IN THIS ISSUE

(;/wr/ps 11. Newman BUT THAT'S THE WAY THE AMERICAN PEOPLE LIKE TO DO

Edith B. Farnsworth POEMS

Carl W. Condit ARCHITECTURE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

David Neelon. and Patricia Rabby POEMS

Gary Lee Blonstoti FUTURE TENSE

Russell L. Merritt THE INTERNAL MONOLOGUE IN BOOKS AND FILMS

Robert Lee Moore POEMS

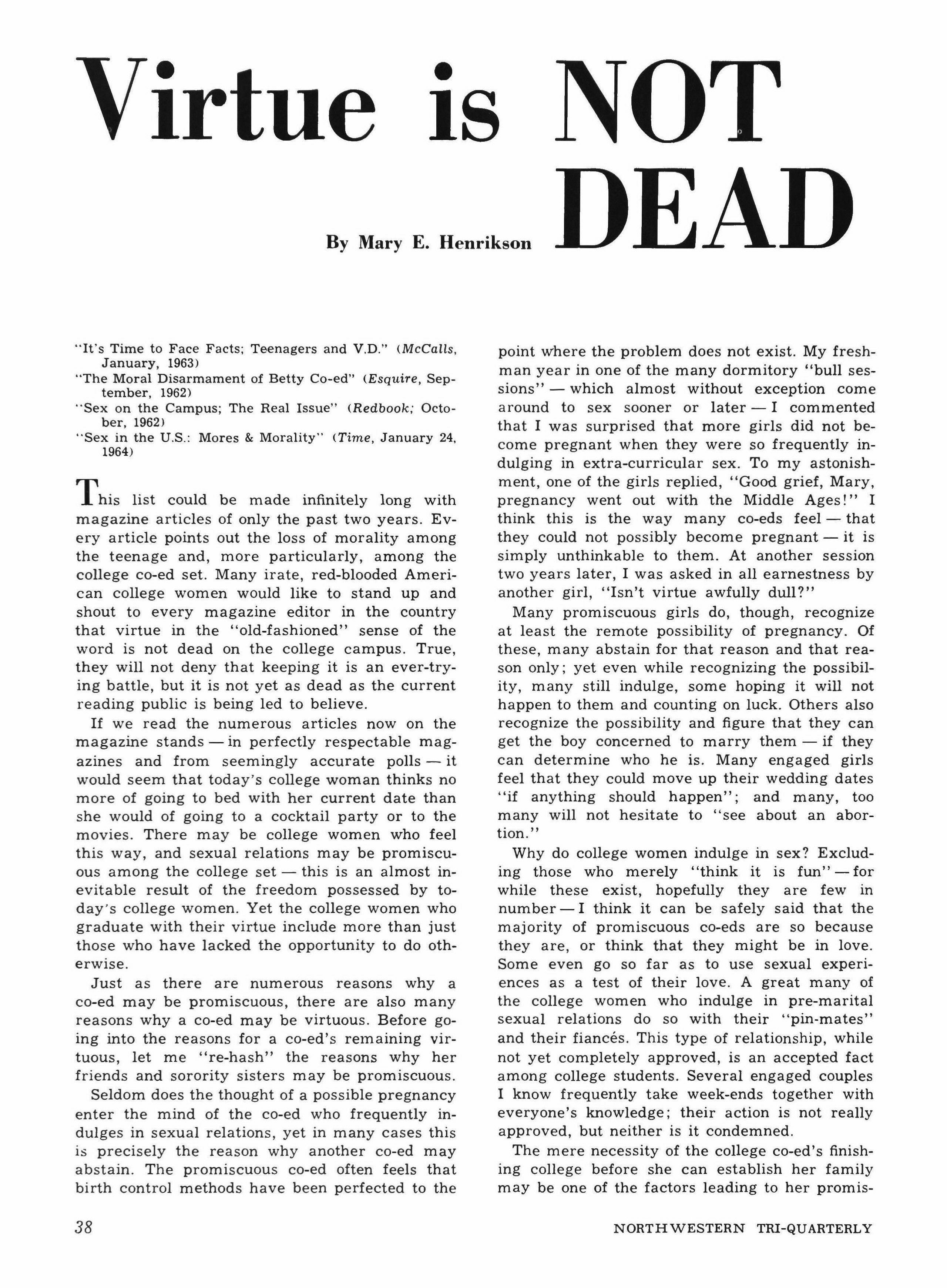

Mary E. Henrikson VIRTUE IS NOT DEAD

R. Barry Farrell THE STUDENT AND THE UNIVERSITY UNDER COMMUNISM

Laurel Tether, Patricia Rabby, Mark Reinsberg, and Vaughn Koumjian POEMS

I t V'

TRI-QUARTERLY VOLUME 6 NUMBER THREE 70¢ NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY SPRING, 1964

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is a magazine devoted to fiction, poetry, and articles of general interest, published in the fall, winter, and spring quarters at Northwestern University. Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $2.00 yearly within the United States; $2.15, Canada; $2.25, foreign. Single copies will be sold locally for $.70. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to THE TRI-QUARTERLY, care of the Northwestern University Press, 816 University Place, Evanston, Illinois. Contributions unaccompanied by a self-addressed envelope and return postage will not be returned. Except by invitation, contributors are limited to persons who have some connection with the University. Copyright, 1964, by Northwestern University. All rights reserved.

Views expressed in the articles published are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the editors.

Tether, Patricia Rabby, Mark

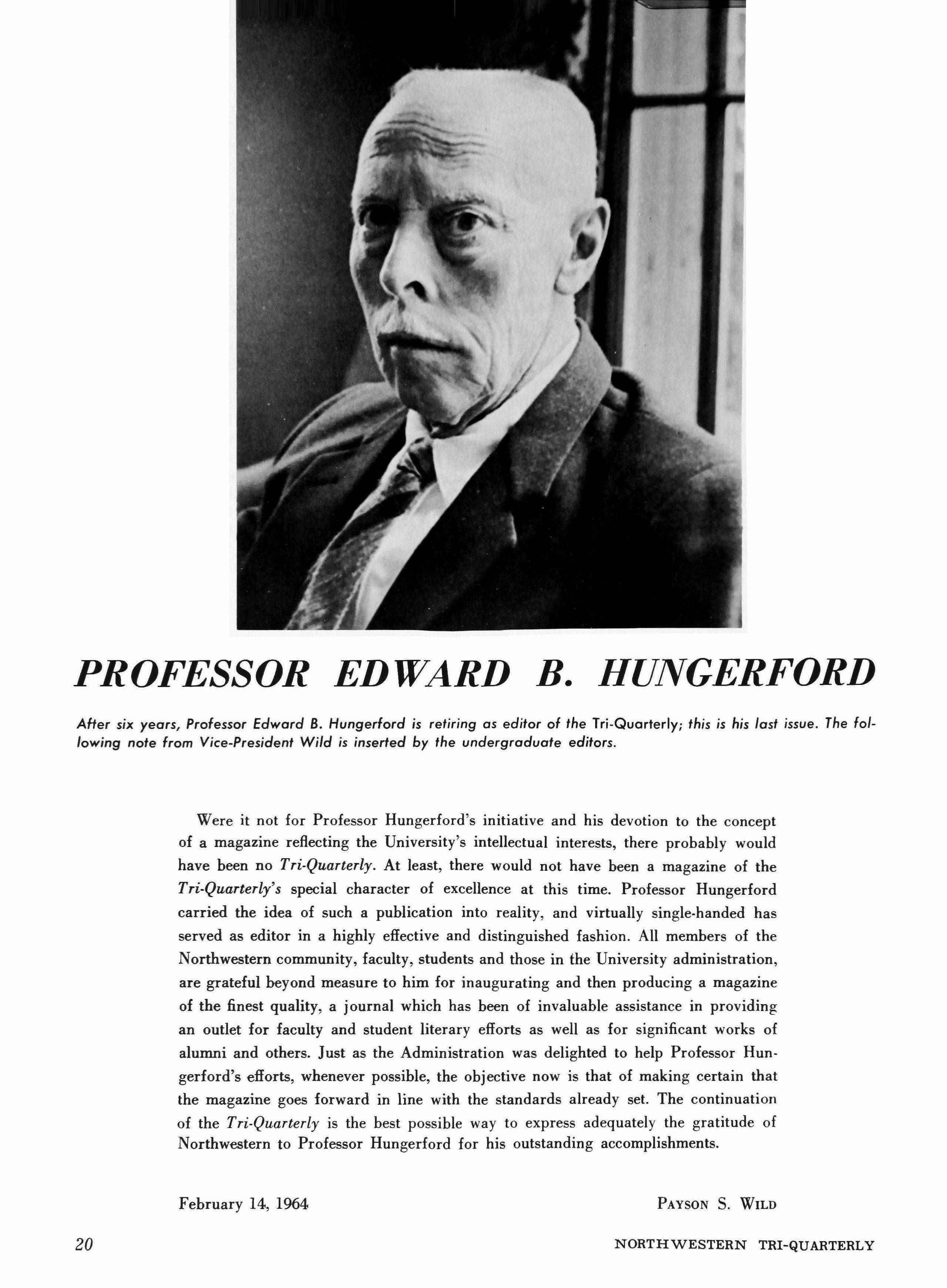

EDITORIAL BOARD: The editor is EDWARD B. HUNGERFORD. Senior members of the advisory board are Dean JAMES H. MCBURNEY of the School of Speech, Dr. WILLIAM B. WARTMAN of the School of Medicine, Mr. ROBERT P. ARMSTRONG, Director of the Northwestern University Press, and Mr. JAMES M. BARKER of the Board of Trustees.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITORS: BARRY G. BRISSMAN, GARY T. COLE, MARY HENRIKSON, LINDA O'RIORDAN, and FRED W. STEFFEN.

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is distributed by Northwestern University Press, and is under the business management of the Press. Design, layout, and production are by the University Publications Office.

Art Editor is Lauretta Akkeron.

Charles H. Newman But That's The Way The American People Like To Do 3 Edith B. Farnsworth Poems 9 Carl W. Condit Architecture In The Nineteenth Century.. 11 David Neelon and Patricia Rabby Poems 19 Gary Lee Blonston Future Tense 21 Russell L.

The Internal Monologue In Books And Films 25 Robert Lee Moore Poems 30 Mary Henrikson Virtue Is Not Dead 38 R. Barry Farrell The Student And The University Under Communism 41

Koumjian Poems 47 Tri-Quarterly

Volume

SPRING.

Merritt

Laurel

Reinsberg and Vaughn

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

6

1964 Number Three

By Charles H. Newman

"But that's the way the american people like to do"

"We are a 'WE', not because we hold communion, but because our contours overlap"

HERMANN BROCH

You can always talk cute," Moult began, his mouth full, "say 'I guess,' take the end off adjectives, say 'sort of' and ramble, but that doesn't fool anybody any more. Maybe you'll understand better if I tell you that I had a professor my first year at Purk who said we ought to get out and meet the Proletariat. The way he said it sounded very much like my mother when she spoke of the 'common people,' although she'd just as soon that I stayed away from them. They were agreed in one respect however; that I couldn't handle them. As I look back on it now, I think the professor's vested interest in me oddly stronger, so it's only fair to begin with him. Because he was frightened (as opposed to my mother who merely suffered) he provided me with a surer principle of selection. He was born on an Iowa farm, the high table gossip went; one of those guys who read all night after the chores were done, standing up of course, "so's he could stamp 'is feet, keep warm." He still worked standing up when I knew him, at a stoolless accountant's desk, but I think more because of bad circulation than from habit. By the time he was twelve, so the story goes, he had read every single book in the village library, including the encyclopedias, mail order catalogs and train schedules. Blessed at birth with an incredible memory, he could recite entire Robert Ingersoll lectures without a stutter. His spelling bees had the quality of a revival meeting. He could tell you today the time, destination, and second-class fare of every train that left Ames, Iowa, between 1913 and 1922.

Spring, 1964

He was not withered by his brilliance largely as a result of his size, a stooped seven feet due to a pituitary as far ranging as his memory. He could fell a small town dolt with either a quip or a fist. And I have seen him many times in the University Post Office go through spectacular feats of coordination to retrieve his mail from a box, allotted on purpose, certainly, in the row six inches off the floor. His face was indented and his skin shingly. His hair was more maroon than red, falling in half-hearted ringlets. His ears were enormous. He walked with his arms motionless and stooped over, like a pajamaed child in the morning trying to conceal an erection. For that, we called him Mr. Pants.

The town banker, as a matter of personal and professional pride, had seen Mr. Pants through the State University, where he had taken a degree in Romance Languages in two years, and then like so many Americans who see their future too clearly, who feel themselves trapped on a gradient even though it is ascending, willfully broke the inevitability of his progress, tried to find out more. He held the usual jobs; he worked for a year on a Ford assembly line, washed dishes, managed a Y.M.C.A. locker room, boxed kangaroos at county fairs, punched cattle, sold encyclopedias door to door, dug graves, edited a radical journal (suppressed in the mails), rode the rods for a time, drove a stock car, painted a mural for the dining room of a Panamanian Hotel, stoked boilers on a freighter; you know, the whole bit that qualifies you for dissent in this country, a book jacket full of occupations to document your

3

sensitivity. The whole world is easier to come by than any single part of it. Particularly if you have a good memory.

Mr. Pants was not as hurt by the Depression as he was fascinated by it: the concept of failure engages us much more than the brute facts of failing - just as it is the idea of success and not its fruits which compel us. For analysis, he chose Marxism, admittedly, because it was quicker. Marxism, he told us once, failed not because of any perversion of the system, but was doomed from the first, since it misunderstood the nature of capitalism. The thing that one learned in the thirties, was not particularly that the Soviets were corrupt, but that capitalism doesn't require prey as much as successive enemies! Without a feudal structure to attack, Capitalism had become unchallenged and irresponsible. The Communists were not destroying capitalism; they were making possible its resurrection - justifying it at the very moment it had become impossible.

Sociological investigation bored him after a time however, and around 1936 he went back to the farm to help. Things got better, but shortly after his return, on a foggy fall harvest evening, his father fell into a reaper and died, as it were, without even jamming the mechanism. His mother had already died and his sisters married, so he went to New York to work simultaneously on degrees in law and medicine. Unfortunately or no, the Spanish Civil War soon cut those interests short. He recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for, purchased a pair of Beretta

These pages are from an unfinished novel by Charles Newman and are printed here at the invitation of the editors.

"This is a bi-valved narrative," Newman explains, "in which personalities are developed, not through plot or psychological prescience, but simply through the metaphors each finds useful. The characters, then, live only through the stories they tell on others."

Newman graduated summa cum laude from Yale in 1960 where he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, won the W. Wilder Bellamy Prize for Scholarship, the Strong Prize for the best thesis in American History, and for two years was editor of the literary magazine Criterion. The following year he studied philosophy at Balliol College, Oxford. He has received both a Woodrow Wilson Teaching Fellowship and a Fulbright Grant. Presently he is an instructor in the English Department, teaching composition.

He has recently been appointed editor of The Tri-Quarterly to replace Mr. Hungerford whose resignation, after six years as editor, goes into effect after this issue.

automatics with guttapercha handles and showed up one night in a hotel on the Via San Antonio in Madrid, where several prominent American journalists were hoarding food. Shocked by this, he allowed himself to be goaded into a fight, subsequently breaking the arm of the largest and most belligerent of the journalists who had to cancel his trip to the front and stayed in Madrid for the duration. Each time the shelling began, this man would dash through the streets brandishing his damaged arm and crying "Falangiste! Falangiste!" in the brevity of which, no one knew if he were cheering or cursing them. (His dispatches were later incorporated into the Alcapulco Notebooks.)

Mr. Pants, who will remain nameless for security reasons (mine, not his) was, incidentally, a member of my secret fraternity. We had a house near the ocean, and once a year, without fail, he would come and tell us about his part in the Civil War. There was neither nostalgia nor feigned dryness to his account. He just related what had happened - about how difficult it was to choose which outfit to fight with - whether it was better to use good Soviet. arms with the labor union front or obsolescent arms with the Trotskyites, things like that - but, as he said, all tension was soon to be relieved by a sniper's bullet in the retreat from Toledo Alcazar! He was shot through the windpipe, and saved himself by performing a self-tracheotomy with his fountain pen. He spent the duration in the hospital like the rest of them, writing gentle letters to the parents of those he had known in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, furious letters to Roosevelt, doing neck exercises, and translating neglected Spanish poets. When he got back to the States, he found that the letters to the President had made him a security risk, and that, coupled with his injury, kept him out of the Great War he had anticipated and fought to prevent. He took a job as a male nurse during the day and worked the night shift in a munitions factory. He did this for four years, until Hiroshima, when he was among the first, in a long letter of denunciation to the New York Times, to protest the act. Later he was arrested for picketing the White House during a national emergency, and spent the duration in a special detention camp in Vermont among Trotskyites, conscientious objectors, anarchists, a few Japanese truck gardeners, and a great many Nazi prisoners of war. Nevertheless, in the aftermath, suspicion gave way to the bull market - he was set free and found to his amazement that not only had his book of Spanish translations been awarded a Modern Library edition, but his letters to Roosevelt had been clandestinely circulated by the Republican National Committee in areas of anti-Catholic sentiment. He made use of several foundation fellowships, took a position at some progressive worn-

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

en's college in the East and then, at the height of the McCarthy scare, presented himself at Purk with an agonizingly long list of his past indiscre tions and dared them to hire him. Of COUriH' thl'Y did. Mr. Pants resisted trends for their own sake, but he knew too the place where one must become irrational- and admit it.

"Irony always saves us from profundity," he used to say to close our secret fraternity meeting; "to stand firm in the middle is, I assure you, gentlemen, the most difficult of stances. But because it is the most difficult, you must not confuse it with the most moral. It is easy to see what is right; the difficulty is to attain the position from which being right matters. That is something I never achieved. Morality without power is meaningless, 'to reverse a political cliche (I assume you are aware it is a cliche), and quite possibly immoral as well. The choice always seems to be between morality and humanity. There are times when civilization itself needs defending; that's humanity. And other times when a single human or perhaps a single idea, must be protected from civilization itself. That's morality. If you ever, gentlemen, see an occasion where the two are combined; don't pass it up."

The secret meetings were good, but the best times were the Thursday evenings when he invited a group of us up to his house for spaghetti. It was a fantastic household. A duplex above a garage on the outskirts of Purk. There were such things as a special chair Mr. Pants had made for himself from seaman's rope and wrought iron, and when he sank into it, it sounded as if a mizzen mast was coming down out of the dark. He was also an amateur archaeologist, and along the length of his concrete block and pine plank bookcases glittered hundreds of arrowheads, amulets, pestles, coprolites and rare quartzes. Once, when I was going through an old National Geographic in the stacks I came across a picture of him. He was on some expedition, Peru, I think, and the picture had been taken with him standing in an excavation to minimize his size in relation to the others clustered about him. His name was in the credits, although misspelled, but you knew it was him - even though he had a sombrero pulled over his face - by how tiny the pick hammer seemed in his hand. He dangled it between two fingers. Yet when I asked Mr. Pants about this, he denied ever having been to Peru.

Mr. Pants had married one of his graduate students, a full twenty years younger than himself, very Jewish, bowlegged, but beautiful like Egyptian queens from the long neck up. She looked as if she had just come in from throwing marbles under the cop's horses' feet at the Haymarket. They had two children when I last saw them, five-year-old-boy-twins, with sharp dark Semitic features and Iowan dispositions. They sat like Roman wolves under his swollen legs the entire Spring, 1964

evening, saying nothing, playing half-heartedly with broken autos and listening to the break and full of conversation. I remember picking them up; they we-rt- always perfectly calm and affectionate, but there was nothing easy about them, they searched you out with their eyes and fingersit was like picking up a miniature concert pianist or physicist. His wife, Katrin, usually stood in a corner with her arms folded, smiling, her head cocked to one side, listening to her husband put his students on. One time she evidently grew tired of this ritual, brought out a balalaika, and sang some central European songs in a pure arching alto. When she was through, Mr. Pants disappeared for a moment and returned with a homemade single-string washtub bass viol, to provide a resonant continuo. Things like that were always happening at his place. The first few times I went, I remember having a terrible compulsion to see their bed, and on the pretext of going to the bathroom I snuck into their bedroom. I was amazed to find only a bed of average size, not even a double, and realized that considering his bulk and the severity of his desires, she must have slept literally on top of him or not at all. The simplicity of the thing made a great impression on me at the time.

I mentioned once, offhand, that the thing which dissuaded me from going into teaching was the general homeliness of faculty wives. Katrin was passing his chair at the time and he grabbed her by the waist, spinning her around to face me.

"You find my wife homely, Mr. What's-yourname?"

I stammered, saying I didn't mean her; that, in fact, I found her quite disconcerting. But both of them just stood there and stared at me, and in the end, I had to get up and kiss her. Just once, lightly. It was the only way to get out of it. He was always putting you in positions like that, and yet he was never threatened. You see, he wanted us to go through the same experiences he had. It was the only way to perpetuate, justify, empiricism. He had to populate that enormous memory. In that, he was like my mother. The educator, like the entrepreneur, wants you free so he can control you. His life was to build us up above our doubts upon his own fine aspirations and sacrifices, knowing that we would inevitably construct our own private Soviet-Nazi pact, and betray ourselves. He personalized what otherwise we could have handled abstractly and saved ourselves. It is what American Progressive .Education is all about and why it is the most brutal in the world.

I didn't see much of Mr. Pants my last few years at Purk. His care for us had its calculated effect. We withdrew more and more into our own confusions. I no longer had the time for a pleasant Thursday evening. He needed us, but it is to his credit that he never catered to proteges.

5

The last time I saw him was during those first days of Their Revolution. There was a rally on the steps of the library to raise money for refugees after it became apparent that we were hamstrung. Mr. Pants had been asked to speak in lieu of the President of PUTk who had cancelled out as a result of cancer at the last moment. There were bonfires in the street, and he stood against the leaded windows casting his absurd shadow up into the arches. He made a short quiet speech in which he quoted Burkeyou know, about" all that evil needs to triumph is that good men do nothing" - and after that, fire buckets were passed for contributions. Then one of the singing groups broke out banjos, guitars, and started yelling the good old songs, "Which Side Are You On," "Row the Boat, Michael," "The Union Way," "This Land is My Land." Can you imagine that? It was fantastic! The same music, the same militance just flip-flopped; they had forgotten everything! I couldn't believe it. Mr. Pants passed me in the crowd and I grabbed his coat sleeve. He winked, stooped beneath an arch, and disappeared into the rare book room.

Incidentally, the money collected brought three Hunky refugees to Purk, fine high-cheekboned very brilliant guys, and one was taken into our secret fraternity for a night to tell how he had pitched Molotov cocktails at tanks, and the rest.

The last I heard of Mr. Pants was in a newspaper clipping somebody forwarded to me. He evidently had been passed up for tenure at Purk: and was out on the West Coast teaching at some big public university. He had caused quite an unprecedented furor there by flunking an entire class for plagiarism. They had all used the same fraternity file or something. He hadn't understood that it had been that way for years, that they knew exactly what they were doing. He thought by catching them up, he could shame them. It was the same thing with us, you see. He believed we were scared because we didn't know the Proletariat, when the truth was, we did our ignoring by choice."

II

I finished eating and said I thought I understood what he meant, which was true. And then I tried to think about all the common people I had known. All those people! The ones who live in towns that have "Join the U.S. Marines" in block letters on the movie marquee instead of a movie, the ones who squat a Jesus on their big dashboards, the ones who wear nylon socks with a little arrow running up the anklebone, the ones who buy the jelly in gas station johns that either speeds you up or holds you back, the ones who buy suction pistols to remove blackheads, the guys who sell four thousand packages of garden

seed for one set of china, the people who almost always have to say hello.

"They were mostly maids in the beginning," I said, "the ones I really knew."

For instance, I can remember lying on the checkerboard linoleum floor of a kitchen, looking up the legs of my grandmother's laundress. She washed, and 1 watched the mammoth pink Irish thighs caress eachother. If she moved, I followed her along the floor, pushing myself on my back like a grasshopper. She always wore sweat socks and crepe soled sandals. I followed underneath her for hours at a time and I can't remember her ever saying anything about it, or for that matter, my seeing anything.

When I was a little older, we moved to the suburbs where we had no basement or attic. That was fine for me as the maid's room could be approached on anyone of a number of pretexts; I hid among the whining gas meters listening to Lena entertaining friends. They would drive for two hours from South Chicago, enormous mortgaged autos, pick her up, go all the way back to the city, get her back in time to fix breakfast. She was a lovely girl and a kind of genius. One night her apron caught fire and she just walked into the dining room ablaze and asked to be put out. My father tore a curtain down and rolled her up in it. In the summer, when she returned from those late dates, I used to climb out on the roof and listen to the Buicks and Mercuries and DeSotos ease her back. I watched the parked cars sway through the pneumatic summer night. And in the morning, at breakfast, I stared at her, amazed that anyone was capable of such savage rhythmic weight.

Otherwise, Lena was unsatisfactory. Her cure for a common cold was to spit it out, and she carried a coffee can with her for that purpose when she was ill, which was often. We used to watch the wrestling matches on TV with a can between us on the sofa. Occasionally, if I concentrated on the spot in the middle of my forehead, I could muster up enough juice to add to the pot.

Then, in the middle of one winter, my mother discovered that all the door handles seemed to slip slightly in your hand, and we let Lena go. And you shouldn't get the wrong idea about that, because she let us go too.

"Well, that's nothing," Moulton said, unimpressed. "On our street, for instance, there was a funny little woman working for the Scribners who turned out to be a Nazi spy. Mrs. Scribner got suspicious because one day she saw her walking into the German embassy in a fur coat. We deported that pervert all right. And then there was the time Mrs. Cole had someone come out for the day from the Domestic Service. She was a big strange black woman, in a big white babushka, who didn't seem to know how to do anything. About noon, she went up to the attic for some

6

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

reason and didn't come down. Mrs. Cole called and called, but she didn't answer. She started upstairs but got scared and, as she said later, very wisely, called the police instead. The police went to the attic and found a Negro man stark naked on an old divan."

"OK," I said, "but I'll bet you didn't know Jimmy Gene Ray, did you? He was common. His father drove a cab in town. They lived in the city and the father brought his son out to play in the park while he worked. That's where I met him. In the rose garden. I knew him before you moved here, in about fifth grade. He used to sit right here and talk or sing. We could pick things off the radio pretty well and harmonize. And we weren't ashamed of it. You'd be surprised how many people are. People would stand around the cupola just to hear us. When we quit they would say things like, "This is certainly a nice way to spend a Sunday." Young girls would pinch their escort's arm, gaze into his face, and he would straighten up and perhaps ask us if we knew their favorite. We never did.

But there were other things we did too. Or rather Jimmy Gene did them, and I went along. That was to run along these walks, right here in the rose garden, and pull up ladies' Sunday dresses. Jimmy Gene would run in front, and run as if I were chasing him, see, and then when we got near the appropriate couple, he would veer in, and with a grand swipe, send that lady's skirt above her midriff.

I never did any of the yanking myself. I ran along in front; at first the pretext, then the judge. I announced the extent of the attempt. 'Legger,' I yelled, if it were that, 'yowsa,' if there was a glimpse of those great pastel triangles, and of course, 'You got it,' too. The thing was incomplete without me. Jimmy Gene did it. But I humiliated."

"So there was Jimmy Gene," I pointed out into the roses, "stooped over at fifty miles an hour, the escort yelling wild with helpless rage, his fine defenses outflanked, the lady locked in a swirl of her own devices, and then me, gliding by, noting the moment.

'Crotch-hopping,' Jimmy Gene called it. He got so good at it that he could run full speed bent close to the ground like an Indian scout and lift everything, crinolines, halfslips, knit wear, even shifts. And we were in dead earnest. We did it because it was better than singing in the cupola, because nothing like that had ever happened in the rose garden before, and because we left in our wake, astonishment. It's a very important thing to be able to pull a big surprise these days."

"You weren't taking any chances," Moult broke in, "those people lost their capacity for disgust a long time ago."

"The people aren't important," I said, "it was the way Jimmy Gene Ray and I worked together. Don't you see that?"

"You were just bored and you know it. If you met this Jimmy Whazit on the street today, that's tho only thing you could talk about. You didn't help him too much, did you?"

"Help him? What more could I do? Jesus, are you ever a snob! I don't pretend to know all the answers but I know something of what Jimmy Gene felt. For instance, I worked a summer in a filling station, Rudy's, up on the main drag. I worked there from six to ten at night, cleaned the grease pits and lift, washed the pumps, closed the place down. Polish Rudy who ran the station was a good guy. He had a knot in his back from a Jap bayonet and whenever he lifted anything the veins stood out in his arms like a road map. Every night when I came to relieve him he asked me good naturedly, "Getting any ass lately, guy? Getting any on the side?" Then he would grin and take a mock swing at me, making a noise of destruction with his tongue.

Once he pulled it in front of a customer, some salesman in a Pontiac. "Hey punk," he yelled. I was washing the windshield while he got the gas. "Getting any on the side lately?"

But I was ready for him. After all, it was at least the hundredth time he had said it. And I went on wiping the window as I answered. "Oh, is there a place for it there too?"

Well, that was it. Again I had humiliated and got away clean, as it appeared I was defending myself. Polish Rudy's mouth dropped open and he doubled up over the fender until the tank overfilled and gas cascaded over the Pontiac's trunk. The salesman was the same way; helplessly pointing a finger at Rudy, then at me, shaken in a noiseless rupturing guffaw. Rudy, soaked with gasoline and tears limped around the car, holding himself, repeating that comeback over and over in hisses between his laughs. "Is there a place Hee Is there a Haa," and so on. Finally he disappeared down the ramp into the grease pit, still squeezing himself.

I made change for the salesman but he closed his hand around mine when I gave it to him.

"Keep it buddy," he said, "You've made my day." Then he put his hydromatic in gear and went.

I had gotten $1.35 clear, and for the first time I knew how Jimmy Gene felt about those strangely flattered ladies in the rose garden, and their tips. Our lasting gifts come through such spontaneous humiliation. But spontaneity, when it works, is deeply practiced. It's practice that makes a comeback to the hundredth repetition possible, the capacity to run at full speed close to the ground. Practicing to be spontaneous has a lot to do with commonness.

At any rate, late that night when Rudy, the salesman, and I had tired of surprising each other, I was very depressed and felt like driving the Jeep. I didn't want to take it out on the highway

Spring, 1964

7

where I was liable, so I just circled the pumps in second, tires hissing on the hot tar, cruising around until it was time to close. So I know what happens when you're common. I've done my espionage.

Moulton didn't say anything at first. Then he stretched out, peering over his glasses. "Wow," he said. "Labor theory of value at thirteen. That must be some kind of a record."

I knew what he meant in a way, but I didn't say anything.

"And I suppose what you're saying," he went on, "is that by going along with these people you aren't helping them. The salesman should just have given you the dough and let it go at that. Even if he misunderstood. And when we're the salesmen, we shouldn't reward because that's so pretentious, and we shouldn't tell them what to do because that's just bossism. We ought to just hand out the cash, to Rudy, to Africa, to Jimmy Gene Whatsit and expect a little civility and be happy that they don't have a reason to beat you over the head."

"Isn't that all you can do? At least then they don't have an excuse."

"Christ, man, who's the snob? You just reverse it, that's all. You don't accuse them; you just assume them. You take them for granted. You leave them alone. That's the final prejudice, you know. That's the last thing people want. To be left alone. The only class distinction I know of is between those people who prefer to be left alone when they're screwed up, and those who want to be comforted. You may be on the right track, kiddo, but you'll take a lot of cleaning up."

It was funny. He ignored them but he liked them. I wanted to help them because I didn't like them.

Moult looked at me quizzically.

"What do you want out of them, anyway?" he asked.

"Well, it's very simple what I want," I said slowly, proud I could make him ask me a big question. "What I want is to be able to take my family to a good restaurant once a week. This restaurant has been around for a long time, always been run by the same family. One of them is always there, overseeing things. On the inside, it has no music or pictures, but just a lot of red wood - not redwood - but real red wood. It is one of the best restaurants in the world. They make their own ice-cream, bread, and chili. They put a dish of butter on the table, and you put it on your plate yourself. And the catsup is in its own unwiped bottle, instead of in a plastic gun with water. They ask you if you want seconds. In this restaurant there is a waiter, say named Hermann, who is not a member of the family, but has been there from the beginning anyway. He knows everyone's name, including mine; he knows my wife and kid on sight. Once a week, we come in. I shake

hands with Hermann, he takes the wife's coat and tells the kid he's bigger. Then we all sit down in the booth and he tells us what's good. We don't ask. He tells us. 'My wife's not very hungry so she wants the small filet, the boy wants a hot fudge walnut sundae without the walnuts, and you know what I want.' He takes the order and then comes back right away with two old John Jamison's on shaved ice and a cranberry cocktail for m'boy.

As we finish I call Hermann over and mention that the kid is captain of his ball team and is currently hitting a hefty .527. Hermann is delighted by this, and the kid dumps on me the rest of the dinner for embarrassing him like that.

When we're done Hermann forgives me for overtipping as I forgive his obsequiousness - and when Hermann goes home to his bachelor fiat, removes his white coat and his enormous black shoes, he lies down on the bed and hopes my kid will keep his streak going so it won't be difficult to ask me about it next week.

See, because if you can't have all that, if you can't pull that sort of thing off effortlesslyyou spend your whole god-damned life looking for it."

Moulton's mouth W3S wide open. "Why, there's more to clean up than I thought," he laughed.

I searched for a few moments for something more to say. I wanted to make it particularly big and reduce the argument.

"OK," I said, "what happens when the common people are Commies?"

It didn't take him any time at all.

"Well, man" he said laconically, "you just gave yourself away, that's all. But if you're interested, just look at our history. Look, we got our wealth looking for something else, salvation or something. And we got our power without looking for it at all. That makes some people think we've been playing our second team all these years. But what it means, I think, is that as long as we keep looking around I mean if we really pay any attention to them, it'll be the first time we ever met anything head-on except ourselves, and I'm afraid, then, we'll lose ourselves."

I had given myself away because I had used up my last Big Question. I was glad it was overwith.

"All right," I said. "I don't have any sharp theories like that, but you didn't let me finish about Jimmy Gene Ray."

So as a finisher, I told Moult as much as I could remember. I told him about how we fished in the park duck pond after dusk. It was full of goldfish, some a foot long, bloated with bread thrown from the shore. Whole loaves were thrown there. Kids slung them like disci. Slice after slice of miracle-whipped sun-cracked, vitaminenriched golden crusted manna spiraled out over the water.

If a duck got to the bread first he would eat it this way: down with the eight-color head like a

8

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

rocker arm, right through the center of the slice. He kept at it, hammering, squeezing the wah'!' from the pulp before he swallowed it, wcrking from the center out, until there was nothtng It-'t but a circle of crust. Then with a single movem ent he broke the circle, dove beneath one tattered end, and leaning back, swallowed it like a snake.

The carp, goldenfish, were more subtle. When they got there first, the slice would quaver, bob, until in a matter of minutes, its miracle fibers sufficiently punished, the bread simply separated like a cloud, broke into a film of particles which sank to orange blunt lipless mouths.

Either way they both got fat. And we would lie in the shrubbery at night, Jimmy Gene and I, with a loaf of bread between us, and with a hooked string and sinker, pull those carp flopping and shimmying across the olive water like nothing at all.

We never ate them, of course, they were filthy fish. We just put them in a pile and let them strangle. They stank even before they died.

Once in a while, too, we got a duck. Unintentionally, of course. When a greedy bill swooped and swallowed in one motion there was nothing you could do. Or rather there were two things. With the hook gone smoothly to the gullet you could just yank and rip that duck right through the throat. The red bread would sink, the duck would scream, stand in the water, swim a spiral, drown.

That only happened a few times and usually we just let the string go. Then the old bird would swing away, trailing twenty feet of twine from the corner of his mouth. He swallowed it slowly, I suppose, unconscious of it at first, only when it caught on some bottom snag and jerked him off course did he know. Gradually, the hook's legacy would be absorbed until it formed a compact sodden mass against the ribs, a false entangled heart next to the gaudy real one.

I did some research once to ascertain whether a duck's gullet is like that of the oyster or deer who make functional use of their cancers. But I found nothing. I would like to think that he has no such coating, no inner defenses, and that the hook, wound with string by the convulsions of his own chemistry, rests against his chest like a locket on the inside of a soldier's lapel. And that one day, while flying south for the winter, a shot will ring out and he will fall into the reeds. But before the dogs reach him, as in the movies, he will awake, and inspecting himself, find that the absorbed old wound has deflected the shot from softer regions, that he just has been dazed, that a miracle has saved his life.

So we lay in the bushes with bread, rolls of hemp, irreversible hooks, and the strench of inconsequential but still immoral death. Jimmy Gene the Carp and me the Duck.

Spring, 1964

POEMS

By Edith B. Farnsworth

The editors are pleased to be able to present these new poems by Edith 8. Farnsworth, Assistant Professor of Medicine at the Northwestern Medical School. The Tri-Quarterly first printed two of her poems in the fall of J959, and in the following fall a much wider selection, together with an article by her on modern poetry. Dr. Farnsworth, who is a practicing physician and a research specialist, as well as a teacher and poet, is a native Chicagoan. She attended as undergraduate both the University of Chicago and Northwestern, and took her M.D. at the latter in J939. She has served Chicago hospitals in various capacities and is presently on the Attending Staff of Passavant Memorial Hospital. She has published extensively in her field of internal medicine.

The Egg-plant of a Prince

Thank Y00 Mr. Stevens*

The prince is written in cuneiform, Molded, imprinted in character, The Prince is a hieroglyph.

Rotunda his egg-plant his leptoderm, Mahogany brown to lavender, By no means a pineapple.

Hieroglyphic is not agitating

And the prince does not prance at night In Thebes or Sebastopol.

But the egg-plant is a sleep-annihilating And if She were sleeker or slender, More perfectly curved, more prescient, exhilarating, Handsomer, more elegant, I could never sleep at all.

"Extracts from Addresses to the Academy of Fine Ideas." by Wallace Stevens.

MY OWN

When I came back to my own, last night, The day, and the day, were nearly gone; The crows still planed in after-light, The low sun stained The empty land with past.

From out of the tall trees

The Red Bird had departed. With its long coiled crest, With its great plumed tail, Male and female subtly expressed, From the tallest of my own fall trees

The Scarlet Bird had taken flight Back to the South Quadrant, broken-hearted.

9

Night Fishermen of Chicago

The fish run by the shores to-night, The fish are running heavy, and from Certain dingy doors emerge

The anglers: let's go down to the Lake to fish, let's sit on the edge, Let's set up our poles and light

Our lights, we'll take a folding chair

And hope, we'll bait our lines

And take a lunch, we'll take a chance, We'll fish through the night to-night

While the fish are running.

The great fresh lake is full to-night

And fuming, straining, out of Mind and into sight, It brims its glooming, ebbing surge

Over the city's concrete shores.

Now from a hot hand eager on the verge Of darkling luck, the baited fishhook flies, Swings on the tensed line to submerge

A sparkling hope into the cold surge, Rising and falling at the city's stony doors.

Behind the curved backs crouching on the brink

Of foundering fortune, flow the damped streets

Apathetic, furnaces nightfallen, banked

For the long rest; the old dog hesitates

At the comer, the cat waits

For the passing car, to slink Into its destiny; the cellar vibrates

With the purring of the ocelot.

With the whining ragweed of the vacant lot Periodic lilacs in the city parks, With rows of elms and prostrate thyme, Tremble damply in their dark procession, Deployed to be the scene of love and crime.

And if in the great dark lake there were Lavender as in the sea, Rockweed, kelp, anemone, What organpoint in harmony, Dissolved, suspended, would concur

To sound the marine litany?

The fishermen, sitting on the floor, In the dark of all that seems to be, On the border of mortality,

The heavy buttocks and the hamstrings

Spry, wind-breakers, sweaters and the denim Fly, all gripping hard within the door

Of the world; those solitaries

Stretched upon the water's flanks

Like suckling cubs in new-born ranks

-They angle for a talisman and Slyly cast the baited soul

Into the swell, beneath the dark pole

Of a dark sky.

Long are the fluent waves that roll In from the south-east. Hand

Over nerveless hand they climb the docks, Finger the slimy piles and spread

Their avid fans over the rocks.

And if from the Great Lake were to come, In the footprints of the long ground-swell

And the deep hours of the night,

The jewelry of beauty from

The dead, if from the drowned who dwell, Dissolved, suspended, in the sight Of none, there were to come

The judges with their white jabots, Evangels and their long flambeaux, The orphans with their dolls; If the divine despair were there

And with its subtle, unpredicted glow

Would flood the water-

Would draw the fishermen to light

Then what allure

Their lights and pass the lonely night

Fishing for perch?

Will they who fish for luck endure

The bleak glow at the edge of the world, The tokens by the long waves hurled

Upon the rocks?

Translucent to the dawning day, The tender, milk-white undersides And moss green scales lie still.

Thirst fills

The gaping mouth and glues

The parching gills.

The sun comes up; the seagull shrills, Soaring from the far seawall.

Wild luck from the dark-bodied lake Springs high with the hook, to fall Expiring in the fisherman's pail.

November, 1960.

Amaryllis

Amaryllis, lily Asphodel, Waxing form Elaborelle;

Does it launch into the ages Or does it only grow, Asphodel, slow, slow In limpid cages Of my eyes?

I cannot tell the time, Decode the rages, Parching in the winter slime.

Soar daily in the twisted ages, Hirondelle, With waxing torrid wings

Tilt, weld the clouded skies, Measure the numbered stages

Undecipherable; With graphic ribs, with swelling heart, Wax slowly, amaryllis, lily Asphodel.

10

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

By Carl W. Condit

ARCHITECTURE in the NINETEENTH CENTURY

The Antecedents of the Chicago School

The architectural and technical achievement of the Chicago school marked the establishment of a new style of architecture, but at the same time it was the culmination of a structural evolution that extended over the century preceding it. This dual character was reflected in the two major developments of the school, which existed side by side throughout the central portion of its history. One was highly utilitarian, marked by a strict adherence to function and structure, and was in great part derived from certain forms of urban vernacular building in Europe and the eastern United States. The other was formal and plastic, the product of a new theoretical spirit and the conscious determination to create rich symbolic forms - to create, in short, a new style expressive of contemporary American culture. Thus the architecture of the Chicago school must be interpreted from several standpoints: first, in terms of the structural techniques and building forms from which it grew; second, in relation to the architectural dress, so to speak, of the reviva1istic building of the nineteenth century; and finally, in comparison with the later development of the stylistic revolution which it set in motion.

Style in architecture represents or stands for those essential characteristics of construction, form, ornament, and detail that are common to all the important structures of any definable period in history. But it also stands for those technical and aesthetic qualities of the artistic product that grow directly and organically out of the conditions of human existence and out of the aspirations and powers of human beings. We rightly feel that the buildings of a certain style - if it is

Spring, 1964

a genuine style - symbolize in their form the realities of man's experience and the attempt to master and give adequate emotional expression to those realities. These buildings are constituent facts of man's history, and their revelation is a part of truth itself.

The refined architectural classicism that became dominant in the latter half of the eighteenth century eventually faced the social and economic revolution brought about by the largescale application of steam power to industrial techniques and by the new mechanical inventions that accompanied this application. The first clumsy steam engine might have seemed remote from the proud dignity of the Royal Crescent or Cumberland Terrace; yet it represented a force that soon engulfed all the arts and all the modes of action of Western civilization. In the face of this unprecedented phenomenon, the ancient and vital art of architecture was threatened by powerful disintegrative forces. With respect to utilitarian needs, the traditional techniques of construction eventually fell hopelessly short of meeting the requirements and taking advantage of the opportunities presented by the new age of mechanized industrialization. Architectural revivalism struggled bravely with the social and technical forces of the age and frequently produced functionally successful and aesthetically valid works of building art, but as the century moved on revivalism grew increasingly out of touch with the realities of the time. The ultimate artistic failure of architecture in the nineteenth century can be stated very simply as the failure to form a consistent style. It was the failure to provide, in its own vocabulary, an aesthetic discipline that would combine the expression of science, technology, mechanized industry, and modern urban life with the deeper-lying emotional needs of the human spirit.

Architecture had once been what it ought to be - the structural art. It is the combined art and technique of designing, shaping, organizing, and decorating the stone, iron, wood, and glass of which a building is composed. It is not one of these activities alone, but all of them together, making an organic unit with a form and expression and use of its own. But as the nineteenth century progressed, the architect, instead of being a master builder or a designer of a whole structure, increasingly became the person who applies an arbitrary dress to a structure which was largely designed and wholly built by others who cared little about the niceties of scale, proportion, and rhythm. The architect did the best that he could in the face of unprecedented demands, but it became more and more difficult for him to develop an exterior form that grew out of and gave expression to the dominant social factors of the time, chiefly the new conditions of urban life in the great centers of trade and manu-

11

facture.

The failure of the nineteenth-century architects, however, cannot be ascribed simply to perversity or to ignorance; nor can it be understood as an escape into fantasies that seemed more pleasing than the harsh realities of the time. It is true that before the challenge of the machine they sought refuge in styles with literary, historical, and even ethical associations. But that challenge was so extreme, so complex, and so unprecedented that much of the best talent went to finding ways in which well-known architectural forms could be adapted to the new exigencies. In a positive sense, the architects of the time reflected the extent to which the age was imbued with the historical spirit and its associated points of view. In this respect the nineteenth century was unique: no other period was so deeply conscious of the historical process as an essential dimension of man's selfawareness. The borrowing of exterior architecturaJ details was often indiscriminate and sometimes merely capricious, so that when we view the century as a whole from our own vantage point, we feel that styles came and went like fashions in dress. But if we consider the names of only a few of the best American architects of the past cen-

This article is, with some additions and different illustrations, the first chapter of Carl W. Condit's book The Chicago School of Architecture, which will be published this summer by the University of Chicago Press. This book is an extensive revision and expansion of his earlier (1952) The Rise of the Skyscraper.

Condit is Professor of English at Northwestern, where he directs the Senior Tutorial Reading Program and teaches a course in the development of science. His interests are primarily technological and historical. His two volume American Building Art (published by the Oxford University Press in 1960 and 1961) is a pioneer work on the history of structural technology in the United States, including bridges, highways, and the structures of waterway control as well as buildings in the usual sense of the word. He was one of the founders of the Society for the History of Technology and is co-editor of its iourna/, Technology and Culture.

tury, we realize that, however much the succession of revivals prevented them from forming an architectural style, they were in no way inhibited from creating impressive individual buildings. Some of them, indeed, are superior to anything we have produced today, at least in the richness of the visual experience that they can offer.

American architecture in the nineteenth century began with the variations on Palladian and allied classical forms which are generally comprehended in the term "Federal style." Thomas Jefferson was the best-known exponent of its Roman enthusiasm, but many others contributed to a body of architectural work distinguished by a harmony, dignity, and repose that seem remote from our frantic time. The Greek Revival might be regarded as a simplification of the earlier movement, sometimes combining a dedicated antiquarianism with a perfectly sound understanding of its adaptability to the needs of the young republic. The possibilities of this romantic classicism, as it has sometimes been called, are most fully revealed in the work of William Strickland, Robert Mills, and Thomas Ustick Walter.

The revivals which followed the Greek came at shorter intervals. By mid-century, Gothic was in the ascendant. It is best represented in the ecclesiastical designs of James Renwick and Richard Upjohn in New York. Shortly after the Civil War the restless age demanded another change, and the Gothic was superseded by the Romanesque, most poserfully and creatively exploited by Henry Hobson Richardson in ways that ultimately pointed toward genuinely contemporary forms. The last phase before the end of the century was the Renaissance Revival, dominated by the great town houses and public buildings of McKim, Mead and White. In the heyday of their lavish practice, however, Sullivan was enjoying his largest commissions and thus providing the perfect antithesis to the revivalistic spirit of the age. Yet eclecticism was to continue as the dominant mode of building until the third decade of the twentieth century.

For all the excellence of individual buildings, the whole pattern of architectural development revealed to a growing degree a serious malaise at the roots of nineteenth-century culture. The artist in part creates the character of his time, but he must at the same time be nourished by what his age gives him. Architecture, in the period of its decline, reflected certain cultural failures of the new industrial age. Most pervasive, as we can now see, was the collapse of the traditional well-ordered cosmos that embraced a moral, or at least a rational, as well as a physical order. Associated with this loss was the progressive decline of a public or civic world in which human beings might find scope for meaningful action and the potential self-realization that accompanies it. The growth of the industrial megalopolis of the

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

nineteenth century quickly destroyed the remaining vestiges of the humane urban order that once provided some measure of self-identity and digmty to the citizen. The past century seemed stubl« on the surface, but in truth the unstable and ephemeral quality of many of its cultural achievements provided increasing evidence of an inner disharmony and confusion that persists to this day, although in different forms.

What the nineteenth century suffered from was in part a split personality, a "cultural schizophrenia," as Sigfried Giedion explained it. This state has been characteristic of other highly creative periods of confused or rapidly changing spiritual orientation. The emotional statisfactions and the aesthetic experiences of people were split off from their intellectual and practical activities. Science and technology parted company from art, and both were ultimately divided into an ever growing number of separate, isolated compartments. Eventually specialization reached such a point that one could not even see the world beyond one's own special activity, much less comprehend it.

Thus at a time when the technical and intellectual elements of culture were most in need of a humanizing discipline, the one best calculated to achieve it in the public world failed to realize its highest function. Architecture in one of its aspects is a utilitarian art. Function, structure, and form are indissolubly wedded. Applied science and technology provide it with materials and with their known mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties; the artist's sense of form and order and harmony, his capacity to create symbolic images, transform the physical elements into emotionally satisfying objects that live in the imaginations of men while giving voice to their ideals, aspirations, and capacities. A genuine architecture is a technical-aesthetic synthesis that makes it possible for the world of technology to enter into the domain of feeling and morality.

In order to achieve this end architects in the nineteenth century eventually had to turn their back on imitations of the past, for they were faced with conditions and opportunities that had no precedent. They had to master new materials and offer solutions to new problems. The forms of the past, however vital they once were, came to have little meaning in the face of the conditions which came to exist in New York or Chicago. But just as the great majority of nineteenth-century architects seemed to have lost contact with the social and technical realities of their time, individuals began to appear who, consciously or unconsicously, accepted the challenge of their age and built directly and boldly on its basis.

It was the engineers who first pointed the way that a new structural art might profitably take. They built primarily for use, and whatever form their structures took at least had the merit of ex-

Spring, 1964

pressing directly, simply, and honestly the system of construction they employed. However, some of the bridge engineers had a strong sense of form. They looked upon techniques somewhat as the artist looks on the material of his painting or poetry, and they wanted to celebrate the powers they possessed by means of a new kind of monumentalism. Industry had provided them with new structural materials, cast and wrought iron, and they exploited their possibilities with an exuberance unparalleled in the history of building. Early in the nineteenth century some of the bridge engineers, imbued with a sense of harmony and proportion characteristic of trained architects, developed structural forms that pointed toward an organic architecture appropriate to a mechanized industrial culture.

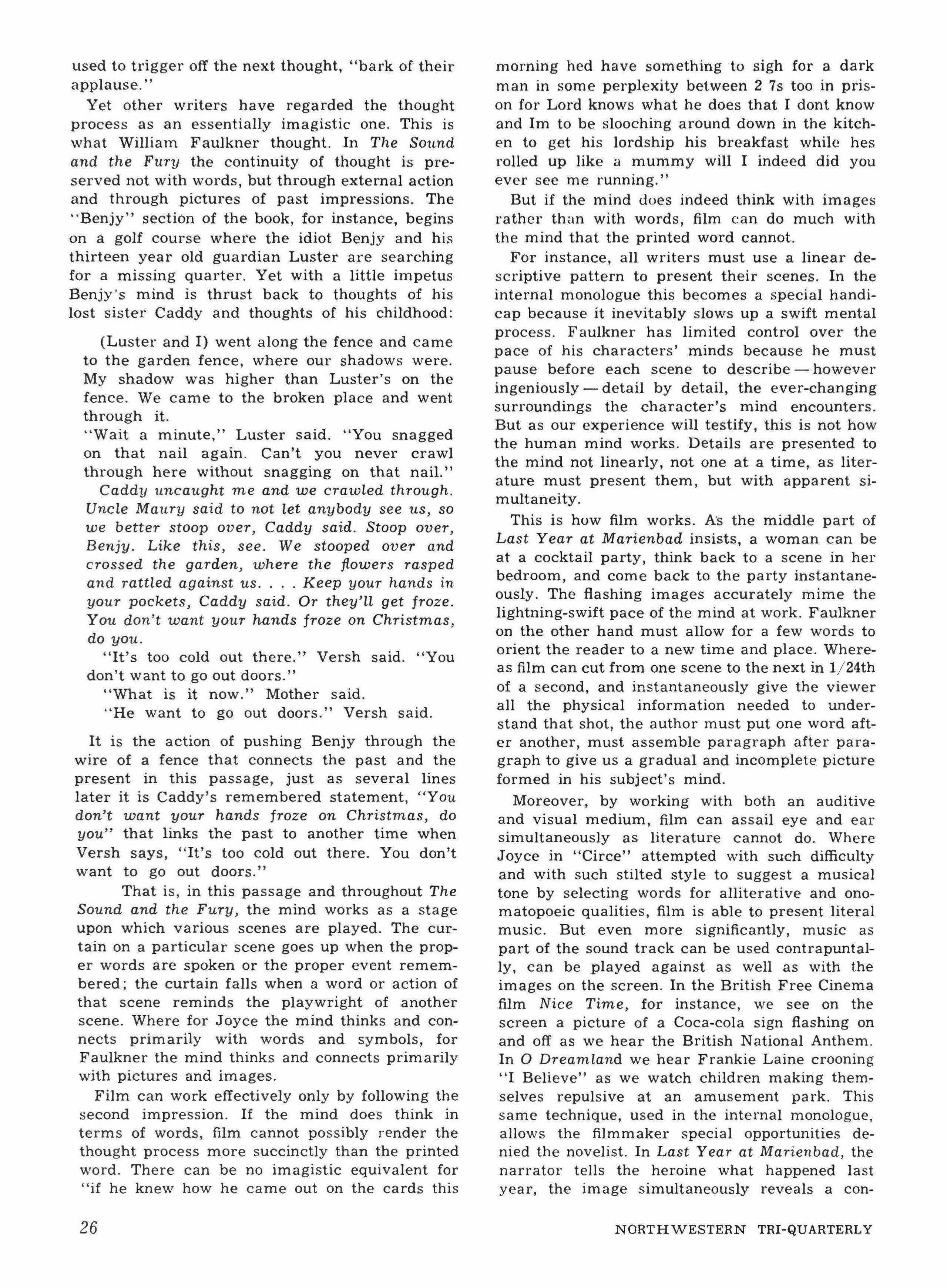

The first cast-iron structure was a small arch bridge over the River Severn at Coalbrookdale, England. It was built by the iron founders Abraham Darby and John Wilkinson between the years 1775 and 1779. Following the precedent of two thousand years of masonry bridge construction, the builders employed the fixed semicircular arch as the only acceptable form. Thomas Telford's great project of 1801 for a bridge over the Thames at London involved a flattened arch of 600-foot span. In its size, its effortless grace, and the delicacy of its iron ornament, it would have been a major aesthetic achievement. Telford's finest completed span was the suspension bridge over Menai Strait, built between 1819 and 1826,

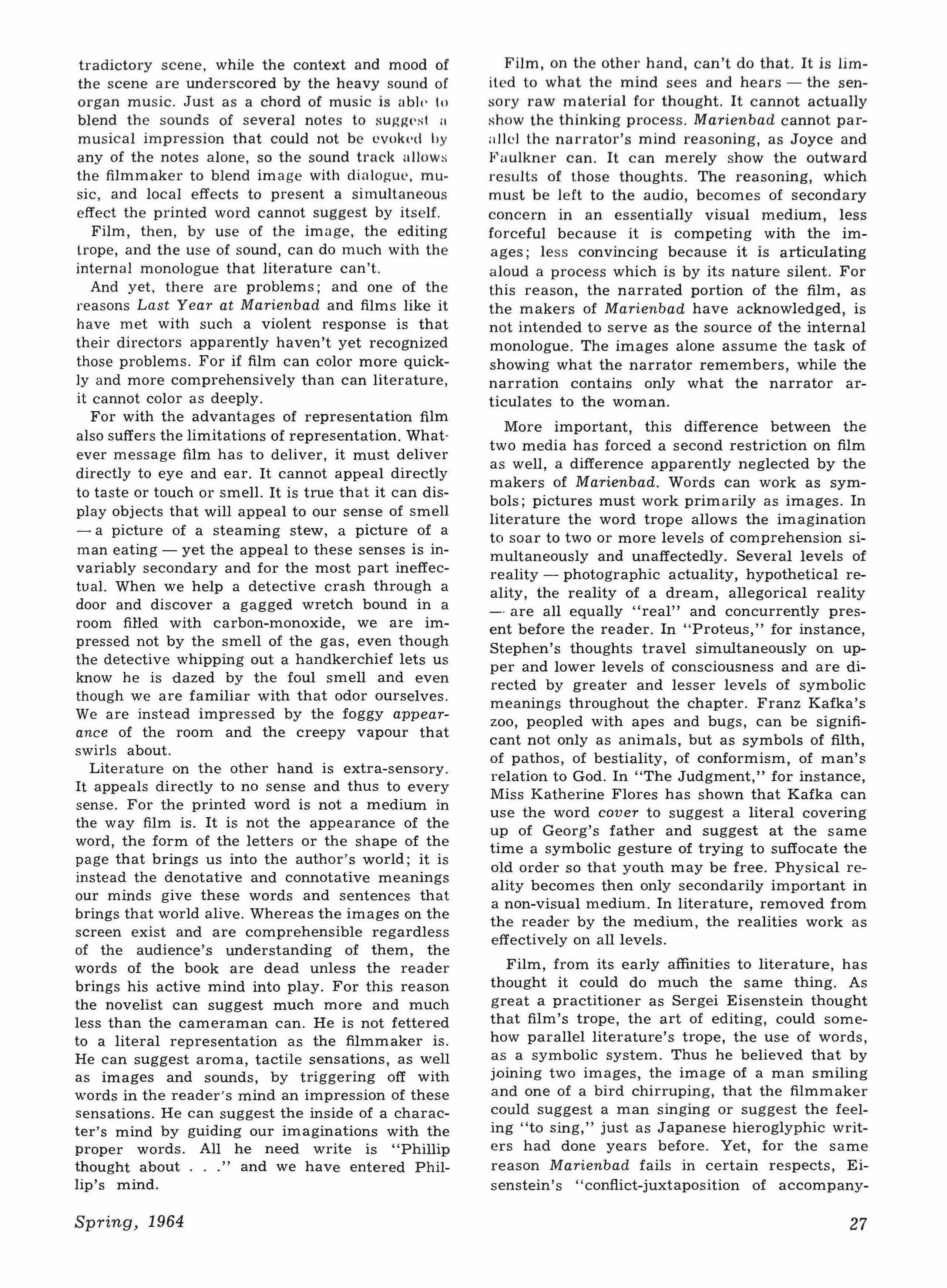

Brooklyn Bridge, East River, New York City, 1869-83. John and Washington Roebling, engineers.

13

the first big bridge to embody the new system of suspended construction.

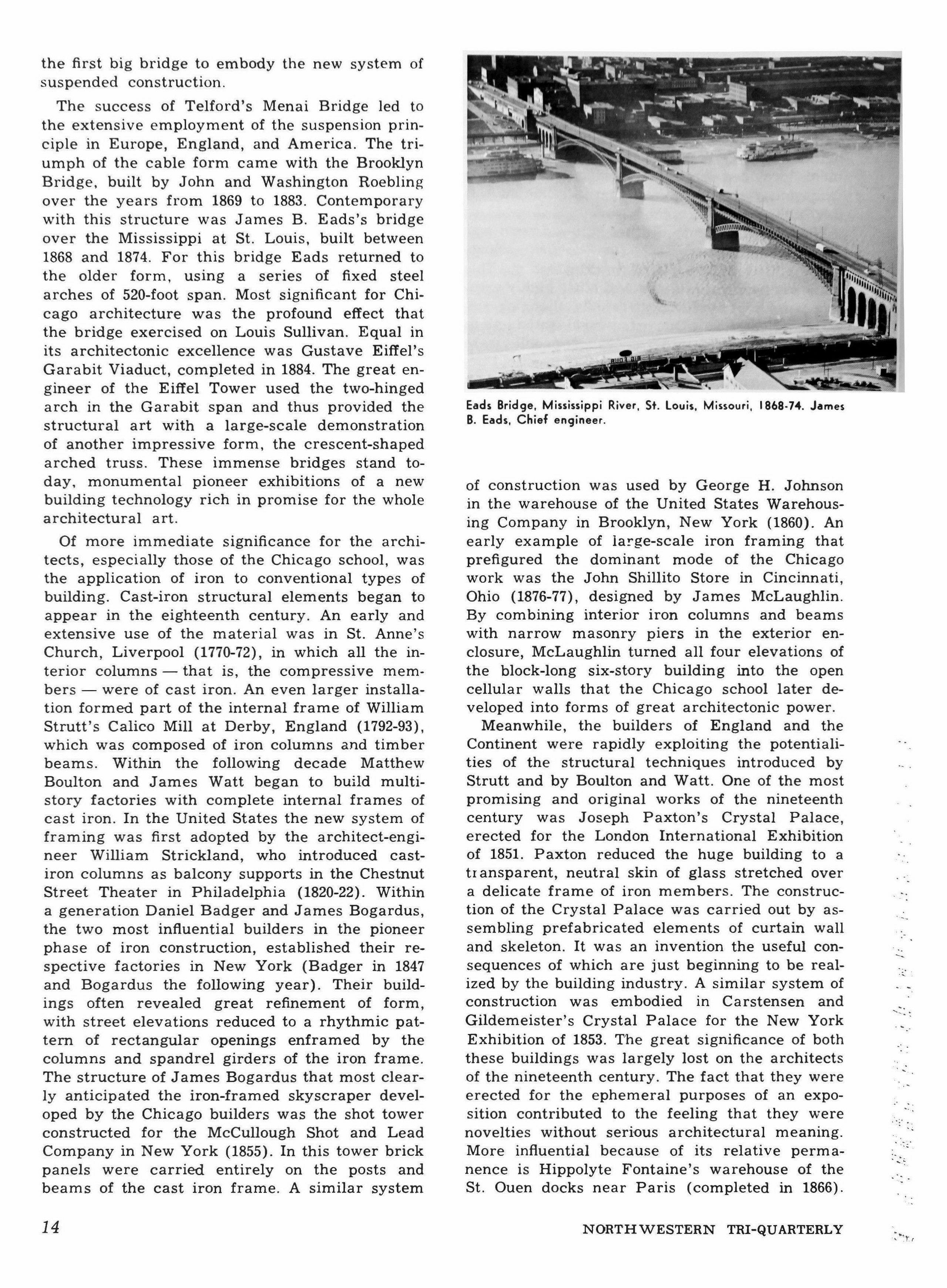

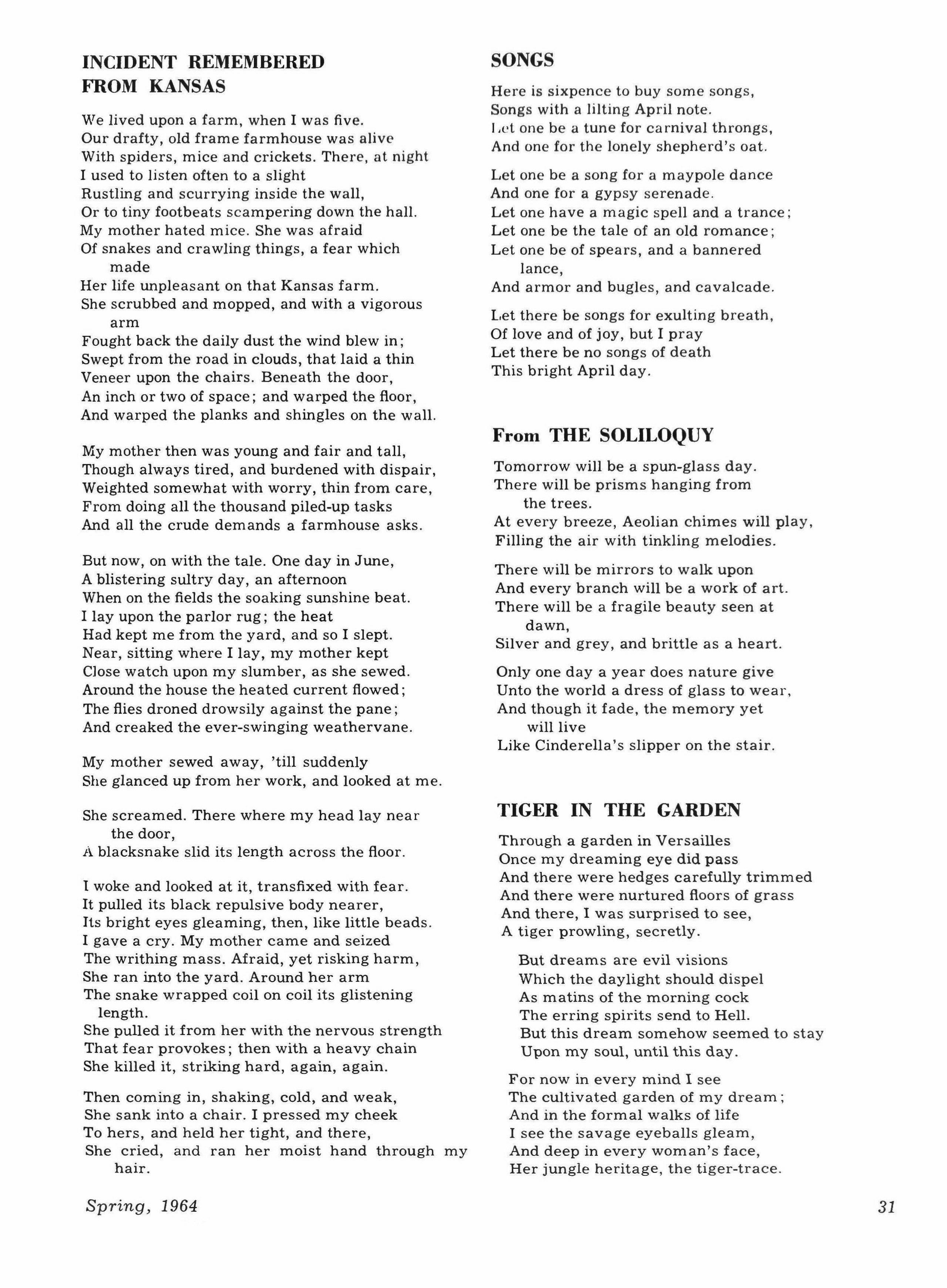

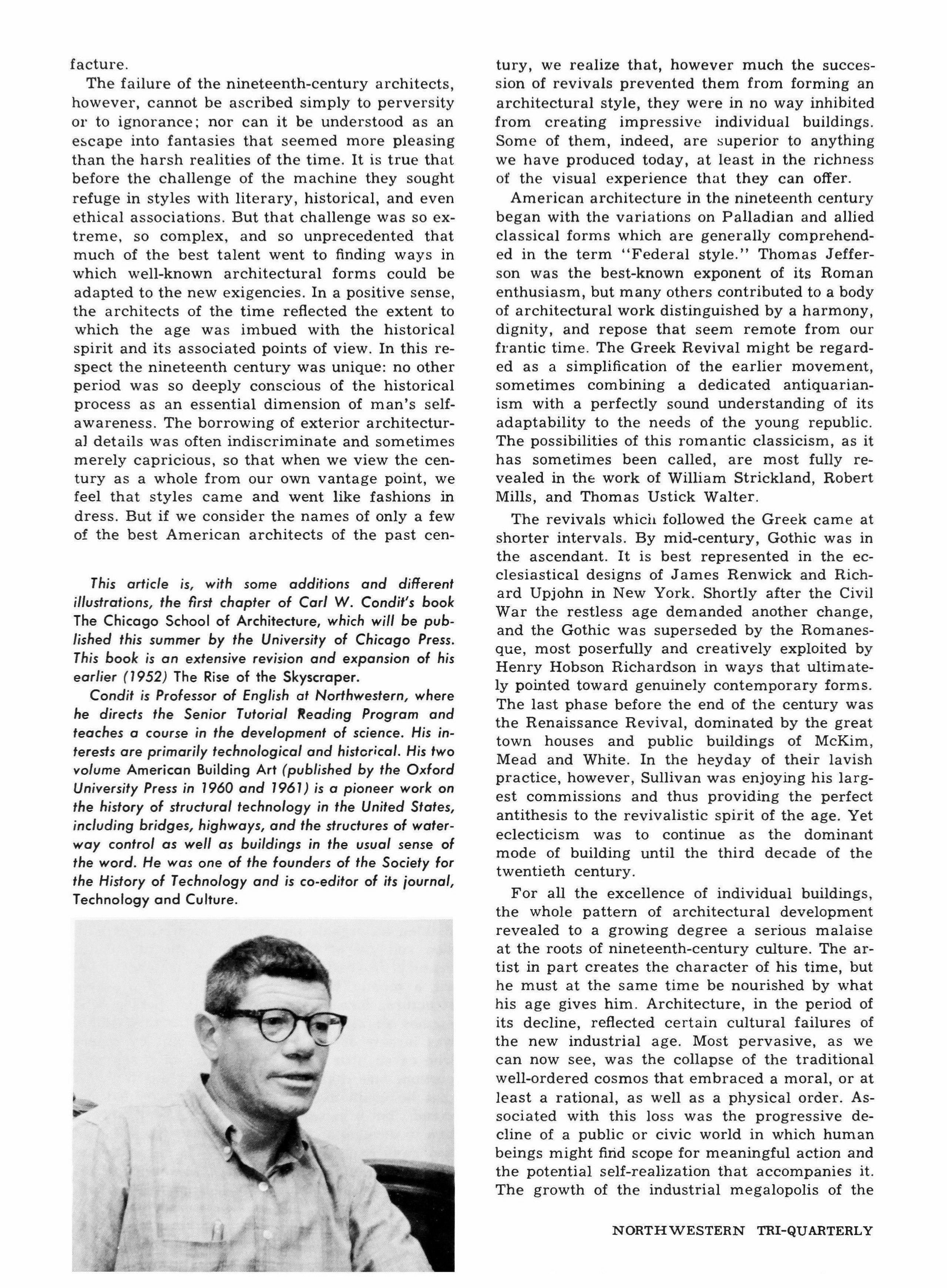

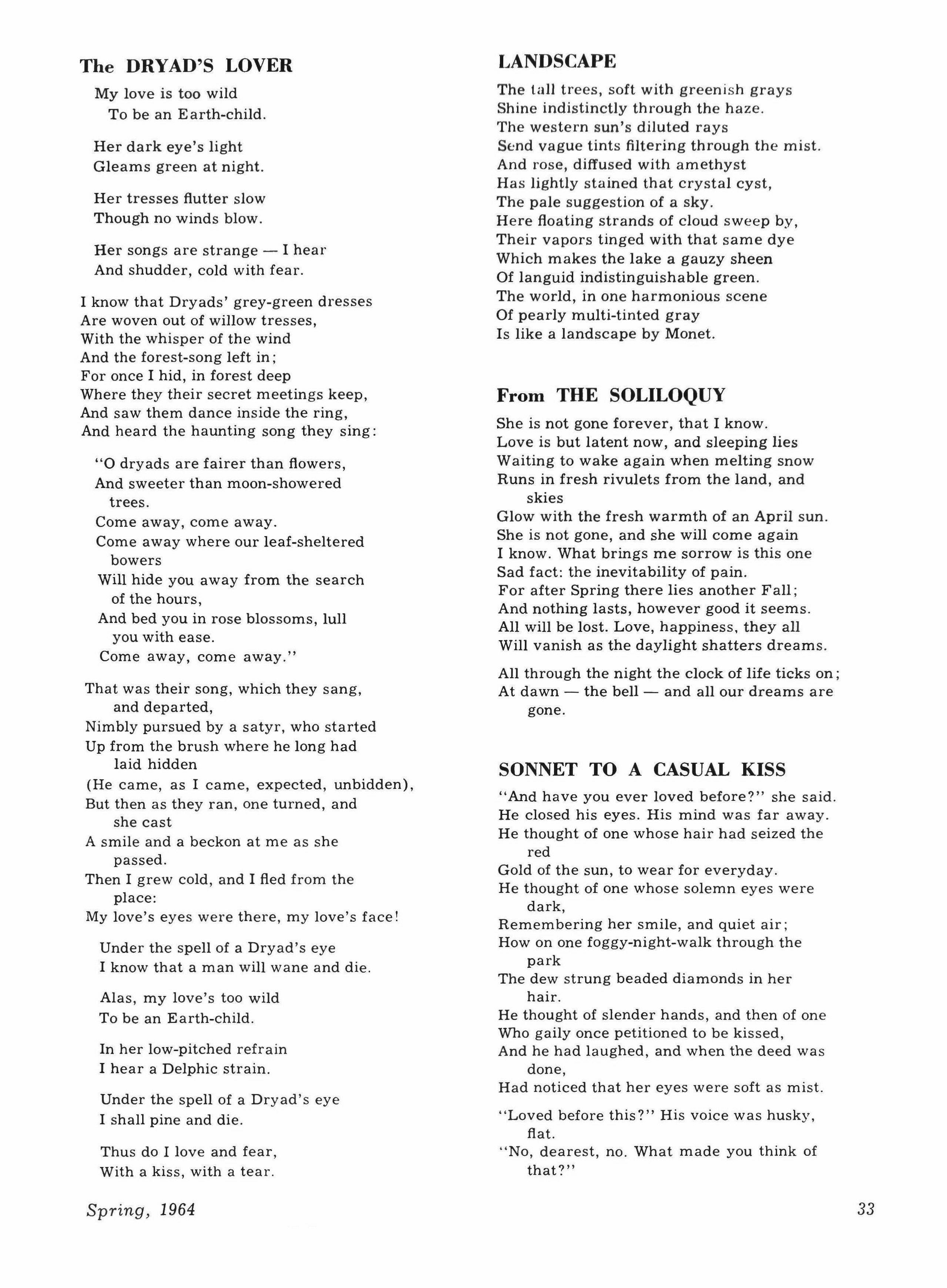

The success of Telford's Menai Bridge led to the extensive employment of the suspension principle in Europe, England, and America. The triumph of the cable form came with the Brooklyn Bridge, built by John and Washington Roebling over the years from 1869 to 1883. Contemporary with this structure was James B. Eads's bridge over the Mississippi at St. Louis, built between 1868 and 1874. For this bridge Eads returned to the older form, using a series of fixed steel arches of 520-foot span. Most significant for Chicago architecture was the profound effect that the bridge exercised on Louis Sullivan. Equal in its architectonic excellence was Gustave Eiffel's Garabit Viaduct, completed in 1884. The great engineer of the Eiffel Tower used the two-hinged arch in the Garabit span and thus provided the structural art with a large-scale demonstration of another impressive form, the crescent-shaped arched truss. These immense bridges stand today, monumental pioneer exhibitions of a new building technology rich in promise for the whole architectural art.

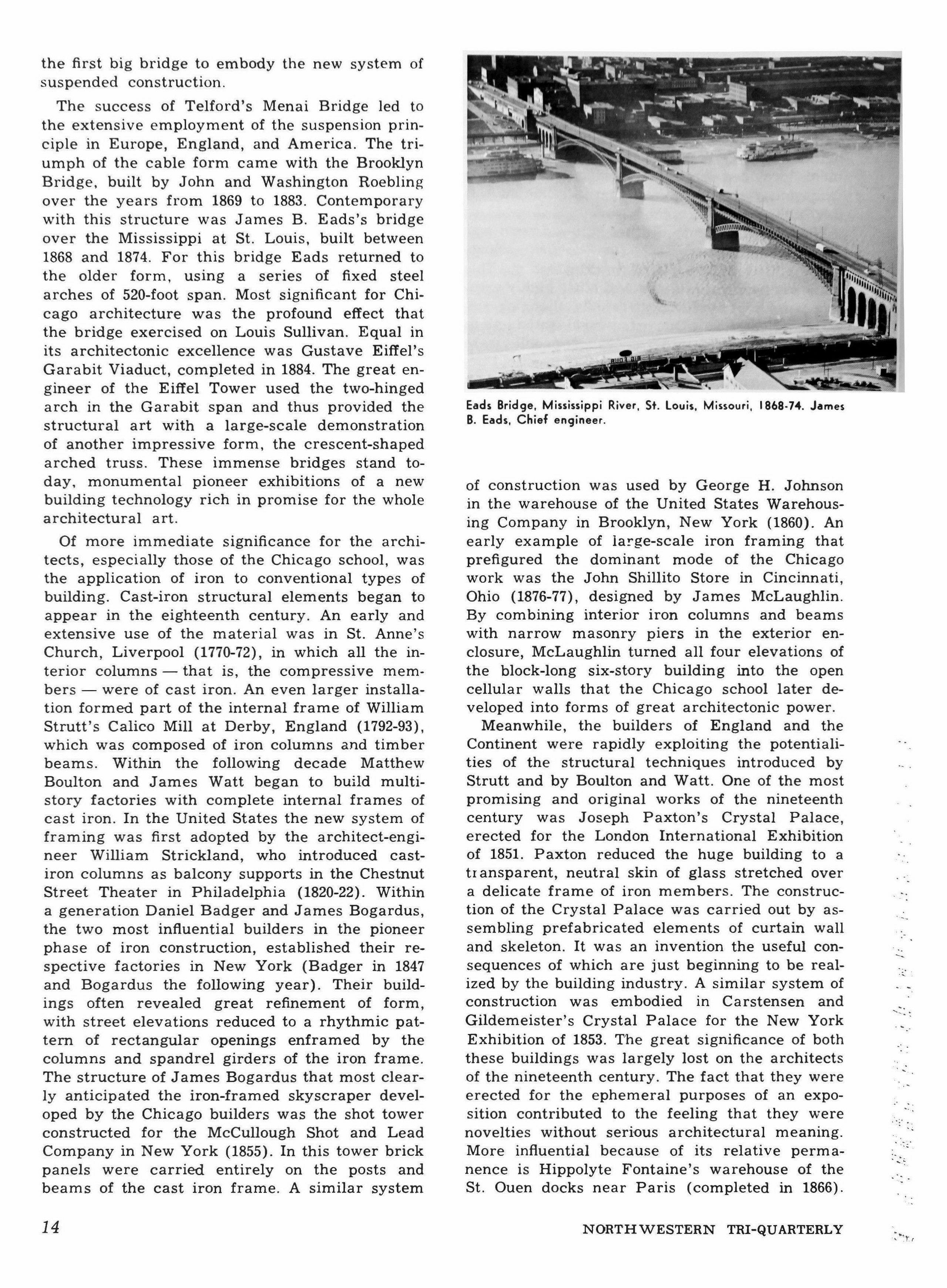

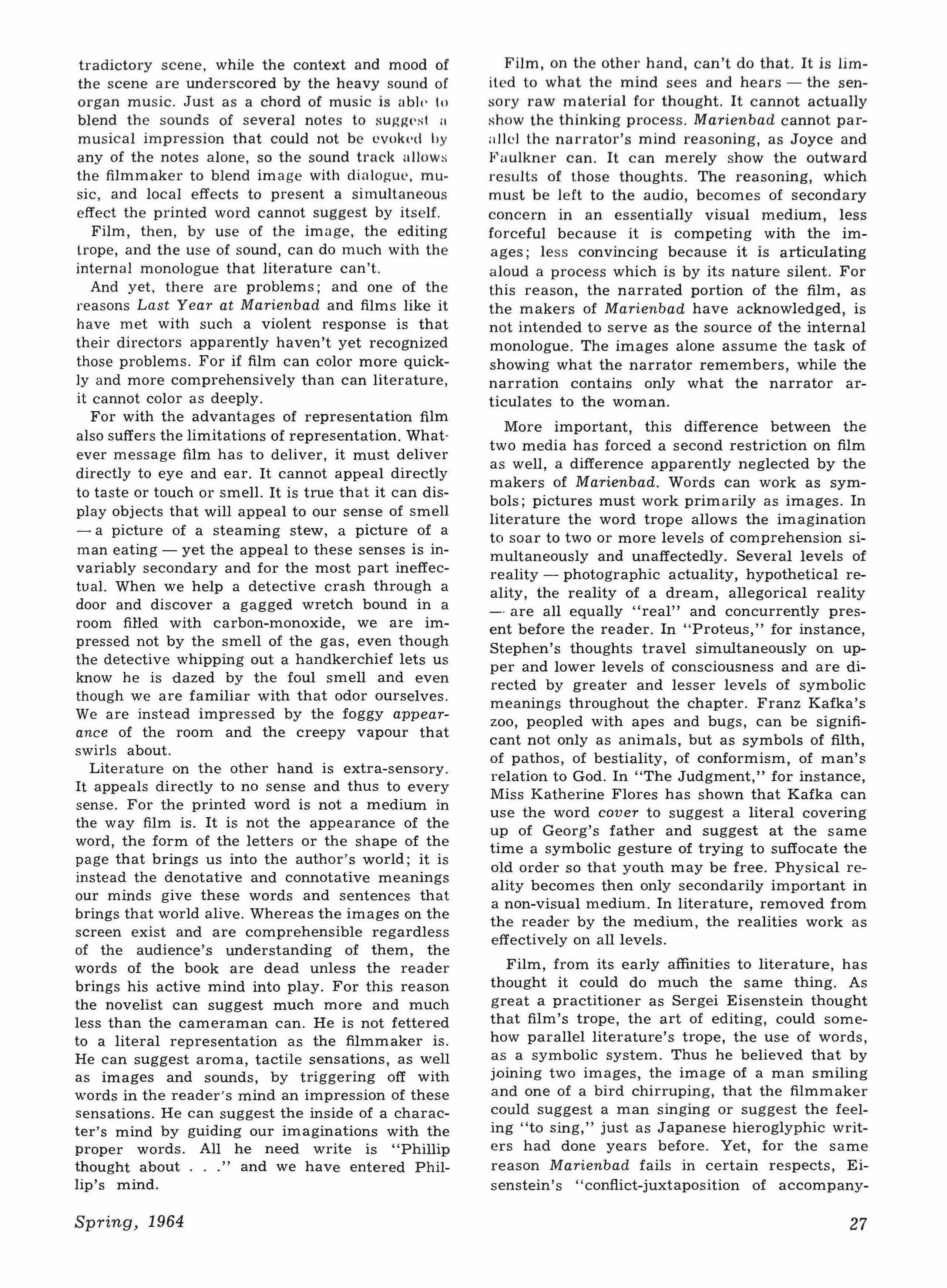

Of more immediate significance for the architects, especially those of the Chicago school, was the application of iron to conventional types of building. Cast-iron structural elements began to appear in the eighteenth century. An early and extensive use of the material was in St. Anne's Church, Liverpool (1770-72), in which all the interior columns - that is, the compressive members - were of cast iron. An even larger installation formed part of the internal frame of William Strutt's Calico Mill at Derby, England (1792-93), which was composed of iron columns and timber beams. Within the following decade Matthew Boulton and James Watt began to build multistory factories with complete internal frames of cast iron. In the United States the new system of framing was first adopted by the architect-engineer William Strickland, who introduced castiron columns as balcony supports in the Chestnut Street Theater in Philadelphia (1820-22). Within a generation Daniel Badger and James Bogardus, the two most influential builders in the pioneer phase of iron construction, established their respective factories in New York (Badger in 1847 and Bogardus the following year). Their buildings often revealed great refinement of form, with street elevations reduced to a rhythmic pattern of rectangular openings enframed by the columns and spandrel girders of the iron frame. The structure of James Bogardus that most clearly anticipated the iron-framed skyscraper developed by the Chicago builders was the shot tower constructed for the McCullough Shot and Lead Company in New York (1855). In this tower brick panels were carried entirely on the posts and beams of the cast iron frame. A similar system

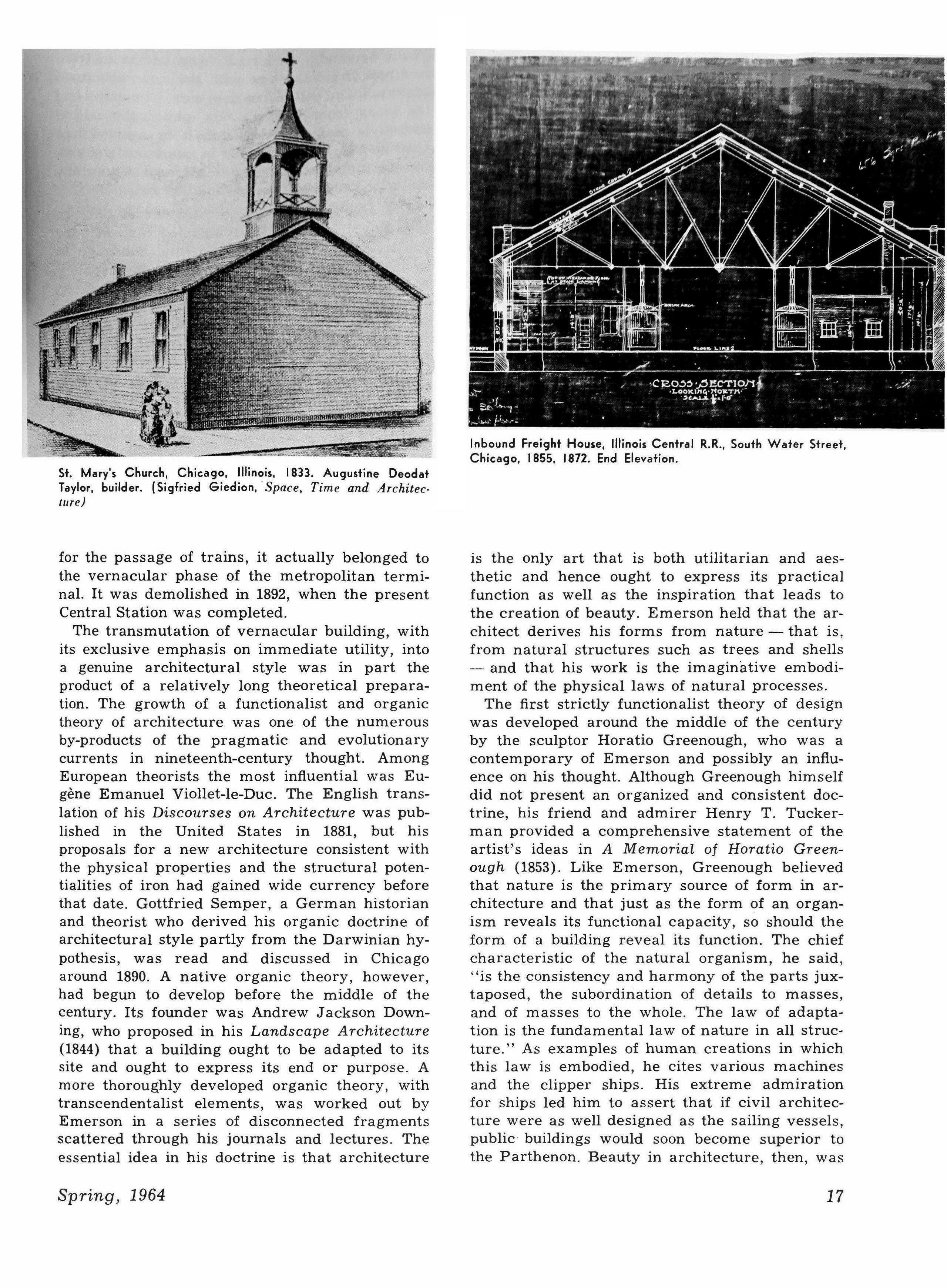

of construction was used by George H. Johnson in the warehouse of the United States Warehousing Company in Brooklyn, New York (1860). An early example of large-scale iron framing that prefigured the dominant mode of the Chicago work was the John Shillito Store in Cincinnati, Ohio (1876-77), designed by James McLaughlin. By combining interior iron columns and beams with narrow masonry piers in the exterior enclosure, McLaughlin turned all four elevations of the block-long six-story building into the open cellular walls that the Chicago school later developed into forms of great architectonic power. Meanwhile, the builders of England and the Continent were rapidly exploiting the potentialities of the structural techniques introduced by Strutt and by Boulton and Watt. One of the most promising and original works of the nineteenth century was Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace, erected for the London International Exhibition of 1851. Paxton reduced the huge building to a tr ansparent, neutral skin of glass stretched over a delicate frame of iron members. The construction of the Crystal Palace was carried out by assembling prefabricated elements of curtain wall and skeleton. It was an invention the useful consequences of which are just beginning to be realized by the building industry. A similar system of construction was embodied in Carstensen and Gildemeister's Crystal Palace for the New York Exhibition of 1853. The great significance of both these buildings was largely lost on the architects of the nineteenth century. The fact that they were erected for the ephemeral purposes of an exposition contributed to the feeling that they were novelties without serious architectural meaning. More influential because of its relative permanence is Hippolyte Fontaine's warehouse of the St. auen docks near Paris (completed in 1866).

14

Eads Bridge, Mississippi River, St. Louis, Mi>5ouri, 1868·74. James B. Eads, Chief en9ineer.

.:....

NORTH WESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

,':

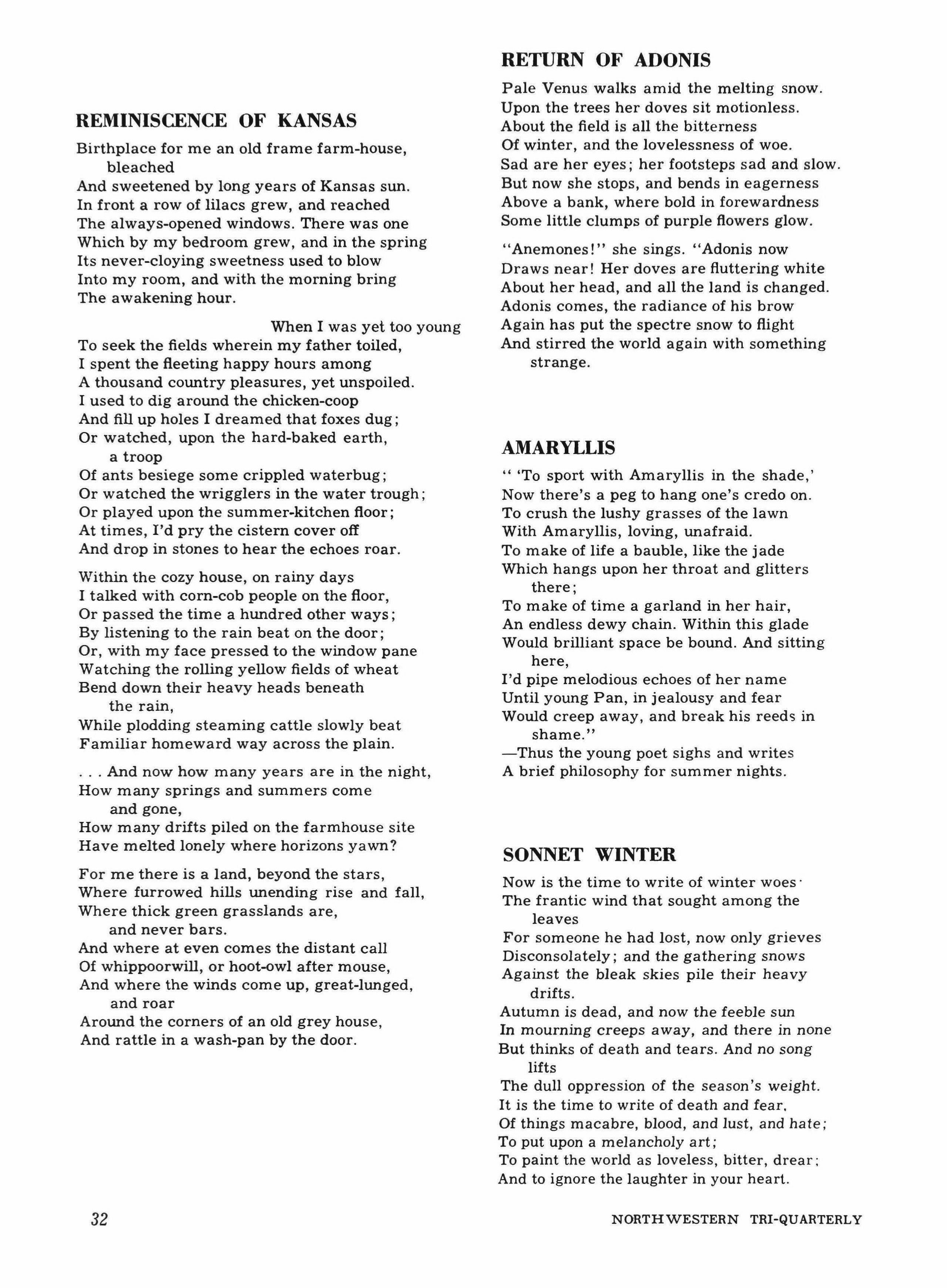

Shot tower. McCullough Shot and Lead Company. 63-65 Centre Street. New York City. 1855.

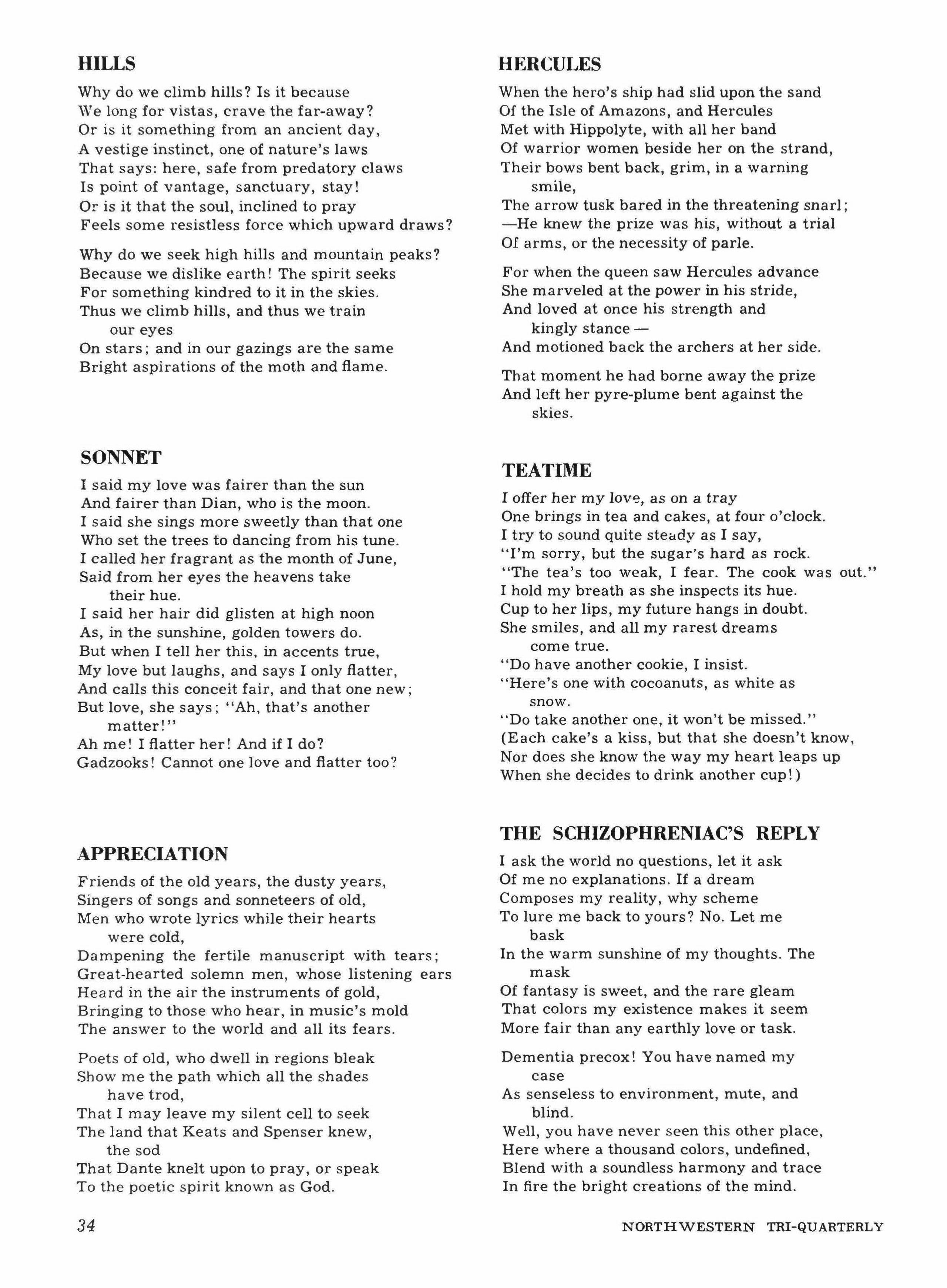

The warehouse is a larger and more thoroughly developed example of the early essays in iron framing produced by Bogardus and Johnson. There is good evidence that this extraordinary building is the first multistory structure carried entirely on an iron frame without any assistance from masonry bearing elements. It is thus a strictly utilitarian forerunner of Jenney's Home Insurance Building in Chicago (1884-85). Within five years Jules Saulnier produced one of the curiosities of early iron framing in his Menier Chocolate Works at Noisiel, France (1871-72). The braced framing in the curtain walls of this building, undoubtedly derived from the iron bridge truss, is an important step in the development of windbracing for the tall building.

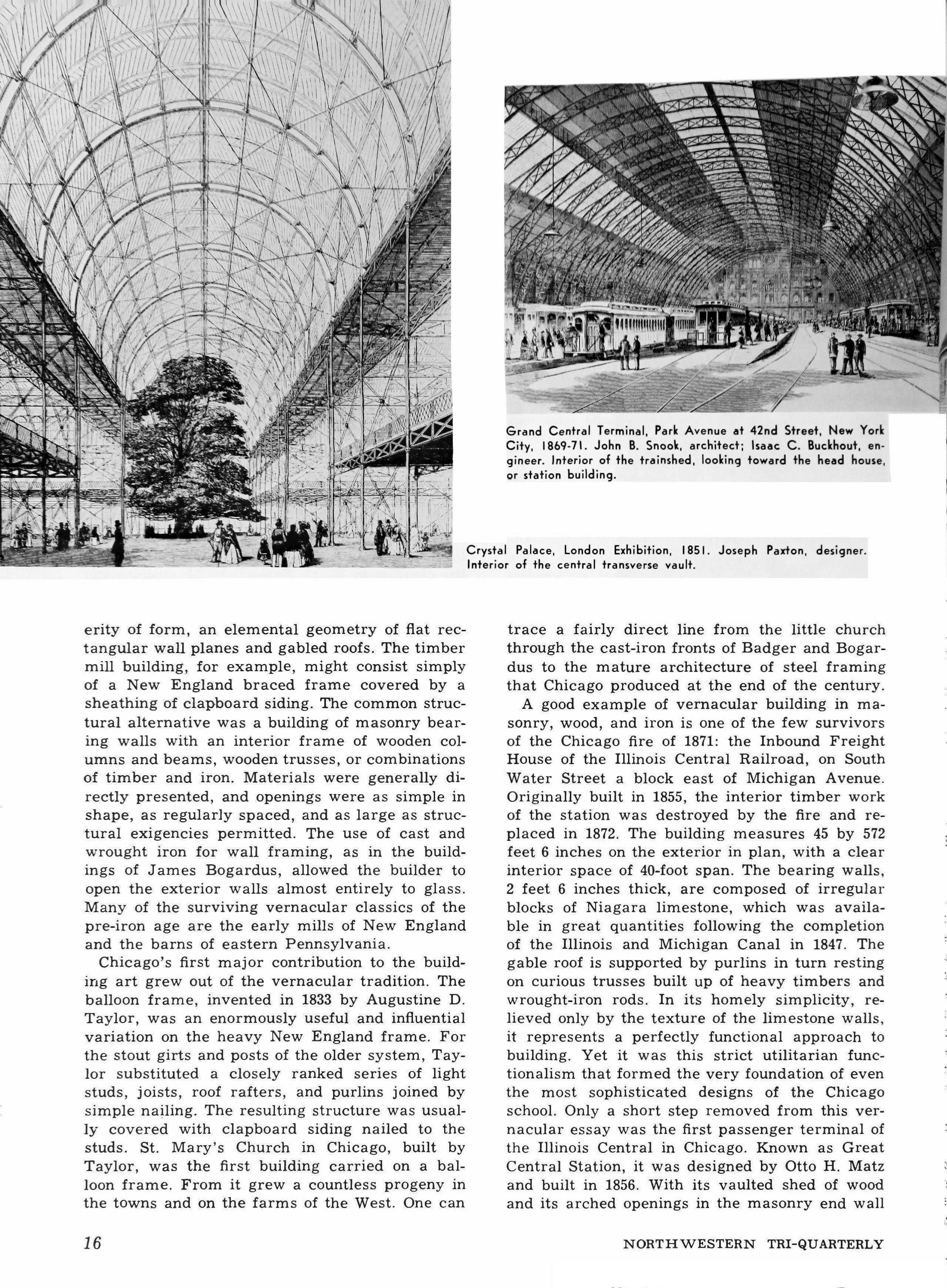

A peculiar problem posed by the industrial demands of the nineteenth century was the need to span wide enclosures without intermediate supports. The early market halls and theaters were examples in traditional forms. The train shed of the metropolitan railway terminal, however, offered novel difficulties because of its great size and unique function. The engineers attacked the problem with characteristic directness and courage, and by mid-century they had produced the great balloon shed that was once the most striking feature of the transportation structures. I. K. Brunel and M. D. Wyatt, in Paddington Station, London (1852-54), created a huge vault of wroughtiron ribs carrying a shell of glass and iron. The Spring, 1964

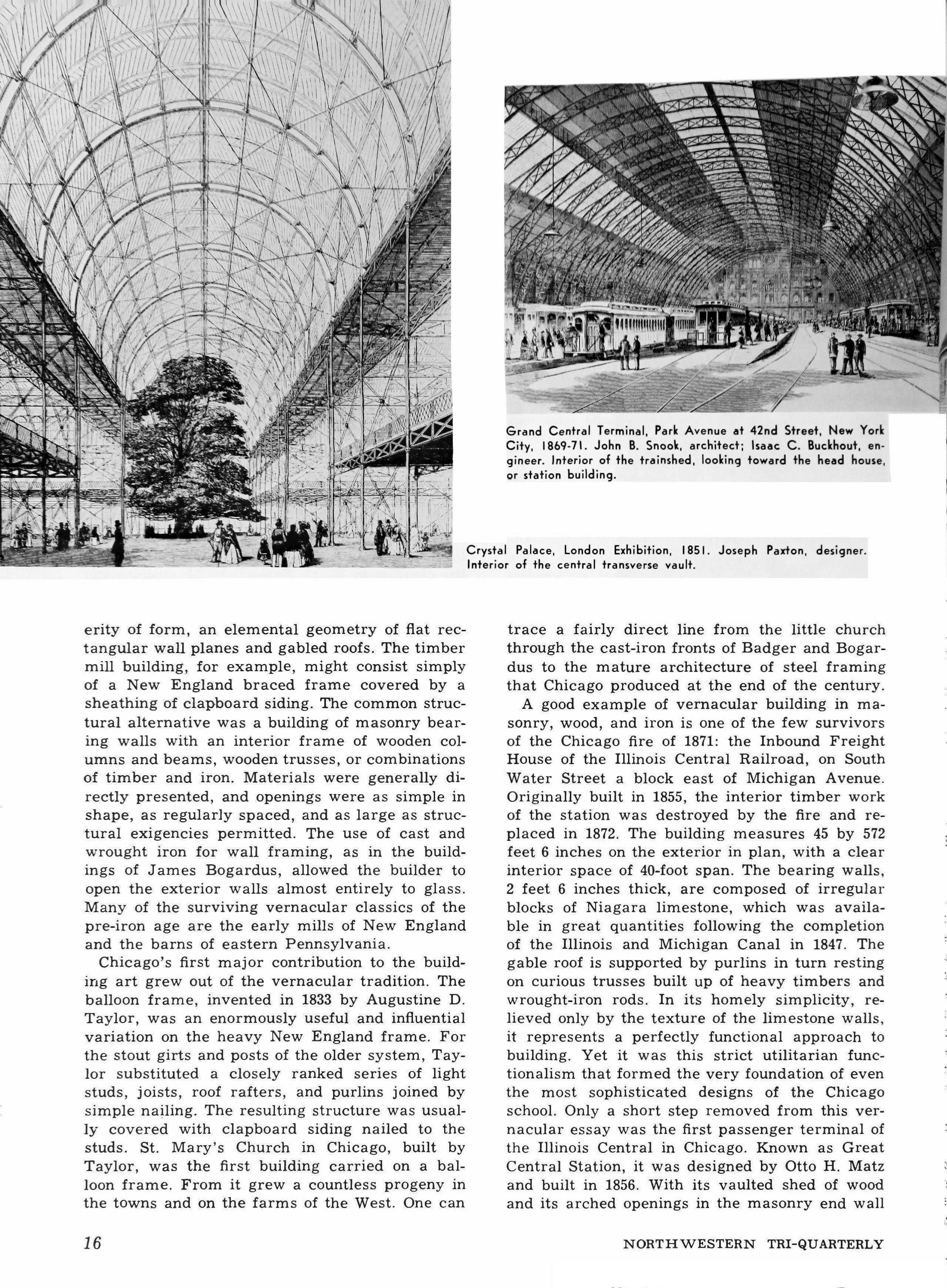

two materials were perfectly integrated in a form of great size. St. Pancras Station (1863-76), the creation of W. H. Barlow, R. M. Ordish, and Sir George Gilbert Scott, revealed further refinements of the glass and iron vault in a structure of even greater dimensions. The first Grand Central Terminal in New York (1869-71), designed by John B. Snook and Isaac Buckhout, was the first American structure comparable to these extraordinary British achievements. The train sheds of the nineteenth century embodied a prevision of the twentieth-century builder's treatment of space, not as an inclosed volume, but as a free-flowing element integrated with an open and buoyant structure.

The great bulk of iron-framed buildings in the past century belong to the domain of vernacular architecture. Although it is impossible to define this type of building exactly and to separate it from architecture consciously designed for expressive and symbolic ends, one can readily distinguish its dominant visual and utilitarian characteristics. Vernacular building comprehends all those structures erected by carpenters, masons, ironworkers, and others with the requisite technical skills but without formal training in architectural design, and planned usually for strictly utilitarian ends such as shelter, containment, and protection. Vernacular form is thus purely functional, but this does not preclude the possibility of its possessing a genuine aesthetic distinction. The earliest colonial residences and churches belonged to the vernacular tradition of the carpenter-builder, but as the American economy expanded, such building was progressively restricted to barns, mills, warehouses, factories, and the like. These structures are usually marked by extreme sev-

Home Insurance Building. Chicago. 1884-85. William LeBaron Jenney, architect. The first multi-story office building supported on an internal iron and steel skeleton and thus the prototype of the contemporary skyscraper.

15

erity of form, an elemental geometry of flat rectangular wall planes and gabled roofs. The timber mill building, for example, might consist simply of a New England braced frame covered by a sheathing of clapboard siding. The common structural alternative was a building of masonry bearing walls with an interior frame of wooden columns and beams, wooden trusses, or combinations of timber and iron. Materials were generally directly presented, and openings were as simple in shape, as regularly spaced, and as large as structural exigencies permitted. The use of cast and wrought iron for wall framing, as in the buildings of James Bogardus, allowed the builder to open the exterior walls almost entirely to glass. Many of the surviving vernacular classics of the pre-iron age are the early mills of New England and the barns of eastern Pennsylvania.

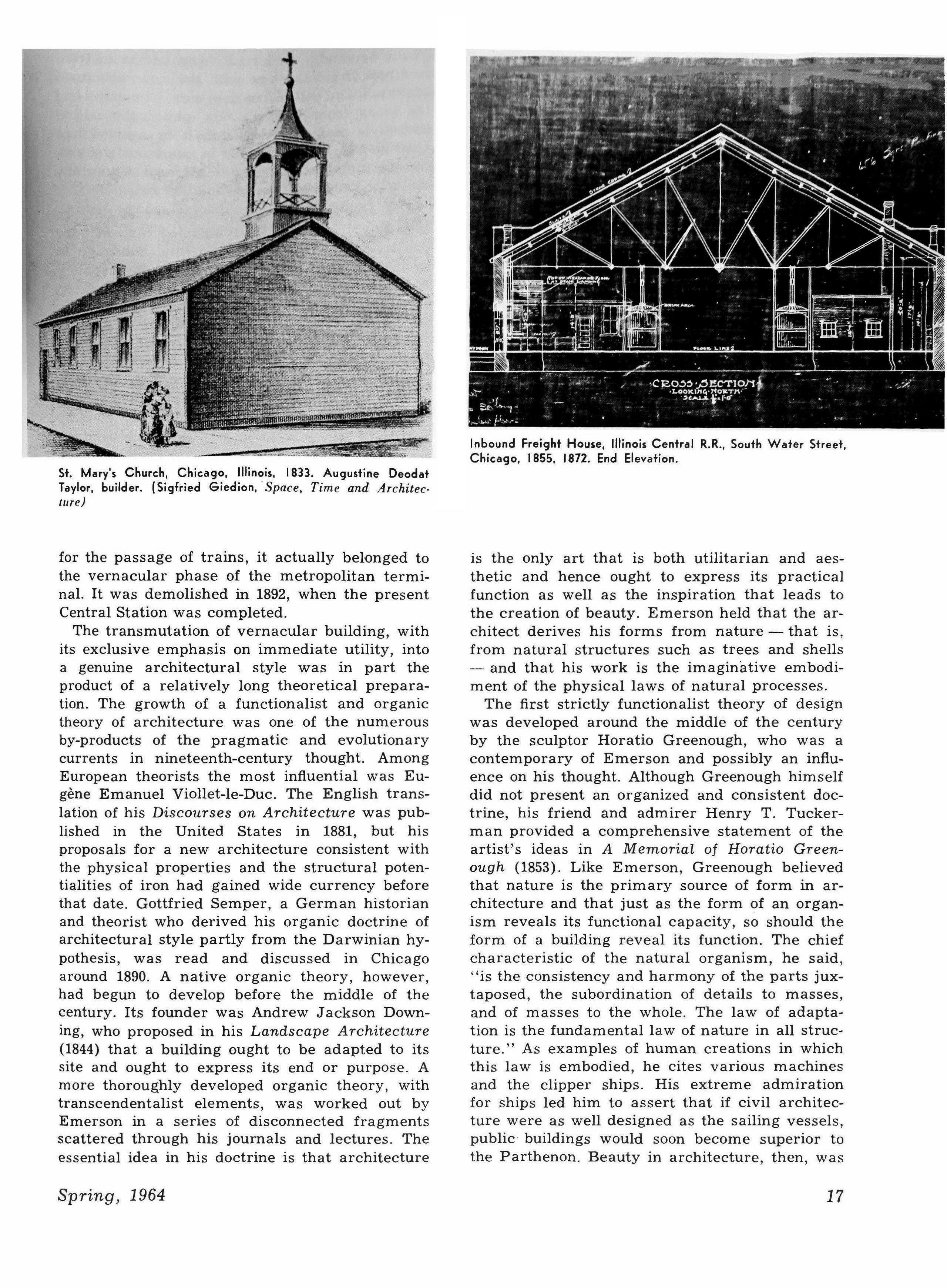

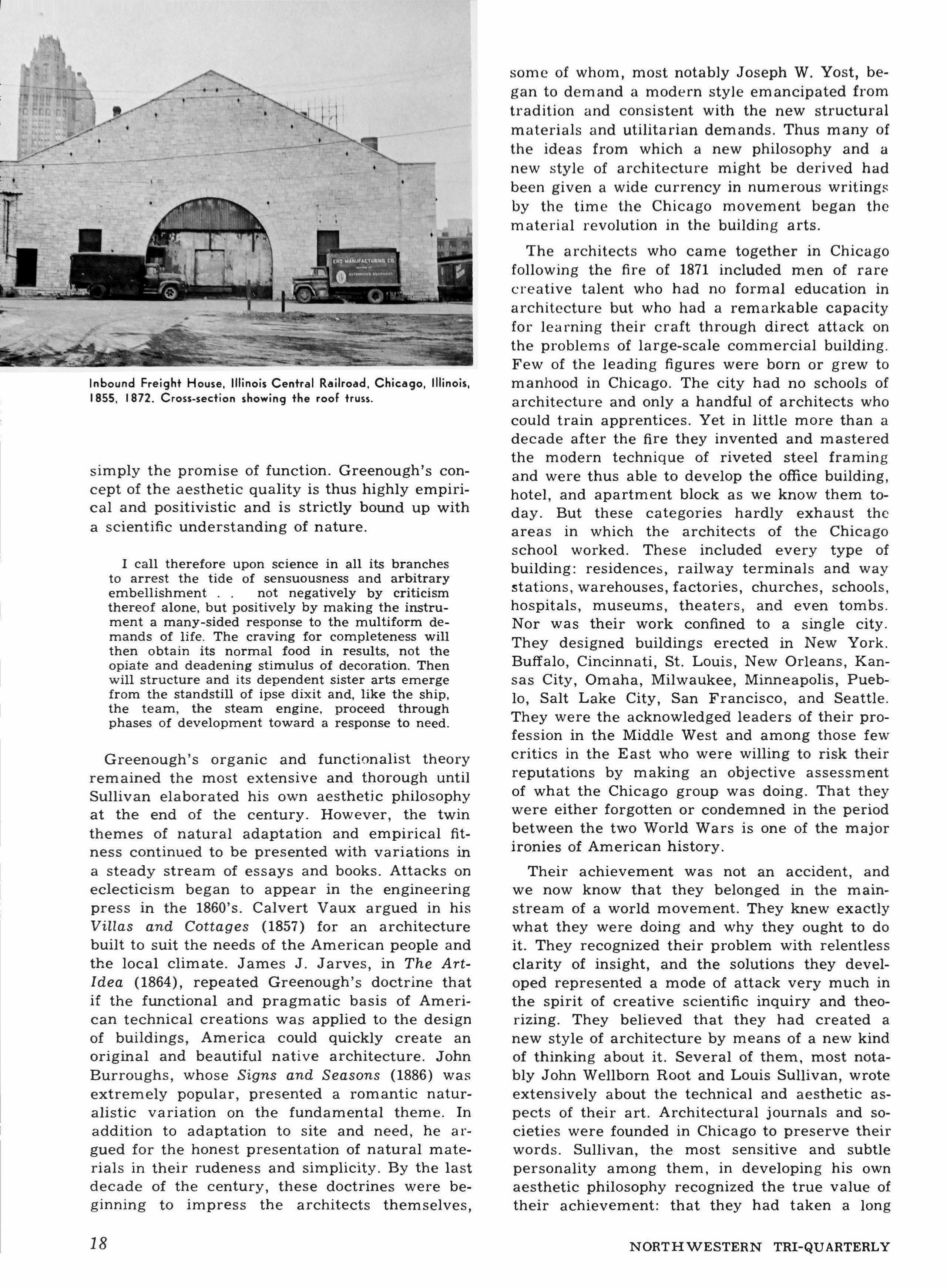

Chicago's first major contribution to the building art grew out of the vernacular tradition. The balloon frame, invented in 1833 by Augustine D. Taylor, was an enormously useful and influential variation on the heavy New England frame. For the stout girts and posts of the older system, Taylor substituted a closely ranked series of light studs, joists, roof rafters, and purlins joined by simple nailing. The resulting structure was usually covered with clapboard siding nailed to the studs. St. Mary's Church in Chicago, built by Taylor, was the first building carried on a balloon frame. From it grew a countless progeny in the towns and on the farms of the West. One can

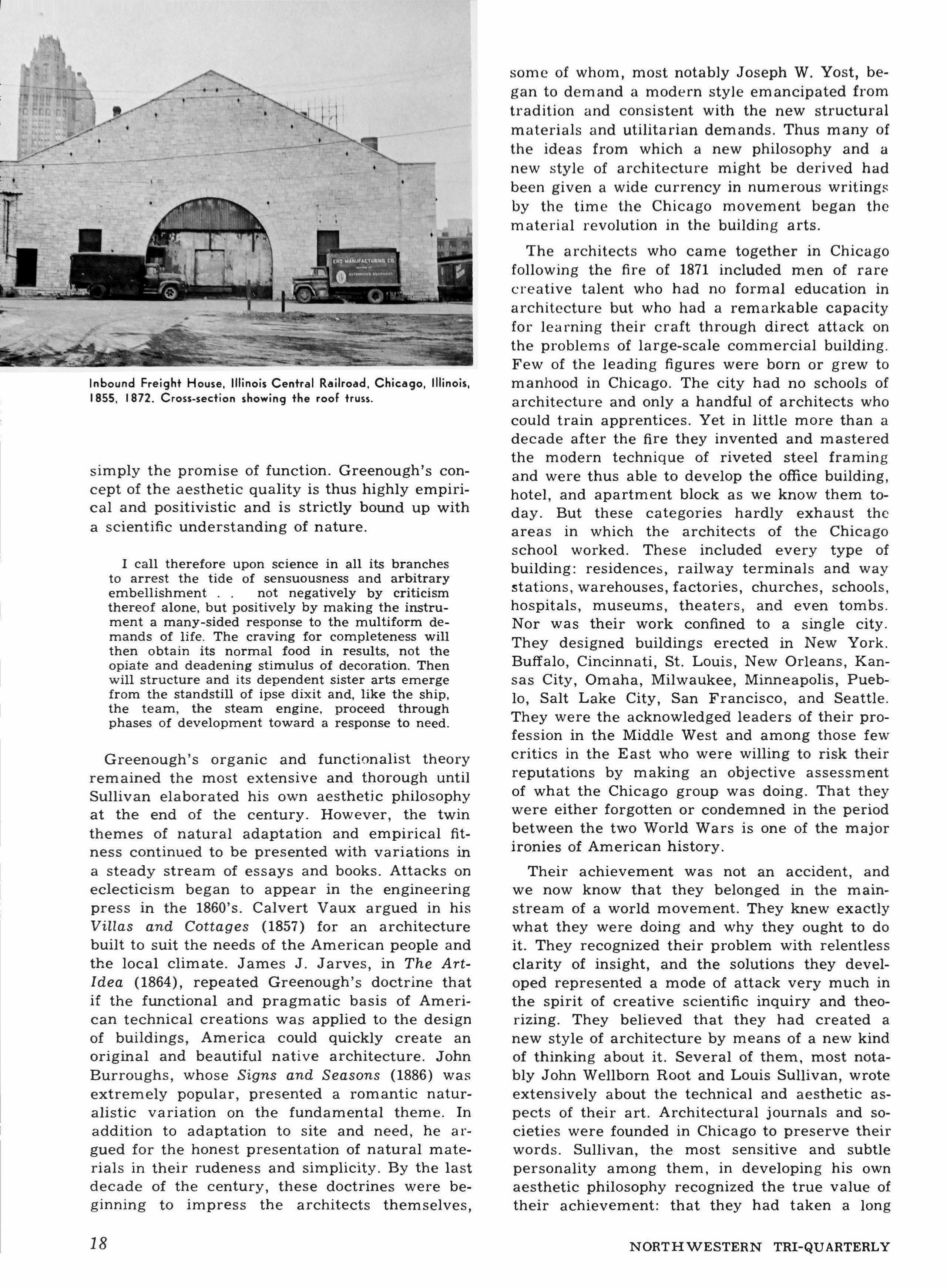

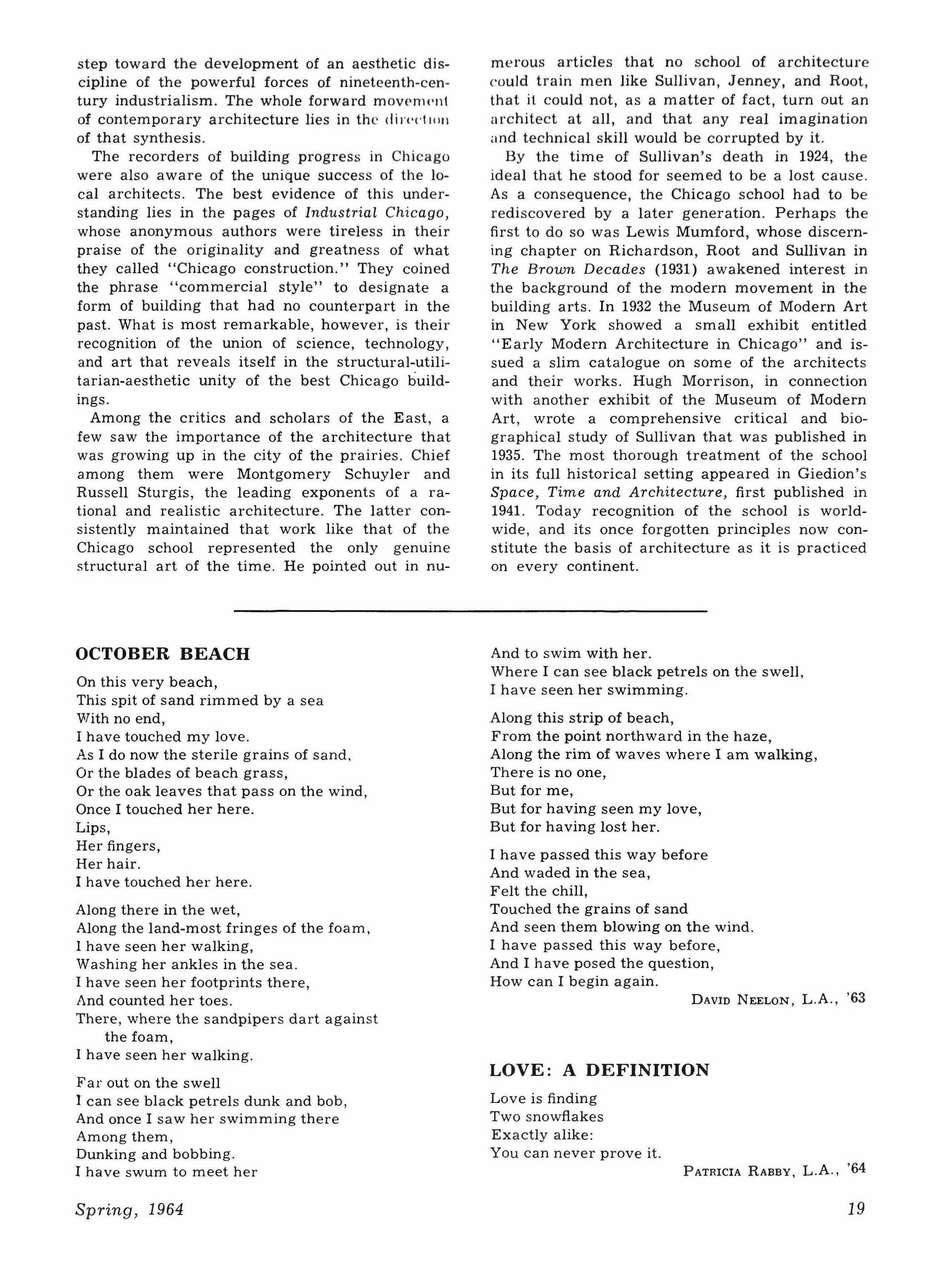

trace a fairly direct line from the little church through the cast-iron fronts of Badger and Bogardus to the mature architecture of steel framing that Chicago produced at the end of the century. A good example of vernacular building in masonry, wood, and iron is one of the few survivors of the Chicago fire of 1871: the Inbound Freight House of the Illinois Central Railroad, on South Water Street a block east of Michigan Avenue. Originally built in 1855, the interior timber work of the station was destroyed by the fire and replaced in 1872. The building measures 45 by 572 feet 6 inches on the exterior in plan, with a clear interior space of 40-foot span. The bearing walls, 2 feet 6 inches thick, are composed of irregular blocks of Niagara limestone, which was available in great quantities following the completion of the Illinois and Michigan Canal in 1847. The gable roof is supported by purlins in turn resting on curious trusses built up of heavy timbers and wrought-iron rods. In its homely simplicity, relieved only by the texture of the limestone walls, it represents a perfectly functional approach to building. Yet it was this strict utilitarian functionalism that formed the very foundation of even the most sophisticated designs of the Chicago school. Only a short step removed from this vernacular essay was the first passenger terminal of the Illinois Central in Chicago. Known as Great Central Station, it was designed by Otto H. Matz and built in 1856. With its vaulted shed of wood and its arched openings in the masonry end wall

16

Grand Central Terminal, Park Avenue at 42nd Street, New York City, ISb9-71. John B. Snook, architect; Isaac C. Buckhout, engineer. Interior of the trainshed, looking toward the head house, or station building.

Crystal Palace, London Exhibition, IS51. Joseph Paxton, designer. Interior of the central transverse vault.

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

St. Mary's Church, Chicago, Illinois, 1833. Augustine Deodat Taylor, builder. (Sigfried Giedion, Space, Time and Architenture)

for the passage of trains, it actually belonged to the vernacular phase of the metropolitan terminal. It was demolished in 1892, when the present Central Station was completed.

The transmutation of vernacular building, with its exclusive emphasis on immediate utility, into a genuine architectural style was in part the product of a relatively long theoretical preparation. The growth of a functionalist and organic theory of architecture was one of the numerous by-products of the pragmatic and evolutionary currents in nineteenth-century thought. Among European theorists the most influential was Eugene Emanuel Viollet-le-Duc. The English translation of his Discourses on Architecture was published in the United States in 1881, but his proposals for a new architecture consistent with the physical properties and the structural potentialities of iron had gained wide currency before that date. Gottfried Semper, a German historian and theorist who derived his organic doctrine of architectural style partly from the Darwinian hypothesis, was read and discussed in Chicago around 1890. A native organic theory, however, had begun to develop before the middle of the century. Its founder was Andrew Jackson Downing, who proposed in his Landscape Architecture (1844) that a building ought to be adapted to its site and ought to express its end or purpose. A more thoroughly developed organic theory, with transcendentalist elements, was worked out by Emerson in a series of disconnected fragments scattered through his journals and lectures. The essential idea in his doctrine is that architecture

Spring, 1964

is the only art that is both utilitarian and aesthetic and hence ought to express its practical function as well as the inspiration that leads to the creation of beauty. Emerson held that the architect derives his forms from nature - that is, from natural structures such as trees and shells - and that his work is the imaginative embodiment of the physical laws of natural processes.

The first strictly functionalist theory of design was developed around the middle of the century by the sculptor Horatio Greenough, who was a contemporary of Emerson and possibly an influence on his thought. Although Greenough himself did not present an organized and consistent doctrine, his friend and admirer Henry T. Tuckerman provided a comprehensive statement of the artist's ideas in A Memorial of Horatio Greenough (1853). Like Emerson, Greenough believed that nature is the primary source of form in architecture and that just as the form of an organism reveals its functional capacity, so should the form of a building reveal its function. The chief characteristic of the natural organism, he said, "is the consistency and harmony of the parts juxtaposed, the subordination of details to masses, and of masses to the whole. The law of adaptation is the fundamental law of nature in all structure." As examples of human creations in which this law is embodied, he cites various machines and the clipper ships. His extreme admiration for ships led him to assert that if civil architecture were as well designed as the sailing vessels, public buildings would soon become superior to the Parthenon. Beauty in architecture, then, was

Inbound Freight House, Illinois Central R.R., South Water Street, Chicago, 1855, 1872. End Elevation.

17

Inbound Freight House, Illinois Central Railroad, Chicago, Illinois, 1855, 1872. Cross-section showing the roof truss.

simply the promise of function. Greenough's concept of the aesthetic quality is thus highly empirical and positivistic and is strictly bound up with a scientific understanding of nature.

I call therefore upon science in all its branches to arrest the tide of sensuousness and arbitrary embellishment not negatively by criticism thereof alone, but positively by making the instrument a many-sided response to the multiform demands of life. The craving for completeness will then obtain its normal food in results, not the opiate and deadening stimulus of decoration. Then will structure and its dependent sister arts emerge from the standstill of ipse dixit and. like the ship. the team. the steam engine. proceed through phases of development toward a response to need.

Greenough's organic and functionalist theory remained the most extensive and thorough until Sullivan elaborated his own aesthetic philosophy at the end of the century. However, the twin themes of natural adaptation and empirical fitness continued to be presented with variations in a steady stream of essays and books. Attacks on eclecticism began to appear in the engineering press in the 1860's. Calvert Vaux argued in his Villas and Cottages (1857) for an architecture built to suit the needs of the American people and the local climate. James J. Jarves, in The ArtIdea (1864), repeated Greenough's doctrine that if the functional and pragmatic basis of American technical creations was applied to the design of buildings, America could quickly create an original and beautiful native architecture. John Burroughs, whose Signs and Seasons (1886) was extremely popular, presented a romantic naturalistic variation on the fundamental theme. In addition to adaptation to site and need, he argued for the honest presentation of natural materials in their rudeness and simplicity. By the last decade of the century, these doctrines were beginning to impress the architects themselves,

some of whom, most notably Joseph W. Yost, began to demand a modern style emancipated from tradition and consistent with the new structural materials and utilitarian demands. Thus many of the ideas from which a new philosophy and a new style of architecture might be derived had been given a wide currency in numerous writings by the time the Chicago movement began the material revolution in the building arts.

The architects who came together in Chicago following the fire of 1871 included men of rare creative talent who had no formal education in architecture but who had a remarkable capacity for learning their craft through direct attack on the problems of large-scale commercial building. Few of the leading figures were born or grew to manhood in Chicago. The city had no schools of architecture and only a handful of architects who could train apprentices. Yet in little more than a decade after the fire they invented and mastered the modern technique of riveted steel framing and were thus able to develop the office building, hotel, and apartment block as we know them today. But these categories hardly exhaust the areas in which the architects of the Chicago school worked. These included every type of building: residences, railway terminals and way stations, warehouses, factories, churches, schools, hospitals, museums, theaters, and even tombs. Nor was their work confined to a single city. They designed buildings erected in New York. Buffalo, Cincinnati, St. Louis, New Orleans, Kansas City, Omaha, Milwaukee, Minneapolis, Pueblo, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Seattle. They were the acknowledged leaders of their profession in the Middle West and among those few critics in the East who were willing to risk their reputations by making an objective assessment of what the Chicago group was doing. That they were either forgotten or condemned in the period between the two World Wars is one of the major ironies of American history.

Their achievement was not an accident, and we now know that they belonged in the mainstream of a world movement. They knew exactly what they were doing and why they ought to do it. They recognized their problem with relentless clarity of insight, and the solutions they developed represented a mode of attack very much in the spirit of creative scientific inquiry and theorizing. They believed that they had created a new style of architecture by means of a new kind of thinking about it. Several of them, most notably John Wellborn Root and Louis Sullivan, wrote extensively about the technical and aesthetic aspects of their art. Architectural journals and societies were founded in Chicago to preserve their words. Sullivan, the most sensitive and subtle personality among them, in developing his own aesthetic philosophy recognized the true value of their achievement: that they had taken a long

18

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

step toward the development of an aesthetic discipline of the powerful forces of nineteenth-century industrialism. The whole forward movement of contemporary architecture lies in the dil'('!'I1111l of that synthesis.

The recorders of building progress in Chicago were also aware of the unique success of the local architects. The best evidence of this understanding lies in the pages of Industrial Chicago, whose anonymous authors were tireless in their praise of the originality and greatness of what they called "Chicago construction." They coined the phrase "commercial style" to designate a form of building that had no counterpart in the past. What is most remarkable, however, is their recognition of the union of science, technology, and art that reveals itself in the structural-utilitarian-aesthetic unity of the best Chicago buildings.

Among the critics and scholars of the East, a few saw the importance of the architecture that was growing up in the city of the prairies. Chief among them were Montgomery Schuyler and Russell Sturgis, the leading exponents of a rational and realistic architecture. The latter consistently maintained that work like that of the Chicago school represented the only genuine structural art of the time. He pointed out in nu-

OCTOBER BEACH

On this very beach, This spit of sand rimmed by a sea With no end,

I have touched my love.

As I do now the sterile grains of sand. Or the blades of beach grass, Or the oak leaves that pass on the wind, Once I touched her here.

Lips, Her fingers, Her hair.

I have touched her here.

Along there in the wet, Along the land-most fringes of the foam, I have seen her walking, Washing her ankles in the sea.

I have seen her footprints there, And counted her toes.

There, where the sandpipers dart against the foam, I have seen her walking.

Far out on the swell I can see black petrels dunk and bob, And once I saw her swimming there Among them, Dunking and bobbing.

I have swum to meet her

Spring, 1964