JEWELS CREATED BY CARTIER

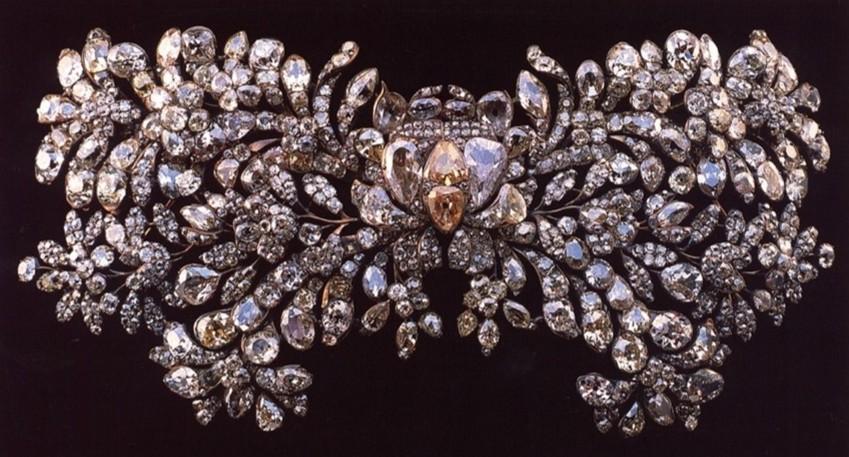

Swags, garlands and ribbon bows make this jewel emblematic of the Garland Style

Featuring an elaborate combination of swags, garlands and ribbon bows, this jewel was created by Cartier, circa 1905. The Garland Style took inspiration from so many 18th century sources, including French neo-classical ormolu furniture mounts.

Jean-Henri Riesener (1734-1806), commode or secrétaire à abattant, oak veneered with ebony and 17th century Japanese lacquer, 1783 | Created for MarieAntoinette's Grand Cabinet Intérieur at Versailles. The gilt-bronze mounts take the form of swags and garlands of flowers, and the Queen's initials appear in the frieze | Metropolitan Museum, New York; Gift of William K. Vanderbilt, 1920

Together with colliers de chien, tiaras and ropes of pearls, the stomacher – or corsage ornament – almost invariably set with pearls and diamonds, was among the prized possessions of fin de siècle society ladies. The delicate design of these jewels was perfectly set off by the pale colours and diaphanous fabrics of the evening gowns fashionable at the time, often heavily embroidered with sequins and glass beads and supported by boned corsets.

Silk ball gown embroidered with rhinestones, House of Worth, designed by JeanPhilippe Worth (French, 1856-1926), 1900 | Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of the Estate of Mrs. Arthur F. Schermerhorn, 1957

When Parisian couturier Paul Poiret launched a new style in fashion which called for column-like tunics, the corset became redundant and, with it, stomacher brooches and other corsage decorations.

Silk ball gown embroidered with rhinestones, House of Worth, designed by JeanPhilippe Worth (French, 1856-1926), 1898 | Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Mrs. Paul Pennoyer, 1965

It is rare and very fortunate that a corsage ornament of this size and importance has survived to our days, with its large, silver-grey button pearl still in place.

A gold, silver and diamond corsage ornament from 1907

This large brooch or corsage ornament designed as an elaborate bow with intricate tassel drops is typical of Cartier’s ‘Garland Style’ production during the early years of the twentieth century and clearly demonstrates its origin in late 18th century design motifs.

Leopold Pfisterer, 1763-1767, diamond court dress trimmings | Moscow, The Kremlin Armoury's State Diamond Fund

It is unusual in that it is also partly set in gold, a metal one associates with the previous century, but which at this time was in a period of transition to platinum for diamond-set jewels.

Louis-David Duval, 1760-1770, diamond bow jewels which could be worn as hair ornaments or pinned to the bodice or sleeves of a dress | Moscow, The Kremlin Armoury’s State Diamond Fund

Very often jewels of this scale were adaptable, so that elements such as the drops in this case, could be used as ear pendants, while the central bow motif could have been attached to a velvet ribbon and worn as a choker.

Jérémie Pauzié, 1740s, Catherine the Great’s diamond mantle fastener | Moscow, The Kremlin Armoury’s State Diamond Fund

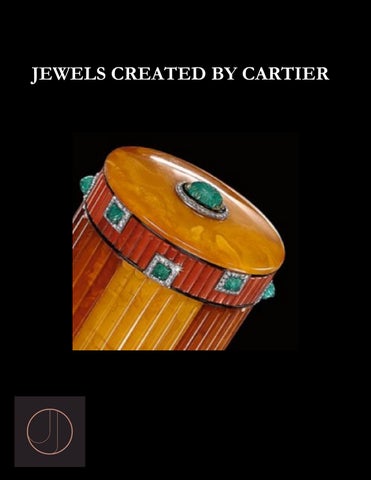

A charming amber, coral, emerald and diamond case, circa 1925

This handsome and imposing tonneau shaped box, which is essentially masculine in taste, may well have been destined to store cigarettes or cheroots, the small cigars which formed part of the smoking paraphernalia so typical of the time. This box could also have been displayed as an objet de vertu when not in use. The use of carved Baltic amber is unusual for such objects, while the cylindrical form and fluted decoration look back to a turn-of-the-century cigar case by Fabergé.

The carved emeralds would have been brought back from India, while the coral details became a sort of Cartier ‘signature’ of the period.

The subtle colour combination of two-toned amber and coral is contrasted by the black enamel, emerald and diamond applied motifs.

An advertising poster for the Belga brand of cigarettes, launched in 1923 and named after Belgium's currency at the time. American illustrator Lawrence Sterne Stevens depicts the Belgian actress Netta Duchâteau as a flapper

A shoot from the 1920s

A delightful and highly successful transformation of a utilitarian object into a glamorous accessory.

Designed as a bowl of flowers, this vibrant brooch was originally in the collection of the Hollywood star, Mary Pickford

This colourful brooch dates from the 1920s, decorated with carved rubies, emeralds and sapphires, and highlighted with diamonds and black enamel, it was originally in the extensive jewellery collection of the Canadian-American actress Mary Pickford – one of the most popular stars of the silent film era.

Wide, flat bowls, urns or baskets filled with fruits and flowers and set with multi-coloured gemstones were typical of the work of Charles Jacqueau (1885-1968), arguably the most innovative of the Cartier designers of his day.

These jewels were the result of the merging of different influences such as the design of 18th century delicate ‘giardinetto’ brooches and rings with the bold chromatic contrast introduced by the Ballets Russes (first performed in Paris in 1909) which mesmerised the public with their colourful exoticism.

Jean Henri Prosper Pouget (died 1769), Traité des pieres précieuses et de la manière de les employer en parure, Paris, 1762; a page of ‘giardinetto’ ring designs

Both Louis Cartier and Charles Jacqueau were fascinated by these performances and were frequent visitors. Although first designed around 1913, these brooches remained popular after the war and remained so well into the 1920s, eventually developing into the iconic Cartier ‘Tutti Frutti’ jewels of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Léon Bakst (1866-1924), set design for the ballet Sheherazade

Charles Jaqueau’s collaboration with Cartier lasted two decades, and his greatest merit is that of having encouraged the firm to abandon the monochromatic formality of the ‘Garland Style’ and embrace bright, colours, bold shapes and exotic influences to become the champion of a new aesthetic.

Mary Pickford (1892-1979) as a Ziegfeld Follies girl, shot by Alfred Cheney Johnston (1885-1971), 1920

It was largely thanks to Charles Jacqueau’s stimulus that Cartier produced some of the most convincing examples of proto-Art Deco jewels well before the outbreak of the First World War, and thereby gained an artistic advantage that distinguished the firm from its rivals.

Designed as a bandeau of aquamarine clusters and diamond leaves

This jewel, which was sold at auction as part of the Estate of Christian, Lady Hesketh, has an interesting history.

Aquamarine and diamond tiara, Cartier, London, 1914

Designed as a series of graduated oval aquamarine clusters set with oval- and hexagonal-shaped aquamarines, interspersed with sprays of diamond myrtle leaves, with millegrain borders of circular-, single- and rose-cut diamonds

Originally designed by Cartier, London, in 1914, as a simple diamond bandeau, it was subsequently adapted by the jewellers in 1938 to suit the rage for aquamarines that swept England in the 1930s and prompted Cartier to produce a series of architectural clips, necklace/tiaras and bracelets featuring these gemstones.

An aquamarine and diamond bracelet, Cartier, circa 1935

Indeed, the passion for aquamarines was so strong that American socialite and interior designer Elsie de Wolfe, later Lady Mendl (1859-1950), had dyed her hair blue in 1935 to match her new aquamarine tiara she had just purchased from Cartier.

It is interesting how the two styles – Garland and Art Deco –while so different, nevertheless sit harmoniously in this exceptionally beautiful tiara which achieves both elegance and grandeur.

Adapting and altering jewels to fit new styles and dress fashions is not uncommon in the early 20th century, especially in the case of tiaras, but rarely was the re-modelling as successful as in the case of Lady Hesketh’s tiara.

Cartier’s fascination and empathy with Indian aesthetics led to the creation of a number of significant jewels in the early 20th century

During the Summer of 1901, while all of London was mourning the death of Queen Victoria, Pierre Cartier was called to Buckingham Palace at the request of Queen Alexandra to commission a necklace of Indian design to complement three Indian gowns she had received from Mary Curzon, wife of the Viceroy. The necklace was to be created incorporating some of the many Indian jewels that the Royal family had accumulated over the years which had been originally designed for men and were unsuited to the fashions of 1900. This commission was to herald the start of a long and prosperous period of Royal patronage as well as introducing Cartier to the exoticism of the Orient.

India had always held a fascination for the West, and in part it was thanks to the British Raj that the appeal was strongest in Britain. Providing exotic backdrops to European society the influence filtered through to the Ballets Russes’ Sheherazde and Paul Poiret’s latest Orientalist-inspired fashions.

Cartier made no distinction between the various oriental influences, describing his jewels as Indien or Hindou, and he looked to both the Middle East and the Far East, utilising a panorama of ornamental motifs from the Ottoman Empire, Persia, and India. One of the main sources for these decorations however was Louis Cartier’s own collection of Persian miniatures – they enthralled him with their jewel-like quality and provided him with designs for cigarette and vanity case and even exhibition invitation cards.

In 1909 the Indian business was handed to Jacques to be run from the London branch, affording him the opportunity presented by the British Raj. In 1911 he was at the famous Delhi Durbar attended by King George V and Mary of Teck, as well as every Indian princely house and nobleman in order to pay homage to the new Emperor and Empress of India, and thereby cementing support for the British Crown. This occasion to field business was not lost on the house of Cartier, and Jacques used the Durbar as an opportunity to identify new clients for the firm from amongst the Indian princes. He also sourced gems and antiquities to be sold from the London branch to European clients.

The Delhi Durbar, 1911, it was the only Durbar to have been attended by a reigning British monarch

On his return to London in 1912 the London branch of Cartier held an exhibition of Oriental jewels, showcasing jewels both inspired by Persian Art and others incorporating antique elements, as well as antique and modern Indian jewels which had not been altered. Later on in the 1920s and 30s Cartier began to incorporate older elements into newly fashioned designs.

Pearl, emerald and diamond pin, Cartier, circa 1925, in the shape of a sarpech, the turban ornament worn by significant Hindu, Sikh and Muslim princes in India, but also by notable men in Persia and Turkey

One of the characteristics of Indian jewels that fascinated Cartier was the use of carved gems – emeralds and rubies formed various floral motifs and in some instances birds and animals. Previously such stones were perceived as primitive and of little value, and they did not appeal to Western European taste, however Cartier diamonds and onyx. The style soon became one of Cartier’s signatures and today is known the world over as ‘Tutti Frutti’. The use of colour with these new found exotic gems from the East appealed to the sensibilities of the new Art Deco look and it was not long until other jewellers began to follow, although none have eclipsed Cartier in this genre.

Henri Picq was the principal workshop working in this style and was soon supplying Cartier with an array of jewels in the new style of the Indian aesthetic.

One of the most iconic ‘Tutti Frutti’ jewels was the necklace created for the socialite Daisy Fellowes in 1936. It was fashioned from three existing Cartier jewels in her collection purchased in the 1920s; the necklace was created with a corded back chain emulating traditional Indian jewels but incorporating carved sapphires to complement the Indian rubies and emeralds, a colour combination which not been seen before in traditional Indian jewellery.

The famous 'Collier Hindou' designed for socialite Daisy Fellowes, 1936, and altered in 1963, and a pair of carved emerald and diamond pendent earrings, 1936

Another equally memorable jewel was the emerald and sapphire sautoir illustrated in Vogue in 1927. It was set with three carved Mughal stones to a sapphire bead chain of pale Kashmir sapphires. This marvellous jewel was purchased by Baron de Rothschild for his new wife, the celebrated divorcee Catherine Wolff, or “Pretty Kitty” as she was better known. Another heiress, Majorie Merriweather Post, also embraced the new Hindou style. Her wonderful Art Deco shoulder brooch created in 1928 and set with Mughal emeralds can be seen today at the Hillwood Museum, her former estate, in Washington DC. The brooch was the prominent, central focus in the 1929 portrait of Mrs Hutton (Majorie Post) and her daughter painted by the Italian artist Giulio de Blass.

Marjorie Merriweather Post's imposing emerald and diamond brooch created in 1923 and altered in 1928 | Marjorie Merriweather Post, Mrs Edward Hutton (1887-1973), wearing the emerald and diamond brooch, with her daughter, Nedenia Hutton (1923-2017), in a painting by Giulio de Blaas, 1929

As well as the Indian inspired jewels created to appeal to Western taste, Cartier also re-modelled historic jewels for the Indian princes. Interestingly, they preferred the use of platinum over the traditional Indian preference for gold and were swayed by the fashion for Art Deco that was taking hold. The culmination of such commissions was an exhibition held by Cartier in Paris in 1928 featuring jewels remounted for the Maharajah of Patiala.

The 9th and last Maharaja of Patiala, (reigned: 1938-1947), Sir Yadavindra Singh (1913-1974), wearing jewels remounted by Cartier for his father, Sir Buphindra Singh

Cartier has continued to hold sway over the interpretation of Indian inspired jewels, even today embracing the exoticism of the East with new versions of its iconic ‘Tutti Frutti’ jewels. However, despite these contemporary examples, the jewels of the 1920s and 30s still retain their power to capture the imagination through their extravagant expression of the Orient.