Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the maga zine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Joyce Foun dation, the Lannan Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Na tional Endowment for the Arts and the Illinois Arts Council.

NOTE: TriQuarterly welcomes financial support in the form of planned gifts. Please write to Reginald Gibbons, editor.

Associate Editor

Susan Hahn

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Janet Vander Kelen

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Assistant to the Editor Janet E. Geovanis

Editorial Assistants

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow Beth DeSchrvver

W. Douglas Fitzsimmons, Amy Rosenzweig, Jo Anne Ruvoli

Advisory Editors

Hugo Achugar, Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Cyrus Colter, Rita Dove, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Grace Paley, Michael Ryan, Alan Shapiro, Ellen Bryant Voigt

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED IN THE FALL, WINTER AND SPRING AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates-Individuals: one year $18; two years $32; life $250. Institutions: one year $26; two years $44; life $300. Foreign subscriptions $4 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly. NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (312) 4913490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and April 30; manuscripts received between May 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1989 by TriQuarterly. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by ThomsonShore, typeset by Sans Serif.

National distributor to retail trade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110, (201-667-9300). Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710, (415-549-3030). Midwest: Illinois Literary Publishers Association, P.O. Box 816, Oak Park, IL 60303, (312-383-7535); and Ingram Periodicals, 347 Reedwood Drive, Nashville, TN 37217, (615-793-5000).

Reprints of issues #1-15 ofTriQuarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. lSSN: 0041-3097.

74

Winter 1989

COVER STORY

If you like this issue's cover, you'll love the 18" x 24" poster version thereof, similarly colored and identical in all respects except that the poster does not have the issue number or date - just the TriQuarterly logo. Created by TQ Design Director Gini Kondziolka and printed on heavy, coated stock, this is a poster to be proud of-and one you may wish to have framed. To order, send $9.00 check or money order per poster to TriQuarterly, 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Or, to charge your VISA or MasterCard, please so specify and include your account number and the card's expiration date. (Please note that the $9.00 price includes handling and shipment in a sturdy, specially designed mailing tube.)

Contents FICTION Two Short Pieces Leo Masliah 5 Fishbone 10 Donna Trussell Cartography 32 Lynn Grossman From Treemont Stone Angela]ackson The Eleventh Edition Leo L. Litwak Engraver's Cove 110 Kate Kaufman 35 84 Alvin Jones's Ignorant Wife 118 Margaret Broucek From The Brothers Karamazov Fyodor Dostoevsky 128 POETRY From Holy Ewe-Lamb, Madonna of the Pressure Cooker 170 Athina Papadaki Diary: Day of Rest Sandra McPherson 180 Three Poems Betsy Fogelman Three Poems 186 Franz Wright Devils Night 189 James Reidel 182 3

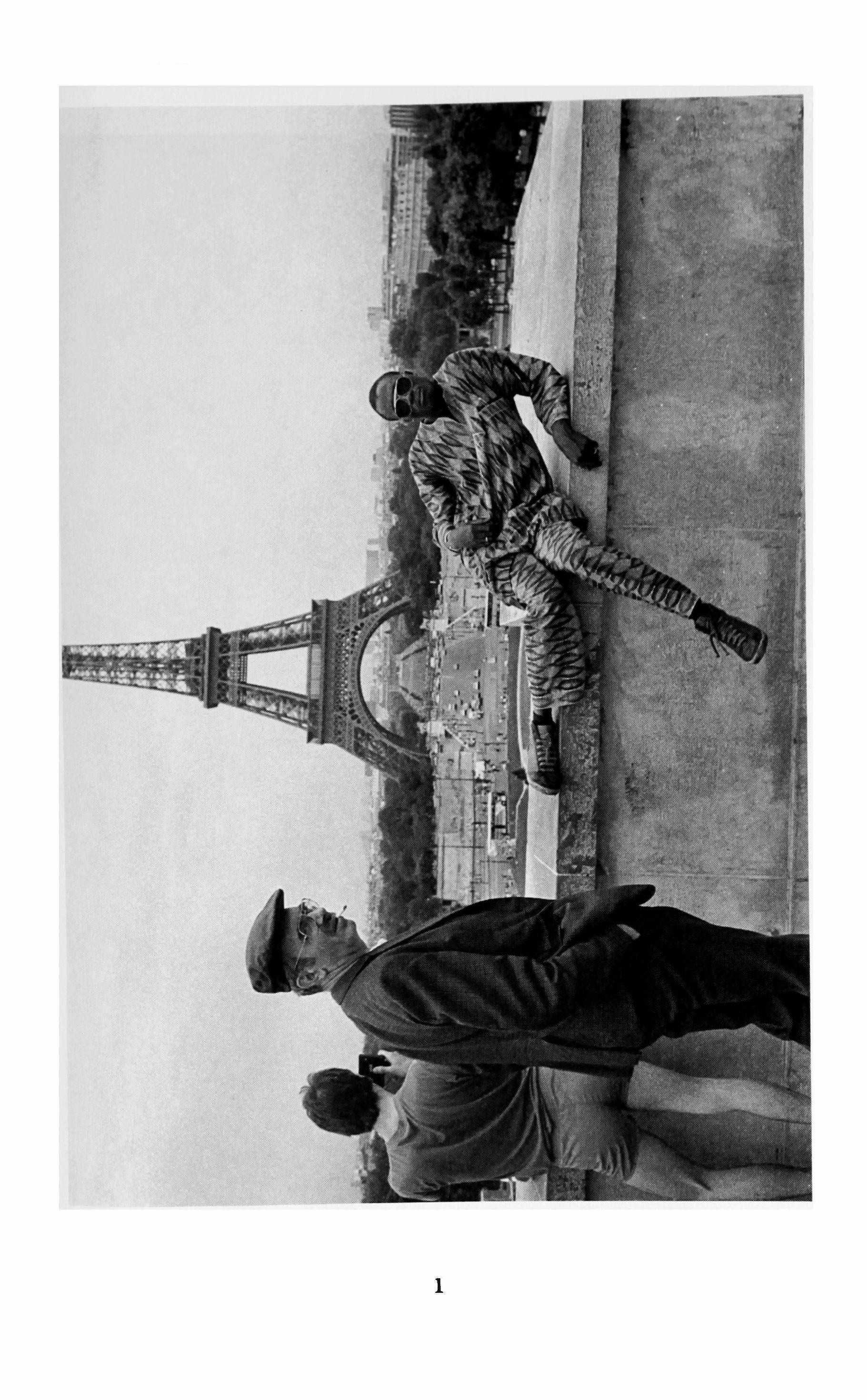

Bye Bye Blackbird 190 Mary Kinzie A&P Nightshift: January 1959 193 Paul Mariani From Donner •. 196 Belle Randall Two Poems 201 Adrienne Rich I. C. U. 203 Robert A. Fink Three Poems 205 Josephine Jacobsen Two Poems 209 Eleanor Wilner Two Poems. 214 Ingeborg Bachmann Antigone 217 Czeslaw Milosz From Martial 221 Laurie Duggan Life of Johnson Upside Your Head Forrest Gander 232 ESSAYS The Sad White Jazz Man 247 Peter Schwendener Teaching, Writing and Politics Roger Mitchell 255 CONTRIBUTORS 264 Cover design by Gini Kondziolka Photographs by Mark Steinmetz following pages 20, 120 and 222.

Two Short Pieces

Leo Masliah

THE TWIN (script for a comic strip)

Frame I-Even before I learned the meaning of the word "hate," I felt unconditional hatred toward my twin brother Franz. (The illustration shows two infants fighting over their mother's breast.)

Frame 2-When I finally learned to read, the dictionary offered me an appropriate means of verbalizing my feelings. (The illustration shows the narrator pointing with his index finger to the word "hate" in the middle of a page; some distance away is the figure of Franz, identical to that of the narrator. Both are schoolboys.)

Frame 3-Subsequent grammatical studies made it possible for me to articulate what I was feeling in complete syntactic units. (The illustration shows the narrator saying "I hate you" to his brother. Both appear wearing uniforms that identify them as secondary school students.)

Frame 4-The happiness of my first amorous experiences failed to overshadow my intrinsic animosity. (The illustration shows the narrator locked in an embrace with his girlfriend on a park bench. She asks him: "What are you thinking about, my darling? You're so quiet." He answers: "I'm thinking a little about how much I love you, but mostly about how much I hate Franz.")

Frame 5 - Franz's wedding day afforded me a first opportunity to manifest my somber inclinations in public. (The illustration shows Franz's wedding. The priest asks "Does anyone have any objection to this union?" The narrator answers "I do. I regard the groom as totally contemptible.")

Frame 6-When I got married, the priest got the papers mixed up and addressed me mistakenly as Franz; the irreverent ecclesiastic lived to deplore his lamentable blunder. (The illustration shows the

5

narrator, next to his bride, slapping the priest and saying, "I'll teach you to confuse me with Franz, you retard!"}

Frame 7 - Because 1 was unwilling to fill out those parts of the application forms requiring a list of my close relatives, 1 had to turn down numerous opportunities for employment. (The illustration shows the narrator inducing the forced ingestion by mouth of a crumpled application form, on the part of the civil servant waiting on him.)

Frame 8-0bliged to placate my rage with an apology of the works of Chopin and Schumann, my piano teacher came to regret having proposed to me the performance of pieces by Liszt and Schubert. (The illustration shows the narrator strangling his piano teacher, and exclaiming, "Just what did you think you were going to make me play, you stupid old cow?" On the floor there appears a musical score bearing the name of Franz Schubert.)

Frame 9-1 had to beat it out of a bookstore in a hurry one day whenwhile rummaging distractedly through the contents of a table full of sale items, I threw up noisily all over a volume of Kafka. (The illustration shows the narrator running up the street as the book dealer shouts to him from the doorway of his store, "Come right back here and clean that up, you existentialist pig!")

Frame 10-My already boundless hatred increased tenfold after 1 discovered that while 1 spent my free time seducing my brother's wife, my own infamous spouse was off making love to none other than Franz. (The illustration shows the narrator in bed with his lover in a hotel room, while in the adjoining room a voice can be heard saying, "Oh, Franz!")

Frame 11-When-following both Franz's and my own divorce, and the loss of our respective jobs due to poor evaluations mistakenly forwarded by us to our respective employers in an inverse exchange of correspondence-we once again found ourselves sharing the same bedroom at our parents' house, base sentiments began to darken my every waking hour. (The illustration shows the two twins in their respective beds, with markedly bellicose expressions on their faces.)

Frame 12 - The night 1 decided to do away with Franz once and for all, 1 discovered that 1 wasn't the only one with guns on my mind. (The illustration shows the twins in their beds, each with his respective revolver sticking out from under his respective blanket.)

Frame 13-At present, however, 1 am under the care of a psychoanalyst who has been trying to convince me that my own name is Franz and 1 never had a twin brother. (The illustration shows Franz.)

6

RODRIGUEZ'S MYOPIA

Rodriguez came into the waiting room. Its only furnishings consisted of some long sofas and a small table, on top of which there stood a lighted lamp; the lamp was topped by a pale yellow lampshade featuring a picture of a boat. In the picture four rough-looking men each held an oar; three of the oars were largely submerged. The fourth, which stood out most clearly in the picture, appeared to be made of cedar. In its lower section-where it was widest-someone had made some fairly deep cuts that resembled a human face, albeit somewhat confusedly; it was difficult to determine whether that form had been sought intentionally or whether it was a mere figment of the imagination, evident only to the observer inclined to see it. The face seemed to be that of an Indianmost notably in the region of the cheeks, from the center of which there emerged groups of bluish lines, like tattoos. The lines on the left cheek depicted a Portuguese or a Spanish galleon, with its sail strained to the breaking point, as if by the force of a strong wind. A tiny lookout, stationed at his observation post, seemed to wave his arms, eager to advise the crew of their possible proximity to land. The captain, standing on the deck, remained absorbed in his own thoughts, oblivious to the gesticulation of the lookout. Nor did he seem to notice a map that lay close by one of his boots, strangely unaffected by the wind which persisted in its struggle to break the resistance of the solid sails. It was a map of Africa surrounded by long lines indicating the circumnavigational routes. One of these routes, marked in bright red, ended at a spot on the coast of what is today known as Nigeria. The tiny piece of continent designated by the end of the red line was occupied by a minuscule drawing in colors, almost certainly typical of a village in the region. It portrayed a hut from which a native was emerging in squatting position, due to the scant height of the space not obstructed by the thatched roof and walls. Next to the hut a woman, seated and with her legs crossed, could be seen inserting a fish into an almost cylindrical opening in the earth. A few inches away was a ceramic jug containing some leftover food that failed to obscure entirely the folk scene adorning the interior surface ofthe receptacle. It pictured a hunting party: a group of aborigines chasing a deer. Their weapons were surely the same ones they used for intertribal combat; otherwise there was no possible explanation for the large shields they carried, all of them bearing colorful illustrations on their external surfaces. Some of these illustrations had been damaged, perhaps by enemy lances in recent skirmishes; but on

7

one of the shields the layer of pigments derived from plant matter had apparently survived intact. The painted areas, the outlines of which were not very sharp, at a distance nevertheless took on the exact shape of a metal saber. Though this weapon surely belonged to a civilization of invaders and not to the civilization of the creator of the shield, its design had been reproduced to perfection: the handle featured a golden cross, on which a Christ of pallid complexion lay dying. A soldier of the Empire, who seemed to spring from the handle of the saber, stood gallantly at the side of the Redeemer; in his right hand he held a parchment containing incomprehensible annotations, no doubt purely a product of the painter's imagination. The only decipherable element on the parchment was a drawing at the top, comparable to a letterhead. It represented the mythological character Perseus, his eyes fixed on .a mirror to avoid the icy gaze of the Gorgon, who stood behind him. However, the image in the mirror was not Medusa's face but a landscape, perhaps the environs of the temple, reflected on the shiny surface through one of the rare openings in its main facade. The landscape consisted of an endless expanse of open field, devoid of trees or any other form of vegetation, topped by a slightly grayish-blue sky in which there appeared only the majestic figure of a gigantic bird, its wings fully spread. The bird was in every respect similar to an airplane; its small eye-the only one visible-could easily have been the side window of a cockpit. Additionally, the creature's small pupil, which contained a blemish at the top perhaps as a result of some eye infection, was the very picture of a pilot's head covered by a visored helmet, in the center of which a golden glimmer evoked the insignia of the air force of a neighboring country. This insignia was comprised of three juxtaposed logotypes, shaped respectively like a ship, an airplane and a railroad-the concomitance of those three objects symbolizing recognition of the brotherhood of all the national transportation networks. The locomotive standing on the railroad tracks displayed the emblem of the staterun company to which it belonged: the sketchy shape of a building behind big letters spelling out the company's name. Without a doubt, the building was the first central railroad station in the country's history, but the schematic quality of the design failed to express that too clearly. One window on the top floor of the edifice was scarcely visible. Judging by what little could be seen, it didn't belong to an office or to any room; it only opened onto a corridor, dotted with two rows ofdoors of diffuse outlines. One of the doors appeared to be open, although it was still possible to discern on the brass plaque identifying it the name and position of a high-ranking public official. Inside the room, the only

8

thing Rodriquez could make out - and that with great effort - was a painting that occupied almost a third of the surface of the wall. But it was impossible to see what that painting contained. Disappointed, he directed his gaze elsewhere.

Translated from the Spanish by Louise B. Popkin

9

Fishbone

Donna Trussell

The other girls from my senior class were off at college or working. Not me. I stayed alone in my room and played The Game of Life. Mama didn't like it.

"Wanda, are you on drugs?" she said.

I shook my head. I spun the plastic wheel-it made a ratchet soundand moved the blue car two spaces, up on a hill. The great thing about The Game of Life was all the plastic hills and valleys. No other game had such realism.

"You need a change," Mama said. ''You're going to Meemaw's."

My bus was leaving early the next morning, so I had to pack in a hurry. But I took the time to put a matchbook in my purse. I don't smoke, but I thought it might come in handy if I needed to send a message to the bus driver: Hijacker, ninth row, submachine gun under his coat.

The sky was overcast, and it was a slow, pale trip. The only rest stop was in Centerville, where I got a fish sandwich at the Eat It and Beat It. Meemaw was waiting for me at the station. She smelled of cold cream and lilacs.

Ed grabbed my suitcase. "Yo," he said.

"Yo," I said back.

Ed's pickup was full of old Soldier of Fortunes. I rested my feet on top of a picture of a tank. Meemaw's life sure had changed since she married Ed.

"My little girl," she said. She patted my knee the way a kid flattens Play-doh.

"She's not your girl," Ed said. "She's your granddaughter."

"She is my little girl."

10

A chain link fence now surrounded Meemaw's garden. "Keeps dogs out," she said. The fence made her farm look even less farmish than it had, with its green shack for a barn and refrigerator toppled on its side out back and giant new house modeled after the governor's mansion.

Meemaw fussed over me at supper: Wanda, can I get you some more roast, would you like another helping of butter beans, how about some corn bread?

Ed had three cups of coffee with supper. He poured the coffee into his saucer and blew on it. I asked him why he drank his coffee that way.

He didn't answer. Finally Meemaw said, "To cool it down."

Ed's cup and saucer were monogrammed in gold. My plate too.

"Meemaw, where's your dishes?" I asked. "The ones with purple ribbons and grapes?"

"Well, we have Ed's china now."

He slurped his coffee, staring straight ahead. He might as well have been talking to the curtains when he said, "I'm glad you're here, Wanda, because I've been wanting to ask you something. All day I've been wondering-who paid the hospital when you had that baby? The taxpayers?"

I smashed a butter bean with my fork. "Excuse me," I said and went outside.

I looked out across the pine trees, dark green. I used to believe trees had people inside them. I wished some God would change me into a tree. That wouldn't be a bad life-sun, rain, birds. Kids looking for pine cones. Me shaking my branches for them.

The peat moss in the garden was warm. I lay down and pulled a watermelon close.

After a while Meemaw came out and sat down near my head, in the snapdragons and cucumbers. Meemaw planted vegetables and flowers together, except for the gladiolas, offby themselves. Pink, peach, yellow, white-a million baby shoes, shifting in the wind.

She smoothed my hair and talked about exercise and how important it was.

"Meemaw, what happened to your strawberries?"

"Birds. But that's all right. Plenty for the birds too."

Every morning we'd go out to pull weeds, and she'd tell me uplifting stories about people she knew. Trials they'd had. A young man wanted to commit suicide because law school was so hard. Once a week his mother wrote him letters full of encouraging words.

"What kind of encouraging words?"

"Oh, 'Don't give up.' That sort of thing."

11

When he graduated he found out she'd been dead for a month. She'd known she was dying, and had written the last letters ahead of time. Meemaw knew lots of stories about people who "took the path of least resistance" and ended up sick or poor. I got back at her by asking personal questions.

"Meemaw, have you ever had an orgasm?"

Yes, she said. Once. "I was glad to know what it is that causes so much of human behavior." She smiled and handed me a bunch of gladiolas. Afternoons I stayed in my room. Mama wouldn't let me bring The Game of Life. I lay on the bed a lot. The light fixture had leaves and berries molded in the glass. Once I wrapped my arms around the chest of drawers and put my head down on the cool marble top.

Meemaw would call me to supper. There wasn't much discussion at the table. If anyone said anything, it was Ed talking to Meemaw or Meemaw talking to me. Except for once, when I went to the stove to get some salt. Ed told me I'd done it all wrong. ''You don't bring the plate to the salt. You bring the salt to the plate."

After supper Meemaw and I went down to the barn. She milked Sissy. I fed the chickens. I'd throw a handful of feed and they'd move in at eighty miles an hour.

Ed never came with us. He hates Sissy, Meemaw told me. "He's jealous."

"Jealous of a cow?"

"Why, of course. I spend so much of my time with her."

Evenings Ed watched Walking Tall on his VCR. Or he went inside his toolshed. He never worked on anything. He looked at catalogs and ordered tools, and when they came he hung them on the walls. He read books about the end of the world: the whole state of Colorado was going to turn into jello, and people will drown. "You've got five years to live, young lady," he told me. "Five years."

He had guns- a whole case-full. Once I saw him polishing them when I was standing in the hall by his study.

"What do you think you're doing?" he said. I walked away. He shut the door.

One day when I was watching Meemaw through a little diamond shape made of my thumbs and two fingers, Ed said, "You planning on sitting on your butt all summer?"

"I haven't thought about it."

"Start thinking."

12

Meemaw knew a man in town who was looking for help. She knew everybody in town.

"It's a photography studio," Meemaw said.

"I don't know anything about photography."

"He's willing to train someone. It's a nice place. There's another studio in town, but everybody says Mr. Lamont's is the one that puts on the finishing touch."

She made the phone call. Ed was smiling behind his magazine. I knew he was.

I drove Meemaw's old Fairmont into town. First Ed showed me all the things I had to do to it, because "service stations don't do a damned thing anymore." He showed me the oil stick and the radiator. He told me to check the windshield-wiper blades once a week. He was just about to make me measure the air in the tires when I said I'd be late for my interview if I didn't get going.

Mr. Lamont wore glasses and a pair of green doubleknit pants that were stretched about as far as they could go.

"Wanda, you put here that your last job was back in December. What have you been doing since then?"

"Nothing," "Nothing?"

''Nothing you'd want to know about."

"But I would like to know."

"O.K. I was in love with this guy. We were going to get married, but then we didn't. And then I had a baby boy."

"Oh."

"He's been adopted."

"I see." Mr. Lamont tried to look neutral, but I could see little bursts of energy flying from the corners of his mouth.

"I can't pay minimum wage," he said.

"Whatever." I might as well be here, I thought, as out on the farm with Ed.

After supper Ed gave me a lecture about jobs and responsibility and attitude. People don't think, they just don't think. World War III is coming, and no one's prepared. All the goddamned niggers will try to steal their chickens.

"But I'm ready for them," he said. "I've been stocking up on hollow points. They blow a hole in a man as big as a barrel." He punched his fist in the air. Meemaw sort of jumped, but she didn't say anything. She clanked the dishes and sang "Rock of Ages" a little louder.

13

I went to bed with the pamphlet Mr. Lamont gave me, The Fine Art of Printing Black and White. The paper is very sensitive, it said.

The next day Mr. Lamont showed me the safelight switch. "See that gouge? I did that so I could feel for it in the dark."

He did a test strip. "Agitate every few seconds," he said, rocking the developer tray.

He let me print a picture of a kid holding a trophy. "Make it light," he said. "The newspaper adds contrast. Look how this one came out." He showed me a clipping of a bunch of Shriners. They looked like they had some kind of skin disease.

After a week I got the hang of it, and Mr. Lamont left me in charge of black and white. I liked the darkroom. No phones. No people, except for the faces that slowly developed before me. Women and their fiances. Sometimes the man stood behind the woman and put both arms around her waist.

Jimmy used to do that.

He held me like that at the senior picnic. It was windy. Big rocks nailed down the corners of each tablecloth. Blue gingham. The white tablecloths had to be returned because the principal thought they'd remind the students of bedsheets. Jimmy and I laughed; we'd been making love for weeks. We got careless, in the tall grasses by Cedar Creek Lake. Night birds called across the water.

When I was two weeks late, I told him. He looked away. There's a clinic, he said, in Dallas. I covered his lips with my fingers.

At Western Auto they said they'd take him on, weekends and nights. At the Sonic, too, for the morning shift. Jimmy and I looked at an apartment on Burning Tree Drive, southwest of town. A one-bedroom. He stared at the ceiling. Jimmy? I said.

Goodbye, goodbye, I told the mirror long before I really said it. I read every book I could find about babies and their tadpole bodies. I gave up Coke and barbecue potato chips. My breasts swelled. I felt great. Hormones, the doctor said.

At first my baby was just a rose petal, sleeping, floating. At eight months I played him records, Mama's South Pacific and Daddy's "Seventy-six Trombones." I stood right next to the stereo, and he talked to me with thumps of his feet.

You want to feel him kick? I asked. Mama shook her head and kept on ironing. Daddy left the room.

I didn't get a baby shower. Mama told everyone I was putting it up for adoption. "It," she called him. I made up different names for him. Fishbone, one week. Logarithm, the next.

14

Mama bought me a thin gold wedding band to wear to the hospital. Girls don't do that anymore, I told her. Some girls even keep their babies, these days.

Not here in Grand Saline, she said. Not girls from good families. My little Fishbone got so big two nurses had to help push him out. Breathe, they said. Pant hard.

Please let me hold him, I said. Please.

Now, Wanda, Mama said. You know what's best. He cried. Then he slipped away, down the hall. The room caved in on me, with its green walls and white light. Mama held me down, saying, we've been through this. We decided.

At the nurse's station Jimmy left me a get-well card. Good luck, he wrote. That's all.

Mama took me home to a chocolate cake, and we never talked about Fishbone again. She never mentioned Jimmy's name.

Sometimes now, before driving home to Meemaw, I stopped at the trailer court at the edge of town. I watched people. A woman would frown and I'd think: that's me heating up a bottle for Fishbone and the formula got too hot. A man takes off his cowboy boots and props his feet on the coffee table. A woman tucks herself next to him. He kisses her hair, her neck.

I remembered love. I remembered it all. Now I felt thick and dull, something to be tossed away in the basement.

"How's the passport picture coming?" Mr. Lamont asked, knocking on my door.

"Don't come in. Paper exposed."

"That man going to New Guinea is back."

The man had worried about his eyes. I've got what they call raccoon eyes, he'd said, is there any way you can lighten it up around the eyes?

He looked disappointed when I gave him the picture. "I know you did the best you could," he said. He smiled. He didn't look like a criminal when he smiled.

When I got home, Meemaw was cutting up chicken wire and putting it over holes in the coop. Making it "snake proof," she said. I took over the cutting. I'd never used wire cutters before. Everything is just paper in their path.

"It's so bare in the chicken coop," I said. "Why don't you put down an old blanket or something?"

"You know, Wanda, I did that very thing one time, when I had a batch ofbaby chicks. I put down a carpet scrap, so they'd be warm. And

15

they died. Every single one! I was just heartbroken. And do you know what I found out? They'd eaten the carpet."

"How'd you find that out?"

"I did an autopsy."

"00000, Meemaw! How awful."

She shrugged. "Nothing awful about it. I wanted to know."

"I could never be a doctor," I said.

I read somewhere that these psychologists asked a bunch of surgeons why they became doctors, and they all said they wanted to help people. And then they did psychological tests on them and found out they were part sadists. They liked knives.

"How about a photographer?" Meemaw said. "I hear they teach photography in college now. I would pay for you to go."

I rolled up the leftover chicken wire and put it away in the barn. Meemaw came in after me.

"Time to milk Sissy, isn't it?" I said. I went to get the milk pail.

"What do you want to do with your life, Wanda?"

"You promised not to ask me that anymore."

She laughed and patted me on the back. "Yes, I did." She set the pail under Sissy, and then turned to face me again. "But what are you going to do?"

"I don't know, Meemaw."

Lately I'd been thinking about the homeless on TV, and how they live. I live in the gutter, I could say. It has a nice ring to it.

"Wanda, I once read a book where the first page had a quotation from the Bible. I thought it was the most beautiful of any Bible verse I'd ever read. It said the Lord will restore unto you the years the locusts have eaten."

She paused. When I didn't say anything, she waved her arms, saying, "Isn't that beautiful?"

"Uh huh."

The barn door swung open. Ed.

"How many times do I have to tell you not to leave the wheelbarrow out? It's been sitting there in the garden since morning."

"I told her it was O.K.," Meemaw said. "It doesn't hurt anything."

"The hell it doesn't. If you leave it out, it rusts. If it rusts, you have to buy a new one."

"I don't think it'll rust for ten years at least."

"Either you use the tools or they use you. That's all I have to say about it."

He stomped off.

16

Meemaw rubbed my arm. "Don't worry about it. Ed's just upset because yesterday you left his mail in the glove compartment instead of bringing it in to him. He's afraid somebody could have stolen his pension check."

"Who would steal it out here in the middle of nowhere? Who'd even know it's there?"

Meemaw went back to milking Sissy. I always thought milking a cow would be fun, till I tried it. The milk comes out in tiny streams, about the size of dental floss. It takes forever.

"You know how Ed is."

"Yeah, I know. Why did you marry him, anyway?"

"He needed me."

"But why not marry someone you needed?"

"I don't need anybody. I just need to be needed. They say money is the root of all evil, but I say selfishness is. Selfishness, and lack of exercise."

That got her started.

"Sweetie," she said, "I once read about a mental hospital for rich movie stars. It costs a powerful lot of money to go there. And you know what the doctors make those ladies do? Run in circles. Why, one movie star had to cut wood for two hours."

I thought about that on the way back to the house, but I couldn't see how cutting wood would make a difference.

That night I wrote a letter to Jimmy: "I hope you like it at college. Do you ever think about our baby? Whenever I take a shower, I think I hear him crying. Do you have this problem?"

I signed it, "Your friend, Wanda," and sent the letter in care of his parents.

"Let sleeping dogs lie," Marna wrote. "Think of the future. Pastor Dobbins will be needing a new receptionist at the church, and he told me he's willing to interview you. It's very big of him, considering."

I dropped the letter into the pigpen. The next day I could only see one corner, and after that it was gone.

I did Dwayne Zook, his sister Tracy Zook, and then I was finally done with the high school annual pictures. Mr. Lamont asked me to sit at the front desk to answer the phone and give people their proofs.

"Lovely," they'd say. Or, "Your boss surely does a fine job." Mr. Lamont told me to answer everything with: "He had a lot to work with." There was this one girl, though, who looked like Ted Koppel. I didn't know what to say to her.

We had lots ofbrides, even in August. I patted their faces dry and gave

17

them crushed ice to eat. I spread their dresses in perfect circles around their feet.

One day Mr. Lamont asked if I'd like to come into his darkroom to see how he did color.

"It looks like pink," he said, "but we call it magenta." He held up another filter. "What would you call that?"

"Turquoise?"

"Cyan," he said.

"Sigh-ann,"

He let me do one, a baby sitting with its mother on the grass. The picture turned out too yellow, so I did another one.

"Perfect," he said. "You learn real quick."

"Thanks."

We goofed off the rest of the day. He showed me some wedding pictures that were never picked up. "A real shame," he said. "That's the best shot of the getaway car I've ever done."

He started going down to Food Heaven to get lunch for both of us. We'd eat Crescent City Melts and talk. He teased me about Ed, asking if it was true that he got kicked in the head by a mule when he was a kid. "Does he really have two Cadillacs?"

"Three. They just sit out back. He drives his pickup truck everywhere."

Sometimes Mr. Lamont would come into my darkroom. He'd check on my supply ofstop bath or Panalure. Then he'd lean in the corner and watch me work. He never touched me. We'd just stand there in the cool darkness.

He told me about his mother and why he couldn't leave her. "Cataracts," he said. "I read to her."

I told him about the book I got at the library, The Songwriter's Book of Rhymes. Also-ran rhymed with Peter Pan, Marianne, caravan, Yucatan, lumberman and about two hundred other words.

In Discovering Your America every state was pale pink, green or yellow. Nebraska had tiny bundles of wheat in one corner, and New Mexico had Indian headdresses. That night I dreamed I was high above Texas, watching the whole pink state come alive. Oil wells gushed. Fish flopped high in the air. Little men in hard hats danced around.

"I don't want to go to photography school," I told Meemaw the next morning. "I want to buy a car and drive to West Texas. Or maybe California."

"You can't do that," Meemaw said. "A young girl, alone."

"Why not?"

18

"It's just not done."

"Why can't I be the first to do it?"

"Oh, Wanda."

Meemaw believes in Good and Evil. She doesn't understand how lonely people are. Anyone who tried to hurt me, I would talk to him. I would listen to his tales of old hotels and wide-hipped women who left him.

On my seventy-seventh day at Meemaw's I came home and found Ed filling up the lawnmower.

"It's about time you earned your keep," he said.

"What about supper?"

"Forget supper. You're going to mow the lawn."

"Oh, is that so?"

"Yes, ma'am, you betcha that's so." He sat down on a lawn chair. "Get started."

A vat of green jello swallowed him up, chair and all.

While I mowed, I thought of another fate for him - a giant cheese grater with arms and legs. Ed ran and ran, and then stumbled. The cheese grater stood over him and laughed as Ed tried to crawl away.

I didn't get to the big finale because the lawnmower made a crunching sound and stopped. Ed came running over, asking how come I didn't comb the yard first, how come I can't do anything right? "You're as lazy as a Mexican housecat."

His red, puffy face pushed into mine. In the folds of his skin I could see the luxury Meemaw had given him, her flowers and food and love. He just lapped it up.

He followed me into the house. Young people! Welfare! Good-fornothings!

"You're a fine one to talk," I said, turning to face him. "I've never seen you lift a finger around here."

He moved towards me, and then stopped. He was so close I could see his eyes roll up into his head, and his eyelids quiver. The room was silent. I heard the hands on the clock move.

"You ungrateful bitch," he said. "Your grandmother thinks you're different, but I told her. I told her what you are."

It got dark while he told me what I was. He must have been rehearsing. I heard words I knew he got out of a dictionary. Meemaw twirled yarn and cried.

He got my suitcase and threw it at my feet.

19

"Get out. Now." He turned to Meemaw. "If she's here when I come back, I'll send for my things."

He slammed the door. His truck roared out, spitting gravel into the night.

"He's a child," Meemaw said. "A grown-up child, and I can't do any, thing about it." She held my face in her hands. "My little girl. My sweetie. What are we going to do?"

She put my head on her shoulder. We stood there, rocking. "I named my baby Fishbone," I said. "Did you know that?" She shushed me and patted my back.

He'd be eight months old now. In twenty years he'll come looking for me. We'll have iced tea and wonder how to act. I wanted you, I'll tell him, but I was young. I didn't know I was strong.

''There's a bus to Grand Saline in the morning," Meemaw said. "I'll call your mother."

We rode a taxi into town. Meemaw got me a room at the motel. She brushed my hair and put me in bed.

"You can go home now, Meemaw."

"Yes, I suppose I can."

She wouldn't leave until I pretended I was asleep. But I couldn't sleep at all. I found a Weekly World News under the bed. I read every story in it. Then the ads, about releasing the secret power within you and True Ranches for sale and the Laffs Ahoy Klown Kollege in Daytona Beach.

At five A.M. I went for a walk. The air was cool and clear as October. I breathed deep.

Waffle Emporium was open. Something about dawn at a coffee shop gets to me. Pink tabletops, and people too sleepy to talk. New things around the corner. Carlsbad Caverns. White Sands.

I thought about what I was going to do next. I had eight hundred dollars inside my shoes. I could go anywhere. San Francisco, to work at the Believe It or Not Museum. Or Miami - I could take care of dolphins. I thought about Indian reservations. Gas stations in the desert. Snake farms. The owner would be named Chuck, probably, or Buzz.

I walked to the bus station and read the destination board. I said each city twice, to see how it felt on my tongue.

20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Captions

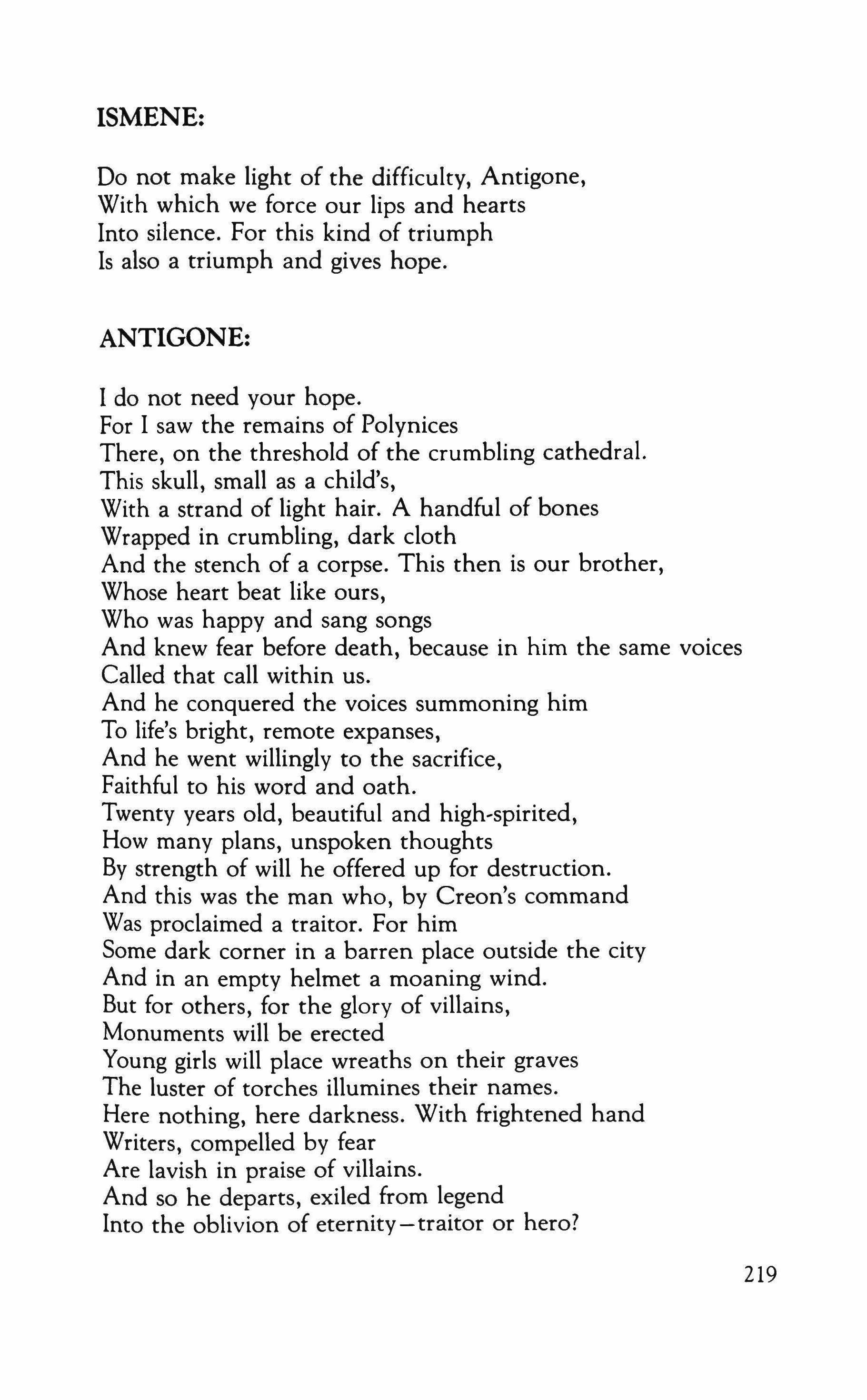

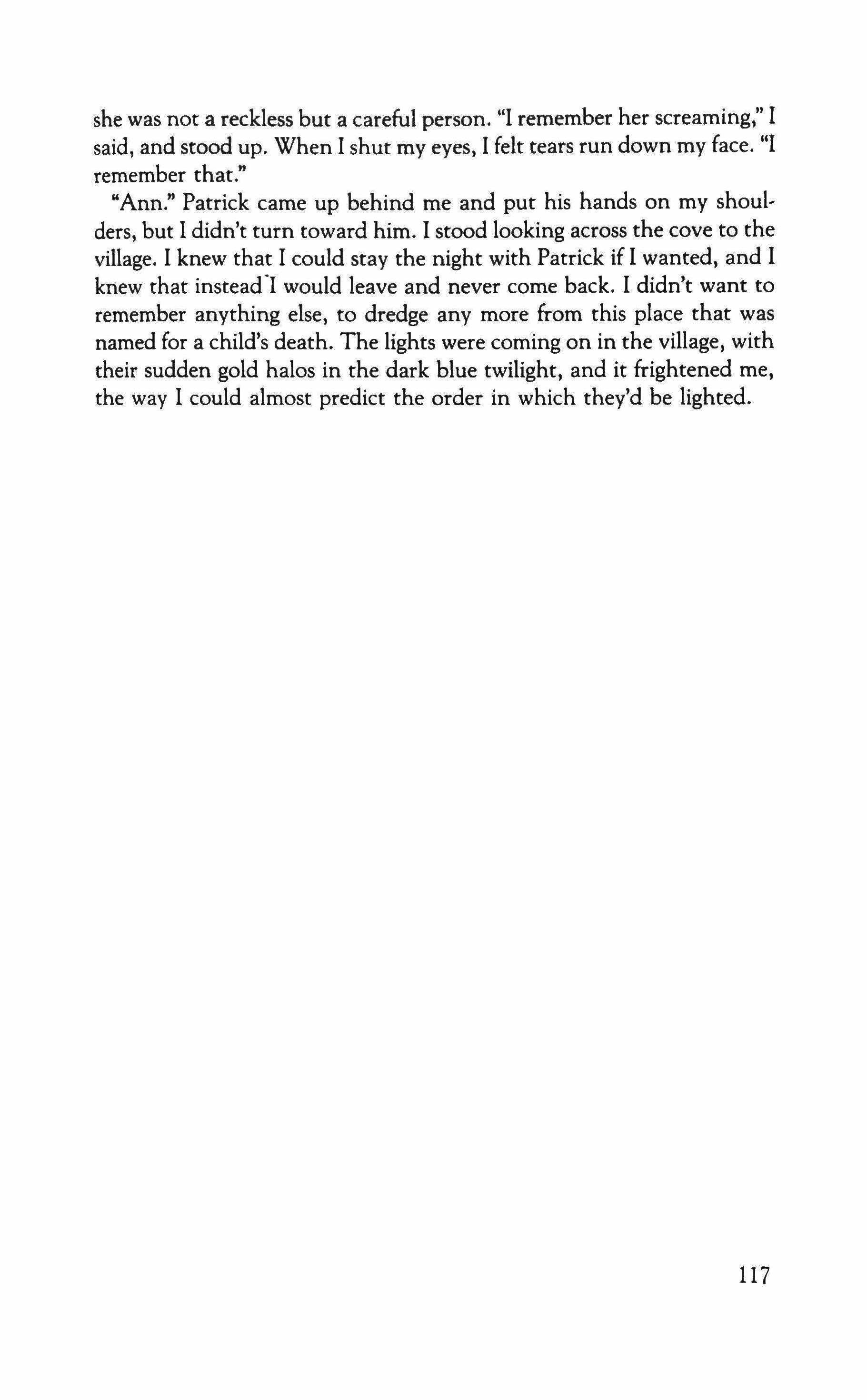

1. Les HaIles, Paris, 1985.

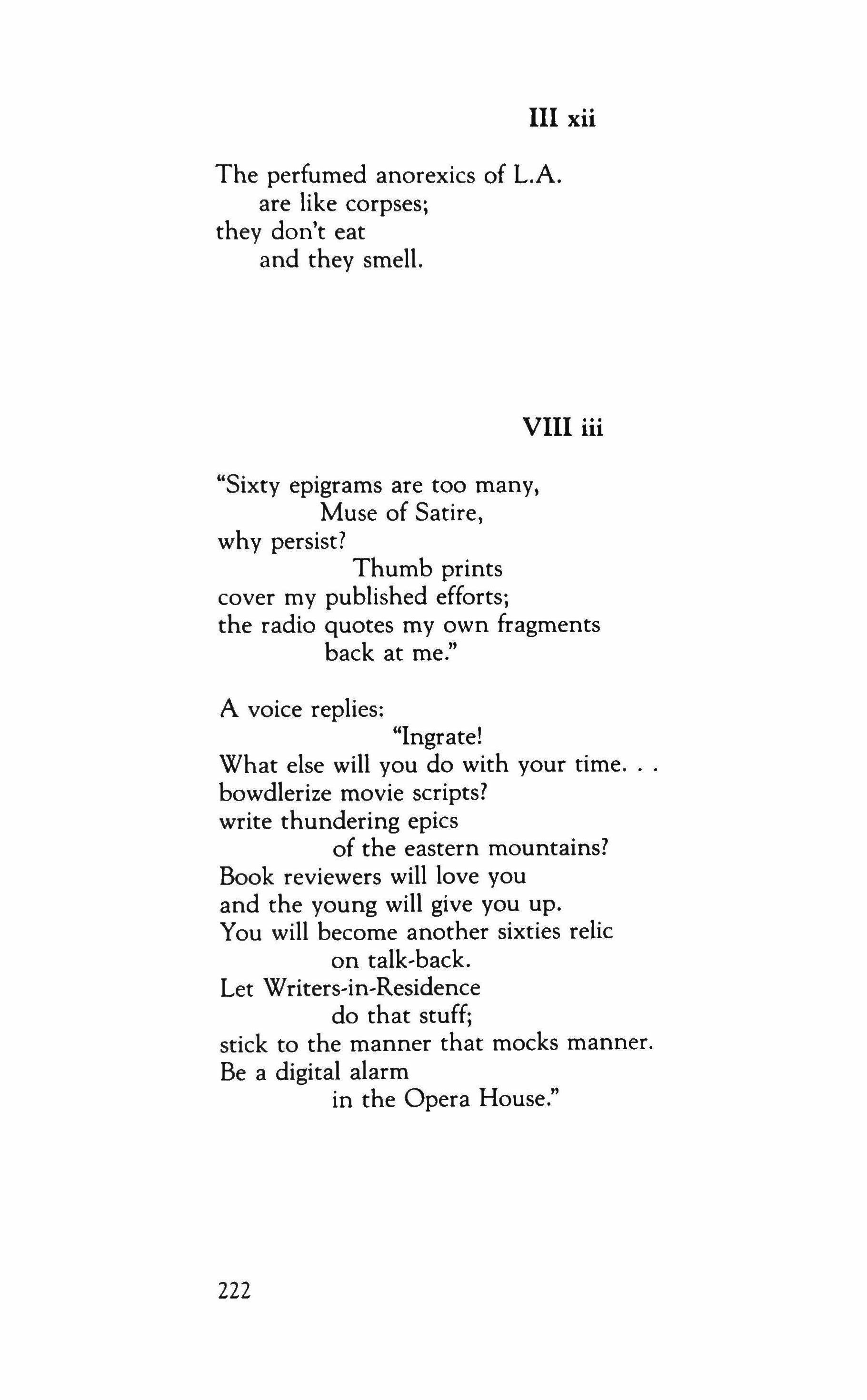

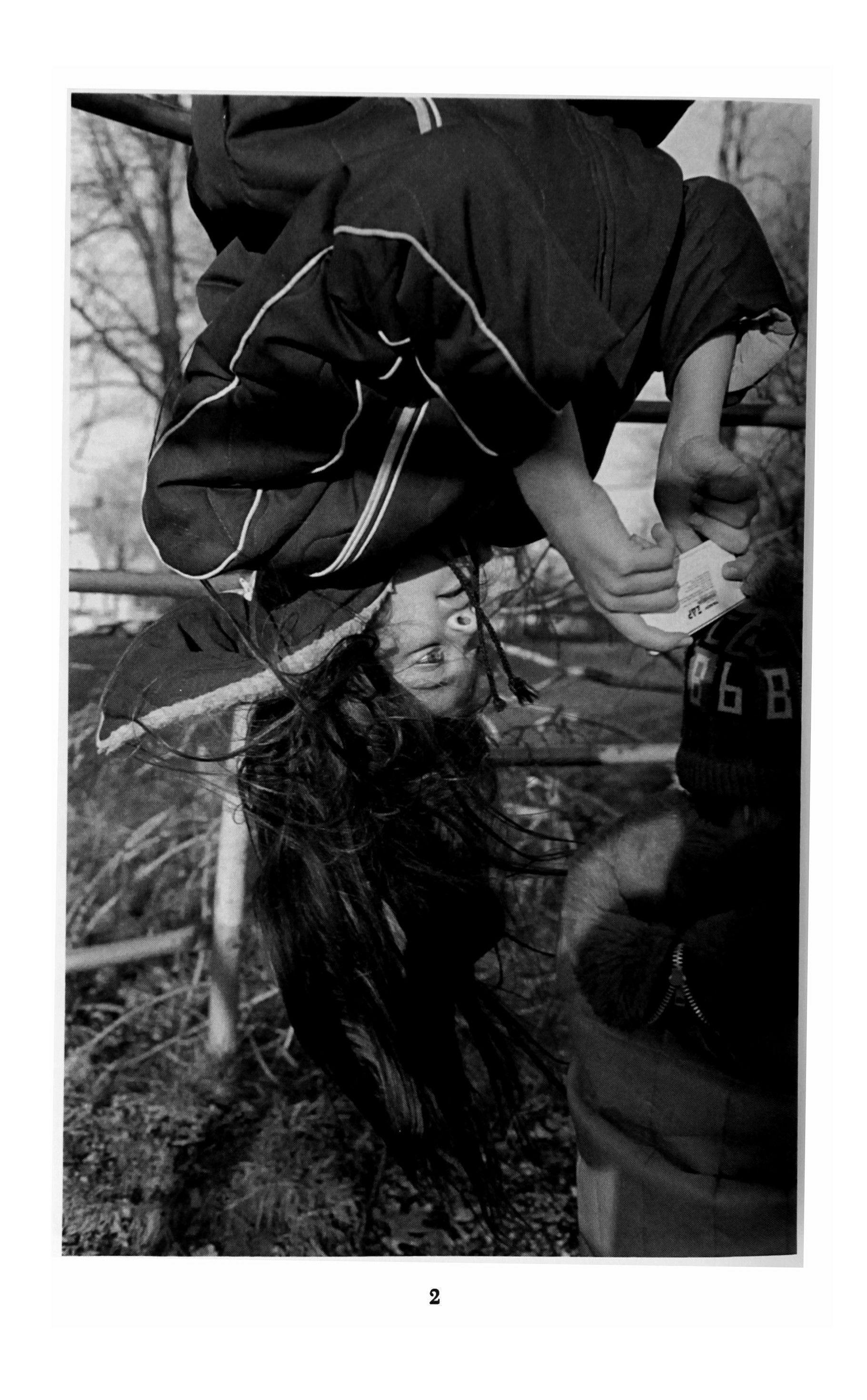

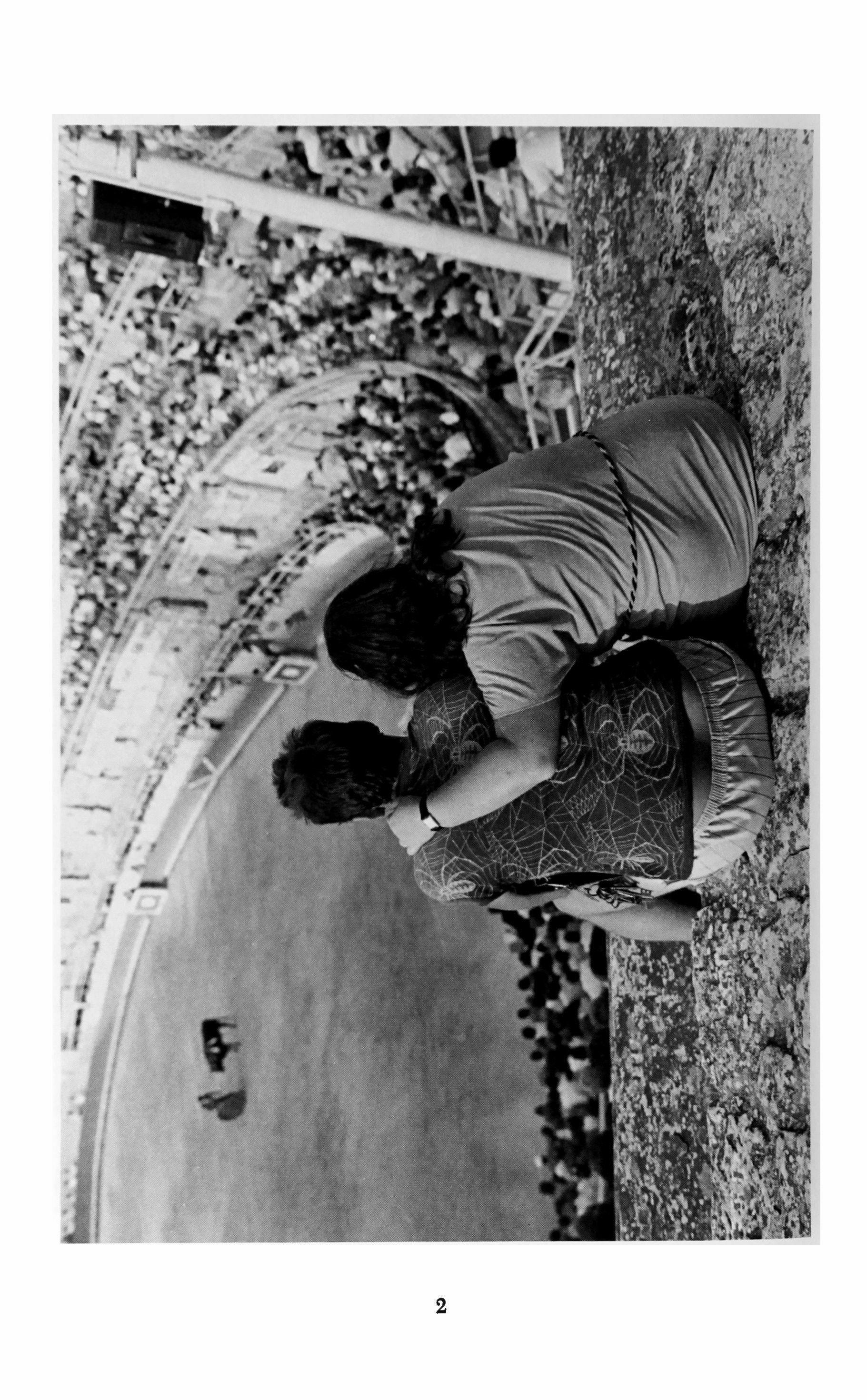

2. Paris, 1987.

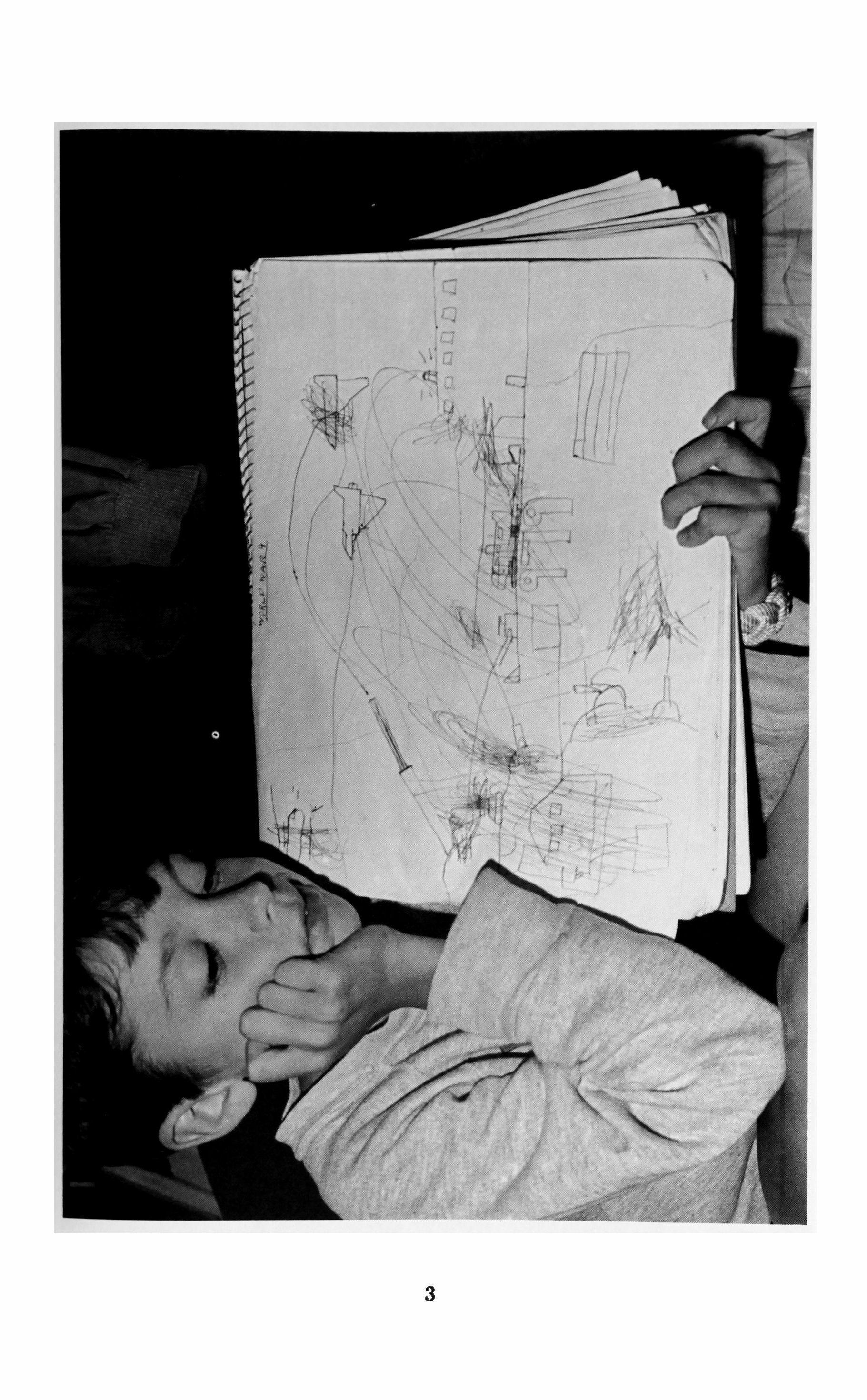

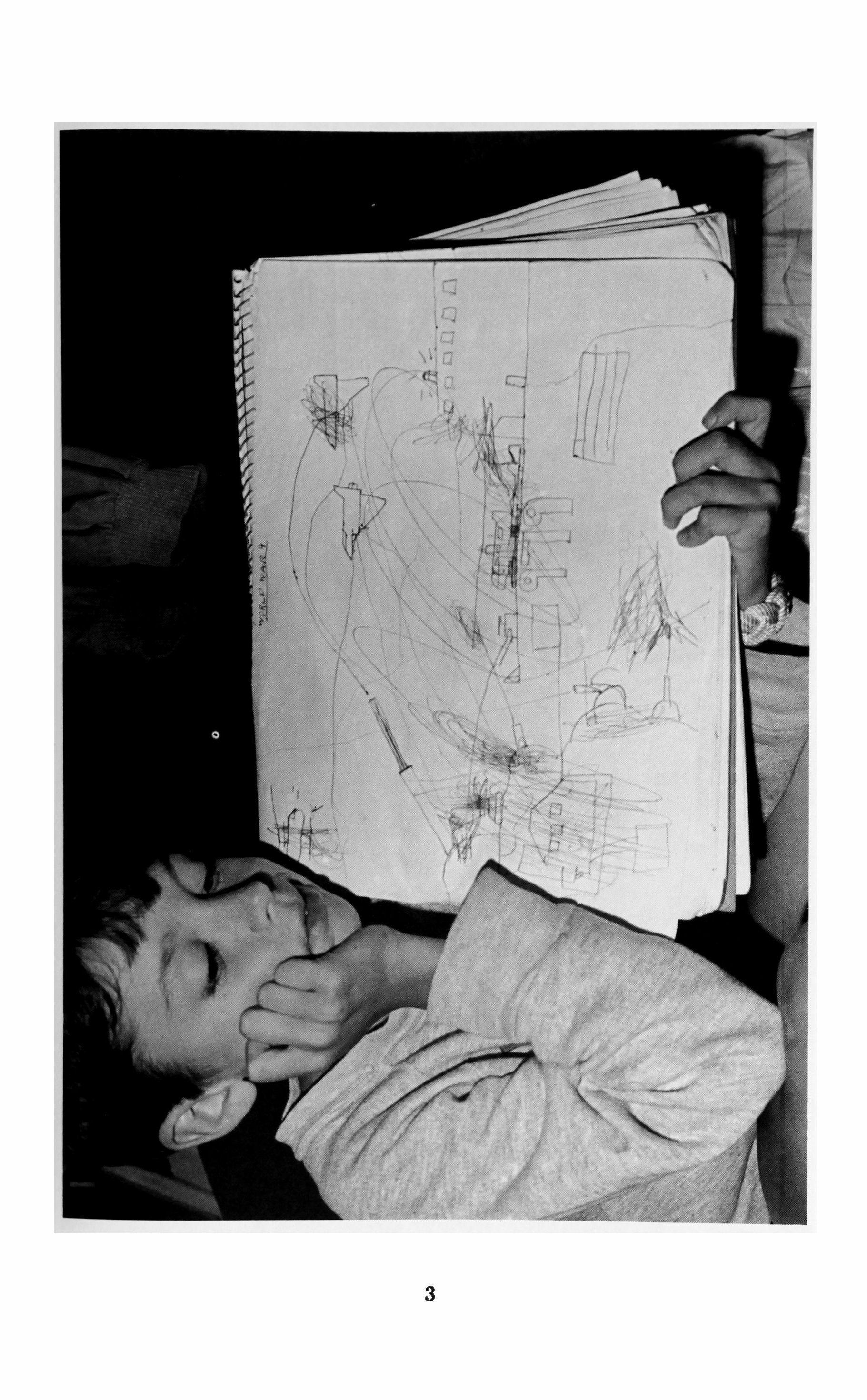

3. Sandwich, Massachusetts, 1986.

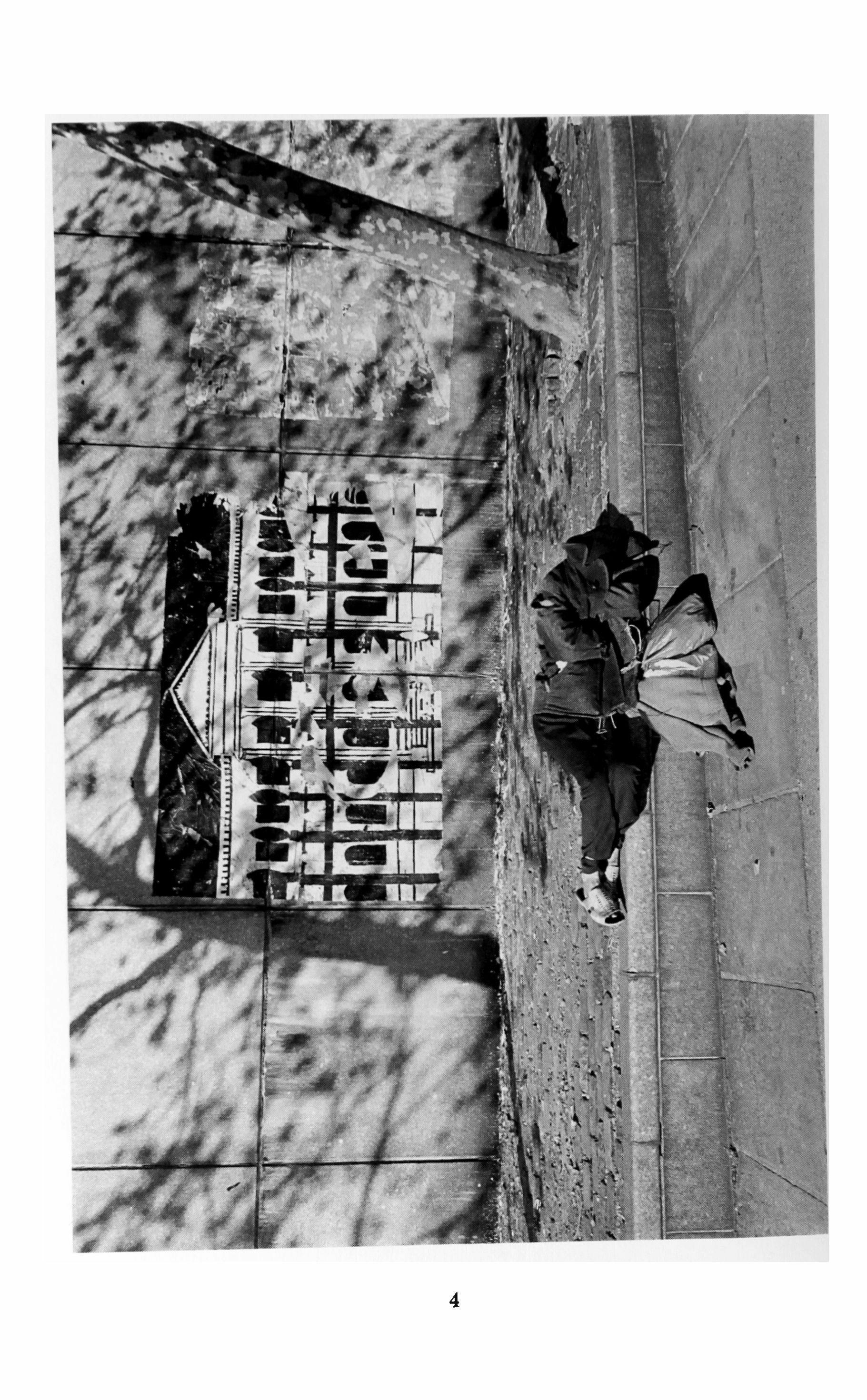

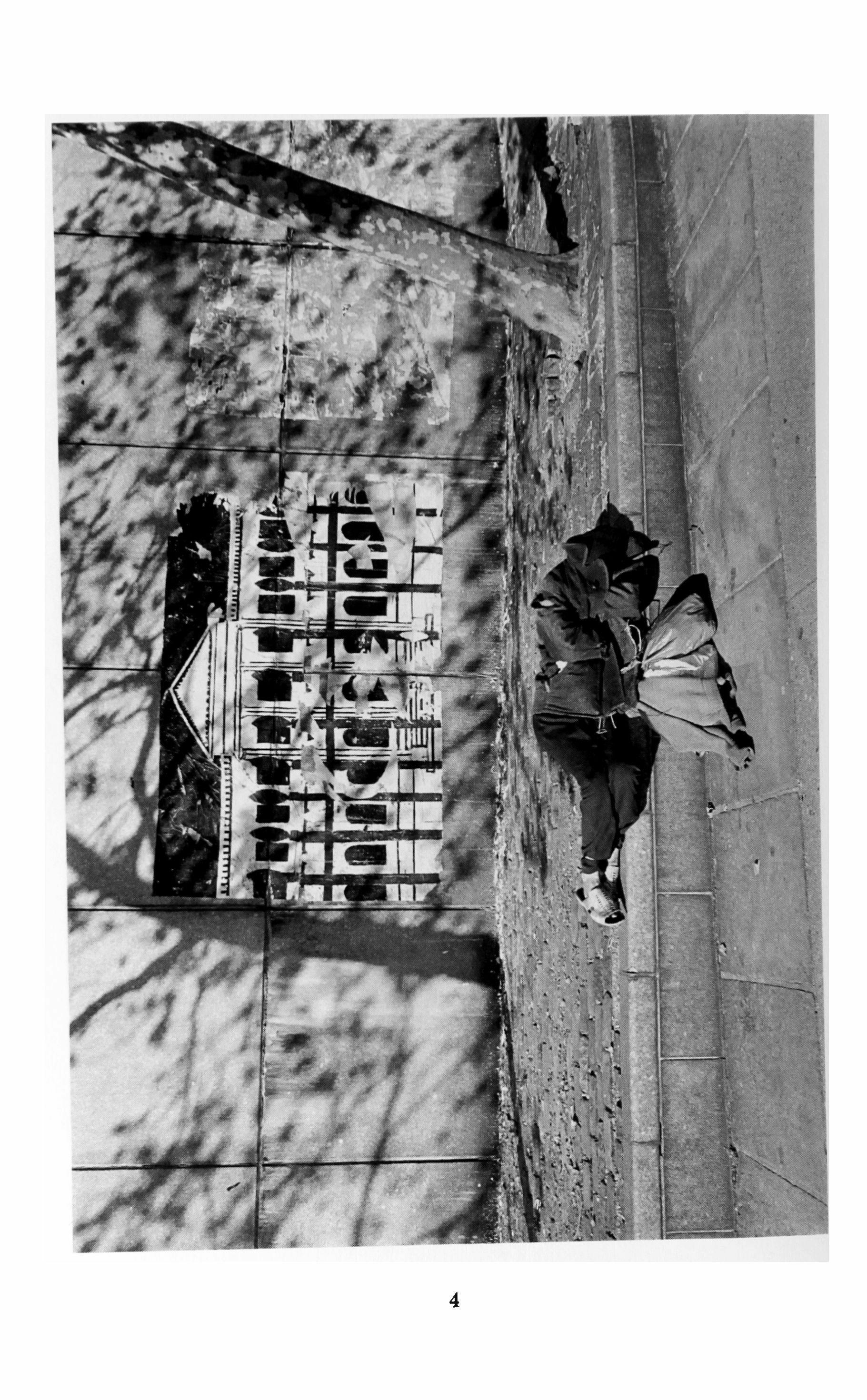

4. Paris, 1986.

5. Boston, 1987.

6. Evanston, Illinois, 1988.

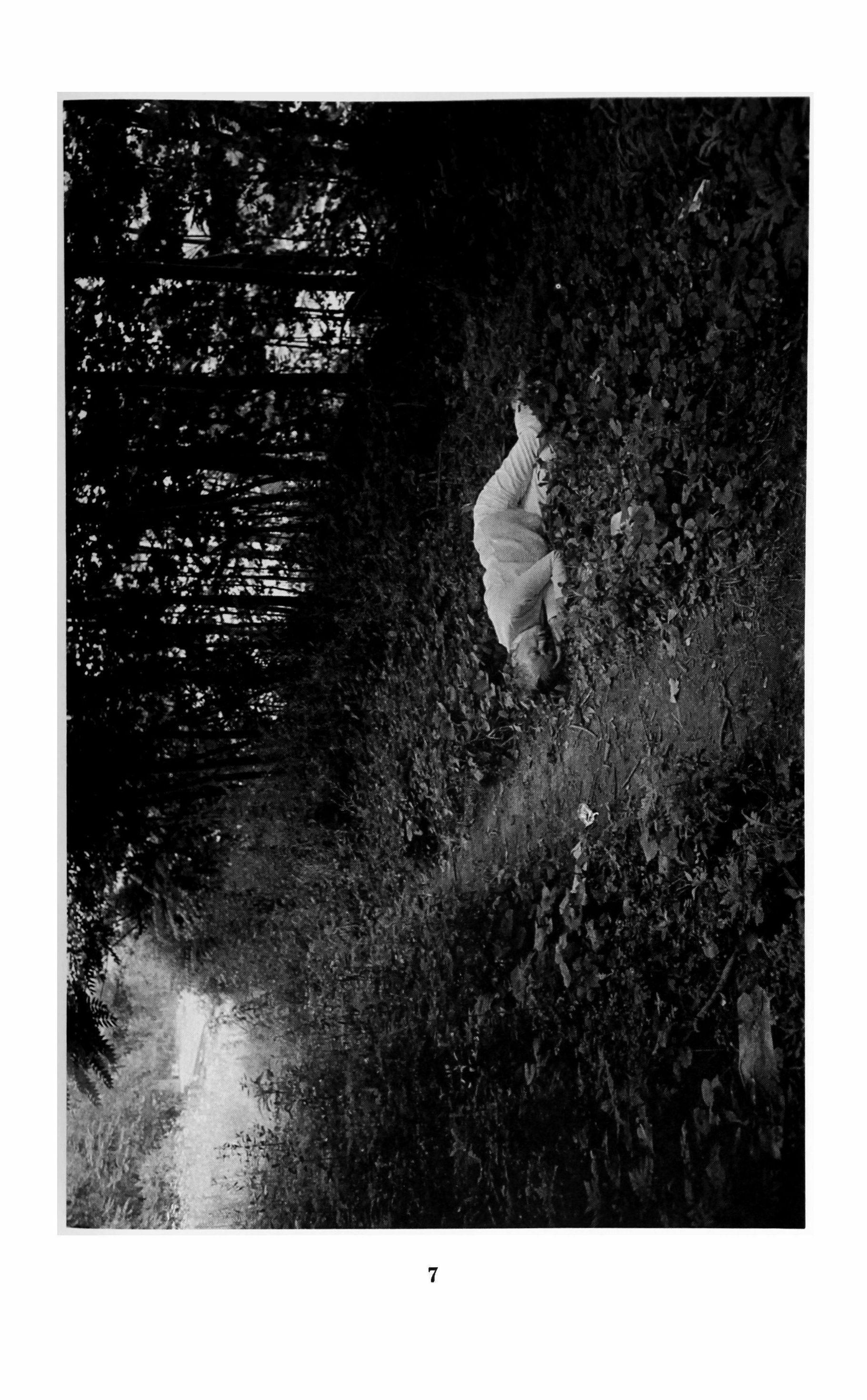

7. Chicago, 1988.

8. Chelsea, Massachusetts, 1987.

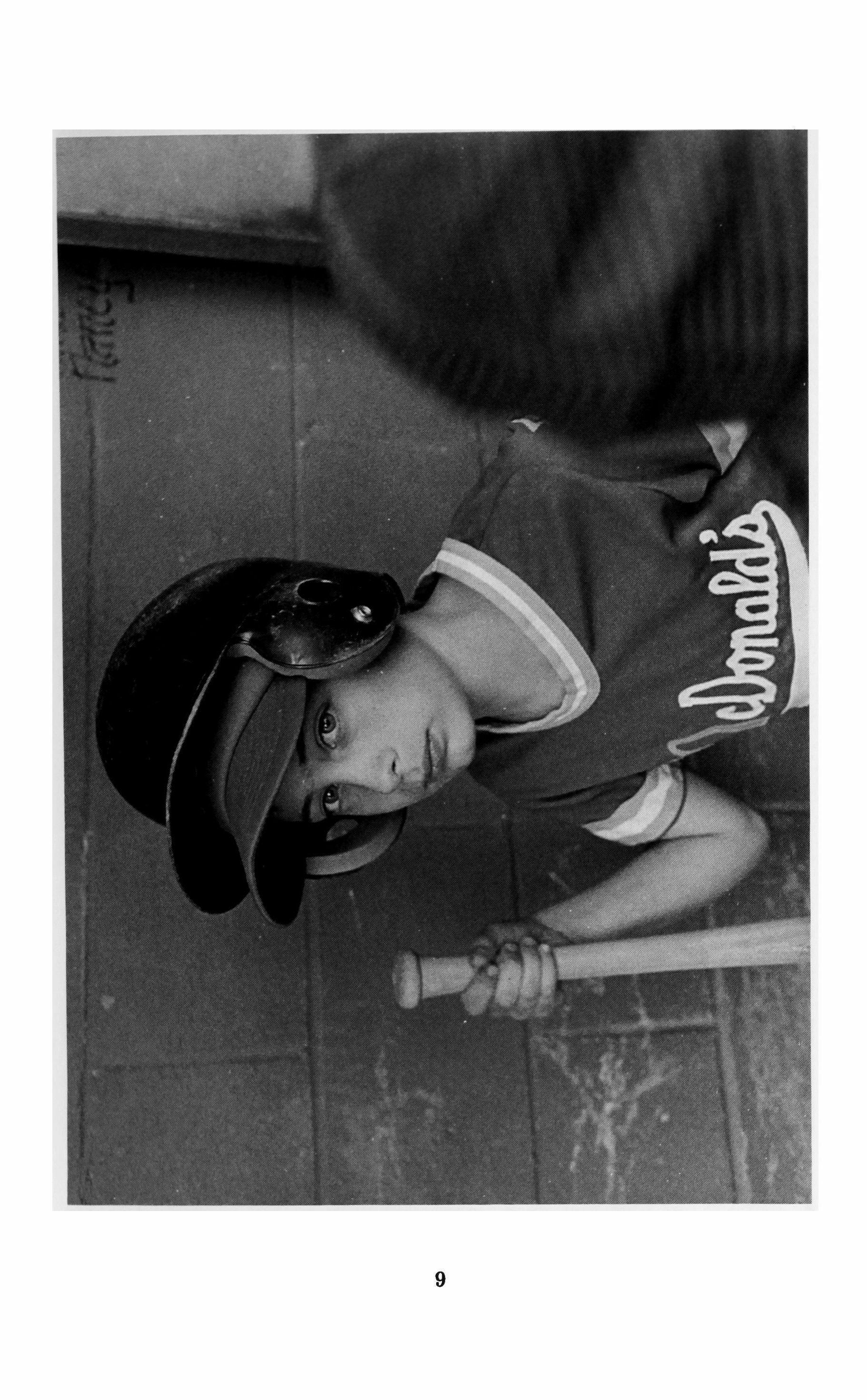

9. Medford, Massachusetts, 1986.

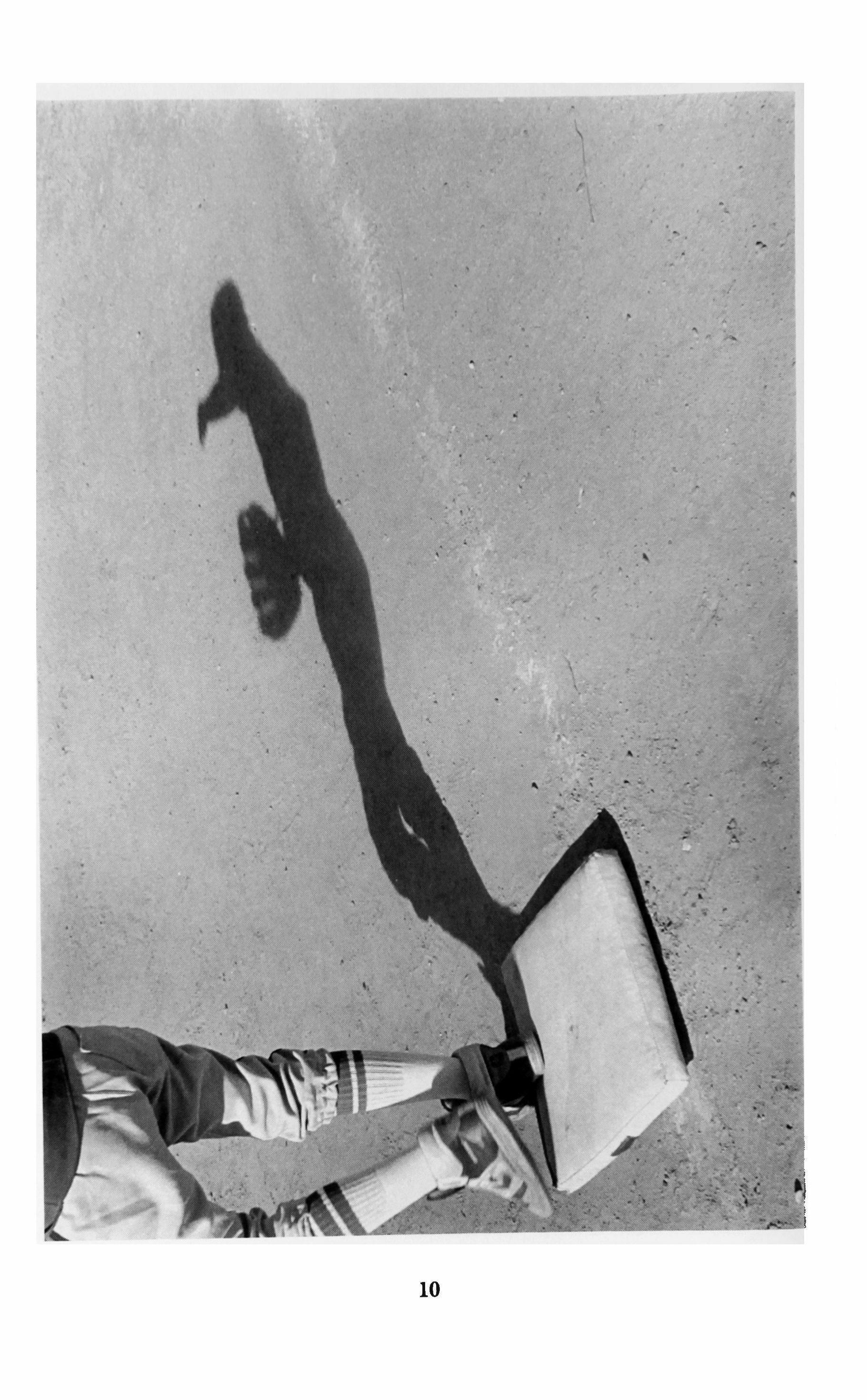

10. Malden, Massachusetts, 1986.

Cartography

Lynn Grossman

The streets in Paradise-by-the-Sea were all named flower names, sweet, smelling places-for-mothers-to-live names like Magnolia Lane, Honey, suckle Boulevard, Lilac Place, Gardenia Street. Mother used to live on Gladiola Avenue in a house that smelled the way mothers' houses smelled then - face powder and grocery bags and mothballs and brewed coffee gone too long in the brewing.

Daughter is driving mother to where mother lives now.

Mother smells.

The smell of mother floats over from the backseat where mother is sitting. Daughter is certain mother's smell is being re-odored around the car again and again by the air conditioner, going smell-in through the low vents, around and into whatever is behind the dashboard and coming out the front vents cold and mixed up with the smells of the engine.

Daughter cracks the no-draft for fresh freeway air and looks in the rearview mirror at mother's face facing out the side window. "Paradise, by-the-Sea," daughter says to mother and daughter points to the exit they are passing. Mother continues to look out the side window, but daughter is not sure if mother sees the exit for Paradise-by-the-Sea.

Paradise-by-the-Sea is not on the sea or near the sea, the sea being ten miles to the west, and that being only an inlet. Paradise is more by the freeway.

Mother's house had a screened,in porch where mother used to sit at night if the wind was up, in the hope of smelling a sea breeze. Daughter would sometimes sit with mother on a wind-up night. "Smell the sea," mother would say to daughter. Daughter would not tell mother that

32

what daughter smelled smelled to daughter like the rubbery smell of cars on a freeway going too fast.

When mother lived in Paradise-by-the-Sea, mother used to ride in the front seat. There was a time before that when mother used to be the driver.

Mother would drive daughter to the real sea past the inlet. Mother would pick up shells from the beach which mother said were dead but smelled the way they did to make you think something was still alive in them. Mother would hold the shells under the bubbling edge of the water and let the water go around and into the shells and when the shells were dripping with the wet sea, mother would hold the shells up to daughter's nose so that daughter would smell the sea smell.

Mother used to say a thing that is wet smells more of what it is than when it is dry.

At the real sea, mother smelled of sun and of seaweed and of coconut lotion she would drip on her body in white curlicues, and she would rub the lotion in and in until the white and the smell went into her body, and then mother would rub what was left on her hands of the coconut smell into daughter's back. Mother would put a sea-cracked rubber cap over her hair and go deep into the water to the place where mother told daughter the sea had no more smell, but tasted, instead.

Daughter thinks mother's smell today is a wet smell, not a dry smell. Daughter opens the front windows so that the air rushing into the car warm and oily and thick will be strong enough to carry the mother smell away with it.

Daughter off-ramps at the next exit, which is not the exit where mother lives now. Daughter opens all of the windows all the way down and she drives west to the real sea past the inlet.

In the rearview mirror, daughter can see mother's hair blowing away and off of mother's face, and daughter can see the shape of mother's skull beneath her face.

When daughter gets to the real sea, daughter drives the car off of the road and into the sand. Daughter smells the sea breeze coming into the car through all of the windows all at once, re-odoring around and around, bringing with it the smell of the sun and the smell of the seaweed and the rotten rowboat wooden smell of the almost wreck of a hull near where daughter has stopped in the sand.

Daughter gets out of the car and pulls the boat across the sand to the edge of the sea where the sand is not sandy, but dark and wet.

Daughter takes mother out ofthe car and helps mother onto the sand. Mother takes slow steps beside daughter, and the heels ofmother's shoes

33

sink down deep into the sand until mother cannot walk forward anymore, and mother cannot walk backward to where she has been.

Daughter lifts mother up high in her arms. Mother seems to daughter to be heavier than a child, but not to be as heavy as what daughter thinks a mother ought to be.

Daughter can smell mother in her arms and the mother smell surrounds daughter like a hug from mother, then the mother smell mixes with the smell of the world outside of the car.

Daughter carries mother to the boat at the edge of the sea. Daughter looks out far to the deep place in the sea where mother used to say things did not smell anymore, not when you were out there that deep.

Daughter holds mother so that daughter can smell more of the mother smell, and what daughter smells when mother is close to her this way is the warm and deep mother smell mixed with the smell of perspiration coming strongly from daughter's own body.

Daughter carries mother into the rowboat and turns mother in her arms so that mother can see the edge of the sea coming up around the boat.

"Paradise," daughter says to mother. "Smell the sea."

34

From Treemont Stone

Angela Jackson

The following excerpts are drawn from different points in a novel whose narrator, Magdalena Grace, has gone from her home in a black neighborhood on the south side ofChicago to an expensive, mostly white private university on the north side of the city, called Eden University. There, among her fellow black students, she has met both activists and dreamers, both serious students and husband-hunters. In the scene just previous, after she and her black friend Leona have been insulted by a white student, Leona has charged Magdalena with being too passive and well-mannered. The year is 1968.

Leona has hurt me. So I move away from her someplace inside and take back the space I had reserved for her and give it to myself. I lie across the bottom bunk and pretend that I am reading a book so that Leona and Essie will not try to talk to me. Actually, I am not studying Art History but studying myself. Because I don't know how not to listen to myself when she is crying and needs me so. I am seventeen years old. Remember?

Sometimes when I am not taking a thought and simply passing a looking glass, a mirror, or a window, I will happen to look up suddenly, come up too fast like a scuba diver breaking the surface too quickly, and be thrown into a time-warp. I will expect to see etched sweetly and vibrantly in the glass my face as I was as a little girl. Round-faced, richly brown, with the straightened hair pulled and twisted into three braids, my impudent edges turning back. My body gently round and long of limb. The eyes busily hiding who I was but witnessing all that I was and would be. The mouth turned up and quick or quiet as the case might be. The hands momentarily landed in my lap folded like birds between extended flights.

35

Even today as an almost-woman 1 am surprised to find that 1 am not the little girl. Her presence is in me indelibly. Her voice talks in my head.

Cain't have no privacy. Tip in the bathroom wid my own bloody nose. Look in mirror at everything swellin. Lip fat. Nose big. Not wide like Mama say from diggin but big on top. Face hurt when 1 touch. I'm touchin anyway because this is my face hurt. 1 halfway cain't believe. So I'm comfortin myself, pattin myself off wid a cold towel. Water droppin over the bathroom floor. Here come Littleson wid his nosy self. Don't knock on the door just walk on in. 1 mighta been doin somethin important stead standin in the mirror. He come all up in my face. Lookin at me. Talkin bout:

"000 wwweeeee, who got you?"

My eyes be wet and 1 starta blinkin. He bringin the shame down front.

"None a yo business, monkevface,"

"Bet you didn't talk that bad to who ever beat yo head."

"I did too." 1 push him out the way between me and the sink. Wettin my towel again.

"Who you fight wid?"

"Ole bald-head Jean." I'm back in the mirror pattin my face. Littleson looking over my shoulder.

"Wha'chall fight for?"

"Stop breathin on my neck." 1 jerk myself so he move back. He move up again.

"Wha'chall fight about, Maggie?"

"She cheat."

"Everybody know that. What yall fight about today?"

"I told you she cheat." I'm tired a his nosy self. He know it. He just sit and look at me. Quiet. Then he say, "Who won?"

1 don't say nothin. Then he say again trying ta get in my business, "Who won, Maggie?"

"Didn't nobody win."

"0."

He watch me watch myself somemore and I'm watchin him out the corner a my eye.

"You wanna fix Jeannie so she don't mess wid you no more?"

1 don't say nothin.

"I said you wanta kick Jeannie's butt?"

1 fold my towel. And lay it on the radiator. I'm cool.

36

"I might be interested."

Then I say, "What I gotta do?"

And Littleson say, "It's my own scientific invention. Don't I win alIa my fights? Lemme teach you advanced technology."

I say, "How much this gonna cost me?"

"Maggie, you my sister. Besides you ruinin the family reputation on the block."

In the book they say when the man drown he go down three times. And his life keep passin before him every time. Same wid fights.

In the backyard me and Jeannie apart for the second time. She been whippin my tail. Eddie push us apart the first time. I say, "Uh uh. Now you goin git it lemme at her," I say to nobody, in the backa my heart wishin somebody would not let me at her. (Who like to hum anyway?)

Anyway that first time and we apart and the ground in my mouth and my hair cryin at the roots in the wind it been pulled so hard and me breathin the jerks in my body lookin at Jeannie and seein her like a twenty-leben times and fights and she half-kill me. And I never remember how the fights begin but know they happen all on top my head. The first time we come apart like a crazy machine comin apart for a second or so and I just look at her and don't know her except as a piece a memachine. And then we come up on each other again botha my arms swingin everyway through the air and Jeannie and her claws tearin every any place she want and her bite and pull and stuffbein hot stingy marks on me. We apart the second time. Is where we at and I'm shakin my eyes clear in my head clearin my lesson rememberin my science gonna whip some advanced technology on this heifer. And I think I got Littleson's voice in my ear sayin O.K. Maggie this called the power punch, O.K. Maggie make a fist make a good tight fist Maggie loose yo body O.K. Maggie think all yo strength in yo super hand swing Maggie swing Maggie go girl swing oooweee Maggie. And Jeannie lookin at me funny then her stomach goin soft around my fist and she double over screamin and I step back lookin at what I done don't believe and Jeannie rise up with double hate and slobbin a little at the mouth her eyes dark and watery like never cause I never hurt her before and Jeannie rise and kickin me and scratchin and spittin and cussin and everything and I don't believe it that this is worse than the first comin apart. And the ground in the mouth and spinnin seesaw in my eye and Littleson standin by the jumpin tree for real and all I can hear him say is, "Awh, Maggie, goddog." While he and Eddie pull us apart.

37

I never learned to fight with any kind of style, unlike my brother who is a black belt in karate. Lazarus-the-Warrior. Yet I am amazed at my early definition. My sure-footed stance in the world in the face of certain defeat. How I wandered wild and protected in the embrace of family. But I cannot be one moment always. More sooner than later womanhood knocked me from the perfect gravity of childhood. And dragged me off by new hair and curving handles that I could not keep from coming. I was off-balance and learning new walks. The world itself would not be still. It was wound up in its own motion. I was caught in the motion of life itself, and I was not alone.

Earnestine spent entire summer afternoons underneath our mother and father's bed, tearing apart whole blue boxes of sanitary napkins. Thinking that within those rectangles of cotton and gauze and blue lines would be found the secret of womanhood. The central mystery of breasts and bras and black or beige silk panties. The busy hands of rosaries, fans, cigarettes and pictureless books. After she tired of Kotex and Modess she turned to baby bottles, sucking the manmade nipple and picking in her hair underneath the bed in which she had been conceived, and under which the water surrounding her still curled unborn had run out. She would experiment with the sensations of objects of womanhood and babyhood, until the afternoon wore out and her interest. Then she would sleep amid the dust and echoes of our footsteps not far from her face. Until she was tired of being alone and not an infant and not a woman.

At this moment I am in love with the way Daniel Moody (like a slim, insouciant Santa Claus) carries his books in a duffle bag slung over his shoulders. By virtue of this infatuation, I am in the club of swooners and piners. Membership temporary, but intense. Essie's a founding member. And Leona's Emeritus. She says she is for the moment. When Essie suggests a late walk for tea and grilled cheese, I'm ready. This gives us a reason to slow walk under a radiant and ponderously full moon which feels like it has dropped down inside me. But Essie says that feeling is just because my period is on its way. I'm at high tide so to speak. A red moon high between my legs about to unravel. My breasts like two moons. I try to think of a planet that has three moons, but astronomy is not my thing. We're into astrology. Essie brings the star books with her and I bring the birth dates and times of the heroes of our hearts. A young woman in love is a zealot detective, an assiduous gatherer of data, cross references and minutiae.

The Saturday dance is over and no one's asked us to the afterset at

38

Blood Island. It's a secret rendezvous closed to singles, open mainly to the royal couples, cuddling consorts and the like. Leona has gone with Steve, because she loves to dance with him. Dancing is what they do. Slow Drag, Walk, Hesitation, Bop, Watusi, Funky Broadway, Jerk and African Twist. They do them all as if they were twins with complementary moves and style. William and Rhonda and the other couples do other things in corners, on the couches, in the closets of hot Blood Island. We, Essie and I, imagine what they do. We don't really know. Later Leona will tell us enough of what William and Rhonda did to send Essie to bed sick and insomniatic.

I feel unearthly and untimely-as if I'm looking back on myself-as we walk the downtown streets ofEden on our way to the quiet greasy spoon where we can spread our American Astrology, Horoscope, and Heaven Knows, and papers over the table, while we nibble grilled-cheese sandwiches and share a large order of salty, greasy fries, sip cherry-flavored Coca-Cola and chart the courses of true love through the heavens. Essie has plaited her hair and tied it with a scarf, so she looks tinier, more vulnerable, than usual. She carries no terrible thundercloud of hair to protect us from the night-terrors that scurry and scramble past midnight, lunatic and howling like frat boys who've drunk too much beer.

Stores hawking records, books, jeans and other fashions, ice cream, drugs and notions and fast snacks, line the neat streets which seem less narrow under the moonlight. As if night gives life here width and breadth. All other eateries, pizzerias and hamburger joints, are crowded or closed except the one we're heading for. Few people are about. And the world howls with such loneliness I feel heroic walking beside Essie. Together, but somehow separate, as we go.

Everything is spooky; pale mannequins in store windows lunge toward us like they want to tell us something heavy, or do us in. Shadows lead us. Yet Essie says tonight is a time for lovers; and why can't William be hers and here with her now? They are meant for each other. She's checked the stars. Too bad she can't do the higher math of it, I tell her, with all the exact degrees and minutes. Maybe then she could plot the inevitable time of their eternal and everlasting union.

Her eyes blur with the faith like some ancient mystic. She talks about the love match unceasingly like somebody hypnotized her and said the chief topic of her life should be William Satterfield. The acuity of her feeling infects me too and I try to stay with her by rhapsodizing about Daniel Moody who totes his duffle bag in such a romantic way. But my evidence is insufficient beside the masses of information Essie has accumulated over weeks. Hers is the love of a lifetime. She and William have

39

actual conversations. He caressed her as they sat on the manmade bluff that juts over the lake. Stroked her back and fit her petite breast into the palm of his hand, his tongue wiggled in her ear, sliding deep in her mouth over her tongue, but he's never done it to her. That would be too dirty. To sleep with both Essie and Rhonda. I guess.

Our game is guessing the identity of Fred (who we've never seen) of Fred's all-night restaurant. Fred Flintstone. Fred Mertz, Freddie the Freeloader. We reel off a list of every round-faced, jovial whiteman named Fred we ever knew from TV. Essie says Fred Weinberg and I never heard of him. He's the man who owns the building her mother cleans, she tells me.

Fredonia Witherspoon is the glamorous one of a crew of Black and Polish women who work the same hours as roaches. Sunset until clean, Fredonia scrubs like a queen, her iridescent red wig glowing in the vacated offices under the flourescent lights. "My mama working nights now," Essie ends.

"My mama do days," I say like we've never talked about any of this before. I launch into the tale of my stolen hair dryer Mama bought with her day-work money a day before I came to Eden. We go over again who might have stolen my hair dryer bought with my mama's red hands. Essie thinks it was the maid who got fired who stole it out of my closet. I thinks it was Truda or Oakland who did it for kicks, because in the early days I was quiet and was tight only with Leona and Essie. They called me ''boojie.'' Me. Because I wore tiny pearl earrings and was always polite enough to say "please," "thank you," "excuse me." And I wasn't free enough to say "shit," "bitch," "motherfucker," "bastard" and "niggah," which I can almost, if I ever open my mouth to do so, reel off rather deliciously by now. But it always happens. Whenever Essie, Leona and I talk about the work of our mothers, I think of the stolen hair dryer and I want to hunt down the person who stole it and with it my mother's sweat. I hope it is a white girl who's stolen from me, but that's unlikely. Someone would have seen her. A white girl going in three black girls' room. Even a friendly white girl.

As usual, Fred is nowhere for our eyes and I am more certain than ever that he doesn't exist outside the booths, the sizzling grill and the little square tables with the formica tops. He's only a figment of the sleepy waitress's imagination. She looks up at us grouchily as if she'd rather not. Only her paycheck is real. If we disappeared back into the dark she'd happily keep leaning on the counter dreaming of new shoes, compassionate kisses, shiny golden hair where the brunette roots don't

40

show as they do now. She snaps her jaw and gives the gum one last crack, then she shoots the wad into a napkin, as she moves toward us.

"Where's Fred?" Essie asks facetiously, imitating the bravery of Leona as she does when Leona's not around. Maybe it's her own bravery that only comes out when she's the bravest one here. I giggle at the audacity of extending the joke of Fred's identity to someone who may know him. "Tell me the truth," Essie keeps on goodnaturedly, "Is there really a Fred?"

"Is there really a God?" I whisper over the saltshaker.

The waitress, Bev in white letters on the black name tag, does not give us a smile. She asks us what we want and we look up and giggle and order grilled cheeses and cherry Cokes and an order of fries between us. This is the ritual meal we eat as we pour over astrology's wisdom. We are severe as we thank the waitress who toots out her mouth and screws her lips like she's holding something nasty like liver or cold cooked carrots. She goes to wake the napping chef.

"Why do white people always shorten their names? Bev instead of Beverly. Sandy for Sandra. Jenny for Jennifer. Ellie for Eleanor. Like they're so friendly. When they are so unfriendly." All this we whisper across the table as we spread out our paraphernalia like cartologers of divine destiny. In the earliest dorm meetings which everyone in Wyndam-Allyn went to in every kind of pajama and gown, the perky white girls called Essie, Essie, and I was Mag until I set things straightMagdalena please, only myoid friends called me Maggie. And Leona was Lee for a day. Penelope, who is Greek, begs us to call her Penny.

We call Bev, the waitress, Miss when we ask for water. She brings it with no ice in the glasses, but plenty in her eyes. Water sloshes over the table. Bev sits down at the counter watching the Black chef in the headscarf shake the basket ofcrispening fries. Too much tolerance in her watchful waiting. Too much insistence and too many directions as she tells him how to do his job. Too much silence on his part tells us he doesn't relish her instructions.

Bev acts all happy when the bell tinkles the arrival of a blond lanky dude and his crinkly-headed date. They slide into a booth near the door, and grinning Bev is taking their orders before their buttocks hit the seat good. They act like they don't know her.

Essie and I avoid each other's eyes because we don't want to see the difference in her treatment of them and us. If somebody else sees you seeing something wrong then you have to speak and get loud. Then you have to do something. And Essie and I want our girlish evening of romantic meanderings; we want to tell each other the birth dates and

41

times and places of the men we love. So we do that. Instead of breaking Bev the witch-waitress's face.

Essie opens the book and begins to read about William born on the cusp between two signs. I draw the symbols for the placements of his signs. If our breath is high in our throats, it is the excitement of love and not the tension of ignoring being ignored.

The waitress saunters to the phone in the corner. She hangs onto the receiver, leans against the wall as weariness watching herself, and listens. After a while she slams the receiver down. Essie and I look at each other to make sure we've both witnessed this business in the corner. We pretend to peruse our astrology charts spread out like ancient sea charts that end in cliffs into the abyss.

Bev, the waitress, picks up the phone again; money makes a lot of noise when the machine swallows it. Bev swallows, drums her long fingernails on the phone, then yells into the mouthpiece.

"Oh, you think you're so goddam smart. You're a stinking son of a bitch, Freddie."

There is a Fred and Bev is on his case. And Bev is about to cry. Essie and I giggle and whisper.

Bev lowers her volume, but we can hear anyway because intensity carries and we listen attentively to it. "Don't screw me like this, Freddie. I told you two weeks ago I need the time off. You may not have to go to your sister's wedding, Freddie, but my family is a family. I'm a bridesmaid."

Bev has won our sympathy now. She's got to dye her dress shoes a funny shade and look happy while her sister gets married and she works at a diner in the middle of the night. She looks like the type I've heard Penelope talk about "Always a bridesmaid, never a bride." I'd never heard that saying before Penelope said it. It's something no one ever said at the Grace house on Arbor. Maybe I didn't hear. It sounds sad, "never a bride." Bev acts like she would cry if she weren't at work. She hangs up the phone again. She flips her eyelash and passes over her wet nose with her index finger.

"I hope she washes her hands before she touches somebody's food," Essie says.

She doesn't. Bev's back at the counter. She pushes the bread down more firmly atop the reuben sandwich and carries it to a truckdriverlooking man across the room.

"Now you know that's nasty. Rubbing snot on that man's sandwich."

42

Essie pushes her plate away and sips the Coke to wash away the nasty taste of unsanitary thoughts.

"Fred better give her some time off before the health department close this place down," I say, just so Essie will choke on her Coke. She chokes. And coughs it all over the table.

Bev looks at our mess out the corner of her eye and I know being Black doesn't pay when a poor white girl's in pain. In a hassle with her boss. Bev walks over to us with a rag in her hand and an ugly look on her face like a squirrel in a trap.

The door opens and I hear it out the corner of my mind but none of us looks that way while Bev slams ketchup and plates around the table knocking our star books on the floor.

"Excuse me," I say as a reprimand.

Bev grunts like she's accepting an apology and is still mad about it.

"She's not the one apologizing," Essie says. "Miss, you messin with our property."

Bev says, "So sorry, big spenders." Then she walks away talking about how she hates to wait on us people because we don't tip from shit.

"I'm going to tip her upside the head," Essie promises and glares so hard at the woman's back I'm nervous she is going to jump on the woman's back and ride her like an addiction. Essie is usually less violent than this. All her injuries internal that she spends her time on; white, people's belligerence goes right past her usually. She lets the racism slide. Not like some of us who ready to jump to anybody white's chest when we having a bad day and somebody white cross that fine line. Somebody like Trixia would kick a white girl's behind on gpo

Trixia says, "Hey, now" from a table behind us. And Essie and I turn to salute them, her and three other sisters. It is they who've just arrived, whose entry we hadn't taken time to note. We don't try to mix company. They can tell I guess that we're in a slow mood, and they are still busy and boisterous from the afterset they went to and we didn't. We pick up pieces of their talk about how the afterset wasn't all that much fun. Couples cuddled up and boredom.

By the time Bev who is busier now makes to move to Trixia's table, Trixia is long past ready to eat. Everybody's starving.

Bev says, "Are you ready to order?"

They had a name for girls like me. They called us smart girls. They had other names for girls who went to all-girl Catholic high schools, who walked on the cutting edge of nuns' habits. They called us whores, nymphomaniacs and lesbians. They called us stuck-up. Sometimes they

43

called us good. I wanted to be good like one of the girl saints, brave enough to look into the mouths of lions without flinching. Being gobbled up singing.

One year when I was thirteen I kept a little spiral notebook, a diary I addressed to Jesus.

Dear Jesus, [I wrote)

The Freedom Riders were on tv. They are brave and holy. I want to be one of them. They ride buses into the jaws of death. People spit on them and they keep coming. They are more like you than the apostles who turned their backs on you. Remember Peter said he didn't know you and lied about it three times. I bet the Freedom Riders wouldn't lie. They'd just go on singing and walking through the spit. The whitepeople pour ketchup over their clean white shirts. On television it looks like blood.

Some of them shed blood for the cause of our people. Like you they were crucified. And their bodies thrown away.

Those four little girls in that church in Birmingham I know they're in heaven with you like the Holy Innocents. I know they are angels with you.

Dear, dear Jesus, I want to be good and brave like the Negro people down South. I was born there, remember in Mimosa, Mississippi. My Aunt Leah-Bethel whom we call Silence is with them and she was never brave before. But now she is. She used to be crazy, but now she's courageous. Sam Jr. said yesterday in the livingroom when we were watching the news. Mama didn't say anything. She smiled. One day I'll walk to school and won't ride the bus because the bus drivers are so mean to us. Some of them are colored. One day when you are with me I1l go to the Catholic Church across the viaduct, right where the Polish and Irish lions stay. They call themselves christians. But we know, you and I, don't we Jesus? The priest over there wouldn't give one of our boys who went to late Mass over there Holy Communion.

Excuse my penmanship, you know I can write better than this. I am real good with my hands. Aren't I? But it's late and I have to finish reading The Bridge of San Luis Rey for school tomorrow. I'd rather read what I want to read, but it's a good book. I just didn't choose it. I'll try to do better. Honest, I will.

In true friendship, Maggie.

I'm still seduced by the spiritual romance of the images of nonviolence, the radiance of bloody submission and transcendence, the neat collegians in white shirts with ketchup splattered over them like blood. I like being good. There's a kind of supremacy in turning the other cheek.

Mama the Roman Catholic and Miss Rose the Missionary Baptist taught me. We are not like whitepeople. We are better than them. No matter what ugly thing they do to you. They are less for it. We are the

44

holy ones. We've held on to that for decades, centuries even. Maybe because it's true.

''Nobody needs as much water as you," Bev says after refilling Trixia's waterglass for the fourth time and setting the pitcher on the table so they can serve themselves. Slamming the check down beside it. "You should take some of that water and wash that black off," she mumbles more to herself than anyone else. She's just fed up because she can't go to that wedding. But what she want to say that for?

Trixia picks up the check, so wet from sploshing water the ink runs, and they can't read the money-numbers due for the hamburgers that were served cold. The chili that came with no crackers and they had to ask for them. The pop with no ice.

Trixia leads the line to the counter and Essie and me bring up the rear. Bev yanks her body to the cash register. Is it fear that slices through the sullen anger in her eyes? Trixia slams her money on the counter and then she hawks and spits in the waitress's eye. And then comes Oakland and Letitia and Ramona, one by one hawking and spitting in the worn, an's face. Paying the money and not waiting for the change, because they know the price and have counted it out to the penny. They open the door and stand in it. The place is still in the first moment when Trixia first hawked and spit and it is Essie's turn and mine and I just put the money on the counter and look away and Essie spits on the money and we walk outside. Bev's eyes are squeezed shut; her mouth wide open. Nothing coming out.

Trixia and Letitia and Oakland and Ramona look at me but don't speak. We are walking down the street, when the truck driver-looking man comes and stands in the doorway and calls after us, "You sonufa bitching black bitches."

And Letitia hollers back, "Come and get us. You so bad, blue-collar motherfucker. It's a ass-kicking moon out tonight and I want yo ass." He gives us the finger and goes back inside.

On the street Trixia and them keep repeating what happened. Stroking the nuances and accelerating the rage every time it slows down. They disturb the peace. One by one they applaud each other-how loud Trixia was when she yanked the phlegm out of her throat and threw it at the white girl, how strict the set of Oakland's neck when she fired, how perfect Letitia's aim and Ramona's scowl. They talked about Essie's imagination to think ofspitting on the money, so the bitch had to pick it up.

When we get to the doors of Wyndam,Allyn they look at me quietly and there is no praise.

45

We come to Letitia's room first on the corridor and she opens the door for all to fall in for a victory celebration, a recounting of the battle for the rest of the sisters.

"Come on in, Essie," Trixia says without looking at me who is next to Essie now, on my way back to the room. Essie looks at me sheepishly and follows them in.

"Tell Leona to come on down, Maggie," Oakland says with a casual fling of her scarf onto the bed.

The hall is quiet except for the noise escaping from Letitia's room. Everything is empty. And I am hollow inside except for the sloshing of like a gallon of water in my stomach and chest and I wish, I wish that I could spit.

Essie Witherspoon was a shy and fragile girl when I first met her. We had grown up in neighborhoods not far from each other. We knew the same bakeries by their smells that rode through our streets on the wings of the Hawk, the one movie house on the boulevard where Sunday shows were $.25 and the projectionist ran ads for the latest Brigitte Bardot movie during the kiddie shows, the same laundromats, grocery stores, churches, rib joints and taverns. The same vacant lots. We came upon the centralizing church steeple from different sides, distances and angels.

Essie knew Jeannie, my childhood friend who had one child at fifteen and another at seventeen. When Essie and I found each other it was as if we had found a new corner of home.

Essie is a tiny-boned girl with the biggest Afro I have ever seen. It stands richly around her head like the cap of a tropical tree. Each night she braids it from the center of her head and sends the twisted plaits down around her face like tamed snakes caught in a dance to a charmer's flute. But Essie is the charmed one. The one who is enchanted.

Essie was watching William and William was watching her while he danced with Rhonda. Rhonda was watching Essie too. She printed her body on William's and held him. Her breasts stabbing him in the ribs. Abruptly, Essie moved to another angle of the room and got too close to the four-foot-high speakers, so that the noise was making her nearly insensible. She watched the two of them, but she didn't see. She only saw herself, miserable and rejected, an ache inside her female organs, a deep sorrow. And she saw at that moment in which William slow-

* * *

46

dragged Rhonda across the floor, the turning points of her life. The points so sharp they pinned Essie in them forever.

"Honey, I like ta died!" Essie was saying into the phone to NeeNee, her best and only friend, when Fredonia's lick unpropped her hand from her imaginary hip and uncrossed her little legs.

"That's for actin grown," Fredonia said. "You ain't no woman." Fredonia scalded herself out of Essie with her eyes; she scolded her own cameo set in the girl's face. Then Fredonia turned back to her steaming stove, top works and to her company. Blinking her Liz Tavlor-as-Cleopatra mascara-ed eyes (a thick, wide black band that outlined the eyes and wound around the side of the head) and sighing, ruffling the coppery waves atop her head with her free and still-stinging hand, she made motions in a pot of chili beans, more concerned with conversation and company than food or child.

Essie's eyes were burning and she rolled them at Fredonia's spine and rounded rump. Fredonia was mouthing some delightful outrage.

"So I told that BLACK nigger, I told him, honey, I am not a player, I do not play."

"That's right, girl," her company said.

"I'm a woman."

"That's right."

"I'm a woman," hand on hip, face thrust forward, slanted eyes wide for emphasis.

You a woman. Ya gotta tell these niggers. That's right." Lorraine sipped Schlitz at the kitchen table.

Fredonia banged the stove with her soup spoon. A flurry of flecks of hot pot liquor popped onto her arm. She cursed, and reached for her towel, which she kept in a corner like a prizefighter. She caught Essie's eyes on her.

"Don't you look at me that way."

"What way?"

"The way you lookin at me now."

"I ain't even lookin at you."

"Don't cut your eyes at me, you little whore."

"Fredonia!" Lorraine incredulous. "Cool down, girl. Don't call the child no whore. Next thing you know she'll be in the bushes."

"She probably already been there

"You was From under Essie's breath.

"I was what? Little bitch. I shoulda left yo skinny ass with yo grandmama."

47

"I wish you hadda Essie mumbled.

"What?"

"I ain't say nothing."

"You a lying little heifer, too."

"Girl, cool down. This heat got you goin," Lorraine interceded again. Fredonia was successfully diverted.

"Girl, this ignorant city ain't shit. You ever felt fall weather like this? Just as hot and sticky." Fredonia was gay with a topic for crisp new talk. She wanted to laugh. She needed to laugh. She wanted to shake her butt. She was still young. Her daughter, Essie, was only ten. And Fredo-nia was tired of Woody, her present husband.

Fredonia and her men did not get along long. Suddenly, she did not fall back against her pillow satisfied; suddenly, she saw him as stingy. One day she realized that he smacked when he ate, "sound like a greasy hog." He was possessive at parties. Talkless after loving. Knocking her against the walls when whiskey rode his mind. Knocking her down and knocking her up.

She had been married three times. No divorces. Just civilized Missis-sippi separations and remarriages. She couldn't live with fault. When she packed Essie from Big Marna's and told Big Marna about Woodrow Witherspoon and her secure family feeling, how she wanted to make a horne for him and her children, how they had applied for living in the high-rises and they were on the waiting list, how she had at last found a quiet man without fault, Big Marna had simply said, "I hope your glass house is shock proof, Fredonia."

As it happened, Woodrow Witherspoon had feet of clay. In a manner of speaking. He never washed his feet. Fredonia, in time, found his silence sullen, and his dependability boring. Again, she was dissatisfied. Again, her laughter turned to tin. And her eyes restlessly ferreted an object upon which to heap her ridicule, because her own life terrified her.

"Lorraine, Lorraine, it's gone rain enough for Noah." She flicked the flimsy curtain at the lonely living-room window. She was in the highrises now, but they were not the penthouses she'd imagined. She called the Homes the "pen house" apartments. "Oh, it's gone rain on the unrighteous can't treat a woman right. Drive all them rats inside!"

Lorraine laughed, "I'ma make like I don't know you talkin about Woody."

"Who a Woody? Or rather, WHAT a Woody? I don't know no goddamn Woody." Her voice had grown slightly ragged. "Woody. Sound like a dummy name to me. And he say bout much as Charlie McCarthy.

48

Damn dummy." She punched holes in a beer can. Sucked. Pulled her blouse at the throat for air-conditioning. Her voice was slurred as she got ready for bedroom confidences. Lorraine slid forward in the rickety kitchen chair that squealed under her thick body's weight.

"You know what he did last night?" Fredonia asked Lorraine.

"Naw, girl."

"Corne crawlin upside me greasy as bacon and smellin like between Miss Lacey's legs-What you doin here? Didn't I tell you to go somewhere?"

Essie wilted under her mother's fresh attack. There wasn't far enough to go inside the small apartment.

"What you lookin up in my mouth for? Don't LOOK in MY mouth. Countin cavities. You ain't no dental assistant."

"I ain't say I was."