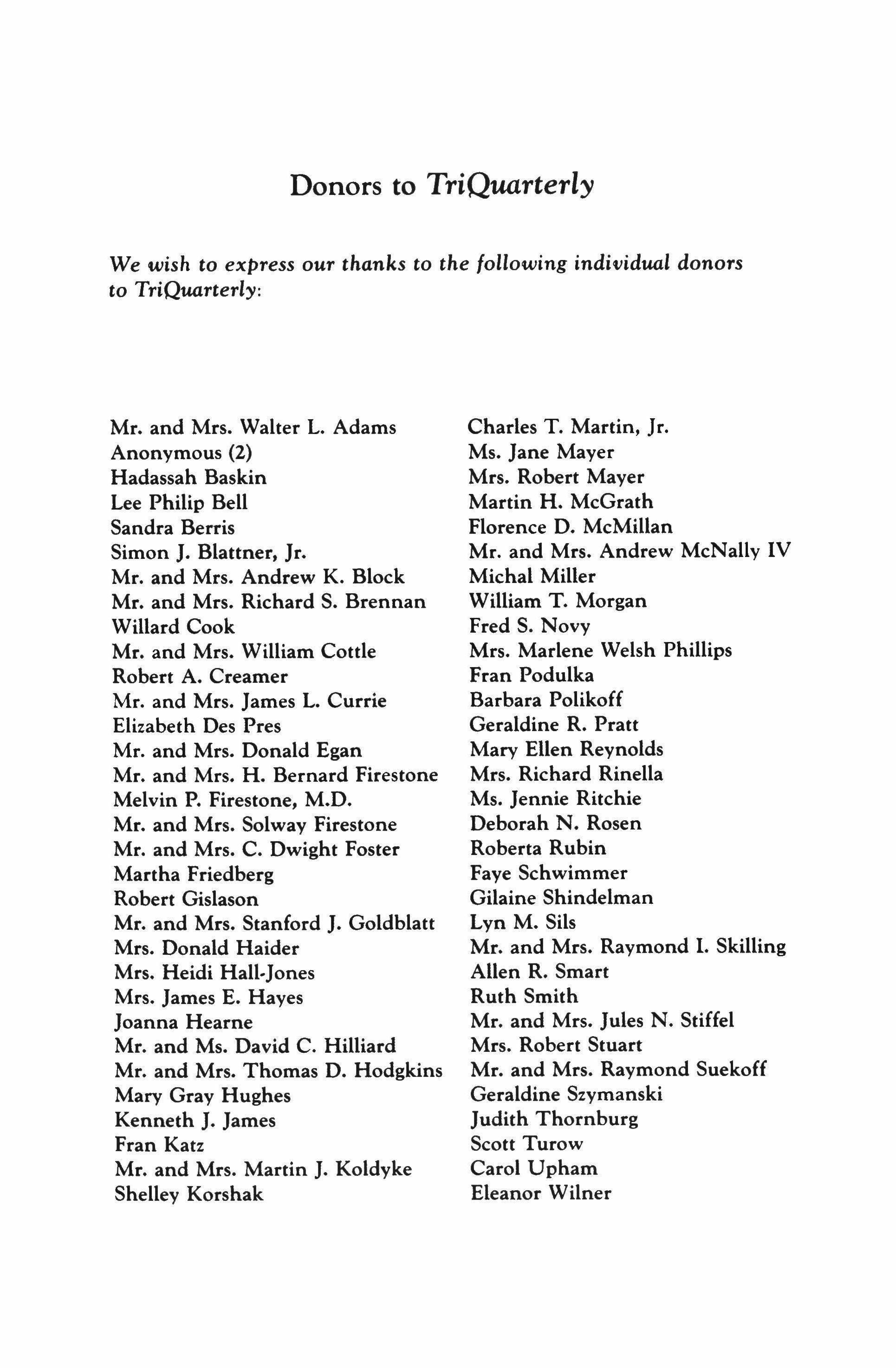

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and many individual donors. Major new marketing initiatives at TriQuarterly have been made possible by the Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Literary Publishers Marketing Development Program, funded through a grant to the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of donations, bequests and planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the inside back cover for names of individual donors to TriQuarterly.

Please sign me up for:

o a one-year subscription for $20.

o a two-year subscription for $36.

Foreign subscribersplease add $5 peryear.

Please begin my subscription with issue#

Please

o

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY!

Please

SUBSCRIBE TO TRIQUARTERLY!

life

Name Address. Or call US toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! BI86

o a

subscription for $500. o $ enclosed. o This is a renewal.

sign me up for:

a one-year subscription for $20.

two-year subscription for $36.

o a

please add $5

year.

Foreign subscribers

per

begin my subscription with issue# o a life subscription for $500. o $, enclosed. o This is a renewal. Name Address, Or call US toll-free at 800-832-3615 to charge it! BI86 GIVE TRIQUARTERLY! o $ Buy your first TriQuarlerly gift subscription for $20, and each additional gift subscription costs only $18!! 1st gift subscription ($20) Name Address Gift-card message Add $5/year forforeign subscriptions. enclosed. Name Address 2nd gift subscription ($18) Name Address Gift-card message BG86

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

TriQuarterly

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY

2020 RIDGE AVE.

EVANSTON, IL 60208-4302

SPRING 1993 BOOKS and selected backlist

EVAN ZIMROTH

Dead, Dinner, or Naked

March 1993

51/2 x 81/2 inches

80 pages

$15, cloth (0-916384-10-1)

$8.95, paper (0-916384-14-4)

We hear in these poems a song of tenderness, anger, intelligence and wit-a new, unsettling music that will not leave us alone. We hear a willful vulnerability. Evan Zimroth's erotic, intense poems are rooted in history, myth and everyday life. Her strong, singular voice makes us look where we might not have looked, see what we might have missed, face what we would avoid. She makes us think in surprising ways. Her poems speak from an unforeseen edge.

I love the combination of smartness, pain, and what one might call conscious postmodern trashiness in this book: a version of the erotic full of nervous tension that animates the sensuality, and also Zimroth's feeling for wordscompressed, ironic, withholding but also 'askingfor it...the siege, the thrill, the battle fatigue.' A profoundly urban book, of harsh memory and fantasy, set in harsher reality.

-ALICIA OSTRIKER

On Hearing That Childbirth Is Like Orgasm

So, maybe it's not a maiming altogether but some weird daylong fairy-tale as the door opens into a new chateau and the moat closes over behind you. It's magic: like pricking your finger, the pin just some new animal, for your pleasure; a kind of tickle, you don't feel it anyway having gone somewhere beyond pain, your body limp and blooming as an anemone, 0 the lush stories to tell! the extravagance! the irresistible rules! to be strapped to stirrups, your wrists chained Classier even than The Story of0 it's what the good fairy promised and the good girls get: the kiss in the turret, the happy-ever-after.

Evan Zimroth was born in Philadelphia, grew up in Washington, IX, and spent her teenage years dancing in the Washington Ballet. She received her Ph.D. from Columbia University, and her first book, Giselle Considers Her Future, was published by Ohio State University Press. She lives with her family in New York City.

New Writingfrom Mexico

Edited by Reginald Gibbons

Beginning in the 1960's, there has been a remarkable flowering of new writing in Mexico. A new generation of writers has come of age. Those writers, born around 1945 and after, have lived through the most dramatic political, social and artistic changes in Mexico's history; they have opened up fiction to new subjects, new places, new techniques; their poetry evokes and meditates on the Mexican reality more fully and more vividly than ever before. Notable among these new writers are the voices of women and the voices speaking from the provinces about their rich sense of place-away from the powerful cultural center of Mexico City. This large anthology is not a documentary representation or a survey, but a carefully chosen and scrupulously translated sampling of the most vigorous and exciting new short fiction, poetry and essays being written in Mexico today

a wonderful and timely anthology. Gibbons has gathered 58 of Mexico's most talented writers, and they are as diverse as their nation ln asking the question "What is Mexican?" and with the talented help of many translators, Gibbons has contributed a great deal to the understanding ofMexico.

-BOOKLIST

6 x 91/4 inches

448 pages

$27, cloth (0-916384-12-8), $15, paper (0-916384-13-6)

MURIEL RUKEYSER

Out of Silence: Selected Poems

Edited by Kate Daniels

In a recent article, someone defined the deplorable state of publishing (and the Republic) by a singlefact: Muriel Rukeyser's poetry was out ofprint. So this is not just another book: it is a restitution. Muriel Rukeyser held her ground at the bloody crossroads ofpolitics and art; she gave the word "witness" poetic weight. The first of our women poets to enter and engage the Western tradition ofprophetic outrage, she warmed it with the living voices of the injured. And in her activism and generosity, Rukeyser was as good as her word. She said it best: "It is a great thing to hear the words of those who are worthy to speak them."

-ELEANOR WILNER

The publication ofOut of Silence is an event worthy of celebration. Finally one of this century's most distinguished, misunderstood and undervalued poets is back in print The time for a just estimate ofRukeyser's contributions is long overdue. Out of Silence is a necessary start.

-THE WOMEN'S REVIEW OF BOOKS

63/4 x 10 inches

192 pages

$28, cloth (0-916384-11-X)

$14, paper (0-916384-07-1)

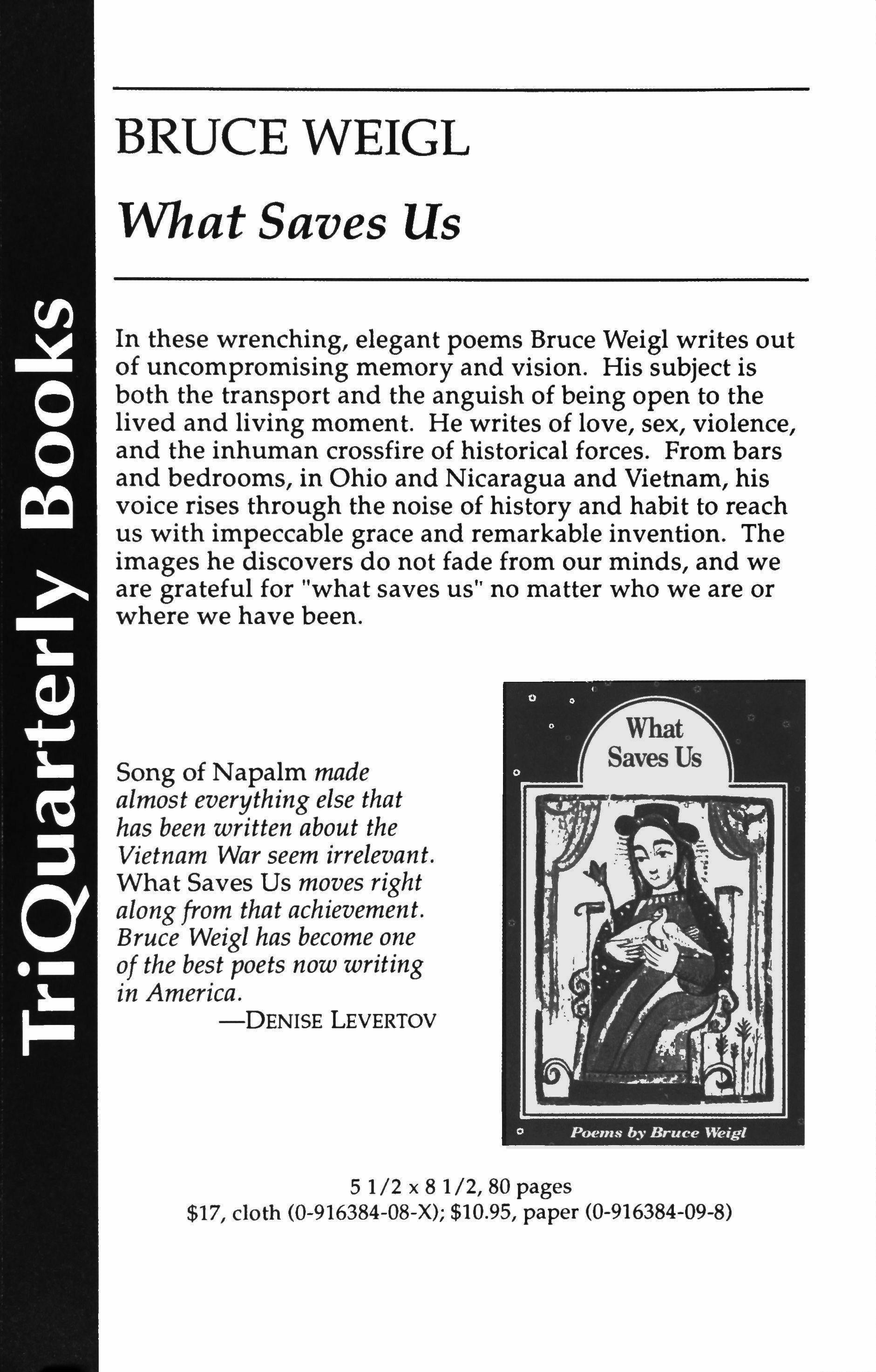

BRUCE WEIGL

What Saves Us

In these wrenching, elegant poems Bruce Weigl writes out of uncompromising memory and vision. His subject is both the transport and the anguish of being open to the lived and living moment. He writes of love, sex, violence, and the inhuman crossfire of historical forces. From bars and bedrooms, in Ohio and Nicaragua and Vietnam, his voice rises through the noise of history and habit to reach us with impeccable grace and remarkable invention. The images he discovers do not fade from our minds, and we are grateful for "what saves us" no matter who we are or where we have been.

Song of Napalm made almost everything else that has been written about the Vietnam War seem irrelevant. What Saves Us moves right alongfrom that achievement. Bruce Weigl has become one of the best poets now writing in America.

-DENISE LEVERTOV

51/2 x 8 1/2,80 pages $17, cloth (0-916384-08-X); $10.95, paper (0-916384-09-8)

LINDA McCARRISTON Eva-Mary

Eva-Mary

Winner of the 1991 Terrence Des Pres Prize forPoetry

NOW IN A THIRD PRINTING!

An extended poetic meditation on suffering and change, on cruelty and innocence, on love and endurance. Exploring what she calls "acculturation in ignorance," McCarriston writes of parents and children, the natural world and domestic and sexual violence; in so doing she powerfullyreshapes her emotional inheritance and creates a passionate form of survival.

51/2 x 81/2 inches

80 pages $10.95, paper (0-929968-26-3)

An immensely moving book, fearless in its passion. Linda McCarriston accomplishes a near miracle, transforming memories of trauma into poems that are luminous and often sacramental, arriving at a hard-won peace.

-LISEL MUELLER

Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

Linda McCarriston

GORDON WEAVER

Men Who Would Be Good

Alcoholism, violence, and free enterprise-all the damage that men can do is visible in thesefiercely comic and alarming stories

-CHARLES BAXTER

In this "diverse collection of masterfully written stories" (Booklist), Gordon Weaver explores with insight, intensity and humor the situations of seven men pushed to the limits of their lives. Weaver's earnest and passionate men have learned the rules for being good, but in following them they arrive at desperate and sometimes ludicrous ends.

Mr. Weaver combines powerful inventiveness with a giftfor exact observation. He gets the gritty details right He has a veryfine ear for ordinary speech and comradely jargon, which he twists brilliantly to reflect the deep unreality that pervades these lives Mr. Weaver has written a sad, sharp, unnerving book.

-NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW

51/2 x 81/2 inches

248 pages

$18.95, cloth (0-929968-17-4) $9.95, paper (0-929968-16-6)

Fiction of the Eighties

Edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn

A landmark anthology marking the 25th anniversary of TriQuarterly, this 592-page volume includes 47 of the best short stories to have appeared during the past decade.

Among those represented are Grace Paley, William Goyen, Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, Amy Hempel, Robert Coover, Joyce Carol Oates and many new writers. These stories range widely over the experience of modern life, and share a high level of artistry and an unmistakable atmosphere of the 1980's. An incomparable primer of the contemporary possibilities of fiction.

For contemporaryfiction [Fiction of the Eighties] is a standardbearer The multiplicity and depth of the fictional lives here are astonishing wisdom and wildness of writers too numerous to thank.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

6 x 91/4 inches 592 pages

$26.95, cloth (0-916384-05-5)

$16.95, paper (0-916384-06-3)

E.S. GOLDMAN

Earthly Justice

First winner of the William Goyen Prize for Fiction, E.S. Goldman brings to these stories a sure mastery of language and an eye for the often shocking moral dilemmas of everyday life. EarthlyJustice is filled with surprise, delight, devastation and poignancy.

Readers discovering E.S. Goldman for the first time will be delighted by this debut collection of short stories and by the depth and variety of the characters who inhabit them.

-PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

Earthly Justice deserves a place on the Americana bookshelf next to Winesburg, Ohio and Spoon River Anthology.

-CHICAGO TRIBUNE

Seldom do short stories leave the reader with so much to think about The characters are ordinary, their concerns universal, and their behavior satisfyingly bizarre.

-Los ANGELES TIMES BOOK REVIEW

EarthlyJustice

by E. S.Goldman

51/2 x 81/2 inches

208 pages

$17.95, cloth (0-929968-13-1) $9.95, paper (0-929968-14-X)

STANISLAW BARANCZAK

The Weight of the Body: Selected Poems

The first winner of the Terrence Des Pres prize for Poetry-these trenchant poems evoke the difficulty of life in Poland before the revolution of 1989 and the sadness of exile. Their astonishing force makes it possible for us to feel how it was in Poland, and-from a special point of view on our own society-what it is like to be living in the U.S. now.

74 pages

$16.95, cloth (0-929968-02-6)

$8.95, paper (0-929968-01-8)

The Collected Poems ofSterlingA. Brown

Edited by Michael S. Harper

Sterling A. Brown is a legend among writers, teachers and readers-an extraordinary poet, the founder of AfricanAmerican literary criticism and a great teacher and scholar. His poems have brought neglected but essential and precious subjects, tones of voice and poetic techniques into American poetry, and remain a living testament that will be read for generations.

280 pages

$12.95, paper (0-929968-07-7)

The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown

\\ mner of the Ierrence [), 1'"-s Prize for Puct!")

I.dll<,d hi! /'dlcihlc/ C; H.71per

Stephen Deutch, Photographer: From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989

The gift book-with stunning photos of Chicago over decades of change, including Deutch's Pulitzernominated photos from the Daily News. This collection and analysis of Deutch's work, with plates both in duotone and in color, is the first full record of Deutch's achievement to be published.

144 pages

$45, cloth (0-929968-05-0)

$23.50, paper (0-929968-06-9)

Writers from South Africa

Based on the proceedings of a literary conference hosted by TriQuarterly magazine and Northwestern University in the autumn of 1987, this collection of speeches and dialogues by fourteen leading South African writers, poets and intellectuals opens up the world of contemporary South African literary culture to U.S. audiences, outlining such concerns as writing and censorship, worker poetry, the place of poetry in society and many others.

Writers from South Africa

128 pages $6.50, paper (0-916384-03-9)

Ste

Pho 1932-J989

De

CULTURE, POLITICS AND LITERARY THEORY AND ACTNITY IN SOUTH AFRICA TODAY '; ,., t. [��·_�'t�..-·�:f � l.

SELECTED BACK-ISSUES

of TriQuarterly magazine

#22 Leszek Kolakowski: co-edited by George Gomori. The first translations into English of this important Polish philosopher. 256 pp.$5.

#25 Prose for Borges: a special issue with an anthology of writings by Jorge Luis Borges and essays and appreciations by Anthony Kerrigan, Norman Thomas di Giovanni and others. 468 pp. $10.

#31 Contemporary Asian Literature: co-edited by Lucien Stryk. With Lu Hsun, Chairil Anwar, Ho Chi Minh, Shinkichi Takahashi, Yasunari Kawabata and others. 244 pp. $S.

#35 A special boxed two-volume set-Minute Stories: eightyseven tiny fictions by W. S. Merwin, John Hawkes, Max Apple, Richard Brautigan, Annie Dillard and others. 112 pp. Selected Poetry: German, American and French poetry selected by Michael Hamburger, Michael Anania and Paul Auster. 120 pp. $S/set.

#39 Contemporary Israeli Literature: fiction by Amos Oz, David Shahar, Yehuda Arnichai, Pinchas Sadeh, A. B. Yehoshua. Poetry by Arnichai, Dan Pagis, Abba Kovner and others. Afterword by Robert Alter. 342 pp. $S.

#47 LovelHate: fiction by Robert Stone, Oakley Hall, Joyce Carol Oates, Angela Carter, Herbert Gold, Alfred Gillespie, Victor Power and seven more. Photographs by Diane Blell with Stephen Sanders. 352 pp. $6.

#54 A John Cage Reader: color etchings by Cage plus contributions celebrating his seventieth birthday from Marjorie Perloff, William Brooks, Merce Cunningham and others; fiction by Ray Reno, Arturo Vivante and others; poetry by Teresa Cader, Jay Wright and Michael Collier. 304 pp. $6.

#57 A special two-volume set-Vol. 1, A Window on Poland: featuring essays, fiction and poems written during Solidarity and martial law. Tadeusz Konwicki, Jan Prokop and others, with photos and graphic works. 128 pp. Vol. 2, Prose from Spain: recent fiction and essays, plus an interview with Juan Goytisolo and eight color pages of street murals. 112 pp. $4Ieach vol., $8Iset.

#59 The American Blues: fiction by Ward Just, Joyce Carol Oates, Gayle Whittier and others; poetry by Bruce Weigl, John Ciardi, John Frederick Nims, Maxine Kumin and others; photographs from Vietnam and of American political figures by Mark Godfrey; II Alberti and Others," a supplement of poetry and prose complementing Prosefrom Spain (#57, Vol. 2). 272 pp. $7.

#63 TQ 20: twentieth-anniversary issue, with fiction by James T. Farrell, Richard Brautigan, Stanley Elkin, Jorge Luis Borges, Joyce Carol Oates, Vladimir Nabokov, Cynthia Ozick, Raymond Carver, William Goyen, Lorraine Hansberry and others; poetry by Anne Sexton, Howard Nemerov, W. S. Merwin, Jack Kerouac, Marvin Bell and others; interview with Saul Bellow; illustrations and photographs. 684 pp. $13.

#65 The Writer in Our World: symposium featuring Stanislaw Baranczak, Terrence Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Leslie Epstein, Carolyn Forche, Michael S. Harper, Ward Just, Grace Paley, Mary Lee Settle, Robert Stone, Derek Walcott and C. K. Williams, with original work by most participants and by moderators Angela Jackson and Bruce Weigl; photographs. 332 pp. $9.

#72

General issue: stories by Norman Manea, Anne Calcagno, Sheila Schwartz and others; poems by Bruce Weigl, Jenny Mueller, Alan Shapiro and others; essay by C. K. Williams; special section of poetry and prose by John Peck. 224 pp. $8.

#73 General issue: stories by Sandy Huss, Carol Bly and Susan Straight; poetry by Anna Akhmatova, Michael Anania, Pattiann Rogers, Sterling Plumpp; special sections on Joyce Carol Oates and Wole Soyinka. 208 pp. $8.

#74 General issue: stories by Leo Litwak, Margaret Broucek, Donna Trussell, Angela Jackson; poetry by Sandra McPherson, Mary Kinzie, Czeslaw Milosz, Adrienne Rich and Eleanor Wilner. 272 pp.$8.

#75 Writing and Well-Being: memoirs, essays and poems by William Goyen, Paul West, Perri Klass, Gwendolyn Brooks, Nancy Mairs, Jay Cantor, Annie Dillard, Maxine Kumin, Paul Bowles, Reynolds Price and others. 208 pp. $8.

#76 General issue: fiction by Francine Prose, Christopher McIlroy, Ami Sands Brodoff; poetry by Rita Dove, Stuart Dybek, Lisel Mueller, Joseph Gastiger; memoir by Peter Kenez; essays by Robert Pinsky and others. 224 pp. $8.

#77 General issue: special section on Modern Indian Poems; interview with Samuel Beckett; fiction by Arthur Morey, David Michael Kaplan; poetry by Eavan Boland, Li-Young Lee, Maxine Kumin, Claribel Alegria. 336 pp. $10.

ORDERING INFORMATION

Individuals

If you are unable to obtain a TriQuarterly Book from your bookseller, you may order directly using the order form on the next page, byphoning 800/832-3615 or via FAX to 708/467-2096. Please include payment with your order and add $2 for postage and handling. Add 50¢ per book for quantity orders.

If you order 5 or more books, you are entitled to a 40% discount.

Trade

Please call us at 800/832-3615 for current distribution information.

Subscriptions to TriQuarterly magazine

TriQuarterly is available to individuals at the following rates:

1 year-$20 2years-$36 Life-$500

Subscribers may purchase additional gift subscriptions for only $17/year. Foreign subscribers please add $4 per year. You may subscribe using our order form, or via phone or FAX with a credit card.

Name

Subtotal. Discount.

Postage & handling, Total,

o Check enclosed (payable to TriQuarterly)

o Visa 0 Mastercard

Acct. no. Exp. date

Signature.

Shipping address ifdifferent from above (TQ Books make fine gifts!)

Name Address

Send

Order

Form Date

Quantity Price

Address Title

orders to: TriQuarterly Books, Northwestern University, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208-4302 Phone: 800 1832-3615 FAX: 708/467-2096

T�u1t<wi])f86

Editor Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Readers

Winter 1992/93

Co-Editor Susan Hahn

Assistant Editor Gwenan Wilbur

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Timothy Dekin, Campbell McGrath, Charles Wasserburg

TriQuarterly Fellow Deanna Kreisel

Advisory Editors

Editorial Assistants Matthew Kutcher, Sarah Kube, Hans Holsen

Hugo Achugar, Michael Anania, Stanislaw Baranczak, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year)-Individuals: one year $20; two years $36; life $500. Institutions: one year $26; two years $44; life $300. Foreign subscriptions $4 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-3490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and March 31; manuscripts received between April 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1993 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore, typeset by Sans Serif. ISSN: 0041-3097.

National distributors to retail trade: Ingram Periodicals, 1117 Heil Quaker Blvd., La Vergne, TN 37086 (800-627-6247, ext. 4500); B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110 (201-667-9300). Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415-549-3030).

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. TriQuarterly is indexed in the Humanities Index (H. W. Wilson Co.) and the American Humanities Index (Whitson Publishing Co.).

We are very pleased to announce that TriQuarterly Books, edited by Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn, will now be published as an imprint of Northwestern University Press. TriQuarterly Books will include new poetry, fiction and other literary titles.

TriQuarterly Books is pleased to announce that the third winner of the biennial Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry is Timothy Russell. His book, Adversaria, will be published by TriQuarterly Books I Northwestern University Press in November 1993. Russell will receive a cash award of $3,000. Stanislaw Baranczak won the first Terrence Des Pres Prize in 1989 for his collection of poems, The Weight of the Body, and Linda McCarriston won the second Terrence Des Pres Prize in 1991, as well as a National Book Award nomination, for Eva-Mary. The Terrence Des Pres Prize alternates by years with the William Goyen Prize for Fiction.

"Red Lipstick," a story by Yolanda Barnes which appeared in TQ #81, has been included in Pushcart Prize XVII: Best of the Small Presses (1992-93 edition), published in cloth in October 1992 and forthcoming in trade paperback from Touchstone Books I Simon and Schuster in March 1993.

"The River Dwight," a story by J. H. Hall which appeared in TQ #81, has been selected for inclusion in Rivers of Dreams, an anthology of fishing stories, edited by Robert Lyon and forthcoming from Orca Book Publishers, Ltd., in the spring of 1993.

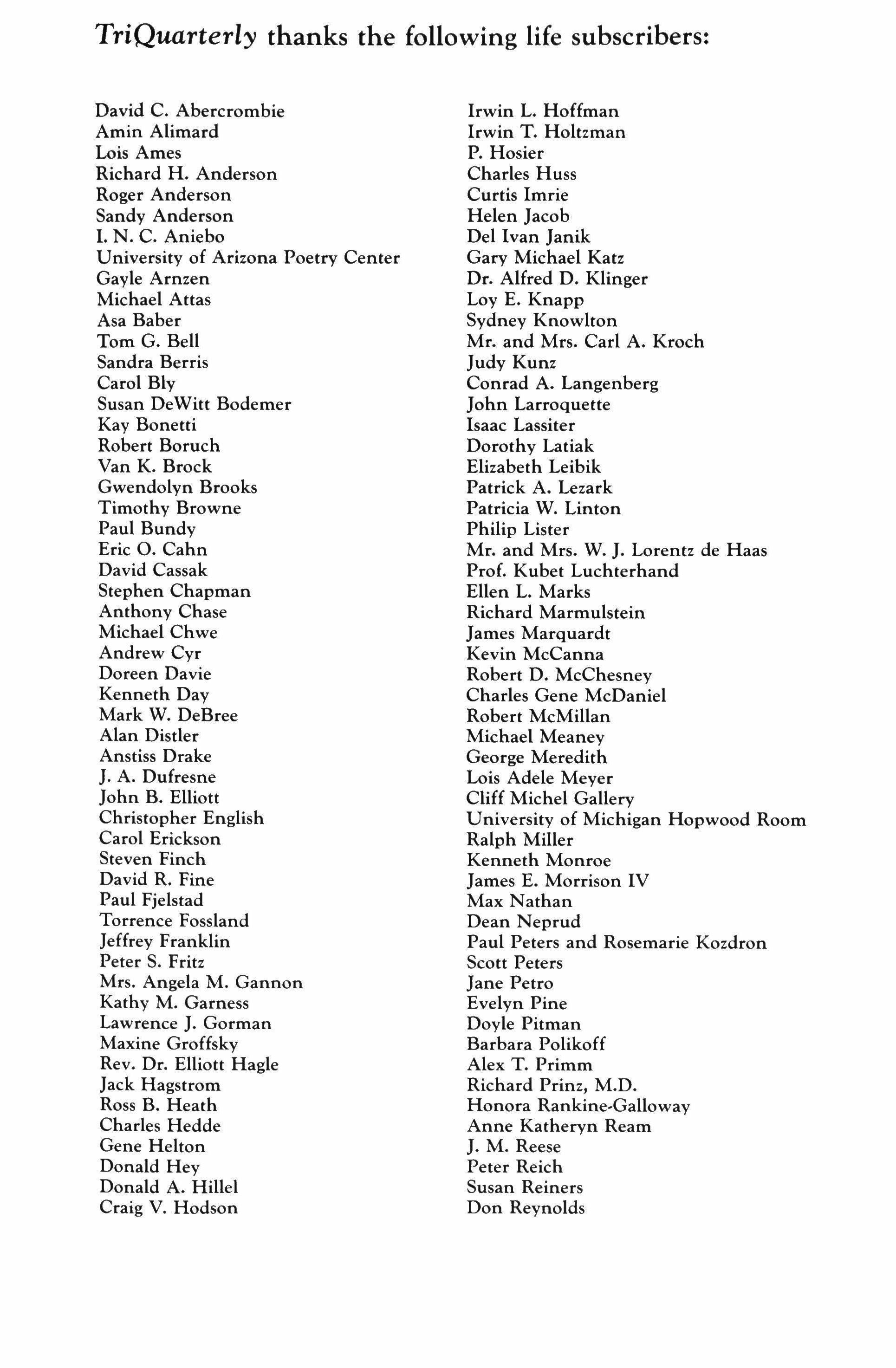

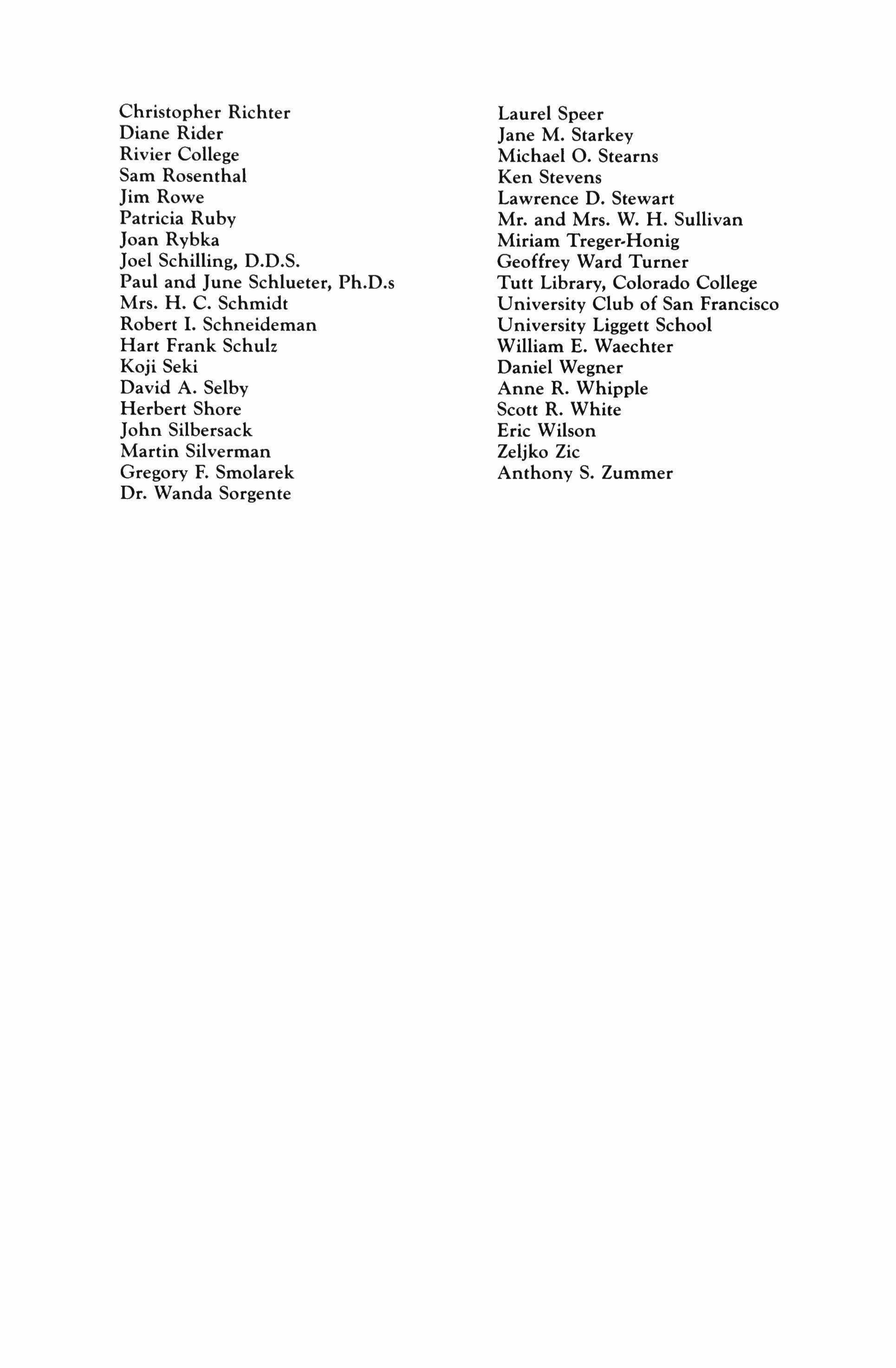

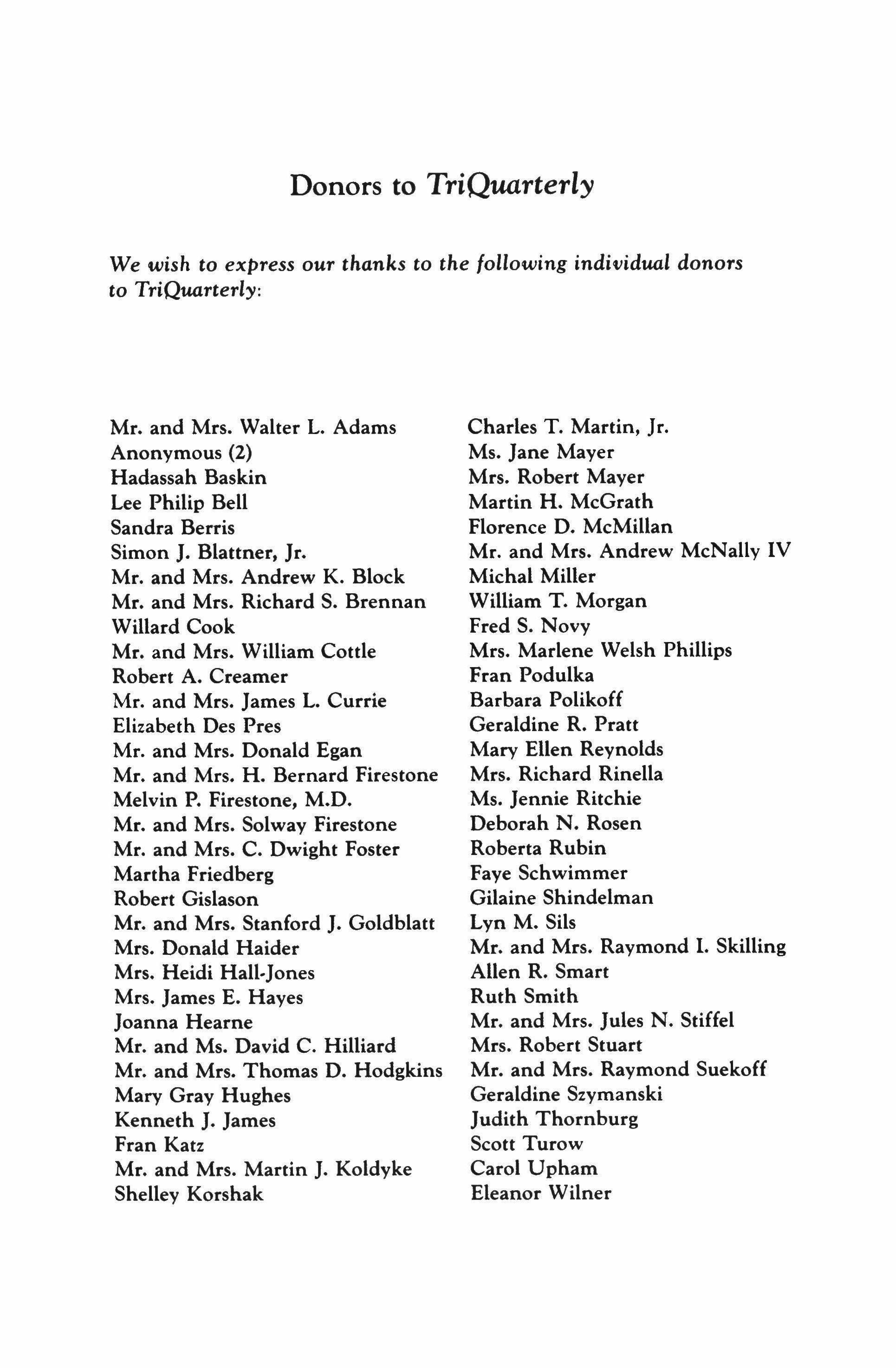

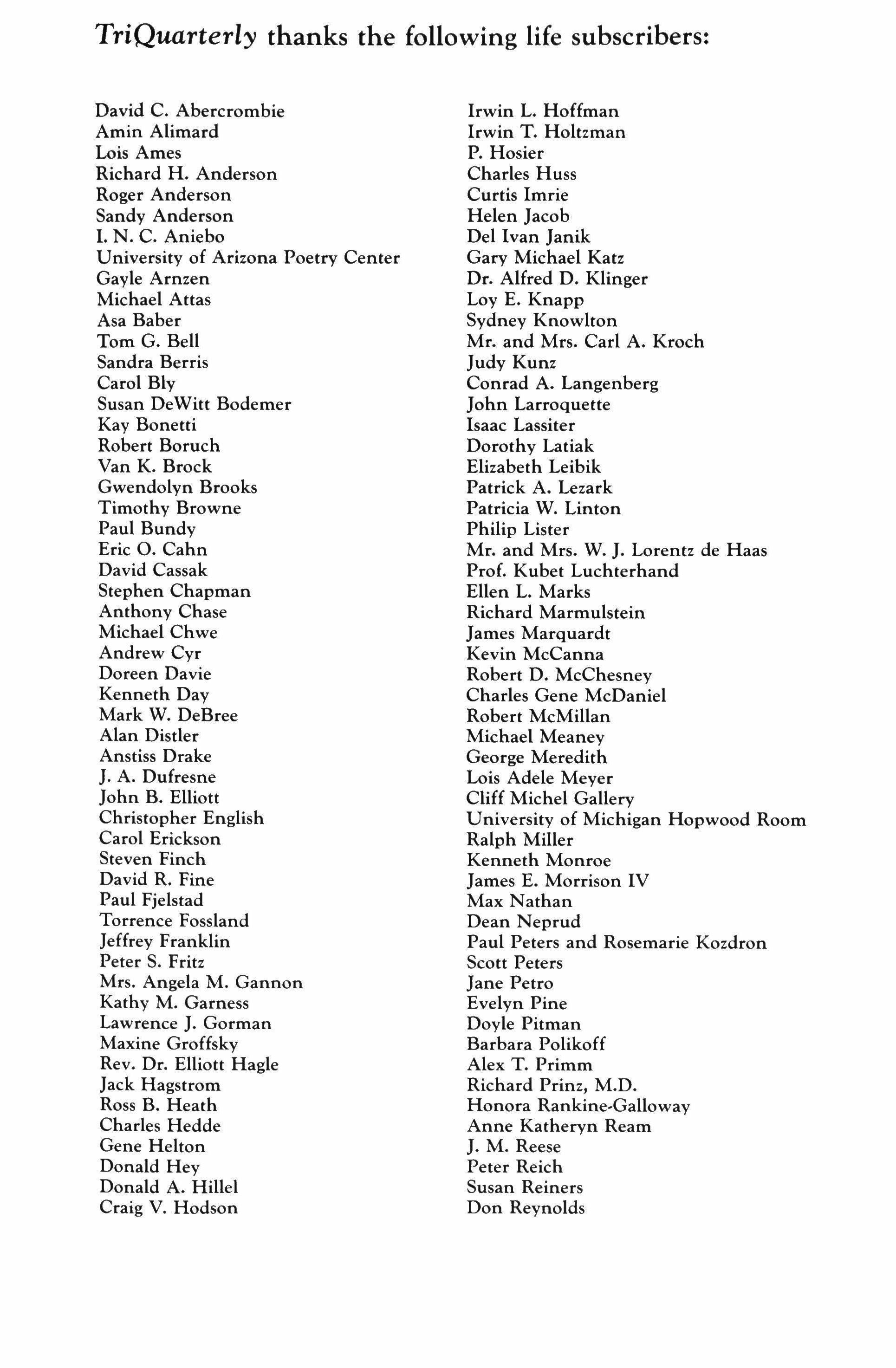

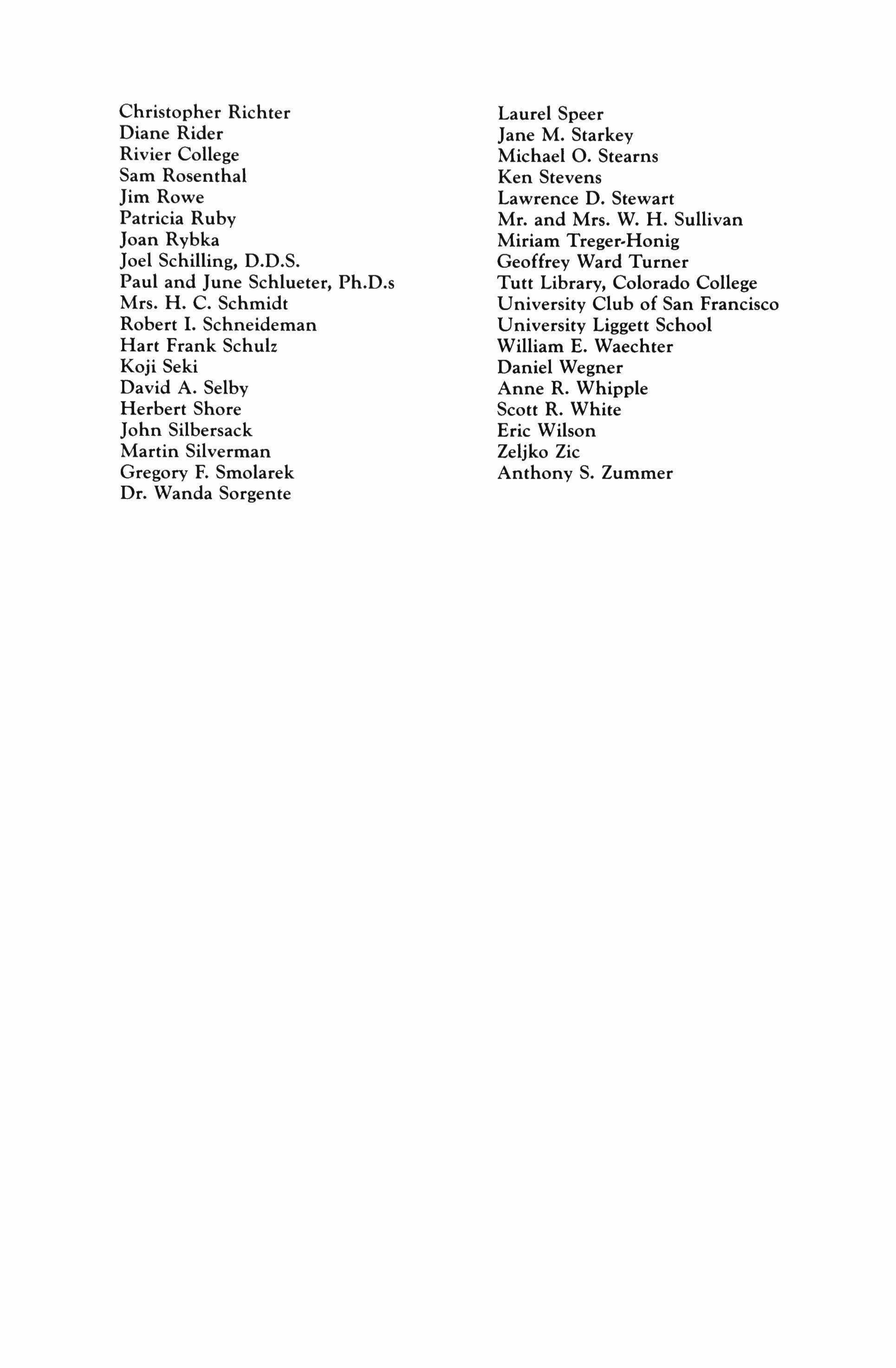

TriQuarterly welcomes life subscribers to the magazine. Life subscriptions, at $500 each, are a major source of support for TriQuarterly, and are acknowledged in every issue.

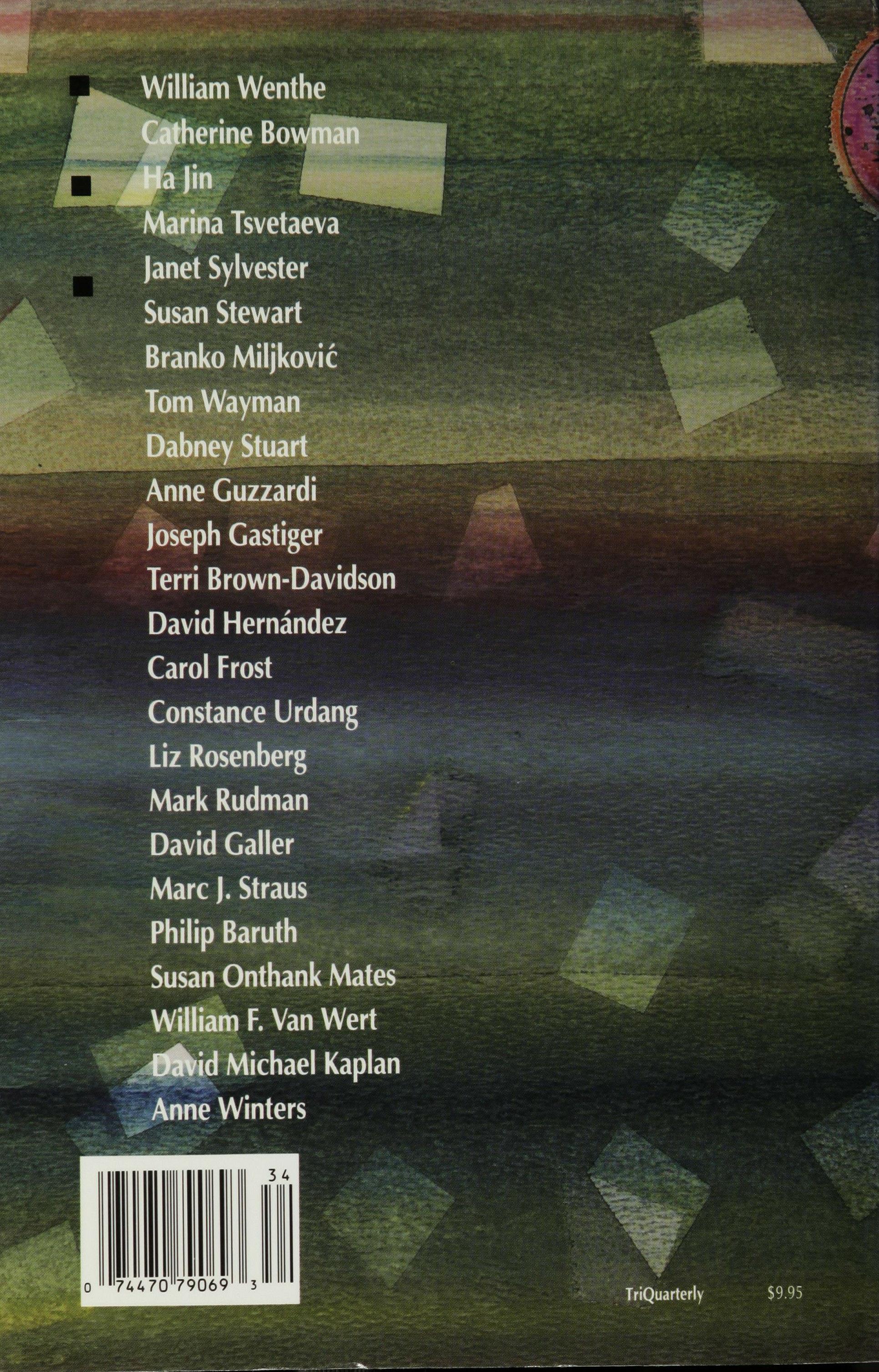

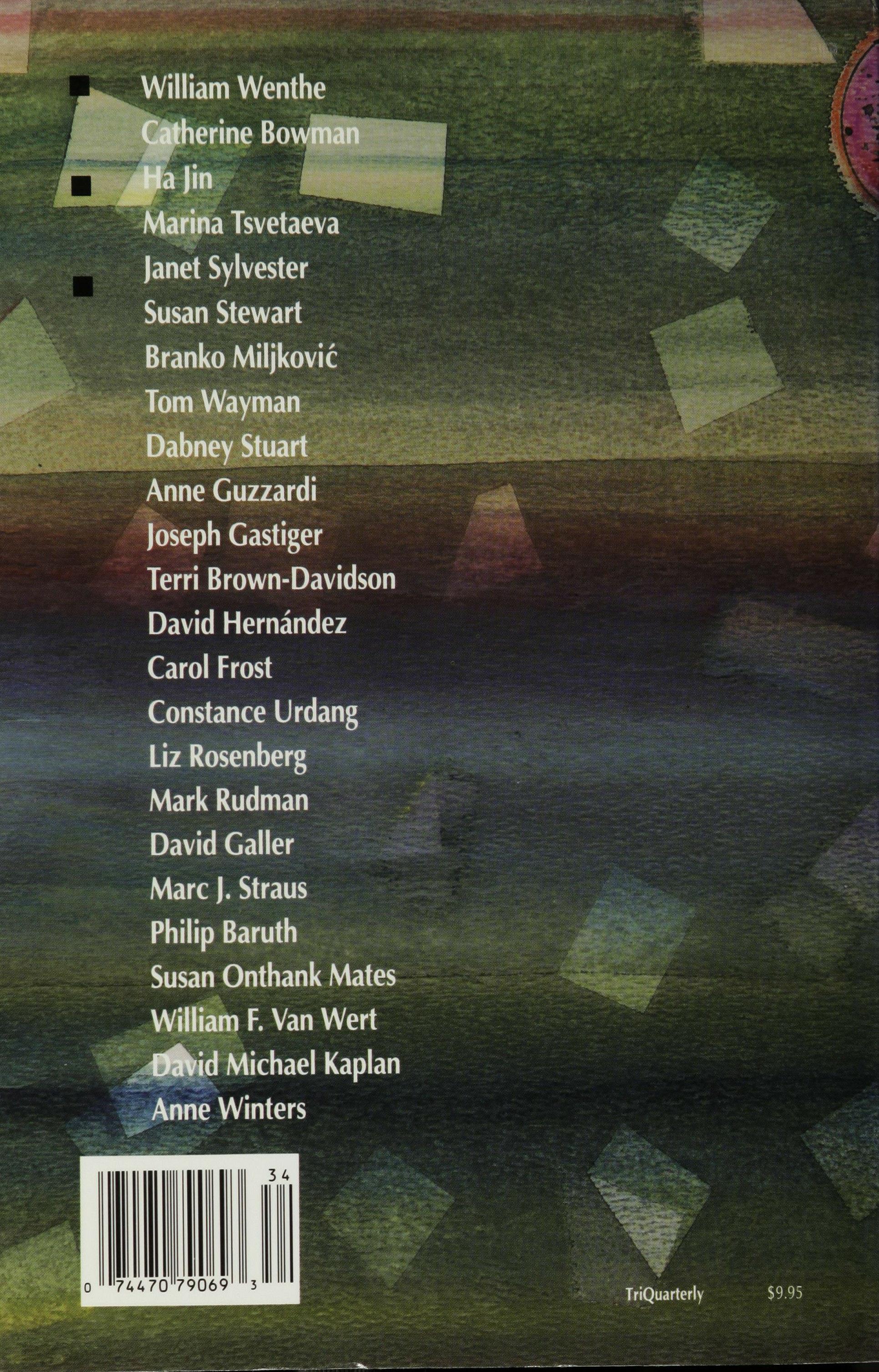

Contents Editors of this issue: Reginald Gibbons and Susan Hahn POETRY Fictions 23 William Wenthe Demographics 25 Catherine Bowman If You Had Not Thrown Me Away HaJin 27 [Untitled] 28 Marina Tsvetaeva The Mark of Flesh 30 Janet Sylvester Goddamn Theology. 32 Pattiann Rogers The Forest; The Meadow 34 Susan Stewart Inventory of a Poem; While You Are Singing; An Orphic Legacy 39 Branko Miljkovic The Iceberg, the Shadow. 42 Tom Wayman Percussion 45 Dabney Stuart The Kiss; Wake 47 Anne Guzzardi Bluegum: On the Curving Paths of Golden Gate Park 50 Sandra McPherson 19

"I Love You Sweatheart"; Emily's Mom; An Horatian Notion; Autobiographical Thomas Lux Half an Hour Before the War 59 Joseph Gastiger Block Bebe 62 53 Terri Brown-Davidson Florencia 64 David Hernandez Harm; Pure 66 Carol Frost The River-Keeper's Song Constance Urdang The Silence of Women Liz Rosenberg 68 69 Notes on Atonement Mark Rudman The Children 81 David Galler 70 Lecture to Second-Year Medical Students; The Log of Pi; St. Maarten Vacation 84 Marc J. Straus You, If No One Else; Promised Lands; Convocation of Words. 91 Tino Villanueva Black Hat; The Siesta; Dancing Richard Jones 98 FICTION The Tour of Helen 120 Philip Baruth Theng 137 Susan Onthank Mates The Function of Description. 144 William F. Van Wert Turk 165 David Michael Kaplan 20

SPECIAL SECTION

Poetry and Second Thoughts; Sappho: A Garland; Afterwords on Sappho 209

Jim Powell

OTHER PROSE

Writing Poetry at the End of the Century: A Letter 103

Joseph Parisi

From Always Running [Gang Days in L.A.] 259

Luis J. Rodriguez

Perfect Strangers [Encounters with the Homeless] 282

Laurie Stone

Research in the Absolute: Robert Pinsky, The Want Bone; Frank Bidart, In the Western Night: Collected Poems 1965-70 (reviews) 302

Anne Winters

CONTRIBUTORS 311

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

Cover art: Dreamscape by Tino Villanueva (watercolor and pencil, 1989)

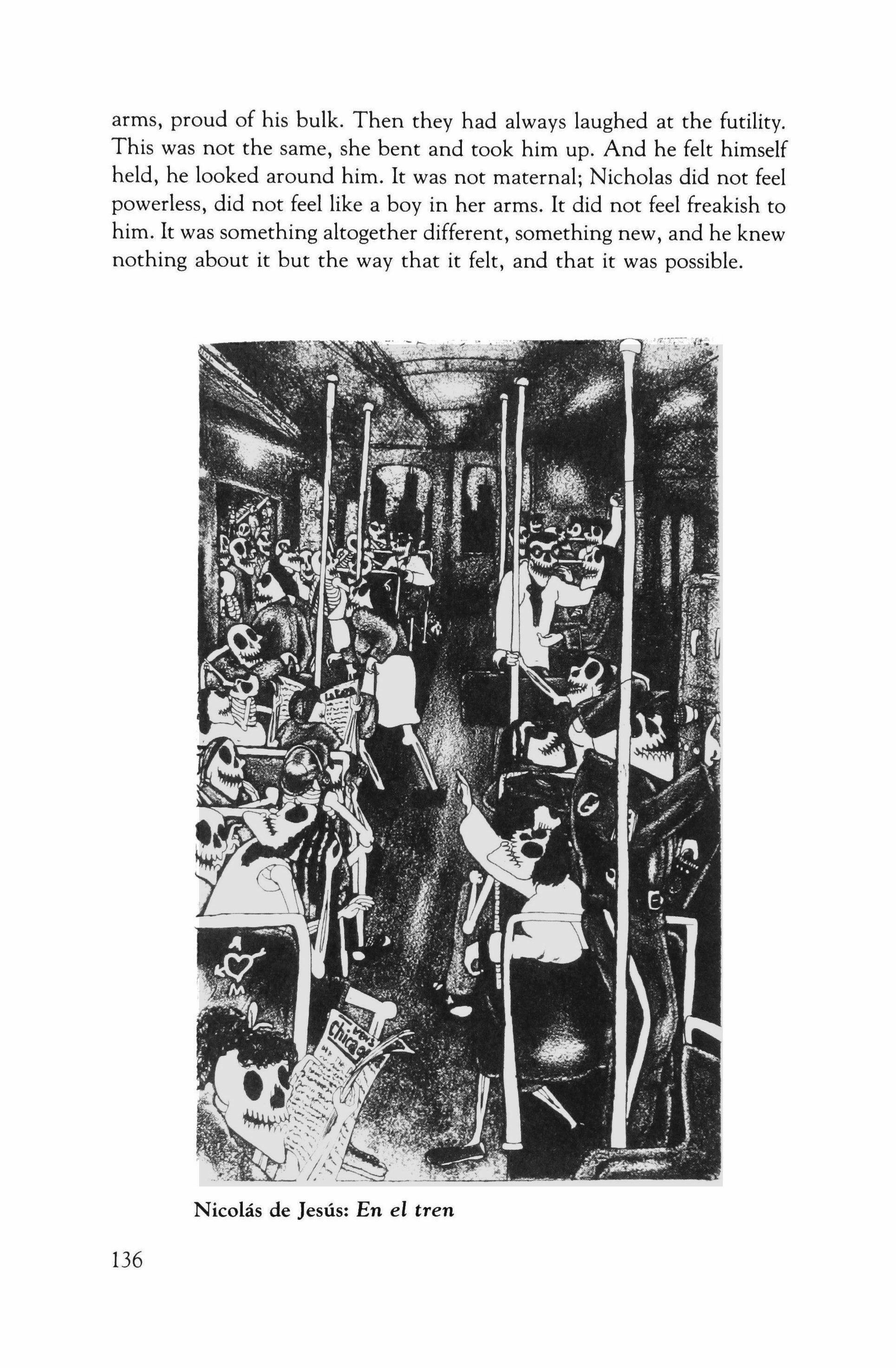

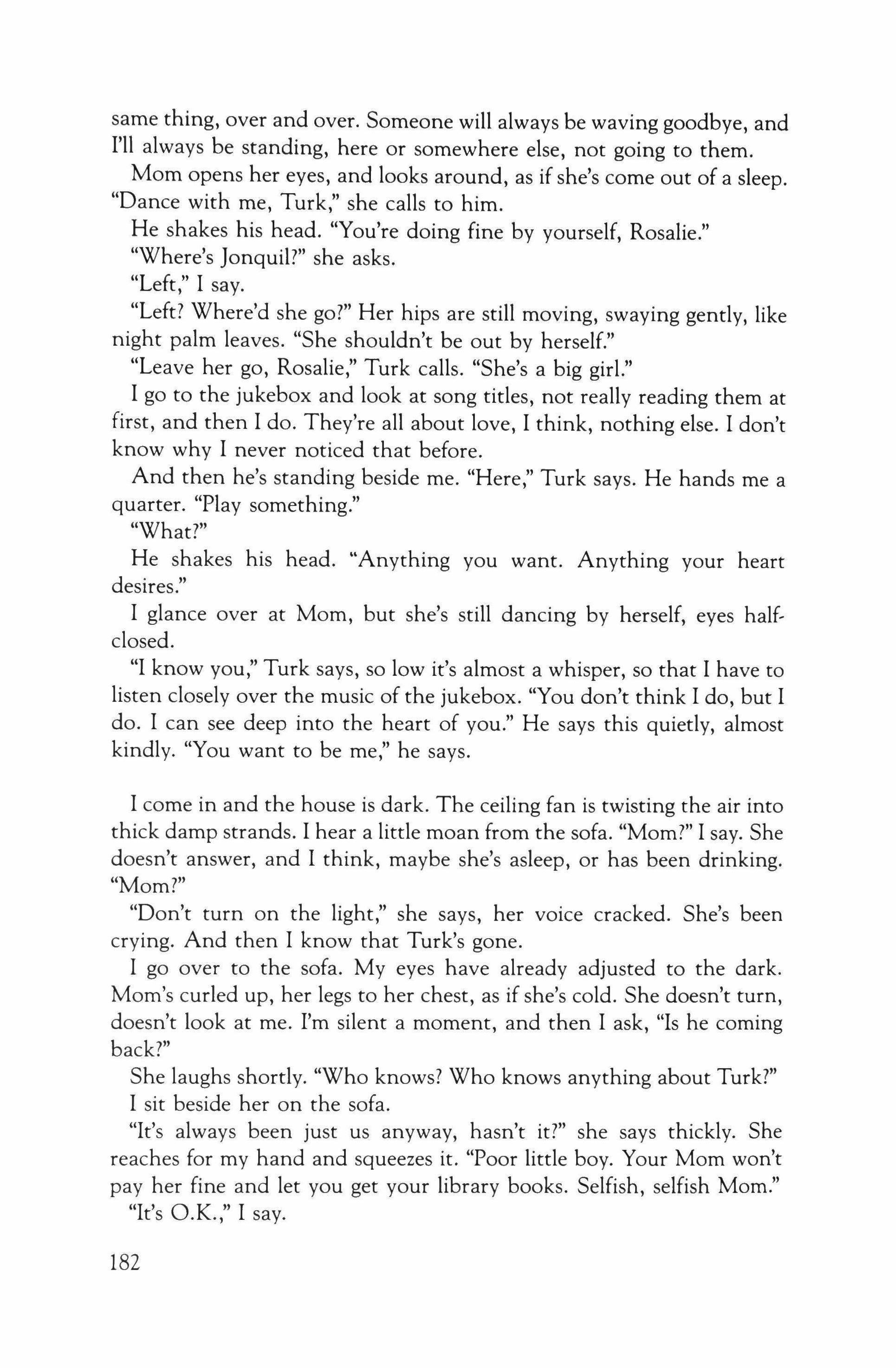

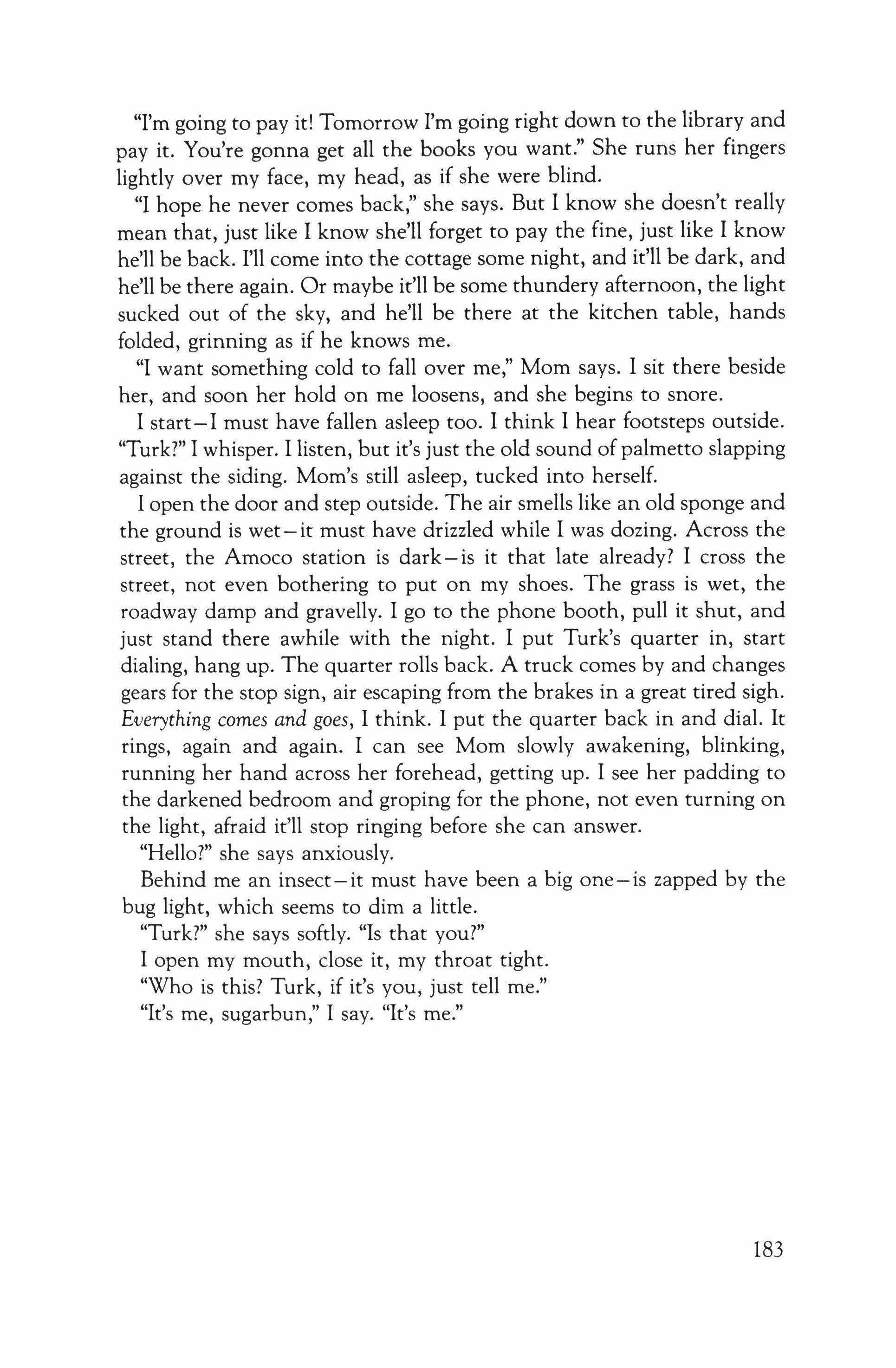

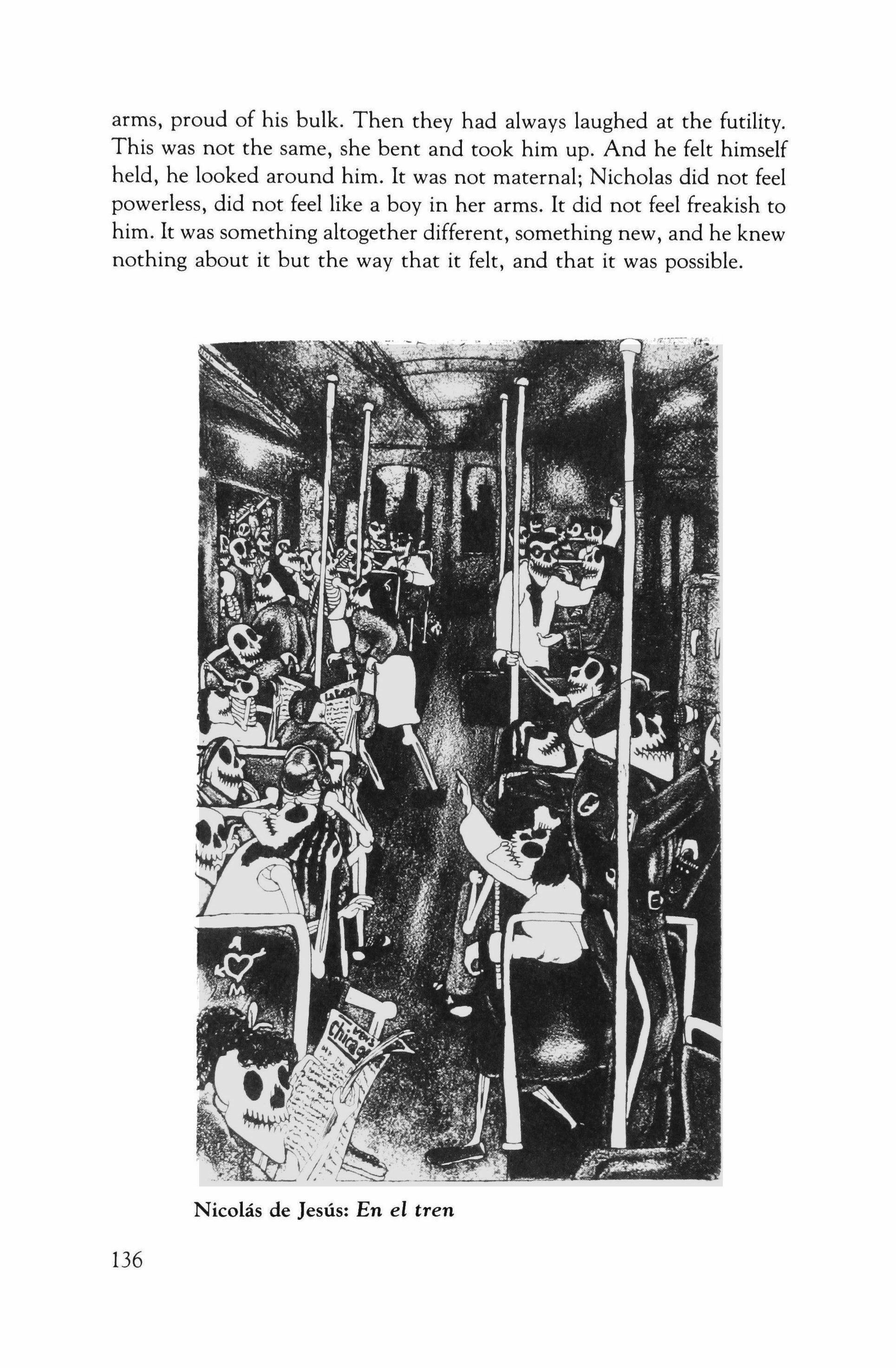

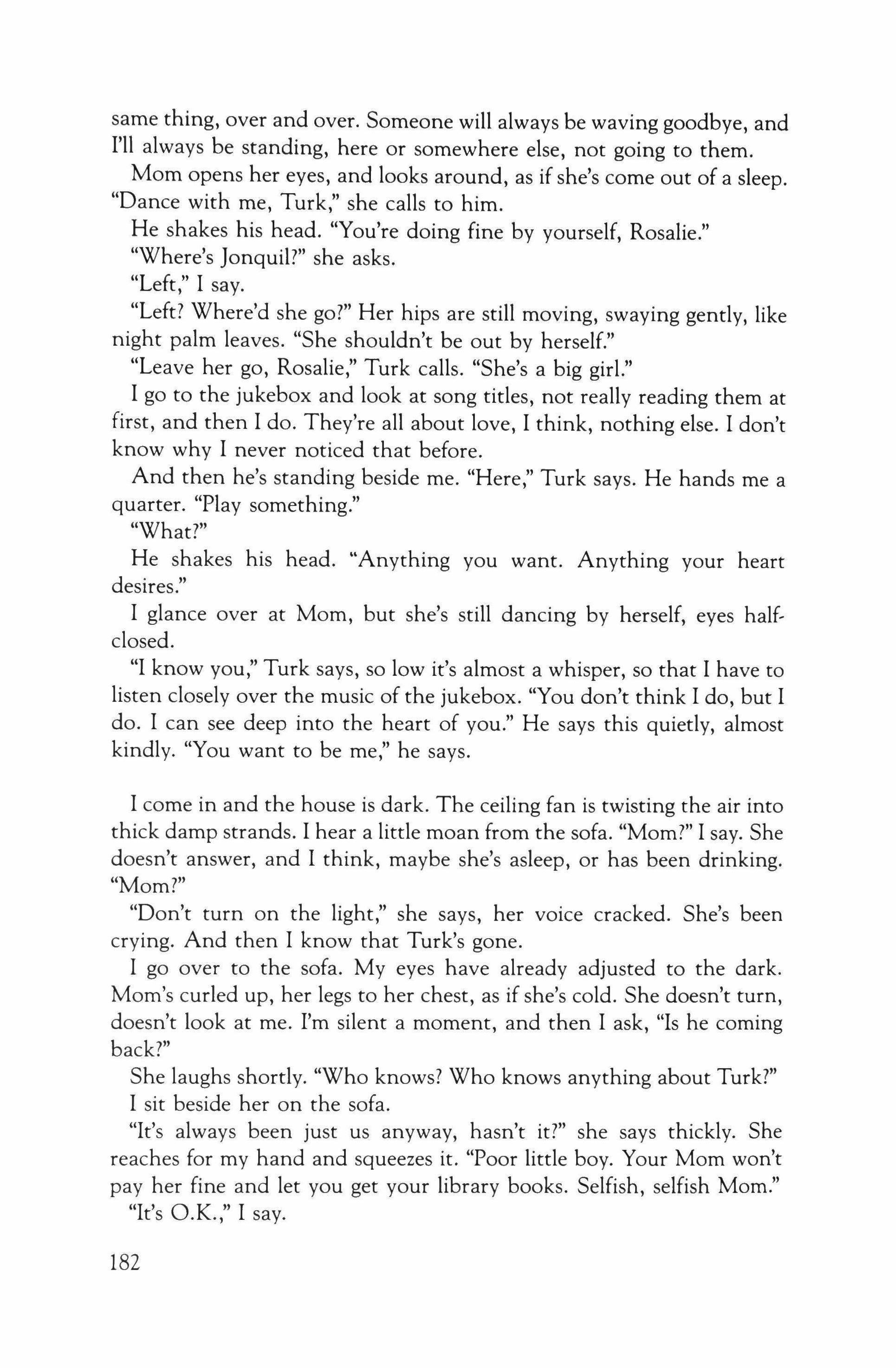

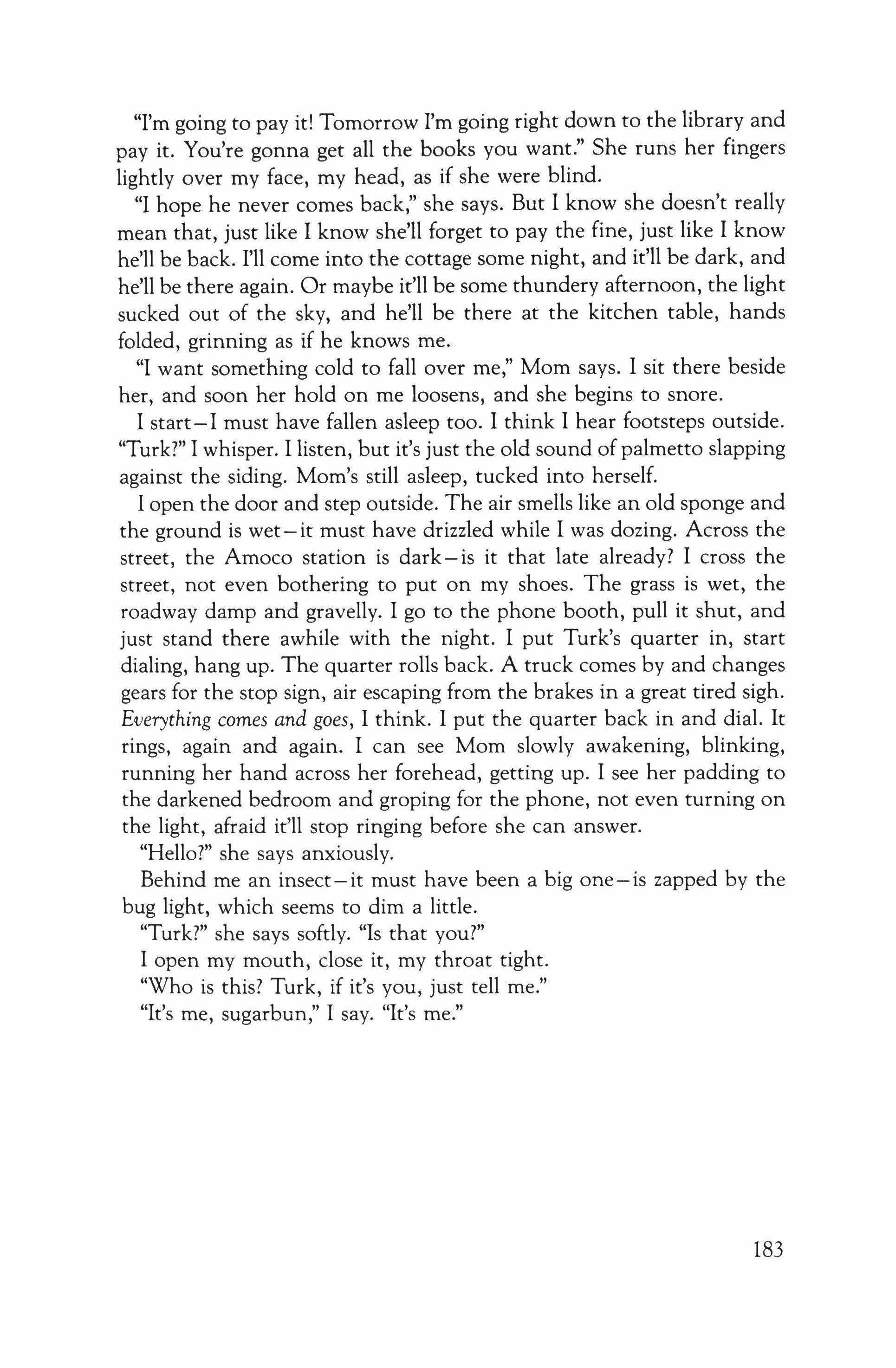

Artwork throughout issue, courtesy of the Taller Mexicano de Grabado (TMG) of Chicago, by Rene Arceo, Nicolas de Jesus, Edgar L6pez, Alfredo Martinez, Joel Rend6n, Elvia Rodriguez and Benjamin Varela.

Deeds of Light

Price 186

Reynolds

21

Fictions

William Wenthe

Last night I finished the Paradisowhere Dante, nearing the center of heaven, had found children. He was so lucky, born into a language with words like rimbombo to render the distant falling of waterstill, the struggle he had, to encompass within the limits of tongue and mind what he saw there; and how he finally had to turn to the earth to explain it: to a rose that gives shape to Paradise, to a river made of light; and a hive of bees tumbling among blossoms - angels ministering to souls.

But if we can translate in the other direction, who, then, are these leaves riding the wind outside my house? They mottle the ground till it quivers like gravel in pools where Rose River filters down from Hawksbill, through greenstone and hemlock, till just looking on them is to expect the darting shadows of trout, wild, panicpulsed by the sound of my steps.

23

Does this river, then, run through heaven? Is it possible to save these leaves from a doom of merely spinning?

I can tell that cluster of flowers, small white petals spaced like babies' teeth, appears different now I've learned to name it white wood aster- but if it's the falling, together, of flowers into form that urges us to name them, or only our need for shape that we name, that I cannot figure. The Bible tells us God gave the naming of animals to Adam, but God is another name too strangely unsayable.

And what is the name of this gesture the asters make in the wind?

And who were these two people, yesterday, huddled in the darkened booth of a bar?

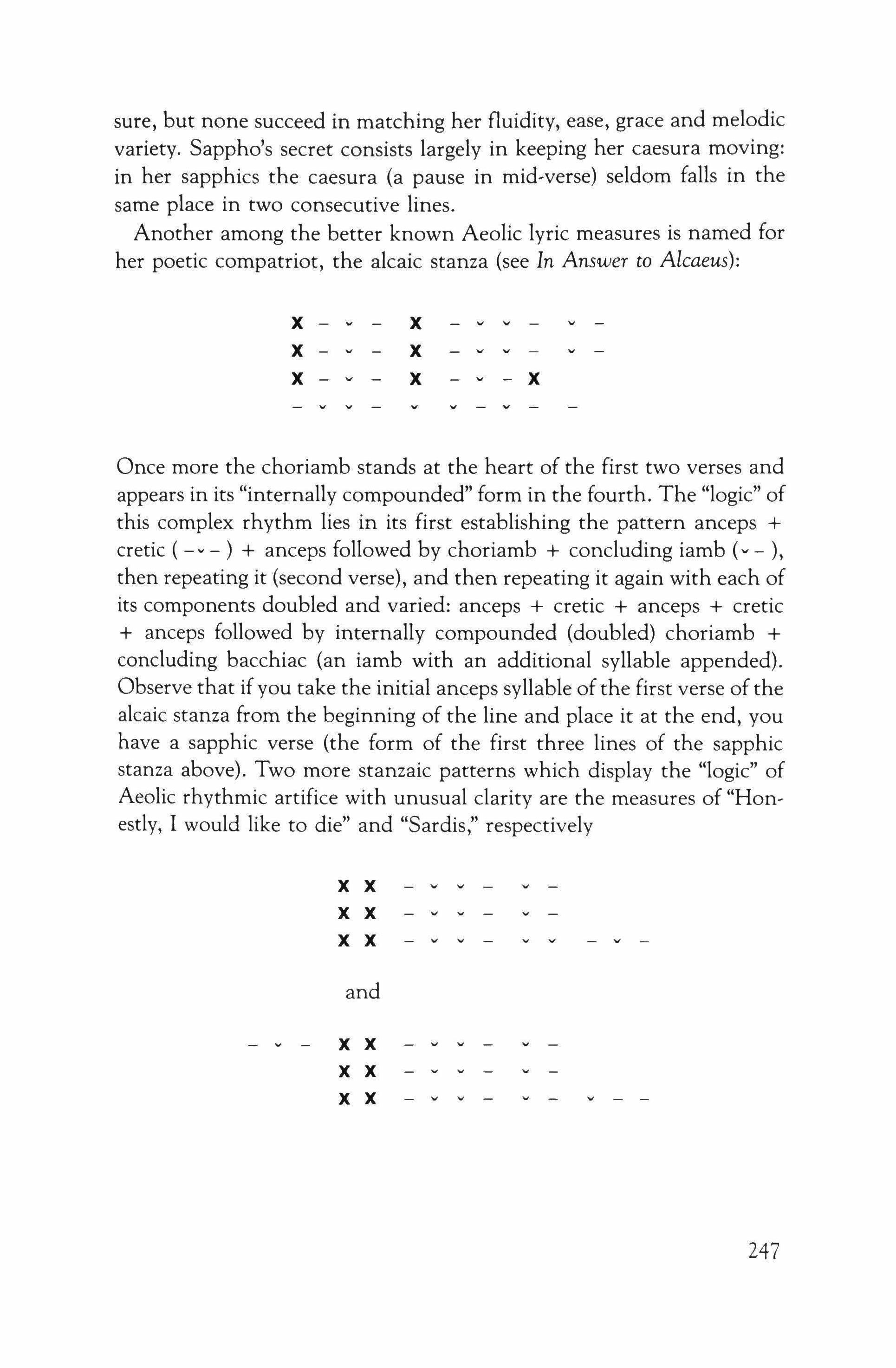

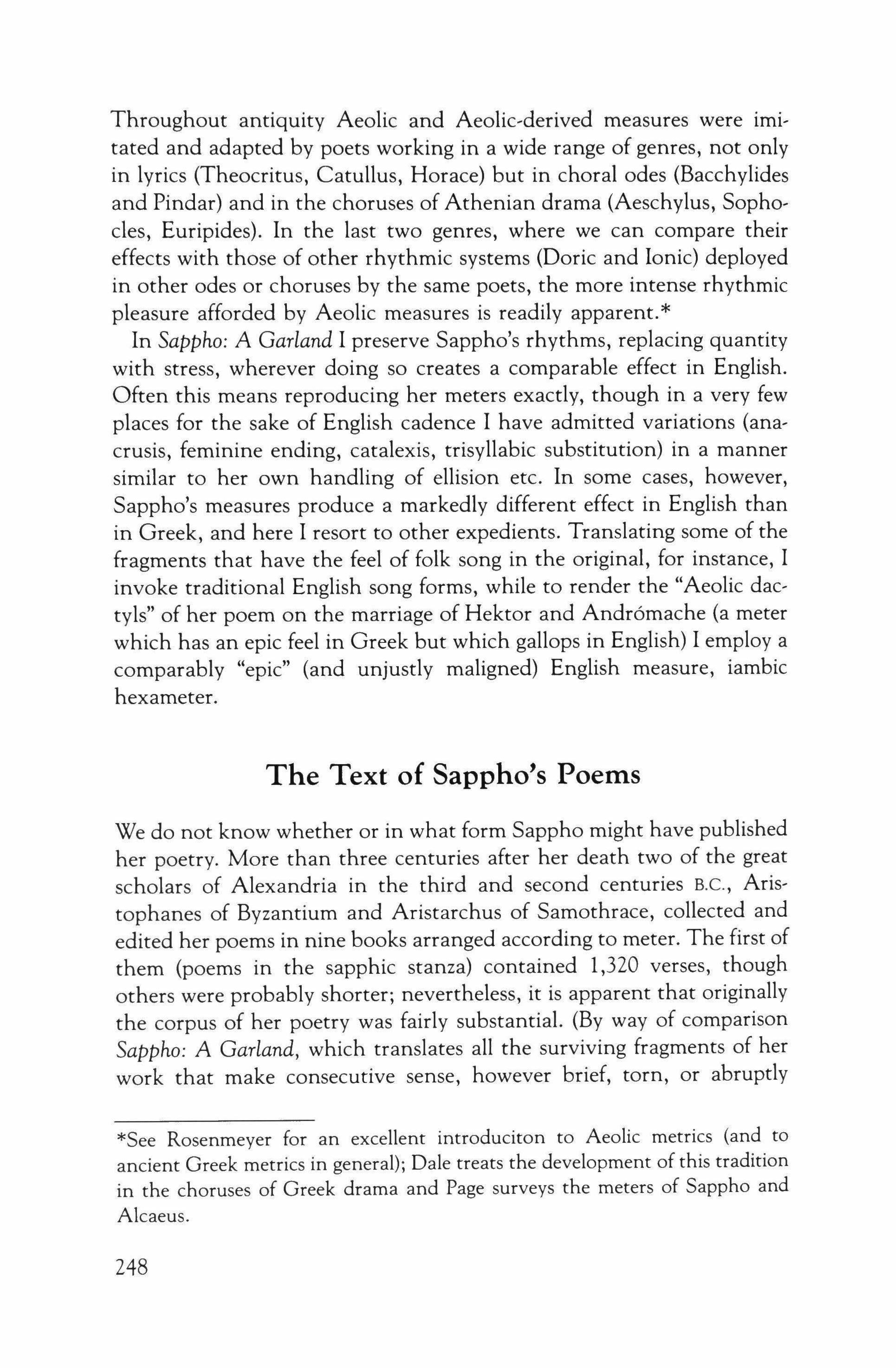

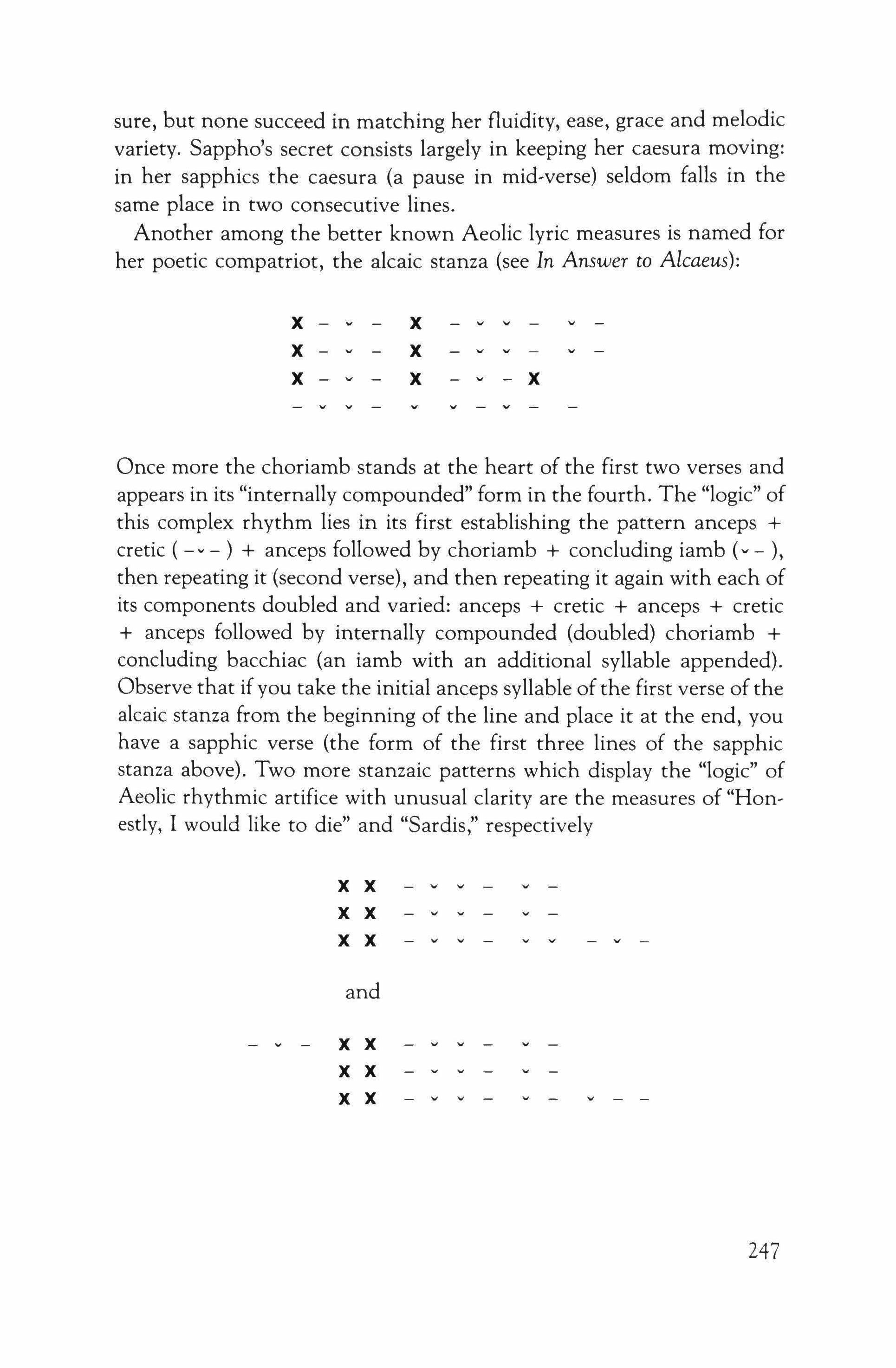

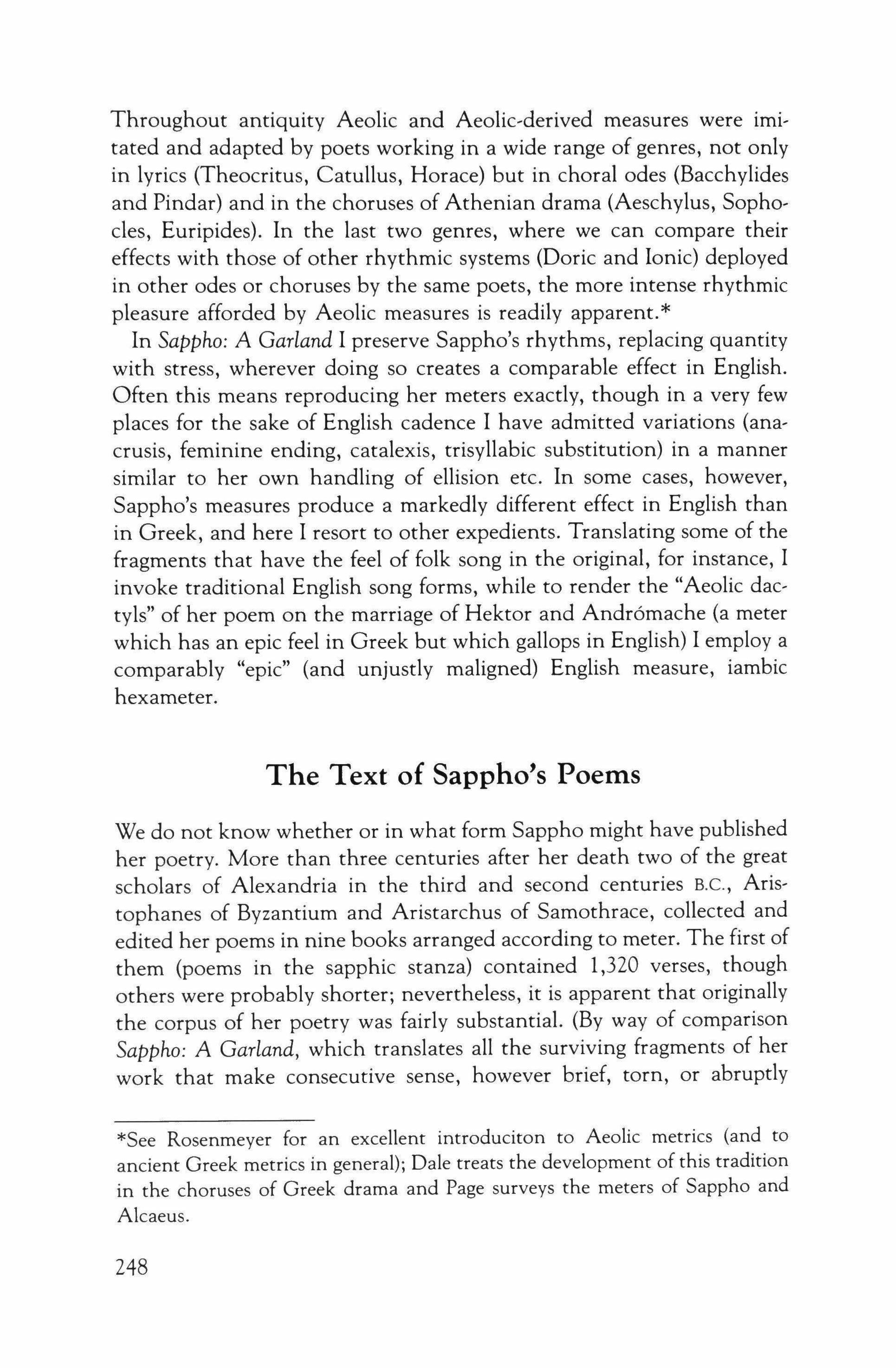

We talked of our love never talked of before, but it was mostly silence, our fight for words almost a third person there with us, when, as if one of us had thought of hera small girl inclined her forehead over the edge of our table, and she became everything we couldn't say.

But when the hand came to lead her away, she left us face to face with our need to do what Dante didn't have to donegotiate a journey back from Paradise to where we are, a glass, a candle, the shadows snagged in the cracks of a table a windy morning, the gesture of the asters inviting us into fictions-extended names, moving like angels or like bees.

24

Demographics

Catherine Bowman

They don't want to stop. They can't stop. They've been going at it for days now, for hours, for months, for years. He's on top of her. She's on top of him. He's licking her between the legs. Her fingers are in his mouth. It's November. It's March. It's July and there's palms. Palms and humidity. It's the same man. It's a different man. It's August and slabs of heat waves wallow on tarred lots. Tornadoes sprawl across open plains. Temperatures rise. Rains accumulate. Somewhere a thunderstorm dies. Somewhere a snow falls colored by the red dust of a desert. She spreads her legs. His lips suck her nipples. She smells his neck. It's morning. It's night. It's noon. It's this year. It's last year. It's 4 A.M. It started when the city shifted growth to the north over the underground water supply. Now the back roads are gone where they would drive, the deer glaring into the headlights, Wetmore and Thousand Oaks, the ranch roads that led to the hill country and to a trio of deep-moving rivers. There were low-water crossings. Flood gauges.

25

Signs for falling rock. There were deer blinds for sale. There was cedar in the air. Her hands are on his hips. He's pushing her up and down. There are so many things she's forgotten. The names of trees. Wars. Recipes. The trench graves filled with hundreds. Was it Bolivia? Argentina? Chile? Was it white gladioli that decorated the altar where wedding vows were said? There was a dance floor. Tejano classics. A motel. A shattered mirror. Flies. A Sunbelt sixteen-wheeler. Dairy Queens. Gas stations. The smell of piss and cement. There was a field of corn, or was it cotton? There were yellow trains and silver silos. They can't stop. They don't want to stop. It's spring, and five billion inhale and exhale across two hemispheres. Oceans form currents and countercurrents. There was grassland. There was sugarcane. There were oxen. Metallic ores. There was timber. Fur-bearing animals. Rice lands. Industry. Tundra. Winds cool the earth's surface. Thighs press against thighs. Levels of water fluctuate. And yesterday a lightning bolt reached a temperature hotter than the sun.

26

If You Had Not Thrown

Me Away

Ha lin

If you had not thrown me away I would have forgotten you; just as many girls' faces emerge in my mind but no matter how hard I try

I cannot remember their names. Those eyes like spring water, those voices like silver bells, those lips like roses, but all these have grown bleary in my memory and are mingled with bus tickets, bills, and syllabi. How often I tap my forehead and swear: "Damn it, my brain has been churned into a bucket of paste!"

I cannot imagine how you look now, how you go to a grain shop to buy rice, how you get to kindergarten immediately after work, how you quarrel with your husband, how you become the "manager" of a family.

What recurs most is your dancing skirt that used to be a colorful UFO carrying my heart to the blue sky.

If you had not thrown me down to the earth, how could I lie watching the white clouds for so long, now lowering my head smiling, now repeating your secret name?

27

[Untitled]

Marina Tsvetaeva

I like it that you're sick, but not for me, I like it that I'm sick, but not for you, That never will the heavy earthly orb Float away from underneath our feet. I like it that one may be whimsicalUnfettered-and not play with words, And not flush in a suffocating wave, Barely having brushed against your sleeve.

I like it, just as well, that in my presence You calmly put your arms around another, That you do not intend for me to burn In hell, because it is not you I kiss. That my sweet name, my sweetest, you Mention neither day nor night - in vain

That never in the stillness of a church Will they sing out above us: Alleluia!

I thank you with my heart and with my hand That you - yourself not knowing it!Should love me so: for my nocturnal peace, For the scarcity of meetings during twilight, For our non-walks underneath the moon,

28

For the sun, which is not above our heads

That you're sick - alas! - but not for me, That I'm sick - alas! - but not for you!

Translated by Gwenan Wilbur

Translated by Gwenan Wilbur

29

The Mark of Flesh

]anet Sylvester

We sprawl, wet and famished, across the sheets of the Grant and Lee Motel in Appomattox, the heat a magnet big enough to lie inside, a micrograph of details. A water glass, marked at its lip, swarms on the table beside the bed, liquid as history. The shower exudes its drip, a water-clock in mildew. The present tense is Sheridan's love-sick answer to Grant: "I'm ready to strike out and go to smashing things." You tongue my ear. I see Georgia barns, empty of horses but still burning, the body politic scarred black, North to South. I tongue your ear, closing my eyes toward the last clear sight of you before I'm home, justice in the contours of another at rest: the torso high-centered, gravid, the breakable, long bone of the thigh, the penis, for a moment, fallen delicately aside. A nineteenth-centurv photographer would get everything in, your concentration, my loosening senses separate "from the service to which I've devoted the best years of my life," my own impatient honor far from that gentleman's code. I drift under your hand lazily cradling me.

30

You turn off the lamp. Gray rain-light slants across what I am: kinds of paling and board fences, enduringly empty dooryards, violet dahlias against red brick. "You're in a state," you say, "Gone again." The old state of emergency deepens now. It's determined to succeed, raising its rash at "the glorious consummation so long devoutly wished for," as the Dispatch reported surrender. Outside, locusts gasp, stop, then saw on. A dog complains in the trailer-yard next to our parked car. I've turned, fetal, against you. I've turned into red dirt, slippery at best, which is half the time not grand, commonly remote. Lee's question, "Dear God, is the army dissolved?" shimmers on the chair's green vinyl arm. The parlor furniture is always carried off by those craving souvenirs, though it's unpaid for. The mortal space transforms to rotten brick, its reconstruction what we love the most: life turned to external exhibit, a metal net out of which a man's voice sieves the narcosis of facts, the civil peace of aftermath, after states collapse, you pushing into me every day, "in a sort of valley with rich slopes of cleared land rising beyond." I say in the small voice which is all I have to command that the place of amnesty is an ambitious odor we'll leave behind after dollars have changed hands, the natural blood gathering to this body, stuttering, trying to speak us fully, as the dark maid tosses pillow-slips in me, a drenched world releasing signals.

31

Goddamn Theology

Pattiann Rogers

It was easier when you were a jonquil and I was a fingertip pressed at the juncture of your radiating petals and stiff stem. And it was not so difficult when I was a Persian guitar and you were the knee on which I lay, my neck held easily in your hand.

But there were problems when you were two hundred years of years, twisted like taffy, twisted and looped like a dry bristlecone in dusty snow, and I was just a beginning fliver of clear, tadpole breath in a whorl of waterweed. I didn't know what to say.

And when I thought I knew your name, and I called it out loud many times, that's when you were a deaf sheaf of catacombed coral with more than one title and no tongue.

I was whole, a burning ball of peach hanging from a branch. You were multiple, sparks struck from a hammer against rock. I split into a showering orbit of mayflies

32

in the evening sun. You congealed into a seeded cow patty in the field.

When the painted pony and I were galloping fast through rabid waves on the beach, there you were, a tiny spire of ship sailing off the edge of the sea.

The night I woke in white, my body moon-gray, you were curled, a black hump of quilt at the foot of my bed, dead asleep.

And later when you were falling rapidly, heavily, raindrops and pockdrops and bullet marks, a mob in the mountain lake, I was precise wing and talon over the prairie, jackknifing and stabbing, lifting the mouse by her spine.

When I was crying, crying and truly sorry, you were a spray of chartreuse and scarlet tinfoil confetti on my head.

That's when I knew for certain it was going to be much more difficult than we'd ever imagined before.

33

Two Poems

Susan Stewart

The Forest

You should lie down now and remember the forest, for it is disappearingno, the truth is it is gone now and so what details you can bring back might have a kind of life.

Not the one you had hoped for, but a lifeyou should lie down now and remember the forestnonetheless, you might call it "in the forest," no the truth is it is gone now, starting somewhere near the beginning, that edge,

Or instead the first layer, the place you remember (not the one you had hoped for, but a life) as if it were firm, underfoot, for that place is a sea, nonetheless, you might call it "in the forest," which we can never drift above, we were there or we were not,

No surface, skimming. And blank in life, too, or instead the first layer, the place you remember, as layers fold in time, black humus there, as if it were firm, underfoot, for that place is a sea, like a light left hand descending, always on the same keys.

The flecked birds of the forest sing behind and before no surface, skimming. And blank in life, too, sing without a music where there cannot be an order,

34

as layers fold in time, black humus there, where wide swatches of light slice between gray trunks,

Where the air has a texture of drying moss, the flecked birds of the forest sing behind and before: a musk from the mushrooms and scalloped molds, they sing without a music where there cannot be an order, though high in the dry leaves something does fall,

Nothing comes down to us here.

Where the air has a texture of drying moss, in that place where I was raised, the forest was tangled, a musk from the mushrooms and scalloped molds, tangled with brambles, soft-starred and moving, ferns

And the marred twines of cinquefoil, false strawberry, sumacnothing comes down to us here, stained. A low branch swinging above a brook in that place where I was raised, the forest was tangled, and a cave just the width of shoulder blades.

You can understand what I am doing when I think of the entryand the marred twines of cinquefoil, false strawberry, sumacas a kind of limit. Sometimes I imagine us walking there ( pokeberry, stained. A low branch swinging above a brook), in a place that is something like a forest,

But perhaps the other kind, where the ground is coveredyou can understand what I am doing when I think of the entryby pliant green needles, there below the piney fronds, a kind of limit. Sometimes I imagine us walking there. And quickening below lie the sharp brown blades,

The disfiguring blackness, then the bulbed phosphorescence of the roots, But perhaps the other kind, where the ground is covered, so strangely alike and yet singular, too, below the pliant green needles, the piney fronds.

35

Once we were lost in the forest, so strangely alike, and yet singular, too, but the truth is, it is, lost to us now.

36

The Meadow

When he returned from the meadow he said that all the high grasses, coming almost to his shoulders, seemed to be dead and yet were also like wheat - brown and yellow with a kind of weaving at the crest - and so, too, could be something that might be gathered. Then he began to tell me about the game all the children had decided to play, how difficult it had been, for some were wild rabbits and others young foxes, though they seemed alike there in the luster cast by the brown-red sun. That day there was no wind, at least not at first, and so he explained that at the start he could see just what was happening: if he could sense some motion in the grass, and yet no wind stirred, he could know "there was some form of life." The teachers told about the tunnels where the mice would spend November. Another boy had found the caterpillar's carapace. But he was unsure of the word: "was that it?" He could not place it, but he pictured it resembling a shell or glossy crust. "The wind came up," and then it was no longer possible to tell what was something live and what was just the wind again-like a hand in the long grass, he said, just as the game was over. And then I asked him about the charred apple tree and the starlings, and how he avoided the thistle's needles, and whether the old snow had stayed there long between the timothy's shafts? (For that is what I thought all the tall grasses must have been.) But he said, "No, the snow had no leaves to hold on to," as it did, of course, when it fell in the forest that was there

37

in the distance. And he said that nothing was alive now that wasn't the color of grasses. He hadn't seen them, was sure he hadn't seen them and he wondered what kind of meadow I could be thinking of.

38

Three Poems

Branko Miljkovic

Inventory of a Poem

for Vasco Papa

Here before all darkness is the darkness which illuminates

After that the freedom of the beast to be a beast and freedom of the snail to be a snail

Before all else the freedom of the birds to lose their way in space

After that the imagination of love

After that prestige of day over the career of fire

After that the first employment of useless things

A stone grows heavier if it doesn't change

After that the celebrated cat under the skin of the sphinx

A beast without a Sunday

39

While You Are Singing

While you are singing

Who will carry your burden?

While you alone defy The poverty of clarity?

While you encounter bitter fruit And the sarcastic dew

While you are singing Who will carry your burden?

Travel. Sing. Defy.

Only the poem desires you And the night reveres you.

But while you are singing

Who will carry your burden?

40

An Orphic Legacy

If you think you want a poem

Descend into the earth

But first domesticate the beast-

Then you'll know it will permit return

If you think you want a poem

Dig it from the earth

But be careful of its habits

And its knowledge of the underground

Words have the soul of a crowd

They're mollified by simplicity and doves

But the dangers overcome by metaphor

Sing more ominously somewhere else

Translated

Translated

by

John Matthias and Vladeta Vutkovic

41

The Iceberg, the Shadow

Tom Wayman

A line of cars speeds down the freeway. Alongside this road, woodlots alternate with light industry. A truck dealership, discount furniture enterprises, approach and then fall behind. And underneath each vehicle regardless of lane or rate of motion coasts a Shadow.

Plato was wrong about shadows. These are not the darkened outline the Ideal casts into the cave of this world.

The Shadow every object throws is the visible memoir of the human lives interwoven with the presence of this thing on the earth: the woman, the man who gathered the materials from which the object is formed, who designed,

42

assembled, tested, shipped, stocked, sold. How doing this work felt, the way each task structured, directed, harmed or enhanced the days and nights of the individual who performed it.

All such actions, concepts, existences, appear now as a blackness hurtling down pavement under drivetrains, fuel tanks, muffler piping that accelerate and switch lanes, or suddenly brake before returning to a constant pace again.

Even the asphalt projects its Shadow on the soil below or on air and water where the highway lifts over a river.

Yet what we observe as Shadow is as ice in salt water: beneath these cars is shown one tenth of what their being in this world involves: how these men and women came to do this job, the origin of the work itself, why the tasks are organized as they are, the history of fire, tools, wages, the shortcuts and substitutions necessary to keep production numbers at a level acceptable

43

to someone farther up the hierarchy - these aspects among others are pulled through the earth, connected to what passes above but unseen.

My hope is for a time when that which is hidden will be openly revealed, considered, changed for our benefit. When this process commences, we will first observe the Shadow under each object lengthen.

Then, imperceptibly at first, the Shadow will grow lighter, become translucent and finally dissolve precisely as an iceberg that reaches warmer waters returns the full cargo of itself to the source of all.

44

Percussion

Dabney Stuart

It's nothing more than last night's coating of ice on the magnolia cracking as the day rises, but it sounds like Morse code-explicit, measured, conversant. The tree rising leaved among bare others becomes isolate, too, in its own sound, self-centered, breaking out in a language that would invent its listeners, the best of whom would dance to it, hearing the beat within the beat sleeved, insistent. Mozart, the Missa Luba. The pupa's first slow distending ticks here, too, in the morning's waste, and the wresting of sound from the joints of a body on the rack. The other person standing across the lawn, just visible through the brittle leaves, holds his upper arm level with the horizon, as if his elbow were strung to a crutch above: his neck tilts slightly, his hand twitches. He moves

45

to walk, but doesn't, and his shadow against the trunk of a bare oak seems to do a little soft-shoe.

It is a fading, brief, as the first ice falls, and the sound begins to diminish, and the leaves' gloss deepens again, and warms.

46

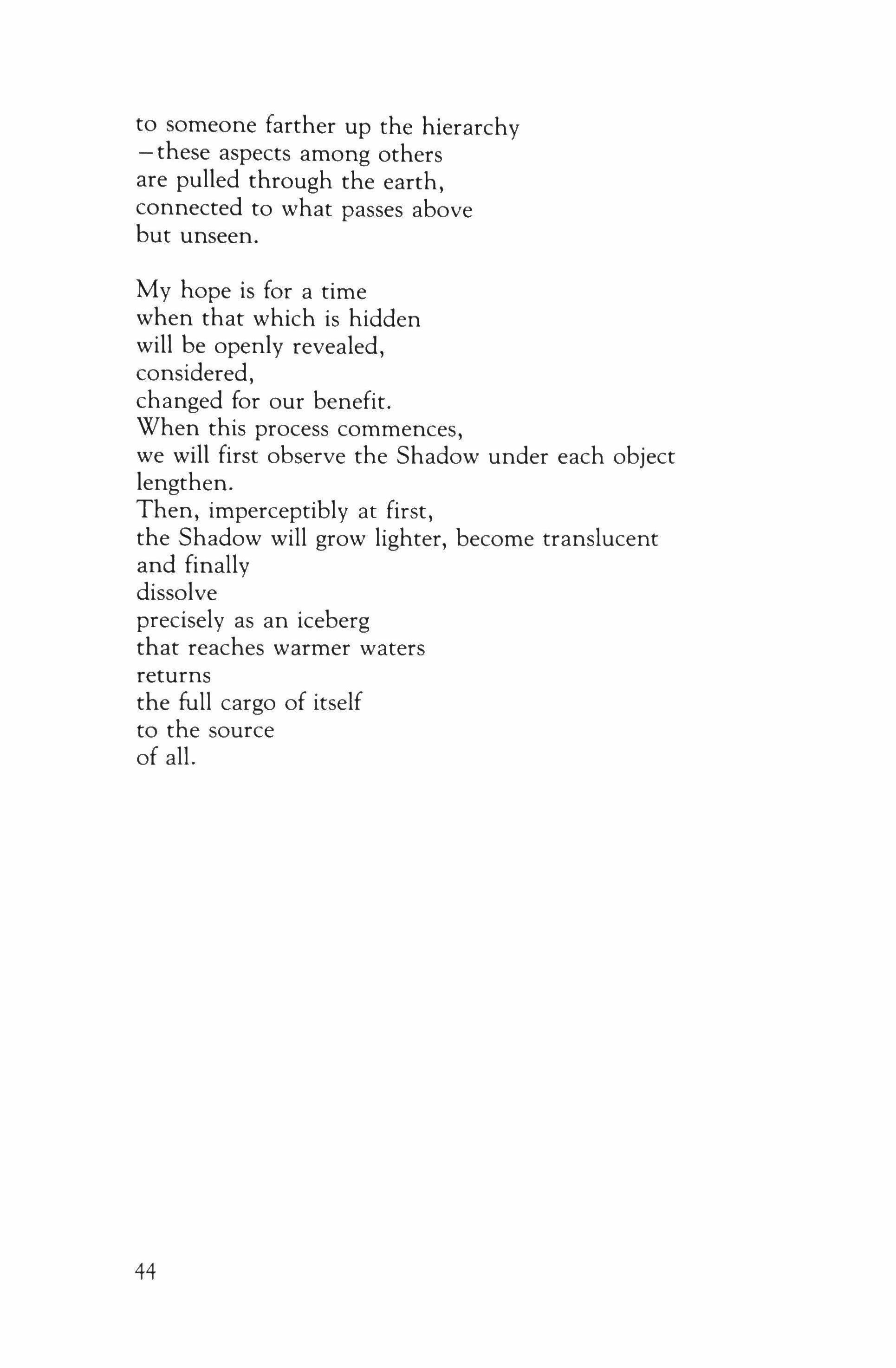

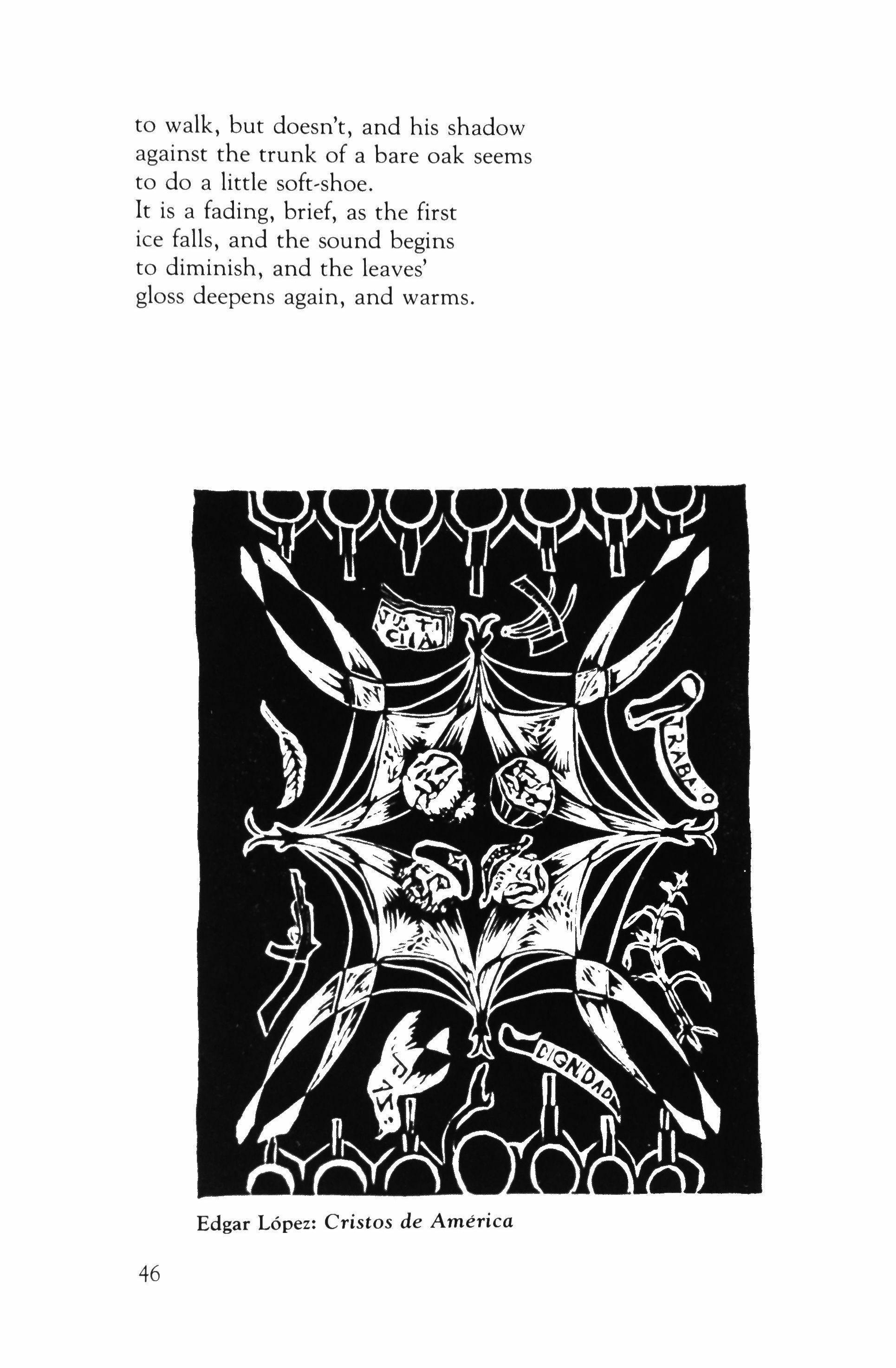

Edgar Lopez: Cristos de America

Two Poems

Anne Guzzardi

The Kiss

Kiss me he said, and I wouldn't do it. Please, just kiss me once. But I held him back, and now I've got my body and he's gone from his and over and over I think of that choice I made to withhold what I could have given.

Not that giving him my body then could make me miss him less now, but more that I was wrong to separate myself in two like that my love and my sex, as though the dying part was the more precious.

47

Wake

fOT M.H., 1914-1989

The slab of casket sealed, brown as a crust of bread but cruel, lacquered round with lilies.

A picture in a frame, a blue gown, a woman's black crown dizzy with tiers of diamond paste.

I loved you, Mary Herman. Three days in a dark room before we found you. So sorry to see your good legs splayed, pubis exposed where your robe lifted. The closed room teeming with the business of your body. Does it matter now that the pills the doctor had you take were the wrong ones? Three young men

48

laughing "long gone" by the flashing car and truck at the corner. So far they think they are from you.

49

Bluegum: On the Curving Paths of Golden Gate Park

Sandra McPherson

A deep blue layer of scent on the ground, long scrolls of bark, fallings, sickles and minisci of leaves on the path edges.

Lakewater loops: each boat is trailed by a duck or two. Nasturtiums climb the frame of a cascade. Painters from a guild even out handmade papers, light-running night scenes, wet octopus, giant iris, tree in half a flail. Tiers and catenas of roofs glitter sequenced across the hills.

Egret among remote-control yachts, sailboats, steam vessels to scale, arm-length submarines submersing.

Anthologies: as time goes on, "new poets" move further toward the front of the book, the "old" end.

I read of journeys to temples, shrines: "Climbing to the Monastery of Perception," "Visiting the Chan Master Chengru & the Kalapati Xiao

at Their Hermitage on Song Hillock," "Traveling to the Dwelling of Li, Man of the Mountains, and Writing This on His Walls."

50

The water keeps gliding, crooking, elliptical. On a stone stage: a pond slider, lifting its neck, acts a still role among currents of boots and toes.

And all around the greenness and living fibrousness, winds in the woods, feathers of fog and real feathers in tops of cypresses, pines.

Mist-drip into ground. Perimeter of houses the tints of beachcombings, shells turned up or over, accordant white and peach-light calciums, pale green nacres, hills of dwelling-shells patterned after, paralleling, waves, water-crests, and sea-fetch valleys. Rooms tight, nearby and deposited, washed across distances, sanddollars blanching, eateries with neon fish-markings for the deep of night.

Wang Wei, translated, says, "When birds arrive he speaks of the Dharma again" and "Before, this far away place just clung to rock amid cloud-mists: Today it is all around my pillow and mat. How can I stay just for a while? I should render service for an entire life."

And to whom? to what? Here I am-oldbut I remember my life

51

from the time I learned of indelible ink, just south, over that blue range white in fog. But the surfaces it was written on-

silk labels, slick box lids, lists for rain and mildew and illuminations that fadeare speckles now and crumbs and wisps.

Service for life:

as red-beaded banks of toyon bolster the birds and leather bergenia's moist leaves soothe the rough newts.

Note: Titles and passages derive from Pauline Yu's The Poetry of Wang Wei, Indiana University Press, 1980.

52

Four Poems

Thomas Lux

"I Love You Sweatheart"

A man risked his life to write the words. A man hung, upside-down (an idiot friend holding his legs?) with spraypaint to write the words on a girder 50 ft. above a highway. And his beloved, the next morning driving to work ? His words are not (meant to be) so unique. Does she recognize his handwriting? Did he hint to her at her doorstep the night before of "something special, darling, tomorrow"? And did he call her at work expecting her to faint with delight at his celebration of her, his passion, his risk? She will know I love her now, the world will know my love for her! A man risked his life to write the words. Love is like this at the bone, we hope, love is like this, Sweatheart, all sore and dumb and dangerous, ignited, blessed - always, regardless, no exceptions, always in blazing matters like these: blessed.

53

Emily's Mom

(Emily Norcross Dickinson, 1804-1882, mother of Emily Elizabeth Dickinson, 1830-1886)

Today we'd say she was depressed, clinically. Then, they called it "nameless disabling apathy," "persistent nameless infirmity," "often she fell sick with nameless illnesses and wept with quiet resignation." The Nameless they should have called it! She was depressed, unhappy, and who can blame her given her husband, Edward, who was, without exception, absent-literally and otherwise - and in comparison to a glacial range, cooler by a few degrees. Febrile, passionate: not Edward. "From the first she was desolately lonely."

A son gets born, a daughter (the poet), another daughter and that's all-then nearly fifty years of "tearful withdrawel and obscure maladies." She was depressed for christsake! The Black Dog got her, the Cemetery Sledge, the Airless Vault, it ate her up and her options few: no Prozac then, no Elavil, couldn't eat all the rumcake, divorce the sluggard?

Her children? Certainly they brought her some joy?: "I always ran home to Awe when a child, if anything befell me. He was an Awful Mother, but I liked him better than none."

This is what her daughter, the poet, said. No, it had her, for a good part of a century it had her by the neck: the Gray Python, the Vortex Vacuum.

During the last long (7) years, when she was crippled further by a stroke, it did not let go but, but: "We were never intimate

54

Mother and children while she was our Mother but mines in the ground meet by tunneling and when she became our Child, the Affection came." This is what Emily, her daughter, wrote in that manner wholly hers, the final word on Emily, her mother-melancholic, fearful, starved-of-love.

55

Rene Arceo: Trudy Bloom y su amiga

An Horatian Notion

The thing gets made, gets built, and you're the slave who rolls the log beneath the block, then another, then pushes the block, then pulls a log from the rear back to the front again and then again it goes beneath the block, and so on. It's how a thing gets made-not because you're sensitive, or you get genetic-lucky, or God says: here's a nice family, seven children, let's see: this one in charge of the village dunghill, these two die of buboes, this one Kierkegaard, this one a drooling

nincompoop, this one clerk, this one cooper. You need to love the thing you do-birdhouse building, painting tulips exclusively, whatever, and then you do it so consciously driven by your unconscious that the thing becomes a wedge that splits a stone and between the halves the wedge then grows, i.e., the thing is solid but with a soul, a life of its own. Inspiration, the donnee, the gift, the bolt of fire down the arm that makes the art? Grow up! Give me a fucking break! You make the thing because you love the thing and you love the thing because someone else loves it enough to make you love it. And with that your heart like a tent peg pounded toward the earth's core. And with that your heart on a beam burns through the ionosphere. And with that you go to work.

56

Autobiographical

The minute my brother gets out of jail I want some answers: when our mother murdered our father did she find out first, did he tell her-the pistol's tip parting his temple's fine hairs-did he tell her where our sister (the youngest, Alice) hid the money Grandma (mother's side) stole from her Golden Age Group? It was a lot of money but Enough to die for? was what Mom said she asked him, giving him a choice. I'll see you in Hell, she said Dad said and then she said-this is in the trial transcript: "Not any time soon needledick!"

We know Alice hid the money-she was arrested a week later in Tacoma for armed robbery, which she would not have done if she had it - Alice was (she died of a heroin overdose six hours after making bail) syphilitic, stupid, and rude but not greedy. So she hid the money, or Grandma did but since her stroke can't say a word, doesn't seem to know anybody.

Doing a dime at Dannemora for an unrelated sex crime, my brother might know something but won't answer my letters, refuses to see me, though he was the one who called me at divinity school after Mom was arrested. He could hardly get the story out from laughing so much: Dad had missed his third in a row the day before with his parole officer, the cops were sent

57

to pick him up (Bad timing, said Mom) and found him before he was cold.

He was going back to jail anyway, Mom said, said the cops, which they could and did use against her to the tune of double digits, which means, what with the lupus, she's guaranteed to die inside. Ask her? She won't talk to me. She won't give me the time of day.

58

Alfredo Martinez: H.I. V. +

Half an Hour Before the War

]oseph Gastiger

There in Mosul the coffee-shop owner sat squinting morosely at dominoes, chiding the cookWe can always buy diamonds just not any onions, just not any grapes

The tech sergeant from Wichita couldn't decide how to break off her third letterTell Jeff I got the tapes, give him a kiss for mewatching her silhouette toss every hiss of a lamp

In Samarra, the imam stirred weak jasmine tea, nodding to the adamant whorls of the suraWhen the sky splits asunder and reddens like a rose or stained leather, which of your Lord's blessings would you deny?*

*From the Koran, Sura 55: "The Merciful."

59

The lieutenant from Tempe unwrapped the St. Christopher medal his uncle had saved since SaipanTio Hector who'd still, at parades, weep for suicides washed up on the beach

While at Baghdad the new bride panted in the blue hotel, kneading this strange pair of shoulders gone slack at lastsmeary with henna, lustrous seventeen years old half an hour before the war

The airman from New Orleans who'd pinpoint that roof wasn't thinking of newsmen regretting collateral damagehe was dreaming some Sunday, beignets at the Cafe du Monde when his daughter had time

And in Basra the shoe repairman, sadly, dreamt of shoes piled for mendingshoes left by cousins insulted he'd charge so much, shoes for the colonels whose errand boys never paid,

shoes of the amputees, the insane ones, the destroyed. But the worst of it nobody wanted to knowfrom the minefields and typhoidal trenches near Fao, a mountain of shoes

60

Cascades of the Tigris collided below the gun turrets, behind the high-rises beside the mosques.

Dry snow dusted down Quail Street in Albany, Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, streaking the dirty cars

In the usual traffic flashing across bridges, flagmen waved on the hypothetical dead Then came jets perforating radarmissiles stenciled with the names of girlsthe gasworks going upthe door of fire-

the neighbor flying off a balcony in her first kiss of ozoneThen came the war

61

Block Bebe

Terri Brown-Davidson

Each night, steam-bright, a cooling slice of moon dangles from my doortop. For seconds I believe I'm dreaming the white-blue flare, the shuddering ash-stub, my uncle's legs.

This dream a life. Blankets frame my breasts as I float awake to a lamplit face against the jamb. Tugging

my baby's hand, my lover escorts her for her goodnight kiss, his cough inquiring when and if I'm ready.

I'm never when he's in me, caught in the mesh of my daughter's howls, imaginingmoving with him - her fists beating crib slats,

eyes hellish with weeping when I shift suddenly loose, steal breath and space until, freed, the stinging arc of my ribs

releases. Then, in my mouth, the silt and grit of memory, pungent as an orange. Tasteless as the blahblahblah of days, and again I'm the block bebe

62

in Rousseau's primitive painting, my wooden infant face mottled ivory-pink, paralyzed with rage as, "pour feter" only I dangle my marionette uncle from his strings, his upside-down heat

irradiant in every pore of his after-shaven face when he presses, slowly as he dares, the still-flaring cigar between my left foot's middle toes.

All that memory or dream. I have a lover, I tell myself now. I desire a lover inside me, yes, the sweat-heat of love parting my lips

though I rise, suddenly, so violently I'm aware, wrap my breasts in their burn-hole robe, hoist my sobbing daughter. Mornings, straddling her rocking horse, for minutes

she chews the mane. Watching her, I pray. Or pretend we're some woman Rousseau never painted, a woman

washing dishes, her apron a pink frill in her lovely, sunlit kitchen

as she pulls strings of caked chili and onions from the pan, slides them into her mouth, their webs separating without giving her pleasure, texture, or taste as she gazes, through the window,

at her daughter in the sandbox, pictures her daughter dead and files another nail on her shapely, wooden hands.

63

Florencia

David Hernandez

I will try to tell it without remorse or impassioned language so you can hear it deep in your heart forever.

My aunt Florencia Marquez was 20 when she began working for an american company in Puerto Rico. The company was taking advantage of a cheap-wage, tax-free economic program called Operation Bootstrap created in the 50's to get Puerto Ricans back in the work-force after having their agricultural jobs eliminated by industry.

My aunt Florencia Marquez had river-green eyes and mountain-brown skin. Sometimes the women who worked for the company would take maternity-leaves and the officials did not like this.

So Operation Bootstrap implemented an island-wide sterilization program since it was cheaper than day-care centers. The women would go to the hospital, give birth and have their fallopian tubes tied in the process without their consent.

64

This was done to my aunt after my cousin Anita was born and after grieving for a while, my aunt went back to work. She eventually saved money, moved to Chicago and got a better job. My cousin Anita and I grew up together on the city's north side.

Around 1962 when Anita was sixteen, she got pregnant and died from a coat-hanger operation because abortions were illegal at that time.

She had river-green eyes and mountain-brown skin.

After grieving for a while my aunt returned to Puerto Rico where Anita was buried and went back to work for the same company that sterilized her years before.

My aunt Florencia Marquez is an old woman now who enjoys the island breezes from her rocking chair on the veranda.

But if you place your ear close to her chest, You can hear the ocean like a hollow seashell on the sand.

I have nothing more to say.

65

Two Poems

Carol Frost

Harm

She had only begun to get used to her body's exposures to pain, like the insinuations behind questions: winter asking the tree, where's your strength? - a priest asking a soul, where's your marrow?

Aversions, truth, invective, it wasn't her answers which mattered, only her lying on a bed being administered shocks until the world grew tired of experimenting with another bit of clay and the inward liberties. So it seemed. And when the intern came into the room, asking how she was and snouting through her chest with drainage tubes, as strong a desire as she'd ever had rose up in her. She must have gestured, or he already knew, because, as if in expectation, he smiled at her and stepped out of harm's way, backward, for just a moment.

66

Pure

He saw that the white-tailed deer he shot was his son; it filled his eyes, his chest, his head, and horribly it bent on him.

The rest of the hunting party found him hunkered down in the grass, spattered like a butcher, holding the body as it kept growing colder in his arms. They grasped his elbows, urging him to stand, but he couldn't. He screamed then for Mary and Jesus, who came and were present. Unable to bear his babbling, and that he might no longer have to be reproached, the men went to get help. He only had left to him his pure hunter's sense, still clean under his skin, a gun, the example of wounds, a shell's ease in the chamber, as he loaded, the speed of the night chill, while his mind like a saint's tried to bear that which God took from His own mind when he could not, not for another moment

67

The River-Keeper's Song

Constance Urdang

In the old days there was no holding her Galloping through the town like a team of runaway horses She stopped for no one, never even pausing In her headlong career over stones, indifferent To what she left ruined behind her, until at last Gasping for breath she tumbled out of sight Plummeting down the tall walls of the canyon.

There were days when the street itself became a canyon

And she fled down its narrow length, carrying with her All the discarded rubbish of our lives, Trash, vegetable parings, bones boiled dry, Bad old ideas, even mistakes and sins

As if the flood could wash away our guilt And purify the world it overruns.

Where is she now? I'm dry, dryas the desert. She has changed her ways, deserted her old haunts; Not even the kiss of the rain will be enough To wake her where she sleeps in earth's buried vaults.

68

The Silence of Women

LiZ Rosenberg

Old men, as time goes on, grow softer, sweeter, while their wives get angrier. You see them hauling the men across the mall or pushing them down on chairs, "Sit there! and don't you move!" A lifetime of yes has left them hissing bent as snakes. It seems even their bones will turn against them, once the fruitful years are gone. Something snaps off the houselights and the cells go dim; the chicken hatching back into the egg. Oh lifetime of silence! words scattered like a sybil's leaves. Voice thrown into a baritone stormwhose shrilling is a soulful wind blown through an instrument that cannot beat time but must make music any way it can.

69

Notes on Atonement

Mark Rudman

Got a letter yesterday from a synagogue on the East Side asking for money to keep my father's name alive. I balked. And would explain (not justify). Wanted to walk into the synagogue across the street for a few minutes just to get a taste. Needed tickets. Father always had tickets for high holy days too (never set foot in a temple on any other day). What

am I getting at? I lived with a Rabbi between the ages of six and fifteen, he was my mother's husband. We were very tight (when I was growing up).

So you never had to buy a ticket because you were the Rabbi's stepson?

No. First, we never used that word "step." Second-and this is what I was getting at - there were no tickets.

Yes, it was assumed that temple members paid dues but anyone who could not afford these dues was still welcome, heartily, not half-heartedly welcome.

Hey, you lived in a lot of places, are you sure?

I'm sure. It's the kind of thing one remembers.

70

There are a lot of advantages to living in the boonies.

I look at it another way. The right to pray.

I don't think you're talking about tickets. You didn't really want to go. A friend offered you tickets and you hesitated

And finally said no.

I had to think about "the little Rabbi" and I didn't want to do it in the presence of another Rabbi.

I didn't call him the little Rabbi when I was a little boy. It wasn't that he was so short (5'9" on stilts) but that he was frail. My mother and I used to elbow each other when he went to lift the Torah out of the Ark: he must have had help from God.

A clearer picture. A Mormon friend in Salt Lake City called him The Brain. First (he broke down his arguments point by point, often, in later years, by pressing his right thumb against the fingertips on his left hand-a habit that drove me mad), because he was the smartest man he'd come across. (By "smartest" I think my friend meant he used words that hadn't migrated to those latitudes-that valley Brigham Young-standing up in his stirrups - called "the place.") Second, because he had this enormous head, and forehead, and nose, which dwarfed his body, his stick-thin arms and legs. He was the most bodiless creature I've ever known.

That may have helped keep him alive for over five years after he had his stomach removed.

I think his body discovered heretofore unknown nutrients in bourbon.

I can't separate his charm-what was enchanting about him-from his size. And the hugeness of his forehead, the jut of his nose, his jug ears.

He never imposed God on me. I was expected to go to temple most of the time but-I who could not stomach school-liked it.

71

He was on such intimate terms with God, had thought so deeply about scripture, made the stories so compelling. And he looked so holy in his robes.

This immense head suspended over the pulpit.

(The anonymous Caxinua poem of the moon's creation: "You going to the sky, head?")

There's more. The small communities we lived in in those first years together were welcoming. It meant something more to be a Jew in small towns in Illinois (in Chicago Heights and Kankakee) where there were, at best, a few hundred out of 20,000

Mourning for him has been difficult. Mourning for my real father took so much out of me (That phrase always makes me bristle.) And then the type of cancer he had, combined with his frailty, made me think of him, in those last few years, in an almost post-mortem way. Every meeting had that feel of "the last" meeting and it began to get to me.

Can you be more specific?

It began to get to me.

I wanted him to live or die, not hover between two worlds-as if this hovering weren't our condition.

And he asked so many questions. He trafficked in confidences.

This is not the time for me to tell you what happened to him in his worldly life in later years. This is not a portrait of my torment and ambivalence about the man apart from being great to me in many ways when I was a little boy

(I came to question too much: seeing him (as an adult) lavish attention on young children I began to wonder just how specific

*

72

his love for me was-or his love for my son-whom he loved-but so did he "love" another two-year-old in his apartment complex in his last place of residence, Florence, South Carolina. He talked and talked about the affection this blond/blue-eyed baby showed him, the hugs, kisses He was nuts about children the way some men are about women.}

And your son, Samuel- can I call him Sam? - isn't exactly cuddle� crazy.

He doesn't cotton-up. He likes to announce how he hates hugs and kisses with an indescribable relish.

You're grateful?

Grateful implies lowed him something.

No, we shared something. We were pals, co-conspirators.

He loved children and as a child I loved him. Tucked him into bed. Felt responsible he was so little.

*

But by the time I was a teenager the drinking had taken him over so that it was as if he no longer cared. He quit the Rabbinate again.

*

What was a Rabbi's salary in the mid�fifties to the mid-sixties]

Thanks for asking. It hovered around the $10,000 mark.

That magic figure cropped up even when he left the Rabbinate and went to work for General Klein and City of Hope: he was offered $10,000 + 10% of whatever money he raised for City of Hope.

Even numbers. Keep it simple.

73

But what made that salary so galling was that his average congregant earned at least twice that, and many three, four, five, twenty times more. And then put that 10% of zero-since he was constitutionally incapable of asking anyone for money, "closing a deal," as they put it in the business-against what the actors made who funded the City of Hope.

1 won't do that. But I get your point.

It was a different world than the world of his childhood.

He tried to marry out of it in marrying your mother.

And look what he got into there: sturm and drang and no reward. Once again he misread the signs. He mistook the fancy address and the accumulated possessions of fifty years for money in the bank he would one day - have access to.

Are you implying something smarmy here?

No, but others have, especially, or should I say predictably, my father.

He called your grandfather a mountebank.

I liked that. But they didn't have to joust and quarrel so much.

I was intoxicated by the Biblical stories he told me as a child; not me really-religion only entered our house on the sabbath-our class at Sunday school. I loved to hear how the Jews overcame obstacles and suffering through miracles and prayer. He spoke "off the cuff," without condescension - as if he knew that children were his deepest (nonworldly) allies in this life.

*

But you never observe holidays.

One December I was startled, like some space creature, to look up and see the bodies in the window huddled around the menorahs, the quiet moment ripped out of time, the blind avenue become

74

human for a moment, out of a time yet in time; only one candle lit the first night, the other branches of the menorah scarcely visible if visible at all behind these gray windows in the winter dusk; the story no more than an image of persistence against the odds; the miraculous oil burning beyond its energy quotient

So oil was an issue even then?

That's what the little Rabbi offered in his sermons: contemporary takes on ancient themes.

Let's go back. You were walking in the winter dusk. You looked up and felt alone: those others still had rituals, like a balm.

To speak of balm is to speak of wounds. These followers of Mammon claim the right to pray; to be heard by a higher order.

You with your "days of the spirit" have no hope that anyone might hear.

But that's another matter. I was talking about lights in windows at nightfall, at that precise moment when something in your brain clicks and knows it's dark (when it wasn't a moment ago), and the bodies outlined. It is an image of what cannot be possessed, what can never be taken for granted, or taken at all.

*

You were a child and children were his allies.

With his congregants, he played cards.

I don't think he ever lost a hand at rummy.

Now you're exaggerating.

Yeah. But he always always always always won, because "the brain" remembered every card that flashed by.

And yet there wasn't a trace

75

of competitiveness in his prowess. Things came so easily to him, a Rabbi at twenty, utterly bored with what had been his vocation at forty, ready to do anything, go into Public Relations, work for the corrupt General ("what, a Jewish General?") Klein, who cashed in his "successful military career" for a Public Relations firm in Chicago "we specialize in trust" (Klein, later tied to the doomed Kerner administration, was not known to be a grafter when Sidney took the job).

I remember my visits to General Klein's office: the grayness and funereal air and squeaky wooden desk chairs; the embossed citations, plaques on the walls, the golden awards. Though in awe of the General's regalia, I was also suspicious about the nature of "Public Relations." It sounded specious, intangible, unnecessary, a cloak of busyness to escape real work.

A Jewish General! I imagined him in a tank in the desert but somehow his pudgy face didn't fit the image. And yet Julius Klein, being a general, was up there with Hank Greenberg in the pantheon of Jewish ubermenschen. I also didn't understand how Sidney could trade what seemed to me his congenial and social job for this lonely, isolated office with its impressively antlered hatrack and daunting phones. There was such an intimidating air of importance in these offices-yet what were they doing that was necessary for the public good? I was very proud of Sidney around the bigwigs: this was man's work.

I couldn't put the two together, a General and Public Relations. True, even the Korean war had receded, but how could a General consign himself to a desk for life?

1 was granted an audience with General Klein around the time of my birthday. He had a drawerful of glossy photos. He pulled one out and signed it. I put on my "awe" face for Sidney's sake, and peeped - "Thanks General Klein," unable to short-circuit the

76

emphasis on his title. "Thanks," Sidney echoed nasally, and ushered me out.

"What would you like to do now?"

"Buy some soldiers."

*

We entered the toy department at Marshall Fields: there I saw a thousand antidotes to loneliness, a way to get through endless solitary hours no matter what else happened. Sidney was big-hearted in many ways. He could be generous with time. He could be warm, which is why children crawled all over him at Sunday School (how could he have sacrificed that for this?). But money made him crazy, penny-pinching in ways that were convenient to him. Cigars and liquor were necessities. Anything I desired was worthy of serious interrogation. Why do you want it, what for, do you need it, why does it have to be this brand and not that one? Maybe he thought that as a stepfather he should go only so far. But the $40 a week my father sent as child-support should have gone a long way to maintaining a child in the late fifties.

He didn't like the idea of soldiers, but after the visit to General Klein's I had him over a barrel. I would have soldiers then. Of course I already had a million generic soldiers, whose likeness I saw right away in the toy section, of green men massed together, piled in bins, and you could get a hundred for $.99. "Here," he said, taking advantage of the opportunity to be done with this expedition as soon as possible, "soldiers. A hundred. That'll keep you busy." I flushed. "No," I said, "I want these." I grabbed a box with a see-through cellophane window from an adjacent table: these men were silver: they had definition; they were three times the size of the generic men; there was one of each type (officer, bazooka wielder, belly-crawling rifleman); they wouldn't fall down when a train went past in the railroad yard below my window. "Why should I buy twelve soldiers for $3.98 instead of one hundred soldiers for $.99?" He had the bag and made a gesture to leave. I broke down. It was my birthday. I wanted a present, a testimony of his love for me. (What, another test? Another test? Don't you ever tire ?) I could not get through to him; I couldn't even get his attention. This was torture for him. He looked

77

overheated too in his fedora and heavy tweed overcoat and cranberry cashmere scarf. "I am not going to spend three dollars and ninety�eight cents on twelve soldiers and that's final. Have these or nothing." Exact amounts of money, dollars and cents, were given the same vocal emphasis as the names of his favorite prophets when he stood on the pulpit. Venom coursed through me: if I'd been a snake I would have hissed. The simplest litany imaginable was running through my head: "I just want you to buy this for me because it's what I want and it's my birthday."

I could hear it coming: the lecture about the Rockefeller children's small allowances.

They worked so hard not to spoil me.

What are you doing now?

Sitting at a white iron table at Cafe 112 on 112th St. and Broadway at 9: 15 (A.M.),

the green letters and intersecting circles of a billboard on a wall above a garage on the east side of 113th St. simply

it says and the G and the A and the R are effaced so that the garage sign reads

and the P on the PARK sign is blotted out by a tree so it reads

*

KOOL

A G E

78

D. H. Lawrence in the TLS anticipates my next thought: "The things one cares about are all invisible, like seeds in the ground in winter. But one has to attend to the things one only half cares about. And so life passes away."

An attractive nun takes a seat on another white chair: the threat of her chastity arouses me. *