•

Eleanor Wilner ON MEDUSA and W. S. Di Piero ON WRITING

FICTION AND POETRY BY

Alberto Savini

Janet Kauffman

Margot Livesey

Joyce Carol Oates

Attilio Bertolucci

Sterling Plumpp

Josephine Jacobsen and others

PLUS A NOVELLA BY Amy Godine

POEMS, TRANSLATIONS AND ART BY

Charles Tomlinson

AND MORE

• • •

• • •

• • •

Publication of TTiQuaTteTly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Sara Lee Foundation, the Wendling Foundation, and individual donors. Major new marketing initiatives at TTiQuaTteTly have been made possible by the Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Literary Publishers Marketing Development Program, funded through a grant to the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

NOTE: TTiQuaTteTly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the last page and the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TTiQuaTteTly.

Please sign me up for:

o a two-year subscription for $36.

o a one-year subscription for $20.

a

Foreign subscribers please add $5per year.

subscription for $500. o $ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal.

Please begin my subscription with issue#

Please sign me up for:

o

Foreign

Please

TO TRIQUARTERLY!

SUBSCRIBE

Name Address Or call US toll-free at 800-832·3615 to charge it! BI88

o

life

TRIQUARTERLY!

SUBSCRIBE TO

a two-year subscription for $36.

o a one-year subscription for $20.

subscribers please add $5per year.

Name Address Or call US toll-free at 800·832·3615 to charge it! BI88 GIVE TRIQUARTERLY! 0$ enclosed. Buy your first TriQuarterly gift subscription for $20, and each additional gift subscription costs only $17!! Name Name Address Gift-card message Address 2nd gift subscription ($17) 1st gift subscription ($20) Name Address Gift-card message Add $5/year for foreign subscriptions.BG88

begin my subscription with issue# o a life subscription for $500. o $._____ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal.

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RI DGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

1993 BOOKS and selected backlist

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes of the Spinners

51/8 x 73/4 inches

100 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5026-3)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5001-8)

This collection by one of the best young poets in America is a superb conjunction of talent and subject. Angela Jackson brings her remarkable linguistic and poetic gifts to the articulation of African-American experience. Notable for its intimate mythmaking, musicality, deft control of the poetic line, and range of tones of voice, Jackson's poetry features an impressive variety of characters in compelling explorations of social identity, the rituals of race relations, the female psyche, creativity and spiritual experience. Informed by AfricanAmerican speech and poetic traditions, yet uniquely her own, these poems display Jackson's stylistic grace, her exuberance and vitality of spirit, and her emotional sensitivity and psychological insight.

ANGELA JACKSON was born in Greenville, Mississippi, raised on Chicago's South Side, and educated at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago. She is the author of four earlier chapbooks and collections: Voo Doo/Love Magic, The Greenville Club, Solo in the Boxcar Third Floor E and The Man with the White Liver. She lives in Chicago and is at work on a novel.

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

51/8 x 73/4 inches

92 pages

$25, cloth (0-8101-5027-1)

$10.95, paper (0-8101-5002-6)

A small town with a steel mill is the focus of these quietly astonishing poems. Adversaria celebrates the roughbeauty of ordinary life and laments its inevitable decline. Ranging from free verse to unobtrusively impeccable formality, the poems enter a conversation with the work of William Carlos Williams and JamesWright. In their depiction of life in and around the mill, these poems, titled in Latin, combine colloquial style with a late imperial tone to capture the stark contrasts and contradictions of a life lived between the steel mill and the quiet grace of the natural world.

TIMOTHY RUSSELL was born in Steubenville, Ohio, and raised in West Virginia. Except for military service, he has always lived within a mile or so of the Ohio River, most recently in Toronto, Ohio, with his wife and children. Educated at West Liberty State College and the University of Pittsburgh, he has been employed at Weirton Steel for twenty years, presently as a boiler repairman. Adversaria is his first full-length book.

11 Of !til TI 'NCf Ott p.e, "1111:1 '011 'OIT.t

ANNE CALCAGNO Prayfor Yourself

and Other Stories

51/8 x 73/4 inches

136 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-8101-5000-X)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5003-4)

Wmner of the 1993

James D. Phelan Literary

Award

This exhilaratinglyoriginal first collection of short stories vividly captures the textures of women's lives. Calcagno'sstyle is at once idiomatic and metaphorical: her dramatic situations are extreme, edgy and utterlyconvincing. Calcagno's characters grapple with problemsranging from domestic violence to obsessiveness with body weight and speak with conviction and authority about the complex obstacles in their lives.

Here are nine stories, poignant and almost shy. Anne Calcagno has written not ofthe sexual politics of strife, but ofthe deeperunderstanding oflife's complicated mismatches and inevitable miscalculations. Calcagno has the clean voice and sharp unblinking eye ofa true storyteller.

-Larry Heinemann National Book Award Winner

ANNE CALCAGNO was raised in Rome and lives in Chicago. She is a professor of creative writing at DePaul University. For stories in Prayfor Yourself, she received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Illinois Arts Council. Her fiction has appeared in TriQuarterly, North American Review, Denver Quarterly and other literary magazines, as well as the anthologies, Fiction of the Eighties and American Fiction.

c.

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise of the Impure: Poetry and the Ethical Imagination

Alan Shapiro is not only a much-lauded poet, but also one of America's most intelligent and clear-headed thinkers about poetry. In Praise ofthe Impure: Poetryand the Ethical Imagination collects his passionate, rigorously argued essays on the situation of poetry in American culture today.

Refreshingly,Shapiro takes an historically and aesthetically comprehensive view of the writing and reading of poetry, grounding the teaching of creative writing in the perspective of the long history of poetic tradition in the West. Suspicious of grand claims of either the excellence or emptiness of contemporarypoetry in America, Shapiro stands against shoddy and loose thinking about poetry and on the side of the most informed poetic practice. This brilliantly reasoned and unusually learned book should be read by any poet who teaches in the United States and by anyone with an interest in contemporary poetry-whether as reader, fellow writer, teacher or student. It will become a benchmark for discussion of contemporary American poetry.

ALAN SHAPIRO is the author of four books of poetry, including Happy Hour, which won the William Carlos Williams Award of the PoetrySociety of America, and Covenant. He teaches at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and is the recipient of a Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Writer's Award.

51/8 x 73/4 inches

104 pages

$39.95, cloth (0-8101-5025-5)

$12.95, paper (0-8101-5028-X)

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

5 1/2 x 81/2 inches

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit-a new, unsettling music that will not leave us alone. We hear a willful vulnerability. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid. She makes us think in surprising ways. Her poems speak from an unforeseen edge.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book: a version of the eroticfull of nervous tension that animates the sensuality, and also Zimroth's feelingforwords-compressed, ironic, withholding but also 'asking for it...the siege, the thrill, the battle fatigue.' A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory and fantasy, set in harsher reality.

-ALICIA OsTRIKER

Evan Zimroth was born in Philadelphia, grew up in Washington, DC, and spent her teenage years dancing in the Washington Ballet. She received her Ph.D. from Columbia University, and her first book, Giselle Considers Her Future, was published by Ohio State University Press. She lives with her family in New York City.

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

Beginning in the 1960's, there has been a remarkable flowering of new writing in Mexico. A new generation of writers has come of age. These writers, born around 1945 and after, have lived through the most dramatic political, social and artistic changes in Mexico's history; they have opened up fiction to new subjects, new places, new techniques; their poetry evokes and meditates on the Mexican reality more fully and more vividly than ever before. Notable among these new writers are the voices of women and the voices speaking from the provinces about their rich sense of place-away from the powerful cultural center of Mexico City. This large anthology is not a documentary representation or a survey, but a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today

a feast ofreading enjoyment. Unlike the too-often superficial characters and solipsistic vision of contemporary u.s. writing, Gibbons's collection gives us people worth caring about and writing not afraid to be at once serious and joyful.

-SMALL PRESS

6 x 91/4 inches

448 pages

$27, cloth (O-916384-12-8), $15, paper (O-916384-13-6)

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out of Silence: Selected Poems

Edited by Kate Daniels

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state ofpublishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser's poetry was out of print. So this is not just another book: it is a restitution. Muriel Rukeyser held her ground at the bloody crossroads ofpolitics and art; she gave the word "witness" poetic weight. Thefirst of our women poets to enter and engage the Western tradition ofprophetic outrage, she warmed it with the living voices of the injured. And in her activism and generosity, Rukeyser was as good as her word. She said it best: "It is a great thing to hear the words of those who are worthy to speak them."

-ELEANOR WILNER

Thepublication ofOut of Silence is an event worthyofcelebration. Finally one ofthis century's most distinguished, misunderstood and undervalued poets is back in print The timefor a just estimate of Rukeyser's contributions is long ooerdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start.

-TIfE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

63/4 x 10 inches

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X)

$14, paper (0-916384-07-1)

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. His subject is both the transport and the anguish of being open to the lived and living moment. He writes of love, sex, violence, and the inhuman crossfire of historical forces. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention. The images he discovers do not fade from our minds, and we are grateful for "what saves us" no matter who we are or where we have been.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right alongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one of the best poets now writing in America.

-DENISE LEVERTOV

5 1/2 x 81/2,80 pages $17, cloth (0-916384-08-X); $10.95, paper (0-916384-09-8)

LINDA McCARRISTON Eva-Mary

Winner of the Terrence

Winner of the 1991 Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

NOW IN A TIDRD PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance. Exploring what she calls "acculturation in ignorance," McCarriston writes of parents and children, the natural world and domestic and sexual violence; in so doing she powerfully reshapes her emotional inheritance and creates a passionate form of survival.

Linda McCarriston

51/2 x 81/2 inches

80 pages $10.95, paper (0-929968-26-3)

An immensely moving book,fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories of trauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace.

-LISEL MUELLER

Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Fiction of the Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

A landmark anthology marking the 25th anniversary of TriQuarteriy, this 592-page volume includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared during the past decade.

Among those represented are Grace Paley, William Goyen, Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, Amy Hempel, Robert Coover, Joyce Carol Oates and many new writers. These stories range widely over the experience of modern life, and share a high level of artistry and an unmistakable atmosphere of the 1980s. An incomparable primer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standardbearer The multiplicity and depth of the fictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness of writers too numerous to thank. -PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

6 x 91/4 inches 592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

Stephen Deutch, Photographer: From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989

The gift book-with stunning photos ofChicago over decades ofchange,including Deutch's Pulitzer-nominated photos from the Daily News. This collectionand analysis of Deutch's work, with plates both in duotone and in color, is the first full record. ofDeutch's achievement to be published.

144 pages $45, cloth (0-929968-05-0) $23.50, paper (0-929968-06-9)

Writers from South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterlymagazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialoguesby fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to U.S. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

Writers from South Africa

128 pages $6.50, paper (0-916384-03-9)

� Ste � De I Pht li �

CULTURE. POUTICS AND UTERANY THEORY AND ACTNITY IN SOUTH AFRICA TODAY 7�.(Jlw""<'T{tS.·,,,,,,, (",/1 .-", nJCullu�.No 2

SELECTED BACK ISSUES

of TriQuarterly magazine

#25 Prose for Borges: a special issue with an anthology of writingsby Jorge Luis Borges and essays and appreciationsby Anthony Kerrigan, Norman Thomas di Giovanni and others. 468 pp. $10.

#39 Contemporary Israeli literature: fiction by Amos Oz, David Shahar, Yehuda Amichai, Pinchas Sadeh, A. B. Yehoshua. Poetry by Amichai, Dan Pagis, Abba Kovner and others. Afterword by Robert Alter. 342 pp. $5.

#54 AJohn Cage Reader: color etchingsby Cage plus contributions celebrating his seventieth birthday from Marjorie Perloff, William Brooks, Merce Cunningham and others; fiction by Ray Reno, Arturo Vivante and others; poetry by Teresa Cader, JayWright and Michael Collier. 304 pp. $6.

#57 A special two-volume set-Vol. 1, A Window on Poland: featuring essays, fiction and poems written duringSolidarity and tnartiallaw. Tadeusz Konwicki, Jan Prokop and others, with photos and graphic works. 128 pp. Vol. 2, Prose from Spain: recent fiction and essays, plus an interview with Juan Goytisolo and eight color pages of street murals. 112 pp. $41each vol., $BIsel.

#63 TQ 20: twentieth-anniversary issue, with fiction by James T. Farrell, Richard Brautigan, Stanley Elkin, Jorge Luis Borges, Joyce Carol Oates, Vladimir Nabokov, Cynthia Ozick, Raymond Carver, William Goyen, Lorraine Hansberry and others; poetry by Anne Sexton, Howard Nemerov, W. S. Merwin, Jack Kerouac, Marvin Bell and others; interview with Saul Bellow; illustrations and photographs. 684 pp. $13.

#65 The Writer in Our World: symposium featuring Stanislaw Baranczak, Terrence Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Leslie Epstein, Carolyn Porche, Michael S. Harper, Ward Just, Grace Paley, Mary Lee Settle, Robert Stone, Derek Walcott and C. K. Williams, with original work by most participants and by moderators Angela Jackson and Bruce Weigl;photographs. 332 pp. $9.

#75 Writing and Well-Being: memoirs, essays and poems by William Goyen, Paul West, Perri Klass, Gwendolyn Brooks, Nancy Mairs, Jay Cantor, Annie Dillard, Maxine Kumin, Paul Bowles, Reynolds Price and others. 208 pp. $B.

ORDERING INFORMATION

TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press

You may order books under the TriQuarterly Books imprint of Northwestern University Press (Jackson, Russell, Calcagno, Shapiro, Zimroth, New Writingfrom Mexico, Rukeyser, Weigl and McCarriston) from:

Northwestern University Press

Chicago Distribution Center 11030 South Langley Avenue

Chicago, IL 60628

Tel. 800/621-2736

Fax 312/660-2235

TriQuarterly Books

You may order remaining TriQuarterly Books titles (Fiction of the Eighties; Stephen Deutch, Photographer and Writers from South Africa) and back issues of the magazine from our editorial office:

TriQuarterly Books

Northwestern University 2020 Ridge Avenue

Evanston,IL 60208-4302

Tel. 800/832-3615

Fax 708/467-2096

Subscriptions to TriQuarterly magazine

TriQuarterly is available to individuals at the following rates: 1

Subscribers may purchase additional giftsubscriptions for only $17/year. Foreign subscribers please add $5 per year. Direct subscription inquiries to our editorial office: TriQuarterly, Northwestern University, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 602084302, Tel. 800/832-3615, Fax 708/467-2096

year-$20 2 years-$36 Life-$500

Fall 1993

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor

Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor

Fred Shafer

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Readers

Timothy Dekin, Campbell McGrath, Charles Wasserburg

TriQuarterly Fellow

Deanna Kreisel

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants

Matthew Kutcher, Sarah Kube, Hans Holsen, Stacy Mattingly, Mark Hartstein

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year}-Individuals: one year $20; two years $36; life $500. Institutions: one year $30; two years $48; life $500. Foreign subscriptions $5 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-3490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts received between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1993 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore, typeset by Sans Serif. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals, 1117 Heil Quaker Blvd., La Vergne, TN 37086 (800-627-6247, ext. 4500); B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110 (201-667-9300); Inland Book Co., Inc., 140 Commerce St., East Haven, CT 06512 (203-467-4257); Ubiquity Distributors, 607 Degraw St., Brooklyn, NY 11217 (718-875-5491). Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415-549-3030).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H. W. Wilson Co.) and the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.).

Anne Calcagno has won the 1993 James D. Phelan Literary Award for stories in her collection Pray for Yourself, forthcoming this fall from TriQuarterly Books and Northwestern University Press. The award, for emerging writers born in California, includes a $2,000 honorarium and a reading at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Laurie Stone has been awarded a $7,000 grant from the New York Foundation for the Arts on the basis of her essay "Perfect Strangers," which appeared in TriQuarterly #86. The essay dealt with some of New York City's homeless.

The Illinois Arts Council has made companion awards of $1,000 each to Mary Kinzie and TriQuarterly for her poem "Sound Waves," which appeared in TQ #81. The awards are intended "to recognize the creative excellence of Illinois writers and to promote awareness of noncommercial publishing in the state."

Editor of this issue: Reginald Gibbons

Contents

SPECIAL SECTION Three poems, five translations of Attilio Bertolucci and four mixed-media works 19 Charles Tomlinson FICTION Radioland 33 Cynthia Shearer Vendetta; Domestic Forest; Rubber Love; The True Metamorphoses of Ovid 41 Alberto Savinio You Petted Me, and I Followed You Home 67 Joyce Carol Oates Etruscan Places Margot Livesey Eulogy 160 Michael Burke 133 Dream On 167 Janet Kauffman Foreign Aid Amy Godine 172 POETRY The Milkweed Parables 53 Steve Fay After Surgery John Skoyles 76 17

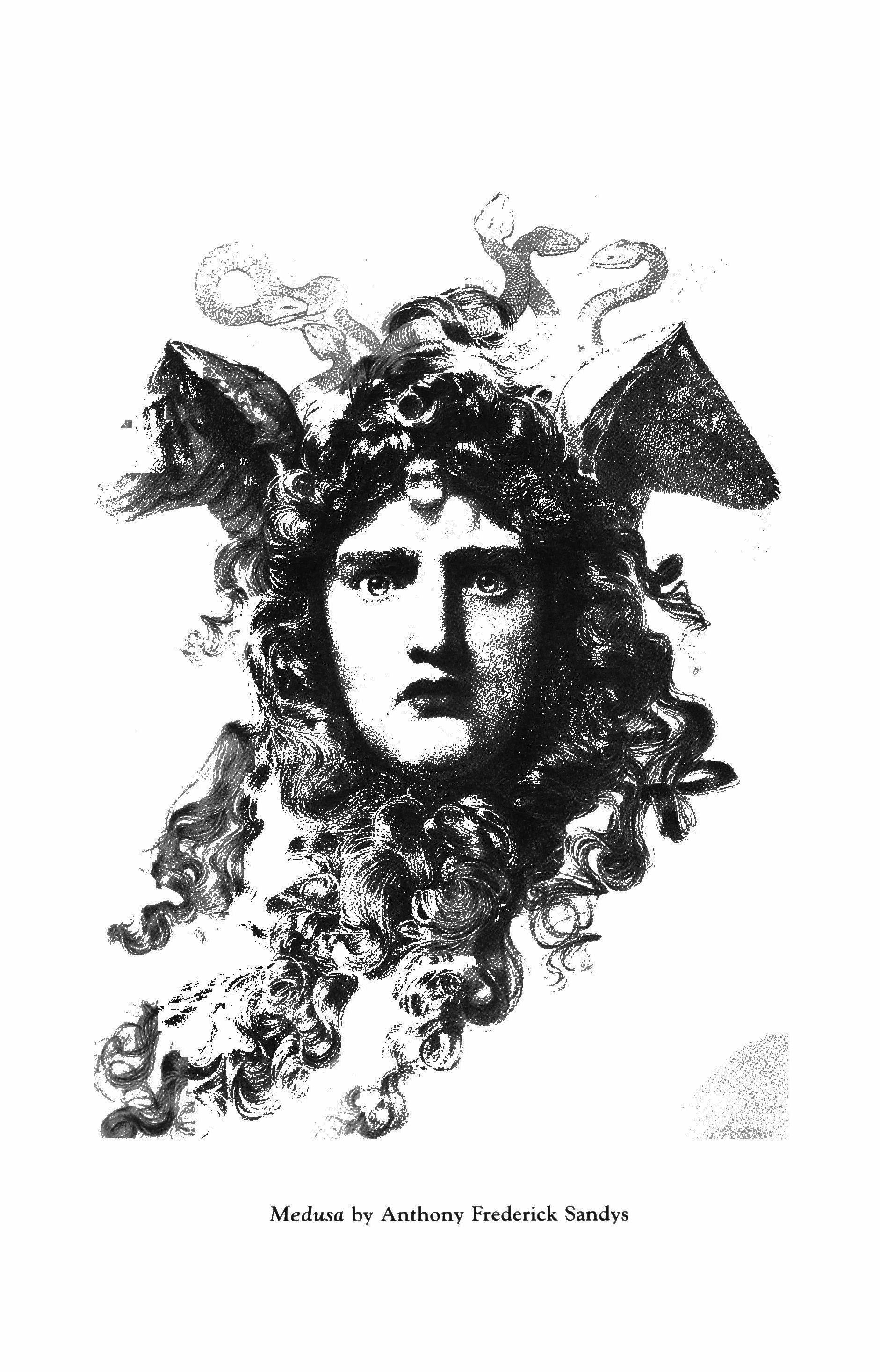

The Fortune; Washington DC, 1990; Recidivist 78 Ellen Dudley First Flight; For My Wife, on Our Son's Third Birthday 82 Ralph Burns Treasure; Thomas's Birthday; What If? Shelly Wagner The Entomologist 88 Michael Bugeja 84 The Lawn Bowlers Josephine Jacobsen Scaffold; Crow Call Brooks Haxton Not Hatred; Are You Now or Have You Ever Been; A Letter to the Denouncers 148 Edwin Rolfe 144 145 Thaba Nchu; Orange Free State; Thabong 153 Sterling Plumpp ESSAYS Shooting the Works 91 W. S. tx Piero The Medusa Connection. 104 Eleanor Wilner Between Salvage and Silvershades: John Berger and What's Left. 230 Fred Pfeil CONTRIBUTORS ................•....• 246 Cover painting and cover design by Gini Kondziolka 18

Three Poems

Charles Tomlinson

Hovingham

The seam that runs sinewing England Crops out here. I recognize The color of home, the Cotswold color, Across these high wolds of the north, In the freestone barrier that divides Lawn from cornfield. An apple Lies like a tiny boulder in the grass Bruised by its fall, and brown as stone; Corn of the selfsame color does not yield To the push of air. It is Yorkshire August here, Cool even in the sun, and calm, So that only the thistledown can show Where the air currents move, and drifts Earthwards with silk-thread tentacles

Reaching for rootage as they brush the ground, Aerial gleams through so much petrifaction, First silent sorties in this truce with stone.

21

Cosmology

Where is the unseen spider that lets down This snow-web from the meshes of whose cold Birds, stung out of stupor, suddenly unfold Into flight? The hungry huntsmen crows Dismember the unmoving, beak them off bushes, Haling them up to their tree-high end. There, strung with sinews of white the boughs Twist into a wickerwork from which a snow Of feathers flows down as the shrieking ceases. The sun emerges now to show it all plain And dazzle us with the same questions still. We pursue them anew with legendary solutions Each dawn disowns, then leaves us standing here Rich orphans among an inheritance of snows, of stones, Feeling the warmth ebb back into the year.

22

To a Photographer

The house in the paperweight is covered with snow: The camera caught it in the boughs' embrasure, And all is a circular window where the glass Is keeping from time this moment of winter leisure-

Before the snowplow has opened the road again, And the white on the roof has started to slide away. The limewash lit by the sunlight seems a glow from within, Like the pleasure of bodily warmth on a winter's day.

I can take up that day in my hand once more, Now the springtime has altered this scene of your art, But must wait out the year to breathe in its cool and find How your image, like air, has entered and tempered each part.

23

Five Poems

Attilio Bertolucci

Translated by Charles Tomlinson

Translated by Charles Tomlinson

Fires in November

They are burning weeds in the fields they set off a lively fire and a cheerless smoke. The white mist takes refuge among the acacias but the slow smoke coming up close will not let it be. The boys run round in a circle about the fire hand in hand, absentmindedly, as if they were drunk with wine. For a long time they will remember with delight fires that men light in November at the edges of the field.

24

April for B-

Oh, you between the half-grown grain and hedge of flowering hawthorn in the shadowy distance which surrounds your solitary childhood, this day that a tender wind annuls that a cool sun inundates. You move in the delicious silence of nature now become a delicate and fabulous labyrinth, child lost in an April hour. Whoever sees you does not hear your words to the man who lops away the branches of the acacia, only hears the swish of the billhook in the risen wind tranquilly mingling life and death.

25

October

On mornings in October when my childish dreams were beginning to fill up with breeze and voices (someone had opened a window and softly gone off), the train which passed at that hour not far away, with its mane of smoke and its whistling, thrilled me with sweet mute terror. I lay there beneath it, without a care, the roar filling my ears until all of it had passed, and mother came hurrying up to me from the horizon, hot and youthful in a pink dressing gown. I was awake and a bee went flying through the radiant air. I wanted to cry out and I kept silent.

26

To

His Mother

Whose Name Was Maria

It is you, invoked every evening, depicted on the clouds that redden our open plain and the one who moves in it, with children as fresh as leaves and wet women traveling towards the city in the light of a shower just ending, it is you, mother forever young in virtue of the death that plucked you, rose at that point just before the petals fall, you who are the origin of all the neurosis and the anxiety that is my torture, and because of that I thank you for time past present and future.

27

To Giuseppe in October

Along what country byroads do you go in the too'hot October sun, with hands tight-clenched, the light upon half your face, the other half shadow?

The quiet afternoon of a fine day: the fine day travels with your uncertain steps among the leaves that stain rust-red Emilia's rural pathways.

As redness dawns on the sparrow's feathers that tells us it is once more morning, so you where you move absorbed make sure the coming of night as your severe child's pupil gathers into itself the colors of sundown. And so one autumn day opens and closes for me, during which the people of the vicinity pass, pause, talk, or are gone

their goodbyes said, while some trundle their buckets of water from far away: winter will soon be here, but let it stay this season lingering over its patient loom.

28

�.Jr' \t'

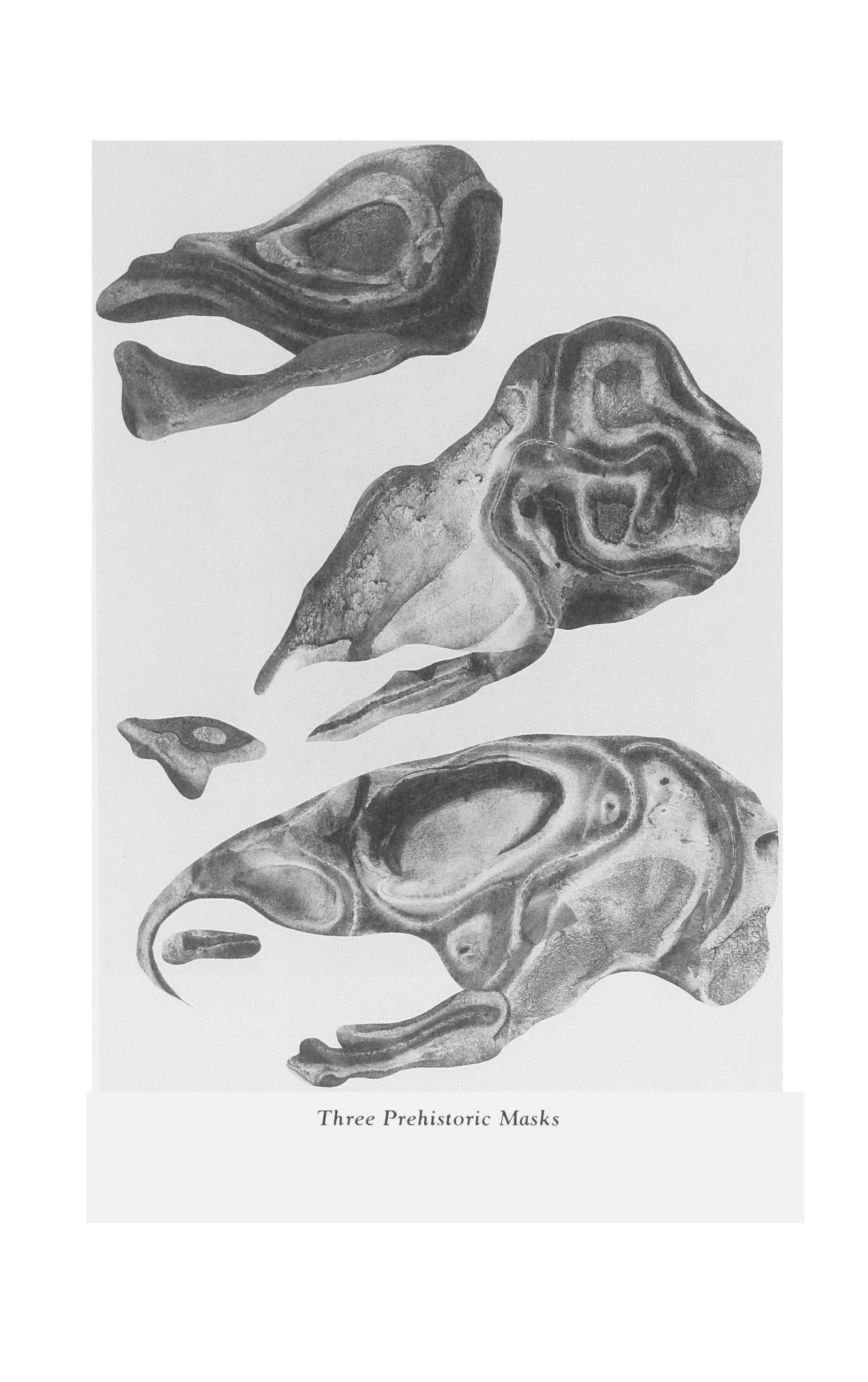

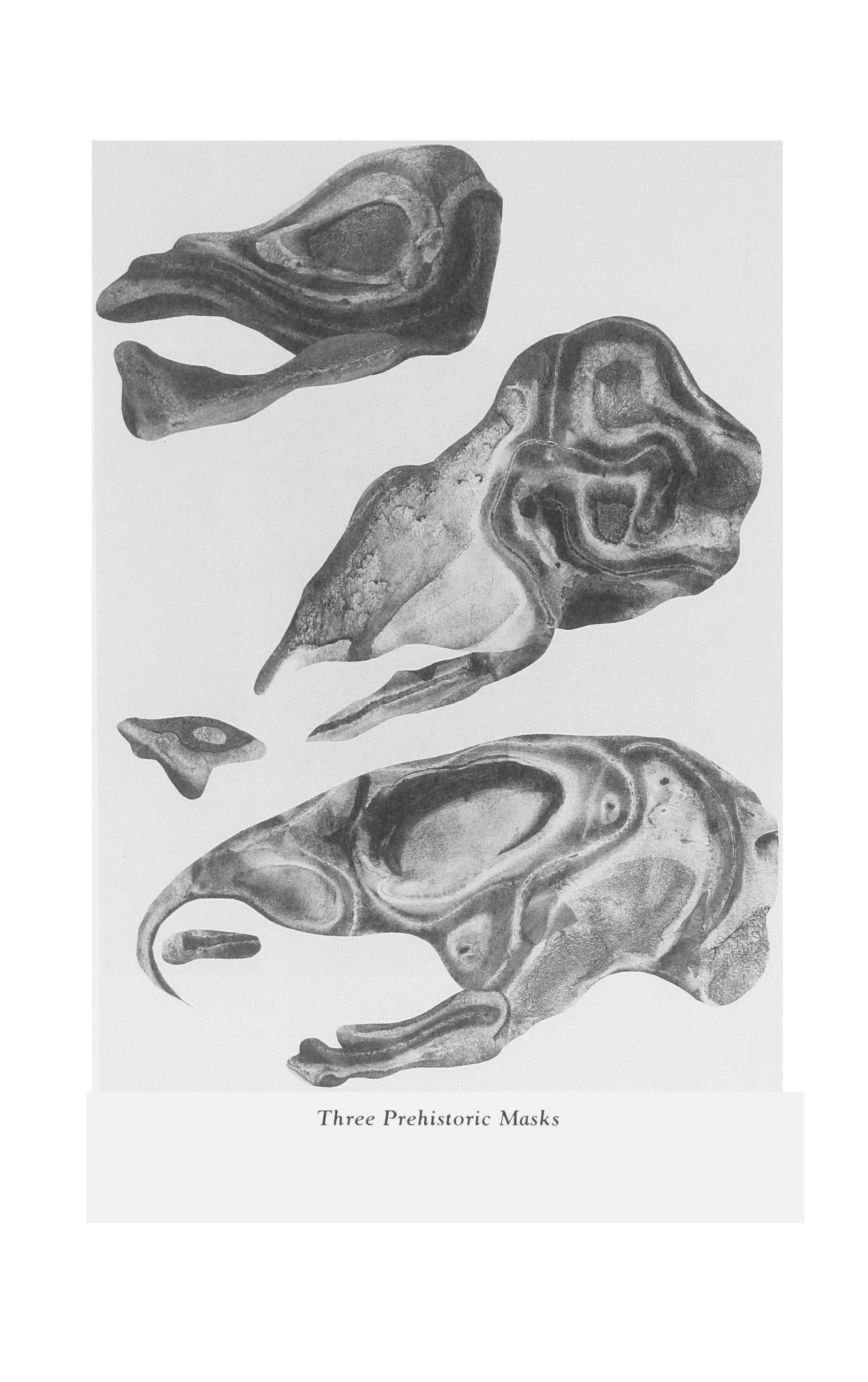

Three Prehistoric Masks

\ I--

-

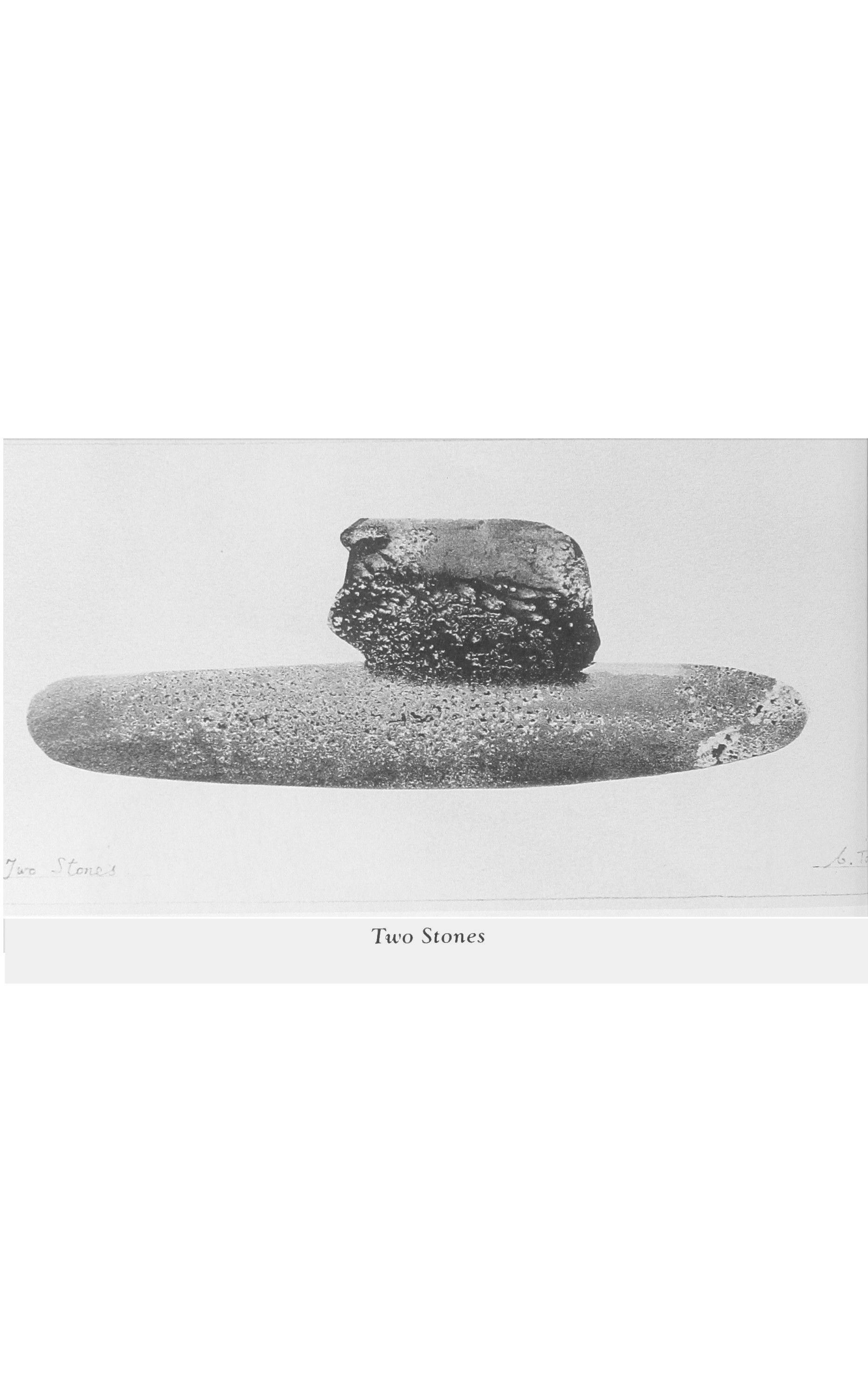

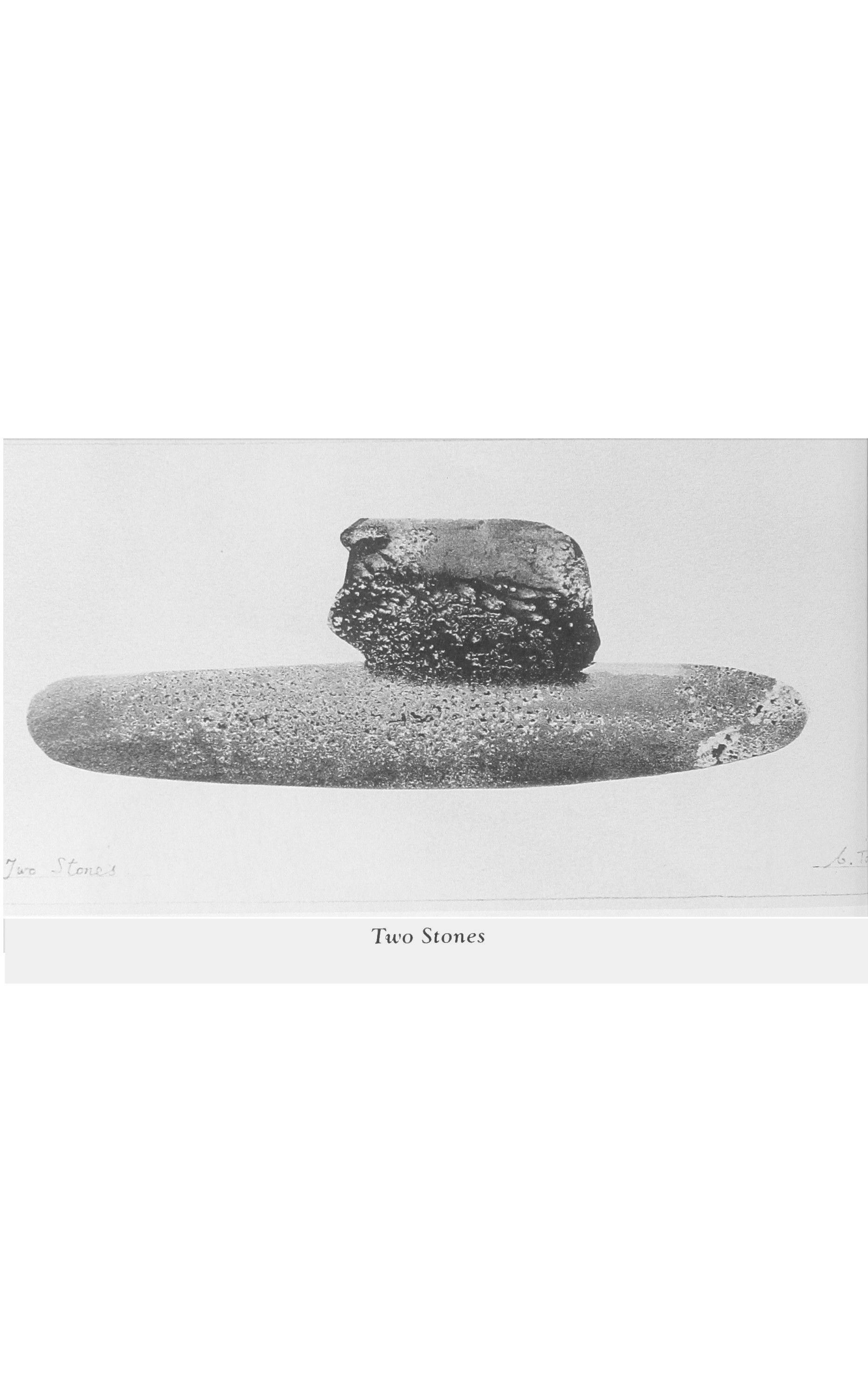

Tt(JO Stones

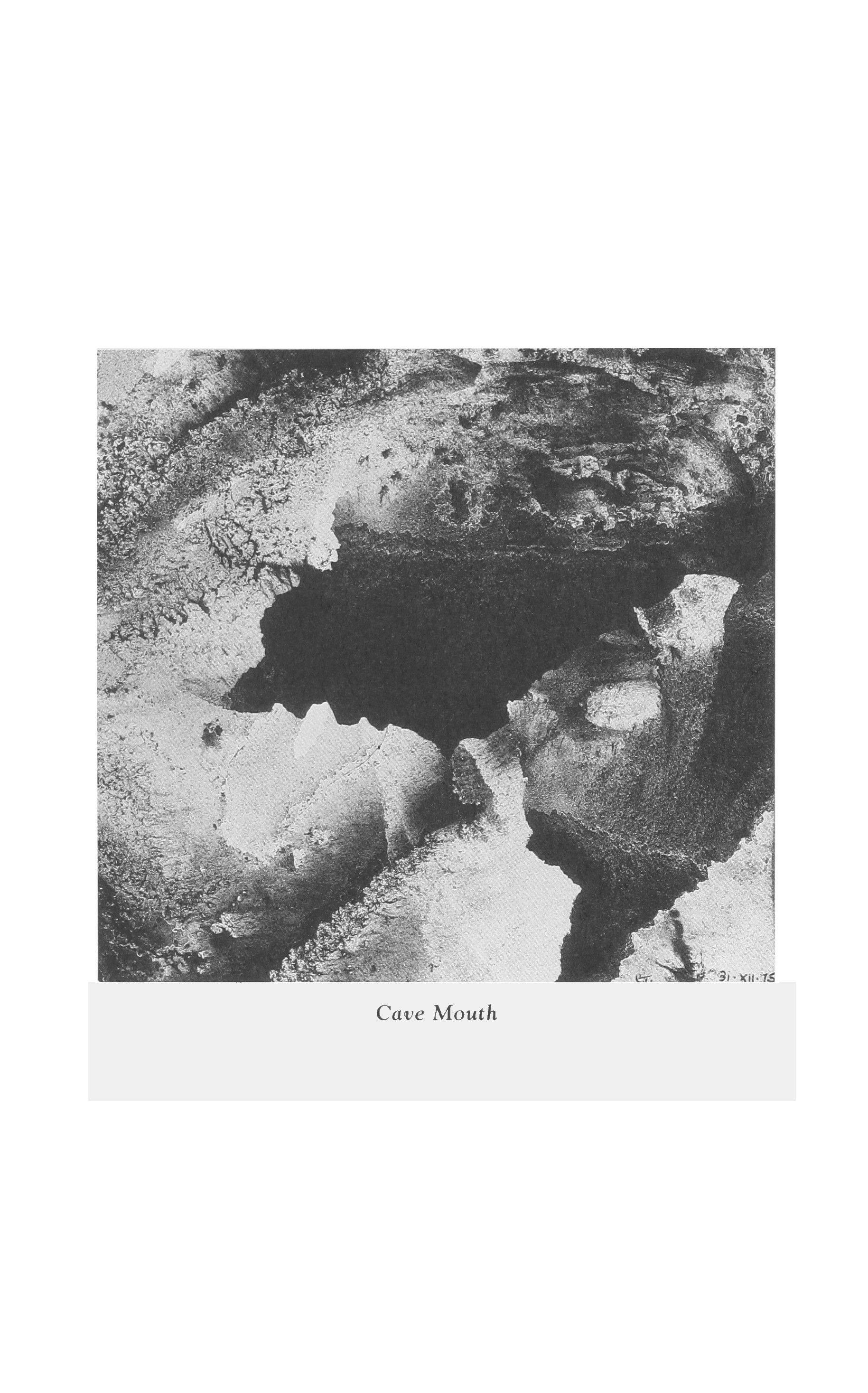

Cave Mouth

Cave Mouth

The Sleep of Animals

:11 Ii ;, wt I I I f t' I

Radioland

Cynthia Shearer

If! told you that I got saved in Eufaula, you'd raise an eyebrow, but that would be close to accurate. We had started out to a Christmas party. Here I am: frippy little blue dress, little frippy shoes. All in good restrained academic taste, of course, right down to the fake pearl earrings. On our way to one of those buffets where the median age of the guests would be seventy. One of those deals where the silver will be named after some king, the tablecloth after some French province no longer extant, and the food after places that the cook has never been.

"I just don't think I can go through it," he has said. "I'm too old. I want you with me. If you go back to school, you'll meet someone else and I'll be all alone."

I turn on the radio, without thinking. He glances over at me, nervously. I usually wait for him to decide if we will play the radio or not. He is more comfortable that way. But this is black gospel music: you know the kind: you can hear the electric guitars tuning up in the background like offstage cats in sour amicable heat, while the black dude is saying, "We'd like to dedicate this number to all our brothers and sisters out there in reddioland who are afflicted or shut in tonight Hello yourself, radioland.

I want to hear this program, having discovered it a few weeks earlier, standing at my kitchen sink washing the supper dishes, with the window cracked to let in a little cold air, and the radio on low to maintain minimal contact with the outside world. I haven't really listened to anything but my husband's music in years. He likes Peggy Lee, and anything with little tinkly eighteenth-century harpsichords or medieval mandolins.

33

Another nervous glance from him. "I have a headache, May," he warns me.

I compromise and turn it down, but I can still hear. He's looking at me with annoyance. Here it comes, something. I brace myself.

"Can't you find something that doesn't sound like whining niggers?" he says, his hands tightening on the leather-covered wheel. And I turn it off.

That's what it is like, when you are May and he is December. We cruise along in silence through the winter-naked woods.

"The Wadlingtons started the museum and then turned it over to the foundation," December is saying. "I want to meet them because they give lots of money for projects like mine."

He's not going to notice if I respond or not, so I don't respond.

"You look nice," he adds, glancing over at me. "You'll be the youngest wife there."

We pass the Headhunters Beauty Salon, the Ola Mae Kitchenette, and the Holy Tabernacle of the Precious Host, where an old school bus painted green and gold is parked, a throng of green and gold people milling around it. "The Lanford Family Singers from Decatur AI," the blinking sign announces to the corridor of air we leave as our car whizzes past. It's like riding in a bullet down a black lace tunnel, the tree branches arching over the road, the headlights fanning out. We pass two men in front of the Super Bad Television Repair Shop, and a woman running toward them carrying a red tulle dress on a hanger.

I close my eyes to see how long the image lingers on my retinas. I'm thinking: Did they ever decide if light is energy or matter or what? Do I carry that red tulle dress with me everywhere I go now? What's to keep it from waiting off in some pigeonhole, then roaring across some synapse years later, hitting me with the same force as, say, the Carmina Burana? Then I'm off and running with a thought about dendrites, and how amazing it is that nervous impulses ever actually make it to their appointed destinations. Could there be an illness where somebody's dendrites get scrambled, and the information misfires? Is there such a thing as a dead-letter dendrite?

"You'll want to talk to Pudge," he is saying. "She's been giving elegant parties since she was a blushing young bride in the Delta." He always has this way of speaking, bogged up in the phrases of some bygone era. He can't help it, he writes history books. "That house is always a showpiece, and she's just perfect. I think you'll like her," he is saying.

It's getting dark now, and the big houses that line the main drag of Eufaula look like moored white-lace steamboats, outlined for the holidays with a wiry thinness, a gold filigree of lights that do not blink. They

34

shimmer softly, like a hazy Hallmark card photo, like someone's idea of Christmas. What is the connection between money and the tolerance one has for colored, riotous, blinking Christmas lights? Why do rich folks tone down their Christmas lights?

did this no-count book illustrating Van Fleet's theory that the cotton economy was doomed anyway," he is saying, and I scramble mentally to try to figure out what he is saying before he figures out my mind wandered. Just like I did seven years ago when I was sitting in the front row of his history class, and nobody had ever showed me any film clips of what happens when a Piper Cub is ready for takeoff at the precise moment in the precise spot that the Concorde has decided to let down the landing gear.

I've got an idea, I say. "Why don't we just spend the night here in a motel, and I'll call Mother from here. We can check in and relax a little before the party, then we can stay as late as we like. And get up early tomorrow and drive the rest of the way."

He looks pleased. We check into the Holiday Inn, perched on the edge of the Chattahoochee River. As he is checking us in, I wait in the car. I don't turn on the radio. He would say something about running down the battery.

Across the river I can see a row of small lights. Georgetown. Funky little dip of a town: gas stations and fishbait sellers. How can two places poised directly opposite each other on the same ribbon of gray water end up so different? I am sure that if I ask him he will explain, with the certainty of a mathematician, that it has to do with state laws of the nineteenth century, or the cotton economy, or some theory of population density. Prosperity equals available capital plus slaves, plus available brains.

I am working on my own theories of history. Maybe Georgetown is not just a town that never became anything. It is the place across the river where they went to get away from all those big pure houses, to drink and dance, or bait fishhooks. Maybe it was meant to be the place they looked over at across the river, those prosperous white men, and those protected white women. Maybe it's just a distant dendrite, housing some genetic memory of a noisier time, ready to come roaring back sometime.

"Room two-fourteen, in the back," December rattles the key as he gets back in the car.

We go to the party at one of the big marooned steamboats. A black man in a white linen coat takes our coats at the door, and I do not speak

35

to him, lest I provoke a half-serious joke from December about how you can tell who Real Ladies are because servants seem invisible to them.

The hostess is a direct descendant of General Quintius Aurelius Cobb, the subject of my husband's second biography, so, in a way, we are guests of honor. Pudge, her name is. She probably weighs 110. "So GLAD to meet you," she exhales with her nicotine-stained voice, breathing bourbon and menthol delicately into my face. "Isn't she cuuuute," she breathes, her way of dealing with the issue when the wife is twenty-nine, and the groom, well, silver-haired.

I would say that it must be a shock to them, to see one of their own tribe who has broken ranks and mated with someone whose diapers they could have changed. These wives recover instantly, and murmur politely, and I acquire the status of an unbelievably tacky centerpiece that they must try to converse around. So as Pudge appropriates my husband to introduce him to the important people, I begin my usual ritual, peeling the wallflowers off the wall and pasting them to myself like stickers on a suitcase.

I introduce myself to an old man who has been parked for the evening in a rosewood and red damask chair. He is not so old that he can't play the game: I am wife to someone who will make a speech later, he is a retired engineer who once worked with Von Braun on a project. We continue, the way ants bump antennae several times before moving on. I am from Georgia, he has been to the Okefenokee Swamp. He is from Des Moines, I had a three-hour layover there once. I ask about his children, and he waves a wobbly hand, as if I've asked him what it was like in the Pleistocene Era. He asks where my children are, and I say I have none. Some little spark of faint gallantry swims up out of him momentarily, and he tells me that I have plenty of time. No, I say, there will not be any. A gentleman to the bitter end, he changes the subject.

I look at the old guy's purple-mottled hands while I'm talking to him, and wonder if I'm looking at the same hands, the same cells, the same molecules that Von Braun did. How long does it take for each cell in the body to be completely replaced by new ones? Does this even happen? Am I the same flesh I was ten, twenty years ago? Is December the same flesh as he was twenty, thirty years ago? Or has the total replacement of cells taken place in just a few years? Is this how it can come to pass that the same man who shyly asks you before your wedding to have his children soon because he's getting old fast-can announce later that he's changed his mind?

Without even looking, I know that December is watching me, even as he is listening intently to someone else's comments. He will later ask me

36

what I found to talk about with such an old fossil. There is one thing about me, at least, that he has never tried to rehabilitate-the way I attend to the lame and the halt at social functions: Hello, so nice to meet you, what a lovely dress, excuse me, but you were so still I was afraid you had died and no one had noticed tell me what it was like to be so young and still rich even after 1929. Did you ever go to Georgetown then? If there are men my own age at a gathering, I do not speak to them. It upsets December, and means that he will question me closely about it later.

I look around at the doors: I am about to go look for a bathroom, when Pudge comes over with a portly maiden lady of about fifty. You can tell by the shoes. Let me guess: English garden history? Alexander Pope dissertation? Wrong on both counts. A librarian named Julia. She was Pudge's roommate at Sweet Briar. Once Pudge has bumped our antennae together, she doesn't abandon us. She stands by, smiling broadly.

"I really like your dress," I say to Julia, and gently lift the ochre-colored sleeve all the way up, like a butterly wing. There is a ragged hole, of the sort that moths or roaches leave, midway down from the armpit. I let the sleeve drop, pretending not to notice. I know the rules.

This lady is tough: she doesn't pretend to see it for the first time. She doesn't give a fig for the rules. Pudge's smile is frozen.

"And what do you do?" Julia demands softly.

I do our laundry, correct his spelling and serve spinach crepes to his friends and enemies. I make his bed and I lie in it. "I'm going to be a molecular biologist," I say.

"Are you happy?" Julia asks, in that soft, all-knowing voice that makes me feel like a kid on an Easter Seals poster.

What? The blood is rushing into my neck, my ears, and my eyes feel hot. She is cheating. No, no, no, no. Ask me where I got my dress, my tan, my degree, or this pickled mushroom, but do not inquire as to my happiness. I look around furtively for December. He would not like this. I stare blankly, with all the grace of something she has poked with a stick.

"I almost married your husband a long time ago," she smiles at me, and I can't read the smile. Pudge's smile is now lurid, like the red wax lips I used to get at Halloween. Is this retribution for seeing the roach hole, or was this planned?

"When did you know him?" I ask tightly, tinnily. "In graduate school. I was one of his students."

Each of us stands beholding what we almost became.

So she is the one, the big one that got away, who walked away from the bargaining table still a virgin. During the year of our Lord 1962.

37

She and Pudge are both looking at me expectantly, the way people watch a polio victim with a leg brace pause at the bottom of a flight of stairs.

"So was I," I laugh, offering redundant information. Pudge relaxes. I have passed some kind of test. They both seem pleased. I am acting pleased. But an image of myself in a previous incarnation comes roaring up out of nowhere, out of some old siderailed memory: me: long-haired and in blue jeans: whizzing along on a ten-speed bike down a hill, on my way to the first class of December's, so fast that it made my earrings whistle.

Later, December is pleased, when I report to him "You handled that well," he says, smiling, and taking off his shoes. He will want to make love. He always wants to make love after a party, after the other men have gone home with their wives. He will especially want to make love to me after seeing, no, after my being seen by, Julia. "I'm a lucky man," he will say, afterwards, smiling up into the dark. "Do you realize that most men my age sleep with women who have stretch marks and varicose veins?"

Our motel room seems haunted, not just with the ghosts of truckdrivers, Sunbelt sales reps and Midwestern tuiistas bound for Disney World. There are also the ghosts of everyone at the party, especially the men who will go home with their tired wives and lie in the same dark that covers us, and think of what December must be doing to me. I speak nothing of these presences to my husband.

"Let's go down to the bar," I say. He looks uneasy for a moment, then he likes the idea.

The bar is smoky; I order a Manhattan, though I rarely drink. He looks at me with curiosity, and fidgets uncomfortably. He doesn't like the music, but I know that he will tolerate it because it will give him a story to tell later: a redneck bar in Alabama: it's the next best thing to seeing snakehandling in a country church. I know this man. Sometimes his thoughts cross through my synapses first, faster. I watch the dancers, he watches me.

December doesn't dance. At least he has never danced with me. Not even at home, with curtains drawn.

I remember the last time I danced. It was in my first apartment. He had told me that once he read my final exam, he knew that I was the one he had been waiting for all his life. I had confessed a similar feeling, like: I know you: you fit this memory I have always had. I had danced across the room towards him with a wine bottle, and he had said, "In my

38

time, the dances all had set moves that people knew how to do. You didn't just make it up yourself."

I never danced in front of him again.

My Manhattan comes, along with December's usual scotch and soda. And roaring up out of some old province of memory comes the feel of dance, of bass guitar and drums so loud that every cell in your body wants to move.

I want to dance. Not that he would ask. I look around the room. Maybe if I watch long and hard enough, he will ask. I single out a couple to watch.

They are December's age, but dressed in work jeans, and slightly flushed with drink. The man's balding head is pale where he has taken his hat off. Her brown hair has been sprayed into an armor-plated swirl. She is looking at him, he at her, and they are smiling. They know each other. They know each other very well: I can intercept the messages that their eyes are sending to each other. Their arms are waving in some crazy way, and their knees bob strangely, but they act like they know what they are doing.

I laugh, delighted, prompting an inquiry from December.

"They can't dance all that well, but they're having a good time," I explain.

"That," December informs me haughtily, "is the Carolina Shag, and they are doing it perfectly."

I look at his glass, his drink's half gone. Maybe when he's finished it he will just ask me, I think. He takes another sip, another and another, until the drink is gone. And he does not ask me to dance. "Teach me how to shag," I say. He shakes his head, annoyed.

After a moment there is nothing but this weird padded silence in the air. His long thin fingers look like foreign objects to me. Then the song cuts through like a message in an airport:

Stay on the streets of this town; And they'll be carvin' you up, all right. They say you gotta stay hungry: Hey baby, I'm just about starvin' tonight.

That's when, from some old retrieval system, two images roar up across the synapses at the same time: me in my kitchen with the window cracked and the radio on low; the Jews in the ovens looking for the cracks at the last minute: air, air.

I look out the bar window, across the river to the blinking bridge

39

lights, and the steadier lights of the little fishbait stores across in Georgetown, and I see it: radioland: right out there in the black air: the messages that crisscross and occasionally connect, hovering over the softness of the rivers and the unyielding cities. Amazingly simple statements, hanging out there to be intercepted and confirmed:

-love: ouch

-are you a believer?

-send help.

You'd probably like it better if I could report that I got up and asked somebody named Bud or Joe Ed to dance, or that Bud or Joe Ed asked me to dance, and that I danced. Or, depending upon your style, that December asked me to dance, or that I called one of the three taxis available in Eufaula, Alabama, or hitchhiked in the blue cocktail dress to the Greyhound bus station, or at least across the bridge to a fishbait shop. I did not. That is not my style.

I kept creasing my napkin and sipping that drink, until, towards the bottom of the glass, I swallowed one molten swallow that seemed to slide like shooting silk, down down down, until I could feel it glowing somewhere deep, like a heavy golden pear, and hanging by a thread. It was all quite simple. There are certain unalienable rights in this world. One is to dance to the music of one's rightful radio tribe, and another is to form a more perfect union.

I had not yet found the man I belonged to: someone who could accept it with equanimity if I ever confessed that I sometimes lie awake in the dark feeling like a cyclops, wondering if radioland is not some holy huge place where it all ends up, melded into one soft sussuration: the protests of the sheep as Noah led them into the ark, the cry that Shakespeare's mother made, and the patter of Navajo code talkers blending with stray drumbeats from the first time Benny Goodman did Sing, Sing, Sing. And I wanted someone who could face with courage the prospect of stepping barefooted in the dark on a Tinkertoy or a cold mashed banana. And so I knew that I must never, ever touch December again, that it would be wrong to do so.

40

Four Stories

Alberto Savinio

Translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

Translated by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

Vendetta

A single, sorrow-filled month after the death of my poor Victor, it takes a rare presumption, Monsieur Ernest, to make me propositions such as these! I don't want to hear them! Go away! No! No! No! A thousand times No! But the indignation of the beautiful Madame Hyacinth is more apparent than real, for Madame Hyacinth is already bending forward, already she is inclining her face, already her head is tilted towards the divan. And the young Monsieur Ernest, conducting his consummate strategic maneuver, positions himself to pluck from the garden of the widow, the same ripe fruit that poor Monsieur Victor savored legally every Saturday night.

At this moment, the door opens without a sound, and a pink foot, a plaster foot, appears on the threshold, pausing just long enough to gather momentum and, after describing a perfect parabola, lets fly a prodigious kick which lands squarely upon the seat of the pants of Monsieur Ernest. Now, lightly and leapingly, it traverses the salon, recrosses the sill, and resumes its place of repose in the broom closet, among the worn-out luggage and old, beat-up mops, where no one has given a thought to it since the day that its creator, the orthopedist, introduced it to this house to serve as a model for the special shoes worn by poor Monsieur Victor, lame in the right foot.

41

Domestic Forest

Everywhere in those days, the press was abuzz with news of a startling phenomenon in the person of Doctor Eleuthere Mikalis, Europe's premier nudist. While visiting the Grecian capitol, I couldn't pass up the opportunity to make the acquaintance of so picturesquely famous a personage. I do not know in which branch of knowledge Eleuthere Mikalis had taken his diploma; I can say with certainty, however, that he was a gentleman both polite and punctual. I sent a letter to him by Thursday's last courier; the next day, I received a reply from the doctor, insisting that I present myself at his house at one o'clock that same afternoon.

I prepared myself for that visit as if for a romantic rendezvous. But I couldn't escape the gnawing fear that our interview might come off badly. Piraeus Street, across from the conservatory, the amiable letter specified.

The afternoon sweltered with summer heat. The windows of the conservatory noisily exhaled the resounding chords of a Chopin polonaise, the liquid arpeggios of a symphony of Saint-Saens, and a creaky chromatic scale executed by a tireless trombone.

I was going to inquire as to the whereabouts of the elevator from a doorman who was braided and epauletted like a general and majestically seated in a glass booth, when I don't know what defensive instinct impelled me to take the stairs; whether to command a more thorough sweep of the zone of operations and to permit myself to monitor any movements around me, or, perhaps, should the need arise, to be situated in the most advantageous position from which to take flight.

The lower floors resembled those of certain commercial office buildings; the other floors were obviously reserved for residential habitation. White wall paneling, rising to the height of a man, was interrupted now and then by a few doors of no particular mystery, doors which gave access, here to the law firm of attorney Spiridion Papanastassiu, there to the workroom of the engineer Protopapadakis, specialist in pumps and derricks; another was the clinic of Sofrosine Koromilas, licensed midwife. But in proportion as I progressed above street level, the doors seemed more and more anxious to conceal some domiciliary secret. From the third floor upwards, the door plaques still stated the names of

42

the residents, but, with regard to their professions and titles, kept the strictest and most rigorous silence. Finally, arriving at the uppermost landing, 1 found myself head to head with a diminutive portal, bearing no nameplate, and marked with the figure thirteen.

A domestic servant bald as an egg brought me into the reception area of a large, formal office, from the far end of which Doctor Mikalis came to greet me with an icy affability. The doctor appeared to be a gentleman bearded and severely dressed in black, but no sooner had 1 formed this first impression, than 1 perceived that, clothed in his "natural" attire, Eleuthere Mikalis was completely nude.

-Are you here to see the forest? he asked me; and, acknowledging my affirmative response, he pointed with his finger to a small door which opened between two sections of the vast library.

-Remove your cloak, instructed the doctor. You may keep your hat upon your head.

-And you?

1 will go as 1 am, Mikalis said.

Down the hallway blew the cool, fresh air of the countryside.

- Let's begin with the vegetable garden, proposed the doctor, opening a small green door as he spoke. Lima beans, chickpeas, string beans, salsify, radishes, parsnip, turnips, navy beans, and chicory were aligned in straight and orderly rows. Mats and canopies protected the more fragile of the plants. A ragged scarecrow completed the scene.

- Does it yield well?

-I supplied the market from the celery surplus. But the Egyptian squash, what a disaster!

-I can imagine how you must have to battle the slugs, the ants, the field mice

But the doctor had already proceeded into the orchard and, indicating with a sweep of his arm the proliferation of pears, cherries, prunes,

* * *

43

medlars and quinces, he said to me: - Actually, I'm beginning to thin them out.

I raised my eyes to the ceiling: frescoes illustrated the entrance of Alcides into the Garden of the Hesperides.

- As you see, the doctor remarked, these paintings leave as much to be desired as does the world from which you come. And he extended his index finger towards the window.

My eyes swiveled in the direction indicated by the doctoral digit; in Piraeus Street a long line of bright, black mushrooms sprouted frenziedly.

-It is raining! I exclaimed.

- Don't let it concern you, replied Mikalis; here, I have my own sun.

Indeed, it was true. A dazzling luminescence shone upon the curly leaves of the lettuce and, among the rosebushes of an Italian garden, the nightingales and finches warbled with delight.

- Now begin the forests, said the doctor with a certain solemnity, and he opened a little white door which gave onto a meadow sown with lilies.

I wanted to enter: Mikalis stopped me.

- Here, one may not enter. He showed me a membrane pulled tightly over the doorway, but so thin and transparent that, at first glance, one wouldn't know it existed.

-In there, continued the doctor while carefully closing the little white door, is the virgin forest.

The light dimmed little by little. Subtle electric glimmerings zigzagged through the air. These glimmerings intensified as we reached the pine forest. The forest swelled with Wagnerian harmonies. A bird sang with the voice of a soprano.

- Would you like to go for a paddle? the doctor asked me as he pointed out a canoe resting on the bank of a stream. But I declined the offer, and

44

we continued our stroll. Car horns and the whine of trolleys diluted themselves in the distance.

We traversed a forest of pines. I shot a glance at the window. I don't know why, but the thought carne to me that this might be my last look at the world of men. The first lamps were lit along Piraeus Street. The lights of the conservatory glowed. I did not want to detach myself from these lights. But already the "real" windows surrendered to the false. The whistling of the wind among the pines heralded the coming storm. The crows, flying low, fled in flocks. A solitary raven' disappeared amid the clouds clustering below the ceiling.

Mikalis preceded me. To bear up against the tempest, he walked with his back bent. The wind plied the tops of the cypresses, shook the silver poplars, flattened the shrubs, and provoked crises of hysteria in the fields of roses, which trembled furiously and stiffened their thorns. I turned up my collar and forced my hat down firmly on my head. I told myself that there, not two yards away, behind these "false" windows, was the city-the lights, the shop windows, the department stores, the cafes, the people, the vehicles, the police, safety and security. Far away, the first lightning bolts zebraed across the ceiling from the deep recesses of the forest. The deafening rumble of thunder mingled with howling gusts of wind. Oughtn't I to have said something? But what was there to say? Mikalis had gone on ahead, without concern for me. This was one of those occasions when, unable to think of anything better to say, we employ some stupid phrase as I did then:

- The upkeep of this forest, doesn't it cost you an arm and a leg?

- No: here, the plants grow by themselves. That is why I have been able to establish, smack in the heart of Athens, and in the present day, a place such as this. This same flooring is equally suitable for the development of the biggest, most robust of trees, the giants of the forest.

Talking all the while, he showed me, in the middle of this scene, a mighty oak which had sunken its roots through the cracks in the floorboards, and spread its gnarled boughs beneath the vault of the ceiling, where its thick leafage covered the entire surface.

- This storm, Doctor, is it possible then, that you are able to govern its intensity, and guide it, as you deem appropriate?

45

-Not on your life! screeched the doctor. I gathered all of Nature into my house, but this tour de force brought with it certain handicaps. Over the elements, I haven't the slightest authority. At some future date, I hope to achieve dominion over them, but for the present it is the elements which dominate me.

A flash blinded me; a sickening terror clutched at my stomach.

The doctor was no longer there. The voice of my father, dead twenty years, called to me from a neighboring room.

The room was deserted: inhabited only by a solitary oak which the hurricane shook and which the thunderbolts lit up with a sinister glow.

The voice called from another place, always farther away. I sped through a labyrinth of chambers, each resembling the one before, each inhabited by a solitary oak, in the middle of a raging storm, chasing after the voice of my father who died twenty years ago

Uneasy about my disappearance, the Italian consulate launched a search, in collaboration with the local police. They found me at the foot of an oak. The storm had passed. A radiant sun illumined the forest of Doctor Mikalis. I was unconscious, but safe.

* * *

46

Rubber Love

In battle formation, the squadron set course for Hawaii. Fred Atkinson, second mate and ship's stoker, and Joe Tuddy, black quartermaster, bumped into one another in front of the doll chest, to starboard, on the third deck of the flagship. The double doors flew open in tandem: inside the spacious chest was but a single doll, beautiful, astonishing, naked, mute as love.

That the captain should have kept for himself the most ravishing of the dolls was not surprising: this was a commander's prerogative. That a dozen dolls, each one of them chosen with the utmost care, should remain exclusively at the disposal of the officers-there was nothing to be said against it. But twelve dolls at most - and none of the best quality - think of it! - twelve dolls between three hundred crewmenthree of them down for repairs, certain others so old that the thought of being served by them after twenty days at sea, in midsummer, along the line of the equator, was enough to fill one with repugnance: these facts alone were sufficient to render the admiralty suspect of so sordid a preoccupation with frugality, that it deprived them of common sense; otherwise one could not help but conclude that so obvious and so blatant a disregard for man's physiological needs could only have been deliberately contrived, with premeditation and by design, as an incitement to brawls and mutiny.

Atkinson was the first to be stricken. But the quartermaster, lively as lightning, seized him by the arm. His right fist shot into the air, and hovered alongside the stoker's head. Who knows why Tuddy, at the instant he was poised to strike, suddenly changed his mind? The arm came down, not upon his adversary, but upon the doll who, sliced across the stomach, fell in two pieces at the feet of her suitors.

Dazed and out of breath, Atkinson and Tuddy bent forward, so as to study more closely the corpse of their victim.

The fatal blow, delivered with vigor and precision, had exposed the complicated maze of tubing which everywhere crisscrossed the insensible cadaver and which had, until now, so wickedly and efficiently.imparted to it a human warmth.

47

Two tears the size of crystal eggs bulged from the eyes of the quartermaster; others began to stream down the sooty cheeks of the stoker. The steel bulkheads reverberated with their sobs of despair. They wrung their hands, bit their tongues, hugged one another frenetically, exchanged consolatory kisses, and howled like hyenas lashed by a bullwhip.

The rubber maiden had been stained with human blood.

Spewing cascades of foam, the squadron came to a stop and dropped anchor in the middle of the boiling ocean.

Down in the hold, on their bunks in the sick bay, lay the two culprits, whimpering like dogs, and writhing in the straps which fastened them to their steel-framed cots.

Four men, the flower of the crew, bore the body of the assassinated doll up to the foredeck and, as the flags were hoisted and the artillery salvos were fired in salute, she slowly descended into the sea.

At precisely this instant, there emerged a magnificent seahorse, black and prancing, which reared up, flashing the yawning maw of its frothy white mouth, between jaws lined with sawlike teeth.

But the monster was not so quick to carry off the protagonist of this drama, to take her with him towards the murky depths and towards the spectral silence of the submarine forests, that she did not have a chance to cast a final glance at the sailors, at the ocean, at the sky - a last glance cast by those haunting eyes, those eyes so glassy and fixed, those eyes that sleep shall never shut, that death shall never close.

48

The True Metamorphoses of Ovid

Poets continue to live in their works, but much more rarely in their own bodies. Bodily survival is a thing for men who are strangers to poetry: Frederick Barbarossa survived in his own body and, couched alongside his faithful broadsword, he waits for his great sleep to end, to rise again and resume the fight. Nostradamus lives on in the tomb, some paper, ink and a writing quill held in his hand; but unlike Barbarossa, who sleeps supine, Nostradamus sleeps on his feet, like a thoroughbred horse. Garibaldi survives in the hearts of his followers who wait for him, day by day, vancouriers of liberty and social progress. Oscar Wilde survives in the sordid quarters of Paris, bloated and pale as a drowned man, well and surely dead in his poet's outer shell, but still living in his obscene and pitiful body like the protagonist of a Black Mass. But who, in truth, can begin to rival Publius Ovidius Naso, who, also a poet, still lives today in his body and prowls night and day the environs of Sulmona, his place of birth?

It was a few months ago that Timoleon and I, arriving by night, came to the Fountain of Love, just outside of Sulmona, and asked for news of Ovid from two young men who were watering their horses at the fountain, and who informed us that they were not personally acquainted with Ovid, but that very nearby, in a hamlet named Maranus, we could find someone who could give us precise particulars concerning him.

I had decided to let Timoleon tag along with me in my peregrinations, the object of which was to seek Ovid in the places which were most familiar to him and which, according to reliable witnesses, he haunts to this day, sometimes in the guise of the Devil, sometimes as a cloud of love.

During his trip to Sulmona in August of 1838, Paul Parzanese wrote that in the surrounding countryside everyone spoke of Ovid: "as they spoke also of the earth and sky, bathed in the light of love." I, too, stopped in Sulmona and, with the patience of a trapper setting his snares, I waited in ambush near the Ettore Ferrari statue, which represents Ovid in the elevated style, spouting verse: next, I staked out a spot close to the window of a little candy shop, full of drawers and display cases bursting with multicolored bonbons, in the hope that Ovid would come to this window the way a lion comes to the river, at evening, to slake his thirst; and finally, I hid at the entrance to the "Santissima Annunziata," where

49

a statue of Ovid represents the poet wrapped in his cloak, one foot posed atop a book. After that, I climbed back into Timoleon's automobile, which made its way towards the "Fountain of Love."

It rained. Our small car splashed a passerby who yelled: "Mannaggia Guiddie," because the inhabitants of Sulmona still swear by the name of Ovid, just as the Galicians still swear by the name of Titus ("Titz horra"), under whose reign the temple of Solomon was destroyed.

We arrived at last at the hamlet of Maranus. Of an old man seated on his doorstep, smoking a pipe, we asked if he had seen Ovid. "Yes," the old man replied. "A while ago, he rained in verse and there appeared such flashes of lightning as are said to turn night into day. I was walking along by myself when, all of a sudden, I heard the sound of a car and the hoofbeats of horses, running all hell-for-leather. I turned around to look, but the car and the horses had passed with the rapidity of an arrow. As I peered deep into the distance, I saw that the horses were made of flame."

Timoleon asked him if the noises which galloped over the countryside, apropos the subject of the survival of Ovid, weren't just so much nonsense, fruits of the fertile imaginations of the inhabitants of Sulmona, too easily inspired by the Dantesque mountains and valleys which encircle their city. But the old man resolutely rejected this explanation, and with a clarity of thought and propriety of expression which revealed in him a sure and long-held knowledge, he said: "Officially, Ovid died at Tomis in the seventeenth year of our era and, ever since, has been undergoing the transformations described in his book The Metamorphoses, itself but a first familiarization with the subject, a mere introductory essay. Ovid straightaway became a necromancer, and went to live on the edge of Moronne, on the mountain alongside which we are presently standing, but which the darkness of night prevents us from seeing. On the slopes of Moronne, distributed over three successive levels, spills the Fountain of Love, first past the place where Ovid flirted with the daughter of Augustus, then past the villa encompassed by gardens, where the poet still lives, and, finally, past the hermitage where Celestin V, the pope who refused to reign, once meditated. People began to regard Ovid as a master of the arts of love. 'Troubled' lovers had recourse to him and, as he knew the science which 'binds us together and pulls us apart,' that is to say which unites and divides, he reawoke, with a potion of his own composition, their dormant passion. Then, tiring of necromancy, Ovid repented of his sins and became Christian. It

50

should be noted, spiritually speaking, that it has always been and still remains the memory of his Christian virtues which mosts endears Ovid to the barbarous populations near whom he spent his bitter exile. The peasants of the precincts still speak of how, in those distant times, a man of extraordinary nobility arrived among them on the banks of the Tiber. He had the sweetness of a child and the benevolence of a father.

"Often, he sighed or softly whispered to himself. But when he addressed someone, it is said that honey and nectar spilled from his lips. The same local denizens affirm that Ovid wrote a few poems in the Moldavian language, of which, unfortunately, there remains not a trace.

"Eugene Delacroix, in one of his frescoes at the Bourbon Palace, depicted Ovid in a soft and languid mood, encircled by admiring Scyrhians who, stupefied and deeply moved, not daring to approach his person, competed with one another to offer him magnificent gifts. Ovid was profoundly learned. His works became innumerable. When he wrote, his plume flew over the parchment without being withdrawn from it, nor ever once being dipped in the inkwell. He attributed his wisdom to his nose, and it is for this reason that he is called Naso. 'A man with a good nose,' as we say in our day, corresponds to the Latin expression: 'emunctare naris.' Jean des Buonsignori, who lived around the year 1300 and wrote Allegorie ed Exposizioni della Metamorfosi, explained that Ovid was also called Naso 'because, just as we use our noses to detect the odors of things, so Ovid was able to detect odor, and came to know all there was to know about his century.'

"Becoming officially Christian, Ovid founded, here where we are, a school where he taught the children Christian doctrine and The Book of Seven Trumpets. He compiled a treasury of Christian maxims and a collection of fables. He transmitted the light of his knowledge to Saint Pierre Celestin, who met with him up there in his hermitage on Mount Moronne, and with whom he talked all night while stalking the cells of the monastery. Of the numerous works written by Ovid 'next,' nothing remains. At the beginning of the last century, there was a dignitary of Sulmona who owned a book of Ovid, but a general of Napoleon, who came upon his house purely by accident, wanted the book and took it. One Monday morning soon after, the general set sail for France, and carried the book with him, thinking to afford his fellow citizens the delight of sharing its discoveries and inventions. The reputation of Ovid reached even the King of Naples, who would no longer make laws

51

without first consulting his Ovid. His best friends were and are, to this day, Cicero of Arpinum and Horace of Rome. Ovid became a monk, a prophet and a saint. He was canonized by the Church of Reims under the name of Saint Ovid, martyr, and was made a bishop of Braga in Portugal where, to the present day, they chant in his honor:

Gaude Sacerdos Ovidii

Tu Bracharensis Pontifex, Qui meruisti filias

Tot ad polos transmittere."

By this time, dawn was breaking, and Timoleon expressed the desire to visit the villa of Ovid. But the old man told us that this was impossible: "Ovid does not permit it. One cannot even hope to get down the road in one piece: Ovid demolished it. A few years back, there was built, near the Fountain of Love, an edifice intended for use as a target range by the national militia, but the same night, Ovid destroyed it. He wants to be left alone. And what is wrong with that?"

In spite of this testimony, Timoleon was not convinced. "This survival, which has lasted century after century, how do you explain it, my good man?" he demanded.

"Poetry" - replied the old man - "the extraordinary power of poetry."

I, all this time, was staring in the direction of Ovid's villa. Then I turned to look at the old man. But the old man wasn't there.

In his place lingered only a ghostly glow in human form.

But all at once it vanished.

52

The Milkweed Parables

Steve Fay

We bear the seeds of our return forever, the flowers of our leaving, fruit of flight

- Muriel Rukeyser

I. The Keeper

1

The girl saw something like it in the eyes of the men as they discussed how best to stack straw or butcher hogs.

Silently stirring the lard kettle with the heavy paddle, she would watch them argue about seasoning the sausage, then later, alone in the woods, try to wrinkle her nose like Augie Ochslein as if to interrupt her uncle, Nein-Kein garlic! Oskar, du weisst-no garlic in mine.

The others would laugh at him, but Mr. Ochslein clearly took pride in being the most persnickety neighbor.

Turning over leaves to find the new ginger shoots, she knew no adult would have appreciated such a finickiness in her, unless it was applied to swishing the bluebottles away from the cooling mincemeat pies.

So her vision grew in her eyes and her fingertips, and was called out at evening when the crows gathered along the opposite bluff of the creek.

53

And she said to no one but herself, Tomorrow the hickory buds will open their small hands and call down rain.

2

A demon of willfulness had once almost come to life before her in the coal oil flicker of the parlor, as her uncle read in the almanac the story of a young girl struck down and disgraced by adventure.

And so she had willingly memorized the verses from the German Bible and stayed away for a month from the catfish hole in the creek and fence posts and other places where it would have been easy for the Devil to reach up from Hell and grab her.

But even then, she knew that she was drawn to another side, though she did not know what was there.

Even her breathing became less girl-like at age twelve, with her turning to walk up the small twisting draws from McGee Creek, watching the growth of the gooseberry leaves, the sprouting acorns where a tree had fallen, arriving home from school so late they assumed she visited Elsbeth.

And so she said she did and made up a story of what the old midwife had asked, something about her boy, Oskar, that made her uncle shift, then smile and forget about more scolding.

She only visited Elsbeth that next week to try to get her to talk about the same things as she herself had told, so that the old woman might later remember and reply about such a visit from the girl once that spring.

She had never gone into the house of a woman who lived alone before, a house with no man and a messy table, and everywhere small piles of leaves and bark and paper.

As she followed hunched Elsbeth into the kitchen, she bumped her head on a low-hanging shock of herbs, and white-plumed seeds fell from narrow pods catching like snowflakes in her auburn hair.

Elsbeth laughed and told her about curing Uncle Oskar of pleurisy with the root of that same plant as they drank sassafras tea and the girl only played at removing the seeds from her hair, admiring the way they glistened there, with Elsbeth's small looking glass.

54

Thus one called may find a mentor.

But there was only that one summer, after she had turned twelve, when she lived with and worked for Elsbeth, as they both told her mother and uncle, Elsbeth paying for the girl's housekeeping with paper bundles of cures and a mixture for brewing tonic for Oskar's mare.

It meant something coming in and nothing more going out to the school next fall, except for Cousin Gus, Oskar's boy; it meant a hardworking, more marriageable daughter for her mother.

But for herself, it meant finding Elsbeth's light in her own hands, feeling the difference between poison and cure, as if in the dark, for it was surely darkness that hid this light from others.

It meant knowing, as surely as knowing straw, or butchering, or burning brick or charcoal, and it meant laughing out loud sitting at the dirty table with Elsbeth or calling in the crows together from the shade of the hickory grove.

When Elsbeth caught the palsy in October's early freeze and could not tell her what herbs to brew, she tried to find them on her own, but Elsbeth was taken in a wagon to town and died.

She never knew if she could have saved her.

No one held her responsible, but they interrogated her, asking why she wanted to keep living in Elsbeth's cluttered house, and for that matter, how had she spent her housekeeper's time if the old woman's place was such a sty.

In less than a month, as Uncle Oskar returned to supper sweaty and nervous, her mother muttered, Fertig-Ganz /ertig-Ende, and a fragrant smoke twisted above the hickories as Elsbeth's herb stores burned.

The girl took up reading Psalms aloud each Sunday night and the questions stopped.

But when Gus choked on a fish bone, the week before Christmas, and she made him swallow bread, as anyone but a child knew to do, Uncle Oskar blurted that God be praised that she had stayed with Elsbeth, but then he glanced to heaven and down again as if embarrassed and quickly went to see about the calf.

Surely, the calfs small nose knew more about the light in yarrow and in chicory and in maple twigs than her uncle, she thought, but he believed his darkness was the light.

3

55

She learned to avert her eyes so that the others would not be troubled by what showed through, and so she grew to adulthood in two worlds, marrying Arnie Ochslein to please her mother, who was ill, and moving back home to have her child when Arnie was hospitalized with malaria in Manila, where he was soldiering.

The influenza took her mother before the cancer and she passed away in spring.

And when the government telegram came about Arnie, Uncle Oskar pledged they would raise her baby as Gus's little brother, while large tears streamed down both sides of his furrowed nose.

Sunday afternoons that summer, when Gus had taken the wagon to a friend's and when her Uncle Oskar napped as if beneath the safe canopy of his pork- chop dinner, she would carry her baby out across the farm, through the hickories and along the creek, the small boy's hands mimicking her own as she reached to touch the leaves or as she knelt to touch the water.

If she handed him a stalk of goatsbeard, he stared transfixed, and he screamed beyond all decorum with delight when she blew away the bouyant seeds.

And the wordless baby, like his mother, hid all trace of these discoveries from the world of Oskar and Gus, kept it wrapped within the pod of his small secret soul.

5

That Monday in September, she hadn't known the cow had gotten down into the west ravine where the white snakeroot grows; Oskar hadn't told her.