•

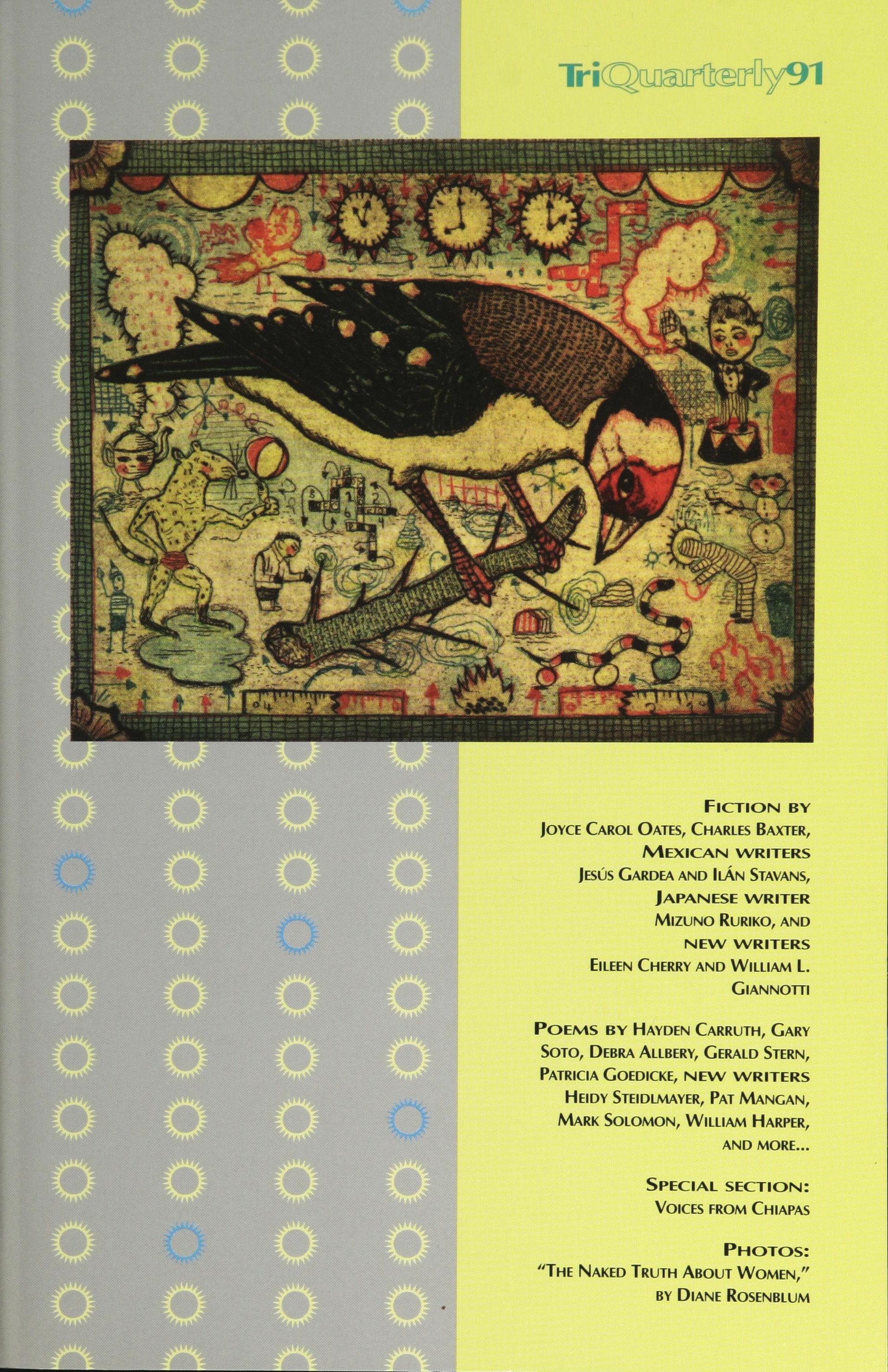

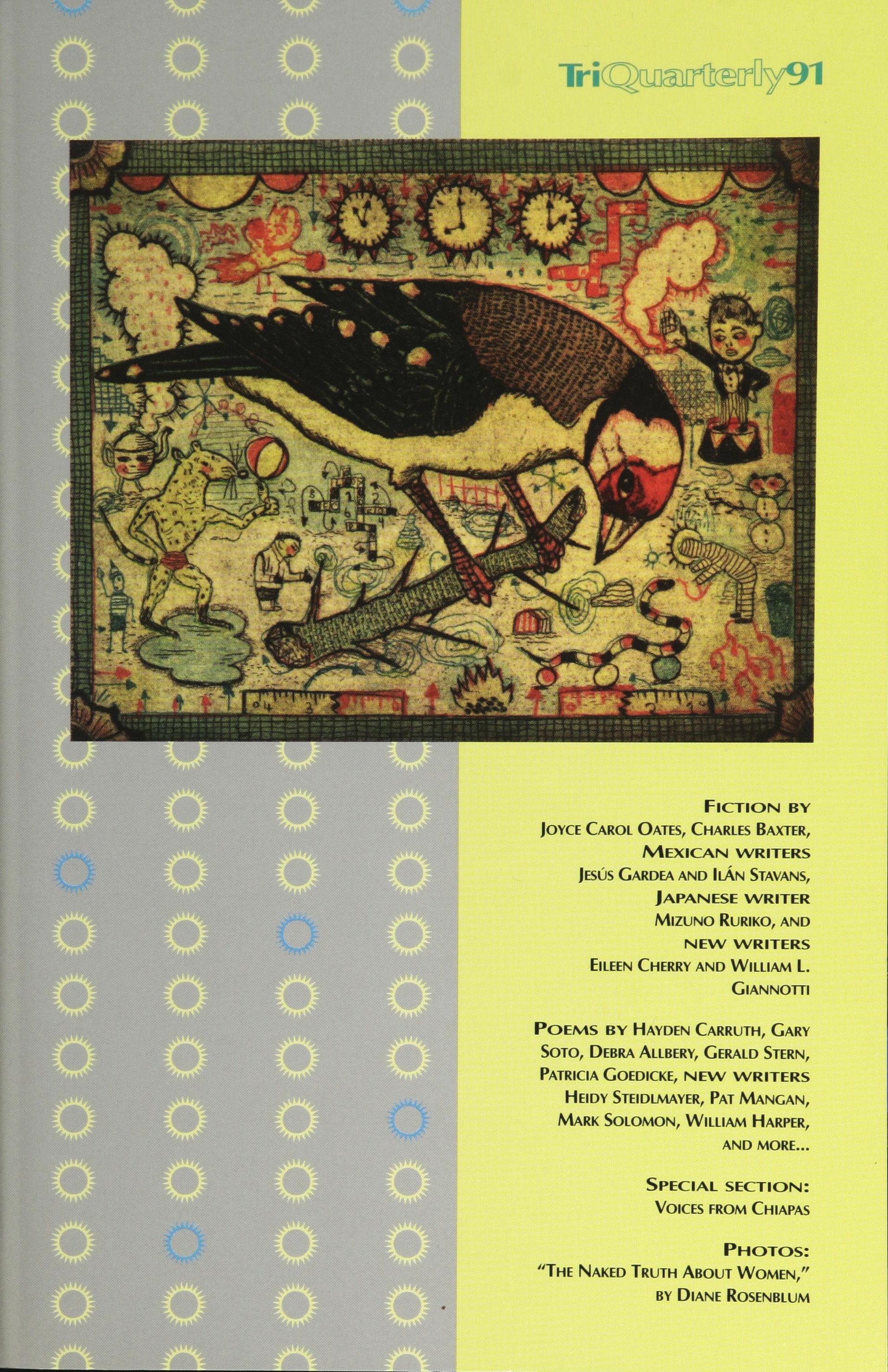

FICTION BY JOYCE CAROl OATES, CHARLES BAXTER, MEXICAN WRITERS

JESUS GARDEA AND ILAN STAVANS, JAPANESE WRITER

MIZUNO RURIKO, AND NEW WRITERS EILEEN CHERRY AND WILLIAM l.

GIANNOTTI

POEMS BY HAYDEN CARRUTH, GARY

SOTO, DEBRA ALLBERY, GERALD STERN, PATRICIA GOEDICKE, NEW WRITERS HEIDY STEIDlMAYER, PAT MANGAN,

MARK SOLOMON, WILLIAM HARPER, AND MORE •

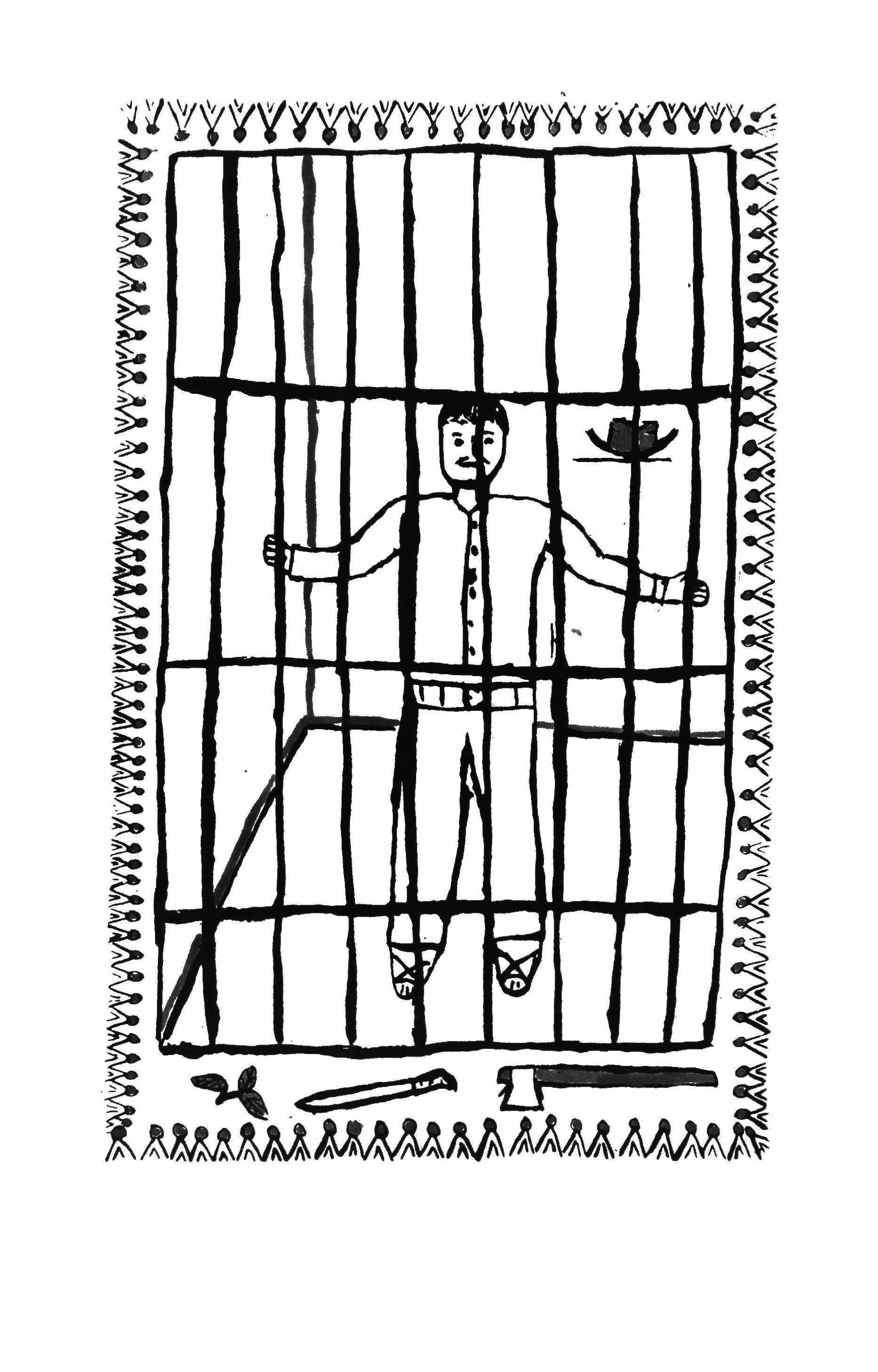

SPECIAL SECTION: VOICES FROM CHIAPAS

•

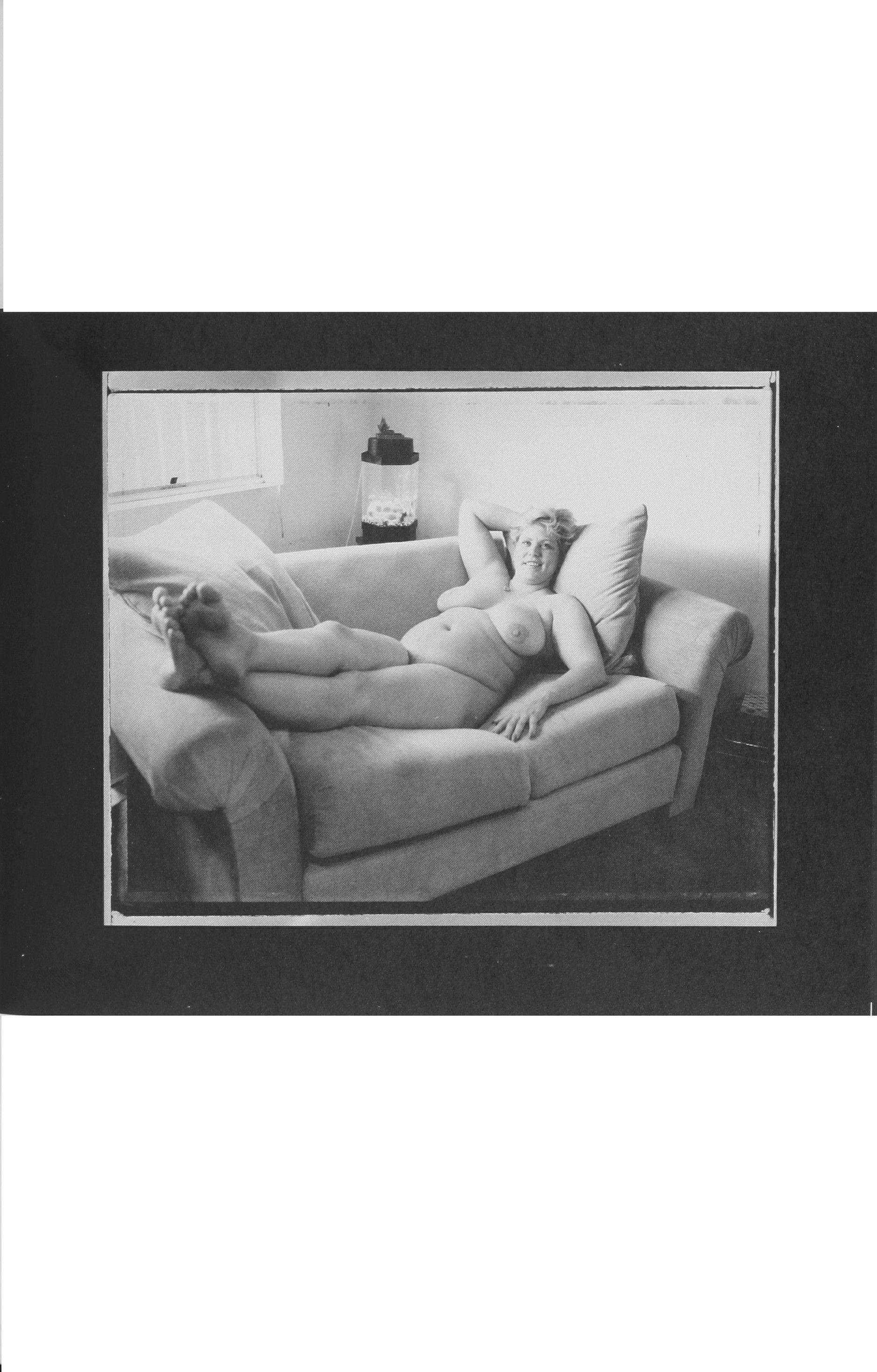

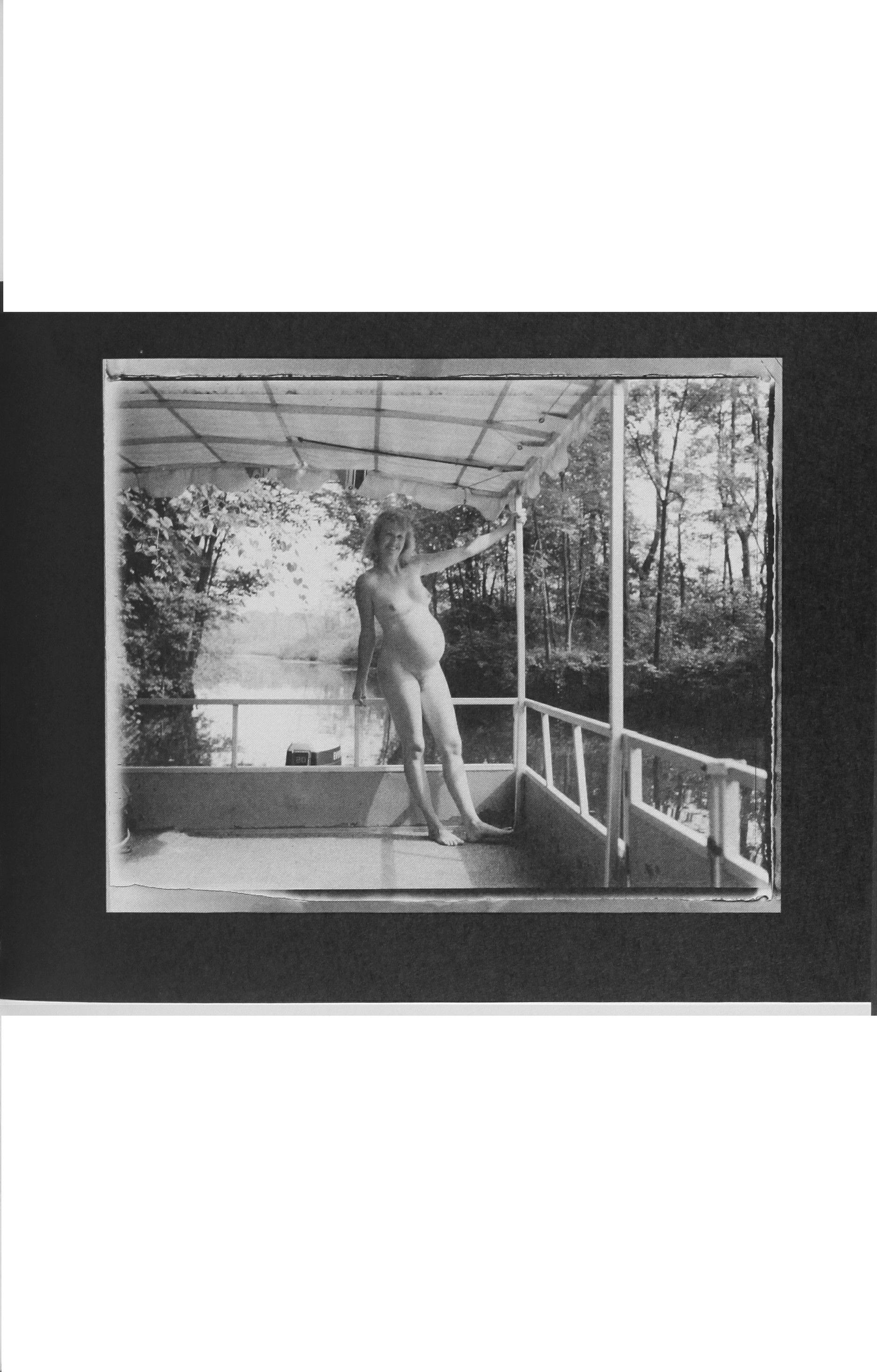

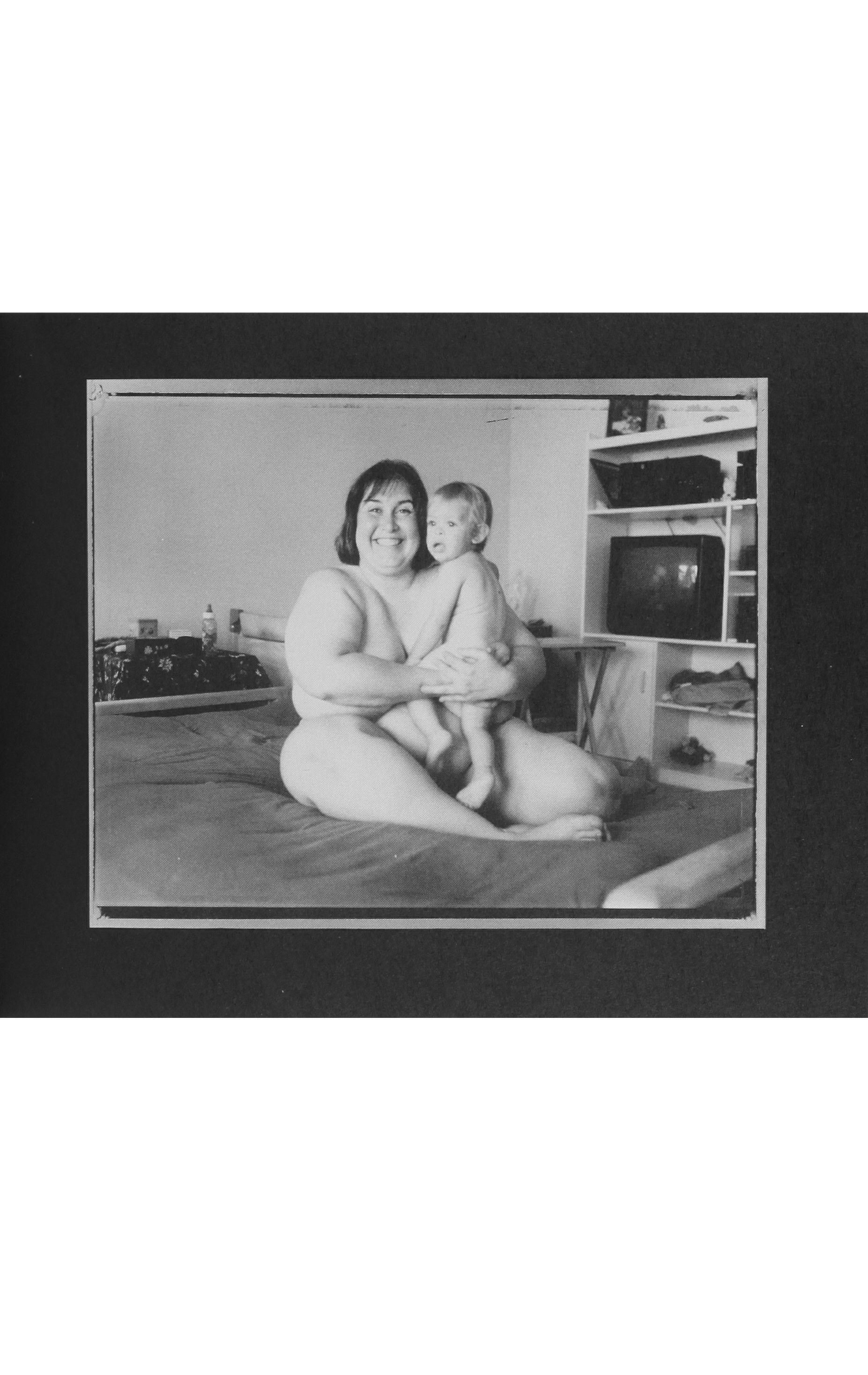

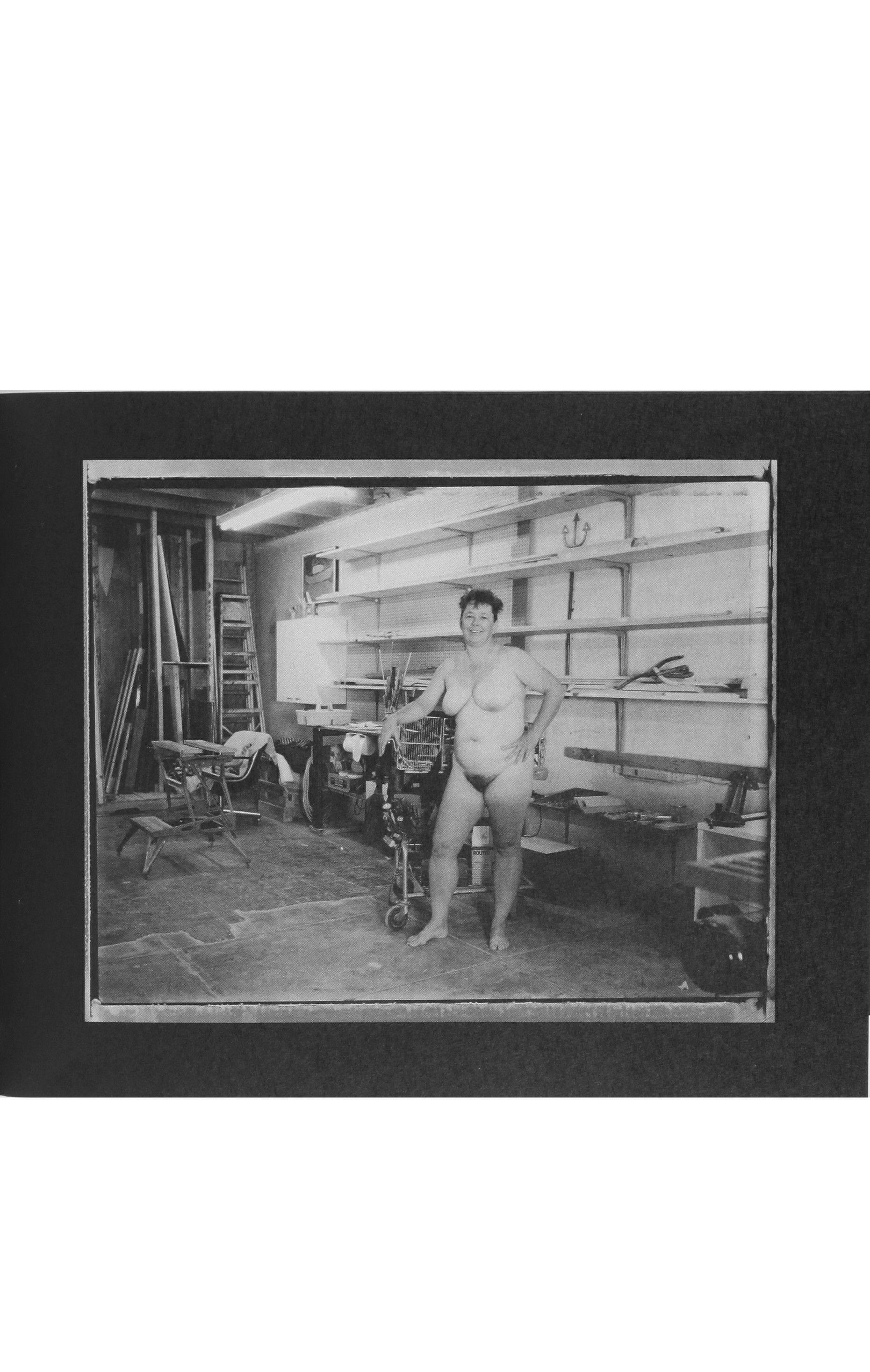

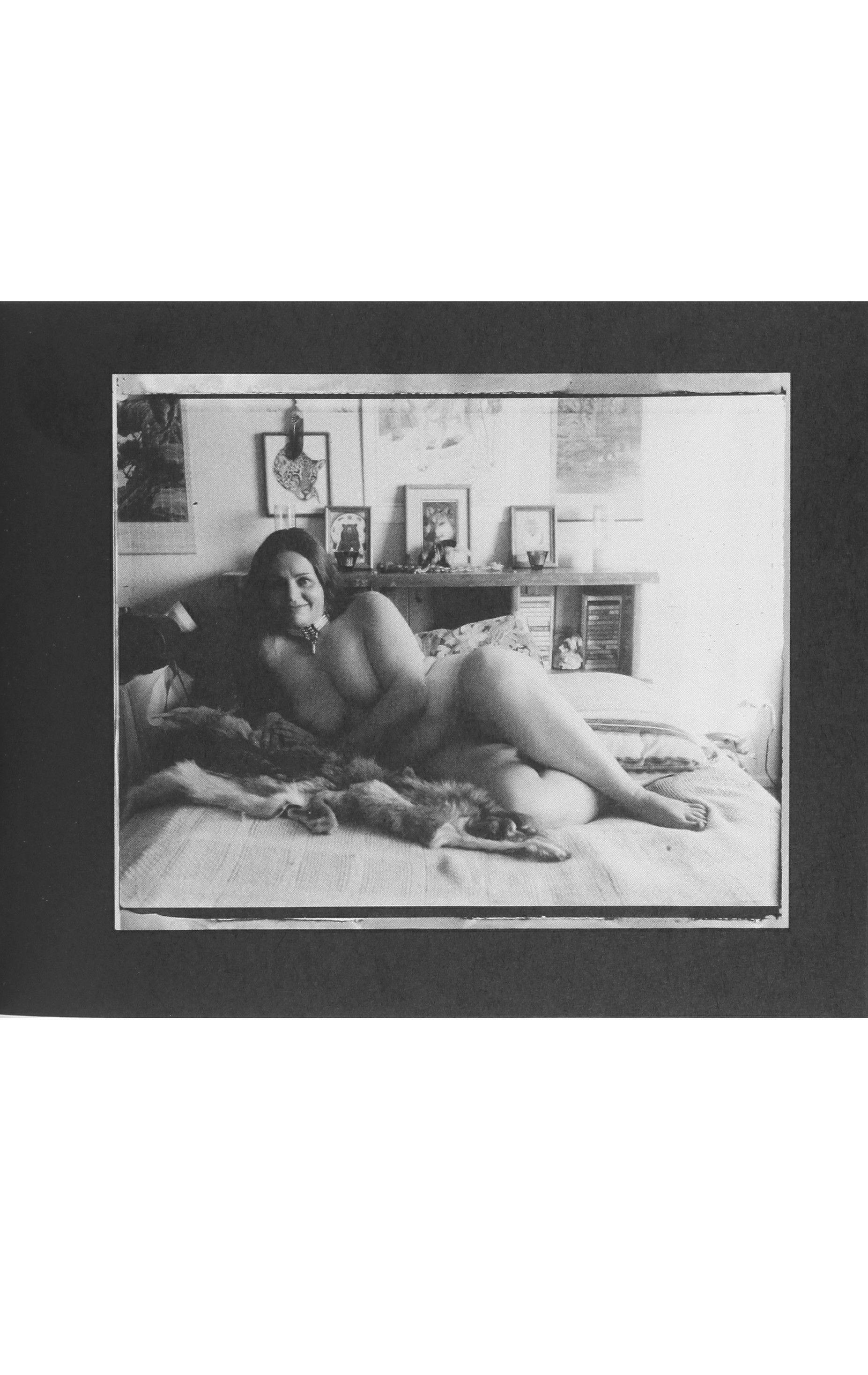

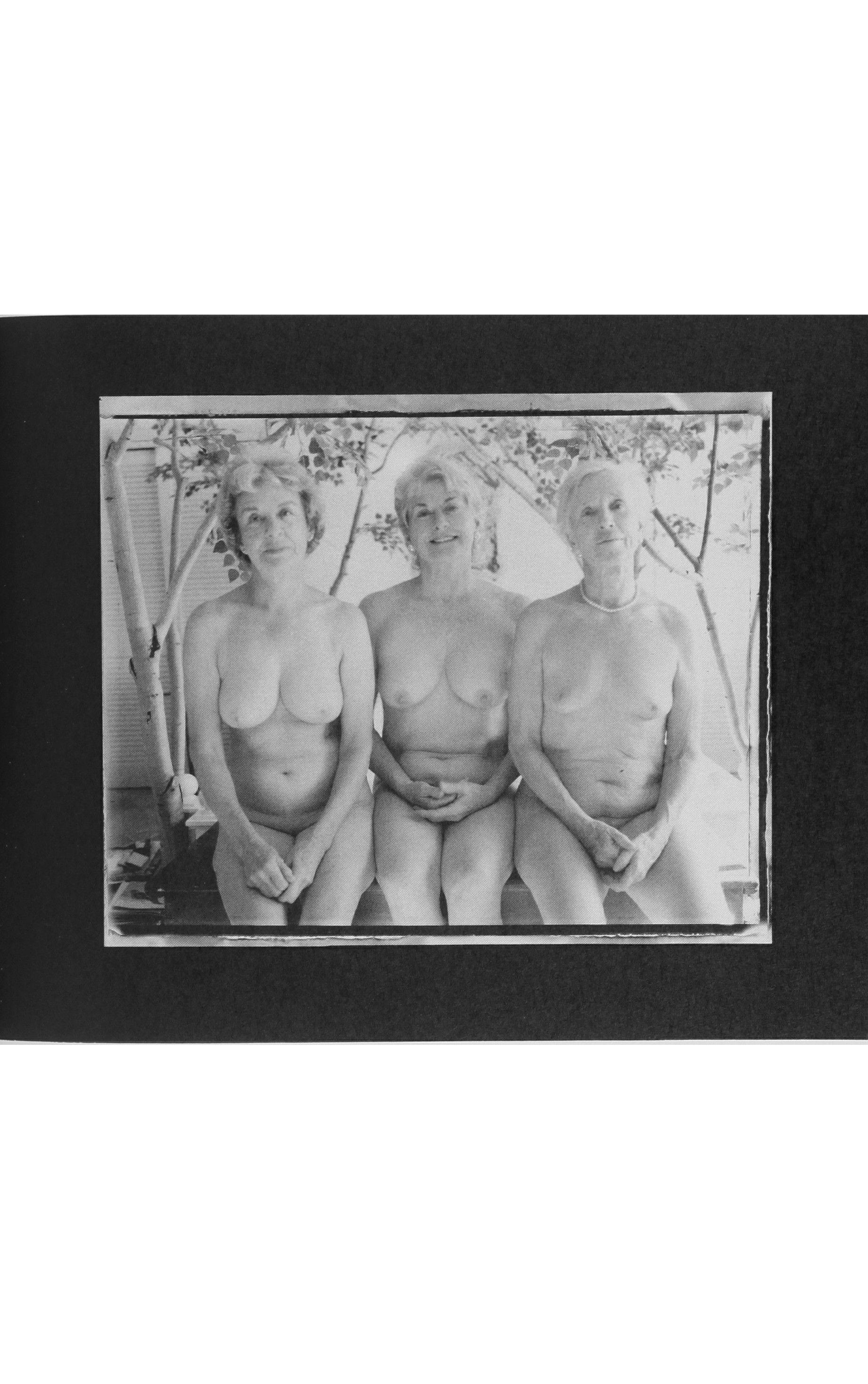

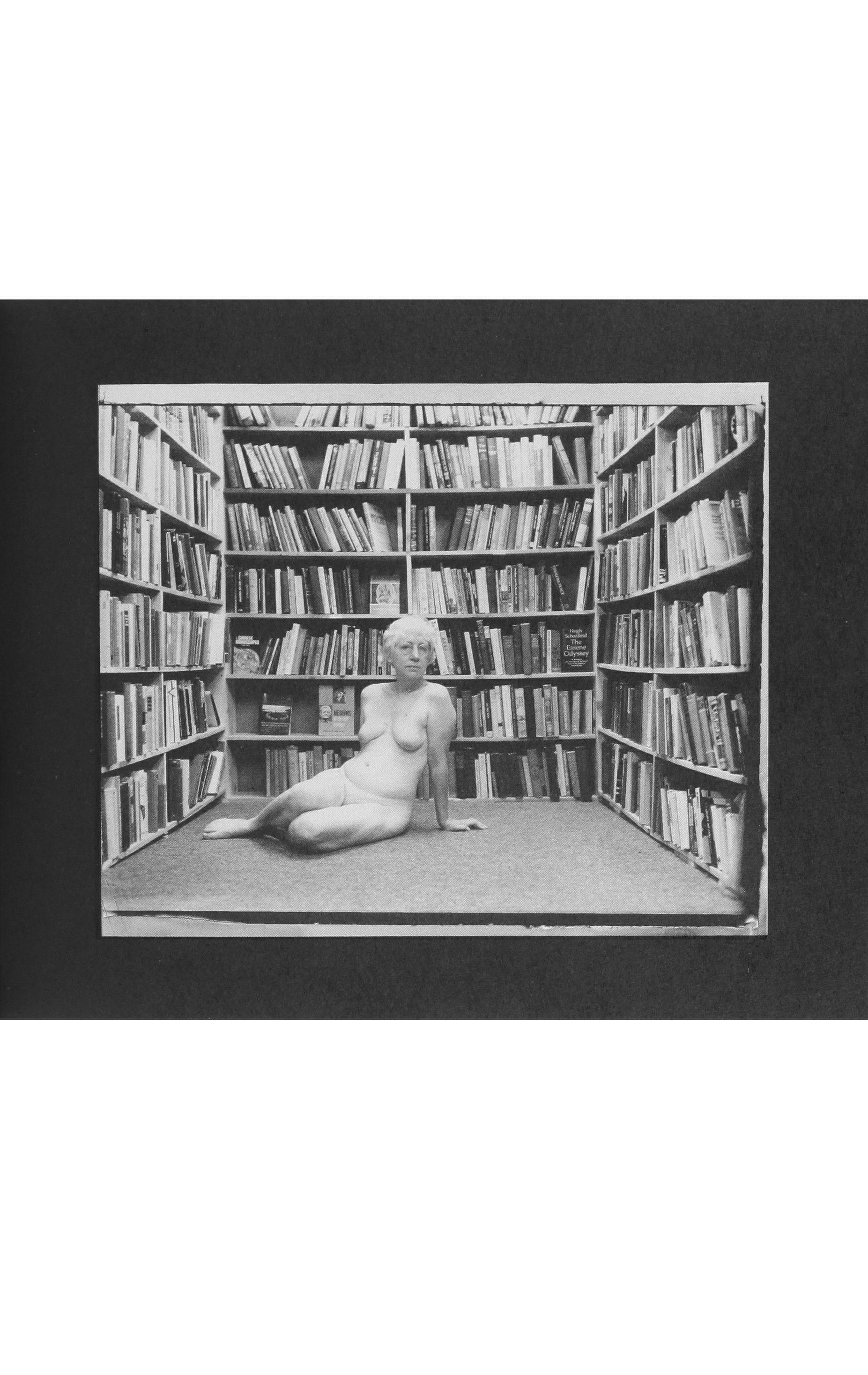

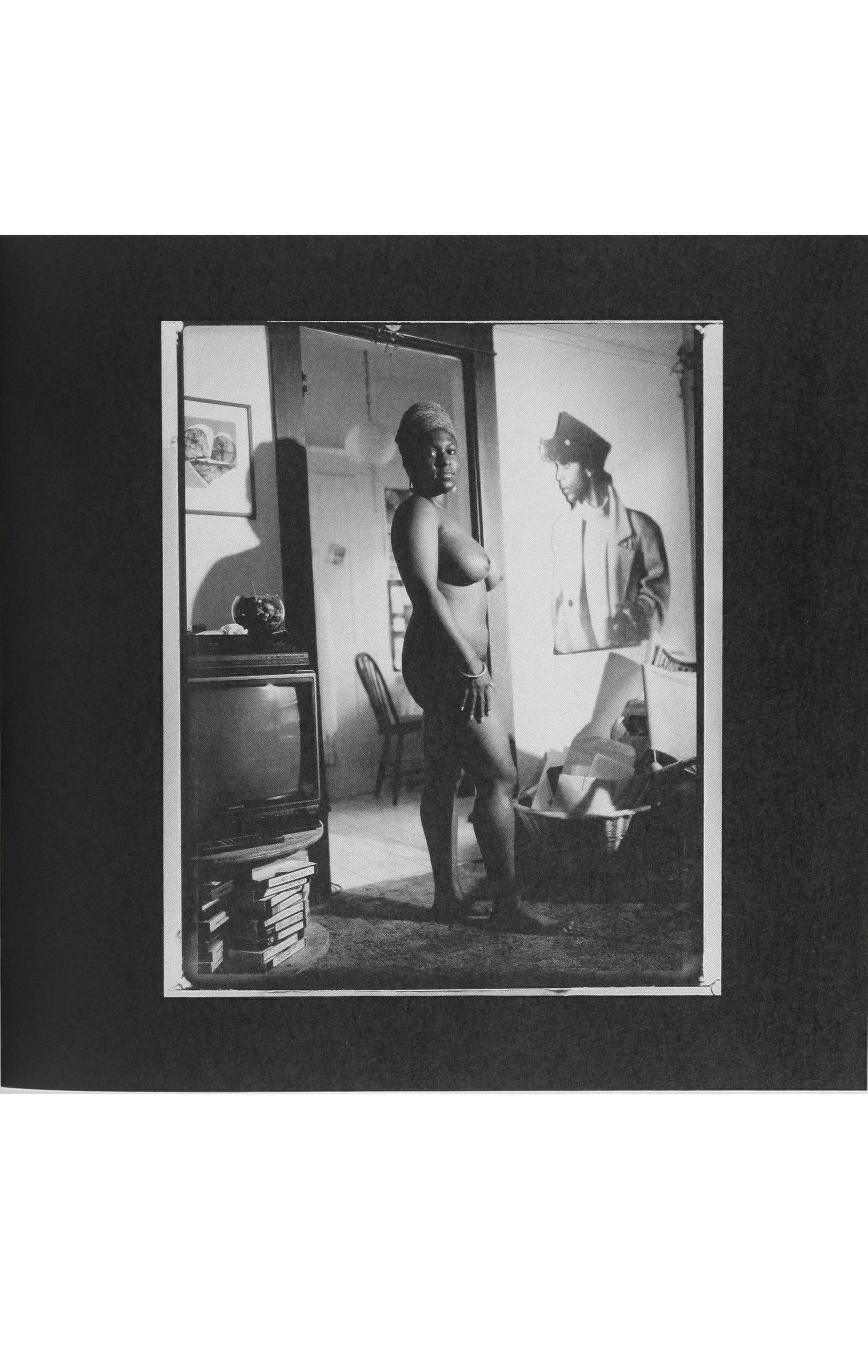

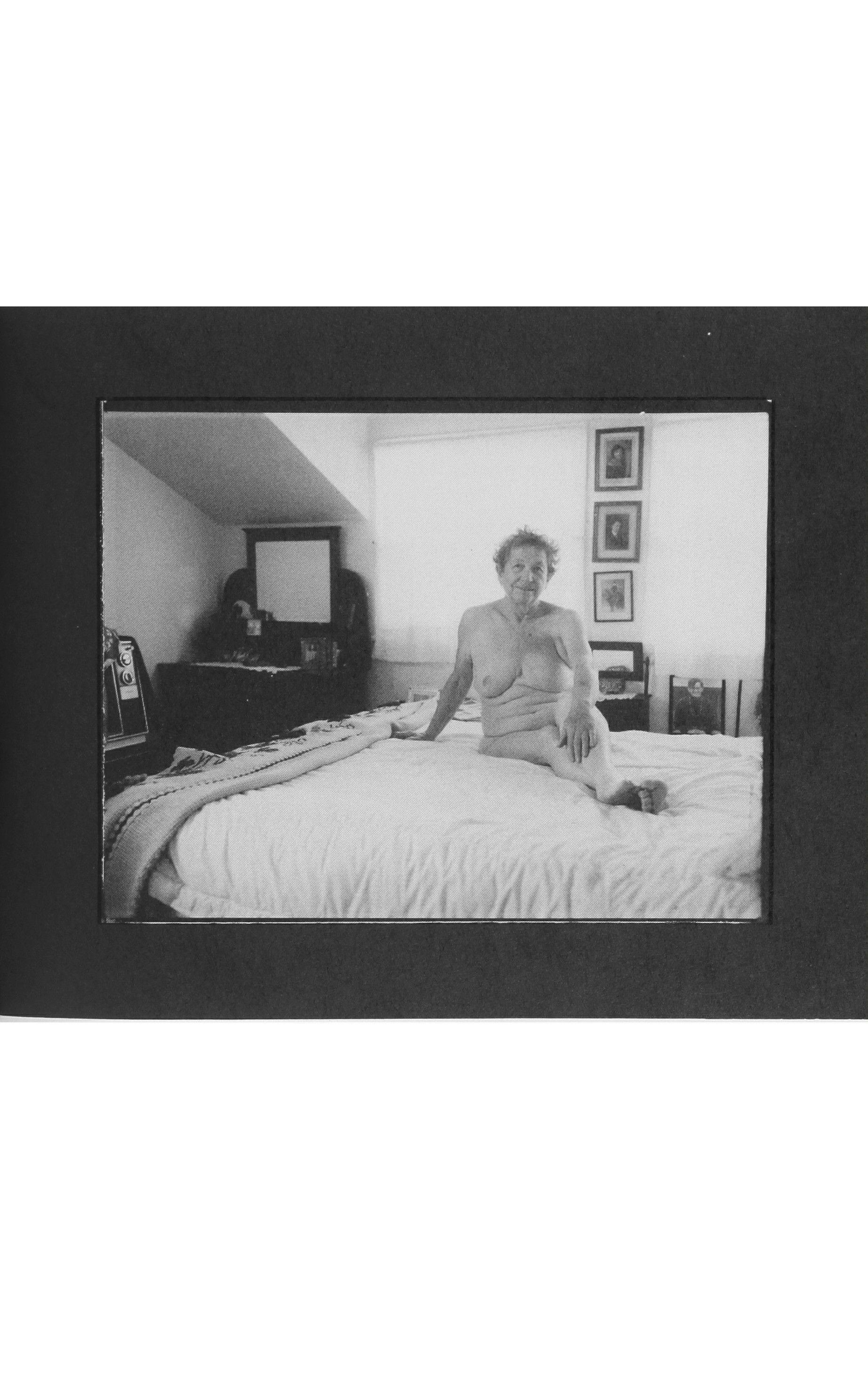

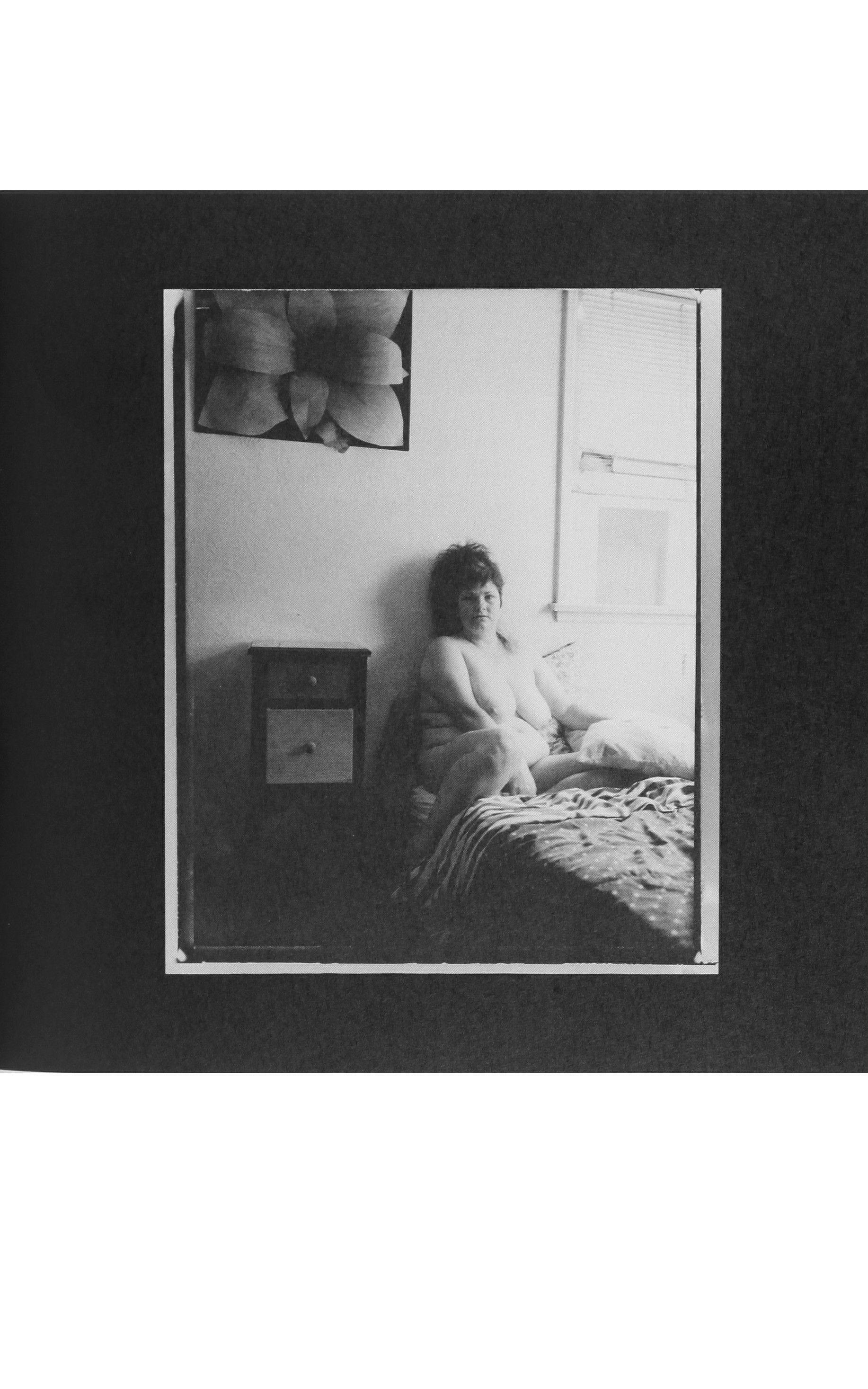

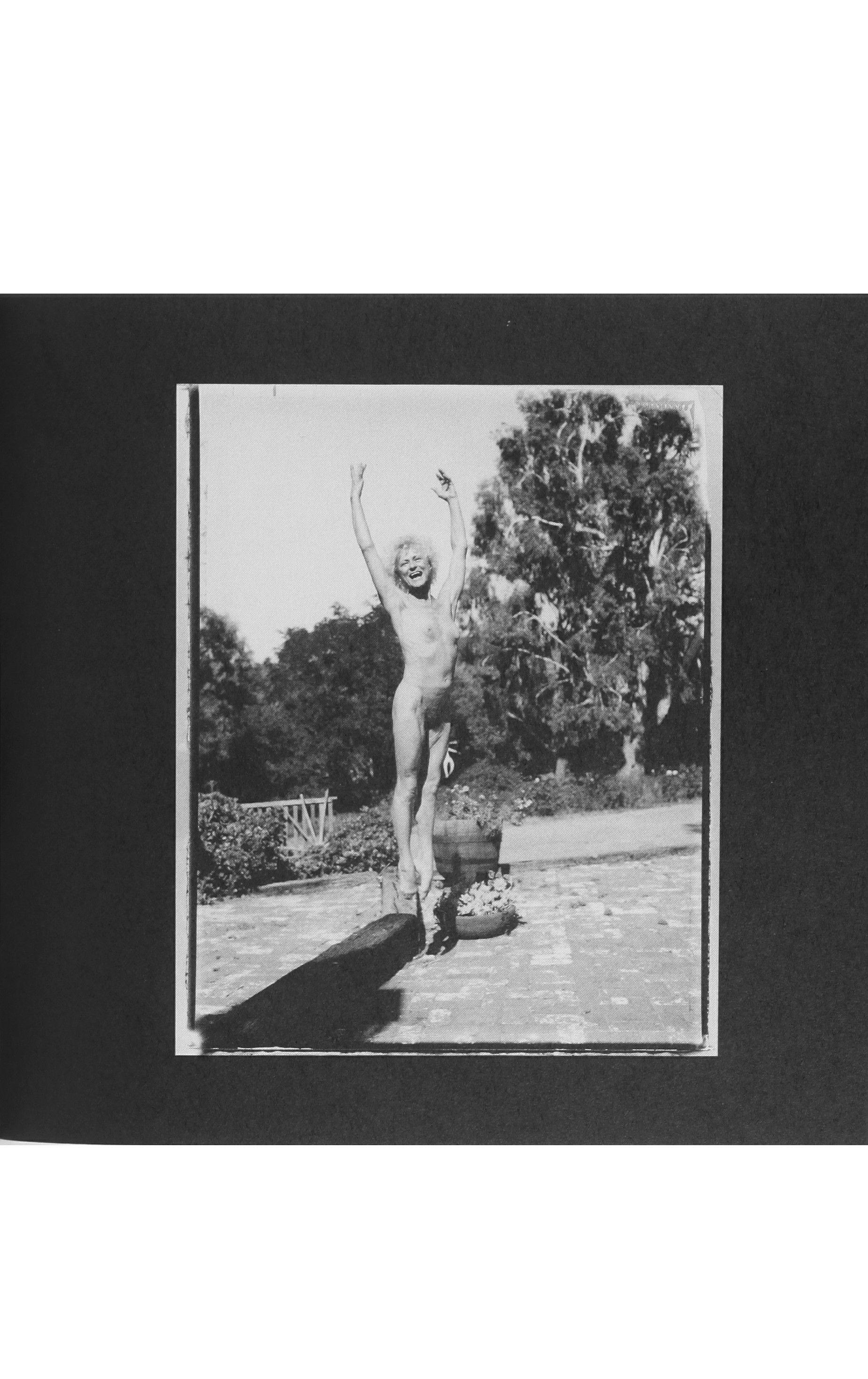

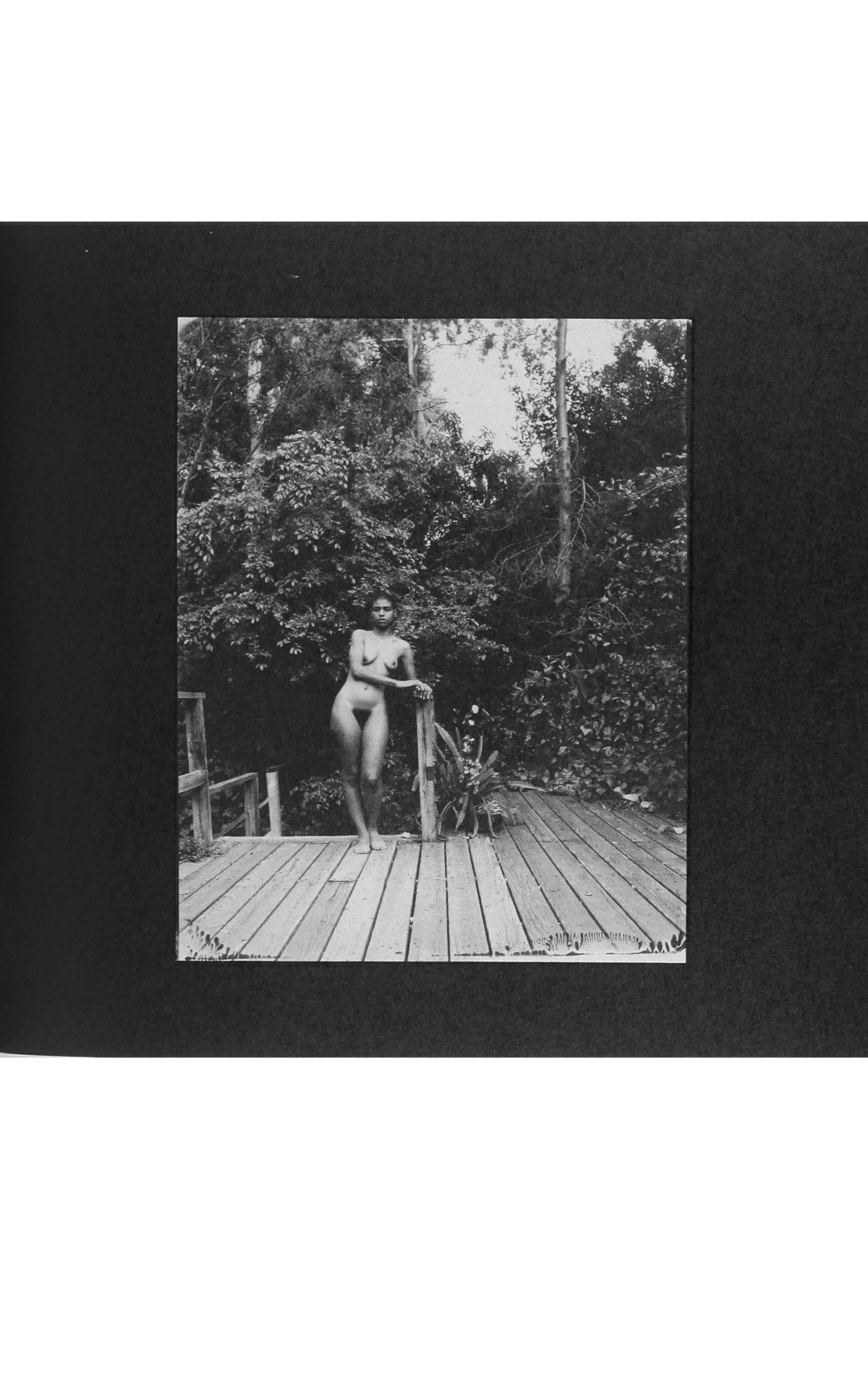

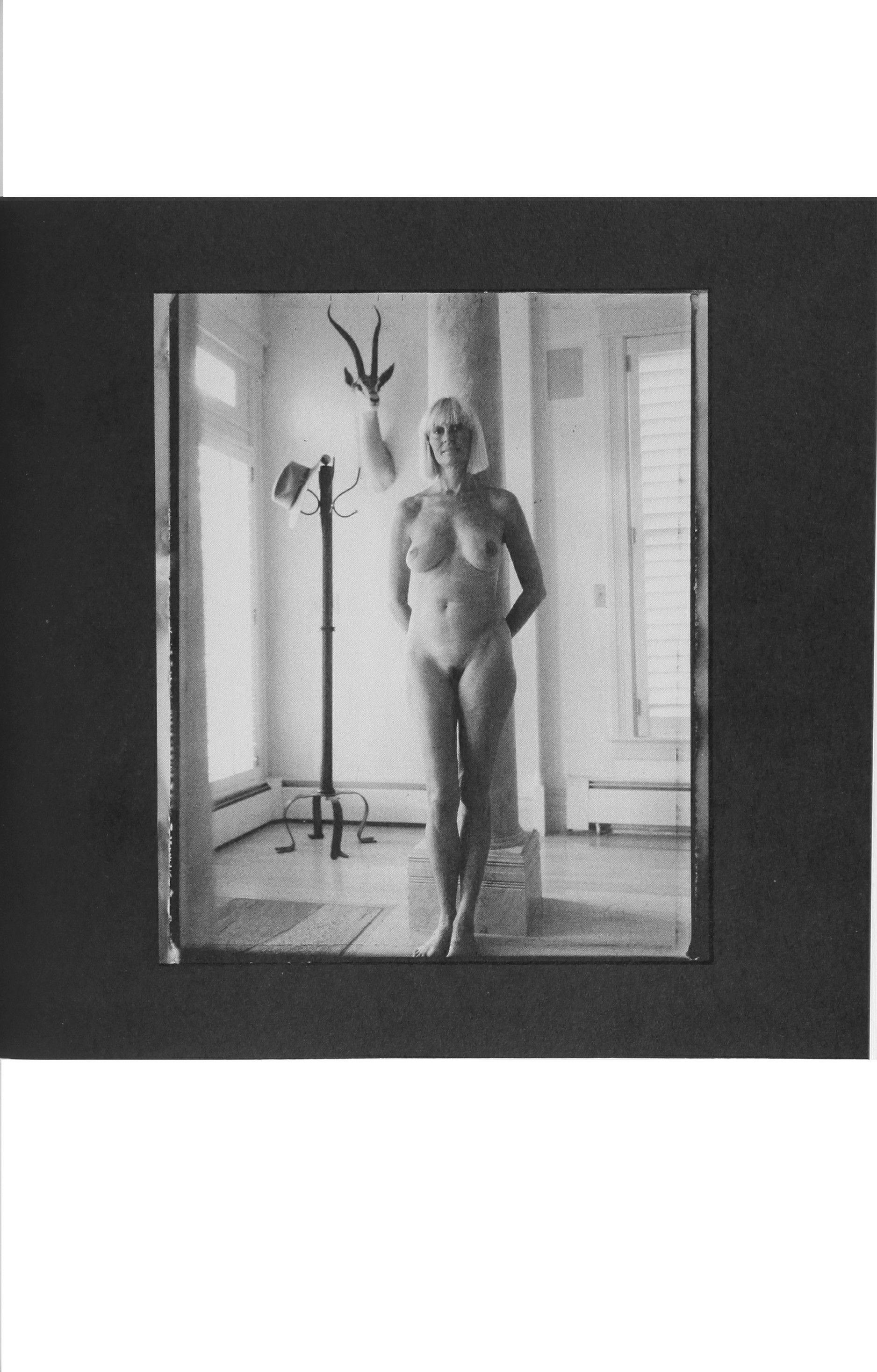

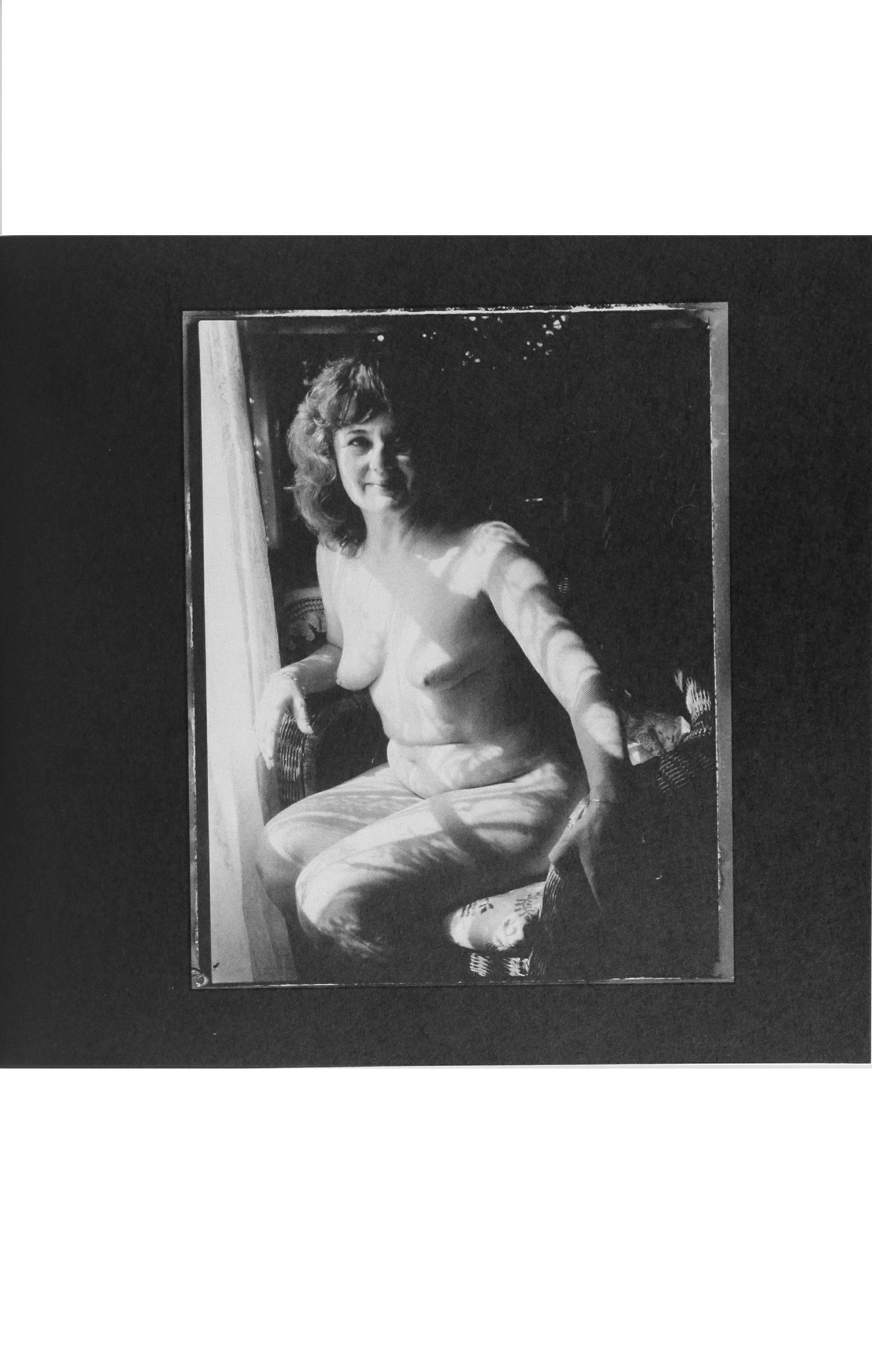

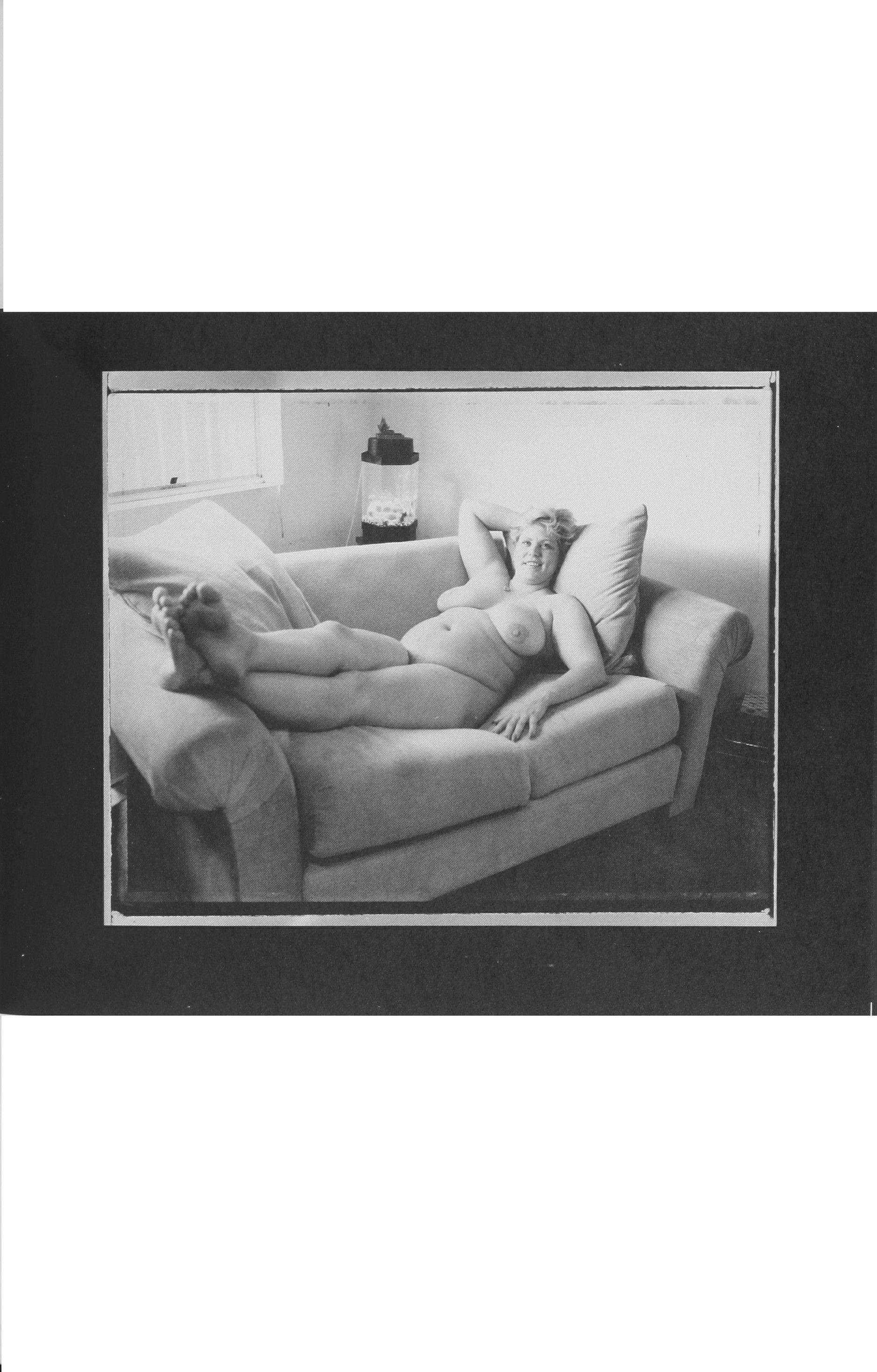

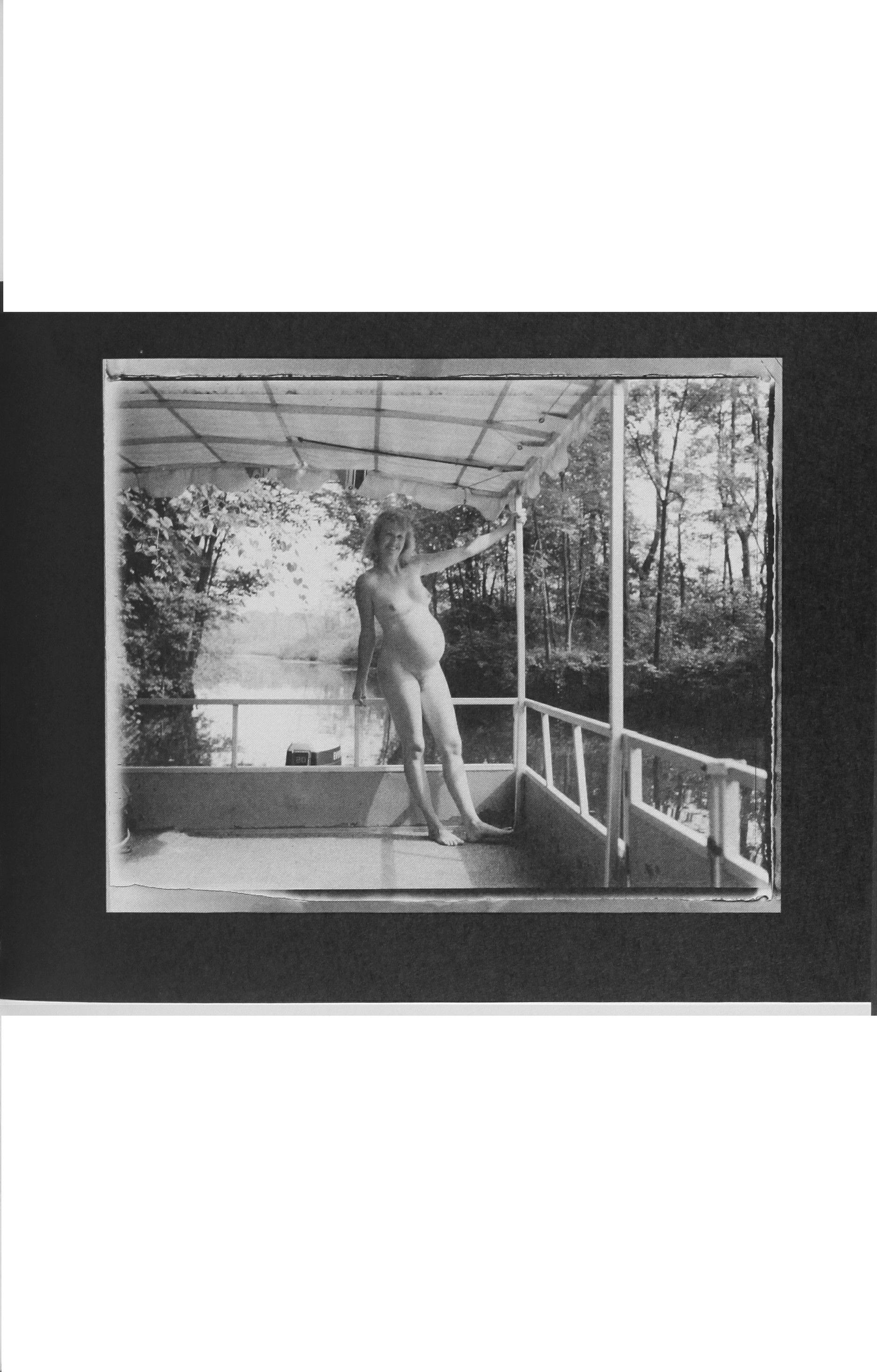

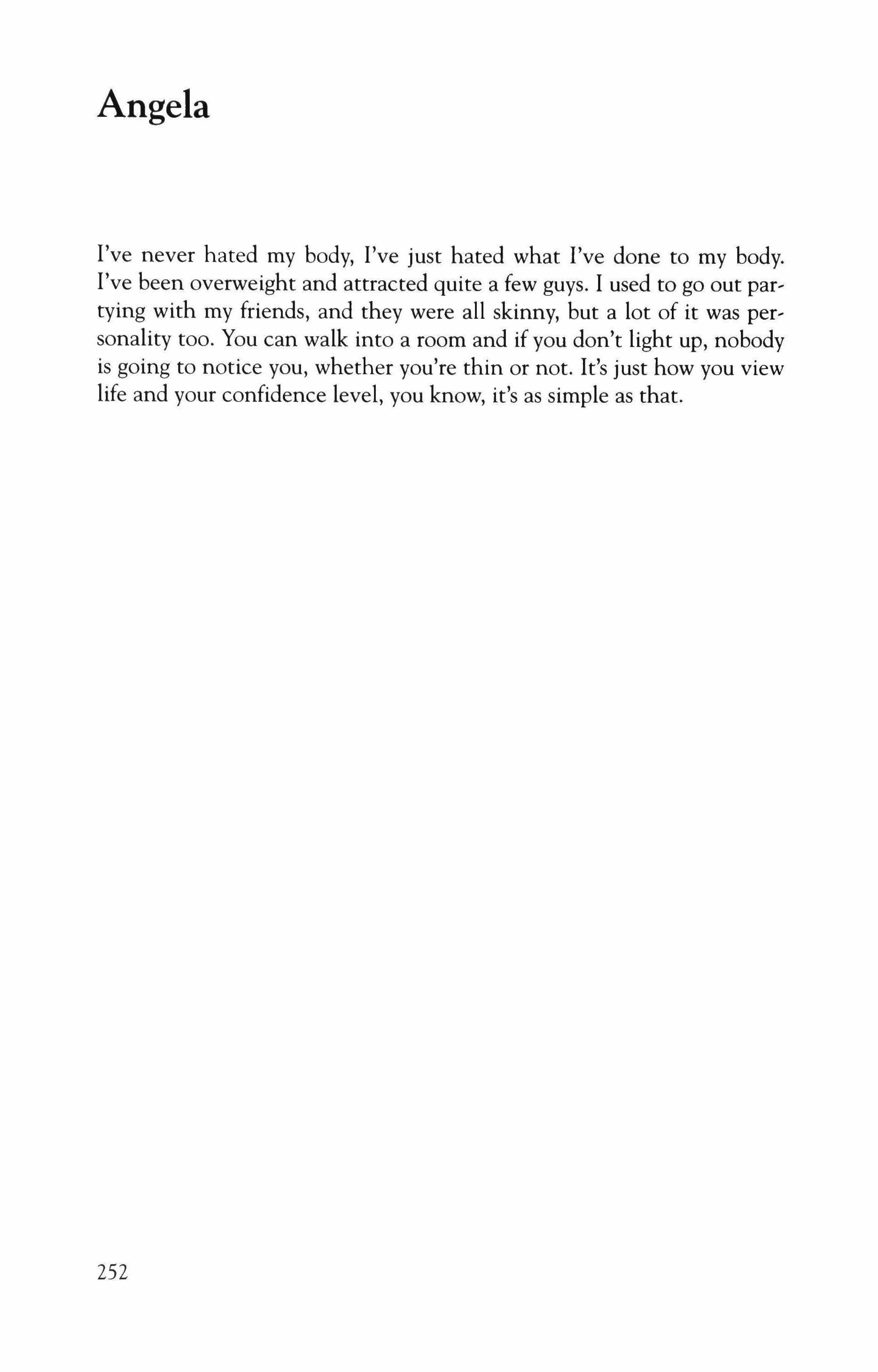

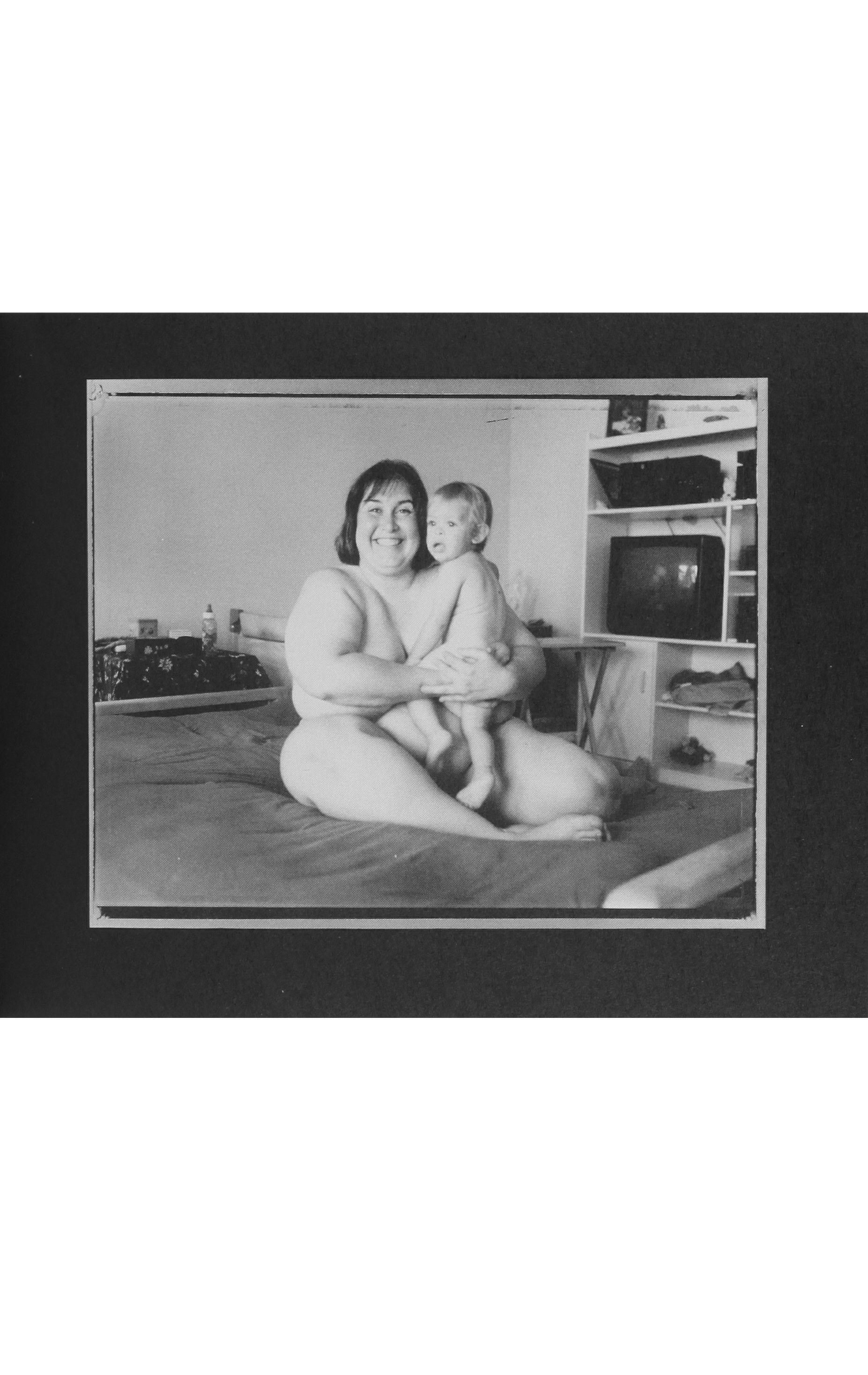

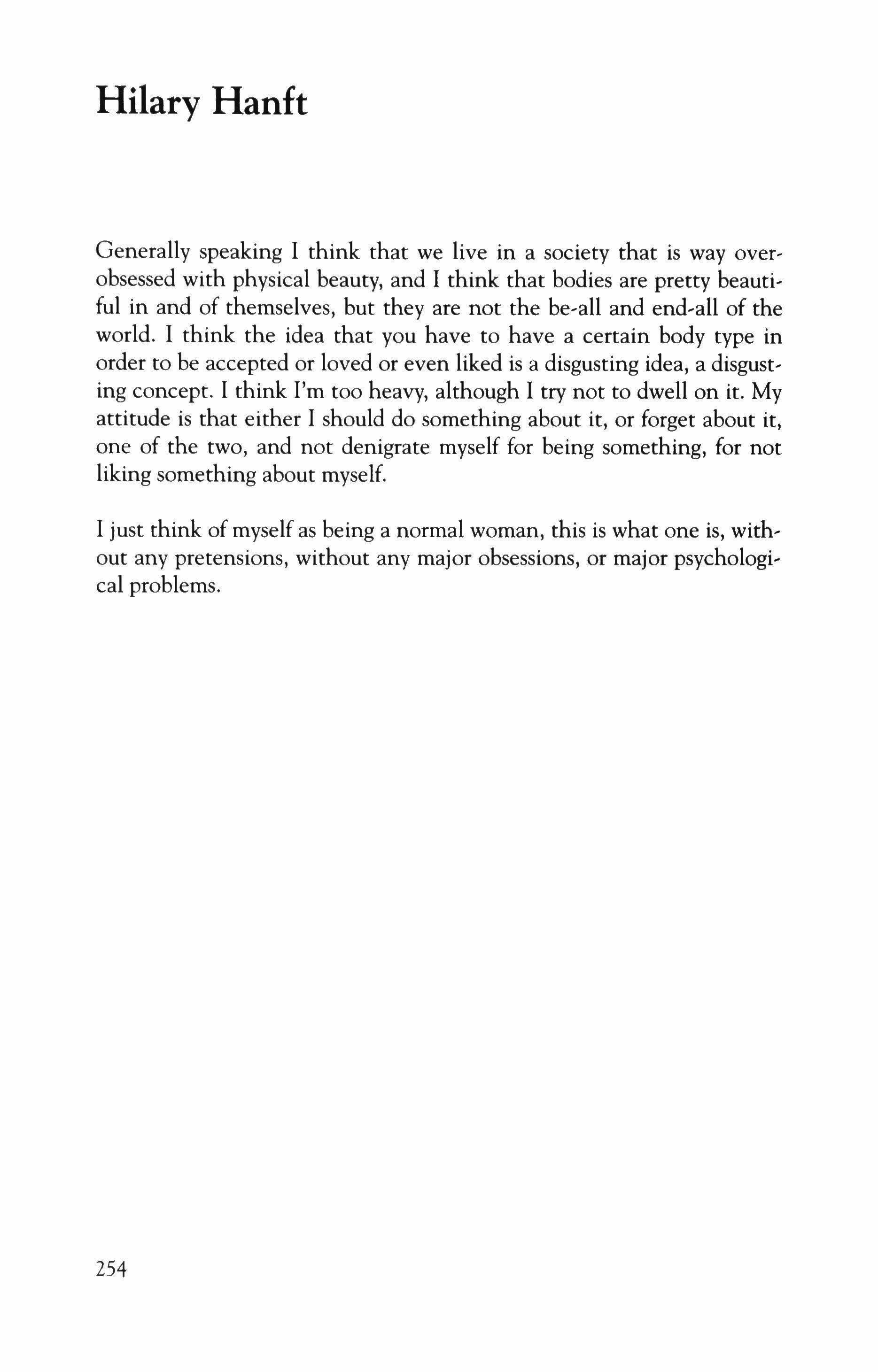

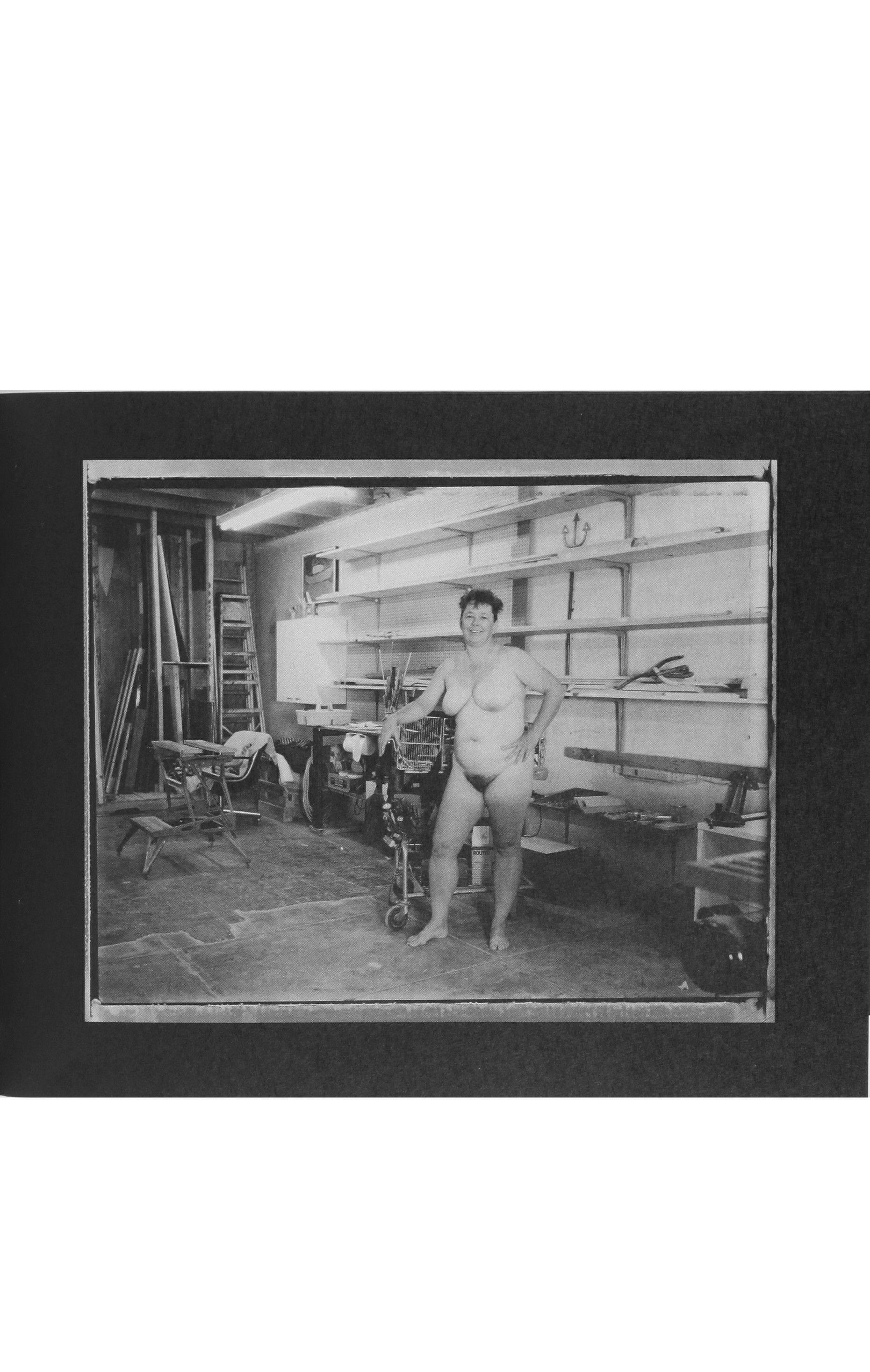

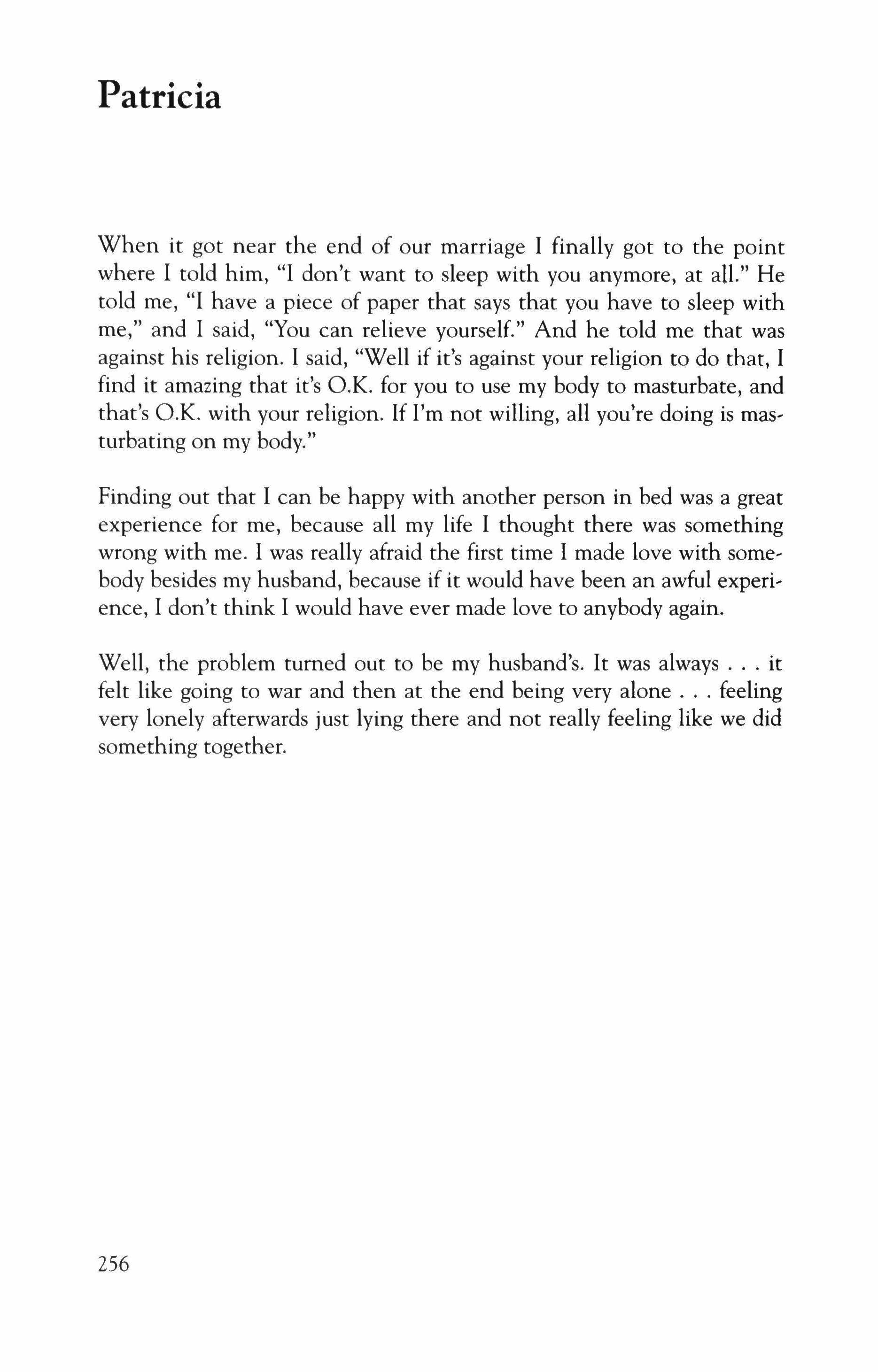

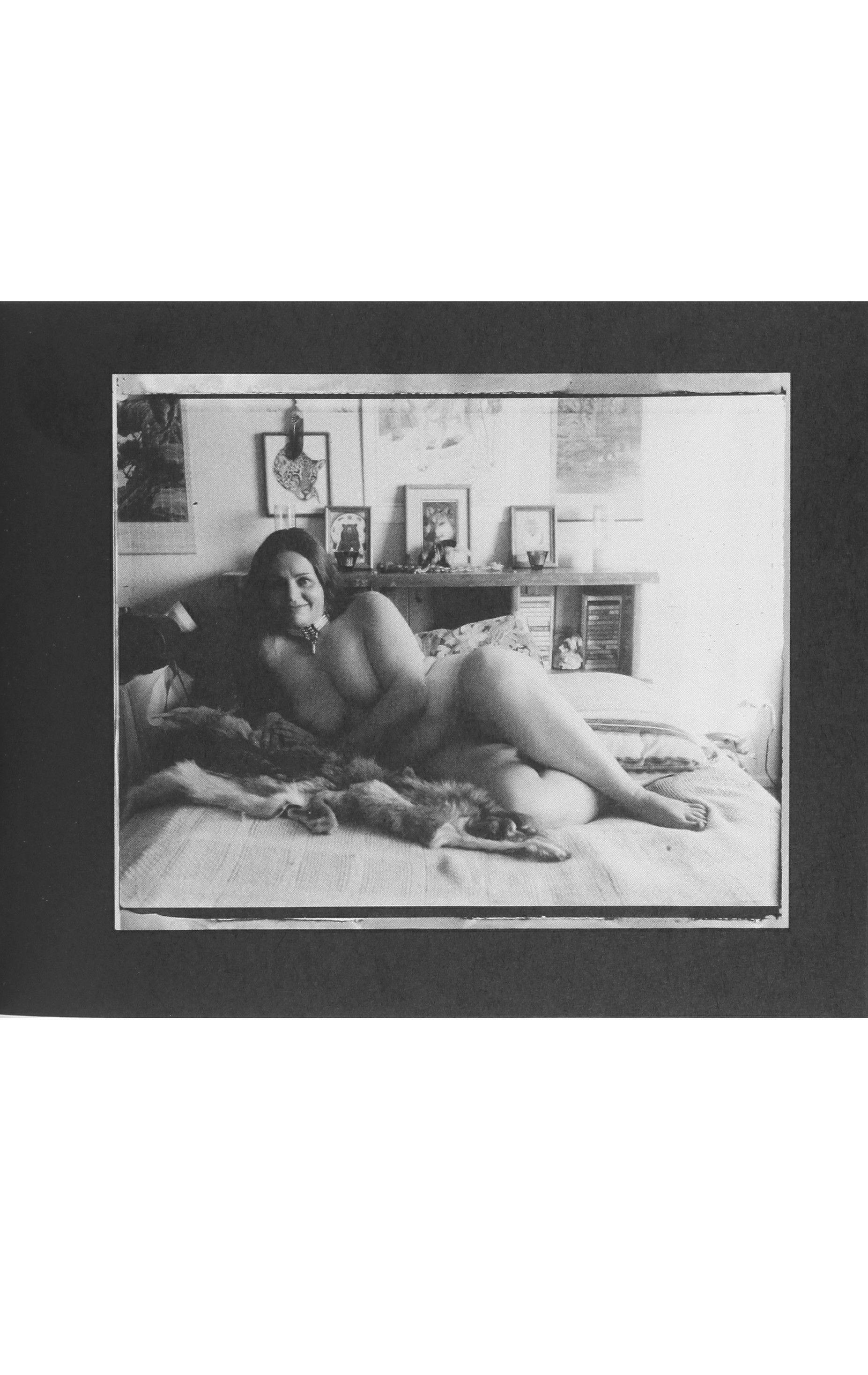

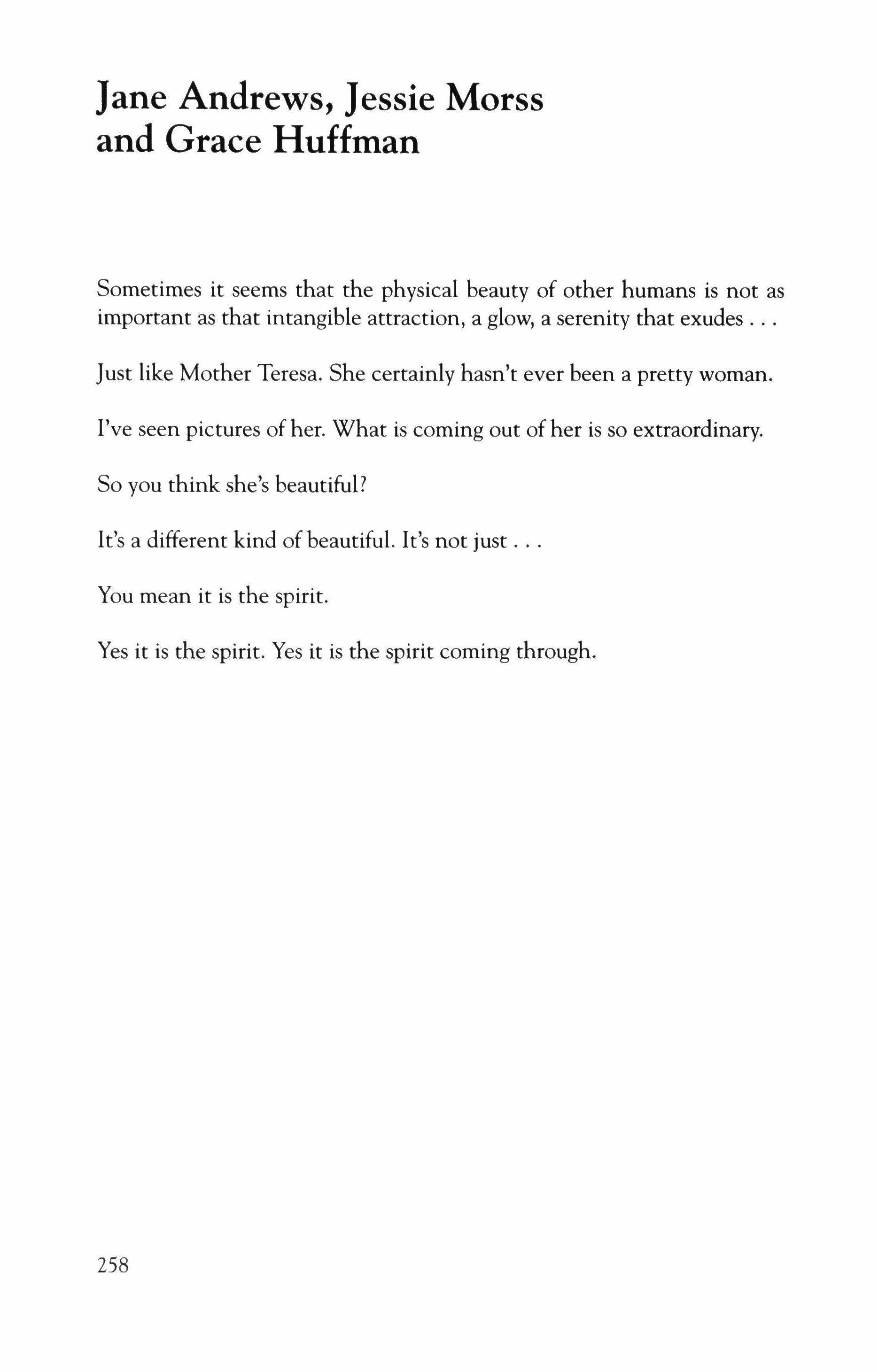

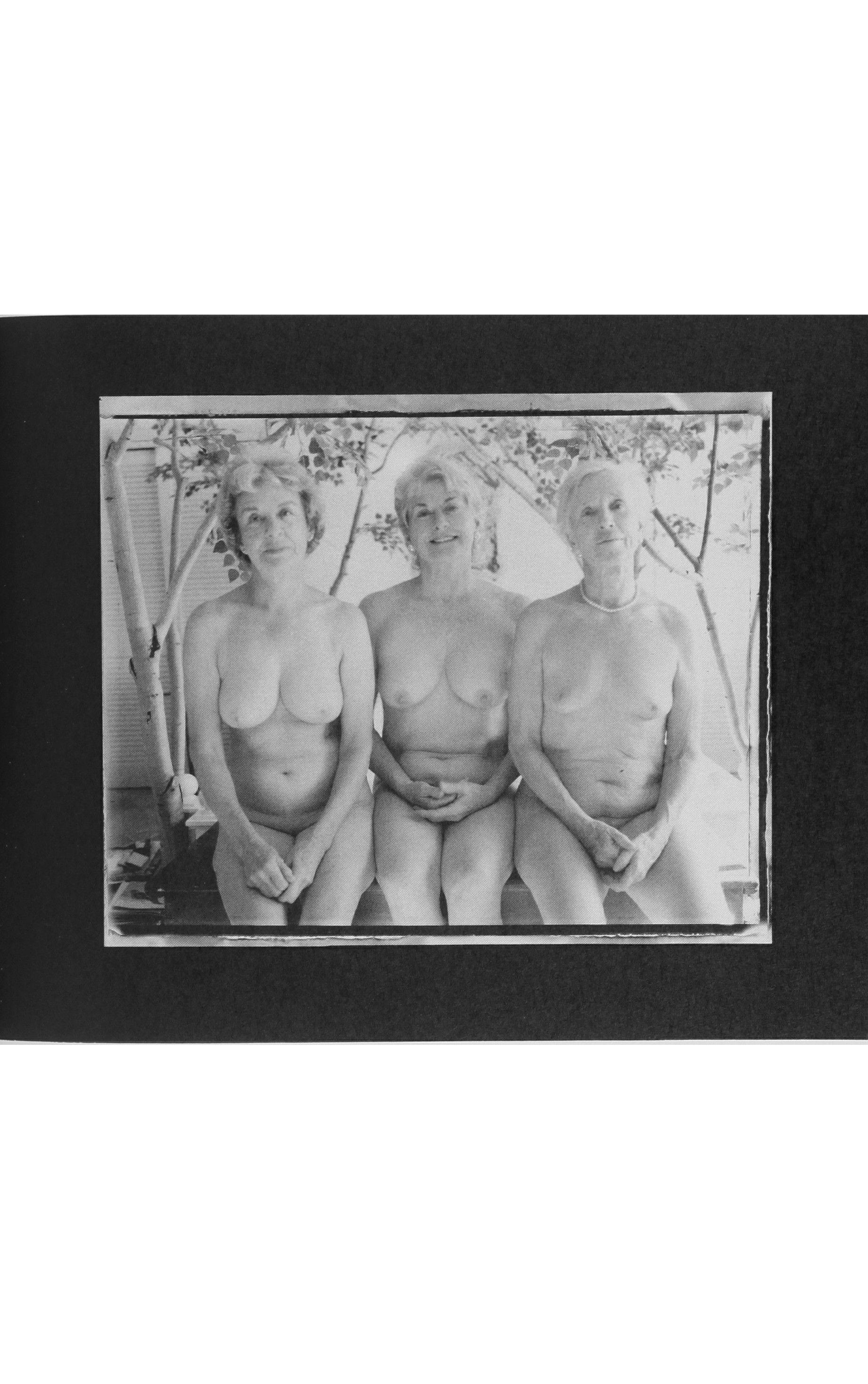

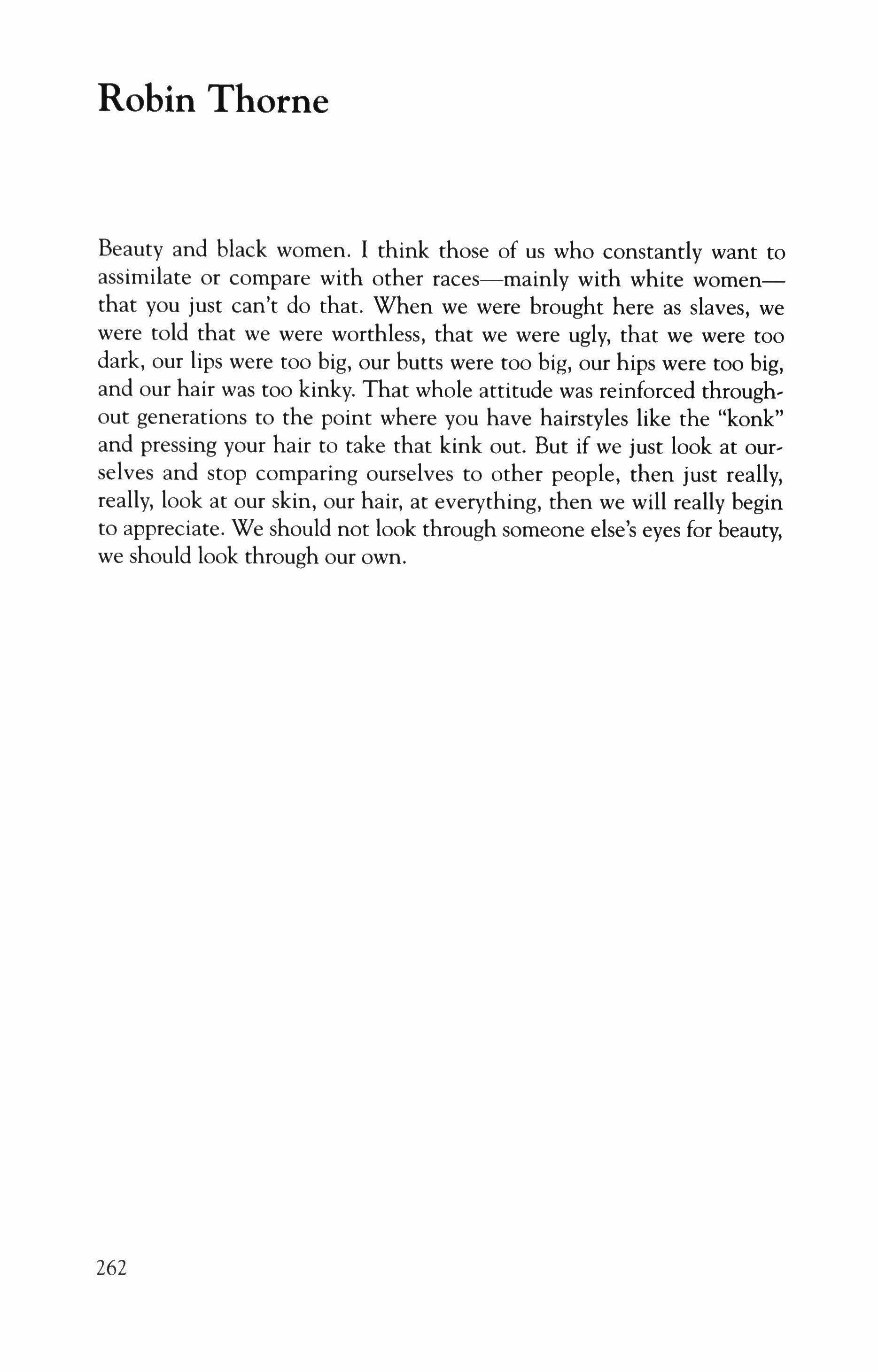

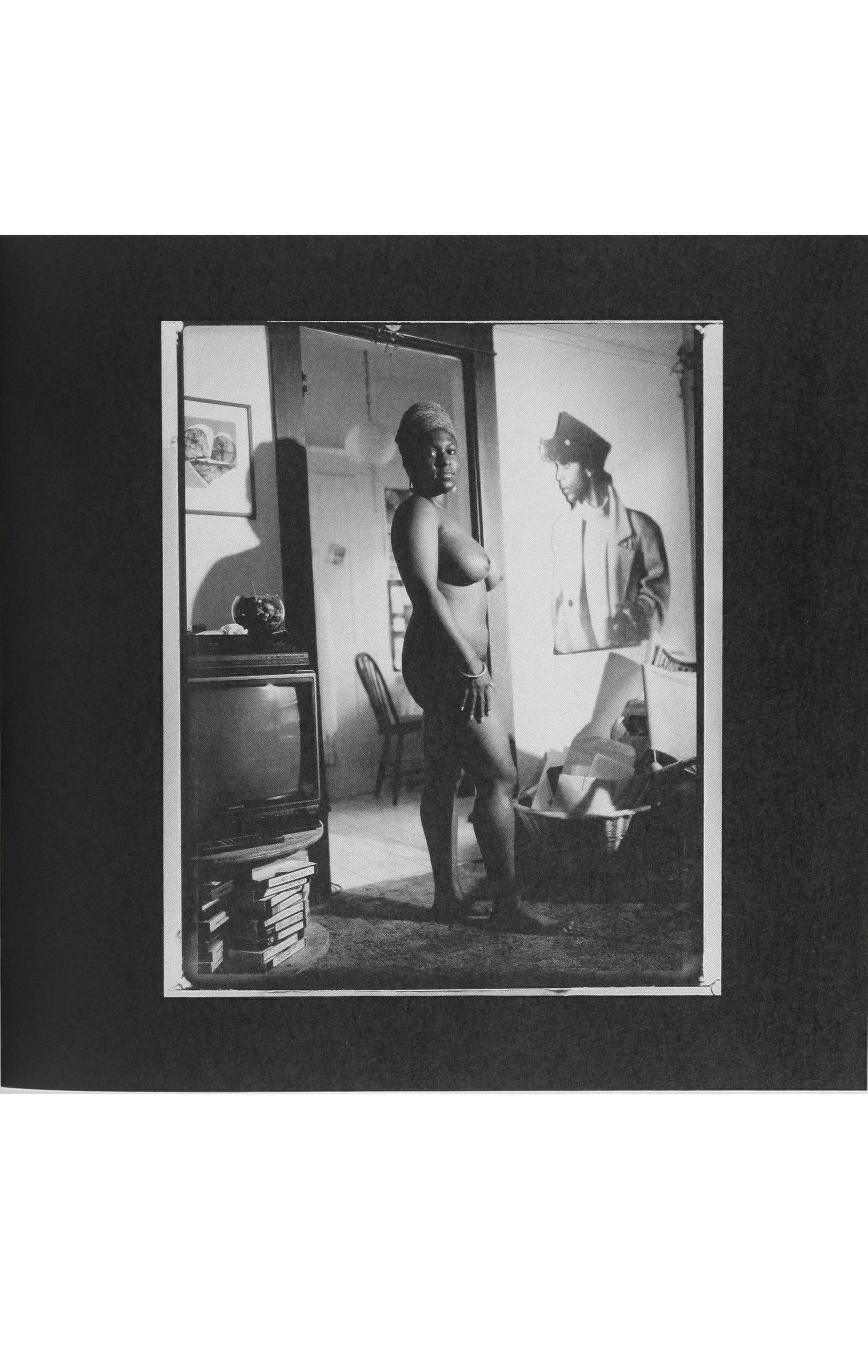

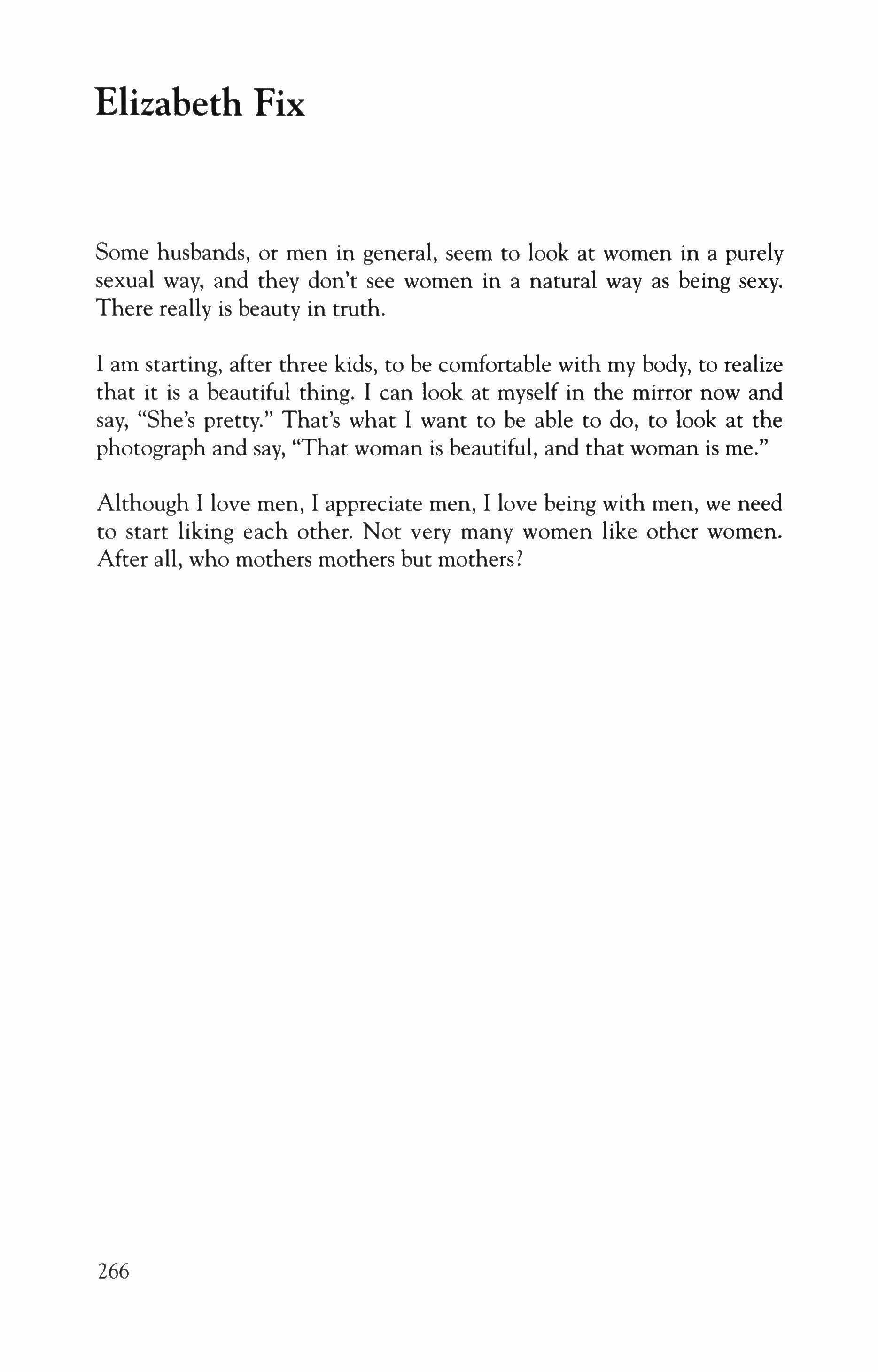

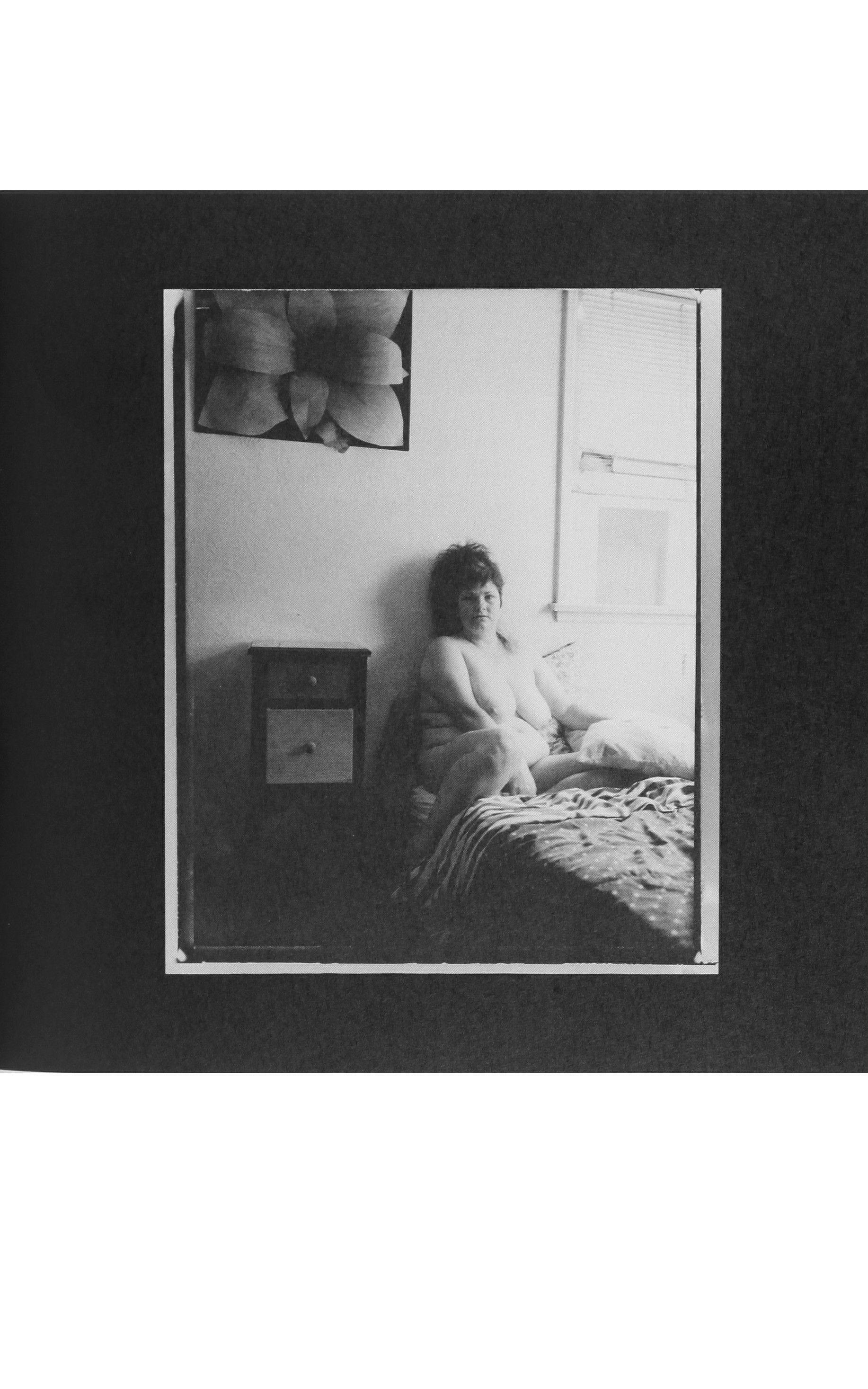

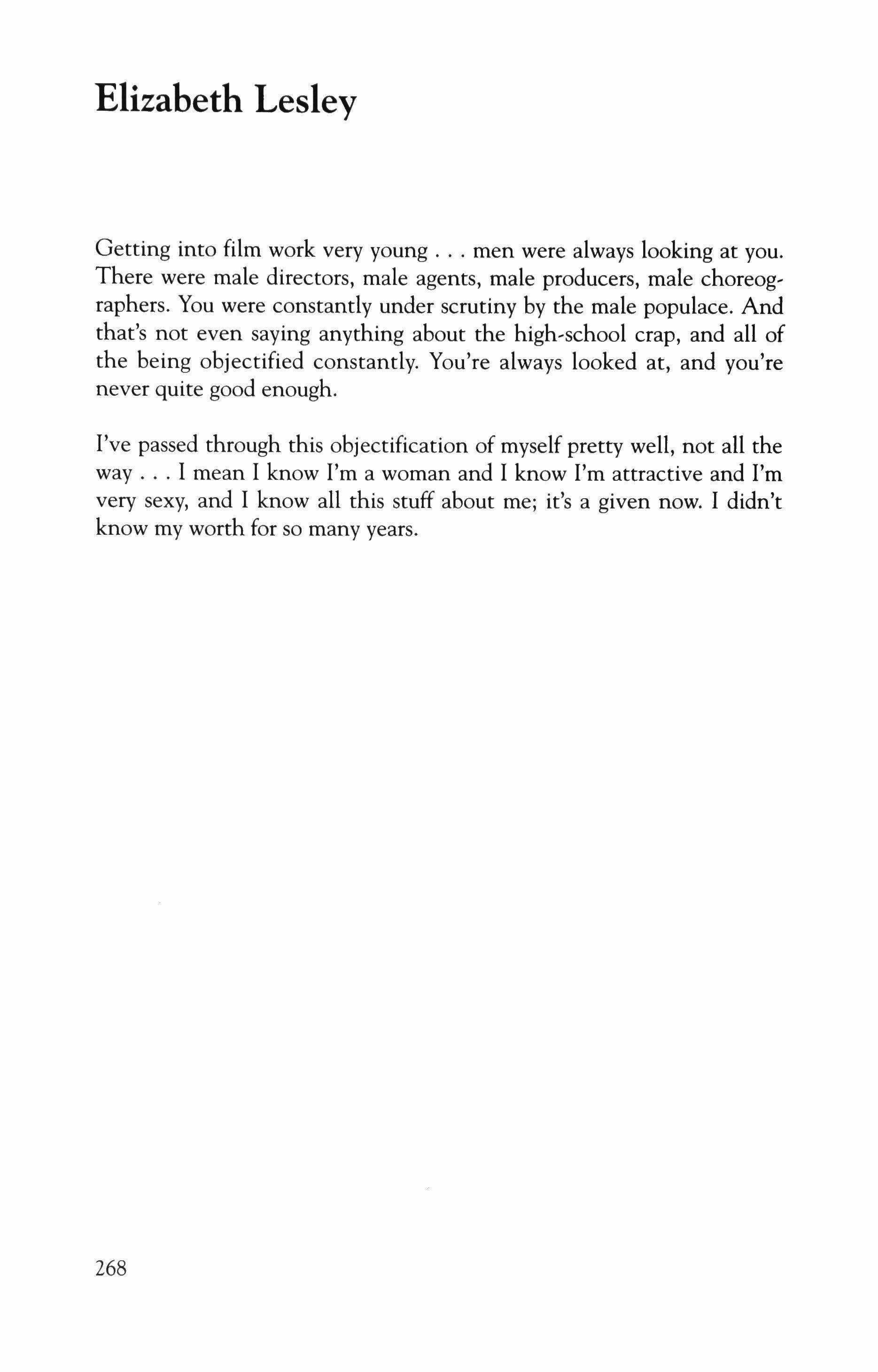

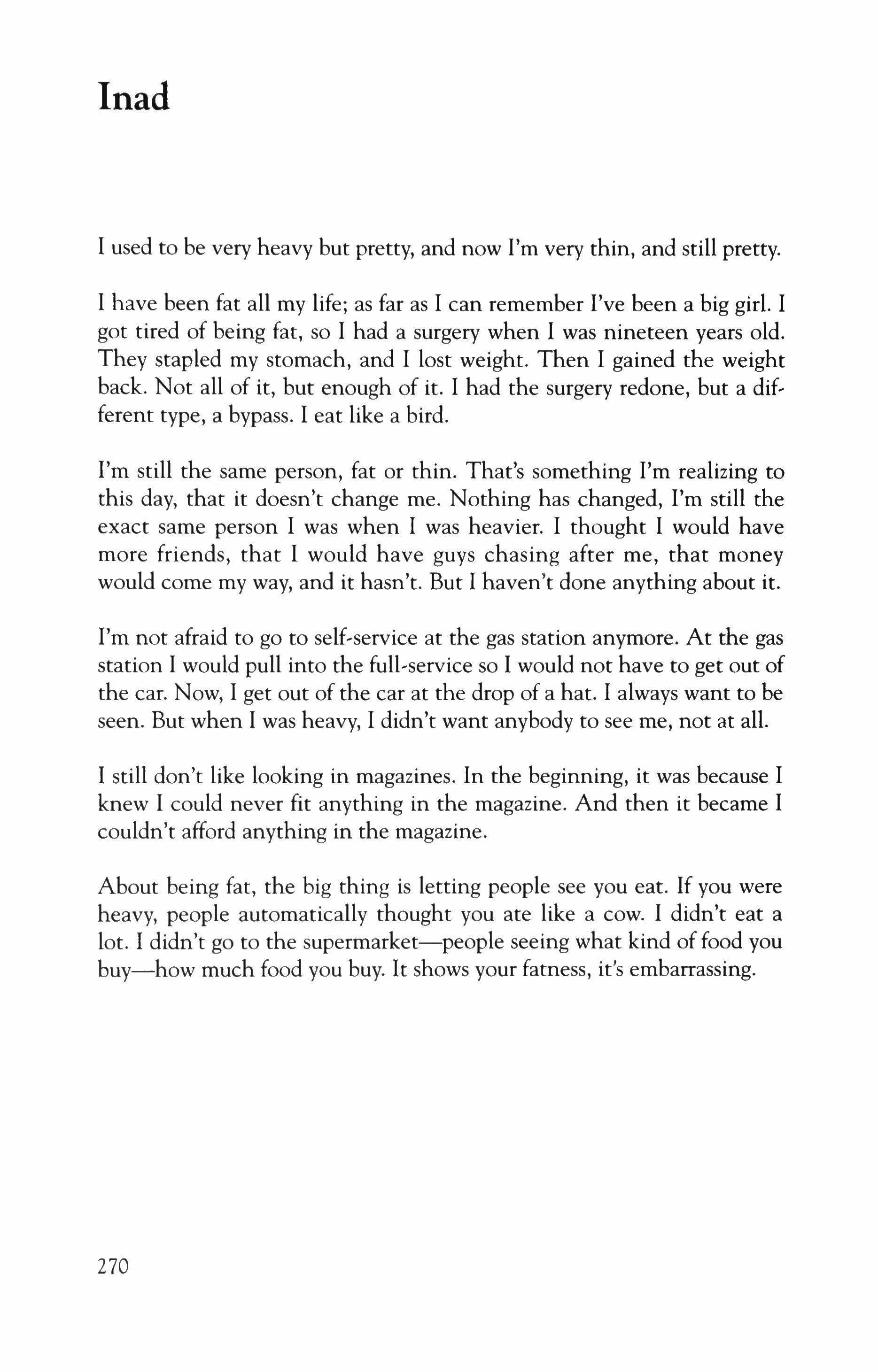

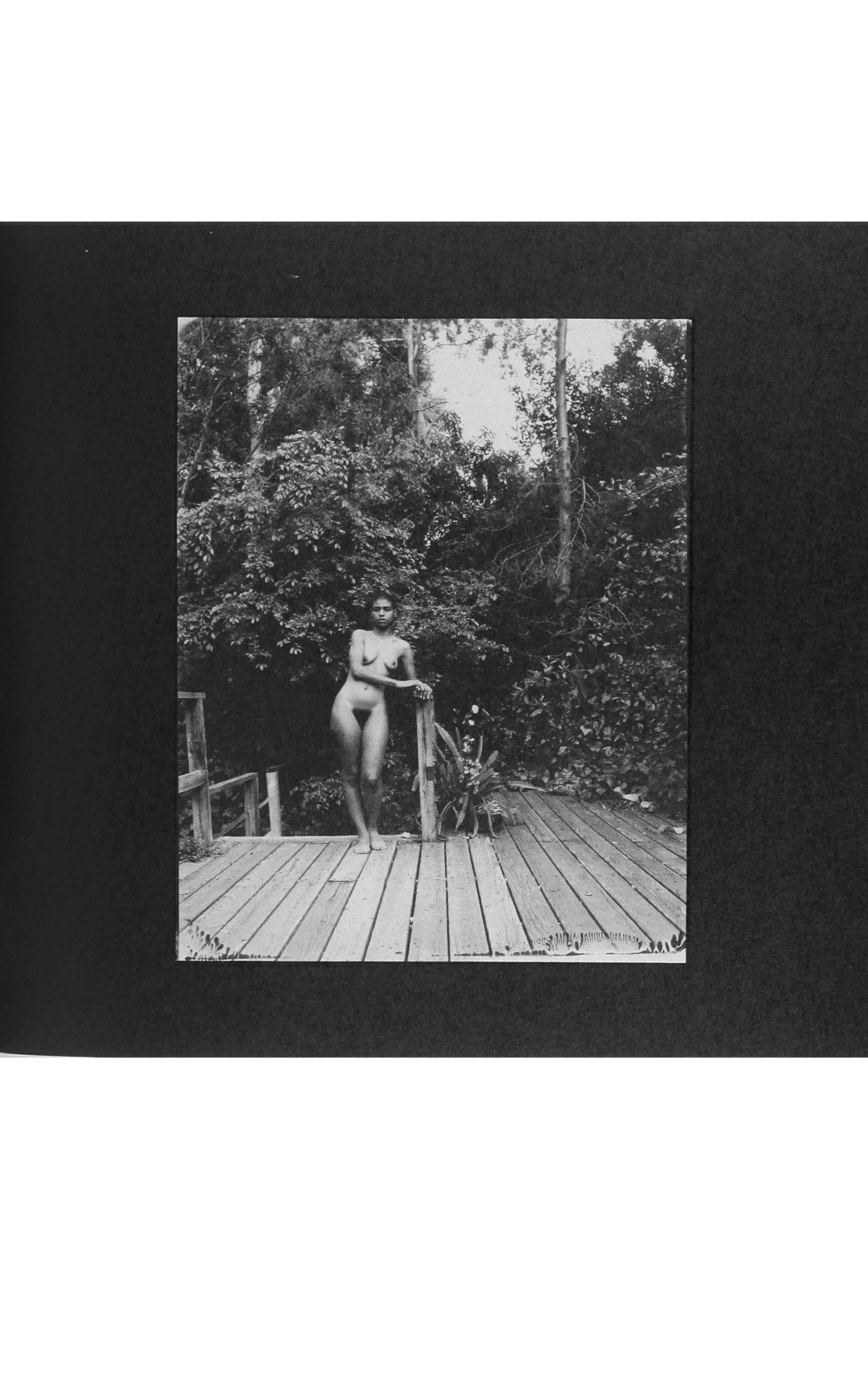

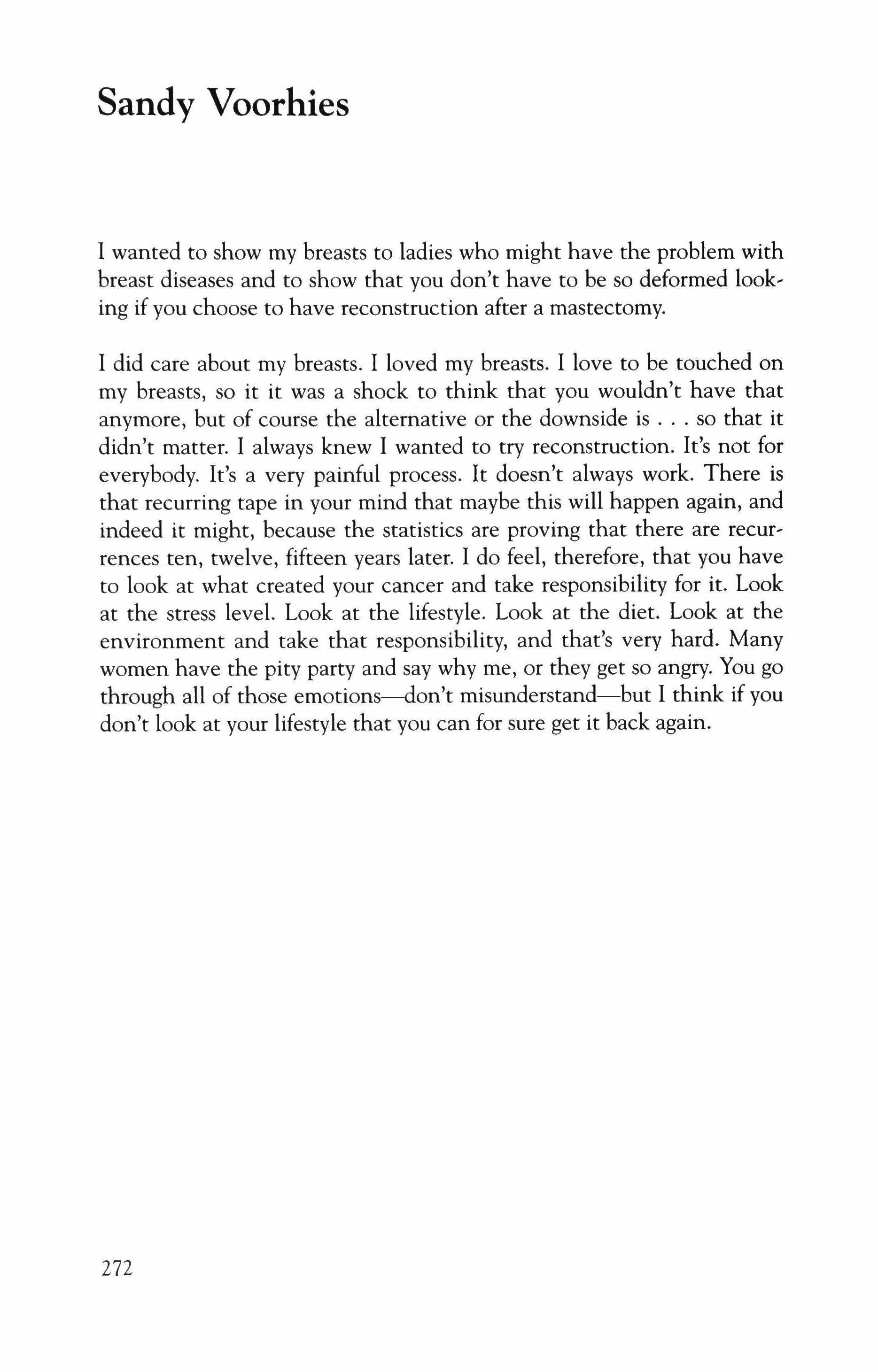

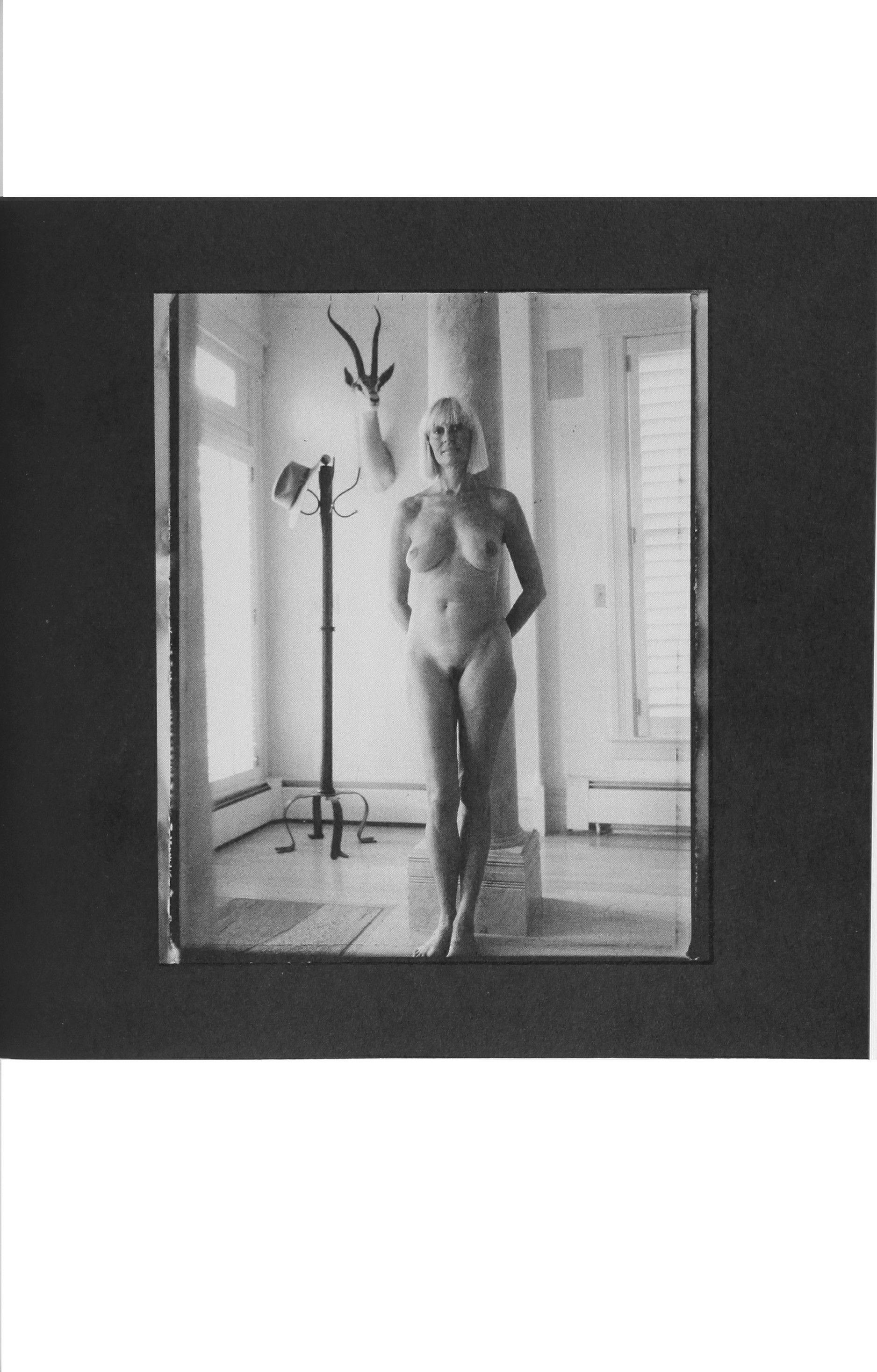

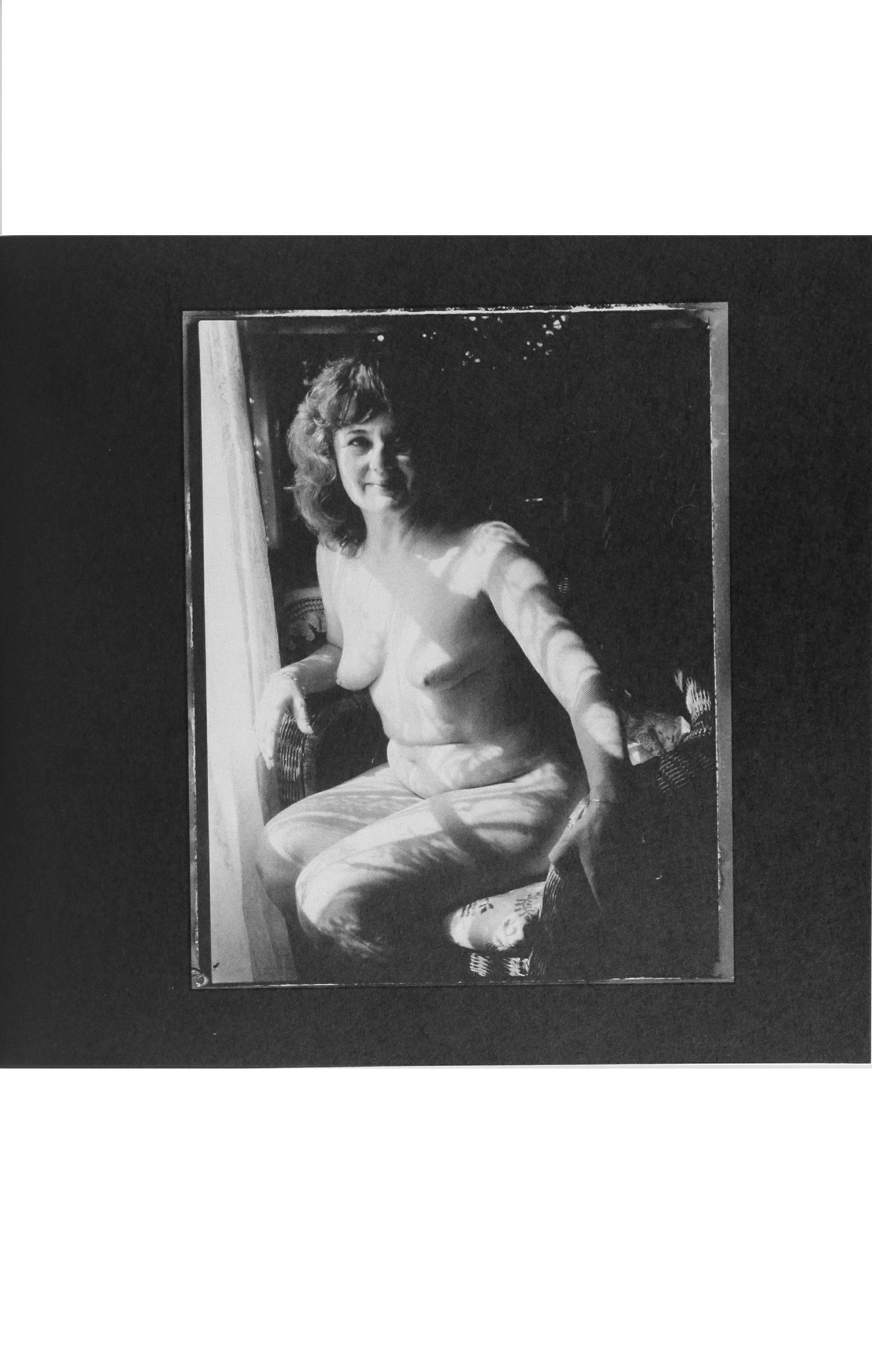

PHOTOS: "THE NAKED TRUTH ABOUT WOMEN,"

BY DIANE ROSENBLUM

• • • • •

• • •

• •

• • • •

•

• • •

•• • •

• • •

• •

• • •

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individual donors. Major new marketing initiatives at TriQuarterly have been made possible by the Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Literary Publishers Marketing Development Program, funded through a grant to the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

Please sign me up for:

o a two-year subscription for $36.

o a one-year subscription for $20.

Foreign subscribersplease add $5per year.

Please

subscription

Please

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY!

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY!

Name Address Or call us toll-free at 800-832·3615 to charge it! BI91

begin my

with issue# o a life subscription for $500. o $ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal.

sign me up for:

subscription for

o a two-year

$36.

one-year subscription for

o a

$20.

please add

Foreign subscribers

$5per year.

my subscription with issue# o

life subscription

o $ enclosed.

renewal. Name Address Or call us toll-free at 800-832·3615 to charge it! BI91 GIVE TRIQUARTERLY! Buy your first TriQuarlerly gift subscription for $20, and each additional gift subscription costs only $17!! 1st gift subscription ($20) Name Address Gift-card message Add $5/year forforeign subscriptions. o $ enclosed. Name Address 2nd gift subscription ($17) Name Address Gift-card message BG91

Please begin

a

for $500.

0 This is a

Tri(Q2(l,l]cal[f{1ce;[f�)f

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVENUE

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60208-4302

Tri(Q2(l,l]cal[f{1ce;[f�)f

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVENUE

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60208-4302

Tri(Q2(l,l]cal[f{1ce;[f�)f

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVENUE

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60208-4302

FALL 1994 BOOKS AND

BACKLIST

TRUDYLEWIS

Private Correspondences

Winner ofthe 1994 William Goyen Prizefor Fiction

This moral thunderclap of a novel portrays a teenagegirl who, attacked by violentevil, chooses not to flee it but to face it, and then to embrace it. Inprose that swingsbetween lyrical moments of illumination and gritty sexual insight, Lewis explores the darkheartof a misogynist culture.

Lewis's shatteringstudyofsexual violence and individual vulnerability is both timely and universally resonant. --PUBUSHERS WEEKLY

5 x 8 / 196 pages $19.95, cloth (0-8101-5033-6)

CYRUS COLTER

The Hippodrome

Set in a Chicago seething with physical and psychological violence, The Hippodrome is an examination of power and exploitation and their entanglement with sexuality.

In the tradition ofhisfictional ancestors, Dostoevsky andFaulkner, [Colter] has produced a work which uses the world ofeverydayreality in a manner beyond the scope of journalism or sociology--as an entree to the soul.

-James Park Sloan CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

51/2 x 81/2/214 pages $13.95, paper (0-8101-5036-0)

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years I Cronica de mis aiios peores

TRANSLATED AND WITH AN AFTERWORD BY JAMES HOGGARD

In this bilingual edition, an established Chicano poet describes with passion and elegance some of the American realities that remain absent from mainstream poetry. Villanueva voices complex and compelling historical, literary and cultural questions as urgent personal utterances.

Tino Villanueva won the 1994 American Book Award for his recent book, Scenefrom theMovie GIANT.

51/8 x 7 3/4/96 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5009-3)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5034-4)

MARC J. STRAUS

One Word

This first collection of poems by a physician combines poetic craft, medical expertise and a keen sense of human vulnerability to pain and suffering in an uncommon portrayal

of the complex and often troubled relations between physician and patient. With directness and power, Straus confronts matters rarely encountered in poetry. These poems are a fine addition to the scant body of imaginative work that speaks with authority from within the medical world.

51/8 x 73/4/80 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5010-7)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5035-2)

unuurt UD win AI Al1l1ttOID If JUts 10"'"

") Tin 0 Villa n u eva

'-_____

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

Completed while he was dying, William Goyen's Arcadio is one of the most affecting and imaginative farewells to life ever written.

Arcadio, whose voice is inimitably Goyenesque, is a creature from beyond the normal walks of life.

Half man, half woman, raised in a whorehouse and for years the veteran exhibitionist of an itinerant circus sideshow, he has escaped from the show and has been wandering in a quest for his lost family. Speaking intimately and secretly to the reader, he tells the bizarre and fantastic tale of his life.

148 pages $12.95, paper (0-8101-5006-9)

WILLIAM GOYEN

Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical Narrative

Chris, whose leg is injured, and his lover Stella, with whom he lives in a ruined, abandoned house; Chris's male nurse; Marvello, the circus aerialist; a lighthouse keeper; a flagpole-sitter in small-town America-these are the creatures of William Goyen's visionary fable of love, lust and loneliness. Because of its central focus on the erotic and its unusual novelistic form, Half a Look ofCain was rejected in the 1950s by Goyen's publisher. The first publication of this novel inaugurates a TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press plan to publish and reprint all of Goyen's out-of-print work.

[Arcadio] virtuallypulses with life; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldlycontemporary as well.

-Joyce Carol Oates

Goyen'sparamount concern is with the ways in which people connect, commune and create, with the ways they hurt and heal one another and with the capacity of everyone to do good or evil [Half a Look of Cain] is the work ofa gifted, intelligent artist.

-NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

220 pages $22.50, cloth (0-8101-5031-X)

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

This large anthology is a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today.

Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution.

-HARVARD REVIEW

afeastofreadingenjoyment. Gibbons's collection gives us people worth caring about and writing not afraid to be at once serious andjoyful.

-SMALL PRESS

448 pages $15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

ANNE CALCAGNO

PrayforYourself

Anne Calcagno vividly captures the textures of women's lives in this exhilarating collection of short stories. Her characters grapple with problems ranging from domestic violence to obsessiveness with bodyweight; the dramatic situations are extreme, edgy and utterly convincing.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye of a true storyteller.

-Larry Heinemann

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as a fifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a singlepiece ofwood.

-Lynda Barry

136 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5000-X)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5003-4)

Q + �

CAROL FROST

Pure

• A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and on the natural world that surrounds and shapes human life. Frost's poems bear the stamp of a thoroughly original artistic vision and style-they are discursive yet filled with concrete images; they inquire into moral issues (responsibility, pleasure, guilt, jealousy) without moralizing; they catch the echoes of western myths in domestic and quotidian events; they sharply diagnose relations

between the sexes.

For all poetry collections.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

PETER READING

Ukulele Music • Perduta Gente

Coo"tlhrlldcttHllte)'3r Im_.., �ct!q8'l<Nog>�<)a:td:.xJd �ro:n... �b:nI<nlobj,ad)O'�.

64 pages

$26.95, doth (0-8101-5029-8)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5004-2)

This double volume of poems is the first U.S. publication of an important English poet. "There is nothing safe about Peter Reading's work," one reviewer has written, and a storm of letters to the London Times and the Times Literary Supplement, attacking and defending Reading's work, has made him the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity, bitter humor and disconcerting honesty.

112 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5030-1)

$11.95, paper (0-8101-5005-0)

'----------------'

The Urgency ofIdentity: Contemporary English-Language Poetryfrom Wales

EDITED BY DAVID LLOYD

This anthology ofpoems and interviews is a double revelation for U.S. readers, presenting for the first time in this country the importantEnglish-language Welsh poetry of the 1980s and 1990s, and illuminating the complexity, constant flux and political implications of the poet's sense of inherited culture. These superb poems have been rigorously selected to showcase the Welsh poets' skill and seriousness, and the sensuous density of their language, which, like that of contemporary Irish poets, offers the reader memorable expressive riches and a striking depiction of landscape and society.

The featured poets practice their craft amid a lively cultural and political debate: although the number of Welsh citizens who do not speak Welsh has grown substantially in recent decades, cultural nationalists view English as the language of oppression. Thus, like Latino writers working in English in the U.S., the English-language Welsh poets create a divided art. Included in the anthology are John Davies, Gillian Clarke and R S. Thomas, among others.

244 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5032-8)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5007-7)

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise ofthe Impure:Poetry and the EthicalImagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today. These essays speak forcefully to the literary debates concerning the use of tradition, the openness of American poetry to diverse subjects, and the teaching of creative writing. This book should be read by any poet who teaches in the United States and by anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. It will become a benchmark for discussion of contemporary American poetry.

200 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5025-5)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5028-X)

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark LeKs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe Spinners

Winnerofthe 1993 Chicago Sun-Ttmes Book ofthe YearAwardin Poetry

AngelaJackson brings remarkable gifts to the articulation of African-American experience. Her poetry features an impressive variety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience.

Angela Jackson is a poet, novelist and playwright who has known,for long, what is rightfor her attention and scrupulous investigation.

-Gwendolyn Brooks

120 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5026-3)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5001-8)

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

Winnerofthe 1993 Terrence Des Pres PrizeforPoetry

Adversaria celebrates the rough beauty of ordinary life and laments its inevitable decline. These poems, titled in Latin, combine colloquial style with a late imperial tone to capture the stark contrasts and contradictions of a life lived between a steel mill and the quiet, graceful natural world.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence of a lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American.

-Li-Young Lee

104 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5027-1)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5002-6)

Wl (� O. TH( ,.tI T(��["C� P�fS ,,�,�£ fO� .o�.". rSC1rl(1 L

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodem trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -Alicia Ostriker

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

BRUCE WEIGL

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right alongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one ofthe bestpoets now writing in America. -Denise Levertov

80 pages

$17, cloth (0-916384-08-X)

$10.95, paper (0-916384-09-8)

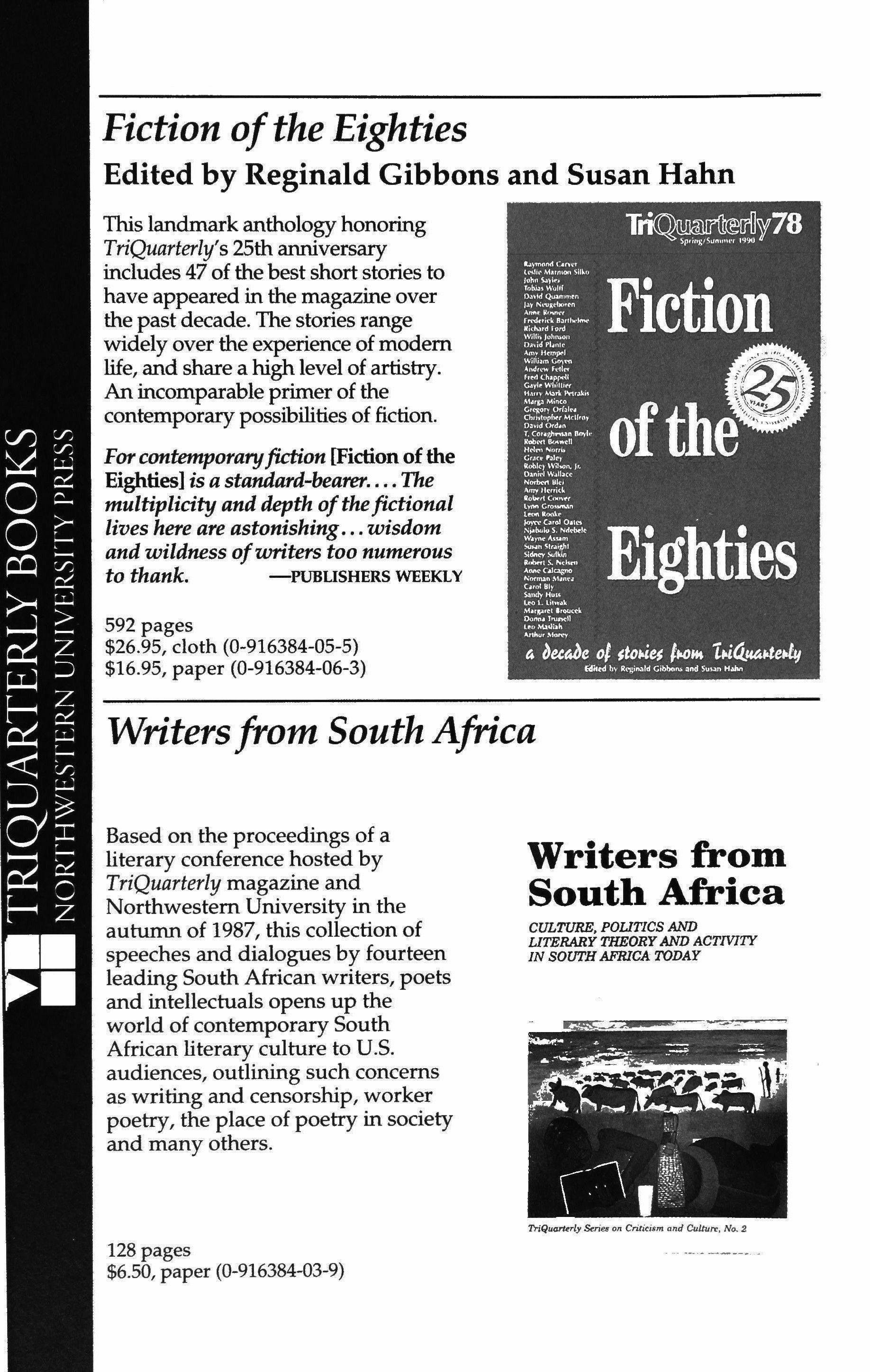

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out ofSilence: Selected Poems

EDITED BY KATE DANIELS

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state ofpublishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser'spoetry was out ofprint. So this is notjust another book: it is a restitution. -Eleanor Wilner

Thepublication ofOut of Silence is an event worthyofcelebration. Finally one ofthis century's most distinguished, misunderstood and undervaluedpoets is back in print The timefor a justestimate of Rukeyser's contn1JUtions is long overdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start. -THE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X) $14, paper (0-916384-07-1)

LINDA McCARRISTON

Eva-Mary

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Ever-Mary

1991 National BookAwardFinalist

Winnerofthe 1991 TerrenceDes Pres PrizeforPoetry

NOW IN A FOURTH PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance.

An immensely moving book,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories oftrauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace.

=-Lisel Mueller

Linda McCarriston

80 pages $10.95, paper (0-8101-5008-5)

Fiction ofthe Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

This landmark anthology honoring TriQuarterly's 25th anniversary includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared in the magazine over the past decade. The stories range widely over the experience of modem life, and share a high level of artistry. An incomparable primer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBUSHERS WEEKLY

592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-S)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

Writersfrom South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterly magazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialogues by fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to u.s. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

Writers from South Africa

CULTURE, POUTICS AND UTERARY THEORY AND ACTIVITY IN SOUTH AFRICA TODAY

128 pages

$6.50, paper (0-916384-03-9)

TriQuarlvly Series on Criticism alld CulluN!, No.. 2

Stephen Deutch, Photographer: From

Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989

A stunning gift book-with photos of Chicago over decades of change, including Deutch's Pulitzer-nominated photos from the Daily News. This collection and analysis of Deutch's work, with plates both in duotone and in color, is the first full record of Deutch's achievement to be published.

144 pages $45, cloth (0-929968-05-0) $23.50, paper (0-929968-06-9)

Order Form

Send this order form to: Nortbwl'stern l!nlversity Press Chicago Distribution Center t t030 South Langley AVl'nue (:hlcago, IL 60628 Name Address City State ,Zip Authorlfitie CUPR Quantity Unit Price Total Q Check or money order enclosed Q Mastercard/Visa number: Expiration Date Signature: Subtotal Shipping and handling* TOTAL *Domestic-$3.50 first book. $.75 each additional book *Foreign-$4.50 first book. $1.00 each additional book NW-123

Fall 1994

Editor Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow Christopher Carr

Readers

Deanna Kreisel, Matthew Kutcher, Charles Wasserburg

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Kemba Johnson, Jennifer Lewis

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $20; two years $36; life $500. Institutions: one year $30; two years $48; life $500. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, Il, 60208. Phone: (708) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions of fietion, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts received between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1994 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore; typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ) Bookpeople (Berkeley, CA); Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillio (Los Angeles, CA); Fine Print (Austin, TX)

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H.W.Wilson Co.) and the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.).

"Theng," a story by Susan Onthank Mates that appeared in TriQuarterly #86, has been included in The Pushcart Prize XIX: Best of the Small Presses (1994/95 edition). The anthology is being published in cloth this fall and in trade paperback in spring 1995.

Illinois Arts Council Literary Awards of $1,000 each have been received by the following poets for works that appeared in TQ #88: Steve Fay {"The Milkweed Parables"} and Sterling Plumpp {"Thaba Nchu"). TriQuarterly, as publisher, has received matching awards.

Susan Hahn, co-eduor of TriQuarterly and TriQuarterly Books, has received the 1993/94 Award for Poetry from the Society of Midland Authors for her book Incontinence, published in 1993 by the University of Chicago Press. Hahn has also received a 1994 Fellowship in Poetry from the Illinois Arts Council.

Contents Editor of this issue: Reginald Gibbons FICTION Super Night 23 Charles Baxter Her Crowning Glory 38 Eileen Cherry Trinitario 46 Jesus Gardea Translated from the Spanish by Mark Schafer Five Prose Poems 56 Mizuno Ruriko Translated from the Japanese by Edwin A. Cranston The One Handed Pianist 66 IUin Stavans Translated from the Spanish by Harry Morales Sunday After the War 72 William L. Giannotti Christmas Night 1962 78 Joyce Carol Oates SPECIAL SECTION: VOICES FROM CHIAPAS Introduction 87 Reginald Gibbons 17

A Letter from Rosario 93

Rosario Castellanos

Translated from the Spanish by Cynthia Steele

Nobody Lives in My Country Anymore (poetry) 95

Juan Banuelos

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

Don Chico Who Flies 97

Eradio Zepeda

Translated from the Spanish by Cynthia Steele

X'anton and the Fox l01

Tziak Tza'pat Tz'it (Diego Mendez Guzman)

Translated from the Spanish by Cynthia Steele

Like the Night (poetry) 107

Jaime Sabines

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

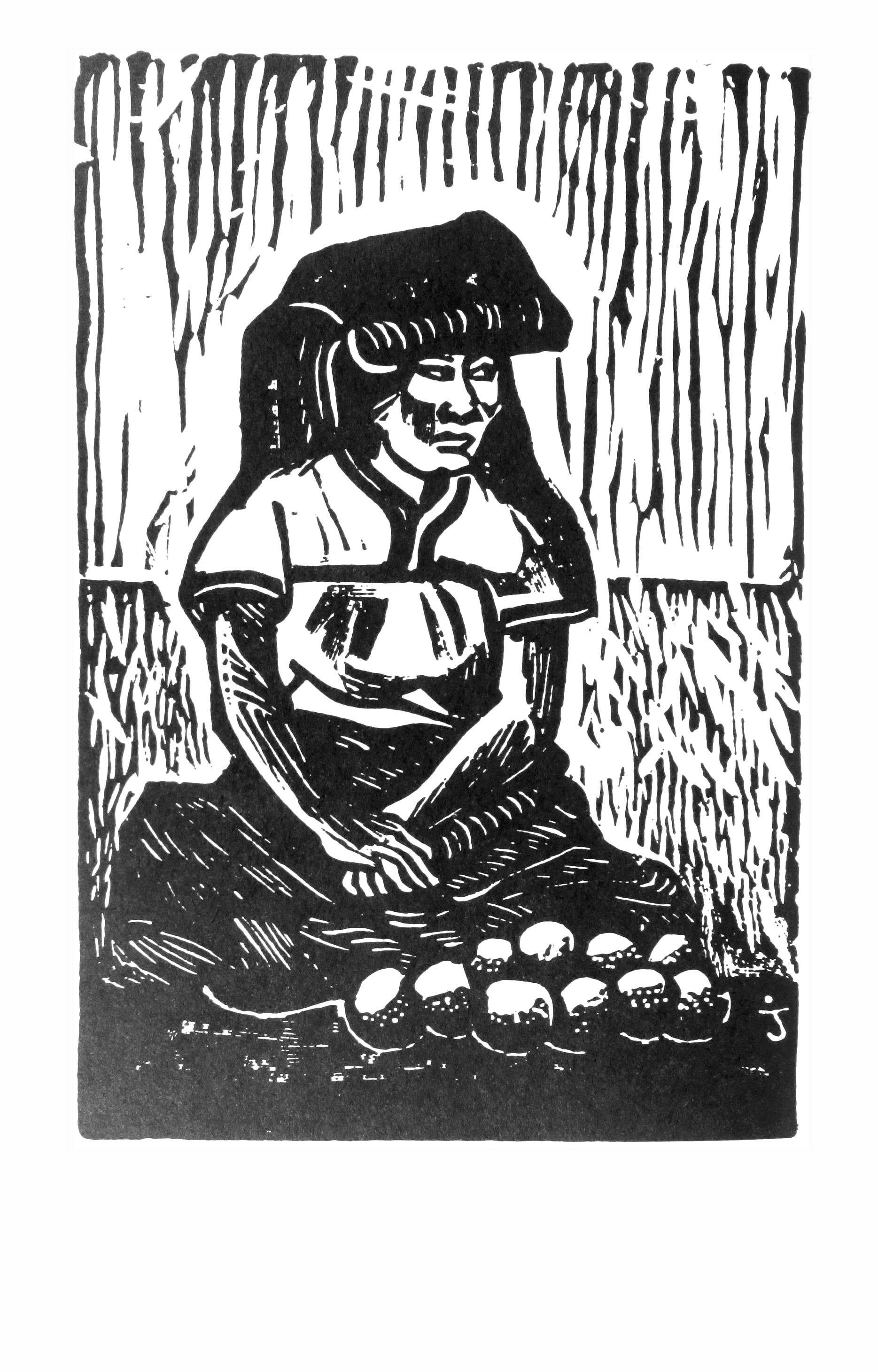

The Rooster and the Woman l09

Chavela Waris (IsabeLJuarez Espinosa)

Translated from the Spanish by Cynthia Steele

Landscape with Dead Anthems (poetry) 115

Ambar Past

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

Flood (poetry) 11 7

Efra(n Bartolome

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

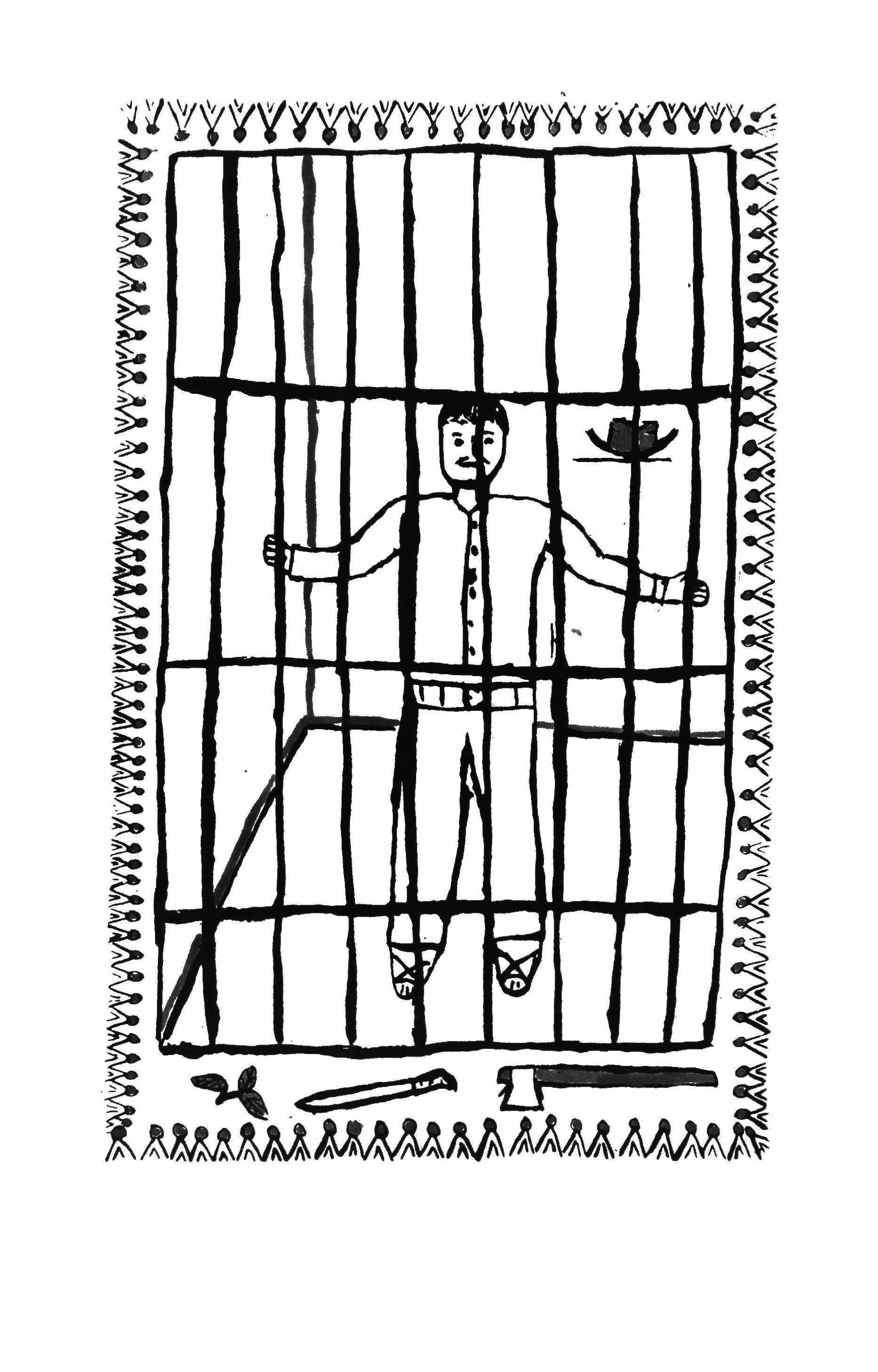

Letter from Subcommander Marcos (1) 119

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

18

Letter from Subcommander Marcos (2) 122

Translated from the Spanish by Brandel France de Bravo

Letter from Subcommander Marcos (3) 124

Translated from the Spanish by Brandel France de Bravo

From an Interview with Subcommander Marcos 127

Vicente Leiiero

Translatedfrom the Spanish by Brandel France de Bravo

Letter from Subcommander Marcos (4) 143

Translatedfrom the Spanish by Brandel France de Bravo

Found in the Armory of a Cyclone (poetry)

Raul Garduno

Translatedfrom the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons and Ambar Past

Jaime Sabines

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

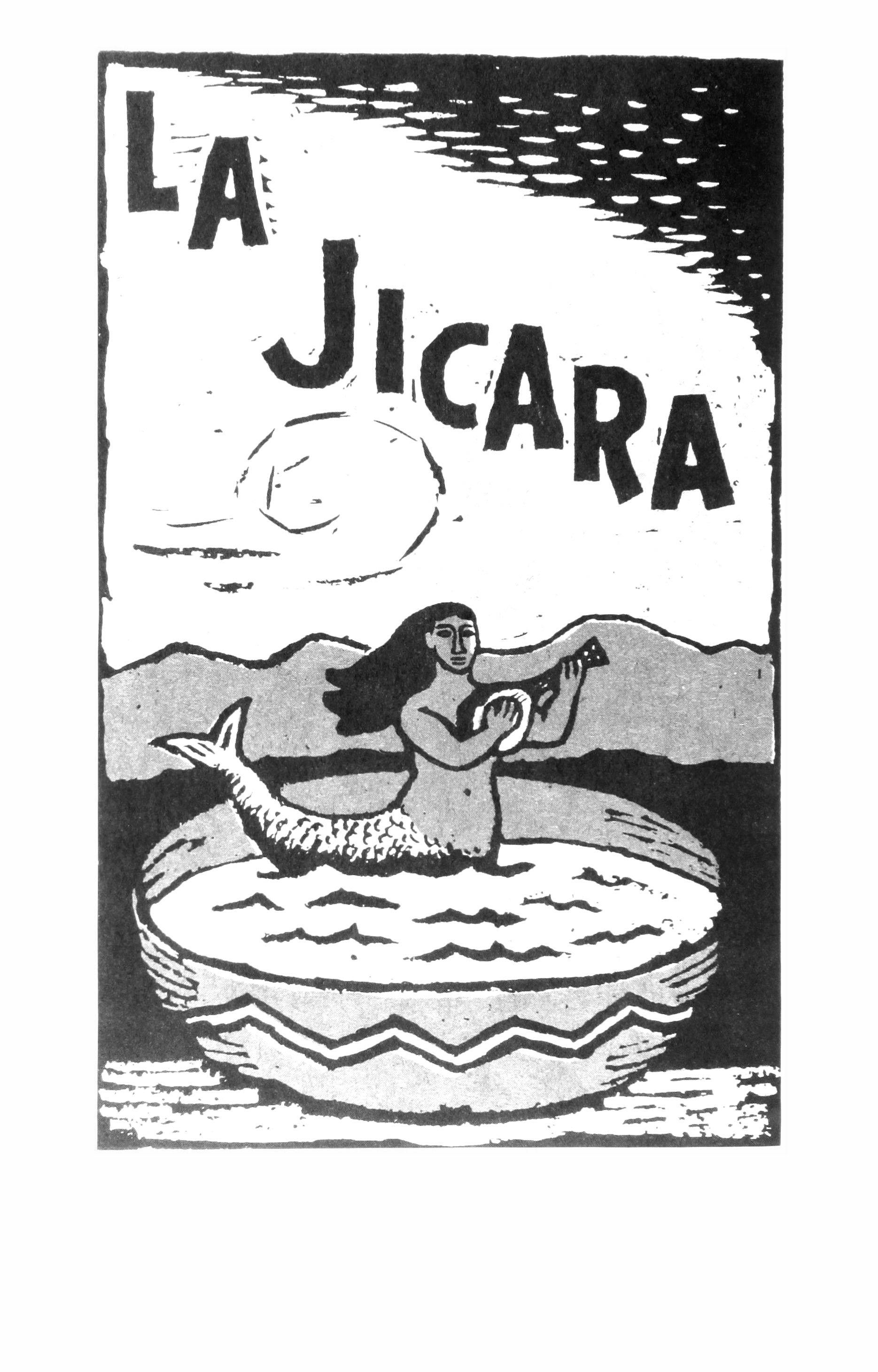

Chamula Carnival, 1994

Xunka Utz'utz'ni'

Translated into Spanish from the Tzotzil by Jan Rus

Translated from the Spanish by Reginald Gibbons

Translated by Reginald Gibbons and Ambar Past

146

All the Buried Voices (poetry) 147

149

Family Portrait (poetry) 154 ]oaqufn

Vcisquez Aguilar

POETRY The Brook; What To Do 161 Hayden Carruth 19

Shrine with Flowers 163 w. S. t» Piero Lamp; Cutlery; Turnstile 170 Heidy Steidlmayer Listening to Jets; The Tuba Player 173 Gary Soto Space Life; Old Things 1 76 Nancy Eimers Fish Crows 183 Don Stap These Are the Streets 185 Mark Solomon Silence and Dancing .•....................•.....••....••••..•• 186 Lisel Mueller F Train; Calf's Head in the Mountains Above Mexico City ••••.••••...••••..•••...................... 187 Pat Mangan The Blessed Word: A Prologue on Kashmir; The City of Daughters: A Poem About Kashmir 189 Agha Shahid Ali After Vermeer; After the Auction of My Grandmother's Farm •••••••••..•••••..........•.••• 196 Debra Allbery The Novel 202 Richard]ones 20

Land Rover; Teaboy 211 Kate Thompson Tuxedo (nocturne) .•...........•••.•..•....•••••••..•......... 213 Charles O. Hartman In the Time of Blithe Astonishments; The Mist Nets 216 William Olsen The Arrangement .••.........••....•........•.•.......•....... 220 Greg Kuzma Recovery 227 Robert Phillips The Bronx, 1942 229 Linda Pastan In the Long Run Like Governments; What Love Does ("With Tear-Floods and Sigh,Tempests") 230 Patricia Goedicke Blacker than Eve •.............................................• 238 Gerald Stern Poetry Slam? 243 William Harper SPECIAL SECTION: THE NAKED TRUTH ABOUT WOMEN Introduction and Photographs .....•..................... 245 Diane Rosenblum 21

Note: Contributors to the Voices of Chiapas section are listed at the end of that section, beginning on page 156.

Cover painting, The Watchman's Bird, by Tony Fitzpatrick Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

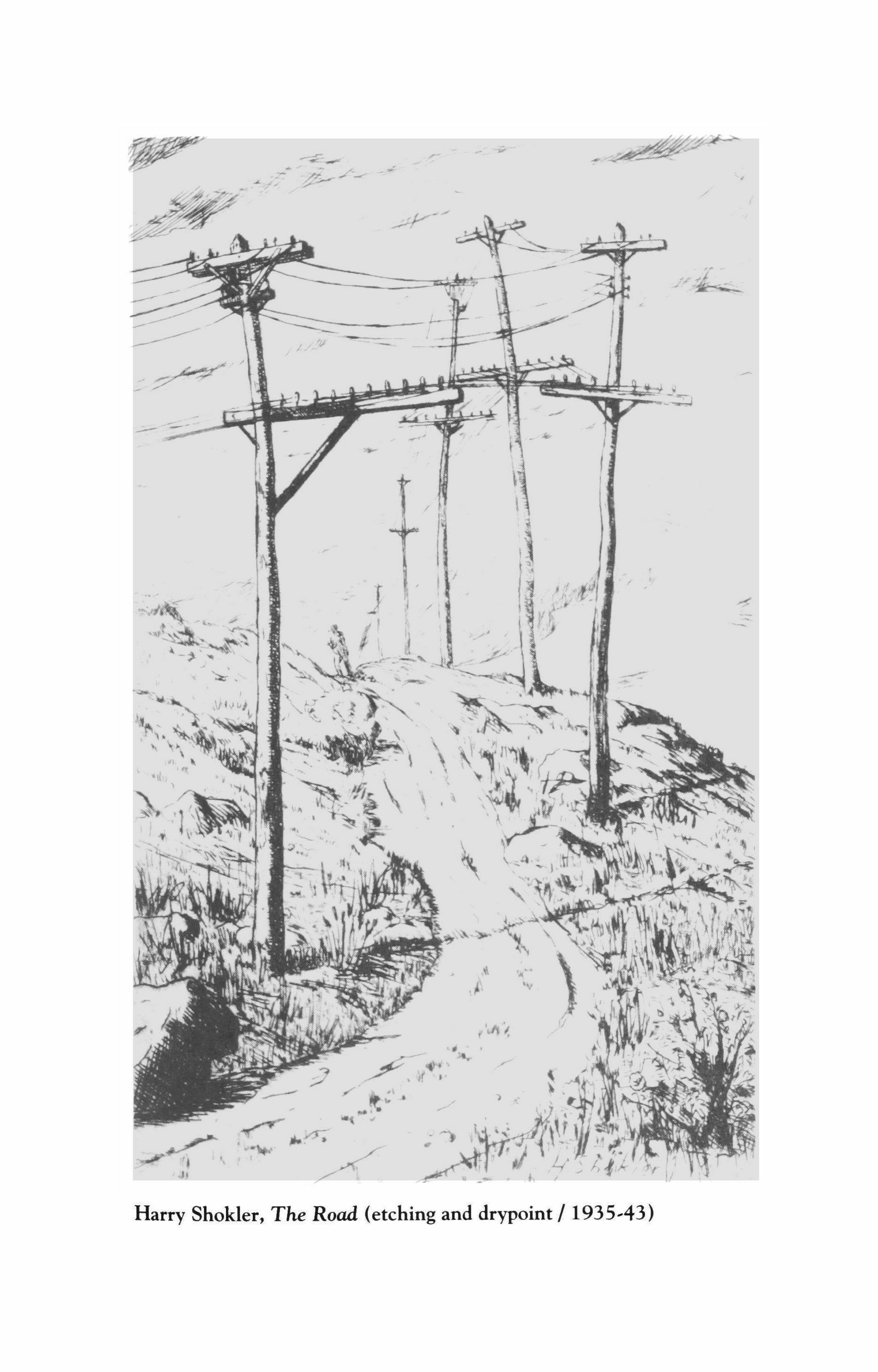

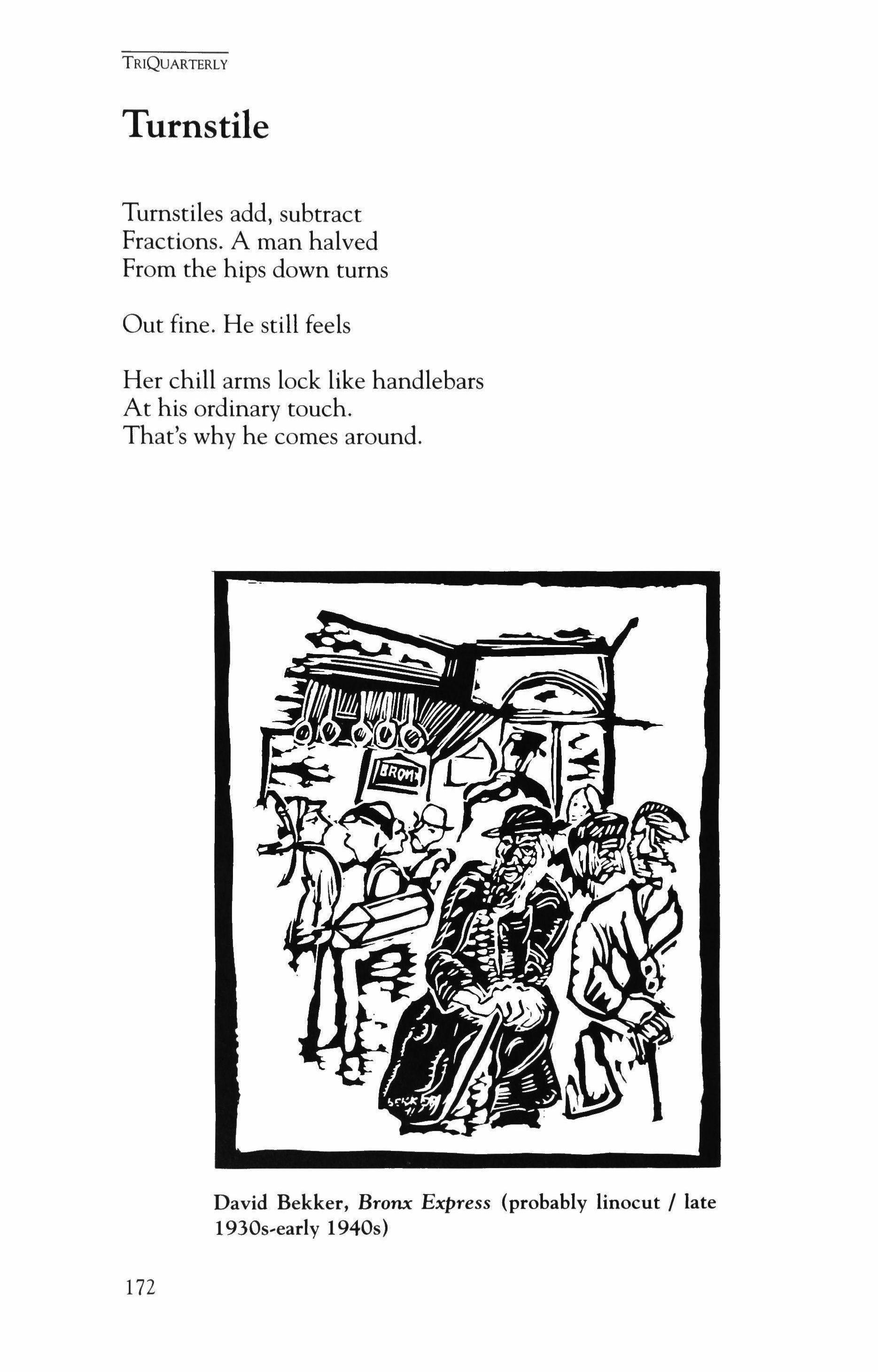

The Depression-era prints that appear throughout this issue (though not in the Voices of Chiapas section) were part of the exhibit, Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?, which was on display at the Mary and Leigh Block Gallery, at Northwestern University, for two months in spring 1994. Drawn from the gallery's collection of fine arts prints, the ninety-three pieces in the exhibit illustrated the social and aesthetic issues, ranging from political satire and social realism to modernist experimentation, which printmakers of the 1930s addressed in their work.

CONTRIBUTORS 277

22

Super Night

Charles Baxter

Earlier in the evening, while searching on the bathroom floor for her reading glasses, Irene Gladfelter had noticed a spidery damp spot on the wall under the sink. She would have to take care of it herself; her husband was out, having a beer a few blocks away in the neighborhood bar, The Shipwreck.

On her hands and knees, she'd worried at the wall-Walt could patch it up later-with a screwdriver and a chisel, making a small neat hole. Then she had remembered that the maintenance man should be per � forming such work, this wasn't her property, and the leak was really none of her business.

But she had found the pipe, rotted away with rust at one of its connection points. The water was dripping down onto a heap of razor blades, a small secretive pyramidal scrap yard. Snaggling the flashlight's beam inward, she saw the piles of edges, not all of them lying flat. A few stood propped against each other like sentries. This mound of blue blades had been inserted one by one through the old medicine cabinet's razor slot by Walt and by the unit's previous renters down through the millennia of shaving. The blades had rusted into a soft metallic brown. She unsettled herself by just looking at them. You thought something as simple as a morning shave wouldn't leave a trace, but then it did.

She hated the look of the dull blue metal. It made her shy.

She made her way back to the bedroom. She found her reading glasses on the bedside table, inside a green box of tissues. Inanimate things liked to hide. She had noticed this again and again. She undressed, turned on the TV, and got under the covers, spreading her catalogs around her in friendly disarray.

TRIQUARTERLY

23

Thursday was her husband's night out. At around eleven-thirty he returned home from The Shipwreck pleased with himself, ripe with cigarette smoke and beer. Knowing his habits, she always left a single breath mint out for him on the kitchen counter, and the fluorescent light on the stove burning, so he could see his way in.

With the cat snoring at her feet, she sat propped up in bed reading her catalogs and watching the movie on TV with the sound muted. Drawer organizers, peg-and-dowel wood wine racks: a physical pleasure that began at her spine and spread upward toward her forehead like a sunflower filled her whenever she gazed at objects she did not need or want. They were her suitors, and she brushed them away.

She liked these occasional evenings alone, these little shallow pools of rest and emptiness. Here was a swivel bookstand, there a typewriter table. The sunflower bloomed again. She glanced at the TV set. When she was in bed, by herself, she had a queenly indifference to the details of the stories. She didn't have to explain the plots to Walter, her usual task whenever they watched television together. Tonight she checked the screen now and then to see, first, a roadster bursting off a cliff into a slow arc of explosive death, and then a teenager putting a black shoe slowly and sensuously on a woman's foot. Apparently this movie was some sort of violent update of Cinderella. Now a man dressed like an unsuccessful investment broker was inching his way down a back alley. The walls of the alley were coated with sinister drippings.

She bathed in the movies more satisfactorily when they didn't make any sense. Tomorrow, at work, during her break, she could reconstruct what the sense was, but she usually didn't bother.

When she looked up from her furniture catalog, hearing Walt unlock the front door and trudge toward the bedroom, she knew the night had gone badly, just from the labored slush of his walk. When he stood in the doorway, his gray hair poking through his oil-stained cap, she forgot to ask him if if he'd taken his breath mint. He had a peevish expression. First he examined the television, then the bedroom window, as if he didn't know what to look at. "Walter," she said. "Now what is it?"

A garage mechanic, now in late middle age having trouble with his knees and his back, he could no longer stand straight. His upper body seemed to perch out at an angle from his waist, like a permanently bent metal beam. And he had pockmarks on his face from an attack of shingles. His spiky hair was his last spirited feature.

"The guy upstairs," he said. "Burt Mink. It beats anything. The guy upstairs is a damn criminal."

TRIQUARTERLY

24

She didn't ask Walter any questions. Burt Mink? The upholsterer? Him? The more awful the story, the better. But it could always wait. It would have to. With Walt, a person exercised patience. When you rushed Walt, he lost his thoughts' thread, and he became a meaningless old guy who could not make himself understood. He came from a family of reluctant speakers: even his mother had never been able to manage more than about twenty words a minute. His father and his two uncles had been laconic farmers in western Michigan, where every word spoken was begrudged, like a mortgage payment. Irene watched as he shambled off irritably into the bathroom.

She understood the slow procession of his moods and knew how to time them. And she was used to his fumes, the oil fumes at least. With their two sons grown and out of the house, the mechanic's smell made her think of her two boys when they'd been younger, teenagers dismanding cars in the garage, surly and sweatily handsome grease monkeys. That was when they'd all been living in the house on Mackenzie Street, before the boys had become men and had left, and she and Walter had moved to this apartment building north of Detroit to save money for their retirement. They hadn't saved any money. Selling that house had been a terrible idea. Once they sold it, she recognized that she had poured her feelings into every floorboard, every ceiling comer.

She heard Walt brushing his teeth and spitting. When he came out of the bathroom he still had his street clothes on. "There's a mess on the floor in there," he said. "Hole in the wall."

"I made it," she said. "I noticed a dampness."

He shrugged the information off with a somewhat alarming indifference. "I don't feel like getting into bed," he told her. "I don't feel like sleeping. I don't feel like any of that."

"You have to sleep. You'll have to go to work tomorrow."

He walked over to the wall facing the bed and adjusted a tilted photo, graph of their younger son in uniform. "I can go to work," he said. "I've done it before. I can work without sleep. I can't sleep thinking about Burt Mink."

"What about Burt Mink?"

He turned, not answering, and went into the living room. She heard him sit down in the reclining chair. It always sighed when people sat down in it. She heard him shuffling a pack of cards.

She fell asleep to the sound of the cards.

At four A.M. she put on her bathrobe. In the living room, playing cards were scattered on the floor like snow. To get to her chair she had to step

TRIQUARTERLY

25

on the jack of diamonds, the two of spades and the six of hearts. Walter was sitting there like a sentry, his hands on his knees, eyes wide open.

"So," she said, almost cheerfully, "what did Burt Mink say? What'd he do?" She was a lapsed Jehovah's Witness. She expected things to tum out badly. It used to excite her-how things always turned out badlybut not now, not anymore.

"You shouldn't hear," Walter said.

"I shouldn't?"

"Pigeon, you shouldn't hear a story like this," he said. He was trying to sound offhand but wasn't succeeding: his voice growled.

"Tell me anyway," she said.

The guy upstairs, the one down the hall, Burt Mink, said he had killed a child and was maybe going to do it again.

He had been completely drunk when he had said this. His mouth'd been open and his words were slurred, and his whole face was a mess, going every which way. He sounded like a man asleep but still talking, one of those still-functioning zombies. His head hung down and his nose got itself to within two inches of the bar.

They'd been talking about fishing, then cars. The guy'd already been drinking too much, and his voice got like a radio that was losing a station. The son of a bitch had been muttering about traffic, then about school buses, like he was interested in school buses. Nobody is interested in school buses. But this son of a bitch was. School buses, for chrissake. With little kids on them.

Somehow this creep admitted he had lured an eight-year-old boy into his car and then done things to him and buried him out at the edge of the county near an apple orchard. The kid had been wearing a yellow shirt. He was buried near an apple tree, what was left of him.

It hadn't taken very long.

He didn't say if he had learned the kid's name. The kid looked like an angel. He actually said that.

Nobody knows who I am, he said. No one ever sees inside anyone else.

Dead drunk but not sorry, this guy, like he'd been discussing the price of nails at the hardware store. Walter got up and left him there on his barstool at eleven twenty. They'd found themselves at The Shipwreck before, but this was the first time he'd ever heard anything terrible coming out of him.

He worked upholstering furniture, after all. You'd never guess this other thing about him.

TRIQUARTERLY

26

The living room froze for half a minute, then came to life again. Irene could feel her breath coming back.

"But that's a movie," she said when Walter was finished. "They ran that movie on TV last month. Remember? Maybe you were asleep. This boy in a yellow shirt was abducted, and the man buried the body in a grove of apple trees. It was the movie-of-the-week. The villain said that no one knew who he really was. Everyone went around saying, 'Yellow shirt, yellow shirt.' I didn't like that movie," she said, almost as an afterthought. "Dina Merrill was in it. She played a psychologist. Wore a pretty pink scarf. You just heard a plot summary."

"What?"

"It's a movie, Walt," she repeated. "He's telling you about a thing they broadcast last week. You didn't see it. But I did. He's confused."

"No. He told me he did it. He didn't say about movies. He said he killed an angel. That was our exact conversation."

Walt stood up and walked to the window, where he stood gazing out in a speculative posture, though bent as always. "Somebody's got to right the balance."

"Don't you do it," she said. "Drop that thought. Burt Mink just thinks he was a character in a TV show, that's all. He's telling you about the movie. That's his business, what he thinks when he's drunk, I guess. Nobody got hurt. I'd watch him, maybe, but a plot summary, that's what he was telling you. My God, Walt, people do worse than that, telling you about movies they think they were in."

She stood up to walk to her room and felt on her back that Walt was staying put, aimlessly thinking.

From the bedroom, she heard Walt say, "I believed him. That's the bad part."

At seven-thirty she put some bread out on the ledge for the birds and dropped a peanut or two on the front sidewalk for the chipmunk. A fine fall day, the air so crisp that you could see the Renaissance Center in Detroit if you looked straight south from Mrs. Gladfelter's bus stop. One of her boys worked in Detroit, and she worried about him sometimes, worried that he'd become part of the daily feast, but he was a big strong kid, a peaceful furry bear, knew his work and didn't go looking for trouble.

She wished she had brought along her new point-and-shoot camera. She had a particular sugar maple in mind for a picture that she planned to send to Ed Oskins's weather show on Channel Four. They showed a weather picture every day, usually a landscape, and she thought she had

TRIQUARTERLY

27

a good chance with this tree right here in Ferndale, growing on the boulevard across from the collision shop. This time of year, the sugar maple looked like a picture more than it looked like a tree. Bright burning red leaves rose from its branches, stopping traffic. It glorified that city block.

You couldn't imagine violent death happening on a day like this. It had to wait patiently for gloom and shadow, a few hours after dinnertime. Just like the movies, it had to have darkness, or it didn't happen.

The bus arrived, hesitated in a jovial roar of diesel exhaust, and Mrs. Gladfelter hoisted herself up.

Although the bus was not especially crowded, she sat down next to a pleasantly dressed woman in a light tan overcoat. Her straight brown hair was braided down one side. Her eyes were alert, more the exception than the rule on these buses. Mrs. Gladfelter liked to sit with other women if she could: less chance of funny business that way.

In the public tone she used with strangers, she said, "They've taken the flowers out." She pointed to a circular area in the median, the marigold spot. "Have you noticed how they put them in to form an F? The marigolds? An F for Ferndale?"

The woman in the tan overcoat turned to Mrs. Gladfelter. She said that she had noticed that, yes. They spoke for two more minutes before they turned back to their own thoughts. Mrs. Gladfelter exhaled. Normal people were sometimes hard to find on the bus. Frequently all you saw were people in various stages of medication. But today: no lost souls on either side of the aisle.

Considering the times, she felt pleased to have her job, checking out food; it was steady, and the manager was a kind man, and though the ceiling lights were too bright, like a toothache, and she had to be on her feet all day, the job had its compensations, especially now that management had installed laser scanners. She could talk to customers, briefly, if they initiated it, and sometimes she could chat with Shirley, her best friend among the other checkout girls.

The regularity soothed her. Food, processing, payment, bagging. The work's rhythms occupied just enough of her mind so that she didn't have to think about anything she didn't want to think about. She kept track of the prices. She wrote down the numbers of the check-cashing cards on the checks. She had no responsibility for judgment calls. It was like being an elevator operator.

TRIQUARTERLY

28

At two in the afternoon, she saw Burt Mink in her checkout line, two carts back. Looking hung over, one eye seemingly glazed and the other with a drooping lid, he was pushing a cart loaded with no-brand frozen dinners, and pre-cut vegetables for salads from the salad bar. He wore a flannel shirt with a hardly noticeable pale white stain. His wet stringy hair was combed over the bald spot at the top of his head, and he had a narrow rodentlike face with protruding teeth, but when he saw Mrs. Gladfelter, he smiled and waved, and the effect was so startling, his face abruptly transformed like that, a superficially ugly pleasantness, that she felt herself go dizzy for a moment before she waved back and continued bagging the groceries of a very young and very pregnant woman who had paid for her chocolates and eggs and ice cream with cash.

Well, after all, she thought, he's been here before. I've checked him through before, and we're neighbors. There's that.

"Here you are," she said to the pregnant woman, handing her her change. "Take care of yourself, honey. You must be due any day now."

"A week," the woman said, tottering out, and Burt Mink advanced in the line. She checked through the woman ahead of him while he scanned the headlines of Weekly World News. Coffee cups had been found orbiting in space. The surface of Mars had been photographed; Graceland, complete with swimming pool, had turned up in the pictures. Earthlings were being teleported to other locales in the galaxy. This was common knowledge.

"Mr. Mink," she said, smiling. "Good afternoon."

He unloaded his cart with all the frozen dinners in front, and he said grimly, "Yeah, but I had too much last night. I got to watch that." He smelled unclean.

"Yes," she said, checking his items through. The frozen dinners chilled her fingers. She thought ofhim eating the food, putting it into his mouth.

"I like to come here," he said. "A familiar face, you know."

"Well, we're neighbors, of course."

"Yeah," he said unpleasantly. "You're downstairs. But I see more of your husband than I do of you."

"Hrnm," she said. "Bars aren't for me. He tells me about it."

Burt Mink nodded. "Not much to see anyway. Not much to do but drink."

She nodded. "I'm better off at home. He tells me what people say." Burt Mink did not react, not a twitch or a glimmer, as he wrote his check. He had dandruff on his ears and another stain on his frayed gray pants. Even for an upholsterer, he was unpresentable. She couldn't

TRIQUARTERLY

29

imagine a woman who would have him. "Time alone, you know. Good for all of us. I'll have to see your check-cashing card."

He extracted his wallet from his trousers and with his scarred fingers began to flip through it. Next to the check-cashing card, in its plastic divider, was a photograph of a child, a boy, a school photograph, rather worn by now, an amazingly unattractive boy with an overbite and a narrow ratlike face, unmistakably Burt Mink himself. Did adults carry their own photos, as children, around with him? This adult did, anyway.

She felt a curious queasy sensation, seeing the rat-faced boy in the photo. She didn't recognize this sensation and wouldn't be able to say what it was. She wrote down his number on the back of the check. After saying goodbye and hoisting his two bags of groceries, he disappeared out of the store like all the other customers.

A harmless and ugly man, she decided, who worked upholstering furniture and who, after hours, imagined himself as a dangerous character in the movies. The movies were getting into everything now. They could spread over everyone, like the flu.

After taking the bus home, she carried her new camera to the corner of the sugar maple and the collision shop. She struggled to frame the tree in the viewfinder properly so that the wisps of vapor trails were visible against the very dark blue of the background, and after several tries Mrs. Gladfelter believed that she had managed it.

She had a simple dinner planned, beef stew, already in the refrigerator. She strolled over to the city park, two blocks west of their apartment.

Perched on the last building before the park entrance, a billboard asked HOW TROPICAL CAN YOU BE? The billboard showed tuxedoed men and sequined women dancing on the deck of a cruise ship. Underneath the picture was an 800 number for a travel agency. The men and women appeared, to Mrs. Gladfelter, to be imaginary. They possessed impossible honey-colored skin. Somebody had spray-painted the word FIRB over one of the women's faces.

Carrying her camera, Mrs. Gladfelter strolled into the park.

A man wearing a Hawaiian shirt and army camouflage trousers and flip-flops sat on the first bench, dozing, but still giving off an air of violence and moonshine. He clutched in his right hand a copy of the Ferndale Shopper's Gazette. She walked past him quietly, wearing her smile-armor.

Kids were kissing on the next bench. They looked about fifteen years old, the two of them, and optimistic, the way people did when they were

TRIQUARTERLY

30

stuck on each other, their tongues in each other's mouths. Making her way to a little rise in the park's center, she placed the camera on a bench for steadiness, pointed it toward the west gate and pressed the super night button, a feature that held the aperture open for two seconds. Then she put the camera in her pocket and headed toward home.

Just before she passed the man in flip-flops it occurred to her that if you were flying over this park at just the right altitude, the whole assembly, including the trees and the bearded man and the lovers and herself, might look like something-a face, or a letter, or a symbol like the F arranged in the marigolds in the middle of Woodward Avenue. But it might look like something else, something terrible and perplexing. She put that thought away and scuttled toward her building.

A few days later, when she picked up the developed film, she was delighted to see that the photograph of the sugar maple was good enough to frame. The super night shot, however, was terribly blurred: streaks of light crossed the sky in it, like meteors, and the west gate of the park had the appearance of fiery brown gelatin.

She put the photograph out on the dining-room table near the place setting for Walt's fork and knife. For the last several days, he had been quieter than usual, losing the thread of conversation, frowning into corners. She thought the photograph might cheer him up, now that autumn was here, the gray skies and soul gloom of winter.

That night, a Wednesday, he trundled himself in from work, and showered as he usually did, and had his beer and watched the local news, saying very little. She tried not to provoke him. When dinner was served, he sat down and began eating. Then he saw her photograph.

"What's this?" he asked. "This is your picture? You took this?"

She smiled proudly. "I'm sending it in to the weather show."

"It's nice," he said. "Real good. They should appreciate it."

He ate everything. He sopped up the gravy with a piece of white bread, and when he was finished, he placed his fork carefully in the middle of the plate and said, "I'm not going to the Shipwreck tomorrow. I believe I'll stay home."

"O.K. with me," she said, although it wasn't. She would miss her catalogs and the expressive solitary quiet. "But I'll bet Burt Mink'll expect you."

"Don't think so. He's had a thing happen to him."

"What thing?"

"Accident. Car accident." Walt rubbed his jaw with his fist. "He's 31

TRIQUARTERLY

banged up. Could have died."

"What?" she asked. "Where? How'd you find this out?"

"I heard," he said, not explaining. He shrugged for her benefit. "Then I called the hospital. He's in there all right. But they said it wasn't criticalor anything of that nature. Just a few bones broken. He wasn't wear, ing a seat belt. That part didn't surprise me."

"A few bones broken!" She showed her teeth. "Like saying a little fire claimed your house. Walter, what happened exactly?"

"Something went out in his car, brakes I guess. He hit a lamppole, but not one of the breakaway kind." He examined his fork carefully. "I heard he was speeding."

"Oh, Walter," she said. From the street a car honked. The chipmunk on the kitchen ledge scrabbled back and forth. "Walter, it was just a story! He never did anything."

"What? What are you saying?"

"You know what I'm saying. What did you do to his car?"

"Let's wash these dishes," he said. "Let's make some coffee and we'll clean up here."

She would not move. "I know you," she said. "I know your mind, and don't say I don't. Now answer me, Walter. What did you do, Walter?"

He sat up, as straight as he could with his bent back. He said, "I'm a mechanic. You can't ask me such a thing as that. Besides, it's technical."

"You could have killed him," she cried out, "and him with his only sin being ugliness!"

"No." He stood, but he still would not look at her. "No. He was drunk and he admitted his crime, and he got away with it. I couldn't stand that. I wouldn't tolerate it when I imagined him doing harm like that to our boys when they were youngsters, and I drew a line."

"What line? He's a crazy man," she said. "Just another damn crazy per' son like you and I see every day on the job. Ferndale's full of them, and Detroit's worse. He saw a story on TV. All he did was repeat it! And who are you to judge, and go and do such a thing to him and his car?"

"The only judge he has," Walter said to her, gazing into her face at last. She raised her hand to cover up the wrinkles. "Hell, I'll do it again. He shouldn't have talked that way. It was so ugly, it kept me awake. Imagine saying those things. I went and thought about it. It stayed with me, Irene. Stayed and stayed. Replacing brake pads, changing oil, there's in my head that boy in the yellow shirt. What kind of story is that, and him wanting to be in it, as the star?"

"You kept it going, Walter. It could've ended with him."

TRIQUARTERLY

32

Picking up his plate and taking it into the kitchen, Walter said,"Wasn't meant to kill him, exactly, what I did. Paralyze him, maybe. That was all. Put him out of that hobby of his." He rinsed the plates in the sink. "I'm not a vigilante. One night while you were asleep, I fiddled with his Chevy. I'm a good mechanic. I know what to do. Anyway," he said, smiling now, "I wasn't sleeping, thanks to him, and now I am."

"It was just a story!" she said, lifting her hands involuntarily. "Like that's just a photograph!" She pointed toward the sugar maple.

"Some stories you shouldn't tell," Walter said, "if you're in them. From where I sat, he had guilt all over him. True or not, I wouldn't abide it."

Suddenly Irene said, "Why do you people do these things to each other? Why do you?"

"What people are you talking about, Irene?"

"You" she said. "You guys. You gibber and jabber and then you just go after each other, fists and guns out, all because of the tales you tell, to make yourselves so big."

"No, we don't," he said. "Where did you ever hear it before?"

He walked past her, apparently at ease with himself for now, and headed toward the reclining chair, to finish the sports page. The chair sighed when he sat in it.

"I shouldn't have said anything," he muttered. "I should have kept you in the dark. It would've been better all around, that way."

That night she stood at the window in her bathrobe and slippers, sipping tap water from a glass with a scoop of vanilla ice cream in it, for her nerves. She was thinking of Burt Mink in the hospital, and of how, years ago, she herself had left the Jehovah's Witnesses, "defellowshipped," as they called it, after she had met Walter.

She had encountered Walter in all his salty early handsomeness when she and her father had been going door-to-door with copies of The Watchtower and Awake! Walter had been up on a ladder, cleaning gutters, and somehow found out her name before she'd reached the end of the block. He called her that night.

He talked her out of Armageddon. He replaced the wild beast 666 in her imagination with four-barrel carburetors and timing lights. Before Walter had come in her life, she could gaze at the bedroom ceiling and see Armageddon happening right up there, all the panic and terror. The truth had been explained. God was hungry for vengeance, thirsty for it. The clouds on Irene's ceiling boiled blood. She felt herself uplifted and groomed in all this bedlam.

TRIQUARTERLY

33

Then Walter took her for rides in his reconditioned Olds convertible. He showed her how to clean fish and how to swing a baseball bat. He said he loved her and repeated it so often she had to believe him.

After three months of Walter, Armageddon lost interest for her. Could an angel turn into a demon, out of jealousy? No. Did angels kill other angels? Probably not. Someone had made it all up.

And after her boys were born, she just didn't care to imagine the death of anything. All that prized calamity was just another story.

Men often puzzled her. A world war wasn't big enough for them. No, they had to have a universe war, and give it a fancy name that most adults couldn't even spell. This end-of-the-world story they could recount until they were blue in the face, going onto strangers' front porches, all dressed up for the sake of the bloodshed to come.

A strange appetite, like something in the Weekly World News, and she had once shared it. You certainly have to believe a lot of things to get through a lifetime.

She stood at the window and sipped her tap water and ice cream.

The soul calms down in middle age, she thought, but it does take some doing, getting it there.

"Pigeon, honey," Walter called from the bedroom. His voice faded and swelled as if someone were manipulating a volume control. "Where are you?"

"Here," she said. "I'll be back in a minute."

She was thinking that she'd call the hospital tomorrow and find out how Burt Mink was, maybe even talk to him. Just because he had a smile that made babies wail and cry didn't mean you couldn't ask after him. As she was toying with these courtesies, she saw a taxi pull up to the curb in front of the building, and there he was, the subject of her thinking, getting to his feet behind the opened car door, as if her mind had given birth to him-Burt Mink--coming out, wrapped in a raincoat and up on crutches. He looked like a bat in splints.

The cabbie carried his overnight bag to the door, and Burt Mink hobbled his way forward. He glanced up, gave Irene a smile that would freeze dogs and cats to stone, and then was gone, upstairs. After he'd disappeared from view, she waved at him.

Two days later around sunset she put a cooked chicken on a tray and walked upstairs. She knocked at Burt Mink's door, and for the longest duration she heard the sound of crutches being gathered and slippers

TRIQUARTERLY

34

whispering along the carpeting. After the door opened, and she saw the full distemper of his face, she wanted, rather desperately, to run away. Instead she said, "Hi. I brought you this." She handed the tray toward him.

"Can't take it," he grumbled. "I got my crutches."

"Well, maybe I can take it inside."

"Guess so," he said. When he exhaled, he sounded as if he were quiet, ly gargling. "Thank you." The words came out dutifully. "I'm much appreciative. You can put that in the kitchen there."

The apartment smelled of burnt lamb shank and curdled milk. The kitchen had few cleared areas: a careless convalescent man's eating space, marked by food spillage and catastrophe. She laughed to let the tensions loose. Then she peered into the living room. "Anywhere here?"

"Anywhere," he said. "I gotta sit down. My bones is all broken."

She tiptoed nervously into the living room. Burt Mink sat in a chair in front of a TV set tuned to a news station. The maladjusted color made the announcers appear to be greenish-purple. She heard the bub, bling of a tropical aquarium and turned to look at it. The aquarium rest' ed on an aluminum stand near a large ashtray filled with chewing-gum wrappers. At the bottom of the tank, a small metal deep'sea diver pro' duced air bubbles that rose to the surface. The diver's arms were thrust out as if in self-defense. Only two or three fish swam back and forth in the water, their eyes perpetually staring, astonished and frightened. They made panic-striken veerings around the stones and seaweed.

"Sit down if you want," he said. "The news is on."

"Everybody's mixed-up," she told him. "The color needs adjusting."

"Not for me," he said. He pointed at his eyes. "Color-blind. Rare form, the blues and the golds." Just then the screen flashed on her weather photo, the sugar maple she had taken such care to photograph. On the screen, the autumn leaves were a lush purple.

"I wanted to say something." Irene held herself against the living' room wall. "I wanted to say how sorry I was. How sorry I was and am about all of this. I'm sorry about your accident. I'm just so sorry. I'm sorry. I can't stop saying it."

"Well, thank you." He examined her with the fixed gaze of someone who may be making some sort of plan, or is considering an idea he has no intention of articulating publicly. With repellent politeness, Burt Mink said, "Go over there and look at those fish. You might like them. I got some neon tetras in there that're still alive."

She walked closer to the fishtank and was pretending to be interested in them when she heard Burt Mink say, "Jesus has a plan for me."

TRIQUARTERLY

35

"He has a plan for all of us," she said, on the other side of the tank. Through the water, fish darting in front of it, Burt Mink's face had a viscous, shimmering irregularity.

"That's not what I meant," Burt Mink said. "He told me I should despair."

"That can't be right," Mrs. Gladfelter said, as the air in the room suddenly took on the smell of the aquarium water.

"You arguing with Jesus?" Burt Mink asked. "That'd be something."

Mrs. Gladfelter noticed some dusty plastic flowers in a chipped vase on top of the TV set. Next to the vase was a bright red apple made out of glass. "I have to go now," she said. "I hope you're feeling better soon, Mr. Mink."

He shrugged from his chair. "I'm in Hell," he said. "That's a certainty. I could make you a map. But thank you for the chicken. I'm much appreciative."

"Oh," she said, reaching out to pat him on the shoulder. Even as she did it, she saw how pointless gestures of kindness were in this roomhow they went nowhere, and stopped right where they happened. Then a thought occurred to her. "You're color-blind? You've never seen a yellow shirt, have you? You've only heard about them. They're just news to you."

He didn't even bother to shrug. He gazed at her for moment with a face so emptied of expression that it seemed like one of those contemporary sculptures she'd seen in museums, so blandly abstract that it didn't stand for anything. He seemed completely absorbed in the TV set again, studying it, as if for a test.

Walking out, her skin puckering from an icy, airy chill that might have originated in the room or might have been in her own mind, Mrs. Gladfelter turned around for a quick last glance. The room looked like a cell inside someone's head, not her own, but someone else's, someone who had never thought of a pleasantry but who sat at the bottom of the ocean, feeling the crushing pressure of the water. An ocean god had thought up this room and this man. That was an odd idea, the sort of idea she had never had before, and it wasn't her own thought, she realized, but Burt Mink's.

She closed the door behind her, imagining the pile of razor blades behind her bathroom wall, maybe behind Burt Mink's, her own good intentions piled up, rusting, somewhere behind a wall, and she had to stop in the hallway for a moment to get her breath.

But in her mind's eye the boy in the yellow shirt appeared before her. His brown hair uncombed, child-debris all over him, a real kid stinking

TRIQUARTERLY

36

of sweat and mud, maybe a real brat, nobody's close friend. Who would trust him? What d'you want, lady? he asks her. Some respect, she said. O.K., he muttered, O.K., Mrs. Gladfelter, not so sarcastic now, sorry. What're you doin' here?

Just run now, she said, past that apple tree, do it, someone's after you, and she pointed, and the boy took off, arms and legs pumping, scabby knees and all, past the grove until he was a small vanishing point near the horizon, alive this time, free of murder, and she inhaled fully, taking the stairs one by one, thinking: he's gone now, I saved him.

TRIQUARTERLY

37

Charles Turzak, Grant Park (woodcut / 1931)

Her Crowning Glory

Eileen Cherry

The day I was baptized was like any other Sunday when I'd help Ma Dear with her bathing and dressing. I was to wait at her dusty dressing table until I was called. When I heard my name at last I had to rise and enter the moist enclosure of her barren bathroom to find her dripping hand extended, her shiny fingers seeking my shoulder. Her palm dug into my small muscles as I steadied myself. While she elevated her soapy body, rivulets trickled from its valleys and folds. The water in the tub sloshed, coughed and gurgled. She paused to make sure her feet were secure-then carefully-she pulled one shaky leg from the water. At one point her weight was totally on me as her dribbling foot jerked then lowered itself to the dry white towel I had placed on the cool floor. Secured. She moved her second foot.

She fussed under her breath. Her breath was landing on my face. She said that I could never move fast enough for her-or anticipate her thoughts. She hated giving directions and I hated concentrating on her needs just as much. I hated having to find things she had hidden in that room of hers, the one that smelled of camphor and rose petals.

I rubbed a towel across her back and she claimed I did it too hard. She snatched the towel and pushed me aside as she staggered into her room and plopped her wide behind on the side of her bed. I stood by and watched her finish toweling her spindly legs and swollen hips. She rolled on her side to wipe her lower back. I reached forward to help her.

"Naw-don't help me, silly girl!" she said. "Just get me my powder from over there!"

She leaned back on the bed and, lifting both legs, she toweled under her butt. Then, rolling up, she tugged at the flabby mound cresting her

TRIQUARTERLY

38

belly, dabbing and buffing the crevices under the great pouch. Her midriff looked like a brown buttoned pillow mounted by long sloping breasts, mutton-chop arms adorned with a half-moon scar where she had once been burned, and assorted pits and dimples. I had turned to the dressing table and couldn't distinguish the powder container from the morass of fancy clutter in the half light. She had all the brown window shades drawn, blocking out the morning brightness.

"Don't you see it?" she insisted. "It's there!"

I didn't see it. But I reached for it, pretending to know where it was. Just to silence her. My eyes, my heart raced. Just to silence her.

"Not there, stupid. There! There!"

I looked back at her, my hands reaching and fumbling over things on the dressing table.

"What are you looking at me for?!" Her eyes widened. "Oh I'm sick of you!" She slung the towel around and cracked me on the arm. "Get out of the way. Get me those things over there-on the chair!"

I went over to the chair and gathered her underthings. I held them as she searched the dressing table for the container of powder. Not finding it there, she sat back in disgust on the bed and studied me for a moment. Then she shifted her left foot and tipped a container of pale pink dusting powder over on the floor. As she bent to pick it up, I wanted to kick her square in the butt. Once she had retrieved it, she did not look at me, but began systematically sprinkling her limbs, her underarms and balding pubic area. She kept her eyes away from mine as she examined the clothing in my arms and snatched off the broad cotton panties. She rolled on her back and thrust her legs through them, carefully fitting the band around her swollen waist. Then she unraveled the bra, standing and bending forward like a Japanese sumo; she poured her ample brown breasts like coffee into the great white cups.

"Go get my uniform," she said, plopping once more on the bed to roll her beige stockings on. Carefully I placed her silk slip beside her and walked around the bed to the gaping darkness of the closet. The air in the closet smelled like tobacco, overripe grapes and allspice. Her white church uniform was secured under a protective plastic garment bag pinned to the wire and cardboard hanger by tiny gold safety pins. She wore it every Sunday she sat on the Mothers' Board and for first Sunday baptisms. I reached under the plastic and removed each pin, closed one, and put it in my mouth. I pinched the metal with my teeth. I remembered Ma Dear and I did this whenever we peeled onions to prevent tears. Feeling the cool clicking of the pin between my clenching teeth, I

TRIQUARTERLY

39

swooped the uniform into my arms like it was Cinderella or Sleeping Beauty. I swirled around and around, enjoying the freshness I stirred in the purple air of the room, a room so groggy and full of sleep, sweat and the light rose perfume of her dusting powder. As I whirled around in that very small space, feeling the warm, delicate cling of the plastic garment bag, I struck my toe against the base of the bed. I anticipated the pain.

"What in the world are you doing!" said Ma Dear. "My dress is not a plaything. You crazy as Deenie MacDaniel! Come here and help me fasten my bra. Why aren't you dressed?"

But I was dressed. She just couldn't see under the housecoat I was wearing. Ma Dear always had me put my dress on last so that I wouldn't mess it up. I had everything on but my dress. The housecoat was pink with a round lacy collar and covered with white hearts. My hair was pressed, pulled and rubberbanded into a little black pigtail cinched on the end by a white barrette. Wavy bobby pins kept the sides of my hair from jutting out like blades of black grass. My breasts were not impressive yet, so I wore a white undershirt, white slip and tights and my black patent leather dress shoes with the Minnie Mouse bows.

I draped the dress carefully on the bed and forgot about dancing with fairy-tale beauties. Ma Dear hunched over while I fastened the little metal claws on the back ofher bra. The safety pin clicked against my teeth.

"Get that thing out of your mouth. You don't need that pin in your mouth."

I slipped it into my pocket.

"Come round here," she ordered. She leaned forward and began sniffing me to make sure I wasn't musty. Then she sat back and studied me some more.

"Thought I caught a whiff of somethin'."

My cheeks tingled and my head raced. Then she spun me around when I finally met her approval.

"I just want to make sure. I'm not havin' you embarrassin' me. Now go put your dress on."

As I ran to my room, I thought about the notorious Deenie MacDaniel who was our neighbor and a sister in our church. Ma Dear detested crazy people. She was never fond of surprises and Deenie MacDaniel was always full of them. First testing Ma Dear's Christian patience when they sang in the Pastor's Choir, Deenie MacDaniel was a bundle of contradictions. Ma Dear was forced to stand next to her in the soprano section. To Ma Dear, Deenie MacDaniel bumped against her

TRIQUARTERLY

40

needlessly. Or sometimes she'd recoil violently from the most innocent touch, accusing Ma Dear of trying to be sexual with her. It got worse during one choir rehearsal following an argument mediated by the choir director: quickly spinning out of control, Deenie MacDaniel marched to the end of the center, consecrated aisle, bent over, lifted her skirt and patted her naked behind at Ma Dear and the other members in the choir stand. Ma Dear threatened to change churches. Pastor Ware counseled patience.

Deenie MacDaniel could have been a tall, bronze showgirl, but she was the mother of nine children and the wife of a dreamer, musician and handyman. She was under heavy strain. The strain meant people putting her in hospitals, having nappy-headed children with no shoes, episodes of walking outside naked, sometimes balancing one of her small babies on the top of her head like an African urn. Those were moments I thought she looked so bizarre, but so beautiful. She would be smiling as if she were in touch with some great vital force that had pulled her out of her clothes and made her walk before the world so we could see her great brown primeval beauty. She walked. Everybody gawked and Ma Dear called the police. Ma Dear's eyes would be transfixed on her, but unlike the other mothers of the church, not one modicum of pity could be found in them. Ma Dear's eyes would freeze over, watering and blinking only when she turned away.

Once my white dress was on, I returned to Ma Dear's room to find her fully clothed and primping in the mirror. She had yet to raise the shades in her room so she was grooming herself by the dim glow of a little angel lamp on her dresser.

"Now, she said, noting my return. "Get me my new hat."

With excitement I reached for a large hatbox she had positioned on top of the chest of drawers. I placed it on the bed and opened the great oval top.

"Have you washed your hands?" she snapped.

"Yes m'am," I lied, scooping the large lovely bonnet into my tainted hands. It was a cornucopia of weaved whiteness, a flying swan, ornamental blossoms and grape leaves whirled into a crown with a brim like a ship's bow. I tugged the ball of paper tissue that held the crown's shape and let it drop into the box with the price tag. I assumed my station behind Ma Dear as she gazed upon her own face which looked suspended in the mirror. Like a royal lady in waiting, I held the great white hat. Raising the hat in my hands, I noticed I was only a dim silhouette in her reflecting glass, her little angel lamp not illuminating me at all. Her

TRIQUARTERLY

41

newly powdered face and great white shoulders filled the dark mirror like an evening moon. She raised her hands and I placed her crowning glory on her fingertips, then she lowered it to her head with the slow and serious precision of a coronation. I watched all this while trying to discern the whites of my eyes in her mirror, with little success. Once Ma Dear's portrait was sufficient in her own eyes, she adjusted her hat with a tap of her finger and sighed.

Cousin Claude was coming to pick us up. I waited in the living room with a three-day-old sheet cake and Ma Dear's large-print Bible. I had wanted a taste of that cake so badly when it was first made. But Ma Dear never allowed it. I was told not to touch that cake until the proper time. So there it sat, under transparent wrap on the milk-white surface of the kitchen table smelling of lemon and cane sugar, gathering dust on the surface of the cellophane. I was always wiping around it with the dishrag, pressing and tucking in the loose ends. Now here it sat, next to me with an added blanket of aluminum foil, with no fragrance at all and hardened icing. The smells of bacon and bath soap were still heavy in the air and the windows frosted lightly from the humidity. Ma Dear told me not to jump around because I tended to give off an odor if I got sweaty. I sat and meditated on Jesus and all the things that were planned for this most important day in my life.

Ma Dear entered the room, studied me for a moment then disappeared into her bedroom. She reappeared holding a white ribbon between her fingers. It was the one that had decorated the hatbox. She smoothed my unruly strands of hair. Then I felt her fingers working and designing a bow for my lone pigtail. She had roses in her skin and peppermint rolling around in her mouth. When money was short, she used vanilla extract and citrus peelings. But on this day, instead of a smooth storebought mint, she offered me the natural bitters of an orange skin to sanctify my mouth. She turned me around and brushed the comers of my lips.

"Smile," she said. I showed her my teeth. She smiled back then pressed her warm, dry lips into my left cheek.

"Ma Dear, you look so pretty," I said. She had added a corsage of silk flowers, rouge and a set of pearl earrings.

"So do you," she answered. "God bless you this morning, child."

"Wow," said Claude, soaking in Ma Dear's noble appearance. "Whose baptism is it today? You look like you going to see the king."

TRIQUARTERLY

42

"Don't walk your Auntie up to heaven so soon," she warned. From the front seat, she reached into her purse and handed me a starburst of peppermint. I was in the backseat of Claude's Chevrolet with the sheet cake. I was happy because something special was going to happen to me. It would be a long Sunday: first Sunday School, then morning service, then dinner, then baptism in the late afternoon. All that mattered to Ma Dear was that I meet the setting sun as a full-fledged Christian and member of the Greater Nicodemus' Rest Missionary Baptist Church. But it was more important to me that something was actually happening to me and that there was a real possibility that some great secret of my heart would rear her head-and make herself known.

Would the world have new colors when I came out of the water? Would I, like some, be seized by the spirit while I was submerged and be driven up from the depths like a holy missile? I smiled to myself thinking once again about Deenie MacDaniel. About how Pastor Ware in his big fishing boots had dipped her down in the water and how she claimed to have become filled with the holy spirit and bucked and breached like a whale. She almost emptied the baptismal pool, drenching the choir pews beneath it. I laughed to myself. Deenie MacDaniel tickled me.

Outside the car window, I could see we were approaching the little On This Rock Holiness Church. I had asked Ma Dear if I could go to that church with my friend LaNell. LaNell was in that church all day long on Sunday and into the evening. If 1 was going by, I would see her enter the storefront temple where it was warm and bright inside with driving rhythms. She was swallowed into a school of clapping hands and tarnbourines. Memphis blues chords dangled like rainbows.

"I don't want you hanging out over there," said Ma Dear. "You can't serve two masters."

Looking in 1 could see the place heating up for a praise dance. I imagined LaNell's feet thumping the floor with all the others, doing steps. I wanted to join the sanctified church. I wanted to dance. When the Holy Ghost touched me, I wanted to do more than the Missionary Baptist could. They could fall out, stretch out, clear out and run outbut not dance. There was no dancing at the Greater Nicodemus' Rest Missionary Baptist Church. That was for "those holy sanctified folk" just to keep up noise, Ma Dear told me. But there was a part of me that was happy in the presence of the drum, in the presence of holy dancers whose bodies stiffened in elegant contortions, searching out steps, unique steps, steps all their own. With rapid sticks and cymbals bashing

TRIQUARTERLY

43

TRIQUARTERLY

the air, I had watched some throw their heads back while others dipped fluidly, arching their bodies, pumping their legs forward to the beat.

"Oh Lord, have mercy!" Ma Dear's sigh was seasoned with anger. Claude was pulling up to Greater Nicodemus' Rest. He seemed to catch what Ma Dear was looking at. His eyes jutted to the backseat and captured mine. Ma Dear was grinding her teeth.

"Sometimes I wish that I could just go crazy! Go stark, raving crazy!"

A chattering flock of church members was hanging outside and gradually entering the red brick structure. There was the usual traffic congestion, honking horns and huddles of the freshly groomed greeting one another. We saw Deenie MacDaniel surrounded by her brood of restless children, squatting on the church steps, adjusting the dress of one of her smallest, who was wedged between her knees. She was smiling, oblivious to the condescending stares of the church members stepping around her. She wore a full gypsy skirt, a graying white blouse and a hat that looked exactly like Ma Dear's.

That was the beginning of our long day. Deenie MacDaniel's hat seemed to knock the wind out of Ma Dear and, as I helped her from the car, she gripped my arm so tight I almost screamed with pain. Deenie MacDaniel's kids were loud, and eager to point out the similarities. Deenie MacDaniel beamed with flattery. Ma Dear was boiling with rage, but she maintained her Christian aplomb and walked through the crowd the best way she could. She had invested too much in that hat to take it off. Then her second indignity arrived during the meal that followed the morning service. The sisters in the basement kitchen found that the great sheet cake she had so carefully prepared three days before was riddled with green mold.

Well, I thought, as Ma Dear's fingers prepared me for baptism, I guess I'm the only pair of eyes around here that she thinks are not laughing at her. She sought them, she needed them without an ounce of mockery. And so I gave them to her. I brushed my fingers, pressed their cool tips to the tender socket around each white eyeball, pressed and pulled. It was my ultimate act of love.

I had to be helped into the baptismal pool, though. Until my spiritual eyes grew I had to rely on what other people told me. They told me I was wearing white socks, a white gown and a white swimming cap. They told me the spirit was so high that Deenie MacDaniel broke into a dance and almost tore off all her clothes. They had to tell me because I couldn't remember the cold climb of chlorine water against my skin, the

44

rubber smell of Pastor Ware's boots, my going down and being raised up through the water. Ma Dear had to tell me because I couldn't remember. There are only these little marks on my forehead-little scratches that remain from the clawed feet of some descending dove.

TRIQUARTERLY

45