Juliana Monteiro is a visual artist with a degree in Linguistics who is currently a researcher in the Aesthetics and Art History post graduate program at MACUSP. Through photographs, words, and collage, she observes the universal character of what is intimate, infancy, impermanence, and the dynamic between word and image. She is the author of the books Pandora (2020), Aprendiz (2021), Queira receber como recordação (2022), Problemas de linguística geral (2024), Álbum (2024), among others. In addition to participating in collective shows in galleries and museums, she is the coauthor—along with the writer João Anzanello Carrascoza—of Catálago de Perdas (ed. SESI – 2017), which was finalist for the Jabuti Prize and won the FNLIJ, and Fronteiras visíveis (ed. Maralto - 2023). In 2024, she created the photo essay for A infância de Joana (ed. Maralto – 2024), written by Mariana Janelli.

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE DOOR

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE DOOR

Juliana Monteiro

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE DOOR

for my girl

I don’t tell you, little one, but one day you’ll know Why we don’t leave the house. Why back-to-school day never comes. Why the television stays tuned to your favorite channels for so long. I try to stifle my responses. While the world leaks out, we live on the inside. Early on, we made playdough with flour, water, and salt. We played detective. We made buildings out of clothespins. Every once in a while, you ask why I’m crying. I smile.

I don’t answer, but I write, so that one day you’ll hear what we lived through, in the voice of the here and now. Without stray memories. You lend me your happiness, and I stumble, sobbing. If we don’t face others, we become almost nothing, little one. In pieces, I complete myself in you.

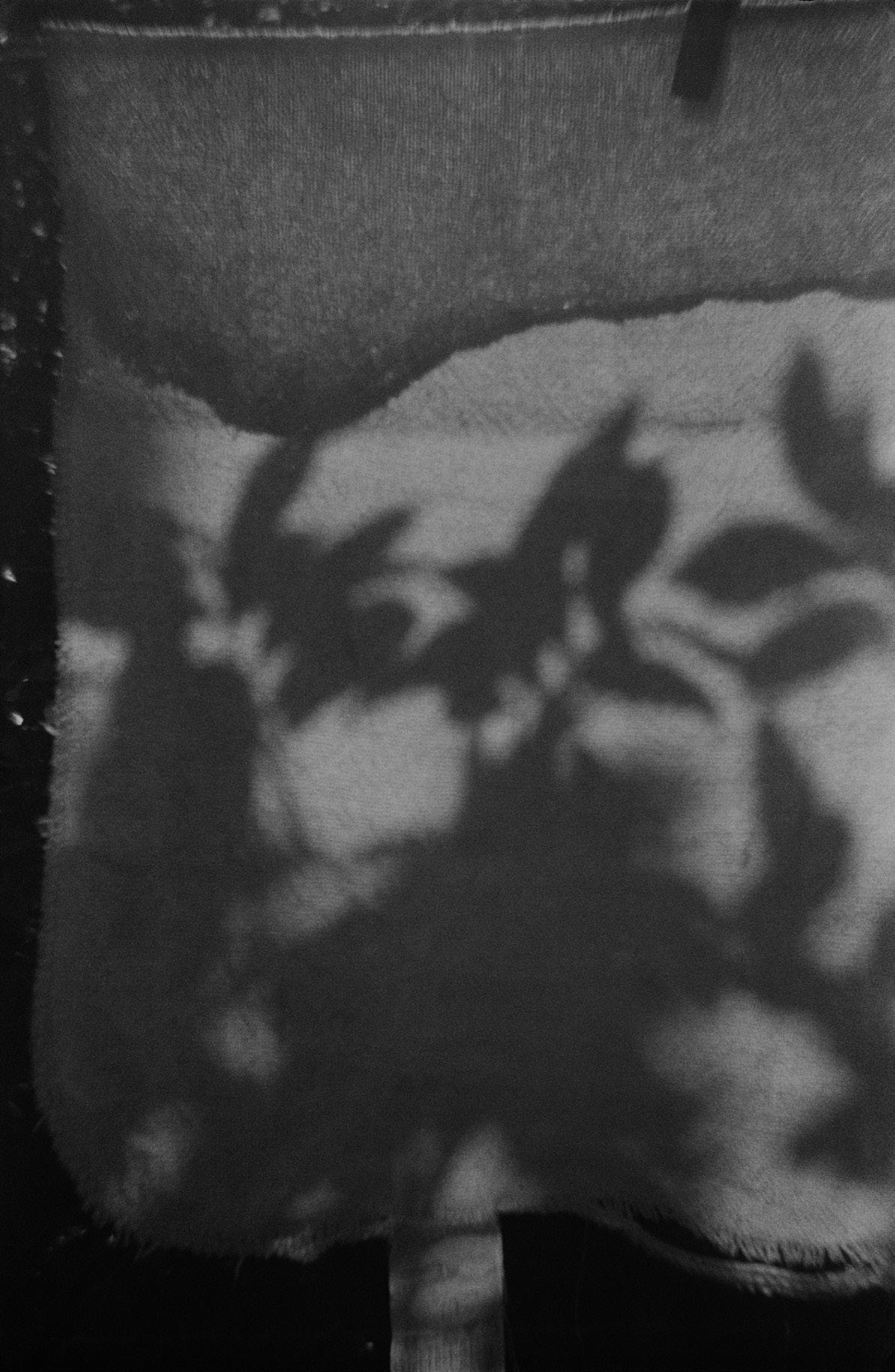

At one year old, you chased your own shadow, trying to catch yourself. Shadows are actions reflected. I learned as I watched you. I’m still in this cave.

Isolated in the room, now. On the other side of the door.

Mar. 23

I can’t breathe. Two unbearable days. Your voice is my breath.

A closed door.

I hear you sing, and I gather the strength to go on.

In the morning, I struggle to say two words. Our good morning through the keyhole. I don’t have the breath to keep talking, little one. I hope you understand the silence.

I washed the entire bathroom. Even though my legs were giving out, I scrubbed the floor hard. I scrubbed the floor like I was scrubbing my insides.

I read people’s complaints about quarantine on the internet, about sheltering at home. I would like to share a table with you, at least. I would like to breathe in the certainty of coming and going to meet you.

I can’t breathe. I need air.

25

My uncle is gone, little one.

I didn’t have the courage to tell you.

I busied myself syncopating the tears and the air I have left. We understand that we’re finite, but we never learn to say goodbye. We won’t see my dear uncle anymore. No funeral. No hug.

Just the goodbye to what we were –and this present that makes reality grow.

You just asked your father for coconut water soup. That’s the first time I’ve smiled since I’ve been locked in. You’re the one who gets me out of here.

February 26th: 1st case of COVID in Brazil

March

day 10 – semiotics class

day 11 – semiotics study group

day 12 – photography study group

day 13 – class at the high school

day 14 – home

day 15 – home (my parents came)

-beginning of quarantine-

day 16 – gynecologist

day 17 – home

day 18 – home

day 19 – home

day 20 – home

day 21 – headache

day 22 – room

I need to move my body. I drag my legs.

I carry the room on my back. I sat on the bathroom floor, cleaned the perfume cabinet. Twenty-one of them belong to your father. Two of them to me.

I scrubbed the shower tiles. There’s no dirt left.

I’m a threat to you, little one. Is love always a threat?

I hear you playing with your father. Finally, communion. Presence. In the small things, we grow.

I heard you ask: “daddy, I want the granola that mommy makes.” Food is also a way to satisfy absence.

I stare at the plate of food for over an hour. Just thinking about putting the fork in my mouth makes me sick. Hours later, I wash the dishes in the shower and leave them on the floor outside the room. Your father gathers it all with gloves and washes it again in the sink.

We can’t leave the house.

I’m the only one isolating, but you two might also be infected, even if you don’t have symptoms. We don’t have masks. I can’t find a test. We’re running out of food, and I can’t buy anything online. I can, but delivery won’t be until the second week of April. You don’t have your favorite foods.

No, I can’t die.

That no lives in my head.

Today, it consumed my whole body. It started in my hands. I couldn’t feel anything I touched.

Sleeping fingers.

Tingling arms.

Anesthetized lips—from lack of words.

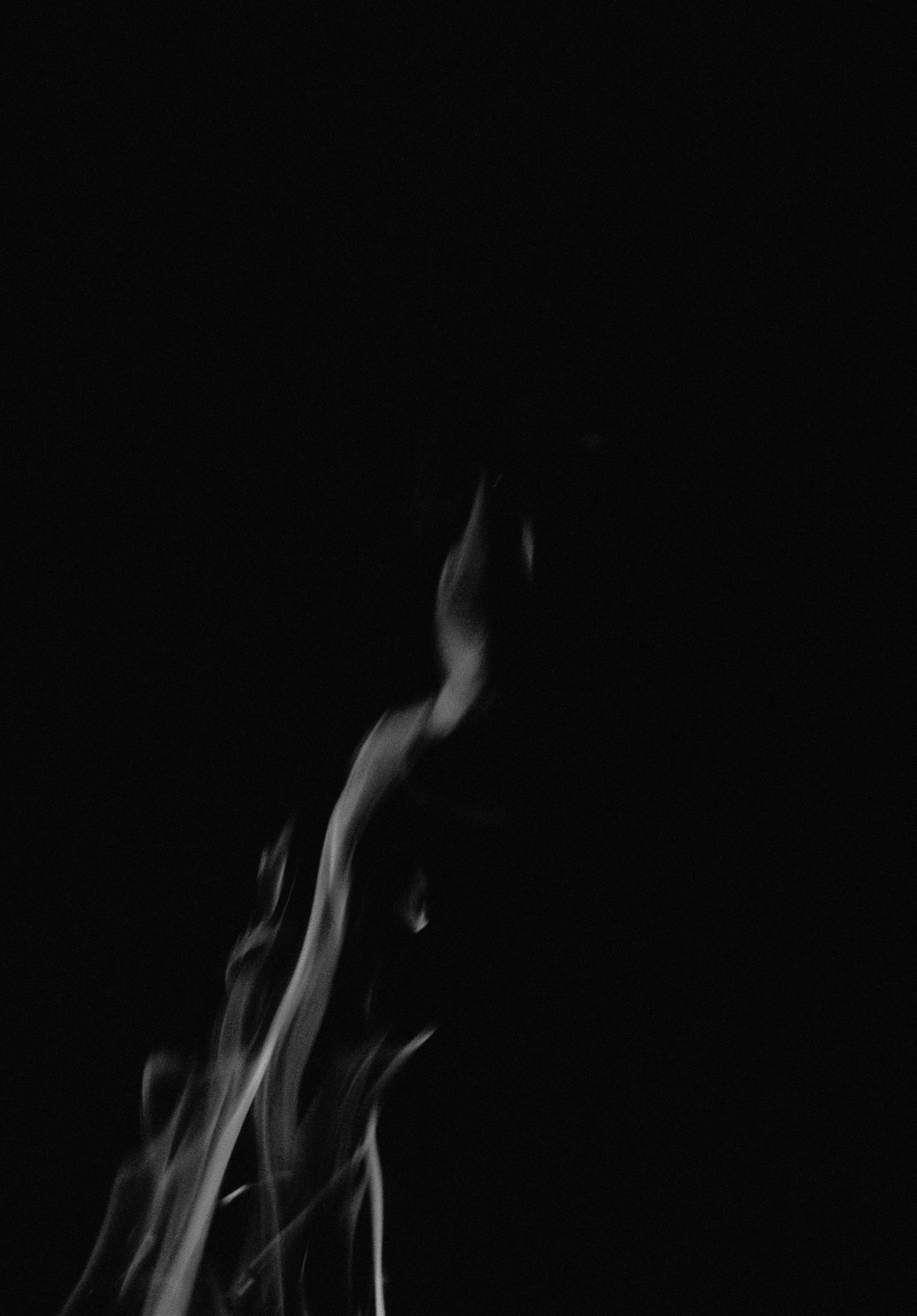

Air—that interval between coming and going—is rare. It takes my whole body to breathe.

It’s suffocating.

I lie on the cold floor, try to get my senses back.

My heart feels like it’s shouting—desperate. I stare at the ceiling.

I’m going to die.

I can’t die.

Moms don’t die, God!

I’m going to the hospital. My father will take me. I leave this notebook open, on this page, on top of the bed. If I don’t come back, please give it to my daughter. Never forget my love, little one.

I’ve been reading. Today, Kazuo Ohno read us.

The universe that we imagine wasn’t one alone. The universe exists in infinitude. This universe, that universe—that’s where desires are born. When you formulate a desire, you’re already acting it out. Instinctually, thus changing the form.

I want the cure. Silently and aloud—I shout!

Your father is drying your hair. From the room, I hear you croon the verb to share in multiple melodies. It sounded like a request. We’re learning, little one.

I bought this Kazue Ohno book a long time ago. I’d left it on the bedside table. I had to read it now. I found myself again in this passage.

Slowly, it doesn’t matter, all moments live. In the same way that through all moments, the world is built. Whether it be the soles of your feet, your back, everything comes together to build the world. It’s better to move slowly. To make sure this world gets through to your soul.

I tried.

I still can’t write about day 28.

I can’t breathe, I’m so desperate.

I love you, little one.

I’m scared of dying and not looking after you.

Mar. 30 You woke up crying. I stretched on the bed, forced myself to say good morning through the keyhole. You didn’t answer. You heard and said nothing. So small, and you already know how to protect yourself.

I stopped reading the news. Left WhatsApp groups. I stay by myself. With myself.

I was pregnant the first time I noticed how time passes through this room of the house. I spent a month lying down, looking at the sun, waiting for you to come.

It’s my grandmother’s birthday. We used to talk all the time. After I got sick, I stopped calling. It’s not fair to share pain with people who only offer the best of themselves. I’m going to call. To force myself to say congratulations without her noticing me.

Your camera is here. I photograph the room’s immensity.

I hear the neighbor fighting with her kids. And here I am, wishing I could cradle you in my lap for the rest of my life.

I cry every day.

I cry because I’m afraid of not getting out. I cry when I read the news (I stopped reading it). I get emotional when I hear you sing. Today, I cried because it was easy to breathe for the first time.

(symptoms so far)

Headache

Body aches

Diarrhea

Fever

Weakness

Nausea

Lack of appetite

Lack of air, lack of air, lack of air, lack of air, lack of air

The feeling that I’m burning up inside

Chills

Weird skin

Eye swelling

Cough

I almost threw up

I’m out of clean pants. For three days, I’ve been wearing a shirt and underwear. You think it’s funny.

I’m cold, but I don’t tell.

My mom has been keeping me company. Her, Carol, the sun, books, and your singing.

I wonder if it’s the antibiotics that are making me sick.

The door is always shut. It might seem like I want distance. All I want is to walk out of here and find you both well.

I’ve been sad, feeling like I’m not getting better. I just took a shower. I cleaned the tiles. I scrubbed them with hate. Threw water around. Shouted at the virus. Get out of my body. I’m ordering you. Get out of my body right now!

Going crazy.

From 4pm to 5pm, I walked.

From the bathroom door to the window.

From the window to the bathroom door. Walking in myself until I set myself free.

I asked my dad to take me back to the hospital. I changed my mind while he was on his way over. I can’t breathe, but I don’t want to have to stay there. I need to be close to you.

(Lala’s recipe)

Lemon and ginger tea (4x/day).

Make a syrup with pineapple, honey, lemon, garlic, watercress, rosemary, ginger, basil.

Alcides Villaca was my professor (and always will be). I’m writing down the poem he posted recently on social media for you.

[retiro]

Look me in the eyes now, yes, from farther away your smile is what touches me there are a lot more distant people around why don’t they walk the streets if the trees are breathing? the dog against the fence barks strangely and insists you have to hold onto something now that the planet spins differently

I fled a little further into myself my dear I found you a little more how much time is still left for us to be something else Alcides Villaça

Apr. 03 When I notice you’re awake, I run to the keyhole.

I describe, aloud, your clothing. You smile and carry with you the certainty that we’re together.

Part of the day went by while I waited for the sun to come in. It never came.

I don’t know how long I’ve been in here anymore. I narrate my life from this present.

Apr. 04 Your dad leaves water, tea, and food at the door to my room. After eating, I toss the scraps in the toilet and wash the dishes in the shower.

I have a sponge, rag, detergent, and alcohol. The sink is clogged. The bathroom floor is covered in clothes, wrapped up in last week’s sheets. Five pairs of underwear hang drying on the rocking chair. I’ve been looking at the armoire door for forty minutes. I’m going to walk.

From the bathroom door to the bedroom window. Seven steps from beginning to end.

1,735 in all.

You woke up with a bad cough. I got sad. I slept all morning. I sheltered in dreams.

(Recipe from Dr. Alexandre, your pediatrician)

Bryophyllum

8:30am 2:30pm 9:30pm Camphora

8:30am 11:30am 2:30pm 5:30pm 9:30pm 11:30pm

Weleda Sleep and Relax drops

11:30pm Apis mellifica

8:30am 11:30am 2:30pm 5:30pm 9:30pm 11:30pm

I can’t die, little one. I can’t leave you without a mother.

I’ve been enjoying your singing for twenty minutes, little one.

Your father asks you to be quiet. He’s working.

You climb the stairs, come to the door, and ask if I heard your new song. You sing for me. You also listen to me.

Your voice echoes through every part of my body.

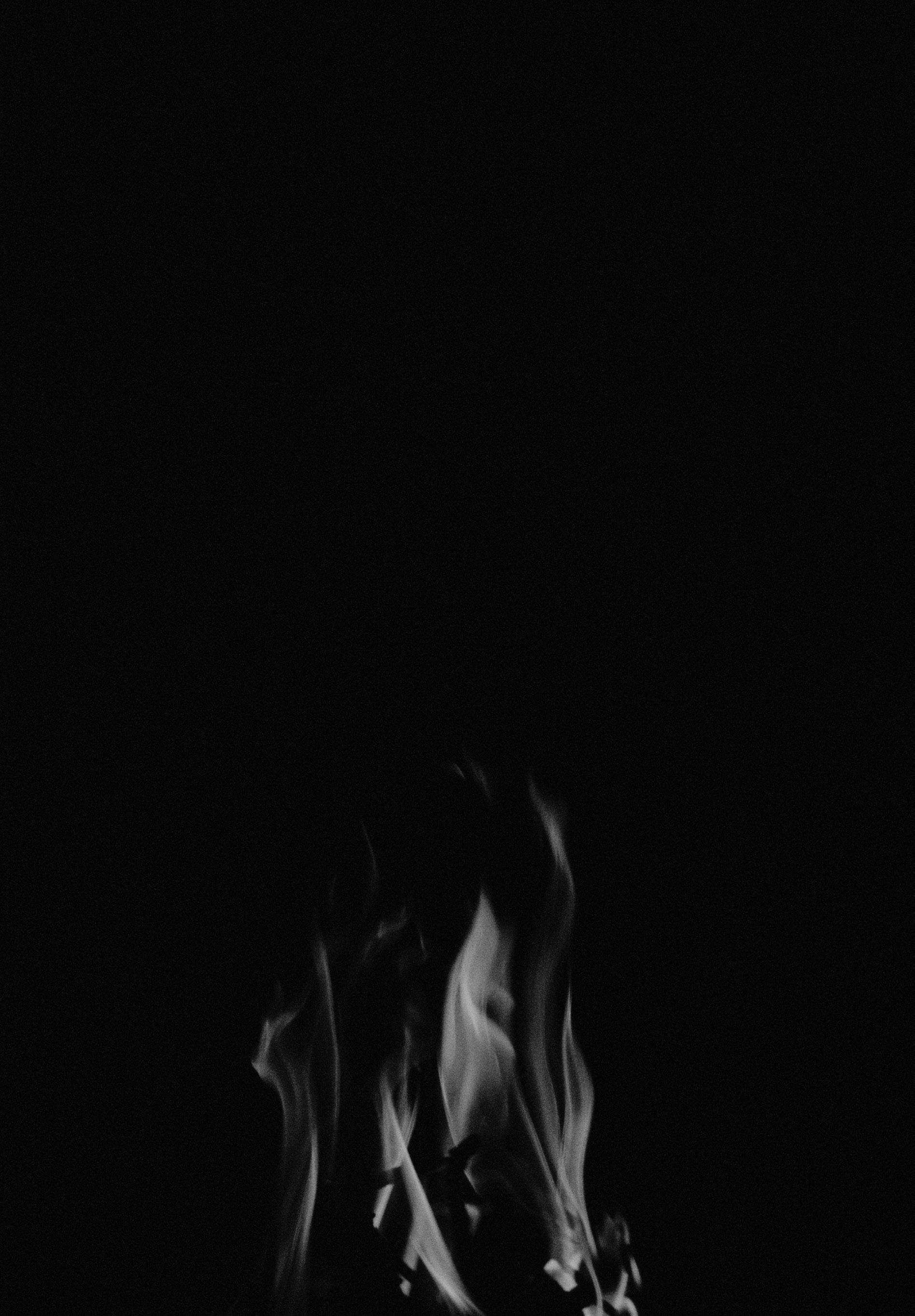

The sun comes in my room at 12:42pm and sketches a diagonal line.

I offer my back, my chest. I turn a blank page. I read as it travels over me. I started watching the sun draw in this room when you were living inside me. All I could do back then—lying down—was look. I said goodbye to the sun recently, but I still feel it in my body.

You’re watching cartoons in the living room. Your dad is showering up here. You call him. He doesn’t hear.

I hear, little one, but I can’t open the door.

I reread a book by Wislawa Syzmborska. Books should be included in wills. This one will be yours. I cried a lot with this poem.

Vietnam

Woman, what’s your name? - I don’t know. How old are you? Where are you from? - I don’t know. Why did you dig that burrow? - I don’t know. How long have you been hiding? - I don’t know. Why did you bite my finger? - I don’t know.

Don’t you know that we won’t hurt you? - I don’t know. Whose side are you on? - I don’t know.

This is war, you’ve got to choose. - I don’t know. Does your village still exist? - I don’t know.” Are those your children? - Yes.

Tomorrow is your birthday, but you don’t know. I felt selfish when I thought about not telling you that, finally, your fourth year had arrived. I thought I was only thinking of myself and the hug that would be missing. That afternoon, you cried, saying everything’s weird. I made a decision. Your birthday will be the day I can hug you—every day—as if it were the first time.

It’s 3pm.

I’m getting some sun, sitting on the floor, looking at this notebook. Curled up so I can fit the light still lingering on the armoire door. I try to redirect my thoughts.

Tomorrow is your birthday, and I won’t be able to surrender to your smile. We won’t commemorate the christening of our hours. I get emotional. When I blink, I see sparkling drops meet the floor. I see the tear’s glint fall from my eyes. From my essence. Light and pain.

I sat in silence, watching you through the keyhole. I didn’t want you to notice I was there. Not all of me.

I felt a cold breeze on my eye. I think my vision has grown more sensitive. To see in a different way. Would be good. I stopped taking pictures. I ran out of film.

I’ve been sad.

My difficulty breathing is back. I stop every third word to catch my breath and regain my energy.

Talking makes me tired. Written words occupy the silence. I read dozens of books. I write to you and to the few who send me messages.

In the last few days, I’ve talked (written) to my mom alone. I avoid other people. Everyone asks if I’m okay. I don’t know if I’m better. I don’t know.

We got infected before quarantine. We didn’t have the chance to defend ourselves.

I write in the plural because it’s me and my mom.

She’s sick too.

The same symptoms, just not as bad.

She got it from me.

I feel guilty. I already apologized. In response, she spent every day with me, especially through the hardest moments. Her in her room.

Me in this one.

A mother’s love.

A daughter’s love.

On this day, at 3:06pm, you were born. It’s been four years.

From inside the room, I recalled the details of our first meeting. I relived our first day.

You taught me to listen to my body.

I’d fall asleep between contractions and the dilation would increase. You were born while I belly laughed. Tears and smiles.

Pain and happiness.

Life, synthesized.

I reenacted our first touch.

I caressed your hair, above your right ear, and I held you in my arms.

Alone in this room today, I took you in my lap. I whispered in your ear—I love you, little one. Today, at the exact minute you were born, I was in the sun.

I faced it until it said goodbye, at 3:12pm. I discovered it was you who brought me to the light.

It’s your birthday and we won’t be together. Today, it was your father who birthed you.

Apr. 07

It rained tonight. There won’t be sun. It’s the second day it hasn’t come.

I finally found a test. The nurse came here. She’s brave. One life risking itself for another to live. I still have symptoms. I need to know if I can leave without getting you both sick.

I’m breathing better. I’m less nauseous.

I haven’t had diarrhea—yet. My hands are peeling. Legs wobbling, but I’m ready to leave. Apr. 08

Your dad is at his limit. Worked up. He shouts. Complains. You, lovingly, respond. “Calm down, daddy, I’ll help. It will be okay.”

I turned the rocking chair around. Now I sit and look at the window. From the window, I can see the neighbor’s wall. On the wall, I read the path of the hours. The sun grows bigger to reach me.

You made a drawing and stuck it to your bedroom door. I saw it through the keyhole. You ask if I saw your art show. Yes.

I see you in me. I see me in you.

Apr. 09 I just got up off the floor. I cried for over an hour.

I’m not contagious anymore, little one. I have to wait for the doctor to call so I can leave the room and keep you both safe.

I’ll leave this notebook, the pen, and the clothes in here. This door will stay locked for a long time. Now, it’s me and you.

(p. 77 - 81)

SEE See the belly of the chaos. See. See yourself Say nothing.

Life fulfills itself of its own volition.

The beginning? The same end. The end? The same beginning. the cycle of the days lives us

This moment: skittish it inaugurates the opening of time

Jul. 20

I haven’t written in a long time. It was hard to return to my body.

Eight kilos smaller.

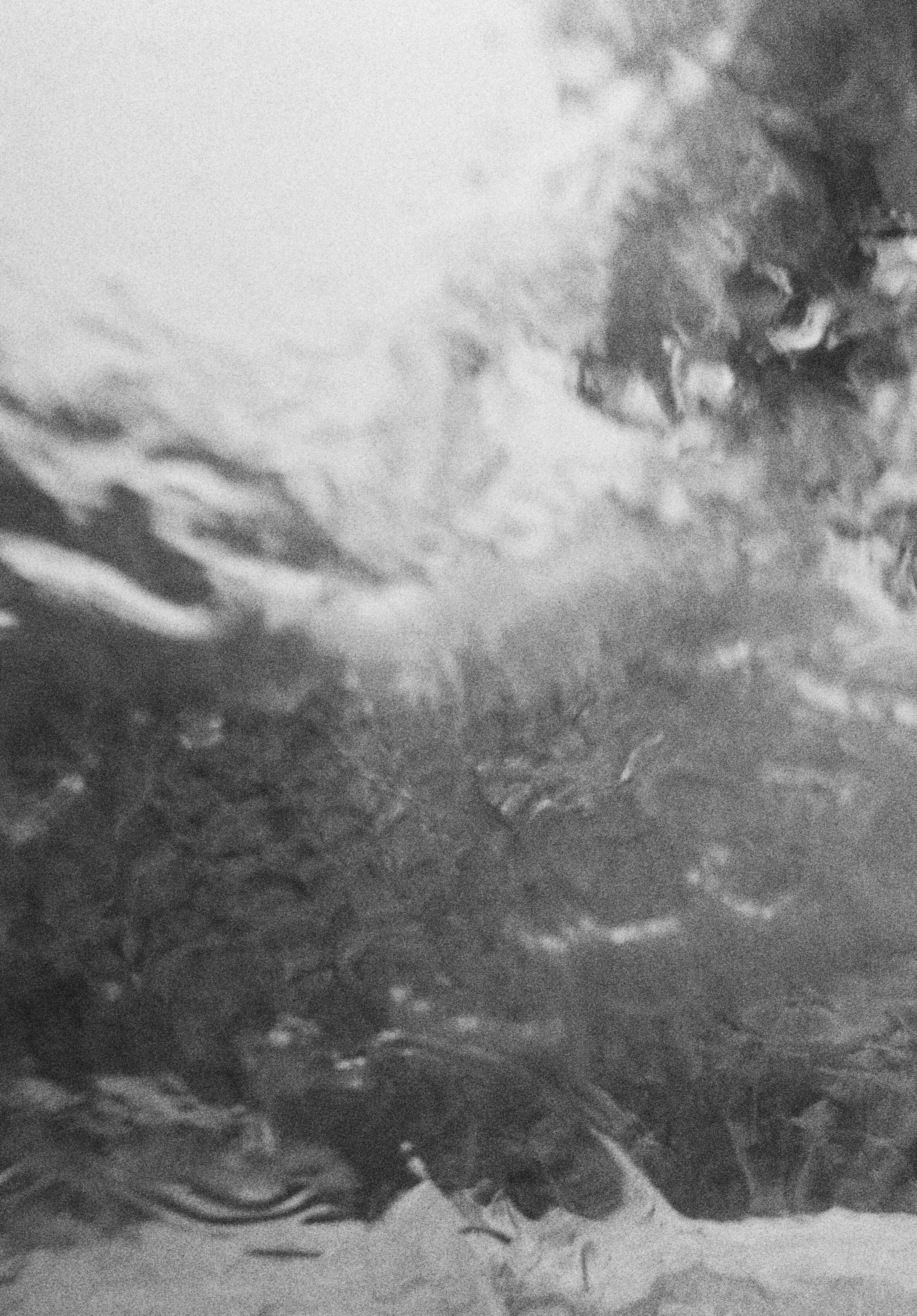

I developed the roll of photos from the room. A lifetime, erased.

We used to gather the flowers that dotted the street where we lived. It’s been five months since we’ve set foot on the sidewalk. Without what we were. Only this immense present.

I write because today is Monday, the day of beginnings. I try to open the notebook and can’t. We go on, little one. I’m here by your side as the day begins.

The groceries arrive and wait for me.

I can’t bring myself touch them. Sometimes, they spend weeks in the utility room. Finally, when I work up the courage, I wipe them all down, and then, I wash my hands compulsively in a desperate plea to be freed from what happened in that room.

This morning, when I brought you your milk, you asked me to lie in your lap. You’re big.

I get the sensation that you carry whole feelings. Full of you. I take care so that life doesn’t tear them to pieces. Aug. 11

I heard the neighbor crying. It sounded like a warning, a sign of how the day would go. You woke up. We played in the hammock. Everything is okay.

I thought about switching the camera I use to document our days. I’ve been using yours, and I can’t control the light. I gave up when I noticed how much it reinforces what I’ve been learning.

I like to observe the way you relate to your body. Last week, you discovered the roof of your mouth and asked me why it’s called a roof if we don’t have stars for it to block out.

I need to write. It’s a way to heal me. I stay here, feeling without saying. Reading my empty spaces.

Our nights go like this. I read three books and tell a story off the top of my head, one I make up just for you. Today, I talked about the giants going extinct from the Earth. Once I thought you were already sleeping, you asked the giant’s mother not to go, “because moms are the last ones to die.”

I couldn’t finish the story. I curled up beside you. We slept together, held fast to our silences.

After I left the room, those days of isolation, I didn’t have the strength to take care of myself. My parents took us in for a few months. As soon as we got there, you started spitting out everything: water, food, saliva. Nothing was permitted down your throat. It’s hard to swallow what we lived.

I can’t leave. I can’t even take the trash out to the street.

You woke up crying.

“I was crying because my dream fell asleep.”

I start my classes by reading poetry. I’ve always done that. It’s my way of requesting silence for the word. People seem to get it.

By the first line, everyone is awake. The body abides by the heart.

(new routine)

I wake up, drink warm water with lemon, do sun salutations, meditate, and read aloud these affirmations:

I am grateful for everything. I am receptive to the abundance the universe has for me. My grandmother wrote this affirmation in a notebook years ago.

I have a healthy and happy body. I deserve the best and I accept it now.

Louise Hay

Word is matter.

We came here to Cravinhos. We walked through the cane fields. Strong sun.

A blazing bliss.

We danced, and ran, and stained our feet with your father’s red soil. Amidst the joy, my body started shaking. I’d hit my limit. I know when I’m about to lose control. We reached the first shade in time for you to know that you’d have to ask for help if I passed out. I want to blend with you. Sometimes I can’t.

We are what we can, not what we want.

Uvaia juice to strengthen the immune system.

We crossed the bamboo tunnel out of your godmother’s house and were met with an immense night. I thought you’d be scared of the darkness, of the song of the trees in the wind, of the discovery of how it feels when we can’t see. Holding hands—pitch black—we walked through the cane fields until you asked me to sit on the ground for “the Milky Way to fall in our laps.” We lay down and everything grew bright.

We were in the car, coming back from a trip, when you asked to take a picture. I put your photo here beside me. I saw you inside of me. I remembered when you were a baby. I lay down next to you to try to see through your discovering eyes. The color, the light, the body, the present. I want to see for the first time what is with me every day. For you to lend me your eyes.

You asked me why some people don’t wear masks. I don’t know why.

At meditation today, I returned to my first feeling. As if going back to the origins would erase what doesn’t fit anymore. As if the first experience could determine the rest. I wanted to find a genuine feeling, the one that gave rise to so many others. Fear was what I felt. And feel.

Everyone is going back to the classroom, and I still can’t leave the house. It makes me ill.

When I went to meet your father’s family in Cravinhos, I took medication to prevent another panic attack. I talked to the doctor about the possibility of going back to the classroom.

She explained what I feel in scientific terms. I translate them for you here.

Fear of this instant, in which I try to see myself, and of the following, in which you can’t see me anymore.

It’s been raining for three days. It’s cold.

You’re bored.

You can’t swing in the hammock, can’t water the plants, can’t play in the sun. When I was small and out of sorts, I’d ask to sleep with my grandmother. That was how I made myself better. I took you to sleep at your grandmother’s house. A little bit of me in both of us.

You’ve been asking me the meaning of words. To explain them, I offer others. Versions of the thing in itself. A word is a translation. We only understand them when they’re shucked.

Sep. 25

Your school reopened, but you don’t know it. You’ll only know once you’re vaccinated. Some parents don’t know what the virus can do to your body. I do.

We made a paper airplane, hung adornments on the wings, and lay down on the floor to fly.

“Mom, give me a hug?”

I took a deep breath. I took some time in you. I filled some corners I’d abandoned in my body. That was how it was the day I left the room, too.

I walked down the stairs in silence—an absence, still— supporting myself with the walls and the possibility of being beside you.

When you saw me, I opened my arms, and, little one, you took me back.

Your night terror woke us up. I followed the doctor’s instructions.

Don’t touch or talk.

Better she wakes up by herself. I couldn’t take it, I started singing. When you heard my voice, the wailing stopped.

Today you took the three vaccines that have been waiting for me since April. We went to the clinic in interior São Paulo, where my parents live.

I’m braver here.

We went out in the morning, your hand glued to mine. I, who can’t touch anything that comes from the outside.

I, who can’t leave the house.

I, who wash my hands compulsively in an effort to cleanse my fears.

I’m the hand you hold in search of some certainty. I had to conquer myself to care for you.

I remember when we got the coronavirus vaccine together. Boldo leaf, dirt, soap, water, blossom, rosemary, nail polish, and paper mixed with strands of mother’s and daughter’s hair. Strands that lead me back to what I am.

When we’re at my parents’ house, I can go out. We never see the neighbors. So I’m able to walk.

I walk on the dirt, observing the trees that bow in search of the sun.

Taking the chance to grab a few flowers. They’re all for you. This afternoon, I fell asleep after meditating. I woke up with a flower beside me, petals rising, no spines.

Both of us grow, collecting these memories.

Today is Teacher’s Day, and I can’t go back. The students are there, I’m not.

I’ve been teaching online for seven months to the names that appear on the computer screen. I can hardly remember their faces. I try to be with them. The best of me in those hours. Tonight, I dreamed we were together in that space where I learn so much. Me and this fearful body.

In the dream, in the classroom, right there, I cried.

My god daughter has just been born. Today, at a little over twenty years old. She’s been born with the ability to choose her own name and new clothes, ones that show her truth. We’ve just chosen—me and you—the dress she’ll get for Christmas, the first she’ll spend intertwined in body and soul. I hope the world also welcomes the swish of her hem, her new—and true—gender.

I found these notes: antidepressant since May 18th

Clonazepam

May 17th

May 21st

September 6th

I balled the paper up tight before I threw it in the trash. I only realized afterwards that I could have glued it in here.

All of us are facing death.

I’ve read parts of what I wrote while I was in the room. It’s a way of listening to myself.

I started reading aloud during therapy.

We cried together, united in this attempt to heal what we lived. Me and my therapist.

She, still a girl, said goodbye to her mother.

I, a mother, almost said goodbye to you, my little girl.

Pain isn’t something shared, but the bonds enlarge us.

You keep searching for the first images, something to give contour to the words you still don’t recognize. I get the feeling I’m meeting the word of the word—the core— every time I find the meaning of what you want to learn.

Our words—the ones you wanted to learn: pressure index fingers objects fuse meanings bad luck feather disorder

Your words: spectaculating eggmazing

You tell me so much without knowing I needed to hear it. Words that write me.

You spent awhile in my eyes. Said you were seeing yourself in me.

You wake up excited, even though you’ve been locked in this house for months.

I marvel at your capacity to remake reality.

It’s so hard to leave the house.

I’m torn between certainty, impulse, and wanting to shrivel up.

Two days from now my good friend is having an art opening. I will shrivel up.

Nov. 27 The day travels through the house. I search the bookshelves for a book that will find me.

I notice the light pointing to the poems I just read, the ones that still fill this hour’s expanse. It’s time for me to say goodbye to the young people who kept me company this year.

I begin class with a verse about the instant, that interval that sows the stitches of our eternal proximity.

We were following our morning routine. You were in the shower when my cellphone rang. It was the school where I work.

I answered with the bliss of someone on their first day of vacation. I was on the phone a long time. You turned off the faucet and got out, made a puddle on the floor. I was still crying, absorbed in the no I had just received. I’d been fired.

You hugged me and said now we have more time to play.

I got agitated when I saw a hospital in front of the office where I had to do my exit interview.

I thought of the sick people, of not being able to breathe. I tried to control my thoughts. When I parked the car, I saw two friends, Carol and Humberto.

They came to make sure I’d be okay. I was shaking when I got out of the car. The waiting room was full.

Even still, I started walking toward reception. My friend by my side.

At the entrance, there was a man wearing his mask around his chin. When I saw him, I hid behind a car and started crying.

My body consumed in feelings.

I couldn’t go in, little one.

Dec. 12

My grandmother hasn’t left the house since March. She’s in complete isolation.

We are too.

We came to Rio de Janeiro to see her. A clear-headed 85 years.

I’ve been doing embroidery.

When I loop the thread of the needlework and crochet, I sew my life to those of our ancestors. Meanwhile, I gaze at you with the same generosity with which they gazed at me.

Familial weavings.

Dec. 18

I made this image while we did yoga. Against the floor, I recognize the depths that have lived in me since I was born.

Dec. 19

My grandmother takes her blood pressure every day. I’ve been joining in the ritual since we got here. 90/60, my breath of life. You put your hand on your heart, then on mine.

Your heart beating fast. Mine, in silence.

Grandma’s house, there’s no other place where I feel more at home. The space that shelters our childhood occupies our being. Origin.

How can we know where we’re going if we don’t know where we came from? Dec. 20

Our breaths

The elf and fairies’ lair

“My grandmother is the night. My godfather is the sun. My godmother is the moon.”

(I wrote it down so I don’t forget the lines)

Dec. 24

It’s Christmas and we’re at home. Me, you, and your father. I made dinner for the first time. You chose your meal— French fries and macaroni. We made the pudding together. That night, you said you saw Santa Claus fly. When I was your age, I could see him too.

My grandmother has six children, fourteen grandchildren, and five great-grandchildren.

We usually spend the 25th together.

This year, she put a photo of each of us on the table and remained faithful to her isolation in solitude. The strength of a person who knows and respects herself.

190 thousand dead and it’s Christmas.

Too many yeses is also a no.

Dec. 31 We came to my parents’ house in the countryside for New Years. I cut up some paper so we could write down our wishes, a ritual that stokes the strength of transformation—not of new beginnings. At least this time.

Jan. 06 We were playing when, hands held, we went to the room where I had quarantined. You asked me to sit on the bed, and, before closing the door, said you’d wait for me in the living room. You wanted to be surprised like you had been that day. I knew what you were asking for, but didn’t rush to comply. I needed to be alone there again. I lay down on the bed. I looked at the armoire door. The wall.

The ceiling.

The spaces of this fragmented self. I waited to join myself with your gesture. You wanted a reunion—maybe with that mom from before. She’s gone now.

I’ll open the door.

I know I’m ready now, little one, after reuniting with myself in you.

This is the first book published by Vento Leste for the Rosa Brava Collection. The Rosa Brava Collection, which has Helena Rios and Marcelo Greco as its art directors, is dedicated to aspects of women’s lives.

On the other side of the door

Words, photography, and collage. Juliana Monteiro

Drawings (second and third covers). Maria Flor Monteiro Carrascoza

Editing and design. Juliana Monteiro, Helena Rios, Marcelo Greco

Copy editing. Luciana Dutra

Translation. Adrian Minckley

Image digitization and treatment. Estúdio 321, Papel Algodão

Graphic production. Helena Rios, Marcelo Greco

ISBN. 978-85-68690-24-6

Copies. 800 exemplares

© texts and images: Juliana Monteiro © book: Vento Leste Editora

This work was printed on FSC® Certified paper, guaranteeing responsible forest management, for Vento Leste, in March 2025. Typography: Adobe Garamond; Body paper: Pólen bold 90 g/m²; Cover paper: Supremo 250 g/m². Printing and finishing: Leograf

This is the first book published by Vento Leste for the Rosa Brava Collection. The Rosa Brava Collection, which has Helena Rios and Marcelo Greco as its art directors, is dedicated to aspects of women’s lives.

On the other side of the door

Words, photography, and collage. Juliana Monteiro

Drawings (second and third covers). Maria Flor Monteiro Carrascoza

Editing and design. Juliana Monteiro, Helena Rios, Marcelo Greco

Copy editing. Luciana Dutra

Translation. Adrian Minckley

Image digitization and treatment. Estúdio 321, Papel Algodão

Graphic production. Helena Rios, Marcelo Greco

ISBN. 978-85-68690-24-6

Copies. 800 exemplares

© texts and images: Juliana Monteiro © book: Vento Leste Editora

This work was printed on FSC® Certified paper, guaranteeing responsible forest management, for Vento Leste, in March 2025. Typography: Adobe Garamond; Body paper: Pólen bold 90 g/m²; Cover paper: Supremo 250 g/m². Printing and finishing: Leograf

What exists on the other side of the door? Something that isn’t ours. What happens when the door opens? In her singular voice, Juliana Monteiro tackles the impossible task of dueling with pain in a book built from thoughts, poems, photographs, collage, and pieces of days and nights scarred by desperation and solitude. The narrative chronicles the intense experience of a mother facing her own mortality, who anguishes not only over her possible end, but the fear that her young daughter will be orphaned. A work that comes as much from the author’s entrails as from the profundity of her visual and written sensibilities. On the other side of the door: the fragmented entirety of a visceral experience.

João Anzanello Carrascoza