VOLUME 5 NUMBER THREE NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY SPRING. 1963 TRI-QUARTERLY

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is a magazine devoted to fiction, poetry, and articles of general interest, published in the fall, winter, and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $2.00 yearly within the United States; $2.15, Canada; $2.25, foreign. Single copies will be sold locally for $.70. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to THE TRI-QUARTERLY, care of the Northwestern University Press, 1840 Sheridan Road, Evanston, Illinois. Contributions unaccompanied by II self-addressed envelope and return postage will not be returned. Except by invitation, contributors are limited to persons who have some connection with the University. Copyright, 1963, by Northwestern University. All rights reserved.

expressed in the

are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the editors.

Tri-Quarterly

EDITORIAL BOARD: The editor is EDWARD B. HUNGERFORD. Senior members of the advisory board are Professor RAY A. BILLINGTON of the College of Liberal Arts, Dean JAMES H. MCBURNEY of the School of Speech, Dr. WILLIAM B. WARTMAN of the School of Medicine, and Mr. JAMES M. BARKER of the Board of Trustees.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITORS: SUSAN F. MC ILVAINE, FORREST G. ROBERTSON, HERBERT M. ATHERTON, and CAROLYN BURROWS.

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is distributed by Northwestern University Press, and is under the business management of the Press. Design, layout, and production are by the University Publications Office.

Art Editor jor this issue is Lauretta Akkeron. Photographs oy Herb Comess.

Views

articles published

Adlai E. Stevenson Foreign Affairs and the United Nations 3 Stephen Spender The Self-Unfeigning 7 Thomas H. Arthur Very Short Stories 8 Jeff Corydon III The Other Side of Saigon 12 Edward S. Petersen Age, Medicine and Money 16 Wilbert Seidel The More Things Seem to Change 20 B. Forrest Shearon The South from a Distance 26 Barry G. Brissman The Pond 30 Yohma Gray The Poetry of Louis Simpson 33 Gary L. Blonston Wedding Knot 40 Austin Stoll The Caste System 44 Poems, Susan Allen 47 Thomas H. Arthur 32 Blake Leach 15 Malcolm McCollum 19. 47 John Stewart Carter 11 Michael Dalzell 15. 19

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Volume 5 SPRING Number Three

Foreign Affairs and the United

Nations

ADLAI E. STEVENSON

An Address Delivered Before the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations

IWhen the United States' Ambassador to the United Nations came to Chicago to deliver an address, on February 19th, at a luncheon marking the fortieth anniversary of the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations, he was kind enough to permit us to print the address in this Spring issue of The Tri-Quarterly. The copy below, taken from his manuscript, omits at his suggestion the introductory portions, which were spoken with pleasant informality merely to the members of the society and their guests.

Since the name Adlai E. Stevenson is known to all our possible readers, even to the youngest visiting student from the farthest part of the world, we note here �nly �n item which gives us an especial pride in print'"g h,s words - the fact that he is an alumnus of Northwestern, having graduated from the Law School in 1926.

I am indebted to Mr. Adlai E. stevenson III for his help, �t a busy time, in obtaining his father's permission and his manuscript.

Spring, 1963

suppose you want me to talk about foreign affairs and the U.N. Well, there have been many long days and nights in New York when I wished I was in Chicago. I am reminded of the young mother who told me her husband was being transferred to New York and when the news reached the children she overheard her small daughter saying her prayers: "God Bless Mummy, God Bless Daddy and Freddy, and now, God, I must say good bye; we are moving to New York." And I could add that moving to New York and the U.N., merits even more divine sympathy. I have heard a psychiatrist say that a diplomat at the U.N. should have a healthy split personality; he should be an idealist but also· practical; stubborn but compromising; spiritual but down to earth; dynamic but reflective. Well, I've concluded that he's right, and that to deal with diplomats from 110 countries representing every culture, race, language, interest and prejudice simultaneously and on every question - political, economic and social - quickly presents one with a choice between galloping frustration, ulcers, or a sense of humor. I've chosen the latter, plus a little perspective and a lot of patience, I hope!

There have been many changes since my previous service at the U.N. The membership has doubled - the first sovereign act of every new country is to apply for membership. The annual agenda of the General Assembly has mounted to 100 questions - and the U.S is involved directly in virtually everyone. The old, more or less kindred and democratic nations, have lost their majority to the Afro-Asians and can no longer easily dominate the scene. The cold war struggle for influence and allegiance among the newer na-

3

tions is much more intense, and neutrality or non-alignment has vastly increased. Peace and development, not cold war politics, are the first interest of the new nations. No, there is only one priority, national independence for all; anticolonialism and equality of status generate a passion that is sometimes irresponsible, but always understandable.

Evidently it has been something of a shock to many Americans to realize how rapidly the world has changed; that others don't always see things exactly as we do; that the U.N. is not a panacea or a wing of the State Department. A lot of people in the U.N., for example, find it hard to understand why the Russians should not have troops in Cuba while we have even more in Turkey.

But in spite of our worries, frustrations and fears the U.N. remains an incalculable asset to the peace and security of our country. So let me in my limited time take you on a short guided tour of the stormy horizon as I see it from my office overlooking the U.N. in New York.

First, by every measure, the United States continues the leading power of the world, as a result of our military power, the abundance and great reserve of our economic power, the world-wide extent of our alliances, and the talents of our people. Yet we have no monopoly of power, nor even of nuclear weapons: and we could not force our will upon the rest of the world even if we wanted to - which we don't.

Second, the new imperialist powers, the Soviet Union and Communist China - despite their profound internal conflicts - both see America as the chief obstacle to world domination. Both would bury us, the Russians by peaceful means, the Chinese by violence. But both are in favor of the funeral. And both strive to extend their power elsewhere. They sharpen every quarrel and inflame every point of friction between the United States and any other non-communist nationand thereby strive to strip one nation at a time of our friendship and our protective power.

But they're not doing very well. None of the defeats in Africa, Asia and the Middle East which the pessimists were confidently predicting not long ago has come to pass. The U.N. frustrated Communist designs to penetrate Central Africa from the Congo. In Asia the Chinese have acutely embarrassed Moscow by attacking India. And instead of taking over the Middle East the Communists are now fleeing headlong from Iraq, and much of the Communist investment there is now down the drain. Meanwhile if General De Gaulle has embarrassed the West the divisions in the Communist ranks throughout the world are far worse.

Third, the great western colonial empires are vanishing. This huge transformation had its roots in the free institutions of the colonial powers themselves, So today a billion human beings are 4

marching on to the stage. If their delegates still have a lingering distrust of the West which so recently ruled over them, they also look to the West for help in pursuing their two great aims of independence and economic and social development.

Fourth, the Communists are trying desperately to capture the great social revolution which is sweeping over Latin America and to divert these vast new energies into channels of violence and hatred. The Alliance for Progress aims to put these energies to work to create a more prosperous and egalitarian society in the Western Hemisphere. Our challenging task now is to make sure that Moscow will never again parlay the tyranny of a Batista into the tyranny of a Castro; and to see to it that a community of freedom in this hemisphere is flourishing long after the Castroism has passed into history. And the challenge in Latin America may be the most critical and difficult we have to face anywhere.

Finally, the free nations of Europe, with our help, have not only recovered from the ruin of the war and turned back the rising tide of domestic communism, but are building a new economic and political community in Europe to replace the old rivalries and civil wars.

All of you are familiar with the situation brought about by France's exclusion of Britain from the European economic community and France's rejection of a multi-national nuclear defense. The headlines have been black, but I think it may be the better part of wisdom to wait and see if the results are as black as the headlines. Few finalities are as final as they seem at first. And this is not the final blow to European unity, to the grand alliance or the Atlantic community.

President Kennedy has reacted with restraint, and I think that is a good cue for all of us, You may recall the universal despair just 10 years ago when France derailed the proposed European defense community. It drove John Foster Dulles to talk of an agonizing reappraisal. But it was not the end of hope for a united Europe and out of that disaster the present day European economic community emerged.

Victor Hugo once said: "There is nothing in all the world so powerful as an idea whose time has come." I believe the time has come - if not today - then surely tomorrow - for not only a European community, but a larger Atlantic community. And it should not be hard for us to understand why General De Gaulle with his views of the historic position of France should want more to say about when and by whom the nuclear weapon is fired. Nor should it be hard for Europe to understand why we expect it to bear a larger share of the defense burden which has been ours for so long.

Now, against this horizon, let us examine how

NORTH

TRI-QUARTERLY

WESTERN

the decision to join the United Nations has served our national self-interest as few other decisions in our history.

What the United States wants for itself - u world free of fear, free of want, free of prejudice, a world made safe by universal adherence to the principles of the Charter - is what free men the world over want. That they do has been demonstrated these past seventeen years by their actions at the U.N., actions which never once have impaired the vital interests of the United States. To frustrate the majority view, the Soviet Union has cast 100 vetoes. The U.S. has yet to cast its first.

Nonetheless, we have, as I say, skeptics who decry our support of the United Nations. Latterly they point to the Congo and Cuba.

In the Congo, the U. N. - for more than two years and with the help of many nations, especially ours - has protected the infant republic from internal chaos, reconquest and communist subversion. Like the previous secessions in Kasai and Orientale, the secession of Katanga has ended, and with it the danger of a great power confrontation in the heart of Africa, with all its ominous implications, has been averted. There was never any valid issue of self-determination in Katanga Province under Tshombe any more than in Orientale Province under Gizenga.

The United States' objective in the Congo was to help establish conditions under which the Congolese people could work out peacefully their own future. And that is precisely what the U.N. has made possible under incredibly difficult circumstances and amid widespread and vocal opposition. This has been the U.N.'s most complex and dangerous peace-keeping mission and its most costly by far. But civil war and the danger of great power intervention has been averted, and a grave threat to the peace removed.

I would like to emphasize that this has not been a victory for the U.N. - for the U.N. seeks no victories - but it has been a notable victory for the rule of law and of peace. And if any Americans still have their doubts about it, I would ask them one question: would they have preferred that American soldiers do the job?

Now that the military phase is over the nationbuilding phase begins, and, if anything, it will be an even harder job. The Congo now faces three key obstacles to progress and survival as a united country:

An underdeveloped political system which cannot yet deal with the country's needs.

An expensive military establishment of dubious effectiveness and uncertain discipline.

A financial administration which collects much less revenue than it could, disburses funds carelessly, and is subject to more pressure than it can handle.

Spring, 1963

More than external aid, success of a nationbuilding effort depends on developing the administrative fiber to train the national army, get the fiscal system under control, and construct a political system featuring a strong executive. If these prerequisites can be met, the Congo should not be a burden to its friends in a few years' time.

As for Cuba, when that crisis erupted, the United States left no doubt about its intention to protect itself and this hemisphere. But we also acted in strict accordance with the Rio Pact through the Organization of American States, and in strict accordance with the charter of the U.N. through the Security Council. The U.N. peace-keeping machinery functioned just as the charter contemplated: it provided a forum for discussion of our complaint against the Soviet Union; it provided a means of marshaling world opinion, and it provided conciliation and mediation services. In that showdown of last October and in our subsequent negotiations with the Russians the most dangerous crisis since the War was resolved without resort to military measures and nuclear war.

And I'd like to bring to your attention some observations by an old friend, Lester Pearson of Canada, who had this to say about our handling of the Cuban crisis:

"When you have a good case, with strength to back it, stand firm: without provocation or panic. When action in defense of that case has to be taken quickly, and by yourself, bring that action before the United Nations at once - as the United States did on this occasion.

"The United Nations, once again, became the indispensable agency through which the Parties could find a way out of a crisis, without war. I know the United Nations can't force a solution on a great power which doesn't want it. But you can't exaggerate its importance as a means for finding and for supervising a solution."

That, I think, just about sums it up.

But now, despite our success in effecting the peaceful removal of the really dangerous weapons from Cuba, some politicians and columnists are suggesting that long range missiles may still be hidden in Cuba and that the remaining Russian forces are a dire danger and should be withdrawn. Of course they don't say how. But I agree emphatically that Khrushchev should take his men home, not just because he said he intended to, but because the presence of any foreign forces in this hemisphere is bound to add to the tension and sharpen the East-West conflict and therefore the hazards in another vast area of the world. And I would not be surprised if he did remove them, unless we make it too embarrassing for him to back down again.

However, having spent a couple of months in almost constant negotiation with the Russians

5

about Cuba this Fall, I am bold enough to suggest to you that we ought to bear two facts in mind.

First, as President Kennedy pointed out, in the unlikely event that any missiles remain hidden in Cuba, they could not be brought out into the open, placed on launching pads, and made operational, without quick detection by the United States. And neither Cuba nor Russia can be in any doubt about how we would respond.

Second, the present military complex in Cuba does not pose a threat of armed aggression. It has no logistical capacity for any seaborne or airborne aggression. And even if it did the United States has made it clear that it would stop in its tracks any adventure from Cuba - with, we can be sure, the support of the OAS.

No, the danger from Cuba is not the military build-up of the past year. The danger is what it has been ever since Castro unmasked his communism. The danger is not attack but subversion, penetration and organized violence. And the danger is not to this country but to Latin America. Venezuela is, of course, the first target. But all Latin America is in the target, and it is virtually all vulnerable. I am far more concerned about the hundreds of Latin Americans flocking to Cuba for training in communist theory and techniques and what they can do to subvert the universal social revolution than I am about the Russian troops.

So let's not lose sight of the forest for the trees. And it might be well to recall what Lincoln told Congress at another critical time:

"In times like the present, men should utter nothing for which they would not willingly be responsible through time and in eternity."

But enough of Cuba and the Congo. In the past year we must add other items to the long list of U.N. peace-keeping activities: West New Guinea; Thailand and Cambodia; Rwanda and Burundi. And Yemen, Borneo and the Malaysian Federation may not be far behind, with more trouble spots on the horizon.

With a record of successes going back to the withdrawal of the Russians from Iran in 1946 one would imagine that there would be little problem of financial support to make the organization an even more vital force for peace. But that is not the case. Some countries that promptly pay their assessments for the regular budget have not supported all the recent peace-keeping operations, notably the Soviet Union, for obvious reasons, and now France. Many smaller countries are hard put to it and feel that peace-keeping is peculiarly the responsibility of the great powers.

So a serious financial crisis is threatening. It will become acute when the proceeds of last year's bond issue are exhausted in June. A committee is now considering alternatives. It may recommend a special scale of assessments in 6

lieu of the present voluntary contributions, which would save us money. A special session of the General Assembly will probably follow in May. And, of course, much will depend on the attitude of our Congress as to the extent and effectiveness of this vital aspect of the U. N.'s functions.

Of course nothing would serve the Communist purpose better than to have America reduce or cut off entirely its financial support for peacekeeping operations that interfere with the Kremlin's designs, as in the Congo. But no matter how rich or strong we are, the United States cannot be the policeman of the world, though, unhappily, many of the smaller nations whose only security is the U.N., and many of our larger friends would gladly leave to us most of the responsibility and most of the burden.

I had hoped to talk to you about the indispensable role of the U.N. in nation-building, which is the first priority of the newer, poorer nations. Pushed to the first outskirts of modernity by western investment and trade, emancipated before they had received either the training or the powers of wealth-creation needed for a modern society, they are caught between two worldsthe powerful, affluent, expanding world of the developed "North," and the traditional, pre-technological, largely poor world of the underdeveloped "South."

As the rich get richer and the poor poorer this division in world society is a great obstacle to the expansion of confidence and community in the world.

I know there is much dissatisfaction about aid, much feeling that it is wasted and never achieves a "breakth"rough," and dribbles away down thousands of unspecified drains and ratholes. Yet just so did the Victorians talk about tax money devoted to lifting the standards of the very poor in early industrial society. But over a couple of generations, it was the raising of all this unfortunate mass of humanity that turned western society into the first social order in history in which everyone could expect something of an equal chance.

And, who can say, in the long run perhaps equal chance and equal dignity for the vast emerging masses may have more to do with peace and security for all than the cold war today or the unification of Western Europe tomorrow.

To conclude these desultory remarks: The U.N. is not the whole answer to world peace, and never was from the day the world divided after the War. It is not a World Government. It is admittedly unable to impose any settlement on the great powers against their will, though it can on occasion exercise a potent persuasive force. It is a reflection of the divided world in which we live, but the consensus of its members represents a moral force that cannot be lightly ignored.

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

We should not think of it just as a convenient repository for insoluble problems, but rather as an instrument of U.S. policy which we should use to further our objectives.

It is a complicated instrument, of course, because it is also an instrument of the foreign policy of 109 other countries.

It is also a limited instrument: if we want to defend Europe, the U.N. is largely irrelevant and Nato is essential; if we want to relate ourselves to the less developed countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America, the U.N. is essential and Nato is irrelevant.

Let me sum up in this way. The United States has an aim in this world, an aim to build a community of nations, diverse, tolerant and genuinely independent - but bound together by a sense of common humanity and by a common interest in peace and progress. In such a community every nation and every man, strong or weak, will have the greatest chance to develop the unlimited possibilities of freedom. In such a community we Americans ourselves will have the greatest chance to hand down our freedom and prosperity to future generations. The growth of such a community, too coherent and too vigorous for Communism to undermine, therefore, is as vital a factor in our security - and for our future - as our armed power.

To build this community one of the instruments is the U.N. It is not a magic lamp. Perhaps it is only a candle in the window. But its spirit is that of community, tolerance, give and takewithout which there can be no peace. Its method is parliamentary diplomacy, debating, voting, the writing and rewriting of resolutions, days and nights of discussion and careful listening

We are successful at it, for both the spirit and the method are second nature to Democracy.

But if Democracy is to be nurtured in new countries, as well as preserved in the old, if the U. N. is to succeed, we must all have time - a time of peace. For it is peace which generates the factors most favorable to the growth of Democracy: prosperity, stability, education, freedom of thought, and the mutual trust which encourages free and fruitful communication between nations.

I cannot agree, therefore, with those who are disdainful and impatient with world opinion as it is reflected in the United Nations. From its beginnings our country has had a "decent respect for the opinions of mankind." Our Declaration of Independence was proclaimed not as the act of separation but in order to make clear to "World Opinion" why we had taken this momentous step.

Indeed, in the new era the greatness of a nation may yet be measured not by its might but by its magnanimity. And by whatever exertions and whatever endurance history may require of us, we intend to pursue the vision of a free world at peace, and to provide other nations an example and a leadership to which "the Wise and Good may repair" - to borrow a phrase from George Washington, whose birth we celebrate at this season.

So, if you conclude from all this that I believe our membership in the U.N. serves us well, you are right. Indeed, I feel a little like the Irish peasant who said to the poet Yeats: "Sure, I believe in fairies. Never seen any, but it stands to reason."

The Tri-Quarterly is pleased to be the first to print this new poem by Mr. Stephen Spender, both for the poem itself and because he gave it to us while he was teaching at the University. What Mr. Spender says in the poem about "the white paper" might well be said by all of us about his teaching. His presence at Northwestern was a happy translation of himself into the minds and lives of his students.

Spring, 1963

THE SELF - UNFEIGNING

He thought of the white paper as Where he should be what he was. The writing was the sap that grows Up the stem to be the rose. If in the heart the blood was song Words from the heart could not be wrung. All he had to do was be His own truth flaming on a tree.

So he wrote without pretence His youth, his truth, his own sentence. What it Showed was him indeed, Judgement there for all to read.

'Ilf "�� �t,;,'"if?\. 'i:

STEPHEN SPENDER

7

very shol't stol'ies

Thomas H. Al'thul'

Thomas H. Al'thul'

Thomas H. Arthur, Speech '59, is currently studying parttime for a master's degree in the expectation of teaching. He is a native Chicagoan, was raised on the North Shore, and now lives in Hyde Park. He has worked for several Chicago area advertising magazines and has been active in University of Chicago theater and other local groups, and in Channel Eleven's Festival Series.

He likes to write short sketches, of which the pieces below are examples, some of which resulted from a recent trip to Europe.

Nuremberg to Zurich

I am on a train riding from Nuremberg to Zurich. Two companions, American soldiers on furlough whom I met at the station, and I have seated ourselves on one side of a second class compartment. A German sailor and an attractive but somewhat faded looking woman sit opposite us.

My friends are curious about the German navy and try to ask the sailor questions. What is his rank and how much do his uniforms cost and how long are his leaves and how often does he get them? The sailor, who is blond, rosy cheeked, and very young, is flattered at their interest but he knows no English and they know little German.

The woman says something to the sailor in their language and then turns to us and in slow, very correct English, offers to translate. She is about fifty years old and she has the air of bittersweet inner exhaustion that I have noticed among so many of the people of her age that I have met in Germany.

The conversation proceeds from one subject to the next and I listen with great interest. My friends ask the woman about the war but she shakes her head and will not talk about it. To change the subject she asks about American politics in which, she says, she has always had a great interest. Our elections are so tumultuous and to her eyes, undignified, and she has heard that the results are fixed in advance.

The soldiers and I become excited and enthusiastic. We all three begin to talk at once. I

talk about the structure and heritage of our system. One of my soldier friends has been a party worker in New York and he gives a colorful account of big city politics. The sailor watches us quietly as we speak with pride and affection about our country. Our elections are not fixed, we say, and if they seem undignified and even funny to the rest of the world, it is because our government actually belongs to the people and is the people. It is a big country with a lot of individuals in it, and we all have the right at any time to sound off and do something about what concerns us. This is what the rest of the world hears at election time and the fact that the noise exists is a great strength and beauty of America so we say.

We pull into a station along the way and the sailor gathers his things together. One of the soldiers leans out of the window and buys a sausage and a beer. He starts to throw the empty containers out of the train but I stop him and put the refuse under my seat. Everything in Germany is so clean that I cannot bear to see him do it.

The sailor stands up and pulls a paper bag from the roll on his back. He hands it to me with a stiff little bow. The woman says, "For the waste," and points under my seat. I open the bag and find two large apples inside. The sailor smiles and indicates that they are to be split between my two friends and myself. We try to thank him but he flushes with embarrassment and leaves hurriedly.

8

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

'f.·uill to Berlin

I am alone in the compartment as the train lurches and sways through the night. From my window the only lights that I can see come from factories, which seem to be going full blastand from regularly spaced spotlights on poles which are aimed down at the tracks. Occasionally I catch a glimpse of the barbed wire which runs along next to the train. Strange gloomy country. There is no light from houses if there are houses, nor from cars if there are roads.

From time to time we pull into stops which are more like dim fortresses than stations. We wait while soldiers climb down and march away and are replaced by other soldiers.

Each new group spreads out through the train searching for refugees, shining lights into compartments, pulling open washroom doors. They are absolutely silent.

The passengers too are quiet. The whole grim ritual seems to take place of its own accord as if an invisible presence is moving marionettes. It is a pantomime unrelated co flesh or sound, suffered by all participants as if they were not really there.

The train moves off again and, as there is nothing to see, I drowse.

I am shaken awake by a soldier. Automatically I hand him my passport and tell him that I cannot speak his language. He thumbs through it, then suddenly slams it shut and puts it in his pocket. He looks hard at me - and goes quickly out the door.

It is a bad moment. I wonder if my papers are in order. What is it that I have done? I am moving across a void - a gap in my own experience - and something is wrong. What will be done to me? Where has my passport been taken?

Finally my door is opened and the soldier comes in leading another soldier and a civilian. I see that a guard is stationed outside in the passageway. Without any preliminaries whatsoever the civilian shouts at me and keeps shouting. I am terrified. I try to explain that I don't understand his questions - his commands - but he keeps shouting as if he cannot hear me.

I am pulled out of my seat and searched. Every-

thing in my pockets is laid out on the seat next to mine. My luggage is pulled open and scattered. All the while the civilian is screaming questions at me.

I try in my terrible German to explain that I am a tourist - going to Berlin to see the city, and that is all. Abruptly he pushes me down and sits opposite me. He scribbles something on a sheet of paper and takes some money. He tucks the paper into my passport and shuts it. Then he looks at me and smiles.

It is not a pleasant smile but I relax a little. His smile grows broader and he leans toward me and holds out my passport. I reach for it but just as I am about to touch it he pulls it back. He is still smiling. My terror grows. Again he leans toward me with my passport in his extended hand. Again I reach for it and again he pulls it back.

It dawns on me that I must do this over and over and it is too much. I am more frightened than I can be and I begin to laugh. One of the soldiers breaks into laughter too and for a moment we both howl.

The civilian literally screams at the top of his lungs at the soldier and then turns to me redfaced and shaking with fury. He rages and bellows and threatens until he runs out of breath. Then he thrusts the passport under my nose. I look away from him and reach for it Again and again I reach for it.

When he and the soldiers have gone, and I have my passport, I fall asleep very soundly asleep, and I do not wake up again until the train stops with a jolt. We have pulled up next to a brilliantly lighted building and platform, surrounded by barbed wire. There are soldiers everywhere.

When the last East German is off the train we begin slowly to move. I see the two soldiers who were in my compartment, walking together. The one who laughed looks up toward my window and I stick out my tongue at him. He laughs again and makes an obscene gesture which I can see until the train curves into the woods that mark the border of Berlin.

Spring, 1963 9

New York Bus

I am on a shuttle bus from the airport into the city. We have pulled off the expressway and are moving along the outside lane on Queens Highway. It is close to midnight but the traffic is still heavy and we must swerve this way and that to avoid it. Suddenly the driver stops in the middle of the lane and pulls on his emergency brake. He swings around in his seat.

"Ladies and gentlemen, may I have your attention please?" We look at him and at each other in confusion. What has happened? What will he say? This is obviously some sort of crisis.

"Ladies and gentlemen," he says, "look around. One of you is sitting next to a louse!" He lets this sink in for a moment and then he says solemnly, "There are thirty-five of you aboard but I count only thirty-four paid fares." We all begin to feel uncomfortable.

"I would like to talk to that thirty-fifth person," he says. "The rest of you can tune out. Sir or Madam, as the case may be, before this trip into the city started, I carefully packed everybody's luggage in the back of the bus. I tried to collect money for tickets at the same time but one of you snuck onto the bus anyhow."

He continues, "I got a wife and three kids to support. My oldest boy is seven, my second is five, and I got a little girl who just passed her

first birthday. They are nice pretty kids." He pauses but does not take his eyes off us. We shift in our seats and sneak suspicious looks at each other. It is an uneasy moment.

He clears his throat and says, "After we pull into the depot I'll have to get the dough together and take it to the company office. I'd appreciate it if the person who cheated would slip me the money as he gets off the bus. I won't even look up to see who it is. If I don't get it back I'll have to make it up out of my own pocket and I ain't got it to spare."

He glares at each of us, one after the other, a last time. "C'mon!" he says. "I done my job, now you take care of yours!" He turns around, releases the brake, and starts the engine. We ride the rest of the way into the city in silence steeped in mutual guilt.

At the bus terminal I stay in my seat to avoid the crush when the other passengers file out. I watch three of them slip money to the driver as they go by. He counts thirty-five fares out after they have passed him and puts this money into a satchel which he snaps shut. He counts the remaining cash, three [ares, out loud to himself, then stuffs this money into his wallet and puts it in his back pocket. He is humming to himself as he leaves the bus.

In Munich

I am in a night club in Munich. My date and I have come to hear what is supposed to be the best jazz in Bavaria. It is a lovely place laid out in two stories with flowers and huge green plants everywhere. A spiral staircase winds from behind the dance area up to the second tier.

The singer is a clean-cut, handsome fellow in a plaid dinner jacket and tight ivy-league trousers with a buckle on the back. He sings German songs and a few American numbers with German words. His finale is the famous "Mack, the Knife," probably Germany's most famous popular song. He does it in English it la Louis Armstrong.

The singer sits down and his group takes off on "j azz." It is very pleasant to listen to - a sort of rag-time done to a strict four-four tempo. It sounds like what might happen if you crossed Benny Goodman with Wayne King and McNamara's band jazz, but sweet and bouncy.

The jazz ends and the combo plays dance music. My date and I get out on the dance floor and when we do the jitterbug, people stare at us, for our version is somewhat different from theirs.

When we are ready to leave, we get up and go towards the door. Several couples block our path. They see us coming but make no move to get out of the way, even though there is no other exit. I think of the grown men and women who have pushed in front of me in lines at airports and restaurants, and looked pleased with themselves for having done so and I get angry. This is the way Germans get along with each other. They are not polite. They are aggressive. They push and jostle. Up till now I have given way quietly, for I have wanted to be a "good ambassador" and not an "ugly American." Now I am mad.

We walk toward the couple nearest us and I bump into the boy hard! The couple gets out of our way, and we march toward the next human blockade. Just before we reach them they move aside. We keep going and a path opens for us all the way to the door.

I begin to feel ashamed of myself, and before we leave I look guiltily back at the dance floor. The boy whom I bumped catches my eye and winks.

10 NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

Over East Gerlnany

I am on a plane flying over East Germany. From my seat on the aisle I am straining to see the ground. The gentleman next to the window smiles and asks me in a combination of English and German if I would like to exchange seats with him. He assures me that he doesn't mind, as he has made the flight many times. I accept his offer, and soon we are talking in a combination of English, German, and French. He is thin and gray haired and dressed beautifully in the double-breasted continental style. He tells me that he is an official of the West German Customs Bureau. He is a native of Berlin and

has lived there all his life. He is attractive, warm, urbane and I wonder to myself what he was doing during the war.

I tell him that I admire his city for its beautiful. churches, its office buildings, its wide streets and lovely parks.

"All of that is new," he says. "You should have seen it right after the end of the war. It was a heap of rubble - a junkyard." His voice is sharp now almost accusing.

I keep quiet but I think to myself, I am a Jew. Would you like to talk?

Uptown New York

I am standing in line at an uptown movie theater. I have been told by a friend that a sneak preview of a movie that I want to see is to be shown here tonight. However, I am evidently not the only one who knows it. There is in addition to the crowd that has come to see the gangster picture being featured, a sizable group of couples who are dressed in the style of the Village. All of them are males.

Inside, the regularly scheduled movie is shown first. It is about the Mafia and its methods of

operation. At the climax of the film all of the killers are gathered together to draw cards for the privilege of executing the hero. The winner in a rather grim ritual is then kissed on the mouth by each of his brothers in crime.

Once, twice, three times he is kissed and this is too much for the group from the Village. Just before a fourth embrace is completed, someone leaps out up into a standing position on his chair. Arms waving and long hair flying he shouts excitedly, "We've won! We've won!"

ROMA

The Via Veneto is wide, the chocolate ice-cream dark at the trattoria Doney where Hadrian's boy sits, new muscled now from naked marble into insolence of flesh contained in faded blue-jeans. Spring, 1963

Immaculate with hyacinthine hair, he fingers sun above the molded plastic table top, and quiet waits in depths of haunted glance antique regard that yields to life

lost imperial eyes.

JOHN STEWART CARTER, L.A '31

11

THE OTHER SIDE OF SAIGON

by leff Corydon III

by leff Corydon III

Jeff Corydon III, born in Chicago, is a Foreign Service officer now serving with the U.S. Embassy in Rabat, Morocco. The present article stems from experiences and observations at his previous post of Saigon, South Viet Nam, from 1957 to 1959. Before two years as a U.S. Air Force officer launched him on a career of government service, he had prepared for a journalistic career at Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism (B.S.J., 1950, M.S.J., 1953). As an undergraduate, he was President of the Northwestern University Class of 1950 and was elected to the Medill chapter of Sigma Delta Chi Professional Journalistic Society. He received the latter's Harrington Memorial Citation as Medill's outstanding student in his graduate class. Between 1950 and 1952, while completing studies for his M.S.J., he worked as Assistant to the Coordinator of the Northwestern Centennial Celebration.

Mr. Corydon has been located in Rabat since October 1961, when he finished a year of Arabic language study at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

Now that the once gainsaid meeting of East and West has become reality - in respect to tourism, at least - Saigon's provisional absence from the travel circuit must cause regret.

Only two decades ago, fattened on the brimming rice bowl which is Indo-China's richest resource, this Asian city was renowned as "The Paris of the Orient." Of course, in those bygone

days when the mysterious East seemed impossibly remote, and before Febris Tourismus infected the American species, most world-voyagers were content to plumb the pleasures of the other Paris and let it go at that. But Saigon already was a favored haven of French administrators and colons, for - aside from the prerequisites to be had serving in an outpost of empire - its exotic qualities piqued the Frenchman's artistic spirit.

The post-war years saw the Viet Namese independence movement flare into armed conflict, climaxed by the defeat of France at Dien Bien Phu which sealed its retreat from Indo-China. But when Viet Nam emerged from colonial status in 1954, the Geneva accords carved away the northern half of the country as the prize of Communist resistance forces. In the southern zone, with Saigon as capital, strongly nationalist and pro-Western Ngo Dinh Diem soon rose to power.

In different circumstances, independence might have opened Saigon to Far East travelers as another port of call - like Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Bangkok. But the South Viet Nam republic was born fighting for its life against entrenched guerillas sponsored by the Communist north, and eight years later the struggle still rages. With the recent neutralization of neighboring Laos, Viet Nam has become the main cold war battleground in Asia.

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

12

Dateline for much of the press's hottest cold war copy, Saigon is now familiar in our lexicon of Asian names. But most Americans have come to know it solely as the command post in Viet Na ms bitter war. A symbol of U.S. resolve to stop Communist aggression, it is today the "Berlin" of the Orient much more than its "Paris," and while violence stalks the plateaus and paddies of the nation around it only the exceptional tourist is tempted to pay a visit.

Thus Americans who have served in Viet Nam have reaped a double satisfaction to offset the sting of those quiet or ugly epithets that occasionally have been applied to their efforts. Besides seconding a valiant fight against uneven odds, they have had the rare good luck to shake hands with Saigon and size up her non-political merits. Most of them have found her, as I did, still an engaging Oriental lady despite the somber days through which she is living.

Saigon's particular charm doesn't lie in outward trappings. For reasons of history, the visage of the present city is much more modern than ancient - not so different from that of a middlesized American or European settlement.

Born as a village within Cambodian borders, it counted only a few thousand inhabitants - as against almost two million today - when it fell before Viet Namese expansion southward from Hanoi in the late 17th century. It flourished sporadically during the turbulent years which followed and even served briefly, toward 1800, as imperial residence of the famous Emperor GiaLong, who unified Viet Nam within roughly the present frontiers to end three centuries of dynastic war. His descendant of our day, ex-Emperor Bao Dai, was driven into exile in France by President Diem's government.

There are few traces in Saigon of these earlier times except scattered monuments and pagodas reflecting the Viet Namese penchant for ancestor worship. Only after the French protectorate's establishment in the 19th century did real impetus to metropolitan evolution come. Saigon's main period of construction, early in the 1900's, bequeathed the present city a fashionable main street with Parisian flavor and surrounding residential districts featuring angular, yellow-stuccoed villas with gardens walled for privacy and generous eaves and unglassed windows calculated to beat the tropical heat.

A major landmark dating to that period is sprawling Independence Palace, the President's official residence, which formerly was the seat of the French governor-general in Indo-China. Ensconced in a park of several acres where deer and an elephant have been known to play - the latter a gift to Diem from another Asian dignitary

Spring, 1963

- its mid-city setting is strongly reminiscent of the White House.

Adjacent to the palace grounds, and throughout the city, course broad avenues arched by a half-century's growth of towering tamarind, a: rustic touch that sets Saigon off from other Asian capitals. It is several minutes' walk, past government offices and the cathedral where Diem and many others of Saigon's large Catholic minority worship, to centre-ville with its inviting open-front shops. Since independence, stocks of colorful native wares have been enhanced gradually by a brisk revival of age-old crafts aimed at the expanding world markets for pottery, lacquers, brassware, wickerwork, and other art of Oriental flavor.

But when all is said, 20 years of war and austerity have kept the city's physical profile unpretentious in spite of its growth in population and importance. Moreover, the improvisations worked by successive generations offer no sharp contrast between past and present, or East and West, as in some former colonial centers. Not streets and structures, but the people they serve, engrave Saigon in the Westerner's eye. Indeed, the city's modesty of architectural aspect somehow magnifies the vitality it exudes - as if figures on a canvas had swarmed from their frame to fill new dimensions unintended by the artist.

* * *

Viet Nam's partition and insecurity of the countryside have helped write the script for a spectacular of human effervescence in Saigon. For years now refugees streaming in from the Communist north and from outlying areas of the south have been swelling the flow through arteries of a structurally middle-sized city. Today, as the rush hour crowds converge on centers of commerce and administration, the pavements become a vast open-air factory, market place, playground, and waiting room of humanity. There is none of the perfunctory motorized unison which marks the streets of most metropolises West and East but a splendid hurry and scurry of daily life with the accent on diversity and individuality. Middle-classmen and the army of functionaries have taken to Western clothes, but the panorama of other apparel in Saigon is still an object of fascination. Varied clothing of the mass of laboring men ranges from peasant outfits of serviceable calico nair or khaki separates culled from military surplus to sporty Western-style pajamas which - in Saigon's climate - qualify as the most

13

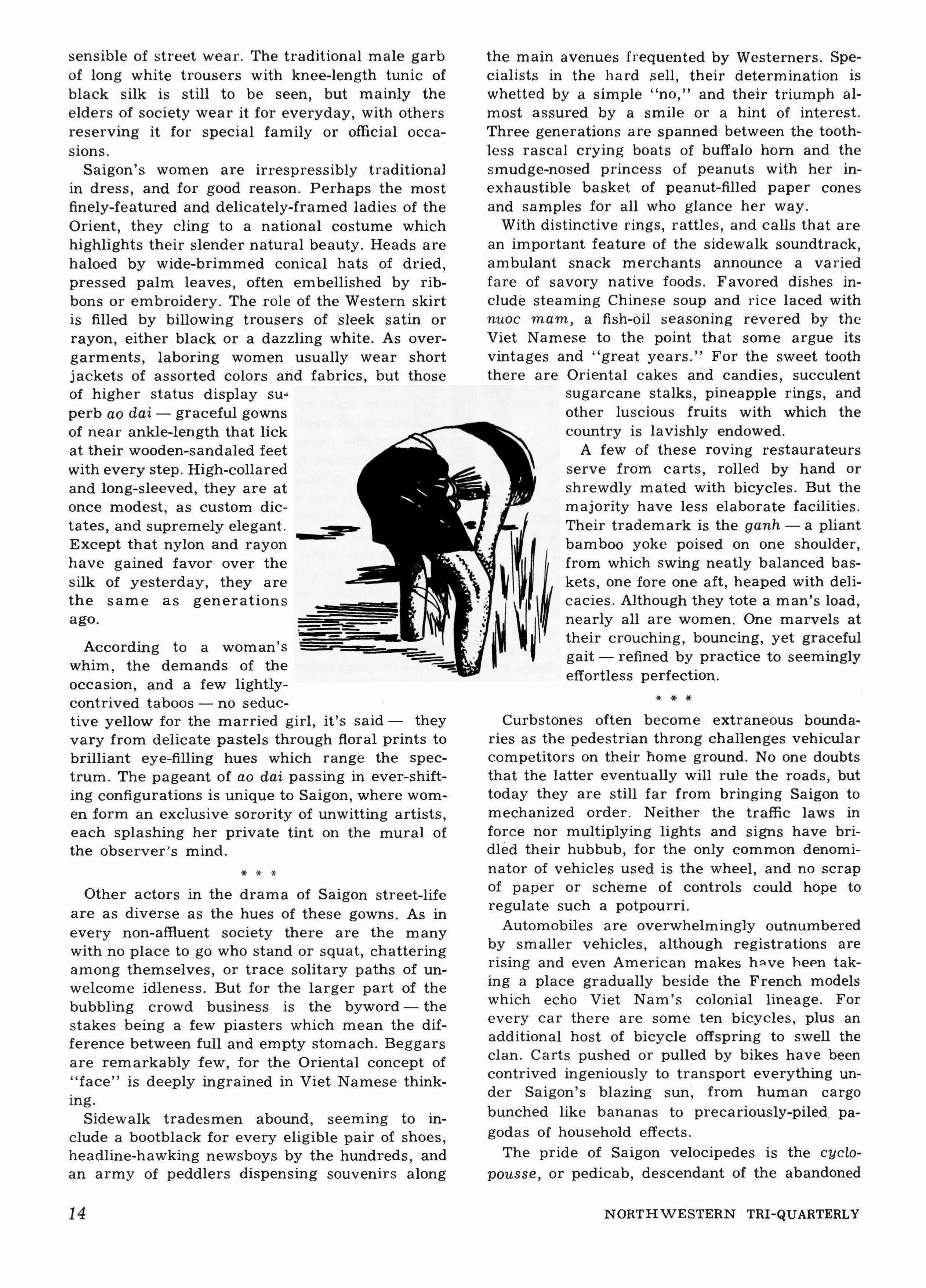

sensible of street wear. The traditional male garb of long white trousers with knee-length tunic of black silk is still to be seen, but mainly the elders of society wear it for everyday, with others reserving it for special family or official occasions.

Saigon's women are irrespressibly traditional in dress, and for good reason. Perhaps the most finely-featured and delicately-framed ladies of the Orient, they cling to a national costume which highlights their slender natural beauty. Heads are haloed by wide-brimmed conical hats of dried, pressed palm leaves, often embellished by ribbons or embroidery. The role of the Western skirt is filled by billowing trousers of sleek satin or rayon, either black or a dazzling white. As overgarments, laboring women usually wear short jackets of assorted colors arid fabrics, but those of higher status display superb ao dai - graceful gowns of near ankle-length that lick at their wooden-sandaled feet with every step. High-collared and long-sleeved, they are at once modest, as custom dictates, and supremely elegant. Except that nylon and rayon have gained favor over the silk of yesterday, they are the same as generations ago.

According to a woman's whim, the demands of the occasion, and a few lightlycontrived taboos - no seductive yellow for the married girl, it's said - they vary from delicate pastels through floral prints to brilliant eye-filling hues which range the spectrum. The pageant of ao dai passing in ever-shifting configurations is unique to Saigon, where women form an exclusive sorority of unwitting artists, each splashing her private tint on the mural of the observer's mind.

Other actors in the drama of Saigon street-life are as diverse as the hues of these gowns. As in every non-affluent society there are the many with no place to go who stand or squat, chattering among themselves, or trace solitary paths of unwelcome idleness. But for the larger part of the bubbling crowd business is the byword - the stakes being a few piasters which mean the difference between full and empty stomach. Beggars are remarkably few, for the Oriental concept of "face" is deeply ingrained in Viet Namese thinking.

Sidewalk tradesmen abound, seeming to include a bootblack for every eligible pair of shoes, headline-hawking newsboys by the hundreds, and an army of peddlers dispensing souvenirs along

the main avenues frequented by Westerners. Specialists in the hard sell, their determination is whetted by a simple "no," and their triumph almost assured by a smile or a hint of interest. Three generations are spanned between the toothless rascal crying boats of buffalo horn and the smudge-nosed princess of peanuts with her inexhaustible basket of peanut-filled paper cones and samples for all who glance her way.

With distinctive rings, rattles, and calls that are an important feature of the sidewalk soundtrack, ambulant snack merchants announce a varied fare of savory native foods. Favored dishes include steaming Chinese soup and rice laced with nuoe mam, a fish-oil seasoning revered by the Viet Namese to the point that some argue its vintages and "great years." For the sweet tooth there are Oriental cakes and candies, succulent sugarcane stalks, pineapple rings, and other luscious fruits with which the country is lavishly endowed.

A few of these roving restaurateurs serve from carts, rolled by hand or shrewdly mated with bicycles. But the majority have less elaborate facilities. Their trademark is the ganh - a pliant bamboo yoke poised on one shoulder, from which swing neatly balanced baskets, one fore one aft, heaped with delicacies. Although they tote a man's load, nearly all are women. One marvels at their crouching, bouncing, yet graceful gait - refined by practice to seemingly effortless perfection. * *

Curbstones often become extraneous boundaries as the pedestrian throng challenges vehicular competitors on their nome ground. No one doubts that the latter eventually will rule the roads, but today they are still far from bringing Saigon to mechanized order. Neither the traffic laws in force nor multiplying lights and signs have bridled their hubbub, for the only common denominator of vehicles used is the wheel, and no scrap of paper or scheme of controls could hope to regulate such a potpourri.

Automobiles are overwhelmingly outnumbered by smaller vehicles, although registrations are rising and even American makes have been taking a place gradually beside the French models which echo Viet Nam's colonial lineage. For every car there are some ten bicycles, plus an additional host of bicycle offspring to swell the clan. Carts pushed or pulled by bikes have been contrived ingeniously to transport everything under Saigon's blazing sun, from human cargo bunched like bananas to precariously-piled pagodas of household effects.

The pride of Saigon velocipedes is the cyclopousse, or pedicab, descendant of the abandoned

* * *

14

NORTH WESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

rickshaw. Its operator pedals from a high tricycle seat behind his fare, one or several persons depending on their build and baggage. Cyclo drivers form a social class in themselves, sr-vernl thousand strong, whose home is the saddle lind whose range is the length and breadth of the city. The main band makes a preserve of the downtown district, specializing in the short hauls which pay off most handsomely, but even at Saigon's remotest frontier the call "cyclo!" seldom goes unanswered. Between fares they congregate in competitive knots at likely pick-up points or patrol in quest of the weary walker. When the drivers weary in turn, they climb down in a spot of public shade and advertise the cushioned comfort of their canvas-topped cabs by personal example.

During recent years a fleet of motor scooters has appeared to rival the bicycle brigade. Variations include scooter-drawn carts, scooter-pushed carts, and scooter-driven cyclos - besides the just plain scooter familiar to Western eyes. For many Saigonese this amounts to the "family car," and among the younger set it is almost de riguer for dating or courting. A common street sight is the Viet Narnese maiden balanced sidesaddle behind her beaming beau, arms daintily waving turns and elegant gown trailing in a swirl of color. If courting days are over, several tots may be crammed in front of the driver or the flowing gown, clinging to one another in approximate order of height and fright.

The quaintest throwbacks still in evidence on the streets are high-wheeled peasant traps which daily make their way into town from the rural suburbs - dubbed "matchboxes" by the French for their miniature size. The "matches" inside are country folk en route to market, conical hats bowed as in prayer beneath low-slung roofs, with baskets and bags of produce jammed among them or lashed space-savingly to tops and sides of the coaches. Some are drawn by lumbering, docile water buffalo on leave from the rice paddies

PRAYER

Behind is a man

With a dog on a leash. The dog is White-muzzled, white-eyed, With a hump in his Back like a pyramid. When he falls, The man lifts him up with A cane made of bone. Kill the dog. The man is Already dead. Amen.

BLAKE LEACH, Speech '63

where they usually toil. But most are pulled by prancing ponies, cockfeather hats aflutter atop bobbing brows. Not quite the festooned headdress of the fierce warhorses of antiquity pictured in Viet Namese art, but one wonders if those steeds of yesteryear ever lifted their plumes of office more proudly,

Even so does Saigon itself face the uncertain road ahead, with chin high, conscious of a past which has known both struggle and splendor. The modest visage it offers today still vibrates with colorful commotion that is at once the result and the rebuttal of the war beyond city limits.

The war is incalculably grim, and its sober details have been advertised widely, so one understands why tourists are not exactly beating a path to this Oriental crossroads now. Meanwhile, Saigon goes on hoarding the ingredients of an eventual pleasant surprise for Far East travelers - including those who thought they had seen everything.

AFTER AESCHYLUS

Gather in the harvest: Time no longer is, No time for time, No room for time's turning upward gaze away from aching eartfi's distress. Pick up the broken apples, and learn to savor the tasteless taste of ashes:

A second harvest sown by the first, and reaped from its blighted fruit.

MICHAEL DALZELL, L.A

'63

Spring, 1963

15

Age,

Edward Schmidt Petersen holds a number of positions in the Northwestern University Medical School-Assistant Dean, Assistant Professor in the Department of Medicine, Oirector of the Medical School Clinics and of the Graduate Division, and Coordinator, for the Medical School, of Medical Education for National Defense. He is Chairman of the Committee on Hospitals and Clinics for the II/inois Public Aid Commission.

Born in Chicago, he received both his undergraduate and professional training at Harvard (M.D. 1945). His internship was at St. Luke's Hospital in Chicago. After service with the U.S. Medical Corps (1946-8) he became Assistant Resident in Medicine at the University of Chicago. He came to Northwestern in 1951. He has held a number of professional positions, and is a fellow of the American College of Physicians and a member of the American Diabetes Association, the American Public Health Association, and the Association of American Medical Colleges.

The article below was wriHen for The Tri-Quarterly at the invitation of the editor.

It may seem puzzling that medication of the aged should have come to share in these times the central political platform, along with the more traditional issues of war, bread and circuses. After all, age is not new: there was a time when good authority states it to have far exceeded the best current record. Nor is medicine: this profession has long called attention to its rank as the second oldest; and medicine has never been dispensed without a reasonable contribution of money, whether requested by Hippocrates for the Temple Treasury at Cos, or by the Director of Internal Revenue for the Temple of Research at Bethesda. But suddenly, in recent years, fission would seem to have stirred in the atoms of each of these factors, and they have fused into a storm blowing candidates from their platforms and legislators from their accustomed log-rolling.

Of the aged, there are more. This is incontestable. In 1920, the American population numbered 106 million, of whom 4.9 million, or 4.7 per cent, were over 65. By 1960, the population had increased to 179 million, including 16.6 million, or 9.2 per cent, over 65. In 1984, 250 million citizens are anticipated, 25 million, or 10 per cent of whom are expected to be over 65.

The aged are poor. This some may contest. But

in 1960, 53 per cent of those over 65 years had a total cash income of less than $1,000. Only 13.5 per cent received an income in excess of $5,000.

The aged are chronically sick. Twice as many of those over 65, in proportion to the population, have one chronic illness; and four times as many have three or more illnesses. Those 65 to 75 are bedridden 11 days annually; those 25 to 45, five days. When hospitalized, the aged remain longer, 14 days as against 8.6 days. They visit their physicians more often, 6.8 visits versus 5 visits per person per year.

Medical care is more expensive. Between 1929 and 1960, the consumers' price index rose 70 per cent for all items, 105 per cent for medical care. From 1950 to 1960, the rise in the medical care index was twice that of the overall, and more than that of any other component. In 1940, private expenditures for medical care amounted to $3.0 billion, public $0.9 billion, totaling $3.9 billion or 4.1 per cent of the gross national product. By 1960, these had increased to $20.3 billion and $6.2 billion respectively, totaling $26.5 billion, now 5.4 per cent of the gross national product. Of this, the senior citizen spends the patriarch's share. In 1958, the per capita gross expenditure for medical care of those over 65 was $177; for those under, $86.

While the costs of medical care are under consideration, a historical digression may prove enlightening. Might it not be appropriate to compare the problem of medicating the aged with that of educating the young? Both activities usually represent the major service effort of a community. There is scarcely a town in which the school and the hospital are not now the largest and finest structures. Both are expensive activities, generally considered to benefit the community. Both require heavy expenditure for an intangible and never guaranteed result. Both, if in varying degrees and at different stages, fall upon every citizen.

If some resemblance of these problems is conceded, then one may wonder why the public support of education was a major issue of the early 19th century in the United States, and that of medical care would seem to be one of the late 20th.

d• � e lei.,

16

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

Ind MODey

It is said that prior to 1800, education was a function of the church, and of the occasional private academy. So, too, was medicine, though subsequent to the Middle Ages with decreasing emphasis on the monastic hospital, and increasing effort by the individual physician. Then during the early decades of the 19th century, debate stirred this country and most of the western world, with the result that public school systems of various types and levels became accepted and established.

The most ready hypothesis would seem to be that a century and a half ago medical care was cheap, and education relatively expensive; and that now both are expensive, medical care probably the moreso. Indeed, reference may easily be found as to how cheap medical care once was. For example, in 1870 an office visit cost 25 cents, a house call 50 cents, and a complete obstetrical delivery $5.00. Unfortunately, national figures for medical expenditures are not available except for relatively recent years. As regards education, in 1850 the total national expenditure is reported as $16 million; in 1870, $95 million; and in 1910, $560 million. By 1940, educational expenditures had increased to public expenditure of $2.7 billion and private of $0.5 billion, totaling $3.2 billion; but at this time, as noted above, medical expenditures were already $3.9 billion. In 1960, public educational expeditures were $16 billion and private $4.5 billion, totaling $20.5 billion, a striking rise but not as great as that of medical expenditures to $26.5 billion. It may well be that expenditures in these two areas have always been approximately the same. At least, were one to base an estimate on the number of physicians as contrasted to the number of teachers, one might conclude that educational expenditures actually have increased relatively more rapidly than medical. In 1870, there were 221,000 teachers and 62,383 physicians in the United States. Now there are 1,400,000 teachers or more than six times as many, and 256,000 physicians, a fourfold increase. Of course, it is not accurate to base an estimate of total medical expenditure on the number of physicians. The percentage of medical expenditures devoted to physicians' services has decreased markedly as other areas of health service have increased far more rapidly. Over the past 40

Spring, 1963

By EDWARD S. PETERSEN

years the number of nurses has grown tenfold, now totaling 504,000. In 1873, there were 180 hospitals; now there are 6,876. By 1957-1958, when the mean private gross expenditure for health care for all persons was $94, physicians' services amounted to $31, hospital care $22, drugs $19, dental care $14, other medical services $8.

Perhaps there was less interest in the provision of public medical care than of public education a century and a half ago for reasons quite other than financial. Perhaps the citizen of that day was only too well aware that the some 30,000 physicians he supported were harmless at best, and quite dangerous at worst. It may be noted that only four remedies of that time were of actual benefit. Those were the prescription of lime juice for scurvey vaccination for smallpox, quinine for fever (if it chanced to be due to malaria), and digitalis for dropsy (if due to heart failure). Essentially all other efforts were useless, or deadly, as was the prevalent custom of massive bleeding, which helped to kill at least one President. In striking contrast, successful educational efforts would seem to have been undertaken by Socrates and other teachers back to Zinjanthropus.

To return from this unresolved historical digression to the medical problems of the currently aged.

The medical care of the aged is currently supported through a great variety of sources. Generally, among those supporting themselves, a much greater proportion is paid directly rather than through insurance, as contrasted to the general population. In a recent survey, those under 65 paid out of pocket less than 30 per cent of hospital bills averaging around $300; those over 65 paid more than 50 per cent of bills around $400. The remainder in each instance was paid by insurance. For those with insufficient resources of their own, sources of support depend on chance, tradition and individual talent for scraping up help. The fortunate citizen who spent at least a short period in the Armed Forces in time of war receives the most excellent of care at no expense. He who presents an intriguing medical problem, preferably one that is surgically removable, and is able to reach a teaching or research center, is as well off technically as the Veteran, if not

17

quite financially. Traditionally, the medical care of the indigent has been provided by the local community or county, supplemented by private charitable resources. Public support has usually been limited to the provision of hospital facilities, with physicians expected to provide their services without recompense. While there has been an increasing tendency to staff such hospitals with salaried physicians, much of the burden of care still falls upon the volunteer attending physician.

The totally indigent citizen, supported through the Old Age Assistance Program, is provided medical care through a combination of federal and state support varying to a great extent in accordance with his state of residence. In Illinois, hospital, nursing home and office medical care are provided by the Program,

Since the passage of the Kerr-Mills Amendment of 1960, the citizen need not be totally indigent and receiving Old Age Assistance to be eligible to receive this new combined federai-state support of his medical care. This program has been implemented in about half the states, and the type of assistance provided varies a great deal, in Illinois being limited essentially to hospital care. There is an inherent administrative difficulty in this program due to the necessity of investigating the patient's financial resources when application for support is made on admission to a hospital. Consequently, by the time the patient's eligibility has been established, he is apt to have died, recovered and paid his own bill, or recov€:red and vanished, leaving the hospital to collect as best it can.

Still another resource remains for the talented and persistent citizen. All he need do is convince the Federal or State Office of Vocational Rehabilitation that given a certain amount of care, a new leg, or a new wig, he is certain to regain employment; all medical expenses involved in his rehabilitation will then be paid.

It would be pleasant to conclude a presentation of the medical problems of the aged with the customary suggestion that given another $20 billion or so for research, a healthy and carefree senior citizenship will become available for all at no expense to anyone. A somewhat different outlook seems more likely. Consider in the future a landscape of giant institutions, anyone of them the size of the collected pyramids of Egypt. There, attached to his artificial heart-lung-kidney, the aging citizen will be sustained in unconsciousness forever, or until the last of his descendants joins him in exhaustion.

In some ways, it may well prove regrettable that the problem of public support of medical care was not raised at the time of its resolution in the field of education. Our present educational system, based upon multiple sources of support, local, state, federal and private, would Seem far

better adapted to a large and varied nation than one supported entirely by the federal government. It is discouraging to see how attitudes have changed, and how the senior citizen now feels that his problems should be solved. In a recent survey, individuals over 6'5 were asked to respond to the following question: "Who do you think should provide for the older person who has stopped working, if he needs help?" Their responses are summarized below. (Percentages total more than 100 because respondents mentioned more than one source of assistance.)

his

The very complexity of the problem leads to hope for an easy solution through bills and amendments in Washington in place of seeking and experimenting with solutions at home. Unfortunately, various national health services have been devised since the first in Germany in 1883, and none has provided more than a temporary and partial solution. All have stumbled against the hard but inescapable fact that every person, especially when feeling under par, prefers to be cared for hand and foot; and nowhere is a totally comfortable environment provided at no cost to the individual save in the hospital of a national health service. It is usually assumed that access to the universally desired, but unfortunately limited and expensive environment of the hospital, can be controlled successfully by the admitting physician. It is too much to expect of a profession dedicated to enhancing the welfare and comfort of mankind to undertake so vicious a task as to deny the patient his one desire. In the first place, the physician himself prefers to have his patient in the well-controlled environment of the hospital; it is much easier for him to care for the patient neatly placed in a hospital bed rather than inconveniently appearing at the office or demandingly calling from his home. In the second place, it may be physically hazardous for the physician to deny to the patient what he considers his absolute right. The life of at least one physician in a government hospital was saved only when the pistol of a patient demanding admission failed to fire.

A new universal law has been recognized to the effect that a hospital will fill to capacity no matter how many beds are available in a community. In the United States, it has been felt for some years that four general hospital beds per thousand people is the most desirable number. In most

18

In taking care of

problems The federal government 53% The company he worked for 45 Each state government 34 His family 33 His union 17 The local government 15 Community agencies 11 In meeting his medical expenses 49% 36 35 42 18 21 18

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

parts of the country, these are now available, and almost everyone is filled. The West Germans have built beds even faster, and have eleve-n P('I" thousand available; these are all filled, and there are long lists of national health service participants waiting to be admitted. Hitherto, the only successful solution has been that of the British, which simply has been to provide no new hospitals at all. The existing ones, many built early in the 19th century, apparently are sufficiently uncomfortable to permit those requiring emergency admission at least to be accommodated. Sweden, where the national health service began in 1955, has not been as fortunate, and already there are complaints of 40 patients dying while on the waiting list of a hospital.

There is nothing whatever to indicate a more successful outcome should the national program under consideration in this country be adopted. While the patient is expected to make a modest contribution, the amount is not such as to exclude the hospital from remaining the best "travel bargain" available to the elderly patient in need of a change. It is most unfortunate that a national health plan has been proposed and seconded in this country when proper attention has not been paid to studying the excellent arrangements devised in Australia and Switzerland; there federal support for those in need is combined with strong local and voluntary programs. Having avoided a fixed national pattern, both countries have been able to evolve and improve their pro-

LAZARUS

All that - the joy so close

To horror in the sisters' eyes, The joy of it: to realize

The awful meaning of repose With ending of it; the force

Beneath the instant earth, churning, Terribly alive, the fearful force Of life, beyond all learning ; All that, the glory of itWe know the story of it.

We know the story, but never Know the end of the endeavour.

Tell me: did that man sever From the earth's behaviour

To deny again his saviour, Jesus, who deprived him of forever ?

MALCOLM McCOLLUM, L.A., '64

grams continually, and adapt them to local conditions. Canada, likewise, achieves its health effort primarily through its provinces, and benefits from vigorous provincial experimentation, as the recent turmoil in Saskatchewan will attest. It does not speak well for the strength of the individual American state, community and citizen that their counterparts from the Swiss canton to the Australian state should show so much more of a forceful, imaginative and adaptive approach to the financial problems of medical care.

The difficulties inherent in financing medical care for the aged, and for all, are not to be ignored, and will not resolve themselves. They will not be cured by an antiquated patchwork; of federal amendments, hastily conceived and pohtically balanced. There is abundant time for thorough study and a search for new approaches at every level, individual, organizational, local, state and national. If we must display immediate political vigor, let it be to dig cellars to fend off the Horseman of War, and fill the holes with grain to drive away Famine. Death and the Devil should be riding with us leisurely for a sufficiently' long time to permit ample planning for their unlikely departure.

Acknowledgement. Factual data in this report are taken primarily from "Financing Health Care of the Aged, Part I: A study of the dimensions of the problem." This was prepared by a joint task force of the Blue Cross Association and American Hospital Association and published jointly by these Associations in October, 1962.

BEACH IN WINTER

The secret snow is falling upon the lonely beach; Blanketing the life-guard chair, a summer object of long ago, The fragile flakes compact, icing smooth rough sand; The dune grass grows stiff, erect with cold. Seagulls leave their crying; a hush entombs the beachA stillness ruffled only by the mourning of the surf.

MICHAEL DALZELL, L.A '63

Spring, 1963

19

the more things seem to change • • •

by WILBERT SEIDEL

It is a temptation for us to describe almost everything we do today in terms of our dramatic break with the past. Our preoccupation with our differenoes from our predecessors implies a belief that ever-accelerating change somehow makes our time as well as ourselves unique. We begin to believe that progress and the value of man's acts are proportional to this change. We forget that the more things look different to us the more they conceal their relationship to the past. For example, in art today everyone observes mostly what is strange, unfamiliar or new, sometimes even to the amazement of the artist who makes it. Occasionally he alone remains aware of his artistic origins when others do not.

Art students in universities naturally reflect the interests and pursuits which characterize the thinking of serious contemporary artists. It is therefore interesting to observe the interaction of tradition and innovation in their work, and to note how the more things seem to change, the more they are the same.

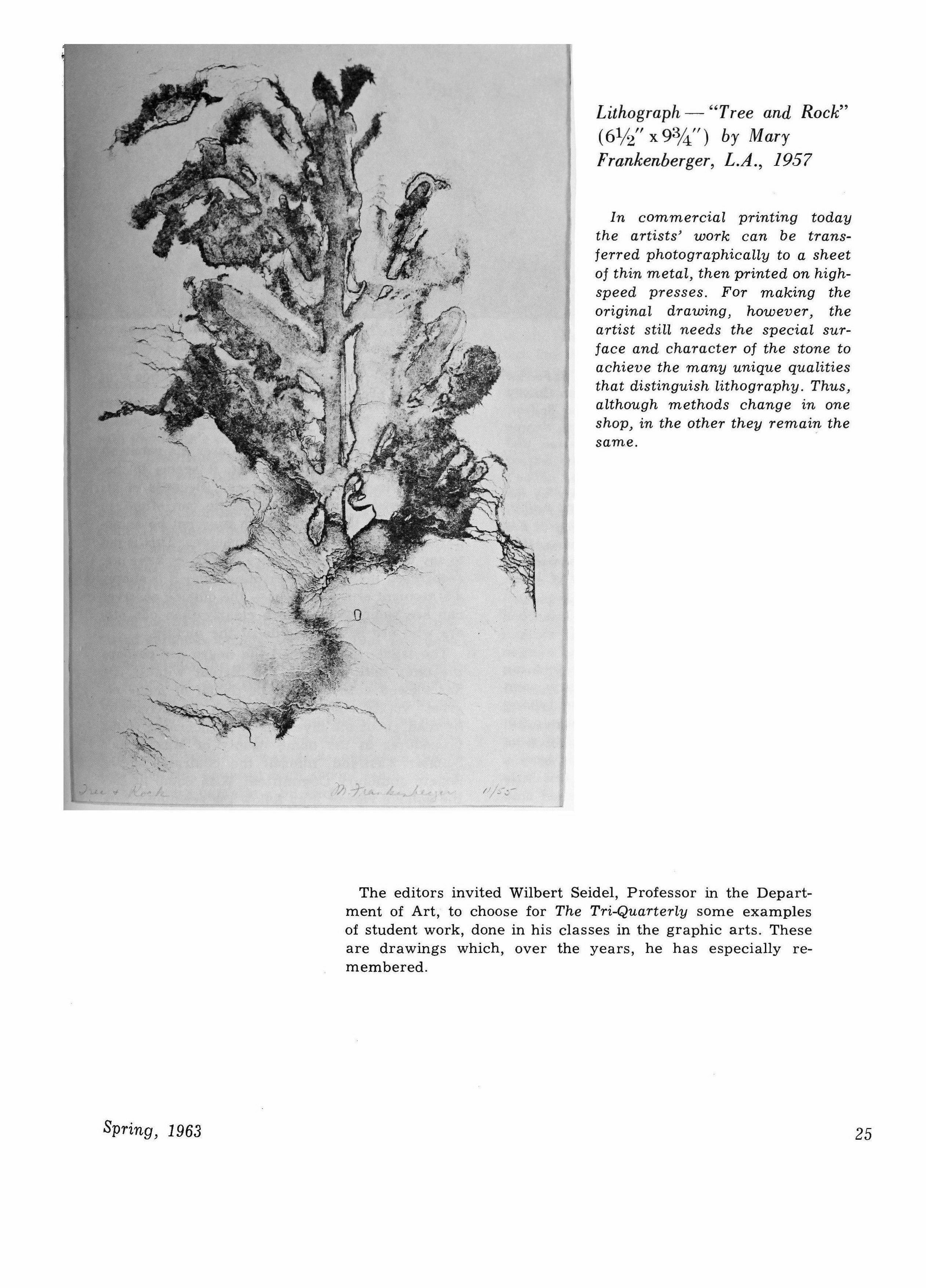

The prints reproduced here are from the collection of undergraduate student work in graphic arts in the Department of Art.

20 NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

A Japanese student draws from her own culture the ancient symbol of youth and courage - the fish - but the vigorous and free carving reflects the interests of the contemporary woodcutter and produces a feeling unlike that of the traditional Japanese print.

A reminder that everyone who has cut a linoleum block remains indebted to the inventive imagination of the Chinese artists of the sixth century who were probably the first to print impressions from carved blocks of wood.

2§' p_ r> n.,_b",-� 1 'I s: (,

Woodcut - "Fish" (201;4" x 43;4") by Fujiko Nakaya, L.A., 1957

Linocut - "Fish" (8" x 3") by Russell Asala, L.A., 1961

Spring, 1963 21

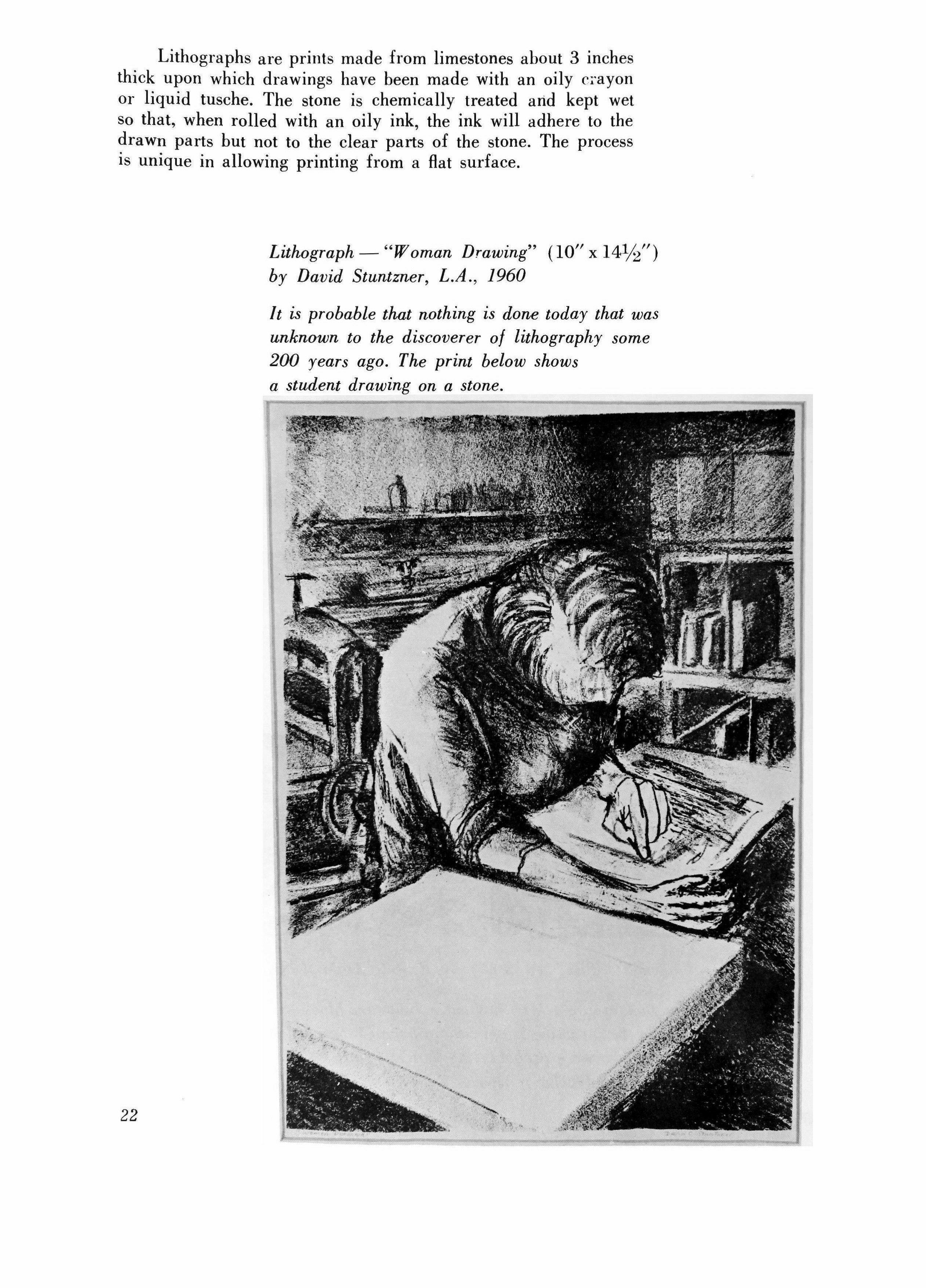

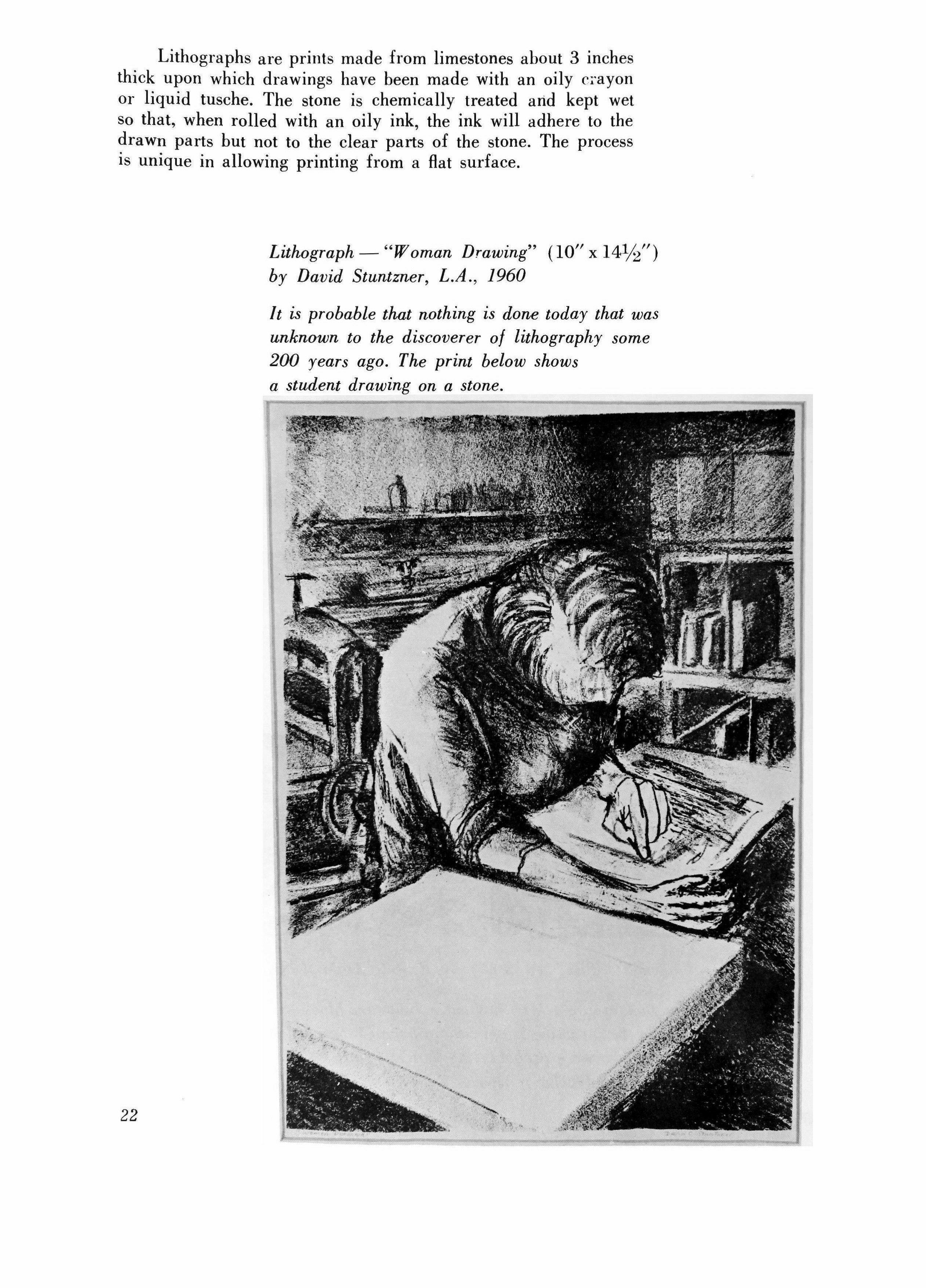

Lithographs are prints made from limestones about 3 inches thick upon which drawings have been made with an oily crayon or liquid tusche. The stone is chemically treated arid kept wet so that, when rolled with an oily ink, the ink will adhere to the drawn parts but not to the clear parts of the stone. The process is unique in allowing printing from a flat surface.

by David Stuntzner, L.A., 1960

by David Stuntzner, L.A., 1960

It is probable that nothing is done today that was unknown to the discoverer of lithography some 200 years ago. The print below shows a student drawing on a stone.

L· h h "W

D'" (10" x 14112.") tt ograp - oman raunng I:

22

Lithograph - "The Burning Bush" (73;.1" x 12") by William Ishmael, L.A., 19.59

Lithograph - "The Hospital Bed" (8Y2" x 10Y2") by Maren Mouritsen, Speech, 1961

Drawing from living models continues to fascinate the artist as it has for centuries. This was drawn in a city orphanage hospital. It was later reproduced on the cover of a hospital publication - The PresbyterianSt. Luke's Review.

Spr.ing, 1963

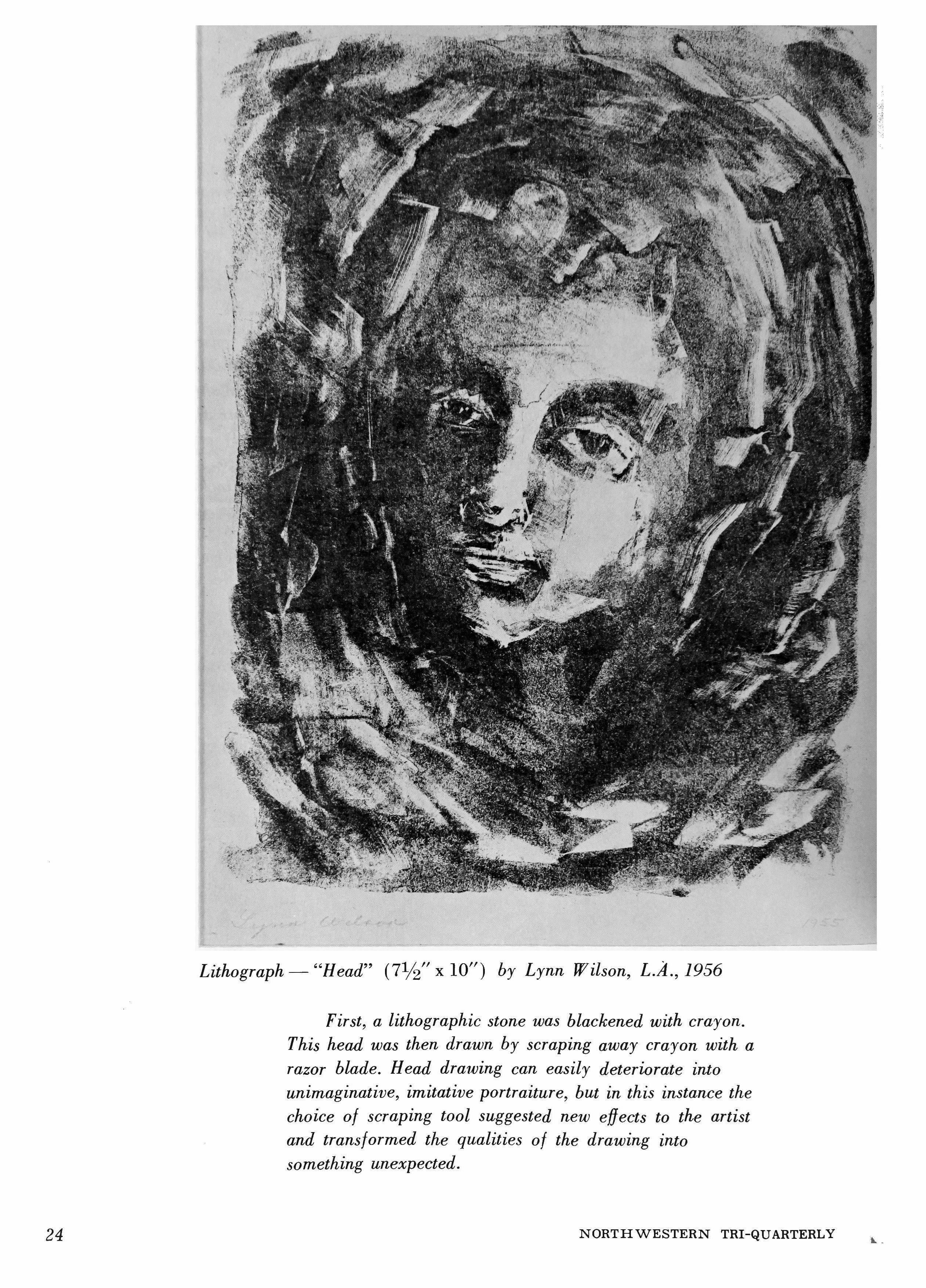

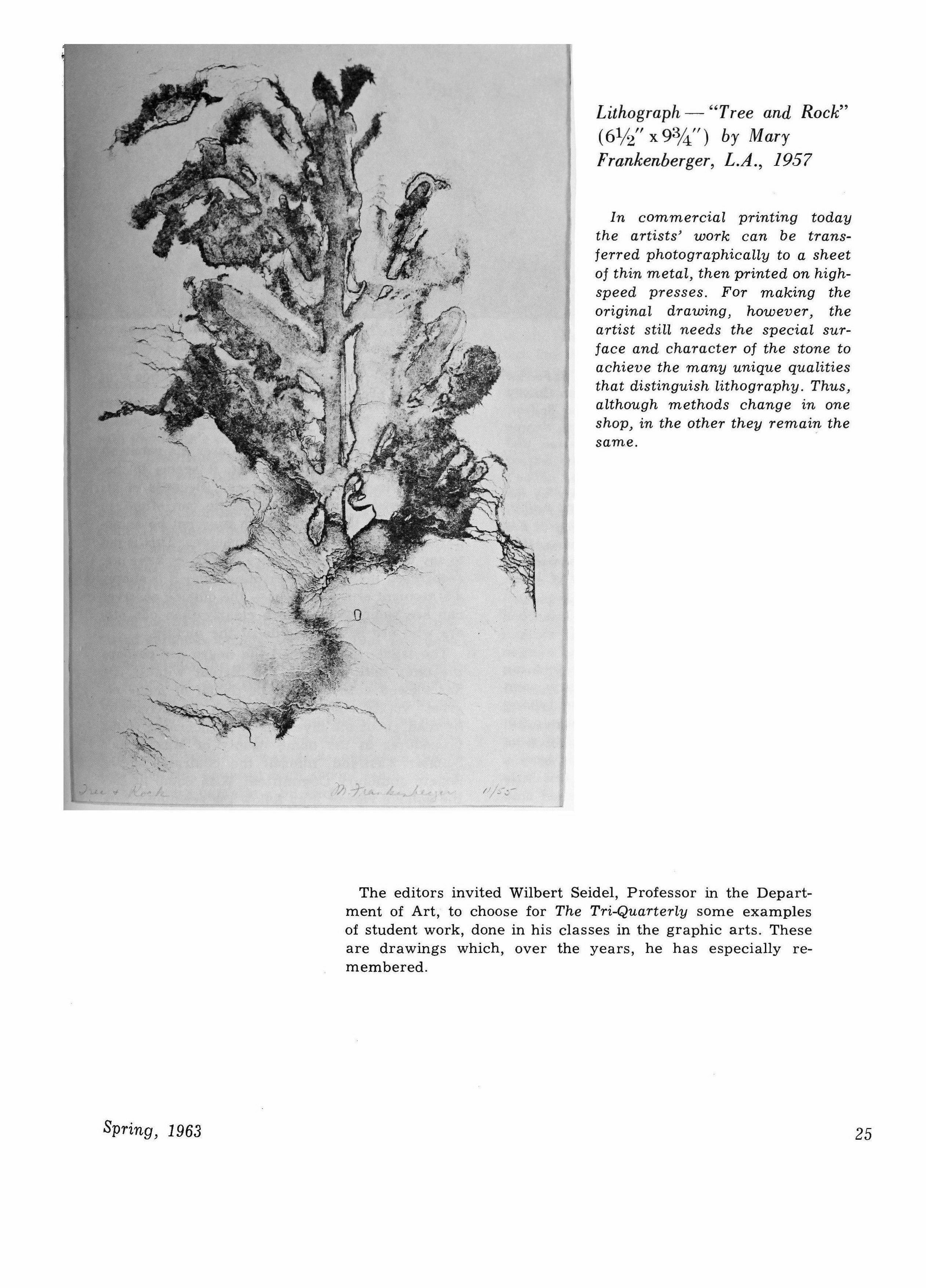

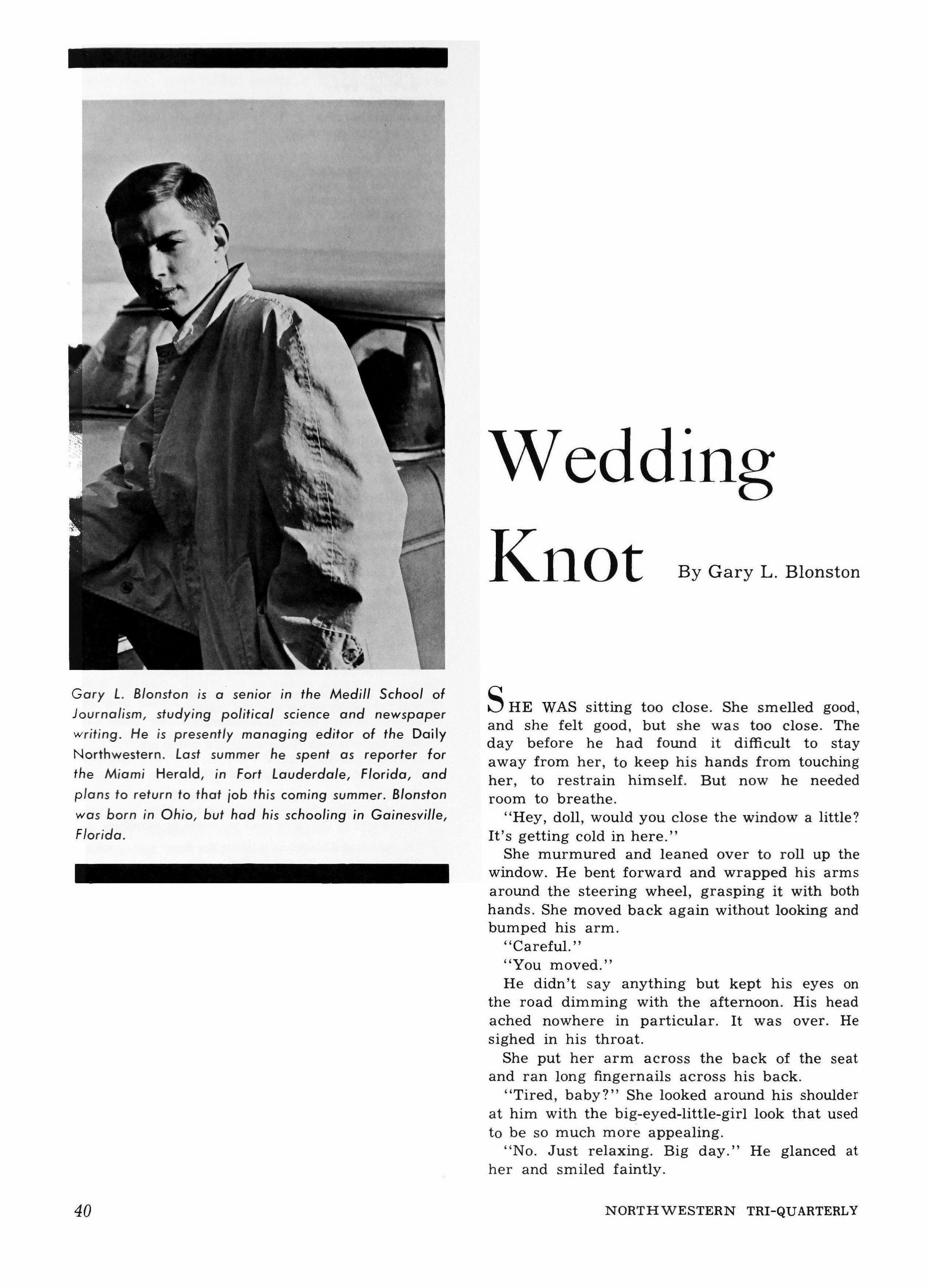

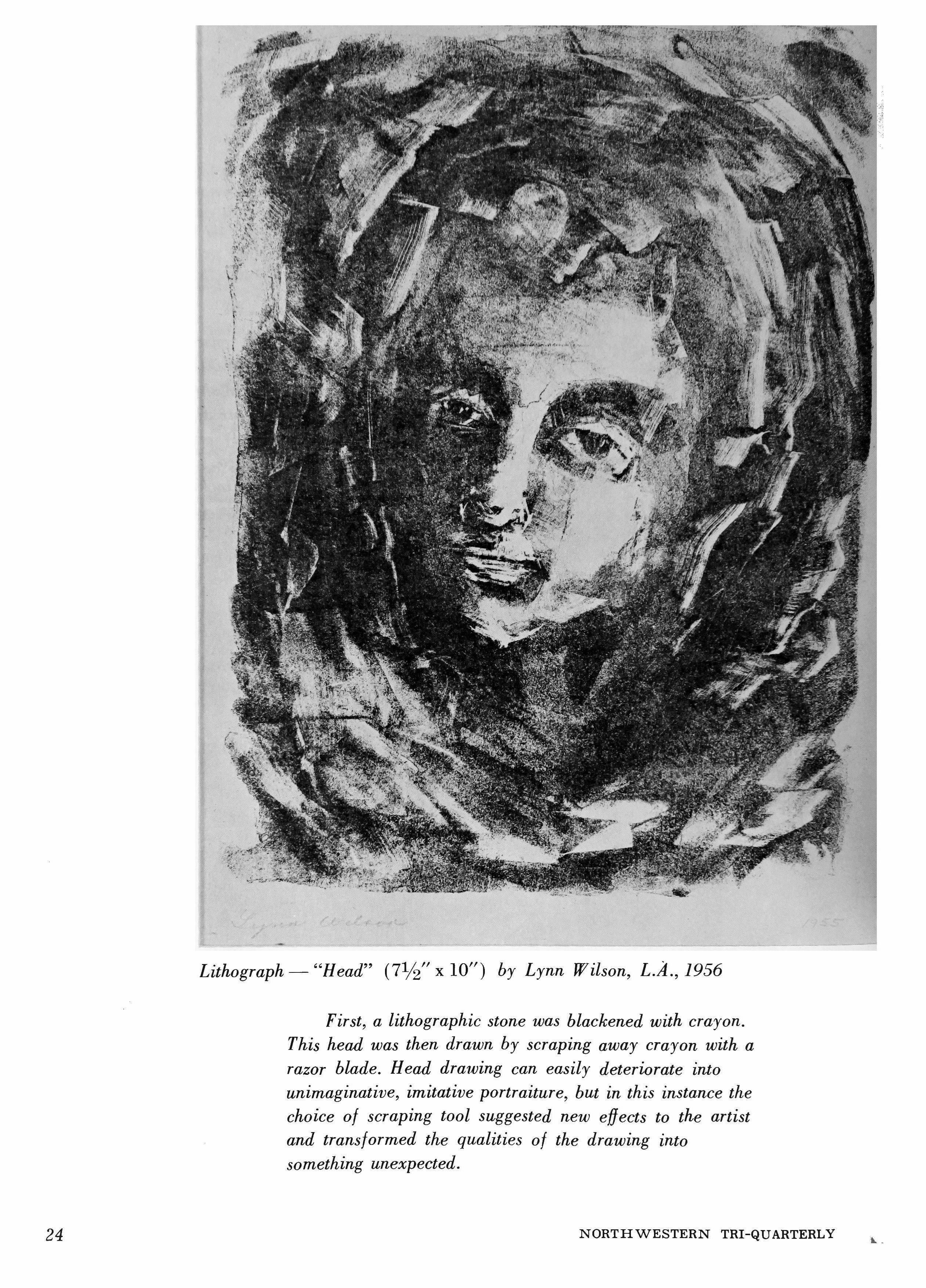

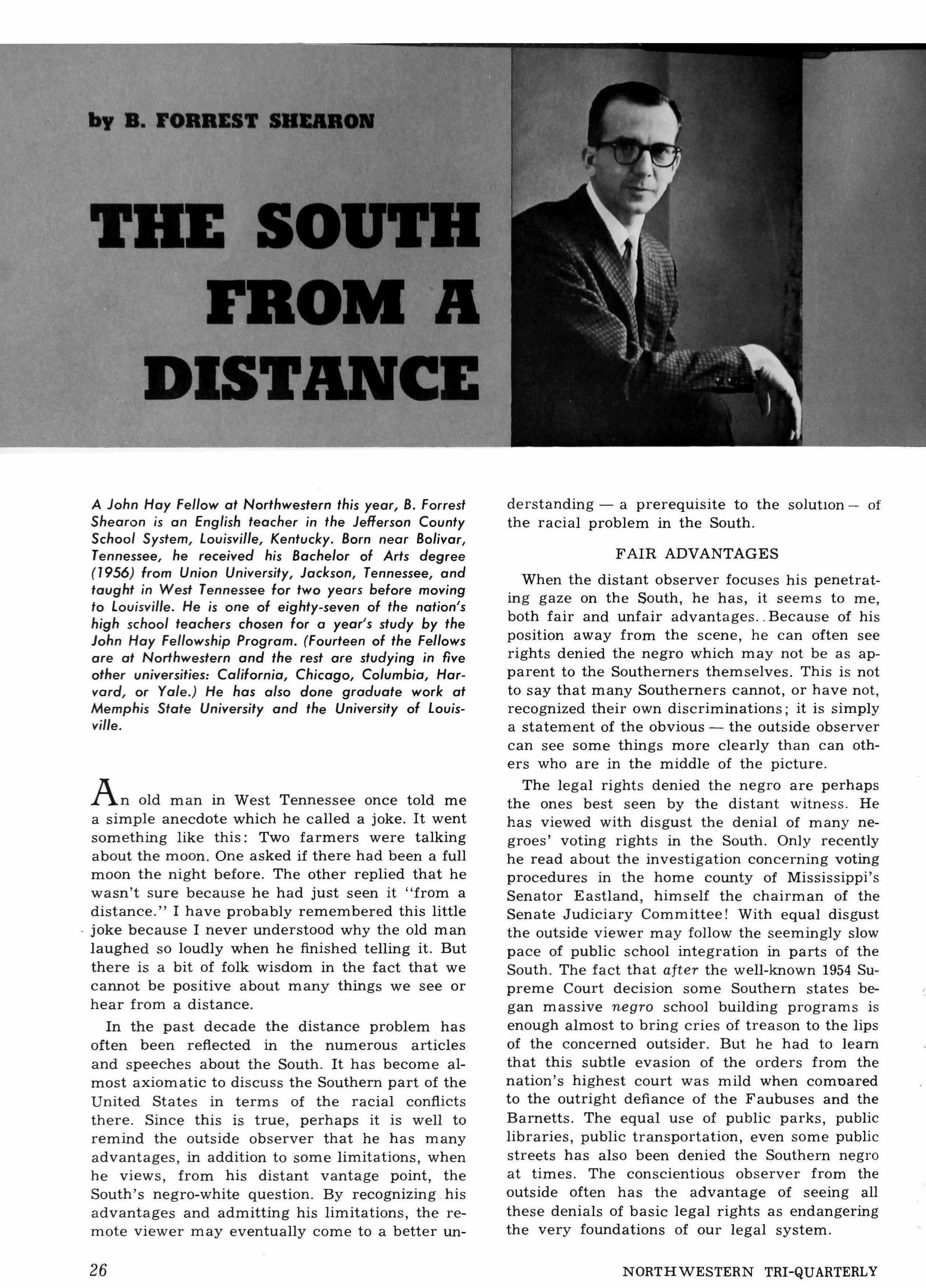

The sense of mystery associated with this traditional subject is achieved through technical means quite different from those customarily employed several decades ago.