Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank The Illinois Arts Council, The Lannan Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The National Endow, ment for the Arts, The Sara Lee Foundation, The Chicago Community Trust, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers:

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Paul Brownfield

Robert Creamer

Eleanore Devine

W. S. Di Piero

John B. Elliott

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

C. Dwight Foster

Amy Godine

Jay Harkey

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Irwin T. Holtzman

Helen Jacob

Loy E. Knapp

Greg Kuzma

Patrick Mangan

Charles T. Martin

Florence D. McMillan

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Dorothy J. Mikuska

Michal Miller

William T. Morgan, Jr.

Alicia Ostriker

Linda Pastan

Fran Podulka

Mark Rudman

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Susan A. Stewart

Lawrence Stewart

Dorothy H. Taylor

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

�_ 9_1!_f!.._c_.!.J &I WK'" rl£I1'11'1 "ILUIII' This program is partially sponsored by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council

Illinois ARTS

1996 BOOKS AND BACKLIST

New Wrzters

EDITED BY REGINALD GIBBONS AND SUSAN HAHN

This unique collection showcases ten new writers (five poets and five fiction writers) who have won recognition only in the medium of the literary magazine. The anthology presents the best of new voices discovered through TriQuarterly magazine and TriQuarterly Books. From an O. Henry Award-winner to an MBA, contributors include Yolanda Barnes, Tammie Bob, Terri Brown-Davidson, Eileen Cherry, Loretta Collins, Page Dougherty Delano, Steve Fay, William Loizeaux, Dean Shavit and Cassandra Smith.

_GIl.nT

TriQuarterly

New Writers

136 pages $39.95, cloth \ $14.95, paper

MEREDITH STEINBACH

The Birth ofthe World As We Know It

IIIIIIIIB SIIIH\CH

208 pages \ $24.95, cloth

In this meditative little novel, Steinbach inhabits thefigureof Teiresias, the Theban seer, and delivers a metaphysical tour de force remarkablefor the light touch it sustains despite its wealth of allusions to Greek mythology. Told from various points ofview, the liquidstoryflows within an elastic timeframe, lightlydecorating the old myths as comments on life today This is all about our repetitions and confusionshistorical, sexual and psychological. Sentence by sentence, Steinbach's writing is as elegant as a neoclassical column.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

MEREDITH STEINBACH

Zara

111111111 SIIII8\t11

277 pages I $15.95, paper

Steinbach's first novel tells the story of a strongyet vulnerable woman's attempts to reconcile hervarying roles as daughter, wife and doctor. Rich, horrific, beautiful, Zara is about the life of a woman extraordinary in every way, and is written in prose as strong and fabulous as Zara herself. I could not admire more this profound and exhilarating novel.

-John Hawkes

Steinbach probes vulnerability, futility in a style interlaced with quality and power.

-LOS ANGELES TIMES BOOK REVIEW

A masterpiece.

-BOSTON MAGAZINE

-

'�.'; '��

CYRUS COLTER

The Beach Umbrella and Other Stories

1his is the long-awaited reissue of the award-winning stories of one of America's greatauthors. Set mostly on Chicago's South Side, these eighteen stories describe ordinary people whose live are transformed by small acts of chance or will. From depictions of the black middle class to the dank and dirty tenements of the lonely city, Colter's sharp, spare prose etches perceptiveportraits ofpeople who endure and overcome the most severe threats to their spirits.

Cyrus Colter tackles epic themes as though they were wild horses-and he tames them. -Studs Terkel

225 pages \ $14.95, paper

WILLIAM GOYEN

Come, the Restorer

Goyen's fifth novel is a fable of sexuality, religious revivalism, and the money madness and ecological destruction causedby the oil boom in early twentieth-century Texas.

William Goyen has always been the most mysterious ofwriters. He is poet, singer, musician as well as storyteller; he is a seer; a troubled visionary; a spiritual presence in a national literature largely deprived ofthe spiritual.

-Joyce Carol Oates

A profoundsympathy combined with a greatpoetic insight constitute Mr. Goyen's wonderful rare gift. -Sir StephenSpender

180 pages \ $14.95, paper

CAROL FROST

Venus and Don Juan

90 pages $29.95, cloth \ $11.95, paper

JOHN PECK

M and Other Poems

136 page $29.95, cloth \ $12.95, paper

In her sixth book of poems, Frost makes striking discoveries in her signature style. Characteristically combining rich description with striking images, she evokes the complexities of emotional and moral states: love, lust, disappointment, competitiveness, loneliness, regret and envy.

Frost has an uncanny ability to disassociatefrom and observe emotion transformingher observations into shimmeringand hauntingimages.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

Frost's work is dense, requiring-and rewarding-the reader's deep attention.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

New work exploring the vulnerability and tenacity of human life from a member of a remarkable generation of poets.

Peck has established himself as a majorpoet, opening up territory no one else has attempted.

-TIMES LITERARY SUPPLEMENT

With his stylistic combination of elementsfrom two heroes: the detailed imagery ofEzra Pound and the conceptual coherence of Yvor Winters Peck's densely allusive and highly cerebral work rewards the rigorous reading that it demands.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

BRUCE WEIGL

Sweet Lorain

An elegist of the lives of those who have been changed by hardship and suffering, Bruce Weigl has become one of the most admired American poets of his generation. In this new volume, Weigl returns to both Lorain, Ohio, and Vietnam, to explore the connection between his childhood in a working-class world, and the powerful effects of the American war in Vietnam on all of us.

PRAISE FOR BRUCE WEIGL

These are hard-edged, partisan works imbued with the spirits of Philip Levine and James Dickey.

-WASHINGTON POST BOOK WORLD

WILLIAM OLSEN

Vision of a Storm Cloud

Olsen's poems are energetic, expansive and romantic; his ability to manipulate language, image and form harkens back to the traditions of Blake and Whitman, while his range of subject and his use of metaphor forge his own uniqueand contemporary-artistic signature. These poems are a rich, dense and polished example of the voice of a strong new poet.

William Olsen teaches English at the University of Western Michigan. His poems have appeared in numerous periodicals, including the Paris Review, the Nation, the New Republic and Crazyhorse.

76 pages $29.95, doth I $11.95, paper

136

pages $29.95, cloth\$12.95, paper

W. S. DI PIERO

Shooting the Works: On Poetry and Pictures

'. :.!'I,.� ,.� SHOOT1NG ''', 1,.1 THE WORKS

230 pages $29.95, cloth \ $14.95, paper

Elegant and passionate tributes to the intersection of art and self, from the most gifted poet-critic of his generation. In brilliant prose, Oi Piero moves from educated ruminations on the frescoes of Florence's Santa Maria del Carmine to the politics of Pound to reflections on his working-classbackground and poetic development. Oi Piero's essays are an autobiographical testing of ideas; in their searching honesty they are deeply akin to Witold Gombrowicz's diaries

Di Piero's taste and judgments are refreshingly idiosyncratic, his frame ofreference broad.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

STERLING A. BROWN

The Collected Poems ofSterling A. Brown

EDITED BY MICHAEL s. HARPER

267 pages \ $12.95, paper

One of the most important of American poets, Sterling Brown is a contemporary of Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Jean Toomer. At once thoughtful and daring, Brown is known for his handling of folk materials, for his lack of pretension, and for his frank and unflinching portrayal of the Southern African-American experience. This is the definitive collection of his poems, and the only edition available in the Ll.S, This is a great book ofpoems, stunning in its artistry andgigantic in its vision.

-Philip Levine

i

K. ULL'CTID IOI: �or

TRUDY LEWIS

Private Correspondences

Winner of the 1994 William Goyen Prize for Fiction

This moral thunderclap of a novel portrays a teenage girlwho, attacked by violent evil, chooses not to flee itbut to face it, and then to embrace it. In prose that swings between lyrical moments of illumination and gritty sexual insight, Lewis explores the effects of male force and brutality on women and the issue of women's complicity in sexual violence.

Lewis's shatteringstudyofsexual violence and individual vulnerability is both timely and universally resonant - PUBUSHERS WEEKLY

This erotic, steamy tightly wound mystery story will holdyour interest to its phantasmagorical conclusion.

198 pages

$19.95, cloth/$12.95, paper

-CHICAGO TRIBUNE

BACKLIST

DAVID BARBER

The Spirit Level

Winner of the 1995 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Filled with rich detail and striking metaphor, these poems are both technically brilliant and irresistibly inviting.

$29.95, cloth \ $12.95, paper

ANNE CALCAGNO

Prayfor Yourself

An exhilarating collection of short stories by an author with an abiding understanding of the fragile yet eduring nature of human relationships and of the textures of women's lives.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye of a true storyteller.

-Larry Heinemann

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as afifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a single piece ofwood. -Lynda Barry

$26.95, cloth \ $12.95, paper

DANCHAON Fitting Ends

Title story chosen by John Edgar Wideman for inclusion in Best American Short Stories 1996.

Each story is a marvel ofcomplexity, dense with meaning and nuance a remarkable collectionfrom a young writer who bears careful watching. Veryfewfirst works are as solid, moving and pitch-perfect as Chaon'.s. -THE G..EVEl.AND PLAIN DEALER

$35, cloth \ $14.95, paper

CYRUS COLTER

A Chocolate Soldier

Colter's crowning work, this novel tells the tale of an unlikely friendship which transcends boundaries nad circumstances in pre-civil rights America. This powerful writer should win the attention ofevery serious reader offiction.

--SATIJRDAY REVIEW

$14.95, paper

The Hippodrome

In the tradition ofhisfictional ancestors, Dostoevsky and Faulkner, [Colter) has produced a work which uses the world ofeverydayreality in a manner beyond thescope ofjournalism or sociology-as an entree to the soul. -James Park Sloan, CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

$13.95, paper

W. S. DI PIERO

Shadows Burning

In its intensepreoccupation with change and thefrailtyofwhatever continuities ofmemory and imagination we deoise to order the unorderoble, [Shadows Burning} makes an important contribution to American poetry. -Alan Shapiro

$29.95, cloth \ $12.95, paper

CAROL FROST

Pure

A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and the natural world.

Through her patient dissection of the mysteries ofnature, [Frost] comes to conclusions that leave us with a prophetic sense ofdarkness.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$26.95, cloth \ $10.95, paper

EUGENE GARBER

The Historian

Winner ofthe 1992 William Goyen Prizefor Fiction

Eugene Garber, casting himselfas both Herodotus and Ned Buntline, has elevated American history in the second halfofthe nineteenth century to the grandeurofa legend about a might civilization ofthousands ofyears ago. -Kurt Vonnegut

$14.95, paper

Fiction of the Eighties

EDITED BY REGINALD GIBBONS AND SUSAN HAHN

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$26.95, cloth /$16.95, paper

New Writingfrom Mexico

EDITED BY REGINALD GIBBONS

A carefully chosen sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today. Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution. -HARVARD REVIEW

$15, paper

DIANE GLANCY

Monkey Secret

[Glancy's} work brims with American Indian characters who teeter precariously on the border that separates time-honored customsfrom stark new realities [Her} latest collection ofshortfictionfeels like an anthologyofsmall, perfectly realized moments.

$19.95, cloth -NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

One of the most affecting and imaginative novels ever written. Arcadio is the bizarre and fantastic account of a man searching through his dark past for his lost family.

[Arcadio} virtuallypulses with life; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldly contemporary as well. -Joyce Carol Oates

$12.95, paper

Halfa Look ofCain: A Fantastical Narrative

Never published in its entirety, this rhapsodic and visionary fable of love, lust and lonelinessis now available for the first time.

The work ofa gifted, intelligent artist. -NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

$22.50, cloth

In a Farther Country

A neglected masterpiece of desire and loss by a renowned twentiethcentury American writer.

Mr. Goyen has he poet's considerationfor the exact word, and he has a great sense oflaughter. -THE NEW YORKER

$13.95, paper

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe Spinners

Winner ofthe Carl SandburgAward and the 1993 Chicago Sun-Times Book ofthe YearAward in Poetry

This volume of poems features an impressive variety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience.

Angela Jackson has known,for long, what is rightfor her attention and scrupulous investigation. -Gwendolyn Brooks

$25, cloth \ $11.95, paper

The Urgency

of

Identity: Contemporary English-Language Poetryfrom Wales

EDITED BY DAVID LLOYD

This anthology of poems and interviews presents for the first time in this country the important English-language Welsh poetry of the 1980s and 1990s. Includes work byJohn Davies, Gillian Oarke and R. S. Thomas, among others.

$39.95, cloth \ $14.95, paper

ADRIAN C. LOUIS

Vortex ofIndian Fevers

Wordplay, metaphoricbrilliance, technical virtuosity and a scathingly sardonic critique of self and society fill this new collection.

Beautifullyaglow with the love oflanguage. -James Tate

Prophetic, terrifyingly intelligent, unconditionally germane. -Hayden Carruth

First person, jugular: That is the voice ofLouis he refuses to scurry and cry and rides right into our lives with the languageofPound, Williams, and Ginsberg, driven mad by all that he sees. Paterson on the High Plains. -mE BLOOMSBURY REVIEW

$29.95, cloth \ $11.95, paper

LINDA McCARRISTON

Eva-Mary

National Book Award Finalistand Winner ofthe Terrence Des Pres PrizeforPoetry

An immensely moving book,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories oftrauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace. - Lisel Mueller

$10.95, paper

PETER READING

Ukulele Music Perduta Gente

The first u.s. publication of the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity.

$26.95, doth \ $11.95, paper

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out of Silence: Selected Poems

EDITED

BY

KATE DANIELS

Thefirstofour women poets to enter and engage the Western tradition ofprophetic outrage, she uarmed it with the living voices ofthe injured. And in heractivism and generosity, Rukeyser was as good as her word. -Eleanor Wilner

ThepublicationofOut ofSilence is an event worthyofcelebration.

-THE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

$28, cloth \ $14.95, paper

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

Winner of the 1993 Terrence Des Pres PrizeforPoetry

Poems elebrating the roughbeauty of ordinary life and lamenting its inevitable decline.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence ofa lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American. -Li-Young Lee

$25, cloth \ $10.95, paper

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise of the Impure:

Poetry and

the

Ethical Imagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today.

$39.95, cloth \ $12.95, paper

MARC STRAUS

One Word

Poems by a physician; informed by a keen sense of vulnerability-to pain, to suffering, and to the joy of life.

Offering a new perspective on patient-doctor relations, [Straus] brings humanity into the sterile hospital environment. -BOOKUST

$29.95, cloth / $11.95, paper

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years I Cronica de mis alios peores

TRANSLATED AND WTIH AN AFTERWORD BY JAMES HOGGARD

Abilingual volume of poetic meditations on Chicano culture and heritage. Villanueva is a writer tospend timewith. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

$34.95, cloth / $12.95, paper

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision.

Bruce Weigl has become one of the best poets now writing in America.

$17 cloth / $11.95 paper -Denise Levertov

THEODORE WEISS

Selected Poems

The definitive selection of poems by one of America's most distinguished and original poets.

[Weiss's poetry] is among the most valuable work produced in our time.

$49.95, cloth/$15.95, paper -James Merrill

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

Poems rooted in history, myth and everyday life.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -Alida Ostriker

$15, cloth /$8.95, paper

Order «'orm

Order from your bookseller or from: �orthwest('rn tnil('rsit� Prt'Ss Chicago Distribution (;(,III('r 11030 South Lallgle� \\(,IIU(, Cbifago. It 60628 'I1\L. 7731568·1550 H\ 7731660-2235

Name Address

City State Zip

Authorlfitle

o Check or money order enclosed

o Mastercard/visa number:

Expiration Date

Signature:

ClothlPaper Quantity Unit Price Total

Subtotal Shipping

handling* TOTAL

and

*Domestlc-$3.50 tlrst book. $.75 each additional book *Foreign-$4.50

book. $1.00 each additional book

Urst

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Co�Editor Susan Hahn

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

TriQuarterly Fellow

James Lang

Advisory Editors

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Kemba Johnson, Jacob Harrell, Dylan Rice, Elizabeth Taggart

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of back issues varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (847) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1997 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ); Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CAl; Fine Print (Austin, TX).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TnQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), Historical Absrracts, MLA, EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CAl.

Contents Editor of this issue: Susan Hahn INTERVIEW A Conversation with Alice Fulton 22 Alec Marsh MEDITATION On Donald Barthelme 41 Edward Hirsch FICTION From The Feast of l-ove •.•.•••.•••••..............•.••.•.•.••• 65 Charles Baxter To China 82 Leigh Buchanan Bienen The Poet 101 Stephen Dixon How to Stop Loving Someone: A Twelve-Step Program .......•..........•.............•..• 167 Joan Connor Men Wearing Eye Shadow 1 77 Cammie McGovern The Rain in Kilrush 193 Michael Collins 15

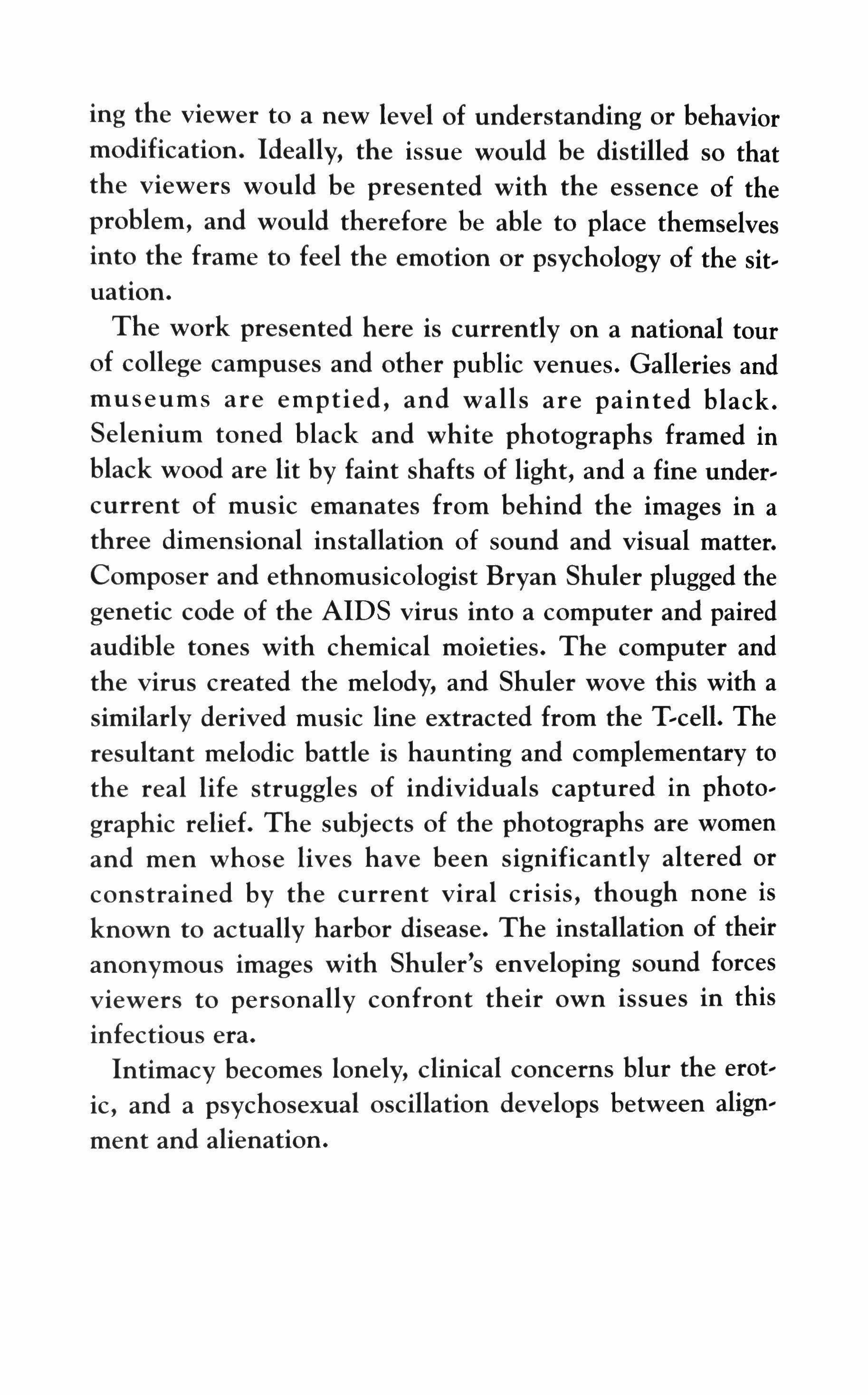

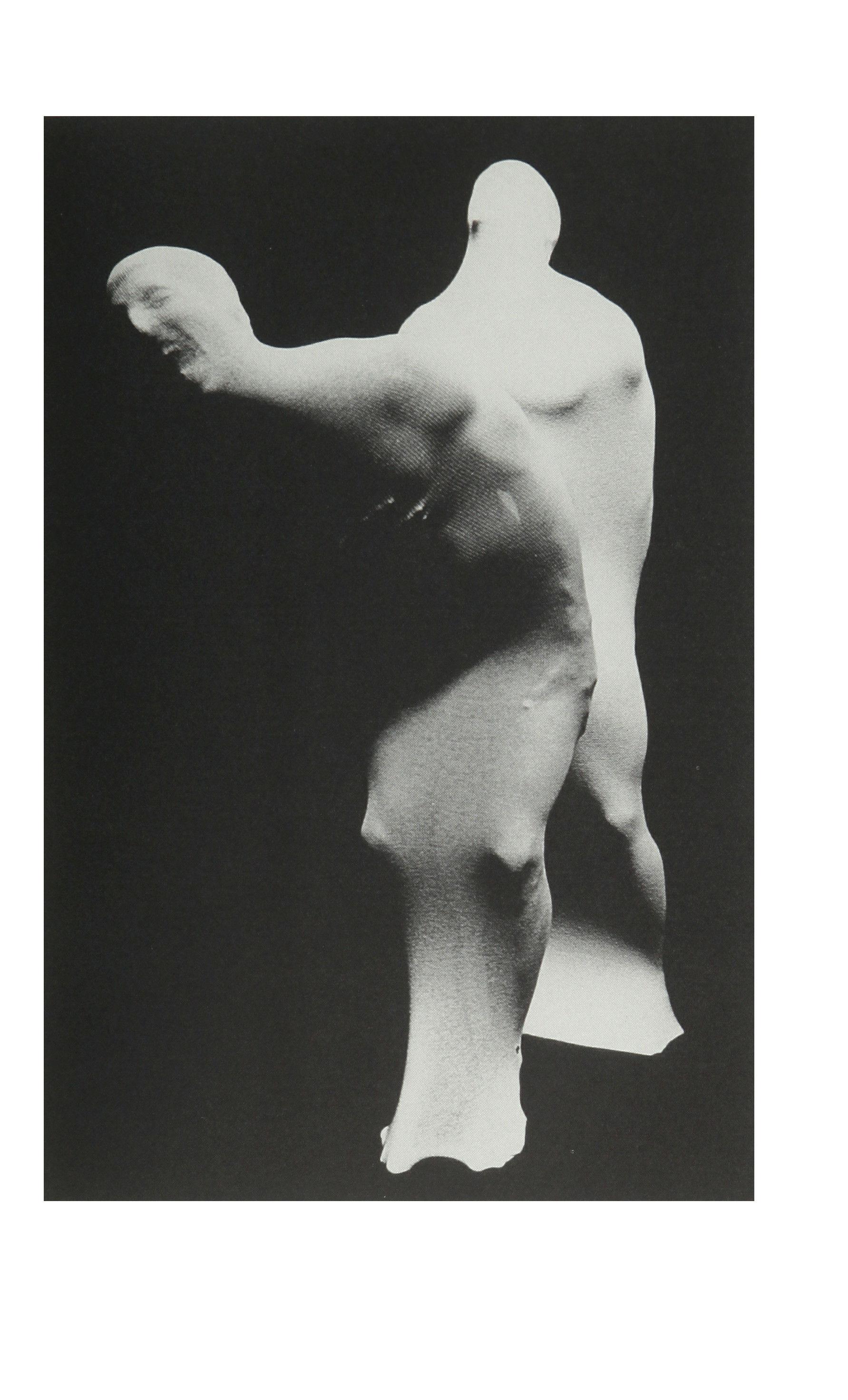

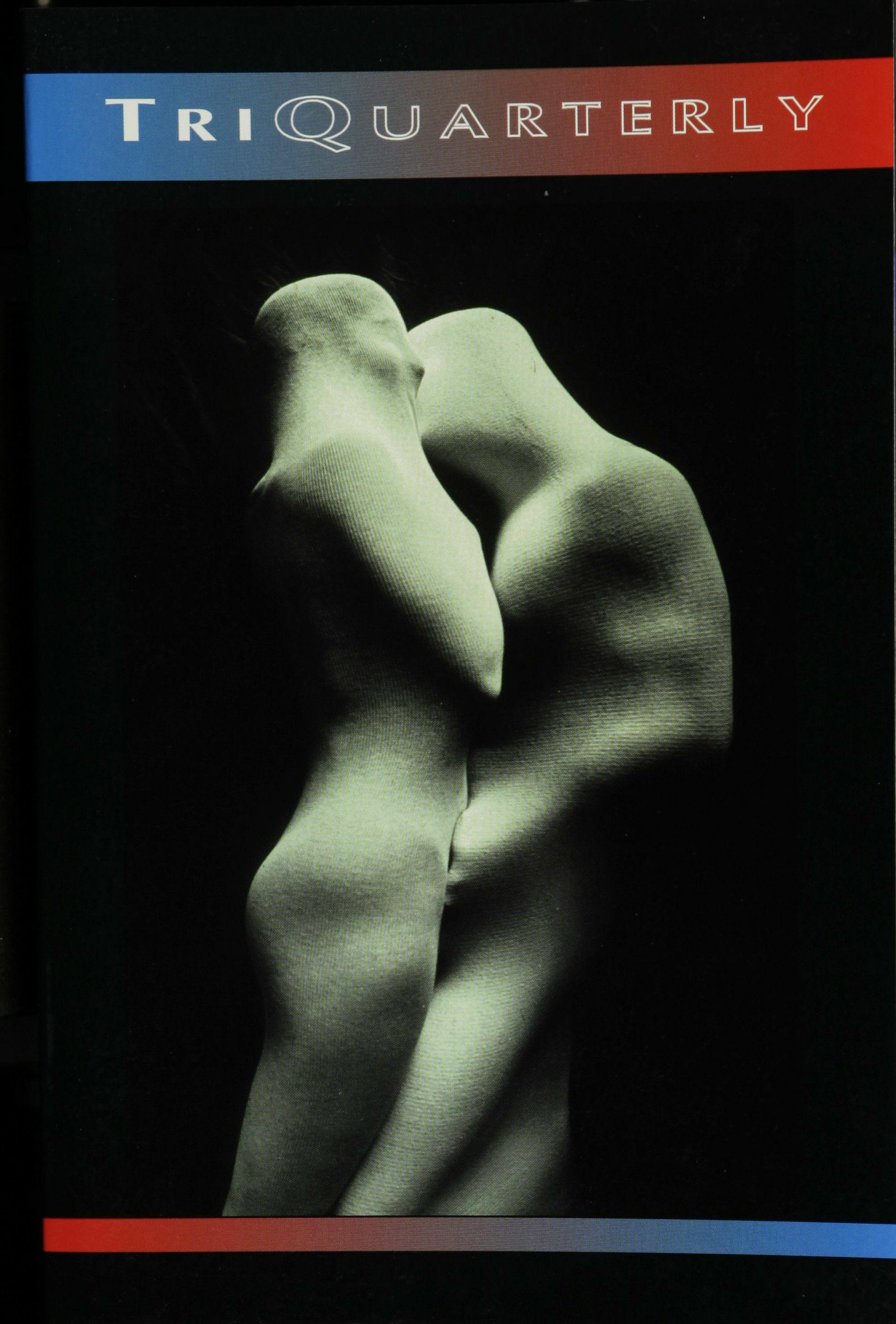

SPECIAL SECTION "Rapture," a Photographic Series ••••..•••.........••.. 145 David Teplica POETRY Transfusion 19 Tom Sleigh Failure 40 Alice Fulton Abundance; Of That Village, the Heart; No Kingdom; Portage ••••••........••.••..............•...•.... 58 Carl Phillips Other People's Troubles; Mengele Shitting 110 Jason Sommer Saturday Morning; Near the Partizan Hall Detention Center, Foca, August 1992 126 Heather Smith Comings and Goings (Bangkok) 129 Pimone Triplett Last Garden 132 David Gewanter An Aerial Meandering ••••••••.........•.•..................• 137 Katherine Soniat Sky Dive 140 Dabney Stuart 16

From Short Lines 159

Alan Williamson

The Angel of Melancholy 163

Eric Pankey

My Groom 165

Jill Bialosky

Easter Raga 251

Vikas Menon

ARTICLE

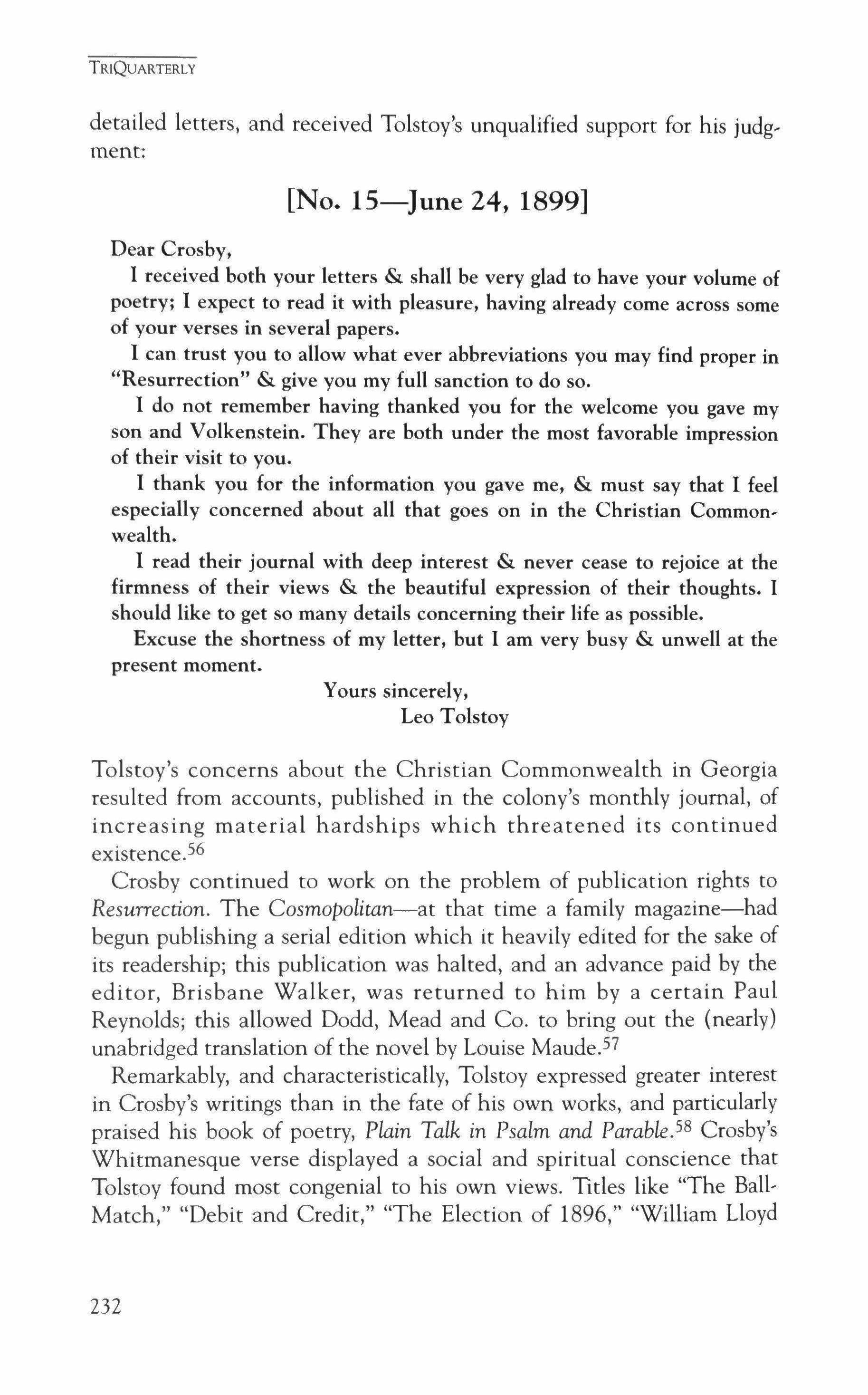

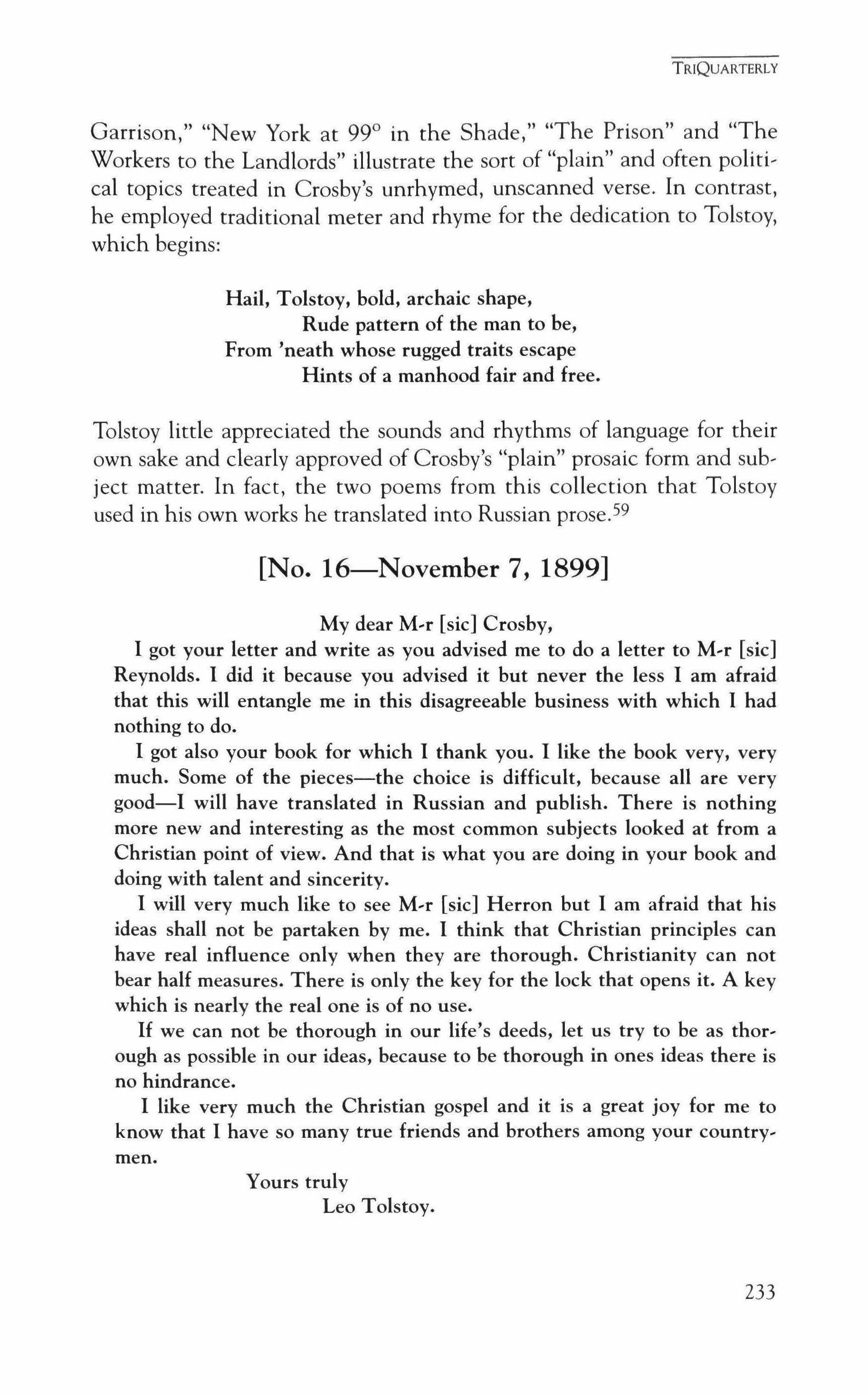

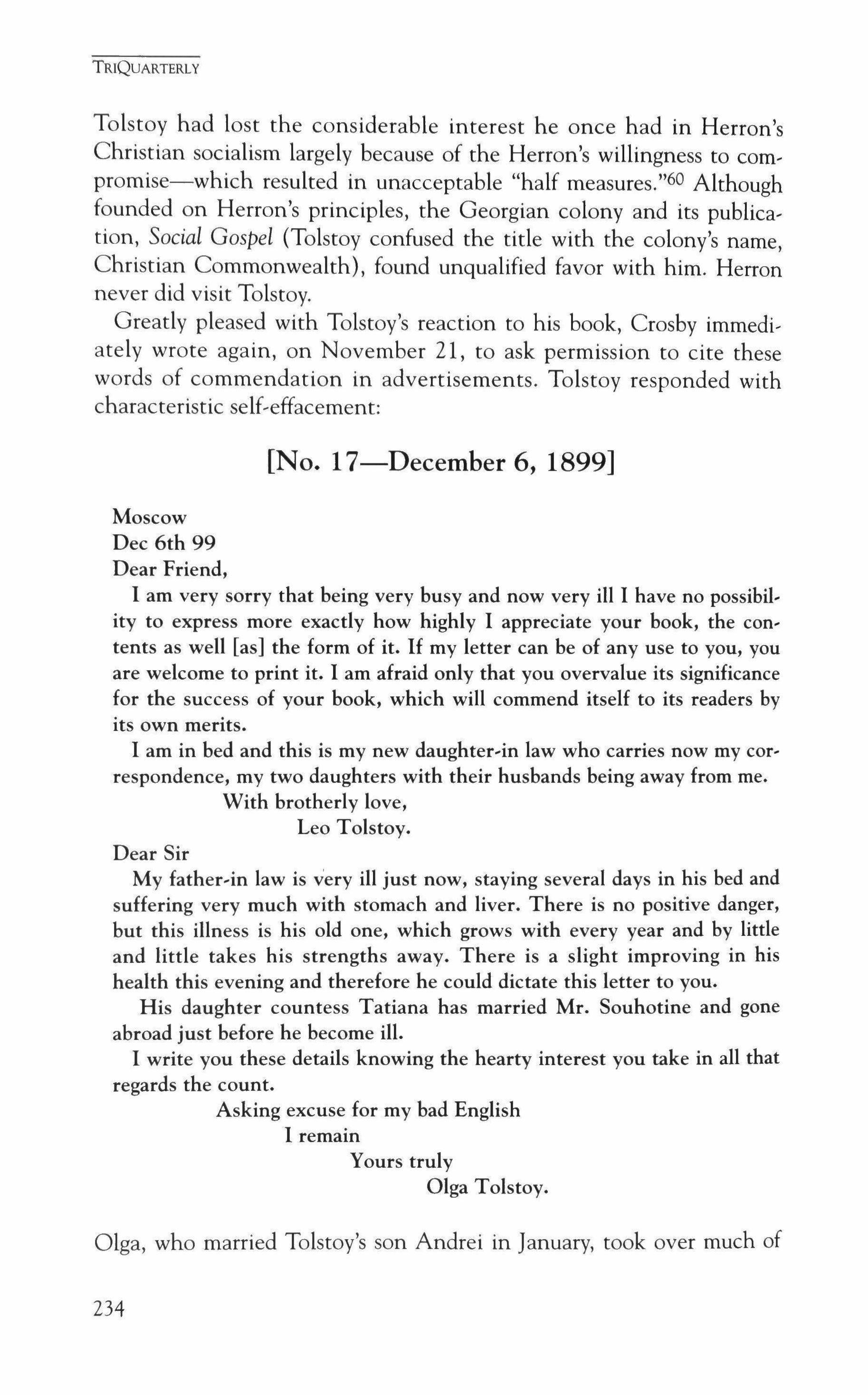

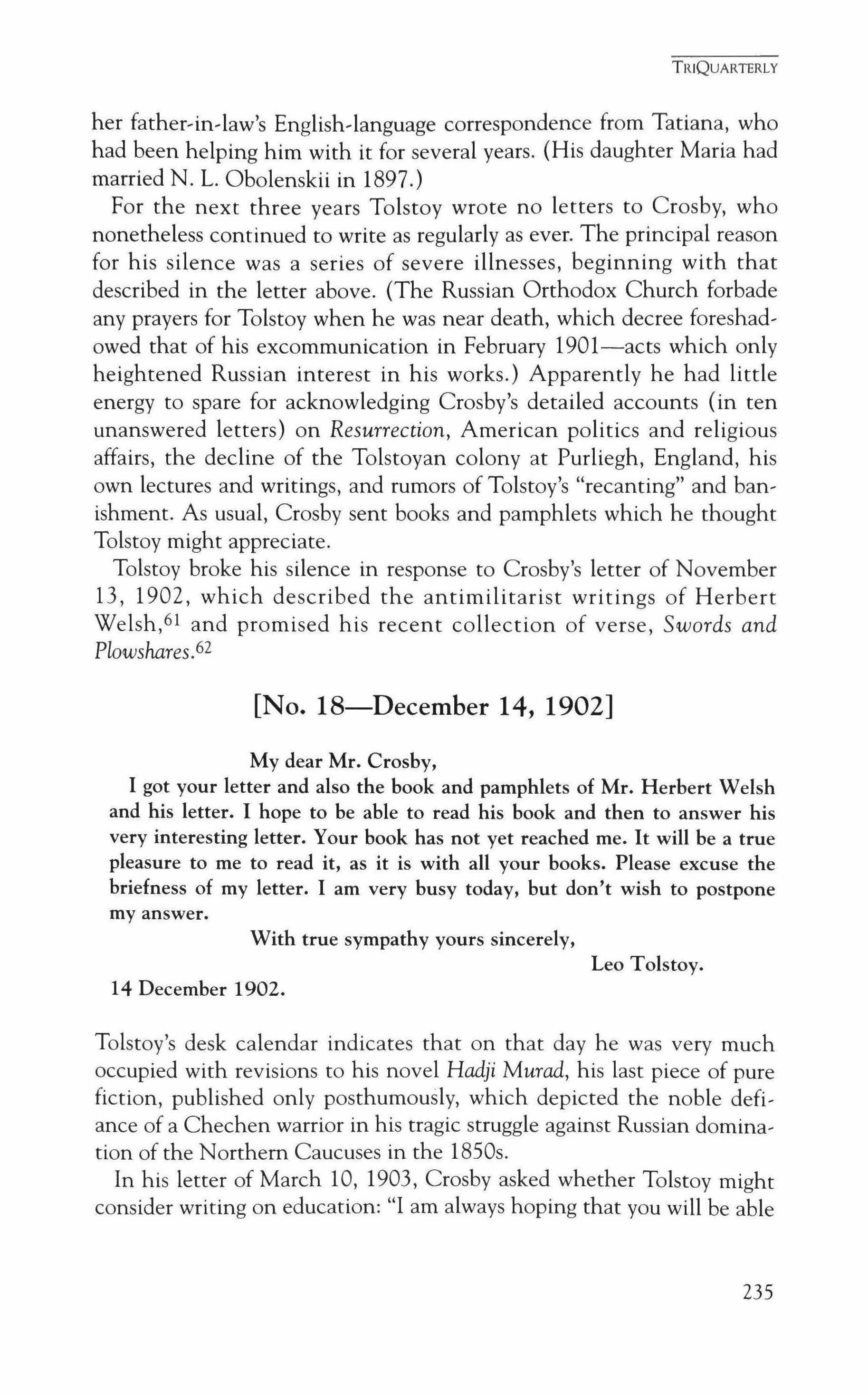

Tolstoy's American Disciple: Letters to Ernest Howard Crosby, 1894,1906 210

Robert Whittaker

CONTRIBUTORS 253

Cover photograph by David Teplica

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

Photographs on pages 14, 18 and 255 by David Teplica

17

Transfusion

Tom Sleigh

I saw it, visible aura, unstoppable flowthe stream pouring down the walls in waters everlasting that the damned below

reach out their arms to with such longingmen, women, their small round bellies attractive in that light, even to the demons tormenting them with pitchforks, voluptuous moments of degradation Suffering souls, what do you ask of us

looking up in wonder at the golden deer in the mosaic dome, its muzzle nuzzling the stream's ruby drops, its eyes' cool glimmer gazing unconcerned ? Ghostly loins flicker in woozy candlelight, the stained glass grimy as linoleum lozenges under

the patients' feet in the hospital across the street, legs unsteady beneath their johnnies as they stagger down the hall

TRIQUARTERLY 19

TRIQUARTERLY

like models on a runway showing off cancer, stroke, immune systems gone haywire, the blood-starved brain straining to remember:

Burning in their eyes gleam the drops everlasting that the nurse's hand controls, screwing down the valve that slows the drops

to a drowsy crawl, the needles aching in their arms leading back up the tubes to the blood bags burning reminding

me of when my own face, pale, too pale, turned like a flower to that draining sun hazy through storming clouds of neon

As I drifted beyond my body in a fever dream, I saw a stag, white-furred, its eyes staring into mine until I

felt suspended in those pupils' dead,level: Swirling round its stamping hoof the stream pulsed in the convulsing light, its muzzle

lowered to drink as that shimmering swept me up and rushed over boulders, the streambed leading to the treeline: Like steam hissing,

somnambulant as lava, the dead gathered, faces sprouting fur, infirmities thrown off in paws and hooves, everything they'd suffered

forgotten but as I moved among their claws and fangs, calling out their names, no trace of who they'd been glistened in their eyes

gone vacant as the dark rearing up in the vaulted nave The golden deer gazes down the aisle at the ghostly loins where sap

20

rises through the stem to flower in the man-god, the leaded panes that shape his face and body seeming almost molten-

as if he'd just taken form from a pool of magma, his face tinged red as a single corpuscle rushing headlong, fraught with potential-until the sun kindles his face to bloody gleams, the walls streaming with his blood in which the damned now seem to hover, their naked limbs

flushing as if they would climb down, hungering to touch our hands, our faces, and be touchedbreasts, bellies, encircling arms, pure flesh dazzling

even the demons' twisted faces, the bleeding dark pierced by whitely flaring eyes, all of us afloat in the ocean of their gazes

-the damned in this light no longer damned, their bodies only bodies, like ours soft, round but then the light shifts, the damned

recede among the demons, their eyes flattening into pain Now, only the deer's eyes pierce the flooding dark, the pupils staring

through us turning us to stone until we tum away abashed before that gaze, as if the soul shed its mask to stare its keeper down.

TRIQUARTERLY 21

A Conversation with Alice Fulton

Alec Marsh

This early�morning interview took place on November 29, 1995, in the recording studio of WMUH, Muhlenberg College's tiny radio station; it has been edited and Fulton has taken the opportunity to expand on some of her responses. The studio setting is one reason we got to talking about popular music and television and its influence on poets. But Fulton's new book, Sensual Math, contains a sequence called "My Last TV Campaign," which raises the issue of the poet's relationship to our electronically mediated world.

MARSH: One of the things we have been talking about this morning is the influence of television on poetry. You are of a generation, as I am, that grew up within the world of television. One of the opening lines of one of your poems in Sensual Math, "Vanishing Cream," begins "TV rules." I wonder if you could talk about what that means to you.

FULTON: In that particular poem it's an advertising executive who's speaking. The first line is "TV rules: it must be visual velcro There's a double meaning on "TV rules," one implication being that it rules in the sense of dominates. But the poem also is listing various rules for the production of a TV commercial, such as it must be visual velcro/ at four grand per second." What does "TV rules" mean to me? Let's see I grew up watching it, but I never liked it very much, truthfully. As a kid there were certain shows I watched. I can't really remember what they were, but by the time I grew old enough to think-at twelve or so---I wasn't watching much TV anymore. My parents would have it on, and I

TRIQUARTERLY

22

would be up in my room listening to records or reading. What was happening to music in the sixties was more powerful to me than anything I saw on TV. I always found TV kind of vacuous and boring, in fact. Other people seemed to find it mesmerizing but at that time and I guess even today I don't find it very engaging. I can walk away from it, tum it off. My husband, for instance, says that he can't do that. He gets sucked in; he's a visual person, a painter, and he finds it much more engaging than I do.

I tend to disagree with many of the values encouraged by TV. In "My Last TV Campaign," the ad executive, after a life of selling dish soap, et cetera, is given the chance-finally-to create a campaign for something she or he believes in, a big idea that could have a positive social impact. The poem considers the difficulties of presenting or "selling" ideas that are not already part of culture. At least, that's one thing the poem does.

MARSH: I wonder if "TV rules" dictate, or give you a structure from which the quick cuts of your poetry are derived. Is there an influence there?

FULTON: Well, in "Vanishing Cream" there might be an influence. That poem quotes from ad copy the speaker is trying to write. It is a little disjunctive at times. But the disjunctiveness in other poems of mine probably comes more from what I've read and from postmodem ideas that question continuity and unity. Shifts of viewpoint and diction are a means of disrupting the poem's surface. I'm interested in dismantling the single, firm, unified speaking voice. Rather than the continuity and smoothness and polish of a steady subject, I'm interested in plurality of voices and registers of diction. My notion of poetry itself suggests quick cuts-those moves that used to be called poetic leaps. They allow the reader to fill in the gaps and participate by recreating the poem's meaning in their own minds. Poetry, to a greater degree than prose, depends on what happens between the lines. The gap between meanings is wider in poetry. My concept of poetry depends upon deletion and non sequiturs that the reader can reconstruct into meaning. To me this is a component of poetry. It has nothing to do with TV.

MARSH: I noticed when you were reading last night that some of the poems that I took to be monologic actually seemed to have a couple of voices coming in. It suggests to me that often lines that are taken off the

TRIQUARTERLY

23

left-hand margin indicate another speaker. Am I making that up?

FULTON: In one poem, "Some Cool," I used indentation to show shifts in thought. When I read that poem, it has the effect of being in different voices because the poem's speaker-me, in this case-is remembering the various voices. She's putting a string of pig lightsthose lights they make in the shape of animals-on the Christmas tree. While doing this, she's remembering two voices: her neighbor and the text of the Elvis cookbook she's received as a gift. But these various languages take place in the speaker's mind, and in that sense are part of her shifting sense of self.

In this poem and other ones there's counterpoint-so I think you're right to pick up on that. To make it easier for people to hear them when I am reading them, I'll say, for instance, "This poem is in the voice of an ad executive." But you don't have to read it that way; it can be read as parts of a sensibility, rather than parts of a single steady speaking subject. There are various polyphonic ways to look at the poems.

MARSH: The first time I picked up the book, I cracked it open to one of the poems in "My Last TV Campaign"; it was the Valentino poem, "Passport," and I thought, "Oh I'm not sure about this." When I realized it was a dramatic poem I felt much better. It made sense as the mind of this TV person. But at first I took it as sincere: this is Alice Fulton speaking.

FULTON: You use the word "sincere" just as I might use it. But I wonder-what do we mean by "sincere"? Are autobiographical poems necessarily "sincere"? It seems to me that lyric poems often assume the pose of sincerity, and I find that posture off-putting, sometimes even offensive. I don't like it when manipulation insists upon its innocence or tries to pass itself off as guilelessness. All writing is manipulative, but writing that admits to its manipulations-by use of surface effects, tone, disjunction, what have you-seems more honest, perversely, and therefore has a better chance of convincing-or moving-me.

Even in lyrics, where it seems I'm the poem's speaker, that sense of self and voice is something of a fiction. I'm wary of being completely identified with the words being said because that way of reading fails to account for the mediation-the screening, selection, censorship=-rhat inflects all writing. On the other hand, I have to admit that whenever I create a persona some of my own beliefs come through.

Basically I think that autobiographical poetry needs to be viewed as a

TRIQUARTERLY

24

construct rather than as a "sincere" unmediated slice of life. At the same time, poetry in voices-or poetry that creates characters-can be read as mediated autobiography, mediated sincerity if you will. During the late seventies, I worked for a brief time as an advertising copywriter in New York City and there is a part of me in "My Last TV Campaign." I sympathize with the intentions of the speaker and the outrageously benign ad campaign she or he is trying to devise. But unlike the persona of the poem, I knew I couldn't stand advertising right from the start. I used to come home, go into the bedroom, and cry. I couldn't have lived the life of the ad executive in my poem. For me, that job was a horror. Yet to write that character, I had to have some area of sympathy or con, gruency.

Some readers have mistaken "My Last TV Campaign" for a satire on advertising, but that wasn't my intention at all. Advertising is a satire on itself already. The poem is much more "sincere" than people might think.

MARSH: Dramatic monologues or dramatic multi-logues, as some of your poems are, do seem to give a poet a lot of freedom about hiding and coming forth.

FULTON: "Multi-logues" is a good term. It describes contrapuntal poems very well. I began writing them because I got so tired of writing from my own experience, writing about my own life; it didn't include everything in a certain way. There were areas of human experience and thought that I wanted to experience vicariously; I wanted to go deeper into otherness. One of the ways of going more deeply into otherness is to write from the perspective of someone who's not you, of course. So that was how I began doing it, just trying to stretch that lyric sensibility a little bit. Now I'm going back more toward my own life and experience and away from other personas.

MARSH: "My Last TV Campaign" seems to have one speakeralthough it's difficult to say just who that speaker is.

FULTON: People read my sequences, like "My Last TV Campaign," and sometimes don't know if it's one speaker. I have no objection to reading the poem as polyphony, but when I wrote it, I thought of it in terms of a single character.

TRIQUARTERLY

25

MARSH: That poem's speaker is deliberately androgynous. When I started reading the sequence I just took it to be a woman, because you're a woman. Very naive. As I got halfway through I thought that maybe it was a male speaker, but it's actually deliberately left fuzzy.

FULTON: Right, the speaker's sex and gender are left open. But people always inscribe it. I think that's because the mind has trouble seeing two things at the same time. You could envision a transvestite or someone who is androgynous, but to envision both a gendered male and gendered female together is, perhaps, impossible. The poem is meant to oscillate between them. Some people inscribe it as male and will tell me about the man in my poem; others will say the woman. But it can be both; it can be either. The two overlap, switching back and forth, shuffling and flexing.

MARSH: Have you ever written dramatic monologues with a male speaker?

FULTON: Yes, yes. Several times. A sequence in Powers of Congress called "Overlord" is spoken in part by a soldier who's landing in Normandy on D�Day. That was definitely a male speaker, and in a recent issue of TriQuarterly, I published a poem called "World Wrap" that was in the voice of a man I'd describe as a feminist.

MARSH: When you write a poem and the speaker is the other gender (if there is just one other gender), it makes one think about the role of gender, or the role that gender is. What's that like for you?

FULTON: Before I answer let me be clear-when I say "sex" I'm referring to biology, while "gender" refers to the social and cultural construetion of the self. Now that we've cleared that up, I think gender is a great inconvenience. I'd like to get rid of it. I don't mean the word "gender," which is very useful, but gender in action. For women it's terribly constricting. The female gender role involves much more artificiality and contrivance than the male-though neither role is "natural."

When I was writing "Overlord," I tried to imagine my way into the consciousness of a soldier in World War II, who found himself in that particular historical predicament. I thought about what his background might be, and I thought of how he regarded women-that was one of the interesting things for me in the poem. When he's at war, he's

TRIQUARTERLY

26

remembering sex and the woman waiting for him back home.

More deeply, the poem's concerns had nothing to do with character. It thinks about the connection between childbirth and warfare as triumphant spheres of endeavor. Since antiquity, childbirth has been woman's means of transcendence and heroic endeavor, and war has been man's. "Overlord" is a means of meditating on that deep structure. There's a childbirth poem in the voice of a woman, too, in that sequence. It gave me a chance to engage with sensibilities and thoughts that I wouldn't have encountered otherwise, and become more of a "chameleon poet," as Keats said.

MARSH: You obviously believe, as most poets of consequence do, that "the poet thinks with the poem" as William Carlos Williams said. You mentioned meditation. How do poems begin for you? How does meditation happen?

FULTON: It depends on whether it's a commission or whether it's something I choose to do on my own. Writing without an assignment is in some ways ideal because you're free to follow the deepest passions and interests. With commissions, the challenge lies in finding a connection between the assigned theme and your own urgencies. When I'm writing on my own, I look into notebooks I keep. And I look at what I have written and see where I was, where I left off, where I was deeply engaged last.

And then, what I haven't said is of interest to me. Have I neglected anything? Was I short-changing some aspect of a subject that interests me? Have I shied away from it? Have I been uncourageous or have I been wimpy about something?

In a way, that's how I got interested in writing more about emotion. Language has always attracted me in poetry. When I read poetry, it's the way things are said that appeals to me. So as a poet, that's very much where I began. That was the praxis or center for me. It still is. But as I thought about it, I realized that I'm also very drawn to poems because of their emotive qualities, because of what they make me feel. That's very hard for the poet to guess, to do, to control. I don't think you can control it really. But by not thinking about emotion at all and just letting it happen if it did, I felt that I was not taking on something that was finally important to me and important to poetry.

On the other hand, it seems to me that too many poets cultivate emotion at the expense of language. There's a lot of sappy poetry being

TRIQUARTERLY

27

written and published. The language in the poems might be plainmonochromatic, beige language-but the content is florid and gushy as cabbage roses. I have a horror of writing that way. When it comes to emotion, I prefer poems that err on the side of austerity. Most contemporary poems want to move the reader. But the emotions I feel when reading them are not the ones the poet intended. I might feel anger or disgust because I sense that the poet is trying to manipulate me with sincerity. All language is manipulative, but the poems that move me are those that seem somewhat surprised, taken aback, by their own emotional developments. I believe that can happen when feeling seeps into the poem without calculation on the poet's part. That's why I've allowed emotion into my work as an accidental {not an accident, but a fortuitous, unforeseen chromatic alteration}, and maybe that's why the emotion in my poetry tends to go unnoticed.

With emotion, you can't only think, because then you're back where you were before, with the analytical. But it's possible to be analytical at first and then to allow spontaneity and feeling-to think and then let the poem rip, in both senses of the phrase. Let it be more vulnerable. Poems of "desire" or loss are the safest, least vulnerable poems imaginable these days. It is far riskier, more vulnerable, to allow contrarian feelings-humiliation, vulgarity, perversity, humor, et cetera-into the poem than to express loss. The emotional range of contemporary poetry seems far too limited. When I think of the poetry of emotion, I think of surfaces that tear. Things are exposed that maybe you didn't intend to show. Those can be the most powerful points in writing.

MARSH: Did those moments happen in your notebooks or only when you move from the notebook to the poem? I'm trying to imagine your notebooks now.

FULTON: I have so many notebooks. Some are just collections of words and phrases that I like. But in them I'll put things I notice, things that I might feel. They are full of observations, aphorisms, about emotions or things that I've noticed about how people are acting-little things that I could work out and develop in a more nuanced and complex way in a poem.

I have a friend I talk to who's a scientist, John Holland, who's a colleague at Michigan, and we have wonderful conversations about science and literature, and I keep notes on that. So I have many different kinds of notebooks.

TRIQUARTERLY

28

MARSH: Do you carry them all around with you?

FULTON: Never, no. That wasn't why my suitcase was so heavy! don't because I'm afraid I'll lose them if I travel with them. I keep them at home. I have one small one that I carry with me sometimes, one where I might just jot something down, like a diary, if something happened. I also keep language in it that strikes me-bits of phrasing and words. There's nothing to notebook keeping that's a "should do." And I like that.

MARSH: I was wondering if you feel you need a subject to bounce off of to begin the poem, or do you sit down and wait for the poem to say itself to you?

FULTON: I usually have something in mind. Very often what I have in mind isn't where I end up. But at least it's something to start from, something to meditate on, to think about, and something that interests me. If the poem is a commission, of course I'm given that start. Then the difficulty is connecting it to my own deep interests. But I don't start with absolutely nothing. The blank slate is off-putting, while words give rise to words.

MARSH: Do you meditate on words or images?

FULTON: I always look at entries in my notebooks. I've occasionally stared at visual images-such as photographs. This morning I was thinking of book titles, and I came up with the word "vinyl." To me it's an interesting word. And not a "poetic" word, not "desire," not "angels." A poem name that came to me was "dirt." I'm interested in the word "failure" as a book title. America is so much about success. The idea of admitting failure, of admitting weakness, is interesting to me at the moment. I'm very interested in the connotations and the feeling and the taste and the texture of particular words. Sometimes I'll copy down a beautiful sentence from someone I'm reading.

MARSH: There's so much energy and tension in a good sentence. I think of prose writers as people who write great sentences. With poets you think great lines. What's the difference between a sentence and a line?

TRIQUARTERLY

29

FULTON: Well, for me, the line is still the unit of composition, which might be a little bit old-fashioned at this point. It's a shame that the posssibilites of the line are being neglected. It's a linguistic structure that I'm not keen on giving up, though writing in lines is certainly a lot of trouble. The line is something that poetry gives us that prose doesn't, a little sculptural thing on the page, a unit of thought with a brief rest at the end.

A line should be interesting in and of itself, and then it has to work within the context of the sentence. The line provides an opportunity for "syntactic doubling"-a wonderful term I learned from Cristanne Miller, a scholar who writes brilliantly about poetry. It is possible to create one meaning when the line is decontextualized and read as a thing unto itself and another meaning when the line is connected to what follows. This sort of syntactic doubling depends upon the multiplicity of the last word in the line. But a word within the line can also act as a syntactic door, opening and closing on meaning, changing from noun to verb, for instance. "TV rules: it must be visual velcro," the line you cited earlier, is an example. "Rules" can be read as a noun or a verb. It isn't something poets want to overdo, but it can add to the richness and ambiguity of the poem. This particular linguistic effect is not possible in prose.

The line makes poets and readers think about language very closely. The end word in a line receives a great deal of pressure and attention. It's interesting to try to move the weight towards the beginning of a line. Enjambments that end the line on function words like articles, little words like "a" or "the," the seam stitching of language, are less teleological or end-driven. They lighten up the right side of the poem. Beginning with a noun or a verb places more weight to the left, frontloading the line.

The most common way to lineate is to simply write lines that follow the syntactical pauses of the sentence. Poets who support this lineation sometimes call it naturalistic and say that it mimics speech. But if you listen to people talk, they pause in ragged places, leaving the prepositions in midair.

The line adds multiplicity and depth to poetry, while asking the reader to slow down. The wide margins of poetry should be read, just as much as the text. The white space and the silent rest at the end of every line conduct the music of the poem.

But when I quote poems, I probably remember phrases rather than lines. I think in terms of the phrase. Last night I was quoting Dickinson,

TRIQUARTERLY

30

"I like a look of agony, because I know it's true." I don't know how that sentence is lineated. I'd have to look it up.

MARSH: What about those dashes in Dickinson? You use them too, and then you also have invented a new form of punctuation, the double equal sign, which is also kind of double dash and must at some level have something to do with the effect of Emily Dickinson on you.

FULTON: Yes, oh absolutely. Her dashes are so mysterious. In her work I feel the dash has been done to perfection. And that's partly why I made up another sign that could be something to think about in terms of punctuation. It wouldn't be the dash because I just can't imagine anyone using it as well as Dickinson. She uses it in ways that let you become more involved with the poem's syntax; you can fill it in, inscribe it. The dash is an empty space, but Dickinson's syntactical deletions often ask to be filled in; they exist to be recovered. Recovering the deletions makes reading her a very active, reciprocal experience. You feel like you're building the poem with her as you read. Sometimes you can't recover the deletions. The phrases on either side of the dash remain non sequiturs. Again, I have to credit Cristanne Miller, whose marvelous book on Dickinson, A Poet's Grammar, articulates these effects.

I also love the way that the dash looks like well, sewing. It suggests the way Dickinson sewed her manuscripts together. For me, it has a feminist aspect: it looks like thread, it looks like sewing, holding the lines together. But mostly I love it because it allows multiplicity. And I like the story of Dickinson's reception. I love the way that they tidied her up and put the periods in, and by regulating her punctuation, removed the single best thing, for us, that she did.

MARSH: It seems to me that one of the reasons that her reception was so belated was that readers had to have already been trained with a little bit of modernism, by Marianne Moore perhaps, to understand those dashes as dashes and not as little Emily's mistakes.

FULTON: I think that's true. She seems postmodern in fact. We needed indeterminacy; we needed all these twentieth-century ideas about turbulence before we could really appreciate what she had done.

MARSH: Now your revision of a dash into this double thing. It's a

TRIQUARTERLY

31

sign that's not voiced when you read the poems so it's a form of punctuation

FULTON: Uh-huh.

MARSH: -and therefore it's a visual sign-

FULTON: Uh-huh.

MARSH: -and you just mentioned that good lines of poetry reminded you of sculpture, which makes me think that you see your lines before you hear them. Always tricky to make a judgment about that, but maybe you could talk about the relationship between sound and sight in your double dash, or "bride" as you call it.

FULTON: Although the sign is visual, as you say, when I'm writing a poem the sound comes first, the music. Again I think I'm old-fashioned that way. Not that the poems have a steady meter, but I hear the music of the words and rhythm. The bride sign is silent and it's mostly for readers of the page, because when I read the poems, you hear a rest or pause, but you don't know what the punctuation mark looks like. There's so much going on, I think, not only in my poetry, but in most poetry, that it's very hard for listeners to hear it and take it in if they haven't read the poem on the page. So, that's the kind of writer I am, the book kind, not the performance kind.

MARSH: Well, having seen you perform last night I want to qualify that. You read your poems beautifully, and you do make the poems complex in a different way, by revealing a play of voices or slight shifts of inflection which give the impression that there is more than one voice.

FULTON: Oh good, it's nice that there's a reason to read them. Thank you.

MARSH: You were talking last night about your "Daphne and Apollo" poem, and you used a wonderful image about how Daphne had been "stirred into" a tree at the moment of metamorphosis. This curling image reminded me again of a word you like a lot: "turbulence." I began to wonder if the bride sign is silenced because it's also a bride-perhaps a woman who has been silenced and who is full of turbulence-it marks a moment of transformation.

TRIQUARTERLY

32

FULTON: Oh that's really lovely. I think it is a moment of transformation; I'd like it to be that. It could also be a hinge; I see it that way too-the hinge that allows the door to open onto another realm. That threshold moment is transformative. Actually, one title I considered for Sensual Math was Transformer.

I also think of the double equal as the sign of immersion. The single equal sign retains the separation of whatever is on either side. We know that separate is not equal. The double equal, as I said in one defining poem, "Means more / than equal to-within." It signals an absence of boundary, that two things are immersed in one another, as in metaphor. A simile is separated by "like," while a metaphor is transformative; one thing actually becomes the other. So, I think of the double equal as a metaphorical sign and a feminist sign, imbued with the qualities of the background, of negative space, of reticence. Yet, it's also very visible. It calls attention to itself because it's a mark that no one has ever seen in a poem before. I like the fact that it both recalls the reticence of women, the way that women have been in the background historically, and it also brings them visibly to the fore.

I also think it's a turbulent sign. To make up your own sign is probably in some ways not a good idea. It could cause some anxiety and hostility. I was aware of that, but I think poetry should be a bit turbulent and should raise arguments. It should have people saying, "Why are you making me notice this?" Those are valid things for poetry to do, that it hasn't been doing. It's been disappearing and being decorous. It's been behaving itself. In making that sign I wanted to take a bit of a risk, the risk of being called gimmicky and contrived and all that. That's part of the turbulence for me, that's the risk of it.

MARSH: It will be interesting to see if this sign will proliferate.

FULTON: Well, that would be the ultimate compliment. That would be an honor to me, because if you wrote a poem with that sign in it, you'd be saying to me that you weren't ashamed of being associated with the ideas that we've been talking about, that you were a fellow traveler. If others were to use the sign, they'd be supporting a world view. I have to add that I don't expect to see this.

It's amazing how conservative poetry is. Many people who get involved with poetry seem to be fearful, easily threatened. Maybe that's just human nature. But I do wish the world of poetry weren't so small and mean. If you change a tiny aspect of poetics it's "Off with her head!

TRIQUARTERLY

33

Off with his head!" It's as if you've done something very rude and con, ceited, calling attention to yourself and so on.

MARSH: It sounds like you've caught some flak about the sign already.

FULTON: No, in fact I've been lucky. I've just been counting my bless' ings. I'm waiting for it, it might happen next week. There's a book review coming out next week, and it might be in that. I don't know.

MARSH: It's always in the next review.

FULTON: In the next one, sure.

MARSH: You'll get slammed-

FULTON: Yeah, you're just waiting for it.

MARSH: Insofar as the sign does have this sense of the feminine, we can interpret the term feminine very broadly to suggest all that is disorderly, contaminated, seductive and therefore problematic in an ordered, male, analytical, philosophical world. The sign seems to remind us that the silence of the silenced is always turbulent, must necessarily be turbulent.

FULTON: Yes, under the surface there's writhing.

MARSH: It reminds me of your Daphne again, stuck in a tree and look, ing out through the cracks in the bark.

FULTON: Waiting for her chance to be seen. She's a figure for what's happened to women historically. I didn't just think of her as a woman in American culture, because women in this country have a much more comfortable way of living than women do worldwide. I was thinking of her in terms of what has happened to women in the biggest ways. At the end of "Tum: A Version," she peers out of a tree waiting to see and be seen. Apollo had installed mirrors in the tree, so that Daphne's reflection of herself is his construction, his idea of her. All she could see was the image of herself that was given to her by the male god. She's trying to open the tree to see the world from her own point of view, and to have someone see her as she is.

TRIQUARTERLY

34

MARSH: If there were such a someone, who would it be?

FULTON: I think it happens when women become more culturally dominant. It occurs when women are empowered (if it ever happens; I don't know that it ever will). If women came to the fore of culture and were more visible, everyone would start to see what women can do. Women's image might not be limited to stereotypical or essentialist notions that define women as part of nature because of their association with childbearing and childrearing. Women could redefine themselves through opportunity, showing that they could do science, they could do math, they could be analytical. The world gaze would be their gaze.

MARSH: I'm beginning to see that the person looking through the crack on the other side might first be a woman poet, or a woman philosopher.

FULTON: Yes, she could be in any number of fields as long as she's a pioneer.

MARSH: Because you mentioned vinyl earlier, because we were talking about growing up in the 1960s, has the poetry of rock 'n' roll influenced your work? I mean, you said that when you were twelve you were upstairs listening to records.

FULTON: Yes, Dylan, the Beatles, [oni Mitchell and all those sixties people.

MARSH: I don't actually hear them in your work as I've read it, but-

FULTON: No, not really. I think they wrote wonderful songs, but I'm sure you've noticed if you write down those lyrics, they don't do very much. It's the music, it's the phrasing, the production that gives them life.

MARSH: It's the particular sneering way they get sung.

FULTON: Dylan certainly sneered. The difference between song lyrics and poetry is that, with poetry, the music has to be in the language itself. The language of the poem has to do everything. Musicians have instruments behind them and they have their singing voices and so on.

TRIQUARTERLY

35

If I wrote words like theirs, the words would fall flat without the tunes and chords.

MARSH: The pretend-book called Vinyl sounds like it might have to do with records. Records are a big image for you. I know you were a OJ once. What is it about records? Say some things about vinyl.

FULTON: O.K. Vinyl is a highly artificial, human-made substance with associations of resiliency, longevity, cheapness and sleaziness. I'm thinking of vinyl car seats, now, not only records. Vinyl is much tougher than natural substances. It doesn't bio-degrade, which is very bad from an ecological point of view. Vinyl is forever. It's a petroleum product, and it looks like solid oil. Vinyl is used in place of leather, but considered declasse, less lovely. However, vinyl is less cruel than leather, a material that evokes suffering-the suffering of slaughterhouses. Leather is fetishistic because it evokes the living and the dead. It's a fabric of domination-evoking not only sexual domination, but the human domination of the natural world. Leather is much more expensive than vinyl, and displaying leather is a means of asserting wealth, taste, class. Vinyl, on the other hand, is a subject of jokes and dismissal. Yet, as I've said, vinyl is more eternal than leather. Vinyl is kinder. The vinyl used in records is a repository that looks unassuming--dark, uninterestingbut within its negative space are sonic complexities, beautiful, invisible harmonics.

You reminded me of something else with your question, actually, about the effect of rock lyrics. (They were all on vinyl, for me.) I think one thing they did for me was not make sense. In those days, the sixties and seventies, lyrics were things that you puzzled over. You heard them again and again, appreciating them for everything that they didn't say clearly. You appreciated the mystery of them. Who is "the Walrus" in the Beatles song? And Dylan was terrific for lines that had resonance but couldn't be pinned down. I think today's popular music is clearer. I don't mean the sort of marginal music that is played on college radio stations but the mainstream. I've asked students, "Don't you listen to music this way anymore?" A way of listening that appreciates something for what it retains and conceals so that you had to hear it again and again. That is the appreciation I took to literature. The need to read that poem again and again was part of the pleasure. The places where the poem interested me most were those places that retained a residue I couldn't completely excavate. One of the deepest pleasures of literature

ThIQUARTERLY

36

for me was the sense that a work had no bottom: it was infinitely understandable because it couldn't be completely understood. It couldn't be seized back from connotation into denotation. There would always be a layer of meaning that I couldn't retrieve.

MARSH: Where did that happen for you? Do you remember a time when you picked up a poem and couldn't get to the bottom of it?

FULTON: All the time in high school. My sister was an English major and her books were up in the attic. Around the time I was listening to records I was also reading poetry anthologies. I'd write out Keats and Shakespeare's monologues in my own hand as a way of appropriating them. I was doing that with the song lyrics, too. It was the same appreciation. They both were mysterious and wonderful things made of words that I wanted to memorize and internalize, but even at the time, I recognized that the rock lyrics were not as good as the language of the poems. When you took away the music, the song lyrics fell flat, while the poems didn't need any music, outside of the music they made themselves. Since I'm not musically talented, I had to write poems rather than music. I would have probably become a musician if I could have.

MARSH: Who wouldn't?

FULTON: Right, who wouldn't? But I couldn't. If you could sing! To me that's the best. Many poets really want to sing, especially lyric poets, but since I couldn't, I came to poetry.

MARSH: Who was the first poet who grabbed you with the same intensity as, say, the Beatles must have grabbed you?

FULTON: Gosh, I read so many, but probably Dickinson, from way back. I loved her work when I was in high school and then of course you just go on and find out that there's a lot more than those pocket-sized, gift-shop volumes of her love poems. That was where I started, and then I realized that it didn't have to end there. Dickinson had this big body of work and so she carried me through. I became fascinated with her biography, of course. The legend of Emily Dickinson seems so romantic when you are in high school, you buy into it. You believe all that, the romantic mythology-

TRIQUARTERLY

37

MARSH: -her lowering the little basket out the window-

FULTON: -exactly, the white dress.

MARSH: Who was the first contemporary poet whose next book you would wait for with the same eagerness?

FULTON: Probably Adrienne Rich. Denise Levertov, Elizabeth Bishop, Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin. I didn't start to read contemporary poetry till the mid-seventies, when I was an undergraduate in college. The first course I took was "Women Poets" at Empire State College. It was a very small seminar, with only about four people, and our teacher, Carolyn Broadaway, was outstanding. She took us to a feminist poetry conference at Amherst College, where Adrienne Rich was reading and speaking, along with other poets of the day, feminist poets. So, I actually was sitting, literally sitting, at Adrienne Rich's feet in this informal meeting. Hearing her speak, hearing her read, and I'd already read all of her books to date in the course, along with all of Denise Levertov. Rich is one poet who made me think this is the kind of thing I wish I could do. So she was an inspiration.

MARSH: Is she still that inspiration for you?

FULTON: She'll always be a wonderful poet for me.

MARSH: A final question. Where do you think poetry's going? Which is just another way of saying where do you think the culture's going?

FULTON: Oh, it's so hard to say where poetry is going. I don't think it's going to become more popular because electronic media are on the rise, our lives are changing. Maybe not mine, I'm very old-fashioned, and I don't have much to do with television or computers, but I think electronic media are increasingly important within world culture. I also think books and poetry will always have their place. Books offer a partieular kind of intense, complex, imaginative experience that can't be found electronically or through visual images. Reading requires a more active reimagining than viewing a screen. TV and film do a lot of the work for the viewer. That's one reason they're popular. But for those who learn to read as children-I mean those who learn to love books=-reading is a kind of deep intoxication, a means of experiencing otherness

TRIQUARTERLY

38

deeply. That, nothing can replace. As long as kids still learn to read that way, I believe some of them will value books and want them around. As long as there's a written language, I think people-certain small groups of people-will prize poetry as the best example of an elegant, and thrilling, linguistic structure.

TRIQUARTERLY

39

Failure

Alice Fulton

Alice Fulton

The kings are boring, forever legislating where the sparkles in their crowns will be. Regal is easy. That's why I wear a sinking fragrance and fall to pieces in plain sight. I'll do no crying in the rain. I'll be altruistic, let others relish the spectacle-

as one subject to seizures of perfection and fragments of success, who planned to be an all-gtrl god, arrives at a flawed foundering, deposed and covered with the dung and starspit of what-is, helpless, stupid, gauche, ouch-

I'll give up walking on water. I'll make a splash. Onlookers don't want miracles. Failure is glamorous. The crash course needs its crash.

TRIQUARTERLY

40

On Donald Barthelme

Edward Hirsch

It is inevitable but still disappointing that Donald Barthelme's fiction has suffered the kind of eclipse that always seems to follow upon a writer's death. A man dies and suddenly his work is over, fully completed, posthumous. Nothing new will usher from his pen and the world passes on. Readers tum elsewhere, students discover a couple of oncefamous texts in a course on "Twentieth-Century Fiction" and wonder, perhaps, what the author was like, scholars go to work on the corpse or "oeuvre." In Barthelme's case the entire postmodern aesthetic with which he was associated-remember the Fiction Collective?-has been eclipsed as well. Barthelme is often identified with his most radical fictions, and what once thrilled other prose writers, graduate students and literary theorists-how he experimented with literary forms and dismantled the traditional short story-has come to seem passe. And yet there is an enormous gap between the reputation of Barthelme's work and the actual work itself. Forget about "metafiction'' or "surfiction" or "superfiction" (all terms he disliked). He didn't have any particular enthusiasm for fiction about fiction, anyway. What he did have was an uncanny sense of how language has been put under terrific stress in our century, of how we all have entered into a "universe of discourse." There is no escaping that universe, except, perhaps, by dying.

To begin: Barthelme is an international figure. Go to your bookshelf and take down his two retrospective collections, Sixty Stories (1981) and Forty Stories (1987). Add the novels Snow White (1967) and The Dead Father (1975). There is a good deal more of value, but you now have in your hands the indispensable work of one of the true American heirs to Kafka and Borges.

TRIQUARTERLY

41

After his death I wrote a memorial poem to a friend. I would now like to unpack that poem-a Bnrthelme-like exercise-in order to help the reevaluation of his work.

Apostrophe

(In memory of Donald Barthelme, 1931-89)

Perpetual worrier, patron of the misfit and misguided, the oddball, the longshot, irreverent black sheep in every family, middle-aged man who languishes on the couch with his head in his hands and often spends the evening drinking by himself, a dualist fated to deal in hybrids and crossbreedings, riddles without answers, slumgullions, impure waters, inappropriate longings, philosopher of acedia, of spiritual torpor, nightsweats and free-floating anxieties, sentencings, sullenness in the face of existence, wry veteran of the unresolved and the self-divided, the besotted, the much married, defender of the unhealthy and the uncommitted, collagist of that mysterious overcrowded muck we called a city, master of the solo riff and the non sequitur, the call and response, voice-overs and backtrackings, sublime bewilderments and inexplicabilities, the comedy of posthistorical desires and thwarted passions, first of the non-joiners, most unlikely, tactful, and generous of fathers, you who embarrassed the credulous and irritated the unimaginative, who entertained the void and recycled the dross, who deflated the pretentious and deepened perplexities, subject to odd stabbing rages of happiness, weird bouts of pleasure, connoisseur of mornings, of sunlight swinging into an open doorway, small boys bumping into small girls, purposefully, most self-conscious and ecstatic of ironists

TRIQUARTERLY

42

who sang uncertainties like the Song of Songs and dwelled in doubt like a habitation, my wary, unreachable, inconsolable friend, I wish I believed in another world than this so I could think of seeing you again raising your wineglass to the Holy Ghost, your "main man," and praising the mysteries, Love and Work, looking down at the weather which, as you said, is going to be fair and warmer, warmer and fair, most fair.

Apostrophe

Apostrophe: "a digression in discourse; especially, a turning away from an audience to address an absent or imaginary person." This puts the reader-the audience-in the position of overhearing that address. John Stuart Mill said, "Rhetoric is heard; poetry is overheard." W. B. Yeats modified this into "We make of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry." Miles Davis took the situation a step further by entirely turning his back on the audience. Donald Barthelme's work is also a turning away, a long quarrel with itself. He called the installments in that quarrel "stories."

(In Memory of Donald Barthelme, 1931 89)

A postmodern elegy, an elegy for a postmodernist. A Homeric sum, moning, a sort of found poem that lifts phrases and sentences from Barthelme's work to create a portrait of him. The effect is in the cross' cuttings. The problem for the poet-indeed, it is the problem of all of Barthelme's work-is what kind of language can one use when language itself is so debased in our time, so much of the problem. The ethic of his work is to go through-rather than around-the barriers of language. "Donald Barthelme": the absent friend has now become an imaginary person, a name attached to a body of work. How to memorialize him? There is a parable by Kafka called not "The Tower of Babel" but "The Pit of Babel." Barthelme is a writer sentenced to digging a passage through that subterranean pit. That is one way of putting it. Here is another: he is known for his laconic wit and astonishing incongruities. But there is a secret in his work: he is heartbreaking.

TRIQUARTERLY

43

Perpetual worrier

He was a world-class worrier. I picture him like the speaker in his story "Chablis," sitting up in the early morning, at the desk on the second floor of the house, facing the street. It is 5:30 and he is "sipping a glass of Gallo Chablis with an ice cube in it, smoking, worrying." Most of his characters, mouthpieces all, are worrying about most things most of the time. The fact that they exaggerate their fears doesn't make them any less real. In truth, they are usually scared.

In The Dead Father Barthelme proposes that the "work ethic" should be replaced by the "fear ethic" and, in a sense, that's just what he has done in his own fiction. He writes of the terror of beginnings, the absence of middles, and the elusiveness of endings." ("The Dolt") The story "Morning" commences, "Say you're frightened. Admit it." The story "The Rise of Capitalism" concludes, "Fear is a necessary precondition to meaningful action. Fear is a great mover, in the end." Fear, like longing, is the engine that turns the world

patron of the misfit and misguided, the oddball, the longshot

He had studied the melancholies and he understood outsiders, being one himself. "What is wrong with me?" the narrator asks in one story: "Why am I not a more natural person, like my wife wants me to be?" All his characters are similarly afflicted. His work is filled with freakish fig, ures whose natural habitat is alienation. The thirty-five-year-old man who absurdly finds himself in Mandible's elementary-school class with eleven-year-olds is a good example. He cries out, "Let my experience here be that of the common run, I say; let me be, please God, typical." ("Me and Miss Mandible") But of course that is not possible.

Another good example is Cecelia in "A City of Churches," who has come to Prester to open a car-rental office. Everyone in town lives in a church of one sort or another, but Cecelia doesn't even have a denomination. What she does have is a Secret.

"I can will my dreams," Cecelia said. "I can dream whatever 1 want. If I want to dream that I'm having a good time, in Paris or some other city, all I have to do is go to sleep and 1 will dream that dream. 1 can dream whatever I want."

"What do you dream, then, mostly," Mr. Phillips said, looking at her closely.

"Mostly sexual things," she said. She was not afraid of him.

TRIQUARTERLY

44

"Prester is not that kind of town," Mr. Phillips said, looking away.

Barthelme's characters are loyal to their dreams, their desires. They will not relinquish them for anything. They are afraid of themselves, but they will not be intimidated by others. They are heroes of longing.

irreverent black sheep in every family

I had gotten myself in trouble and he said that he had once been a black sheep like me, and that he would no doubt become one again. All black sheep have to stick together and help each other out, he said. He was reticent, but he was also kind. All writers are really black sheep, he said. A writing community is a whole flock of them.

In "Chablis" he remembers:

I didn't go to church because I was a black sheep. There were five children in my family and the males rotated the position of black sheep among us, the oldest one being the black sheep for a while while he was in his DWI period or whatever and then getting grayer as he maybe got a job or was in the service and then finally becoming a white sheep when he got married and had a grandchild

Barthelme's characters are ironic about everything, but especially about being respectable.

middle,aged man who languishes on the couch with his head in his hands

This is not just a matter of temperament. There is a philosophical position staked out by the non-joiner. Barthelme was a writer who always took a certain pride in distancing himself from reigning orthodoxies. He was a skeptic at heart. The theologian Brecker in the story "January" says that because you are not an enthusiast "you languish on the couch with your head in your hands." This is a stance toward the world.

and often spends the evening drinking by himself.

There were some (not all) evenings when the world seemed "fraught with the absence of promise." On those nights there was nothing to do 45

TRIQUARTERLY

"but go home and drink your nine drinks and forget about it." ("Critique de la Vie Quotidienne")

a dualist fated to deal in hybrids and cross breedings •..

Barthelme was a moral writer. His morality consisted in turning everything inside out, in seeing everything as if in a reverse lens. He called himself "an incorrigibly double-minded man." This is to say he had a dialogic or double-minded imagination and tended to see everything in contradictory or irreconcilable terms. Thus the omnipresence of two conspiring voices in his work: the Q. and A., the call and response, the open-ended dislocated conversation

riddles without answers

"It is appropriate to pause and say that the writer is one who, embarking upon a task, does not know what to do."

"A writer, says Karl Krauss, is a man who can make a riddle out of an answer." ("Not-Knowing")

slumgullions

He said:

I'm fated to deal in mixtures, slumgullions, which preclude tragedy, which requires a pure line. It's a habit of mind, a perversity. Tom Hess used to tell a story, maybe from Lewis Carroll, I don't remember, about an enraged mob storming the palace shouting "More taxes! Less bread!" As soon as I hear a proposition I immediately consider its opposite. A doubleminded man-makes for mixtures.

impure waters

All the waters, but especially the linguistic ones, are polluted now. Barthelme understood this. He could not forget it.

inappropriate longings

Barthelme greatly admired Walker Percy's book The Second Coming. In his Paris Review interview he said that "When the hero's doctors diagnosed wahnsinnige Sehnsucht or 'inappropriate longings' as what was wrong with him I like to fell off my chair. That's too beautiful to be real.

TRIQUARTERLY

.•.

46

philosopher of acedia, of spiritual torpor, nightsweats and free-floating anxieties .•.

In his last story "January," which is a kind of farewell performance in the form of a mock Paris Review interview, the theologian Thomas Brecker has written a dissertation on acedia. He explains:

Acedia refuses certain kinds of relations with others. Of course there's a concomitant loss-of being with others, intersubjectivity. In literature, someone like Huysmans exemplifies the type. You could argue that he was just a 19th Century dandy of a certain kind but that misses the point, which is that something brought him to this position. As ever, fear comes into it. I argued that acedia was a manifestation of fear and I think that's true. Here it would be a fear of the need to submit, of joining the culture, of losing that much of the self to the culture.