-_.:;::-_:--- � "/. .17 :,,; �-,: -: I .:; , II"�' ;-

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individual donors. Major new marketing initiatives at TriQuarterly have been made possible by the Lila Wallace,Reader's Digest Literary Publishers Marketing Development Program, funded through a grant to the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

Please sign me up for:

o a two-year subscription for $36.

o a one-year subscription for $20.

a

subscription for $500.

Foreign subscribers please add $5 per year.

$ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal.

Please begin my subscription with issue#

Please sign me up for:

o a two-year subscription for $36.

Please

TO TRIQUARTERLY!

SUBSCRIBE

Name Address Or call US toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! Bl90

TO TRIQUARTERLY!

o

life

o

SUBSCRIBE

o a one-year subscription for $20.

Foreign subscribers please add $5peryear.

Name Address Or call US toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! GIVE TRIQUARTERLY! o $ enclosed. Buy your first TriQuarlerly gift subscription for $20, and each additional gift subscription costs only $17!! Address Bl90 Name 1st gift subscription ($20) 2nd gift subscription ($17) Name Name Address Address Gift-card message Gift-card message Add $5/year for foreign subscriptions. BG90

begin my subscription with issue# o a life subscription for $500. o $_____ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal.

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, I L 60208-4302

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

TriQuarterly

FALL 1994 BOOKS AND BACKLIST

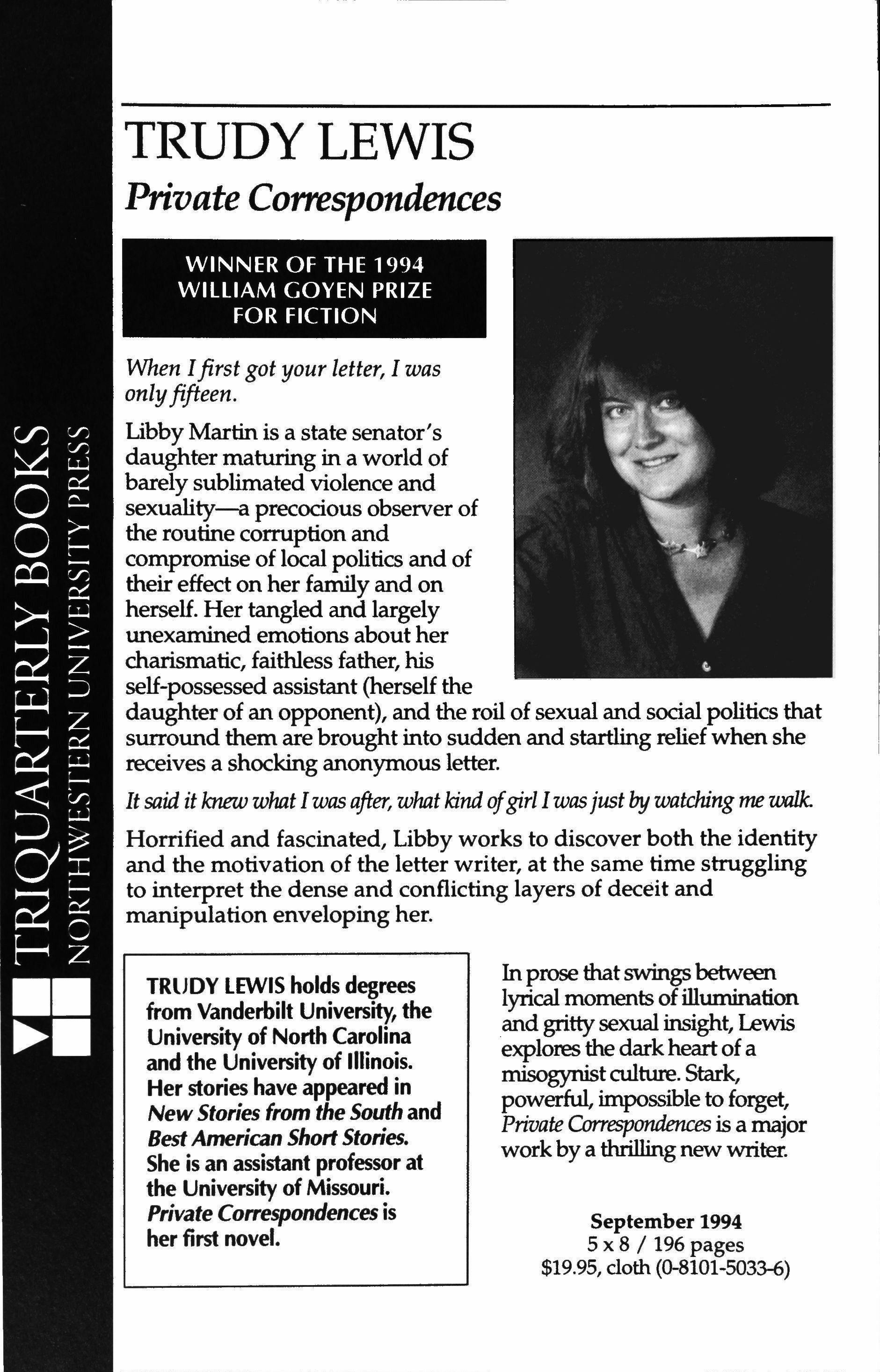

TRUDY LEWIS

Private Correspondences

WINNER OF THE 1994 WILLIAM GOYEN PRIZE FOR FICTION

When Ifirst got your letter, I was onlyfifteen.

Libby Martin is a state senator's daughtermaturing in a world of barely sublimated violence and sexuality-aprecocious observer of the routine corruption and compromise of local politics and of their effect on her family and on herself. Her tangled and largely unexamined emotions about her charismatic, faithless father, his self-possessed assistant (herself the daughter of an opponent), and the roil of sexual and social politics that surround them are brought into sudden and startling relief when she receives a shocking anonymous letter.

It said it knew what I was after, what kind ofgirl I was justbywatching me walk.

Horrified and fascinated, Libby works to discover both the identity and the motivation of the letter writer, at the same time struggling to interpret the dense and conflicting layers of deceit and manipulationenveloping her.

TRUDY LEWIS holds degrees from Vanderbilt University, the University of North Carolina and the University of Illinois. Her stories have appeared in New Stories from the South and Best American Short Stories. She is an assistant professor at the University of Missouri. Private Co"espondences is her first novel.

In prose thatswings between lyrical moments ofillumination and grittysexual insight, Lewis explores the dark heart of a misogynist culture. Stark, powerful, impossible to forget, Private Correspondences is a major work by a thrilling new writer.

September 1994 5 x 8 / 196 pages $19.95, cloth (0-8101-503�)

CYRUS COLTER

The

Hippodrome

Set in a Chicago seething with physical and psychological violence, Cyrus Colter's The Hippodrome is an examination of power and exploitation and their entanglement with sexuality. The central character, Yeager, has murdered his wife and her white lover. Fleeing the police, he is both offered refuge and held captive in the Hippodrome, a ghetto house where a troupe ofblack men and women stage sexual theater for white audiences. The murderer becomes a victim; the fugitive becomes a performer.

Colter so carefully delineates each character's self-contradictory motives that the reader cannot entirely condemn or entirely approve of any of them, but is forced instead to reflect on their power-the power to redeem and the power to destroy.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., has said of Colter's short stories: "When I came upon his tales I suddenly found myself having a lovely time. He was telling me all sorts of magical things about life I'd never known before."

In the tradition ofhis fictional ancestors, Dostoevsky andFaulkner, [Colter] hasproduced a work which uses the world ofeverydayreality in a manner beyond the scope ofjournalism or sociology-as an entree to the soul.

-James Park Sloan Chicago Sun-Times

October 1994

51/2 x 81/2 / 214 pages $13.95, paper (0-8101-5036-0)

A distinguished attorney and public servant, CYRUS COLTER took up writing in midlife and, after retiring from the law, devoted himself to his art and to teaching. He held the Chester D. Tripp Professorship in the Humanities and chaired the Program in AfricanAmerican Studies at Northwestern University. His first book, The Beach Umbrella, won the Iowa School of Letters Award for First Fiction in 1970. His other works include The Rivers ofEros, Night Studies, The Amoralist, and A Chocolate Soldier. He lives in Chicago.

Displacements: South African Works on Paper, 1984-1994

Edited by David Bunn and Jane Taylor

This volume,published in conjunctionwith the Mary and Leigh Block Gallery's 1994 exhibition, offers significantinsights into politics, subjectivity, and aesthetic practice in contemporary South Africa. Photographs of over 125 imagesexplore the dimensions of possibility of a singlemedium, paper. Essaysby the editors and others shed insight into the complicated relationship between figure and ground, and body and landscape, in works produced within a political and historical situation which has, for generations,legislated space and subjectivity.

In addition to including work bySouth African artists such as Alan Crump,TommyMotswai, GideonMendel and PippaSiopis, the volume extends the definition ofwork on paper to include a selection of new works of fiction byJoel Matlov, Zoe Wicomb, Ivan Vladislavic,John Miles and others.

DAVID BUNN and JANE TAYLOR teach in the Department of English at the University of the Western Cape in Bellville, South Africa. They are at work on a collaborative project on poisons and the colonial imagination.

September 1994

83/8 x 11 /300 pages

125 illustrations

$4D, cloth (0-8101-5012-3)

l

A Rainy Day at the Farm, Gail Caitlin, 1988, pencil and charcoal

TINO VILLANUEVA

Chronicle ofMy Worst Years I Cronica de mis aiios peores

TRANSLATED AND WITH AN AFTERWORD BY JAMES HOGGARD

In this bilingual edition, an established Chicano poetwith passion and elegance describes some of the American realities that remain absent from mainstream poetry. Villanueva voices complex and compelling historical, literary and cultural questions as urgent personal utterances.

Tino Villanueva won the 1994 American Book Award forhis recent book, Scenefrom theMovie Giant.

October 1994

51/8 x 7 3/4/96 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5009-3)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5034-4)

MARC J. STRAUS

One Word

This first collection ofpoems by a physician combines poetic craft, medical expertise and a keen sense of human vulnerability to pain and suffering in an uncommon portrayal of the complex and often troubled relations between physician and patient. With directness and power, Straus confronts matters rarely encountered in poetry. These poems are a fine addition to the scant body of imaginative work that speaks with authority from within the medical world.

October 1994

51/8 x 73/4/80 pages

$29.95, cloth (0-8101-5010-7)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5035-2)

WILLIAM GOYEN

Arcadio

Completed while he was dying, William Goyen's Arcadia is one of the most affecting and imaginative farewells to life ever written.

Arcadio, whose voice is inimitably Goyenesque, is a creature from beyond the normal walks of life.

Half man, half woman, raised in a whorehouse and for years the veteran exhibitionist of an itmerant circus sideshow, he has escaped from the show and has been wandering in a quest for his lost family. Speaking intimately and secretly to the reader, he tells the bizarre and fantastic tale of his life.

148 pages $12.95, paper (0-8101-5006-9)

WILLIAM GOYEN

Half a Look of Cain: A Fantastical

Narrative

Chris, whose leg is injured, and his lover Stella, with whom he lives in a ruined, abandoned house; Chris's male nurse; Marvello, the circus aerialist; a lighthouse keeper; a flagpole-sitter in small-town America-these are the creatures of William Goyen's visionary fable of love, lust and loneliness. Because of its central focus on the erotic and its unusual novelistic form, Halfa Look ofCain was rejected in the 1950s by Goyen's publisher. The first publication of this novel inaugurates a TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press plan to publish and reprint all of Goyen's out-of-print work.

[Arcadio) virtuallypulses with lifo; it is both audacious and wise; a timelessfable that manages to be boldlycontemporary as well.

-JOYCE CAROL OATES

WILLIAM GOVEN (1915-83) was one of the most innovative American writers of fiction. Read and acclaimed abroad, while remaining too littleknown at home, his work has transformed his readers' understanding of inner life and of the novel itself.

220 pages $22.50, doth (O-8101-5031-X)

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

This large anthology is a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today.

Gibbons has been guided by a healthy eclecticism and a sense offreshness and authenticity ofconception and execution.

-HARVARD REVIEW afeastofreadingenjoyment. Gibbons's collectiongives us people worth caring about and writing not afraid to be at once serious andjoyful.

-SMALL PRESS

448 pages

$15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

ANNE CALCAGNO

Prayfor Yourself

Anne Calcagno vividly captures the textures of women's lives in this exhilarating collection of short stories. Her characters grapple with problems ranging from domestic violence to obsessiveness with body weight; the dramatic situations are extreme, edgy and utterly convincing.

Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye of a true storyteller.

-LARRY HEINEMANN

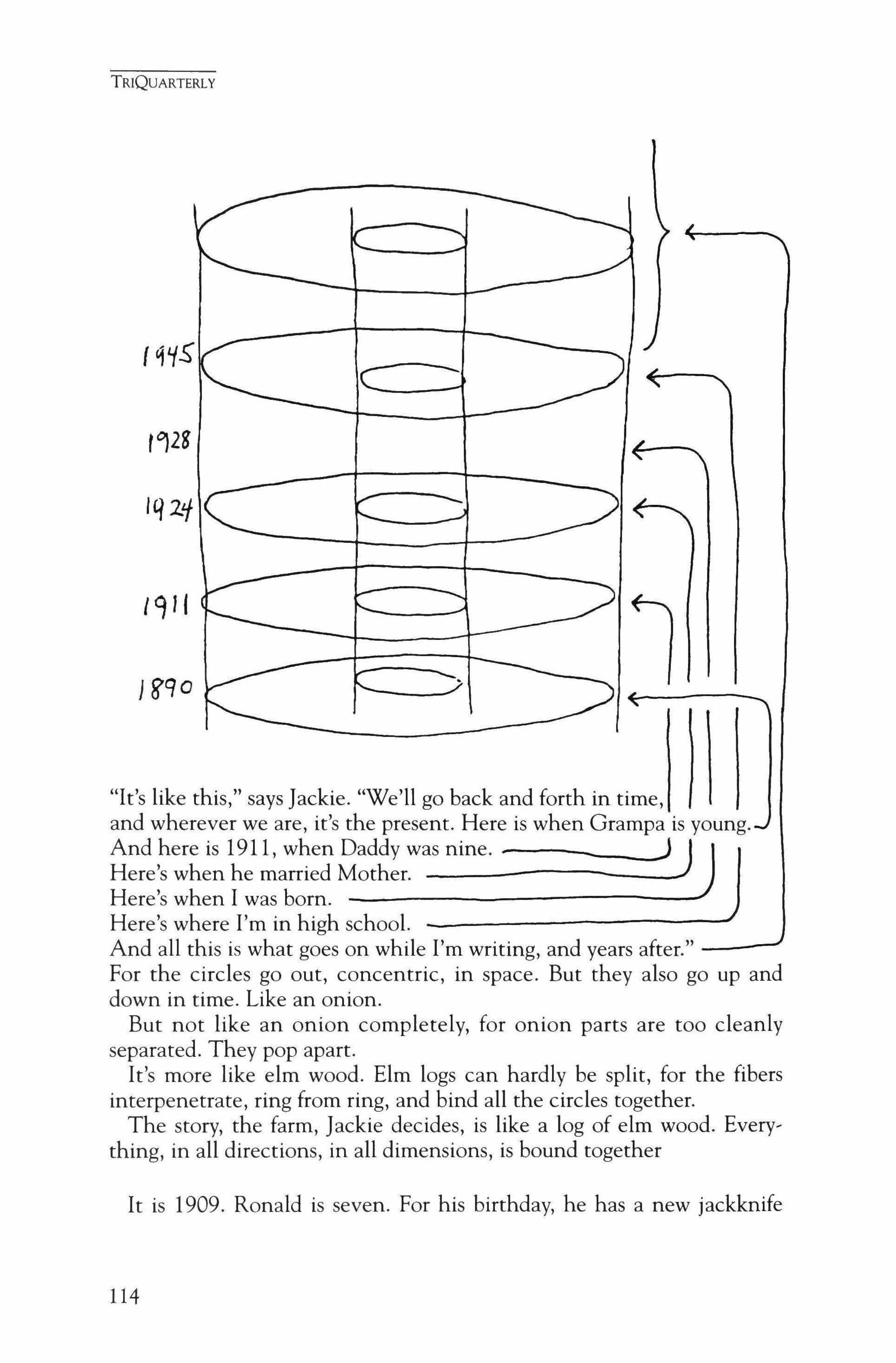

Language as maddeninglyfascinating as a fifty-car locomotive, perfectly carved, from a singlepiece ofwood.

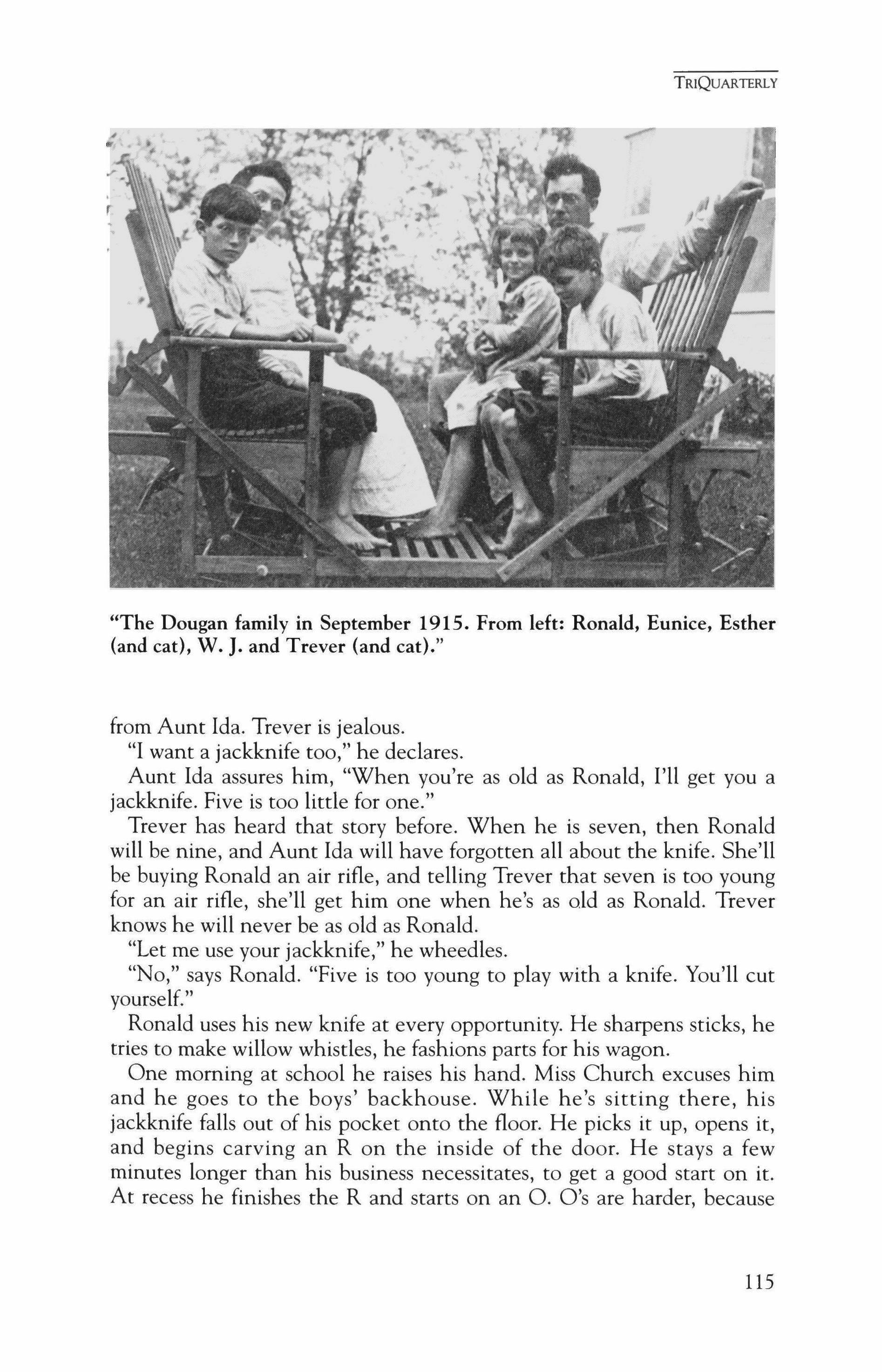

136 pages

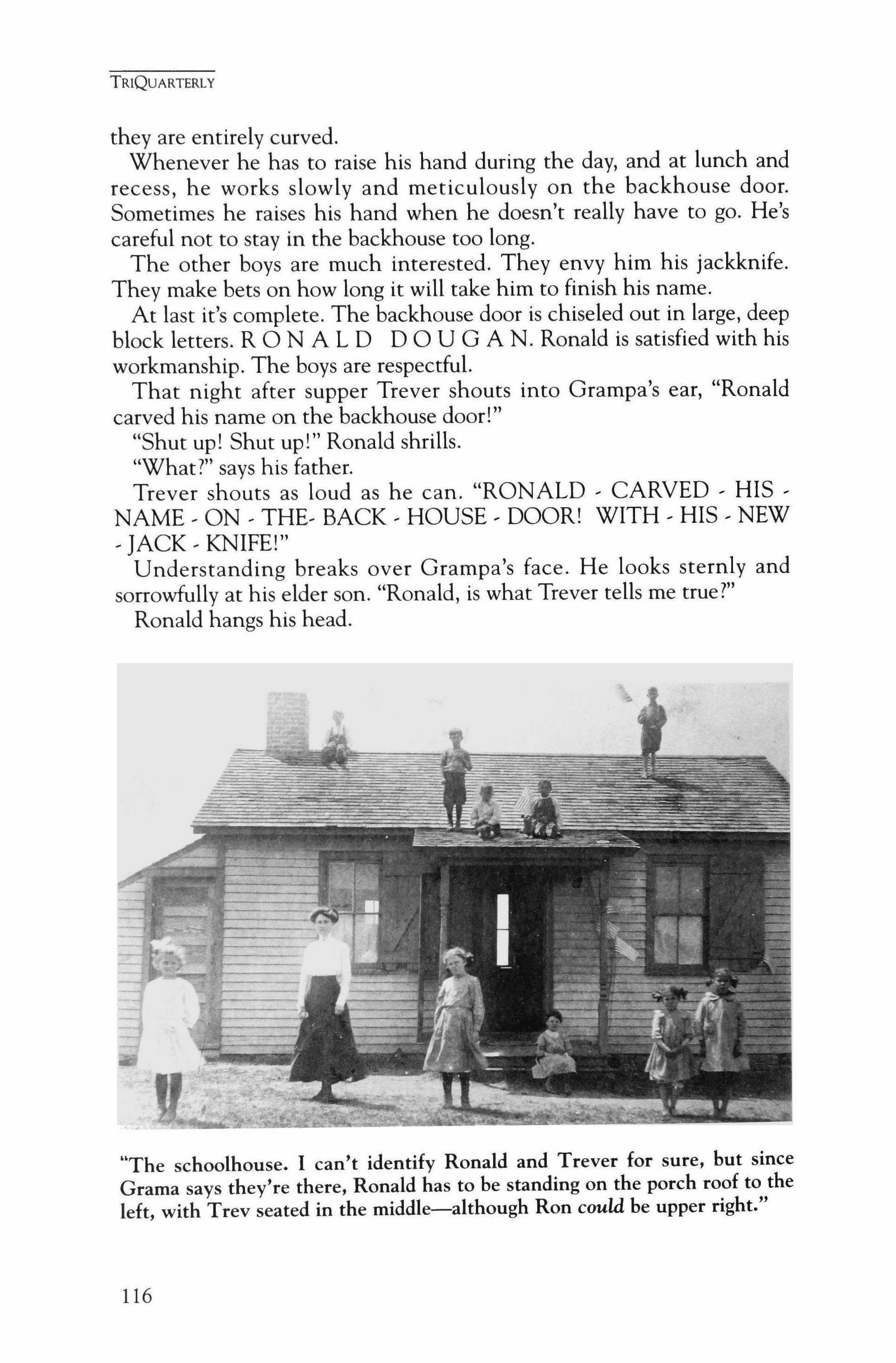

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5OOO-X)

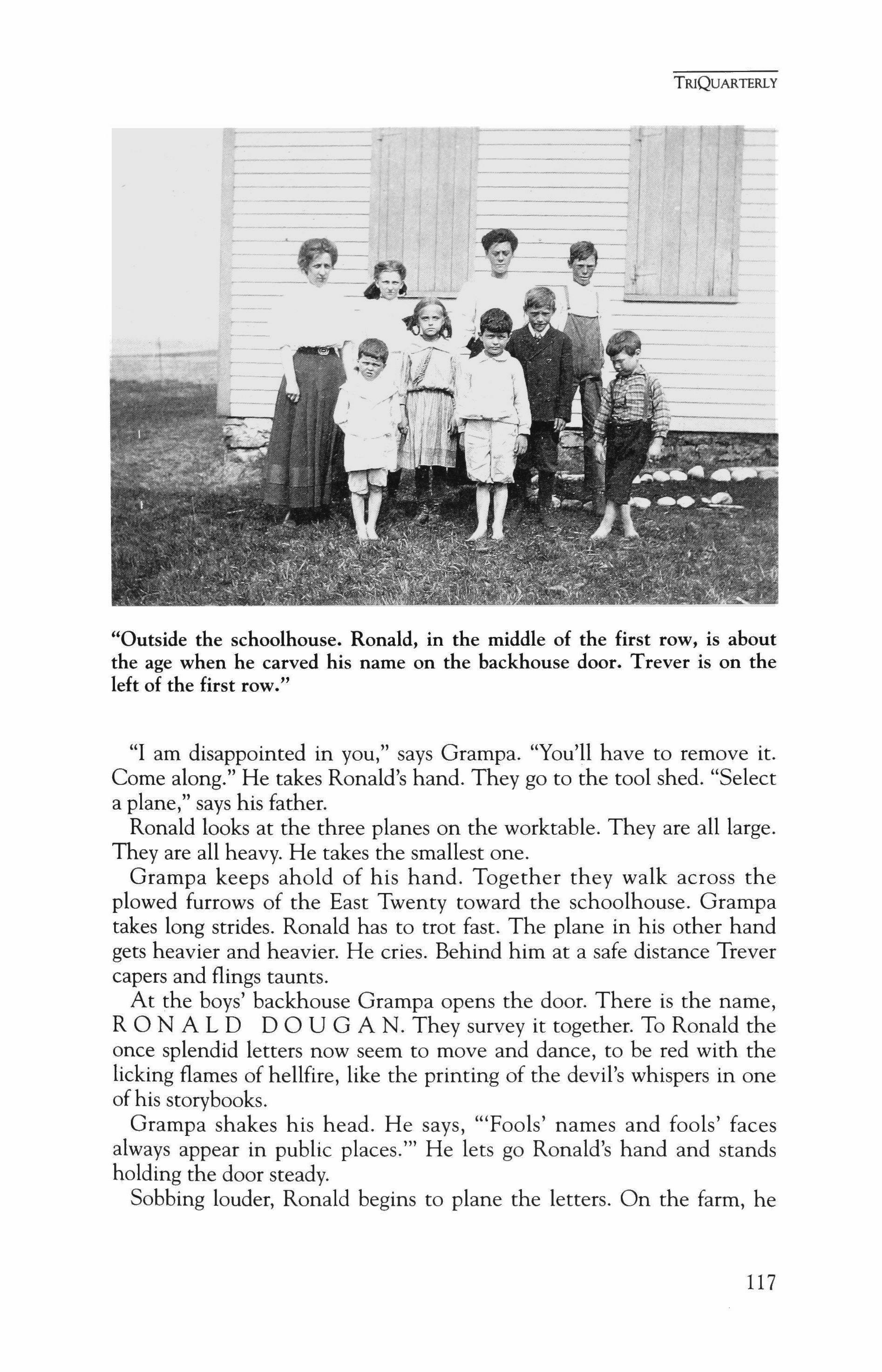

-LYNDA BARRY

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5003-4)

�"'n

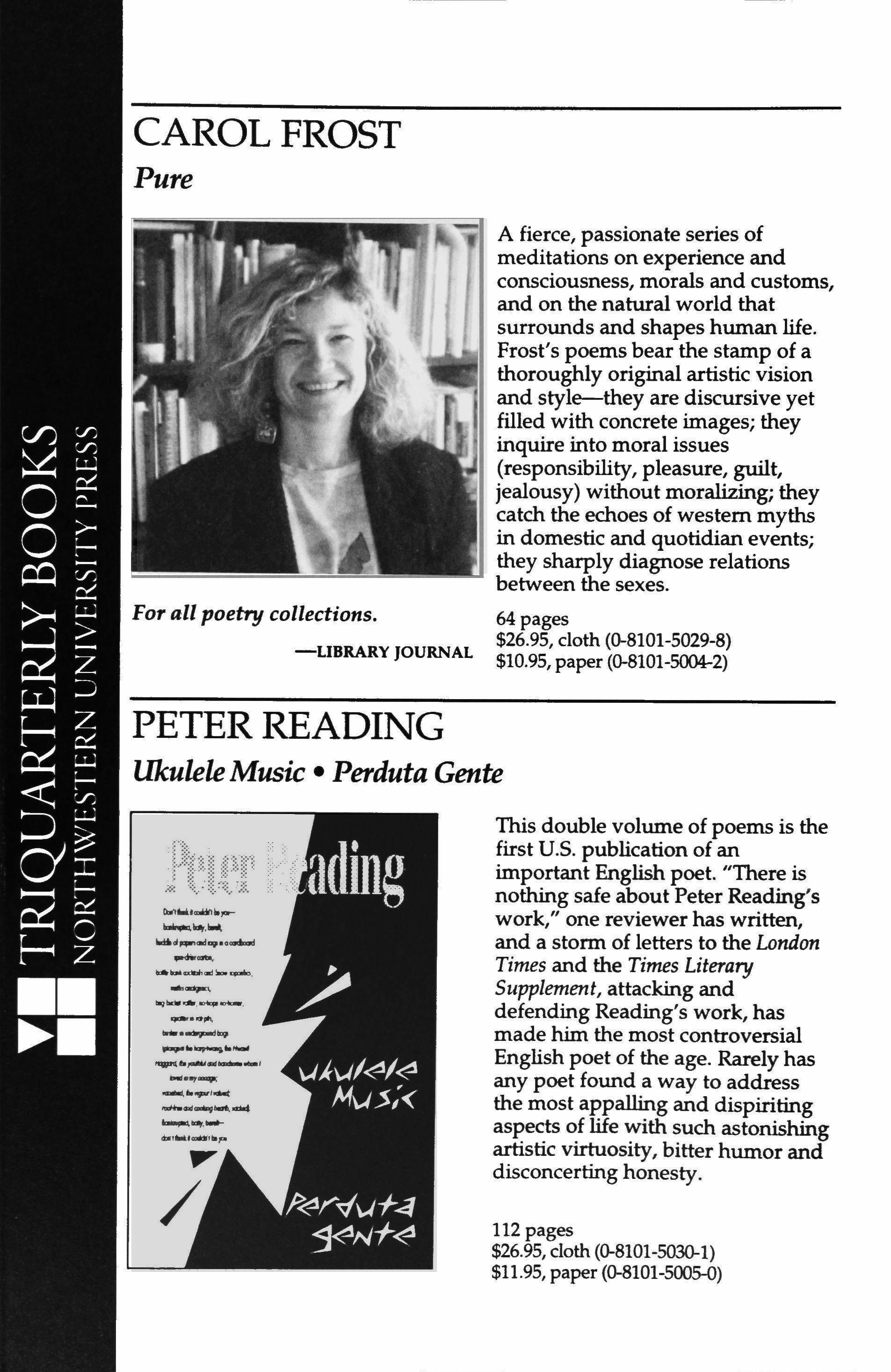

CAROL FROST

FOT all poetry collections.

-LIBRARY JOURNAL

PETER READING

A fierce, passionate series of meditations on experience and consciousness, morals and customs, and on the natural world that surrounds and shapes human life. Frost's poems bear the stamp of a thoroughly original artistic vision and style-they are discursive yet filled with concrete images; they inquire into moral issues (responsibility, pleasure, guilt, jealousy) without moralizing; they catch the echoes of western myths in domestic and quotidian events; they sharply diagnose relations between the sexes.

64 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5029-8)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5004-2)

Ukulele Music • Perduta Gente

This double volume of poems is the first u.s. publication of an important English poet. "There is nothing safe about Peter Reading's work," one reviewer has written, and a storm of letters to the London Times and the Times Literary Supplement, attacking and defending Reading's work, has made him the most controversial English poet of the age. Rarely has any poet found a way to address the most appalling and dispiriting aspects of life with such astonishing artistic virtuosity, bitter humor and disconcerting honesty.

112 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5030-1)

$1l.95, paper (0-8101-5005-0)

D.i .,1IIIIIp; 1 _-_""r.

The Urgency ofIdentity: Contemporary English-Language Poetryfrom Wales

EDITED BY DAVID LLOYD

This anthology of poems and interviews is a double revelation for U.S. readers, presenting for the first time in this country the importantEnglish-language Welsh poetry of the 1980s and 1990s, and illuminating the complexity, constant flux and politicalimplications of the poet's sense of inherited culture. These superb poems have been rigorously selected to showcase the Welsh poets' skill and seriousness, and the sensuous density of their language, which, like that of contemporary Irish poets, offers the reader memorable expressive riches and a strikingdepiction of landscape and society.

The featured poets practice their craft amid a lively cultural and political debate: although the number of Welsh citizens who do not speak Welsh has grown substantially in recent decades, cultural nationalists view English as the language of oppression. Thus, like Latino writers working in English in the U.S., the English-language Welsh poets create a divided art. Included in the anthology are John Davies, Gillian Clarke and R S. Thomas, among others.

244 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5032-8)

$14.95, paper (0-8101-5007-7)

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise ofthe Impure:Poetry and the EthicalImagination

A collection of passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today. These essays speakforcefully to the literary debates concerning the use of tradition, the openness of American poetry to diverse subjects, and the teaching of creative writing. This book should be read by any poet who teaches in the United States and by anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry. It will become a benchmark for discussion of contemporary American poetry.

200 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5025-5)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5028-X)

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes ofthe Spinners

Winnerofthe 1993 Chica�o Sun-TImes Book ofthe YearAward m Poetry

AngelaJacksonbrings remarkable gifts to the articulation of African-American experience. Her poetry features an impressive variety of characters exploring social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritualexperience.

Angela Jackson is a poet, novelist and playwright who has known,forlong, what is rightforher attention and scrupulous investigation.

--G�NDOLYNBROOKS

120 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5026-3)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5001-8)

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Winnerofthe 1993 TerrenceDes Pres PrizeforPoetry

Adversaria cel�brates the roughbeauty of ordinary life and laments its inevitable decline. These poems, titled in Latin, combine colloquial style with a late imperial tone to capture the stark contrasts and contradictions of a life lived between a steel mill and the quiet, graceful natural world.

To read Adversaria is to be in the presence ofa lively and supple and various mind, as tough as it is American.

-Ll-YOUNG

LEE

104 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5027-1)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5002-6)

Adversaria

O. TH' .,') '111111"'. 01 ,.,a. 'Oil ,,011'." ImO,hYRusstll

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodem trashiness in this book A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality. -AUCIA OSTRIKER

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching,elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention.

Song of Napalm made almost everythingelse that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right alongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one ofthe best poets now writing in America. -DENISE LEVERTOV

80 pages

$17, cloth (0-916384-08-X)

$10.95, paper (0-916384-09-8)

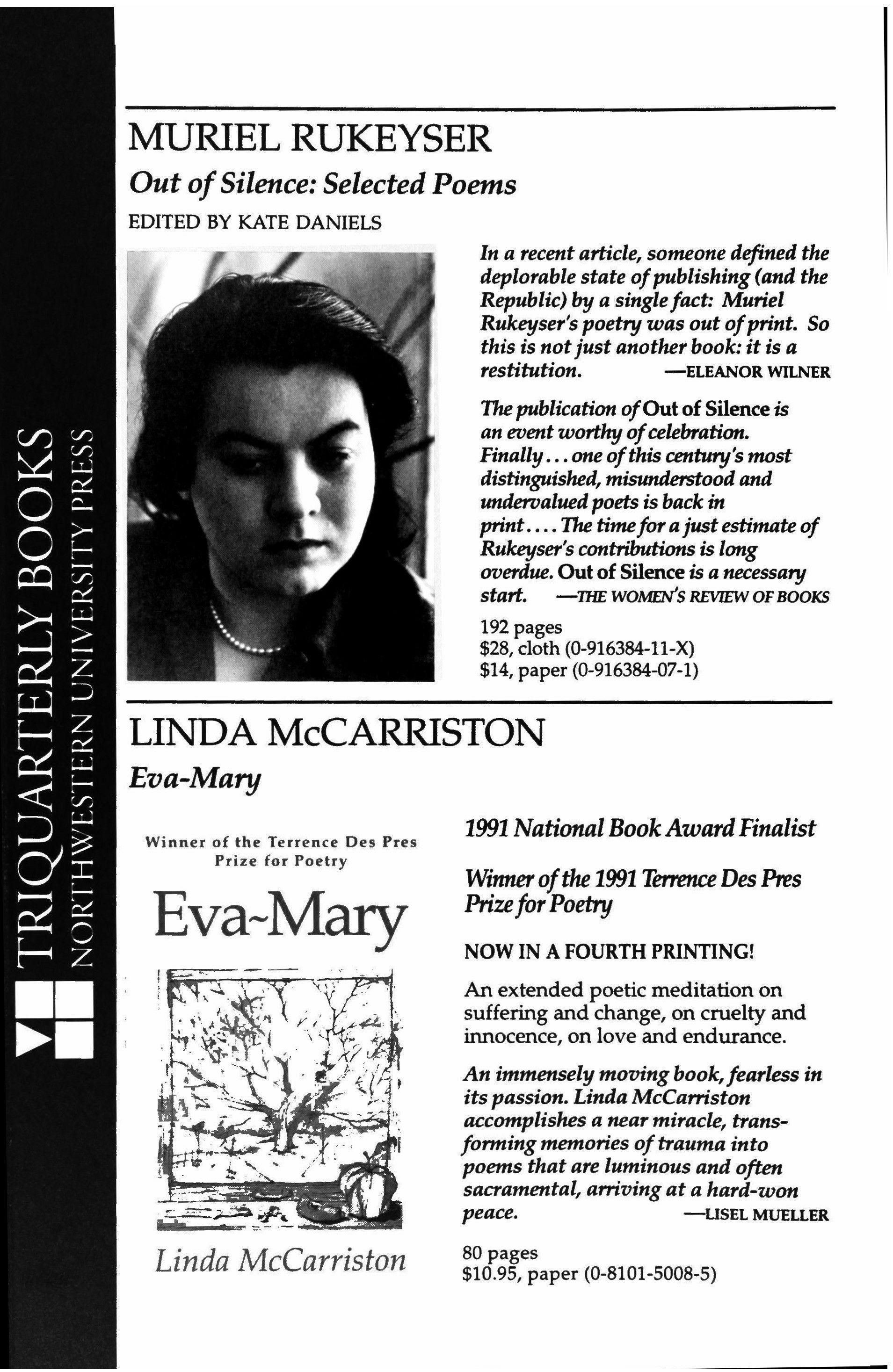

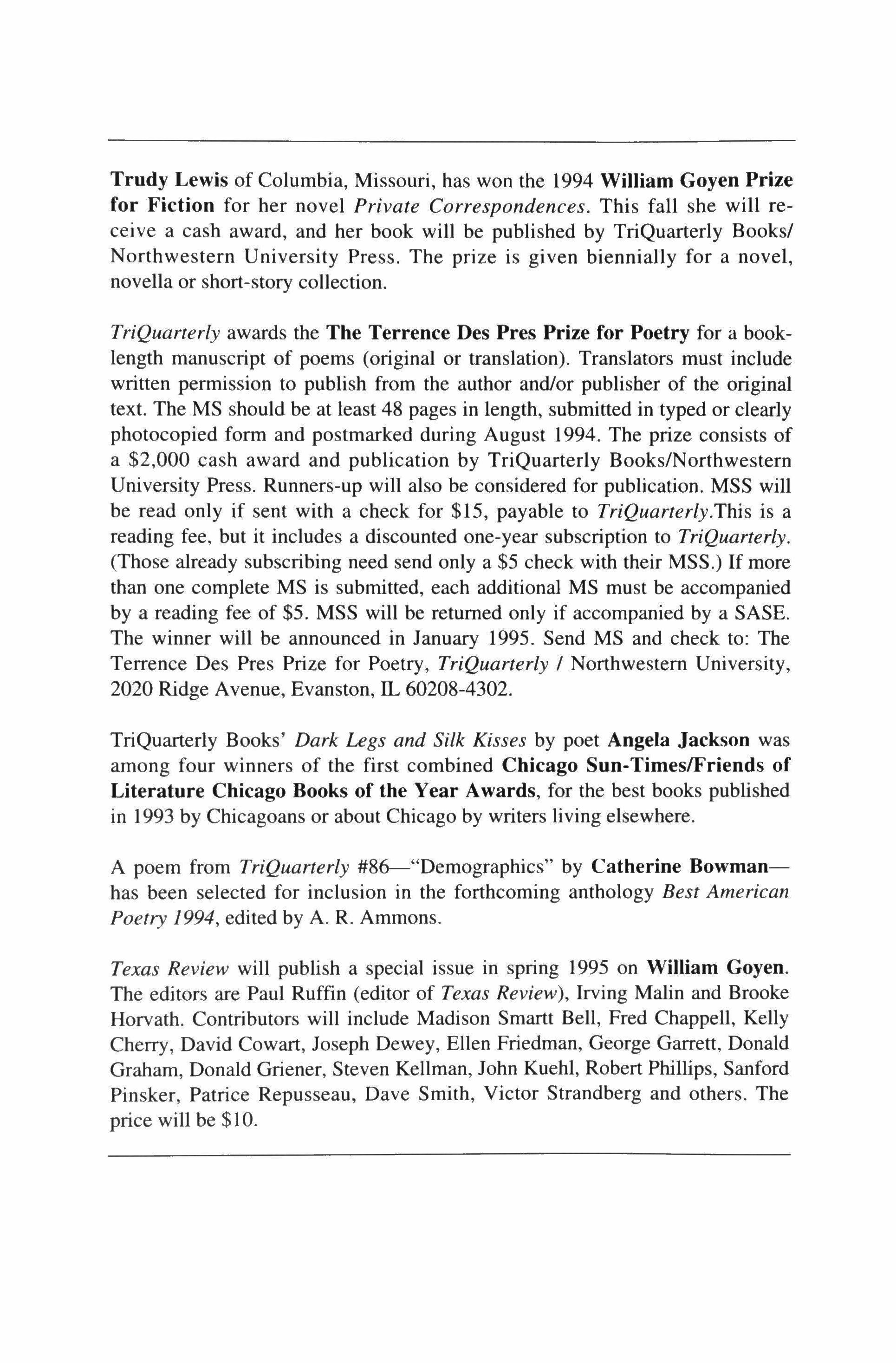

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out ofSilence: Selected Poems

EDITED BY KATE DANIELS

-ELEANOR WILNER

-ELEANOR WILNER

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state ofpublishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser's poetry was out ofprint. So this is notjust another book: it is a restitution.

Thepublication ofOut of Silence is an event worthyofcelebration. Finally one ofthis century's most distinguished, misunderstood and undervaluedpoets is back in print The timefor a just estimate of Rukeyser's contributions is long overdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start. -THE woMEN's REVIEW OF BOOKS

192 pages

$28, cloth (O-916384-11-X)

$14, paper (0-916384-07-1)

LINDA McCARRISTON

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Eva-Mary

Winnerofthe 1991 Terrence Des Pres PrizeforPoetry

NOW IN A FOURTH PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance.

An immenselymoving book,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories oftrauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace.

-USEL MUELLER

80 pages $10.95, paper (0-8101-5008-5)

1991 NationalBookAwardFinalist

Linda McCarriston

Fiction ofthe Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

This landmark anthologyhonoring TriQuarterly's 25th anniversary includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared in the magazine over the past decade. The stories range widely over the experience of modem life, and share a high level of artistry. An incomparableprimer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

Forcontemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standard-bearer The multiplicity and depth ofthefictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness ofwriters too numerous to thank. -PUBUSHERS WEEKLY

592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

Writersfrom South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterly magazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialogues by fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to U.S. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

Writers from South Africa

CULTURE. POLITICS AND LITERARY THEORY AND ACTNITY IN SOUTH AFRICA TODAY

128 pages

$6.50, paper (0-916384-03-9)

Tn(Ju.iJrkrl. Sr:�/, "II CntK'u ,-",dCullu,..- No 2

Stephen Deutch, Photographer:

From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989

A stunning gift book-with photos of Chicago over decades of change, including Deutch's Pulitzer-nominated photos from the Daily News. This collection and analysis of Deutch's work, with plates both in duotone and in color, is the first full record of Deutch's achievement to be published. 144 pages $45, cloth (0-929968-05-0) $23.50, paper (0-929968-06-9)

Order Form

Send this order form to: Northwestem University Press Chicago D1strlbuUon Center 11030 South Langley Avenue Chicago. IL 60628 Special Limited Offer: 20% off aU orders received by September t, 1994! Name Address City State �--Zip Authorlfitle CUPR Quantity Unit Price Total o Check or money order enclosed o MastercardNisa number: Expiration Date Signature: Subtotal Shipping and handling* TOTAL ·Domestic-$3.50 first book. $.75 each additional book ·Forelgn-$4.50 first book. $1.00 each additional book NW-121

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Reader Bobby Reed

Advisory Editors

Spring/Summer 1994

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow Deanna Kreisel

Editorial Assistants Hans Holsen, Sarah Kube, Kemba Johnson, Amy Rosenthal, Kelly Riggio, Brittany Walker

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year) - Individuals: one year $20; two years $36; life $500. Institutions: one year $30; two years $48; life $500. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-7614. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts received between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1994 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States ofAmerica by Thomson-Shore, typeset by TriQuarterly. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals (La Vergne, TN); B. DeBoer (Nutley, NJ); Bookpeople (Berkeley, CAl; Ubiquity (Brooklyn, NY); Armadillo (Los Angeles, CAl; Fine Print (Austin, TX).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H. W. Wilson Co.) and the American Humanities Index (Whitson PublishingCo.).

Trudy Lewis of Columbia, Missouri, has won the 1994 William Goyen Prize for Fiction for her novel Private Correspondences. This fall she will receive a cash award, and her book will be published by TriQuarterly Books/ Northwestern University Press. The prize is given biennially for a novel, novella or short-story collection.

TriQuarterly awards the The Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry for a booklength manuscript of poems (original or translation). Translators must include written permission to publish from the author and/or publisber of the original text. The MS should be at least 48 pages in length, submitted in typed or clearly photocopied form and postmarked during August 1994. The prize consists of a $2,000 cash award and publication by TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press. Runners-up will also be considered for publication. MSS will be read only if sent with a check for $15, payable to TriQuarterly.This is a reading fee, but it includes a discounted one-year subscription to TriQuarterly. (Those already subscribing need send only a $5 check with their MSS.) If more than one complete MS is submitted, each additional MS must be accompanied by a reading fee of $5. MSS will be returned only if accompanied by a SASE. The winner will be announced in January 1995. Send MS and check to: The Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry, TriQuarterly / Northwestern University, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208-4302.

TriQuarterly Books' Dark Legs and Silk Kisses by poet Angela Jackson was among four winners of the first combined Chicago Sun-TimesIFriends of Literature Chicago Books of the Year Awards, for the best books published in 1993 by Chicagoans or about Chicago by writers living elsewhere.

A poem from TriQuarterly #86-"Demographics" by Catherine Bowmanhas been selected for inclusion in the forthcoming anthology Best American Poetry 1994, edited by A. R. Ammons.

Texas Review will publish a special issue in spring 1995 on William Goyen. The editors are Paul Ruffin (editor of Texas Review), Irving Malin and Brooke Horvath. Contributors will include Madison Smartt Bell, Fred Chappell, Kelly Cherry, David Cowart, Joseph Dewey, Ellen Friedman, George Garrett, Donald Graham, Donald Griener, Steven Kellman, John Kuehl, Robert Phillips, Sanford Pinsker, Patrice Repusseau, Dave Smith, Victor Strandberg and others. The price will be $10.

Editors

Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

FICTION

Contents

of this issue:

In Bed with Lola 21 Daniel Hayes Rapid Transit 57 DanChaon Vital Statistics 153 Richard Dokey The Snow Goddess 186 Dennis Hathaway Whorl 201 Steve Fisher Heat 220 Jennifer C Cornell Sap 225 Beth Simon The Product 226 Eleanore Devine 17

David

The Mill.Race; Sonnet: Three Images ......•••••••••••

Manufacturing

Fever Dream in Hanoi; Three Meditations at Nguyen Du; What I Saw, What I Did, in the Alley; Words for the Husky Girl. .•••••••••••••••••••.•••

Bruce Weigl

The Bogeyman; A Big Black Crow; Dr. Gold and Dr. Green; Dr. Gold and Dr. Green, 11

Marc J. Straus Fury; Truth; Judgment; Apology; Crying Wolf •••.

Carol Frost

For My Lakota Woman; Spirit-Deer Deep in Pine Forests; How Verdell and Doctor Zhivago Disassembled the Soviet Union; The Boys Cruise Seattle; A Savage Blood Thirst; Last Song of the

The Intruder 238

POETRY

53

Lethe;

71

Three

75

Stink 78

Gates

Anne Winters

Alan Shapiro

Marys

Terri Brown,Davidson

John Engels

83

90

133

18

Dove; Graffiti Dialogue in a Nebraska Bordertown; Laundromat .•••••....•••••••••••..•••••...••• 138 Adrian C. Louis Six Entries on the Invention of Paper; Invisible Order 150 Teresa Cader Red Dahlias; Night Dive; Moonsnail and Cockle; Kit 166 Anne Reynolds Voegtlen Ghosts of Las Colinas; IS, BIG and FATAL. 170 Pamela Bernard After the Evening News; Delinquent 173 Bruce Smith Mulgrave; Footbottoms Up.......•...•....•............•..• 176 Dorothea Edmondson Poetry Overdose 179 Tom Wayman Acid; Thompson; Roots; Boil 181 Pat Mangan OTHER PROSE From Working Papers ..............•.•..•••.•.........••........... 94 John Skoyles 19

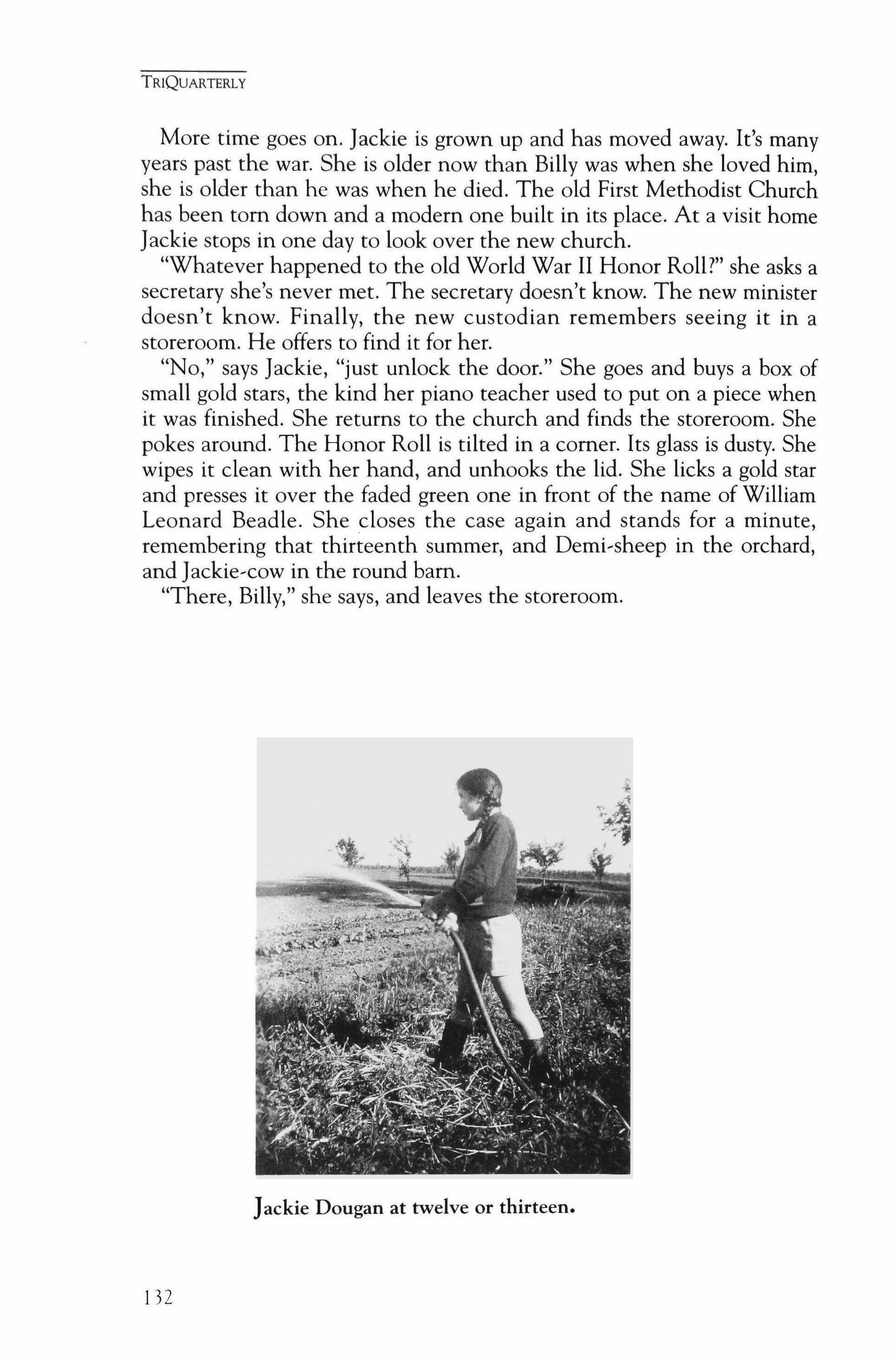

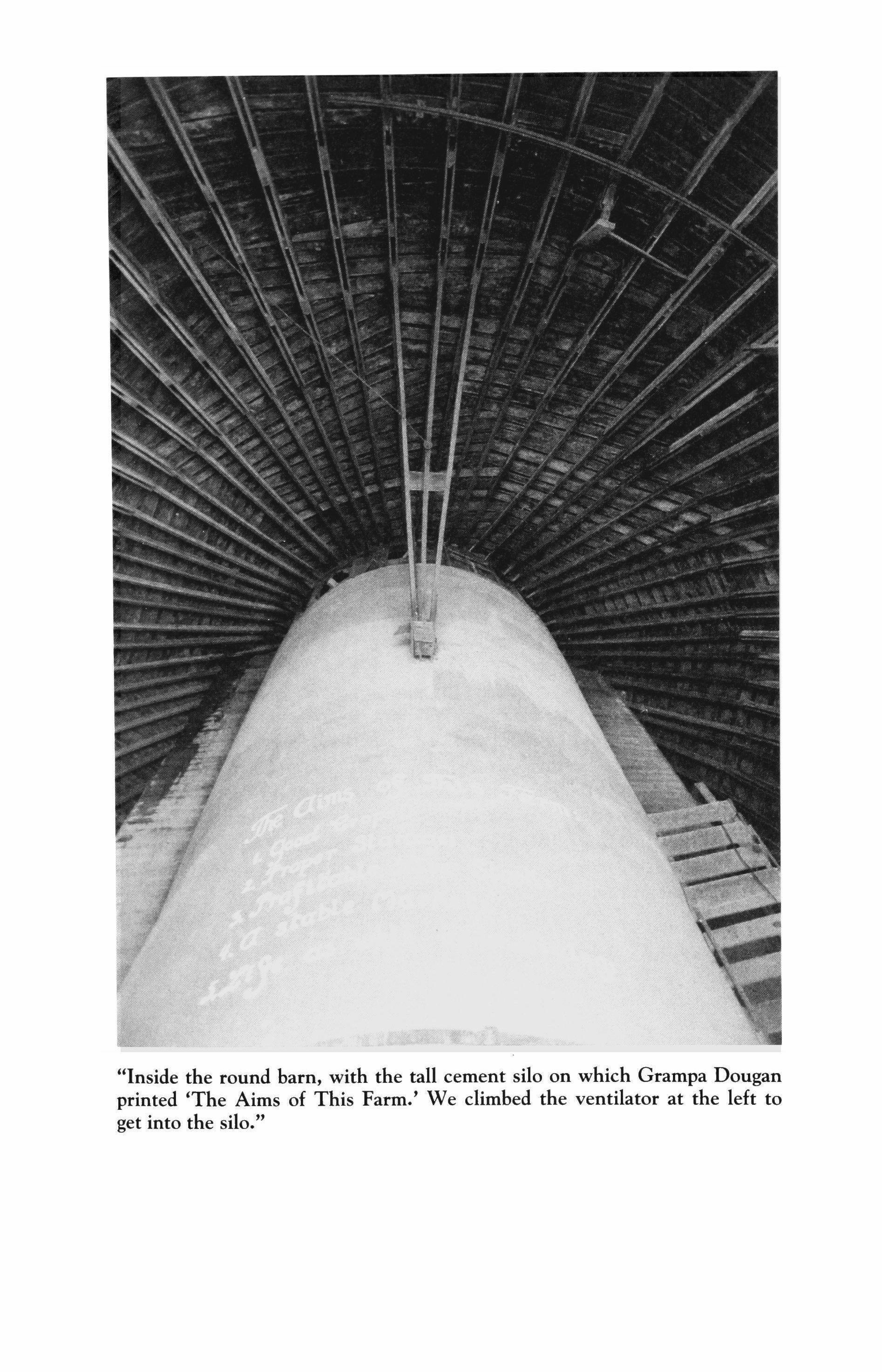

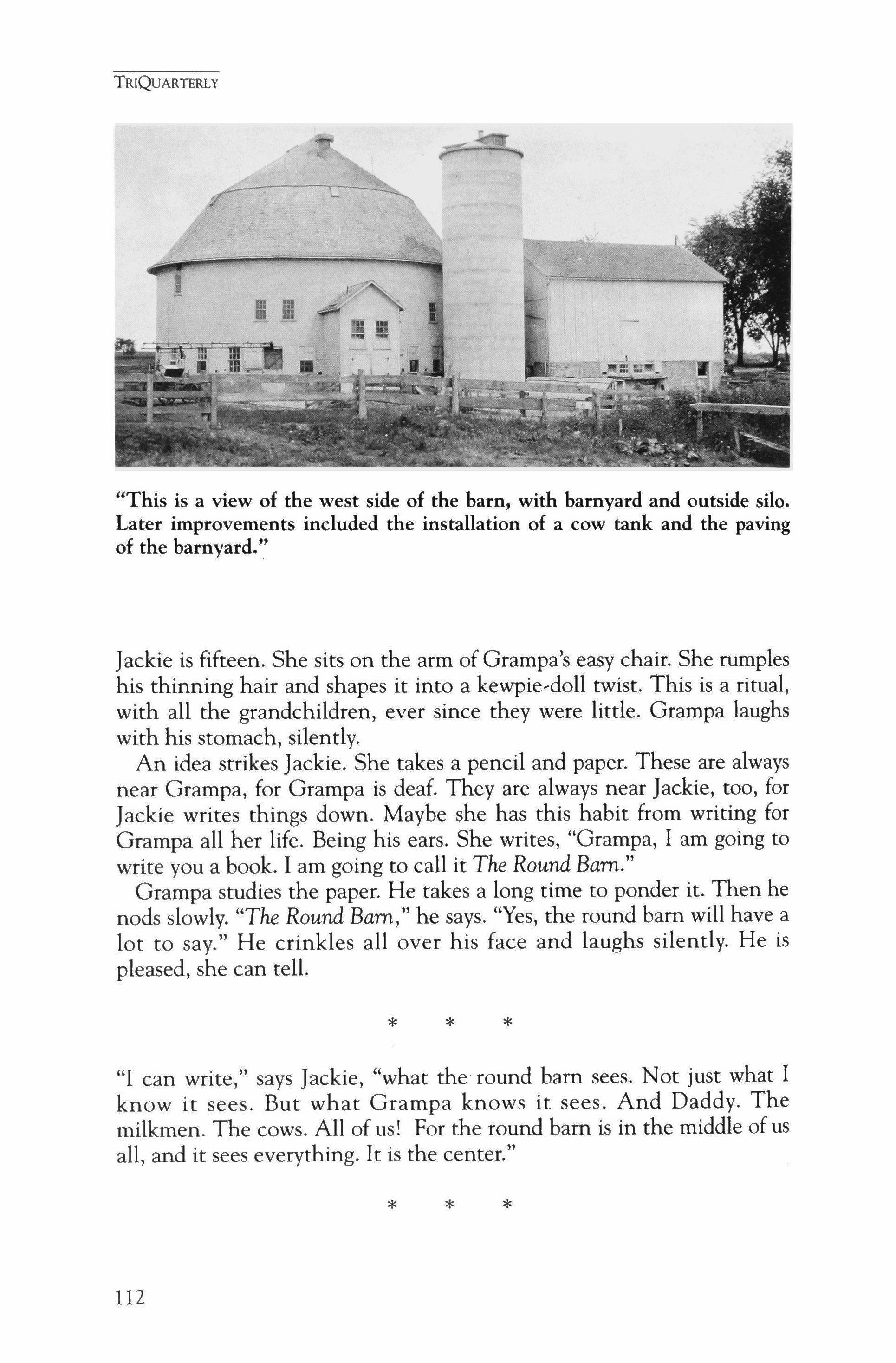

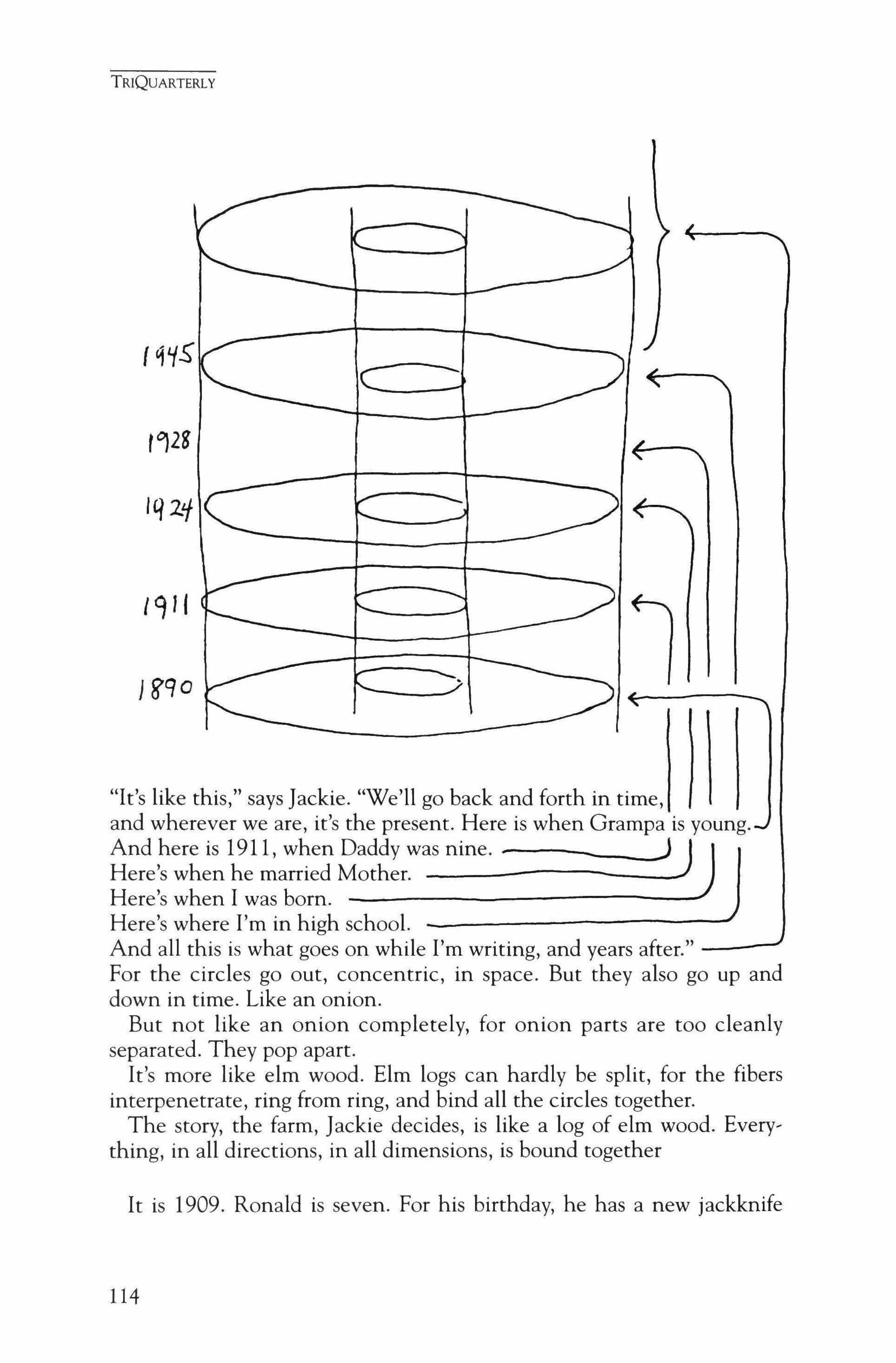

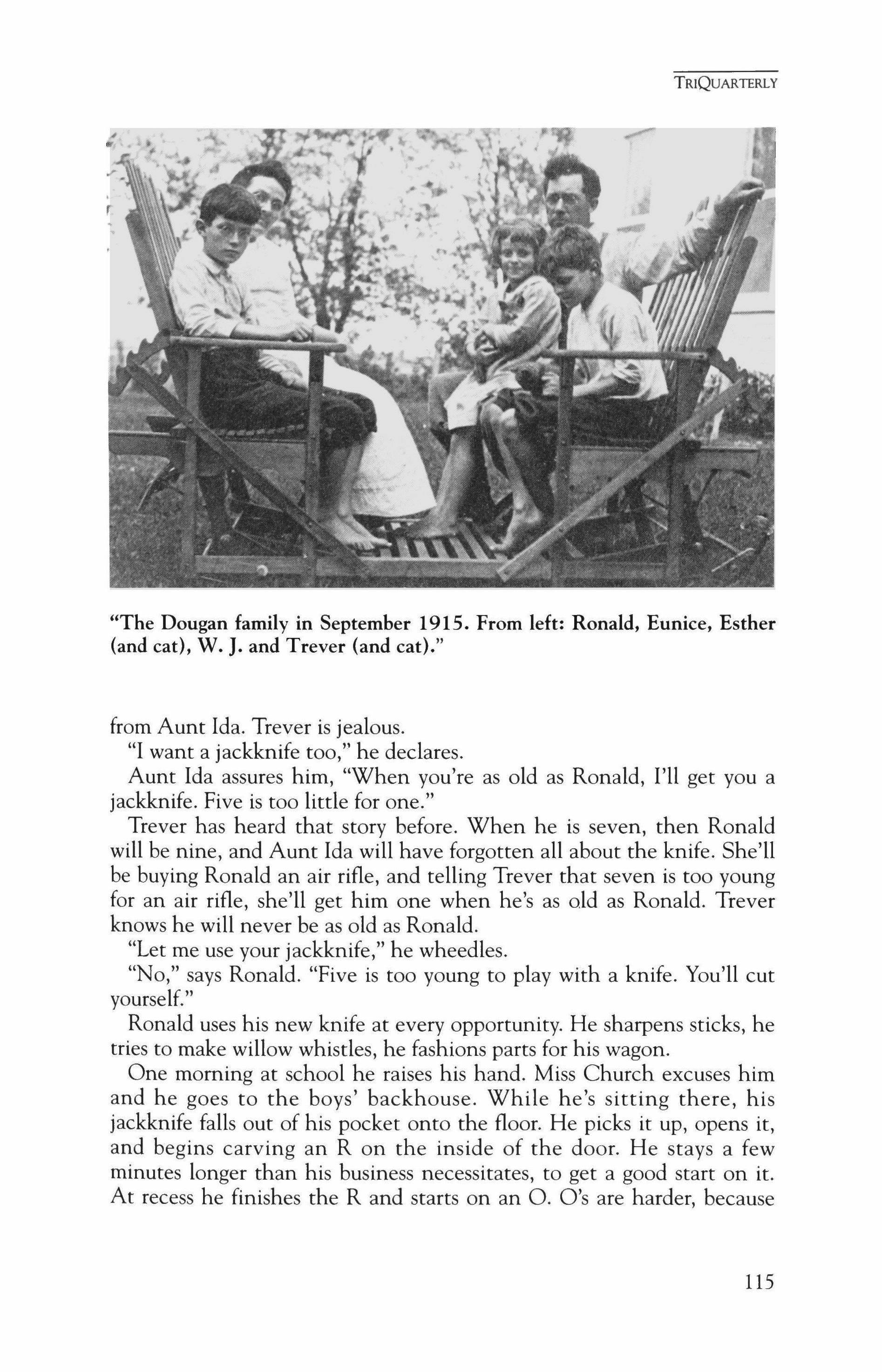

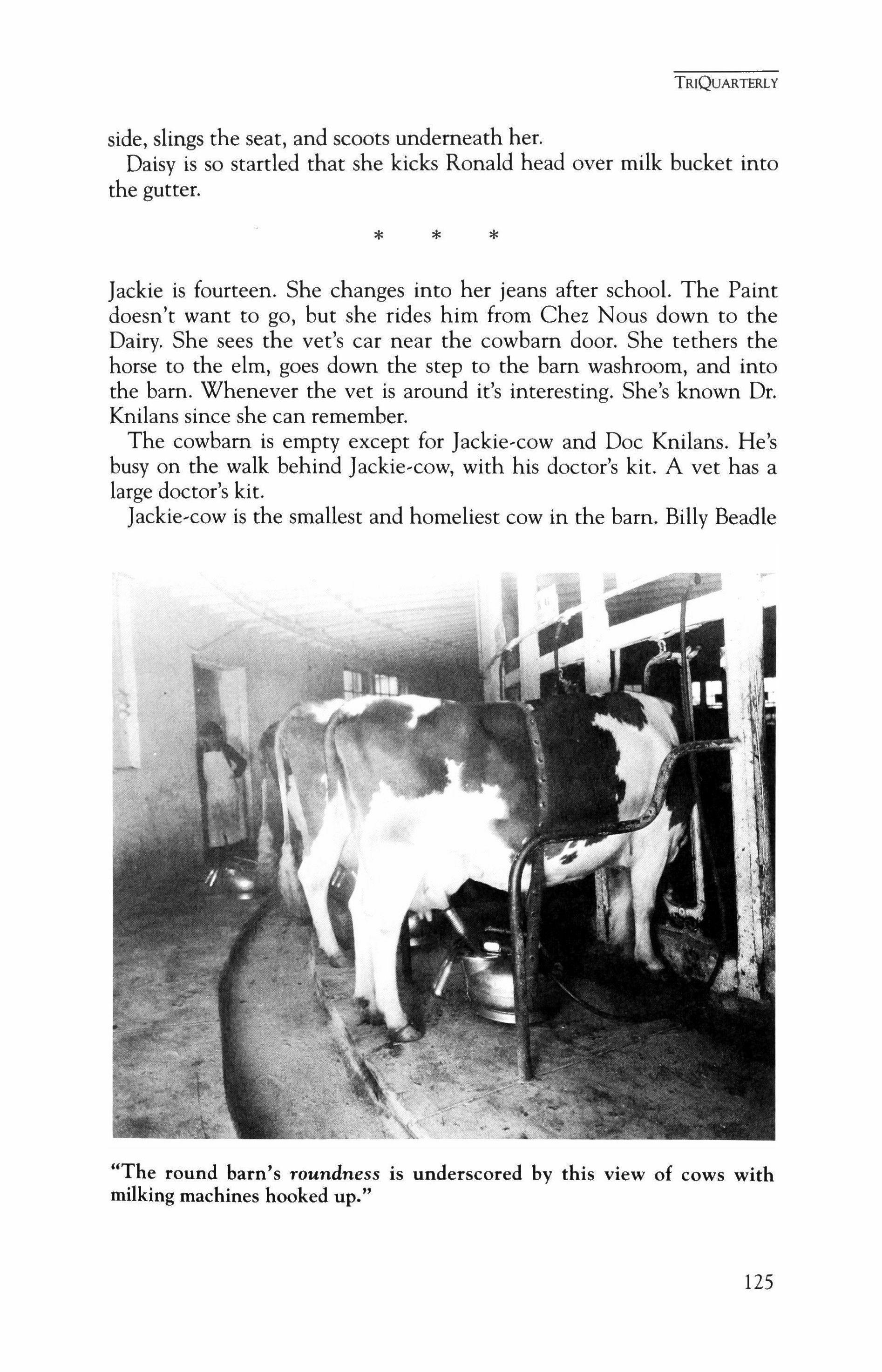

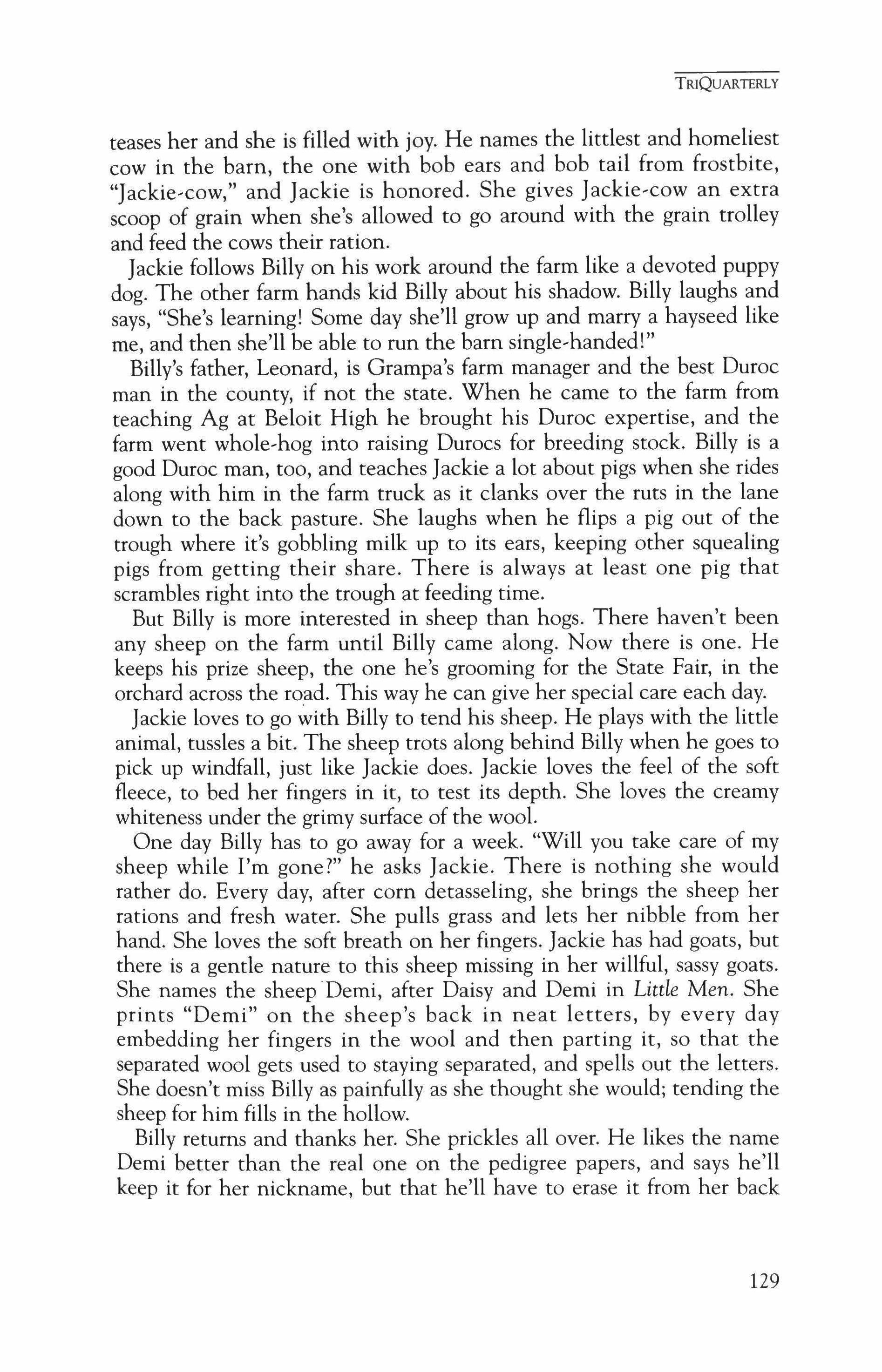

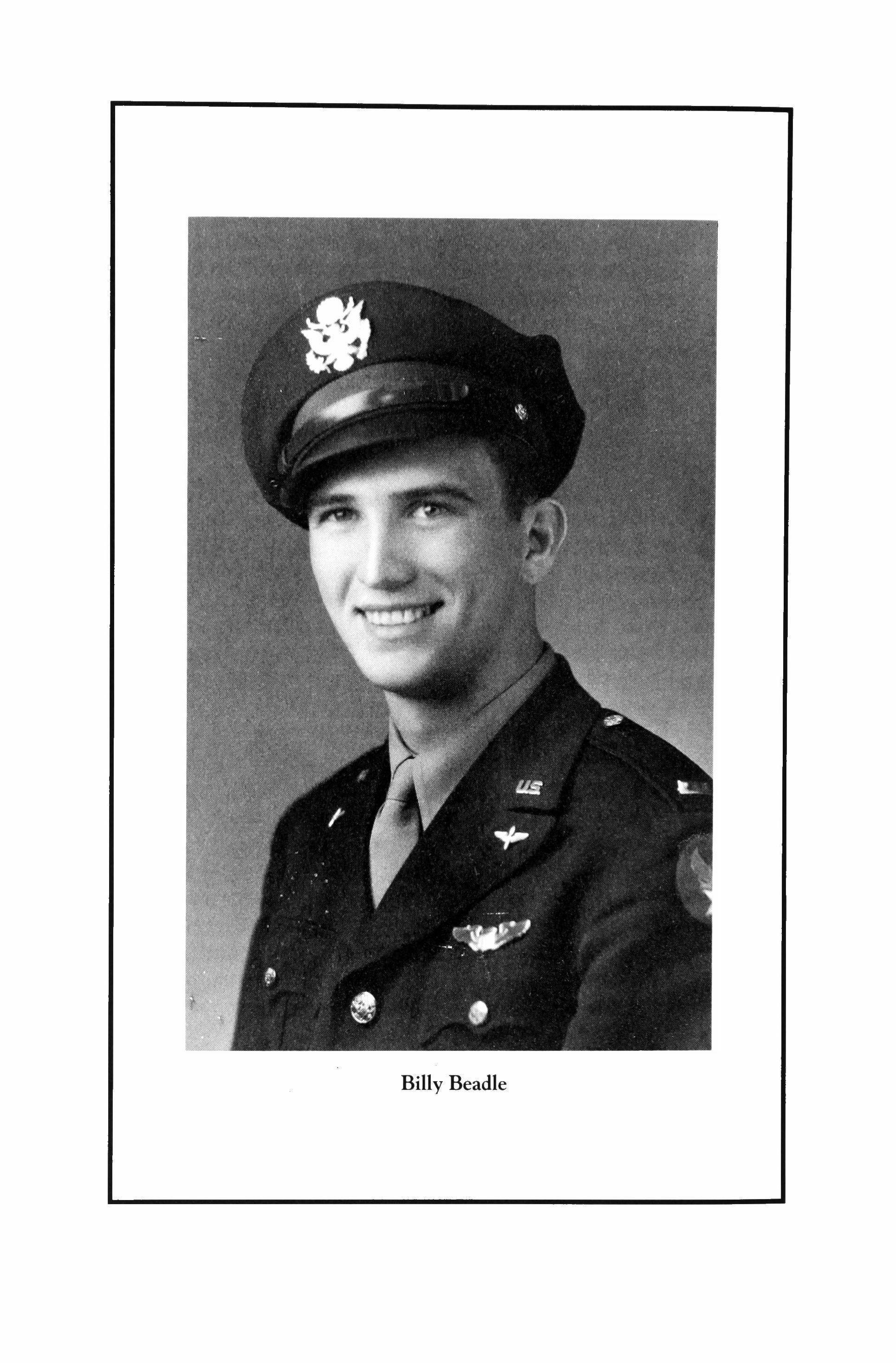

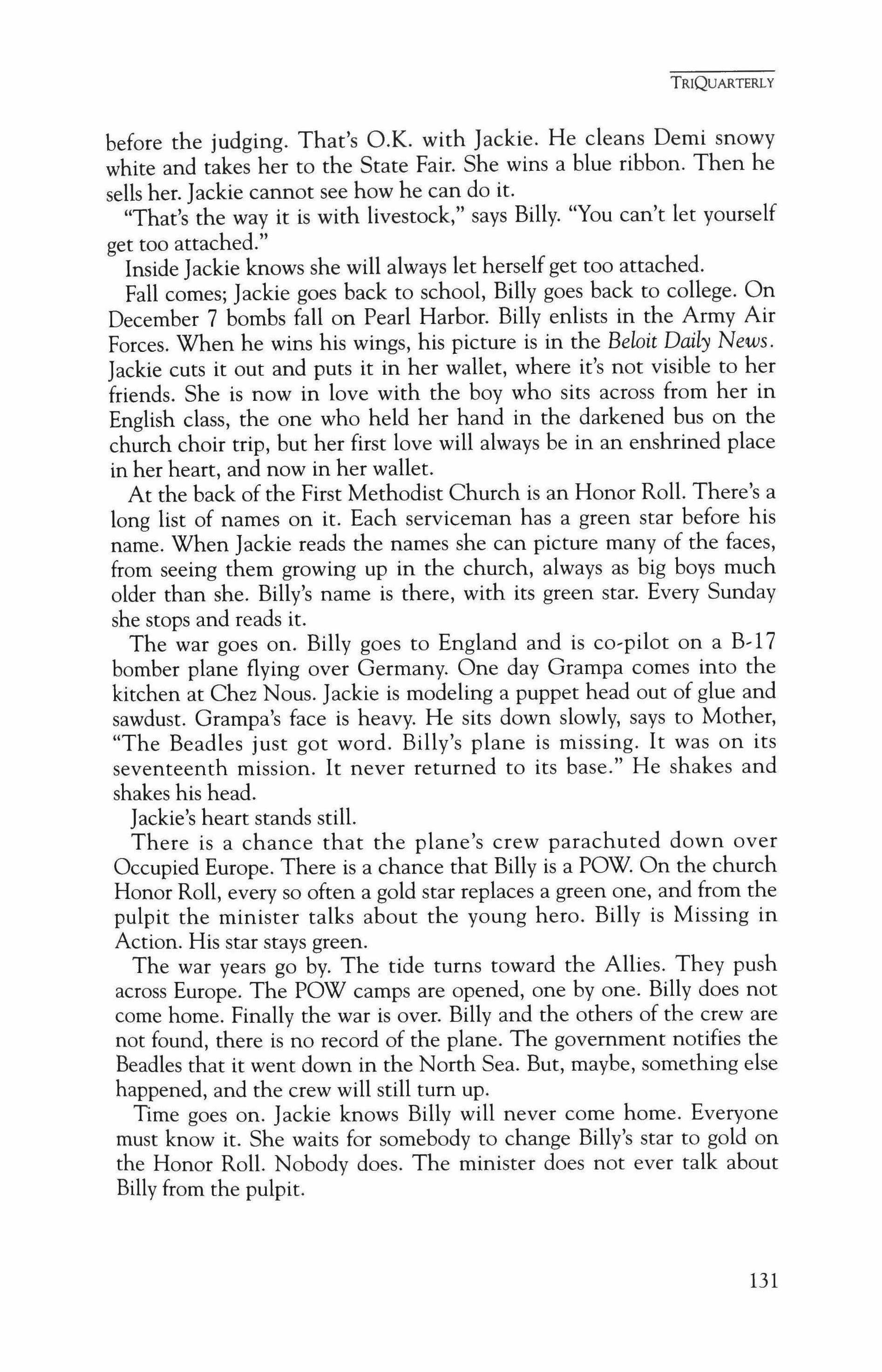

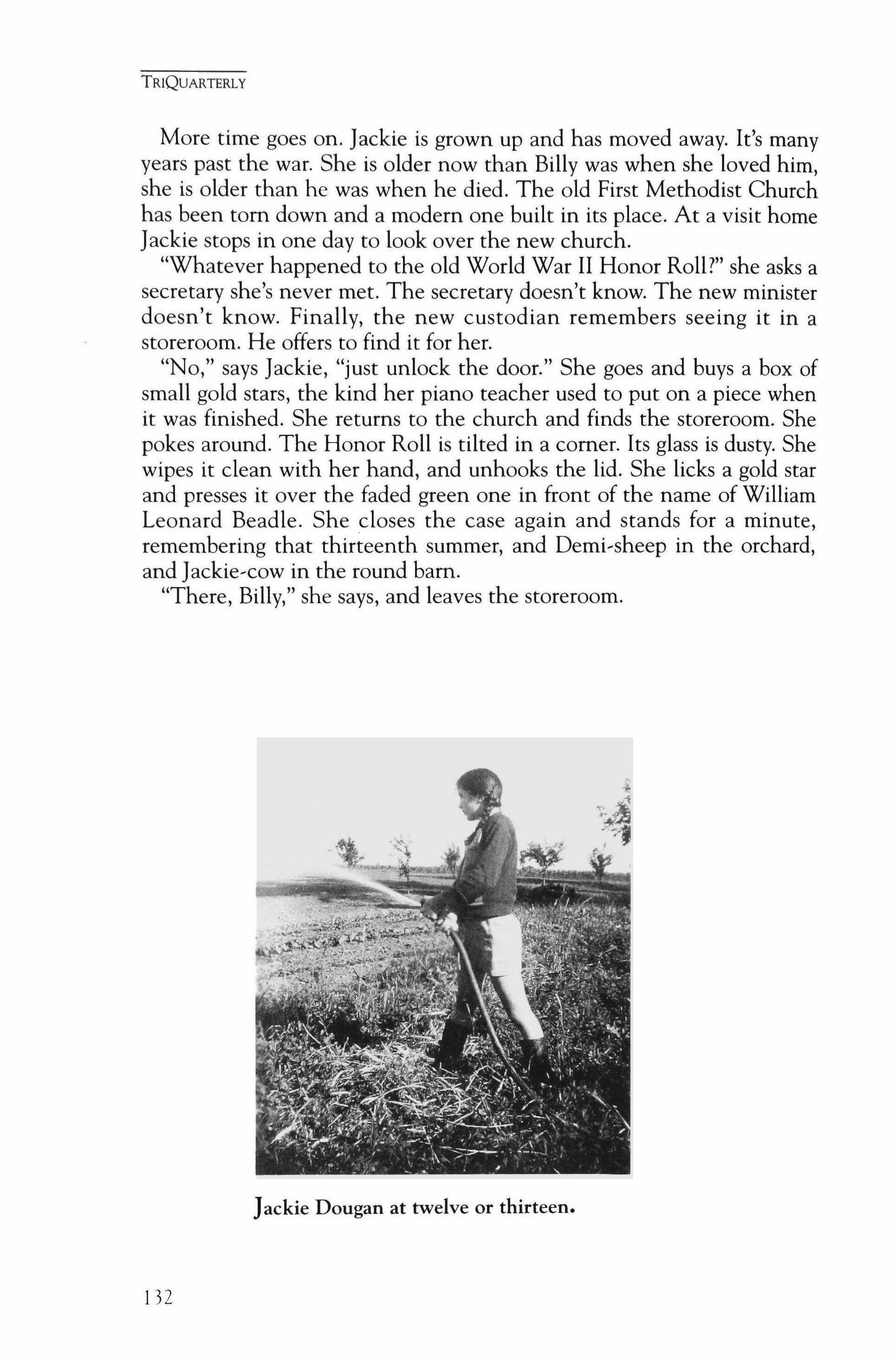

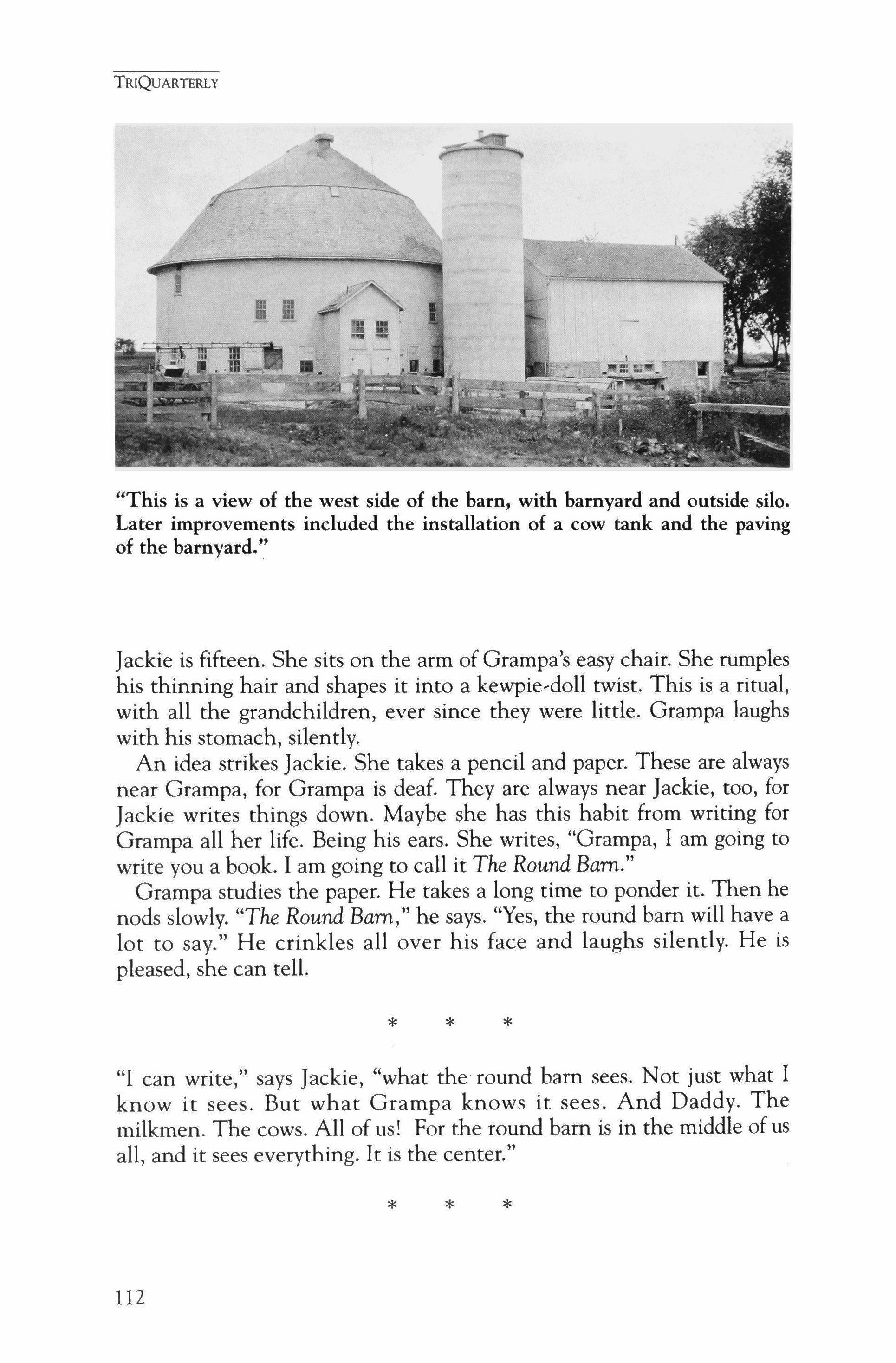

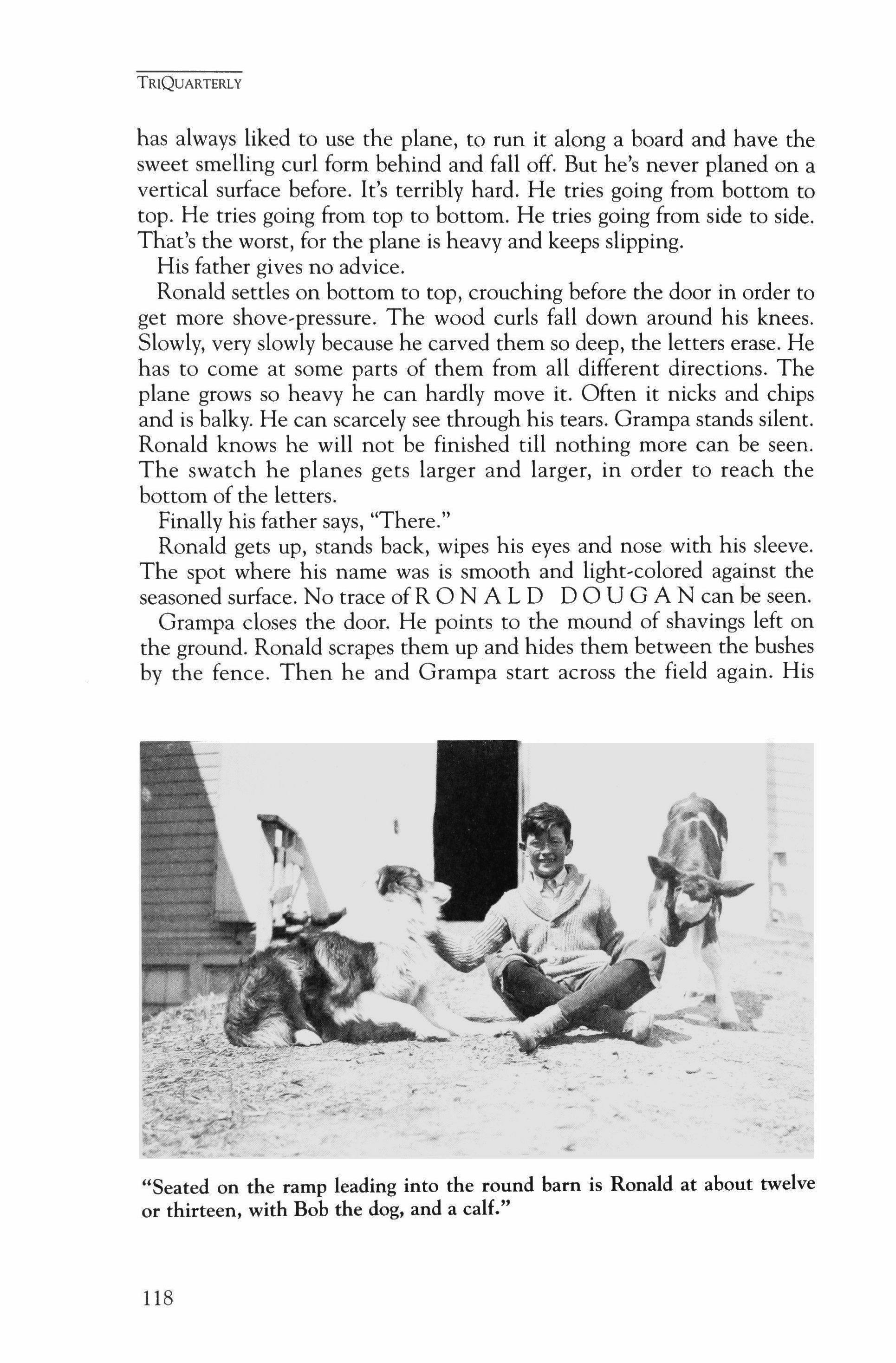

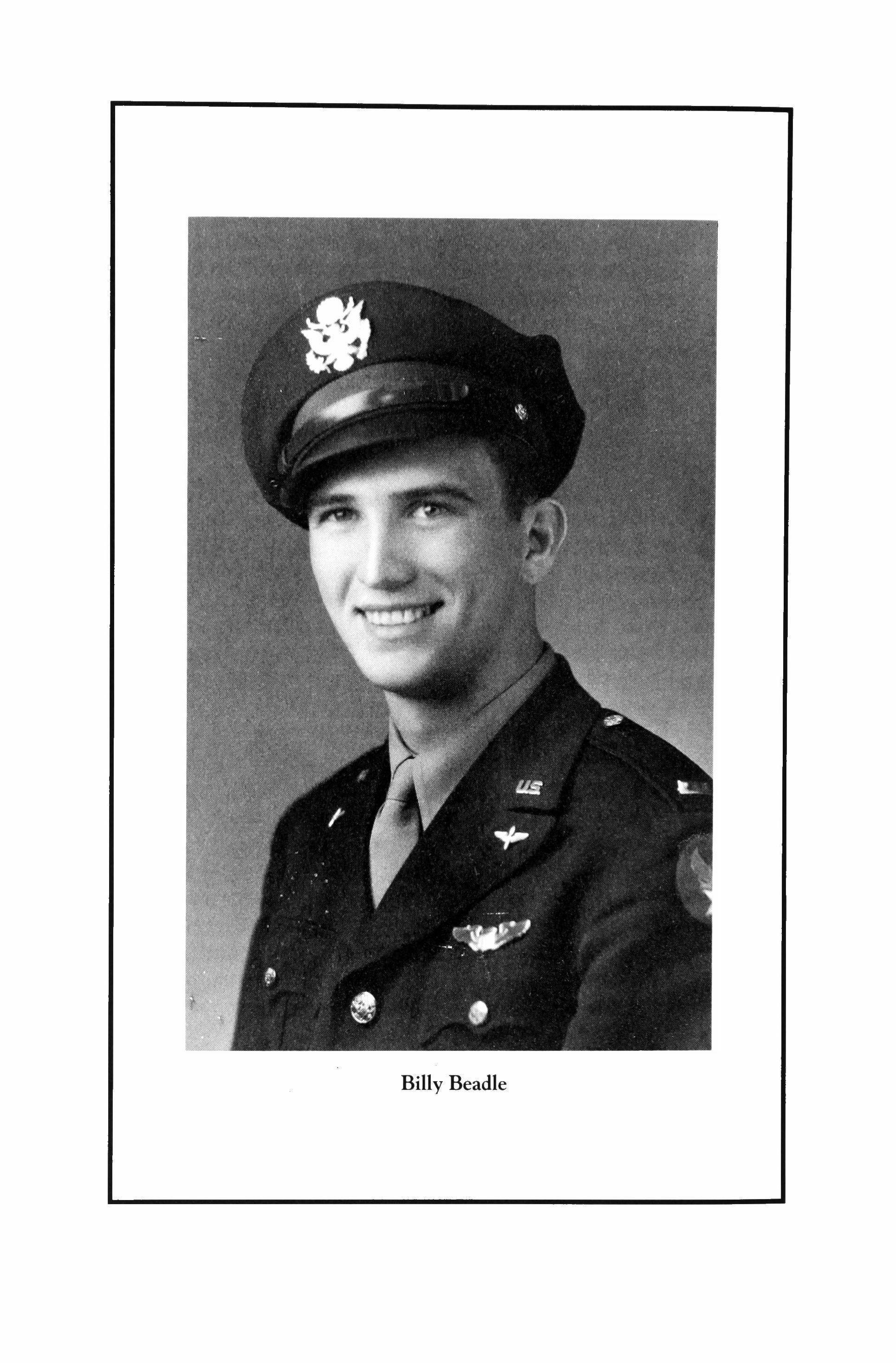

From The Rourul Bam

Jacqueline DouganJackson

From Shaving

Stephen Berg

CONTRIBUTORS

Cover art and cover design fry Gini Kondziolka

110

214

261

In Bed with Lola

Daniel Hayes

There's a point in any romantic relationship wondering what the other person is doing for you why you're what exactly is the rationale behind the fact that, good or bad the way these things happen you're with this other person and it's not really not the same as when you ask yourself, years into a relationship, what the person has done for you tallying it up changing your life, even improving it everything up to that point, summed up in a language of a kind of scorecard approach to love but by then it's become a more distant

it's a more pragmatic way of it's an easier question to answer and early on, it's harder asking the question because you you think you realize it's strange, isn't it, the way you need to see this person thinking about her talking to her on the telephone, day after day, as though she was she's been sent from heaven, you tell yourself, to right your life bringing the pleasure you'd always who knows, maybe you'd even deserved it which is why it's finally it's arriving a little late, but still someone telling you that you yourself a story about how you'd

TRIQUARTERLY

21

descended from heaven and somewhere along the line you'd simply forgotten.

You find yourselfrelying on a perfect stranger or maybe she's not perfect what's perfect about a stranger but someone who almost a stranger, a few weeks or months ago she was to you a perfect stranger, and you think thinking of how it's about it's a question of trust, about how you yes, that's it thinking, Well, yes, she was once a perfect stranger and somewhere along the line I gave her testing her two hundred and seventy-five times taking a chance on her, and now I can see answering the question of why, for what reason she is trustworthy, and so that's why I rely on her why it's this particular woman living with me, eating dinner with me the secrets of my life safeguarded in her heart and so it seems reasonable, making perfect sense it didn't before, but that was before proving herself, earning my trust, and now I realize just

what a wonderful woman she is, even if she's not nobody's perfect.

Except that's not it, because the question isn't about how she might making a fool of you, broadcasting your every secret

given the fact that she might, for all you know, stab you in the back

but that isn't it, because the question's about not trust, but the way you the way I look at people, and what is it I see when I see them

what do I think I see and I can't be alone in having this

what is it I want to see it's as though I were once again it's a childlike reliance on other people

a visitor from heaven, swooping down needing this one particular person and then very soon, as time passes, habits taking over forgetting what a strange thing it is how strange it once was and then bills to be paid, clothes to buy, vacations to plan, meals to arrange starting to take the whole

TRIQUARTERLY

22

thing beginning to take it for granted, more or less thinking about how it's a proposition it's an arrangement that works.

You don't take her for granted no, never but more than that it's a matter of well, sometimes you do taking the tie for granted, the thing that binds you attraction of opposites, or whatever the sheer necessity of the feelings you feel and how it gets to be difficult figuring it out, making sense of why going beyond love, and even that word obscuring what it is

how it has you in its grip covering it up in nice sentiments allowing you to reach a point of composure, whereas before back at the beginning of things you were utterly shameless feeling crazy reaching for the phone again, against my better intentions, and I'm feeling so those voices inside of me asking, Who is she, and why are you calling her and couldn't someone else just as easily be visiting from heaven

and isn't it just the luck of the giving you her telephone number instead of and isn't it childish to dial her number feeling that desperate need dialing her number hard to live without dialing, without hearing her voice, hearing that particular hi the one that greets you changing your disposition a miracle in a world where nothing changes, and things written in stone whereas her voice, that particular hi allowing you to breathe easily again, even as it managing, at the same time, to take that very same breath away.

That's what happened with Lola taking my breath away, almost immediately thinking it would be another kind of woman surprising me, because she wasn't Lola look my breath away, but I resisted her dismissing her, trying to tell myself that she wasn't going to enter my life and because she couldn't, and I was smart enough leveling with myself, calling a

TRIQUARTERLY

23

spade a spade, because she was to begin with, she was too earnest an initial impression or I thought she was earnest, because I hadn't yet seen not understanding her skepticism blind to what was in the cards, a habit of mine and the contempt she felt an intolerance she showed toward people who were themselves as she got to know me, better and better feeling contempt for me and I began to feel her contempt, maybe especially after she apologized for it never having really considered myself far from earnest, or I'd never thought of myself as earnest until I met and Lola was also a little maybe not the right word an initial impression swearing a lot, getting angry with slight provocation, easily excitable finding her a little coarse seeing humor in others' misfortune, telling dirty jokes and nevertheless, at the same time, a streak of sincerity in everything when it came to the big picture

becoming humorless when it got right down to it and so she was herself earnest, even if she wasn't exactly no sewing, no cooking trying to imagine her as a little girl, but I can't not having the demeanor of a girl scout impossible, or at least hard to imagine selling cookies door to door, earning merit badges, putting a bandage on the skinned-up knee of a doll even looking at the pictures on her bedroom wall in her apartment, wandering around, collecting initial impressions looking when she wasn't looking pictures of herself as a little girl, one after another, hanging on the wall.

There was something about Lola how her apartment seemed everything a little haphazard, willy-nilly uninviting chairs, an uncomfortable couch suggesting that she wasn't her kitchen, nearly bare, minus the rudimentary appliances she wasn't getting around to not taking an interest in creating a more stable

TRIQUARTERL

Y

24

TRIQUARTERLY

establishing a horne for herself too fickle, too wacky believing in grand sentiments, nonetheless, and especially in her ability telling a story about how she'd managed wresting control of her life from the others their attempts to have control over her, to keep that control telling her, silently, what to do and I thought, a gripping, personal tale of such an unsympathetic way of thinking her story was a little simplistic, slightly naive everything wrapped in complexities is how I usually saw everything nothing dramatic, nothing simple never enough of the clean, clear and bright ideas that tell the story the very idea of having power over ourselves dreaming of getting to that point

wresting control, convincing ourselves of how and feeling bad for thinking that a gripping, personal tale of I mean, what's wrong is there anything is there something wrong with taking control of your life?

I liked the spareness of Lola's kitchen, and the fact that she didn't frilly apron, sound of kitchen drawers opening and closing when I see a woman cooking, it makes me think of giving me the shakes making me feel the fatigue of feeling like a child all over again my mother doing what she does cooking in the kitchen, in the dull hours of afternoon the smell of meat sizzling the hour corning, sooner and sooner

my father walking in the door, briefcase in hand, stories of his own and so I liked Lola's refusal to do the kinds of things bucking against expectations, and how she was a little coarse

maybe not the right word showing a fierceness in almost everything never mincing words, never flinching from a fight even if it did bother me how she wasn't she wasn't the opposite of what she was never having thought of myself as sentimental until I met even if Lola had moments of being romantic and

25

visions of seeing her father, looming, I think vulnerabilities out the window a strong man, even if he wasn't a face that said let's get it done! foreign language to my ears and so men roaming around in her mind, opening doors and flourishing flowers and, above all, the idea of stability wanting me to be romantic, but her own ideas were including one in which together in a big old house, and she turns to me a fantasy about being old and married not saying, Goodnight, as you'd expect end of the evening, time for bed but instead, Fuck you and these words are to which I reply, Fuck you they're said softly, in the spirit of love being large enough encompassing the hatred we inevitably feel it's no use denying the fact that sharing our every emotion, even the ones that why is it that the ones with whom we share the people closest to us are almost always the brunt of telling me her fantasy but not

wasting time on explanations, exegesis what's the point, exactly not explaining it, discussing the intricate motivations just a fantasy, a spur-of-themoment making her laugh in the telling, as though she'd let something slip out of control, minus the responsibility and feeling absolute envy for that, even if it wasn't her fantasy wasn't one that routinely sprung to my mind, but still not calling it my own, but then maybe never having thought of myself as sentimental until I met not my idea of love even if I could easily imagine Lola's fantasy liking it, chuckling at it, imagining it as my own, and that meant something.

My fantasy was much more immediate, and simpler alone with Lola, removed from the trials of everyday a beautiful house up in the mountains, or maybe it's near the beach it doesn't really matter quibbling over details, squandering the currency of fantasy

TRIQUARTERL

Y

26

it's somewhere remote, that's the having this supply of cocaine, but not enough it's an extravagance, that's the point sitting down and figuring out parceling it out, deciding that we get so many lines so many days a week and Lola thinks I'll hog it because she wants to hog it, and I like that the feeling of competition camaraderie is maybe a better way of like children willing to openly admit our greed, and like reasonable adults coming up with a canceling out each other's greed, ensuring equal distribution scarcity, the mother of all pleasure a point we agree on when often it seems there's nothing we forced to compromise, and feeling the pleasure of that miracle passing each other in a hall and saying hello, chatting not in each other's way, within the bounds of our beautiful house a day going by and we haven't really talked never getting tired of each other sleeping eight, nine, even ten

hours

maybe it's this bed, this immense, king-size boat ofa going to bed at one in the morning, having finished an exhausting game of cards the feeling of competition the deepest sleep, and then finding ourselves in each other's arms, opening our eyes, one at a time looking at a clock that tells us it's almost noon and when it comes to O.K., so no monkey business, but lots of kissing here and there, in the interstices of the day reaching out with her hand, touching my face, bending down to kiss me standing barefoot in the kitchen, cutting fruit for her own consumption not even asking if she can be so selfish arguing about that, maybe touching her, underneath some little dress she's wearing arguing sometimes, maybe because it's there it's a possibility, and you wouldn't want to miss out on one but then Lola says, You're an idiot and that's pretty much the end of

TRIQUARTERLY

27

I say, Hey fuckface as simple as pie, as easy as not nearly as frightened as we once were, which is what makes it it's just a fantasy.

We were, both of us in the beginning, and even later, in the real world of inviting me over to her apartment, before we went out to scaring me a little frightened down to our socks asking, over the phone, whether it might be better to meet at the restaurant the intimacy of someone's apartment, a woman's and she said no, why don't you just incense burning when I arrived walking into her apartment, and smelling it wanting to tum around, go out the door and leave because of the a bad sign, anathema everything the incense represented walking into the wrong world feeling the impulse to stop things wishing for the strength of my instincts ending things before they'd even why make a mistake when the instinct itself becoming a

kind of challenge but then turning things upside down in my mind, and so I'm no longer sure if it's really shuffling the deck, shaking out the rugs I mean, how would I would I know an instinct if one bit me on the nose?

And I remember seeing them again a dozen rings the same as I'd seen them the first day I met her her hands, so small in the kitchen, at the party, looking for ice seeing Lola's rings the first night I met her a dozen rings on her right hand, not to mention maybe not that many, even on her right hand, but it's the impression that and now, showing up at the door, shaking hands the incense wafting the apartment cluttered, the same as her hands, so small she never throws anything away, that's for sure feeling as though I've walked into the world of a woman who has a history, and maybe it's what if her life's as cluttered as overrun with men and

TRIQUARTERLY

28

disappointments, scars and expectations sitting down, on uncomfortable furniture she was doing most of the talking, and so I listened, asked questions trying to think of what to say making an impression, accounting for myself anxiety at the heart of taking its toll, turning me into a gentleman looking off at the walls, at reproduced artwork a polite mute, nodding his head

having a private conversation is she, or could it be a kind of tussle between me and me

needing to use the bathroom as soon as I arrive, and again fifteen minutes later and so something must be going through my slight embarrassment in that, the second time what's going through my mind

source of the embarrassment not that I know what it is but something must be, since I'm not particularly interested in this woman

seeing this encounter, in Lola's apartment, as just another calling it friendly telling myself that, a story I've written inside my

romance not in the cards, because of the incense and the rings shaking hands and getting to know each other writing about it, inside my heart the cluttered apartment her hands, so small as I sit and listen to a nonstop delivery of information talking too much, revealing too much a crash course in Lola.

If she was nervous then, she wasn't nearly as nervous as two nights later waiting for Lola, at the restaurant, glancing at my watch is she irresponsible, am I doing the right not a good sign that she's and finally she walks in, looking harried trying to slide between the two tables, knocking over the woman's water apologizing to the woman, yes, but hitting the glass with her bag a crotch full of cold, icy water a look of shock on the woman's face and wanting Lola to apologize more to the woman, because she looks the woman's distraught and angry, and apologies are

TRIQUARTERLY

29

very important as a test of character and so I watch carefully thinking, Who is this woman, and why is she coming to sit at my table?

I was scrutinizing Lola's behavior, wondering whether on some superficial wondering if she were a nice person and it's not a good idea there are people in this world who aren't nice, and probably it's not a good idea to get into bed with someone who worrying that Lola might eventually spilling water on me not seeing that she'd hurt me, not noticing the damage and so there it was, Lola's obliviousness not that big of a deal, mountains out of molehills appearing nonchalant, and when a woman women shrug their shoulders and I find myself gasping for air

hurting me even more than whatever it was, the original thing and there's nothing worse than a woman unaware of herself except if she's oblivious to me or that's not really

and Lola relayed to me worse yet is a woman who disapproves of me warning me that she was critical slipping them into her sentences a series of minor complaints, almost from the beginning wearing too many loafers and I hadn't thought of myself as wearing too many loafers, but within days thinking that, yes, there were a lot of more like minutes right now, at this point in my opening my closet, looking down at all of them bending down and counting them and even the word loafers suddenly sounded stupid cringing to think that sometime in the future I'd think back to now and see sad, scary image an army of open-mouthed loafers and feeling like a fool for wearing those loafers almost every day for a period of my life

telling me, confessing to me I wore too many loafers, Lola said, and then telling me a few weeks later that she was a go-go dancer during one period in her life listening, slack-jawed

TRIQUARTERLY

30

she was a go-go dancer before I knew her, and not believing her, not at first she didn't seem like a person who was who could've been in the past a go-go dancer and wondering, getting competitive, even in moments of intimate exchange asking myself, What's worse, wearing loafers for too many years or dancing dark, sleazy bars the tongues of men hanging out of their mouths?

What would I have done if I'd just met Lola in the kitchen, at the party, looking for ice the words dribbling from her mouth the first night I met her what would I have done telling me that she was right then, right at that moment of her life the period she was going through she was a go�go dancer and maybe, for a moment, the idea might've struck mE as unlike the other women I've known this one's unusual, exciting you can get into a rut, I tell myself, when you might benefit from occasionally

but I've never at the time I'd never had a fantasy of being with a go-go dancer but close to another one, adjacent a different fantasy about being with a prostitute she's your girlfriend, but she's also sleeping with zillions of other for purposes of making money, let's be clear and it disturbs you, for the obvious how she's a prostitute but flattering, as well, so many men wanting to sleep with your but no, that isn't that's never been one of my favorite a virtual line of customers wrapping itself around the block imagining what it would be like

O.K., yes, I've thought about it, but nice to have men who want to sleep with your girlfriend, but why does it have to be why do they get to sleep with your girlfriend?

Lola said she didn't enjoy gogo dancing, like some of the other girls exhibitionists, taking pleasure in the

TRIQUARTERLY

31

getting a kick out of it

making a bundle of she kept using that phrase, a bundle of money in a single evening, in a few short hours and once you started making that kind of money, it was hard to not having other talents with which to make that kind of at least at that time in your life an explanation that made sense, though not enough of it and she said, Do you hate me now that you know that once I was a go-go dancer?

When she first she's telling me about it imagining these girls you sometimes see when you go to nightclubs or dance clubs up in elevated cages, wearing short yellow dresses and boots

making you think, creating the illusion it's 1967 or thereabouts the world's on fire and you're young and a whole bunch of people aren't staring up at this girl, watching her dance, and she's very good at she's moving her body so that and it's a little strange, since she's in a

staring at the animals at the zoo

it's tongue-in-cheek

it's a parody after all, and so you can relax, loosen your tie, enjoy the voyeuristic shtick

you were a little boy in 1967, and now a boy all over again, and this larger-than-life girl is dancing away totally oblivious to you it's enough to bother you, but then it doesn't really if suddenly she waved letting you know that fantasies, thoughts of you streaming through her mind, just at that point when fantasies about her were streaming through your you wouldn't know what to do, how to react if suddenly she waved realizing that it was precisely cherishing the distance that anonymity provides imagining that kind of go-go dancer, but it wasn't Lola wasn't the kind who dances in a staring at the animals at the zoo

dancing up on a platform, instead, or maybe on the bar itself

Lola telling me that she was never completely beers and shot glasses and

TRIQUARTERLY

32

napkins with the logo of she wasn't naked, and it wasn't exactly a striptease the slipperiness of exactly a cross between a striptease and the girl in the yellow and it did bother me men looking up and watching and tossing dollar bills at her feet telling myself, Don't let this bother you warts on the bottoms not having that kind of control thoughts coming into my head without even asking permission couldn't stop myself, couldn't help myself beside myself with and so it did bother me, just as it bothered me that this one other thing finding out about the other men it bothered me, just a little, that Lola slept with men I wouldn't have telling me about some of the men who not many, many men, that's not my point but seeing myself as these men not quite in the category that I saw myself in, which made me wonder maybe I'd placed myself in the wrong lying to myself, seeing myself as

walking around in a stupor my whole adult life or maybe it was that she was breaking free of a bad run, a string of a collection of undesirables a long streak of the worst kind of luck wishing to be special, to be different, a visitor from heaven and Lola and I had that in common

a dozen porcelain angels sitting on her entry table, just for starters a visitor arriving at exactly the right moment, and so maybe I was myself tom wing, the overall whiteness dirtied a shade or two asking myself, Am I only more of the same, or am I different?

That was the question that ran through my meeting a woman, feeling a little wondering about myself, getting a little self-conscious, worrying about a version of that question zooming through my mind whenever popping up, out of nowhere, as though I hadn't asked that same question every day of my fooling myself that way

TRIQUARTERLY

33

wondering, Is it that you're fucked-up in major ways, or that you're aware of yourself the degree to which you're somewhat and that's better than if you didn't know how tucked-up you were, how would you such an ugly way of putting it and I sometimes wish a mind isn't a pretty place, let's face it always wanting to get to the point of speaking my mind, but there's this feeling immediately afterwards your mind having dribbled its dribble thinking it would come out a lot better more sophisticated, and sounding coming out ugly, and there's not much except maybe go back, clean it up having decided not to do that shaking the person's hand, so to speak, even if your own is a little wet.

So Lola said, Do you hate me now that you know that once I was

I don't hate you, I said and she said, But you're disappointed Well, I'm just trying to get my bearings

you were once a go-go dancer and hard to imagine you as you don't seem like a go-go dancer and it's slightly disappointing to know that you were once but it was a period of your life, and now that period is and I wouldn't have guessed, wouldn't have wanted to guess knowing how once you were a go-go dancer and she said, You hate me but I could see that she knew that I didn't hate her, and that

knowing I didn't but asking anyway that seemed like a good sign a strange habit of hers liking the way she managed to have it both ways knowing that I didn't but asking anyway and knowing better but not being able to stop myself.

I'm in the bathtub, and she comes home and walks into the bathroom sitting down on the toilet, the lid down and I remember how she sitting there and looking beautiful hair everywhere, black sneakers another of her bulky

TRIQUARTERLY

34

sweaters, a pair of orange sweatpants small holes here and there, as though at some point she'd tossed acid on them having seen better days and I have the feeling that Lola isn't beautiful she shouldn't be not now, as tired as she absolutely disheveled but she is beautiful, and I can't look at her without seeing it, sensing it the beauty beneath everything every bit of evidence to the contrary creating the impression in my mind, irrespective of and I can't look at her without wanting to tell her, to pay her the compliment explaining the discrepancy pointing out the clothes, the fatigue, lines around her eyes, thinness of her lips when you can't help wishing for and yet the beauty that I sense, looking at her knowing that at that moment I'm utterly beside myself with hair everywhere, black sneakers desire mixed in, too, swirling around and telling her, or imagining it if I told her, she'd only belittle it

her sickness, her resistance making fun of it, calling it craziness to feel that way she's frowning and listening intently and then Lola's having difficulty with one in the middle of everything I've just my heart emptied out she's having difficulty with this one particular word not important which one and saying, in summation, that the thoughts and sentiments are nice but one of her favorite words, corny using that word in talking of how I and I think to myself, What's wrong with this woman listening to her, and watching the way she scrunches up her nose when she says corny my heart emptied out a dismissal of everything and so out of anger I say, Lola Green's a woman incapable of loving herself, and so when a man expresses and when that love is genuine, or as genuine as it ever under the scrutiny of someone like the way that she's so resisting what I say because it forces her to thinking of herself as lovable,

TRIQUARTERLY

35

and it's virtually impossible for her to do that and then she reacts by getting angry at me, saying that I'm cold-hearted the tone of your voice, just listen to it that flimsy kind of dime-store, psychological analysis not an entirely unfair assessment, but I'm not in the mood for I won't admit the degree to which and so an argument begins, if that's if what's been going on isn't already and arguing with Lola is like having your head pulled in two different never hearing, not even for a single moment, that voice inside your whispering to you, You're totally right and she's totally wrong and wanting to hear that voice.

She hated the way that I kept saying that how I'd tell her she was sweet and thinking this time it'd be different that was a little stupid of me her above me, moving slowly, swimming on my wanting to tell her fucking me, and I'm telling her not knowing exactly how to

saying to her, You're so the look on her face at that moment, after I'd said, You're so sweet a little corny, I guess the word loosened, lost, floating out into wanting to grab it back and put it in my mouth, which was where my heart under scrutiny even though later, only a few weeks calling her sweetie, and somehow

I'm not sure exactly why or how, but it was different in her mind passing the test, overcoming whatever it was saying to me, Say it, please say it again loving to hear it come out of my mouth, and maybe the gift of sweetie knowing better but not being able to stop herself from smiling time passing, defenses loosening or maybe there's some other reason the linguistic subtleties I don't know.

There were times when she'd ask me why you love me but why and I couldn't very often think of

TRIQUARTERLY

36

let alone a convincing response, and what was it she wanted me to say something, but what and what did I want to say because I wasn't sure why I loved her, and if you stop to think

wondering why you love this or that person it's magic, or it's an arbitrary this one particular person and you can't exactly say but Lola wasn't asking for maybe she was asking for that, but a habit of hers, realizing her mistake

asking you if you hated her when she knew you didn't letting you know, as she's making it it's an outrageous or unreasonable request trusting her, as a consequence, more than if she asking for something and not seeing how it was nearly impossible winking her eye instead, letting you know that she knew and knowing that, that she knew

making you happier than if it was only a matter of a question of Lola's intransigence getting into arguments, suffering her anger losing hope in everything,

thinking that she was hating each and every bone in her and then looking at her and seeing just a hint of it getting this little glint in her eye

having it both ways yelling at me, and meaning what she said, but also realizing having the presence of mind to see showing me that she didn't hate me as much as I hated her, which made me hate her less than I might've maybe even less than she hated me.

I was a different kind of person around Lola because she wanted to see getting me to see that it was O.K. to let things everything getting a little out of control wanting to see my anger, out in the open and exhilarating to feel, at least for a moment, like a different kind of someone who'd do exactly what he wanted not looking in the mirror every day and seeing the same liking the idea of leaving myself, getting away from you know who

TRIQUARTERLY

37

and I remember one night going to a movie feeling that feeling, afterwards without Lola, as it turned out having become a different kind of person walking out of the theater, into the night, and feeling becoming like the male protagonist in the movie his girlfriend asking him, point-blank looking directly into his eyes, to conjure honesty asking him if he's seeing anyone else and he maintains the eye contact and says, No saying it firmly, insistently, in order to create the impression that but we know he's lying the audience gasps shuddering at this betrayal, whereas it didn't bother us fucking with the other woman, tearing at her clothes we liked seeing the first betrayal a shared silence, in the dark, mouths agape because seeing what's not supposed to happen is it's exciting to see life getting a little out of control but this betrayal lying to his girlfriend is somehow and what is it, anyway a good man would've betrayed

his girlfriend and then offered prompt notification and afterwards, feeling like a different kind of coming out of this movie with two friends and a friend of theirs inviting me at the last minute to this movie in no way trying to set me up with their friend Suzanne and so it was incidental; then I'm a man and she's a woman even if it doesn't feel incidental, because it never does, even if you trying to hold onto the feeling that it's only sitting in the theater, next to her, and I don't know this woman, and it's chatting, getting to know each other and it's always intense, even when it's taking place in the five minutes or so finding seats, waiting for the previews to screen she's a woman and I'm a man, whereas if we were both at least from my standpoint the conversation wouldn't feel so direct, and I wouldn't feel why is this other person so her face two, maybe three inches away it's hard to get that close and not think of not meaning to, not really, but what if

TRIQUARTERLY

38

things getting out of control opportunity knocking mouths moving closer, in a sudden, abrupt the surprising warmth of it kissing for the very first time my friends looking over in utter surprise or no, leave them out of it, and so make it after the lights have in the darkness, feeling her hand suddenly in mine fingers in between fingers squeezing in a kind of secret language we're making it up, just the two of us.

A friend told me a story about visiting a college giving a lecture on the plight of a presentation on the reasons behind the necessity for and afterwards going out a group of the students, administrators, professors at a table, sitting next to a woman he found attractive, but he hadn't giving her no sign, and having no intention of but a half-hour later, feeling her hand it was a secret, he thought reaching over, reaching under, taking hold of his, squeezing it and he told me this story, and

he said sounds silly now, I know, looking at it from a more mature perspective it was the single most exciting whether or not anything ever came of it another story, another kettle of the surprise of finding out that someone the sheer unlikelihood of her hand in his and so it's not just the whims of your and now imagining that at that moment you'd want to squeeze her hand just to keep yourself from crying confirming that it is there someone thinking the very same thoughts as you a moment like the moment when it's a sudden convergence, a confluence of and later you talk about it early in a romantic relationship talking about how it happened a secret history of what took place before you even you didn't even know it was taking place the mutuality of the feelings you felt she was thinking of you at the same moment as and your finger, together with her finger, running down a list of salient moments

TRIQUARTERLY

39

bumping into each other on the street, and then the telephone conversation supposedly incidental, purely business and it's only now that you can seeing the true story, the deeper meaning and imagining what it's like when that meaning isn't most of the time it's simply drained off bleeding into oblivion and how awful, to suffer the fate of thinking thoughts that never reach the point of only one person thinking too much, thinking extravagantly and you tell yourself, if you're that one person and she's thinking about telling yourself, Stop thinking, but it's not that easy thinking what a weird face you have, or about meeting someone else the next day, someone truly exciting remembering an errand that she needs to do the dog must be getting hungry, or God knows what.

We came out of the movie and talked about going out to get something agreeing on a restaurant a few blocks away telling them to go ahead, that I'd only be a minute needing to make a phone call leaving me alone to call Lola,

who answered on the very first

saying she'd been trying to call me, and hadn't we agreed to talk this evening saying she was worried about or, worse yet, I'd been killed fantasies about how I'd met another woman spinning it out, telling me about how I'd met this woman in a cafe getting to know each other in a hurry, and then making a serious attempt nice of Lola to imagine it trying to stop things from tumbling in the direction of not a total louse but not trying hard enough, and so this woman and I it was about how your life can change in an instant we'd gotten somewhere we hadn't even imagined getting an hour of conversation driving you it's almost the way a marble works its way down a maze, Lola said and she was describing I realized that this was how Lola and I not in a cafe, maybe, but talking in her apartment, before going out one form of hunger in lieu of meaning to leave but talking much longer than we'd planned the incense wafting

TR1QUARTERLY

40

and I felt myselffalling for her, and it wasn't neither of us intending for it to happen no consolation in having consciously decided and a voice inside my head said, Slow down wanting to close my eyes and find out where it was I'd end up paying little attention to that voice opening them and seeing how far I'd gotten and that was very much the idea, whether or not I wished at the time to admit it and now Lola was saying imagining that it could've just as easily been another woman

falling in love as a kind of daily a habit of mine, which it wasn't and so I told her that I hadn't met another woman, and I wasn't dead and she asked who I went to the movies who was I going to dinner with my friends and a friend of theirs, Suzanne, I said and there was a silence at the other end knowing what was wrong, what was going through her liking what was going through

her mind asking her what was wrong knowing I was being disingenuous she was jealous, whereas too often it was I was usually the jealous one in those first few withdrawing, making me wonder if conjuring up the worst fears and so I liked the silence on the other end of the phone, even as I felt the need to say something and finally Lola asked who was this woman telling her about Suzanne, what I'd picked up in the five or so minutes of and Lola said, You're double, dating and I said, What?

She said, You're double, dating and that seemed I couldn't help finding that a very hilarious an odd way of putting it I wasn't double-dating, and I hadn't ever double,dated, and to this day choosing to refer to it as I wasn't the kind of person who dated, let alone and when my mother asked me if I was dating anyone, I never what in the world was she

TRIQUARTERLY

41

talking about image of a single malt, two straws and so no, I wasn't doubledating and right then, at that very moment, feeling as though I were lying it wasn't true, but I felt as though realizing how much I felt like the male protagonist taking on the same gestures, the same mannerisms lying to his girlfriend, shamelessly leaving a movie and feeling like someone in the movie and now I was on the phone with Lola answering his girlfriend's question, as though from the heart

feeling as though I were the whole time speaking through his hat feeling more vapid than I'd ever never having been a particularly adept liar slightly amused, dumbly smiling, phone in hand not really feeling much of but somewhere in the back of my mind lying to her, but not feeling much of imagining what it would feel like if you were the other person

the pain of betrayal but I wasn't feeling the pain, and I wasn't lying and I told her that I was wild about her, trying to reassure her, but it sounded a little I was feeling vapid, spewing out sentiments, even as I knew I was wild about her knowing she could hear the insincerity in my imagining this as a dramatic juncture in my life standing at the phone booth, the moment of betrayal lying to my girlfriend, in a movie, and the audience can see and she knows it, too, since she is the audience listening to me and feeling the lie behind the saying I felt as though I were lying and so I told her a funny, exhilarating feeling of and Lola huffed, asking whether I was lying and I said no asking whether I would ever lie to her about something like that a kiss out of nowhere, an instance of betrayal and I said no asking what would happen if a familiar, imagined scenario, believe me in a cafe, sitting down, and a beautiful woman sits next

TRIQUARTERLY

42

to me and starts talking and I said yes, that would present a definite and Lola seemed pleased with the honesty of my even if it sounded a little vapid.

She asked me if I loved her asking me even though she already telling her that I did and I couldn't immediately think of asking me how much how do you quantify a thing like quantifying the love that I felt for Lola and a moment later I said, A carload of love, that's how much I out of nowhere, a carload of love an entirely stupid way of feeling like a puppet, manipulated by an idiot drowning in my own and so I said, I love you very, very trying to cover up the stupidity of what I'd just a carload of love and then Lola said, You sound like an airhead right now, and I liked the idea of being the kind of man who couldn't express himself trying unsuccessfully to reassure his girlfriend saying a carload of love, and

thinking, Yeah, that's a great way of and I wasn't that kind of man thinking too much, or taking things too Lola often accused me of analyzing things unnecessarily saying she wanted me to focus less on and so maybe it was a good idea, showing her just how easily I could think less about me, she'd say

becoming vapid with a vengeance imagining myself as a man who didn't keep her in mind, forgetting about her for long stretches and if I didn't think of her, didn't call her, or if I wasn't worrying that she was the farthest thing from my mind a peculiarity of her psychology worrying and not being able to stop thinking of me because I wasn't thinking of her and so I'd met a woman in a cafe

kissing her, or even worse lying on the bed, on my stomach, and asking her to lie on my back, like a koala bear on a branch and when I'd first asked Lola if she'd saying how strange it was, being asked to lie on my back

but then telling me once, later

TRIQUARTERLY

43

TRIQUARTERLY

on, how it would be far better it would bother her less if I cheated on her, sleeping with better to fuck someone than to ask someone to lie on my back, like a koala bear on a branch

liking it when she said those kinds of things to me imagining Lola's anger, rage coming out of every exciting me with that kind of what made her tick, or what I thought made her tick wondering what it was exciting me, scaring me, frustrating me sequestering myself, asking myself shaking my head and asking, What exactly do you want from Lola?

I wanted her to adore me, even if I didn't want to want that knowing there was nothing wrong with wanting that and sometimes I wanted to stop giving her things so that she'd ask and wanting to give her things whether she asked or not that was generous of me exploring every permutation, touching every wanting to tease her, and have her tease me

losing control and watching her lose control wanting to want to tease her and not being able to not wanting to give Lola what she wanted as much as wanting to want what she wanted, as though you could thinking you knew what you wanted a worn-out, private catalog of wants but the whole time you really had no idea what you could want and wanting to watch Lola indulge herself becoming a person she'd always wanted to be, or even someone saying the things, and feeling the things, that made her embarrassed making Lola want things she never thought she'd want, never before allowed herself a little corny, I know indulging me as she indulged herself and wanting to go places with Lola eyes closed, fingers crossed, leaping out getting there and not being able to figure out how a blindness to who was who, who'd stumbled along the way, who'd helped who up not wanting to have doubts

44

about her, but also knowing wanting to reveal those doubts, listening to hers and somehow accepting that fact

shrugging our shoulders, in unison, and then talking about nonsense, the price of tea in China.

I wanted all of these things, not to mention that was the other thing wanting them right now, in a wild flurry, and that was knowing that that was part of the problem, and wanting the patience never giving up on all the things I wanted weathering their absence, or even getting tired of wanting to get tired of wanting knowing that there would soon come a time when all of it would interest me again, and just as intently but meanwhile, wanting Lola to tell me things letting me see inside her mind, revealing things about herself telling me she was once a go-go dancer and if she didn't do that and she wasn't always forthcoming telling me about the warts on her feet, but never letting me

covering them up with little bandages because of her embarrassment making fun of herself and her complex joking along with her, and trying to get ahold of one of her

calling it that, a complex trying to pull back the bandages to look at the each one an excuse not to love her

reason enough, Lola said thinking of the warts, imagining what they look like and yet I do love her, in spite of the warts, and even if using the phrase warts and all a dozen rings on her right hand, the cluttered apartment trying to get used to the idea of who she is and she wasn't always forthcoming imagining myself as someone else, someone I'm not.

As a boy, I had a tiny wart on my wrist and then a slight scar reminding me of telling me about a time when I was wanting no one to see me reveling in embarrassment, prone to it, lying in it, wallowing in any number of my vanity, for instance looking in mirrors, seeing me,

TRIQUARTERLY

45

or maybe not a residue of adolescent anxiety, I tell myself and a stutter that still shows up a dozen or so times a year, unannounced forgetting how that happens, and then it happens at the most inopportune moments, which is why I guess that's why it happens if it's not one thing, it's reveling in embarrassment, prone to it earliest forerunner of all masturbating as the very epitome of seeing, of course, that there's nothing wrong with it coming upon that realization, like spotting a twenty'dollar bill in the gutter and if I had a nickel for every it helps, I guess, but it doesn't help you the way you realizations piled up high, and meanwhile a hole in my pocket and it's my only hobby, even if it makes me feel making me wonder, if it didn't make me feel guilty, would I like it as much?

I found myself wanting to O.K., I didn't find myself wanting to, but not all at once, not every last detail, but

wanting to hear about Lola's own habits of broaching the topic, you might say asking her about playing with herself and so I asked her, and she said, It's none of your business the limits of intimacy when it comes right down to just like that, a frank denial a question of how far Lola wanted to how much she wanted to say and that could be frustrating, but talking about go,go dancing, constipation, previous boyfriends, the painful procedures of extracting money, for instance, which for some reason I've never understood why people get so and masturbation was a touchy topic, too, and if I asked methods and such, the intricacies associated with any hobby interrupting me and saying, I don't want to know about any of this hands over eyes, the scary parts of movies and if I asked Lola a question about how was it that she or when exactly was it what she thought about when

TRIQUARTERLY

46

she masturbated one day telling me" how once it wasn't that Lola never said anything her mother seeing her, catching her this once she'd been doing it since childhood warning her about how habits can form that might possibly stunt the natural that was all that Lola said, its beginning and end, and I wanted to hear wanting doors swung open, and then wanting to open my own and I, too, found it difficult to find the words as a general rule, I mean opening those doors, my doorsfinding it difficult, but not so difficult when someone else it's a life inside someone else's head, and you could never begin to listening to the complexity of you could never have guessed at the contents sneaking a look, sticking your head around the comer and as a boy I knew a girl who asked if I wanted to in the privacy of her bedroom saying she'd show me hers if I showed her mine except for the presence of her little brother, edging in on things an early, sexual regret

waving him aside, having already seen his always wishing I would've made the trade.

Sometimes, in the middle of making love, I'd abruptly stop telling Lola that I was very feeling excited, as though I might even though I had no interest in coming and wanting very much not to come, to be able to continue to not at that point, anyway without the worry of and the only way I could do that was to tell her revealing the fear, the sense I had that I was on the edge falling over that edge bridging some imaginary or not-so-imaginary gap between us telling her, and then no longer feeling all alone that was always the problem, that feeling feeling excited, as though I might talking like that, as I and by the end of this little speech I was nowhere near coming, though I wasn't any less funny how that works, a trick at your disposal admitting a secret, an

TRIQUARTERLY

47

embarrassing worry, and then when it comes down to it, it's really the only trick I've ever and it's always exhilarating to suffer zero consequences, or at least not the ones imagining them, mapping out the disasters having nothing better to do with my spare time a series of terrifying scenarios, like out of a child's head and the saying, An idle hour is a devil's playground, or whatever it that's not it, I know warning against masturbation, as though a hand with nothing better to do and as a kid with lots of spare time the dull hours of afternoon, cooking in the kitchen the hour coming, sooner and sooner

frightening me, as a child, making me wonder filling up spare time like a blank chalkboard just asking for it

a series of terrifying scenarios thinking too much, analyzing things unnecessarily better to masturbate, probably, but at the time unlike the quick-fingered Lola the difference between us.

I was waiting for a time when she'd feel more and at the very beginning Lola was more comfortable, but then

scaring me to see she wasn't exhilarated by confession getting excited by my own guilt, my own shortcomings, not to mention embarrassing to put it that way, exhilarated by confession turning things upside down in my mind, and so I'm no longer sure if it's really asking Lola if she could whether I could get to the point of forgiving myself living a less terrorized existence, feeling the acceptance of coming to accept my silly mind

working, meandering, stumbling, tripping over its own

not to mention the pleasure it gives me.

It was strange how Lola was sometimes prudish, even if at other times she was having it both ways asking her to do things, sexual things and I asked her to tell me wanting her to ask me but she never did that, except when she'd ask me to hold her, hug her

TRIQUARTERLY

48

except when she'd ask me to be inside of her, above her she did ask for that, but there were other things and knowing she enjoyed many of the other she couldn't ask, or she thought those things were just meant to not to say that Lola didn't have her own little whims, strange proclivities telling me how she'd slept with making a list of them in my head, pencil scratching the history of these things unraveling, like a ball of not many, many men, that's not my point meeting the man, going to bed

it's the first time, and it's the start of it's the feeling of the beginning of hope, but mostly one-night stands, it turned out having next to nothing to do with go-go dancing, she said just a period in her life telling me, laughing, closing her eyes and shaking her head and that's when I wanted to hear about it

getting more and more curious, it seemed, while we were it didn't seem that way, it was