A REJUVENATION CURE?

Inventing Yogya Silver, Saving a Perishing Javanese Industry

Marjolein van Asdonck

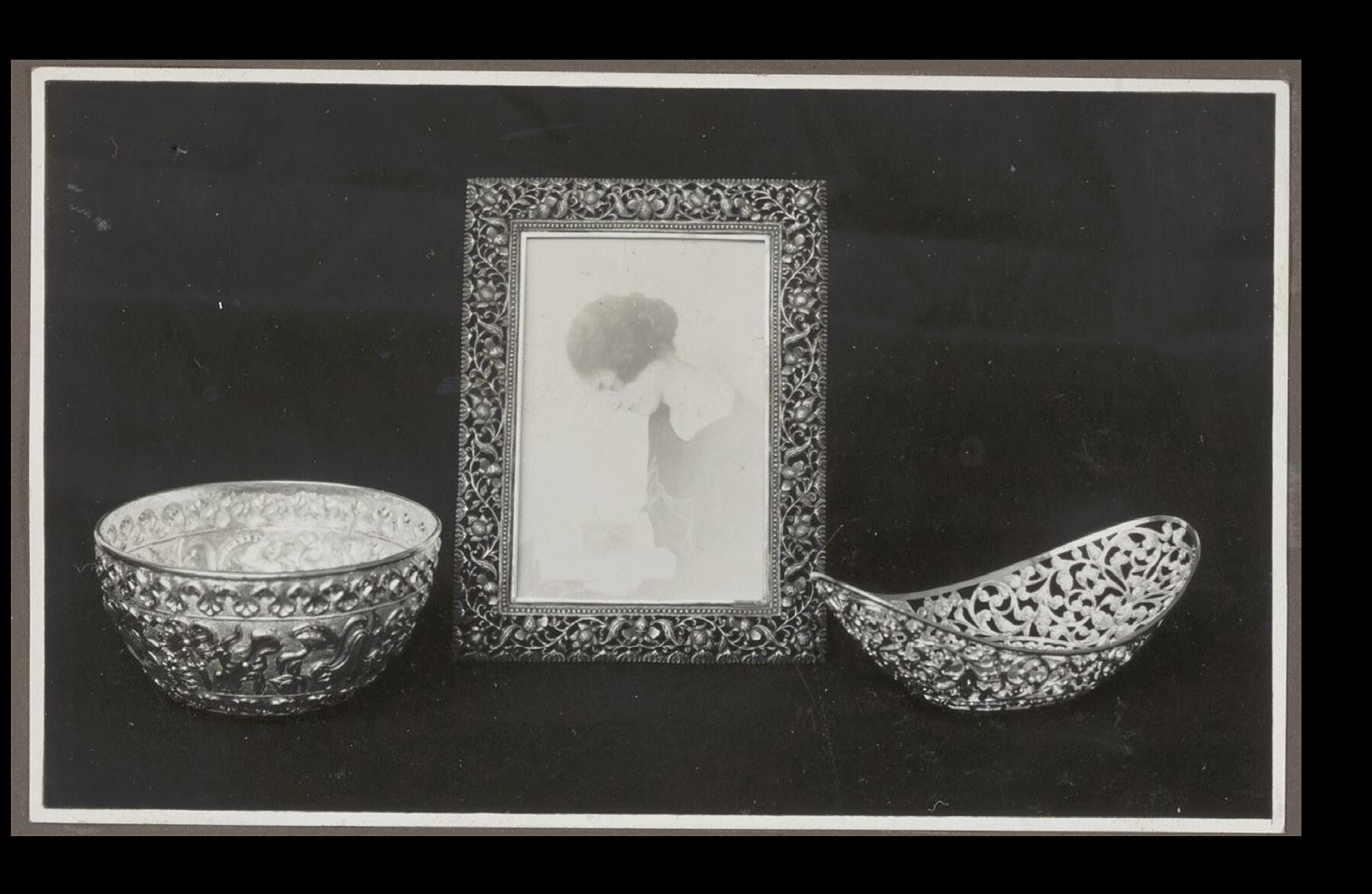

FIGURE 1

Silver objects for sale at the shop of Pakarjan Ngajogijakarta. Wereldmuseum Collectie TM-ALB-1986-12.

In the 1930s, so-called Yogya silver became a 'rejuvenated' craft by Mrs. Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall. In close collaboration with the Archaeological services, Mrs. Van Gesseler VerschuirPownall would select 'authentic' motifs, after which she would commission silversmiths to produce these objects for a European market. Van Asdonck looks at the causes of the 'decline' of the silversmith industry in Java, and the violent nature of the Ethical Policy in the field of arts and crafts. Rather than understanding Yogya Silver as a revival, Van Asdonck understands it as an invented practice of erasure in the context of colonial and imperial relations.

But there is one great danger for that industry: that it will lose its own character, either by languishing or by transforming itself into a European spirit. In the first case, giving up the fight against Europe as a powerful competitor; or in the second case, seemingly saving itself, but in fact just as likely perishing.1

This was written by Gerret Pieter Rouffaer (1860-1928), an ethnographer from Leiden, in 1901 in De Indische Gids about Indonesian arts and crafts. Rouffaer was not the only one within the colonial milieu who was concerned about the supposedly ‘languishing’ Indonesian arts and crafts.2 That is why his plea in which he, in the footsteps of parliamentarian Conrad Theodor van Deventer (1857-1915) in 1899, spoke of a ‘debt of honour’3 towards Indonesian ‘art and crafts products’,4 was widely heard within the government. Rouffaer applied the ‘Ethical Policy’5 to the arts.6 As he wrote: ‘Our knowledge of the Indisch industry and art must promote the prosperity of the natives’.7 Rouffaer stated that one of the ways to save the ‘perishing’ Indonesian industry, was that the colonial government had to methodically and professionally inquire into ‘means to promote that industry’ and ‘carefully preserve, possibly strengthen the artistry that was alive.’8

This article examines which means the colonial government used to ‘promote’ Indonesian arts and crafts, how ‘preservation’ and ‘strengthening’ took place, and how the colonial government used a concept such as ‘authenticity’ to support a colonial narrative. Using the collection of the Wereldmuseum, I look at the practice of so-called Yogya silver and how we should understand it within the context of the substitution of existing practices, colonial social relations and imperialist violence and expansion.

‘Innate Decorative Arts’

The colonial regime used various methods to promote Indonesian arts and crafts. Societies and institutions were established, but also (sales) exhibitions were organised. Additionally, attempts were made to establish craft schools for Indigenous Indonesians (ambachtssonderwijs), previously only accessible for Indo-Europeans, in the hope of promoting an Indonesian craft and industrial industry.9 Rouffaer also urged for a ‘technical study’ of these arts and crafts.10

1 G. P. Rouffaer, ‘De noodzakelijkheid van een technisch-artistiek onderzoek in Ned.-Indië’, in: De Indische Gids 23:2 (1901), p. 1201.

2 In his article in 1901, Rouffaer uses the words Indonesisch, Indisch, inlandsch and inheemsch alternately in this context. While Indonesisch, inlandsch, inheemsch all refer to indigenous Indonesians, the meaning of the colonial term ‘Indisch’ is more ambiguous. It evolved from denoting Indonesians in the 19th century to refer mostly to Indo-Europeans in the 20th century, or occasionally to a European who had lived for a long time in ‘the Indies’. See: Words that Matter: An Unfinished Guide to Word Choices in the Cultural Sector, p. 118, accessed through: https://amsterdam. wereldmuseum.nl/en/about-wereldmuseum-amsterdam/ research/words-matter-publication. I will use the word Indonesian in this article unless I am quoting.

3 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1201.

4 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1205.

5 E. Locher-Scholten, Ethiek in fragmenten. Vijf studies over koloniaal denken en doen van Nederlanders in de Indonesische Archipel, 1877-1942. Leiden: Hes & de Graaf Publishers, 1981, p. 194.

6 B. Waaldijk and S. Legêne, ‘Oktober 1901. Gerret Rouffaer constateert een artistieke ereschuld. Vernieuwing van de beeldende kunsten in een koloniale context 2001-1901’, in: Rosemarie Buikema en Maaike Meijer (eds), Cultuur en Migratie in Nederland. Kunsten in beweging 1900-1980. Den Haag: Sdu uitgevers, 2003, p. 19.

7 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1207. See also footnote 2 for an explanation about the term Indisch

8 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1202.

9 H. Laloli, Technisch onderwijs en sociaalekonomische verandering in Nederlands-Indië en Indonesië, 1900-1958 [Scriptie Vakgroep Economische en sociale geschiedenis Universiteit van Amsterdam, 1994], pp. 20-21.

10 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1201.

According to Rouffaer, the civil servants charged with this task should possess the knowledge and expertise ‘to perceive the technical, and understand and recognise the beautiful in order to bring it to light with joy as a precious treasure among the natives’.11 This characterisation and appreciation of Indonesian arts and crafts as a ‘precious treasure’ began to gain more ground in the Netherlands during this period due to the growing popularity of the European Arts and Crafts movement, which had a great interest in arts and crafts in general and – certainly within the Netherlands – Indonesian arts and crafts in particular.12 Rouffaer therefore criticised the fact that arts and crafts from the Dutch East Indies had until then only been viewed with an ethnographic perspective and was not considered art.13

In the inventories colonial civil servants were supposed to select Indonesian arts and crafts that were ‘authentic’ and traditional; they had to register the ‘superiority of true Indisch production’.14 Forms of modernisation, initiated from the second half of the nineteenth century to respond to European demand, or inspired by European influences in the archipelago, were dismissed by Rouffaer as ‘bastard products’.15 As historians Waaldijk and Legêne demonstrate, colonial racial prejudices played a role in the debate on arts and crafts.16 With his specific choice of words, Rouffaer touched on the colonial fear of ‘racial degeneration’, in which ‘metissage (interracial relationships)’ – in colonial Indonesia referred to as ‘verindischen’ (to become Indisch) – ‘represented the paramount danger to racial purity and cultural identity in all its forms.’17 According to Rouffaer, the Indische market had to be ‘purified of bad taste’ above all and return to ‘innate decorative art’.18 In this way, Rouffaer followed prevailing ethnological theories in which authentic ‘primordial cultures’ were continuously under threat of modernism.19

Anthropologist and former Tropenmuseum curator Pienke Kal, like other authors, points out in Yogya Silver: Renewal of a Javanese Handicraft the ambiguity that was used around the concept of authenticity when it came to Indonesian arts and crafts.20 For example, the incorporation of European motifs in batik was detested by Gerret Rouffaer, or simply not included in ethnographic inventories by government official J.E. Jasper. However, floral motifs that were ‘freely’ drawn after the ones found in the Mantingan mosque were considered ‘authentic’ and applied onto European products, such as silver tableware. The making of European products such as tablecloths and pillowcases in traditional batik, was permitted in order to ‘find another market for arts and crafts products.’21

One of the best-known government officials who was involved in inventorising arts and crafts ‘on behalf of the government’22 was Johan Ernst Jasper (1874-1945), briefly mentioned above. Together with the Javanese artist Mas Pirngadi (1875-1936), he carried out a ‘technical-artistic’ study of Indonesian

11 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1202.

12 Waaldijk and S. Legêne 2003, pp. 24-25

13 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1204

14 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1208.

15 Rouffaer 1901, p. 1205.

16 Waaldijk and Legêne 2003, p. 30.

17 A. L. Stoler, ‘Making Empire Respectable: The Politics of Race and Sexual Morality in 20th-Century Colonial Cultures’, in: American Ethnologist 16:4, 1989, pp. 634-60, p. 647.

18 Rouffaer, p. 1207 and p. 1195.

19 A. Geurds and L. van Broekhoven (eds.), Creating authenticity. Authentication Processes in Ethnographic Museums, Sidestone Press/Mededelingen van het Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde no. 42, p. 4; M. Rössler, ‘Die deutschsprachige Ethnologie bis ca. 1960. Ein historischer Abriss’. Department of Cultural and Social Anthropology, University of

Cologne, 2007, p. 13. Via: M. Shatanawi, Making and unmaking Indonesian Islam: Legacies of colonialism in museums, 2022, PhD dissertation, University of Amsterdam, p. 32.

20 P. Kal, Yogya Silver: Renewal of a Javanese Handicraft, KIT Publishers, 2005; A. Geurds and L. van Broekhoven (eds) 2013.

21 J.E. Jasper and Mas Pirngadi, De Inlandsche nijverheid in Nederlandsch-Indië. IV: De goud- en zilversmeedkunst, Mouton & Co,1927, p. 12.

22 As can be read on the title page of the series. J. E. Jasper and Mas Pirngadi, De Inlandsche nijverheid in Nederlandsch-Indië. I: Het vlechtwerk, 1912; II: Weefkunst, 1912; III: De batikkunst, 1916; IV De goud- en zilversmeedkunst, 1927; V: De bewerking van niet-edele metalen (koperbewerking en pamorsmeedkunst), 1930.

arts and crafts between 1912 and 1930. It resulted in a five-part series of publications in which techniques, types and kinds of wickerwork, weaving, batik art, gold and silversmithing and the working of non-precious metals were recorded and depicted; as if they were sample books of prototypes. Each book included numerous illustrations drawn by Mas Pirngadi. Jasper and Pirngadi's publications are still considered standard works by academics and museum curators studying the field of Indonesian craftsmanship.

2

Screenshot taken from:

J. E. Jasper and Mas Pirngadi, De Inlandsche nijverheid in Nederlandsch-Indië IV De goud- en zilversmeedkunst, 1927, p. 228.

In Jasper's working method we can recognise the paternalistic framework of the Ethical Policy, which allowed for colonial officials to dictate what was and what was not considered 'authentic' Indonesian arts and crafts. This concept of authenticity was, among other things, linked to a colonial narrative that rejected certain forms of modernisation because of an association with 'racial degeneration'. Colonial officials and the colonial elite selected which forms of modernisation would lead to the so-called ‘elevation’ of Indonesian craftsmen and their arts and crafts. This will be explored further on in this article.

‘Rejuvenation Cure’

One of the forms of arts and crafts that, according to the colonial government, was threatened by this notion of ‘decline’ was Javanese silversmithing. Historically, the city of Kotagede – from 1586 to 1645 the location of the kraton of the Javanese empire Mataram – was the centre of silversmithing, as the Central Javanese royal courts were the primary clients of the silversmiths. This mainly involved ceremonial and royal objects, and in addition the royal courts had luxury objects made that served as diplomatic gifts.23

After the Diponegoro War (1825-1830) (known in the Netherlands as the Java War), the colonial government severely restricted the political power and land ownership of the Central Javanese royals; the land was needed for the introduction of the Cultivation System. Royals who resisted this new system were threatened with exile. In 1830, Paku Buwono VI of the Surakarta court was banished by the Dutch to the island Ambon for protesting, and replaced by a more compliant member of the royal family.24 The courts responded to this loss of power, prestige and income by withdrawing into Javanese court culture, with the extensive courtly diplomatic protocol concealing this loss.25 This was stimulated and financed with annuities by the colonial rulers, for whom it was important that the Islamic nature that had characterised the royal courts in earlier periods disappeared into the background.26 However, it was necessary to maintain the authority and prestige of the courts to a certain extent because of the dual colonial administrative system. Within this system, the colonial government ruled through the Javanese aristocracy, which controlled the population, while European colonial officials of the so-called Binnenlands Bestuur were placed at various levels of authority for supervision.27 Historian Sutherland describes their interaction as ‘a continuous bargaining between elites […] each with its own vested interests, its own traditions and received wisdom, its own values, perceptions and prejudices’.28

With the ever-diminishing wealth of the royal courts in the second half of the nineteenth century, orders for Javanese silversmiths also fell short, and this took place at a time when there was already competition from European silver companies in the colony. In addition, silversmiths were confronted with a shortage of their preferred raw materials due to an import embargo on silver Mexican dollars and Straits Settlement dollars.29 The Javanese silversmiths responded to this by, among other things, shifting their focus to the upcoming market of European tourists and producing affordable objects for it. The price could be kept low by greatly reducing the silver content. Perhaps these were the ‘bastard products’ that Rouffaer was referring to? Some Javanese silversmiths also started working for European silver companies.30

In the meantime, the regime continued to look for ways to preserve and to stimulate the Javanese silver craft. By finding a new market and through ‘systematic training’, the silversmith’s art, according to Jasper in his technical

23 P. Kal, 2005, p. 19.

24 M.P. van Bruggen and R.S. Wassing, Djokja en Solo. Beeld van de Vorstensteden. Asia Maior, 1998, p. 25.

25 H. Schulte Nordholt, Een geschiedenis van ZuidoostAzië, Amsterdam University Press, 2016, p. 159; Van Bruggen and Wassing, 1998, p. 25.

26 Schulte Nordholt 2016, p. 159.

27 Van Bruggen and Wassing, 1998, p. 29.

28 H. Sutherland, The Making of a Bureaucratic Elite. The Colonial Transformation of the Javanese Priyayi, Heinemann Educational Books (Asian Studies

Association of Australia), 1979, p. 2.

29 Kal 2005, p. 100.

30 Kal 2005, pp. 22-23.

FIGURE 3

study, could undergo a ‘rejuvenation cure’31 that would bring ‘artistic skill and technical dexterity’ to a higher level again.32 In his publication from 1927, he did not address the underlying causes of its decline – colonial expansion and exploitation.

To further prove my point about the violent nature of the Ethical Policy I would like to bring to mind the conquest of the last kingdom on Bali in 1908, where the construction of the Bali Museum was one of the very first missions of the colonial government after the brutal conquest, in order to preserve Bali’s traditional art and culture.33 First ‘pacify’, then preserve, was the motto under the Ethical Policy.

Active Involvement

Within the collection of Yogya silver of the Wereldmuseum, the collection of Mrs. E.W.S. (Ernestine Wilhelmina Sarah) James-van Gesseler Verschuir (1916-2008), the daughter of Mary Agnes van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall (1882-1962), stands out. With the exception of one object, this collection was acquired in 2008. Through the mediation of former Wereldmuseum curator

Portrait of P.R.W. van Gesseler Verschuir, his wife M.A. van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall and their daughter, Bandoeng. Kreuger & Austermühle (Photo studio), Bandung 1928. Collectie Wereldmuseum TM-ALB-1986-42.

Pim Westerkamp, the collection was partly donated , and partly purchased with financial support from the VriendenLoterij (formerly BankGiro Loterij). The collection consists of 20 Yogya silver objects, 41 design drawings, 2 evening dresses from Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall and 1 photo album with 48 photos.34 The collection is important because, in addition to the great

31 J.E. Jasper en M. Pirngadi, IV: De goud- en zilversmeedkunst, 1927, p. 12..

32 J. E. Jasper en M. Pirngadi, IV: De goud- en zilversmeedkunst, 1927, p. 12.

33 W. Bakker, Visual Art in Bali: A Century of Change 1900-2000, Lecturis, 2018, p. 43.

34 TM-6233-1 (2005), TM-6326-1 t/m -19 (2008), TM6316-1 t/m -41 (2008), TM-6328-1 en -2 (2008), en TM-ALB-1986 (2008).

craftsmanship and knowledge of materials of the silversmiths, it shows how Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall put into practice the ‘rejuvenation cure’ of Yogya silver, recommended by Jasper.

FIGURE 4

The finishing of silver in a silversmith's workshop. Yogyakarta, approx. 1932. Collectie Wereldmuseum TM-ALB-1986-4.

Mary Agnes van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall (fig. 3) is still known in the Netherlands for her involvement with Yogya silver. Her husband Pieter Rudolph Wolter van Gesseler Verschuir (1883-1962) succeeded Jasper in 1929 as governor of Yogyakarta. The role assigned to European35 women within the civilising mission of the Ethical Policy was that, as guardians of the moral level of the colony, they practiced and propagated European norms and values within and outside the household and family. Wives of colonial administrators were also expected to play a representative and actively supportive role in the administrative career of their husbands.36 According to historian Drieënhuizen, for these women, deepening their knowledge of Indonesian arts and crafts was one of the few available ways within the colonial straitjacket to acquire a position of respect. By caring for the welfare and ‘elevation’ of Indonesian craftsmen (and often also women) in line with the Ethical Policy and by stimulating ‘authentic’ arts and crafts, ‘European women could publicly profile themselves in the Indies and the Netherlands as good citizens who, like men, could participate in society’.37 Around the time that Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall settled in Yogyakarta, other women from the European elite were also active in the Javanese cultural scene, such as Anna Resink-Wilkens (1880-1945) and Trijntje ter Horst-de Boer (1861-1938).38 As collectors and advocates of Javanese arts and crafts, both maintained very friendly relations with the central Javanese royal courts, who sometimes also offered these women financial support, for example with acquisitions or the necessary shop space to sell Javanese arts and crafts products.39 Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall also had close contact

35 Mary Agnes van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall was not a newcomer to Indonesia. Her family had lived there for several generations and was of Armenian, Javanese and European descent, among others. Legally, Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall fell within the population group of Europeans. See also: C. A. Drieënhuizen, Koloniale collecties, Nederlands aanzien: De Europese elite van Nederlands-Indië belicht door haar verzamelingen, 1811-1957, 2012 [Thesis, fully internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam]. p. 275.

36 E. Buchheim, ‘De illusie van tropisch Nederland.

Brieven van Nederlandse vrouwen in Indië’. In: E. Captain, M. Hellevoort and M. van der Klein (eds), Vertrouwd en Vreemd. Ontmoetingen tussen Nederlands, Indië en Indonesië, Verloren, 2000, p. 74.

37 Drieënhuizen 2012, p. 244.

38 Drieënhuizen 2012, p. 227, p. 248.

39 Drieënhuizen 2012, p. 249, p. 274.

FIGURE 5

with the royal courts because of her husband’s position. Unlike Rouffaer and Jasper, who were mainly concerned with preservation and inventory, Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall was actively involved with form, function, decoration and object. Her method of saving Javanese silversmithing was threefold, as Kal describes.40

Polishing objects in Yogyakarta, approx. 1932. Collectie Wereldmuseum TM-ALB-1986-7.

First, Europeans had to commission Javanese silversmiths to make European products such as breakfast and tea sets, desk and dressing table accessories. This way, the European elite would take over the cultural patronage of the Javanese courts after their power and wealth had been largely constricted by the government. This happened around the same time, from the end of the 1920s, for example in Bali, where tourists and artists from Europe and the United States largely took over the cultural patronage of the Balinese royalty after their courts had been destroyed.41

Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall was involved in introducing various decorative motifs on these products intended for the colonial market in Indonesia. The decoration on the Central Javanese royal and ceremonial objects had generally been limited to a decorative border with leaf tendrils or tumpal (triangular motifs).42 In close cooperation with the Archaeological Services (Oudheidkundige Dienst), established in 1913 in Jakarta (‘Batavia’) for the research and restoration of antiquities, Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall selected motifs from the Borobudur, the Prambanan temple and the Mantingan mosque. The Javanese aristocrats she worked with were enthusiastic about using these motifs, originating from Javanese heritage.43 The Archaeological Services photographed the motifs (fig. 6), after which the photos were converted into a design drawing (fig. 7). The Javanese silversmiths then had to reproduce the motifs on their silverware in their workshops based on the various design drawings (fig. 8).

40 Kal 2005, p. 42.

41 Bakker 2018, p. 43.

42 Kal 2005, p. 19. A similar bowl, originally a sirih bowl, was included in the Wereldmuseum collection in 2008 after it was purchased from Ernestine Wilhelmina Sarah James-van Gesseler Verschuir, TM-6326-3a.

43 Kal 2005, p. 76.

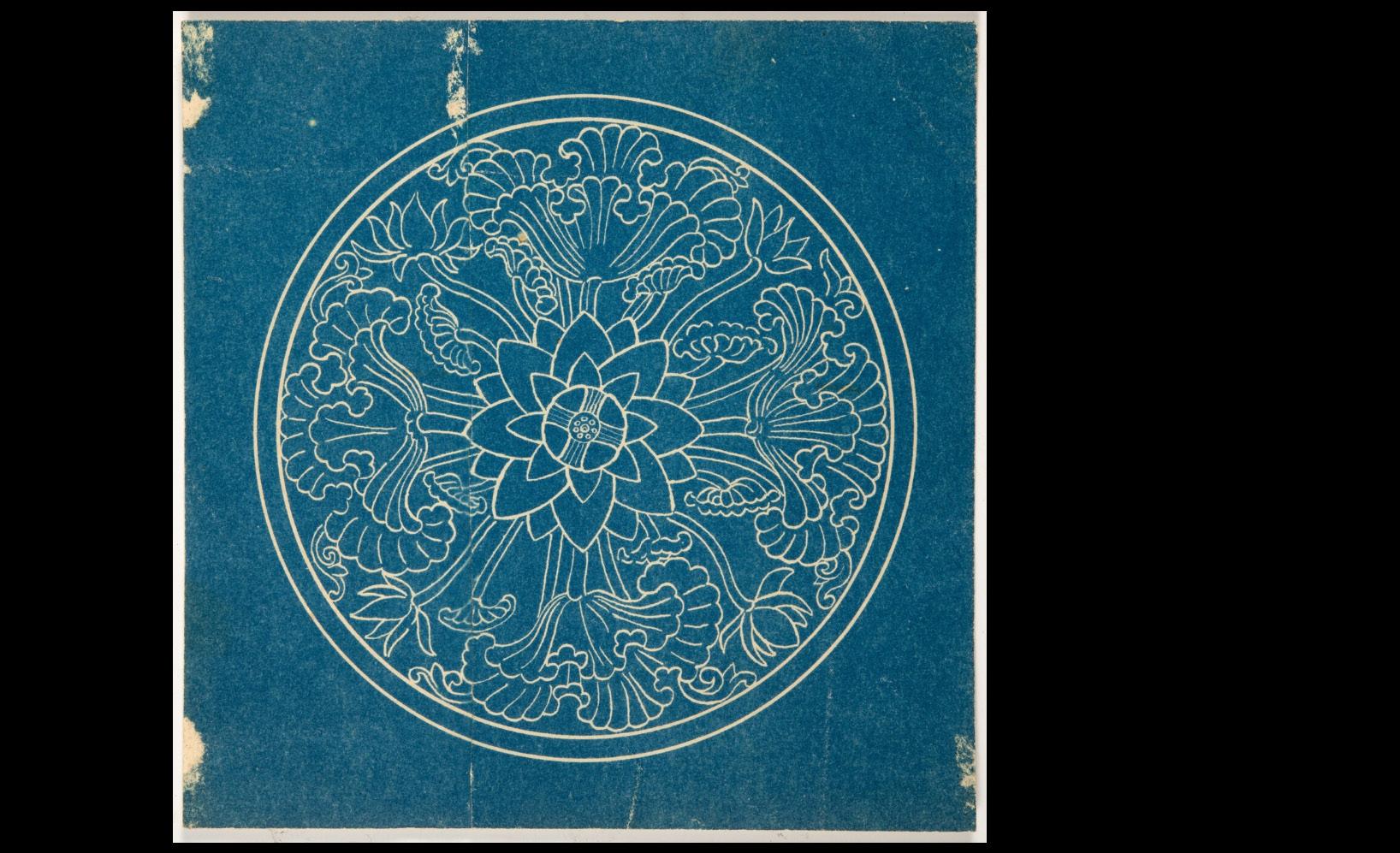

FIGURE 6

A 1930 photo from the Oudheidkundige Dienst (by Jean Jacques (Jan) de Vink) of a relief from the Mantingan mosque located in the Japara Regency and established in 1559 AD by the female ruler Kali Nyamat. The depicted lotus flower motif was seen as a remnant from the socalled ‘Hindu-Javanese’ period and therefore considered suitable for Yogya silver. Collectie Wereldmuseum TM-6316-38b.

FIGURE 7

The design drawing commissioned by Mrs. Van Gesseler VerschuirPownall. Collectie Wereldmuseum TM-6316-38a.

FIGURE 8

The design executed by Javanese silversmiths on, possibly, a powder box. Dimensions: 2.9 x 7.7 x 7.7cm. Collectie Wereldmuseum TM-6326-12a.

FIGURE 9

These so-called ‘Hindu-Javanese’ motifs from the court culture, from before the arrival of Islam, were regarded by the colonial government as ‘authentic’ Javanese. According to the colonial narrative, the arrival of Islam had a devastating effect on the arts, in Rouffaer’s words ‘much destructive but little edifying’.44 Certainly after the Java War and the Aceh War (1873-1904), in which Islam formed an important part of the resistance against colonial rule, Islam was seen as a constant threat to the colonial regime and therefore increasingly marginalised as merely ‘a shallow overlay on deeply entrenched older Indic

The shop of the foundation Pakarjan Ngajogijakarta, approx. 1932. Wereldmuseum Collectie TM-ALB-1986-9.

traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism.’45

Finally, Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall wanted to open a shop where customers could buy Yogya silver from stock. To achieve this goal, she established the Pakarjan Ngajogijakarta foundation (stichting ter bevordering van het Jogjasche Kunstambacht) in February 1932 (fig. 9), in collaboration with a number of European men and aristocratic Javanese men.46 Sultan Hamengkubuwono VIII made a building available on Petjinan/Malioboro for the showroom that sold the silver objects of the silversmiths on consignment. The shop was very popular with the colonial elite, as evidenced by the visit of Governor-General De Jonge to Yogyakarta, when his wife and ladies from his entourage visited the showroom on 20 October 1933.47 All objects were tested for quality and consisted of silver of a standardised grade (800). In some cases they were marked by the maker. In addition, Pakarjan Ngajogijakarta provided training and encouraged silversmiths to participate in (inter)national exhibitions.48

By providing the building, Sultan Hamengkubuwono VIII restored, as it were, the original connection between the royal house and Central Javanese silversmithing. The royal courts had their own interests in following and contributing to the colonial movement that wanted to preserve and stimulate ‘authentic’ Javanese arts and crafts. They saw the growing interest in Central Javanese culture as a way to create a Central Javanese self-awareness, which would

44 Shatanawi 2022, p. 303; Rouffaer 1901, p. 1189.

45 M. Shatanawi, Islam in beeld. Kunst en cultuur van moslims wereldwijd, SUN, 2009, p. 236, p. 237; L. Sears, Shadows of Empire. Colonial Discourse and Javanese Tales, Duke University Press, 1996, p. 23.

46 Including Gotz van der Vet, R. Katamsi, Moens, Resink, Sitsen, Soepardi, Soerachman and R.P. Warindio, together with princes and other royal members. See: Kal 2005, pp. 44-45.

47 ‘BEZOEK LANDVOOGD’, in: Algemeen handelsblad voor Nederlandsch-Indië, Semarang, 20-10-1933, p. 14.

48 Kal 2005, p. 48.

49 Drieënhuizen 2012, p. 247.

eventually result in a political-nationalist ideology.49 They also used this interest to perpetuate their legitimacy as royal courts among the colonial elite, with long historical lines to the old kingdoms that left behind the ‘Hindu-Javanese’ buildings.50

‘Raising to a Higher Level’

A few years after Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall left for the Netherlands because her husband’s term of office had ended, Museum Sono Budoyo opened on 6 November 1935. This museum’s aim was to ‘give a general picture of the historical development and the current state of Javanese and related Sundanese, Madurese and Balinese cultures, but the aim of the collections was not only to study but above all to promote the cultures mentioned.’51 Museum Sono Budoyo was founded by the Java Institute, a colonial institute that was established in 1919 to ‘study the culture of Java from earlier days and the present and to define the direction in which it should develop in the future.’ Members of the Java Institute consisted of the colonial European elite and the Javanese elite. During congresses of the Java Institute they gave advice on various issues concerning Javanese and related cultures, art, education, economy and politics. On 6 November, 1935 – the date was suggested by the sultan because it was his birthday – Hamengkubuwono VIII gave the opening speech, performed the opening ceremony and accepted the patronage.52 It was an excellent opportunity to consolidate his position. Museum Sono Budoyo still exists today and is celebrating its 90th anniversary this year.53

A wave of cheap imported factory products created the impetus for the establishment of the Arts and Crafts School (Kunstambachtsschool) for wood, silver and copper processing in Yogyakarta in 1939. The management and teachers were all Javanese.54 Here too, the financing came from the Java Institute. The training was intended for

young gifted toekangs [craftsmen, MvA] from various regions of Java and Bali, who in a two-year course, closely linked to the Indigenous craft, are taught some additional development in technical, economic and artistic areas, on the basis of traditional arts and crafts; after returning to their environment, they will then be able to raise the local art craft to a higher level, both for themselves and by spreading what they have learned.55

A boarding school was connected to the school, modelled on the pesantren; the traditional Islamic boarding schools where religious education was taught. The Kunstambachtsschool broke with the tradition of passing on the silver craft from father to son and was thus able to teach more students how to make the silverware that Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall had made a commercial success among Europeans in the colony in the four years she stayed there.56

50 Ibid., p. 248.

51 ‘Opening Museum „Sono Boedojo.” Zeer Groote Belangstelling voor Bizondere Gebeurtenis te Jogja. Z.H. de Sultan Spreekt Openingswoord Inleidende Rede van prof. dr. Hoesein Djajadiningrat. Vele Gelukwenschen.’, in: De locomotief, Semarang, 6 November 1935, p. 7

52 Ibid.

53 www.sonobudoyo.com

54 Kal, 2005, p. 48.

55 Author unknown, Locale Techniek. Technisch orgaan

voor de vereniging van locale belangen, Bandung, 1938. pp. 7-6, 178.

56 For numbers, see: Kal 2005, p. 46.

Photographs in the collection of Museum Sono Budoyo and publications show that the Kunstambachtsschool, following Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall, continued to use motifs and design drawings in the so-called dynamic-naturalistic style.57 The Javanese aristocrat Raden Panji Warindio Dirdjoamiguno (1898-1984) played an important role in this. Interested as he was in Javanese arts and crafts, he had worked with Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall for a couple of years, was one of the co-founders of Pakarjan Ngajogijakarta, taught decorative motifs at the Kunstambachtsschool and from 1950 at the Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia (ASRI).58 With the establishment of Museum Sono Budoyo and the Kunstambachtsschool, the methods proposed by Rouffaer and Jasper for the success of this colonial project had been implemented.

Conclusion

Rouffaer’s plea to apply the Ethical Policy to Indonesian arts and crafts resulted in various interventions initiated by members of the colonial elite to promote arts and crafts and thus the socio-economic circumstances of the craftsmen. Europeans determined the conditions for the ‘rejuvenation’ that Indonesian arts and crafts had to undergo, according to them, for the sake of their self-preservation. In the case of Javanese silver crafts, not only the form and function of the objects, but also the decoration and the silver content were controlled by the colonial administrative elite.

After the colonial conquests in the nineteenth century, the Javanese royal courts had insufficient resources to continue acting as clients for the silversmiths. The colonial government then presented itself as the ‘saviour’ of Javanese silver crafts, without acknowledging its own involvement in their socalled decline. One of the ‘rescue’ methods consisted of the European colonial elite largely taking over the cultural patronage from the Javanese nobility. In addition, the concept of ‘authenticity’ was introduced, which served the colonial narrative. On the one hand, it carried out the colonial policy of ‘racial purity’. On the other hand, it marginalised as much as possible the influence of Islam, which was a threat to the colonial status quo. The old ‘original’ Indo-Javanese culture was considered authentically Javanese. Yet, as seen in the selection made by Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall, Islamic motifs were chosen too, signifying not only the invention of authenticity, but perhaps more importantly, the ignorance and inconsideration of the colonial elite vis-à-vis the very diverse local cultural heritage and the meaning and social context of the original designs. Motifs were simply cherry-picked for their aesthetic ornamentation. What started as an inventory and preservation method by Rouffaer and Jasper, under the leadership of Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall, led to new forms of arts and crafts supported by the colonial elite that were given the hallmark of being ‘authentic’. According to the standards of the Ethical Policy, the colonial project of silversmithing could be deemed successful. Yogya silver was very popular among the colonial elite and provided an increase in employment on the Javanese side. With mostly European, rather than Javanese

57 Ibid., 2005, p. 47, p. 90.

58 Ibid., p. 48.

59 After: ‘Balinese were taught to be "Balinese" in the image of the Dutch colonial ideal.’, I.K.D. Noorwatha, I. Santosa, G. P. Adhitama, and A. A. G. R. Remawa, ‘East meet West: the Balinese undagi-Dutch architect cross-cultural design collaborations in Bali early colonial era (1910-1918)’, in: Cogent Arts & Humanities, 11(1), p. 7.

clients and consumers, along with the introduction of decorative motifs mostly based on ‘authentic’ Indo-Javanese motifs (from before the arrival of Islam), and finally with the opening of a shop, a museum to preserve and develop Javanese culture, followed by an arts and crafts school that spread the desired forms of silversmithing on a larger scale, Javanese were taught to be ‘Javanese’ according to the ideal image of the Ethical Policy.59 Because Sultan Hamengkubuwono VIII was able to move along with these developments, the court succeeded in re-appropriating the connection with arts and crafts.

Epilogue

What is the current status of Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall’s legacy in Kotagede? In 2005, Pienke Kal concluded, after conducting on-site research, that the colonial intervention in silver crafts was no longer part of the collective memory of the silversmiths, let alone the supply of Javanese motifs.60 In a more recent publication, the success of the silver trade in Kotagede during this period is mainly attributed to the intervention of the Sultanate of Yogyakarta, as a provider of subsidies, exhibition space and as a link between the silversmiths and international networks.61 This could imply that the involvement of Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall was entangled mostly with Javanese aristocrats, who took this opportunity to restrengthen their patronage to silversmiths. Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall stood outside of this dynamic between silversmiths and said Javanese aristocracy. It could also imply that contemporary historians are not interested in bringing back a European woman into the collective memory, or that the four years of her involvement was simply too short to leave a lasting impression. Museum Kotagede does mention Van Gesseler Verschuir-Pownall as ‘a driving force’ behind the development of silverware in the 1930s but only in connection to the European household items ‘such as spoons, forks, rice spoons, pans, plates and cups’. The motifs used are referred to here as ‘unique and distinctive’ for silver from Kotagede, but are without any doubt belonging to Javanese culture, regardless of any colonial interference.62 Reclaiming their craftsmanship, it was – according to tradition – the silversmiths themselves who had agency and together with the customers, determined the object and the decorative motif, using pattern books. Kal states that the name Raden Panji Warindio Dirdjoamigoeno is sometimes mentioned in this respect.63 In any case, the greatest admiration today goes to the makers; the silver workshops in Kotagede that have been passed down from generation to generation and have managed to survive the various challenges in the field of silver, even after the colonial period, thanks to their great craftsmanship.64

MARJOLEIN VAN ASDONCK works as the Curator Southeast Asia at the Wereldmuseum, with a focus on Indonesian material culture, colonial history and communities from the Indonesian diaspora. Prior to this, she was editor-in-chief of the magazine Moesson, founded in 1956 by the Eurasian community in the Netherlands. She studied Indonesian Languages and Cultures at the University of Leiden.

60 Kal 2005, p. 92.

61 Muhammad Iqbal Birsyada, Septian Aji Permana ‘The business ethics of Kotagede’s silver. Entrepreneurs from the kingdom to the modern era.’ In: Paramita: Historical Studies Journal 30(2), 2020, pp. 145-156, p. 151.

62 A. Pratiwi, 'Perkembangan Perak Kotagede dan Klaster Kemahiran Teknologi Tradisional Museum Kotagede’, website of the Department of Culture Yogyakarta, June 2023.

63 Kal 2005, p. 92.

64 Chris Pudjiastuti, ‘Perak Kotagede untuk para bangsawan’, in: Kompas, 30 March 2018.

This text was written for the Design/ing and the Ethnographic Museum project for the Research Center for Material Culture, and republished in the Recall/ Reclibrate series. The text was written in Dutch, and translated by Rosa te Velde and Ilaria Obata.

The text is published under CC BY-NC-ND license, which enables reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.