-

Publication of TriQuarterly is made possible in part by the donors of gifts and grants to the magazine. For their recent and continuing support, we are very pleased to thank the Joyce Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Illinois Arts Council and the Borg-Warner Foundation.

Associate Editor Susan Hahn

Editor

Reginald Gibbons

Managing Editor Janet Vander Kelen

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Assistant to the Editor Janet E. Geovanis

Editorial Assistants

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow Cynthia M. Gould

Catherine Ferreira, W. Douglas Fitzsimmons, Amy Rosenzweig, Jo Anne Ruvoli

Advisory Editors

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Elliott Anderson, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Elizabeth Pochoda, Michael Ryan

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WRITING, ART AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED IN THE FALL, WINTER AND SPRING AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY.

Subscription rates-Individuals: one year $18; two years $32; life $150. Institutions: one year $26; two years $44; life $300. Foreign subscriptions $4 per year additional. Price of single copies varies. Sample copies $4. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterlv. NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY. 2020 Ridge Avenue, Evanston, IL 60208. Phone: (312) 4913490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry and literary essays, which must be received between October 1 and April 30; manuscripts received between May 1 and September 30 will not be read. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1988 by TriQuarterlv. No part of this volume may be reproduced in any manner without written permission. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America by ThomsonShore, typeset by Sans Serif.

National distributor to retail rrade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Centre Street-Rear, Nutley, NJ 07110 (201-667-9300). Distributor for West Coast rrade: 8ookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710 (415-549-3030). Midwest: Ingram Periodicals, 347 Reedwood Drive, Nashville, TN 37217 (615-793-5000).

Reprints of issues II-IS ofTriQuarterlv are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, NY 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106. lSSN: 0041-3097.

72 Spring/Summer

1988

"In the Air, Over Our Heads," a story by Amy Herrick that appeared in TriQuarterly #67, has been included in The Editors' Clwice, Volume IV, a Bantam/Wampeter Press book compiled by George E. Murphy, jr., and published simultaneously in hardcover and trade paperback.

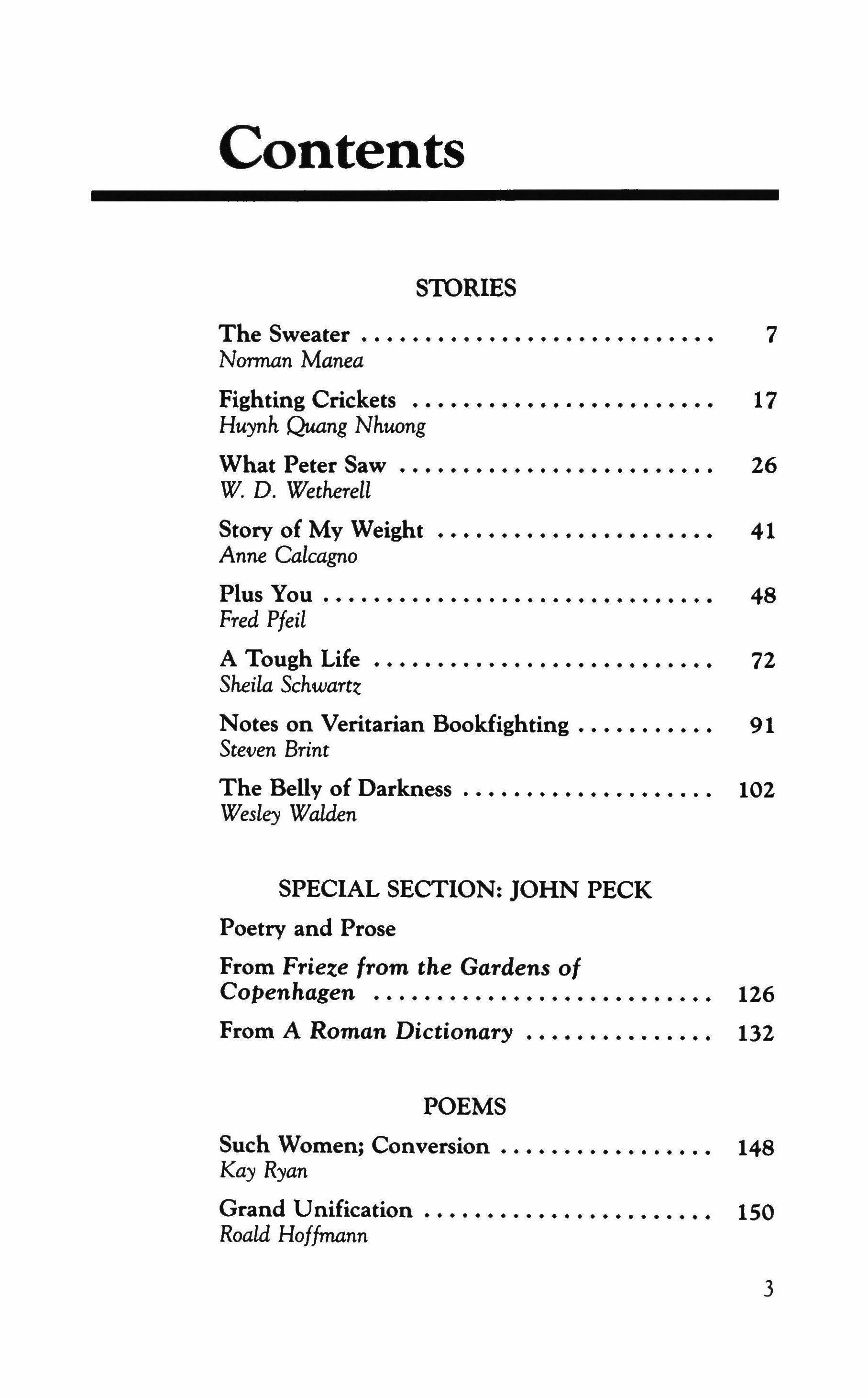

Contents STORIES The Sweater 7 Norman Manea Fighting Crickets 17 Huynh Quang Nhuong What Peter Saw ••••••••....•.•.•..•••••• 26 W. D. Wetherell Story of My Weight •••••.....••....•••••• 41 Anne Calcagno Plus You. 48 Fred Pfeil A Tough Life 72 Sheila Schwartz Notes on Veritarian Bookfighting 91 Steven Brint The Belly of Darkness 102 Wesley Walden SPECIAL SECTION: JOHN PECK Poetry and Prose From Frieze from the Gardens of Copenhagen •.••.••.•••••••••••.•••.••• 126 From A Roman Dictionary 132 POEMS Such Women; Conversion. 148 Kay Ryan Grand Unification 150 Roald Hoffmann 3

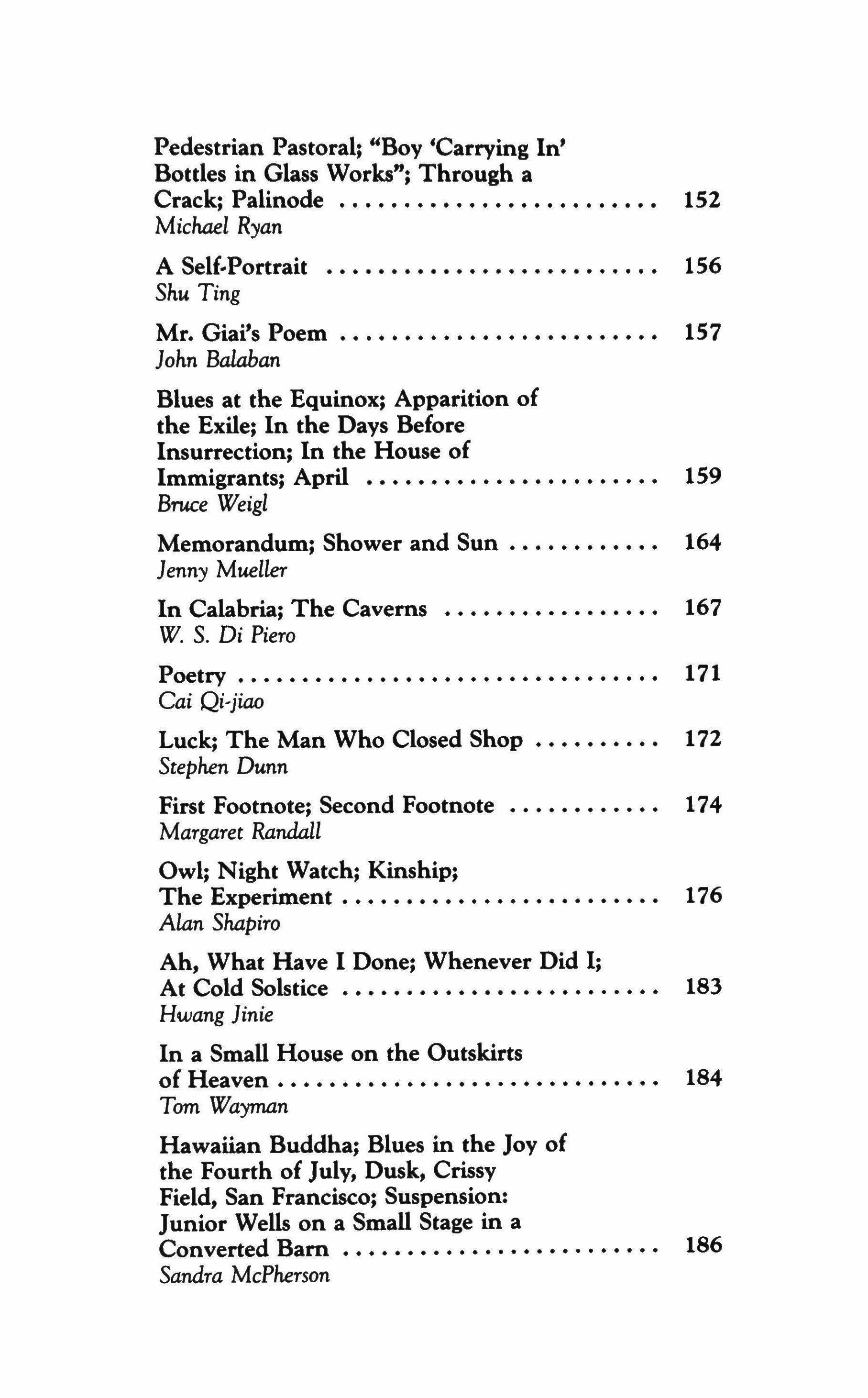

Pedestrian Pastoral; "Boy 'Carrying In' Bottles in Glass Works"; Through a Crack; Palinode ..••..•.•...•••..••..•... 152 Michael Ryan A Self-Portrait 156 Shu Ting Mr. Giai's Poem 157 John Balaban Blues at the Equinox; Apparition of the Exile; In the Days Before Insurrection; In the House of Immigrants; April •.••••••••••••...•••••• 159 Bruce Weigl Memorandum; Shower and Sun. 164 Jenny Mueller In Calabria; The Caverns •.••...•...•••••• 167 W. S. t» Piero Poetry 171 Cai Qi-jiao Luck; The Man Who Closed Shop •.•••••••• 172 Stephen Dunn First Footnote; Second Footnote ....•....... 174 Margaret Randall Owl; Night Watch; Kinship; The Experiment 176 Alan Shapiro Ah, What Have I Done; Whenever Did I; At Cold Solstice 183 Hwang linie In a Small House on the Outskirts of Heaven 184 Tom Wayman Hawaiian Buddha; Blues in the Joy of the Fourth of July, Dusk, Crissy Field, San Francisco; Suspension: Junior Wells on a Small Stage in a Converted Bam •••.•.•...•...•.....••..• 186 Sandra McPherson

The Poet and History 193

C. K. Williams

CONTRIBUTORS 208

Cover design by Gini Kondziolka

ESSAY

5

The Sweater

Norman Manea

She would leave Monday and return on Friday. She would leave crying as if it were for the last time. Next time she would not have the strength to leave us alone-so much can happen in a week. Or at the end of her days away a miracle would occur; she would not have to leave us anymore.

The sky would suddenly open; we would find ourselves in a real train, not like the one they unloaded us from, like cattle to slaughter, in this empty place at the end of the world. A warm, brightly lit train with soft seats kind, polite ladies would serve us any kind of food we wanted, as is the right of travelers returning from the other world. Or by Friday, when she should corne back, this endless ashen sky, which we kept waiting with dread to enter at last, and have done with everything, would corne crashing down and swallow us up.

She returned hurriedly, panting, bent under the weight of her sack, which bulged with the days and nights she labored for us. She looked like a shadow; she had withered; she had turned black. We waited at the window for her to rise slowly out of the smoke of the plain as she approached feverishly, a phantom. She had fought, we knew, she had begged; finally they had allowed her to go to the foreign village nearby. She had nowhere to run, and we stayed where we were. They paid for Father's work with a quarter loafofbread a day. Without her, we would have died at the beginning.

So they had let her go, with their cynical goodwill accepting her pleas as a game worth playing a while longer, if only to interrupt it suddenly with an abundance of cruelty and pleasure.

Monday to Friday she knitted for those local peasants whose language she did not know.

7

The game could be interrupted at any time, we knew, in the hovel where she left us, or in the warm houses where she worked mutely to earn her potatoes, beans, flour too, sometimes even cheese, dried prunes, apples. She alone still believed that we would survive, and so she held fast to anything that might save us.

Friday meant, then, a kind of new beginning, as if we had received yet another reprieve. She staggered toward us, crushed by the weight, as she dragged herself along, bent under the sack. The joy of seeing each other again became so sharp that none of us could speak. She would move about for a long time like a madwoman, as if she could not believe that she had found us and was seeing us again. She ran helplessly from one wall to the other, frightened, without coming near us. She came to her senses with difficulty, looking for enough strength to open the sack she had thrown down when she entered the room. When she bent over to divide up the contents, it meant that she had calmed down.

She had taken out and set on the floor, as she always did, six mounds for the following six days: potatoes, beets; she set aside three apples. None of us expected anything different from what we were used to. She passed her hand over her forehead and huddled exhausted beside the sack. "I've brought something else, too"; this did not necessarily mean a surprise. We were not expecting anything new; we had forgotten how to wish for any other kinds ofgifts and were amazed that she was able to do even this much.

With difficulty she pulled it out from the bottom of the sack, as if she were lifting it by its ears or its big front paws. She did not have the strength to hold it in her arms and show it to us. She let it slip down from her skeletal hands, to fall onto the opening of the sack. There it looked even thicker, stuffed.

It could only be for Father, of course, but it seemed too beautiful, perhaps for the very reason that it would have tempted anyone who saw it to simply take it for himself, even if it were not meant for him. It brightened everything with its colors, as if a magician who would save us wanted to show what he was capable of. At night only smoke, cold and darkness breathed around us; we heard nothing but explosions, screams, the barks of the guards, crows and frogs-we had long ago forgotten about glitter.

She had not opened it up so we could see it whole, but it no longer mattered. Clearly it was something real. Even our rescue now seemed closer, or at least possible, if we could see and touch such a miracle.

I could not resist it; I had come close to stroke it. It looked fluffy, obedient; you could wrap yourself in it and not care about anyone

8

anymore. I brushed my hand against its sleeves, its neck. I held it tight, turned it this way and that, and it submitted to my will. I laid it down and unfolded it; then I folded it back together and picked it up to take to Father. I would have forgotten about everything had her voice not stopped me in time, as I was waiting for her to do: to hear that it was really mine.

But if it could be desired at all, he deserved it most of all; he had been the first, long ago, to lose all hope.

It was thick; it looked big; it had been made for him, without a doubt. I had to give it to him; there was no reason for me to delay any longer.

"No, it's not for Father," she managed to whisper, as if she were guilty of something.

I stopped, bewildered, still holding it in my arms and blinded by its colors and warmth. I realized that I should have kept out of it or at least have known how things stood from the very beginning.

At last the poor woman had made something for herself. On the snow-covered roads of the steppe, she would have more use for it than we. I should have thought of it myself; I should remind myself how she always left-wrapped in a sack, her feet swathed in rags. Such blindness, such stupidity was inexcusable. I almost wept with mortification. I would not have wanted to let go of it; it looked soft and obedient, but if it was hers, I no longer had anything to say. I unfolded it to look at it one more time. Now it did not look so big. She had made it for herself; for once she had thought about her own needs. I turned toward the good fairy huddled in the corner of the room where it seemed to be warmer.

"The sweater is for Mara," she smiled, or wept, I do not know.

It had gotten dark, and I could no longer see her. I could not tell if she had smiled at me as I had thought, or whether she had collapsed, as sometimes happened. A purple haze fell over and around me; perhaps evening was setting in.

I should not have done it, but I remained still for a long time, with my head buried in the softness of the sleeves and body, nestled in with no intention of leaving. Through the thick layer of wool, however, the icy silence, which they could no longer stand, grew heavier; I could not even hear their breathing anymore.

I turned around and walked resolutely toward Mara. In the end I went in the direction I was supposed to, I maintain this, and deposited it in the girl's arms.

Only the next day did I look at it more carefully. It no longer looked so marvelous, first because it had been knitted only out of knots, you could

9

see that. I turned it inside out and showed Mara to convince her, knot next to knot, as though it had grown only out of odds and ends barely tied together. Then the color. It seemed to have some more red here and there, it is true, but beyond that it was a mixture; you couldn't make anything out of it. White with gray, black, a trace of yellow, a remnant of green and another, darker green; a gray stripe, a bit of rotten earth brown next to a purple plum; over there a tip of pink ham, next to it a bird's red-and-yellow beak. Of course it had not been fashioned for a girl; anybody could have seen that. But I did not tell her. Mara's position, they told me, was special, and had to be preserved at all cost.

We loved her too much; we protected her more vigorously than ourselves-that is what they always told us. I could not show her that it was too big for her, and with a crew neck like a boy's. She could have seen that for herself, after all-she was old enough-but to do that she would have had to take it off again and look at it. She was allowed everything, of course. When she asked to keep it on they let her. The first few days at least she even slept in it, completely dressed. The cold froze us both day and night, it is true, especially at night. But if you tried to dress more warmly, the same plague befell you every time: lice. Undress, wash, cover yourself with other rags, clean ones; we boiled them and checked all their seams; otherwise it was disaster. I know very well that they would not have allowed me to sleep with all my clothes on three nights in a row. Even if she was the one they watched over most diligently. The moment they heard that someone had gotten sick at the other end of the pavilions, they would start to examine her. Obsessed, they felt her forehead, her neck; they would peer into her eyes, at her hair, her nails. What panic if she should have a hot forehead or warm hands

She had to go back alive at all cost, they would whisper. She had ended up among us by mistake. What would be said if she of all people were lost, and we returned, as if we had been careful to save only our own skins? Perhaps her mother had already found out where we were and was on her way here with proof to establish the truth. The little girl had nothing to do with our curse; she was innocent. Her mother had sent her to stay with an old friend for a few weeks, far away from the hospital where she had been admitted. Caught in the fury, taken together with us, she had come as far as this. Protests convinced no one; they did not have time for clarifications. They did not believe us. Of course we too, in our own way, were innocent; everyone shouted it to keep hope alive. But the case of this guest of ours seemed much more serious to us all. If the situation were not cleared up and the unfortunate

10

girl had to be held with us longer, she had to be the last to go, in any case-everyone agreed-to outlive us all. They would whisper in corners when the little girl did not hear them; they vied with each other over who watched over her, not knowing what to do to please her and protect her from harm. I should have guessed from the beginning that the gift could only be for her, that they would let her do with it as she pleased.

Only now, on the fourth day, could I look at it calmly. A miracle, I could no longer deny it. I might have asked for it for one night at least. She would have let me have it; she would have even let me keep it, had I asked her. She was always kind to me. But it was not allowed, I knew. I could admire it without embarrassment for hours on end, however, Not even the most clever magician would have been capable of something more wonderful. The knots made it stronger, concentrating and increasing the warmth beneath while allowing the sweater to look light and smooth on the surface. As for the colors, strange islands of dye, black, green, blue, to run your fingers and eyes over and sink them deeply wherever you pleased until you came across a red palm of African sand, an ashen tip of a cloud touched by golden stripes, the sun or flowers. A whole day would not have been enough for all these continents that grew one from the other, bewildering you.

I did not have time to get bored looking at it. Nor to borrow it or wear it until I became indifferent to it. The following week Mara had cheeks red from fever, and she abandoned it, leaving it to lie alone in the corner next to the window. I looked at it; I thought about it, but I did not touch it, although I longed to.

Mara was feeling worse and worse; she was dying. Since the time my grandparents had taken ill, I knew what would happen at the beginning and later. She would die soon; they would not be able to help her. The hours when she revived, happy and talkative once more, were plain deceptions, I knew.

She would not have had any reason, then, not to give it to me. The disease would progress. The days became longer; death was drawing near, I could feel it. Frightened, I waited to see the beloved little girl suddenly freeze. I do not know if by offering it to me now as if reclaiming it could alter the natural course of events. They would have given it to me to save her, though it was not my fault that she was ill and they would not find the medicines to save her.

I was not involved in their words or sobs when they decided to bury her, together with all the things that had been hers, at the edge of the forest beside my grandparents.

11

I waited, trembling, still hoping they would forget. But Mother snatched it out of the corner and threw it savagely on top, over the other things.

They stood near the little girl a few moments more, sobbing, suffocating, holding one another close. Although she was not one of us, Mara was the first to follow my grandparents. She had become ours. When they were ready to carry the coffin out of the house, Father put his big hand above it, felt around, found it, pulled it to one side and let it fall behind him. Mother had seen; she looked at him long but said nothing. She agreed to save it.

Shivering, we returned late from the forest. It was raining, the mud stuck to our rags. Clods of earth full of water had covered 'Mara. I knew, since what had happened with my grandparents, that she would not return. I remembered how she used to huddle up against the cold with her arms around my neck. Her sudden full laugh had charmed us. Silent, we stretched out on the mud floor, where night found each of us.

I had not gone near it, did not touch it. I only stole a few glances at it, as it lay abandoned and numb in the approaching darkness. Nor did anyone tell me to take it the next day, although the room seemed to have become even colder and damper. Monday, Mother left again; that afternoon when we were alone, Father put it on my shoulders. I felt the sleeves slide over my chest; I pulled them on and put my head in its warmth. It fit snugly, as if it had been made especially for me. I would have gone out in the yard to show myself or would have walked around the room with it at least, but I did not dare. I crouched; at last I had what I had wanted for so long. I was trembling, I could no longer suppress it.

My joy, however, was short-lived. The very next day I felt it hanging limply on my shoulders. This was the signal, I remembered. It had started the same way with my grandparents and then with Mara. The sickness was stalking near; it crept in slowly, unnoticed; seeping in little by little, only to break out suddenly toward evening when those who were attacked shook, dizzy with fever, and collapsed, unable to say even a word.

The agitation would start: asking the neighbors for medicine, an aspirin at least, or a little alcohol. In the end the thermometer appeared. It was the only one in the entire camp, always kept in the same dirty patch of blanket by an old madwoman. The thermometer was hard to obtain; you had to demand it loudly. It passed carefully from hand to hand, like a talisman, until it reached the sick person. If it had broken, our last ties

12

with the normal world would have disappeared, and we still wished to be tied to it.

This time too the doctor would follow. The distinguished gentleman with slender glasses and confidence in his cures had been replaced by a tired, ragged, hunched-over consumptive. We called him doctor also; he too had small white hands, although he did not wash them at the beginning and end of his visit, as in the past. His gestures and consultations were as short as possible.

He had laid his hand on the little girl's forehead, he had looked at her fingers; then he had felt for her veins and counted the number of pulsations with his lips. He had uncovered her thin yellowish body and turned it to this side and that to show the spots, more and more of them: the disease had completely taken over the body of the little patient. There was nothing else to do but raise his hands and mutter the name of the agony, which would last only a few days more. Only if a miracle, only a miracle he raised his hands once more, limply, to beg, as did everyone, for the miracle; then he slipped out, bent and ashamed, just as he had come.

Evening was approaching; I felt the light growing more and more tired, ready to give up, and especially the bitter cold that suddenly pierced me. The evening chill had begun to settle in when I felt some' thing strange; it was as if it had abandoned me, as if it were no longer protecting me; inert and cold, it now hung exhausted over me. It must have been carrying the disease within it the whole time. It had betrayed Mara too, but she had not been able to take it with her when she died. My turn had come. I would have taken it off and burned it, thrown it out, but it was too late; that would serve no purpose now.

I would not have wanted to end up in that dark wet grave where you did not know what would follow. I admitted guiltily that I should not have pursued the colors and the warmth so impatiently. I should have controlled myself, waited; I should not have followed Mara's suffering so shamelessly, and afterward, not content until I felt it cover me. I should not have been so weak and blind, so impatient that when I had it I was overcome by tears of joy. I must have been seen, noticed for my base behavior and greed. Had I given it up, if not at the beginning, at least after Mara's death, the punishment might have been avoided.

I could take it no longer; I went to the window. Father as usual was looking through the narrow aperture of light for a miracle or a disaster. Toward evening hopelessness would overcome him; he no longer knew how to suppress it.

"The disease. The disease, I'm sick." But at first he did not hear me. He

13

turned suddenly, put his hand on my forehead, my neck. He pulled me in front of the window and asked me to count, to stick out my tongue and to open my eyes. "You're pale, very pale, but you'll be all right," he said and picked me up in his big arms to sleep.

I did not have the strength to speak. I pointed a few times to the poisoned sleeves and raised my hand toward the diseased collar, but he did not notice. It had become very dark. I was covered by his big smile as he bent over me and put his palm on my moist brow.

I woke up in a coffin being lowered into a grave next to Mara; then I forgot everything. I was shivering; day had come; I wanted to tell them that I would not make it to Friday, so there would be no one to save me. Night came; I saw nothing except a thick cloud, ever thicker, and I heard the frightened voice above.

I felt the puff of hurried breathing. "Good that I've come, I've come in time," she said. I also heard the high voice of the doctor gasping nearby. "He doesn't have spots; there are no symptoms," that is what he said: "symptoms." It sounded nice, "symptoms." I dragged the word after me; I was falling, tumbling down; symptoms, it was almost a caress. I was sliding, going down; I no longer knew anything. Wet slippery fish passed over my burning lips; they licked my ears, and I flowed with them. Now and then I shook the waves from my chest and tried to open my eyes. I saw Mara, transparent, made of wax; the sharp yellow teeth of the doctor, the grave again.

The drowning probably lasted several days, until I again heard that familiar voice. "I feel better about leaving; I'm glad it's over." I had escaped the arms of death; coming to, I staggered as I attempted my first steps along the walls, with Father's arm to support me, to the window facing the steppe, which had swallowed everything.

I managed to ask if I still had spots.

"You never had them. You weren't sick. Only a scare, that's what the doctor said. You were delirious, raving the whole time. 'It's stuck to me,' you kept saying. 'It's stuck to me,' and you tried to raise your hands."

He lifted me under my arms so I could look out the window. He gave me hot gruel. Friday morning, the steppe gave Mother back to us. "I came earlier; I told them you were sick. They gave me some lard to give you strength."

And so I gained strength; I could look at it again. Defeated, diminished, obedient in a corner, ready to serve me. But I had become some' one else. I let it wait; I no longer looked at it. They had covered me with a thick blanket; I no longer felt even a trace of cold. Everyone revolved around me, determined not to abandon me again.

14

It had shrunk smaller and smaller. I allowed it finally to embrace me, and it proved not to be so dangerous. In the time it had lain thrown rolled-up next to the humid walls, its prickly uneven hairs had softened somewhat. I put my nose, my whole face in the roughness ofthe sweater, once so soft and good, to be intoxicated with its warmth, like that of toasted bread or baked potatoes, or fresh sawdust, or the fragrance of milk, rain, leaves, the longing for pencils and apples. But it was not like that; it was more like a strange odor, of mold. Something rotten and heavy. Or only sharp, choking, I don't remember. It had blackened and dried; it was becoming a weary stranger.

We got more used to each other in the next few days; we were begin' ning to recognize each other. We were slowly finding each other again. It was becoming its old self, more and more fluffy and warm. The colors had come alive; again there was a world of dyes. Still, its nearness frightened me, oppressed me. I had wanted it to be mine alone. My impatience had hastened Mara's death! I shuddered although no one but it had found me out. I approached it without courage, weak. My arms would get tangled in it; I could not get it over my head. When at last it clung to me, already too tight, it seemed to choke me. I was no longer afraid of the sickness. Mara had taken away its power, I knew; it could not give me the sickness. Only the guilt, the terror, the embrace of the hot sleeves around my neck as the little girl tried every night to huddle next to me against the cold.

But I was getting used to it, and it had also calmed down. It no longer caught my eye to keep reminding me. It obeyed me; it served me as it faded, adapted. Often I forgot about myself; I had acquired a certain confidence.

But I did not take it to the doctor's burial; that would have been too much. It was during a terrible snowstorm; I trembled with horror and bitter cold. I had hidden it well so no one would find it. I forgot about it for quite a few days and set it free only much later, when the burials had multiplied to several every day. There were no more reprieves anywhere; there was no longer any reason to be careful. They died by the dozens; the curse fell at random, exactly on those who least expected it. They no longer had time for me, nor I for myself; the terror had become every' one's, huge, ready to swallow us all. We shrank stunned; we forgot about ourselves and everyone else.

Baseness, guilt, nothing counted anymore. It had understood that too. Its color and smell faded, allowing it to pass unobserved. It was merely functional: I took it with me every day; it protected me, that was all. It stretched out perfectly, a shield, without a hint of our former glorious

15

intimacy. We did not see each other; we defended ourselves the best we could although there was no defense. The winds of the steppes kept coming nearer to take their pick of us. Their greedy roar covered all terrors. No one could have heard a single sob, guilty and base.

Each day stalked us. We forgot the days; we waited, listening for the maddening screech of the night. Time pursued us; there was nothing left to be done. Time itself had sickened, and we belonged to it.

16

Translated from the Romanian by Cornelia Golna

Fighting Crickets

Huynh Quang Nhuong

During the dry season in Vietnam, which lasts from January to July, farmers' children catch fighting crickets and sell them to the town people. Students often bring their crickets to school and let them fight against others. When two male crickets are put together in the same box, they will sing fighting songs to threaten each other and then fight furiously. Sometimes the owners have to separate them lest they kill each other.

For three weeks a golden cricket had retained the championship at Trung's school. It was so strong and big that it either scared other crickets away or if they stayed and fought, the champion would butcher them. When Trung had the chance to look carefully at the powerful cricket, he perceived a defect. The body of the fierce fighter was too long. Consequently, the champion did not have perfect mobility when being attacked on the flank by a strong and quick opponent. No matter how strong it was, a perfect fighter had to have both strength and quickness. An adversary could attack on its side and chew off one or two legs if it was too slow in turning around. However, the formidable champion was almost invincible because it was very difficult to find another cricket possessing the same strength and also being quicker.

Trung was obsessed by the idea of getting a better cricket that could defeat the champion. The following weekend he and Hong, the daughter of Mrs. Hoa in whose boardinghouse Trung stayed, went to the rice field near the town, searching for the best cricket.

In the dry season crickets live in cracks of a dried-up field or in holes deep in the hard clay soil. If one finds a cricket in a crack, there is always a connection to other cracks, and one has to use sticks to block the escape routes. One can dig out the crack and catch the cricket gently so

17

it will not be hurt, trying to jump away. If the cricket lives in a deep hole, water has to be used to make it come to the surface.

During that weekend Trung caught several crickets, but each time after having looked at them, he let them go. When Hong asked him why, he said, "There is no use to take them home. They'll run away from the champion without putting up a fight or if they stay and challenge it, they'll get killed." Once Trung caught a particularly large cricket, and Hong thought it might do the job, but he told her it should be freed. He explained, "This one possesses a large body, but its head is small. When it opens its jaws to fight, they are not any bigger than the jaws of a medium-size cricket, and it will be no match against the champion."

Three days later Trung was awakened in the middle of the night by the trumpeting sound of the fighting song of a cricket just outside his room, in the garden. At first he thought he had been dreaming, but the song remained clear and real after he was totally awake. As he quickly got out of bed and grabbed a flashlight, the song stopped. He could not pinpoint the place from where the song had come. Nevertheless, he went to the garden and looked around with the faint hope he might find the cricket which had made the powerful sound. This cricket, like other insects, was attracted to the town by the light of the street lamps. When Trung could not find the cricket, he returned to his bed. During the rest of the night, off and on he was awake, but he did not hear the cricket make any more noises.

The powerful sound of the brief fighting song of the cricket in the garden reminded Trung of a formidable cricket he had caught three years earlier. He had once had a bamboo cage full of fighting crickets, planning to sell them when he accompanied his father to town the next day. In the morning, to his dismay, most of his crickets had died from multiple wounds. Some of them had lost their legs, and the others had their chests or abdomens opened. When his father looked into the cage, he detected a very much alive cricket, hidden at the upper part of the cage. As soon as the father took it out of the cage, he noticed that it was a quail cricket. Since Trung did not know anything about quail crickets, his father proceeded to explain to him about all the characteristics of those precious fighters. He said, "A quail cricket takes its name from the fact that it doesn't have silk wings, and as a result, its tail looks much like the tail of a quail. Without the silk wings, it depends totally on its legs, especially the hind legs, to jump away from danger. And as it uses its hind legs so often, the legs become so strong that a normal cricket, even much bigger, can't sustain its charge during a fight. If a person is

18

lucky enough to find a quail cricket, he has a future champion, unless there is another one around. The chance of getting two quail crickets in the same area is remote because for some reason, they are extremely rare." By then Trung understood that it was the quail cricket that had killed all the others in the cage. His father then added, "You shouldn't be disappointed at the loss. This fierce cricket will bring you ten times the money you could get if all the other crickets were still alive." His father then changed the schedule for the day - instead of going to town and returning home on the same day, he planned to prolong his trip a few days so that he could find the owner of the champion cricket in town; then he would let Trung's cricket challenge the champion.

After having taken care of all his business, Trung's father took a room at a hotel. In the same evening he found the owner of the champion cricket, the Chinese man who owned the largest restaurant in town. The restaurateur had bought the cricket, which was already a cham, pion, from a schoolboy. His main purpose was to attract customers to his restaurant, since most of the people who came to see the championship fight would stay and have a meal afterward. For that reason, he always staged the fights during breakfast or lunch or dinnertime. Despite the danger of having their crickets killed, people kept bringing them to the restaurant for the championship matches because if a cricket defeated the titleholder, it would become very valuable.

Late that evening Trung and his father came to tell the restaurant owner that they would like to have their cricket fight for the title. The good,natured Chinese cautioned them about the danger of losing their cricket, because the champion was the most savage and strongest fighter he had ever owned. He added that most of the time it killed the opponents before he could stop the fight. He invited them to come to the room where he kept his cricket so that they could have a look at the champion. He expected that they would change their minds after seeing the powerful fighter. When the owner opened the box, they saw a very impressive golden cricket calmly eating a piece of bean sprout. It had all the characteristics of a dangerous fighter-huge head, massive body and sturdy legs.

Cricket owners use two or three hairs stuck with wax to a tiny round stick to brush the head of a cricket, to make it angry before the fight. When the restaurant owner brushed the hairs against the head of his cricket, it stopped eating and opened its huge jaws and sang fighting songs. When the owner moved the hairs away, it walked around in the box with all its confidence and eagerness to fight. It was truly a magnificent cricket, with its bright golden wings contrasting strikingly with its

19

black-jade legs and head. Its two intact long feelers waving around proved that it was in perfect health; the feelers of a tired or sick cricket always remain still.

As Trung and his father did not change their minds, the restaurateur scheduled the fight for the next day, at lunchtime. The following morning, on the board in front of the restaurant was this advertisement: "Championship fight at noon. The young and determined challenger comes from the highlands." Around noon quite a few people had already gathered in the room where the match would take place. The arena was in an all-glass cage designed in such a way that the spectators could see the fight from different angles. When Trung opened the box and people saw his cricket, they did not give the challenger any chance at all, because the champion was much bigger. They became more disappointed when they heard that Trung had just caught the cricket the day before. Usually the challenger had won several fights before fighting for the title. It was not a rule that the challenger had to defeat many opponents, but an owner always made sure that his cricket would put up a good fight for the championship. It was embarrassing for him if it gave a poor fight, and even worse if it ran away from the champion after just hearing his threatening fighting songs.

According to the rules, the two crickets had to be transferred to the arena at the same time to avoid any disadvantage to either of them. A cricket might be a little bit bewildered after being taken out of its box. If the opponent had been put in the arena before, it might already get used to the new place and attack the newcomer before it was ready to fight.

When the two fighters were in the large cage, each at the far side ofthe arena, the champion moved around with confidence, because it had been there before. As for Trung's cricket, it remained at the same place, but its feelers waved around, trying to detect anything abnormal in the new place. Before long the two crickets felt the presence of each other, and they positioned themselves for the initial charge. The champion stopped moving, and the challenger ceased to wave its feelers and turned around to face its adversary. The challenger started singing its fighting song when the champion began his. The sound of the challenger's song was so loud that it immediately attracted the attention of all the spectators. And for many years later, Trung did not forget the sound he had heard for the first time at the restaurant. The challenger, while singing, revealed to the spectators that it had no silk wings. And without the cover of the silk wings, the lower part of its body looked very grotesque. Since most of the townspeople did not know much about fighting crickets, especially quail crickets, some of them laughed at the funny sight,

20

but none of them knew that the champion was going to fight the most dangerous opponent.

The two fighters prepared for the initial charge, because neither of them had scared the other away with its fighting song.

When a cricket charges it does not run with all its force toward its adversary, as a water buffalo does. At first it crawls with its body almost touching the ground while widely opening its tusks. The tusks under normal conditions are folded beneath the upper jaw; but when deployed during a fight, they resemble the pincers of a lobster. As a cricket comes close to its opponent, it dashes forward with all its strength, intending to knock the adversary over. The cricket with stronger hind legs has the advantage. Sometimes an initial charge is so powerful that it catapults its enemy in the air and overturns it. In this case, the fight may end immediately, since an overturned cricket can be fatally bitten in the chest or in the abdomen.

In the arena the two fighters came very close to each other. Suddenly the challenger attacked and knocked the champion backwards. The charge was so powerful that it smashed the titleholder against the glass cage. And while the champion was still stunned, Trung's cricket dashed forward, grabbed the helpless opponent, and bit it on the forehead. The champion made a few desperate jerks and then remained motionless. Things happened so fast that nobody could do anything to save the great fighter from sudden death. The Chinese man's face turned pale, as he could not believe his eyes that his cricket lay there, dead. He then took the late champion out ofthe arena to examine it. Shortly afterward he announced to the spectators that the initial charge had broken one of the hind legs of his cricket and twisted the other, and that the instant death had been caused by tusks cutting deep into the forehead. He then put the dead cricket in a small box and told his friends he would bury it in a corner of his garden. And while people looked at the new champion with incredible looks in their eyes, the restaurant owner invited Trung and his father to another room to have a drink with him. During the following conversation he expressed the desire to acquire the new titleholder in exchange for a large sum of money. Trung and his father accepted the offer, which was much higher than the restaurant owner had paid for the late champion. Then he invited them to a free dinner at his establishment. Before they left for home, Trung and his father had urged the Chinese man to keep the new titleholder in a tin box. The quail cricket with its sharp tusks might chew through a box made of clay or cardboard, to free itself.

For the next three years, whenever Trung caught a cricket, he looked

21

carefully at its tail, but he did not find another quail cricket. And the one he sold to the restaurant owner remained champion until the day it died of old age, two years later.

Three years had passed, but the powerful sound of the quail cricket's fighting song at the restaurant still remained vivid in Trung's memory. He had recognized it in a sound from the garden. He longed to show those town boys how much a boy from the highlands knew about fighting crickets. In the morning he again looked very hard in every place of the garden, but he could not find any traces of the cricket.

Three days later, while studying with Lim, his roommate, he was startled by the same sound. Then he witnessed a short but violent fight between two crickets at the window. The encounter was so brief that before he and Lim could react, one of the crickets had been smashed against the frame of the window and lay there unconscious. As for the other cricket, it had slipped back into the darkness of the night outside the window. During the brief moment ofthe fight, the victorious cricket had drawn up its wings to sing fighting songs. Trung noticed that it had no silk wings. Trung then examined the unconscious cricket, and he realized that its hind legs were twisted and its head was bruised, but it slowly regained consciousness. Finally, as it was able to move around again, Trung put it back in the garden. For the rest of the night Trung could not go to sleep, thinking about how to catch the precious quail cricket. By the next morning he had thought up a plan, and he discussed it with Hong and Lim. He told them that any fierce cricket always sought out its opponents to fight them. In order to make his plan work, after the last class of the day he would go to the rice field to catch as many crickets as he could. And during the evening he would make them sing fighting songs to lure the fierce quail cricket into the room and then shut the window behind it. After bringing home several crickets at dusk, Trung ate quickly and went to his room to prepare the trap. At first he tied two long strings to the shutters of the window so that either he or Lim could shut the window without leaving their hiding place. He borrowed the butterfly net from Hong, so that if the quail cricket were trapped inside the room, he could avoid injuring it by catching it with the net. He took this precaution since a strong jumper like a quail cricket might hurt itself when cornered. When everything was ready, Trung and Lim withdrew to the corner of their room and, in the dim light of their hiding place, each of them held a string tied to the shutter, and at intervals between study times they took turns making the captured crickets sing fighting songs by brushing

22

hairs against their heads. They kept waiting and waiting and finally Trung dozed off since he had not slept the night before and had spent most of the afternoon catching fighting crickets in the rice field. Suddenly he woke up as Lim pulled at his shirttails. His heart almost stopped when he saw the quail cricket at the window. They would have to wait until the cricket was almost a yard away from the window, and well inside the room, before shutting the window by pulling on the strings; if not, it might be able to jump back into the garden before (he window was closed. Fortunately, one of the captured crickets in the box kept singing. While the two friends were in a frozen posture, its song drew the quail cricket farther and farther away from the window, and finally Trung and Lim shut the window and trapped the cricket inside the room. Trung seized the butterfly net, crawled toward the cricket and netted it. It tried to escape but, thanks to the net, it did not hurt itself. Trung gently took the cricket out, cupped it in his hand and softly blew air at it. At the same time he made chuckling noises that resembled closely the love song of a male cricket. This calmed the upset cricket. And as soon as it started singing love songs itself, Trung carefully transferred it to a sturdy tin box. Immediately Trung wrote Hong a note: "We captured the quail cricket. We will let you see it tomorrow." He then slipped the note under Hong's door and went to bed.

Early the following morning Trung apologized to Mrs. Hoa about all the noises made by the angry crickets the night before, but she had been amused rather than annoyed by all those loud fighting songs. Although she did not know anything about the subject, she said that the quail cricket looked strong and fierce. Hong observed the cricket for a while, then agreed that its tail did look like that of a quail. Then she added jokingly that perhaps the cricket wanted to fight all the time because it was mad about not having silk wings. Lim seemed oblivious to all this talk while burying himself, as usual, in his book. However, at one moment he broke the silence by saying, "I was the one who detected the first appearance of the cricket at the window as I took my eyes off my book for a moment, whereas all that time Trung was dozing."

The next morning the other kids in the school knew that Trung had brought a cricket with him and there would be a championship fight, and they anxiously waited for the first recess. Since the boxes in which the students kept their crickets were too small to be used for arenas, they put their hands together on the ground to form the four walls of a bigger enclosure then removed their hands when the crickets started fighting. This method had the advantage of making for a longer match since there were no walls or corners against which one ofthe opponents might

23

be crushed. Consequently, the danger of the fighters being killed or maimed was also reduced. At the beginning of the first recess most of the students went to a smooth place of the school yard and formed the hand walls. As soon as the makeshift arena had thus been made, Trung and the owner of the titleholder put their crickets in it. At first the two fighters looked a bit bewildered in the new place and constantly moved their feelers. Soon they felt that they were not alone, and each became wary of the presence of the other and ceased to wave its feelers. The champion started singing its fighting songs when its owner brushed hairs against its forehead. However, when Trung tried to excite his cricket, it bit the hairs of the brush instead of singing fighting songs. Finally, when it located the champion, it moved steadily toward its opponent. The champion was forced to stop singing and face the determined challenger. Right at this moment the students removed their hands because once the two crickets had decided to fight, there was no need to prevent them from escaping. It took no time for the challenger to read the champion, but it stopped in front of its adversary instead of making the charge immediately. The feelers of the two crickets almost touched each other. Their bodies were very close to the ground. Suddenly the champion charged and succeeded in pushing the challenger a few inches backward. By now all the spectators who had witnessed the champion's previous fights knew that the challenger was no pushover. Those unsuccessful challengers had been all knocked off the ground by the first charge. Some had been courageous enough to stay and fight for a while longer, but the others had been scared to death and had run away from this terrible hit. Trung's cricket did feel the impact of the powerful attack, but its legs did not leave the ground at any moment. Besides, it did not look scared or nervous at all; instead, it used its forelegs to brush its tusks, and that was the sign of a very confident cricket during a fight. The two opponents moved closer to each other again, and all of a sudden the challenger made his own charge. He hit the titleholder so hard that the latter, despite its massive body, was catapulted in the air and landed on its back. The champion succeeded in getting back on its legs, but it was not quick enough to turn around to avoid the attack of the challenger on its flank. In a split second, Trung's cricket overturned its enemy again, grabbed it and bit its legs and body. Before Trung could separate them, the quail cricket had chewed off two of its opponent's legs and opened a huge gap in its abdomen. The champion died a few minutes later.

After the fight, students surrounded Trung to look at the winner, even though they had already seen it during the match. They disbanded

24

only at the sound of the tarn-tam drum which signaled the end of the recess. Hong did not watch the match because she did not like cricket fights. Lim as usual kept himself away from the crowd and seemed to ignore the excitement of the event. Later on in the classroom, when the teacher looked away, Hong handed Trung the following note: "Too bad that your cricket killed its opponent. Don't let it do that anymore, will you?"

The next day a rich boy at the school offered a large sum of money for the new champion, but Trung refused the offer. In the following days the same student increased the money, but Trung was determined not to sell the cricket to anybody. In the following weeks the current titleholder easily won fight after fight until it ran out of challengers. Trung sueceeded in saving the lives of all the challengers by taking them away as soon as they were overturned. Students did not witness any more good fights, but they still enjoyed seeing the other crickets knocked into the air.

One evening Trung came back to the boardinghouse a little later than usual, as he had gone to the field to release the quail cricket there. He had given freedom to the undefeated champion despite the much larger sum of money the rich student still offered him. He did so because of his fondness for the quail cricket. When Hong knew about that, she told him, "You are crazy!" Mrs. Hoa smiled at the news and said, "My late husband did incredible things like that. But it was strange, because all this made me love him more."

When the restaurant owner who had bought Trung's first quail cricket heard that the second one had been freed, he stomped the ground, scratched his head, and then gazed into the sky with a look ofdespair on his face.

25

What Peter Saw

w. D. Wetherell

The first timeless thing Peter ever saw was on August 29, 1968 at two o'clock in a humid Friday afternoon. It was in his own bedroom that he saw it, though at the time he was outside peering in, his face camouflaged by the yellow blossoms of his mother's roses. What was taking place there beside the bed was so strange to a child's imagination, so simple, so touched with grace, that he knew even then the sight of it would remain with him the rest of his life. Remembering, the 1968 part faded away, and it could just as easily have been a moment in the 1940's somewhere, or 1914 in the last twilight of the Edwardian summer, or even further back, back beyond all his history books, back to the days when Greece was taking boys with no malice in them and sticking spears in their hands and shipping them off to Troy.

The place was moveable, too. It was at his family's summer home on Cape Cod - a small house of cedar shakes and eccentric windowing set above a saltwater pond that hadn't yet been developed or spoiled. It was as remote a spot as the Cape had, and yet what he remembered most about it were those things that linked it with all the other places in the country. The beach grass, for instance, that enveloped him when he came back from one of his rowing expeditions: the way the tops intertwined themselves in golden tassels like prairie grass on the Nebraska plains. The way the humid air would be blown out all at once by an exhilarating northwest wind that had more of Colorado in it than Massachusetts. The way the pond was dimpled at dusk by feeding minnows - how the outspreading rings smoothed the water's turbulence and drew the landscape in upon itself, so that by the time the sunset turned purple their cove was as placid and self-contained as a pond on an Indiana farm.

26

It was the summer he turned twelve - old enough to get serious about two pressing ambitions. The first was to row the family's skiff all the way to Martha's Vineyard and not just the breakwater where the pond opened. The second, more universally, was to see a girl without any clothes on.

Ofthe two, he spent rather more time working on the first. By August he had gotten his biceps to the point where he could row from the dock to the breakwater in forty minutes flat. He would pause in the channel there at the end of the run, ship oars and stand precariously upright so he could stare toward the Vineyard seven miles away - a low smoky shape like a punctured cloud. Beneath him he could feel the incoming tide tugging the skiff back toward home, but at the same time he could feel the horizon tugging him the opposite way, so for that one fragile moment he was equipoised between forces and perfectly content. When the tide became stronger, he brought the stern around and rowed furiously home, working his stroke up to a pitch that nearly burst him, but which he would need in order to make any headway against the notorious Vineyard chop. The rest of the day he would spend going over his equipment list, reducing to the barest minimum the supplies he could take along.

These were as follows: Two one-gallon cans of Hawaiian Punch, to be drunk when necessary, then stowed away beneath the bow seat to serve as sea anchors in case of storm or water wings in case of swamping. An orange beach umbrella to keep the sun off his neck. A fishing line to use if the current carried him out to sea and he was starving. A bottle of ketchup to drown out the fishy taste. Five flashlights. A BB gun to use as a deterrent against gulls. Reading matter in case of boredom-comic books, but also biographies of Knute Rockne and Jim Thorpe. Matches, their ends dipped in nail polish. An Esso highway map of southern New England. Salt tablets. A gallon of antifreeze to pour on the water in case of sharks.

Fully loaded, the skiff weighed in the neighborhood of 658 pounds. It still wasn't enough, though, and on the day of the final dress-rehearsal launch, his father, in his careful inspection, thought of one last thing. "A compass," he said, frowning in the serious way he had that lent importance to all of Peter's projects. "What happens if it's foggy out and you miss the Vineyard? The next stop after that is Brazil." They went out and bought a compass that same morning, but it still put a damper on things. There were a lot of foggy days in August, and Peter didn't like the thought ofrowing all by himself to Brazil. More and more his thoughts began trending toward the fulfillment of his second

27

summertime ambition: to sneak through the pitch-pine woods that began past their driveway, then the cranberry bog beyond that, then the fence beyond that until he reached the high, concealing meadow grass surrounding the bunkhouses of Camp Merry B. Wampanoag for Girls. He had no idea what he would do once he got there. See a naked girl, he supposed. But what that meant he wasn't sure, no more than he was sure what would happen when he finally took the skiff out into the choppy waters of Vineyard Sound. At night after everyone had gone to bed, he would lower himself feet-first through his window outside, crawling past the cars and the drying beach towels until he reached the protection of the first brittle pines.

But once gained, the woods only confused him. The dark marbled shadows from the moonlight became mixed with the dark marbled thoughts in his head until he all but reeled from excitement and skipped toward the cranberry bog like a horny chipmunk. By the time he reached the bog he was completely disoriented; he tried wading across, but the mud was too thick for him; he tried circling around one side, but the bog was endless. In the end he would find the highest rise he could and stand there blinking his flashlight toward the unreachable camp, hoping by some miracle the beams would find a magic current and become X rays powerful enough to penetrate bunkhouse walls. They never did. After a while the batteries would start to wear down, and he would have to find his way home in the dark, chilled now from bog water, his pants ripped by thorns. When he came back from his rowing trips he always felt cleansed and uplifted, but these nighttime crawls left him feeling humiliated, defeated past words. He would karatechop any tree that got in his way, kick the thinner ones, scream at the top of his lungs so as not to be crushed from sheer implosion of the groin.

The last of these trips - the one he went on the night before the Gerards came-was particularly disastrous. He lost the flashlight in the bog, karate-chopped a sapling that turned out to be an iron boundary post and fell into one of the pit traps his younger brother Gordon was always setting for raccoons. By the time he returned to the driveway he was beaten and in tears. His father's voice, gentle as it was, fell across his back like the last stroke of the lash.

"That you, Peter?"

He was standing in the circle of cedar where the flagpole was, dressed in the gym shorts that were all he ever wore to bed, his shoulders as white and full as a sail.

"Yeah, Pop. It's me."

28

Peter stepped into the circle, ready to raise his hands like a prisoner turning himself in. His father, seeing the scratches on his face, the tatters of his shirt, only smiled.

"Been out for a stroll, have you?"

Peter thought fast. "I was out checking the oyster traps."

He wasn't sure why he said it. There were no oyster traps in the pond, not even any oysters, but it was the first thing that came to mind. His father nodded at this in his grave, thoughtful way. Peter could have told him he'd just gotten back from Uranus and he would have nodded. Perhaps because his own life had been filled with so many disappoint, ments, he was the kind of man who understood the correct proportions of dreams.

"I couldn't sleep myself," he said, gesturing vaguely toward the house. "I've been awake violating one of our rules. I was listening to the news."

There was an actual list with these rules, pasted to the refrigerator door where guests couldn't miss it. The first rule was about not mixing burnables with non-burnables in the trash; the last rule forbade academic gossip at the dinner table or in the boats. Not listening to the news was somewhere toward the middle of the list, just before the one about not complaining about the rain.

"You listened to the news?" Peter said, putting all the accusation in his tone he could.

"Yep. The entire five minutes. I listened out on the porch where your mother couldn't hear. I've been doing it all summer."

Strange as his confession was, what he did next was even stranger. He crossed over to the flagpole and started unfastening the rope from its metal cleat.

This flagpole was the highest on the pond, a proud varnished thing of genuine beauty. His father had carved it himself from a white pine that had come crashing down on the roof during Hurricane Carol back in the fifties; the flag that flew there was the old kind with forty-eight stars, and they kept it flying night and day in defiance of all convention.

It only took a moment to loosen the rope. The pulley on top made a squeaky sound, then warbled like a bird. His father, staring upwards, lowered the flag until it was halfway down the pole, tied the rope back around the cleat, then-after hesitating-added two knots more.

"There," he said. "I think we'll leave it like that for a while." He rubbed his hands on his shorts like a man who has just finished a heavy piece of work, and put one of them on Peter's shoulder. "All set now, son? We'd better get some sleep in. We'll need all our energy for the Gerards."

Peter's first thought when he woke up in the morning was that the

29

entire episode had been a dream. But no-when he rushed outside to check there was the flag at half-mast where his father had put it. It didn't look airy and perky like it usually did. The fabric, wet from ground mist, clung listlessly to the pole.

In a way he couldn't understand, the lowered flag seemed to set the mood for the entire day. Over the pond the fog was heavy and lifeless, pressed down by heat. The crickets back in the meadow sounded labored and slurred. Socrates, their Labrador, had already dug a hole for himself in the cool dirt behind the bulkhead. It was going to be hot, brutally hot. His father was rigging a tarpaulin over the patio to keep off the sun. His mother, her face dabbed in mayonnaise, was mixing chicken salad in the deep green bowl she only used when they had guests.

There were a lot of these each summer. His father liked to have the younger faculty members down; his mother was always inviting her French majors, so there were few days when the lawn and beach weren't noisy with happy sounds. Most of these guests were in their twenties, athletic and handsome. They would overcrowd the sailboat and laugh when it capsized; there were furious games of water polo that churned the water into froth. And while Peter still thought of his future as something distant, something that had to be rowed to or snuck up on and only achieved with tremendous effort, they were on the very edge of their destinies and bright with it - bright and sunny and wet.

The Gerards were in a different category altogether. What this category was, it was difficult to say. "Our distant relations," his father said, and left it at that. "Those poor people in the truck," was how Gordon put it, snobby at seven. "A good Catholic family from Providence," said his mother, shaking her head in a way that managed to combine nine parts admiration with one part distaste.

It was this last phrase that summed them up best. The Gerards were Baptists, not Catholics, but there was a generosity about them both in number and in spirit that was reminiscent of the huge, fiercely loyal Italian families in the North End. Aunt Alice had already given birth to four kids by then, and there would be another three before she was through. She had a bosom as wide as Kate Smith's, a laugh so deep it could make your ribs rattle and a total disregard of what you did or where you were from or anything except whether or not you were the kind of person who could look life in the face without flinching.

Uncle Norbett, perhaps because he worked bottling Coke all day, was much quieter-the kind of man who liked to wear green work clothes even on his days off. As a boy, he had worked as a logger in Maine, and

30

knew the names of every tree just by examining the bark. He was always chiding his wife about something or other, acting as the gentle brake on all her enthusiasms; "Now Alice" was his favorite phrase. The two of them were always holding hands with each other or with one or more of their kids. The Gerards were the kind of family that even then was almost extinct-the kind that presented themselves to the world not as separate individuals but as one unseverable chain.

They arrived at eleven, just as the heat became unbearable. Socrates heard them first-he barked once for form's sake, then ran off to hide in the garden. A moment later their horn could be heard as they pulled off the macadam onto the dirt, and a moment after that Gordon, posted as lookout, came tearing down the driveway pursued by a vast cloud of dust.

''They're here!" he yelled, though it was hardly necessary. ''Mom! Pop! They're here!"

The horn beeped louder, there was the sputtery clanking noise of bad gears being thrown into neutral and then around the driveway's last curve in a shimmer of heat waves coasted the Gerard's orange van.

Their arrival was always the same. Before the doors were opened, before the van had even stopped, the kids were squirming backwards through the windows, so there were a good fifty yards between the spot where the first one landed and where the last one tumbled out. They immediately gathered themselves into a swarm and set out for the beach, not to be seen again until lunchtime. Norbert, waving his porkpie hat, jumped out the driver's seat and trotted around to help Alice down. She had remarkable daintiness for a woman her size, and held her hand out to him with all the dignity of a Fijian queen. Once established on the ground, she immediately swung her arms open, ready to embrace the first thing that came into reach.

It was Gordon this time-at the sight of her smile, all his snobbiness melted away. A moment later Peter's father was there, then his mother, and there were kisses all around and handshakes and the quick unpacking of hampers, coolers and kegs.

"We've brought some hamburg," Alice said, holding out a basketballsized wad of wax paper. "Throw it right into the chicken salad, Barbara-Norbett likes his substance. Here's some watermelon to go into the icebox. David, you're handsomer and more distinguished every year. That beard suits you. Where's that pooch gone off to, I've brought a bone. Socrates! Now don't say anything but I've baked some pies and later we'll go out and get ice cream to put on top. Wipe that smile off

31

your face, Peter. Haven't you ever seen a fat woman perspire? Now get busy and help your uncle unload those chairs."

It was because there was no refusing one of Alice's commandsbecause he stood toward the back of the van, reaching in to pull out the last supplies-that Peter turned out to be the one to see them first. But even Peter, quick as he was, didn't see them actually descend. They were just there - there like people on a police lineup or a slave platform are there, without any preliminaries.

They held hands and faced him, smiling bashfully. The girl was about nineteen, pretty in an average sort of way, with blond hair piled over her head like a swirl of banana ice cream. She had on a white blouse that was feminine and soft-looking: below it was a miniskirt that showed off two crusty, angry red knees. Seeing Peter stare, she dropped her eyes to the ground, tucked her head into her shoulder and began very carefully to scratch.

The man was about the same age. Like her, he was the kind of person your eyes could slip right off without seeing. He had acne. He had red hair cut short in bristles. His complexion, like hers, was unhealthily pale-the white of the generic cartons that were just then starting to show up on the supermarket shelves.

So it wasn't anything about his looks that captured Peter's attention, it was what he was wearing. Not the Levis that might be expected, not the shorts or bell-bottomed cords. This average-looking man of average height and average weight and average probably intelligence had on baggy green army fatigues that - after billowing out around his waist like bloomers - bunched in tight to his calves and disappeared into the blackest, shiniest, hottest-looking combat boots Peter had ever seen.

Seeing their polish was like watching a light flash on. It was the only thing about either of them that possessed any vibrancy or life.

"Hey," the man said, with a trace of a drawl. He looked down at his hand to see if it was dirty, rubbed it vigorously on his belt, then stuck it out in Peter's direction. "Danny Doe like in John?" He tilted his head the barest minimum. "The wife."

The girl was looking up at the trees like someone seeing skyscrapers for the first time. Realizing she'd been introduced, she stuck her hand out, too, and opened her mouth just far enough for Peter to see she was chewing purple gum.

"Hi ya," she said.

Around on the other side of the van things were finally sorting themselves out. Aunt Alice, who liked billowy dresses and always seemed a step ahead of her own blur, came over to formally introduce everyone.

32

Peter wasn't sure, but there seemed to be something hesitant in the way she did this; finishing, she stood back and watched them like a matchmaker anxious everyone should get along.

"These are the Does," she explained. "Doreen is Gouger Rogowski's cousin twice removed, you remember Gouger don't you, David? That makes her my third cousin, if that still counts. She lives in Cranston, or at least she's going to now. And this," she said, worry creeping into her tone, "is Danny Doe. Danny's a private in the Army, from South Carolina originally, right, Danny? He's on leave so we can't stay very long. Danny and Doreen, I want you to meet our other cousins, the Shrivers."

The Does smiled, passively, and moved a step closer together.

"It's all right we brought them along, isn't it, Barbara?" Alice asked. "I would have called, but it all came about very suddenly."

"Of course, of course," Peter's mother said, frowning the way she did whenever she was computing portions. "Uh, would they care to go for a swim before lunch?"

Danny mumbled something in Alice's direction. "They don't swim," Alice said.

"Oh. Well, would they care to lie out in the sun then?"

Danny mumbled something again. "She burns," Alice said. "Oh," Peter's mother said. "She burns."

Everyone would have stood there forever if it weren't for Peter's father. He waved his arm around in a gesture that took in everything and made his voice turn hearty.

"Well that's fine then and you two make yourselves right at home. We have the hammock all rigged up. There are plenty of beach chairs around. Peter will lend you his fishing rod, if you don't mind catching snappers. We're glad you're here and if there's anything you want, just give a yell."

His father was hard to resist when he spoke that way. The Does walked slowly in the direction of the water, as if his hand were on their backs pushing. By the time they got to the stairs leading to the beach they had stopped again. They stood there holding hands, looking down to where the Gerard kids splashed in their floats.

Under normal circumstances Peter would have been down there with them, showing off his skiff. But so unexpected was the Does' appearance there, so out of character Alice's worried tone, that he lingered behind hoping to get some more information.

It was Alice who explained things, talking quickly in case they came back. The Does had only been married eight weeks, she said, Doreen

33

having met him when she had gone down to Georgia to visit her brother Mark in basic training. They had lived for a while on base, but with Danny due to be shipped out any moment, she had moved back to Cranston to her folks'.

It was the next part of the story that was extraordinary, at least to Peter. Danny, having just graduated from advanced infantry school in Oklahoma, was in the middle of a twenty-four-hour pass that had started twelve hours ago back in Fort Sill. By hopping a transport to Chicago, then a regular shuttle flight to Boston, then a Trailways bus, he had managed to reach Cranston at ten that morning in time to surprise Doreen just as she was climbing into the Gerards' van for the drive to Cape Cod - a drive that was originally intended to cheer Doreen up. There was a transport back to Oklahoma leaving Otis Air Force Base at four o'clock in the afternoon. Danny would have to be on it or risk going AWOL.

Two things about this story mystified Peter. The first was that a man would travel 4,000 miles to spend six hours with a girl like Doreen. The second concerned the word Alice had used when she told them where he was being shipped out to. She had said it quickly the way his mother did whenever she lapsed into French-quickly, in a blur of unintelligible syllables that left Peter groping. Where? he wanted to say, but Alice was already past it onto something else.

"There's no bus to Otis, is there? We'll drive him then. Doreen was so surprised to see him I thought she'd faint. Time for lunch and a swim and we'll be going. But it's good they got together even for a little while." She hesitated - her face, usually so vibrant, was as limp and heavy as the flag. "Things being what they are, that is."

No one said anything when she finished; everyone turned to stare toward the cove. Instead of going down to the beach, the Does had walked toward the trees that began there on the cliff's edge. They were scrub oak and maple, mostly-green and inviting from the distance, but littered with poison sumac and thorns. The Does started in anyway; Danny pushed one of the branches out of their way, then quickly drew back his hand, stung. They both took a step backwards with that. They stood peering into the shrubbery like children on the marge of an impenetrable jungle.

"What time is it?" Peter's mother asked.

Uncle Norbett squinted down at his watch. "Eleven thirty-five."

"They're welcome to use the boats," Peter's father said. He cupped his hands around his mouth. "You're welcome to use the boats!"

34

The Does remained where they were, staring into the woods. Alice, without losing her worried expression, forced out a laugh.

"Here we are standing out in the hot sun like somebody's concrete statuary. David, I want to inspect your garden. Our eggplant is mushy this year. Peter, you go down and see my babies don't drown. Norbett, there's your hammock sitting ready for use. Say what you want to, there's no place like the Cape on a nice summer day."

For a while after that things were normal. His mother busied herself getting lunch ready, Alice went around inspecting his father's latest improvement and Norbett fell asleep beneath the apple tree just as he did every year. For a while it was easy to pretend there was nothing different about this visit than any of the visits that had corne before, but then Peter would look up and see the Does standing by themselves on the lawn holding hands, and feel a strange prickly sensation on the back of his head that left him feeling irritated and confused.

There was an old Wilson football lying abandoned in the grass. Danny, after staring down at it for five minutes, picked it up and threw it in a clumsy spiral toward the bird feeder. When it landed, he went over and threw it back toward the clothesline. Doreen walked with him between throws. Except for this and going over to stare into the trees once in a while, they did nothing else until lunchtime.

They ate on the patio beneath the tarpaulin his father had rigged for the sun. As shady as it was, the air was lifeless and it was an effort just to pass around the various dishes. The Does ate with the same shy, slow motion they did everything else in. Peter, sitting across from them, watched in fascination as they poured ketchup over their coleslaw and stirred with their forks until everything was red.

"Can I ask you something?" Danny said, leaning over. He lowered his voice and clamped one eye shut in a wink. ''There any snakes in those woods back there?"

Certain questions startle a lie out of 'you. "Yes," Peter said, though there weren't.

Danny's frown, already droopy, sagged even further. "Told ya!" Doreen said triumphantly, but her expression was crestfallen, too, and after a few listless tries they put their forks down and sat there like kids waiting patiently to be excused.

Up the table, the others were already finishing. The ice cream was brought out, served, then gulped down before melting; Norbett took a carving knife and sliced apart the watermelon in a dozen quick whacks. Lunch with the Gerards was usually a noisy, drawn-out affair lasting

35

half the afternoon, and here they were pushing back their chairs ten minutes after they'd sat down.

"Everyone's acting nuts today," Peter mumbled. No one heard him. On the edge of the patio was a redwood chair with an umbrella mounted on the back. Danny stood beside it saying something to Alice, who looked off toward the water and bit her lip. Not right then, but a few minutes later she came over to where Peter's mother was wiping off the picnic table with a wet paper towel.

"May I ask a favor, Barbara?" she said, in an oddly formal tone. "Danny and Doreen are a bit tired out after all the excitement. They wanted to know if it was all right for them to take a nap somewhere."

"A nap?" His mother's eyes met Alice's and something was exchanged there too quickly for Peter to tell what. "There's Peter's room. They can have that, I suppose. We haven't gotten around to insulating the ceiling yet. This time of day it's hotter than an oven."

"Oh, that's O.K.," Alice said. "They just want to take a nap, just a short one."

The conversation was normal enough, but both women seemed relieved when it was over. Alice went back and said something to Danny; Danny turned and said something to Doreen. A moment later they disappeared through the screen door into the house, holding hands with each other but differently than before, tighter somehow, higher.

"Just a little nap," Alice whispered, watching them trudge off. "We'll give them an hour, then it will be time to go Hey!" she yelled, as ifthe thought had just struck her. "I don't know about you two, but I'm dying for a swim."

A swim for Aunt Alice meant wading around the shallows with her dress bunched up around her waist. But at least it got everyone moving again. The water felt like hot alphabet soup, one of the Gerard kids thought he saw a jellyfish and Gordon cut his foot on a shell, but for an hour or more they all went through the motions of a good time.