’t know. Without the ability to test autonomous fleet support, the nation will never be ready to manage and support the robotic navies of the future.

As large-scale building programs get underway, other federal stakeholders can start grappling with larger management issues. The Maritime Administration owes America a full, condition-based inventory of America’s piers, moorings, and other things. As an autonomous buildup looms, it is high time to figure out just where waterfront gaps and opportunities exist. There’s no need to wait — state and local officials who want to become centers of autonomous expertise can quietly start their capability assessments, figuring out where to put autonomous combat ships once they arrive.

On the operational side, a fleet of basic autonomous ships can get about grinding through some boring proof-of-principle operational challenges. If ASVs are to operate in large numbers, they will, for example, need to conserve pier space. Cadets in the Japanese training fleet can come alongside and “nest” next to other ships in less than 15 minutes, but “nesting” protocol for autonomous ships may still be evolving. Given the Navy’s timorous approach to experimentation, some of these basic port maneuvers — maneuvers that ports will require to manage big autonomous fleets — may not have even been tested yet. A fleet of reasonably capable test articles can help move things forward, pushing commandand-control, autonomous systems, AI, and even tired old regulatory frameworks to get better.

Coast Guard and Navy approaches to vessel management have a lot of growing to do as well. Hosting a visiting U.S. Navy ship in the post-USS Cole world is a regulatory nightmare. Aimed at ensuring both crew and vessel safety, port visit pre-meetings can begin months in advance. Navy personnel need half a year or more to march local port authorities through a bewildering — and often hard to justify — array of additional security assessments, pier surveys, ship husbandry demands, and other requirements.

With autonomous ships, tiresome regulatory protocols won’t go away, but they will change. Autonomous fleets are likely going to be accompanied by a large shoreside entourage that may require secure harborside accommodation. Basic security, fire-watch, and other tasks will likely fall upon busy local harbor personnel. Lines of authority for autonomous ships have yet to be fully defined, and they will likely struggle under initial mishaps, accidents, or other stress tests.

These shifts will work themselves out over time. But, as boatbuilders rush to support an expected national call to build a massive fleet of simple, modestly-scoped unmanned small craft, America’s oft-ignored waterfront must get a chance to gear up and get ready, too.

Lubriplate is committed to providing you with the right lubrication for your vessel and other equipment affected by (VGP) Vessel General Permit regulations. Designed specifically for use in harsh marine conditions, these high performance, Environmentally Acceptable Lubricants (EAL)s deliver all the performance and protection you need, while maintaining compliance with regulations protecting the environment.

ATB BIOBASED EP-2 GREASE

• This versatile grease meets U.S. EPA Vessel General Permit (VGP) requirements.

• Passes U.S. EPA Static Sheen Test 1617 and U.S. EPA Acute Toxicity Test LC-50.

• ECO-Friendly and Ultimately Biodegradable (Pw1) Base Fluid – 75.2%.

• Designed for use on Articulated Tug Barge (ATB) notch interface, coupler ram and drive screws, above deck equipment, rudder shafts, wire rope, port equipment, cranes, barges and oil platforms.

• These fluids meet U.S. EPA Vessel General Permit (VGP) requirements.

• High-performance, synthetic polyalkylene glycol (PAG)-based formula.

• Non-Sheening – Does not cause a sheen or discoloration on the surface of the water or adjoining shorelines.

• Provides long service life and operating reliability, lower maintenance costs, and reduced overall downtime.

• Excellent anti-wear performance - rated as anti-wear (AW) fluids according to ASTM D7043 testing and FZG testing.

• High flash and fire points provide safety in high temperature applications.

• All season performance – high viscosity indices and low pour points.

• ECO-Friendly and Readily biodegradable according to OECD 301F.

• “Practically Non-Toxic” to fish and other aquatic wildlife according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hazard classification.

COMPLIANCE STATEMENT LUBRIPLATE ATB BIOBASED EP-2

and BIO-SYNXTREME HF SERIES HYDRAULIC FLUIDS are Environmentally Acceptable Lubricants (EAL)s according to the definitions and requirements of the US EPA 2013 Vessel General Permit, as described in VGP Section 2.2.9

Newark, NJ 07105 / Toledo, OH 43605 / 800-733-4755 To learn more visit us at: www.lubriplate.com

Drill once, drill twice, then drill again

BY CAPT. ALAN BERNSTEIN

Alan Bernstein, owner of BB Riverboats in Cincinnati, is a licensed master and a former president of the Passenger Vessel Association. He can be reached at 859-292-2449 or abernstein@bbriverboats.com.

Those of us with long careers in the maritime industry know that accidents often happen when we become too comfortable in our roles. It’s easy to fall into the trap of believing we have all the answers and have seen everything there is to see. In reality, we haven’t — and we must be the first to acknowledge that change is the only constant we can rely on, both in life and in our professional careers. Regular training and drills are essential for staying adaptable. They keep us sharp, informed, and engaged.

My company, BB Riverboats, recently took part in a series of important training drills aboard the Belle of Cincinnati, in coordination with federal, state, and local agencies. Participants included the Coast Guard, Department of Homeland Security, FBI, local police SWAT and K-9 teams, and local

BY RICHARD PAINE JR.

Richard Paine, Jr. is a licensed mariner and certified maritime safety auditor with over 25 years of maritime industry experience. He is currently a senior VP at the Hornblower Group and can be reached at rjpainejr@gmail.com.

One of my maritime passion projects has been exploring the potential of short-sea shipping as a viable solution to reduce roadway congestion and emissions while capitalizing on the strengths of maritime transport. Nearly 25 years ago, as a new SUNY Maritime graduate, I found a creative way to attend a Manhattan conference on the subject, and ended up discussing its future with Maritime Administration (Marad) leaders. Now, two and a half decades later, we’re still striving to make short-sea shipping an alternative to road and rail. Earlier this year, Marad expanded its Marine Highway Program to include 35 designated routes in an encouraging step forward for the United States and maritime operators, particularly those in the tug-and-barge sector. This expansion supports efforts to evolve traditional practices and better

fire departments. The exercises included a man-overboard drill, an active-shooter drill, a bomb-detection exercise, and an attempted-vessel-takeover drill.

While this may sound like a lot to coordinate, the Coast Guard handled the logistics, allowing my crew to fully participate and gain valuable experience from the drills. The participating government agencies also benefited — not only by working together through realistic, scenario-based training, but also by becoming familiar with one another and with the deck plan of the Belle of Cincinnati. As a result, they are now better prepared to respond effectively in the future.

The goal of these drills is to ensure first responders and crew can work together to respond to emergencies quickly and effectively. Although the drills are simulated, they feel very real, and everyone involved — from first responders to citizen actors to marine crew — has a critical role to play. This type of role-playing builds trust among participants and reveals gaps in procedures and practices that need improvement.

If you’re not already conducting regular drills with the Coast Guard and your local agencies, I strongly encourage you to start. The return on investment is significant: increased situational awareness among crew, faster emergency response times, improved on-site coordination, and most importantly, a higher overall standard of safety for both passengers and crew.

utilize our waterways. The U.S. still lags regions like Europe, where 40% of freight moves by short-sea shipping, compared to just 6–7% here due to our reliance on road and rail.

I believe two longstanding challenges continue to hinder the effective implementation and expansion of short-sea shipping: speed and politics.

First, the need for speed. To support a shift from commercial trucking, both vessel speeds and supporting infrastructure need to improve. Tug and barge operations have long proven their ability to move containers and dry and liquid cargos efficiently across domestic waterways. But we haven’t seen speed improvements that let operators consistently compete with trucking, even on the most congested highways. In a world filled with same-day and overnight home shipments from Amazon Prime, our society thrives on speedy delivery, and shipping must keep pace.

Second, politics. This goes beyond the typical four-year shifts in Washington. This includes government policies like the Harbor Maintenance Tax, which unfairly taxes waterborne cargo while exempting goods moved by road. There’s also a persistent lack of federal and state investment to drive the structural changes needed for short-sea shipping to thrive. Compounding this is the complex political landscape surrounding labor, where maritime, trucking, and rail unions each advocate fiercely for their members’ jobs, livelihoods, and dues, often making compromise difficult.

Until these challenges are met with modern solutions, U.S. short-sea shipping will keep coming up… short.

By Eric Haun, Executive Editor

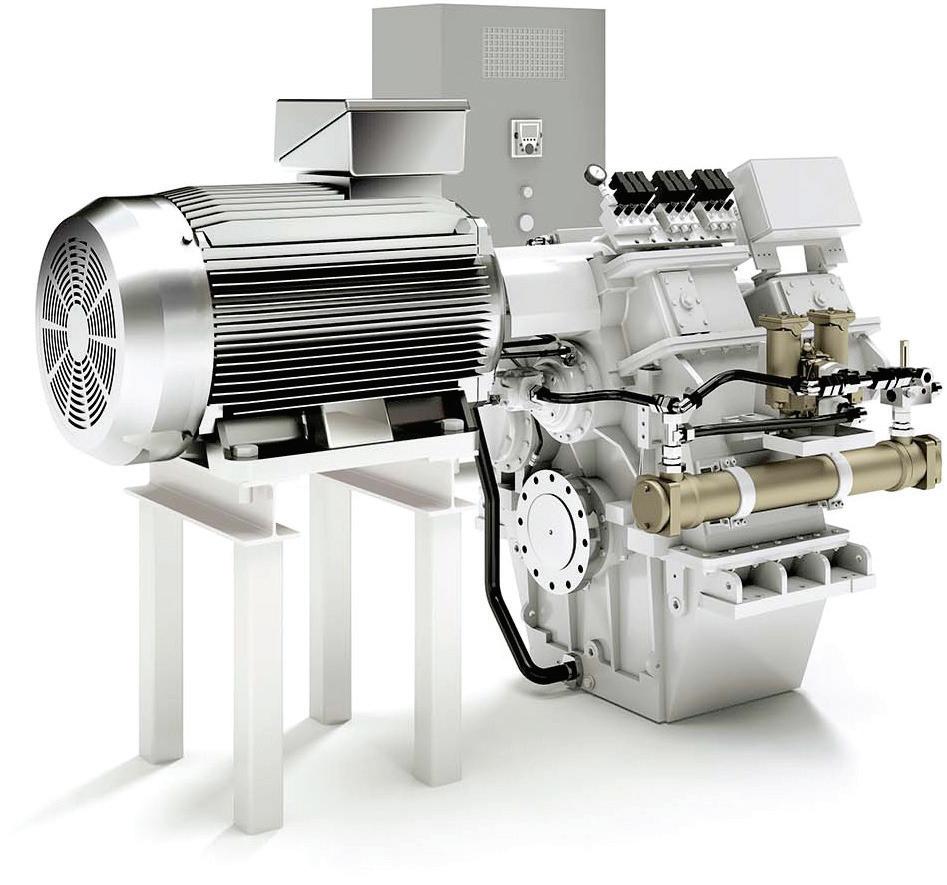

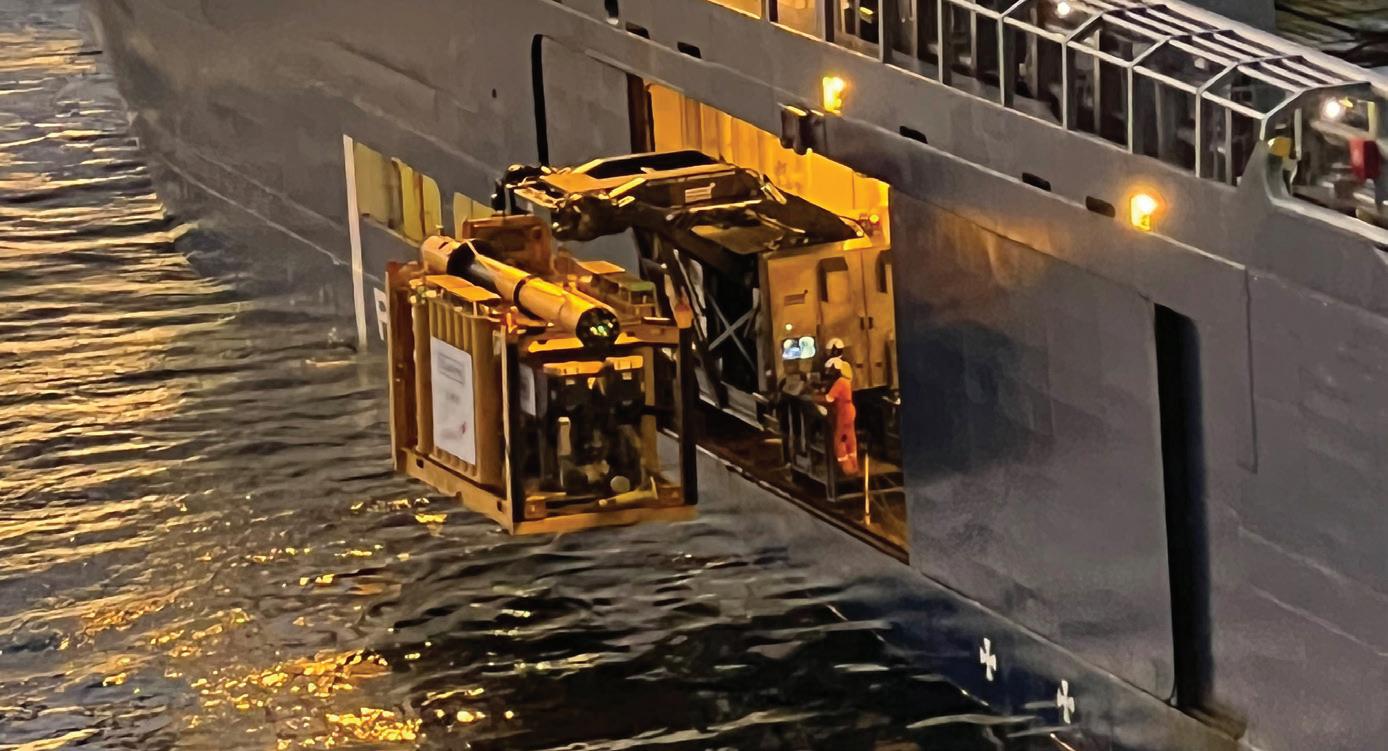

Remotely operated vehicles, or ROVs, are the underwater workhorses of offshore energy production, tethered from a vessel or rig and deployed deep beneath the waves to perform essential functions in environments that are too dangerous or inaccessible for human divers.

The largest and most powerful of these vehicles are work-class and heavy work-class ROVs, which are often used in tasks such as subsea construction as well as inspection, repair, and maintenance (IRM).

These vehicles predominantly utilize hydraulic pow-

er for their thrusters, manipulators, and auxiliary tooling.

An onboard hydraulic power unit (HPU) provides the necessary power, typically in the 100-hp to 250-hp range.

While hydraulics still dominate, a growing interest in electric work-class ROVs is starting to reshape the seascape, offering improved ef ciency, precision, and reliability. These electric systems aren’t poised to replace hydraulics entirely — at least not anytime soon — but they could carve out a growing niche in subsea operations, signaling a shift toward smarter, more efcient underwater tools, and potentially, wider adoption of subsea-resident vehicles

Electric propulsion is faster acting and provides greater controllability, said Mark Collins, director of innovation at SMD, Wallsend, England. In 2019, the company announced plans to introduce its 268-hp Quantum EV, and in 2022, the 10'10"x5'11"x6'3" electric work-class ROV began in-water testing. Trials wrapped up earlier this year, and ve units have been sold to customers in Europe, the Middle East, and the AsiaPaci c, including the rst to marine contractor Jan De Nul Group, Capellen, Luxembourg.

Another electric workclass option from SMD

is the more compact 8'6"x4'11"x5'1" Atom EV, which provides 135 hp and is geared more toward datagathering applications. Both the Atom EV and Quantum EV are rated for water depths of 10,000', with optional upgrades available for 13,000' or 20,000'.

Operating an electric ROV is largely the same as a hydraulic vehicle, but the advanced technology makes it easier to use, said Collins.

“The control you have with an electric propulsion module is quite incredible,” he explained. “And with that controllability, you can start to do a lot of clever things. The vehicle stability can be vastly improved because it can hold station with much more accuracy, provided it has complementary ight control computers.”

While ight control systems and auto-functions can be added to hydraulic ROVs, their response time is signi cantly slower than that of electric vehicles, Collins continued. “So if you’re getting into a situation where you’re trying to hold station in a three-knot current, or something pretty high like that, the hydraulic vehicles won’t be able to do that very easily… which makes it really dif cult for the pilots to undertake work in those environments.”

Because electric vehicles can better manage their

own stability and ight characteristics, automatically correcting as needed, control can be shifted from manual joystick input to more intuitive, point-and-click operation.

With a highly stable machine and an onboard ight control processor, ROV pilots can use “set point control” — simply tell the vehicle what to do (e.g., “go forward”), and it will maintain that course regardless of currents or other conditions, said Collins. Additional features like waypoint navigation can also be layered in: “Go to this position and report when you arrive.”

While some might refer to this as “de-skilling”, SMD sees it as enabling consistent performance from a broader good for our clients,” he said.

companies such as Equinor ASA, Stavanger, Norway; Shell plc, London; and Petróleo Brasileiro SA, Rio de Janeiro. Another manufacturer, Saab AB, Stockholm, has developed the 9'4"x5'11"x6'3" Seaeye SR20 eWROV, which is rated to 10,000' water depth (16,000' optional) and delivers 241 hp.

Oceaneering International Inc., Houston, has been offering electric ROVs for many years, starting with a pair of 8'6"x5'x6' eMagnum vehicles, the rst of which was deployed in 2008. The next to come along was the 8'6"x5'x6' work-class vehicle, eNovus, which is rated to 16,500' water depth and features a 235-hp power system. Two eNovus systems have been in operation since 2018, amassing a total of 50,000 dive hours.

Today, as Oceaneering is gearing up to debut its next generation of underwater vehicles, the company aims to leverage the bene ts of electri cation.

“When you convert electricity, send it down the cable, down the umbilical and tether to the ROV, put it into a transformer, operate an electric motor, spin a pump, run an HPU, pump that uid around the vehicle to spin thrusters, around 30 percent of the power at surface gets turned into thrust at the ROV,” said Nicholas Rouge, subsea robotics product manager at Oceaneering. “When we make that whole system electric, eliminating the hydraulics, we get around 60 to 65 percent ef ciency.”

This translates to more thrust on the ROV itself. During trials, Oceaneering’s engineers had so much more power than expected they had to add extra weight to the vehicle to hold it in place during thruster testing.

In addition, because the ROV draws signi cantly less power from the vessel or rig it is tethered to, less fuel is burned and the vessel’s carbon footprint shrinks.

Another environmental bene t, said Rouge, is that the volume of pressurized hydraulic oil and the number of leak points on the ROV are reduced. “We use environmentally friendly uids, but still, if you have an unplanned leak of any uid to the environment, depending on where you are in the world, you have to report that to the government. And that goes against your rating when you come up to contracting for future projects,” he said.

Both Collins and Rouge said their companies’ electric ROVs are still of-

fered with hydraulic packs to cater to legacy equipment.

“Our clients have a lot of older manipulators or tools; they don’t want to just throw them in the bin,” said Collins. “And some electric tools aren’t quite available yet, so the vehicle does have the ability to run hydraulics from a very small pack that’s on the machine.

“We’ve managed to get the size of the hydraulic pack down, but the power out of the pack is still very high, because we’re using new technologies like permanent magnet motors and DC power.”

That hydraulic power system can be removed as the shift toward electric tooling takes place. “We’re seeing in the market that more electric tools are starting to come out, and they’ll just plug directly into the vehicle,” said Collins.

In 2020, Oceaneering began developing another electric work-class vehicle, which entered the test tank as a prototype in 2024. “Between January 1 and the end of June, we have 600 hours of operation in the test tank,” said Rouge.

The rst production vehicle will be delivered into the company’s operations in October or November. “It will go to work from an Oceaneeringchartered vessel [doing IRM work] in the Gulf of Mexico, so that we can build a track record on that vehicle in

the eld,” said Rouge. “And then we have at least two more vehicles coming in late Q1 of 2026.”

“Beyond that, it all depends on market uptake. So if we have a large number of customers who want electric work-class ROVs, and their operations justify the premium, we will bring more into our eet.”

Oceaneering doesn’t sell its electric work-class vehicles. Instead, customers pay for the service. Rouge noted that it’s dif cult to directly compare costs with a hydraulic vehicle, but the electric ROV service will come with a daily premium. Capital expenditure is higher, he said, but “we’re going to save money on the maintenance, we’re going to save on troubleshooting, and we’re going to be in operations more.”

Collins said SMD’s electric ROVs cost roughly 10% to 15% more than hydraulic equivalents — for now.

“We expect that as the adoption of the technology grows, the costs will start to come down to parity, or even less than, because the whole world is electrifying,” he said, referencing the ability to translate components and knowledge from other industries into the offshore sector.

Ultimately, the market is driving demand for greener, more ef cient technologies, said Collins, as companies seek to reduce pollution and power use while improving performance. He added that cost pressures and tight working windows, especially in challenging environments, are

further accelerating this push. “It’s like a three-dimensional value map,” said Collins, where electric ROV technology can “help customers lower the cost, do jobs faster, and do things better.”

While hydraulic ROVs typically require maintenance daily or at least every few days, Rouge said that electric ROVs are more reliable and can remain underwater for longer periods, extending dive durations and opening the door to the next phase for workclass ROVs: subsea residency.

Subsea residency refers to the ability of underwater vehicles to remain deployed on the sea oor for extended periods without needing to return to the surface. This enables continuous underwater operations, reducing launch and recovery costs and improving ef ciency.

IKM Subsea AS, Bryne, Nor-

way, claims it is the rst company to successfully demonstrate a subsea resident ROV. It has had a 8'2"x4'11"x4'11" Merlin UCV (ultracompact vehicle), rated to 10,000' water depths, operating for Equinor in the North Sea since 2018.

Oceaneering has a subsea-resident ROV, too. “Any solution like that, short- or long-term resident, absolutely will be an electric vehicle,” Rouge said. “We’re going toward 30 days with no touch maintenance… That’s the key. Electri cation gets us there.”

Of Oceaneering’s two eNovus ROVs in operation today, one is deployed in a standard drilling operation, and the other is the short-term resident Liberty system that deploys throughout the Norwegian Continental Shelf for Equinor, both in the North Sea.

“[The Liberty vehicle] has its own cage with batteries that deploys to the seabed, and it deploys a buoy to the

surface that provides communications back to shore. The vessel then is able to perform other functions without staying on location while the ROV is working,” said Rouge.

Instead, the ROV is piloted from one of Oceaneering’s onshore remote operations centers, located in Stavanger, which, according to Rouge, is an important piece of what makes electric ROVs appealing. “Uncrewed surface vessels, residency, and remote operations are going to push the industry toward electric,” he said.

“I don’t know what the uptake is going to be, to be honest. We will not replace our entire eet in the next 10 years. We will target operations and customers that see the value proposition over the next 10 years, and maybe the electric vehicles account for 50% of our eet in that timeframe; it could be 25%, it could be 75%. That’s really going to depend on how well these vehicles realize their bene ts.”

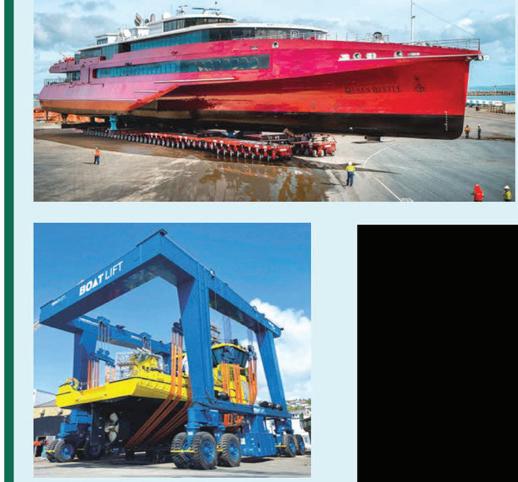

As San Francisco Bay Ferry awaits the arrival of its zeroemission newbuilds, the agency is ensuring that the final diesel-powered vessels to be built for its fleet are the cleanest in the nation.

In April, SF Bay Ferry took delivery of the high-speed passenger vessel Karl, a 137'x36.45' aluminum catamaran designed by One2three Naval Architects, Pyrmont, Australia, and built by Mavrik Marine Inc., La Conner, Wash., with construction management services provided by Aurora Marine Design, San Diego.

The boat’s EPA Tier 4-compliant propulsion package includes quad MAN D2862LE48B diesels that produce 1,450 hp at 2,100 rpm to power four HamiltonJet HTX-52 waterjets through Reintjes WVS440 DR DL gears. The ferry, which has 2,000 gals. fuel capacity and runs on R99 renewable diesel, cruises at 40 knots.

Karl features selective catalytic reduction (SCR) systems to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions, and it is the first passenger ferry in the United States to be equipped with diesel particulate filters (DPF). The vessel’s four MAN DPF units — one for each engine — filter virtually all the soot particulate from engine exhaust, ensuring compliance with California Air Resources Board (CARB) harbor craft emissions regulations.

Karl is the third of four Dorado-class

commuter ferries for SF Bay Ferry, following Dorado and Delphinus delivered in 2022 and 2024. However, it is the first to have DPF units on board. The series’ final vessel, Zalophus, which will have an engine and emissions package identical to Karl’s, including SCR and DPF units, is expected to arrive in the Bay Area at the end of the year.

This propulsion arrangement was chosen early in the build program to ensure the Dorado-class design could accommodate the SCR and DPF units once approved, a San Francisco Bay Ferry spokesperson told WorkBoat.

Industry groups such as the American Waterways Operators have advocated against the mandatory installation of DPFs, citing safety concerns and a lack of suitable marine-certified equipment. The Coast Guard has also expressed concerns about DPF’s fire safety. Nevertheless, CARB moved forward with its mandates, requiring DPFs beginning Dec. 31, 2024.

The new equipment brings updated training protocols for captains and crews, but SF Bay Ferry believes running the units will demand minimal operational adjustments. “The MAN DPFs are passive and regenerate (selfcleaning) at sufficiently high exhaust temperature,” the agency’s spokesperson said. “In Karl’s use case, the regeneration curve corresponds to full regeneration at a low rpm, theoretically

allowing minimal maintenance requirements.”

SF Bay Ferry secured federal funding for DPF technology through U.S. Sen. Alex Padilla and U.S. Rep. John Garamendi, both Democrats of California. This included a $1.52 million congressionally directed spending request from Garamendi to purchase DPFs for Karl and Zalophus. The request covered 80% of the cost, with the remaining 20% funded by local bridge toll revenue and state transit assistance.

“We’re so proud of the work SF Bay Ferry has done along with CARB, the U.S. Coast Guard and other partners to advance clean maritime technology in the Bay Area,” Jim Wunderman, SF Bay Ferry board of directors chairman, said in a statement. “It’s exciting to see state-of-the-art innovation providing passengers with safe, reliable, and affordable transportation across all of the communities we serve.”

Manned by a crew of four, plus one bartender, the 46 CFR Subchapter K ferry has capacity for 320 passengers and 37 bicycles, with a fully enclosed upper deck area. It holds 500 gals. potable water and 500 gals. sewage.

Karl features HamiltonJet AVX controls, Furuno electronics, MTU NautIQ alarm and monitoring system, and a Humphree trim control system. Service power is provided by a pair of Northern Lights M99C13 gensets.

The new ferry, which began serving the operator’s Vallejo route in May, was named through a youth-led regional contest. High schooler Sean O. submitted the winning name, inspired by the Bay Area’s iconic fog, popularly known as “Karl the Fog.” It topped a public vote and was approved by the SF Bay Ferry Board.

The four Dorado-class vessels will be the final diesel ferries to join the SF Bay Ferry fleet. CARB recently approved the agency’s plan to accelerate the transition to zero-emission technology for new short-run and existing transbay routes. The first five batteryelectric ferries are now under construction, with the first set to enter service in early 2027. — Eric Haun

Afew years back, the Anne Arundel County Fire Department was gearing up to order a new fireboat to replace one of its aging vessels. Then, in 2022, another one of its boats sank.

The department, which serves a large area with over 530 miles of Maryland shoreline, suddenly needed to order not one, but two new fireboats.

“The fire chief immediately started to talk to state representatives to see what kind of funding we could get. We had already had it in the future budget to get one boat. It just made sense to get two if we could get the funding,” said Capt. Jennifer Macallair, the department’s director of communications. “We were able to secure $1.5 million in grant money toward one of the boats.”

After considering options from several builders, the department ordered a pair of 50 Defiant NXT pilothouse fireboats from Metal Shark Boats, Jeanerette, La. The all-aluminum Klas-y Lady (Fireboat 19) and Miss Avalon (Fireboat 41) were constructed at Metal Shark’s Franklin, La., shipyard and delivered in August 2024 and April 2025. The price for both vessels was $5.6 million.

A benefit of ordering the two boats simultaneously was that the department was able to get identical vessels. “That allows our personnel to go back

and forth and operate either boat pretty seamlessly,” said Chief David Chen. Designed in-house by Metal Shark’s engineering team, the semicustom fireboats sport deep-V monohulls with outer chines and lifting strakes, and at 50'x16', they are larger and heavier than the other vessels in the department’s fleet, said Chen. Additional stability comes courtesy of Humphree Interceptors installed on the transom.

“We were looking for something able to handle the bay chop in the bay, to cut through that adequately, to provide a smooth ride for both the passengers and patients and the crew, for crew fatigue also,” said Chen. “Between the increase in weight and the change in the hull design, this boat cuts through the chop much better — provides a much smoother ride.”

Metal Shark, which continues to see its list of fire department customers expand, touts visibility as one of the key advantages of its Defiant-class designs. The company’s signature “pillarless glass” improves visibility by eliminating the blind spots common in traditional pilothouse vessels. “The visibility is great,” said Chen. “Within the cabin, they have a really good two-level glass all the way around the pilothouse.”

Each boat is equipped with a pair of MAN V8-1200 diesels that together deliver 2,400 hp to HamiltonJet HTX 42 waterjets through Twin Disc MGX5146 gearboxes, enabling a top speed of 44 knots. The boats have an operating

range of approximately 250 nautical miles when cruising at 30 knots.

“One of our other requirements was the speed — being able to move. These are faster boats,” said Chen, noting that the department’s existing vessels barely reach 30 knots. “There’s an almost 50% increase in speed, which cuts down our [response time].”

The boats have HamiltonJet AVX digital controls, and a Cummins Onan Marine QD 11.5-kW generator provides service power. Electronics include a Raymarine Zxiom pro package and a ICOM ICM506 VHF radio.

Firefighting duties are the task of twin Darley ZSF self-priming pumps and Elkhart Brass Spitfire electronic monitors. The pumps, which are driven via power takeoff from the main engines, are rated at 3,000 gpm, “but we’re seeing over 4,000 out of them because they’re mounted below the waterline,” said Chen. “We’re seeing 8,500-9,000 gpm out of the new boats on any given day, compared with about 3,000 out of our old.”

From a port helm fire control station, flow is managed via electronically actuated 8" slow-close valves with manual backups. Each vessel is equipped with a remote-operated electric rooftop monitor, two aft-mounted monitors, two aft dual handline outlets, and two 5" Storz hydrant outlets. Dual 55-gal. reservoirs provide a total of 110 gals. of aqueous film-forming foam per vessel.

— E. Haun

Marine Group Boat Works (MGBW), Chula Vista, Calif., has completed the conversion of its diesel-powered yard tug Marco V to full battery-electric propulsion. The retrofit replaces the vessel’s original Tier 3 diesel engines with four electric motors using Torqeedo Deep Blue 100i inboard systems and battery modules, each generating 135 hp at 900 rpm.

The vessel, originally built by Progressive Industrial Inc., Memphis, Fla., was operated briefly with its factory diesel engines before being stripped and

converted to electric.

MGBW CEO Todd Roberts said the shipyard considered building the electric tug in-house but determined it was more cost-effective to purchase a ready-made truckable tug.

The repower required over 2,000 labor hours and included removing the engines, clearing the engine room, and installing a modular electric drive system and charging infrastructure. The 25'x14'x5' tug now operates daily at the yard and charges overnight using 480V shore power through a ve-pin Hubbell plug.

Roberts told WorkBoat that the decision to electrify the tug was part of a broader effort to develop a standardized battery-electric propulsion package for small workboats, passenger vessels, and truckable tugs.

“The goal was to build a platform that we could have as an off-theshelf solution,” he said. “We’ve been involved in so many electri cation projects. … ABB wanted to do one. Corvis battery wanted to do one. BAE hybrid wanted to do one. And everybody had custom parts. Nobody … could tell you what it cost.

“There was no matrix for an intelligent boatowner to say, ‘Hey, how do I do this?’” he continued. “We thought, ‘Man, there is such a huge opportunity’ in the dinner cruise, charter, ferry eet, and truckable construction tugs … if you could just tell them what you were selling.

“In other words, ‘Hey, if you buy this package for X dollars, I can get

you eight hours of an 800-horsepower equivalent tug for $752,000. Or, ‘I can give you a dinner cruise boat operating at clutch ahead on a three-hour wedding tour for $748,000,’” Roberts said.

“Now that’s something that a boatowner can grab onto and can say, ‘Okay, I can make a business case for this,’ or ‘I can apply for a grant for this,’” he continued. “But that didn’t exist.”

Roberts said the California Air Resources Board’s South Coast Air Quality Management District funded roughly half of the project after MGBW decommissioned an older Tier 0 tug as part of its clean air compliance.

“We actually had another tug that we started the project with,” said Roberts.

“That hull was so compromised that we went back to the Air Resources Board and said, ‘instead of converting our existing boat, let us take this brandnew boat and build this demonstration platform that we could then take out to market and really be able to encourage more people.’”

When asked about weight differences and engine control room recon gurations, Roberts said that they were negligible. “Everything oats at the same point,” he said, noting the vessel weighs within 10% of its original build. “We removed the diesel tanks and the diesel engines. The shaft line didn’t change.

The fendering didn’t change,” he said. “It just worked.”

Additionally, MGBW mounted the battery packs on a removable skid for ease of servicing, and the bolted pilot house can be removed with a crane for maintenance access.

As for change in horsepower, Roberts said that the Torqeedo’s torque equivalent is greater than that of the 400-hp Cummins at 1,800 rpm, and he noted that the existing diesel props were spinning faster than expected.

The Marco V is now out tted with 28" Michigan Wheel four-blade propellers.

“We ordered new propellers, and we’re actually torquing the propellers

up. The boat was going too fast,” he said. “It was nose-diving when we put it in the water.”

Roberts pointed to ef ciency and environmental bene ts as hallmarks of the Marco V conversion. “This thing stacks just on top of a semi, just like any other truck, but you don’t have to fuel it,” he said. “If you’ve got generators working on-site anyway, you just run this thing off of your generator, so you don’t have to worry about the logistics of bringing diesel in.”

Roberts said it takes roughly eight hours to charge the tug’s batteries from zero to full.

Additional projects at MGBW include a 750kW solar array scheduled to come online later this year. The system is expected to support yard operations by powering the tug’s charging station and supplying electricity to more than 85% of the shipyard’s electric vehicle and forklift eet. — Ben Hayden

Washington State Ferries’ rst plug-in hybrid-electric vessel, Wenatchee, returned to service in July after a challenging and longer-than-expected conversion process.

“We have a lot to learn from this experience and room for improvement moving forward,” said Stan Suchan, practical solutions manager at the Washington State Department of Transportation. “Modifying existing vessels for new technology is inherently challenging because you must work within as-built conditions. This is particularly challenging on the rst conversion of a vessel in its class.”

The 460'2"x90' Wenatchee, built at Todd Paci c Shipyards, Seattle, in 1998, is one of WSF’s three Jumbo

Mark II-class vessels — the largest in its eet, with capacity for 2,499 passengers and 202 vehicles. In 2023, as part of WSF’s $4 billion electri cation plan, the Wenatchee entered Vigor Marine’s Seattle shipyard to begin the process of being converted to hybrid-electric propulsion.

Design and integration of the new battery-hybrid system and propulsion controls were led by Siemens Energy, which hired naval architects Glosten for the preliminary, contract, and functional design work.

In the shipyard, two of the ferry’s four EMD L16-710G7A diesel generators were removed, and new battery rooms were constructed on both ends. Siemens Energy supplied 864 Blue Vault energy storage modules that deliver 5,702 kWh in total, a pair of energy storage switchboards, and a 12.47-kV NXPLUS C switchboard for charging. The vessel also received transformers from TMC

Catalina Express , Long Beach, Calif., has ordered a 160' low-emission, renewable diesel-powered passenger ferry. Designed by Incat Crowther, Lafayette, La., and to be built by Marine Group Boat Works , San Diego, the new ferry will form part of the Port of Los Angeles’ $31 million Los Angeles Marine Emission Reduction project, funded by the California Air Resources Board. Catalina Express was awarded a $15 million grant to match its own $15 million contribution to the project.

The service operations vessel (SOV) ECO Liberty was christened in New Orleans June 28 before its deployment this summer to Equinor ’s Empire Wind project off New York. Built by Edison Chouest Offshore, the 262' hybrid-powered SOV will be offshore quarters for 60 workers for the 810-MW wind energy project.

American Cruise Lines Guilford, Ct., christened the 243'x56' passenger vessel American Patriot in Newport, R.I., in July. The ship is the first in the company’s new Patriot class, a fleet of new 130-passenger ships designed for U.S. cruising. Patriot-class sisterships American Pioneer, American Maverick, and American Ranger are scheduled to launch later this year and into 2026. Built at Chesapeake Shipbuilding, Salisbury, Md., some Patriotclass vessels are powered by Caterpillar diesels and some by Cummins

RIBCRAFT, Marblehead, Mass., recently delivered a RIBCRAFT 5.85 to the Coventry, R.I., police department. The specialized RIB enhances the department’s patrol and response capabilities while providing a platform for public safety efforts during on-water events. The 19' boat features a center console with front bench seat, operator leaning post, full- size windscreen mounted to a T-top, fore and aft tow posts, engine crash rail and keel guard. Powered by a 115-hp Yamaha outboard, it reaches speeds over 42 mph.

Rocket Lab Corp., Long Beach, Calif., has selected Bollinger Shipyards, Lockport, La., to convert a 2010-built, 400'x105'x25' deck barge Oceanus, acquired from Canal Barge Co. Inc., for use as a specialized platform to catch at-sea rocket landings. Work is taking place primarily at Bollinger’s shipyard in Amelia, La., for scheduled delivery in early 2026. The barge will be renamed Return On Investment

Great Lakes Dredge & Dock Corp., Houston, announced the launching of its 461' rock-dumper Acadia at Hanwha Philly Shipyard, Philadelphia. The ship is the first Jones

Act-qualified subsea rock installation vessel, engineered to transport and install up to 20,000 metric tons of rock on the seabed.

Delta Launch Services LLC, Metairie, La., has ordered two new pilot boats from Gladding-Hearn Shipbuilding, Duclos Corp., Somerset, Mass., for scheduled delivery in 2027. The custom, all-aluminum launches — each measuring 44.3' overall, with a beam of 13.1', a shoal draft of 2.5', and a Ray Hunt Design deep-V hull — will be the first of Gladding-Hearn’s new Venice-class vessels. The boats will be powered by twin Caterpillar C-9.3 EPA Tier 3-compliant diesel engines, each delivering 476 bhp at 2,300 rpm and a top speed of 34 knots. The engines will be connected to Twin Disc gearboxes and propelled by twin HamiltonJet HTX-30 waterjets.

Maritime Partners, Metairie, La., has added the newly built Joan Pluck to its portfolio of inland towboats, supporting the company’s bareboat charter and vessel leasing services. Designed by Entech Designs LLC, Kenner, La., and built by FMT Shipyard & Repair, Harvey, La., the ves-

sel is powered by twin Mitsubishi Tier 3 S6R2-Y3MPTAW engines, each delivering 803 hp at 1,400 rpm. The engines were supplied by Laborde Products, Covington, La. It is a sister vessel to the Parker Brooks, which was delivered earlier this year.

Brix Marine, Port Angeles, Wash., is completing two 46'x15'7" aluminum tour boats for Blue and Gold Fleet, San Francisco. Each vessel carries 49 passengers and a two-person crew. The hulls are built from 5086 aluminum alloy, with yellow Naiad D-shaped foam collars made of heavy-duty Erez and reinforced with double black PVC rub strips. Propulsion comes from four COX CXO300 4.4-liter twin-turbo V8 diesel outboards with stainless steel props. Crescent Towing and Blakeley BoatWorks, Mobile, Ala., are extending their partnership with the construction of a new 6,000-hp, Tier 4 Z-drive tugboat. Designed by Crowley Engineering Services, the 92'x38' vessel with a

as well as thousands of feet of electric and fiber optic cable.

WSF’s original plan included the conversion of its other Jumbo Mark II-class ferries, Tacoma and Puyallup, but in March, Gov. Bob Ferguson announced those projects would be postponed due to systemwide reliability issues and delays in the Wenatchee conversion program, which extended well beyond its one-year timeline.

“This is our first vessel conversion,” said Suchan. “This is a program unlike anything our organization has previously delivered.”

WSF had to adapt quickly to meet the demands of the project, which ultimately proved to be larger than originally anticipated. “WSF rapidly resourced the project, including management, engineering,

and oversight,” said Suchan. “Our ability to build organizational capacity and expertise lagged behind the conversion project, which led to issues like design and production engineering challenges.”

Vigor’s $100 million contract covered the conversion of two vessels, with a fixed-price option to convert a third. WSF now expects the cost to refit the Wenatchee alone to total around $133 million — $96 million for the hybridelectric conversion and $37 million for technology and safety upgrades, along with miscellaneous improvements such as painting and upholstery repair, said Suchan.

“Inflation and labor shortages raised costs on many major construction projects, including shipbuilding. Design changes and production engineering

challenges also contributed to delays and costs,” said Suchan.

The ferry — now the largest hybridelectric passenger vessel in the United States — began sea trials in May, marking the first test of its new propulsion system.

“This is a huge moment for us. It’s the first ferry in our system to run fully on battery power,” WSDOT Deputy Secretary Steve Nevey, head of WSF, said in a statement. “I went down into the engine room and watched as the crew started up the engines on diesel. Then, it seamlessly transitioned to full battery power. It was smooth and quiet. Seeing it work was one of the most exciting things I’ve been part of in a long time.”

After WSF accepted the vessel, crew training began while a final Coast Guard review was performed, and additional preparations were made at WSF’s Eagle Harbor maintenance facility on Bainbridge Island.

The Wenatchee officially returned to service on July 18, running part-time in the evenings on the Seattle/Bainbridge route before returning to full-time service in the following few weeks.

“We don’t yet know whether or to what extent the new propulsion system will differ from previous performance, but Wenatchee will continue to operate within our standards for speed, maneuverability, and ability to stop,” said Suchan. — E. Haun

New ship procurement model could benefi t the Navy and small shipbuilders.

By Craig Hooper, Correspondent

For almost 250 years, the U.S. Navy has procured vessels one ship at a time. The process is essentially unchanged from the late 1700s, when Congress authorized the fabrication of America’s rst six frigates. Though time and manufacturing technologies have marched on, the Navy’s procurement process, built around buying one ship after another, has remained frozen in place.

This model is increasingly being scrutinized by analysts and stakeholders who question whether it remains effective for modern naval demands and a dynamic threat environment.

Some experts argue that buying ships individually and procuring material that is hull-speci c may no longer be an effective model and could concentrate too much control in the hands of a few large prime contractors. As government vessels grow more complex, these multibillion-dollar programs are becoming harder to manage. Delays and quality concerns have emerged in various programs. Despite the incremental improvements being realized from supply chain investment

and budgetary enablers like advanced procurement funding for critical programs, material availability and shipyard sequencing and build rates remain challenged.

One proposed alternative is to break down the procurement process by buying ships in parts — such as modules and subsystems — with the Navy’s acquisition community distributing more work to smaller Tier 2 and 3 shipbuilders directly, not through a prime contractor. Advocates suggest that this could promote competition, improve quality control, and encourage standardization across the industry.

For traditional stakeholders, the idea of buying big government ships piecemeal is crazy. It’s not. Prime contractors already relegate all kinds of independently procured ship components and systems to their supply chain. Analysts have proposed expanding the use of government-furnished equipment (GFE) — where the government purchases and provides components directly — as a way to restructure procurement.

Whitney Jones, former deputy director of the Maritime

sprawling, geographically distributed enterprise ripe for reinvention. For submarines, 2,646 first-tier suppliers from 48 states provide an array of pieces, parts, and systems. According to the Aircraft Carrier Industrial Base Coalition, “aircraft carriers are built and maintained with parts built by over 2,000 businesses spread out across the United States.”

business directly with the government opens up opportunities for competition, integrates a wider set of shipbuilding competencies across the industry, and insulates the shipbuilding economy from the exploitive practices increasingly meted out by prime contractors.

Industrial Base Program and founder of the consultancy Whisky Tango LLC, said, “We need a maritime ecosystem that is encouraged and incentivized to manufacture material and components ahead of individual contracts, independent of bespoke hull numbers, and inserted into programs and build cycles as they are ready and delivered.” She added, “In our conventional acquisition of maritime systems and platforms, we are not optimizing our production lines nor creating any of the conditions needed for scale and speed. It’s a perpetual game of ‘just enough, just in time.’” Today, government shipbuilding is a

To support demand, shipyards across the nation have been recruited to build everything from basic foundations to entire ship modules. At a superficial level, this massive distribution of shipbuilding work has been cast as a great thing for small shipbuilders — an opportunity to pump life into shipyards and sub-tier suppliers, some of which might otherwise be starved for work.

In reality, life in a shipbuilding supply chain isn’t easy. Big prime contractors are tough customers, and keeping suppliers in check is part of the game. The last thing a prime contractor wants is to lose its vise-grip lock on its shipbuilding program, and that means few subcontractors in the “complex government ship” supply chain will be encouraged to grow in scope and scale.

Advocates of modular procurement say enabling small shipbuilders to do

Take cash flow, which has been cited as a key concern for shipyard suppliers. Prime contractors, according to some accounts, often attend to their own needs first, transforming suppliers from partners into short-term banking instruments. Few contracting officers are willing to mete out penalties for nonpayment, so when earnings numbers are due or a contractor tries to look like a good buy-out candidate, suppliers don’t get paid. The consequences ripple through the entire industry. Those problems might be alleviated if the government becomes the primary buyer.

Prime contractors have argued that they offer the government and their supplier base unique benefits by handling red tape and making the government’s task of managing shipbuilding less onerous. That is true, to an extent. But technology is getting to the point where the government should be able to manage the work to break a ship into separate, manageable components

and procure them independently and at quantities that maintain hot production lines and leverage efficiencies.

There is precedent. Modern shipbuilding involves dividing production into manageable parts. Complex Navy vessels are regularly described in terms of “modules,” or partially completed pieces of a ship. The Coast Guard’s polar security cutter is comprised of 85 modules. The Gerald R. Ford-class aircraft carrier is made up of around 445 “superlifts” that are, in essence, modules. And the Columbia-class submarine is made up of six “supermodules”.

Some of the modules for complex government ships are routinely being outsourced to other suppliers and becoming relatively independent products. Austal USA, Mobile, Ala., and other companies make submarine modules for General Dynamics Electric Boat Complex structures for Ford-class aircraft carriers are fabricated far away from Huntington Ingalls Industries’ Newport News (Va.) Shipbuilding

Strategic outsourcing of largescale fabrication and heavy manufacturing is hardly a new concept. What is new is the government owning the decision space as to what is getting outsourced.

If modules and subsystems are treated as GFE and purchased directly by the government, smaller shipbuilders might gain better access to defense contracts. The Navy could then assemble final

ships using pre-acquired components, rather than starting from scratch with each individual vessel.

The challenge is seen as more cultural than technical.

Ship components have historically been interchangeable at scale. America has regularly swapped entire parts of ships to facilitate repairs. During the Korean War, a mine explosion blew the bow off USS Ernest G. Small (DD-838). The bow of the unfinished USS Seymor D. Owens (DD-767) was appropriated for a fix, and the rebuilt Gearing-class destroyer went on to serve the U.S. Navy for 18 more years, decommissioning in 1970. It was a solid fix, and,

after transferring to the Taiwanese Navy, the Small served until 1999.

This type of old-school interchange between ship pieces has also worked for complex, modern vessels. In 2005, after the Los Angeles-class submarine USS San Francisco (SSN-711) slammed into a seamount, the Navy decided to replace the boat’s shattered bow with the bow from the USS Honolulu (SSN-718).

This model of interchangeability may offer flexibility for modern fleets. Proponents argue that having critical parts like bows or propulsion systems in reserve could reduce downtime when vessels are damaged.

Plans and technology might evolve, forcing inventory issues, but that is often not a total loss. Obsolete or unneeded parts, tucked away in storage, have saved many government vessels. In late 2020, a Coast Guard icebreaker, the USCGC Healy (WAGB-20), suffered a potentially catastrophic engine fire. The ship was saved only because Coast Guard contractors had, decades ago, purchased some spare parts and tucked them away. An extra propulsion motor had been sitting in a warehouse for 23 years, waiting for just this scenario, and, in the end, the old icebreaker was sidelined for only a few months.

Had the government proactively procured a few extra submarine bows or other easily damaged components

Meets 2 mile requirement for marking of dredge pipelines

1 to 3 mile visibility for aids to navigation and applications such as buoys, docks, barges, and temporary lighting

Permanent mount LED lighting for bridges, docks, and barges

Navigation Lights

For vessels greater or less than 50 meters Certified to meet UL 1104 and Subchapter M Platform Marker Lights

Solar or battery powered barge navigation lights for unmanned barges per UL1104

Available for all applications

*Available with or without lighting*

for Seawolf-class submarines, the USS Connecticut (SSN-22) — which was heavily damaged in a collision with an uncharted seamount in the South China Sea in October 2021 — would likely be back in service by now, rather than having consumed more than 10% of its service life sitting pier-side, broken.

Much of the shipbuilding industry has shied away from attempts at standardizing or broadening geographical reach. There’s something comforting in building ships one at a time, and every time America has tried to do things differently, the effort hasn’t ended particularly well. The list of failures is long.

After World War I, a massive effort to manufacture standardized troop and cargo ships at Hog Island Shipyard, Philadelphia, collapsed as geographically diverse suppliers struggled to deliver standard parts and the shipyard struggled to manage its inventory.

In the run-up to World War II, old-

school shipbuilders pushed back on Henry Kaiser’s relentless application of mass production-oriented practices and struggled to standardize combatant production. After the war, innovative experiments, like the effort to kit-fabricate destroyer escorts in the “Shipyard of the Rockies” — Denver — disappeared.

Today, modern efforts to employ modular methods are meeting mixed success. A collaborative vision of producing Zumwalt-class destroyers crumbled early, as technical tools used to share design work collapsed. A modest effort to build an advanced composite deckhouse and hangar on the Gulf Coast collapsed as well, with Bath (Maine) Iron Works building the nal Zumwalt-class superstructure for USS Lyndon B. Johnson (DDG-1002).

Modular submarine production has had more success, though not without friction. Behind the scenes, production has been acrimonious at times. Companies like W International, Goose Creek, S.C., struggled to meet quality

goals. Some large modules have experienced issues with tment, and suppliers of key systems are under pressure to meet rising demand.

Despite these issues, the defense industrial base appears to be gradually moving toward modular production and standardization.

Large shipbuilding contracts are big business and often high-pro le congressional wins. A shift in procurement strategy would face institutional resistance from industrial and political powers seeking to maintain the status quo.

Additionally, both Congress and the Pentagon have built a system to support this type of procurement model, and any changes would require new frameworks in budgeting, acquisition, and oversight.

For the Navy, scaled modular procurement would demand earlier design nalization, and at some level, designs would need to be oriented to suit the base requirements of ship assemblers