HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE ONLINE VERSION OF UnderstandingJewellery

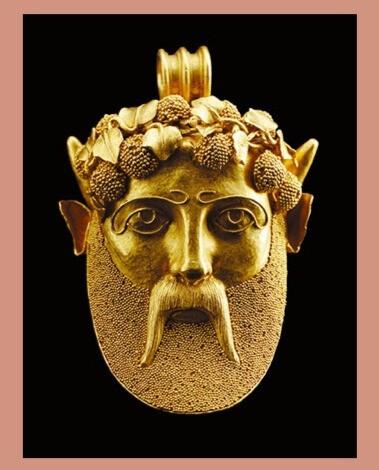

A superb Archaeological Revival gold pendant, circa 1870

Although unsigned this jewel has been attributed to Castellani on the basis of the excellence of the workmanship and the fact that its design is based on an Etruscan pendant which resided in the famous Campana Collection and is now in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

Pendant necklace in the shape of Acheloos’ head, gold, c. 480 BC, Etruscan/Chiusi | Campana collection purchase, 1861, Louvre Museum, Paris

The Castellanis were in fact instrumental not only in the acquisition and restoration of the jewels in the Campana collection, but also in the negotiation of its sale to the French in 1861. The firm frequently draw from these models for inspiration.

Left: Giampietro Campana (1808-1880) - Campana, an Italian art collector, assembled a highly significant collection of Greek and Roman sculpture and antiquities. He worked in the mid-19th century, a time when the archaeological field was still seen as a source of 'treasure', and brought an intellectual rigour and discipline to the study of antique civilisations

Right: Fortunato Pio Castellani (1794-1865) - Castellani opened his first workshop in Rome in 1815, and his early designs reflected the fashions of the day as seen in English and French jewellery. From the 1820s he began to develop his signature style utilising finds from archaeological sites, particularly those dating from the preRoman Etruscan era. The Castellani dynasty spanned three generations, with many family members being renowned antiquarians

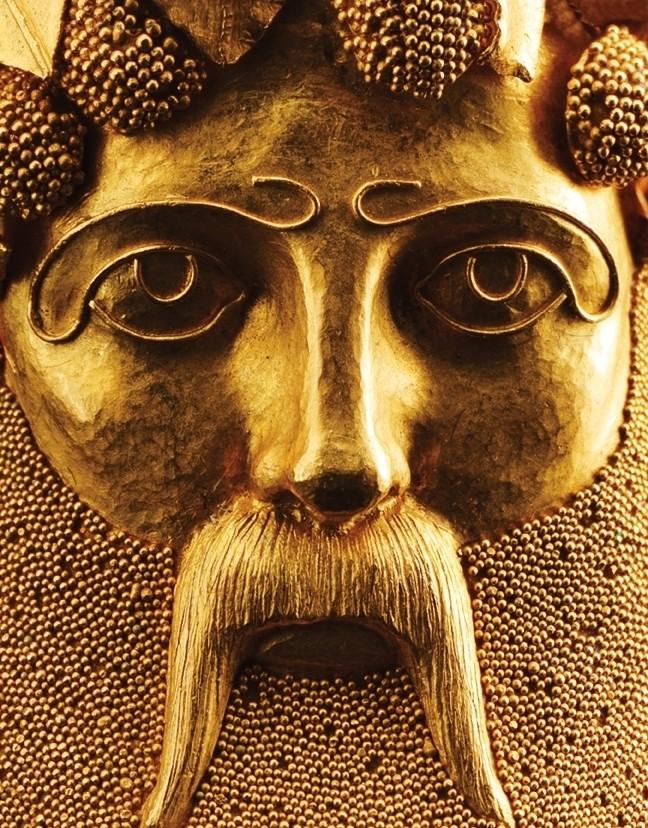

In this case, although the original 5th century BC pendant depicts the mask-like head of Acheloos, the river god, with his horns and pointed ears, Castellani beautifies the features of the mask and transforms it in a daunting mask of Dionysos/Bacchus. The imposing beard and the rich fruiting vine wreath encircling his head being the typical attributes of a mature Dionysos.

A silver stater (coin used in various regions of Greece, in circulation from the 8th century BC-AD 50), weighing 11.97g, Boeotia, Thebes, circa 405-395 BC. The reverse depicts a Boeotian shield, the obverse the head of a bearded Dionysos, turning slightly to the right and wearing an ivy wreath

An Etruscan antefix - a vertical block terminating and concealing roof tiles, also protecting the join from the elements - representing the head of the river god Acheloos

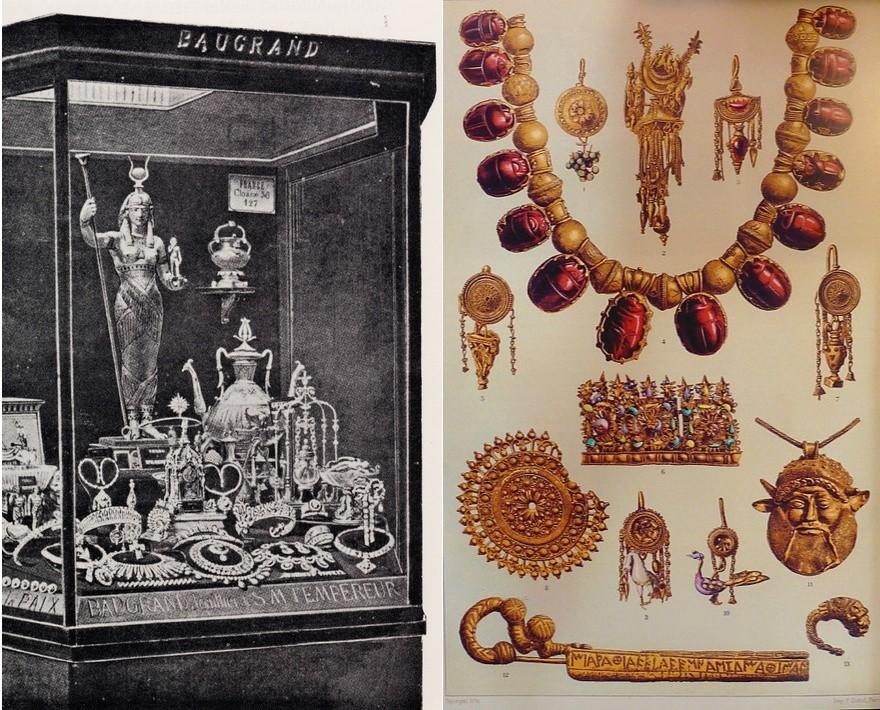

The work of contemporary jewellers was such that at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris almost all exhibitors presented jewels in Archaeological Revival style. Fascinated by the fine quality of the goldsmith work of these antiques, the Castellanis strived to emulate their fine filigree and granulation.

Left: The Parisian jeweller Baugrand's vitrine at the Exposition Universelle, Paris, 1867

Right: Lithographic plate from L'Art Étrusque, Jules Martha (Firmin Didot, Paris, 1889) - the work documented Jewels from the Campana collection and other jewels from the François and Bolsena tombs

The superb granulation of this pendant became a source of inspiration for most 19th century jewellers working in the Archaeological Revival style who sought to reproduce the technique which had been lost since antiquity.

The perfection of the minute granulation, the boldness of the image and the haunting expression Castellani has brought to the face of the god make this pendant one of the most powerful examples of Archaeological Revival, and a veritable tour de force exhibiting the jeweller’s technical skills and historical knowledge.

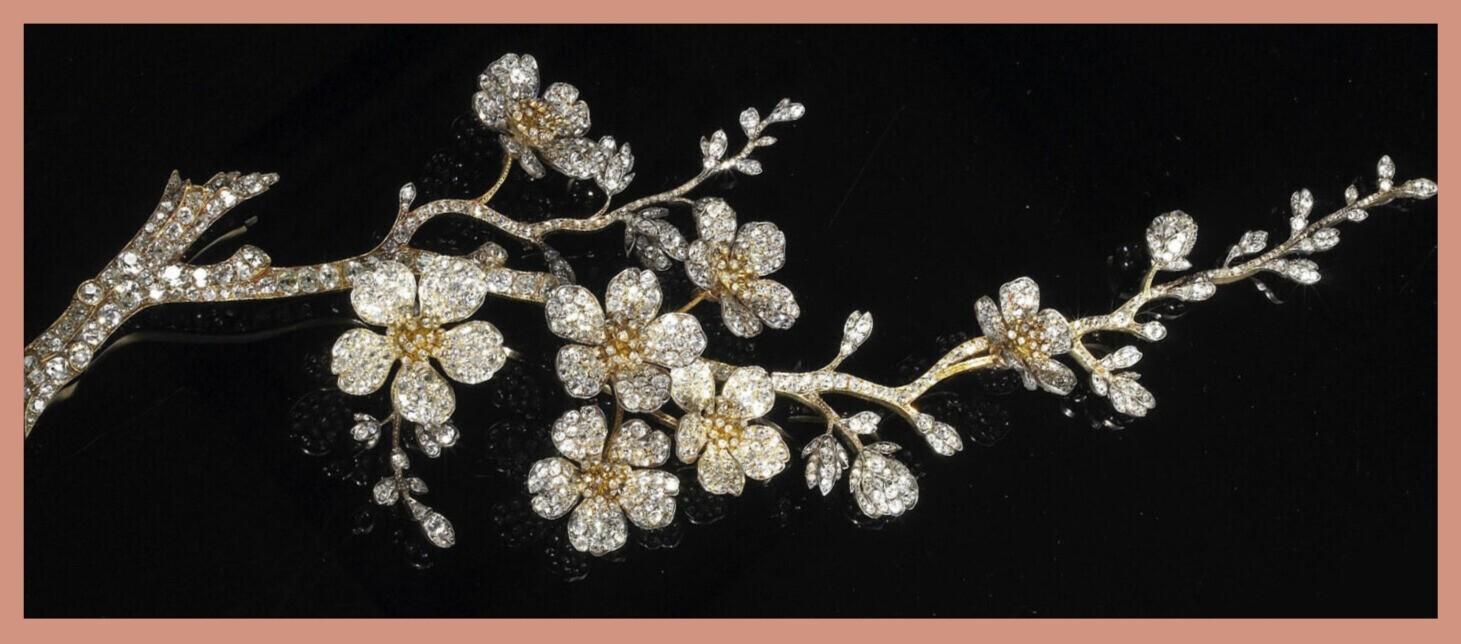

A remarkable diamond corsage ornament created in collaboration with Henri Vever

Before René Lalique (1860-1945) became famous for his extraordinary creations in the Art Nouveau style, which broke away from 19th century mainstream jewellery, he had been collaborating with the major Parisian jewellery houses of his time including Cartier and Boucheron.

A magnificent diamond corsage ornament, French, circa 1890 by Henri Vever and René Lalique in the form of a spray of prunus (sakura)

In this jewel, created in association with Henry Vever (18541952), in Paris, probably in the late 1880s, one can already detect elements of Art Nouveau. The jewel was part of the collection of the Belgian Princess Louis de Cröy and is of extraordinary size. At 29 cm long, the spray would extend from the top of the shoulder down towards the waist and could be separated into three smaller jewels.

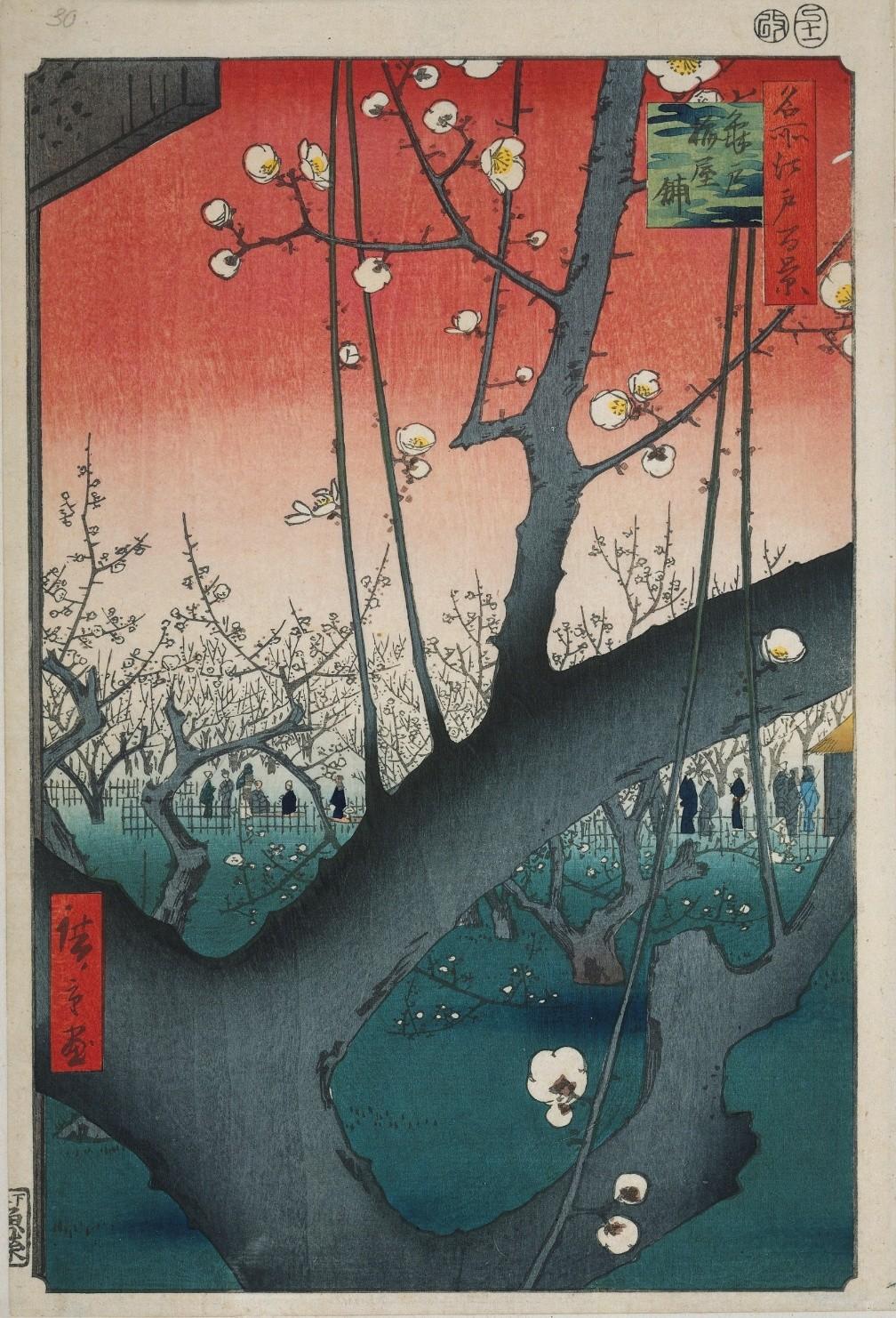

The choice of subject itself – a spray of sakura (prunus) – so beloved by the Japanese, closely follows the fashion for all things Japanese that artists such as Whistler, Van Gogh, Monet, Klimt and many others were incorporating into their work at that time. This was a consequence of the arrival in Europe of Japanese prints, artefacts and traditional ornaments, which followed the opening up of Japan after the Meiji restoration in 1868.

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Almond Blossom, oil on canvas, 1890 | Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

This jewel would certainly have created a sensation when it was first worn, perhaps at a Court ball at the end of the 19th century, and possibly pinned on a pastel-coloured gown created by the House of Worth.

House of Worth, evening gown, 1897 | The Olive Matthews Collection, Chertsey Museum, Chertsey, UK

A daring Lalique creation through its use of materials and the subject matter

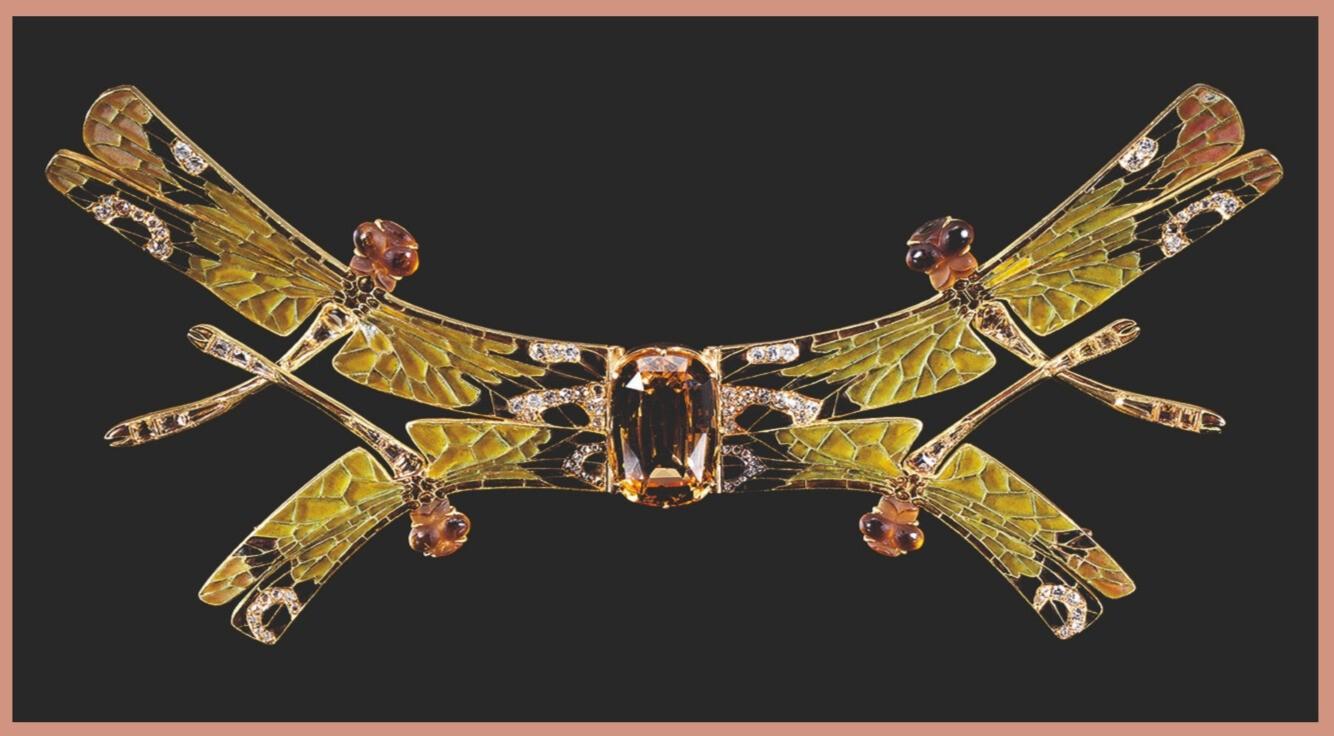

This highly stylised and avant garde design, at first perceived as exotic butterfly is actually formed of pairs of mating dragonflies and illustrates the fin-de-siècle obsessions with ideas of death, transfiguration and regeneration.

Created by René Lalique around 1900, this is an extraordinarily modern jewel to the twentieth century eye, that, in its day, would have challenged the basic tenets of mainstream society jewellery not only through its form but also in its subject matter and choice of materials.

The muted autumnal palette of golden brown, sage green and tan is in line with the chromatic preferences of Art Nouveau.

The choice of the delicious honey-coloured topaz for the central stone is in perfect harmony with the colour of the plique-à-jour enamel of the wings and the pâte-de-verre heads of the insects.

Diamonds are kept to a minimum and their function is simply to draw attention to elements of the design.

Created at the time when the interest of the art world in Japanese works was at its height, this jewel is clearly indebted to the Japanese interpretation of the natural world, as depicted in the work below:

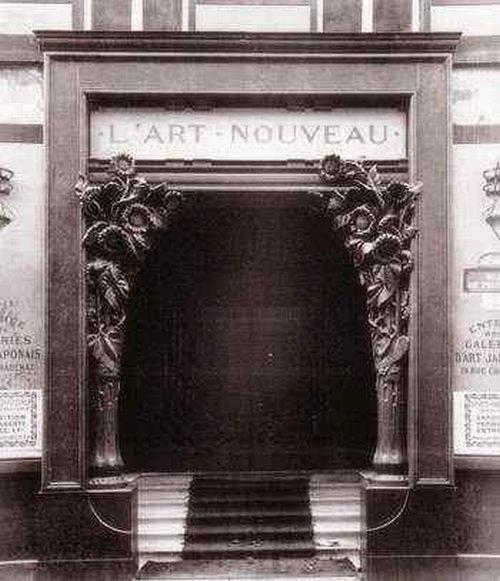

The red dragonfly and locust depicted previously appear in the Edo period work the Picture Book of Crawling Creatures, (woodblock-printed book, ink and colour on paper, 1788), published by Tsutaya Jūzaburō, with illustrations by Kitagawa Utamaro (c. 1754-1806). The poet and scholar Yadoya no Meshimori wrote the introduction to the book which featured fifteen designs of insects and other garden creatures, he also selected the poems to accompany each illustration. One of the consequences of the re-opening of Japan to the western trade in the late 1850s was a steady flow to Europe of Japanese works of art. In Paris, the activities of Samuel Bing were crucial to the Japanese influence on Art Nouveau. Édouard Pourchet (1848-1907), Entrance of the Maison de l'Art Nouveau, 22 rue de Provence, Paris, 1895

From the early 1870s, he specialised in the importation and sale of Japanese and other Asian objets d’art. Between 1888 and 1891 he published a monthly journal, Le Japon Artistique, and eventually in 1895 he opened his famous gallery, the Maison de l’Art Nouveau, which showcased the works of artists, including Lalique. Their output would become known as the Art Nouveau, (see the previous photograph).

Lalique is without doubt the undisputed genius of Art Nouveau. He produced a large body of work that included many masterpieces; we believe this jewel should certainly be counted among them.

The dramatic colours seen in this Art Deco Cartier brooch indicate that it could be a unique jewel

One of the characteristics of Art Deco jewels, together with geometrical design, is vibrant chromatic combinations. However, the unusual and dramatic colours of this brooch, which was created by Cartier in 1926, are probably unique.

Fine gem-set and diamond brooch, Cartier, 1926 | Of buckle design set to the centre with a cluster of seed pearls, further set with buff top calibré-cut and cabochon sapphires, circular-cut coloured and colourless diamonds

The contrast between the lime green, highly fluorescent diamonds and the steely-blue sapphires which may well have been found in the ‘new’ mines of Montana is extremely effective, and is set off by the soft sheen of grey, gold, cream and grey pearls.

The old cushion shape of the diamonds suggests they may have been previously set in a late 19th century jewel, while the calibré sapphires had clearly been clearly cut to fit the mount. We like the effective detail of the two small sapphires, highlighting the trefoil terminals of the brooch: an elegant touch consistent with the work of a master jeweller.

We can imagine this brooch worn at the hip of the low waisted tunic dress fashionable at the time, realised in a fabric of contrasting colour, texture and pattern (see image above).

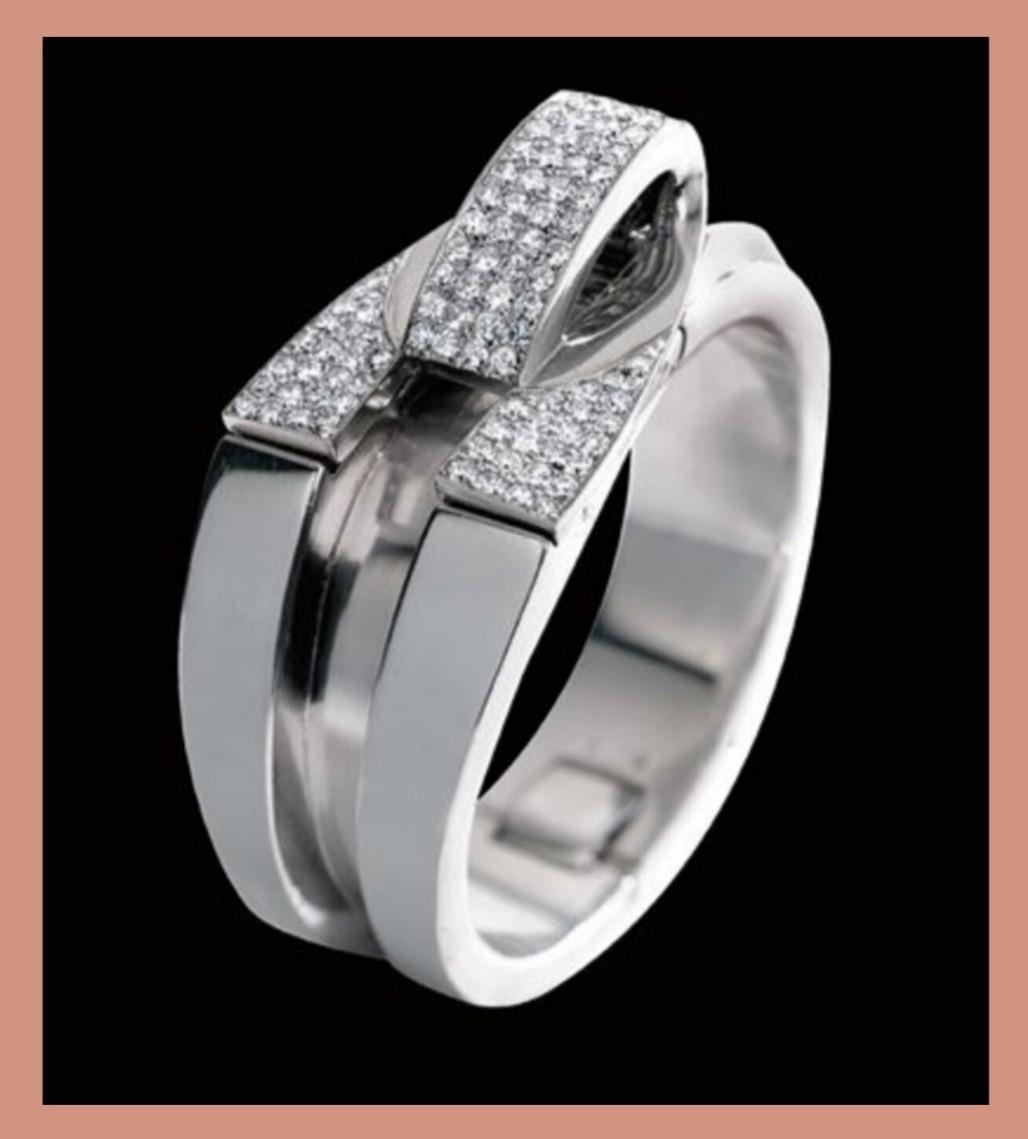

Templier demonstrates his characteristic focus on form and design

Few jewellers from the Art Deco period are as distinctive in their designs as Raymond Templier (1891-1968).

Born into a dynasty of Parisian jewellers, Raymond Templier joined the family firm in 1922 and distinguished himself with the creation of bold, daring and unusual jewels, showing a debt to Cubism, African art and industrial design.

A poster advertising the first exhibition of the Union des Artistes Modernes, Paris, 1930

Templier was a founder member of the Union des Artistes Modernes – a group of innovative architects and decorative artists who, in 1929, broke away from the Société des ArtistesDécorateurs and wanted to “…rise up against everything that looks rich, against whatever is well made, and against anything inherited from grandmother’.

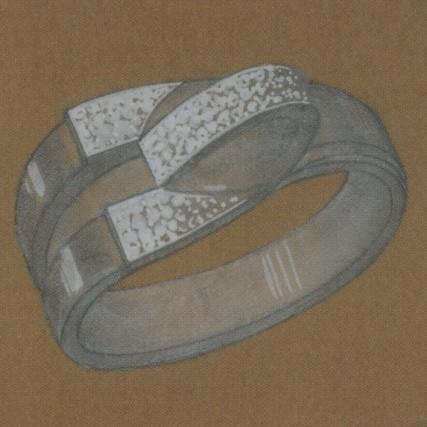

The original design for the Templier bangle

Templier conceived ornaments that transcended the field of traditional jewellery and entered the realm of art. His creations are characterised by a contrast between matt and shiny surfaces, an exciting play of light and shade, and rich volumes employed with sculptural effect. He created jewellery that was principally about design, and not simply about materials. In fact diamonds and precious stones enter his creations to give light and colour to his sculptural shapes.

The bangle and its detached clip

This white gold convertible hinged bangle of asymmetrical design, set at the front with a detachable diamond clip is an example of Templier’s art at its best: an object of contemplation and yet emblematic of the mid-1930s. Timeless in its sophisticated elegance.