- A 1UJl1e11aby

JOHNNY PAYNE - EtImojiaitmby

JOHN STEWART - Surjiaion/mtijiaionby

RAYMOND FEDERMAN AND GEORGE CHAMBERS

-Stm'iesby

ANrONYA NElSON AND DAN CHAON

-Atulby

DAVE SMITH,STERLING PLUMPP, PETER READING, JAYANTA

MAHAPATRA, RENATE WOOD, REGINALD SHEPHERD, JosE EMILIO

PACHECO AND DoN SlAP - Writi�anJ Thinking at theEnJofan�

HENRY S. BIENEN

EWA KURYLUK """"'�""'�

ELISABETH SIFTON

ADAM lAGAJEWSKI

TED SoLOTAROFF

JOSEF KROUTVQRJ

EucE ScHMtmR.

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers:

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Paul Brownfield

Robert Creamer

Eleanore Devine

W. S. Di Piero

John B. Elliott

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

Mr. and Mrs. C. Dwight Foster

Martha Friedberg

Amy Godine

Jay Harkey

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Irwin T. Holtzman

Helen Jacob

Loy E. Knapp

Greg Kuzma

Patrick Mangan

Charles T. Martin

Florence D. McMillan

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Dorothy J. Mikuska

Michal Miller

William T. Morgan, Jr.

Alicia Ostriker

Linda Pastan

Fran Podulka

Mark Rudman

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Susan A. Stewart

Lawrence Stewart

Dorothy H. Taylor

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

FALL 1995 BOOKS AND BACKLIST

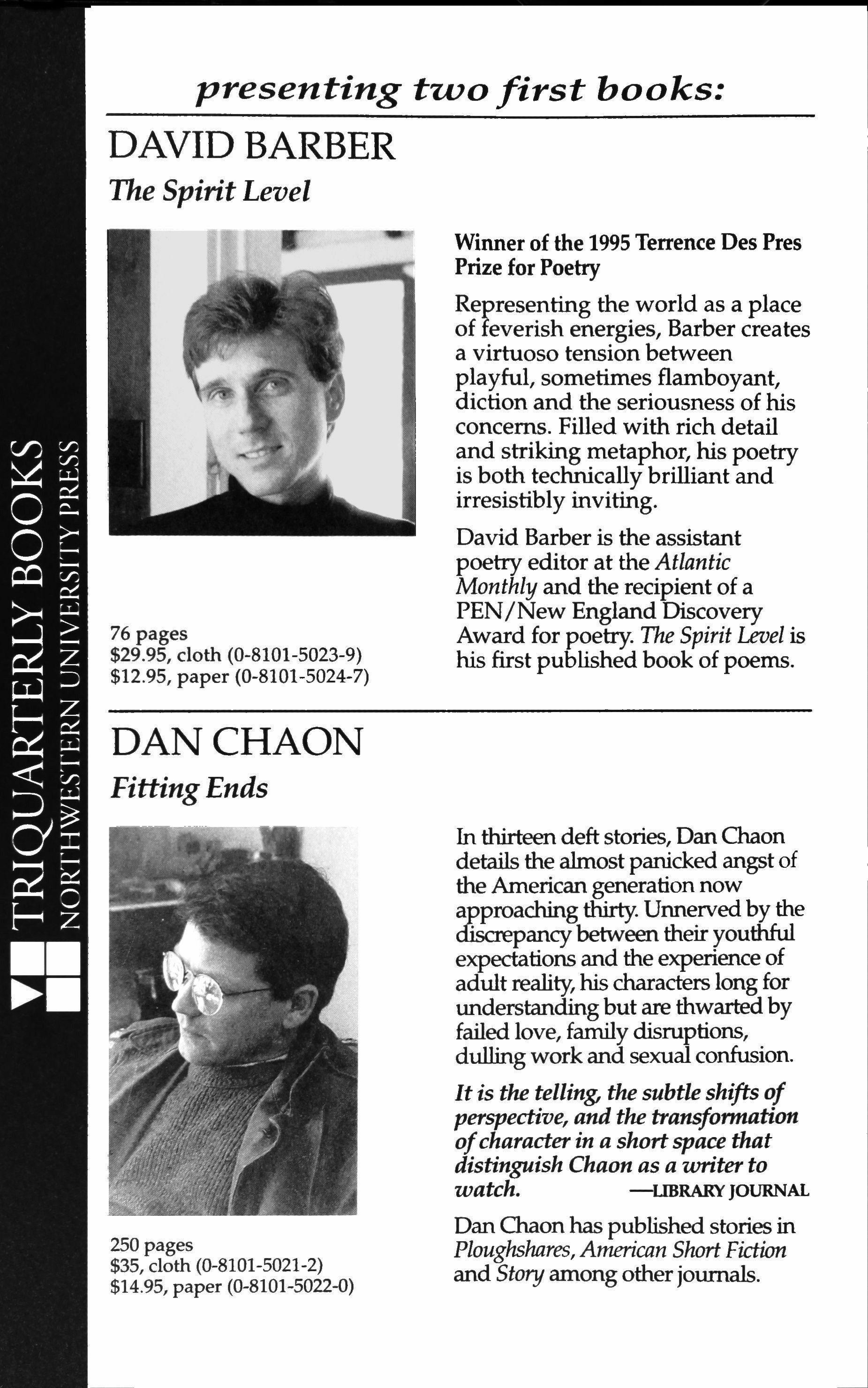

presenting two first books: DAVID BARBER

The Spirit Level

76 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5023-9)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5024-7)

DANCHAON

Fitting Ends

250 pages

$35, cloth (0-8101-5021-2)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5022-0)

Winner of the 1995 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Representing the world as a place of feverish energies, Barber creates a virtuoso tension between playful, sometimes flamboyant, diction and the seriousness of his concerns. Filled with rich detail and striking metaphor, his poetry is both technically brilliant and irresistibly inviting.

David Barber is the assistant poetry editor at the Atlantic Monthly and the recipient of a PENINew England Discovery Award for poetry. The Spirit Level is his first published book of poems.

In thirteen deft stories, Dan Chaon details the almost panicked angst of the American generation now approachingthirty. Unnerved by the discrepancy between their youthful expectations and the experience of adult reality, his characters long for understanding but are thwarted by failed love, familydisruptions, dulling work and sexual confusion.

It is the telling, the subtle shifts of perspective, and the transfonnation ofcharacter in a shortspace that distinguish Chaon as a writer to watch.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

Dan Chaon has published stories in Ploughshares, American Short Fiction and Story among otherjournals.

w. S. DI PIERO

Shadows Burning

Few other poets of his generation have succeeded in forging a style as original as w. s. Di Piero's. This sixth volume moves backward through the poet's life and American history, returning to origins both cultural and personal. With imaginative and linguistic power, Di Piero creates an elusive proportioning, a mourning and celebrating of his material.

In its intense preoccupation with change,hopelessness and thefrailty ofwhatevercontinuities ofmemory and imagination we devise to order the unorderable, [Shadows Burning] makes an importantcontribution to American poetry. -Alan Shapiro

EUGENE GARBER

The Historian

Winner of the 1992 William Goyen Prize for Fiction

This rollickingmetaphysical tale takes readers on a rich fictional odyssey that is a meditation on the American character and experience. The historian's quest to find the American Woman, whose vitality has been all but written out ofhistorybypuritan consciousness, leads him to muses, lovers, figures ofsensual liberation, frontierswomen and powerfulagents for social change. Thebattle between myth and fact, between romance and science, to grasp the soul of historythe so-called truth of a given time-is at the heart ofGarber's compelling tale.

FIRST PAPERBACK PUBUCATION

80 pages $29.95, cloth (0-8101-5019-0) $12.95, paper (0-8101-5020-4)

236 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5018-2)

THEODORE WEISS

Selected Poems

This definitive selection of poems by one of America's most distinguished and original poets recovers work that is immensely contemporary and at the same time reaches back to the roots of an accomplished generation of poets that includes Lowell, Jarrell, Berryman and Bishop. Weiss's distinctive, idiosyncratic poems, noted for their syntactic compression and linking of intimate experience and historical incident, are a majoraccomplishment. [Weiss'spoetry] is among the most valuable work produced in our time.

-James Merrill

ADRIAN C. LOUIS

Vortex ofIndian Fevers

260 pages

$49.95, cloth (0-8101-5037-9)

$15.95, paper (0-8101-5040-9)

Beautifully aglow with the love of language.

-James Tate

Prophetic, terrifyingly intelligent, unconditionallygermane.

-Hayden Carruth

Wordplay,metaphoricbrilliance, technical virtuosity and a scathingly sardonic critique of selfand society fill this new collection Louis celebrates life amid hardship and self-destructiveness, and consecrates a part of the past as a source ofideals for the present. N. Scott Momaday has characterized Louis's work as /I acceptance and defiance brought into delicatebalance." Fueledby both anger and irony, Louis analyzes, excoriates,jests, praysand mourns. The result is psychologically and culturallycomplex.

76 pages

$29.95, doth (0-8101-5017-4)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5042-5)

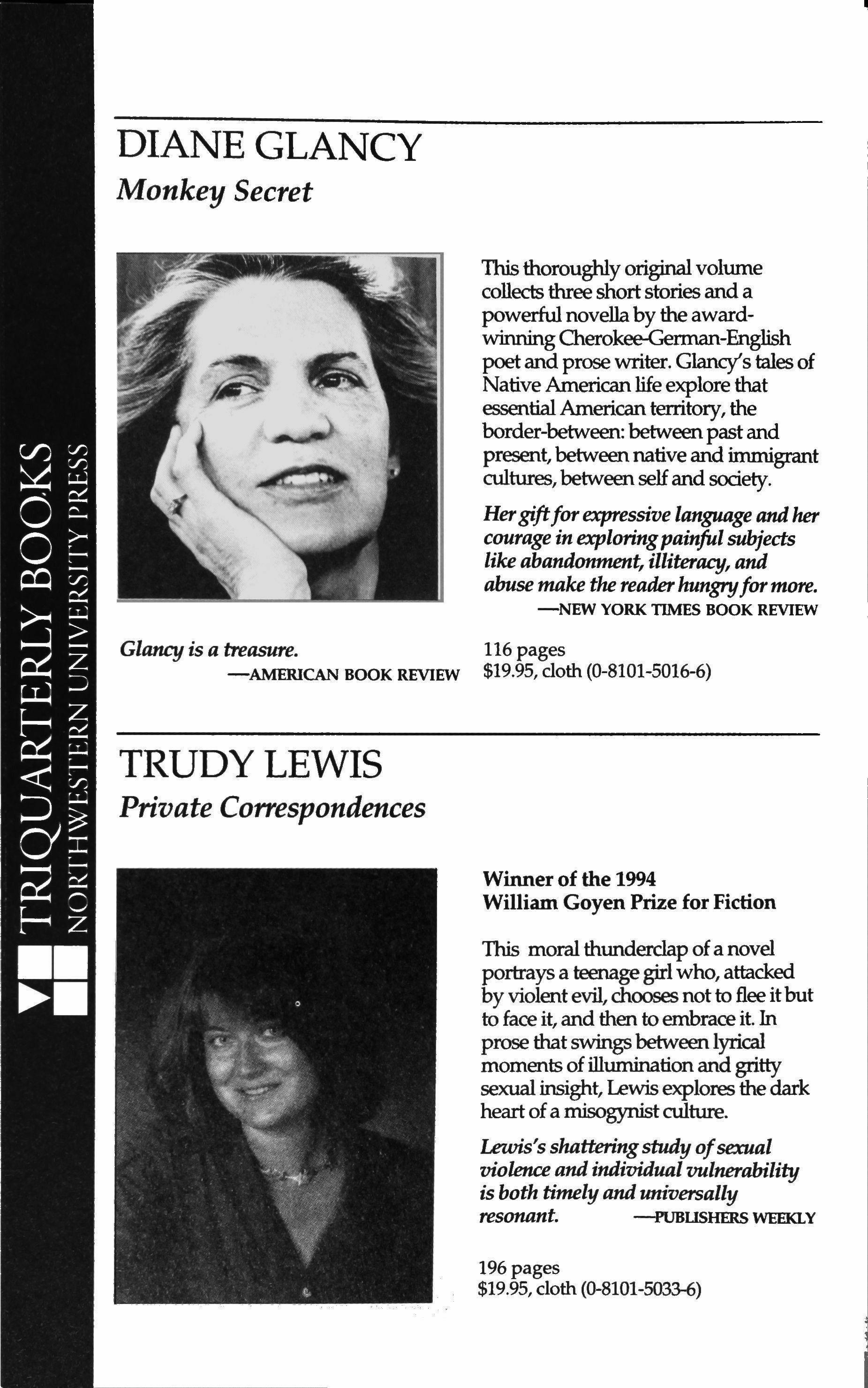

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years I Cronica de mis aiios peores

TRANSLATED AND WTIH AN AFTERWORD BY

In this bilingualedition, an established Chicano poetrepresents withpassion and elegance some of the American realities that remain absent from mainstream poetry. Villanueva voices complex and compellinghistorical, literary and cultural questions as urgent personal utterances, investing the book with appealingintimacyand seriousness.

Villanueva is a writer to spend time with.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Tino Villanueva won the 1994 American Book Award for his recentbook, Scene from theMovie GIANT.

96 pages

$34.95, cloth (0-8101-5009-3)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5034-4)

MARC J. STRAUS

One Word

In his first collection of poems, physician Marc J. Straus combines poetic craft, medical expertise and a keen sense of human vulnerability in an uncommon portrayal of the complex and often troubled relations between physician and patient. With directness and power, Straus confronts matters rarely encountered in poetry. These poems are a fine addition to the scant body of imaginative work that speaks from within the medical world.

Offering a new perspective on patientdoctor relations, [Straus1 brings humanity into the sterile hospital environment. -BOOKLlST

80 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5010-7)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5035-2)

JAMES HOCGARD

"US"'" ," tr ,UIl 1

Tino Villonueva

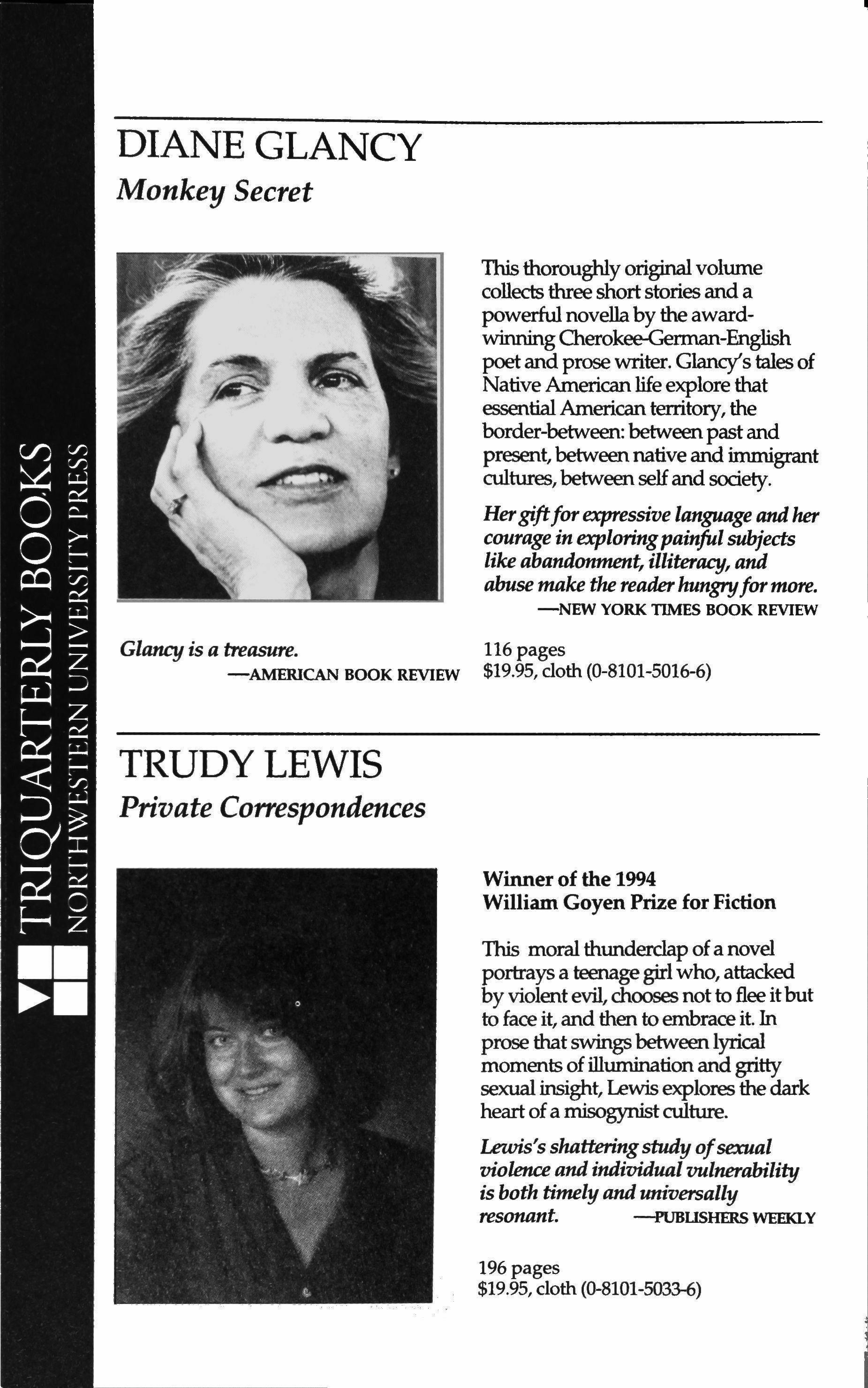

DIANE GLANCY

Monkey Secret

This thoroughlyoriginal volume collects three short stories and a powerful novellaby the awardwinningCherokee-Gennan-English poet and prose writer. Glancy's tales of Native American life explore that essentialAmerican territory, the border-between:between past and present, between native and immigrant cultures,between selfand society.

Hergiftforexpressivelanguage and her courage in exploringpainfulsubjects like abandonment, illiteracy, and abuse make the readerhungryfor more. -NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

Glancy is a treasure.

116 pages -AMERICAN BOOK REVIEW $19.95, cloth (0-8101-5016-6)

TRUDY LEWIS

Private Correspondences

VVnruner of the 1994 VVilliam Goyen Prize for Fiction

This moral thunderclap of a novel portrays a teenagegirlwho, attacked by violentevil, chooses not to flee itbut to face it, and then to embrace it. In prose that swings between lyrical moments ofillumination and gritty sexual insight, Lewis explores the dark heart of a misogynistculture.

Lewis's shatteringstudyofsexual violence and individual vulnerability is both timely and universally resonant. --PUBUSHERS WEEKLY

196 pages $19.95, doth (0-8101-5033-6)

CYRUS COLTER

A Chocolate Soldier

Colter's fourth novel is a cautionary tale of revolutionary dreams, bitter realities, and the persistence of both hope and falsehood. A kind of historical fable about the possibilities and perils of black revolution within and against twentieth-century white America, this novel is brilliantly structured and voiced. It is Colter's greatest and crowning work, and no reader will forget the tale it tells.

This powerful writer should win the attention ofevery serious reader of fiction.

SATURDAY REVIEW

278 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5038-7)

CYRUS COLTER

The Hippodrome

Set in a Chicago seething with physical and psychological violence, this novel examines power and exploitation and their entanglement with sexuality.

In the tradition ofhisfictional ancestors, Dostoevsky and Faulkner, [Colter] has produced a work which uses the world of everyday reality in a manner beyond the scope ofjournalism or sociology-as an entree to the soul.

-Jailles Park Sloan CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

Colter is a writer ofdistinction. --{CHOICE

214 pages $13.95, paper (0-8101-5036-0)

� • • • • , • • :n �: ".,C' ,.. (>�, .., .\ cIIC)C!()I••\ a r I: S() I. ') II� I�

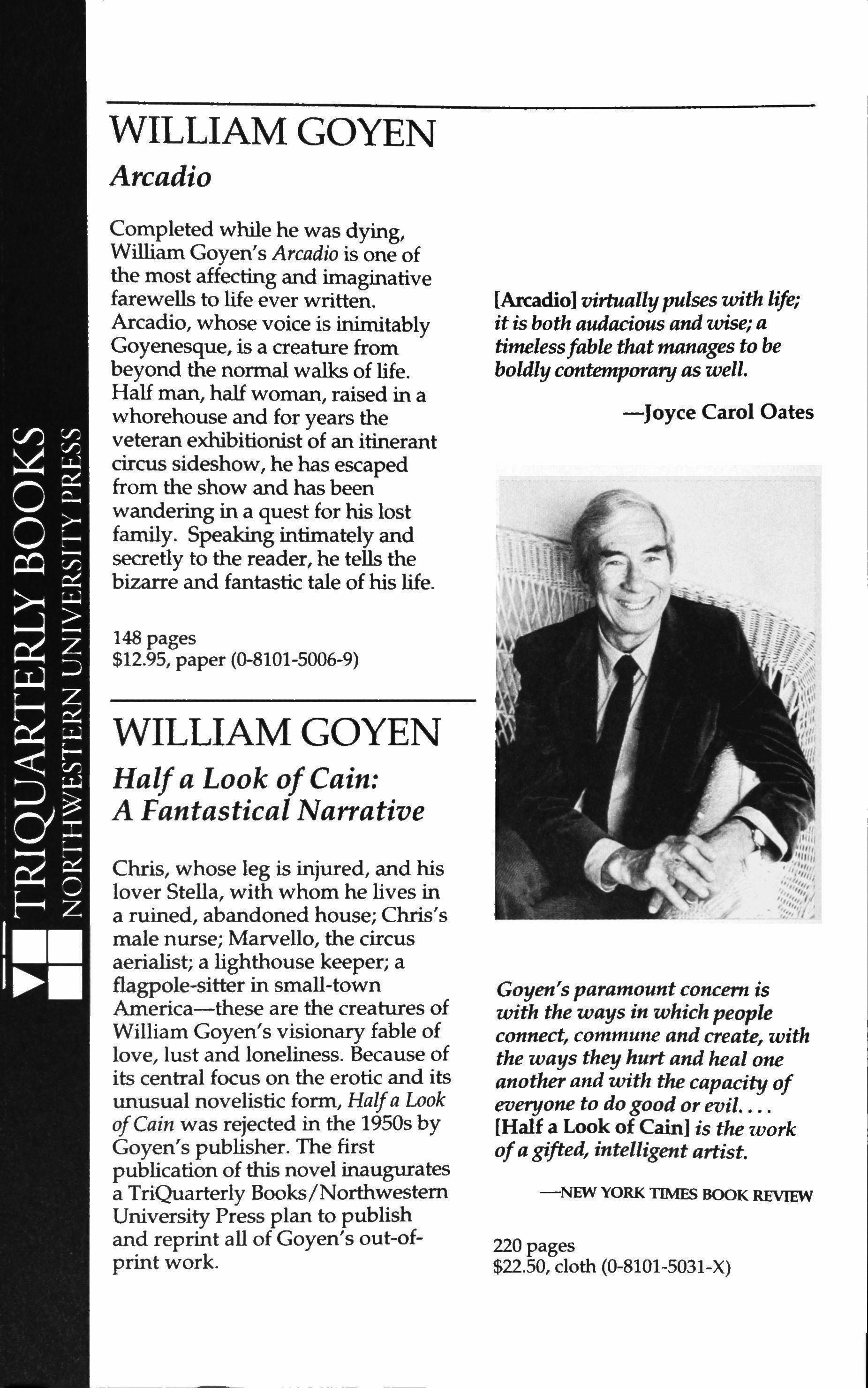

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

Completed while he was dying, William Goyen's Arcadio is one of the most affecting and imaginative farewells to life ever written.

Arcadio, whose voice is inimitably Goyenesque, is a creature from beyond the normal walks of life. Half man, half woman, raised in a whorehouse and for years the veteran exhibitionist of an itinerant circus sideshow, he has escaped from the show and has been wandering in a quest for his lost family. Speaking intimately and secretly to the reader, he tells the bizarre and fantastic tale of his life.

148 pages $12.95, paper (0-8101-5006-9)

WILLIAM GOYEN

Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical Narrative

Chris, whose leg is injured, and his lover Stella, with whom he lives in a ruined, abandoned house; Chris's male nurse; Marvello, the circus aerialist; a lighthouse keeper; a flagpole-sitter in small-town America-these are the creatures of William Goyen's visionary fable of love, lust and loneliness. Because of its central focus on the erotic and its unusual novelistic form, Halfa Look ofCain was rejected in the 1950s by Goyen's publisher. The first publication of this novel inaugurates a TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press plan to publish and reprint all of Goyen's out-ofprint work.

[Arcadio] virtuallypulses with life; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldlycontemporary as well.

-Joyce Carol Oates

Goyen'sparamount concern is with the ways in which people connect, commune and create, with the ways they hurt and heal one another and with the capacity of everyone to do good or evil [Half a Look of Cain] is the work of a gifted, intelligent artist.

-NEW YORK TIMFS BOOK REVIEW

220 pages $22.50, cloth (0-8101-S031-X)

WILLIAM GOYEN

In a Farther Country

Subtitled II A Romance," In a Farther Country is an intense performance, both lyrical and colloquial, shaped as a series of meditative narratives. Set in a Spanish arts factory in New York City, the novel grows around the conflict of its main character's mixed ancestry. Marietta McGee-Chavez and her friends and acquaintances populate a world in which they experience dreams and reality, sexual desire and loneliness, triumph and defeat. This is the first paperback edition of Goyen's small neglected masterpiece.

182 pages

$13.95, paper (0-8101-5039-5)

ANNE CALCAGNO

PrayforYourself

Anne Calcagno vividly captures the textures of women's lives in this exhilarating collection of short stories. Her characters grapple with problems ranging from domestic violence to obsessiveness with body weight; the dramatic situations are extreme, edgy and utterly convincing.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye of a true storyteller.

-Larry Heinemann

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as a fifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a singlepiece ofwood.

-Lynda Barry

136 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5000-X)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5003-4)

�-UVt"

WIUBUI

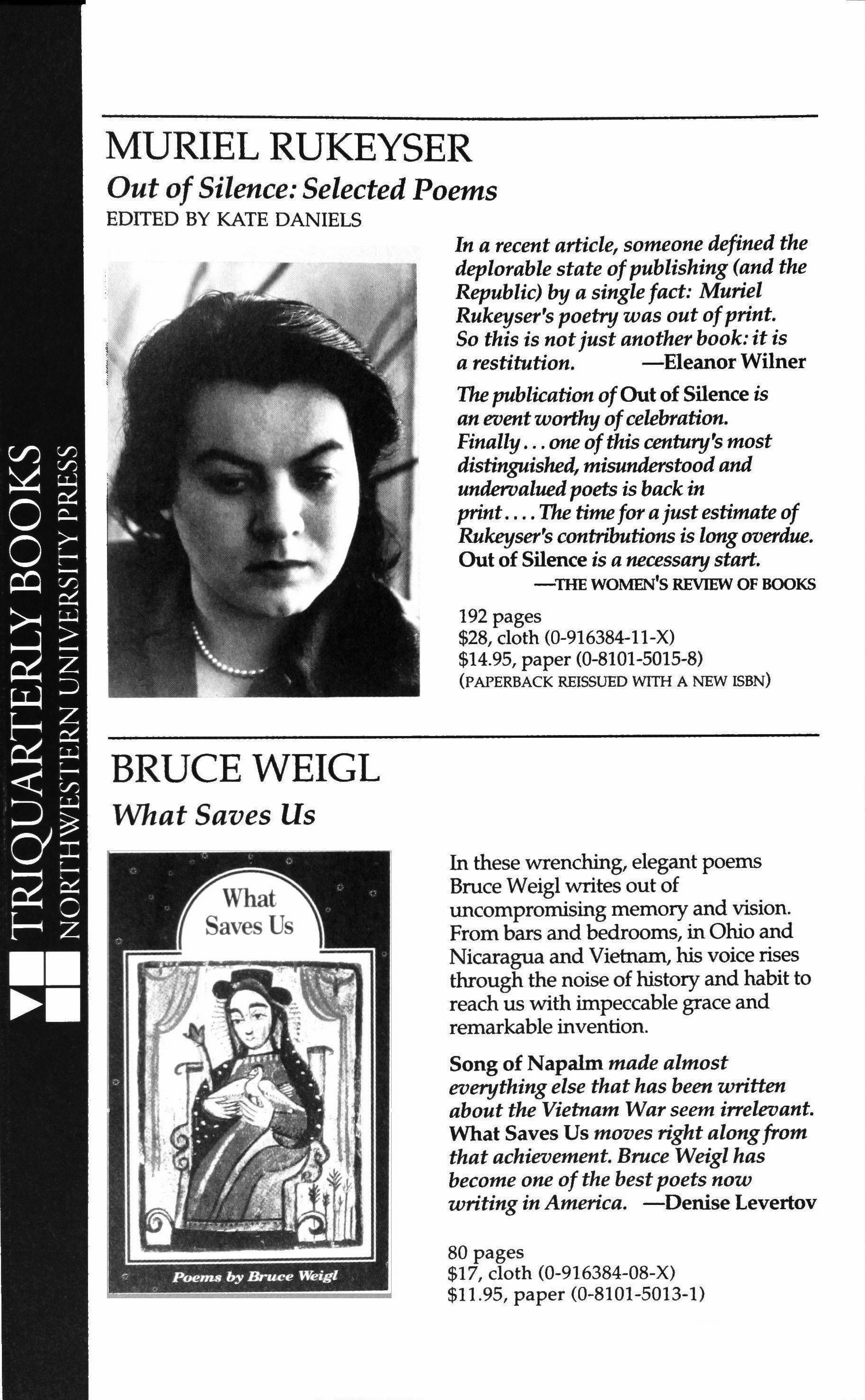

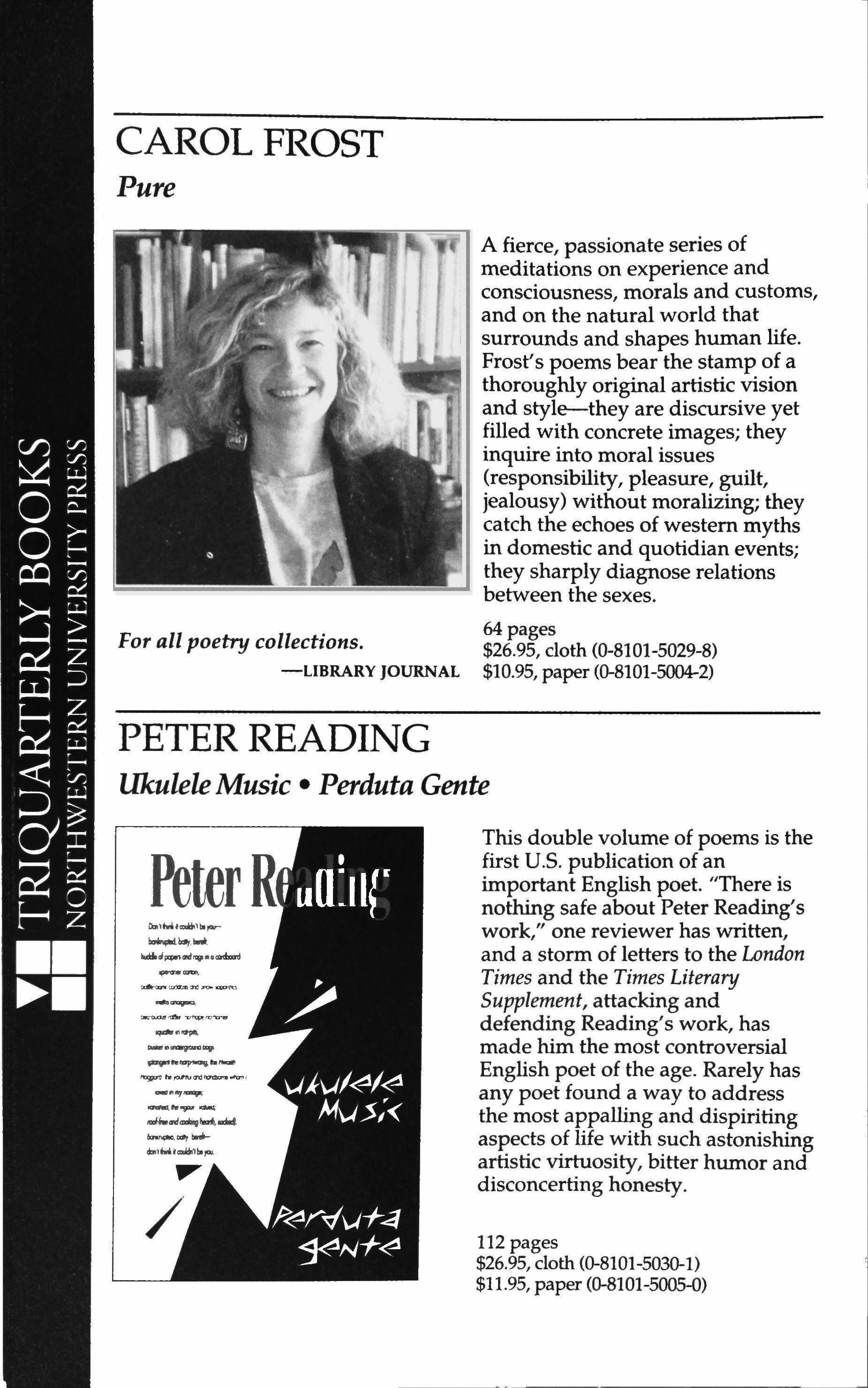

CAROL FROST

Pure

For all poetry collections. -LIBRARY JOURNAL

PETER READING

A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and on the natural world that surrounds and shapes human life. Frost's poems bear the stamp of a thoroughly original artistic vision and style-they are discursive yet I filled with concrete images; they inquire into moral issues (responsibility, pleasure, guilt, jealousy) without moralizing; they catch the echoes of western myths in domestic and quotidian events; they sharply diagnose relations between the sexes.

64 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5029-8)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5004-2)

UkuleleMusic • Perduta Gente

DllMlJII.-patqjJ

This double volume of poems is the first u.s. publication of an important English poet. "There is nothing safe about Peter Reading's work," one reviewer has written, and a storm of letters to the London Times and the Times Literary Supplement, attacking and defending Reading's work, has made him the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity, bitter humor and disconcerting honesty.

112 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5030-1)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5005-0)

� ltlIJ1P1)"tohua'I:J�-"OT<1 -".,�

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe

Wmnerofthe Carl SandburgAward andthe 1993 Chicago Sun-TImes Book ofthe YearAward in Poetry

AngelaJacksonbrings remarkable gifts to the articulation of African-American experience. Her poetry features an impressivevariety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience.

Angela Jackson has known,for long, what is rightfor her attention and scrupulous investigation.

-Gwendolyn Brooks

120 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5026-3)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5001-8)

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

Wmnerofthe 1993 Terrence Des Pres Prize forPoetry

Adversaria celebrates the rough beauty of ordinary life and laments its inevitable decline. These poems, titled in Latin, combine colloquial style with a late imperial tone to capture the stark contrasts and contradictions of a life lived between a steel mill and the quiet, graceful natural world.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence of a lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American.

104 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5027-1)

-Li-Young Lee

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5002-6)

Spinners

"""UI:IIII (II' fltl �".1 T llle,.CIII DU. ""'IU ".101.. '011 rOlTIliT -.ussell

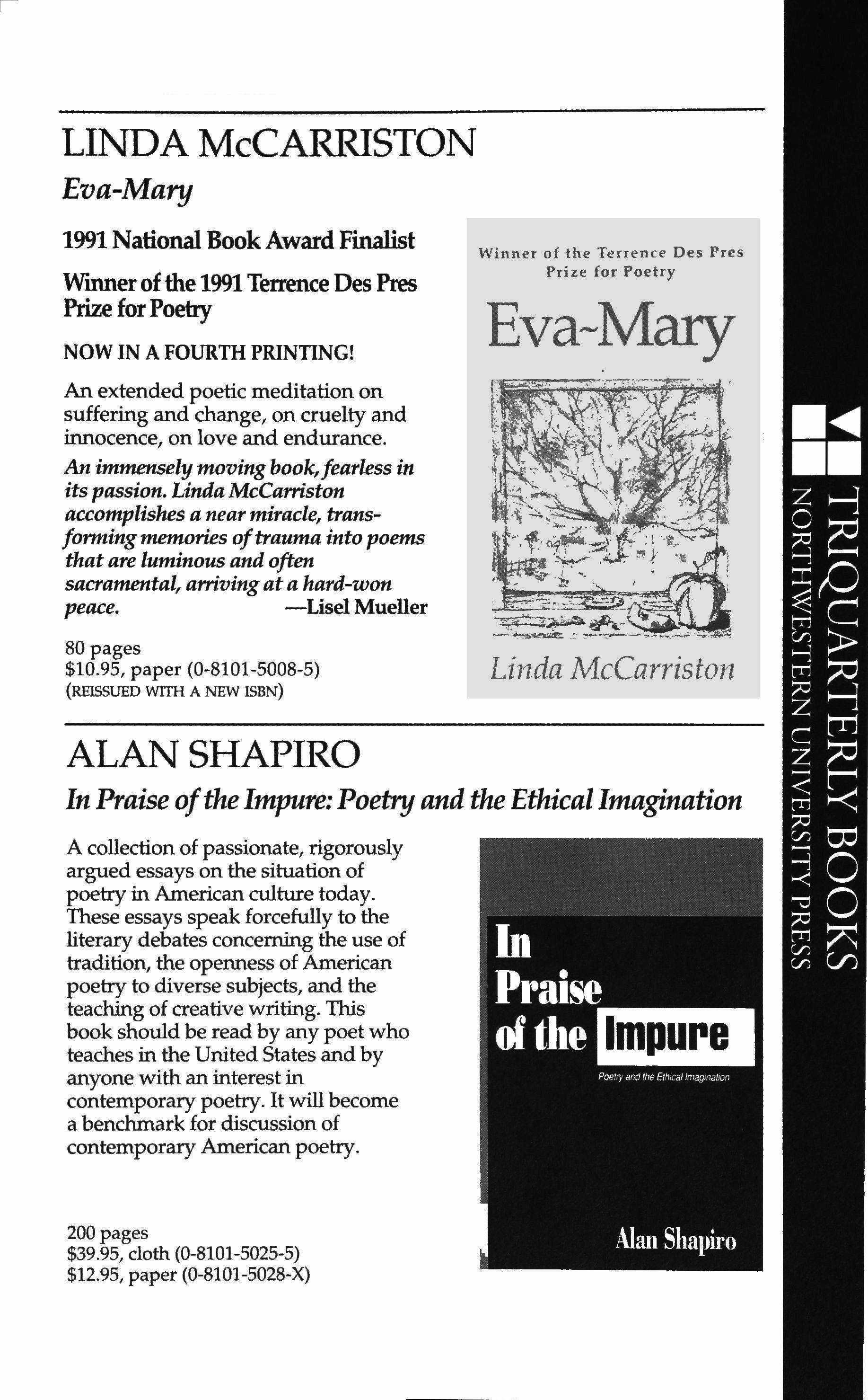

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out of Silence: Selected Poems

EDITED BY KATE DANIELS

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state ofpublishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser's poetry was out ofprint. So this is notjust another book: it is a restitution. -Eleanor Wilner

ThepublicationofOut of Silence is an event worthy ofcelebration. Finally one ofthis century's most distinguished, misunderstoodand undervaluedpoets is back in print The timefor a just estimate of Rukeyser's contributions is long overdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start.

-THE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5015-8) (PAPERBACK REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right alongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one ofthe bestpoets now writing in America. -Denise Levertov

80 pages

$17, cloth (0-916384-08-X)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5013-1)

LINDA McCARRISTON

Eva-Mary

1991 National Book Award Finalist

Wmner ofthe 1991 Terrence Des Pres Prize forPoetry

NOW IN A FOURTH PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance.

Eva-Mary l

An immenselymovingbook,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories oftrauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace.

80 pages

-Lisel Mueller

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5008-5) (REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise ofthe Impure:Poetry and the Ethical Imagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today. These essays speak forcefully to the literary debates concerning the use of tradition, the openness of American poetry to diverse subjects, and the teaching of creative writing. This book should be read by any poet who teaches in the United States and by anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. It will become a benchmark for discussion of contemporary American poetry.

200 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5025-5)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5028-X)

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Linda McCarriston

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodem trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -Alicia Ostriker

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

Fiction ofthe Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

This landmark anthologyhonoring TriQuarterly's 25th anniversary includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared in the magazine over the past decade. The stories range widely over the experience of modern life, and share a high level of artistry. An incomparable primer of the contemporarypossibilities of fiction.

Forcontemporaryfiction [Fiction ofthe Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBllSHERS WEEKLY

592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

The Urgency ofIdentity: Contemporary English-Language

Poetryfrom Wales

EDITED BY DAVID LLOYD

This anthology ofpoems and interviews presents for the first time in this country the importantEnglish-language Welsh poetry of the 1980s and 1990s, illuminating the complexity, constant flux and politicalimplications of the poet's sense of inherited culture. Superb poems have been rigorously selected to showcase the Welsh poets' skill and seriousness, and the sensuous density of their language, which, like that of contemporary Irish poets, offers the reader memorable expressive riches and a strikingdepiction oflandscape and society. Included in the anthology are John Davies, Gillian Clarke and R S. Thomas, among others.

244 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5032-8) $14.95, paper (0-8101-5007-7)

New WritingfromMexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

This large anthology is a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today.

Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution.

-HARVARD REVIEW

.•. afeastofreadingenjoyment. Gibbons's collection gives us people worth caring about and writing not afraid to be at once serious andjoyful.

-SMALL PRESS

448 pages $15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

Writersfrom South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterly magazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialogues by fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to U.S. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

128 pages $6.50, paper (0-916384-03-9) Order Form

Writers from South Africa CULTURE, POLITICS AND LITERARY THEORY AND ACTIVITY IN SOUTH AFRICA TODAY

Order from your bookseller or from: Northwestern llnil'ersity Press Chicago Distribution Center 11030 South Langley Avenue Chicago, IL 60628 TEL. 800/621-2736 OR 3121568-1550 FAX 8001621-8476 OR 3121660-2235

Address City State Zip AuthorlI'itle ClothlPaper Quantity Unit Price Total :.:J Check or money order enclosed o MastercardlVisa number: Subtotal Shipping and handling* TOTAL Expiration Date Signature: *Domestic-$3.50 first book. $.75 each additional book. *Foreign-$4.50 first book. $1.00 each additional book

Name

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor

Fred Shafer

Co-Editor

Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow

James Lang

Reader

Christopher Carr

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Deanna Kreisel, Hans Holsen, Kemba Johnson

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $24; two years $44; life $600. Institutions: one year $36; two years $68. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $5. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions offiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1995 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ) Bookpeople (Berkeley, CA); Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CA); Fine Print (Austin, TX).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuaTteTly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CA).

Fall 1995

Due to rising paper and postage prices, TriQuarterly must raise its cover price and subscription rates starting with this issue. The cover price is now $11.95, and the prices for individual subscriptions are now $24 for one year and $44 for two years. Institutional subscriptions are $36 for one year and $68 for two years. Life subscriptions are $600.

Illinois Arts Council 1995 Literary Awards of $1,000 each have been received by the following writers for works published in TriQuarterly: Tammie Bob (for "The Match [Blessed Is the Match]," story, TQ #89) and Richard Jones (for "The Novel," poem, TQ #91). TriQuarterly, as publisher, has received matching awards. In addition, Tammie Bob received for her story the fifth annual Daniel Curley Award of $1,000 for Recent Illinois Short Fiction, given to the author of the highest, ranked work of short fiction.

"Super Night," a story by Charles Baxter that appeared in TQ #91, has been included in The Pushcart Prize XX anthology (1995,96 edition).

Editor of this issue: Reginald Gibbons

NOVELLA

OTHER FICTION

From The Twilight of the Bums ("Foolish Questions," "The Turncoats," "This and That," "The Beauty of Loneliness," "The Story of the Sparrow," "Commentaries on the Story of the Sparrow," "Winter Wheat," "Making a Distinction," "A Quiet Evening at Home") (surfiction/critifiction)

Contents

The Ambassador's Son .•••....•.........................•..... 23 Johnny Payne

94 Federman

Fitting Ends (story) 195 DanChaon Ancestry (story) ..........••.•...••........................•••• 212 John Stewart Irony, Irony, Irony (story) •......•..•..............•....... 244 Antonya Nelson 19

/Chambers Chambers/Federman

Louis Armstrong and the Astronauts Meet at the Langley AFB Pool; A Supernatural Narrative; A Librarian's Gift; Mississippi River Bridge; Nature Moment; Another Nature Moment; About the Farmer's Daughter; Irish Whiskey in the Backyard

Smith

POETRY

••....•..... 71 Dave

Statement and Poem ("Translations"} ••••....•..•••...• 79 Michelle

Translated from the French by Serge Gavronsky Lucretian 109 Peter Reading Poet; When the Spirit Spray,Paints the Sky 113 Sterling Plumpp Bluejays 120 Don Stap Black Hat; My Mother's Hand Thinks; The Nightgown 122 Renate Wood Two Sections from The Bob Hope Poem ("The Secret Life of Capital" and "The Triumph of Capitalism") 170 Campbell McGrath Prison for Stars; Illumination; Rough Being; Citadel 191 Claire Malraux Translated from the French by C. K. Williams 20

Grangaud

A Hint of Grief; Bazaar Scene; Living in Orissa 229

Jayanta Mahapatra

Narcissus in Plato's Cave; Narcissus Learning the Words to This Song; Narcissus as Gnostic 232

Reginald Shepherd

Parejas/Couples; Los condenados de la tierra/ The Wretched of the Earth; Para ti/For You; Walter Benjamin se va de Paris/Walter Benjamin Leaves Paris 236

Jose Emilio Pacheco

Translated from the Spanish by Cynthia Steele

Preface

Reginald Gibbons

Opening Remarks

Henry S. Bienen Intellectuals, Be Intelligent

Ewa Kuryluk The Future of Institutions of the Printed Word

Elisabeth Sifton

Zagajewski

CONFERENCE: WRITING AND THINKING AT THE END OF AN EPOCH

127

129

131

136

Of Violence and Naivete ••••.•......••...••••....•....•.•.•. 141 Adam

21

Ted Solotaroff

Prague Report: Literature Remains Alive and Well

]osefKroutvor

Translated from the German by Richard Drury

Boycott Lufthansa: Literature and Publicity

Today-A Few Ruminations and a Suggestion

Elke Schmitter

Translated from the German by Wilhelm Werthem

Epitaph as Prologue (Literature at the End of the Century)

Norman Manea

Translated from the Roumanian by Patrick Camiller

Cover painting (detail), Wave, by Denyse Thomasos

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

The Post-Cold.War Scene and the Literary Market 145

150

155

161

CONTRIBUTORS ...........•................•............. 265

22

The Ambassador's Son

Johnny Payne

IWhat are those men doing, Chuck?

Checking the level of contamination in the water. They're going to run chemical analyses on the samples. Rumors are going around that there's been an outbreak of some unusual disease. Some people say that it's being caused by waste released from oceangoing ships. It's all my employees can talk about this week. I called the Ministry of Health this morning, to get the straight dope on it and try to allay fears. You know how Fujimori's ministers and their staff are masters of indirection and euphemism. Saniferal malfestations of seafoam. I always feel like they're speaking Old Norse. They're not sure at this point what to call it.

Any speculation?

Cholera, maybe. But they don't want the word to spread just yet.

Just the disease. Isn't cholera usually confined to livestock?

It's been pretty rare in these parts for a long time, I gather. But they've gone so far as to discourage people from eating marine products, and posted signs on some of the beaches that prohibit swimming. I can't imagine who would want to swim this time of year anyway. It was low tide, and debris littered the beach, branches of kelp with floaters like arthritic joints, fish heads, clam husks, the carcasses of crabs. Workers wearing oxygen masks wandered about the sand spearing pieces ofplankton and garbage with pointed sticks, depositing them in small plastic bags and tagging each.

Except you. Chuck's the original polar bear, General. Every day at sunrise, he's out in the pool, splashing around in the shallow end to wake himself up. The maid thinks he's demented. Back when we lived

TRIQUARTERLY

23

in Boston, he used to try to coax me down to the harbor to recreate in early March, with promises of oysters on the half shell afterward. Why did you bring us to this ghastly beach for lunch? This is supposed to be a special occasion, with Vic's having come. In addition to which we're all freezing to death.

This is the best restaurant on the whole Costa Verde. You'd pay forty bucks a head in D.C. for a meal like you can get here. I can't help it if the entire coastline is a disaster area.

The maitre d' stood by, discreetly rubbing the sandy sole of his oxford against the plank floor to get their attention. I hope everything is satisfactorily private for the Ambassador and his party. I'm at your disposal whenever you wish to inquire about any item on the menu.

I think we're about ready, Romualdo. The diphthong on his father's lips was perfect as a kiss, mua, as he switched into Spanish and pronounced Romualdo's name. Have you made up some ceviche fresh this afternoon?

Always fresh, sir. The prawns will be virtually gasping on your plate.

How about it, Vic? You ever tried ceviche? It's raw shellfish marinated in lemon. A local delicacy. From the shelter of the cabana, Vic watched the gray surf try to roll in. The undertow sucked the waves back out almost before the whitecaps could break. Gusts blew through the cabana's bamboo slats. Vic shivered in a summer suit, stylish and impossibly wrinkled, linen mottled with bright points of thread.

I don't think we ought to be offering shellfish to our son, Chuck, or eating it ourselves, if the Ministry of Health has advised people to exercise caution. Those are bottom feeders.

The worst thing that can happen to this country right now is for a scare to start up about the seafood. None of these so-called health risks has even been confirmed yet, and I would certainly have been called in for the recitation of the whole Icelandic saga if there were anything definite to know.

Death is circumspect here in this city of ports, General Villanueva remarked, exhaling a puffand scanning the horizon with a squint.

I hope it stays circumspect. The economy depends heavily on the fishing industry, and even with these vague rumors in the air, suddenly nobody wants to risk eating out. Several of the best seafood restaurants have already gone out of business as a result, and the whole thing could snowball. A country as poor as this one doesn't need any more economic shocks, right after their first dose of Fujishock. I want you to know, Romualdo, that come what may, you can continue to count on seeing us here. I'll throw any business your way that I can.

TRIQUARTERLY

24

We appreciate your patronage, Ambassador. We always look forward to your proximate appearance. Finding a water stain on Vic's knife, Romualdo burnished the utensil, making diversionary eye contact all the while.

Plus, there are all kinds of other things on the menu. Beef hearts on a skewer. Nobody at this table has to eat seafood if he doesn't feel cornfortable. I'm not forcing anyone.

All right, then, I'll try some of the seafood, but only for the sake of solidarity. I'm not even in the mood for it. How is the sole, Romualdo? Oh, but that's a bottom feeder too, isn't it? It has both eyes on the same side of its head.

Senora, not to apply undue pressure or suasion to your selection, but we take the utmost precautions in all of our preparatory techniques, even during seasons when there are no plagues in the offing. The sole is first steamed in addition to being braised, in order to purge it of any impurities. The resulting entree is indescribably tender and exquisite.

O.K., I'll bite. How about you, Vic?

I'll have the beef tongue, please. Medium rare. Wouldn't you prefer it a little more cooked, honey? That's how I eat it.

O.K., your funeral. General Villanueva?

Whatever the senora is having.

Give me the ceviche, and bring us a couple of bottles of Chilean Chardonnay to start.

Are you all right, son? You're shaking, and your lips look blue.

I'm O.K. It will take me a few days to get acclimated.

Let's move indoors, Chuck. It doesn't even smell that fresh out here. You'd think with the coastal wind we'd at least get that.

I'll buy a sweater tomorrow.

The salt air out here will be salutary for him. But the beach is a disgrace, there's no question about it. You see that kelp lying there rotting? That's what you smell. I was talking the other day to a young marine scientist down here working with the Ministry of Fisheries on a Fulbright. He's doing a study, says that all that kelp, instead of uselessly decaying, could be harvested and put to use. Apparently it's a natural source of iodine if you tum it to ashes. He's proposing a massive water purification system using iodine extracted from kelp as its main active ingredient. It's ecological, uses native resources, and if there is contamination in the ocean, it might squelch this supposed epidemic in the making before it really gets started. At first I was skeptical, it sounded about as realistic as

TRIQUARTERLY

25

one of Vic's off-the-cuff scientific hypotheses, but after hearing him out, I told him to send me a copy of the report, and that if it looked feasible, we'd do whatever we could to promote it. As far as I'm concerned, that's the kind of thing we're here for-to foster innovative thinking about these crises. Taking something that's a social menace and turning it into a solution to the problem. Doesn't it sound feasible to you, Vic? You've studied chemistry. Iodine has all kinds of medical applications, right? You see, General, our son has spent tens of thousands of dollars dabbling in different courses in medical school, and devising amateur experiments in his ample spare time. Not to get a degree, of course, but so he can answer questions like this authoritatively.

Sweetheart, please don't start. Vic has flown all this way to see us.

I'm sorry, Vic. That was a cheap shot. He took a long drink off his pisco sour. I just want him to know that I have my progressive side. I'm not a reactionary puppet of the imperialist state, or whatever else men in my position are being called these days.

I didn't hear him call you anything of the kind, darling.

Well, he's implied it clearly enough, with his sullen, adolescent refusal of the minor perquisites of power. It's as though he's ashamed of us. And plenty of other people are saying worse about me outright. The other day the head of the Internal Police showed me the latest issue of that student rag the Shining Path publishes at San Marcos University, which they've also infiltrated. It refers to me as "the genocidal Featherston." I'd like to see them try to do my job. They can't even spell my name right.

They're only kids.

Kids don't blow up electrical towers.

You're father's been a little tense. Somebody raked the wall of the compound with bullets again last week.

In broad daylight. And the Peruvian government subcontracts out to hire our security people, so I have absolutely no say in who is protecting your mother and me. It doesn't make a person feel very secure. Then the Shining Path, at least they claimed responsibility, blew up the storefront of the Kentucky Fried Chicken right up Avenida Arequipa, not twenty blocks from the compound. Give me a break. As if killing three innocent wage earners is really going to advance the proletarian cause. They probably did it because they suspect that Colonel Sanders is the name of a covert U.S. military advisor.

His beard alone would disqualify him from our domestic ranks, said the General. The military code tolerates mustaches, but frowns on beards.

TRIQUARTERLY

26

The ambassador downed another Pisco sour as soon as the waiter set it in front ofhim, and the unmelted ice cubes left in the glass shone perfect as crys, tals of quartz. With a sigh, he let his body sprawl in the chair. He seemed to have given up the losing battle of competing with General Villanueva's erect posture. But we're really glad to see you, son. You look fit. Been doing some running? You could probably beat the general at tennis. I hardly ever can because I'm too dissolute; I bet I've put on ten pounds since we arrived. Can you believe the physique on a guy his age? He never touch, es anything but Earl Grey tea. At least have some wine with us this time, Villanueva.

It would be an honor, said the General. All in moderation. Let me take you to Club Regattas sometime, or the Cfrculo Militar, I notice from watching you pick up your glass that you are a leftist, like your father. I will have to take advantage of that defect by serving consistently to your backhand. A small stab at mirth on my part, as I hope you realize. My opinion is that all political differences should be worked out on the tennis court, in a spirit of camaraderie.

The military here is the most apolitical bunch of people I ever met. When it comes to the war on coca or anything else, they just execute the orders they're given. They realized after the failure of Morales Bermudez, and the upsurge of Shining Path, that the hot seat of power wasn't a very good place to be. General Villanueva, for instance, declined an official post in the ministry. He prefers to act as an unofficial advisor on the counterinsurgency. But what he'd really rather do is read Conan Doyle and skunk me on the tennis courts. Isn't that right, Villanueva?

I concur in your assessment of me. Without epaulets, one accomplishes more. But you are too modest about your own prowess on the clay. So, how's law school coming along?

I finish this coming spring, and take the bar in September. That's the plan, at least.

Fantastic. I was afraid to bring the topic up, but now I'm glad I did. Ambassador Featherson shifted forward in his iron garden chair. What specialty are you favoring? Do you plan to clerk?

Probably not. I kind of missed that opportunity. I'd like to try straight off to do something with international law. With glasnost in the ascendant, there's talk that there might be opportunities abroad for attorneys who speak fluent Russian. I want to get in the thick of someplace where history is being made, as soon as possible.

With all due respect, Young Vic, said the general, the Soviet Union

TRIQUARTERLY

27

continues to be socialist. Can one teach an old bear new tricks? Ursa semper sinister est. And yet, Mrs. Thatcher did say she could do business with him. We could use some Thatcherismo ourselves. Too bad about the Falklands, though. Maggie's great faux pas down here. They really ought to be called the Malvinas.

Not clerk? What are you talking about? You can't expect to get anywhere in Washington until you've paid your dues clerking. That's the protocol nowadays, unless you simply plan to hash around.

I didn't say I wanted to work in Washington. That's always been your idea. I may fly to the Soviet Union next month to have a look around and see what's there. Somebody I know is negotiating with high-level officials in Moscow, about helping them finance the building of a new airport. He said he might get them to pay my airfare and lodging if I go along for a few weeks to translate technical documents and conversations, and advise him on some of the legal aspects of the joint project. I've always wanted to see Russia, I speak the language without ever having set foot in its borders, and it's an incredible time to be over there. Legislators and legal scholars are actually redrafting the Soviet constitution right now, and I thought I might be able to get in on that, even in just an unofficial way. All kinds of arcane language has to be overhauled. The link between insanity and criminal behavior, for instance. Going through the subclauses is like reading Dostoyevsky.

And how do you plan to be back in time for your exams, if you're going to be overseeing Soviet affairs of state?

I don't have to be back. I took a leave of absence this semester. I needed a break from law school. I've been having-well, a little trouble keeping my concentration. My mind keeps wandering to other things.

So that's how you managed to find leisure to travel here. I told your mother that mid-October seemed like an odd time for you to be coming. You're not cracking up, are you?

Please don't psychoanalyze me. Why do you have to reduce everything to a mental aberration?

I was against your visit, but she assured me that law schools have some kind of peculiar Gnostic calendar of their own. Not having had the advantage of attending one myself, I'm not in a position to know. And on top of it all, you fail to tell us precisely when you plan to arrive, so we can't even extend our own son the courtesy of a limousine and driver on his first visit here. It's embarrassing to us. Your mother was mortified when you showed up at the security gate in a taxi. She'd been waiting by the phone all morning.

TRIQUARTERLY

28

Just layoff me, will you? I didn't ask you to foot the bill for this trip or any other. Or my law school. So if I want to go to Russia, or to hell in a handbasket for that matter, I don't know how that's any concern of yours.

Where do you hatch these pathetically grandiose notions that you're going to sweep in somewhere you've never been and alter the course of history, the fate of humankind? I hate to tell you, but that's not how it works. Except for the uncombed shock of hair, you're not Rasputin. Whatever megalomaniac fantasy you may have constructed in your mind, Gorbachev is not going to appoint you on the spot as a shadow advisor to prophesy for him. World leaders don't operate that way. O.K., Reagan used psychics, but he's in his dotage now, thank God. That's probably how he chose my assignments back in the early eighties, come to think of it. I can't figure out any other explanation. But on the whole, civilization gets built and unbuilt stick by stick. When you get to be an elder statesman, then you can dispense wisdom. In the meantime, when are you going to get down to work like all the rest of us? I'd like to see you change one person's life, just one, or even execute a specific order to satisfaction, then come back and talk to me about history.

The platters arrived, garnished with lettuce, tomato, and shreds of onion, and they ate without speaking, except for Vic's mother reminding him not to eat the lettuce, as the men in oxygen masks drifted further down the beach, brandishing their spears. Uncorked wine flowed, the ambassador devoting himself to refilling everyone's glasses in spite of the maitre d's repeated attempts to beat him to the bottle. The general dabbed at his mouth with delicacy and returned the napkin to his lap. All this talk of lawyers by the seaside reminds me of a joke I heard not too long ago from a good friend of mine, a former colonel whom I recently visited in San Francisco. We lost contact, because he was living under an assumed name there after he was spuriously charged, on minor legal technicalities, with various crimes against humanity for his participation in the Argentine junta. But they found him out, alas, and are now trying to extradite him to stand trial, poor fellow. In the face of all this harassment, he somehow retains his sense of humor. Ahead, death lurks patiently in the barrels of the guns. And yet he remains stoical. He said there were three professionals out fishing in a boat-a doctor, a priest, and a lawyer. A squall blew up, and carried them far from the shoreline, damaging their sail beyond repair. They decided amongst themselves that one of them would have to try to swim to shore for help, but the waters were known to be infested with sharks, and none of them was anxious to volunteer. I

TRIQUARTERLY

29

shouldn't be the one to go, said the doctor. If we all fall sick, as we eventually shall, then the two of you will require my medical services. All the more reason why I shouldn't go, said the priest. If we do indeed sicken, we may end up on the point of death, and the two of you will need me to perform your last rites. They sat in silence for a while, no one budging, until at last the lawyer stood up, smiled at his companions and said, Don't worry. I'll go. He stepped off the side of the boat, and before his feet were able to touch even a single drop of water, two sharks leapt out of the ocean, one under each foot, and buoyed him smoothly off toward the horizon. It's a miracle! cried the priest. No, said the doctor, shaking his head. Professional courtesy.

Funny, Villanueva. I hadn't heard that one.

I have an idea. Maybe it would be good for Vic to use these couple of months off to get some practical, hands-on experience. He could stay here with us and help represent the Thomases in their adoption case. The final papers would have to be signed by a degreed attorney, but there's no reason why he can't help them through the legal hurdles. He knows far more than any paralegal, even if you take into account that this is a different context, and he speaks good Spanish. The Thomases have been down here five months, and their case has gotten nowhere, even with my intervention. They need somebody who has the time to stick with them day by day. This wouldn't be anything stressful. Just something to keep your mind occupied while you rest and recuperate.

Who are the Thomases?

One of your mother's latest crusading passions.

Bill and Hannah. He's a carpenter in the States, and she's an interior design person. They rehab Victorians in the Midwest and live in them until they sell. A childless couple who are dying to have a baby. I know they'll be impeccable parents, if they can just get their hands on a child. They tried for months, then resorted to fertility drugs and finally conceived, but the baby was born with all kinds of complications, and then liver failure, and they couldn't find a donor in time, so the baby died. After that, she couldn't seem to conceive again, and they've been on an adoption waiting list in the States forever. It's one of the real classic horror stories.

What are they doing down here?

The Peruvian government has set up incentives for citizens who want to give up their children for adoption. The birth rate is at panic levels. Birth control isn't a real option because of the heavily Catholic culture, you know how that goes, and the shantytowns are exploding in every

TRIQUARTERLY

30

direction. You surely noticed them on your way in from the airport. Tawantinsuyo, Villa Hermosa. Gigantic-whole colonies unto themselves. I've been out to visit a couple of them and, as a mother, it makes my heart sick. There might be one running faucet for every three hundred people, and the infant mortality rate is unbelievable. The babies are all dying of diarrhea. I hate to think what's going to happen in those places if we really are on the verge of a cholera epidemic. It's fine to tell people to wash their hands and make sure the baby stays hydrated, but it's a little tough to do when hardly anybody has potable water. It makes me tremble to try to imagine what it would have been like to raise you in an environment like that.

So basically they're selling children to the first world to alleviate the problem?

I know what you're thinking, son. It's true that the parents are paid a compensatory fee by the adopting couple. But the applicants are all screened very carefully, as they would be anywhere. We're not talking child slave trade. The only people making real money off this are the lawyers. That's what troubles me. A whole corps of shysters has sprung up, including, in my opinion, this one representing the Thomases. They string the adoption process out forever, and milk the hopeful couples, most of whom don't even speak the language, of every cent they possibly can while leading them by the nose through a maze of regulations. The foreign hopefuls camp out in hotels here for weeks or even months, waiting to get approved. Occasionally the babies are delivered over to them by desperate mothers before the paperwork is through, and these would-be adoptive parents have to call room service for thermoses of hot water, which get put on their growing hotel tab, so they can sterilize bottles. They bathe their new infants in a hotel sink, without even knowing for sure that they'll get to keep them. Some of them return to the u.S. without anything to show for the ordeal except the gouge marks in their life savings. It's an imperfect system, inhumane really, to everybody concerned, but you could help soften the blows, at least in this case. I'm especially concerned about Hannah and Bill, because they're just working people, really nice, who have been to hell and back trying to get a baby of their own. You would think they wouldn't have to go through any more suffering. He said that the day before yesterday they were sitting in the Cine Orrantia watching a kung-fu movie, dubbed in Spanish, at two in the afternoon, killing time, and he suddenly thought about where he was, and what he was doing, and thought he was going to go insane. What do you think, Chuck?

TRIQUARTERLY

31

I think Vic should be back in law school, finishing his degree. But since he's already taken a leave of absence, I'd rather see him doing something practical, getting concrete experience, instead of traipsing off half-cocked to the Soviet Union. He's already here, so I guess we can give it a try.

How about it, Vic?

Vic chewed the succulent piece of steak in his mouth. The chef had cooked the tongue to perfection-tender and not too done, just shy ofbloody. He was feeling anemic after the longflight, and could use the iron. I don't know. I'm pretty strung out right now. Maybe we can discuss it further tomorrow. I've got a horrible case of jet lag, and I feel one of my insomnia binges coming on. I'd like to nip it in the bud. Tonight, I'm going to be really decadent, and sleep for twelve hours. Don't anybody wake me in the morning, O.K.?

II

Let me pour you some more tea. Demetrio, please fix us another pot, would you? Young Vic has a little stomach problem. His mother spoke Spanish to the butler with an accent that would have to be described as fair to middling. She had never possessed an ear, a natural musical gift, like his father's, but her grammar was absolutely correct down to the last suffix, her subjunctives and imperfects always cultivated to perfection. She lifted the tea cozy from the ceramic pot, poured Vic another cup of chamomile, and handed the empty pot to Demetrio. This stuff grows in the garden. I stick whole stalks and flowers in. You can buy all kinds of medicinal herbal teas in the marketplace. I've never even heard of some of them. I have a few packets wrapped up in newspaper in the kitchen cabinet, but I don't know exactly what they're for. The cook doesn't either, or if she does she's not letting on.

On the whole, Sandy tended to go native, to throw herself as entirely as possible into learning the customs, history, cuisine, furniture, architecture, language, of each place she inhabited for short stretches of two or three years. She had always taken her role as the ambassador's wife at its stated official value, attending Women's Days, elementary-school parades with patriotic fanfare, off-key and fortissimo, the openings of gallery shows devoted to local up-and-corning artists, especially those with a flair for indigenous themes. She hosted the requisite number of official dinners for state dignitaries, and attended her share of opera pre-

TRIQUARTERLY

32

mieres. Sandy much preferred, though, what she called, with the slangy aplomb of Evita, "the real thing or at least a good cheap imitation." Moving, for her, did not entail transporting a cargo hold of steamer trunks filled with Wedgwood and table linens at taxpayer expense, or having a pongo haul a meat freezer up a mountainside on his back. On the whole, she'd given away the acquisitions of each phase before leaving the country in question, keeping back only a few sentimental favorites for herself: an Ibo mask carved in the uncanny likeness of a high school beau she had always referred to as El Greco, or a chador given to her by the Kuwaiti women she played canasta with, who underneath the black robes they donned in public, wore brilliant Christian Dior dresses seen only by their husbands and other women in the group. The bulk of Sandy's shipped items consisted of an ever-growing collection of books. But to each of the countries they'd lived in while Vic was growing up and after, she'd brought along a few constant and unchanging necessities, such as the tea cozy and the ceramic pot Vic recognized from childhood, to keep her civilized, as she always said in a voice that could be either ironic or sincere, depending on how you chose to take it.

Now he was drinking from that teapot in unfamiliar surroundings once again. The two-story villa had timbered ceilings and a sloping clay roof (a luxury of strictly aesthetic value in a city where it never rained, she explained to him). The walls and patio around the swimming pool were inlaid with genuine Spanish tile, aquamarine, hand painted with what looked to be scenes from an illustrator she guessed to be a modem follower of the artist and chronicler Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala. He watched her move about the spacious rooms with obvious pleasure, as she apologized for the obscenely long trestle table, made of heavy oak and surrounded by high-backed throne chairs. She complained of the villa's having been furnished in Late Conquistador, assuring him that she and his father always ate in the kitchen or out on the patio unless they were entertaining local or foreign brass.

Beyond the swimming pool lay her secret garden, its walking paths lined with peonies, roses, carnations, other flowers he didn't recognize, lemon grass, crooked shade trees, all heavily irrigated. A hose ran uninterrupted. The two of them had spent a twilit half-hour kneeling in the damp grass, searching without success for the phantom house mascot while humidity evanesced close to the ground, the outermost reach of the moist breath exhaled by the earth's molten core. The tortoise in question had been presented to her and the Ambassador as a ceremonial gift by the head of a jungle tribe in Iquitos, and had traveled back to

TRIQUARTERLY

33

Lima in its wire cage in the hold of a Faucett Jet to be set free in Sandy's hothouse locus amoenus. It disappeared at once into the dank vegetation, and hadn't shown its leather face since. Demetrio, the butler, was the same way. He made himself present when called for to perform a specific service, such as bringing tea, but otherwise vanished into one of the many bone-chilling rooms.

The villa had an actual study, in the old-fashioned sense of the word, one with deep chairs, a working fireplace piled with fast-burning and aromatic eucalyptus, the only readily available wood, and plenty of shelf space crammed with books. Vic had already decided on it as his preferred room, and had spent the early morning hours stoking the fire with branches, watching the leaves on them flare, shrivel, and fall into the deepening bed of ashes. None of the shelves housed sets of tomes with oppressive leather bindings and uncut pages, of the kind one found in the bad Southern romance novels Sandy read with relish during her trash binges. Waugh's Decline and Fall was there, Tennyson, Plato, Euripides, but most of the shelf space was dominated by hard-used paperbacks in languages both classical and declasse. Here was something called Gregorio Condori Mamani, the oral autobiography of a campesino who had devoted his life to carrying bundles on his back, with a rope, in an Andean marketplace. That much Vic could glean by skimming the Spanish.

The Quechua text on the facing page remained runic and impenetrable. Last night, he'd given up on his tax-law textbook, and studied the Indian language by the vacillating lamplight in the guest room. (I hope it's not another electrical tower blown by the guerrillas, his mother had said, poking her head in the door, but here's a flashlight just in case.) Before long, his eyes watery, he began to experience odd, vaguely nauseating twinges of remorse in the pit of his stomach about having come home at all to this most recent of homes. Given the current atmosphere, it probably wasn't the best of places to collapse into a temporary state of inertia. Llaqtaymanta hanpurani mana mamay taytay kaqtin, totalmente q'ara, wakcha, madrinaypa makinpi karani. Paymi chukchayta rutuwaran, hinaspa huk p'unchay hatunchana kashaqtiy niwaq: Nataq hallpayoqna kanki, tullu takayasqa, chayqa llank'aqmi rinayki. Both his parents read widely and deep, especially his mother; they'd take a stab at anything and they believed in noblesse oblige even though they hadn't really come from the noblesse themselves. They were traitors both to their native class and their adopted class. I came here from my birthplace when I realized that I had no mother and no father. I was a complete orphan, poor,

TRIQUARTERLY

34

given over into the hands of my godmother. She sheared my hair, and one day, when I had come of a certain age, she said to me: Now that you've hoarded some strength, and your bones are starting to harden, you must go find work. Someday you'll have a wife and children, and with your luck, you might end up with a wife who won't be a good helpmeet, and you may curse me. And I don't want anyone to curse me after my death; because in that way, I might become a condemned soul, wandering the earth without rest. In this manner, she spoke to me. And I said: All right, mama.

Demetrio had returned, bearing the tea service. His hair was dark, thick and coarse, and his cheekbones salient, almost Asiatic, the same racial characteristics Vic had observed in many of the people at the air' port and in the street. But Demetrio also had reddish highlights to his hair, and freckles. His eyes were green, too, or more of a hazel, really. Demetrio set down the tea service, straightened, and fastened his green' ish gaze on the mistress's son. So, you're Young Vic. We've all been hearing a great deal about you, and waiting breathlessly for your arrival.

Well, here I am. Puny as I sit before you.

Demetrio flashed him a sly smile. You know, he said, there's a theater in London called the Young Vic.

You've been to London? Were you a butler there too?

Oh no, I've never set foot outside Peru. I'm a bachelor with a small orbit. The world came to me instead. My mother is of Irish descent. My father died in prison a few years back.

I'm sorry to hear that. What from?

Unknown causes. Possibly an outbreak of socialism. But before that, he was a local actor who studied abroad for a year at the Old Vic. The English wanted to have some third-world ethnic types around-perhaps because Shakespeare's plays are full of blokes named Gonzago. So they gave out a few fellowships, and he happened to get one. I'm the fruit of that fellowship. As I recall, they featured my father in a revival of Synge's Playboy of the Western World.

Forgive me for staring at you when you came in. You didn't look exactly Peruvian, and I couldn't peg you.

Quite understandable. I'm the product of miscegenation. Mandingo, I believe you call it in your country. Anyway, this isn't Jane Austen. In Kafka, you don't expect to find all gypsies and Slovaks.

You're right. I-I hadn't thought of it that way.

Well, here's a fresh pot. Cheerio. Hoq ratu kama. Demetrio vanished again like the Cheshire cat, only his faint overbite and green eyes left glinting in the doorway.

TRIQUARTERLY

35

TRIQUARTERLY

Drink the tea before it gets cold. Sandy laid the back of her hand against Vic's brow. Have your bowel movements started to return to normal?

My stomach's still a little loose, and I'm limp as a rag, but at least I'm not speaking melancholy Danish into the toilet bowl any more. And doing other equally disgusting things. I don't think there's much left inside me. Did I keep Dad awake all night with my retching?

He can cancel his meeting with that journalist from El Comercio, and take a nap this afternoon. The man never prints what he says anyway. He makes up his own quotes and arranges them in interview format, so I'm not sure what he needs Chuck for.

I guess you didn't sleep much either, coming in to give me water and hold my head. I'm really sorry. Sorry? Sorry for what?

You know. It's all so gross. Dealing with my bodily fluids. I kept hoping I would die and have a closed-casket service, so I wouldn't have to look you in the eye again. I really wish I'd checked into a hotel. At least nobody would have known me. I could have listed my profession as land surveyor in the register.

What sort of nonsense are you talking? I'm your mother. When something like that hits you, you can get dehydrated in a critical way, before you even know what's happening. I shouldn't have to tell you of all people that. I'm only glad we had enough bottled water on hand. I happened to send Chela out to stock up yesterday, on account of your arrival. Otherwise you would have been drinking a case of Inka Cola instead. Speaking of sleep, you couldn't have got more than half an hour yourself. Why don't you go lie down?

No, I'm not sleepy anymore. The wave passed. Besides, I'd rather hang out here in the study with you. This is the one room I really like. Whatever it was that hit me, I don't feel much like moving around.

At first I was certain your symptoms had to do with this cholera thing. You can't imagine what a scare you gave me. I had Chuck wake up the staff doctor over at the Embassy. He didn't seem terribly worried about it. Then I remembered that you'd ordered beef tongue. You should have eaten the fish; all the rest of us seem to be fine. Or at least had the tongue cooked well. Maybe it was trichinosis-do you get that from beef?

Pork.

Well, everybody seems to be catching livestock diseases these days. You probably just came down with a quick case of Montezuma's

36

Revenge. That's what you get for being the son of the genocidal Featherston, sic. Your father and I have already gone through all the local bugs. Or mostly me, I should say. You know how Chuck never succumbs to anything.

I do feel a lot better.

Good enough to go shopping for a sweater this afternoon? There's a tourist shop I want to take you to. Quality goods, not this cheap stuff crowding the stores on La Colmena. Beatriz, the woman who runs it, has become the unofficial godmother to a lot of the adoptive couples who end up hanging around here while they're waiting for their babies. It gives them somewhere to drink coffee and commiserate.

You know, Mom, I was considering your proposition last night, between heaves, and I really don't think it's something I should get involved in. I need to withdraw for a week or two. Anyway, the legal system here is completely unfamiliar to me. It's based on the Napoleonic code, isn't it?

It can't be any more difficult than helping rewrite the Soviet constitution. And I know it would give your father a lot of pleasure, even if he didn't say so directly.

Why can't he say it directly, if that's what he thinks? Why do you always end up serving as his intermediary and interpreter, to soften his sarcastic remarks? You have your own life to live, without the extra pressure of tending to his. I thought he was the one who is supposed to be the ambassador, spreading goodwill throughout the world and functioning as the go-between.

He has a very full schedule, and he sees to it admirably.

I don't know how conscientious a job he can be doing here, in the kind of shape he's in. His complexion looks jaundiced, he's put on weight, and he's drinking far too much. Did you see him put the booze away at lunch? He looks at least five years older than he did the last time I saw him.

Please don't make him into the drunken consul in Under the Volcano, son. You've been known to exaggerate for effect. Pretty soon you'll have him hanging upside down by his ankles in a Mexican Ferris wheel with his keys and change falling out of his trouser pockets. While little children gather up the scattered coppers on the ground.

It's your allusion, not mine. And it doesn't seem that far off the mark. Vic, don't insult my intelligence or your father's. He's been under incredible pressure since we arrived here. Do you know what it's like to try to sleep at night, when bombs are going off in the vicinity every cou-

TRIQUARTERLY

37

ple of weeks? Fujimori's very secretive and has appointed a dummy cabinet, in addition to the real one, so you don't always even know if you're dealing with the right person. He likes to have several "teams," as he calls them, for everything. He probably uses a stunt double for his public appearances. Besides, all of the diplomatic assignments your father has been given, even before this one, were to hard places at dangerous times-Kuwait, Nigeria, Nicaragua. For better or worse, he's strictly an organization man, a bureaucrat, and not an ideologue. He didn't come through the old,boy network, and for that reason the Republicans don't really like him. He doesn't submit his country assignment preferences on the basis of the number of available golf courses per square mile. He came up through the ranks, taking the foreign-service exam, without any of the advantages. But he's a senior diplomat, so they give him assignments that look good on paper, but that none of the cronies really want anyway.

And I've had all the advantages. He'll never let me forget it, either. He won't be satisfied until I cop a government post myself. Only not too big of one, because he couldn't stand to be one-upped.

Vic, listen to yourself. You're talking about your father.

O.K. That was my cheap shot. I take it back. I still don't like the way you get dragged around the world, though. I know you're sick of it. You've told me so before in your letters. You should be a university pro' fessor somewhere, teaching English literature and explaining to students what a bailiwick and a barouche landau are. I would have killed to find a teacher as smart as you. Instead, you're having lunch on a garbagestrewn beach with General Villanueva.

You're just mad because he told a lawyer joke.

Told to him in tum by the Butcher of Buenos Aires. I'm sorry, but that guy gives me the creeps. I can't believe Dad plays tennis with him. It doesn't make him look so hot either.

I'm not wild about Villanueva myself, I'll confess, but it's not for me to judge. I try to be polite. They're both involved in overseeing the military aid that's getting funneled into the war on drugs and the counterinsurgency. The administration is putting lots of pressure on all the ambassadors down here in Latin America to take a hard line on drug production. That's why we flew to Iquitos last month. I went bird, watching and your father visited captured cocaine factories. There's some huge aid package pending in Congress, and the money's all mixed up together. I don't really know the ins and outs of it myself. My domain is slightly different.

TRIQUARTERLY

38

How do you stand that? You're in it, but you're not of it. I try to keep my fellow students at law school from even knowing that I'm the son of the Peruvian ambassador, because they expect me to have a privileged and cogent take on what's going on down here politically. I don't know how to tell them that I don't have the slightest idea, or not any more of one than they do. That I only speak to my father once or twice a year, and even then it's usually to argue about money that lowe somebody or other. But for you, it's worse. You attend one social and cultural function after another, and entertain the people who make the policies. You get facts and snippets, rumors, form your hypotheses, but without knowing the whole picture. And then you're supposed to help relocate all the displaced orphans. I know that my questions are probably naive as hell, but why doesn't Congress appropriate some of that money to put running water in those shantytowns you were telling me about? Have you asked Dad to request that they do that?

I can't tell your father what to do, Vic, any more than you can. You know how reticent he can be. Our philosophies are not precisely the same either, as I'm sure you've noticed. And in any case, he was sent here to implement foreign policy, not to make it. He has a certain narrow latitude, on a day-to-day basis, but he prefers to exercise it with caution. That probably seems like a conservative approach to you, but it starts to sound pretty appealing after you listen to some of the junket cowboys who come down here, have a few whiskies with us by the pool, and start wondering aloud why we don't just nuke the hell out of these slums and take care of the problem that way. They always meant it as a joke, of course, when I inquire whether the Congressman's remarks are to be construed as on or off the record. They'd have us using Agent Orange in the Peruvian jungle if they thought they could get away with it.

Well, I certainly can't judge the situation any better than you can. I really just came down here to spend a little time with you, and recharge my batteries. I used the student loan for this semester to pay for the ticket. They're probably going to revoke the loan and stick a hefty penalty on me when I get back. I'm glad that the university doesn't have a brig, because I'd spend all my time in it.

You're hopeless, Vic. I wish you would find somebody to keep you on the straight and narrow. I don't suppose there's any chance of your getting back together with Felicia. She was so bright and serious. An intellectual like you. You shouldn't hold it against her that she came from Brahmins. I know you couldn't stand to be tainted with blue blood, on

TRIQUARTERLY

39

top of being an ambassador's son. But if it will make you feel any better, a Brahmin is also a breed of cattle, you know. Even cows have pedigrees. It has a hump between the shoulders, and a pendulous dewlap. You could tell people she's a rodeo cowgirl, or a veterinarian. Or that she works in a freak show.

I don't hold her pedigree against her. We just had different expectations about things. Anyway, that was long ago.

I suppose you're still seeing that Andrea girl.

Your tone of voice tells me that you may yet be withholding a drop or two of approval.

I liked her quite well the time I met her in Boston. I found her positively--charming.

That's the most noncommital, nondescript, diplomatic adjective you could have selected.

1 know Andrea is smart, in her own way, but if you want me to be blunt, she struck me as a bit too much of the California golden girl. She's even tawny. I simply think that you need someone more ambitious and less frivolous. She's doubtless a delicious find for most any healthy young male, including yourself, but I can't imagine that it's going to last.

That's my affair. O.K.? End of discussion. In any event, I don't think I'm in much of a position to be judging the ambition of others.

You have plenty of ambition. The problem is that it shoots out of your pores in every direction, wreaking carnage, like Saint Sebastian's arrows in reverse. Do you understand how close you keep coming to messing up your life for good?

1 agree. That's why I don't think I'd be a very good choice for shepherding this couple through their troubles. It's the blind leading the blind.

Vic, please help me out on this. I need someone I can put my trust in, and I've seldom asked anything of you. The things I do may seem useless or strange, from your vantage point, and it's true that I do on occasion complain about them. Every task I perform here is based on half-truths, partial knowledge spoken in whispers at the bottom of a well. But an ambassador's wife is what I am, son. That's my life. I wield mandarin courtesies that I've spent my existence honing to razor sharpness. I can't sit here waiting for the ethical complications to sort themselves out. All I can manage is to exercise my peculiar, rarefied little domain of social clubs and the wives of prominent citizens in the best way I know how. And right now, what I want more than anything is for the Thomases to take possession of that baby waiting for them in Tawantinsuyo. That's

TRIQUARTERLY

40

something I can actually make happen. It's a task that's manageable enough to see through to the end. I even have dreams about it. When they told me their story, I felt as sad as if I had been the one to watch my child die. As if I'd lost you for all time, and could never live through the experience of holding you in my arms when you're weak and sick and limp, and in spite of the fact that you're twenty-eight years old, still be able to hear you cry out in the middle of the night Mama, Mama help me I think I'm dying. You gave me a real scare. I thought I was going to have to give you up, and I discovered that I'm not quite ready to do that.

In this manner, she spoke to him. And he said: All right, Mama.

III

They chose to have the driver leave them at the comer of Caruana and La Colmena, but within two minutes had reason to regret their decision. The moneychangers thronged about Sandy and Vic, brandishing solar calculators the size of credit cards, holding them heavenward so the digital display would receive the maximum exposure to the winter sun's rays, as they babbled hypothetical equations of intis to dollars, in thousands, tens of thousands, some running off like auctioneers on ether into the millions, or turning the calculators askew so that they flashed an endlessly repeating decimal, 6666666 or 8888888. As she and he pushed their way up the block, still more people milled about with placards lettered by hand. At first Vic feared a protest had formed on short notice. He didn't know whether or not his mother's face recognition and perceived importance were sufficient to summon up an event of that kind, whether she was serving as a second-string lightning rod for wrath about a recent visit by the IMF, or the coca policy, or the changes taking place in Czechoslovakia. But the signs all pertained to currency exchange, pure and simple. I ACCEPT TORN TAPED STAPLED BURNT RIPPED DOLLARS. BUY OR SELL ALL THE SAME TO ME.

She took him by the arm with surprising strength, and using her elbow as a rudder, hustled him through the gauntlet with her head down, as if they were attending a rowdy political rally and she wanted to keep him from being assassinated. He felt instinctively that if someone had in fact begun sniping, she would have thrown her body across his without hesitation to receive the bullets herself. She was not the type to be left a grieving mother or widow. At length they came out on a wide

TruQUARTERLY

41

plaza, where carts were set up everywhere to sell slabs of cake iced with brilliant pink dots of hard sugar. A man was performing a frenetic dance around a pair of scissors set in the middle of a sheet, his back to it as he sang its praises, hunkering down and leaping outward to shout the scissors' virtues to a group of bystanders, black, Hispanic, Indian, mulatto, mestizo. Many of the bystanders were dressed in purple, one or two wearing cowls. Two or three spectators would move off, and two or three more would take their places. The piles of painted wooden Jesuses arrayed on blankets had crowns of thorns so sharp they looked like coils of barbed wire wrapped tightly about the bleeding heads.