BEGINNING

VOLUME 5 NUMBER ONE 70¢ NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY FALL

TRI-QUARTERLY

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is a magazine devoted to fiction, poetry, and articles of general interest, published in the fall, winter, and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $2.00 yearly within the United States; $2.15, Canada; $2.25, foreign. Single copies will be sold locally for $.70. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to THE TRI-QUARTERLY, care of the Northwestern University Press, 1840 Sheridan Road, Evanston, Illinois. Contributions unaccompanied by a self-addressed envelope and return postage will not be returned. Except by invitation, contributors are limited to persons who have some connection with the University. Copyright, 1962, by Northwestern University. All rights reserved.

Views expressed in the articles published are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the editors.

EDITORIAL BOARD, The editor is EDWARD B. HUNGERFORD. Senior members of the advisory board are Professors RAY A. BILLINGTON and MELVIIJLE HERSKOVITS of the College of Liberal Arts, Dean JA.MES H. MC BURNEY of the School of Speech, Dr. WILLIAM B. WARTMAN of the School of Medicine, and Mr. JAMES M. BARKER of the Board of Trustees.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITORS, SUSAN F. MC ILVAINE, FORREST G. ROBERTSON, HERBERT M. ATHERTON, and CAROLYN BURROWS.

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is distributed by Northwestern University Press, and is under the business management of the Press.

Alvina Krause Forever Beginning 3 William Thomas Page A Primer for The New Student 13 Richard W. Ralston No Time of Day 16 David W. Minar Democracy in the Suburbs 22 Ray Ripton Poems 28 Shirley (Stuckert) Zoeger Incident on the Czech Border 29 Carolyn Burrows Nobler in the Mind 34 Mark Reinsberg Notes on Mobility 39 Emily (Singer) Kaplan Poems 42 Charles-Gene McDaniel Portrait Gown 44 Tri-Quarterly NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Volume 5 FALL Number One

FOREVER BEGINNING

BY ALVINA KRAUSE

For a school teacher, interviews with the press are invariably disturbing. Theatrical stars have learned all the answers to a reporter's questions; at tongue's tip they have the right words: the colorful words, the sparkling words, the intimate words, the words revealing such tantalizing glimpses of personal lives, the words selling acting as the most carefree, fascinating of all careers. The teacher, however, is not conditioned to this process of enlightening the public. Truth has been her rule - concise, frank, unadorned truth. And so it is that when a reporter asks, "What, in your estimation, is the secret of this actor's success?" she can only tell the truth. "Hard work. An actor is a human being who has the capacity through hard work to master the techniques of his profession." Silence. The interview is abruptly terminated. Her life in theatre is no longer news. This drab statement will never make a headline. If she could divulge secret stories of psychological traumas as the source of an actor's success,

Fall, 1962

3

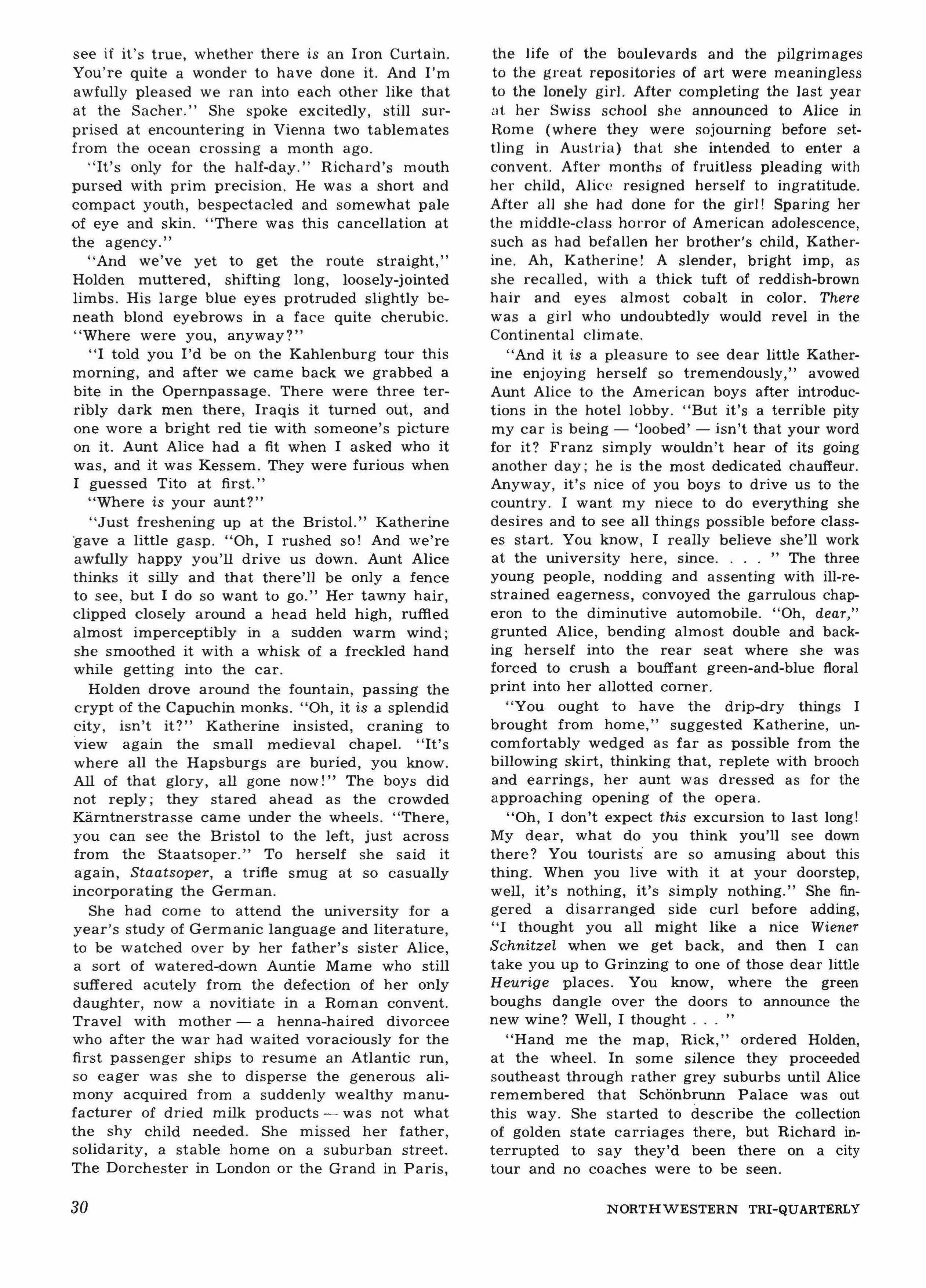

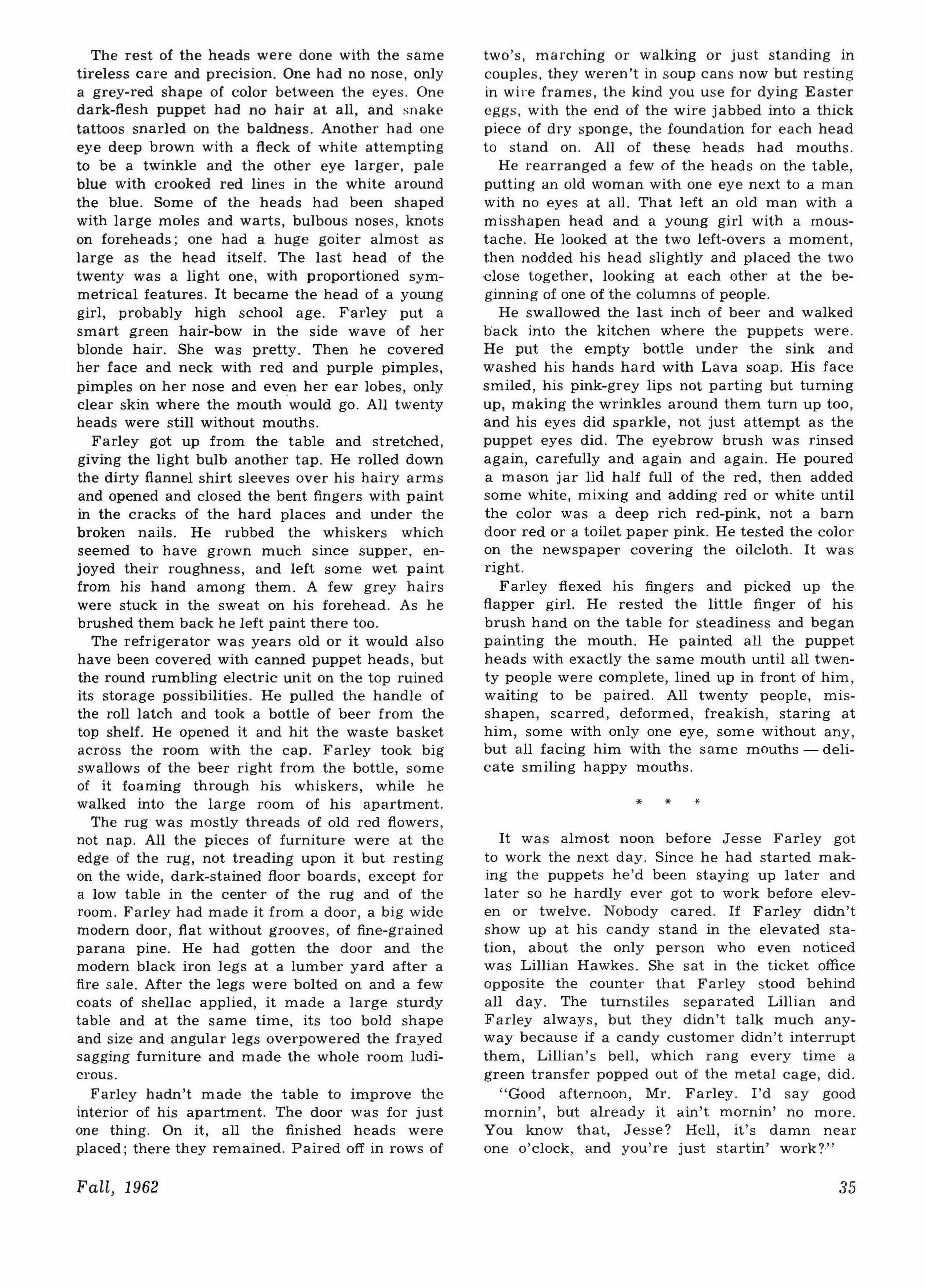

On the stage of the University Theatre, Annie May Sun]: Hall, Inga Swenson appeared as Isabelle in a production of Lean Anouilh's Ring Around the Moon.

It ;s characteristic of Alvina Krause that, although two years ago she joined the list of professors emeriti, she is teaching and directing, full time as usual.

Born in New Lisbon, Wisconsin, she began her collegiate education at Northwestern's School of Speech, graduating in 1928. Two years later she joined the faculty as Instructor in Voice and Interpretation, and, as Associate Professor and presently Lecturer in Dramatic Production, has been a member of the Theatre Department ever since. She received an M.S. at Northwestern in 1933. Since 1945, at The Playhouse, Eagles Mere, Pennsylvania, she has been director, manager, and producer of her own summer company, composed chiefly of undergraduate and graduate students - theatre majors - from Northwestern. Many of her distinguished students have begun their careers there. This year was the eighteenth season for the company.

The article below was written for The Tri-Quarterly at the invitation of the editor.

or talk in rapturous terms of the mystical process of creation - this might be news. True: miracles have been known to happen. In the course of many a student-actor's training they happen; in every successful production, they must happen at least once. But always it is hard work which has cleared the way. The time is right for inspiration's release when the techniques have been mastered and forgotten. That the actor as an exotic phenomenon without virtue, or a complex of neuroses, Freudian or otherwise, may be a myth created by press agents whose advertising plays upon the 4

imagination of adolescent minds, is inconceivable in an age when living realities like work are no longer admirable, believable, and certainly not glamorous. That an actor is a human being like other human beings - with this special exception that he has a particular talent for mastering the arts of a particular profession as another individual has the talent for mastering the arts of medicine, law or finance - that he pursues the study of these arts with the same thoroughness, the same concentration, the same dedication, as does any human being preparing to earn a living

....". t ,; 1. •• I ,

• ,. ,. .'t,

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

with his talents, whatever they may be: this is a concept of actors which is too contrary to the popular image to be tolerated or even understood. There are in theatre schools show-off's and dilettantes engaged in self dramatizations, who are inevitably by their antics the focus of public attention; but do we not meet similar specimens, for instance, in the schools of medicine, law, journalism? Strange: it seems now that I have forgotten these sad seekers of theatrical identities, and their names are too seldom in lights to remind me of their brief, flamboyant moments in the University Theatre Green Room.

I do, however, remember Inga Swenson. As a student she was too interested in too many things to have time to linger in the lounge dissecting the performances of the latest University Theatre leads. She played no spectacular roles in this same University Theatre. Yet when she was on stage in a supporting role, other, more colorful actresses, faded out; attention always went to a tall, quietly beautiful girl seemingly doing nothing to achieve focus. How .she acted was a mystery: she used no tricks of characterization, no incomparable vocal eccentricities: there was nothing in her work to label "theatrical," no moments of bravura acting; yet she invariably wove her spell. From the innocence and purity of Isabelle in Anouilh's Ring Round the Moon to a pointedly satiric Charles Adams comic moment in Waa Mu, she was Inga. She found in a character an idea; she discovered what was most significant, most essential to that idea; she discovered the dramatic force of this idea and she brought to it a radiance and, sometimes, a devastating light. The frame of reference for her acting was that of a perceptive human being, intelligent, well read - a participant in life, not a passive observer. As a director you had only to say to her, "This young girl is French," and a spring was tapped. From a store of knowledge gained from books, music, living, her imagination took off to endow a role with qualities unmistakably Gallic. Or say to her: "This is the period of the Italian Renaissance"; and without long involved searching within or without herself, she was the embodiment of the culture of that brilliant age. Within her was a rich store of images, ideas, sounds, responses to life waiting to be touched off by a playwright's word, a director's suggestion. Furthermore, most rare in actors, she possessed innately a sense of form. There was music in her acting: a rhythm, a tone, a melody, that gave continuity to a role: a direct line to the ultimate goal. Her sense of style pervaded all her work. A director, or the mood of a situation, had only to touch it off. I remember one night: at curtain time in our summer theatre the lights went off, a power failure on the mountain. We held the curtain twenty minutes, the audience getting restless. Announcements were not going to hold it. This was a crisis. The silence

Fall, 1962

of disapproval fell upon the audience, the atmosphere was pregnant with it, when suddenly from the back of the auditorium: music. Ing a softly walked down the aisle singing an old English song; just a girl singing absently, no more. She hesitated for a moment near the stage and then sat down on the apron, still singing, remembering old tunes. She seemed not to see the audience, not to know that listeners were there, yet somehow you knew that she knew that you were there. She sang to you individually, all three hundred of you - an artist in command of herself, the situation, the audience. Fifteen minutes passed, thirty - who knew or cared? When I try to teach the art of good showmanship I think of a girl singing, unaccompanied, "Cockles, mussels, alive, alive-o." I wish I knew how to teach that art!

One September Dean Dennis asked me to hear with him auditions of new students applying for theatre scholarships. Among them was one exceptionally grave young man who read from Maxwell Anderson - a natural selection for one aspiring to theatre honors. Anderson was the new hope of the American theatre with his stirring espousal of the theatre as a temple, a cathedral. My present impression - and it may be false, for imagination plays strange tricks with memory - is that this serious contestant read from Valley Forge. Certainly the image that sticks in my mind is that of Washington: a most somber, tragic figure at the Delaware. I know there were no costumes at these tryouts, yet I have a mental vision, not only of an aquiline profile, but of cocked hat, great coat and all. I still hear a fine, resonant voiceoh, so resonant! - speaking every wordyes, every word - with deep, vibrating significance. Fisk Hall became indeed a cathedral! When the last contestant had finished the Dean raised an eyebrow.

"Well? Anybody you'd care to gamble on?"

"One potential. The tall, lank chap with the tight jaw and the heroic mask."

"What kind of potential?"

"Histrionic. Not fake. Takes himself too seriously, but theatre is where he belongs. Who is he?"

"Chap from Wilmette. Heston. Charlton Heston."

For two years, until he was called into service, he was the epitome of the serious acting-student. He was dedicated to his search for the "inner truth." To discover the playwright's implicit truth, his research was endless. (It still is. The depth and breadth of his private research on The Ten Commandments merits a University degree.) So deep was his concentration during a performance that he spoke to no one backstage. The realistic world of technicians, stage hands, gossiping actresses did not exist for him. He was the world of the character he played. Played? No, he was. He doggedly aimed at mastery of the inner experience which motivated behaviour. He sought

5

to develop the biography of each character he studied. He was determined to create on stage the effect of life as it would go on if there were a fourth wall between actors and audience. He stopped at nothing in achieving that goal. At one time he was playing in a Workshop production of Riders to the Sea, thoroughly immersed in the life of these Irish fisher folk. He came on stage carrying a rope. I remember thinking: "That's no stage prop, no 'illusion' of a rope. That's the real thing." It was! Next day a note came from the head of the department: "Tell your actors they can't cut down the backstage lines. I don't give a damn how dedicated they are to truth!"

Charlton's last performance in University Theatre was Judge Brack, man of the world, in Hedda Gabler. His performance may have lacked some of the polish requisite to a complete realization of that cock-of-the-walk character, but it was surprisingly good. Charlton had a natural, innate gift he may have been unaware of at that time, or if he was aware of it, he fought it as a threat to truth. The gift was a histrionic sense which gave theatricality to his work, lifting his creation of Judge Brack above mere realism. It was the actor's sense that acting is communication: the awareness that out front are people wanting to be entertained. I could not discuss this with him at that time: such words from me might have destroyed an ideal that acting is truth, not the illusion of truth. He was called into military service before we could progress to acting is art, not life. He has done very well since, on his own.

In one of Patricia Neal's press releases she was asked: "Just what did you do in your acting classes at Northwestern?"

"I had to be a pistol- an army pistol."

It makes a good press release. People like to laugh at that which they do not understand. The story is true, but it is not all the truth. Patricia was told to go on stage to be an army pistol. All sophomore actresses aspire to play Hedda Gabler, and Patricia was no exception. Her attempts on this particular day displayed an awkward girl struggling to act "mortally bored." The torment of defeat was in Patricia's eyes as she slumped into her seat, crawling into herself for protection from classmates in whose eyes she always feared she might read: "Pat Neal? An actress? Did you see her Hedda Gabler?" Fear of failure distorts the vision of many a young actor. Patricia believed with every muscle and fibre of her being that she could be an actress. It was a belief in which she received little support on campus. She was honest, so honest that she called the score straight on all her failures. She had no capacity

to rationalize her defeats, to bolster her ego. The image of the actress she wanted to be was brilliantly clear to her; the step-by-step slow progress to that goal was agonizing. Passionately she wanted to be the ultimate in greatness at once, in one gigantic leap. To play Hedda was not a wishful actress dream for Patricia, as it is for most wouldbe actresses. She did not mentally transform Hedda into Pat Neal; rather, she sensed in herself a capacity to become Hedda, to assimilate Hedda's traits, to think, feel, live as Hedda: to turn Patricia Neal into Hedda Gabler. This sense of character is the mark of an individual who can be more than a personality actress; it is the mark of creative talent. Following Patricia's stage appearance on this particular day, there was the usual discussion of character traits. First the trite, general cliches came like "fascinating," "dangerous"; they were rejected. The actor must have the poet's gift of conceiving in images, of thinking in metaphors. "Fascinating," "dangerous" are labels which sum up appearances. Acting that illuminates the script springs from an imagination which, like the author's, creates from images that are clear, unmistakable like "pistol," Ibsen's metaphor for Hedda. To stir the actor's imagination into creativity, he is asked to dramatize metaphors. When Patricia walked on stage to be

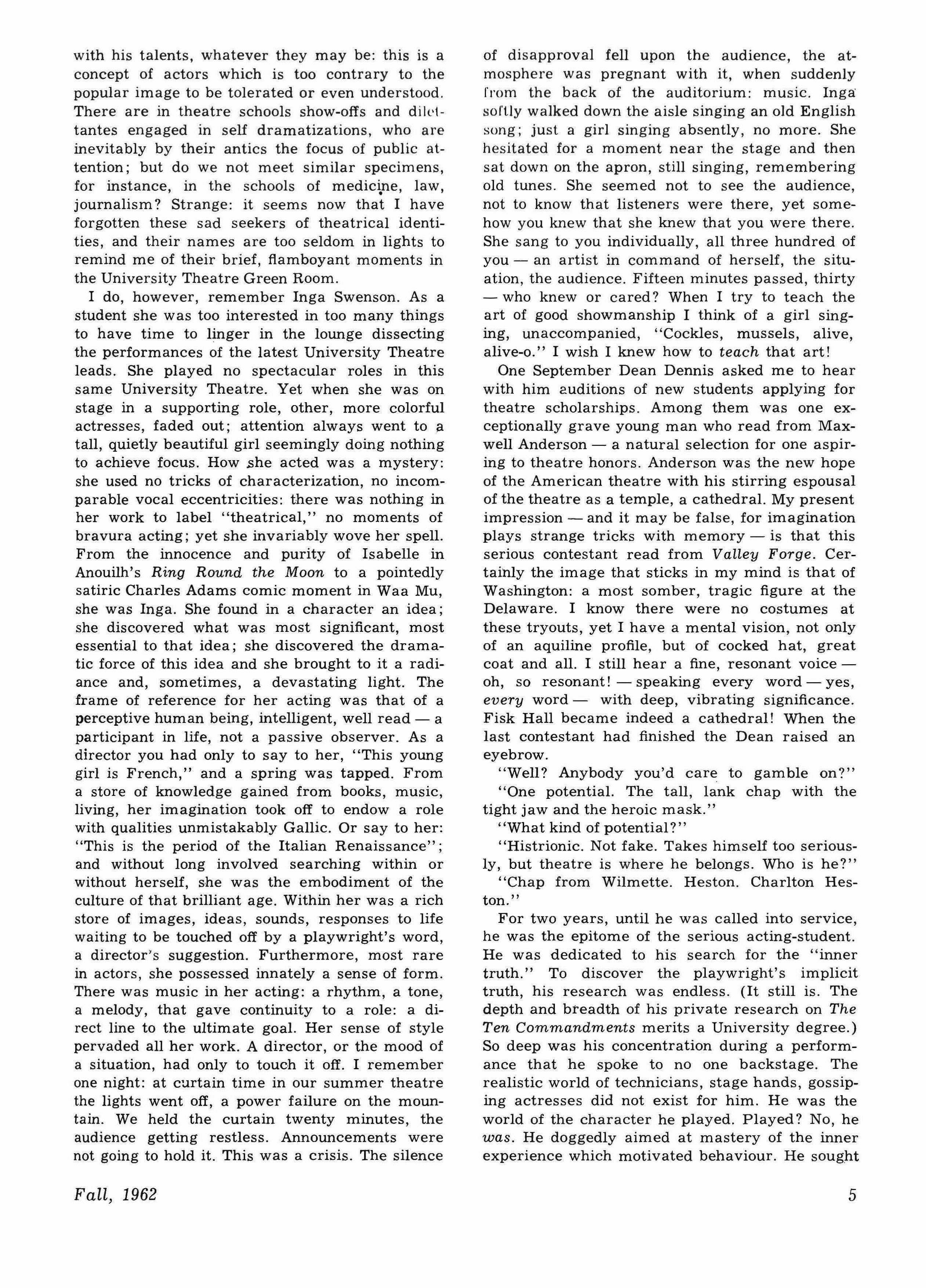

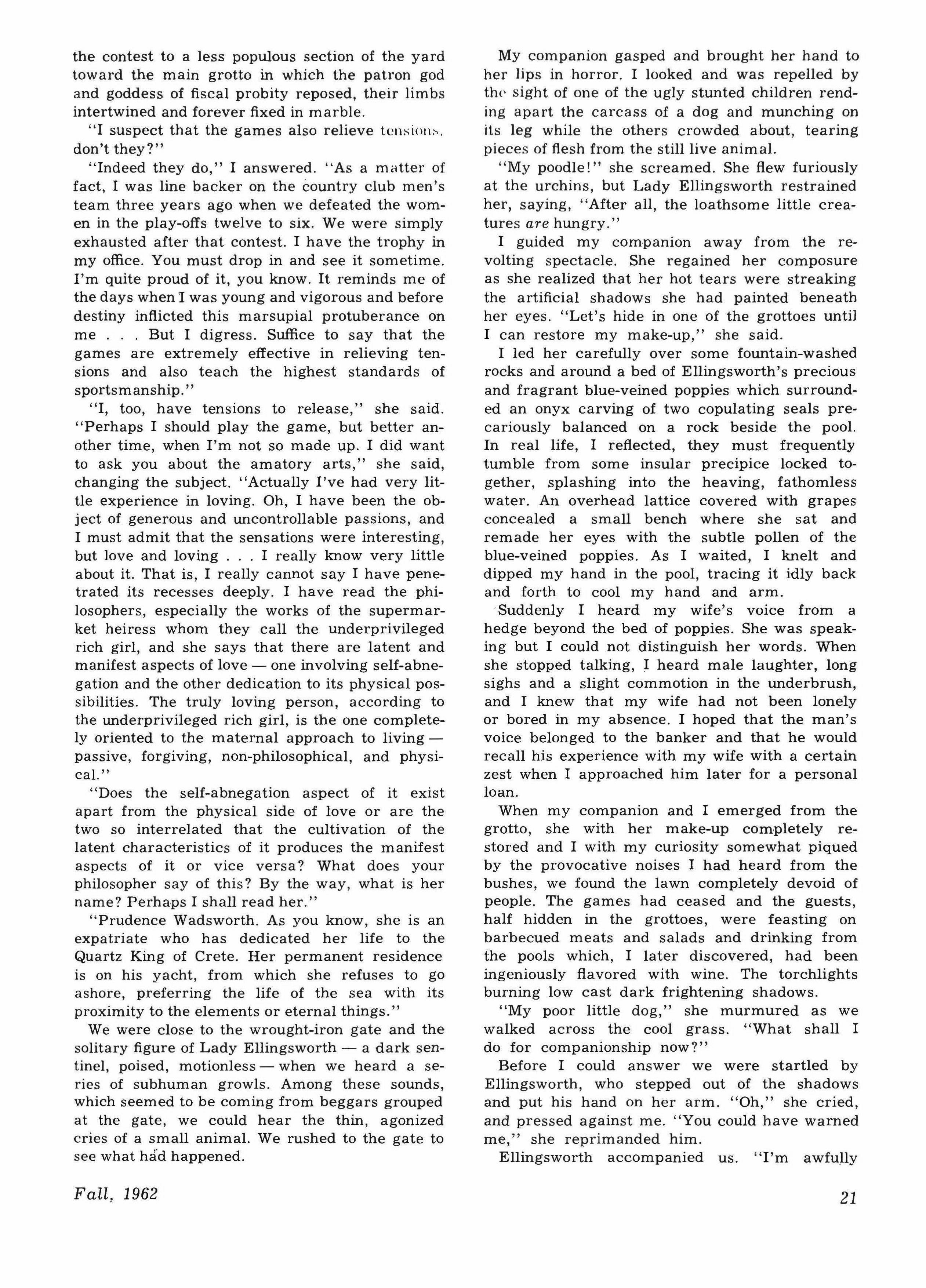

Charlton Heston appeared in the role of the cock-of-the-walk character, Judge Brack, in Henrik Ibsen's Hedda Gabler.

6

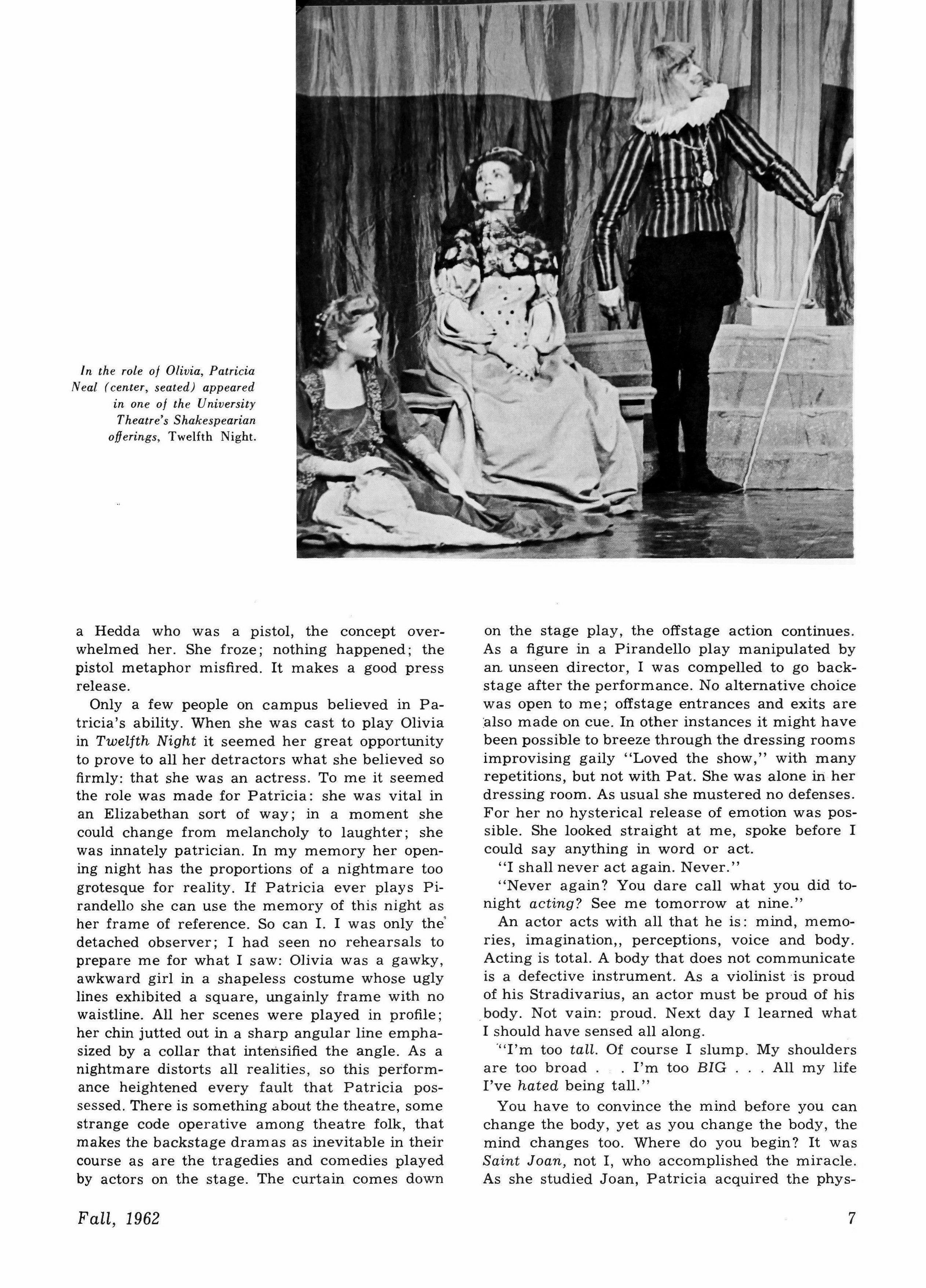

In the role of Olivia, Patricia Neat (center, seated) appeared in one of the Unioersity Theatre's Shakespearian offerings, Twelfth Night.

a Hedda who was a pistol, the concept overwhelmed her. She froze; nothing happened; the pistol metaphor misfired. It makes a good press release.

Only a few people on campus believed in Patricia's ability. When she was cast to play Olivia in Twelfth Night it seemed her great opportunity to prove to all her detractors what she believed so firmly: that she was an actress. To me it seemed the role was made for Patricia: she was vital in an Elizabethan sort of way; in a moment she could change from melancholy to laughter; she was innately patrician. In my memory her opening night has the proportions of a nightmare too grotesque for reality. If Patricia ever plays Pirandello she can use the memory of this night as her frame of reference. So can 1. I was only the' detached observer; I had seen no rehearsals to prepare me for what I saw: Olivia was a gawky, awkward girl in a shapeless costume whose ugly lines exhibited a square, ungainly frame with no waistline. All her scenes were played in profile; her chin jutted out in a sharp angular line emphasized by a collar that intensified the angle. As a nightmare distorts all realities, so this performance heightened every fault that Patricia possessed. There is something about the theatre, some strange code operative among theatre folk, that makes the backstage dramas as inevitable in their course as are the tragedies and comedies played by actors on the stage. The curtain comes down Fall, 1962

on the stage play, the offstage action continues. As a figure in a Pirandello play manipulated by an. unseen director, I was compelled to go backstage after the performance. No alternative choice was open to me; offstage entrances and exits are also made on cue. In other instances it might have been possible to breeze through the dressing rooms improvising gaily "Loved the show," with many repetitions, but not with Pat. She was alone in her dressing room. As usual she mustered no defenses. For her no hysterical release of emotion was possible. She looked straight at me, spoke before I could say anything in word or act.

"I shall never act again. Never."

"Never again? You dare call what you did tonight acting? See me tomorrow at nine."

An actor acts with all that he is: mind, memories, imagination" perceptions, voice and body. Acting is total. A body that does not communicate is a defective instrument. As a violinist is proud of his Stradivarius, an actor must be proud of his body. Not vain: proud. Next day I learned what I should have sensed all along.

'''I'm too tail, Of course I slump. My shoulders are too broad. I'm too BIG All my life I've hated being tall."

You have to convince the mind before you can change the body, yet as you change the body, the mind changes too. Where do you begin? It was Saint Joan, not I, who accomplished the miracle. As she studied Joan, Patricia acquired the phys-

7

ical coordination that is Joan's, the joy in movement that was the Maid's. When the following autumn she opened on Broadway as the vital, beautiful Regina of Another Part of the Forest she was hailed by critics as the season's most promising actress. And beauty played no small part in the decision.

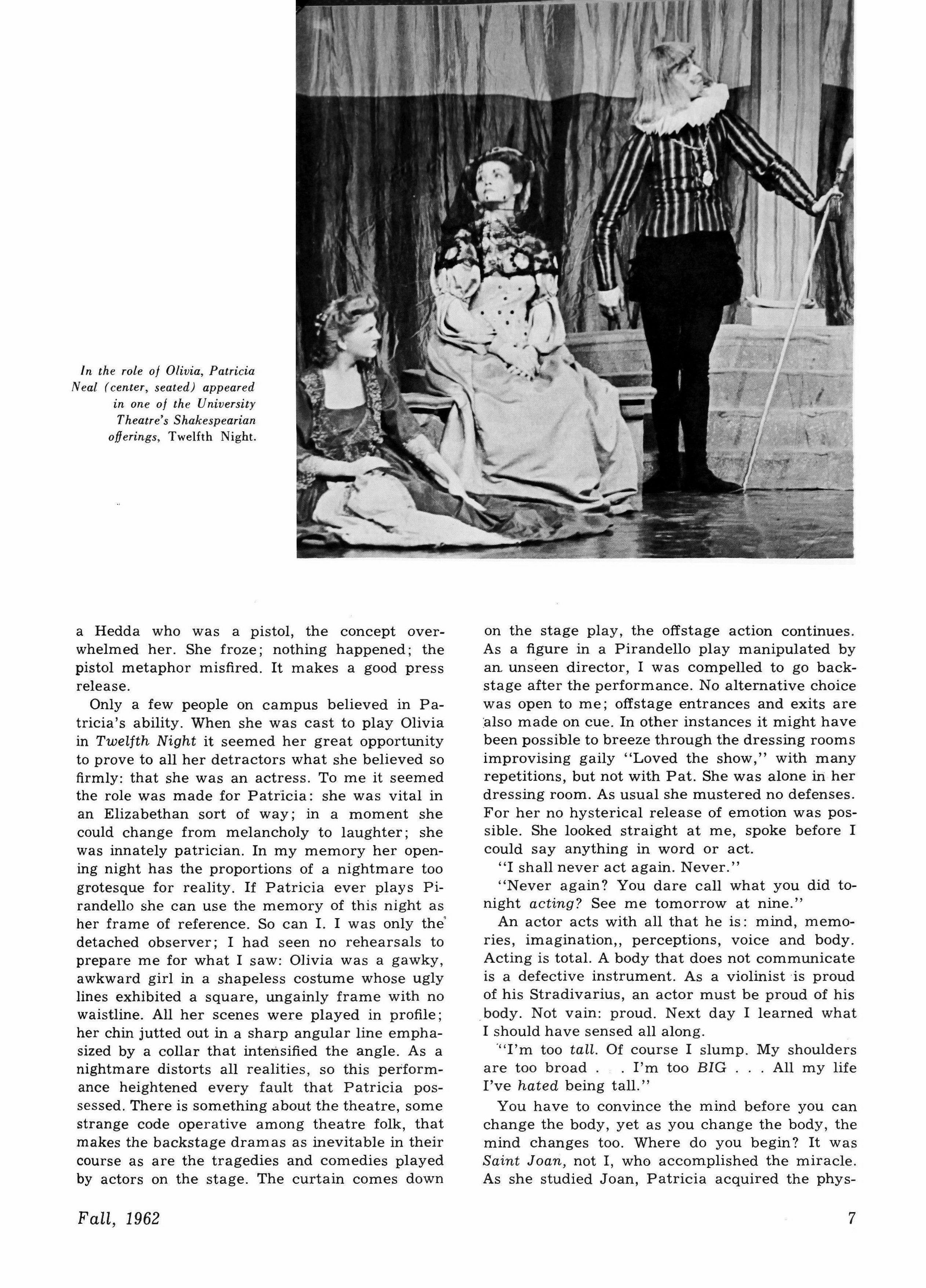

Patricia had a quality that is rare in actors: a quality that cannot be taught: a sense of tragedy. Like the sense of comedy, it must be innate. It can be discovered, trained, developed, intensified, but it cannot be given to any student of acting. A teacher can lecture on the subject; the head can learn about tragedy; but to know about it is not to sense it. Acting which has depth springs from something which is part of the fibre of being, from a grasp, an awareness, a capacity to experience indignation - indignation above the level of personal emotions. It is this grasp which gives to acting the imperative plus so difficult to define. Intellectually an actress may grasp the concept of tragic action. If her knowledge goes no deeper, she will act, as we say, "from the neck up." The result may be art, but art that is intelligent but unmoving. The emotional actor, on the

Theatre production.

other hand, may run his gamut, ironically and illogically untouched by the actualities which motivate his tears, his manifestations of physical anguish. The result may be "exciting" but unilluminating. The actress with a tragic sense of life, and of drama, has the capacity to realize in every fibre of her being the consequence of her tragic decisions. With sensibilities fully vibrant as Antigone, loving life, she chooses death because obedience to eternal laws is more important than life. With her complete being, this actress realizes totally - head, heart, body - the loneliness of the road to her living death. Not only on the personal level does she realize: hers is a world view - the dramatist's view - of the tragic waste of human potentialities. The actress with a tragic sense has the vision and power to speak for all people, of all times, who have known the suffering we call "tragic." Patricia had this power; I believe she still has it. She could today create a Rebecca West that would have the strength, power, passion that would make a production of Ibsen's Ros,mersholm a memorable one. These thoughts make me a little sad.

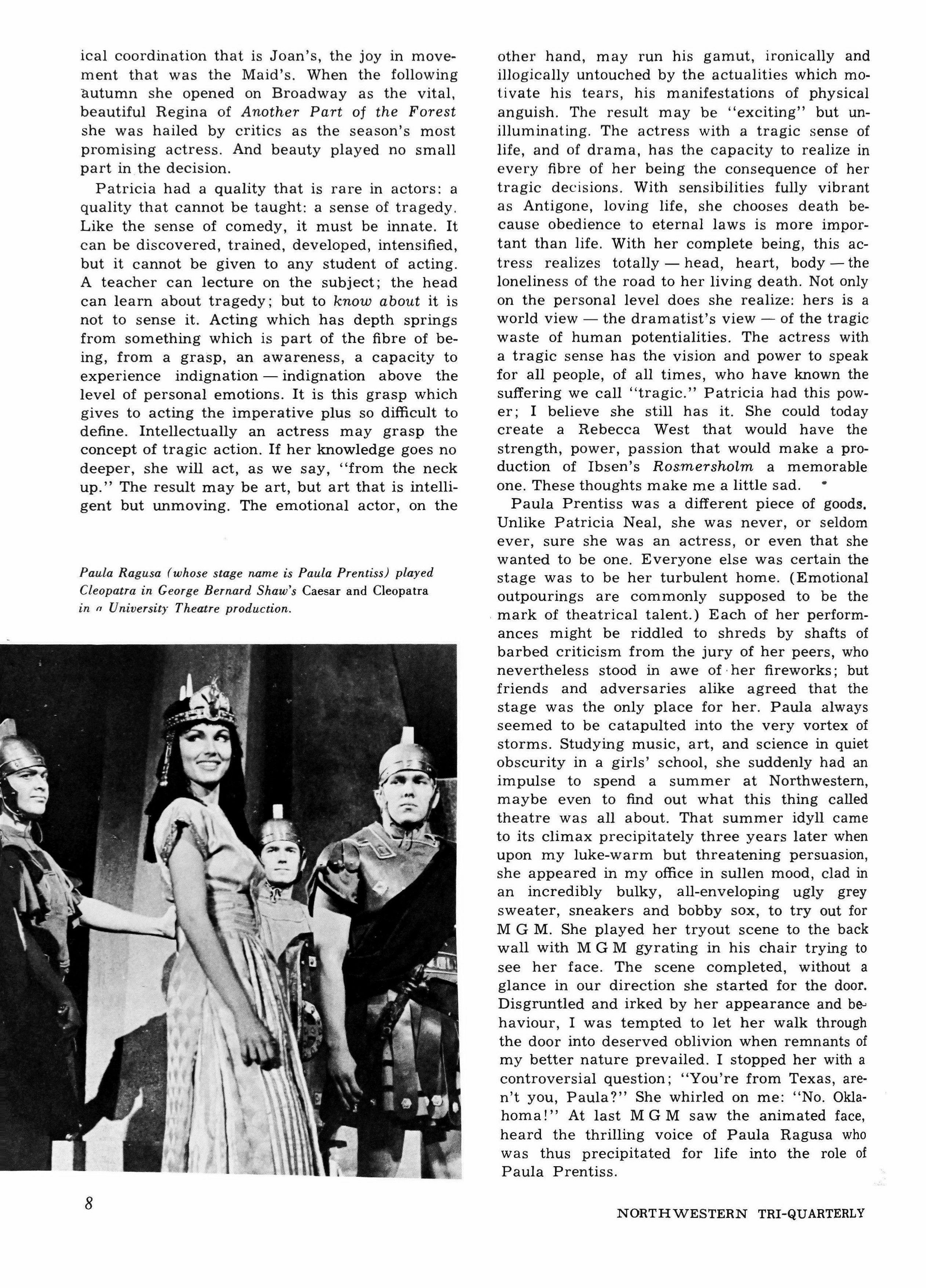

Paula Prentiss was a different piece of goods. Unlike Patricia Neal, she was never, or seldom ever, sure she was an actress, or even that she wanted to be one. Everyone else was certain the stage was to be her turbulent home. (Emotional outpourings are commonly supposed to be the mark of theatrical talent.) Each of her performances might be riddled to shreds by shafts of barbed criticism from the jury of her peers, who nevertheless stood in awe of, her fireworks; but friends and adversaries alike agreed that the stage was the only place for her. Paula always seemed to be catapulted into the very vortex of storms. Studying music, art, and science in quiet obscurity in a girls' school, she suddenly had an impulse to spend a summer at Northwestern, maybe even to find out what this thing called theatre was all about. That summer idyll came to its climax precipitately three years later when upon my luke-warm but threatening persuasion, she appeared in my office in sullen mood, clad in an incredibly bulky, all-enveloping ugly grey sweater, sneakers and bobby sox, to tryout for M G M. She played her tryout scene to the back wall with M G M gyrating in his chair trying to see her face. The scene completed, without a glance in our direction she started for the door. Disgruntled and irked by her appearance and behaviour, I was tempted to let her walk through the door into deserved oblivion when remnants of my better nature prevailed. I stopped her with a controversial question; "You're from Texas, aren't you, Paula?" She whirled on me: "No. Oklahoma!" At last M G M saw the animated face, heard the thrilling voice of Paula Ragusa who was thus precipitated for life into the role of Paula Prentiss.

8

Paula Ragusa (whose stage name is Paula Prentiss) played Cleopatra in George Bernard Shaw's Caesar and Cleopatra in n University

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

The road to that moment had been tumultuous all the way for everyone involved in Paula's life. I remember Caesar and Cleopatra. One night, at last, the opening scene clicked. Weeks of improvise-run-the-scene-, discuss-run-the-scene, improvise-again procedures at last paid off: the scene crystallized; it was ready for performance.

"That's it! Excellent. Keep it just like that, Paula. Understand?"

A grunt and an affirmative nod.

"You and Caesar played together brilliantly. It was witty; even had style. Keep it just like that. Understand, Paula?"

Another indeterminate sound and nod, not so positive.

"No changes after tonight." I was pleading now. "Understand, Paula?"

She found a stick of gum, meditatively unwrapped it, gave it full concentration.

"Want to run it again? To set it permanently?"

A negative response.

You reiterate with Paula because, for all her deep concentration you can never really be sure that her concentration is with you, or whether she has already departed for that little world of her own: her private, creative world. My palpitating hope on this occasion was short lived; the next rehearsal sent it spinning into limbo; despair took its place. If I was baffled by the tenor of the scene, Caesar was dumbfounded. He was too humane to strangle a demonic actress; he could only stare with blank, uncomprehending eyes, and mutter senseless, unmotivated words. This was a Cleopatra created neither by Shaw, nor by any one else in all history.

"Paula, what in heaven's name are you doing?"

"Hm? What's the matter, Miss Krause?" No one in a lifetime of teaching could so confound me with so simple a question, asked in so innocent a tone.

"What's the matter! You were going to keep this scene as it was last night, remember?"

"Oh well. I got to thinking about Cleopatra you know how men fell in love with her I just got to wondering you know Paula's voice always rises softly into the unknown and dies away on an unresolved chord. You feel you must follow her into infinity, into the mysteries of the creative state; but production dates are set and immovable, awaiting the inspiration of no artist. Once more you start back at the very beginning, with the careful underscoring of quiet desperation.

"You see, Paula, you have to play the author's idea Not Paula's idea of Cleopatra. This little, housewifely creature you are creating tonight does not fit in Shaw's framework. She is lovely, fascinating, adorable; but that isn't Shaw's idea of this malicious little queen. You must act the playwright's idea I wish we were doing a movie!

Fall, 1962

Last night's performance would be permanently recorded; you could never, never tamper with it agHin.

At least once in rehearsal or performance Paula ga vo a perfect interpretation of each individual scene. How often we thought: "If only an audience were here tonight!" Paula, however, could never do the same thing twice; she could never repeat. Praise works with many actors; Paula was deaf to it. Not through wilfullness nor temperament, nor temper, did she deviate. She simply could not turn off the creative spring. In Paula's shows we never had to worry each night about creating the illusion of the first time. With her, every night, whether it was rehearsal or performance, was the first time - sometimes chaos. Carefully, on performance nights, I used to plan what I might, casually, say to her - or should I write a little note? - that would keep the stream flowing in the direction of the drama's objective. I would watch her brown eyes light up with agreement as I spoke. Then having made my point by subtle implication, I thought, I would retire to watch from a distance until she started to the stage, praying that on the way no one else would let fall a chance remark that might turn loose again that fantastic, creative imagination.

Paula evolved a theory for her acting: every character, everyone, young, old, sad or comic, fat or leaneveryone - "has a little secret." (Being tall- five feet nine inches - and aware of her height, Paula describes everything in wishful diminutives.) The "little secret" may be labelled by psychologists as the subconscious, and by erudite actors as subtext; but in Paula's world these prosaic terms are not stimulants of the dramatic imagination. In solo performances in class she was always at the peak of her form. There was the time when for twenty minutes or more we watched with delight rare in a class room, while on stage a commonplace "little" woman with a "little" secret humming its tune inside her, removed items of food from an imaginary refrigerator. Not a word was spoken, although inarticulate, indescribable sounds communicated a world of meaning. There before us on a bare stage was the bread and butter world of gadgets and things; there, too, was an inner world in which quite a different woman was sweetly singing, I imagined, something like "I think I'll put a spider in Mrs. Applebaum's tea.. a red spider, or a green spider or a striped spider I'll watch Mrs. Applebaum swallow the black spider and I will say, 'Do you like sugar in your China tea, Mrs. Applebaum dear? Of course, I don't know what the little secret was exactly; but it was believable and entertaining, and I could not call time on the assignment.

With most actors, I wish devoutly for power to ignite inadequate, dormant, or lazy imaginations. With Paula I could only pray for the patience I

9

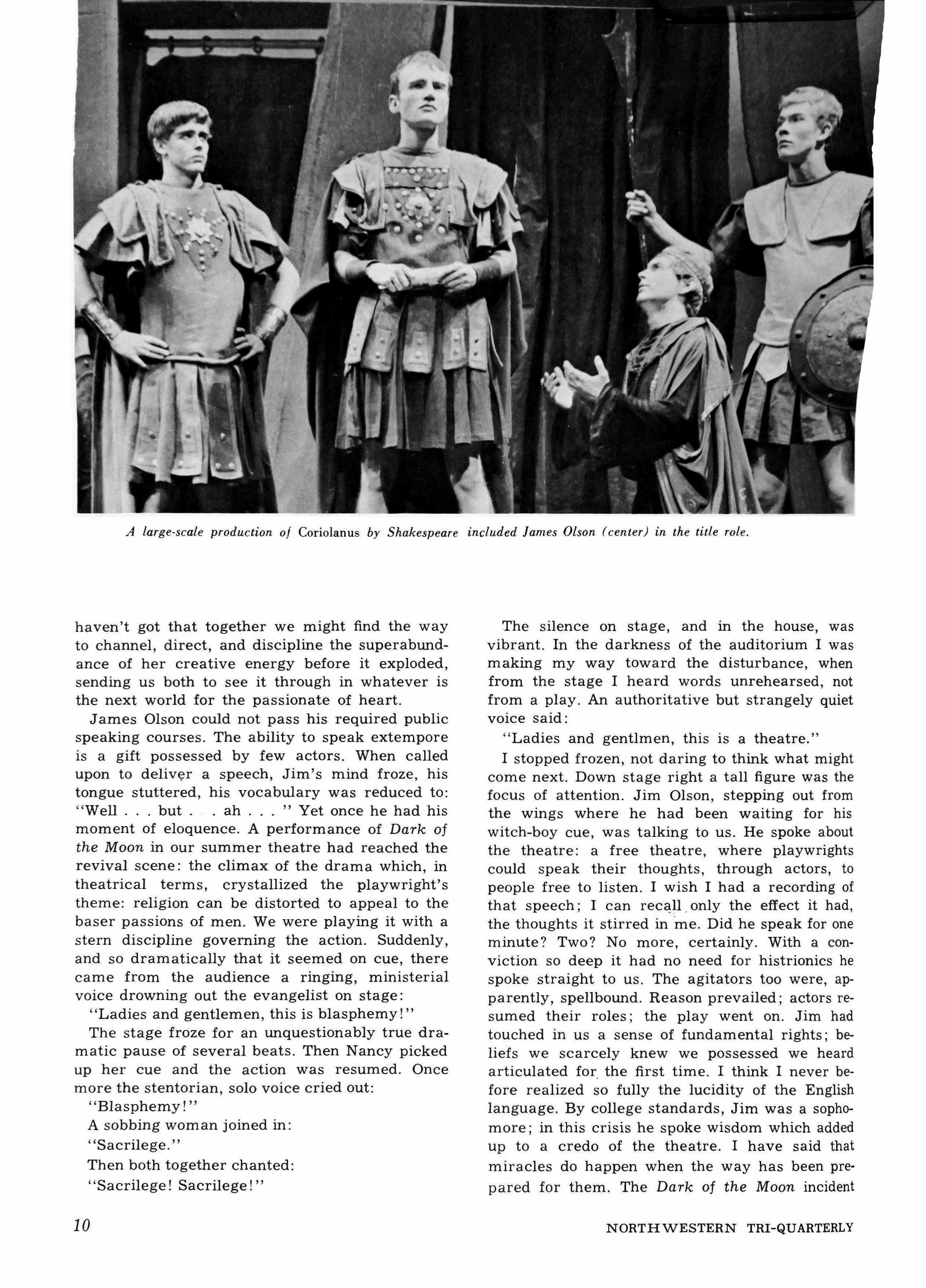

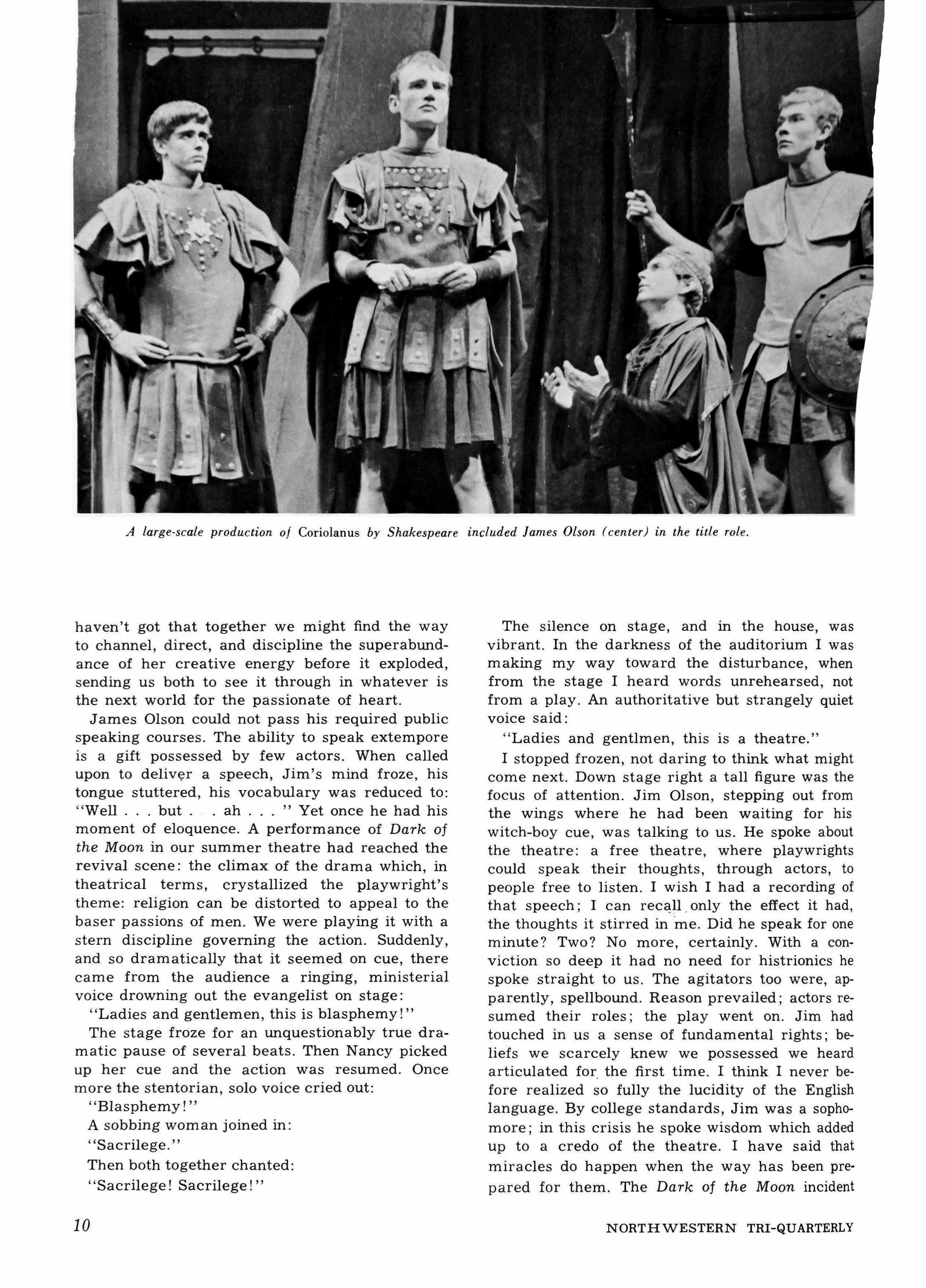

haven't got that together we might find the way to channel, direct, and discipline the superabundance of her creative energy before it exploded, sending us both to see it through in whatever is the next world for the passionate of heartJ ames Olson could not pass his required public speaking courses. The ability to speak extempore is a gift possessed by few actors. When called upon to deliver a speech, Jim's mind froze, his tongue stuttered, his vocabulary was reduced to: "Well but. ah Yet once he had his moment of eloquence. A performance of Dark of the Moon in our summer theatre had reached the revival scene: the climax of the drama which, in theatrical terms, crystallized the playwright's theme: religion can be distorted to appeal to the baser passions of men. We were playing it with a stern discipline governing the action. Suddenly, and so dramatically that it seemed on cue, there came from the audience a ringing, ministerial voice drowning out the evangelist on stage: "Ladies and gentlemen, this is blasphemy!"

The stage froze for an unquestionably true dramatic pause of several beats. Then Nancy picked up her cue and the action was resumed. Once more the stentorian, solo voice cried out: "Blasphemy!

A sobbing woman joined in: "Sacrilege.

Then both together chanted: "Sacrilege! Sacrilege!"

The silence on stage, and in the house, was vibrant. In the darkness of the auditorium I was making my way toward the disturbance, when from the stage I heard words unrehearsed, not from a play. An authoritative but strangely quiet voice said:

"Ladies and gentlmen, this is a theatre."

I stopped frozen, not daring to think what might come next. Down stage right a tall figure was the focus of attention. Jim Olson, stepping out from the wings where he had been waiting for his witch-boy cue, was talking to us. He spoke about the theatre: a free theatre, where playwrights could speak their thoughts, through actors, to people free to listen. I wish I had a recording of that speech; I can recall only the effect it had, the thoughts it stirred in me. Did he speak for one minute? Two? No more, certainly. With a conviction so deep it had no need for histrionics he spoke straight to us. The agitators too were, apparently, spellbound. Reason prevailed; actors resumed their roles; the play went on. Jim had touched in us a sense of fundamental rights; beliefs we scarcely knew we possessed we heard articulated for the first time. I think I never before realized so fully the lucidity of the English language. By college standards, Jim was a sophomore; in this crisis he spoke wisdom which added up to a credo of the theatre. I have said that miracles do happen when the way has been prepared for them. The Dark of the Moon incident

A large-scale production 0/ Coriolanus by Shakespeare included James Olson (center) in the title role.

10

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

supports my belief. An actor can speak extempore when he has discovered for himself that drama is more than individual roles in a play; he can be eloquent when the theatre is for him more than actors strutting on a stage.

James Olson was an all-theatre man: actor, designer, technician, director. By his very nature he was compelled to master each of the theatre arts in order to function more totally in the one which meant most to him: acting. There was no indecision in his approach: the theatre was. to be his profession, his way of life; excellence was his measuring rod. In summer theatre he designed a set, constructed that set, played the leading role in that set - A Herculean accomplishment by any standard. Jim was an actor who, as a designer, designed for actors. As he designed, he saw characters emerging from backgrounds, saw people in movement. No wonder his sets were a joy to directors! As actor, designer, technician he demanded perfection. Jim could not compromise. An actor who professed a love for the theatre and then gave to that theatre less than his best, was guilty of hypocrisy which Jim could not accept nor tolerate. He struck an actor once during a final dress rehearsal. It was one of those times when morale was low, fatigue had mastered the will to do: an apathetic rehearsal. Suddenly Jim's powerful arm shot out: he struck a fellow actor. Physical violence is unjustifiable under any circumstances. What others who condemned him, and rightfully, could not know was that Jim was as horrified by his act as they. Temper was too simple an explanation. Jim was torn by the knowledge that the motivation lay much deeper. He could not understand it, much less formulate it.

Slowly we groped our way to the cause. To Jim, an artist, a play was a work of art, perfect in form, a marvel of unity, balance, rhythm, proportion. Any violation of that form was to him a kind of murder; it produced chaos within him, stirring his indignation to the breaking point. His act of violence itself was unjustifiable; the motivation for that act is something every true artist understands and has experienced when he has witnessed the mutilation of artistic form. The response to such desecration does not necessarily manifest itself in violence; our culture demands that even the artist conform to passive acceptance or indifference. How I long to hear from an audience someday, one frank, resounding "Boo!" when actors on a stage forget the unwritten laws of their profession, when they violate the principles by which we recognize theatre as an art. Such a demonstration might foretell a renaissance in the American theatre.

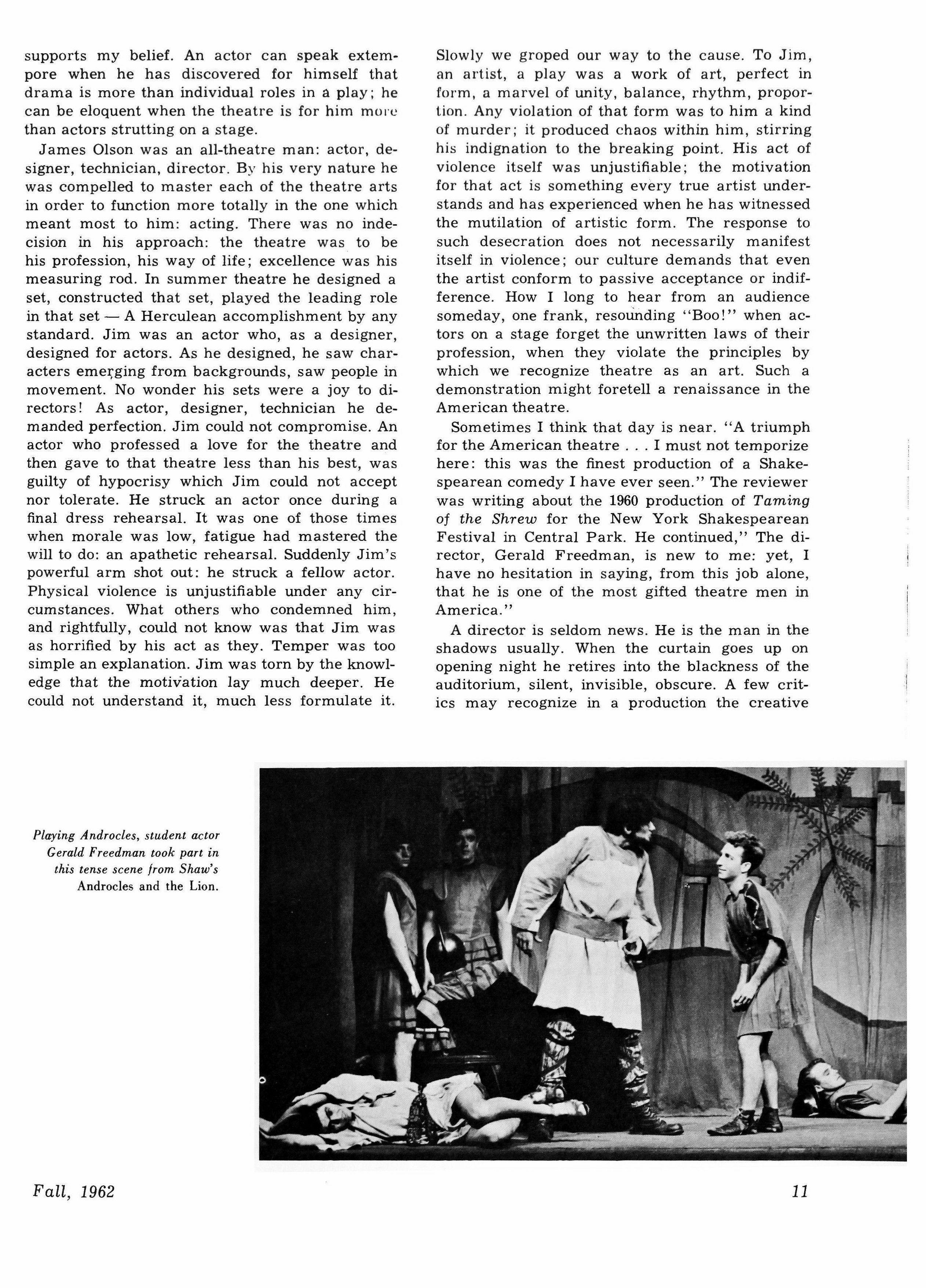

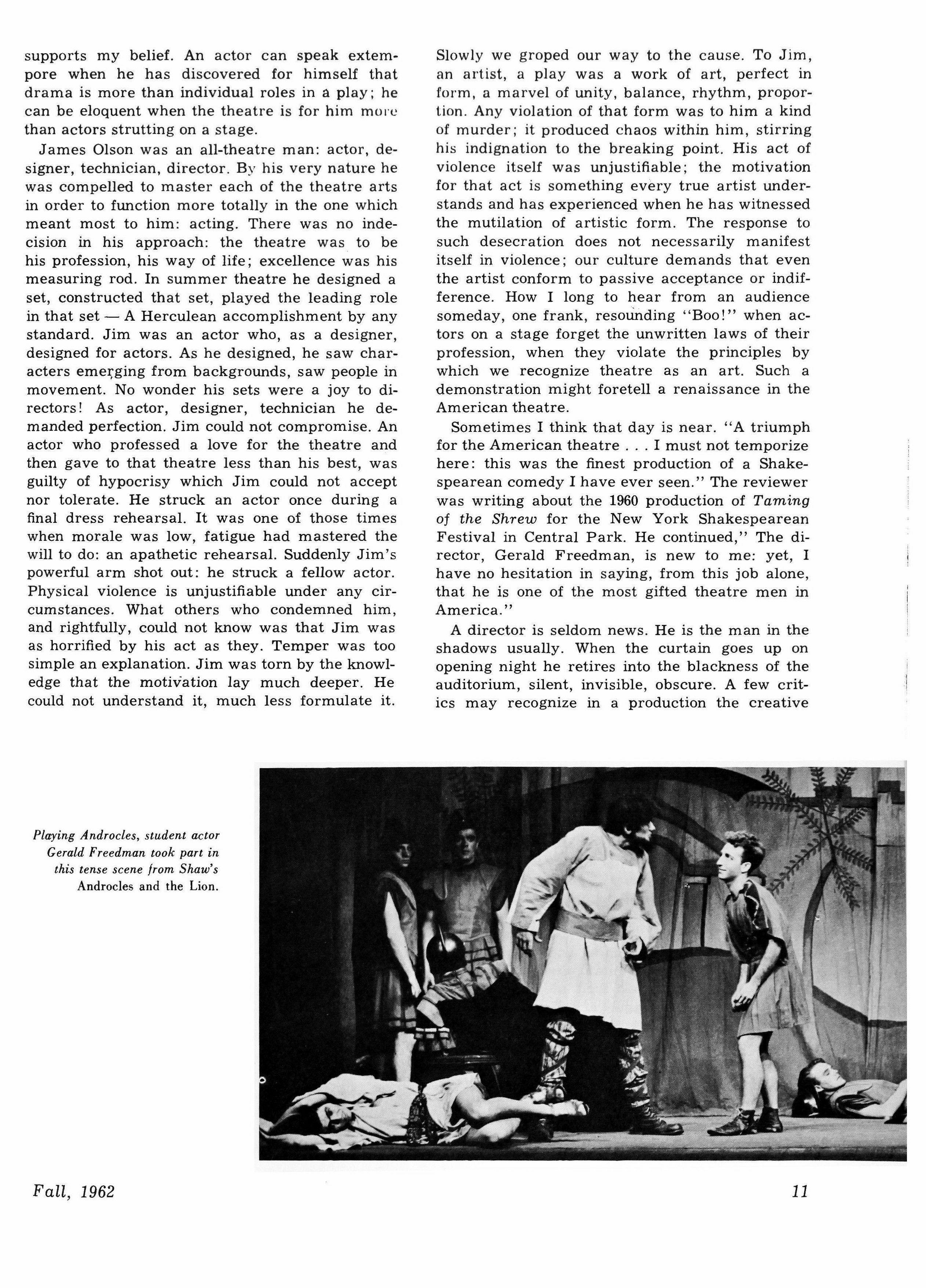

Sometimes I think that day is near. "A triumph for the American theatre I must not temporize here: this was the finest production of a Shakespearean comedy I have ever seen." The reviewer was writing about the 1960 production of Taming of the Shrew for the New York Shakespearean Festival in Central Park. He continued," The director, Gerald Freedman, is new to me: yet, I have no hesitation in saying, from this job alone, that he is one of the most gifted theatre men in America."

A director is seldom news. He is the man in the shadows usually. When the curtain goes up on opening night he retires into the blackness of the auditorium, silent, invisible, obscure. A few critics may recognize in a production the creative

FaZZ, 1962

Playing Androcles, student actor Gerald Freedman took part in this tense scene from Shaw's Androcles and the Lion.

11

mind of the director. The audience, however, sees, hears, applauds the actors and sometimes, astutely, the play. Only the theatre-wise patron looks first of all for the director's name on a program. Yet Jerry was wise to choose directing as his activity in theatre, for Jerry is a man of many talents; only directing can use them all. On campus we knew Jerry as an actor. Shakespeare, Shaw, Sophocles, Sartre: he was a master in the interpretation of all. I have seen the greats of the commercial theatre attempt Androcles; but Jerry is the only actor I have ever known who could hold a totally logical, intelligent, Shavian conversation with a lion. Others can't resist the temptation to "play for comedy," to burlesque, distort, or play the scene swiftly as too ridiculous to make sense. Jerry had the mind to grasp the Shavian intent; he had the capacity to understand both man and beast. Not only that, he understood all eras. When he played Shakespeare, he was the Elizabethan Renaissance personified. With sufficient pressure, and much kinetic participation on my part, I can induce actors, perhaps in self-defence, into a state of Elizabethan total activity. Knocked about enough, they can be forced out of their contemporary torpor, their physical passivity, so that a stage can come alive with some semblance of the physical joy of living, the mark of the Elizabethans. But the Renaissance mind, that stimulating, many-faceted, creative mind that motivated the activity of the age - how do you endow actors with that? Jerry possessed it: a word, suggestion, a scrap of pantomime, and he could toss off an Elizabethan sonnet, sing a madrigal, fight a duel, bait a bear. So it was with all eras. I might say to actors, "In this play you must be continental; you must discover how the European mind works, how it activates behaviour." They stare at me helplessly. I talk to them at great length, I send them to books, to art, to living people: French, German, Italian. Eventually, with great effort we arrive at some degree of understanding. Not so with Jerry a word, a description, a stage direction, and he walks on, for instance, as an Austriannot an American imitating the outer vestures of an Austrian, his voice and behaviour - this is no imitation: Jerry is what he imagined. He had the ability to conceive what eternities had produced, the historical insight to give substance to his thought, the flexibility of mind and body to transform himself into the role imagined. Other actors, with difficulty, draw upon their memories of personal experience as frames of reference for their characterizations. "With difficulty," I say advisedly, for how limited they are in their store of significant experience; and in their passive state, how unreceptive to the stimuli of life about them! Actors today must be taught to hear, to see, to experience before they possess a memory vivid enough to draw upon. No so with Jerry. His memories went deeper than the personal. Racial mem-

ory ? I do not know the source of this creative spring. I can not endow actors with it; I can only make them aware of the need. Jerry was endowed with it. And he had a greater gift: the gift of communicating, of sharing his experience. Unaccompanied, sitting in a chilly living room after a later rehearsal, Jerry sang Hebrew chants. He is a musician - another of his talents: he writes music, has a tenor voice of unusual beauty. But it was not the beauty or, at least, not the beauty alone, that moved us. As we listened we were one with him; we knew, we understood, deep within us, the origin of those laments. The tribulations which were their source were our tribulations. As an artist-actor Jerry could, always, for a time at least, change the tenor of our lives.

Jerry is a designer too. When he entered the university he had to choose between an art scholarship and his theatre interest. Theatre won, but during his stay here we had many private showings of his paintings. In the theatre this talent was released in scene designs. His set for Midsummer Night's Dream was visual music. It is obvious, then, why Jerry was wise to choose directing as his career, for only in this capacity could he use all of his arts. As a director, he plays not one role in a drama, but all roles. As an artist, he fills his stage with pictures which interpret the play with visual connotations in fluid patterns of color, movement, design. As a musician, he balances voices in harmonies and dissonances; as a symphony conductor produces musical form out of many instruments, so a stage director creates a dramatic structure which is not unlike a symphony - when that director is a Gerald Freedman.

I am often asked by actors, columnists, and laymen, "What makes an actor an artist? What makes him great?" Depending upon my mood I may mutter: "Bloody hard work," or "Who do you think I am: God?" The truth is: I do not know the answer. Sometimes in the class room or in a rehearsal it happens: that electric moment when student-actor is transformed into actor-artist. Why? How? For an instant I think I know: all our work has added up to this inevitable achievement. But that moment of rationality is instantly followed by a deepened sense of the mystery of the metamorphosis. I leave the question now to the researchers: let them find the answer if they can. I think, perhaps, I do not want to solve the riddle, for if I did might I not lose what is the most dynamic reward of all: the eternal astonishment of teaching?

I am indebted to Professor Lee Mitchell for finding early photographs, from plays produced at The University Theatre, of the actors mentioned by Miss Krause. E.B.H.

12

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

By William Thomas Page

The new student at Northwestern will often find himself in a quandary, not knowing what to do in many situations; or he may think he knows the proper choice to make when he actually does not, and thus his decision may be incorrect. In either case the results will be unfortunate. I hope that I can establish some rules that will help new students to avoid incorrect decisions. Adherence to my simple set of maxims should guarantee success to anyone.

As a new student, you must always remember that your most important goal (at least at this time) is to win acceptance. Everything must be sacrificed for this one goal if you are to have a happy, successful college career.

Developing an adequate vocabulary is the first step in gaining acceptance. Every day, practice using several significant terms, and you will have flO difficulty comrnunicating exactly what you mean. If you want to praise someone or something, say it is "tough," "cool," or "sharp." You can always make these words more emphatic by prefixing them with "really." The phrase, "got the hots," also indicates something desirable. A boy may say he's "got the hots" for a girl, but a girl may apply the expression to almost anything, even to professors. If you wish to malign someone, you can say he is a "kook" or a "loser." If a person is extremely undesirable, "neatsie" is a powerful term which has as many connotations as anyone cares to give it. But the strongest appellation (and consequently one which must be saved for special occasions) is "nurd," a term which can be applied to anyone who is thoroughly disgusting. "Spastic" can also be used to describe someone you don't like. When anything bad happens, you can say you "took gas." This is particularly good when you think you failed an exam. "Lunch" is also popular. A woman will say, "She is lunch," to describe some one who is "out-ofit," while a man may say he "caught his lunch," which means he "took gas" on a test or broke his ankle in an I.M. basketball game. Don't worry if you don't know the meanings of all these - nobody is sure of what they mean anyway. If you use them, you will reveal what you want to reveal, which is not that you know the meanings of the words, but that you are "cool" enough to use them.

You must also be able to talk about fine arts if you want to make a good impression. Making sure that you are familiar with Ray Charles, Josh White, Miles Davis, and the Kingston Trio, will establish you as an authority on music. In the field of literature, a working knowledge of Catcher in the Rye and "Peanuts" is absolutely indispensable. However, any indication that you are sincerely interested in theatre, painting, serious music, or literature will lead people to assume that you are too cultured, too much a part of the avant-garde to be socially acceptable. Nevertheless, you should drop names such as Albee, Webern, Ives, and Chagall into your conversation, but be careful not to reflect any understanding of their

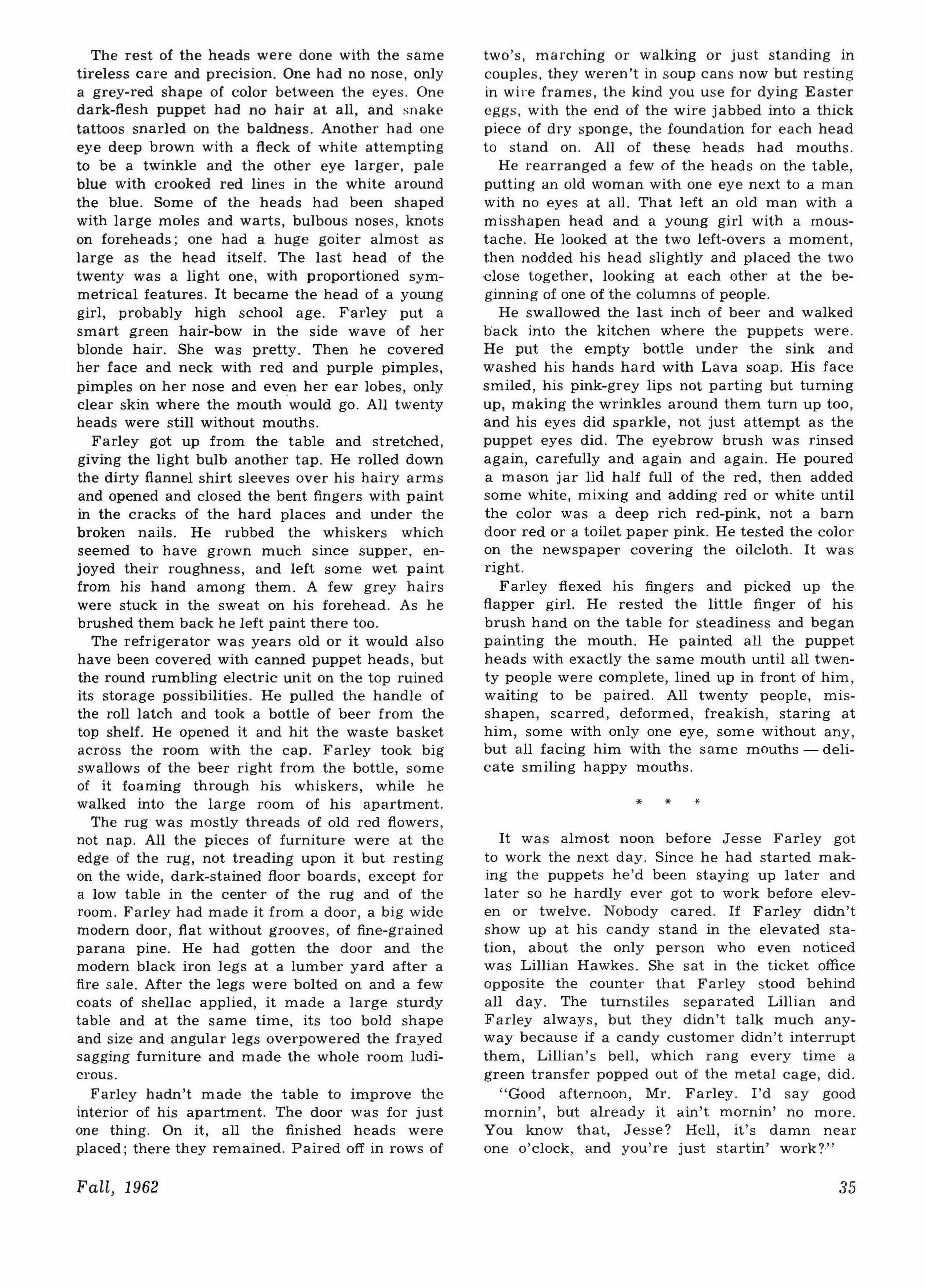

William Thomas Page is a senior in the School of Speech. Born in Farmington, Illinois, he went to school there, spending his vacations in northern Minnesota, and sometimes helping in his father's clothing store. Recently he has worked in the strip mines of the southern lJIinois coal fields. He has not yet decided what he will do after graduation.

Fall, 1962

13

works. Cover Time every week and you will have enough cultural information.

To be accepted, you must also speak derogatorily of the University administration. This is one of the easiest requirements to fulfill since you only need to learn a few simple phrases. Both, "The University is too paternalistic," and, 1'1 don't see why we have women's hours - aren't we old enough to manage our own lives?" are useful. Malign the Health Service every time you get a chance, and ask why they take your temperature every time you go in. Refer to Dean McLeod as "The Great White Father." The expression, "Patsy Thrash, All-American Girl Scout," is essential for every coed. Be sure to use these phrases, even if you don't believe in them. (It follows from this that you will be admired for breaking as many University regulations as you can without getting caught.)

Having a number of psychological terms ready for instant use is also essential. The only important psychologist is Freud, and fortunately you can talk about his writings without understanding them. Just remember that he reduced all behavior to sex, and memorize a few Freudian terms such as suppression, fixation, ego, and libidinal energy, and use them to describe your own behavior and everyone else's. A sketchy knowledge of the Oedipus Rex story is imperative.

Of course if you really want to be accepted, you should not appear to be an intellectual. This does not mean that you aren't allowed to earn high grades; it only means that you aren't allowed to work on Friday nights or to sacrifice a date so you can study at the library. "Study dates," on the other hand, are highly desirable, so long as you don't try to study too hard. (If you're actually working for a graduate fellowship or to get into a professional school, you may be exempted from this rule in some instances.)

But on the other hand, you must not appear to think irrationally. I am not trying to say that you need to think clearly; you only need to make others believe that you do. For this purpose, remember the phrases, "I don't think that's very rational," and, "You're not being very objective," and be sure to drop one of them into every lengthy conversation. Try to utter something serious occasionally, but don't dwell on it.

You will lessen your chances of being accepted if you appear to try hard in class. The person who does this is easy to spot. He usually sits in the front row and answers more questions than anyone else, although many of his answers are obviously wrong. If you need to "brown-up" a professor, go see him in his office, and don't tell anybody that you went. Or if you mention it, be sure to add that you were only trying to make a good impression.

Although I have said that diligent study is frowned upon, you should remember that it is

very important to keep off the probation lists. A few simple rules for writing papers will nearly always guarantee a "C" or better. Be sure to support the same position the teacher holds. Instructors have a most difficult time finding fault with a rguments that coincide with their own. The pass-word on papers is "intellectual restraint." Professors love it. Understate absolutely everything. The word, "perhaps," will save you from criticism in many instances. Practice using the phrase, "in a sense." When you use it, you cannot possibly be wrong; you are always right "in a sense." Say you are not certain even when you are sure you are right. The best way to close a paper is to list all the intervening variables which you have neglected to consider and which will completely invalidate everything you have said. (If you don't know any authentic points you have overlooked, make some up. It shows you're thinking.) Finally, write the introductory page to your paper after you have covered the material and know what you have said.

Another good trick is to tell your teachers that you are really here to learn, since this establishes you as one who shares their values. Professors grow tired of dealing with pre-professional students who are out to make a "fast buck." Therefore, the best way to gain an instructor's respect is to tell him that you want to teach in college. Ask for a list of books that will help to broaden your interests.

Remember that engineers as a group are social and intellectual outcasts, commonly known as "Tech Wienies." The best way to jeopardize your grade in Freshman English is to let the professor know you're in Tech. If he asks you about it, tell him you're transferring into Liberal Arts. Hide your slide rule - never hang it on your belt.

Being seen in acceptable places is important. Plan now to spend at least an hour every day in the Grill. Arrange to frequent Lou's and the Orrington's sidewalk cafe. Going to the Hut is another matter. Often the people who go there are known as the "Hut set" and are looked upon as a group of pseudo-intellectuals who don't bathe over once a week. But you can go there after midnight, so long as no other place is open.

Whether you are expected to drink or not depends on the group you happen to be in. In some cases a person will be rejected if he doesn't drink - regarded as "out-of-it." Women are not disturbed with women who don't drink as much as men are annoyed by teetotaling males. Many men will not date a woman who doesn't drink, and there are women who are not happy to date a man who doesn't. A man must always buy for his date, even if he doesn't drink. Although some groups of women frown on drunkenness at any time, getting drunk often is always bad. If you come in smashed once in a while, be careful where yOU barf. Under-age men who intend to drink should

14

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

have fake I.D.'s. Blank draft cards are plentiful and can be obtained for a reasonable price. These also provide a certain satisfaction associated with violating the law. Subsequently, the best polic-y is to go along with whatever crowd you happen to fall into. Never brag that you abstain.

Some people will snub you if you don't smoke, but this attitude is not typical. No man should ever smoke Kents; if he does, women will think he is effeminate, and other men will warn him that he may become sterile. The notion that a man should smoke non-filter cigarettes is popular in only a few circles, but he must be absolutely sure that he doesn't hold his cigarette as a woman does (or, for that matter, do anything that might lead others to think he has homosexual tendencies, for this will immediately label him as unacceptable). No woman should ever smoke anything stronger than MarLboros - Winstons sometimes permitted - for this tends to distort her image of femininity. Spring cigarettes are definitely forbidden. Whether women prefer men who smoke pipes has never really been decided.

Admitting you're from a small town (under 50,000) leads to certain rejection. Among those with city and suburban backgrounds, this just doesn't set well. Telling people about a childhood in the country makes you vulnerable to attacks which people might not have considered ordinarily. If you have a problem with this, name the largest city within a hundred mile radius of your home and say you live in a suburb of it.

What you do about sex is unimportant, so long as you have at least one date every quarter; but what you say about your experiences is vital. Opinions on this matter vary from group to group. Find out the norm for your group before you start to talk. A woman may fall into a situation in which it is desirable to rave about her chastity, telling everyone how she has resisted the attacks of many men. In this case she should develop a backlog of stories to use on the proper occasions. The group may take a different attitude, and talk more freely about such experiences, especially if the women happen to be pinned or engaged. Still a third group never discusses the matter at all.

The norms for men are somewhat different, but the pattern still varies from group to group, and even from individual to individual. If you are popular otherwise, you can claim ten or more seductions and at least some of your friends will believe you and look up to you as a "cocksman." But if you are not well-liked, you will be resented for describing even one conquest. Never talk about the girl you are dating at the time - wait till you've given her up. Never brag about being chaste, or someone will say you are self-righteous. Just be sure that everyone feels that you are tolerant of his position and that you believe his stories. Remember that this is a losing proposition, because someone will call you a liar no mat-

Fall, 1962

ter what you say. But as a general rule, when somebody asks you if you "got any" last night, say, "yeah, a little," and in most instances everyone will be satisfied.

Just how much profanity to use is another problem you face. Both men and women swear more freely among members of the same sex. A man can often use profanity to establish a more virile image with women, provided he doesn't say anything coarser than "son of a bitch," and saves this for special occasions. Some girls, however, will tolerate swearing only on rare occasions. A woman must use more restraint. She sacrifices some of her femininity when she goes beyond "damn" or "hell" before a man, and some men object to this. No one should act surprised at anything he hears.

The great emphasis on blasphemous jokes seems to have tapered off, but you are still expected to laugh when you hear one. You will be entirely correct if you refer to the Holy Spirit as the "Big Spook," but to refer to God as the "man upstairs" is taboo. Speak against conventional religion occasionally, remembering that some people think it is contrary to human intelligence. Trying to start a prayer and Bible-study group will most certainly lead to total rejection.

The importance of Greek affiliation is also variable. The affiliated woman assumes, in many cases, that the independent woman must be completely undesirable, although exceptions to this rule do exist. As freshmen and sophomores, affiliated women will have nothing to do with a male independent ; as juniors and seniors, they may admire the man who has de-activated or remained independent; or they may just forget about it. Affiliated men are more apt to view independent men as their equals, except when the former group is composed of freshmen. As far as most men are concerned, there are so few independent girls on campus that whether to date them is rarely a problem. The important thing, then, is simply to be "sharp" and to associate with "sharp" people.

Knowing how to dress is another significant part of your fight for acceptance. Survival without a trenchcoat is impossible. No man can get along without an Ivy League suit. Loafers and white socks are essential for everyday wear. Pleated pants are out of the question. Almost all shirts should have button-down collars, although tab collars can be worn for dress. A large supply of sweaters is helpful, so long as the sweaters reflect a recent style, not one that disappeared two years ago. The supreme commandment is this: everything must be subdued; nothing gaudy is permitted.

For women the traditional camel's hair coat is no longer as popular as it once was. Consequently the color and style of the coat are not important,

15

so long as it has a fur collar. White socks are equally important for women, and white tennis shoes are the generally-accepted everyday fashion. Aside from these things, the most important consideration is skirt length. Even if short skirts look terrible on a girl, she will be "uri-cool" if she fails to follow the present trend. The best way to dress is the way everybody else does.

In the area of politics, campus elections have verified that a rather conservative outlook prevails, but no strong stereotype can be developed. The safest political position is somewhere between the views of Everett Dirksen and those of Nelson Rockefeller. Never attach yourself to an extreme group on either side. The John Birch Society and the Americans for Democratic Action are both condemned. Selecting an acceptable political position is not as difficult as I have made it seemjust don't have any strong convictions, and you will have no difficulty, since most students have a very limited knowledge of this field anyway.

When you first come to Northwestern, everyone expects that you will be appalled by the apathy of the student body. As a freshman you should go to football games and ask why nobody cheers. But after the football season is over, try to become apathetic, as almost everyone else is. Don't get excited about student government, even if you dabble in it. Remember to say, "The Senate never does anything," and "Student government is just a rubber stamp for the administration."

As you have probably expected, you will find some beatniks at Northwestern. You must either become one of them or avoid them entirely. There is no middle ground. The true individualist is somewhat respected; but if he fails to meet the standards, he will be classed as a "pseudo-" or a "phony" - the worst possible categories. No "beat" ever enjoys widespread acceptance; he is fully accepted only by those who are like him. As a result, any indication that you are different will interfere with your popularity.

A few miscellaneous rules should be covered. Don't carry a green book bag, or you will be classed as a pseudo-intellectual. Take aspirin tablets, No-Doz, and Dexidrine occasionally so people will realize that you, too, are under strain. Never take an examination confidently - tell everyone you're clutched. Take fashionable courses. Physical Geography, Nationalism, and BIO Literature are valuable to the accepted person. Men should scan Playboy every month and remember the Playmate's measurements. Don't be happy all the time. Cynicism and stoicism are more popular attitudes. This is imperative: If your mother had to go to work so you could come here, don't let anybody know it.

Summarizing these rules is simple: Remember that you have nothing to gain by having strong convictions. Try hard to be like everyone else.

Richard W. Ralston, currently the Director of Development of Roosevelt University, has appeared in this magazine twice before. He was once an official of Inland Steel, and his article, "The Dialogue of the Deaf," published in The Reporter magazine last year, was one of the first major critiques on the 1959 steel strike as well as an assessment of the effects of the Common Market on steel's pricing behavior. Ralston's articles have also appeared in the Chicago Tribune magazine, and other journals. He was graduated from Northwestern University in 1943, in absentia, as an English major while serving as a Marine officer in the Pacific.

NO TIME OF DAY

Hewore a watch whose face was divided into two sections: night and day. No numbers were printed on it and only one hand, instead of two, moved slowly around the circumference of the dial three times every twenty-four hours.

"All I give a damn about is when it's night and when it's day. I won't be a slave to minutes and hours like the rest of you time-bound creeps," said Lord Ellingsworth Jones, an Englishman turned American, who was the world's greatest authority on the liquid position of the reserve banks and who was employed by our company because of his British "style" and commanding manner.

Furtively I concealed my conventional wrist watch by plunging my hand more deeply into the pocket of my trousers.

Time to do many things, I reflected, the illusion you get when you watch the face of the clock, is not the measure of your progress, but the way you handle the intervals between night and day, not counting the minutes and hours, not even being aware of the movement of the hands of the clock. Tiempo para gastar, as the Spanish say.

Passing the display window of the corporate gymnasium on our way back from lunch, we

16

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

By Richard W. Ralston

stopped for a moment to watch a voluptuous model subject herself to the kneading and rolling of a body-conditioning machine. It was equipped with a set of rollers that firmly embraced her buttocks and hips and moved up and down, vibrating her entire body from the forelock of her tinted hair to the points of her breasts indifferently supported beneath her tight transparent blouse. She was an executive secretary on detached duty to demonstrate the organization's voluntary bodyconditioning program.

Lord Ellingsworth didn't even look at his watch, so intent was he on the functioning of the phenomenal machine - a contraption, when you studied it, that seemed to work on the model's body with an almost human intelligence. I felt a little jealous of it.

"One would think," observed Lord Ellingsworth, "that such a machine would put the human body through an almost insupportable ordeal, that the process might, indeed, be quite painful. Nevertheless the girl does have an enraptured look that probably stems as much from an atavistic sense of sacrifice as from the sensation she gets from the machine. In any case, it's all very odd, and I don't know whether body-conditioning is worth such trouble, particularly in view of the urgency

Fall, 1962

in our balance of payments problem, and the outflow of gold. Yet he paused, "the young lady is quite fetching jiggling about and well, g('nerally being sculptured like that. Live sculpture, that's what it is."

I caught the girl's eye and she smiled at me, bravely attempting to convey a look of dignity and aplomb, which I considered impossible for her to achieve under the circumstances.

"I should like very much to ask her about her experiences," Ellingsworth said as we took the automatic elevators up to our offices. "Perhaps I'll spend a little more time in the corporate gymnasium this afternoon, loosening up a bit, trying to reduce the old waistline, what?" he said.

I decided to accompany Ellingsworth. Our firm was not enjoying good business at the moment, what with the financially unsound high discount rate and a precipitous drop in the fluidity of our reserve accounts. There was very little for us to do except to man the telephones and keep the secretaries busy. It seemed to be an appropriate time to look into body-conditioning. I had been short-winded lately, running to and from the train. A few nights before I had developed heart palpitations. Exercise, well-timed, not too severe, performed in moderation might be just the toning up I needed.

I explained my intentions and my apprehensions to Ellingsworth and he agreed that exercise seemed indicated by my predicament. However, I could tell that his mind was fixed so completely on the body-conditioning machine that I decided to set out at once for the corporate swimming pool, freeing him to go to the machine.

I splashed around in the pool for a while, conscientiously avoiding over-fatigue and the bulbous body of the vice president in charge of sales who rolled, heaved, puffed and panted like a sounding whale. As he listed over, a leviathan of modern merchandising, his rosy arms and shoulders awash, I could read the locker number, a high status single digit, stamped on one of his buttocks. I reflected on how delightful it would be to attain the vice president's stature in business.

After I had finished (my blood was running fast), I clapped my hands and summoned one of the corporate towel room attendants, a young virgin, recently employed, whose classification tests qualified her for development and training leading eventually to our mail room or to some other more lofty position. The small-breasted nymph wore no clothes, in keeping with the company policy of compulsory exposure to the healthful ultraviolet rays emanating from the floors and ceiling of the corporate athletic plant. Self-consciously, ·1 tried to hold myself more

I..

17

erect to minimize the obtrusiveness of my swelling abdomen. My "obesity" was embarrassing to me, but evidently not to the girl, for she smiled and extended to me those delicate but important attentions usually reserved for directors and officers of the company. Although they induced some coronary palpitations, they were relaxing and thoroughly delightful and I patted the young girl on the forehead and told her that I would look favorably on any request she might make to attend one of my secretarial development conferences, a training program usually restricted to more mature and fully developed women.

She thanked me and danced away, twirling the towel with which I had dried myself, as though it were the diaphanous veil of some Attic bacchante.

I then sought Ellingsworth and found him in the body-conditioning room. Here there were no ultraviolet lights and the mandatory rule about total bodily exposure was not enforced, although most of the devotees of this kind of conditioning wore brief costumes covering only those parts of their anatomy they were modest about. Curiously, there was little conformity in the participants' anatomical sensitivity, some covering their fingers, others their feet, some their eyes, but most their ears. Our psychologists referred to this phenomenon as tactile regressivism.

I found Ellingsworth talking with great animation to the secretary whom we had just observed demonstrating the body-conditioning machine. She was reclining on a floor mat, resting from her exertions, dressed in a skin-tight leotard.

Ellingsworth was in shorts, T-shirt, and tennis shoes. Even in this costume he had an air of sartorial elegance that radiated more from his carriage and nobility of expression than from the clothes he wore.

"Ah, then, it is not painful, but really pleasurable, as I first imagined," he was saying. "And I must confess that it has either helped you to fashion a delightfully healthy body for yourself or else you came to the conditioning process already so generously endowed. How thankful you should be for such an incomparable gift, and how grateful I am for the pleasure of your companonship and the contemplation of your form."

"Oh, sir," she managed to respond, blushing.

Ellingsworth caught my eye and asked the girl to rise so that I too might appreciate how effectively corporate body-development had worked for her. She complied readily, indeed quite proudly, I thought, and even offered to remove all her clothing in order to present more convincing evidence of the state of her health and the efficacy of the system. Ellingsworth demurred at her offer and said, "Another time

perhaps, but now I think you should take a little rest while I tryout the machine."

With that, Ellingsworth mounted the platform and adjusted himself into the contraption while the girl stood by and told him how to brace his body while the machine was performing its good works on him.

"You must hold yourself firmly," she advised, "but you must also be in a receptive frame of mind. You can achieve that by watching me. Oh, yes, and you simply must take off your watch. The motion might disturb its accuracy, and you know

Ellingsworth refused this advice. "It is now daytime. I shall not worry unless it says nighttime in the daytime and I can still observe the sun. Well, start it up, my dear, and let's have a bloody go at body-conditioning, eh?"

The girl pressed the button and the machine started, or I should say, it literally sprang into action like some automated panther, seizing Ellingsworth's hips and thighs and rapidly, but with rhythmic precision and also with a certain relentlessness, beginning to reform his body, according to some specifications that were punched on a card which the girl inserted into the machine. The card contained precise measurements, medically approved and laboratory tested, for the soon-to-be-reconditioned Ellingsworth.

The power and intensity of the machine seemed to frighten him at first, and he uttered a few gasps of apprehension, which brought smiles to the girl's lips. But as soon as it began to hum at its "cruising speed," and he grew used to its motion and touch, he settled back, smiling with godlike indifference at the world beyond the contraption. "May it never stop," he sighed, closing his eyes in ecstasy.

At that point I became conscious that I was undressed and that the ludicrous locker-room stamp was visible on me, but the girl, like the virgin in the locker room, seemed oblivious of my inelegant body and focused her attention on Ellingsworth. While she observed the machine, I studied her, speculating about her probable efficiency at classifying delinquent accounts and her competence in the arts of nonvocational, executive attentiveness - a technique closely related to love and that many progressive corporations had incorporated into their body-conditioning programs, but which ours had not yet adopted because of our uncertainty over its effect on our insurance liability.

I knew it would be only a matter of time before we became committed to a "love" program, since its power to produce a consistently high state of euphoria in executives had been thoroughly demonstrated in the laboratories of the social scientists.

"Night and day, you are the one," was played in the company gymnasium where my wife

18

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

worked and where the amatory arts had been practiced for several years. How grateful I was, I reflected, to the Synthetic Fiber Company fOI' nurturing those natural talents of my wife, refining them, so to speak, and what is more, bringing out latent possibilities of whose existence I had been totally ignorant when we first began living together.

But the present moment demanded that I discover more about the girl in the leotard while Ellingsworth languished in technological bliss.

She wasn't angry when I touched her, oh, so deferentially; she merely smiled and came closer to me so that I might participate in the warmth of her body in the lower-than-office temperatures of the athletic plant.

"You are very generous," I told her. "But I can't, for the life of me, understand how they prevailed on you to spend your lunch hours and coffee breaks demonstrating the body-conditioning machine. Are you receiving extra compensation ?"

"Oh, yes, I am excused from my duties for a certain time every day, and I am really improving from my experience on the machine, so I don't consider it work as much as a planned program to develop my character and body in an integrated fashion. It's the Greek ideal, after all, and lowe it to the organization to remain in good physical condition.

"Would you like to see me as I really am, without these clothes? They're really just worn to protect me from the machine, and I shouldnt be wearing them in the plant."

What could I say? She stepped out of her clothes and I had to admit that her body was a tribute to any machine.

"Splendid development," I told her. "Yet I wonder if you are completely euphoric, as you should be? You realize, don't you, that soon the love program will become mandatory for everyone except the towel room virgins, as soon as the question of insurance liability is cleared up?"

"No, I'm not euphoric," she answered. "The coffee in the cafeteria is bad and the cloak room is too small for my umbrella. Oh, I'd better slow down the machine. Mr. Ellingsworth seems to be falling asleep."

She pressed a button and the machine decelerated. Ellingsworth opened his eyes and gazed about the room as though he had never seen it before. "By George, that was an experience! Let me have one more go at it, will you? Or were you waiting to use it?"

The secretary pressed the starting button and the machine had another "go" at Ellingsworth, while the girl and I resumed our discussion.

"Bad coffee, eh? Highly destructive of morale. Well, I'll have a look into it tomorrow with the Director of Participation and Leisure. But getting back to the love program I thought you

Fall, 1962

might want to know about it and, of course, I should like to get your reaction to it - the prospect of its being done here at Ajax Refining, I rnean.

"Well, love, I guess Well, I mean everyone seems to need it and some like it more than others, yet I suppose everyone really likes it, but if it's to be mandatory, as you say, how will everyone work? I mean, how can it all be worked out? It sounds so terribly complicated."

Meanwhile, Ellingsworth was humming and cooing with motion-induced contentment.

Suddenly, a bell rang indicating the change in classes for body-conditioning, and the machine automatically stopped. "I guess it's time to go," she said sighing. She smiled provocatively at me and suggested that we meet a little later to go into the love program more thoroughly. * *

It was time for the corporation's annual nocturnal cook-out and Ellingsworth's patio and wide expanse of lawn where the festivities were taking place were ablaze with the dancing flames of mosquito lanterns and the glowing coals of the barbecue pits. Now and then the outline of one of the naked lawn gods was revealed by the flames. A fat little boy was offering grapes to a round-bodied young man who was playing a flute. I heard Ellingsworth describe the pair as the deities of crab grass, and one of his guests walked away sadly murmuring, "We have become cynical. We no longer believe in the old gods." Images of the traditional deities were placed in the sacred grottoes half hidden behind the rose beds near the barbecue pits.

E,llingsworth's wife, a tall desiccated harpie, her body partially covered by a length of brassstudded calfskin thrown over one shoulder and wound around her hips, stood at the wrought-iron gate and frightened away the starving youngsters and their parents who were begging for food.

Ellingsworth was at the opposite end of the lawn greeting the guests and seeing to it that they were supplied with drinks and condiments. Soon the yard was full of the hubbub of talking and laughing people and, as the evening progressed, the steady droning of the group became more strident, with the women speaking shrilly and the men talking and joking hoarsely.

I had come with my wife, but we soon separated in the dark, promising informality, she retiring to one of the holy grottoes with Ellingsworth's assistant and I explaining our body-conditioning program to one of my banker acquaintances whose friendship I had been cultivating in order to obtain a low interest personal loan. "Too many dollars chasing too few goods. Overproduction and underconsumption with bad payment balance overtones and overextended credit hmmm," he said.

The night breezes, clear and warm, made the

19

lights flicker and lent a weird perspective to the yard, accentuating the soft lines of the statues in the flowered grottoes and shimmering on the bodies of the women. Silver and gold snowflakes, the fashion representing the latest in epidermal haute couture in our suburb, adorned them.

Before dinner, one of the men was elected Eros and given a bow and an arrow whose tip was saturated with a flammable liquid. At the stroke of ten, he dipped the arrow into a hot coal, whereupon it burst into flame, and shot it toward the moon while the guests stood nearby chanting the lunar anthem of thanksgiving. It was a touching moment and many of the women wiped tears from the edges of their eyes.

1 approached one of the barbecue pits to inspect the food and to escape the dreary financial analyses of the banker. 1 was indifferent to the prospect of offending him, since other bankers, more laconic, were at the party searching for customers and 1 could always make a proposal to one of them.

A small animal impaled on the barbecue spit turned slowly over the coals, dripping grease which sputtered in the flames. Its flesh was white like that of a fowl, delicate looking, but 1 could not identify it, and decided that it was some kind of rare fowl which Ellingsworth had obtained from Europe especially for this occasion. As 1 adjusted my eyes to the brightness of the flames, 1 became conscious of another presence close by, and ,I turned and encountered the secretary who had been demonstrating the body-conditioning machine earlier in the day.

She had been dipped in a fragrant mosquito repellent, a tub of which Ellingsworth kept at the front gate for those of his guests whose bodily condition entitled them to frolic unadorned. She was carrying a toy poodle cradled in her arm, a stratagem that enabled her to assume a statuesque position whenever she stopped to converse.

"I'm not euphoric again tonight, surprisingly," she said.

"Not even after the machine?" 1 asked.

"Oh, it helped, but 1 need something more than that, valuable as it is. There is desolation in my spirit, a certain emptiness. Ii pleut dans mon coeur, as the French poet said. I've forgotten his name."

"You know French. How interesting and yet how important for an understanding of AngloSaxon belles-lettres."

"Yes, but 1 return always to my spiritual desolation, and 1 feel utterly without fulfillment. Actually, as 1 said to Lord Ellingsworth, 1 feel terribly utterly," she said.

"I know exactly. Yet you shouldn't feel that way. We have structured an entire human relations program down at Ajax, just to eliminate spiritual desolation. Our gymnasium, the forthcoming program in amatory arts during coffee

breaks, the sensuous isolation cell for the refinement of tactile sensitivity - the entire range of our human relations program 1 took her arm and guided her away from the barbecue pit toward one of the grottoes with a small fountain whose waters splashed over mermaids and water babies holding tridents. "I will admit that we haven't devoted enough time to the purely spiritual, but here at Ellingsworth's you see before you, in grottoes like this, evidence of the tastes of a contemplative man, a person for whom the worship of the holy naiads is as important as speculation about the nature of man."

We stopped and looked into the pool, amusing ourselves by watching the shifting configurations of our reflections on the rippling water. I was a hydra-headed man, hovering over a maiden with tiers of copper-pointed breasts. It was diverting and absorbing and we shifted our positions from time to time to create new and unexpected reflections of ourselves. I reached out and clasped her waist to prevent her from falling into the pool, a disaster which appeared imminent as she leaned over too far. Her poodle growled and snapped at me.

She apologized for the dog's behavior and put it on the ground, slapping it lightly but affectionately so it would run away. "Be sure and come back now, Simone," she admonished it. Then she turned to me.

"I would rather you didn't try to embrace me just now. I can feel your affection spiritually. It is palpable and I need no physical demonstration of it, at least not for the moment."