Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Illinois Arts Council, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Robert R. McCormick Charitable Trust and the National Endowment for the Arts.

NOTE: TriQu4rterly welcomes financial support in the form of planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor. Please see the inside back cover for names of TriQuarterly Council members and Friends of TriQuarterly.

Fall 1989

Associate Editor Susan Hahn

Editor Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Kirstie Felland

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

Editorial Assistants

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Assistant to the Editor Janet E. Geovanis

TriQuarterly Fellow Belinda Edmundson

Jo Anne Ruvoli, W. Douglas Fitzsimmons, Amy Rosenzweig, Arthur Amaker, Hyonmyong Cho

Advisory Editors

Hugo Achugar, Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates (three Issues a year)-Indlviduak one year $18; two years $32; life $250. lnsritunons: one year $26; two years $44; life $ 300. Foreign subscripnons $4 per year additional. Price of 'Ingle copies vanes. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarlerly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (12) 491· 34l}0. The editors Invite subrmssrons of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October I and April 30; manuscripts received between May I and September 30 WIll not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarlerly, unless otherwise indicated. Copvnghr © 1989 by TriQuarlerly. No part of this volume may be reproduced In any manner without written permission. The views expressed In this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by Thomson-Shore, typeset by Sans Senf.

National distributor to retail trade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110 (201-667·9300). DIstributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeoplc, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415·549·3030). MIdwest: ILPA, P.O. Box 816, Oak Park, IL 60303 012·383·7535); and Ingram Pcnodicals. 1117 Heil Quaker Blvd., La Vergne, TN 37086 (800·759·5000).

Reprints of Issues 11-15 of TriQuarlerly are available In full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues In microfilm from University Microfilms lnrernanonal, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. ISSN: 0041·3097.

76

"The Eleventh Edition," a story by Leo E. Litwak that appeared in TriQuarterly 174, has been selected for inclusion in Prize Stories 1990: The 0. Henry Awards, edited by William Abrahams. The anthology, due out from Doubleday in April, will be published simultaneously in hardcover and paperback.

Sandy Huss's story "Coupon for Blood" and Pattiann Rogers's poem "The Family Is All There Is" - both from TQ #73 - have been selected for reprint in Pushcart Prize XIV: Best of the Small Presses.

TriQuarterly Books currently available:

The TriQuarterly 1989-90 Appointment Book Writers !rom South Africa

Stephen Deutch, Photographer: From Paris to Chicago, 1932-1989, with essay by Abigail Foerstner and preface by Studs Terkel

Selected Poems: The Weight of the Body by Stanislaw Baranczak

Forthcoming:

The Collected Poems of Sterling A. Brown For ordering information, please see page 203.

Contents FICTION Love Out of Bounds 5 Ami Sands Brodoff Simplifying 17 Christopher McIlroy Fado 35 Katherine Vaz Amazing............................... 48 Francine Prose Going Out Dan Chaon Taco Mask Steve Fisher 60 74 POETRY The Island Women of Paris; Political; And Counting; In a Neutral City 86 Rita Dove Mysterious-Shape Quilt Top, Anonymous, Oklahoma 90 Sandra McPherson Nursing Home Andrew Glaze Mowing 94 Stuart Dybek 93 Your Man. 96 Patricia Smith Post-Larkin Triste 98 Mary Karr The Children of Mechanics 100 Joseph Gastiger 3

Evensong; Road Overgrown 102 Michael Dennis Browne Life After; Post-Op, January Ice Storm; Waiting Room ................•..•...... 104 Sandra Steingraber Mary; Oral History 107 Lisel Mueller Four Poems from YEA; Two Poems from OF 109 Cid Corman From a Compostella Diptych: Part I: France: The Ways 113 John Matthias MEMOIR Budapest, 1944 Peter Kenez 123 ESSAYS Not a Beautiful Picture: On Robert Frank 146 W. S. t» Piero The Flexible Rule: An Essay on the Ethical Imagination Alan Shapiro 166 A False Mustache, A Frozen Swan: The Holocaust from a Distance 186 Robert Pinsky CONTRIBUTORS 200

by

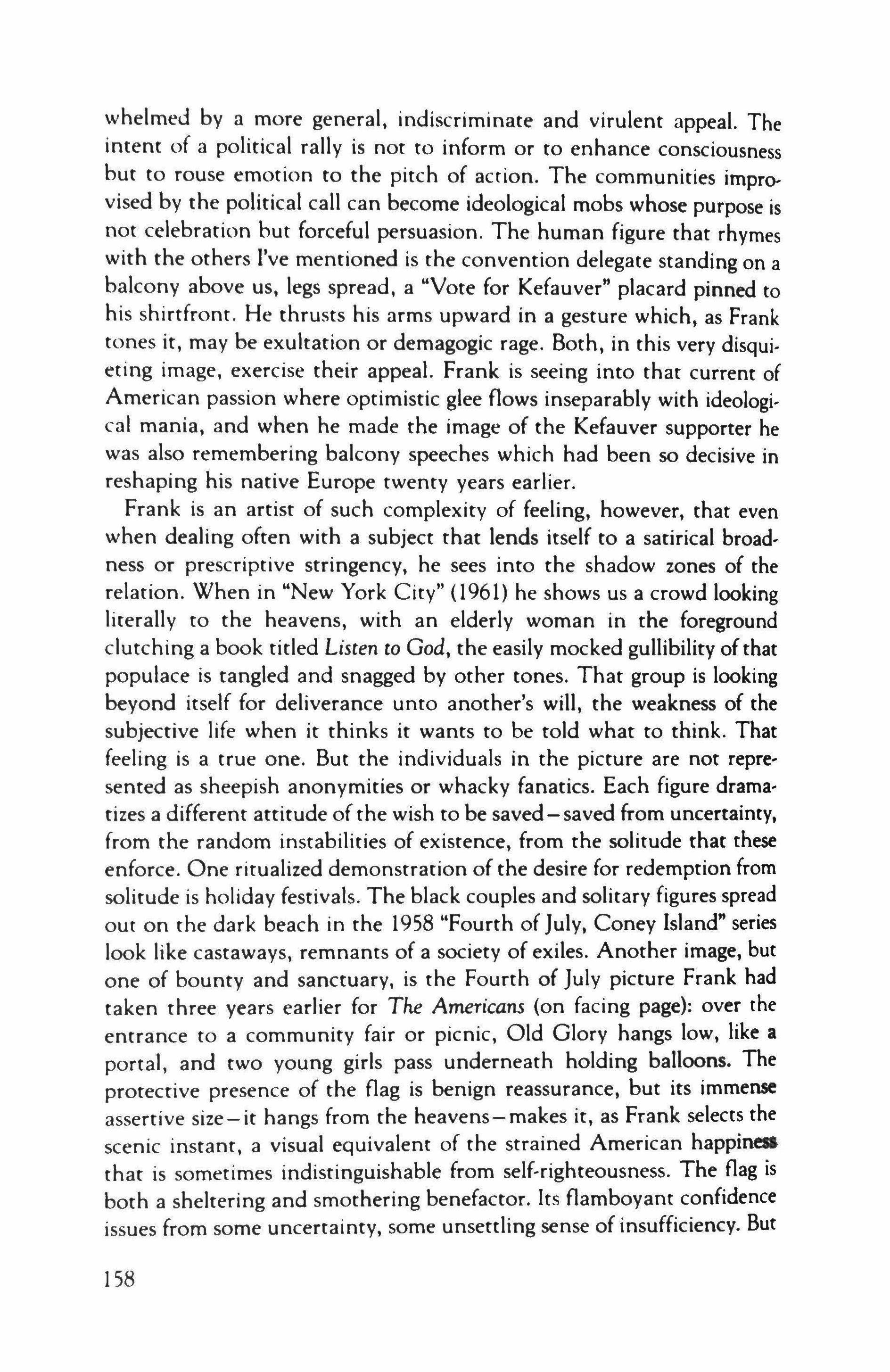

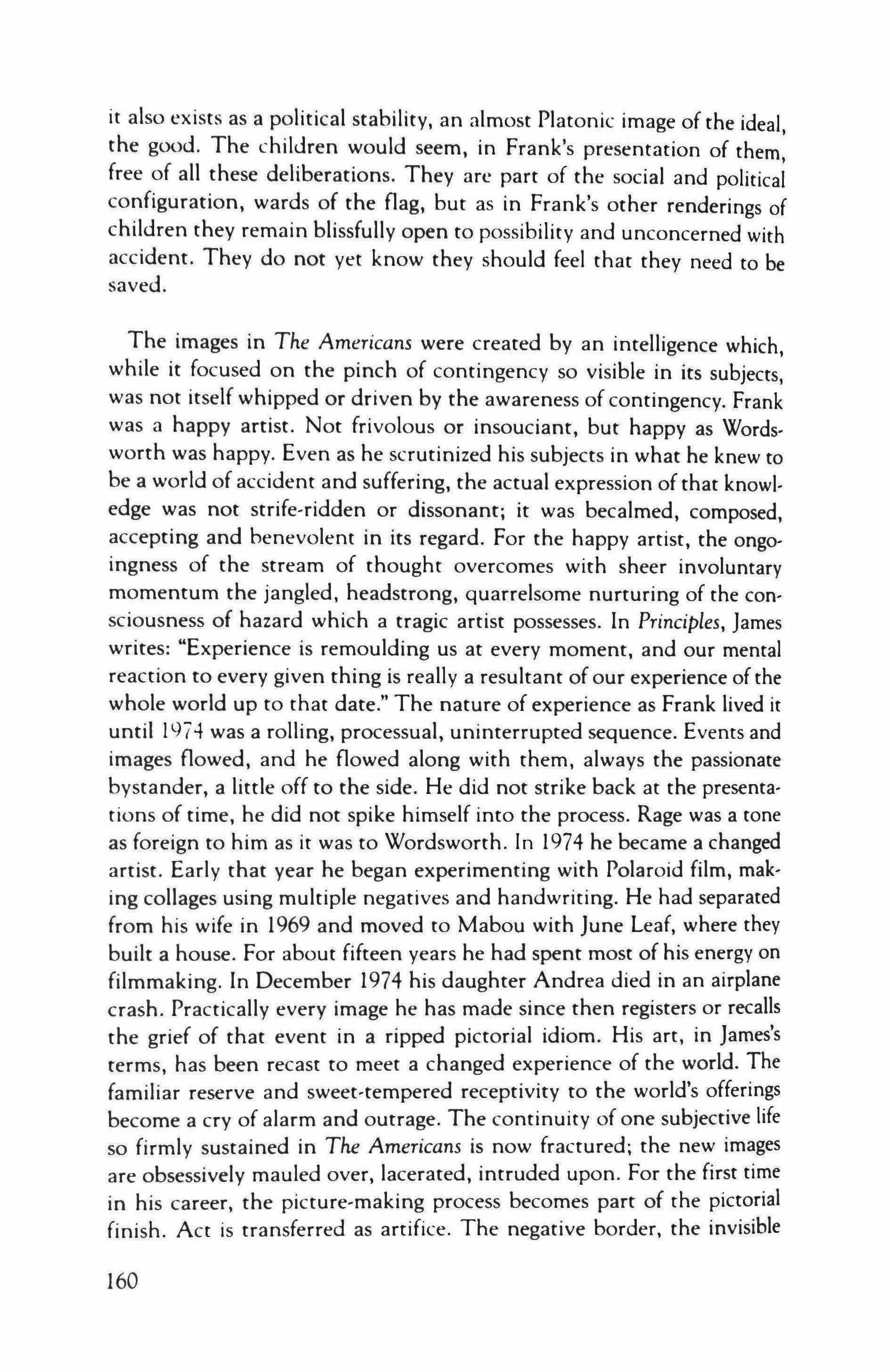

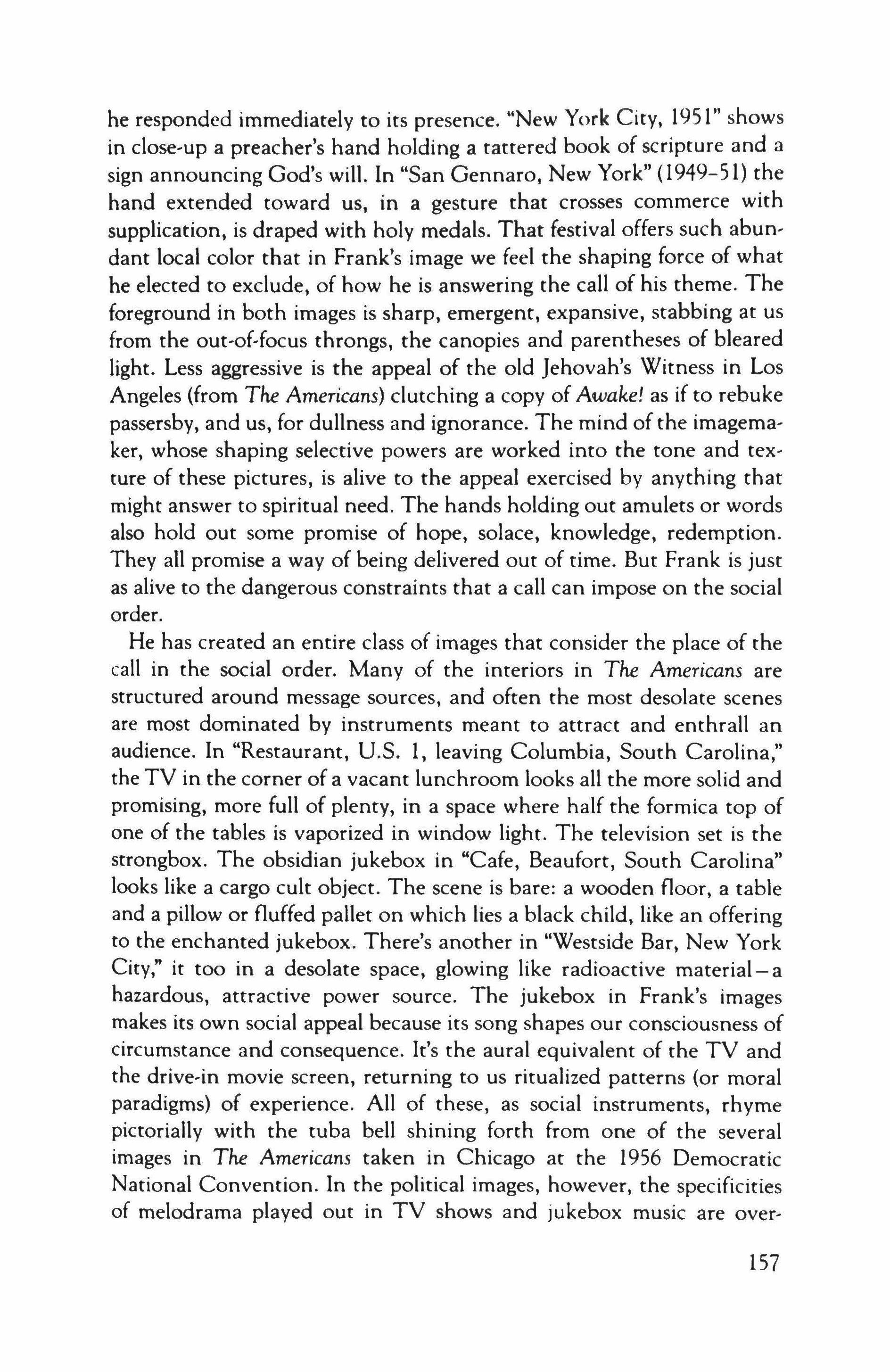

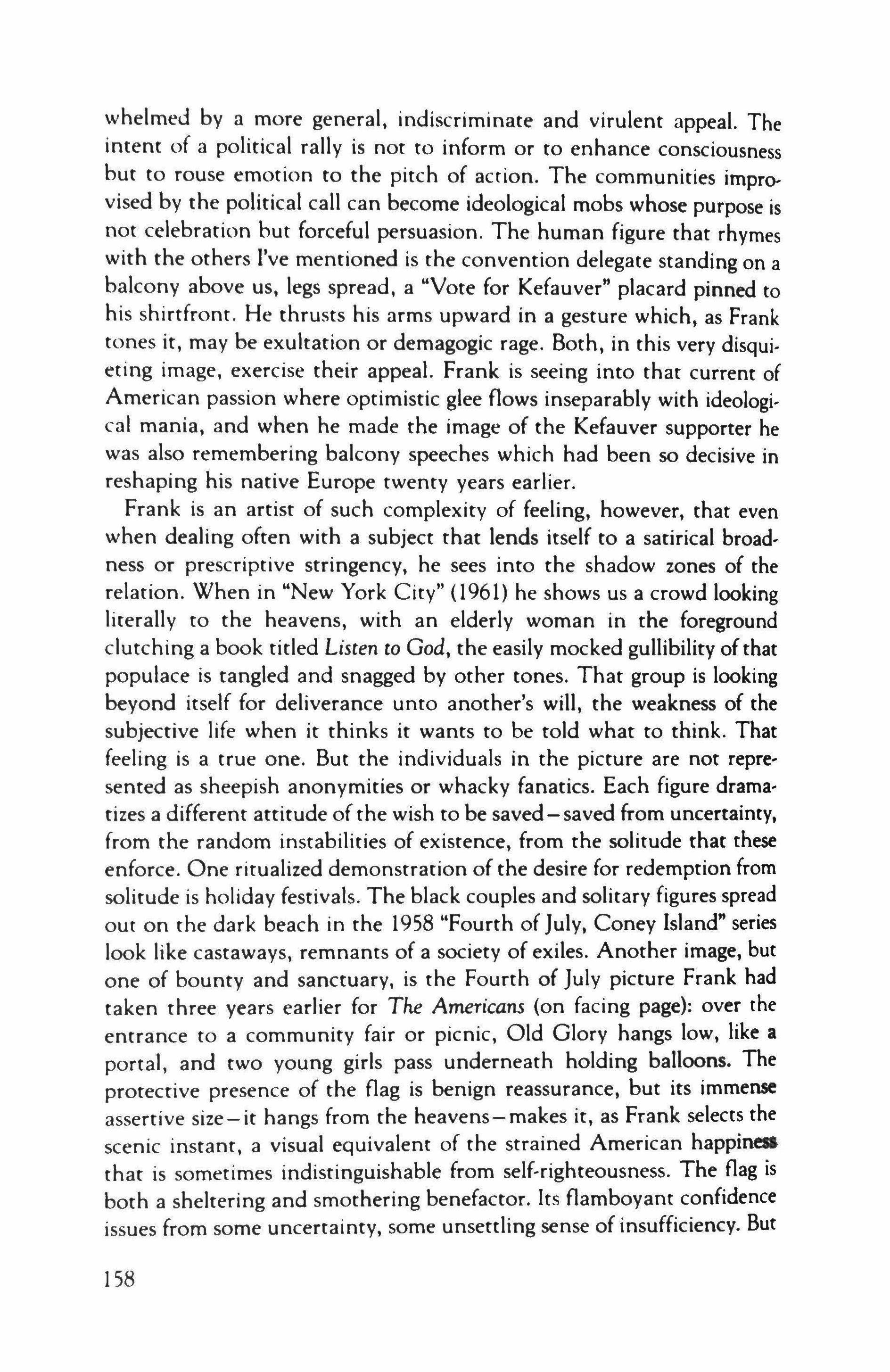

Phocographs on pages 159 and 163 by Robert Frank 4

COtler design

Gini Kondziolka

Love Out of Bounds

Ami Sands Brodoff

fOT Michael

fOT Michael

II don't live here anymore but myoid key still jingles on the chain mixed in with all the new ones. The deadbolt slides back without making a sound and I'm inside, feeling like a burglar.

Doren is standing at the top of the stairs, a beam of light touching his hair and beard. He's holding a doll I recognize immediately. That delicate ivory lady is Mom's favorite from her collection of doctor dolls. I wonder how Doren has slipped her from the glass display case since our mother is the only one with the key.

"Hey 0," I call up to him, trying to sound bright and normal. My brother runs down the spiral stairs, his upper body erect and still, just like Dad's when he jogs in place before bed. "Deeb, it's good to see you."

"Hey Sarah." He looks at me expressionlessly.

"I heard you were home and I wanted to come see ."

"See what?"

I look at my older brother. He is all sucked out, whippet-thin. Last time I saw him he was almost stocky like Dad. Now, he borders on emaciation. His eyes are as beautiful as ever: hazel with a dash of yellow in the center, changing color depending on what he wears. Today, they are a startling green that makes me think of traffic lights. His new beard is streaked russet, crusted in places with a dry yellow resembling egg yolk.

"I wanted to see you," I answer, moving to hug him. Doren's body

5

stiffens as though about to be struck, but I embrace him anyway. He mimics my hug, thin arms like a robot's.

"What have you been up to?" I ask.

"Thinking. Just thinking." His eyes stare into blank space, unfocused and glassy.

"That's good. You're better, Deeb, you're home."

"That proves my mind doesn't sound. They disguised those controls but they still snap."

We are both quiet for several moments. "What are you thinking about, Deeb?"

"I have too many thoughts. All sorts of thoughts come to me. Take that ashtray." He lifts the heavy crystal ashtray from the marble elephant whose back is a coffee table. "They put my ashes in there, but there are hundreds of other things I'm connected to simultaneously."

"Like what?"

"I can't get specific." He looks irritated. "North, South, East and West. Thoughts stream in from four different directions." He shrugs. "These thoughts don't mean anything to me. But I get distracted. They forget what I'm saying."

"Who? Mom and Dad?"

Doren's lips work, a gesture between chewing and speaking though he does neither.

"They coming home tonight?" I ask.

"Still shrinking in Vegas."

"Oh yeah. Mom gives her paper tomorrow. 'Boredom and Anxiety: The Ineluctable Link.'" I look to my brother for a smile or a snicker but I've already lost him. He gazes out the bay window toward the spacious, manicured lawn that sprawls away from the house. It is blazingly green, as if lacquered. Late afternoon sun streams in, casting a funnel of light on the hardwood floor. My brother stands in the orange light, rubbing his hands together as if to warm them over a fire.

"Over here," I say, not making much sense, thinking how lonely and unreal it is to miss someone who's right there. Doren comes over to me, tenderly rubs his face against mine, then pats my cheeks with both his hands, chanting.

Ah sista goah, I love you and the pack I give you juice and candy to make them both go back

I join in and we chant and chant and chant. When we were kids, our private language muffled the sounds of Mom and Dad downstairs, their

6

voices sharpened like instruments. Doren caresses the scarlet sleeve of my sweater. "I have one for you, Deeb, in green. Extra tall. Shall 1 get it from my suitcase?"

"No. Stay. Right. Here." His eyes get vacant, then terrified. "Can you see me?"

There's a burning behind my eyes. For a moment, the tears feel like someone else's. "Yes, Deeb, 1 can, even from far away."

My brother smiles. " 'Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in,'" he says.

"Was it unbearable at the hospital, Deeb? How did you get out of there?"

"No bolt was necessary. When I'm without, she's gone kidnapping. 1 reimburse that equilibrium. But you," he finishes, "1 love out of bounds."

For me, it's his most lucid sentence all afternoon.

That night, I dream of Doren's car. I see the headlight eyes, hood ornament nose and wide grille mouth approach me on the road. 1 get in, zoom down the highway, Springsteen's "Spirit of the Night" on the radio. Suddenly, the car stops, its motor still running, ragged and guttural. 1 get out, open the hood, tinker with the car's innards. Soon, I'm tangled in a sinewy web of wires: one tube is fastened to a vein at my wrist; another feeds me through the nose; a thick bandage-colored cylinder pumps air in and out of a perfect hole in my throat. A shadowy figure unhinges me from the car. My body writhes and twitches in rhythmic spasms. Ghost-Man stands by transfixed, like he's watching the scene on television.

1 wake up shivering and sweating, the sheets cold, damp towels over my body. Downstairs, 1 make a cup of hot, sweet tea and drink it in a bubble bath, imagining the bliss of pure black space, a deep and dreamless sleep.

II

Morning brings one of those dazzling days of early spring and 1 take my coffee out to our circular driveway. Sun glints off Doren's derelict red Chevy, its body bruised and cratered from a series of crack-ups. Takeout coffee cups, squashed beer cans, piles of clothes for every season, an upended box of kitty litter and butts and ashes from dozens of cigarettes coat the upholstery and carpet. The car looks like an SRO someone hid

7

out in for awhile, then abandoned. On the dash sits my first princess phone, severed at the cord.

I toss armloads of junk into big plastic bags, working up a sweat. Just as the nightmare's hangover hegins to evaporate, Doren comes out front, smoking, the cigarette burning dangerously close to his fingers. I spot Mom's doll- an elegant lady in miniature-peering from his pocket.

"What a mess! Want to help?"

"Not really." Doren drags deeply, sucking in smoke like breath. "Chaos escapes the boundaries of my mind and finds expression in this car." He snuffs the cigarette out against his wrist, not seeming to feel much.

"Careful. You say the most amazing things sometimes, Deeb."

"You don't say these days."

I stop working, take a sip of coffee. "I know it's been awhile. I'm sorry." The truth is I haven't been home in over a year, haven't seen Doren since he was admitted to Mcl.ean's Hospital. That was about the time I graduated from Parsons, about two years after Doren's third and final drop out of Amherst, an anniversary he liked to celebrate.

When I heard he was in the hospital, I went through my daily routine on automatic. The F train from Brooklyn to my sealed-windowed office at Heat and Fridge News. Paste-ups all day for the "Story of the Soft Switchover," a micro-processor-driven, set-up, set-back, heating-cooling system for the whole household. Back home on the F to my studio. Evenings and weekends, I holed up in that studio sorting through stuff in Doren's old Superman lunchbox. Growing up, he'd given me all kinds of things-a slab of mica from a cave-in accident; arrowheads, marbles and bits of quartz; a leopard-print shell and colored-glass unicorn. When he was in the hospital, I pored over the stuff in that lunchbox like a young girl pores over mementoes in a hope chest. I didn't visit him, didn't speak to him.

Staring at patterns of sparkle in the mica, listening to the whooshing of the sea inside the shell, I lost myself in a videotape loop of savior fantasies. If a chunk of masonry came loose from the Flatiron Building, I would whisk Doren out of its way; hoist him onto one shoulder out of a burning brownstone; lift him from the brackish waves into my rescue dory after his kayak capsized, paddle and boat having floated away! Embarrassed, I crush several styrofoam cups, then toss them, avoiding Doren's eyes. "I don't have a good excuse. Will you forgive me?"

"Let bygones be gone by."

"I will if you will."

He rolls up his sleeves and finishes the job with the careless whirlwind

8

of motion he reserves for all household chores. After we cart the last garbage bag out to the dump, Doren looks at his wrist, though he has no watch.

"C'mon," he says. "Time to blow this insalubrious locale."

"I'll drive." He tosses me the keys.

We head southwest on the Deegan, cross the G.W. Bridge and continue on the Jersey Turnpike through the flatlands.

"Uglification, next twenty miles," says Doren, and he is right. We're deep into a geometric wilderness of plant-works and manufactory. Oil refineries spew forth continuous eddies of smoke and blue-orange orbs offlame seem to light the grimy sky from within. It's an iridescent play of color you just don't see in Nature. Just as we're beginning to appreciate the surreal beauty, the landscape turns lush, as quick as a scene-change in the movies.

My brother points to a gargantuan billboard that seems to take up our whole visual field. A colorful globe whirls bull's-eye center.

LAND OF FANTASY AND WONDER

2 miles COLOSSAL COSMOS

Doren makes the thumbs-up sign and I follow arrows around several sharp curves.

500 ELECTRIFYING RIDES

FAMILY FUN AT ITS BEST!

COLOSSAL COSMOS-l mile

We hadn't planned a destination but these corny signs have me hooked. When we finally pass through the gilded, curlicued gate, I want trumpets to sound, feeling just like Dorothy entering Oz. We can already hear the low, thunderous rumbling from the killer coasters, long, drawn-out shrieks and cries and disembodied Muzak lilting out of hidden loudspeakers everywhere.

9

ZOOO ANIMALS ROAM FREE

NATURAL LANDSCAPED SETTING

DRIVE·THROUGH SAFARI-liZ mile

Doren starts jumping up and down like a kid, guiding the wheel toward the Safari - "the world's largest," another sign proclaims, "outside Africa itself."

With tickets, we pass through an ersatz wilderness in convoy where bison, llamas, elks and deer whiz-bang by, inhaling dust fumes from dozens of cars. Doren reaches his leg across to the driver's side, pressing on the brake. A long-legged bird has already come right up to him, beating mottled wings. She bends her sinuous neck inside the window, rubbing her head back and forth against Doren's cheek. He opens the car door a crack and rips up a handful of Safari grass; it makes a sucking sound as it comes uprooted. Chewing on a blade of grass, he feeds the bird from his open palm. He mumbles made-up words and sounds, a lover's language I've heard him use only with animals.

In "Africa," monkeys fasten themselves to the sealed capsules of cars, claws scratching, jaws gnawing. Behind electrified fences, leopards and tigers move in suspended animation, languid and dazed from the unrelenting sun, the snaking monotony of cars. I stare into the marble-green eyes of one tiger. He stares back. A dull, hooded gaze, lifeless as the torpid tiger at home who doubles as a chair.

When we were kids, Mom redecorated our house as a jungle. A dense, long-haired scarlet-and-green rug stretched from wall to wall like untended grass on fire. Plants on every surface, in every corner, suspended from windows and ceiling. Huge Wandering Jews and snakes, asparagus ferns and gloxinia.

I remember those days we were left alone in the house from first light and dawn chorus till the mosquitoes began to bite. The notes signed with XXX's love mother pinned to the fridge door with fruit or vegetable magnets.

First, we'd let out Elixir and Rosmoor, Monty and Nighrsprite, who were screeching and yowling behind the utility-room door. Sounds that made me imagine an ambulance coming. Elixir sharpened her claws in the plush giraffe's flank; Rosmoor burrowed in red-green shag; Nightsprite swiped at tropical birds, making Mom's mobiles fly.

We crawled around through the rooms and rooms, playing snakes, tongues darting like flames. One day, Doren started another game. He

10

ripped leaves off the plants, chewing on buds, laughing and laughing without taking a breath. He crammed leaves in my mouth, still laughing - it sounded like a yell. By dusk, we'd stripped Morn's jungle bare.

Out back, we stretched out on the close-cropped lawn, wet and steaming in the twilight. Soon everything turned black. He held my head between both hands when my stomach lurched and I retched up green.

III

Doren's hand over my eyes is cool, so large it wraps around both temples. We pick up speed, whirling faster and faster, our car swings out sideways, lifting, revolving till we're vertical, spinning madly upside down. Between Doren's fingers are slats of light. In the orange darkness, I see us shaking and spinning, flying right off the rail. My brother pulls his hand away and the sunglasses on top of my head clatter to the car's ceiling, the world turns blindingly bright and blurry till Doren retrieves them, hair fluttering against my cheek.

Down on the ground, the crowd is dense and teeming. All the good rides have endless lines and it's just too hot to wait in the stinging glare of the sun, so we stroll off to the Garden of Eatin', choosing a canopied table overlooking the big pretend lake.

Doren eats like a blind man, touching everything on his plate before beginning, as if to memorize its position. He takes Morn's doll where he's wedged it between a couple of corn cobettes and a giant-sized Coke, carefully wrapping it in a napkin and laying it on its back. Swathed in white, the doll stares out of sightless eyes into the unvarying blue sky.

"They're not ordinary dolls," Morn once explained while dusting each doll lovingly as she always did on Saturdays. I was, maybe, eight. She told me how an elegant lady would use the doll to show her doctor the part of her body that hurt. With fingers manicured pearl-white, my mother lifted the doll's hair, which was carved in a bun. She swung that bun open on its hinge like the lid of a box and pulled out the tiniest silver spoon I'd ever seen. "The lady who owned this doll used the spoon to take her medicines"-she pointed to the pillbox-sized space inside the doll's head - and with a lingering look, replaced her favorite in the case and clicked it closed.

"Why did you take it?" I ask my brother.

Doren pockets the doll, then sips his Coke. "There's electricity cours-

11

ing through my veins." He is matter-of-fact. "If I.Q. doesn't circuit short, I'll shock people."

I concentrate on figuring I.Q., blocking the rest. Ivory Queen. An easy one. Doren upturns the doll like a saltshaker, spilling the tiny colored pills from inside its head into his palm.

"Wouldn't it be better if you took those?"

He pours them back into the Ivory Queen and smiles. "I already get medicine secretly. She's got a syringe inside her, pumps it right into my bloodstream."

I feel a funny pulsing in my neck. "C'mon, Deeb. You don't have to pull that on me."

Doren sighs deeply.

"Doesn't the medicine help?"

"Yeah sure. If you like being buried thousands of miles below the earth and windowless." Doren double-crosses his legs, wrapping himself into a caduceus.

"That's awful. Maybe the dose is too high?"

Doren unravels his legs. "I forgot," he says, getting up from the table. In five minutes, he's back with coffee and a handful of gem-colored swizzle sticks, their tips molded into tiny figures of Adam, Eve and the Serpent.

"Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eatin'. Can I have those?" It always calms me to collect things for the Superman lunchbox. I reach for the mixers but Doren pulls them away.

"You can't go on saving so many things," he says, snapping them in two. "Now, that's better, isn't it?"

"Sometimes, I can't stand you." Can't stand. Don't want to know. Like in high school at Treemont. I'm waiting by my locker. See Ross coming, Doren just behind. My brother's wearing stuff that doesn't fit or match; he's shaved his head for no apparent reason. He stops, freeze-frame, listening, as to a voice out of earshot or some pressure beneath all the other voices. I link my arm through Ross's. Doren's breath at the back of my neck, that funny pulsing, as if a small animal were trapped there. I want to blast out of there like a bat out of hell or some other creature that hasn't yet been created. I pull Ross down the long, dark hall, turning back before we round the corner. Doren gives me a weird smile, his mouth stretched tight, all his teeth showing. It reminds me of that painting, "The Scream," the woman suspended in the road, she's shutting her ears to something deafening though all around her is silence. Hundreds of kids went to Treemont. At least ten of them were Solomons. Only a few people knew for sure Doren and I were related.

12

I feel my brother's knee tapping restlessly under the table.

"Ready for the mind-bending, brain-blowing, Blockbuster Buccaneer?" he asks, putting an arm around my shoulder.

"You know I'm a wimp about scary rides." But before I can protest further, he's pulling me toward a line so long and labyrinthian, I can't see where it begins or ends.

IV

The ticket-taker rips coupons from our booklets and we're part of the line, enclosed behind velveteen ropes. The queue is as dense and long as any line for a newly-released film, Saturday night, in the Village. Up ahead, an outsized owl consults a Salvador Dali watch. "One hour till you board the Buccaneer."

"This is nuts, Deeb." I consult my watch, as if we're due somewhere soon. "We've got better things to do

Doren shakes his head, gives me a toxic look.

"Patience, patience," he says. "The day is a clock without hands."

A middle-aged woman on her own turns around, stares at Doren, then winks. I catch a glimpse of what she's reading; it's Kafka's short stories.

I see people getting off, lining up again. Incredible. I'm trying to fathom out the pull of this place, a come-on that breaks through all kinds of boundaries. Everybody's dying to relinquish control, to surrender.

"No matter how many times you zoom up and down this thing, you know you'll get to the bottom in one piece," I say to my brother.

"The velocity's the same, the peril's predictable," he answers.

The woman ahead of us turns around again and smiles winningly at Doren. There's some rapport there.

I fall into a trance observing a cool-looking androgynous couple in peekaboo Spandex. They're holding hands, each in separate worlds. She's eating a candy apple layer by layer, picking off the nuts, then chewing on the caramel. He's listening to his Walkman, bopping to the beat. It's turned up so loud, I can hear the tinny rhythm seeping through the phones. "Dontcha want somebody ta love. Dontcha need somebody Watching them makes me lonely as hell but, like picking a scab, once I start, I can't stop.

My worst days these past months, I've lived my life from inside a spacesuit. Everyone's voice sounds metallic and strange, distant, without

13

color and muddled like bees buzzing. It's the background noises-traffic horns beeping, trees rustling, children whispering and weeping-that are deafening. It takes all my concentration to make out what people are saying. My own name-Sarah Solomon-starts to sound strange, too, like I've never heard it before. I repeat it over and over in my head but the name has been cut off from the language by a knife. I can't picture my face, either. I have to reconstruct it the way you do when you've just met someone and want to visualize their features. I pretend I'm in lifedrawing class, with me as the model. First, I draw in one almond-shaped eye, then another; next, the thin straight nose, small mouth, upturned chin and long neck. While I draw, I recite out loud the story of what I'm doing, third-person-journal style, everything happening right now. Just a few minutes of head drawing and third-person journal is usually enough to do the trick. I coalesce.

What's important, I can always function on the outside, even with all this brain cacophony going on. At times, I wonder if this is the only thing that makes me different from Doren. I admit, it's a struggle, like trying to sing a favorite song in your head while another one is playing. But I can do that. It's my gift.

I hear a pealing roar reverberating from the coaster; it sounds like an airplane about to land on our heads. Only ten people are ahead of us now and each car takes two.

A big sign in bold block letters warns that this ride is not recommended for pregnant women, people with heart conditions, people with back or neck ailments, people with disabilities, those subject to motion sickness, and anyone under the influence of alcohol or drugs. I begin to panic.

"You go." I touch Doren's shoulder. "I'll watch, take pictures." I rummage around in my shoulderbag for the portable camera.

"No way, S.O.S. You gotta get dirty with life."

I notice all the cars have headlights, though under the bright glare of the sun they're barely visible. A red car glides up, jolts to a stop. Only one headlight. A cyclops. I want to mention this to the guard but feel stupid. The headlights serve no function.

The watchman puts out his hand to help me in, Doren slides beside me. The safety bar grazes our thighs as it locks into place. Another sharp jolt and we're moving. The car makes a clackety-clacking noise as it rises up the first steep incline.

At the peak, we idle for a split second; I see the pulse-movement of people way below, one amoeba-like organism, moving, spreading in

14

every direction. Plunging down, my heart rises with a live flutter, leaving me weightless, emptied out, like free-falling in a dream. On the sharp turns left, then right, I swing against the sidebar, then slam into Doren. I feel a cool breeze against my face and a sharp tingling, as if my whole skin has fallen asleep and is regaining consciousness. On the next downslide, I scream, dizzy and exhilarated; I'm getting into this, despite myself. Like motorcycles.

"Look!" I shout to Doren as we reach the crest of the next hill, pointing to the bird's-eve view of the park. "Now, that's something."

He's got his right arm cranked back like a pitcher's, Mom's doll in his fist. "The I.Q.'s kayoed!" he yells, hurling the doll into the blue sheet of sky.

I lean forward against the safety bar, almost standing, following its high graceful are, then fall, the tiny colored pills exploding from its head like pool balls scattered by the cue. Suddenly, the safety bar flies open and I'm suspended in midair, screaming, with no voice at all: Everyone is screaming. In an instant, Doren's arm is around my waist, pulling me back into the seat. He holds his arm across me, the safety bar swinging wildly in the wind.

I bury my face in Doren's shirt, hear his blood beating as I flow into the roar and motion of the car till I can't feel my body anymore.

On a twisting turn, there's a sharp metallic clank. I open my eyes. The safety bar's locked itself right back in place.

Slowing, we glide into the final straightaway, a quick jolt forward, then back, as the force of inertia brings our car to a halt.

"Whaddya wanna do, put a monkeywrench in the works!" The guard shouts at Doren as we stumble out of the car.

"There's something wrong with that one." I point to our car as the next couple climbs in. "It's the safety bar."

The guard checks the bar twice. "Looks fine to me." He gives Doren a sharp, warning look. "What's the matter with you, chucking things off the top!"

"My mother and father are doctors, both grandfathers are doctors, all my uncles are doctors, three cousins are doctors, and I'm a patient," says Doren.

The man looks uneasy, then chuckles. "That's a good one." He pushes the button on his remote-control box. The car bucks, then lurches into motion.

We weave through the shimmering sea of metal trying to find our car. My legs are wobbly and trembling, the asphalt's turned to Jell-a. I lean

15

into my brother for balance. A few feet ahead of us, I see a shard of ivory, white against the pavement. I remember all those Saturdays I watched my mother dusting her doll collection. It was easy to imagine the doctor's healing hands palpating the doll as meticulously as a miniaturist might work on a prize painting, while the real woman lay languishing in pain.

"It's like no one noticed, like nothing happened," I say to my brother.

Doren nods. 'Not waving but drowning.'

I stoop to pick up the shattered piece of ivory and hold it in my palm. Nothing in its shape or texture suggests the part of the doll it once formed.

16

Simplifying Christopher

McIlroy

Easter morning Julia was dressed for church, watering her plants, when the air left her, as if her chest, while straining to expand, had flattened. From her knees she dialed 911.

The oxygen mask was a fuzzy lump in her field of vision. Whitejacketed EMTs circled her. At Emergency her gurney flew down the corridor.

Her son Tim stood over the bed, hair awry, shirttail untucked. He squeezed her hand.

After visiting hours the busy noises ceased, replaced by the wheezing of therapeutic machinery, the bellows-like breaths of hospital maintenance systems, punctuated by rhythmic groans of a patient across the hall. Uniform gray light left objects distinct but without relation to each other. Certain her breath would stop if she slept, Julia remained vigilant.

Since the moment was unendurable, she chose another-Tim's first apprehension of her, not as food or warmth, but a person, age four months. She had been swinging him in his canvas pouch. With his every downward swoop she reared back, hands upraised, in open-mouthed astonishment. Tim's laughing shriek squinted his eyes and showed his pink gums. But then he simply stared at her, I know you, you wonderful being. For two or three passes they beamed at each other.

The gray set around her again, like gelatin.

"All this brouhaha for someone who's dying," she said to the nurses and technicians who monitored and tested her the next morning.

No, the doctor insisted. Although bronchitis had degenerated into emphysema, her most acute symptoms were anxiety and fatigue. "You will never lose this disease, and it will shorten your life, but we're talking

17

years," he said. Unless she continued to smoke. "Then you might as well hop under a bus."

"Stay with me tonight," she told Tim. He fussed. "Against hospital regulations, I'm not a watchamacallit, garlic around the neck for vampires, a talisman."

"Make an effort," Julia said

Tim arranged a bed of chairs beside her, and she slept. Within a week prednisone had stabilized respiration, and she was discharged.

When Julia stepped into her townhouse, even the gaudy Persian carpet was stale with her confinement. She had been ill for months before hospitalization. Nothing had changed except she wasn't coughing. She would watch PBS, and attend theater and symphony with her reliable friends. Tim would appear at metronomically-paced intervals. The current agreement was once per three weeks.

Julia tried to organize a routine. Retired two years, she was a zoo docent, but the connection had lapsed. Phoning booked her three days in the zoo's information booth.

Paying for groceries at the supermarket checkout, Julia yearned for a cigarette, that perfect moment when the body relaxed, the smoke jetted through mouth and throat to the lungs, out the nose, a continuity, complete. At even the crinkle of a package in her hand she was swollen with fondness like an escaped balloon. She bought Carltons.

Lighting the cigarette, she hyperventilated, and it burned halfway before she could inhale. She sipped experimentally, drew more deeply. After fifty-three years of a carton a week, she must retrain herself to smoke.

Sunday, when the Unitarian congregation volunteered personal announcements, a man named Philip said, "1 love to cook, but there's no one but myself to enjoy it." He wanted to exchange dinners. A newcomer, he was six-and-a-half feet tall, with a beard like fleece, sooty highlights, to his chest. He wore a gold earring.

To Julia the moment presented itself as a question: am I acting for my life or against it? She felt she existed only through what she did. She stood. "I would like that, too," she said. They agreed on the following Saturday.

Since her husband's death six years before, Julia hadn't "dated," not from deference-they had been divorced sixteen years-but simply believing that whole business was over.

18

Saturday Julia chose a heavy cotton smock, jungle-green threaded with scarlet and yellow. She even brushed on makeup.

Philip's second-floor apartment was one room with bath and kitchenette, walls bare. Though he had lived there two years, stacked books occupied the floor, crowding desk and futon into a corner.

Philip's meal consisted of thin-sliced abalone stir-fried with vegetables, and fat black mushrooms like those unspeakable sea-bottom creatures that one tried to accept as equal living things. The whole was drenched in chili oil.

Crosslegged on a mat, they ate from bowls. The food scalded Julia's mouth and flushed her skin. Their eyes teared, faces dripping sweat. Rocking, they laughed at the ridiculous agony.

"I'll never eat anything like this again," Julia said. "Whoops, no, give me the recipe and I'll cook it for my son. Just kidding."

"He lives with you?"

Julia explained the schedule, one visit every three weeks, that Tim had dictated.

"Grotesque," Philip said. "A crueler deprivation than absence altogether."

"No. At least I have him this much."

Philip was childless. "For my wife and me, making a baby would have implied too much optimism about our future," Philip said.

Tim was an only. "Opportunities for conception in my marriage were rare," Julia said lightly, but again her face burned. She had decided to hold back nothing from Philip. "If we're going to be friends, I don't want to offer myself under false pretenses. I've been through a difficult episode."

"Oh?"

Since childhood Julia's sicknesses inexorably progressed to bronchitis. "I can't sleep with your barking all night," her father had told her. Every winter, for two or three weeks, a month, coughing from a chest cold interrupted conversation, eating and her job as a home visitor for D.E.S. She canceled outings with friends.

The past November a tickle in her throat descended to her lungs. For five months the cough flapped her like a rag. Sleepless at night, Julia fell into afternoon naps on the couch. Without appetite, she drank soup. By Easter catches occurred in her breathing, when the ribcage would lift, diaphragm push-finally, whistling, a shallow expansion of the lungs.

Bent, hacking, Julia felt inescapably herself. Her shame at the noise, helpless jerking, sputum balled in Kleenex, was linked to the profounder

19

embarrassments: her husband locked in the study with vodka and the Sons of the Pioneers. Tim accusing her, "You give me a Peanuts cartoon book, and when I don't laugh you say I've lost my sense of humor. Your sense of humor. When I'm with you I have to make a mental checklist of who I am."

Embarrassment alone could make her cough, knocking the air out of her.

Julia had begun smoking in boarding school, where the girls called their cigs "Little Man," as in "I have a rendezvous on the balcony with Little Man." Beyond this delicious intimacy, Julia's cigarette was a complete if momentary satisfaction, a devotion to wholeness in things, the opposite of embarrassment. Of course it aggravated the cough.

As she concluded with her release from the hospital, Philip wrapped her in his arms. "Poor Julia."

"That's not what I meant," she said, but his broad hands cradled her back, and she settled into his embrace as if it received her exhaustion, not only from the recitation, but the months themselves. Philip straightened his legs to give her a lap. Smelling him through the faintly soapy denim shirt, Julia lay without speaking until, nearly asleep, she said, "I've got to go."

Philip was unavailable the next weekend, so they set Thursday before, at her place.

When he arrived, Julia suggested a turn around the zoo. The coq au vin she had stewed the previous night; it needed only reheating. The park was so near her townhouse that nights she heard whooping, roaring and trumpeting.

May was still spring, temperature 85, and evening shaded the paths. Philip strode leisurely, hands in pockets, head swiveling with curiosity. In the aviary his eyes, intent, enlarged comically, tracking parrots' arrows of color.

"Why don't I do this?" he said. "The air is marvelous. I never go out."

Julia chirped to the elephant. Swaying toward them, it greeted her with raised trunk.

"Julia, Dame of the Beasts," Philip said.

"This is Philip," Julia said. "Let's see, we toured the cat enclosures, and the lions were asleep, but the tiger was swimming, which I've never seen before." His flanks had dripped, the sheen of his coat red-gold.

The elephant slapped its trunk side to side, head down, in cadence with Julia's voice.

20

"That great head with its ludicrous tweak of hair. The animal is so unselfconscious," Philip said. "What separates them from us," he muttered. "But not you. You don't seem to formulate yourself for the world."

Quickly Julia skirted the sun bears, who, still awaiting their promised habitat, paced the cage, thrusting reproachful noses.

"For all that I love the tiger," Julia said, "and the elephant - and the otters-and the polar bears-and the birds"-she laughed-"I keep coming back to the monkeys." The macaques showed their gums and launched into a dizzying orbit of stump, trapeze and bars.

Leaping for an overhanging mesquite branch, Philip swung onearmed, grinning. His teeth were weathered like piano keys. The plummet of feeling about him, not yet for him, filled Julia with dread.

Though landing softly, Philip winced.

"You're quiet," Julia said presently.

"My feet." His gait became delicate. "According to the doctor, heaving around my bulk all these years has jumbled the bones. Like a paleontological dig, fossils heaped up. I like to think that the burden has left the bones sad, disoriented. Anomie has set in."

"That's the most highly developed thought about anyone's feet that I've heard."

He laughed. "Curse of my life."

Sunset ignited the haze of dust over the veldt herds. In the fullness of the moment Julia opened her purse for a cigarette-she'd kept a halfpack daily limit - but imagined Philip's exclamation, "Emphysema?" Idiotic, she agreed, abashed as if he'd actually spoken, and withdrew her hand.

At the dinner table Julia fork-separated the tender chicken, but Philip ate with his fingers, gray sauce running into his beard, bones protruding like catfish barbels beyond his face.

"You look like an amiable sea monster," she said. "Mmm." He seized her hand and nibbled up her arm. She scrunched back in her chair.

Rising, stooping over her, Philip lifted Julia in his arms until she stood tight against him. His heartbeat accelerated by her ear.

Julia's hands pushed against his chest. "Not yet."

But when?

Julia poised on the deck of the community pool. Since her hospitalization the mere thought of swimming, the labored breaths, had con-

21

stricted her chest. Now she craved the churning of arms and legs, the euphoric fatigue.

Julia had not made love as an old body. To conceal loosening skin she wore garments to her wrists and ankles. For occasional dips, always at night, she'd hiked panty hose under her suit.

But this shyness would not lessen with waiting. Refusing Philip now, she understood, would be final.

Floodlights fanned a seething blue across the pool's surface. Beneath, the water was black, leaves circling. Julia would be diving into her own shadow, a thought she found unnerving and recklessly pleasurable. She splashed in, stroking easily.

When she and Philip undressed, Julia was compelled to imagine herself through his hands-skin sagging from the bone, flesh shrunken-and she could not respond.

Driving home in lemony brightness, Mother's Day, Julia resigned herself to not seeing Philip again. The affair already was a gift, more than she'd expected from her life. She memorized, for the future, Philip's trunk of a body at the window, arms spread, sunlight playing over chest and belly hair.

Awaiting her guests, Julia felt acute but out of control, like a clearheaded drunk whose body consistently lurches into furniture. She drilled the vacuum cleaner into a spot of ground dirt by the entranceway.

Two weeks before, as "an amendment" to Julia's celebration, Tim had requested including his new girlfriend, Linda.

"Come yourself on Saturday then, for lunch," Julia had said.

Recognizing the ploy, an extra visit, Tim hesitated.

"Mother's Day is a freebie," Julia said.

Tim blushed. "Sure."

"I've had two dinner dates."

"Wow. Congratulations." The burden of her affections visibly slid from his shoulders.

"He's a poet but looks like a pirate. Gilbert and Sullivan, pirate and pilot."

'Apprentice to a pi-rate,'" Tim had sung, surprisingly. Penzance was a childhood enthusiasm.

Julia had sung a verse. "I'll put it on," she had said, starting for the records.

"No, that's O.K.," Tim had said.

22

Julia stuffed the vacuum in the closer just as Tim arrived with steaks and Linda, a woman with flat, functional hands and a stupendous bust restrained by a snug, flowered jumpsuit.

"What a relief," Linda said, admiring the lace-embroidered bodice of Julia's blouse. "I was afraid I'd overdressed." She and Tim were going dancing later, she explained.

"Tim might not remember, but he's always been a dancer," Julia said. The blunder loomed, yet she couldn't fend off the words. "Until he was seven or eight we would dance naked together, Shostakovitch, running up and down with scarves."

"Great." Tim flipped his hands. "Now tell her how I breast-fed until I was twenty."

But Tim, who honored holidays, righted himself, telling amusing work stories. He was Target's store manager.

Through dinner Julia's stomach still clenched from his anger. "Katherine," she said, "could you pour me more wine while you're up?" Katherine was Linda's predecessor, and Julia's favorite, in Tim's succession of women.

"Mom!"

"I'm sorry. Linda. It's habit."

"I understand." Linda smiled as if to gobble the world's unhappiness, bite by bite. "Your vinaigrette was delicious." She complimented each course in detail, wielding praise like an iron over a wrinkled shirt.

The pie was heated. Linda chatted through hers, Julia dawdled, Tim ate silently and quickly. Utensils clicked on the plates. The scrapedclean surfaces gleamed as if the evening had disappeared into them. Pressure built in Julia's chest. She gasped and swallowed air.

"I bought Kahlue," she said.

No, the couple said, the club already would be crowded.

At the doorway Linda kissed Julia thanks, twined her arm around Tim's waist. Solitary, Julia felt conspicuous, as if the others were ignoring a comical deformity-hands sewn on the wrong wrists, maybe. "Tim, I almost forgot," she said. "I've organized my papers in a filing cabinet. insurance, the will, investments, taxes. Alphabetized. It'll only take a minute. You must know, in case anything happens to me. Much as we want to avoid the fact, I am ill."

"Mom, good God, not on Mother's Day."

By 10:30 Julia had smoked her daily quota. The pact with herself was inviolable. Instead she watched a Cary Grant double feature. Cary waltzed and feinted through the heroine's amorous lunges as if waxed. At midnight Julia lit #1 for the following day.

23

Julia awoke with what she thought was a severe hangover, though she had drunk moderately. After phoning in sick to the zoo she returned to bed with the blinds drawn, a shirt over her eyes. She saw Philip turning from the window, approaching, nothing between them but the sheet drawn to her chin. Cigarettes tasted like smoldering chemicals and made her head throb. Julia wasn't aware when night fell. The next day was no better, so, she decided, there was no reason not to work.

"I have something for you," Philip called to say. Julia said fine but didn't fix her hair or change clothes, drawstring pants and a jersey. He arrived empty-handed. "It's a massage. No protests." He covered her mouth. She was clairvoyant, he said; the outfit was perfect. He was unrolling a pad, popping a Bach harpsichord concerto on the stereo. She was face down on the floor.

"Petrified wood," he laughed, fingertips playing over the base of her skull, her neck, back, legs. Indeed, Julia felt all hard grain, indissoluble knots. As his fingers probed she yelped and started to rise.

"Patience. Bear with me," Philip said.

Flowing blood did tingle in unexpected far parts of her body. Philip cautiously gave weight to his hands, then lifted her from beneath, let fall. Julia had the image of a board, clapped to her back, being pried loose. Now Philip could knead her flesh. The circling strokes of his palms were erasing her form. Even the pressure released her further.

"I don't feel anything," Julia mumbled into the cotton. "I mean, 1 do"she laughed - "but I'm disembodied." The music advanced and receded, lacy waves breaking on the beach. She was a bubble, zigzagging from spume into the pure air.

Julia became absorbed in the carpet before her eyes, its thickness, geometry, flagrant colors. She tumbled through the weave, the pile separating, closing over her. "It yields like water," Philip panted, "and the colors stain your skin." Their merging of thought Julia accepted as natural.

Philip rolled her over, kissing. Their stripping altered nothing. She might always have been naked. At Philip's touch nerves opened until she was entirely this fresh, ageless openness. Caresses were partaking and giving in the same movement.

"These are your hands," she exulted.

Julia was swimming powerfully from shore, cutting a straight line through the water. When they finished she floated in a million square miles of sunswept ocean, one with the currents.

"Now we truly are bonded," Philip said.

24

Energy begets energy-Julia's credo. Editing the zoo newsletter, she also drafted press releases and mailings to fund the stalled sun-bear enclosure. Days off she and Philip might decamp for an Anasazi ruin, Mexico, the Santa Fe Opera.

Swimming sixty laps a day had firmed her muscle-and toughened the cardiopulmonary system, the doctor commended, examining her.

She had virtually quit smoking. In Philip's presence she wasn't tempted. Exercise suppressed the desire in four-hour blocks, one before, one during, two after. The surviving indulgences, over tea and at bedtime, didn't satisfy as before, the inhalation pinched, and often Julia skipped even these.

A slow, hot July morning, Julia daydreamed in the zoo's information kiosk. Until he was upon her she didn't recognize-Philip, in floppy beach shirt patterned with exploding firecrackers, cantaloupe-sized knees protruding beneath green Bermuda shorts.

She laughed uncontrollably. "Alaska. Gigantic vegetables that grow in two weeks." She clipped the price tag from his belt loop.

Together they cast fish food from a keeper's bucket, a privilege of the veteran docents.

"Nice motion," Philip said of their arms' lazy sweeping. Cattails nodded in a breeze skimming cool off the water. Clouds puffed by.

"I'm happy," Julia said.

Linda, who missed the large family left behind with a past marriage, adopted Julia. Accompanied by Linda, Tim dropped by as often as twice a week. Without complaint he replaced a leaky faucet washer and soldered a loose connection in the stereo. "Need anything from Target?" he said. "I'm right there." A haunter of swap meets, Linda brought ceramic owl salt-and-pepper shakers, a touching, unusable gift.

"What do you do," Julia asked Philip, "on those weekends when I don't see you?"

"My survivalist cadre holds its potlucks," "O.K." Julia held up her hands. "No questions."

"You know what would be lovely?" Julia said. "A joint dinner for Philip, Tim and Linda."

Philip was noncommittal.

After a few days Julia mentioned the idea again.

"My interest is in you," Philip said.

"But they are me, Tim is."

25

"That's an overpopulated armful for me." Philip smiled.

"Don't put me in a position where I have to have all these little drawers, 'Tim: 'Philip' Please."

"I like my drawer."

Though she hadn't disbelieved him, the tangible evidence of Philip's literary accomplishments stunned Julia. She turned over in her hands the hardpaper quarterlies with their austere cover designs, to read his name on the contributors' lists. The most recent was ten years old.

She borrowed them. Rhymed but metrically unpredictable, his poems, even the youngest, were predominantly elegiac. One conjured a circus from its abandoned grounds, overgrown with thorns. In another, two friends discoursed ironically on love amid the fleshpile of a public beach.

Always a reader, Julia now studied literature systematically, analyzing texts in a notebook, to prepare for talks with Philip. For his birthday she composed a poem.

"Poetry isn't your forte," he said, adding hurriedly, "but you are definitely in this poem. The sentiment is quite affecting."

When a rancher friend presented her with veal steaks, Julia again proposed the family dinner.

"Our balance is delicate," Philip said. "Let's not tip it."

"I wasn't aware. I thought we were quite robust. Tim and Linda keep asking to meet you."

Philip was adamant. "You haven't made Tim sound like the greatest company."

"How can you care for me and not want to know him?" Tightening vocal chords made Julia's voice strident. "You can't squirm away from them indefinitely. It's absurd."

"Why not? I'll credit them with going cheerfully about their business, content without stalking me."

Citing a need for "heart gossip," Linda brought lunch. So eager was she that Julia confessed, yes, she and Philip were "intimate."

"All right!" Linda pumped her fist.

Frankly, Julia said, the intervals between dinners were lengthening. Weekends, especially, were canceled. "A person doesn't need sex. For nine years I did without. I didn't join a nunnery or the Communist Party. I wasn't bulemic. Flying penises didn't flock the skies."

26

Linda rolled onto her back, feet kicking. "You didn't grow a beard. You didn't put ice cubes in your undies."

"How come I feel like I'm going nuts?" She'd awaken fighting to breathe, as if steel bound her chest. The cough, when it came, was a relief.

"I never know when Tim's going to show up, either, two days, a week, three in the morning."

"How do you stand it?"

"Here's me," Linda said, semi-crouching. "I can go this way, that." She pivoted left, right. "I never see Tim again, I'm sad, I'll live. Meanwhile I have a helluva lot of fun. Take it day by day.

"Tim zips me off to a ballgarne, or picnicking in the mountains. One night we made masks and grass skirts from newspaper, and called the house 'Hawaiian Zone.' And then Linda whistled, drumming her fingers.

"Good for you. I don't see that side of Tim."

"I should hope not." Linda laughed.

"My idea of heaven," Julia said, "is two people giving excessively to each other, world without end. Amen."

"Why do I always initiate our lovemaking now?" Julia asked Philip.

"You're the one who holds back sometimes. So I let you choose."

"Don't you think maybe I'd like to be compelled by you, for that to make my choice?"

"I'm not much for coercion."

"It's persuasion I'm asking for. I don't want it to be all the same to you if I say yes or no."

Philip prepared an evening of tantra, "a true yoga, serenity in motionless sexual union."

He positioned himself on the mat, the half lotus. Setting Julia on his lap, hooking her feet around his back, he entered her. Within minutes his breathing had subsided to a dilation of the nostrils, sigh. His eyes shut, the blue-veined lids unclenching. The forehead smoothed.

Julia's skin burst with excitement and frustration. When finally he stirred, Julia choked her limbs around him, mauled his chest with her teeth. Quick-quick-quick she moved, bouncing her rear on his ankles, beating against him.

"I have to beg off tonight," Philip said over the phone. "My feet won't get me down the stairs." He'd been complaining. Julia covered the hot dishes in foil and drove them over. "This place

27

may have had its day," she said. "If you were closer at hand, I'd be more available."

"Is that a suggestion that I move in?"

"I suppose it is. The shambles is charming" - she gestured around the apartment - "hut why not live graciously for a change?"

"Can you imagine us rattling around each other twenty-four hours a day?"

"It's not so outlandish," Julia said. She'd keep the top floor, he'd have the bottom, more territory than he was used to.

"Julia, your forays tire me."

"Me, too, Philip, I couldn't agree with you more. Please do me the one favor. Meet Tim."

A day later Philip agreed. "A concession on my part is called for."

Philip was due at six. Tim and Linda arrived an hour early to help set up. Linda, diminutively voluptuous in a tight sheath, hair coiled, arranged the snack tray. Acting out family stories, she revealed a flair for mimicry. Tim had prepped for the evening to the extent of dredging up college lit notes. He discoursed on symbolism in The Mill on the Floss. Dusting the London broil with garlic, he quoted verbatim passages from Anna Karenina in the dog's point of view.

"Sweetheart," Julia said. "I'm really moved by this support." Tim kissed her.

A glass of sherry, intended to calm, made them giddier. Picking at the hors d'oeuvres, they had nearly emptied the tray when, at six sharp, the phone rang.

"I'm sorry, it's wrong. I feel coerced. We need to talk," Philip said.

Julia turned to Linda and Tim. "You guessed it."

"Shit," Tim said. The explosive t made the word particularly ugly.

Julia and Philip stood at his kitchen counter half an hour, as if sitting hadn't occurred to them. They conversed with a distracted fluency, statements already thought through that they now borrowed from themselves. Neither referred to a purpose for the meeting.

Julia asked why Philip no longer wrote.

He did, but rarely, nothing to keep. "I won't write depressed," he said. "That's ego, not poetry. I have no affinity with the vogue of inflicting one's every hidden recess upon eighty million readers."

Why so depressed? "Your feet," she joked.

"Yes." he laughed. "And my wife."

"Your ex-wife."

28

"My once and current wife. I've decided to pinh my hand in there again."

Julia rejected the attempt to believe she had misheard.

Vera was fifty, Philip said, still beautiful, copper hair and cream skin.

"Where do you go?" Julia asked numbly, as if interviewing.

"Here in town. Unfortunately, she's hopelessly unstable." After leaving him, serving divorce papers, Vera had jumped off a bandshell roof during a rock concert. The decree wasn't finalized. "I compromised," Philip said. "I moved her back in the house, and I left. She's been more at peace there."

Driving home, Julia awaited the inevitable cough. Like the braying of an onager, it came, accompanied by runny nose. She screamed in the closet, muffled by coats.

By phone she broke off with Philip. "I can't think of words to despise you enough," she said.

To expand the newsletter Julia recruited correspondents. The sun-bear drive cracked its goal, and construction began. Member of a YWCA with indoor pool since fall set in, she slogged through laps when the cough allowed. Sunglasses hid the dark circles around her eyes.

The following weeks Tim was so peevish and erratic - most often Julia entertained Linda alone-that Julia considered imposing a once-amonth quota on him. Despite the persistent cough she again bought cigarettes. Linda berated her.

"At a certain age character becomes simplified," she told Linda. "Julia plus Philip equals Tim minus smoking. Julia minus Philip equals smoking minus Tim."

Bundled in a quilt against the damp chill, feet to the electric heater, Julia thought of Easter, herself in the ambulance, a gray stick, tassel of brownish hair, the oxygen mask a malignant flower covering her face. The cough boomed.

Napping, Julia dreamed of Philip in the form of a joke. The prototype she'd actually heard, a series of exchanges, increasingly damning accusations culminating in a punchline that was, as usual, all she could remember.

In the dream the words were enormous stone monuments, unreadable from her perspective. Among the letters Philip scurried, a gnome with hairy rump and tail, mischievously peeking.

Some of the joke's lines, rather than words, were film clips of himstriding naked; leaning back from the table, wiping his beard; among trees, tinted green from their leaves.

29

At the punchline - "Well, nobodv's perfect" - Julia awoke laughing.

Through the church grapevine Julia learned that foot surgery had confined Philip to his apartment, his wheelchair unable to navigate the stairs. She assembled a CARE package of deli items, fresh fruit and a bottle of Dry Sack, along with mundane necessities.

Grinning, Philip held out his arms. Even seated he was huge.

"I've missed you so much," Julia said.

"Moscarpone! Smoked oysters!" He twisted the sherry cork and poured two glasses.

Lit only by a gap in the venetian blinds, the disheveled room showed no sign of outside intervention - a wife's, for instance.

Philip's bandages were cloddy white blocks. "The idea of someone cutting," he said. The wince bared his teeth. "I keep imagining them stepping into an egg slicer." For another two months he mustn't walk.

Julia did some "picking up."

"Today's man on wheels needs room to roll," she said, shoving books against the walls.

Philip beamed, sipping. "You are dear," he said. "Now we have a dance floor." He put on Vivaldi. Grasping Julia's hands, he lilted her to and fro. From behind Julia lumbered him through figure eights. A hub caught books, loosing an avalanche. Deliberately Philip rammed another tower, toppling books and a broom, spilling the wastebasket.

Flouncing her onto his lap with a thick arm, Philip said, "Have you ever made boom-boom with a mechanical centaur?"

"Philip," she said. "I love you, but that aspect of our relationship is past."

"My regret." Stretching for their glasses, he clinked. "And deepest apology."

Leaving, Julia demanded a key, and they fought. "What if you called for help and couldn't get to the door?" Julia said.

M All right." He slapped the key on the counter. "Not because I need it, but because you deserve it."

"Thankvou thankyou." Julia curtseyed. "I shall wear it like a diadem on my forehead."

"I'm an ass," Philip said. "Please take the key."

The morning of Christmas Eve, a dressed goose under her arm, Julia unlocked Philip's apartment and stepped into a glow like played-out neon, candles in red glass chimneys. "Boo," said the black hulk in the corner. "Happy Halloween."

Julia set the bird in the refrigerator and poured herself wine.

30

"I apologize," Philip said. "I'm undergoing a seizure of reminiscence."

"You can talk about Vera," Julia said.

As if continuing an interrupted monologue, Philip said, "We were trekking in Nepal, our honeymoon. The sun fell toward the peaks" - his head dropped to one side, and his voice thinned - "which went molten orange, as ifjust pulled from the fire by the glazier's tongs. Then we were rising, forced apart, until we found ourselves on separate peaks. The burnished ice fell away in all directions. We regarded each other across great distance, yet in perfect awareness and sympathy."

Philip's hands pressed together. "I steered our lives by that vision for years. So what if we were miserably incompatible. I willed us a couple, and now she can't live without me."

"I married my husband for his sadness," Julia said. "A mistake I undid. You're not bound to this lunatic!" she exclaimed.

"I become loquacious," Philip said, toneless. "I'm imposing on you."

"No, Philip. Wrong. This is what people do. They talk to each other." Her arm wrapped around his head, fingers in his beard.

Philip jerked back. "Ah, yes, the orgy of 'sharing':

'I have cancer of the bowels, and your breath stinks.'

'Thank you for sharing that with me.'''

"Call me when you are yourself," Julia said and ran out the door.

From a pay phone Julia retracted "lunatic." Until ambulatory, Philip said, he was unfit for company. They should limit contact to the telephone.

Obsessively Julia pictured Vera, red hair billowing, filmy dress clinging to her white limbs, bouncing on the pavement. Appalled at herself, Julia researched outings for Vera, chamber music, gallery openings, the botanical gardens, a bird sanctuary an hour's drive away. Reporting these to Philip, she added recommendations for therapeutic books and magazine articles.

"How is Vera today?" she asked Philip.

"Buzzing off the wall,"

In this proxy existence, through Vera, Julia felt disconnected, as if there were no footing beneath her.

"Julia," Philip said, "our material is stale. My topics are few." He would be responsible for calls, which stabilized at two a week. Tacitly the phone arrangement remained in force even after Philip's first gingerly steps, on crutches.

Linda commiserated over the passing of Julia's sex life.

"It's not even the sex," Julia said. "When he calls, I feel the same as when we used to make love. When he doesn't, it's just as maddening.

31

Suffocating." In fact, she was resorting to a Bronkaid inhaler frequently for shortness of breath. Coughing fits had ended the swims. Mornings, swinging her legs out of bed, she'd fall back, dizzy. Her limbs always were cold, her legs felt leaden, two minutes' walk tired them.

The inability to smoke enraged Julia. To outwit her lungs she puffed while limp in a hot bath, or nearly asleep, over bourbon or steaming tea. Her lungs convulsed.

"I'm glad to see you and Linda working out," Julia said.

"I'm in a holding pattern," Tim said. "Eventually we'll break up."

"You were a sweet boy, Tim. There, I'm Generic Mom. But it's true. I have every card you handmade for me, birthday, Mother's Day, Christmas, Easter, Valentine's, for twelve years.

"Our first visit to the Grand Canyon," she said, "we stepped to the edge and the ground was broken in pieces as far as we could see. We grabbed hands, clasping so tight I think we both believed we could have floated down together.

"And you know what? That boy still exists, as much as you do."

"You mean in your head. These guys are thirty-one." Tim wiggled his fingers.

She'd depended on Tim for a sense of future, Julia thought, not happy, simply tangible. But he defeated her like a TV after sign-off, a gray static buzz.

Philip sent a letter. "Our phone calls have outlived their usefulness. Increasingly they are an obligation."

Julia laughed out loud at herself, pacing the floor until she gained the equanimity to sit and type:

You will be happy to read that this letter relieves you of your duties. Please don't call. Don't write. The books I've lent you, you may keep. Their meaning to me henceforth would be deformed.

You probably consider withholding yourself as manly, a guarding of old virtues. It is not. It is monstrous selfishness. Caring people share themselves. I feel sorry for you The loss is to us both.

For the record, those burdensome phone calls, as our entire association, were delightfully stimulating to me.

Philip wore a loose gray shirt outside his pants, loafers sans socks. "Come in." He beckoned like a hotelier. The room was unchanged, though brighter, blinds open.

Julia handed him the envelope, which he laid on the counter.

32

"Don't put it aside. Read it."

"Not under this scrutiny."

Julia slit the envelope with her fingernail and read the letter aloud. Philip rubbed his face. "Quite fair," he said. "Points well taken." Off to the house, he said, for a packet of old manuscripts. Come with? He hadn't invited Julia to his home before.

"Will she be there?"

"No. At the shrink."

Driving, Philip was expansive, head dipping toward her, hand flashing.

In fantasy Julia had made this journey repeatedly - rescuing Vera from another suicide attempt, supporting Philip across the threshhold after her death, tipsily dousing him with champagne after Vera's divorce. That she was actually rounding Philip's corner Julia attributed to two factors. One, without a more satisfying resolution, which she would not get, she could not give up this final moment. Two, in Philip's view she no longer existed.

Tidiness shielded the interior of the solid brick house. Amazed at her detached curiosity, Julia searched for clues, nothing so obvious as a photo presenting itself. A pleasant scent, spicy, lingered. Philip rummaged in another room, drawers slamming. By the open French doors a curtain stirred.

Julia stepped into a profusion of snapdragons, tiger lilies, gladiolus, trillium, red poppies, crocus-plants Julia hadn't seen growing in the Southwest. Rustling trees filtered the sunlight. Cool, broad leaves slapped Julia's thighs as each tread crunched, releasing a musky vegetable smell.

"1 haven't trimmed the fruit trees. They're looking shaggy," Philip said. "I've wanted to introduce dogwood-those starburst blossoms are a vivid growing-up memory - but I suspect the climate would be too much of a shock." He lowered himself, knees swaying, to pull a weed. "Planting the rosebushes was hell on my hands. My gloves weren't thick enough. Beyond punctures. Lacerations."

He looked up at Julia. "1 retreated here from our love affair. This suits me. Vera and I scarcely meet. She's content to know I'm puttering nearby."

Julia saw the scene as a paperweight, an exquisitely wrought foliation of colors, encased in glass. In the midst stood Philip, feet transfixed by long pins topped with red hair. Placidly he stooped with the watering can. It was set in Julia's mind, the vision of what he'd chosen over her.

33

Although lying still in bed, curled on one side, Julia felt as if she were bounding. Flinging out her limbs brought no relief. She wrenched from side to side.

She dreamed she was floating on a sea of burning oil, the ship's prow silhouetted, sinking. Fire crawled over her skin. Thirst cracked her mouth. Flaming vapor wriggled skyward, sucking oxygen, as the hot air collapsed, closed like a fist. Inhaling, her lungs seared.

Gasping, the sheets drenched, Julia yanked the chain to the bedside lamp. The room's whites and greens harmonized tranquilly to the point of eeriness; the scene looked stilted. Julia read.

A canopy of flame crinkled overhead, following her. Julia would sit, hand to her chest, laboring for air. After a few yards' walk her knees buckled.

Without loving Philip, Julia thought, she had sickened. Loving him, she had sickened worse, more quickly. How could it have become so simple?

Rising from the typewriter, the newsletter complete, Julia lost her balance. She could not control her legs, which skidded from under her. The second fall she waited until sensation returned, rubbing her calves. Crawling, she backed downstairs to the phone.

Within minutes Tim was carrying her to the car. "Oh, no," he said, shutting the door, but the sound, broken as the latch clicked, had no origin. It could have been spoken by the dashboard.

Tim whizzed through red lights, emergency flashers blinking, horn beeping. His face was serene with purpose.

Traffic in the left-turn lane slowed them. Alongside, in the center median, a cloud of butterflies bobbed across shrubs, an entity not quite whole, not quite dispersed. They reminded Julia of a meadow she'd once hiked years before, as a teenager. Breaking from the woods, she'd happened on a field strewn with deliriously yellow flowers. The air was so clear she'd felt no barrier between herself and the sky, earth, the fluttering petals. Running, with cleansing, full-chested pants, she leaped into their midst.

34

Fado

Katherine Vaz

One morning I could not find Lucia, my stuffed toy pig. I ran crying next door to Dona Xica Adelinha Costa. Xica buried her St. Anthony and told him he would stay there until he helped us. Then she kissed me and sent me home. That night I saw Lucia's cloven hoof jabbing out of my bed, and with a shriek I clutched her in a dance. Xica left Anthony in his grave another day to teach him to be faster in finding what was lost.

When the California valley heat pressed down on us, Xica would lift my hair, so electric it leapt to greet her approaching palm, and she would blow on the back of my neck. Summers the fuchsia hung swollen like ripe fruit-the dancing-girl's skirts mauve, cherry, scarlet-and Xica taught me how to grasp the long stamen running up into the core and with a single sure yank pull it out with the drop of watery honey still glistening at its tip. My parents urged me to spend time with Dona Xica. We were lucky to be neighbors. I had never known my real grandmothers, and Xica would never have a real grandchild because a car wreck had made her married son an idiot.

Bicho vci, Bicho "em, Come 0 pai, Come a mae, E come a menina tam bern!

* * *

35

The worm-monster goes, The worm-monster comes, It eats the (ather, It eats the mother, And it eats the baby too!

Marnae walked her fingers up my leg singing this rhyme, and on the final line she attacked my stomach until I squealed with laughter. I would beg her to do it over and over. 0 bicho never got to my throat. I kept him down where it tickled.

I met worse night-things as I grew up. If I stared too long at those red and white pinpricks in my dark room they rolled into constellations that burst alive, into pirates and dogs speaking guttural English. When they came for me I would sign crosses in an invisible picket fence around my bed. The beasts roared but none of them could get me.

One night I finally kicked my sheets over the cross-fence and thought: Climb in with me. Xica is not afraid of you and neither am I. I am more afraid of being alone.

* * *

The old stories said that our Azorean homeland was Atlantis, rising broken from the sea. We all have marks and patches surfacing on our skin. I have a fierce dark animal erupting from my side.

Xica had a wine-colored star in the cove at the base of her throat. When she drowsed in the sleeping net that swung between two trees dividing our yards, I liked to touch the star and the bones of her face. She had a long nose ridge, arcing like a dolphin's spine from between her eyes. Inside her hands and chest more bones floated, like those soft needles that poke unmoored in fish's meat.

My fingers could never drink up the rheum t�, always trickled from beneath her closed eyes. We are so sad, so chemically sad, that it leaks from us. The [ados wailing from our record players remind us that without love we will die, that the oceans are salty because the Portuguese have shed so many tears on their beaches for those they will never hold again.

* * *

Xica Adelinha Costa could faint at will. She would quicken her breath toward that giddy unlatching when the spirit shoots from the body. Then all is cold and black, with a prickle of nausea. One day when I was thirteen I fell with her at the Lodi post office. We were in line to

36

pick up the ribbon do Nosso Senhor do Bonfim sent from her cousin in Brazil, and suddenly Xica could not wait anymore. She shook so much I shook too, and then she collapsed into my arms and drove us both to the floor.

Most townspeople already knew that when Xica could not be without something another moment she hurled herself into the dark. Postmaster Riley did not rush over, but he tossed me Xica's package. I unwrapped the thin blue ribbon do Nosso Senhor and tied it around her wrist. She woke up because now she could make her pact with God. Xica whispered this prayer:

o Nosso Senhor: Heal my child. He has not spoken a single word since his accident.

o Nosso Senhor: You threw my husband off that whaling boat and did not return him when I was young and pretty in Angra-lift the fog from my son.

o Nosso Senhor: Make his wife love him again.

When the knot broke on its own, those wishes would come true. "Rosa," she said, "I can almost hear my boy saying my name." She smiled at the man offering her water and kissed the wrist tie that marked her as a woman of divine desires.

For sprawling in public with charms my parents made me recite all the rosary Mysteries-the Joyful, the Sorrowful and the Glorious-to scrub out my soul.

My father's lavender soap always drew me from sleep. The maleflowering scent came for me before dawn, as he padded around the house until his veins breathed open. He insisted I do his morning exercises with him. Out with the violet bristles protruding from the artichokes, there in the dark-claret light.

"Inhale with me, Rosa," said Papai.

In-let it fill you - out.

Sister Angela, my eighth-grade teacher, explained the heart:

Old tired blood of night and sleep starts out purple. It goes through the heart to wash itself red.

The morning sky is red and purple to remind us that we walk in the air of burst hearts.

* * *

37

I would sit on the porch awhile holding my father's hand. It was the first time I already missed someone I still had, and my first lesson that true joy creates not memory but physical particles. My Lodi mornings hid embers in me that will float upward when I die, to burrow in someone else, because they have nothing to do with dust.

Marnae would bring out mayonnaise-and-tomato sandwiches. We ate together before my father left for his milk route, and then she and I went back to bed. Sometimes it is beyond endurance, the separateness of all our lives.

Manuel was soft and red-streaked as crabmeat now instead of big-framed and handsome. Xica led him by the hand and said aloud what everything was. He never spoke, but she refused to give up. When her ribbon broke she wanted him to awake with the world already learned. She told him about things that could be held:

Brier roses: Same genus as the strawberry. But you would never guess they were one family. Perfumed, pink. Careful how you touch it, love. Not a few big thorns but a hundred little stabs.

Cat: Venha cd, gatinha, gatinha! Here kitty kitty kitty. It brushed your legs and then disappeared, Manuel. Ate breve, gatinha. Don't cry, Manny.

Rocks: They stay in one place even if you turn away. Let me brush your fingers against them for you.

Brick: Watch me scrape my frayed ribbon against it to hurry your cure.

Before school I took Manuel's other hand. His wife Marina sat watching. An earthworm sometimes stitched through her bare toes in the mud, but she did not move. She liked belly crawlers: A recurring tapeworm let her stay thin and eat madly. We all ate pork - vinho d'alhos, rorresmos=Iaden with invisible cooked trichinae, but only Marina would not flinch at finding alive in the ground what also churned dead in our stomachs.

In terrible heat she poured honey-water or lemonade on herself, whatever was near in the pitcher, and her skin glistened with sugar. Marina was twenty-three, four years younger than Manuel, the most beautiful animal I will ever cross.

* * *

38

Because Manuel said nothing, Xica's morning lessons often veered off into history stories:

Lace: This at my throat, from my sister Clara. She lost her husband off the same boat that killed your father. She went blind hooking webs the old way, with an open safety pin. Flowers and faces white and matterless as the drone after the hive sucks him dry. The drone is left jelly. The drone is soft quiver.

Rosa Santos: Her blood grandparents are all buried home in the islands. Rosa came here as a baby and does not remember her birthplace. She has no brother or sisters - her birth ruptured her mother's tubes.

Because Manuel still said nothing, Xica sometimes cried untranslatable words, things that could not be held or seen, anything that might unfasten the spirits in him: