Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Chicago Community Trust, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers:

Walter Adams

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

C. Dwight Foster

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Charles T. Martin

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Michal Miller

Fran Podulka

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Marc Straus

Lawrence Stewart Geraldine Szymanski

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors.

Illinois ARTS c o_u n� &I AlEICY OF 'BlIUU Of IUI••IS

This program is partially sponsored by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council

Spring/Summer 1997

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow

James Lang

Reader Ian Morris

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Kemba Johnson, Jacob Harrell, Dylan Rice, Elizabeth Taggart

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of back issues varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (847) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1997 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ); Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CA).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), Historical Abstracts, MLA, EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CA).

A story that originally appeared in TriQuarterly #97-"Transactions" by Michelle Cliff-is to be included in The Best American Short Stories 1997 (Houghton Mifflin), edited by E. Annie Proulx and annual editor Katrina Kenison. The book will be published in December.

The poem "No Sorry" by Catherine Bowman, which originally appeared in TriQuarterly #95, has been selected for inclusion in The Best American Poetry 1997 (Scribners), edited by James Tate and series editor David Lehman. Publication will be in September.

"On with the Story" by John Barth (TQ #95) has been chosen for publication in Prize Stories 1997: The O. Henry Awards (Doubleday/ Anchor), edited by Larry Dark. Publication will be in October.

Gibbons FICTION

Contents

this

When Treading on Soft Earth,; Horizons West; Long Gray Line 7 Kanai Mieko Translated from the Japanese by Sarah Teasley The Orderly 30 Douglas Gilmore Power The Dinner Party 49 Robert Girardi The

Soup;

Dr. Soup by Himself; The Dream; Chloe; The Bow,Wow; An Incident on the Georgian Military Road ..•..•.•. 63 Clarence Brown The Lights of the World •........•••••••.....•••.........••... 92 Jesus Gardea Translated from the Spanish by Mark Schafer The Age of Anything ..•..••.......•••.......••......•••....••• 99 Brad Bostian POETRY The Greeks; Elm Street, October 1977 ........•.... 105 Linda McCarriston 3

Editor of

issue: Reginald

Groom; Ink

The Adventures of

At Least I Know What My Hands Are; Jasmine Dreams; The Forgery; You Could Have Been Me; An Engine Fire Over the Ocean Compared to the Suburbs 108 Belle Waring Marrakesh Express •..••••...•.......................••••...... 11 7 Manuel

Translated

Reginald Gibbons American

Body

Soul; Sophie's Friend •............•••••••••••• 121 Barbara

Translated from the German

Waldrop Thirst 128 Deanna K. Kreisel Hill Prospect of Kalamazoo; On the County Line; Three Observations on Vinal Street 130 James Armstrong White Milk at Daybreak; You Watch

Wait; When the Page Is Full; The Screenhouse; What Haunts Me 135 Lucille Broderson SPECIAL SECTION: SELECTED STORIES OF STEVE FISHER Taco Mask 143 Whorl ••..........••.....•....••..................................... 155 4

Ulacia

from the Spanish by

Way of Midlife; Self-Portrait; Poem; Navigation; World View with Conquerors;

and

Kohler

by Rosmarie

and

ETCHINGS BY TONY FITZPATRICK

Izzy's Trumpet; Birth of a Kingsnake; Carnival Cat; The Atomic Ant; The Shroud; The Songbird; Crow in the Service of Ghosts; Orbit Dog; Zombie Seal; Apparition of the Racehorses; The Mange Dog; The Cat Driven Mad by Swallows; Rat Tormented by Ghosts; The Slugger; Lightning Born; The Matador's Bad Dream, on pages 6, 29, 81,91, 104, 109, 112, 116, 127, 131, 134, 140, 154,168,184,202

Cover etching (The Eternal Snake) by Tony Fitzpatrick

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

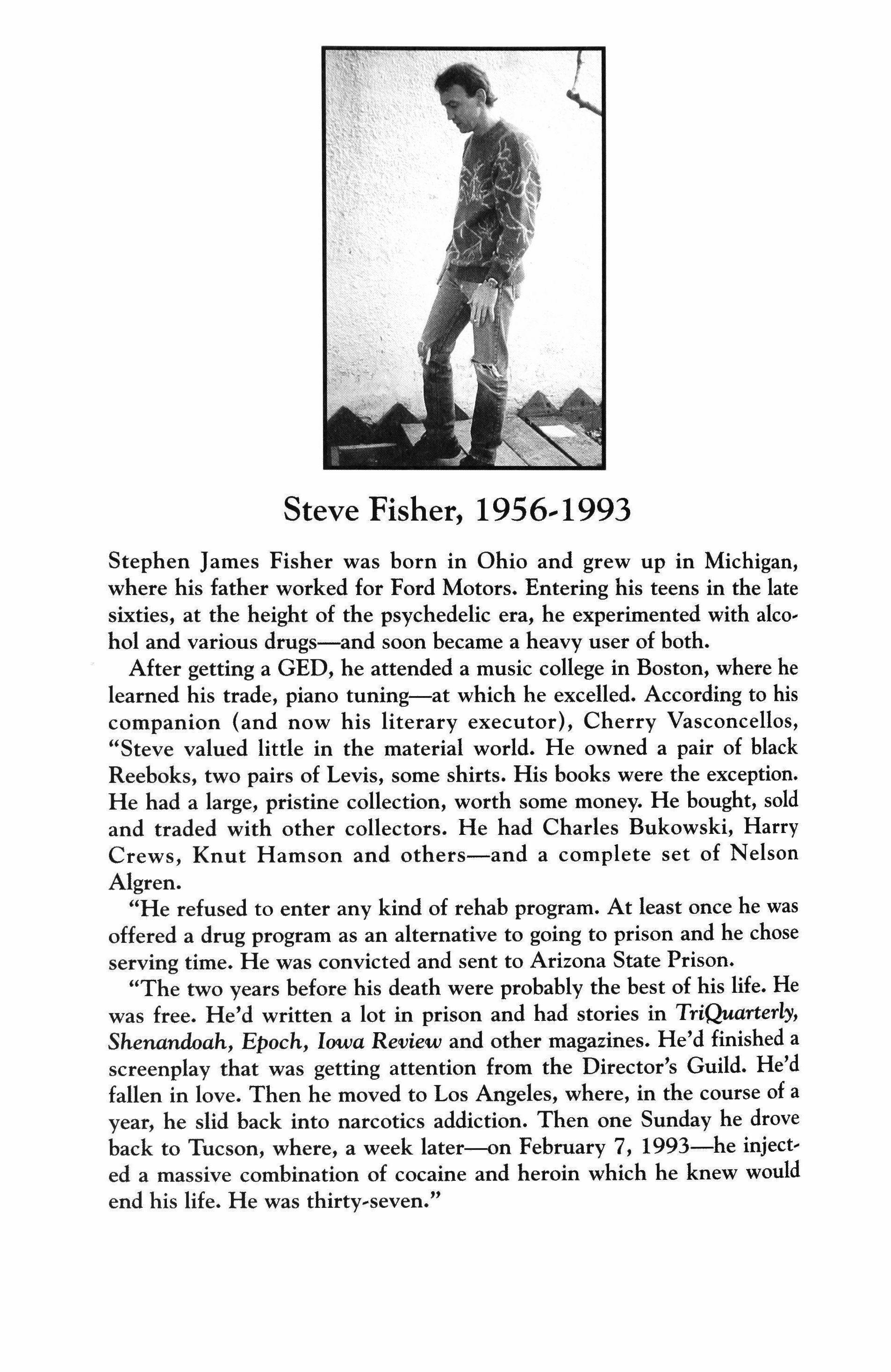

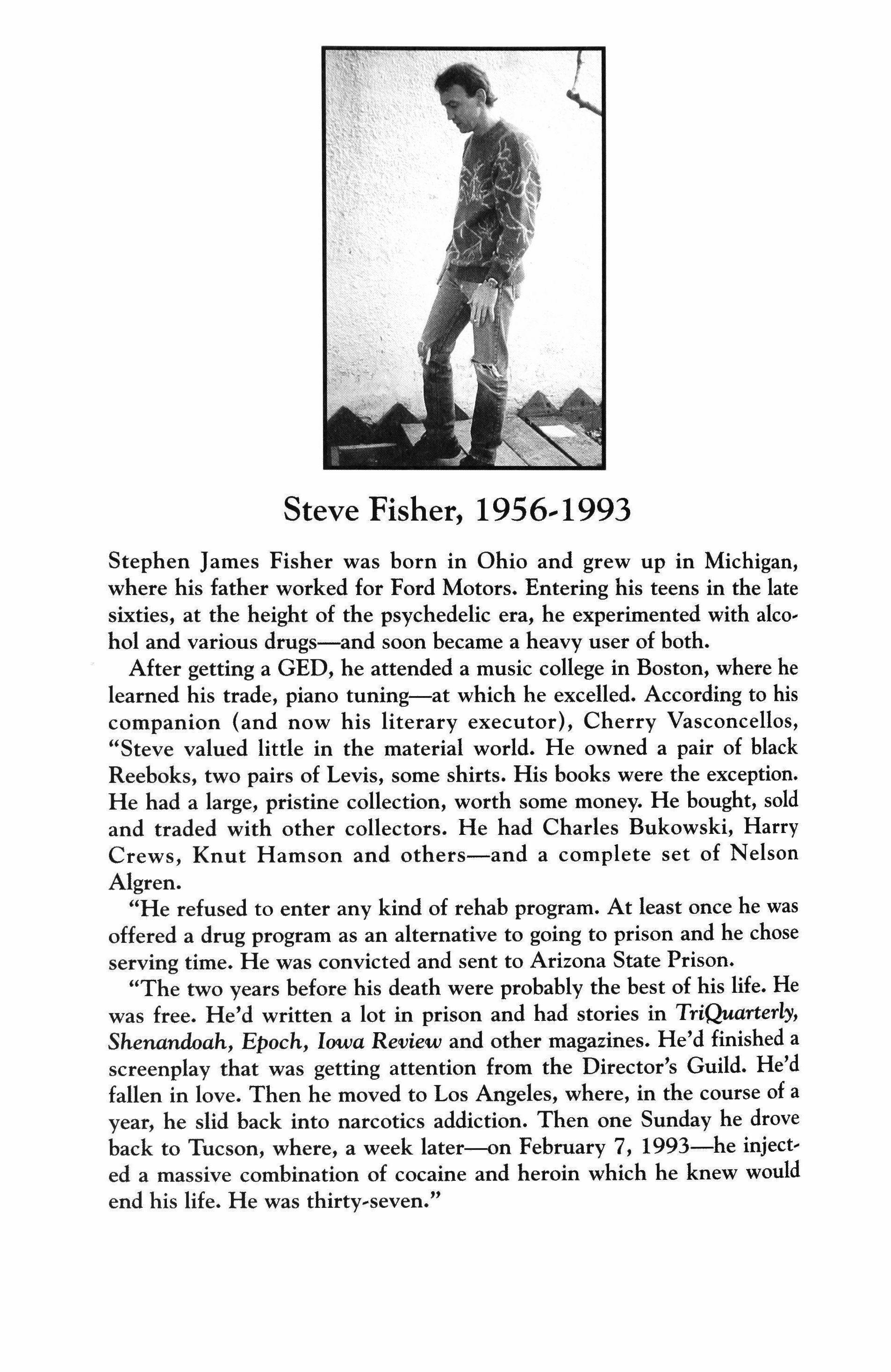

Photograph of Steve Fisher on page 142 by Cherry Vasconcellos

Windy Gray 169 Electric Latches 185 Variations on the Robe 203 Soap Line 221 Underdose 229

CONTRIBUTORS .......•...••...••....•................•.. 240

5

Izzy's Trumpet [black-and-white]

Izzy's Trumpet [black-and-white]

Three Stories

Kanai Mieko

Translatedfrom theJapanese by

Sarah Teasley

When Treading on Soft Earth,

When treading on soft earth, or even if not, the naturally soft pads of feet seldom make any noise: those extremely soft fleshy objects make only a faint sound when they touch something, hard concrete or brick, or black-and-gray marble spread like a chessboard on the front wall and floor of the first floor of a building-was it the young man wearing blue overalls (there was a red line around the collar, and the company name was written in red letters on the chest, although I haven't read what it says) who came from a cleaning company every other week on Sunday afternoons to clean the floors and windows of the building, speaking broken Japanese (always listening to tapes of songs by Taiwanese or Chinese popular singers with the volume turned up as he chattered, and sometimes there was a melody I knew; I have gone for a walk in the evening and realized that I was humming that song, the one that says Even though I always knew the only person I wanted to meet was you, my heartstrings would not tie), was it he who showed me the cross-section of a small trilobite fossil emerging from the face of a stone against which it had been pressed, or maybe it was the newspaper-delivery boy-in which the shape of a trilobite appeared, and even though it was summertime it was chilly; when running on hard concrete or on marble, that sensation of stretching so far as if wanting to grasp onto things with the claws of the forelegs, so that the faint dry clicking sound was the noise made by the pointed tips of the small half-transparent hooked claws, hollowed and tinged with light purple in the middle, claws like however many folds of epidermal tissue piled on top of each other, as they touched the hard floor, now not stealthy steps on the ground like 7

TRIQUARTERLY

TRIQUARTERLY

soft moist red earth littered with fallen pine needles, but walking slowly with an easy step-it flares moist rough orange nostrils slightly and makes small drops of water at the ends of shining white whiskers sparkle-the eat's coming is watched, and it pauses at the edge of the pond, its circumference lined with bricks reached by the morning sun, bricks lying width-wise around the circumference of the rectangular pond three-and-a-half tatami mats large in which float lotus leaves; on summer evenings, a rod-shaped bug-light like vaguely pale lukewarm water is switched on, and the edges of the light peach-colored petals layered over and over each other take on a blue cast tinged with green, while reddish-purple lines diverge finely like capillaries in the white part near the calyx; it was possible to replace the water in the pond, its mud settled at the bottom, through a pipe buried underneath the bricks, but mosquitoes appeared and it became clear that the bug light had no effect, so by way of a countermeasure to the clouds of mosquitoes the manager thought to put toad eggs from the pond of a nearby park's Japanese garden into a plastic bag and to bring them for release into the pond; one morning in May when the continual rain had just stopped, he brought the eggs lined up neatly like brown beans in a transparent graytinged string; back in his elementary-school days at the school in the center of the town they had been made to write a tadpole group observation journal for science class and he had been the group leader, so he had labored valiantly at finding tadpoles, he told the watching residents; the fat woman up in room 302 on the third floor said afterwards, He said he'd written a tadpole observation journal in a group and he'd been the group leader, so that manager, he must be a lot younger than I'd thought, and speaking of group leaders, the army, what's it called, it's called a regiment? things like that make me think of group leaders, and she had laughed while saying it; she sat down on the bricks around the pond in which float the round dark green leaves of small lotuses-the pale rod-shaped flame of the bug light made the twilit green leaves and black surface of the water shine-and put the soles of her feet on the damp bricks, and wind came blowing between the pines, the locust trees, the dark peach-colored oleander and the white cotton roses; the smell of paint on the steel frame of the just-painted gray fence around the yard facing the hill road mixed together with the stench of decaying mud from the bottom of the river that had remained on the roads, in gardens and below the floors of the houses along the river when the river flowing along the private railway line connecting the suburbs and the city center down the hill road and across the four-lane street was

8

flooded by heavy rain, it was a smell like the fish- and blood-smelling secretions of goldfish scales from the water in the pond; she was wearing a summer dress with a print of small yellow flowers-buttercups, forsythia, yellow roses, saxifrage, mimosa, which was it?-and green leaves on a background of extremely pale white flax that left shoulders, arms and neck bare and gathered fully at the waist-there were three thin straps (the same color as the yellow flowers on either side of the green of the leaves) on each shoulder connecting the deeply plunging back to the front with its built-in rubber bra with nylon-lined cups-every time she moved her body slightly the light flax fabric made the hushed sound of a dress rustling-that summer dress wasn't one with fasteners in the back, but once undone fastened from the left armpit to the narrowest part of the waist with two-piece hooks made from small silver pins, and there was also a zipper to zip from the hips up towards the waist, so that every time she went to take it off-even though she had on only small damp panties under that summer dress with its background pattern of small yellow flowers-slight confusion arose, the thread in the part where the thin straps attached to the body would loosen, and when she took off the large quantity of rustling cloth that was the skirt by pulling the lining over her head, the small gold hair pins in the shape of musical notes fastened above her ears by which she held her hair back and up fell out and her brushed, waved hair became disheveled and tangled in the fasteners, what annoying clothes; her pale face was thrown onto the surface of the water that reflected pale light; two frogs lying concealed in a grassy part of the garden jumped lightly to appear at the edge of the pond paved all around with bricks, while watching them stay as they are, motionless, I say I've heard it said that if one of the frog couple dies the other one will stop eating and die too, but where did I hear that, and raise my voice softly and laugh; the black tiger-striped cat jumps up lightly onto the edge of bricks around the pond, extends its neck far and begins to lick the surface of the water with its peach-colored gracefully supple tongue as if whipping something.

The calm, slender voice might have faded away above the waves. On the hill road on the far side of the fence, its greenish-gray paint peeling away and brown varnish to prevent rust flaked off here and there so that the roughened earth colors emerge, red rust and black iron, a young girl riding a bicycle with light reddish-yellow birch-colored legs bared from gray shorts bends forward and pedals to come up the hill so that her hips seem to float, pulls up right in front of the window, puts one foot on the 9

TRIQUARTERLY

ground and wipes sweat from her forehead with the sleeve of her white cotton sweatshirt; she notices the cat, sitting half-asleep on the brick border, its forelegs folded up beneath its body, and pouts her lips, flicks the tip of her tongue against her upper jaw and cries like a mouse to attract the eat's attention, but the cat, its eyes narrowed, only moves its ears back slightly, after a moment cuts across the yard paved with bricks and comes walking towards the window without giving the young girl any attention and takes one bite of the tips of the long, thin, stunted, light-green leaves, their roots growing in the earth of the cracks between bricks; the young girl following the eat's figure with her eyes meets the gaze through the window, and looks away slowly, neither smiling nor hurrying in confusion, leans her body forwards and at the same time lifts her right foot from the ground onto the pedal, pedaling once, moves her delightful suntanned legs, all birch- and rose-colored speckles, up and down slowly in a large arc and rounds a curve up the hill road; the yellow-fuzzed skin of fruit, the moon like a peach beginning to tum pink, sizzles as it begins to rise in the space between the storehouse, its earth walls creeping with withered ivy, and the charcoal-gray slate roof surrounded by a long stone wall; An encounter in Venice, an unexpected second meeting, says the young man, and pauses a moment: bog moss constantly dampened by water sank down into the stairs of the palace's stone boat dock, and the small sound of footsteps on the stairs resounded and echoed in the corridors of the palace, the sound of water slapping against the gunwale and the long wooden pole pulled by the boatman passed through the water, the creaking sound of the iron crutch crossed the surface, and the canal spreading out around the stem shattered the moon's reflection, he continues in a hushed voice; the woman who brought melting frozen cod fillets in a white plastic bag enters, Why didn't you bring in the wash while the sun was still out, didn't I ask you to, I had to do it all, this is so tiresome, and Because of this, I answer, because of this I say we ought to buy a clothes dryer; she begins to cry from this stupidity, buries her chin in the big roll collar of her sky-blue coat, it certainly seemed to take a long time, but in all honesty I don't really know.

The bricks were always wet from the humidity and their rough dark red surface was cool; during the rainy season light green moss grew and the whole surface looked as if mold had grown on it, but the ground near the fence was dry narrow red earth, so her opinion that the earth in this area was naturally moist had been incorrect; but even so, the old

TRIQUARTERLY

10

house to the west had a well which became the well designated as drink, ing water in times of emergency, so they were just dredging it the other day, and from what the manager who had been to see it said, the fact that it was a much shallower well than had been thought was proof that the earth there had a high moisture content so that's why the bricks are always wet; when the rainy season cleared and the summer sky spread out, the foreigners who were temporary employees of the cleaning com' pany played Chinese or Taiwanese pop songs on the tape recorder with the volume turned up all the way as they ran water from the waterpipes out of a light blue vinyl hose, and after they had scrubbed off the moss with a long-handled brush used for cleaning the deck, she opened up a folding deck chair upholstered with red, yellow and blue-striped canvas onto the brick patio, saying Because it's cool here and feels better than being in an air-conditioned room, she's sensitive to heat and perspires heavily, so to cool down her body that never stops perspiring from a bath, she turns off the lights facing the window in the room, lights spiral anti,mosquito incense on a white cake-plate, puts on a soccer-field-style dressing gown meant to be worn after the bath and sinks into a deck chair; she puts a towel wrung out in ice water on her red, glowing face and sweats continuously, always saying Because it flows like a waterfall until I simply can't take any more; she wipes perspiration from the back of her head and the nape of her neck, and from her chest, with its seem, ingly grayish cast in the shadow of the two full breasts, in which ribs float up between the breasts, full but whose shape had begun to collapse with the sensation of hanging down a little, in the center nipples like black cherries and elliptical areolae with grainy pinkish beige skin, soft and heavy flesh that when lifted up with the palm of the hand quivers wetly like a white custard, then quivers slowly while returning to its original shape when let go of with the upraised hand, with a towel soaked in ice water then wrung out; even though there was no intention of stealing a glance (or anything to steal a glance at) from the dim room-because of the bluish radiation from the television screen, vague light seeped from the room with its lights turned off-the line of the body, held in cloth stretched curiously taut and unaccustomed to skin, light-blue, violet and bright brown stripes on a beige background, had begun to collapse but still had elasticity, white skin wetted by perspiradon and emanating rose-colored light-a member of the cavalry brigade wearing a white hat with his uniform, blue trousers with a yellow stripe, and riding a Morgan horse with a rounded body and a short arched neck that inclined forwards, its whole body gleaming lustrous vellow-gold->-

TRIQUARTERLY

11

TRIQUARTERLY

the Morgan horse and the man had become one like a centaur from myth-galloped through the desert dried reddish-yellow with snow, white clouds dense like whipped cream floating in the parched ultramarine sky above soaring crags; the camera moves sideways along the long rail as if sliding, she brings her wet upper body up from the deck chair as if leaning and bends her neck forwards, slowly raises her fattened white arm bared from the curiously cut sleeveless soccer'field clothing, holds up the clean wet hair at the nape of her neck so that it hangs down in front of her face and keeps the towel soaked in ice water at the nape of her neck without moving; Indians fiercely riding gray, chestnut, brown, and-white-spotted and black-and-white-dappled Appaloosas follow behind the man galloping on a Morgan horse, The towel's lukewarm from my body, so won't you go soak it in ice water in the sink then wring it out for me, she calls out with a gesture-she ought to do it her' self-Or it would be good to put some water with ice floating in it in a plastic washbasin and put it out near the deck chair-but even so, I get up from the sofa, open the window, approach her deck chair, and take up the moist towel, lukewarm from absorbing the heat of her body and smelling of the sweetness of perfumed soap-the plump warmth of her damp body temperature held up with unexpected heaviness in the palm of my hand-the hoofs of however many horses resound across the earth like grains of an easily crumbling sweet rice cake or red,brown tobacco leaves, and yellow dust rising wildly like clouds in the sky blown away in a gust of wind winds in front of, behind and around the Appaloosas and the Indians as it moves.

The kitten with soft, bright orange fur on its stomach, white fur around its mouth and under its chin and chestnut and umber stripes everywhere else peeped out its dark red rose'colored tongue with the sharp tip and cried in the entrance to the parking lot; If you'd seen that it would have become unbearable, and there's nothing I need to tell you, but since the child laid down was still an infant, I remembered the time when, eyes closed and stuck fast to a nipple, it drank from my breast, she said; the small living creature that seemed buried in soft fur climbed up on my lap with helpless lightness, got its light violet claws curved like hooks caught in the weave of my wool pants, the tips of the pointed claws opening out from the soles of the feet pricked as they pierced the skin: we raised it from the evening of that day on; I heard it from the fat lady upstairs, she said while pulling wet spinach out of a white plastic bag from the supermarket, the office on the fourth floor that up until

12

two years ago was called a "model club" was really the office for a call, girl organization, and one morning three patrol cars pulled up without sounding their sirens and raided the office, and the girls that were in the office were handcuffed, tied together with a rope and taken to the police station, did you know that had happened? she asked; but Of course I'd neither known that story nor heard such a rumor from anyone, I answer; That's because you're not in the habit of standing around exchanging greetings and small talk with the building's other residents and the man' ager, she said; It's the same thing in the long run, she says, bringing up something completely unrelated, in the long run what had changed: in the beginning I myself had invisible desires hidden in depths that choked my breath as it was blown by the strong hot wind, desires that flowed through my whole body as if softly dissolving and overflowing, and thought it meant that I myself had changed; but meanwhile because of that alone it cooled down suddenly, and in the end nothing had changed even a little bit, and daily life only dragged on as slowly as before; I haven't a set address or anything, she begins to cry, says that the soles of her feet are hot and puts her bare stockingless legs down on the damp bricks, I'm so unsure I can't stand it; she wipes her sweat-moistened forehead and cheeks damp with tears with a gauze handkerchief pulled from the pocket of her skirt, and a skin-colored makeup stain sticks to the gauze handkerchief; she doesn't notice that a small box tied with a brown velvet ribbon and wrapped in paper falls out of her hand, bag, put down as if thrown down on the floor, but when she turns around suddenly it catches her eye; and because the smells of the wax polish on the hall floor and the sugary-sweet chemical cleaner had waft, ed into the room from the open windows down the hall it was Sunday, so it must have been ten days later-she had left, and the cat that hated the smell of wax polish twitches its nose, sneezes delicately, runs outside the window with small steps, nibbles the long thin leaves of grass grow, ing in the cracks between bricks, walks over slowly to leap up onto the edge of the rectangular pond and begin to doze with its front paws folded under its chest; the red earth, dried by the lukewarm breeze, flies up soft, ly and small round lotus leaves quiver and sway from the small waves on the surface of the pond; I yawn, and the skin under my eyes that feels stiff as if sleep dust has stuck to it itches faintly from a small tear leaked from the comer of my eye, so I wipe it away with my finger.

TRIQUARTERLY

13

Horizons West

The white neck wrapped in a soft lustrous long-haired black fur had the shape of a smooth column, and to delicately lick with the tip of the tongue the downy hair at the nape of the neck, arranged into two wedge-shaped pieces by the thin sharp blade of a razor as if just trimmed at the hairdresser's, might have produced the faint taste of metal. Cool and chilled, the taste of cool, chilled metal spread to each taste bud on the rough, disordered tip of the tongue: the skin on the smooth neck shivers slightly as if being tickled and pricks like small waves in excitement; she looks down as if burying her jaw into the soft black fur with its lustrous gleam, and her neck becomes level, the surface of its skin raised in small prickles, as her pointed vertebrae emerge; the soft fur around her buried jaw ruffles faintly in her breath, and she suddenly thinks of the cool deep dark silence that enwraps the round head-eyes gleaming like deep-colored amethysts or small black beads, the wet nose trembling minutely as it senses its surroundings, whiskers transparent and silver, sharp tensed claws that eat into the earth and the full round tail, quietly laid down on the frozen earth-of the whole of the small living creature wrapped in fur gleaming smoothly in waves as if wet; her jaw buried in the fur collar, she moves the soft kid square handbag carried on her left arm to her right arm, and grips the sleeve of the thick coarse tweed coat with her gloveless hands. The tweed is rough to the touch, the oversweet smell of lanolin remains in the stiffly twisted yam, and the nap of the stiff thread must leave a pricking sensation in her fingertips; the strength in her cold fingers comes through layers of cloth wrapped around the arm; the thread of the grainy tweed is chafed by nails stained with pearl-colored nail enamel, and an extremely faint rasping sound passes to the ear.

The daughter I had left at home was already a high-school student, and although when younger she had called me "Mama," she had for some time been calling me "Mother," even though I had liked the sound of small soft lips springing open twice that is "Mama," the close sweet childish sound springing open, whenever it was it had changed to the cool-feeling name "Mother" I had definitely had a lover; like a shipwrecked sailor, that sound opened wide my despairing eyes in the mornings and nights of my solitary life-The clothes Mother buys me are nasty, she says defiantly, opening to the whites her eyes like her father's, no one wears things like this, such a frilly dress-spotting the shadow of

TRIQUARTERLY

14

a white sail in the deep thick milk-white fog that wiped out the distant horizon, I didn't know if whatever was loaded to overflowing on that boat meant new distress or good fortune; every morning I open my eyes, and without thinking Surely that will happen today, prick up my ears at every sound, spring to my feet, am surprised it isn't happening and in mad and sudden melancholy have nightmares and cry in bed. Lukewarm tears cling to my cheek and drip from my chin onto my neck: turning my head sideways on the pillow, tears spill from the comer of my eye to flow along and into the outside of my ear, before long entering inside; the small volume of liquid that spills lukewarm from my eye has chilled completely to become cool by the time it flows into my ear, like words whispered to my ear alone-No matter how long you wait, that's something that will never happen, you've been betrayed again-something to freeze the soul; that man appeared like a white sail materializing out of deep milk-white fog. But of course that's the beginning of new despair, and before long another man will appear enveloped in deep milk-white fog; the mother who never uttered one word in the form of half-tacit approval about her only daughter's infidelity says That's a loose thing to do as she pours tea from an old, old light brown teapot cracked in the shape of the character shi and bordered with a pattern of small light-blue flowers and yellow citrons into cups with the same pattern, could it have been your upbringing that's at fault, she added while sighing; it wasn't the owner of the boat Tsubame with its four hanging bunks that she meant when speaking ill of younger men proposing marriage and living with the child. The small girl manikin wearing a thin pink dress like a ballerina's costume with layers of rows of white lace ruffles on the skirt had a light-blue grosgrain rosette hanging down low in the back; it could have been because I didn't buy you that thin starched straw hat decorated with cloth-dyed red, orange and yellow artificial anemones, says the mother, and the daughter gives a <smile as if snapping>; in the end she married the younger man, and the daughter demanded to live with her grandmother and her grandfather, opening wide to the whites her eyes, resistant like her father's; you understand how I felt at the time, don't you.

Of course I didn't understand, but what would have changed had I said It was because I understood?

Treading on soft earth, clods of damp black earth were stuck in a dappled pattern to soles of feet that had tread on moist earth thickly layered

TRIQUARTERLY

15

TRIQUARTERLY

with soil from decayed leaves fallen to the ground; the smells of rotted plants and sweat mixed together, and I say You have to wash that off, but Putting the burning soles of her feet on the damp earth feels as if the heat remaining in her veins is chilled, and that feels so good, she says; I hug the black silk-lace shawl covering her bared shoulders, and in the slightly sour smell mixed with the simultaneous fragrance of orange blossoms, the drenched hair, drenched shawl and drenched skirt that had lost its shape and sagged somewhat, and as a contrast to the two cool and firm arms, the warmly glowing chest, lower back, abdomen and thighs make soft muscles flex while inside my arms: That's completely unbelievable, I mutter, but it's the truth, she continues, murmuring in a damp voice that conveyed the entirety of her soaked body in my arms; It's destiny that things tum out this way, she whispers, her throat trernbling as if swallowing saliva, and in the mixing together of the raw smell of rotted water plants and the smell of dust trapped in a room, I press my lips to her face, become an irregular pattern of heat and cold. Teeth wetted with lukewarm saliva, swollen lips slightly chapped as if feverish, the smooth taste buds inside them with their faint salt taste, her ears become hot and red, a neck that sounded the gushing noise of the blood flowing in its veins, the mass of long sodden hair coiling around the neck, nipples pressed softly whose stiffness could be seen through the bra, and below them to the left the heartbeat that continued to sound, all of these were inside my arms, and even though that was clear, the area around my stomach was oppressively sore and my throat severely parched.

As if in afternoon sunlight gradually becoming delicately fainter, I'm not sure if I'm looking at the ocean or the earth's horizon, and my dim impression of space in the distance becomes increasingly unclear throughout; I realize I am being won over unawares by sleep and try faintly to resist, but from the tips of my hands and feet begin to dissolve into gray space, and before long heavy sweet gray starts to spread around my lower back and in the area around my forehead; it looks as if this causes the faint smile that floats up around my mouth, but my consciousness no longer makes judgments, and the gray space dissolving from the tips of my fingers is vague like thick dust; in that way however many days and nights passed by, and the grayness that dyed me from the tips of my fingers enwrapped me softly, softly; It changed into something like a kind of anger, she says, and adds at that time I bought this expensive fur-trimmed coat on impulse; the long-haired black fur with its Ius-

16

trous gleam has become the circumference of a stand-up collar and hidden buttons that make the black cashmere coat look flat, decorated from the chest around the waist to the hem, the fur draping from the chest left and right and at the hem quivers and moves gently; dropping her head as if burying her chin in the fur worn in a circle around her neck, the fur ruffles faintly in her breath, become white steam beneath the bluish-white glow of streetlamps in the park; she switches the square kid-leather handbag carried on her left arm to her right arm, and the distance between the two of us walking side-by-side lessens, she wraps her left arm, empty now that she has moved her handbag, around my arm, the feel of her cold hands passes through the coarse stiffly woven fabric of my heavy tweed coat.

He realizes suddenly that his throat is severely parched, and-the mucous membranes in his oral cavity smart and his esophagus is drying out and becoming choked-slips out of bed without making a noise to go barefoot to the kitchen, opens the door and flips the light switch; the soles of the feet that had been warmed in the blanket feel the roughness of the cool, chilled linoleum floor covered with dust as he takes a glass from the cupboard, turns on the faucet and fills the glass with water. The small window above the sink is open and cool, damp air flows in; in the obscured dark gray gloom, a hydrangea shakes in the wind, halfspherical heavy-looking flowers and large leaves swaying slowly from right to left, and the tip of the Himalayan cedar in the garden near the fence facing the road quivers; the rain that until then had appeared to continue to fall gently slantwise suddenly becomes stronger; closing the kitchen window, small drops of rain spread across the dirty and clouded window pane, and the figure of the man looking like an old man standing in pajamas before the window is reflected, drinking dry a cup filled to moderation with lukewarm water; because it probably had not been washed well, a rotting odor remained in the cup; on the dusty stainless steel countertops next to the sink, a small white plate with one round cookie covered in granulated sugar, a round nibble taken out of it, remaining on it sits lined up next to milk glasses used either before going to sleep at night or before leaving in the morning, it's unclear which-a faint white film of milk fat had stuck to the inside and dried that way, half-transparently cloudy; even though he'd thought he was so thirsty the water he had drunk sits heavily in his stomach, not mixing with gastric juices but forming a layer of water on top of those gastric juices, heavy and viscous-like water in a moat with aquatic plants

TRIQUARTERLY

17

growing densely and rotten mud at the bottom-as if rippling in waves while flowing back up through his throat to overflow into his oral cavity. Lotus leaves float on the surface of the water, freshwater plants grow luxuriously as if whipped to a froth, at the bottom dead fish, crayfish, tadpoles that had failed to become frogs, leftover food and the corpses of cats dumped by neighborhood residents and fallen leaves from the cherry trees planted on the embankment decompose in the thickly resting mud; it doesn't have a strong smell year-round from the water with its mud become greasy black sludge, but the water in the moat always has a faintly rotten odor, and on summer evenings before nightfall, rain striking the surface of the water with fierce vigor churns in places all the water in the moat that encircles the castle ruins with however many bends, and the rotting odor rises up amidst the dark green clouded surface of the water, water that looks olive green from the color of the water plants dissolved in it becomes the yellow ochre of mixed mud. Even though he thought he had shut the window, the heavy sweet smell of double-flowering gardenias drifts in from somewhere, and turning around on the coarse dust-covered linoleum kitchen floor to look back, white lace curtains become full and swell from the wind in the recesses of the dark living room, rain shining like silk thread floats up in the blue-white glow of the garden bug-light, the surface of the rectangular pond bordered by bricks makes waves and the round leaves of lotuses quiver; going over to the window, a spray of rain hits his swollen eyelids and dry lips with unexpected force, drops of water under the long thin cylinder of the bug-light that adhere to the surface without falling link pale light-blue glitterings in a line; coarse reddish soil mixed with dust, torn-off scraps of faded paper, a contorted handkerchief, white polkadots on a red background bleached however many times by the rain and stuck twisted to the floor, a potted jasmine, long since withered, a deck chair covered in dust, its paint beginning to peel and the red, yellow and blue of its canvas matching exactly sit on the veranda: now all of those things are soaked by the rain.

She turns off the lights in the room facing the window, puts on a soccer-field-style dressing gown meant to be worn after the bath and sinks her body into a deck chair, puts a towel wrung out in ice water on her red and glowing face, perspiration running continuously; Because it flows like a waterfall to the point that I simply can't take it anymore, she says while wiping with a wet towel-Since she perspires heavily in the summertime, no matter how skillful the hairdresser razor marks are left on her smooth white column-like neck and stinging, smarting

TRIQUARTERLY

18

grainy rose'colored spots float up in relief, so motionless thin and downy hairs that look light silver-gray and brown lie as if gauze has been draped over her neck's whiteness, and the sharp outline like a column is softly obscured-the perspiration that has outsprung on the back of her head and the nape of her neck; her ribs float like a shallow relief between her breasts, full but whose shape has begun to collapse with the sensation of hanging down slightly, in the center nipples like black cherries and elliptical areolae with grainy pinkish beige skin, soft and heavy flesh that when lifted up with the palm of the hand quivers like a white custard or a blancmange, then shakes slowly while returning to itsr original shape when let go of with the hand that had seemed to scoop them up; small points of perspiration spring up on her chest with its seemingly gray cast in the shadow of the two full breasts; on the television screen, seen from the garden so that it looks like it emits strong bluish-white light, a gunfight between two men in early old age in a desolate rocky area that reflected pure-white light in the intense strong afternoon sunlight may have been beginning. The aging sheriff had to pull metalframed reading glasses from the inner pocket of his jacket to read the murderer's arrest warrant, and the young blond-haired girl in the desert in a checked dress with her chest bound by a whalebone corset that also emphasized the swell of her breasts glances with seeming compassion at the light eyes-gray eyes tinged with blue, maybe faded and bleached by the sun-in the sunburned face like leather of a not very good quality, its wrinkles sliced deeply and weathered for a long time by sun and dust in the desert and the rocks and at the brown hair mixed with white that could be seen under the hat with blackish beads of sweat surrounding its circumference between the crown and the brim, then raises her eyes towards the clear horizon, Something's on the horizon she begins to mouth the words, but the man at the edge of old age grumbles, It's clear that realistically, from my eyes on, the limiting horizon of my age and physical strength has shrunk; the checked skirt with its two bands of black taffeta around the hem is stirred up by a sudden gust of wind that steals through the desert and wraps itself around legs covered in blue jeans above spurred boots; the man in early old age moves one leg backwards as if avoiding entanglement in the heavy hem swelling out from the skirt's full gathers, the checked taffeta,trimmed entwining skirt and the leg with its spurred boot appear for a moment as if in the middle of a revolving whirlpool in a light waltz step, and the figures of the two are erased by a sandstorm flying up from the horizon.

TRIQUARTERLY

19

Long Gray Line

Enduring the repetition of long, dull time-like an accumulation of fine dust, dry and withered, or something sticky at the tip of the finger like blood or like bodily fluids circulating persistently, not to ask here and now which it was-and the endurance of its repetition; to record it anew, the endurance of the repetition of long, dull time, a ballpoint pen with black, water-and light-resistant ink used for recording documents-no, not that, the hand and fingers with sticky fluids coiled around on them seem to remember that an H.B. or B. Yacht pencil with green {dark olive green} and yellow {deep bright yellow} stripes, or more likely a green Castell pencil tinted khaki with a slightly less bright tinge of olive green, slid the sounds of those words {those writings} onto the smooth, white, high-quality paper-or not, rather an H.B. or B. pencil scattered exceedingly fine dust made of a mixture of graphite and clay like a somewhat lustrous powder slippery as talcum powder or face powder on the white paper, and the pinky finger curved to hold the pencil and the swelling of the palm of the hand under the pinky finger became completely black as the words "the endurance of the repetition of long dull time" were written down. Those words had no great meaning in themselves, but the hands dirtied with exceedingly fine powder made of a mix of graphite and clay like somewhat lustrous black dust, slippery as talcum powder or face powder, must be washed over and over again on that occasion with brown soap that is worn away and reeks of tallow {or perhaps it was soap the color of milk tea with the fragrance of violets or yellow soap with chamomile}. She wipes her hands wet with water on the towel with a lattice pattern wrapped around her waist while shifting the direction of her body, glances in the small mirror that hangs like a picture frame on the wall and, with the tips of her fingers, arranges the short soft thin hair coiled in disarray in waves on her forehead and temples that perspire from the steam filling the kitchen from hot water from the gas hot-water heater flowing out of the tap and from the pot sending up whitish steam over the blue hissing flame of the gas stove; almost unconsciously she hums a song, removes orange-red rouge from her lips, the color of their lipstick faded-with the part of the lipstick in its gold tube designed like a Grecian column, its small edge pointed like the tip of a claw, she draws the heart-shaped outline of her upper lip, then stains the whole of her upper lip with lipstick and presses her upper and lower lips together, quickly applying one coat inside; as she does this,

TRIQUARTERLY

20

the rouge staining her upper lip follows the outline of her lower lip and is transferred like a print, moving one coat of lipstick in the small gold cylindrical container-and using the pad of not her ring finger but her pinky finger acquaints the soft, vertically-lined skin of her lips with lipstick; she moves her head one way and the other in order to inspect the sides, and in the smooth, rounded, amber-colored picture frame, her slightly perspiring, flushed cheeks, shiny forehead extending into the hairline, painted curving like a stiff bow, and eyes opened wide in deep concentration to inspect the details of the face are for a moment stilled; then her face is immediately turned this way and she makes a smiling face that could be called intentionally mischievous. She apologizes for having made a little mistake, or for a serious failure as if the meat in the oven has roasted for too long and been charred black or the stew has boiled down and stuck to the bottom of the pot so that from those mishaps, the meal on the dinner table has become meager, and to hide the absentmindedness that caused the failure of the meal and whatever seemed to have been the cause of the absentmindedness, says I have a bit of a headache; If she'd take <not just any kind of> medicine for the headache that has visited her (especially in the bedroom with the lights extinguished) intermittently for days (no, for months) it would soon get better, he says, It's nothing to worry about; but as he tries to feel her forehead saying Don't you have a fever she throws her head back as if her whole body unconsciously moved that way; of course that's a refusal to be touched, or more than a refusal, it might could be called a hatred of being touched, he confirms with a bitter thought what he seems to have realized long ago. Of course a knife with a thin sharp flexible blade is emphasized. The woman's thin graceful white neck is shaped like a smooth column, and to delicately lick with the tip of the tongue her hairline at the nape of her neck, its downy hairs arranged into two wedge-shaped pieces by the thin sharp blade of a razor as if just trimmed at the hairdresser's, produces a faint taste of metal similar to that of cool, chilled blood; in the heat of the tongue wet with saliva the chill of metal tasting of blood runs through each taste bud on the rough disordered tip of the tongue and the graceful neck in the shape of a column is caressed by <these withered fingertips, neither puffed nor damp> as if extremely unwilling to part with its thin grace; of course that continues to imitate the sensual relation between the eat's smooth throat with its soft, slippery fur that grows luxuriantly and the hands that caress it; the long thick fingers at the neck and the hands thick but not at all puffed, seen as ever so uncouth-s-even though it wasn't "a profession in which

TRIQUARTERLY

21

TRIQUARTERLY

you must wash your hands before arriving at the table," the hands and fingers were soiled black with fine particles of graphite and clay, and minute amounts of blood and whitish skin scraped off remain in the space underneath the nails from the time the nails had stood in the face and throat stiff from the strained muscles and swollen blood vessels of the man with the long flat jaw that looks like a knife in the deep shadow cast by the line of the soft gray hat-just like a hint of the faint, thin blade's keen, supple, gleaming sharpness, the dexterous hands that enjoy this habitual motion are spread with gentle, delicate caresses (those hands take up her neck as if it is a small chicken with its wings not yet sprouted and wrapped in down like cotton chaff, fallen from a nest up in a tree and that stimulates its parent birds' nurturing instincts with a yellow bill awfully large for its body; they touch her luxurious white skin softly, softly, with gentle care and even deeper affection than the parent birds as if it is something above which there is nothing more valuable, something so precious so that handling it with gentle but half-witted care and even slight violence would break it) around the sharp, slightly thin lips and the area near them in an entangling of tension and joy when she sizzles bacon in the frying pan with unexpected skill or slices thin lumps from liver, or when he applies layers of thinly dissolved paint soaked into the tip of the paintbrush on the canvas with deep concentration; before long they convulse violently and tighten around the top of the round neck shaped like a smooth column. But in order to achieve a luster like that of a pearl and a still, soft rose-colored gleam on the graceful neck like a column, the smooth roundness of the shoulders, the cheeks gleaming with youthful elasticity and tight plumpness and the rounded forehead, those hands apply layers of thinly dissolved paint soaked into the tip of the paintbrush on the canvas while mumbling as if reciting from memory. <Select extremely good quality Venetian oils, fresh if at all possible, and just-refined turpentine oil.> He selects the quality of the materials with care, moreover with deep concentration. The Sunday painter continues to wait with much patience for the girl who not only finds posing boring but reads a novel with her legs flung out untidily as she holds her pose. As he continues to be absorbed in gazing at her in the lightbeams that flow falling in like transparent water from the large opened atrium window on the north side, he can't help but be fascinated even by her manner of not trying seriously to hold a pose but immediately and languidly moving her slovenly body; of course painting the picture is also something important. You can't use too much Venetian oil paint. It's slow to dry, and because of that it's easy for

22

dust and minute sable hairs shed from the paintbrush to adhere to the canvas sticky with oil. <But on the other hand, if you use Venetian oils, no matter how many times you add paint to the original sketch the surface of the painting doesn't get heavy. If you work like this, blending certain forms into shades and these shades into the surface of the color, bringing the original colors into appearance again with stronger lines, then with this control still concealed by a soft veil that holds stiffness at bay you can do it before the surface of the paint begins to stiffen.>

Doing animal-like things like that with you is nasty, the young girl on whose skin the scent of orange blossom-scented bath oil remains from her bath opens her eyes affectedly like a little girl or a maiden in a silent film full of fear and hatred, yet he gazes at the revealed shoulders, breasts, and buttocks with their soft skin elastic in curved lines like rolling waves wrapped in the white satin dressing down with fur decorations around the neck, down the front and along the hems and at the calves like those of a farmer woman with her muscles revealed half-hidden in the soft imitation ermine fur and-the camera becomes a look of desire and with a short, rigid shot of blank amazement for his erection, shoots the young girl's calves (given their nature, the well-defined rnuscles of her buttocks that continue from there seem to press forcefully with instinctive rhythm against the protruding part of the other body placed perfectly on hers) and her two good, richly fleshed white arms touched by the soft fur; the young girl laughs scornfully through her nose as if he's the fool this time, and in a tone that says this astonishing and shameless matter won't be a problem roars forcefully with scornful laughter, Old men like you who do things like that look like fools (even though you don't have the resources or the right to do such a stylish thing); of course there's no need for the young girl to ridicule the older man's sexual desire to such an extent, but the old influential man's prosaic Figaro-like existence or a feeling of revenge against that was probably included in that. For some time the young girl laughs with coarse, hysterical exaggeration, then sprawled on the sofa bends her whole body like a stretching cat, stretches her arms, putting on airs coldly picks up a book with a woodblock print on the cover from the artificial marble one-legged coffee table and begins to read the sequel. Orange-blossom perfume with the same scent as the bath oil-the exceedingly pure essence of young all-white orange blossoms with a strong fragrance, raised in the clear California sunlight, a picture of a young girl wearing Hollywood-style white clothes in the spirit of the orange blossoms against a background of branches laden with the fragrance of blooming

TRIQUARTERLY

23

orange blossoms against the blue sky is printed on the perfume box. You know, a sweet kiss wafting the scent of orange blossoms, that's what makes snow-white petals into a crown for a bewitching, burning bridehas been sprinkled liberally on the silk dressing gown, and the sweet, cheapish smells of the orange blossoms, emitting the sweet fragrance of the inner part of the flower as if inviting honeybees to fly about the orange trees with their blossoms in full bloom bathed in the warm California sunlight mix with the ever so strong animal smells of the young girl's body and the volatile smell of Venetian oils in the room filled by hushed, peaceful sunlight, flat and transparent like water from the large opened window on the north side; because the heater has been set too high those smells are crowded stuffily in the room; when in the book with its woodblock-printed cover framed in acanthus leaves in an arabesque pattern, a man's strong arm wrapped around her waist as both arms stretch obliquely, twisting her body and showing her defiance even as the neck curved backwards and the face adjusted to look upwards with an expression of rapture double-cross the refusal in her gestures; the beautiful orphaned heroine was forced to confess to her husband the fact that at fifteen she had her maidenhood taken from her by the lecherous older landlord who is her legal guardian and the young girl sympathizes entirely with the unhappy fate of the pitiful orphan girl heroine at the point she is being made to confess, and her breast shakes like a small dove as if that fate were her own. What a hateful brute he is! Isn't he just like a dog that wags its tail as it's thrown a scrap of meat, it's because his own wife had been with another man before their marriage, she was laughing at me as she flirted wholeheartedly with him, wasn't she; why, a man who talks like that is worse than a dog; and in addition, he rubs his wife's head against the leg of the bed, pulls her hair and drags her around the room, then when she tries to get up strikes her and pushes her back to the floor, using despicable violence, she explains the plot of the story to a girlfriend, and her girlfriend takes a showy ladies' cigarette case from her small patent-leather handbag, slowly opens it and puts a cigarette between her lips; she blows out cigarette smoke from her pointed lips painted red in the shape of a heart, then says with an ill temper Look how he beat you because you said you didn't sleep with the man? I don't know which one's the beast, him or the husband in that book? she says ill-temperedlv, The young girl with blond bobbed hair that reveals the nape of her neck opens wide her eyes emphasized by black mascara, distinct eyeliner and bluish-gray eye shadow speckled with sparkling gold powder and discontentedly sticks out her lower lip

TRIQUARTERLY

24

drawn in cherry-red with lipstick, But that's a story in a book, you skip over the boring, irritating parts when you read (but because it has no relation to the plot of the story), But don't you start to wonder what's going to happen to "her"? A cast-iron art-nouveau railing on a terrace that faces the street-a design of tulips and lilies-a white parakeet's wings wave like the shape of a crown (pointing backwards heroically like the headdress of an Indian warrior or the wings on Hermes' ankles) in a dome-shaped chrome birdcage that shines brightly, suspended in the open window facing the inner courtyard, white tulle curtains that wave in the wind swell; the maid whose face has been seen in the window of the third-floor kitchen across the courtyard paved with stones, an old well and a stone washtub at its center, turns towards the woman washing sheets by the well, calls out My match just went out, do you have any on you? and the woman washing the sheets wipes her waterwet hands on her apron before pulling a small box of matches from the pocket of her blouse, places the matchbox on the palm facing upwards, swings her arm backwards in a great motion, and fixes her aim; she flings it high forwards, upwards and with a speed like that that the captured bird with wings in the shape of a crown like those that decorated Indian warrior headdresses must have had when it flew through the sky, the small yellow matchbox soars as if painting a line in the air; the arm with the blue sleeve of its uniform turned up stretches from the kitchen window, and the five opened fingers gently catch the small yellow bird; around the washerwoman children scream and cry making a noise with the soles of their wooden shoes as if killing centipedes that move about, changing color from gray to grayish blue, from blue to violet, and from violet to green like peacock wings; from a neighboring window the pure white languidly large cat that had been looking down over the courtyard follows the small yellow bird's painted, somewhat curved line with its eyes; a round glass goldfish bowl is placed on the upright piano with its lace cover, and one green waterplant and a vermilion fish float in the small spherical water in which sink smooth pebbles like small round sugar candies filled with almonds; a small girl in her best dress of thin white cloth with light pink ribbons decorating the waist and the large round collar falters while repeating interruptedly the same melody over and over again with clumsy fingers, earnestly playing an old folk song; matching the piano's liability to falter, before long the maid wiping the dust from the furniture with a feather duster ignores the piano's accompaniment and hums a song, Oh, oh belo-ved Genevieve, oh, dear Genevieve, oh, I'll cross the ocean to bring you home, bring you back to 25

TRIQUARTERLY

your green homeland, your rosy cheeks may have paled, your hair may be white and the sparkle in your eyes may be faded, but Oh Genevieve, I'll cross the ocean to bring you back to your green homeland; to test the comfort of the springs of the bed, its cover soft cloth on which appears a luxurious mass of Turkish embroidery, the young girls stretch out both hands backwards, lean to the rear and repeatedly make their ample, round, unsagging and well-fleshed buttocks jump lightly with a snap so that the feet in high heels with a button on the strap over the arch of the foot and the legs encased in charming silk stockings knitted in a faint diamond pattern, legs bared from the hem of the short pleated skirt, rise into midair like a spring'loaded toy; the four legs encased in lustrous silk stockings flash and look like dolphins soaring artlessly out of the ultramarine sea; in the stimulating book, the heroine drunk with desire as if glowing from the inner core of her small-framed body breathes out a long sweet sigh as if she would faint away as for the first time she entrusts her body to passionate embraces and caresses in the arms of her lover; the blond,haired girl raises her voice while reading these "amazing" pages aloud. The heroine with the small frame and the slim, well,stretched posture is rearranging the inside of a drawer-non, chalant signs of impressive and romantic episodes are engraved in the midst of those unimportant, mundane little jobs-and pricks her finger with something: it's the metal pin attached to the corsage of her wed, ding dress; the ironed, revived swellings of flower petals in the artificial orange blossoms on the thin silk are yellowed with dust, and the thin satin ribbon lined with silver picot stitching is frayed along the edges; she throws that bouquet into the fire in the hearth. The bouquet burned up faster than dry straw, and before long it became a bright red grassy field and rotted away slowly above the ashes while the small paper fruits exploded; the metal pin twisted sinuously in the heat and the artificial orange blossoms shrank and floated along an iron plate at the back of the hearth before rising softly like black butterflies and, after a while, flying out the chimney. Whatever kind of woman she was, all women would find it impossible not to identify with her beauty and unhappiness as they read; the woman who is far and away clever and wise when compared to the weakness of her appearance but while foolish and sullied was at the point of not being able to refrain from destroying her lover and is fated to be purified in happiness like a little girl because of love is enraptured and drunk with love in the man's strong, gentle arms, and whispers in a sweet, hushed voice mixed with a sigh, I have lived far, far more in the few minutes I spend with you is far, far greater than

TRIQUARTERLY

26

the sum of all the time of the life I have lived to this point; the luxurious black lace shawl that had covered her head entirely to hide it from notice crumples at the foot of the bed, and reflected in the hearth flame thrown about as if playing with flickering shadows and light the two pairs of soft lips fit perfectly, burning with heat in that exact covetousness of love; together they drank dry the water of life thicker, thicker than high-grade sake, didn't they; but this is the kind of thing that happens in a novel, it's not necessarily not going to happen in reality. She was wearing a black silk lace shawl to hide her bare shoulders, chest and upper arms-or was it to protect her bare shoulders, chest and upper arms from the cool evening wind-and every time she moved her body slightly the light transparent flax fabric-a decorative skirt with a shorter hem divided into four panels at the waist is layered above the underskirt of the full gathered skirt made in two layers-made the hushed sound of a dress rustling, and through the transparent part of the decorative skirt that was not in two layers the roundness of her calves wrapped in shadow was made apparent. You came, you came, you really came, but why did you come, she calls; embracing her closely, shawl and all, the slightly sour, animal-like smell mixed with the fragrance of orange blossoms, the simultaneously wetted hair (the deep black lustrous hair parted down the middle and folded back had curled at the forehead and temples from humidity and perspiration-it isn't as long as one strand of the blond hair brought across the sea in the beak of the stormy petrel that had told the old man of her existence, but reacts by expanding and contracting to the humidity as if showing the changes of the barometer-and small, small waterdrops from the mist are bound over the whole surface of her hair as if she is wearing decorative netting or a silver veil; touching it with a finger it becomes slight, cool water and runs as if perspiring from the pad of the finger to the joint), wet shawl and wet skirt that has lost its pleats in its dampness and hangs down ever so much and the cool, stiff arms, chest, waist, abdomen and thighs make the soft muscle undulate in his arms; in a moment all of that is pushed violently and perfectly against my chest, abdomen and thighs, My thigh is wet, and my hair too, soft, warm, trembling lips bite at my lips from which words were about to escape; for a long time after coveting the saliva that is wetting the lips and the tongue she shifts her neck as if to throw her head back and her face changes expressions like the moon; the red "kiss-proof" lipstick in a gold tube shaped like a Grecian column hadn't run around her lips, but the sticky oval traces wet with saliva catch the light from the dim lampshade as if they are dim shadows or

TruQUARTERLY

27

bruises and the faint, faint sticky water reflects in ovals. She sighs, bends forwards her neck that had been thrown back and presses her forehead against his left shoulder blade; the lustrous hair put up but slipped out from its pins falls with loose waves from her neck to her shoulders, and the parts of the loosely curved waves shine glossily at their crest as if painted with dark brown varnish; faint shivers run up his shoulders and back, and her rising heartbeat and the beating movement that make her temples pulsate repeat entrusted with heat across the hot skin; the Sunday painter carries a glass container filled with freshly mixed Venetian oil paint, bought to supplement that which he had entirely used up and of which only a small amount remained, goes in the entrance to the apartment and completely undampened, hums as if executing a nimble dance step quite at ease in his loose, fat body and comical, bestial face that looks like that of an old man three bars of the tune of the sweet song sung by a young boy to accompany the melody of a hand-organ on the street, with melancholy just like a circus acrobat, a dancing bear or a big dog that shakes hands, hums three bars, sings three bars with consecutive "la"s and "hum"s, here and there faking the lyrics he remembers faintly-Please be sweet my dreamed-of dear one, la la la la, sweet one I have yet to see, wherever we might meet, hum hum hum hum, I'll know at a glance that you're the one, kiss me sweetly, he says, I am yours-while climbing to the fourth floor as if bouncing as he sings the three bars; he knocks rhythmically on the young girl's door like the rapturous "lover" in commedia dell'arte or in a puppet show, raises the pitch and extends his voice as if making an appeal, smiles gently and sings the last line of the sweet ballad off-key, Kiss me please; as he opens the door, the young girl and her lover lying together on the bed with its cover on whose soft fabric appears a luxurious mass of Turkish embroidery appear in the soft, silent, flat beam of light flowing in like water from the large open window on the north side; rather than become angry at that situation he is simply surprised and confused, and closes the door quietly as if he is ashamed and it was entirely his own conduct which was inappropriate. When he returns to the room to forgive her, the foppish man like a small cunning fox has disappeared, and distorting her lips stained with heavy rouge the color of cherries (the color of darkly stagnant blood), the young girl screams As for you, a doddering old man like you, I've never loved you, and stamps on the ground with her small foot in its high-heeled satin mule decorated with a peach-colored pompom made from swan down like a spoiled child that has lost its temper as she flourishes her arm, Don't be so full of yourself, don't be so

TRIQUARTERLY

28

full of yourself, have you looked in a mirror? Do you think that's a face a woman could love? You're just jealous, she cries. The young girl wearing a silk dressing gown decorated with white fur from the collar down the front, around the hem and at the mouths of the arms was lying down on the bed reading a love story that made her heart beat; she looks at the man who has come for the second time, takes a paper knife by its handle from the artificial marble table to put it into a book, and after she has boldly reviled him tells him in a cool hard voice Won't you get out so I can read. The Sunday painter trembles as he asks, Get out? How should I do this, he mutters, tightly grasps with a shaking hand the handle of the paper knife stuck inside the book with the woodblock-printed cover, and the young girl crosses both arms and covers her face in fear; because her arms are raised the heavy fur on the cuffs slides down to her upper arms, and the bared white richly fleshed arms cover her face; the inside of the upper arms now exposed tremble out of the cuffs of the gown, and in the soft, flat water of the light streaming in from the large open window on the north side, the knife grasped tightly by the man is buried deeply over and over and over again like a silver shower or the sharp beak and flashing wings of a bird gliding in the sky in the soft flesh of the young girl, deeply and slowly swallowed up and enwrapped in the soft, ever so soft skin of the young girl.

TRIQUARTERLY

Birth of a Kingsnake [black-and-white] 29

The Orderly

Douglas Gilmore Power

It was twelve-fifteen by the time she locked her car in the nursing-home parking lot and went in the back door near the dumpster hoping no one would see. But Charlene was standing outside her small office down the hall just as if she'd expected a black orderly to be trying to sneak in.

"My son got hurt in the elevator," she said, taking her coat off fast to stop it being a coat still on and a person coming in late. "I mean in the elevator shaft. A man threw him. We had to go to the police station so my son could identify him in a lineup."

Charlene looked at her. "I'll have to dock you," she said.

"It wasn't my doing! They took him out of school and I couldn't let him go by himself. He's only six!"

"A man threw him in the elevator shaft?" Charlene said like it pained her mouth to repeat it. "Where was the elevator when all this was going on?"

"It's broken."

"Then why would your son and some man be trying to use it?" she said as though this sprang the trap closed.

"I'm not making this up if that's what you're thinking. Right after I got home last night the police brought my son to the door, and then today I had to get him out of school and I just now got here. Couldn't I use sick time?" She opened her locker and hung up her coat, keeping her back turned so she wouldn't have to see whatever disapproving face Charlene might choose to display.

"Sick time is for when you're sick," Charlene said.

She made a quick round of her rooms to see who wanted help going to

TRIQUARTERLY

30

the potty or had a bedpan needed cleaning, then returned to the locker room to steal a few minutes to study for her night class. Charlene burst in and she threw the book under a sheet in the laundry cart to hide it.

"Are you sleeping in here?"

"No ma'am," she answered like a caught orderly, caught sleeping, caught lying, looking up at Charlene's face as though too stupid to be much at lying but not so stupid as to be untrainable. Then she couldn't help smiling at the concept of pegging the right level of stupid and Charlene's eyes widened in fury that she was being insolent. She sat straighter on the short bench. Charlene walked close in front of her, wanting to emphasize the supervisor badge with her name on it that sat on the slope of her breast like a prize.

"You were sleeping with your head in that laundry cart," said Charlene, the look on her face painting Linda as someone who had no objection to touching her face to other people's dirty sheets. "This is a locker room, not your bedroom." She glanced from side to side as though she might find a lover hidden inside a gray metal locker with his brown peeker sticking out.

"I was feeling sick," Linda said.

"Are you pregnant?" This seemed to amuse Charlene until she remernbered it might have happened on her time. She crossed her arms and drummed her fingers, that were thin considering how plump she was, on the leather,bound pad she always carried. Linda shook her head.

"Have you missed your period? Do you keep track?"

"Of course I keep track."

"Well, Mrs. Aspen's been buzzing for ten minutes. Maybe you could try keeping track of that." Before Charlene turned away she looked once more with disgust at the dirty sheets and a corner of the book was stick, ing out. Linda stood up to block her view but Charlene had already stepped past, moving as though still twenty and used to dancing. She seemed confused to find it was a textbook in her hand and became angry when she saw that it was calculus. "What's this, another way to get free money?"

"I'm taking night classes in nursing. You'd hate that, wouldn't you? If I was a nurse like you." She saw Charlene shrink back from the terrorist revealed in her voice and eyes, hiding in the rooms of the nursing home like a sniper, having opinions that couldn't be monitored.

"In your dreams. You'll never get past calculus. If I had to work my butt off, what do you think's gonna happen to you?" Charlene smiled to convince her it was hopeless. "And what do you think would happen if

TRIQUARTERLY

31

TRIQUARTERLY

you got fired from this nursing home? You don't even clean bedpans right. I'm keeping the book. You'll get it back at the end of your shift. You aren't studying on my time." She turned, having reclaimed her advantage, and swirled out of the locker room.

Linda stood for a time without moving. Finally she went to make another round of the bedpans. Charlene was standing in the central hallway that connected all the rooms. She'd handed the calculus book to the other white nurses standing next to her who were passing it back and forth. All three of them looked at her and grinned. She had to con, centrate not to trip.

"I've been pushing this buzzer for half an hour," the old woman said, elevating herself to a sitting position on the bed with trembly arms, squinting at Linda like she must be new to the home or so slow she'd forgotten what the buzzer meant. "Can't you orderlies ever be prompt?" She looked like a baby bird straining to see if momma had brought her something and Linda felt sorry for her, then was mad at her because she didn't want to feel sorry.

"I'm here now, Miz Aspen," she said, walking to the bed. "I was work, ing on a problem. If a bullet," and suddenly her brown hand flew out over the top of Mrs. Aspen's thin lump underneath the sheets, "is shot horizontally at nine hundred miles an hour from the top of a building that's a thousand feet high, how far will it travel before it lands? And how fast will it be going when it hits?"

"Well I-it's Mrs. Aspen, as you very well know. He was a judge. And he'd turn over in his grave if he could see the way I'm treated. He and I both know who stole his lucky rabbit's foot, and I want it back!" Linda watched Mrs. Aspen's hand on top of the sheet, her thumb stroking the fur of a rabbit's foot that wasn't there. "Please help me to the bath, room," she said.

Linda rolled the wheelchair to the bed and eased Mrs. Aspen into it, pulling her nightdress down when it rode up dry white-stick legs sliding off the mattress. Her hair was a whiter white but her eyebrows were stern and black over gray metal eyes. Linda got her settled and, imagining for a moment she was herself looking out those gray eyes to see what it would be like to get old, she didn't swivel the chair enough going through the narrow door to the bathroom and Mrs. Aspen's big toe got squeezed between the footrest and the door frame.

"Ow! You did that on purpose! I'll tell Charlene, and my son when he comes to visit. He's coming tonight, don't you know," she added like she

32

was talking about her husband.

Linda bent over to look and was frightened to see the toe turning pink. "Sorry, Miz Aspen." She blew on it. She hated the wheelchairs because they were heavy and hard to get going. It was like the grocery cart when her son was mad because she couldn't afford chocolate cereal or ice cream and he'd stopped walking and sat in the aisle. She felt she had to show she loved him by letting him ride then in the cart, and sometimes she hated him just for that moment, when the cart wouldn't want to budge from his weight.

"Are you O.K.?" She glanced up and could see it didn't hurt anymore but Mrs. Aspen wouldn't admit it, frowning like everything was her fault. Linda stood up. "I did ask you before not to stick your feet out."

"You did not."

"It was just this morning," she said, carefully maneuvering the wheelchair next to the toilet. "Or I guess it could have been yesterday. I'm not saying that it wasn't my fault."

"Help me to the seat." Mrs. Aspen pointed at it.

Linda bent over Mrs. Aspen from behind to lift on her elbows as she was slowly straightening her legs. "Can't you be a little bit gentle?" Linda saw one of her feet suspended above the floor as though the knee had frozen. She came around to the side, still holding her upright, and stooped over to reach with one hand to push down on the ankle.

"Were you the one who took my rabbit's foot?" Mrs. Aspen whispered. "No. I didn't." She pushed harder and noticed at the same time that Mrs. Aspen's flannel nightdress smelled like diapers. She wanted to pinch a tiny bit of skin between two purple-blue veins on her foot to make her yell and pretended that she was going to do it to see how it might feel and then while pretending she did it.

She was standing straight again before Mrs. Aspen said Ouch. "What's the matter?" Linda asked. "Can I help you with something?"

Mrs. Aspen was confused. Linda smiled and let Mrs. Aspen see, so she'd understand that Linda could tell everyone how forgetful she was, how useless and old. "Don't forget to raise your nightdress," Linda said. Yesterday she hadn't remembered and got the smell on her Linda smelled now.

"Not in front of you I won't. You're no nurse; you're just an orderly. Get me on the seat and then get out."

"What if I told you I was studying to be a nurse? A lot of nurses are black, you know."

"Not at this nursing home."

TRIQUARTERLY

33

TRIQUARTERLY

Linda was patiently keeping her in balance but upon hearing that she let her go. "Help me," Mrs. Aspen pleaded, suddenly feeble again.

"I'm just an orderly," Linda said, placing, however, her hands on the outside of each of Mrs. Aspen's upper arms and assisting her to shuffle in a slow quarter turn. "Down now," Mrs. Aspen said.

Linda knew she was hurting. The skinny-as-a-stick bones poked sharply from inside her skin and Mrs. Aspen knew she was dying. When she was safely on the seat Linda removed herself from view and closed the door. She wouldn't have done what the old lady wanted except Mrs. Aspen's pain made her move so slow it reminded Linda of her grandma and her momma. Each was grouchy the same way and she'd had fights with them before they died of their white blood cells going on a rampage. Linda checked in the mirror above the sink near the built-in dresser to make sure the plastic sanitary cap was covering all her hair, more concerned with keeping germs out than in, hoping she wouldn't ever get something growing in her she didn't ask for, a lump or a bump or another baby.