BIOCULTURAL PATHWAYS

RECLAIMINGGREENWAYSWITHʻIKEʻĀINAAND PASIFIKAAGROFORESTRY

JadeRhodes,MLACandidate

Biocultural Pathways: Reclaiming Greenways with ʻIke ʻĀina and Pasifika Agroforestry

A capstone design research project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Plan B requirements for the degree of MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

May 2025

By Jade Rhodes

Capstone committee: Heather McMillen

Judith Stilgenbauer, Chairperson

Keywords: agroforestry, food systems, biocultural heritage

This research is dedicated to the seven generations before me, whose wisdom, labor, and love have paved the way, and to the seven generations to come, in hopes that they inherit landscapes of abundance, justice, and care.

A heartfelt mahalo to my family, whose sacrifices, grounding, and unconditional love have sustained me throughout this journey. You are my first teachers of resilience, compassion, and kuleana.

To my mentors, friends, and ʻohana who have held and nurtured me mahalo nui for walking beside me. This work is rooted in the ʻike of the stewards of ʻEwa Moku. Your teachings, trust, and aloha have made this work possible.

I extend deep gratitude to my chair, Professor Judith Stilgenbauer, for her guidance, patience, and belief in my vision. To Dr. Heather McMillen, your mentorship has been a beacon, sharpening both the rigor and heart of this work.

Mahalo to the Office of Indigenous Innovation, led by Kamuela Enos and Kari Noe, for stewarding a space where ancestral knowledge and contemporary innovation meet.

To Manu Meyer and Hui o Hoʻohonua mahalo nui loa for living the practice of healing with land and community. You have shaped not only this capstone, but my becoming.

To my research peer and collaborator within the Office of Indigenous Knowledge and Innovations, Oli Carbi thank you for your unwavering partnership, your brilliance, and your trust.

To the many alakaʻi (student leaders) and co-designers of our community of practice over the last three years mahalo for your courage, joy, and commitment to collective transformation. You remind me that restoration is relational. Lastly, to ʻāina itself the ancestor that nourishes, remembers, and teaches. This work is an offering back to you, in gratitude for every lesson, every step, and every seed of possibility you have provided.

01 INTRODUCTION

To imagine the future of Hawaiʻi’s urban spaces, we must first understand that cities are not devoid of ʻāina they are layered with it. Beneath paved corridors, behind fences, and within fragmented greenways lie landscapes that once thrived as biocultural systems: spaces of abundance, healing, and ancestral technology. ʻIke ʻĀina, the embodied, experiential knowledge of land, is not lost. It waits to be reactivated.

This capstone investigates how traditional Hawaiian and Pasifika agroforestry systems can serve as guiding frameworks for reimagining underutilized urban corridors specifically the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail as edible greenways rooted in biocultural memory. Agroecological systems in Hawai’i were a gradient of adaptable ancestral technologies of the wettest and dryest landscapes, foundational to the concept of ʻāina momona (land of abundance), were cultivated through intergenerational knowledge systems that embedded food, medicine, and ceremony into the land itself Reintroducing them into Hawaiʻi’s built environments offers a way to restore not only ecological function, but cultural integrity and community connection

Yet the urbanization of Hawaiʻi has not been neutral. U.S. colonization, militarization, and plantation economies have profoundly reshaped the physical and spiritual contours of ʻāina. Today, this trauma is visible in contaminated waters, hardened soils, and restricted access to its shores. These disruptions are not isolated, they reflect a broader pattern of fragmentation across Indigenous land systems and urban landscapes throughout Hawai‘i.

This capstone investigates: How can traditional systems recover after socioecological systems have been disrupted?

In response, recognizing that the trauma inflicted on land, water, and people has been intertwined, and so must be their healing.

Inspired by the concept of Urban ʻĀina, this capstone rejects the notion that urbanization and Indigeneity are incompatible. It instead proposes a community of practice that reclaims public space as a vessel for ancestral knowledge and communal well-being. Here, agroforestry is positioned as a biocultural technology, a method of re-stitching fractured relationships through reciprocal, place-based design. When integrated into existing infrastructure, these systems function as sutures or pewa, binding together broken ecologies and cultural memory across generations.

Ultimately, these edible greenways are not passive pathways of movement, but active sites of transformation. They are contemporary expressions of ancestral knowledge systems pathways forward that align ecological regeneration with cultural revitalization, and public space with the transmission of intergenerational resilience through ʻike ʻāina and diasporic knowledge systems.

This capstone research explores an integrative approach to transform existing urban greenways into abundant, culturally significant agrosystems. The work aims to challenge the existing approaches to designing underutilized monofunctional green corridors in Hawai’i. Through this lens, the project explores how the reintroduction of Pasifika and Hawaiʻi’s agroecological systems into public corridor infrastructure can serve as a living framework for community healing, biocultural resilience, and ecological regeneration.

AG·RO·FOR·EST·RY WHATIS

theintentionalintegrationoftreesandshrubs intocropandanimalfarmingsystemsto createenvironmental,economic,andsocial benefits. / ˌaɡrōˈfôrə trē/

In indigenous frameworks, agroforestry is a traditional ecological technology that involves bioculturally diverse ecosystems. They are managed to provide food, fuel, building materials, agricultural and plant-tending tools, hunting and trapping equipment, baskets, and ceremonial spaces essential to life and maintaining cultural traditions

TEK refers to traditional ecological knowledge systems. k(new) + k(now)ing

“Native Hawaiian agricultural practices are grounded in a sense of kinship, in which integral linkage between human and environmental health are recognized”(Lincoln et al., 2023).

DEFINITIONS

BIOCULTURAL RESTORATION

people and place are revived to restore the health and function of socialecological systems

Winter, Kawika B , Kevin Chang, and Noa Kekuewa Lincoln Biocultural Restoration in Hawaii MDPI-Multidiscip inary Digital Publishing Institute, 2022

BIOCULTURAL HERITAGE

local ecological knowledge and practices, and associated ecosystems and biological resources, to the formation of landscape features and cultural landscapes, as well as the heritage, memory and living practices of the humanly built or managed environments.

AGROECOLOGY

refers to applied ecological and social concepts and principles to the design and management of food and agricultural systems.

MĀ’ONA

refer to “being full”, having enough, just the right amount

GREENWAY

linear corridors of land and water and the natural, cultural, and recreational resources they link together.

Science of The Total Environment, 2018

EDIBLE GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

(EGI) refers to the role of urban landscapes in producing food while simultaneously providing ecosystem services such as biodiversity enhancement and climate resilience

Russo et al 2017

ʻĀINAMOMONA

refer to “feeding lands” that are fertile and abundant. Productive and thriving communities of people, place, and natural resources.

‘IKE ‘ĀINA (KNOWLEDGE FROM/ABOUT LAND)

culturally rooted Hawaiian approach to place-based learning that is useful in teaching writing and cultivating indigenous literacy H

02 METHODOLOGY

PEWA AS PRACTICE, MEMORY AS METHOD

This research adopts a methodological framework rooted in the Pewa Framework, an Indigenous philosophy that centers healing, repair, and relational knowledge drawn from McMillen et alʻ s Urban ʻĀina paper. Inspired by the fishtail-shaped patch used to mend wood in traditional Hawaiian crafting, the Pewa symbolizes healing that does not erase fracture but instead makes it visible. In this capstone, the Pewa becomes a conceptual and spatial tool to re-stitch fractured relationships between land, community, and knowledge systems across urbanized landscapes.

Pewa Framework as Epistemological Repair

Emerging from Urban ʻĀina practice, the Pewa Framework calls for “epistemological equity” (McMillen et al, 2023), a refusal to separate Indigenous knowledge systems from design, research, or planning processes. As a methodological principle, it emphasizes the activation of land-based knowledge, stewardship practices, and reciprocal restoration. In applying this framework, the research is not just about site analysis, but about mending the cultural and ecological wounds left by colonial fragmentation.

Urban ʻĀina as Cultural Kīpuka

Urban ʻĀina practices treat surviving pockets of unactivated land typologies as cultural kīpuka Just as forest kīpuka provide refugia for biodiversity after lava flows, urban kīpuka preserve place-based memory, food practices, and spiritual connection in the aftermath of concrete urbanization These spaces are engaged as living laboratories for cultural resurgence, offering communities places to kilo (observe), mālama (care), and hana (make) This project views the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail as an urban kīpuka of biocultural potential, one that, through design, can support intergenerational learning, ecological repair, and food sovereignty

restorative interventions in urban infrastructure

Pewa Framework

integrated landscape analysis activation of public corridor space as biocultural access memory of land, place, people

Urban Kīpuka

Biocultural Heritage

Biocultural Heritage as Knowledge Network

This capstonealso draws from Lindholm et al.’s (2019) Biocultural Heritage Framework, which identifies five linked elements of memory and stewardship to guide place-based research:

Ecosystem Memory – Biological remnants of cultivation and stewardship (e.g., limu beds, legacy trees, fallow terraces).

Landscape Memory – Material and spatial memory held in terraces, ʻauwai, stone alignments, and settlement patterns.

Place-Based Memory – Oral traditions, mo ʻolelo, place names, and community practices that embed identity into place.

Integrated Landscape Analysis – A cross-disciplinary methodology combining GIS, ethnography, ecology, oral history, and spatial storytelling

Stewardship and Change – An evolving practice of co-management, guided by kuleana (responsibility) and generational transfer of knowledge.

03 RESEARCH + SITE ANALYSIS

AGROFORESTRY IN GLOBAL CONTEXT

Globally, agroforestry systems (AFS) offer a holistic framework for restoring ecological function and food security through the integration of trees, crops, and culturally appropriate land practices. These systems are rooted in Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and emphasize local, small-scale farming that is ecologically sustainable and culturally embedded. Increasingly, agroforestry is being recognized not only as a climate adaptation strategy, but as a public health intervention, supporting biodiversity, improving environmental quality, and nourishing communities physically and spiritually (Fort et al., 2025; Zomer et al., 2014).

According to the FAO (2022), agroforestry occupies approximately 43% of agricultural land globally and continues to expand in popularity, particularly in regions where conventional agriculture has failed to meet the intertwined needs of climate resilience and food justice. Through a One Health lens, which recognizes the interdependence of human, animal, and environmental health, agroforestry is positioned as a systems-level solution that can support climate-adapted, regenerative food systems.

Agroforestry’s value extends beyond productivity. It supports food sovereignty, defined as the right of communities to define their own food systems using ecologically sound and culturally rooted methods (Jernigan et al., 2023; Jones et al., 2015). When implemented through Indigenous or community-centered frameworks, AFS strengthens autonomy over land and food, promotes emotional and spiritual well-being, and supports practices of cultural resilience. Agroforestry systems are often deeply entwined with traditional healing, ceremony, and intergenerational knowledge, reinforcing the idea that restoring food systems must also restore cultural and ecological relationships. Despite their global significance, Indigenous agroforestry systems have long been disrupted by colonization, militarization, and the industrialization of agriculture. The global shift to monoculture farming has led to widespread biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and the disconnection of people from their ancestral foodways, particularly in urban contexts where public access to ʻāina has been restricted

A A

These disruptions are not only ecological, but epistemic, erasing landbased knowledge systems and community health practices rooted in reciprocity and care.

Agroforestry, when grounded in Indigenous principles, becomes a vehicle for biocultural healing. It empowers communities to reclaim ancestral agricultural techniques, many of which are better adapted to local ecologies and more resilient under climate stress (Lelamo, 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2021). In particular, the inclusion of Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS) nutrient-rich crops often excluded from industrial food systems offers a promising pathway for restoring biodiversity, cultural nutrition, and community agency (Barrett, 2024; Ickowitz et al., 2024).

AGROFORESTRY OF PASIFIKA + HAWAI’I

CANOEPLANTSANDSETTLEMENTTHROUGHOUTPASIFIKA

The reclamation of Pacific Island identities begins with the recognition that colonial borders are arbitrary drawn across ocean nations whose genealogies of land, people, and plants far predate modern political boundaries. To speak of Pasifika is to acknowledge the deep interconnection between Melanesians, Micronesians, and Polynesians as voyaging peoples, whose knowledge systems, languages, and ecological practices were carried across vast ocean highways. These migrations did not simply move people they carried canoe plants, foundational crops such as kalo, ʻulu, niu, and ʻuala, as living archives of ancestral memory and sustenance.

Each planting was an act of cultural continuity, each agroforest a reflection of a specific island’s climate, cosmology, and community governance.

Across the Pacific, these Indigenous agroforestry systems evolved into sophisticated agroecological structures of permanence (Clarke, 1977) diverse, climate-adapted systems capable of sustaining food security, ecological resilience, and cultural identity across generations. On islands like Pohnpei, multistory tree gardens yielded over six metric tons of breadfruit per hectare annually, alongside diverse starches such as yam and taro (Fownes & Raynor, 1993). These systems, rich in vertical layering and spatial complexity, fostered microclimates that buffered crops from climate extremes and helped communities adapt to shifting environmental conditions.

Agroforestry across the Pacific has long functioned not only as a food system, but as a disaster-resilient infrastructure. Crops such as Cyrtosperma taro thrive in saline soils where Colocasia may fail. Breadfruit and figs like Ficus wassa continue to produce even under cyclone stress. Wild and “cyclone foods,” including yams, ferns, fungi, and drought-tolerant tubers, were historically planted as insurance against seasonal and climatic disruptions (Rarai et al., 2022; Clarke & Thaman, 1993). These strategies demonstrate how Pacific Island food systems are built on adaptive redundancy, community-scale planning, and a deep understanding of environmental variability.

Table12CurrentandpotentialagroforestsonPacificIslands

PacificIslands(USaffiliated) Totalacreage

The transition to cash crop monocultures, outmigration to urban centers, and reliance on imported food have led to the erosion of TEK and local food sovereignty. In Hawaiʻi, the collapse of plantation economies left behind degraded lands, while global climate change continues to accelerate sea level rise, salinization, drought, and extreme weather across the Pacific (Keener et al., 2012; IPCC, 2014).

Yet Pasifika communities continue to adapt. Islands are not static; their agroforestry systems evolve with each generation. Farmer-led programs, university partnerships, and regional knowledge exchanges are revitalizing traditional planting methods, experimenting with drought- and salt-tolerant cultivars, and advocating for cultural food species to enter cash economies without losing their ancestral meaning (Merlin & Raynor, 2005; Englberger & Lorens, 2004).Whether practiced on high volcanic islands or low-lying atolls, agroforestry remains a key strategy for biocultural resilience, one that centers Indigenous relationships to land, honors intergenerational stewardship, and supports survival in the face of colonial disruption and climate change.

As Pacific Island communities face intensifying environmental precarity, the restoration and adaptation of these systems will be vital not only for food security, but for cultural continuity, healing, and the reassertion of Pasifika sovereignty through land-based practices.

A A A

Guam

Micronesia Palau Hawaiʻi Fiji

Nauru

Kiribati

Melanesia

Vanuatu

NewZealand

FrenchPolynesia

EasterIsland

PASIFIKA: identities related to diaspora of Pacific Island origin, including Melanesians, Micronesians, and Polynesians.

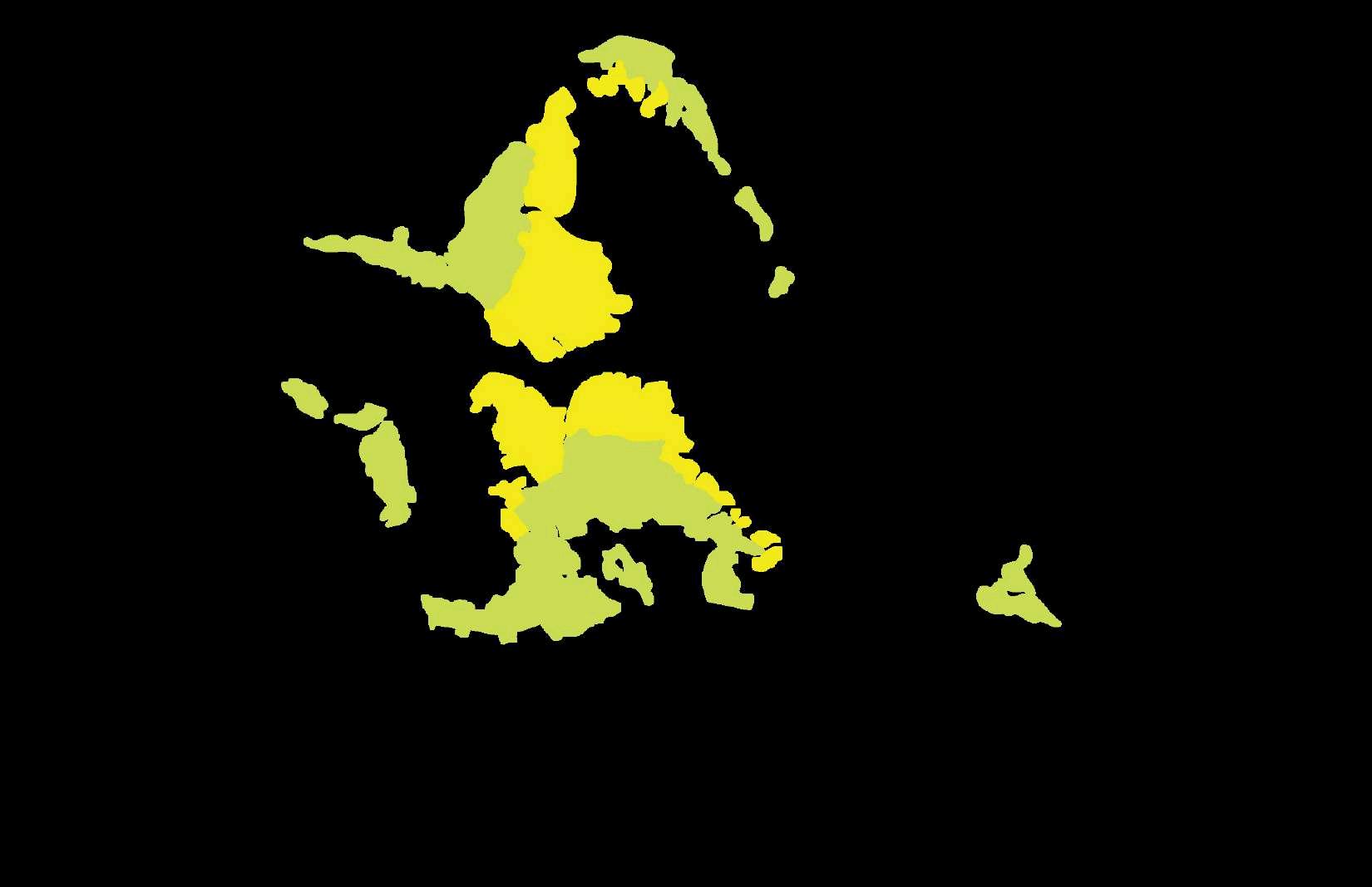

SPACIALIZING AGROECOLOGY OF HAWAI’I

Traditional Hawaiian agriculture represents one of the most ecologically refined and socially integrated food systems in the world. Rather than imposing a singular model, Native Hawaiian farmers adapted their cultivation systems across an extraordinarily diverse archipelago which is shaped by gradients of rainfall, elevation, soil fertility, and topography. These systems were not only tailored to the land; they were rooted in genealogies of relationship between people, plants, and place, maintained over generations through ʻike kūpuna (ancestral knowledge) and hands-on ecomimicry

Recent research by Lee and Lincoln (2023) offers a transformative reassessment of these systems, revealing that previous narratives have vastly underestimated the extent and complexity of Hawaiian agroecological land use. By georeferencing historical maps and modeling seven pre-contact agroecological archetypes, the authors show how cultivation extended well beyond the conspicuous infrastructure of loʻi and irrigation encompassing arboriculture, agroforestry, dryland field systems, and seasonal management zones. Their work affirms that Native Hawaiian agriculture was not marginal or peripheral; it was deliberate, sophisticated, and scaled to support an island population of hundreds of thousands.

The significance of these agroecological systems lies not just in their spatial expanse, but in their strategic alignment with microclimates and environmental constraints. Agroforestry and arboriculture systems, for example, were cultivated in dry leeward zones or rocky slopes where intensive irrigation was not feasible. These systems prioritized drought-tolerant species like ʻulu, maiʻ a, wauke, and niu, often arranged in multistory plantings that mimicked native forest structure. In more humid or riparian areas, loʻi systems were developed for kalo cultivation, using carefully constructed ʻauwai (irrigation channels) to distribute water in ways that maximized flow and minimized erosion.

Each cropping system was not simply a technical response, but an expression of a broader worldview: that land is kin, and farming is a reciprocal relationship that must sustain people and the land simultaneously.

These systems also centered Neglected and Underutilized Species (NUS) plants like ʻuala (sweet potato), kī (ti leaf), and kō (sugarcane), that were highly adapted to specific ecological niches but have been overlooked by global agriculture Such crops were not only staple foods, but sources of medicine, fiber, ceremony, and social exchange. Their marginalization under colonial plantation economies disrupted both food systems and cultural identity. Reclaiming them within agroecological restoration efforts is therefore not only agronomic, but political and spiritual.

In acknowledging the adaptive radiation of Hawaiian agroecosystems of canoe plants that were distributed across vastly different environments with site-specific cultivation techniques we begin to understand the landscape as a living archive of innovation, stewardship, and ecological design. Each system represents a distinct response to place, informed by generations of experimentation and embodied knowledge.

Today, as Hawaiʻi faces climate disruption, sea level rise, and ongoing food insecurity, these traditional systems offer a blueprint for restoration, not only of ecosystems, but of values, relationships, and sovereign food futures. Reintegrating these agroecological archetypes into land use planning and urban design allows us to activate the memory of abundance embedded in the land and adapt ancestral technologies for contemporary resilience.

As Lee and Lincoln (2023) argue, the key is not simply in reviving crops, but in understanding the cropping systems, environmental contexts, and cultural relationships that supported them. Only then can underutilized species be fully re-integrated into systems that are regenerative, relational, and rooted in Hawaiʻi’s enduring ecological wisdom.

AGROFORESTRY OF HAWAIʻI

Puʻuloa, momona political bears the pollution

Puʻuloa, political including

NTBG, Kauai

Heʻeia,Oʻahu

OK Farms ,Hilo,Hawai

Map adapted from Lincoln, Noa & Lee, Tiffany & Quintus, Seth & Haensel, Thomas & Chen, Qi. (2024). Agroforestry Distribution and Contributions in Ancient Hawaiian Agriculture. Human Ecology. 51. 1-13.

AA A

“Tree crops, such as 'ulu (breadfruit, Artocarpus altilis), kukui (candlenut, Aleurites moloccanus), niu (coconut, Cocos nucifers), hala (Pandanus tectorius), and ' ohi'a'ai (mountain apple, Syzygium malaccense) were employed extensively by Hawaiians, primarily in places that were too dry, too rocky, too steep, too salty, too infertile”

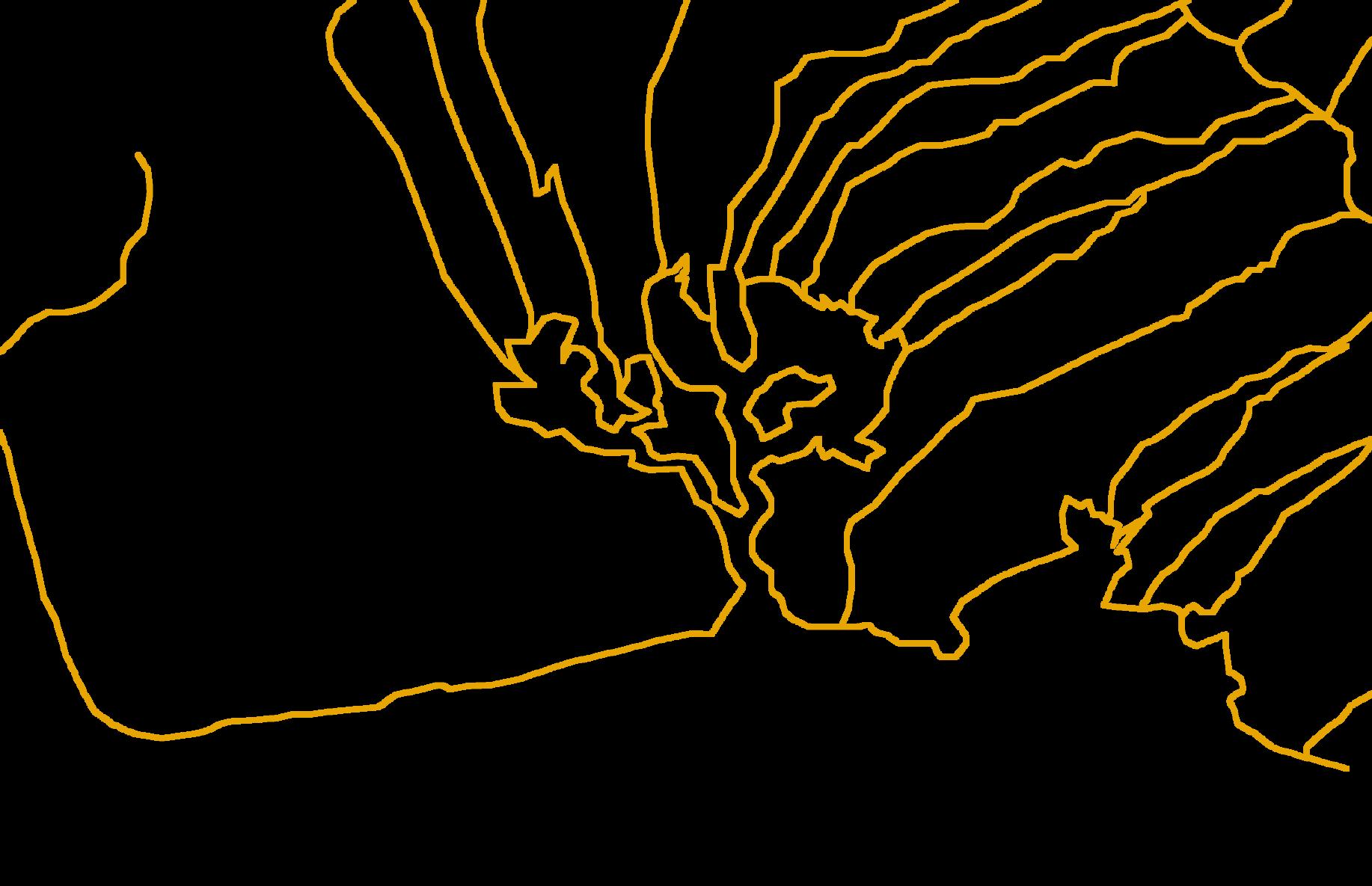

An1836drawingbyPersisGoodaleThurstondepictsthedifferent rainfedfarmingzoneswithinKona,Hawai‘iIsland

A A Aʻ

The background image is an artist's rendition of the agricultural zones of Kona, consisting of the dry lowland plains (kula), the breadfruit plantations (kalu’ulu), the intensive tuber crop gardens (' ā pa'a), and the modified upland forests ('ama'u). Reinterpreted from the Bishop Museum.

Lincoln, N., & Ladefoged, T. (2014). Agroecology of pre-contact Hawaiian dryland farming: the spatial extent, yield and social impact of Hawaiian breadfruit groves in Kona, Hawai'i. Journal of Archaeological Science, 49, 192-202.

LITERATURE REVIEW

At the heart of Indigenous agroecology lies the recognition that knowledge is not merely technical but cultural, spiritual, and relational. Indigenous agricultural practices reflect thousands of years of adaptive observation, experimentation, and ecological kinship, embedding environmental stewardship into social structure and cosmology (Altieri, 2018; Lincoln & Vitousek, 2017) Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) centers land-based learning systems that emphasize resilience, reciprocity, and the interconnectedness of food, culture, and biodiversity

Noa Lincoln’s extensive work on Hawaiian agroecology positions traditional agricultural systems not as static relics, but as evolving agroecological technologies finely attuned to island biogeography. Lee and Lincoln (2023) expand this lens by mapping underrecognized forms of arboriculture and agroforestry in Hawaiian systems, revealing how dominant Western land-use narratives have long overlooked cultivation that left minimal infrastructure yet maintained profound ecological influence. Their findings argue for a new recognition of Hawaiian agriculture as adaptive, dispersed, and ecologically comprehensive especially in urban planning and restoration contexts.

Building on the legacy of ʻike kūpuna (ancestral knowledge), the Urban ʻĀina framework reclaims urban space as ʻāina relational land deserving of stewardship.

Beamer, Enos, and collaborators emphasize the role of cultural kīpuka remnant pockets of urban green space, as sites for reactivating biocultural memory and intergenerational healing. The Pewa Framework conceptualizes design and research as epistemological repair, inviting practitioners to mend the fractures left by settler colonialism through visible, land-based practices of restoration.

This is particularly resonant in the context of the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail, where concrete and militarization have overwritten ecosystems that once functioned as food forests, fishponds, and loʻi networks. As Urban ʻĀina practices affirm, these spaces are not dead zones but latent infrastructures of memory and abundance, awaiting reconnection through agroecological design.

Biocultural Heritage and Landscape Memory

BIOCULTURALHERITAGE

Stewardship and change

resevoir of knowledge + experience for landscape management

Integrated landscape analysis

landscape memories place memories ecosystem memories inclusive network based approach to knowledge intangiblr living features of human knowledge + preserved/ transmitted intergenerationally

biophys cal properties non-human organisms and agents change directly/indirecty by humans

tangible human practice + ways of organizing landscapes

The concept of biocultural heritage as articulated by Maffi, Ekblom, and Woodley further scaffolds this project’s methodology. It describes the deep entanglement of biodiversity with cultural and linguistic diversity, offering a holistic view of landscapes as living archives shaped by generations of humanenvironment interaction. The five dimensions: ecosystem memory, landscape memory, place-based memory, integrated landscape analysis, and stewardship provide a toolkit for understanding how land holds and transmits knowledge (Ekblom et al., 2019).

The loss of traditional food systems in Hawaiʻi is not accidental it is the result of settler colonial disruption. Kameʻeleihiwa (2005) traces the systematic dismantling of the ahupua‘a system through privatization (Māhele), plantation expansion, and the marginalization of Indigenous land stewardship. Her work underscores that the reactivation of Hawaiian food systems is not just a sustainability issue it is a sovereignty issue. Hutchins (2024) reinforces this by mapping the socio-ecological intelligence of Kānaka ʻŌiwi agroecosystems, highlighting how loʻi, kuaiwi terraces, and colluvial field systems were designed to optimize microclimates, promote biodiversity, and sustain community well-being. These agroecologies are not monolithic; they respond dynamically to slope, soil, and season, forming a resilient web of cultivation practices across ʻEwa and beyond.

Figure interpretat on o b ocultural heritage rameworks noted by Maffi Ekblom

ʻĀina of Kaʻōnohi, Anthony K. Deluze, Kamuela Enos, Kialoa Mossman, Indrajit Gunasekera, Danielle Espiritu, Chelsey Jay, Puni Jackson, Sean Connelly, Maya H. Han, and et al. 2023. "Urban ʻĀina: An Indigenous, Biocultural Pathway to Transforming Urban Spaces" Sustainability 15, no. 13: 9937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15139937

PRECEDENT STUDIES

FRAMINGLINEARINFRASTRUCTUREASMODESOFHEALING+FOOD ACCESS

This capstone draws on precedent studies from the continental United States to explore how linear infrastructure can be reimagined as sites of healing, ecological repair, and food access. Although rooted in different geographies, the Dequindre Cut Greenway (Detroit), Bronx River Foodway (New York), and Atlanta BeltLine (Georgia) offer valuable lessons for Hawai‘i particularly in adapting underutilized or post-industrial corridors to meet contemporary needs for public greenspace, community resilience, and food justice.

These case studies illustrate how edible land typologies can be embedded within urban fabrics shaped by disruption: contaminated soils, fractured neighborhoods, and legacies of disinvestment. Each precedent demonstrates how design can transform linear corridors into cultural and ecological infrastructures that serve as accessible, multi-use public spaces.

Dequindre Cut Greenway — Detroit, MI

Originally a Grand Trunk Railroad line, the Dequindre Cut is now a below-grade linear park connecting Eastern Market to the Detroit Riverwalk. Designed by SmithGroup, the corridor integrates walking and biking trails with public art, native landscaping, and food-oriented programming.

Lessons Learned:

Design as reclamation: The transformation of industrial infrastructure into a greenway demonstrates how cities can reclaim neglected land for public use without erasing its history.

Art + access: Murals and underpass installations activate the space, contributing to a sense of ownership and cultural relevance.

Edible integration potential: While not a full foodway, the project’s proximity to Detroit’s Eastern Market supports a networked approach to food sovereignty, inviting expansion into edible corridors.

Bronx River Foodway — Bronx, NY

The Bronx River Foodway is the first legal edible landscape on New York City parkland, developed through a community-driven design process led by the Bronx River Alliance and landscape architect Sara Fern Fitzsimmons. Located in Concrete Plant Park, the foodway contains over 50 species of edible and medicinal plants, all open to public harvesting.

Lessons Learned:

Civic ecology as infrastructure: The Foodway bridges urban agriculture with ecological restoration, modeling how food access can coexist with riparian habitat.

Policy innovation: The NYC Parks Department granted a legal exception to allow foraging in the foodway a precedent-setting policy shift that legitimizes cultural and subsistence practices in urban parks.

Programming + stewardship: Community organizations maintain the site and host workshops, highlighting the importance of longterm stewardship and public programming.

Atlanta BeltLine — Atlanta, GA

The BeltLine repurposes a 22-mile loop of former railway into a greenway that links 45 neighborhoods. While best known for its recreational path, the BeltLine is a framework for urban redevelopment, public art, affordable housing, and community agriculture.

Lessons Learned:

Multi-use layering: The BeltLine integrates bike paths, housing, parks, and edible landscapes, showcasing how green infrastructure can be woven into broader urban systems.

Edible trails + food forests: Initiatives like the Westside Park Food Forest incorporate fruit trees, herbs, and perennial crops into accessible public spaces.

Land acquisition challenges: The BeltLine also reveals tensions between green investment and gentrification, highlighting the need for equity-based land use strategies.

3.65 MILES

BRONXRIVERFOODWAY

Native + Culturally Relevant Edible Species

Hands-On Learning Spaces

Public Food Forest Land Designation

Edible space is not a novelty it’s a civic right

0.5 MILES PU’ULOAHISTORIC BIKETRAIL

1.5 MILES

BRONX RIVER FOODWAY

AA A

A A

Craig Elevitch’s Agroforestry Landscapes for the Pacific Islands (2015) is one of the most comprehensive and practically applicable resources for understanding traditional and contemporary agroforestry systems across Oceania. Framed around Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), the book presents a detailed and placebased synthesis of Pacific Island agroecosystems that integrate food production, ecological function, and cultural practice. Elevitch documents multi-layered agroforestry strategies adapted to both wet and dry conditions, offering design templates for restoring degraded lands while maintaining community autonomy and biodiversity.

Elevitch’s work is notable for its systematic treatment of site-specific plant guilds, spatial configurations, and ecological services. By detailing plant functions including shade, mulch production, nitrogen fixation, erosion control, and materials for cultural use he outlines how agroforestry systems serve as integrated land management frameworks rooted in Indigenous epistemologies. The book emphasizes species such as Artocarpus altilis (ʻulu), Cocos nucifera (niu), Cordyline fruticosa (kī), and Morinda citrifolia (noni), not only for their food and medicinal value but for their broader role in ecosystem stabilization and biocultural continuity. Elevitch also introduces companion planting strategies and tree spacing considerations that have informed agroecological design across the Pacific.

In the context of my thesis, Elevitch’s work offers a methodological and conceptual foundation for applying Pasifika agroforestry principles to urban greenway transformation. His documentation of spatial logic and ecological layering directly informed understanding of “kīpuka” planting schemas

What makes Elevitch’s contribution particularly relevant is his framing of agroforestry as both an ecological and cultural infrastructure. His work underscores that traditional cropping systems are not static relics, but dynamic technologies capable of responding to climate change, food insecurity, and urban disconnection. In mapping these systems across ecological gradients from dryland orchards to wetland gardens Elevitch also highlights the genealogical movement of plants and practices across the Pacific. This translocal framing affirms a shared heritage and adaptive intelligence among Pacific Island societies, supporting the application of regional TEK to contemporary design and planning challenges in Hawai‘i.

In sum, Agroforestry Landscapes for the Pacific Islands serves as a critical reference point for integrating TEK into urban landscape design. It bridges ecological design and Indigenous knowledge systems, offering clear pathways for reestablishing culturally grounded agroecosystems in spaces that have been fragmented by colonial, military, and industrial legacies.

Extensive open field cultivation

‘ulu overstory mounding ditching

Extensive open field cultivation

cassava

sloped rainfed

Coastal edge niu rainfed rocklay

Chuuk

Samoa

Chuuk

Kohala, Hawai’i

PRE-COLONIAL AGROECOLOGY

MAPPINGBIOCULTURALABUNDANCE

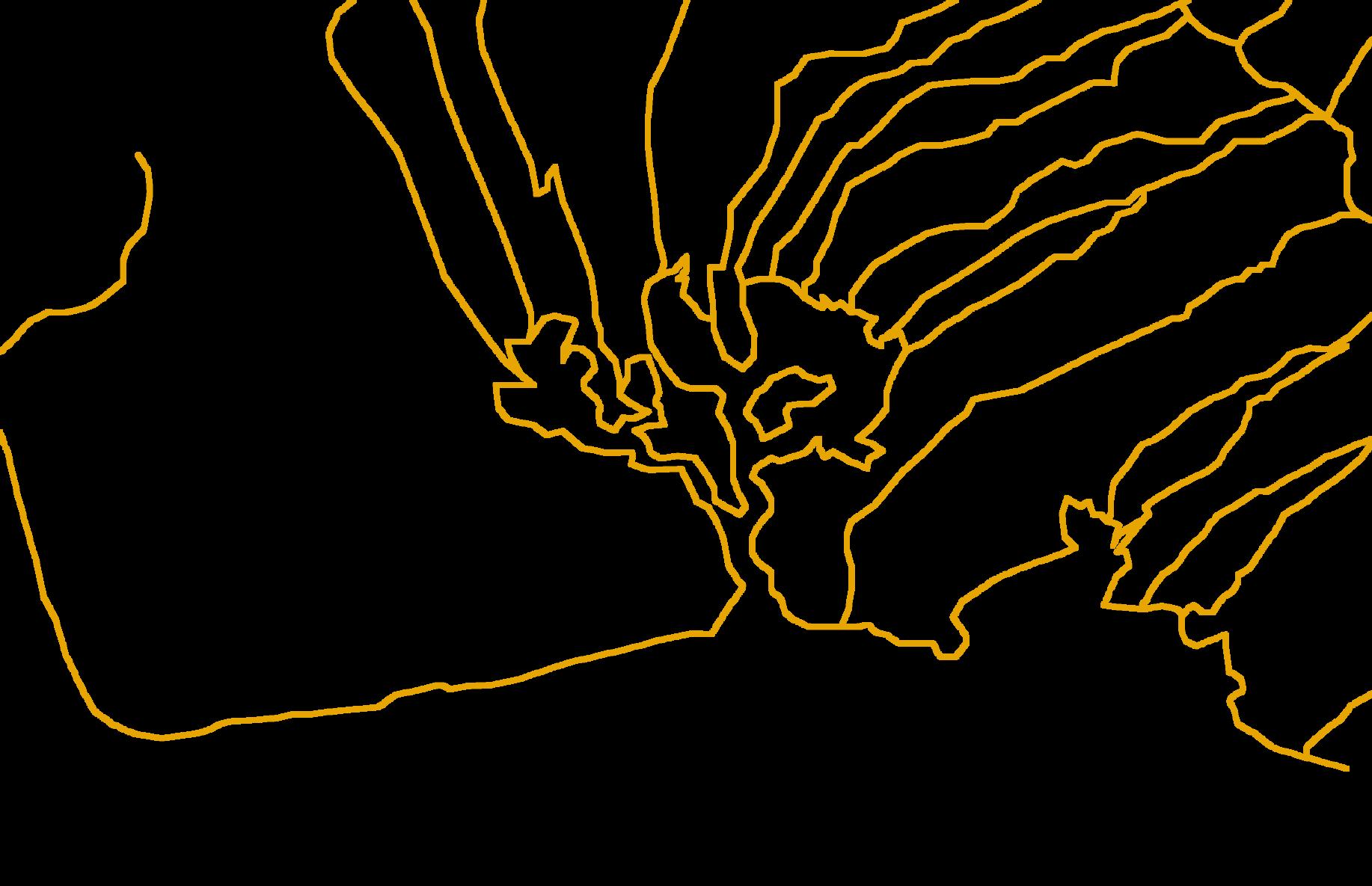

Before colonization fractured land relationships and reorganized landscapes to serve extractive economies, the island of Oʻahu supported a sophisticated mosaic of agroecological systems engineered to sustain abundance. These systems were grounded in a Kanaka ʻŌiwi worldview that understood land not as property but as kin, and food production as an act of care, ceremony, and ecological stewardship. Nowhere is this more evident than in the ahupua‘a of ʻEwa Moku a storied region once considered the political and agricultural heart of the island.

Hutchins (2024) articulates that Native Hawaiian agroecosystems were not merely productive; they were socially and ecologically embedded systems that created reciprocal relationships between people, soil, water, and the gods. These systems flourished through intentional design across a range of landscapes from wetland loʻi kalo complexes to dryland agroforests, colluvial terraces, and saltwater fishponds. In these spaces, agriculture was ecological architecture: a complex web of place-based technologies that managed water flow, maximized biodiversity, and nourished both community and ecosystem resilience.

On Oʻahu, the diversity of agroecosystems reflected the island’s topographic and climatic heterogeneity. Hutchins identifies key agroecological typologies including: Marginal colluvial systems, often found along steep slopes and rockier soils, where planting mounds of ʻuala (sweet potato) and other drought-tolerant crops mimicked the land’s contours and maximized moisture retention.

Intensive colluvial systems, constructed along more moderate slopes, which utilized stone terraces (kuaiwi) and mulching strategies to manage runoff and retain fertility, often integrating arboricultural species like ʻulu and maiʻ a.

Traditional agroforestry systems, cultivated in both upland and coastal zones, interweaving native and canoe plants into multistory systems that served as food forests, medicine gardens, and biodiversity reservoirs.

These systems were not siloed, but part of a coordinated land-and-sea management strategy embodied in the ahupua‘a system. As Kame‘eleihiwa notes, the ahupuaʻ a was an Indigenous political ecology that linked upland forests to coastal fisheries through reciprocal management of water, soil, and human responsibilities. In ʻEwa, this meant coordinating loʻi kalo cultivation in the stream-fed valleys with the stewardship of loko iʻ a (fishponds) in Puʻuloa. Every element was part of a dynamic socio-ecological web a system designed to be adaptive, not extractive.

However, this intricate system was profoundly disrupted through the colonial dismantling of land tenure and water governance. The Māhele of 1848, as Kame‘eleihiwa underscores, marked the legal severing of land from community through the introduction of private property. The commodification of land and labor led to the degradation of oncethriving agroecosystems, transforming ʻāina momona into sites of plantation monoculture and militarized infrastructure. ʻEwa Moku once famous for its breadfruit belts, ʻuala fields, and fishponds was transformed into a zone of sugarcane extraction, military staging grounds, and later, suburban sprawl.

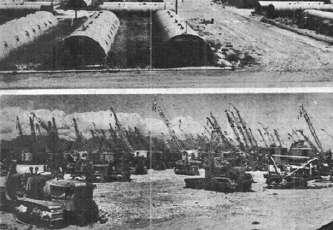

DISRUPTION

MAPPINGBIOCULTURALDISRUPTIONS

The transformation of Hawai‘i’s landscapes cannot be understood outside of the historical disruptions imposed by settler colonialism, extractive agriculture, and militarization. These forces severed Indigenous relationships with ʻāina (land), altered ecological function, and left lasting wounds on biocultural systems. In particular, the lands surrounding Puʻuloa have become emblematic of these disruptions, bearing the ecological, political, and cultural consequences of centuries of imposed land use regimes.

The first major catalyst was the arrival of Western settlers in the late 18th century, initiating a cascade of changes that displaced Indigenous lifeways. The subsequent imposition of the plantation economy reoriented land toward monoculture production of sugarcane and pineapple, disrupting polycultural agroecosystems and privatizing lands previously governed through the ahupua‘a system. These economic shifts were reinforced by legal and political mechanisms, most notably the Māhele of 1848 and the U.S.-backed overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom in 1893. These acts formalized the alienation of Kānaka ʻŌiwi from their ancestral food systems, displacing communities from the ecosystems that had sustained them for generations.

Militarization compounded these harms. Following the illegal overthrow and annexation, large tracts of land, especially around in Pu’uloa, were repurposed for military use, resulting in ecological degradation, restricted access, and the desecration of wahi pana (storied places). Superfund sites, fuel leaks, and heavy metal contamination now mark many areas once used for lo‘i kalo, loko i‘a, and native forest cultivation. The accumulation of toxins in soil and water reflects a deeper cultural trauma: the contamination of life-giving sources. This is not only a disruption of land, but of identity, health, and sovereignty.

To understand the geography of these layered harms, I used publicly available GIS datasets, including EPA Superfund inventories, DOH brownfields, and military lease maps, to spatially analyze the extent of contamination across the ʻEwa Moku and the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail corridor. These visual layers reveal layers of occupation: lands once abundant are now constrained by overlapping legacies of plantation and military infrastructure. Stream corridors, wetlands, and dryland terraces have been repurposed, drained, or buried beneath concrete, rendering food cultivation and cultural practice difficult or unsafe

This spatial and historical analysis underscores the core premise of this thesis: that restoring biocultural resilience requires not only replanting food systems, but healing the layered wounds of land use, policy, and memory. Design in this context becomes a tool of suturing acknowledging what was lost, tracing the contours of harm, and cultivating pathways of return through ʻike ʻāina (land-based knowledge) and regenerative practice.

Pineapple Plantation

Oahu Railway and Land Company

Cane Plantation

Pearl Harbor Defensive Sea Area

Honolulu Defensive Sea Area

Kaneohe Defensive Sea Area

TRANSPORTATION

LAYERSOFLEGACY

Current transportation systems in the ʻEwa region are deeply imprinted by historical patterns of movement and disruption. The linear infrastructure we see today roads, rail beds, and highways originated in systems built to serve the plantation economy, designed to move goods and labor efficiently rather than connect communities equitably This legacy has left a lasting imprint on urban form and mobility. Today, movement across the region remains overwhelmingly cardominated, with pedestrian, bike, and public transit infrastructure treated as secondary or even tertiary considerations.

The Pearl Harbor Historic Trail, which overlays the former Oʻahu Railway and Land Company (OR&L) rail lines, was once envisioned as a transformative multimodal corridor. However, the trail has not fully realized that promise. It suffers from fragmentation, safety concerns, and a lack of continuous, meaningful connections to neighborhoods, schools, and cultural spaces along its length. Despite this, it holds significant potential as a backbone for equitable, ecologically regenerative, and culturally resonant movement.

Recent planning efforts, including the vision for a connected South Shore Greenway Trail, reflect an emerging recognition of the need to integrate multimodal transportation infrastructure into the region’s fabric. Yet, many of these proposals remain underfunded or lack coherent community-grounded implementation strategies. This capstone recognizes that any intervention in the mobility network must contend with these layered histories and structural gaps while also seeing transportation as a tool for reconnection: of people to place, communities to each other, and movement to memory.

Remnant OR&L Plantation Train

ʻThe ʻEwa Moku has historically served as the the food and political center of Oʻahu, the shores of Puʻuloa introduced the staple ʻUlu (artocarpus atilis) and had the capacity to feed and nourish the entire isand

"The imposition of Western notions of private land ownership into law in the Hawaiian Kingdom resulted in the Māhele ‘Āina (land division) of 1848

foreigners came and bought large amounts of land to develop cattle ranches and agricultural plots

1893, Illegal overthrow and Annexation

Ewa Plantation Company

The Hawaiian gazette, August 14, 1878

Ewa Plain Kanehili freshwate karst ponds

1850: The ranching and grazing of small herds of cattle, beginning in the 1840s, eventually resulted in larger ranching operations found in Honouliuli.

1826 that the US Navy had its first contact with the Hawaiian Islands

Pearl Harbor Bombing, 1941 Honouliuli Concentration Camp, 1943

1943: Construction of Red Hill Fuel Storage Facility

1900: Military Occupation: The US military presence in Hawai‘i altered the face of Honouliuli Areas where native Hawaiians and large landowners lived at Pu‘uloaHonouliuli were condemned

“Urban 'Āina can be viewed as a cultural kīpuka which we conceptualize as literal but also metaphorical islands of Native Hawaiian biocultural expression in otherwise built, often hardened urban settings. Urban Kīpuka are refuges for trees, plants, and animals that represent cultural keystones [81] and support the continuation of Indigenous lifeways, knowledge, and practice.”

“The health of people and the health of the land are one and the same. In Indigenous frameworks, this relationship is neither symbolic nor metaphorical it is physiological, spiritual, and ecological. In mapping the disruption of Hawai‘i’s biocultural systems, this research also mapped the corresponding impacts on human health using spatial datasets that reveal patterns of vulnerability, illness, and disconnection. Tools such as the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) and Hawai‘i PolicyMap, which compiles state, county, and federal health and economic data, offer a layered view of how historical trauma continues to manifest socially, economically, and environmentally across the landscape.

In the urban corridors of ʻEwa and along the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail, many of the communities with limited access to green space and fresh food also rank highest in social vulnerability. These areas often overlap with former plantation lands, military-occupied zones, and Superfund sites regions where the soil has been degraded, water systems contaminated, and ancestral access severed. The spatial correlation between degraded land and poor health outcomes is not coincidental; it is the result of systemic disruption to ancestral relationships of care, cultivation, and kinship with ʻāina.

This framing is critical: the disruption of land is also the disruption of health. Contaminated soils and restricted land access represent more than ecological harm they are expressions of severed ancestral relationships. The trauma of dislocation reverberates through communities in the form of chronic illness, mental distress, food insecurity, and cultural disconnection. These conditions are not isolated phenomena, but cumulative results of land dispossession, militarization, and the dismantling of Indigenous land management systems.Conversely, healing ʻāina activates the potential to heal people. Agroecological restoration and culturally grounded food systems can serve as pathways to ʻāina momona, where land and people are once again in reciprocal relationship. By reintroducing traditional practices into urban environments particularly through edible greenways, community-managed agroforests, and outdoor learning spaces.

This capstone views agroforestry as a public health strategy rooted in cultural practice. Through the integration of spatial datasets, oral histories, and TEK, it affirms that the regeneration of Hawai‘i’s landscapes is inseparable from the regeneration of its people.

For Kānaka Maoli, health is understood holistically. As Keli‘iholokai et al. (2020) describe, Native Hawaiian well-being encompasses not just physical or mental health, but lōkahi isa state of balance between spirituality (Akua), humankind (Kānaka), and land (ʻĀina). The Kūkulu Kumuhana framework, adapted from the social ecological model, outlines six interconnected concepts foundational to Kānaka health: Ea (self-determination), ʻĀina Momona (abundant and healthy land and people), Pilina (mutually sustaining relationships), Waiwai (ancestral wealth), Ke Akua Mana (sacred spirituality), and ʻŌiwi (cultural identity and intelligence). These elements span individual, ʻohana, community, and policy scales highlighting that healing must occur across systems.

LŌKAHI AKUA

KĀNAKA

Figure : Adapted diagram o Lōkahi Triangle from Mau, M K (2010) Native Hawaiian & Other Pacific Islander Older Adults

The gesturing fish of ‘Ewa.

‘opae huna

pipi nahawele

nehu

Ka i‘a kuhi lima o ‘Ewa

Climate change presents a critical turning point for Hawaiʻi’s urbanized landscapes.

With sea level rise projections showing dramatic inundation scenarios for the coastal zones of Puʻuloa, the need for regenerative, place-based redesign becomes urgent. GIS modeling and scenario planning tools including the State of Hawai‘i’s

Sea Level Rise Viewer and NOAA’s coastal risk models clearly demonstrate that much of the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail corridor, and surrounding low-lying communities, will be increasingly vulnerable to chronic flooding, saltwater intrusion, and compromised infrastructure.

As the ocean encroaches inland, it threatens to disrupt sewage systems, raise water tables, and flood impervious surfaces that currently dominate the built environment. The compounding effects of storm surge, groundwater inundation, and contaminated runoff pose grave risks to community health, ecological integrity, and food system resilience. Without thoughtful intervention, these pressures will exacerbate existing vulnerabilities, especially in historically marginalized areas of ʻEwa where industrial land use, military occupation, and limited green space converge.

Yet this disruption also opens a design opportunity: to transform risk into regeneration. Rather than resisting rising waters with hardened infrastructure alone, climate adaptation in Hawaiʻi must turn to ancestral knowledge systems that have long embraced dynamic hydrology. In this light, the return of Puʻuloa’s waters can be seen not as a threat, but as an invitation to re-establish Indigenous water technologies auwai (irrigation channels), loko iʻ a (fishponds), wetlands, and permeable agroecological systems that absorb, redirect, and filter water while sustaining life. Designing with climate and not against it calls for turning impervious surfaces into living infrastructure.

Mapping community networks along the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail reveals a living framework of resilience already in motion. These spatial and relational maps highlight the presence of active stewards, community groups, schools, cultural practitioners, who are piloting new models of care and comanagement. Urban ʻāina is well and alive in Puʻuloa, where grassroots efforts reclaim public space as sites of healing, food sovereignty, and cultural resurgence. This mapping repositions the trail not just as infrastructure, but as a corridor of collective memory and regeneration.

Integrating pewa as a physical and spiritual manifestation of place can help us rethink modalities of healing through indiginous epistimologies

Policy Gaps in

Urban

Agroforestry

Zoning: Existing zoning and land use policies do not fully support or recognize long-term community agroforestry on public land.

Fragmented Interagency Coordination

Lack of Maintenance Infrastructure

Soil Health

OngoingagroforestrydemonstrationeffortsnearLehuaAvenueinPearlCity, Oʻahu,ledbyHuioHoʻohonua,aretransformingsegmentsofthePearl HarborHistoricTrailintoregenerative,place-basedlearninglandscapes. Thissitecurrentlyservesasapilotforpropagatingregionallyadapted, culturallysignificantcropssuchasʻuala(Hawaiiansweetpotato)andkalo, whilealsotestingtheuseofCommunityGIStoolstodocumentstewardship, plantingpatterns,andecologicalrestorationprogress.

Thiseffortissupportedbyathree-yearMemorandumofAgreement(MOA) betweenHuioHoʻohonuaandtheCityandCountyofHonolulu’sMālama OKaʻĀina(MOKA)Program,operatedundertheDepartmentofFacility Maintenance(DFM).Notably,thissiteisthefirstofficiallydesignatededible landscapewithintheMOKAprogram,markingasignificantprecedentfor integratingIndigenousagroecologyintomunicipallandmanagement.

Hoʻolu ‘Āina

Hoʻoulu ʻĀina seeks to provide people of Kalihi ahupuaʻ a and beyond the freedom to make connections and build meaningful relationships with the ʻāina, each other and ourselves. Here, the community comes together around forest, food, knowledge, spirituality, and healthy activity.The goal is to restore this land to wholeness, giving back the values of our ancestors, we remember that healing is reciprocal.

Brownfields are areas of land that were once used for industrial, agricultural, or military purposes, and are now underutilized or abandoned due to real or perceived contamination. In many urban landscapes, these sites represent not just ecological degradation, but severed relationships between land and people.

In Hawaiʻi, brownfields are layered with deeper historical trauma land once cultivated for abundance has been made toxic by plantation monoculture, military occupation, and unchecked development. Yet these places still hold the potential to be transformed through community-led stewardship, agroecological restoration, and cultural reconnection.

This capstone embraces brownfields as starting points not endpoints for healing. Rather than viewing contaminated or degraded sites as static liabilities, they are seen as spaces in transition. Through phased interventions that respond to the unique social, ecological, and cultural conditions of place, these sites can be transformed from extraction zones into living classrooms and productive food forests.

Today, after a century of militarization and land alteration, it is marked by pollution, neglect, and restricted access. The land remembers its abundance, but that memory has been buried beneath compacted soils, runoff contaminants, and industrial legacies.

Mālama Puʻuloa a program with this community non-profit Hui o Ho’ohonua, has taken bold steps to restore productivity and ecological health in this context Their work at Kapapapuhi Point Park and surrounding areas has included the establishment of a community food forest, native habitat restoration, and stream revitalization Their approach aligns with my own methodology: to phase restoration over time, using low-cost, culturally grounded interventions that restore both ecological function and cultural practice.

Intervention Approach

Phase 1: Remediation and Testing (Years 0–2)

Begin with identifying hazardous and invasive plant species, followed by soil testing to assess heavy metal content, salinity, pH, microbial activity, and fertility. Elevated levels of arsenic are typically found in soils at locations formerly used as sugar cane fields, pesticide mixing areas, sugar cane plantation camps, canec production plants, wood-treatment plants, and golf courses.

Phase 2: Soil Amendment and Light Cultivation (Years 2–5)

Introduce low-input soil amendments such as gypsum, magnesium sulfate, and nitrogen-rich organic fertilizers like Sustane 4-6-4. Prioritize top-dressing and companion planting with nitrogen-fixers. Begin light food forest planting with resilient crops like ʻulu (breadfruit), ʻuala (sweet potato), and maiʻ a (banana), focusing on areas with low metal concentrations.

Phase 3: Agroforest Expansion and Community Activation Continues (Years 5–10)

Scale up production, integrate culturally significant crops, and expand infrastructure for community-based education and stewardship. Continue testing and maintenance, and introduce interpretive signage, gathering areas, and kilo (observation) spaces that link ecological function to ancestral knowledge.

In early efforts, soil testing by UH Manoa’s NREM and local organization Hui Ho’ohonua revealed both promise and concern: organic carbon levels and waterholding capacity were within range for planting, but certain plots contained elevated levels of arsenic, cadmium, and chromium. These results prompted targeted phytoremediation, community education, and cautious food production practices. Through this process, the brownfield becomes not only a site of remediation, but also of learning. By foregrounding soil health, layering interventions over time, and rooting each phase in cultural practice, sites like Puʻuloa can serve as models of brownfield transformation in Hawaiʻi and beyond.

04 DESIGN LOGIC + PRINCIPLES

The spatial logic of this project draws inspiration from the natural patterning found in ʻulu (breadfruit) skin, a biomimetic expression of abundance, resilience, and connectivity.

The cellular structure of ʻulu skin, composed of interlocking segments, reflects a nonlinear, polycentric spatial order. This became the foundational design language for organizing interventions across the site, toward a more fluid, culturally resonant form.

To model these biomimetic structures, I utilized Voronoi diagrams generated in Rhino 3D and Grasshopper to break the linearity of the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail. Instead of organizing planting beds and interventions in the form of traditional row-based orchards,

Voronoi tessellations allowed for a more interconnected and flexible arrangement of agroforestry nodes. These tessellated zones invite gathering, kilo (observation), and making, creating spaces of intergenerational exchange rooted in ecological rhythm rather than industrial logic.

Voronoi

in Design Context

Voronoi patterns are spatial tessellations based on proximity: each cell is generated from a central point and defines the area closer to that point than to any other. Found in nature across scales from the pattern of turtle shells to coral polyps and plant skins Voronoi structures offer a framework for equitable distribution, adaptability, and connection.

In this approach, Voronoi serves as both a tool for organizing space and a symbolic language of kinship, where each intervention site is a node in a network of restoration.

These cells create micro-kīpuka: patches of renewal, healing, and cultural activation. The flexibility of the Voronoi structure allows spaces to grow, overlap, and adjust to landscape conditions, soil remediation needs, and cultural programming.

Biomimicry and the D4G Framework

This approach is grounded in the emerging D4G Framework (Dimension, Domain, Distribution, Dominance, Generator) developed by Habib et al. (2024), which decodes natural geometries for built environment design. The framework classifies Voronoi diagrams based on their origin, purpose, and adaptability across design scales from interiors to urban landscapes. In this thesis, Voronoi is applied at the urbanagroecological scale, using the Generator (ʻulu skin), Domain (urban greenway), and Distribution (non-linear planting schema) as key components of spatial logic.

By simulating these patterns through Rhino and Grasshopper, the design introduces irregular, non-hierarchical land divisions that echo ancestral modes of planting more adaptable to microclimates, hydrological shifts, and cultural use. This breaks the monoculture logic often seen in urban tree planting or industrial food forests and instead fosters diversity, permeability, and community connectivity.

Photo reference: Growables. (n.d.). Breadfruit skin close-up [Photograph]. Retrieved May 14, 2025, from https://www.growables.org/information/TropicalFruit/breadfruit.htm

Hawai‘i ‘Ulu Cooperative (n d ) Ulu fruit harvesting [Photograph] Retrieved

ʻUlu (breadfruit)wasfirstbroughttoHawai'iinthe 12thcenturyatPuʻuloabyKanehunamoku*

Voronoi Patterns

Voronoi patterns are used as a mean to explain tangible natural phenomena and non-tangible social phenomena. program

Fornander, Abraham Fornander Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folk-Lore Vol 4

Edited by Thomas G Thrum Memoirs of the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum of Polynesian Ethnology and Natural History, Vol 6 Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1916

building + supporting urban kīpuka framework become nodes for biocultural regeneration

Each cell become a kīpuka, both physically and methaphorically

anchor points effect gathering and circulation behavior

kīpuka growth patterns

The planting logic of Polynesian forest gardens is rooted in a layered system of interdependent plant relationships, typically organized into overstory, midstory, and groundcover strata This multistory design supports both ecological resilience and human sustenance by mimicking natural forest structures

In this project, I use Voronoi tessellation to spatially define zones within the site, breaking from linear or monocultural layouts Each Voronoi cell becomes a distinct ʻoutdoor classroom, a learning and gathering space embedded with food and medicine systems that mirror the logic of Polynesian agroecology The result is a spatially legible and culturally meaningful landscape, where plants grow in symbiotic layers and community members are invited to engage, observe, and learn. These tessellated spaces create an environment that is both socially navigable and ecologically adaptive, promoting stewardship and intergenerational knowledge exchange.

By extracting and abstracting the pewa form, developing a logic system of triangular geometries that modulate across the site to guide orientation, movement, and gathering These geometries echo the concept of lokahi, which reflects balance and harmony between kanaka (people), ʻāina (land), and akua (spirit), manifesting not only symbolically but physically through furnishings, wayfinding elements, and signage.

stack + scale

modulate

As modular interventions, pewa forms appear in seating arrangements, standing tables, and trail markers, helping to delineate learning zones and transition spaces while offering cultural cues for rest, reflection, and reconnection. Through this, pewa becomes more than a motif; it becomes a spatial strategy for healing, visibility, and orientation across layered landscapes.

PLACEMAKING INTERVENTIONS

STEWARDSHIP ANCHORS

stewardship anchors serve as nodes to begin phasing interventions and partnerships to build pilina to sites and traingulate stewardship at different levels from Lehua elementary school to waipahu high school and leeward community college

Waipahu High School

Leeward Community College

Lehua Elementary School

evaluate assess community need

formation of core stewardship group current knowledge indentify uncertainty implement monitor

EXISTING CONDITIONS

SYSTEMPHASING

INVASIVE SPECIES UTILIZATION

BIOCULT

ECOLOGICAL

TREE STUMP SEATING RAINW CATCH

LIVING NURSERY

p hytoremediation identifytestplantingsitesdevelopanchorsites (schools)pollinatornodes cultivate tacticalstructures participatoryplacemaking propagateregional cultivar

onsitecompostselectiveremovalamend

SYSTEMPHASING

RESTORE ESTABLISH MANAGE

(re)learn

McGrane, S. (2016, August 9). Productive, protein-rich breadfruit could help the world's hungry tropics [Photograph]. NPR – The Salt. Retrieved May 14, 2025

(re)learn

olena,

awa, other dye plants

(re)learn

ʻAkulikuiwetlandpatches

Hawaiian pipi

Pinctada radiata

Dwarf Niu Nursery

Coco nucifera

waipahu aloha cubhouse rehabilitation center

kono [Marshalls], nawanawa [Fiji])

Kou Grove

Canoe material

Carving Lei

waipahu high school

iving shoreline hala grove

fibers+limu+propagationlei

removeinvasivelimu+vegetation

likethebirdsspreadplantseedsonland,thefishspreadthelimuspores

gathernode

aweoweofortools+medicine makaloafilterbuffers

coastal access filter

pohakutoanchorlei

Urban kīpuka are created and tended specifically for pilina with kūpuna and ʻāina These living spaces support efforts to (re)learn and (re)establish place-based knowledge, serving as sutures, pewa, and conduits of intergenerational resilience. This capstone affirms that the future of urban design in Hawaiʻi lies not in separation from ʻāina, but in deeper relationship with it. Cities are not voids or neutral grounds. They are layered with histories, ecologies, and genealogies that continue to live beneath concrete and infrastructure. In this project, I have reimagined the Pearl Harbor Historic Trail not simply as a transit corridor but as a living system a place of nourishment, learning, remembrance, and communityled healing. This edible greenway serves as both a spatial and cultural intervention, rooted in the belief that landscape architecture can be a vessel for restoring Indigenous knowledge systems and designing for abundance.

Urban ʻāina, as articulated in recent scholarship by Mahina Paishon-Duarte, Kamuela Enos, and others, is not only a geographic condition. It is a methodology grounded in kuleana (responsibility), pilina (relationality), and ancestral memory. Urban ʻāina insists that even in dense metropolitan spaces, land remains sacred, and the relationships between people, land, and water are central to well-being. This capstone takes inspiration from that framework, demonstrating that fragmented lands can become cultural kīpuka. These spaces act as regenerative nodes of knowledge, biodiversity, and reciprocal care.

My design process builds on the insights of Lee and Lincoln (2023), who revealed the underrecognized spatial extent and diversity of Hawaiian agroforestry systems. Their research challenges dominant narratives that have underestimated traditional land use by overlooking arboricultural systems. Hutchins (2024) adds critical depth by analyzing Kānaka ʻŌiwi agroecosystems as socio-ecological webs of care, where relationships are cultivated alongside crops. Likewise, Kame‘eleihiwa’s (2023) work underscores how colonial ruptures to the ahupuaʻ a system severed Indigenous foodways and community governance. These studies collectively frame the urgency and possibility of restoring abundance through land-based knowledge systems.

This capstone contributes to that growing body of work by demonstrating how landscape architecture can engage in applied biocultural restoration. It models how Polynesian and Pasifika agroforestry principles can shape urban public space as infrastructure for resilience, cultural transmission, and ecological repair. Using spatial strategies such as multistory planting schemas and voronoi tessellations, drawn from biomimetic analysis of ʻulu skin patterns. These interventions challenge the monocultural linearity of urban green corridors and instead propose a logic of interwoven relationships and ancestral technology.

Framed by the Pewa Framework and informed by biocultural heritage theory (Lindholm & Ekblom, 2019), this methodology foregrounds healing as a design ethic. The pewa , raditionally used to mend cracks in wood, serves as a metaphor and strategy for place-based restoration. Rather than hiding damage, the pewa reveals it with intention and care, enhancing both integrity and beauty. In this way, biocultural mapping, Indigenous material practices, and ʻāina stewardship become more than tools. They become modes of accountability and ceremony.

As climate change, militarization, and urban expansion threaten both land and community, this project proposes that landscape architecture must evolve. It must serve not only as a means of mitigation but as a platform for transformation. Design must center ʻāina momona land that is productive, cared for, and remembered. Edible greenways should not be seen as speculative experiments, but as urgent and replicable infrastructures for food security, cultural survival, and ecological justice.

This capstone does not offer a singular solution. Instead, it offers a pathway, a process of returning to place through reciprocal design. Urban ʻāina, when nurtured, becomes the connective tissue between past and future, between ancestors and descendants. It becomes the soil of memory, the water of healing, and the pillars for community futures. This is the promise of biocultural pathways and the kuleana of design grounded in aloha ʻāina.

A1. Lee, T. M., & Lincoln, N. K. (2023).

Forgotten Forests: Expanding Potential Land Use in Traditional Hawaiian Agroecosystems, and the Social-Ecological Implications. Ecology and Society, 28(4). Urban Kīpuka are created and tended specifically for pilina (connection) to kupuna these purposes, thus supporting community members’ efforts to (re)learn and (re)establish plants and places. Applicability to existing urban infrastructure as a suture/ pewa/ conduit of intergenerational resilient knowledge

2. Hutchins, L. L. II (2024).

Abundant Lands, Thriving People: Examining the Socio-Ecological Web of Kānaka ʻŌiwi Agroecosystems. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley.

3. Kameʻeleihiwa, L. (2022).

The Demise of Native Hawaiian Food Systems and the Ahupuaʻ a System under Colonial Influence. In Food Democracy and Colonialism.

4. Beamer, K. (2022).

Biocultural Restoration and Aloha ʻĀina Futures. Hūlili: Multidisciplinary Research on Hawaiian Well-Being.

5. Maffi, L., & Ekblom, A. (2010).

Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook. Earthscan.

6. Guillen, K. U. (2023).

Reorienting Urban Identities: Form and Function Follow Foodscape. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

7. Paishon-Duarte, M., Enos, K., et al. (2023).

Urban ʻĀina: Toward Indigenous Frameworks in Urban Planning. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems.

Urban Kīpuka are created and tended specifically for pilina (connection) to kupuna these purposes, thus supporting community members’ efforts to (re)learn and (re)establish plants and places. Applicability to existing urban infrastructure as a suture/ pewa/ conduit of intergenerational resilient knowledge

8. Habib, F., Megahed, N. A., Badawy, N., & Shahda, M. M. (2024).

D4G Framework: A Novel Voronoi Diagram Classification for Decoding Natural Geometrics to Enhance the Built Environment. Architectural Science Review.

Urban Kīpuka are created and tended specifically for pilina (connection) to kupuna these purposes, thus supporting community members’ efforts to (re)learn and (re)establish plants and places. Applicability to existing urban infrastructure as a suture/ pewa/ conduit of intergenerational resilient knowledge

9. Elevitch, C. R. (Ed.). (2015).

Agroforestry Landscapes for Pacific Islands. Permanent Agriculture Resources.

Urban Kīpuka are created and tended specifically for pilina (connection) to kupuna these purposes, thus supporting community members’ efforts to (re)learn and (re)establish plants and places. Applicability to existing urban infrastructure as a suture/ pewa/ conduit of intergenerational resilient knowledge

10. Fornander, A. (1917).

Collection of Hawaiian Antiquities and Folklore. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Press.