TriQuarterly

TriQuarterly is an international journal of writing, art and cultural inquiry published at Northwestern University

TriQuarteri¥-_____,

Editors of this issue: Susan Firestone Hahn and Ian Morris

Editor

Susan Firestone Hahn

Associate Editor

Ian Morris

Operations Coordinator

Kirstie Felland

Cover Design

Gini Kondziolka

Assistant Editors

Joanne Diaz

Jean Hahn

TriQuarterly Fellows

Laura Passin

Carolina Hotchandani

Editorial Assistants

Maria Lei

Margaret McEvoy

Contributing Editors

John Barth

Lydia R. Diamond

Rita Dove

Stuart Dybek

Richard Ford

Sandra M. Gilbert

Robert Hass

Edward Hirsch

Li-Young Lee

Lorrie Moore

Alicia Ostriker

Carl Phillips

Robert Pinsky

Susan Stewart

Mark Strand

Alan Williamson

135/136

Don't cry because it's over.

Smile because it happened.

Dr. Seuss all forty-five years,

with one more print editionguest,edited by Edward Hirsch

Susan and Ian

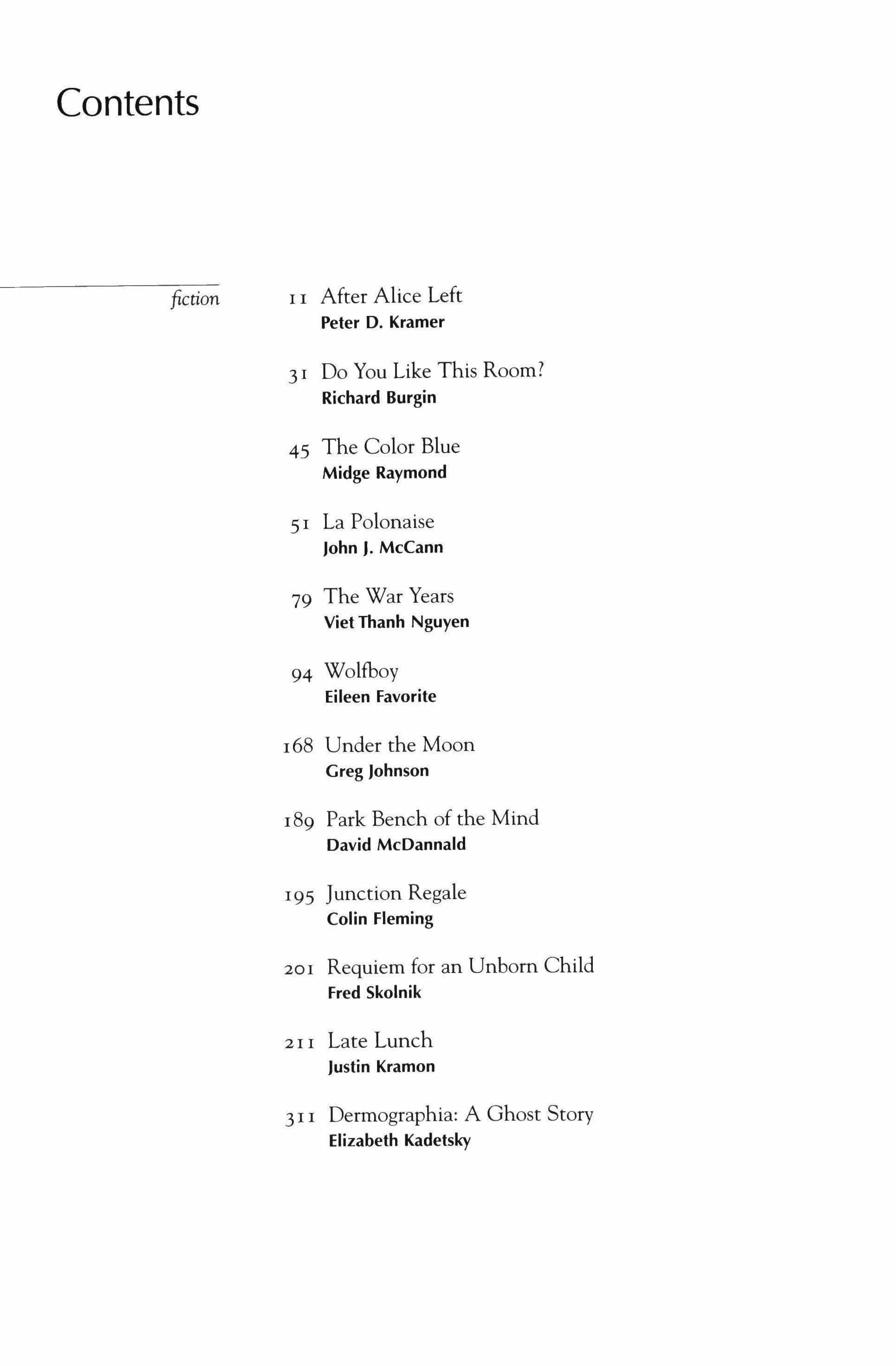

Contents fiction II After Alice Left

D. Kramer 31 Do You Like This Room? Richard Burgin 45 The Color Blue Midge Raymond 51 La Polonaise John J. McCann 79 The War Years Viet Thanh Nguyen 94 Wolfboy Eileen Favorite 168 Under the Moon Greg Johnson 189 Park Bench of the Mind David McDannald 195 Junction Regale Colin Fleming 201 Requiem for an Unborn Child Fred Skolnik 211 Late Lunch Justin Kramon 311 Dermographia: A Ghost Story Elizabeth Kadetsky

Peter

340 Leaf House

Karen Brown

356 The Turetzky Trio

Jay Neugeboren

365 Slipknot

Adam Stumacher

378 Safe

Glen Pourciau

382 My Name Will Live Forever

Michael Kobre

397 New Berlin

Josh Wallaert

410 Edward Grace

Cecilia Pinto

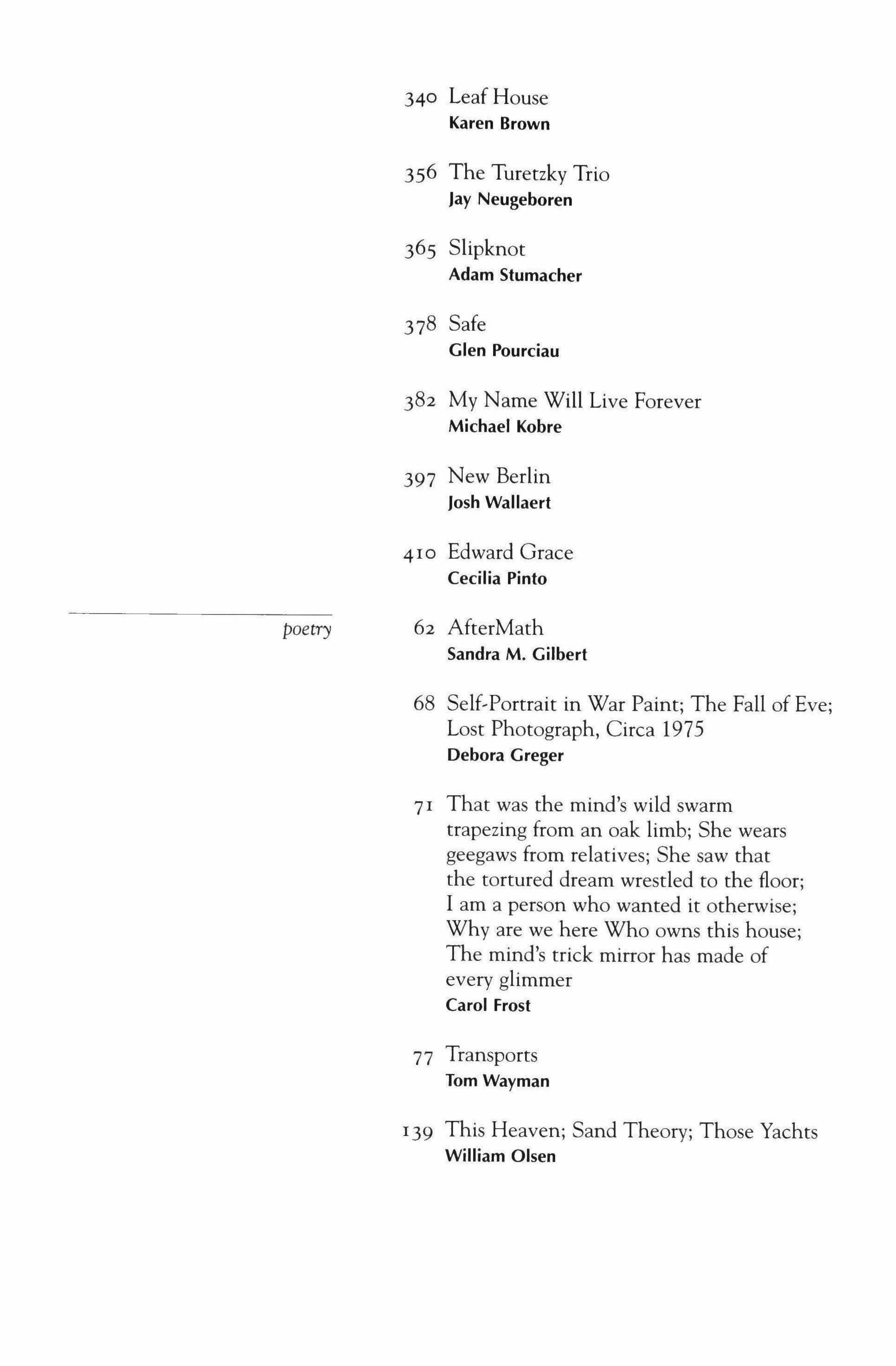

62 AfterMath

Sandra M. Gilbert

68 Self-Portrait in War Paint; The Fall of Eve; Lost Photograph, Circa 1975

Debora

Greger

71 That was the mind's wild swarm trapezing from an oak limb; She wears geegaws from relatives; She saw that the tortured dream wrestled to the floor; I am a person who wanted it otherwise; Why are we here Who owns this house; The mind's trick mirror has made of every glimmer

Carol Frost

77 Transports

Tom Wayman

139 This Heaven; Sand Theory; Those Yachts

William Olsen

poetry

150 Conflagration and Wage: The Triangle

Shirtwaist Factory Fire, 1911

Jonathan Fink

240 Early mourning

Denis Hirson

243 Outage; Towns of South Dakota; Dropped

John Barr

246 Some Roses & Their Phantoms; Black

Canvas

Rick Barot

252 The Pilot; The Accident

Victoria Chang

254 The Theft

David Yezzi

259 Ode to a Pair of Spectacles; The Harvest; Homage to the Left-Hand

Bruce Bond

267 Family Album

Jack B. Bedell

268 From the Book of Mothers

Shara McCallum

276 Boy Playing Violin; Sunrise in Cassis; Pharos

Jennifer Grotz

280 Profit Margin; On Slenderness; Filmic

Christina Pugh

283 Letter to the End of the Year; Art Lessons

Susan Rich

455 A Paris Conference

Paul Breslin

essays

translations

461 The Compulsive Liar Apologizes to Her Therapist for Certain Fabrications and Omissions

Josephine Yu

463 Sestina to the Editors of McSweeney's Internet Tendency, and Vice Versa

Campbell McGrath

105 Politics By Parable: Denise Levertov and the Gulf War

Laurence Goldstein

122

Bottom, Thou Art Translated

Ewa Hryniewicz-Yarbrough

225 Two in a Bed of Woe: A Love Story

William Giraldi

286 Lasting Impressions: A Portrait of Ree

Morton

Donna Seaman

434 Original Sin: The Ineradicable Stain in the Novels of Don Delillo

Gary Adelman

446 (Hidden Track): Poetry in Public Places

Kevin Stein

465 The Handmade World

David Kirby

264 Bandage; Salmon

Ales Steger

Translated from the Siovenian by Brian Henry

477 Contributors

Cover: Forty-fifth anniversary design by Gini Kondzioka

Peter D. Kramer

After AIice Left

Although he has lost the privilege of chaperoning Alice beneath it, Harry Givens keeps an art museum umbrella on the rear seat of his car. He had selected the design with her in mind, a William Morris print with brown vines to complement a raincoat Alice loved. When Alice packed to leave, Harry urged the umbrella on her. "No more gifts," she told him. She complained of what she called his mild virtues, courtesy and generosity. They had bound her to a stifling marriage.

Harry does like to be of use. In the parking lot behind the fitness center, he calls out to Jack Katz, an elderly member. "Tuck in, tuck in."

Harry sweeps the gym bag from the trunk ofJack's Audi.

"I'm here for the exercise," Jack protests, curling a biceps within his puffy parka. Under Harry's protection, Jack shuffles down the icy path. Jack's buddy Joe Manso waits at the door.

"Hey, who sleeps with cats?" Joe asks, an Italian offering a Jewish joke.

"Yah, yah." When Jack doesn't bother with the punch line, Harry supplies it. "Mrs. Katz He collapses the umbrella and taps the tip on the cement. Icy droplets cling to the cloth.

Joe roars out the finish, and sometimes Mrs. Cohen."

"In the day," is Jack's comment. "In the day."

Inside, Ginnie is covering the desk. A gruff Cerberus, she scares Harry a little. Since the divorce, not a few women scare Harry, but he acknowledges everyone.

"Floralinda's better?" Harry asks. One thing Harry likes about the center is the density of acquaintance. Floralinda is Ginnie's partner, a

I I

willowy blond who "in the day" would have hidden her tendencies. Now Harry, who knows Floralinda only from here-she is Membership Coordinator-has been privy to stories ofher inseminations, miscarriages, and once optimistic, now desperate gynecologic surgeries. Harry looks for, ward to that moment in the early morning when Floralinda drops by and gives Ginnie a peck on the cheek. He feels advanced for experiencing the poignancy of it, the slender reed's devotion to the sturdy oak.

Ginnie looks past Harry. "What, they emptied out the old age home?" She's no fan of the Jack and Joe show.

Jack reclaims the bag from Harry and fumbles in it until he finds what he wants. He waves his membership card under Ginnie's nose. Then he sees the new poster. "The sign," he says, "you stole it from a nursery school?" Deliberately, Jack read phrases aloud: "Respecting others. Giving space. Showing consideration." The Yiddish inflection ex, poses comedy in the word pairs.

Ginnie goes, "That notice is for you, Mr. K. You and your pal Manso. It says put your tongue back in your mouth so's you don't drool over the young mothers."

The center had been founded as a physical therapy clinic for the local Jewish hospital. This was two decades back. Anyone could join, but the emphasis was on the injured. Harry had brought his father after the first heart attack. There was no loud music, no fancy dress, no exhibitionistic athleticism. Any intrusive glances came from widows trying to catch the eye of a gentleman on the mend. Harry signed on and felt at home.

Recently, a childcare facility opened across the road. The young moth, ers, as Ginnie calls them, discovered the gym. They lodged complaints, ran for board seats, recruited personal trainers, and decked the walls with flat,screen TVs. The women gossip competitively about their husbands' careers and their children's precocity. Harry's not sure he'll re-up.

For now, he arrives at six-thirty, so he's done before school drop-off The problem is, his ex-wife's friends come early, too, Suzy, Joan, and Tara.

"And you, Mr. Givens," Ginnie is saying. "You're no saint."

Harry is a deep blusher. He had hoped it wasn't obvious, his lapse in decorum. In the young mothers' wake have come single women in their early thirties, drawn by the up-to-date amenities. Harry, who is forty, should find the new members attractive. Mostly he's cowed by their intensity. And yet-there is the one exception. Harry finds him' self fixated on a demurely tattooed bottle blonde, Lena Jadov. He does try to be discreet, believed he had been. In Harry's own book, leering is wrong. Leering, ogling-the very words are ugly. He has undertaken

12

various expedients to dampen his interest. Not that he can discuss these efforts with Ginnie, but in the grand moral accounting, they must work in his favor.

Seeing Harry flustered, Ginnie relents. "Flora's back on her feet. Thanks for asking."

Lena's all about fun. She's fab. She's sporty. She's into fashion.

Harry knows as much from Lena's Friendster Web page, where he has (a third ugly word) lurked.

She adores [lirting, keg parties, Bellinis, and mornings after. She's into men. She's between relationships.

This last is good news, or would be, were it not that Harry's aim, when he accessed the site, was to end his preoccupation. As he learned about Lena, he would find her pedestrian and so earn his release.

Harry happened upon Lena's last name when she dropped her ID and he retrieved it for her, at the sign-in desk.

"They shouldn't need these," Harry had said, as if to ally with Lena over the security policy instituted by the young mothers.

Lena pretended not to hear.

Harry recognized a calculus of politeness. If his staring had been obnoxious, his chitchat was gracious; since Lena had been rude in return, a rough balance had been restored. But ogling was the greater sin. And then there was the issue of subtler signals. Standing behind Lena's cornpact buttocks, entering into the halo of her fruity perfume, Harry had been aroused. They say women sense these things.

Harry did not find Lena pretty. Her face was broad and doughy. Yes, she had big eyes and Slavic cheekbones, but she overemphasized them with mascara and blush. The tattoos, waistband level on her back and left side, bespoke impulsivity. Perhaps the slight trashiness appealed, and the youth. Hints on the website put Lena at thirty-three. Still, younger women passed through the gym. He dreamt only of Lena.

Before he went into advertising, Harry had been trained as a sociologist. He knew that you never understand the individual case. Trends, perhaps. Men injured by divorce seek out women beneath their social class-that sort of generalization might be studied, but never the lust of this man for that woman. Besides, Harry's goal was not to explain his desire but to mute it.

Her favorite singer is Springsteen. Her favorite band is the Beatles.

Harry did not know pop music, but he saw that Lena's choices were

13

banal. It's as ifhe were to name Mozart and Shakespeare. Harry's favorite gas is air; his favorite liquid is water. His favorite state of being is life.

Denigration did not break the spell.

Late nights, you'll find her at La Rondine! She loves the bartender, Gia� como. She loves people who are beautiful not just on the outside, but through and through.

Lena had put these thoughts on display. Was the openness an oversight? (She did seem a sloppy person.) A Google search of "Lena Jadov" summoned up two listings. For the new profile on Facebook, access was restricted. The recently abandoned Friendster pages-the last bubbly comment was ten days old-remained viewable. They were rich enough. Lena had posted two hundred twenty snapshots.

Lena's makeup takes on sheen as an evening progresses, and yet she mugs, confident of her beauty. Black-rimmed eyes and a clownish smile are Lena's trademarks.

She had labeled the photos. Me in my apartment! (Clothes are strewn on chairs.) I love to entertain! (Balloons, streamers.) Barry came for cappuccino! (In her right hand, Lena raises a glass coffee cup, the contents neatly layered; the left hand sits under her breast, seeming to offer an alternative.) Kevin came for cappuccino! (It's an arty shot. A brimming coffee cup sits in the foreground; in the distance, seen through a door, a man's naked body sprawls on a mussed-up bed.) Tony! Dave! (Tony is bald. Dave's fifty ifhe's a day.) I can't believe I left the neighborhood to spend Halloween at La Rondine!

A cluster of photos follows. Women in fetching costumes. Menacing and macho men. Giacomo mixes brightly colored cocktails, neon orange liquid accessorized with licorice swizzle sticks. Lena poses as a sexy nurse. The sequence ends with three down-the-cleavage shots, no face, just the decolletage, a triptych self-portrait to which Lena has affixed the comment, "No man's complained yet!"

In the gym, Lena wore a midriff top and matching boy-cut stretch shorts. Each day, she featured a set in a different color; there were four in all. The outfits exposed a belly that verged on plump, an imperfection that had brought Harry comfort. But at the computer, confronted with the coned-down view of her bust, Harry saw that this judgment had been wishful thinking, a way of denying the undeniable, Lena's conventional, marketable sexiness. He was willing to believe her boast-no complaints.

This Internet excursion had led to a second step in Harry's program of desensitization. When business brought him to the Armory district,

he had dropped in to La Rondine. He had imagined he might see Lena there, buy her a drink, and enter into a conversation that would end his infatuation.

He was early. The bar was empty.

"What were those cocktails you mixed on Halloween?"

Giacomo gave Harry the once-over, trying to place him in the swirl of masks three weeks back. "Zombie Sunsets?"

Harry settled for what Alice had loved, an old-style dry martini. He imagined a gin-flavored kiss.

"Great party," Giacomo offered, restarting the conversation about Halloween.

Harry dropped Lena's name.

"Good kid. Easygoing." Giacomo had stories to retail.

Harry overtipped, content to be remembered.

Now again, at the center, he's too early for Lena. On the way to the machines he uses for warm-up, he passes the trio of Alice's friends. They wear oddly formal sports togs that echo dress-far-success pantsuits. Canted forward, taking exaggerated elliptical trainer strides, the women seem bent on progress, like bold workers from a propaganda poster. Their eyes are cast upward at the cooking section of a news show. Avanti popolo! Crossing in front, Harry nods hello. The women's gaze stays fixed on the screen.

Harry begins with the reclining bicycle. The young mothers have mandated a hip-hop beat. To restore privacy, Harry inserts a pair of orange foam earplugs. So as not to appear odd, he dons headphones and sticks the loose cord in his T-shirt front pocket. Then he turns to reading.

Today's book concerns a boy growing up in rural Norway. As usual, all roads lead to Alice. A descriptive passage causes Harry to think of a bike ride he and she took on a woodland trail. Dappled sunshine is a phrase on the page. The bike's rhythm alone can have this effect, casting Harry back to better times.

Here and now, Harry catches Suzy throwing a glance in his direction. He doubts a response is called for. Immediately, Suzy's back to the TV screen.

When Harry and Alice were first married, Suzy and the rest invited Alice to girls-only events. Alice was an artist and "interesting." The others had grander homes on leafier streets. Their husbands made real money.

Time has taken its toll. Tara has seen her Arthur run his investment advisory business into the ground. Joan is living apart from Zack. Suzy,

15

who left her husband for his partner, Bill, took years to regain her foot, ing after Bill moved in with his assistant, Zoe. In his graduate school days, Harry charted changes of this sort, using a system devised by his research advisor, neighborhoods reduced to intersecting colored lines. Each crooked inflection point bore symbols denoting status modifierson the downside, divorce, illness, arrests, bankruptcy.

Of the women, Suzy had been most opento Harry during his mar, riage. She liked to spar over current events, though she seemed not to read the paper. When he was struggling, in the wake ofhis divorce, Harry had left Suzy a phone message. He had thought that she might know how one copes. She ignored the call and then avoided him in the grocery.

Harry's academic training steeled him against insult. We experience our leanings as outgrowths of character and choice, but we act as slaves to hierarchy. Suzy had her wealth, her classic if sterile beauty, her affiliations in the private schools and country clubs. To think that she could transcend convention Who does, finally? Seen from without, we are cliches.

And now? Demographics come into play, the widely rumored dearth of single men. Sometimes Harry looks at people and sees the charts. If Suzy's status curve, on the way down, has crossed his own-it would not be a bad life, joining forces. So what if Suzy is predictable in her opinions? To share household routines, to resume engagements with other couples Harry misses being married.

He casts his own covert glance. Suzy is too composed, too proud a woman to settle for him. Harry knows as much. No, he will not be saved by statistics. He is an anomaly in the social marketplace. As single men are grabbed up, he will gather dust on the shelf.

This train of thought absorbs Harry. When he looks before him, Lena has taken her place in the bike's apparent path, in a space reserved for floor exercises.

Lena is chatting with a companion. Vera? Velma? Vida? Harry has overheard the name but not registered it. Arguably, V is the prettier of the two, but it is Lena who holds Harry's gaze.

Lena resets a sweatband around her forehead. She stands on tiptoe, reaches both hands to the ceiling, and leans back in an arc. Today, she's in gold, a cheerleader theme. She looks immature. That's what he's been grasping for, in his assessment of the photos. She's a thirty-something clinging to the life of a kid just out of college. There's sadness therealthough he may over-read melancholy in women.

Harry takes care to look down at his book and only then peer dis,

16

erectly over the plasticine rack that holds it open. Having viewed the shots on the website, Harry sees now how the bit of belly lends charm. Lena continues her warm-up, extending her arms to the side, raising each leg in tum.

Alongside V, who is lithe, Lena appears awkward. Harry lets his eyes linger. Lena glares at him.

Joe and Jack have taken over the upright bicycles to Harry's left. Jack points in the direction of Lena. She is doing a new exercise, one that involves rotating her backside over the curved surface of a half ball that Harry knows is called a balance trainer. Sweat breaks out on Harry's forehead.

Mortified, he fixes his eyes on the novel. Despite the story's idyllic setting, Harry foresees injury, violence, and life's bitter lessons.

Lena is upright again. Arms akimbo, she and is rotating from the waist. Harry sets his gaze into the distance. He imagines sitting alongside Lena at La Rondine, then walking her home, as if they were both kids.

Absorbed, Harry is surprised when Joe taps him on the shoulder. Straight ahead, V appears to be yelling, and now Ginnie bears down. Lena is reaching for V, to calm her. Something, Harry gathers, has gone very wrong.

He shakes his head and points to his ears, to signal deafness. "What's the matter?" he asks, wondering if he's speaking loudly or, over the bass beat, inaudibly. He pulls off the headphones, revealing the foolish orange plugs. It takes a second to ease them out.

V is yelling about a hostile environment. "Do you know this woman? Besides that she's got tits, do you know the first thing about her?"

At the desk, Floralinda mutes the Muzak. Suzy and the others stop striding.

"About Lena?" Harry asks.

"How do you know my name?" V and Lena stand before him in joint confrontation. Harry's pedaling slows. He sees what's at stake: Suzy's fleeting interest and the final slim chance that Alice will think well of him. He scarcely understands the accusation. Has he been staring after all? Harry does poorly with anger directed at him, and yet he manages an answer. "You introduced yourself. Lena Jadov, no?"

"I've never spoken to you," she says.

V adds, "She never would."

Harry sees hope in insults. V does not know him. Her hypothesis, that he is unworthy of Lena's attention, is less well buttressed than his own, that connection is possible.

As if in service of this line of thought, Harry addresses Lena. "I bought you a drink," he says. He is astonished at his own choice of words. He has never lied to a woman-never to Alice.

Y will have none of it. "What does she drink, big shot?"

Harry's deception must be apparent, because Jack Katz moves to shield him. "Another," Jack goes. "Our friend Harry bought your Lena what men offer women. Another of the same."

In touch with his fantasy, Harry can defend himself. "You were drinking-something orange-with a black licorice twizzler. Giacomo had a name for it."

Lena pauses, struck by doubt.

"A Zombie Sunrise-no, Sunset!" Harry says. "You were drinking Bellinis and switched to Zombie Sunsets, at La Rondine." He uses the Italian pronunciation. "I bought you one, and then you were called away."

The fuss seems to be quieting, but Ginnie will not let go. "You buy a girl a drink, it doesn't mean you can stare at her."

Joe protests: "That's what it does mean."

Jack chimes in, "The housing industry's collapsing, you want to put beverage services in a slump?"

"These women are exercising," Ginnie argues, "not putting on a show for your benefit."

Finding his nemesis in retreat, Joe presses his advantage. "She shows off her belly for whom? Young men only? We're talking now age discrimination?" He's been sitting in this very seat twenty years. The babes show up, he should tum away?

Jack makes an appeal in Suzy's direction. "Harry, whom you know well-upstanding man-brings his father here, nurses him through two heart attacks, and then Harry's in the year of grief, and his wife, who could have been kinder, deserts him so at last Harry takes an interest again in life, and all of a sudden he's a criminal?"

Whether this recitation serves his cause is unclear to Harry. But the tide has turned.

Lena remains puzzled. "You mean, Halloween?"

Harry knows that Giacomo put Lena in a cab that night. She seems to search her memory, to make it accord with Harry's account. "You had on a dementor mask?"

That's what they're called, Harry realizes, the condomy things that guys in the photos had over their heads.

"You thanked me, but then you were pulled away. You'd invite me for espresso was what you said."

"Cappuccino," Lena goes.

Harry has made the slight error on purpose. It's a trick he learned in his marriage, making mistakes to gain acknowledgment. "Cappuccino."

"Oh my Lena continues, in a sudden access of insight. "You were so " She giggles, fetchingly.

Ginnie, in her official role, must be more direct. "Harry, I owe you an apology. The policy is new. We'll need to discuss how to apply it."

"You buy this bullshit?" Like a lawyer for a client who has concealed a salient detail, V finds her case in ruins.

It's Jack who frames the encounter as Harry would wish. "It seems our Miss Jadov owes Mr. Givens a cuppa."

"Shoe's on the other foot," Joe says. "Who's impolite."

Lena has made as if to retreat to the locker room, but the attribution of rudeness makes her hesitate.

"Coffee's on me," Harry says, by way of peace offering. "Shower up. I'll buy you a Starbucks."

Lena is busy. Another time will have to do.

To his surprise, two days later, Harry receives a call from Suzy.

"So unfair!" she says. "As if you would intrude on that girl!"

Harry is not cynical, and yet he can hardly avoid the assumption that his fictional behavior has nudged Suzy into action. For a man of middle age to dress in costume, show up at a singles bar, and court young women by standing them to drinks-if asked, Suzy would mock every step of this sequence. And yet, the image of the evening has put Harry in play.

Harry thanks Suzy for her concern. He doesn't blame Lena. Too often men do intrude.

"Did she apologize?"

Harry gathers that Suzy wants to know whether the meeting over coffee took place.

"Not in so many words." The answer, he trusts, leaves enough to the imagination. He adds, "I wonder whether words are her forte."

"I should think not." Then, ignoring what Harry has just said, Suzy asks, "What do you talk about with her?"

The question of conversation has been on Harry's mind. He's fiddling with the idea of teaching a sociology course at the community college. In Alice's absence, in the long nights, he has pulled old books from the shelves: Marx, Weber, even Baudrillard. Harry has read about prestige, how it emerges in the web of relationship, our fortune arising from

19

the abasement of another. In the small hours, at all hours, he finds he craves converse with lively minds. In college and after, he and Alice and the others had been earnest, set on understanding the human predicament through debate. Now, what are the topics ofdiscussion? Ailing relatives and failing marriages. Home repair, summer plans, and, with those who have them, children.

Can what engages Lena be less central to the life well lived? Harry has imagined hooking up with her, bearing any conversation with loving grace, humbly burying his face, when Lena permits, in her belle poitrine, and then, if insomnia supervenes, rising from bed and turning in bachelor fashion to Barthes, de Saussure, and Derrida for other sustenance.

"Failed romance is a topic," Harry says.

"I can imagine." Suzy is contemptuous.

"No, no," Harry defends his love. "The losses are heartfelt." There has yet to be a cappuccino with Lena. Still, Harry can elaborate the content of an imagined rendezvous. "What they share, those women, is bodily confidence. What they lack is judgment. I suppose that's where I come in, offering hope of a stable life."

Suzy snorts in disgust. All the same, Harry's confirmation of a relationship seems to satisfy her. She asks, won't he join her for dinner?

Suzy might well-Harry knows she is the type-strike up a conversation with Lena and gauge how far things have gone. He will be judged pathetic. Well, often in courtship the odds are double or nothing. Might not the lie's discovery lead in good directions? Even before Alice left him for her smooth talker, Harry had understood that women can prefer men with facile tongues and roving eyes. He is not built that way, but if he stumbles into favor, where's the harm?

In the post-Alice era, Harry finds that his moral standards have loosened. As intimate wrongdoing goes, surely his is trivial. Suzy had set herself forth as a friend, and then, where was she, in his months ofpain?

When Harry does worry, it is over the wine he will bring to the dinnero Which bottle bespeaks munificence, not desperation? He fusses over clothes, haircut, shoe polish, time of arrival, the many social sig� nals a man bears when he appears at the door.

And then he finds he can scarcely pull it off, an informal evening with a woman he has known for years. The trouble begins with the scent of lamb. Suzy has been braising a shank in burgundy.

"I remember how you love lamb," Suzy says. Harry knows she does

20

not. Alice must have urged the recipe on Suzy. The dish was his favorite, from Alice's small repertory. It breaks his heart that his wife should con' vey him to her friend.

"Let's break into this bottle," Harry suggests, though liquor in any amount makes him sentimentaL He needs help immediately, if he is not to bolt.

Suzy has her hair swept up. She is Scandinavian, cool, and com, manding. "You were never a drinker."

Harry pours two glasses. He's willing to be less staid, if Suzy prefers, though his leanings are all the other way, toward reliability. Immediately, Harry asks about Suzy's son.

Sven is playing guitar in New York. He's finding gigs-supporting himself, other than the health insurance.

"Really, he's doing well?" Sven had problems with drugs, petty theft, hepatitis. If a difficult son, a heartbreaker, comes with a woman Harry might love, there's no need to shield him from that truth. Harry has been married. He can bear imperfection.

Suzy is on to other topics. She talks of her work in interior decorating. She is adept with design, but not with billing. She underbids jobs. Harry hears Suzy to be saying that her flaws are genial ones.

She carries on about a particular failed negotiation. Her nattering contains a welcome message, that she is still here, with him.

Afraid that the odor of lamb will make him gag, Harry pours him, self another glass. Suzy looks alarmed. "Shall we move on to the meal?"

She excels at presentation. The table has a starched white cloth edged with Swedish embroidery, Dala horses in orange and blue. Down the center Suzy has laid an indigo runner and topped it with a blue glass bowl holding iris and centaurea. The cloth napkins are orange linen. Harry will listen, and Suzy will decorate; that seems a plausible division of labor, intimacy could take that form.

Harry marvels at the decor. Suzy professes modesty. To Harry, the dining room feels oppressively large, the meal dauntingly formaL As old friends, should they not be sharing leftovers in the kitchen? Harry and Suzy both pick at their food. The lamb tastes metallic.

Suzy discusses the weather. A nor'easter is forecast. Is it true that global warming pushes the jet stream off track?

Buying a drink may or may not confer the privilege, but certainly when sharing dinner a man is free to admire his companion's features. Suzy's face is elegantly composed, vulnerably human. Her skin retains its fairness and fine freckling. Suzy is like a Swedish movie star, Bibi

21

Andersson or Ingrid Thulin, only horsy. That's what they're like, beauties you might meet, flawed variants of the iconic. It is a pleasure to sit in Suzy's presence.

All the same, a smidgeon of warm feeling would be welcome. Harry asks Suzy how she manages in the face of loss. Oddly (to Harry's way of thinking), it is not her marriage she turns to, but the affair and Bill's injustice.

"I left my husband for him. Whatever do men think? Bill makes himself out as my soul mate and then he leaves me for a child who's attacking zits with Clearasil. How cheap is the soul, to him?"

"Reliability is everything," Harry says, meaning the word as encouragement, though what Suzy hears is not wrong either.

"You think a woman is foolish, to leave a husband for a soul mate."

It's true. To Harry's ear, "You're a soul mate" is a weak hypothesis, "I do," a strong commitment.

Suzy asks, "Do you imagine there are no legitimate dreams, beyond companionship?"

Harry knows he is being diminished. He speaks of a men's group he spends time with, guys from the local universities mainly. They go out for ethnic food.

Harry tells Suzy that the men discussed this question once, of aspirations, and in these very words. "Dreams must be illegitimate," one of the guys said. Another countered, "Every dream carries its own legitimacy."

"But we mustn't pursue dreams," Suzy says. "I believe as much myself. Dreams lead to disaster."

"You have me wrong," Harry objects.

Suzy has not paused. "Absolutely no dreaming in this house!" She pats Harry's hand. He ignores the condescension. If dreamless domesticity has become acceptable to Suzy, that aim will suit him fine.

As if to enact the thought, Harry moves to wash the dishes. Suzy protests. They work together, the dinner's high point, for Harry. The sad part is that even counting the Dutch oven there is little to clean. He and Suzy are two people alone in a vast world, that's the feeling the neat kitchen gives Harry.

What shall they do with the long evening ahead? Harry would like to pay bills while Suzy speaks by phone with her friends. Or he could hear how Suzy estimates decorating jobs and then encourage her to assert herself and not care whether she will. Yes, that is Harry's idea of happiness, playing the dutiful spouse. He asks Suzy about her clients.

22

She throws her hands in the air. If she could do it again, she would become a real artist, a sculptor.

"You should." Harry could support Suzy-not lavishly, but if he sold his house and moved into this condo, they could manage. She is young, is the message. Also: she is old. Why postpone aspirations?

"Shall we throw in a movie?" Harry asks.

"Movie?"

Harry nods in the direction of the entry hall table. The stack of envelopes includes two DVD mailing sleeves.

"Oh, my goodness," Suzy says, and she starts laughing. It is a joke he is not privy to, the ridiculousness of the suggestion, he and she and those particular entertainments. He assumes that the films have a sexual content, Suzy's chosen perversion. Evidently, the kinkiness is not one in which she is willing to assign him a role. A sort of hysteria overtakes Suzy. Her eyes are watering and she is breathing hard. Now she is holding his shoulder for support, which is pleasant, even if her face has gone puffy. "Oh, Harry!"

Some idea or image has got hold of her. She heads to an armchair without thinking to release Harry. He is dragged along.

At last, she puts her hands to her hair, in a gesture of self-control, patting the chignon into place. When she can manage a full sentence, Suzy asks, "Harry, you old fool, did you really dress up and go stalking that bubble-headed thing?" The fit returns as snorting that requires Suzy to put both hands over her eyes and nose.

Harry sees that the other girls and Alice put Suzy up to this evening. He may look bumbling, but he's solid in his way, and good company. Would they say that about him, good company?

Suzy acceded, but she has not managed. She can't get her mind around an association with such an old fool. That's the trouble with forty, isn't it? Our agemates are unstimulating, while we remain in our prime. Harry has read as much, in studies about attitudes at midlife.

At the door, Harry thanks Suzy for the pleasure of her company. It's a matter of saying any words that come to mind as he gathers his coat and checks for his scarf and cell phone. He says that he is sorry he crossed whatever boundary he did cross in suggesting they prolong the evening. He sees that Suzy is tired after a workweek with unappreciative-unremunerative-clients. It is hard to entertain on Friday. But he has enjoyed catching up. And the food! Her remembering his taste for lamb He will reciprocate.

"No, no, stay," Suzy protests. She has a big laptop. She can download

23

a film from the Internet--does Harry know you can do that now? They'll watch it on the couch. It will be cozy.

Harry is aware of the harsh light in the hallway, how wrung out he appears.

"Oh, my," she says. "You're not upset because I laughed just now?"

It is true, Harry is hurt by Suzy's finding him ridiculous, albeit for acts he never performed. As is his custom, he turns upset into an occasion for reassurance.

He tells Suzy that moods come over him as well, not so much in company, but when he is alone. He may find himself smiling over nothing or anything. It's only that his men's group believes

As he speaks, Harry realizes that sober friends would tell him to drop all thought of Lena and make this evening work. Gather round the lap' top. Fashion an upbeat conclusion. But he finds himself taking the opposite tack.

He says that the group insists that even mild mockery signals time for a breather, so that no one is cornplicit in his own humiliation. Avoid that sin, and intimacy remains possible. The contretemps can be forgotten.

"J "S "M h " esus, uzy says. en ave got so sensztwe.

Harry understands that the attribution, sensitivity, is grave-much worse, for social purposes, than lying or lechery.

The next morning is unpleasant. Percussive sounds of wind and sleet set an ominous tone. Harry has slept poorly. Wine has that effect on him.

In his new bachelorhood, Harry has trained himself to go against in' stinct. The worse you feel, the more you stick to routine. After a rough night, rise early, and head for the gym.

When Harry arrives, the parking lot is empty. Is there a Jewish holiday he has not heard of? No, it's that the storm has knocked out the center's power. Just to be certain, he snaps open the umbrella and turns its dome into the wind. Using the stretched cloth as a shield, Harry eases his way down the steps. There, under the door's small awning, stands Lena. She has a bedraggled Lillian Gish look.

"But you're soaked!" Harry protests on her behalf.

Lena explains her circumstances. The gym must have announced the closing by email, but this morning she left her computer turned off. Vema had given Lena a ride. Vema stopped here at the back door and then headed off to her own job. Not until Vema had left did Lena real, ize that this place was shut up tight.

Harry is sheltering Lena now, smelling perfume and wet hair. He listens to the litany of circumstance. This week, she started at the childcare facility. But they'll be closed, too. She's just gotten the call from her supervisor. Lena's voice is all appeal. She's chilled to the bone, her work clothes are ruined, she does not know which way to turn.

"Let's get you someplace warm and dry." Harry thinks of the storm that drives Aeneas and infelix Dido to the cave-speluncam-where they will consummate their wild love. It has been years since he has grasped at Latin. The thought signals his anxiety over the social distance that separates Lena from him.

She offers, "Zee breedge is out; you vill haf to spend zee night viz me." Which is much the same thing, stranded woman, opportunistic man.

"My car's just above."

Lena wants to head home, and why not? Her teeth chatter. She is all apology, for Verna's attack, for not having remembered Harry from the party, for soaking his front seat.

Harry turns the heat blower to high. Lena speaks over the white noise. She has only worked at the preschool for a few days, but she is disenchanted. Even at age four, the kids act over-privileged. They share poorly. Ordinary bumping and shoving reduces them to tears. Her nephews are not that way. They're rough-and-tumble boys. They're bear cubs, rolling about, biting and punching, having a good time without parental intervention. She, too, was a physical child. She doesn't see herself in the group she's monitoring.

Harry says that she will do the children a service. "You'll show them that they can do fine on their own."

"If the mothers let me."

"Unspeakable women," Harry agrees.

He has said the right thing. Or perhaps it is only that there is no other choice. Since they are at her threshold, since her time is known to be free, and since Harry has rescued her, what is there for Lena to say but what she does come out with, "I suppose I should offer you that cappuccino?"

Harry opens the umbrella and circles to the passenger door. Perhaps the unthinking chivalry is a mistake. Lena says, "I don't think I've had anyone your age in my apartment."

Intensity of desire sharpens the mind. "No?" Harry asks. "Giacomo said he thought you had a thing

Lena interrupts, "He must have mentioned Tony, or Dave--or Lenny Shipley." Her memory stands corrected. If Harry is to be dismissed, it will

not be on categorical grounds. "I was only thinking, the place is such a mess."

This time, Harry does not bother to shake out the umbrella. The goal is to get inside the door, and that he does. The living room is in what he knows to be its usual state, with Lena's terrycloth wrap thrown over a chair and beer mugs on the buffet. As in the online photos, an espresso machine dominates the sideboard.

Though the apartment is toasty, Lena makes a show of shivering. Harry takes the hint. "Shower and find dry clothes. I'll straighten up as best I can. If you don't mind, I'll phone my office, so the staff doesn't worry. Then, we can get to know each other in the way we'd-the way we hope to." Promised ourselves is the expression he sets aside. Harry does not want this rendezvous to arise from past commitments. No, from current dreams.

The bed and bath are down a short hallway. Lena slams drawers. Judging from the opening and closing ofdoors, Lena, sans robe, has leapt across the passageway. Harry has not peeked. The sounds of a woman changing are enjoyment enough. Lena runs a bath. The thought of Lena's body in soapy water makes Harry's eyes tear.

Once his hostess is set-warm, immersed-Harry makes himself useful. He rearranges glasses in the dishwasher to make room for more. There are surfaces to wipe, objects to store behind cabinet doors, more work for a cup of coffee this morning than for dinner last night. How rewarding it is to be of service.

The refrigerator is cluttered with leftovers, delivery and take-out. Harry takes liberties. He culls the crusty and unsanitary. He sniffs milk cartons, consolidates old bottles of cheap wine, and scrubs glass shelves.

This fussing while Lena lolls reminds him of routine weekend rnomings. "Take your time," he would urge Alice, and he would putter. He realizes that while he lay awake last night, he had sketched out a Sunday routine with Suzy.

Suzy might yet come round. Harry's had tentative offers for his ad firm. Another solid quarter, his accountant has suggested, and Harry will face gratifying decisions. Of course, in the current climate, a solid quarter may be some time coming. But sooner or later, Harry is certain, his graph will take a sharp tum upward. It may not be romantic to say so, but there are disparities of status that become hard to resist. Whatever she thinks this morning, nine months out, or twelve, or fifteen, Suzy will look back on last night and say, "His walking out told me something about his character. To find a man like that, self-aware and sure of him-

self, and to know him already as a friend " Or else she will say that her growing realization dated back to the encounter in the gym, when she observed Harry's calm in the face of the girls' attempts to rattle him. "That winter is when I began to understand how right we were for one another." People tell themselves these stories.

Harry phones his assistant, Sally, at his office. He's not sure when he'll be in. Something has come up, a client who's a Springsteen fan. Yes, the Patrick account. The industrial washer-dryer people. Don't ask. Would she check the tour schedule? The best seats she can roust up. No, just one pair. But whatever people like-backstage passes. Right, contact the Miranda Agency and call in a chit. Short notice, yes. He's sorry for the foolish burden. Right, that's why they call it work.

Harry inspects the espresso maker. He fills the reservoir and pushes the preheat button. He sets out a can of coffee, a container of milk, and the frothing pitcher. He arranges the tamper and baskets.

It does seem a long tub. Behind the iPod speakers, there's a CD player. Harry finds a Springsteen disc. He wonders whether there's a right time of day, like for ragas. He gets the music working. Best to lock in the second date before the first is far along.

"Lena, are you okay?" From the bathroom, no reply.

Harry believes he knows who Lena is. Not in detail. But Harry has dealt with Lenas for decades. They're the young women you hire at minimum wage or near it. They're blamers. They nurse resentments. They display their quirks without apology. They specialize in wishful thinking, imagining that what they can't handle will disappear on its own.

Once Harry took on a young woman as a receptionist. Her first morning on the job, he noticed that no calls were coming through. When he asked what was up, the girl announced that she had a phone-answering phobia. Not to worry, it was intermittent. But when it came on, she preferred to speak only face-to-face. Another new hire found men with forceful voices threatening. She hung up on them. Harry did not fire these women. Harry coaxed and trained and motivated. Convincing others was his trade. Why should he not put his skills to use?

Besides, he was capable of appreciating these difficult employees. In time, a cause for a woman's bitterness might emerge, ill-treatment by a parent, long childhood hours spent caring for an impaired sister, and then the problems associated with immigration and poverty and trouble learning in school. All that's behind you, Harry would say. You're doing

27

well. Asked directly, none of these young women would have styled herself handicapped, but each understood that she would not fare better elsewhere than in Harry's shop. In time-Sally was this way-the anger faced outward, so that Harry had a tigress at the desk, protecting his time and interests.

Harry can imagine Lena turning fierce and loyal. Is she a worse bet, finally, than a professional woman who sees commitment as contingent, who sums the pluses and minuses rationally and leaves you with a broken heart?

He assumes now that Lena is lengthening her soak in the tub, simply hoping that her problem-Harry-will go away.

Approaching the door, Harry notes a lifesaverish cherry fragrance. Bath oil, he assumes. "Are you okay?"

No answer. Where drowning is at issue, does one not have permission to enter?

The door handle has a child-saver feature. Harry crosses the hall. On Lena's dresser, he finds a hairpin. He pops the bathroom lock. Once inside, he snaps the lock on again, as if to leave matters undisturbed, only with him where he belongs, in the room with his beloved.

Lena is lying in a half-full tub. A thin stream of water flows from the tap. Harry knows the method. He has used it in his new bachelorhood, on days when the world beyond the bath seemed bleak. You drain some water, and refill slowly from the hot pipe. Lena has extra help, from an infrared bulb overhead. The glow lends the scene loucheness. Lena has turned away from him. Harry can make out the tattoo on her haunch, but Lena's position and a clear plastic curtain distort his view of the parts he longs for, those breasts, that monkey face.

"You can't break in on me," Lena informs him, like a child who demands another reality.

"You didn't respond."

"This is rape." In this pronouncement, Harry hears Vema's voice. Harry does not deny the basic truth, that he has been forcing himself on Lena. But is insistence violence? They say that rape is about power. Harry feels none. He has enjoyed no sadistic pleasure, no consummation.

Lena looks in the direction of a cell phone that sits on the tub's ledge. "Verna's on her way. She says if you're still here, she'll have you arrested."

"You're stunning," Harry tells Lena, and here he includes her peasant face, free of makeup, moon-round and innocent. "As beautiful as I had imagined."

Lena does not reach for a towel, though she has two folded on the tub's ledge.

"Explain you what mean," Harry asks, "about rape."

"Verna spoke to Giacomo that afternoon, on the day she yelled at you. She says you'd been to the bar, but not that night. Not Halloween. Well, Giacomo says you were there, but Verna's pretty sure you weren't. So that was a violation, too, the way you stared at me, at the gym."

Here is good news in the guise ofbad. Lena did not believe his story, and yet she invited him in for coffee.

"You're crying," Lena says. "Why ever are you crying? Oh, please."

He has not seen a woman in this way, not since Alice moved out of the bedroom. Others come upon nudity so easily. Barry and Tony do, and Kevin and Dave, despite their receding hairlines and their indifferent careers, despite their disadvantages in every marker of worth. But only through rape or, to put a truer word to it, bad faithhis lurking, his lies, his fabricated need to check on Lena in the bath-only through betrayal of his better nature has Harry caught this glimpse.

Lena does seem good-hearted, And self-assured in the body, just as he had imagined, with no hint of prudery.

Harry hears the front door open. Verna will see the results of his cleanup and will know what's afoot.

And so Harry dives for Lena. He throws back the curtain and buries his face where it wants to be, amidst those marvelous breasts. It is an awkward move. His pant legs are wet, and his shoes. It's no never mind. Here is what life has deprived him of, despite his reasonable credentials: the smell and taste of flesh.

Lena does not cry out. Instead, she sobs and holds Harry to her. They make a moist tableau, a perverse Madonna and child.

"Don't," she says. Before he can plead his case, she continues: "Don't be like all the others."

Vema is shaking the door. "Lena, Lena, I can hear you." And "Fuck with me, you pervert, I'll have the cops on your ass so fast-."

Lena cuddles Harry. He sees that the website postings were her lies, her way of putting a good face on a series of dating disasters.

Here is the deep truth. Harry will be kindly and understanding, right to the limits of his quite substantial and proven ability. Only he does crave this hungry gratitude. That is what he has seen in Lena all along, beyond the chipper photo captions and the modest limberness

of body and the faultless bust. He adores her for her evident possession of what he, too, has in abundance, hurt and uncertainty and oh such need.

Harry's right arm is going numb and his neck is seizing up. Water scalds his left ankle. The tub may flood, and the police may drag him down to the station, and his marriage is well and truly over. Before him floats a vivid image, all his colored tracings in steep decline. Harry Givens has no complaints.

30

Richard Burgin

Do You Like This Room?

"Do you like this room?"

"Yes, it's very nice."

"You don't say that with much conviction," he said, leaning forward in his chair that faced her on the sofa.

"It's a fine room, really. It looks like it's your entertainment center."

"Why do you say that?"

She pulled back some of her hair that had fallen over her eyes, hair that she now realized was the same color brown as his. "Because there're so many things here that are entertaining like your giant TV and your stereo."

"Do you think the TV is too big?"

"No, it's a wonderful size. It must be great to watch movies on."

He seemed to relax a bit but was still looking at her intently as if checking her face against an identification card.

"Did you like the restaurant we went to tonight?"

"Yes, very much."

"The food, the service did it live up to your expectations?"

"It exceeded them."

"And was your creme brulee all right? I remember you hesitated before choosing it. Was it too sweet or too bitter?"

"It was too good. I hadn't meant to eat all of it. I meant to share some of it with you, but I guess it turned me into a little pig," she said, laughing for a few seconds.

He nodded and watched her drink her gin and tonic.

31

"So did the restaurant seem the kind ofplace you thought we should go to? I mean on a second date. Did it meet those expectations?"

"Yes, of course. I mean I didn't have any expectations 1-"

"Why not?"

"Anything would have been fine but what you chose was excellent, just right. Why are you asking me all these questions? It's starting to make me a little nervous."

"Do you really want to know?"

"Yes, I do," she said, finishing her drink and setting it down on the glass table in front of them. He watched her cross her legs-her skirt just above her knees-before answering her.

"It's because of the last woman I was with."

"Oh."

"There are probably other factors involved but for the most part I lay this at her feet."

She made a supportive sound that stopped short of being a word.

"You look mystified," he said. "See, just before she left me she said I never asked if she was happy, so now I've learned to ask."

"OK, I understand," she said, nodding.

He also nodded, as if imitating her, and finished his drink. "You may be wondering why I didn't ask you any of these questions during our first date. It's because I figured I'd get my answer when I asked you out again. That if you said yes it meant you liked the first date."

"I did like the first date. I liked it quite a bit."

"I guess you think I'm being silly saying all this since you're here in my condominium, right?"

"It's not silly," she said, straightening her skirt so that it was at knee level now or perhaps just below.

"Hey," the man said, his green eyes suddenly becoming animated, "are you in the mood to playa game?"

"What kind of game?" she said, smiling and wondering if he was finally going to make a move.

"A surprising game. A game you would never think of playing."

She looked at him-it was as if a whole new side of his personality was suddenly opening like a door revealing a garden. It gave her more hope about him since he'd seemed a trifle bland until now, although also very nice.

"Everyone likes surprises if they're fun," she said.

"Would you like to play one of the games I invented?"

"I'm not sure I understand. You mean a board game or? "

32

"No, this isn't the kind of game you could buy in a store. We play it with our minds."

"Well, maybe you could tell me about it first."

"I invented it a few minutes ago while you were asking me why I asked you so many questions. Here's how it works. One of us plays the role of God, I mean the typical Christian all-knowing God and the other plays a person, or is just ourselves. Don't worry, we can switch roles. Anyway, God asks the person questions about how he likes the world, and the person asks God if He approves of his behavior as a person."

She told him she wasn't sure she understood, while trying to camouflage her disappointment. He assured her she would understand and said he'd start off by playing God.

"Did you like the sunset I created today?" he said. "Go ahead, answer."

She looked a little flustered. "Yes, it was beautiful," she said, managing to smile.

"Now ask about something specific you did and whether God approves of it. Go on."

"I don't know. I can't think."

"OK, OK," the man said, holding up his hands. "You play God and I'll ask you the human questions."

"All right," she said.

"Did you hear my prayer last night? It was windy where I lived, almost a storm, and I didn't know if you heard it."

"Yes, I heard it, I hear everything, my son," she added, smiling.

"Go on. It's your tum now."

"OK, OK. Did you enjoy the stars I made last night? Did you notice the patterns they formed over your head?"

"When I remembered to look up I did, though it was just for a few seconds because I live so far away from them, and I don't know exactly what they're for and why you made so many of them in the first place. You never tell."

"Good line," the woman said, hoping her compliment might lighten his mood, which had turned serious again just when she was feeling encouraged.

"Sometimes I wonder if my prayers bounce off them on their way to you-ifyour stars just bat them back and forth so they never get to you."

He looked at her and noticed a sour expression on her face. "Are you upset by my implicit criticism of you my God," he added, to be sure she understood.

33

"No, no, my Phil, I understand and forgive everyone."

"Since I can't do either, that puts me at a great disadvantage. Go on, it's your tum again."

She looked at him uncertainly. "Did you enjoy the flowers I created that were in Tower Grove Park near the restaurant where you ate last night?"

"I did enjoy the flowers," he said, "as well as the stars, though they require two opposite motions of my head to see. You've made so many things but you've placed them too far apart and in so many directions I'd have to have a very flexible head like an owl to appreciate them all, or even a hundredth of them."

"One billionth of them would be more like it."

"Yes, my head would be very sore even noticing one trillionth of them. My head would be sore and useless and probably fall off."

"I wouldn't let that happen to you, my son," she said, adjusting her skirt again so it revealed more of her leg.

"But you do let many people's heads fall off all over the world. I watch this on my giant television and am puzzled."

He looked at her quickly and noticed her sour expression was back. Her name was Courtney, he suddenly remembered. He didn't know why he kept forgetting it tonight, didn't think he had on their first date. He could see she was a little high, too, which had originally been one of his goals, but now it didn't matter. He was thinking of Melanie, the woman who left him. Courtney asked her question and he heard himself say, "I don't think my game is a big hit with you."

"No, no, Phil, it's really interesting. I'm just not very good at playing God or talking to Him either."

"Even though you're a therapist?" he said.

She forced a laugh then excused herself to use his bathroom, leaving him alone with his thoughts. When she returned he said, "I'm sorry for what I said about you being a therapist. It was just a little joke."

She made a disparaging little gesture with her left hand. "I know, it was a joke. It was funny, really."

"I respect you a lot for being a therapist. It's very important work."

"Thank you," she said, smile intact.

"You know, I prayed about our date last night." "Really?"

"Yes, I prayed that you'd like it and would want to see me again."

"Well, I did like it, but now it's getting kind of late so I'm afraid I

"Why didn't you tell me before?" he screamed. She thought he

34

might have pounded the table with his fists, too. It had all happened so fast like a lightning flash that she couldn't be sure.

"I'm sorry," she mumbled.

"Excuse me, do you suppose we could have a little sincerity here? Wasn't that one of the points of the game we just played, the game that bored you so much."

"It didn't bore me and I have been sincere," she said, raising her own voice although it trailed off by the end of her answer.

"What I'm asking is, once you wanted to go home, why didn't you say so? Why did you only bring it up after playing the game much longer than you wanted to? This, after all the questions I asked you before to try to find out what you liked or didn't, trying to tell exactly what pleased you just so I could avoid this kind of humiliation."

"No, no," she said, gesturing vaguely with her right hand.

"No, no what?" he said. "You've got to explain better than that. You're a therapist, for Christ's sake. It's your job to explain things, isn't it?"

"I enjoyed playing the game. I enjoyed all the other things we did tonight, too, so much that I didn't realize about the time and then as soon as I did, I merely said I needed to go home to get some sleep, 'cause I have clients in the morning."

"And whose home are you in now?"

She said nothing. She thought she'd made a diplomatic answer but it didn't seem to have made any difference.

"You're in my home now, aren't you, which I guess makes you my client."

"Yes, of course."

"And a man's home is his castle, am I right? I didn't pluck that saying out of the air, did I?"

"No, you didn't pluck it out of the air," she said softly, feeling that her lips were starting to quiver and wondering if he noticed because he was looking at her in a kind of inhuman way, like a camera recording everything.

"I can stay a few more minutes," she said.

"I'll say how long you can stay."

"I don't understand what's happening."

"Seems clear enough to me," he said, staring directly at her.

"I don't understand why you're talking this way to me-it's scaring me."

"It's a pity," he said.

35

"What? What is?"

"That understanding so often lags behind activity, or to put it another way a therapist understands but a God acts."

"OK. That's interesting. All your ideas are, but now I really do have to go." She said this in what she considered a fairly even tone of voice, though she felt she was shaking a little when she stood up and that he noticed it, of course, looking at her the way he was, like some kind of X� ray machine.

She took a definitive step or two before he sprang up from his chair tiger-like and, grabbing her arms just below her shoulders, forced her down on the sofa. She let out a little half scream just before his hands fastened on her neck.

"Be quiet. Don't ever scream again in here or things will get a lot worse for you."

She said nothing. She was breathing heavily, felt for a moment that she might pass out. His hands were holding her firmly-not quite causing pain, but more like a relentless pressure.

She looked at him closely. The physique that he'd bragged about on the Internet, that had attracted and surprised her on the first date by being almost exactly what he'd described, was now her enemy. He was a little older than her, but still in his thirties, and he was taller and of course much stronger, too.

He released his hands and walked a little away from her.

"I'm sorry. I don't know what I did to make you so mad, but I'm sorry," she said.

"You tried to leave after all the reassurances and tawdry little cornpliments you threw my way."

She nodded, as if acknowledging a crime.

"Even after I told you how I prayed about this date, how I bothered God Himself about it. That's why I'm keeping you like this. Do you think you understand now?"

"I understand," she said

"You should understand. You're a psychotherapist, aren't you? Isn't that what you told me?"

"Yes."

"Doesn't your training cover people like me? People who are really in pain."

She said nothing, and bowed her head. She suddenly felt exhausted and wondered if he'd somehow drugged her. She heard him walking across the room, but still kept her head down. Maybe he'll just go into

his room and let me leave, she thought. But his steps were getting closer now instead of further away.

"I asked you a question," he screamed, and her head jerked up and stared at him in disbelief. He was standing five to ten feet away from her, pointing a gun directly at her with one hand while gripping some kind of bag with the other.

"Jesus," she said.

"No, it's Phil. Jesus isn't here now, Dr. Courtney, but I am."

"What? What are you doing?"

"I'm commanding your attention. You were starting to fall asleep and I think therapists who fall asleep should lose their licenses, don't you? At the very least they need to be woken up."

She gazed at him. He seemed much taller now-as if holding the gun had suddenly turned him into a giant.

"Please put the gun away, please, so we can talk."

He shook his head no, so rapidly it was like a twitch. "I'll tell you what I will do," he said. "I'll even things up a little."

"Please," she said. She wasn't aware that she was crying and the tears falling down her face felt like another shock.

"Let's playa different game," he said. "This one might interest you more than the last one."

He was withdrawing something from the bag, then in one fluid motion it came flying at her like a bat, landing beside her on the sofa. She let out a gasp and saw the light come back into his eyes.

"Yes it's real, you can touch it if you want. It's a real gun it's all yours to use as you wish as long as we play the game."

"Please don't

"Please don't what? Play the game? Why don't you hear what the game is before you reject it? The rules are simple enough. One of these guns has bullets in it, the other has blanks. If you have the gun with bullets you can leave now simply by shooting me. You look surprised, but don't be. And don't assume I know which gun is which. They're twin guns, have you noticed? They're linked forever just like you and me."

"I know that woman hurt you. I know you're feeling a lot of pain."

"Do you know what I'm feeling? Haven't you already generalized me away into some psychological category-the better not to really know me."

"There's some truth in what you say. I know there are psychologists who are too analytical and not always empathetic enough. I've had them myself."

37

"Then you've had problems, too? Problems you apparently couldn't manage."

"I've had issues I needed to have some help dealing with. It's very frustrating when you feel a doctor doesn't understand the uniqueness of your pain, no question. Now could you please put "And what side of the fence are you on as a therapist: analytical or emotional?"

"Can you put the gun away first?"

"No. Answer me."

She could feel herself trembling slightly while she spoke. "I like to think I'm both, but if I had to be on one side I'd say I'm more on the feeling side."

"Do we really get to choose which side we're on?" he said, taking one step closer. She looked at his gun, couldn't help it, then at hers a couple feet away from her on its side against the sofa pillow.

"I could talk about this a lot better if you'd put the guns away."

"We've talked about that already. That's not an option for you."

"OK, would you like to talk some more with me about this?" she said, feeling it was crucial to keep a dialogue going.

"I'm all ears," he said tonelessly. "No, literally, I'm sometimes entirely made up of ears. I paid a doctor to sculpt some of my ears so they'd fool you by looking like other body parts. But that's just an illusion. Look at my mouth more closely. If you do, you'll see that it's really an ear."

"Did your ex used to talk too much? Did you feel you weren't listened to?"

He laughed ironically.

"Your mother, too, perhaps?"

"When you're composed entirely of ears it's kind of hard to compete as a talker, wouldn't you say?"

She tried to force a smile to show she appreciated his humor. She had to still try to believe that empathy could have some impact on him, although he appeared to have none for her whatsoever.

"What's the matter? You're not saying anything. I thought therapists had mouths as well as ears."

"I know that being disappointed by someone you love is the worst pain in the world," she finally said.

"You're a fool if you only become disappointed after they leave you."

"What do you mean?" She couldn't tell if he'd said something insightful or not. She kept looking at the gun that was still pointed at her, although its angle was less direct now.

"Disappointment begins way before a person leaves you. Even ear people know that. The question is: is there enough there to counteract the disappointment? That's what love really is, it's just tolerated disappointment. You're lying if you define it any other way."

"I don't know," she said, thinking of the man who'd recently broken up with her {a professor of architecture at her university}. "Maybe you're right."

"Seems like I'm right about people more than you are. Of course, I don't have a license, so what good does it do me?"

"Insight is always valuable, what else do we have?"

"I have insight into what's wrong with a lot of things, but what good does it do if you can't ever fix any of them?"

"You can use your insight on yourself, can't you?" She was leaning forward as she often did with her clients when she was excited about making a point.

"Sit back," he said sternly. "Don't get too close to my gun. I already gave you your own, didn't I?"

It got darker outside. It was a cold night in early spring and there were lots of clouds out. She could see through the Venetian blinds that were still open until he finally noticed and closed it. What was she thinking by going back to his place in the suburbs? They could have gone to an after-hours bar in University City. She could have stayed in the city with him until she knew him better. Why hadn't she? Her rule of thumb was to only go to a man's place if she was prepared to sleep with him. She didn't think she was thinking that with Phil {although lately she'd been feeling so lonely}, so why had she broken her own rule? It was because his behavior was so impeccable on the first two datesconsiderate, generous, animated but not aggressive. Also, he seemed to be doing well at his business, which she couldn't quite remember but had something to do with computers. So there were no warnings, at least none that she caught until they were already at his place.

It had gotten hot in his condominium but she was hesitant to mention it. Maybe she'd just take off the pink cardigan sweater she was wearingthe one she had picked because it looked so good with her black skirt.

"What are you doing?" he said. He was a little further away but his gun was still pointed at her.

"I'm just feeling a little warm. Is that OK?"

He didn't say anything. She felt it was right to take it off (she was wearing a white blouse underneath) because so far, thank God, he'd

39

shown no sexual interest in her. Meanwhile, he lit two candles on the glass table in front of them. {It was ironic, she thought, about the candles. On her Match.com profile, which was how they met, she'd listed candlelight as one of her "turn ons.") She placed the sweater carefully beside the gun.

"Hey, what are you doing?" he said again.

"What? I just put my sweater down."

"I thought you might be reaching for your gun, which is OK, of course, I completely encourage that."

"I don't believe in guns. I wish you'd throw them away."

"Why's that?"

"Because they're dangerous-they can kill people, and I don't want to be part of that."

"But you are part of that now, aren't now? From an objective point of view, I'd say you should keep your gun. You can never tell when you might need it, when it might be all you can reach for in this world."

"What do you want from me? I don't understand," she said, starting to cry again.

"I'll answer that question when I feel like it, Herr Doktor, or maybe you'll just figure it out in time speaking of which, time passes slowly in here, doesn't it. It's not at all like a therapist's hour."

She stopped crying and tried to laugh at his joke.

"It's funny how things happen," he said, stroking his chin for a moment with his free hand. "For many years I was very unlike other people and then after my ex, I began to do online dating, which is how I met you, and I became more like other people then, but now, I'm not acting like other people at all, am I? I've come back full circle to my original oddness."

She snuck a look at her watch and was shocked to see it wasn't even one A.M. He'd said he was keeping her here all night-did he mean that literally? Although he often spoke in riddles or metaphors, he was also at times literal to a childish degree. In that case, her night might have just begun and who knew what it would eventually include? So far, he hadn't been violent since he pushed her down on the sofa, but she could still remember the pressure of his hands on her neck. He hadn't made any sexual demands yet either, but who knew when that might happen or what the meaning of his long looks at her was? One time she knew she'd caught him staring at her legs

It was stupefying, how slowly time passed. Sometimes he talked in manic little fits and starts about his ex, whose name was Melanie, a

name he never said again, as if saying her name would make her even more intolerably alive. Other times, there was unadorned silence which made her listen for the little noises that every home makes, yet his didn't, as if it were as silent as a vault in a museum.

Always she tried to keep eye contact with him and always he kept his gun pointed at her until she thought she might lose her mind.

Then she needed to urinate but was afraid to ask him-afraid he would go with her to the bathroom and who knew what would happen then? Maybe she should take her gun with her but that might provoke him somehow. Probably it was better to somehow hold it in and if worse came to worse, do it in her underpants. But what if some of it trickled onto his sofa? Who knew how he'd react to that? In his cosmology his sofa might be sacred and that might be all it would take to make him shoot her.

"You seem restless," he said, without a trace of irony. "I'm OK."

"Are you worrying about what's going to happen to you?"

"Yes to a degree."

"Are you afraid I'm going to attack you in some way?"

"No, I don't think you'd do that."

"How do you know what I'm going to do? Why do you say that?"

"I don't think you really want to hurt me."

"What am I going to do then? Tell me what I'm going to do."

"I think you want me to stay so you won't be alone with your feelings. I think maybe you'd like me to help you. Maybe that's why you answered my ad and wanted to ask me out in the first place?"

"Because you're a therapist?"

She smiled and shrugged.

"What else do I want from you? assuming that you're right about any of this."

"Maybe you want to see if you can trust me or any person, after what happened to you."

"Trust you to do what?"

"Stay here with you tonight. Listen to you, if you feel like talking." He turned his face away, staring into space.

"Do you think I should trust you?" he finally said. "Yes."

"Because you're a therapist?"

"That's only part of it. I haven't given you any reason not to trust me, have I?"

41

"Women are trained to lie. To act and flatter and deceive and lie. It's what we call their personality."

"I don't believe that," she said, although there was some truth in what he said, she thought. But that was only because women had always been oppressed, didn't he know that? Didn't he understand about social conditioning and sexism?

"You're the exception to the rule, I suppose," he said.

"I don't believe there is a rule."

"But as a 'good' woman, and certainly as a psychotherapist, you would never break a trust, would you? You would always keep your promise and never manipulate me, right?"

"Yes. You can definitely trust me. I'll stay here with you tonight."

"Along with your gun."

"I told you I don't want it."

He smiled and nodded ironically.

"I prayed for something else about you tonight," he said.

"What was that?"

"I prayed I wouldn't hurt you."

"That prayer has been answered."

"You think so?"

"Yes, I do," she said, trying not to let her voice shake. Have you done it before, she wanted to ask, rape or worse? He'd seemed so affable and solicitous {albeit slightly nervous} on both dates-he hadn't even tried to kiss her good night. But she saw now that he was just waiting for the chance to terrorize her, that that alone made him feel alive.

"A man is always alone," he said calmly but definitively, as if commenting on the weather. "In the end, he's deserted by everyone, his parents, his women, and of course by God, the original deserter, and he's left only with regret, his infinite regret and his anguish."

"I haven't left you. I'll listen to anything you want to tell me. Maybe if you tell me the story about your ex you'll feel better."

"There are no stories-at least that's the way it is for ear people like me. For us, stories go in one ear and out the other. Anyway, I'm going to make a leap offaith and trust you, simply because I have to use the bathroom. But I'm leaving the door open a little so I can hear you very easily and I'll only be fifteen or twenty feet away with my gun in hand and all my ears wide open, and then I'll be back in less than a half minute."

She nodded to reassure him as she watched him cross the room, go into the bathroom, and close the door but not completely shut it. The moment she heard him urinate she took her shoes off, grabbed her

pocketbook and gun and bolted for the door, leaving it open so perhaps he wouldn't hear her from the bathroom. She ran down his steps, worrying that she'd fall, then past two or three houses until she went into a neighbor's backyard. That way if he chased her she could scream and someone might hear her.

It was extremely dark out-a cloudy sky covered a hint of a moon. She nearly bumped into an enormous tree, then put her hand on the tree trunk to steady herself. She was not one who ran regularly or even exercised, and was out of breath-panting heavily-which made a strange kind of music in the night as she put her shoes on.

She had a horrible thought then, but it disappeared as soon as she reached in her pocketbook and found her cell phone. Why hadn't she taken her car on this date? Why? Finally she felt herself get her breath back, then realized how cold she was and that she'd left her sweaterher favorite one!-back at his place. She opened her phone to get a Itttle light and call 91 I, when she realized she didn't know what street she was on and wasn't even sure of the town-was it Ballwin, Wildwood? Perhaps at 9 I I they could tell where she was, she wasn't sure. But what could she tell the police? There'd been no rape-no sex at all-and as far as violence was concerned, just the time he threw her down on the sofa, and pressed his hands on her neck. But there'd be no sign of that either. Nor would there by any sign of the threat he constantly posed to her with his gun-that he would have hidden by now or perhaps even have a license for and wouldn't need to hide. She opened her pocketbook and felt the gun he gave her, cold and heavy like a snake. What would she say about it? She didn't know. (She wished she'd taken her sweater instead.) She only knew that she'd throw the gun away as soon as she got home.

He'd been clever, diabolically clever, she saw that now, in his selfrestraint-turning her night of torture into a long mock therapy session of a kind, more than anything else.