Volume 2: Prose from Spain

SprinK/Summer 1983

Volume 2 of 2 Volumes: Prose from Spain

Editor

Coeditors of this volume

Associate Editor

Managing Editor

Manuscripts Editor

Assistant Editor

Design Director

TriQuarterly Fellow

Editorial Assistants

Advisory Editors

Reginald Gibbons

Reginald Gibbons, Anthony L. Geist, David Hayman, Suzanne Jill Levine

Bob Perlongo

Molly McQuade

Susan Hahn

Fred Shafer

Gini Kondziolka

Chris Olson

Will Johnson, Joe laRusso, Michael Lindsay, David Simpatico

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Elliott Anderson, Terrence Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Elizabeth Pochoda, Michael Ryan

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART. WRITING, AND CULTURALlNQUIRY PUBUSHED IN THE FALL, WINTER, AND SPRING AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY. EVANSTON, ILLINOIS 60201.

Subscription rates: one year $14.00; two years $25.00; three years $35.00. Foreign subscriptions $3.00 per year additional. Life subscription $100.00. USA or foreign. Single copies usually $5.95. This issue: $3.95 each volume. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to Tri�rterly, NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY. 1735 Benson Avenue. Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions of fiction. poetry. and literary essays. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped. selfaddressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterIy, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1983 by TriQj.Jarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers. not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America.

National distributor to retail trade: B. Deboer, 113 East Central Street-Rear, Nurlev, New Jersey 07110. Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2940 Seventh Street. Berkeley. California 94710. Midwest: Bookslinger, 330 East Ninth Street, St. Paul. Minnesota 55101 and Prairie News Agency, 2404 West Hirsch Street, Chicago, Illinois 60622.

Reprints of back Issues of Tri�rterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company. Route 100, Millwood. New York 10546, and in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106. ISSN: 00413097.

57

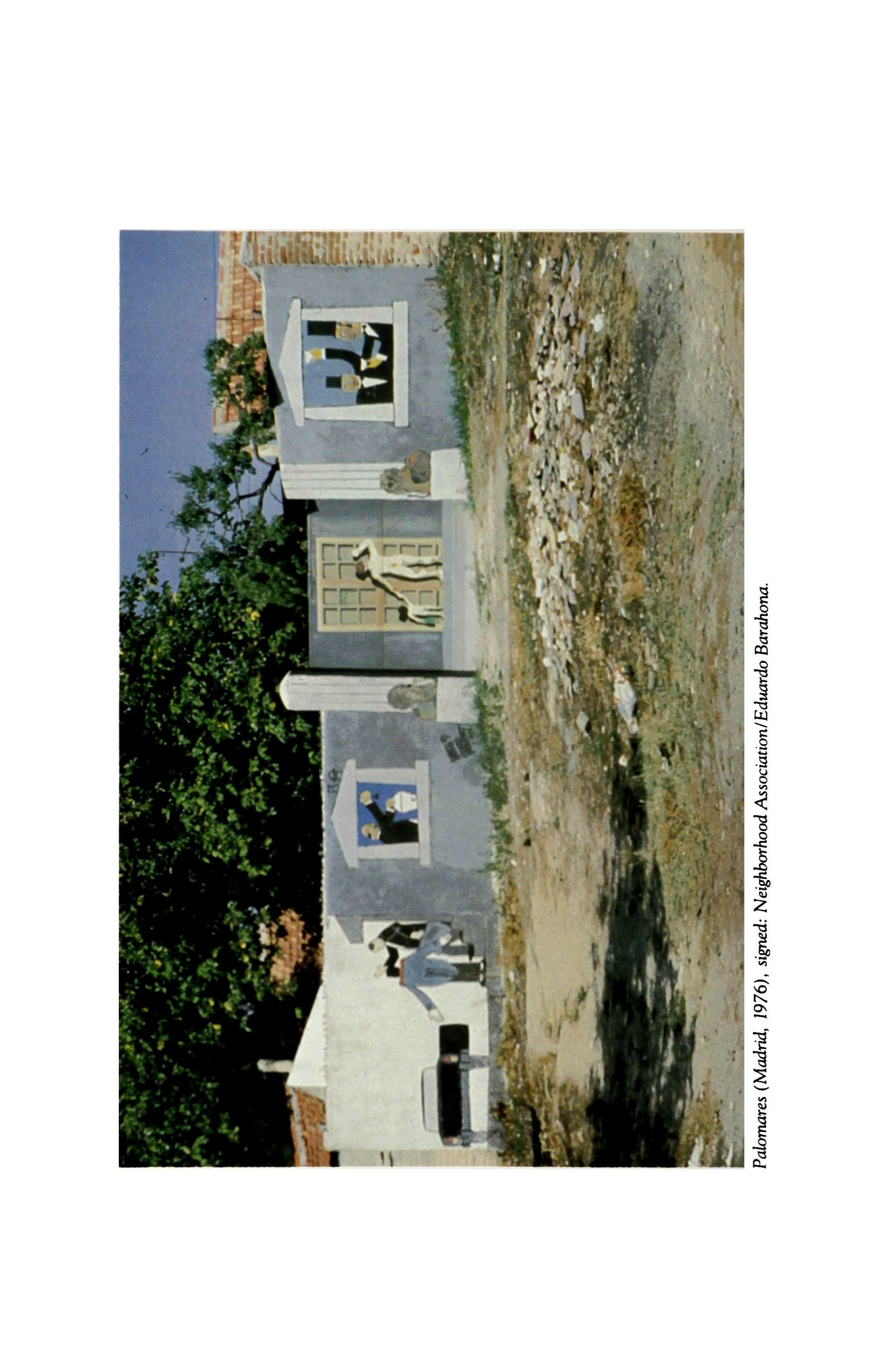

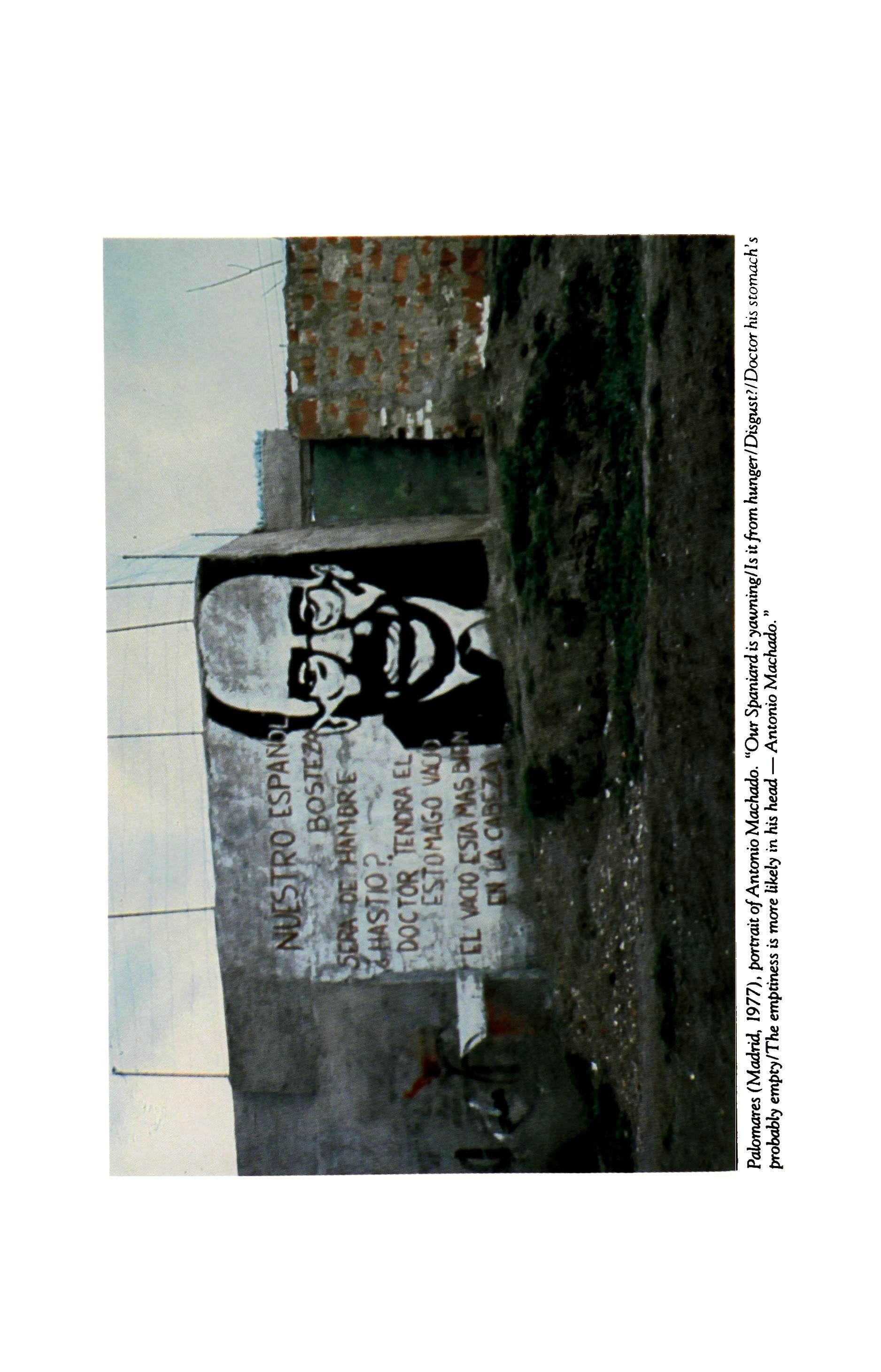

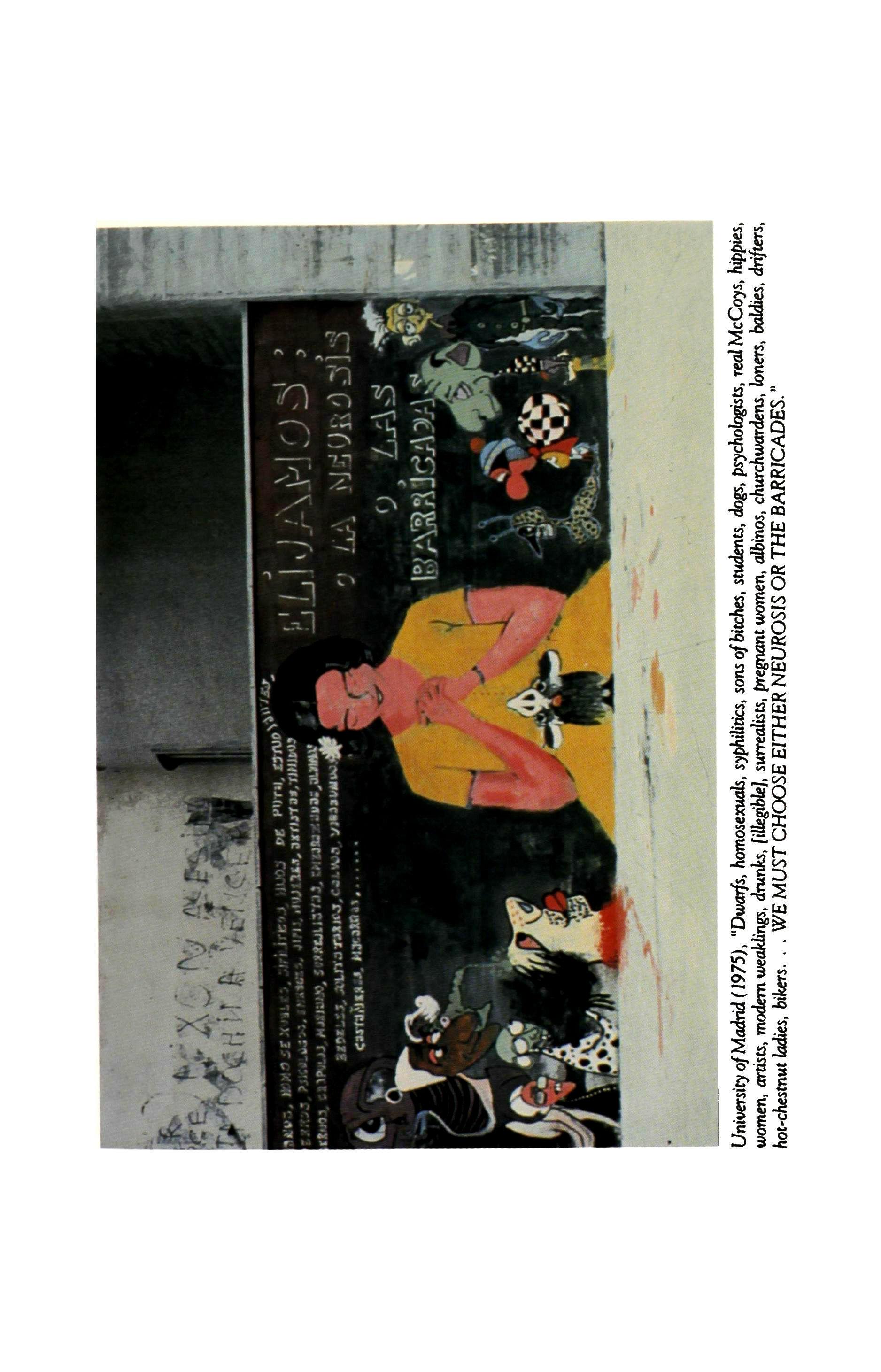

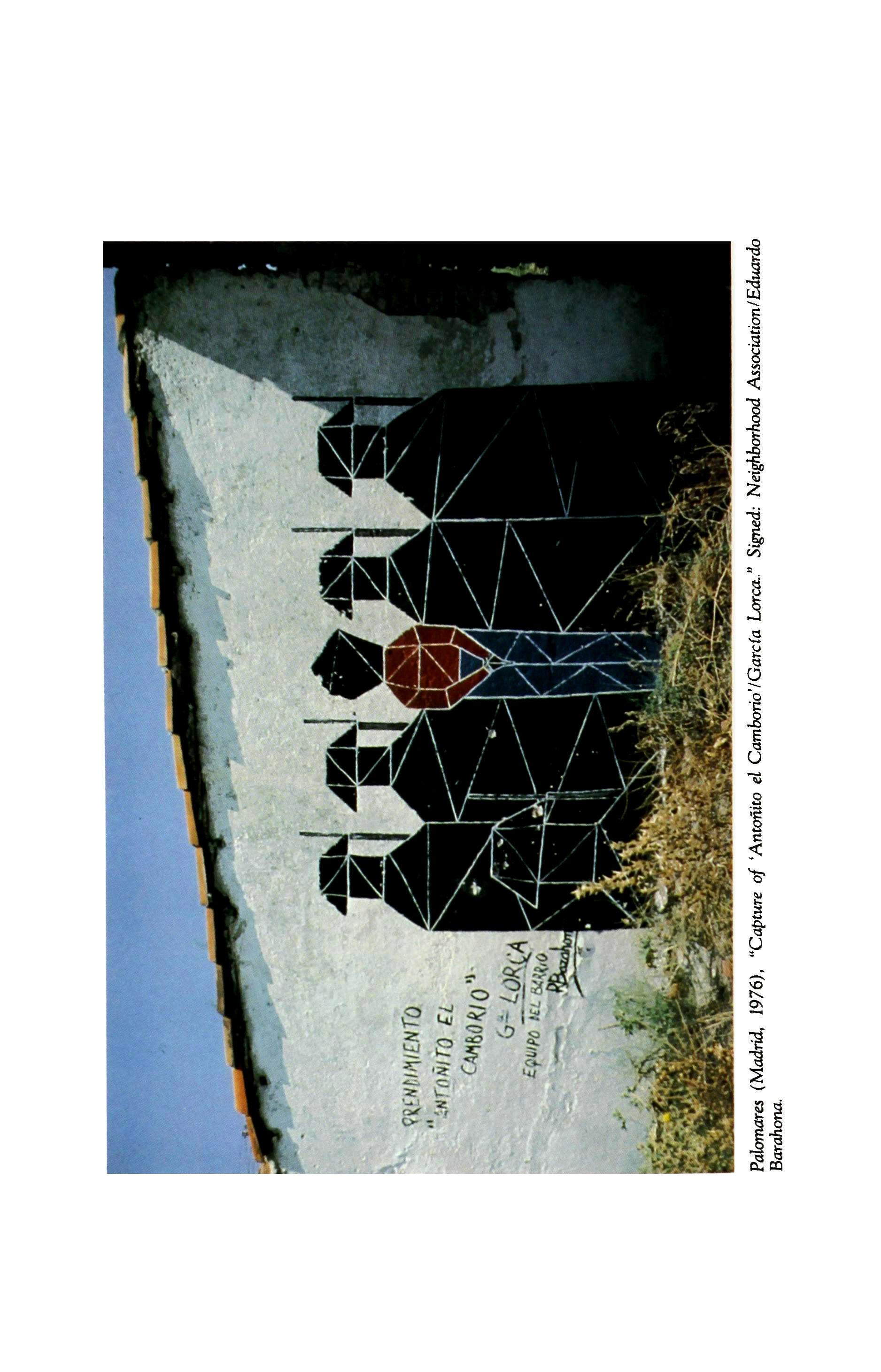

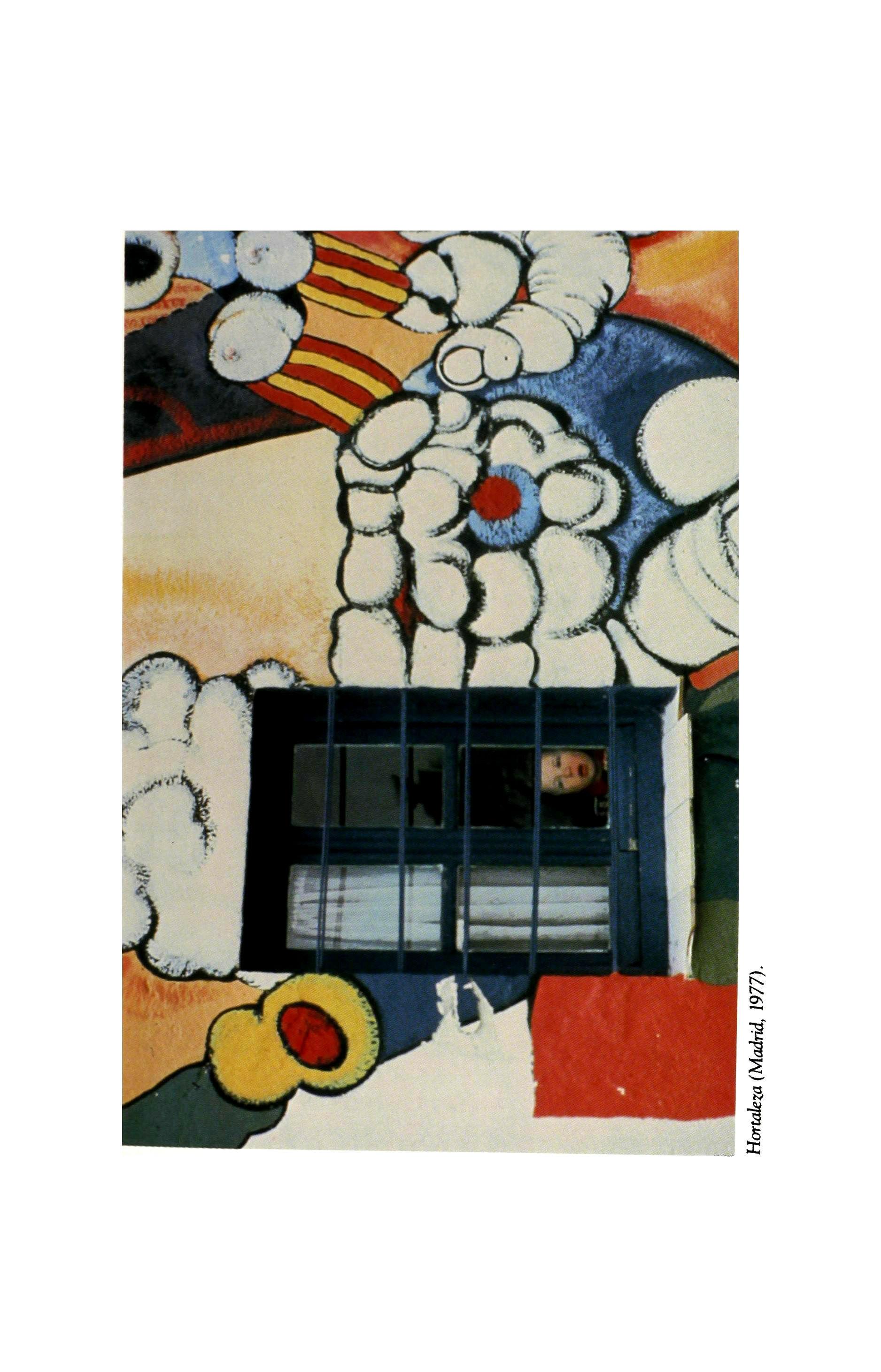

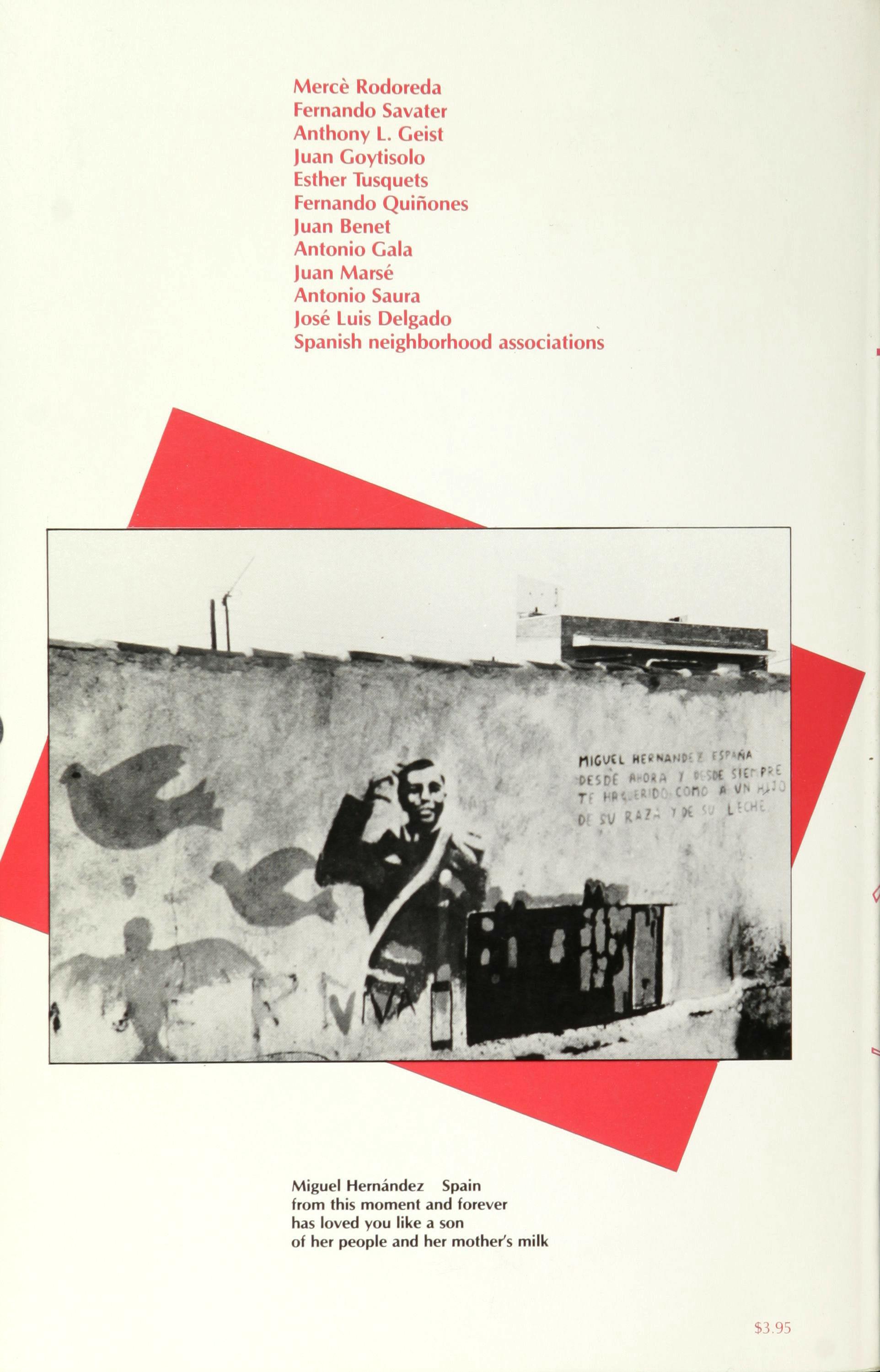

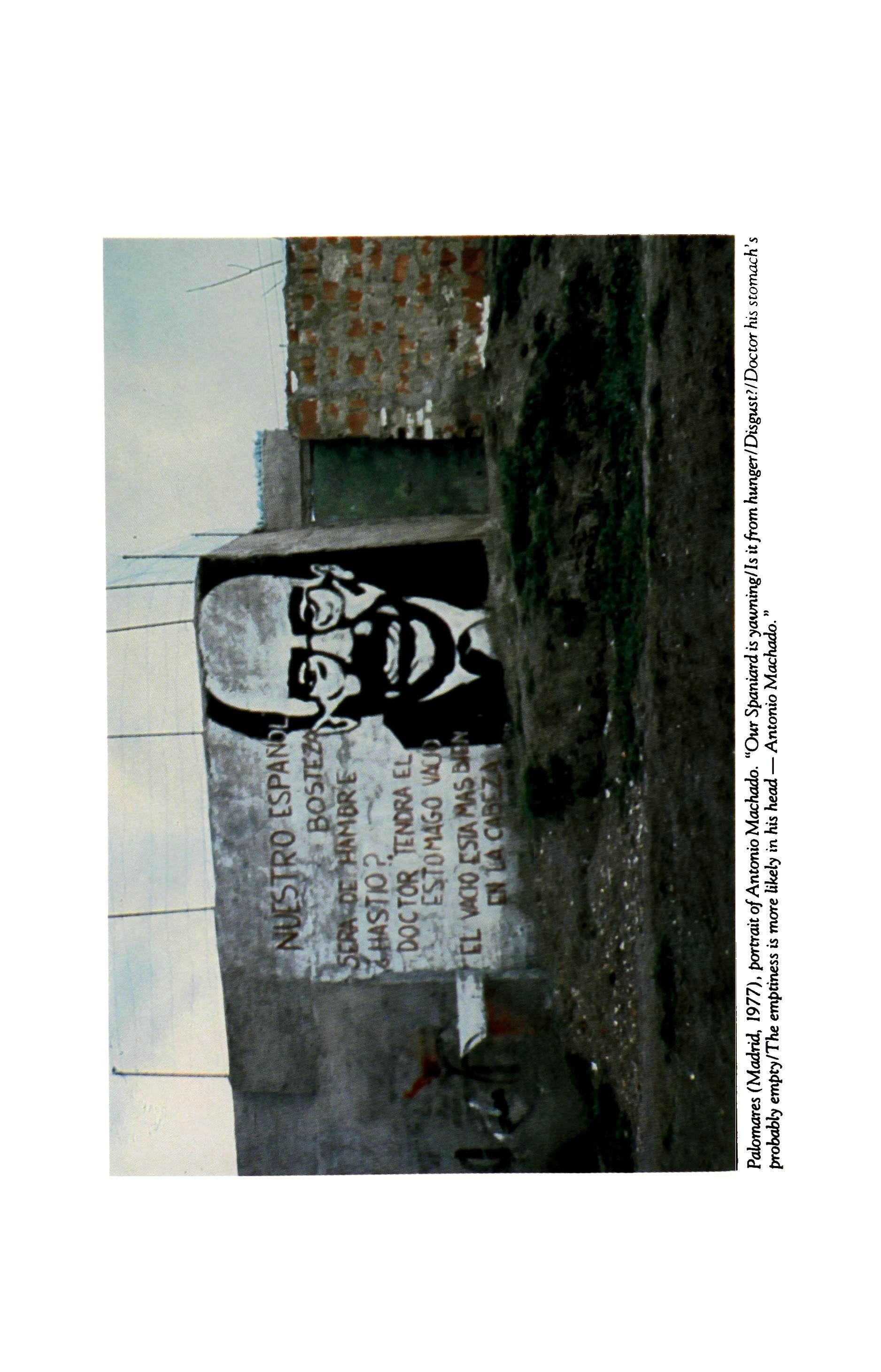

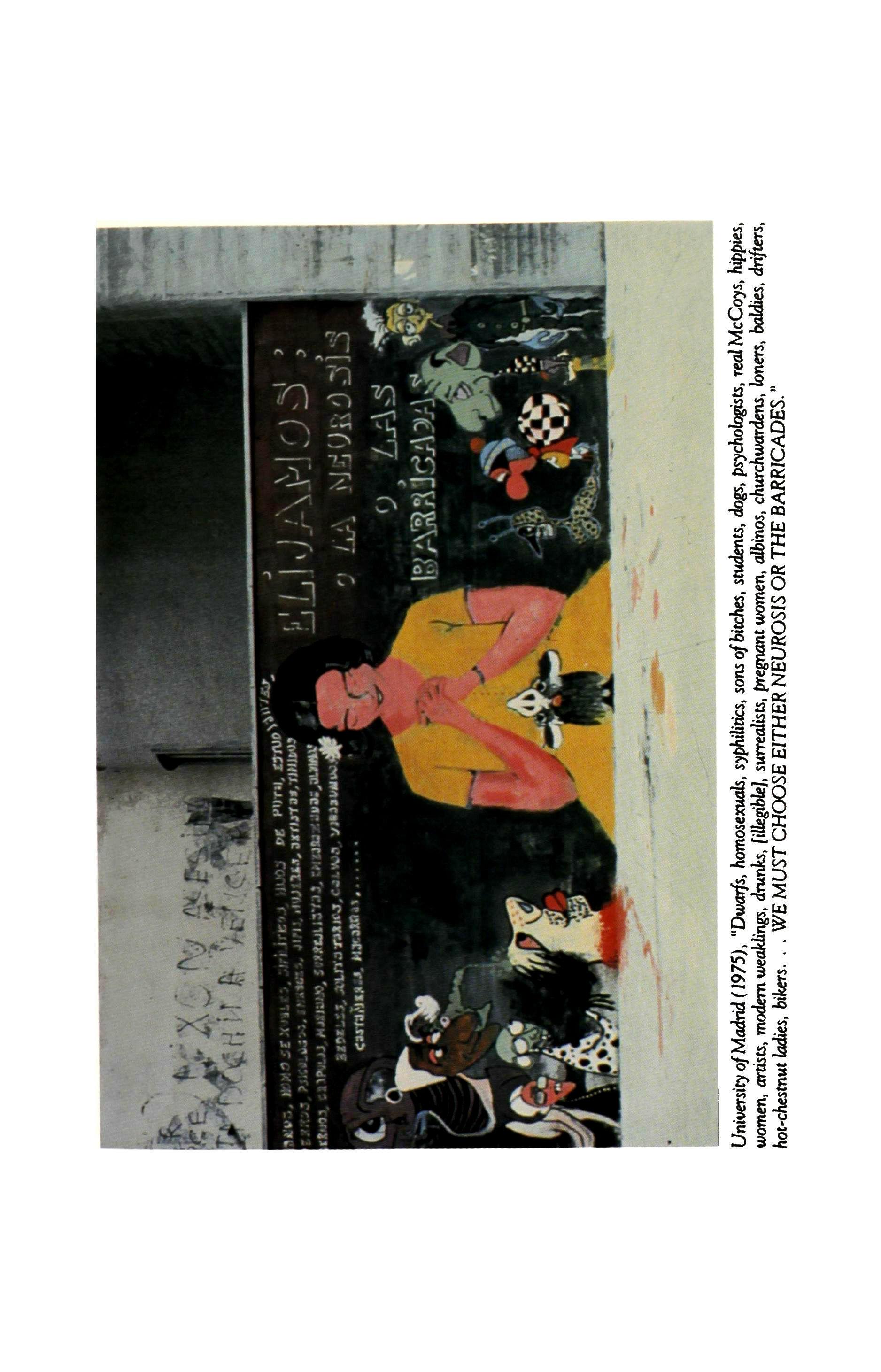

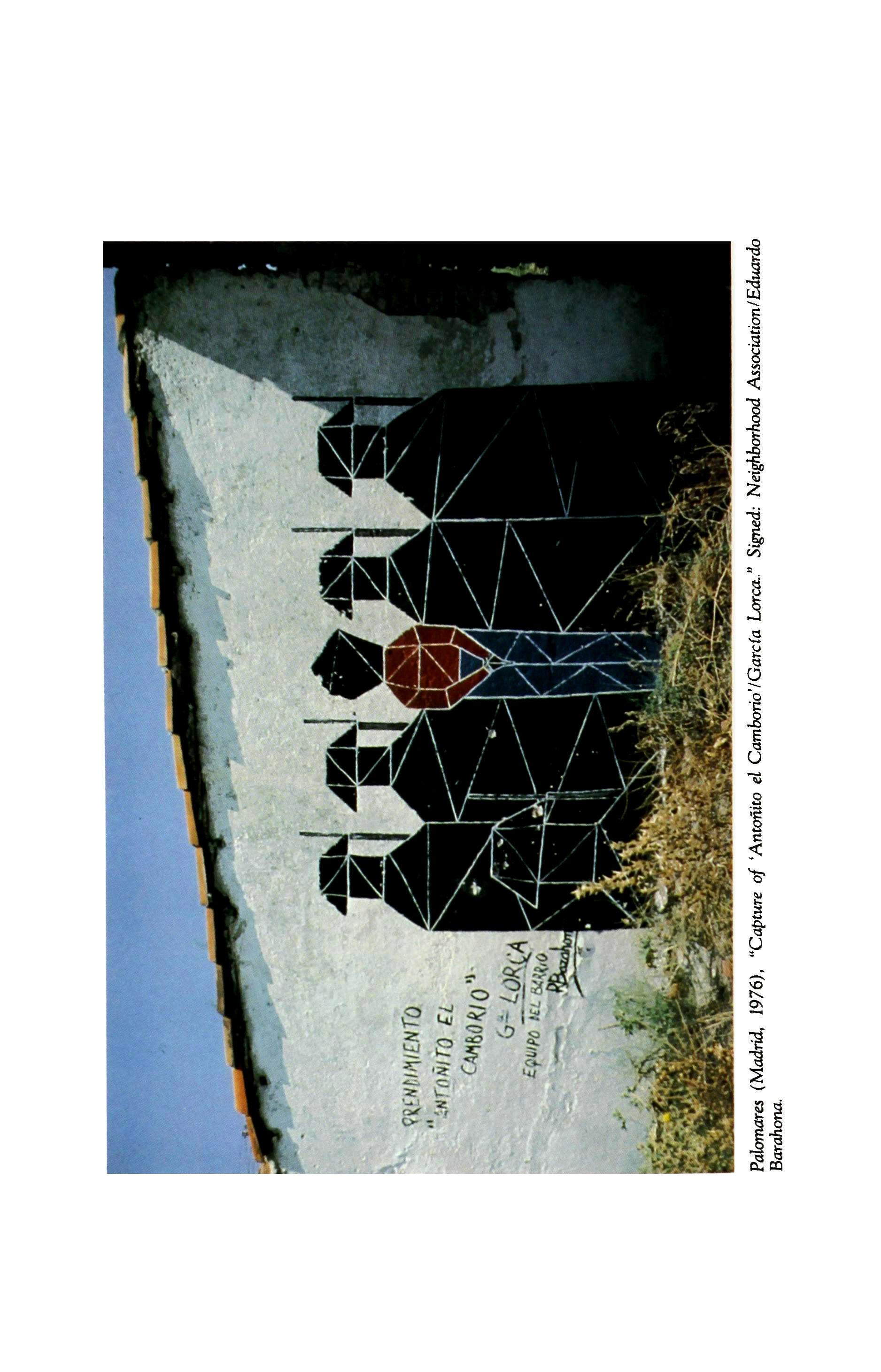

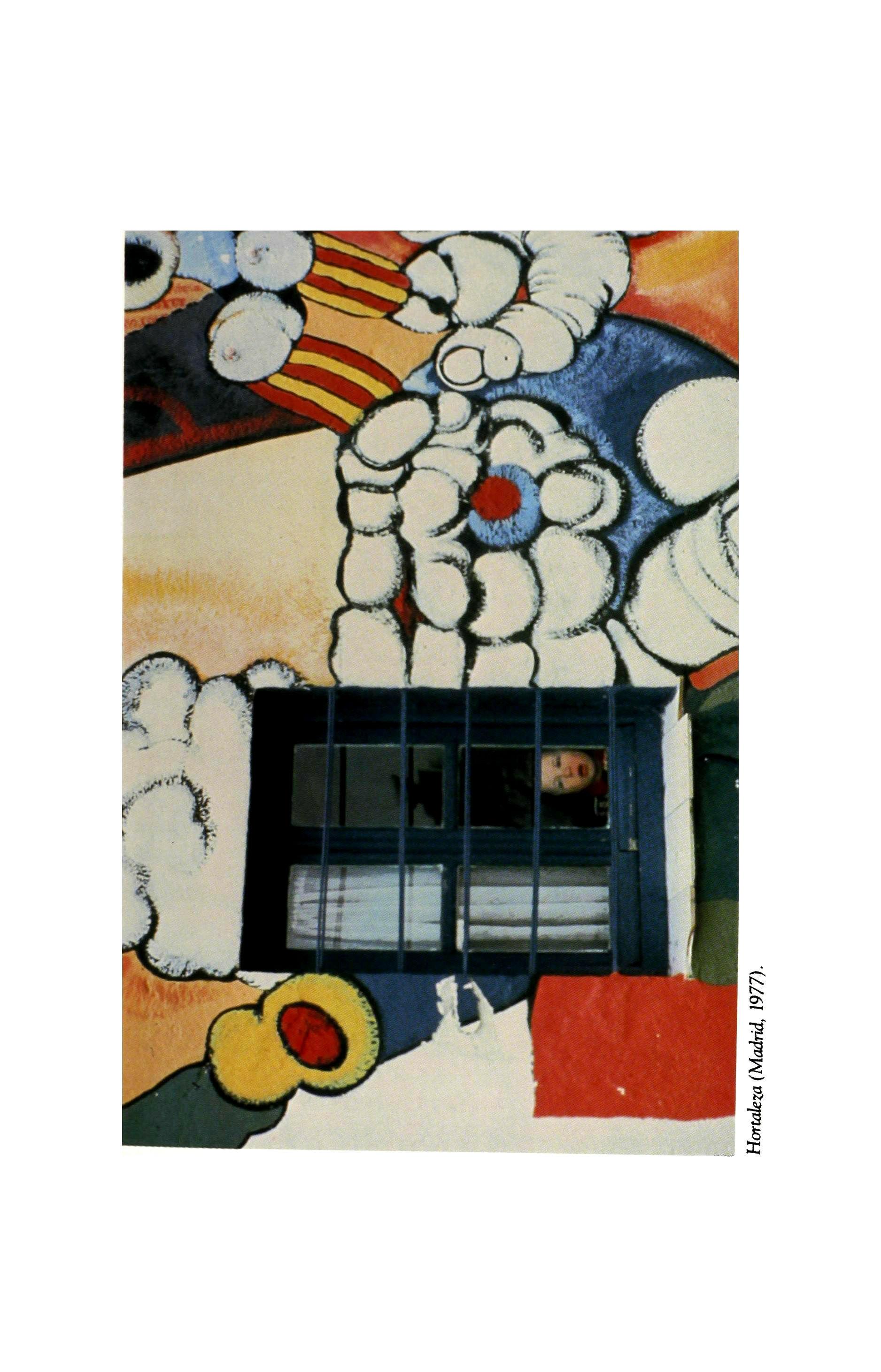

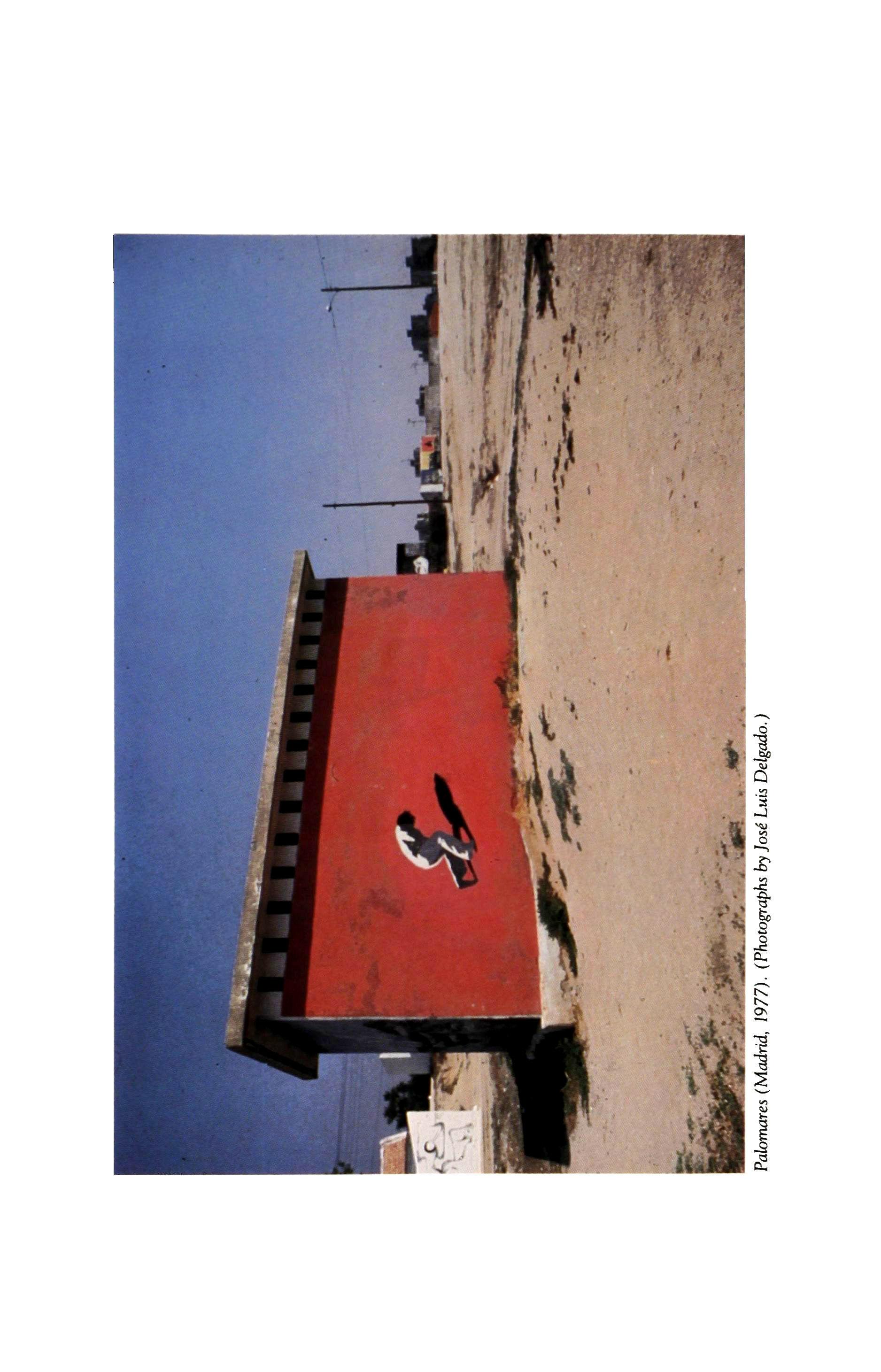

Contents Preface 3 From So much of such a war (fiction) 7 Merce Rodoreda On the use, abuse, and discomposure of culture (essay) Fernando S£lVater 34 An interview with Juan Govtisolo 38 Anthony L. Geist Street murals At 48 Spanish neighborhood associations From Landscapes after the battle (fiction) 49 Juan Goytisolo From The same sea as every summer (fiction) 56 Esther Tusquets From The thousand nights of Hortensia Romero (fiction) 67 Fernando Quinones Fables (fiction) 79 Juan Benet Two columns from Chatting with Troylo 84 Antonio Gala The aunt, her nephews, the ticket girl, and the punk (f-rction) 90 Juan Benet From Someday I'll be back (fiction) 97 Juan Marse Contributors 110 Front-cover painting by Antonio Saura. Back cover and insert: street murals by Spanish neighborhood associations, photographs by Jose Luis Delgado. Publication of the back-cover and insert photographs in this tlolume was made possible by a generous gift from the Embassy of Spain in Washington, D.C. 2

Preface

This issue of TriQuarterly collects prose works written roughly since 1975, the year Franco died. The atmosphere created by the changes in government, the end of official censorship, and the return of literary as well as political exiles, has led to an expectation that Spanish writing would show a definitive break with its recent past, and move quickly into a period of greater strength and honesty, that it would adopt the role of cultural adversary that had been denied to it for forty years. The presence in Spain of some notable Latin-American writers, in refuge from the oppressive governments of their own homelands even before Franco died, has added to this expectation.

But as Juan Goytisolo succinctly observes in an interview in this issue, the expectation of seeing masterpieces of new writing has been for the most part simplistic. While there has been an undeniable and remarkable transformation of many aspects of Spanish society and culture, it is difficult to say that without official censorship and subtler forms of cultural domination, literary works are better. The general vitality of literary culture is certainly greater, but that, as Goytisolo suggests, is a different question. The freedom to publish has in itself created excitement and enlarged the possibilities of writing, and this development can only help create the atmosphere in which great works can appear. But Goytisolo points out as well that even before Franco died there were significant developments in Spanish writing, in response to the cultural changes of the 1960s in Europe-those could not be kept out of Spain merely by having the border guards check suitcases. (They were, in any case, notoriously ignorant. Once, when I crossed from France into Spain in 1972, guards suspiciously questioned me about books by Pedro Salinas which had in fact been published in Madrid, and were innocuous enough by Franco-era standards; it was the mere presence of books in a suitcase that excited the thickheaded inquisitions.)

Part of the new literary climate is due to the resurgence of regional

3

cultures. The Catalans in the east and the Basques in the north have benefited in that their languages are no longer proscribed by law (a state of affairs most people outside Spain did not even know about); regional culture in Andalusia, while linguistically Spanish, has begun to explore more energetically and honestly the local life of the language, for the dialect is distinctly different from the Spanish spoken in the historically dominant central plateau of Castille. Added to regional identity and the freedom to publish, there is the return of the exiles. Rafael Alberti was given a public birthday party (for his eightieth) in Madrid in December 1982, and read his poems to thousands of listeners in a stadium. Representing a younger genera, tion, Juan Goytisolo, whose earlier novels have savaged many elements of Spain and Spanish culture, has returned to give readings of his work to large admiring audiences, though he still lives in Paris. And although many of those who would have returned are dead, from the generations that left the country at the time of the Civil War (1936-39), their memory continues to animate literary interest and perhaps literary practice as well. Goytisolo's chapter on the "being from Sansuefia" in this issue reflects the exile's continuing obsession with events in his homeland; and the regional cultures are represented here by Rodoreda and Marse, both Catalan, and Quinones, who is Andalusian.

Two notable aspects of this volume need brief explanation. First, the absence of poetry. It was not the original intention to concentrate exclusively on prose, but given our limitations of space, and the interesting thematic affinities and contrasts of the prose works, it seemed finally advisable to postpone the publication of translations of recent poetry, and bring them to readers of TQ as a small section of a future issue: poetry is, in this case, a literary sampling that is less identifiably national than the prose, and that phenomenon in itself may warrant some future comment. The second aspect is the presence here mostly of excerpts from long works of fiction rather than short stories. There is no tradition of short fictional forms in Spain to compare with what we are accustomed to in the U.S.; Spanish prose writers tend to turn first to the novel, and even to the essay, before they take up the short story. This is a matter for literary historians to analyze and perhaps to explain; for our purposes, we can only bow to it as a condition of presenting Spanish fiction fairly. There are good short stories, but in addition to having a different significance as a genre in Spanish, they are harder to get hold of, so there is a practical reason for their absence here as well as a literary one. The selection of work makes no pretense to being comprehensive, but merely representative.

4

With its sister volume devoted to writings from the last two years in Poland, the Spanish volume appears at a moment when the two cultures of Spain and Poland offer interesting perspectives on each other. The first notable contrast is that the Polish work tends to be much more documentary, and this contrast has its root in the fact that under Franco's censorship, the Spanish writers had no underground publishing, but instead, reacting as if literary conditions in Spain were much more like those in France, say, than those in Poland, continued to publish what it was possible to publish-work that did not openly criticize the regime or strike the censors as immoral under Franco's repressive standards (which now, having vanished, have of course left the door open to pornography, also). Foreigners and Spaniards alike were much freer to enter and leave the country than in any East European country, and a strong semblance of openness was maintained. Foreign literary publications could be received, even if they could not be published in Spanish translation. But the final result among writers was the habit of self-censorship in a very subtle and pervasive form, and a kind of demoralization that sent writers like Goytisolo abroad to stay. So Spanish writing during the Franco years and afterward tends to reflect the formal experimentation of writers in other western countries, and conveys an impression ofstrictly literary value that contrasts with the impression one gets from recent Polish writing of aesthetic concerns often subordinated to documentary ones.

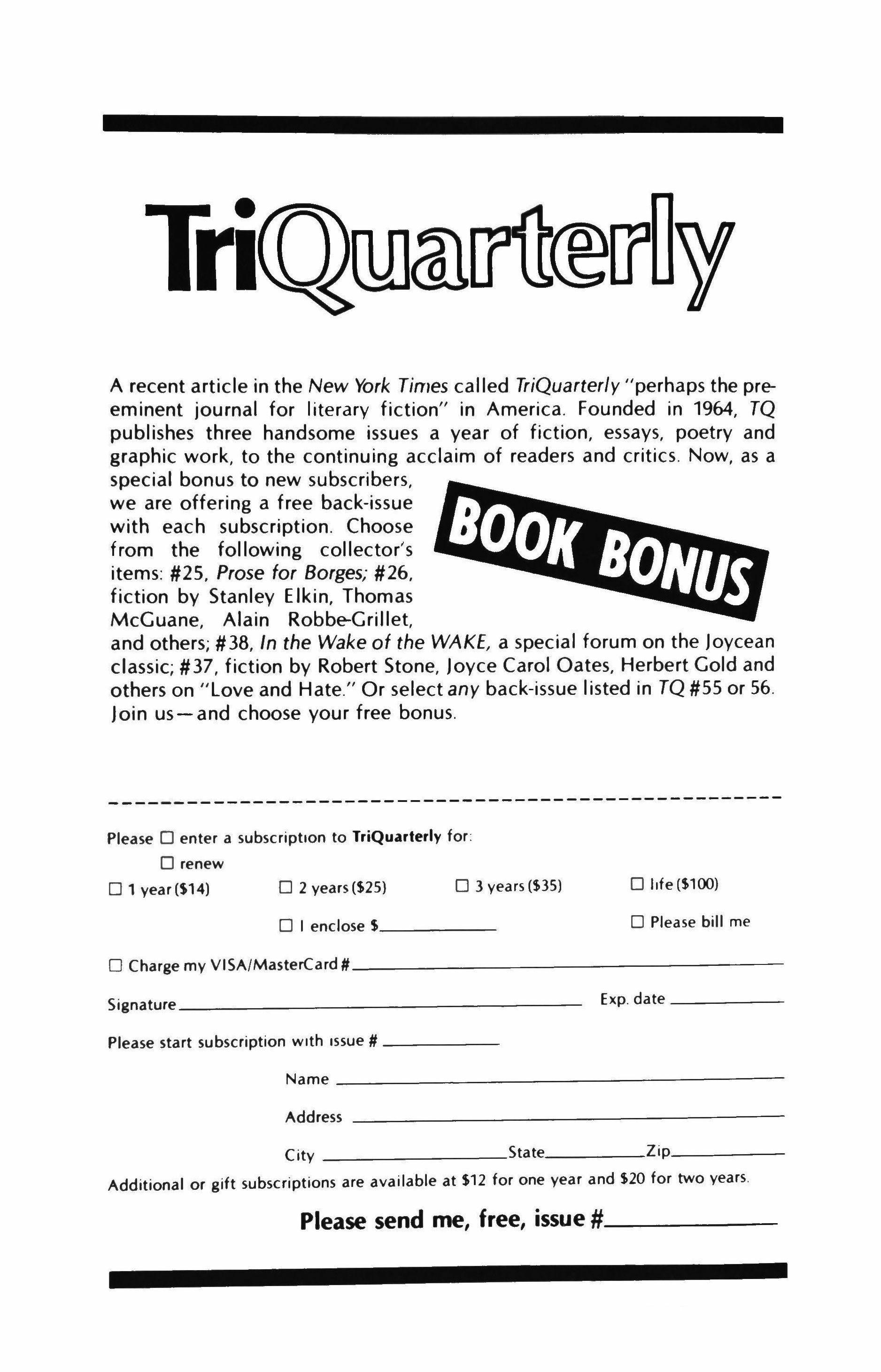

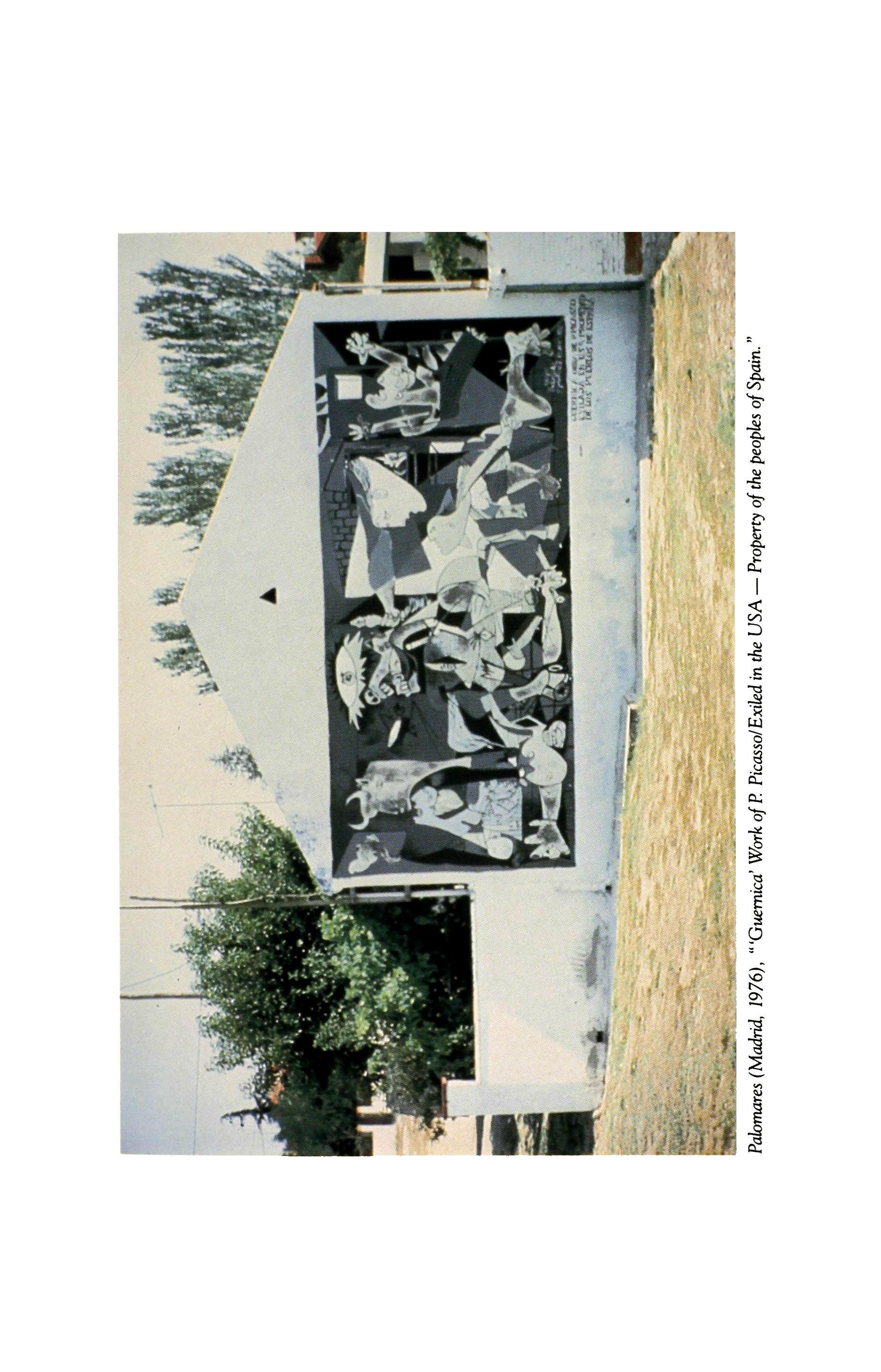

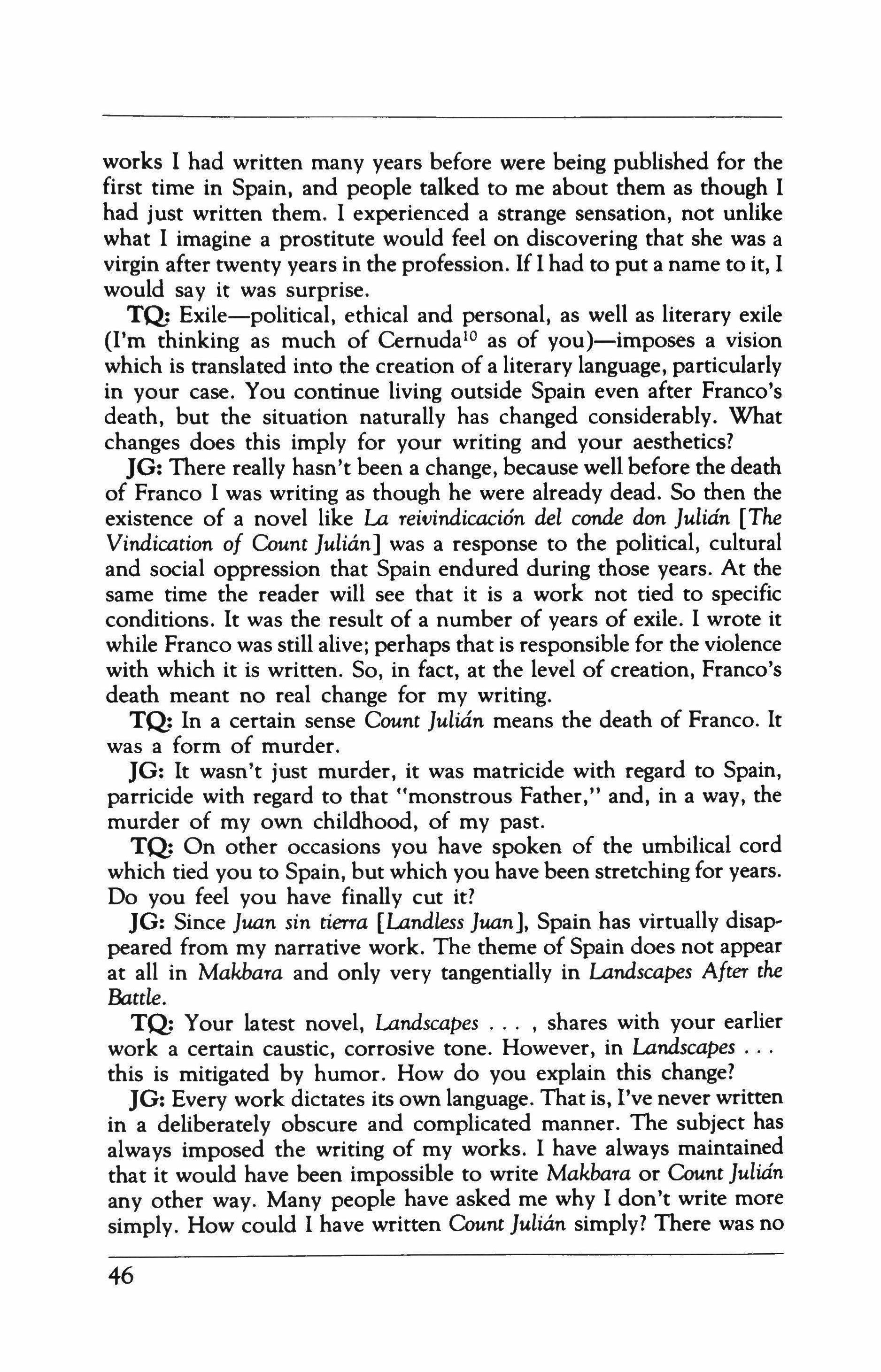

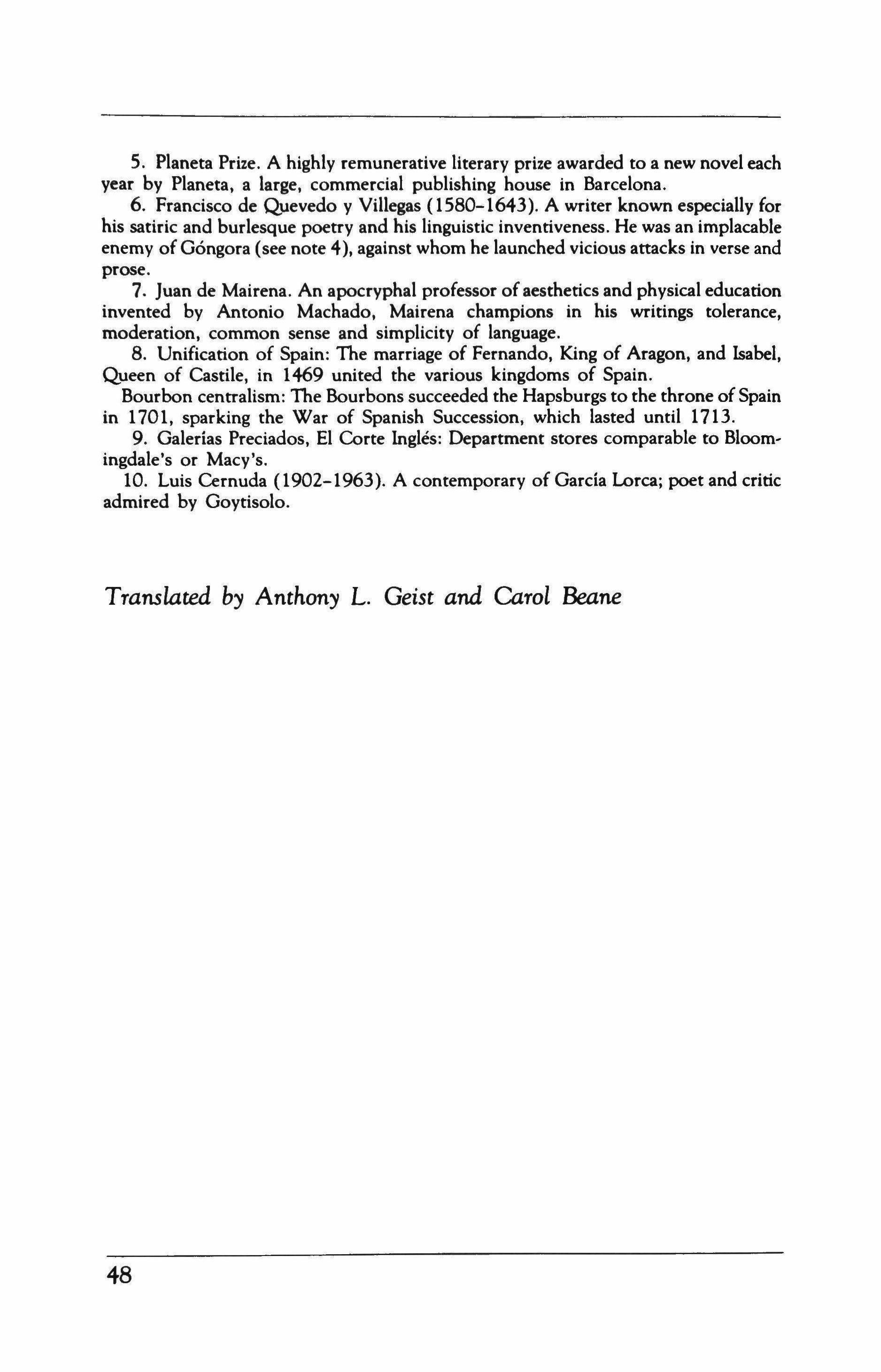

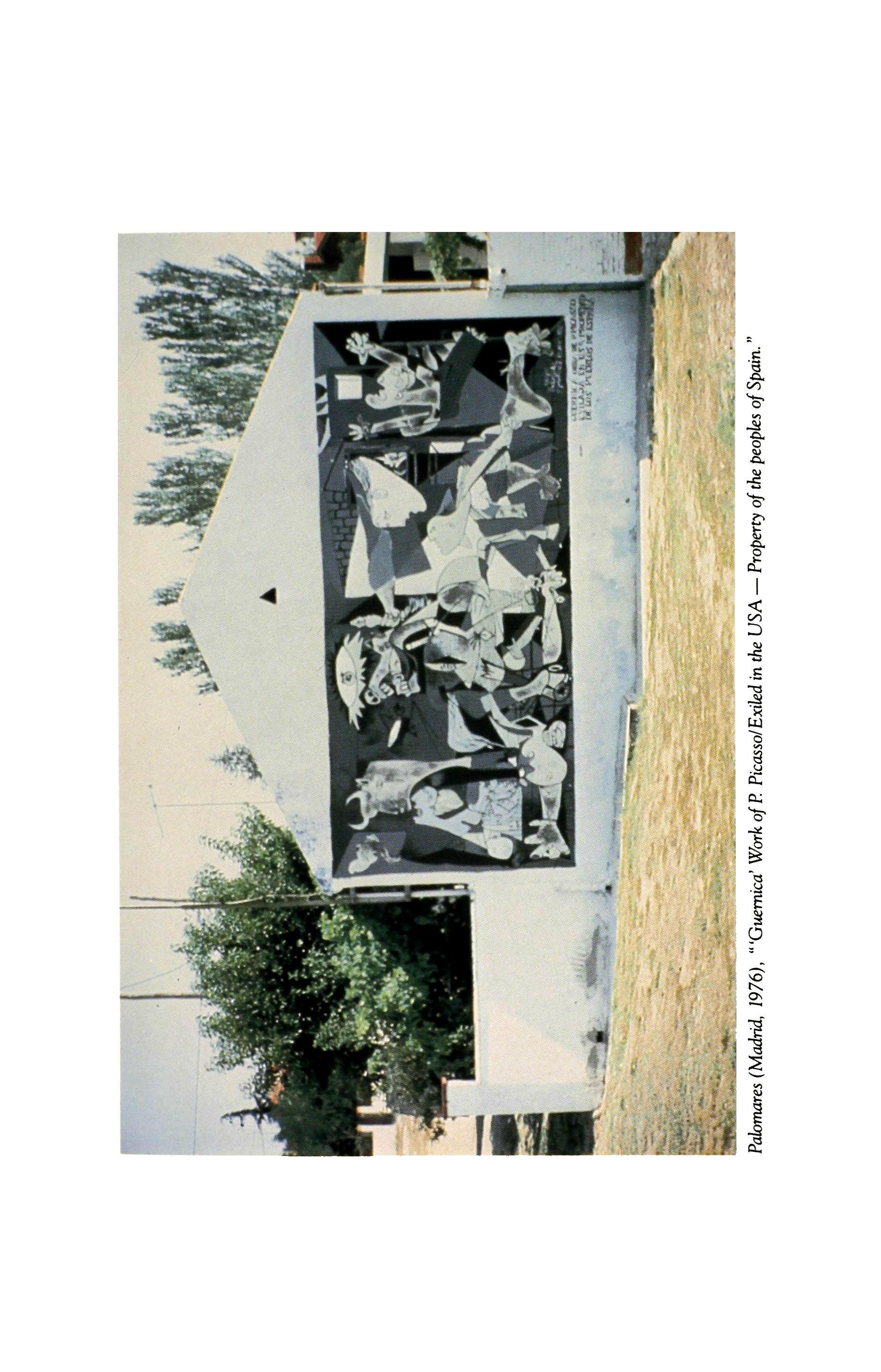

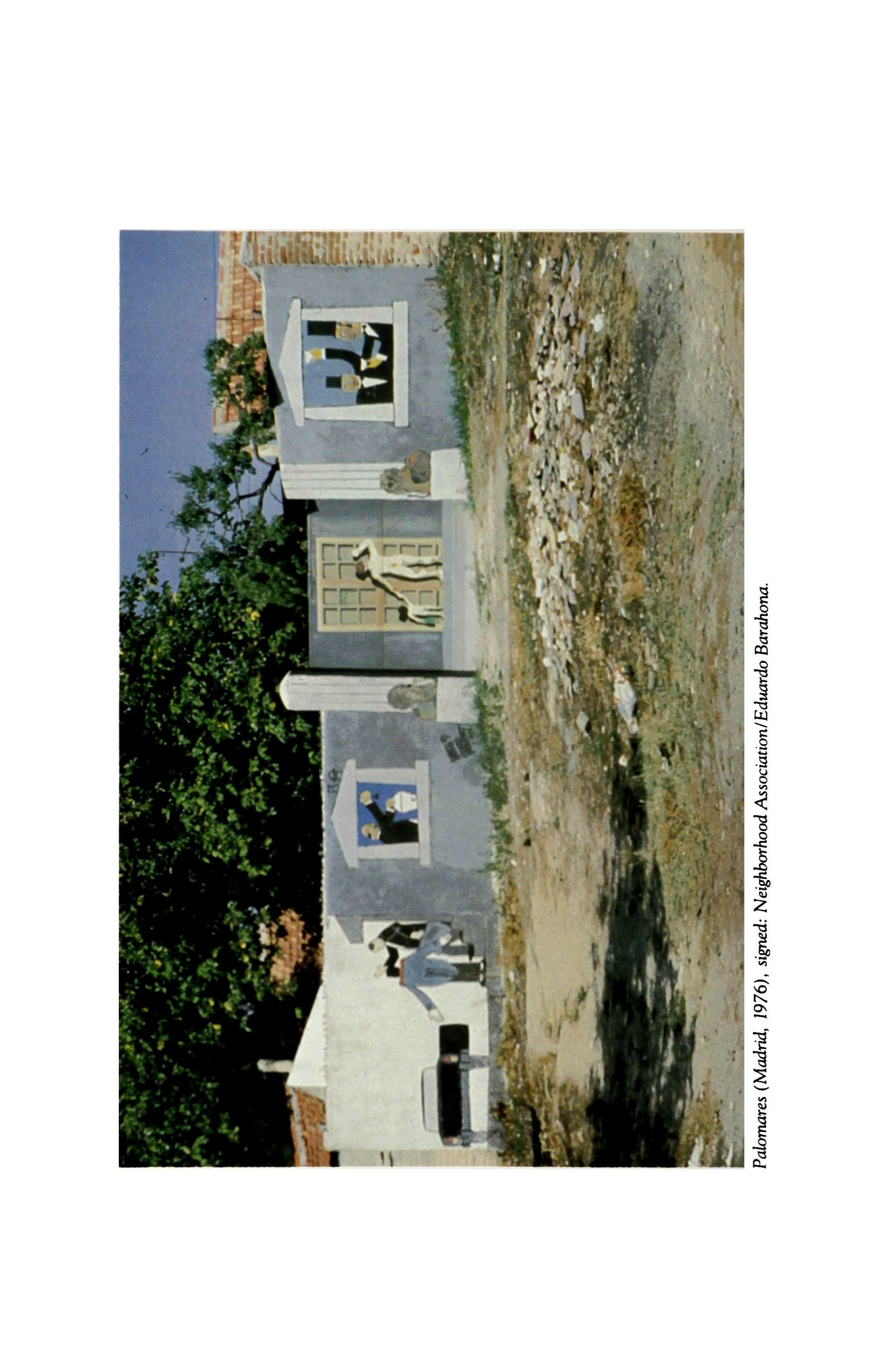

This does not mean the Spaniards acquiesced to past oppression. Now, in fact, they are quite unwilling to let go of memories of the official shackling of culture. The photos in this issue of street murals, all of which were painted by Spanish neighborhood associations, vividly recall the Civil War and its long aftermath, and do so not only in political but also in cultural terms. Picasso's "Guernica" appears on the side of a small building; the poets Miguel Hernandez, who died in prison shortly after the end of the Civil War, and Antonio Machado, who died after crossing the border into France with other refugees, are both memorialized. These two portrait murals were painted in 1976. When Jose Luis Delgado, who has photographed perhaps hundreds of these murals since 1975, went to Andalusia in January 1983, he discovered that many of the murals were gone-the walls on which they had been painted, invariably humble, had been torn down to make way for.condos and office buildings. Progress in art had yielded to Progress.

This points again to the fruitful contrast between the Spanish and Polish volumes of TQ. If the Polish writers wish to have the "normal" life of men and women as their subject (see the diary by Kazimierz

5

Brandys in TQ #57, Vol. I) rather than a life distorted by the extremes of censorship, internment, shortages, and the absence of basic human freedoms, the Spanish writers have found that their versions of these problems, once removed, give way to other problems-bespeaking fuller life, indeed, and no less of a challenge to the writer. But it may take some time before the wounds of the Civil War and the long bleak years that followed it are healed, and before writers feel free this time not from an oppressive government but from the present compulsion to address the way those lives must negotiate an enormous maze of cultural and political, as well as domestic, difficulty. Perhaps it is we who are too unthinking in separating the two spheres, however, and they who-having had the necessity forced on them by their historyare now exploring connections that we should heed more than we do.

This project was postponed many times, until, when I took it on in late 1981, some of the works that had been gathered by the original coeditors, David Hayman and Suzanne Jill Levine, had already found their way into print in English elsewhere. A few others I chose not to include for editorial reasons. But Juan Benet's story and the excerpt from Esther Tusquets' novel date from the project's beginnings. With the help of Anthony L. Geist, the rest of the volume was assembled over the space of many months. A sign of the changing times in Spain is a generous contribution by the Spanish embassy in Washington toward the costs of producing this volume. A few years ago, this would have been as unthinkable as the presence, in Spain, of Picasso's "Guernica.

-Reginald Gibbons

February I9B3

6

From So much of such a war

Merce Rodoreda

The escape

A light breeze came in through the window. When the clock in the dining room struck three I got up and made my escape without, as they say, washing my face and with only what I had on. After going about fifty steps something made me turn around and look at the house. It was shining bright in the moonlight. Standing there in the doorway with me in his arms when I was a child was my father, looking at me. It was the first time I was going out alone at night in streets that weren't in my own neighborhood. I ran. Goodbye, carnations, goodbye! Rossend and I were supposed to meet in the jardinets: he was going to come with a van that he didn't know how to explain to me that he had gotten. I am the friend of a very important Captain and we do what we want to. Rossend wasn't in the Jardinets, and there wasn't any van. But, whatever happened, I couldn't go back home. It had gotten stuck in my head to go to the war, and to the war I would go. Maybe Rossend, who had to escape in secret also, hadn't been able to come. After waiting a little while under the blue street lights, I sat down on a bench, I got up from the bench, and I sat down again. I crossed the street and half hid in a doorway because people were coming. I sat down on the doorstep. Opposite me were the fountain, the plants, the trees. The moon was coming through the leaves and spattering the ground with light. I got up from the doorstep and went over to the bench again. For a good long while I couldn't stop going from one side to the other. Finally a white van with black and red letters plastered all over both sides stopped in front of me. Rossend and three other boys jumped out just as the sirens began to wail. And right away the beams of the antiaircraft searchlights began to sweep the sky. I would have liked to see a bomb fall. The airplane passed over us,

7

very low; we could hear the engine almost on top of the houses. The antiaircraft guns were spitting fire. Get down. Get against the wall, the antiaircraft guns are more dangerous than the bombs. Those sirens Rossend covered his ears and closed his eyes. One of the three boys, the one who seemed to be the youngest of the three, said in a deep man's voice, if those sirens bother you I'd like to see what you look like at the front, where they never stop. I just came from the front, said another of the boys, who was wearing a red handkerchief around his neck and a knife stuck in his belt, let them bomb as much as they want; it won't do them any good. We're stronger. You can't mess around with the People. The other side, they start to run when they see us. Word of honor. They hide. I stand up on the top ofthe trench with the butt of the gun on my thigh So they can take your picture, said the one with the deep voice. Shut up. Rossend asked him: and they shoot to kill? Shut up. And the boy who hadn't said anything the whole time said without looking at us, but you've never been to the front, have you? What do you mean? And this wound here in my leg, what does it say? He rolled up a pant-leg and showed us a red scar near his knee. You got that wound from who knows what kind of animal kicking you. You always have to contradict me. Because I know you and I know you lie more than you talk straight The sound of the airplane was getting farther away. The antiaircraft lights were still clawing at the sky. Everyone in the van! Now we're beginning to live, Rossend said, grabbing the steering wheel. The boy with the red neckerchief sat next to him. I got in the back with the others. In one corner were half a dozen rifles. If I liked the idea of going to the war, it was, among other things, because of going with Rossend; I had known him since we were children, we had played together, we were friends, he lived near my house. These others I didn't know where they came from, where they had been born, or who their parents were.

They were a drag If Rossend had at least let me sit next to him I crawled into a corner. The boys were stretched out on the floor and I stretched out too. They stank. They were breathing heavily. The one with the deep voice made a strange sound with his teeth every once in a while. The shaking of the truck was putting me to sleep. Why did Rossend have to be such good friends with the boy with the red handkerchief who stood up on the trench if the others said he was a liar? A dream was jumbling up my head and I began to see my father waving goodbye to me beneath a house hanging in midair all tiled with shining colors and the blue streetlights and the moonlight through the leaves and everything was beginning to spin: father, father's hand, shining house, moonlight, blue streetlights, spears of light against the sky I got to the front lines fast asleep.

B

The hanged man

Sticking out of a huge sack which was hanging from a tree and swaying back and forth was a man's head, with a taut, straight rope behind it. The skin on the face was white, the tongue black, the lips purple. Next to the tree, just underneath the feet of the hanged man, was a rock; I got up on it and cut the rope. The hanged man hit his head on the ground and scared me; I thought I had killed him instead of saving him. He was young, with dark hair and thick eyebrows. When I thought he had already given his soul up to God he opened one eye and then immediately closed it again. He didn't have the strength to look. After a little while he half sat up and with lots of work I helped him get out of his sack. With a voice that rattled more than if he had come from the other world he said in a rage: Why did you cut the rope?

It took who knows how much time for him to breathe right again, give me water I'm suffocating It took me four strides to get down to the river and I brought up some water in a jug I had found in his knapsack; with one hand I held his head and with the other I poured water down his gullet. He coughed with every swallow and then dropped his head off to the side, exhausted. Then all at once he recovered, I got into this sack to hang myself because I wanted to die with a shroud on, so the birds wouldn't peel my bones in case no one found me in time to bury me. And your head? I asked him. My head, he said, they could have that, for all the good it's done me He grabbed his neck with both hands and squeezed Maybe that way it won't hurt so much. Pour some more water down me. You look hungry. There's some bread in the knapsack. I can't even swallow my own spit. My tongue is all swollen up. Keep me company. He made me lie down next to him and covered us with a sack. Half asleep, surrounded by all the smells of the woods, I heard a low murmur of words as if in the distance. I didn't remember anymore that I was sleeping next to a life I had just saved. I would travel the world, helping people and saving lives. High above, over my head, it seemed as if the stars would carry the night away even though it was still a long ways until dawn

I made this sack with four other sacks I stole from a mill. Lying there with his face towards the sky the hanged man was talking as if in his sleep. From time to time he turned his head and looked at me. It took me the whole day to undo the seams and then do them up again a different way with some twine that I pulled through the holes with a sacking-needle. I had to make one sack out of four. I didn't sew up two

9

of the holes so I could get my arms out and tie the sack around my neck and then put the rope collar with the slip knot around my neck. The hanged man began to cry, I gave him a good whack on the back to make him stop his weeping, and I got up. Don't leave me, don't leave me When I decided to snatch Ernestina out of the arms of that buzzard of a husband, she left me. And went back to him! One day the husband came to see me and he put all his trust in me. He confessed on his knees that without Ernestina he was a lost man. Swear to me that you won't take her from me Give me some water. I told him that Ernestina and I had broken off a while ago. And the husband said it must be someone else then. We hugged each other and went out in the street When I met her she was wearing a red dress and a daisy in her hair we were going from bar to bar; in every bar a beer. Then came the surprise. In the Papagai Bar I met Faustina. He coughed and his voice, already rough and raw, got rougher the more he went on talking, and it was like Ernestina had never existed. Then he didn't open his mouth for a while and when I thought he had come to the end of his strength, saying it had been a rotten day that she had ever let me come into her house, he went on. The day that Faustina let me come into her house and let me give her a kiss behind the ear, she coiled herself up in me like a snake. I told Ernestina's husband about it right away, and he told Ernestina. And I confessed to Faustina that I had been in love with Ernestina and that her husband and I were brothers and even today I don't know what happened but a little after that the four of us were going to the bars, Ernestina was Faustina's friend, Faustina was friends with Ernestina's husband, and the three of them all glued to me. There wasn't an hour of the day when I didn't feel like I was being watched, spied on, being followed every step. Me against three. Three against me. One night Ernestina was sticking up for Paulina when the four of us went to some street, I don't remember the name. I asked her who Paulina was and after thinking about it for a bit she told me she had made a mistake, that she had never known any Paulina, and that instead of saying Paulina she should have said Faustina and I couldn't put up with that kind of life anymore. No one was making love, they were all just criticizing me; I hated all that glueiness and I couldn't live without that glueiness until finally the war came and I went to the front to save my soul. And the war has killed me. I feel so empty, surrounded by death and blood I died some time ago. Why do I have to take another breath and have a body that I don't like very much and that never stops asking to sleep, to be hungry and sad? I mean, it's only asking for some happiness even if it's just a little happiness and all it gets is sadness Why, why did you cut me down? He hurled himself forward to punch me and fell backwards as if

10

I had punched him. I wrapped him up in the sack and dragged him behind the rock, next to the tree where he had hung himself. Little by little I covered him up with stones. I couldn't dig a hole to bury him in because I didn't have even a hoe, or a pick, or a shovel.

The girl at the river

There were a few rinds of cheese on the floor and three or four crusts of bread. I ate everything quickly. I picked some more blackberries. And little by little I went on down to the river. The water on the other side wasn't blue: it was green, with clouds sliding over it. I would have liked to be a river so I would feel strong and I got right in. I swam like a fish; the beating didn't hurt anymore. My father had some cousins who lived in Barceloneta on Atlanrida Street. We used to go looking for seashells with his children and a girl named Monica. I learned how to swim and row with them. After I was in the water I pulled the bandage off my arm; the flesh around the wound that I got one day when I fell on a pile of broken bottles, was all purple. On the other side of the river there was a big stand of cane and reed and through the reed and cane I saw her: prettier than life, standing, naked, with a pitchfork in her hand. Her hair was light blond like mine when I was a boy; her waist slender, each thigh a sight to behold, as my mother used to say about the carnations, each carnation a sight to behold, each of them a fruit, and fully ripe. I got closer and closer to her, she saw me and when I was right beside her, smiling, she stuck me with the pitchfork. Her teeth were like the very whitest little river stones. The sun came out. All the cane and all the leaves were swaying back and forth. She tossed the pitchfork away and threw herself into the water. I began to swim up the river with her following behind.

Stretched out in the sun we stuffed ourselves with blackberries. She looked at me. Her eyes were violet, specked with gold like that neighbor girl with the cat whose mother had me take care of her one afternoon. She told me her father was a miller at the mill farther up the river and I couldn't stop looking at her eyes. Her father was fighting in the war and she only saw him on Sundays. Her mother's name was Marta. Hers, Eva. She would have liked to be a boy instead of a girl. She hunted birds with a slingshot. She went fishing and if the fish were too small she threw them back in the river, and she liked to do it because it was like she was giving life to them. She hunted rabbits and

11

quail with a dog and a shotgun. If she had been born a boy she would have gone to the war, she was dying to go, but her father had made her promise not to leave him and he wouldn't let her do what she would have liked to do. Out of the blue she asked me if I liked soap bubbles. The most beautiful thing about soap bubbles was that after being so patient and watching them come out of the pipe all filled with colors, they flew away and came apart as if someone had pricked them. She was talking on her back, with her hands behind her neck and looking at the sky. I wanted to touch her, to lay her down on a bed of green leaves pulled off of violets' stems. But if the war that has gone on so long goes on any longer, I'll cut my hair, I'll dress like a boy and go to the front. She stopped talking because on the other side of the river, higher and farther than the place where I had seen her with the pitchfork, was a man coming our way on a donkey with a gun slung over his shoulder. That's my father, which means today is Sunday. It was a long time before we raised our heads and when we raised them who knows where the miller was by then. A light breeze was playing around us and we fell asleep when the moon came out. She woke up before I did and when I opened my eyes she wasn't beside me. She went for a swim and I did too. I couldn't hold myself back and I grabbed her foot. It slipped through my fingers like an eel. Let's get out! Three black shapes were coming down the river. They were dead soldiers. They threw them from the Merlot Cliffs to save themselves the trouble of burying them. I pushed them away with the pitchfork so they wouldn't get stuck and rot in the reeds and cane that are my palace.

The chicken coop was on the far side of the garden. With the stealth of a wolf I closed in on it through the artichoke plants. A chicken began to cackle like crazy. I was going to eat her egg. Terrified, up in her box, her feet sunk in the straw, she watched me. That egg tasted like hazelnuts. Three more chickens, stuffed into their boxes, poked their heads out, as quiet as death: their fat wattles hanging down, their crests hanging down, they were old chickens, they had laid a lot, they had seen a lot of chicks. From the side of the house I heard a door slam, then a pulley squeaking. The egg had made me hungry. I left the garden. I couldn't see any sign of a town nearby. There were fields all around me. A bolt of sadness crackled through me and made me

Eva

12

shake. I would find what I needed and I went on with my eyes screwed halfway down because a sun more the color of egg yolk than the egg yolk I had drunk was dazzling me. It was because I was distracted by that sun that I fell and bloodied my knee. The blood was red, redder than a red carnation, redder than the wilted crests of those golden chickens.

To get over my hunger I tried to sleep along the edge of the road between some clumps of broom. To get over my hunger and with the hope that someone would come by like the old man with the peaches

When I was dreaming that I was a boy and still didn't know how to walk, and that I was looking at a stopped train, a very long one, and covered with fog someone took my hand. It was a friend's hand. A hand in the middle of a river with garlands of cane and reed along the banks. The hand was Eva'S, her own; she had seen someone lying there, perhaps wounded, and had come to help. She had on the blue overalls that militiamen wore, boots, a faded sweater and a cap. Her violet eyes were looking at me as though they were looking at the whole world, everything good in the world, and that thought made a wave of shame rise up through my cheeks. She told me that seeing me had finally brought peace to her heart. She had seen so many people die that sometimes when she thought of me she saw me dead and she suffered Dead in the assault on the mill that belonged to her parents, who weren't her parents. Her real parents, those she had chosen, were the earth and the sky, he, full of stars, she, full of flowers. I wanted to ask her if she had been the one riding the white horse that had run from the mill that night and why she had told me on the riverbank that if she were a boy she would go to war and then she had gone even though she was a girl and why she hadn't told me that she wanted to go when we were at the bridge and she had told me to wait for her and how she knew the mill had burned down and I didn't ask her anything because she sat down next to me and leaning over a little she took the knife I had given her out of her pocket and showed it to me, it's broken, she said. I wanted to open a box and I used the screwdriver blade like a pry, and look, the screwdriver broke. She was happy to see me again and added in a low voice that she didn't like people who loved her. When they loved her it was as if they were tying her up, as if they wouldn't let her move. She needed to feel able to go where she wanted to go and to help whoever she wanted to help without it becoming an obligation. I like you because you don't tie me down and because of your face. I have only seen you for a few hours of my life but I always think of you and I remember you often, as much if I don't see you as if I saw you. We met in the water She was quiet for a while: I wasn't able to think about everything you said

13

to me. Sometimes this way I am makes me run only the dead don't frighten me. They don't ask for anything; that's why they make me so sad and why I love them so much, and even more when sometimes I think that I'm one of the living dead that I have died many, many lives ago, other people's lives They have to be buried in the deepest parts of the earth so they can rest forever near their roots. And become trees.

She let go of my hand and I had the feeling I had been left alone. She looked at the ground for a while and without raising her eyes she told me she had carried three badly wounded soldiers to a hospital in the rear so they could die in peace. They were young like you and wanted to live just as much as you. Do you see the Red Cross truck over behind the bushes? It has a cross on the sides and on the top too. Do you see the red color of the cross? When I was little, my father, I don't know what he had against it, killed a cat; I saw it and my heart broke. I buried it at dawn near the entrance to the bridge where I told you to wait for me, do you remember? The day we met? I made a cross with red flowers and put it on top. Some afternoons when the setting sun is all covered with clouds and it throws out its fan of sunbeams I can see myself climbing up the ribs of the fan with the cat beside me; it looks at me every once in a while and what is this?

She had discovered the cord hanging around my neck and pulled it out. Are you wearing a scapular? She laughed. She pushed the cap back on her head and it fell to the ground. Her hair was cut short, shorter than mine and I was a boy. It's Our Lady of the Angels, I told her. She looked at it a moment. How ugly it would get on my nerves to wear such an ugly Virgin around my neck. I told her: a very wise man gave it to me and he told me that as long as I wore this scapular no bullet could kill me. She laughed again and before getting up she leaned towards me and kissed me on the scar on my forehead. Do you want to come? I shook my head no. Then I heard the motor of a truck. In the glow of the disappearing light I looked at the em' broidered Virgin. Even though the clothes, the irises and the leaves of the irises were pretty colors, the Virgin, with a face like the ugly old lady of the woods, made me not want to look at it. I tore it off my neck and stuck it in my pocket; but before that I looked at it again and saw over the ugly old woman's face, Eva's face. Do you want to come? No. I said no to make her happy. If the grass, there where Eva had sat, hadn't still been pressed down, I would have thought that Eva and Eva's kiss had been one of those dreams you never want to wake up from.

14

Lice

The order to retreat was given that same afternoon. juli-juli came to tell me and I still don't know how he wound up at the place where the horse had thrown me. There were about a hundred men, all of us young, all tired, all fed up. The column didn't halt until it came to an abandoned farmhouse, surrounded by acacias, with a hill behind it. We got out of the trucks and pitched camp right away. The air we were breathing seemed so peaceful it was as if the world had never had a war. I learned to load and unload a rifle; to shoot. How old are you? Fifteen. You seem older. There you go, let's see if you can learn to aim it right. I didn't want to learn. I pointed it farther up or farther down, or more to the right or more to the left of the cardboard men we had to hit. I didn't want them to show me how to kill anyone. The kick of the gun-butt almost dislocated my shoulder. I got the bad habit of going up the hill to walk my worries out. Pretty soon a guy from Gracia, a neighborhood in Barcelona, followed me. His name was Agusti. He had been born in Torrent de les Flors. They made a living in his house by selling milk, and everything stank of cows, he said, because the stable was next to the back wall. All the cows in the house! He said when they called him to the war he couldn't sleep without that cow stink he had been born to. His mother woke him up every day at four o'clock in the morning to go deliver the milk. He was only eight years old. With his eyes half closed and his heart still not awake he went from one street to another loaded down with pots and measuring cups; sometimes he had to go up three flights on a dark stairway to sell a miserable quarter porron of milk that only cost five centimos. But at seven o'clock he left everything: pots, measuring cups, and the whole mess, and went off to mass, he said. The smell of incense drove him crazy; the silence, the priest's words that I liked so much because I didn't understand them. He was an idiot over the chasubles whites, pinks, yellows, purples, all edged in gold, and the irises climbing up the altars and the halos of the saints, saints with one pink knee peeking out the opening of their robes. A neighbor com' plained to his mother that her husband had to go to work often without eating anything because I hadn't brought them their milk; she knew as plain as ink that it was because of the mass. He goes to mass every day. My mother, who kept a very close watch over the business, showered me with slaps and made me go for two nights without supper. But I went down at night to milk the cow and I swallowed it so fast, so I could go back to bed, that I choked. Your duties first! my mother shouted. Your devotions first! Father Camilo said at school, joining his hands together and then opening his arms. I didn't know

15

what to do; but I went to mass even if I got there halfway through and couldn't see the beginning of the angel's work when he made the floor of the church blue and crimson with spots or when he was blowing up the bubble that covered the church and the petals that held it up from the great altar to the last row of benches. What are these petals? He looked at me: the leaves of plants are called leaves. The leaves of flowers are called petals. And with sad eyes he went on that it was the fault of the milk deliveries that he couldn't watch when angels and more angels were blowing to help the highest angel while the rays of the sun were going from the altar out to the faithful and from the faith, ful back to the altar. I wanted to cry because I felt so tied to my home and I couldn't be with God who made the churches and when I think of how many they are burning now I want to kill them, the ones who are burning them, even though it's forbidden to kill. And you, I asked him, who told you all this business about the angel who blows and the bubble that grows? He was quiet for a minute and then told me in a low voice, it's a secret, and added, scratching his armpit fiercely, there they are: the lice. Within two days I was scratching too. A little shiver, that began as sweet as honey and kept on growing until it made you crazy. Within four days there wasn't one soldier whose hair, as well as every crease in his clothing, wasn't a lice hatchery. Little ones, big ones, eggs about to burst, as white as chicken brains. Bartomeu said that against the light he could see them fly. juli-juli said we worried too much. Kill them but don't talk about it. We all went down to wash in a big tank of water that had been caught from a spring that never stopped running. We couldn't get rid of that plague. They fly! I'm telling you they fly! juli-juli squashed them between two fingernails, very slowly. When he got a really fat one he showed it to us. It's the louse of a king! The kings were the lice. They lived off of us and then played dead when they were full. I saw one fly from Ximeno's shirt to Viadiu's shoulder. They were eating us up. Always with a mouth ready to suck some blood. They don't have mouths, they have trunks!

One day, when it was still dark and five or six of us went down to wash, I stayed, hiding behind the water tank, and deserted. The war had stopped as if the peace were pushing me to go someplace where I could get rid of the lice and the soldiers.

I wasn't happy anywhere. Not in the fields, or underneath the trees, or in abandoned houses, until one afternoon I saw a man in rags, he was already just three steps away from me. His hair was white and so was his beard. The buckle on his belt was in the shape of a skull. He sat down beside me without saying anything, took two peaches, the kind grown without much water, out of a dirty old basket and gave me

16

one. We looked at each other's eyes and I had the feeling we had known each other forever, that I had known him before, I didn't know from where or when, on an afternoon like that one, seated alongside a road. After all the tough sweet meat of the peach had been chewed and swallowed, without looking at me, he told me: the important things are the ones that don't seem to be. More than wearing a crown, more than having the world at your feet, more than being able to touch the heavens with your hand, there is this: a ripe piece of fruit to sink your teeth into in the last glow of an afternoon that's coming to an end look at the sunset! He threw the stone of the peach as far as he could, wiped his lips with the back of his hand and left me alone with my mouth filled with the taste of peach.

The man with the cat

I crossed the open lot. Right outside the door of the cafe was a fig tree. Inside it was a ruin of broken bottles. I sat down at a table to think for a while. I didn't have time to think about anything because almost right away a man carne in, limping, with shoulders like under a weight. He was carrying a basket in his hand. He took out a full bottle of wine and half a loaf of bread stuffed with bacon. He looked at me: are you waiting for someone? Here, as you can see, life has stopped. Did you corne by the highway or through the town? By the highway. Then you haven't seen the piles of ashes in the streets. There isn't a dog left around here to wag its tail. I shrugged my shoulders and said if life had stopped it was all the same to me because I wasn't waiting for anyone. He tore off a bite of bread and a piece of bacon followed it like that piece of ham had followed for me, from the sandwich of that lazy man on the beach. Get to work, you're young. Bring me a knife, second drawer to the right, in the counter. I should have given him the knife and left then because I didn't really want to sit around and chat with anyone, but I liked being inside, with all those broken bottles, with all those empty shelves, looking at four flies making lazy circles in the air. The man with the basket drank the wine from the bottle, with his eyes closed and a hand under his chin. He said that the cafe was his cafe, not owned, but his cafe for his whole life where he had begun to corne as soon as he reached the age of reason. He made a living by castrating cats and doing other small jobs. When they killed the owners of the cafe it's sad, isn't it? They killed them at the request of some distant relatives who had once asked the owner for a hundred thousand pesetas and he said he didn't have it and that was the truth. They believed he was just putting them offand when everything was revolu-

17

tioning, bang. But anyway, this has always been my cafe and it always will be because I don't have anywhere else to go. Where I live, half the ceiling has fallen in. He was quiet then and looked at me with his head lowered and his eyes looking up a little. Do you want to see the cat? Pretending to be thinking about something, I looked outside. I know I'm not much of anything. My father was different he made pitchers and washbasins. When he touched the clay a form was born. And since the man with the basket was looking at me while he was talking, and smiling as though he thought I had just hatched from an egg, I told him his father wasn't his father at all. He grabbed a bottle and was about to throw it at my head but he held himself back. His father, I told him, had only made his body; his soul was a lost soul that for years had been looking for someplace to go. And that the moment he had taken his first breath it had entered into him. His eyes filled with rage and he asked me if I had drunk from a fountain full of water mixed with moonlight. To shut me up, I thought, he took a package out of the basket. Do you want to see it? It was a stuffed cat with the tail stuck into the body and the ears standing straight up. Tiger' striped. My wife couldn't stand even a picture of it and I always put it on the night table that's what I would like to do to a lot of people; stuff them with straw and make them be quiet. Stuff them nice and full of straw. The cat, this very one, belonged to some neighbors. It was a great ratter, a royal cat. Its owners showered it with attention: it ate from a china plate and slept on velvet; some rich neighbors, who could keep as many cats as they wanted. Every night I used to chew on my pillow, envy was eating me up. And in order to get it I learned how to stuff. I tempted it into my house by showing it a chicken head tied to a string it came into the garden, very cautiously, and I got it for myself. Ever since then I have slept with the cat next to me. My wedding night too. When my wife died, may she rest in peace, I learned to meow, and before going to sleep, with the cat in the bed, I would meow for a while as though it were the cat singing me a serenade. And I still meow. And that's how I fall asleep.

Pride

It was getting light. I had slept badly, my arms on the table and my head on my arms. My neck hurt and my mouth tasted like copper. On the far side of the empty expanse, half covered in fog, a few dark shapes were getting in and out of a small truck with the lights on. Two men were coming over, each with a box on his shoulders. Just as they came into the cafe there were two shots. That does it for them. The

18

man with the cat woke up, his eyes filled with terror. It's nothing old man, nothing. A two-gun salute. They began to take bottles of cognac out of the boxes and put them on the counter.

Some more men carne in, talking in loud voices. Only one of them, the last one in, with all the color drained from his face, turned to look back at the open ground. The one who seemed to be in charge, more than anyone else, was tall and had a small head. He had a thick moustache and a scar crossing his cheek; his nose was thin and straight and he wore a wide-brimmed hat with a feather in it and a shiny hunting jacket; hung over his shoulder was a rifle with the muzzle still smoking. He uncorked a bottle and half emptied it with one swallow. From now on, he wiped his mouth with the back of his hand, I can have everything I've never had: a big, wide bed to sleep in, across or up and down. Whatever I want. And two or three high-class dollies held prisoner in the next room who will come in to pay me homage with their frightened faces and their tits sticking out of their blouses. He turned towards us: the guy we just liquidated, along with his adopted son, was my cousin and owned all the vineyards in this area. We only wanted to kill the old man but the kid insisted on hugging him for the last time and we sent them both to heaven hugging forever. He sat down at our table and after staring off into space for a while sent the cat rolling towards the door with one good thump of his foot. I inherit it all! And he shouted: A bottle! And glasses! One ofhis men pointed to the floor. There aren't any glasses. He looked at the old man, instead of wandering around the world with that animal that has already given you everything it's got you'd be better off to come with us and clean our guns, and you too, pipsqueak!-my cannon is always hot and I don't want it to get cold before we win this war. Then the man with the cat began to smile as though he would split and they all stopped drinking to look at him and the man with the cat told them that none of them were their fathers' sons. A gray-haired man with a blue shirt and a red handkerchief around his neck came over to him brandishing a bottle and told him he would break his head if he repeated such a lie. I didn't say it, this kid said it, that the parents only make the flesh and bones of a baby so a soul that has been looking around for a long time can corne in just when it cries for the first time. The tallest one looked coldly at me: show us a soul! I got up and charged the gray-haired man who was in my way and I started to run. I stumbled over the cat and with one kick it sailed up and landed on the top of the counter. The man with the cat meowed without stopping. The fog had gotten thicker and it was probably because of that they weren't able to kill me even though they were shooting like crazy men.

19

Matilde's beautiful belly

I was trying to look at the sun, like the old man at the hermitage, to see if it would burn my pupils, when that game was stopped by the thunder of a motorcycle that braked suddenly almost right on top of me. The man on the motorcycle said, if you want me to take you someplace just say where straight out, because I'm not going anywhere in particular. His mouth was twisted up in a grimace of disgust. His teeth were long, the eyeteeth like a dog's. His eyes were so nervous that they were looking every which way without coming to rest on anything. Haven't you decided? He took a pack of cigarettes out of the right-hand pocket of his hunting jacket and stuck it right in front of me, saying, my boy, they left you looking like a new man. He put the pack so near my nose, he was so insistent that I take a cigarette, I had to assure him that I had never smoked, except for a few weeds when I was a boy and wanted to be a big man hiding from my mother. Smoke! The first drag on it made me cough. My eyes watered. And the man on the motorcycle said that he smoked fast so the cigarette would be finished in a hurry and he could light another one right away. The best part is lighting them. That's why men who have lost their sight don't smoke when I get tired of smoking I'll fix up that awful hair of yours. Who in the hell left you looking like that? I liked him because he had those eyes that wandered from the branches to me, from the highway to the weeds, from the end of his cigarette to the end of mine that was slowly becoming an ash.

He began to tell me his story, saying that he had a ship in a bottle and that if he had become a barber it was his father's fault: when he was a boy his father used to ask him to cut the hair on his neck because he couldn't do it himself. The barber who lived two doors down the street took me on as an apprentice; he was a sad man, and bald, and suffered from liver problems and lived only on boiled rice. He died just when I finished being a soldier and so I was left with the barber, shop. All the customers knew me and kept coming. It had two big windows, one on the main street and the other on a little side street, full of bottles with labels for quinines and essences and one huge bottle that had been full ofcologne and that I filled with water. On the opposite corner was a bakery. When my boss died the baker did likewise. Two months later the bakery became a florist shop. It took me quite a while to notice the mistress. Finally, on the feast day of Saint Magdalena, I went in to buy a rose because I was tired of hearing Magdalena's complaints that I never gave her anything. She was a manicurist and on Sundays she used to come to the house, we would

20

sleep together for a while and then do the housework. Magdalena was a quiet girl, from a poor family, but good.

The owner of the flower shop wrapped the rose up in silver paper and sprayed it. Her eyes changed color and the skin on her face was smoother than the petals of the rose she sold me. From that day on I began to watch her from behind the huge cologne bottle. She was like a little girl with two legs like swords. She was always dressed in a black skirt and a white blouse. Finally I couldn't hold myself back anymore and I went in to buy a begonia to put in the front window, I told her. I had to water it a lot. With the begonia as an excuse I went over to see her from time to time. It seems like the leaves are wilting. It seems to me I don't water it enough. Her name was Matilde. I finally fell in love with her. I broke it off with Magdalena.

I didn't want Matilde to work. I wanted her to be completely mine. Sell the flower shop. And her, always there, with the boxes of flowers, with the spray bottle to mist them. I won't tell you about the wedding night but I will tell you that she got into bed with her black skirt and white blouse on. I pulled the zipper down. Underneath she wasn't wearing anything. I couldn't breathe; I had never seen such beautiful white thighs and belly in all my life. And I worshipped them every night. I never got tired of looking. I deserted my friends. I didn't go to play pool anymore. There weren't enough nights, there weren't enough Sunday afternoons or holidays for me to worship, worship and worship some more. I lost customers. I kept asking her to leave the store. It was a war of nerves. Sell the store, sell the store. And she, nothing. Until, defeated and disappointed, I learned to keep my mouth shut. After I had gone maybe three months without talking to her, one night, after bringing me dinner, she stayed standing at the other side of the table and with her eyes lowered and then with one motion she lifted her skirt and showed me that bare belly of hers. I went on eating as if nothing had happened, as if she was in the kitchen fixing something to eat. And from that night on, always at the dinner hour, she did the same thing: skirt up and everything on show. I stopped eating dinner at home. I stopped eating supper at home. I went to the bar, I played pool, I went home at daybreak. She didn't give up. She showed herself to me when I got into bed, when I came out after washing up, as soon as I opened my eyes. I was sick of her. Then, luckily, the war! I ran to join up. And now I am a messenger; I was. I deserted from the batallion and I might open up a barbershop in France. Do you want to come with me? I told him I liked to be alone to walk the roads by myself so I could look at things slowly. With his tongue clucking he went over to the motorcycle and took wind-up hair clippers and a razor out of the knapsack that was hanging across the

21

back. He left me with my head like a ball and my face without a whisker. He took off in a cloud of dust.

The bricklayer

In front of a bombed-out house, the walls just charred rubble, was a man walking from one side to the other, beating his head with his fists, and cursing. He must have sensed me more than seeing me and he suddenly stopped talking. The top of his head was bare with a lot of hair down the sides and thick eyebrows that joined in the middle. He sat down on a chopping block, put his hands on his thighs and raised his head: this morning my wife was buried. It was only by luck that my boy went to visit his grandparents a week ago and doesn't know anything about the bombing or his mother's death. And maybe because of that his life was saved. When the bomb fell I was in the vineyard. But why? Why did they have to drop a bomb here, just one bomb, when this is a dead-end town, with no young people or anything? His voice was choked: or anything just to make people's lives miserable. A woman like her dying in the ashes ofher own house, alone in her own house, who never did anyone any harm The day I die, if I die with my head still clear, I will be thinking about her, about my Eulalia. And do you understand? Even though my heart is aching I can't believe she's dead, it isn't possible; I hear her going from one side to the other, always looking around, always cleaning, always darning, always wanting the house to be as clean as a gold platter, everything just so I would die myself right now if my son weren't still a little boy, as good as his mother. Ever since I got married I've had nothing but happiness. Never the smallest complaint. And that says a lot. Look at my hands: bricklayer's hands-you can tell, can't you?-with the skin hard from carrying so many bricks, and eaten up by the lime. We built this house with our sweat, both of us. Always saving like maniacs to be able to buy a sack of cement here, a couple of sacks of sand there, or a pile of bricks. It was like a big party for us! And the plasterer came, Estanislau who was poor himself, and he didn't want to charge us for the material or for his labor. Then the electrician came, Jeremies, and he didn't want to charge us his day's wages. And Manuel came, the carpenter, and he made me a gift of the scaffolding. And Belloc came, the painter, and he gave me the paint. And all of us, electrician, carpenter, plasterer, painter and me, we painted it: with blue shutters. Eulalia fixed food for everyone. What a glorious time. You have no idea what it is to build a house, from foundation to roof.

22

To watch it going up. To pick up a brick, to slap cement on three sides and-whoomp!-to fit it right there. To set the rafters and to cover them over and make the lattice-work like someone doing an embroidery And setting the roof tiles: one belly up and the next belly down, and there you go, troughs and ridges for the rain to run off like a song. He looked at me for a while and suddenly turned away. There behind me was a thin young man, brown from living so much in the open air at the front, it was obvious he had been to the war: he had a bandage around his arm as well as one on his forehead. I am crying, he said, over this man's house and over the death of his wife. We have always been like brothers even though I am much younger. I am an electrician and my name is Jeremies; just when I finished learning my trade they gave me a gun and off I went to live in the fields, chased by the Moors, better traitors you couldn't get made to order, and one day without even knowing how to shoot I pulled the trigger because one of them had me in a corner, it fired a bullet and the Moor, before falling like a log on the floor, gave a jump and I ran, terrified of having killed him, and look here, out jumped two bullets and chased me down, one in the arm and the other in the head, and at the hospital, which they bombed three times even though the roof is covered with a sheet with a red cross If he really wants to raise the walls again, he said, then I really want to put the wiring for the wallboxes in them, come untangle them so the lights can be lit. Then another man came over to us, younger than the bricklayer, older than the electrician, and he began talking in a low voice like he was making a confession. 1 volunteered to go to the war and I've lost everything: workshop and tools. Tools I began buying when I was working as an apprentice, and tools my father gave me, starting with the chisel. You name it, 1 had them all: hammer, all kinds of saws. A plane that made such soft shavings they seemed like the ringlets of those giant dolls they carry in parades. A little plane that planes the door that doesn't hang straight, the little shutter that's too long so everything opens and closes, so nothing doesn't work When I told them 1 had a field of carnations they said that was all very good but that it was better to have a vegetable garden, especially during a war when you never know if you are going to eat the next day. This war's a terrible thing. Can you tell me what we're fighting for? The bricklayer said, it was to fight the enemy but the carpenter said that for the enemy we were also the enemy. The electrician said: even if we win, it will be like losing; a war makes losers out of everyone. The specialist in building fireplaces joined us and said to go ahead and cry, now that there wasn't anything to cry about; that we were cannon fodder and nothing more than cannon fodder. The bricklayer raised his head. Three men were coming over pushing

23

wheelbarrows loaded with picks and shovels and brick hammers. They were the painter, the plasterer and the carpenter's son. They were coming to help him build his house again. They went right into the rubble; so did I. Then it got too dark and the bricklayer said, shall we eat some supper? Together we went to the church; the bricklayer lit a lantern and set it on the altar. There wasn't a saint to be seen. The benches were piled up in a corner, the plasterer grabbed one and he and the carpenter broke it up to build the fire. When it's all over I'll make prettier benches than these. They put a pot, filled to overflowing with kidney beans and bacon, on the fire.

The carpenter asked the bricklayer if he knew who I was. I don't know, he was passing by and we started talking. Soon I was alone with the bricklayer. That's it, let's get some sleep. We stretched ourselves out on the floor. I couldn't have been asleep for more than two hours when a voice woke me up: Go back home.

At daybreak everyone came back to start work again. I stayed with them for three days, helping pile the rubble up and knock cement off the bricks, but on what would have been the fourth day I left them, not to get away from them but to get away from the voice that woke me up whenever I slept, go back home, go back home

The red earth

The road was narrow and not very long, taking off from the curve of the highway, crisscrossed with ruts and covered with big rocks. To the left was the garden of an ancient tower that was almost hidden behind cedars and cypresses. The fence was made of wood stakes with pointed ends and tied together with rusting wire, half hidden by a great mass of honeysuckle with a string of lilacs behind it, the pods bursting with dry seeds. To the right, after going by a fountain with no water in it, you saw the patio of a big farmhouse, surrounded by red geraniums and rosebushes dying of thirst with almost no flowers. Under a vine, next to a chicken coop with no chickens, was a dead cat. The sun was high, shining on a wall which had a sundial on it, made of yellow and blue tiles with drawings of branches and leaves. It was twelve noon. The road came to an end in a plaza which had only three houses on it, all clustered together, with blackened tiles on the roofs and their gates wide open as though the people were out in the fields. Opposite the house, set against a bank of red earth, also rutted and lined, was a horse trough, without any water. I sat on it for a while, to one side was

24

a cart piled high with hay and turned over on one side in a pool of blood. I stood in front of one of the houses and shouted, with my hands cupped on both sides of my mouth and no one answered. I shouted again in front of one of the other houses; my own voice echoed back to me. I shouted a third time and when no one answered I let myself in, walking almost on tiptoe. On top of a round table there was a pot of coffee that was still warm, and in a basket some leftover pieces of black bread. As I had done in the house with the mirror in the front hall I salted the bread before I put some olive oil on it. 1 didn't hear any noise at all; only my chewing and a light breeze which was just enough to bring in a few dead leaves and swirls of dust.

In the bedroom on the second floor, where I didn't see him right away because he was covered by a bed, was a dead man with both eyes open, staring at the ceiling; one hand, with short fingers and blackened nails, had a fly on it, cleaning its legs. There was a wound in the middle of the man's chest and the whole front of his shirt was red. In the other house all the furniture was turned upside down and the clothes pulled out of the closets and thrown all over the floors and walked on as if they had been used to dance on. I went into the last house, too; there were half-burned papers in the fireplace and next to the balcony was a shotgun with metal engravings set into the stock. A glass door with the glass broken opened onto a patio ringed by empty flowerpots; thrown into one of the pots was a doll without any hair and with no eyes and with the hand touching a half-deflated ball.

In the distance there were mountains and more mountains, a scale from gray to blue. The peace of the earth was breathing all around me. However much I looked I couldn't see anything; however much I listened I couldn't hear anything. Everything-mountains, houses, road, water trough-dissolved into me. I didn't want to think about the blood; I dissolved into everything.

The road went on from the other side of the plaza. A halfof a snake was lying across my path: the part with the tail. A wheel must have cut it in half and the part with the head must have gone off to hide in the woods. The road wasn't very straight, and halfway down it in front of some pine trees covered with caterpillar cocoons, I heard water running. Then the road ended in a little plaza with an iron railing around it. From there, the valley was a patchwork of colors that died out at the foot of a tree-covered mountain. I stuck my head over the railing of the lookout spot and staggered back in horror. Right below was an enormous pit, recently dug out, with the earth piled up on both sides, scattered with picks and shovels, full of dead people: arms, legs, heads, stomachs, shoulders all in a jumbled heap, stained with streams and pools of blood shining in the light of that day that was so

25

bright. I ran from there with my head going in circles. I vomited up bile, next to the honeysuckle where the road began.

The snake lay across my path again. I spent two days and two nights without eating or drinking anything, throwing shovelfuls of dirt over the bodies. Finally I covered them up. And, before I left, facing the rising moon, I entrusted them to God.

The river

I walked a lot; I went from one town to another, from one road to another. All the roads were deserted, all the houses in ruins. One day at dawn I stumbled over a dead dog: a piece of cardboard was hanging around his neck with writing half washed away by the rain; it read: "Follow this dog. It will bring you to me. I am wounded." Sometimes I would see men approaching me with gaunt faces, wasting away, as if they were all holding each other up, their feet and legs wrapped in rags tied on with string; I would leave the road. Three or four times an airplane flew over me, so low that, even though I threw myself down, it must have seen me. But I wasn't even worth a bullet anymore, much less a bomb. A bell tower, in what was left of one town, gave me a little sense of security. That arrow pointing straight towards the sky stayed with me for a while and after leaving it behind I turned around often to look at it. A covey of crazed little children jumped up from behind some clumps of broom, clutching pistols in their fists; they ran off toward a hill shouting, Kill! Kill! Finally I found myself facing a wide river that I had never seen before, the banks blown apart and sown with corpses as though they had been collected there to be carried on somewhere else, one on top of the other. Corpses as though they were sleeping, on their sides, their legs drawn up; corpses with their eyes open and staring at the sky; corpses without legs, without arms skeletons of soldiers, their bones stripped bare by the birds. And scattered among the corpses, trucks overturned with their wheels in the air, half-burned, destroyed machines, tanks stopped, their drivers dead on top of the turrets. A burned hand with stiffened fingers near a gun. Tents, pieces of canvas ripped off the tents and tossed here and there by the wind. Bombed bridges pulled down by the river, still clinging to the banks, clumps of thyme, scorched and crushed. In one trench (yes, and there were so many!, as deep as the tracks left by giant snakes) three dogs heard me and took off running down the trench, tails between their legs, except one, thin and mangy, which turned and bared its teeth at me. And over all the dead, big birds with long bare

26

necks were circling. On the sloping edge of an airplane wing, half sunk in the earth, surrounded by small boats and burned lumber, a line of crows were searching their wings and chests for lice. I raised an arm to scare them off and they lazily took flight. Three of them stayed on the wing of the airplane that was halfburied in that earth and in that water sliding by so smoothly, broken only by the pilings of the bridges that stood in its way. And floating everywhere, the stench of death. They will have them buried soon. They come every two or three days with trucks. In the beginning they had to run away because they machine-gunned them. Not any more Finally that voice made me turn around. What a relief to see a living person, a young woman, but totally worn-out; she still had bright eyes. She was carrying a dead baby in her arms; I could see at once that it was dead by the waxen color of its legs and from the wayan arm was dangling. She was talking to it as if it were still alive, my love, my boy And with a strange look she stared at the eyes of a dead man lying on the riverbank, not far enough into the water to be carried away, as if that poor corpse with its head and chest split open was the one responsible for the war. They throw them into grave pits farther up the river and sometimes, not always, they burn them. They don't have the stuff to do it with. Meanwhile the buzzards fatten themselves up. Luckily the war's over. I saw how it was ending, it ended here, at this river, this river carried it off to the sea. I used to have a house up there. All that's left is four walls. We had a garden that was a delight imagine, with so much water nearby to irrigate with. Now I sleep far away from here but I come every once in a while in case there are any soldiers still alive who can tell me if they know where my husband died They all tell me not to wait for him I listen to them but I don't say anything because I don't believe he is dead. Did you fight in the war too? Your skin is dry like all those others who have gone hungry, your eyes are so sunken there wouldn't be anything left of them if they weren't full of-not fear, no, not fear, no of horror If you knew the screams I have heard, the screams of the wounded asking for help, crying and screaming out all the misery of their souls and all at once I saw a hand rise up, searching for who knows what comfort and then fall again to the ground because everything was over. Come with me you are so young, I'd like to be able to help you My husband's name was Pere, he was taller than I am and had eyes that were black, like his hair maybe you knew him She stared into my eyes and I was filled with shame, so much that I couldn't stand it; shame at having run from the war like those who run from the plague, alone, always alone, by myself, shame for not having defended something, not knowing what, but that I should have defended like so many

27

others had done all of me, imprisoned in my poor skin, dry from having gone hungry, like that poor woman with the dead child in her arms said, with its face against her chest. She shifted her hold on the child, she held it with its face towards me, its eyes were open and its mouth tightly closed. I helped them fill sacks with sand; all the women of the village, here at the river side, filling sacks with earth. They needed a lot of hands. If you had heard the cannons and the machine guns, if you had seen how the airplanes let fall rosary after rosary of bombs. If you had seen the glow of fires in the dark night months and months of hell. Years and years years will pass before anything can be planted along the river because, if they start to dig they'll find bones instead of earth. That's all there is here, bones. The bones of dead who have no names. That range of hills, do you see it? They knocked its head off with their endless punishment, the shells and shrapnel. Punishing just to be punishing. I still don't know how it is my son and I are still alive but with all the fear we've been through he can't even close his eyes, even to sleep. He and I might both have been dead and you wouldn't have found anyone to explain it all to you She fell quiet as she faced the river, widening as it went, with her eyes fixed on the swirling water that must have calmed her and carried her thoughts away. After a while, without saying anything else to me, without looking at me again, she left.

Rage

Pushed up against the wing of the airplane was an old, ruined boat: painted, weathered and repainted again. The river slipped smoothly by, the afternoon seemed distant, an afternoon alone in the middle of the earth. Only the flight of birds, soaring and soaring again before dropping down on the dead, gave it any life. The other side of the river was the same as the one I had left behind, with the corpses being devoured by the birds of prey. I pulled the boat as far up the beach as I could, so the river wouldn't carry it away. As evening was falling I arrived at the edge of some woods. I smelled the trees again; I felt the comfort of the roof of leaves and branches over me. The path I was following went into the woods through some tall grass. From some distance away I could make out a window with a light in it. It was a deceptive light; when it seemed to be close it was still far away. I had to walk quite a while before coming to the clearing where I found a little cottage, half made of wood and halfmade of stone, with a well nearby. The light from the window fell on the well and something was shining near its base. Before looking through the windows to see who was

28

living in the house in the woods, I bent over I picked it up, but even then I wasn't able to understand. There in my hand was a knife, like one of those that can be used for so many things and that I had given to Eva that day I met her, so she would remember me. The end was missing from the screwdriver. Who could she have given it to, or who had taken it from her, and how had it come to be in this corner of the woods? Had the one who had taken it from her lost it pulling the bucket up out of the well? One day after a battle? I was so lost in thought, holding that knife in my hand, that it was a long time before I went to the window to look inside the house.

On the far side of the room was a flowered blue and yellow curtain and in front of it an old woman was sitting with a dark colored kerchief on her head, a black shawl and thick glasses. A hand, at the end of an arm, rose and fell rhythmically, pulling a thread. To one side of the curtain was a cupboard with two doors and a green pitcher and a bottle with a candle inside. The old woman got up and came over to the window. I crouched down quickly and went around the house almost on my hands and knees. In the back, next to a high window with the shutters closed, there was a tree, taller and with a bigger trunk than I had ever seen in my life. I could hear birds moving around up in its branches. A pile of firewood next to a cage was blocking my way; farther on was a chicken coop. I couldn't see any window in the wall which had been covered by the flowered curtain inside, but there was a pile of wood that reached almost to the roof and that covered the whole wall. And there were bunches of heather. Just as I went around the corner of the house and was about to try to spy on her again the door opened and a voice shouted: Who is running around out there? The old woman came outside, with an axe in her hand, silhouetted against the light inside; she was short and squat, with a powerful voice: Why don't you answer? Why are you watching me and not answering? If they told you she is beautiful you got here too late! By three weeks! She got closer to me and when she could see me clearly by the light coming out of the house she lowered the axe. What are you doing here? Answer up! I told her I had come through the forest, that I was thirsty, that the river water had made me sick with disgust, that I hadn't dared to draw water from the well for fear that the pulley would squeak and she would hear me. Why didn't you want to be heard? I said the first thing that came into my head: So I wouldn't frighten whoever might be in the house. She threw her head back and began to laugh. Go in, she ordered, when she had finished laughing. Do you have any money? I told her no. Go in!-so no one can say that for once in my life I haven't been charitable. Who told you there was a

29

house here, in such a secluded place? I felt like telling her my feet had led me here but I was afraid it would make her mad. I followed the path, I was running away from the river The axe was shining and it looked very sharp.

Inside it stank of smoke and boiled cabbage. The fireplace, a very small one, was lit and in a box beside the seat where I had seen the old woman sitting there were skeins of colored threads. Hung on the chimney was a black picture frame, the glass in it more dirty than clean and behind the glass was an embroidered Virgin: the same one as on my scapular. I put my hand in the back pocket of my pants: it wasn't there. I touched my neck: I wasn't wearing it. And then I looked at the old woman from top to bottom, ugly as a bad dream, with a snub nose, small, wide-set eyes, a low forehead, puffy cheeks and a big mouth. She cleared a pile of odds and ends offof the round table, and once she had it straight she put down a botde and two glasses. You'll see how well sit down here, opposite me. Let's hear it! I looked at the chimney and looked at her; I couldn't help comparing the ernbroidered face to the real one. She guessed what I was thinking and began to laugh again the same way, throwing her head back, the skin tighten, ing on her neck and her adam's apple bobbing up and down. You're seeing things. Take a good look at me. Are you a mute? Is that why you aren't talking? I tell you you're seeing things. She was lying more than the lyingest liar that ever lived. That Virgin was her; that man had already told me: the Virgin of the scapulars, all the faces of those Virgins, were her face. She was in love with herself. Ugly as sin and she was in love with herself. How could anyone so fat and ugly love herself? Well, I would really have to be something to embroider my own face, with all the other faces there are in the world. When I was a child the nuns taught me how to embroider. You can't imagine how often I've blessed them. But I have some other income, don't think She got up and opened the flowered curtain; behind it was a cot covered with a red blanket and an armchair with some ropes hanging from the arms and legs. Fairly new ropes, fairly white, not very thick. She brought over an ashtray and put it down on the table, sat down and lit a cigarette. Do you smoke? I said no, with a shake of my head. I do. The soldiers got me used to it. They always brought me some. Have a smoke, old woman, have a smoke it will take your mind off things and at my age I smoke and watch the smoke coming out of my mouth and my nose. Leaning all the way forward she put the cigarette right in front of my face. I feel like I am going to have to pinch you awake. I don't know how you can wander around the world with those eyes you have, like a defenseless child. Aren't you a man? Come on! Where's your courage! And long live war and long live

30