FIVE INFLUENTIAL COLLECTORS AND THEIR JEWELS

It is well known that Napoleon’s wife Joséphine (1763-1814) was a great admirer of sapphires and owned a suite of splendid stones mounted into brooches, necklaces and a tiara. What is less well documented is what happened to these stones after her death.

Henri-François Riesener (1763-1814), detail from the portrait of Empress Joséphine Beauharnais, oil on canvas, 1806 | Malmaison, Castles of Malmaison and Bois Preau

Joséphine is depicted by Henri-François Riesener in an oil painting, showing previously, from 1806 in which she is wearing a number of her sapphire jewels.

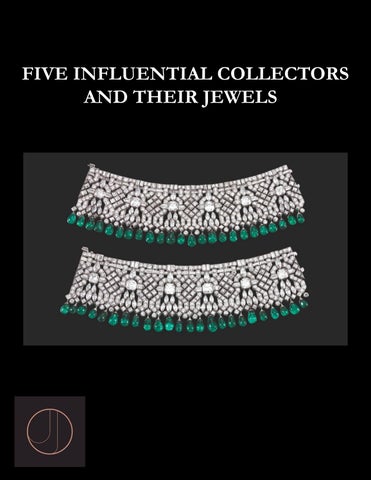

In 1996 an extremely impressive and extensive sapphire and diamond parure was sold at auction at Sotheby’s in Geneva. The consignor was Henri d’Orléans, (1933-2019), Comte de Paris and the senior in male-line descendent of LouisPhilippe I d’Orléans, King of France from 1830-1848.

Left: the impressive sapphire, pearl and diamond parure, early 19th century, sold at Sotheby's, 1996 | Right: the sapphire, pearl and diamond tiara from the parure At the time of the auction in Geneva we were very impressed by the overall quality and the uniformity of colour of the sapphires – they were typical of the finest stones from Sri Lanka.

The pair of earrings and sets of brooches from the parure

The parure, consisting of an imposing tiara of diamond scrolls supporting sapphire and diamond clusters on a base of natural pearls, a pair of earrings and a set of brooches, was housed in a sumptuous red morocco case lined with red silk stamped with the name of Bapst, the French crown jeweller entrusted with the re-modelling of the set. However, the parure which sold at auction in Geneva was part of a much larger suite of sapphire and diamond jewels some of which can be seen worn by Queen Marie-Amélie (1782-1866) in her portrait painted by Hersent in 1836, to follow, also note the sapphire brooches pinned to the skirts of the Queen’s gown.

Detail from the portrait of Queen Marie-Amélie, showing the tiara before Bapst's modification

The sapphires in this suite are likely to be those inherited by Joséphine’s daughter Hortense, she sold this large quantity of sapphires in 1821 and the buyer was Marie-Amélie’s husband, Louis-Philippe. Another portion of Marie-Amélie’s sapphire and diamond suite was acquired by the Louvre Museum in 1985, and these jewels are displayed in the Galerie d’Apollon of the Louvre, together with other items from the French crown jewels.

Crown jewels of France on display at the Louvre Museum, Paris. Queen MarieAmélie's set of sapphire and diamond jewels are in the centre. On the left: the tiara and crown of Empress Eugénie, on the right: the crown of Louis XV and the emerald and diamond diadem of the Duchess of Angoulème

When precisely the re-modelling of Marie-Amélie’s tiara took place is not clear, but it would seem to have occurred around the time the set was intended as a wedding gift from MarieAmélie to her grandson, Louis-Philippe Albert, on the occasion of his marriage to Maria Isabella of Spain in 1864. The substantial change in the design of the tiara is clearly visible, and would be due to the change in fashion: the elaborate and extravagant hairstyles of the 1830s, as seen in Marie-Amélie’s 1836 portrait, which incorporated feathers and velvet hats decorated with jewelled ornaments soon became obsolete and the tiara had to be re-shaped to complement the more traditional hairstyles favoured in the second half of the 19th century (compare the tiara as seen in the images on page four and page seven).

Queen Marie-Amélie’s jewels, acquired by the Louvre Museum in 1985

Seven diamond jewels, circa 1810-1820 | Each oval open work plaque set with circular-cut, old mine and rose diamonds, mounted in silver and gold

This unusual set of seven diamond jewels, circa 1815, that can be incorporated into a tiara, were the gift of the Prince Regent, later King George IV, to his secret and illegal wife, Maria Anne Fitzherbert. It is easy to underestimate the importance of a royal provenance to the value of the jewel.

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830), George IV (1762-1830), 1821, oil on canvas | The King is depicted wearing his Coronation Robes, designed by himself. His hand rests on the 'Table des Grands Capitaines' beside the Imperial Crown, and he wears collars of the Golden Fleece, Guelphic, Bath and Garter | Royal Collection

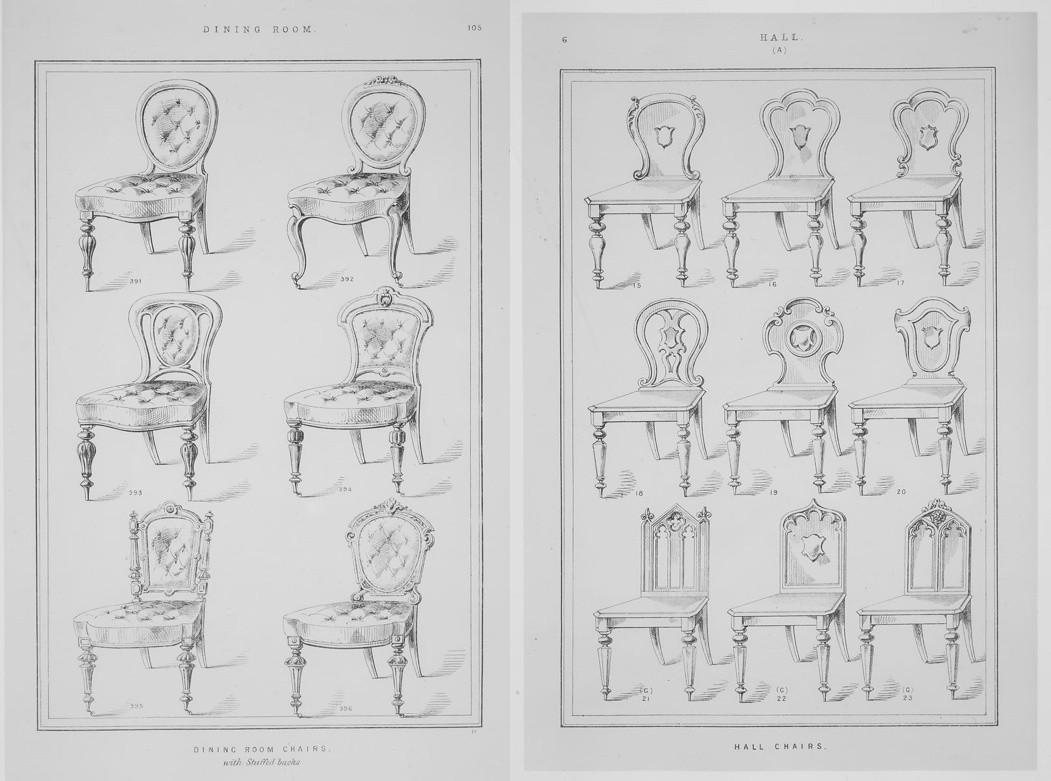

In this case, the set of jewels was commissioned by George, Prince of Wales, during the course of his secret union with Maria Anne Fitzherbert. The design of the bombé confronted volutes is very typical of this precise period and can also be found in the decorative details of contemporary furniture and silver.

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), Maria Anne Fitzherbert (1756-1837), circa 1788, oil on canvas | National Portrait Gallery | George, then Prince of Wales, and Maria went through a form of marriage in December 1785. The union was invalid as the permission of George III had not been sought in advance, and even had the King had been consulted it is unlikely he would have allowed a legal marriage to take place. Maria was a Catholic, and therefore the Prince of Wales would have been removed from succession to the throne

The jewels, mounted in a laminate of silver at the front and gold at the back, would have probably been sewn on to the bodice or the sleeves of a formal dress as was the fashion of the era, and can also be mounted as a tiara.

James Lovegrove Holt, (British, active early 19th century) Modern Furniture. Original and Select, circa 1820, published by Jenks and Holt (London) | Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Left: Sheffield plate coffee pot, circa 1815 | Right: Miniature silver teapot, John Troby, London 1805

Both images: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

DIAMONDS

THE

OF ‘THE QUEEN OF KEPT WOMEN’

Arguably the most famous courtesan of 19th century Paris, Esther Lachmann (1819-1884), who later became known as 'La Païva' through her marriage in 1851 to Albino Francisco de Araújo de Païva, the self-styled Marquis de Païva, was an avid jewels collector well known by the great jewellery maisons in Paris.

Count Horace de Viel-Castel, a society chronicler, called her “the queen of kept women, the sovereign of her race”. Throughout her life, as one of Paris most famous Grandes Horizontales she amassed a vast quantity of gems and jewels which were reputed to rival those of Eugénie, Empress of the French.

It is said that her jewels were stored in two large safes which had been installed at each side of her bed at her magnificent hôtel particulier at 25 Avenue des Champs-Élysées. This building had been financed by her new husband, Count Guido Henkel von Donnersmarck, one of the richest men in Europe at the time, at a cost thought to have been as much as half that of the Palais Garnier Opera House.

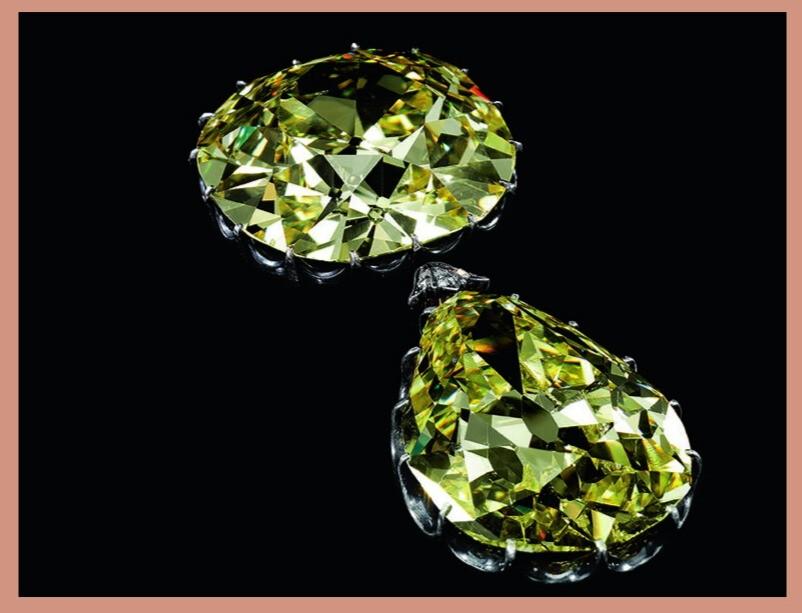

It seems that these two diamonds were acquired by La Païva during her marriage to Count Guido. The cushion-shaped weighing 102.54 carats and the 82.48 carat pear-shaped, were eventually mounted together as a pendant. Both stones were probably found either in Brazil or – more likely because of their colour – in South Africa’s Cape Province. La Païva had a flourishing salon in Paris, and no doubt these two diamonds would have caused a sensation when worn at one of her many famous soirées.

La Païva in an 1860s portrait by Marie-Alexandre Alophe (French, 1812-1883)

One of the last times the two diamonds were seen together in Paris was when we had the idea, before their sale at auction at Sotheby’s in Geneva in 2007, to show them at a press conference at La Païva’s hôtelparticulier on the Champs-Élysées, now home to the Travellers Club. We had no doubt La Païva was watching the proceedings with some amusement.

This magnificent brooch formed part of the unforgettable collection of jewels that were sold at auction in 1992, coming from the princely Thurn und Taxis family of Regensburg.

The brooch was a wedding gift from Prince Albert von Thurn und Taxis to his bride Archduchess Margarethe of Austria. The Archduchess also received from Prince Albert, on the same occasion, the fabulous pearl and diamond tiara which Gabriel Lemonnier created in 1853 for the wedding of Eugénie de Guzmán, Comtesse de Teba to Napoleon III, Emperor of the French. The pearls used by Lemonnier to create the tiara, came from

the French Treasury and were believed erroneously, at the time, to have belonged to Queen Marie Antoinette, another Austrian Archduchess – which led Prince Albert to consider the tiara very appropriate for his bride. Prince Albert purchased the tiara from the jeweller Julius Jacobi who had acquired it at the auction of the French Crown Jewels in Paris in 1887.

The brooch is unsigned but bears French gold marks and may well be the work of Gabriel Lemonnier or François Kramer who, in 1853, also created pearl and diamond brooches for Empress Eugénie.

In the portrait photograph overleaf, dated 1899, the Archduchess can be seen wearing both jewels, the Lemonnier tiara (now on permanent exhibition in the Louvre Museum in Paris) and this imposing brooch. In fact, both these jewels were included in the same auction at Sotheby’s, Geneva in 1992 and so we had the rare opportunity of examining and comparing them both in detail.

This image also shows how important pearls were to confirm and demonstrate status at the turn of the century. Certainly, we find the three huge pearls at the centre of the brooch to be unforgettable and they are among the finest we have ever seen, not only in terms of colour but also in terms of lustre.

The Empress Eugénie tiara, showing overleaf, created by Gabriel Lemonnier, Paris, 1853, featured pearls from a parure created for Empress Marie-Louise, the wife of Napoleon I.

In 1992 natural pearls were not in demand and consequently we had placed a rather modest estimate in the catalogue. Nevertheless, the pre-sale catalogue estimate of CHF200,000-300,000 was comfortably exceeded by the final, achieved price of CHF517,000.

In our opinion, however, and in the current market, this brooch could well sell for twenty times more than the 1992 realised figure.

Natural pearls have justifiably regained their former appeal and status as the ‘queen of gems’.

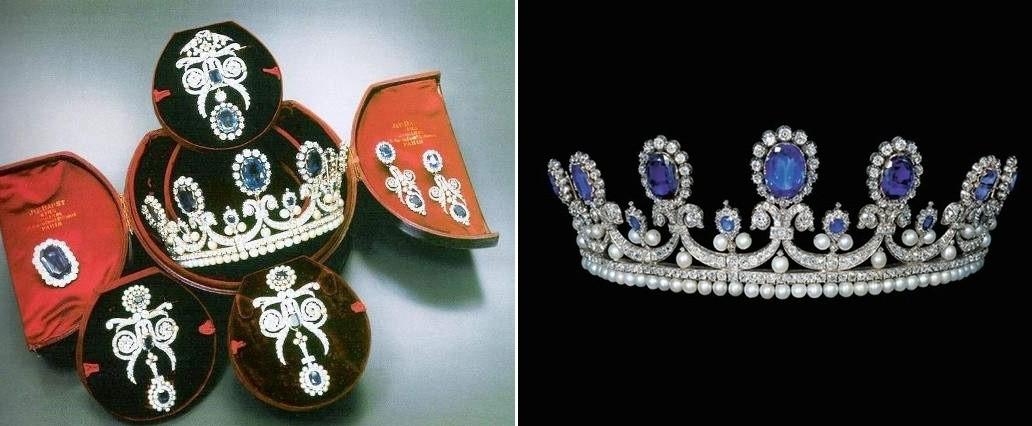

A pair of emerald and diamond bracelets, by Van Cleef & Arpels, made respectively in 1926 and 1928 | From the collection of Daisy Fellowes

These spectacular bracelets, designed as articulated flexible cuffs, set with variously cut diamonds and supporting fringes of emerald bead drops are beautifully crafted and as supple as a piece of fabric. They were intended to be worn on the upper part of the hand rather than tight around the wrist but could also be worn together as an impressive choker. The geometric openwork pattern of the wide diamond bands and the juxtaposition of diamonds of different cuts (step, baguette, circular and marquise) make these bracelets perfect examples of Art Deco jewels.

Daisy Fellowes wearing the Van Cleef & Arpels emerald and diamond bracelets, circa 1930

Here the inspiration has been drawn from Islamic architecture as suggested by the repeated niche motifs. In addition, the fringe of irregular emerald drops adds an exotic element which strongly evokes India. Emerald beads had for long been favoured in the jewellery of the sub-continent, and their inclusion in these bracelets imparts a striking and somehow ethnic character.

Cartier's 'Collier Hindou' created for Daisy Fellowes in 1936 and re-modelled in 1963 As an important style icon and socialite, and a devoted supporter of the avant garde, Daisy Fellowes contributed to the interest in Indian-inspired jewels among the élite of American and European society. One has only to think of the magnificent multi-coloured gemstone ‘Collier Hindou’ created for her by Cartier in 1936 with carved gemstones brought back from India by Louis Cartier, closely inspired by the traditional bib mâlâ of Rajasthan.