Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individ ual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life sub scribers:

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Paul Brownfield

Robert Creamer

Eleanore Devine

W. S. Di Piero

John B. Elliott

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

C. Dwight Foster

Amy Godine

Jay Harkey

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Irwin T. Holtzman

Helen Jacob

Loy E. Knapp

Greg Kuzma

Patrick Mangan

Charles T. Martin

Florence D. McMillan

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Dorothy J. Mikuska

Michal Miller

William T. Morgan, Jr.

Alicia Ostriker

Linda Pastan

Fran Podulka

Mark Rudman

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Susan A. Stewart

Lawrence Stewart

Dorothy H. Taylor

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

TriC02Q1J@uQce[J�)f95

Editor Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor

Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Reader

Christopher Carr

Advisory Editors

Winter 1995/96

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow James Lang

Editorial Assistants

Deanna Kreisel, Hans Holsen, Kemba Johnson, Jacob Herrell, Dylan Rice

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of back issues varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions offiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1996 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ) Bookpeople (Berkeley, CA); Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CA); Fine Print (Austin, TX).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), Historical Abstracts, MLA, EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CA).

issue: Susan Hahn

Contents

this

ARTICLE Tolstoy's American Mailbag: Selected Exchanges with His Occasional Correspondents •...•...•••••..••.••. 7 Robert Whittaker DISCOURSE A Conversation with Philip Levine 67 ESSAY From Translation ..••......•...............................••.. 249 Robert von Hallberg FICTION On with the Story ..•.....•............•...................••••.. 49 John Barth Courting a Monk 101 Katherine Min Lovesong...•................••..............•.................•.... 114 Lynn Marie Sadness of the Body 191 Jason Brown Marsena Sportsman's Club 219 Joyce Carol Oates 3

Editor of

On a Windy Night•........•..•............••.......•......••.. 240 Stephen Dixon SPECIAL SECTION Blizzard into Text: Contemporary Cross Gendered Verse .•••••..••••••••.............••.•••..•. 125 Alan Michael Parker and Mark Willhardt The Sibyl 146 Carl Phillips Hephaestus Alone 151 Linda Gregg The Muse 152 Michael Heffernan I Pushed Her and She Fell Down 153 Diana Hume George How William Solomon Invokes Free Will; Frank Blank Whose Depression Was Banished; The Great 14th Street Costume Company Clarence Ernest Klister, Prop 156 Cynthia Macdonald The Bridge Builder 162 Maxine Kumin Ballad of Ashfield Avenue 167 ]oyce Carol Oates Maizel at Shorty's in Kendall 169 Campbell McGrath 4

She Speaks Across the Years ..•...•...................... 170 David Ferry World Wrap 172 Alice Fulton A Fate's Brief Memoir 1 76 Agha Shahid Ali Moon Goddess 180 Alec Marsh Krishna Speaks to the Summer Carpenter .•.••..... 182 Alicia Ostriker Moses in Paradise .............................................• 183 Jacqueline Osherow POETRY Iowa City: Early April 46 Robert Hass The Harbor at Nevermind, 1915; The Seven Doors; On the Run; Out of Work and Out of Luck •..•••....•.............................•...................... 83 Philip Levine Her First Week; His Father's Cadaver; West 89 Sharon Olds My Father's Gun; Stealing 94 Elise Paschen Stir Crazy 97 Edward Kleinschmidt 5

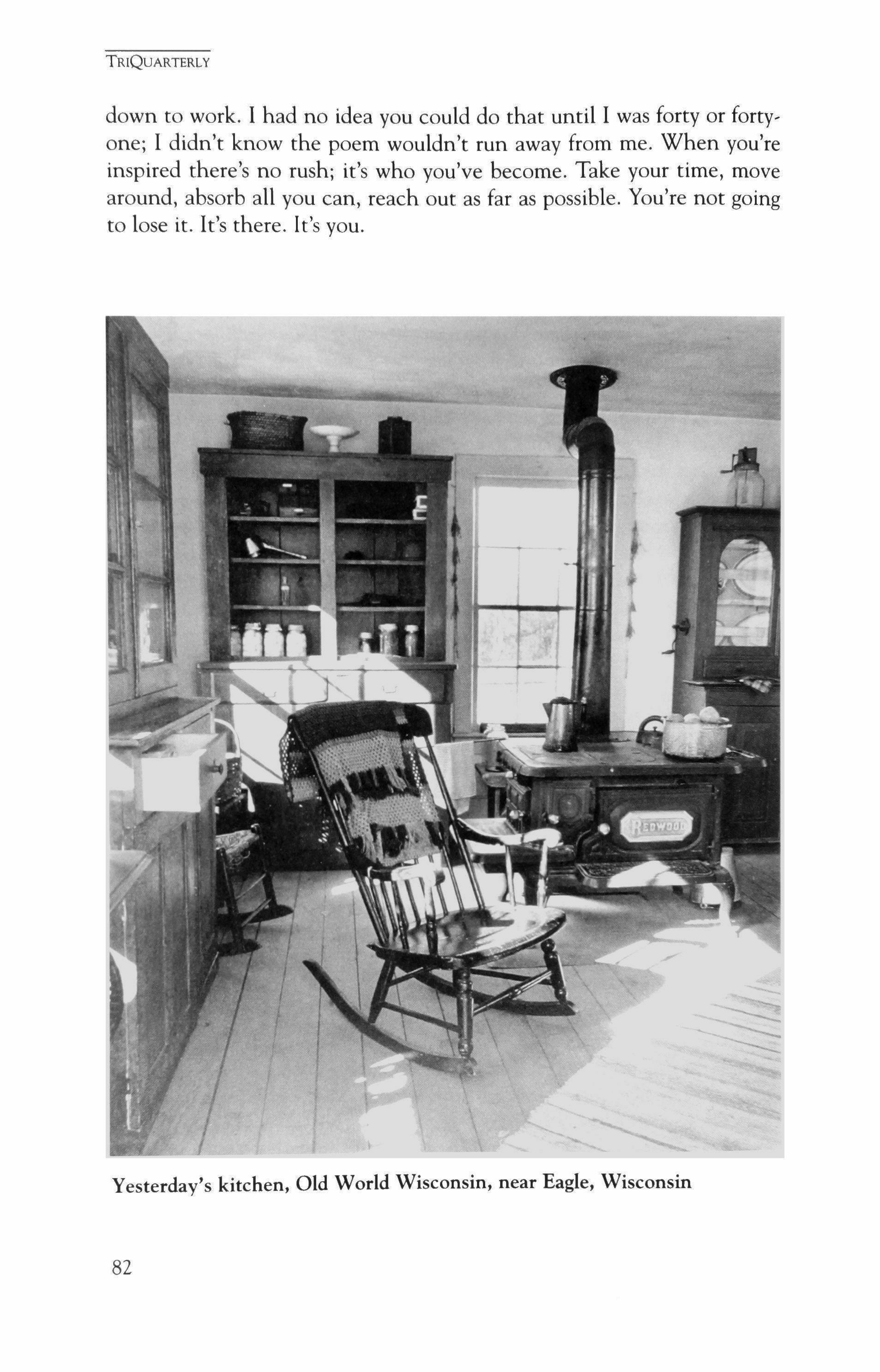

Cover illustration courtesy of Special Collections, Vassar College. Cover design by Gini Kondziolka. Letters on pages 2 and 45 courtesy ofL. N. Tolstoy Museum, Moscow. Photographs throughout issue by Arthur W. Schaefer.

The Sex 99 Billy Collins No Sorry 200 Catherine Bowman Evidence of Bear; The Day I Take Her to the Hospital 202 David Breskin Revelation 207 Richard Chess Ragtime 209 David Zivan First Death; Around the World; First Language 211 Ann Townsend The Widow 215 Alan Michael Parker

Figure; Speech

Oracle;

223

Wojahn In the saliva / in the paper 276 Frida Kahlo Translatedfrom the Spanish by Robert Hass CONTRIBUTORS 277

Rajah in Babylon; After Wittgenstein; Hey, Joe; Allegorical

Grille;

Dirge and Descent

David

6

Tolstoy's American Mailbag: Selected Exchanges with His Occasional Correspondents

Robert Whittaker

Americans read Leo Tolstoy's writings, embraced his ideas, and in their enthusiasm wrote him letters. His philosophical, political and religious writings affected his American readers more than his fiction and elicited by far the greater response. In 1885 the publication of Tolstoy's My Religion ushered in what one historian has called the "Russian craze" in Arnerica.! For the next twenty-five years, until his death in 1910, Tolstoy's words and works were published with increasing frequency, making him one of the most influential essayists and thinkers for Americans who believed in social, political and religious reform. His fie-

This publication presents material resulting from the joint U.s.-Russian project "Tolstoy and His U.S. Correspondents," begun in 1986 under the auspices of the International Research and Exchanges Board, the Association of Learned Societies, and the Academy of Sciences of the U.S.s.R. After 1991, support for this project was taken over by the Russian Academy of Sciences, and it continues to be sponsored by the Gorky Institute of World Literature in Moscow. The project has received major and essential institutional support from the Tolstoy State Museum in Moscow, especially the staff of its Manuscript Division. Activities of the project in the U.S. have greatly benefited from the support of the staff of the Slavonic and Baltic Division of the Research Libraries of the New York Public Library. The director of the project for the Russian side is Dr. L. D. Gromova, the chief editor is N. P. Velikanova; the activities of the American side are coordinated by the author of this publication, who expresses his gratitude to the staff of the Tolstoy State Museum and its Manuscript Division for assistance in this research and for permission to publish from these letters of Americans and Tolstoy.

TRIQUARTERLY

7

tion written during this period, especially The Kreutzer Sonata and Resurrection, promulgated Tolstoy's radical moral and religious views and enjoyed a succes de scandal or d'estime, depending on the audience. (Tolstoy's fiction before 1881, especially his novels Anna Karenina and War and Peace, regularly attracted the attention of reviewers, but evoked significantly less response from American letter writers.)

Caught up with the moral and religious message of Tolstoy, Americans wrote him over 1,700 letters.2 (This number, given Russian government censorship, is probably less than the number of letters sent and does not include hundreds of books, pamphlets and other publica, tions received from the U.S.) These American correspondents provide a fresh indication of who was reading Tolstoy and how these average read, ers reacted to his works. Surprisingly, there are very few letters from leading American political, social or intellectual figures. The only politician of national reputation to write was William Jennings Bryan; the most prominent social activists to contact him were Henry George, Frances E. Willard (head of the Women's Christian Temperance Union), Clara Barton and Jane Addams (who visited him but did not write); and among writers and poets, only Edward Markham. Who then comprised his American correspondents? A remarkably various collection of men and women who shared Tolstoy's concern for "true" Christianity and the teachings of Christ, for nonviolence and nonresistance, for social justice, for abstinence from meat, alcohol, political activity and sexual relations, for land reform and the single tax, for free' dom from government interference and coercion. Their reasons for writ, ing were equally varied: to share religious and moral views inspired by his works; to ask for interpretations of his writings; to receive his reactions to their own writings; to share views of other writers; to explain their own similar ideas; to receive his advice on troubling questions; and even simply to get Tolstoy's autograph.

Tolstoy responded to this flood of American letters as best he could. He or his daughters, wife and assistants (at his direction and on his behalf) wrote several hundred answers, almost all in English. Records indicate over three hundred responses; however, only half of these let' ters have been found) Tolstoy responded to all sorts, ignoring no type of letter except the frivolous. Still, he could manage to answer only one out of every five or six he received. Almost all exchanges were limited to a single response to a single letter. Rarely (in only fifteen or so cases) did he write more than a letter or two to the same correspon-dent+ In these brief exchanges Tolstoy wrote to over a hundred different individ-

TRIQUARTERLY

8

uals. The letters of these occasional correspondents and Tolstoy's responses are the subject here.

Whom did Tolstoy answer of these occasional American letter writ, ers? The largest group are those who sent money or books and other published materials. A number of Americans sent unsolicited contributions to Tolstoy in support of his activities to feed starving peasants during the famine of 1892,93, and to these correspondents Tolstoy and his family responded most conscientiously. To the many Americans who sent gifts of publications-their own books and writings, the brochures and clippings of others, tracts of various sorts-Tolstoy regularly expressed his thanks. Understandably, when the material was of particular interest to him, he responded in more detail. In some cases he arranged for the American's writings to be translated and published in Russia. Tolstoy least often responded to requests for autographs, although he was more likely to provide copies of his signature to those who expressed support of his ideas. The Americans who wrote in syrnpathy with Tolstoy's principles or who wrote for advice and assistance occasionally received thoughtful, even extensive responses, and these remain among the most interesting of his letters to America.

Americans quite rightly associated Tolstoy with the antiwar move, ment, even though his writings against the Spanish-American War were not translated in Arnerica.l Thanks to his American disciples, and especially Ernest Howard Crosby (1856,1907), Tolstoy was identified with the antiwar movement and with those who opposed the subsequent U.S. military action in the Philippines at the turn of the century. In 1902 Crosby sent Tolstoy a copy of his own satiric novel on the Philippine military action, as well as a work by Herbert Welsh (1851, 1941), editor of the Philadelphia weekly City and State.6 Welsh wrote a long letter to Tolstoy in November 1892, expressing his hope that "the people of the United States might exert a powerful influence in the direction of preventing throughout the civilized world this scourge of war." He based his hope on "our geographical position, our traditions, our professed Christian belief, and our commercial interests," which he believed destined the U.S. for a peacemaking role. While he believed the U.S. was defending oppressed Cubans against the cruel tyranny of Spain, he was appalled at the American military aggression in the Philippines. Welsh wrote to ask whether Tolstoy agreed with his hope in America's peaceful mission and with his condemnation of its activity in the Philippines." If he expected encouragement for his optimism, Welsh was disappointed.

TRIQUARTERLY

9

On December 15 Tolstoy responded with his views on the Philippine military action:

Dear Sir,

I received your letter, book and pamphlets.

I can not help to admire your activity, but the crimes which have been committed in the Philippines are special cases, which by my opinion, will always occur in states governed by violence or in which violence is admitted as necessary and lawful.

Violence, which in itself is a crime, can not be used to a certain extent. When it is admitted it will always transgress the limits which we would put to it. Deeds as those that have been done in the Philippines, in China and are daily done in all pseudochristian states will continue till humanity will accept violence as a means to produce good results and will not accept the chief precepts of Christianity-to act on our brethren not as on animals by violence, but by sweet reasonableness (as Matthew Arnold termed it) which is the only way to act thoroughly and durably on reasonable beings.

Hoping that my bad English will not hinder you to understand what I mean to say, I remain, dear Sir, yours truly

15 Dec. 1902.8

Leo Tolstoy.

Tolstoy's position leaves no hope that any government, even the U.S., can avoid atrocities of the sort Welsh deplored. What to the American seemed the exception, to Tolstoy was the rule. His uncompromising positions would often surprise and disappoint his American correspondents, and this pattern recurred not only in discussions of politics, but also in matters of religious faith and morality.

Tolstoy's writings against war and violence were widely read and appreciated by American pacifists and frequently republished. My Confession, which defined Tolstoy's philosophical stance against violence, especially in nonresistance to evil, was reissued in 1904; his attack on the Russian government and the Russo-japanese War"Bethink Yourselves!"-appeared in various periodicals and was issued in separate editions throughout the United States.? Tolstoy received many letters from American pacifists, not all as sophisticated as that from Welsh, but no less impassioned. At times these letters suggest complete agreement with the most extreme positions of Tolstoy. For example, on July 31, 1904, a certain J. H. Reeve wrote to Tolstoy from San Francisco, apparently in reaction to his recently published "Bethink Yourselves!":

TRIQUARTERLY

10

Dear Esteemed Friend:-

Today I read yours and others of your countrymen's sentiments on the war. I have your book entitled My Confession, My Religion.U' Knowing your position in this regard, for some time I have felt that I would like to write to you and thank you for your "Confession" and disapprovals of wars. It never appeared to me so dreadful before I read your book. Kindly accept my thanks for the impression you have conveyed to my life. Your sentiments are on the tongues of every fair minded man and woman in this great country. Thousands have resolved to take your stand. And thousands more will I say are on their journey. I have been thinking how dreadful it is for a so called Christian nation like ours, having the audacity to boast of her Institutions where they are teaching good creatures to kill the same. War is as black as you have painted it. And in the words of Hood, "0 God: that bread should be so dear, And flesh and blood so cheap: Selfishness so cruel." Pardon me for the liberty I am taking, I am sure you will, I want to ask you what Jesus meant by saying: "I come not to bring peace but a sword" and what is meant by your quotation in Luke XII, 49? 11 Does it all mean that out of these great appalling conflicts or through them, there will be more speedily ushered in the millennium of peace? History repeats this dreadful crime over and over again. As far back as we can go. When will this all stop? And when will the nation know the value of a human soul? There are many more things I would like to speak of. But knowing how valuable your time is in service to your people especially at this time, when aching hearts are bleeding on every hand; I will refrain from so doing. Kindly accept my sympathy in woeful calamity which this war has brought upon you and your people. I am yours in the love of Jesus, "Peace on earth, good will to men,"

J. H. Reeve

PS I am sending a paper with your article. And an open letter to W. J. Bryan, the gentleman who called on you about a year ago. Yours

J. H. Reeve

San Francisco Cal.12

Upon receiving this letter, Tolstoy responded without, however, addressing Reeve's specific questions. Nonetheless, his brief letter of September 2 was deeply appreciative:

Dear Sir, I received your letter and thank you for the sentiments that you express in it. It is a great joy for me to know that-not I, but truth, has so many friends.

TRIQUARTERLY

11

2.IX. 1904.13

Yours truly Leo Tolstoy.

Although Reeve did not acknowledge this response, he did not forget it. Four years later he wrote Tolstoy again, now on a more personal subject. On November 18,1908, he wrote:

Dear Sir:

With greetings and longevity in health and happiness yet to come. Are my sincere wishes. I have eagerly watched the papers through your sickness, am very glad to know that you are well again. Words cannot express the feeling and consolation there comes to one who have learned to love; (as St. Paul says) "One whom I have not seen I love." Your writings have been the greatest blessings to myself and friends. Our best wishes are upon you at all times. Pardon me for the request I am about to ask. I have a little girl. And I wish you would kindly consent to give her a name. I have given her one. And would very much like you to give her the second. The name I have given her is Calfrence, taking the first syllable of California and the last of San Francisco. I will forward you a photo of the baby. This request is my wife wishes and self. Trusting you will grant the same. Thanking you in advance for the name. If beyond this life there is a joy which passes all understanding I hope to meet you there. The truth is all I crave. Goodly the blessings of all there is remain upon you and yours. I remain your very sincerely

J. H. Reeve14

No record remains of a photograph of the child or of Tolstoy's response. Tolstoy's political philosophy went hand in hand with his religious views, no less than it did for his American sympathizers. They responded to his Christian anarchism and individual understanding of Christ's teachings just as enthusiastically as to his pacifism. One of the more interesting exchanges between Tolstoy and his American admirers is with a Christian sectarian from Belton, Texas, Mrs. Martha McWhirter. On August 28, 1891, she wrote to Tolstoy:

Dear Sir

Having heard of you and read some of your writings an anxiety has been awakened to hear somewhat of you personally.-We as a community of Christians, about thirty in number, have been for the last twenty years, holding the truth in our lives against great opposition. We, like thousands of others, belonged to the common sects, among us Presbyterians,

TRIQUARTERLY

12

Methodists, Baptists, etc.

When the spirit of Christ was given, with it was a light and understand, ing that we realized what we had been serving was not of God, but of man. As we received the light, we tried to give it out. Consequently, we were taken up in the churches as heretics, turned out and persecuted, even to being whipped and stoned. We have been led in a way that we little thought of, hired as servants (not for a living, we all had plenty to live comfortably on) but that we might be crucified to the world, went in the kitchens of those that were in the higher circles of society (that we had lived in social intercourse with for years). Our families have all been broken up, separated from husbands & wives and children. All family relations gone, we have our property in common, live together as one family, labor with our hands for a living, bringing up our children beside us, not allowing them to mix with the world socially in any form, teach them at home.-The work of purification through these means is constantly going on. As the time draws near we realize the fire grows hotter, so much so that we feel the need of encouragement from those that have gone further in the way. Believing from the truth we have read from you, we therefore ask a reply to this letter, hoping thereby that there maya mutual fellowship and benefit be derived by a correspondence between us.

(Mrs.) Martha McWhirter Belton Bell CoTexas

P.S. I intended to have mentioned how much pleased we were in reading Kreutzer Sonata to realize that every word of it was truth. That is the rea, son it was suppressed through the mails, but it was God's way to have it circulated, that the truth might prevail.

MM

P.S. A gentleman stopping with us translated this letter to the French language. If you answer, I would prefer to have it in English.

MM15

Indeed, this letter with its desperate plea for guidance and support arrived both in English and in French. Tolstoy was deeply affected by the letter and offered help in the form of a critical appraisal of the group's principles according to his own beliefs. He responded from Yasnaia Poliana on September 22:

Mrs. Martha MCWhister [sic], Dear sister!

I was very glad to receive your letter and to know that there are people who live as you live and that you know me and wish to have intercourse with me.

TRIQUARTERLY

13

Please give me more particulars about your kind of living: have you property, how do you manage it, are you non-resistants] What you write me about your taking low positions, working as servants, your laboring with your hands and your freedom of all acknowledged confessions seems to me to be true conditions of a Christian life. But I will be quite sincereI hope you will be the same to me-and tell you what seems to me not right in your way of living. I think that to abandon husbands, wives and children is a mistake. A Christian I think must learn to live with all men as with brothers and sisters; and husbands, wives and children should not make an exception. The more it is difficult for a Christian to establish brotherly relations between himself and his nearest relations, the more he must try to do it.

The other thing that I do not approve is that you do not allow your children to mix with the external world. I think a Christian must not enclose himself and his children in a narrow circle of his community, but must try to act towards the whole world as if the whole world were his community and so he must educate the children.

Please explain to me your words "when we received the light." How did you receive it? and what do you understand by the word "light"?

Please also give me more details of the history of your community, I will be very thankful for it.

My address is: Tula, Russia.

Thanking you again for your letter I remain Yours truly L. Tolstoy 22 September.16

Martha McWhirter responded to Tolstoy's letter with the details he requested. Her letter, however, expressed some surprise and, indirectly, disappointment in Tolstoy's moral support. Her account of her conversion provides a striking, if simple, portrait of American fundamentalist faith and enterprise:

CENTRAL HOTEL

Belton, Texas

Oct. 10th, 1891

Mr. Tolstoy

Dear Brother

Your letter of 22nd Ult received. We all were glad to get it, but a little surprised that you see the plan of salvation different from what we do. We feel glad of your plain and honest way of writing and take pleasure in answering your questions to the best of our ability. You ask how we

TRIQUARTERLY

14

received the light and what we mean by the word light. We see the whole so called Christian world in darkness, thousands of honest souls blinded, the whole sectarian world-the Babylon that is spoken of in the 17th and 18th Chapters of Rev.-that has now fallen and all that the spirit of light can reach is coming up out of her before the final distraction. We were in that place twenty four years ago, groveling in darkness, trying by earnestness and prayer, keeping the commandments of the sects we belonged to, visiting the poor even in houses of ill fame, prisons, and to people of the lowest degree, denying ourselves to give of our means, so much so, as to keep up disturbances in our own families. In the midst of this, a great power fell upon me in my own home, made me see and realize that these works were nothing, that the powers that be was the works of the devil, worked by man. Right there is where we date our being ushered from darkness into light, right there the battle began (we were and had been for two years holding weekly meetings from house to house). Upon that occasion the spirit took deep possession of me. Others were soon added by the same power, but not in as deep a way. The Bible was a new book to us. We studied it by day and night. As we received the light, we gave it out by the changes in our lives and by telling it to everyone that would listen both in public and private. We turned the different churches upside down, shook their foundations until we had the whole town in an uproar. (We all were of the first families, had plenty of this world's goods.) The churches finally (after seven years war) turned us out for heresy. The war in the meantime had been going on in our families; our husbands and children, trying to force us, to keep our mouths shut, and let the people go to the devil if they chose. We were governed by the spirit of God, and they by the spirit of worldliness and fear. It went on in this manner for years till there was no fellowship between us. It finally came to the place where they give us our choice, to break up and quit these meetings (in short to give up our religion) or they would give us up. Some of them left home, others left our beds. In this time these scotch brethren were taken out by a mid-night mob and whipped unmercifully. The breach had grown so wide, the feeling and disfellowship so great between us, that when they were ready to come to our beds, we were shown that we dare not, that God had chosen us out of the world and to be joined with a harlot or an adulteress, our bodies would become defiled. They were of the world and friendship with the world was adultery in his sight. He also shamed us through the power of the spirit and dreams that his people were our mother, brother and sister and also that whosoever did not forsake father, mother, brother, sister, husband and wife, houses and lands, could not be his disciples. I don't believe we could have had the strength for these things if they had not have forsaken us and driven us from our homes. I will give you one case that you may have a clearer understanding. One of the sisters (Mrs.

TRIQUARTERLY

15

Margaret Henry by name) had a husband that drank considerably, a very large man in size, that had great bitterness against us. He sent each one of us a written notice not to come to his house again (he was wealthy), we stayed away about two years; in the meantime we had opened up a laundry; were doing a great deal of washing for the town (this was before we went out as common servants); it was our taking low calling that made our aristocratic families mad enough to kill us; we moved the laundry from house to house, to be furnished with water, and also to bear equally the shame of having a laundry in our houses and of being common washerwomen (which we had been raised in a country where we would have had menial labor to have done). Mr. Henry told his wife to put the laundry out of his house. She thought as the law gave her half of the homestead, she ought to have equal right in it. He run the girls off with sticks and stones, before hundreds of people (we have thought that we done wrong in resisting but God has worked it out to honor us in the end); he went for the officers, had us all arrested and carried to the court room at 9 o'clock at night for disturbing his peace.-They would have put us in jail that night but some of our husbands and sons heard of it, went on our hands to be at the court the next day.-We went from the court room to our homes, sister Henry with her children passed by her own home told her husband that she never, no never would live with him again without he was a changed man. We all went to work and built her a house with our own hands; had two boys 10 & 14 years old that had worked some at the carpenters trade, the house has four rooms and an attic two fireplaces.-(The people would ride by and make all kinds of sport, say that we were building a tabernacle to receive the Lord in.-Twelve months found Mr. Henry a corpse, dying a miserable death, took four men to hold him in bed). After he was buried, sister Henry came home (an old fashioned stone house with four rooms and a dining room and kitchen). One block from the public square, she soon had an application for the place for a boarding house. We rented it, rooms were called for, we added them out of our common fund, till the place began to look quite pretentious. Through circumstances, we were forced to come in the house, and open a hotel. All the boarders left as soon as they found we had taken possession-we quietly went along, would ring the bell as though we had a house full, the whole town making fun of us, that we would for a moment think any body would stop with the fool fanatics-this went on for twelve months (of course very mortifying to us). At the end of twelve months a noted harlot (a very nice girl in appearance) came to board with us. We took her in, not knowing at the time what she was, but finding it out soon after, we felt afraid to turn her out of the house, believing that God worked all things pertaining to us. They reported around that we were keeping a fancy house, the girl stayed about six weeks, found that we knew her character and left (she done nothing wrong while she was with us). The same week

TRIQUARTERLY

16

that she left, we had our rooms filled with boarders. The first people in the town from bankers down; we had to build more rooms for transients, and from that day to this (six years)-we have a houseful all the time; we now have party rooms besides the rooms the church occupies. The house has a reputation even in other states of being the best hotel there is in the state.-We never have asked anyone to stop, or stay with us, it seems ever since it was put on wheels it has been rolling of itself.

We find all these things are means to purify us, it is a continual fire burning out all dross till the metal will reflect His own image.-You ask of our not mixing with the external world-will oil and water mix? There is one family (a banker's) that has been boarding with us four years past (we visited socially when we were of the world), we pass and repass every day, pass compliments of the weather, crops, and any rooms are opened to them, they know they can come in at any time. They do come but the atmosphere is such that they can't breathe freely in it, and of course don't stay long and now at the end of four years we are exactly where we commenced.-I cite this case to give you an understanding of our world relations. There are families with children in the hotel. Our children all have their allotted work in assisting in the dining room, chamber work, kitchen work. When the morning work is done they are taken by one of the sisters to one of our houses one block away and taught in the common branches of an English education, at night (when the nights are long, one of the sisters teach them in Spanish-that language is spoken a great deal in this state).-Another of the sisters and one of our sons have learned dentistry. Have an office in one of our own houses. The people come and have their teeth made and filled, pay for them and that is the last of them, except they brag on the work and some one else comes through them; we never advertise, but our work we try to do well and that advertises us. We rent in town and three farms in the country. Our tenants brag about what kind and good people we are, that we make them comfortable and never oppress them-we pay ($600) six hundred dollars taxes per year. We never buy on credit. Merchants vie with each other to get our custom. We are now called the best people in the world, only a little peculiar in our religion (are known far and near as the sanctified). To the world it seems that we are conforming more to it-but with us, we are dead to it-we had to be separated from it in one sense, till we could be crucified to it-now we can be thrown in it if necessary in any business capacity and yet not be of it. Our girls are learning bookkeeping, short hand, typewriting, etc., that if the Lord calls in a different direction we will be ready for it, but so far we have to work with our hands, not for a living but for an example.-One of the professors of the state university at Austin, with his family spent the summer with us to write up our lives. He is a strong believer in the community system, has studied and read a great deal on the subject, he says there is nothing like this community in the world, and believes by having

TRIQUARTERLY

17

TRIQUARTERLY

it published it will be a great benefit to the world.-We told him without the spirit that people cannot live together as we do, that all property has to be taken out of the heart, then we can hold it for the Lord, but of course he couldn't understand it.-I see from your questions and your suggestions of us living in a proscribed circle that you don't understand, you will I think draw different conclusions after you have read this letter. In a private family you often go weeks without seeing and having intercourse with any but their own family. We are mixed up with the world every hour in the day, till we often long for one afternoon that we could be free to be to ourselves.-Two years ago we rented a house in New York City-went in different parties till all the church made a visit to the northern cities and Atlantic seaside resorts, and I will venture to say there never was a set of tourists respected as we were, our plain dress and quiet manners commanded respect. We never talk religion to anyone. When the people came to us to know of us, we never refuse to give them the desired information.-There may be questions asked in your letter that I haven't answered as full as you would like.-I sent your letter to the farm (that some of our people live on) this morning, as I would now refer to it to see, but any way-you can when you write again, let me know.-Now in conclusion we would like to know some of the particulars of your life, we think you surely must have gone through the experience that is held forth in Kreutzer Sonata to have known the truth as is given out through its pages.-We have written for two more of your books (Church & State and four acts,17 I have forgotten the rest of the title).-I have given you an outline of our lives, to tell the particulars would be hard to do for it is an every day experience for twenty four years and would fill volumes, will always take a pleasure in giving you any information that you may desire. We all join in love and good wishes for your welfare

Yours in the truth Martha McWhirter, Belton, Texas

PS: I send you a lot of papers. They will give you a better idea of our state-you will find the Iconoclast an outspoken paper. The Flaming Sword is edited by a man (Cyrus) that claims to be Christ-we have several false Christs in the United States)8

Tolstoy answered this letter, although there is no record or copy of his response. To judge from the following letter from Texas, he suggested that Mrs. McWhirter and the members of her commune read his works. Five years after this last, above, Tolstoy received a third letter from Texas. The letterhead announced that Mrs. McWhirter's entrepreneurial efforts continued to succeed: she was now the proprietress not only of the Central Hotel in Belton, but also of the Hotel Palmo in Waco. The writer this time was one of the group's members, Mrs. Ada Haymond:

18

Count Lyof Tolstoi

Dear Sir: I have just finished reading one of your books, "Two Generations." 19 Once when we wrote you and asked you your belief in full, you referred us to your books and that has been one reason that we have read them, but this one that I have just finished I cannot see what you had in your mind or what was the object. I do not mean to reflect on you, but having heard of you so often as one having an object in life, believe that you must have something in view in everything you do and write, and not a pecuniary object, as money, I have been led to believe, is not sought by you, but on the contrary, I have heard or read that you have almost beggared yourself and family by giving to the poor. If I am not encroaching on your time and forcing myself on you in answer some questions will you tell me the moral to be gotten from Two Generations. Do not think me inquisitive for I assure you it is from an interest in you that I make the above request.

Yours sincerely, (Mrs.) Ada Havmond-P

Tolstoy read the letter but did not respond (marking the envelope "b.o."-Russian for "no answer"). When he suggested that they read his works, Tolstoy no doubt had in mind his philosophical and religious writings, and perhaps his later fiction, written after his conversion in 1881. Mrs. Haymond's confusion suggests that Tolstoy's didactic writings were more accessible to the general reader than was his fiction. Mrs. Haymond's letter is not unusual. Americans wrote to Tolstoy about his works, asking for interpretations, information about his views, even suggestions of what to read. Several requests came from members of discussion clubs and study groups with a literary or ethical dimension. Typically this correspondent, having been charged to report on or to lead a discussion on Tolstoy, turned to the author himself for information and assistance. One such occasional correspondent was Edward Braniff, an employee of the Kansas City Star:

Kansas City Mo., Sept. 5, 1900

Count Leof N. Tolstoi,

Dear Sir:-lt has been assigned to me to read a paper this winter in this city before the Greenwood Club-an organization composed mostly of school teachers & professional men---on some topic concerning yourself & your work. It is my wish to choose that part of your work as the subject of my paper which best represents you. I desire to understand and to make clear to others that part of your work which you yourself regard most highly so that I may say: "This is the very best of him; it is at this art & these teachings he has finally arrived."

TRIQUARTERLY

19

TRIQUARTERLY

I am 24. I have read nearly all your works & part of your religious teachings, including "My Religion" & "My Confession." I believe in you. I desire that others should believe in you & be helped by you as I have been helped.

Will you do me the kindness to advise me what works of yours you would prefer me to consider?

Very sincerely, Edward A. Braniff

c/o The Kansas City Star, Kansas City, USA21

Tolstoy responded briefly and to the point:

I think that my book "The Christian Teaching" renders the most completely my ideas.

Yours truly,

Leo Tolstoy. 14 October 1900. 22

This was not a popular or well-known work: although an American edition had been published two years earlier, The Christian Teaching was not included in the popular collection of Tolstoy's works edited by N. H. Dole.23 Braniff wrote again to ask for clarification:

November 26, 1900 Count Leo Tolstoi,

Dear sir:-I have your reply in answer to my letter of last September asking you what book of yours renders the most completely your ideas on religion. You say this book is "The Christian Teaching," but I have no such book in the Scribner Edition of your works edited by Nathan Haskell Dole.

Will you be so good as to tell me whether the title of "The Christian Teaching" has been changed in the English translation?

I thank you for the courtesy of your first reply.

Very sincerely

Edward A. Braniff

The Kansas City Star Kansas City, Mo., USA24

Unable to help this young correspondent any further, Tolstoy did not respond. Although he considered it the best statement of his views, the work remained relatively unknown and was reprinted only in the collected works edited in America by Leo Wiener.2S

The translating, editing and publishing of his writings interested

20

Tolstoy very little. His only wish was that none of his author's rights would limit the dissemination of his works. One American correspondent repeatedly tried to elicit from Tolstoy which of the several editions of his works he preferred. In early 1900, James Carleton Young of Minneapolis wrote the first of several letters to Tolstoy in the hope of receiving the author's autograph on editions of his works.26 That December he repeated his request: "In a collection intended to embrace the five thousand best books of living authors are some of yours. Would you be so gracious as to inscribe them in case I forward by express paying charges both ways?" Tolstoy did not answer; Young repeated the request three years later. In April 1903, he sent clippings of Boston and Minneapolis newspaper articles explaining his library and added: "My collection will be incomplete without the books of Russia's most brilliant writer." This time Tolstoy's daughter Tatyana answered with his consent, to which Young responded on May 29, 1903: "Your place of immortality is so assured in the world's literature that I desire to have your writings complete and I beg you to honor me with your consent. Is there not some manner in which I can reciprocate such kindness? In Bucharest I have the finest edition of your complete writings I have seen in America published by Scribners.27 Would you prefer I sent those volumes or would you desire me to purchase them in the Russian language? Some authors really care very much and I want to please if I only know." He sent his own photograph with the letter, as well as what he described as "some dainty books from one of our more famous American presses" (whose titles are not known). This letter brought the following response from Tolstoy on June 16:

Dear Sir, I received your books and thank you for them.

As regards the most complete and best edition of my works I have no opinion about it because I have not seen any of them. It is quite indifferent to me on which to inscribe my name, and I will do it on any you send me.

Yours truly Leo Tolstoy. 1903. 16 June.28

This response seems remarkably patient from an author who had renounced all interest, material or otherwise, in the publication of his works. Ultimately, the only book to make its way to Minneapolis was an edition of Anna Karenina signed by Tolstoy. On January 4, 1904, Young

TRIQUARTERLY

21

wrote to express his gratitude: "The copy of Anna Karenina has reached me in good order. I am delighted with the inscription. The precious volume has already been placed in a sacred niche among my rarest treasures. I trust by this time you have received the other books. I appreciate the honor you do me and will take pleasure in giving your works the most conspicuous place in my collection. As you become better understood in America your brilliant writings are more appreciated." This volume has not been discovered, and so the inscription remains unknown. It seems that this was the only volume of Tolstoy that Young received, although he persisted in his attempts with four more letters, the last of which he wrote in November 1905. The project foundered, apparently on the rocks of Russian customs officials, who energetically enforced government censorship of Tolstoy's writings.

Of Tolstoy's answer to a similar request-for his favorite Bible versewe know only from a note on the letter containing the request. A certain Frederick Barton of Cleveland, Ohio, wrote to Tolstoy on April 25, 1900:

Dear Sir,

Of all the means used to make the world better, none is so powerful and yet so quiet and far-reaching as the knowledge of texts from God's word. The custom of committing texts or chapters to memory is disappearing. Will you not assist in creating a renewed interest in special texts or chapters of the bible by writing me (with your own signature if you please) what is your favorite text or chapter.

Should you be sufficiently interested in my effort to add any incident that may have been connected with your choice it would be very gracious in you and greatly appreciated by Yours very respectfully, Frederick Barton29

On the bottom of the letter is written in Russian that Tolstoy responded and a notation "Matt. 6:33."30 Unfortunately, Tolstoy's letter to Barton has not been found: it is not known whether he complied with the second request, to describe an incident connected with this verse.

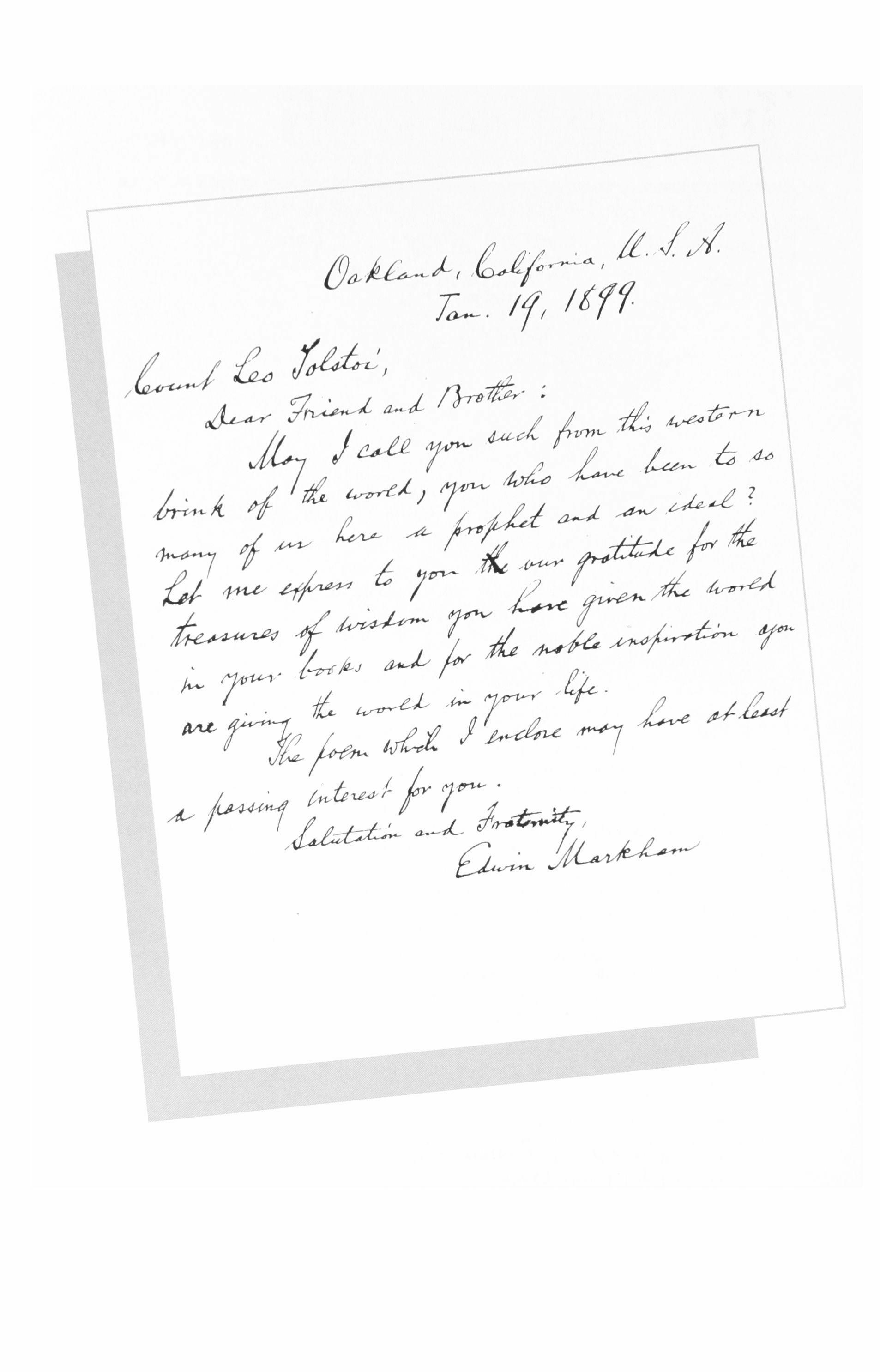

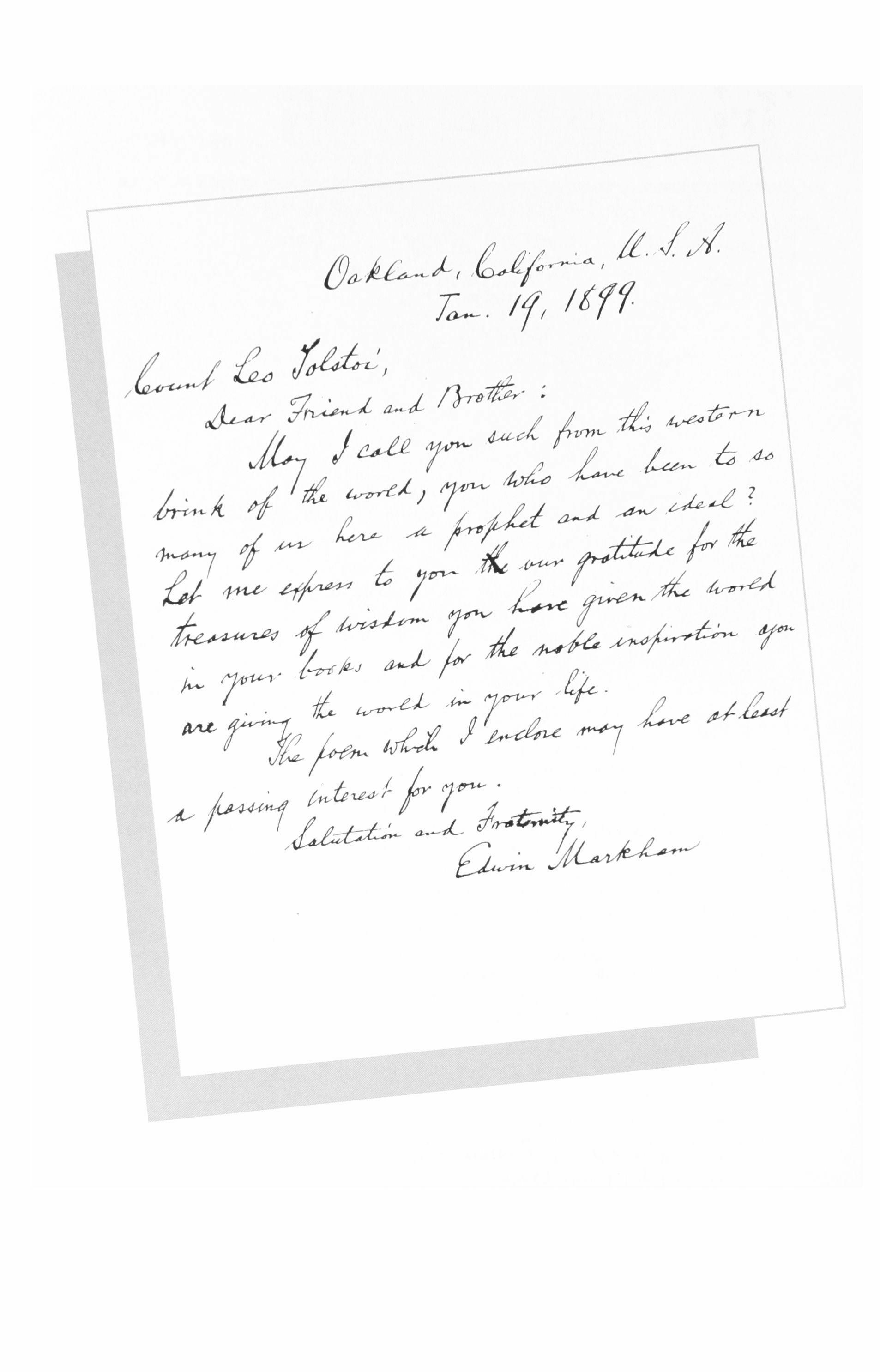

Generally Tolstoy's American correspondents showed less interest in his interpretation of his own writings than in his reaction to their works, and usually these were writers of philosophical, religious, social, economic and political works. An exception, and the only major American writer to correspond with Tolstoy, is the poet Edwin Markham. On January 19,1899, he wrote from Oakland, California:

TRIQUARTERLY

22

Dear Friend and Brother:

May I call you such from this western brink of the world, you who have been to so many of us here a prophet and an ideal? Let me express to you our gratitude for the treasures of wisdom you have given the world in your books and for the noble inspiration you are giving the world in your life. The poem which I enclose may have at least a passing interest for you. Salutation and Fraternity, Edwin Markham) 1

Markham correctly assumed that the enclosed newspaper clipping would generate more than just "passing interest" in Tolstoy: it contained his "The Man With the Hoe" (subtitled: "Written After Seeing Millet's World�Famous Painting Now in This City"). The Russian writer was deeply impressed by this poem's sympathy for the oppressed peasant and its warning to "masters, lords, and rulers in all lands." In conversation with an American banker from California, John J. Valentine, who visited the Russian author in Moscow on November 22, 1899, Tolstoy mentioned Markham's poem. The Californian promised to send him a book of the poet's verse. Valentine apparently contacted Markham, who provided a copy of his book, The Man with the Hoe. And Other Poems, with the inscription: "For Count Leo Tolstoy with affectionate salutation across the world. Edwin Markham, Brooklyn, N.Y. Jan. 5, 1900."32

Shortly thereafter, on January 20, 1900, Markham wrote again to Tolstoy:

Dear Teacher:

Let me call you so, for you have long been a light to me, as to many another in America. Seeing the same star of truth that you follow makes me feel near and akin to you, though separated by the diameter of the world.

I find that Mr. J. J. Valentine of California (a good man) is sending you a copy of my little book of poems. If it should fail to reach you have the kindness to inform me of the fact.

I wish you many years yet for the service of God in the rediscovery of Christianity.

Very sincerely yours, Edwin Markham33

Tolstoy received both the book and Markham's letter, to which he responded on February 5:

TRIQUARTERLY

23

Dear Sir,

I received your book of poems and thank you very much for sending it to me with your kind letter.

I like your poetry and especially the first poem which gives the key to the whole book

It is a great joy for me to have such friends as you across the world, as you say it.

Yours truly, Leo Tolstoy.

5 February 1900,34

The first poem in the collection is the title poem: Tolstoy's response was predictable, given his deep sympathy for the lot of the peasant.

Most of the other American writers who sent their works to Tolstoy and wrote on occasion were religious and social activists who saw in him an ally in their various causes. Among the more noteworthy requests to read his works came from George Davis Herron (1862,1925), a Congregationalist minister, theology professor and leader of social Christianity. The Christian Socialists stressed full participation in worldly affairs with the aim of transforming social institutions. Early in his career he sent the following letter to Tolstoy:

Department

of

Applied Christianity

Iowa College Grinnell, Iowa

June 3, 1895

My Dear Count Tolstoi

You have long been one of my few teachers. Though I have seen you not, I feel that I know you, and know you reverently and affectionately. You have done more than any living teacher to restore to the world the knowledge of the Christianity of Christ.

I am a young man, a professor in Iowa College, of the state of Iowa, in America, and, in the midst of much discussion and bitter and fierce antagonism, I am trying to teach Christ's law of life in its application to our institutions.

I take liberty of sending you a number of my little books. If you can find time may I ask you to kindly read my little book, "The Christian State," and graciously write me your thought of it.

Most Faithfully Yours, George D. Herron35

Which of the several works he had published in the past five years Herron sent to Tolstoy it is difficult to say. Only one-The Message of

TRIQUARTERLY

24

Jesus to Men of Wealth (32 pages)-would seem to qualify as a "little work"; the others were substantial tracts of over a hundred pages each.36 His latest work, The Christian State, was the largest he had written (at 216 pages, also not a "little book") and had the subtitle: "a political vision of Christ; a course of six lectures delivered in churches in various American cities."37

Tolstoy, who had discovered Herron and seen his works before receiving this letter, responded cordially to Herron's request with a promise to read his latest work carefully. He wrote on June 13:

Dear Mr. Herron,

I had in my hands one of your books, but I had not time to read it, so that I knew before you wrote to me your name and your work, and greatly sympathized with it, that is with your work.

I thank you heartily for the books that you sent to me. I received them today and will begin with the Christian state and hope that I will be induced to read them all. I have finished the first. I will write to you my genuine opinion of it.

Yours truly38

What "first" work Tolstoy finished is not known. However, his initial reaction to The Christian State is documented in Tolstoy's diary. On June 18 he wrote: "Read Herron-Christian State-undistinguished, cold, vague."39 Herron's work predicted a social revolution based on the political leadership of Christ. His belief that the state was essential to the search for justice appears diametrically opposed to Tolstoy's Christian anarchist views. When Tolstoy had finished, he wrote a long, detailed critique of the work to Herron. On July 2 or 3 Tolstoy wrote the following draft (all but the first sentence is in Russian):

I read very attentively your book: "The Christian State" and will try to give you a candid opinion of it.

I completely share your view of the significance of Christianity as a political and economic teaching. Many of the places in your book where you point out the sins of our life and the anti-Christian position of our society are strikingly true. I was especially struck by your bold judgment of the American people for not fulfilling their vocation. Generally, this entire book is permeated with the most profound Christian spirit. But I find one important shortcoming in it which undermines its significance. I hope that you will accept my opinion, whether it is just or not, with the same religious awareness with which I address you, namely that our attitude on this subject is not the attitude we have towards one another,

TRIQUARTERLY

25

Tolstoy and Herron, but is our attitude towards God. The entire book and your sermon, in my opinion, is weakened by the fact that you are trying to pour new wine into old skins.

The old skins which you attempt to fill with new wine are the state and church. The state is a pagan form, and a state with self-sacrifice is the negation of the state. What is more, that church which we know, be it Catholic or Protestant, as soon as it ceases to be self-sacrificing Christian in the person of its members and becomes an institution that serves its own aims, at that time the church has already ceased being a form that is capable of taking a Christian content into itself. The fact that you wish to resist the irresistible, what has outlived its time-the church and statedeprives your work of clarity and force in many places and leads the reader into a region of something vague and ill defined. Therefore 40

Tolstoy's rough draft ends abruptly. However, the substance of his objection seems clear from this fragment: that it is pointless to write of church and state in Christian terms, since both are antithetical to true Christianity.

Herron responded with thanks, acknowledged the justice of Tolstoy's criticism, and admitted the futility of his own earlier attempts:

Department of Applied Christianity

Iowa College Grinnell, Iowa Sept. 4th, 1895

My dear Count Tolstoy:-

I wish to thank you for your very kind criticism of my little book, "The Christian State." Your criticism is just and has encouraged me to take the step I have for two years been doubting and hesitating before. I fully know I have been pouring-c-or trying to pour-new wine into old bottles. I have worked in this way with a distinct purpose-the purpose to win, if possible, the church to a new conception of Jesus. I have tried to translate the old religious terms into the terms of brotherhood and the social life. Being a young man, I have felt my way, in declaring my message, step by step. I do not see now through a glass darkly as I once did. I think I see clearly my true work and message. The church no longer affords, if it ever did, any adequate channel for the realization of Jesus' doctrines of life. It is time to begin to attend to righteousness, and let church and even state alone.

When my further books are published, I will take the liberty of sending them to you. If I come to the continent, as I hope to do one or two years hence, I may be enabled to talk with you for a moment, face to face. I believe all you teach about Jesus' doctrine is true, but I believe that there

TRIQUARTERLY

26

is much more truth to be told. Faithfully and affectionately yours, George D. Herron+!

Herron may have attempted to follow Tolstoy's advice, but his subsequent writings continued to pursue this same topic of church and state. It is not clear whether Herron sent more of his works to Tolstoy; no more of his letters arrived, nor did Tolstoy write again to him. Nonetheless Tolstoy followed Herron's subsequent writing; in 1899 the English translator and Tolstoyan Aylmer Maude sent Tolstoy a copy of Herron's Between Jesus and Caesar, in which he published a series of eight lectures he delivered on the subject of the relation of the Christian conscience to the existing social system.42 Tolstoy commented on this work in a postscript to his letter to Maude dated December 15, 1899:

I am very displeased by Herron's basic position. If we will strive with all our soul's power to not depart from an ideal guiding principle, nonetheless in our weakness we will unwillingly depart from it. If we decide beforehand that we must make a compromise, we will not only depart to a much greater degree than in the first case, but we will loose the guiding thread and risk going completely astray.43

The American's pragmatism represented an unacceptable departure from the absolute principles Tolstoy sought to follow.

Of the Christian principles Tolstoy professed, one of the most controversial and attractive to his American correspondents was nonresistance. Among the American practitioners of this doctrine to write to Tolstoy was a founder of a commune of nonresistant Christian socialists; he invited the Russian writer to participate in their quite successful publication, The Social Gospel. The Christian Commonwealth of Muscogee County, Georgia, was organized in 1896 (with the communist motto "From each according to his ability: to each according to his need").

According to the description on its letterhead, the Christian Commonwealth had "1000 acres of land twelve miles east of Columbus on Central of Georgia Railway," was "a purely socialistic colony where all fare alike: sympathy with its principles [was] the only condition of membership; in six months [it had] grown to seventy-five members with its own post office, railroad station and public school." George Howard Gibson, a leader of the Commonwealth and editor of its monthly publication, wrote to Tolstoy at the suggestion of Ernest Howard Crosby on February 22, 1898:

TRIQUARTERLY

27

My Dear Sir:-

Some two weeks since we sent you by mail a copy of our new magazine, The Social Gospel, and hope it will reach you. Let it serve as an introduction. We have long known you through your writings, which we much admire. You will notice Ernest Howard Crosby of Rhinebeck, New York, is one of our Associate Editors. I am as entirely committed to Christ's non-resistance teachings, to the Wisdom of overcoming evil with good, as is he and yourself. And our other Editors and writers are becoming more and more possessed with this truth of love.

Mr. Crosby in a letter rec'd yesterday writes:

"Tolstoy's address is Yasnaia Poliana Toula, Russia. You should write him. I think he and Kenworthy would write for the paper, if they understand your field."

Our field is as large as the world and very few publications have passed its borders. You will judge what I mean by reading our initial number.

Let me say, we have been long preparing a list of the most enlightened people, those who are seeking earnestly the light of heaven, and that our magazine reaches the people who believe in brotherhood and the practical love of Christ, who was "the first bom among many brethren." We have readers in America, England, Russia, Hungary, Switzerland, France and New Zealand, and feel assured that our message is to men of all classes in all the world. We are insisting on repentance of selfishness, separation from the selfish commercial struggle, and living the brotherhood life. And we practice what we preach.

If you can help us with your pen to make known the truth we shall be very glad indeed.

Yours for humanity, George Gibson44

Tolstoy read the inaugural issue of Social Gospel, as well as a handbill, "Think About This," enclosed with Gibson's letter. No doubt impressed by the recommendation of Crosby and the participation of Herron in the issue, he responded to Gibson's letter with extensive, detailed, and unsolicited criticism of their undertaking-not of the journal, but of the community itself. On March 23 Tolstoy wrote:

My dear friend,

I duly received your letter and magazine, both of which afforded me great pleasure. The first number is very good and I liked all the articles in it. It is quite true, as you say it in your article "The Social Need," and Herron in his, that a Christian life is quite impossible in the present unchristian organization of society. The contradictions between his surroundings and his convictions are very painful for a man who is sincere in

TRIQUARTERLY

28

his Christian faith, and therefore the organization of communities seems to such a man the only means of delivering himself from these contradictions. But this is an illusion. Every community is a small island in the mist of an ocean of unchristian conditions of life, so that the Christian relations exist only between members of the colony but outside that must remain unchristian, otherwise the colony would not exist for a moment. And therefore to live in community cannot save a Christian from the contradiction between his conscience and his life. I do not mean to say that I do not approve of communities such as your commonwealth, or that I do not think them to be a good thing. On the contrary, I approve of them with all my heart and am very interested in your commonwealth and wish it the greatest success.

I think that every man who can free himself from the conditions of the worldly life without breaking the ties of love-love the main principle in the name of which he seeks new forms of life-I think such a man not only must, but naturally will join people who have the same beliefs and who try to live up to them. If I were free I would immediately even at my age join such a colony. I only wished to say that the mere forming of communities is not a solution for the Christian problem, but is only one of the means of its solution. The revolution that is going on for the attainment of the Christian ideal is so enormous, our life is so different from what it ought to be, that for the perfect success of this revolution, for the concordance of conscience and life, is needed the work of all men-men living in communities as well as men of the world living in the most different conditions. This ideal is not so quickly and so simply attained, as we think and wish it. This ideal will be attained only when every man in the whole world will say: Why should I sell my services and buy yours? If mine are greater than yours I owe them to you, because if there is in the whole world one man who does not think and act by this principle, and who will take and keep by violence, what he can take from others, no man can live a true Christian life, as well in a community as outside it. We cannot be saved separately, we must be saved all together. And this can be attained only through the modification of the conception of life i. e. the faith of all men; and to this end we must work all together-men living in the world as well as men living in communities.

We must all of us remember that we are messengers from the great King-the God of Love with the message of unity and love between all living beings. And therefore we must not for a minute forget our mission and do all what we think useful and agreeable for ourselves only so long as it is not in opposition to our mission which is to be accomplished not only by words, but by example and especially by the infection of love.

Please give my respect and love to the colonists and ask them not to be offended by me giving them advice, which may be unnecessary. I advise them to remember that all material questions of: money, implements,

TRIQUARTERLY

29

nourishment, even the very existence of the colony itself,-all those things are of little importance in comparison of the sole important object of our life: to preserve love amongst all men, which we come in contact with. If with the object of keeping the food of the colony or of protecting the thrift of it you must quarrel with a friend or with a stranger, must excite ill-feelings in somebody, it is better to give up everything, than to act against love. And let our friends not dread that the strict following of the principle will destroy the practical work. Even the practical work will flourish-not as we expect it, but in its own way, only by strict following the law of love and will perish by acting in opposition to it.

Your friend and brother

Leo Tolstoy.

March 23. 1898

I had just finished this letter, when I received from the Caucasus news from the Duchoborys ("spirit wrestlers") that they had received an authorization to leave Russia and emigrate abroad. They write to me that they have the intention of going to England or America. They are about 10,000 men. They are the most religious, moral and laborious, and very strong people. The Russian government has by all sorts of persecutions quite ruined them and they have not the means to emigrate. I will write about it to the papers in America and England. Meanwhile you will oblige me-you and your friend Herron, Crosby, and others-if you give me some suggestions about this matter.

Yours L. T.45

This letter was presented to the entire community, which responded with offers to assist the Dukhobors. On April 21 Gibson communicated these while defending the principles of his Christian Commonwealth. Like other American correspondents, he differed from Tolstoy in his belief that social institutions, like individuals, can be converted, i.e. changed and Christianized:

My Dear Tolstoy:-

Your good letter of March 23d reached me two days since, and at a wood cutting picnic yesterday it was read aloud to all our people. How blessed is this brotherhood spirit which unites us across seas and continents!

We recognize the fact we can live in Christian relations only with those who will meet us as brethren. We cannot force love upon any. And while we may be entirely saved from the spirit of selfishness, we can be only partly saved from the evils of it so long as selfish forces enthroned in the world dictate laws, contracts, prices, etc. The individual can no longer be free. The small community can only partly emancipate itself. The industri-

TRIQUARTERLY

30

al-commercial, or producing and distributing, unit must be saved, Christianized, made unselfish as a whole, in order that the individual parts may be wholly saved. But if two or more families do not begin to live the life of love, it cannot spread and reorganize society and make it Christian. The individual can not remain in the midst of the selfish struggle without being involved in it, without partaking of its sins and plagues. It seems to me, wherever modem machinery and capital have taken the power of independent Christian action away from the individual and compelled him to gather his living through the selfish machinery processes, prices, relations, he is called by God to come out of such evil combination (as in Rev. 18); and if he be too poor and helpless to support life apart for himself and family, they must be redeemed, by those who have means.

Be very free to advise us always. The Colony leaders have a great respect for your opinions and wisdom. We need the counsel of the wisest students of the social problem. We all need all the help, light, power that each can contribute. Write us as often as your other duties will allow.

We are most deeply interested in what you tell us of the commanded removal from Russia of the "Spirit Wrestlers." We have the little book introduced by Kenworthy giving us their history. We are their brothers, and wish to help them to the utmost. We believe we can find friends who will furnish the means to buy sufficient land to place them on in this country, if friends across the sea can raise funds to bring them to it. Will at once write to Crosby about it, also to Herron.

What do you think of this climate for them-rarely any snow, extremes of thermometer two years we have been here have been 99° in hottest summer day, 12° above zero in coldest winter day. The soil is a sandy loam with clay subsoil, needing fertilizer, but producing a great variety of food products, two or three crops a year. Good fruit country. Plenty of fuel, and timber to build. Land is $2.22 to $10.22 an acre. We are 200 miles west of Savannah, Georgia. Most of us are from the Northern States, one family from Canada. Consider it a healthy climate.

Would these people prefer to settle in the higher regions of the moun, tains north of us? How many can come or be sent to America? How soon must they get out of Russia?

We will do our utmost for them, to prepare a place for them, to help them to self-support. Tell them we are members of "The Universal Brotherhood," living to serve. We think plenty of land can be secured for them here. Will write to Crosby today, and suggest that he begin lecturing and raising funds to buy land for them. Will insert at this late moment of going to press best notice of their need we can.

Yours for Humanity, George Gibson46

Tolstoy did not respond. Meanwhile, after considerable searching for a

TRIQUARTERLY

31

suitable home, the Dukhobors were settled in Canada, their passage financed in part by proceeds from Tolstoy's Resurrection. The fate of the Christian Commonwealth continued to concern Tolstoy, however. In a letter to Aylmer Maude of December 12, 1898, he asked Maude his opinion of the Commonwealth and its promise. The following year Tolstoy wrote to Crosby with similar concerns. His letter of June 1899 included this passage:

I thank you for the information you gave me, & must say that I feel especially concerned about all that goes on in the Christian Commonwealth.

I read their journal with deep interest & never cease to rejoice at the firmness of their views & the beautiful expression of their thoughts. I should like to get so many details concerning their life as possible.47

Crosby did not directly respond, but rather passed on this request to Gibson, who took Tolstoy's request to heart. The next month after Crosby received Tolstoy's request, Gibson sent the following letter to Yasnaia Poliana, which illustrates a characteristically American combination of enterprise and fundamentalism as well as an unbounded faith in the power of religious belief to alter human nature and social institutions:

Commonwealth, Ga., July 24, 1899

My Dear Friend:-

Your recent words to Ernest Crosby expressing your deep interest in Commonwealth stimulates me to open my heart to you, for advice and conference, concerning the things of the Kingdom of Love.

We have from the first realized the imperfection of our method, of taking people up-a family here and a family or individual there-and regrouping society, according to what may seem the leadings of God's Spirit. The people of God, as a rule, are needed just where they are; and the problem is, how to leave them where they are, and yet keep them from the evil of competition, strife, self-seeking, the entanglement in the acts and evils which are involved in market prices, etc. I can see but one way out of the evil entanglement. And that is, to preach universal love and organize a religious Order of Brothers, like and yet unlike the Brothers Minor of St. Francis. Of course it should not be an ascetic or celibate or ecclesiastically ruled Order. It should have but one rule, the rule of love, but that rule should be plainly preached and faithfully lived, as the most advanced teachers would say are Love's leadings. Let it be an Order of Business Brothers, whose spirit is to serve instead of to get.

TRIQUARTERLY

32

With the present light we have would not such an Order and such preaching, backed by example, move the world mightily? Can we not com, mand and secure a more perfect, a wiser and more effective, consecration than could Francis and his disciples? Can we not institute a religious Order of economic Brothers that, with Christ as its head, would be stronger to unite than is individual or family selfishness to divide? At Commonwealth we have demonstrated that individual and family selfish, ness can be overcome. But we need to go farther and prove that the spiritual bond can be established across space, when there is no corporate oneness beyond that which must grow out of a union of hearts. The Order of Brothers must be stronger than all old forms, and its life must not depend on form but spirit. It could not allow luxury or less than utmost toil to serve while real needs were left unsupplied. In the common life of love less needs must be subordinated to greater needs without respect of persons. The rule of the Order must be stronger than the spirit of private property. Property might remain in individual hands in cases where it would be lovingly and economically administered. But the Order should control capital enough to keep all its members employed.

Another thing I have on my mind to say. Do you not feel moved to write a story of God's Kingdom come and coming? That we-the whole world-may have the benefit of your powerful reason and imagination to aid its forward gropings after God and the abundant life of love? Do write such a story and let us have a chance to circulate it thru The Social Gospel. I mean not that we be given it exclusively, but with others, to spread the light.

I shall see Crosby next week at the Marlborough, N. Y., Conference of the Brotherhood of the Kingdom, where I am on the program.

We hope to make mechanical and other improvements in The Social Gospel soon.

If you can do so, make us glad by writing anything that we may print in the Social Gospel. It would serve our cause much if we might use your name as an associate editor of the S.G., but I suppose you never have done such a thing, for any publishing house.

With great respect and love

George Gibson48

Tolstoy responded to Gibson's explanations, although his letter has not been located, and no copy of the text has been found. That this response was negative and critical, can be deduced from Gibson's letter, which was the last that Tolstoy was to receive from him. One is left to imagine Tolstoy's reaction to Gibson's commercial, capitalistic Christianity:

TRIQUARTERLY

33

Commonwealth Ga. Oct. 5, '99

Dear & Revered Brother:-

Your recent letter came duly and was read with great interest. There is much truth and wisdom in what you say. I am past putting any reliance on force or machinery as means of salvation from selfishness. What I have proposed (and more elaborately reasoned for in Oct. Social Gospel) is a love movement in mutual service, such as you believe in, which shall in some measure emancipate individuals from the ways and entanglements of the selfish system of life. I wish to see a voluntary union of men to serve, to serve all men or all whom they have power to reach and bless. See closing paragraph of argument in "Love at Work," Page 27, Oct. Social Gospel.

I think the primitive church was a Divine institution. The church today is largely a selfish institution. I feel inclined to make whatever use can be made of the church and the government in their very imperfect state. We are dealing with men, and with men whose prejudices and ignorance and narrowness need, for their sakes, to be borne with. I do not believe in bullets or ballots as a means to change men's hearts. But in political cam, paigns here questions of justice are often freely and beneficially discussed, and if I can by some mixing in politics get the ear of people who otherwise would not hear me, I feel that I may extend my usefulness by so doing. So, having thought myself clear of ceremonialism and narrow dogma and theological systems supposed to be infallible, I yet think I should mix and min' gle with church people, my object being to spread truth among them as much as possible. I sometimes write for church papers, even as you do. I also attend church in order to meet and form ties of friendship with people whose confidence I would win in order to serve them. Is not this right?

Yours for all humanity, George Gibson49

Gibson continued to send issues of The Social Gospel to Tolstoy, although the Russian writer never contributed to the journal. Soon the community ceased to exist: a summer drought, then heavy snow in the winter of 1899 destroyed their crops; a typhoid epidemic felled scores of members; one disgruntled member spread the rumor that the commune was a free love colony (to discredit it in the eyes of the conservative South); and finally, after an attempt to preserve property by incorporation (thereby retreating to the protection of the state), the community was dissolved and its assets divided in July 1900.50

Perhaps the most interesting group of Tolstoy's occasional American correspondents were those who wrote to him for his reactions to issues of the day. Many letters asked Tolstoy to support issues on which he had written extensively, e. g. pacifism, nonresistance, anti-statism, Christian

TRIQUARTERLY

34

anarchy. Less common are the occasional requests to support positions outside this political and religious sphere. For example, Tolstoy received a request from a certain Sue M. Farrell to support her campaign against vivisection. On May 2, 1909, she sent Tolstoy a brochure with anti-vivisectionist quotations from various well-known sources with the following letter:

My dear sir: