Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers:

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Paul Brownfield

Robert Creamer

Eleanore Devine

W. S. Di Piero

John B. Elliott

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

C. Dwight Foster

Amy Godine

Jay Harkey

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Irwin T. Holtzman

Helen Jacob

Loy E. Knapp

Greg Kuzma

Patrick Mangan

Charles T. Martin

Florence D. McMillan

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Dorothy J. Mikuska

Michal Miller

William T. Morgan, Jr.

Alicia Ostriker

Linda Pastan

Fran Podulka

Mark Rudman

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Susan A. Stewart

Lawrence Stewart

Dorothy H. Taylor

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

SPRING 1996 BOOKS AND BACKLIST

SHOOTING THE WORKS

w. s. DI PIERO

Shooting the Works: On Poetry and Pictures

These essays are elegant and passionate tributes to the intersection of art and self, from educated ruminations on the frescoes ofFlorence's Santa Maria del Carmine to the politics of Pound to reflections on his workingclass background and poetic development. Di Piero may be the most giftedpoet-critic ofhis generation.

Di Piero's taste andjudgments are refreshingly idiosyncratic, his frame ofreference broad. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

W. S. Di Piero is the author of six volumes of poetry and two earlier volumes of essays on art, literature and personalexperience. He has also produced acclaimed translations from Italian poetry. He is a professor of English and creative writing at Stanford University.

230 pages $29.95, cloth (0-8101-5051-4) $14.95, paper (0-8101-5052-2)

•• ••

TriQuarterly New Writers

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

words, words, words.

Paint's the thing. The rich, rhythmic slide through veins drained of blood. The heart

stripped to brittleness and ache, the job that deadens, the devouring, cowering family, all, all, all

redeemed -from "The Sexual Jackson Pollock" by Terri Brown-Davidson

136 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5057-3)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5058-1)

BRUCE WEIGL

Sweet Lorain

76 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5053-0)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5054-9)

This unique collection showcases ten new writers (five poets and five fiction writers) who have won recognition only in the medium of the literary magazine. The anthology presents the best of new voices discovered through TriQuarterly magazine and TriQuarterly Books. From an 0. Henry Award-winner to an MBA, contributors include Yolanda Barnes, Tammie Bob, Terri Brown-Davidson, Eileen Cherry, Loretta Collins, Page Dougherty Delano, Steve Fay, William Loizeaux, Dean Shavit and Cassandra Smith.

Bruce Weigl is an elegist of the lives of those who have been changed by hardship and suffering, especially by war. In his continuing quest for emotional and spiritual enlightenment, he explores the connections between his childhood in a workingclass world, and the effect of the American war in Vietnam on all of us. With characteristic fluid syntax and strong metaphor, Weigl vividly depicts one life lived in two vastly different worlds.

Bruce Weigl teaches at Pennsylvania State University. Sweet Lorain is his seventh collection ofpoems.

Bruce Weigl has become one ofthe best poets now writing in America.

-Denise Levertov

STERLING A. BROWN

The Collected Poems ofSterling A. Brown

EDITED BY MICHAEL S. HARPER

One of the most important of American poets, Sterling Brown is a contemporary of Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Jean Toomer. At once thoughtful and daring, Brown is known for his handling of folk materials, for his lack of pretension, and for his frank and unflinching portrayal of the Southern African-American experience. This is the definitive collection of his poems, and the only edition available in the U.S.

This is a great book ofpoems, stunningin its artistry andgigantic in its vision.

-Philip Levine

WILLIAM OLSEN

Vision of a Storm Cloud

Olsen's poems are energetic, expansive and romantic; his ability to manipulate language, image and form harkens back to the traditions of Blake and Whitman, while his range of subject and his use of metaphor forge his own uniqueand contemporary-artistic signature. These poems are a rich, dense and polished example of the voice of a strong new poet.

William Olsen teaches English at the University of Western Michigan. His poems have appeared in numerous periodicals, including the Paris Review, the Nation, the New Republic and Crazyhorse.

267 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5045-X)

136 pages $35, cloth (0-8101-5043-3) $13.95, paper (0-8101-5044-1)

THE COLLECTED POEMS OF + STERLING A. BROWN -t:r £tI;/uJity/lfic/" IS.H4,],"

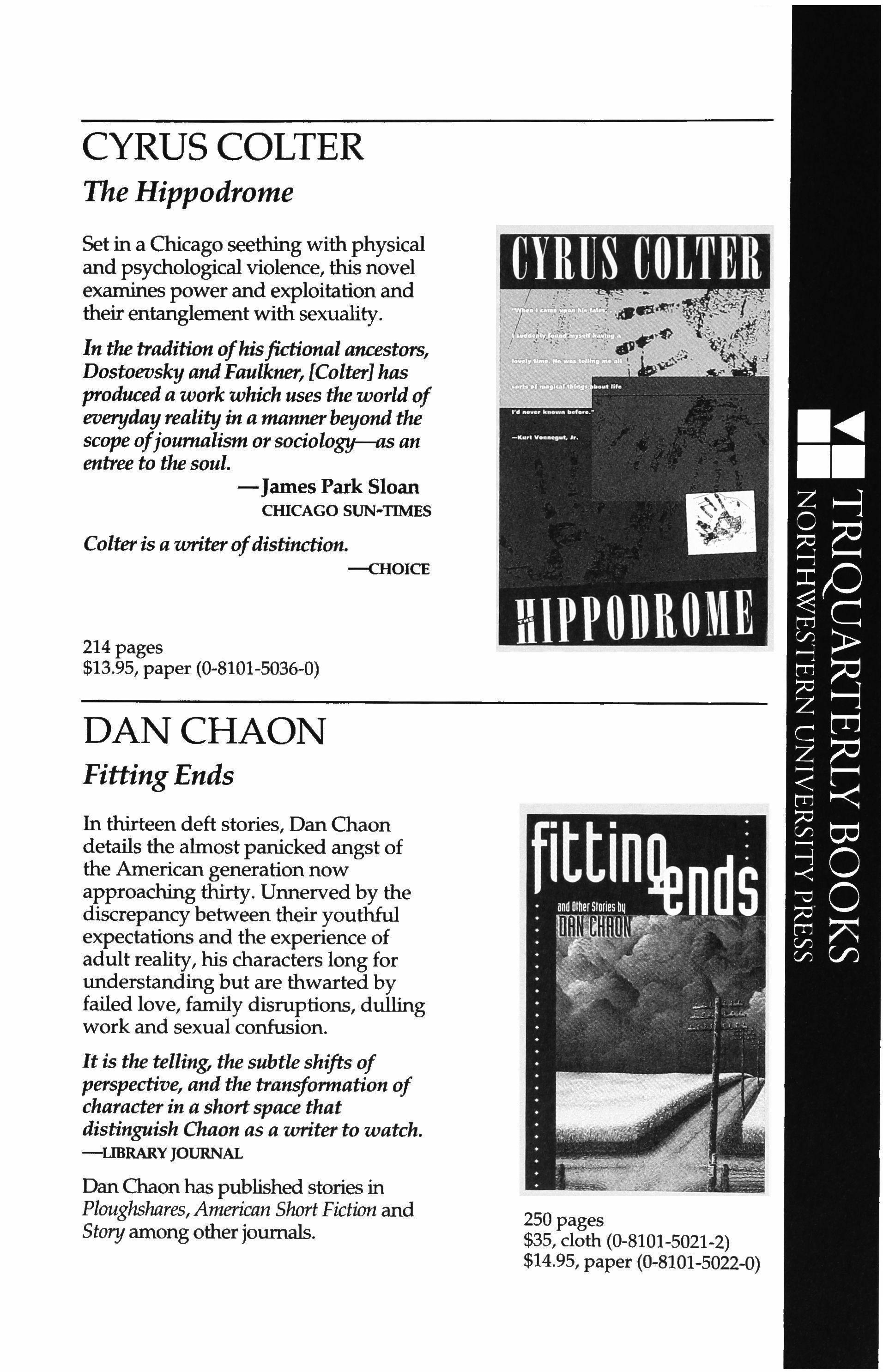

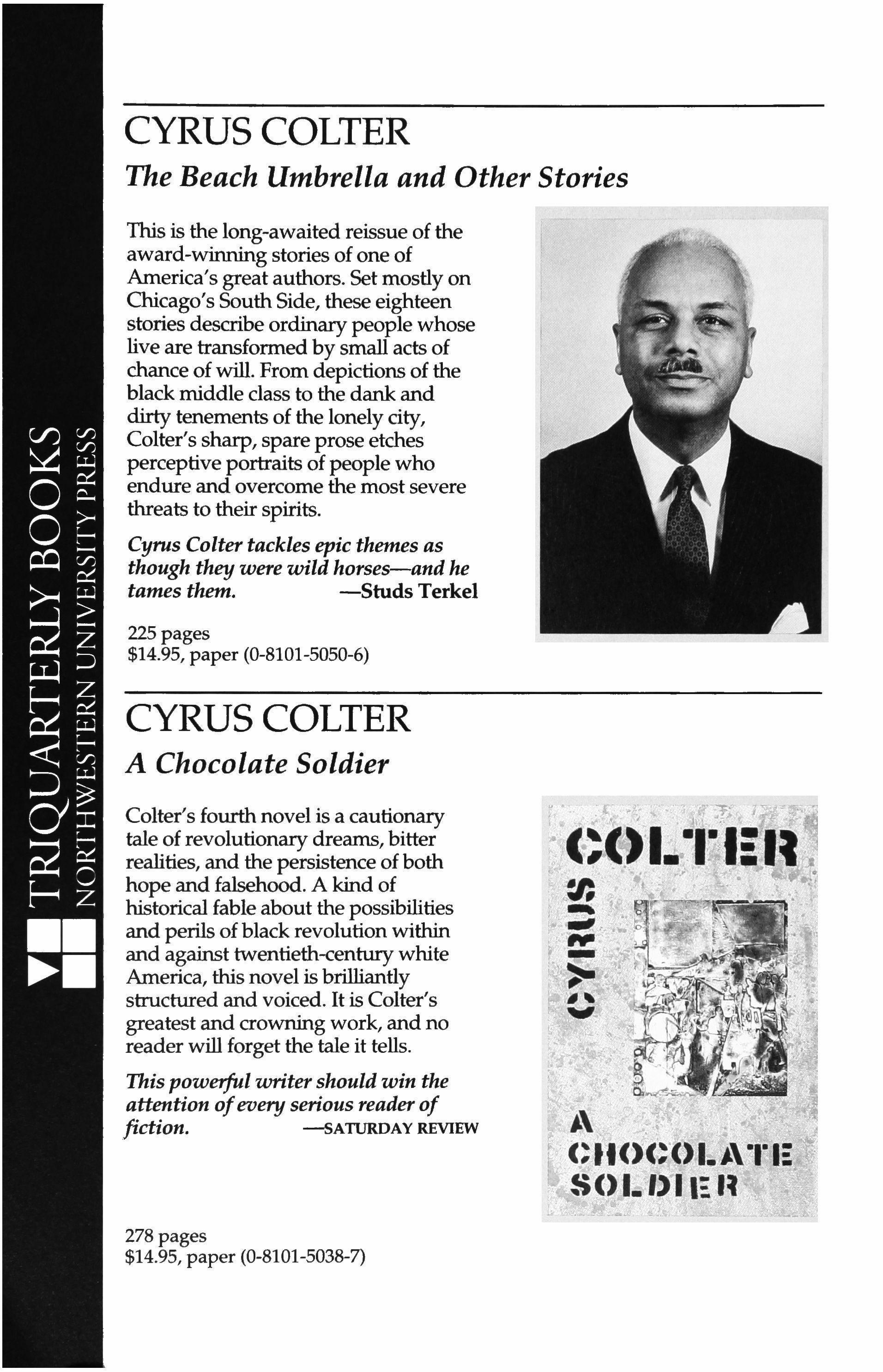

CYRUS COLTER

The Beach Umbrella and Other Stories

'This is the long-awaited reissue of the award-winning stories of one of America's great authors. Set mostly on Chicago's South Side, these eighteen stories describe ordinarypeople whose live are transformed by small acts of chance of will. From depictions of the black middle class to the dank and dirty tenements of the lonelycity, Colter's sharp, spare prose etches perceptive portraits of people who endure and overcome the most severe threats to their spirits.

Cyrus Colter tackles epic themes as though they were wild horses-and he tames them.

-Studs Terkel

225 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5050-6)

CYRUS COLTER

A Chocolate Soldier

Colter's fourth novel is a cautionary tale of revolutionary dreams, bitter realities, and the persistence of both hope and falsehood. A kind of historical fable about the possibilities and perils ofblack revolution within and against twentieth-century white America, this novel is brilliantly structured and voiced. It is Colter's greatest and crowning work, and no reader will forget the tale it tells.

This powerful writer should win the attention ofevery serious reader of fiction.

-5AruRDAY REVIEW

278 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5038-7)

CYRUS COLTER

The Hippodrome

Set in a Chicago seething with physical and psychological violence, this novel examines power and exploitation and their entanglement with sexuality.

In the tradition ofhisfictional ancestors, Dostoevsky andFaulkner, [Colter] has produced a work which uses the world of everydayreality in a manner beyond the scope ofjournalism or sociology-as an entree to the soul.

-James Park Sloan CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

Colteris a writer ofdistinction.

---ClIOICE

214 pages

$13.95, paper (0-8101-5036-0)

DANCHAON

Fitting Ends

In thirteen deft stories, Dan Chaon details the almost panicked angst of the American generation now approaching thirty. Unnerved by the discrepancy between their youthful expectations and the experience of adult reality, his characters long for understanding but are thwarted by failed love, family disruptions, dulling work and sexual confusion.

It is the telling, the subtle shifts of perspective, and the transformation of character in a short space that distinguish Chaon as a writer to watch.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

Dan Chaon has published stories in Ploughshares, American Short Fiction and Story among otherjournals.

250 pages

$35, cloth (0-8101-5021-2)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5022-0)

THEODORE WEISS

Selected Poems

This definitive selection of poems by one of America's most distinguished and original poets recovers work that is immensely contemporary and at the same time reaches back to the roots of an accomplished generation of poets that includes Lowell, Jarrell, Berryman and Bishop. Weiss's distinctive, idiosyncratic poems, noted for their syntacticcompression and linking of intimate experience and historical incident, are a major accomplishment. [Weiss'spoetry] is among the most valuable work produced in our time.

-James Merrill

DAVID BARBER

The Spirit Level

260 pages

$49.95, cloth (0-8101-5037-9)

$15.95, paper (0-8101-5040-9)

76 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5023-9)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5024-7)

Winner of the 1995 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Representing the world as a place of feverish energies, Barber creates a virtuoso tension between playful, sometimes flamboyant, diction and the seriousness of his concerns. Filled with rich detail and striking metaphor, his poetry is both technically brilliant and irresistibly inviting.

David Barber is the assistant poetry editor at the Atlantic Monthly and the recipient of a PEN/New England Discovery Award for poetry. The Spirit Level is his first published book of poems.

w. S. DI PIERO

Shadows Burning

Few other poets of his generation have succeeded in forging a style as original as W. S. Di Piero's. This sixth volume moves backward through the poet's life and American history, returning to origins both cultural and personal. With imaginative and linguistic power, Di Piero creates an elusive proportioning, a mourning and celebrating of his material.

In its intensepreoccupation with change and thefrailtyofwhatever continuities ofmemory and imagination we devise to order the unorderable, [Shadows Burning] makes an important contribution to American poetry.

-Alan Shapiro

ADRIAN C. LOUIS

Vortex ofIndian Fevers

Wordplay,metaphoricbrilliance, technical virtuosity and a scathingly sardonic critique of self and society fill this new collection Louis celebrateslife amid hardship and self-destructiveness, and consecrates a part of the past as a source of ideals for the present. N. Scott Momaday has characterized Louis's work as /I acceptance and defiance brought into delicate balance." Fueled by both anger and irony, Louis analyzes, excoriates,jests, prays and mourns. The result is psychologically and culturallycomplex.

76 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5017-4)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5042-5)

80 pages $29.95, cloth (0-8101-5019-0)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5020-4)

Beautifullyaglow with the love oflanguage. -James Tate

Prophetic, terrifyingly intelligent, unconditionally germane. -Hayden Carruth

DIANE GLANCY

Monkey Secret

This thoroughlyoriginal volume collects three short stories and a powerfulnovella by the awardwinningCherokee-German-English poet and prose writer. Glancy's tales of Native American life explore that essential American territory, the border-between: between past and present, betweennative and immigrant cultures, between self and society.

Hergiftforexpressive language and her courage in exploringpainfulsubjects like abandonment, illiteracy, and abuse make the readerhungryfor more. -NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

Glancy is a treasure.

116 pages -AMERICAN BOOK REVIEW $19.95, cloth (0-8101-5016-6)

TRUDY LEWIS

Private Correspondences

VVUruner of the 1994 VVilliam Goyen Prize for Fiction

This moral thunderclap of a novel portrays a teenage girlwho, attacked by violentevil, chooses not to flee itbut to face it, and then to embrace it. In prose that swings between lyrical moments ofillumination and gritty sexual insight, Lewis explores the dark heart of a misogynist culture.

Lewis's shatteringstudyofsexual violence and individual vulnerability is both timely and universally resonant. --PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

196 pages $19.95, cloth (0-8101-5033-6)

ANNE CALCAGNO

Prayfor Yourself

Anne Calcagno vividly captures the textures of women's lives in this exhilarating collection of short stories. Her characters grapple with problems ranging from domestic violence to obsessiveness with bodyweight; the dramatic situations are extreme, edgy and utterlyconvincing.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye of a true storyteller.

-Larry Heinemann

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as a fifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a single piece ofwood.

136 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5000-X)

-Lynda Barry

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5003-4)

EUGENE GARBER

The Historian

Winner of the 1992 William Goyen Prize for Fiction

This rollickingmetaphysical tale takes readers on a rich fictional odyssey that is a meditation on the American character and experience. The historian's quest to find the American Woman, whose vitality has been all but written out of history by puritan consciousness, leads him to muses, lovers, figures of sensual liberation, frontierswomen and powerful agents for social change. The battle between myth and fact, between romance and science, to grasp the soul of historythe so-called truth of a given time-is at the heart of Garber's compelling tale.

FIRST PAPERBACK PUBUCATION

236 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5018-2)

CAROL FROST

Pure

For all poetry collections. -LIBRARY JOURNAL

PETER READING

A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and on the natural world that surrounds and shapes human life. Frost's poems bear the stamp of a thoroughly original artistic vision and style-they are discursive yet filled with concrete images; they inquire into moral issues (responsibility, pleasure, guilt,jealousy) without moralizing; they catch the echoes of western myths in domestic and quotidian events; they sharply diagnose relations between the sexes.

64 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5029-8)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5004-2)

Ukulele Music • Perduta Gente

tl:rt aJQ,rba.,w�ot>tbn\ ILGJeJptp'1cnl'otllIllOurtbml �"",,",,"orloO..I;.,..,.,.., """""'" I.q!.dd"""""'''''= lC!"*.,1tf-pb iIh9n,....,_,. �_�-pftJtni�...o:r..f 1-fllrrrtllrlJ9l!, ..:mJ.I.hoqul..d.Ji ""-!."nJ � ..,.Iri--

This double volume of poems is the first U.S. publication of an important English poet. "There is nothing safe about Peter Reading's work," one reviewer has written, and a storm of letters to the London Times and the Times Literary Supplement, attacking and defending Reading's work, has made him the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity, bitter humor and disconcerting honesty.

112 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5030-1)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5005-0)

i I

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years I Cronica de mis aiios peores

TRANSLATED AND WITH AN AFTERWORD BY

In this bilingual edition, an established Chicanopoetrepresents withpassion and elegance some of the American realities that remain absent from mainstream poetry. Villanueva voices complex and compelling historical, literary and cultural questions as urgent personal utterances, investing the book with appealingintimacy and seriousness. Villanueva is a writer to spend time with.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Tino Villanueva won the 1994 American Book Award forhis recentbook, Scene from theMovie GIANT.

96 pages

$34.95, cloth (0-8101-5009-3)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5034-4)

MARC J. STRAUS

One Word

In his first collection ofpoems, physician Marc J. Straus combines poetic craft, medical expertise and a keen sense of human vulnerability in an uncommon portrayal of the complex and often troubled relationsbetween physician and patient. With directness and power, Straus confronts matters rarely encountered in poetry. These poems are a fine addition to the scant body of imaginative work that speaks from within the medical world.

Offering a new perspective on patientdoctor relations, [Straus] brings humanity into the sterile hospital environment. -BOOKUST

80 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5010-7)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5035-2)

JAMES HOGGARD

-

TUNSUHO AND WITH AN AmlWOID IT JAMB HOGGARD

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

Completed while he was dying, William Goyen's Arcadia is one of the most affecting and imaginative farewells to life ever written.

Arcadio, whose voice is inimitably Goyenesque, is a creature from beyond the normal walks of life.

Half man, half woman, raised in a whorehouse and for years the veteran exhibitionist of an itinerant circus sideshow, he has escaped from the show and has been wandering in a quest for his lost family. Speaking intimately and secretly to the reader, he tells the bizarre and fantastic tale of his life.

148 pages $12.95, paper (0-8101-5006-9)

WILLIAM GOYEN

Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical Narrative

Chris, whose leg is injured, and his lover Stella, with whom he lives in a ruined, abandoned house; Chris's male nurse; Marvello, the circus aerialist; a lighthouse keeper; a flagpole-sitter in small-town America-these are the creatures of William Goyens visionary fable of love, lust and loneliness. Because of its central focus on the erotic and its unusual novelistic form, Half a Look ofCain was rejected in the 1950s by Goyen's publisher. The first publication of this novel inaugurates a TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press plan to publish and reprint all of Goyen's out-ofprint work.

[Arcadio] virtuallypulses with life; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldlycontemporary as well.

-Joyce Carol Oates

Goyen's paramount concern is with the ways in which people connect, commune and create, with the ways they hurt and heal one another and with the capacity of everyone to do good or evil [Half a Look of Cain] is the work of a gifted, intelligent artist.

-NEW YORK TIMFS BOOK REVIEW

220 pages $22.50, cloth (0-8101-5031-X)

WILLIAM GOYEN

In a Farther Country

Subtitled U A Romance," In a Farther Country is an intense performance, both lyrical and colloquial, shaped as a series of meditative narratives. Set in a Spanish arts factory in New York City, the novel grows around the conflict of its main character's mixed ancestry. Marietta McGee-Chavez and her friends and acquaintances populate a world in which they experience dreams and reality, sexual desire and loneliness, triumph and defeat. This is the first paperback edition of Goyen's small neglected masterpiece.

182 pages

$13.95, paper (0-8101-5039-5)

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise ofthe Impure:Poetry and the EthicalImagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today. These essays speak forcefully to the literary debates concerning the use of tradition, the openness of American poetry to diverse subjects, and the teaching of creative writing. This book should be read by any poet who teaches in the United States and by anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. It will become a benchmark for discussion of contemporary American poetry.

200 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5025-5)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5028-X)

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out ofSilence: Selected Poems

EDITED BY KATE DANIELS

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state ofpublishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser'spoetry was out ofprint. So this is notjust another book: it is a restitution. -Eleanor Wilner

Thepublication ofOut of Silence is an event worthyofcelebration. Finally one ofthis century's most distinguished, misunderstood and undervaluedpoets is back in print The timefor a justestimate of Rukeyser's contributions is longoverdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start.

-TIlE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5015-8) (PAPERBACK REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right alongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one ofthe bestpoets now writing in America. -Denise Levertov

80 pages

$17, cloth (0-916384-08-X)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5013-1)

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark

Legs and Silk

Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe Spinners

Wmnerofthe Carl SandburgAward and the 1993 Chicago Sun-Tunes Book ofthe YearAward in Poetry

Angela Jacksonbrings remarkable gifts to the articulation of African-American experience. Her poetry features an impressive variety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience.

Angela Jackson has known,forlong, what is rightfor her attention and scrupulous investigation.

-Gwendolyn Brooks

120 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5026-3)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5001-8)

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

Wmner of the 1993 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Adversaria celebrates the rough beauty of ordinary life and laments its inevitable decline. These poems, titled in Latin, combine colloquial style with a late imperial tone to capture the stark contrasts and contradictions of a life lived between a steel mill and the quiet, graceful natural world.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence of a lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American.

-Li-Young Lee

104 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5027-1)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5002-6)

W'NH£I\ O� TNE ''') T(��( eE OfS �1I(5 '�Il( fOil 'OETIIY TmothYR"mil

LINDA McCARRISTON

Eva-Mary

1991 National Book Award Finalist

Wmnerofthe 1991 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

NOW IN A FOURTH PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance.

An immensely moving book,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories oftrauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace. -Lisel Mueller

80 pages

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5008-5)

(REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit. Evan Zirnroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -Alicia Ostriker

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Eva-Mary

Linda McCarriston

The Urgency ofIdentity: Contemporary English-Language Poetryfrom Wales

EDITED BY DAVID LLOYD

This anthology ofpoems and interviews presents for the first time in this country the important English-language Welsh poetry of the 1980s and 19905, illuminating the complexity, constant flux and politicalimplications of the poet's sense of inherited culture. Superb poems have been rigorously selected to showcase the Welsh poets' skill and seriousness, and the sensuous densityoftheir language, which, like that of contemporary Irish poets, offers the reader memorable expressive riches and a striking depiction of landscape and society. Included in the anthology are JohnDavies, Gillian Oarke and R S. Thomas, among others.

244 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5032-8) $14.95, paper (0-8101-5007-7)

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

This large anthology is a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today.

Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution.

-HARVARD REVIEW

afeastofreadingenjoyment. Gibbons's collection gives us people worth caring about and writing not afraid to be at once serious andjoyful.

-SMALL PRESS

448 pages $15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

Fiction ofthe Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

This landmark anthology honoring TriQuarterly's 25th anniversary includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared in the magazine over the past decade. The stories range widely over the experience of modem life, and share a high level of artistry. An incomparableprimer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction ofthe Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

Order Form

ThL. 800/621·2736 OR 3 t 21568·1550 1'>\.\ 800/621·8476 OR 3t 21660-2235 Narne Address

Distribution Center

60628

State Zip Authorlfitle ClothiPaper Quantity Unit Price Total Subtotal Shipping and handling* TOTAL

enclosed

*l>omestlc-$3.50

*Foreign-$4.50

Order from your tJookseJ/er or from' Northwestern Universily Press f:birago

11030 South Langley Alenue Chicago, IL

City

o Check or money order

o Mastercard/Visa number: Expiration Date Signature:

first book. $.75 each additional book

first book. $1.00 each additional book

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow

James Lang

Reader

Christopher Carr

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Deanna Kreisel, Hans Holsen, Kemba Johnson, Jacob Harrell, Dylan Rice

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of back issues varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, Il, 60208. Phone: (847) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions offiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1996 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ); Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CAl; Fine Print (Austin, TX).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), Historical Abstracts, MLA, EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CAl.

Spring/Summer 1996

TriQuarterly is pleased to announce that two stories it published are to be included in The Best American Short Stories 1996 (Houghton Mifflin), edited by John Edgar Wideman and annual editor Katrina Kenison: "Some Say the World" by Susan Perabo (TQ #92) and "Fitting Ends" by Dan Chaon (TQ #94). The book will be published in December.

Five poems originally appearing in TriQuarterly have been selected for inclusion in The Best American Poetry 1996 (Scribners), edited by Adrienne Rich and series editor David Lehman: "The Mill-Race" by Anne Winters (TQ #90), "Transfer" by Ingrid de Kok (TQ #93); "The Steadying" by William Heyen (TQ #93); and "Poet" and "When the Spirit Spray-Paints the Sky" by Sterling Plumpp (TQ #94). Publication will be in September.

Editors

Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

Contents

of this issue:

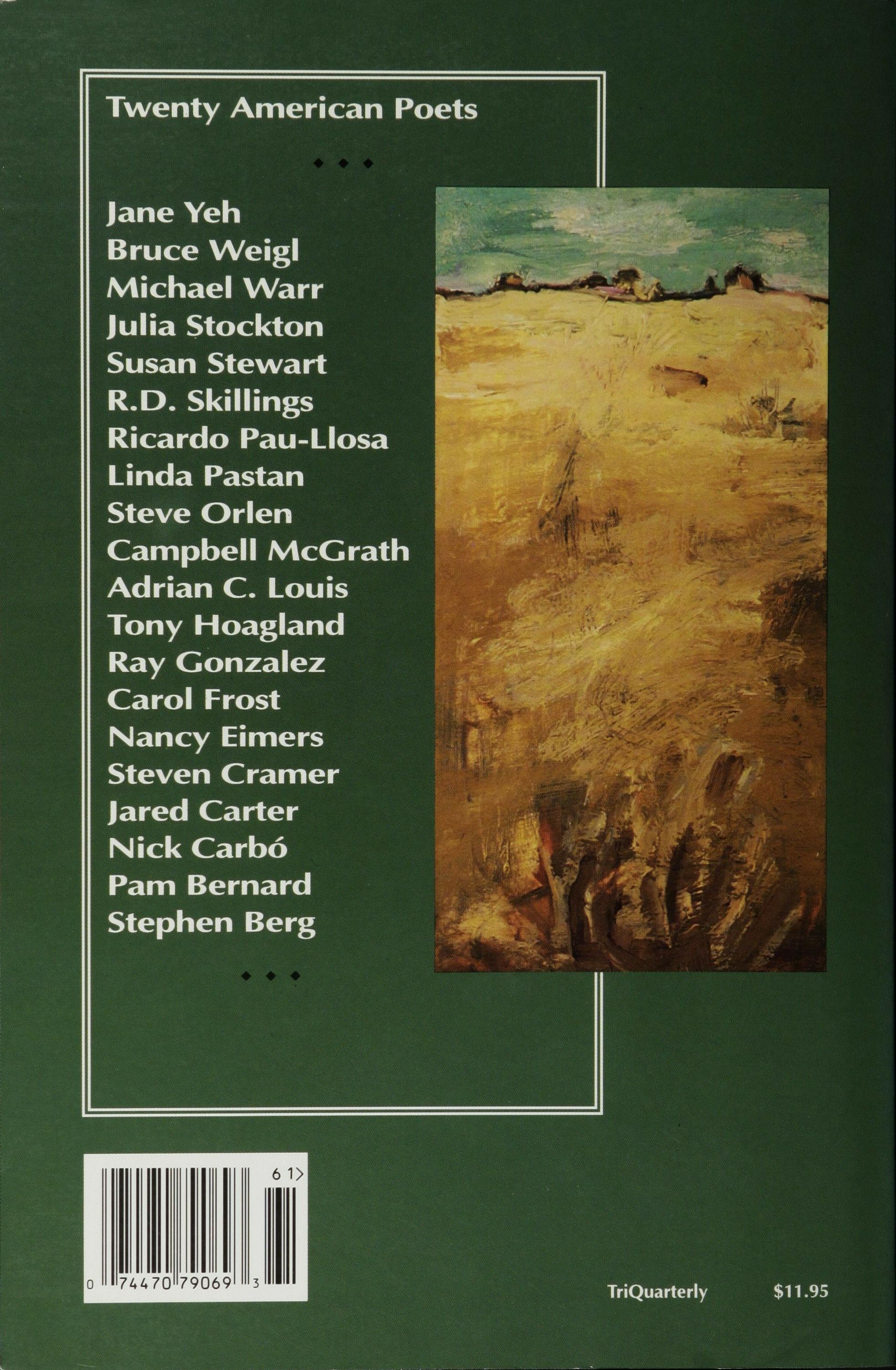

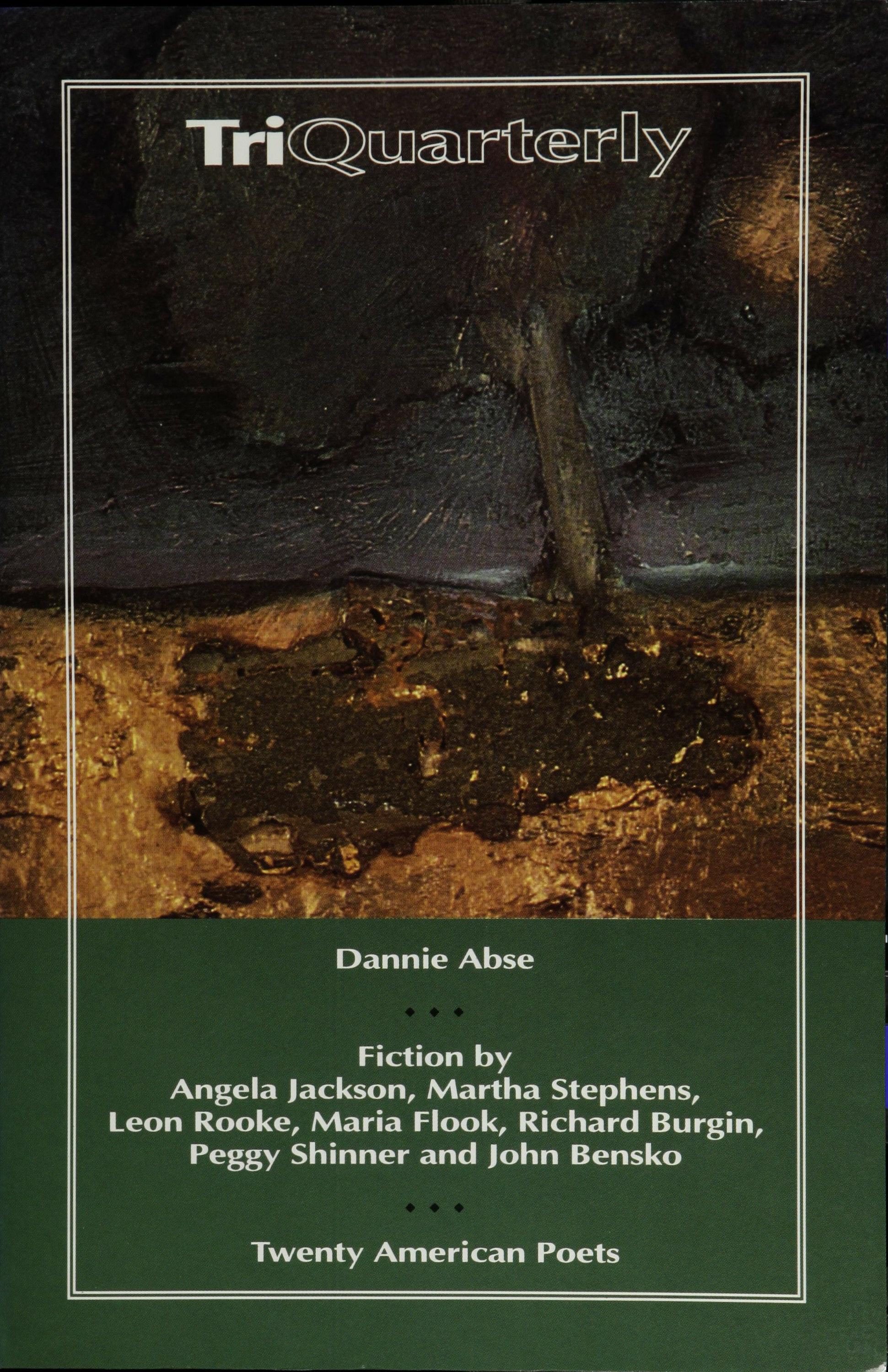

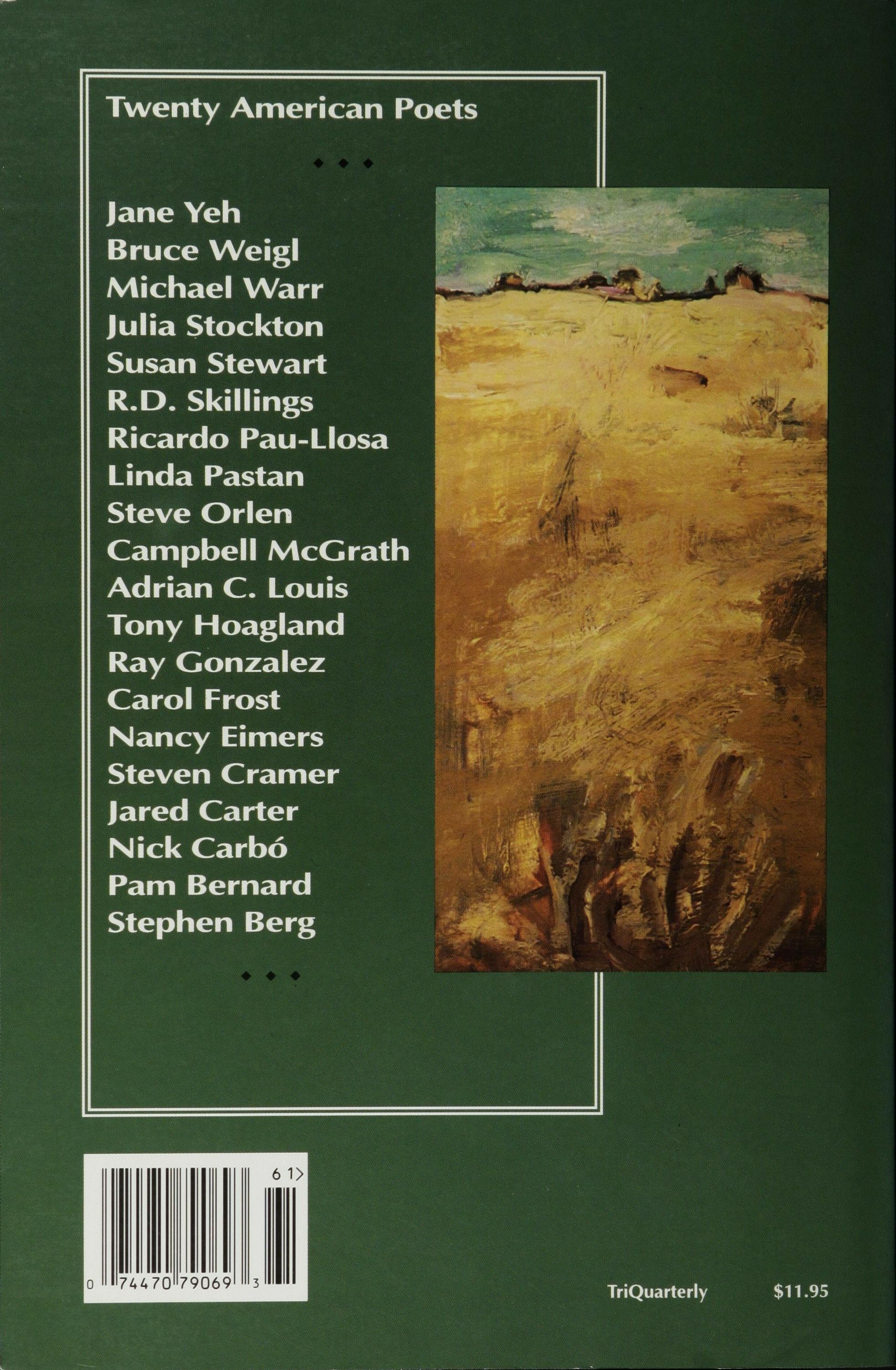

Souls; A Heritage; Photograph and White Tulips 25 Dannie Abse FICTION Great Zimbabwe (from Treemont Stone) ••••.•.••••••• 30 AngelaJackson Two Women 44 Martha Stephens The Lithuanian Wife •...........••••••............•.•.....••••• 62 Leon Rooke Prince of Motown 70 Maria Flook Mistakes 92 Richard Burgin Do I Know You? 106 Peggy Shinner As the Hawk Flies 118 John Bensko 21

POETRY

SPECIAL SECTION: TWENTY AMERICAN POETS Blue China; Shoemaker's Holiday ...................•. 131 Jane Yeh My Early Training; Hymn of My Republic; Seeking the Redwing; Hanoi, Christmas 1992; At the Dreamland Theater, 1959 134 Bruce Weigl Duke Checks Out Ella as She Scats Like That; Her Words 139 Michael Warr My Aunt's Niece's Anamnesis; The Grass Is a Genre on the Other Side 143 Julia Stockton Little Night Songs; Awaken 145 Susan Stewart King's Dock 153 R. D. Skillings Guayaquil; At the Bar 162 Ricardo Pau�Llosa Anna at Eighteen Months 168 Linda Pas tan The Rumanian Exquisite 169 Steve Orlen Dinosaurs 1 71 Campbell McGrath 22

Reductio Ad Absurdum; Love Strikes; She Speaks, He Listens; Listening to The Doors; At the Freight Yards; Pacific Highway: 1967; San Francisco: 1969; Trees, Rush Limbaugh, and the Failed Exorcism of China Girl's Ghost; Star Quilt; This Is the Rez 174 Adrian C. Louis

Adam and Eve; The Teacher Listens to the Past; Why We Went and What We Found 186 Tony Hoagland

Angelo; Mexican 193 Ray Gonzalez

Brave; Obsession; Comfort; Patience; Void; Conscience; Time •••..•••••••.•.•••...............•..

Frost

Aphasiac; The Match Girl

Nancy Eimers

God's at the Top of the Stairs ••••••••••••.••.........•••••

Steven Cramer

Covered Bridge; Recollections of a Contingent of Coxey's Army Passing Through Straughn, Indiana, in April of 1894 •••••.••........••...••.......••••

Jared Carter

Eras del Lugar; Mojacar Love Poem; El Camino 225 Nick Carb6

196

Carol

203

207

209

23

Social Studies; Of Sameness and Thirst; Campanile; Wakened; Lipstick 230

Pam Bernard

From Treatise on the Rainbow: Thirst; Death; Cap; Speak; Caritas; Shit-Stick: Thread; Hooks; Windows 236

Stephen Berg

PHOTOGRAPHS

From the Series NOW (Dachau)

Alan Cohen after 144

MIXED�MEDIA COLLAGES

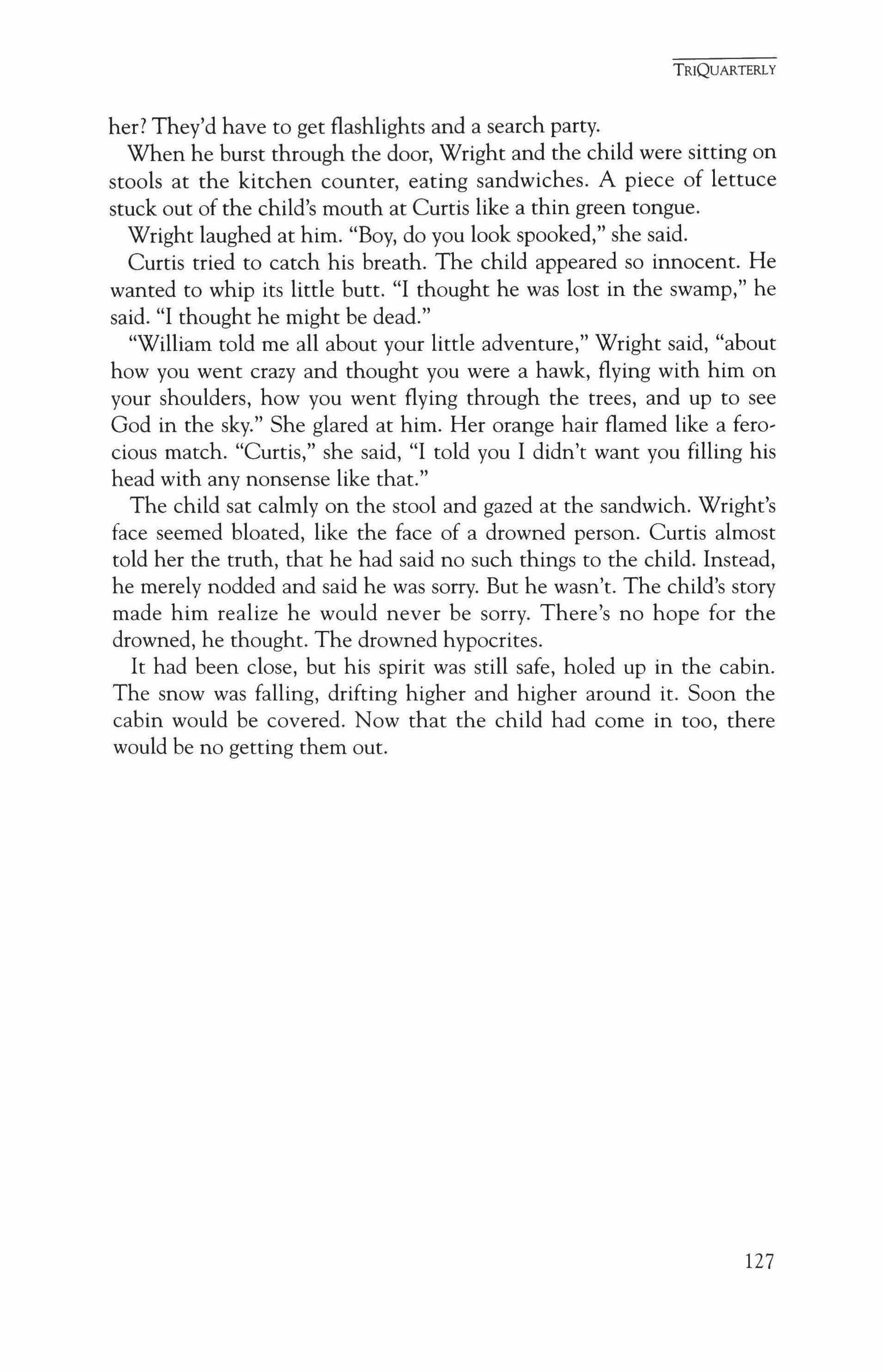

Fruits 'n' Nuts; Rock of Ages; Jack; Bob White; Rocky Road; Gander; Ebb Tide; Marriage on the Rocks;

Alexis Smith 69, 91, 117, 128, 173, 185, 249, 250

CONTRIBUTORS 251

Cover paintings by Pam Bernard

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

The photographs of Alexis Smith's works appear by courtesy of Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles, © Douglas M. Parker Studio.

TRIQUARTERLY 24

Three Poems

Dannie Abse

Souls

"After the last breath, eyelids must be closed quickly. For eyes are windows of the soul -that shy thing which is immortal. And none should see its exit vulnerably exposed,"

proclaimed the bearded man on Yom Kippur. Grownups believed in the soul. Otherwise why did grandfather murmur the morning prayer, "Lord, the soul Thou hast given me is pure"?

Near the kitchen door where they notched my height a mirror hung. There I saw the big eyes of a boy. I could not picture the soul immaterial and immortal. A cone of light?

Those two black zeros the soul's windows? Daft! Later, at medical school, I learnt of the pineal gland, its size a cherrystone, vestige of the third eye, and laughed.

But seven colors hide in light's disguise and the blue sky's black. No wonder Egyptians once believed, in their metamorphosis, souls soared, became visible: butterflies.

TRIQUARTERLY 25

Now old, I'm credulous. Superstition clings. After the melting eyes and devastation of Hiroshima, they say butterflies, crazed, flew about, fluttering soundless things.

TRIQUARTERLY

26

A Heritage

A heritage of a sort. A heritage of comradeship and suffocation.

The bawling pit-hooter and the god's explosive foray, vengeance, before retreating to his throne of sulfur.

Now this black-robed god of fossils and funerals, petrifier of underground forests and flowers, emerges with his grim retinue past a pony's skeleton, past human skulls, into his half-propped-up, empty, carbon colony.

Above, on the brutalized, unstitched side of a Welsh mountain, it has to be someone from somewhere else who will sing solo

not of the marasmus of the Valleys, the pit-wheels that do not tum, the pump-house abandoned;

nor of how, after a half-mile fall, regiments of miners' lamps no longer, midge-like, rise and slip and bob.

Only someone uncommitted, someone from somewhere else, panorama-high on a coal-tip, may jubilantly laud the re-entry of the exiled god into his shadowless kingdom.

TRIQUARTERLY 27

He, drunk with methane, raising a man's femur like a scepter; she, his ravished queen, admiring the blood-stained black roses that could not thrive on the plains of Enna.

TRIQUARTERLY

28

Photograph and White Tulips

A little nearer please. And a little nearer we move to the window, to the polished table. Objects become professional: manikins preening themselves before an audience. Only the tulips, self-absorbed, ignore the camera.

All photographs flatter us if we wait long enough. So we awkwardly Smile please while long-necked tulips, sinuous out of the vase, droop over the polished table. They're entranced by their own puffed and smudgy reflections.

Hold it! Click. Once more! And we smile again at one who'll be irrevocably absent.

Quick. Be quick! The tulips, like swans, will dip their heads deep into the polished table frightening us. Thank you. And we turn thinking,

What a fuss! Yet decades later, dice thrown, we'll hold it, thank you, this fable of gone youth (was that us?) and we shall smile please and come a little nearer to the impetuous once-upon-a-time that can never be twice.

(Never, never be twicel ) Yet we'll always recall how white tulips, quick quick, changed into swans enthralled, drinking from a polished table. As for those white petals, they'll never fall in that little black coffin now carrying us.

TruQUARTERLY 29

Great Zimbabwe (from Treemont Stone)

AngelaJackson

My daddy told me the story of that block. It was across the street from the end of a mile-long parkway; the parkway's end jutting out like a pier of grass into the concrete. Sometimes the street is so bumpy it feels like it has waves. At one time the block-long building there had housed a thriving catering business that serviced prosperous (need I say) white civic leaders given to giving gala festivities. The colored caterer expertly constructed boats of shrimp and ice, frappes, succulent hams, and dishes of freshly slaughtered beef sauced in light butter and spices the names of which he would not reveal. The civic leaders gorged themselves on his repasts regularly, till they grew most corpulent and the veins in their noses and cheeks swelled to bursting. That chef sent them into epicurean ecstasy. So my daddy said and I don't know who told him these things, because he was still in Mimosa then, or a dream in his daddy's eye in a farm outside Letha. My daddy talked to other men who knew though, in the places where men tell things.

In the same lifetime as the caterer, the huge graystone was also the location of a grand gambling house of silver roulette wheels, loaded dice, and round card tables in small smoky enclosures. It was an immensely beautiful club-not only because its sporting-life clientele dressed in such satin finery, the pomade-headed men in black and beige polished-cloth vests and sleek pants that obediently followed the flow of their sex and limbs; the beige women in overly-ruffled pale satins, their kinkless, genetically Caucasian-like hair eschewing the need for the newly devised straightening comb or, before that, the endless need for endless brushing.)

The Ace of Spades, generally regarded as the king of such clubs, was a

TRIQUARTERLY

30

beautiful place because there beautiful music charged the air. Not the arias of overstuffed or desiccated sopranos; not the mellifluous guitarstriped wail of the Moor-inspired Spaniards; not the chants of whiterobed choirs reading black notes dancing on white sheets and the rapid arm-signals of the choir director. Not exactly the hypnotic dust-dancing ritual songs of African cloth-makers, reapers and sowers, grain-grinders, masked and masqueraded priests and country people binding a nation together with the bloody threads of song. Not exactly that African song, but close. A song divided from the older African ones.-drvided by guns, bead-barterings, war-instigators, fearful, duped, or greedy and duplicitous leaders, suicide and oceans and a land where burdens were so heavy and the lash so cruel its cut snaked and churned in the blood and the song lay down too much of memory and picked up new habits.

Still, the Ace of Spades, slightly seedy, of limited opulence and mimicking decadence, was beautiful when the musicians came up the long river and the segregated train and brought the music. The stiff-backed piano opened its black-and-white mouth and laughed when the velvetfingered player brushed its teeth. Saxophones and trumpets at the big lips of round-cheeked horn men became the fabled horns of plenty. A cornucopia of life-fulfilling sound.

Some woman, big-bosomed-and-buttocked, big-footed and fine, a shimmy dress fitting tight around the hips, a feather poised in her hair, a river in her throat, would flood the night with blues. Or a slip of a girl would loose all night long a stream of pain and wit and dignity and sensuality that would work a groove in a heart of granite.

That was in one life.

In another lifetime, after the death of the renowned chef, the shop and club gave rise to a series of ill-financed clubs that opened and promptly failed. In 1939, while Europe flamed, the old Ace of Spades had been gutted by a fire. In 1942 The Colored Bugle Corps opened and closed.

Throughout World War II only rats and black black marketeers made quick, scuffling music in the once-regal graystone building. In 1945 two veterans of the Negro corps of engineers (chain gangs of black collegetrained volunteers and draftees who built airstrips in the Pacific theater) came home. They pooled their resources of accumulated Army pay and opened the Club Desiree. Negroes, buoyed by the job booms during the War, dressed up and went out at night. The Club Desiree was the place to go. Brown-toned women pressed their hair, curled it, then pinned it into upsweeps that ended in frizzy cliffs over their foreheads.

TRIQUARTERLY

31

This is where Mama and Madaddy went when they first moved up from Mimosa. I've seen the one picture of them, seated in a booth behind the curve of a round table. Mama is pretty under a little hat with a black net that crisscrosses finely in front of her shining eyes. Her dress is long-sleeved with puffs of air in the shoulders; the neckline swings down to her bosom. She had nursed five babies by then. Looking gorgeous as any woman in love, with her husband home and her cottonpicking days over. Looking relieved as any good mother with her babies safe at home in bed, and another one-Earnestine--quiet in her belly.

The evening is "a salute to Negro veterans," posthumously honoring Dorie Miller. Dorie Miller, the cook who picked up the rat-a-tat-tat of the machine gun and shot down enemy planes that swooped down over Pearl Harbor. My father, Sam Grace, bird-tail intact in the front of his Negro regulation haircut, has donned his eight- or nine-year-old Army uniform. He is handsome and still hopeful, having found a decent job (two decent jobs), having made steady payments on a house in a neighborhood where whites were caught as if by a slow-motion camera in mid-flight, having moved his young yet sizable family up from Mimosa to that street that was Arbor in one spot and Plenty in another. His eyes are dreamy and his mouth is pursed as if he is about to sing.

There is attitude in this photograph of my parents taken I am told by a "cute little" meandering photographer who doubled as a hatcheck girl when somebody called in sick. It is a special occasion. I think the chorus line kicks moon-high. This picture in the shadow. Two visitors have arrived from Mimosa, Mississippi; just stepped off the platform from the City of New Orleans. They all lean forward around the curve of the table. My Uncle Lazarus, whom we call Uncle Blackstrap, who is Mama's brother, seated on the edge of the curve beside my father, leans so far across the table the top of a bottle of Scotch seems to pierce his heart. My Aunt Leah-Bethel, my father's sister, sits next to Mama, her elbow propped on the table, a cigarette burning down to her knuckle. She doesn't seem to notice.

My mama told me the singer that night was Mockingbird July. I laughed at the name. I had never heard of her. My daddy didn't look at me, but sat in his chair and half-chuckled, half-giggled in his deep voice. He rattled his magazine. I felt like saying, "What's so doggone funny?" in just the tone he used on one of us, belligerent, defensive. I rolled my eyes at him and looked again at the picture. Looking at pictures was one of my favorite things to do. Hearing Mama and sometimes Madaddy tell about them was another.

TRIQUARTERLY

32

"Mockingbird sure sang that night." Mama closed the album clumsily and threaded a wisp of hair back into her knot. She shrugged as if she had nothing more of interest to give me, and she were less for this. I kissed her on the cheek because this was enough. Is.

My daddy finished telling me the story of that block. I listened without knowing I was listening. The Club Desiree was the place to go for more than fifteen years, till downtown clubs opened up to Negro patrons and the more�than�three�quarters�of�a�century-old buildings of Bronzeville began to fall into extensive, nearly irredeemable, disrepair.

My daddy said Mr. Rucker said in the barbershop that time Mr. Rucker happened to go, "Any fifty-year-old man's plumbing fall down, what you expect from a building?" "Mortar and brick ain't no better than mortal man." The barber concurred. So the Club Desiree went into gentle decline as Negro entertainers popped up open-mouthed and soulful on Ed Sullivan. "Right in her own living room-Nat King Cole," Mama pretended to faint, acting like Honeybabe and her friend Charlotte would over Smokey Robinson or Sam Cooke at the stage show. Mockingbird July, however, never came on Ed Sullivan nor did she grace the downtown clubs. I would have heard of her if she had.

The momentum of the war boom had turned into a cold war. During an especially harsh and frigid winter, pipes burst in the Club Desiree, flooding the basement, warping the dance floor, ruining the walls. After the thaw and survey of the water damage, a mysterious fire swept through the club. In 1960 the Club Desiree shut down.

And that is where my daddy's part of the story ends.

Seven years later my part of the story begins.

We disembark from the yellow school bus in front of what once was the Ace of Spades, king of clubs; briefly, the Colored Bugle Corps; and, finally, The Club Desiree, before this incarnation as Great Zimbabwe (House of Stone), so called after the eleventh-century religious ruins of southeastern Africa. Great Zimbabwe is a mecca for the Black Arts Movement-revolutionary poets who dip and dance like sanctified preachers when they read, saxophonists, and flutists who combine the quirky beauty of bebop with the atonal freedom of African ritual music and the lyricism of Ellington, dancers who wide-leg leap to ceilings like spiders on fire under history's inflammatory eye. Artists, who carry their paint supplies on their backs in bundles like African women toting newborns, washed down the ruined walls of Club Desiree and created a mural documenting Black History from ancient pyramid to urban projects and South shotgun shacks. From the magician-warrior Sunni Ali

TRIQUARTERLY

33

to the murdered Malcolm X. From Sheba to Gwendolyn Brooks, poet.

As the final segment of Freshman Re-Kinkification ("Guaranteed to put the beautiful, complex curl back in yo mine and on yo haid," says William), we welcome anything after the somber news from the EARTH even a quiet dinner at Aisha could not obliterate. A plethora of color and sound greets us. The murals dwarf us. Women and men wrapped in loud prints assail us with warmth.

"It's like going into a new land," Leona says what I am thinking. I am more certain than ever that this long-legged, obsidian-dusted girl with the half-inch Afro, shorter than my daddy's bird-tail, is kin to me, like my cousin say. Leona has her own mind. She cut her hair down to express her own style. She's always talking about getting to the root of the matter.

With new, EARTH�sobered eyes, we look around us at the brilliant banners of struggle and ancient glory none of us had really heard about before.

Essie is looking tight in the shoulders, all bunched up. She hugs herself. All three of us are miniskirt wearers by now. It is Leona who stomped back to the dorm one evening, flung open the closets, pulled out our three entire wardrobes (not that much really), cut off hems and rehemmed for three needle-clenching hours straight. She is a swift, obsessive worker. Her hands fluid and swift like a spider at its craft. I ironed down her handiwork. Essie kept asking, "Should we?"

We march into Great Zimbabwe; an army of miniskirted Afroed girlwomen and knit-topped or shirt-and-jacketed boy-men mingling with smiling hordes of cornrow-headed women in colorful long dresses and bearded men in bright dashikis. They stand ready to reclaim our lost consciousness. That is their mission. Blessedly, they don't look nearly as mean as Alhamisi and his crew.

I am hypnotized by a huge poster of a muscular, ox-weight Aunt Jemima arm-wrestling with a helmeted policeman. The nightstick in both their hands. Or is it only in his? Her apron whips and tangles. Her neck is stout and knotted in rage. On other posters, a host of haughty African queens, pitch-eyed and sloe-colored like Leona, glare disdainfully down at us. I want to rise muscular, ox-blooded, and haughty. Be "Magnificent Magdalena Grace-isn't she incredible! Her work is so wondrous." My hands itch for the possibility. But what if the prophesied Armageddon the brothers at the EARTH promise comes to pass before I do, and it is so terrible I cannot join my destiny with it after all?

Brothers in bright-striped pointed cloth caps sit astraddle big drums.

TRIQUARTERLY

34

Callused hands pound and tap into blurs of loud rhythm. We move toward the center of the sound. The drummers make an arc on the stage. We head toward front-row seats. Leona boogaloos on down the aisle-both arms raised, fingers popping, shoulders shifting and hips shaking, stepping forward by gliding from side to side. I follow suit, more subdued but just as glad about the drums and being black. Essie looks for William to be sure of what she should be. But he doesn't see her so I guess she decides to be invisible. William flings his arm back behind him and Rhonda has his hand and falls into his footsteps.

We sit down and bob in our seats, clapping hands in answer to the drums. A tiny, bearded man in a black and purple velvet gown sweeps onto the stage. He gives us a gap'toothed smile, lifts his delicate brown hands and the drumbeats cease. Our hands stay poised, apart in midair, in unfinished applause. Open'mouthed we sit, welcoming the wonders of Great Zimbabwe which tell us our Africanness lives forever. Which is a curative, since the EARTHmen have told us we'll die tomorrow.

Hazes of incense hang over the purple-draped stage. We inhale deeply, breathing the magic in, imbibing the purple of the little man.

"Who the fuck is he: Tiny Tim?" Oakland is vicious, comparing the purple magician to the lank,haired flower child who sings "Tiptoe through the tulips" in falsetto on the Tonight Show. I don't relish sitting next to her through the whole show. I've had my quota of disparage, ment.

Leona gets away with playing sergeant,at,arms a lot. The tall have an aura of authority. She reaches the long arm of the law across my lap and taps Oakland on the arm. "This is serious business, sister." She cautions Oakland, who promptly rolls her eyes and tosses her vinegar-rinsed, relaxer stripped, meticulously curled, instant'albeit,harshened Afro. Leona makes a soundless "Bitch" with her mouth, but only I see this and tell her she ought to be shamed. We in the temple and all. And she The Law.

The tiny priest speaks. "Welcome, my young brothers and sisters, down from the Halls of Whiteness into the Temple of Blackness. The young brother here, William Satterfield, informs me that you are stu, dents at Eden University." He renders a low hum and rumble of a laugh here-wise and dismissive. Whereas my parents levitated with pride at my scholarship to Eden, folks around here act like they think it's no big deal.

"We know Eden was not the beginning. It's only as far as they choose to record. We speak of the home of the original man-the Blackman-

TRIQUARTERLY

35

the original man."

"No women in this original land. Right?" Leona whistles renegade and salty.

William and Rhonda, sitting in front of us, tum around. "Sister, why don't you just listen," Rhonda says like she's an exasperated teacher of sixth graders. William takes this opportunity to stare into Essie's eyes. I can't stand this: Rhonda trying to put Leona down while William's hitting on Essie, keeping her hoping, so I say as loud as I can, "Excuse me, Rhonda, but would you turn your 'fro another way. I cairi't see." Everybody in earshot, which is everybody from Eden, hoots.

Then Essie comes alive, "You too, William," she yells as loud as I did. William turns red, but he's got the panache to smile. Rhonda just turns around. It's Essie, Leona, and me, vigilante and vindicated, with our eyes on the stage.

The little man in the long gown lifts his arms and horns swell up, the sound pushing the ceiling. The sounds swoop like huge birds with indigo wings. Flutes zigzag through the waves of saxophone and trumpet like moths newly spun out of cocoons. The tiny man's fine-boned hands hold a thumb piano while his thumbs race crazily over the metal slices, leaving heavy throbs in the air.

Then the dancers leap onto the stage; the one male dancer in a ritual costume of straw that covers his face and torso. His bare feet crossing and stampeding, then parting from the floor, going high in the air. Each woman dancer is in one piece of cloth tucked at the hips, and another crisscrossing, upholding breasts. They sway like hot ice is in their hips and livid embers under their feet like the priests of Shango Professor Turner told us about. The Eden brothers look pleased with the rapid intensity of their thighs and pelvises, their legs and ankles.

A girl dancer's breast breaks out of the cloth and male voices break out in spontaneous pleasure, "Good googa mooga!" and "Good golly, Miss Molly!"

The women die of embarrassment: we imagine our own breasts so unwrapped before the crowd. The dancer dances on, while other men watch the nipple bob like an overripe cherry on a watery surface.

"God gone strike you blind," a cool female voice sails over our heads. And we know it is Christmas with a Biblical prophecy for the salacious. At last the sister tucks the disobedient breast back into the fold.

When the dance is over the priest lectures on African sexuality. There conjugating, is not dirty. Secondary sex organs are more functional than obscene or provocative. The women of some peoples may dance

TRIQUARTERLY

36

unbound. Puritanism has made us all dirty children in the eye of the nipple. His audience properly chastened, the priest introduces John Olorun, master poet.

"He's so fine," Trixia already in the know about Olorun oozes at the name, as another underfed fine-boned man moves into the lights.

John Olorun wears shades that wrap around his eyes like raccoon's markings, or a Zorro mask. He slips through the crowd of students, the brothers studying his stance and walk; the sisters casting dreams of rescue and romance into the slight mold of his physique. Longing thuds heavily in my chest like a stone tossed into a dry well. I can hear the same desire echoing among sisters gathered here. We've seen pictures of Olorun, minus shades, smiling from a poster Great Zimbabwe sent to Eden, which we unhesitantly posted in Blood Island. Somewhere around Marcus Garvey. An homage achieved in the space of a slim volume of poems, black acts.

I wish I could draw in the dark.

We dream of his eyes-a dense brown we imagine losing ourselves in and find the lost secrets of cathartic release and serene repose under the gaze of a tender god. The wish-stone vibrates inside me. Like an egg cracking to life. He of the hidden eyes has a voice that barely slips out of hiding; it comes out of him husky, covered in innuendo, furtive, quiet as wine. We lean forward, us would-be-women, closer to his whisper; we wait for the heady rush of flight, lifting wish-stones out of our insides. He knows, doesn't he, his power? He draws images in the air, whispers, and does not look at us with his hidden eyes. All his nuances enchant.

He makes a joke about bloods ripping off sisters; laughs without sound. A twinless dimple flashes in one cheek. A sigh at the sight of the tiny triangle in his cheek ripples through the sisters. Most brothers study him with greater intensity-searching for flaw or scar. The remaining brothers guess what gesture, eccentricity of Olorun's to cop and incorporate into their caches of coolest mannerism. Always there are one or two who listen only to the words.

Ducking his head shyly under the blue glow, John Olorun reads a poem he calls "Promiseland."

Race-keeper, Warm-bringer, Misunderstood by her man.

I have seen you sisters, Lovely queens, quiet in your beauty.

TRIQUARTERLY

37

"Talk to me, Black man," Trixia says, lust making her voice old and rusty.

Unwrap the brother from the lamppost. Make him stand. So he can lead you into tomorrow-woman.

"Lead me," Oakland exclaims like Great Zimbabwe is Great Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church instead of a remodeled Club Desiree.

Angel of destiny. Queen of horizons.

John Olorun dips and bends in his knees like a doo-wop crooner pouring out basement music. Smokey Robinson or Sam Cooke, who we still miss even in his scandalous gaudy death. John Olorun has the moves.

You withstood the ocean. You withstood the lash. You without anyone withstood the cold corners of our lost manhoods. You cried in the nightthe bed empty beside you Rise in the morning, sunshine. Warm-bringer. Light-keeper. Sister, Mother, Destiny daughter.

I bring you bloody roses of struggle. I bring you a tall shadow to walk inside safe, protected away from evil men's eyes away from mud-mouthed usurers, pawn-brokers,

TRIQUARTERLY

38

and death-pushers.

Unwrapped from the lamppost the brother reveres you. Out of his Cadillac lean, he stands a Black man. He will guide you, milk and honey woman, to the only Promised Land.

John Olorun ducks his head in a quick nod to us as all of us rise like pieces of dawn in the darkened theater after he finishes three more poems. (One more to black women; the others to the Negro man.) Sisters, leaping in place like light racing up and down through blinds, whistle and cry out. He has changed the hint of vinegar to wine, wishstones to iridescent blossoms yawning seductively under his poems. The brothers take his words for the ones they couldn't find. They whistle and pound their palms together. The poet slips from the stage, quick and quiet as the shadow he promises promised-land women.

We are properly primed now for the segue into LeRoi "Get Down" Clay, the King of Primeval Funk, the Original Toe-jammer, the Consummate Lover, the Sweet Papa Stopper Do Wopper, who steals daughters into righteous frenzy. He does. Even if we're not overcome by him, we act like it, 'cause he's so much fun. A dynamo of hair, deep dark skin, white perfect teeth, encased in a psychedelic suit-a red that throbs. The color thunders. He lands on stage in a James Brown split, mimicking a hyena with his scream. The spectacle is atavistic wizardry; an answer to an ancestor's prayer, "Do Lord Remember Me."

He steps over the blue horizon of lights and says, "We here. We might as well make it all right."

The Great Zimbabwe Orchestra in the background is too loud to be background. More like a complement. He is Brer Rabbit Foot Clay rising out of spit, thighs tremulant and shimmering, fire in his mouth, and visions of the chimera in his hands. Any animal you can name commanding his body. Each finessed gesture an African survival.

I don't know when it happens but I'm in the aisle with everybody else. Re-Africanized. Jubilant. Dancing in the aisles to the Clay version of "Papa's Got a Brand New Bag."

And we all dance till we can't.

TRIQUARTERLY

39

In the lobby of Great Zimbabwe called The Marketplace, like the selling place of an African town, Levergate and Christmas are standing at a book table, both of them reading one copy of Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth. I thought they'd have read that by now. I have. I see Christmas's hand tremble and Levergate reaches out with his other hand to still the quiver in the pages. Then Christmas lets go and reaches for Why We Can't Wait, which I know she's read because she marched with King. And Christmas has read everything. Levergate looks at her in a shady way. I drag my feet a little when I tum away, caught in the glance. Magdalena, the Superwoman, guilty as Superman with Xvray vision that sees through propriety and poses.

I walk behind Oakland. She makes flirtatious eyes at a flute player who says he wants to give her lessons. Oakland twirls a stick of incense, lights it, and blows away the fire. She gazes at the man through a twist of smoke; her lips still puckered from the blow.

"My two wives play flute," the musician says.

"Two who?" Oakland sputters. She recovers real fast.

"Great Zimbabwe is so wonderful," she trills. "Goes to show you how African majesty can last forever. I'm never going to straighten my hair again." With a grand gesture she touches the nappy edges at her ternples. Does not disturb her kitchen, which I am looking into from behind. The Man with Two Wives smiles wanly, bidding Oakland all praises, and telling her anytime she wants to soar, he is here.

The minute he steps away, she turns to me, "Did you hear what that bigamistic baboon said?"

I love to know more than she does. "It's not bigamy in Africa, Oakland. It's polygamy. In many countries it's entirely acceptable." Oakland, not to be outdone, says, "Everything African ain't wonderful, Maggie. They don't kiss, do they?"

I can't argue with that. Mainly because I don't know if Africans kiss or not. Oakland doesn't care about my comeback anyway. She's off after some new adventure to report at the midnight dorm session.

The Man with Two Wives has found Leona and he's telling her he's looking for a third wife who looks just like her. Tall and dark. His other two wives are yellow and short and red and medium-height, respectively. Leona listens politely while she slides away quick as LeRoi Clay does the J ames Brown one-foot shuffle.

TRIQUARTERLY * * *

40

I feel sorry for the Man with Two Wives. Because two aren't enough for him.

Simba is an artist selling his paintings in the Marketplace. He wants to paint Leona and Essie. Leona introduces me.

"You study art, huh? You gone teach it? Don't know many female artists." His glance sweeps over me like an old broom, passing over, leaving debris. My breath is high in my chest with the vanity,induced hope that he will say he wants to paint me too. But he doesn't. He arranges to meet my two best friends for Saturday sittings at his apartment. I may tag along. My build is heaviest. I must be the bodyguard. He might be Bull Connor in a master disguise.

Now Essie is studiously listening to a brother with the biggest gap between his front teeth I've ever seen. It looks like the place the Red Sea came apart and the Israelites ran through. She's concentrating so hard on the brother with the gap, her shoulders are tense, and I guess she misses William and Rhonda at the next table cuddling and being sweet. William's mouth brushing the edges of Rhonda's hair.

Leona is free of Simba, having set the time and place, and she whisks Essie from the gap'toothed wonder. I'm glad because Mama and Miss Rose say that's the sign of the liar. Then again, in Africa I hear it's a beauty sign.

Whichever it is, he's moving on me now and I turn fast to go the other way. To the Queen's Room. Which is a dungeon off to the side of the lobby, led into by many narrow steps.

The Queen's Room is occupied by someone from Eden. "I hope you don't have to use it," she advises, "because it can't be used."

"Beautiful," I say to the toilet that doesn't work. "I didn't have to use it anyway," I say to the girl called Hamla. "I was escaping from a gap' toothed man who tried to swallow me alive."

"Him," Hamla says and goes on working on her hair in the shadowy mirror.

Already she has acquired an African name-Hamla-and Lumumba for the President of Congo who danced the rumba in a silly song. Under the radio, head bowed to a scaly fork, I remember his name announced. He fought for something. I liked him. We are surprised when professors say her slave name, Camille Loomis. She is Hamla Lumumba and she writes poems. On occasion brothers have called me Hamla. "Ain't you the sister who writes?" An upperclassmen asked me when I got on the bus going into the city. "Naw, I'm the one who paints." Before that, in one day, three different brothers yelled, "Hey, Hamla, what's happen,

TRIQUARTERLY

41

ing?" to me. Into the dorm room I had flown to the mirror to engage my true identity. In the mirror we stand together today. And I search out the distinction between us.

Hamla's skin is like polished pecans. So is mine. Hamla's eyes are almond-shaped. So are mine. Hamla's eyes are keen with intelligence and soft with imagination. Aren't mine? Hamla's body is ripe and curvaceous, innocently curved in jeans and sweaters or skirts that are modest as minis go. So is my body curved so. Hamla's hair is gently sculptured. So is mine, shined with Afro Sheen. Hamla is shy with restrained pride, tender ego. So am I.

In the mirror I am gloomy because I am not spectacularly individual. I search for exemplary deviation-my cheekbones are higher, my face fuller, my hips rounder, my arms thinner, one tooth almost imperceptibly chipped one day when I was seven and drinking water from the kitchen faucet. A piece of tooth, like a large grain of sand, in the palm of my hand. I trace the tiny dent in my tooth, relieved to be set apart by the smallest memory. Hamla leaves me in my minuscule victory. I comb my hair.

When I re-enter The Marketplace, Hamla who looks like me is talking to John Olorun, the poet. I recognize the glow around her as she hands him a notebook full of what must be her poems. She bows a little when she talks to him; he looks earnest, ducking his head like a retarded goose like when he performs his poems. I observe him coldly because he's not talking to me. Envy crawls from under my wish-stone, slips through me like a snake. I have nothing to show a poet. My right hand lifts to the tear duct in my right eye. I want to ask why my hand paints instead of writes at a time like this, when poets rule hearts and imaginations. And get so much applause and approval in The Marketplace. I scoot near enough to hear John Olorun promise to give Hamla a call after he's read her poems. What's she doing carrying poems around with her anyway? I don't carry an easel. But I sure wish I could.

Everybody but me has found something to treasure in the club known as desire. It feels like that.

* * *

Trixia has a craving like she's pregnant all the time. This time she longs for barbecue with mambo sauce. She moans for it so loud and long we start to want some too. Leona swears her daddy's barbecue is the best in the city, but Pryor's BoneYard is too far to go.

TRIQUARTERLY

42

"The bus leaves here at 11:30 and we're not keeping colored people's time," William warns us in case we're having second thoughts about trying to make it to Leona's Daddy's for free ribs or chicken and back in time for the bus to Eden. Essie knuckles her hunger under William's warning. She gets on the bus obediently, which makes Leona and me more determined to taste the forbidden sauce.

"I heard about a place," Leona declares. Mutinous. "Three blocks from here."

"Who's hungry?" Trixia announces the question to the crowd. And Oakland, Hamla and two other sisters line up with their tongues hanging out.

Stomachs rumbling, mouths watering, we go in search of mambo sauce and bones to suck on.

"Flesh Eaters. Flesh Eaters. That pig, cow, and bird will kill you, beautiful sisters." We beautiful sisters now. The Man with Two Wives admonishes us, loud as neon, painting us scarlet. Like the kids sing, "Yo mama got the measles and yo daddy got the pox." Mama laughed one night at the window, crying from it, "When we was little pox meant syphilis." Anything evil and contagious. We the ones.

"We gone die smiling," Trixia trots on down the street behind Leona. Then we follow.

TRIQUARTERLY

43

Two Women

Martha Stephens

I"I believe it was the first time the two of them had ever seen each other.

"I don't know if you can picture it the field hospital the great big broad tents like we might see at a revival meeting but with walls that were not canvas but that light-colored thick netting that lets the light in the zippers that did not always want to work on the door-flaps the stretchers of course going in and out things operating on batteries the difficulties at night providing enough light for what had to be done all of that you see and then the two women-who, as I say, had not known each other before this particular evening-working with the others in their respective places around the table where the operations were going on. It must have looked something like what we see these days on television and on those programs about medical workers in Korea or perhaps Vietnam and those movable tent hospitals of theirs out in the countryside.

"Still the whole thing at the time I'm speaking of was a whole lot more basic and difficult than anything we might see on TV. I see it all in shades of a quite indistinct gray and everything in general muddier and more make-do, more solemn, than anything that came afterwards in those other places in the east although even so, everything was organized, they said, brilliantly, within the means available.

"But the medical outfits, for instance, the fatigues, were not that pretty smart green that you can see on color TV. You could hardly tell they were fatigues or what they were because by this time everything had

TRIQUARTERLY

44

come to a sorry pass, and those for instance who were doing the operating and sewing and fixing up were working very long hours, day and night even though at night they could hardly see what they were doing and so the most important people would be the ones standing right over the wound of the figure on the table and holding the extra lights in exactly the right position above the hands that trimmed and cut and tied off and sewed and certainly they said there was no humor or entertaining conversation like they have on television and the workers in fact hardly spoke to each other because there was no time for it, and it was simply solemn and serious and completely organized and methodical.

"And so-in any case-the two women I'm speaking of were among those around the table on this particular night, and the younger one was one of those assisting and even, at least once, she said, giving the anesthesia, although she had only learned how to administer it a few days before, at a hospital in a district nearby. Because you see-as she later recounted-she had come over from this other site one that was a little better off for general supplies and appurtenances and for instance she did have on a nurse's dress that was still fairly white and she said she felt she looked strangely luminescent up against the rest of them.

"But what fascinated her from the beginning, she said, was this: the thin, quick hands-the light-skinned, scrubbed-looking, slightly freckled hands-of the woman who was doing the operating that night. She said she did not believe she had ever seen a surgeon's hands move with such agility and rapidity and yet so little hesitation, such assurance and when they did pause, by necessity, then be held so completely still and steady, with no tremor or nervous mannerism whatever. On this night, the hands, she said, would cease to move while a mental calculation, for instance, was being made, and then they would suddenly begin flickering again under the strange lights, touching and flickering and reaching and holding and almost strumming over the wound like one would over a delicate guitar.

"But in any case that was apparently the way it was and if you can picture all that, perhaps you can imagine as well the two of them afterwards when they happened to find themselves alone in another poorly lit place, no in fact a much darker one out in back of the tent in a close dewy space smelling of damp grass and of various kinds of mold collecting on cartons and wooden supply chests and old barrels and so on. And then the thing was that she saw the thin hands moving

TRIQUARTERLY

45

to accomplish, haltingly now, a quite different task the hands barely flickering, this time, in what was mostly starlight. And what took place next was something that was, somehow, as small a matter as it was, eternally fascinating for the younger woman ever afterward. We have to picture the surgeon this older woman, you see sitting out there in that near darkness in a solemn hunch of fatigue on some kind of stand or stool or perhaps it was simply a low barrel while she attempted to light a cigarette, and was finally unable to do so because now she could not steady her hands.

"I know the younger woman said, later on, that after all there are a great many times in our lives when we wish we could help another person through some segment of their existence and are helpless and simply cannot find any way to do so and so, looking back, she said that on this occasion she felt she had been able to perform one of the most gratifying deeds she had ever performed then or since-which was simply to help this doctor light her cigarette.

"Later, she knew that the woman did not have the habit of smoking, was a smoker on only this one occasion: when she had finished an operation, or what was more often the case a series of operations in which her hands and mind would not have trembled, not hesitated, except by necessity, for a moment sometimes for a period of hours. But then afterwards she had the habit of going, always, to some silent, private, preferably dark or shadowy place in the unsheltered out-ofdoors, taking with her an old limp black medical bag and of rummaging in the bottom of it for a mashed and tattered pack of cigarettes, and then taking two of them out along with a small square box of those old-fashioned wooden matches.

"In the process of all this, the younger woman said, and she would observe these actions a good many times after this night I'm speaking of, the surgeon's hands would begin to tremble and sometimes she could not even remove the pack of cigarettes from the lumpy bag or the cigarettes from the pack and almost never could she herself place a cigarette between her lips and light a match to it.

"But in any case, on that evening we are speaking of, this new acquaintance, this young nurse, happened to be standing nearby and she said that once the woman had succeeded in finding the pack of cigarettes, that somehow she, the onlooker, had understood the whole situation and was able to take, lightly, the woman's hands and hold them steady, and then take from them the cigarettes and so on and succeed in providing her with a smoke. She said it was one of the most

TRIQUARTERLY

46

gratifying acts she had ever been able to perform.

"The woman sat and smoked, she said, and looked, seemingly without expression, into the night sky, or over the dewy field, and said nothing. She accepted the girl's help as a matter of course and without noticing what or who she was. After a time she began to speak in a very low voice apparently just to herself to murmur and question herself about the work she had just performed which seemed to be simply the regular postmortem that any artist or performer or worker in any medium has to enact before they can go forward to the next event.

"The girl said that she and the woman did not exchange on this occasion any personal information of any kind or even give each other their names, and that she did not know the woman's name for several days. The woman did not ask her from what other place she had come, and why on this particular day and to this particular stage of operations although as the hour in the night air wore on, on that first night, she said the woman did raise her eyes to her face once or twice and more or less look at her and then drop her gaze again over the field.

"The second cigarette she was able to light on her own and she smoked it more slowly and then rested her face on her hands and seemed to think deeply about something and that was the first night they were together in this world."

The woman who spoke was relating this incident to a friend sitting across from her at a picnic table in a little park. It was a late September afternoon and a wind-spun, speckled patch of sun skimmed over their tabletop now and then and seemed to be swept back up, instantly, into the trees overhead. A sniff of fall blew about in the air and you could hear a thin wispish rustle and crack of the winter to come amidst the animal life in the brush.

The speaker was a large vigorous woman in her seventies, a person who simply thought a great deal about all the human scenes she had known, both in her own country and in those other countries during the war and afterwards. The woman she spoke to was a rather new companion who had become interested in an exchange of life-remembrances of this kind.

The two women were interested in the past and they were interested in the present, and they were especially interested in the connections between the two.

The speaker contemplated for a time the scenes she had been describing and then she spoke again. "Of course the person who came to see

TruQUARTERLY

47

me last week the visitor I had caused me to think once more about all of this and these two women I had known during the war and to relate to him certain things that-" She smiled faintly.

"I probably sound like that old book Wuthering Heights the old woman telling that peculiar story by a fireside years later after the main characters, if I may put it that way, had all died." The speaker smiled wryly at herself. "I know I used to like that book very much. But in fact I did speak to this young visitor quite frankly since he seemed to want that very much, and these days, especially with the new attitudes that people have about all kinds of relationships Her voice drew itself out and she looked away for a moment into the green hedges of the park and listened to the thin crackle of the insect life within the brush.

"Of course I myself was not in their line of work and although I was in the same army, I was not usually involved in that district. But I visited them once in the town where they went to live afterwards sometime, that is, after they had worked together in the field hospitals of the army and then been transferred or assigned in some way-I'm not sure I understood it even at the time-to an organization of European doctors who were treating the noncombatants, the common people themselves living in the zones of war.