Editor of this issue: Donna Seaman

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Assistant Editors

Joanne Diaz

Jean Hahn

TriQuarterly Fellow

Laura Passin

Editorial Assistants

Maria Lei

Margaret McEvoy

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dvbek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

David

essays

269 The Un-son

Yannick Murphy

280 Sex Kills

Alexis J. Pride

296 From Reel Shadows

Don De Grazia

307 The Pearl Canon

Gina B. Nahai

16 House Made of Tracks

Charles Bowden

85 The Rains in September

Rick Bass

100 Haunted by a Poem

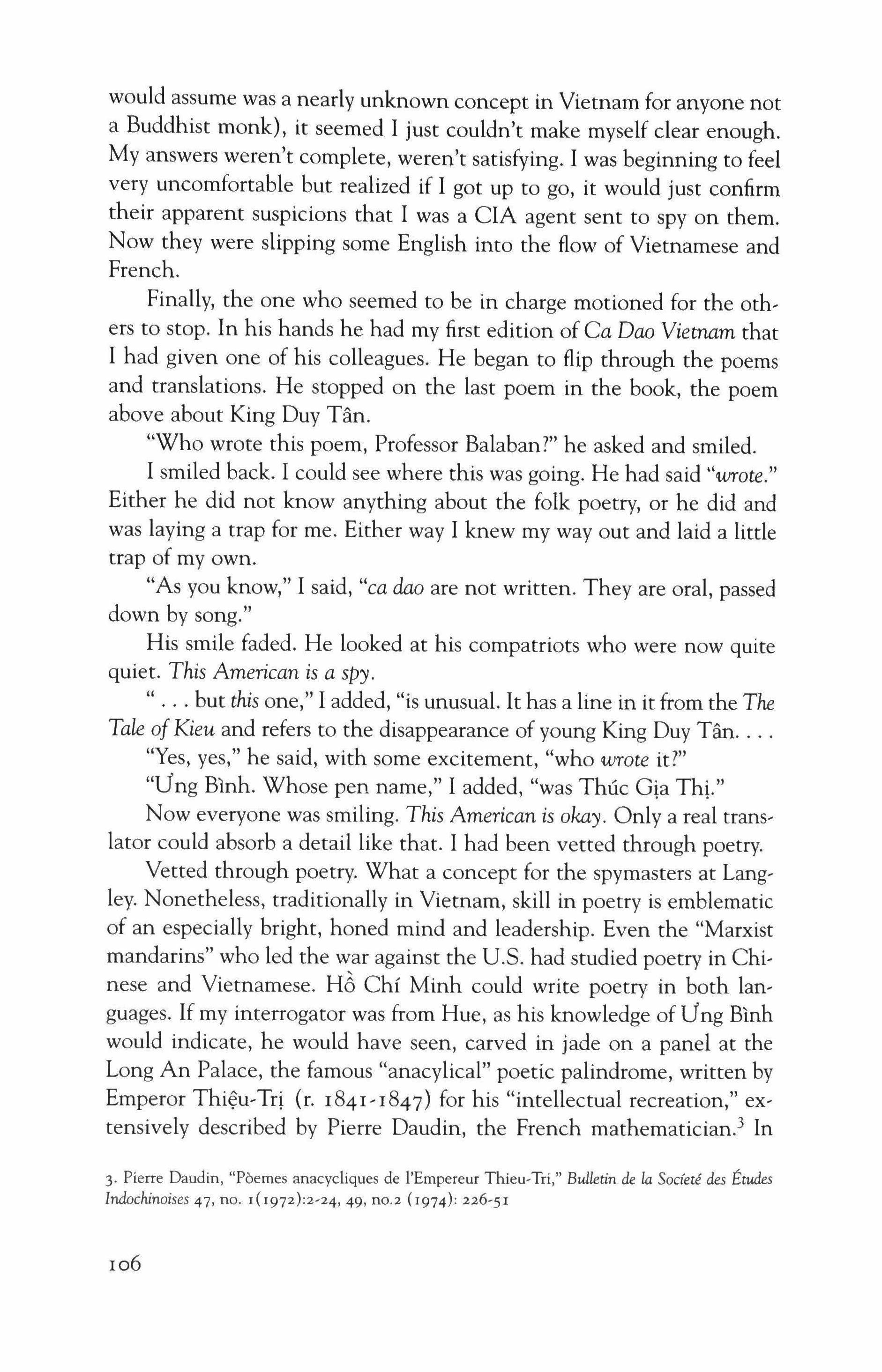

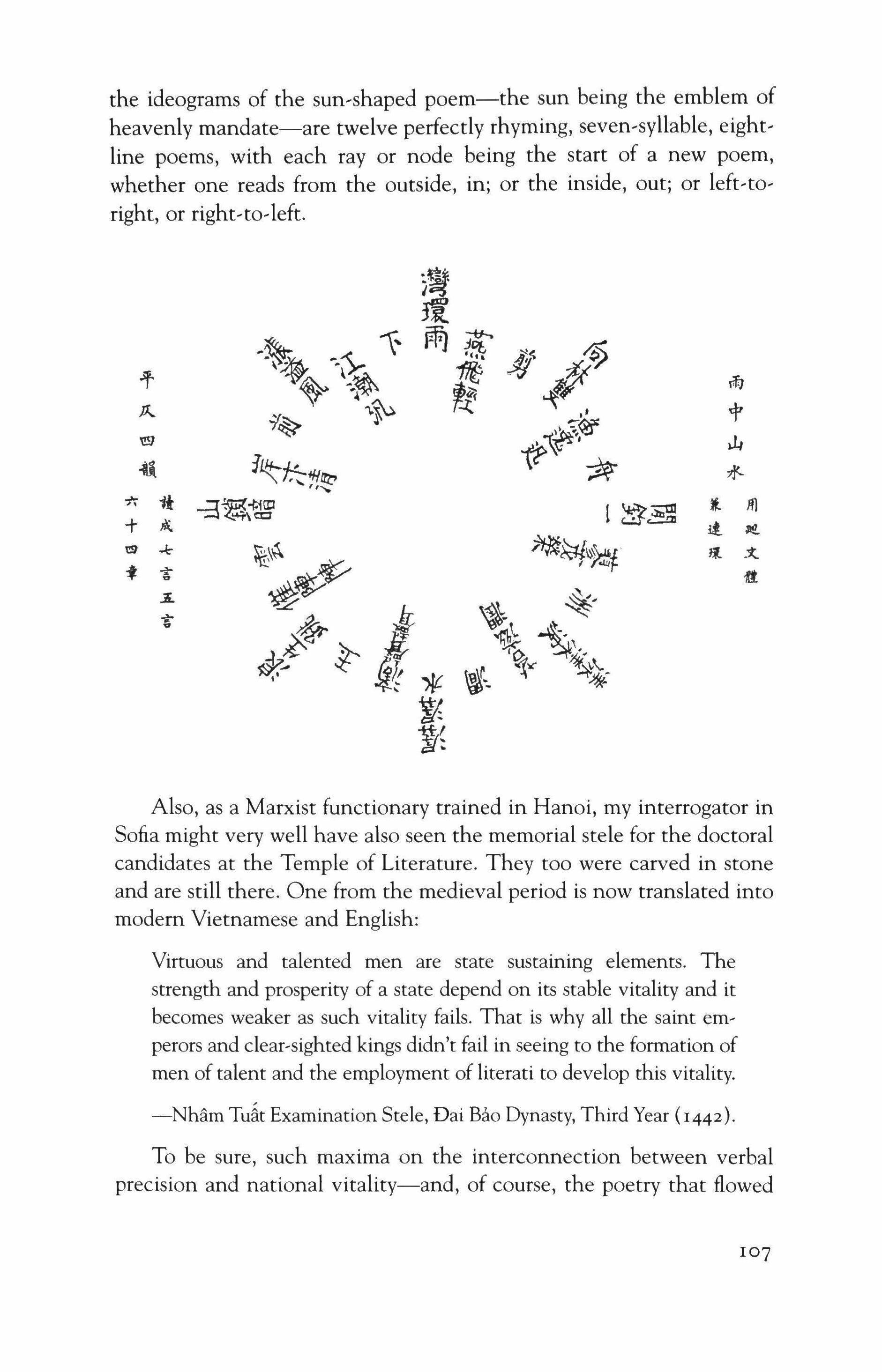

John Balaban

III A Journey on the Yangtze River

Eliot Weinberger

136 Trip to Baghdad-March 2007

Daniel Rothenberg

152 Going to the Coast

William Kittredge

156 A Mother's House

Annick Smith

170 Place of the Red Rock

Alison Swan

227 Weeding the River

Akiko Busch

247 Mac: A Memoir

Debra Gwartney

252 Terra Firma

Amy Irvine

318 Bed Times

Angela Bonavogliapoetry 15 I Believe

Jim Harrison

66 Nothing Was Ever Better Than Before

Barbara Ras

92 after an apocalypse, China 2008; Qi

Steven Schroeder

150 Twenty-nine Palms

CristinaGarda

220 From A Monster's Notes

Laurie Sheck235 Goldenrod; In Palm Beach

Diane Ackerman

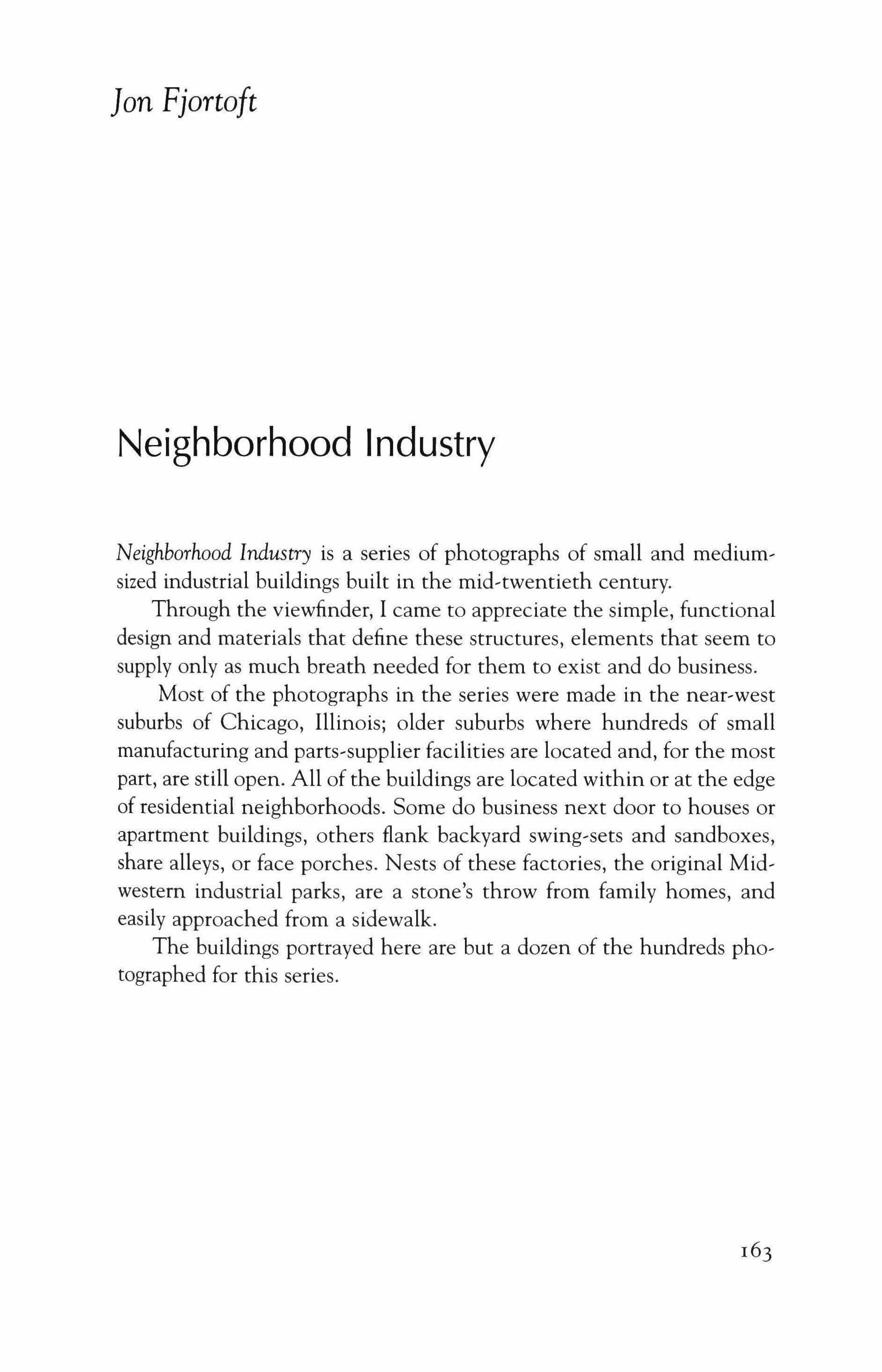

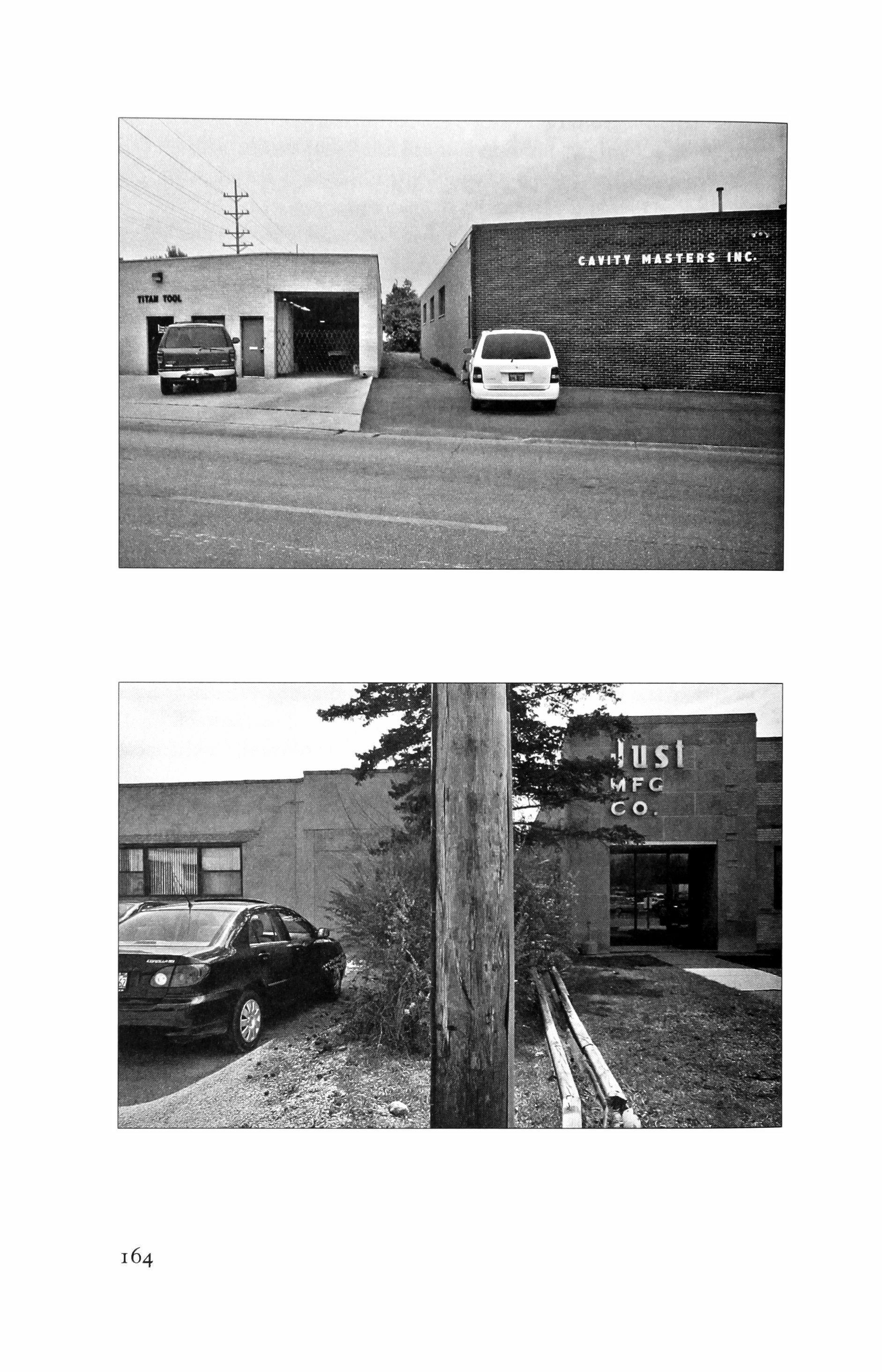

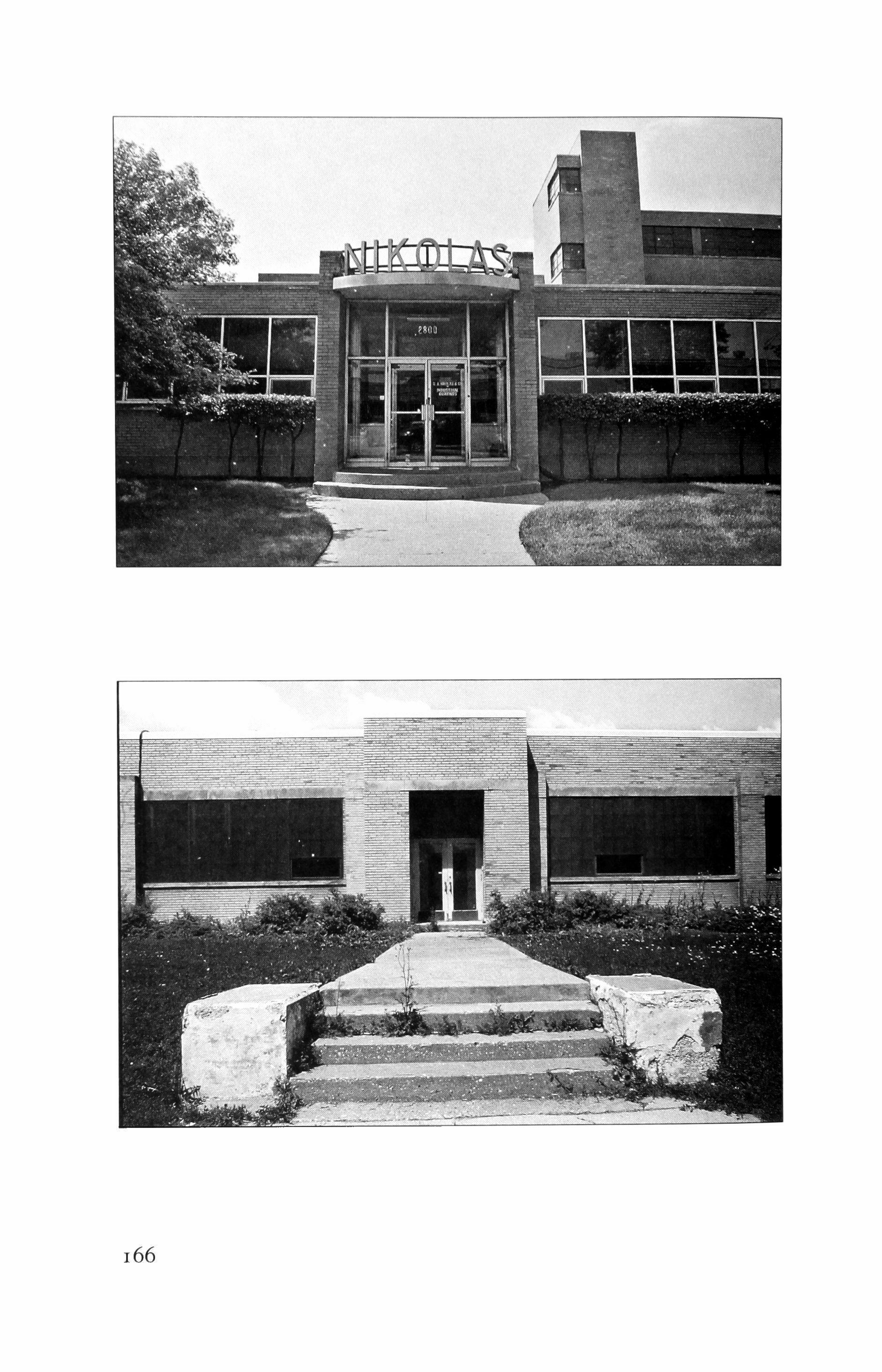

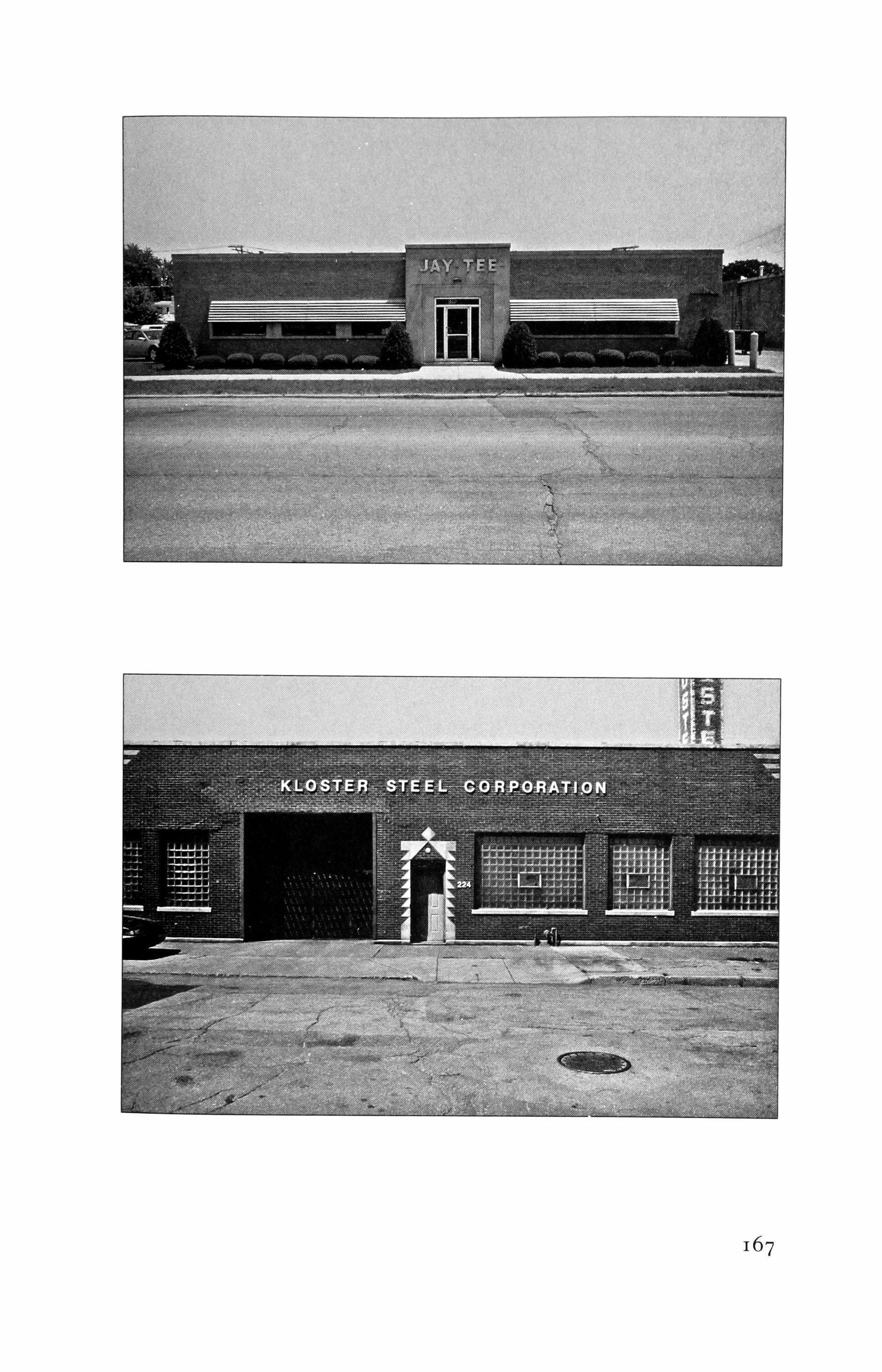

photography 163 Neighborhood Industry

Jon Fjortoft

323 Contributors

Cover painting: Snapdragon by Jayne Hileman

Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influences of each. Let these be your only diet-drink and botanical medicines.

Henry David Thoreau, from Huckleberries

My respect for the mystery implicit in creativity runs high, so I decided not to interfere with the process in my role as guest editor for this brimming issue of TriQuarterly. I did not name a theme, or assign a topic. Instead, I sought out writers who see life whole, who are curious about the interconnectivity and complexity of existence, and who care, deeply and unabashedly, about the world. When asked what I was looking for, I simply said, "strong medicine."

Medicine, the dictionary tells us, is not only "a substance or preparation used in treating disease." It is also "something that affects wellbeing," and "magical power or a magical rite." Reading and looking at art are not only intellectual and emotional pursuits. We read with our entire body; we take in a painting, photograph, or sculpture with every cell. We feel the impact of stories, images, and music in our very bones. There are, after all, no divides between body, mind, and spirit, and many of us rely on literature and art to keep us alive and well, just as we need food, air, and water, sleep and touch. Good writing is a

tonic. The work of inquisitive, imaginative, unfettered, and courageous observers, thinkers, and dreamers provides succor. Heat and light. Food for thought and balm for pain. Lucid and compassionate literature breaks the isolating fever of the self.

Clarion writing is strong medicine for what ails us, and the list of our disorders, our follies and crimes, is long and harrowing. The suffering we cause and endure is beyond diagnosis; our destruction of the living world is suicidal, malignant, terminal, evil. Yet we do try to make sense of our perversity, our brutality. We do learn; we do change. And it is the stories we tell that alert us to our maladies and suggest modes of healing. Without stories, chronicles, and poems, we would have no clue to what goes on in the minds of others, no insight into how other people live and define life. Right and wrong are embedded in stories; the great, glimmering web of life is best traced with words; the symbiotic relationships that make possible this planet's mantle of green and intersecting family trees of creatures great and small, marine and legged, are best revealed by those who have a gift for precision and metaphor, for finding words for the beauty and wonder they discern everywhere they look and listen.

I treat my own afflictions of the spirit with art and writing that is revelatory, insurgent, and transforming. I imbibe images and language electric with that green force that through art's alchemy reorients and recalibrates our perceptions, affirms our belonging. That essential radiance is present in each of the poems, essays, stories, and photographs that follow. Here is serenity and anger. Tragedy shocking and ordinary. Satire and suspense, lyricism and irony, desire and elegy. The brazen and the enigmatic. The absurd and the dire. Writers cross borders between the past and the present, the wild and the cultivated, the personal and the universal, the actual and the imagined, the rational and the incomprehensible, the horrific and the sublime. The creators take risks, and we the readers take chances as we accept each infusion, elixir, shock, or shot.

Treatment begins with the cover art, a drawing titled Snapdragon by Chicago artist Jayne Hileman, whose vibrant and earthy drawings and sculptures embody wit, conscience, the body's knowingness, and a whirling-dervish beauty. Jim Harrison, a versatile writer who draws on nature's glory, stoniness, and gore, and on a spirituality rooted in attentiveness, protest, and compassion, provides this gathering's credo and benediction with his resounding poem, "I Believe." Next up is Charles Bowden, an underworld investigator who channels his hard-

won knowledge, stoked fury, and cloaked concern into high-voltage reports from the edge. His blazing essay, "House Made of Tracks," set on our nation's desert borderland, marks out the terrain for all that follows, a place of struggle, blood, and buried memories where the dead are always with us.

This is a landscape and mindscape David Treuer knows well, and he takes us there in "Hard Body," a wrenching short story about a soldier back from Iraq working as an ambulance driver on an Indian reservation. Kate Braverman is also attuned to the shadow side of human endeavors, and fuses a radioactive lyricism with a cauterizing view of societal ills in "Autumn Alchemy," a short story about a mercenary molecular biologist who undergoes a radical metamorphosis. A Komodo dragon, Sharon Stone, and an Indonesian billionaire convene in "The Lady and the Dragon," a shattering story by Lydia Millet, a writer who conducts eviscerating moral and spiritual inquiries in fiction that melds sorrow and wit, sensuous realism and precise satire. In Egyptian writer Hamdy el-Gazzar's riveting tale, "Two Killings," one man's need to make a living, and his longing to make something of himself, turn treacherous in a land poisoned by violence and corruption. Set a world away in Chicago, Barry Lopez's stabbing story, "Hidian," is also an intense first-person tale about a man in trouble, albeit in a more subtly bankrupt society.

Poems punctuate the flow of stories and essays with injections of beauty and to-the-pointness. Barbara Ras, fluent in our species's contrariness and earth's resplendence, takes aim at our delusions in "Nothing Was Ever Better Than Before." Cristina Garda, revered for her inventive, culturally rich fiction, performs a stunning feat of distillation in her poem, "Twenty-nine Palms." Diane Ackerman brings overlooked aspects of nature to the fore in unexpected and striking ways in "Goldenrod" and "In Palm Beach." Laurie Sheck writes from the point of view of the "monster" in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, imagining that the monster is alive and busy studying humankind. While poet Sheck humanizes an imaginary, misunderstood monster who has become part of our collective consciousness, the incomparable and irrepressible storyteller and exuberant etymologist Paul West revisits a true-life monster in his audacious and devilish story, "Goebbels Aloft."

What we call nature, that is, everything on Earth that isn't human, has been the subject of our art and stories since the earliest cave paintings to today's most expressive environmental writing. The art of nature

writing-ofdelving deeply into the life and history of a certain valley or desert, mountain, coast, river or pond-has been a key and increasingly urgent aspect of American letters as generation by generation we have heedlessly exploited, looted, and abused the living world. Rick Bass is an essential voice in praise and defense of the wild. His essay, "The Rains in September," is from a journal covering a year watching a cherished Montana marsh. Alison Swan writes in a similar vein about a small bedrock island in Lake Superior, and Akiko Busch chronicles the impact of an invasive species in the Hudson River. Each of these attentive and knowledgeable writers reveals dimensions of life most of us never detect.

Photographers also capture facets of life that are hiding in plain sight. The Midwest can seem uniform and dull, but look more closely and you'll discern its muted beauty, its prairie luster. Jon Fjortoft focuses on the meeting of the organic and the human-made in his Illinois architectural series, "Neighborhood Industry." Low-key in their elegance, wit, and appreciation, Fjortoft's portraits of small industrial buildings invite close reading.

Place and work give shape and velocity to fiction, and no setting combines the two with more resonance than a family farm. Two heartland writers take very different approaches to farm life, blasting assumptions and tracking an immensity of change. Bonnie [o Campbell portrays an independent woman and a mother of five who finds herself welcoming unforeseen variations on life and love on her loosely tended Michigan farm. In "Faith of Our Fathers," Randall Albers digs deeply into the loam of pride and misery tilled by several generations of a stoic Minnesota farming family.

While many writers concentrate on home, others write of journeys. China is both destination and catalyst for Steven Schroeder's gracefully unnerving poems, two devastating short stories by Wang Ping, and Eliot Weinberger's poetic and sly travel essay. Poet, memoirist, and translator John Balaban takes us to Vietnam in his deeply affecting meditation on war, poetry, and healing. Philosopher and musician David Rothenberg, whose nonfiction books offer new insights into the songs of birds and whales, presents a work of fiction about a quest for wisdom in Norway wryly tided, "Is Your Journey Really Necessary?" Writing with stinging matter-of-factness, Daniel Rothenberg, of DePaul University's International Human Rights Law Institute, chronicles his quest for justice in real-life dispatches from Iraq.

Family life is the crucible in which the self takes shape, and the wellspring for stories true and fictional as writers confront the mysteries and complications of inheritance and circumstance, strife and loyalty. In his haunting short story about a family under pressure, "The First Time You Are Punched," Billy Lombardo writes with stunning authenticity from a young boy's point of view. The dark side of motherhood in all its raw emotion and cosmic implications, a volatile and dangerous subject, inspired works of startling candor and ravishing imagery from forthright memoirist Debra Gwartney, fiery environmental writer and courageous memoirist Amy Irvine, and daring and unpredictable novelist Yannick Murphy. With ruefulness and love, Annick Smith pays tribute to her mother and William Kittredge remembers his father.

Terror and death, sex and ambition, prejudice and deprivation propel the last three unflinching, edge-of-your-seat stories in this strong medicine apothecary: Alexis J. Pride's tale of lust, risk, and bad luck in the Deep South; Don De Grazia's story of a Chicago writer in peril in Rio; and Gina Nahai's drama of murder in Los Angeles's Jewish Iranian community.

And finally, Angela Bonavoglia tells us an atypical bedtime story. This is an ardent reader's assemblage, and my reading life is nourished by my work for Booklist. I'm grateful to my colleagues for their inspiration and all that they do to keep literature alive and accessible. I thank everyone who participated in the creation of this issue. By virtue of luck and love, this collection contains works by two brothers and three married couples. I'm thrilled to count among the contributors writers who live on my home ground in the beautiful Hudson Valley. A Chicagoan by chance, then choice, I was determined to include Chicago writers and artists, and what a boon their work is. I then looked to the North and West for further enlightenment. My list of strong-medicine-makers is long, and were there pages enough, I would have included many more. As it is, TriQuarterly has been munificent. I am grateful beyond words to the generous, adventurous, and creative editor, Susan Hahn, and to patient and expert Ian Morris.

Strong medicine may make you sick before it makes you better. Here, writers and readers alike face harsh truths about humankind's diabolical paradoxes and planet-altering endeavors. Strong medicine goads us into asking questions, articulating objections, and fueling the coalescence, let us hope, of new ways of seeing, and new ways of being.

Bitter and sweet, caustic and cleansing, chilling and warming, these works of art deliver insight, catharsis, and communion, and heighten our appreciation for life's insistence and splendor, pattern and randomness, vulnerability and resilience.

I believe in steep drop-offs, the thunderstorm across the lake in 1949, cold winds, empty swimming pools, the overgrown path to the creek, raw garlic, used tires, taverns, saloons, bars, gallons of red wine, abandoned farmhouses, stunted lilac groves, gravel roads that end, brushpiles, thickets, girls who haven't quite gone totally wild, river eddies, leaky wood boats, the smell of used engine oil, turbulent rivers, lakes without cottages lost in the woods, the primrose growing out of a cow skull, the thousands of birds I've talked to all of my life, the dogs that talked back, the Chihuahuan ravens that follow me on long walks. The rattler escaping the cold hose, the fluttering unknown gods that I nearly see from the left comer of my blind eye, struggling to stay alive in a world that grinds them underfoot.

Everybody knows this is nowhere.

To the west, the ground is largely a mystery to whites, an enormous grassland where the great southern herd feeds. Deserts brood and men dream of mines. Jagged mountains slice through the ground. The fangs of canyons assault any notion of easy passage.

The weather is not faithful. The rains come or do not come, the storms rage or there is nothing in the sky for months. The beasts thrive, or vanish without warning. Some years the rivers rise. Other years, the rivers die. People steal other people. And then the stolen people sometimes become new people. There are many tongues, and many kinds of faces and colors.

Old ways of knowing meet even older ways of knowing and this collision of beliefs draws blood.

We are body and souls the result of unsteady weather. The last million years were kind of crazy after sixty-five million years of slow change, a long drag we call the Tertiary. And then in a moment we've dubbed the Pleistocene, the very time when we belched forth as a species from the cauldron of life, the skies mutinied and no one could trust the weather. The ice left twelve to eight thousand years ago, and things got pretty calm and dependable and we set about this gambit called civilization.' Except here, in this place to which we now come.

I. For a concise overview of the recent arrival of the grasslands of the West see Stephen R. Jones and Ruth Carol Cushman, The North American Prairie, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 2004, pp. 7-2I.

Here, the weather never settled down, not really, and the very forces that raked out lives earlier persisted, the uncertainties that made us such inventive, conniving and opportunistic creatures. Here, both the better and darker angels of our nature could endure in a state of high barbarism. Here, the wellsprings of our genius and violence remained as sharp as the crack of dawn on the deserts of our life.2 And now, the wild swings of weather are back everywhere and the lash of the sky is felt here more than other places.

Here, our ultimate dreams of power erupt and here these dreams tum to nightmares that still haunt our lives. The ground remains, un� caring, unconcerned, and beyond our destruction and redemption. The ground in this zone is both our touchstone and our terror and it owns me and has brought me to this book and journey.

They meet in 1870 in Fort Worth, an outpost staring into a void. Texas is part of a nation, but the real force of that nation lies to the east where the rains come and the world seems normal. To the south is Mexico, but it too only really exists more than a thousand miles to the south where the great central plateau has been the floor under civilizations for more than a thousand years. Between these wet centers is a zone without a name, a place where rains often fail, where men and women and children live beyond the control of the official nations.

So Edmund Jackson Davis comes with his young boy, Britton, to meet with the chiefs of two peoples, the Comanche and the Kiowa. Davis is governor of Texas. The chiefs have brought him a present to seal a peace between his people and their people, a big robe made from the skins of six lobos, the wolves of the plains. The robe runs eight to nine feet long and four to five feet wide. The chiefs apologize that the peace conference has been called so suddenly that the robe is, alas, unfinished. They point out to the governor that both sides and one end are festooned with human scalps, one dangling from each running foot. Three of the scalps are ripped from the heads of women.

But the fourth side is as yet unfinished.

The chiefs also tell the governor that they have taken care to make sure that none of the scalps are from white people-simply the hair taken from other Indians or from Mexicans. This selection, they note, is deliberate, so that the governor will feel no discomfort from the gift.

Davis speaks with great diplomacy. He tells the chiefs that he knows

2. R. Dale Gutherie, The Nature of Paleolithic Art, University of Chicago, 2005, p. 22.

the scalps are proof of valor for the warriors, and because of that fact, he cannot accept them since they belong with the men who took them in combat. So they are removed and the unadorned robe is given to the governor.

Now all four sides are naked. The great robe will never be finished. And in time will vanish into the dust of history and be lost to memory.

A kind of peace will eventually come, just as claims of power will be made by the nations. The boy Britton, for example, will become a soldier and fight in the Apache wars against Geronimo, then start up a cattle operation in Mexico, become worth at least $750,000, and then lose everything in a whirlwind called the Mexican Revolution. The tribes will be crushed and penned in a place called Oklahoma. The great herds will die and other beasts will enter the country. The wolves will disappear and howl no more.

The great grasslands that ride high benches in the hot desert will persist. The tumult of the zone claimed by two nations, and controlled by no one, will persist also. The lines on the map will be etched with more and more force and yet remain frail on the ground itself.

The great robe never gets its rightful complement of scalps. There is that naked side at the treaty signing. And then, because of decorum on the governor's part, there is the mutilation of the gift that cleanses it of the real life of the place.

My life is as broken as the ground that made me. I have spent a lifetime now on this line watching the murder of the earth all around me. We are heavy feeders and rough estimates now indicate we consume through our throats and hungers and those of our beasts somewhere between thirty and fifty percent of the photosynthesis of the planet.' The grasses vanish, the forests go, the fish disappear from the sea, the howls end in the night, and we sleep with a lullaby of sirens in our ears. I am not here to lament, or complain. I simply wish to stop denying this obvious past and present.

This place strikes a history of tumult, one lost to view in the fantasy of power buried in the word "settlement." The borders are seen as sacred, the populations as part of an almost divine plan, the Indians as something that grew out of the ground and communed with deep spirits, the stability of title and law as inevitable and irrevocable. All this

3. Marc L. Imhoff, Lahoauri Bounoua, Taylor Ricketts, Colby Loucks, Robert Harriss, William T. Lawrence, "Global Patterns In Human Consumption of Net Primary Production," Science, 429, (June 2004).

is a fantasy, a false reading of little more than a century of calm on this ground."

It is fall in 1660 and Diego Romero and five other men ride from Santa Fe into the grasslands to the east. The governor has sent them to buy the hides of buffalo and antelope. They find an Apache village, and Romero announces to the tribesmen he would like to haggle awhile. And he would also like to leave a son behind. There is a dance, Romero is placed on a hide and tossed in time to the movements. Then he is thrown into a tent, and a young girl is given him. In the morning, the tribesmen check to see if he has had sex with her. He has. They place blood on his chest, a feather in his hair, announce he is now a captain of their nation. And also, they give him the promised hides.i

The moment hangs there and is a mystery to us just as the Apaches and other Indians were baffled by the large bones left by the vanished, giant creatures from the ice age that had receded from memory. A Spanish governor wants hides. He sends a small party east into the grass. The leader of the party wants to impregnate a woman. He does. And is brought into the tribe.

It is a whisper from a past characterized by instability, slavery, and murder. And carelessness about the land. Now my ears are full of talk of security and homeland and invasion by other bloods. I live in a place driven by greed and fear, a place fed by ignorance.

What happened in North America was not an isolated instance. From around 1500 forward, Europe exploded onto the surface of the earth for reasons still debated over sherry and port by scholars. For example, the Russian empire from the mid-fourteenth century onward grew at a rate of 55 square miles a day, or about 20,000 square miles a year and did this day after day and year after year for four centuries.? The Spanish and Portuguese over the same centuries swallowed South and Central America plus chunks of Africa and Asia. And then, of course, there is Great Britain, France and Germany and their creative appetites

4. For a graphic representation of the tumult of the continent over time see Helen Hornbeck Tanner, ed., The Settling of North America: the atlas of the great migrations into North America from the ice age to the present, Macmillan, New York, 1995. Note especially the computerized map of Arkansas on p. 14 with the 21,700 known pre-European occupation sites. And the Clovis kill sites on p. 21 with a mammoth kill in the state of Puebla in Mexico. This landscape has always been in play.

5. James F. Brooks, Captains & Cousins: slavery, kinship and community in the Southwest borderlands, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 2002, pp. 28-29.

6. Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game: the struggle for empire in Central Asia, Kodansha International, New York, 1994, p. 5·

for empire. But on my ground, all this is seen as beside the point, as material for some other story, an evil story, of imperialism, rather than the spread of democracy and the true faith.

This is an error, a lie and the bedrock that sustains my nation. And now, right under my feet it is being challenged by both the sky and by other human beings.

This ground has never belonged to anyone for long. The dream of dominance is fading and yet, as the ground slips from fantasies of control, there is an insistence that this cannot be allowed.

Rollin' and tumblin', cryin' the whole night long.

They will come, they always have.

They will flourish, they always do.

They will fail, that always happens.

Life goes on and lines get erased, they always are.

I'm flying high, the men are dancing, tossing me in the air from my perch on a hide. The maiden flies through the air into the tent, where I wait with lust in my heart and greed in my mind.

They always come, they always have.

There is a giant robe of wolf skins, scalps dangling, a gift to yet a later governor. Such moments are quaint to us as we fatten on our certainties. We have managed to make sense out of the future by walling off the past. And yet our future is floored on a tiny, immediate present that has almost no connection with the long past of this ground we lord over with iron wills.

I always rise before dawn with coffee in my hand and yes in my mouth. But it has taken a fierce act of will to salute these dawns as the beasts go down, the ground dies, the waters vanish, the tribes spin into alcoholic fogs, and torrents of humans pour into the parched ground chasing some dream of wide-open spaces which they systematically obliterate. Still, I persist and believe that the riptide of flesh tearing the entrails from the land will pass, the sun will still rise, the beasts will emerge from hiding, the plants cast down seed and the ground come back to life. I will stand there, no doubt a ghost, my tongue coated with pollen, my dead ears ringing from the songs of birds. I believe this with my heart and soul, but my God, it has been a struggle to keep the faith.

George Gershwin in the white heat of the creation said, "My place is America and my time is now.?" I have not heard that kind of talk

7. Wilfrid Sheed, The House That George Built: with a little helpfrom Irving, Cole, and a crew ofabout fifty, Random House, New York, 2007, p.IO.

lately. There is a silence out on the land and whispers in the locked houses. Something is breaking up and something is being born amid the slippage. I have spent my life on a fault line that tears human cultures and biological communities. The great wolf robe with scalps spoke of two worlds--one of buffalo-hunting plains Indians, the other of Europeans and their native converts who would murder the world of buffalo hunters.f Now both seem the dreams and boasts of a lost world. And I stare into a world being born. The fantasies of power have faltered. Only the doomed believe in communism or socialism or capitalism. I see their blank faces at the meetings and in the coffee houses and cocktail lounges. And yet fantasies of power flicker at the edge of the light.

There is a faith that the land was made for us and that we are the meaning of the land. Any fact that questions this belief is ignored or erased or denied. But the tension remains between this faith and rising of the ground to assault our senses and strike down our dreams of power.

Human, All Too Human, says Friedrich Nietzsche and he continues, "Every tradition grows ever more venerable-the more remote its origin, the more confused that origin is. The reverence due to it increases from generation to generation. The tradition finally becomes holy and inspires awe."

In the cold hours of this night when our faith fails us, some tum to drink, others to drugs. Others tend to the altars of various gods. None of these gestures touches what is taking place in this place. The power of the human cultures rakes the earth and yet at this very moment of triumph, fears seize the preachments of these cultures. The ground rebels, rains go away, wells sink, the wind rises, red eyes stare back in the night. And the wars come and come and come.

I have no feel for doom, nor have I ever. But I think the play of life leaves tracks and these marks can be glimpsed on my native ground. What path we take and where it leads us depends on how well we read these tracks. Where I live and plan to die and also, plan to keep on living, here a chunk of the earth spreads out that many nations have sought and claimed because it connected them to dreams of riches

8. By the early 1850S Mexican, American and Indian harvest of the great herd of the Southern Plains had already exceeded carry capacity-meaning the bison were on their way to extermination years before the industrial killing that followed the Civil War. See Brooks, Captives & Cousins, pp. 225-228. Also, see Colin O. Calloway, One Vast Winter Count: the Native American West before Lewis and Clark, the University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2003, 31I-JI2. For details on this ecological crisis, which began in the early years of the nineteenth-century, see Hamalainen, The Comanche Empire, PP.294-295.

and power. The people and other life forms that lived here at the time the decisions were made had to be crushed because they stood in the way of this larger appetite for riches and power.

I have spent my life listening to their muted voices.

There is a house and it is in the woods and it is by the creek and it is in the mountains and it is on the hot desert and it is by the dry arroyo and it is down by the river and it is under the ground and it is in the sky. There is a house without walls or floor or ceiling.

There is a house and it is not made of dawn and it is not made of dusk and it is not bright and it is not dark.

There is a house.

I am finally home.

I am not a man who dreams and my sleep is almost always deep and unbroken. But since childhood, there has been one recurrent night visitor. In this dream I am on a black horse and looking at a house that is blazing. The house is my own. I have set the fire.

At Hot Springs, South Dakota, far to the north of my ground, there in the Black Hills on the edge of the Great Plains, a trap persisted for a spell twenty thousand years ago that enticed mammoths into a hot and verdant hole and then they could never escape and so died inside a natural dream that became a natural tomb. Dozens of such creatures slumber in this trap. But there is a curious thing: none of the dead are old males, none of the dead are mothers, none of the dead are calves. Every single trapped mammoth was a young male, some willful spirit that went down into the hole where hot water bubbled and lush grasses grew and could never climb out again." I am not about to mock these young males, nor celebrate them. I am too old now and too cautious to fall into the trap that killed them. But my life and the life of my ground have been similar to that warm, beckoning doom. The beasts and plants and humans of my ground also have felt this tug toward doom and some resisted and some did not and all came to make this ground the home that it is.

That is why the peace offering, the robe of wolves and scalps, is not simply a curiosity from the dusty cabinet of the past but the persistent wager that comes from this place and is this place.

The dead voices still whisper, "Are you feeling lucky?"

The hairs on the robe are like so many blades of grass. The lush scalps, the three long tresses of the women, astonish one like the glens

9. Guthrie, The Nature of Paleolithic Art, p. 44·

and canyons and springs of the region. The peace treaty fails, the wars go on for a spell. The governor loses the next election and is sent pack, ing. The dreams of power and dominance never really go away. Nor are the lessons ever really understood. The robe requires more scalps. That is clear. 10

10. Britton Davis, "Recollections of the Kiowas and Comanches," in Peter Cozzens, Eyewitnesses to the Indian Wars, r865-r890, Volume Three: Conquering the Southern Plains, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2003, PP-419-420.

Eugene had been driving the reservation ambulance for a year when, between Chris Buckley and the crop report, he heard about the contest sponsored by the reservation casino. The rules are simple. You put on the white gloves and stand at arm's length from the truck. You place one arm out so the palm is flat against the body like a cop stopping traffic. And you wait. One five minute break an hour; fifteen minutes every four hours. The last person standing wins a Dodge Power Ram, Magnum V8 Extended Cab. A Man's Truck. All you have to do is out stand the other thirteen contestants.

Technically, Eugene and the other five members of the ambulance team are known as first responders, but on the rez, where the woods give over to northern prairie, he isn't sure what the second response might be. Maybe the Mennonites from down the highway are required to sing a hymn, or maybe after a moment of silence, all the white farmers will tum on their combines and get back to work, rumbling out a low diesel chorus. Up there most accidents involve beer, a truck, and a tree. The first response is usually to cover the body. The second response is to get high.

Eugene has spent twelve months jumping from the ambulance to scrape wrecks out of the ditch, to pump hearts bruised to a stop on the steering wheel, to stop the bleeding somehow. The moment he heard about the contest he knew it was his chance. A chance for what, exactly, was harder to say. He looked over at the other medic. Franklin raised one eyebrow but didn't move his head from the nest he made between the door and the seat.

"That a long box or short box?"

Eugene hadn't thought about this.

"Short, I think."

"Hard to haul studs or standard plywood in a short box."

Eugene pondered this.

"Can always put the tailgate down," he suggested.

"You'll never be able to afford the gas. It'll cost over one-hundred just to fill it up."

"I don't got nowhere to go."

"Diesel would be better."

Eugene punched the casino number on the cell phone anyway. He ended the call and looked over at Franklin. He was already asleep, oblivious to the sirens as the ambulance rolled toward another set of victims, all of them thrown clear when their pickup rolled over.

The wreck was worse than he thought it would be. The father had fallen asleep at the wheel, and when the front tires dug into the shoulder the old truck had over-ended twice. The four children had been in the back with two washtubs of speared rough fish. What was amazing was that as the truck rolled it spit the family out and arranged them in the ditch according to age.

Billy, age four, lay on the shoulder, one thin brown arm thrown over what remained ofhis head. Estelle swam face down in the sloping ditch, as if angling toward deep water. Brian, sixteen, and Dennis, seventeen, slept side by side in the marsh grass, the same way they shared a mattress on the thin floor of their doublewide. The mother was jammed down in the swamp edge mud while the father hung in the diamond willow, a leg and an arm propped in the branches as if he had walked from the front window of the truck and planned on stepping up beyond the swamp into the sky. A trail offish stretched from Billy to the father, glistening in the morning sun. The whole family wore scales plastered in their hair and stuck to their skin.

Eugene stood with Franklin on the shoulder as the state troopers measured the skid marks though there wasn't much reason to. The reservation police stood around their cruiser and looked blankly at the wreckage.

"Family night," said Franklin. He always thought of things like that to say. When the tribal chairman had driven through the ice Franklin had said "Gone fishin'" as the diver pulled the body out. Four months

before a skidder dumped its load of pulp on top of a tail-gating station wagon full of vacationing Iowans, and Franklin yelled "Timber!" as he dove into the mess.

Eugene was different. He tried not to make jokes. He tried to be nice. He stared at the trail of bodies and then over to the upside down truck. He said nothing and tried to force his mind to stay put. That was the least he could do. When he came home from Iraq, the tribal council gave him a citation during the Fourth ofjuly Pow-wow, But still. The whole time he wasn't proud, wasn't as tucked and square as his uniform. All he could see, as the flags and eagle staffs were marched by, were the trees at boot camp in Mississippi, the fantastic growth of creeper, great drooping branches. That and the prostitute in Dubai. As the color guard posted the flags all he could see was the look on the hooker's face when she asked him You like tight? Tight okay? Who doesn't? he said. Who doesn't? The hash he'd smoked made the question seem both stupid and profound. The girl had looked over his laboring, shuddering shoulder at the dry vista.

Eugene thought about her as the colors were posted and the host drum began an honor song for him, and thinking about her felt wrong somehow. Honor and war deserved a concentrated mind. So did death. So he never told jokes like Franklin.

He tried to keep his mind from wandering as he and Franklin examined the bodies in the ditch. But all he could think of was the truck, of how beautiful the truck was or would be compared to the junked out Ford bottom up in the ditch.

Five days later the Dodge was on display outside the casino. Eugene shook his head, amazed that some guys in Detroit could make a truck that nice. A four-wheel drive, metallic-blue vision. On the tailgate, in what looked to Eugene to be stunning detail, was an airbrushed painting of a huge buck, standing guard over a doe curled up with a spotted fawn.

"That the truck?" asked Franklin as they stood and sipped coffee.

"That's it."

Franklin took it in and nodded slowly. "Helluva truck."

"I think so."

Franklin stood back from the tailgate. "It ain't realistic."

"I know."

"This painting. It ain't accurate. No buck would be hanging out with a doe when she's still nursing. He'd be packed up with the rest of the boys, getting ready for the rut."

"Maybe? You ever see a family of deer? A nuclear family? Shit. It don't exist. My brother shot so many fuckin' deer before he got sent to Nam, and he never saw nothin' like it. Makes you wonder. They must not hunt over in Michigan." He shook his head. "A truck should be accurate."

The day before Labor Day the casino manager drew fourteen names. Eugene was among them.

By nine a few media people had gathered to take pictures and interview the contestants. Most of the fourteen had families who came to support them. They brought quilts and fry-bread they had cooked the night before. They planned to eat in the shade of the pavilion set up in the parking lot. Eugene's mother had refused to go with him. "Come downtown to watch you stand around? I been watchin' you stand around since 1984." She scoffed. "If I want to see a bunch of people leaning on a truck I'll go and look at construction on the interstate."

Franklin, at least, promised to come down every four hours and bring food.

The organizers arrange the fourteen contestants at three-foot intervals around the truck. A farmer Eugene went to high school with is placed at the center of the grill. A heavy machine mechanic gets the driver side door. Eugene is placed between a young Indian girl, probably eighteen or even younger, whose too-large IHS glasses look as if they hail from the mid-seventies, and an Indian fishing guide he knows, but barely. The girl's thin hair is pulled away from her face making her head seem too small to deal with life to her advantage. There are others around the truck, most of whom he knows. He looks at the section of truck that will be his: the window of the passenger side of the club cab. He thinks it is a good spot.

The emcee blows a whistle and they all pull on white cotton gloves. A judge inspects their hands and arms. The judge nods at the emcee who counts down from ten to one and fires a starter pistol. The basketball shot clock borrowed from the reservation high school bangs out one second, two seconds, three. The contest begins.

At first they don't talk to each other. They stamp their feet on the plywood and glare at each other like sumo wrestlers. Even the fishing guide behind Eugene does this. The girl in front of him holds his eyes. She refuses to look away, as if to say: Damn you, this truck is mine. With her

free hand she pushes the glasses on up higher on her nose. Her ferocity scares Eugene so much he is forced to look elsewhere, over the treetops along the edge of the parking lot, into the brittle sky, at the tinted windows that not only paint the reflections cast there a shade darker but elongate the cars that pass by so that a Pinto has become a hearse.

After the first couple of hours the families that have come to watch their uncle or brother, or mother, grow restless. Some retreat into the cool interior of the casino to play nickel slots until something happens. The journalists have left.

During their five minute breaks everyone goes and sits down in the shade. They squat and wring their hands and drink down little paper cups of Kool-Aid provided by the casino. It is hot for September. Eugene knows what the heat and sun can do to the body and made sure to wear jeans instead of shorts. That morning he even stopped at the E-Z Stop for sunblock on his way to the casino.

"Got suntan lotion?" he asked the clerk.

"What SPF?"

"SP what?"

"How strong. You want a tan? You want to be so dark they count you absent at night school? Total block?"

"Total. I'm gonna be in the sun a while."

Toward the afternoon the contestants begin to get uncomfortable. Their feet hurt, and the ones in shorts regret it as the sun moves and they bum with its movement, as if they are being rotisseried.

The girl in glasses in front of Eugene scratches her leg.

"Hot, huh?" ventures Eugene.

"Not bad. I'm gonna win. Heat don't matter." She doesn't seem able or willing to speak to Eugene in complete sentences. "Up here," she says, tapping her temple that is collecting sweat like a cup, "I'm prepared up here. More than that. I want this truck. More than anyone and that's what matters."

Eugene doesn't say anything, but he thinks she's wrong. It's more than that. The men in his platoon who were misted by mortar fire or tom in half by IEDs didn't want to die. They wanted to live. Wanted it as much as he did. When he came back he had wanted to go to school, had wanted school, a job, a family. He'd hungered for those things. Had dreamt of a brown, round, smiling wife. He'd tried, but school ended for him because no one took it seriously. The other students laughed at the professors and the books they had to read. What you know can save

you, he thought. But the laughs and smiles, the ease with which they set out to fail made him want to punch them square in the nose, to crush the soft bone so the blood pouring over their tanned legs would teach them life was real, that what they said mattered. Finally, he gave a laughing football player a shot in the jaw that tipped him over in his seat, packed his backpack, and took the next bus back to the rez. The rest of it never happened. Some things don't happen even if you want them to. Wanting something is one thing. Getting it is another. Instead of a job he took pleasure in, he ended up driving an old Continental to the Cities and back every couple of weeks with the trunk packed with weed. His cousin paid him thirty dollars a trip plus expenses, which sometimes including stopping off at Sugar Daddy's, near St. Cloud for a lap dance or two.

The ambulance job had been the first real job in the four years since he got back from the war. After living for twenty-five years and just coasting, just accepting what life gave him he found something larger than himself he could dive into. He kept all his notes from training and held on to the trauma manual they used in class. He returned again and again to the pictures. Full color pages of what can happen to you if you're not carefuL Scalp lacerations, contused eyes, the eyeball hanging down your cheek. Whole flaps of skin lifted from your scalp with one swipe of a bear's paw. Legs that doubled in size and turned black from snake bite. Arms that were caught in drill presses and spun like dishrags. He never felt faint or got queasy looking at the pictures. Amazed more than disturbed, he is surprised at how many ways you can pull apart the human body without actually killing it.

It wasn't until the second four hour break that Franklin showed up with food. Two Deli Express Chicken & Swiss sandwiches and a Coke.

"Couldn't make it earlier," he explains, "some farm kid stuck his finger in the tractor hitch and got it sheared off." Eugene nods thoughtfully, chewing his sandwich. The farmer he went to high school with on the other side of the truck had done the same thing before shipping out to Vietnam. Everyone knew it then and they hadn't forgotten. Right before he was supposed to ship out he went and did that. No one said much, even the old timers could understand wanting to. Franklin's brother hadn't dodged and had gotten himself killed. Franklin never talked about it, though he brought his dead brother's opinion to bear on almost all topics of conversation.

"Blood?" Eugene asks finally.

"That farmer the one who cut off his own finger?"

"Yep. You put your finger on it." He smiles, proud of his joke. "Yeah."

"Shoulda gone out in the field to find it."

"Why?"

"So someone at the hospital could shove it up his ass and sew it there."

Eugene said nothing.

They eat in silence and then the fifteen minutes are up.

It is almost four o'clock and the contestants are beginning to feel the strain. Gradually they lose their fierce demeanors and Eugene hears conversation on the far side of the truck.

An hour later the first of the contestants gives up. "Shit," says the four-fingered farmer on the grill, "I got better things to do than this shit." He stands straight and wipes off his hands, crumples the gloves and tosses them down on the gleaming hood.

Everyone looks away. They are ashamed for him, but glad they aren't the first to cave in. The woman in front of Eugene sighs and looks up at the sun, at five-thirty just scratching the tops of the trees.

"Thank god it ain't June."

Eugene nods. He is grateful, too, that the sun will go down soon, at seven instead of nine.

At dusk two more contestants drop off.

It is dark now and he lights a cigarette, the flame bright in the paint of the truck. He puts the lighter back in his pocket and exhales. He holds it out toward the girl.

"Want one?"

"Naw," she says, "got to think about the bun in the oven." He hears her pat the taut skin of her belly.

Eugene withdraws the cigarette, surprised that he never thought of pregnant women, and whether or not they smoke, or if they should. As a healthcare provider he feels guilty about this. He has seen them, in over-sized Chicago Bulls 'Tshirrs puffing away at bingo, ashing with one hand and daubing with the other.

"Who's the dad?"

"That's personal. I don't even know your name."

"Eugene."

She laughs and it rings out clear. "This one's daddy is named Eugene, but he's off in jail."

"That a good thing or a bad thing?"

"Good, goddamn him. I put him there."

"What's yours?"

"My what?"

"Name. Your name."

"May."

In the parking lot light he sees her bend her knees and straighten.

"I think I shipped out with your brother."

"Maybe."

"I did."

"If you say so."

The clock ticks on. By morning three more people have dropped off. One full day has gone by and only eight contestants are left. Eugene is getting tired. His feet are swollen and press out of the tops of his sneakers. His back is pinched and his outstretched arm has gone numb. The five minute breaks help some, though when he palms the side of the truck, the pain and then numbness creep up more quickly. Franklin missed both fifteen minute breaks.

At six-thirty the sky is getting light. It is going to be another hot day. The referee blows the whistle and all of the contestants lift their hands clear and begin wringing them out, stamping their feet and performing stretches to get the blood going again. They move away from the truck. When they started they couldn't take their eyes off it, now it is the last thing they want to see. May casts a sidelong glance at Eugene.

"Where's your support?" she asks, looking around the parking lot for Franklin.

"Franklin? Probably sleeping."

"Come on," she says, "I got an extra cheese sandwich."

They troop over to the pavilion and sit down.

"You single or what?" asks May, chewing but speaking delicately around her sandwich.

"Yep. Single."

"That the way it is?"

"The way it is."

He concentrates on his sandwich.

Finally, his courage in place, he says, "You're nice, May. Real nice." She looks offended.

"No I'm not."

"I mean

"I know what you mean. I do." May's voice softens. "I know, Eugene.

I know. But wanna be straight with you. You know? And the thing is, I'm not nice. I don't know shit."

"Oh."

"And neither do you. You don't know shit either."

Eugene looks first toward the truck and then at the front doors of the casino.

Soon the fifteen minutes are up and they all groan and complain to one another as they head back to the truck.

The day is a blur. The heat comes off the asphalt and the truck in waves, tamping out any sparks of conversation that might have sprung up. There is only so much conversation they can sustain. The light, the unending heat, the nakedness of their hardship; all of it makes it difficult to speak. Across the parking lot the casino-cool and communallooks a lot like what paradise must look like. They only talk at night. Though nighttime begins to prove difficult as well. Without sight, not being able to move, everything else crowds in: memories, regrets, what has remained for each of them unmentionable, all of it is given new life, room to breath in the cloister of their confinement.

Franklin is still a no show and Eugene begins to feel faint, wobbly on his legs. Soon they begin to tingle then he loses all feeling from the waist down.

"Oh shit," he murmurs.

May strains forward when she hears him, trying to see what's the matter.

"What's wrong?"

"Can't feel my legs."

She leans back. It is hard to see, but her face is oily enough to pick up the ambient light from the casino. Her glasses hover on the tip of her nose.

"Not so bad," she says. "It's just like being pregnant."

He knows she is trying to comfort him, though it doesn't help. He'd thought he'd experienced most of what life had to offer: pain, injury, the loss of loved ones, moments of calm, even ofjoy. He'd traveled overseas. But, he realizes, as May retreats into the darkness, there is a host of unknowns, crowding around the edges of his life, just out of rifle range. Pregnancy for starters, fatherhood, even the notion of standing with his hand on a truck for two days. He's never done that before either. There

is a point in your life when you stop thinking in terms of the unknown; when everything that happens gets compared to some previous experience. There has to be a moment when this happens. Instead of youth and old age, there are two more important stages, one when everything seems new, and a paler, quieter, that's-just-like phase which stretches out indefinitely into the future. We reach a certain point and what is not known makes life too precarious. It is the terror of what the future holds that makes us want to believe this.

The night draws on. Eugene is beyond hunger. He doesn't flinch or complain when Franklin fails to show up again. May makes her sandwich offer. He looks at her and her meager provisions.

"I ain't even hungry."

"You need energy."

"No," he answers, "I'm okay."

"Where's Franklin?"

"He'll come around."

"You think?"

"No. Not really. He ain't coming back. He's not good for some things."

She shrugs and munches away while he strolls around the pavilion.

The breaks feel shorter. Five minutes has dwindled into nothing, fifteen minutes barely feels like enough time to take a full breath, while the four hours of standing take an eternity. Eugene feels pathetic, what he has set out to do so inconsequential that the sun is loathe to rise. No one watches the contest anymore. Occasionally a car honks its horn while driving by in either derision or solidarity. No one along the truck can tell. There are only five of them left.

Then. At four in the morning Eugene feels the truck begin to move. At first he is not certain. It has become part of the landscape, a great blue rock he and May are anchored to. But then, just a little, it shifts. He can feel the V8 humming quietly under the hood and it begins to roll. He keeps his hand on the panel as it gathers speed. Just an easy jog to keep up. Eugene feels like a Secret Service agent running alongside a presidentiallimousine. He turns his toes in and affects the wolf-like lope he has seen on TV and in the movies. It is a relief to be in motion.

He is content to do this, to run along the truck, feeling the chill air, getting the circulation back in his legs. Then he hears laughter. He looks in the windows and he sees a man and a woman sitting in the front, laughing, the man bending to turn the radio up. Eugene glances

in the back of the truck and there are four children and two tubs of fish. The children are playing hand games and eating ice-cream sandwiches.

"Get out," he tells them. "This here's mine."

They look at him lightly, the flow of their game only barely interrupted.

"Get out!" he says more loudly.

The youngest one, Billy, gets up from where he has been sitting on the edge of the tub and walks to the back of the truck. With some effort he manages to lift the catch to the tailgate and drops it down. They are going faster now.

Eugene looks behind the truck. In the darkness he can barely make out the shape of people running behind. They are getting closer. When the first one enters the faint red circle of the running lights he sees that it is Franklin. With the agility of a cat he jumps into the bed of the truck and turns to lend the next person a hand. Eugene's mother. They sit down side by side on the wheel well and Franklin takes a brown paper bag from under his arm and starts handing out whole fried chickens.

"You come for them but not for me?" asks Eugene. "For them?" His mother and Franklin look up calmly, as ifseeing Eugene for the first time.

"Well, well," says his mother, chewing on a drumstick, "didn't think you'd make it this far." She resumes eating, taking leisurely pauses to chat with Franklin and to make cute faces at the children. Eugene hasn't seen his mother exhibit this kind of calm and goodwill since before he left for Iraq. Her face is smooth, not tied up in a grimace. The rancor he has come to associate with her has been erased.

"Eugene. Eugene, you're talking to yourself."

He looks ahead, trying not to stumble. May is still attached to her part of the truck.

He looks back at the truck, at his mother. At Franklin who is talking up a storm, amiable for once instead of sarcastic. He puts down the bag of endless chicken and dusts the grease off his hands and walks to the tailgate. He extends his arm and begins to pull people into the bed. Eugene cranes his neck and sees most of his squad from Iraq jumping in. The ones who made it and the one who died. They are whole again, their arms reattached, their eyes focused. They settle in and make room for others: Eugene's first girlfriend, shy and beautiful at thirteen. Now she is an adult, confident, even more beautiful. Womanly. "It's not fair," he says. "It's not fair."

They get to change. They get a second chance. It is all Eugene can do to keep the past where it belongs, while worrying about the reasons;

about why he made it out of the war alive, why his mother turned sour, how come Franklin lost all of his compassion for the dead and dying. Every day it takes all his energy to acknowledge the reasons for life's shape. Eugene's mother pulls a harmonica from under her bra strap, and, her foot thumping the floorboards, starts a long delta wail.

The truck keeps filling up. His junior-high basketball team, in uniform. Even the cheerleaders from their rivals climb on with their pompoms. One of them looks familiar and he suddenly remembers.

She cheered for the next town off the reservation. Eugene's team had lost at the regional championship. The walk from the gym to the bus seemed like an eternity, the sweat drying inside his jersey, his face hot with shame. And this cheerleader ran up to him, still wearing her pleated skirt, her sweater hidden under a letter jacket. Eugene barely acknowledged her.

"Hey," she said. Breathless from her run, or maybe he thinks now, because ofwhat she was trying to say to him in front ofher friends, clustered at a safe distance under the light at the gym door. "Hey, you were real good."

"Not good enough," he muttered.

She smiled, and she touched him on the hand.

"You were," she paused for courage and leaned in to whisper so no one else could hear, "you were beautiful out there."

He looked up then, but she was already running back to her friends, out of the circle of light. On the bus his friends teased him about "not getting some" and launched into a chorus about her breasts. At the time he was embarrassed by his inertia, his terminal shyness. Now he recognizes the tranquility, the roundness of the frozen moment, complete in itself: the autumn air, this beautiful girl running up out of breath, the skirt oflights around their half-lit exchange, his muteness, and her reaching across all that distance to touch his hand and call him beautiful.

"You're beautiful, too," he says.

"Me?" whispers May.

He focuses on her, on the swelling of her belly, her coarse affection. The way she clears her hair from her forehead. He sees for the first time how unsure she is, how much she wants to believe him.

"Who else would I be talking to?"

What a truck, he thinks. All these people. It can hold all these people, and there is room for more. There is room for everyone.

He looks around for the other contestants but he sees only May. They are the last two holding on. It has been three days.

He is still running along side.

"How can you keep up?" he asks May.

"We're standing, Gene. We're still in the same place."

He isn't winded from the constant jogging. His legs feel good.

"If I win I'm gonna give the truck to you," he tells her.

"If I win I'm gonna keep it. Just so you know."

It's either you or me. He realizes that standing still takes as much courage as running. That she is trembling. So is he.

"Let go," she says. "Let go, we can share it."

"I'm holding on, May. I'm holding on."

He is laughing, euphoric. For once he knows he can do it. He can hold on. The truck picks up speed but running is effortless.

"I can do this. For real. I can do this."

"No you can't Eugene. You can't."

"You're wrong."

He can do this. Forever. He sees now how nobody considered how hollow each day is for Franklin without his brother, how Eugene's mother wanted another try with her husband but never got it. He sees it now, in the back of the truck, how our losses always keep us company. As the truck gathers speed it attracts more people. They cling to the running boards, sit on the hood, the ones in the very back help them jump on. There is room for everyone. Eugene runs alongside, his hand still touching. He can hold on, no matter how fast, he can hold on. He was made to do this, has been waiting for the chance to hold on.

When the grant at Scripps in San Diego ended Bobby Stein wasn't surprised. He simply poured another drink. He was a mercenary in the DNA wars, a molecular biologist with good hands, impressive ingenuity, and intuitive capacities. Directors of competitive research institutions considered him interesting, despite his lack of pedigree and inability to remain attached to any organization longer than two years. Bobby Stein worked eighteen hours a day, seven days a week and slept in the lab. He was thirty-eight, with ten years more experience than the ordinary postdoc and he worked for the same substandard wage and with the brutal intensity of a researcher a decade younger.

After years as a professional lab rat he had grown into a lab monster, immensely talented and wildly unstable. Lab monsters created the newest protocols and were objects of terror and awe to lab rats. Bobby Stein had a questionable resume, a substantial list of scientific publications and biographical gaps that reinforced his reputation as a gifted scientist with antisocial tendencies. He didn't play tennis or golf. He didn't attend dinner parties or the obligatory Christmas gala. His conversations were confined to the details of the research, analysis of results and strategies for the next experiments. He moved through the white-tiled corridors between laboratories and computer facilities in his white lab coat with a rapidity that made him seem always on the periphery and already vanishing into a bleached distance that both camouflaged and justified him.

Before San Diego, he had spent a year cloning Hepatitis B coat proteins in Taiwan. He mapped the genome of a virulently pathogenic

cotton fungus in Arizona. In India, he isolated antibiotic resistance genes from strains of tuberculosis bacteria. Two years at MIT growing protein crystals for Xvray diffraction. Then a year at Berkeley extracting complex structures from the patterns with computer modeling. He had been in Brazil and Spain, cloning and sequencing, but he wasn't certain in what order or why.

During his year and a half at Scripps, yards from the ocean, he rarely considered the possibility of actually interacting with the water. The Pacific existed as a fluid abstraction, another blue void that had nothing to do with a western blot, a polymerase chain reaction or a runoff transcription. The idea of voluntarily leaving the facility did not occur to him. He did not have an apartment. He possessed no personal effects that could not be transported by a midsize sedan.

He was not uncomfortable with his existence. Research facilities were distinct ecological systems, millennial city-states with equipment and protocols that did not require translation. He knew the hum of the ultracentrifuge and high-voltage sequencers, the smell of Luria broth and double-distilled phenol, the pulse of chromatography pumps. The stained whites of the corridors and walls and lab coats were a form of mathematics that did not alter when one crossed an ocean or hemisphere. There were no time zones or dialects or cultural distractions. There was only one word and it was science.

He began drinking when he woke. First brandy or kahlua in his coffee. When the lab quieted in mid-afternoon, when the secretaries and staff departed, he switched to bourbon. He bought it by the case and kept it in the walk-in cold room near his Plexiglas containers of radioisotopes and mutagenic compounds necessary for his research, P�32, I�I25, and Ethidium bromide. He made weekly trips to Trader Joe's where he bought pounds of high-protein cashew nuts and dry-roasted soybeans. For the rest, he subsisted out of food machines.

By late afternoon he was a third of a bottle of bourbon into his day, which was just beginning. Alone in the lab, his speed increased, his sense of energy and purpose. The emptying of the building was a form of purified oxygen, and he could breathe and think with ease. Absence filled him. He worked with a walkman attached to his lab coat, listening to [imi Hendrix and Cream and John McLaughlin at full volume. He kept his .22 Beretta in his lab coat pocket. He finished the bourbon bottle on the sofa, often taking his 1966 Gibson SG and amp from his office cubicle and improvising riffs that bounced through the tiled walls, supplying excellent acoustics. Sometimes he sang.

Several nights a week he spent an hour practicing the distilled essence of his martial arts training. Just the moves sure to kill or disable, the fingertips to the eye, the knee to the genitals, the elbow to the throat. Periodically, he took out his nine-millimeter Glock from his locked cabinet, and moved through the lab as he would a hostile environment, a dark unknown warehouse in Oakland or Baltimore, perhaps, crouching, taking aim, moving low along walls, crawling beneath windows, remembering the weight of the gun in his palm. The janitors never saw his night exercises and ignored him. That was part of maintaining his Zen awareness. When the bottle was finished, he threw it in the radioactive trash container to torment the safety officer. Beretta under the sofa cushion, he wrapped a Mexican serape around his shoulders and fell into a kind of sleep.

When the Scripps grant funding ended Bobby Stein was the first person terminated. He responded to this information by spending the next three days drunk. He found himself holding the lab phone having what he gathered was his second or third conference call with the Dean of the Science Department at something called College of Northern Pennsylvania, Allegheny Hills.

"We're excited about your background," Dean Nevins said. "Your range of capabilities. We're building up our science skills here."

"What do you have now?" Bobby asked. He had a splitting headache, double vision, and a cough he considered disturbing.

"We're installing a computer lab next year. Two biologists. One is retiring. We're down to one math guy. He's on sabbatical. Computer gal took a job elsewhere at the last minute. So there's opportunity," Dean Nevins said. Even through his hangover and the distorted speakerphone, Bobby detected desperation.

"I've never taught before," he admitted. "Not since graduate school."

"We're just undergraduate liberal arts here," Dean Nevins reassured him. "After MIT and Berkeley, you'll do fine. Can you be here in a week? Classes begin August 20. We're in a bit of bind time-wise," the Dean said. "I'll fax you a contract."

Bobby Stein didn't actually see the ocean until the day he left California. He bought a used pickup truck north of San Diego. It was hot, his guitar and amp and assorted possessions were on the car lot pavement. The Beretta was in his pocket, the Glock in the belt of his faded black jeans against his spine. The heightened awareness necessary to carry these weapons without discovery was a spiritual exercise. Then he

saw the ocean just across the highway and it occurred to him that he wanted to touch the water, just once. He let the thought pass.

Bobby purchased two tweed sports jackets, dress shirts, and a black tie at a Salvation Army store in Cleveland. He arrived in Allegheny Hills six days later. Math 102. Introduction to Biology. Introduction to Computer Science with hours to be arranged. Of course, there was no computer lab yet. The biology department was an alcove with thirtyyear-old microscopes, several Bunsen burners, amphibians in jars and frog-dissecting kits. The liberal arts students could barely do high school algebra. No one had taken a biology course before. He didn't know how to teach, and they didn't know how to learn.

He lived in his truck, off the highway on a back road behind a farm for the first two weeks. He took showers in the school gym. He was planning to move into the empty computer lab where he could plug in his guitar and amp when Dean Nevins called him in.

"You're doing a great job. Our art students have science anxiety. They say they're enjoying their science experience. It's a relief to me," Dean Nevins admitted. Then, brightly, "We arranged housing for our computer gal who decided, in undeniable violation of her commitment, not to join our Allegheny Hills family. So there's a house available."

Bobby Stein didn't say anything. He had never really lived in a house before. Not his own house. With an address, a kitchen, a bedroom, a bathroom.

It was an old farmhouse in town about two miles from the college. Seventy-five years old, Bobby concluded, noting the two by four windows, a stone chimney, and three lightning rods. A kitchen with stove and refrigerator. Windows facing an apple orchard and miles of maple forest. Deer hunting country. Probably bear, fox, and raccoons. Electrical outlets in every room. The closest house was a quarter of mile down the road. It was painted yellow and surrounded by a white picket fence. Red, pink, purple, and white roses were planted behind the wood.

"Who lives there?" Bobby Stein asked.

"Jessica Blum," Dean Nevins said. He seemed to pause. "Professor of Creative Writing. Jesse, she's one of our prizes."

Bobby Stein unloaded his truck that night and slept in his sleeping bag in the living room with his Glock next to his side. He still had half a case of bourbon. By habit, he woke whenever he heard an unknown sound and moved cautiously from room to room, Glock in his hand, feeling the walls behind his back, memorizing the spectrum of creaks in

the wood planks beneath his bare feet. He studied the trees by moon' light out the windows, calculating their shadows and wind sway.

Jessica Blum believed she possessed a unique form of telepathy that allowed her to sense impending emotional events. Not global catastrophies like earthquakes in Turkey or monsoons in the Philippines. It had nothing to do with politics or the stock market. It was strictly confined to the intimate components of her life. She felt there was a forest fire in her forehead ignited by the flow of loss and desire appearing in random stray spasms. She wanted to chart these conflagrations. There were psychological equations in a partial gesture or a lamp-lit pause that implied entire personal histories she could decipher.

This unusual sensitivity was a natural element of the terrain of her profession. She was a romantic modernist, a creature adorned with rare proclivities, wearing her wounds like lesions that glowed. Her skin was a lattice of luminescent etchings, tattoos in reverse; they burned out, ward, a compendium of secret torches and flames.

It was the end of August and Jesse sensed a vast ineluctable current moving in her direction. Her private El Nino. It knew the elaborate sub, terfuges that defined her strategies of survival. And it was coming. It was not a bullet. It was a heat-seeking missile. It was airborne, and it wouldn't miss her.

The cusp between seasons was always a problem. There was an absence of definition and too much sketchy shadow. The world turned strange and ragged. She was walking a trapeze in a tent illuminated by miniature bonfires and tiny votives. Outside, the maples were not merely a leafy chorus but an intimation of an inland ocean assembling itself for autumn, slowly finding its collective red mouth. Then it would start howling. In a month, there could be blizzards. She needed to fill the basement with twenty-five cords of ash, hickory, and oak.

In the transitions between seasons, she experienced a clarity, yellow and solid. It felt ancient, like the end of summer in Syracuse or Thebes. A distilled yellow of augury, rumor, and dream. It was the time to engage in acts of private arithmetic, wins and losses. The physical isolation of the Allegheny Mountains. Her personal exile within it. The great zero of solitude in which the senses were starved and con' fined. The late afternoon light rendered the sky too naked. Soon the leaves would be crushed by winds that ate them like rabid dogs, all growl and teeth. Then the squalor of fall, an anatomy of abandoned nests finches left, pebbles and gravel mouth thunder storms. More

subtraction. Now her age. Four with another zero. There was obviously too much nothing. Still, she believed her formulas were increasingly elegant and stark, leaner and to the point like spears.

In the Allegheny Mountains, fall begins on Labor Day. Autumn frightened her, with its palette of manic soils demanding their harvest of pumpkins, corn, and sunflowers be acknowledged and sanctified. Then the maples assumed the texture of hypnosis and somnambulism, a dangerous abrasive conjunction that suggested walking in your sleep and drowning. The cusp of seasons was an exposure, acres of encrypted air dense with equations of how the heart sickens and does not heal. Every autumn is an assembly of personal atrocities and cumulative small betrayals that should require ambulances. Then winter comes.

Jesse Blum had the persistent and unexpected sensation that she would somehow fall in love. It was the autumn cusp of her fortieth year. She would open her mail or pick up her phone messages, and it would be him, unequivocally. Or she would turn a corner on campus and notice a pergola covered with wisteria that she had never seen before. She would find it called Poets Walk. He would call her name, and she would recognize him instantaneously. He would be dressed entirely in black. Black leather jacket, black jeans, boots and sweater, dark sunglasses. She could put on her make-up by looking into those mirrors. She could rewrite her face. He would be leaning against a birch trunk, one leg slightly raised, as if intricately balanced with the tree. He would just come out of the forest as if part of the fabric.

It was late afternoon and the knocking on the door startled her. No one arrived unannounced at her house. Her perimeters were defined and respected, as if constructed of electrified barbed wire. She was an artist, everyone recognized this, and her seclusion was not violated.

She opened the door to the man. She had seen him before. The latest science replacement. His clothing was wrong, too large, as if the jacket was a kind of camouflage or the garments belonged to someone else, had been borrowed, slept in, and assembled in a borderless confused morning. I will have to move carefully, she thought. He was feral and nervous, radiating a bright-yellow agitation like a faulty lamp. He would need to see empty hands. He would need to be tamed. She would have to cook for him, yes.

"Jessica Blum, I presume," he said, reaching out his hand for her to shake. She took it. "Bobby Stein. I live next door. I've run a computer search and read all your books, interviews, and magazine stories. Twice. You're a genius. And I've been waiting all my life for you."

"For what?" she asked, gentle but cool. She was not entirely surprised. "For what? For my lessons. Monday is Neruda. I bring you white orchids. You read me Neruda in Spanish. Your interviews stated that his poetry is your favorite. I learn the language through our lips, when you kiss me." Bobby Stein began. "I trust that is not inappropriately forward?"

Jesse Blum considered this professionally, the quality of his word choices, the cadence of their composition, the precision and music they produced, their sophistication. This was a dialect in which she was flu, ent. "Would you like a cup of coffee?" she indicated the interior of her house with her fingers.

"I would indeed," Bobby Stein entered her house. Jesse poured coffee into china cups. They were standing in her kitchen. He held his cup with surprising authority. She thought he might be a juggler.

He stared at his coffee. "Do you have any whiskey to put in this?"

"No," Jesse said. "I'm a perpetually recovering drug addict. So I don't drink."

"That's an excellent decision. I'll stop drinking as of this moment." Bobby Stein studied the kitchen chairs. "Might I sit down?" He adjusted the chair so that his back was against the wall.

Jesse carried her cup to the kitchen table. She found two napkins and spoons and placed them side-by-side. "Why have you done such ex, tensive reading?"

"I'm a molecular biologist. A research scientist. It's a kind ofpoetry." He said, "I create new life forms."

"What parts of my literary explorations most interest you?" Jesse inquired.

"The drug descriptions are indelible. But I was most taken by your picture. Then I saw you at school. Photographs fail to transmit your beauty and depth. Is that politically incorrect?" he asked.

"Political correctness bores me," Jesse admitted.

"It's like painting by the numbers for the morally bankrupt," Bobby agreed. "Is this a good moment for a fair and frank exchange of views?"

"Actually, you caught me between suicide attempts. I was engaging in small acts of unnatural alchemy. Fueled by deviant ambitions, I'm presently devising methods for night flying. That has a month of com, plete silence requirement. Then I'm wallpapering the bedroom with my collection of murdered women obituaries." Jesse smiled. "What happens Tuesday? Have you prepared that dialogue?"

"I have. Tuesday you wear a white, silk slip. I watch you stand in

your garden watering geraniums in terra-cotta pots. You employ this metaphor as a recurrent leitmotif. While you bend in the garden, you tell me that, at this precise instant, women with the names of flowers and film stars and saints are watering flowers on balconies and roof gardens above alleys and city parks with bougainvillea and statues ofbutchers who became generals. You discuss the etiology ofheartbreak with the precision of a master engineer." Bobby Stein finished his coffee.

"And Wednesday?" Jesse stared at his face. She was thinking all Wednesdays are ashes. He was extremely pale, as if he inhabited a subterranean region of caves and tunnels. She remembered a performance she had given at Attica prison, where inmates had skin so bereft of color, their faces appeared translucent blue. But this man was fierce with energy, anger, and intelligence. His vocabulary was exciting. From his mouth came flares and she thought of stars and their orbits and conjunctions. Such celestial manifestations were called brilliant.