Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Sara Lee Foundation, and individual donors. Major new marketing initiatives at TriQuarterly have been made possible by the Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Literary Publishers Marketing Development Program, funded through a grant to the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

Please sign me up for:

o a two-year subscription for $36.

o a one-year subscription for $20.

Foreign subscribers please add $5peryear.

Please begin my subscription with issue#

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY!

Please sign me up for:

Foreign

Please

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY!

life

Name Address Or call US toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! BI87

o a

subscription for $500. o $_____ enclosed. 0 This is a renewal.

subscription for

o a two-year

$36.

one-year

for

o a

subscription

$20.

subscribers please add $5peryear.

my subscription

issue# o

life

$ enclosed.

Name Address Or call US toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! BI87 GIVE TRIQUARTERLY! o $ enclosed. Buy your first TriQuarlerly gift subscription for $20, and each additional gift subscription costs only $18!! 1st gift subscription ($20) Name Address Gift-card message Add $5/year forforeign subscriptions. Name Address 2nd gift subscription ($18) Name Address Gift-card message BG87

begin

with

a

subscription for $500. o

0 This is a renewal.

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

1993 BOOKS and selected backlist

Coming in Fall 1993

The new TriQuarterly Books imprintof Northwestern University Press will presentfour new titles in the fall of1993. We are pleased to be able to offer readers ofTriQuarterly magazine this excitingpreview ofthings to come

ANGELA JACKSON

Dark Legs and Silk Kisses: The Beatitudes of the Spinners

A unique perfomance of mythmaking and song by a quintessential Chicago poet.

Angela Jackson was born in Greenville, Mississippi, raised on Chicago's South Side, and educated at Northwestern University and the University of Chicago. She is the author of four earlier, smaller collections: Voo Doollote Magic, The Greenville Club I Solo in the Boxcar Third Floor E and The Man with the White Liver. She lives in Chicago and is at work on a novel.

TIMOTHY RUSSELL

Adversaria

Winner of the 1993 Terrence Des Pres Prizefor Poetry

A book of poetry celebrating the rough beauty of ordinary life in an Ohio steel town.

Timothy Russell was born in Steubenville, Ohio, and raised in West Virginia. Except for military service, he has always lived within a mile or so of the Ohio River, most recently in

Toronto, Ohio, with his wife and children. Educated at West Liberty State College and the University of Pittsburgh, he has been employed at Weirton Steel for twenty years, presently as a boiler repairman. Adversaria is his first fulllength book.

ANNE CALCAGNO

Prayfor Yourself

A powerful first collection of stories by an author with an abiding understanding of the fragile yet enduring nature of human relationships.

Anne Calcagno was raised in Rome and lives in Chicago. She teaches writing at DePaul University and the School of the Art Institute. For stories in Prayfor Yourself, she received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Illinois Arts Council. Her fiction has appeared in TriQuarterly, North American Review, Denver Quarterly and other literary magazines, as well as the anthologies, Fiction of the Eighties and American Fiction.

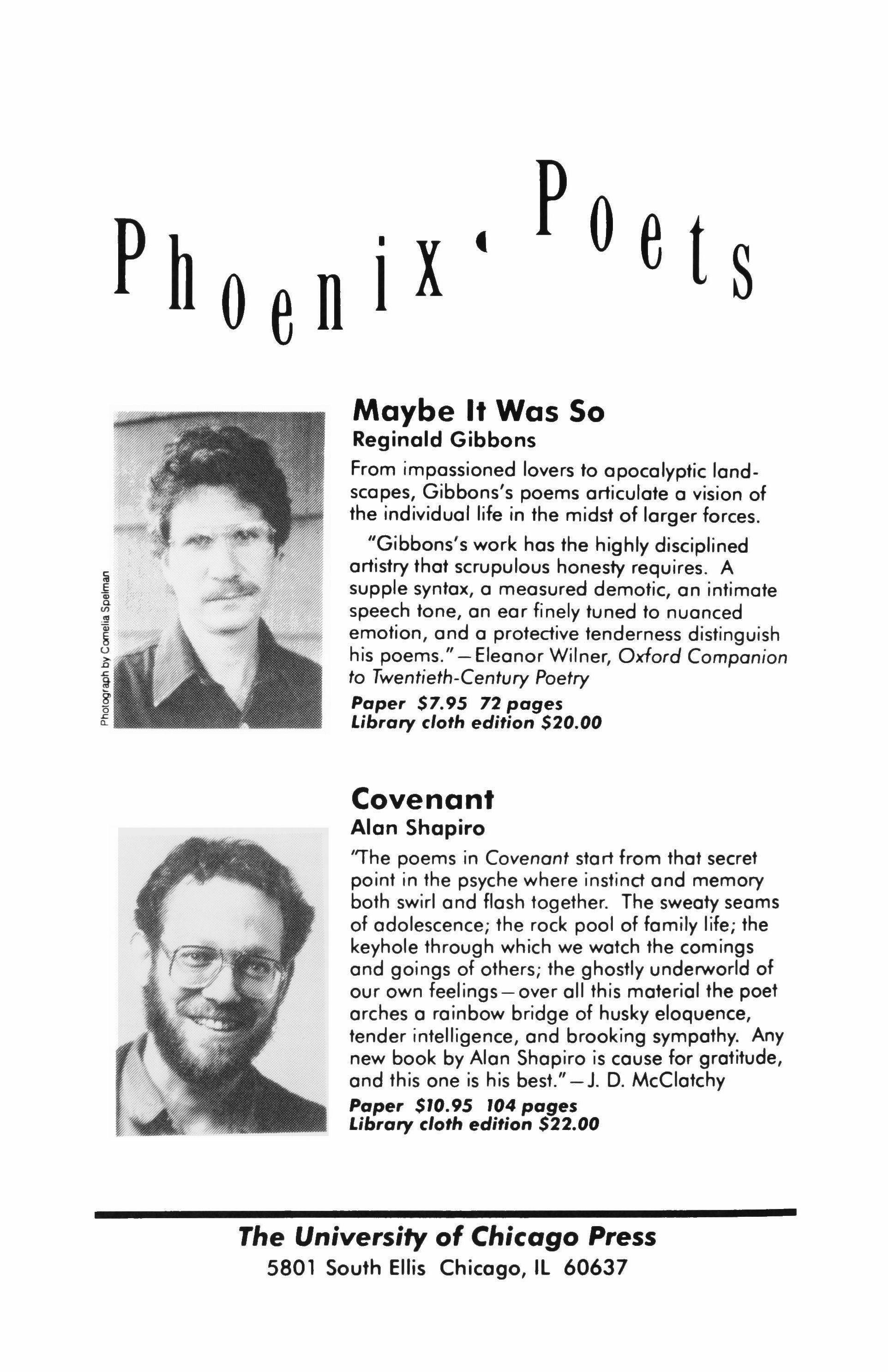

ALAN SHAPIRO

In Praise of the Impure: Poetry and the Ethical Imagination

An exciting exploration of the passions and problems of writing, and of the state of contemporary American poetry.

Alan Shapiro is the author of four books of poetry, including Happy Hour, which won the William Carlos Williams Award of the Poetry Society of America, and Covenant. He teaches at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, and is a 1991 recipient of a Lila Wallace-Reader's Digest Writer's Award.

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

51/2 x 81/2 inches

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit-a new, unsettling music that will not leave us alone. We hear a willful vulnerability. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid. She makes us think in surprising ways. Her poems speak from an unforeseen edge.

I love the combination ofsmartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book: a version of the eroticfull of nervous tension that animates the sensuality, and also Zimroth's feelingforwords-compressed, ironic, withholding but also 'asking for it...the siege, the thrill, the battle fatigue.' A profoundly urban book, ofharsh memory andfantasy, set in harsher reality.

-ALICIA OsTRIKER

On Hearing That Childbirth Is Like Orgasm

So, maybe it's not a maiming altogether but some weird daylong fairy-tale

as the door opens into a new chateau and the moat closes over behind you. It's magic: like pricking your finger, the pin just some new animal, for your pleasure; a kind of tickle, you don't feel it anyway having gone somewhere beyond pain, your body limp and blooming as an anemone, 0 the lush stories to tell! the extravagance! the irresistible rules! to be strapped to stirrups, your wrists chained Classier even than The Story cfO it's what the good fairy promised and the good girls get: the kiss in the turret, the happy-ever-after.

Evan Zimroth was born in Philadelphia, grew up in Washington, IX, and spent her teenage years dancing in the Washington Ballet. She received her Ph.D. from Columbia University, and her first book, Giselle Considers Her Future, was published by Ohio State University Press. She lives with her family in New York City.

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

Beginning in the 1960's, there has been a remarkable flowering of new writing in Mexico. A new generation of writers has come of age. Those writers, born around 1945 and after, have lived through the most dramatic political, social and artistic changes in Mexico's history; they have opened up fiction to new subjects, new places, new techniques; their poetry evokes and meditates on the Mexican reality more fully and more vividly than ever before. Notable among these new writers are the voices of women and the voices speaking from the provinces about their rich sense of place-away from the powerful cultural center of Mexico City. This large anthology is not a documentary representation or a survey, but a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today

a wonderful and timelyanthology. Gibbons has gathered 58 of Mexico's most talented writers, and they are as diverse as their nation ln asking the question "What is Mexican?" and with the talented help of many translators, Gibbons has contributed a great deal to the understanding ofMexico. -BOOKLIST

6 x 91/4 inches

448 pages

$27, cloth (0-916384-12-8), $15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

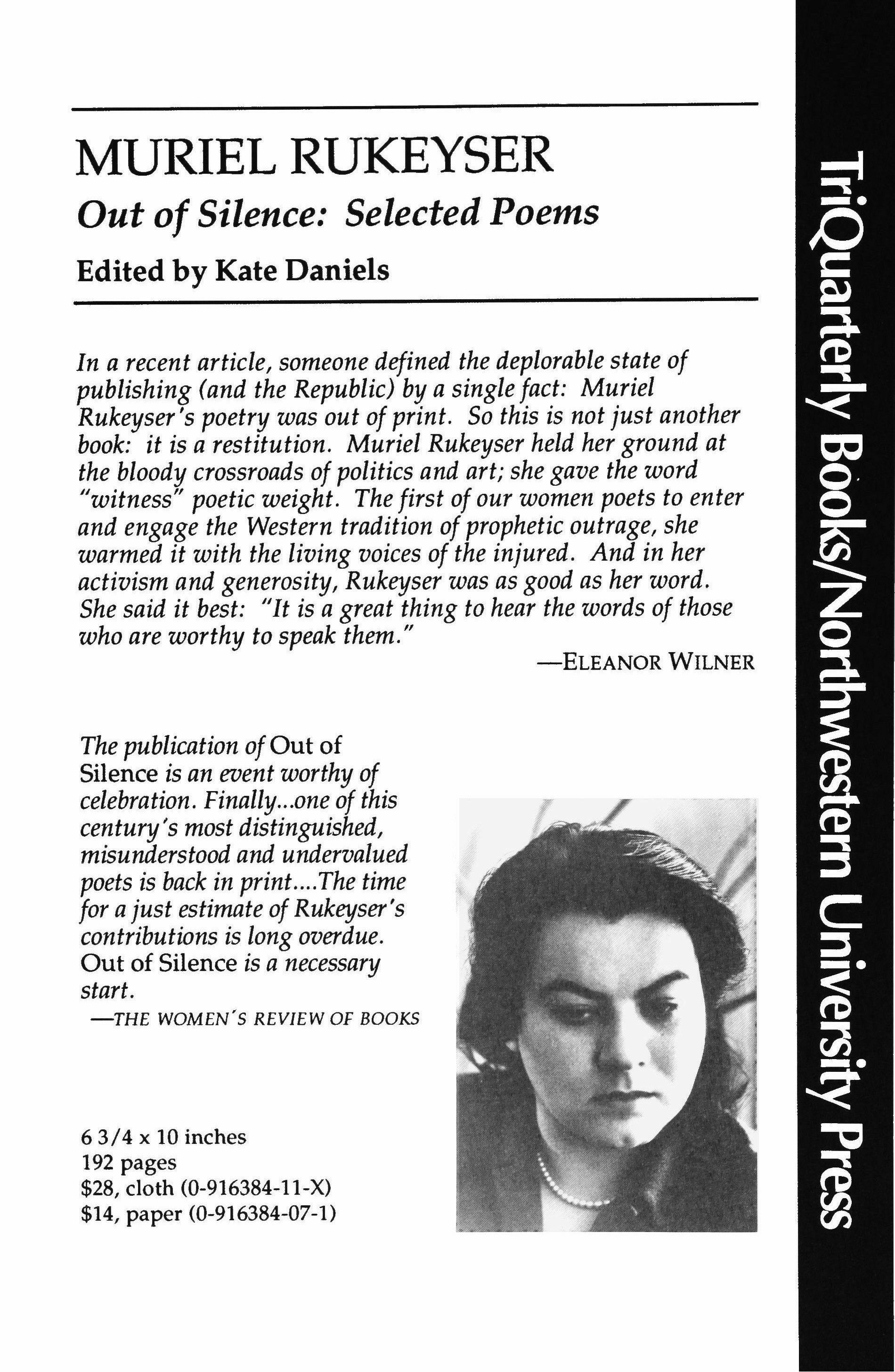

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out of Silence: Selected Poems

Edited by Kate Daniels

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state of publishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser's poetry was out ofprint. So this is not just another book: it is a restitution. Muriel Rukeyser held her ground at the bloody crossroads ofpolitics and art; she gave the word "witness" poetic weight. The first of our women poets to enter and engage the Western tradition ofprophetic outrage, she warmed it with the living voices of the injured. And in her activism and generosity, Rukeyser was as good as her word. She said it best: "It is a great thing to hear the words of those who are worthy to speak them. II

-ELEANOR WILNER

The publication of Out of Silence is an event worthy of celebration. Finally one of this century's most distinguished, misunderstood and undervalued poets is back in print.. The time for a just estimate ofRukeyser's contributions is long overdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start.

-THE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

63/4 x 10 inches

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X)

$14, paper (0-916384-07-1)

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. His subject is both the transport and the anguish of being open to the lived and living moment. He writes of love, sex, violence, and the inhuman crossfire of historical forces. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention. The images he discovers do not fade from our minds, and we are grateful for "what saves us" no matter who we are or where we have been.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right along from that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one of the best poets now writing in America.

-DENISE LEVERTOV

51/2 x 81/2, 80 pages $17, cloth (0-916384-08-X); $10.95, paper (0-916384-09-8)

LINDA McCARRISTON Eva-Mary

Eva-Mary

Winner of the 1991 Terrence Des Pres Prize forPoetry

NOW IN A THIRD PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance. Exploring what she calls "acculturation in ignorance," McCarriston writes of parents and children, the natural world and domestic and sexual violence; in so doing she powerfully reshapes her emotional inheritance and creates a passionate form of survival.

51/2 x 8 1/2 inches 80 pages $10.95, paper (0-929968-26-3)

An immensely moving book, fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories of trauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace.

-LISEL MUELLER

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Linda McCarriston

Fiction of the Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

A landmark anthology marking the 25th anniversary of TriQuarterly, this 592-page volume includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared during the past decade.

Among those represented are Grace Paley, William Goyen, Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, Amy Hempel, Robert Coover, Joyce Carol Oates and many new writers. These stories range widely over the experience of modern life, and share a high level of artistry and an unmistakable atmosphere of the 1980s. An incomparable primer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standardbearer The multiplicity and depth of the fictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness of writers too numerous to thank.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

6 x 9 1 /4 inches

592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5) $16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

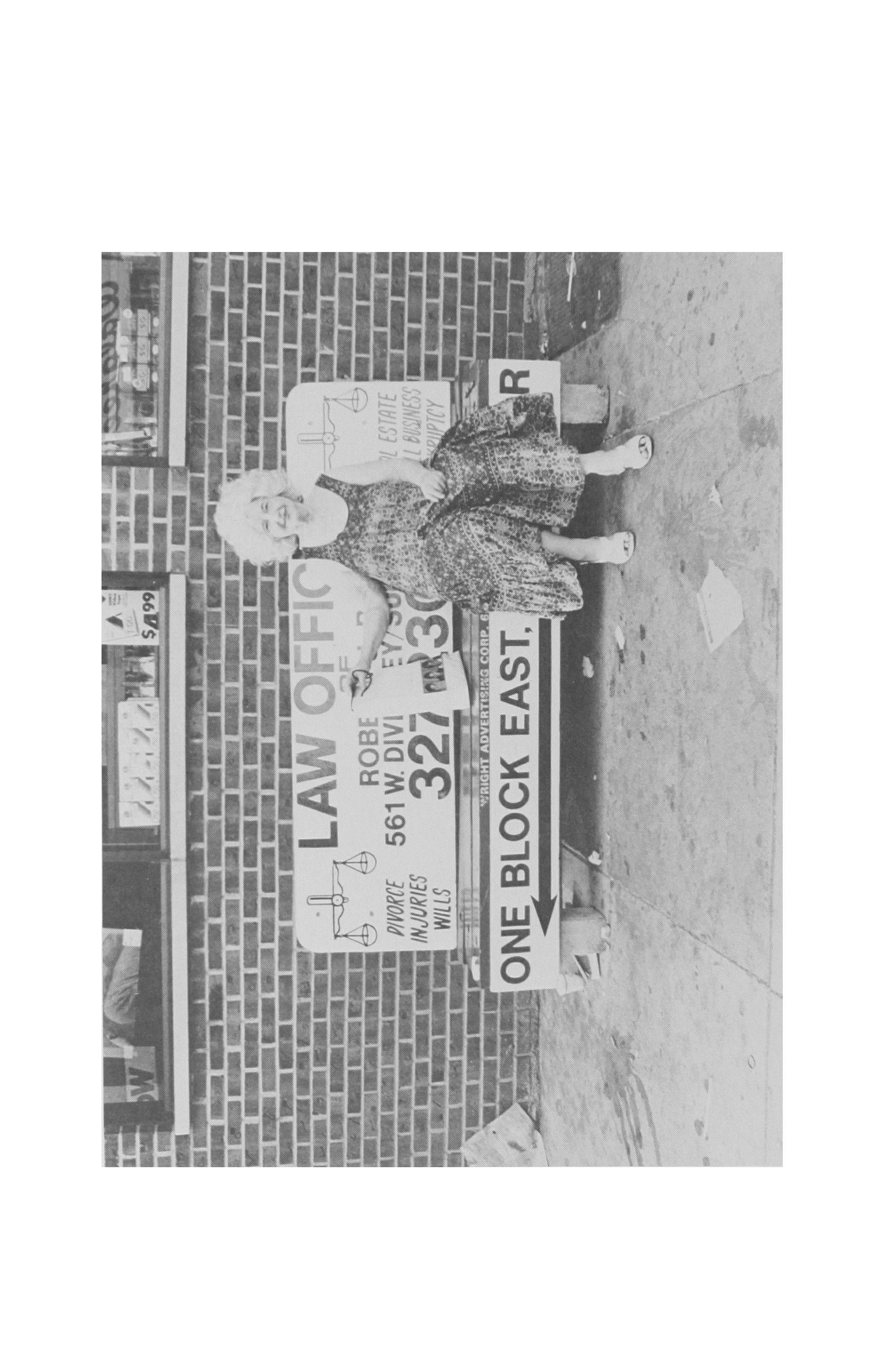

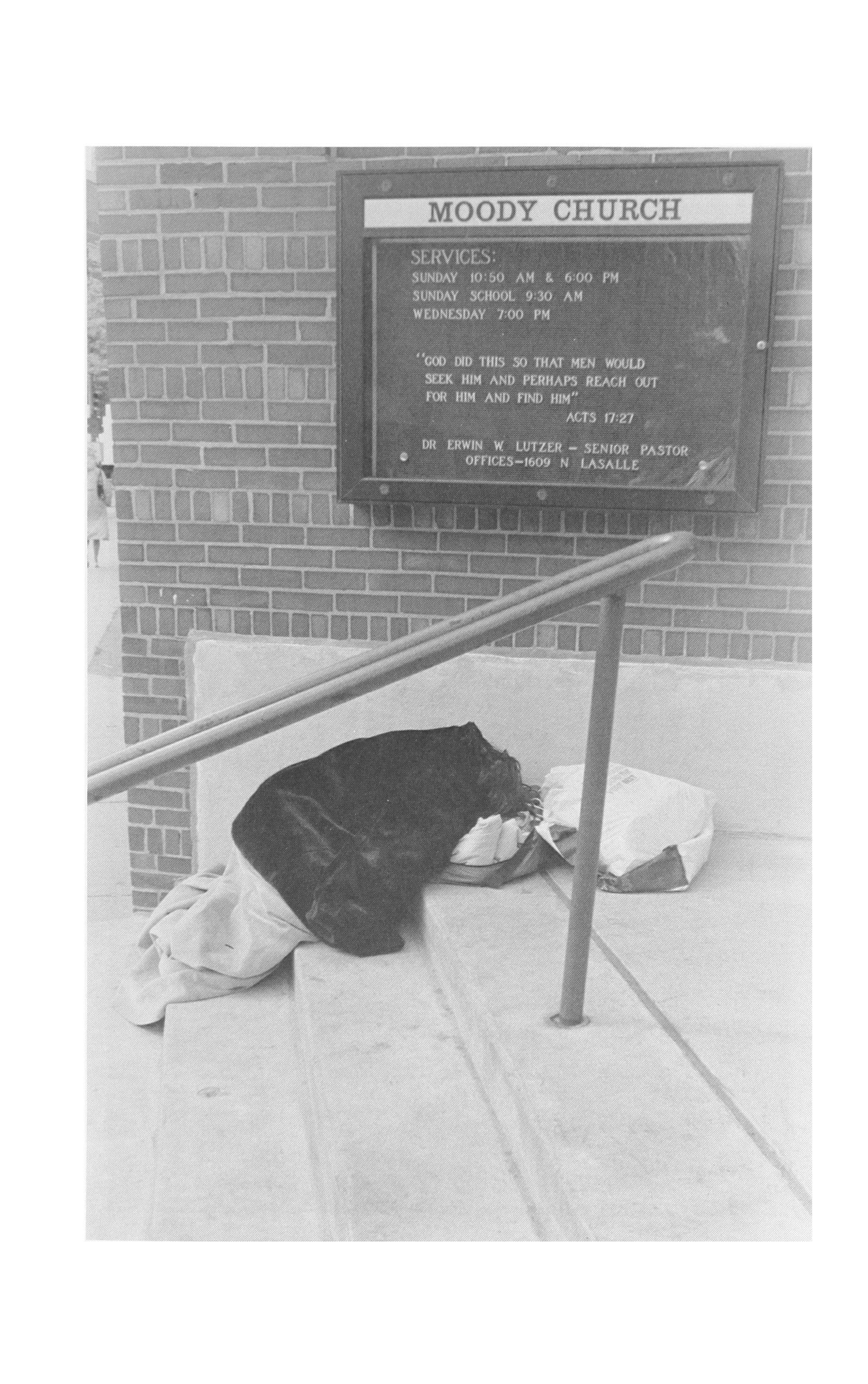

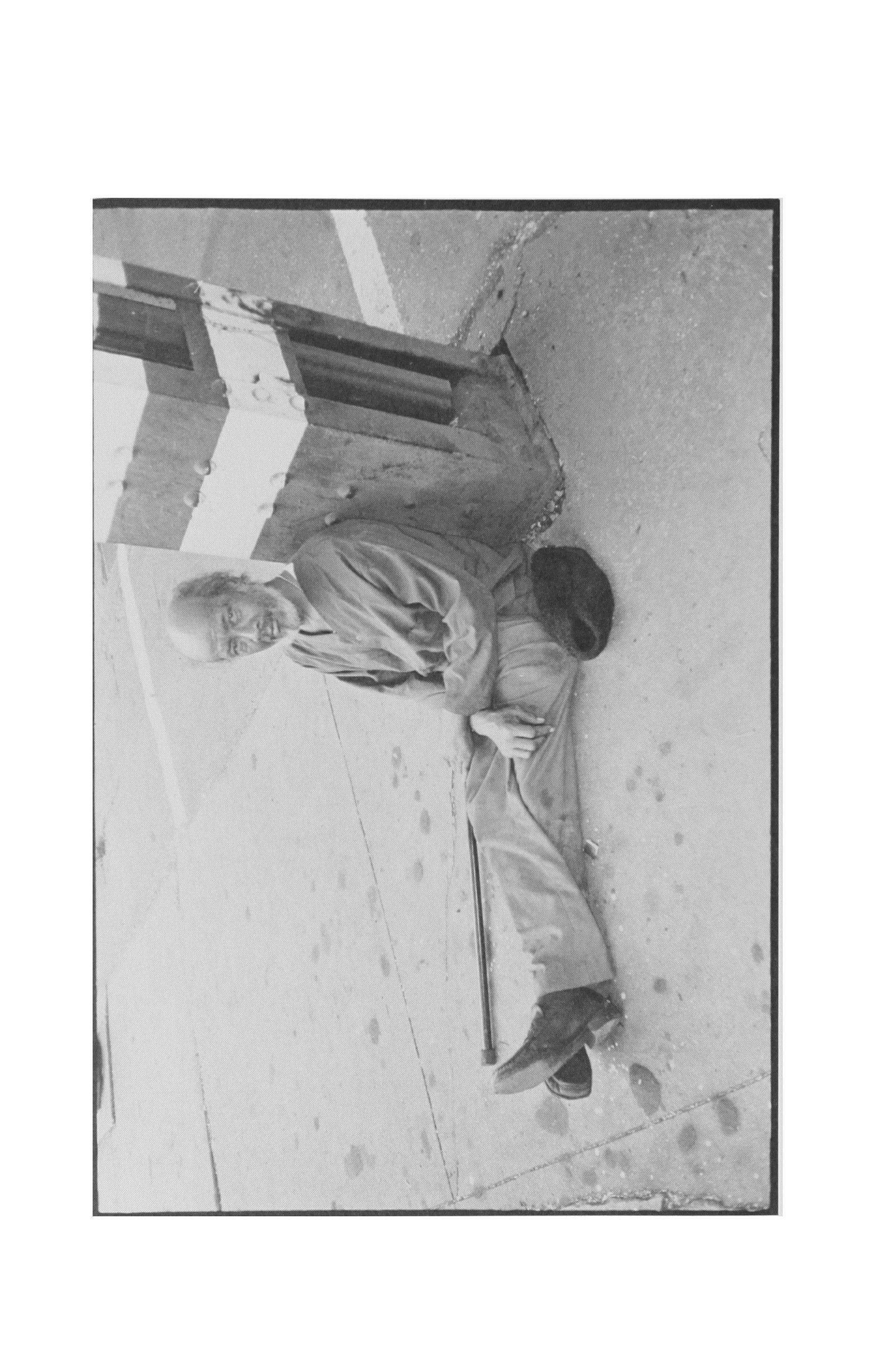

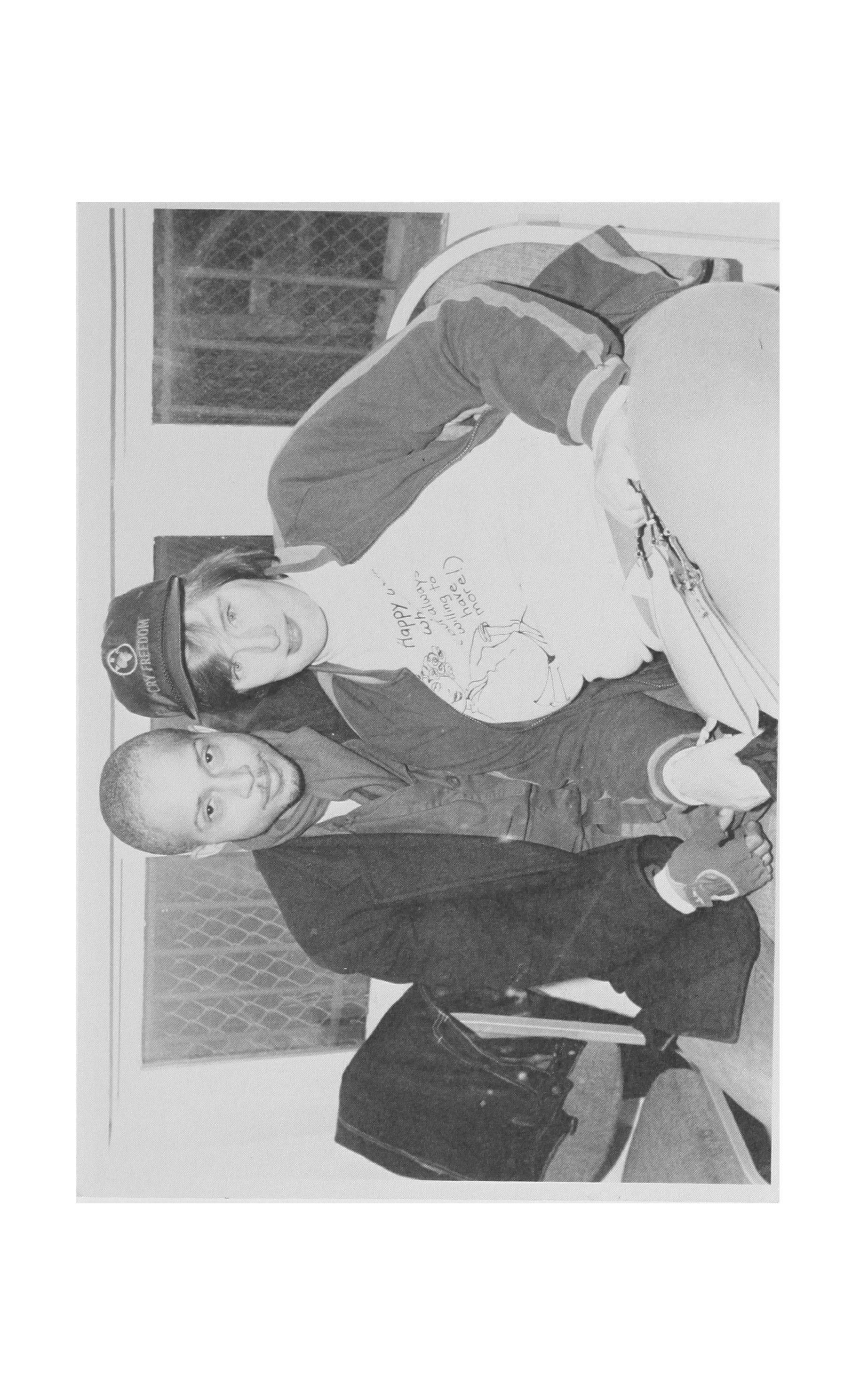

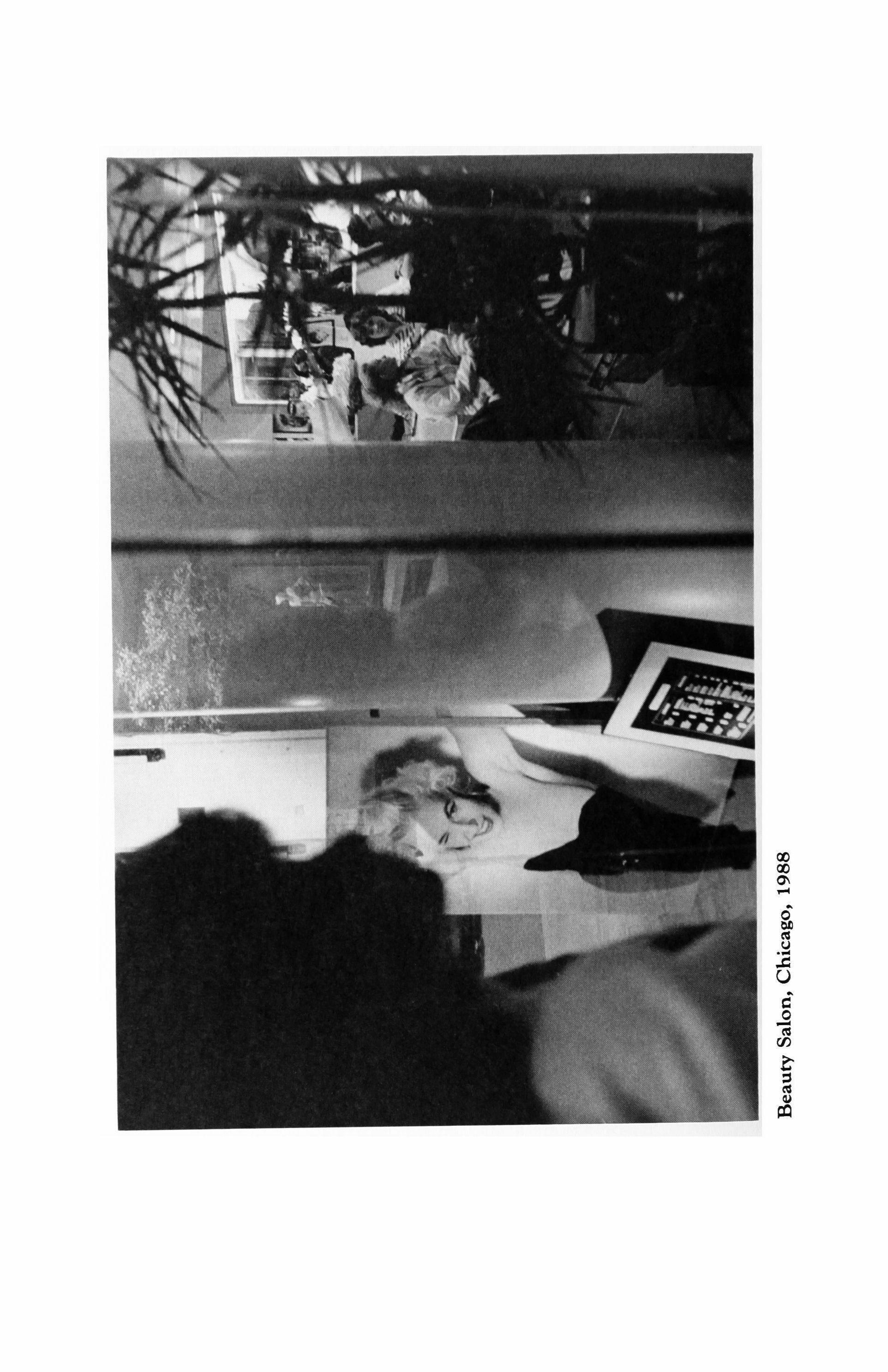

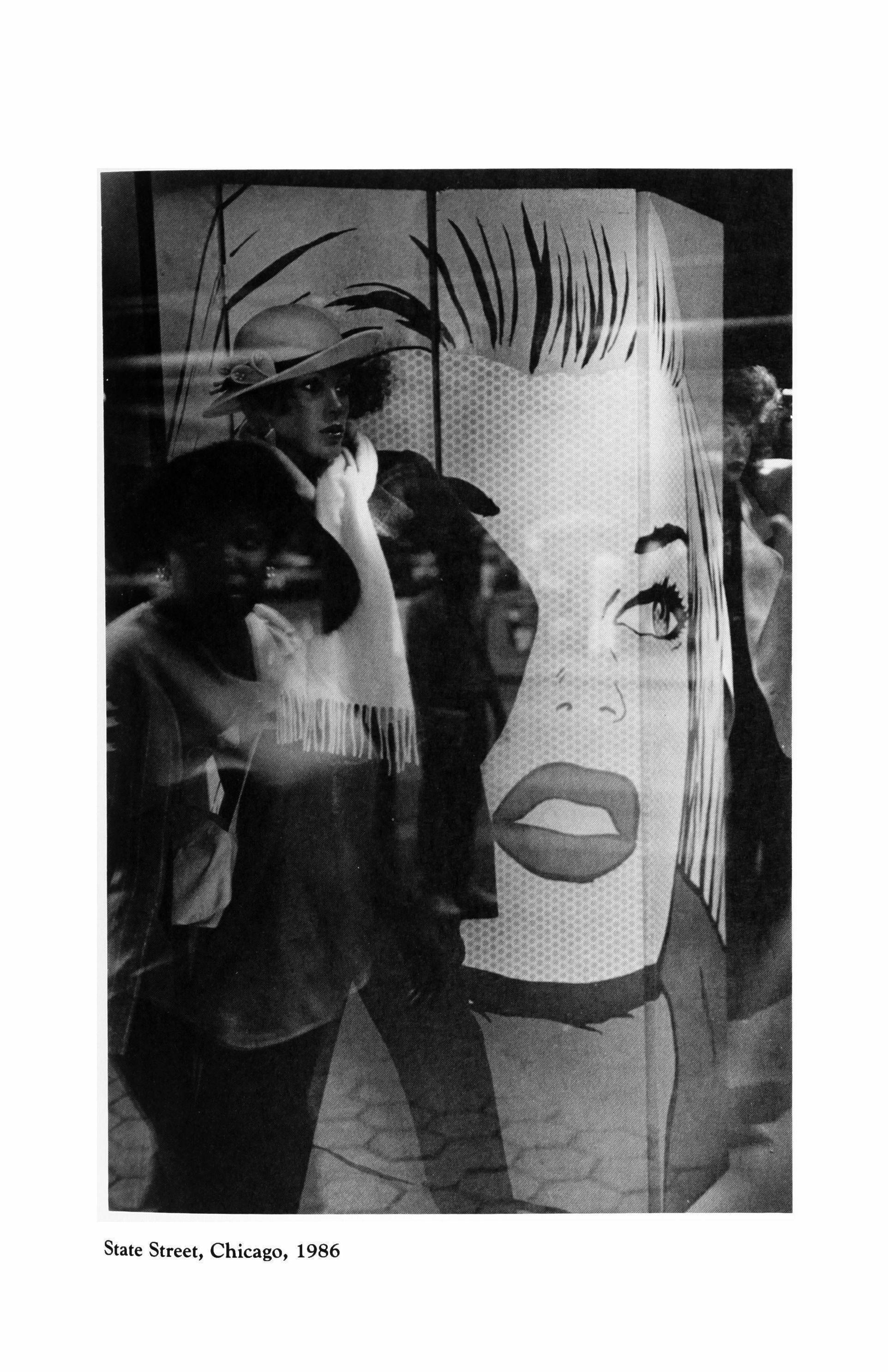

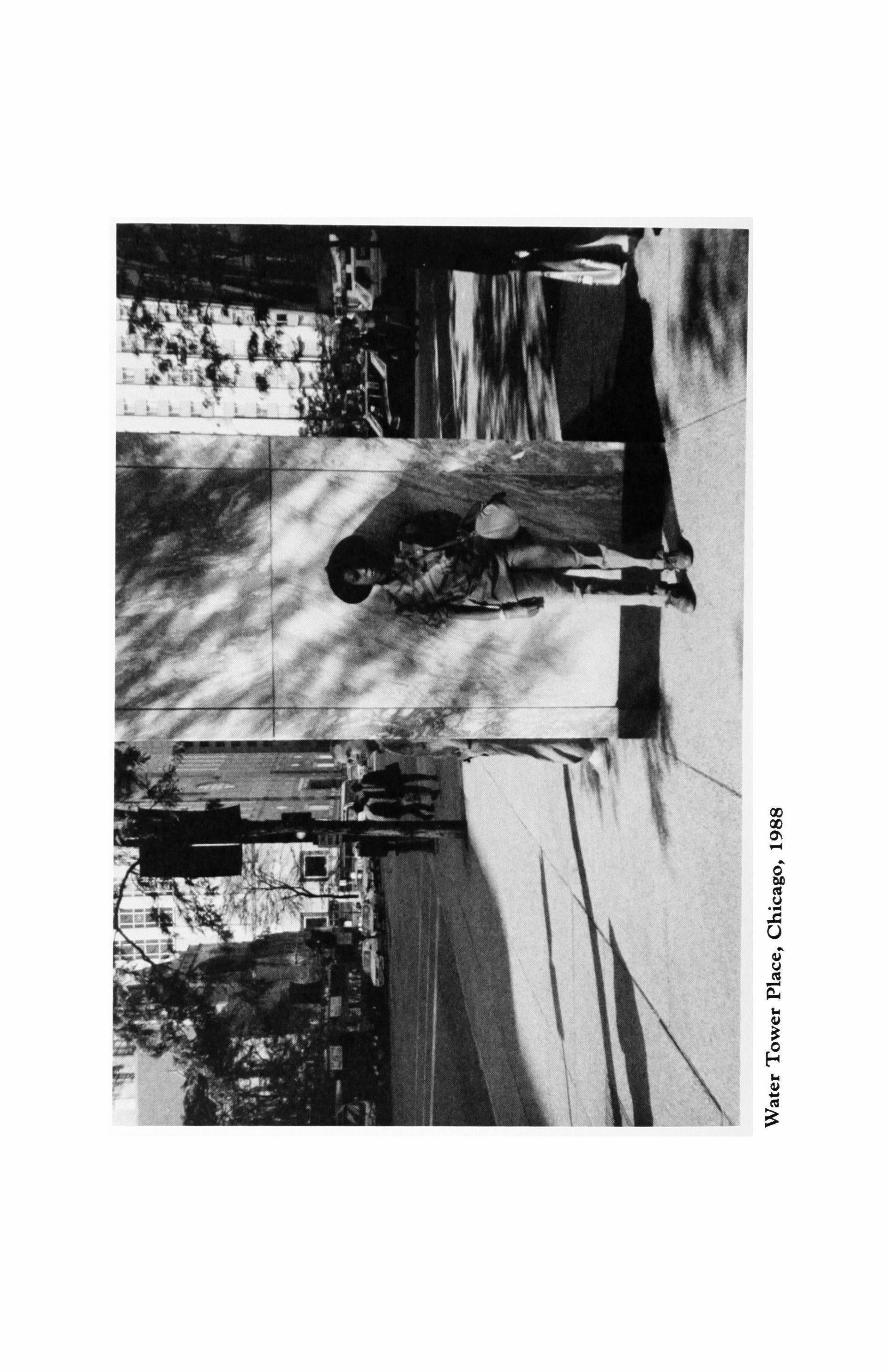

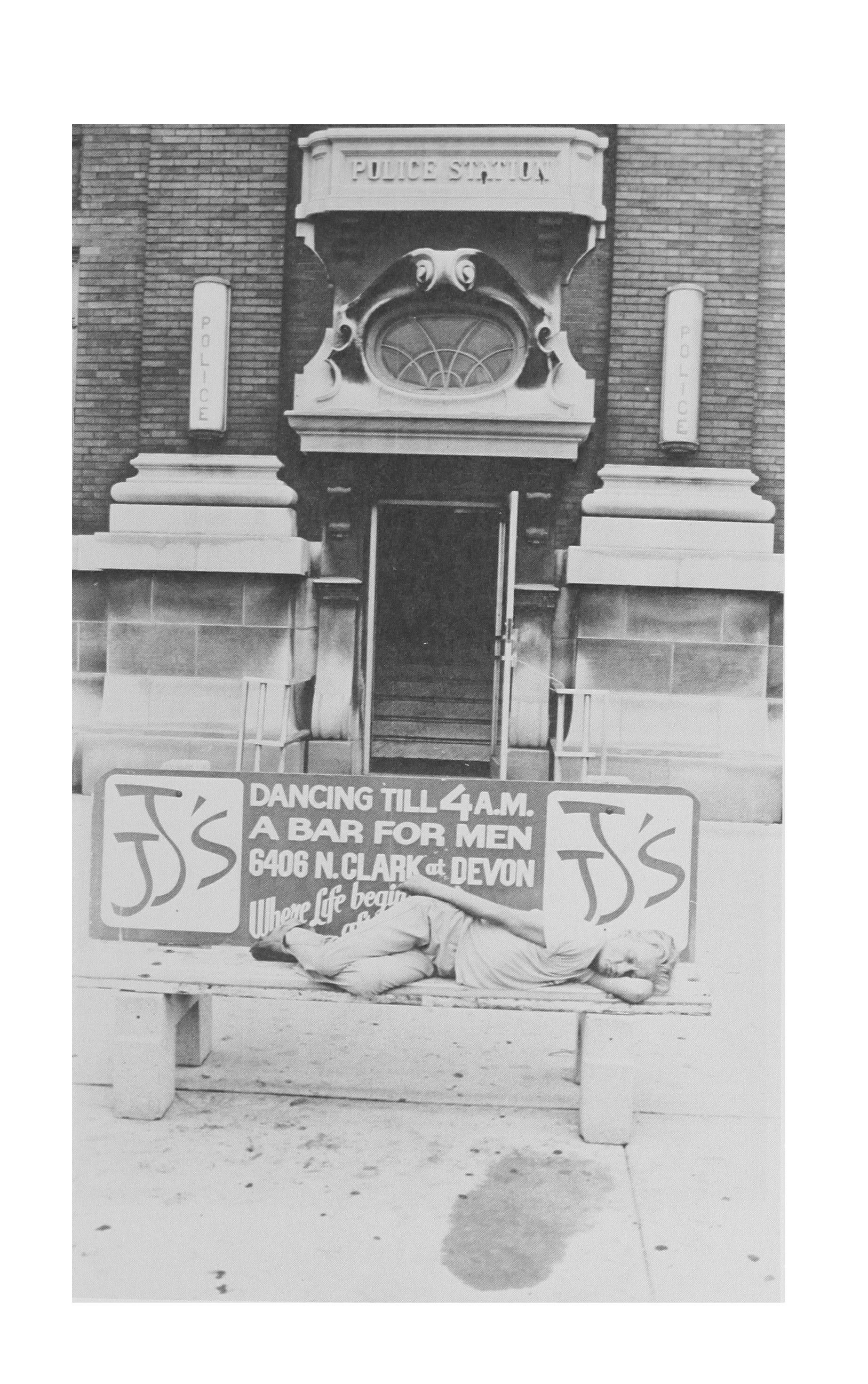

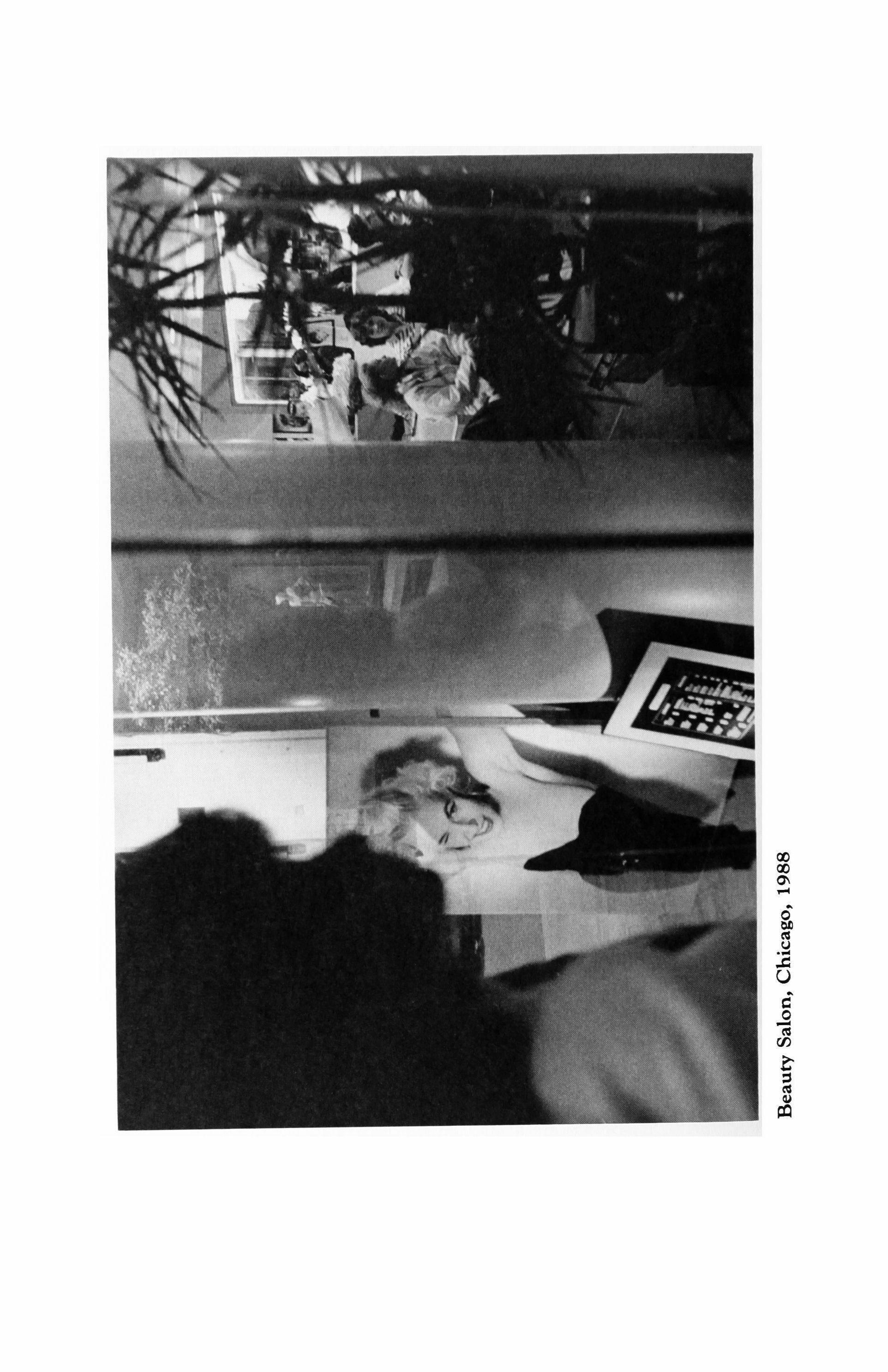

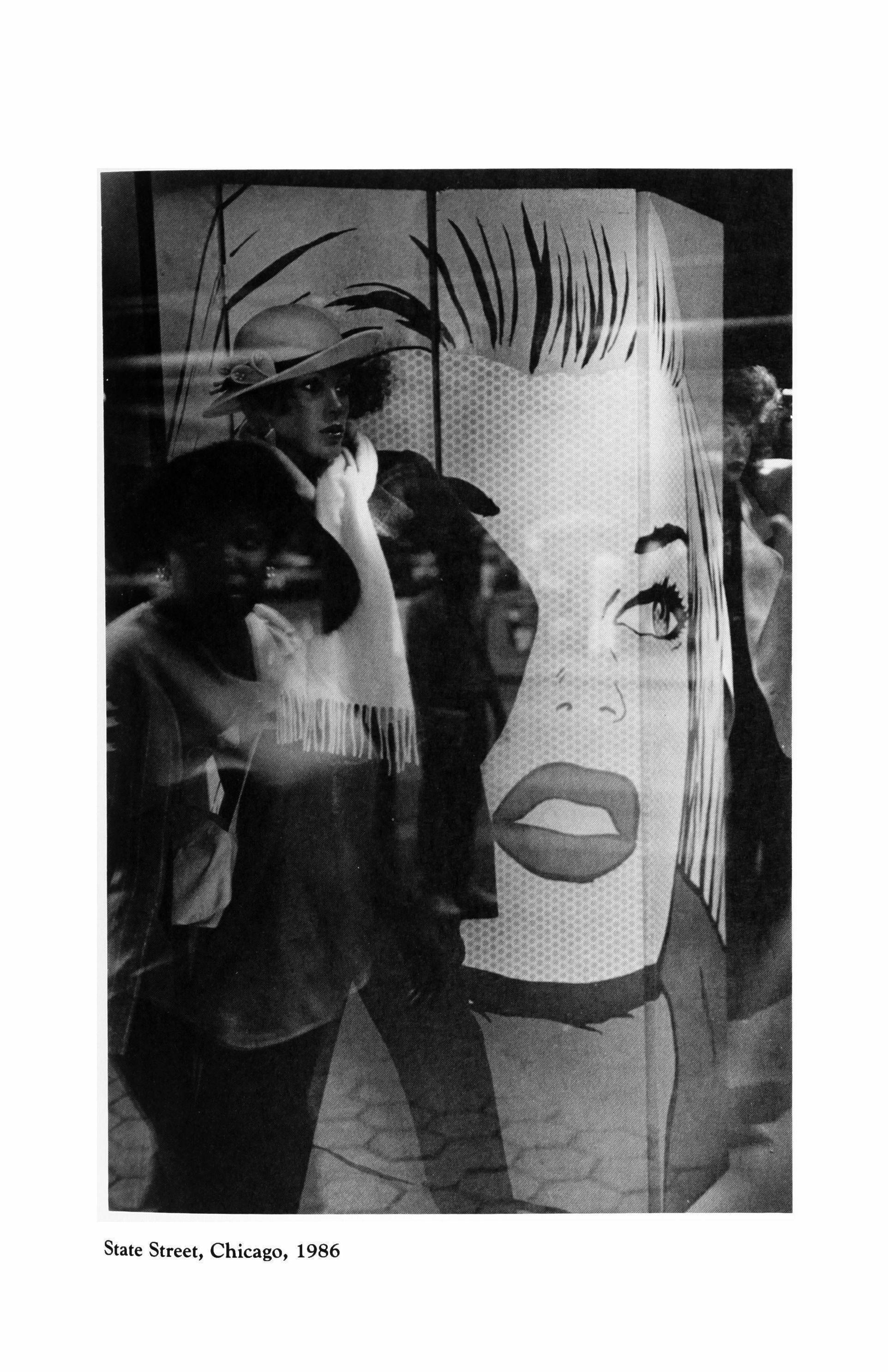

Stephen Deutch,

Photographer: From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989

The gift book-with stunning photos of Chicago over decades of change, including Deutch's Pulitzernominated photos from the Daily News. This collection and analysis of Deutch's work, with plates both in duotone and in color, is the first full record of Deutch's achievement to be published.

SteJ Del Ph

144 pages

$45, cloth (0-929968-05-0)

$23.50, paper (0-929968-06-9)

Writers from South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterly magazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialogues by fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to U.S. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

Writers from South Africa

128 pages

$6.50, paper (0-916384-03-9)

hI-. "iJI' / ( \ \/) 'I.\/-;) I {HJi' \ '\ I ,(If TlI Iff. '( I II/I) \ 1

SELECTED BACK ISSUES of TriQuarterly magazine

#22 Leszek Kolakowski: co-edited by George Gomori. The first translations into English of this important Polish philosopher. 256pp.$5.

#25 Prose for Borges: a special issue with an anthology of writings byJorge Luis Borges and essays and appreciations by Anthony Kerrigan, Norman Thomas di Giovanni and others. 468 pp. $10.

#31 Contemporary Asian Literature: co-edited by Lucien Stryk. With Lu Hsun, Chairil Anwar, Ho Chi Minh, Shinkichi Takahashi, Yasunari Kawabata and others. 244 pp. $5.

#35 A special boxed two-volume set-Minute Stories: eightyseven tiny fictions by W. S. Merwin, John Hawkes, Max Apple, Richard Brautigan, Annie Dillard and others. 112 pp. Selected Poetry: German, American and French poetry selected by Michael Hamburger, Michael Anania and Paul Auster. 120 pp. $5Iset.

#39 Contemporary Israeli Literature: fiction by Amos Oz. David Shahar, Yehuda Amichai, Pinchas Sadeh, A. B. Yehoshua. Poetry by Amichai, Dan Pagis, Abba Kovner and others. Afterword by Robert Alter. 342 pp. $5.

#47 Love/Hate: fiction by Robert Stone, Oakley Hall, Joyce Carol Oates, Angela Carter, Herbert Gold, Alfred Gillespie, Victor Power and seven more. Photographs by Diane Blell with Stephen Sanders. 352 pp. $6.

#54 A John Cage Reader: color etchings by Cage plus contributions celebrating his seventieth birthday from Marjorie Perloff, William Brooks, Merce Cunningham and others; fiction by Ray Reno, Arturo Vivante and others; poetry by Teresa Cader, Jay Wright and Michael Collier. 304 pp. $6.

#57 A special two-volume set-Vol. 1, A Window on Poland: featuring essays, fiction and poems written during Solidarity and martial law. Tadeusz Konwicki, Jan Prokop and others, with photos and graphic works. 128 pp. Vol. 2, Prose from Spain: recent fiction and essays, plus an interview with Juan Goytisolo and eight color pages of street murals. 112 pp. $4/each vol., $Blset.

#59 The American Blues: fiction by Ward Just, Joyce Carol Oates, Gayle Whittier and others; poetry by Bruce Weigl, John Ciardi, John Frederick Nims, Maxine Kumin and others; photographs from Vietnam and of American political figures by Mark Godfrey; "Alberti and Others," a supplement of poetry and prose complementing Prosefrom Spain (#57, Vol. 2). 272 pp. $7.

#63 TQ 20: twentieth-anniversary issue, with fiction by James T. Farrell, Richard Brautigan, Stanley Elkin, Jorge Luis Borges, Joyce Carol Oates, Vladimir Nabokov, Cynthia Ozick, Raymond Carver, William Goyen, Lorraine Hansberry and others; poetry by Anne Sexton, Howard Nemerov, W. S. Merwin, Jack Kerouac, Marvin Bell and others; interview with Saul Bellow; illustrations and photographs. 684 pp. $13.

#65 The Writer in Our World: symposium featuring Stanislaw Baranczak, Terrence Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Leslie Epstein, Carolyn Forche, Michael S. Harper, Ward Just, Grace Paley, Mary Lee Settle, Robert Stone, Derek Walcott and C. K. Williams, with original work by most participants and by moderators Angela Jackson and Bruce Weigl; photographs. 332 pp. $9.

#72 General issue: stories by Norman Manea, Anne Calcagno, Sheila Schwartz and others; poems by Bruce Weigl, Jenny Mueller, Alan Shapiro and others; essay by C. K. Williams; special section of poetry and prose by John Peck. 224 pp. $8.

#73 General issue: stories by Sandy Huss, Carol Blyand Susan Straight; poetry by Anna Akhrnatova, Michael Anania, Pattiann Rogers, Sterling Plumpp; special sections on Joyce Carol Oates and Wole Soyinka. 208 pp. $8.

#74 General issue: stories by Leo Litwak, Margaret Broucek, Donna Trussell, Angela Jackson; poetry by Sandra McPherson, Mary Kinzie, Czeslaw Milosz, Adrienne Rich and Eleanor Wilner. 272 pp.$8.

#75 Writing and Well-Being: memoirs, essays and poems by William Goyen, Paul West, Perri Klass, Gwendolyn Brooks, Nancy Mairs, Jay Cantor, Annie Dillard, Maxine Kumin, Paul Bowles, Reynolds Price and others. 208 pp. $8.

#76 General issue: fiction by Francine Prose, Christopher McIlroy, Ami Sands Brodoff; poetry by Rita Dove, Stuart Dybek, Lisel Mueller, Joseph Gastiger; memoir by Peter Kenez; essays by Robert Pinsky and others. 224 pp. $8.

#77 General issue: special section on Modem Indian Poems; interview with Samuel Beckett; fiction by Arthur Morey, David Michael Kaplan; poetry by Eavan Boland, Li-Young Lee, Maxine Kumin, Claribel Alegria. 336 pp. $10.

ORDERING INFORMATION

TriQuarterly Books/Northwestern University Press

You may order books under the TriQuarterly Books imprint of Northwestern University Press (forthcoming fall titles, Zimroth, New Writingfrom Mexico, Rukeyser, Weigl and McCarriston) from:

Northwestern University Press Chicago Distribution Center 11030 South Langley Avenue Chicago,IL 60628

Tel. 800/621-2736

Fax 312/660-2235

TriQuarterly Books

You may order remaining TriQuarterly Books titles (Fiction of the Eighties; Stephen Deutch, Photographer and Writers from South Africa) and back issues of the magazine from our editorial office:

TriQuarterly Books

Northwestern University 2020 Ridge Avenue Evanston, IL 60208-4302

Tel. 800/832-3615

Fax 708/467-2096

Subscriptions to TriQuarterly magazine

TriQuarterly is available to individuals at the following rates:

1 year-$20 2 years-$36 Life-$500

Subscribers may purchase additional giftsubscriptions for only$17/year. Foreign subscribers please add $5 per year. Direct subscription inquiries to our editorial office: TriQuarterly, Northwestern University, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston,IL 60208-4302, Tel. 800/832-3615, Fax 708/467-2096

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Readers

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Timothy Dekin, Campbell McGrath, Charles Wasserburg

TriQuarterly Fellow Deanna Kreisel

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants Matthew Kutcher, Sarah Kube, Hans Holsen, Stacy Mattingly, Mark Hartstein

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year)-Individuals: one year $20; two years $36; life $500. Institutions: one year $26; two years $44; life $300. Foreign subscriptions $4 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-3490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts received between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1993 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore, typeset by Sans Serif. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals, 1117 Heil Quaker Blvd., La Vergne, TN 37086 (800-627-6247, ext. 4500); B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110 (201-667-9300). Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415-549-3030).

Reprints of issues # 1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H. W. Wilson Co.) and the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.).

The following material from TriQuarterly #83 has been chosen for reprint in the Pushcart Prize XVIII: Best ofthe Small Presses (1993-94 edition), to be published in cloth (by Pushcart) in fall 1993 and in trade paperback (by Touchstone/Simon & Schuster) in spring 1994: "The Life of the Body" (story) by Tobias Wolff; "Green Grow the Grasses 0" (story) by D. R. MacDonald; and "Ginza Samba" (poem) by Robert Pinsky.

"Queen Wintergreen," a story by Alice Fulton which appeared in TQ #84, has been selected for inclusion in the 1993 edition of The Best American Short Stories, guest-edited by Louise Erdrich (with Annual Editor Katrina Kenison) and published by Houghton Mifflin.

TriQuarterly welcomes life subscribers to the magazine. Life subscriptions, at $500 each, are a major source of support for TriQuarterly. The list of life subscribers is published in every issue.

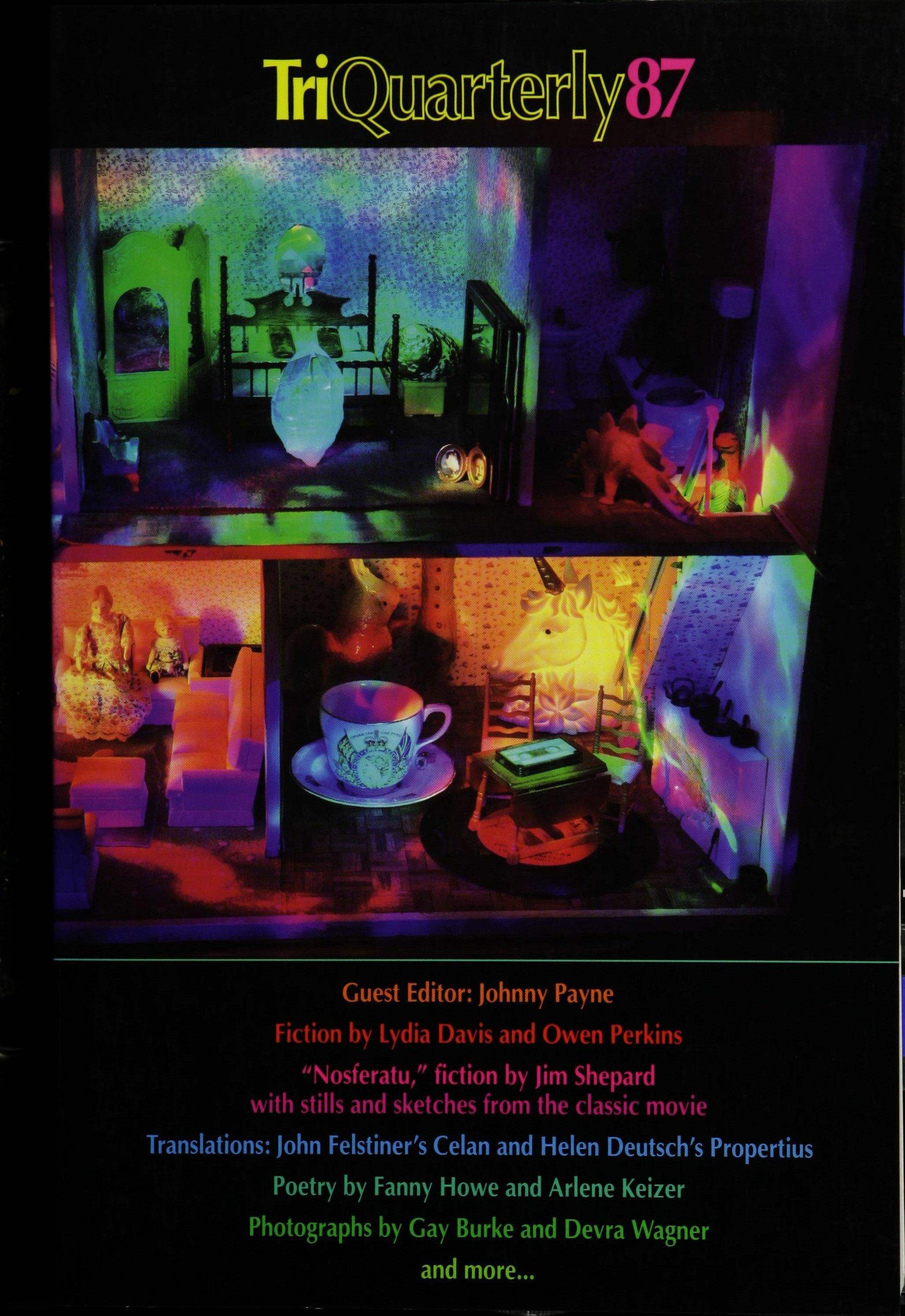

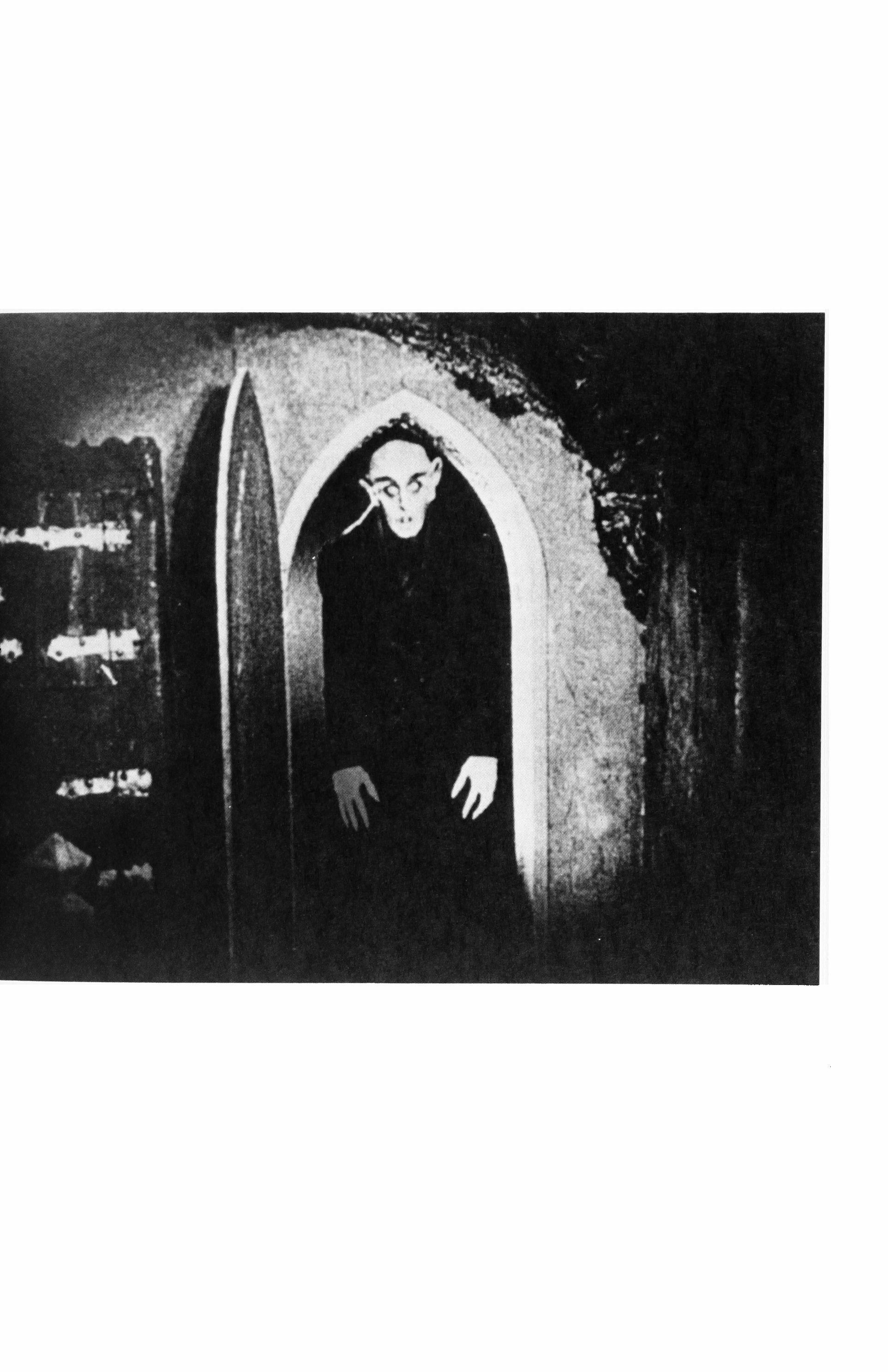

Contents Editor of this issue: Johnny Payne FICTION Algebra: A Problem with Words. 21 Owen Perkins Scraps 33 Patricia Otway-Ward Days of Indulgence ................•..... 71 Jack Heffron Nosferatu 88 Jim Shepard Forest Garnet's First Journey to the Spirit World ......................•..... 118 Philip E. Simmons Small Adjustments. 122 Caila Rossi Meat and My Husband Lydia Davis The Clock ................•....•.....•. 168 132 Cassandra Smith Jasper Joyce; Johnny Powers. 171 Ron Whitehead A Singular Beauty George Cruger 176 POETRY Democracy: Chapters in Verse 59 Fanny Howe After the War; El Salvador del Mundo; Leaving the Old Gods ..............•..... 144 Janet McAdams 17

Awkward Passions: Confessions of a Black Catholic; Migrants 150

Arlene Keizer

Because I Used To Be a Good Girl; Dynamics.. 155

Holly Welker

The Psychology of the Sentence: Case Histories; Emmet Street ......•••..... 164

Rene Steinke

Childhood; The Nakedness of Fathers; First Child; My Father's Crucifix ..•........

Donald Platt

Hitting a Skunk at 60 Miles Per Hour.

Bruce Cohen

Rembrandt Drawings: Standing Beggar, c. 1629; The Naughty Child, c. 1635; Saskia Sitting Up in Bed, c. 1639-40

Charles Wyatt

Propertius: Four Poems

Translated by Helen Deutsch

ESSAYS

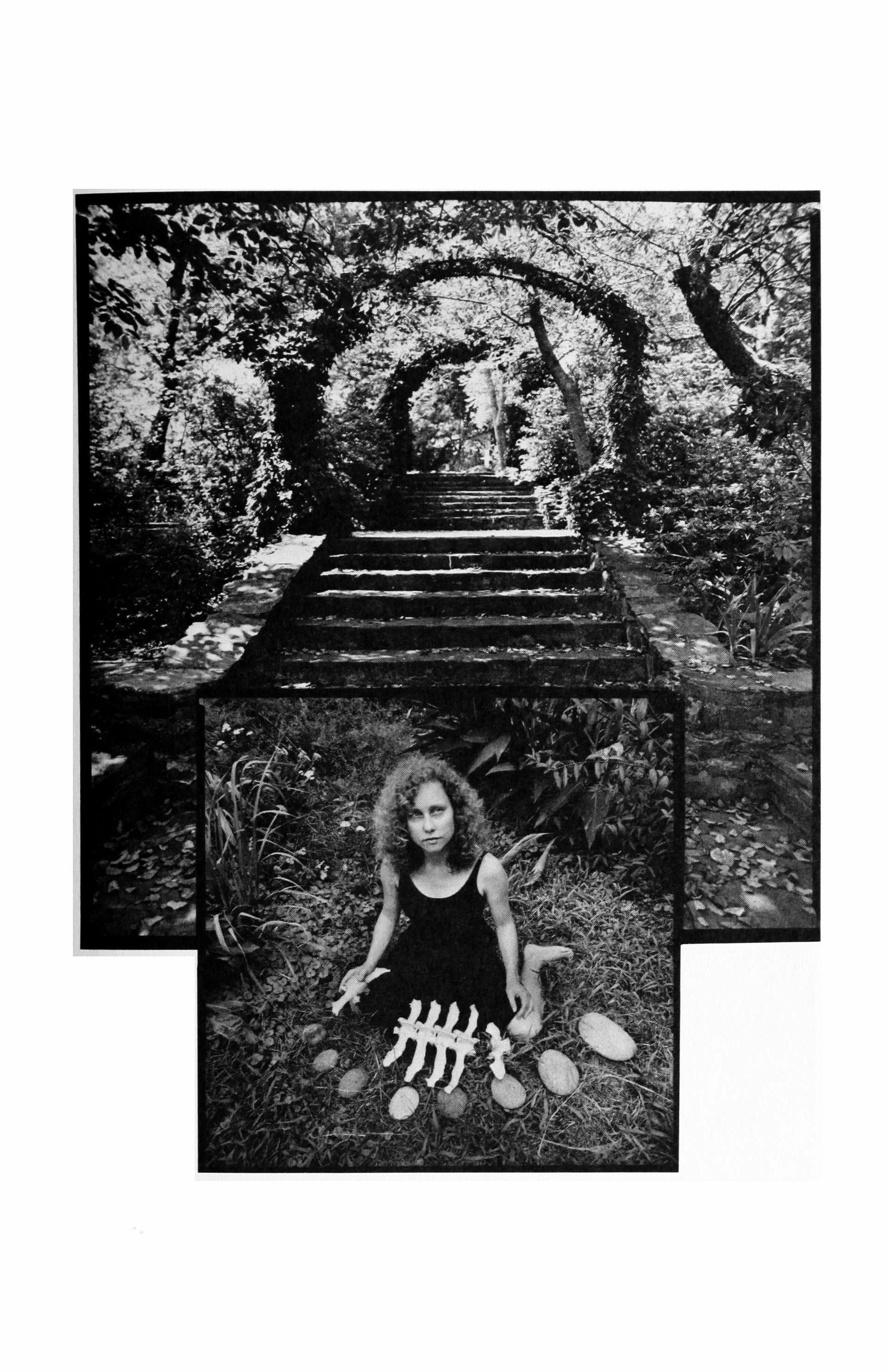

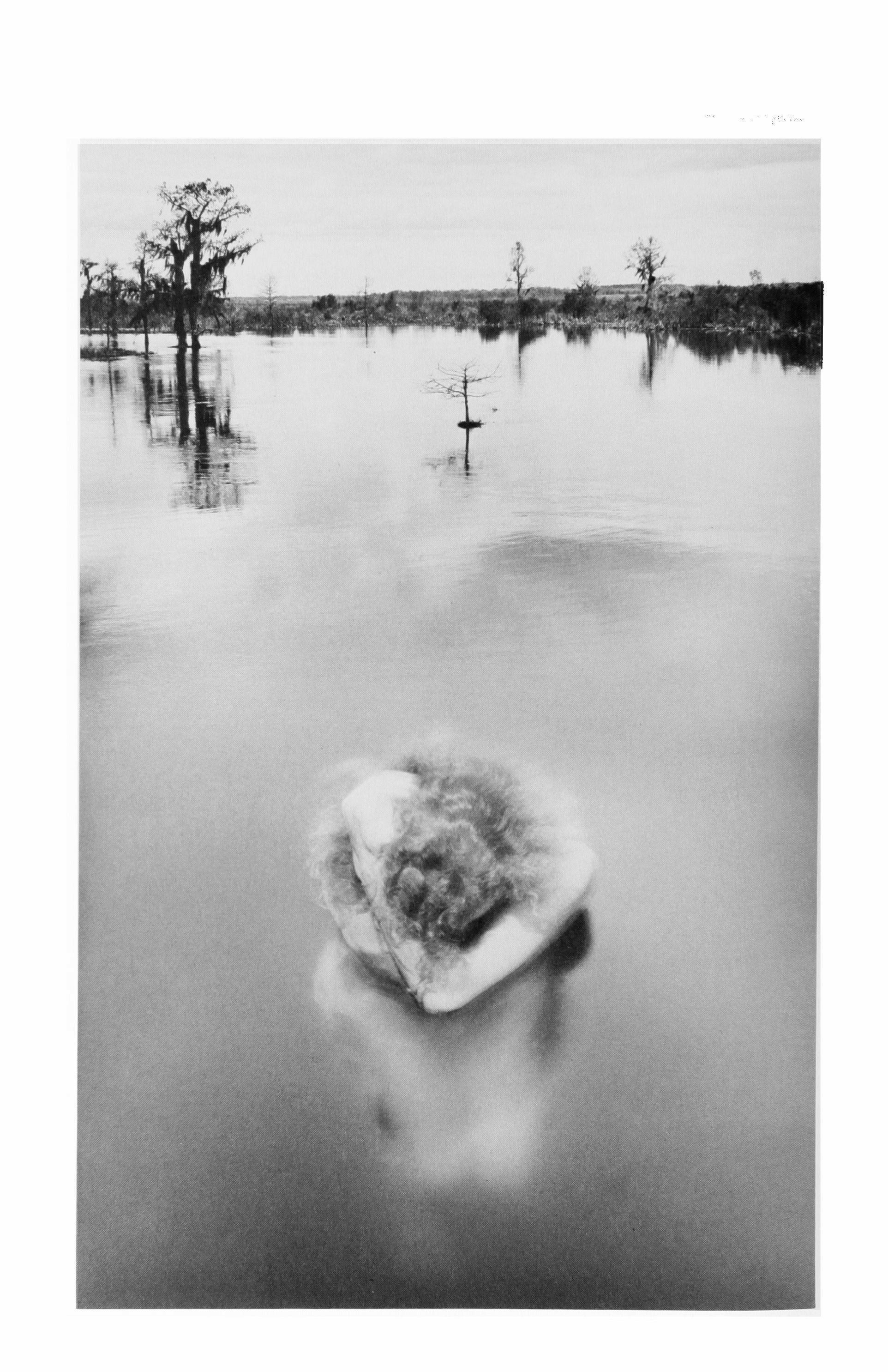

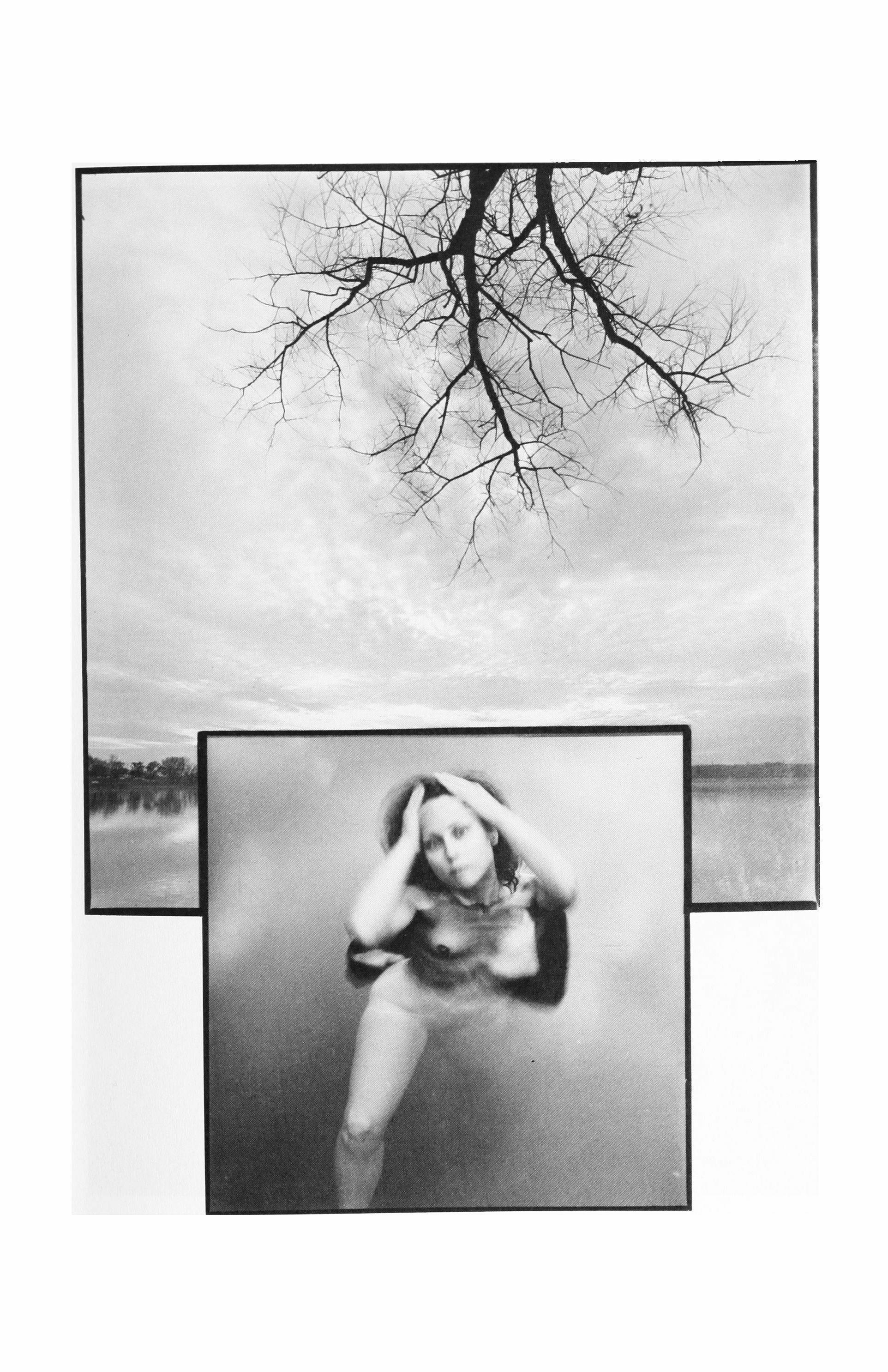

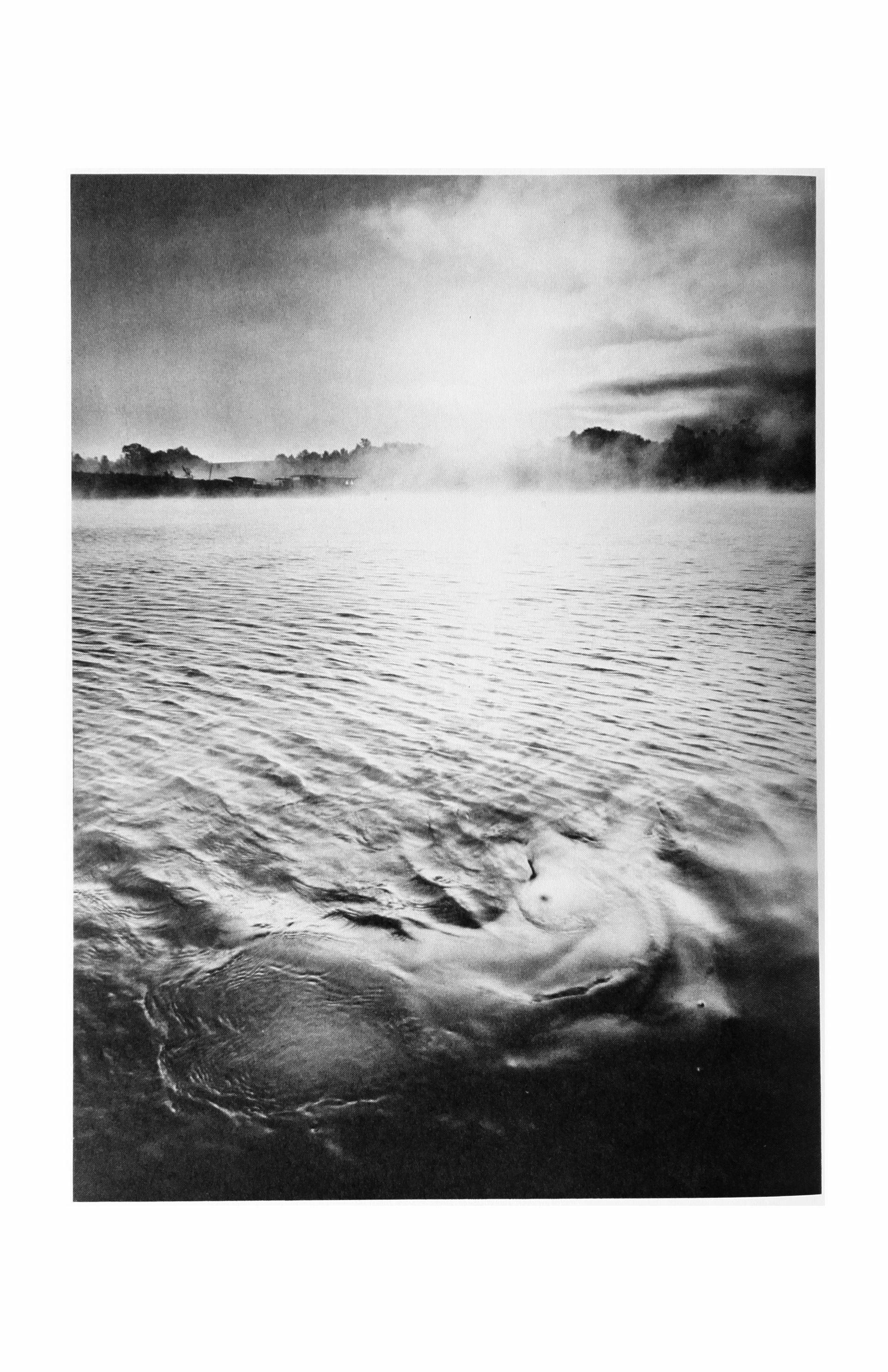

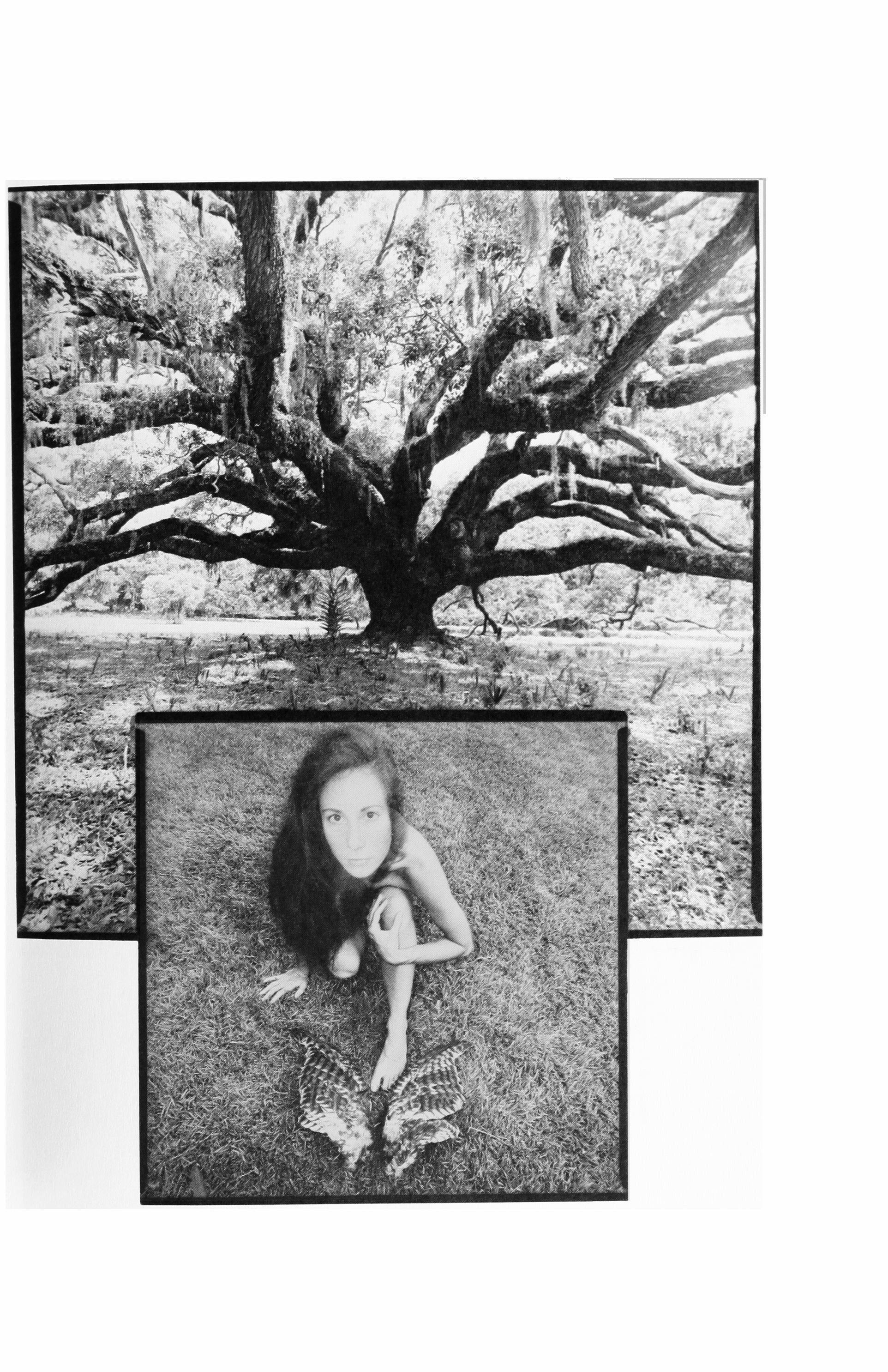

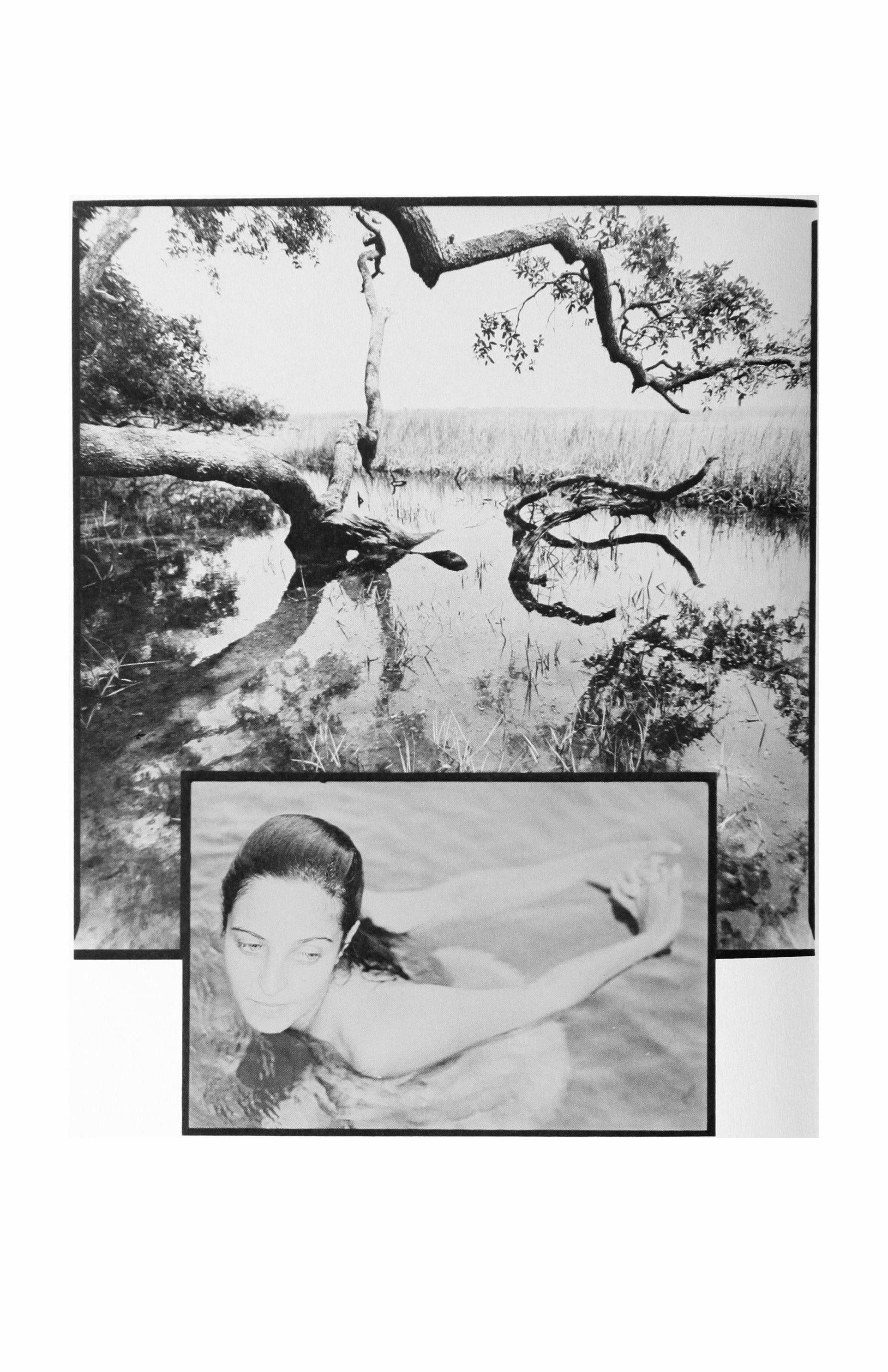

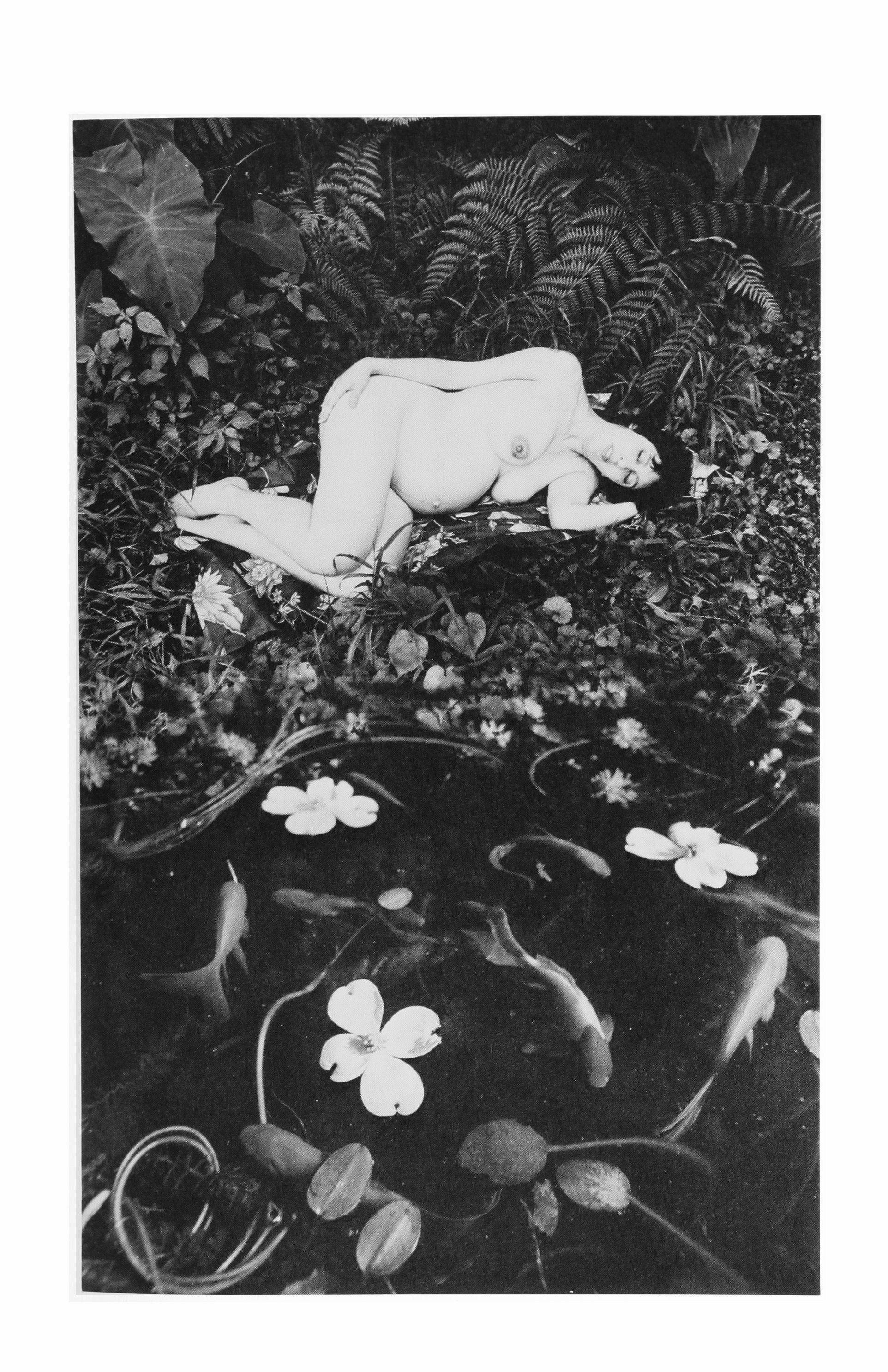

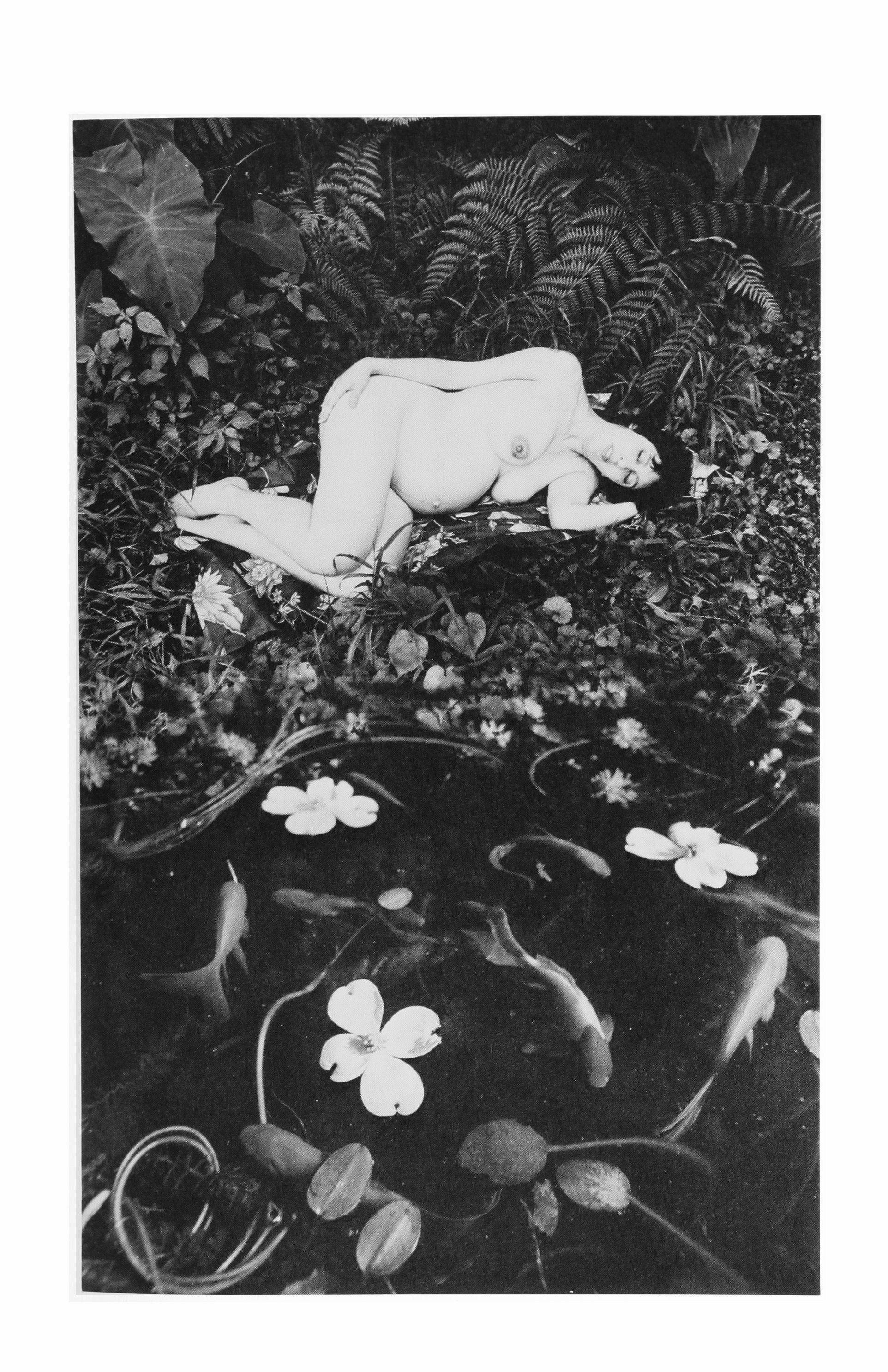

Women: Image and Myth

Barbara Thomas

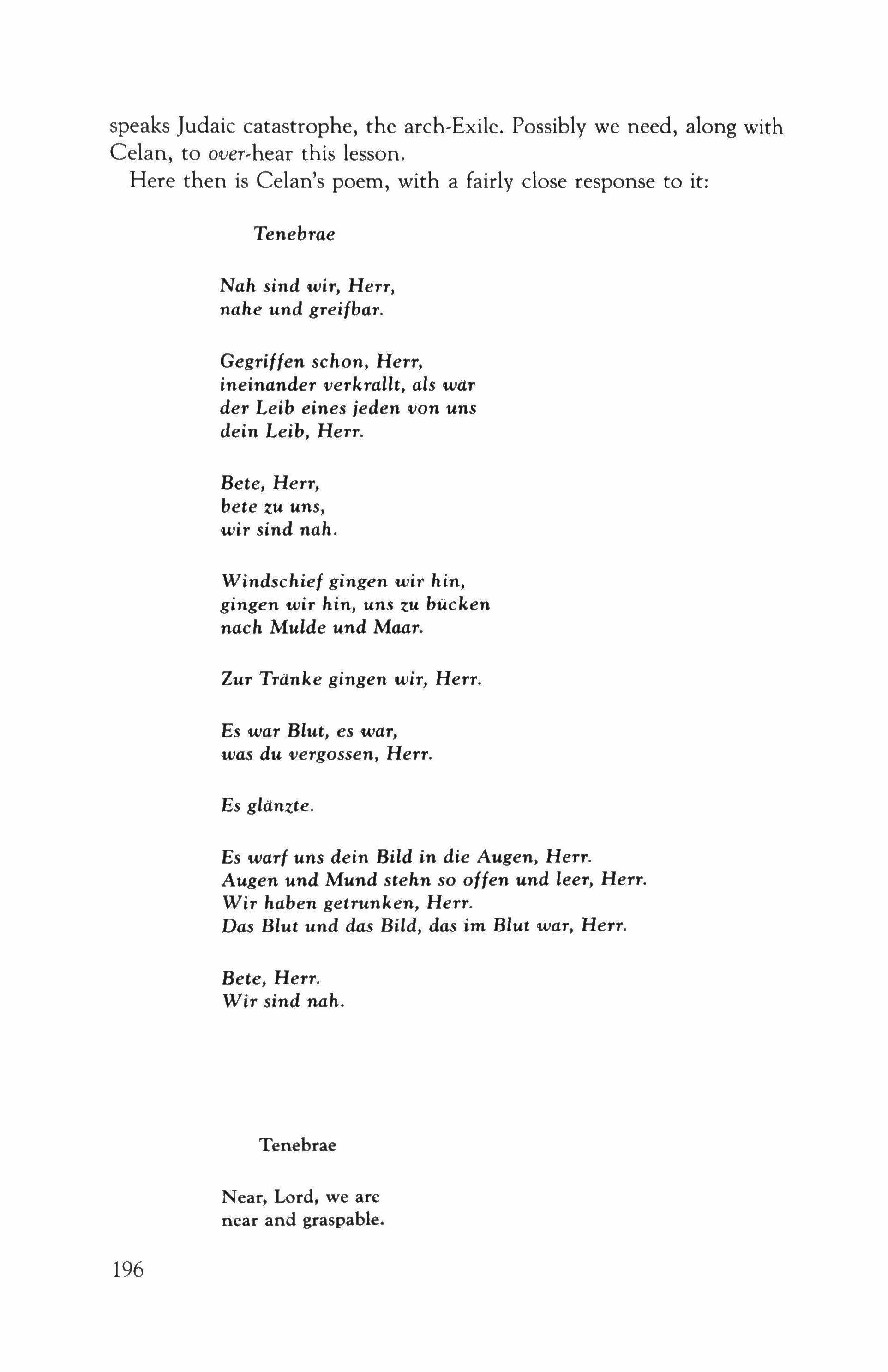

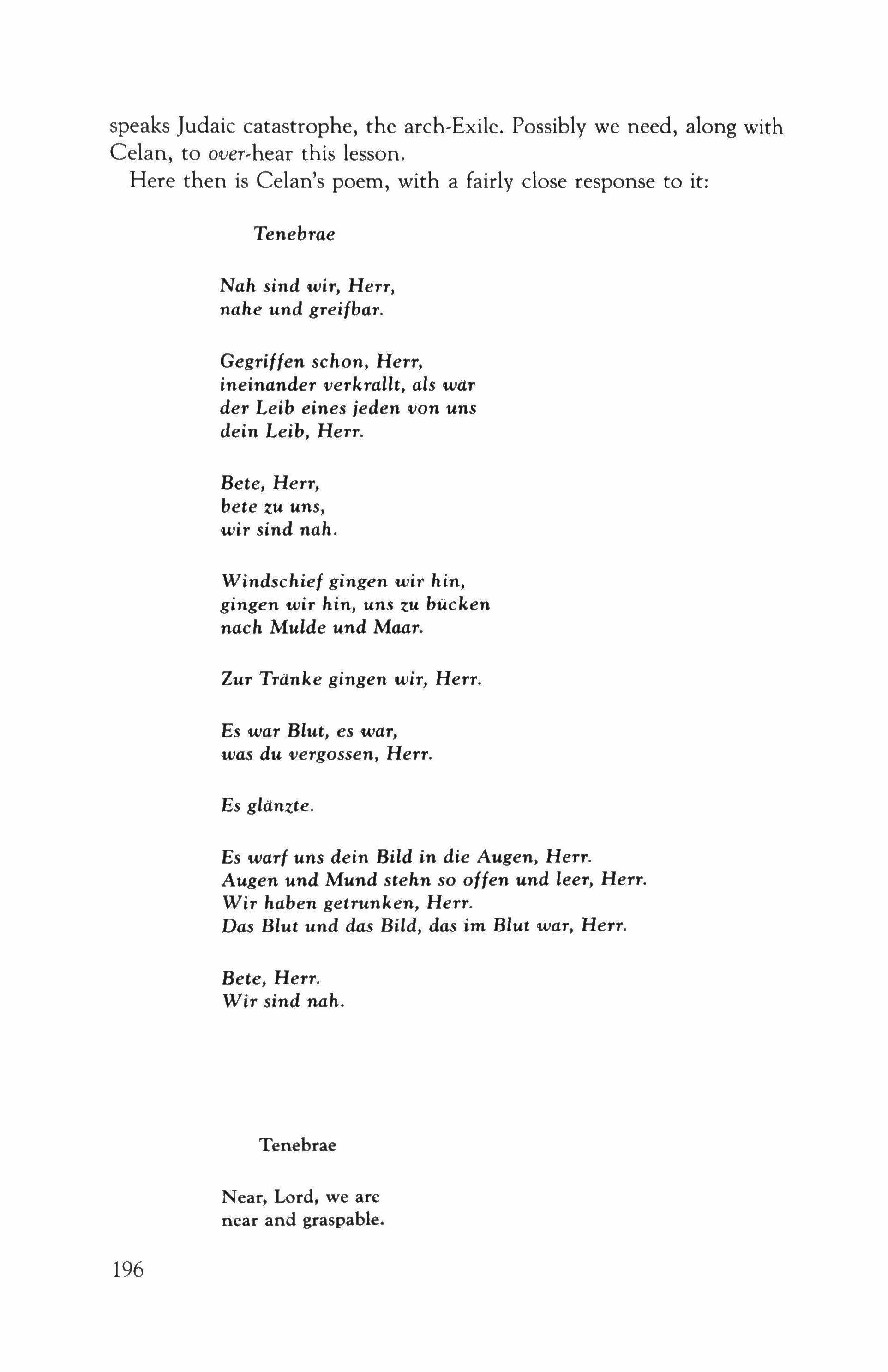

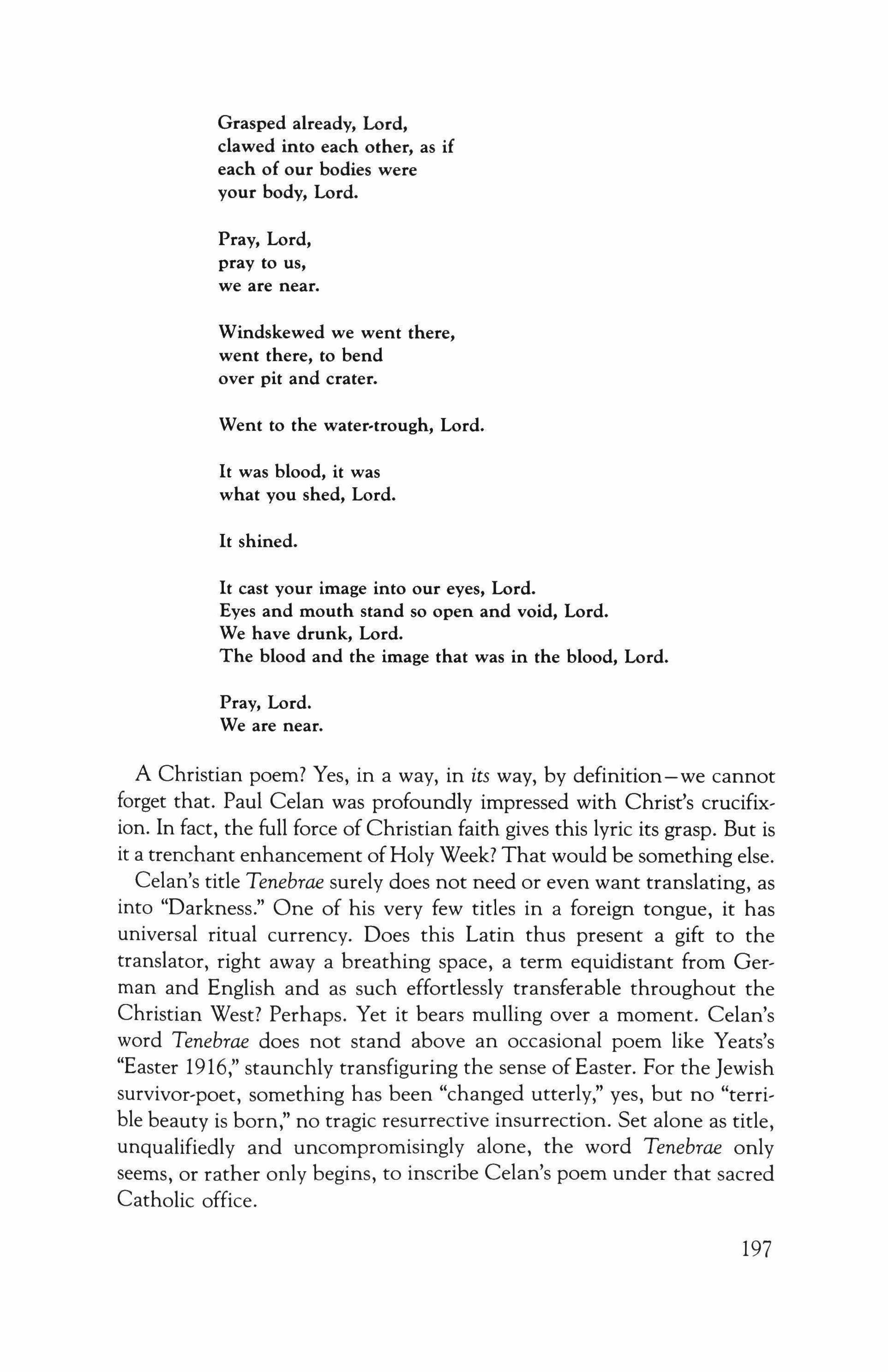

"Clawed into Each Other": Jewish vs. Christian Memory in Paul Celan's "Tenebrae"

John Felstiner

Death, Desire and Translation: On the Poetry of Propertius

Helen Deutsch

182

187

190

225

158

193

204

SPECIAL SECTIONS

43

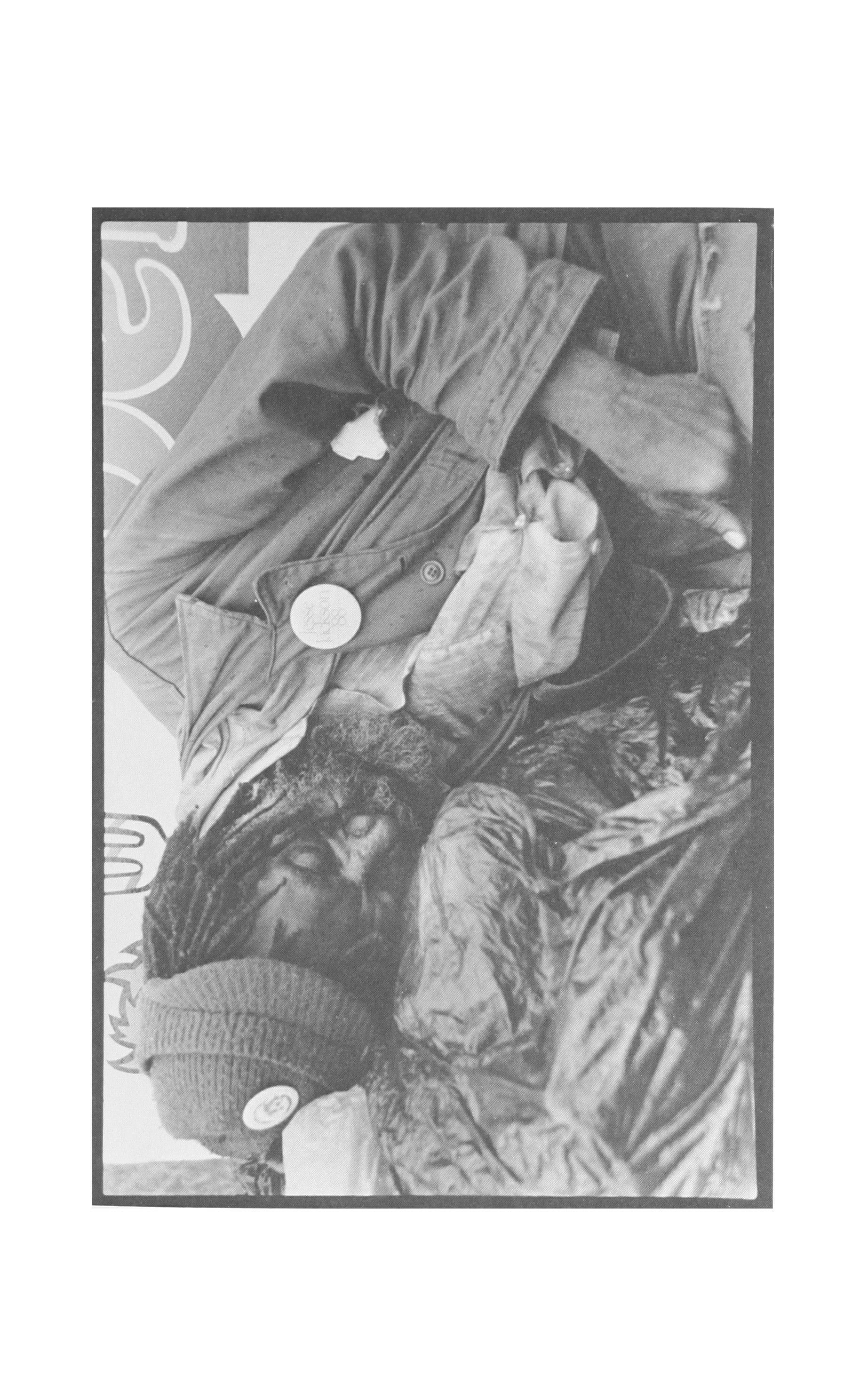

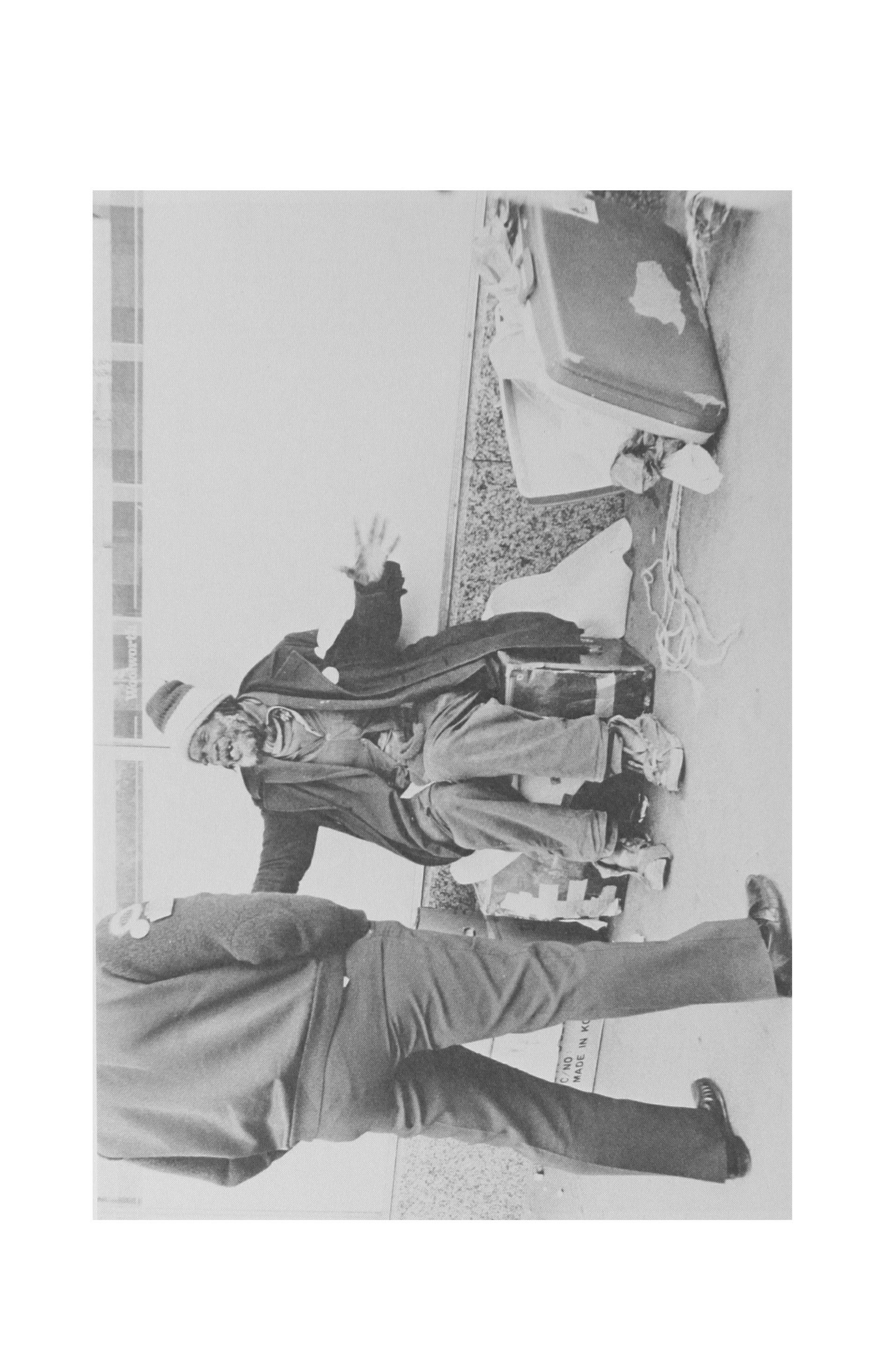

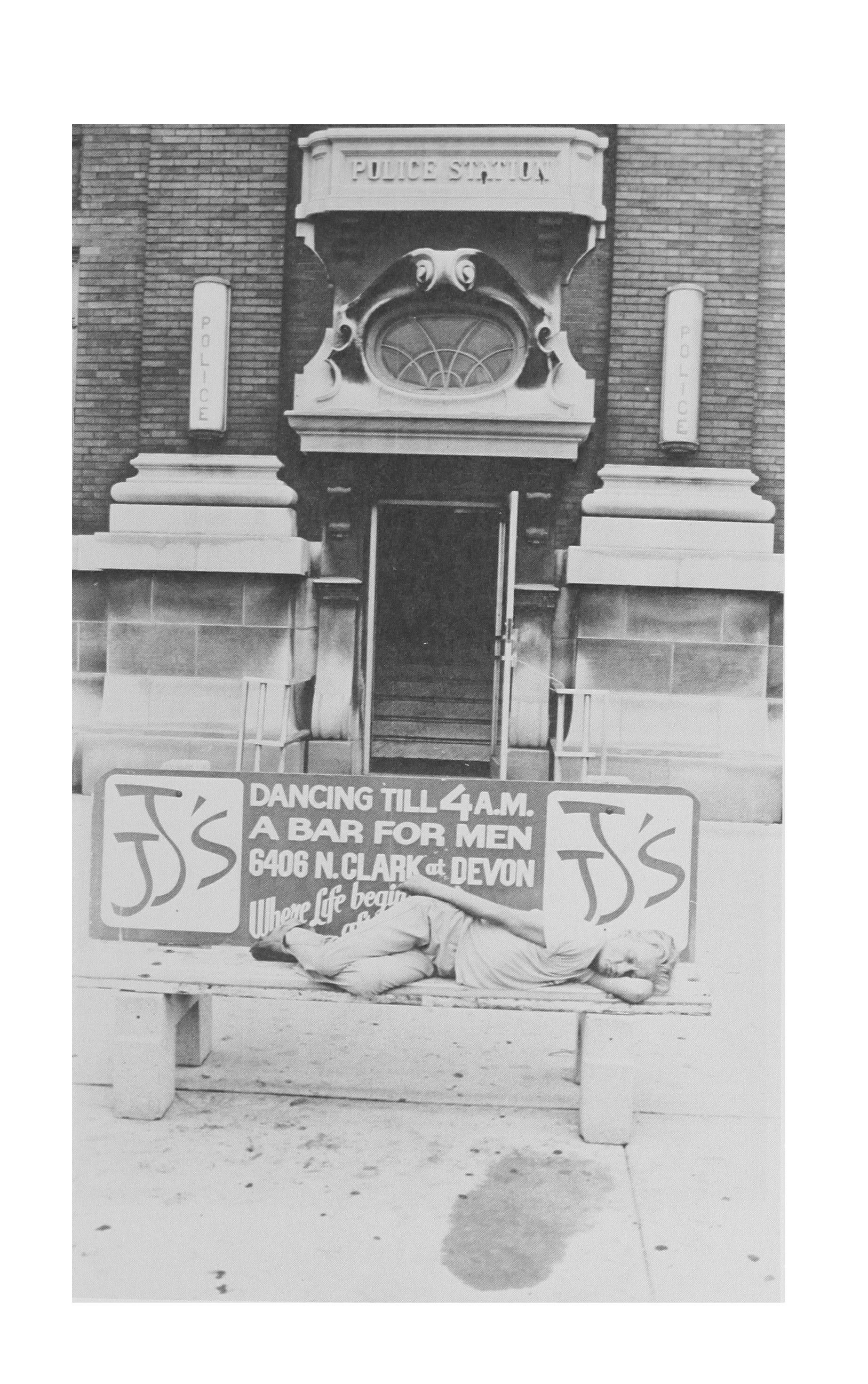

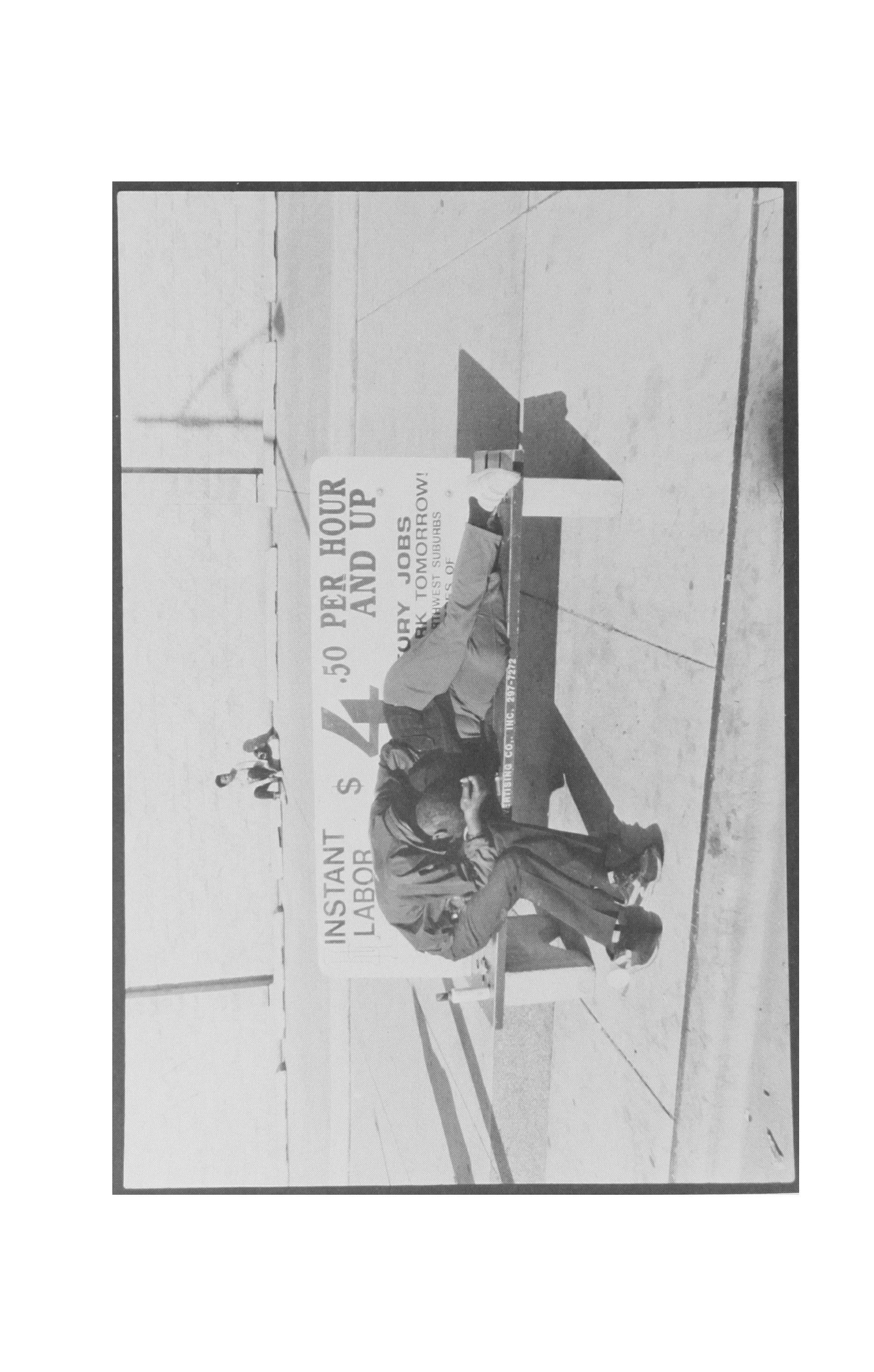

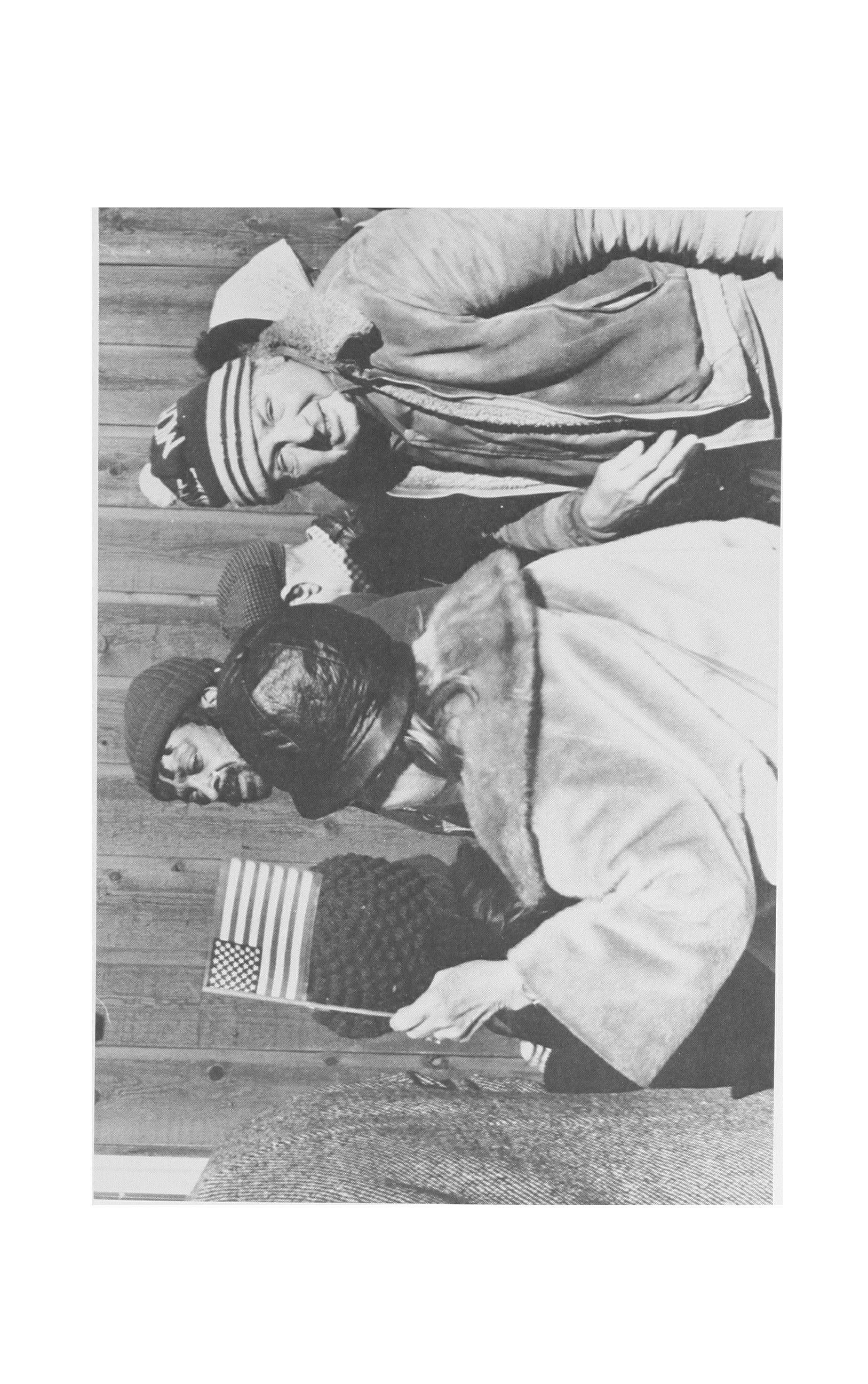

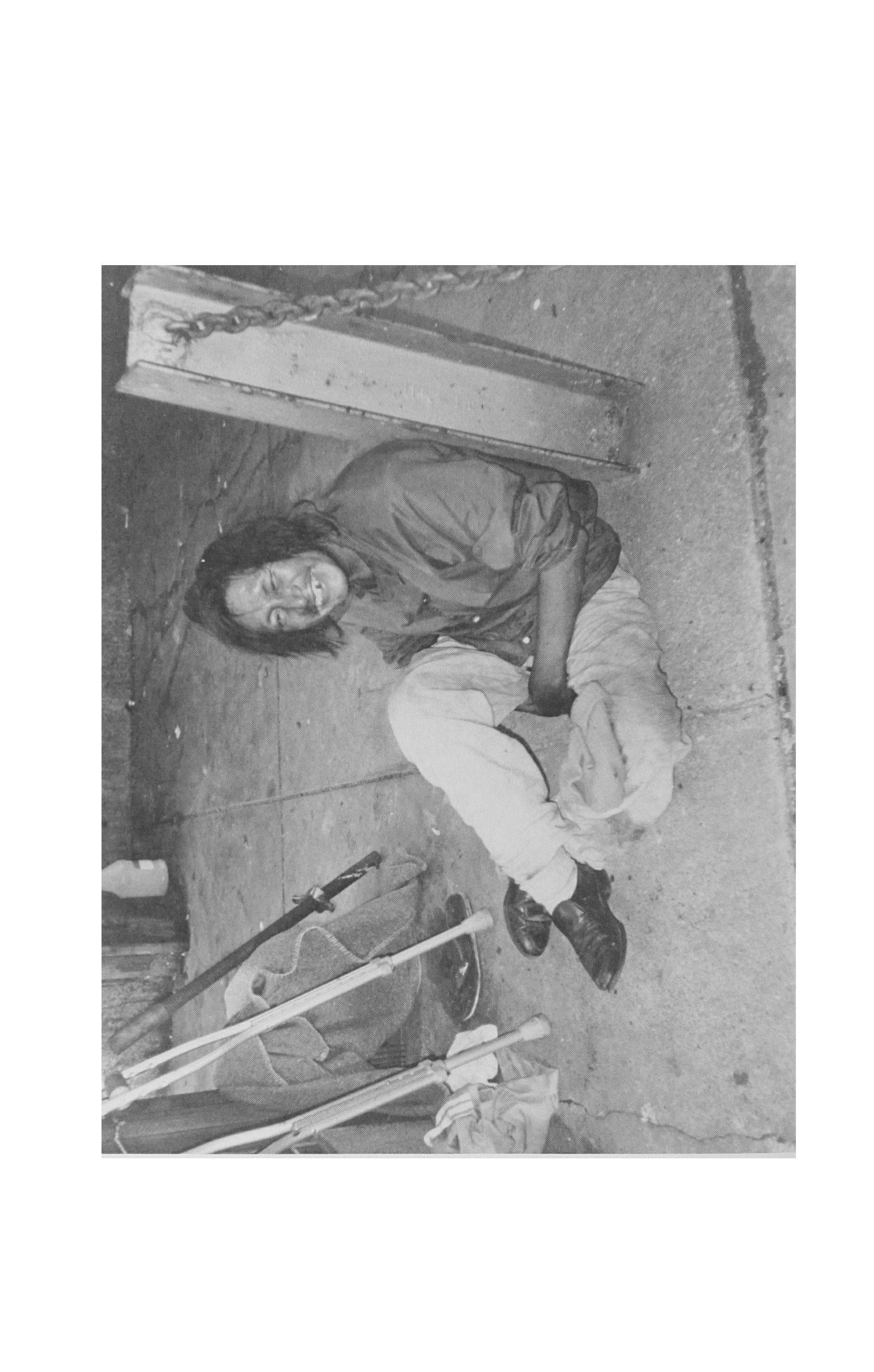

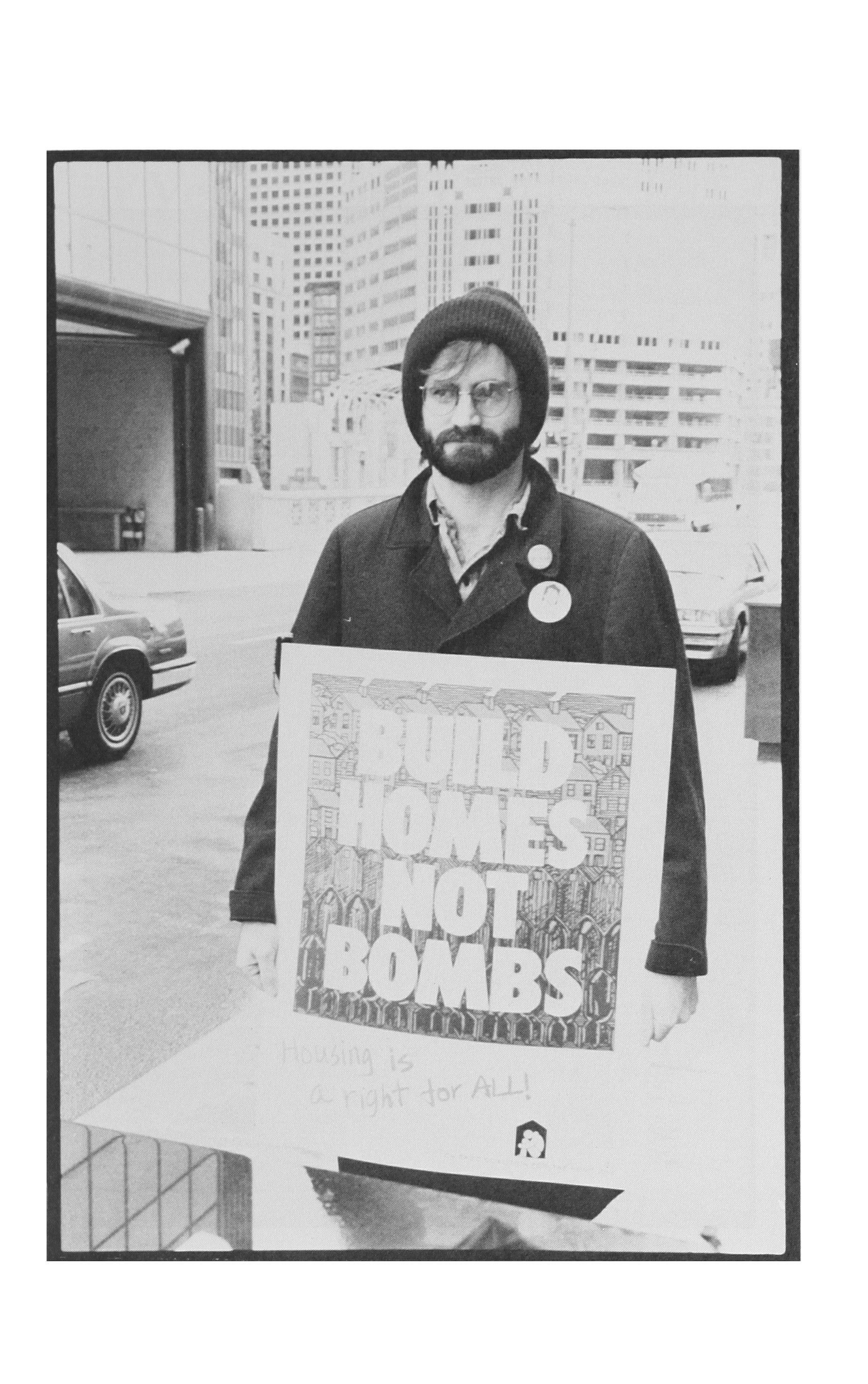

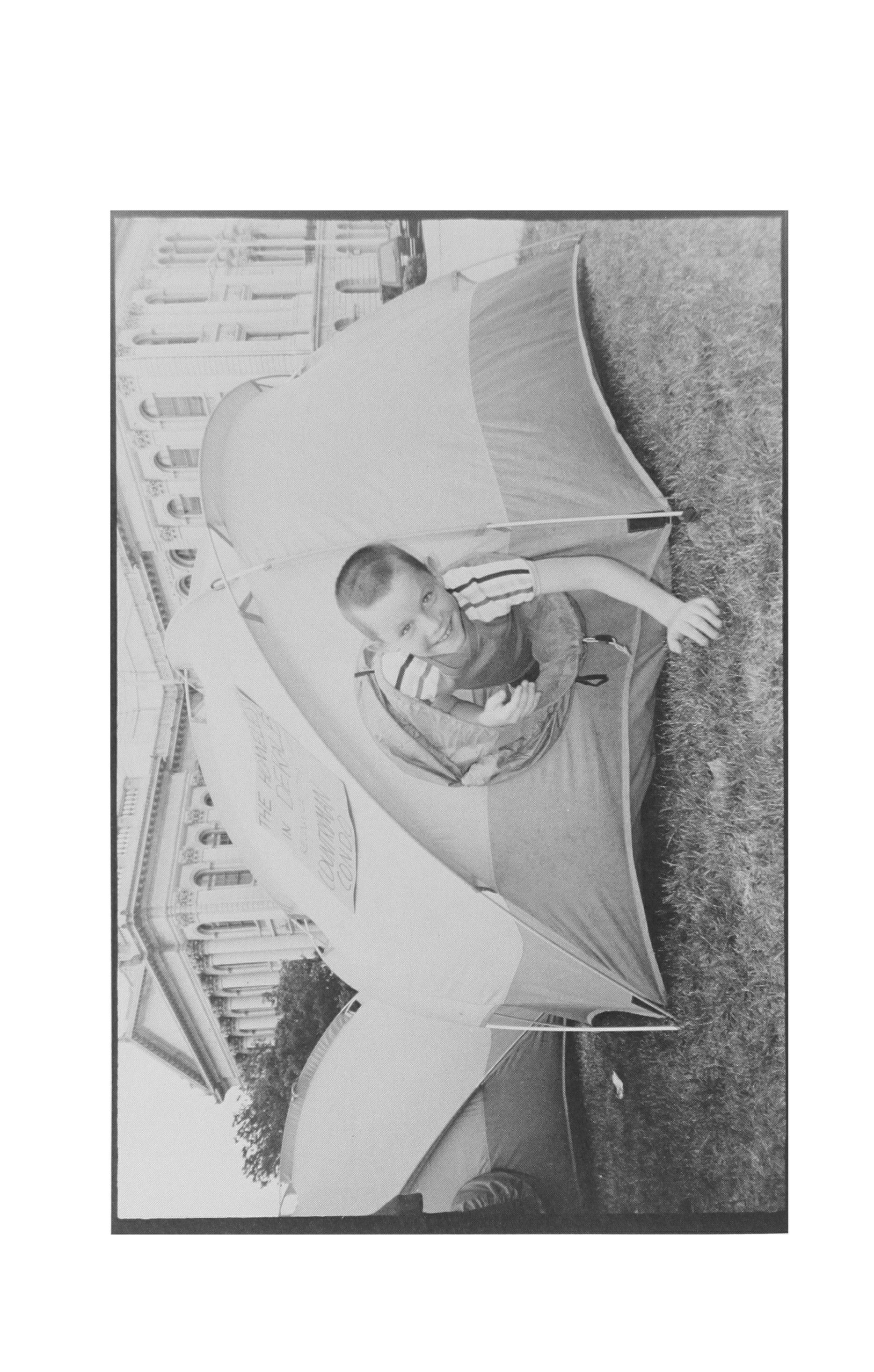

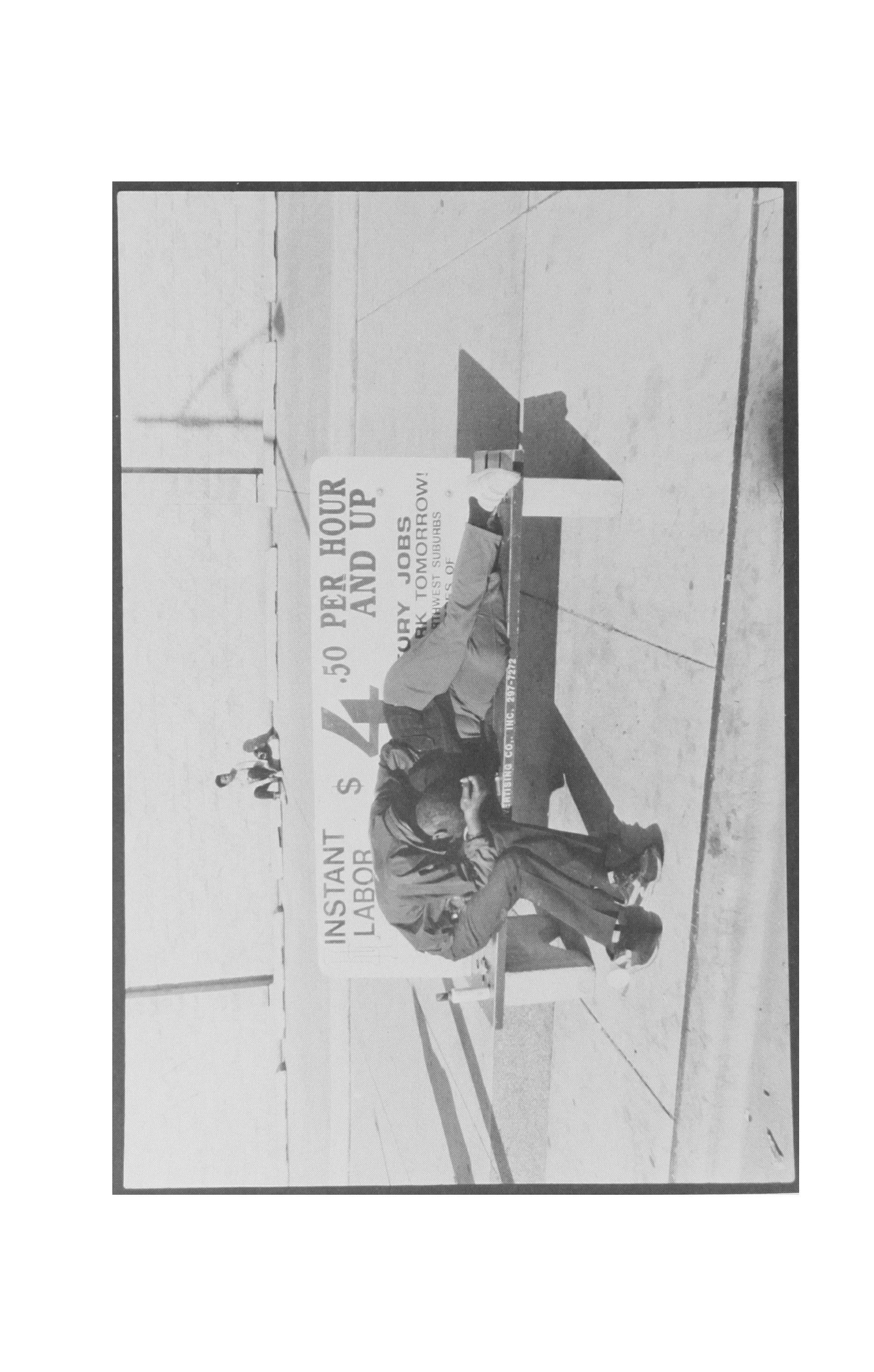

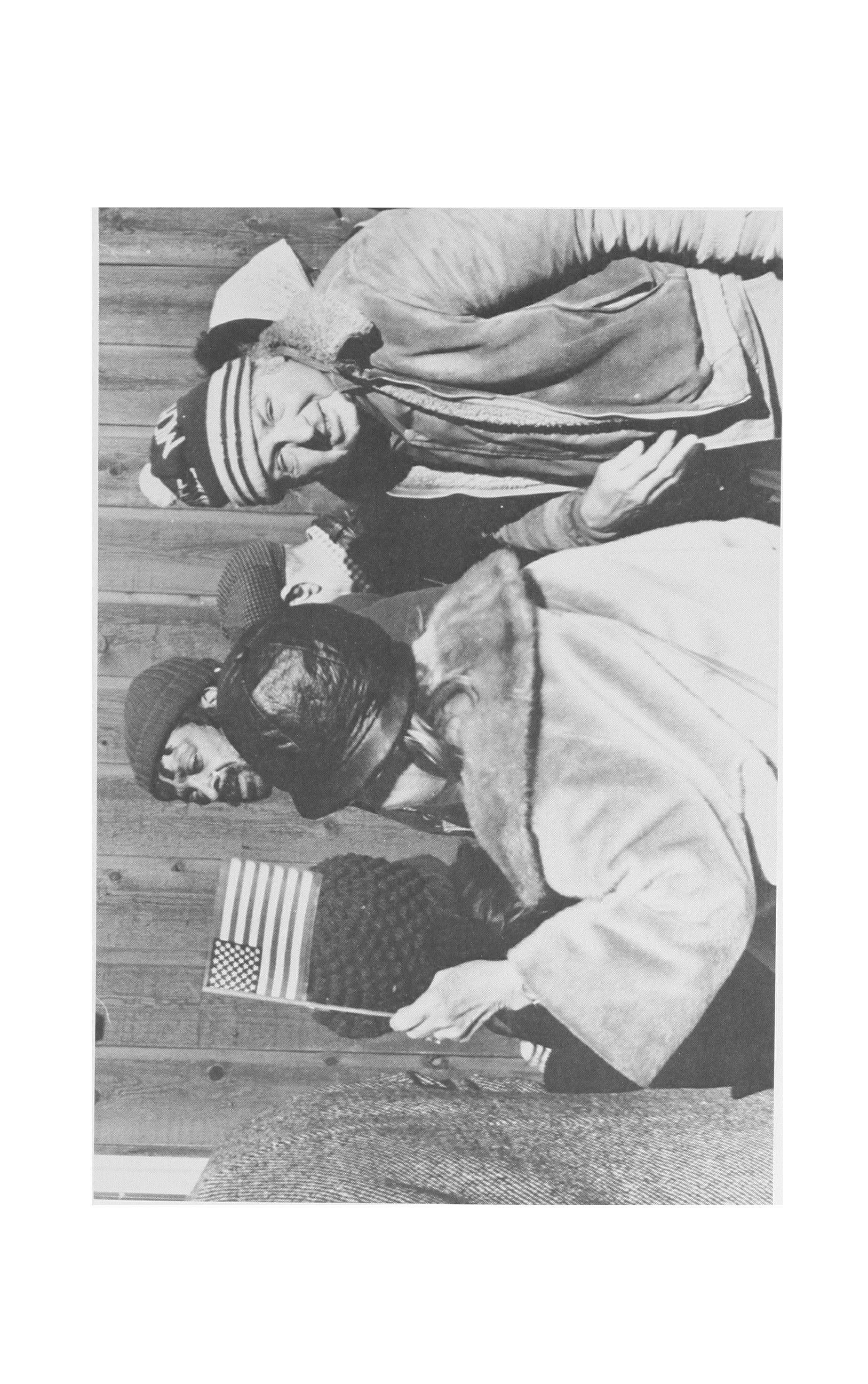

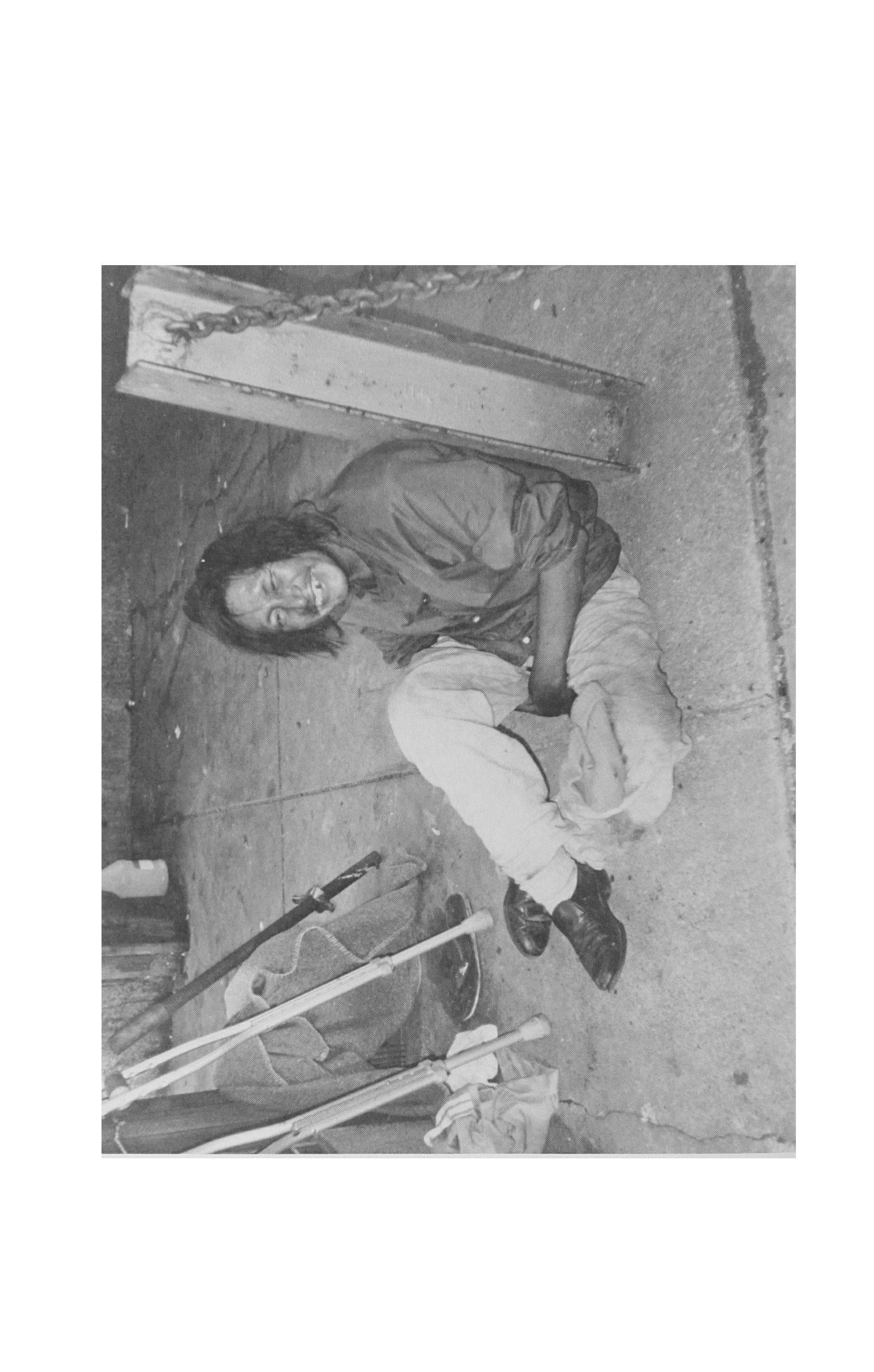

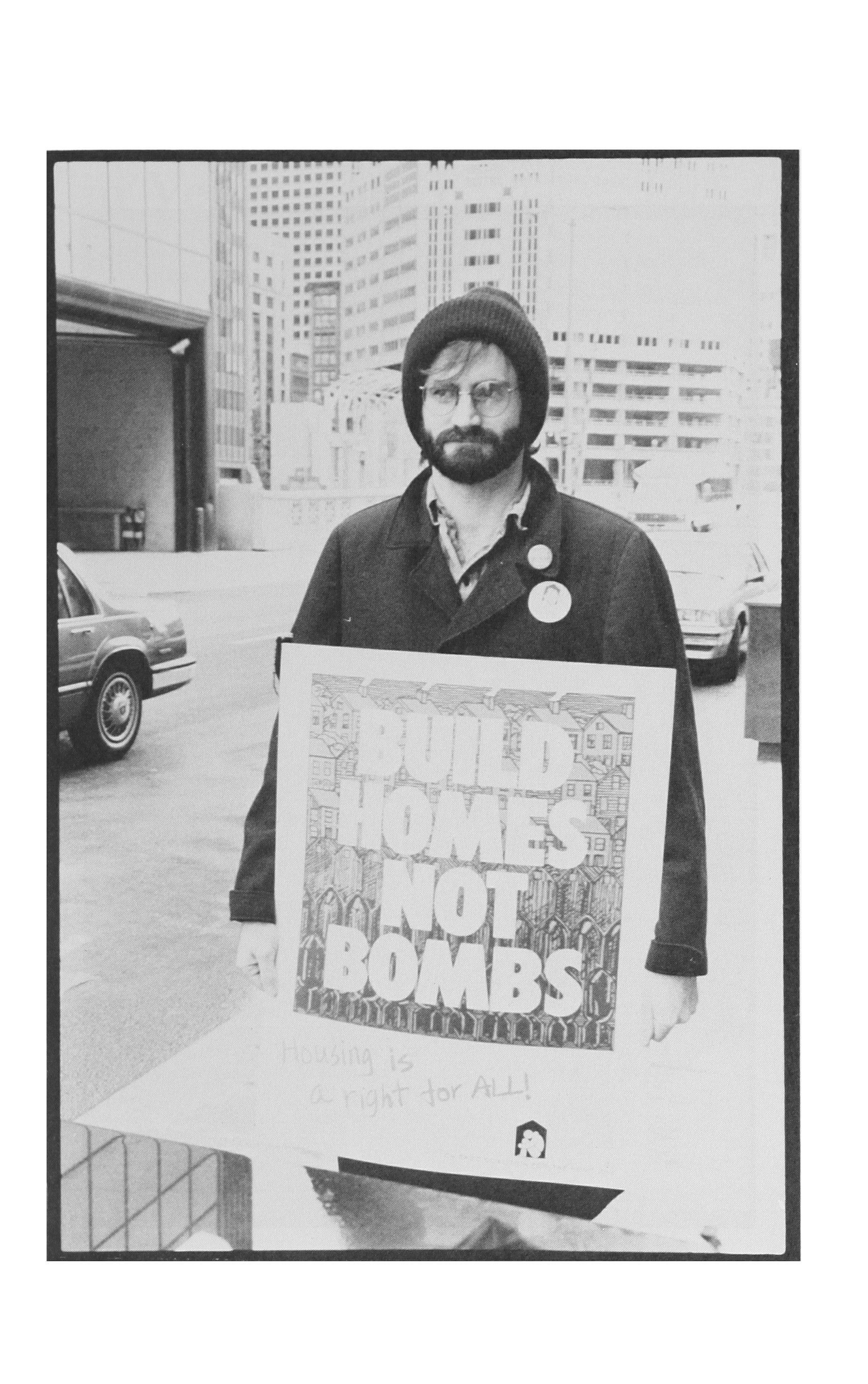

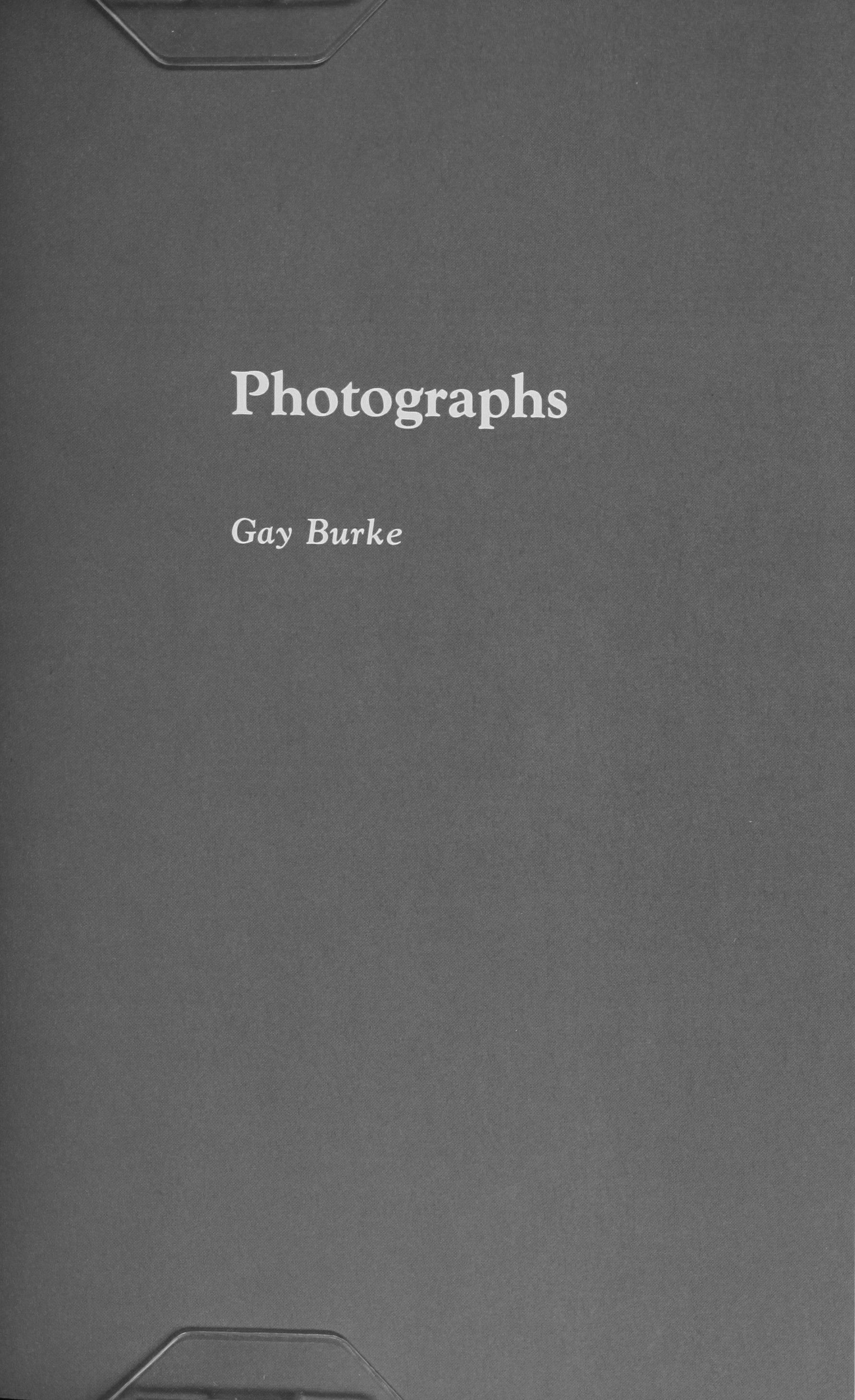

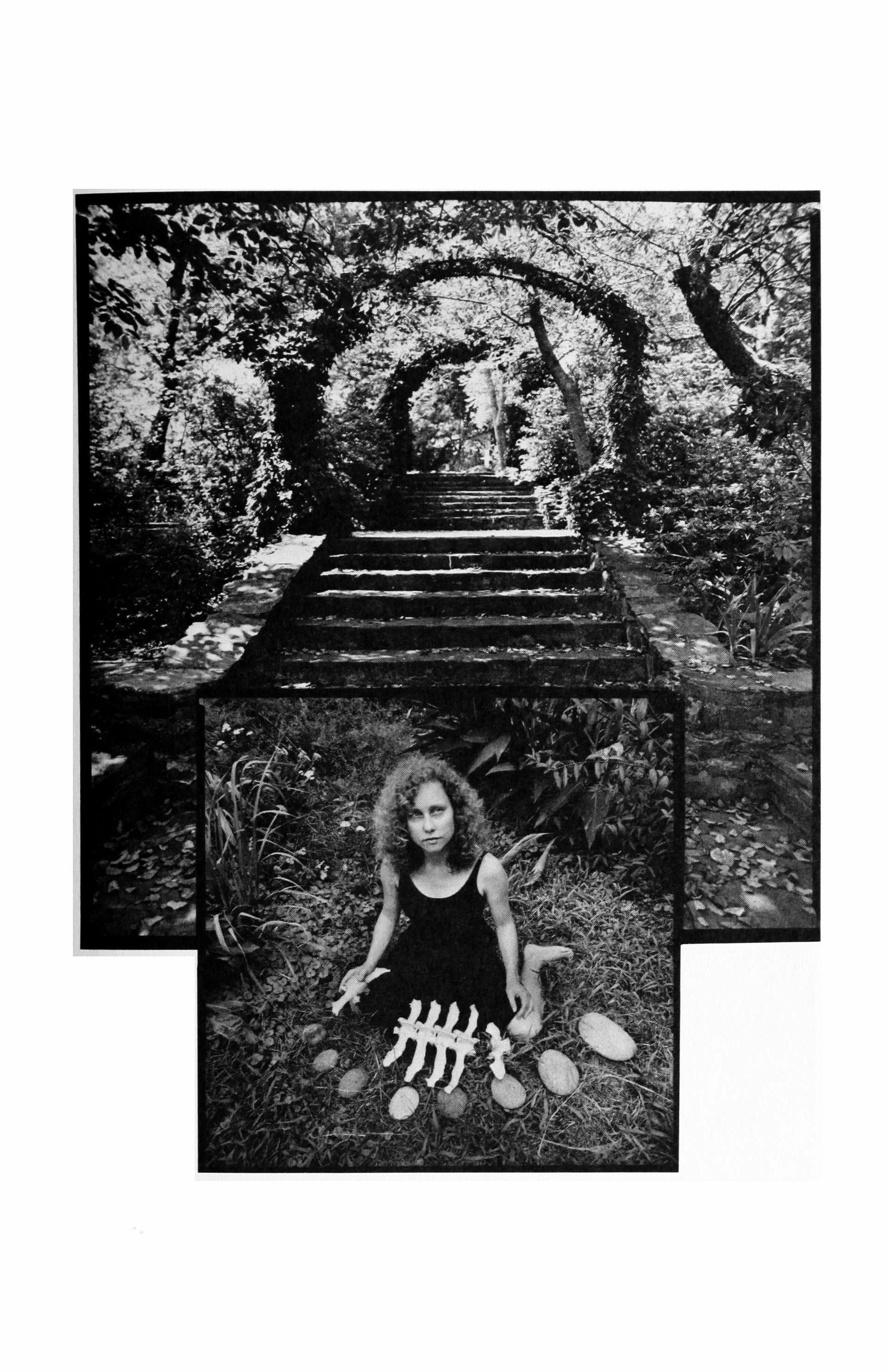

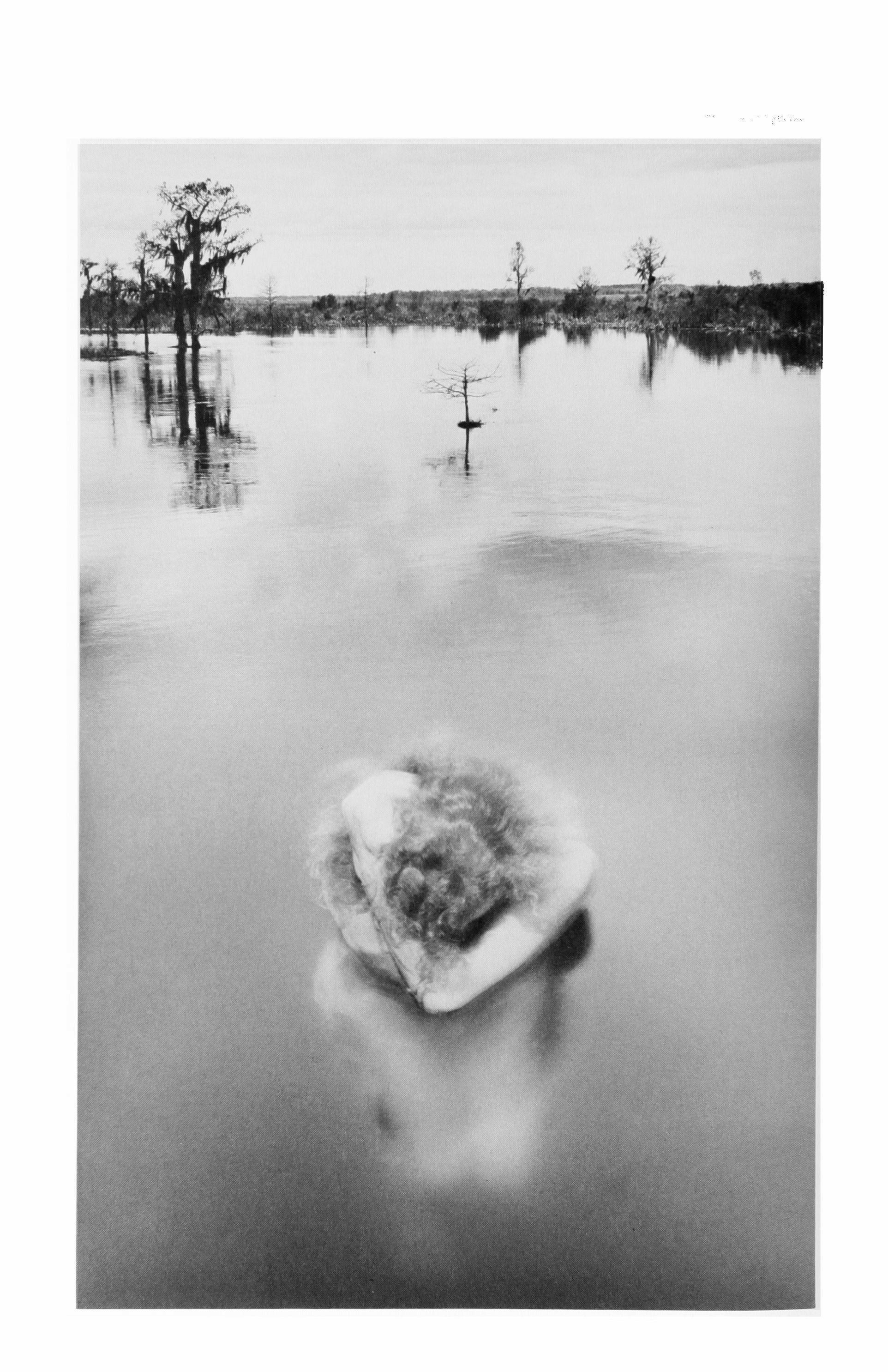

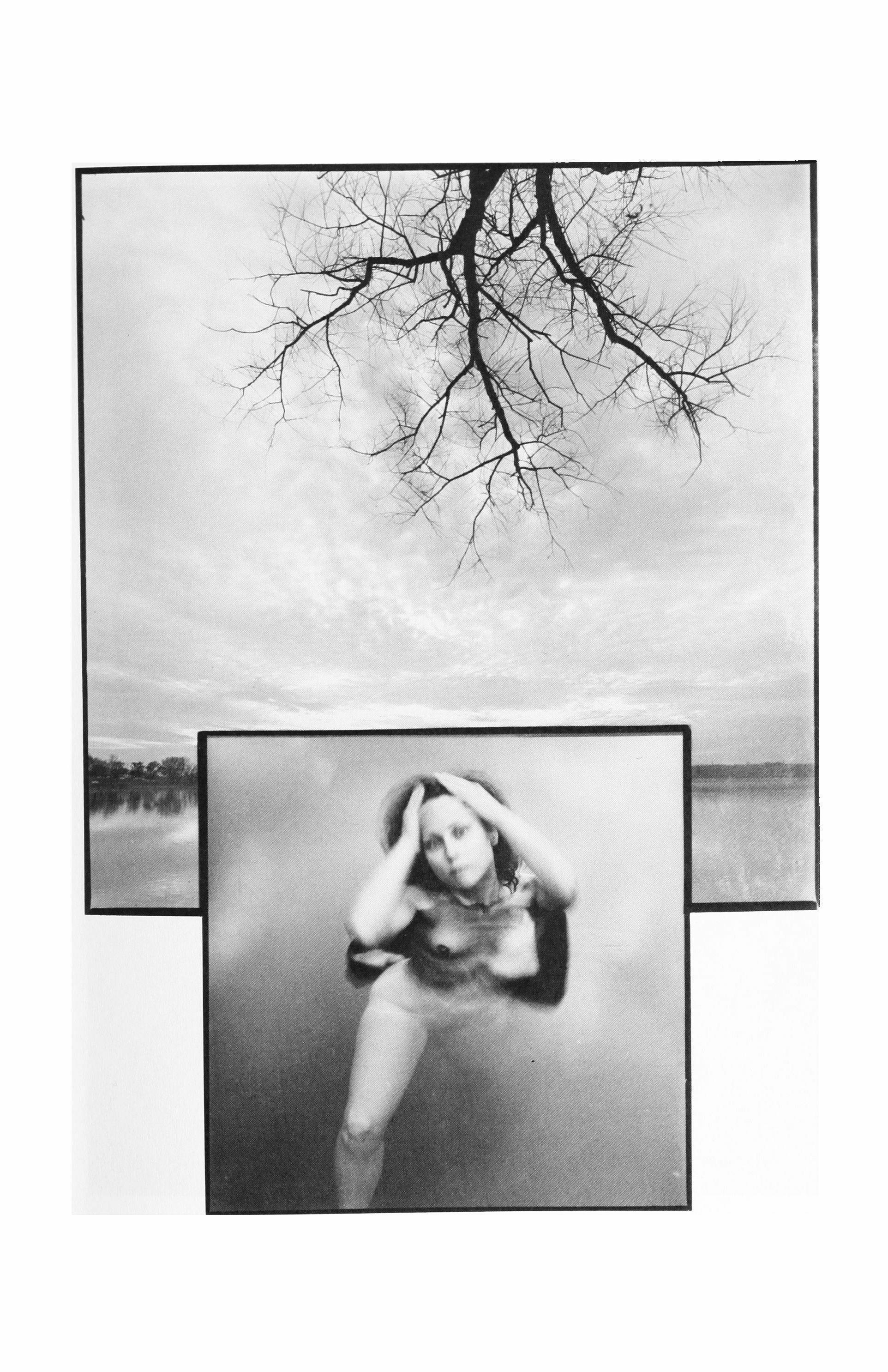

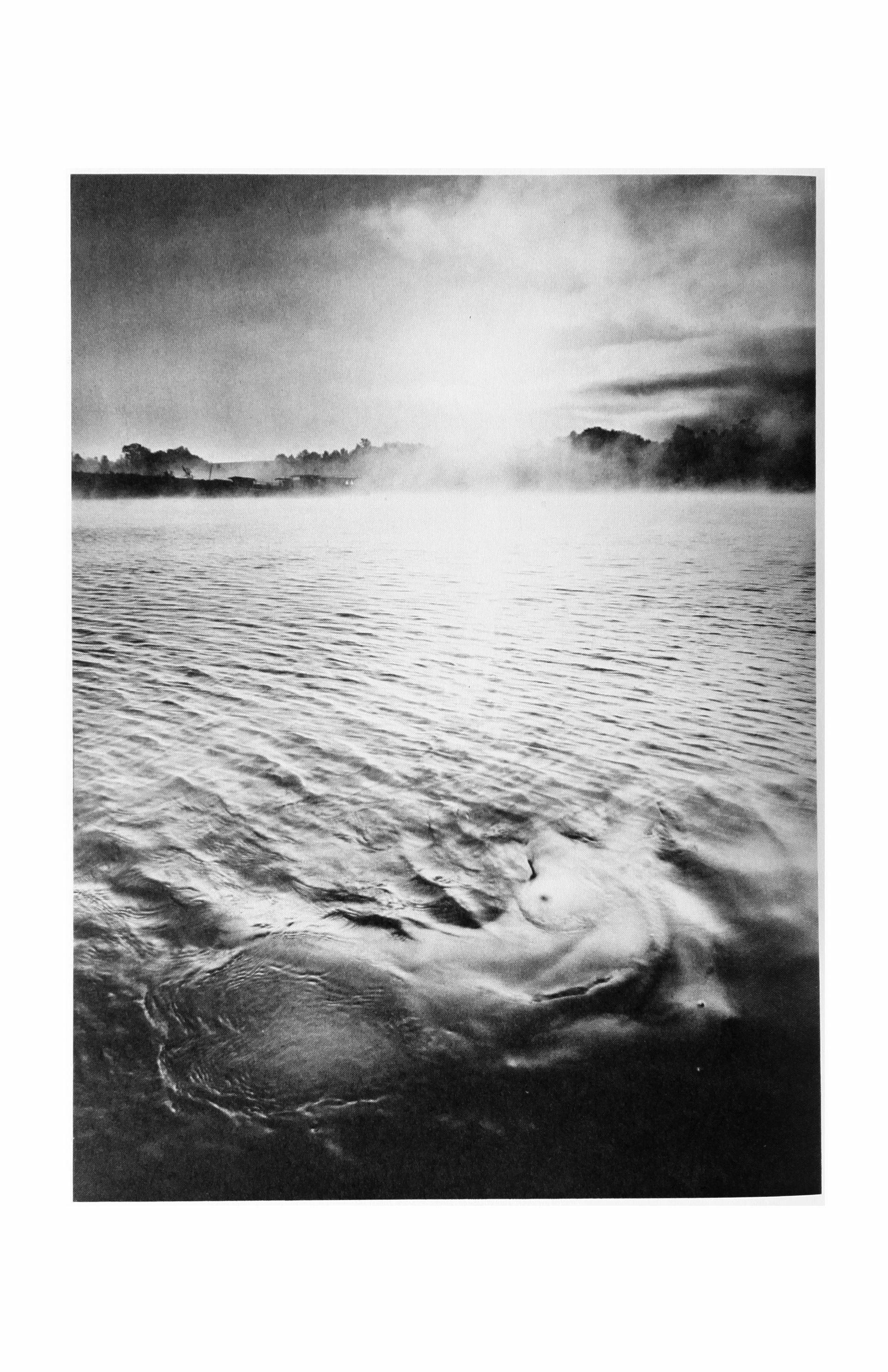

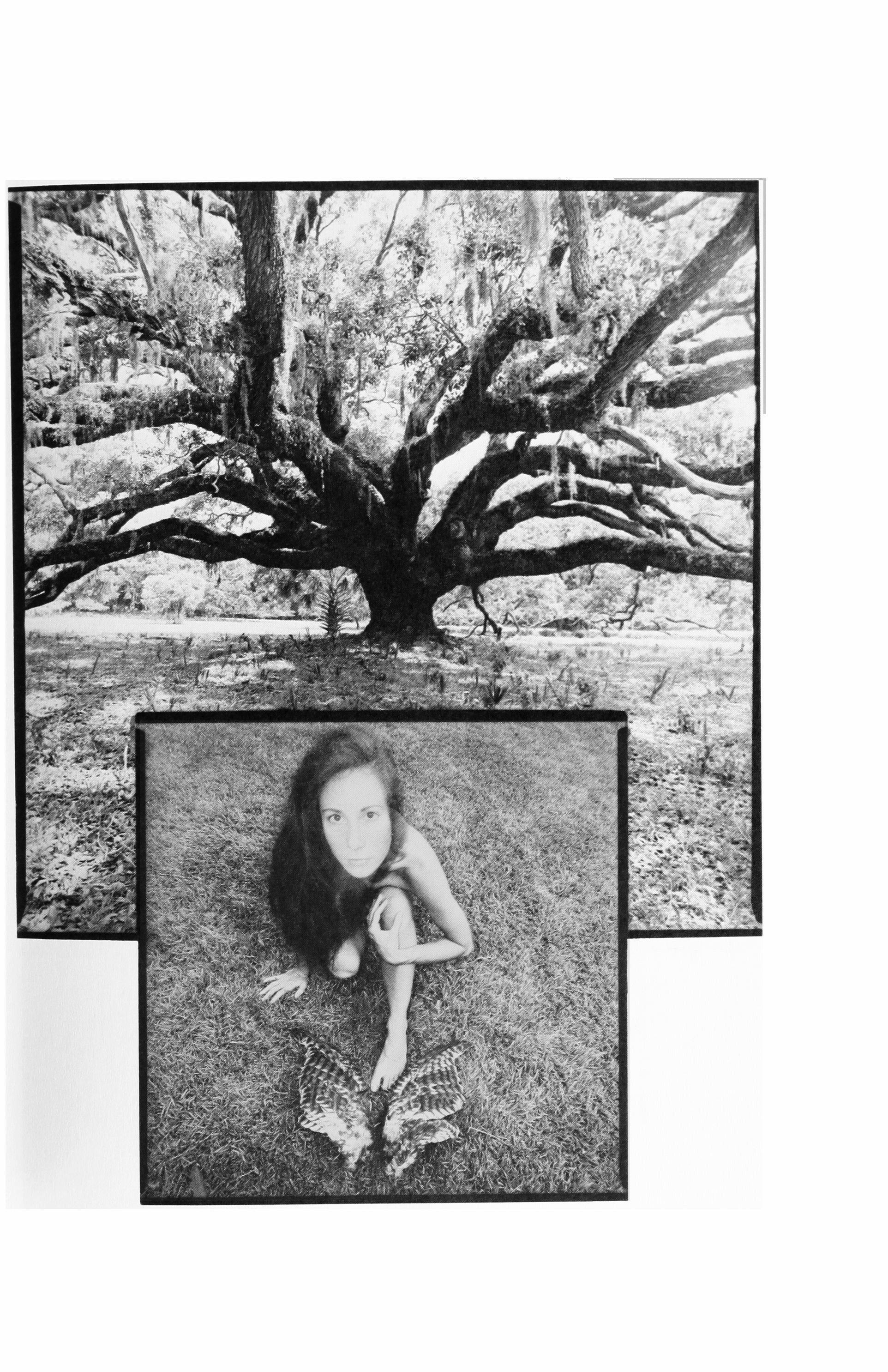

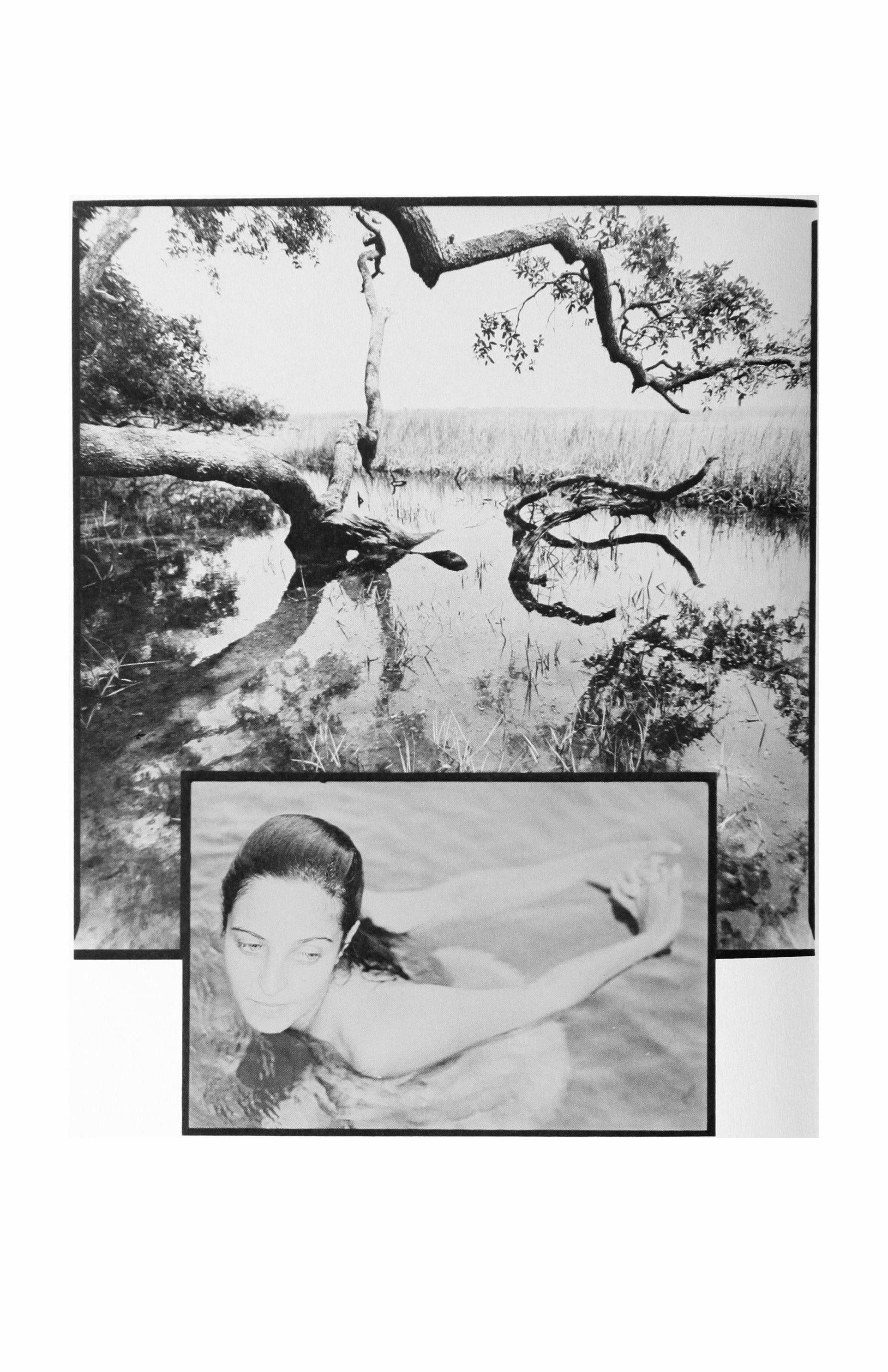

Fourteen photographs

135

18

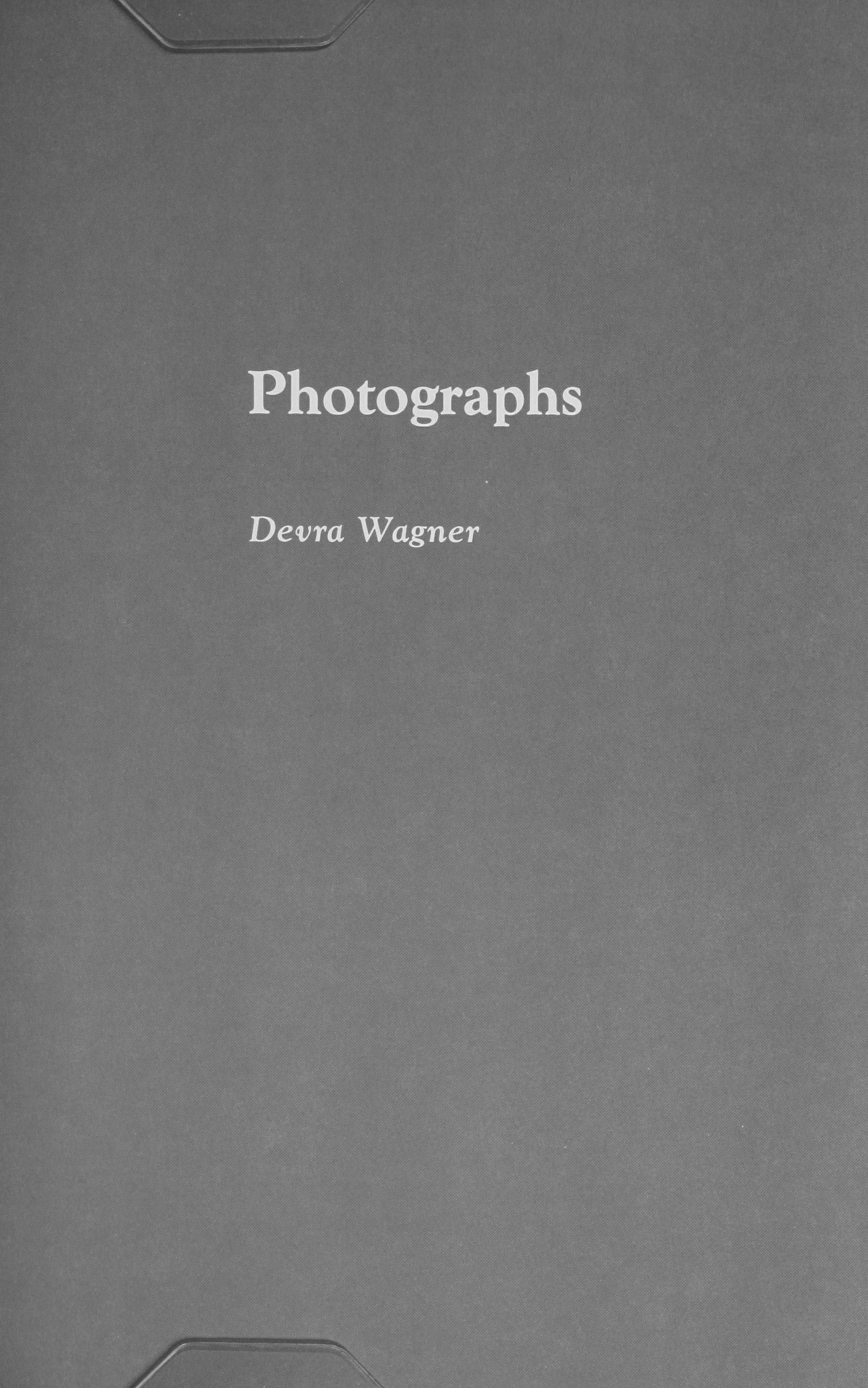

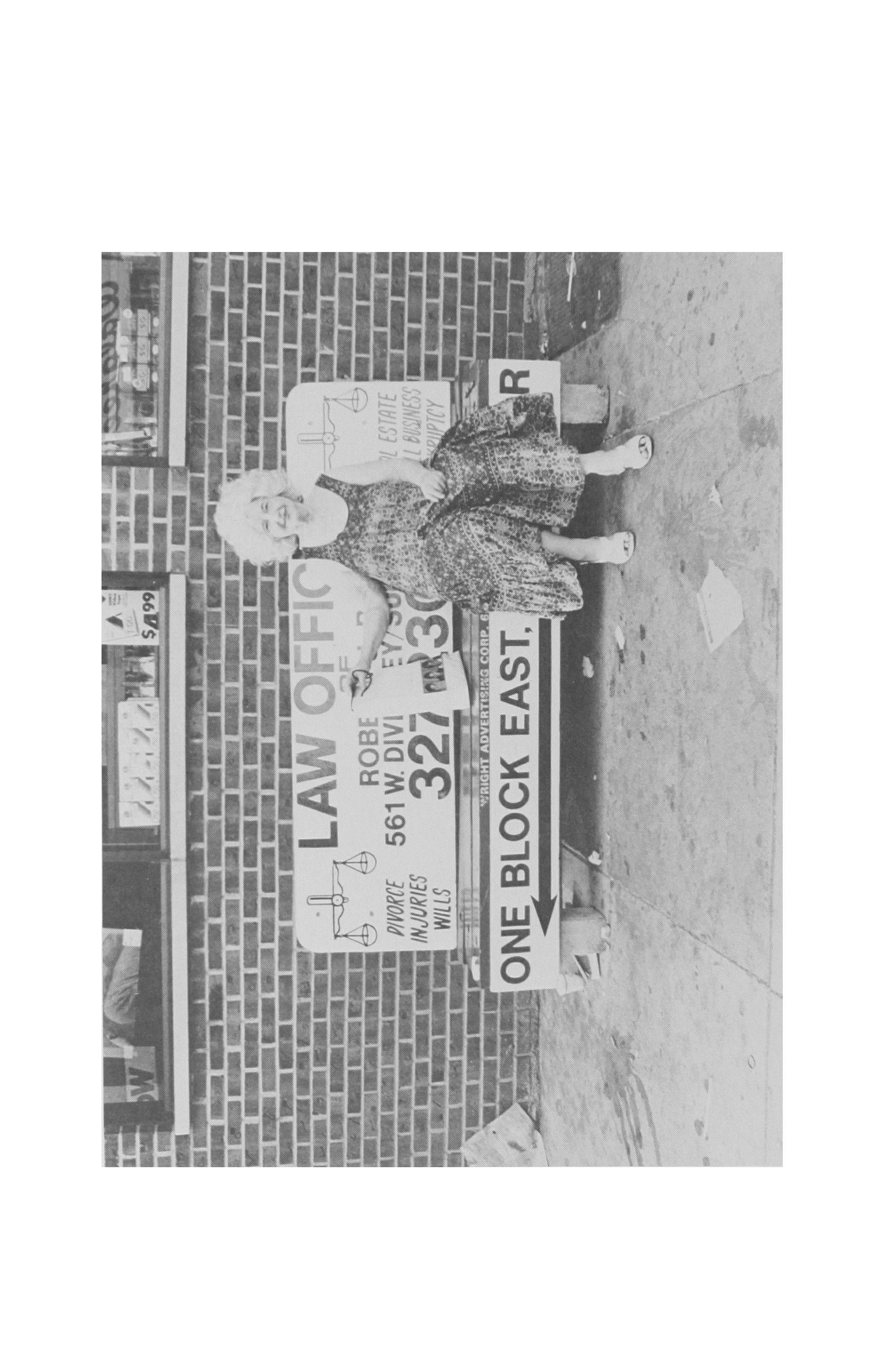

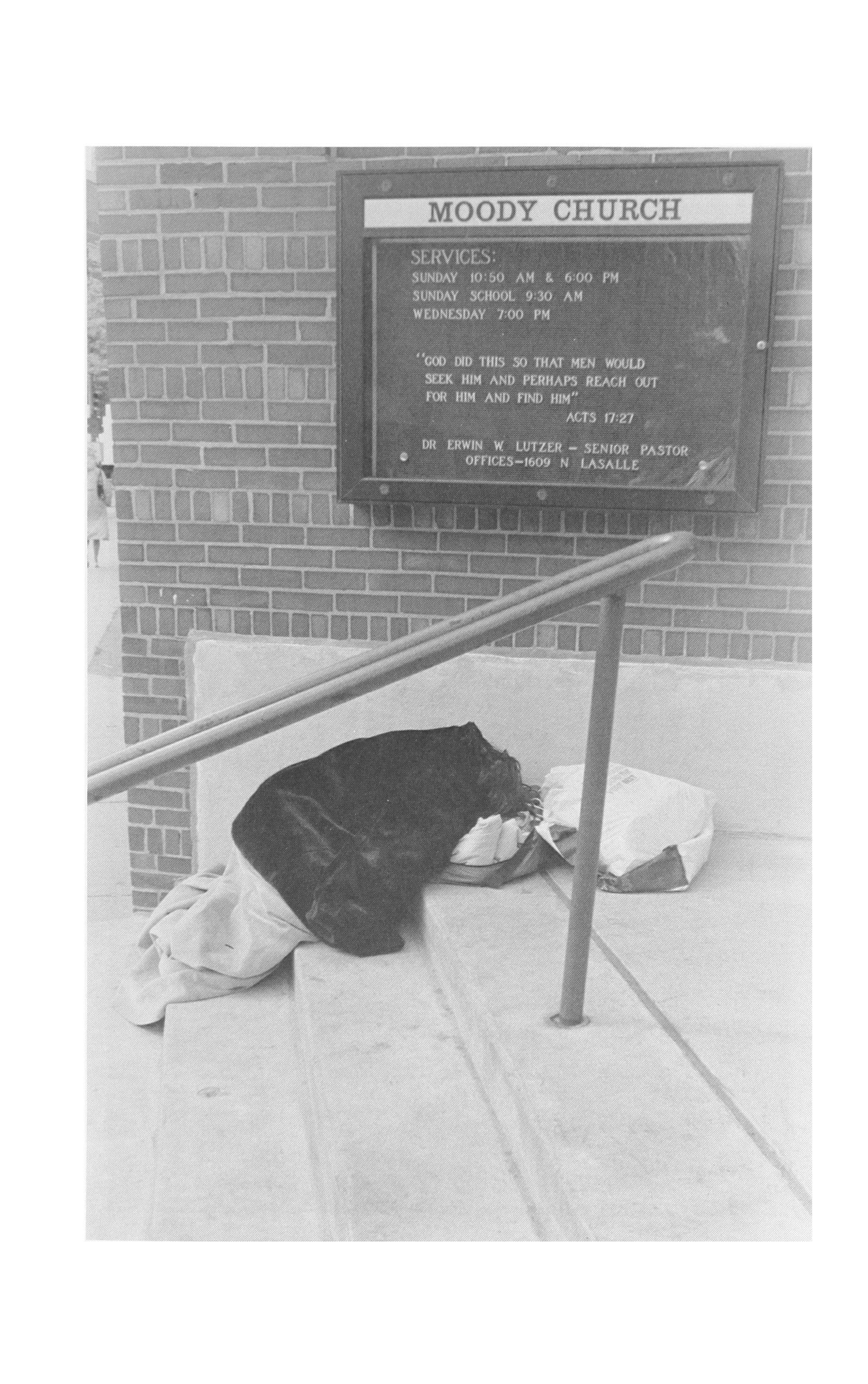

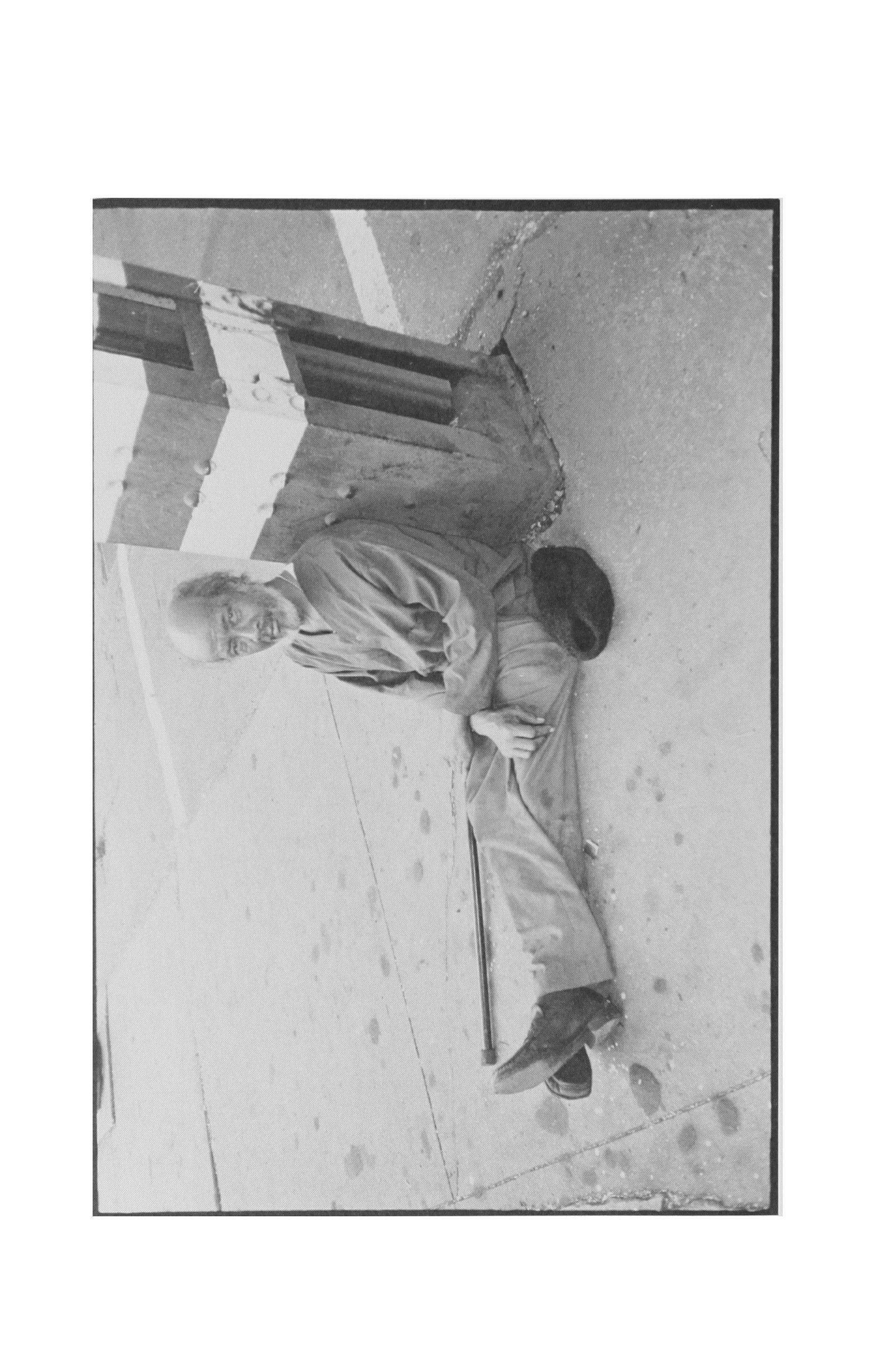

Devra Wagner Seven photographs.

Gay Burke

CONTRIBUTORS 233

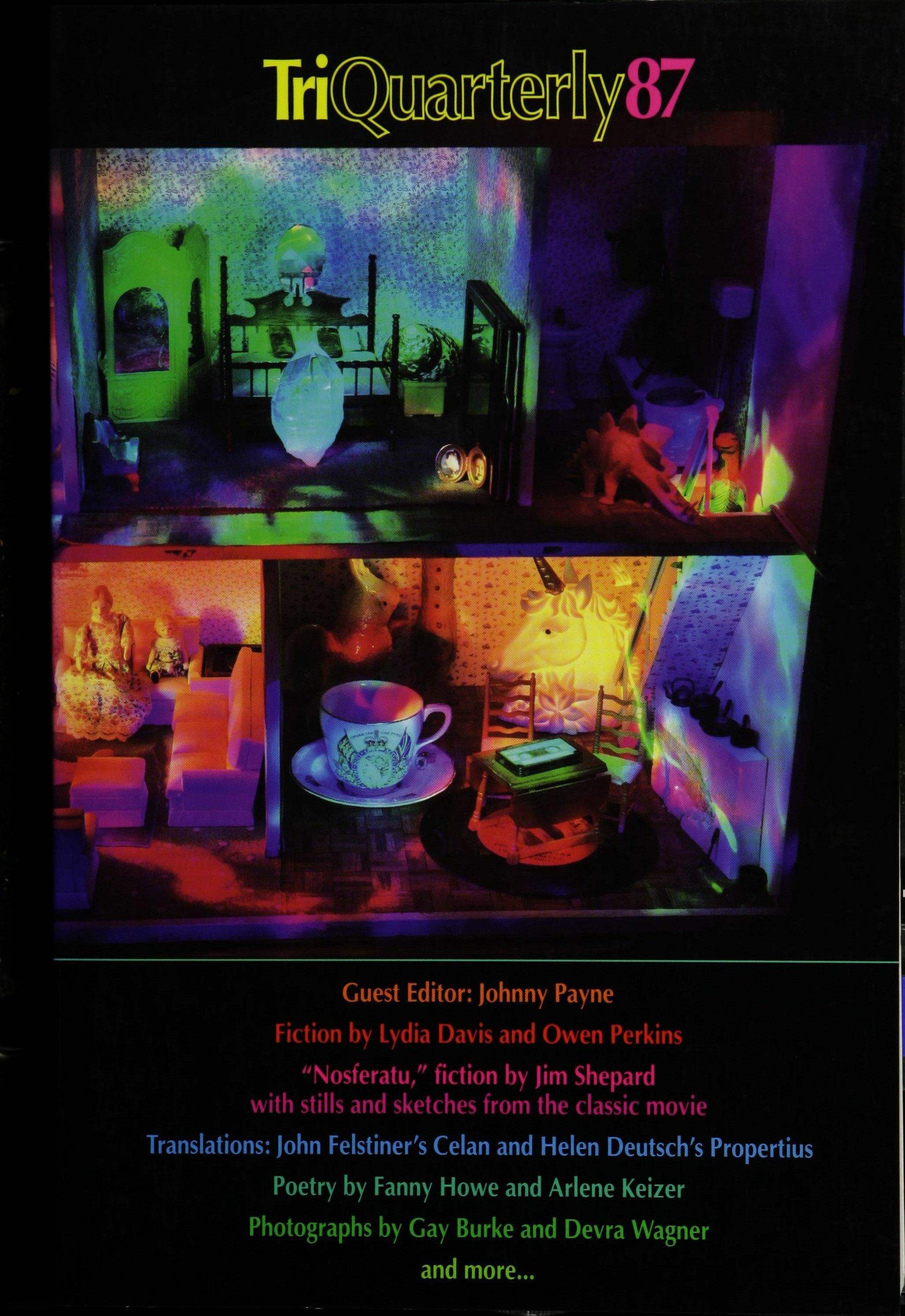

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

Cover art: Home Life, photograph by John C. Hesketh

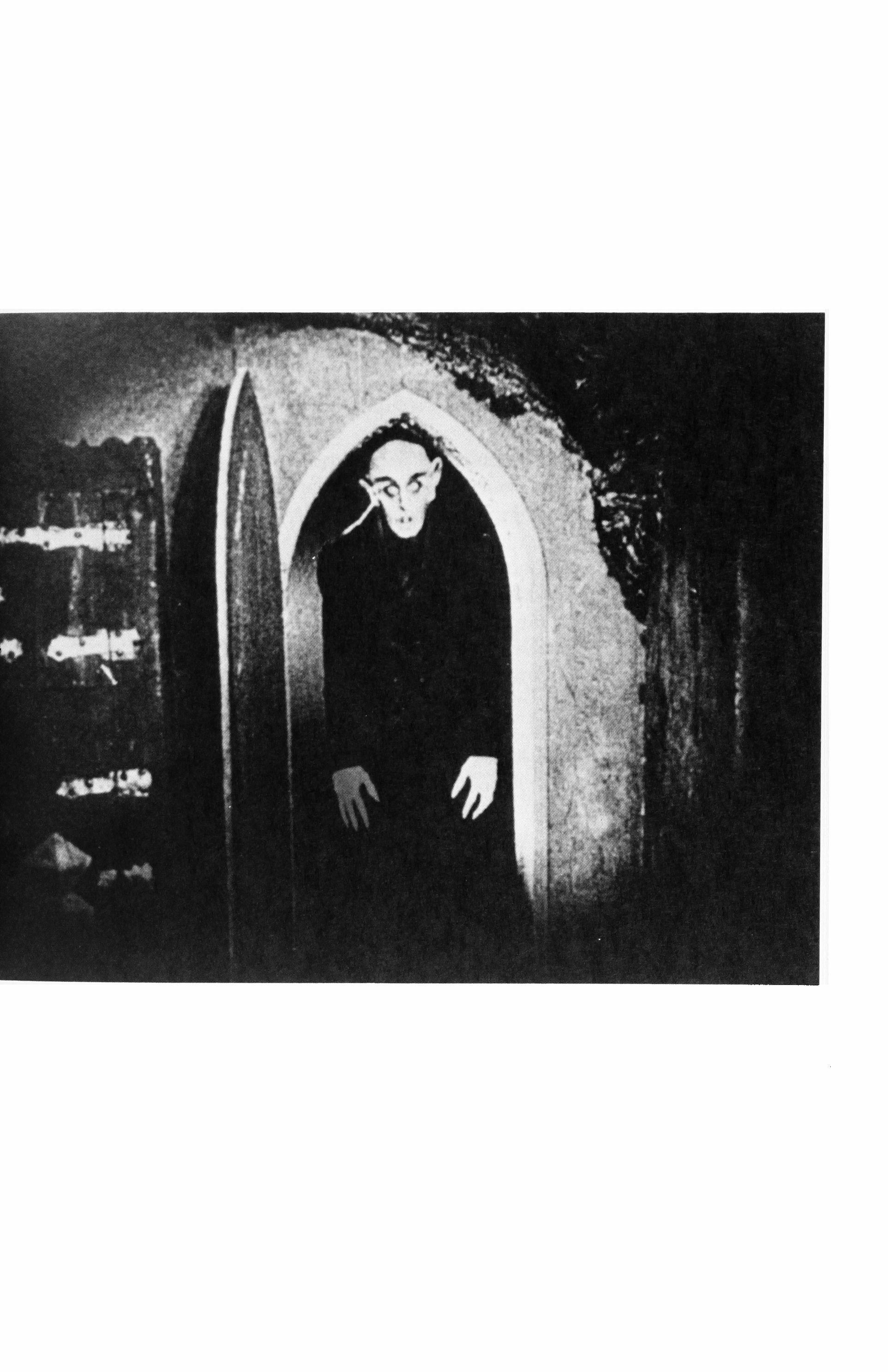

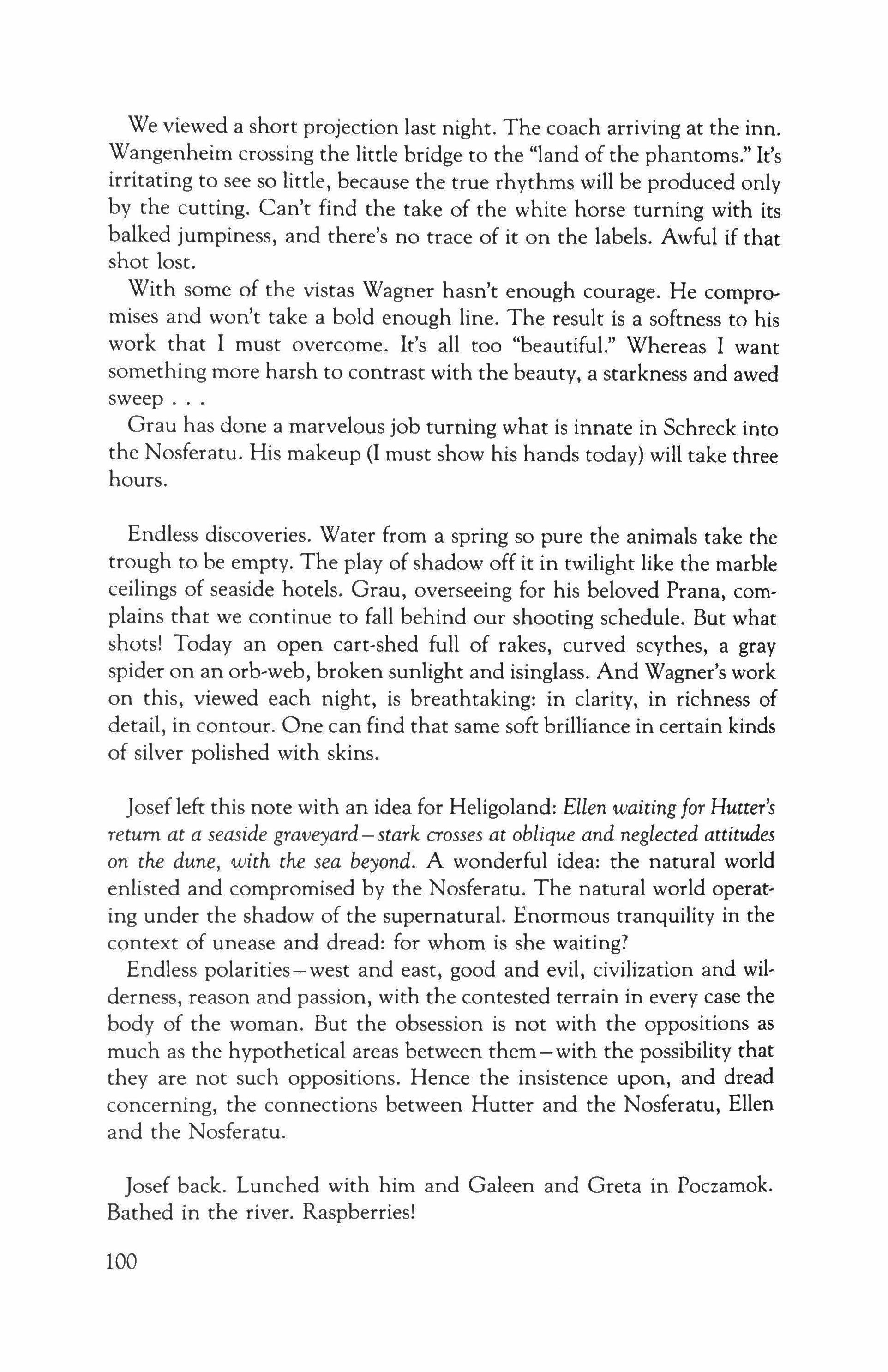

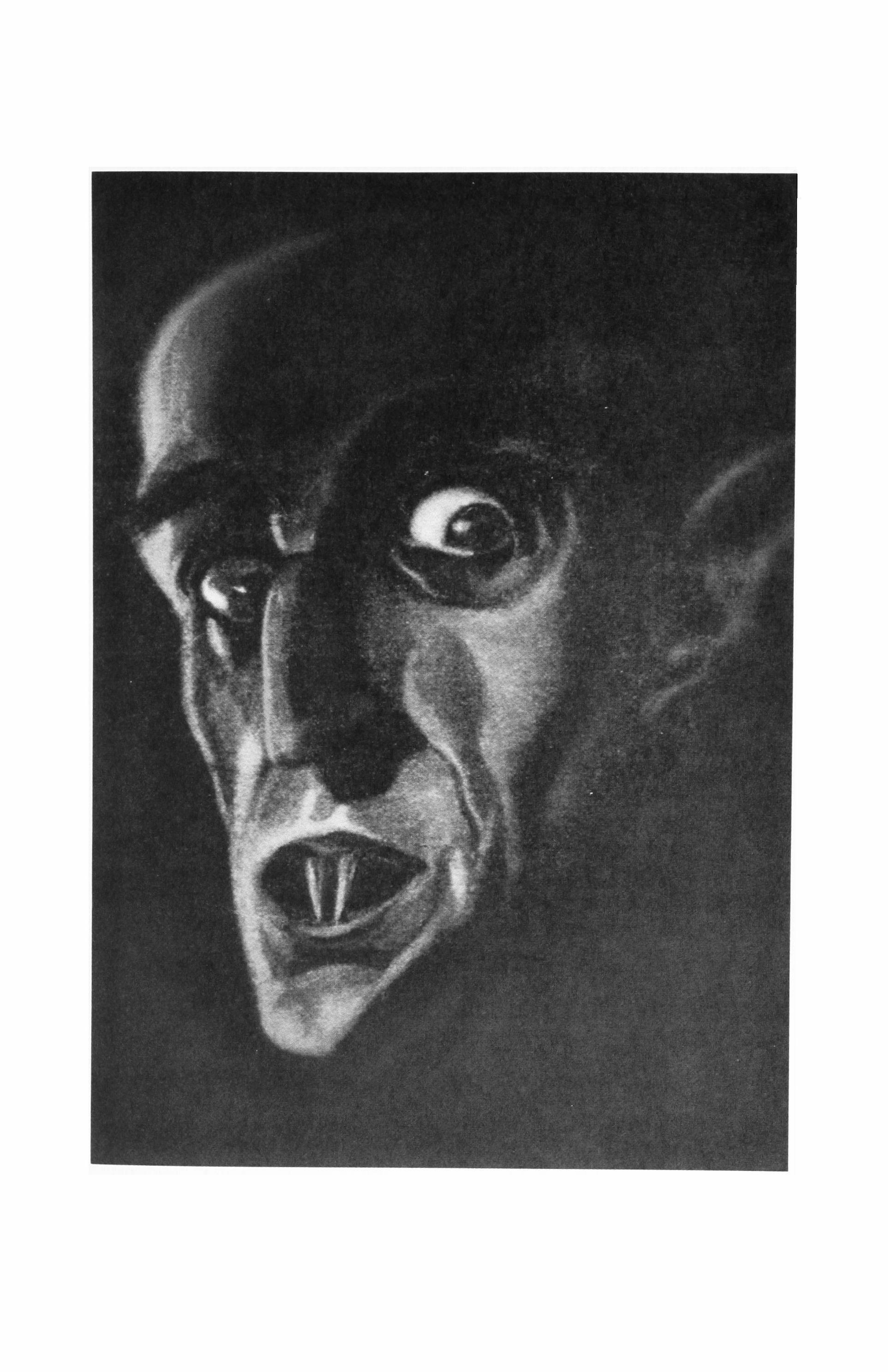

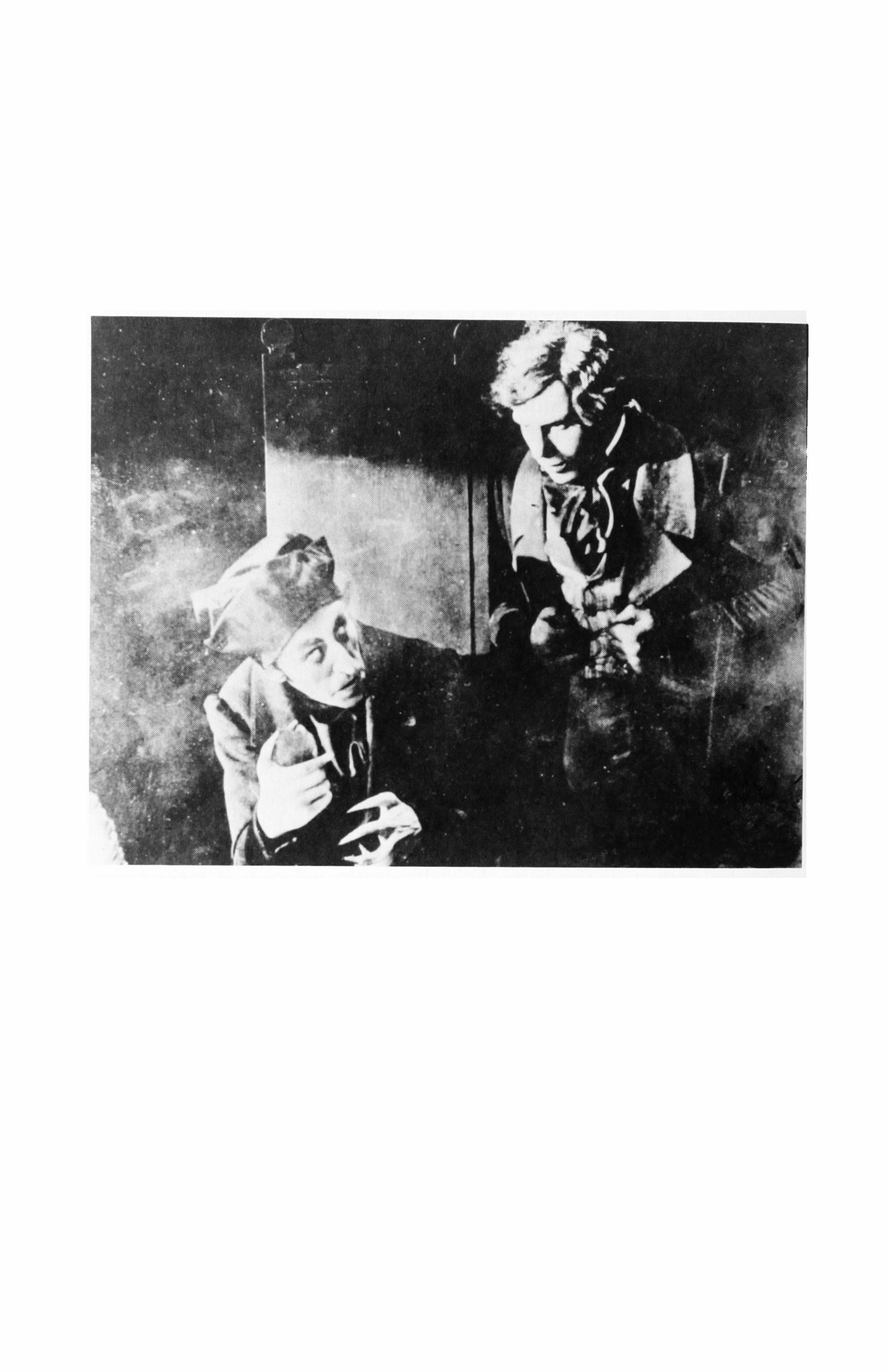

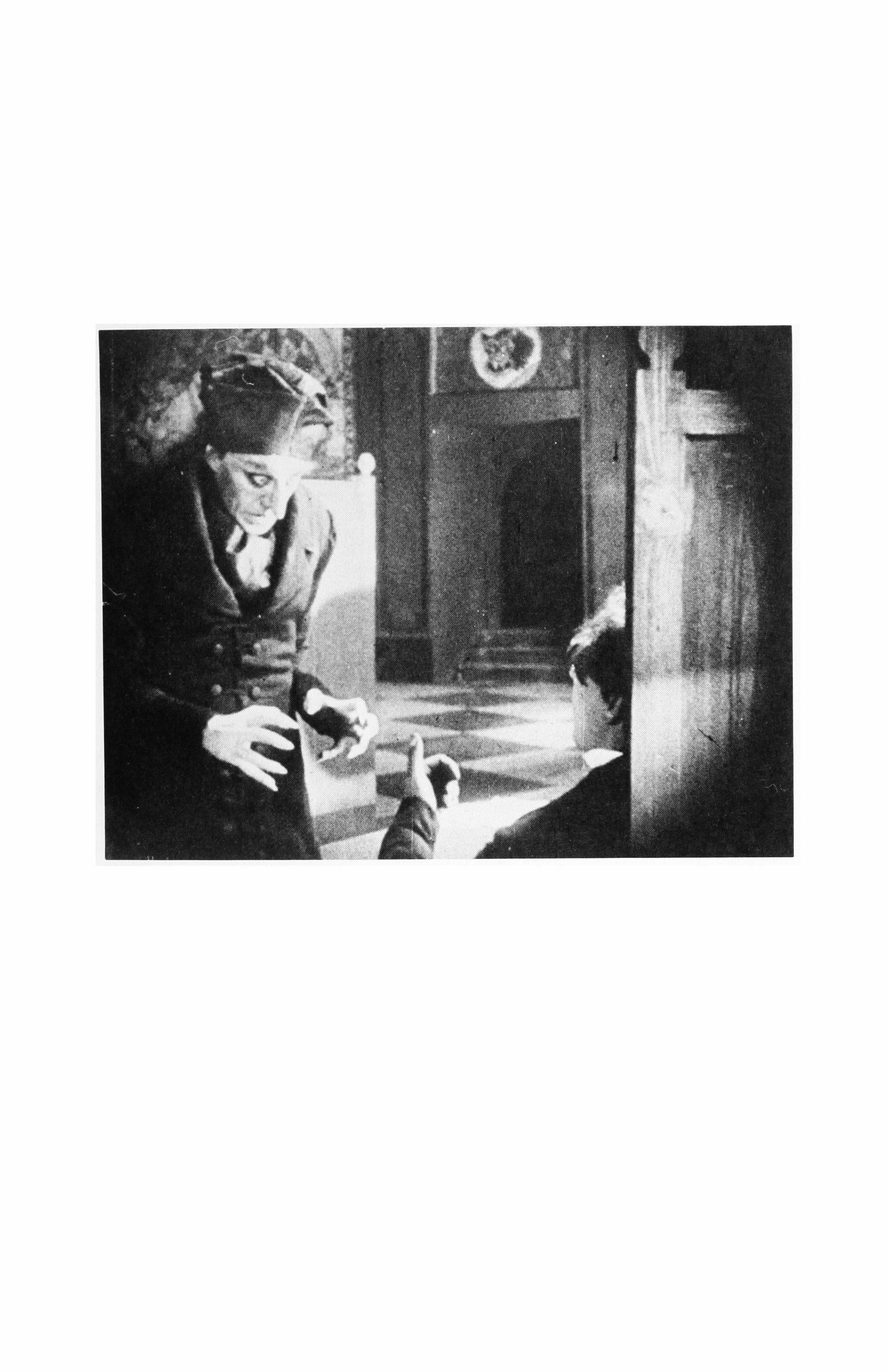

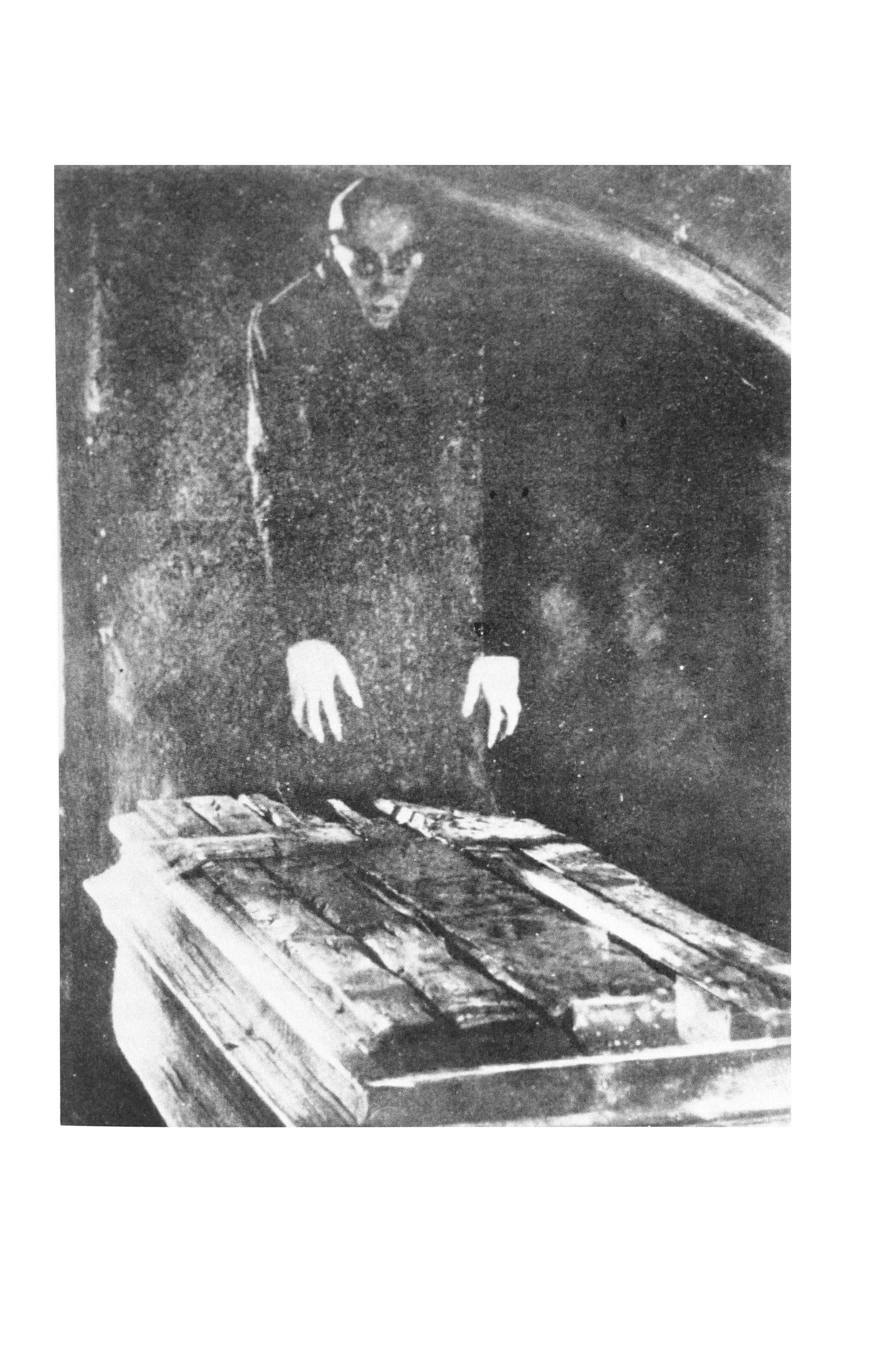

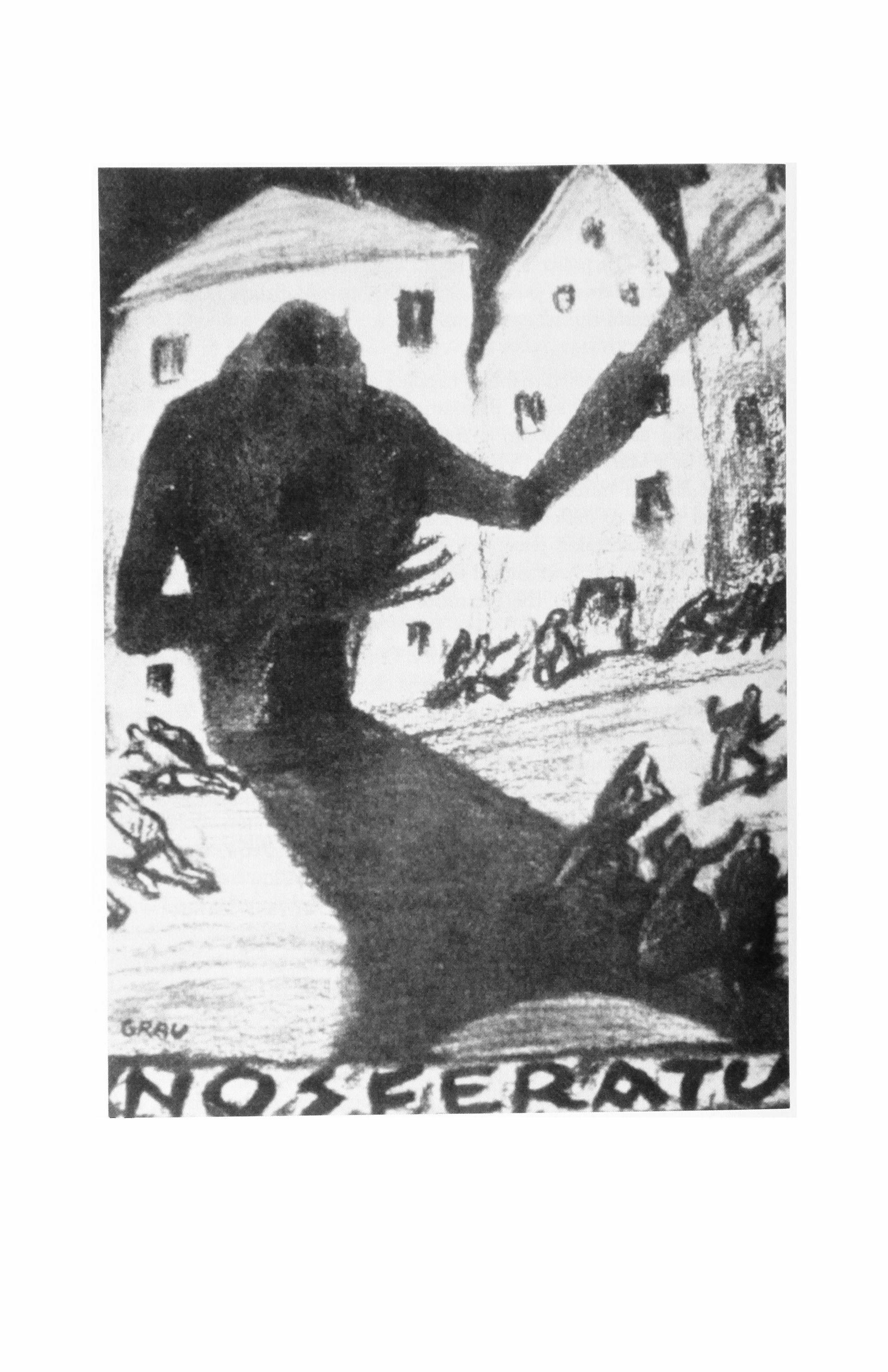

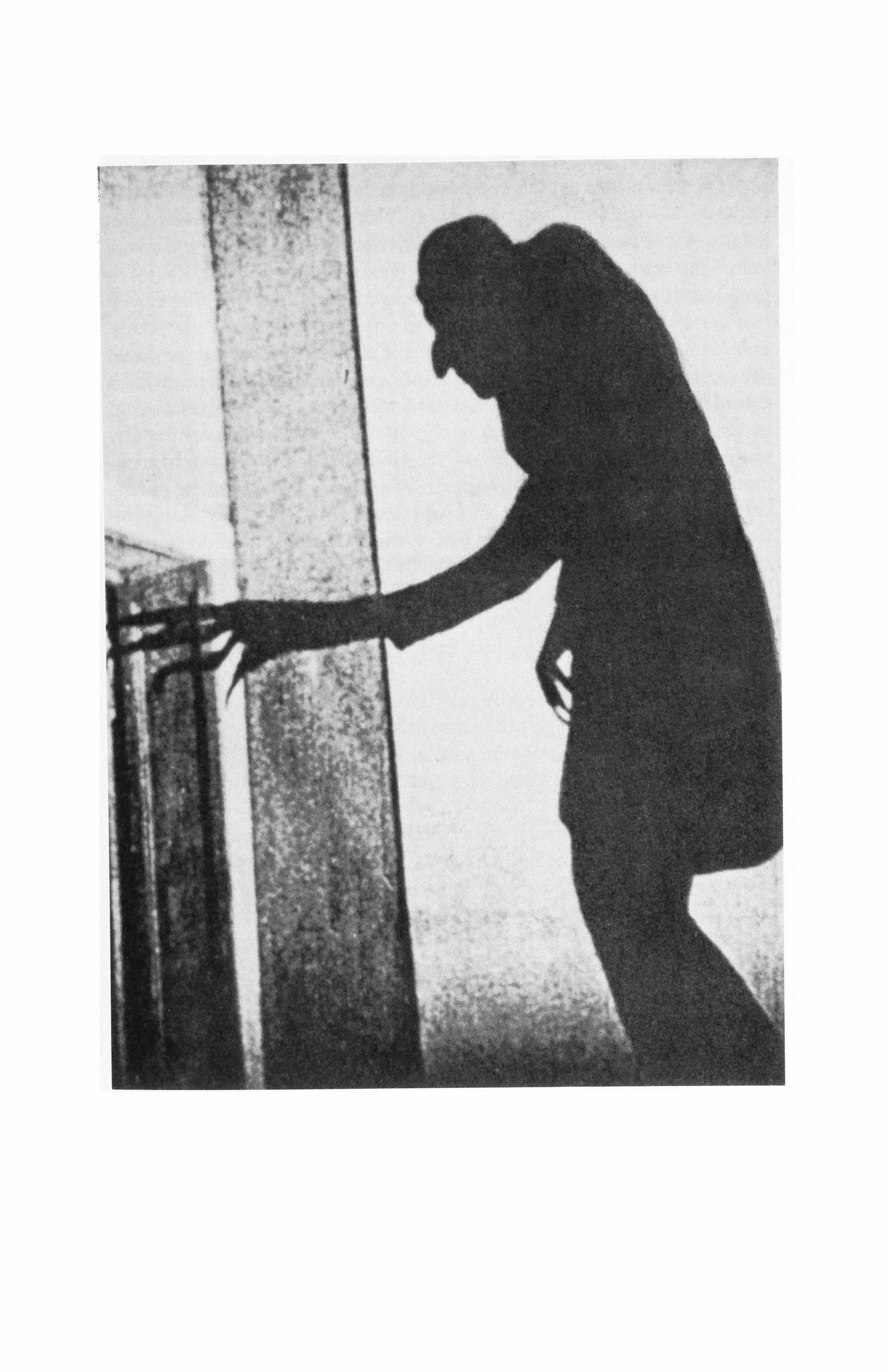

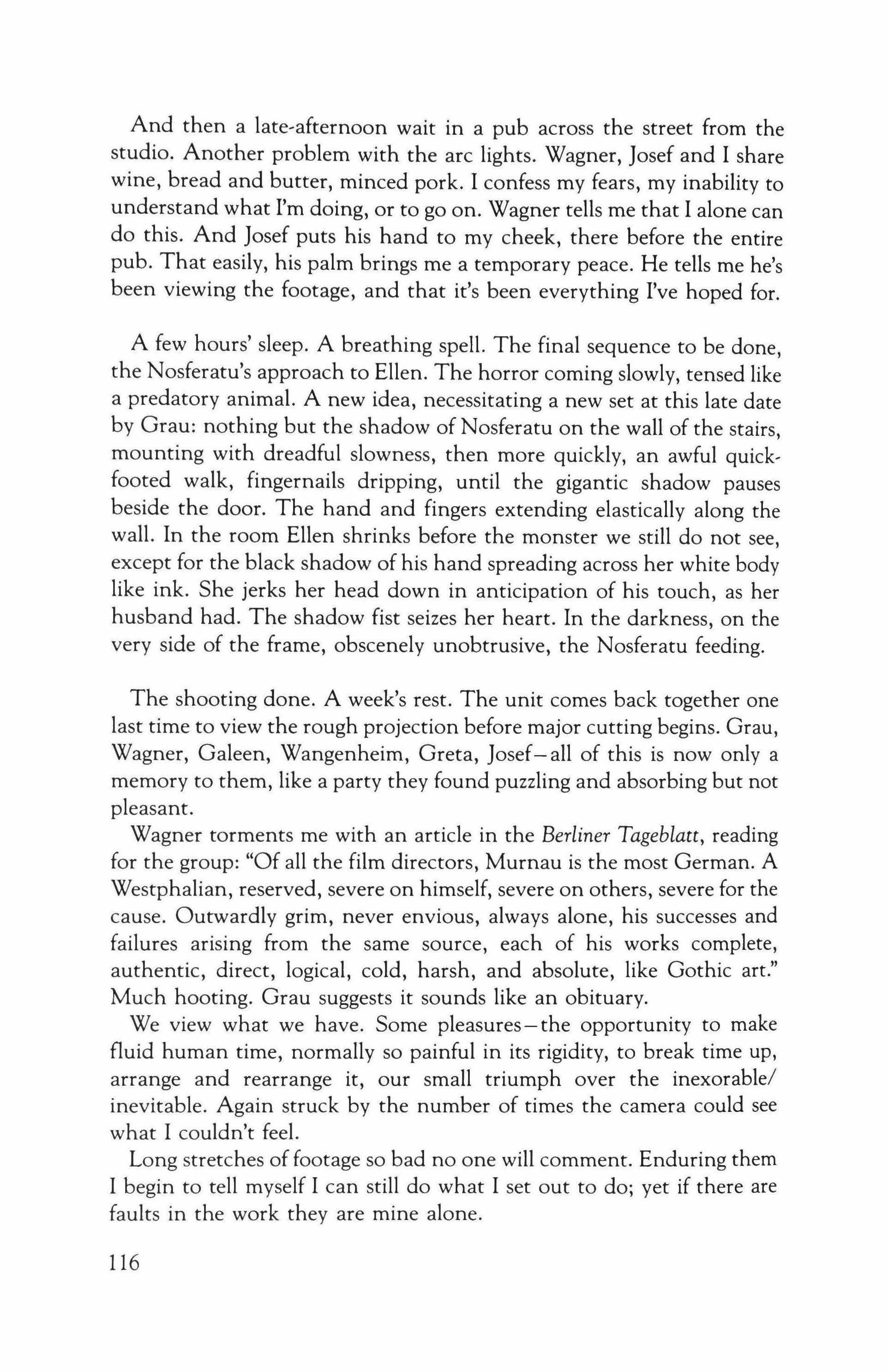

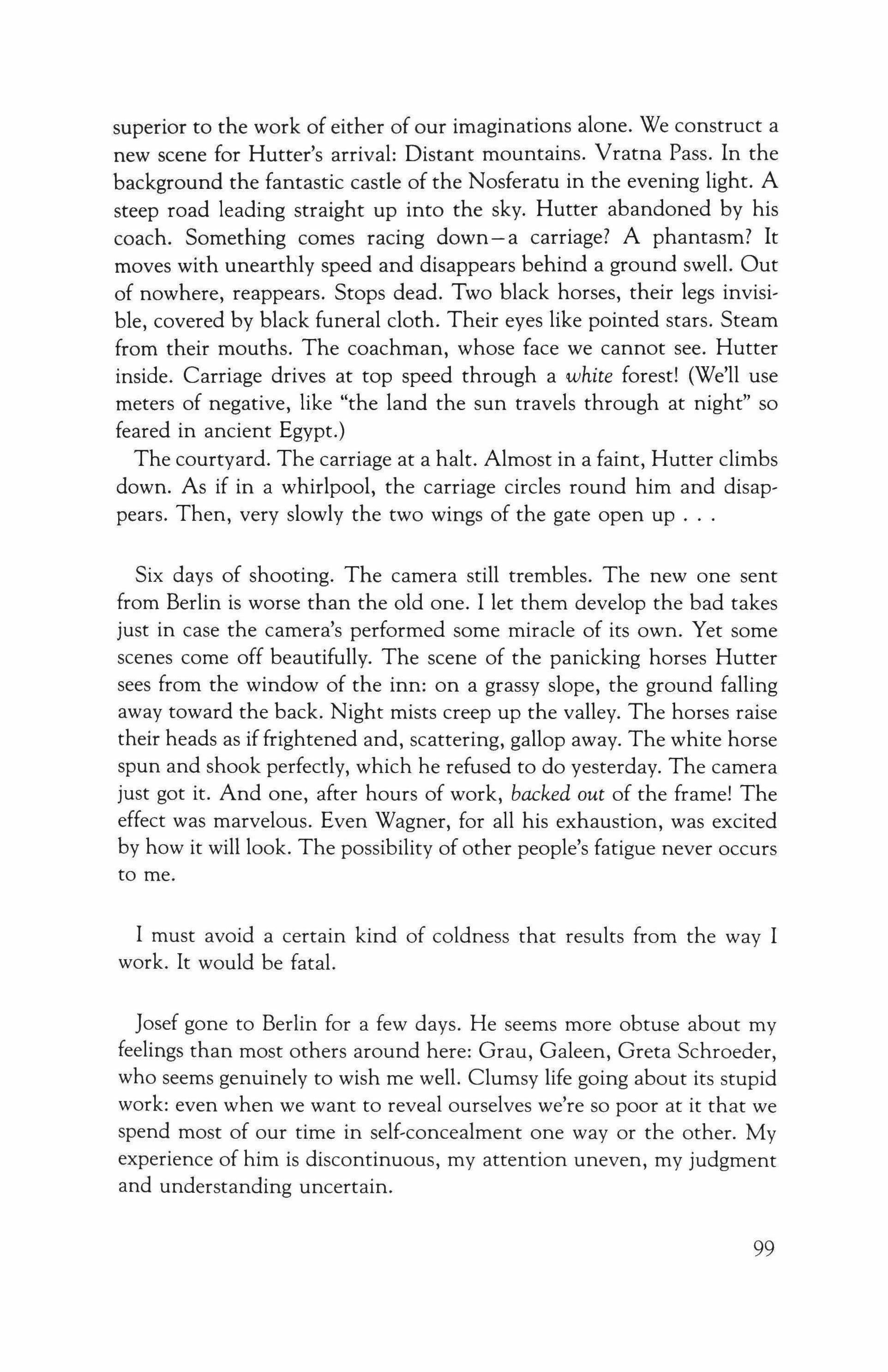

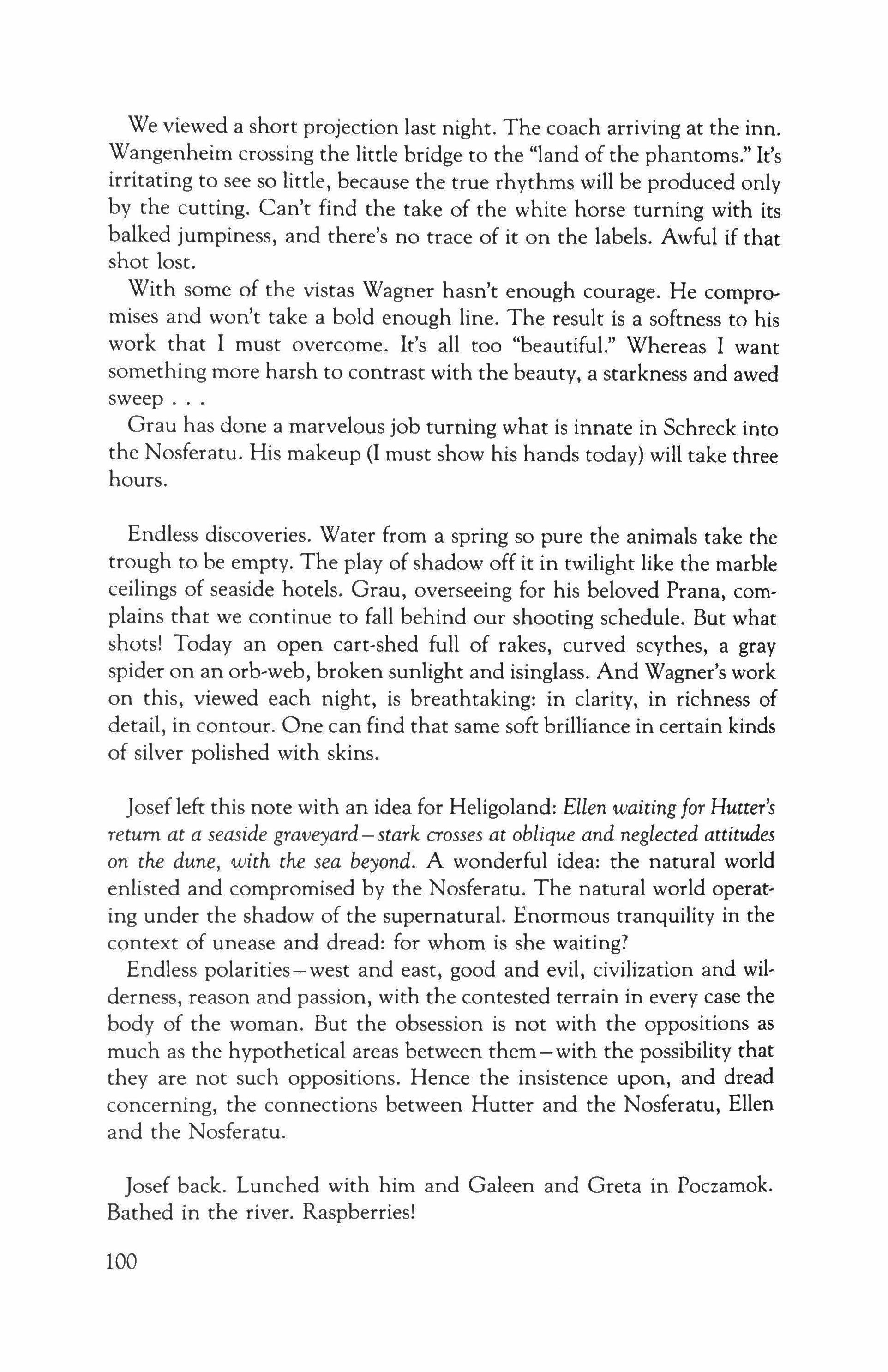

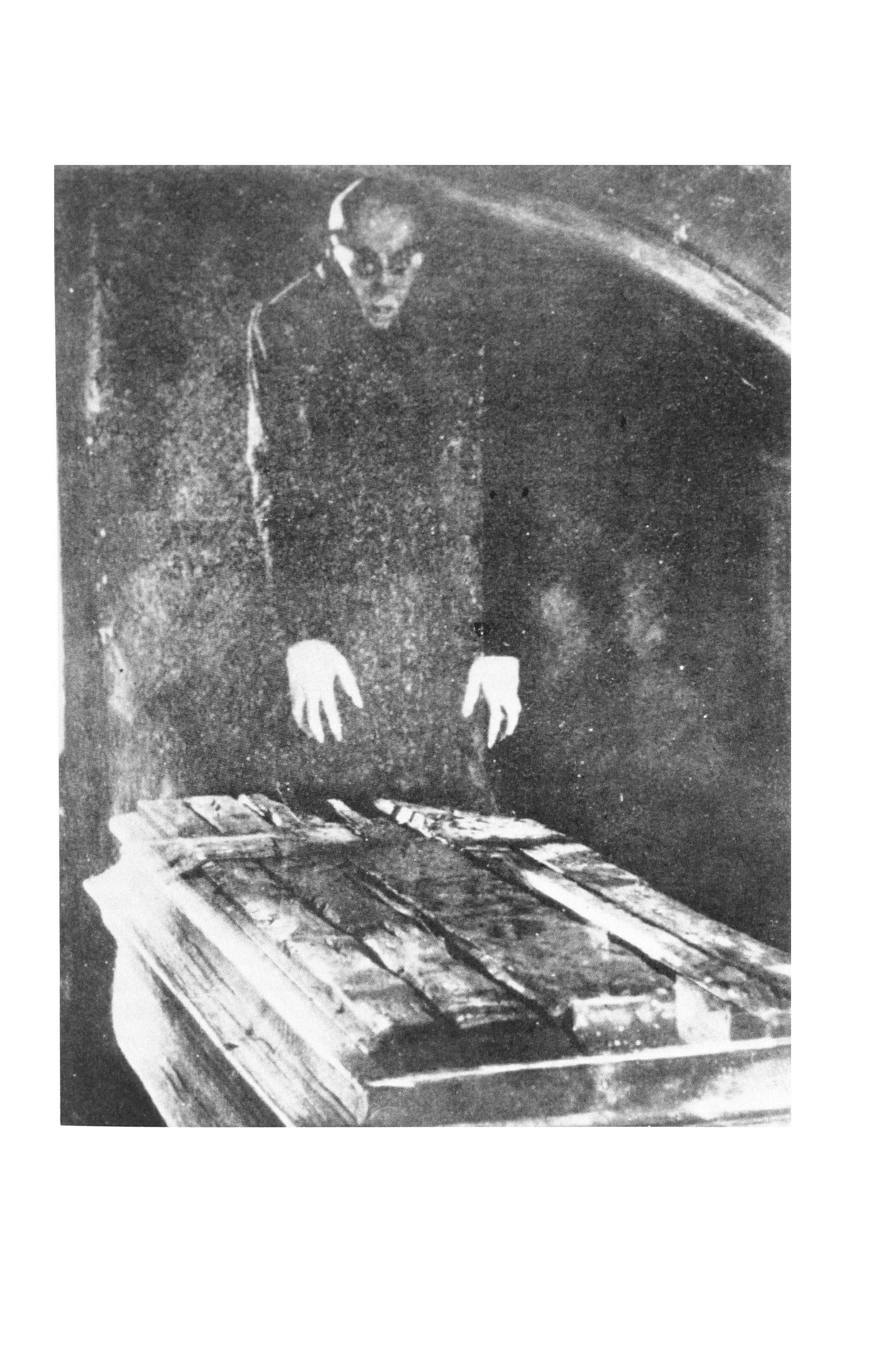

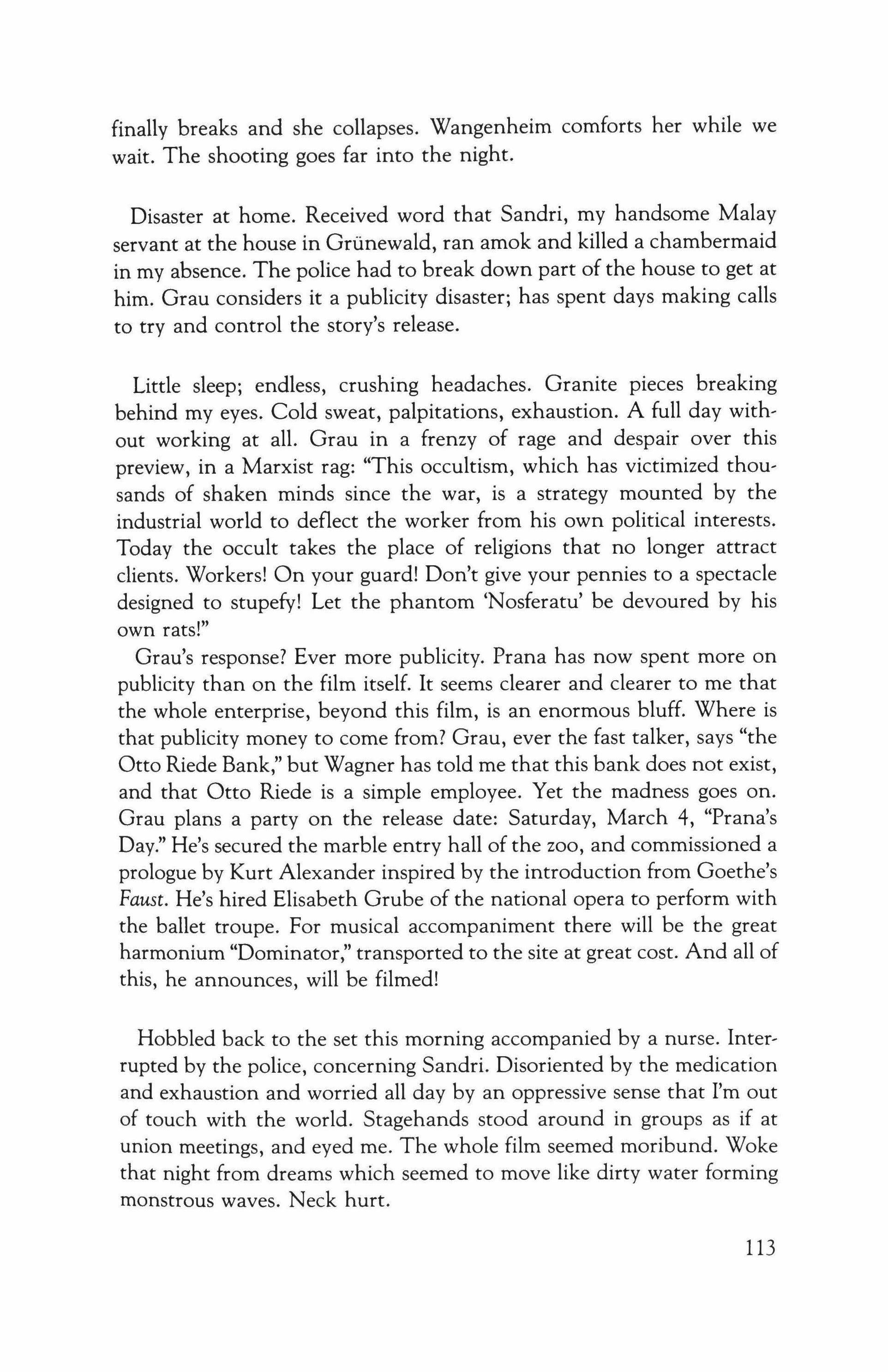

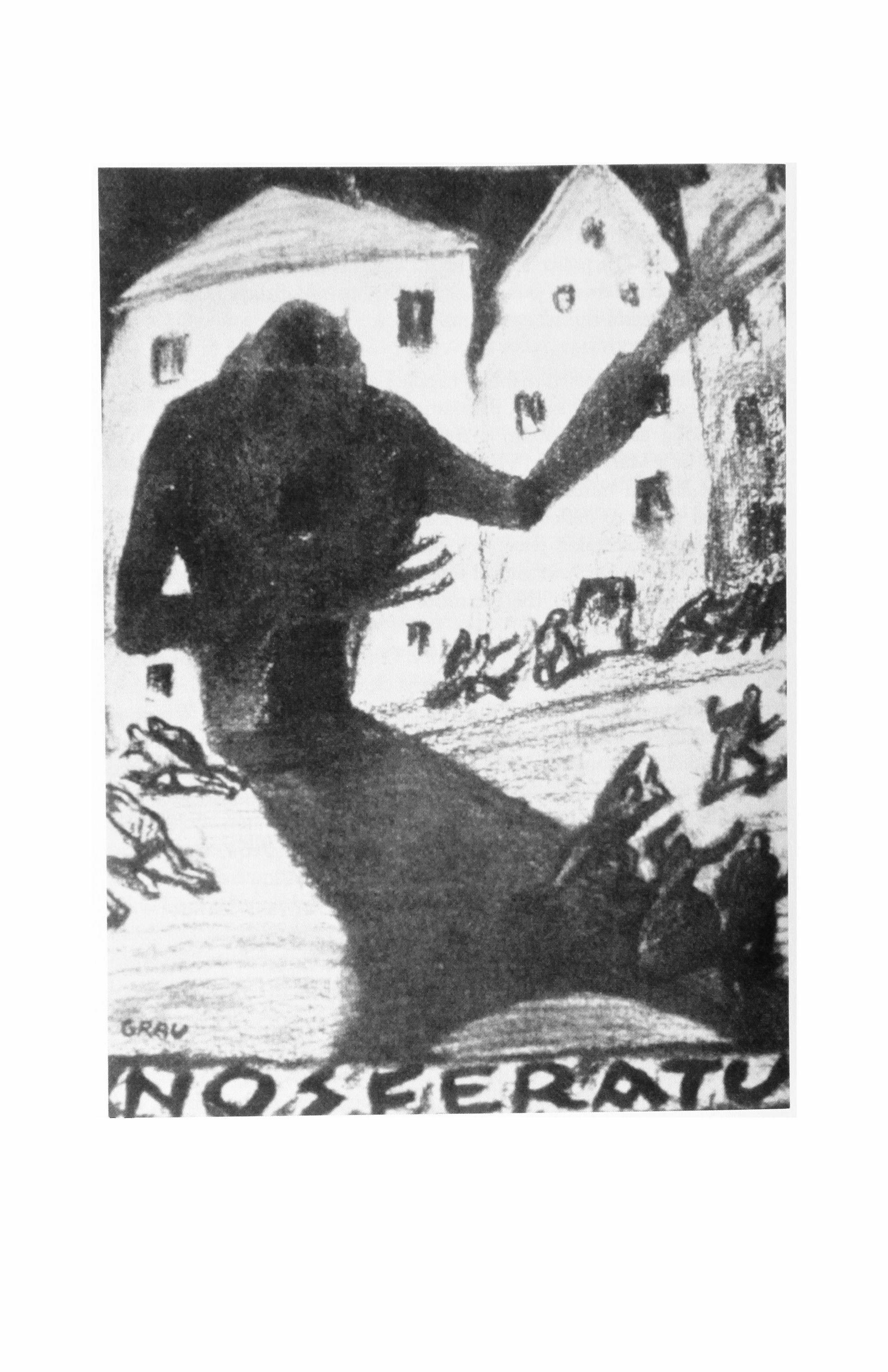

The illustrations accompanying "Nosferatu" were supplied by David J. Skal and are from his book, Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula from Novel to Stage to Screen (Norton, 1990). Notes on the illustrations appear on page 236.

19

Algebra: A Problem with Words

Owen Perkins

A man at a station in Baltimore gets on a train traveling at sixty miles an hour headed for New Haven at 10:00 Monday morning. Another man at a station in Santa Fe gets on a train traveling at seventy miles an hour headed for Colorado Springs at 9:30 Tuesday morning. Will the two trains meet? What time will the two trains meet? What variables will determine where the two trains meet? Who do the two men on the trains meet? Even if the two trains do meet, do the two men on the trains meet each other?

The man at the station in Baltimore does not carry a guitar. But neither does he carry the New York Times. He does carry three papers from Baltimore, the Baltimore Sun, the News American, and USA Today. He buys three papers a day to read the sports section. The dates of the papers are not important. What is important is that the Orioles are winning. The important thing about winning is to win every game.

The man at the station in Baltimore wishes he had packed a glove as the train starts to move and he realizes that it won't get cold again. He laughs to himself as he remembers the last time he was in New Haven, when they wouldn't let him play even though they needed a couple extra players because the other team thought he was a ringer. The other team had never seen him throw from third to first.

The man at the station in Santa Fe carries a guitar. That guitar can play no role in the outcome of the question of whether or not the two trains meet, but it may playa central role in determining whether or not the two men meet. That should suggest that the two trains do not crash, leaving everybody dead. That would be funny. This is a problem.

21

The man at the station in Santa Fe has just eaten a great big meal of Mexican food at his favorite restaurant in Santa Fe. He has been there only long enough to find a favorite restaurant. He has had no interest in finding another one. He can't remember the name for the food that he ate, but as the train starts to move he realizes that it is going to make him sick. He can never remember the names for the Mexican meals he eats.

The man at the station in Baltimore hasn't bothered to check the time the train will arrive in New Haven. Neither does he wear a watch. He has made a guess at the time the trip will take after nodding up and down the way people on trains do when they fall asleep. But he has not thought to assign a variable for all the stops the train makes along the way. The trip is twice as long as he anticipates, but it is not twice as good.

With each stop of the train between Baltimore and New Haven one must realize that it is almost twice as far to go from Santa Fe to Colorado Springs. Twice the distance is one quantity and far fewer towns is another quantity. With all of the unknown quantities and parallel directions in separate time zones, it becomes increasingly apparent that the two trains will never be likely to meet.

Does the man on the train to New Haven realize that his train will never meet the train with the man on his way to Colorado Springs? He probably doesn't think about it. He is expecting to meet a friend in New Haven and wants to open the window and let the baseball in the air fill the train.

It would be too easy to look ahead and see the change in the weather. He knew enough to expect a lot, but he could never anticipate the wind blowing hard enough to take down a tree in the front yard where he would have stayed. And so what, really? How can anybody honestly believe that the sky cries or that the moon can cast a spell? Really. Who talks about the weather when there is phone sex at the fingertips?

In northern New Mexico, the man with the guitar thinks that there is no doubt that his train will someday meet in a station with the train that runs from Baltimore to New Haven. In the long run, he feels a confidence that the trains are all running on the same track anyway, but he doesn't tell that to the bartender in the club car. There are not many people on the train today, and she has time to talk. But just because the

22

man carries a guitar, he is not necessarily the kind of man who would tell somebody he has just met that all of these trains run on the same track anyway.

He thinks she takes too many risks, spending her days wrapped up in the system of mass transportation. But he is also not the kind of man to say that to a woman like her. He will tell her the next time he sees her. Something she says about her son makes him realize that her son had heard him play guitar a week ago. Is that part of the problem?

When he plays guitar, he realizes that there are one or two things he is capable of pulling off, and a week later he realizes that playing the guitar is not one of them. Not everybody who sees him play realizes that, and he wonders if the bartender's son is not everybody.

What if the man who left Baltimore does everything right and the man from Santa Fe doesn't do anything right? Wouldn't it make sense for them to meet? Shouldn't their trains collide? What if they have already met? What if they are the same man on two different trains at two different times? What if they are the same man on two different trains at the same time?

They probably need each other to keep from losing balance. Without the man who does everything right, the other man would be falling on his face. Without the man who can't do anything right, the other man would be flying.

I am the man on the train from Santa Fe to Colorado Springs. If you happen to know me, you can already tell I'm telling the truth. You can see me sitting in that club car drinking a margarita with an upset stomach from some Mexican food I ate earlier and talking to the bartender. Otherwise, it could be anybody.

But that still doesn't explain how I know what was going through my mind as those trains headed for a collision. Imagine, crossing that much country without colliding into something. I had been reading Don Quixote. Or I had the house to myselffor a while and I looked at myself in the mirror a lot. Or I met somebody who forced me to think of a man on a train moving sixty miles an hour between Baltimore and New Haven.

In fact, however, the man on his way to Colorado Springs gets off at the end of the trip and goes home with a friend.

The man at the empty station in New Haven can't hear the train anymore as it heads back to Baltimore. Things are not as he expected. Nobody is there. In New Haven. There is nobody home.

23

For security, he puts a quarter in a newspaper machine and opens the sports section. Football scores. Where will he go when nobody is home?

If a man sits alone in a train station in New Haven and reads football scores during baseball season, is the station empty? Sooner or later, the man in the empty station will have to answer that question. But he is not the kind of man who thinks about things like that. This man thinks about baseball scores. How much does that reveal about this man? He has bought four papers today to read baseball scores. He is seen finding football scores when he reads the fourth sports section. What did he find in the other three sports sections in the other three papers? Is this man in control of himself? Is buying four papers a day to read box scores enough to make a person beautiful?

The man who got off the train in Colorado Springs is drinking a Dos Equis in Manitou Springs. His friend has brought home two T-bone steaks for them to eat. They sit in the backyard with the steak on the barbecue and the sun sitting high in the afternoon above Pike's Peak works its way into his mind. The dog is in a good mood, because he will get to eat the steak bones. See? I told you I am the man from Santa Fe. His friend hasn't noticed that the sun is on his mind and she goes on talking. The sun in his mind becomes only a part of the larger story. The larger story in his mind is about seeing her again and watching the sun catch her laughter as she continues.

Part of the story is a flashback to the fires he lit as soon as the sun went down behind the Jemez mountains outside of Santa Fe. Although she had been there in the firelight it was still different from being in the backyard in Manitou Springs. Sitting on a train all day has made a big difference.

Nobody answers the phone. Nobody is home. The man leaves the empty station in New Haven and decides in which direction he should head off. He walks toward the water, stopping a couple of blocks later when it comes into view. Does he have time to go sit by the water? Does anybody have time to go sit by the water when they arrive at an empty station to find that nobody is home?

Down at the edge of the water he sits and enjoys the phone sex. There is no indication that the phone sex will change. Storms like the one that is coming come too quick to be predictable. One minute everyone is enjoying the beautiful phone sex and the next minute is lifethreatening.

The water is one of the things that keeps the man in New Haven from

24

thinking about people on trains traveling from Santa Fe to Colorado Springs. The water can keep a man from thinking about anything.

She is a whole new part of the story. It makes such a difference that she is there. She has a mind of her own. She is so interesting, so alive. She will be out of the story soon enough.

How does she get around? Does she ride trains, too? Who does ride trains? Is there any way that she could cause the man from Santa Fe to meet the man from Baltimore, now that the two trains have both left the picture? There are dozens of ways, but none of them happens to matter in this case. Why don't they teach that in school?

What has she been doing since the fire light in Santa Fe? That is what the man who got off the train in Colorado Springs wants to know. He doesn't ask her. Not in any way that she would know what he is talking about. He won't worry about what she has been doing if she doesn't worry about what he has been doing. But I am the man who got off the train in Colorado Springs. And I want to know what she has been doing since the fire light.

The man in New Haven thinks about going to the graveyard, but once was enough. Things are not the way he expected. He never realized that he would be lonely. Changes frighten him more than he will admit when he hasn't expected them. He doesn't want to become unstuck.

A man in New Haven might just as well be in Baltimore if he is alone in a city. And if a man in New Haven might just as well be someplace else, why should it be New Haven? Or Baltimore? The man doesn't know the answer. The man in New Haven rides trains and keeps other people out of his life.

He is back at the train station where his four sports sections sit untouched on a bench beside the tracks. He begins to consider going in a different direction on a different train at a different speed. The man thinks over the idea of dropping off the radar screen. The four sports sections sit untouched on the bench beside him. The man thinks.

You are the man sitting in the backyard with the steaks on the barbecue in Manitou Springs. Can you think of any reason you would have left Santa Fe on a train at 9:30 Tuesday morning heading north into Colorado? If you can't, then you are fooling yourself to think that you are the man with the steaks on the barbecue and the friend in the sunshine who decides to stop laughing.

The day is special if only because you had that Mexican meal in Santa

25

Fe and now you are having steaks in Manitou Springs. It is a good thing that she eats meat. Would she be there in the backyard if she didn't eat meat? Would you? Where would you be if you didn't think that eating a barbecued steak was the single most satisfying experience a person could have alone? You would not be in the backyard. You might be in Connecticut. If you are in Connecticut then you are fooling yourself to think that you are the man eating meat in the sunshine.

You notice many things about your friend laughing in the backyard. But you never notice the right thing at the right time. Like the sunshine catching her laughter. That is the wrong thing to notice at the time. As nice as you are, it aggravates her to no end when you notice the wrong thing.

You can be so insensitive. You are always thinking about yourself. You are like most people in that respect. If you are like most people, you might as well not be in the backyard. Somebody else might as well be in the backyard. That is what she thinks sometimes.

The man in New Haven rides trains and tries to forget that he will die one day. He spends too much time wondering what will happen to the energy that keeps him alive. He deliberately avoids trying to answer that question whenever possible.

He is interested in the reaction various friends would have if he were to drop by out of the blue after seven years of incommunicado. They might think he is dead. Unless he drops by. He would like to drop off the radar screen, but he does not want to be dead.

He likes to be living a hundred years ago. He likes it better when there is no radar screen. What would happen, he wonders, if we were suddenly without our myriad methods of proving our identity? What if he was just whoever he said he was? Like a man on a horse riding into town. Who are you? Who wants to know?

Perhaps that is why he rides trains. Because trains are so much more linear than airships. Is it fair to say that this man worries too much about how to get places and not enough about what to do when he gets there? Could that be why he reads box scores instead of playing the game? Maybe. It could be. It isn't his fault.

It is his problem. He used to drink too much. It was part of his personality. You could never tell if he was drunk or if that was just him. Is that a problem? A problem is how long it will take to get from New Haven to somewhere else on a train moving at sixty miles an hour. It is easier to be a man on a train heading west at sixty miles an hour than it is to be a man alone in a city.

26

He hears a train approaching the station and everything he sees begins to shake. He cannot keep his focus on anything because he is shaking too. The train approaches. Tropical marimba beats his ears. Does he see the name of the train as it passes in front of him? Does he know which direction it is going when he gets on it? Why does he get right back on a train again? Couldn't he think of anything else to do?

He thinks he might be dead. He is interested in the reactions his friends would have if he suddenly popped up at their door after being dead. It sounds like a soap opera to him, but he thinks it is possible that he had gotten out of the car to take a piss and that it was some hitchhiker who went through the windshield into the back of the truck quicker than you could say smash.

Is death like being alone in a city? What a random thing for death to be like. The man on the train leaving New Haven thinks it might be easy to understand why.

You are still the man in the backyard in Manitou Springs. You can never do anything right. And now she is really mad at you. People only get mad at you when they've got some silly reason to be mad. She is not even in the backyard anymore she is so mad. She will get over it. You know she will get over it. But you wish you didn't have to wait.

The sun is on the other side of the mountain, and you are growing cold. But not too cold. The dog looks up at you as you collect the plates and head inside, but he keeps chewing the bone. The fluorescent glow above the sink is not real. Pieces of fat and gristle are electrically disposed of and you don't want to think about where they go, what they become.

Do you look forward to settling down? Are you eager to stay put for a while? Are you ready to develop a sense of obligation? If you are, or if you do, then you will not make anyone believe that you are the man washing the dishes in the fluorescent light.

She is in the living room. It's not too warm for a fire. But you are not sure if it is worth it. Do you want me to start a fire, you ask her. She doesn't want a fire. It might be nice, you say. Like in Santa Fe. She tells you not to get her temper up.

She tells you that she loses control when her temper flares-as if you didn't know-and that she killed a man she slept with once over the twenty-eight dollars in his wallet. Your expression doesn't change, but your mind does. She does not intimidate you; she does scare you. You decide not to start the fire.

You are going to sit there and nod your head. You will make some

27

concessions. You will do anything. Will that work? How could she already be so angry when you have only just gotten there?

Do you want to know what she has been doing since the fire light in Santa Fe? She has been thinking through this whole thing. Just let her talk, will you? She has been thinking this whole thing over, and she's come up with a couple conclusions.

You better let her talk. You had a right to be moody for a while. Everybody put up with you for a while. But now you're just being rude. And nobody wants to stick around someone as rude as you long. Nobody in the movies, nobody on television, and nobody in books. Just let her talk.

She wants to be let go before someone is hurt, before the pain becomes an explosion, blinding and numbing her from consciousness, tearing down the wall between this side and the other. She will kill you if it will make the day pass any easier.

She is tired. Tired of never having enough, tired of being short, tired of being with you, tired of carrying around a pack full of clothes suited to weather she doesn't want to endure, of utensils she doesn't want to use, of somebody else's dinner. She wants you to let her drop the pack right there and go to the horne you made her leave.

Your expression never changes. You don't want her to go, but you don't tell her that yet. You say, it isn't up to me. You tell her she's free to do what she wants without changing your expression, and she screams trying to convince herself that what she said was true.

The life of the man on the train from New Haven has changed since he picked up the morning edition of the Baltimore Sun and got on a train headed for New Haven at sixty miles an hour. He is no longer a man with a destination. He is more now. He is a man who thinks he is losing his mind and doesn't know why there is nobody in New Haven or why the sports sections are full of football scores.

The train is running and it gives him time to think as it rides west across the country. Leaves swirl around the train and follow its wake as if it were autumn. He wants to visit somebody, but he's afraid of surprising people. He needs to visit someone who could deal with him dropping in like that.

He is generally a lucky man. Things like this never happen to him. His imagination will never be the same. He walks up and down the train looking for the club car. The first time he walks the length of the train he thinks it will never end. The second time he knows it will. Under-

28

standing the distinction gives him hope. He has narrowed the scope of the train itself. One more run at it and he is bound to find the club car.

If life is a mountain range then death could be a train riding along beside it. The man on the train wonders if there is any difference between death and riding on a train. He thinks about an old friend who would freak out but who would get over it. He bites his fingernails. He wishes he had brought his baseball glove. He thinks about me and my baseball glove. He remembers baseball gloves like I remember guitars.

My baseball glove is memorable because it is left-handed. I am memorable because I am a left-handed third baseman. I would be more memorable if I were any good. He remembers things the way I always thought I would when I was a kid. All the souvenirs I thought would be important relics someday are still important to him. It is nice that somebody remembers.

He remembers when I played on a different team than he did. I played third base on my birthday and I was nervous about doing something memorable. As long as the ball wasn't hit to me, I could convince people that I wasn't just out there because the manager got a lot of pressure from parents to play everybody in every game. The man on the train leaving New Haven slid into third base, and although there was no play on him, he could tell from the dirt around third base that I was nervous. I tried to work the dirt down deeper into the basepath, but it only spread wider. Having the man on the train slide into third base was a sobering moment for me. It is nice that somebody remembers.

A hundred years ago the man on the train is whoever he says he is unless somebody remembers. Sometimes he comes into town and tells stories to the people at the bar. Some of the stories are true. Some of them are about himself. Other times he goes to the bar without saying a word to anybody. He leaves with a smirk on his face and a squint in his eyes for anyone who wants a word with him. He drinks too much.

She is out of the story. She has gotten out of the story without even riding a train. She will be back. She will get back in the story without even riding a train. How does she do that? She is out walking the streets of Manitou Springs and I don't know where she will end up. I think I should be the man in the living room with the unlit fire again, since it is me. I don't know where she will end up. I don't think she will come back here until I have gone to sleep. Or at least until I turn the lights out. It doesn't take me a moment to get into my part.

I turn the lights out because I want her to come back. I light a fire because I want to please her if she does come back. It is probably the

29

wrong thing to do. I always do the wrong thing. I am not generally very lucky. I am lucky that she is angry with me. She is not angry with you. I prefer fires to almost anything. I am good at making fires. She doesn't even try anymore. I am so smug when she needs me to start the fire. It comes from not doing anything right. I think she will understand when I make a big deal about one or two things that work out for me. She doesn't. She says it's just me and my macho male-ego bullshit.

The dog comes inside when I turn out the lights. Turning out the lights doesn't impress him. Starting a fire doesn't even impress him. He knows there are things I can do that he cannot. He knows it is usually a slow night when I light a fire. I sit on the couch and stare at the fire. The television has begun to make sense to him, but he doesn't understand the hours in front of a fire.

The Mexican food from earlier in the day is still with me. The silver buckles on my guitar case shine in the fire light. The dog follows my eyes to its shine. The dog doesn't care much for my music. Sometimes I think he only really understands me when I speak French.

It is embarrassing to play the guitar. I am not good enough to make a living at it, but not enough people realize that. She could make a living singing while I play the guitar, but she is out walking the streets of Manitou Springs. She is out of the story.

Sometimes I sat in the dark in Santa Fe and listened to a tape of a song I had written. I had taped some of my friends singing the song over the telephone. She wouldn't sing on the tape. She is out of the story. Another friend sang and told some jokes. He is dead now, but he is on tape. He always tells the same jokes.

I think you should be the man on the train. You are part of this. You are laughing at an old joke that comes to your mind. You are thinking about when we were in school together. You were a good student. I never did anything right. The train you are riding on is going to blow up, but you have no way of knowing that.

It is always a long ride through Kansas. There was only one newspaper, and the sports section must have fallen out. If you can find your way to Manitou Springs, you know that I am always following the Orioles. I am not expecting you. You will be dropping in out of nowhere. I will be surprised to find that I am not freaked out. That will come later.

I want to see this through your eyes. You are on a train coming out of Kansas, finally, you say. What do you think when you first see the mountain? It must feel different from when you first saw the water a

30

couple blocks away from the station in New Haven. Are you going to stop in Colorado Springs? Are you just passing through? Are you a man on a train traveling sixty miles an hour, or are you a man who is going to visit a friend in Colorado Springs? Do you think anyone will be there when you get there?

I will be out walking along the railway tracks. It is the only way to cross the river there where the dog likes to walk. I will be crossing the river and you will be coming from behind in the train. I will be worried about the train forcing me and the dog to jump into the river below. I don't think the dog will jump. I will probably have to drag him over with me. What a mess it will be.

I am also worried about the train. I know it is going to blow up. It is like speaking in tongues. I just know. If I have to jump in the river, there will be no way to warn anybody about the train. I don't know if it's going to derail or crash or just explode. I want to do what I can. I don't know that you are on the train.

Of course, you are unaware of any of this. You can't see what is in front of the train. Only what is beside it. You look at the river as you cross over it. It is the first river since the other side of Kansas. The water keeps you from thinking about the train blowing up.

The train crosses the river and you look forward through your window again after turning your neck to follow the river. You are surprised to see someone running alongside the train. You are even more surprised to see me. Somebody is home after all.

You wonder how I knew you were coming. I am making all kinds of hand gestures. A heavy accent to my body language makes it impossible to understand. You look at me with a quizzical expression on your face. Don't you understand? I'm trying to save your life. This train is going to blow up. Get off it. Before it's too late.

In a moment I am gone like the river behind me. In a moment you are gone, without a sound, without a vibration. What can I do? The dog didn't understand my body language either, and he wants me to put my hand on his head. You have presented me with a problem, but I have already done everything I can do about it. The dog and I walk home where she is still out of the story. Surprisingly.

At home I sit in front of the television and wait for a bulletin. I drink chocolate milk. The phone rings. I am afraid to answer it. Who do I think it is? Who is there to be afraid of? I have not had any use for incoming calls since the mortuary man called me from Idaho Springs. I once came in third place on a religious-trivia television game show. A

31

mortuary man from Chicago came in first place. Anyone who needs me knows where to find me. Except you. How will you ever find me here in Manitou? I pick up the phone, but if it is you, you have already hung up.

I change the channel. I change the channel about thirty times, because I have cable television. There is nothing on. I pick up the guitar which is sitting in the chair where she should be this morning. All my picks are broken. I sing a song. I'm hungry for a cigarette, I could use one now. My hands are in a cold cold sweat, 'cause I'm sitting here right now.

You don't know what to make of my body language. The dog has perked his ears and is softly growling in the direction of the street. You take to wandering the train again. I love it when the dog barks at her. You still can't find the club car. It makes her face how things stand around here. You find your way into the conductor's compartment. Sometimes she makes herself out to be such an alien in our house. There is a wasp in there. Dogs can sense something like that. The wasp is going to surprise the conductor. The dog barks. As I understand it, you take care of the wasp.

There is no bulletin. Nothing happens. A man sits on a train headed west at sixty miles an hour. Another man sits in his backyard facing the sun. The man in the backyard is alone with his dog because he never does anything right. If not for the man in his backyard, the man on the train would be flying. All the news is about the storm in Connecticut. You are grateful. When did you learn to think like that?

32

Scraps

Patricia Orway-Ward

Police, Ma'am, you called us? May we come in? Doesn't look like much was burned. Did you put out the fire yourself? You say you got home a few minutes ago from class, that would make it about 10:30 P.M., right? And you found this pile of ashes in the hallway here, just the way it is now? Look, Jack, even the linoleum's melted. So I'd say it was burned right here and not somewheres else and then dumped. I wonder why the smoke detector didn't go off. Probably not enough smoke.

What was burned, Ma'am, do you know? Yes, I see there are a few charred scraps of paper. But why would someone want to burn your journals? Where's your daughter now? What was the fight about? Well, Ma'am, these things don't stay personal when the law's involved. This is arson, even though Linda obviously didn't try to set the whole place on fire.

Is this her picture here on the table? She's a pretty girl. Fifteen, you say? We'll have a look around, see what the neighbors know. Sorry, it's our job to investigate, and that means asking the neighbors if they saw anything. She's probably run off to a friend's house. We'll be in touch. Let us know if she comes back. Sounds like one very angry teenager.

I see, I see, I see, I see. Uh huh, yes, I see. No. I can't possibly come up there. I have a lot of business trips and meetings in the next few weeks. I know it must be rough going, but after all, she's your responsibility. I pay the child support and college for the other two besides. Perhaps, if you'd been more consistent in disciplining her as she was growing up-my analyst says you always punished her too much and then gave in when

* * *

33

she got upset. You're too weak. Four years worth of work, huh? All your notes for stories, novels, articles, research projects up in flames, huh? Poems, too, gee, that is too bad. Well good luck!

* * *

No sign of her yet, Mrs. Toland. As police chief, I'll tell you we see this kind of thing every day. Teenagers don't have enough responsibility. Truancy laws are still on the books, but there's no teeth in them anymore. Kids don't have to go to school. So they're running around getting into dope and the hard stuff.

How much is Linda into drugs? Well, I realize you didn't mention it, but I took it for granted. I mean, what else does she do all day at the beach with her friends except toke up and booze up?

Thanks for bringing her picture down. Such a pretty girl! Fifteen? Boys really go for these golden girls. Does she have a lot of boyfriends? Just the steady one, eh? I hope she has the sense to use birth control. Well, at least you don't have to worry about that. Did you turn her on to Planned Parenthood, or is that something she found herself? But I'll bet you were relieved.

Don't be so hard on yourself. Families break up, mothers have to go to work. What are you studying at the University? History was always my weak subject. Are you on Aid there? Food stamps, too, I suppose. Well, it just gives me a picture of Linda's home, you know.

So you had a fight with her because she wanted to go on a weekend camping trip with her boyfriend. And you said-what was it? I have it in my notes here-you said you wouldn't give her money for the Halloween dance, the yearbook or anything else if she went. But does that work really, Mrs. Toland? I mean, most kids these days, when they need money, they sell some herb. Doesn't Linda do some selling? Not that you know of, eh? No, I know nothing works. Believe me, I sympathize. I get a lot of mothers sitting in that very chair telling me they can't go on.

Now, besides truancy, alcohol, drugs, sex and arson, what else has she done?

Mrs. Toland, is Linda in jail? Susie says she tried to burn your apartment down. Is she coming back? What are they going to do to her? Can I visit? I've never been in a jail before. My mom says I can't visit her, but what does she know?

* * *

34

Hello, Mrs. Toland? This is the Attendance Office at Grant High. I've been trying to reach you for weeks. Linda hasn't been in school since September. We'd like a conference. You can't? She won't? When will she be back? Mrs. Toland, I wonder if you realize what a serious matter this is. We lose money from the state every day she's absent. It's your responsibility to see she attends school. It's the law!

Sit down, Mrs. Toland-er, Ms. Parkes, excuse me. Well, naturally, since Linda's last name is Toland, we just assumed

I'll call Linda in a few minutes, but first I want to discuss some things with you. Linda's still pretty mad-that's one angry teenager. She was pretty shocked when she was arrested and brought here to [uvie. Being handcuffed is a traumatic experience for a youngster. In fact, we had to put her in the Adjustment Room for awhile-she was really mouthing off. No, I'm afraid we ask you not to smoke here.

Anyways, she was kicking hell out of the A.R., you know that huge glass window that looks out on the front desk? Only it isn't glass, it's heavy-duty plastic. She must have seen paint flaking off the edges, because she started tearing at them trying to push the window out. She's a very bright kid, I guess you know that. The room's soundproof and padded, so she couldn't hurt herself too easily, but we keep a careful watch on them anyway, we're very careful with these kids. Lawsuits are expensive.

I've been appointed her Probation Officer. I must admit a P.O. doesn't have a heck of a lot of choice in matters like this. She did set a fire in a building. Arson is a felony, even if the point is to get back at Mom and not burn the place down. That's quite all right, there's a box of tissue right beside you there, help yourself.

From the conversation you and I had on the phone, my talks with Linda and the police reports, it seems to me she's out of control. I'm not sure what the court will decide, but I think a foster placement might be called for here. Families get into scraps with each other all the time, but they don't all do this. And as you point out, the family counseling you had previously didn't work out too well, because she refused to come. A condition of her foster placement will be regular counseling, probably with Children's Protective Services.

What does your husband think of all this? Your ex-husband, sorry.

* * *

* * *

35

Her father. So there's no chance of placing her with him? Don't forget, this might work out well for you, too. As you say, it's a terrific strain being a full-time graduate student, working as a teaching assistant, and raising a troubled teen. She's your last, isn't she?

Ms. Parkes, it's only temporary.

Oh, Mrs. Toland, I've been meaning to visit. The police were by and told me about what Linda did, and I just want to say, if there's anything I can do What happened exactly? The police said she burned some of your things. Why would she do a thing like that? The kids say she's been arrested and taken to Juvenile Hall. What are they charging her with? When's the trial? How's she taking it? What will happen to her do you suppose? I only ask because I'm concerned. This is no time for false pride. Now's the time to accept help from your friends, Mrs. Toland. What? Parkes?

Will you kindly tell the court the value of the burned items? I understand that to you they're invaluable, four years of notes, et cetera, but tell us in dollars and cents. Well, were they for publication? Did you have a contract for any of the material? How much income have you earned from your writing in the past year? Make it two dollars for the notebook. What, Ms. Parkes? Ink? Make it a dollar for the pen, and we'll stipulate a total value of the burned items at three dollars.

Young lady, this is a serious proceeding. If you insist on laughing, we'll have you removed and conduct this hearing without you. What's so funny? Nothing? Well, your mother's over there crying, I don't think she finds it amusing, and neither do we. May we have the Officer's initial report, please?

At 10:57 P.M. on the night of October 24, we were called to the student apartment complex at 31117 Columbia Way, where Mrs. Toland aka Parkes showed us a pile of ashes in the entrance hall. She reported that the burned items were letters from childhood friends, a high-school diploma, two journals and a diary, and I quote, "in which I've tried to

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

36

make some sense out of the last four years of my life," end quote. A group of teenagers in the complex reported that Linda's mother set the fire in order to get Linda into trouble.

In summary, I examined Linda Toland at the request of her Probation Officer on November 12 and November 15. Her performance on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale was over 140, a very superior result. On the MMPI her Lie Scale was sufficiently elevated to invalidate the other findings. The Rorschach protocol shows defense mechanisms of projection, intellectualization and denial. There was a strong undercurrent of hostility toward her father, which in my view is displaced on to her mother since she returned to school. Linda feels rejected by both parents as a result of their divorce, and she is acting out hostile impulses in the home, the school, and through forbidden activities with her peers.

In conclusion, her id processes are erupting through immature ego defense mechanisms which the weak superego is powerless to preventall a result of incompetent upbringing and insufficient identification and introjection of parental norms.

My diagnosis is borderline personality disorder with sociopathic tendencies. Prognosis in these cases is not good; however, her high intelligence could be a mitigating factor if she procures adequate treatment.

According to the Police Chief's interview with Linda's mother, her problems with Linda are of long standing and include drug and alcohol usage, possible sale of drugs, truancy, promiscuity of which the mother apparently approves, and incorrigibility.

Ms. Parkes, it's in the record, and I caution you not to interrupt these proceedings again.

Supermom neglectful and incompetent? That's funny, really funny. Like the world, Mom has always been too much with us.

* * *

* * *

* * *

* * *

37

It was just so funny. Everyone was so serious, and here I was on the stand, a celebrity practically. I can't remember when so many people fussed over me, and I have my own lawyer and everything. It's like I'm an actress, and the part I have to play is juvenile delinquent, oh wow! I know I'm supposed to act the part-tough, freaked-out, dumb. But that's not me.

Am I supposed to go home with you now? Or do we just wait here in the hall until they bring my things?

Oh, Mom's just crying because she's sentimental. Mom's a very senti, mental person. I knew just what to burn.

Mrs. Toland? I mean, Parkes? This is Linda's advisor at Grant High. I guess you know we haven't seen much of Linda this year. She's not going to make it into college with her present record. Some of the parents tell me Linda's in a jam. They say she's in juvie. What a shame! She was always such a bright, talented girl, so pretty and enthusiastic. I always liked Linda. She had such a charming smile. What? Yes, I know she isn't dead.

Please, both of you, sit down and make yourselves comfortable. As I explained on the phone, this is the intake interview which we always do here at Children's Protective Services to try to understand the problem. Counseling is a condition of foster placement. Otherwise, Linda, you'd have to return to juvie.

Now, Mrs. Toland-Ms. Parkes? You're remarried? Oh. Why did you take back your maiden name? I imagine that sometimes gets confusing for you, Linda, having your mother stop using your name?

Now, I understand you're a student and work, Ms. Parkes? So you probably don't have much time to spend with Linda? Communication in families is so important. If you're hardly ever home, she's bound to get into trouble. Yes, long talks at night are nice, but they haven't been enough, have they? She did get into trouble. Denial isn't particularly helpful.

If you're home and Linda isn't, how did that pattern get started? You see, there are patterns, and they generally start in childhood. No, her childhood. Yes, I can see how you might resent Linda being away so

* * *

* * *

* * *

38

much. She's a pretty girl. As we get older we start resenting our daughters. They're popular and have boyfriends. They're out on dates, while we're stuck at home, feeling over the hill. I don't mean you're over the hill, Ms. Parkes, though I imagine you feel that way sometimes? You don't? You needn't be defensive here. It's not particularly helpful. If you're jealous of your daughter, you can come right out and say it. That's what we're here for. I mean, your husband divorced you, you're stuck at home nights while your pretty young daughter is out. You're bound to feel rejected and resentful of your daughter's happiness. No? Well, let's move on, then.

You say you work, go to school, and keep house. Do you have any hobbies, any fun out of life? What do you do to pleasure yourself? You correct papers. I see. Well, that must be some fun. Why did your husband divorce you? O.K., pardon me, why did you and your husband get divorced?

Ms. Parkes, I'm the one who decides what gets talked about, and right now I think Linda's truancy, drug activities, lying, stealing, promiscuity and arson are beside the point. We treat the whole family. You see, the identified patient-that's Linda-got that way through her life situation. But her school, community, father, older sisters, and friends aren't here. You're the one who's responsible for her, Mom.

You don't like being called "Mom"? When did you first start feeling that way? How do you mean, I'm stereotyping you? You're feeling a little persecuted, perhaps? A little out of touch with reality?

Now, Linda, you don't have to defend your mother. She can't hurt you anymore. Well, it was probably so long ago you don't remember. Really, Ms. Parkes, Linda, I must insist-come back here! Walking out isn't helpful at all!

I can really empathize with what you've been through. She's awfully tough to handle. Art and I have been foster parents for over ten years, and we've never had such a difficult teen, partly because she's so smart. I was going to bring her here with me to pick up the rest of her clothes and records, but she disappeared at the last minute. I think she's afraid of seeing you.

I drop in unexpectedly at school and at her fast-food job to check up on her. No, I don't mean you should have done that. No I'm not trying to tell you how you should have raised her. I'm just assuring you she's very closely supervised.

* * *

39

Oh thank you. I may look soft and speak softly, but there are rules, and she has to follow them if she doesn't want to go back to juvie, and she doesn't. Art's told her if she so much as gets pinkeye, he'll send her back. You see, we have that advantage. Of course, she uses eye dropsthey all do.

But, you know, there's a lot that's good about Linda. She's smart as a whip, gets along well with people, has a lot ofcharm. So I think, if you're going to take the blame for what went wrong, you should take the credit for what's right with her, too. That's only fair. No, I'm not being kind, I'm just being fair.

Art and I find our religion has helped us a lot over the rough spots. Do you believe in God?

I can't understand why your performance was so poor on your final exams. Your graduate record until now has been excellent. What happened? We all have our little personal problems. We can't let them interfere with our work. Everyone's praised your teaching highly until this quarter. Now, you're unavailable for student conferences and haven't corrected that last batch of essays. You're paid to do a job. I hope you can get your personal problems straightened out before you seriously jeopardize your standing here.

It's about time you cried, Debbie. It's been two months, and in all that time you haven't had a really good cry. Oh, I know you let the tears seep out, but you're always trying to stem the flow. It's had me worried. Let it all out, that's right. How's your weight? Are you eating better? That's good. Do the sleeping pills help? Down to one a week, that's good. I'd rather not renew them, it's too easy to get hooked.

Research shows crying releases brain chemicals similar to painkillers. You should feel very relaxed after a good cry. After all, this business with Linda has been like a death for you and there's grief work to be done. You've lost not only four years of creative work, but your daughter as well-that happy vision we all have of the ideal relationship with our child. You've had to face up to how far short the reality falls.

Good for you! I've been wondering when you'd start getting in touch with your anger. But, who sold you that bill of goods, Debbie? Motherhood's supposed to be the ultimate fulfillment. It wasn't, was it? And you sacrificed your gifts to be a mother. But who made that choice?

* * *

* * *

40

How is it a setup?

I see. You mean, you're told you're responsible for your child. But what with the schools, courts, the drugs out there, you feel powerless. You know there are good reasons why Linda can have birth control and abortions without your permission. Still, you're blamed. Does that make you feel clear? Of course, it doesn't.

Well, I know the financial inequity doesn't help. Yes, I hear you saying you've raised your daughter on practically nothing. Her father made his career while you were staying home with the children. Now, he's wealthy, has job security, health insurance, the whole bit. Just explain that he can afford all these expensive gifts, and you can't.

I hear your anger, yes, Debbie, I hear it. But whoever told you life was fair?

My opinion? I think you did the best you could as a mother. Don't you? Well, even ifthat best wasn't very good, it was still your best, wasn't it?

That's real progress, Debbie. Next week, I'd like to see you wearing lipstick, if you feel up to it.

Mom, I can't stand living with Ann and Art, I just can't. Ann got mad at me for smoking in the house and pushed me down in the hall, and I hit my head and blanked out, and they thought I might have a concussion, and they had to wake me up every hour all night. And they make me do all the housework. Their own kids don't have to do a thing. And I just miss you, Mom. No, I'm not trying to get away from their discipline. No, I'm not trying to go back to spending nights with Wade. It's just they love their kids, and they don't love me, because I'm not their real family. Nothing can replace your family, Mom. I'm sure I can get my P.O. to let me live with you again, if you say I can, and I promise promise promise

Hi! Well, actually, no, I wanted to speak to you. I talked to Linda a few days ago. I guess you were at your classes. Sounds like she's doing great with you. Turned over a new leaf. Going to school, working, off the stuff. Sounds like those people at the Hall really straightened out the mess you made-not deliberately, I know.

Well, Linda and I were thinking, maybe she'd like to come down and live with me awhile. I could give her a few of the things she wants, a new

* * *

* * *

41

car, clothes, she'd be in the right neighborhood with the right people again. I know you want what's best for her. She could keep house for me. Now that the other two are in college, I never see them except at Christmas. And you'd have a chance to pursue that promising career of yours in peace.

Yes, I know it's much easier, now, or I wouldn't be suggesting this, ha, hal

Dear Mom,

Things are going great down here. I got a used silver BMW and my own charge card. And I got into State U. I miss Wade, but I have lots of other boyfriends. Sis says you got a new little place all to yourself and that you get to teach your very own course this summer. Congratulations!

There's something I've been meaning to ask you. It's no big deal. Just if you wanted to tell me, you could. Did you ever forgive me for burning those papers?

Love, Linda

* * *

42

-

"'� I' --{� � \t t � t " ' '" f:i:l>I� W 00 I .� a:� « U) Lt) , , \

I \ \ \ \

I\

•

I I

:. ,-.,,'-., .;-.i#JI",>,

I �=.. � 0", ;:J� Cl)O:cn 0: a: 0 alo� =Q o :;ii if, � , "0," j, �iI!'! f-� �< > '-....._ ex Q.,. o 11") I I I

\

, ••••• ••••• II' I II. I II II ••1 II JI f • " II 'Ill ., II fj II II II II II If .t !

Democracy: Chapters in Verse

Fanny Howe

If you have no expectations, you can't be disappointed. - a survivor of Hurricane Andrew

1

After the storm the word WATER kept rising and circling the color oil. The snow of the ocean blued and whirled. There was water in all the machinery. Waves knocked a water tower into a boat thrown off-course by the hurricane. A ruined deck and dock, trees uprooted from the heaving ground.

2

Gloved and cycling, the worker leaves the house. His forehead is gleaming like David's. The ground can hear his motions, the grass divides. Pink hibiscus in the mist: for many like him all this has been hellish. Compressed by the cosmos, not embraced, he knows the dread that can't say yes.

59

3

It's as if money's eyes are located inside a pyramid. Unfit for the rest of human habitation. Not like a cone, generously spilling, he decides, passing a blind couple walking, sighted child between. Hard luck stories are never boring.

4

After a storm there's a powerless period, when the word POWER keeps repeating, and when will the clock go on in the kitchen and the trees finish falling in the mind. He recalls his mother whose days have the resonance of drums played on the shins of a lazy teen. Her nouns are thoughtless as shoes to be worn till the soles of the feet show. To begin again where? Near the pink dollop at the back of the tongue.

5

The playing field is disheveled. His anger's target is on his way to a party near the drive-by harbor slow-boated by boys in motorized canoes. His power is out. Only cars fathom the between, obsolete as soon as seen. Nothing tech can stay: rust of entropy edges even a bloated bike tire laid out on a stump.

6

The worker's mother was always seeking the problem behind the fix and wanting him to solve it. With thread on her lip she, at home after work, nagged him. Meanwhile an orderly twilight inks the twinkles and the mathematics of stillness 60

is holiest when everyone is changing for bed, or in it. If a star is in her eye, she knows the star is finding itself, there, in her eye. Enlightenment is a level without measurement.

7

The worker played king on a bike through seven gates where trees lead to capitalist parties, cocktails and the kitsch of four cultures. The maid washed the dishes and spat in the chocolate. Fill in the blank where that man stood not a day earlier as Everylove to this woman at the end of her bed. Her maintenance since then: the wind, emptying-an emotion to lean on. Often in her melon-yellow uniform melancholy wouldn't quit her till she hit the kitchen and the dishes waiting to pay her.

8

Summer of the linoleum tulips. Storm entropied into drips. She will, for days after the gale winds blow over, bear fruit and bag her own vegetables. Friendship she offered others into the moon-hours, drink from supernatural grapes and potatoes. Rubber slicked on asphalt under the branches, saws attacked the remnants of trees. Her psyche cracked where a mirror made the candle brighter.

9

She is making a cake in the post-storm kitchen. Outside champagne rains air in a bottle. Desire simulates fire as sure as she has heard a voice in her ear call her. The head at her feetthe eyes in her palm-the supplicant dishes look up-

61

indications of Saint Monica wanting to appear in her consciousness. Ordinary time's daily prayer for the conversion of workers to angels.

But only pure prayer makes the air into an ear.

10

After the storm, the long-limbed oak trees twist. Corkish. They drank in kitchen wicker, and watched. Are those half-people or chairs at a bar? He held her ankles with his feet.

People are begotten from eternity, only to be returned. And the animals of Paradise?

Let fortune smile on them! Or: send someone to burn these monsters up. A person worthy of a sparrow's ashes. Together one night they hosed down his anger, and learned that a wound is only the edge of self-awareness.

11

At the capitalist party, the eros of a dress suggesting tips reinforces the connection between pyramids and money. Corks are unplugged from the green, which is then drunk with the savage concentration of bees wanting honey from a color.

Gossip evolves like a sourball growing smaller in a mouth.

12

Apparatus, don't be embarrassed by my life as a dishwasher. In an undeveloped tract, I too thought about meaning, and the body as a bit of technology. This put my little coffin aloft in a whirl of stars with the origin of numbers.

What if we destroy the earth?

What if I am never again touched? What if the weak are overcome?

62

What if winning is a sign of God's love? What if women made men so mean?

13

When you eat alone you don't exist for anyone but the dish. Like the spaniel (the dog of invincible obsession) you might stare fixedly into a water glass for hours.

14