TRI-QUARTERLY VOLUME 6 NUMBER ONE 70¢ NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY FALL. 1963

W. Leopold

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is a magazine devoted to fiction, poetry, and articles of general interest, published in the fall, winter, and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subcription rates: $2.00 yearly within the United States; $2.15, Canada; $2.25, foreign. Single copies will be sold locally for $.70. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to THE TRI-QUARTERLY, care of the Northwestern University Press, 1840 Sheridan Roael, Evanston, illinois. Contributions unaccompanied by a self-addressed envelope and return postage will not be returned. Except by invitation, contributors are limited to persons who have some connection with the University. Copyright, 1963, by Northwestern University. All rights reserved.

Views expressed in the articles published are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the editors.

Since this issue of THE TRI-QUARTERLY contains stories by three of our undergraduate editors. I should like to make clear that the decision to print the work of student editors is wholly mine, not theirs. The undergraduates whom I invite to serve as editors are students who are known to me as able writers, and the invitation is made with some expectation that they will be contributors to the magazine. E.H.

EDITORIAL BOARD: The editor is EDWARD B. HUNGERFORD. Senior members of the advisory board are Dean JAMES H. MCBURNEY of the School of Speech, Dr. WIlLlAM B. WARTMAN of the School of Medicine, Mr. ROBERT P. ARMSTRONG, Director of the Northwestern University Press, and Mr. JAMES M. BARKER of the Board of Trustees.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITORS: BARRY G. BRISSMAN, GARY T. COLE, LINDA O'RIORDAN, and FRED W. STEFFEN.

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is distributed by Northwestern University Press, and is under the business management of the Press. Design, layout, and production are by the University Publications Office.

Art Editor is Lauretta Akkeron. Photograpns by Herb Comess except that of Barry Brissman.

Richard

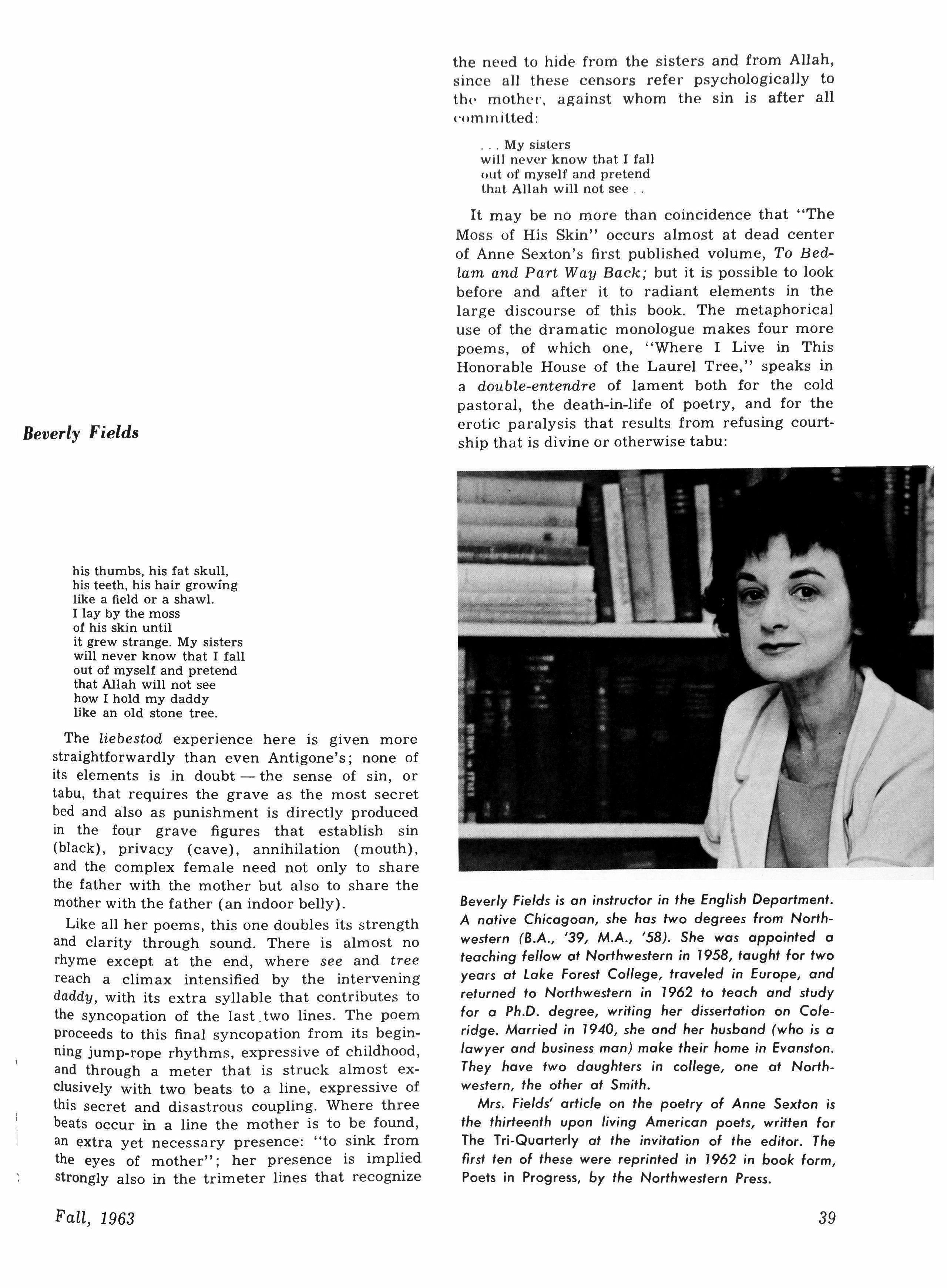

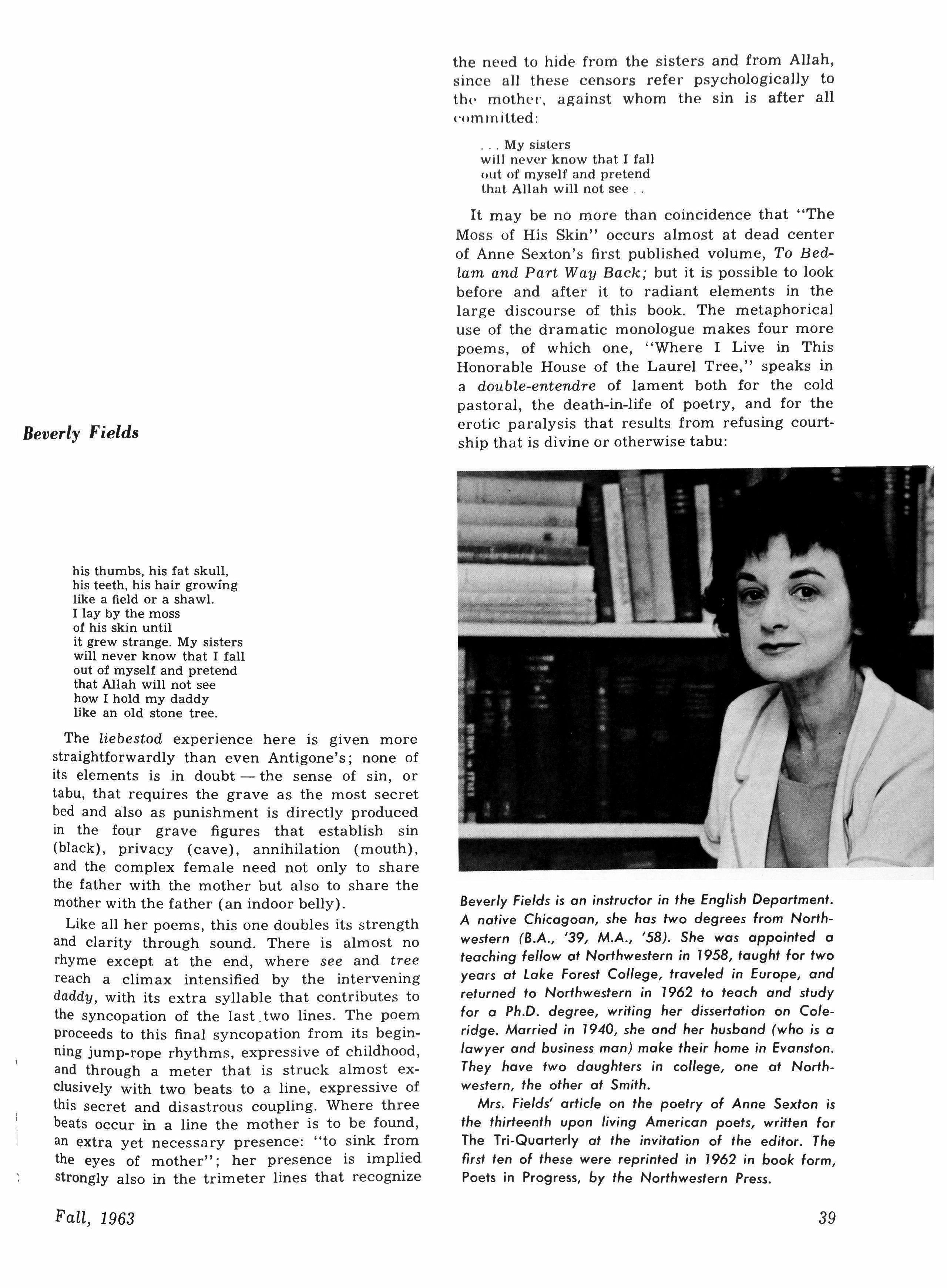

The President and Foreign Policy: The Two Roosevelts 3 Daniel Johnson The Vast Land 10 Russell Warren Nystrom Poems 15 Herbert Comess Photographs 17 Barry G. Brissman The Death 22 Linda 0'Riordan They Are in Love 27 Homecoming 28 Malcolm S. McCollum Poems 30 Gary T. Cole They Found The Yellow, Sloping Rock 32 Beverly Fields The Poetry of Anne Sexton 38 Tri-Quarterly NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Volume 6 FALL Number One

THE PRESIDENT AND FOREIGN POLI[Y: THE TWO ROOSEVELTS

By Richard W. Leopold

The problem to which I address myself in this paper is the limits of the powers of the president in foreign affairs. It is a timely topic. Once again, as so frequently in the past, the executive and legislative branches disagree as to the precise steps to take for coping with danger from abroad. Once again, we face the risk of divided counsels and even a deadlock in the decision-making process. Once again, we see the possibility of a president being compelled to act against his own judgment. We must again ask who controls or makes foreign policy in the United States.

It is impossible in a short essay to make a complete analysis of this problem, and it is premature for a historian to concentrate on the most recent occupants of the White House. Hence I have chosen to illustrate the topic by examing the record of two men on whom we have some perspective, Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin D. Roosevelt. There are several reasons for selecting this pair, quite apart from their popular appeal. The two Roosevelts have much in common. Both were fascinating individuals, wide-ranging in their interests and far-reaching in their influence. Both were acute observers of the world scene; both were vigorous exponents of presidential powers. Both have been accused of usurp-

ing the prerogatives of Congress and of trampling upon the Constitution. Both contributed to the growth of American foreign policy and to the office of the presidency. Each had a sense of history. Each has been subjected to changing tides of historical opinion.

No one questions that the framers of the .Constitution intended to make the president 'the central figure in foreign policy. To the delegates who met at Philadelphia in 1787 one lesson of the preceding years was clear: the new government must have an executive. And perhaps the most compelling argument for the presidency was the need to handle external affairs more efficiently; for from 1775 to 1789 foreign policy was made by a unicameral legislature, working first through a committee and then through a secretary. Hence the new Constitution assigned four categories of power to the president. It said explicitly that he would communicate with foreign nations, negotiate and ratify treaties, and act as commander-in-chief of the armed forces. It implied, rather than stated explicitly, that he would formulate and initiate foreign policy.

It is clear that the founding fathers did not wish to give the president complete control over foreign policy. They were too addicted to theories

Fall, 1963

3

on the separation of powers and too mindful of the tyranny of some colonial governors to leave the executive unchecked. Hence they required the Senate to confirm all appointments to diplomatic posts and to consent, by a two-thirds majority, to all treaties. Most important of all, they gave to Congress as a whole the power of the purse and the power to declare war. This division in the management of external affairs between the executive and legislative branches was, in the words of Edward S. Corwin, "an invitation to struggle for the privilege of directing American foreign policy." That struggle has characterized much of our history.

That struggle can take many forms. It is enough here to mention three. One is over treaties, where the president proposes but the Senate disposes. Given our party system it is relatively easy for a minority of one third plus one to block a treaty. A second point of friction is the overlapping of the power of the president as commander-in-chief and the prerogative of Congress to declare war. By deploying men, ships, and planes, the executive can precipitate hostilities and thus deprive the legislature of its most cherished right. The third area of conflict is in formulating policy. Although the president normally takes the initiative, Congress may at any moment hobble him by launching investigations that disrupt his negotiations, adopting resolutions that condemn his course, or passing laws that narrow his jurisdiction.

I have pictured the worst. Most policies have been formulated by the executive, as the origins of isolationism, neutrality, the Monroe Doctrine,

This article, first delivered in ledure form on February 28, 1963, in the Alumni Fund series, is now slightly altered for inclusion, at the invitation of the editor, in The Tri-Quarterly.

Richard W. Leopold came to Northwestern in 1948 and is presently the William Smith Mason Professor of American History, teaching primarily in the field of American foreign policy. He was educated at Princeton (B.A., '33) and Harvard (Ph.D., '38). He taught at Harvard from 1937 to 1948 with a World War 1/ interval of four years as Lieutenant in the U.S. Naval Reserve, aHached to the Office of Naval History. He is a member of the learned societies in his field, serves on The Advisory CommiHee on Naval History for the Navy Department, on The Advisory Committee on Foreign Relations, a publication of the State Department, and The Advisory Committe on the Papers of Woodrow Wilson. His books include Robert Dale Owen, A Biography, 1940, Elihu Root and the Conservative Tradition, 1954, The Growth of American Foreign Policy, A History, 1962; and he is now revising for book form his Albert Shaw Lectures in Diplomatic History, given in April, 1963, at The Johns Hopkins University.

and the open door attest. Yet only four years before Theodore Roosevelt took office, a Republican chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee threatened impeachment of a Democratic president if he refused, as it was alleged he would refuse, to carry out a joint resolution directing him to recognize the so-called rebel government in Cuba. Twenty years later Woodrow Wilson publicly warned that he could not conduct delicate negotiations with Germany over the submarine if Congress adopted, as it seemed about to adopt, certain resolutions. In 1916 Wilson repeated what men as diverse as Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and John Marshall had said earlier: in foreign affairs the republic can speak with but one voice, and that voice must be the voice of the president. Who speaks for the republic today on Cuba, Russia and China?

As to treaties, most have been approved, yet the deadlock over the Versailles settlement in 1919-1920 caused many to fear paralysis in the conduct of foreign policy and some to advocate a change in the treaty-making process. Most wars have begun with a vote by Congress, yet at the outset of the air age Franklin Roosevelt was accused of waging undeclared war in the Atlantic and of provoking Japan to strike first so as to present Congress with a fait accompli. Today, in the thermonuclear age, we cannot expect the Senate and House to debate the issue of war during the fifteen minutes that we know an intercontinental ballistic missile is in flight. Of course, under any system of government we must distinguish between the formal grant of power and the way in which it is used. Common sense, compromise, and individual leadership all enter in, and it is precisely on that last point that the record of the two Roosevelts is instructive.

Let us turn to the first Roosevelt. What image does he conjure up? What mark did he leave on the presidency? What contribution did he make to foreign policy? I think of his boundless energy, his inquisitive mind, his voracious reading, his extensive friendships, his cosmopolitan outlook. To be sure, he was an incurable romantic in many things and a captive of late-Victorian standards of morality. His ideas on war sound ridiculous today, and no modern politician would talk of standing at Armageddon and battling for the Lord when he referred to a presidential nominating convention. It is easy to poke fun at Roosevelt, and he could laugh at himself - as when Elihu Root said: "The thing I most admire about you, Theodore, is your discovery of the Ten Commandments," or when Finley Peter Dunne suggested that Roosevelt's book on his exploits in the War with Spain be entitled Alone in Cuba. Yet he is still very much with us today - and I am not thinking only of President Kennedy's fifty-mile hikes (an idea first suggested by TR) or of Mrs. Kennedy's televised tour in which the names of

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

James Monroe and Theodore Roosevelt stood out as renovators of the White House (and Monroe had more reason to refurbish after the British got through with Washington in 1814).

As president, Roosevelt understood the potential of the office. Power and responsibility, he Iiked to assert, must go hand in hand. The executive must employ not only those prerogatives which the Constitution explicitly grants to him but also those which it does not specifically assign to the legislature. Where Wilson later regarded himself as a prime minister whose function was to guide through Congress a positive program, Roosevelt saw himself as a commander-in-chief. "In a crisis," he wrote in 1913, "the duty of a leader is to lead and not to take refuge behind the generally timid wisdom of a multitude of councillors."

Roosevelt did lead, but he also drew upon the advice of strong men like Root and Taft who were anything but timid. Through skillful publicity and a laudable cultivation of the press Roosevelt focused attention on the executive. Through a voluminous correspondence with eminent citizens at home and abroad, with his envoys overseas, and even with heads of state or government in Europe he kept himself superbly informed. He was a mobile president, and he was the first to leave the country while in office. One technique he overlooked, and probably he never forgave Wilson for reviving it. That was to deliver in person his messages to Congress, a practice dormant since Jefferson discarded it in 1801.

As president, Roosevelt also understood the enlarged role the republic must play in world affairs. Where Grover Cleveland had resisted stubbornly the trend toward great-power status and William McKinley had chosen reluctantly the path of empire, Roosevelt faced the twentieth century with a bold excitement. Speaking in 1903, he said: "We have no choice, we the people of the United States, as to whether or not we shall play a great part in the world. That has been determined for us by fate, by the march of events. All that we can decide is whether we shall play it well or ill." Roosevelt sought stability and order in his day not by paper agreements and sweeping pledges but by an equipoise of power. More fully than most presidents, he comprehended and preached the need of correlating foreign policy and military strength. He never faltered in his adherence to civilian supremacy, but he knew at first hand and respected the fighting force and the men in uniform.

The first Roosevelt did not alter markedly the basic guidelines of foreign policy. At the outset he moved cautiously. He was an accidental president and, remembering the difficulties of others who had inherited the office - Tyler, Johnson, and Arthur - he promised to carry out McKinley's POlicies. He endorsed several far-reaching decisions of his predecessor: to retain overseas coloFall, 1963

nies, to build an American-owned interoceanic canal, to demand a favored status in liberated Cuba, to promote the open door in China. The main steps that he took in his first term were to choose the Panama route, to benefit from (though not instigate) a timely rebellion against Colombia on the Isthmus, to force a favorable settlement of a long-standing boundary dispute with Canada, to persuade Germany and England to end a blockade of Venezuela, and to add a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. Some of these developments would have occurred if McKinley had lived; others had a flavor distinctly Rooseveltian.

It was on the larger world stage that Roosevelt made his most novel contribution to American foreign policy, and the opportunity did not come until he had been elected in his own right in 1904. The occasion was the Russo-Japanese War over Korea and Manchuria and the Franco-German rivalry over Morocco. In both episodes he sought to promote peace because he felt a major war in any quarter of the globe could imperil American security. This notion is commonplace today; not so in 1905. When Japan attacked Port Arthur in 1904 without declaring war, Roosevelt's sympathy, like that of his countrymen, lay with the Japanese. Since 1900 Russia had been the chief threat to the open door in China, whereas Japan had long been considered a protege of the United States. But when Japan's uninterrupted victories revealed the appalling weakness of the Tsar's forces in East Asia, the President feared that the balance of power there would disappear. He counted upon an equipose to uphold American interests. Hence he accepted invitations from both belligerents in 1905 to use his good offices to bring about an end to hostilities. In responding to such pleas, Roosevelt showed a completely opposite attitude from that of President Cleveland ten years earlier when China and Japan were at war. Cleveland took the position that the conflict then raging in the Orient touched no vital interest of the United States. Thus where the Sino-Japanese peace was written at Shimonoseki in 1895 under Russian, German, and French pressure, the Russo-Japanese peace was signed at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1905 under American auspices at the request of the belligerents.

Roosevelt's role in resolving the Moroccan controversy, which threatened to drag the rival alliance systems into a general war, was not so decisive. Many factors were at work. But the important thing is that he was willing to venture into the forbidden arena of European power politics. He helped organize a conference at Algeciras, sent American delegates, and authorized them to sign a treaty in 1906. Because of criticism at home Secretary Root had to justify this attendance as protection of American trade, while the Senate appended a reservation which dis-

5

claimed any intention to depart from the policy of isolationism.

An earlier generation of historians accused Roosevelt of stumbling in ignorance into world politics. Today 's verdict is more favorable. Although no statesmen at the time grasped all the forces at work, Roosevelt's perception was as good as anyone's, and he achieved what he set out to do. Nor did he overestimate what he might accomplish. Writing to the ambassador in England in August 1905, he said: "In all these matters where I am asked to interfere between two foreign nations, all I can do is this. If there is a chance to prevent trouble by preventing simple misunderstanding, or by myself taking the first step when it has become a matter of punctilio with the two parties then I am entirely willing and glad to see if I can be of any value in preventing the misunderstanding from becoming acute to the danger point. If, however, there is a genuine conflict of interest which has made each party resolute to carry its point even at the cost of war, there is no use in my interfering." This would not seem very ambitious or effective today, but in 1905 it was unprecedented. It was also enough to win Roosevelt the Nobel Peace Prize.

Although Roosevelt clashed frequently with Congress on matters of policy, he aroused relatively little conflict over prerogative. He was criticized for sending as delegates to Algeciras men who had not been confirmed by the Senate for that purpose, but most of the critics were opposed to participation in any case. He did stir up protest when, as commander-in-chief, he sent the battle fleet on a practice drill from the Atlantic to the Pacific and then kept the vessels going around the world; but the success of the feat quickly silenced objectors. The bitterest hassle came when he attempted to establish a customs receivership in the Dominican Republic by an executive agreement rather than by a treaty; and even when he backed down, the Senate refused for two years to sanction his action. There were several reasons why this disharmony over prerogative remained in a minor key. The Republicans had large majorities in both houses and were reasonably united. After 1905 Secretary Root handled the Senate with skill. But most of all, there was no major crisis as there had been under Madison and Polk and as there would be under Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, for it is during crises such as these men faced that presidents are most likely to stretch their powers and set off a countervailing force.

Now we must turn to the second Roosevelt, who entered the White House twenty-four years after his distant cousin and namesake left it. Much had happened in the interim in respect to foreign relations. Under the stress of the Great War Woodrow Wilson had challenged his country-

men to abandon the policies of isolationism and neutrality - to recognize that war or threat of war anywhere in the world was their concern, to join a concert of free peoples designed to keep the peace, and to agree to defend the independence and territory of any member under attack. Wilson had failed, but in failing he left his mark on American foreign policy. The United States could never again remain indifferent: what had been the exception under Theodore Roosevelt became the rule under Wilson's successors.

Presidential procedures had also changed between 1909 and 1933. Wilson had not only left the country for an extended period (over seven months less a three-week return visit) but also negotiated directly with heads of government. The Great War saw the beginning of the practice where foreign rulers or leaders visit Washington for ceremonial or diplomatic reasons. The interim witnessed too the advent of radio. If that medium of mass communication had been available in 1919 and if Wilson had chosen to use it rather than embark on an exhausting transcontinental speaking tour - which led to a paralyzing stroke - the outcome of the League fight might have been different. Finally, there had been the inevitable reaction in Congress to Wilson's broad use of presidential powers in wartime, and even in 1933 the relations between the White House and Capitol Hill were influenced by experience of the battle over the Versailles Treaty.

Franklin D. Roosevelt possessed a temperament and talents well suited to exploit the potential of the presidency. Even more than Al Smith, he was the Happy Warrior. Sanguine and gay, he was instinctively a leader. Despite his privileged upbringing, he had the common touch. He coined phrases that inspired his fellow men. He could say "My friends" in ten different ways. A superb speaker with a mellifluous voice, he developed the medium of radio with effective fireside chats. A skilled actor with a flair for the dramatic, he gave the impression of moving forward even when he stood still. He traveled constantly through the land, perhaps to 'compensate for his inability to walk unaided. He revolutionized the press conference and endeared himself to correspondents whose newspapers excoriated him. He enjoyed personal diplomacy, corresponding not only with his own ambassadors abroad but also with the heads of other states or governments. Like the first Roosevelt, he understood the need to correlate foreign policy with military capability. He, too, loved the sea and the ships that sailed it. Most important of all, he viewed the presidency as a place to exercise both political and moral leadership.

On taking office, Roosevelt did not institute a new deal in foreign policy. His immediate goals differed little from those of the Hoover administration. Although the depression was global in its

6

NORTH WESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

ramifications, he concentrated on domestic problems and gave priority to relief, recovery, and reform. The world, of course, did not stand still as he tried to build a new America. His first years saw the collapse of the Versailles settlement and the American compromise between traditional principles and Wilsonian precepts. So spectacular were Roosevelt's initial triumphs at home that we forget his many setbacks abroad. In July 1933 the World Economic Conference broke up in failure, partly because he refused to stabilize the dollar. In June 1934 the World Disarmament Conference reached a deadlock because no one could reconcile Germany's demand for rearmament with France's insistence on security. More revealing were his defeats on Capitol Hill where the Democrats enjoyed large majorities in both houses. In May 1933 he lost his bid for a discriminatory arms embargo designed to discourage revolution and aggression. In January 1935 he was beaten on the World Court Protocol. In August 1935 he signed a neutrality law he did not like. With many of his staunchest supporters on domestic matters disagreeing with him on foreign affairs, Roosevelt shrank from showdowns. Certainly he cannot be accused in these years of exceeding his constitutional authority or stretching the limits of the presidency in foreign affairs.

The real controversy over whether Franklin Roosevelt usurped the powers of Congress in foreign policy began as Europe careened toward war. The President was appalled by his inability to awaken the people to the dangers which, he felt, beset them. "It's a terrible thing," he said later, "to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead - and to find no one there." He did try to secure a change in the existing neutrality laws, a change which would allow the executive discretion in applying the arms embargo, a discretion that might be used against the aggressors. Though he had wanted this discretion since 1933, and had sought it openly and by constitutional means, he was unsuccessful. Then the outbreak of war in September 1939 persuaded Congress to give him half a loaf.

With the fall of France Roosevelt took the first of several steps for which he has been severely criticized. This was the Destroyers-Bases Agreement of September 1940 by which the United States transferred to Britain fifty overage and decommissioned destroyers in exchange for ninetynine year leases on six Caribbean sites, suitable for naval and air bases, and the outright gift of two additional facilities in Bermuda and Newfoundland. Little fault could be found with the provisions. They amounted to the most advantageous acquisition for defense since the purchase of Louisiana. To be sure, the agreement was not consonant with traditional neutrality, but after the Nazi invasion of Holland most Americans realized that traditional concepts afforded no protection

for the neutrals. What bothered many citizens was the method used, an executive agreement instead of a treaty. The Senate had been bypassed. Why? Not because he feared publicity - the text was published immediately. Not because he feared defeat - he could have mustered a two-thirds majority eventually. Rather he feared delay, a long debate during which Germany might invade England. The tempo of war had quickened; the air age had made obsolete the leisurely processes established in 1787. Modern planes, Roosevelt had warned four months earlier, had eliminated oceans as defensive moats; modern bombers could hit the United States from Greenland in a six-hour flight.

The Lend-Lease Act of March 1941 was the next step in an unprecedented response to what Roosevelt believed were unprecedented dangers. Note the word "Act." Lend-Lease was a law, a statute passed by Congress. It may have been unneutral; by nineteenth century standards it was. It may have been unwise; I do not think it was. It may have delegated extraordinary powers to the president, and it did. But it was not usurpation by the executive. It was openly debated after full hearings in both houses; it was passed by substantial majorities. It conformed to the democratic process and was flawed only by premature assurances, implied rather than explicit, that American warships would not be needed to insure the safe delivery of Lend-Lease goods.

We come now to the climax of Roosevelt's prewar diplomacy - the undeclared naval war with Germany in the Atlantic and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Did the President exceed his powers? Did he so maneuver the situation that he robbed Congress of the right to decide whether war should be declared? There is much about his course in the Atlantic that may be criticized, even if you agree - as I do - with his basic assumption that American security required that Lend-Lease goods reach England. On occasion he was not candid, even devious. He seemed afraid to tell the people bluntly what must be done. In this connection Secretary of War Stimson, a Republican who had served the first Roosevelt, Taft, and Hoover, later expressed the opinion that in 1941 Theodore would have done a better job than Franklin. "TR's advantage," Stimson said in 1947, was "his natural boldness, his firm conviction that where he led, men would follow Franklin Roosevelt was not made that way. With unequalled political skill he could pave the way for any given specific step, but in so doing he was likely to tie his own hands for the future, using honeyed and consoling words that would return to plague him later."

On September 11, 1941, Roosevelt ordered all American warships to "shoot on sight" any Axis naval vessel encountered in waters which the United States deemed essential to its defense-

Fall, 1963

7

roughly the western half of the Atlantic. Five days later he put into effect an order, frequently canceled and long delayed, permitting belligerent and neutral merchant craft to join convoys destined for Iceland and escorted by the American navy. Both steps were taken publicly, but without congressional consent. Since the President was acting as commander-in-chief, such consent was not required, though he might have been wise to seek it. A month later Roosevelt did ask Congress to repeal certain outdated clauses in the neutrality laws, and by a close vote (close because of extraneous issues) that body went farther than he had requested. Paradoxically, in late 1941 Congress and the people would have opposed a flat declaration of war against Germany, yet a sizable majority favored a course that at any moment could precipitate full-scale hostilities. This confusion persisted until Japan struck in the Pacific.

The events leading to Pearl Harbor were diplomatic and military in character and thus, constitutionally, the concern of the executive. The deployment of ships and planes was the responsibility of the commander-in-chief; the dialogue with Tokyo to resolve Japanese-American differences fell to "the chief organ of the nation in its external relations." There was more secrecy surrounding developments in the Pacific than in the Atlantic, but then publicity is not customary during tense diplomatic negotiations or frantic military preparations. Certainly Congress could not be given the intercepts of secret Japanese dispatches which we were able to read after breaking the diplomatic code. The legislature could have acted, if it had wished, on perhaps the most decisive move in the long drama - the freezing of Japanese assets and the beginnings of an oil embargo. This step was taken by an executive order, but it was done openly and dealt with something within congressional jurisdiction. There was, however, no protest on Capitol Hill where a "get tough with Japan policy" was more popular than in the White House or the War and Navy Departments.

Roosevelt has often been accused of wanting to enter the European war through the backdoor of Asia. He is charged with provoking Japan to strike first (thus insuring united support at home) by presenting her with impossible demands. This premise and this charge I believe are false. Roosevelt had no desire to enlarge the war. His main aim was to help England contain and defeat Germany. America was unready to fight a two-front war. His military chiefs in November 1941 were begging for time, beseeching him to avoid a showdown, at least until April 1942 when they would have enough flying fortresses in the Philippines to make those islands safe from a Japanese invasion, or so they thought. The President concurred, but he also knew there were

concessions beyond which he could not go to avoid war and there was a deadline beyond which the Japanese would not talk lest the season for amphibious operations pass. One can legitimately argue that a more flexible American policy might have postponed the clash with Japan - I do not think anything could have eliminated it - but that is not the same as saying that the president usurped the powers of Congress and insured war by compelling Japan to fire the first shot.

Roosevelt has also been charged with exceeding his authority by promising England and the Netherlands to come to their aid in event of a Japanese attack in Asia. This assurance the President consistently refused to give, at least down to December 6 when any such promise could not possibly affect Japanese policy. He was, to be sure, worried lest Japan weaken Hitler's foes by invading Malaya and the East Indies. His military advisers told him that a Japanese conquest of parts of Southeast Asia would imperil our own security. The dilemma was what to do if Japan did so invade without attacking American soil. That was a tough one. On November 28 the President and his cabinet agreed that he must go before Congress and request authority to use force to defend certain non-American territory. He planned to do so on December 8 or 9. Obviously he never had to go because the attack on Pearl and the Philippines removed the necessity. But here Roosevelt recognized the limits of his power and was ready to request Congress to supplement them. This was not usurpation.

The question of blame for the military disaster at Pearl Harbor does not properly belong in a discussion of the powers of the president in foreign affairs; but since it continues to arouse controversy, I shall offer a few observations. Few Americans, it seems to me, save those under fire, showed to best advantage in that tragedy. The failure was universal. At every level, from the White House to the destroyer patrolling the harbor entrance, there were mistaken judgments and errors of omission. Not everyone was later judged by the same standards, but sympathy for those who were made the scapegoats must not lead us to accept their charges that a military defeat was staged in order to escape from a diplomatic impasse. Similarly, the refusal of officials in Washington to assume some of the blame must not cause us to conclude that they had a despicable plot to hide. There was no treason in high quarters in 1941, there is no unsolved mystery of Pearl Harbor. The true explanation of the debacle lies in the realm of human frailty; and since no O'1e saw the portent clearly at the time, it behooves a later generation not to be omniscient after the event.

Once the United States was at war, Roosevelt faced a different set of problems regarding his powers. In time of crisis presidents have always

8

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

stretched their authority - none more so than Lincoln and Wilson. The commander-in-chief acts differently in war than in peace. The line between military and diplomatic aims diminishes. Thus Roosevelt resorted to greater secrecy. He consulted Congress less. He relied more on the Joint Chiefs of Staff than on the State Department, more on personal emissaries like Harry Hopkins than on regularly accredited ministers. Often, not always, this was unwise. The air age made possible personal diplomacy - today we would call it summit diplomacy; and here the advantage offset the disadvantages. The precarious nature of the fighting forced him to make far-reaching decisions that could not be publicized. Stresses within the anti-Axis coalition compelled him to make broad agreements that affected the future peace. It was impossible to debate on Capitol Hill the meaning of unconditional surrender, the wisdom of cross-channel invasion, and the need for Russian participation against Japan. We often forget that the much criticized conferences at Casablanca, Quebec, Tehran, and Yalta were concerned primarily with winning the war. One may rightly argue that Roosevelt became too preoccupied with immediate, as against long-range goals; but it is not likely that close collaboration with Congress would have produced a different result. In the one area where legislative support was essential- membership in a postwar international organization - the President proceeded with full publicty to inform Congress and educate the people in a way that Wilson had never done in 1917 and 1918. The result was overwhelming support for adherence.

Some lessons can be learned from Roosevelt's wartime actions. There is no more difficult diplomacy than the diplomacy of a coalition, as we realize all too well today. The end of war is not victory on the battlefield. The fog of war envelops statesmen as well as generals. At several key points Roosevelt was the victim of faulty intelligence. On some occasions he carried secrecy to unnecessary extremes. This was particularly true at Yalta. A man with too much authority tends to lose humility and patience. Roosevelt's handling of sensitive Charles de Gaulle, his callousness toward a solution of the Polish question, his willingness to act for Chiang Kaishek on China's postwar boundaries all suggest that power demeans, if it does not actually corrupt. A parallel could be drawn with Wilson who, at the end of his career, seemed to lose his political touch and his knack of conciliation. Perhaps the first Roosevelt might have manifested the same tendency if, at the end of his administration, he had faced a comparable crisis.

With the passing of Franklin Roosevelt an inevitable reaction against the powers of the president set in. The Twenty-Second Amendment was one manifestation. The cluster of ill-digested

ideas associated with the proposed Bricker Amendment was another. I believe it is well that Bricker did not prevail; but some of his objectives, notably a curb on executive agreements and a reduction of secrecy in government, were an understandable response to the events of 1941 to 1945.

I like to think Bricker and his associates did not prevail because we know deep down inside that the United States cannot afford to hobble the powers of the president in foreign policy. As we pass from the air age to the nuclear age to the thermonuclear age, those powers must expand. And expand they have. There was Truman's heartrending decision in August 1945 to drop the first atomic bomb. There was his courageous and prompt decision in June 1950 to repel the North Korean invader. Yet what began as a police action that did not, at first, seem to require a formal declaration of war escalated into a bloody and frustrating conflict. And just as I think Truman was wise to respond as he did initially, I think he was unwise not' to seek, later, a legislative endorsement of what he had done. He could have gotten one easily.

Congress has been loath, of course, to surrender its prerogatives and accept a lesser role in foreign policymaking. It tried, unsuccessfully, to alter Truman's strategy of fighting a limited war and of simultaneously stationing more divisions in Europe. Its opposition has made recognition of Communist China a political impossibility. The more tactful and soothing Eisenhower recognized this fact when in 1955 and 1957 he sought prior congressional approval for any military move he might have to make in the Formosa Strait or the Middle East. Yet when a revolution in Iraq in July 1958 compelled him to act within hours, he merely told the leaders on Capitol Hill that the marines would land in Lebanon. And when Iraq's withdrawal from the Baghdad Pact threatened the existence of a shaky Middle East alliance, which Dulles had consistently refused to join, the Secretary then joined indirectly by concluding defensive agreements with Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan. And he did so by executive agreements, not by a treaty.

But we have gotten well beyond the two Roosevelts and what their careers tell us about the limits of the powers of the president in foreign affairs. I would like to conclude with an apt quotation from one or both of those facile phrasemakers; but in this case the appropriate sentiment was coined by a less gifted speaker and writer from Independence, Missouri. On the desk of Harry Truman in the White House there long stood a little white card describing the vast authority of the presidency in four awesome words - awesome in a day when all we hold dear can be destroyed in minutes. Those four words were: THE BUCK STOPS HERE.

Fall, 1963

9

By Daniel Johnson

THE

AND

parody (pare-di) n. (pl.parodies (-diz», (F'r.parodie ; L.parodia; Gr.paroidia, counter song para-, beside & oide, song), 1. literary or musical composition imitating the characteristic style of some other work or of a writer or composer. but treating a serious subject in a nonsensical manner, as in ridicule. 2. a poor or weak imitation. v.t. (parodied (-dtd). parodying), to make a parody of. - SYN. see caricature.

For Hannah Lyons qui n'aime pas T. S. Eliot

I. THE BURIAL OF THE INDIVIDUAL

June is the cruelest month, breeding Bachelors' degrees out of the dead campus, mixing

Commencement and job-seeking, stirring Dull brains with summer anxiety.

Winter quarter kept us warm, covering The University in forgetful snow, feeding Student life with dry lectures.

Summer surprised us, coming over Deering Meadow

With a shower of rain; we stopped in the Speech Annex

And went on in sunlight, into the Grill, 10 And drank coffee, and talked for an hour.

Je ne crois pas qu'elle est une vierge.

And when we were freshmen, staying at the dean's,

My master's, he took me out in his Rolls-Royce, And I was impressed. He said, Zelda, Zelda, hold on tight. And off we went.

In Lake Forest, there you feel important. I study, much of the night, and go to Daytona Beach in the winter.

What are the students that clutch, what grade averages grow

Out of this archaic system? Son of alum, 20

You cannot say, or guess, for you know only

A heap of graded blue-books, where fluorescent lamps flicker

And the grade report gives no solace, the instructor no assistance,

And the dry professor no sound of excitement. Only

There is shadow under this multi-colored rock (Come in under the shadow of this multi-colored rock),

And I will show you something different from either

Your pinmate at morning striding behind you

Or your pinmate at evening rising to meet you; I will show you fear in a handful of paper forms. 30 Plenus rimarum sum, hac atque mac effl,uo

"You gave me Shakespeare first a year ago; "They called me the Shakespeare girl."

-Yet when we came back, late, from Shakespeare Garden, Your cheeks glowing, and your hair mussed, I could not

Stop, and my advances failed, I was neither Satisfied nor dissatisfied, and I knew not why, 40 Looking toward the lake fill, the money. Quel noir.

Miss Yearly, famous Director of Women's Housing,

Has an infallible memory and Is known to be the most gung ho woman on the staff,

With a wicked pack of I.B.M. cards. Here, said she,

Is your card, the undergraduate on probation, (Those are F's that were his C's. Look!)

Here is Ann-Margret, the Girl of Hollywood, The girls of B-flicks.

Here is the man with three A's, and here the BMOC

And here is the introverted teacher, and this card,

Which is blank, is some system by which he grades exams,

50

10

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

Which I am forbidden to see. I do not find

The Coach hanged in effigy. Fear death by registration.

I see crowds of students, walking along the luke. Thank you. If you see dear Miss Campusquecn.

Tell her I bring the beer myself: One must be so careful these days.

Unreal University, 60

Under the constant jack-hammering of construction workers,

A crowd flowed across Sheridan Road, so many, I had not thought drinking had hung over so many.

Sighs, long and frequent, were exhaled, And each man fixed his eyes on a sweater. Flowed past Scott Hall and down University Place,

To where the Alpha Chi's kept the hours

With a muffled sound on the final stroke of two.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: "Beret!

"You who were with me in Phys. G! 70

"That brown-nosing you did last quarter in U.H. 304,

"Has it paid off? Will it raise your grade?

"Or did the final exam shoot you down?

"Oh keep the monitor far hence, that's friend to no student,

"Or with his eyes he'll catch you cheating again!

"You! professeur!-mon ami,-mon frere!"

II. A GAME OF CHEST

The Chair she sat in, like a hardwood box, Deadened the gluteus maximus, where the coffee cup

Balanced on a saucer marked with small chips

On which a reddish lipstick stain glared out 80

(Another hidden on the other side of the cup)

Doubled the danger of getting trench mouth

Reflecting unsanitary conditions in the kitchen as Her trembling lips rose to meet it, From a face made-up with expensive cosmetics; In containers of metal and paper

Uncovered, bubbled her strange poorly-mixed sodas,

Pepsi, phosphates, or secret Coke - gastric, barfy

And drowned the stomach in carbonation; stirred by the milk

That lay in waxed cartons, these assisted 90

In fattening the overweight co-ed, Flung their effects onto bathroom scales,

Disturbing the pattern of eating habits.

Large wall-to-wall carpets fed with dirt

Burned with cigarette stubs, framed by the pastel walls,

On which hung mirrors for self-indulgence. Above the antique mantel was displayed

As though anyone gave a damn

Fall, 1963

The metamorphosis of Pledges, by the barbarous Greek Life

So rudely forced; yet there the individual 100 F'Illed all the house with rebellious ideas

And still she demanded, and still the campus pursues,

"Join Join" to dirty ears.

And other withered stumps of college life

Were told upon the walls; verbose actives

Leaned there, leaning, speaking the room full.

Footsteps stumbled on the carpeted stair.

Under the lamplight, under the brush, her hair

Dangled in frizzy ends

Clumped into knots, then would be angrily washed.

"My nerves are shot tonight. Yes, shot. Stick around.

"Say something. Why don't you ever say anything. Huh?

"What are you thinking about? About sex? Again?

110

"I always know what you're thinking about. Sex."

I think we are in Fisk parking lot

Where the freshmen girls lose their virginity.

"What's that noise?"

A cop checking the lot.

"What the hell's that noise? What's the cop doing?"

Looking again looking.

120 "Do"

'You hear anything? Do you see anything? Don't you remember

"Anything?' I remember

Those are F's that were his C's.

"Are you whapped, or not? Isn't there anything on your mind?"

But

Come O-o-o-n-n Baby, Let's Do the TwistIt's so swingin'

So life-givin'

"Now what do I do? What do I do?

"Hell, I'll rush out as I am, and walk the street

130

"With my skirt off, like this. What are we going to do tomorrow?

"What do we always do?"

A hot bath at seven.

And if it rains, a closed car at eight.

And we'll playa game of chest,

Pressing hot bods and waiting for that damn cop with his flashlight.

When Judy's pinmate got de-pledged, I saidI didn't kid around, I told her straight, 140 COME ON, LET'S GO, GRILL'S CLOSED

Now that your father's coming out to see you, shape up,

He'll want to know what you did with that money he gave you

11

To buy books with. He did, I heard about it. You spent it all, Judy, better get some books, He said, damn it, I can't afford any more.

And I sure can't lend you any, I said, and think of your poor father, He's been with that company twenty years, he's hard up,

And if you don't explain about the money, there's others will, I said.

Is that so, she said. That's right, I said. 150 Then I'll know who told him, she said, and gave me a dirty look.

COME ON, LET'S GO, GRILL'S CLOSED

If you don't like it you can lump it, I said. Others can find ways if you can't.

But if Daddy cuts you off, it won't be because nobody wised him up.

You ought to be ashamed, I said, to be so selfish.

(And her only nineteen.)

I can't help it, she said, getting ticked-off, It's my childhood rearing, my parents' fault, she said.

(She's done this five times already, and nearly got caught last quarter.) 160

My analyst explained it to me; but I couldn't grasp it all.

You are a nurd, I said.

Well, if your father keeps bugging you, what the hell, I said,

What did you come to school for if you don't know how to handle money?

COME ON, LET'S GO, GRILL'S CLOSED

Well, that weekend Daddy showed up, they got smashed,

And the two of them forgot all about moneyCOME ON, LET'S GO, GRILL'S CLOSED COME ON, LET'S GO, GRILL'S CLOSED

See 'ya Bill. 'Nite Bob. 'Nite Sue. 'Nite. 170 Ciao. Ciao. 'Nite. 'Nite.

'Nite, guys, 'nite, babes, 'nite, 'nite.

III. THE SNOW JOB

The lake's pier is broken: the last remnants of beach

Are eroded and washed away. The wind Crosses the barren campus, cold. The students are home for the holidays.

Erode away, damn it, till I finish my bitching. The lake bears no beer cans, lecture notes, Used condoms, Daily Northwesterns, cigarette butts

Or other testimony of summer nights. The students are home for the holidays.

And their enemies, the members of the faculty - 180

At home, are grading final exams.

Behind Tech I sat down and cursed

Erode away, damn it, till I finish my bitching, Erode away, damn it, I'm almost through.

But behind me I hear the construction workers

The pounding of jack-hammers, and the fact of $3.90 an hour making them grin.

A maintenance man tramped across the lake-fill dirt

Dragging his snow shovel behind him

While I was busy trying to figure out the Liberal Arts Bulletin

On a winter afternoon round behind Deering Library

Thinking about my quarter on pro

And about the quarter before that.

White bodies naked in the back seats of cars

And crap shooting over in Garrett,

190

Shaken only by the dean's approach, year to year.

But behind me from time to time I hear

The sound of horns and motors, which shall bring

Students to parking lots in the spring.

Oh the moon shone bright on parking spaces

And on frenzied chases 200

They leave the cop with scattered traces

Et 0 ces voix d'etudumt», chantant chaque mai!

Study Study Study

Join join join join join join So rudely forc'd.

Ross Barnett

Unreal University

Under the constant jack-hammering of constructionmen

Mr. Lotsabucks, the Evanston merchant Cleanshaven, with a pocket full of twenties

T.t.s. Evanston: shaking my hand, Asked me in colloquial English

To luncheon at the Orrington

Followed by a sales pitch about obtaining new student customers.

At the purple hour, after the bells

Have rung to end classes for the day, when the student waits

Like the old man's car throbbing waiting, I class prophet, though nearsighted, throbbing between two girls,

Young man with hands seeking breasts, can see

210

At the purple hour, the evening hour that strives 220

Dormward, and brings the student home from classes,

The faculty typist home at quitting time, clears her breakfast, lights

Her gas range, and lays out food in Corning Ware

Out of the window perilously spread

Her underthings dry in the sun's last rays, On the hide-a-bed are piled (at night her stereo)

Stockings, girdle, Mad Magazines, chewing gum.

I class prophet, young man with eager hands

Saw this bit, and imagined the rest-

I too waited for the expected guest.

He, the young student horny, arrives,

A short cat in Speech, with hungry eyes, Some wiseass who thinks he's sharp

12

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

Like some of those longhair drama majors.

His timing is great, he figures, She's through eating, she's bored and easy, Tries to slip a hand into her dress

Which he does, though inaccurately.

Hot and bothered, he tries her; Fumbling hands are not discouraged; 240

His maleness requires a response, And makes the most of the offering.

(And I class prophet have been there

Right on this same hide-a-bed ; I who have sat outside deans' offices

And walked among the independents.)

Lays one last kiss on her, And stumbles down the apartment stairs

She turns and looks a moment in the glass, Quite aware of her departed lover; 250

Her brain allows one thought to pass; "Well I finally did it: I'm sorry it's over."

When a faculty typist resorts to students and Paces about her room again, alone, She smooths her hair with trembling hand, And calls his house mother on the phone.

"This jazz drifted by me upon the gutters" And along the sidewalk, up Foster Street. o University university, I can sometimes hear

Inside a public bar on Howard Street, 260

The swinging sound of a juke-box

And a chugging and a mugging from within Where seniors drink at midnight: where the walls

Of Talbott's hold

Unexpected knotty pine varnished and old.

The lake floats

Fish and bugs

The barges carry Rock to the lake-fill

White sails

Still

At Lee Street, look odd on tugs.

The barges carry

Tons of rock

Down Clark Street beach

Past the U.H. clock.

Wildcats go Wildcats win Miller and Doney

Beating doors

Their sterns were formed

In cushioned chairs

Purple and white

Their thinning hair

Repulsed the whores

Ticker tape

Counted out loud

The advance of shares

Ivory towers

Wildcats go

Wildcats win

"El trains and elm trees.

Chicago bore me. Madison and Fond du Lac

Undid me. In Madison I raised my knees

Fall,

On the floor of some eat's Cadillac."

"My feet are at Allison, and my tradition

Under my feet. After the affair

He laughed. He promised 'a new position.' I made no comment. What did I care?"

"With Indiana Sands.

300 I can get Nothing for nothing.

The terrible cost of filled-in lands. My adviser satisfies people who expect Nothing."

go go

To Columbus then we came

Fighting fighting fighting fighting

o Coach You won that game

o Coach You won

310 fighting

IV. DEATH BY REGISTRATION

Melvin the Music Major, registered on time, Forgot the time schedule, and the schedule cards

And the books and fees.

Pre-registration

Closed his courses in minutes. As he passed the guards

He counted his class cards once again

Entering the check-out area.

Grad or Undergrad

o you who stand in line and wind your watch, 320 Remember Melvin, who was once eager and on time as you.

V. WHAT THE W.e.T.U. SAID

After the spotlights white on surprised faces

After the snowball fights in the streets

After the panty raids in freshman places

The shouting and the jeering

Dormitory and apartment and renewal

Of sirens of police cars around familiar corners

He who was shouting is now running

We who were shouting are now leering

Though from a distance

Here is no beer but only Pepsi

Pepsi and no beer and the asphalt street

330

The asphalt street winding between the buildings

Which are buildings of Pepsi without beer

If there were beer we should stop and drink

Amongst the Pepsi one cannot stop or think

The town is dry and teetotallers are in the city council

If there were only beer amongst the Pepsi

Lousy building full of aldermen who will not vote

Here they always get my goat

There is not even action in the buildings

But long boring speeches without results

There is not even democracy in the buildings

But pale stupid faces grin and smile

From doors of expensive houses

If there were beer

340

1963 270 280 290

13

And no Pepsi

If there were Pepsi

And also beer

And beer

A six-pack

A barrel among the Pepsi

If there were the sound of beer only

Not the W.C.T.U.

And church choirs singing But sound of beer from a tap

Where the student sings in the taverns

Slurp chug slurp chug chug chug chug

But there is no beer

Who's the clown who always walks with you? 360

When I'm around, there's only you and I together

But when I see you from a distance

There's always this clown walking with you

Talking dressed in a brown suit, tweed

I don't know whether an SAE or a Sigma Nu

- So who's that clown who always walks with you?

What is that noise coming from the lake

Hammer of handsome wages

Who are those book-toting broads swarming

From endless doors, stumbling on cracked sidewalks 370

Ringed by the frat men only

What is the university over the buildings

Student unions and humor magazines and riots in the purple air

Losing influence

Minnesota Iowa Purdue Michigan Wisconsin

Unreal

A co-ed drew her long black hair out tight

And played folk music on those strings

And cats with bearded faces in the purple light 380

Listened, and had their flings

And walked head uplifted down a well-lit street

And back in the dorms were showers

Dripping familiar leaks, that kept up for hours

And voices singing out of empty Teem machines and exhausted candy vendors.

In this dismal hole among the buildings

In the faint moonlight, the church choir is singing

Over on south campus, about the chapel

There is the new chapel, only the icon's home.

It has no purpose, and it's ugly besides, 390

Rich alums can harm everyone.

Only a liberal stood on the corner

Hear me hear me hear

In a show of spirit. Then an Evanston cop

Bringing a warrant

Courage was punished, and the apathetic students

Waited for graduation, while the discontented ones

Gathered together, over in the Hut.

The student body waited, sitting anxiously.

Then spoke the W.C.T.U. 400

DRY

Dry: what have we gained?

My friend, shaking my 1.0. card

The awful daring of a moment's rebellion

Which is short-lived and never effective

By this, and this only, we have existed

Which is not to be found in our commencement invitations

Or in year books censored by the beneficent administration

Or in dresser drawers opened by the house maid

In our vacated rooms 410

DRY

Drier: I have heard the counselor

Turn and go in the corridor and turn and go once only

We think of the counselor, each in his room

Thinking of the counselor, each confirms a room

Only at nightfall, aethereal rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Regulation

DRY

Driest: The old ladies responded Gaily, to the speaker expert with word and logic

The auditorium was quiet, your soul would have responded

Angrily, when challenged, opposing mightily

Their controlling hands

420

I sat upon the shore

Reading, with the lifeless campus behind me

Shall I at least set my courses in order?

Pearson Hall is falling down falling down falling down

Fata viam inveniunt

o Willie Willie

What if the homecoming queen is a lesbian! 430

These facts I have stored in my notebook.

Why then damn it all. The student senate is mad again.

Dry. Drier. Driest.

Shut up shut up shut up

NOTES ON THE VAST LAND

Not only the title, but the plan and a good deal of the incidental symbolism of the parody were suggested by T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land (1922), the precursor of modern symbolic poetry, and one of the most powerful and magnificent poetic works ever created. Indeed, so deeply am I indebted, Mr. Eliot's poem will elucidate the difficulties of the parody much better than my notes can do; and I recommend it (apart from the great interest of the poem itself) to any who think such elucidation of the parody worth the trouble. The subject matter of the parody was chosen because of its relevancy to my present situation and, of course, that of Miss Hannah Linda Loretta Lyons, to whom it is dedicated. Although some may find reason to object to my bastardizations as well as my often (not really) unjustified pricks at the great helium-filled balloon of university administration, injury was not my purpose.

14

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

I am not retracting anything, but there are places in the work where distortion served my purposes much more readily than real situations would have.

I. The Burial of the Individual

31. Terence, Eunuchus, 1, ii. 25. "I am full uf cracks, I leak on every side."

49. One of many names appearing in university propaganda which is associated with the Great American Dream Dump in southern California.

68. A phenomenon which I have often observed firsthand.

74. Cf. any of several species of large, flesh-eating lizards of Africa, southern Asia, and Australia: so called from the notion that they warn of the presence of crocodiles (lecturers).

II. A Game of Chest

98. Some do.

100. Actually, this process is characterized by politeness and good manners.

115. A prevalent myth (?)

138. Cf. the game of chest in Johnson's Guide to EnLightened Living.

III.

The Snow Job

186. Estimated.

191. Winter quarter, 1960-61.

202. Cf. May Sing.

209. Cf. manager, Grabdo Dept. Store

211. Thanks to students.

218. Class prophet, to my knowledge, is not an official student office at N.U.

257. Overheard in the No Exit Cafe.

264. An excellent pub on Paulina St. Try the ribs.

V. What the W.C.T.U. Said

358. Cf. Talbott's, Hamilton's, The Candlelight, and others, esp. Wednesday and Friday nights.

402. 'Dry, drier, driest.' The fable of the meaning of Evanston is found in the liquor stores of Skokie.

428. Virgil, Aeneid, III, 395. "The Fates find a way."

434. Shut up. Repeated, as here, a formal ending to this parody.

POEMS

After graduating from DePauw University in 1959, where he studied psychology and sociology, Russell Warren Nystrom worked for two years in a psychiatric ward of a local hospital in order to fulfill - as a conscientious ob;ector - an alternative Service obligation. He is married, has three children, and has been taking courses in literature in Northwestern's Evening Divisions.

I'M TERRIBLY SORRY

Under what marker that I have not seen Lies my dream in her disfigured reality

Her slender innocence called me from among the cattle Into this foreign land where I am lost and alone

Fall, 1963

Daniel F. Johnson, L.A. '63, was co-winner of this year's Faricy Award for poetry at Northwestern, and is now editing new novels published in paperback by Novel Books, Inc. in Chicago.

After attending high school in Evanston, where he was born, he ;oined the U.S. Navy and had two years of duty af/oat. He served on an ammunition ship and a tanker, touching at ports in Cuba, Scotland, England, France, Portugal, and Spain, and at Mediterranean ports in Italy, Sicily, Sardinia, Greece and Turkey - a good deal of traveling. His freshman year was at Kendal/ College, where he was named a member of Phi Theta Kappa, the National Junior College Scholastic Honorary Society.

His "The Vast Land" made a considerable stir in campus circles. He was invited to read it in several classes and copies of the manuscript have been in demand. The close parody of Eliot's "The WaSte Land" becomes, ingeniously, a satire on the various levels of collegiate life.

Red, orange and yellow sun spots

Burn still into my shuttered eyes

Though I am in a cluttered closet

Full of dinner jackets and moth balls

With my head upon a rubber boot

That jabs its buckle into my neck.

Yet I dare not scratch or stretch for fear Of tumbling off this pillow altogether

On to the dusty wood floor so far away.

I can not remember if the door is locked or If I am some fallen suit of winter underwear. I have forgotten all the cotton summer clothes

And can remember only these drab heavy wools

That hang long as my long covered hours that Drape over this precarious and stuffy vigil Imposed on me for my naked search into that sun.

;··::f·-· /

Russell Warren Nystrom

THE BURNING CRIME

15

REBUTTAL

Go away in the woods somewhere gone away

Like Thoreau or like that Babbitt

You'll come back to me.

Go away in the woods somewhere gone away

I have plenty of frightened shoes

Scraping off their dirt on me.

Clean still the green somewhere gone away

You'll sell it all for Butchered meat and secret waste.

Though he is in the somewhere gone away

You'll come back to nest in Mother's sweating fat hand.

A DREAM FROM THE MEADOW

From

Where I know not came

A delicate yellow bird

Singing

Light

She manifest in song

And in her harmony

Color

Alone

She winged towards me

Completing this solitude of

Form

THE FATHERLAND LET FALLOW

what regret that dwells beneath the earth unspent ghosts that sense the grass's new lush the pregnant blossom's turning to common maturity that smells eventually of brown nuts and orange fluttering wind then disappears undercover to be the new ghost of Spring unrealized my name continues new but oh my miserable eyes that see too little not to hunger and see too much not to sleep

AND ON THE SEVENTH DAY

On the seventh day the factory rests

Near by an empty warehouse

And a lonely stranded box car

While the dust of six days settles slowly.

There are no people to color

The cyclone tan and grey stillness; There are no people except the three Who on the seventh day inherit the discarded world.

And the old man is the old man

Whom all have seen and smelled

And given a dime to make him go away

From all the driving plastic days before.

And the fat old woman has an old fat woman's Flowered and faded kerchief covering her head

And her eyes are bland and staring

Into a far preoccupation of tired vacancy.

Yet the boy would shuffle if he walked at all

Because his feet are lonely for the unknown sea

And his eyes are ever watching

For the stray cat that he does not miss,

Three parenthetical forms in a tableau

Listening to the slowing of the dust

They are always the same, the same three On an empty waiting seventh day street.

And still. And still again the remnant stench Of the factory fills the hollow warehouse

With a mild and useless desire to house The stranded traveler until yet another day.

WAITING IN A CLOSET ON A SLOW SUNDAY

Search search search search searching I am the stuffed full man

I have just eaten Shakespeare and Freud

Nor were they polite at table

We are the stuffed full men

Now with tight belly I play hide and seek With my children who never find

AN OCCASION FOR NEARNESS

It travels from an ancient depth up through the root searching for the small pore that flowers into one pregnant scent forcing song to open the throat of a waiting bird that startles up an insect fly from its dark habit and calls the worm to open the earth hole into fertility as my eyes open wet through the happy slime of this slippery joy.

16 NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

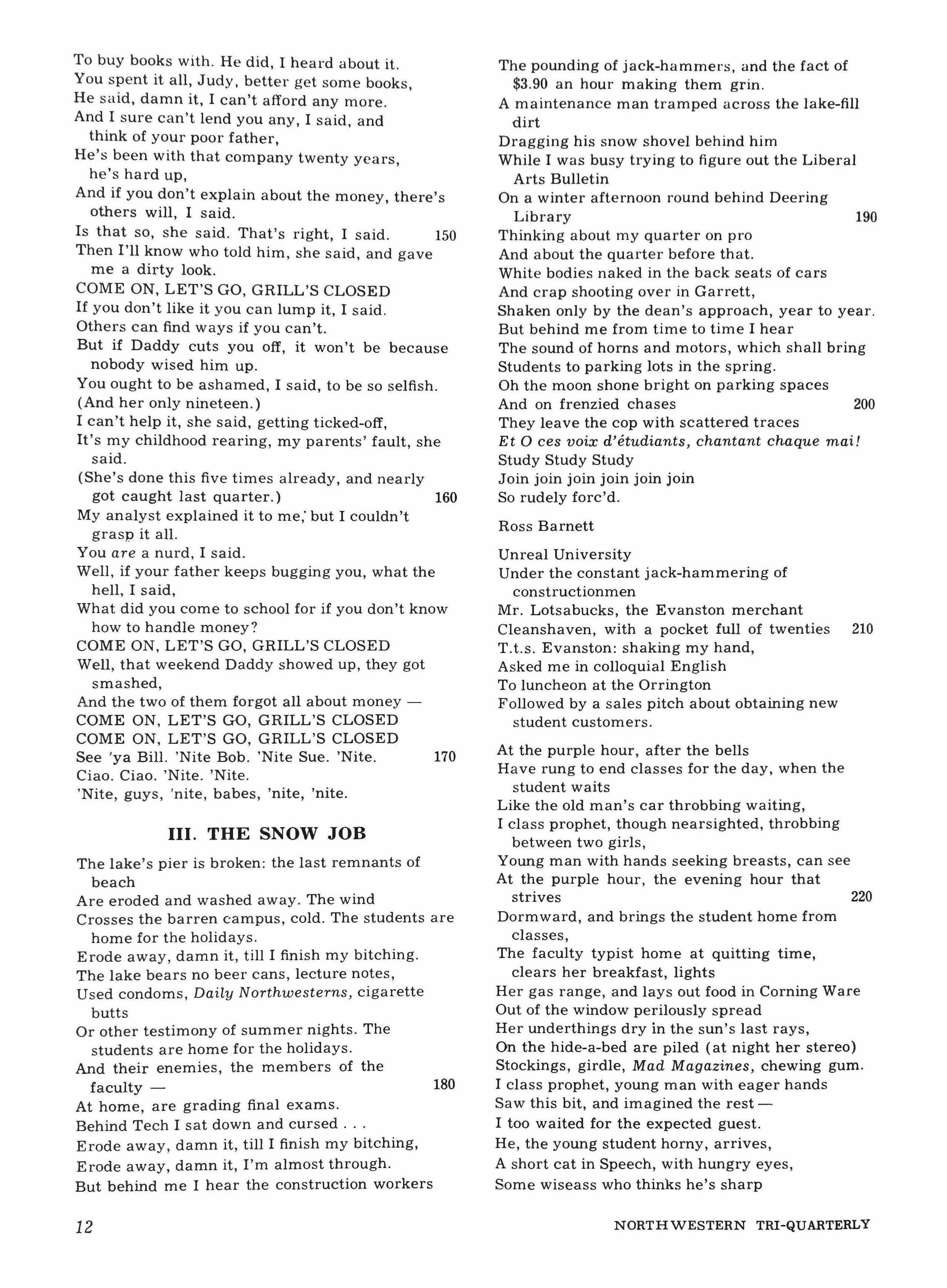

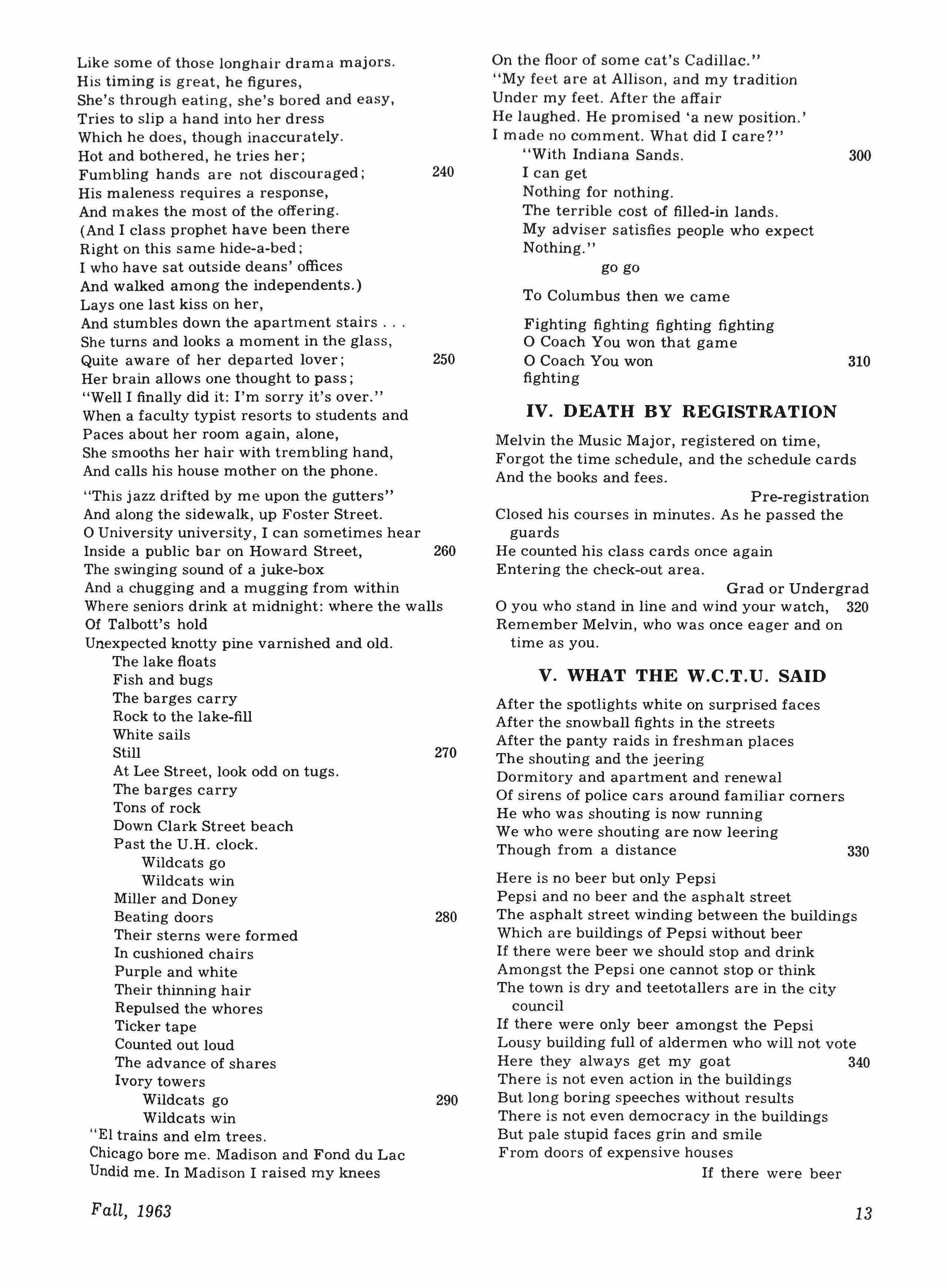

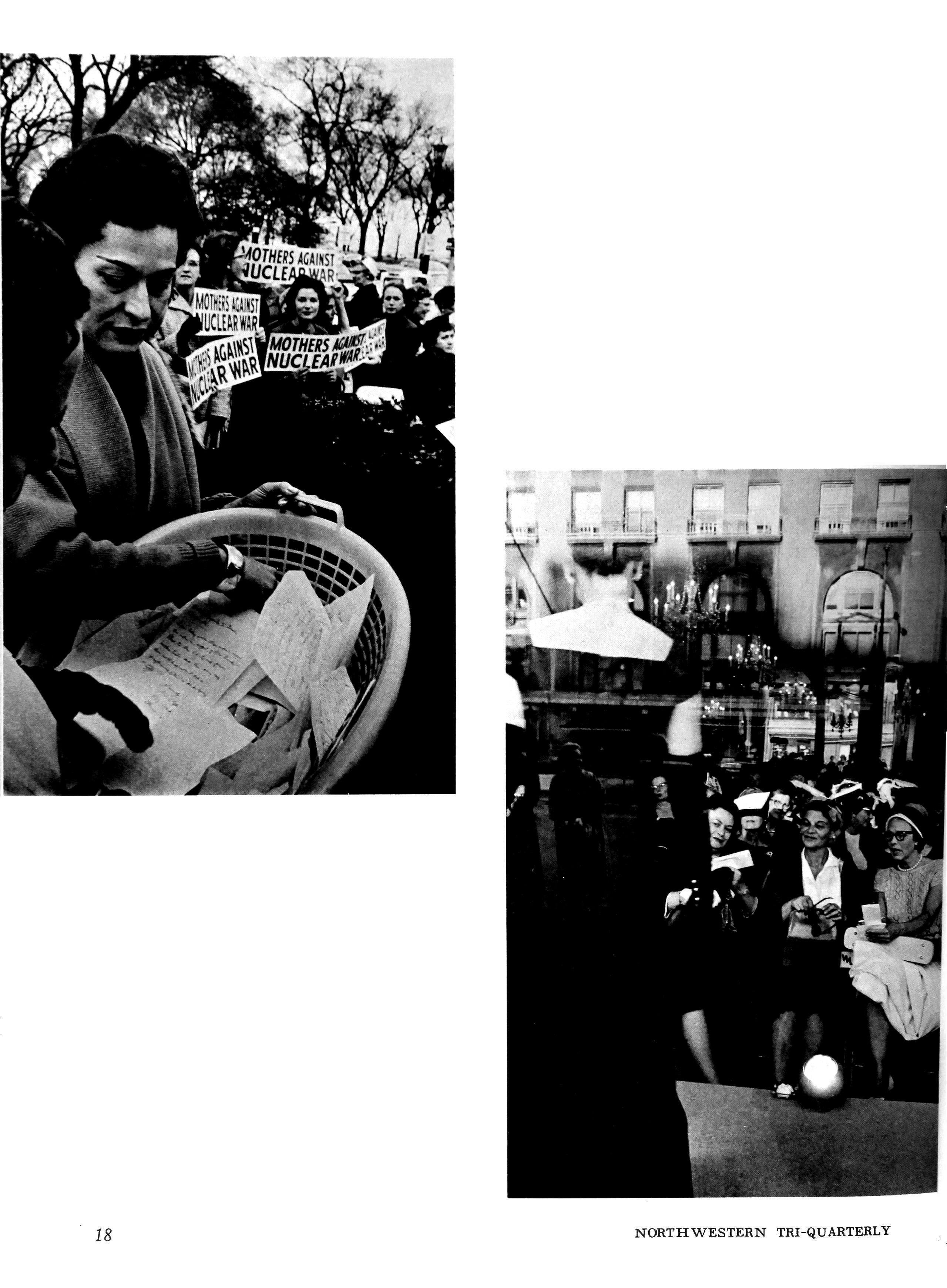

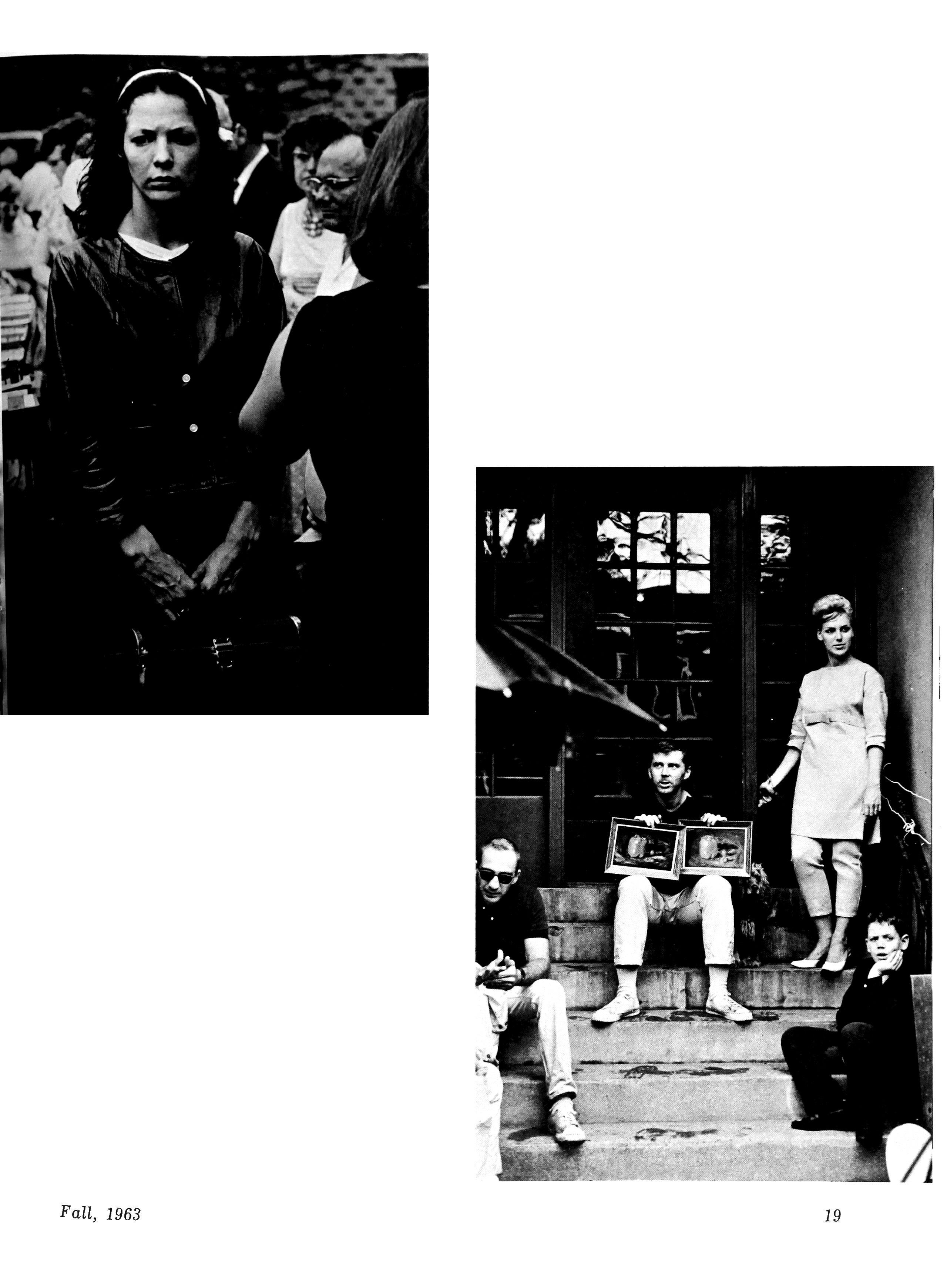

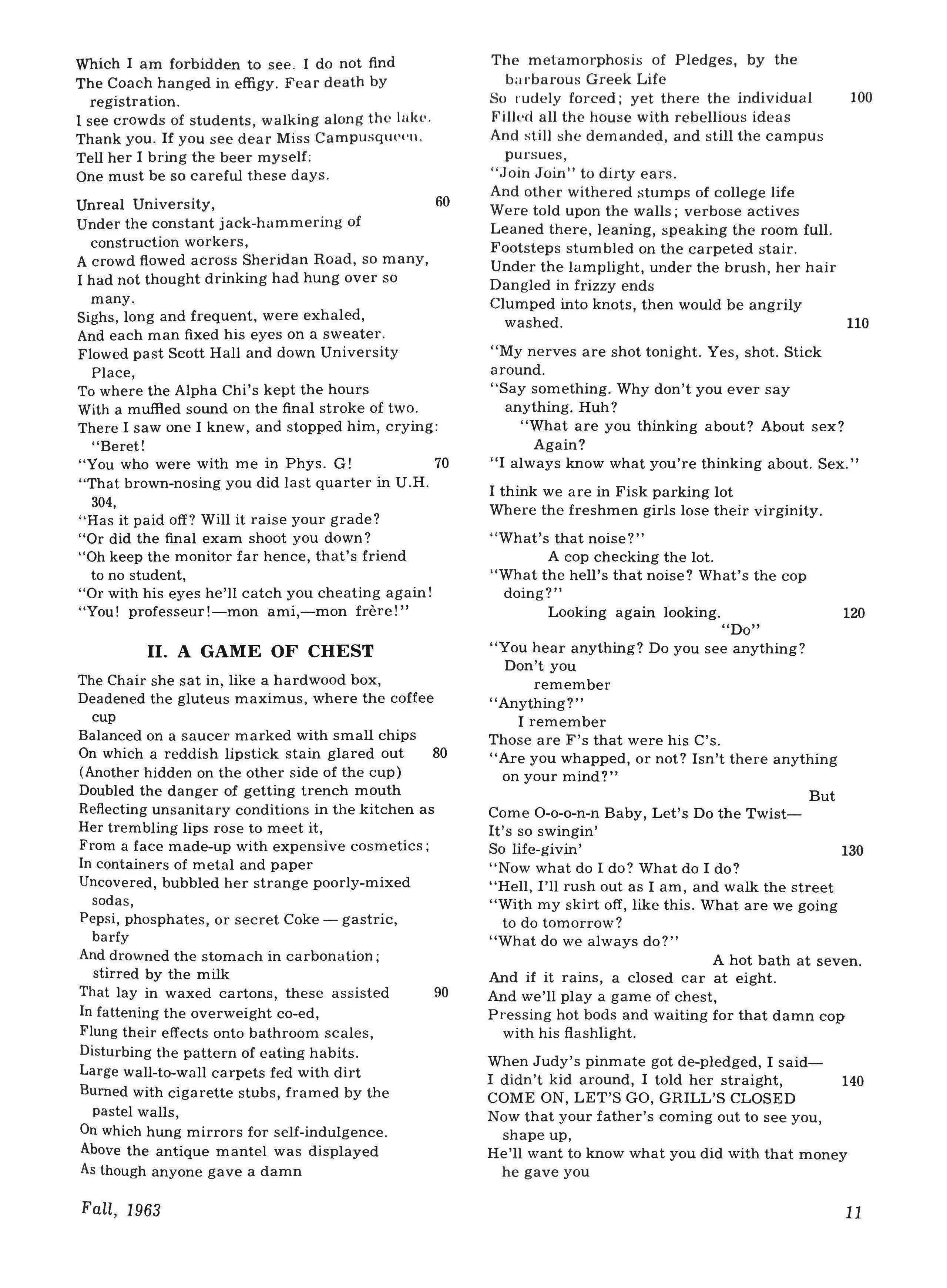

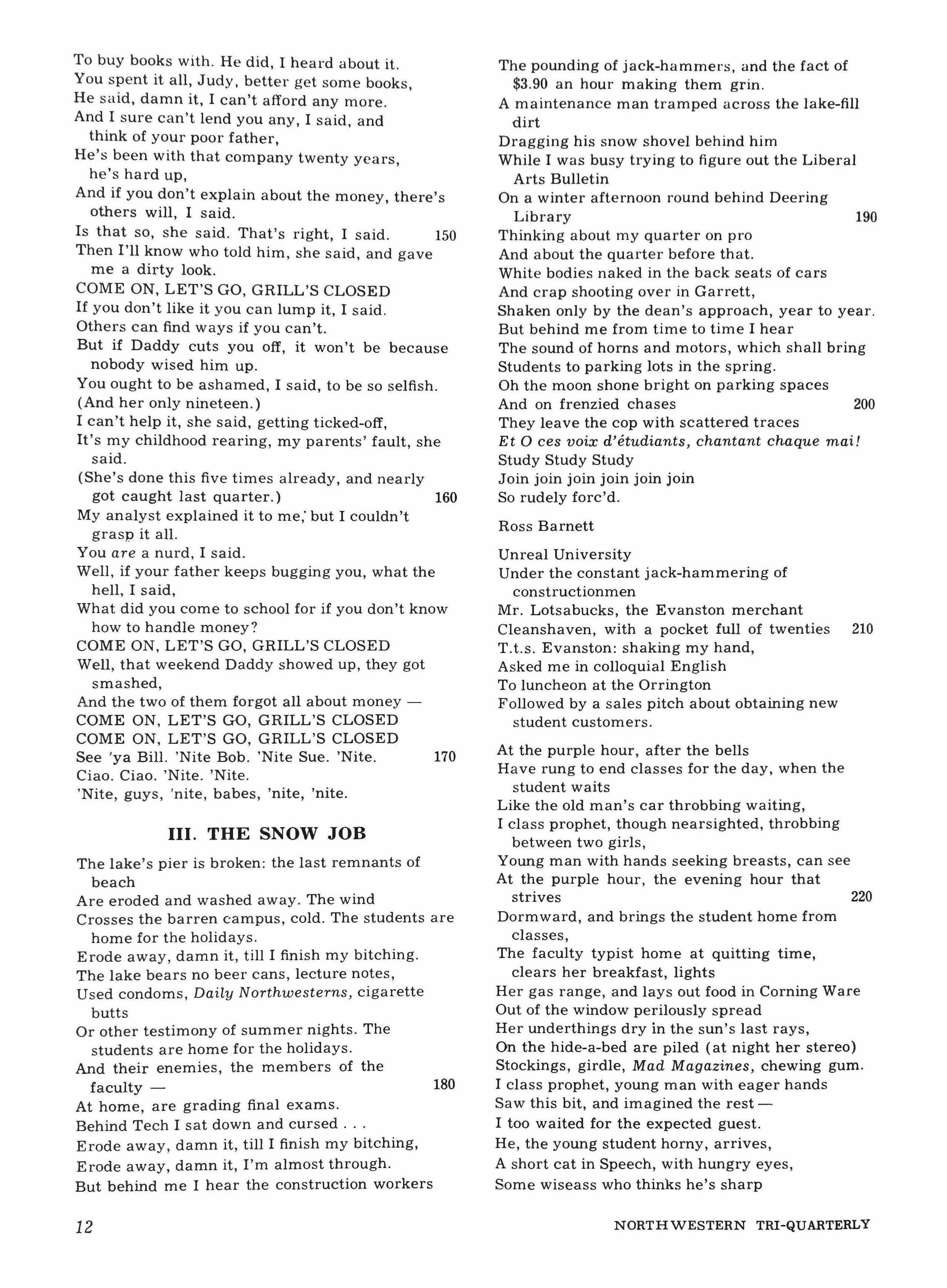

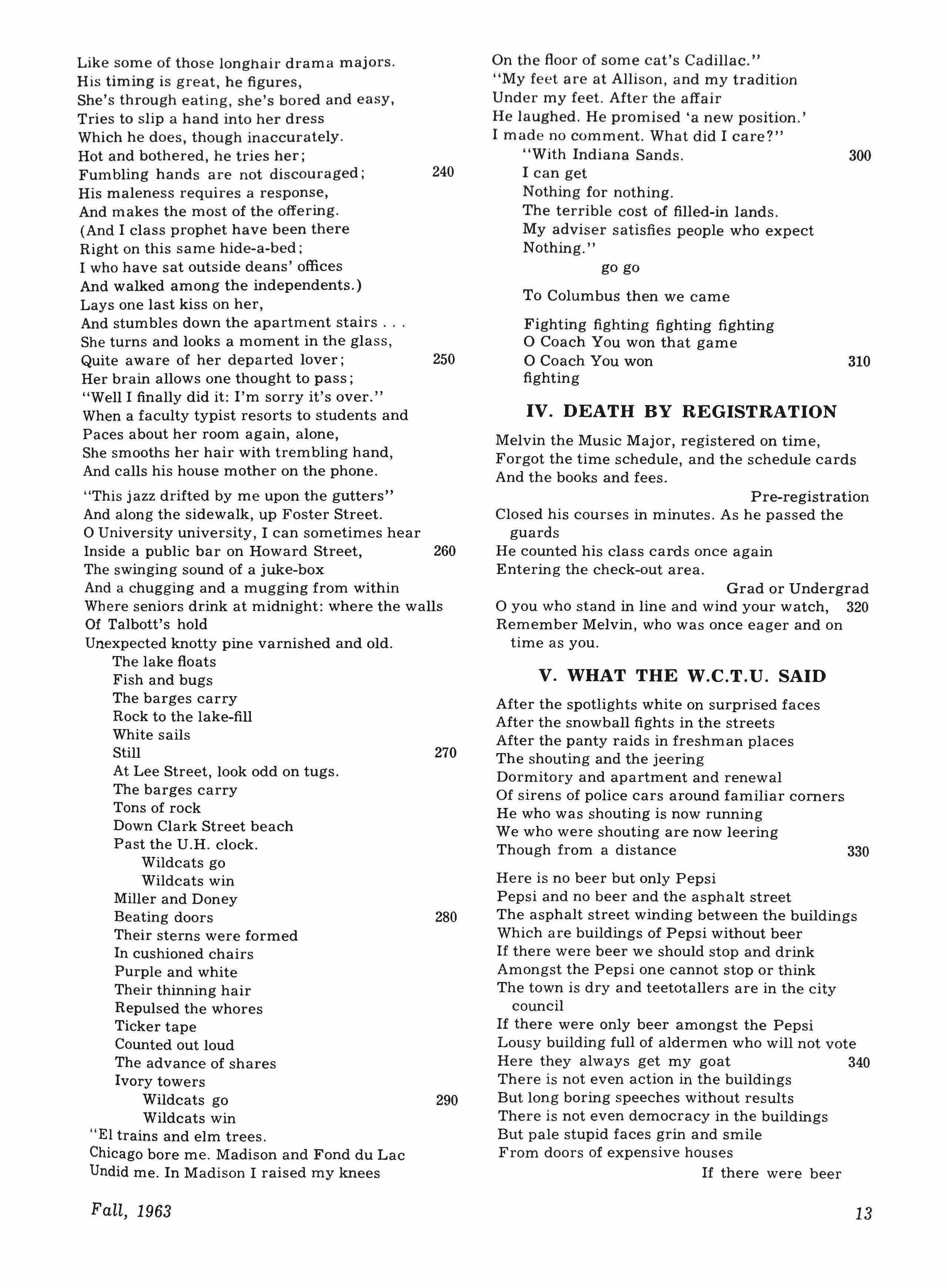

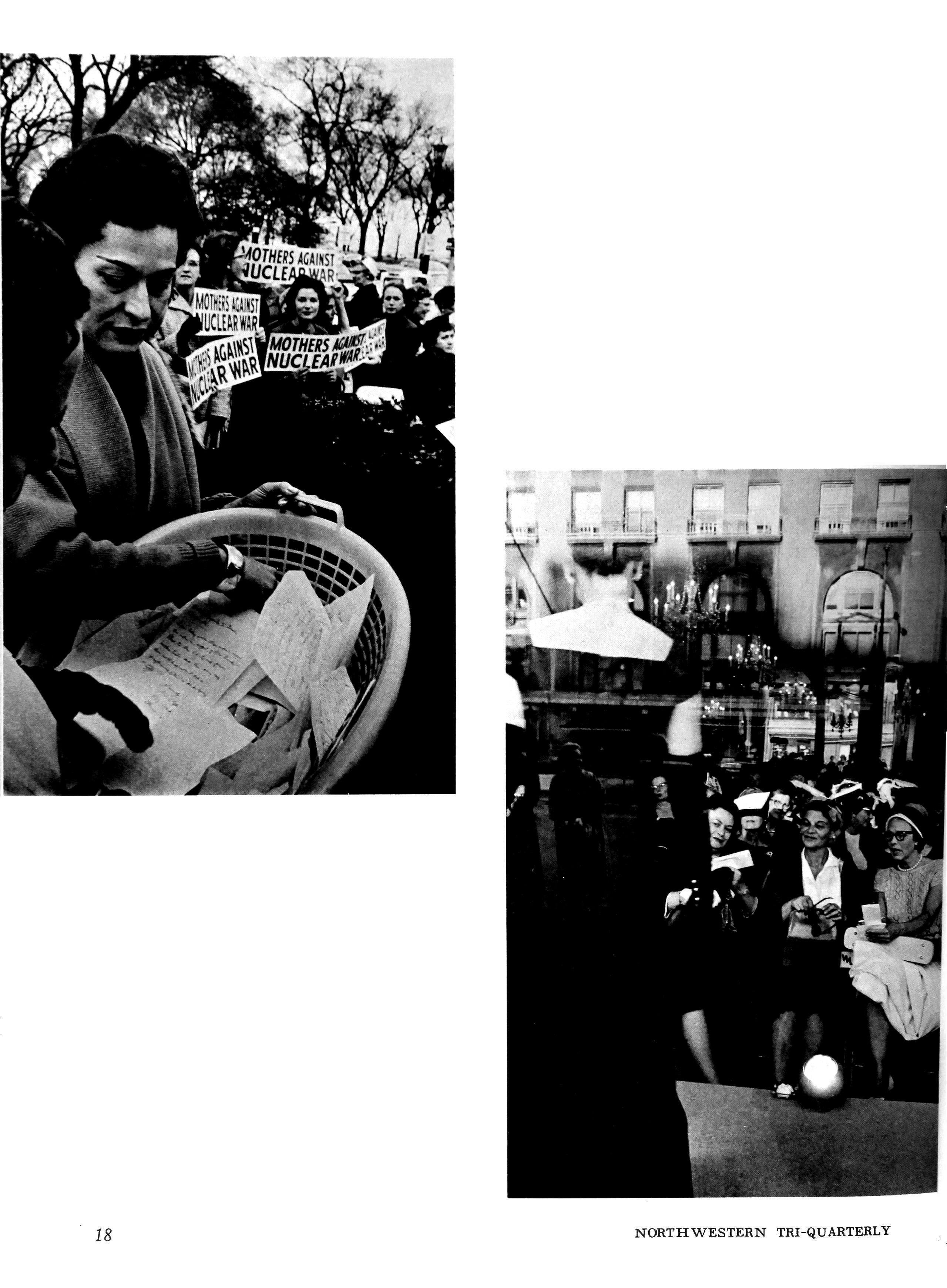

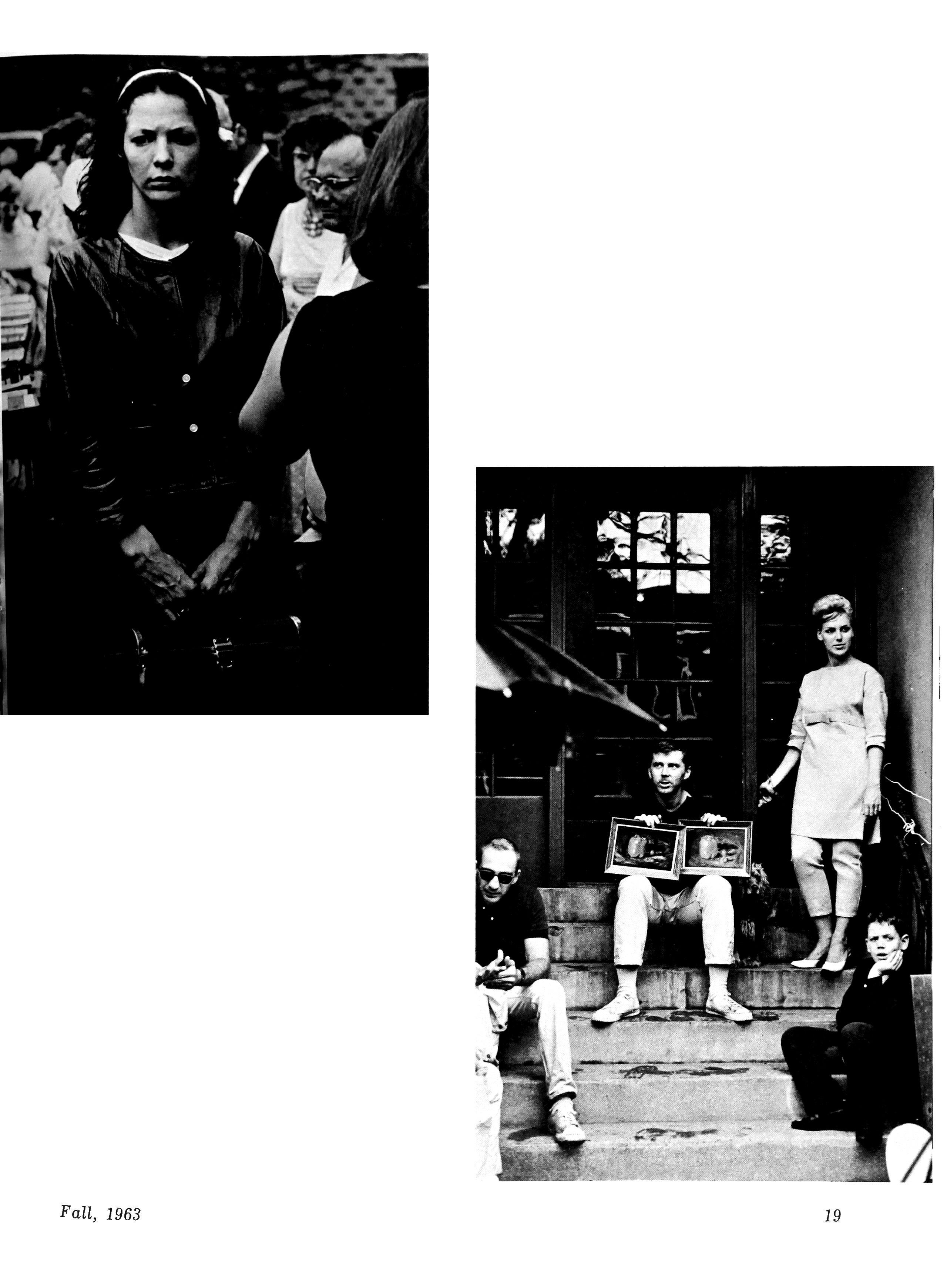

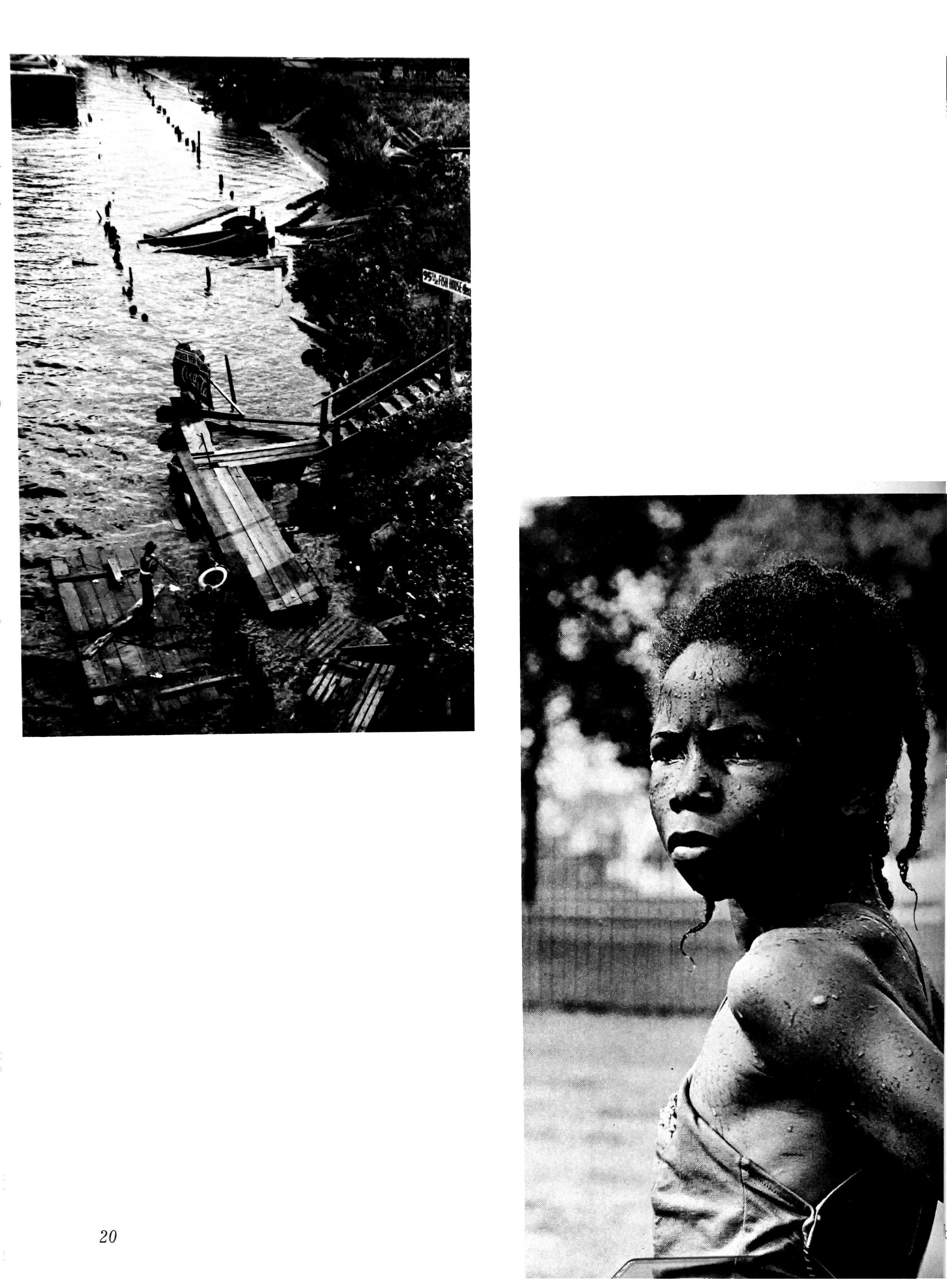

Herbert Comess came to Northwestern in 1959 as Staff Photographer and his work has contributed substantially to The Tri-Quarterly. For this issue the editors invited him to show some of his independent work, and the pictures on these pages are the ones which he has chosen. He presents them without titles or comments since he believes that a photograph should stand as a separate statement. His favorite examples have not always been of University scenes or persons.

A native Chicagoan, he enlisted in the Air Force and served for four years as Information Specialist attached to t'he wing which had dropped the first atomic bomb and which, at the time of his service, kept its live atomic bombs in a building next to his office. The journal which he edited was called The Atomic Blast.

He was a philosophy major at Roosevelt University (B.A. '55), after graduation became a civilian photographer for scientic research for the U.S. Government, worked in New York on magazine photography (advertising), and was later aHached to the Commercial Division of United Press International.

BY HERBERT COMESS

photographs

Fall,

1963

17

18 NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

Fall, 1963 19

20

Fall, 1963 21

by Barry G. Brissman

THE DEATH

Barry G. Brissman, whose liThe Pond" appeared in the spring issue of this magazine, holds the J. Scott Clark Scholarship, awarded for literary merit. He is interested in problems of style and craftsmanship. In the story below the shift in narrative person after the twenty year time gap is unorthodox but, as he explained to his classmates, lithe immediate intensity of the first person seemed right for the way I wanted to make Jonathan return after so many years./I

Brissman is a senior in the College of Liberal Arts, majoring in English and serving as an undergraduate editor of The Tri-Quarterly. His home is in Naperville, Illinois.

I.

and Lloyd was in the stall; at intervals a forkful of manure would appear out of the doorway and land on the back of the spreader. Boris leaned on the tractor wheel smoking cigars that were the same short stubby shape as himself.

"Nope, you're wrong," Boris said. "If ya' want people to remember you, slap 'em in the face. Yup, slap 'em in the face, and then ya' can bet they'll remember ya'."

The spreader was full and Lloyd came out of the stall shaking his head and looking at the floor as he walked. "Me, I'll get along with folks. Ya' ain't never dead long as someone remembers and thinks kindlymy brother al'us said that." The thin figure limped to the tractor and climbed on clumsily. Jonathan slid the doors open; amid the roar of the engine echoing off the walls the rig slowly passed out into the light snow, Lloyd perched atop the tractor like a sparrow. A minute later he was dead.

Somehow they all knew that eventually it would happen. In the first month he'd come to work he'd cut the four fingers off of his left hand while trimming firewood with a power saw. And he limped because once he'd turned his back on the bull. And there were all the little things. Lloyd himself always said he was unlucky - never complained about it, just mentioned it ruefully from time to time - and he never understood why. But the rest of them understood and weren't surprised when it finally happened that winter. The tractor slid into the ditch and turned over and crushed his chest.

They forgot about it pretty quick, but in the back of the mind it lingered, especially for those who'd been there and seen him all crushed out of shape under that tractor. Mostly it was what he had said, the words having barely died on his lips before he himself was dead: "Ya' ain't never

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

dead long as someone remembers and thinks kindly." In the back of the mind it lingered.

and Jeanie was beside him; after till' spring rain the scent of sweet clover carne to him as delicate and as deep as she was, the sweet clover that she always called her favorite smell. They walked along the dirt road that ran through the fields. Behind them the clump of farm buildings and trees loomed indistinct in the dusk; lights twinkled along the highway in the distance. It was their third year, and feeling her small hand in his, hearing her voice beside him, Jonathan knew that pretty soon, when he got the money, he would ask her. They walked slowly; the dirt road was soft underfoot.

"What about your brothers?" she asked.

"Oh, I don't know," Jonathan said. "When Arly graduates from high school this spring I suppose he'll stay here and help me do the farming. Pa can't ever work again with his heart like it is. Arly and I will take over the farm eventually, I suppose."

"Oh. And Ben?"

Jonathan shook his head. "He never cared for the farm. I don't think he'd be interested. He gets back in a month and he'll have to tell us then, when he's decided for sure. Pa always says Ben will never make a good farmer. I think Pa's right.

Jeanie lifted her eyes from the road and looked up at him. "You didn't used to get along with Ben too well the year just before he left, did you? Mavbe it's just as well he won't be working with you."

"Ben was awful wild," Jonathan said. "He never had any time for farming."

For a moment there was only silence, and then her voice came small and thin, hesitating. "Sometimes it's not so bad to be wild." Jonathan said nothing, but when she stopped walking he turned to her and waited. "I have something to tell you," she said. She bit her lip. "I think we should go out with other people."

Silence for a moment, then: "Is there someone else that you

"No, no one else, really. It's just I'm not sure. The love part."

"Oh." He tried to smile, put both hands on her shoulders and squeezed gently. "Okay," he said. His voice was a whisper. "I understand."

That was all. They turned around and walked back to the farm and Jonathan drove her back to town. Even along the road the warm wind whipping through the window brought the scent of sweet clover strong and clean.

and Arly was late getting home from school. Jonathan, working by the shop putting new cutters on the mower sickle, looked up when Arly walked over to him, and he saw Arly''« bloody

lip and bruised eye. "What happened to you?" he asked.

"Had a little trouble," Arly said.

"Looks like."

"Yeah, I was walking home passing in front of Toby's just as Bill Larson was coming out, and I bumped into him and knocked the beer can out of his hand. So he picked a fight I told him I was sorry and, well, I guess I lost mostly."

Jonathan dropped his wrench in the dirt and stood up, wiping the grease off his hands with a rag. He started walking towards the pick-up. "C'mon," he said.

"Now what you gonna' do, Jonathan? He was drunk." But Jonathan kept walking and Arly followed him, climbed into the pick-up beside him. Jonathan drove out of the yard fast and Arly started again. "I don't think you ought to make a thing of it, because he was drunk, after all, and I mean, it ain't his fault, really."

"Whose fault is it, yours?"

"No. Nobodys, I suppose. Maybe I'll be drunk sometime and do things and I'll want folks to make allowances. It ain't that I'm afraid of him."

"I know you ain't afraid, but he's thirty years old, and he ought'a know better. If he's drunk, he got himself that way."

"Well, I wouldn't make an enemy over it," Arly said slowly. "Seems we'd do best to forget it; he'd do the same, I think."

Jonathan kept his eyes on the road. "I don't forgive him; it don't work that way."

They parked in front of the bank and got out. Jonathan was not much bigger than Arly about an inch taller, a little wider. "But he was harder and he was two years older. Larson's car was still parked in front of Toby's. Larson was leaning on the fender. A beer can was in _his hand. It happened fast. Jonathan said, "Larson!" (the man turning and looking at him dumbly, Jonathan nodding toward Arly) "You cut my brother up like that?"

Larson set his beer can down on the hood of the car and straightened up his hulking body. "Yeah," he said. "He bumped _"

But before he could finish Jonathan hit him, hit him hard in the face. He swung with the right arm; the left hung relaxed at his side. As Larson staggered back against the car Jonathan hit him again, then turned away and walked back to the pick-up without watching him slump to the pavement.

People were on the street as there always were about quitting time. They were standing talking, or walking along casually, or getting out of cars and going into the drugstore to buy the paper, or into the grocery store for a quart of milk But it happened fast and not many of them noticed. Jonathan and Arly got into the pick-up and drove off, the engine whining its metallic

Fall,

1963

23

whine as they turned into the stream of traffic on the highway, heading into the sun.

and Ben was home after two years; it was early Sunday morning in June. He looked strapping in his uniform as he came smiling up the front walk and leaned over and kissed Ma. There was something very human about Ben, something winning. Everyone felt it.

That morning he went to church with Ma. He'd traveled all night and the uniform was a little rumpled, but he insisted, and he went to church the way he always used to. Jonathan couldn't go because there were sixty acres of alfalfa to be cut. Ma was disappointed that his own brothers couldn't at least go to church with Ben and give thanks on the day he came home safe from the Army. So Arly went along to help keep the peace. Arly always kept the peace.

For about a week Ben just loafed, helped in the fields when he felt like it, slept when he felt like it. And he drove around and talked to the neighbors, leaning on a fencepost or a truck or a tractor, telling about women and guns, how he hated the guns and loved the women. "Who wants to be fighting when you can be loving, anyway?"that's what he always said, even before he went away to the Army. And now he was confirmed in the opinion. He didn't care much for the Army, that's what he said. And he told about the women not with braggadocio, rather with a kind of fondness, a kind of sensuousness that was his nature. Ben told everything as a joke. When he talked the men listened and laughed.

Finally the talking and the loafing wore thin, and he began to spend more time working in the field. For several days straight he helped them haul hay. Sometimes he'd straighten up and look across the flat land and say how this work sure beat digging trenches with a shovel. And then he'd heave a hay bale up to Arly who was standing on the load eight tiers high off the wagon bed; that was the signal for Jonathan, a game they played. He'd holler for Ben to stand back and watch a man do it, and then he would heave a bale.

Then the working wore thin too, and Ben started looking for a job in the city. It was a fifteen mile drive each way, and he spent the day there and came back at night. But he didn't find anything that suited. And there was a blond that began keeping him out till three and four in the morning, so he didn't get started the following day until nearly noon.

Jonathan got the first cutting of alfalfa in that month, and he plowed up a twenty acre piece of summer fallow that hadn't been done in the fall. Working alone far out in the fields he thought of Jeanie. He saw her in the cold brilliant mornings, in the black earth flowing before the plowshare, in the hawk turning slowly in a blue sky

- in everything that he found beautiful and clean and good. But most of all she was in the scent of the sweet clover. It was planted amongst the alfalfa, and there was a whole field of it just east of the house. It drifted through the sultry days and was carried on the evening breeze, intoxicating. Somehow he felt that, whatever happened, she would always be the same Jeanie, changeless as the land.