Three recent TriQuarterly contributors have been honored with Illinois Arts Council awards worth $500 each: Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer for his review of Evan S. Connell's book, Saint Augustine's Pigeon (TQ #56); Alan Shapiro for three poems (TQ #58); and John Stewart for his story, "Community Center" (TQ #58).

Two works published recently in TriQuarterly have been chosen for inclusion in the Pushcart Prize Anthology IX: Tadeusz Konwicki's excerpt from his novel, A Minor Apocalypse (TQ #57, Vol. 1) and William Goyen's essay, "Recovering" (TQ #58).

Guild Books of Chicago gave a publication party for Chicago (TQ #60) on August 10, which was attended by many of the writers whose work was published in that issue.

On August 16 Chicago radio station WFMT-FM broadcast excerpts from "The Writer in Chicago: A Roundtable," which appeared in TriQuarterly's special "Chicago" issue (#60).

TQ has received grants from the Woods Charitable Fund, Inc., and the Lloyd A. Fry Foundation in support of the symposium of writers November 9-10, "The Writer in Our World," meeting in Evanston to discuss questions related to contemporary imaginative writing and American society.

A benefit for TriQuarterly was held October 20 in Chicago. The party celebrated the magazine's twentieth anniversary, and honored the writers and photographers published in TQ #60.

Choice Magazine Listening, the periodic audio anthology for the blind, the visually impaired and the physically handicapped, has selected a poem and two stories from TriQuarterly for inclusion in upcoming issues of its publication, CML-Poet Bruce Weigl's "Snowy Egret" (TQ #59), Gayle Whittier's "Turning Out" (TQ #59) and Maxine Chernoff's "Bop" (TQ #60).

Editor Reginald Gibbons

Executive Editor Bob Perlongo

Managing Editor Joseph LaRusso

Fiction Editor Susan Hahn

Special Projects Editor Fred Shafer

Design Director Gini Kondziolka

TriQuarterly Fellow Greg Meyerson

Editorial Assistants Brian Bouldrey, James Bryant, T. R. Johnson, Sheelagh McCaughey

Advisory Editors Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Elliott Anderson, Terrence Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Elizabeth Pochoda, Michael Ryan

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART, WRITING, AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED IN THE FALL, WINTER, AND SPRING AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, EVANSroN, ILLINOIS 60201.

Subscription rates-Individuals: one year $16; two years $28; life $100. Institutions: one year $22; two years $40; life $200. Foreign subscriptions $4 per year additional. Single copies usually $6.95. Sample copies $3. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterlv, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 1735 Benson Avenue, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Phone: (312) 492-3490. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry, and literary essays. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterlv, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1984 by TriQuarterlv. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America.

National distributor to retail trade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Central Street-Rear, Nudey, New Jersey 07110. Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2929 Fifth Street, Berkeley, California 94710. Midwest: Bookslinger, 213 East Fourth Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101 and Prairie News Agency, 2404 West Hirsch Street, Chicago, llIinois 60622.

Reprints of issues #1-15 of TriQuarterlv are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, New York 10546, and all issues in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106. ISSN: 0041-3097.

Publication of this issue of TriQuarurly is supported in pan by the llIinois Am Council.

Fall 1984

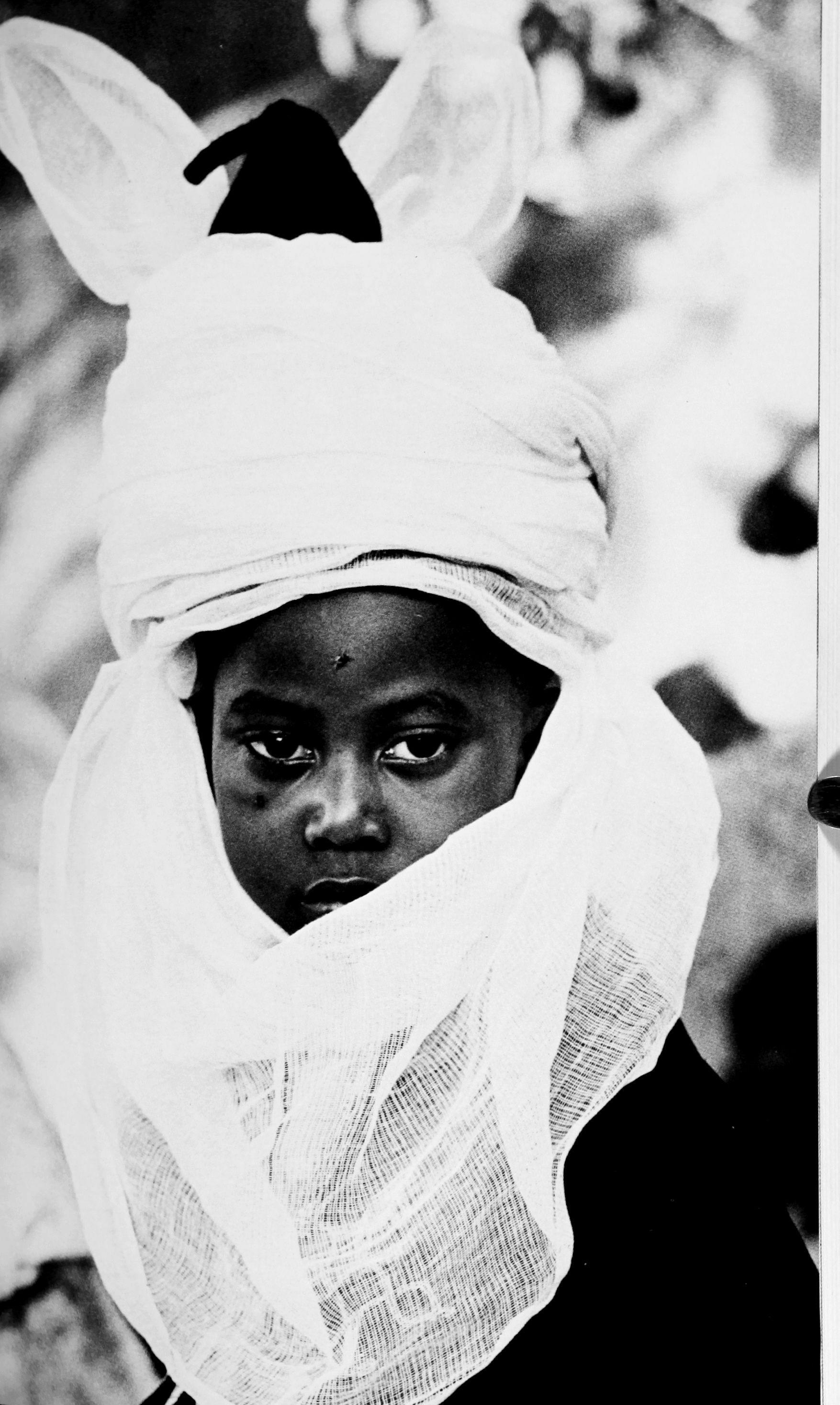

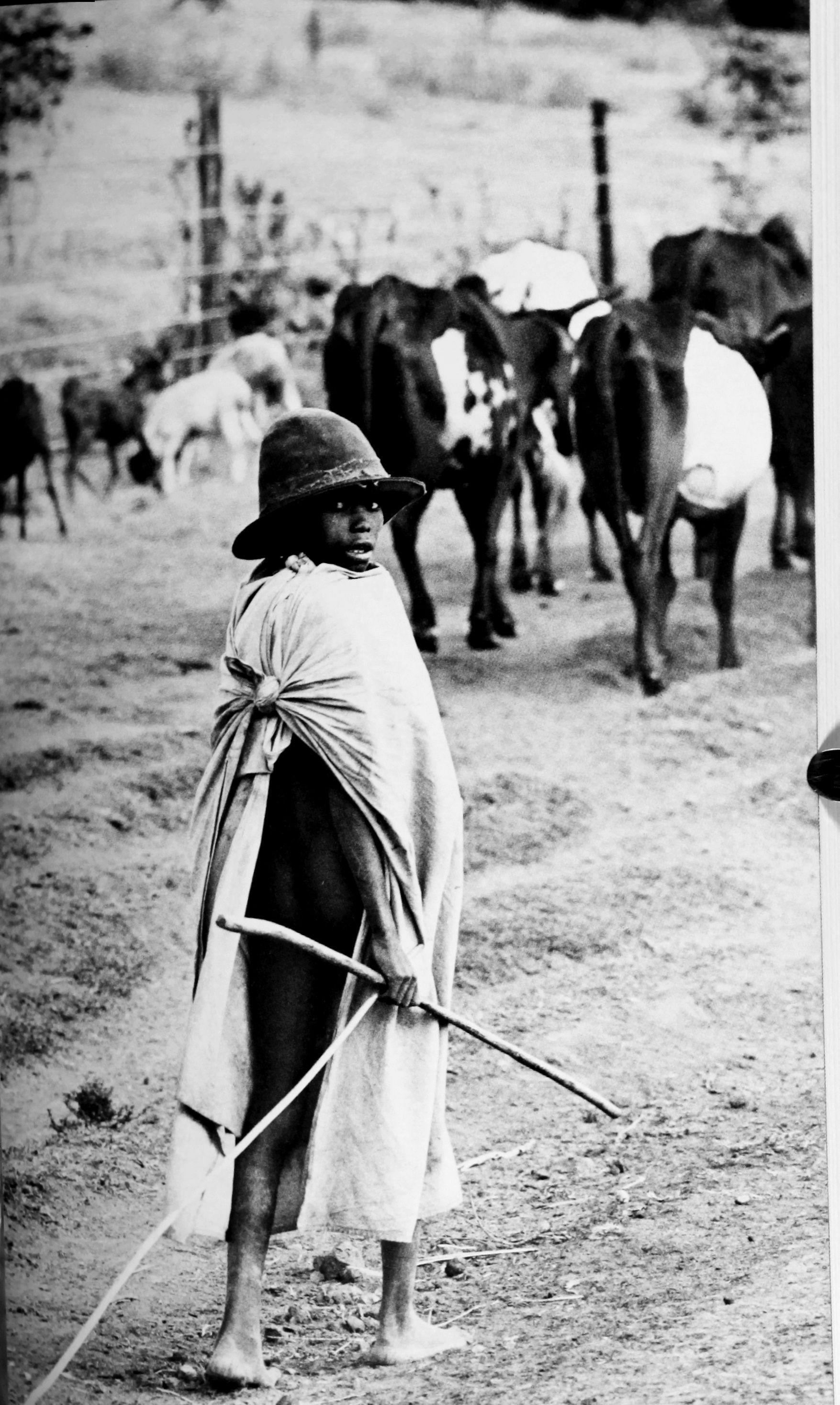

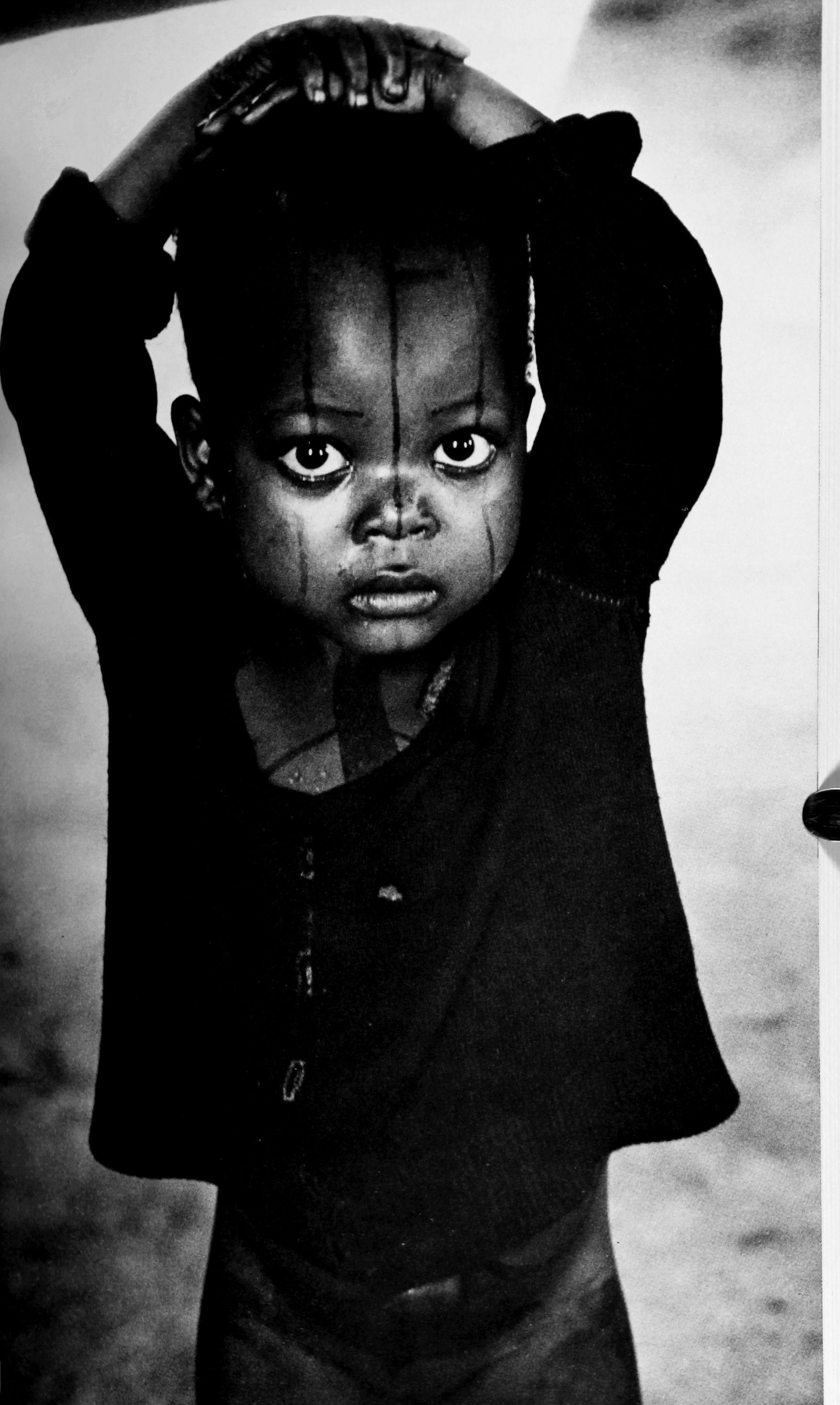

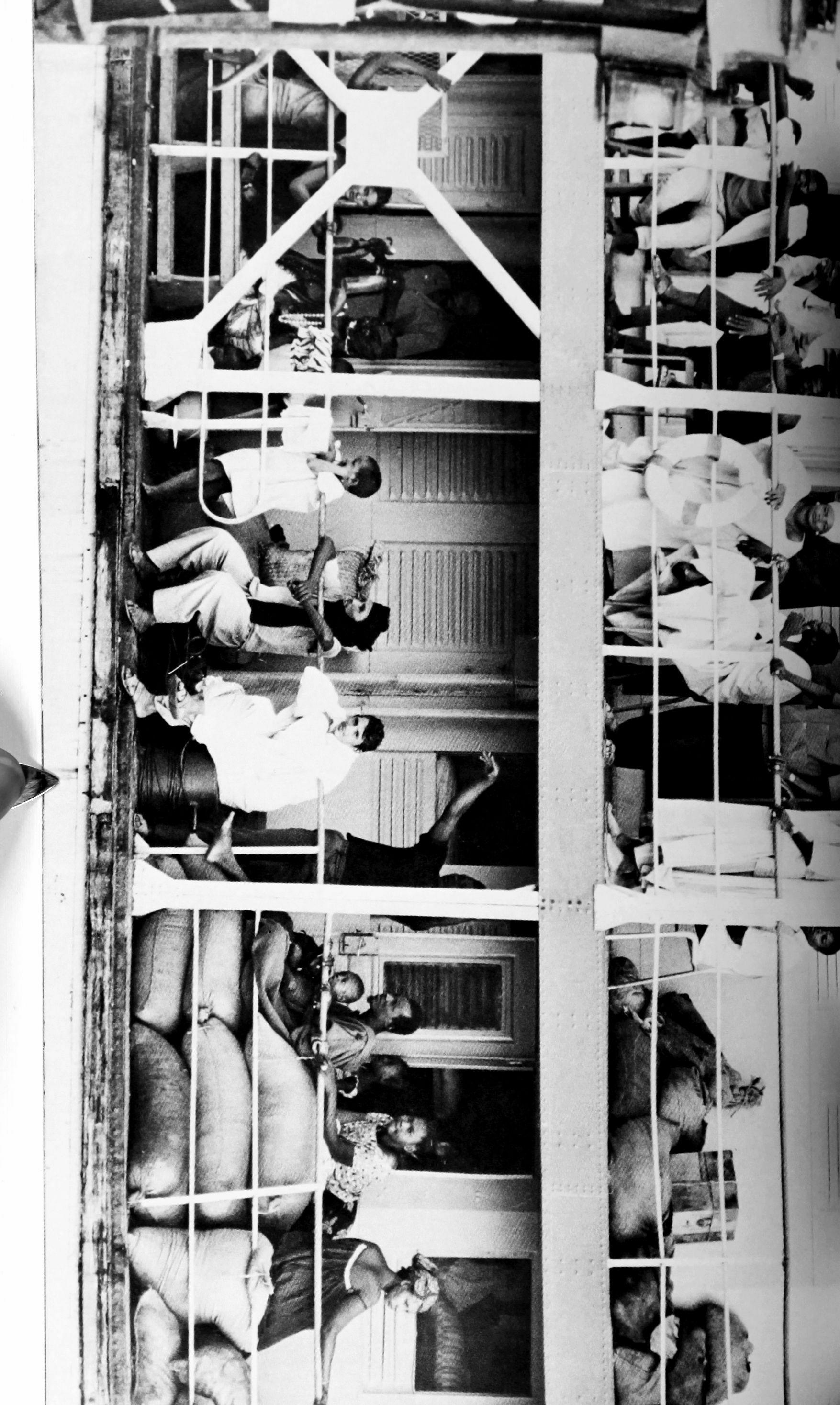

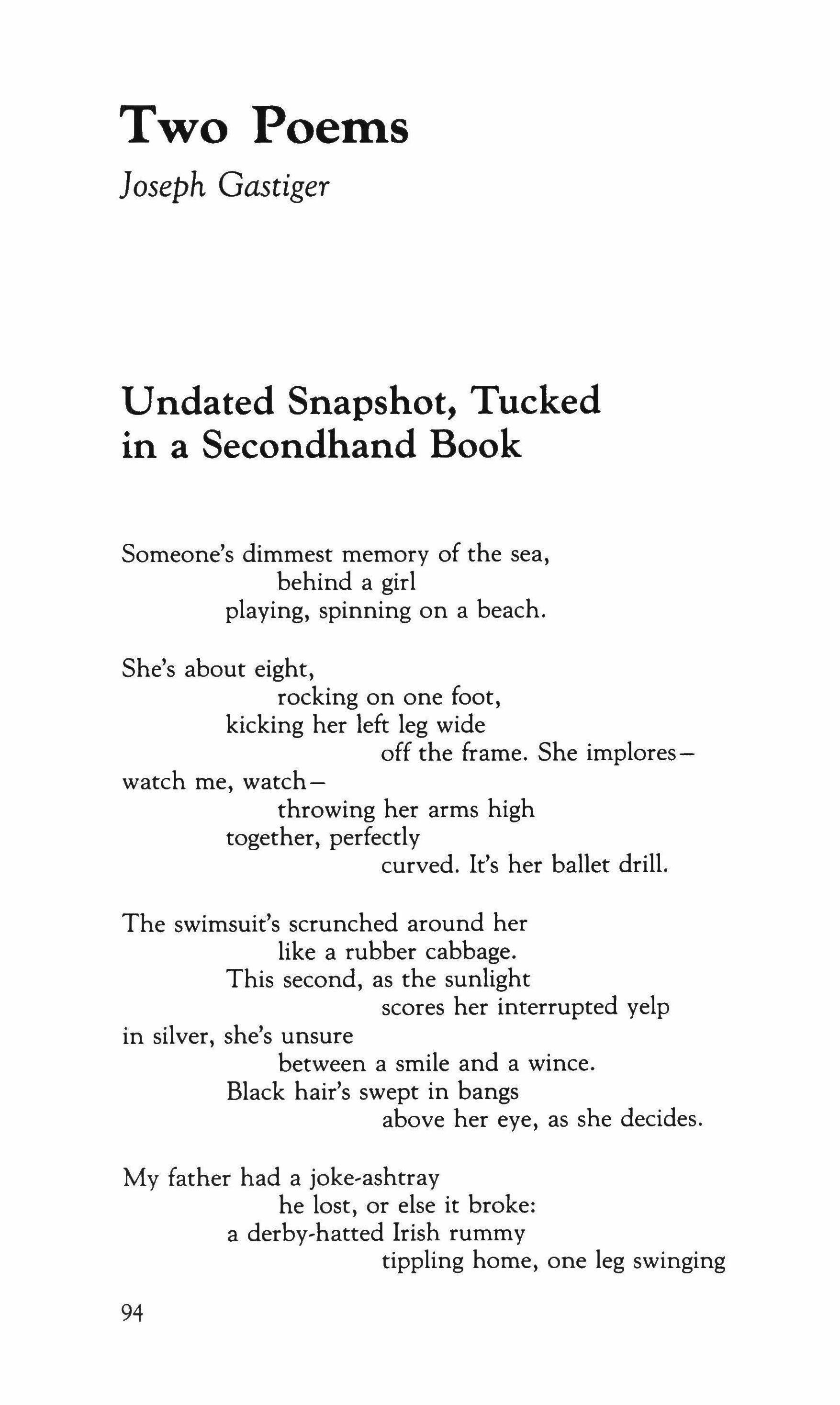

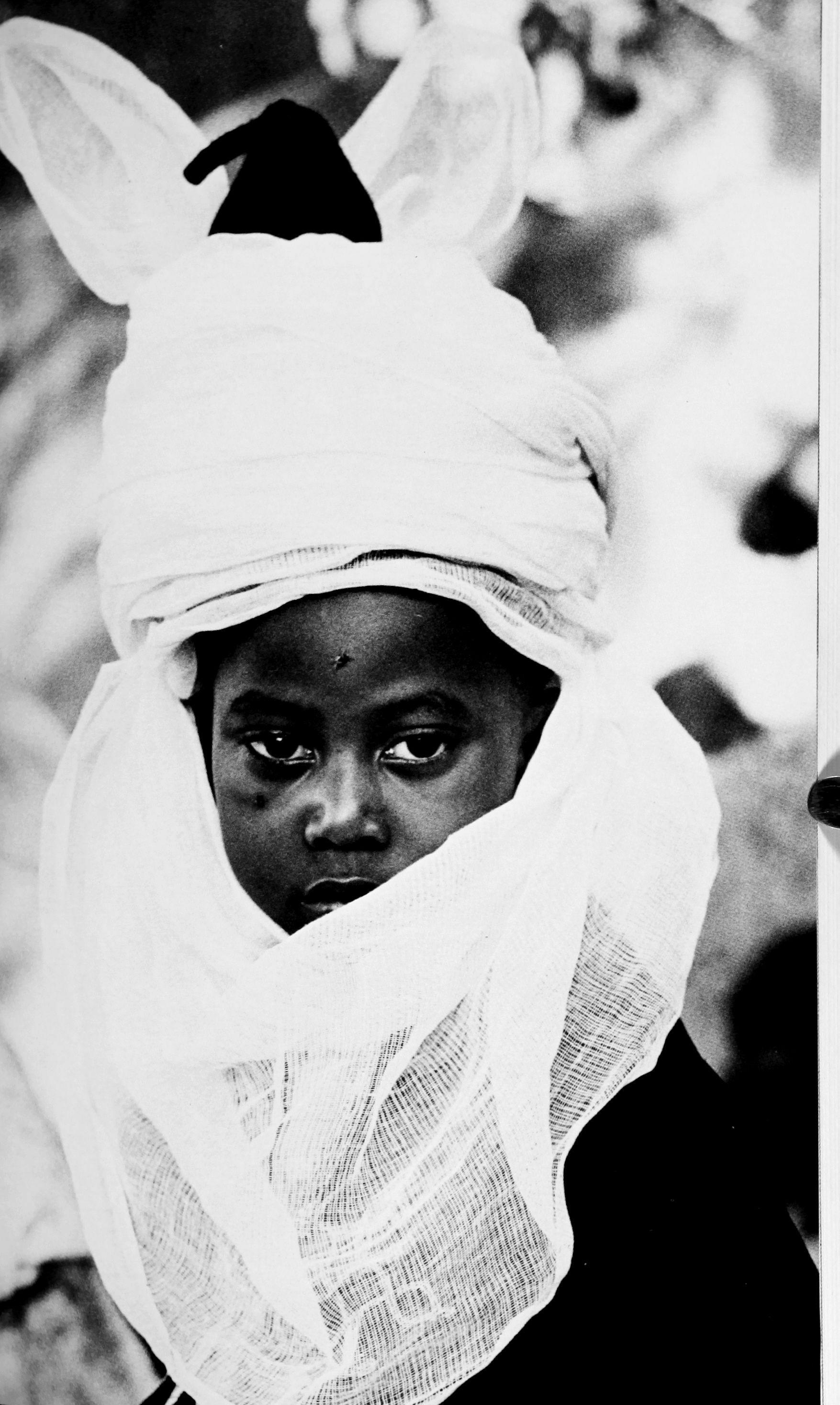

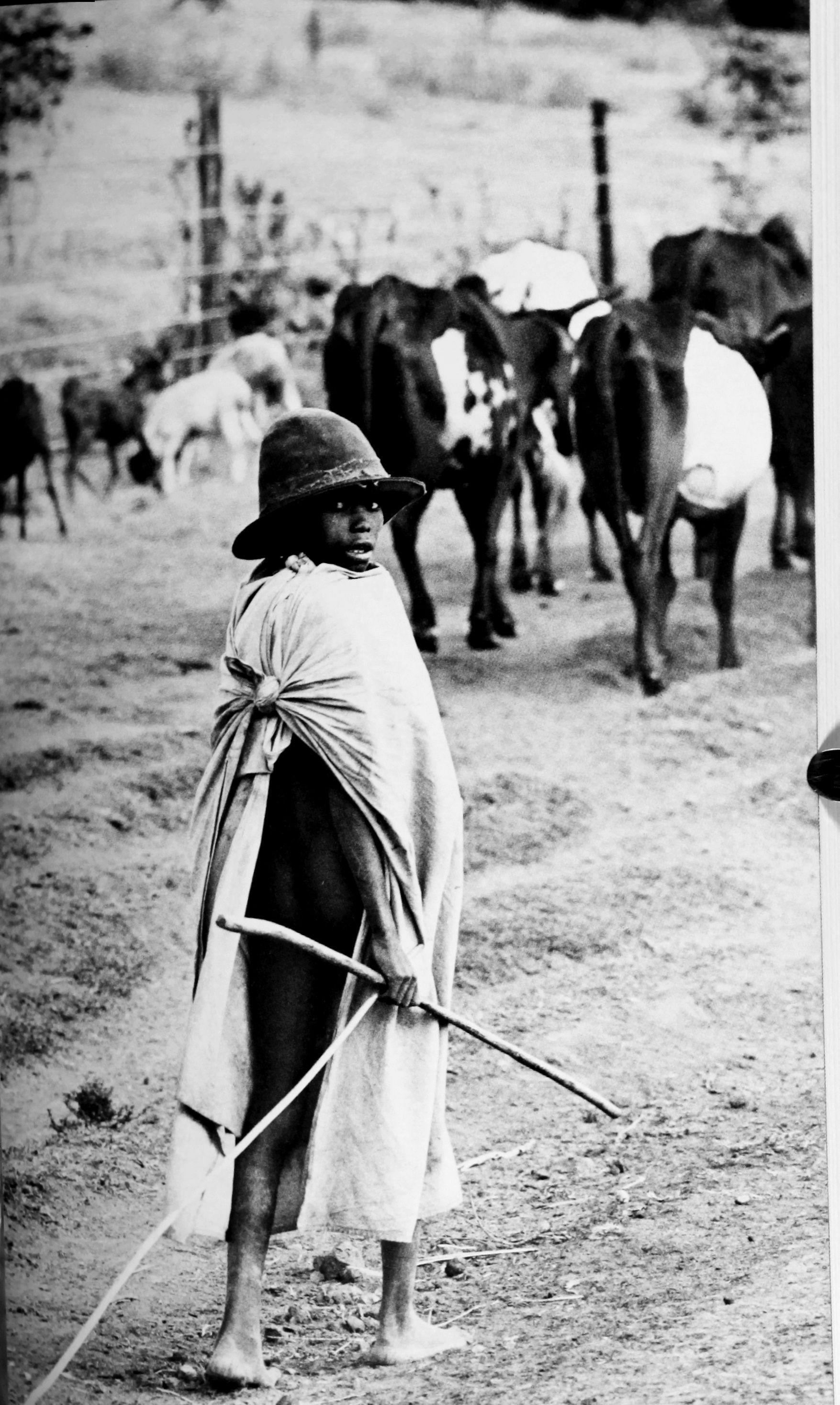

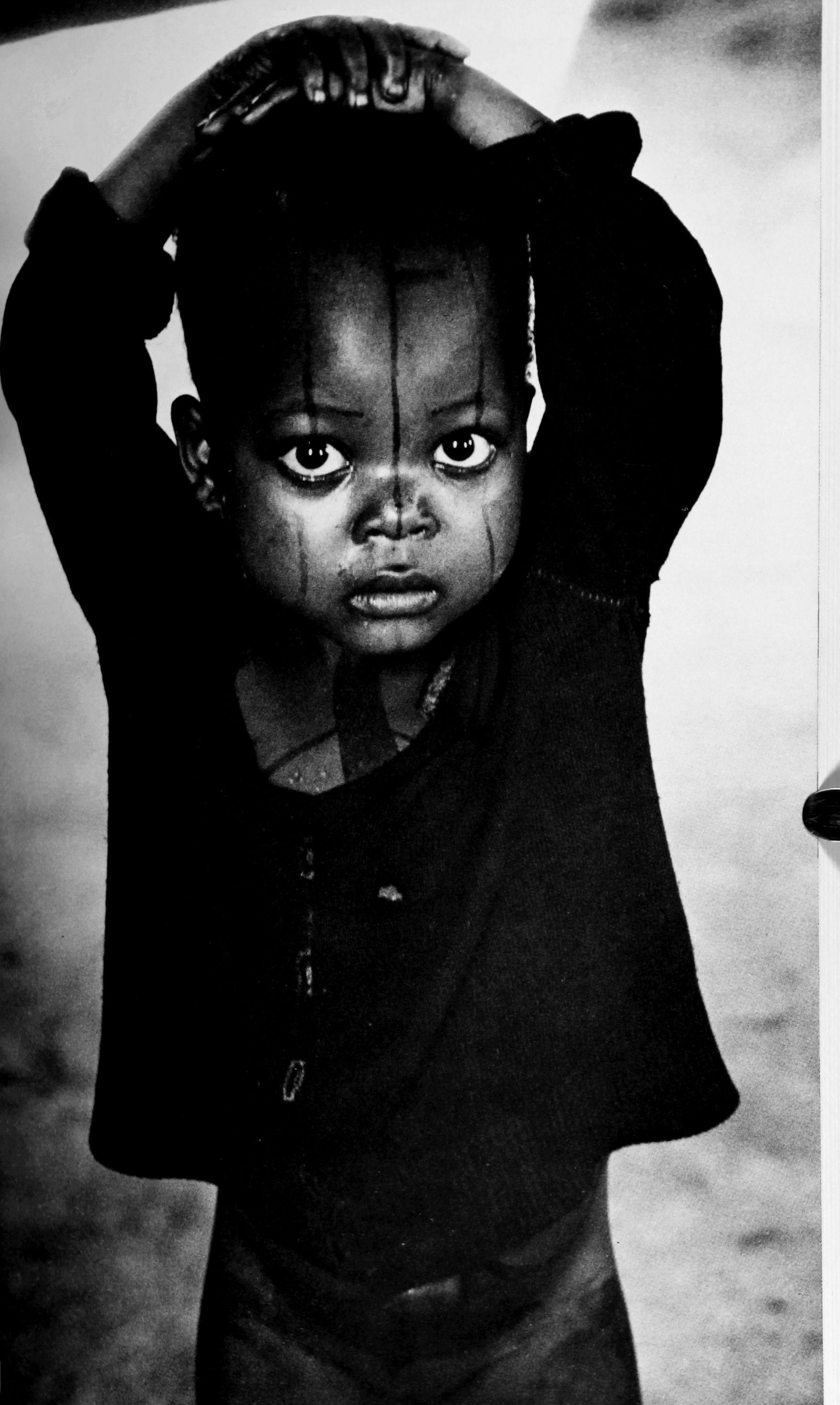

Contents Two Stories 7 Dino Buzzati House Snake (poem) •. 15 Reynolds Price The Chandelier (story) ••••••••••.••••••.•.• 27 Gregory Orfalea Two Stories 37 Marga Minco From A Wilderness Called Peace (Excerpt from Novel) •..••.•••••••.••.••••• 51 Edmund Keeley The Dead Alive and Busy (essay) ••••••.•••.• 62 Alan Shapiro Three Poems 71 flayden <:arruth Three Poems 75 Linda Pastan Five Poems 80 John Peck Two Poems 89 Paul Mariani Two Poems 94 Joseph Gastiger African Photos, 1968 ••..•. � ••..•.•.•.•.•• At 96 Denis Cameron Two Poems 97 Carole Oles Sleeping Beauty (poem) 99 Stacy Doris Three Poems 100 flans Magnus Enzensberger Two Poems 103 Michael Knoll Two Poems 105 Gerald Mc<:arthy Like Hunger and Thirst (essay) ••......••.••• 108 Josephine Jacobsen Two Poems 118 Josephine Jacobsen Three Poems 121 Brendan Galvin 4

Two Stories 125 Stephen Dixon Winter Love Story (story) 134 Martha Bennett Stiles The Oddment Man and the Apocalyptic Beasts (story) 145 Eugene K. Garber Hippopotamos (story) 154 Meredith Steinbach Three Stories 190 Kobo Abe Contributors 202

5

Cover design by Gini Kondziolkalphoto by Denis Cameron

Two Stories

Dino Buzzati

Duelling Stories

The old doctor Nunzio Toro, an exceedingly intelligent and genial man who is nonetheless thought dangerous by some people, loves to enter, tain his friends with a game he calls "duelling stories." One person begins a story, another intervenes, developing it however he likes, then the first takes another turn, and so on. A player cannot of course prepare his story beforehand: if he did, that would be cheating, and the entire thing would turn into a joke. All the same, Toro is always the one who, one way or another, determines the course of the narrative.

Here is an example. He and I are sitting on the porch of his house in the country. It is six in the evening, on a restless day with the sun going in and out of the clouds. As usual he goes first:

An elderly married couple, well-dressed, sad, are talking about their son, who has taken a job in Peru.

"I don't know," says the husband, "the more I think about it, the more I worry. It'll be an unpleasant surprise for him."

"Why unpleasant?"

"Because he doesn't know we're coming, and we'll be a bloody nuisance to him."

"With that immense house he's let!"

"It doesn't matter. You forgot there's his wife, and his wife's family."

"We should've written ahead."

'That's a bright one. Then he could've written right back and told us no."

"Fancy you! Frank is generous. He adores us. You'll see, he'll be happy to see us."

Excerpted from The Siren: Selected Scories of Dino Buzzati. Translated by Lawrence Venuti. Copyright 1984 by Lawrence Venuti. Published by North Point Press and excerpted by arrangement.

7

"Enough. Now it's your turn."

I continued:

While these two were talking, a little distance away, a priest was busy writing up the speech he would deliver tomorrow as the inaugural address for an international geophysics conference. It is Monsignor Estogarratz, the noted seismologist, although today, to tell the truth, he is considered past his prime. And he knows it. He also realizes that his appointment as chairman of the conference is due to the support of the "old guard," men like Dorflinger, Stoliepkin, Estancieros, Mandruzzato. And of course his speech cannot disappoint them; if it does, it would be a terrible show of ingratitude. Yet the. monsignor believes that his speech shows him to be an adherent of certain avant-garde positions, especially those concerning innovations in the rates of compensation. On the second page, in fact, there is a problematic passage that-

Nunzio Toro's eyes are sparkling.

"Marvelous!" he interrupts me. "The monsignor is an inspired idea. You seem to have read my mind. Now let me continue."

But the seismologist is disturbed by two ladies who are chattering away just behind him. They are about forty years old, still attractive, beautifully tanned.

"Then you saw him too?"

"Of course! At first I didn't even recognize him."

"Destroyed in the space of a few months. Poor Giancarlo. You can't know how sorry I am. It's such a trauma. I don't have a dearer friend."

''You'll see, he won't come in the winter-"

"Oh, please be quiet! Don't even mention it. And to think of the injustice of fate. An important man like him, in that condition, and wretched me, who never did a blessed thing, with my iron constitution."

''You're telling me? You know that at my last checkup they found me-in their words-like a little girl, perfect from head to toe, inside and out "

Doctor Toro breaks off and with a wave of his hand invites me to continue. I am ready:

The monsignor is also disturbed by two very excited young men who are wearing strange athletic outfits and trying to attract attention to themselves.

"Do you have the enlargement with you?" one asked the other in a loud voice.

"I hope so. But you have to dig through this stack of papers to find it."

He rummages through a leather briefcase, and after a little while, he draws out a large photograph: it is a gigantic pear-shaped wall of rock and ice. The young man points to an area precisely in the center of the photograph.

8

"Here it is. You can't see it in the small print. We will naturally have to examine it up close, but one could say that this perpendicular ledge is actually detached from the rock face, and that behind it there is something like a shaft, or a tunnel. I would swear that you can go through-"

"Formidable! We're in rare form tonight. These seemingly unconnected fragments fit perfectly together to signify a leitmotiv: the future. The husband and wife, the monsignor, the two women, the two mountain climbers are all thinking of the time to come, they have a sort of blind faith in it. But now that the story has developed and found a meaning, we must give these characters a setting. Tell me: where do you prefer that we put them?"

"No," I said, "you won't trap me this time. I may not be very crafty, but from the very beginning I knew where I was heading. And I'm amused that you should ask for my assistance. But enough now. It's as plain as day: the husband and wife, the monsignor, the two women, and the two mountain climbers are traveling. Where? From the episode with the married couple we can infer that the destination is South America. How are they going there? On an ocean liner, perhaps? But no: if that were the case, the monsignor would be able to write his speech in the peace and quiet of his own cabin. So how are they traveling? It must be by air! There is no other alternative. And now it will happen, right? The accident, the crash, the sudden catastrophe, the thing from which the conservations and worries we have described, all focused on the future, will acquire a cruel, ironic significance. I didn't expect this from you, dear Doctor Toro. It's much too banal, truly unworthy of you who are usually so imaginative. No, forget about the airplane. Let's start over instead."

The old doctor answers me with one of his malign little smiles.

"It isn't my fault," he exclaims. "I swear, I myself would have been more cautious, but And he points toward the sky.

I look up. At that moment a plane is emerging from a huge storm cloud that is rapidly passing overhead-the sky is in fact clearing-at an appreciable altitude of not more than three thousand meters. Its right wing is trailing a thin, dense plume of black smoke. Something disastrous has happened, and the plane is losing altitude in search of a possible landing field.

Paralyzed with amazement at the diabolical coincidence, I am silent. Three or four seconds pass, then a black, smoking object breaks away from the plane and, after tracing the briefest curve, plummets with lightning speed.

"My God, that's an engine!"

Doctor Toro nods yes.

The plane, now smoking a little less, proceeds on course without banking, and I am already reassuring myself when it suddenly begins to

9

roll over and over and the wings, like the blades in a fan, describe four, five, eight very rapid circles.

Then, as if it were carrying out a suicide pondered for a long time, the plane points its nose toward the surface of the earth and falls vertically, with all its might (or so it seems).

The gigantic coffin disappears behind the crest of a nearby hill. And that's it. There is no crash or explosion, no flames or smoke.

"It's frightening," I say, breathless. "You're the Devil himself."

"They were up there."

"Who? The married couple, the monsignor, the ladies, the mountain climbers?"

He nods yes.

"And how did you come to know it?"

"How did we come to know it, you mean. You too were a contributor. It's simple: we are the ones who made the plane crash."

"No, there wasn't any disaster in our story. We mentioned only conversations, that's all."

"But the content of the conversations foreshadowed the disaster, in fact rendered it inevitable, from the point of view of the narrative. You yourself recognized it."

"Nonsense! You're mad. And no matter what you say, I had no part in it. The airplane was your idea, right from the start. I had no part in it, I tell you."

"Calm down. Don't take it that way. Even without the air crash it would have been the same for those people."

"What are you saying?"

"Absolutely the same. The future, calculations about what will happen, plans catastrophes. You saw, didn't you, how this thing fell. Do you think the hours, days, months, years that cascade over us move any slower?"

Translated by Lawrence Venuti

10

A Difficult Evening

With a strange urgency myoid friend Gianni Soterini invited me to supper at his villa in Bograte, about twenty kilometers outside the city, in the heart of the forest of Slenta. It's a hilly area, snobbish and isolated.

When I arrived a little before eight, I immediately perceived, from the facial expressions and the tone of the voices, that something was not right.

I was welcomed by the beautiful Stefania, Gianni's wife: "I am sorry you have to see me like this. Just last night Aunt Gorgona had one of her usual crises."

Aunt Gorgona, the sister of Gianni's father, is a corpulent person, rather eccentric and moody.

"What kind of crisis?" I asked, deliberately tactless.

Stefania tried to gloss over the incident: "But all she needs is a pill. Now she's sleeping like a baby."

In the meantime, Aunt Gorgona had appeared at the top of the staircase, irreproachable, wearing a long black dress, her shoulders wrapped in a shawl that was popular fifty years ago. And she was covered with all her diamonds.

She came to greet me, smiling. "What a pleasure, dear." She took my arm and pulled me toward the door that leads to the garden, insensible to the calls ("Aunt, please!").

"They probably told you that I was off my rocker, right?" she whispered as soon as we were alone. "That I had one of my crises. It's true, I can't deny it. Such childish things. Of course, there will always be crises. But to be afraid You noticed it, I imagine."

"Afraid of what?"

"Paolomaria and Foffino yes, the boys, the children There was 11

a phone call that said they were coming here tonight with a group of their friends."

"A call from whom?"

"Anonymous, of course."

"But even if they arrive-"

"The call added that the little ones were coming to do away with papa and mama -" and here she burst into a hearty laugh.

Stefania was calling us. "Please, come to the table. What were you two plotting?"

We were joined at the table by old Father Emigera, the family's confessor for three generations. He and I were the only guests.

"I imagine:' Gianni began, "that Aunt Gorgona has already explained everything to you."

"I don't know if she told me 'everything,' but-"

"So what do you think of it?" Stefania intervened.

"An anonymous phone call -this was certain to gain time"maybe it's a stupid joke."

Gianni was serious: "I don't think so. In the months before they went away to college, Paolomaria used to look at us in a certain way."

"Foffino too, for that matter," said Stefania.

"But why don't you just lock the doors and windows?"

"That's the worst thing we could do," said Gianni. "It would aggravate them even more."

"But college will keep them in line, won't it?"

"Don't make me laugh. Paolomaria is such a devil. He could escape from Alcatraz."

"Would Paolomaria and Foffino really come to kill you?"

He shook his head as if to say: it is inevitable.

And Stefania: "This is the way things are today. Parents are killed today. It's the latest fad."

"Killed? Who was killed?" It was the troubled voice of Father Emigera, in the clouds as usual.

"Us, Gianni and me!" Stefania snapped, exasperated. "The children are coming to do away with us-understand, Father? To do away with Gianni and me, Gianni and me-"

"Calm down, Stefania," Aunt Gorgona interrupted. "Please don't make a scene After all, let's be honest, these kids are not entirely wrong."

"What do you mean?"

"It isn't that they're all wrong. Let's be fair. What kind of life can they look forward to? What kind of example have we set for them? What have we done to guarantee them a happy future? If they protest, contest, revolt, how can we blame them?"

"But in this case they actually want to kill us," Gianni dared to object.

12

"Kill, kill! What a pessimist you are!" Aunt Gorgona was in rare form. "While we're waiting, let's consider how they'll go about it. It wasn't said that they would be so wicked. It wasn't said that they would cut you into little pieces. It wasn't said that they would douse you with gasoline and burn you alive. I may understand Paolomaria better than you. He has such a big heart. Paolomaria is a generous boy I would swear that he won't make you suffer."

"What?"

"I don't know, maybe it will be a shot in the neck Or zip-a blade in the cardiac muscle Ah, that would be beautiful!" Aunt Gorgona shook with laughter.

Gianni turned pale. He changed his mind. He called the butler Ernesto. "Listen, Ernesto, don't worry about us. Please hurry and close the doors and windows. And make sure they're locked."

"Locked?" said Father Emigera. "Why are you closing them? It's hot tonight, really, Stefania, aren't you hot?"

"Yes, it's hot, Father," Aunt Gorgona chimed in. "But in this case they're shutting up everything because they're afraid that the brood is returning to the nest to get rid of the parents."

Until this point I had been only an observer. "If you are so afraid, why do you stay here? You should flee, shouldn't you? The world is a big place. Your dear children won't follow you to the North Pole!"

Gianni: "Flee? Where? This is my home, this is my family's old house. Flee where? No, no, I prefer to confront my fate."

"Fate!" It was Aunt Gorgona again. "What a big word They are your sons, after all And I understand them, the poor boys You gave them life, and they are coming to take it away from you The account will be settled in a certain sense, right?"

Stefania: "What do you want me to tell you? Think whatever you like, you can believe I'm senile, but I find the whole thing a little exaggerated."

"Did you hear that?" said Gianni, lowering his voice. "What?"

"Those steps on the gravel did you hear them?" "I didn't," said Stefania.

Father Emigera looked at the clock (coffee was now being served). "I'm sorry, my friends, but tonight at the church the culture committee is meeting again I wouldn't want to be discourteous."

He stood up, brushing the bread crumbs from his cassock with his right hand.

I too stood up.

"No, not you, Buzzati," Stefania protested, pleading. "It's still early. You have to try some of this tart. Another tiny half-hour, please Shall we go and sit over there by the fireplace?"

Aunt Gorgona: "Let him go, Stefania. The prospect of being a witness

13

isn't very attractive. Forgive me, but I couldn't bear" - she was unable to repress her giggles-"to witness your execution."

There was a moment of silence. And in that silence the night entered, the mysterious rustling of the garden, of the country, the trees, branches, leaves, meadow, the animals' faint voices, the wolves' soft padding through the paths, the wild rabbits, the elves, the crickets' lament, the liquid hiss of the snails and the snakes, the impalpable grating of the grasshoppers and spiders. And amid all these nocturnal sounds, forcing them to strain their ears, was a distant tread over the grass and twigs, very soft, scarcely audible.

"Did you hear that?" Gianni repeated, pale as death.

"No, Gianni, I didn't hear anything."

Coward that I am, I stood up again.

"It's late, Gianni. Forgive me, but tomorrow I must leave to Trieste at seven-thirty. Anyhow it seems clear that it was all some sort ofbad joke."

Aunt Gorgona practically jumped out of her chair.

"Of course! A joke! How is it possible that you, Gianni and Stefania, still haven't gotten it?"

It was Aunt Gorgona who wanted to accompany me to the door. (Gianni and Stefania were too exhausted to move from the table.) And she told me: "They will be here in a little while, I can feel it. But they aren't bad boys, believe me, dear friend, they will take care of everything with the smallest expense of energy, without a fuss and painlessly It won't take but a few seconds, you'll see, what I have in mind is that little shot in the neck."

1 had already started the engine of my car. 1 rolled down the window.

"But you, Aunt Gorgona 1 wouldn't want you to get involved too."

She burst into another hearty laugh: "Me? Of course I will be involved. In fact, from the beginning Do you want me to abandon my nephews? We've worked so hard, haven't we? Splendidly, patiently we have fixed things so this might happen, can you deny it?" (1 shook my head no.) "But go on, hurry, my dear, so you can avoid the trouble 1 sense a certain suspicious movement among the bushes."

She turned toward the pitch darkness and asked, affectionately: "Paolomaria Foffino Are you here?"

Translated by Lawrence Venuti

14

House Snake

Reynolds Price

All summer it seemed a fair exchangeBlack snake on the lot, better mouser

Than a cat (the previous winter I'd lost Eighty pages of Marcus Aurelius and a Phaidon Michelangelo to squads of mouse teeth). He could prowl the crawl space Round furnace and pump, have whatever Life was separate from me-frogs, Baby birds, chipmunks, scuttling mice, The chance copperhead wandered up From the pond. I'd receive the service Of his plunder and pay only rarely In frigid instants of seeing him-

Breakfasting, sapped by bliss, on the porch; Turned by the chime of a silent signal To find him embossed on the beechtree

Above me, string of hot tar

Ready to pour (does he see me?) Or thrust down, rigid as a cane, From the gutter, devouring raw wren

Hatchlings in the house I'd suspended on wire To miss his reach.

I learned to take

That much - and with measured pride: One of my early templates was Mowgli, An agreeably imitable brunet boy

Whom large beasts loved or anyhow

15

Addressed in lucid warnings and thanks For service; so his tolerance in admitting

My presence was a parched hard honor

I mentioned to no one, though aloud

I thanked him one late August morning

As he elevated his bullet head

And ten inches of neck from unmown

Grass at the utmost limit of the neutral Zone where fear began-mine

And his, I'd thought; the line of our agreement, Real on the ground as a chain of voltage. I watched him, still as he; then smeared

A palm on intervening air,

Set down my coffee, and said "Thanks, Nero" - naming him as Adam

Named the stock of Eden, spontaneously,

Straight homage to his essence: clandestine, pure Black. I turned to eat again and by The time I remembered him, he'd soundlessly dissolved. That afternoon I needed a book

From the dining room (semi-basement, Drowned in must). I was wearing shorts

And no form of shoes; the room was shuttered, Slotted dark. I was down-six feet

Toward the dimmest core-before a voice, Clear as airport advice, said "You should have worn shoes this far Underground." I stopped, midstride, And solicited my feet. It took a long Moment for eyes to gape the stagnant Murk-two beige feet, flat

As buckwheat cakes (apparently mine)

And one crooked yard of black snake

Watching, a step to the right.

Nijinsky at his zenith never equaled

The leap I launched on the instant. I swallowed a lobe of my heart, sorted Options - fetch the shovel, chop him up (And the rug) or pin his head, lift him; And restore him to his beat, his larger half Of the premises: nature. He made no feint

16

As I padded to the stairs, seized the stout' Handled broom, and (ignoring my bare legs) Descended to snare himevery nerve by now Worming through my pores to cling aghast To the upright hairs of neck, arms, calves. He'd waited, so still that-a light switched onI wondered for the first time if he might Be dead. He was not merely flat From nose to tail but deflated, Merging with the rug, seeping down. I extended the blond broomstick, Brushed his neck.

Ignition.

He flung two-thirds of his length up and back, Parabolic stake in the new Usurpation, and defied my intent. Frozen at the marrow, I at once took The dare and thrust the first stroke For my demesne-floor, walls, roof; Hope of unscathed nights, companioned By my own taste in guests. I'll take him; Expel him, alive and whole, to the zone Conceded.

He fenced, live leather, Through dazzling changes - hydra, basilisk, Devouring rod.

I steadily assured Myself he was harmless-baby, Teeth and no venom sacs - as I Parried his lunges, resplendent in power And perfect in aim: strike after strike He gummed the broomstick, sparing me (I assumed I was spared).

After maybe two Minutes of torrid duel, he betrayed Exhaustion - a shudder at the pitch of his grandiose Lash. In thirty more seconds, I pressed him to the rug and, before I could climb

A new rung of fear, bent And firmly clamped his neck in thumb And forefinger. I paused for his answer,

17

More than half-expecting a last transformation To steal him from me; but he Bore our juncture, my victory, Pressing on me nothing worse than skin With the dry packed vigor of slate. He was straight as Aaron's magic staff, Unmoving. So in that clutch, poised Between grip and strangulation, I rose; He streamed down viscid from my fist; I stepped toward the yard doorOne, two strides.

He threw

A lightning coil round my wrist; Then as I halted, astonished, threw Bracelets toward the hinge of my arm, His whole present self consumed In the work. Constriction began-uniform Clasp of a blood-pressure sleeve Pumped toward implosion.

I knew he could do

No serious harm; but stalled at the door, I thought of one sure way To shed him-chop my arm off. We moved into tons of sunljght, I at least glad to be back in his Place. At the edge of trees, I raised My captive-capturing hand and faced His face-no face: machined Consumers of sight, smell, prey. The black tongue stroked at air For my plan-death or release. I Asked him his. No more answer from that Ensemble of obsidian curves and plates

Than from my own species at similar bay. But I knew a way out. Had he thrilled That toward me through thickening light?-light Was stacking round us, too humid To speed.

With my left hand I took

18

The blunt tip-end of his tail

From my right armpit and, holding The garlanded arm out - caduceus!From my body, I slowly untwined in broad Safe loops. He barely resisted. When I had him (straight as he'd ever been) Before me, I extended him westward; Then realized I'd generated one more Vatic pose-hierophant In some unmanageable rain forest, Placating night as it eats another Day. I'd seen a last problemHow to set him down. If I dropped him at my feet, He could launch a final bite. With arms

Still out and up, his undulance between Them, I threw him broadside. He landed

In undergrowth three steps beyond, Calm gelid S, monogram Of something. He was not watching me Or the walls of my house nor was he fleeing; And only a hardened anthropomorphist Could entertain the thought that he thought of me; Remembered me even now, a moment Apart.

I reminded him "Out here." If the sounds ever reached him, He didn't budge. I turned And went in, lit the downstairs Room to stadium brilliance, and searched The floor-clean as a surgical scrub brush, No cast skin, no tail. I headed For the sink and scoured my own hide; And within half an hour was mostly My self, altered only by the burr Of one new fact - He knows The way in, a secret Way. The whole next morning I roamed my perimeters, chinking holes, Blocking grills; and for two weeks After, I never saw him once-

19

Though the number of times I told the tale Of our congregation might have lured the shyest Monster back for a second go At the battle bard.

Then an ordinary night (Nearer four a.m., heat a steady Hand at my mouth), I woke on my back, Aware of company. Dazed, I shuffled Candidates-visitors longed-for, two Or three dreaded. I turned my head Right and kissed the spare pillow, cool, Unburdened. My arms swept slow half, Circles at my sides, unrewarded. I was three-fourths gone again before my left Hand on its own recognizance slid From the one sheet and scouted my chest, Belly, thighs, groin-usual

Automatic meaningless tumescence, Concomitant of dreams erotic as knitting. Below the compact bulse of scrotum, Fingers encountered another coiled Mass that - stroked on the grain - was fish-skin Rough and remarkably cool in the ambient Swelter. I suspected it was he; no fear Arrived, fast or slow. I was somehow Resigned or, truer, curious.

He apparently Reciprocated. A minute to read the coded Data of my sluggish blood; then he calmly Rose through unresisting hands (My right hand had joined him); through Genitals, belly, breast to my neck. My hands trailed his abandoned wake Of body that seemed more an odor Than palpable presence, rank not putridAnother staked claim to be Here, safe. His tongue lapped The stubble point of my chin, fed There by whatever mineral scurf or exhalation He'd hunted out. My hands felt Wrenching swallows down his sides-

20

A nourishment urgent as the wolf-found Boy's, drunk on death, and slow As the parting of tectonic platesBut he didn't grow. Some poised stasis Was eventually achieved, entire annexation In which I concurred. I assumed he rested, Converting what he'd skimmed off me Into the strength he needed most. I frisked my body for depredation And found no change-same moderately well, Formed limbs, going slack (no fault Of his). In hopes of guessing his purpose Here, I searched his length again - firm As old bread but warmer, stiller: No rigor of anger, vengeance, or famine (Benevolent incubus-succubus-both), And no detectable tick of intent. So I lay suspended in active patienceTired but not fearful so much as alert, Passively watchful like any gripped creature And fending off rags and flares of dream, The traps onto sleep. He spoke at last Or managed to speak; had he tried from the start? Had our transaction awarded him power To say his piece? There was nothing a monitoring Instrument could have caught; yet I heard it as voiceThe lean andante clarification Native to youthful baritone humans But flat inhuman, like nothing born Of woman since the picnic grounds of the Olduvai Gorge were discontinued. His head Was somewhere below my left ear, Not touching skin. His tail still Looped at evident random in my now, Cool groin where my right thumb Flicked the free rim of scales; So the voice may have transpired by bone Osmosis-an uncanny sympathy Of all-night companions, however Bizarre. I affirm this true report:

21

"They watch you with interest After so many years. One of us has sampled You at least each year For the hours prescribed Of sleep and day, Employing the usual Sounding procedures; Instructed till now

To avoid detection. I alone failed But, since you spared me, Am sent back On sufferance

To meet your mercy With payment renderedThe essence we know, Having known you entirely (Your private titles, Precise destination, Balance to date.)

1 require permission, However; you are free To refuse receipt." I at once

Refused - who would bear his sentence an instant Early or from any mouth but the Certified Horse's Himself, enraged, and attended By seraphs congested with ire, not a renegade Egg-thief's, terror of wrens? And of all Things, I dozed then, drugged On awe.

Dawn-rare work-bound Cars on the road, my own mouth slimedI woke alone. Hands affirmed His absence; eyes gauged the room. Unaltered, spared-all but memory, Me. I replayed the theophany in fine Particular; and while I again weighed The chance that what I'd endured was retrograde Delusion (legacy of childhood days

22

Bogged in Poe), the certainty of earnest Visitation outweighed. I'd balked at revelation. Who else in the record of Israel and Christendom Had flat said No to a visible, audible, Graspable deputy of Central Wisdom

With news at his lips? -my secret name, Point of my life, debit or gain. First I bathed (no punitive scouring now); Then searched the house - nothingThen chose a slow breakfast on the porch

As my sign of regret and proffered submission. A ragged parade of other beasts passedSpiders drugged with expectance, strolling ants; Sixty feet downhill, the spinster muskrat

Endlessly nesting in the pond's clay dam For broods that methodically decline to appear, An obese cock-robin of startling eloquenceTill I'd also sunk in dumb blind patience. There.

Two yards northeast of my seat, Conformed to white creek-rocks in the ditch, He'd materialized (how long ago?)-

Right eye toward me. I wiped One hand, slow, between us in air

Much cooler than the night. I said "Permission." He moved-or managed to advance two lengths From rocks to ground (I saw no motion, Only registered change). On the brilliant moss

Of my acid soil, he was his precise Self again-common yard-dragon, Wholly unearthly. 1 sat, assuming he Posed for me (his head was barely Up, immobile; no sign of the tongue).

Then 1 saw beyond him a condensed brown Toad, appalled in his glare. The three of us Froze-a garden-group, mixed media; "Permutations of the Hunt." Toad and I Had mutely yielded to what seemed A hunger ferocious as dwarf stars'The bungholes of space, cold ravening. It would not take us.

23

Never turning to me Again, he broke his stare at the toad; dropped His head through minute fractions of space, Joined the ground in all his length, and movedHauling on through dead leaves, the spindly azalea, With languid sidelong flings of the spine Till I'd lost his wake.

The toad gave no sigh Of gratitude, relief, only kept its place With the ponderous contentment that implies complicity. Had my refusal of the daunting message Demoted the messenger to predator now? Had I been his chance at ascent on any Ladder he climbed? I rose to find him; The toad flinched (a heartening proof Of my weight). He'd left no discernible trail Or trace-not even the customary bellySweeps of a doomed ground-dweller. On the chill face of evidence, I could Say he vanished a hand-span beyond The desolate peach tree I'd planted years Before that failed to thrive-it stood on Gamely, limber as a buggy whip, one lateral Branch with six tender leaves And the thickening knuckles of premature age. Even there, in real sun, I clearly thought "Will I now be host to botanical marvels?"

And recalled the hapless bush flamed For Moses, the fig cursed by Jesus, The thorn in Lourdes creaking into diffident Bloom for Bernadette through mountain frost. Was I in for armloads of luscious peaches Or a pocket-display of selective blight, The innocent switch smoked to jerky by sunset? And how would I read either wondrous pole? Would fruit mean Praise. Continue as now? Would blight be the tangible verdict for Turn Or Wrong. Too late. Prepare to pay? How would I answer? Who would I tell?

A baffled week later I drove to the garden Shop and chose the makings of a small

24

Commemoration - three dozen

Of the homeliest plants known to science, All succulents: stonecrop, echeveria, Aloes, sempervivums. The troll-woman Ringing my purchases said "You're not Expecting flowers from these?" I said "Flowers Never meant much to me." "Me

Either;' she whispered, "but that's a trade, Secret."

I promised silence and she warned me not To eat them, "though they look good enough." Home, I half-stripped; scooped A bowl in the unnourished earth By the peach, and set the green flesh

Of thirty,six low and blind, Faced lives at the mercy of the site of his exit.

They've flourished, yes, but nothing prodigiousWithin two years under light care

From me, they'd filled their bed: huddled And plump. Guests remark their oddness, Their sturdy pluck in prospering on ground Hospitable as sulfur. I offer no homily

On their local meaning, and no one's asked For usable cuttings. The peach tree's holding Its desperate own; I went once to move it But stopped myself-if it means anything, it means It in place (like ninety-eight percent of anything Radiant). Since I live by a pond and its draining Creek, I've met other snakes fairly often

In the time. Mostly harmless-red rat snakes, King snakes, garters - they're asking only for sunning, Space athwart my drive and the excess Lesser reptilia to eat. Two weeks Ago, I came on a large king Resting at the chore of consuming a slightly Thinner king-four inches of the vanquished Neck were still free, apparently Serene as a griddled saint - but the few

25

Black snakes are smaller than my visitant And keep a skittish distance from the human Zone. If his sons or avatars, they're plainly Branded with the serpent-curse, not spies Or receptacles of my daily failure. Me? - I poison my mice and harvest Their frozen corpses from the crawl space before They ripen. I work long days in nearSolitude, am praised for my trick of making The ecstasy of oneness look princely, And sleep less each year-no dreams I care to recall on rising.

I'm simply

The one happy man I know, Assured of witness and judgment entirely Beyond my power to guess or changeAbsent proprietor of gardens unthinkable For beauty or pain.

26

The Chandelier

Gregory Orfalea

Mukhlis drives up Asbury Street in Pasadena and brings his green Buick to an easy, slow stop underneath the largest flowering eucalyptus in southern California. The first door cracked is that of his wife, Wardi, who gets out as she has every week for the past forty years, as if she were with child. She has not been with child for many years, but her body at center is like the large burl of a cedar and her legs are bowed as an old chair's. Mukhlis emerges from the Buick. He looks left and right for cars-a short, searing look either way. And the sun tries to plant its white seed on the center of his bald head.

Mukhlis has made a small fortune in real estate. He has apartment complexes here and there in the city, and many of his tenants are black or brown. He himself is brown, or rather almond, and his eyes, like those of many Lebanese and Syrians, are blue. He owes this hue to the Crusaders. A continent man, Mukhlis' eyes are the last blue twinkle of a distant lust.

What words there are to say, Mukhlis rarely says. His eyes and body speak - a body made to withstand. As he ascends the steps of his sister's home, the collar of his gray suit pulls taut around his neck. And his neck has the thickness of a foundation post; it welds his head to the shoulders. For years it has been bronzed by the sun. So tight is the tie and collar around his neck that his nape stands up in a welt of muscle. It is not a fat neck - nothing about the man is fat, save a slight bulge to his belly, brought on, no doubt, by forty years of Wardi's desserts, among the finest Arabic delights in Los Angeles. Mukhlis has learned it is useless to compliment her because Wardi (Rose, in English), like most Arabs, does not react to compliments; she prefers to go to great lengths to pay a compliment, instead. But not Mukhlis. He says not two crooked words about Wardi's knafi, the bird's nest whose wafer-like shell must be rolled with the patience of Job before it is filled with pistachios

27

as green as Mukhlis' Buick-and probably greener-then topped with a spoon of rosewater syrup.

Mukhlis kisses his sister, Matile, and booms a greeting to the air behind her in a robust voice that speaks in simple sentences and laughs silently. His large head, sapphire eyes and corded neck all shake with his laughter.

And if it is on a summer evening, with a large group ofpeople chatting on Matile's porch, all will be aware of Mukhlis, though he will surely say the least, and when his hands come apart after having been clasped tightly on his belly for so long, people will take a drag on their cigarettes and turn in his direction.

"No one wants to work, and so the devil has his pick of the young people."

Wardi, who clasps her hands on a more bulbous belly, will nod and sip her coffee from the demitasse.

"Matile, do you have any cream?" Mukhlis asks his sister.

"Certainly, my honey," she sings. "Anything for you."

When Matile's voice sings it is to smooth over rough spots in conversation; her feigned joy or fright has saved many a wounded soul. But when Mukhlis sang-the fact that he once did sing is his most guarded secretit was with the voice of the hassoun, the national bird of Lebanon, multicolored red, yellow and black, prized for its rich warble, and fed marijuana seeds by children.

Sitting among immigrants from the First World War, Mukhlis was asked to fill the gaps in all hearts over the strange Atlantic, which in Arabic is called "The Sea of Darkness." Please, Mukhlis, sing the praise to the night! Sing of the moon and its white dress! Huddled on the stoops in Brooklyn, they asked for the song of two lovers separated by a river. The one of the nine months of pregnancy, in which Mukhlis stuffed a pillow under his shirt. Sing, cousin Mukhlis, for we are tired of the dress factories, we are tired ofthe fish market. Sing the Old Land on the Mediterranean!

And sing he did. His voice was effortless and sweet; it was made all the sweeter by the immense power everyone knew lay under it. Then one day this unschooled tenor, this voice dipped in rosewater, simply stopped. It stopped cold when Mukhlis' mother died in a little loft above a funeral parlor in Brooklyn. It died when he covered the four long white scars of her back, from the lashes of the Turks, for the last time. No one in California has ever heard him sing.

All of this is whispered from time to time behind Mukhlis' back. None of it is spoken directly to his ears. He will not tolerate it. His usual response to any mention of the latest atrocity in Lebanon is: "How is your dog?" or "The apricots are too thick on the boughs this year. They need to be snapped off."

But today the large porch is empty, except for Matile herself and her

28

oldest grandson, Mukhlis' great-nephew. This young man has been traveling for years. He is a restless soul, thinks Mukhlis, as they take their places on the porch - he on the legless couch, his wife on a white wrought-iron chair with a pillow of faded flowers made by Matile. The great-nephew takes to the old iron swing. What is it about this day? Mukhlis says to himself, noticing a vine in the yard. The wind is hurting the grape leaves.

Matile brings a tray of coffee and announces dinner is not too far off, and all must stay.

"It is never too far off with you, Matile," Mukhlis says, blowing over the coffee.

"You must stay," she sings. "I am making stuffed zucchini."

"Never mind," he says. "Have you got a ghrabi?"

"Ghrabi?" Matile stands so quickly she leaves her black shoes. And goes into a litany of food that last five minutes.

"No, no, no," Mukhlis punctuates each breathless pause in her list. "Ghrabi - just give me one."

"One!" she cries. "I have a hundred."

"One, please, is all I want."

She brings a dish piled high with the small hoops of butter, sugar and dough, each with a mole or two of pistachio.

"Eat:' she says.

Wardi takes one. Mukhlis shakes his head and breaks off half a ghrabi.

"Isn't that delicious?" Matile asks, preempting the compliment. Mukhlis chews. "You look real good today," she smiles with a brightened face, disregarding his nodding. Mukhlis turns to the young man.

"And so, what are you doing here?"

"Looking for work," says the great-nephew, a dark, slender fellow with broad shoulders. These eyes of his, Mukhlis thinks, have a dark sparkle. He's cried and laughed too much for his age; his laugh is a cry and his cry is a laugh.

"It's time for you to get serious and stop this wandering and get a good job in business:' Mukhlis says rather loudly.

"You are playing with your life. When are you going to get married?"

Mukhlis gleams his crocodile smile and laughs silently. Then he becomes solemn, and touches the pistachio on a ghrabi with a thick forefinger, taps it several times, then removes it.

"Aren't you ever really hungry, Uncle Mukhlis?"

The old realtor looks out past the stanchions of the porch, past the thickened apricots.

"Boy, have you ever seen a person eat an orange peel?"

"I've eaten them myself. They're quite good."

"No, no, boy. I mean rotten orange peels, with mud and dung on them. Have you had that?"

The great-nephew purses his lips.

29

"Well, I want to tell you a story. I want to tell you about hunger, and I want to tell you about disgrace."

Matile gets up again, and lets out in her falsetto, "Don't go no further till I come back."

Mukhlis disregards her and squeezes a faded pillow on the legless couch, as if he were squeezing his brain. What is it about the breeze and the light today, the crystal light? Will he go on? He does not know. His great-nephew is too silent. Mukhlis does not like silence waiting for silence. He likes his silence to be hidden in a crowd. From the dome of his almond head, he takes some sweat and smells it. Wardi continues to eat.

"I was the oldest of us in Lebanon when we lived in the mountain, but when World War I started I was still a young boy. They cut off Beirut harbor in 1914. You see, the Germans were allied with the Turks who had hold over all the Arab lands. And so the Germans become our masters for a time. When it was all we could do to steer clear of the Turks! The Allies blockaded Beirut harbor, and for four years there was no food to be had in Mount Lebanon."

At this moment Matile puts a heap of grapes in front of him.

"Nothing like this purple grape, I can assure you! These were treacherous times of human brutality. People were hungry and hunger is the beginning of cruelty. The Turks themselves would tolerate no funny business. Ifpeople refused to cooperate with them they would take it out on the children. I saw them seize a small boy by the legs and literally rip him in half. I saw this happen with my own eyes; one half of the child flew into the fountain we had in Mheiti, which is near Bikfaya. The fountain was empty, but even after the War when it had water and the remains of the child were dried up no one would drink there."

"Yi! You tell them, Mukhlis! You tell this to show what happen to us!" Matile's voice rises as she lays down a plate ofgoat's cheese and bread. "It was terrible."

"Food was so scarce people would pick up horse dung, wash it, and eat the grains of hay left. It was common to go days without eating or drinking, because the Nahr Ibrahim and the Bardowni Rivers were contaminated by dead bodies. The Germans and the Turks would throw traitors into the river then there was the chandelier."

Matile clicks her tongue, "I could tell you story, boy, I could tell you story."

"Did you know 'Lebanon' means 'snow'?" Mukhlis raises his pointer finger. "It means 'white as yogurt' because the mountains are covered with snow. It was very cold in the winter, and we had to stay in. Without food, it was colder."

"What about restaurants?" the great-nephew ventures.

"Restaurant? You are an idiot, young man, forgive me for saying. Any restaurant was destroyed in the first year, any market plundered by the

30

soldiers. We had to find food for ourselves. Each day for four years was a battle for food."

"I could tell you story," Matile puts her eyes up to the stucco ceiling of the porch and shakes her hands. "Thoobs! A crust ofbread was so rare it was like communion. My mother she had to go away for days to trade everything we had for food on the other side of the mountain -

"Matile, 1 " - she give us a slice of bread before she leaves and she shake her finger at us and say-Matile, Mukhlis, Milhem-you don't take this all at once. Each day you cut one piece of the bread. One piece! No more. And you cut this piece into four pieces-three for you, and then you break the last one for the infants. You understand? Like one cracker a day for each of us. Little Milhem and Leila, they cry all day. They want more. They too little to understand, and the baby ah! Milhem hit us for the rest of the slice of bread. 1 hide it under my pillow one night. And that night oh 1 could tell you story make your ears hurt!"

Mukhlis shifts in his seat and flings out his arms, "Now, when 1 went off in the snow ."

"The chandelier, you remember."

"Yes, Matile, of course 1 do."

"You remember, Wardi, you wouldn't believe it."

Wardi's eyes are large as a night creature behind her thick eyeglass lenses, and she nods.

Mukhlis clears his throat loudly. "My mother gave me the last piastres we had and told me to go through the snow over the mountain to the village in the dry land, to fetch milk and bread. I was not as strong as my mother but I was strong, and so I tried. But the first day out I was shot at by a highwayman, a robber. I hid behind a rock; still he found me and stripped off my jacket and took the piastres. I was glad he did not kill me. But what was I to do? I could not go home. I continued walking until I came to the monastery. I thought I would ask the monks for some milk. They were not there."

"They die."

"Matile, please. They were not there. Perhaps they went to Greece. They were Greek monks. The place was empty. The door to the chapel opening with the wind that moved it back and forth. Inside the candles were snuffed. And the candlesticks were cold, and all the pews were covered with frost. It was winter, inside and out. Up above was a "Chandelier!"

"Yes, Matile, a huge crystal chandelier. In all my life I have never seen one larger. Its branches were as far across as this couch, made of solid gold. Inlaid in the arms were rubies the size of your eyes, nephew! I remember standing in that chapel that day thinking how we had corne to worship there with my father when I was a very young child; the chandelier was something I would worship. I would look up and its great

31

shining light would say to me-God. This is your God, Mukhlis, here on Mount Lebanon. He brims with light and He will sit in your eyes, in your dreams. I had never thought of touching it. For one thing, it was too high. It was at least fifteen feet above my head. Well, so help the Almighty, I was hungry. And my mother was hungry. And so were my brothers and my sisters. And we had not heard from our father, who was in America, for two years. Before God and man, I committed a sacrilege. The mosaics, you see, on the wall were shot out and in tatters. I crawled up the wall where the tile was gone. I crawled up that mosaic until I made it to the crossbeams of the ceiling. And I had to be very careful not to knock loose the mosaic where I was hanging-a mosaic of Our Lady it was, and who knows? Maybe my foot was in her mouth."

"How sad!" sighs Marile.

"But I hoisted myself onto the crossbeam and slid-like this, yes-slid across the beam. It was cold enough to hold my hands fast as I tried to balance. But finally I made it out over the nave of the chapel, to the chandelier."

"Yi!"

"The chandelier was held to the ceiling with tall iron nails. Carefully, carefully I put my hands through the crystal teardrops, to latch onto the gold arms. And then you know what I did, young man? I became a monkey. I swung free on that chandelier! I pulled up and heaved down on it, trying to loosen it. I yanked and yanked with the crystal hitting my eyes and the rubies sweating in my hands. And I swung back and forth in the cold air. For a long time the chandelier would not loosen. It seemed like God Himself was holding onto the chandelier through the ceiling and saying to me: No you don't, Mukhlis! You do not take the chandelier from this church. This is mine, Mukhlis. This chandelier was given to the worship of the Almighty. And youyou are a puny human being who deserves to rot in hell for this.

"I am not talking about playing in the acacias. I am not talking about swinging about from those miserable apricot trees, which need to be cut back by the way, Matile,"

"Anything you say, my honey."

"I am talking about a tree of crystal and gold. I am talking about food."

"Wardi, would you like more coffee, dear?"

"Matile, I am talking about food."

"So am I!"

Wardi's enlarged eyes close and her big bosom vibrates with mirth, like a dreaming horse.

"Oh it's useless. Why talk about it?" Mukhlis folds his hands, as if to tie up the story once and for all and leave everyone hanging on the chandelier.

Matile speaks with alarm: "Please, tell them, tell them. I won't get up

32

no more. This is story you never heard the like of before. It can't be no worse!"

Mukhlis gets up, paces on the clay porch, and goes over to the apricot, breaking off a branch crowded with fruit.

"Here, Matile, here is your dessert," he spits and continues, still stand, ing. "Finally, I heard it come loose. The plaster dust rained on my face and I heaved on this chandelier one more time. And then I fell."

Mukhlis raises his thick forearms and grips the air.

"It breaks, ah!"

"No, Matile, it does not break. Please, you are killing my story at every juncture."

She laughs and gets up for some rice pudding that is cooling in the refrigerator.

"I fall with it. I fall with it and I fall directly on my rump. This is why I walk slowly to this day, young man. Because of the chandelier. That chandelier had to become milk. It was going to save my life, our lives. What did my bones mean? Nothing. But I was a tough young fellownot like you soft people today - and not one teardrop of that crystal was scratched. I got up, and my hip was partially cracked. But I got up. I carried the chandelier to the entrance of the church. No one was around. No one saw me do it."

"God finally let go?" the great-nephew asks, with a smirk.

"God never lets go. I yanked it out of His hands. But I could not carry the chandelier far-it weighed a ton. In the vestibule of the chapel was a small Oriental rug. I placed the chandelier on top of that, took the cord of chain, tied it around the branches of gold, and dragged the whole mess out into the snow. No, Matile, no rice pudding. For the next three days, I dragged the chandelier over the snow to get to the village over the mountain in the hot land of the Bekaa. For three days I walked and pulled it behind me."

Mukhlis stops and wipes his brow. He is sweating heavily now, even though the California air is dry.

"I was exhausted by the end of the first day. I lay down in the snow by a cedar. I did not want to damage the chandelier, so I left it on the rug and tried to sleep on the snow with as much of my body as I could against the cedar. I was so tired and fell fast asleep."

"Did you dream?" asks the great-nephew, taking a spoonful of the sweet rice pudding.

"I don't remember. No, I don't dream. Dreams are for soft times," Mukhlis grunts. "You've dropped some pudding." His listener takes up the white spot on the porch with a finger. For a while Mukhlis says nothing, and listens to them eating. His blue eyes stare out into the warm air past the apricots, past the flowering eucalyptus, to the cloud, less sky.

"I awoke to the sound of licking in the dark. I felt warm breath near

33

my face. I sat up. There were six eyes, six greenish eyes in the darkness. My blood went cold. Wolves. I got up fast, grabbed the chandelier and swung it around and around, turning inside it myself. It made a tinkling noise that was loud in the dead forest and the wolves howled and scattered back into the night. I was breathing so hard my heart felt like it would come out of me. I was much too awake now and decided to go on dragging the chandelier in the dark. All through the night the teardrops clinked against each other and the rug rubbed over the snow. My eyes have never been so wide as that night. I looked on all sides and hurried until dawn, then rested. I remember lying down by a boulder, hooking the chandelier with my arm. When it dawned, the sun sent it sparkling. It made rays of red all over the snow, and the rubies looked like drops of glistening blood. I rested a while, my eyes opening and closing, but I did not let them close completely. No, not again! The second day I met a family trudging in the snow-a mother, daughter and two babies. The mother asked if I had any milk. I said I was going to get some for the chandelier. She shook her head and kissed me on the head. Her daughter's eyes were rimmed with blue and she was shaking. She had nothing on but a nightgown and thin sweater, and her toes showed through her leather shoes. They went on-they were going to Zahle, they said. I said I thought Zahle had no food, because my mother had been there and had bought the last scoop of flour in town. The mother asked where my family lived and I told her. They said they would try and go there. I said, Please do. The mother stared at me a while with her own blue-rimmed eyes. One baby had blue lips. The other was whimpering and breathing quickly in the daughter's arms. I went on. I went on and on, with the snow wedged in my socks and pants. That night I slept with my head inside the chandelier, my arms coiled in it, my legs twisted inside it so that if wolves came they would not want me, for they would think I was part of the chandelier. It worked. I was not bothered by wolves that night. The third day I descended from the mountain. I saw the dry lands in the distance-the rust-colored sand and rock of the Bekaa-and I broke out laughing, I was so happy. But I descended too quickly, and a thread of the rug snagged on a twig raised out of the snow. The chandelier slid off and down a smooth embankment of snow which the sun had turned into a plate of ice. I plunged down the cliff after the chandelier. But when it reached a ledge it fell. It fell about twenty feet. I cried out and rolled like a crazy dog down the snowbank and fell on my face in front of the chandelier. Luckily it had landed on snow that had not iced over, that had some shade from the ledge. I moved it slowly. One ofthe gold arms was bent and five or six teardrops of crystal were shattered. I turned it and stepped back. It did not look too bad if one looked from this perspective, with the broken part to the back. The rug was still above, so I fetched it and carefully laid the chandelier on it, like a wounded human being, and went on. Slow now,

34

Mukhlis, slow now. I did not let myself be excited any more by the nearness ofthe Bekaa. I have never let myselfbe excited again because of that chandelier breaking over the ledge. That day, around four o'clock, I reached the small village my mother had told me about. The villagers there were healthy. They still had some fields producing corn and wheat and lentils, and the road to Damascus was open. When they saw me-a little runt dragging this chandelier on the dry, dusty road - they gathered around me, asking all sorts of questions. I was too tired to answer. I just said, 'Take me to a cow-farmer. Please, as soon as you can.' They led me to such a man. I said to him, 'Look, I have come from the mountain where it is very cold and no food is there. My family is starving. I will give you this chandelier for milk and anything else I can carry.' The farmer inspected the chandelier, God damn his soul. Our people! They will try to strike a deal no matter what. You may be flat on the ground, your legs chopped off, and they will throw dust in your eyes while they cheat at backgammon. This farmer held up the chandelier with the aid of another man and said, 'It is broken. It can't be worth much.' I said to him, 'Please sir. It is made of gold and rubies and crystal.' 'Where did you get it from?' he asked. I said, 'I got it from the mountain.' He nodded. He did not want to ask me the next questions. 'I'm not sure,' he said. It was then that his wife, God save her soul, slapped him on the eyes. He pushed her away. 'All right,' he said, 'Two jugs of milk and we will put a pack of bread on your back. Can you carryall that?' I said, 'Yes, yes, I can carry as much as you can give me.' And he gave me two lambskins of milk and hoisted the bread on my back. The wife put in two bags of dates and dried apricots when he wasn't looking. And she kissed me on the head.

"I stayed in that town to rest for the night. They fed me a good meal. It felt good to sleep, to sleep thoroughly. But by morning I was ready to go. I walked back up the mountain, rising from the warm air to the cold, walking back into the snow world and the dark forest. I walked steadily, though my back and pelvis were hurting. When I made it back to Mheiti in a few days, I found myself running through the worn path in the snow up to my little house-a house made of limestone blocks, a good, sturdy house in normal times. My mother spotted me through the window and came running. She shouted in a hoarse voice, 'Mukhlis! Oh Mukhlis, you've come!'"

Matile is standing rigid. She does not speak, or offer food. She watches her brother's sapphire eyes melting in their own fire.

"My mother threw me above her-ya rubi, she was strong-and then carried me into the house before she even saw the milk. When she did, she nearly tore it off my neck. She gave some to Matile, to my brother Milhem, and to the baby Leila. But there was the infant to go-my brother Wadie. She frantically squeezed the lambskin's tip into his mouth as he lay in his crib. It was a wooden crib. A small wooden crib. I

35

watched her force it on him. I saw that his eyes were stunned open as if he had seen a large rock toppling on top of him. She kept squeezing the lambskin of milk until half of it was dripping out of his mouth to the floor. 'Mother!' I called to her. 'Don't, don't! You're wasting it.' She wouldn't stop. I had to pull it from her hands. She squeezed the infant's cold cheeks and then took her nails directly to the wall and clawed it. She claws it, yes. After a while she put a sheet over the whole crib."

Mukhlis looks down, then far up to the ceiling of the porch. "1 never knew him."

"Ach!" Mukhlis stands slowly. "Let's go, Wardi."

"No, no," Matile wakes from her trance. "You must stay for supper."

"We can't. 1 must go pick up a rent."

But Matile will not be swayed. She lifts her urgent voice, as if the food were gold and they were turning their backs on precious things. Mukhlis relents while shaking his head. All move into the dining room.

They sit under the chandelier, and pass the grape leaves, the stuffed zucchini, the swollen purple eggplant. They eat in silence, the unlit chandelier struck by the California sundown. It breaks into light above the food; it breaks in pieces of light on Mukhlis' almond head. When he finishes he stands, and ticks one of the crystal droplets with the thick nail of his finger, and does not speak.

"You hear what we went through?" Matile says after they are gone. "That was not all of it." She hugs her grandson, but not long. Even before she is through crying she has opened her mammoth horizontal freezer and said, "We need more bread, more bread."

36

Two Stories

Marga Minco

The Address

"Do you still know me?" I asked.

The woman looked at me, inquiring; she had opened the door a crack. I carne closer and stood on the front step.

"No," she said, "I don't know you."

"I'm the daughter of Mrs. S.," I said.

She kept her hand on the door as though she wanted to prevent it from opening further. Her face didn't betray any sign ofrecognition. She kept looking at me silently.

Maybe I'm wrong, I thought, maybe she isn't the one. I had only seen her once in passing, and that was years ago. It was quite likely that I had pushed the wrong doorbell. The woman let go of the door and stepped aside. She was wearing a green hand-knitted sweater. The wooden buttons were slightly faded from laundering. She saw that I was looking at her sweater and again hid partly behind the door. But now I knew that I was at the right address.

"You knew my mother, didn't you?" I asked.

"Did you corne back?" said the woman. "I thought that no one had corne back."

"Only I," I said. In the hall behind her a door opened and closed. A stale smell carne out.

"I'm sorry," she said, "I can't do anything for you."

"I've come here especially on the train. I would have liked to speak with you for a moment."

"It's not convenient now," said the woman. "I can't invite you in. Another time."

She nodded and carefully closed the door, as though no one in the house should be disturbed. I remained on the front step for a moment.

37

The curtain of the bay window moved. "Oh, nothing," the woman would say, "it was nothing."

I looked at the nameplate once more. It said "Dorling," with black letters on white enamel. And on the doorpost, a little higher, the nurnber. Number 46.

While slowly walking back to the station, I thought of my mother, who had once, years ago, given me the address. It was during the first half of the war. I had come home for a few days, and it had struck me right away that something had changed in the rooms. I missed all sorts of things. My mother was surprised that I'd noticed it so quickly. Then she told me about Mrs. Dorling. I had never heard of her before, but she seemed to be an old acquaintance of my mother's whom she hadn't seen in years. She had suddenly turned up and renewed the acquaintance. Since that time she had been coming regularly.

"Every time she leaves she takes something home with her," my mother said. "She took all the silver flatware at once. And then the antique plates which hung over there. She really had a tough job lugging these big vases, and I'm afraid that she hurt her back with the dishes." My mother shook her head with compassion. "I would never have dared to ask her. She suggested it herself. She even insisted. She wants to save all my beautiful things. She says that we'll lose everything when we have to leave here."

"Have you arranged with her that she'll keep everything?" I asked. "As though that were necessary," my mother exclaimed. "It would be an insult to agree on something like that. And think of the risk she takes every time she leaves our house with a full suitcase or bag!'" My mother seemed to notice that I wasn't totally convinced. She looked at me reproachfully, and after that we didn't speak of it again.

Without paying too much attention to the road I had arrived at the station. For the first time since the war I was walking again through familiar districts, but I didn't want to go further than absolutely necessary. I didn't want to torment myself with the sight of streets and houses full of memories of a cherished time. In the train back, I saw Mrs. Dorling before me again, the way I had met her the first time. It was the morning after the day my mother had told me about her. I had gotten up late, and as I went downstairs I saw that my mother was just seeing someone out. A woman with a broad back.

"There is my daughter," said my mother. She motioned to me.

The woman nodded and picked up the suitcase which stood under the coatrack. She was wearing a brown coat and a shapeless hat.

"Does she live far?" I asked after seeing how laboriously she left the house with the heavy suitcase.

"On Marconistraat," said my mother. "Number 46. Do try to rernernber."

38

I had remembered. Except that I had waited quite a long time before going there. During the first period after the liberation I felt no interest at all in all that stored stuff, and of course some fear was involved. Fear of being confronted with things that had been part of a bond which no longer existed; which had been stored in cases and boxes and were waiting in vain until they would be put back in their places; which had survived all these years because they were "things."

But gradually everything had become normal again. There was bread which was steadily becoming lighter in color, there was a bed in which you could sleep without being threatened, a room with a view which you got more and more used to every day. And one day I noticed that I was becoming curious about all the possessions which should still be at that address. I wanted to see them, touch them, recognize them. After my first fruitless visit to Mrs. Dorling's house, I decided to try it a second time.

This time it was a girl of about fourteen who opened the door. I asked whether her mother was home. "No," she said, "my mother is just on an errand."

"That doesn't matter," I said, "I'll wait for her."

I followed the girl through the hall. Next to the mirror hung an old, fashioned menorah. We had never used it because it was much more cumbersome than candles.

"Wouldn't you like to sit down?" asked the girl. She held open the door to the room and I went in past her. Frightened, I stood still. I was in a room which I both knew and didn't know. I found myself among things I had wanted to see again but which oppressed me in the strange sur, roundings. Whether it was because of the tasteless manner in which everything was arranged, because of the ugly furniture or the stuffy air, I don't know, but I scarcely dared look around me anymore. The girl moved a chair. I sat down and stared at the woollen tablecloth. I touched it carefully. I rubbed it. My fingers got warm from rubbing. I followed the lines of the design. Someplace on the edge there should be a burn hole which had never been repaired.

"My mother will be back very soon," said the girl. "I had already made tea for her. Would you like a cup?"

"Please," I said. I looked up. The girl was setting out teacups on the tea table. She had a broad back. Just like her mother. She poured tea from a white pot. There was a gold edge just around the lid, I remembered. She opened a small box and took some teaspoons out of it. "That's a lovely little box." I heard my own voice. It was a strange voice. As though every sound in this room had another ring to it.

"Do you know much about that?" She had turned around and brought me my tea. She laughed. "My mother says that it is antique. We have lots more." She pointed around the room. "Just look."

I didn't need to follow her hand. I knew which things she meant. I

39

kept looking at the still-life above the tea table. As a child I had always wanted to eat the apple that lay on the pewter plate.

"We use it for everything," she said. "We've even eaten from the plates which hang on the wall. I wanted to. But it wasn't anything special."

I had found the burn hole at the edge of the tablecloth. The girl looked at me inquiringly. "Yes," I said, "you get used to all these beautiful things at home, you hardly look at them anymore. You only notice when something is not there, because it has to be repaired, or, for example, because you've lent it to someone."

Again I heard the unnatural sound of my voice, and I continued: "I remember my mother once asking me to help her polish the silver. That was very long ago, and I must have been bored that day, or maybe I had to stay home because I was ill, for she had never asked me to do that before. I asked her which silver she meant, and she answered me, surprised, that she was of course talking about the spoons, forks, and knives. And that was of course the odd thing, I didn't know that the objects with which we ate every day were made of silver."

The girl laughed again.

"I bet you don't know that either," I said. I looked at her intently. "What we eat with?" she asked.

"Well, do you know?"

She hesitated. She walked to the buffet and started to pull open a drawer. "I'll have to look. It's in here."

I jumped up. "I'm forgetting my time. I still have to catch my train." She stood with her hand on the drawer. "Wouldn't you like to wait for my mother?"

"No, I have to leave." I walked to the door. The girl opened the drawer. "I'll find my way." When I was walking through the hall I heard the clinking of spoons and forks.

At the corner of the street I looked up at the nameplate. It said Marconistraat. I had been at Number 46. The address was right. But now I no longer wanted to remember it. I would not go there again, for the objects which in your memory are linked with the familiar life of former times suddenly lose their value when you see them again, torn out of context, in strange surroundings. And what would I do with them in a small rented room in which shreds of blackout paper were still hanging along the windows and where in the narrow table drawer there was room for just a few dinner things?

I resolved to forget the address. Of all the things I should forget, that one would be the easiest.

Translated by Jeannette K. Ringold

40

The Day My Sister Married

On the day my sister married I got up early, even before the sound of my alarm, which I had set for seven o'clock. I walked to the window, which stood halfway open, pushed it open further and leaned out.

A woman came out of her kitchen door barefoot and in a pink bathrobe. Carefully, as though she were testing the first ice, she took a few steps over the flagstones to the garden path, after which she quickly went back, pulling her legs up high. It was still chilly, but the grayish white sky had already started to lighten and it looked as though it would be a sunny spring day. A few gardens away someone let a bucket roll down a step. A red tomcat was balanced on top of the fence. Perhaps he was the one who in the middle of the night had given the intense scream that had awakened me with a start. I had remained still, listening, but heard nothing else. Everyone had seemed to be sleeping quietly. For a moment I had the sensation that I was in my room in our old house. Lately that had happened more often. I had to look intently at the door and the window, which were located differently with respect to my bed, to confirm that it had been a dream. As I closed my eyes and turned over on my other side, I heard it again. It came from outside. It was the piercing screech of a tomcat, and I didn't understand that I had mistaken this sound for a human scream. I shivered from the morning cold coming in and closed the window.

"May is a lovely month to get married," the grocer had said yesterday as he placed a big box of food on the kitchen table. "People are marrying anyway. All that continues as usual." It was early in May '42 and we had been wearing the stars for a few days. It was not our intention to give a real wedding party, but my mother thought that we couldn't just let it go by and that we should invite some family members. "Who knows," she said, "how long it will be before we have the opportunity to be all together again." Not much family could come, a few uncles and aunts. It

41

was no longer as before in our larger house in Breda where every occasion was seized upon to invite as many people as possible. If it had been up to my sister, they would have just gone to the synagogue for the wedding service, nothing more. 1 believe she found it a relief that without any of us present, they had had the civil service in Amsterdam. One week before the wedding day she'd called me to ask if I would take care of the bridal bouquet. "That's much easier for us," she'd said. "Then we don't have to bring it along from here." I promised that I would go to the florist that very day. "What should it be?" I asked. "Just choose something you find appropriate," she said, as though it went without saying that 1 was experienced in such things.

1 went downstairs and found my mother already quite busy in the kitchen. "You're early too," she said. "That's very convenient, there is still a lot to do."

"It won't be that busy." I looked into the box with the rented glassware. "How many people are you counting on anyway?"

"Oh, you never know. It's always possible that more people will come than we had thought. And perhaps they'll be bringing friends along from Amsterdam."

"She didn't say anything about it."

"That isn't necessary. She knows that everyone is welcome here."

"I wouldn't know who would be coming with them."

"Oh, we'll see." My mother gave me a tea towel. "Will you please polish these glasses?"

She left the kitchen. I had a strong feeling that she wanted to pretend that nothing had changed, that she was going to have a house full of guests. She would walk through the rooms again and picture the way it had always been: furniture pushed aside, long rows of chairs, tables pushed together, everywhere vases with flowers. And my father seemed to subscribe to that view, for I heard him say: "I'll leave the front door ajar, then they can push it open with one knee." It was a standard joke of his.