WIU7'ING AND WIUl'ERS:

SPECIAl. SlEenON: VO'CIES IFROM A WAR ZONE

PJ.US "enON AND POI/ETRY BY

TRICQ(1JA�u[E�[LV

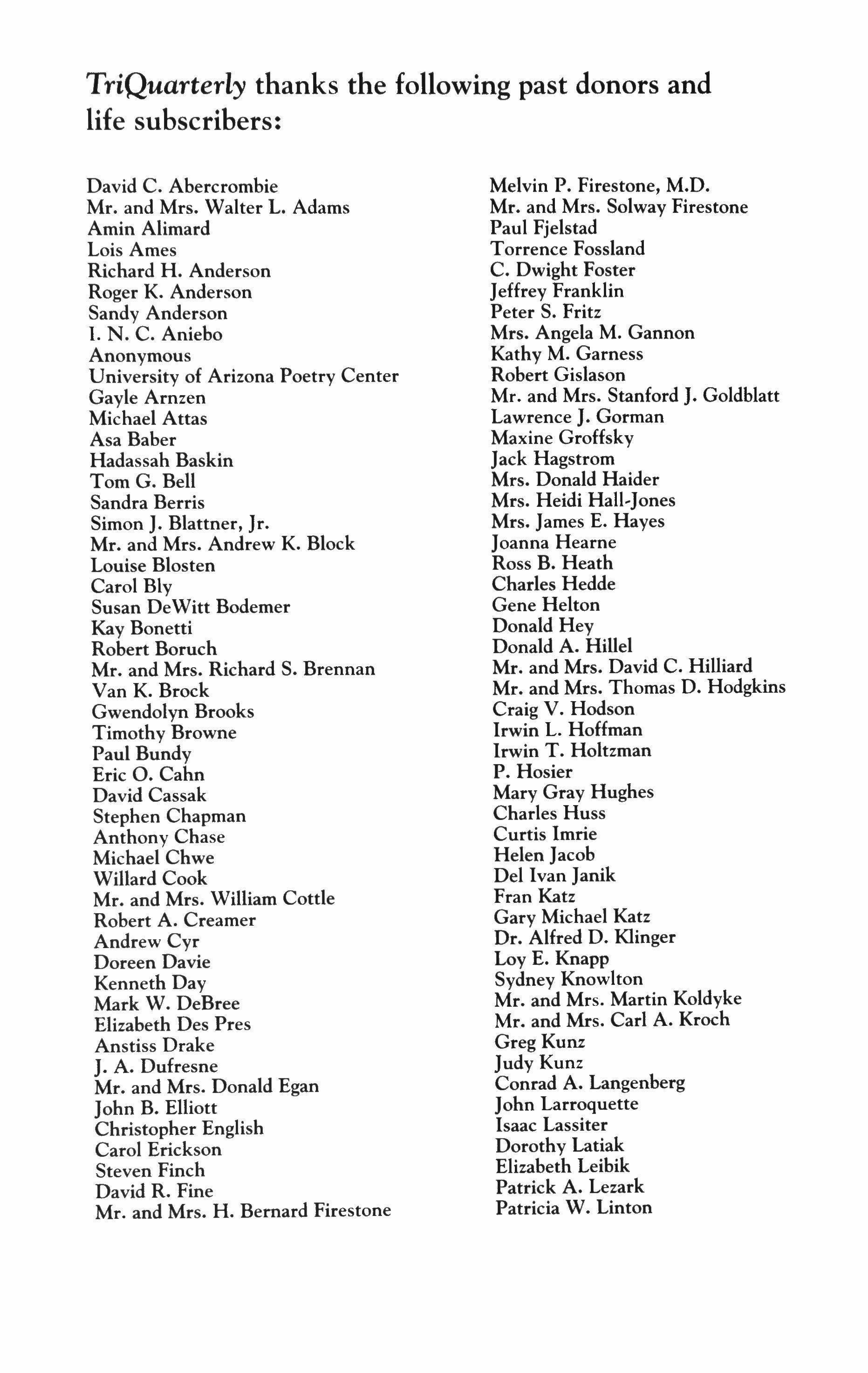

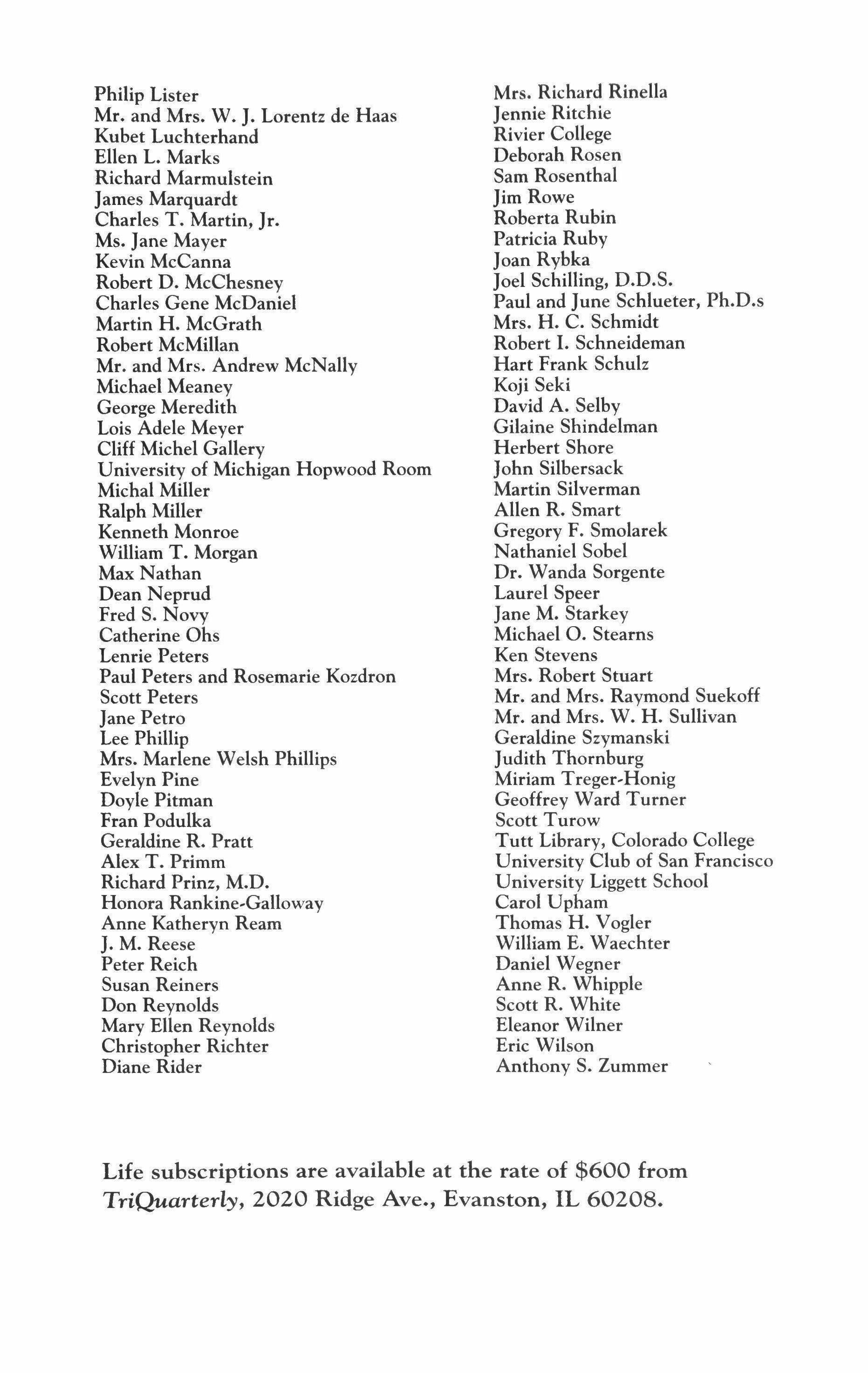

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank The Illinois Arts Council, The Lannan Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The National Endow, ment for the Arts, The Sara Lee Foundation, The Chicago Community Trust, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers:

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Paul Brownfield

Robert Creamer

Eleanore Devine

W. S. Di Piero

John B. Elliott

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

C. Dwight Foster

Amy Godine

Jay Harkey

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Irwin T. Holtzman

Helen Jacob

Loy E. Knapp

Greg Kuzma

Patrick Mangan

Charles T. Martin

Florence D. McMillan

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Dorothy J. Mikuska

Michal Miller

William T. Morgan, Jr.

Alicia Ostriker

Linda Pastan

Fran Podulka

Mark Rudman

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Susan A. Stewart

Lawrence Stewart

Dorothy H. Taylor

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

Fall 1996

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Reader

James Lang

Advisory Editors

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Deanna Kreisel, Hans Holsen, Kemba Johnson, Jacob Harrell, Dylan Rice

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of back issues varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (847) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions offiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1996 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ): Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY): Armadillo (Los Angeles, CAl: Fine Print (Austin, TX).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), Historical Abstracts, MLA, EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CAl.

The Illinois Arts Council has given the sixth annual Daniel Curley Award for Recent Illinois Short Fiction to "the author of the highestranked work of short fiction" in its competition for annual Literary Awards. The 1996 winner is Sharon Solwitz, for her story "Mercy," published in TriQuarterly #92. This $1,000 award, honoring the late writer and editor ofAscent, was given to Solwitz in addition to a regular $1,000 "companion" award for 1996, under the terms of which TriQuarterly, as publisher, received a like amount. An additional lAC Literary Award and companion award of $1,000 were given to Jean Thompson and TQ for her story "Forever," which appeared in TQ #93.

TriQuarterly is pleased to announce that three selections from TQ #92 will be included in Pushcart Prize XXI: Best of the Small Presses (1996�97 edition): "Mercy" by Sharon Solwitz and "A Man-To-Be" by Ha jin (stories), and "Fetish" by Loretta Collins (poem).

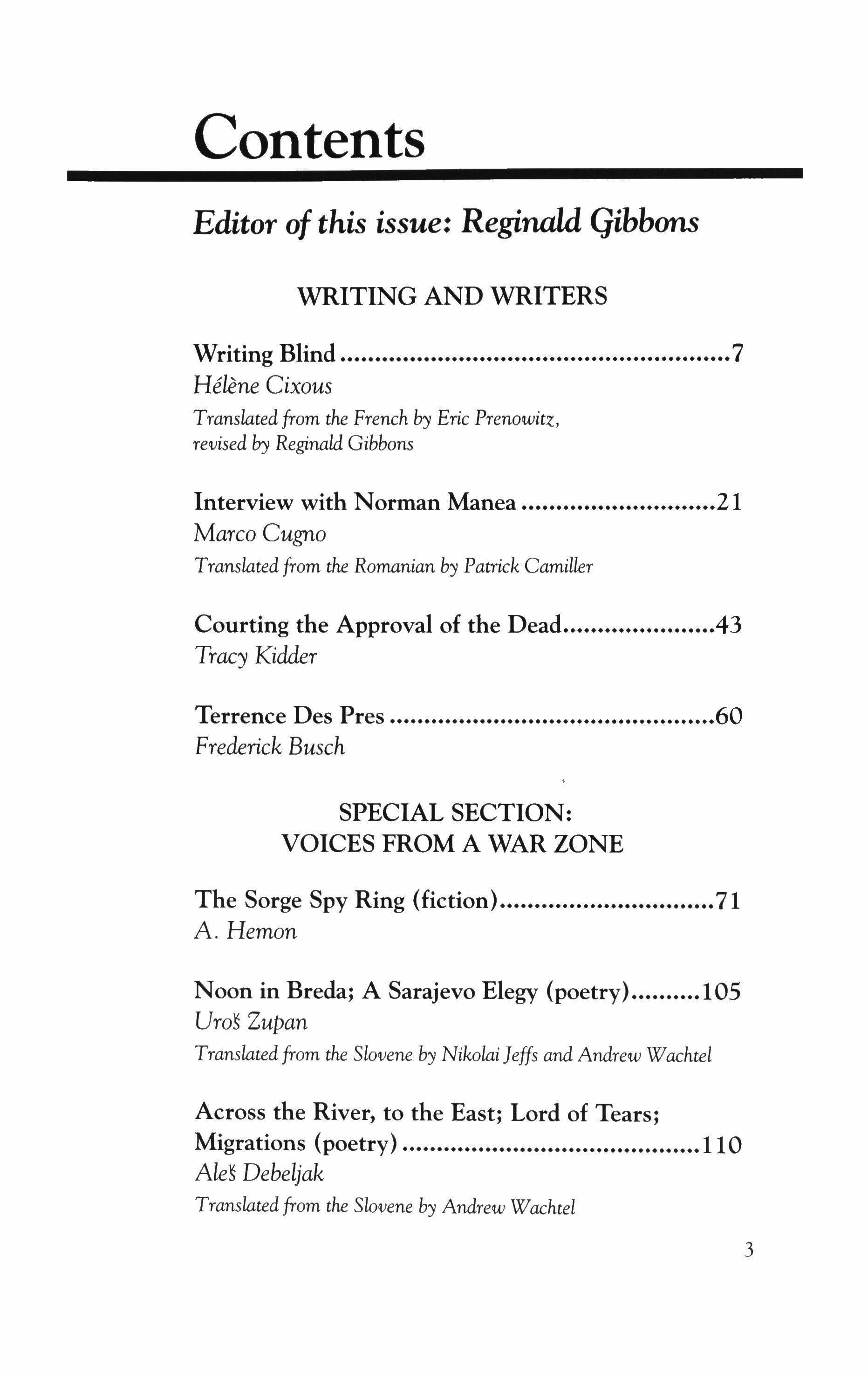

Editor ofthis issue: Reginald Gibbons

WRITING AND WRITERS

Writing Blind

Helene Cixous

Translated from the French by Eric Prenowitz, revised by Reginald Gibbons

Interview with Norman Manea 21 Marco Cugno

Translated from the Romanian by Patrick Camiller

Courting the Approval of the Dead .43 Tracy Kidder

Terrence Des Pres 60 Frederick Busch SPECIAL

The Sorge Spy Ring (fiction)

A. Hernon

Noon in Breda; A Sarajevo Elegy (poetry)

Uro� Zupan

Translated from the Slovene by Nikolai]effs and Andrew Wachtel

Across the River, to the East; Lord of Tears; Migrations (poetry) 110 Ald Debeljak

Translatedfrom the Slovene by Andrew Wachtel

Contents

7

VOICES FROM A WAR ZONE

SECTION:

71

105

3

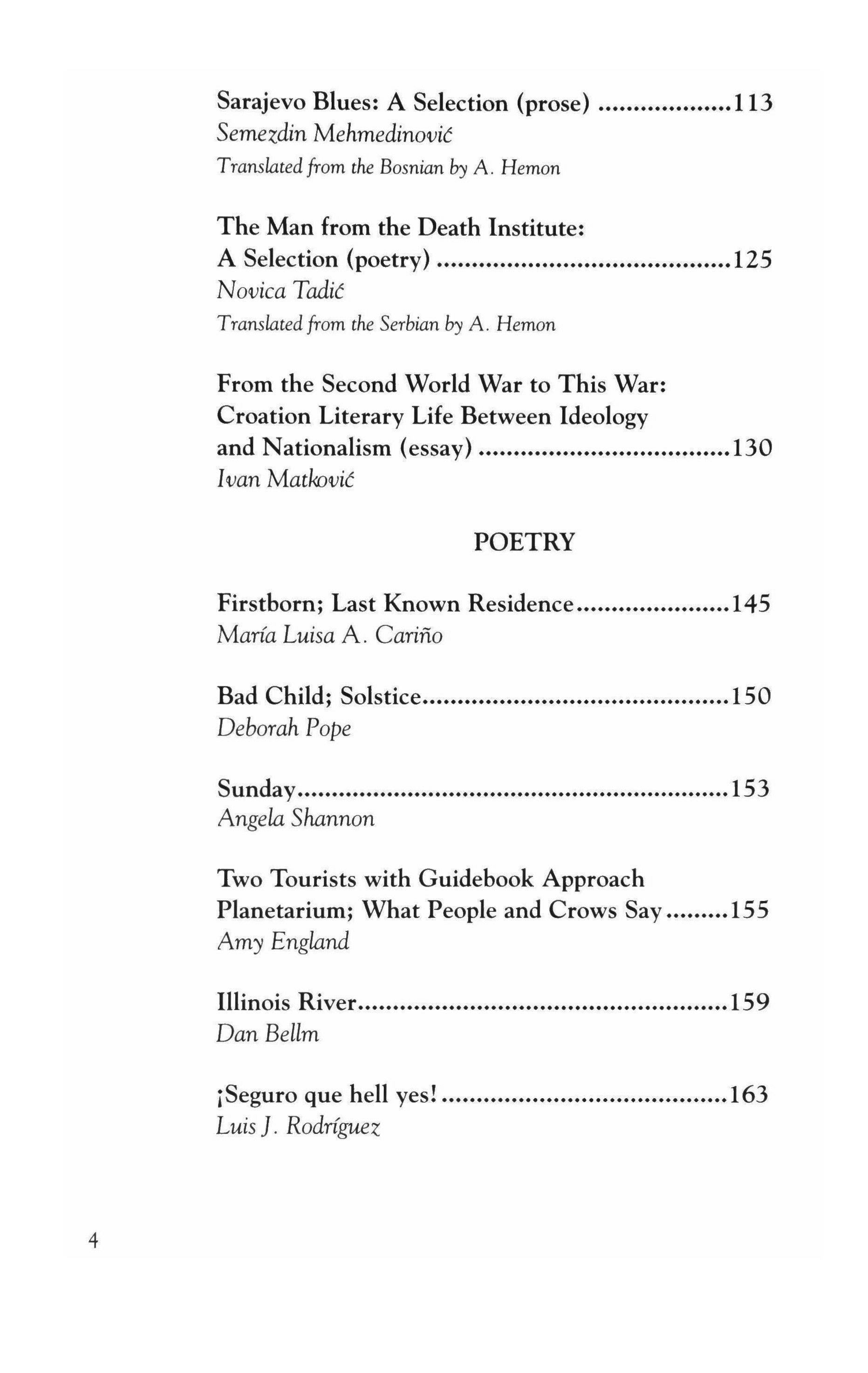

Sarajevo Blues: A Selection (prose) .........••...••••• 113 Semezdin Mehmedinovit Translated from the Bosnian by A. Heman The Man from the Death Institute: A Selection (poetry) .......••..•.....•..••......••............ 125 Novica Tadit Translated from the Serbian by A. Hemon From the Second World War to This War: Croation Literary Life Between Ideology and Nationalism (essay) •••....•..••..•..............•••.... 130 Ivan Matkovit

Firstborn; Last Known Residence 145 Mana Luisa A. Carino Bad Child; Solstice 150 Deborah Pope Sunday 153 Angela Shannon Two Tourists with Guidebook Approach Planetarium; What People and Crows Say 155 Amy England Illinois River 159 Dan Bellm iSeguro que hell yes! 163 Luis]. Rodnguez 4

POETRY

The Hole; Regulations; Barbarian; Yesterday in Elsinore; In a Second Class Compartment ...•••

Adriana Szymanska

Translated from the Polish by Ewa Hryniewicz�Yarbrough Tempo Rubato 1; Fall Recurrence; Swim;

Liliana Ursu

Translated from the Romanian by Bruce Weigl and the author

165

•••.................•.••••••••..................... 170 Elizabeth

Playing

Say; American Night 1 75

The Boat Man

Arnold

with the Mirror; What My Eyes

Ode 11.5 / To a Suitor 179 Horace

from

David Ferry Gone; Still 180 M. Wyrebek 1991 ; Peephole ........••.••..•••....••.•............... 183 Ilya Kutik Translated

Boatyard Mechanic; The Revolver......•.............. 186 Ralph Sneeden FICTION Bad Day 188 William Tester A History of Boys 197 Margot Livesey 5

Translated

the Latin by

from the Russian by Andrew Wachtel

Michelle Cliff

Portrait of Pancho Villa's Lieutenant, Manuel Hernandez Galvan, Shooting a Peso at Fifty Paces

Kevin McIlvoy CONTRIBUTORS

Cover painting, Bay ofFundy, by Kate Javens

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

TRIQUARTERLY 6

226

Transactions

237

249

Writing Blind

Helene Cixous

Translatedfrom the French by Eric Prenowitz, revised by Reginald

Gibbons

What we call the day prevents me from seeing. Solar daylight blinds me to the visionary day. The blaze of day prevents me from hearing. From seeinghearing. From hearing myself. Along with me. Along with you. Along with the mysteries.

To go off writing, I must escape from the broad daylight which takes me by the eyes, which takes my eyes and fills them with broad raw visions. I do not want to see what is shown. I want to see what is secret. What is hidden amongst the visible. I want to see the skin of the light.

I cannot write without distracting my gaze from capturing. I write by distraction. Distracted.

Whenever I go off (writing is first of all a departure, an embarkation, an expedition), I slip away from the diurnal world and diurnal sociabilitv, with a simple magic trick: I close my eyes, my ears. And presto: the moorings are broken. At that instant I am no longer of this political world. It is no more. Behind my eyelids I am in Elsewhere. In Elsewhere the other light reigns. I write by the other light.

When I close my eyes the passage opens, the dark gorge, I descend. Or rather there is descent: I entrust myself to the primitive space, I do not resist the forces that carry me off. There are no more genres [genders]. I become a thing with pricked-up ears. Night becomes a verb. I night.

I write at night. I write: the Night. The Night is such a great deity

Keynote address delivered at the conference on "Memory, the Body, and Life Writing," sponsored by the Women's Studies Program, Northwestern University, September 19,1995.

TRIQUARTERLY

7

that one day she ended by incarnating herself and appearing in one of my plays. The Night is my other day. The most prodigious half of my life. The most prodigal half. It is out of admiration and passion for her that I make the night by day. Even with my eyes open at noon, I am able to not see. When I am in pursuit of a thought which bolts off before me like some marvelous game, my eyes see only the neutral and empty space where its shadow darts away.

There is surely a scientific explanation for the way in which my eyes are capable of non-seeing my family circle, my friends, my books, my audience, but I do not know it.

Not seeing the world is the precondition for clairvoyance. But what does it mean, to see? Who sees? Who believes they know how to see?

All human beings are blind with respect to one another. The "sighted" do not see what the blind see and do not see. Non-seeing is also a kind of seeing. The blind person sees. I who am not blind do not see what the blind person sees.

To be neither blind nor very nearsighted causes a sort of blindness.

By misfortune and by secret good fortune I was born very myopic. The blind person was always my neighbor, my cousin and my terror. A little more and I was he.

My nearsightedness is the secret of my clairvoyance (I will not speak of this today). lowe a large part of my writing to my nearsightedness. I am a woman. But before being a woman I am a myope. Myopia is my secret. A secret? But what if you reveal it? Even when it is avowed, the secret is not aired: extreme myopia is inconceivable to those who are not extremely myopic. I belong to the Masonic Order of Myopes.

But myopia does not suffice to make night.

Let us close our eyes. The night takes me. Where do we go? Into the other world. Just next door. So close yet so difficult to access. But in a dash we are there. The other side. An eyelid, a membrane, separates the two kingdoms.

My myopic name, my nom de myope, is Miranda. I pass from the blurry to the clear, crying 0 Brave New World. Illusion! Indeed. What is important to me is not the appearance, it is the passage. I like the word passage. Pas sage (ill-behaved / unwise). All the passwords, all the passing and border-passwords, the words which cross the eyelid on the interior of their own body, are my magic animots, my animal-words. My philtres.

At dawn, barely awake but not yet having passed to an upright position, still on all fours and on the run, still clothed in sleep, but already convoked, I put on the brakes, I slide very slowly toward the day.

TRIQUARTERLY

8

Between the night and the day there is a long vivacious but precarious region where one can sleep even while being awake, where even standing on two legs one is still a phantom, where the doors do not yet exist between the two kingdoms, where what will be past survives, lingers, stays.

It is a fragile region that can be shattered by too brusque a gesture, a magic hour that can be chased off by too brusque an encounter with an inhabitant of the day.

What I write then knows neither limit nor hesitation. Without censorship. Between night and day. I receive the message.

Then I raise the visor, I tum my naked eyes toward the world. And I see. I see! with the naked eye, and it is exaltation itself. I pass from non-seeing to seeing-the-world. The features of the world's face rise, emerge, pass from the unperceived into presence. It is a sudden, dazzling, engendering passage. I feel myself see. Eyes are the most delicate, most powerful hands, imponderably touching the over-there. I feel a self return to me from the over-there.

Me is thus the meeting place between my seeing [sighted] soul and you. I raised the visor and behold: the world rises for me. Is given to me. The gift of the world. What is given to me in this sudden rising is at once the world and giving. I say world: its face: the physical world. Its landscape.

Now I write. That is to say that in my black interior softness, the rapid footsteps of an arriving book print themselves.

My book writes itself. Creates itself. In French [se cree]: secret. With jubilation and play. With French. Within French, riding French. Afrenching itself from French.

It amuses itself in creating itself. This also is my secret: the proof of creation is laughter. It is a marvel to feel the innumerable vibrations of the soul make themselves, collect themselves, crystallize themselves into words, to witness the rain of atoms of which Lucretius made us dream. Millions of signs rain down and in their flood they stick to one another, they kiss.

I want to write before, at the time still in fusion before the cooled-off

TRIQUARTERLY

* * *

* * *

9

time of the narrative. When we feel and there is not yet a name for it. The scene is in the entrails [gut / womb] with turmoil [commotion / tumult]' impulses [fervors / surges]. Knees knock, the heart catches fire, a great repulsion, a great attraction, later it will be pacified into a name [noun]. But first it is passion. Our common fate. The tempest before fixation. The l-know-not-what-torrnents-rne. The inexhaustible manifestation of nerves. With confusion and summits. Heartrending joy. In the anguish, hope. I want to paint our subterranean soul. There are already words. But not yet proper names. Here, by the way, before, nothing is proper, nothing is of its own. This is why my books have no titles. Giving a title is an act of appropriation. The books for which I am the scribe belong to everyone. An employee of Air France tells me: I like your books because they touch me. We all like to touch-to be touched. Above all by the books that have a soft and violent gaze. The Air France employee, the Algerian actress, my unknown and my known friends, we have a great many atoms in common. My business is to translate our emotions. First we sense things. Then I write. This act of writing engenders the author. I write the genesis that occurs before the author. How does one write the genesis? Just before? I write on writing. I turn on the other light.

This is done in the way life happens to us, by gusts, by events, depositing discontinuous elements. The link exists, however: it is the thread of breathing. It continues to discontinue.

To write by shreds, by storm clouds, by visions, by violent chapters, in the present as in the archpast, in pre-vision, in the true chaos of verbal tenses, crossing over years and oceans at a god's pace, with the past on my right and the future on my left-this is forbidden in academies, it is permitted in apocalypses. What joy it is. All those who secretly have not broken with the earliest times are so happy when they find the giantities [geances] of their magic oral stage behind the policed mask of a book.

It is always there, just behind thought, behind the eyelids: the kingdom whose queen is poetic freedom, and where all these values that do not have civil rights in reasonable and so-called democratic society are reaffirmed: there we can say: justice, truth, love, forgiveness, responsibility, we can speak a language that is laughable in the city governed democratically by law, Realpolitik, conflict, hate, state lies, media irresponsibility.

No, I am not painting for you a picture of an ideal kingdom. On the other side there is good with evil. Good in evil, evil in good, and above all: difficulty. Life-on-the-other-side is difficult, you feel you are some-

TRIQUARTERLY

10

what alone, or very alone, very mad, in climbing the slopes of what Kierkegaard calls the absolute.

And if there were not that donkey to keep Abraham company it would be infernal. But there is the donkey. The animal-I will come back to this-that puts a limit on abandonment. The Bible does not report the conversation Abraham had with the donkey on Mount Moriah. And this does not surprise me. I want to give the donkey with Abraham a chance to speak. I want to give the donkey the floor.

One does not say foolish things [betises] to a donkey, don't you agree? Nor to a cat. It is only to another human being that one says foolish things, that one chats, that one strays from the point, that one lies. It is the human who is a dunce

With the donkey, we ride straight to the essentials, and right away.

I write on the donkey. (Dunce and donkey. Duncity is a human, not a donkey.)

I am trying at this moment to capture the mysteries of passage so as to confide them to you, this is an attempt to note down what goes much faster than my consciousness and my hand. But passage, luckily, leaves traces. One must act fast. And no time to learn.

I do not command, I do not concept, I chase after what goes beyond me. On occasion I try to go after four hares at once and I am all out of breath and contorted [dislocated]. So then 1 stop and I get my breath back.

When 1 write 1 do nothing on purpose, except stop. My only voluntary intervention is interruption. Breaking. Cutting. Letting go. Cutting is an art I have acquired. There is nothing more natural and more necessary. All living beings, mammal or vegetable, know that one must cut and trim to relaunch life. Do harm to do good.

In language I like and I practice the leap and the shortcut, ellipsis, amphibology, speed and slowness, asyndeton. Speed is a means of defending oneself against dishonesty. An actor who plays too slowly, lies. But of course an actor who plays too fast, in a single tone, swallowing the words, also lies.

One must play language quickly and in pitch like an honest musician, not leap over one single word-beat. Find the slowness inside the speed.

Language has innumerable resources of acceleration, and this is how it gets close to the vital processes which go faster than lightning.

TRIQUARTERLY

* * *

11

This speed is not superficial. It strikes deep. It is grace. I have an idiomatic gift of grace. I do not know why or how it was accorded to me. I receive it and foster it.

The text comes over me too fast for my slowness in recording. What to do? I take down the squall in notes. My sentences retain something of this telegraphy.

A book writes itself quickly. How long did it take you to write this book? There is a long time and a short time. Add on my whole life.

There is gestation and giving birth. The book is written at full speed when it is ready. I have always given birth quickly and without pain-at full term. A detachment. Maturity.

But beforehand, before term, where is it, where is that which will come into the world, how does it prepare itself? The womb is all the world. The child is made from all sides. Throughout months, years. It is not me, it is at the crossing of my thinking body and the flux of living events that the thing is secreted. I will only be the door and the spokesperson supplying words. The linguistic receptor. The scribe.

Then comes the time of imminence. A desire to write rises in my body and comes to occupy my heart. Everything beats faster. My entire body readies itself. I say to my daughter: "I feel like writing." Thirst cannot be refused or rejected. I do not say: I have an idea. I have no idea what this book will be. But very quickly scenes, sentences press forth and scarcely have I noted down twenty pages or so, when I discover not the content but the direction, the paths and the song of the book.

At times I prepare myself to speak. "I have a few things to say," I say to myself. This is how I prepare my seminar, for two or three days. When the day comes for it, it does not at all happen as planned: what I say is infinitely far from what I had counted on saying.

At times I want to say essential, complex things to the someone I love. I note them down. I will say them later on the telephone. The telephone is the indispensable medium for profound exchanges. The voice plunges its sentences directly into the depths of the other person. Now the telephone is ringing. I begin. With you I always avoid chatting because it falls dead before life. To say what is essential, I hurry, I launch a sentence of great density which burrows into your deep mysterious internity. With all the lightning weight of a prayer. There. The sentence now voyages into your internal silence.

We never reach the goal hoped for. But we can reach a goal unhopedfor. At times this can hold good surprises for me.

TRIQUARTERLY

*** 12

A book does not have a head and feet. It does not have a front door. It is written from all over at once, you enter it through a hundred windows. It enters you. A book is just about round. But since to appear, i.e. to be published, it must adjust itself into a rectangular parallelepiped, at a certain moment you cut the sphere, you flatten it, you square it up. You give the planet the form of a tomb. The book has only to await resurrection. Quickening.

They have to be written to the quick, on the now, Live,

All these scenes, all these events which only happen once. All the second starts are new beginnings. (Garden moments in springtime: the walks in the garden with daughter and mother remain unforgettable. Ten-years-ago grows back today. My mother, my daughter and I, in the garden we engender ourselves reciprocally.)

If you do not grab them in the instant they pass, these pulsations are lost forever. In the moment where in passing they brush by us, they whisper at our neck, knocking at the doors of our senses, at our ears, at our nostrils, they wake in us thoughts never yet formed. If you do not grab them "in flight," by the fringes of their dresses, by the edge, by the verbal traces, by the tips of the fingers.

So, have on hand a notebook, a bit of paper, and capture the rapid traces of the instant, which the past, arriving at full speed, will engulf in a few minutes. What has just happened will perish. Strange and exultant encounter between the quick and its end. One moves ahead leaving behind. Human destiny: to be flesh of forgetting. And to have no more vivacious desire than to wrest one's prey from forgetfulness, to keep the passing in the present.

A combat with bereavement. One must forget in order to re-present oneself virgin, to offer oneself virgin to the new year.

One must make allowance for death.

We die very much. We bury a great deal.

We cover the tombs and the burials with fertile earth.

One must take the living instant with the closest and the most delicate words. Without words as witnesses the instant (will not have been) is

TRIQUARTERLY

* * *

* * *

13

not. I do not write to keep. I write to feel. I write to touch the body of the instant with the tips of my words.

Above all do not waste time passing from the outside to the inside. Don't waste time wiping your feet before entering. The first sentence takes off like an arrow, and sticks in the heart of internity. It plants the earth of internity. Before it, there was no earth. And already, right away, under the hooves of the sentence bursts forth the expanse of a land to discover.

Neither preamble, nor antechamber. A foreign language must ring right from the first words.

Enter a sentence. And there was the book. And it had never before been seen. We leap from sentence to sentence.

I adore the multiple powers of sentences.

Often the events in my life come in sentences or are sentences.

But no manufacturing, no mechanical fabrication. Astounding or stunning sentences come by surprise. Like divine messages: prophecies of the present. If only we heard (ourselves: s'entendre)! If only we saw (ourselves)! If only we read (ourselves). A comma is worth Cleopatra's nose. And vice versa. Destinies balance on a word [are toppled over by a word]. On the unfathomable ambiguities of a verb in the present tense, the present that is the future: I call you: je r'appele.

Words-what chance and what energy!

However much we may forget where we come from, from what distant foreign countries, the words remember, in our very mouth.

They say everything, in Gothic and in Greek, they make us spit out language. They avow our hidden worst thoughts, our unknown thinking. It suffices to listen to our politicians: the twisted use they make of words. The words denounce them. So many people imagine that words are teeth in a pair of dentures. Or fossils.

But not at all. Words (l saw them with my eyes when I was three years old) are our dwarfs, our gnomes, our minuscule workers in the mines under the language. They perforate our deafness. They forethink. And at times they are the Scandinavian tomtes or else the imps. Naturally they know what goes on, in the more or less well-tended corners of the back of our mind. As everyone wants not to know, we all have the words we deserve. These little agents which are so ancient never stop joking and bringing us gifts in secret. Too bad for those who consider words to be worn-down pebbles. An etymological presentiment guides me. Call it a good nose. I smell the odor of origins on the most familiar words. At this very moment I am addressing you in Indo-European. Words go half the

TRIQUARTERLY

14

way for us, they do half the transportation, rushing from the Scamander and from the Rhine and from the Ganges they launch forth and with never-worn-out feet they come to strike the earth of the text.

I sense that in each book, words with hidden roots come and go in the thick of the text and carry out some other book between the lines. Suddenly I notice strange fruits in my garden. It is these verbal dwarfs who have made them grow.

And what words do between themselves-couplings, matings, hybridizations-is genius. An erotic and fertile genius. A law of life presides over their crossings [cross-breedings]. Only words in love inseminate [and disseminate: Seulement des mots que s'aiment semeru]. Superior semantics.

Language is not finished. We are all capable of being provisional demiurges, in creating newborns. Language lends itself willingly to these genetic miracles.

A newborn word moves us. A word born out of the love of two words is not a concept. Pfeilige. lnternity. It is only a poetic individual. Models? No models: there are none where I go, the savage earth is still being invented. But while I move ahead alone in the mobile night, I perceive the signals of other nocturnal vessels sailing under the same sky. It is because there is always that famous secret society, the Masonic Order of the Alert, the entirely diasporated people of border-jumpers. No one of them imitates another. But each one recognizes that the other is also responding to the [a] calL And we hear their passwords resonate. There is not one unique password, one shibboleth. Each has his own according to his language, and it is all the language of each that is shibboleth. The sonorous night is a caravan. Kayrawan came from Persia in the thirteenth century. And to sense that dead and surviving starsearchers share the solitude is reassuring. The solitude of each writing is always shared [partagee], partaken.

About the author

It is undoubtedly the death of my author that grafted in me the obligation to make sentences. I must write, or else the world will not exist. I must make everything: the world, the night, the day, the garden, the cooking, the childing, the countries; and I myselfdepend on this gesture. I write to replace the deceased author. I do not say "disappeared," because he is not entirely disappeared: he returns. I cannot not write: I must weave the firstdays of the year [New Year's days]. Planting, constructing, raising All of this is to keep death at a respectful distance.

TRIQUARTERLY

15

Death and I, we dialogize.

It is not a desire for mastery or for triumph. It is the fabrication of the raft riding on nothingness.

I have often said that my father, in going off precipitately, took with him the floor of the world and all the temple. It was terrifying to see that ruin. And so what happened to the family? Each one made a gesture to saturate the abyss. My mother became a midwife. My brother is almost a midwife, he is a pediatrician. Each one of us got busy around the process of bringing the world into the world. I set myself to weaving time. A year without a book-this has never happened to me, a year without the fabric of life. But I can go for as much as eight months, nine months, without putting into the world a world where I can put myself. But not longer.

But this world is first of all a stage, so that the characters of the theater's play can make their entrance.

A book and I are the hen and the egg. A self-fertilizing, dense, precise, polyglot and polyphonous language-in who engenders whom, who engenders who.

But how is it that I do not speak that language of writing when I speak? I cannot write in the air with my voice? When I speak-no writing, only discourse.

Answer:

The text needs the paper. It is in the contact with the sheet of paper that sentences emerge. As if coming out with great wing-strokes from a nest hidden beneath the paper. Maybe the sheet of paper is Khora?*

It is not written in my head. There must be the contact between my hand and the paper. I am not an intellectual. I am a painter. No computers. You do not paint with a computer. I paint, I draw the sentences from the secret well. I paint the passage: one cannot speak it. One can only perform it. No, never computers. The idea of the machine-that-isnot-me and that looks at me with its eye and reflects words in my eye reminds me of Polyphemus. Straight away I slip under the belly of a sheep, and body against body with the animal, my face buried in the wool, I flee the Computer that stares at my Night.

No, no eyes facing my blindness. I write without seeing that I write and what I write. As when we make love. It is a making with perfect dexterity and necessity, but we close our eyes so as not to distract our

* See Plato, Timaeus.

TRIQUARTERLY

16

body, not to divert it from its intimate course.

As when we make love with the loved one, the only one, the one who is me, the one we trust as our own mother, the one I believe with my eyes shut, and I close my eyes so as better to believe, and so that the exterior will not exist, and so that we will be the two of us together in the hand of one same Night.

About the person whose name is You

I write you: I write to you and I write you. I will never say enough what my writing owes you.

I address myself to you. You are my address.

Each book is in a certain way a letter that wants to be received by you.

But it is not for you that I write: it is by you, passing through you, because of you-and thanks to you each book takes every liberty. A crazy liberty. The liberty, the freedom to not resemble, to not obey. But the book itself it not crazy. It has its deep logic. But without you I would be afraid of never being able to return from the ascension of Mount Crazy. But I can lose myself without anxiety because you keep me. The book is not a narrative, it is not a discourse, it is a poetic animal machine; the grain of its skin is pure poem. Because you keep watch.

The book gives itself the freedom to escape from the laws of society. It does not fit the description. It does not answer the signals. It does not get a visa.

For the police-force reader it seems to be an anarchic thing, an untamed animal. It incites and triggers the reflex to arrest. But the freedom my book gives itself is not insane. It exercises the right to invention, to research. We only search for what no one has yet found, but which exists nonetheless. We search for one land, we find another.

The word God in French: Ie mot Dieu: Ie mot d'yeux: the word (of the) eyes. Melodious. The name God: Ie nom Dieu.

Whom do I call God, what do I call god? The necessity of the word god. No language can do without a word god. I like the French word dieu. The word-god: Ie mot-dieu. Le mot dit eux: the word says them. God is dog in the English mirror.

This page writes itself without help, it is the proof of the existence of gods.

God is always already di�eu [go-d], di/vided, aimed at by us, hit, split.

TRIQUARTERLY

* * *

17

Lips open in his absence of face. And he smiles on us. Dieu's smile speaks of the wound that we are to him.

* * *

I have never written without Dieu. Once I was reproached for it. Dieu they said is not a feminist. Because they believed in a pre-existing God. But God is of my making. But God, I said, is the phantom of writing, it is her pretext and her promise. God is the name of what has not yet been said. Without the word Dieu to shelter the infinite multiplicity of all that could be said, the world would be reduced to its shell and I to my skin. Dieu stands for all the names that have never yet been invent, ed. Dieu is the synonym.

God is not the one "known" in religions, the one who is attached like Samson the donkey to the wheel of religions.

His true name? We will know it on the last day, it's promised.

The force that makes me write, the always,unexpected Messiah, the returning spirit or the spirit of returning-it is you.

Everybody knows that one must not wait expectantly for the Messiah, he can only come unexpected.

* * *

You have always just left, you come from leaving: tu viens de partir. Leaving is the condition for returning. Then there is the beginning of an "l-believe-you-will-return." It is always accompanied by a "But if ?," in French a Messie, a Messiah, But if-mais si-you did not return?

It is an I want that does not dare to believe. Not-daring-to-believe is a very delicate form of belief.

The temptation to not believe and belief breathe in the same breath. I believe that you will come and this belief is accompanied by its indissociable double which is (a) but if: a messie-messiah.

Just before you arrive, when I almost hear your footsteps, I am struck with belief, even though I knew you would come. I did not know. And I begin to tremble.

Knowing is not believing. Knowing does not believe. Knowing is with, out fever and without life.

My thinking self waits for you. And there is another myself who trernbles.

I myself, I do not believe in miracles. One must not believe in mira' cles. If you believe in miracles, then there are none.

TRIQUARTERLY

*** 18

I have a cat who took me so much by surprise that she is named Miracle. In the night of my writing I am subject to the laws of hospitality. I welcome new-comer terms. And if they want to leave again, I do not hold them.

I have a submission for what arrives, and a submission for what returns. This is why I tremble and fear. I fear that the Messiah will arrive and I fear that the Messiah will not arrive.

If I had known that I would come to (have) a cat or that one day a cat would come to me, I would have said no. I would not have wanted it.

This is how she came. Unwanted. Entirely unexpected. Never desired beforehand.

And so I love her. We cannot not love the found child. What we love is the undesired. The arrival of what is desired satisfies us but does not fill us with enthusiasm. Enthuse, says the god.

More than everything in the world, we love the creature we would never have expected. Never thought of loving.

Me, a cat?

This is a chapter of a book that could be called the imitation of the she-cat.

How does a book arrive? Like a barely weaned she-cat who sticks a small hand out from under the wood-stove. And a few days later it is she who explains humanity to you.

Who would have believed that I could love an animal and imitate a she-cat? And now I believe.

I have already learned a lot from her. She brings me closer to the formation of the soul.

I will stop shortly.

The sense of the ridiculous is the first difference between a god and me. The sense of the ridiculous is my modem comic dimension. I burst out laughing in the tension between the two measurements of our own character. Between the giant and the dwarf that we are. When the dwarf puts on a dress that is too big and the giant a shoe that is too small, we stumble. Walking is difficult, uneven. Freudian slip, subconsciously deliberate mistake, lapsus, disjunction, inadequacy-my story is ridiculous, as is yours. The smallness of the great character is multiplied by his greatness.

The Fall is ridiculous. But in the Bible no one laughs [we do not laugh / there is no laughing]. The sense of sin keeps God from laughing. It is coming up against the limit [going against the limitation] that makes us laugh.

TRIQUARTERLY

19

In my Bible, we have the sense of the ridiculous. It is a great liberty. We enjoy it when we do not have the constraint of contrition. So chased from paradise, I go off precipitately and concretely without having had the time to take my shower. Then I spend the whole day looking for a bathroom. In complete contravention of the sense of epic decorum.

And glasses [spectacles]? Can we imagine a literature without glasses today? How did the myopic heroes manage before the walls of Troy?

We cannot imagine Phaedra entering on stage with glasses. And yet? Cleopatra with glasses is a violation [act of violence]. I want Phaedra not to be ashamed to wear glasses.

My effort in language and in thematics is to break with interdictions and false modesties. This is why I go so willingly into the house of dreams: I admire them for their aptitude for nondiscrimination. It is in their house that the equal light from before the guilty feeling reigns. Neither pride, not shame. It is only in dreams that we are strong and generous enough to look God in the face while he bursts out laughing. That creation, really! Those creatures! It takes some doing! And I laugh also to have caught God doing what he has never done elsewhere.

TRIQUARTERLY

20

Interview with Norman Manea

Marco Cugno

Translated from the Romanian by

Patrick Camiller

You left Romania in 1986, in the final period of the Ceausescu dictatorship. After a short stay in Germany, you have been livingfor a number of years in the U. S. Could you perhaps give us the outlines of an autobiographical portrait?

At the end of the war, in 1945, I returned from the camp where I had been deported by Hitler's ally, the Antonescu government, together with my family and all the Jews from Bukovina. I was then nine years old, and on my birthday I was given a book of Romanian folktales. That was a crucial moment, when I discovered with fascination the miracle of the word, when I fell in love with books and language. The magic of lit, erature probably started then. A deep aspiration towards something else, beyond the banality and triviality of everyday life. Illness and therapy at the same time. An obsession that intensified or diverted or deformed, in a special way, the episodes of my life-story. After I finished school, I would have liked to study literature, of course. My family was, I think, already scared by my reading and my interests, but also by what they saw as my vulnerability. In the end I studied engineering-not because I had been convinced of the advantages of a "safe job," but because it was still the high,Stalinist period and Professor Marco Cugno of the University of Turin conducted this interview, which appeared in the review Linea d'Ombra (February 1995), on the occasion of the publication by Feltrinelli of Norman Manea's Un paradiso forzato.

TRIQUARTERLY

21

I hoped that a concrete, useful occupation would give at least some pro' teetion from the surrounding ideological pressure, and because I was disgusted by the stupid demagogy in which "socialist literature," still strongly Proletkultist, indulged at the time. I wasted the best years of my youth in a quite unsuitable and extremely tiring profession. But it did make me directly familiar with interesting people and situations that I would not otherwise have come across. While an engineer, I naturally continued to read intensively and to write. Once the so-called "liberalization" came in the mid-sixties, I began to be published. My debut was in 1966, in the tiny literary review Povestea Vorbii, run by the "talentspotter" M. R. Paraschivescu. In just six issues, before it was suppressed, the journal's four mini-pages promoted unknown names who would later become some of the most important poets and prose writers of contemporary Romanian literature. In 1969 my first volume of short stories, Noaptea pe latura lunga [The Night on the Long Side], was published with a preface by the same M. R. Paraschivescu, who saw in me his great "coup." Other books followed in subsequent years. I could probably write a small volume about my "adventures" with publishing houses and censors in connection with each book of mine that appeared in Romania, whether because it was apolitical or because it had a political theme. But somehow or other, I had published ten volumes in Romania by 1986 (short stories, novels and essays).

The joy of reading and the fervor of literary projects make up for a lot of misery in the real world. The writer finds refuge in books and language, "even when the language is German and the writer Jewish," as Celan once said. Life is unpredictably short: you can't touch off too many changes if you want to have anything to show for it-that's how I used to think in my years as a writer in Romania. When there was no longer anything to hope for, I still delayed leaving for too long. And when I was forced to leave, I still hoped to return to my books, to writing and language. I hesitated for an inadmissibly long time, before I accepted exile.

I left Romania in 1986, "at the very last moment," with a one-month tourist visa. I wasn't at all decided to remain abroad. But I have never once been back, not even for a visit. In 1988, when I was already in Washington, my mother died. And in 1989 my father, then eighty-one years old, emigrated to Israel.

You were born in Bukovina, like Paul Celano What has Bukovina represented in the history ofRomania?

TRIQUARTERLY

22

It would be too complicated here to dwell on Bukovina's historical position as a borderland between empires and a zone of traffic and exchange between Romania, Poland, Ukraine, Austria, and so on. Bukovina has a superb natural location in northeast Romania. Thanks to its past as a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it has been a fertile medium for stimulating intellectual communication, a cosmopolitan region in which Romanians, Jews, Germans, Poles and Ukrainians have lived side by side. Bukovina also occupies a privileged position in creative life, not just for Romanians but also for the other ethnic groups. It has sometimes been called "the placenta of Romanian literature," because of the important writers who originated there, but it has also produced Yiddish, Hebrew, German and Ukrainian writers of undoubted value. Unfortunately part of Bukovina was taken from Romania by the Soviet Union in 1940, in accordance with secret clauses of the MolotovRibbentrop Pact. So today the famous Cernauti (Czernowitz), once known as the "little Vienna," is absurdly a "Ukrainian" city.

Can you tell us something about your family and its origins? Also about how the Jews came to Romania, the role they played, and their integration or non' integration?

A "family tree" is much harder to draw up for a Jew than for a member of a static and stable community who has been spared the hostility of the surrounding world and the need to migrate from one place to anether. I have tried without success, for example, to discover the real origin of my name, Manea, which sounds distinctly Romanian. Did it come from Mann or Manes, or perhaps even Manovici? No one in my family has ever been able to clear up the mystery for me. My grandfather on my father's side already bore this name. He had it when he fought as a soldier in the Romanian army. I actually knew my grandfathers: they were very different from each other. Each occupied himself with a key element in life: books and bread. I was closer to my maternal grandfather, a bookseller from a traditionally Jewish, religious family linked to books; it was the cerebral and depressive side of the family, full of anxiety and humor. That grandfather was deported with us, and he died in the camp during the terrible winter of 1941�42. I also knew my other grandfather a little: he was a baker, the type of the Jewish peasant looking after a farm with horses, cows and sheep, and having lots of children. That was the calmer, more balanced side of my family, more bound up with nature and the immediate joys of life.

TRIQUARTERLY

23

The first Jewish presence in Romania was already noted during the time of the Romans; the legions stationed in Dacia included a number of Jews, probably drawn from the Middle East. Then they came in sever, al waves-hounded by History but also, more than once, invited by Moldovan princes to stimulate trade and develop market centers. They mostly originated from the great Ashkenazi communities of Russia and Poland, but some came from the Sephardi communities of Turkey, Bulgaria and Greece to the south. Their relations with people in the country of settlement were not simple-as they have never been any' where, especially throughout Eastern Europe where the hostility of the local population has expressed itself also in cycles of violence. The situ, ation in the whole region was sometimes better, sometimes worse. But what distinguishes Romania from neighboring countries is that it was the last to grant civil rights to the Jews, and then only under great inter, national pressure and after numerous protests inside the country, some by sections of the intelligentsia.

My own family was typical of a certain middle position when the war broke out and everything became caught up in the pathological whirlpool of nightmare. At the time my father was a bookkeeper at a factory: his material situation was quite good and his social position was developing.

Your childhood experience of being deported to a Nazi camp in the Ukraine has marked you forever as a man and a uniter. Some of your most moving short stories (I am thinking, for example, of "Proust's Tea" or "The Sweater" in the October Eight O'Clock collection) are bound up with this experience. Would you remind us of what happened in Romania during those years?

Nationalism and anti-Semitism had become a danger throughout Europe in the period immediately after I was born. In the case of Romania, nationalism had already picked up steam after the First World War and the Treaty of Versailles, which made it possible to declare a Greater Romania including the whole of Transylvania, Bessarabia, Bukovina and parts of Dobruja. This brought in not only the extra Romanians who formed the majority in these areas, but also sizable minorities of Hungarians, Germans, Jews, Ukrainians and others. By the late thirties, Romanian anti-Semitism was a dynamic, exuberant and aggressive force, with real power to lure the electorate. The question of emigrating naturally arose in many Jewish families. But my parents had no spirit of adventure and (like me, though for different reasons) proved

TRIQUARTERLY

24

vulnerable to the snares of hope. "We were never educated to give up hope, and that is why we are dying today in the gas chambers," wrote Borowski, a non-jewish Polish author interned at Auschwitz.

In the autumn of 1941, when we were squeezed into cattle trucks to take us across the Dniester to the camps of Transnistria, my parents managed to take along money they had saved up as newlyweds to buy a house. But they would never have a house of their own-not after the war, either. The sufferings of Transnistria taught them enough, of course, about the destructive power of hope-but also about its miracles, because we did survive in spite of everything.

Transnistria was a terrible experience, but it was not Auschwitz. (That can be seen from the number of survivors-about fifty percent, I think.) Unlike Auschwitz, however, which was a German camp, Transnistria was a Romanian camp set up by the Romanian regime of Antonescu for [ewish-Romanian citizens of the Romanian state. The words of Jean Paulhan are difficult to forget: "Ah, I would like to be Jewish to say, with more authority than I can have, that I have forgiven France once and for all for its powerlessness to defend me."l In our case it wasn't that our state had been powerless to defend us; it had intended to exterrninate us.

After the war, a part of my family left Romania. The youngest of my aunts came one day to announce that she had bought tickets for us all on a ship to Palestine. My father's reply was: "I haven't got the strength to pack again. I've only just finished unpacking." A bitter joke, because we did not have a thing to our name. We had just returned as skeletons from the camp, and no one had "compensated" us either for the goods we had lost, or for the unhealable trauma through which we had lived. We were starting again from "ground zero," in the hope that the tragedy just over had taught people to be more tolerant and intelligent and better. All we had to lose were the chains of hope. Very soon we would be prisoners of a different kind-in the communist paradise of great compulsory hopes, where hopelessness invented new codes and new frontiers for itself.

What did it mean for you to be Jewish? Did you feel first and foremost a Romanian or a Jew? In a country where you "really tried to find roots" as a man and writer, but where nationalism took the path of anti,Semitism at vatious historical moments, did it ever happen that you felt yourself to be "some, one apart"?

TRIQUARTERLY

25

Freud rightly asked what is still Jewish if you are not religious or nationalist, and if you don't know the language of the Bible. What is still Jewish, that is, in a Jew who has lost everything that would define him as such? A lot, perhaps the main thing-replied the ultra-assimilated Austrian Jew, but without defining the main thing.

When you discover your [ewishness in a camp at the age of five, your options disappear as you are instantly connected to an ancient collective tragedy. At too early an age, the Holocaust was my first brutal initiation into existence. Later, communist totalitarianism meant not only the banning and uprooting of the tradition, but also a complicated instruction in what it is to be marginal as a suspect. Finally, on the threshold of old age, exile returned me to the condition of alien and nomad which I had thought to overcome by rooting myself in the Ianguage and culture of the land of my birth.

But the Jew is not, as Sartre thought, defined only by the antagonism of others; nor is it enough to be born of Jewish parents, like Jesus of Nazareth. In the end we are defined by what history does and by what each of us makes of this "misfortune," as Heine put it. The Jewish Diaspora, stretching back thousands of years, has made it difficult to define Jewish identity, and not just because a Jew is also Russian, Romanian, Argentinean or American, or even Israeli. Jewish transcendence remains contradictory and paradoxical, but resistant to disasters, and so easily demonizable in the hostile world in which it has always disclosed itself.

The Jewish destiny is in the end only an exacerbation, through suffering, of the human destiny. A passing exile in the earthly adventure, a sarcastic initiation in the drama of being a man among men: the mirror that the Jew holds up to the world is not at all indulgent. Yet the history of the outcast which has left the imprint of creativity in his halting places, as a spiritual trace in the culture of the peoples whose paths he has crossed, seems to me to be one of the most stirring human records. In this respect, despite its unparalleled traumas, the Jewish destiny carries an exemplary constructive accent, at once generous and stimulating. It is not easy for me to redefine myself, after all that has happened and is still happening to me and the country in which I lived, as well as between me and the country to which I belonged. I remember the amazement I felt in 1971 when I leafed through a book published abroad under the title Romanian�Speaking Jewish Writers. The anthology contained my first text published abroad, in Israel. It was a most elegant and presentable volume, but I thought of myself simply as a Romanian

TRIQUARTERLY

26

writer. The question of my ethnicity-which I had never exalted and never denied-seemed a purely personal matter that concerned no one but me. That is how I thought then, and it is how I would like to think today. Meanwhile, however, too many sad incidents in Romania and in the Romanian emigration have reminded me of that moment in 1971 and forced me to think more about it, to realize that rather few people see things as I do and that I may have been wrong in not taking into account the many, too many, who think differently.

The truth is that art is the most individualized profession, and one's implicit or explicit membership in a community enters too capriciously into the ever-fluid equation of creativity for its effects to be foreseen. A book stands alone in the dock; no ethnic emblem can save it. Nor can the writer's loneliness be pacified simply by falling into line with the community. If the poet has always been considered a kind of Jew, the Jewish writer, accustomed at too early an age to the ironies of fate, can claim a binary risk as a result of his writing and his Jewishness.

Would you say something about the period of your human and intellectual formation? In "The Instructor" you describe a young man's dual initiation: into Judaism (through his family) and into communism (through the state). Does the story permit of a biographical reading?

I was formed, by way of deformation, in postwar Romania. Despite the terrible pressure that the so-called socialist system exerted through every means, I struggled as best I could to expand my opportunities for information, reading and intellectual development.

Evil is rarely perfect. The communist evil was not perfect, either. To demonize totalitarian communist society would today be too easy a simplification; it would be to ignore the fundamentally imperfect nature of human reality, which remains essential to an understanding of that malign human experiment initiated by men, executed, tolerated and sabotaged by men, and for that very reason capable of being regenerated some day, in one form or another.

Beyond its many ambiguities, "real socialism" was essentially a system of "institutionalized lying." What were the enclaves in which resistance was possible-that is in which truth and individuality could be protected? It was only by finding solutions, even partial ones, involving authenticity, intimacy and personality, that the self could resist the constant external pressures. In other words, it was through reading, friendship, love, belief, sex, everything that could be defended (from state ownership of

TRIQUARTERLY

27

our thoughts and our soul) as the last, secret, coded expression of personal wealth (and life). As Primo Levi said about the camps, even "thinking and observing were factors of survival."

No one escaped without being affected, however. The survivors are partial victims (the full ones being dead), but their wounds do not just go away.

Yes, "The lnstructor'f can be related to my own experience. As a teenager I was tom between the communist utopia and my family tradition, which-without being bigoted-preserved some of the more important Jewish rituals. At the age of thirteen, I was a fiery and dreamy young communist whose family wanted at all costs to celebrate his male coming of age in accordance with Jewish tradition. At seventeen I was already cured of communist illusions-and there was no special merit in that. You just had to keep your eyes open, not to be seduced by the vice and adventure of deception, not to want to climb the social ladder at any price. But my moving away from communism did not mean a return to Jewish tradition. The hero of "The Instructor" eventually chooses the third way-the path of creation and art. That is, he chooses the chimera of writing. It is his way of bestowing durability and even transcendence upon his fellow creatures, who are gradually leaving the biography of the place, and even his own biography. It is, in the end, an attempt to bestow posterity upon them through art.

Literature was a great chance in the effort to resist degradation and to survive the darkness. During the wartime siege of Leningrad, when people would eat mice and freeze alive, many found an extraordinary regenerative power in the re-reading of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Primo Levi, in Auschwitz, revived by reading Dante again, not antifascist poems. In the conditions of the socialist regime, literature increased its chances as a kind of revitalizing dialogue with elevated voices of invisible friends. In my life as a reader, and not just as a writer, there has been a moment of Proust, a moment of Faulkner, a moment of Latin American literature, a moment ofJoyce. I could never forget the joyful excitement with which I read Musil, Kafka, Svevo Schulz or a lot of contemporary American literature. I was especially concerned with the modem "fissure" in art and its literary expression. Books from another world helped me to return to writing after cyclical periods of depression. Similarly, in my youth the great Russian writers, who were copiously translated during the Stalinist period (Turgenev, Pushkin, Lermontov, Chekhov, Tolstoy, Goncharov, and later Dostoevsky), helped me to resist eretinization through "socialist realism" and to keep as far as possible from official literature.

TRIQUARTERLY

28

In a book recently published in Romania called Incursions into Contemporary Literature, a young critic, Ion Simut, considered your work in a chapter entitled "Escapism Literature." I was very surprised by this: 1'd have thought the most suitable chapter was the one devoted to "Subversive Literature." What is your own view of this? As a writer, did you think of yourself then as a dissident, as an oppositionist?

In this case, I suppose "escapism" meant work whose concerns were mainly aesthetic, though written in a closed, ideologically rigid, totalitarian society. I haven't read Ion Simut's book, but I gather from a survey in a Romanian magazine that I have been placed in several categories: escapist, but also subversive and exile literature. To be fitted into one category would anyway probably have been too simplistic-and not just in my own case. The postwar decades in Eastern Europe were not uniform, nor was the literature written during them. In fact, an alternation between severe "closure" and hesitant "opening," between terror and relative relaxation, marked the dynamic of the time I lived there.

My first short story, "Ironing Out Love," which was published in 1966, contradicted official canons by its lack of any political content, at a time when literature was still always required to be outspokenly "com' mitted." It was an erotic story full of anxiety, which tried to recover a naturalness of language and subject matter. It was immediately attacked in the official press, together with other texts published in the same avant-garde magazine, which was suspended after just a few issues.

My last book to appear in Romania-The Black Envelope, in 1986was an edgy and violent allegory of daily life under the Ceausescu regime. It had serious and far-reaching political implications, at a time when the authorities were happy for a writer to remain a mere "aesthete," indifferent to the terrible reality around him. It is understand, able why The Black Envelope was repeatedly turned down by Ceausescu's censorship, and why it eventually appeared only in a mutilated form. In Romania, I once wrote about aesthetics [estetica] as "East-ethics" [est, etica], and it wasn't just playing with words. A writer's integrity required that he remain faithful to the artistic criterion that was defied and defiled by the tricks of official politics. But it also entailed moral and civic fortitude in the face of the living, manipulation and masquerade directed by the country's rulers.

I was not a dissident. Nor was I some vicious "renegade" from the Party who, barely yesterday, had drooled over the utopia of general hap, piness and its immediate privileges, only to become frenzied with disap-

TRIQUARTERLY

29

pointment at the broken illusions and lost privileges. 1 was just a writer who thought it necessary to defend the quality of his writing, and at the same time, as citizen, to express whenever possible an honest opinion about the reality in which he was living. 1 thus differed both from colleagues who were concerned in their writing only to praise the regime (or only to attack it) and from those who considered that any risky "commitment" was a stain on the noble art.

Now that the system has collapsed, 1 am not at all sure what will remain from the texts 1 published in those hard and complicated times. 1 am sure, however, that they do not contain a single line about which 1 should feel morally ashamed-not a trace, that is, of complaisance or complicity towards the system. That stubbornness in defending my integrity probably deserves some good words. But that doesn't mean 1 was some kind of hero. As a matter of fact, I'm not very keen on those who set themselves up as professional victims or martyrs, as spotless embodiments of suffering or courage. There were quite a few honest writers even in those harsh conditions. And there were also many nameless people who, without being writers, and without the resonance of a public name or the justification of a "lofty spiritual mission" with which some like to puff up their words, nevertheless managed to remain honest in their silence and solitude, marginalized within that dumbly "laughing popular chorus," as Bakhtin would put it.

What made you decide to take the path of exile in 1986? For a uniter whose main fatherland is language ("language was my only support"), it must have been an extremely painful and traumatic thing to go through. Did your expertence ofuniting The Black Envelope and getting it published as you described it in "Censor's Report"3 playa role in your decision? Had you lost all hope of being able to write and publish in those conditions a work that was really yours? Had "internal exile"-a condition to which nonopportunistic uniters were in effect condemned-become such an unbearable solution for you?

However difficult things may be, you don't leave your country and language just like that. 1 had gradually learned to dissimulate my vulnerability, to protect it, to convert it into the energy of reading and writing. What could 1 do with that vulnerability in exile, in the West? During all those years 1 could have emigrated legally to Israel. But I kept on resisting, in the broad abode of my language, and in the ever smaller, darker and unfriendlier abode of the country where I was born. Despite the suffering and humiliation which had already been reserved for me in child-

TRIQUARTERLY

30

hood, and which continued in different ways, I actually looked even with a certain condescension at those who were fleeing towards something better.

In the years I lived in so-called socialist, "multilaterally developed" Romania, it seemed to me that we had all become ")ews" to such an extent that it would have been indecent to complain of the extra burden placed on "nonnatives." Yet in 1981, when nationalism, chauvinism and anti-Semitism reached a nauseating level, I suddenly had the feeling that the nightmare of 1941�42 was returning. Then, in an interview with the magazine Familia, I was the first to protest against the famous nationalist and anti-Semitic manifesto "Ideals," which was published in the official weekly Saptamina, a kind of disguised cultural organ of the Securitate. The man responsible for the article was one of the Party's most irritating gutter-publicists, who is today prominently seated in Romania's new parliament. Anyway, after the interview I immediately became the object of violent attacks in the official press, which continued well into 1982. I was called "anti-Party," "cosmopolitan," "extra-territorial," and so on. The pressure kept growing around me-as I could feel whenever anything of mine was published. There was already a black aura around my name; I could easily detect it during "negotiations" with the censors about my volume of essays Contour, which was published in 1984. The Black Envelope adventure really was a nightmare. The hope without hopes that kept me tied to place and language was called literature. But the chimera kept growing weaker as it receded into the distance, tired, sullied, disjointed, diminished as I already was myself. Even in 1987, however, finding myself in Berlin, I did not accept the idea of a break when I learnt that Romania's grandiose Council for Socialist Culture and Education had revoked the literary prize just awarded to me by the Writers' Union. There was no precedent for such a measure in the forty years of "socialist culture" since the war. I answered the absurdity with an absurdity of my own: I protested to the president of the Union, in a letter that I knew would be intercepted by high "organs" of the state. Radio Free Europe explained the cancellation of the prize by the anti-Semitic attacks on the author that had been appearing for a long time in the official press, and concluded that "as far as the censorship of names is concerned, that of Norman Manea is one of the most undesirable." How unprepared I was to swap internal exile for exile properly so called, can be seen from the fact that once I arrived, without great enthusiasm, in America, I delayed for three years before resigning myself to the new situation.

TRIQUARTERLY

31

Would you explain more precisely how the censorship functioned after its offi� cial abolition by Ceausescu in 1977? In fact, there were different forms of censorship during those forty years ofdictatorship.

With the liberalization of the mid-sixties the censorship criteria became more ambiguous. This made it possible for major works of world literature, both classic and modem, to be published at a dizzying pace, as well as some valuable contemporary Romanian literature that could never have appeared in the Stalinist period. Very soon, the system rernernbered the danger that exists in words, in books. But the censors could no longer simply return to the militarv-tvpe regulations of the Stalinist period, even though they tried to stop the liberalization process through various tricks and delays. In the eighties Ceausescu had one of his "genius" brain waves: he would abolish censorship, in a move designed to confuse absolutely everybody! In reality, it was a "substitution" much as meat was substituted for by soya salami, wine by a kind of wood-juice, and television by two hours a day of songs in praise of the matchless Blabberer with whom providence had presented us. The dismantled censorship would be replaced with "self-responsibility." In other words, special committees of "working people" at newspapers, magazines and publishing houses, as well as at their printers and, even higher, at the ministry upon which everyone depended, would take the decisions and "assume responsibility" for what was published. Thus, instead of one central body with official authority, there appeared a series of successive "filters," so that not even a funeral announcement or an advertisement could be published without "the approval of the working people." Furthermore, the Council for Socialist Culture and Education gradually set up "reading committees" which, like the old censorship, "reviewed" what had already passed the exacting demands and the "responsibility" of the poor "working people."

I remember that in 1982 or 1983, at a literary colloquium in Belgrade, a Romanian publisher was asked if it was true that censorship no longer existed in his country. Yes, it's true, he proudly confirmed. So why do pornographic or anticommunist or religious books not appear in Romania? Not because we have censorship, but because we ourselves do not want such books-answered the director of one of the best foreignliterature publishing houses in socialist Romania. And he did not bat an eyelid.

And how did selfcensorship "function"?

TRIQUARTERLY

32

In the post-Stalinist decades, self-censorship also became more flexible, more complex, more treacherous-sometimes, of course, even paradoxical. I know from my own experience that in the eighties many of us were used to "overdoing it": that is, we would put into the manuscript submitted for publication a mass of irritating but superficial details about everyday reality which were not at all indispensable to the critical message we wanted to convey, so that in the likely "haggling" with the censor we could give some of them up while actually keeping the text as we wanted it to be. The strategy sometimes proved risky, especially in the final years when the administrative apparatus of a system macerating in its own morbid juices took on quite demented forms. The very word "chemist," for example, was suspect and hard to get printed, because it might allude to the country's number,one chemist, Elena Ceausescu, who had not finished primary school on time, yet was a member not just of the Romanian Academy but also of many prestigious foreign academies.

For all the censorship and selfcensorship, though, a number of more daring books and other texts continued to be published. Was there some kind of "complicity" on the part of the authorities? Did they consider some texts as necessary safety valves to be tolerated or even "provoked"?

There were some areas of complicity, of course. It has always been said in Romania that the law lasts for three days, that what really count are "connections." As for texts "given the go-ahead by the police," as we used to say, and launched with a label of great courage, they only increased the suspicion surrounding writers who were genuinely suspect, troublesome or subversive.

Most texts of that kind had a political theme, of course. Sometimes they focused on a Party activist, an ideological colonizer of the present, showing a conflict between the "good," progressive communist in step with the times, and the "bad" communist who had been left behind. Usually, such "courageous" works appeared after some tactical shift by the Central Committee, when it was admitted that "mistakes and even serious breaches have been committed" but that the very fact of selfcriticism demonstrated "the Party's strength and the correctness of its basic principles." The authors in question were really like activists with vague literary pretensions: they used a simplistic narrative structure, and a solemn tone, as at a Party meeting. "Combative" and easy to read,

TRIQUARTERLY

33

such concoctions had huge pressruns and sometimes enjoyed success among a public thirsty for any criticism, even within the rhetoric of the Party. It was a fundamentally deceitful literature in keeping with the duplicity of the system; its themes of major importance were reserved for those who enjoyed, among other privileges, the possibility of criticizing from "inside" the Party's fraternal milieu, the passing and evidently cur, able shortcomings of the society. The "dialectical" rhetoric of these seemingly courageous works meant that the meaning could be cleverly turned around at any moment; the most violent accusations could thus be "positively" recuperated by the system, as in that standard lawyer's trick of adopting the opponent's arguments and turning them to one's own advantage. Such works "debated" the great problems of great moments, at a time when "true" reality was unfolding beneath the sur, face, in a confusing state of atomization which constantly ground to dust both great and minor events, and which was ultimately characterized by a persistent absence of epic qualities, by the annihilation of the epic. The situation facing writers has never been easy anywhere in the world. On the threshold of a new millennium, when it is hard to foresee whether and in what forms literature will survive, the difficulties facing writers in the ex-communist countries are, to be sure, far from trivial. The "closed," repressive society honored them with excessive privileges and sanctions, giving them a greater role than they had ever had before. And so today it is not easy for them to learn to negotiate, not with one all-powerful and astute Maecenas, the State, but with a host of small and big,time literary "sponsors" whose popular, commercial tastes are often not at all better than those of the single Party. They have to face the harshly competitive world of publishing houses, the trivialization of mass,audience television, even the weariness of genuine readers of liter, ature, not to speak of the psycho-cultural makeup of the new genera, tion. These are all symptoms of a terrible crisis in the "open society" as well-a crisis of all possibilities, competitions and manipulations. But if we were to compare literature written in the open society, for all its "democratic" shortcomings, with what has been written in the past forty or seventy years in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, in the conditions of "closure" of totalitarian communism, then we would see that it is preferable, even from a literary point of view, to confront democratic difficulties rather than the opposite kind. Very soon, the problems facing writers in Eastern Europe will no longer be part of "the transition" but belong to present-day capitalist society, where culture is commercially "democratized" and trivialized, but where there are still writers of

TRIQUARTERLY

34

great originality who defend their artistic integrity. And great books of modernity do still appear there-works of this complex and painful twentieth century, not of that totalitarian "blind alley" which disastrously shaped the backward sensibility and thought of millions of people and held back a whole geo,cultural area with huge spiritual potential from entering the crude truth of modernity.

Do you still feel a writer in exile? Some writers in exile are now shuttling back and forth. Others, such as Paul Goma, have explicitly and categorically refused to return to Romania. Is it possible that you will return? Do you think you will go back?

I don't feel at all tempted to stroll in Bucharest today, along a boulevard that might be named after Marshal Antonescu, the military dictator who sent me as a child in 1941 to the camps for Jews in Transnistria. Nor do I feel tempted to look at shop windows displaying Nicolae Ceausescu Vodka, to witness the attempts to rehabilitate the dictator who poisoned the years of my adult life, or to contemplate the victorious cynicism of his cultural flunkies again dominating the public plat' forms of Romanian demagogy. I don't imagine I would get much pleasure from beholding Romania's new parliament or the new pan' tomime of some old clowns. And I must confess that I am scared by the evolution of certain people to whom I once felt close.

Before the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellites, Brodsky said that the writer returns even when he does not return. He was referring, of course, to the return of his work. In the current atmosphere I am still hesitating even about the repatriation of my writings! In recent years I have often thought of the Austrian writer Thomas Bernhardt, who, though living in Vienna, forbade the publication of his books in an Austria that refused to examine its sores and its guilt. Bernhardt did, of course, publish in other German-speaking countries, so that his writings also reached his own country. And Bernhardt was not a Jew: his defiant action therefore had a different weight, expressing a kind of "national" pride. Moreover, a certain seriousness is required for such a serious decision to be contemplated. In Romania it does not seem to matter very much whether you do or do not return, whether your writings do or do not return. Such a spectacular gesture, especially on the part of a "non, native," would probably do no more than raise some skeptical smiles of disdain. I would therefore prefer to run down my presence in the literary and public life of today's Romania, in a rather discreet way.

TRIQUARTERLY

35

You wrote a much-discussed essay on Mircea Eliade, also published in Italy, which was really about the "responsibility" of intellectuals. What was the responsibility of intellectuals during the period of communist dictatorship? Can one speak of a "trahison des clercs," to use Benda's expression?

I would like to dwell for a moment on the Eliade essay, because it has some connection with your previous question. It was first published in 1991 in the American journal The New Republic, and reprinted the next year in my own Clowns collection.