Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individual donors.

TriQuarterly also thanks the following recent donors and life subscribers:

Simon J. Blattner, Jr.

Louise Blosten

Paul Brownfield

Robert Creamer

Eleanore Devine

W. S. Di Piero

John B. Elliott

Mr. and Mrs. H. Bernard Firestone

Mr. and Mrs. C. Dwight Foster

Martha Friedberg

Amy Godine

Jay Harkey

Mr. and Mrs. David C. Hilliard

Irwin T. Holtzman

Helen Jacob

Loy E. Knapp

Greg Kuzma

Patrick Mangan

Charles T. Martin

Florence D. McMillan

Mr. and Mrs. Andrew McNally

Dorothy J. Mikuska

Michal Miller

William T. Morgan, Jr.

Alicia Ostriker

Linda Pastan

Fran Podulka

Mark Rudman

Gilaine Shindelman

Allen R. Smart

Gary Soto

Susan A. Stewart

Lawrence Stewart

Dorothy H. Taylor

Scott Turow

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

Please

Please

Please

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY! (before our rates go up in September 1995)

o a life subscription for $500.

sign me up for:

o a two-year subscription for $36.

year.

o a one-year subscription for $20. Foreign subscribers please add $5per

begin my subscription with issue# o $ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal. Name Address Or call us toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! BI93 SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY! (before our rates go up in September 1995)

sign me up for:

a two-year subscription for $36.

a one-year subscription for $20.

subscribers please add $5per year.

begin my subscription with issue # o a life subscription for $500. o $, enclosed. 0 This is a renewal. Name Address Or call us toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! GIVE TRIQUARTERLY! o $ enclosed. Buy your first gift for $20 (before our rates increase in September 1995), and each additional gift costs only $1711 1st gift subscription ($20) Name Address Gift-card message Add $5/year forforeign subscriptions. BI93 Name Address 2nd gift subscription ($17) Name Address Gift-card message BG93

o

0

Foreign

Please

Tri�MM<e[f�

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVENUE

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60208-4302

Tri�MalIJ'(t<e[f�

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVENUE

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60208-4302

Tri�<e�

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVENUE

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60208-4302

THEODORE WEISS

Selected Poems

This definitive selection of poems by one of America's most distinguished and original poets recovers work that is immensely contemporary and at the same time reaches back to the roots of an accomplished generation of poets that includes Lowell, Jarrell, Berryman and Bishop. Weiss's distinctive, idiosyncratic poems, noted for their syntactic compression and linking of intimate experience and historical incident, are a majoraccomplishment. [Weiss's poetry} is among the most valuable workproduced in our time. -James

Merrill

260 pages $49.95, cloth (0-8101-5037-9) $15.95, paper (0-8101-5040-9)

�. ••

SPRING 1995 BOOKS AND BACKLIST

CYRUS COLTER

A Chocolate Soldier

Colter's fourth novel is a cautionary tale of revolutionary dreams, bitter realities, and the persistence of both hope and falsehood. A kind of historical fable about the possibilities and perils of black revolution within and against twentieth-century white America, this novel is brilliantly structured and voiced. It is Colter is greatest and crowning work, and no reader will forget the tale it tells.

This powerful writer should win the attention ofevery serious reader offiction. -SATURDAY REVIEW

278 pages $14.95, paper (0-8101-5038-7)

DIANE GLANCY

Monkey Secret

Three short stories and a powerful novella by the award-winning Cherokee-German-English poet and prose writer explore that essential American territory, the borderbetween: between past and present, between native and immigrant cultures, between self and society.

Hergiftforexpressive language and her courage in exploringpainful subjects like abandonment, illiteracy, and abuse make the reader hungryfor more.

-NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

116 pages $19.95, cloth (0-8101-5016-6)

'I..·� t -: �f;'(' .-;;.oj ,�:()I�·I·I:I� ["" �I

ADRIAN C. LOUIS

Vortex ofIndian Fevers

Wordplay, metaphoric brilliance, technical virtuosity and a scathingly sardonic critique of self and society fill this new collection. Louis celebrates life amid hardship and self-destructiveness, and consecrates a part of the past as a source of ideals for the present. N. Scott Momaday has characterized Louis's work as II acceptance and defiance brought into delicate balance." Fueled by both anger and irony, Louis analyzes, excoriates, jests, prays and mourns. The result is psychologically and culturallycomplex.

76 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5017-4)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5042-5)

WILLIAM GOYEN

In a Farther Country

Subtitled 1/ A Romance," In a Farther Country is an intense performance, both lyrical and colloquial, shaped as a series of meditative narratives. Set in a Spanish arts factory in New York City, the novel grows around the conflict of its main character's mixed ancestry. Marietta McGeeChavez and her friends and acquaintances populate a world in which they experience dreams and reality, sexual desire and loneliness, triumph and defeat. This is the first paperback edition of Goyen's small neglected masterpiece.

182 pages

$13.95, paper (0-8101-5039-5)

WHlUlm I�VtH

TRUDY LEWIS

Private Correspondences

CYRUS COLTER

The Hippodrome

Winner of the 1994 William Goyen Prize for Fiction

This moral thunderclap of a novel portrays a teenage girl who, attacked by violent evil, chooses not to flee it but to face it, and then to embrace it. In prose that swings between lyrical moments of illumination and gritty sexual insight, Lewis explores the dark heart of a misogynist culture.

Lewis's shatteringstudyofsexual violence and individual vulnerability is both timely and universally resonant.

- PUBUSHERS WEEKLY

196 pages $19.95, doth (0-8101-5033-6)

Set in a Chicago seething with physical and psychological violence, The Hippodrome is an examination of power and exploitation and their entanglement with sexuality.

In the tradition ofhisfictional ancestors, Dostoevsky and Faulkner, [Colter] has produced a work which uses the world ofeveryday reality in a manner beyond the scope of journalism or sociology -as an entree to the soul.

-James Park Sloan CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

214 pages $13.95, paper (0-8101-5036-0)

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years / Cronica de mis afios peores

TRANSLATED AND WTIH AN AFTERWORD BY JAMES HCX:;CARD

In this bilingual edition, an established Chicano poet describes with passion and elegance some of the American realities that remain absent from mainstream poetry. Villanueva voices complex and compelling historical, literary and cultural questions as urgent personal utterances.

Tmo Villanueva won the 1994 American Book Award forhis recent book, Scenefrom theMovie GIANT.

96 pages

$34.95, cloth (0-8101-5009-3)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5034-4)

MARCJ. STRAUS

One Word

This first collection of poems by a physician combines poetic craft, medical expertise and a keen sense of human vulnerability to pain and suffering in an uncommon portrayal of the complex and often troubled relations between physician and patient. With directness and power, Straus confronts matters rarely encountered in poetry. These poems are a fine addition to the scant body ofimaginative work that speaks with authority from within the medical world.

80 pages

$29.95, doth (0-8101-5010-7)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5035-2)

Tino Villanueva

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

Completed while he was dying, William Goyen's Arcadio is one of the most affecting and imaginative farewells to life ever written.

Arcadio, whose voice is inimitably Goyenesque, is a creature from beyond the normal walks of life.

Half man, half woman, raised in a whorehouse and for years the veteran exhibitionist of an itinerant circus sideshow, he has escaped from the show and has been wandering in a quest for his lost family. Speaking intimately and secretly to the reader, he tells the bizarre and fantastic tale of his life.

148 pages $12.95, paper (0-8101-5006-9)

WILLIAM GOYEN

Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical

Narrative

Chris, whose leg is injured, and his lover Stella, with whom he lives in a ruined, abandoned house; Chris's male nurse; Marvello, the circus aerialist; a lighthouse keeper; a flagpole-sitter in small-town America-these are the creatures of William Goyen's visionary fable of love, lust and loneliness. Because of its central focus on the erotic and its unusual novelistic form, Half a Look ofCain was rejected in the 1950s by Goyen's publisher. The first publication of this novel inaugurates a TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press plan to publish and reprint all of Goyen's out-ofprint work.

[Arcadio] virtuallypulses with life; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldly contemporary as well.

-Joyce Carol Oates

Goyen's paramount concern is with the ways in which people connect, commune and create, with the ways they hurt and heal one another and with the capacity of everyone to do good or evil [Half a Look of Cain] is the work of a gifted, intelligent artist.

- NEW YORK TIMFS BOOK REVIEW

220 pages $22.50, cloth (0-8101-S031-X)

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

This large anthology is a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today.

Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution.

-HARVARD REVIEW

a feastofreadingenjoyment.

Gibbons's collection gives us people worth caring about and writing not afraid to be at once serious andjoyful.

-SMALL PRESS

448 pages

$15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

ANNE CALCAGNO

Prayfor Yourself

Anne Calcagno vividly captures the textures of women's lives in this exhilarating collection of short stories. Her characters grapple with problems ranging from domestic violence to obsessiveness with bodyweight; the dramatic situations are extreme, edgy and utterly convincing.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye of a true storyteller.

-Larry Heinemann

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as a fifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a singlepiece ofwood.

-Lynda Barry

136 pages

$26.95, cloth (O-8101-5000-X)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5003-4)

o � o

CAROL FROST

Pure

For all poetry collections.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

PETER READING

A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and on the natural world that surrounds and shapes human life. Frost's poems bear the stamp of a thoroughly original artistic vision and style-they are discursive yet filled with concrete images; they inquire into moral issues (responsibility, pleasure, guilt, jealousy) without moralizing; they catch the echoes of western myths in domestic and quotidian events; they sharply diagnose relations between the sexes.

64 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5029-8)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5004-2)

UkuleleMusic Perduta Gente

This double volume of poems is the first U.S. publication of an important English poet. "There is nothing safe about Peter Reading's work," one reviewer has written, and a storm of letters to the London Times and the Times Literary Supplement, attacking and defending Reading's work, has made him the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity, bitter humor and disconcerting honesty.

112 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5030-1)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5005-0)

�""�h,� _,,,,.,m,,,,,,,,,,,,,,",,,,, �.,"'� �fo."1»IOd """''''''''''''''''"''..,.".."...,1mI>-

The Urgency ofIdentity: Contemporary English-Language Poetryfrom Wales

EDITED BY DAVID LLOYD

This anthology of poems and interviews presents for the first time in this country the importantEnglish-language Welsh poetry of the 1980s and 1990s, illuminating the complexity, constant flux and politicalimplications of the poet's sense of inherited culture. Superb poems have been rigorously selected to showcase the Welsh poets' skill and seriousness, and the sensuous density oftheir language, which, like that of contemporary Irish poets, offers the reader memorable expressive riches and a striking depiction of landscape and society. Included in the anthology are John Davies, Gillian Clarke and R S. Thomas, among others.

244 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5032-8)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5007-7)

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise ofthe Impure:Poetry and the Ethical Imagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today. These essays speak forcefully to the literary debates concerning the use of tradition, the openness of American poetry to diverse subjects, and the teaching of creative writing. This book should be read by any poet who teaches in the United States and by anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. It will become a benchmark for discussion of contemporary American poetry.

200 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5025-5)

$12.95, paper (O-8101-5028-X)

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe

Spinners

Wmner of the Carl SandburgAward and the 1993 Chicago Sun-Tunes Book of the Year Award in Poeby

Angela Jackson brings remarkable gifts to the articulation of African-American experience. Her poetry features an impressive variety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience.

Angela Jackson has known,for long, what is rightfor her attention and scrupulous investigation.

-Gwendolyn Brooks

120 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5026-3)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5001-8)

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

Wmner of the 1993 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Adversaria celebrates the rough beauty of ordinary life and laments its inevitable decline. These poems, titled in Latin, combine colloquial style with a late imperial tone to capture the stark contrasts and contradictions of a life lived between a steel mill and the quiet, graceful natural world.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence ofa lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American.

104 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5027-1)

-Li-Young Lee

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5002-6)

w r. Of l><t "'1 TI�.I"Ct DI' �.(' .�,J_( 'all .O(T'� InOliJYR II mil

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -Alicia Ostriker

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves rightalongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one ofthe best poets now writing in America. -Denise Levertov

80 pages

$17, cloth (0-916384-08-X)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5013-1)

(PAPERBACK REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out of Silence: Selected Poems

EDITED BY KATE DANIELS

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state ofpublishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser's poetry was out ofprint. So this is notjust another book: it is a restitution. -Eleanor Wilner

Thepublication ofOut of Silence is an event worthy ofcelebration. Finally one ofthis century's most distinguished, misunderstoodand undervaluedpoets is back in print The timefor a justestimate of Rukeyser's contributions is longoverdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start.

-TIlE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5015-8)

(PAPERBACK REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

LINDA McCARRISTON

Eva-Mary

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Eva-Mary

1991 National Book Award Finalist

Wmnerof the 1991 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

NOW IN A FOURTH PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance.

An immensely movingbook, fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories of trauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace. -Lisel Mueller

80 pages

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5008-5)

(REISSUED WITH A NEW ISBN)

-.� "';'"

Linda McCarriston

Fiction ofthe Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

This landmark anthologyhonoring TriQuarterly's 25th anniversary includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared in the magazine over the past decade. The stories range widely over the experience of modem life, and share a high level of artistry. An incomparable primer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

Forcontemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

Writersfrom South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterly magazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialogues by fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to Ll.S. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

Writers from South Africa

CULTURE, POUTICS AND UTEItARY THEORY AND ACTIVITY IN SOUTH AFRICA TODAY

128 pages

$6.50, paper (0-916384-O3-9)

Stephen Deutch, Photographer:

From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989

A stunning gift book-with photos of Chicago over decades of change, including Deutch's Pulitzer-nominated photos from the Daily News. This collection and analysis of Deutch's work, with plates both in duotone and in color, is the first full record of Deutch's achievement to be published.

144 pages $23.50, paper (0-929968-06-9) Send this order form W: !'1Iorth\\t'slt'rn l niwrsil� PrI'SS Chical!o ()Ist ributlon Center 110:10 South IAlngil'} \\l'nut' Chicago, 11.60628

Zip

Cloth/Paper Quantity Unit Price Total o

money order enclosed CJ MastercardlVisa number: Expiration Date Signature: Subtotal Shipping and handling* TOTAL *Domestic-$3.50 first book. $.75 each additional book Foreign-$4.50 first book. $1.00 each additional book NW-123

Name Address City State

Author/Title

Check or

Spring/Summer 1995

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor

Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor

Fred Shafer

TriQuarterly Fellow

Christopher Carr

Co-Editor

Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director

Gini Kondziolka Reader

Deanna Kreisel

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Kemba Johnson, Lorin Cohen, Keith Newton

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, John Peck, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $20; two years $36; life $500. Institutions: one year $30; two years $48; life $500. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions of fietion, poetry and literary essays, which must be postmarked between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts postmarked between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1995 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ) Bookpeople (Berkeley, CAl; Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CAl; Fine Print (Austin, TX)

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.), the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.), EBSCO Publishing (Peabody, MA) and Information Access Co. (Foster City, CAl.

After seven years of administering open competitions for the William Goyen Prize for Fiction and the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry, TriQuarterly will discontinue the competitions for these prizes. Both administrative limitations and financial constraints in a time of dwindling funding for the literary arts have contributed to this decision. In the future, Des Pres and Goyen Prize winners will be selected from among manuscripts accepted for publication under the TriQuarterly Books imprint of Northwestern University Press. There will be no application process. TriQuarterly Books welcomes queries with sample chap, ters of prose or up to ten pages of poetry, but we cannot consider unsolicited book manuscripts.

Due to rising paper and postage prices, TriQuarterly must raise subscription rates starting with our Fall 1995 issue (TQ #94). The new prices for individual subscriptions will be $24 for one year and $40 for two years. Subscribe or renew your subscription before September 15 to take advantage of our current low rates ($20 for one year; $36 for two years)!

Are you a life subscriber to TriQuarterly? Please make sure we have your current address so we can continue sending you issues, as well as print, ing your name on the last page or an inside cover of the magazine.

Two poems from TriQuarterly have been selected for inclusion in the anthology The Best American Poetry 1995. edited by David Lehman"Unearthly Voices" by Edward Hirsch, from TQ #89, and "Manu' facturing" by Alan Shapiro, from TQ #90.

From time to time TriQuarterly makes its subscription list available to responsible publishers. If you subscribe and would like to restrict the commercial use of your name and address, please let us know.

Contents Editors of this issue: Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn FICTION Penguins for Lunch ........••.•...•.......•••.................•• 21 Scott Bradfield Almonds 45 Richard Stern The Life and Work of Alphonse Kauders ..•.•.•...... 65 A. Hernon Baby Girl 77 Fred G. Leebron The Woman from Russia ..............................•.... 111 David Plante The Cat and the Clown 134 Maura Stanton Wild Indians & Other Creatures 1 75 Adrian C. Louis Forever 191 Jean Thompson The Clouds in Memphis 206 C. J. Hribal 17

Ingrid de Kok

In Extremis; Hotel Orvieto; The Amazing Vanishing Grace

Myrna Stone

The Flat Road Runs Along Beside the Frozen River; Aesthetics of the Bases-Loaded Walk; "Flowers are a tiresome pastime"

Joe Wenderoth

Century Flower; The Black Raincoat; The Nature of the Beast; Ray

Brooks Haxton

conversation with the stone; long afterwards; light; to the beloved dead; rather free. after Brecht

Yaak Karsunke

Translated from the German by Andre Lefevere and Marc Falkenberg

POETRY

••••........ 91

Transfer; Keeper; The Resurrection Bush

95

....................•••.. 99

•..•....•.•.•••.••••.••••••. 103

Days;

119

For Billie; Male Trio 124 David Galler Marie at Tea; Brooklyn Twilight 126

Ostriker The Scar; Transgressor ••••••..•••••••••••.•...•........•••. 130 Sharon Kraus

Distance;

Evanescent Things; The Logic of Opposites 145 Alane Rollings 18

Alicia

In Touching

The Substance of

Poems of Horace: 111.26 To Venus; 1.34 Of the God's Power 151

Translated by David Ferry

Breasts; Government Protection; An Officer's Story; Duration; Before; The Herd; The Tooth; Visitor (April 1978); The Bear; Placefulness; Repossession; Scenarios; Grasshopper Sperm; Sorrow Village; Texas Gulliver Malaria; The Grave; Mushroom River; Blood & Sage; Flame; The Steadying 153 William Heyen

ESSAY

Yellow Peril 238

Jianying Zha

CONTRIBUTORS 265

Cover painting, Tethered Bird, by Lorna Marsh

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

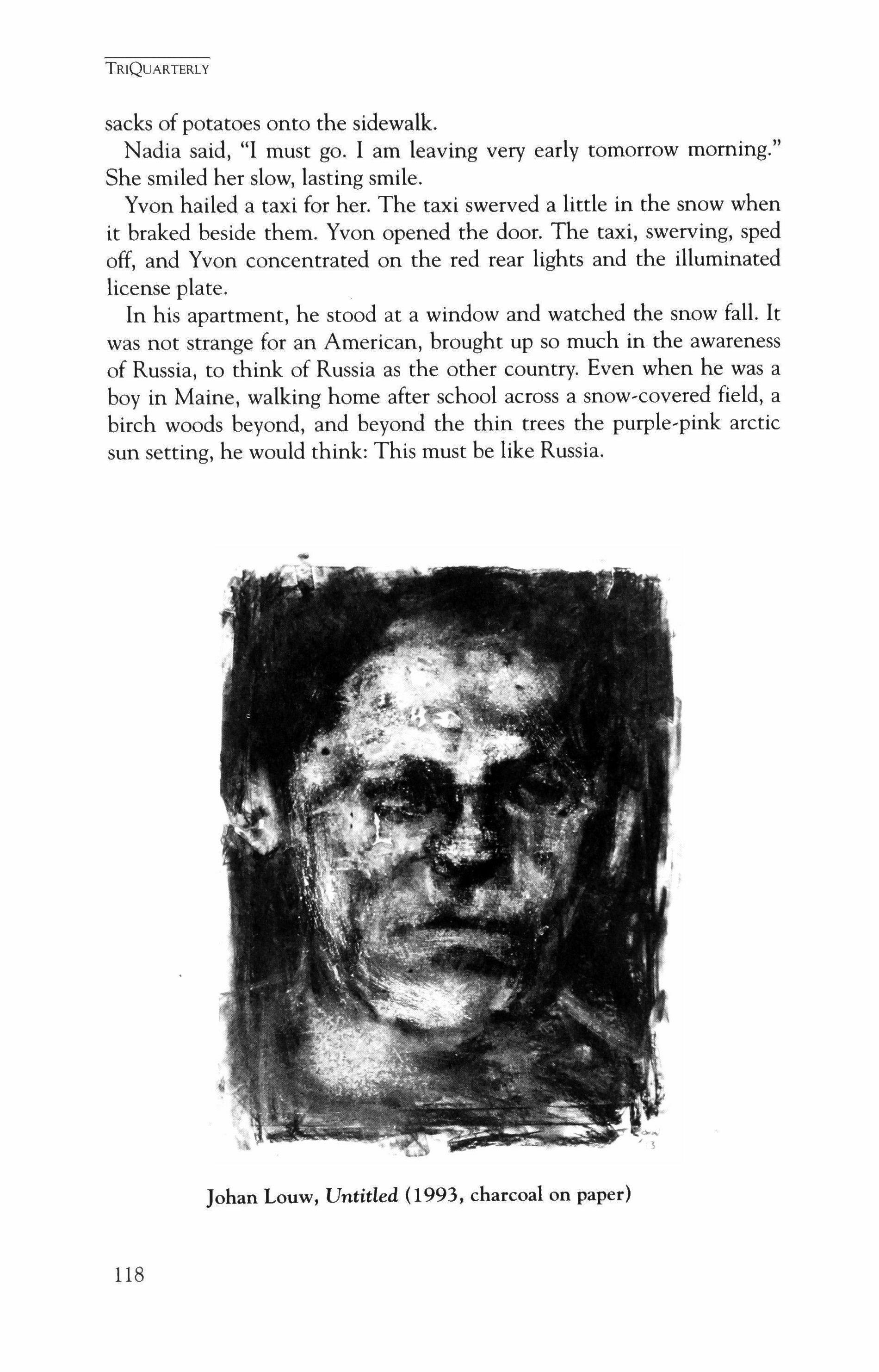

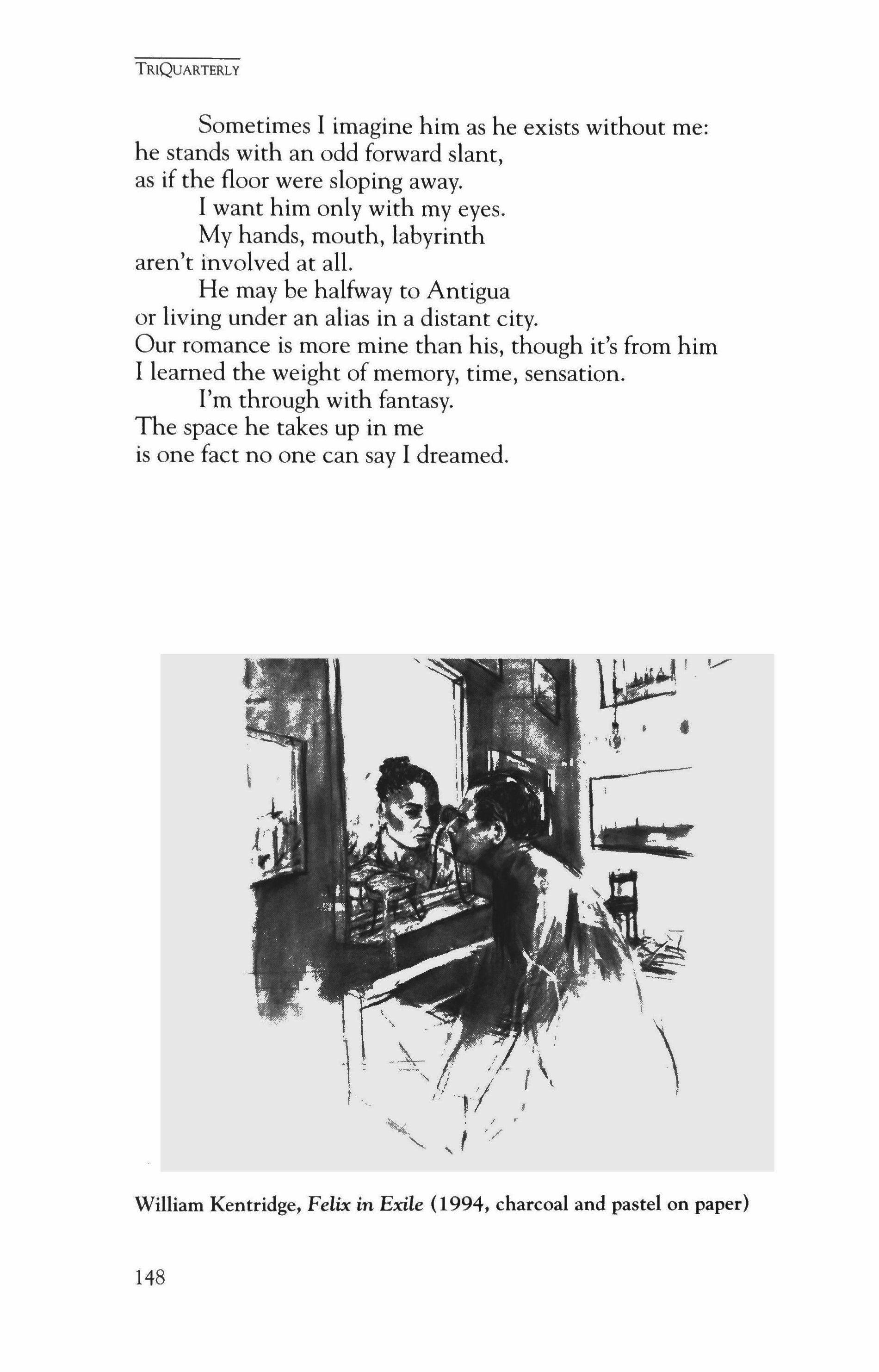

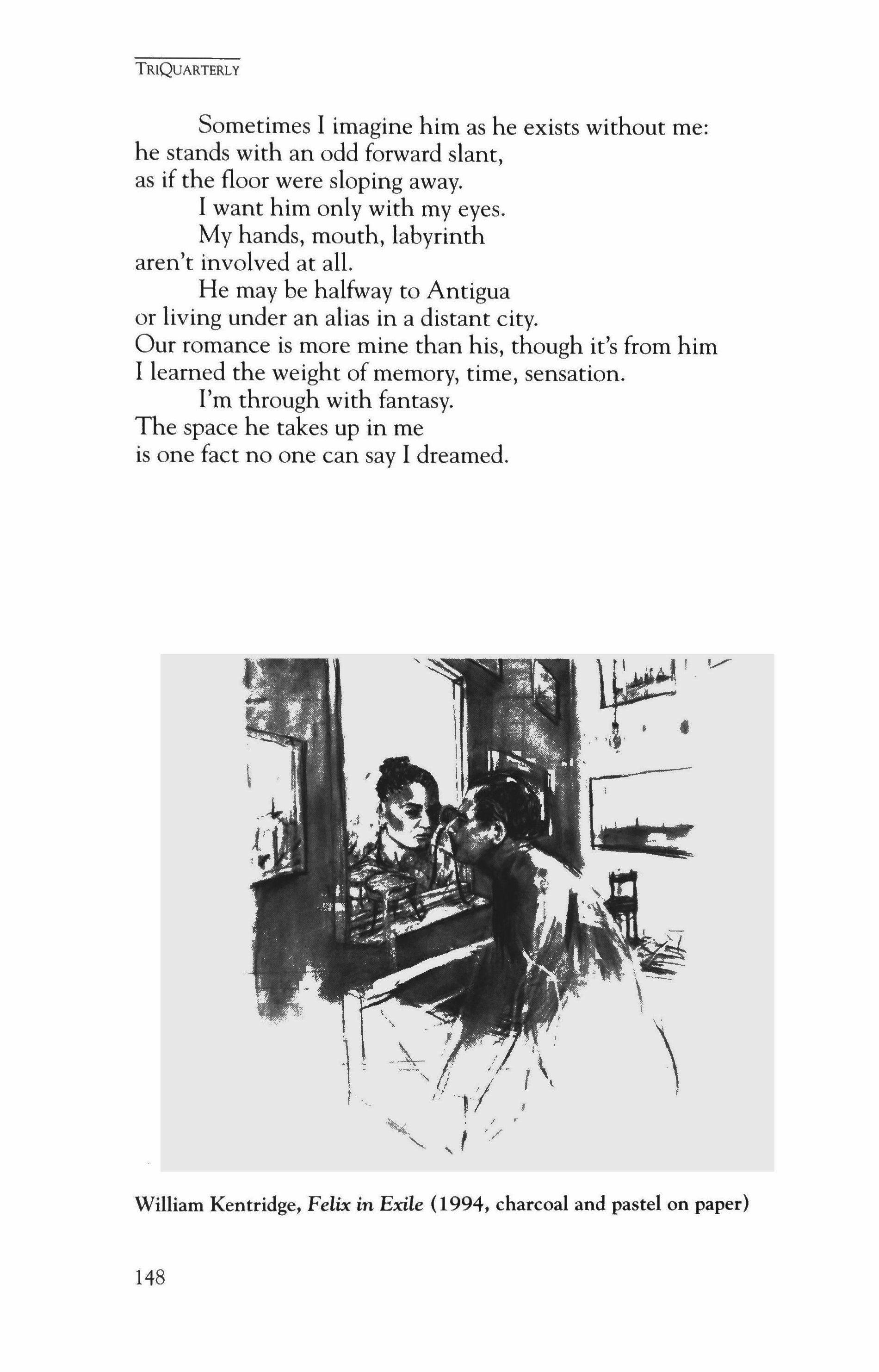

The artwork appearing throughout this issue is from the exhibition Displacements: South African Works on Paper, 1984� 1994, which was recently on view at the Mary and Leigh Block Gallery at Northwestern University. A list of acknowledgments concerning these works can be found on page 268.

19

Every year since 1981, the National Endowment for the Arts has awarded TriQuarterly grants in support of the magazine's ongoing mission. For most of these years, we have requested and received grants mostly for support of contributors' honoraria. The U.S. Congress has been debaring, in one way or another, the fate of the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Institute of Museum Services, for several years now, and the prospects of these federa1 agencies, which exist only to contribute to the national culture in a modest way, are troubled. Yet these agencies have done great good in making all sorts of cultural events and accomplishments possible, sustainable and available to audiences, and there are lots of good reasons why our national government should support them. We therefore urge you, our readers, to communicate to Congress your support of this good work. Perhaps it is even more important to communicate to local and state governments-and to local corporations and private funders as well-your belief in the value of contemporary literature and your hope that they will support it in every way they can. Contemporary literature, although representing the most widespread engagement of the American people with any art form, receives an astonishingly small amount of financial support. Every voice raised on behalf of the value of poetry and fiction, as well as every dollar donated to this cause, really does make a difference.

Penguins for Lunch

Scott Bradfield

Though dabbling in all three elements, and indeed possessing some rudimentary claims to all, the penguin is at home in none. On land it stumps; afloat it sculls; in the air it flops. As ifashamed of her failure, Nature keeps this ungainly child hidden away at the ends of the earth.

-Melville, "The Encantadas"

1. The Ice Floe Bar and Grill

"I'm a high-rolling entrepreneur on the free-market of love," Whistling Pete told his closest friend, Buster Davenport, one sunny afternoon at the Ice Floe Bar and Grill. "You don't blame Mercedes for selling cars, do you? You don't blame McDonald's for frying burgers, or the [aps for peddling cheap cars. Well, what I've got just happens to be what the little girlies want. And when the little girlies want it, well. I don't mean to sound rude, Buster-but I happen to be just the guy that's gonna give it to them."

The Ice Floe Bar and Grill was one of a series of new up-market franchise restaurants that had recently opened all across the tundra. As part of their inaugural promotion campaign, the Ice Floe was offering dollar Margaritas during Happy Hour, along with all the free mackerel you could lay your flippers on.

Whistling Pete slid a creamy oyster into his throat and sighed. He patted his firm white belly, as if testing for tone.

TRIQUARTERLY

21

"This is the life, Buster," he said philosophically, leaning back in his green vinyl lawn chair and folding his sleek muscular flippers behind his head. He and Buster were sitting on a veranda overlooking the outdoor pool. "Sunny days, starry nights, envelopes of rich fatty tissue to keep our butts warm, and loving spouses to go home to. What more could we ask? What more, that is, than maybe a hasty little frolic in the frost with one of yonder ice-maidens?"

Nodding towards the various lithe Penguinettes sporting themselves seductively around the pool, Whistling Pete clock-clocked his black tongue. His entire body shivered with a slow delicious enthusiasm for itself.

"Yeah, well, I just hope you know what you're doing," Buster said. Buster's gaze was roving back and forth across the restaurant and patio. He kept glancing sheepishly over his shoulders, as if he expected their indignant wives to appear at any moment brandishing blunt objects.

When the waitress came up behind him and said, "How you boys doing?" Buster nearly jumped out of his socks.

"Whoa, there, Buster-relax, old buddy. It's not the gendarmes, you know." Whistling Pete cautioned his friend with an upraised flipper and presented the waitress his best award-winning smile. "And how are you doing this afternoon, sweetie?"

"If you boys don't need anything," she said, "I'll go check on my other tables."

Buster, slightly out of breath, was still smoothing his ruffled tail feathers. "I guess I'll have another Margarita," he said, looking forlornly at his empty white side dish. "And if Happy Hour's still on, could you maybe find us a little more mackerel?"

Whistling Pete unashamedly examined the waitress's fatty deposits.

"Me," Whistling Pete said, "I'll have what some of what she's having."

He indicated the large commercial advertisement posted behind the bar. The ad featured a lithe, lovely Penguinette scantily clad in a white silk top hat and baggy white fishnet stockings. She was leaning against a sporty red snowmobile and stroking a large icy bottle of Smirnoff's.

The bold black caption exclaimed: IT'S PENGUINIFIC!

While Buster resumed his edgy lookout for wives, Whistling Pete appreciatively watched their waitress waddle back to the bar with their order.

"Vah-vah-vah-voorn!" he said, and saluted her departing buttocks with the dissolving ice in his glass. Then he tossed down the slush with the last of his oyster sliders. His toes evinced a self-satisfied little wriggle.

TRIQUARTERLY

22

"Life's definitely the coolest," Whistling Pete pronounced. "The sun rises, the sun sets. And so do I, Buster, old pal. So do 1."

Whistling Pete slammed his glass down on the table with a familiar emphasis.

"Yeah, well." Buster's eyes flicked from Entrance to Exit, from restroom to window to door. He picked up the extinguished mackerel plate and sadly licked it.

"I just hope you know what you're doing," he said.

Whistling Pete arranged for a clandestine rendezvous with one of his ladies nearly every day at noon, just when the twilight sky was beginning to generate something like phosphorescence. They met unashamedly at the Ice Floe for drinks and quick, light lunches while Pete proffered flowers, compliments, stockings and chocolates. Then, as fast as their little legs could carry them, they dashed next door to the Crystal Palace Motel where Whistling Pete kept an open account. They ordered caviar and champagne through room service, sported themselves silly across the taut-fitted coverlets, and made the most they could of an hour-sometimes an hour and a half.

"This is the life," Whistling Pete muttered every so often. "This is what the All-Mighty Penguin had in mind when he designed such cute little Penguinettes."

Infidelity took all the knots out of a morning. The bad breakfast with the screaming baby, the frantic rush of late orders at the warehouse where Pete worked, and the sense of blue dissolute formlessness Pete experienced whenever he gazed out his office window at the utterly black sky littered with cold white stars.

"It's the worst weather in the entire universe," Pete regularly complained to his early morning mug of Earl Grey. "Icicles, icebergs, icemountains and ice-rocks. I'm not ashamed to say it. Antarctica really sucks, even for penguins."

Then, looking up, he found himself exchanging a quick, illicit glance with Berenice, an Accounts secretary across the hall. A warm amorous pulse filled Whistling Pete's sinuses and face.

After a moment, Berenice smiled and waved. Then, after another moment, Whistling Pete smiled and waved back.

One of these days, Pete reminded himself, I really must go over there and chat up our little Berenice.

The Penguinettes he did chat up were invariably young, impressionable, intelligent and very quick to please. Some of them worked in

TRIQUARTERLY

23

Whistling Pete's office at Consolidated Fish, but mostly he met them during Happy Hour at the Ice Floe, or while swimming in the local ponds. They were office girls in a hurry to be young and didn't bother themselves too much about moral imperatives or social graces.

"I just figure we have nice times together," Whistling Pete's favorite girlfriend, Melody Long, frequently explained, usually after her second gin-and-tonic and a quick steamy romp in the Motel Sauna. "So maybe you're married and have a baby-that's cool. I'm not a material girl. I don't need, like, to own a boy just because I like him."

Then, with a bubbly flirt and a giggle, she pinched Pete's belly with one hand, and soothed his inflated pride with the other.

"Not that we can call our little whistler a boy exactly," she reminded him, and began nibbling playfully at a stray chest-feather, "Mr. Pete is more what you'd have to call a dirty old man. Isn't that right, cutey? Isn't that right, you big bad boy, you?"

Lunchtime was what Whistling Pete lived for-brightness, intoxication, energy and truth. Lunchtime was the passion and the glory. Lunchtime was life.

By the time Pete returned to his office he was already subsiding into a post-coital melancholy which wasn't altogether unpleasant. He felt his mind descend into the sluggish depths of his own body, drifting through continents of ice, landmass, gravity and weight like a sort of bathysphere. Down here the green, gnarly water was populated by pulsing black shellfish, gigantic cyclopean squid, translucent spiny seaweeds, and dark brooding prehistoric entities squeezed into barnacled caverns and shipwrecked galleons.

"Hey there, bro," Buster said, leaning into the office around four P.M. The day's tentative flare of sunlight was already extinguishing. Weird bright glows and refractions cast themselves across the planes of dazzling white ice like spinning crystal discs. "We hitting Happy Hour today or what?"

Buster was already glancing anxiously over both his shoulders. He was not the sort of penguin who rushed headlong into life's vast hiss and adventure. Instead, he anxiously avoided every bit of life that came rushing after him.

Whistling Pete took his feet off the desk and sat up abruptly in his spring-cocked office chair. He saw the binders and ledgers, the interoffice memos and gray, slimy faxes. This desk, this office. These hours measured by dollars, these dimensions demarcated by ice.

TRIQUARTERLY

24

(And somewhere else entirely: Melody, Martha, Trudy, Dallas, Pippa, Dolores and Joyce.)

Or perhaps, Pete realized, Buster simply pretended not to know.

"Buster, old pal," Pete said finally, and clapped his flippers together with brisk authority, "has the sun stopped shining or the earth ceased to spin? Of course we're hitting Happy Hour. And if I recall correctly, I believe it's your tum to pick up the tab."

2. Making Marriage Work

"It's just a phase Pete's going through," Estelle said, and succinctly regurgitated chunky blue broth into a white ceramic bowl. "Ever since he turned forty, he can't seem to sit still anymore. He stares at himself in the bathroom mirror all morning, combing his feathers and picking his teeth. Every day on his way home from work he forgets to pick things up at the store-milk, bread, mineral water, you name it. He's wandering around in a dream world, Sandy, I swear. I know I should probably be hurt or angry, but I can't help feeling sorry for him. I think he's going through some pretty heavy emotional changes right now."

Estelle dabbed her beak with a pastel cloth napkin. Then she passed the bowl of broth to their six-month old fledgling, who was presently conducting a happy inner symphony with an upraised wooden ladle.

"Fish," Junior exclaimed. "Fish-jishy-fish."

Estelle sighed. Then, almost imperceptibly, belched.

"Excuse me," Estelle said.

Buster's wife, Sandy, lit another menthol cigarette and shook out her paper match with bristly impatience.

"For chrissakes, Estelle. Read the writing on the wall, will you? Your lousy husband's out fertilizing every yolk in town. What are you-blind or something?"

Estelle gazed out the sparkling window and sighed, leaning her beak on one cocked flipper. Sometimes she just wanted to sit in her clean kitchen, watch the thin sunlight and feel the deep, immanent warmth of her own body. She was so bulked-up with raw meat after months of gravid-gorging that she could hardly waddle to the sink and back without falling out of breath. And now Sandy, lean and mean, telling her what to do with her life, as if she were some sort of expert.

"You don't understand, Sandy," Estelle said. "If you want to make a marriage work, then some things just aren't that simple."

TRIQUARTERLY

25

"Things are that simple, Estelle, and let me tell you how simple they are. Pete's screwing every cow on the island. He's dipping his wick in every candle on the beach. You can either tell him to shape up or move out. Or you can hack him to death with the stainless steel. I'll tell you one thing," Sandy said, punctuating her resolve by flicking a long, intact gray ash onto the checkered tablecloth, "if Buster ever pulled a fast one on me, boy, I'd bite out a long message in his fat butt, that's what I'd do."

Estelle wanted to explain, but she couldn't seem to work up any words from the mulchy depths of her overloaded body. It was strange how flesh could reshape itself around you, as if it possessed mind and intention all its own. Estelle looked at the flaring brightness outside. Then she looked at her six-month-old fledgling, Pete Junior.

Without a second thought, Estelle thumped the side of Junior's high chair.

"Don't play with your food, Mister," she said.

Caught in mid-gargle with a bolus of macerated mussel, Junior swallowed abruptly. He looked at his Mum with wide eyes and slowly put down his wooden ladle.

"Fish," he said evenly, indicating his chunky broth. "Mum's fish."

Estelle felt the sadness in her body start to rotate.

"Yes, baby," Estelle said. "Mum's fish."

Then, lowering her head to her folded and glistening black flippers, Estelle began to cry. Softly at first, but with a slowly rising intensity, like the sound of distant winter thunderclaps.

Sandy bit off another tiny puff from her menthol cigarette. She looked at Junior and Junior looked at her.

"There there, honey," Sandy said softly. "It'll be all right, honey. There there, there there."

Then, extinguishing her cigarette in the glass ashtray, Sandy leaned over and took Estelle gently in her arms.

Some days Whistling Pete didn't have any patience for family life. Grocery bills, diaper services, overpriced podiatrists, peeling linoleum and faulty pipes. "Domesticity is for the birds," Pete pronounced solidly, walking home with Buster through the starry night. Atmospheric strobes and opacities wheeled across the high black sky like chapters out of Revelation. "I'm talking the feathery, flighty kind of birds, you know? The ones with their heads in the clouds? Sure, it sounds nice and allbig tract houses, gas central heating, indoor plumbing and all that.

TRIQUARTERLY

26

Trade, commerce, low,tech industry, certified schools for the kids, com' munity rep, all the bread in one basket, that sort of domesticity, you know. But basically, man, it's an idea cooked up by the little girlies. Wives, man; females seeking security for their babes. Girlies are home' builders, but us guys, we're like homebreakers. It's not our fault, Buster, it's just our nature. Girlies like home and hearth, three square meals, new wallpaper for the nursery, church weddings and matching cutlery. Us guys, however, we're hunters and gatherers. We don't want cornflakes for breakfast-we want the hot blood of the kill in our mouths. We want to venture beyond what we already know, and stop remembering the boring old places we've already been. Nature's cruel, Buster, just like us. Nature's cruel, and so are us guys."

The long white road descended into the village, leading Pete towards the smell of yeasty bread baking. He saw yellow light glowing in the windowpanes of his house, and the idea that he was anticipated made him edgy and ungallant. Two strange minds waiting in a house where he didn't belong. They knew he was coming. They knew he was already late.

He put his arm around Buster with a comradely squeeze and gestured downhill. "There it is, buddy. Our little village in the snow, the home our forefathers and foremothers planted in the wilderness. Back in the old days our ancestors waddled around on rocks, man. They starved, hunted, mated and died without proper funerals or mortgage insurance. The only education they got came from the School of Hard Knocks. And who do you think first initiated the idea of houses, man? Why, the ladies, of course. 'Let's stack a few ice blocks over there as a sort of lean, to,' they told their weary, flatulent old husbands. 'How about four walls, honey? A roof and a floor?' Us guys would have lain out there scratching our lice on that stupid rock forever if we'd had the choice, but the choice wasn't ours, no way."

Buster, well-oiled with budget tequila, was waddling along beside Pete with uncustomary resolution. Instead of glancing over his twitchy shoulders he gazed dreamily into the endlessly illuminated sky. Showers of meteors, swirls of galaxies, planets entrained by moons and whorling dust. Buster loved the night when it got like this: vast, unencompassable and rinsed with sensation. It was a time when everything, even the universe, seemed at once awesomely complicated and weirdly specific. "Actually," Buster muttered out loud, "I always kind of dug domesticity. Beds with sheets, down comforters, canned lager and imported salsa. I like knowing I'll get paid every Friday, week after week, as regular as

TRIQUARTERLY

27

clockwork. Some days, Sundays especially, I lie in my warm bed and let my mind wander. I don't go anywhere. I just let my imagination loose and I wander."

Pete whistled softly to himself. He wasn't listening to a word Buster said, but then he hadn't been listening to anybody for months now. He was thinking: Melody, Marianne, Gwendolyn and Jane. Tomorrow at noon and next Wednesday at twelve forty-five. While Pete's body waddled down the steep slope towards the hard, unendurable village, his mind journeyed into different realms altogether. Places with thrill and expectation. Places of slow tongue and undress. Times like this, Pete believed he would never die. Even when the hard village stopped enduring, Whistling Pete wouldn't.

"Men may build the cities," Pete said softly, just before they arrived at his white doorway, his paved driveway, his leaning mailbox, "but. believe you me. It's the little girlies who make us live in them."

Despite his protestations to the contrary, Pete arrived home each night aching with apology and self-reproach.

"I know I should have called," he told her. "I know it's late, and I forgot to buy milk again. And yes I did drink too much, and spent too much money, and Little Petey's gone to bed again without kissing Daddy good night. I'm sorry, Estelle, I really am. I'm sorry but I can't seem to explain. Some nights I just have to get away with my buddies, have a few drinks and unwind. No, and I can't say it won't happen again. I wish I could, Estelle, but I can't."

Later, in bed, Estelle pretended to sleep. Pete could feel the slow breath of the hard house around them, the ticking radiators and ruminating clocks. Next door in the nursery, Little Petey, true to his genotype, faintly whistled while he snored.

"I'll try to be better," Whistling Pete told his wife, pretending he believed her when she pretended not to hear. "But that doesn't mean I'm going to. Maybe I can tell you what you want to hear, Estelle. But that doesn't mean I can be somebody I'm not."

Then, too tired for remorse, he fell asleep with a hypnagogic little kick. And descended into the dreams he pretended not to know.

"Of course I worry about Estelle and Junior," Buster told his wife that night, tossing and turning among the knotted sheets and lumpy pillows. "But Pete's my friend, Sandy, and I'm not just going to lie here and listen while you trash him."

TRIQUARTERLY

28

"Trash him?" Sandy said, in a rising crescendo of disbelief. "I'm trashing him?"

Buster turned onto his other side and gazed out the bare, glistening window. The full moon glared at him like a primitive mandala; Buster could feel the cold, deep resonance in his bones like a hum.

"What about Estelle, huh?-Who's trashing her, Buster? Who's doing the serious emotional trashing in this morbid little scenario of ours? Me, or your close friend, Whistling Pete?"

Buster submitted with something like relief. Sandy was like a geyser or an earth tremor. He could hear her about to happen all day, charging the dark air with rumor and electricity.

"So I guess poor little Estelle is supposed to grin and bear it-is that what you mean? Because if she calls her wonderful husband a liar and a cheat then she's trashing him? And if I start calling him a louse-which is exactly what he !S, Buster-then I'm trashing him too? I guess if it's a man doing the trashing then that makes it O.K., huh? Is that what you're saying, Buster? If men trash women, then that's the proper order of things, right?"

Buster took a long deep breath and sighed.

"That's not what I said, Sandy. That's not what I said and you know it."

Every morning after a fight, breakfast became a ceremony of courtesy and toast. While Sandy brought in bottles of frozen milk from the front porch and thawed them on the stove, Buster took up the sports page and read through yesterday's skating and ice-hockey scores, enjoying the cool comfort of abstractions, a sort of rousing statistical hum. Click, clicks-click-click. Clicka-click-click.

"I'm going shopping," Sandy said flatly, peering at him across her china teacup.

"That's a good idea," Buster said, nervously glancing at the wall clock. In another few minutes he might be able to leave for work without appearing too obvious.

"I'm getting a beak trim and a pedicure at Valerie's. Then I'm meeting Estelle for lunch at the Green Kitchen."

Buster felt the weight of depth charges hidden beneath the surface of Sandy's blithe words. He refused to look up from his paper.

"Have a nice time, honey," he said. "I should be home by dinner."

Later, traipsing back up the long winding road to the Factory, Buster rehearsed his concern until it resembled indignation. He gestured

TRIQUARTERLY

29

severely with his red metallunchpail.

"Enough's enough, buddy," he said. "And believe me-I'm telling you this for your own good. If you want a little fling now and then, that's cool. But these daily rallies of yours are getting to be too much. Show a little discretion, man. What do you think we are-seals or something? Happy flappers lying out on the beach all day, mating indiscriminately, barking like morons? No, Pete, we've built something for ourselves out here. Homes and schools and factories and jobs. So if you want to shoot off your mouth about how rotten civilization is and all, well, that's your prerogative. But if you're going to continue living here, then you've got to start taking responsibility for yourself. I hate to be so hard on you, bro'-believe me, I don't like it anymore than you do. But I'm being hard on you because I care. And if you don't understand that, well, just forget it. Maybe I've been wasting my time with you all along."

Steaming with resolution, Buster chugged into the Factory just as the second whistle blew. Grizzly fishermen were dragging weirs-full of squirming carp and tuna from the harbor while the Factory gates were rolled open by large, muscly-looking penguins in greasy gray overalls.

By the time Buster reached Pete's office he knew he was finally going to do it. He was going to tell Whistling Pete what he thought about him once and for all. The hot energized words carried him up the stairs and down the hall. They carried him through Payroll, Group Insurance and Personnel, past filing cabinets, bulletin boards and water fountains. Buster was finally going to speak his mind, come hell or high water. Or perhaps he was just going to let the unrestrainable anger in his mind speak for itself.

Inside Pete's office, Nadine, the Accounts secretary, was stirring a big pot of tea with a wooden spoon.

"Let me speak to Whistling Pete," Buster told her. "And tell him I mean muy pronto."

Nadine took a moment to understand. She looked at Buster, then at the open door to Pete's office. She was smiling faintly, as if she had been expecting this pathetic little display all morning.

"Sorry, Buster," Nadine said, "but your buddy's not around." Then she placed the teapot on a wooden tray alongside four chipped ceramic mugs, one tarnished teaspoon and a bowl of brown, lumpish sugar. "If there's an emergency, though-and it better be one hell of an emergency-you can always leave a message for him at the Crystal Palace Motel."

TRIQUARTERLY

30

3. Mordida Girls

Spring returned and the squat white sun wouldn't leave, skating round the horizon's meniscus of thinning ice and dripping mountains like a sentry. Time grew increasingly diffuse, gray and immeasurable.

Not that time mattered to Whistling Pete anymore-only the quick lapse into timelessness he regained every afternoon in the arms of his adorable Penguinettes. Often he trysted two or three of them on a single afternoon, bang bang bang, beginning each session with a few shots of Jack Daniels and a plate of imported caviar. Often by the third or fourth session he fell rudely asleep and dreamed of white, sandy beaches and tropical heat. Later he awoke in the dim room, saw the windows hung with thick black curtains like a shroud, and heard the hissing radiators. Sometimes his latest Penguinette was sitting in front of the vanity mirror gazing dreamily into the vertex of her own multiple reflections.

Usually, though, Whistling Pete awoke to an empty room laced with perfume and musk. Hotel personnel knocked summarily at the door.

"Maid service," said a woman with a heavy Dutch accent. "Should we clean up, Mister? Or you want we should come back later?"

By the time Pete waddled into work it was often as late as three or three-thirty, Fellow administrators and their assistants looked up distantly when Pete skirted through the halls. Back in Accounts his assistant, Nadine, was always in a furious temper.

"Mr. Oswald came by from Marketing, and Joe Wozniak asked again about your expense receipts. I've tried covering for you as far as the sales conference, but I can't do anything if I don't see some retail brochures pretty damn soon. Oh, and your wife and little boy popped round asking for you-you were supposed to take your son fishing today. I think you blew it, Pete."

"Oh shit," Whistling Pete said, and slumped into his swivel chair. He checked both his vest pockets for stray cigarettes but located only twisted bits of tobacco and a small white business card. The card said:

Henrietta Philpott

Public Relations Consultant.

He wondered if he and Henrietta had spent any time together. Or if maybe they were about to.

"I knew I'd forgotten something," Whistling Pete said. He knew but he couldn't quite bring himself to care. He had passed

TRIQUARTERLY

31

through a barrier of some sort, and was now journeying fearlessly into some primitive wilderness of the mind penguins weren't supposed to know. Cold black spaces where the sun never got to. Huge white polar bears roaming about, cracking shellfish against rocks. Dark hot shapes swooping overhead while strange animals cried in the distance, hungry for fresh meat. When you journeyed this far south, the old rules didn't apply. The only thing you could do was keep moving forward and never look back.

Pete continued making excuses, but they felt more like formalities than contentions.

"But I'm going to take Junior fishing," Pete declared, with a forced sincerity even he didn't recognize. "I want to help teach him to fish. But I got delayed meeting a distributor on the Stroud Islands. What do you want me to do-neglect my job?"

"I sure wouldn't want that," Estelle said emptily, leaning against the kitchen table. She held a Mackerel-Cracker in front of her face like a cue card. "Obviously, neglecting your job's all you're worried about anymore. So tell that to your year-old son who adores you."

"I'll make it up to you, sport-I really will." Pete paced back and forth in the living room while Junior lay on the floor perusing his geography homework (Fishing Routes of Our Polar World, Twelfth Edition). "We'll go camping, that's it. A weekend on the Outer Orkneys. Just you, me and those mackerel. We'll bring along that new sealskin pup tent we've been meaning to use."

Junior didn't look up. He tapped a pencil against his beak, and turned the page of his textbook. In the last few months since being weaned, Junior's body had grown angular and weirdly composed. It wasn't a body Pete entirely recognized anymore.

"Like, that's cool, Dad. It's no big deal or anything. We'll go fishing some other time. When you're not so busy, that is."

"I've got the expense receipts," Pete told the Executive Staff in the Factory Green Room. "Of course I've got the expense receipts." The Executive Directors had called him in during lunch break. They sat around the long black conference table, munching processed-salmon sandwiches and prawn-flavored crisps.

"It's just that, well, Payroll screwed up the Group Finance Report, and by the time Nadine and I got that mess straightened out with the Commissary it was time for the Monthly Service Catalog, and, well, I

TRIQUARTERLY

32

know it sounds like a bunch of half-assed excuses and all " A bright cold sweat broke out on Pete's forehead; he tried to shake a little ventilation into his facial feathers and felt a faint dizzying rush, as if he were falling through vortices of warm air. ". and of course I'll get the reports to you by Friday, and I don't like to sound like I'm trying to divert blame or anything, right, 'cause of course Nadine's a great girl and all, but she does have something of a temperament. I'm not trying to cast aspersions or anything but I mean, like, she's always blaming everything on the system, right, and the male-dominated patriarchy and all that, and, well, it's sort of hard to get Nadine to cooperate as far as her official responsibilities are concerned. I'm not blaming Nadine for all the screwups, understand. I'm just saying there's only so much I can do, right? I've only got two flippers, you know."

But no matter how hard Whistling Pete expostulated, prevaricated and fibbed, he knew the game was coming to a rapid conclusion. Even though he'd ordered a new company-account checkbook only two weeks ago, he had already used it all up. He'd paid last month's motel, room service, and bar bills, but now this month's bills were beginning to fall due, and Finance wouldn't be forthcoming with another checkbook until May. Pete had purchased a half-dozen pearl necklaces, brooches and earrings, but couldn't even remember which Penguinettes he had distributed them to, or for how much in return. He journeyed through each day in a weird sort of somnambulism, never certain of the time, suffering sinus headaches and blurred vision. He began to avoid his own bloodshot eyes in the bathroom-cabinet mirror.

A line from an old Dylan song kept recurring to him: "To live outside the law you must be honest." What Pete decided was: To live outside the law you must work really, really hard. He awoke every day at seven, gulped black coffee, and hurried to the Factory where he unsuccessfully tried to catch up with the work he'd been neglecting for weeks. Then he fell asleep at his desk, awoke to Nadine's pottering, and skipped off in a faint anxiety rush to the Crystal Palace Motel, where he encountered the silk-clad bodies of Stella, Ariadne, Velma and Chloe. Then he returned home each evening through a slow dull daze of incertitude, to be greeted by unpaid utility bills, humming kitchen appliances and stiff, intricate silences. Estelle in bed with her book. Junior out gallivanting with his friends.

Some nights Pete found the bedroom door bolted shut and he knocked politely like a timid solicitor. "Estelle?"

TRIQUARTERLY

33

"What?"

"Are you in there?"

"Of course I'm in here."

"Can I come in?"

"No you can't."

"I'm really bushed, Estelle. I need to lie down and sleep."

"So sleep on the couch."

"I feel very strange, you know, all run down and everything. I've got stomach pains, my liver's enlarged, there may even be something wrong with my spleen. I've got a rash on my inner thigh that bums like crazy. I'm really beat, Estelle, and I think, well. Maybe we should talk."

"There's nothing to talk about," Estelle said with calm conviction, as if she were slipping a form letter under the door. "I'm afraid the time for talking is over."

Her voice was clipped and regular, like the Factory's canning machine. Whistling Pete leaned against the flimsy plywood door. He could detect her warmth in there, like radium or metal. It felt very far away, divided from him by distances more extensive than space.

"Oh Estelle," Pete sighed, feeling his entire body slump into itself like an expiring party balloon. "Maybe you're right, honey. Maybe you're right."

"If you don't mind my saying so, Pete-you're starting to look pretty thin and unraveled lately."

Melody was sitting on the edge of the mattress and pulling on her baggy white fishnet stockings.

"I'll do what I can," Whistling Pete said dreamily. He imagined himself floating downriver on a wide jagged platform of ice. He was gazing up at the white sky, the thin white sun and moon.

Melody gazed distantly at her herself in the shimmering vanity mirror. "You're starting to lose a little of your, oh, what do you call it? Your getup-and-go. I don't mean to sound impolite or anything, baby, because we've had some great times together. But I just don't look forward to seeing you anymore. I mean, when I know we've got a date coming upoh, how do I say this? Knowing I've got to see you is getting to be a big bummer."

Melody anchored the tops of her stockings to a matching pair of elasticized red-velvet garters. Her body gave off thin, languorous heat and a sense of benign inattention.

"Even General Motors suffers an occasional financial slump,"

TRIQUARTERLY

34

Whistling Pete said, smiling fondly at the clock on the wall. "Even the Japanese experience an occasional recession."

Melody pulled on her short black cocktail skirt with a wriggle. She scowled faintly at herself in the mirror as if she remembered something anterior to her own reflection. Some memory which did not belong to this face, these eyes, this body, this occupied and lonely room.

"I worry about you, Pete. I really do. You used to be fun. You used to be a lot of laughs. What happened to the old Whistling Pete I used to know?"

Drifting in the direction towards which all currents yearned, Pete saw empty planes of ice, tall white mountains, gaping crevasses, rust-red lichen the size of dinner plates. We've lived for thousands and thousands of years, the lichen collectively muttered. And want to know what's happened out here in all that time?

Nothing, man. Nothing nothing nothing nothing.

"I'll be fine," Pete said. He reached for his glass of Smirnoff's. "A bit of the bug, probably. I've been working too hard. I need to relax."

"Yeah, well." Melody got up and brushed herself off. She was wearing a lot of crushed black velvet and pink powdery body-blush. "You take care of yourself, Petey, because I worry about you, I really do. But until you get your act together, I think maybe we shouldn't see each other for a while."

4. The Crystal Palace Motel

Buster sat at the lee Floe sipping a strawberry margarita while Al the portly bartender swabbed everything down with a damp dishcloth.

"He's been over there every night," Al said. He shifted a toothpick from one side of his beak to the other, and nodded in the general direction of the Crystal Palace Motel. "Every day and night, actually. And when he comes in here-usually for another bottle of Smirnoff's-he doesn't say hi or anything. He just takes what he needs and leaves."

"No skin off my butt," Buster said, and lit another menthol cigarette. Buster had recently taken up smoking, just to give his hands something to do. "He doesn't need my help with anything. He's got his little girlies to keep him company."

"Little girlies," Al said, and poured himself a soda water from the hand-dispenser, "Little girlies and God knows what else."

Buster sat at the bar and watched Al gaze abstractedly across the

TRIQUARTERLY

35

TRIQUARTERLY

empty restaurant. It was three P.M. and Buster had just finished a late lunch of oysters in clam sauce.

"And God knows what else," Al said again. He refused to look at Buster, and there was something in this refusal that Buster took as a reproach.

After lunch and a second margarita Buster tried calling Pete's room at the Crystal Palace Motel but there wasn't any answer. When he stopped by the lobby on his way back to work he found the day clerk playing a new hand-held electronic ice-hockey game. The day clerk swung the beeping computer toy back and forth, as if he were steering a particularly nasty slalom down the rocky hillsides of his imagination.

"Is Whistling Pete still in Room 408?" Buster asked. Buster lit a fresh cigarette off the old one and crushed the old one out in a hip-high, sand-filled aluminum ashtray.

"Ah shit," the day clerk said.

The computer beeped its tiny contempt and the day clerk looked up.

"Whistling Pete, huh?" He gave Buster the once-over. "He's not the sort of guy who has many friends. So you must be another customer, right?"

Before he knew what he was doing, Buster was lifting the stroppy, bell-hatted little penguin up over the countertop and slamming him rudely against the clattery ashtray.

"What's that supposed to mean, Numb-nuts?"

"Hey, I was just kidding, is all."

Buster heard a tone in his own voice he didn't recognize.

"I'll ask you one more time," he said simply, "and don't give me any more blather. Just tell me where can I find my friend, Whistling Pete?"

By the time Buster found him he wished he hadn't. The day clerk had come clean, and as a result left Buster feeling irredeemably dirty.

"You know what I'm talking about, Mister-don't play Baby Innocence with me," the day clerk had replied, hitching up his uniform blue-serge slacks with a pompous little swagger. "I'm talking seals, man. Otters. Big slimy lady walruses with fat blundery arses. It's like the Tart's Grand National around here-them strutting their stuff up and down those stairs day after day. And your pal, Mr. Pete, he doesn't even leave the room at all anymore. You can't imagine the sort of disgusting activities that're going on in there. It's sick, that's what it is. There should be a police ordinance or something. Not to mention his hotel tab, which

36

has gotten completely out of hand. In another couple days, your old buddy's going to find himself tossed out on the tundra with the wolves and the polar bears."

Pete's room had recently been relocated to the second-floor servants' quarters. Buster took the service elevator and arrived at a long angular hallway dingy with infrequent lighting, where the linty velour carpets emitted a greasy, unsavory sheen. The entire area smelled of cigarettes and spoiled vegetables.

When Buster knocked at Room 7, he heard a slow slumberous rouse from deep inside.

Buster coughed awkwardly. Then he knocked again.

"Yeah, well, it's not paradise," Pete conceded. "But then, who's looking for paradise, right?" He was sitting on the edge of his frayed, sunken mattress, scratching his genitals through tatty checkered boxer shorts. The room was littered with bottles, newspapers, and fast-food wrappers.

"Why don't you take a shower, Pete. Put on some clean underwear, for godsake. Then I'll take you home to your wife and kid."

"My wife and kid are history, Buster. Estelle took Junior to her sister's on the Fimbullce Shelf."

Buster refused to be deterred. If Pete was ever again to have faith in himself, Buster would have to be the one to teach him how.

"First we'll get you squared away," Buster said. "Then we'll go bring her back. She still loves you, Pete. I know she does."

"Bring her back to what?" Pete asked. His voice and eyes were phlegmy and aimless. He picked a white sticky substance from his ear and wiped it on the mottled sheets. "What's left of me ain't exactly a work of art, you know. And you must have heard about the expense money I embezzled. Nadine getting fired for my incompetence and graft. The fact that I've lost what little reputation and self-respect I had leftand the funny thing is, I don't give a goddamn. I don't miss any of it.

Especially not the self-respect."

Buster, embarrassed by the false assurances he was tempted to offer, looked away. He saw the messy bathroom, the broken dripping toilet, towels on the floor.

"We'll find you a new job," Buster said. The lie echoed hollowly in the filthy room. "With Estelle and Junior's help we'll get you back on your feet again. Hell, buddy-I can loan you a few bob till you get yourself straightened out. What are friends for, huh?"

"Oh Buster," Pete sighed. "Wake up and smell the coffee, will you?"

TRIQUARTERLY

37

Pete indicated his entire body with a small ironic flourish. The high strain of ribs, the frazzled patchy feathers, the haunted and thinning gleam in his eyes. "All my nice sleek body fat has melted away. No job, no family, no savings to speak of. It's quite ironic, really. Because civilization has given me the luxury of thinking, I've had time to disrespect all the civilized comforts that allow me to think."

"Don't," Buster said. He knew he was in trouble if Pete started talking. "Stop it, Pete. Stop winding yourself up."

Pete was on his feet again, waddling back and forth in front of the bed. "But that's the point, isn't it? What do you build when you build yourself a civilization? Nice warm houses, nice warm restaurants, nice warm places to go to the bathroom. What does civilization give us, Buster? Temperature. Heat. Oxygen. Light. And what do we do with all this, this energy, this year-round fat and reserve? We burn it, pal. We use it to stoke the fire of our bodies all day and all night. Heat and oxygen fuels the brain to think, the loins to procreate, the body to consume. We are burners of hard fuel, Buster, and thinkers of hard thoughts, and we can't ever rest until we die. Civilization doesn't solve problems, Buster. It reminds us of all the problems we haven't yet solved. What we don't have. Who we haven't been. How much we haven't spent. How many little girlies we haven't plugged. It doesn't end, Buster. I keep thinking it will end, but it doesn't end, not really."

"Don't do this to yourself, buddy," Buster said desperately. "Turn it off, man. Give yourself a good swift kick in the backside and shut your damn brain off."

Pete came to a sudden halt and he turned. His face was sunken, his eyes lit with a fire that burned itself as much as the things it saw.

"But Buster," he said, "the only way to turn it off is to stop living. The only way to forget what you know is to pretend not to be."

At which point, Whistling Pete fell to the floor with a terrible crash.

With friends from the Ice Floe Buster managed to transport Pete back to his home, where the atmosphere had grown stale, sluggish and unreal, almost as bleak as Pete's room at the Crystal Palace. The walls, beds and furniture were icy with neglect and disuse. The pilot light had extinguished in the furnace, and a shutter in the bedroom had ruptured under the impact of a recent storm, permitting an avalanche of rocky ice and sludge to build up around the dressing table. The only whiff of life remaining in the entire house was exuded by the bowels of the refrigerator, where shriveled vegetables and garlic bulbs blossomed. When they

TRIQUARTERLY

38

laid Pete out on the cold bed, he tossed and turned in his sleep, muttering against the tide of visions only he could save himself from. Buster wasn't able to reactivate the pilot light in the furnace, but he did manage to get a good blaze started in the fireplace.

"More," Whistling Pete murmured, drifting in the depths of oceans much deeper than sleep. "More yesterdays. More todays. More tomorrows."

"Sleep tight, old buddy," Buster said, posting himself in a cracked wooden chair beside the bed. He had just started a pot of canned soup simmering over the fireplace. "And if you need anything, you know where to find me."

Sandy didn't understand, but Buster never thought she had to.

"Who's your real wife, anyway?" she asked him. "Me or Whistling Pete? And since when did you take up cooking and housecleaning? I never even seen you open a can of beans before."

Buster was wearing one of Estelle's frayed white aprons and scrubbing rusty pans in the sink.

"It's just something I've got to do," Buster said. He felt strangely peaceful and solid. "If you love me, you'll try to understand."

"Try to understand," Sandy said. Suddenly, like a wind snuffing out a candle, all the fight went out of her. "Try to understand."

Buster took his overdue vacation time from the factory and repaired Whistling Pete's window and furnace. Every afternoon, after preparing a lunch of chicken broth and fresh fruit salad, he helped Pete out of bed, walked him around the room a few times, and changed the linen. Whistling Pete's body was all slump and desuetude, his complexion jaundiced and scabby. He was losing feathers all around his skull and under his armpits.

"We'll get you a nice wool cap," Buster promised one day during their exercise session. "The body loses ninety percent of its heat through the old skull, you know. In order to keep the body warm, you gotta keep your lid on-get me?"

"That's why we've got gas fires," Pete said. "That's why we've got central heating."

"Go back to sleep now," Buster said, laying him back in the cool fresh linen. "You don't have anything to worry about for a long, long time."

Usually Whistling Pete drifted off again, but some afternoons, as if driven by the momentum of his own feverish imaginings, he started talking out loud in his sleep.

TRIQUARTERLY

39

"I dreamed all night of the white ice," Whistling Pete said. "I was walking south, into a region of thin air and dazzling aurorae. I knew I was heading into the big nothing, but I couldn't seem to stop myself. I knew I had to keep going, not because I wanted to get anywhere specific, but because I couldn't bear to remain anywhere I already was."

The dreams seemed to increase in force and volume, and Buster could never decide whether this was a good omen or a bad one. Sitting beside Pete's bed with his newspaper, Buster watched his friend toss and turn with slow, gathering intensity, like a kettle heating on a stove. Sometimes he cried out or started upright and Buster soothed him with a steaming wet towel.

"Human beings are the next step," Whistling Pete cried out from time to time. "They'll be here any day now. And if human beings don't get here pretty soon, then I'm afraid us penguins won't have a choice. We'll start turning into human beings. You, me, Estelle, Junior, Melody, the girls, the beautiful girls. Big fat hairy human beings with guns, oil and machinery. We'll start erecting supermarkets and shopping malls. We'll drive like maniacs across the ice on motorbikes and mopeds. We'll start shooting each other in the head, and chewing tobacco, and pissing on our own front stoops. I have seen the future, Buster. I have seen the future and it is us. Animals who can't stop themselves anymore. Animals who always want more than they've already got."

"It's O.K., Pete," Buster said. He shook and repositioned the foam pillows, helping Pete subside back into them. "Stop worrying. Stop thinking and just relax. It'll be O.K.-I promise. I'll stick by you. All you've got to do is get better, Pete. I'll take care of everything."

They buried Whistling Pete beside the pond where he first went fishing with his father. A lid was cut in the ice and Pete's naked body inserted into the frothy, secret currents beneath. The various attending penguins seemed too stunned, disoriented or angry to look at one another. On the fringes of the small crowd a few lonely, heavily veiled Penguinettes sobbed quietly into black satin handkerchiefs.

When the lid of ice was refitted into place a few words were said by each of Pete's surviving friends and relatives. Usually they offered slow, awkward condolences like, "He will be missed," or, "He was always a hard worker and good provider," with a dull casual flourish, as if they were signing a form letter. The last person to take the mound was Pete's father, who had swum in that morning from his retirement village on Carney Island. (Pete's mother had died two years previously in a freak

TRIQUARTERLY

40

skiing accident.)

"Whistling Pete was a good boy," his father said in a cracked, halting voice, trying to read from a sheet of foolscap in his trembling hands. He wore a faded gray flannel shirt, a black wool stocking cap and wire-rim bifocals. "He was always polite to his parents. He always did well in school and helped his mother with the housework. Now maybe he exaggerated the truth every once in a while, but that's just the way he was, 1 guess. He found the truth a little too boring, so he tried to embellish it a little, it was kind of like generosity. Pete always thought big. He was ambitious and talented. Ever since he learned to swim, he dreamed of going to faraway places and accomplishing great deeds. 1 remember when he was little, he was such an enthusiastic fisherman. He kept bringing home sacks and sacks of them, more fish than we could possibly eat in one modest household. So then he started giving away all the extra fish he caught to the poor homes and convalescent hospitals. He always gave that little bit extra to everything he did. Maybe some people considered it selfish. But 1 always thought he gave life everything he had because he loved it so much."

Mr. Pete paused to wipe a frozen teardrop from one eye and continued in a wet, quavering voice. "Maybe he made some mistakes when he grew up. He never visited his mother and me after we retired, but by then he had a family of his own, so 1 guess he just got too busy. But he was always good to me and his mother when he was little, and that's, that's Abruptly, Mr. Pete began to sob. A hush fell over the mourners. Even some of the succinctly sobbing black-clad Penguinettes fell respectfully silent.

Buster stepped up and whispered something in Mr. Pete's ear.