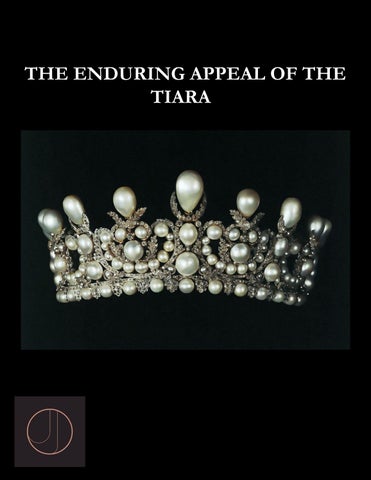

THE ENDURING APPEAL OF THE TIARA

EARLY SIGHTINGS: FROM MESOPOTAMIA TO REPUBLICAN ROME

The form first seen in ancient civilisations has a long and distinguished history, and today the tiara is still the star at important state occasions and private events.

A gold headband with heads of gazelles and a stag between floral motifs, Egyptian, circa 1648-1540 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

During Dynasty 15 the rule of a line of kings now known as the Hyksos dominated a large part of northern and middle Egypt. The northern Hyksos culture combimed Egyptian and Near Eastern traditions and this diadem with animal heads alternating with flower motifs is a good example of the blend of artistic styles | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Conceived as a simple wreath of branches and leaves, tiaras were, in their earliest form, mainly connected with religious and funerary ceremonies. Wreaths of natural leaves and flowers have been found in Egypt on the head and on the breasts of mummies of pharaohs dating from the XX and XXI dynasties (1200-945 BC) possibly confirming the general assumption that tiaras originated in the oriental world.

However, these wreaths of natural leaves and flowers are predated by imposing gold head bands decorated with animal heads and stylised floral motifs from the Second Intermediate Period (1648–1540 BC) and from the New Kingdom (1479–1425 BC), as seen in the previous image and the one below.

A gold, cornelian and opaque turquoise glass diadem with two gazelle heads, Egyptian, New Kingdom, circa 1479-1425 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The gazelle heads are indicative of Near Eastern influences

In Mesopotamia, excavations of the royal tombs at Ur –Southern Iraq – have brought to light a wealth of gold ornaments including stunning head ornaments designed as

chains of gold leaf motifs alternating with hardstone beads dating from around 2600 BC.

A gold and lapis lazuli headdress, Sumerian, circa 2600-2500 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This chaplet of delicate gold leaves, cornelian and lapis lazuli beads adorned the forehead of one of the female attendants in the so-called King’s Grave in the cemetery of the city of Ur. As gold, lapis lazuli and cornelian are not found in Mesopotamia, their presence in burials in Ur is proof of a complex trade system that extended far beyond the valley between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers

In ancient Greece, wreaths of leaves were beautifully crafted in gold to adorn the statues of gods and goddesses in shrines and temples: oak for Zeus, olive for Athena, myrtle for Venus, ivy for Dionysus, and laurel for Apollo. Gold wreaths were offered to divinities as ex voto, their weight carefully

accounted for by the priests in the inventories of the temples. Wreaths of natural leaves, flowers and berries were worn during religious processions by priests and sacrificial victims, and in funeral rituals, gold wreathes were buried with the deceased to signify their victories in the battle of life.

A gold stater, circa 323/2-315 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The head of Alexander the Great facing right is encircled by a wreath of laurel leaves, a statement of his power and status

The ritual and religious dimension and the sacred character of the wreath of leaves probably promoted its diffusion in different contexts. The wreath – stephane – in Greek –became a symbol of political status and was awarded as a

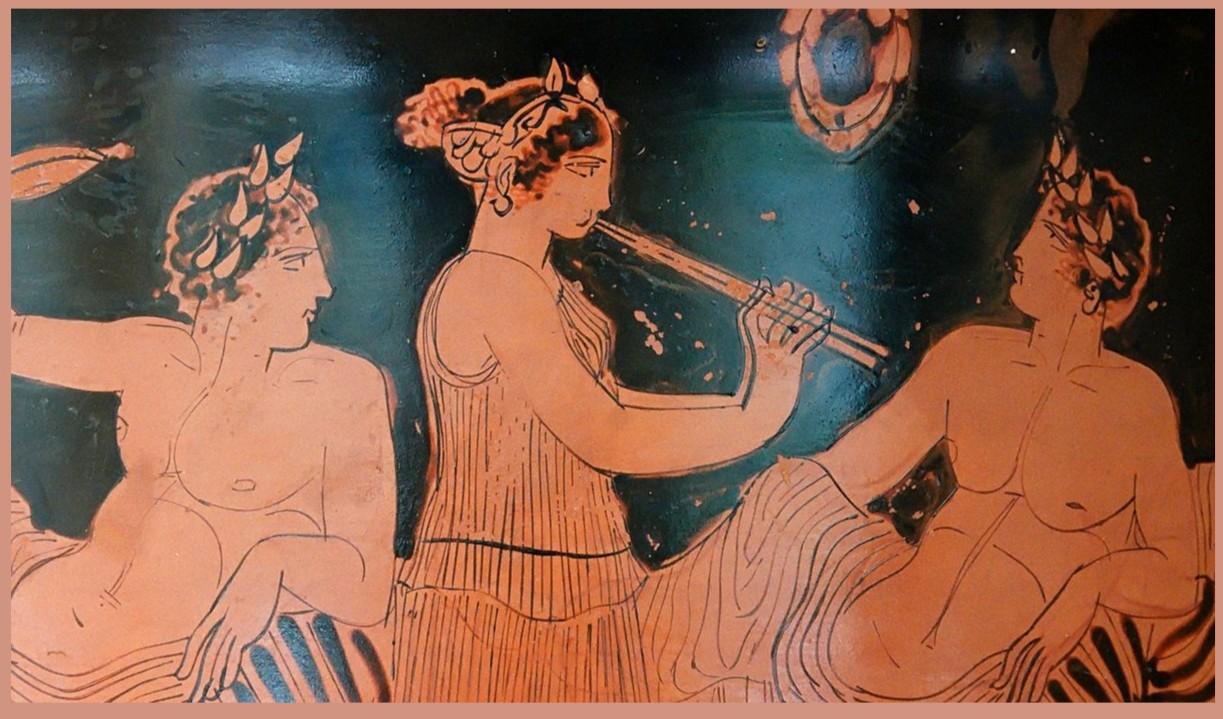

military honour. Winners of musical contests and athletic games were crowned with wreaths and the habit of wearing a wreath purely as a form of adornment at banquets and weddings spread among the wealthy of both sexes and is amply testified to by literary sources and vase painting.

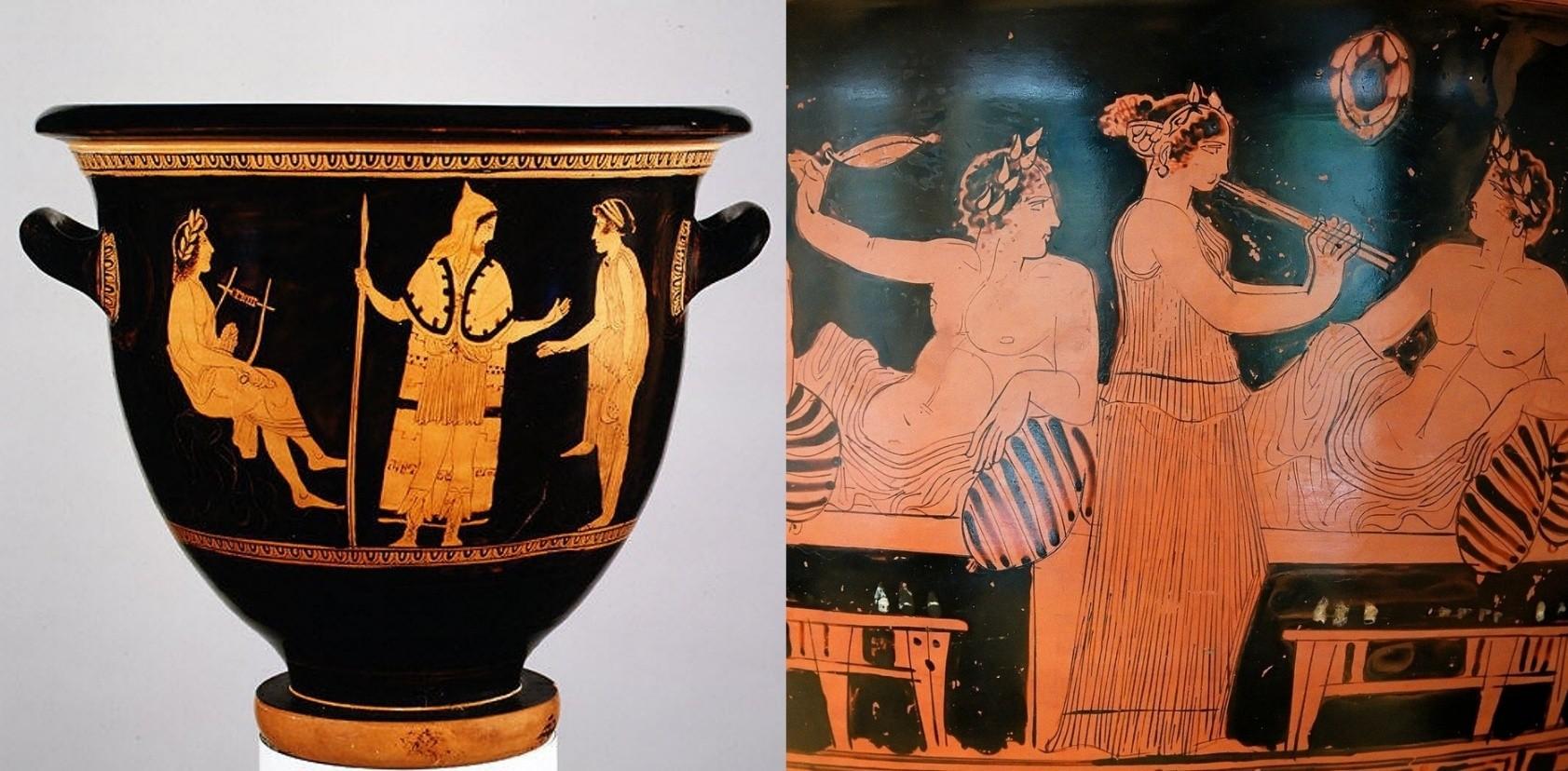

Left: A terracotta bell-krater, Greek, circa 440 BC, attributed to the Painter of London | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The figure depicted on the left wearing a laurel leaf wreath and playing the lyre is Orpheus, the best known of the mythical musicians who learnt his great skills from Apollo

Right: A terracotta bell-krater, Greek, circa 420 BC, Nikias Painter | © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Museo Arqueológico Nacional de España, Madrid

The scene depicting a banquet shows the habit of wearing a wreath purely as a form of adornment

Archaeological excavations in Southern Italy, Macedonia and Southern Russia, brought to light fabulous gold examples of tiaras made of olive, oak, laurel, myrtle leaves and at times

interspersed with berries, flowers and insects, realistically rendered.

A gold ivy wreath, from Kastellorizo (Megisti), Greek, mid 4th century BC | George E Koronaios / National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Although impressive looking the vast majority of these wreaths are too flimsy to have been worn by the living, and must have been especially made for funerary use, to secure the maximum effect with the minimum outlay of precious metal.

The other form of head ornament worn in ancient Greece was the diadem (from ‘diadein’, to bind around) a gold band embossed or applied with rosettes or other floral motifs.

More elaborate examples consisted of a crossover of gold bands connected by a Herakles knot motif.

Top: A gold diadem, Greek, 4th century BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The thin gold sheet in the form of a pediment is decorated with motifs of palmettes in low relief. This type of diadem, made from thin gold sheets with impressed decoration, enjoyed long-lasting favour. Similar examples have been found in tombs that range in date from the 5th century BC to the Roman period

Bottom: A gold diadem, Greek, 3rd century BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This elaborate example, probably from Southern Italy, consists of band of gold applied with fourteen floral motifs interspersed with gold beads. The petals of the rosettes are secured to the band by a gold sphere decorated with granulation

In Hellenistic times, these ornaments, often rising to a pediment at the centre, were invariably decorated with more elaborate figurative scenes inspired by Greek mythology. Later, the word ‘diadem’ came to

denote the purple band with a white decoration, worn by Persian kings around their high-peaked headdress. Interestingly, the name for this type of headdress was ‘tiara’ the word now widely used with minimal variations in many languages, to indicate a variety of head ornaments that embraces circlets, diadems, wreaths, and kokoshnick.

Top: A gold cross-strap diadem, Greek, circa 300-250 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In this example found in a tomb in the island of Ithaka, the straps meet at the centre to form a Herakles knot embellished with rosette motifs and set with garnets.

Bottom: A gold diadem, Greek, circa 330-300 BC | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This gold pediment diadem is said to have come from a tomb in Madytos, on the European side of the Hellespont. The thin gold band is decorated in repoussé with a rich and intricate pattern of leaves and volutes. At the centre sit Dionysos, the god of wine, and his wife Ariadne, and at their sides, perched among the volutes, muses play musical instruments.

In Republican Rome, jewellery was for long under official disapproval. The Law of the Twelve Tables, in the 5th century BC, limited the amount of gold with which the dead could be buried, and in the 3rd Century BC the Lex Oppia stipulated that an ounce of gold was all the precious metal a Roman lady could wear. The situation changed in the late years of the Republic and by the time the Empire was inaugurated in 27 BC well born women had acquired a taste for wearing pearls, gold and gemstones in great abundance. The Romans adopted the gold wreath as the supreme indication of rank and honour for both men and women.

Left: Mummy portrait of a young woman, Egypt, Roman period, AD 90-120 | Note the gilt wreath encircling her head

Right: Mummy portrait of a man, Egypt, Roman period, AD 140-170 | Both images: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Roman imperial wreaths are often very different from the realistically rendered Hellenistic examples, they are made up of stylised gold leaves often attached in groups of three to a band of material, alternating with gold berries.

A gold funerary wreath of acorns and oak leaves, Roman, 1st–2nd century AD | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Egyptian mummy portraits of the Roman period often show the deceased wearing such wreaths. This is true for both men and women, as seen in the previous images

DEVEOPMENTS IN DESIGN TO THE NAPOLEONIC PERIOD

With the spread of Christianity and the collapse of the Roman Empire, the fashion for wearing head wreaths and diadems, probably considered ostentatious and deeply charged with pagan connotation, gradually disappeared. Crowns remained the symbol of power worn by royalty, but we have to wait until the Middle Ages to see the return of tiaras in the shape of garlands of floral motifs, chaplets or bandeau worn around the head, frontlets and circlets of leaves, roses or trefoils worn as symbols of wealth and status.

The Imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire, 10th-11th century | With its characteristic octagonal shape, this crown was used until the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. Comprising eight hinged golden plates, it was probably made in Western Germany for the coronation of Otto I in 962.

By the end of the 13th century, the coronal (circlet), consisting of a gold band surmounted by a series of fleurons variously encrusted with pearls and precious stones, had become the badge of rank proper for a king and princes, noblemen and noblewomen, knights and esquires and their wives and daughters. Coronals were certainly worn at court and at festivals, both solemn and light-hearted but also on more ordinary occasions by royal and princely ladies. A coronal was amongst the wedding gifts a bride might expect from her father or bridegroom, a gift she would wear on her wedding day.

Statue of Gräfin Reglindis | Saxon-Anhalt, Germany, mid 13th century Reglindis (c. 989-1016) was the daughter of Polish King Bolesław I the Brave, and the Sorbian princess Emnilda; her husband Herrmann I (c. 980-1038) was Margrave of Meissen from 1009

Tiaras disappeared again during the Renaissance when women chose to wear their hair elaborately dressed and pinned with gem-set ornaments or entwined with strands of pearls and band of stones, and later with gem encrusted aigrettes worn in combination with feathers.

Piero del Pollaiuolo (1443-1496), Portrait of a Woman, tempera on wood, Florence c. 1480 | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Piero del Pollaiuolo along with his brother Antonio, who had originally trained as a goldsmith, were responsible for some of the most distinguished female portraits produced in Florence in the third quarter of the 15th century

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), Idealised Portrait of a Lady, (Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as a Nymph), mixed technique on poplar, Florence c. 1480 | Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Germany

At the age of sixteen Simonetta, (c. 1453-1476), known as la bella Simonetta, married Marco Vespucci in Florence was soon noticed at court. At a jousting tournament held in 1475, Giuliano de’Medici entered the lists with a banner featuring the image of Simonetta as a helmeted Pallas Athene, painted by Botticelli, with the inscription ‘La Sans Pareille’, or ‘The Unparalleled One’; Giuliano won the tournament and he nominated Simonetta as ‘The Queen of Beauty’, in a chivalrous gesture of courtly love.

Simonetta’s pendant positions her closely within the Medici circle, as it imitates a famous cameo from the family’s collection.

It was only in the last quarter of the 18th century that tiaras came back in the form of naturalistic sprays and wreath of flowers which soon morphed, under the influence of Neoclassicism, stimulated by archaeological discoveries in Pompeii and Herculaneum, into formal wreaths of laurel leaves and pediment-shaped diadems.

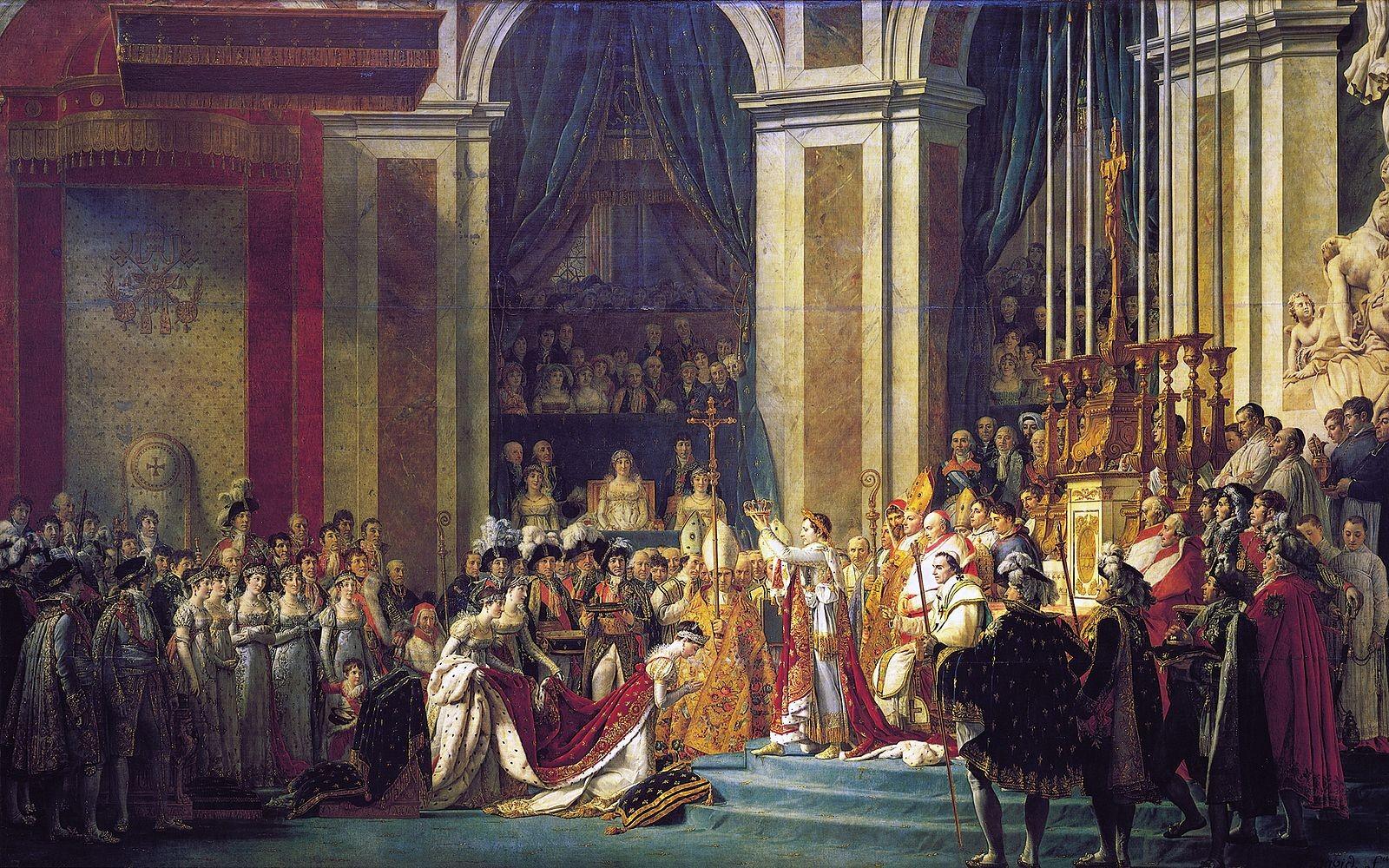

Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), The Coronation of Napoleon, oil on canvas, 180507 | Louvre, Paris, France

The work was commissioned by Napoleon in late 1804, with final finishing touches completed in January 1808, and the painting was exhibited that year at the Salon annual painting exhibition.

Napoleon, wearing a gold laurel leaf wreath, crowns Josephine

Left: Josephine wearing a diamond pediment tiara

Right: Napoleon’s sisters and sisters-in-law wearing jewelled tiaras of classical inspiration

Napoleon Bonaparte, who lacked the aristocratic background of his predecessors, sought to endorse his regime by association with Imperial Rome, and as a Roman Caesar, chose to be crowned with a formal gold wreath of laurel leaves. The painting Le Sacre de Napoléon by Jacques-Louis David captures the moment in Notre Dame on 2nd December 1804 when Napoleon, wearing a diamond laurel leaf tiara, crowns his wife Josephine who kneels in front of him wearing a diamond pediment tiara. Behind Josephine, Napoleon’s sisters are in attendance, clad in lavish jewels, their humble origins elevated to royalty by sumptuous tiaras of classical inspiration.

The Russian Nuptial Tiara, a spectacular diamond and pink diamond pediment tiara, Russian, 1800-1810 | Diamond Fund, Kremlin, Moscow, Russia The centre of the tiara holds a 13 carat pink diamond from the Treasury of Paul I, (Tsar of Russia, 1796-1801), and it is likely that the tiara was created for Paul I’s wife, Empress Maria Feodorovna. The tiara can be seen in a photograph of the confiscated inventory of Romanov jewels and precious objects.

Diamond tiara, formerly in the Thurn und Taxis collection. The rounded profile of this head ornament conforms to the fashions of the Imperial Court of France which were followed everywhere from the first decade of the 19th century. The jewel appears in the Tiara section of the 1750-1820 chapter of the online Understanding Jewellery

Contemporary tiaras made all over Europe conform to this style which remained throughout the 1810s. They tend to be formal and symmetrical in design, decorated with motifs taken from classical antiquity: these include pediments, palmettes, laurel leaves, ears of wheat, volutes and Greek-key patterns

Emerald and diamond diadem created by Maison Bapst, jeweller to the French Court, in 1819 for the Duchess of Angoulême, Princess Marie-Thérèse, the only surviving child of King Louis XVI and Queen Marie-Antoinette. Made many years after the French Revolution with stones from the French Treasury, the centre emerald weighs nearly 16 carats and the tiara is set with 40 emeralds making the total weight 79.12 carats. The French state sold the tiara, along with the other French Crown jewels, in 1887 and it was acquired by the Louvre in 2006 in a later auction | Louvre, Paris, France

Set with pearls and diamonds, the most praised gems of the time, or embellished with rubies, emeralds and sapphires, these head ornaments, were designed to indicate the wealth and status of the wearer.

Robert Lefèvre (1755-1830), Portrait of Maria Paola Bonaparte (1780-1825), wearing a hardstone cameo diadem and matching comb | National Museum of the Château de Malmaison, Paris, France Napoleon, Maria Paola’s elder brother, made her the first sovereign Princess and Duchess of Guastalla, however, she soon sold the duchy to Parma, for six million francs, whilst retaining the title of Princess of Guastalla. Maria Paola died at the Palazzo Borghese, Rome, at the age of forty four.

Napoleon’s personal interest in the glyptic art prompted the production of equally stunning, if less expensive examples, set with engraved gems, cameos and intaglios carved in shell or hardstone with scenes taken from classical mythology and surrounded by borders of small pearls or gold filigree and enamel.

A gold and hardstone mosaic tiara, Italian, circa 1808, believed to have belonged to Napoleon’s sister Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples (1782-1839).

| The Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Collection, on loan to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Worn by high-ranking women, tiaras were not confined to coronations and court or to formal occasions but were worn at weddings too.

THE INFLUENCES OF ROMANTICISM, NATURALISM AND IMPERIAL RUSSIA

The Empire style influenced the design of tiaras for a long time but by the 1830s, prompted by Romanticism, naturalistic elements started to infiltrate into classical formality. Gradually, realistically rendered garlands of leaves, berries and flowers, roses, lily of the valley and daisies took over and by the mid-century the most popular form of head ornament was a tiara composed of three floral sprays framing the face rather than encircling the head.

A magnificent diamond tiara, circa 1830. Note the proto-naturalistic foliate scrolls. The jewel appears in the Tiara section of the 1820-1840 chapter of the online Understanding Jewellery

Diamonds were still the favoured choice of gems for these naturalistic creations, occasionally highlighted with pearls and coloured gemstones. The flower heads were often mounted en tremblant so that they could quiver at the slightest movement of the wearer, catching and reflecting light, and decorated en pampille with cascades of gemstones to simulate rain or dew drops. In the 1850s, in line with this interest in all that was natural, tiaras entirely made of branch coral became very fashionable.

Top: A mid 19th century diamond tiara designed as a wreath of leaves and berries.

Bottom: A diamond hair ornament designed to frame the face, composed of three detachable brooches, the design is typical of the mid-19th century

The splendid tiara commissioned by Napoleon III to Gabriel Lemonnier on the occasion of his marriage to Eugénie de Guzmán in 1853, was designed as a garland of delicately rendered diamond leaves and entwined with formal scrolls of pearls and diamonds is the perfect example of a jewel where the naturalism fashionable at the time is combined with the formality required by a royal head ornament.

The Empress Eugénie tiara. Made by Gabriel le Monnier, Paris, in 1853, employing pearls from a parure formerly created for Empress Marie Louise, the wife of Napoleon I Empress Eugénie was frequently portrayed wearing this stunning tiara made employing pearls from a parure formerly created for Empress Marie Louise, wife of Napoleon III.

Portrait of Empress Eugénie in court dress wearing the pearl and diamond tiara created by le Monnier | Etienne Billet (1821-1888), After Franz Xaver Winterahalter (1805-1873), oil on canvas | Musée de la Marine, Marseille, France

Naturalism continued to be the main theme of a vast number of tiaras until the end of the century. The botanical obsession of French jewellers prompted the creation, throughout Europe, of perfectly executed and realistically rendered garlands of traditional and unusual leaves and flowers such as ferns and clovers, laurel and ivy, pansies and roses, fuchsias and lotus.

Top: A diamond tiara designed as a wreath of ears of wheat and wild roses, 1870s. The ears of wheat and floral motifs are detachable from the tiara frame and can be worn as brooches and pendants

Bottom: A diamond tiara designed as a wreath of fern leaves, probably created by the Parisian jeweller, Bapst et Files around 1875. A perfect example of botanical naturalism at its best

Also fashionable, in the closing decades of the century, were more formal tiaras designed as elaborate diamond scrollworks or festoons, often rising from diamond clusters and surmounted by pear-shaped diamonds, drop-shaped pearls or, less frequently, coloured gemstones.

A diamond tiara of elaborate scroll design, circa 1890

In the 1890s Imperial Russian themes became the rage all over Europe. The designs loosely based on the traditional Russian headdress, the kokoshnik, consisted of a graduated row of upright and radiating leaf motifs.

Princess Alexandra wearing her diamond ‘kokoshnik’ tiara, by Garrard, a present from the 365 peeresses of the United Kingdom on the 25th wedding anniversary of her marriage to the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII

They shared their popularity with circlets surmounted by sets of five or seven star-shaped motifs, sunbursts or florets that first made their appearance in the 1860s.

A diamond tiara, circa 1880, designed as a graduated row of five star jewels, which can also be worn as either brooches or hairpins

Although not mainstream, a mention needs to be made of tiaras produced in the second half of the century in historical revival styles. Created for a cultured élite, they ranged in inspiration from Greek Hellenism to Renaissance and relied on the effect of the intricate working and enamelling techniques of fine goldsmiths, rather than the sparkle of diamonds. Amongst the most spectaculars examples are the bandeau, the coronet and the diadem that form part of the parure commissioned by the 6th Duke of Devonshire made and designed by C.F. Hancock, incorporating carved gems from the extensive collection of the 2nd Duke of Devonshire in a framework of diamonds and enamel of Renaissance inspiration.

A gold, enamel, diamond and carved gem diadem, part of the Devonshire parure, created by Hancocks with carved gems from the 2nd Duke of Devonshire’s collection. The parure was commissioned by the 6th Duke of Devonshire in 1856 for Maria, Countess Granville, the wife of his nephew, to wear in Moscow for Tsar Alexander II’s coronation celebrations

The firm of Castellani in Rome both pioneered and dominated the production of archaeological jewellery and its success encouraged many jewellers to work in a similar historicising vein. The Castellanis produced a series of stunning diadems, either inspired by antiquity or faithful copies of antique originals.

Top: Diadem by Castellani, circa 1870, a copy of an Etruscan original from the 3rd century BC from Cumae. The elaborate gold work is enhanced with blue enamel, pearls and agate and glass beads | Metropolitan Museum, New York Bottom: Gold diadem by Castellani, circa 1870, its design clearly inspired by ancient Greek and Roman wreaths of gold laurel leaves

The last two decades of the 19th century saw the rise through society of a new, highly wealthy class with enormous spending power, along with the increased availability of diamonds, recently discovered in South Africa – this combination was conducive to the creation of numerous fabulous tiaras proudly worn by their owners not only at court on formal occasions and at wedding, but, now at the opera, grand dinners and even in restaurants. Throughout the Belle Époque, tiaras were de rigueur with evening gowns. The wives of American millionaires competed and often outshone European aristocrats with their splendid head ornaments commissioned in Paris to Cartier, Chaumet and Boucheron, and American millionaires, keen for they daughters to marry into European aristocracy, made sure that their trousseaux included abundant jewels and at least one stunning tiara.

Left: Mary, Lady Curzon, Vicereine of India, wearing her diamond tiara created in 1898 by Boucheron

Right: Consuelo, Duchess of Marlborough wearing her diamond tiara created by Boucheron on the occasion of her marriage in 1895

INTO THE 20th CENTURY: THE GARLAND STYLE, BANDEAUX AND THE RETURN TO VINTAGE DESIGNS

Tiaras are perhaps the most characteristic jewel of the opening decade of the twentieth century: worn for formal and festive occasions they are characteristic of an exuberant, stylish and wealthy age. Jewellers were literally flooded with commissions for this desirable, obligatory accessory, and arguably more tiaras were constructed at this time than at any other.

A turn of the century pearl and diamond tiara. The fluid foliage design is the transitional stage between the realistic naturalism of the late 19th century and the formal neoclassical motifs of the Garland Style

A diamond necklace/tiara, circa 1900-1905 in the Garland Style. Note the delicate running leaf motifs and slender ribbon bows

The Garland Style dictated the design, mainly set with diamonds in platinum, and decorated with garlands and ribbon bows, entwined ribbons and delicate scrolls, and at times suspended with drop-shaped pearls or diamond briolettes.

A diamond tiara by Cartier Paris, a special order of 1911. A good example of the Garland Style, largely inspired by 17th and 18th century decorative motifs

Among new designs were tiaras in the shape of spread wings, first designed by Cartier in 1899, inspired by the winged helmets worn by the flying Valkyries in the operas of Richard Wagner. Another favourite among the novel designs was the meander tiara, designed as a band of rigorously geometrical Greek key motifs. Parisian couturier Paul Poiret, prompted by the success of the Ballet Russes’ production of Scheherazade, first performed in Paris in 1910, launched a series of fantastic, fluid gowns

inspired by Persia and the Far East, accompanied by oriental turbans decorated with gem-set jewels and osprey or ostrich feathers.

An impressive diamond tiara created by Cartier Paris in 1905 for Mrs Mary Scott Townsend, an eminent member of Washington’s high society at the turn of the 20th century. The seven pear-shaped diamonds weigh approximately 17 carats in total

A diamond tiara created in Vienna around 1911 by the Austrian court jeweller Köchert. Commissioned by Emperor Franz Joseph (1830-1916) it was a gift to Archduchess Marie Anne of Austria (1882-1940) on the occasion of her wedding to Prince Elie de Bourbon-Parma (1880-1959) in 1903

A pearl and diamond tiara, Cartier Paris, circa 1909. The rigorously geometrical Greek key motif is typical of the period. Commissioned by Sir Hugh Montagu Allan for his wife Marguerite Ethel, this tiara accompanied her on the ill-fated last voyage of the RMS Lusitania in 1915 when it was sunk by a German submarine. The tiara was saved by Lady Allan’s maids when they were rescued from the shipwreck.

A diamond tiara, circa 1910, of meander design

Tall, rigid and structured, the tiaras of the preceding centuries where not compatible with the new dress fashion and jewellers strived to create less formal but equally glamorous head ornaments. Aigrettes, jewelled ornaments to be worn in combination with the feathers they were named after, and bandeaux literally bands of gems worn low

on the brow, often decorated with a vertical motif at the centre embellished with natural feathers, were favoured.

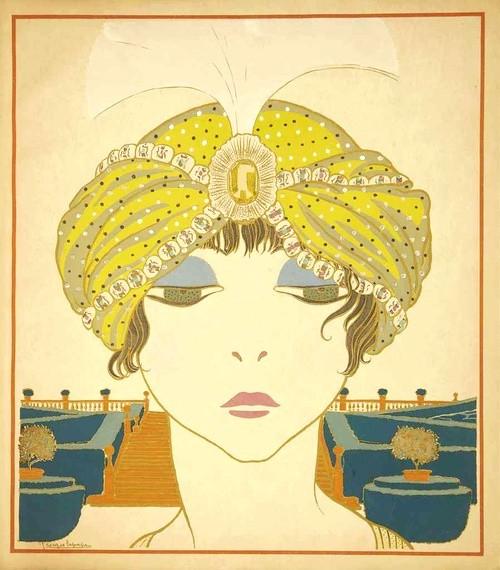

From Les choses de Paul Poiret, Georges Lepape (1887-1971), 1911, Woman with a Persian turban, plate 6

A model wearing a Poiret evening gown and an aigrette, 1914

The bandeau became the most characteristic head ornament of the 1920s. With its simple, linear shape well-suited to the Art Deco style and, worn low on the forehead, below a bobbed style, it was the ideal complement to the new haircut à la garçonne. The bandeaux of the 1920s abandoned the delicate decorative motifs of the garland style and adopted the geometrical shape which characterized Art Deco, namely meanders, lozenges, honeycomb patters, palmettes, stylised lotus flowers and the like. Diamonds remained the favourite gemstones to illuminate the delicate features of the face, but the chromatic obsession of the 1920s discretely appears in many examples. In line with the typical multi-purpose characteristic of 1920s jewels, bandeaux were often designed to form bracelets, clips, brooches or chokers to be worn when the head ornament was not required.

American heiress Evelyn Walsh Mclean (1886-1947), in 1912 wearing a feathered aigrette set with the 94.80 carat Star of the East diamond purchased at Cartier

A diamond wing aigrette/tiara, circa 1910. This jewel would have been worn in combination with real feathers

In the 1930s bandeaux assumed architectural forms often raised at the centre in skyscraper-like motifs. More traditional tiaras assumed the shape of elaborate haloes decorated with the palmette and fan-shaped motifs favoured by Art Deco.

A diamond bandeau designed as a graduated series of open work plaques of palmette design, French, probably by Chaumet, circa 1920

A diamond bandeau by Cartier, purchased in 1912 by Mrs Nancy Leeds, later Princess Anastasia of Greece, one of the firm’s most loyal customer prior to the First World War. In this jewel platinum threads form a grid of “fabric” onto which diamond tendrils are “embroidered". Like many jewels of the period, this bandeau is multi-purpose. The two shield-shaped ends can detach allowing the central portion to be worn as a bracelet. Joined together, these ends form a elegant brooch

The outbreak of the World War II and the austerity of the years which followed were not conducive to the creation of tiaras but they made a come-back in the 1950s: débuts, court occasions, balls and the rich, sumptuous evening dresses of the time required the wearing of precious tiaras, but the era of purpose-made hair ornaments was over and most tiaras in the

1950s simply consisted of necklaces suitably supported by a rigid metallic structure. A particular style or design for tiaras therefore did not exist, but all types of draped, swagged, floral or foliate necklaces fashionable at the time, when turned upside down, became suitable hair ornaments.

Princess Andrée Aga Khan, neé Andrée Joséphine Carron, (c. 1898-1976), third wife of Mohamed Shah Aga Khan III, wearing her 1934 Cartier halo tiara

The advent of the 1960s and the great changes in social attitudes that followed, marked the final disappearance of tiaras from the design books of the jewellers. With very few exceptions all tiaras worn after this date were the product of

the previous decades or of the 19th century, and since the occasions that still required them tended to be formal –weddings or state related – the lack of contemporary designs for this type of jewel did not really matter.

A diamond tiara by Cartier, 1930s, created for Mary, Duchess of Roxburghe, of imposing architectural design

However, the advent of the new century, brought back a revival of the fashion for jewels for the hair. Elton John’s White Tie and Tiara balls and similar glamorous events in private houses reignited the interest in tiaras and encouraged jewellers such as Chaumet, Cartier, Boucheron,Van Cleef & Arpels and Tiffany, to produce, in the last decade of the 20th century, sleek and modern interpretations of these classic head ornaments that met the taste and style of the younger generations. Tiaras – vintage or new – together with necklaces and brooches worn in the hair have definitely made a statement on the red carpet in recent years, encouraging

women to adorn their hairstyles with jewels not only on their wedding day but also for special occasions.

A diamond necklace/tiara by Mellerio dits Meller, Paris, circa 1960. A simple but elegant design popular with many jewellers in the 1950s and early 1960s