1{1I 1\: )

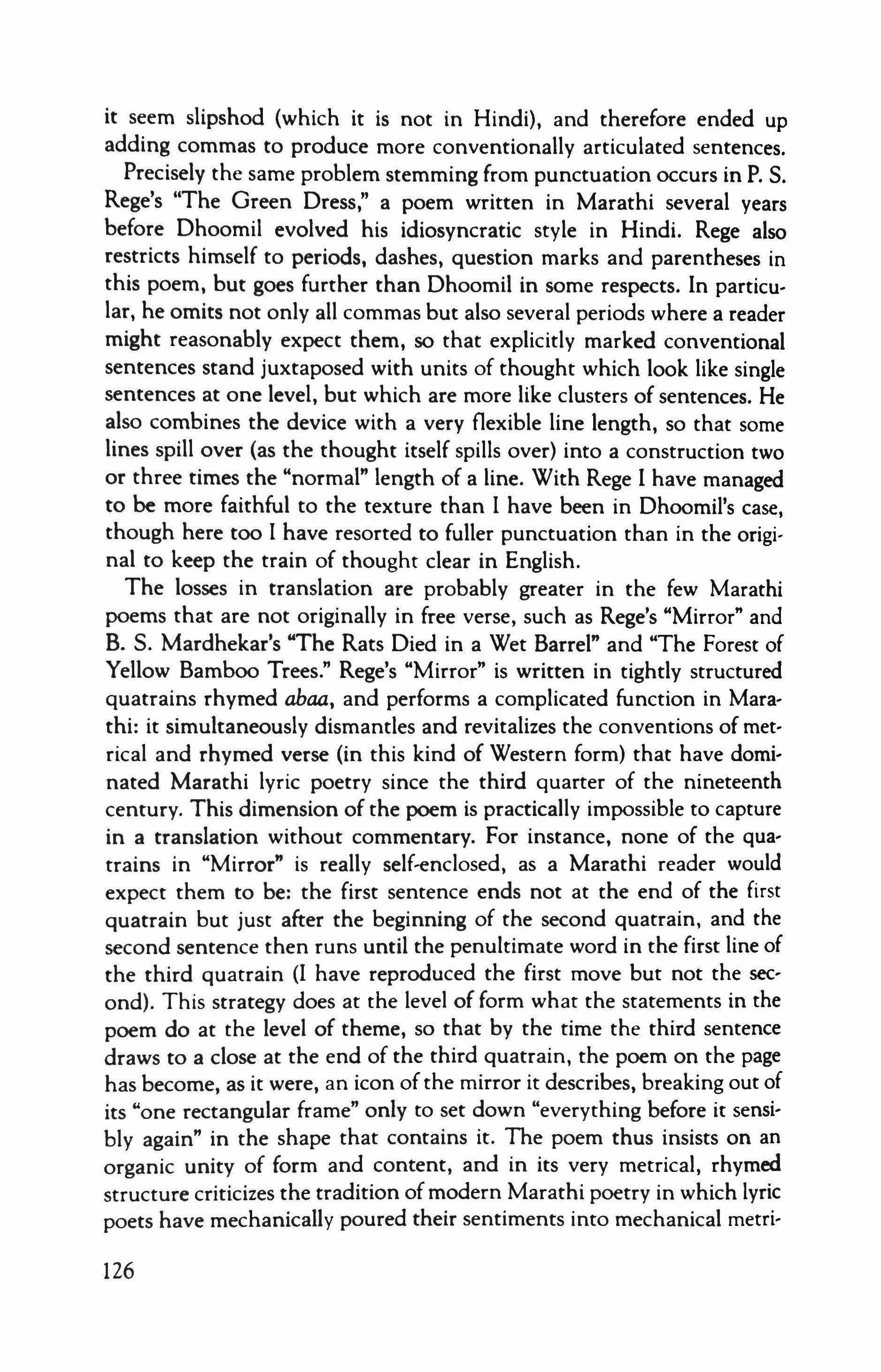

Featuring:

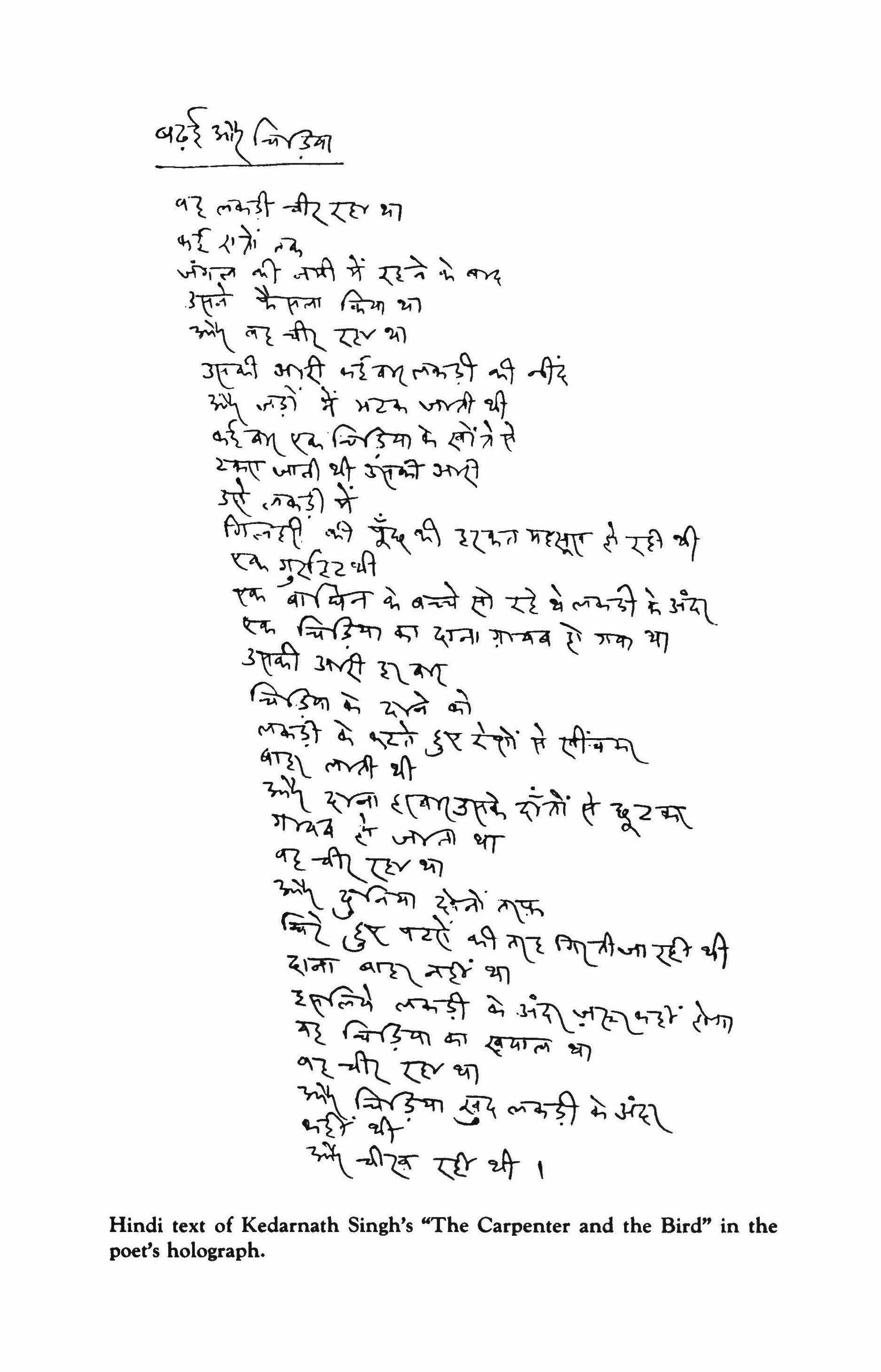

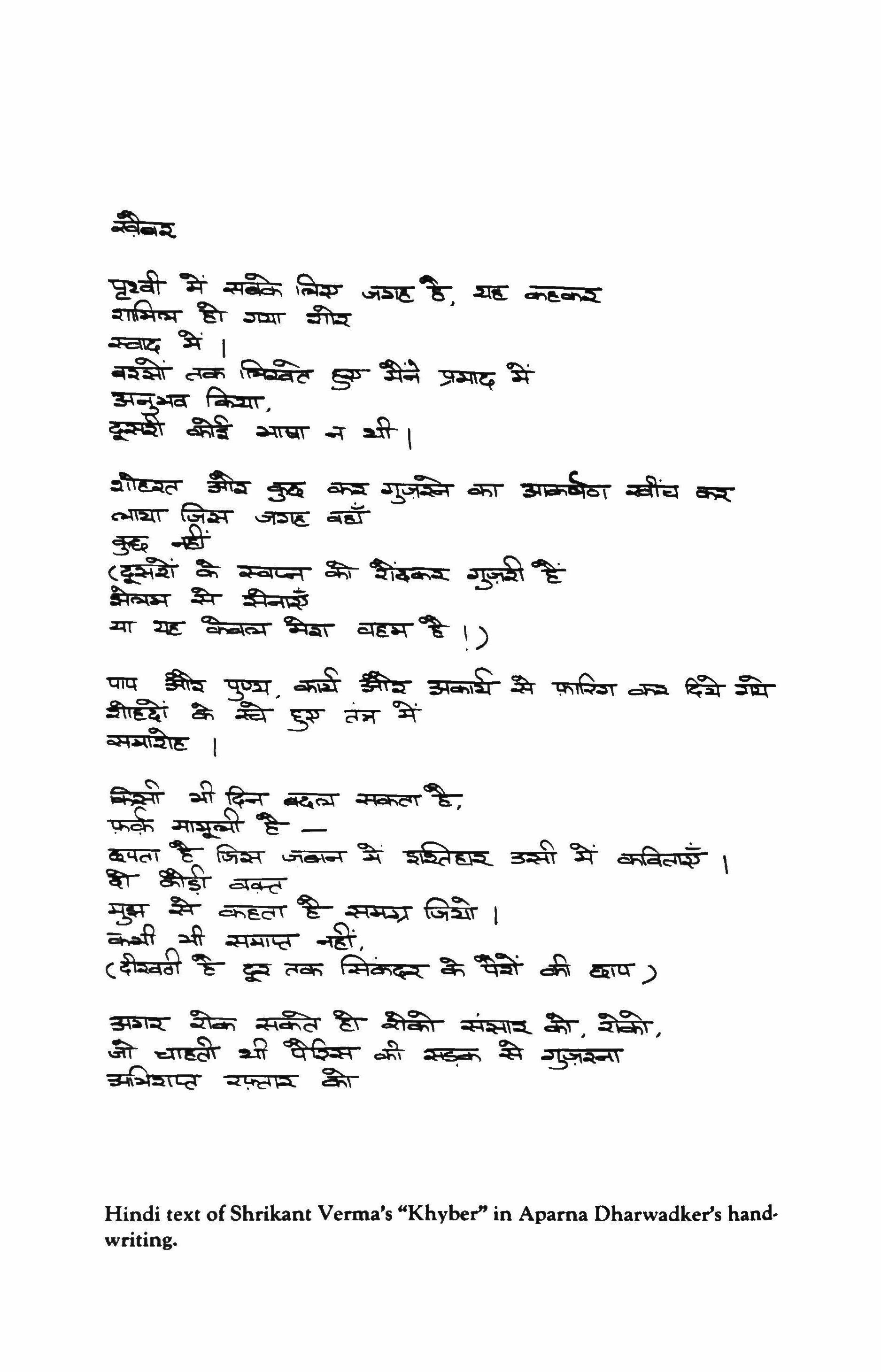

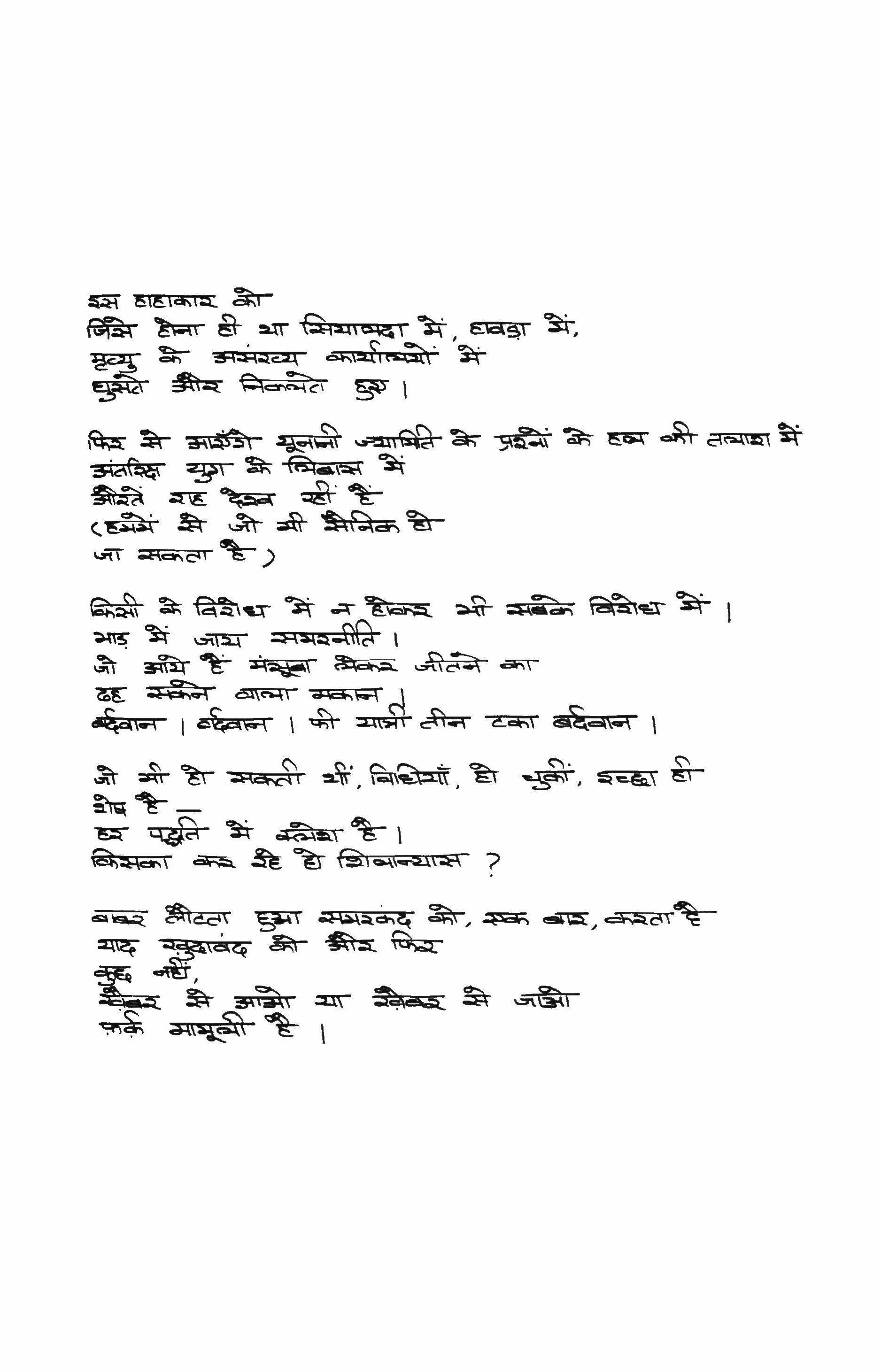

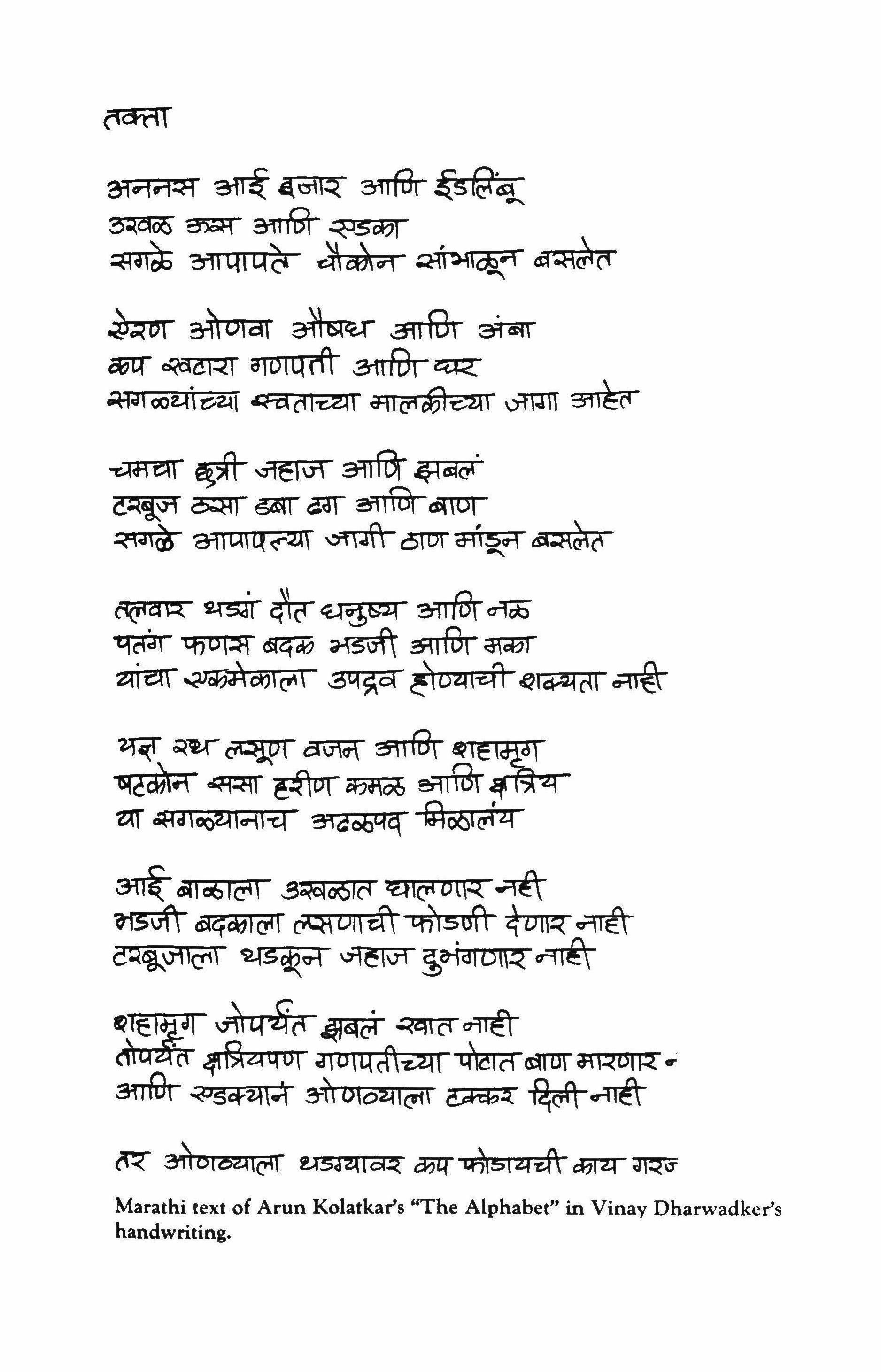

Twenty-nine Modern Indian Poems translated from Hindi and Marathi by Vinay

Meeting Beckett by

�

I'll .: .!.. /

Dharwadker

Charles Juliet

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Chicago Tribune Foundation, the illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Robert R. McCormick Charitable Trust and the National Endowment for the Arts.

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the inside back cover for names of TriQuarterly Council members and Friends of TriQuarterly.

As!ociate Editor Susan Hahn

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Assistant to the Editor Janet E. Geovanis

TriQuarterly Fellow Belinda Edmundson

Jo Anne Ruvoli, Amy Rosenzweig, Jane A. Francis, Ryan Tranquilla (Winter Intern)

Advisory Editors

Hugo Achugar, Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQVARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three issues a year)-Individuals: one year $18; two years $32; life $250. Institutions: one year $26; two years $44; life $300. Foreign subscriptions $4 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TTiQuarteTly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (708) 491-3490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and April 30; manuscripts received between May 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuaTteTly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1990 by TTiQuaTteTly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore, typeset by Sans Serif.

National distributor to retail trade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110 (201-667-9300). Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415-549-3030). Midwest: ILPA, P.O. Box 816, Oak Park, IL 60303 (708-383-7535); and Ingram Periodicals, 1117 Heil Quaker Blvd., La Vergne, TN 37086 (800-759-5000).

Reprints of issues 11-15 of TTiQuaTteTly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. ISSN: 0041-3097.

77 Winter

1989/90

The past three years have seen the emergence of TriQuarterly magazine as a publisher of a series of highly regarded books, in addition to its regular issues - an exciting development that has owed much of its success to the efforts of its Assistant to the Editor, Janet E. Geovanis. Her many and varied duties have included coordination of publicity and distribution for TriQuarterly Books/Another Chicago Press, and writing and producing TQ News, the TriQuarterly newsletter. It is with great regret, therefore, that we inform our readers that "Geo" will be leaving TQ to accept the position of technical writer in the computer field. Her intelligence, quick wit and wide-ranging talents will be sorely missed. We wish her well in her new endeavor.

TriQuarterly is pleased to announce that the first winner of the William Goyen Prize for Fiction is E. S. Goldman, whose collection of short stories, Earthly Justice: Cape Cod Stories, will be published by TriQuarterly Books/Another Chicago Press in November 1990.

Manuscripts are invited for consideration for the second annual Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry, awarded biannually by TriQuarterly for a booklength MS of poems. The MS should be 48 to 64 pages long, should be submitted in typed or clearly photocopied form and must be postmarked during June 1990. The prize consists of a $3,000 cash award and publication by TriQuarterly Books/Another Chicago Press. MSS will be read only if sent with a check for $15; this is a reading fee, but it includes a discounted one-year subscription to TQ. (MSS sent by persons who already subscribe to TQ need only a $5 check.) MSS will be returned only if accompanied by a SASE. The winner will be announced in the fall of 1990. Send MS and check to: The Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry, TriQuarterly/Northwestern University, 2020 Ridge Ave., Evanston, IL 60208.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York has added to its collection two photographs by TriQuarterly contributor Mark Steinmetz. Portfolios of Steinmetz's work appeared in TQ #64 and 74.

TriQuarterly Books currently available: Writers from South Africa

Stephen Deutch, Photographer: From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989, with essay by Abigail Foerstner and preface by Studs Terkel

Selected Poems: The Weight of the Body by Stanislaw Baranczak

The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown selected by Michael S. Harper

For ordering information, please see page 324.

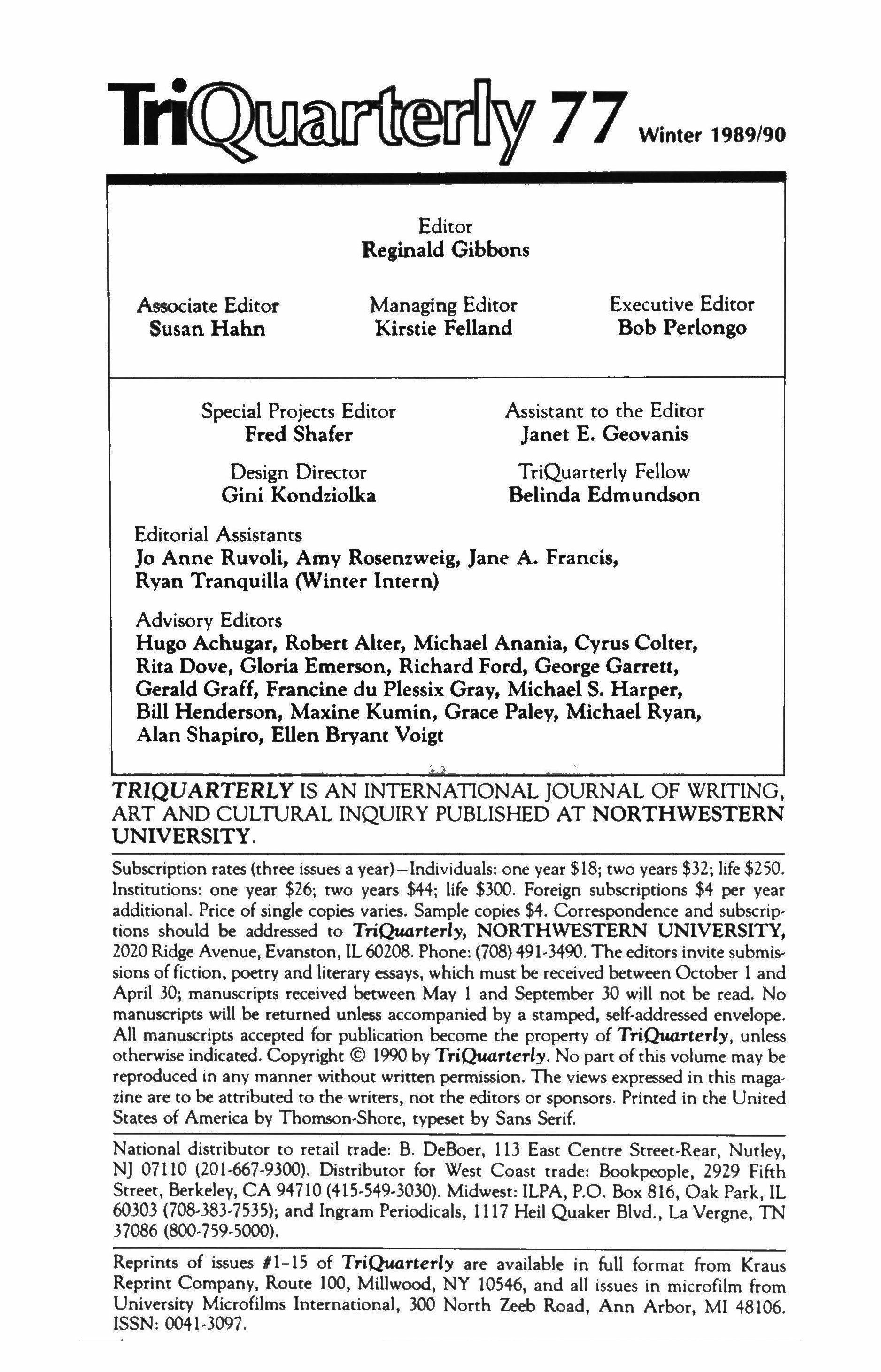

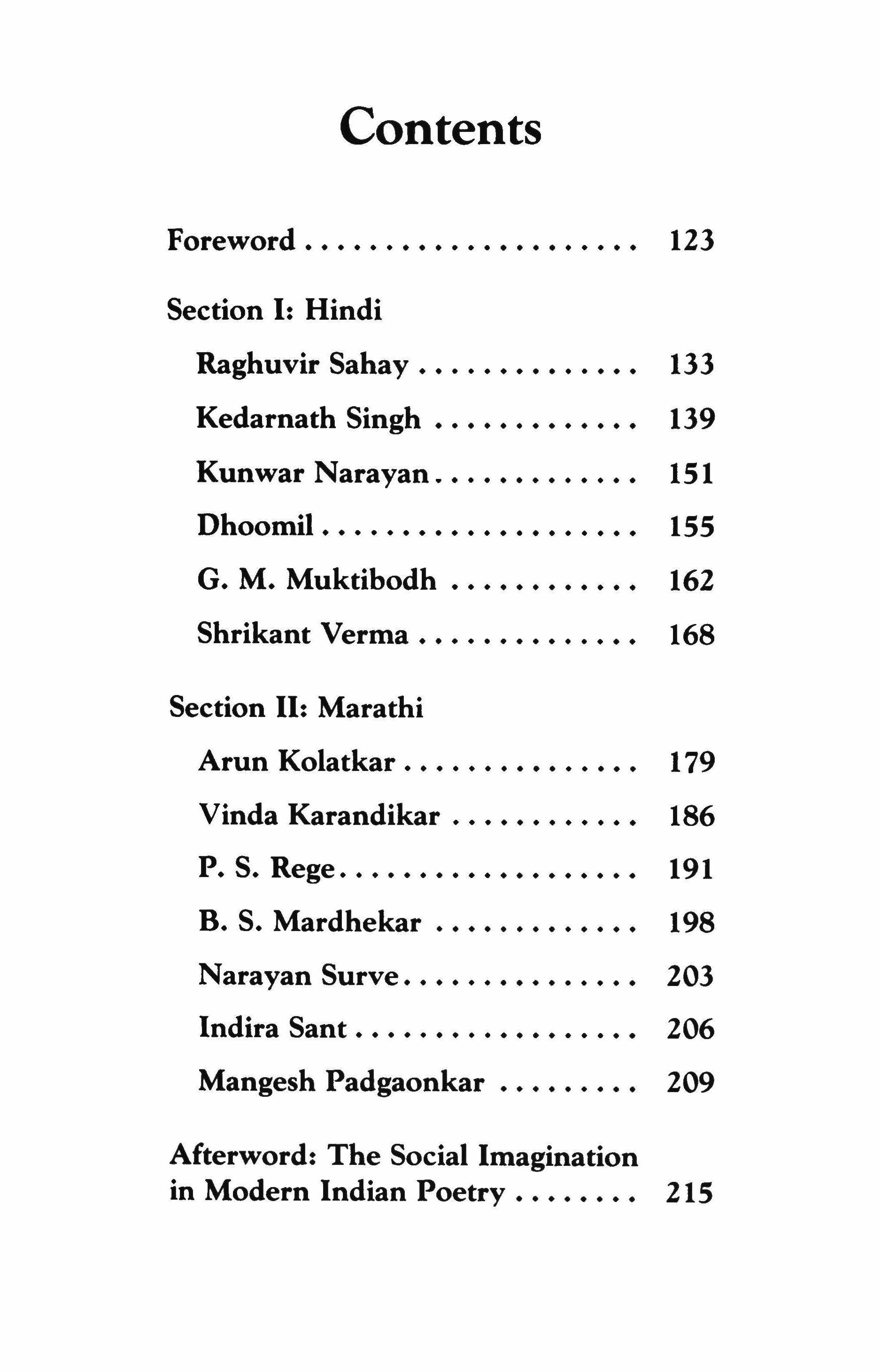

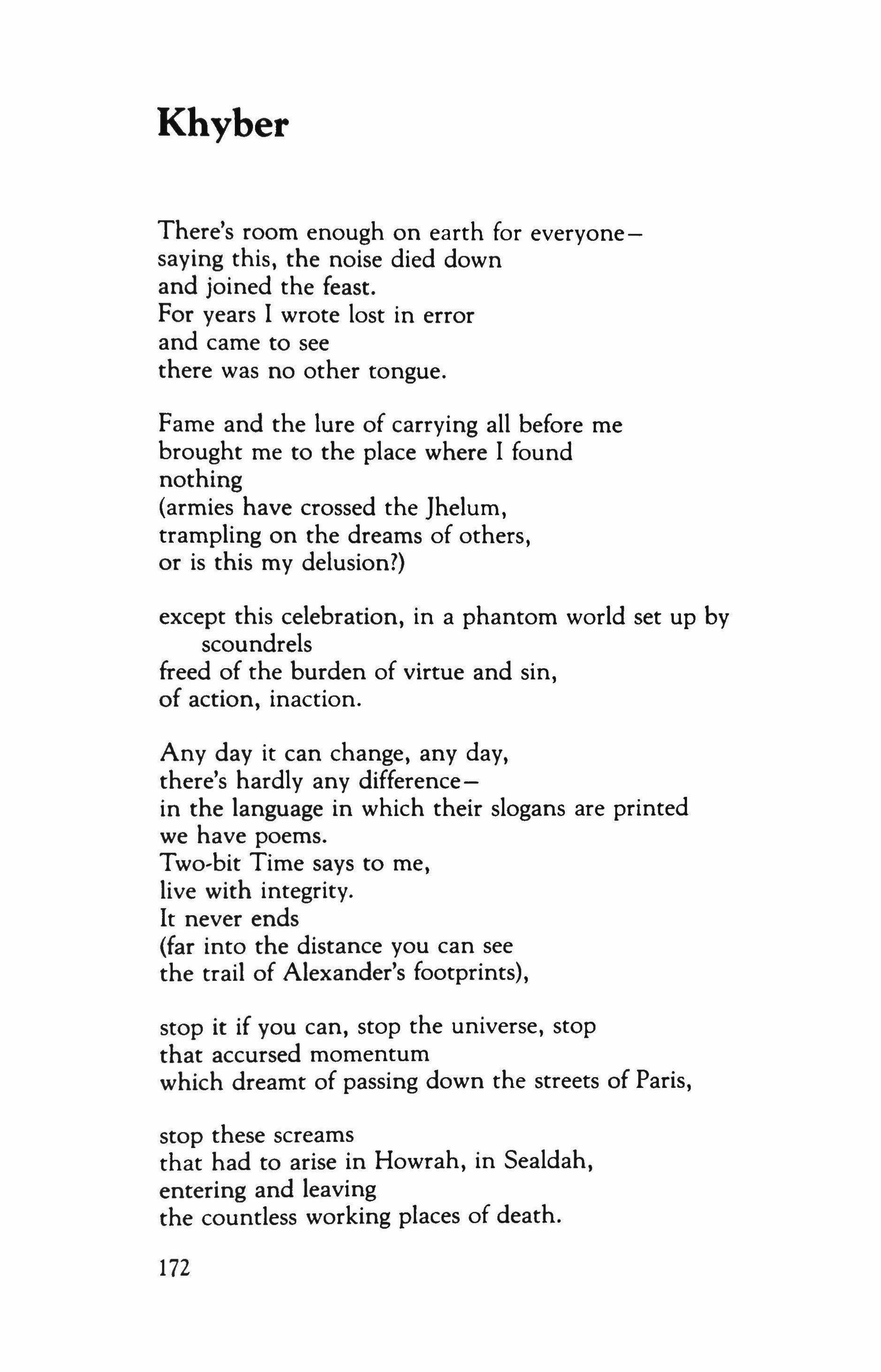

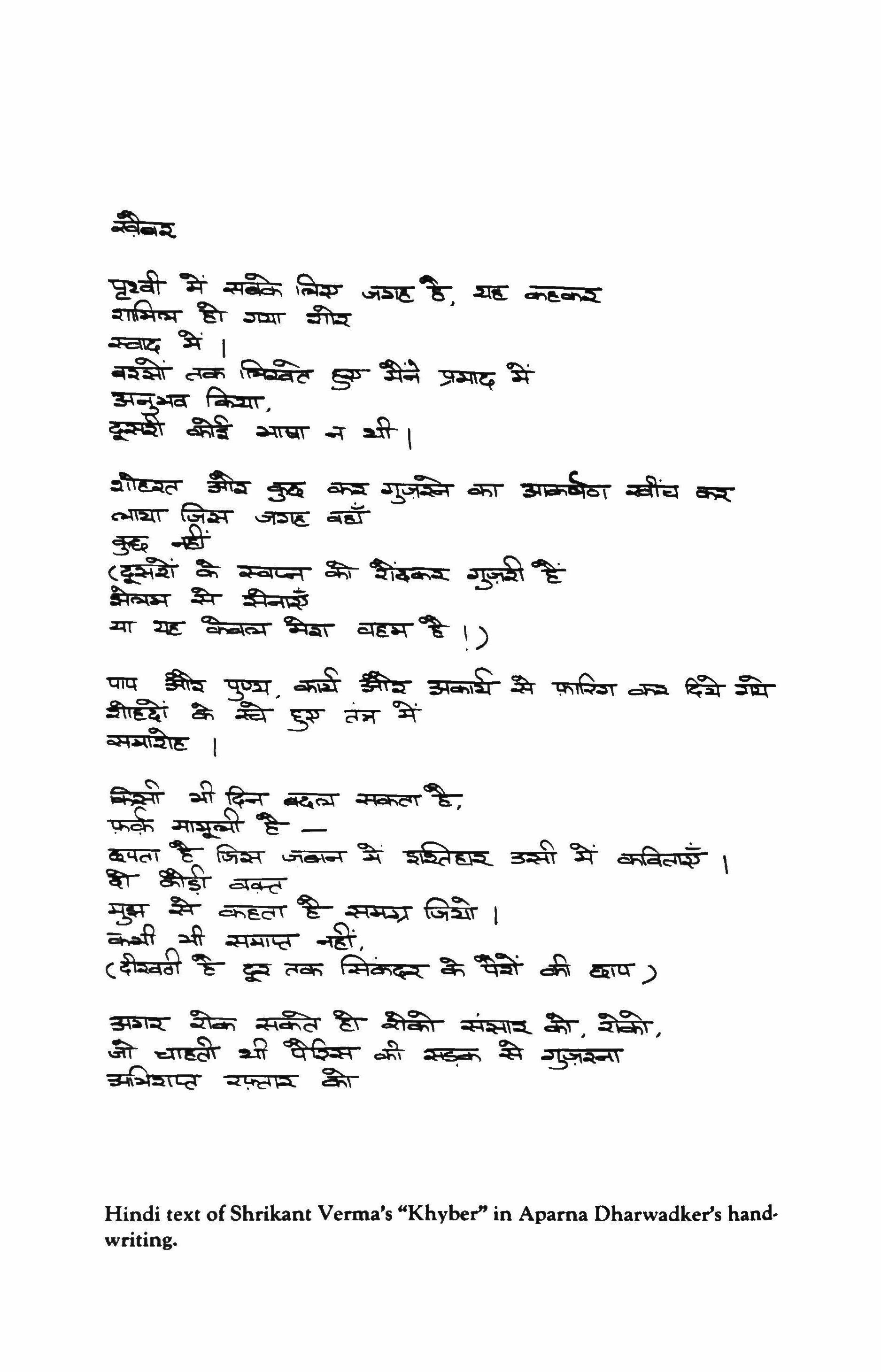

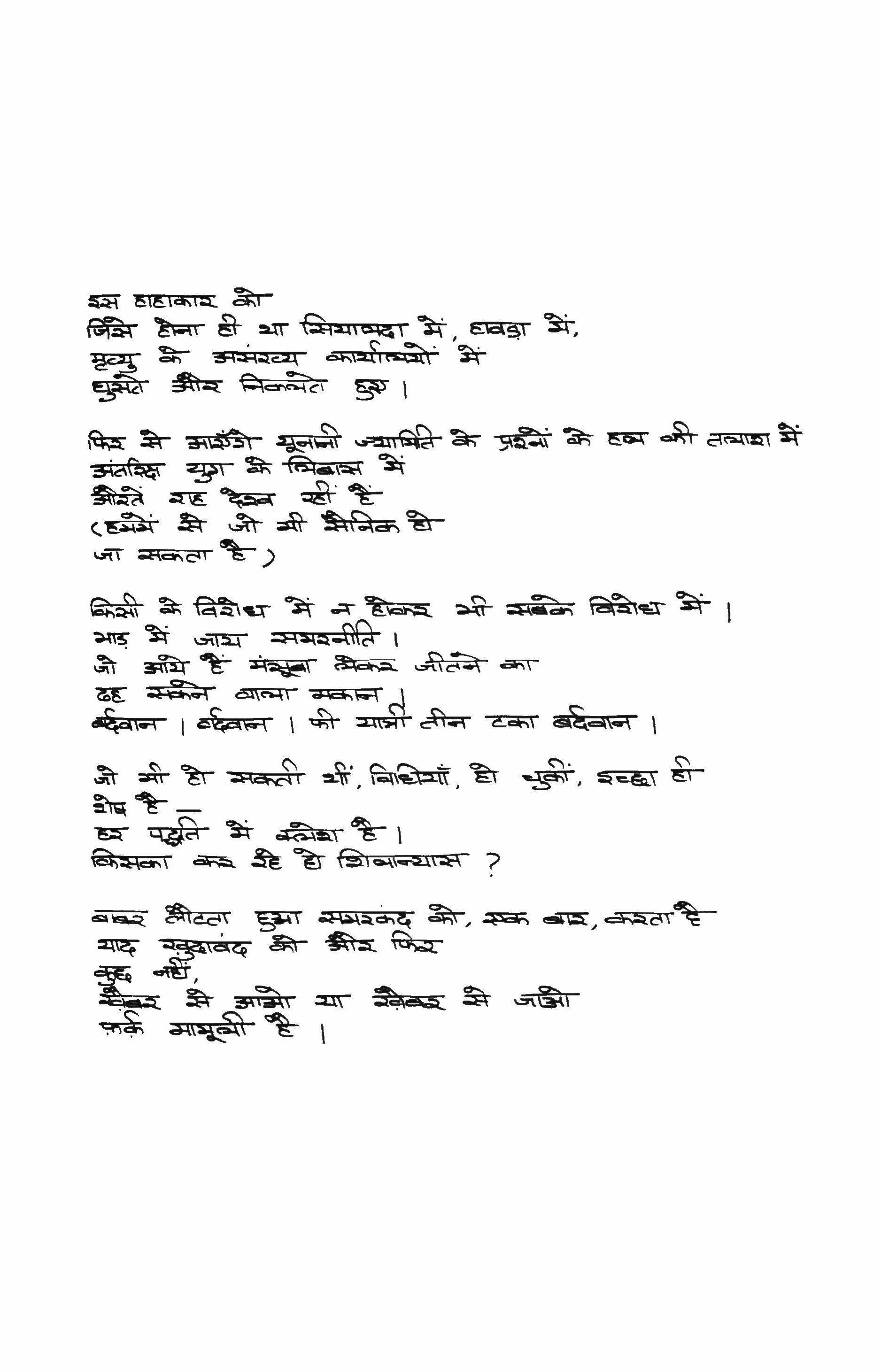

Contents Stanislaw Baranczak: First Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry. 5 Remarks by Peter Balakian INTERVIEW Meeting Beckett 9 Charles Juliet Translated and edited by Suzanne Chamier FICTION Ghost Nets Karen Heuler 31 Perjury 41 Russell Working Good Samaritans R. D. Skillings Retreat 86 Arthur Morey Fireflies 104 David Michael Kaplan 65 SPECIAL SECTION Twenty-nine Modern Indian Poems 119 Translated {rom Hindi and Marathi with a Foreword and Afterword by Vinay Dharwadker LECTURE Orpheus/Philomela: Subjection and Mastery in the Founding Stories of Poetic Production and in the Logic of Our Practice. 229 Allen Grossman 3

The Rooms of Other Women Poets; We Are Human History. We Are Not Natural History; Outside History; In Exile

Eavan Boland The Waiting; The Cleaving.

Li-Young Lee Manifest Destinv, Being Caught Coming and Going

Little Cambrav Tamales (5,000,000 bite-size tamales); Snapshots ••••........•••.......

Claribel AlegrIa

The Hammer; Above the Irish Sea, 1971

David Galler

The Stairs of the House; Time and the Tide; Text and Scholar; Two Doors Down

Paul Breslin

Alan

When Now and Then We Run Into Each Other; After We Broke Up; It Was Still

Imre Oravecz The Dancer or the Dance

Rebecca Seiferle Hector Returns to Trov: The Iliad, Book VI

POETRY

249

254

267

Blind 271

.....•.•........•...••••.••..

Tira Palmquist

L. S. Asekoff

273

276

280

Taking

285 Maxine

The

286

295

298

302 Translated

CONTRIBU1URS .•.................... 320 Cover design by Gini

the Lambs to Market

Kumin

Lesson

Shapiro

Summer

by Robert Fagles

Kondziolka

Stanislaw Baranczak:

First Winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry

TriQuarterly Books and Another Chicago Press are proud to announce that the first winner of the Terrence Des Pres Prize for Poetry is Stanislaw Baranczak, for his Selected Poems: The Weight of the Body.

In addition to awarding Mr. Baranczak $3,000, the presses copublished his book in both hardback and paperback editions (see page 324 for ordering information). At an award ceremony for Baranczak held on November 4. 1989 in Chicago, the following remarks were delivered by Peter Balakian:

Terrence Des Pres came of age in a university climate that was heavily dominated by New Criticism and myth criticism, methodologies defined primarily by formalist and esthetic approaches to literature. He found such methodologies too narrow for the serious issues he believed literature embodied in our troubled century. Though he had been interested in Shelley's politics in the dissertation he wrote as a graduate student at Washington University in the late sixties, it was his encounter with the narratives of Jewish Holocaust survivors that propelled him into the large-minded interdisciplinary thinking that came to define his work.

As you know, his first book, The Survivor: An Anatomy of Life in the Death Camps (Oxford University Press, 1976)-a study of human survival in the most hideous conditions of extremity, the Nazi concentra-

5

tion camps-was a ground-breaking book for both Holocaust studies and in some sense for literary studies.

Having written that book, Terrence seemed forever restless in pursuit of knowledge that could open up the problems of the pressing moral issues that human language embodied in our age. He found critical approaches in science, philosophy, the history of ideas, formalist analysis, feminism, biography, social theory, et cetera. Aristotle, Adorno, and Northrup Frye were all grist for Terrence's pen.

He never considered himself a critic for the academy. He eschewed specialized lexicons, fads and pedantries. He wrote for the world - his ideal civilization of common people with intellectual and moral concerns. His language was always limpid and elegant - always conveying a tone of civic necessity.

Terrence lived on that fence where moral issues and esthetic forms converge. Not an easy place to inhabit. He wrote in and provoked a cross fire of opinion and controversy about the political nature of poetry. He always had a sense that bullets were flying by his headknowing full well that in extolling poets like Bertold Brecht and Thomas McGrath he was asking the American poetry establishment to rethink some of its assumptions about art. Perhaps no book in recent years has asked us to evaluate those assumptions as has his last book Praises and Dispraises (Viking, 1988).

Terrence defended those who had been victimized by brutality, totalitarian power and racism. His writing illuminated the struggle of the whole human self to resist evil. It's pertinent to note that Terrence was greatly influenced by the political foment of American life in the 1960's: the Civil Rights Movement and the popular protest against the Vietnam War. During that time he was a graduate student at Washington University and then a Junior Fellow at Harvard, and he witnessed how human voices could make a difference in civilization's struggle for justice. He came to believe that the world out there and the life of the mind should never be severed.

Terrence believed in poetry as few critics do. He loved its ranges of music, its textures and its voices. He thought of poems as living, actioninducing passions that inhabit the world of social and political events as well as the daily worlds of men's and women's lives. Poetry, he believed, should provoke us to see, act and stand up. He cared about the wellbeing of those who wrote poems, especially those who wrote poems he believed to be living poems. He was a friend and aider to so many of us,

6

and now it hardly seems possible that he's not here to offer his insights and words, his tender and funny and manic energy.

There was no other critic like Terrence in America in the 1970's and 1980's. While he often spoke against the grain, it seems more and more that the grain is speaking with him.

While we continue to miss him and mourn his loss, we remain grateful for what he left behind. I know I speak for many of us in the literary world and for Terrence's ideal audience when I express my gratitude for the important prize that is being given in his honor and memory tonight.

7

Meeting Beckett

Charles Juliet

Translated and edited by Suzanne Chamier

La ou nous allOns il la lois l'obscurite et la lumiere, nous awns aussi l'inexplicable.

Where obscurity and light meet, there we lind the inexplicable.

- Samuel Beckett

1. October 24, 1968

I call him on the building intercom; he tells me to come upstairs. I step off the elevator, nearly bumping into him. He had been waiting for me. In his office, I sit down on a small sofa across from his desk and he sits across from me on a stool. He has already taken up his familiar posture, one leg wrapped around the other, his chin resting on one hand, body slumped forward, eyes fixed on the floor.

Not a word is spoken. I sense that it will not be easy to break the silence. Strange thought, I say to myself, to be asking questions of someone whose literary self embodies the very act of questioning. He looks away, and when I sense his eyes returning to meet mine, I too glance away. Thus I find myself in the presence of the person whose writing has meant so much to me and with whom, in my solitude, I have pursued endless dialogues. For all of these reasons, I think of him as a friend. It is astonishing then to admit to myself that I am a stranger to him; and this irony preoccupies me as we talk.

The silence seems at once elastic and rigid. Not without apprehension, I suddenly remember what Maurice Nadeau once told me: Beckett is capable of meeting someone and leaving again hours later without having uttered a single word.

I observe him out of the corner of my eye. Serious, somber, knitted brow. I look in his eyes of unbearable intensity. I feel more and more serious, as though I might panic if I don't say something soon, yet I am able to make only a vague sound. In a barely audible voice, I begin to tell

9

him that at age twenty-two, I had tried to read Molloy but hadn't really understood it or grasped its importance. I obtained all of his other books, without really intending to read them. After reading a few lines from Texts for Nothing completely by chance in 1965, I couldn't put the book down; devoured it passionately. I then threw myself into his writing and was overwhelmed by it, reading and rereading each of his texts. I was most of all struck by that strange silence in Texts for Nothing, a silence that can only be found at the utmost of the most utter solitude, when one has left everything, lost everything when one is nothing more than a listening device picking up the voice that murmurs when everything else is still. A strange silence, yes, and prolonged by the bareness of words. Words without style or rhetoric, without the noise of storytelling. With only the minimum necessary for what must be said. He acknowledges what I have been saying.

SB: Yes, when one listens to oneself, it is not literature that one hears.

I know that he has been seriously ill during the past few months. Our first meeting had originally been scheduled for May 3, 1968. But the night before, after attending a preview show for an exhibition, he felt ill. Madame Beckett met me at the door; she said something about the flu. We agreed to a brief postponement. Yet I waited in vain for a telephone call. Four months later, I learned that he was suffering from an abscess on the lung, perhaps a consequence of an event that had occurred some years before the war, when, for no apparent reason, a derelict had knifed him one evening on the street.

I ask about his health, and the conversation turns to aging.

SB: I always wanted to be poised for action in old age. One's being can burn brightly while the body decamps. I've often thought about Yeats. He wrote his best poems after age sixty.

I ask more questions. He cannot recall. Or prefers not to think about this period of his life. He talks about tunnels, about a state of mental twilight.

SB: I have always sensed that there was within me an assassinated being. Assassinated before my birth. I needed to find this assassinated person again. And try to give him new life. I once attended a lecture by [ung in which he spoke about one of his patients, a very young girl. After the lecture, as everyone was leaving, [ung stood by silently. And then, as if speaking to himself, astonished by the discovery that he was making, he added: In the most fundamental way, she had never been really born. I, too, have always had the sense of never having been born.

10

The conclusion of the [ung lecture reappears as an episode in All That Fall:

MRS. ROONEY I remember once attending a lecture by one of these new mind doctors, I forgot what you call them. He spoke-

MR. ROONEY A lunatic specialist?

MRS. ROONEY No no, just the troubled mind, I was hoping he might shed a little light on my lifelong preoccupation with horses' buttocks.

MR. ROONEY A neurologist.

MRS. ROONEY No no, just mental distress, the name will come back to me in the night. I remember his telling us the story of a little girl, very strange and unhappy in her ways, and how he treated her unsuccessfully over a period of years and was finally obliged to give up the case. He could find nothing wrong with her, he said. The only thing wrong with her as far as he could see was that she was dying. And she did in fact die, shortly after he washed his hands of her.

MR. ROONEY Well? What is there so wonderful about that?

MRS. ROONEY No, it was just something he said, and the way he said it, that have haunted me ever since.

MR. ROONEY You lie awake at night, tossing to and fro and brooding on it.

MRS. ROONEY On it and other wretchedness. (Pause.) When he had done with the little girl he stood there motionless for some time, quite two minutes I should say, looking down at his table. Then he suddenly raised his head and exclaimed, as if he had had a revelation, The trouble with her was she had never been really born! (Pause.) He spoke throughout without notes. (Pause.) I left before the end.!

In 1945, Beckett returned to Ireland to visit his mother whom he had not seen since the beginning of the war. He returned to see her again the following year, at which time he suddenly realized what he had to do.

SB: I understood that things could not go on any longer as they were.

11

He told me then about his experience in Dublin one night at the end of a jetty in the midst of a raging storm. The story that he shared with me is told in the following passage from Krapp's Last Tape (pp. 20-21);

Spiritually a year of profound gloom and indigence until that memorable night in March, at the end of the jetty, in the howling wind, never to be forgotten, when suddenly I saw the whole thing. The vision, at last. This I fancy is what I have chiefly to record this evening, against the day when my work will be done and perhaps no place left in my memory, warm or cold, for the miracle that (hesitates) for the fire that set it alight. What I suddenly saw then was this, that the belief I had been going on all my life, namely-(KTapp switches off impatiently, winds tape fOTwaTd, switches on again)-great granite rocks the foam flying up in the light of the lighthouse and the wind-gauge spinning like a propellor, clear to me at last that the dark I have always struggled to keep under is in reality my most-(KTapp curses, switches off, winds tape fOTwaTd, switches on again)-unshatterable association until my dissolution of storm and night with the light of the understanding and the fire

He talks about finding a suitable language to convey his thoughts and about throwing away "all the poisons," a phrase that puzzles me somewhat. I think that he means all the intellectual solutions, the reasoned decency, the need to dominate life.

SB: When I wrote the first sentence of Molloy, I didn't know where I was headed. And when I finished the first part, I didn't know how to go on. It all came out as it is. Without any revisions. I hadn't prepared anything or worked out anything in advance.

He stands up, takes a fairly thick notebook with a worn cover from a drawer, and hands it to me. It's the manuscript of En attendant Godat [Waiting for Godat]. The block-designed gray paper is rough, of the inferior quality available during the war. Small slanted writing, difficult to read, covers the right sides of the pages. Deeply moved, I leaf through the manuscript. Toward the end, the pages on the left are also used, and to read them, you have to turn the notebook around. This text has actually been written without revisions. As I try to decipher some lines, he murmurs: It all came together between the hand and the page.

I continue with my questions and learn that he has not read the Oriental philosophers and thinkers.

SB: They suggest a solution, a way out; and I sensed that there was none. Death is one solution.

I ask whether he is writing, whether he still can write.

SB: Earlier work rules out further attempts along the same lines. Obviously I could write texts like Teres mortes. But I don't want to. I just

12

threw away a short play. With each attempt there must be a step forward.

A long silence follows.

SB: Writing has led me to silence.

Long silence.

SB: Still, I have to continue. I am facing a cliff, yet I have to move forward. Impossible, isn't it? Still one can move forward. Advance a few miserable millimeters.

We discuss his health, in particular the strict orders that his doctor has given him and the medications he has to take. He apologizes for the brief interruption in our conversation as he attends to these obligations. In my letter requesting an interview, I mentioned that I knew Bram van Velde. Beckett and Bram have been friends for many years, but Bram, who lives in Geneva, does not correspond regularly; and they no longer have much contact. He asks me about Bram. I notice that one of Bram's paintings is across from his desk, therefore behind me. I turn to view it. An enigmatic composition, it was painted during a transition period for Bram before the war.

I know how much this painting means to Beckett, yet I also suspect that by purchasing it he was trying to help a struggling painter. While still standing to look at the painting, I glance out the window. In the fading light of this gray autumn day I glimpse the roofs and walls of the La Sante prison.

The tone of his voice in talking about Bram van Velde reveals his deep affection for him.

SB: Dreadful time. Bram had just lost his wife and was very depressed. He was living alone in abject poverty in an atelier full of his paintings, which he showed to no one. He let me approach him somewhat. But I had to find a language, had to reach out to him.

Beckett asks about me. About my own itinerary. But I soon turn the conversation back to his life and work. He says that he has no idea what an energizing charge his books contain nor what they represent to his readers.

SB: I am like a mole in a tunnel.

After he began to write, Beckett gave up most reading, for he considers the two activities to be incompatible. He thinks that his essay on Proust is pedantic and opposes its being translated into French. He chose to write many of his texts in French because the language was new to him then and thus retained an essence of unfamiliarity, which enabled him to escape the automatic expressions inherent in a maternal language.

13

When he began to write Molloy, he worked afternoons. But he could not fall asleep at night after writing, so he began to write mornings. His work contains weaknesses, he says. Certain characters, he claims, aren't right.

SB: There are some necessary weaknesses but others that I cannot forgive.

I ask how he spends his days and whether all of his achievements really help him during those moments of profound anguish when one senses that being itself vacillates and flounders.

SS: At those times, illness has helped me immensely. He stands to reach for one of his books, then sits down again to dedicate it to me. I let my gaze linger on him. His solemn, handsome appearance. His surprising timidity. The density of his silences. His concentration. The intensity with which he makes the invisible exist. If he impresses me to this extent, I say to myself, it is obviously because of what he is but also, perhaps especially, because of his absolute simplicity. A simplicity of behavior, thought and expression. Beyond a doubt, someone who is essentially different. A superior being. I mean: a person who stands fast at the bottommost point, someone who intimately and endlessly examines fundamental issues. Suddenly this realization: Beckett the disconsolate.

We continue to talk for a moment on the landing. He tells me that he has not yet fully recovered from his illness and apologizes for not having me stay for dinner. We agree to meet the following spring and to dine together at that time.

He wants to know what I plan to do during my stay in Paris. I reply that I have no other plans. My only purpose in coming to Paris was to meet him.

SB: Oh but you shouldn't have come from Lyon just to see me,z

2. October 29, 1973

Why have I let five years go by without seeing him? In the spring of 1969, I didn't go to Paris. And in the fall, as I was thinking about writing to him, he received the Nobel Prize. Admirers, academicians, former acquaintances, old friends from school and university days, family members flocked to see him from France, England, Ireland, even the United States. Beckett was inundated with visitors, and he told Bram that his apartment had become a real madhouse. From that moment on and for the next five years, I resolved not to press myself on him.

14

Finally I contacted him and we arranged to meet at the Closerie des Lilas, my first visit to that legendary brasserie made famous by Joyce, Hemingway, the surrealists and so many other renowned writers. At exactly 7 P.\l., the time scheduled for our meeting, I glimpse his tall silhouette. Dark glasses, sheepskin jacket. A beautiful pale red muffler. I walk up to him and introduce myself. Grasping my hand, he looks at me for a few seconds without saying a word. As we go inside, he removes his glasses. He takes off his jacket, motioning for me to sit in a booth while he sits in a chair so that we are not directly across from one another. Dark corduroy trousers, slightly worn. Blue-gray turtleneck, sleeves pushed up. He is tanned and relaxed and smiles at me; then he immediately becomes self-absorbed and a heavy silence descends upon us like a yoke.

How shall I ever being to speak? Talking about trivialities seems as impossible to me as beginning all at once with my questions. Yet his solemnity calms my agitation, pulling me toward a center while eliciting dormant thoughts and feelings.

For a while, I am unable to say anything at all. Then our conversation slowly begins. He tells me about five weeks just spent in Morocco where he toured the countryside in a rented car, slept on the beaches, walked through the souks. I ask whether he worked a little.

SB: No, it was more escape than involvement.

We talk for a long time about Bram - how he is, what he's painting, whether he still takes walks, whether he's still so taciturn. Beckett notes with regret that Bram and he no longer have the opportunity to see one another. I assure him that Bram thinks of him often. The conversation then turns to Jacoba, Bram's sister. She lives in Amsterdam with a friend who is paralyzed, and her life is not easy. Does Bram know about this? he asks. But before I can answer, he smiles and says kindly: No, Bram is apart from all of that.

He speaks in a low voice, uttering short sentences that I cannot always hear because of the background noise at the Closerie de Lilas.

We discuss his plays, in particular the stage productions in Germany that he has recently assisted in directing. I ask whether such work interests him.

SB: Yes, but it's really a diversion, an entertaining diversion.

He deplores the fact that in the Cologne production of Endgame the play was situated in a home for the elderly, a staging that disregarded Beckett's directions and caricatured the scene.

I mention that both Watt and Molloy received numerous rejection

15

slips, and he acknowledges that he had given up all hope of ever being published.

SB: It was my wife, Suzanne, who insisted that we keep on trying and who found [jerome] Lindon at Les Editions de Minuit.

I try to put into words why his writing would inevitably meet with opposition.

SB: There was a kind of indecency involved, yes, an ontological indecency.

I bring up the problem of translations, and he explains why he does them himself. Leaving the task to someone else would only oblige him to edit the text word-for-word later, an even more difficult task.

And what does he think about all of the academic essays and theses devoted to his writing? I express my own aversion to such analyses, which often strike me as senseless, useless vivisections. He gestures in the air, as if to brush away something annoying, then murmurs: that university madness.

He talks for a long while about growing older, in particular about the importance he places on hearing since his eyes have weakened. No, he no longer has insomnia. Doesn't write while walking.

He is surprised to learn that I have read Fizzles. Will send me his latest play, Not I, already staged in England and Germany. In the French production, Madeleine Renaud will portray the main character- a mouth, only a mouth.

For a new edition of Molloy and the trilogy, Beckett recently had to reread the books. I ask about his reaction. He lowers his head, looks into space; I note that it is not easy for him to find a response. His expression suddenly changes, and his face takes on a stone-like fixity. I can see that he is now very far away, that he has forgotten everything, and that for the moment he has not the slightest awareness of time and place. A fascinating sight. Sitting less than a meter from him and quite moved by it all, I study him with rapacious attention, certain that he does not observe my scrutiny.

I had forgotten how impressive yet natural his demeanor is. As handsome full-face as he is in profile, he expresses sensitivity, energy and the extraordinary intensity of a visionary. His forehead is grooved by deep lines. His cheeks are hollow and unevenly shaven. An aquiline nose. Shaggy, uneven eyebrows. Wide mouth, fine lips. Thick, disheveled gray hair.

Two, perhaps three long minutes pass. Then the stone revives, and I look away. Still another endless silence. And as I prepare another ques-

16

tion, convinced that he has lost sight of the preceding one regarding Molloy, he observes: I no longer feel at home there.

From my reading of his work, I had sensed Beckett's capacity for total and spontaneous self-absorption. He invests all of this energy, concentration and inventive spirit into his writing-in his choice of words and distinctive use of metaphor; in surprising deductions and unexpected displacements. Strokes of genius, cascading one after another.

Quite cautiously, I offer my own view of artistic activity: it is unimaginable, I say, without an accompanying sense of rigorous ethical urgency.

A long silence.

SB: What you are saying makes sense. But moral values are not accessible nor can they be defined. To define them, one would have to judge value itself, which is impossible. That is why I have never accepted the notion of a theater of the absurd, a concept that implies a judgment of value. It is not even possible to talk about truth. that's part of the anguish. Paradoxically, through form, by giving form to what is formless, the artist can find a partial way out. Perhaps it is only in this sense that there may be any underlying affirmation.

I again ask about his life. As an adolescent, Beckett had no intention of becoming a writer. After receiving his diploma, he began a university career lecturing in French at the University of Dublin. But after one year, he quite literally fled from a style of life that he found unbearable. His letter of resignation was sent from Germany.

SB: That wasn't a very nice thing to do.

When Beckett went to France, he had neither identification papers nor money. It was 1932 and President Paul Doumer had just been assassinated. Foreigners were under careful surveillance. A translation of Rimbaud's "Bateau ivre," which he had undertaken for an American magazine, brought him a small remuneration. In order to avoid deportation, he returned to London. He thought for a while about becoming a critic and, with this in mind, contacted several newspapers-but to no avail. He returned to his parents' home where his father, who had been forced to leave school at age fifteen, was understandably dismayed by his son's decision. At twenty-six years of age, Beckett thought of himself as a failure. The loss of his father the following year, in 1933, was a blow to him. With a small inheritance, he went back to London, where he took a furnished flat and lived quite frugally.

Following a long and difficult period of crisis, Beckett went to Germany where, in 1936, he traveled around by train and on foot. In 1937, he arrived in Paris and remained there, meeting Giacometti and

17

Duchamp and forming a close friendship with Geer and Bram van Velde.

In 1942, during the war, Beckett and his companion, Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil, took refuge in the Vaucluse at Roussillon after having narrowly eluded the Gestapo.! In 1945, he was finally able to travel to Dublin and see his mother. Upon returning to France, he worked as a storekeeper-interpreter for a hospital established by the Irish Red Cross in Sainr-Lo,

When in Ireland in 1946, Beckett experienced, as I said earlier, an upheaval that radically changed his approach to writing and his conception of narrative. I ask whether his change of consciousness occurred precipitously or over a longer period. He responds by talking about moments of sudden revelation during a time of crisis.

SB: Until then, I had thought that I could trust knowledge. That I was supposed to prepare myself intellectually. That day, everything collapsed.

His own words come to my lips: "I wrote Molloy and the trilogy when I began to comprehend my own stupidity. Then I began to write about the things that I feel." He smiles and nods his head.

He again describes the night in Dublin when, walking alone at the far end of a storm-whipped pier, everything suddenly seemed to fall into place. Years of searching and questions, of doubts and failures, suddenly took on meaning. As he approached forty years of age, he clearly saw, as in a vision, what he would have to do.

S8: I glimpsed the world that I had to create in order to be able to breathe.

He began writing Molloy while still at his mother's home, continued it in Paris, then at Menton, where an Irish friend offered him his house as a place to work. But after the first part was completed, Beckett didn't know how to go on. Although he no longer felt as anguished as in preceding years, everything remained very difficult for him. Thus we read on the first page of the manuscript of Molloy; "En desespoir de cause."4

During his intensely creative period from 1946 until 1950, Beckett wrote Molloy, Malone Dies, The UnnamabLe, Waiting for Godot and Texts for Nothing, all of which he still regards favorably. But texts written after 1950 are in his view tentative experiments with the only exception being a few good pages, as he puts it, in a few plays.

He notes that his writing no longer communicates the feverish tone that impressed me so much in Texts for Nothing and The UnnamabLe. He

18

has less and less to say, yet he thinks he may be closer to grasping, or at least discerning, the process of reduction.

We talk about the very brief texts-only a few pages in length-that he has just written. He mentions the seventeenth-century Dutch momento mori paintings, in particular one in which Saint Jerome is meditating on a skull. In the tradition of the painters who left us these canvases, Beckett would like to be able to express life and death in an extremely limited space.

Again he talks about aging, but without the least hint of bitterness. Even in a spirit of playfulness. The serenity that he now feels allows him to write with more calm, but he fears lapsing into a kind of formalism. These brief, highly crafted texts have gone through several drafts. For example, Imagination Dead Imagine underwent eight revisions, theoretically progressing each time toward reduction or "lessness."

Another text, entitled Still, originally published in Italian, is only one and one'half pages long. I ask whether he continues to remain silent and inactive for long periods of time, observing what goes on within himself and listening to what he hears there. He reiterates that the faculty of hearing has become more and more important for him in old age, far surpassing sight.

Again he talks about aging, this time with a sense of overpowering resignation. I remind him that he had told me during our first meeting how much he admires Yeats's experience of old age.

SB: Yeats and Goethe, yes. The active, productive old age of the great creators.

He mentions my first book, Fragments, saying that he senses great anguish in it. He asks whether things are going better for me now, then inquires about my work and my life in Lyon. I mention my journal, accepted for publication and then not published.

SB: Being published isn't what matters. One writes in order to breathe.

He asks me to send him some of my own writing. After our first meeting in 1968, in response to another request, I sent him some thirty poems. From his letter in response, I shall cite only one sentence: "Eloignez-vous et de vous et de moi."5

We talk about painting and discuss in particular Matisse, Picasso and Dubuffet, a retrospective of whose work I have just seen. He agrees with everything I say. He is serious, smiling, quick-witted and extremely attentive.

After about an hour of conversation, I am less and less guarded and even begin to feel very close to him, as if he were an old friend in whom I

19

could confide absolutely anything. Perhaps that is why. to my own astonishment. I became so bold as to reveal to him how crucially important the encounter with his writing has been for me and for my life. I began to tell him. doubtless somewhat passionately. how his work has given me the impression of discovering language and writing. Wrested me from a kind of perplexity. taught me lucidity. pointed the way toward essential issues. And I explained how. in great inner turmoil. I returned through the strange and unfamiliar landscapes of his writing to things that have been tormenting me since adolescence. I said that I love the trenchant quality. stripped bare of cerebrality and rhetoric. of his writing. That I've spent hours upon end reading. questioning. interpreting his texts in which I felt as though I were hearing my own voice. That I've discovered through the silence filling the pages of Texts for Nothing regions of my own being where. until then. I had never dared to venture. Admitted that his work. in a sense. destroyed and shattered me. but that I have also received tremendous energy from it. Said each text corresponds to a sense of urgent necessity in the perfect curve of his work. Expressed my admiration for him and his exemplary life. Declared that he-and not some other writer more in tune with the times-that he alone had been able to reveal to readers what contemporary humanity really is. Added how grateful I am that he has remained somewhat elusive and apart. for only on the margins can one form a vision that is at once incisive and inclusive. I acknowledged that his work does not affirm but instead proceeds by negation. then by negation of negation so that those things that must be grasped. but that words will never fully capture. may melt into one stream in the space between the negations. I confessed having asked myself dozens of times what kind of person could have written pages of such fundamental truth and delved so deeply into anguish. projecting such a merciless light while laying bare humankind and the limits of our condition. Said that I am no longer sure whether I should keep trying to write since he seems to have so completely exhausted the terrain where I feel I must carry out my own excavations. All of this I said somewhat confusedly and very rapidly. Suddenly Beckett stands up. He asks me to excuse him for a moment. I am brought back abruptly to the reality of the moment as I observe him throw back his head. pull back his shoulders and gasp for breath. He takes a few steps and walks away. leaving me to my utter distress. embarrassment and stupor. Three or four very long moments go by. Then he returns. An unending silence. impossible to break. I finally manage to ask what he plans to do during the next few days.

20

SB: I'm going to the country for a few weeks so that I won't be disturbed. Paris is impossible. Too many interruptions.

As he speaks, I recall what a mutual friend told me: at his country house, Beckett plays the piano, writes, does errands, prepares meals, takes long, brisk walks-and also spends hours doing nothing, remaining still and open to whatever solicits his attention. And I remember what happened when I visited the village where his country house is located. Upon arriving, I noticed a passer-by not much younger than he, and I asked whether she knew where a writer named Samuel Beckett lived. Since she was able to tell me, I assumed that she also knew him and asked whether she would be willing to tell me something about him. She seemed somewhat surprised, then answered in a quiet voice: "Oh, well, Mr. Beckett Mr. Beckett You know, he is really quite a fine gentleman. A fine gentleman." I understood that she wanted to sum up in these few words everything that she knew and thought about him, and I did not press her any further.

I tell Beckett that I have visited this spot, seen his house, and walked in the fields and woods surrounding it. Then I ask: But when nothing is happening, what do you do?

SB: There's always listening.

3. November 14, 1975

We meet again at the Closerie de Lilas. Again I note how serious, reflective and self-possessed he is; and how handsome. His short hair, thick and barely combed. The ridges at the end of his nose. His face, furrowed and made spiritual by inner suffering and intensity. And yet, I sense youth and vitality. Each time that we meet, I am struck by his silence and serenity, gentleness and passivity, acceptance and vulnerability. These characteristics join with qualities that are generally regarded as their opposites: for example, the strength and energy so clearly and distinctively manifested in his expression, the eagle eye that seizes you.

Already silence has settled in, and again I don't know how to initiate dialogue.

Recently I received a copy of a monograph on Bram van Velde just published by Galerie Maeght." I ask Beckett whether he would like to see it. He takes it, leafs through it, looking attentively at the photo reproductions and reading a few pages of text here and there. We talk for a long time about Bram, and he asks me a few questions.

21

Then I ask about his work.

SB: I always have something in progress. It may be long at first, but gradually it's reduced.

He says that he likes what he writes less and less.

I ask whether it has been difficult for him to arrive at a point of nonvolition and nonaction.

SB: Yes, I tried until 1946 to discover a kind of knowledge that would permit me to act. Then I realized that I was on the wrong track. But perhaps there are only wrong tracks. You must nevertheless find the wrong way that suits you.

Have you read the mystics?, I ask.

SB: Yes, when I was young I read them. But I didn't really understand them.

Then, in a despondent tone: And besides, I've never really understood anything.

I hide my astonishment. A long silence follows. Then I begin again: In the works of the mystics, there are dozens and dozens of phrases similar to what you have written. Don't you think that, putting aside the question of religious belief, one can find many points in common between you and them?

SB: Yes. Perhaps there is a similar approach to the experience of the unintelligible.

I continue, mentioning Bernard de Clairvaux, in whose writing, I maintain, one finds some passages that have the rhythm, genius and impact of the best pages of The Unnamable. He laughs openly, stops me and says that he has some reproaches to make of Bernard de Clairvaux.?

We again discuss his writing. He acknowledges having effaced himself more and more from his work.

SB: Finally one no longer knows who is speaking. The subject disappears completely. That's where the crisis of identity ends.

He believes that artists must absent themselves as individuals from their work. I come back to Texts for Nothing. He smiles as I quote a few lines: "Ce rien foisonnant. ."

He talks about Joyce and Proust, both of whom sought to create a totality and to render it in its infinite abundance. It's enough, he observes, to examine their manuscripts or the galley proofs that they corrected. They never stopped adding, then adding still more. Beckett, however, goes in the opposite direction, toward nothingness, always compressing his text more and more.

I bring up the "poverty" of his universe with regard to both language

22

and technique: a minimum of characters, dramatic events and issues; yet everything important is said with vigor and singularity. He nods his assent with a smile, saying that somewhere the two methods must come together.

I continue talking: Often I've wondered how it is that you were not overwhelmed by feelings of guilt and remorse.

He is about to respond but decides otherwise. As in the preceding meeting, he becomes totally immersed in himself, as if nothing within him were still alive. His incredibly intense expression is fixed and unseeing; his face and body turn to stone.

After a long silence of several minutes, he emerges. Another long silence. But I feel I must continue. I must tell him how amazed I am that his faith in writing and communication has survived. He too is amazed and acknowledges a sense of mystery.

I now turn to the universality of his writing. To the fact that thousands of people the world over have discovered, by reading him, innermost depths of which they were not aware. He nods his head: Yes, that's another mystery.

He continues but some of the words, spoken in a very low voice, escape me.

Then X., a writer-editor, interrupts our meeting, asking Beckett to sign a petition. When X. leaves, after having made his importunate demands, I know that our conversation is over.

A silence of four or five minutes follows, and I wait for him to give me the signal to leave. But instead he asks me questions about myself and my work. And we discuss his plans. He's leaving for Morocco in December to avoid being in Paris during the holidays.

I bring up Ireland. I know that he spent five days there in 1968 because of a death in the family. But he does not intend to return again. I ask what he thinks about the war in Ulster. He replies that he's not interested in it. But after a second, he begins to talk about it with a certain vehemence, quoting [Francois] Mitterrand who said: "Le [atuuisme, c'est la betise"

SB: In Ireland, there are not two fanaticisms but three, four, fiveeach torn apart by the others.

We talk about Spain and he explains why they are trying so hard to keep Franco alive. If he lives until November 25, a member of Franco's party would be able to name the head of the government, which would then continue pro-Franco; but if he dies before then, someone from the other side might be named.

SB: Even Goya did not imagine such things.

23

He still goes to his country house and remains there alone for two or three weeks at a time. In the mornings, he writes. In the afternoons he does odd jobs, walks in the pastures or perhaps goes by car to a more isolated spot to walk there. Does the solitude bother you? I ask. He seems surprised, then replies: No, no, not at all. Quite the contrary. but when I was young, I couldn't have endured it.

He talks fervently about silence. About his pleasure in being able to follow the course of the sun from dawn until dusk.

Then, as if echoing what X. had said, he talks about the desire for literary success and mentions Van Gogh.

SB: When you think that he did not sell a single painting during his lifetime.

Do you admire Van Gogh very much?, I ask. He looks at me so unwaveringly that I know my question has touched him deeply.

Two or three times he is about to respond but he is unable to do so. The silence persists. Contact between us was broken by X.'s interruption; when we part company, I cannot deny my feelings of frustration and disappointment.

4. November 11, 1977

Late morning. I am waiting for him at the bar of one of the main Paris hotels, across the street from his apartment. As I arrive, I see Madame Beckett, who is just leaving on errands.

Some Japanese tourists are sitting at the next table, creating a lot of commotion. I begin to think about the kind of silence that Beckett seems to need, a silence that I delight in detecting behind his words. A story that Bram van Velde tells (he heard it from Beckett) comes to mind:

A writer is working at his desk across from an open window. Suddenly a voice booms from a radio turned up as loud as possible in the concierge's apartment on the floor just below. After a few moments, the writer, unable to endure the noise any longer, rushes to the window and shouts: "Something terrible is about to happen!" In a tone at once apologetic and beseeching, the concierge replies: "But sir, that radio is my whole life." The writer: "Well, if that's the case, forget everything I said."

Beckett arrives, looking relaxed; we begin talking without difficulty. First we discuss Bram van Velde- his health, work, habits. Whether he still likes to walk. Whether he still makes the characteristically inci-

24

sive remarks that are his hallmark. How he has taken the recent ordeal of his brother's death. Beckett seems perplexed that the two brothers, Geer and Bram, went so many years without seeing one another. I try to explain why. In Beckett's reply, I hear sadness and incredulity: Even so, they were brothers.

Beckett admires Geer van Velde's work and still has two paintings by him acquired before the war. He had not seen Geer for several years when Geer's wife contacted Beckett, telling him that as Geer lay dying, he spoke Beckett's name.

Beckett has just returned from three weeks at his country house where, as usual, he played the piano a lot, read a little and went for walks. He has recently been engrossed in Heine's last poems, which he says are like lamentations. Beckett enjoys silence and doing nothing, spending hours simply looking out the window. He describes the beet wagons that pass noisily by his house.

I ask how the passage of time affects him.

SB: It doesn't bother me. I even find, to my amazement, that the days go by far too quickly. When I was young, I would not have been able to remain alone for such long periods of time. Smiling, he adds: I sometimes find myself counting my steps when 1 go walking.

I ask what he has been working on lately.

SB: I couldn't sleep last night, and I thought of a play lasting only one minute.

Suddenly he becomes animated, changes the position of his chair to face me, pushes back our drinks, his lighter and a metallic box of little cigars.

SB: Someone is standing alone, silent and immobile, a little off-center, not far from the wings.

Gesturing with his hands, he indicates positions using the tabletop as a stage, then continues: Everything takes place at nightfall. A second character emerges. Advances slowly. Sees the other one, still immobile. Appears overwhelmed; stops. Then asks: Are you waiting for someone? For something? The first character gestures: No. Then after a few moments continues on. Second character: Where are you going?

Response: I don't know.

After a moment, Beckett smiles: Perhaps it's something to develop.

As we talk about the play-Pas [Footfalls]-he discusses the importance of our steps on this earth, human steps.f With his hand, he portrays the movement of an animal in its cage, a prisoner in his cell.

SB: Always these comings and goings. That's something Bram knows well, the sound of footsteps.

25

Images come to mind and I talk about his writing. About his global vision of a totality. And about his latest plays and stories in which, with remarkable brevity, human experience is expressed with very few words: waiting, anguish, hope, love, death I note his attention to detail, whereby he seizes upon the slightest detail, yet at the same time seems, as if transfigured by Sirius, the brightest -rar in the sky, to embrace the whole.

He assents, pointing with his index finger first to the table, then away: One must be present there and also millions of light years away. At the same time.

A long silence.

SB: A leaf that falls and the fall of Satan, it's all the same thing. His face is animated, he laughs easily and openly: Marvelous, isn't it? All the same thing

A long silence.

SB: But how to say this: there are no pronouns. The I, he, wenone of that works.

Another long silence.

SB: In this forsaken world, everything invites us to feel indignant. But as far as one's work is concerned, what is there to say? Nothing is sayable.

I try to say that his work is exceptional. I argue that humankind has been trying desperately for the past four centuries to create a reassuring and gratifying self-image. But it is precisely this image that Beckett has set about with great application to dismantle. He reminds me that Leopardi and Schopenhauer, among others, have preceded him on this path.

I continue with my argument.

He acquiesces, but adds: Perhaps they hoped for a response or a solution. But I don't.

As I understand it, I reply, you have given up speaking in terms of positive forces and have preferred to turn yourself over to an approach based on negation and the "not."

He disagrees with me somewhat.

SB: Negation is no more possible than affirmation. It's absurd to say that something is absurd, for that too implies a value judgment. You can neither protest nor assent.

After a long silence, he continues: You must stay firm where there are neither pronouns nor solutions, where neither responses nor realizations are possible. That's why it's all so damnably hard.

I ask about his work in progress. After years of writing in French, he is

26

again writing in English, which for him now is like a foreign language that he must translate back into French. He would gladly do without this extra task, for he doesn't like going back over a text once it is finished.

Madeleine Renaud's performance of Not I was a resounding success in Japan. Beckett finds it hard to understand why his work would be so well-received there.

We talk about Ireland, then about his family. No one in his immediate family really knew what he was writing. Neither his father, who died in 1933, nor his mother, deceased in 1950, had read a single page of his work. Nor had his brother, deceased in 1954, read his work; moreover, he viewed Beckett's commitment to writing with loathing.

We discuss religion, and I ask whether he has been able to free himself from its influence.

SB: Perhaps in my external behavior, but as for the rest

He inquires about my writing. After responding, I continue with my questions. With a bit of a laugh he says that he has just written some short texts that he calls mirlitonnades.9 Somewhat boldly, I ask him to send one to a friend who has just begun a little magazine, and he is kind enough to accept. Then we talk about Holderlin. He especially admires the poems about madness but admits that entire pages fail to keep his interest. Seven or eight years ago, when working in Stuttgart on a television project, Beckett visited Tubingen and saw the tower where Holderlin, by then a prisoner of his own madness, spent the last thirty or so years of his life.

I ask more questions about his reading. Yes, he reads Shakespeare. When he was young, he read the Bible in the King James Version, full of mistranslations but extremely beautiful. Since his family was Protestant, he knew the Old Testament especially well.

I talk about the prophets: Isaiah, Jeremiah, Amos. He adds pensively, almost in a whisper: Job.

I bring up the mystics-in particular, Saint John of the Cross, Meister Eckhart, Ruysbroeck - and ask whether he ever feels like rereading them and whether he admires the spirit of their writing.

SS: Yes, I admire them. I admire their disregard for logic, their burning illogicality - the flame that consumes the rubbish heap of logic.

27

Afterword by Suzanne

Chamier

Chamier

Charles Juliet is one of France's leading autobiographical writers, recognized in particular for his Journal and for meditative essays such as Meeting Beckett, based upon his discussions with artists and writers. Juliet has also published numerous volumes of poetry, essays on art and artists, and an autobiographical novel of initiation, L'annee de l'et/eil [The Year of the Awakening], that is attracting the attention of both critics and the general public, for example, the readers of Elle, who awarded the book their Grand Prix 1989.

Who, then, is Charles Juliet? And what led him to Beckett? Despite his extreme deference toward Beckett, translated in these meetings by his stammering, stupefied approach, Juliet also attempts to steer Beckett. In these discussions, for example, Juliet frequently evokes the mystics and Old Testament prophets. It would seem that only when Beckett also mentions them-specifically Job, toward the end of the last meeting-is Juliet willing for the conversations to end and his own writing to emerge. Yet the discussions end, as does the book of Job, somewhat inconclusively.

In 1977, when the last meeting took place, Juliet was only just beginning to publish his work. It was not clear at that time whether he would eventually find a place of his own within contemporary French literature. As pere spirituel for the younger writer, Beckett doubtless represented what Juliet both sought and feared: literary affiliation, but within a patriarchal tradition capable of devastating its scions. Juliet's desire to meet Beckett was matched only by the intense self-doubt and diffidence of a then still young, virtually unpublished and reclusive writer. Beckett, who surely did not seek out the problematic role of mentor, consistently challenges and encourages Juliet while gently-and on occasion quite explicitly - distancing him.

For approximately fifteen years, Juliet wrote regularly but did not seek to publish his work, which was keenly personal; during these years of despair, when he was often tormented by thoughts of suicide, Juliet was sustained by projected, and later realized, conversations with such figures as Michel Leiris, Bram van Velde and Beckett; and by those other spiritual guides, Jeremiah and Job. Texts such as his Journal, "Meeting Beckett," and other life-writing bear the traces, as does Juliet's deeply lined countenance, of these inner struggles.

Juliet's preoccupation with human suffering stems from personal rather than theological questioning. Traumatic events-such as his mother's suicide when he was an infant - resulted in Charles and his siblings being placed in various foster homes where Charles was occa-

28

sionally mistreated. Feeling abandoned by his father and somehow re, sponsible for his mother's death, he considered himself an orphan. Com, petitive examinations enabled him to pursue schoolwork at the spartan Military School of Aix-en-Provence where, despite the defeats and reversals described in L'annee de l'eveil, he learned to love literature, box, ing and rugby. During "les annees d'Aix,"Juliet, who received little mail of his own, bartered his desserts for correspondence: two figs for any letter, four for correspondence from someone's mother. Unjustly punished during his second year at the school, Juliet spent two weeks in solitary confinement, nurtured by a quotation from Jeremiah and an inner strength that he learned to recognize only years later (see L'Annee de l'eveil). Juliet's personal commitment to writing, together with his desire to reflect upon events such as these, may have drawn him to reading, then wanting to meet, Samuel Beckett. It is from this vantage point that Juliet doubtless imagined Beckett in 1968, when the meetings began: with the phantasms of sheer hero-worship and the gawking admiration of the supplicant who, years later, decides to share the story, "the starnmering start of an aventure" ("le balbutiant debut d'une aventure").lO

For Charles Juliet, the story has continued in various forms, from his Journal, whose fourth volume is forthcoming, to radio plays for France' Culture (a national radio network), theatrical pieces (including the stag, ing of his conversations with Bram van Velde) and documentary films. His work is being translated into Italian, Spanish, Chinese, German, Dutch and English. For example, Louis Olivier's English translation of short selections from the Journal appears in Chariton Review 15.1 (Spring 1989), pp. 76-87.

1. Samuel Beckett, All That Fall in Krapp's Last Tape and Other Dramatic Pieces (New York: Grove Press, 1957), pp. 82-84. Subsequent references to this text will be given in my translation. All That Fall was translated into French by Beckett and Roger Pinget as Taus ceux qui tombent (Editions de Minuit, 1957). Krapp's Last Tape (1957) was translated into French by Beckett and Pierre Leyris as La Demiete bande (Minuit, 1960). Regarding Beckett's creative application of his bilingualism, see Beckett Translating/Translating Beckett, edited by Alan W. Friedman, Charles Rossman and Dina Sherzer (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987).

2. This section was first published in Entailles: Revue de litterature 17 (1984), pp. 24-28.

3. Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil died in Paris on July 19, 1989 at age 89.

29

She and Beckett had been companions for more than fifty years; they were married in 1961.

4. "Not knowing what else to do" (written quotation).

5. "Distance yourself both from yourself and from me" (written quotation).

6. Jacques Putnam and Charles Juliet, Bmm tlan Velde (Maeght, 1975).

7. The twelfth-century monk, Bernard de Clarivaux (l090-1153), helped to obtain the Condie de Sens judgment against Abelard in 1140. Abelard had already been severely punished (by castration) for his clandestine marriage to Heloise.

8. The "dramaticule" Footfalls was written in English in 1975 and first produced on May 20, 1976 at the Royal Court Theatre under Beckett's direction. Pas, the French version, was written in 1977, the year this conversation took place.

9. Mirlitonnades (Minuit, 1978) contains thirty-five short poems written between 1976 and 1978. The text that Beckett sent to Juliet's unidentified friend follows:

lueurs lisieres de la natlette plus qu'un pas s'eteignent demi-tour remiroirent

halte plut6t loin des deux chez soi sans soi ni eux

10. Charles Juliet, POUT Michel Leins (Paris: Fourbis, 1988), p. 23.

30

Ghost Nets

Karen Heuler

Rachel rowed sometimes, and then her father rowed. He was a square man, taut-skinned and solid. He had a gray mustache and short gray hair, which he brushed with his hand when he was tired, instead of rubbing his eyes. His eyes were brown.

Rachel always called him Papa. It was a name that caused him to pause, split-second, when she said it. He would have felt more comfortable with his own name, Wendell Dupeen; or Wen. as his friends called him. He had no objection to having a daughter, he rather enjoyed it, in his own taciturn. slow-turning way; but he had never gotten used to Papa.

Rachel was fifteen. She still went out with him, fishing late at night for pleasure, or early morning for work. In a year or two, he supposed, this would stop.

She wore her hair braided in two plaits down her back, shrugging them over her shoulder when they wandered forward, even tying them in a knot when they threatened to get in the way. He approved of her: long-legged, skinny, sunburnt nose, loose shop-print dresses she'd outgrown, shapeless things, really, but on Rachel you saw they were a covering, not an advertisement.

Rachel was quiet when she was around her father. After all, he was a silent man. She had learned to read his eyes and the lines around his cheeks to know what he was thinking, and those lines, on a brilliant moonlit night out in the channel, with the slap of the water and the slap of the oars, were conversation enough. Rachel could handle silence; she wasn't yet made uneasy by it.

Nighttime fishing was the best, because it didn't matter if you caught anything. No need to check the charts, the calendar or the logbook

31

Wen kept on the fish. It was done for yourself, for the simple, silent, bracing, awful beauty of the sea. Things could be laid to rest at night, little things that otherwise smoldered or nicked at your skin. When everything was out of sight but the dim edge of the horizon, when there was no voice but the hum of the sea, what did anything matter? Rachel could understand her father's silences; they washed him clean.

So that night-full moon hung almost orange, blotting out the starsboth kept a companionable quiet. Everything had already been said, anyway. Fishing was bad; that is, the trade was bad. Fish rolled up by themselves on the shore, belly up, bloated. "Red tide," the knowing ones said. Meanwhile, rowboats, motorboats, small trawlers smacked hungrily in the bay, tied up, leaking oil.

The bay itself looked like a picture of Greece Papa had once shown Rachel. Water, then houses along the shore, then steep hills hanging over the water, jutting with more houses. But Greece was warm and very likely didn't have the red tide, or the bacteria that crept in and killed the oyster beds, or the mysterious iodine level that kept the lobsters off the market.

Fishermen were never rowdy, as far as Rachel knew. From her experience they were a band of tight-lipped men and women who looked out to sea quickly, briefly, as if avoiding a disappointment; who studied the notices tacked on the pier with pretended indifference, if not scorn.

The great tuna days were over: the large fleets had taken off, hauling them in like rice. Bluefish, flounder, any fish paid little and sometimes showed in such poor numbers that it would have been cheaper to leave the boat home.

More and more people were turning away from the sea. The richer ones, those capable of judging events as a trend rather than a circumstance, had started looking elsewhere years ago. They sold what they had and moved inland or, like the ex-mayor, turned their houses into hotels, bed-and-breakfast places with checked curtains and racks of picture postcards, all of them over twenty years old, showing men hauling in their catch. These men, twenty years later, looking more than twenty years older, would stop by the little shop for cigarettes or matches and hold the cards in their callused, scarred hands, for a moment rueful and indulgent. Imagine! They thought it would last forever! The first shipment of cards had been sold to the men themselves, or to their wives and sweethearts, and cards all over the island lay hidden in drawers or packed in the bottom of a souvenir box up in the attic. They were even used as memorials, sometimes, when relatives visited old or new graves: a picture postcard, the color a little too alert, maybe even slightly out of

32

register, propped against a headstone, or held down by a rock so the wind wouldn't blow it away.

There was always a wind, even when there were no fish. Rachel liked to stand at the end of the bay where it jutted out to sea, leaning against the seawall, the fantastic wind holding her pigtails straight out behind her, whipping her dress around her thighs, her eyes squinted into the air, wet just from the water the wind carried.

Her father lit a cigarette. On dark nights she would watch the burning ember so she could locate where his face was. On a bright night such as this she watched the smoke spread around him and disappear like a fog.

He looked around him carefully, as if there were variations on the surface of the water that would tell him where the fish he sought were hiding. She believed it was possible. She had read that robins could see the vibrations of an earthworm tunneling underground. If so, why not her father catching vibrations of the fish?

When he was done with his cigarette, he threw it on the water and they both watched the small white speck bobbing on the waves. In a minute an unseen mouth took it. Rachel imagined its dumb disappointment: the acrid, brown taste.

Her father jerked slowly on one oar, moving them farther out. He had made up his mind about where they'd fish.

Rachel dipped into the bucket of bait and slipped a herring onto her hook. She trailed her line slowly from the back of the boat as her father maneuvered into place. She carefully buttoned her thick wool sweater. Wen never seemed to notice the cold and disliked it when she shiveredhe would have to take her back. He often gave her his own sweater, when he wore one, but once Rachel got cold it seemed she couldn't get warm, and he could tell by the way she huddled-knees drawn together, arms around them, chin tucked down-that he would have to cut his fishing short and head for shore. He never complained, he never refused to take her along, but his disappointment on such nights hung in the air, palpable, like the whine of insects.

Tonight was warm, and there was little wind. In the past, these were the nights when she would end up cold, because she was tricked by the onshore heat. Now, however, she made sure to wear jeans, socks and sweaters. When you got away from the land there was a different climate.

Her father stopped rowing. He baited his hook carefully and then cast. Now was the best time, before the first fish bit. Her senses were alert, her fingers alive to every movement on her line. She thought she could detect the subtle probing of a fishrnouth at her bait, testing it. Her father

33

had once told her that he could feel the ripple of a fish approaching, its halt at the hook. Maybe he could even feel it treading water, taking time to decide. The fish around here had generations of hooks in their memory. Still, they bit. It was like those primitive people who never connecred sex with babies. You'd think, after a while, they'd figure it out.

Something took her line. She tensed, fighting her excitement. Her father seemed to get slower when he pulled in a fish, testing it, working with it, not to lose the line or the fish. She glanced at him. He smiled, his mouth clamped shut. She could tell by the lines around his eyesthose filigrees of skin that all the people had from the sun - that he was happy for her. He wouldn't speak. She suspected that his silences on the water were almost a magical belief in invisibility. Fish would bite anything, so they obviously couldn't see; but did they hear?

She nodded at Wen, and pulled slowly, patiently. But she lost it.

There were hours ahead, so she tried not to be disappointed. Even if they caught nothing-and when had that ever happened?-it was still a good feeling. She was close to her father because of these nights. They were wrapped together in the dark and the water like unborn twins.

The moon was sinking lower, and it cast broad shadows from their boat. They looked like a castle - she and her father the towers - on some vast moat.

She felt it when Wen's line pulled taut, and gripped her own rod sympathetically.

He hauled it in slowly, and she could feel the weight, a good size, before it slapped into his hands.

Her father held it, taking out the hook. He glanced at it quickly, then slipped it back in the water. She eyed him questioningly, and he shrugged lightly, just a suggestion at the shoulders.

There must have been something odd about it. Her father always threw back deformed fish-with one eye, with a ripped fin, with a fungus at the gills. He wanted only perfect things, or his sympathies were tricked out by losses. Someday she would have to ask.

The moon was so low it ran a ladder on the water. Her father cast into the ladder, moving with a slight ripple. He pulled slightly on the line, then slightly again. Rachel could see his line snag. Her father tugged thoughtfully and his motions became very delicate, as if he were testing a bruise. Rachel stared into the water. She could tell what her father was thinking just as if he said it out loud. What's this? Caught? On what? Too high to be a lobster trap. No marking for a buoy. A bag of garbage just below the surface? Possibly that.

If it were garbage, then he could save his hook and lure. He lifted one

34

hand to the oar. Rachel's line was on the other side of the boat; she could leave it there without any problem if they moved.

Her father didn't like losing hooks, so she figured she knew what he would do. But even if it was a forgone conclusion he would take the moment to weigh his actions. Then, as she anticipated, he dipped one oar into the water and they slowly revolved straight into the ladder, climbing up to the third rung.

Wen's fingers followed the line into the water, breaking the surface, which shimmered giddily for a second. His arm was clear in the moonlight as it searched deeper along the line. She felt his surprise at whatever he'd found, the way his busy fingers crept along whatever it was, deciphering its form. He leaned lower and Rachel automatically leaned the other way to steady the boat.

She was tempted to ask him what it was. But she decided not to; once her father knew, she would know. He would nod to himself and she would understand.

Clearly, he thought he could get the hook because he continued to probe under the surface. He was lower now, his shoulder in the water, his ear almost on the surface, as if listening.

There was a sudden shift, almost unnoticeable, it was so graceful. Leaning far over to balance the boat, Rachel saw a look of surprise on her father's face, a gaping glance at her, and then he was pulled into the water-so silently it was like a trick he'd long planned on producing, as if he'd finally found the moment when it was right.

He didn't even splash her. She stretched her arms out to steady the boat and then scurried over to his side.

The ladder was swinging. She blinked, glancing quickly at the moon. It would set soon. She swept her hands into the water, as if she could clear it away. Her fingers caught on strands of something, and she jerked back.

She grabbed an oar, sweeping it into the water. She had to find him. The water had a thick consistency to it, and the oar had trouble. She pulled it out-straight out and up-and used it to push the boat closer up the ladder. She peered intently, searching for Wen. Her heart was beating very fast and she could see a shape about a foot below. She reached down and grabbed it. Wen's hand closed on hers and she pulled with all her might. There were webs surrounding him, webs of colossal weight. She held onto him with one hand and with the other frantically tried clearing the net - it was a net, a huge net, folding back and forth in on itself. She was convinced that if she could find the edge she could clear it away.

35

She pulled at Wen, scrabbling around him to find the net. No matter how much she pulled there was more. But Wen's hand was above the water now. She bent down, searching for his head, following his arm to the elbow. She pulled and pulled, straining her feet against the seat of the boat, calculating how much she could move without capsizing. She couldn't afford to lose the boat; it gave her the only solid yield.

She could see her father's face. His eyes were open, looking at her, pleading. His lips were moving as if he would speak. She was wildly anxious to know what he was saying. Was he telling her what to do?

A piece of the net rolled back on him and covered his face. She held onto his hands as the tide moved, pulling him away. The boat moved with her. Her feet were curled around the seat; she was straddled on her stomach now to steady them all-boat, father, self.

The ladder was breaking up. A sudden lip of light crept down to Wen's face. He was still speaking-or was it a trace of net across his chin that moved, white and sibilant, like a mouth?

With a startled cry she felt his hand relax and move away. It was like a farewell, the way it just gave up.

The ladder was falling apart as Wen's hand swept down. She scrambled for the flashlight, peering left and right. On the surface now, licking up and down, were terrible strands of the net. She swept her flashlight around, probing the floor of the boat for the knife. When she found it she began cutting at the web, but it took both hands. The net was tough plastic.

She pushed her oar against it to move, always sensing where her father would be, under the surface, rolling up in his shroud.

Until finally the net began to edge down, disappearing, and she knew she had lost.

She wept. Her shoulders bowed down, her hands clutching the sides of the boat, she sobbed in great shattering bursts that eventually shocked her into silence. Wiping her face on her sweater she looked despondently again on the water. She stared and drifted, and finally a thought occurred to her, a thought that developed into a certainty. What she'd seen just couldn't be true. Her father had swum to shorewas, even now, swimming-or had been hauled on board by some other fisherman, astonished at what came out of the sea-or it had been a joke, one that baffled her, but a joke nonetheless.