CONTRIBUTORS IN THIS ISSUE:

Walter A. Netsch, Jr.

Susan McIlvaine

Marion and Ali Bulent Cambel

James R. Johnston

Frederick S. Stimson

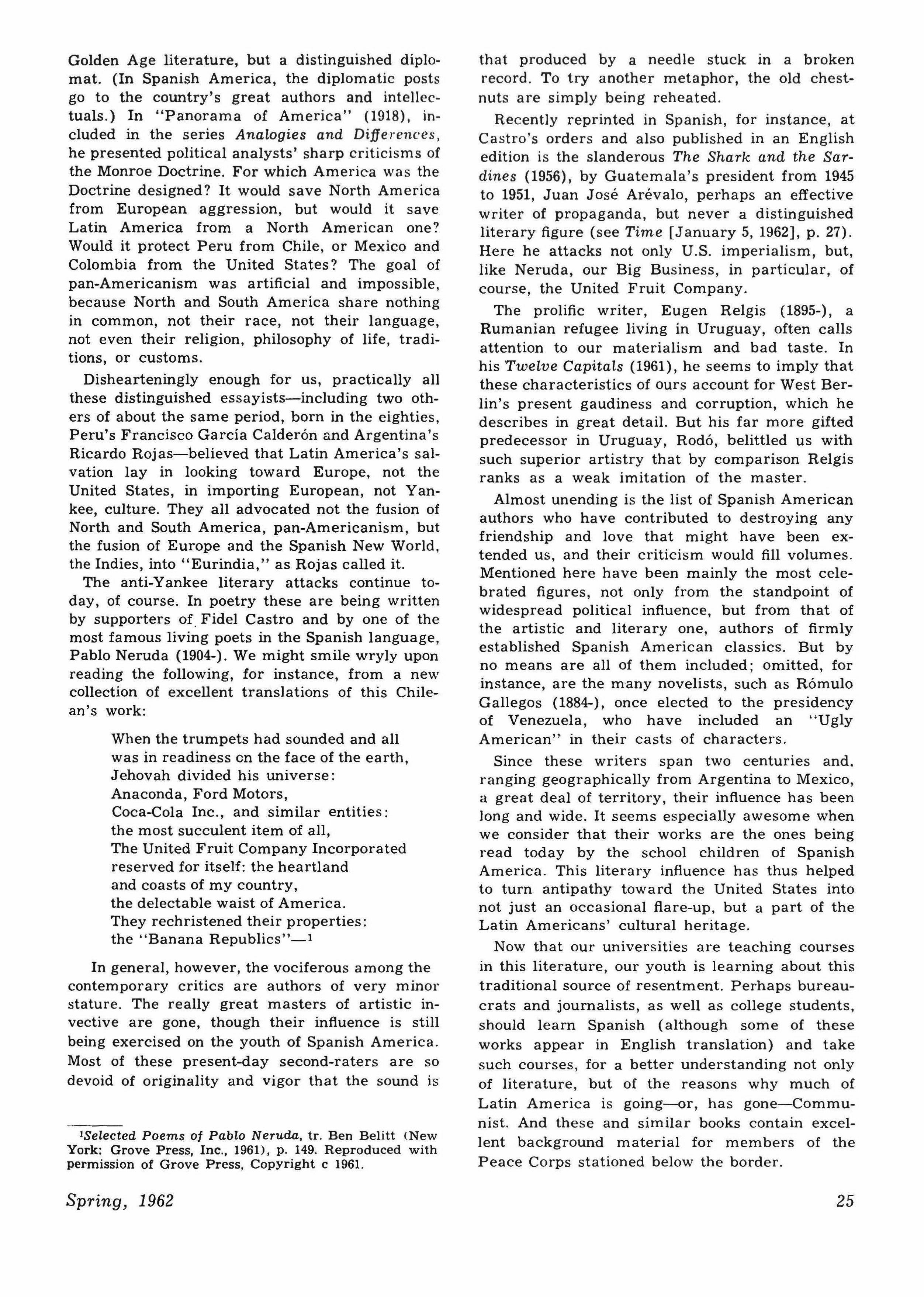

Meno H. Spann

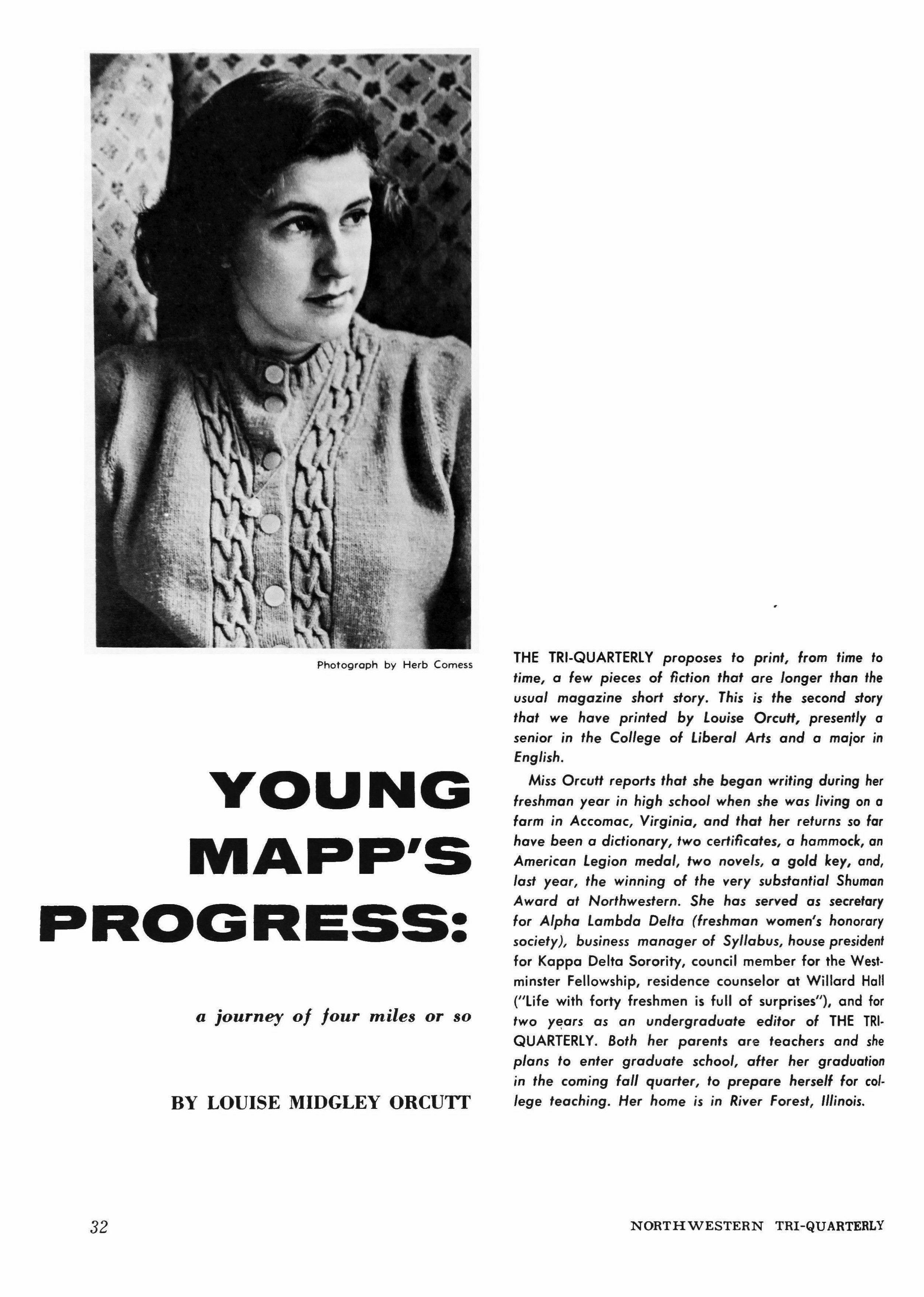

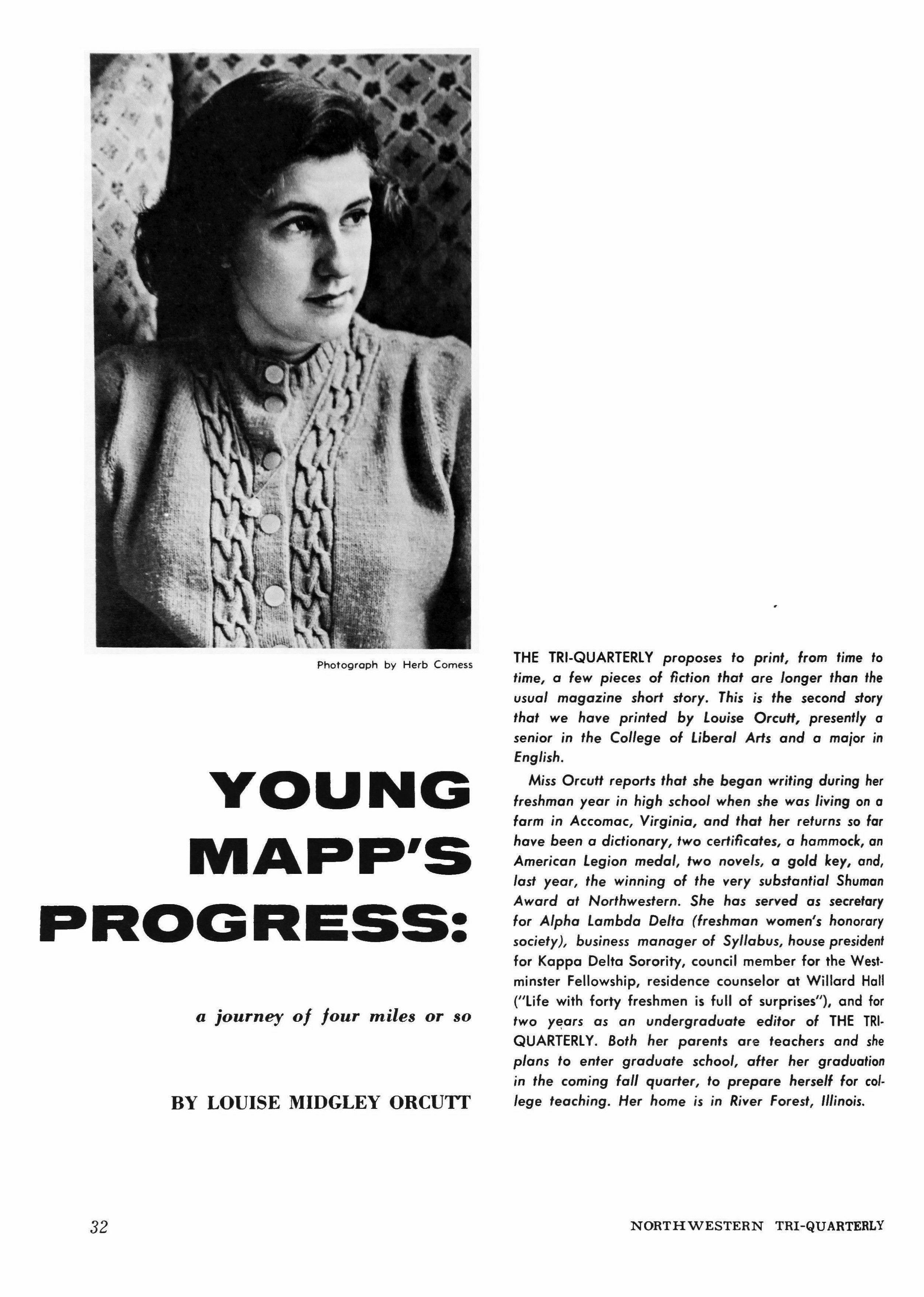

Louise Midgley Orcutt

Marcia Masters

JoAnna Sympson

Knox Munson

Felix Pollak

SPRING

Volume 4 Number Three 70c NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is a magazine devoted to fiction, poetry, and articles of general interest, published in the fall, winter, and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $2.00 yearly within the United States; $2.15, Canada; $2.25, foreign. Single copies will be sold locally for $.70. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to THE TRI-QUARTERLY, care of the Northwestern University Press, 1840 Sheridan Road, Evanston, Illinois. Contributions unaccompanied by a self-addressed envelope and return postage will not be returned. Except by invitation, contributors are limited to persons who have some connection with the University. Copyright, 1961, by Northwestern University. All rights reserved.

in the

are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the editors.

EDITORIAL BOARD, The editor is EDWARD B. HUNGERFORD. Senior members of the advisory board are Professors RAY A. Bll.LINGTON and MELVllJLE HERSKOVlTS of the College of Liberal Arts, Dean JAMES H. MC BURNEY of the School of Speech, Dr. WILLIAM B. WARTMAN of the School of Medicine, and Mr .JAMES M. BARKER of the Board of Trustees.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITORS, LOUISE M. ORCUTl', SUSAN F. Me lLVAINE, and FORREST G. ROBINSON.

THE TRI-QUARTERLY is distributed by Northwestern University Press, and is under the business management of the Press.

Views expressed

articles published

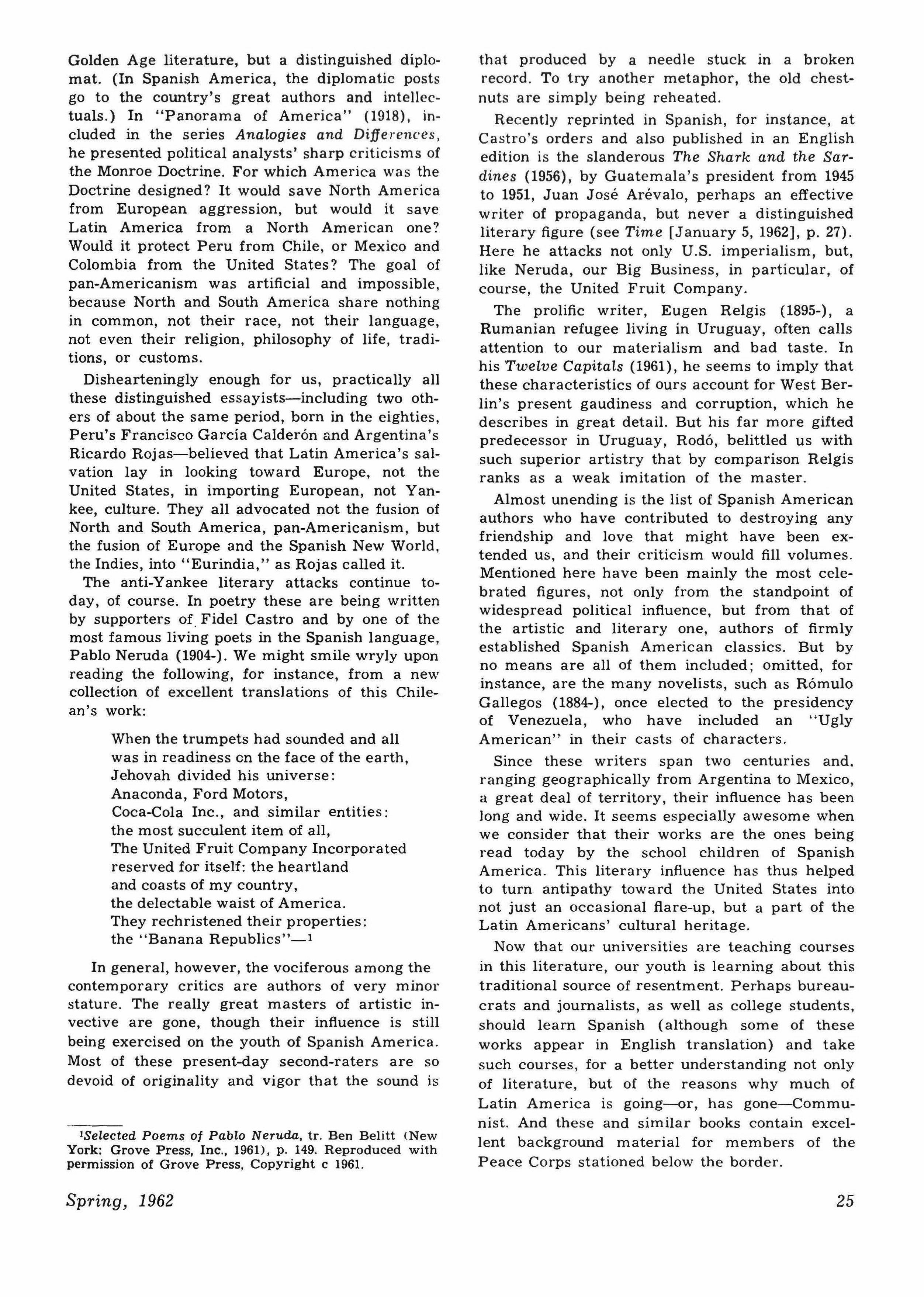

Walter A. Netsch, Jr. Master-Planning the College or University 3 Susan McIlvaine Loss 12 Marion and Ali Bulent Cambel Magnetoftuidmechanics and The Fourth State of Matter 15 James R. Johnston Something Old 21 Frederick S. Stimson Ariel and Caliban 22 Meno H. Spann The Horned Hero, The Noble Savage The Detached Tooth 26 Louise Midgley Orcutt Young Mapp's Progress 32 Marcia Masters One Evening at Mrs. William Vaughan Moody's 42 JoAnna Sympson Variation of a Theme 43 Knox Munson What Might Is Spring 46 Felix Pollak Communion with a Thief 46 Tri-Quarterly NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Number Three Volume 4 SPRING

The plan to extend the Evanston campus of Northwestern University by building man-made land in Lake Michigan has begun an exciting adventure in campus planning. Mr. Walter A. Netsch, Jr. is the architect for this project.

Mr. Netsch received his architectural training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and is presently general partner in charge of design for the Chicago Office of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. He has been responsible for such projects as the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California; the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado; the New York Life Insurance Company Lake Meadows Apartments and Club Building in Chicago; the Grinnell Col/ege Library in Grinnell, Iowa; the Chicago Undergraduate Campus for the University of Illinois; and for various plans connected with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the Westinghouse Research Laboratories in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

He is a member of the Metropolitan Housing and Planning Council of Chicago, the Advisory Committee for the Graduate School of Architecture at the University of Illinois, the State Board of Architectural Examiners for the State of Illinois, the M.I.T. Jury Thesis Committee, and the Committee for the Advancement of Architectural Education for the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, the University of Michigan. He has lectured at many colleges and universities in this country and in Canada.

The article following was written for THE TRI-QUARTERlY at the invitation of the editors.

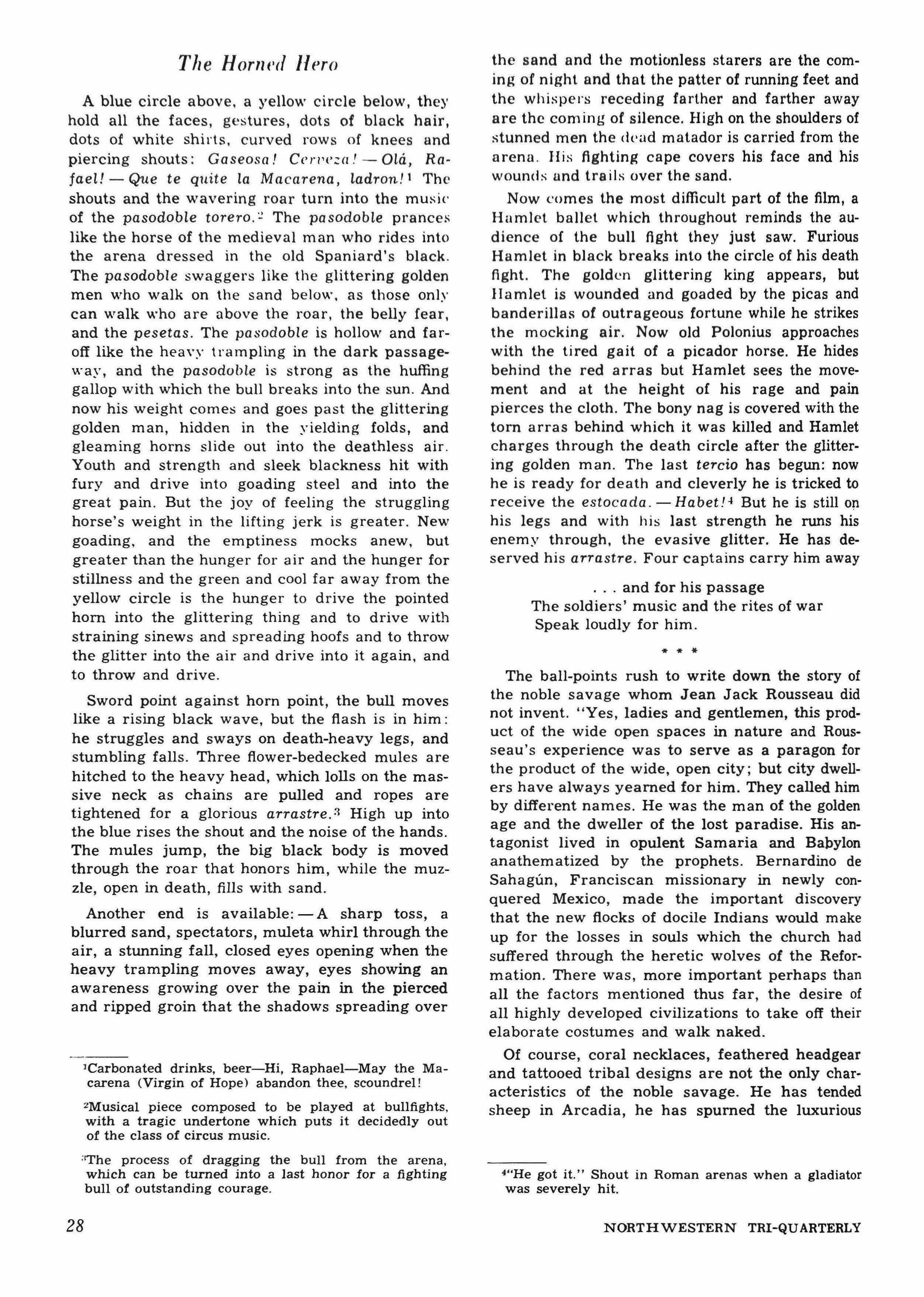

MasterPlanning the College or University

By Walter A. Netsch, Jr.

3

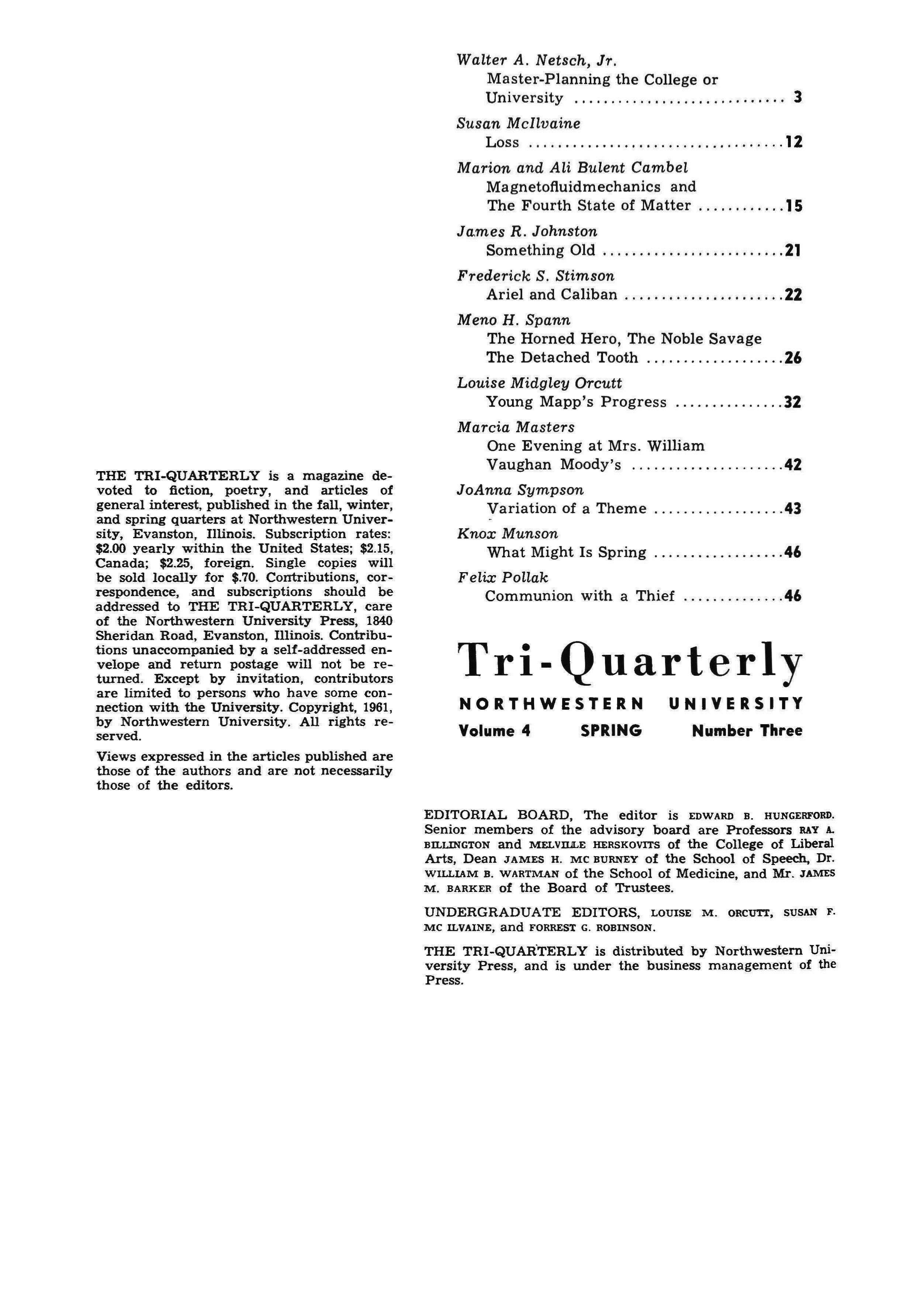

Acollege or university today provides in its complexity most of the elements, frustrations, and confusions of an urban society. Many believe that directions in planning for the campus, which is a special segment of that society, can lead to directions applicable to the urban planning problem. While this is abstractly true, no evaluation of this particular problem or the opportunities has been undertaken. The college and university are currently being dissected in social, economic (in relation to society or salaries), or academic areas and these analyses are invaluable documents for testing the environmental fabric and capacity for planning a campus. In this presentation the emphasis will be placed upon the resources, history, contemporary factors, congenital influences, possibilities, and examples of planning the college or university.

The smallest portion will be the historical section, for while extremely important, it is best left to the architectural and social historians. One of the most prevalent assumptions is that planning is an abstract visual process and can occur in a vacuum. Assuming that capability and artistry exist, the resource most required is a Gestalt between planner and the college or university as to the possibilities and aims that reflect an ongoing purpose and vitality for the institution. If the quality of a campus is measured by the aims of the students, the faculty, the academic resources, and the administration, it is also measured and influenced by the community, the alumni, economic capability, and the environment and the physical structures. As in any urban fabric, the incongruity of any factor influencing the aims must be recognized and isolated as it occurs. In the most idealistic generality, a college or university exists to provide the student the cultural, physical and intellectual stimulation for beginning maturity and the desire to continue the search for fulfillment when leaving the campus. To the faculty falls not only the responsibility of fulfilling the students' needs, but that of preserving and extending cultural and intellectual knowledge. With the early academies in Western Civilization, diversity in teachers and methods was already required and the storage of information was a first demand. The resources were not very complex but the environment, whether Sparta or Athens, reflected and influenced the educational process. Mark Hopkins' log never existed. With the increase in knowledge, administration assumed more and more responsibility for the organization of the educational process and the need for physical environment and the physical requirements. Therefore, for many centuries administrative policy was assumed by religious groups or monarchies which influenced and determined not only the rate and growth of knowledge but also its dissemination. Through this time, the most

limiting factor was the dichotomy between past and new beliefs and the relegation of education to the prerogative of the few. With the advent of science and industry and the rebirth of classical knowledge, educational institutions became one of the primary industries of an industrial society and were instrumental in accelerating academic demands for economic capability and structures. Through these beginnings the importance of campus environment prevailed, for the cultural responsibility of environment was accepted by the administration and academic community. Although untrained eyes are not aware, Oxford was built in its time of its time, changing and evolving, maintaining in its college program a mytosis, a repetitive cell process with logical limits, a factor long forgotten by both planners and administrators and culturally unrecognized by faculties themselves. The insistence on selectivity and limited enrollments alone preserved our original colleges and universities as environmental and cultural fabrics. It is interesting that the informal solutions have survived better, and this can be visualized in a comparison of the site plans of Harvard University and the University of Virginia. However, where social mores and "stage set" attitudes attempted to reproduce the success of the earlier institutions in the growth west, failure has been the general rule. This rule is most often interpolated as the failure of the stage set itself, but more consideration should be given to the failure in scale and hierarchy, for the stage set seldom measured the environmental relationships of structures which made a group of buildings a community and was forced to emphasize individual structures outside of their cultural value or out of context with the basic educational needs. (Classical solutions have provided fluidity in changing educational patterns when the scale is monumental. Environmentally scaled plans have provided fluidity for growth in repetitive patterns, and the overscaled environmental patterns have provided opportunities for demolition and new construction.) A detailed site plan growth pattern of three campuses - classical (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), environmental (Harvard), and the monumental environmental (University of Illinois - Urbana) show directly in their several stages of development the success and failures in the periodic assessment of concept, growth and scale.

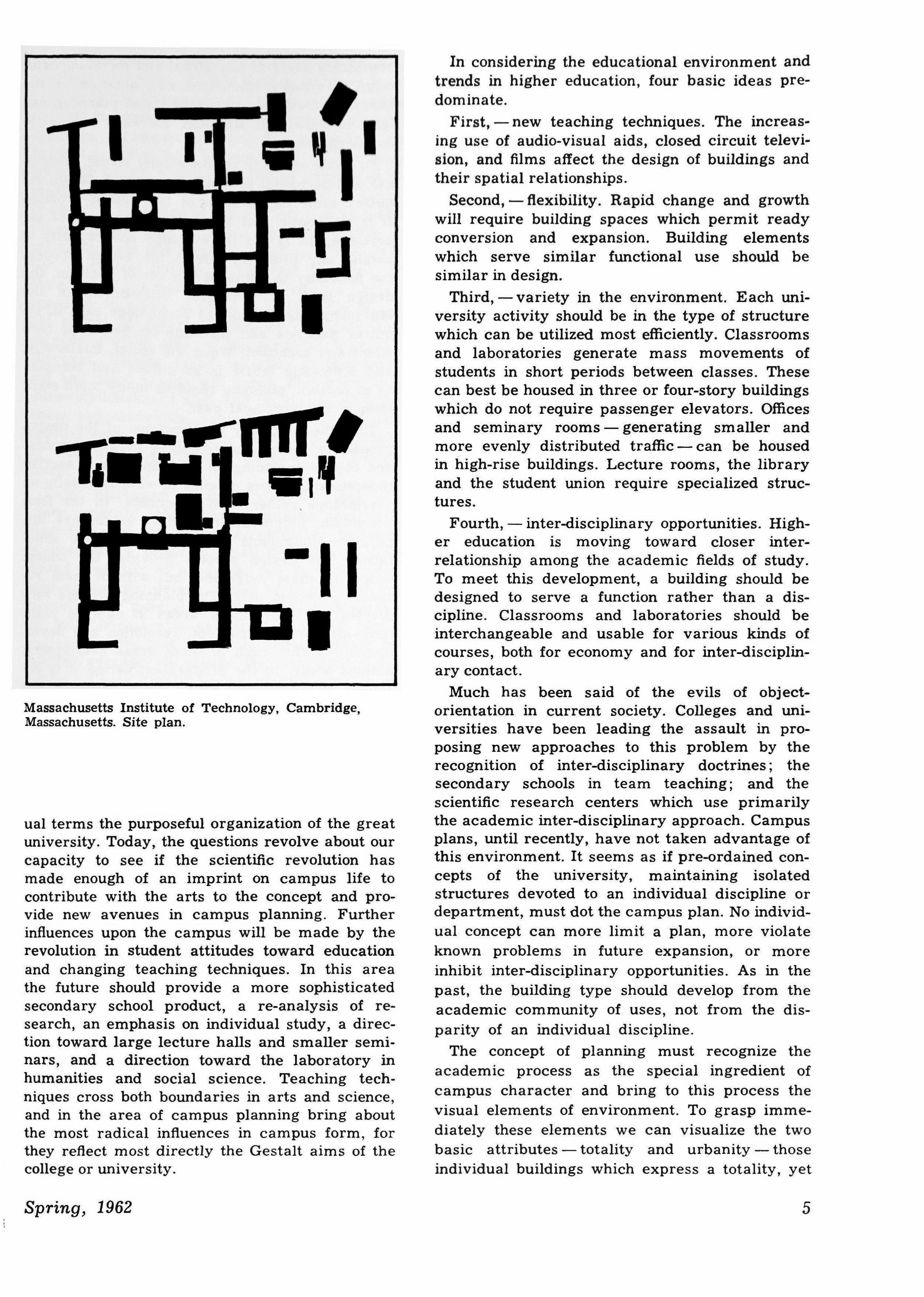

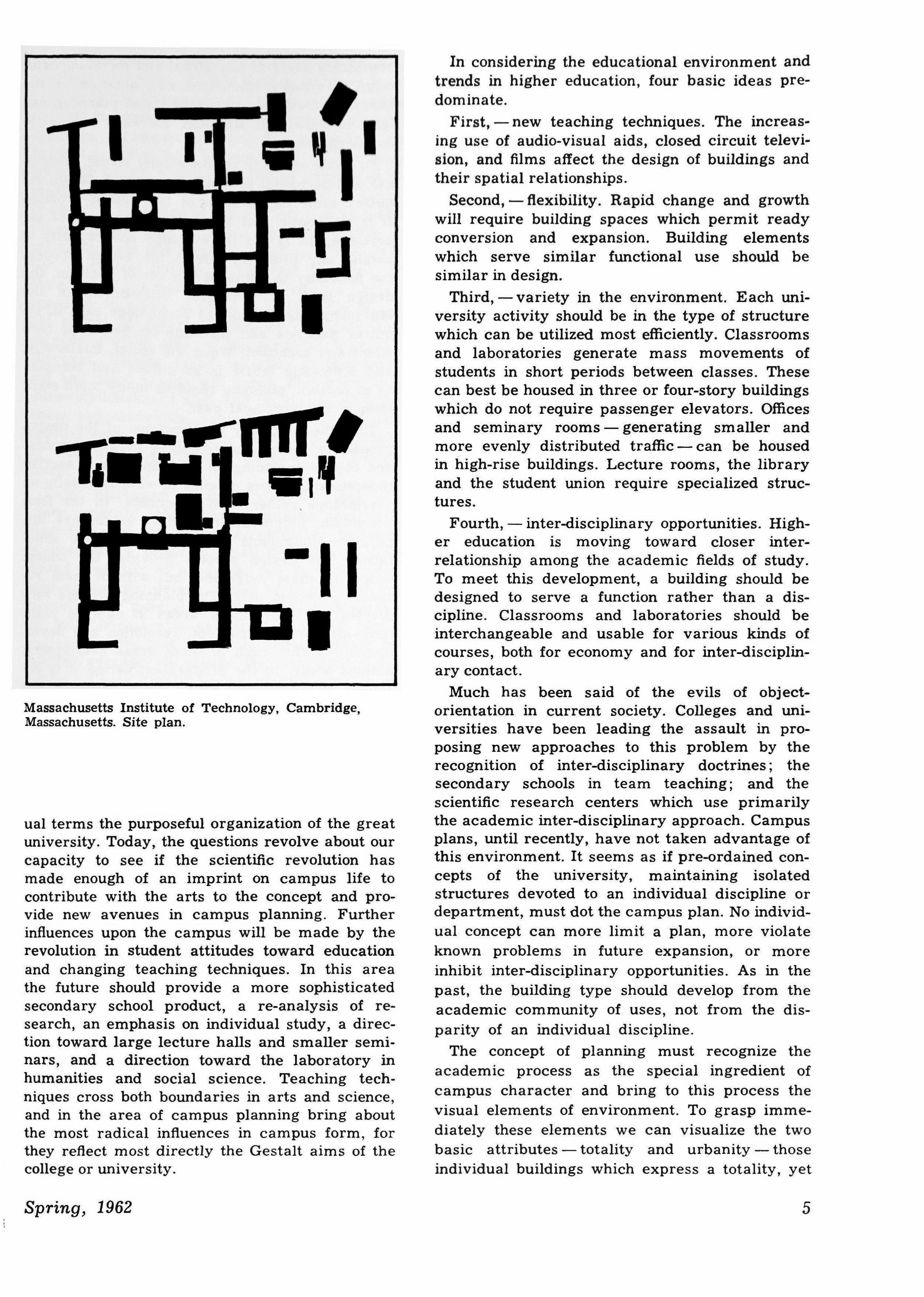

As an example, the site plan of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology shows the contrast between the effect of temporary and heterogeneously located structures and the current Master Plan extending the formal concept originally established - reestablishing the advantages of formal planning.

The most successful campus in the past has been the one that recognized beyond purely vis-

4

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

I�I--.:·.:...ii_�II -!j

In considering the educational environment and trends in higher education, four basic ideas predominate.

First, - new teaching techniques. The increasing use of audio-visual aids, closed circuit television, and films affect the design of buildings and their spatial relationships.

Second, - flexibility. Rapid change and growth will require building spaces which permit ready conversion and expansion. Building elements which serve similar functional use should be similar in design.

Third, - variety in the environment. Each university activity should be in the type of structure which can be utilized most efficiently. Classrooms and laboratories generate mass movements of students in short periods between classes. These can best be housed in three or four-story buildings which do not require passenger elevators. Offices and seminary rooms - generating smaller and more evenly distributed traffic - can be housed in high-rise buildings. Lecture rooms, the library and the student union require specialized structures.

Fourth, - inter-disciplinary opportunities. Higher education is moving toward closer interrelationship among the academic fields of study. To meet this development, a building should be designed to serve a function rather than a discipline. Classrooms and laboratories should be interchangeable and usable for various kinds of courses, both for economy and for inter-disciplinary contact.

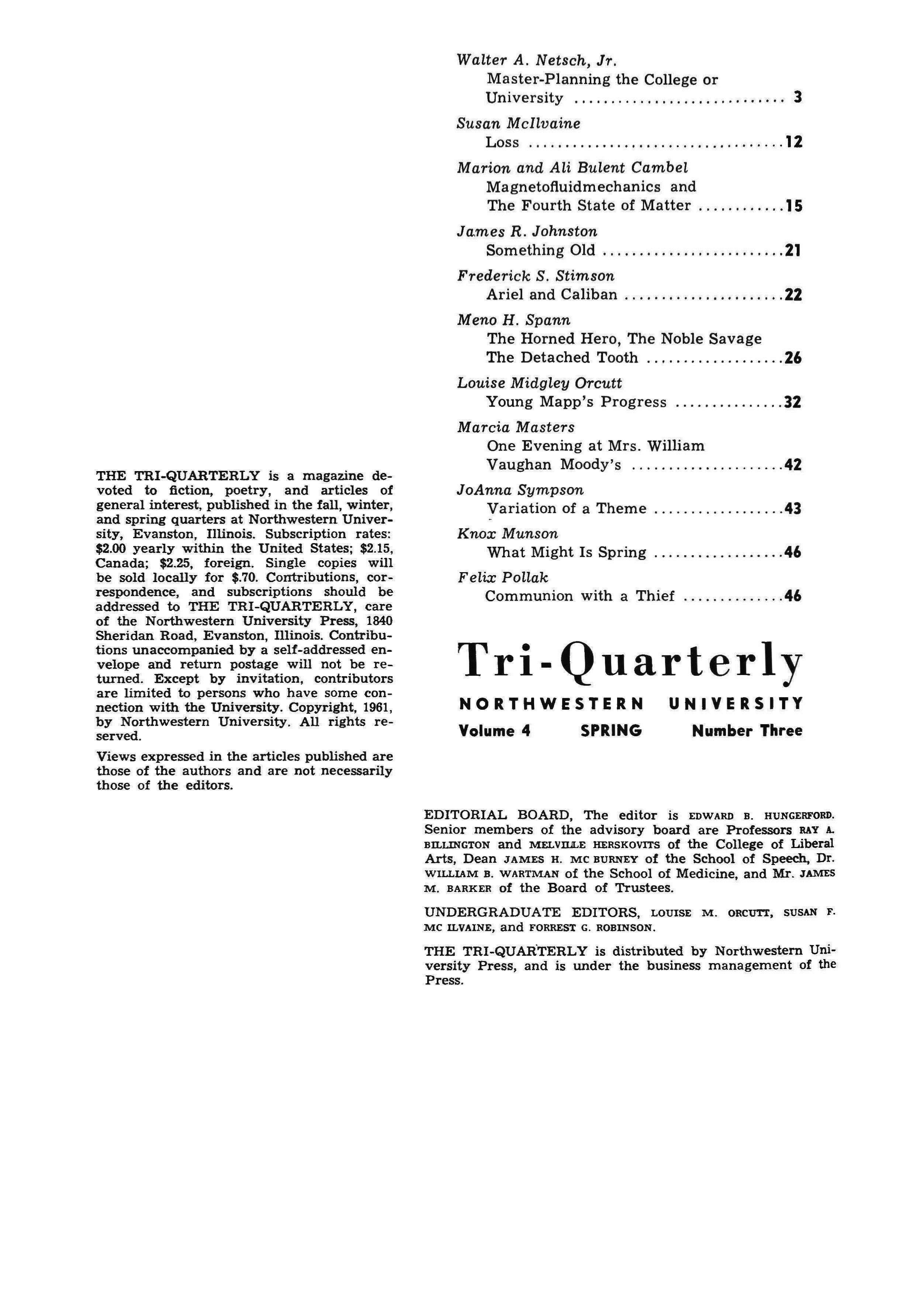

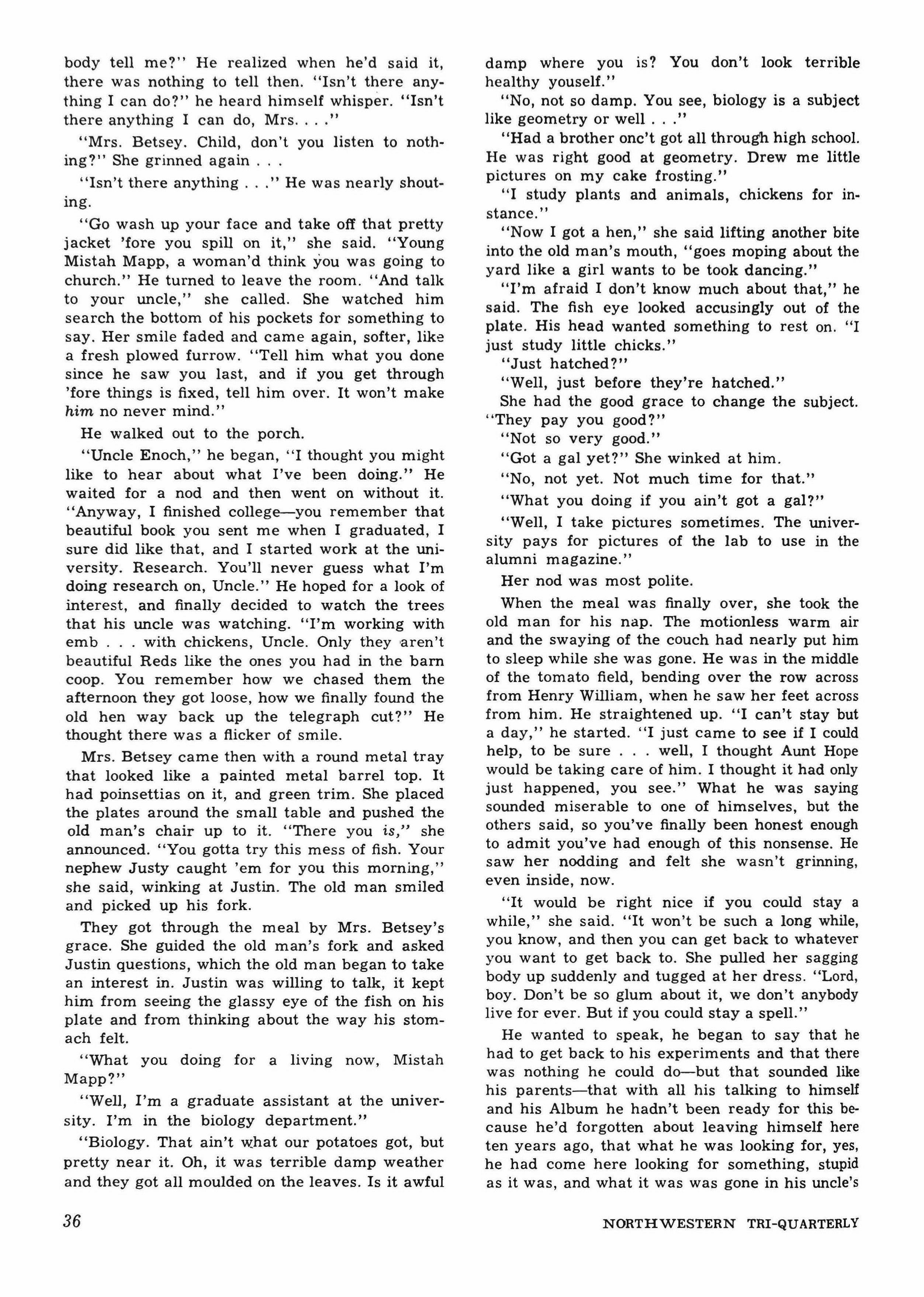

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Site plan.

ual terms the purposeful organization of the great university. Today, the questions revolve about our capacity to see if the scientific revolution has made enough of an imprint on campus life to contribute with the arts to the concept and provide new avenues in campus planning. Further influences upon the campus will be made by the revolution in student attitudes toward education and changing teaching techniques. In this area the future should provide a more sophisticated secondary school product, a re-analysis of research, an emphasis on individual study, a direction toward large lecture halls and smaller seminars, and a direction toward the laboratory in humanities and social science. Teaching techniques cross both boundaries in arts and science, and in the area of campus planning bring about the most radical influences in campus form, for they reflect most directly the Gestalt aims of the college or university.

Spring, 1962

Much has been said of the evils of objectorientation in current society. Colleges and universities have been leading the assault in proposing new approaches to this problem by the recognition of inter-disciplinary doctrines; the secondary schools in team teaching; and the scientific research centers which use primarily the academic inter-disciplinary approach. Campus plans, until recently, have not taken advantage of this environment. It seems as if pre-ordained concepts of the university, maintaining isolated structures devoted to an individual discipline or department, must dot the campus plan. No individual concept can more limit a plan, more violate known problems in future expansion, or more inhibit inter-disciplinary opportunities. As in the past, the building type should develop from the academic community of uses, not from the disparity of an individual discipline.

The concept of planning must recognize the academic process as the special ingredient of campus character and bring to this process the visual elements of environment. To grasp immediately these elements we can visualize the two basic attributes - totality and urbanity - those individual buildings which express a totality, yet

#

I

5

integrate in this environmenta Greek temple, a Gothic cathedral, or cities which have an urban quality, regardless of size - the city that has a series of major and minor important spaces with visually ordered connections such as Florence or Venice, parts of Paris or London, and in academic communities - Oxford or parts of Harvard. Each of these - totality and urbanity - reflect known visual attributes but rely on specific use of the basic planning process. Listed they appear prosaic, but if tested against actual environmental conditions, reveal major failures in campus planning:

1. Are the constant factors in campus planning being utilized to self-generate the campus community - the library, lecture center, cultural areas, social areas, community areas?

2. Is the transposition and movement of students and faculty, as pedestrians, as bicyclists, as autoists, planned to reinforce the campus pattern or as deterrents and energy expenditures?

3. Is the use of the four social areas of space creatively developed - private, semi-private, semi-public, and public?

4. Is the hierarchy of space consonant with the use of the space on the campus?

5. Is each building vying for attention, or is there a capacity to integrate visual environment towards a total concept?

6. Are the problems of flexibility, integration of technical services, and new teaching techniques being reconsidered in new orders of geometry, or new concepts in "surge" spaces?

7. Is the campus considered as a pedestrian community, or even as a community?

8. Are individual structures still related to dream fantasy architecture of bygone eras or business fantasy architecture for "middle majority" acceptance?

9. Are the administration and the faculty willing to attempt a reintegration of the teaching Gestalt and the visual environment?

10. Does the college community accept the responsibility of visual environment?

Master-planning a college or university has basic ground rules but the application of these rules to actual conditions requires an honest evaluation of social and scholastic goals. As much as we may desire an intellectual nirvana, most colleges and universities have not and will not attain one. However, a re-evaluation of the

energizers in terms of cultural and social opportunity, an equally important re-evaluation of the effects of restraint in uncoordinated planning can lead to individual solutions for each scholastic environment.

To relate verbally an essentially visual, statistical and perpetual problem as campus design requires some explanation of the design process. It is axiomatic that the greater the fund of experience, the larger the empathy and capacity to handle any problem, but in the design process the necessity to withhold the act of decision, the design leap, as Professor Bush-Brown of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology calls it, requires patience and fortitude on behalf of both client and architect. When the social, intellectual and scholastic fabric is as diffuse and complex as at present, planning requires many more steps than in the historical past.

The other difficulty in discussion of the design process is the misunderstanding between process and object-including an unwillingness to ascribe theoretical qualities or aims in what is usually an assemblage rather than a concept. In the final resolution, judgments respecting values are imperative-judgments that escape complete annotation. The design process provides the widest scope for these judgments but without them remains a system only. The planning process subdivides into four major areas in campus planning-preparation, concept, resolution and development. Within each of these areas overlapping actions occur. In the preparation period it is essential to synthesize within each category the aims of the institution, the statistical program for the institution, the visual and technical characteristics of the site and the surrounding environment as well as special theoretical and practical research on educational theories, spatial orderings, aesthetics and new materials and techniques. The first three can be charted, diagrammed, and described to provide the basis for the conceptual phase. Included in this area are both the hopes and the hard facts of a campus plan. The second phase of the preparation requires the synthesis of the- elements into two areas-the first, an objective resolution combining the basic program aims and site factors into an analysis through flow diagrams of the hierarchical relationship of the program, the inter-demands of spaces and volumes, and the effectiveness of energizers for campus community life. Here, specific opportunities in teaching techniques, concepts of growth, areas of community life, and regional planning provide not one but a series of different diagrams available for review. Concurrently, with this analysis, certain abstract possibilities in concept will become apparent and these concepts at this stage are abstract compositions explaining the visual potential that social theory, spatial

6

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

theory, structural theory may inspire from the program diagrams. At this time a program may appear diffuse and unresolvable. To emphasize the realism in programming, an assumption could be made on a campus plan that the automobile be omitted as policy from consideration. At this time, policy or no, the problem should be interjected to make certain what effects would occur. An equally effective challenge in assumptions can be made regarding the size of a library, its relation to undergraduate and graduate programs, the question of central library or separate libraries, or the scope of the materials considered as a library resource. In either of these examples, the physical effects of different decisions eliminate and determine whole areas of the preparation period. However, without broad searches at this time cut and patch results will occur. For in the free inter-relationship of aims and programs, all influences and economics, value judgments, and perceptual goals (or dogmatic decisions) contribute to one most appropriate scheme-the Design Leap.

Later discussion of three specific plans will show separate resolutions of specific programs. Knowledge of structures contemplated becomes increasingly a factor in detail development. The broad spectrum of allocation can be determined without specific details. Rules of thumb are appropriate for general assumptions only. A survey of most liberal arts campuses including junior colleges shows that academic undergraduate facilities average 125 square feet per student enrolled. Where greater scope in programs is offered or better library or lecture programs occur, the individual average would rise. A figure closer to 150 square feet per student is more appropriate. When graduate programs are added, this figure rises above 200 square feet per student, and as advanced research programs develop, especially with special grants, the square footage relationship to enrollment disappears. However, the concept of scale is immediately heightened when living requirement areas are added. This averages approximately 235 square feet per student housed. An automobile requires 300 square feet per parking and maneuver area so that exclusive of the demands for physical education fields recreation or special cultural elements, the spa�e program� per student are competing beyond those required for pure academics. Partial or ignored answers to these "peripheral" areas have destroyed many campus plans. Campuses originally pedestrian in nature now resemble urban parking lots with buildings. Walking distances are often lengthened beyond reasonable limits. Today a campus of 5,000 students or more is an urban unit and requires new and special answers. As the primary aim of an academic community is determinable, a concept utilizing the whole spectrum of the de-

Spring, 1962

United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Site plan.

sign process coupled with perceptive knowledge of teaching environment can lead to new theories and plans. If, for example, the land use of a campus could be totally integrated without relegating living to defined peripheral areas, new uses of teaching spaces, library and study areas could be considered. Concepts analyzing enrollment size in major and minor units or colleges could also be re-evaluated.

In applying the primary aims to campus planning, the examples following relate to three campus plans: one existing, Northwestern University; and two new, University of Illinois-Congress Circle, Chicago, and The Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Each has an entirely different academic program, site location, student size and relation to the community.

The Academic Campus of the Air Force Academy is situated on a mesa at the base of the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, which rise abruptly 2,000 feet and form the backdrop. The mesa site sloping to the east provides the articulation of levels which not only defines the cadet and public activities but provides a three dimensional terrace enclosed by natural land forms to contrast with the architectural character of the buildings. The Cadet Quarters are the focal point of the cadet activities. From this center the cadet has access at the intermediate or campus level to the formation area, the large paved area south of the

7

University of Illinois, Congress Circle Campus, Chicago. Illinois. Site plan.

Quarters, the Dining Hall, the Academic Building and the Library. From the formation area the cadets can march by ramps to the Parade Ground east of the campus. The pageantry inherent in such activities is dramatized by the ramps, while protecting the privacy of the campus area. The cadets and the public jointly use the Social Hall, Administration Building and the Chapel which are located west of the immediate campus on a large plaza or Court of Honor overlooking the Cadet Campus. The natural land forms intrude into the Court articulating the Chapel. The cadet circulation level joins at the Court of Honor through the Reception Gardens, and this junction provides access to the Auditorium, Ballrooms, and Social Rooms.

The University of Illinois 'at Congress Circle, situated at the city's crossroads, will be composed of five high-rise buildings-staff and administrative offices, engineering and science offices, Union high-rise, and two research, graduate and service buildings; several low-rise buildings, including two laboratory buildings, engineering and science; fine and applied arts building; three groups of classroom buildings; two major parking structures, each with a capacity of 3,000 cars and a 200-car lot on the east -side ; research, graduate and service centers; the Auditorium and Exhibit Gallery; the Hull Mansion, after restoration; and 8

the Campus Center, with the Library, Lecture Center, and Student Union.

To move through the campus, most students will enter along the two-level express walkway running north and south. The walkway connects directly with major campus buildings, and the lower level provides all-weather protection. Entrance points can be controlled for security.

Northwestern University, situated in a northern suburb of Chicago facing Lake Michigan, found it necessary to consider the problem of expanding its 86-acre campus. Most of the future building sites needed are going to be in the Evanston Campus area. In surveying new land to the west and north of the present campus, the University found the cost might run to $350,000 an acre-if property could be purchased. Then, remembering a campus-expansion plan suggested, toward the end of the last century, for filling in an area of Lake Michigan, we turned our eyes eastward to this vast, open expanse.

An engineering survey determined that building man-made land in the lake would cost only onequarter the amount of purchasing land in Evanston. In addition, this new land would permit (1) the design of a dramatic, inspiring campus, and (2) the expansion of the campus without reo moving land from the Evanston tax rolls. The proposed lake-fill will total 65 acres and will

Gf!n 1 '_I 1====::::::::[0 � ]Il,��

71

Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Site plan.

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

double the land area east of Sheridan Road, permitting an unusual land-space-to-building ratio.

One is first impressed by the grain or scale between the smaller and older buildings on the Northwestern campus and the larger, new buildings on this campus and the other campuses. This change in scale reflects the integration of more than one discipline into the structure and the larger enrollments of current campus programs. The differences between the sizes reflects the grain of the individual campus and its relation to the environment. A different grain, the awesome scale of the broad plains and mountains -the problem of infinity-determined in part the plan of the Air Force Academy. The other determinant was perceptual in explaining to the visitor the activities of the campus. As over one million visitors come to the Academy, watch a parade or tour the grounds, the campus must lead both a public and a private existence. Here the natural environment touches and intrudes at specific points peripherally.

At Northwestern, the expansion program developed along the lake shore reintegrates the lakefront into the campus, preserving a vista of water and varying the character of the water and land forms, reflecting not only the characteristics of the natural environment but their relation to the specific potential needs of the campus.

Spring, 1962

United States Air Force Academy Colorado Springs, Colorado. View of campus.

United States Air Force Academy Colorado Springs, Colorado. View of campus.

J v 9

United States Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colorado. Flow diagram.

The University of Illinois at Congress Circle is contrastingly urban, surrounded on two sides by major expressways. Here, also, the initial program of 20,000 undergraduate students, and 6,000 cars is a core of smaller scaled structures. In these three campuses, varying in student size between 2,500, 9,500 (projected) and 23,000 (projected), emphasizing both liberal arts, science and engineering, individual plans have resulted, varying in scale and grain as influenced by the program and by site characteristics.

The illustration adds the human scale in the basic pedestrian pattern. Patterns of access from living units, public transit and parking areas dissolve into problems of the pedestrian alone. Walking becomes a destination pattern establishing focus. At the Air Force Academy, living and study. academics, dining and library facilities revolve about a triangular pattern scaled to the ability of the total student body to assemble and march between elements. The proposed preliminary plan for Northwestern develops from the existing struc-

tures to separate patterns for Liberal Arts and Science and Engineering linked by social and cultural group activities. Again, the natural environment provides a series of foci contrasting the urban character of the Liberal Arts Plaza and the urban and scientific character of Science and Technology with the informal open area of Deering Meadow and the water areas. Here scale, numbers, and circulation patterns form the internal net. The Air Force Academy has two-dimensionally a single net, but the inter-relationships within a single structure (and a smaller enrollment) simplify the order. Lecture rooms occupy the center vertically with laboratories at the lower level, classrooms, staff and library at the upper level, and parking at grade level. Essentially a similar pattern develops at Congress Circle effected by increased enrollment and no restrictions on public access.

The Congress Circle campus develops a single center with intensive uses concentrated in that area, gradually diminishing as the intensity of use diminishes. Here 20,000 or more students will

10

University of Illinois, Congress Circle Campus, Chicago, Illinois. View of center of campus.

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

University of Illinois, Congress Circle Campus, Chicago, Illinois. Flow diagram.

generate an urban atmosphere about a single focus-a university square or plaza. Lecture units and seminars join with outdoor theatre and plaza surrounded by classrooms, teaching laboratories, library and student center, and then peripherally with heavy laboratories, research and staff offices and administration.

The Northwestern program is not completely formulated but anticipates generation about a greatly enlarged library at Deering, a complex of units incorporating the arts, the theatre, as well as additional programs to enrich the curricula for existing student enrollment. The science and engineering unit will also rotate about the science library as research enrichment occurs in this area. A series of foci will develop, contrasting the academic and cultural elements with recreation and student activities.

Each of these campus plans is obviously different in two dimensional site drawings. As the final determinant is three dimensional, the eventual character is determined by the building design

and the campus plan. Here the differences are revealed in scale and structure, the surrounding environment, and the interpretation by the architect of form and enclosure.

If we are to find solutions for planning in the urban environment, the college campus plan can be the catalyst. In no other segment of the environment exists a grouping with greater capacity to assist in establishing both the problem and the potential. Despite this, most campuses will continue to be an assemblage, without visual purpose or beauty, until the problem of the visual environment is considered worthy of research, theory, process and discrimination.

The philosopher Paul Weiss, in his recent book Nine Basic Arts, re-affirms this need when referring to architects in saying ". not until they take seriously the need to explore the possibilities of bounding spaces in multiple ways will they become alert to architecture as an art, as respectable, revelatory, creative and at least as difficult as any other."

University, Evanston, Illinois. Flow diagram.

Spring, 1962

Northwestern

11

Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. View of Lakefront Development.

Photograph by Herb Comess

By Susan McIlvaine

By Susan McIlvaine

Susan Mcilvaine is a senior in the College of liberal Arts, majoring in English. 80rn in Summit, New Jersey, she has spent most of her life in Skaneateles, "a small New England town in Upstate New York." At Northwestern she has been a member of the freshman and sophomore honorary societies, recipient of the J. ScoH Clark Prize for creative writing, a member of the Symposium Speaker's CommiHee, and a student editor of THE TRI-QUARTERlY. After graduation in the fall quarter this year, she intends to do graduate work in the Russian language.

They arrived on the beach in the middle of the afternoon, six of them, all jabbering and laughing in French. There had been one or two Italians lying out in the sun, but after awhile they became annoyed at the students' loudness and left. The warm Riviera beach belonged to them for the moment, so they capered and teased each other kicking sand all over their white tropical pants. �e weather was still cold for swimming, even wading, but the sun warmed the sand until it steamed deceptively, and the atmosphere seemed almost tropical. Then the six students began the game of daring each other, with the obsessive gaiety of friends who are not yet close friends. Finally the blond boy from Bretagne demonstrated with energy that he would be the one to take the first dip in the Mediterranean. The others rushed around him and coaxed, glad that some one of them at last might break the monotony of being gay with no reason. He began to tug at his tight-fitting slacks and they to goad him; now the

teasing became more urgent. They hoped he would not disappoint them.

"AUez-vous-en," they taunted him, and so he tore off his clothes and flung them to either side shutting his eyes and grinning roguishly. H� stepped to the edge of the wash, where the waves left a pile of debris, and watched the waves lapping. With one glance over his shoulder he bounded away into the water, knees high, looking very pale in the bluish reflection of the sea. In a second he had bellied out into a dive and was paddling seaward, his blond head soaked dark. He swam in a circle, only the wet head showing, with his brilliant grin. The others squinted at him in admiration, and the small Parisian started to remove his clothes, casually, careful not to disturb the cigarette in his mouth. They watched for a few minutes, their excitement diminishing. The dark one, who had taken off all except his sweatshirt, sat down to finish his cigarette. The others followed and arranged themselves cross-legged, still watching the watet. The blond head disappeared, leaving a small whirlpool in one of the swells. The five on the beach began halfheartedly to throw sand at each other and to pull off their shirts. After five minutes they looked closely at the place where their friend had ducked under the water. One by one they fell silent and smoked their cigarettes and began to feel sticky from the frantic running around. The air was becoming uneasy.

Then they saw the lighter patch of something floating a little under the surface of the incoming swell.

Leo the Turk sat hunched forward on the pier, staring at the ocean with his usual expression

12

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

of mild indifference. Beside him the policeman sighed reproachfully and tried again.

"Now, please, will you try to tell me about it? Now?"

Leo the Turk shrugged his shoulders and rested his hands, gently folded, between his knees. He watched his feet dangle over the water. "Yes, yes, in a minute, please."

The policeman sat down beside him and began to slap his notebook against the concrete of the pier. "Sir, you must understand you are the last and I must have your statement, just like the rest. Please?" He was tired; it was the sixth witness he had interviewed. The others had been ashamed and incoherent and not much help, and now this one, the last, did not seem to want to talk, and when he did, his Italian was poor. Exasperating. Sitting around on the hard stone pier 'that shook every time a wave rammed it, waiting for this bland-faced, black-eyed Greek or Turk or whatever he was to speak.

Leo looked up and over the water to where the sky began. "No, it is not there, not at all." The policeman hurriedly fumbled open his book and scratched on the first page.

"Not where? What?" he asked. Leo the Turk turned his face slowly and looked dazedly toward him.

"Nowhere. In me. But first you must understand that I am really not a Turk, and not terrible. Turks are very .passionate."

"Yes. Go on." The policeman wrote down "not Turk, not terrible" in his book.

"That is what they call me, Terrible Turk. But that is not what you want, I suppose. You want what I saw of that." He pointed to the mound covered with a striped blanket on the beach. "But I felt nothing."

"Yes, yes. That makes no difference."

The black eyes of Leo the unterrible non-Turk pored over his face. "Yes, yes what? So you understand?'

"Of course. This happens all the time during the season. I understand." He nodded sympathetically. "Go on, go on."

Leo shook his head.

"No? Oh, come, sir, I haven't

"You don't understand at all, you know. 1 think perhaps because you never had it in the first place. Of course you don't miss it when it is gone if it was never there." The policeman sat abjectly, saying nothing. It was impossible to write down what this Turk was saying. "Feeling, you know. You never know until it is gone, unless of course it was never there, and then it makes no difference." Once again the policeman closed his pad and settled himself to wait. Leo went on, his eyes squinting at the waning sun, so only black crescents of eyelashes showed against his pale face. "1 did not know until today. Shall I tell you

Spring, 1962

how I found out?"

His companion nodded absent-mindedly, then realizing that Leo had begun his story of the drowning, he stabbed at his notebook once more.

"This afternoon earlier the sky was very blue. You probably saw it where you were. Perhaps you did not notice it. But always I notice blue skies. That is what 1 come to the Riviera for, to notice them. So I look out of my hotel window and there is the sky so blue that 1 must squint to see it, and little droplets of water make it hazyyou see there? Look where I am pointing. No horizon, yes? That is what the droplets do. You cannot tell sea from sky.

"It is warm, but I know that it will get colder later, so I put on a sweater, this sweater." He plucked at the black turtle-necked sweater he was wearing and peered over at the policeman's writing. "So I run downstairs and outside. I am going for a walk. Here is this blue sky and this blue Mediterranean and out in the middle are little white wispy clouds that you know must be in the sky but you can't really tell because there is no horizon.

"I walk down to the beach to kick stones and listen. Thud, thud, that is the ocean dropping on the beach. A tense sound. Waves breaking are very tense things, you know. One watches this definite flowing ridge of water, waiting and knowing that in a second it will break into a million bits, but never knowning exactly when. Like people.

"Soon I find myself getting tense too. Or perhaps I have been tense all the time and simply impose my own mood on the waves, but I don't realize the tenseness until I have been sitting on this flat rock watching for some time

"What flat rock a excuse me."

"Over there. A mile, I suppose. But you must understand that I sit there and get more tense and more tense. I imagine the waves are getting bigger and bigger. Swishthumpswish. 1 think of those who come to find peace in the ocean and wonder how, because now all I can hear is the swishthudswish and the throb and the insistent moving in on me and I am tense.

"I have to get up and walk. This sitting is no good for me now. Along that line where the waves stop there are pink rocks with long strands of seaweed growing from them. They wash up and down like sirens' hair. There is a crowd of people at the end of the beach that I am walking on. Something to distract me from myself, I think, so 1 begin to walk toward them with my arms swinging, very relaxed." Leo the Turk stood up on the pier and began to walk back and forth behind the policeman. He pushed his hands into his pockets.

"Well, 1 am not fooling myself. Still arm-swinging I look at the sea and suddenly 1 am underwater swimming.

13

"How did you get underwater? Dive, wade. the policeman interrupted.

" A long silence. The policeman looked up to see Leo the Turk hunched and shivering.

"No, no, listen. I see myself as though I am underwater swimming, swimming as hard and fast as I can, trying to reach a place I must get to. I know I must, but I cannot see where it is because the water is filled with little bits of seaweed and tiny things that color everything the same, and only a little sun filters down. There is no height or depth or distance or weight or sound and I don't know whether I am swimming the right way or not, or whether I am far away or so close I can almost touch. My lungs begin to feel as though they will burst and they burn at the bottoms and my throat burns and I am dizzy, but I must take another stroke and another. I realize that I am feeling despair and then I hear a shout and I am really only walking along the water holding my breath. I let it out, feeling very silly. My fingers are cold, so I rub them.

"Still I walk toward the people who are shouting at something. I intend to walk past them, just looking. I know that I must think this out by myself, just as one swims underwater always alone." Leo stopped and looked down. "You are not writing."

"You are going too fast. Besides, I need facts. How many people?" The policeman drew his head closer to the notepad.

"Six. They are students. I can tell because of the way they all have the same haircuts and talk in French and wear same-looking old clothes; I don't know why I think this except that it is the -way I dressed as a college student. For a second I become interested in them and the feeling of despair at whatever I am despairing of is submerged. I surmise they are from Paris, living on the Italian R-iviera for a vacation because it is cheaper, but still Riviera. They are all active and daring, talking much too fast for me to understand. One begins to pull off his clothes; he is thin and pale, with dry blond hair fallen diagonally across his forehead. His trousers are very tight and his legs slender under them. He tosses himself back and fourth ridding himself of his coat and shirt, his eyes closed as if attending to a tribal rite. A look of rapture-no, that is not so-a look of relish on his face. Another catches his coat before it falls on the sand; they all laugh happily. I stand back from them, only watching, because they seem so young and unconcerned, though only two or three years younger than 1.

"The thin fellow tears all his clothes off, and he stands at the water's edge, looking down at the wash as it sidles up to his toes. He peers over his shoulder at his fellows and I hear a word I understand. It means "go ahead." He answers back "cold." I feel I should tell him the water is very cold this time of year, but the French does not come, and besides it seems not so important."

"Go on, please. You did not tell him the water was cold."

"Yes, because I did not feel the importance. I did not feel that ." Leo passed his hand in front of his eyes to blot out the still-blue sky.

"Yes. So I walk away then, because I am beginning to realize that this is the despair, that nothing is so important any more. Everything is smaller than life-size, and the horror is I am becoming used to it. So while I am walking away I hear splashing sounds and suppose the boy is running into the water, and the others scream and shout at him. I go along the beach over more rocks that are covered with seaweed hair. I begin to run as fast as I can over the rocks. Behind me still in the background is the shout, even the wave-thud cannot shut it out. I reach the end of the beach and start back, very slowly. Everything seems calmer now. The shouting is gone. Did you ever notice that sometimes in the late afternoon the sea becomes quite calm? Of course I had forgotten the time.

"But the waves slip quietly to my feet and I am careful to make footprints that point straight ahead, like some child's game.

"So I am watching my feet carefully, and before I know it I am back at the place where the boys were shouting. All is very quiet now, and calm." Leo's voice went on in a hypnotized whisper. The policeman strained to hear, on the verge of telling him to speak up.

"The boys stand there on the beach and once more they do not see me. They look down too, and I see that there are five of them now; the sixth, the bold blond boy, lies on the beach covered with his coat. I must walk close by them because the tide is making the beach narrower. As I look down I see his face is blue-white, and his hair damp. One of the others is brushing it across diagonally as it should fall on his forehead, but it is stiff and gummy with sand. He is dead, of course. That is all I feel. He is dead, of course. Then I am shaking, and my hands sweat and I think I will be sick. But not for the drowned boy, for myself. Some of the others' pants are wet; they are all slumped over and pale and tired and sick. They say nothing to me and me to them, but I just walk on, out to this pier. I sit down and watch them, the underfed sand birds, aimlessly pecking and casting around for something, if only to look at. Then one goes, I suppose to summon you. And I sit and wait for something to happen. To me, I think. But nothing does."

The policeman sat for awhile, waiting for more. Finally, "Is that all?" There was a touch of sarcasm in his voice. He passed the notebook mechanically to Leo for his signature.

"Of course that is all. It is more than all. I am sorry. I ramble too much."

14

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

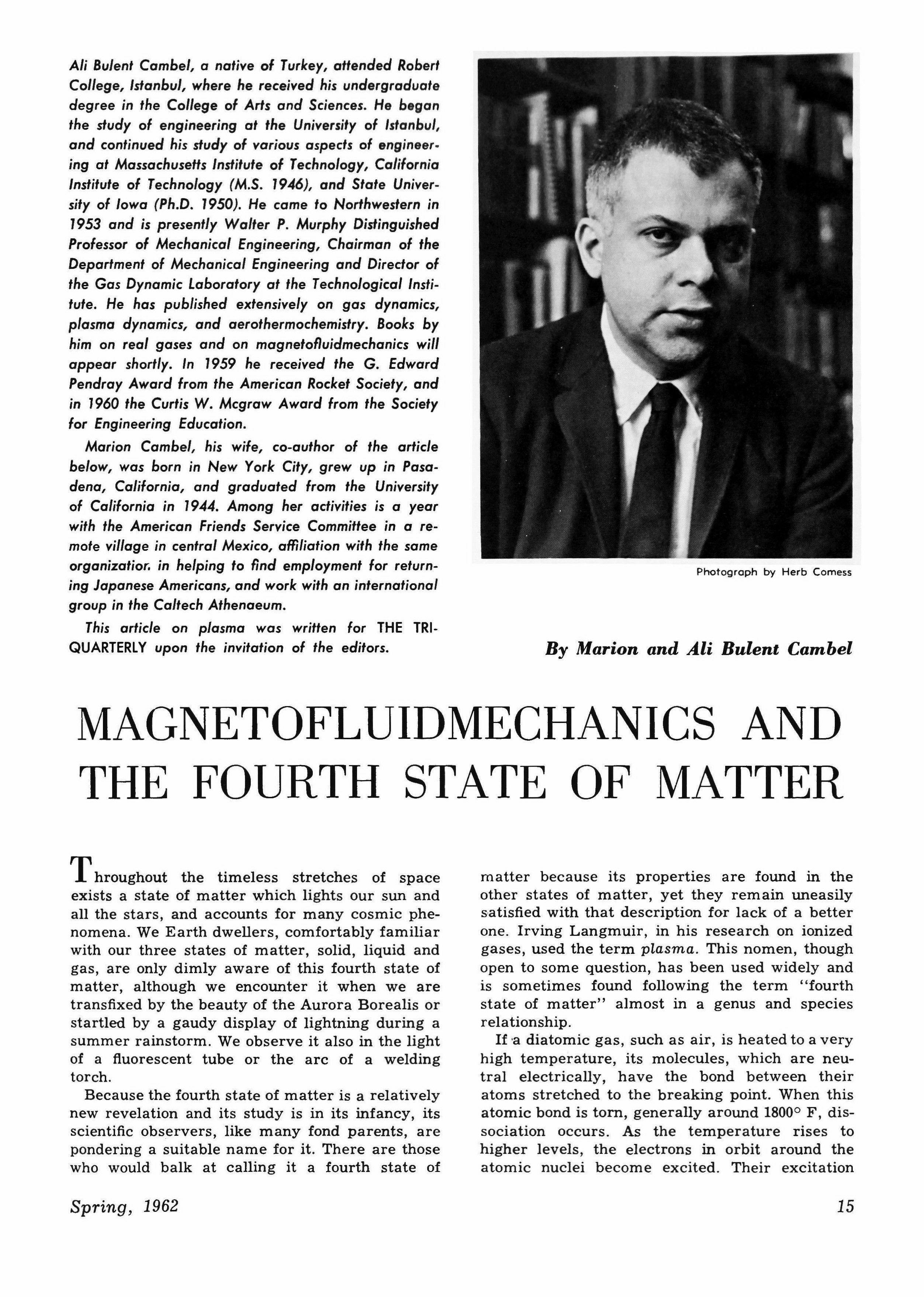

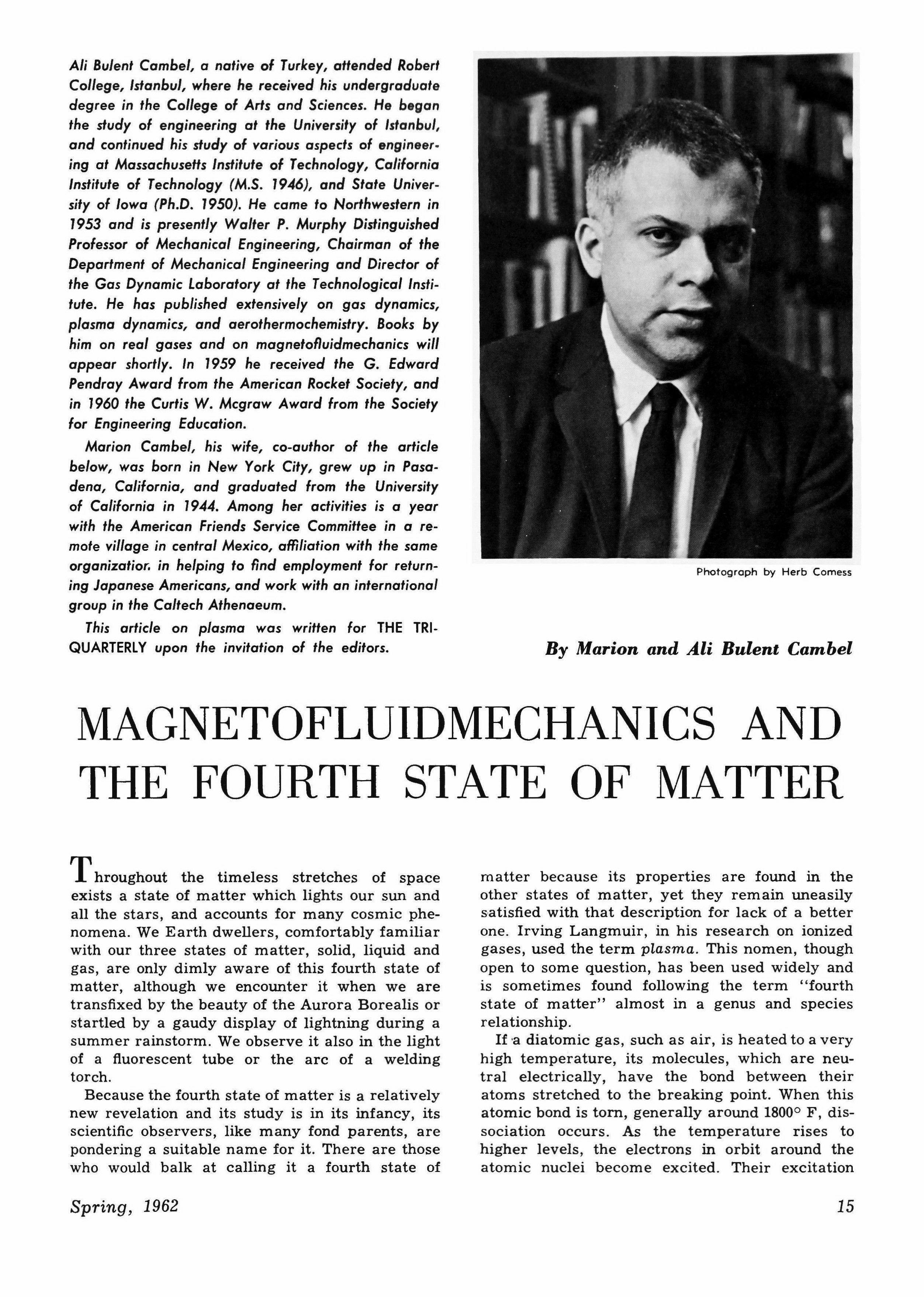

Ali Bulent Cambel, a native 01 Turkey, offended Robert College, Istonbul, where he received his undergraduate degree in the College of Arts and Sciences. He began the study of engineering at the University 01 Istanbul, and continued his study 01 various aspects of engineer. ing at Massachuseffs Institute 01 Technology, California Institute 01 Technology (M.S. 1946), and State University of Iowa (Ph.D. 1950). He came to Northwestern in 1953 and is presently Walter P. Murphy Distinguished Prolessor 01 Mechanical Engineering, Chairman of the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Director of the Gas Dynamic Laboratory at the Technological Institute. He has published extensively on gas dynamics, plasma dynamics, and aerothermochemistry. Books by him on real gases and on magnetolluidmechanics will appear shortly. In 1959 he received the G. Edward Pendray Award Irom the American Rocket Society, and in 1960 the Curtis W. Mcgraw Award from the Society for Engineering Education.

Marion Cambel, his wife, co-author of the article below, was born in New York City, grew up in Pasadena, California, and graduated from the University of California in 1944. Among her activities is a year with the American Friends Service Committee in a remote village in central Mexico, affiliation with the same organizatior. in helping to find employment lor returning Japanese Americans, and work with an international group in the Caltech Athenaeum.

This article on plasma was written for THE TRIQUARTERLY upon the invitation of the editors.

By

By

MAGNETOFLUIDMECHANICS AND THE FOURTH STATE OF MATTER

ThrOUghout the timeless stretches of space exists a state of matter which lights our sun and all the stars, and accounts for many cosmic phenomena. We Earth dwellers, comfortably familiar with our three states of matter, solid, liquid and gas, are only dimly aware of this fourth state of matter, although we encounter it when we are transfixed by the beauty of the Aurora Borealis or startled by a gaudy display of lightning during a summer rainstorm. We observe it also in the light of a fluorescent tube or the arc of a welding torch.

Because the fourth state of matter is a relatively new revelation and its study is in its infancy, its scientific observers, like many fond parents, are pondering a suitable name for it. There are those who would balk at calling it a fourth state of

Spring, 1962

matter because its properties are found in the other states of matter, yet they remain uneasily satisfied with that description for lack of a better one. Irving Langmuir, in his research on ionized gases, used the term plasma. This nomen, though open to some question, has been used widely and is sometimes found following the term "fourth state of matter" almost in a genus and species relationship.

If a diatomic gas, such as air, is heated to a very high temperature, its molecules, which are neutral electrically, have the bond between their atoms stretched to the breaking point. When this atomic bond is torn, generally around 1800° F, dissociation occurs. As the temperature rises to higher levels, the electrons in orbit around the atomic nuclei become excited. Their excitation

Photograph by Herb Comess

Marion and Ali Bulent Cambel

15

accelerates as the temperature increases until one or more electrons are ripped from their orbits, a condition which causes the atoms to be no longer neutral electrically because of the deficiency of electrons. The resulting mixture of molecules, atoms, positively charged ions and negative electrons is called a plasma.

If, in this process, everyone of the atoms has lost at least one electron, the mixture is termed a fully ionized plasma. However, a plasma state may exist when not all the molecules have their atomic bonds torn. The latter state is called a partially ionized plasma. In space, environmental conditions are conducive to the development of fully ionized plasma, but on our cold and dense planet certain hospitable conditions must be provided artificially for its generation.

The range of plasma temperatures is considerable. Some plasmas are fairly cool, while other plasmas are exceedingly hot. In the case of hot plasmas, there is no known earth substance which can survive their contact. On our sun and other enormous stellar bodies, the gravitational forces are sufficiently strong to hold the hot plasma particles together, but on the earth the gravitational field is too weak to be of practical value. This difficulty can be overcome by the use of magnets. Plasma is a good conductor of electricity due to the presence of electrons, and electricity is subject to magnetism, hence, with the application of a magnet the plasma will tend to stick to invisible lines of magnetic force.

A variety of oscillations is present in a plasma by virtue of its most important characteristic, namely the electrical properties caused by charged particles. Consider an electrically neutral plasma, that is, one consisting of equal numbers of electrons and positive ions, and assume that the charged particles are arranged in a hypothetical equilibrium position. To visualize this, it might be helpful to think of a Chinese checkerboard where one playing space is filled with the round checkers. Every other checker represents an electron, while the checker between two electrons represents a positive ion. By some technique, the nature of which is immaterial, one or more tiny and active electrons having a negative charge are dislodged from the equilibrium position while the more stable and massive ions with positive charges remain firmly in their equilibrium positions. The displacement of the electrons produces a surplus of positive charges which constitute an attractive force in recalling the departing electrons. The electrons rush back with such intent that they overshoot their original equilibrium position, effecting another inequality of charges. As the process repeats itself, the electrons oscillate about their equilibrium position in a state of great agitation. If the Chinese checkerboard idea is still in mind, imagine moving the

board back and forth rapidly so that the round checkers hit each other, and bounce back and forth without finding their proper holes. Though crudely oversimplified, this macroscopic image simulates the process of oscillations.

Some scientists liken plasma oscillations to the trembling of jelly in a bowl when the bowl is shaken. The comparison probably is responsible for the word pLasma, first used in the term protopLasma which was introduced into scientific terminology in 1839 by the Czech biologist J. Purkynie for the jelly-like medium interspersed by numerous particles which constitutes the body of cells.

It may be inferred from the foregoing that the study of the fourth state of matter involves an intertwining of customary disciplines, for its apparent simplicity is really complex, yet a zealous specialist might claim his discipline to constitute a unifying core. This may account for the multitude of names that have been used in attempts to describe it. The astrophysicists, who first observed the natural phenomena, labeled their study cosmical electrodynamics. Experiments with magnets and mercury yielded the name mercury-dynamics. Physicists and electrical engineers have called their study plasma physics or plasma dynamics, although these terms do not necessarily imply the presence of an externally applied magnetic field. Magnetohydrodynamics, or the use of a magnet with conducting fiuids in motion, has been designated by at least one physicist as "the most active, the most widely studied and most important branch of modern physics." Aerodynamicists have highlighted their discipline with magnetoaero-dynamics which, of course, suggests experiments with magnets and air in motion, while mechanical engineers, experimenting with magnets and gases in motion, coined the word magnetogasdynamics.

With the abundance of names describing different facets of this infant study, some clarification was needed. It was provided by Theodore von Karman, the dean of modern engineering, who devoted a major portion of a lecture to the use of magnetofluidmechanics when treating the subject in a general sense. A perusal of current literature still finds most of these descriptive names, with a bow in the direction of von Karman, and a leaning towards magnetohydrodynamics. Nevertheless, because of the American penchant for reducing all affectionately regarded entities to letter abbreviations, magnetohydrodynamics most often is referred to as MHD.

In preceding paragraphs plasma was described as a gas heated to such a high temperature that its particles are charged and agitated to a great degree. Also it was suggested that with the introduction of a magnet the behavior of a plasma can be controlled, or at least modified. Magnetofiuidmechanics, using the general term, comes about

16

NORTHWESTERN TRI-9UARTERLY

when a magnetic field is applied at right angles to an electrically conducting fluid in motion. Due to the interaction of the two fields an electric field is induced at right angles to both. At this point a number of phenomena and forces occur which are explained and utilized by equations from various disciplines of science and engineering.

The net effect is the production of useful thrust.

Why should useful thrust be obtained in this manner? Has not the jet engine, to use one example, furnished man with useful thrust? The answer is provided by the designers of energy conversion devices who invariably refer to the first two laws of thermodynamics and the Carnot cycle efficiency.

The Carnot cycle, a highly idealized hypothetical cycle devised by N. L. Sadi Carnot, who was a contemporary of Napolean Bonaparte, considers no losses whatsoever; yet its efficiency is not 100 per cent because the second law of thermodynamics states that any engine must operate between two reservoirs of thermal energy, one source having a high temperature from which the cycle obtains its input energy, the other a sink at a lower temperature to which an engine must reject or discharge the thermal energy which it cannot use to advantage. Although the Carnot cycle can never be built and may be termed a "dream engine," it serves as a model to emulate. In the case of a fast airplane, the source of energy is at the temperature of the fire in its engines, something around 3000 F. The thermal energy entering the engine is partially converted into the thrust which enables the plane to travel. During this conversion, the gases of combustion lose part of their thermal energy and leave the engine .at around 800 F. They are discharged to the sink, in this case the air, which is possible because the air is at a much lower temperature.

Carnot showed that the efficiency of an engine is improved if the range of operating temperatures is increased; it is ideal to have a high source temperature and a low sink temperature. Chemical kinetics indicate that fossil fuels, even with exotic additives, cannot yield burning temperatures much higher than 3000 F. But because plasmas occur at much higher temperatures the source temperature will be high, and hence a high Carnot cycle efficiency can be achieved. Therefore, plasmas offer the possibility of designing highly efficient energy convertors.

In accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, it is necessary to dispose of the rejected energy to the sink. In outer space there is little if any air, and it seems difficult to find a useful scavenger. Yet it is known from electromagnetic theory that energy may travel through a void. In fact, in a void energy can be transferred by radiation alone, and furthermore the

Spring, 1962

rate with which energy is radiated improves with increasing temperature. The law which governs this action is called the Stefan-Boltzmann law. Indeed, if there were no such action, radiations from the sun which foster life on earth would never reach our planet. Thus, because the sink temperature of a magnetofluidmechanic device will be relatively high, though not so high as its source temperature, rejected energy can be radiated away into the emptiness of space.

Among the numerous applications of magnetofluidmechanics, seven merit special attention:

In the realm of materials science and production techniques, the engineer is vitally interested in determining the properties and in observing the behavior of materials at high temperatures. For this purpose, not even solar furnaces similar to Archimedes' burning mirror, reputed to have destroyed a fleet of Roman ships off the slope of Epipolae, produce sufficiently high temperatures. The high temperatures associated with plasmas make them ideally suitable for such studies. Further, the cutting, formation and coating of materials can be accomplished conveniently and rapidly with plasma torches.

Flow control is another area where magnetofluidmechanics can be of valuable assistance. The flow of liquid metals, for example, molten sodiumpotassium solutions found in nuclear reactors, necessitates unusual pumping, controlling and measurement techniques. Also, flow measurement is promising in medical applications where the flow rate of blood or other saline solutions can be measured.

In the field of communications, there are several directions in which magnetofluidmechanics research should bear fruitful results. The ionosphere consists of the strata of the earth's atmosphere where high intensity radiations from the sun ionize the gases. These layers of plasma have been used for decades as a communications mirror in transmitting radio waves over oceans and across continents. Further information can be added to the fund of knowledge through continued study of the ionospheric layers. In front of hypersonic ballistic missiles there occurs a plasma sheath due to the conversion of high kinetic energies to thermal energy through which the communications engineer must devise means to propagate signals for homing or other modes of communication and guidance. Further, because the jet trail emanating from chemical rockets contains electrically charged particles, guidance and other telemetering devices must take cognizance of the influence which ionized gases have on electromagnetic signals.

Within the realm of the flight sciences, the ever increasing speed of flight vehicles makes necessary a rigorous understanding of boundary layer control and re-entry schemes. For instance, by in-

17

corporating suitable magnetic fields in the nose cone of a vehicle, it is possible to modify the velocity and the temperature gradients in the boundary layer of the conducting gases adjacent to the surfaces. To make the safe re-entry of hypersonic vehicles into the atmosphere possible, various modes of ablation cooling, gliding or drag increasing devices may be applied. More simply, with schemes developed through the study of m agnetofluidmechanics, a braking action can be applied to vehicles entering the atmosphere just as an automobile is braked by the friction of mechanical devices. In research laboratories aerodynarnicists concerned with high speed flight are particularly interested in the plasmas generated by shock waves of missiles. With a plasma arc jet. or an electromagnetic shock tube, which simulates hypersonic effects, the air stream is rippled by a standing shock wave upon meeting a solid body. Because the temperatures encountered approximate actual values, it is possible to study in the laboratory an otherwise inaccessible problem.

One of the most difficult problems encountered in working with extremely hot gases is the containment of fusion processes, often referred to as the "controlled H-Bomb." There was a period when the subject of plasma physics, in the words of an anonymous scientist, was "becoming unfashionable and was regarded by most physicists as a rather charming subject, full of small, colorful experiments, where there was little left to discover and whose only real justification was the amusement of those who bothered to waste their time on it." With the search for a mechanism to control fusion, plasma physics again became a subject of interest to the physicist and engineer. A better understanding of the allembracing discipline of magnetofluidmechanics may bring controlled fusion closer to reality.

The fuel for fusion is found in ordinary water. It is deuterium, a heavy isotope of hydrogen. Although only a small fraction of the hydrogen in natural water is deuterium, the deuterium in one gallon of water has an energy equivalent to 350 gallons of gasoline. When two deuterium nuclei collide at a very high temperature, they fuse to form helium. The temperature of the deuterium nuclei (deuteron) must be about 6,000,000 F for such a process to be self-sustaining. When vast amounts of energy are released in nuclear fusion, the hot plasma particles can be bent into tight helices and "tied" around the lines of force by an externally applied magnetic field. This gives rise to the popular expresson "magnetic bottle." It is essential to use a mechanism that will stabilize the hot plasma in such a manner that it will not escape from the magnetic lines of force to squirt rapidly against -the walls of the container where it would dissipate energy, thereby causing a collapse of the fusion reaction.

Assuming this stability, the plasma particles move across the magnetic field lines. On the other hand, their motion along the magnetic lines is unimpeded. The problem, in this case, is to develop configurations of the magnetic field which will prevent hot plasma particles from escaping out the ends of this route. A number of configurations have been proposed which form the basis for various approaches; among them, experimental efforts have been based upon the pinch concept, the stellerator concept, and the magnetic mirror concept.

The race to tap thermonuclear power by way of the fusion process is not necessarily a race to obtain a more effective and clean weapon of destruction. Contrary to what the anti-science humanist may think, both the scientist and the engineer are very much concerned about continued generation of life. It is a recognized fact that at our present rate of consumption and at the rate of population growth, fossil fuels may be insufficient within a century. Both the nations rich in fossil fuels who see inroads into their reserves and the "have not" nations are seeking methods to augment the supply. In several countries electrical power already flows from nuclear fission plants, but fissionable fuels, too, are an exhaustible supply. Furthermore, fission power presents another problem: disposal of radioactive waste. If the fusion reaction can be tapped and put to work, it will solve the fuel supply problem as long as there is water on our planet, and solve it without appreciable radioactive by-products.

Another application of magnetofluidmechanics is in the field of propulsion. In general, electric space propulsion systems may be classified under three headings, namely, electrostatic, electrothermal and electromagnetic. In electrothermal propulsion engines, electrical energy is used to generate high temperature plasmas which are then accelerated in a suitable nozzle, converting the high level thermal energy into kinetic energy. Because no external magnetic field is applied, the acceleration is quite similar to that encountered in chemical propulsion devices. The difference is that in chemical engines, the stored energy is transformed into thermal energy by virtue of a chemical reaction, whereas in an electrothermal engine the stored energy is converted into thermal energy during a physical reaction. In electromagnetic propulsion engines the plasma is produced as in the electrothermal engine and may be accelerated similarly. However, added thrust or acceleration is produced by applying an external magnetic field. Finally, in electrostatic propulsion engines, charged particles such as ions or colloid droplets are ejected in streams.

In conventional or nuclear steam power plants the chemical energy stored in the fuel is converted into thermal energy, thence into mechanical energy and finally into electrical energy. In

18

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

the magnetoftuidmechanical power plant one or more of these steps may be obviated. However, the greatest advantage is due to the fact that in the generator, the rotating armature consisting of the copper wire conductor is replaced by a linearly accelerated stream of electrically conducting plasma and thus there are no moving parts which are subject to mechanical stress.

With these sketchy description of applications the story of the fourth state of matter might end. But it would be a poor chronicle which did not include the antecedence of these applications. Who were the curious ones of the past who observed nature minutely and jotted down their findings, or sat in secluded rooms to formulate the great physical laws which now are interlaced within this intricate study?

In tracing the history of magnetofluidmechanics, it would be helpful to know the origin of the Universe for, as indicated earlier, our planet swirls in a veritable ocean of plasma. As yet scientists have not found the key to that secret, and theologians are still wrestling with it; hence this outline of magnetofluidmechanics begins in a later period.

Although history records magnetic effects as early as 50 BC when Thales of Miletus first described the magnetic properties of lodestones, true magnetoftuidmechanic effects, as we now wish to exploit them, were not recognized until the latter part of the 16th century. It was William Gilbert, who, then serving as a court physician to Queen Elizabeth I, recognized our planet to be a giant magnet. Gilbert conducted many experiments on magnetism and published his observations in 1600 in a book entitled De Magnete which still is of classical significance since scientists continue to study the Earth as a magnet.

More than a century and a half later the studies of Andre Marie Ampere in France and Michael Faraday in England culminated in establishing the close relation between electricity and magnetism. In fact, Faraday may be credited as being the first magnetohydrodynamicist. Recalling Gilbert's observation that the Earth is a magnet and knowing the Thames River to be an electrolyte and thus a conductor of electricity, Faraday suspended two electrodes into the Thames and attempted to measure the electricity produced. Although Faraday failed in this one particular experiment, he was supremely successful in others as witnessed by the Faraday generator and the Faraday pump, both of which still bear his name as tribute to his original conception of them. Most theorists of that period who tried to analyze the relationship between electricity and gravitation used the term" action at a distance." They envisioned a charge (or mass) at one point in space influencing a charge (or mass) at another point in space without any linkage between the

Spring, 1962

charges (or masses). Faraday, proposing to explain electricity as a mechanical system, asserted the existence of lines of force running through space: actual physical entities with properties of tension, attraction, repulsion and motion.

Ampere and Faraday had been keen observers of experimental evidence. Now there was need for someone with a command of theory to develop their investigations and, as so often it occurred in that remarkable "age of enlightenment," a brilliant Scotch theoretician, James Clerk Maxwell, was moved by the genius of the empirical laws that Ampere and Faraday had propounded. Maxwell believed in Faraday's concept of lines of force. In developing it, he tried to imagine a physical model embodying the lines whose behavior could be reduced to formulas and numbers. The resulting paper, published when Maxwell was 25, explained many of the observed facts concerning electricity. Faraday was delighted and appreciative. He wrote to Maxwell: "I was at first almost frightened when I saw such mathematical force made to bear upon the subject, and then wondered to see that the subject stood it well." A few years later Maxwell again returned to Faraday's concepts. After questioning, experimenting and theorizing, he wrote the now well known and constantly used field equations which were incorporated in his Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, published in 1864. It was H. Hertz who found the applications of Maxwell's theories in radio transmission.

In 1901, a clever experimentalist, the Italian Guglielmo Marconi, succeeded in sending a wireless message from Cornwall to Newfoundland, a distance of 2100 miles. From a practical viewpoint, sending messages over such long distances was a great achievement; however, Marconi's experiment also led to a breathtaking scientific conclusion: the signal must have followed the earth's curvature. The probable phenomenon was explained by Oliver Heaviside, an English physicist, and A. E. Kennelly, an American electrical engineer, who suggested that Marconi's signal reached Newfoundland after having been reflected down to the earth by a reflecting zone in space. E. V. Appleton carried this study further, showing the existence of ionized layers surrounding our planet.

As one individual after another on the trail of electromagnetic phenomena added a marker indicating a possible direction to the next curious observer, yet other scientific trails were being marked in similar fashion.

The general fluidmechanic equation of motion bears the name of both Navier, who first derived it in 1822 and Stokes, who discussed its details in 1845. Louis Marie Henri Navier was a French engineer, with the usual academic training of his time and place, who taught mathematics at the

19

Ecole Polytechnique. In the one major scientific paper of his life, which he presented to the Academie des Sciences, he extended the basic Eulerian equations of motion to include molecular forces. During the next twenty-five years there were a number of attempts to make Navier's equation more workable. It was Sir George Gabriel Stokes, a professor of theoretical physics at Cambridge, who replaced Navier's general coefficient with one which stood for dynamic viscosity.

Advances in thermodynamics, too, were contributing to the many laws which would later be brought together in the discipline of magnetofluidmechanics. And here again James Clerk Maxwell applied his patient, able mind. Maxwell examined mathematically the behavior of gas particles as if they were perfectly elastic spheres, such as billiard balls, acting on one another during impact. The German physicist, Ludwig Boltzmann, who recognized the significance of Maxwell's work in this area, refined and generalized Maxwell's proof, showing that Maxwell's distribution was the only possible equilibrium state of a gas. However, both Maxwell and Boltzmann realized that this equilibrium state is the thermodynamic condition of maximum entropy, the most disordered state in which the least amount of energy is available. Working independently and in friendly rivalry, Maxwell in England and Boltzmann in Germany made notable progress in explaining the behavior of gases by statistical mechanics, but after a time they ran into difficulties; for instance, they were unable to write theoretical formulas for the specific heats of certain gases. The result of their work led to the MaxwellBoltzmann distribution function which, though inadequate because of its extreme idealization, served the purpose for over forty years, and still is in use.

Between 1910 and 1920, M. N. Saha, a professor of physics at Calcutta University, was pioneering in research on the progressive breaking of atoms and molecules of matter into their constituent parts at high temperatures. The significance of Saha's work is that ionization of a gas is encouraged with increasing temperature and decreasing pressure.

The appropriate basic theory of an ionized gas was developed by Irving Langmuir, the American chemist, in the early nineteen-twenties. Throughout the next fifteen years a number of investigations continued to add to the subject but in a relatively isolated manner. It was inevitable that the moment in history would come when someone would see that the trails of electromagnetic theory, fluid mechanics, statistical mechanics and thermodynamics must converge.

The Dane, J. Hartmann, broke the new trail from the juncture. In 1937, working towards improved streetcar service in the city of Copen-

hagen, he revived Faraday's experiment in the Thames but this time in reverse. Whereas Faraday had attempted to produce electricity from a conductor flowing in a magnetic field, Hartmann attempted to pump mercury by subjecting it to a magnetic field. Hartmann was no mere gadgeteer. With Lazarus he studied the fluidrnechanic pheonomena associated with the flow of mercury in a magnetic field and gave the subject its first of many names, mercury-dynamics.

A strong impetus surged into the field of magnetofluidmechanics when, in 1942 Hannes Alfven, Professor of Electronics at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, combined the equations of Stokes-Navier with the equations of Maxwell to show analytically that waves must rise in a conducting liquid when the liquid is subject to a magnetic field and when the latter is pulsed. Suggesting that his waves were electromagnetichydrodynamic waves, Alfven reported his findings in a short letter to the editor of Nature Magazine. Today Alfven's waves are to the experimental fluidmechanician as rocks in white water are to the canoist: they are always there; something of which to beware.

A monumental classic called The Mathematical Theory of Non-Uniform Gases was published in 1939. Written by two English mathematicians, Sydney Chapman and T. G. Cowling, it incorporated the solutions of the Maxwell-Boltzmann distributions which Sydney Chapman and David Enskog had analyzed independently and with different details within the year 1916-17. In addition, the book described the mathematical theory of gaseous viscosity, thermal conduction and diffusion including quantum theory. It was also Sydney Chapman who later predicted the existence of the Van Allen belts.

Between 1950 and 1957 magnetofluidmechanics gained considerable momentum. In 1950 de Hoffman and Edward Teller formulated the theory of magnetohydrodynamic shocks and in 1956 Walter Elsasser formulated the magnetohydrodynamic dynamo theory. It was also in 1956 that Lyman Spitzer wrote an elegant, small monograph entitled The Physics of Fully Ionized Gases in which he sought to analyze theoretically the behavior of a gas composed entirely of electrons and bare nuclei, and in so doing incorporated the investigation of all those who had contributed to the field before him. One year later T. G. Cowling published his Magnetohydrodynamics. A significant event occurred in 1957 when the United States Air Force announced its entry into the field of magnetoftuidmechanics on the Evanston campus of Northwestern University.

Since 1957 two trends have become evident in the study of the fourth state of matter: one is the widespread effort to convert the science of rn agnetofluidrr-echanics into technological appliea-

20

NORTHWESTERN TRI-QUARTERLY

tions, some of which have been mentioned here; the other involves the many scholars who continue scientific studies related to the properties of plasma and the motion of conducting fluids under the influence of magnetic fields. Despite the numerous obstacles to be overcome within the twopronged attack, there are individuals who claim that magnetofluidmechanics is est a blished sufficiently so as to pose no further major problems. They are already out on the scientific frontier probing unknown areas of relativistic and quantum magnetofluidmechanics. To them Alfven's waves serve only as a darkened lighthouse serves

SOMETHING OLD

JAMES R. JOHNSTON, who sends us this short shortstory, lives in Michigan City, Indiana. He graduated from the School of Journalism in 1958.

THE NURSE'S HEELS dully sounded down the shiny linoleum hallway and faded behind a swinging door.

Mary Garback uncrossed and recrossed her long nyloned legs, critically studying her ankles, which she always considered too thick.

She looked over at her father, sitting next to her, staring blankly at a bad picture of a meadow scene hanging on the opposite wall of the small waiting room.

"Dad.

The old man neither turned his head nor gave any indication that he had heard her.

"Dad, listen to me." Her voice was taut with close-lipped emotion. The old man shifted his weight in the chair without taking his eyes from the picture on the wall.

"You've got to understand about this, Dad. There's my side too. It's not as if I'm committing some awful crime. Is it, Dad?"