The Power of Color in Hawai'i’s Landscapes:

Designing Impactful Environments

Rooted in Ecology and Culture of Place

Keywords: Color, Endemic, Flora, Fauna, Hawaiian’s use of color

Thesis Statement:

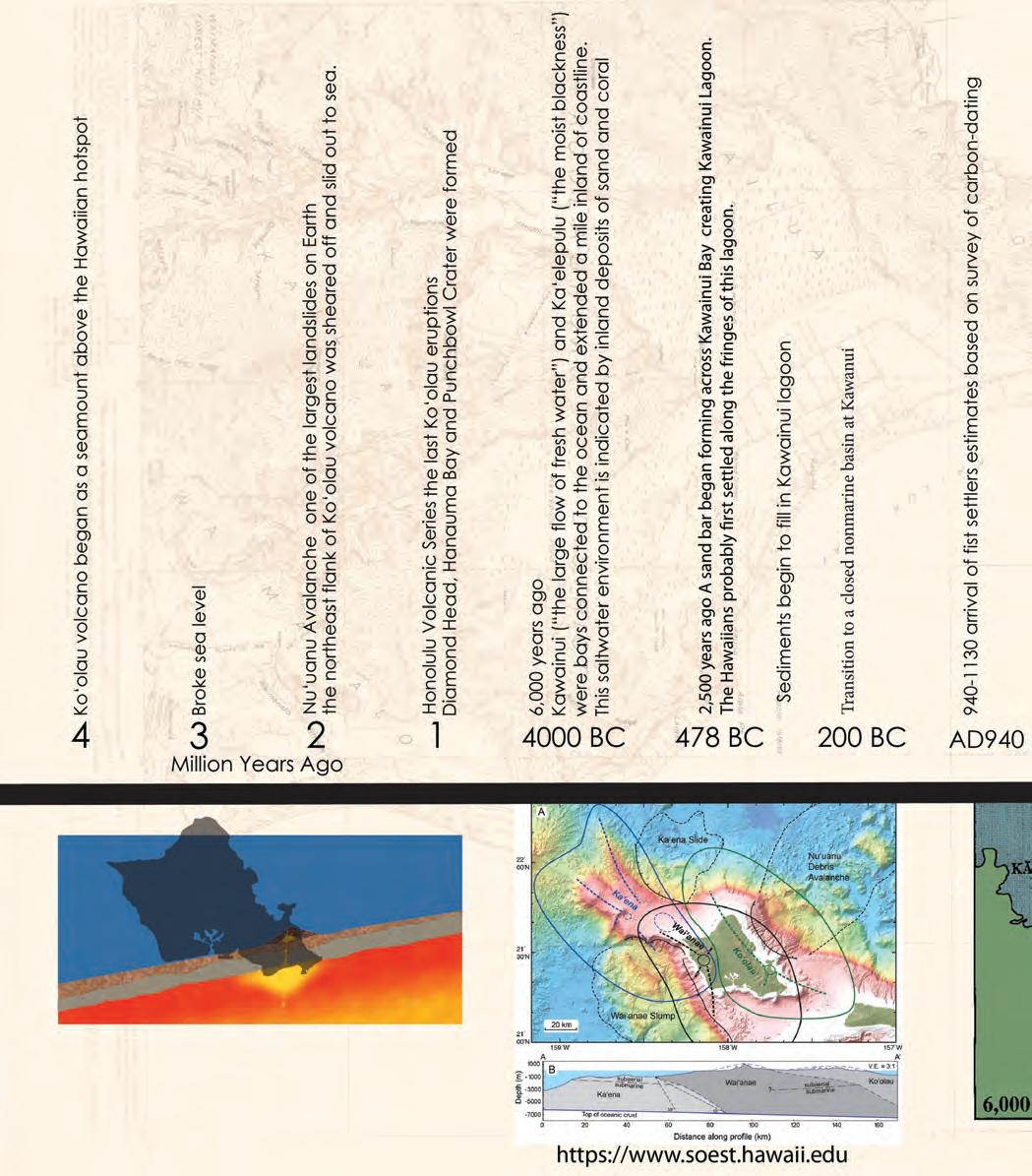

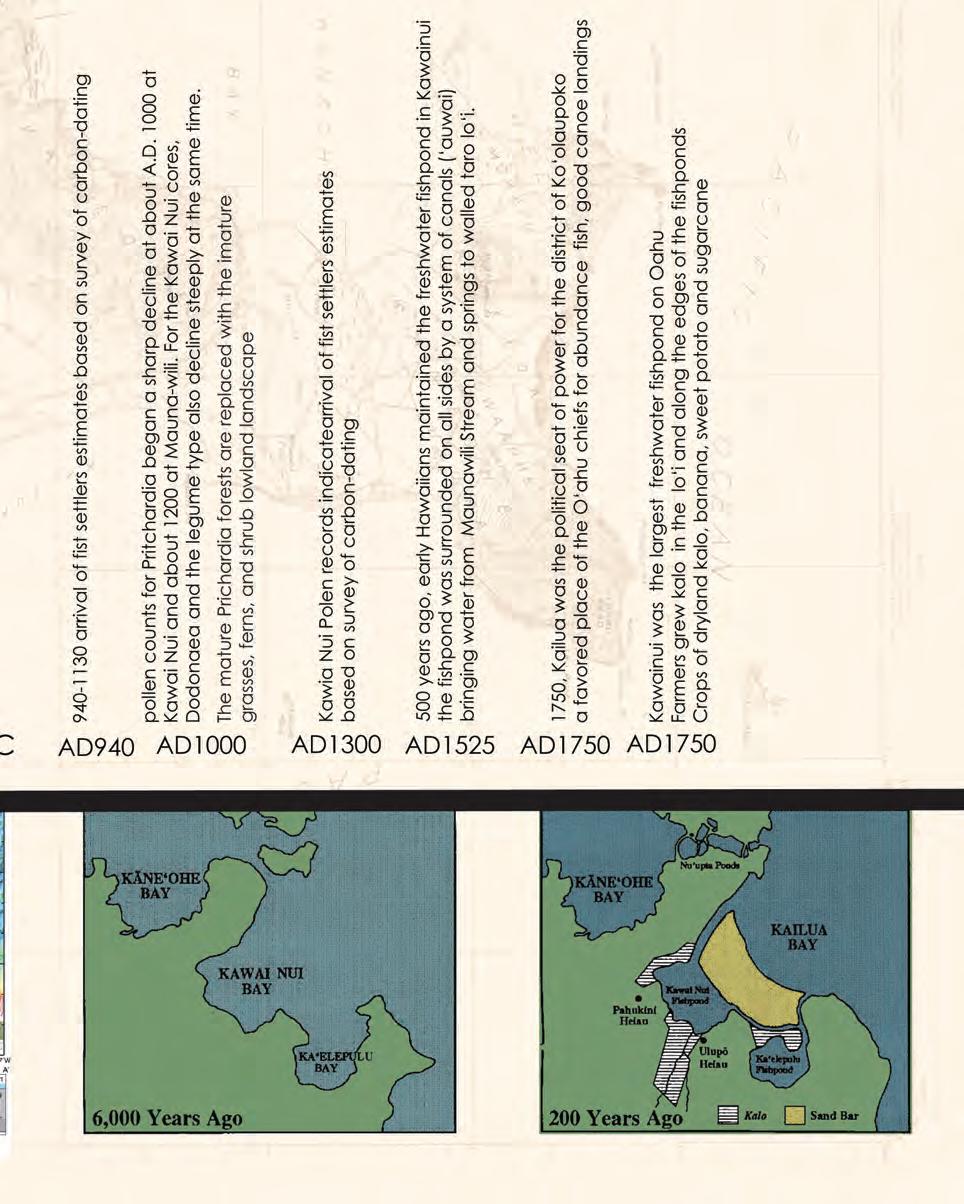

Color, when rooted in the ecology and culture of place, can serve as a powerful design tool for restoring connection, identity, and ecological memory in Hawai‘i’s landscapes. Through an invesgation of endemic flora and fauna, paleoenvironmental history, and cultural narrative at Hāmākua Marsh in Kailua, this project develops a site specific design that reclaims color as a language of place, countering the neutralization of contemporary landscapes dominated by concrete and asphalt with a palette that is both ecologically meaningful and culturally resonant.

Color is a language that speaks to our instincts and emotions. It is what we notice first before any other detail. Color grabs our attention, guides our path, and influence our mood and heart rate.

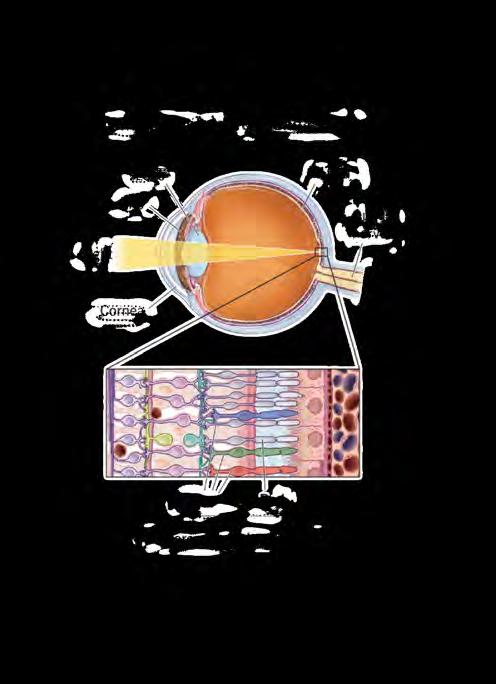

Photoreceptors (rods & cones)

Photoreceptors (nerve cells)

Color is a complex phenomenon shaped by physics, physiology, and psychology. Its perception varies between individuals due to differences in eye anatomy, neural processing, and cultural context, deeply influencing how we feel, behave, and interpret the world.

Cleveland Clinic 2024

Light strikes an object. Depending on the object’s material properties, certain wavelengths of light are absorbed, while others are reflected.

The reflected light enters the eye through the cornea and is focused by the lens onto the retina.

Photoreceptor cells in the retina—rods and cones—detect the light.

Cones are responsible for color vision and function best in bright light.

Rods are more sensitive to low light but do not detect color.

The cones encode the light’s wavelength (color) into electrical signals. These signals travel through the optic nerve to the brain’s visual cortex.

The brain processes these signals via networks of neurons and interprets them as color.

https://en.meteorologiaenred.com/newton%27s-prism.html

Our experience of color is deeply shaped by biophilia. It is an innate human instinct to connect with nature and other forms of life. This connection influences not only the colors we’re drawn to, but how we feel in different environments. Across cultures and history, people have consistently shown a preference for natural colors, especially greens and blues, which are known to evoke calm, comfort, and a sense of well-being. These preferences are not just aesthetic; they’re rooted in evolution, from when our survival depended on reading the landscape for food, shelter, and safety. Color, in this way, becomes both a sensory and emotional bridge to the natural world.

Biophilic design builds on this relationship by intentionally incorporating nature-inspired elements, including color, into the built environment. Using hues drawn from plants, water, sky, and soil, these spaces help foster a deeper connection to place and enhance our physical and mental health. Even culturally, while individual color associations vary, the instinctive pull toward natural palettes remains remarkably consistent. In my work, this informs how I use color not just to beautify a space, but to root it in ecology, memory, and a sense of belonging. Color becomes a quiet but powerful tool for healing our relationship with land and ourselves.

Cultural Color Narratives

One of Oahu's most prominent color stories, the Royal Hawaiian Hotel was influenced by Hollywood film star and legend Rudolph Valentino and his Arabian movies.

photo: https://www.kapacurious.com/new-blog/2022/3/24/

photo: https://thenextcrossing.com/lisbons-architectural-history

New York firm of Warren and Wetmore Designed the Royal Hawaiian Hotel -opened 1927 Kamehameha V's summer Residence at Helumoa.

King Kamehameha l had a field of Milo trees near this site.

The color choice for the Tripler Army Medical Center was influenced by the Royavl Hawaiian Hotel’s “Spanish-Moorish pink in 1948

photo: https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/helumoa/

https://www.army.mil/article/191568/tripler_past_and_ present

photo: https:// https://www.marriott.com/en-us/hotels/hnllc-the-royal-hawaiian-a-luxury-collection-resort-waikiki/overview/

Color can serve as a living dialogue between culture and place, connecting aesthetics with the dynamic relationships among living and non-living elements of an ecosystem, including plants, animals, people, soil, climate, and water.

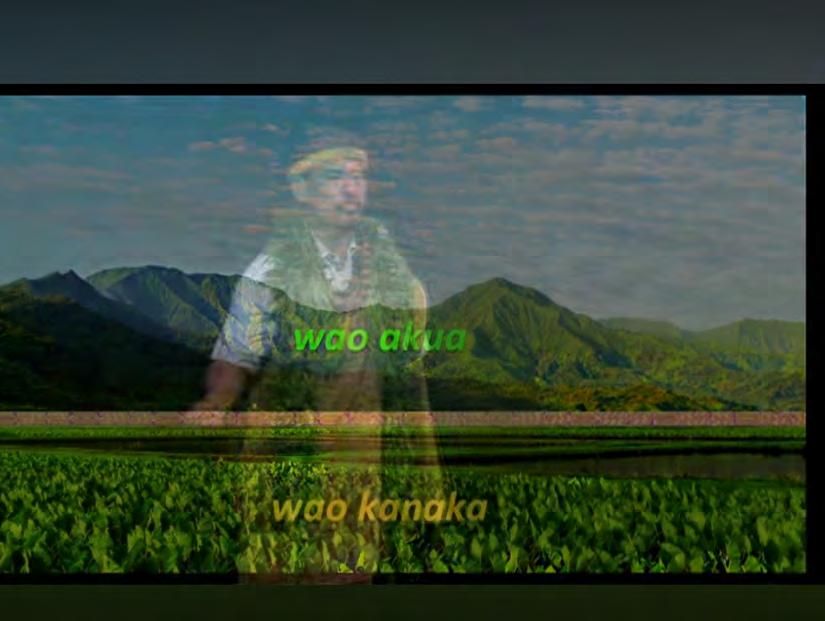

"(Re)learning our perception and interpretation of color orients us in both time and space; it connects us to the long breath of our ancestors and binds us to this specific and special place– Hawai'i."

Kū'i'olani Cotchay (Relearning) Learning

WindWaves W i n g s

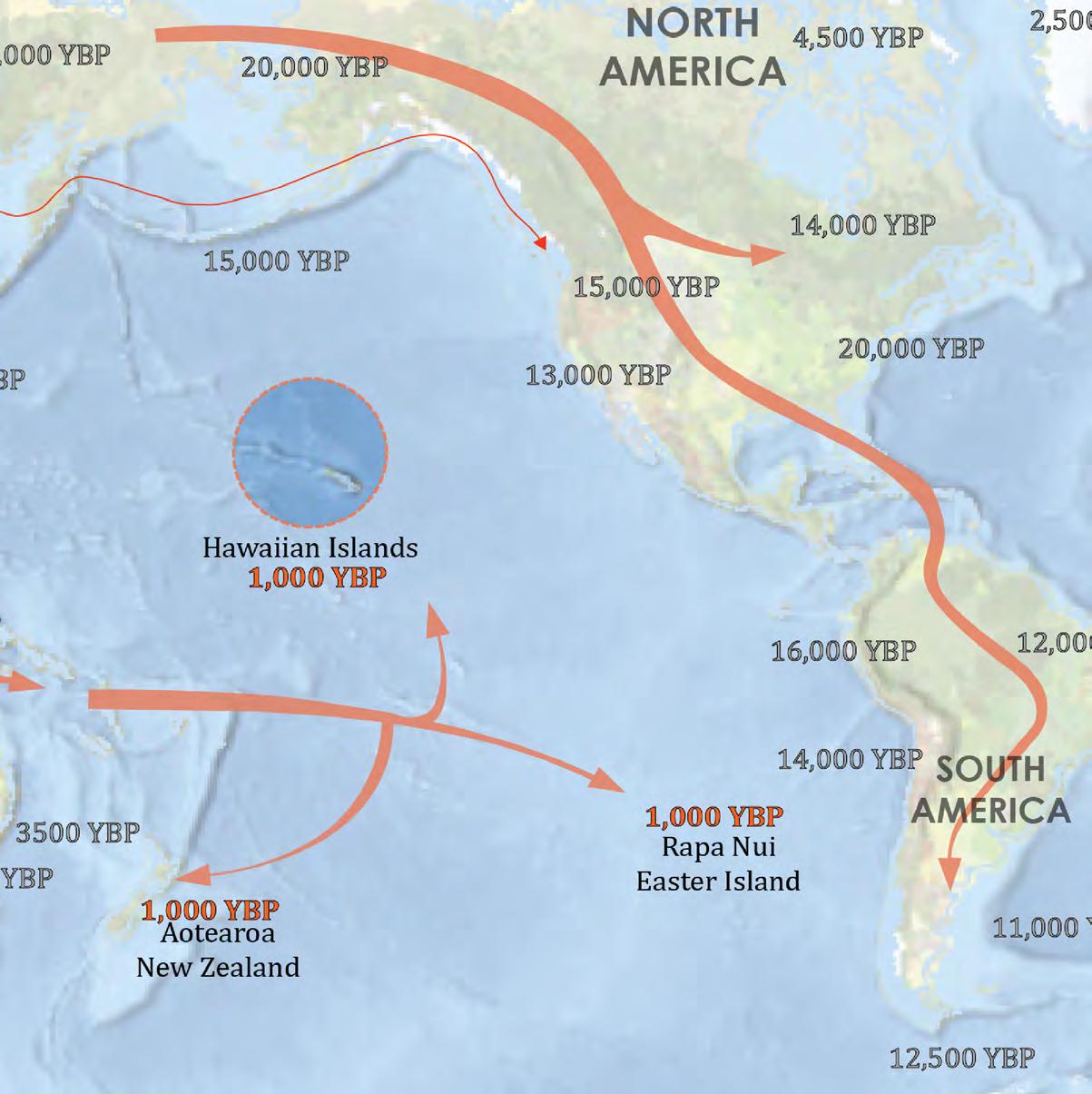

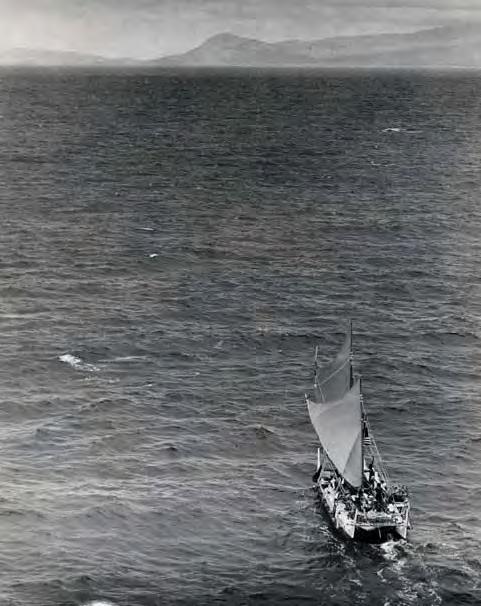

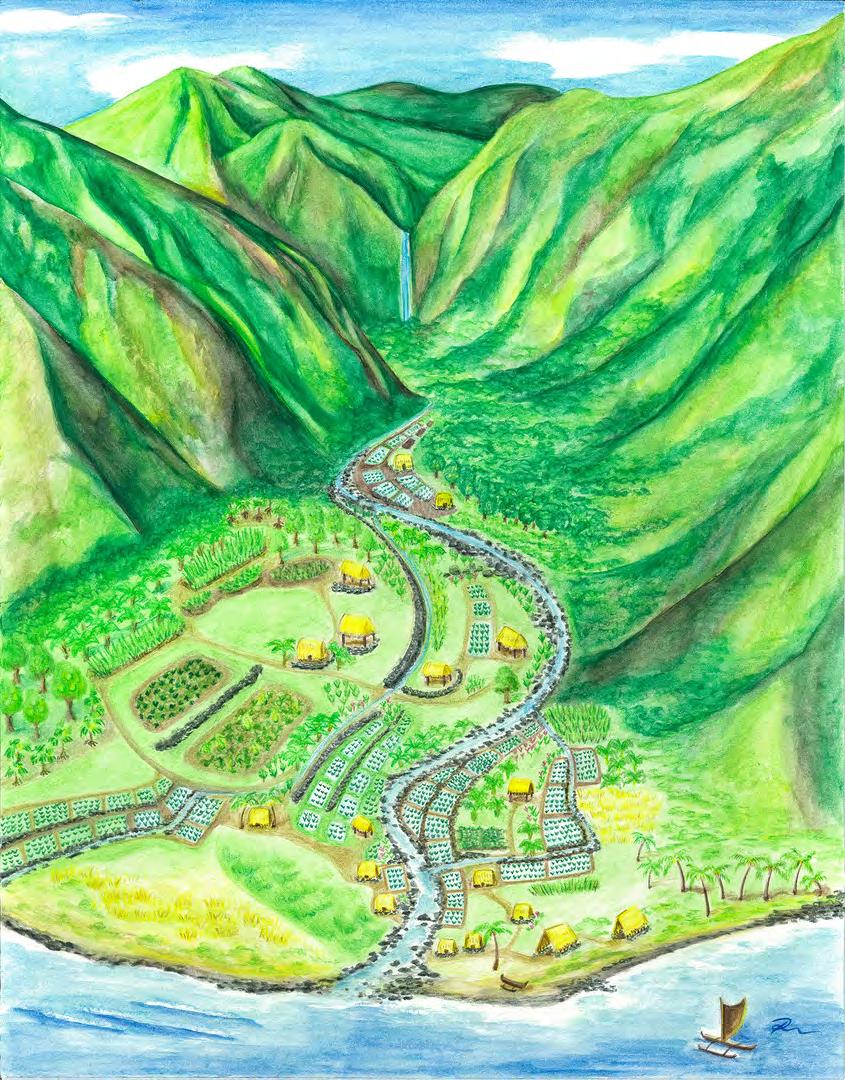

For nearly two million years, the Hawaiian Islands remained one of the most isolated archipelagos on Earth. During this time plants and animals arrived either carried by the wind, swept in by ocean, or brought by birds. These early arrivals adapted to the islands’ diverse microclimates and geologies, slowly evolving into entirely new species. This long period of geographic and biological isolation fostered an exceptional level of endemism, shaping a landscape found nowhere else on the planet.

Polynesian Hawaiian settlement evidence beginning around AD 1000–1200.

Descended from the first Hawaiian settlers would cultivate an island civilization that flourished, untouched by the outside world, for nearly 800 years. The population of Hawaii at the time of first western contact is increasingly a figure of at least 500,000.

(Kirch and Rallu, eds., 2007; David A. Swanson 2019)

Photo:

Canoe Plants & Animals

https://plantpono.org/canoe-plants/

Animals were brought for food, labor, companionship, and cultural purposes.

Hawaiian Name Common Name Purpose

Pig (Sus scrofa) Food, offerings, important in mythology

Chicken (Gallus gallus domesticus) Food, feathers

ʻIlio Hawaiian dog (Canis lupus familiaris) Companion, food, hide Pololū or ʻIole Polynesian rat (Rattus exulans)

Canoe Animals

Canoe Plants

Polynesian plant introductions to the Hawaiian Islands

ENGLISH NAME SCIENTIFIC NAMECOMMENTS

Elephant ear taro Alocasia macrorrhiza Pig fodder, famine food

Kava Piper methysticum

Bitter yam Dioscorea bulbifera

Bottle gourd Lagenaria siceraria

Taro Colocasia esculenta

Alexandrian laurel Calophyllum inophyllum

Ti Cordyline fruticosa

Sugarcane Saccharum officinarum

hi‘a ‘ai

Candlenut Aleurites moluccana

Banana Musa hybrids

Coconut Cocos nucifera

Psychoactive drink, used ritually

Famine food

Used for containers, rattle; South American origin

Staple starch; leaves eaten also

Hardwood tree, used for carving

Starchy root, leaves used in various ways

Stalk chewed; planted as windbreak in dryland systems

Tree with oily seed

Fruit eaten raw or in some varieties cooked

Nut eaten, leaves used for mats

Indian mulberry Morinda citrifolia Fruit used medicinally

Bamboo Schizostachyum glaucifolium Used for fishing poles

Mountain apple Syzygium malaccense Edible fruit

‘olena Turmeric Curcuma longa Reddish pigment extracted from tuber, ritually important

pia Polynesian arrowroot Tacca leontopetaloides Starchy tuber

‘uala

Sweet potato Ipomoea batatas

Greater yam

Dioscorea alata

Breadfruit Artocarpus altilis

Major starch staple in dryland areas; South American origin

Dryland starch crop

Large tree with starchy fruit; wood provides useful timber

Paper mulberry Broussonetia papyrifera Used for barkcloth

variegated landscapes required many kinds of local adaptation in planting practices. The second process was expansion, the pioneering process of transforming a natural landscape into a managed agroecosystem. As populations grew and agricultural fields were expanded, lowland forests were cleared, slopes were terraced, and field plots laid out. Third was the cation, in which technological innovations and greater labor inputs were

AGRICULTURE AND AQUACULTURE • 143

Kirch, Patrick Vinton, and Mark D. McCoy. Feathered Gods and Fishhooks : The Archaeology of Ancient Hawai'i, Revised Edition, University of Hawaii Press, 2023. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uhm/detail.action?docID=30655005. Created from uhm on 2025-05-11 00:24:41.

Color in ‘Ōlelo

Waihoʻolu'u

Kai kohola was the shallow sea inside the reef, the lagoon.

Kai pualena was the yellowish sea, presumably where streams flow in and roil the waters.

Kai ele was the dark sea,

Kai uli the deep-blue sea,

Kai-popolohua-mea-a-kane the purplish-blue reddish-brown sea of Kane

‘ele‘ele dark black

hinahina gray silvery

kahakaha striped, streaked

kea, keakea white

hakea, hakeakea whitish

ke‘oke‘o light or whitish green

hake‘oke‘o whitish

kikokiko speckled

lenalena yellow

halenalena yellowish

melemele amber, buff

oma‘oma‘o green

onionio mottled, variegated, with patches

poni purple

‘ula‘ula red, pink

ha‘ula‘ula reddish, pinkish

uliuli dark, dusky, deep green or blue

hauliuli darkish

MLA 9th Edition (Modern Language Assoc.)

E. S. Handy, et al. Native Planters in Old Hawaii: Their Life, Lore, and Environment. Bishop Museum Press, 1972. APA 7th Edition (American Psychological Assoc.)

blue, green, black, and brown—are broad, these colors correspond to dark colors.

Uli and Its Dark Connotations

Uli is a word for dark colors, including deep blue, green, and black and brown. However, it also carries negative or supernatural connotations, as seen in Hawaiian proverbs and chants. Uli is associated with darkness, misfortune, and the goddess Uli, known for sorcery.

Examples:

Kai uli - The deep blue sea

Nā pali uli - The green cliffs

Uli ka maka - A black eye or bruise

Uli māhole ka 'ili - The skin is bruised black-and-blue

Black, white, and red are significant colors in traditional Hawaiian spirituality:

ʻEleʻele (Black) – Represents darkness and the deep origins of life in Hawaiian creation stories, such as Kumulipo.

Puaʻa hiwa

(a completely black pig)

The night (pōʻeleʻele - deep darkness)

Human skin tones (pāʻele - dark skin)

Plants (kalo lauloa 'ele'ele - a dark variety of karo)

Hawaiian chiefs and warriors sometimes had black tattoos covering one side of their bodies as a sign of power. Chief Kahekili’s tattoos symbolized his connection to the god Kānehekili.

Black, white, Red were not just aesthetic choices but symbols of divine power, creation, and sustenance.

Keʻokeʻo (White) – Symbolizes brightness, light, and warmth, associated with the sunʻs life-giving power.

Moa

lawa (a

white chicken)

White (keʻokeʻo) is associated with light, clarity, and sacredness. It is often contrasted with black.

Kea: kea, keakea, kekea, ōkea, etc.

Ali: ali, aliali, aʻiai, huali, etc.

Keʻo: keʻo, keʻoke'o, hākeʻokeʻo

Liʻu: ahuliʻu, lehuliʻu

White is significant in Hawaiian religious and social practices. For example, white chickens (moa lawa) were considered sacred offerings.

ʻUlaʻula (Red) – Represents blood, life force, and sacred offerings.

Iʻa ʻula (a red fish)

The color red is a royal symbol, seen in the regalia of chiefs, such as feather capes and helmets.

‘ele‘ele (black) ula‘ula (red)

There are up to 17 terms for black color-related elements.

ELE: ʻele, ʻeleʻele, ʻeʻele, ‘ele‘elekū, ‘eleuli, ‘elemoe, ʻelekū, ‘eleʻī, hā‘ele‘ele, kā‘ele, poliʻele, pāʻele, pōʻele, pōʻeleʻele, ‘e‘elekū, ‘ene‘ene (16)

ULI: uli, uliuli, hāuli, pāuli, paulihiua, pouli, pūuliuli (7)

KUHE: akuhe, kuhe, kuhekuhe, kukuhe (4)

HIWA: hiwa, pāhiwa, polohiwa (3)

NIKA: nika, pūnika, pūnikanika (3)

PANO: pano, panopano, panopa‘ū (3)

LIPO: lipo, lipolipo (2)

WEHI: wehi, wehiwehi (2)

KŪMOLE ʻOKOʻA: ila, hākuma, kahaea, kokōhi, palaki, palapō, polina, lalawahi, luluhi, makauli, mahamoe (eleven unique categories)

There are 39 words related to red. The stem of ‘ula is the most significant having 13 in total.

‘ULA: ‘ula, ‘ula‘ula, hai‘ula, hā‘ula, hā‘ula‘ula, kiawe‘ula, mā‘ula‘ula, ‘āʻula, ‘ulahea, ulahiwa [‘ulahiwa], onohiula [‘ōnohi‘ula] (11)

KOLE: kole, kolekole, mākole, mākolekole, mūkole, mūkolekole (6)

NONO: nono, kūnono, pūnono, nonono, manono (5)

HE‘A: heʻa, heʻaheʻa, kāhe‘a, kīhe‘ahe‘a (4)

‘EHU: ‘ehu, ‘eʻehu, hā‘ehu‘ehu, kama‘ehu (4)

OKOOKO: okooko/okoko [okōko], kāoko, puokooko [puokōko] (3)

HEKA: heka, hekaheka, piheka (3)

HELO: helo, hehelo, helohelo (3)

KOKO: koko, pūkoko, mākoko (3)

WEO: weo, weoweo, weweo (3)

WENA: wena, wenawena, wewena (3)

HELA: hela, helahela (2)

LELO: lelo, lelolelo (2)

MEA: mea, meamea (2)

WE‘A: weʻa, weawea [weʻaweʻa] (2)

‘ALAEA: ‘alaea, ma‘alaea (2)

KŪMOLE ‘OKO‘A: hilihili, hiʻohiʻo, kaʻaona, makou, māku‘a, moano, nohi, nononi, ‘āpane, ‘ea, ‘iwi (only one group of 11 items)

(orange)

There are three words in the orange category: ʻALANI: ʻalani, ‘ili ‘alani (2 words)

OTHER TERMS: ki‘i (1 word)

Orange and pink may have been seen as shades of red rather than distinct colors, which could explain why separate words did not develop for them early on.

The native Hawaiian orange tree exists, but its name does not seem to be the origin of the word for the color orange ("ʻalani"). In Bishop’s vocabulary list and Andrews’ dictionary, "ʻalani" refers to the fruit (orange). Both Andrews and Pukui state that the word "ʻalani" (for the fruit) originates from English. In Pukui’s dictionary, the term "melemele ʻili ʻalani" is defined as "orange-yellow color," suggesting a connection to the Niʻihau term for "ʻalani," which is "ʻiliʻalani." (Mawae, interview, 2008)

akala (pink)

There are five words in the pink category:

ʻĀKALA: ‘ākala, ‘ākalakala (2 words)

OTHER TERMS:

hā‘ula‘ula, puakea, ‘ōhelohelo (3 words)

In Bishop’s vocabulary list, "akala" (ʻākala) refers to "raspberry," with no meaning of "pink." Likewise, in Andrews’ dictionary, "pink" is not one of the three meanings listed for "A-KA-LA" (ʻākala). Among the three meanings in Andrews' dictionary, the second definition refers to a type of cloth, "similar to alaihi fabric." "Alaihi" (ʻalaʻihi) refers to a red fish and a type of reddish fabric.

ulivuli (blue)

The words "polū" and "palaunu" for blue are borrowed terms from English. These new words were adopted, probably because Hawaiian vocabulary did not have precise terms for new western contexts, such as blue eyes.

(purple)

"Poni," the color of the sky in the morning - just before dawn breaks,

The

day is the time of whiteness.

Regarding the category of "mākuʻe" (brown), there is a relationship between brown and red, seen in words like "mea," "ʻea," "palaʻā," and "kaʻaona."

‘ehu (reddish)

‘ōma‘oma‘o (green)

‘ahinahina (gray)

For Native Hawaiians, lei-making is more than craft — it's a living art form rooted in deep cultural and spiritual connection. Each lei tells a story, using natural materials like flowers, leaves, and vines that hold meaning beyond their beauty. Some are even seen as physical forms of gods — what we call kino lau.

Kino lau expresses the idea that deities are present in the natural world — Kāne in freshwater and taro, Laka in the forest plants of hula, Pele in lava flows. Wearing or weaving a lei made from these plants is not just decorative; it's a way to honor these forces and invite their presence. In this way, Hawaiians show their oneness with nature — a world alive with story, spirit, and ancestral memory.

From Martha Warren Beckwith's book Hawaiian Mythology, published in 1940, we learn that We learn that plants were thought of as transformaion bodies of gods. She writes,

“Hawaiians are extravagantly fond of perfume, and frangrant plants are invariably associated with deity. Color is also indicative of devine rank, yellow and red being the colors sacred to chiefs. Yellow seems to be primarily the Kane color. The use of flower wreaths and decorations of woodland plants for a dance hall carries with it a sense of divinity which strengthens the emotional satisfaction with which such things are regarded. Certain red flowers are sacred to the gods and those whom they love. Like the red iiwi bird, so is the red iiwi blossom of the vine sacred. No one not beloved of the gods will dare to pick and wear it lest he be haunted by a headless woman carrying her head under one arm.”

Kalo & Color:

Prior to 1850, Hawaiians had developed over 400 varieties of kalo adapted to different growing conditions and with a great variety of color. Pounded kalo made different colors of poi - from red, pink, yellow white grey, purple, and brown. Today,we just have about 80 native varieties left.

These colors were not incidental—they were the result of generations of careful selection, cultivation, and observation by Native Hawaiians. Color was one of the distinguishing features used to identify and name varieties, signaling deep knowledge of the land and plant.

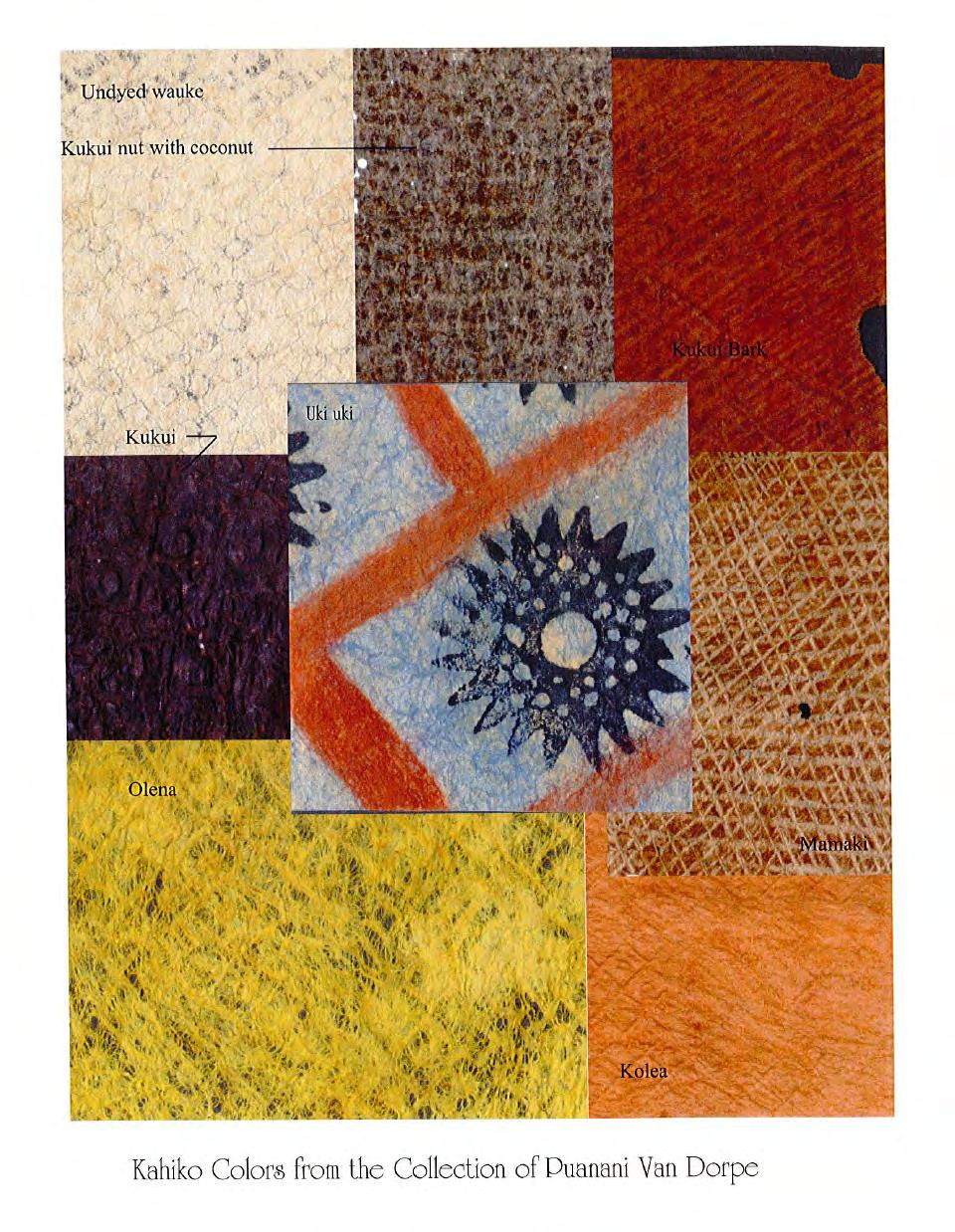

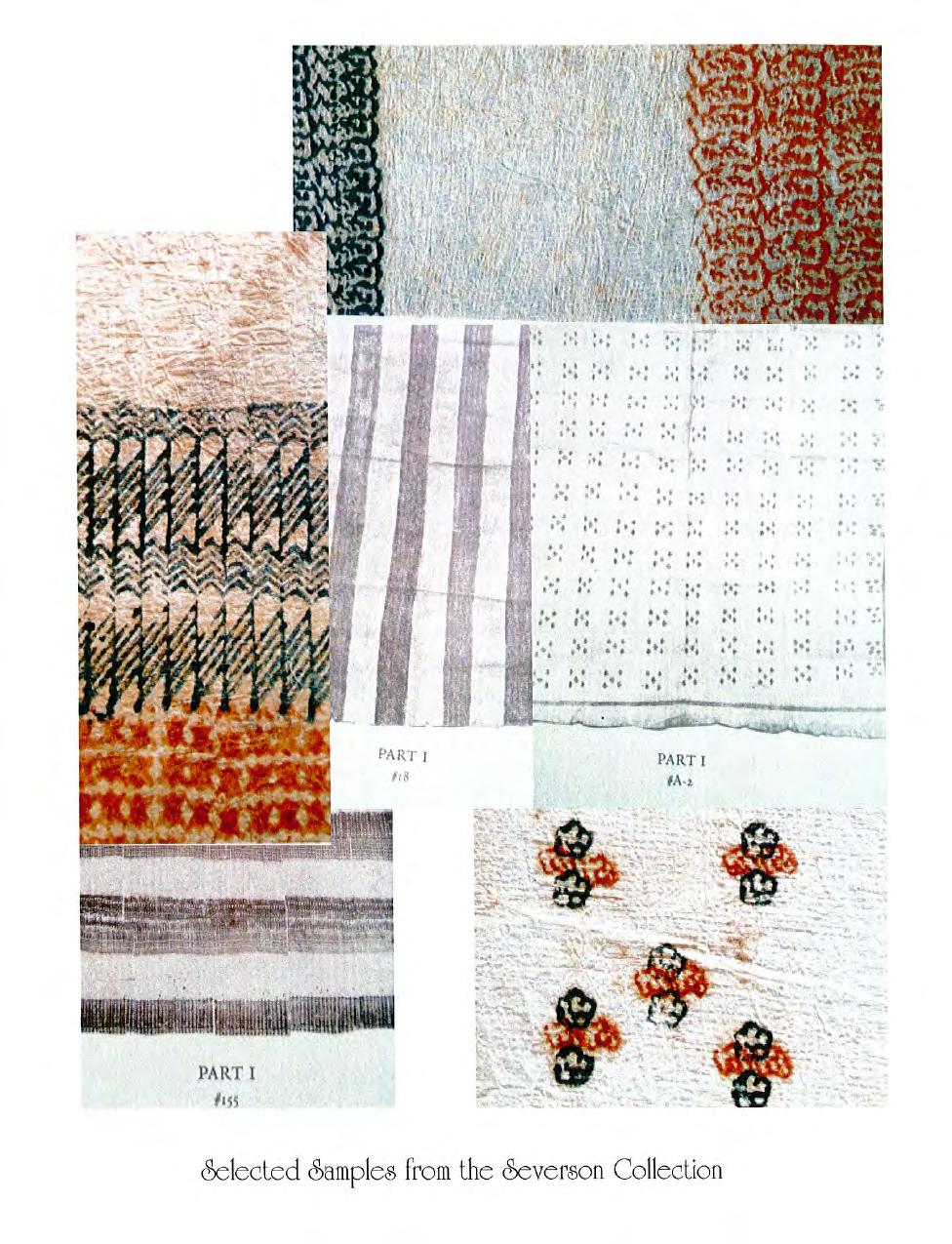

Kapa Color: A Hawaiian Palette

Location: Honolulu, Hi

Designer: Sheryl Seaman, AIA

Client: UH ARCH 600 Research Methods

Year: 2001

Tapa cloth was produced by beating and matting the inner bark of trees and decorating it with natural dyes. Patterns were created with carved narrow strips of bamboo as well as stamps made from the cut stems of plants.

Hawaiians called the cloth kapa or tapa. They used it for clothing, Accurate details of the methods of producing and dyeing tapa were guarded and historical knowledge was lost. Modern practitioners have done much to research ancient methods of tapa making and revive the art form.

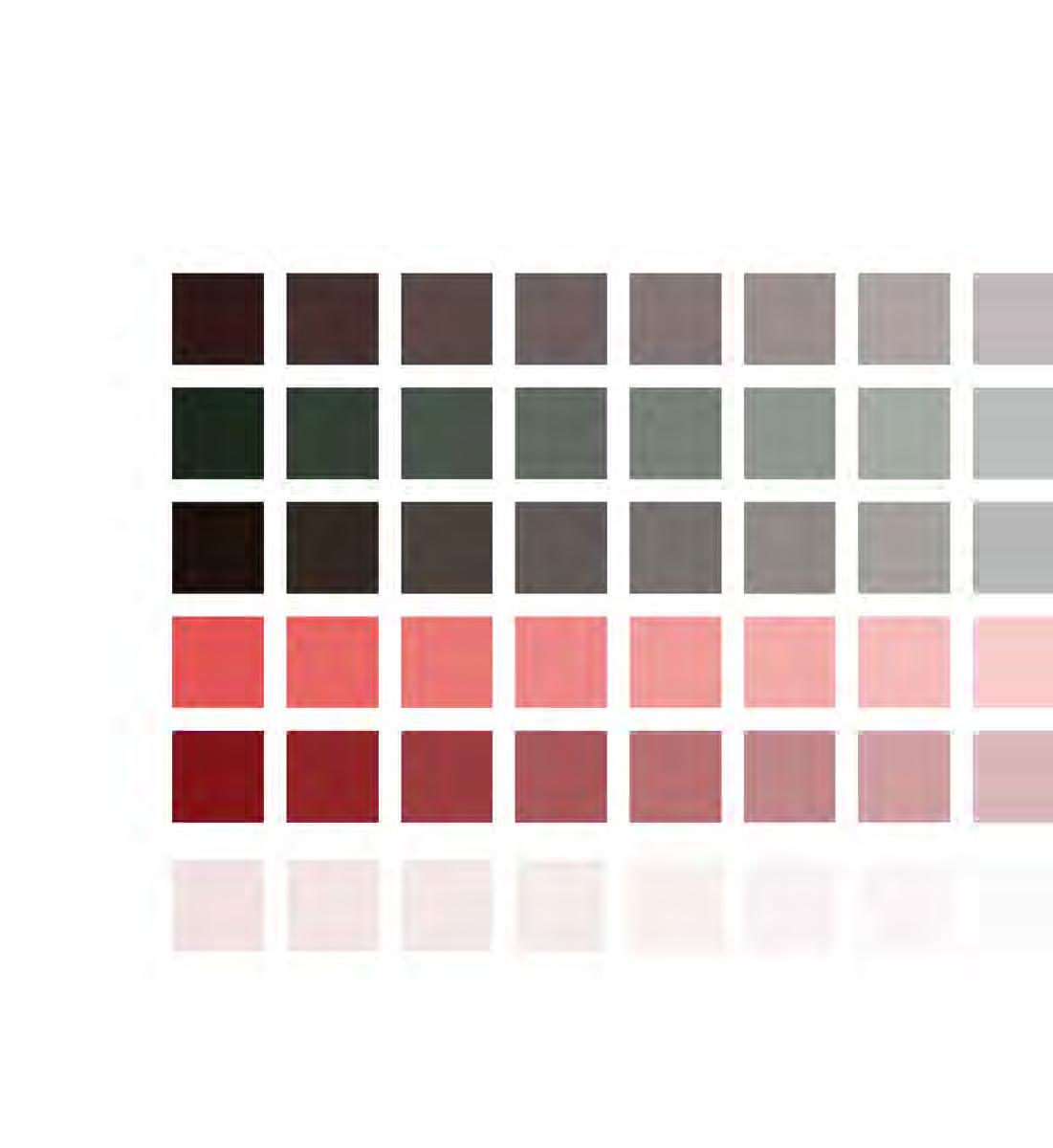

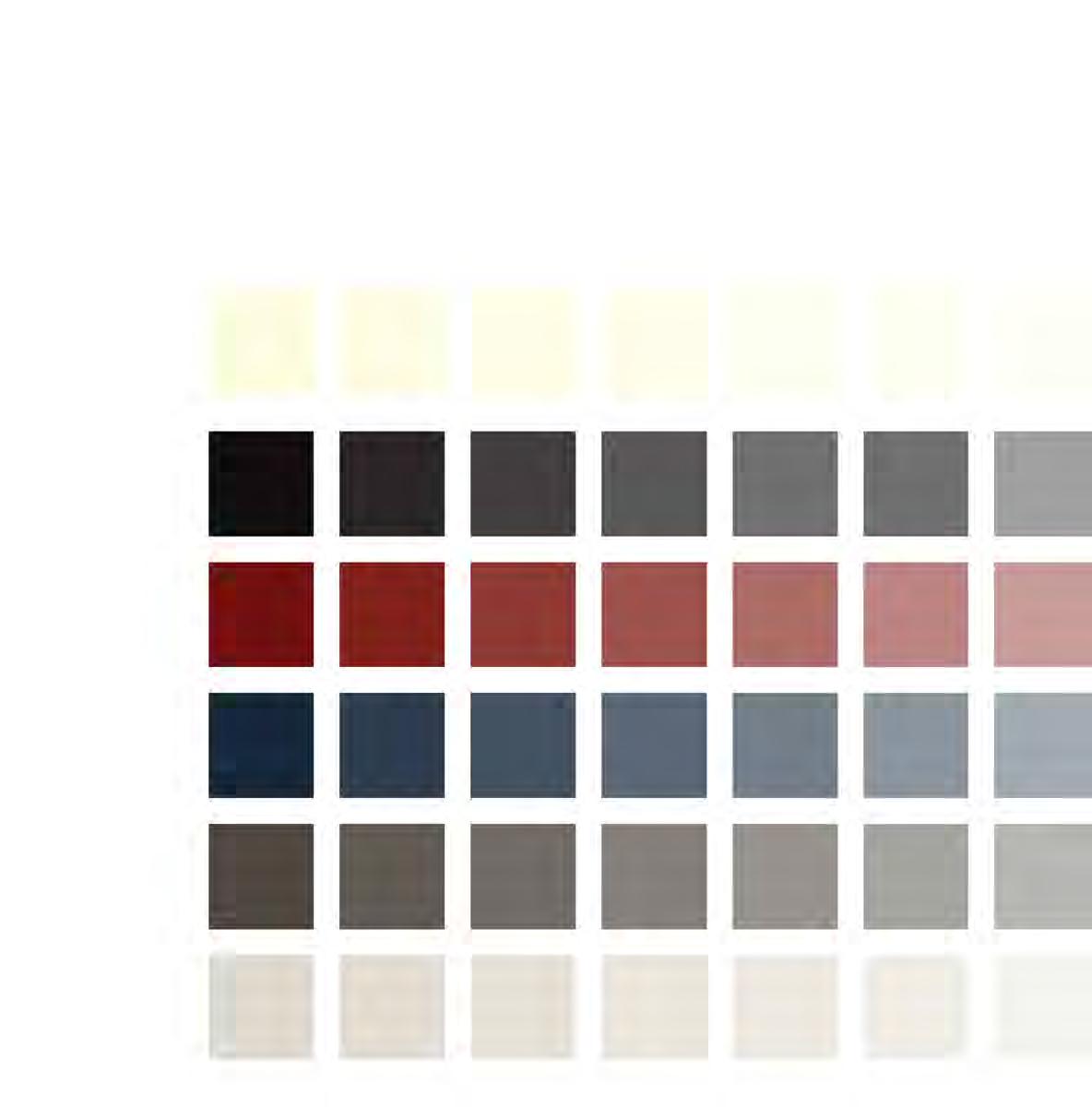

Local Interior designer, Sheryl Seaman shared her research on Hawaiian Tapa color. All images and color pallets shown here are from Sherly's reasearch. Sheryl notes: "Many other Pacific Islands have a history of tapa making but none of them had such a variety of texture and certainly not of color. "

Sheryl notes, “Colored Tapa was generally reserved for the Alii. Skilled craftsmen created beautiful kapas with " brilliant to subtle colors and complex geometric patterns."

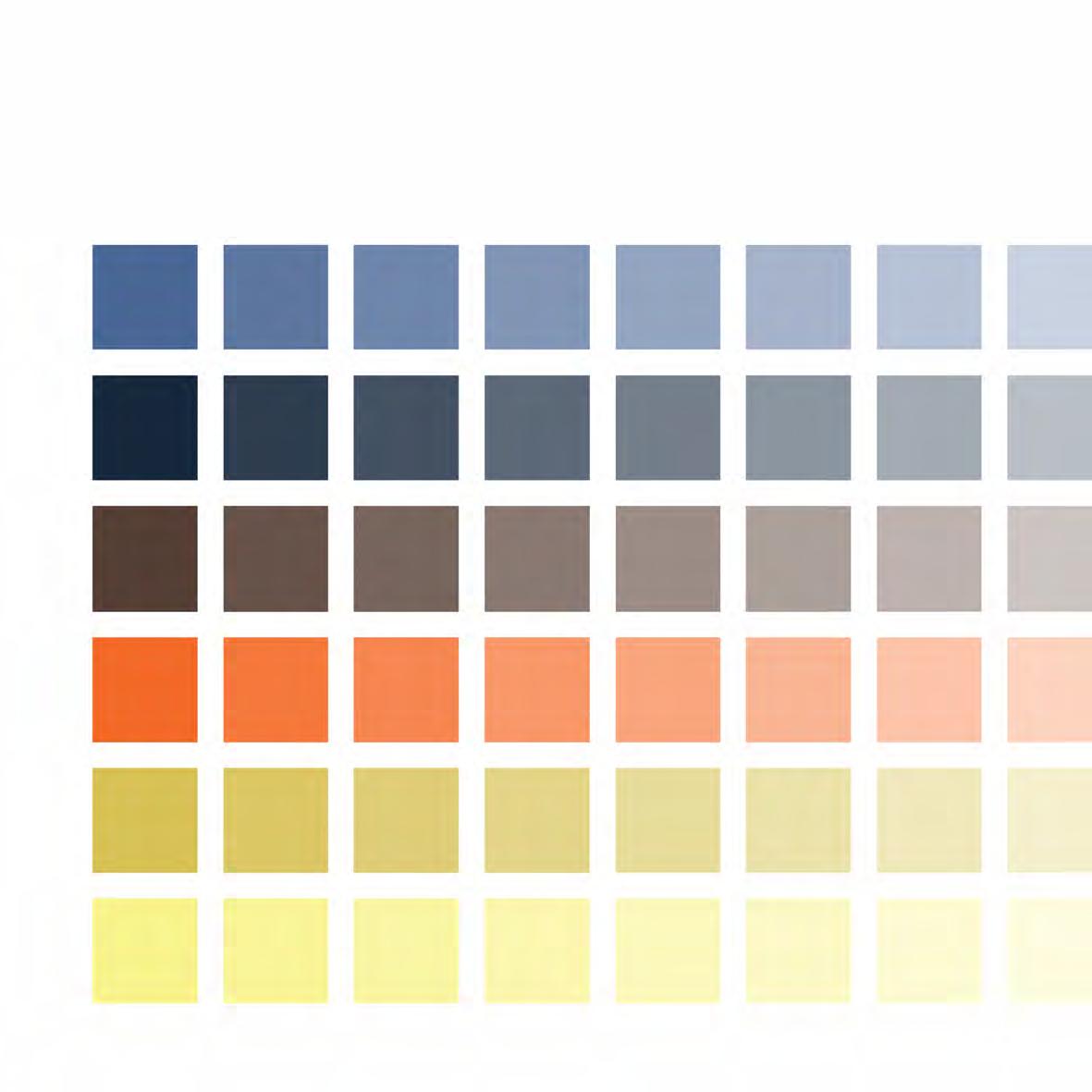

Traditional Hawaiian Fibers & Dyes Color Swatch Selection

Reds & Pinks

Toned

Oranges

Yellows & Greens

Oranges

Blues

Browns

Nuetral

Grays

Kahiko Colors

from the collection of Puanai Van Dorpe

Selected samples from the Severson Collection

Roberto Burle Marx

Artist, landscape architect, the father of modernist landscape architecture

Location: São Paulo, Brazil

Client: São Paulo, Brazil

Year: (1909-1994)

Flamengo Park

Cavanellas Residence

tablecloth, 1989, acrylic on cotton

210,000sq m

sweep of red Iresine herbstii, which contrasts deliciously with the spring green Duranta repens var. aurea

Cavanelas granted both men carte blanche to construct an architectural and horticultural jewel in the middle of a valley, one that still enjoys international admiration today.

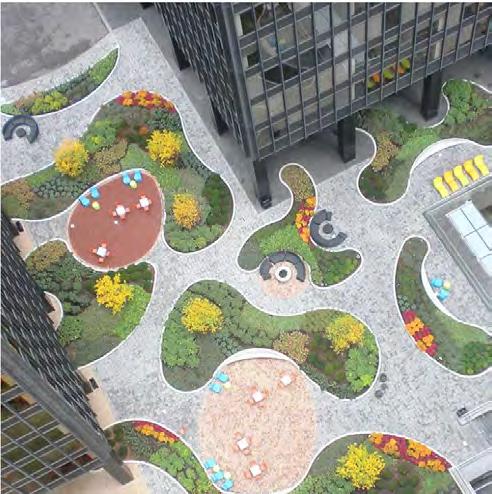

233 North Michigan Ave

Plaza Renovation

Location: Chicago, IL

Designer: Confluence

Client: REIT Management & Research, LLC

Year: 2014

Size: 1 acre

Awards: 2015 Merit Award - Illinois Chapter ASLA

The new transformational plaza design is a complete break with the post-Miesian past and serves as a strong contrast to the surrounding corporate architectureserving as a garden instead of a plaza. The goal was to create a fresh and memorable urban space. The curvilinear organic forms encourage visitors to stroll through and explore the garden’s offerings which include moveable seating, a performance space, seating areas in weathered granite, and a fire pit.

Bright pops of color are introduced through site furnishings, and two smaller seating areas are positioned in sun pockets that focus views to Michigan Avenue. Waterproofing repairs and other technical details were addressed during the project, which was completed on time and on budget.

Key Take Aways:

Re-branding of building desired by new owners. Circa 1970’s building and plaza They wanted to attract a younger demographic. Introduced bright pops of color.

The goal was to create a fresh and memorable urban space. The curvilinear organic forms encourage visitors to stroll through and explore the garden’s offerings which include moveable seating, a performance space, seating areas in weathered granite, and a fire pit.

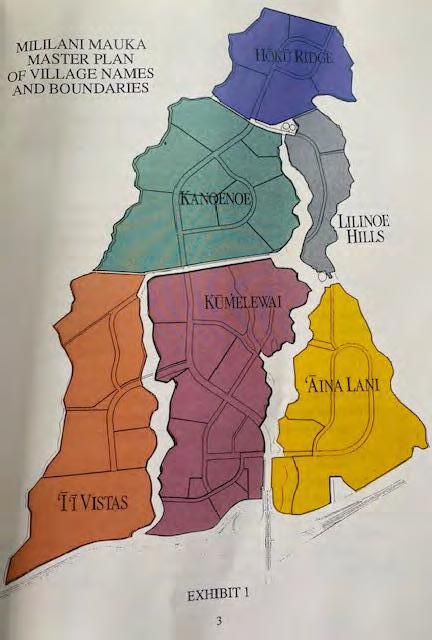

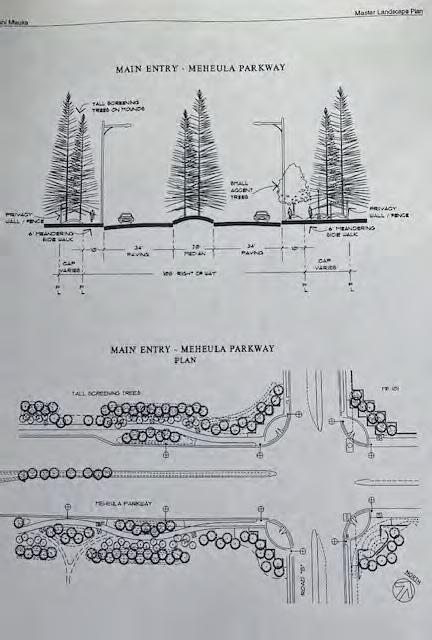

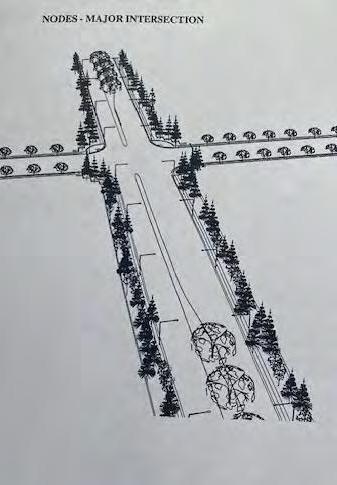

Mililani Mauka

Design Guidelines and Master Landscape Plan

Location: Mililani, Hawaii

Designer: Lester Inouye & Assoc

Client: Castle & Cooke

Year: 1983 -1996

Size: 1200 Acres

Key takeaways:

Landscape concept to create an upland and sense of place for Miliani Mauka Objectives:

Healthy, active place with walking, jogging, bicycling.

Used color to provide orientational information and distinguish each village.

Plant pallet supports color designation. Heights of trees help to identify important nodes

Photos: https://atsukobarth.com/mililani-town-and-mililani-mauka

Photo: https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/forestry/plants/wiliwili/

Photos: https://www.kupunakalo.com/kalo-variety/akado

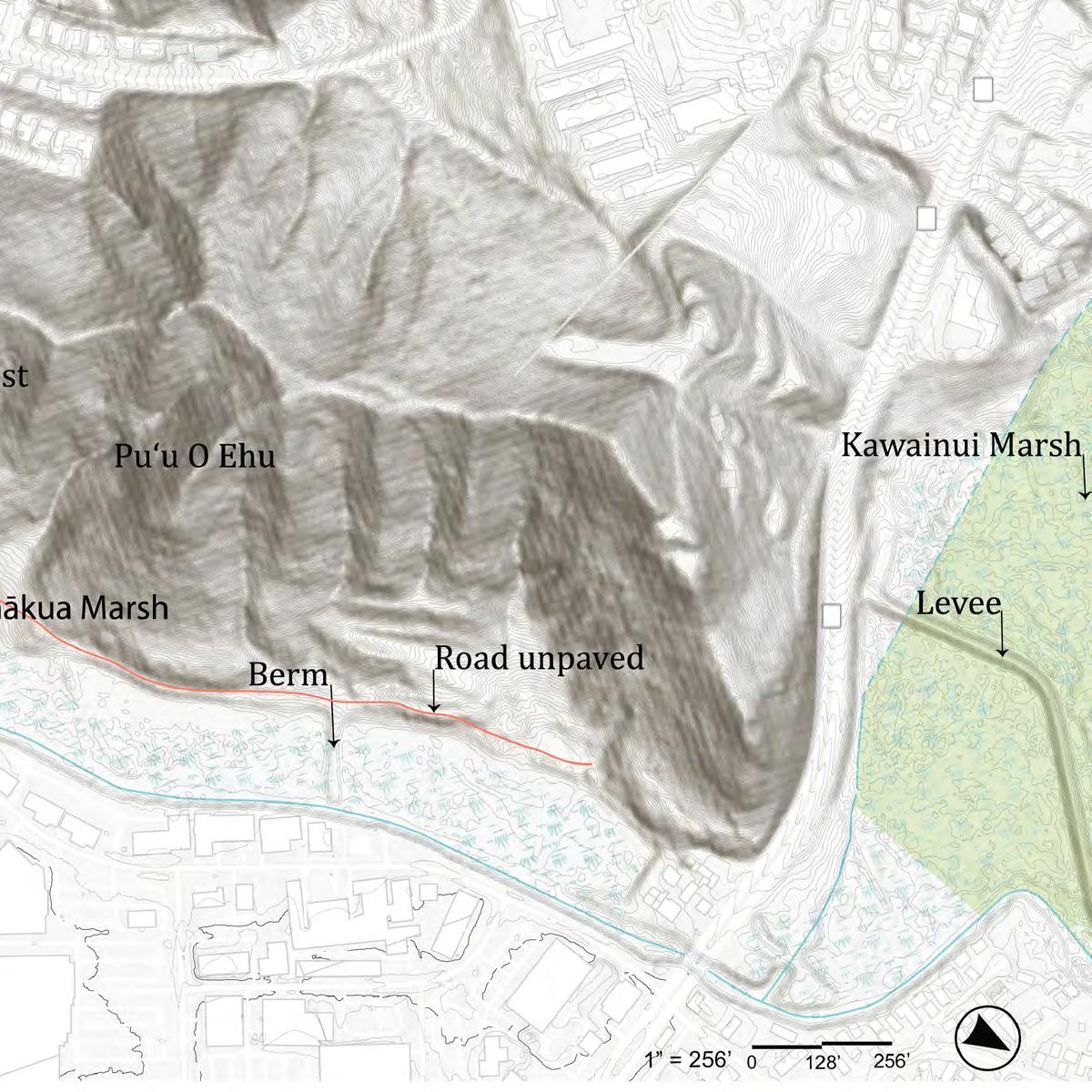

Kawainui Marsh

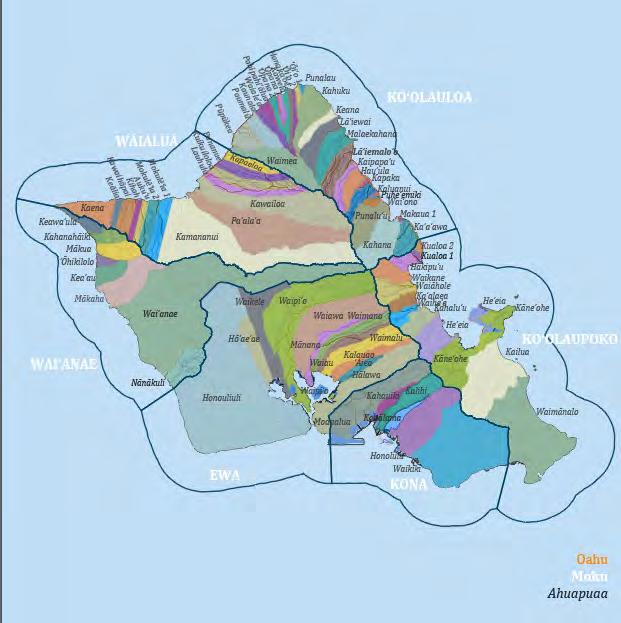

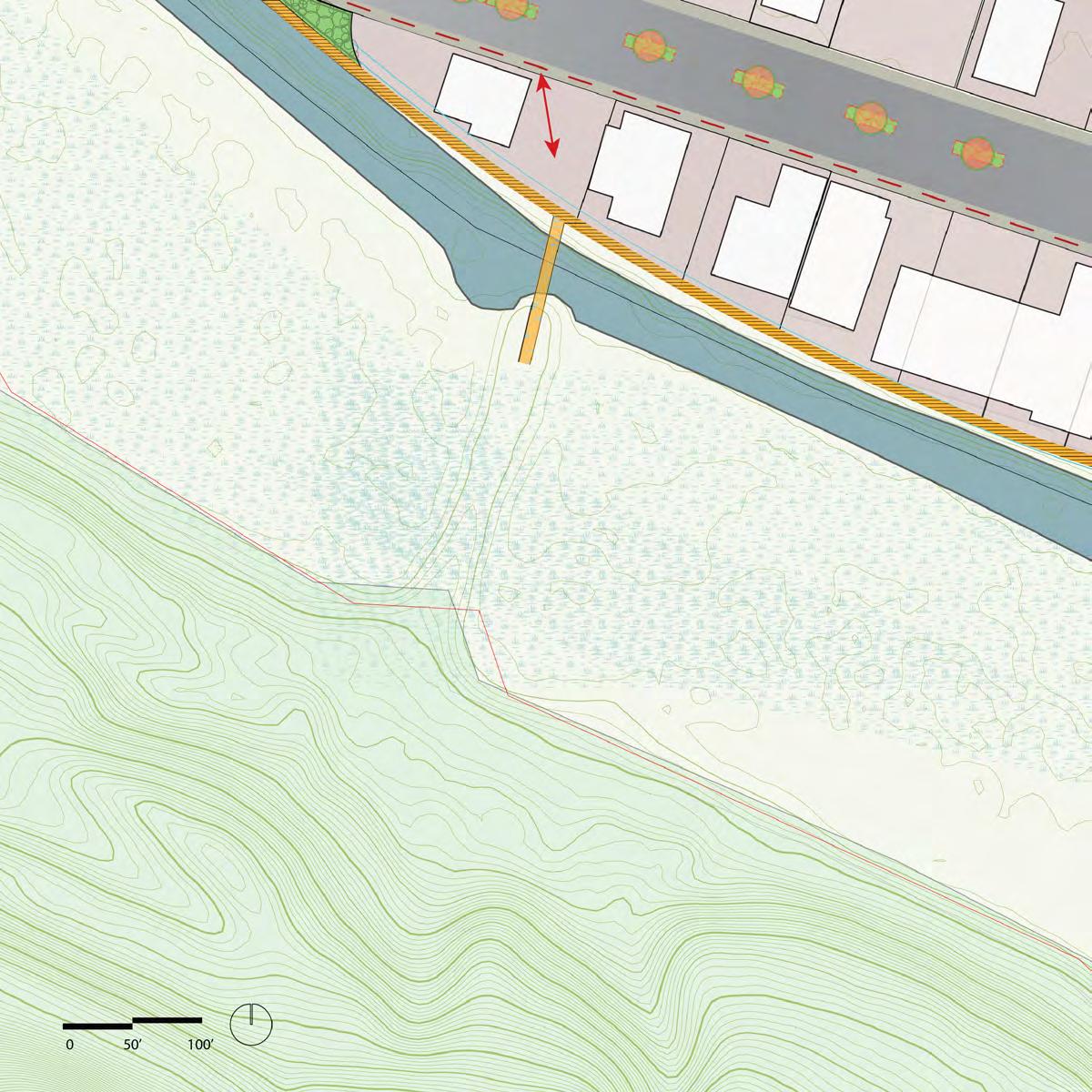

Marsh

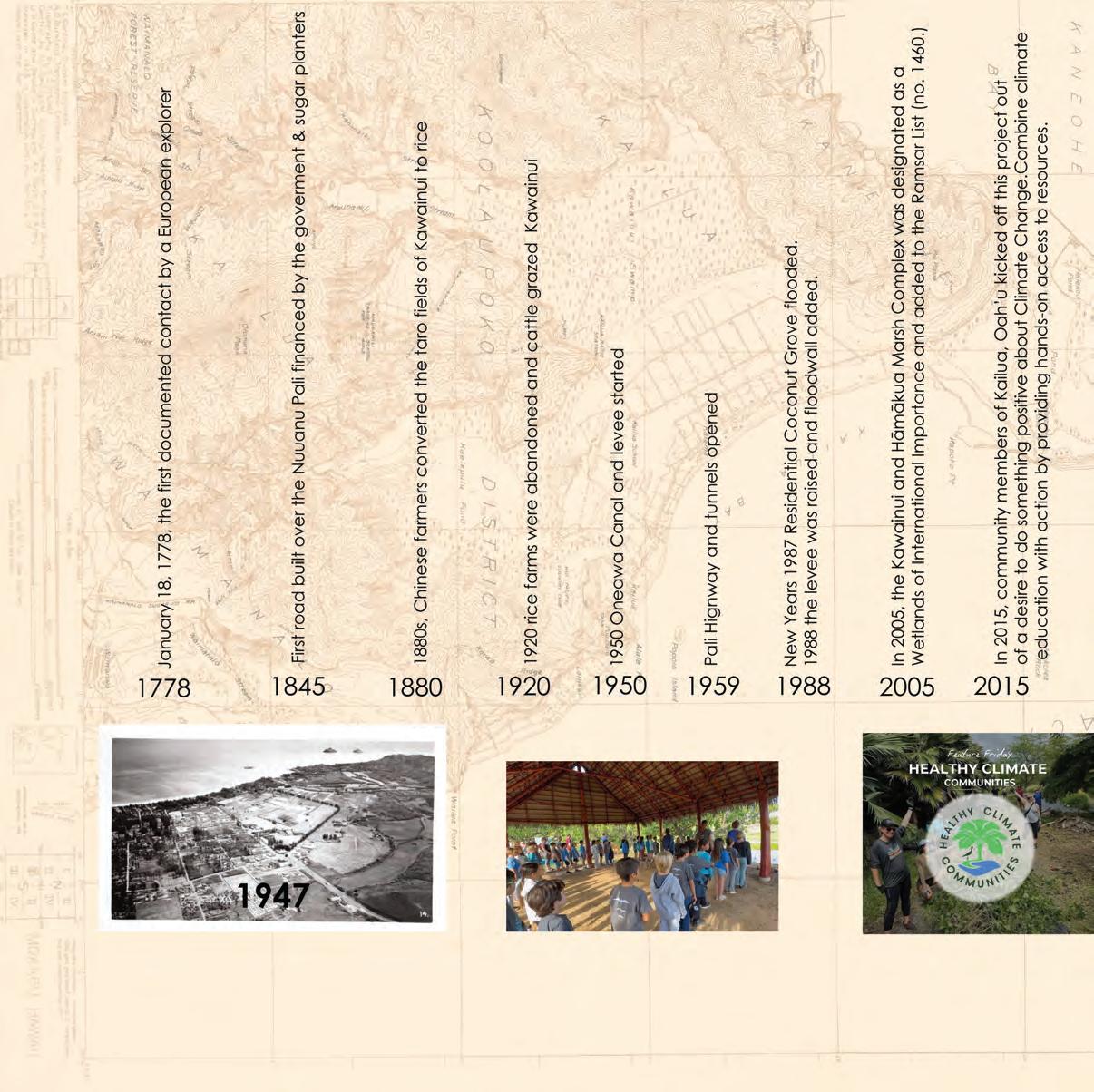

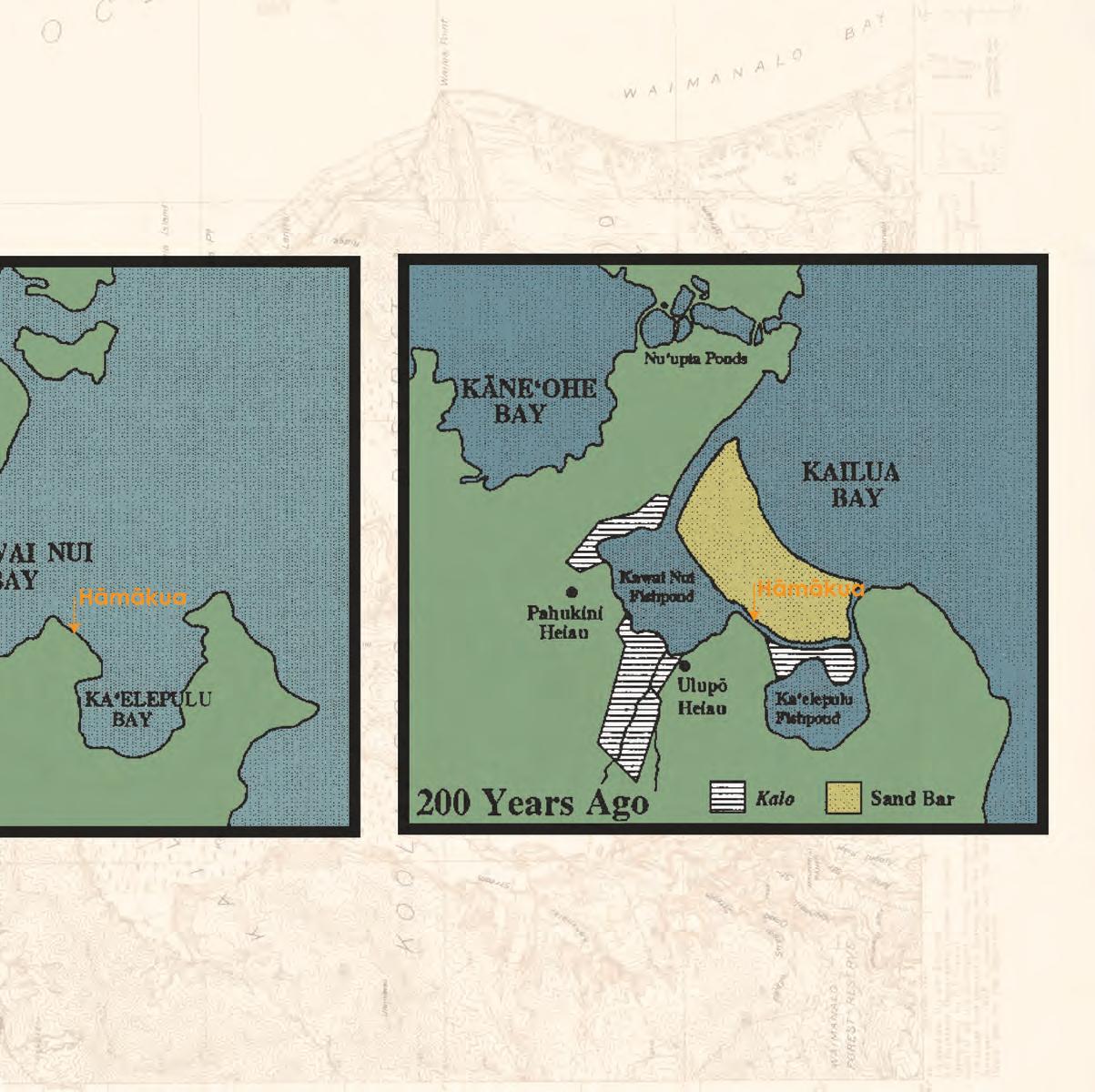

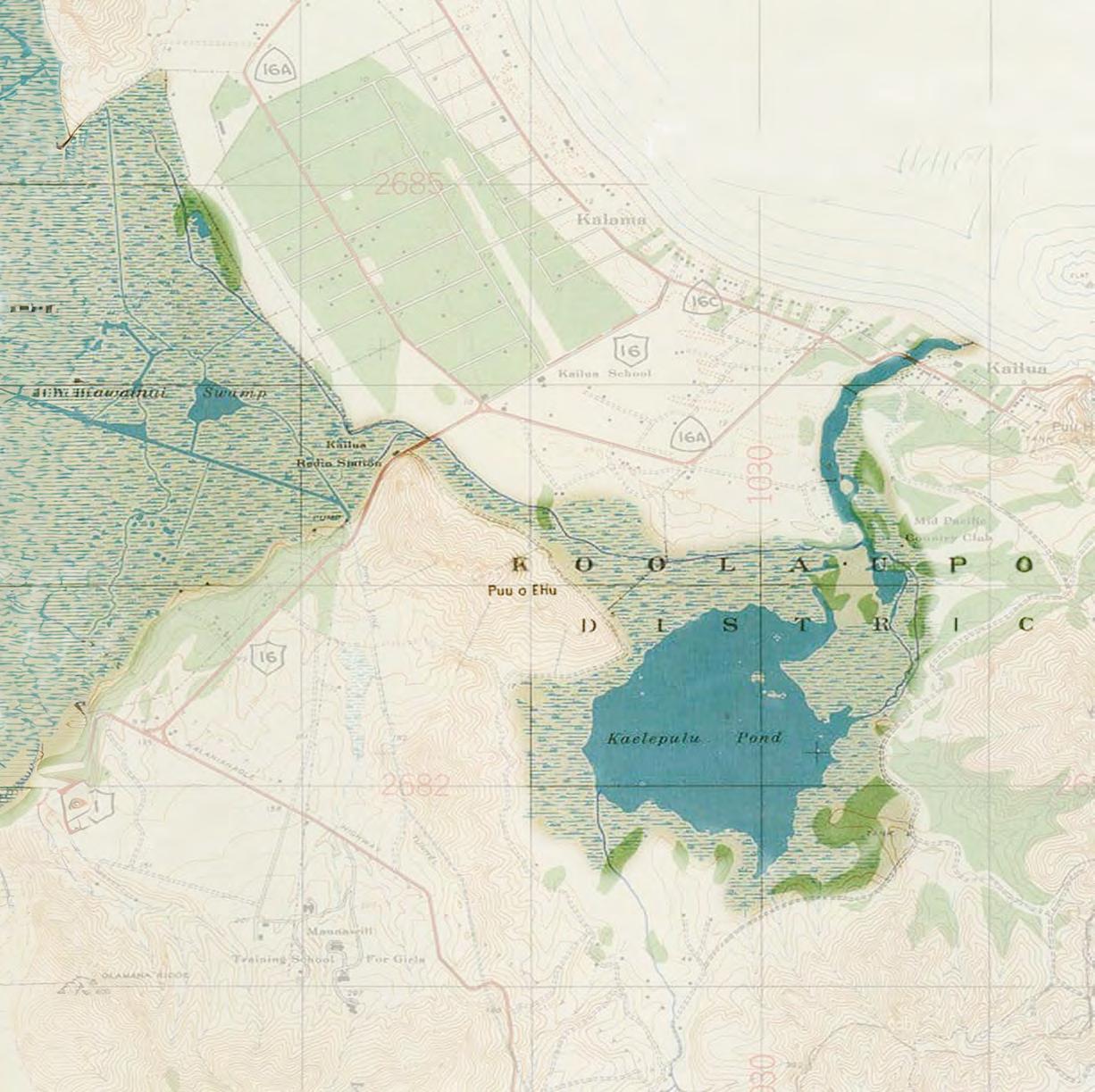

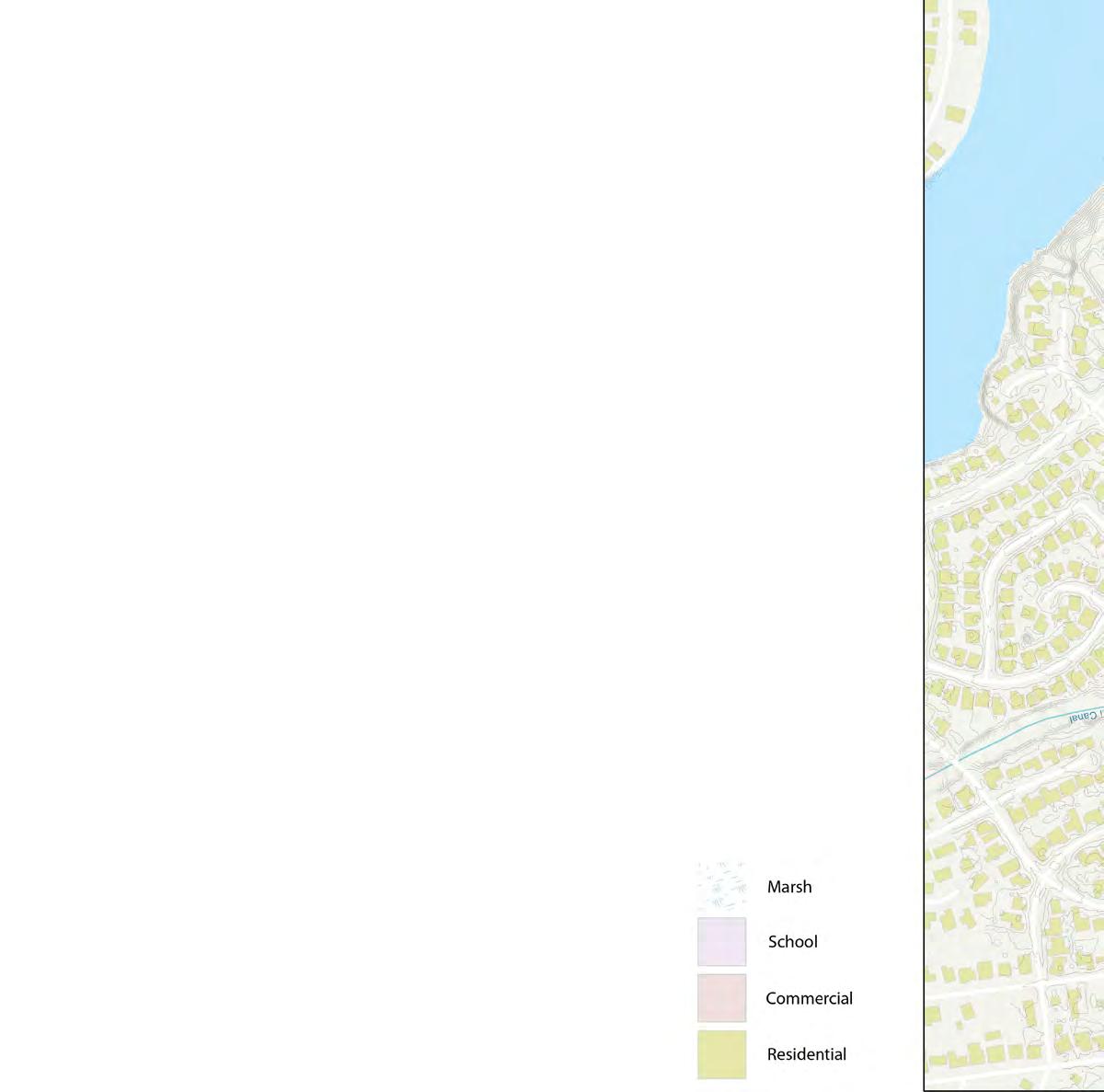

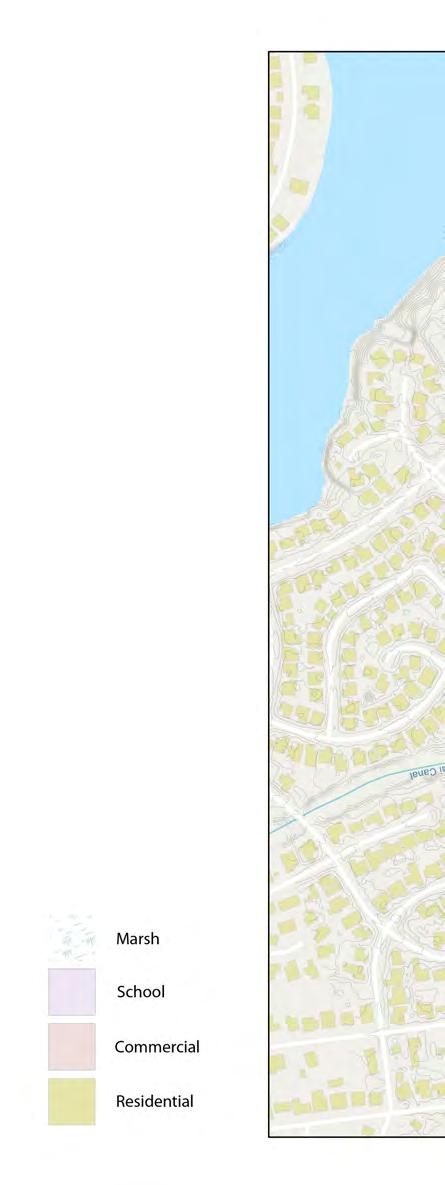

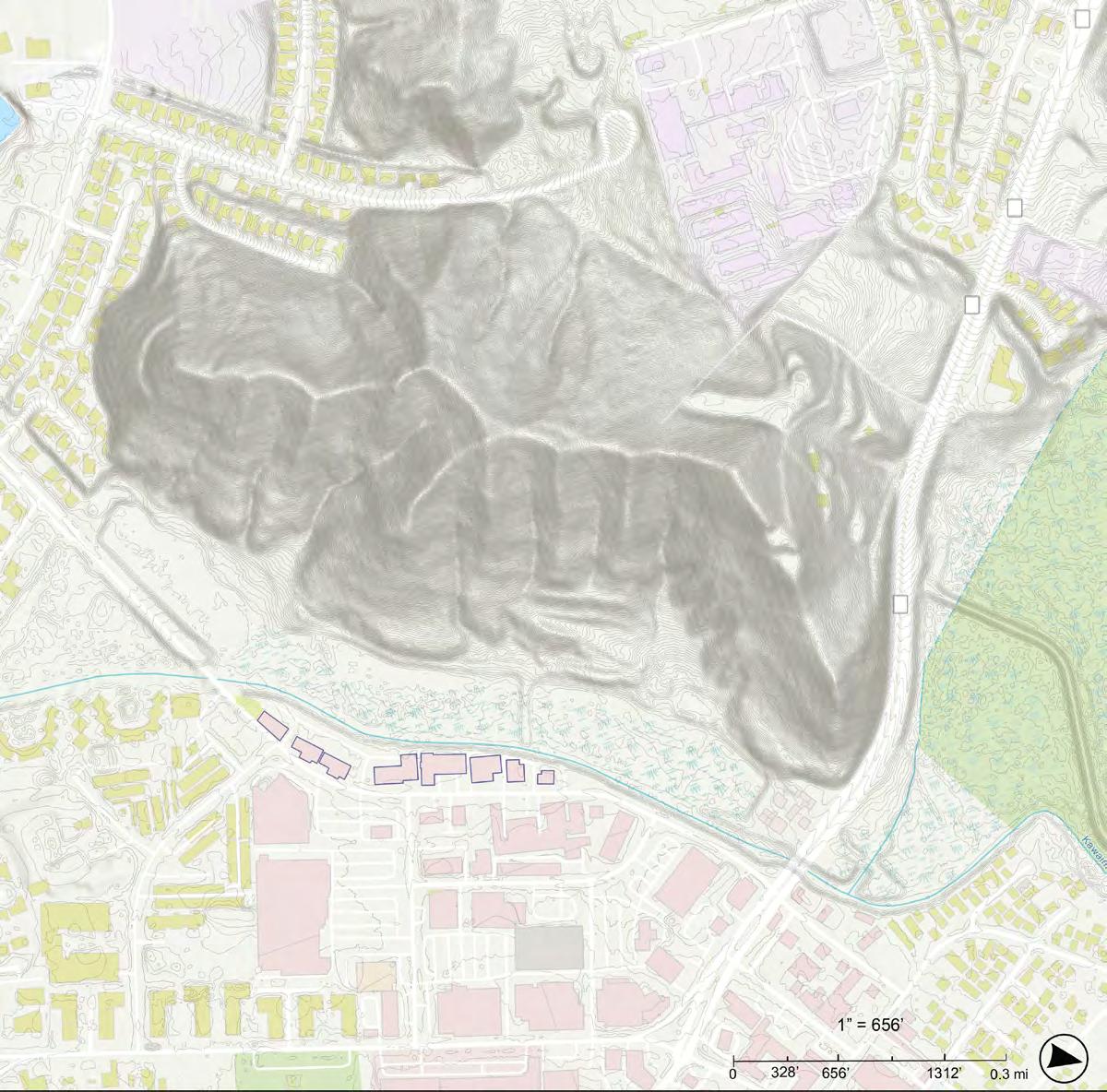

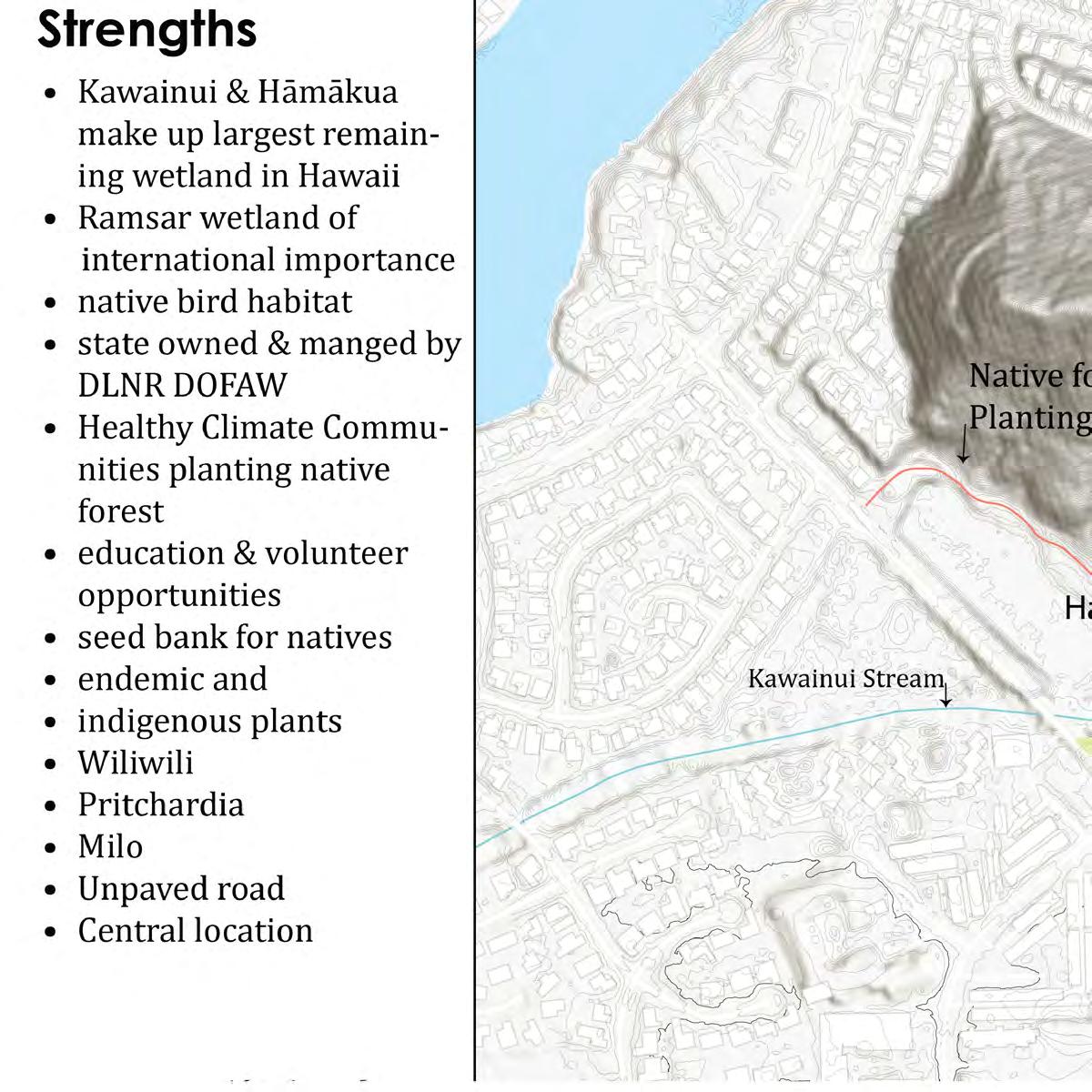

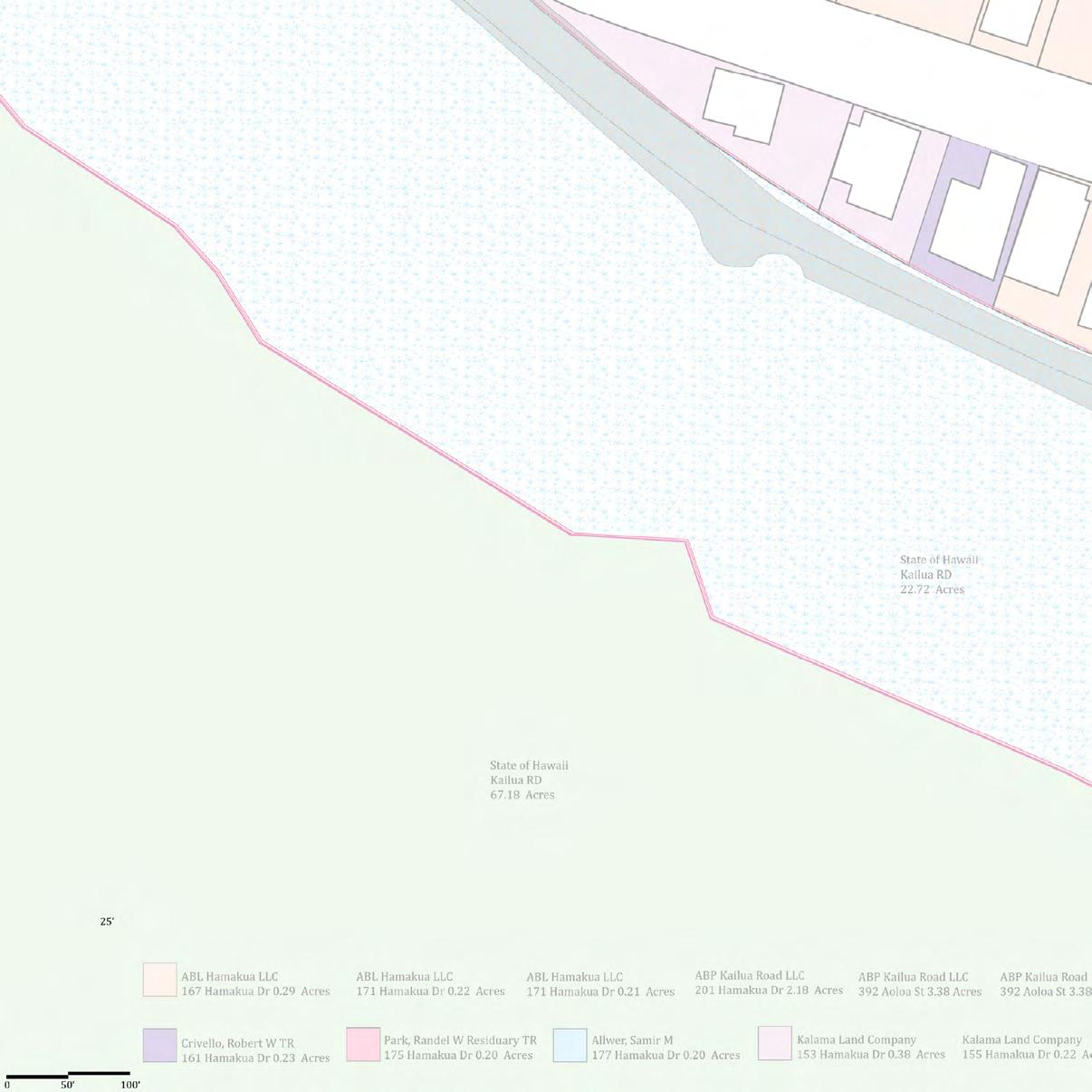

Hāmākua Marsh along with Kawainui Marsh make up the largest remaining wetland in Hawai‘i. They cover approximately 830 acres of land in Kailua, Oahu.

Hāmākua

Kaʻelepulu

Koʻolau volcano

Waiʻanae volcano

Puʻu o Ehu

Kawainui Marsh

Hāmākua Marsh

Kaʻelepulu Pond

The Kawainui levee was constructed by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1966 to protect homes from flooding. It is a 6,300 foot earthen berm with a concrete wall.

Water that flowed from Kawainui Marsh to Hāmākua Marsh has been diverted since the 1960s construction of a flood-control levee adjacent to Kawainui.

waterflow Kawainui waterflow Hamakua

Hamakua Marsh

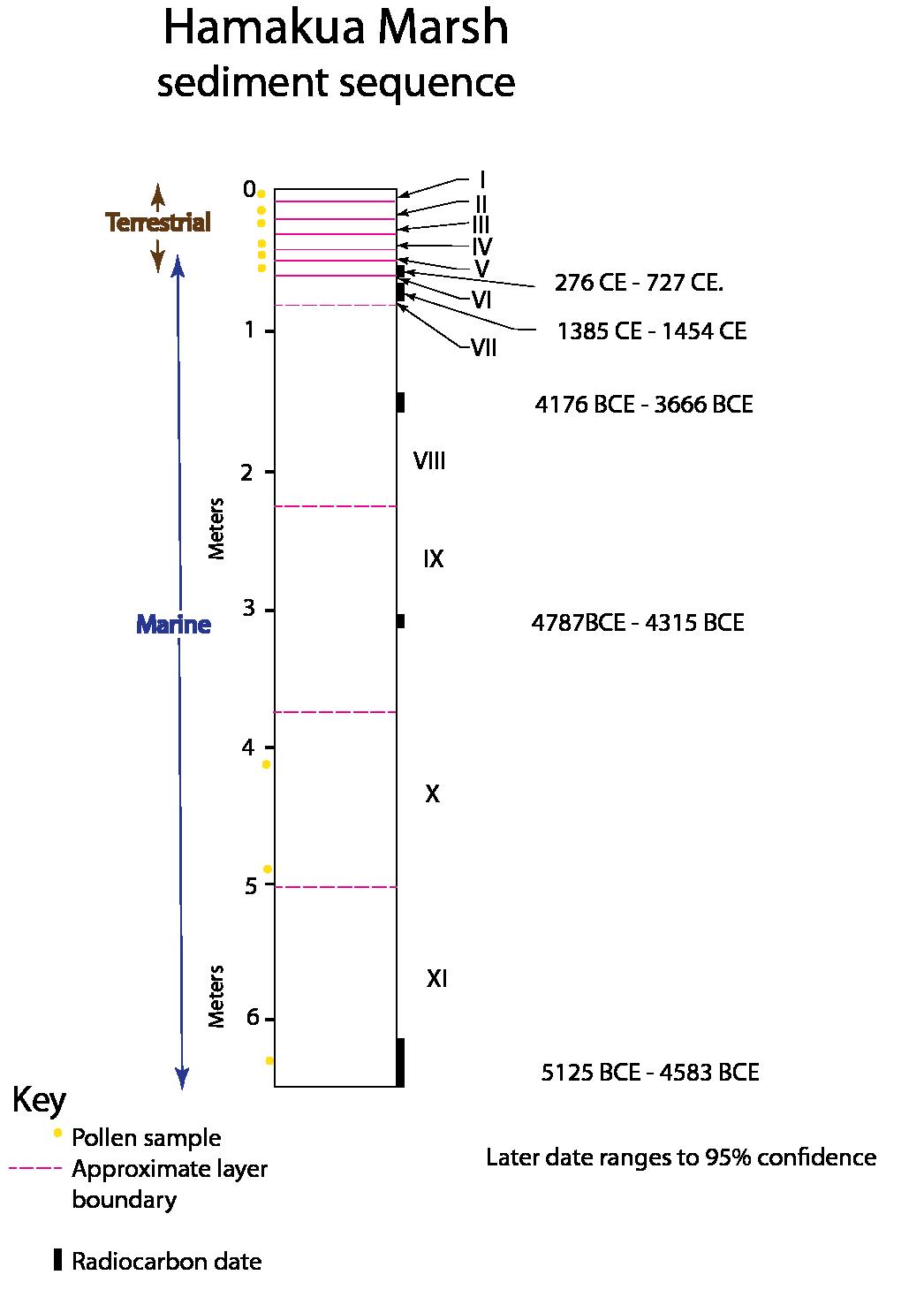

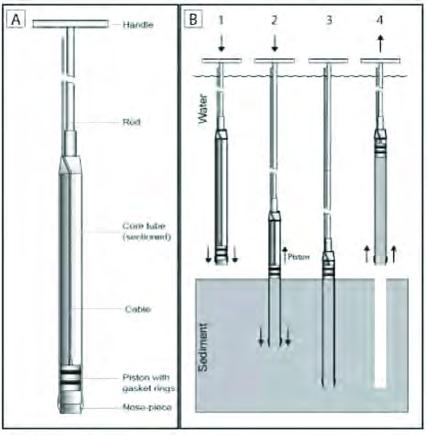

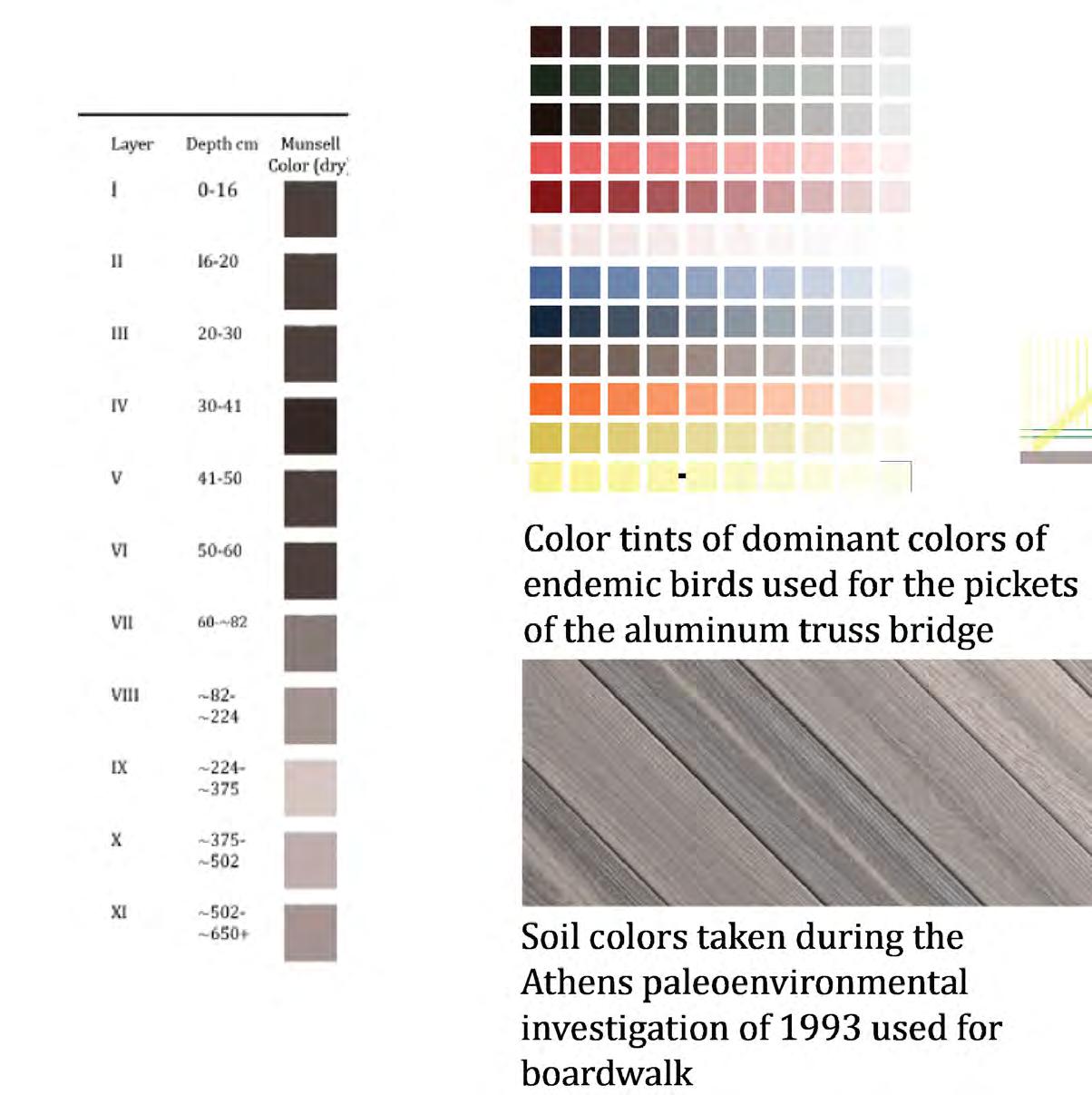

Fieldwork conducted April 30, 1993

3.5 inch diameter hand-driven bucket auger

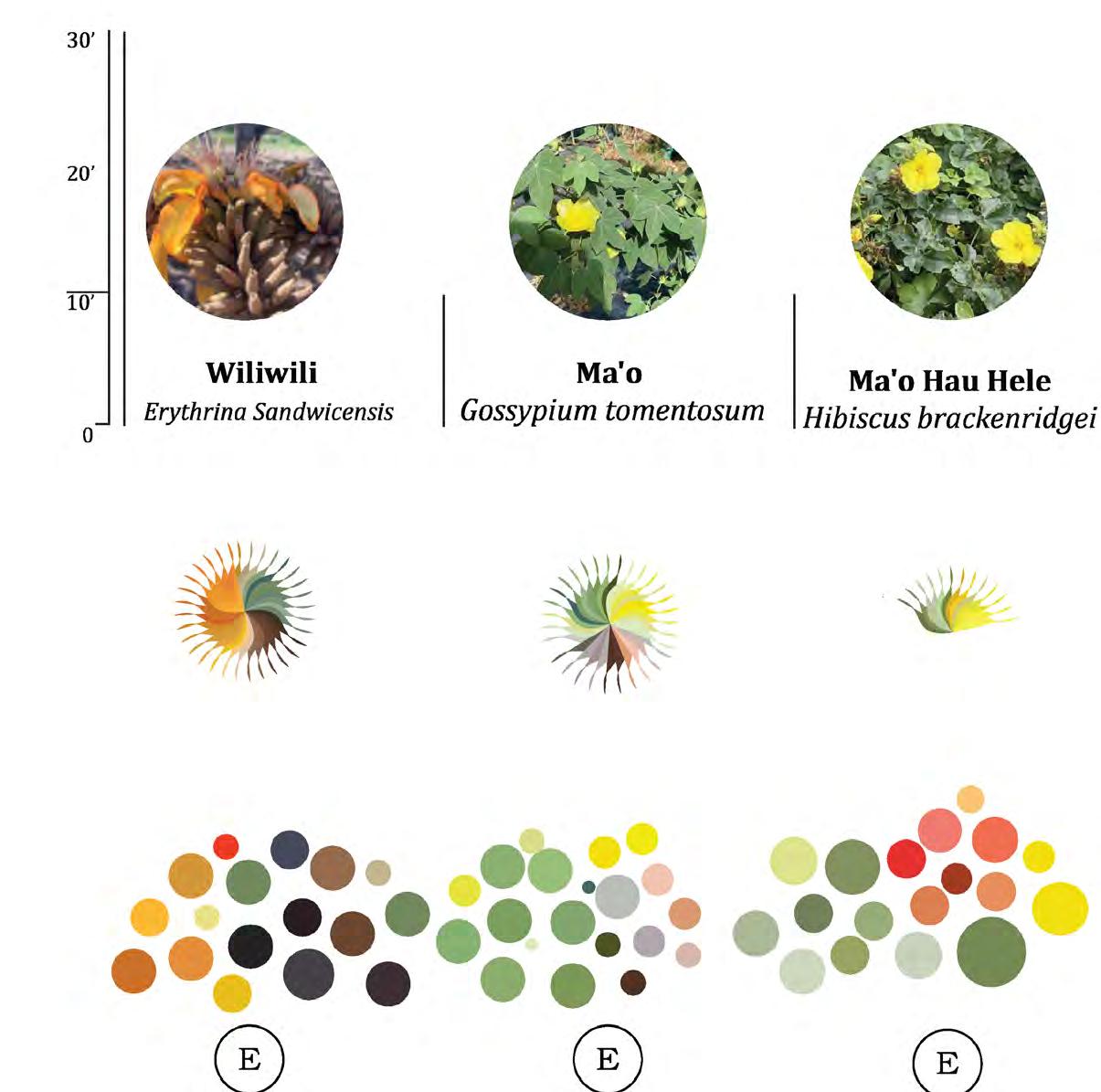

Endemic to Hāmakuā

Fieldwork conducted April 30, 1993

Fan Palm

Pritchardia sp.

ʻAʻaliʻi

Dodonea viscosa

colorful seed capsules were used in lei

Koloa kahoowaensis

one of the top 5 endangered plants in the world

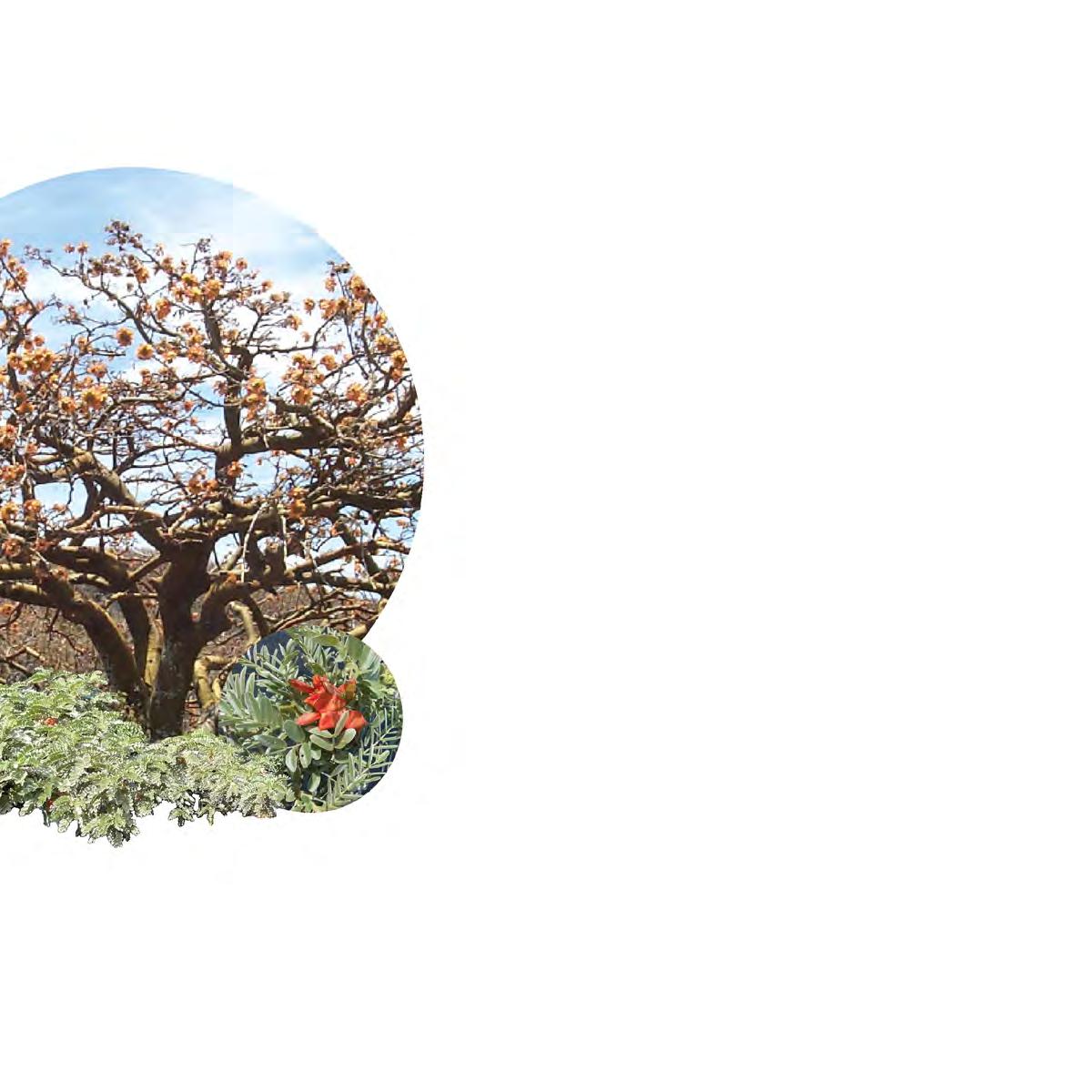

Wili Wili

Erythrina sandwicensis

deciduous attacked in 2005 by gall wasp

2008 biological controls saved the wiliwili

Koa

Acacia koa

prized for beautiful wood

Sestania tomentosa

Federally Listed as Endangered Aweoweo

Chenopodium oahuense

leaves, flowers, and fruit can range from scentless to very distinctly scented, smelling like fish (ʻāweoweo).

Hāmākua Marsh

Hamakua Marsh

Hāmākua Marsh

Kawainui

Marsh

Old Quary

68 ACRES UPLAND

Puu O Ehu

22 ACRES WETLANDS

Old Quary Kawainui

Utility of color in landscape design

Use color to set mood, tone of the project

Concealment: Use colors to blend objects into their surroundings. Using earth tones in a garden to blend structures and paths seamlessly with the natural environment.

Highlighting: use contrasting colors to make objects stand out.

Using a bright accent color on furniture to make it a focal point.

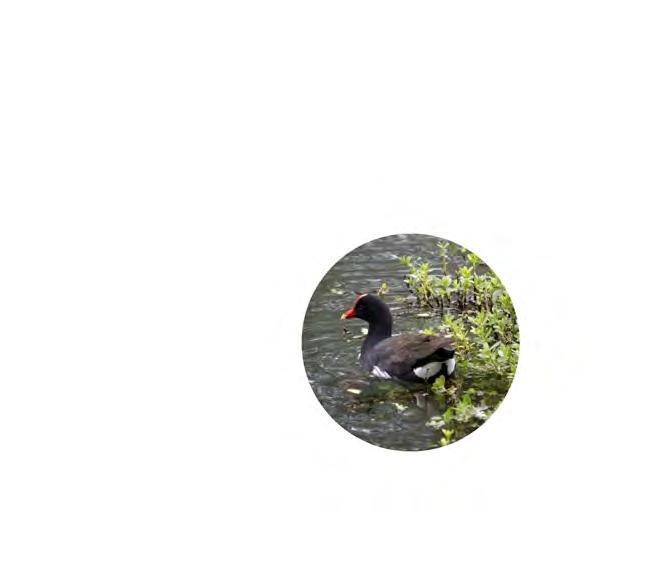

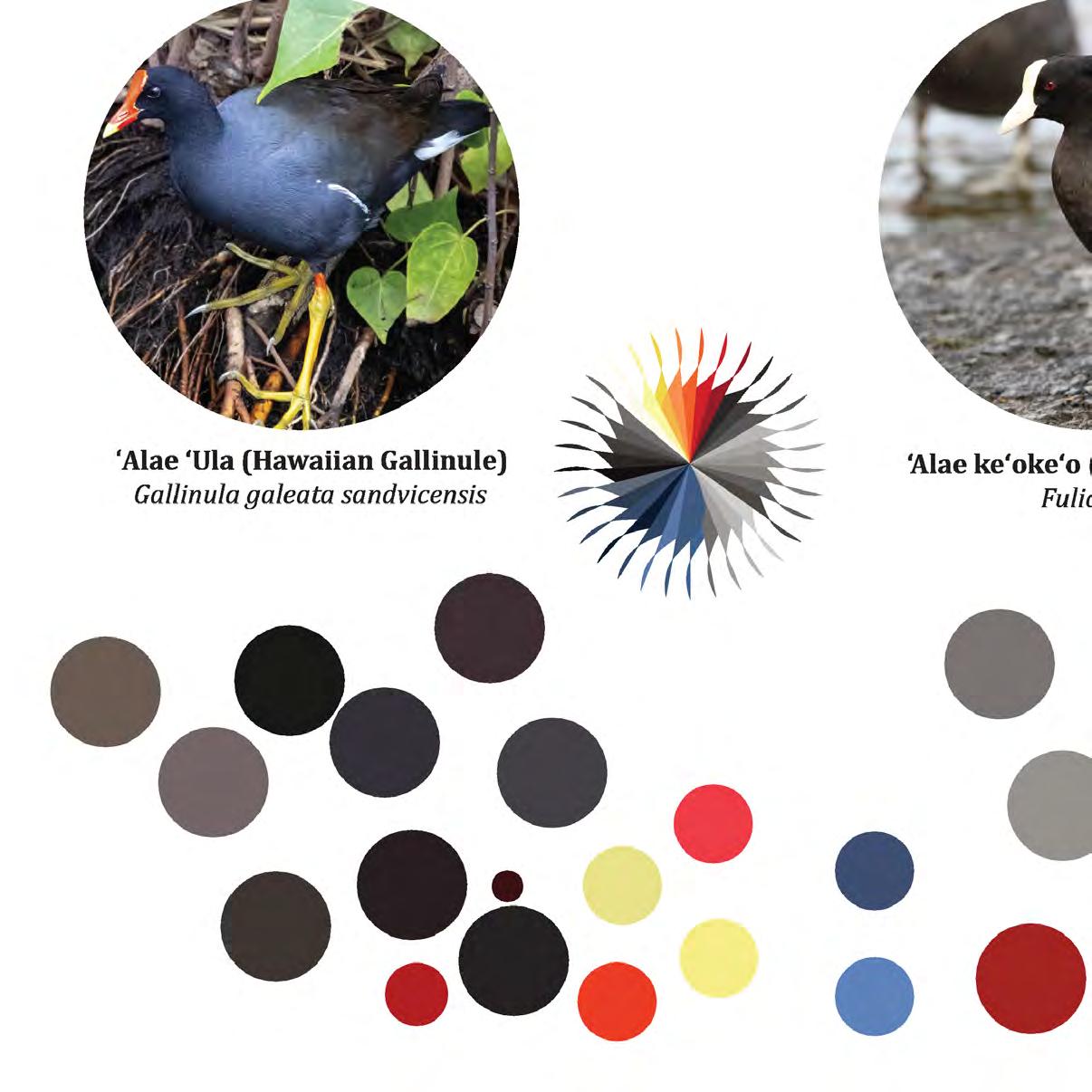

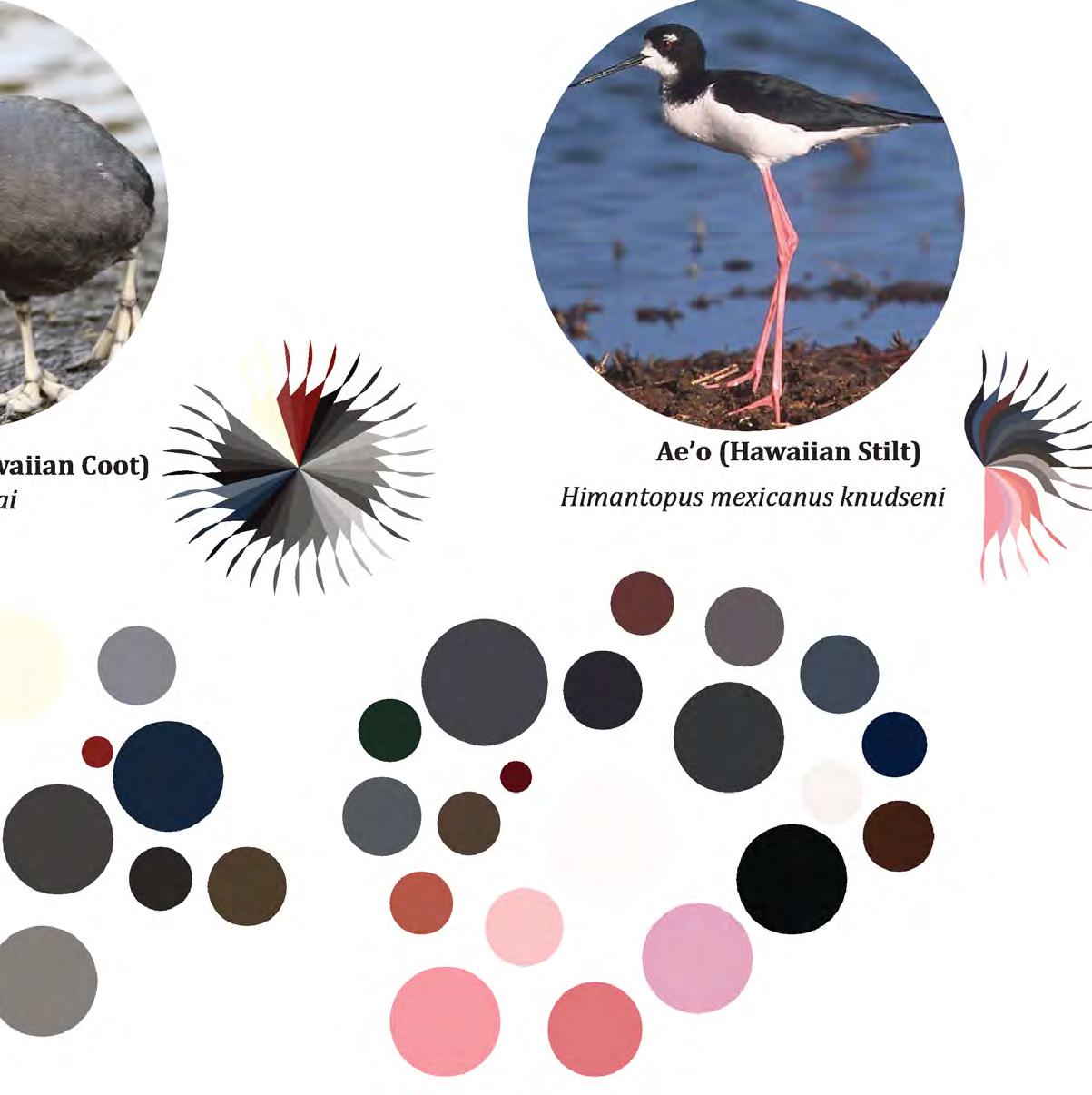

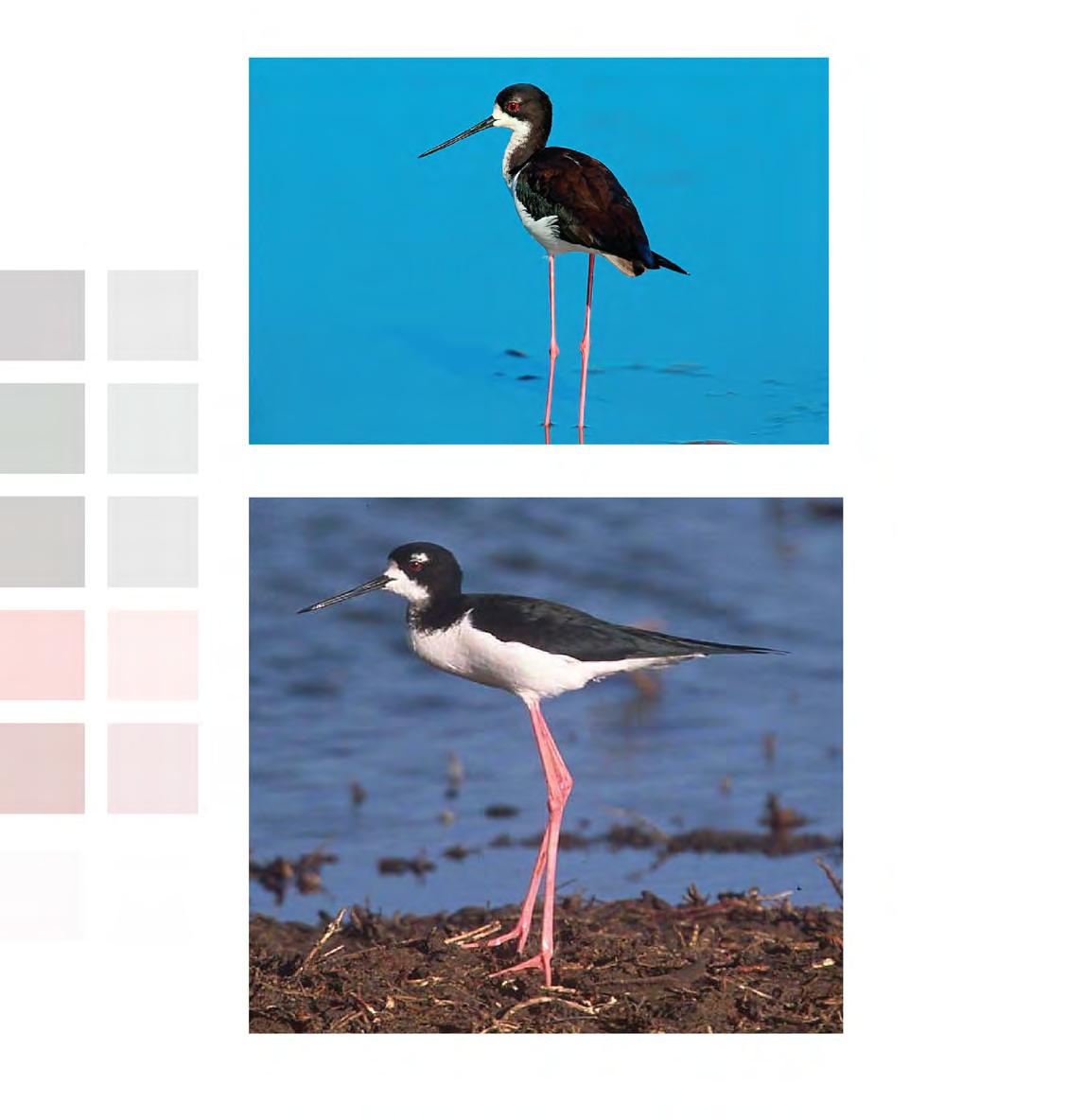

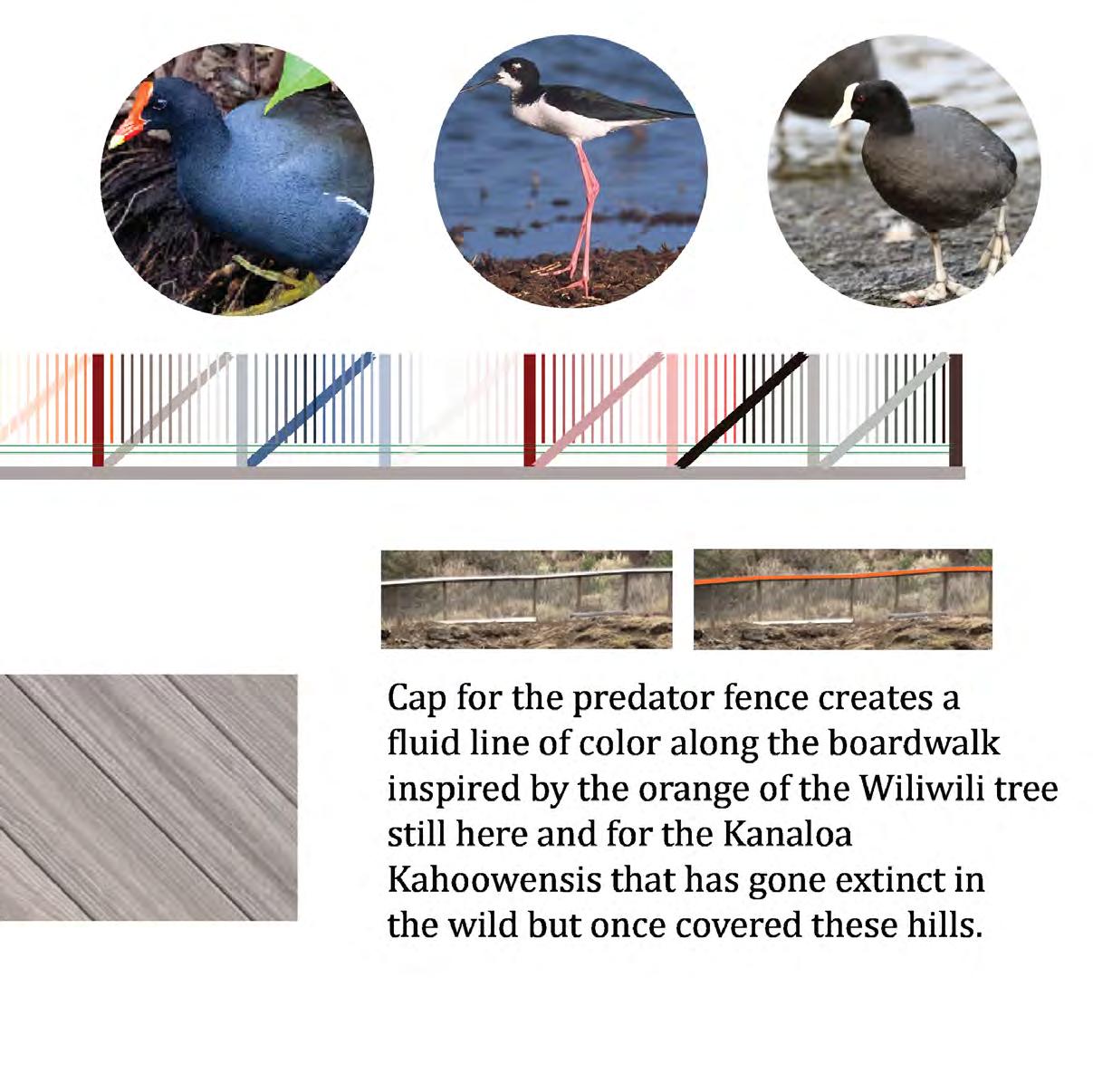

Ae’o (Hawaiian Stilt)

Himantopus mexicanus knudseni

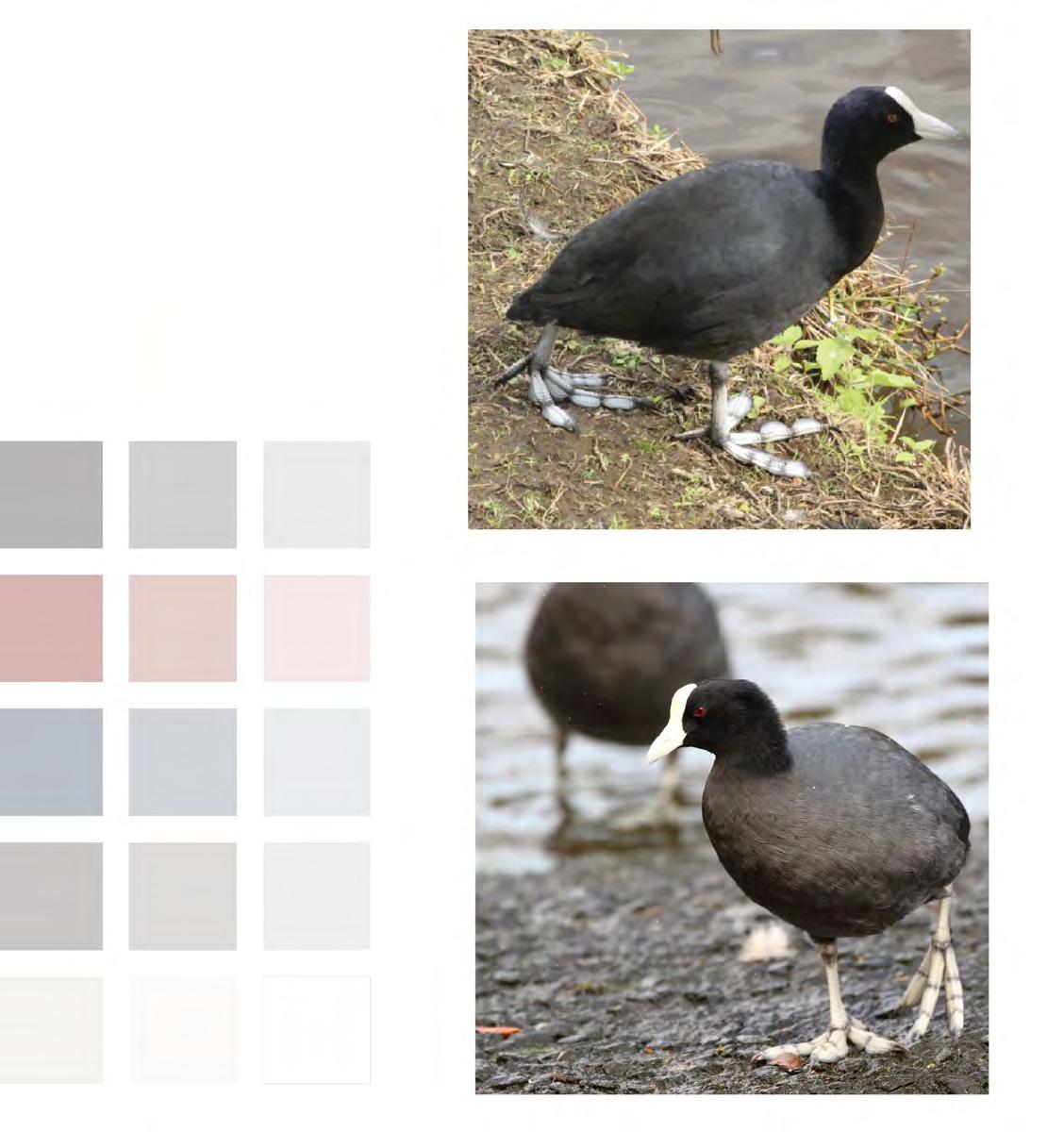

‘Alae ke‘oke‘o (Hawaiian coot)

Fulica alai

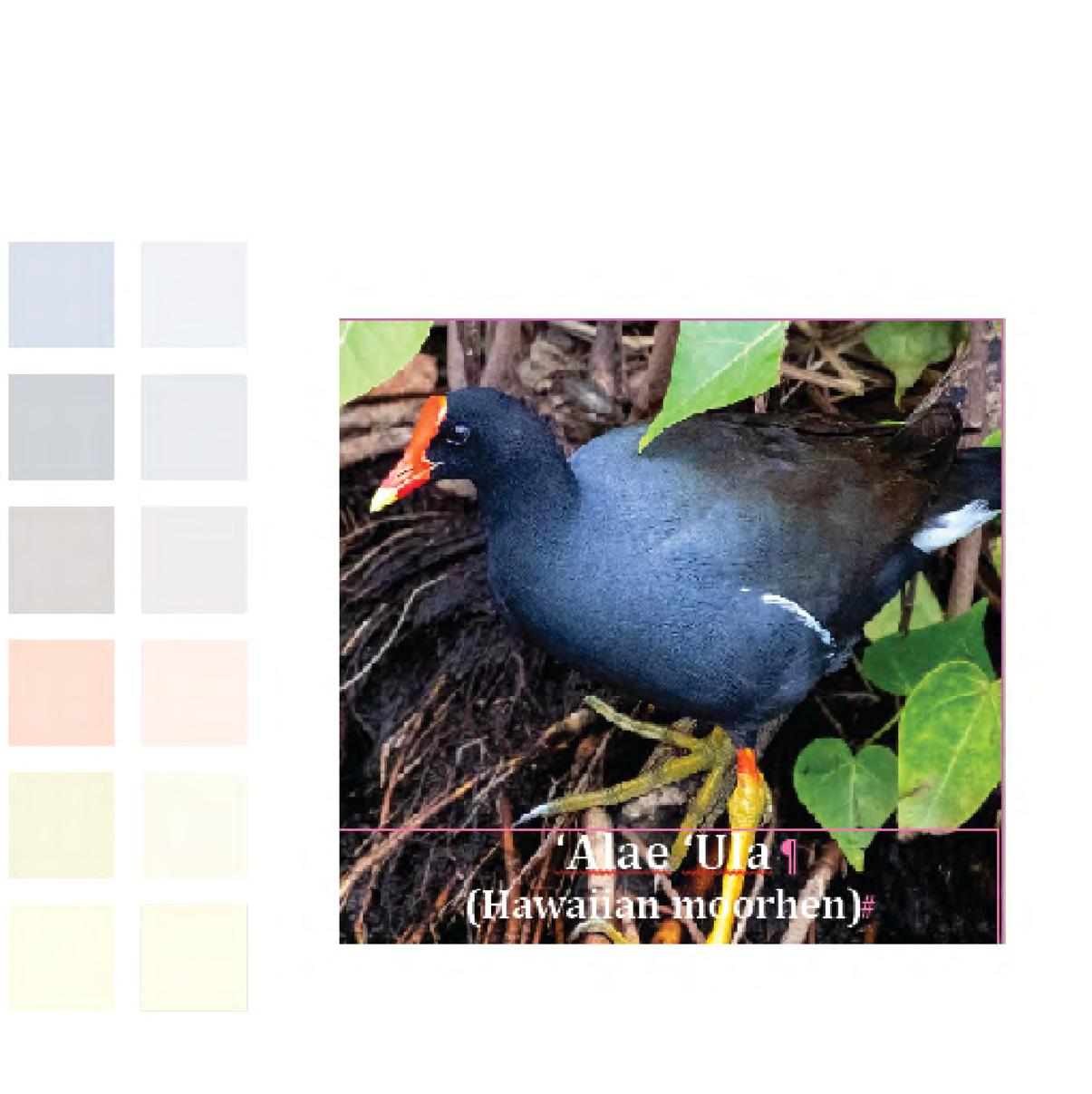

‘Alae ‘Ula (Hawaiian gallinule) Gallinula

galeata sandvicensis

Hamakua Drive Median Planting Pallet

‘Alae ‘Ula Planting Pallet

‘Alae ke‘oke‘o Planting Pallet

Aeʻo Planting Pallet

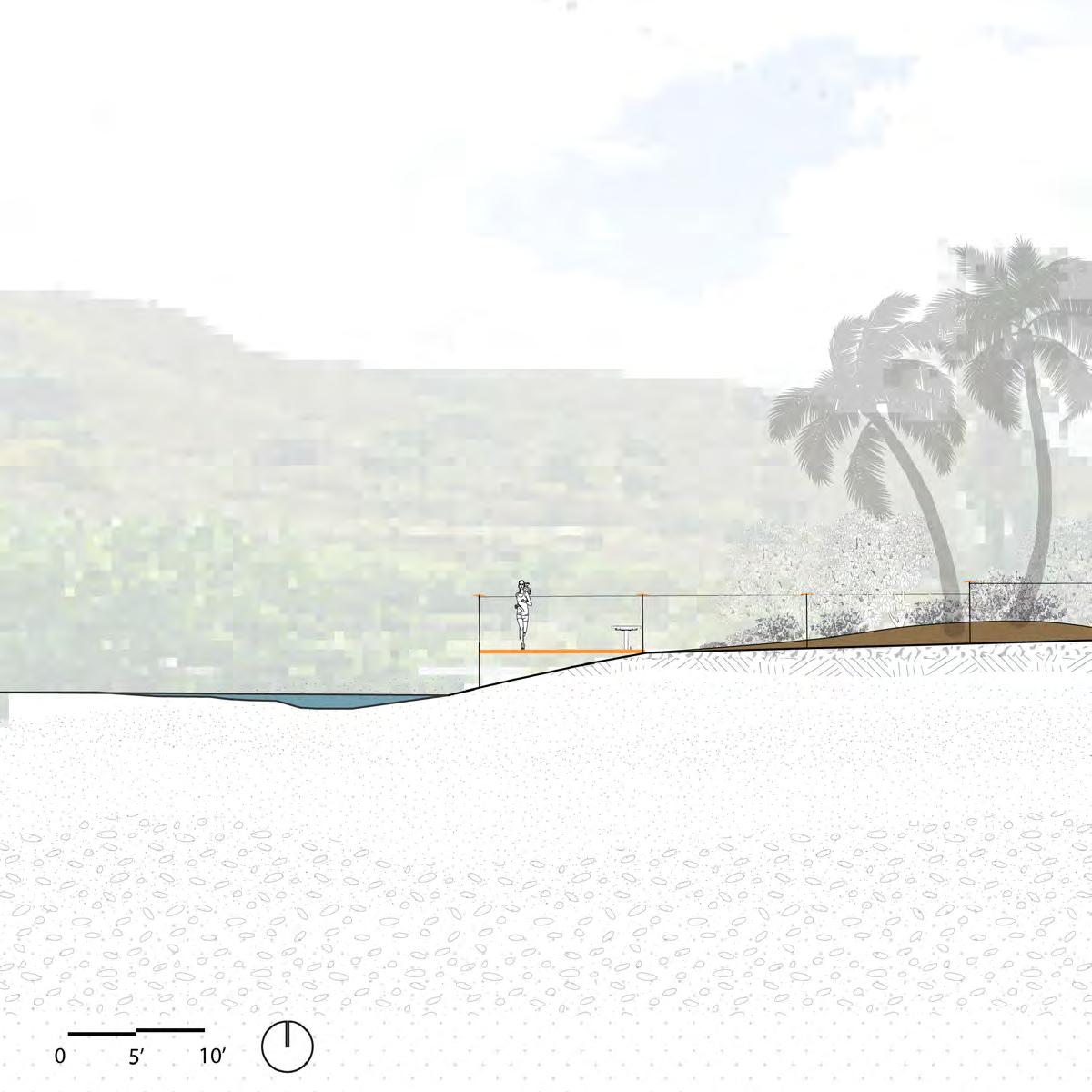

Installation of Preditor Fence

Predator Fence

Installation of multimodal 8’ boardwalk

Businesses orientate to engage with the Marsh

Invasive plants are replaced with endemic and indigenous plants original to the site

Kanaloa kahoolawensis

The lowland shrub was once a dominant species of the lowland forest across all islands. Two remaining plants were discovered on remote cliffs of Kahoolawe which have since died. It is one of the top 5 most threatened spicies in the world. 20 plants exist today because of intensive efforts.

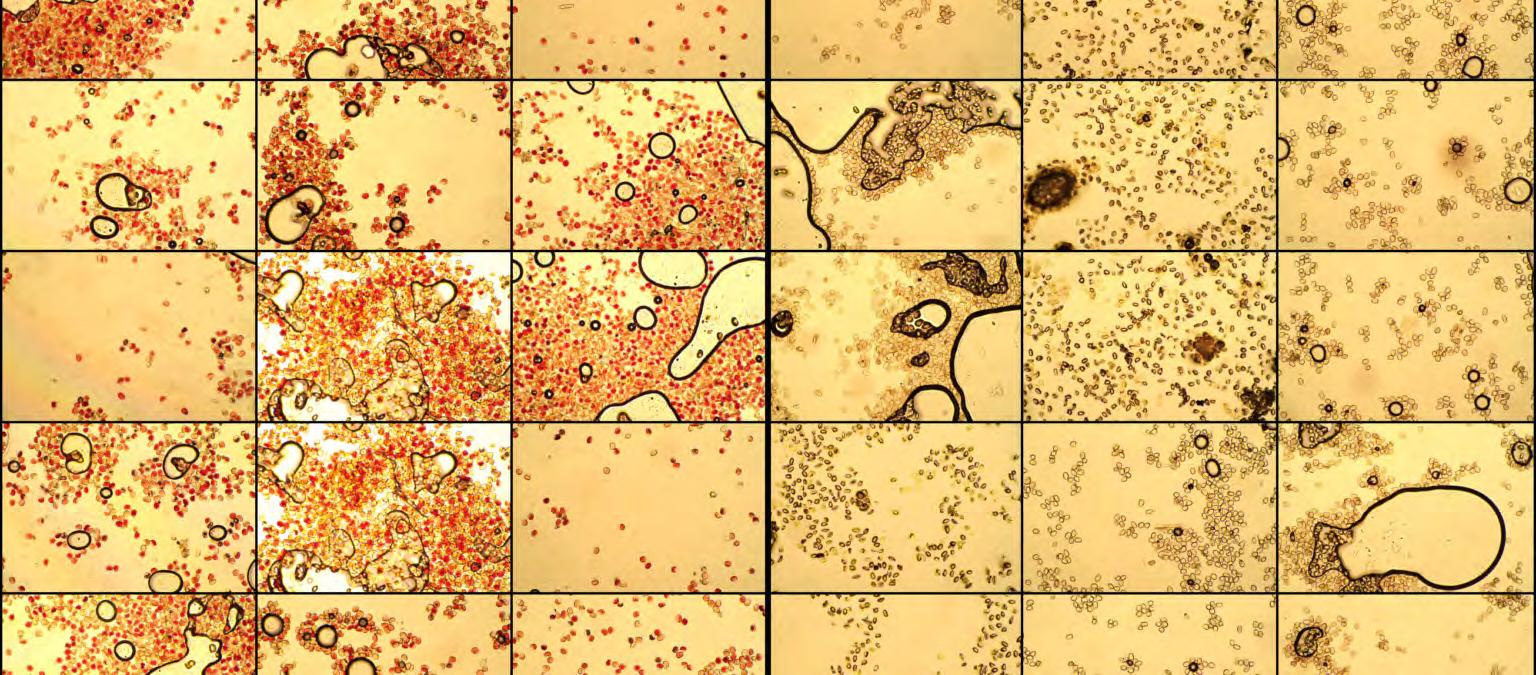

Bottom:Panels representing single microscope views of pollen after oven treatment. Photo by NTBG staff/partners.

Top: Dehydrated Kanaloa Kahoolawensis pollen grain image magnified 8,000 times. Photo by Radha Chaddah.

Conclusion

The Hawaiian islands evolved for over 2 million years without human contact. The Hawaiians established a thriving sustainable society for 800 years. They supported a population in excess of 500,000 and were completely self sustaining. There was a loss of 15% of the native ecosystem.

It has been 247 years since western contact. Since then Hawaii has experienced a loss of 85% of the native ecosystem and become the extinction capital of the world.

It is important to see the endemic and indigenous plants and animals that we have left. To learn their color stories and be vigelant in their cultivation and protection.

Kanaloa kahoolawensis

Ka Palupalu O Kanaloa

Photo: Ken Woods

332 Species of Conservation Importance – Oʻahu

Created August 26, 2024 by Laukahi Network

taxonName

Abutilon menziesii

Abutilon sandwicense

Acacia koa

Acacia koaia

Achyranthes splendens var. rotundata

Adenophorus haalilioanus

Adenophorus periens

Alectryon macrococcus var. macrococcus

Alphitonia ponderosa

Alphitonia ponderosa

Alyxia stellata

Anoectochilus sandvicensis

Antidesma pulvinatum

Asplenium dielerectum

Asplenium dielfalcatum

Asplenium unisorum

Astelia menziesiana

Athyrium microphyllum

Bidens amplectens

Bidens campylotheca subsp. campylotheca

Bidens cervicata

Bidens molokaiensis

Bidens populifolia

Bobea brevipes

Bobea elatior

Bobea sandwicensis

Bobea timonioides

Bobea timonioides

Boehmeria grandis

Bonamia menziesii

Bonamia menziesii

Capparis sandwichiana

Carex alligata

Cenchrus agrimonioides var. agrimonioides

Charpentiera obovata

Charpentiera ovata var. niuensis

Charpentiera tomentosa var. maakuaensis

Cheirodendron platyphyllum subsp. platyphyllum

Cheirodendron trigynum subsp. trigynum

Chrysodracon forbesii

Chrysodracon halapepe

Cibotium chamissoi

Cibotium glaucum

Cladium jamaicense

Claoxylon sandwicense

Clermontia fauriei

Clermontia persicifolia

Colubrina oppositifolia

Coprosma ochracea

Cryptocarya mannii

Cryptocarya oahuensis

Ctenitis squamigera

Cyanea acuminata

Cyanea calycina

Cyanea crispa

Cyanea grimesiana subsp. grimesiana

Cyanea grimesiana subsp. obatae

Cyanea humboldtiana

Cyanea konahuanuiensis

Cyanea koolauensis

Cyanea lanceolata

Cyanea longiflora

Cyanea membranacea

Cyanea pinnatifida

Cyanea purpurellifolia

Cyanea sessilifolia

Cyanea st-johnii

Cyanea superba subsp. regina

Cyanea superba subsp. superba

Cyanea truncata

Cyclosorus boydiae

Cyclosorus interruptus

Cyperus laevigatus

Cyperus pennatiformis subsp. pennatiformis

Cyperus trachysanthos

Cyrtandra crenata

Cyrtandra dentata

Cyrtandra gracilis

Cyrtandra polyantha

Cyrtandra rivularis

Cyrtandra sandwicensis

Cyrtandra sessilis

Cyrtandra subumbellata

Cyrtandra viridiflora

Cyrtandra waiolani

Cystopteris sandwicensis

Delissea subcordata subsp. obtusifolia

Delissea subcordata subsp. subcordata

Delissea takeuchii

Delissea waianaeensis

Dianella sandwicensis

Dicranopteris linearis

Diospyros hillebrandii

Diospyros sandwicensis

Diplazium molokaiense

Diplazium sandwichianum

Dissochondrus biflorus

Dodonaea viscosa

Doodia lyonii

Doryopteris takeuchii

Dubautia herbstobatae

Dubautia sherffiana

Elaeocarpus bifidus

Embelia pacifica

Eragrostis fosbergii

Eragrostis variabilis

Erythrina sandwicensis

Eugenia koolauensis

Euphorbia arnottiana

Euphorbia celastroides var. kaenana

Euphorbia clusiifolia

Euphorbia deppeana

Euphorbia haeleeleana

Euphorbia herbstii

Euphorbia kuwaleana

Euphorbia rockii

Euphorbia skottsbergii var. skottsbergii

Eurya sandwicensis

Eurya sandwicensis

Exocarpos gaudichaudii

Flueggea neowawraea

Freycinetia arborea

Gahnia aspera subsp. globosa

Gardenia brighamii

Gardenia mannii

Gossypium tomentosum

Gouania meyenii

Gouania vitifolia

Gynochthodes trimera

Heliotropium anomalum var. argenteum

Heliotropium curassavicum

Hesperomannia arborescens

Hesperomannia oahuensis

Hesperomannia swezeyi

Heteropogon contortus

Hibiscus arnottianus subsp. arnottianus

Hibiscus arnottianus subsp. punaluuensis

Hibiscus brackenridgei subsp. mokuleianus

Hibiscus kokio subsp. kokio

Hibiscus kokio subsp. kokio

Hibiscus tiliaceus

Hillebrandia sandwicensis

Huperzia nutans

Hydrangea arguta

Ilex anomala

Ipomoea tuboides

Isachne distichophylla

Ischaemum byrone

Isodendrion laurifolium

Isodendrion laurifolium

Isodendrion longifolium

Isodendrion longifolium

Isodendrion pyrifolium

Jacquemontia sandwicensis

Joinvillea ascendens subsp. ascendens

Joinvillea ascendens subsp. ascendens

Kadua affinis

Kadua coriacea

Kadua degeneri subsp. coprosmifolia

Kadua degeneri subsp. degeneri

Kadua elatior

Kadua fluviatilis

Kadua littoralis

Kadua parvula

Korthalsella degeneri

Labordia cyrtandrae

Labordia hosakana

Labordia kaalae

Lepidium arbuscula

Lepidium bidentatum var. owaihiense

Leptecophylla tameiameiae

Lindsaea repens var. macraeana

Liparis hawaiensis

Liparis hawaiensis

Lipochaeta remyi

Lipochaeta tenuifolia

Lipochaeta tenuis

Lobelia gaudichaudii

Lobelia koolauensis

Lobelia monostachya

Lobelia niihauensis

Lobelia oahuensis

Lysimachia filifolia

Machaerina angustifolia

Marsilea villosa

Melicope christophersenii

Melicope cinerea

Melicope clusiifolia

Melicope cornuta var. decurrens

Melicope hiiakae

Melicope kaalaensis

Melicope lydgatei

Melicope makahae

Melicope pallida

Melicope saint-johnii

Melicope sandwicensis

Melicope spathulata

Melicope wawraeana

Metrosideros macropus

Metrosideros polymorpha var. glaberrima

Metrosideros polymorpha var. incana

Metrosideros polymorpha var. polymorpha

Metrosideros polymorpha var. pumila

Metrosideros rugosa

Metrosideros tremuloides

Mezoneuron kavaiense

Microsorum spectrum var. spectrum

Myoporum stellatum

Myrsine degeneri

Myrsine fosbergii

Myrsine juddii

Myrsine lessertiana

Myrsine punctata

Myrsine punctata

Myrsine sandwicensis

Nama sandwicensis

Neraudia angulata var. angulata

Neraudia angulata var. dentata

Neraudia melastomifolia

Nestegis sandwicensis

Nothocestrum latifolium

Nothocestrum latifolium

Nothocestrum longifolium

Nototrichium humile

Ochrosia compta

Oreobolus furcatus

Osteomeles anthyllidifolia

Pandanus tectorius

Panicum fauriei var. carteri

Peperomia membranacea

Peperomia oahuensis

Perrottetia sandwicensis

Peucedanum sandwicense

Peucedanum sandwicense

Phyllostegia glabra var. glabra

Phyllostegia hirsuta

Phyllostegia kaalaensis

Phyllostegia mollis

Phyllostegia parviflora var. lydgatei

Phyllostegia parviflora var. parviflora

Phytolacca sandwicensis

Pipturus albidus

Pisonia sandwicensis

Pisonia umbellifera

Planchonella sandwicensis

Plantago princeps var. anomala

Plantago princeps var. longibracteata

Plantago princeps var. princeps

Platanthera holochila

Polyscias gymnocarpa

Polyscias kavaiensis

Polyscias lydgatei

Polyscias oahuensis

Polyscias sandwicensis

Portulaca villosa

Pritchardia bakeri

Pritchardia kaalae

Pritchardia kahukuensis

Pritchardia martii

Pseudognaphalium sandwicensium var. molokaiense

Psychotria fauriei

Psydrax odorata

Pteralyxia macrocarpa

Pteris lidgatei

Ranunculus mauiensis

Rauvolfia sandwicensis

Rhynchospora chinensis subsp.

spiciformis

Sadleria cyatheoides

Sanicula mariversa

Sanicula purpurea

Santalum ellipticum

Santalum freycinetianum

Santalum haleakalae var. haleakalae

Sapindus oahuensis

Scaevola coriacea

Scaevola glabra

Scaevola taccada

Schenkia sebaeoides

Schiedea adamantis

Schiedea globosa

Schiedea hookeri

Schiedea kaalae

Schiedea kealiae

Schiedea ligustrina

Schiedea mannii

Schiedea nuttallii

Schiedea obovata

Schiedea pentandra

Schiedea trinervis

Schoenoplectus tabernaemontani

Sesbania tomentosa

Sesuvium portulacastrum

Sicyos lanceoloideus

Sicyos waimanaloensis

Sida fallax

Sideroxylon polynesicum

Silene lanceolata

Silene perlmanii

Smilax melastomifolia

Solanum americanum

Solanum nelsonii

Solanum sandwicense

Sophora chrysophylla

Spermolepis hawaiiensis

Spermolepis hawaiiensis

Sporobolus virginicus

Stenogyne kaalae subsp. kaalae

Stenogyne kaalae subsp. sherffii

Stenogyne kanehoana

Streblus pendulinus

Strongylodon ruber

Strongylodon ruber

Syzygium sandwicense

Tetramolopium filiforme var. filiforme

Tetramolopium filiforme var. polyphyllum

Tetramolopium lepidotum subsp. lepidotum

Touchardia latifolia

Trematolobelia singularis

Urera glabra

Urera kaalae

Vaccinium calycinum

Vaccinium reticulatum

Vigna owahuensis

Viola chamissoniana subsp. chamissoniana

Viola kauaensis var. hosakae

Viola kauaensis var. kauaensis

Viola oahuensis

Wikstroemia oahuensis var. oahuensis

Xylosma hawaiense

Zanthoxylum dipetalum var. dipetalum

Zanthoxylum kauaense

Zanthoxylum oahuense

Bibliography

Anderson-Fung, Puanani O. “Hawaiian Ecosystems and Culture,” n.d. Baker, Tawrin, Sven Dupré, Sachiko Kusukawa, Karin Leonhard, Sachiko Kusukawa, Karin Leonhard, Tawrin Baker, and Sven Dupré. Early Modern Color Worlds. 1st ed. Boston: BRILL, 2015.

E. S. Handy, Elizabeth Green Handy, and Mary Kawena Pukui. Native Planters in Old Hawaii: Their Life, Lore, and Environment. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin. Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press, 1972.

Earth@Home. “Geologic History of Hawaiʻi.” Accessed January 26, 2025. https://earthathome.org/hoe/hi/geologic-history/.

Engler, Mira. Landscape Design in Color : History, Theory, and Practice 1750 to Today. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2023.

Garcia, Shirley Naomi Kanani. “MASTER OF ARTS IN GEOGRAPHY DECEMBER 2002,” n.d. “Hawaiian Native Plants, UH Botany.” Accessed September 21, 2024. http://www.botany. hawaii.edu/faculty/carr/natives.htm.

Holtzschue, Linda. Understanding Color : An Introduction for Designers. Understanding Color : An Introduction for Designers. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995. Images of Old Hawaiʻi. “Kawainui Marsh,” May 25, 2019. https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/ kawainui-marsh-kailua-oahu/.

Kobayashi, Shigenobu. Color Image Scale. Color Image Scale. 1st ed. Tokyo ; Kosdansha International, 1991.

Kobayashi, Shigenobu, and Nihon Karā Dezain Kenkyūjo. Book of Colors : Matching Colors, Combining Colors, Color Designing, Color Decorating. Book of Colors : Matching Colors, Combining Colors, Color Designing, Color Decorating. Tokyo ; Kodansha International, 1987. Krauss, Beatrice H. Plants in Hawaiian Culture. Plants in Hawaiian Culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1993.

McDonald, Marie A., and Paul R. Weissich. N⁻a Lei Makamae : The Treasured Lei. N⁻a Lei Makamae : The Treasured Lei. A Latitude 20 Book. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2003.

Meilleur, Brien A. “Hawaiian Seascapes and Landscapes: Reconstructing Elements of a Polynesian Ecological Knowledge System.” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 128, no. 3 (2019): 305–36.

———. “Hawaiian Seascapes and Landscapes: Reconstructing Elements of a Polynesian Ecological Knowledge System.” Journal of the Polynesian Society 128, no. 3 (September 2019): 305–36. https://doi.org/10.15286/jps.128.3.305-336.

M.Pharm, HH Patel. “Anatomy of the Human Eye.” News-Medical, September 24, 2018. https://www.news-medical.net/health/Anatomy-of-the-Human-Eye.aspx. Oudolf, Piet. Designing with Plants. Portland, Or: Timber Press, 1999.

Sherrod, David R, John M Sinton, Sarah E Watkins, and Kelly M Brunt. “Geologic Map of the State of Hawai‘i—Islands of Ni‘ihau and Kaua‘i,” n.d.

“The Color Eye: Coloring the Landscape - Video - Films On Demand.” Accessed May 24, 2024. https://fod-infobase-com.eres.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/p_ViewVideo.aspx?xtid=185604.

“The Science of Color.” Exhibition, 2015. https://library.si.edu/exhibition/color-in-anew-light/science.

“TNC_Geospatial_Annual_Report_2023.Pdf | Powered by Box.” Accessed February 3, 2025. https://tnc.app.box.com/s/kgro5kyigrtei1tkk60sah1oxm2gx2a0.

Yu, Beichen. “Understanding New Colors in Urban Environments: Deciphering Colors as Semiotic Resources.” Color Research & Application 48, no. 5 (September 2023): 567–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.22871.

Zarzycki, Lili. “Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994).” The Architectural Review (blog), February 3, 2021. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/reputations/roberto-burle-marx-1909-1994.

Zhang, Longlong, and Chulsoo Kim. “Chromatics in Urban Landscapes: Integrating Interactive Genetic Algorithms for Sustainable Color Design in Marine Cities.” Applied Sciences 13, no. 18 (September 14, 2023): 10306. https://doi.org/10.3390/ app131810306.