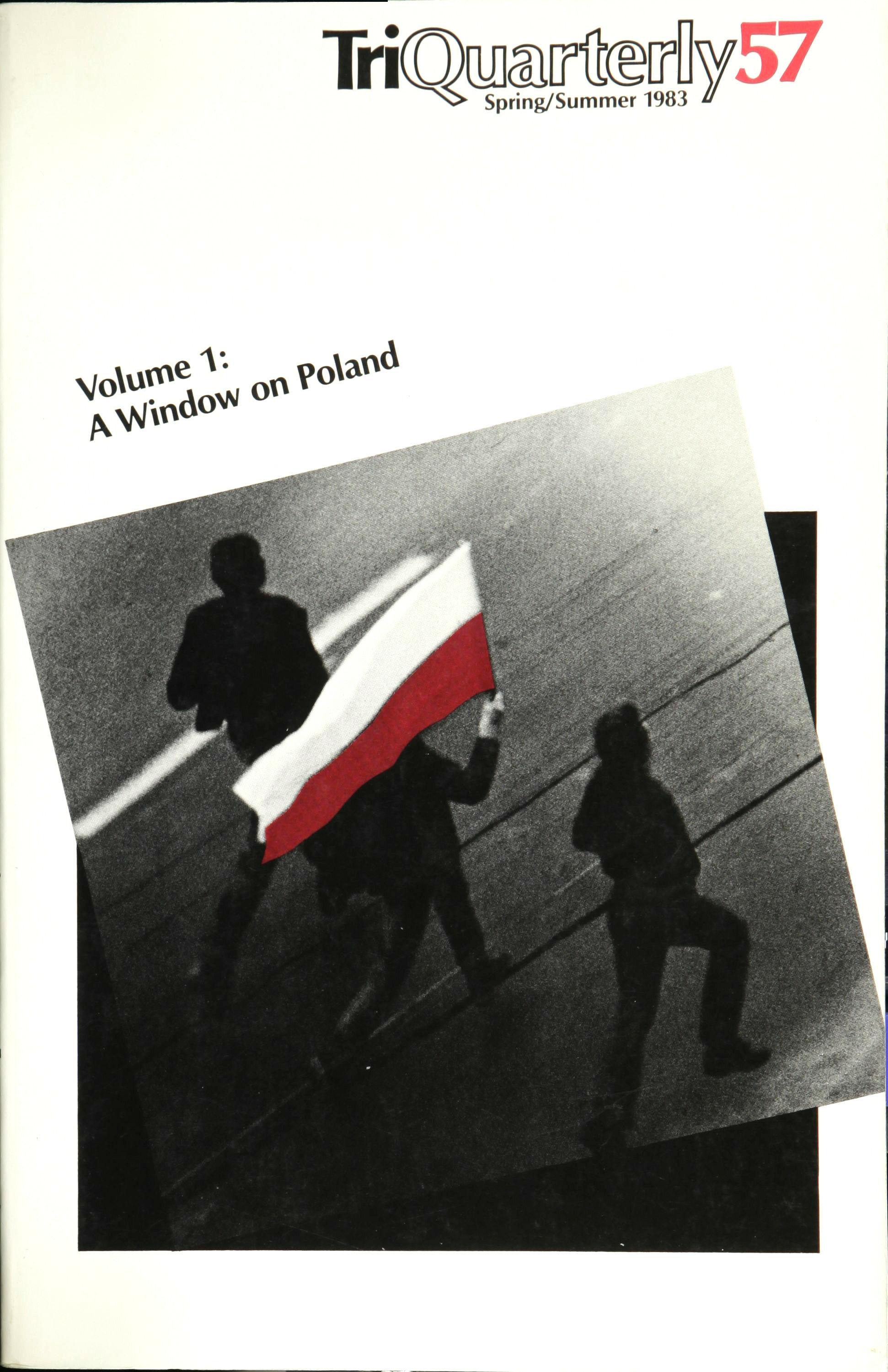

Volume 1 of 2 Volumes: A Window on Poland

Editor

Coeditors of this volume

Associate Editor

Managing Editor

Manuscripts Editor

Assistant Editor

Design Director

TriQuarterly Fellow

Editorial Assistants

Advisory Editors

Reginald Gibbons

Reginald Gibbons, Timothy Wiles

Bob Perlongo

Molly McQuade

Susan Hahn

Fred Shafer

Gini Kondziolka

Chris Olson

Will Johnson, Joe laRusso, Michael Lindsay, David Simpatico

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Elliott Anderson, Terrence Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Elizabeth Pochoda, Michael Ryan

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNAnONAL JOURNAL OF ART. WRITING. AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED IN THE FALL. WINTER. AND SPRING AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY, EVANSTON. ILLINOIS 6020I.

Subscription rates: one year $14.00; two years $25.00; three years $35.00. Foreign subscriptions $3.00 per year additional. Life subscription $100.00, USA or foreign. Single copies usually $5.95. This issue: $3.95 each volume. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQ!.aarterly, NORTIlWESTERN UNIVERSITY, 1735 Benson Avenue, Evanston, lllinois 60201. The editors invite submissions of fiction, poetry, and literary essays. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, selfaddressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of Tri�arterly. unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1983 by TriQuarterIy. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America.

National distributor to retail trade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Central Street-Rear, Nutley, New Jersey 07110. Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2940 Seventh Street, Berkeley, California 94710. Midwest: Bookslinger, 330 East Ninth Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101 and Prairie News Agency, 2404 West Hirsch Street, Chicago, lllinois 60622.

Reprints of back issues of TriQ!.aarterly are available in full format from Kraus Reprint Company, Route 100, Millwood, New York 10546, and in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106. ISSN: 00413097.

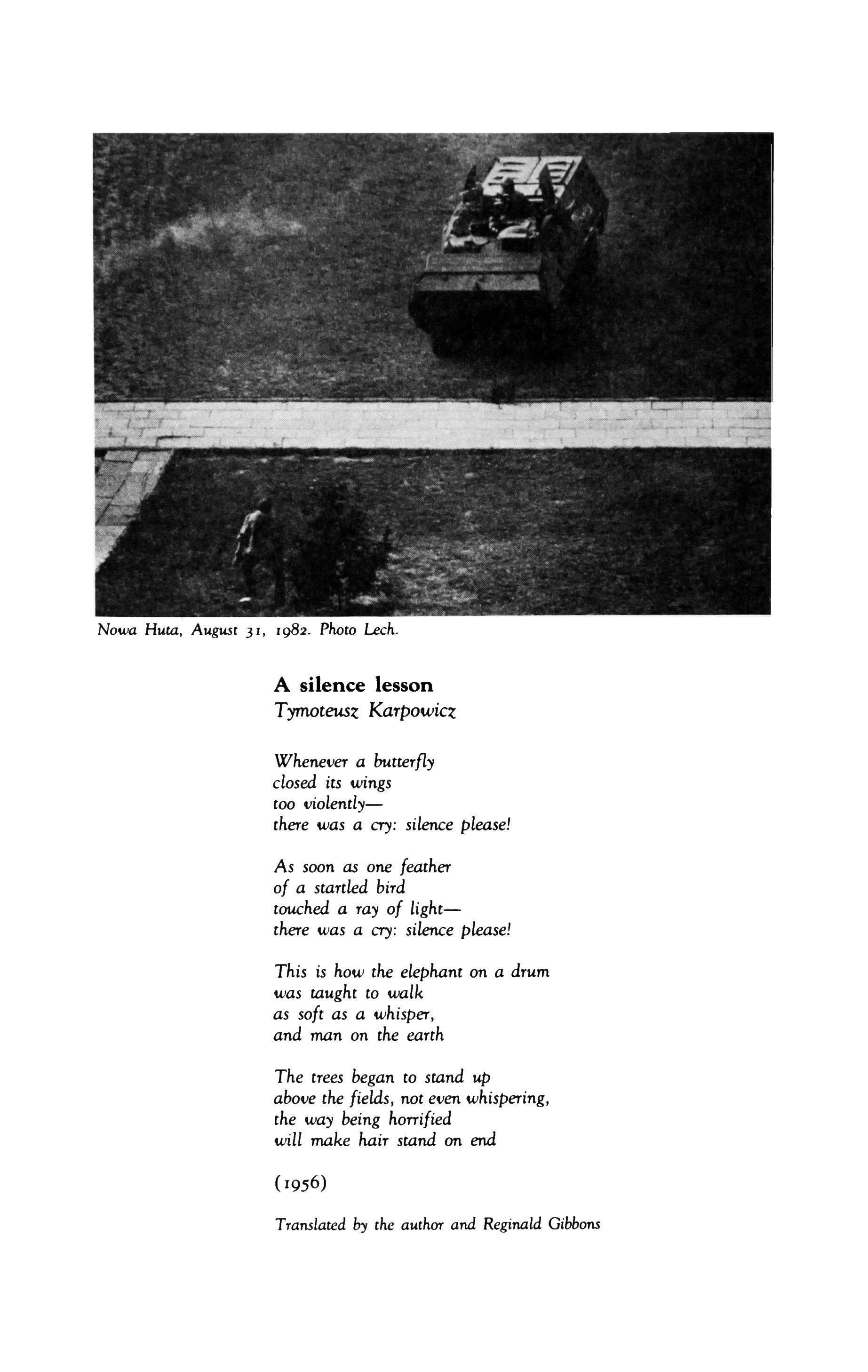

A silence lesson Tymoteusz Karpowicz

Whenever a butterfly dosed its wings too violentlythere was a cry: silence please!

As soon as one feather of a startled bird touched a ray of lightthere was a cry: silence please!

This is how the elephant on a drum was taught to walk as soft as a whisper, and man on the earth

The trees began to stand up above the fields, not even whispering, the way being horrified will make hair stand on end

Translated by the author and Reginald Gibbons

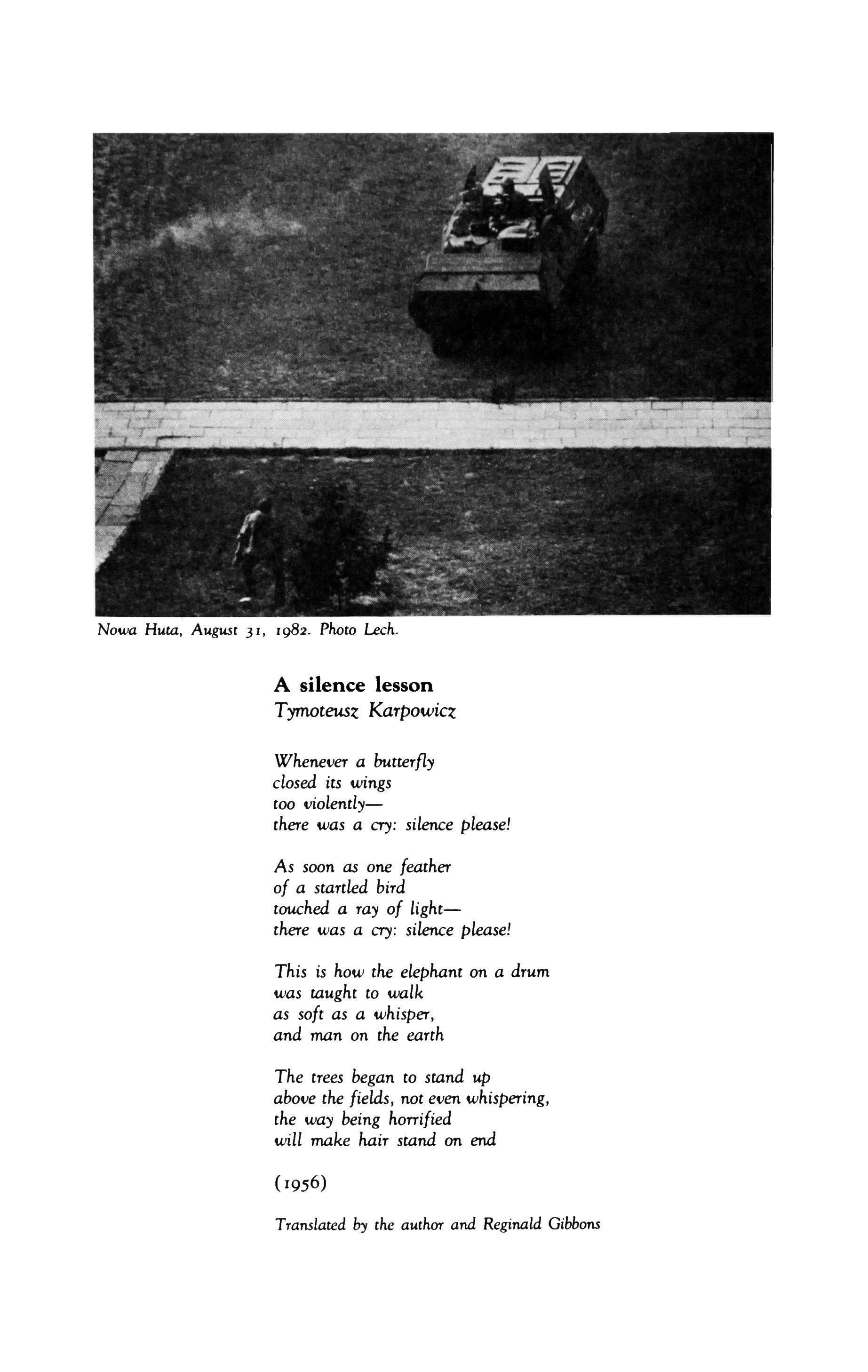

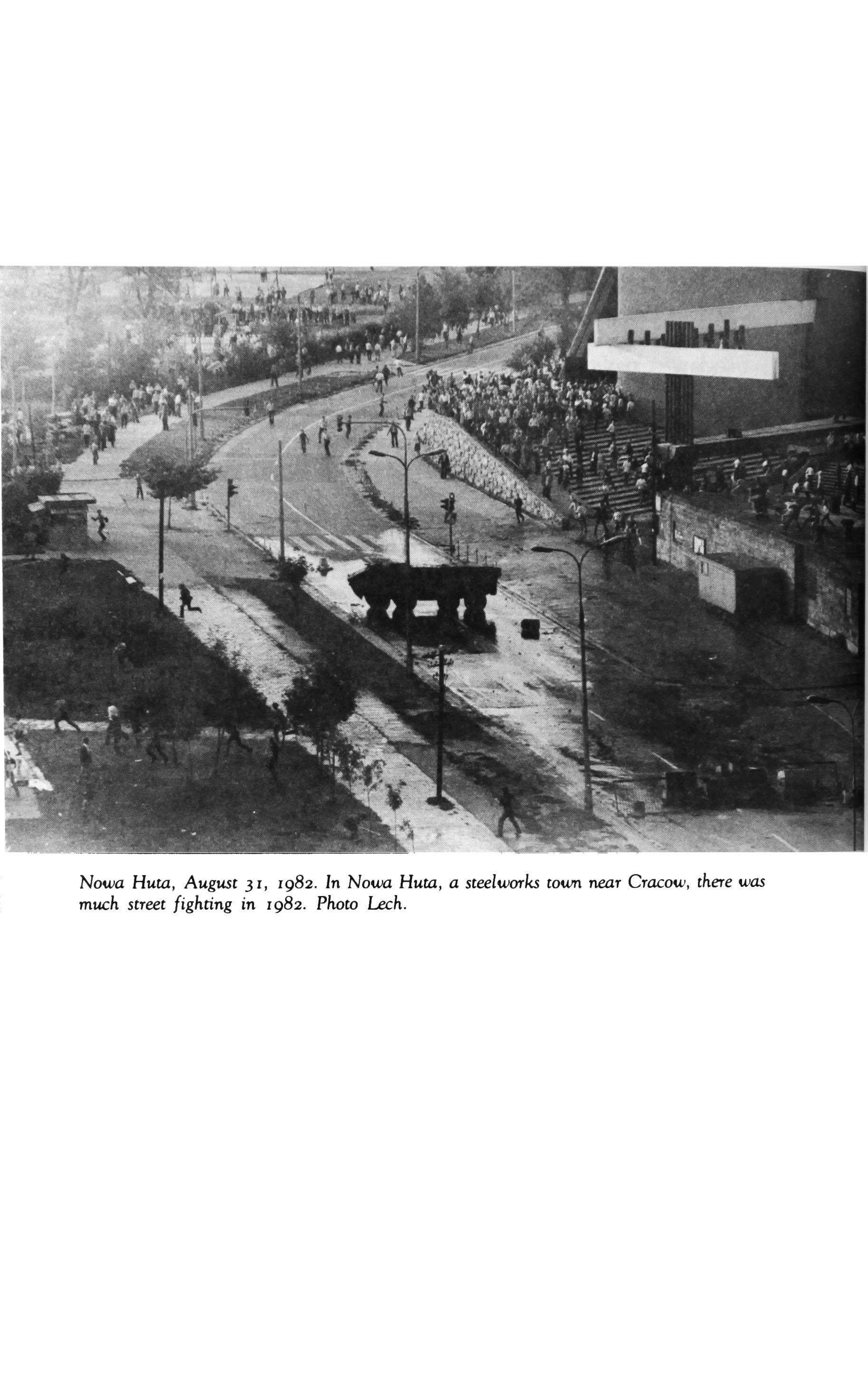

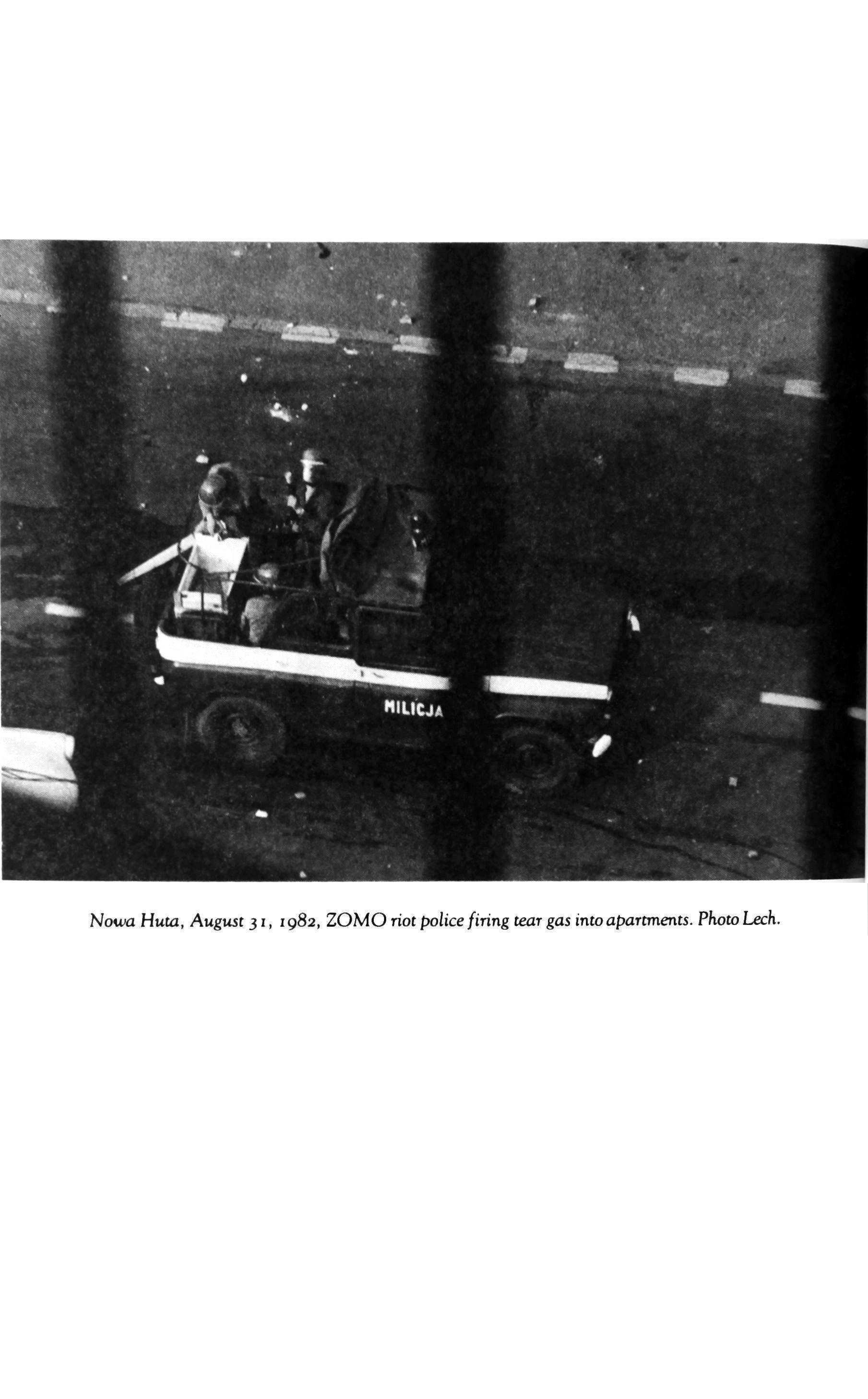

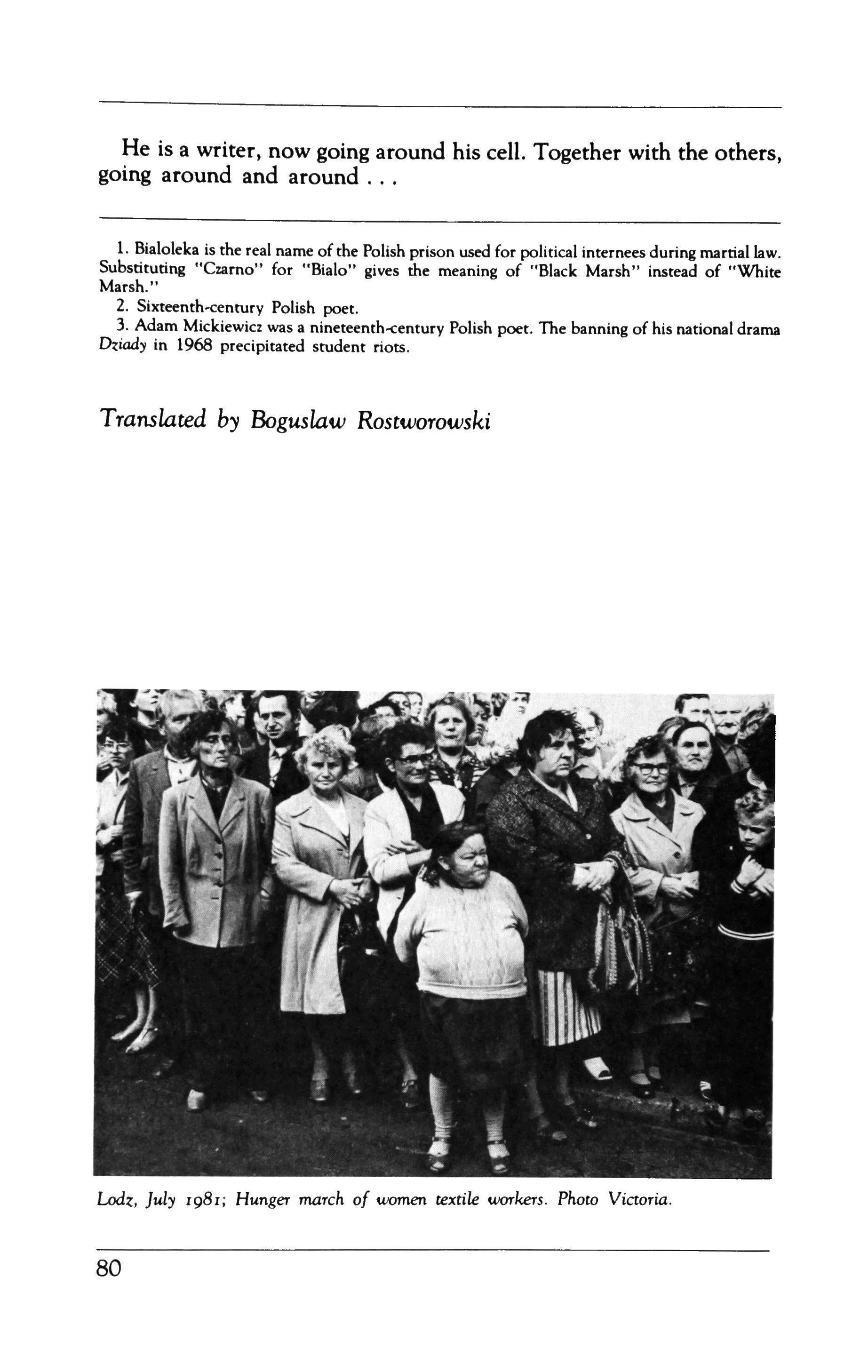

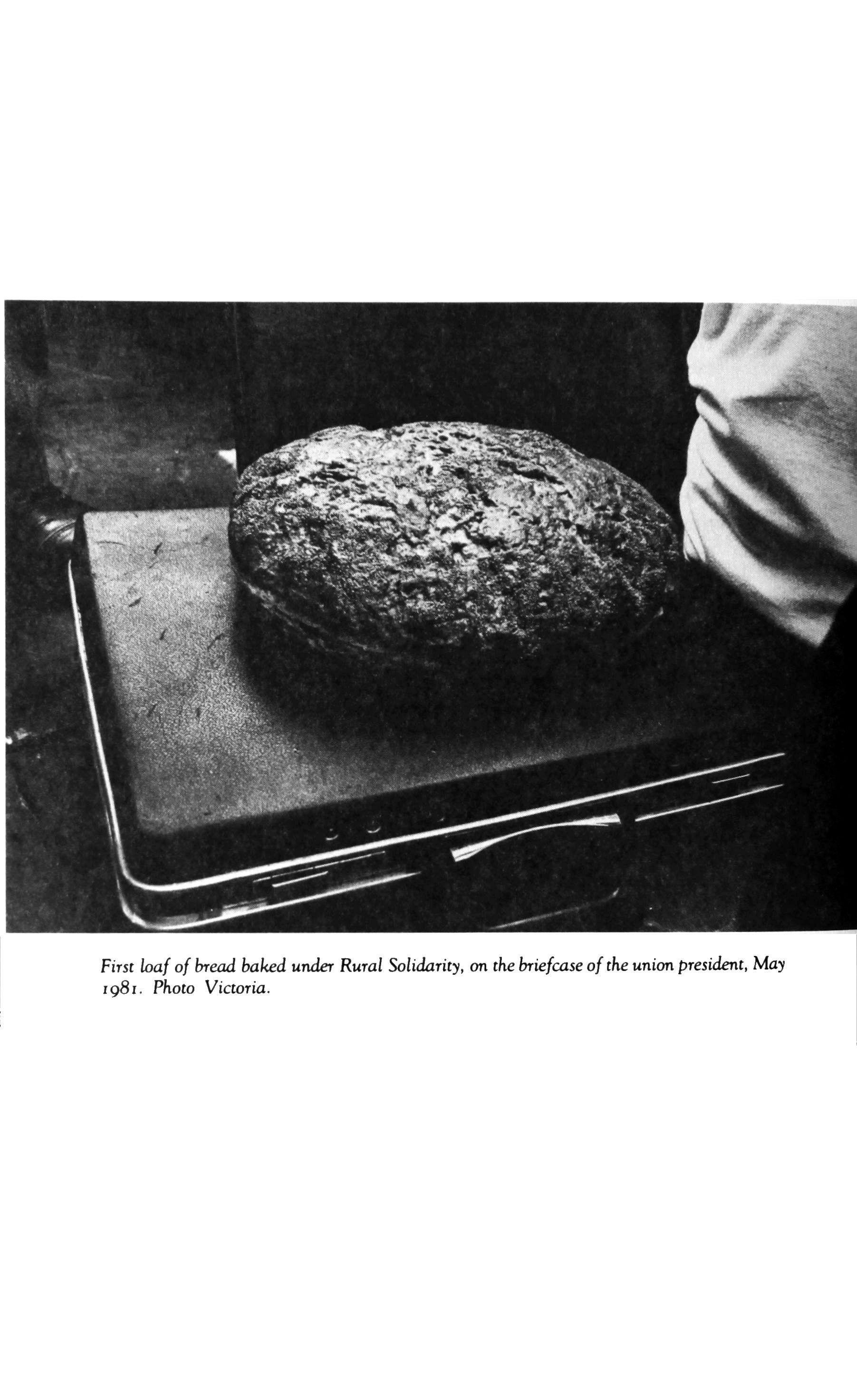

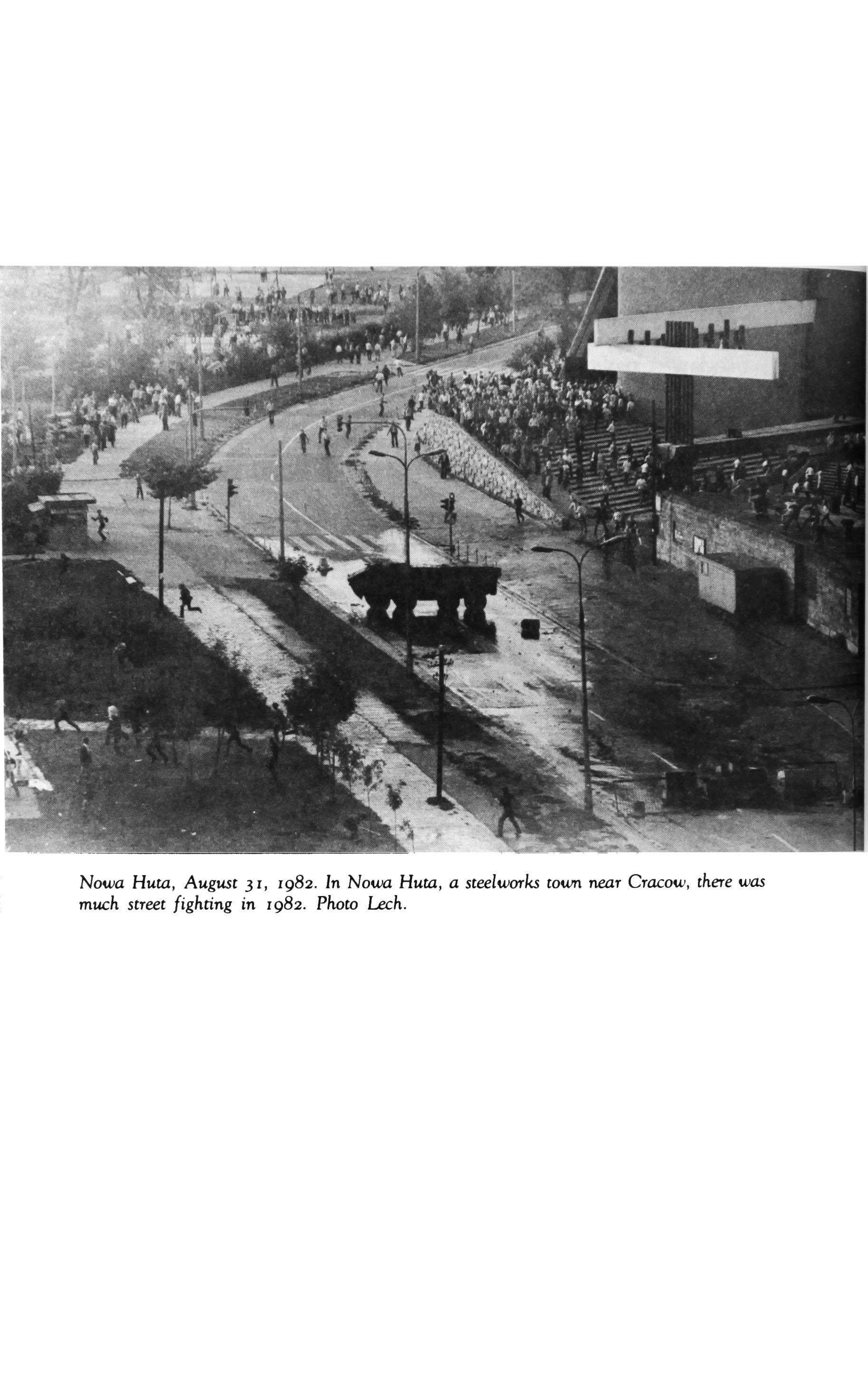

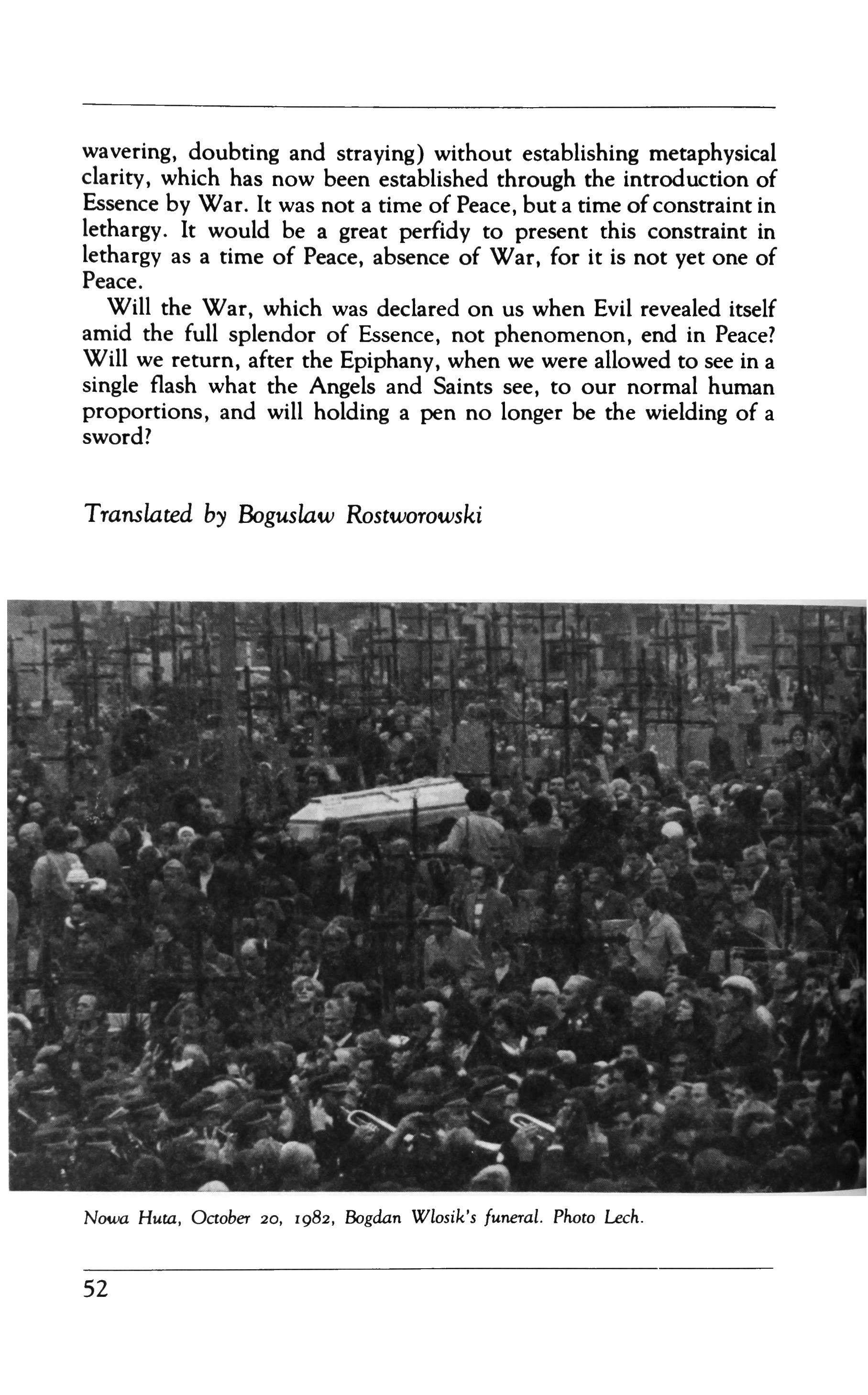

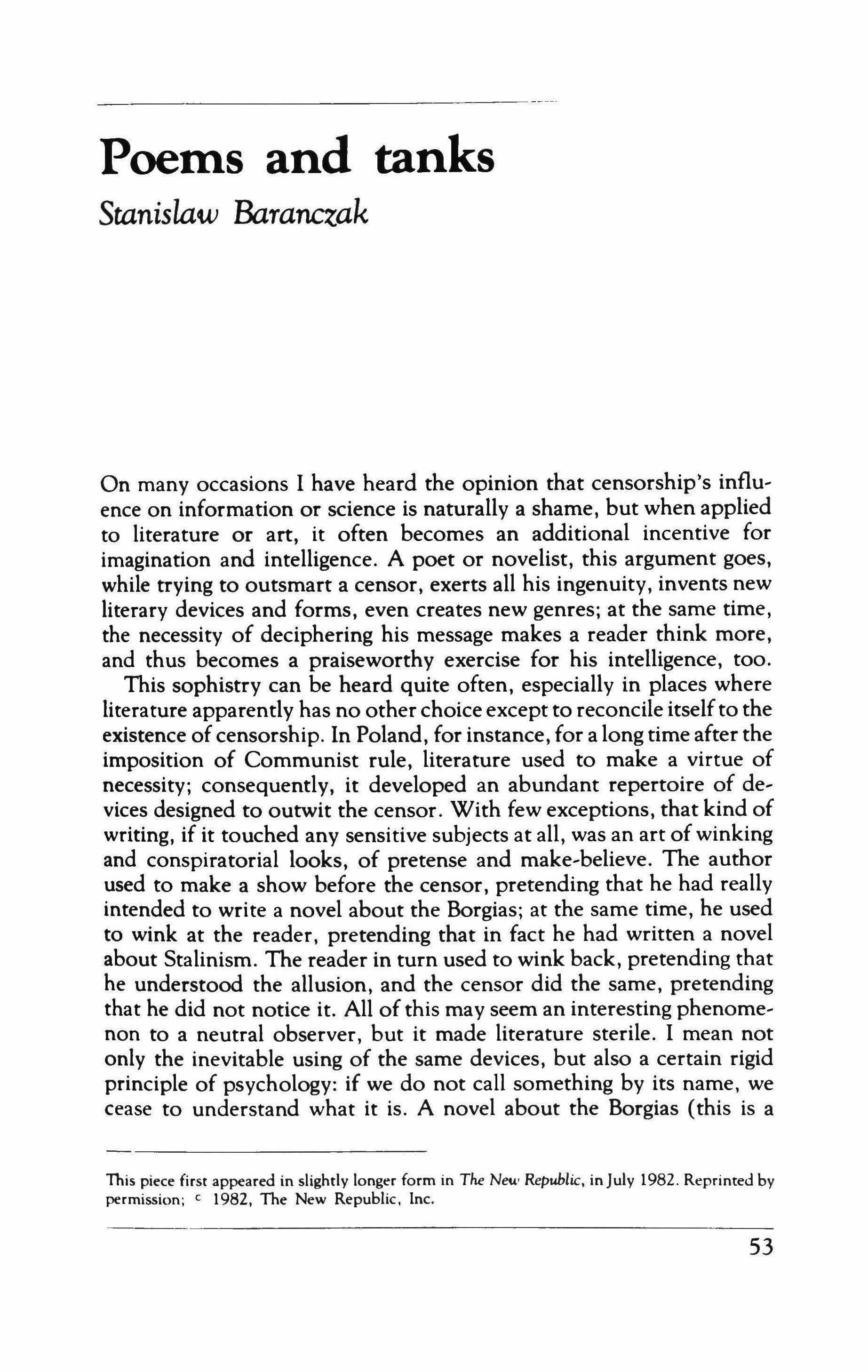

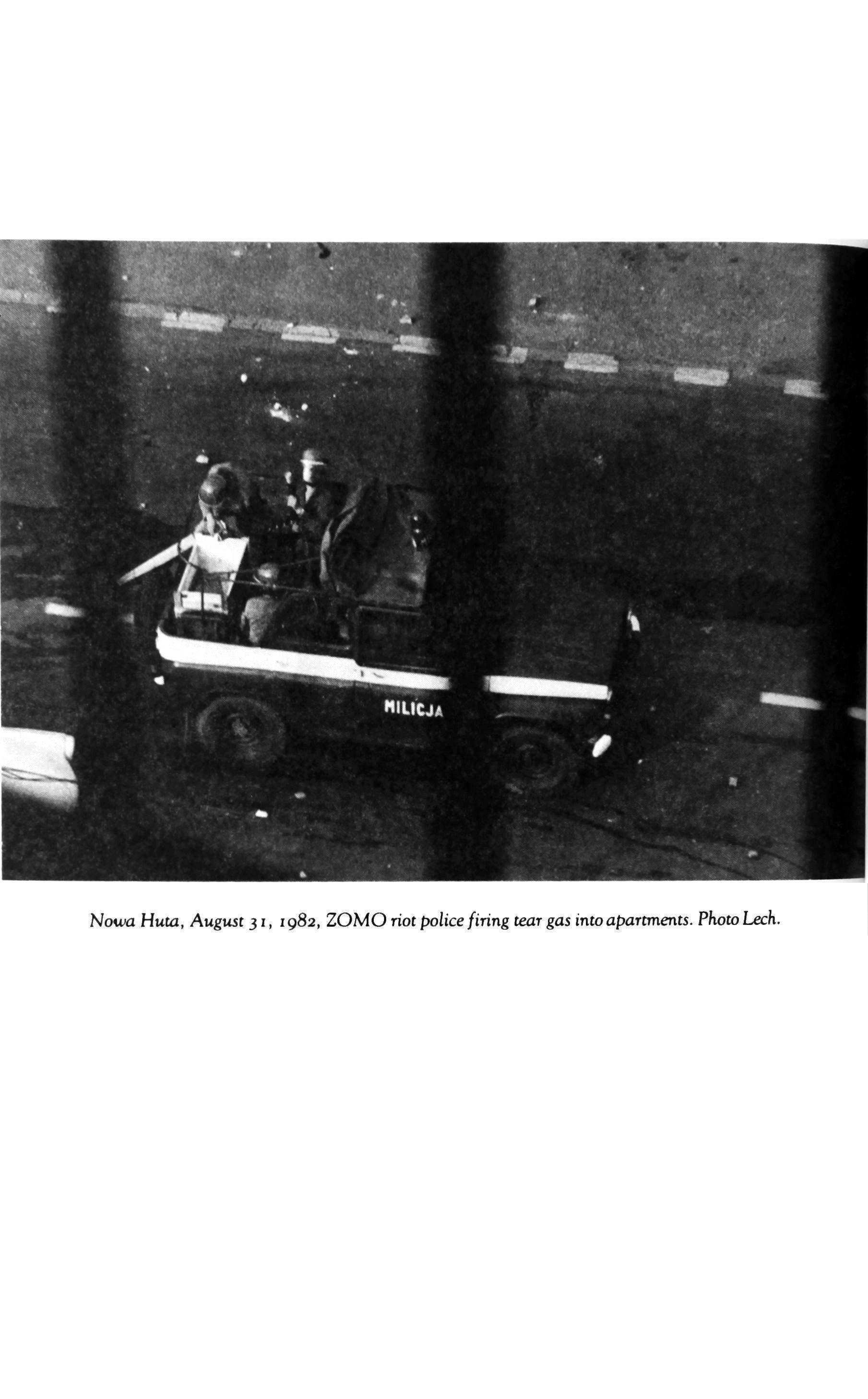

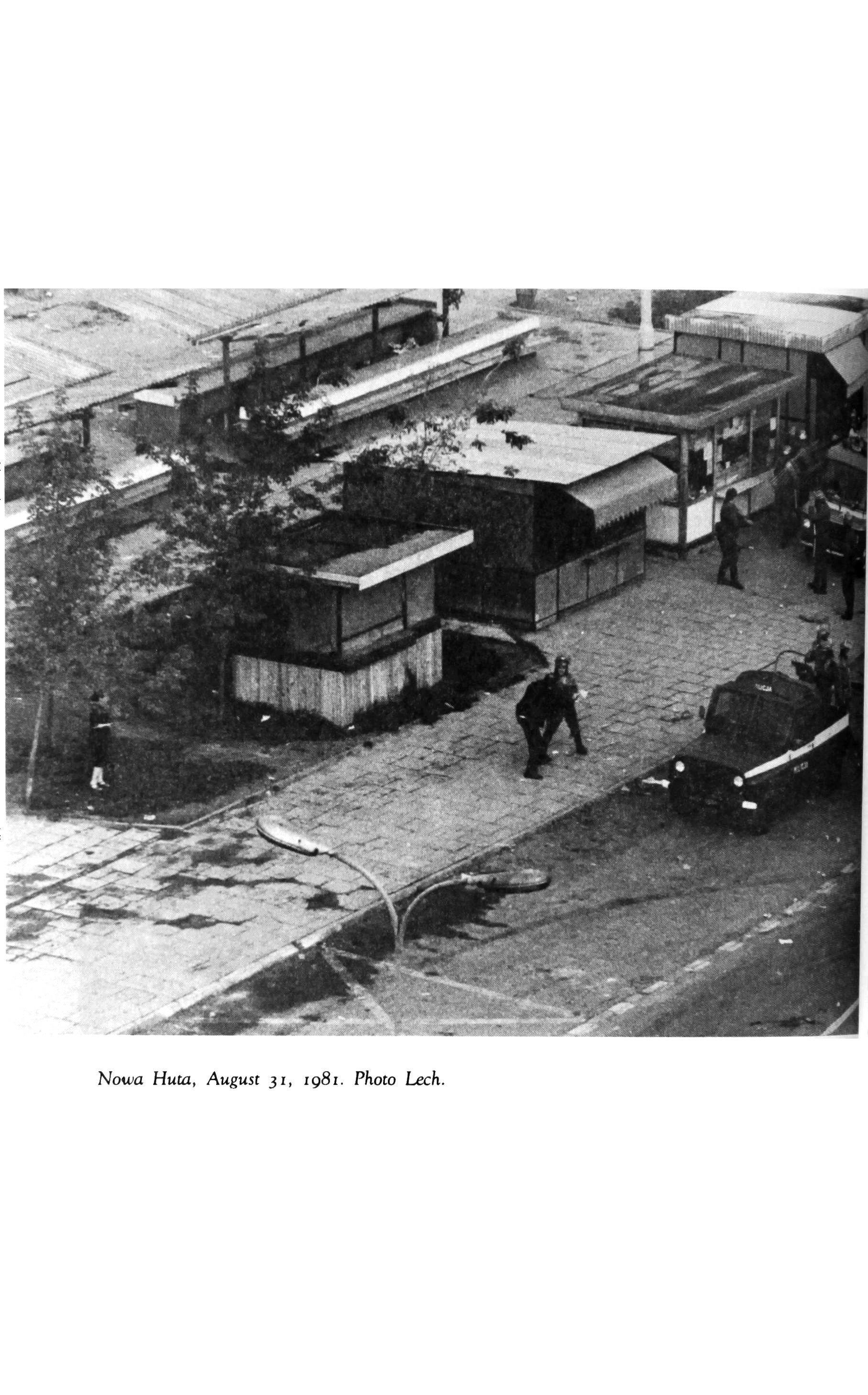

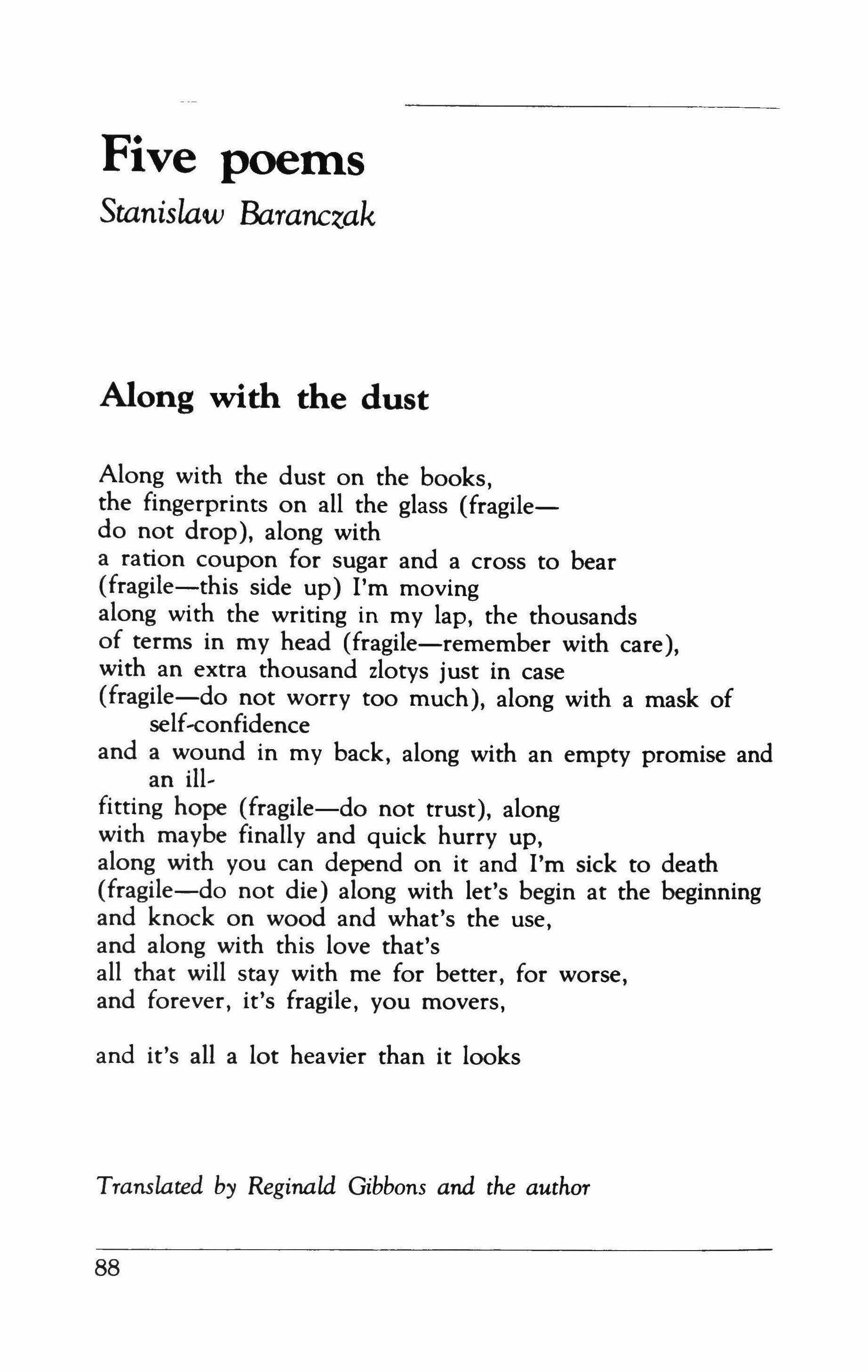

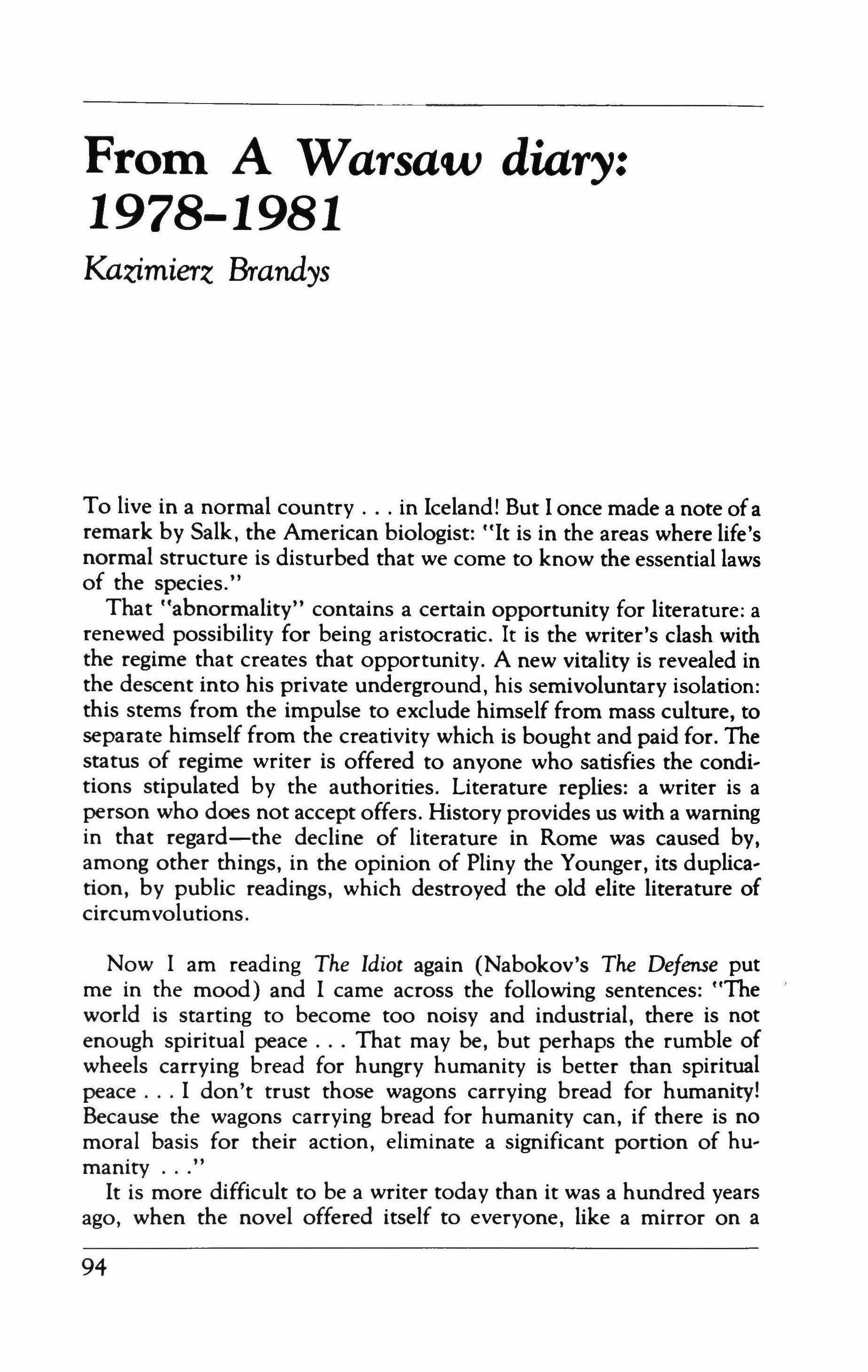

Nowa Huta, August 31, 1982. Photo Lech.

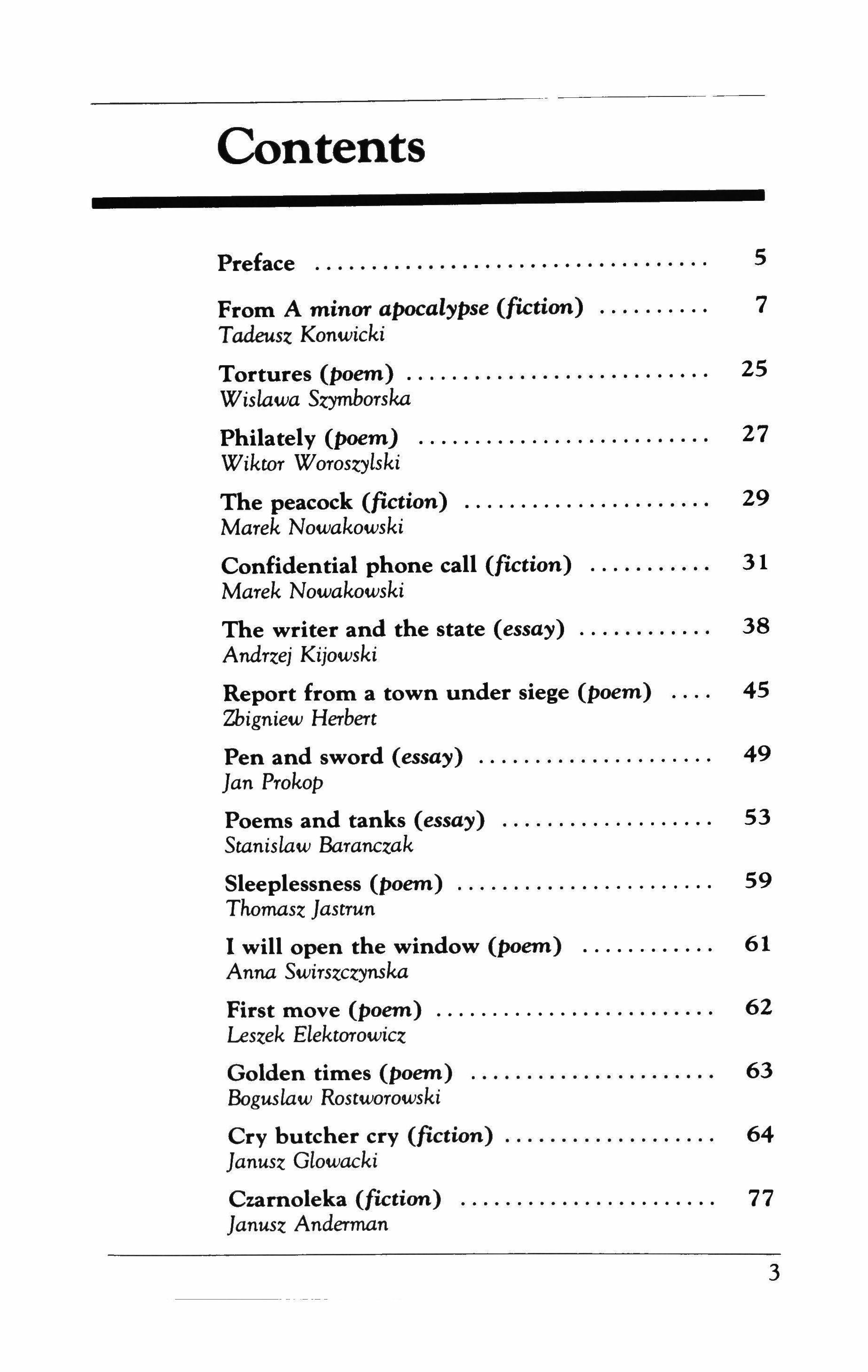

Contents Preface 5 From A minor apocalypse (fiction) Tadeusz Konwicki Tortures (poem) 25 Wislawa S:omborska Philately (poem) 27 Wiktor Woroszylski The peacock (fiction) 29 Marek Nowakowski 7 Confidential phone call (fiction) Marek Nowakowski The writer and the state (essay) 38 Andrzej Kijowski 31 Report from a town under siege (poem) 45 Zbigniew Herbert Pen and sword (essay) 49 Jan Prokop Poems and tanks (essay) Stanislaw Baranczak Sleeplessness (poem) 59 Thomasz Jastrun 53 I will open the window (poem) 61 Anna Swirszczynska First move (poem) 62 Leszek Elektorowicz Golden times (poem) 63 Boguslaw Rostworowski Cry butcher cry (fiction) 64 Janusz Glowacki Czarnoleka (fiction) 77 Janusz Anderman 3

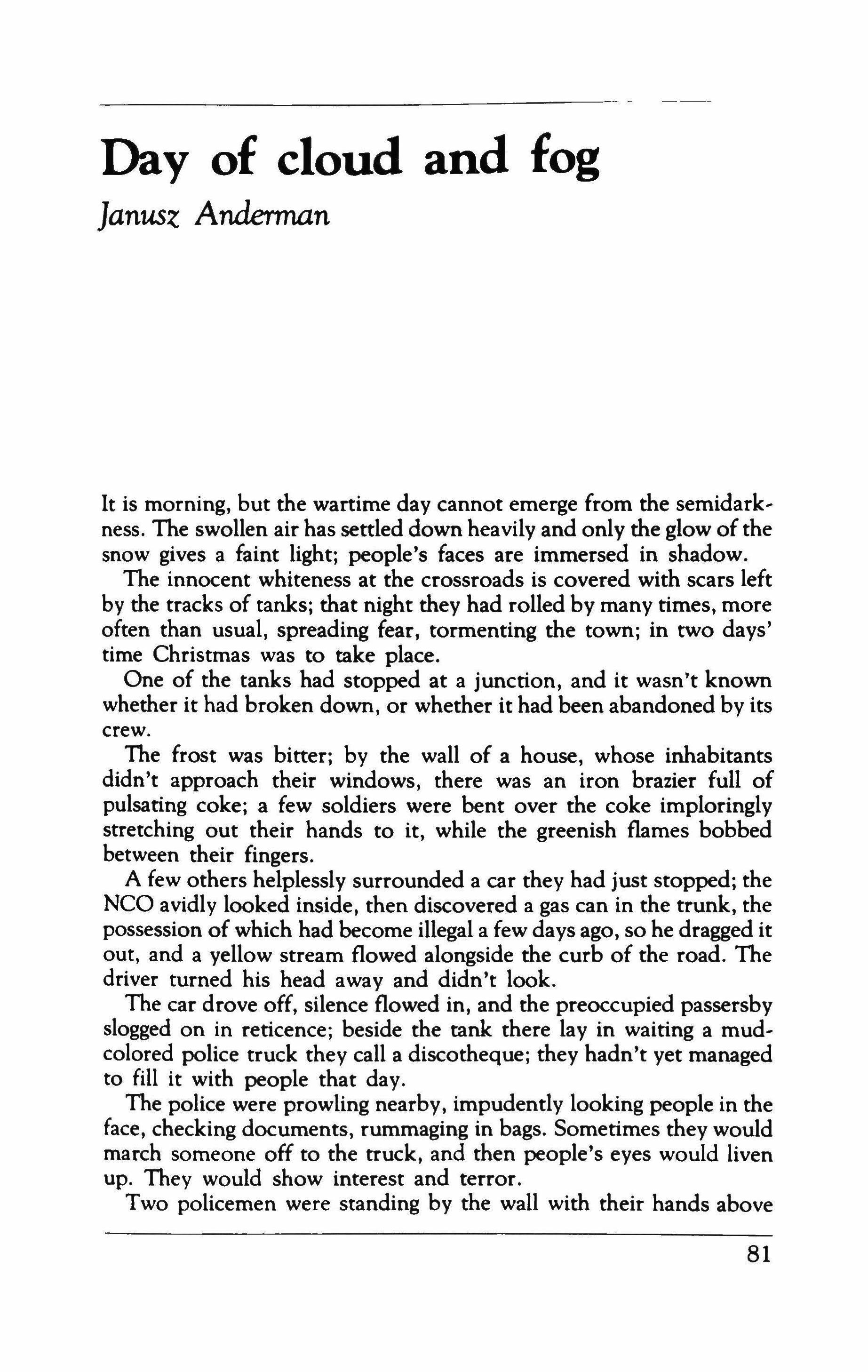

Day of cloud and fog (fiction)

Janusz Anderman

Three poems from Diary of internment (Darlowko, 1982) 85

Wiktor Worosz.ylski

Five poems................................ 88

Stanislaw Baranczak

From A Warsaw diary: 1978-1981

Kazimierz Brandys

Report from the state of war: Recent writing in Poland (essay)

Timothy Wiles

Contributors and acknowledgments

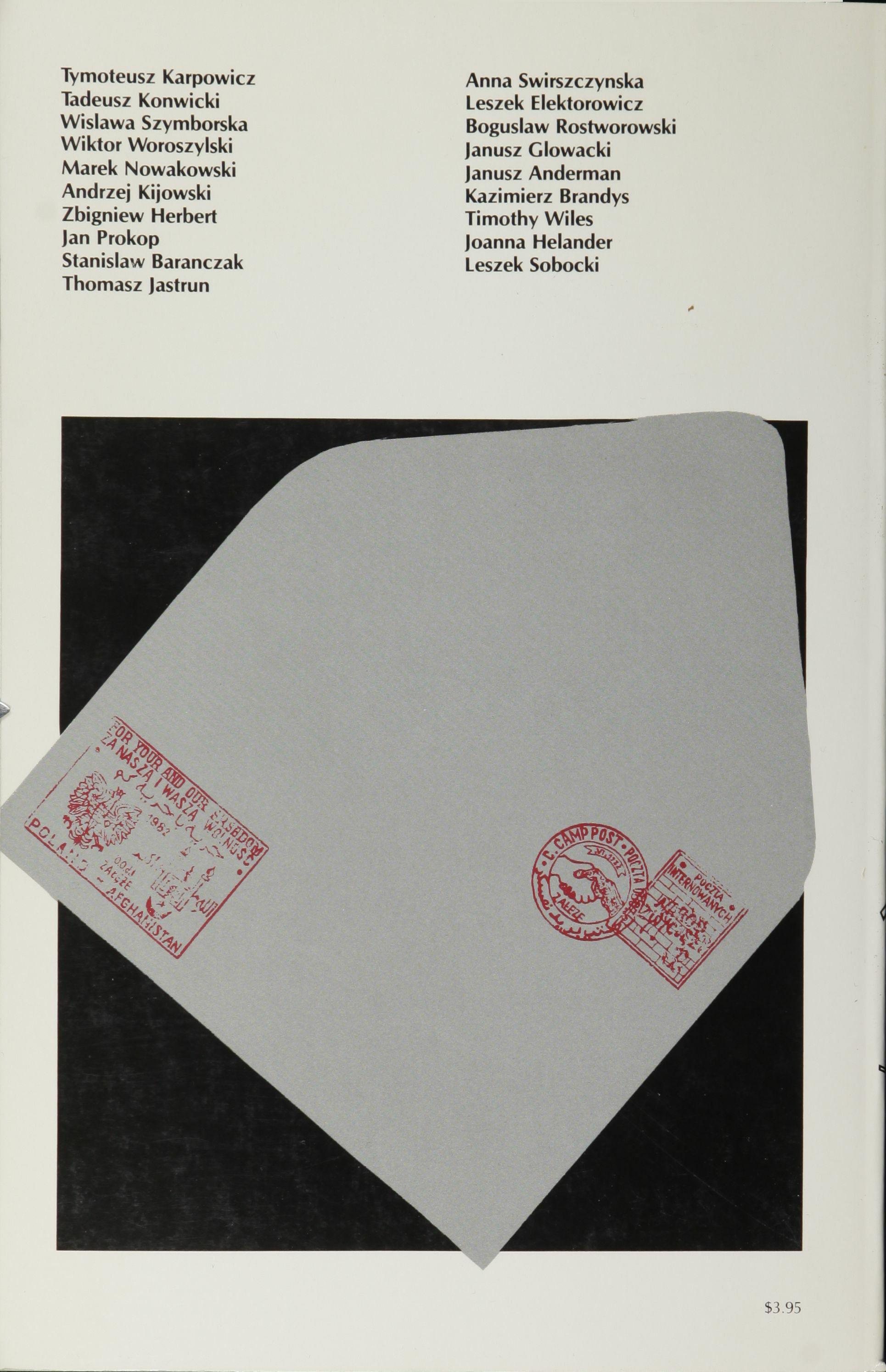

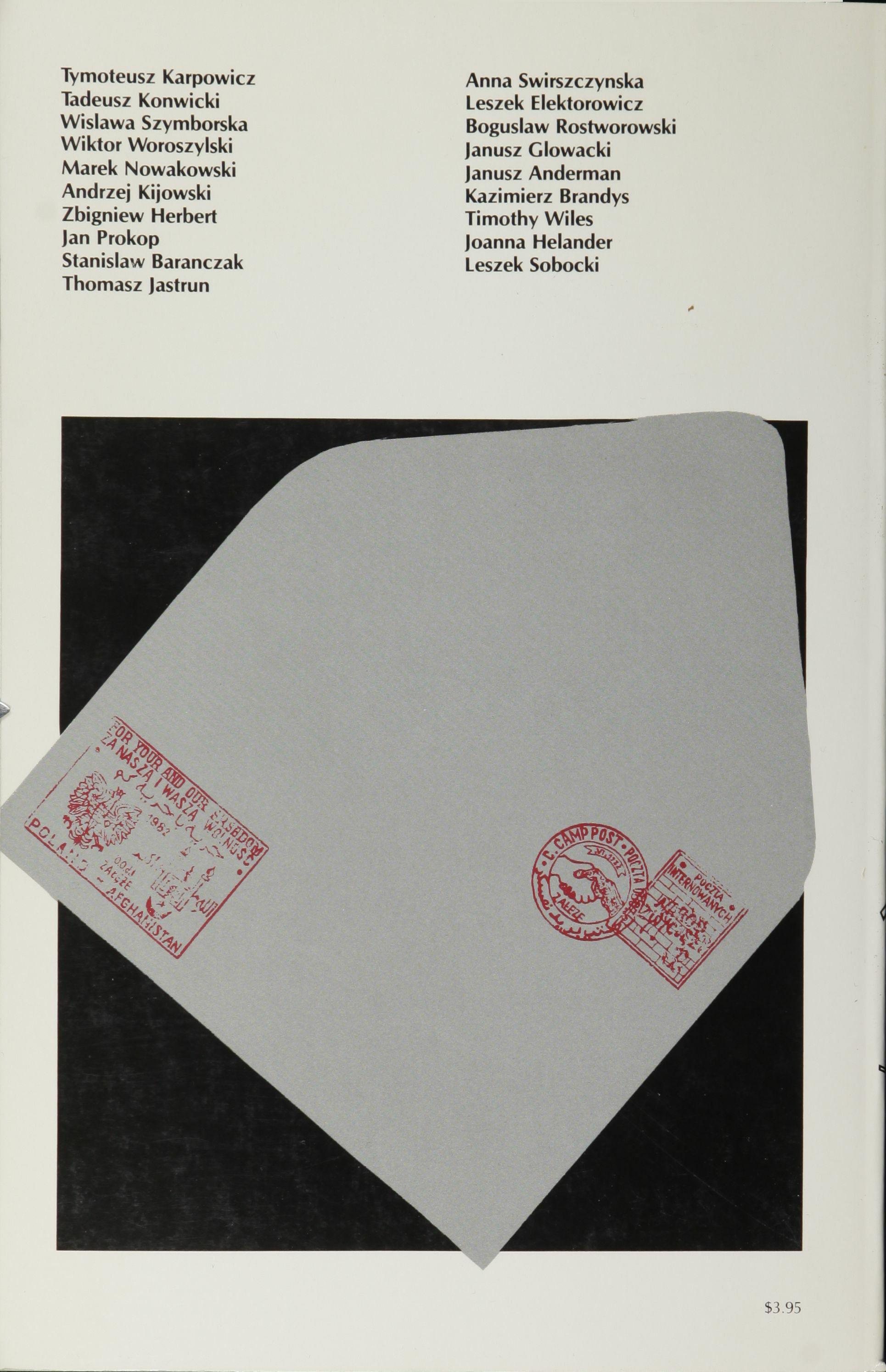

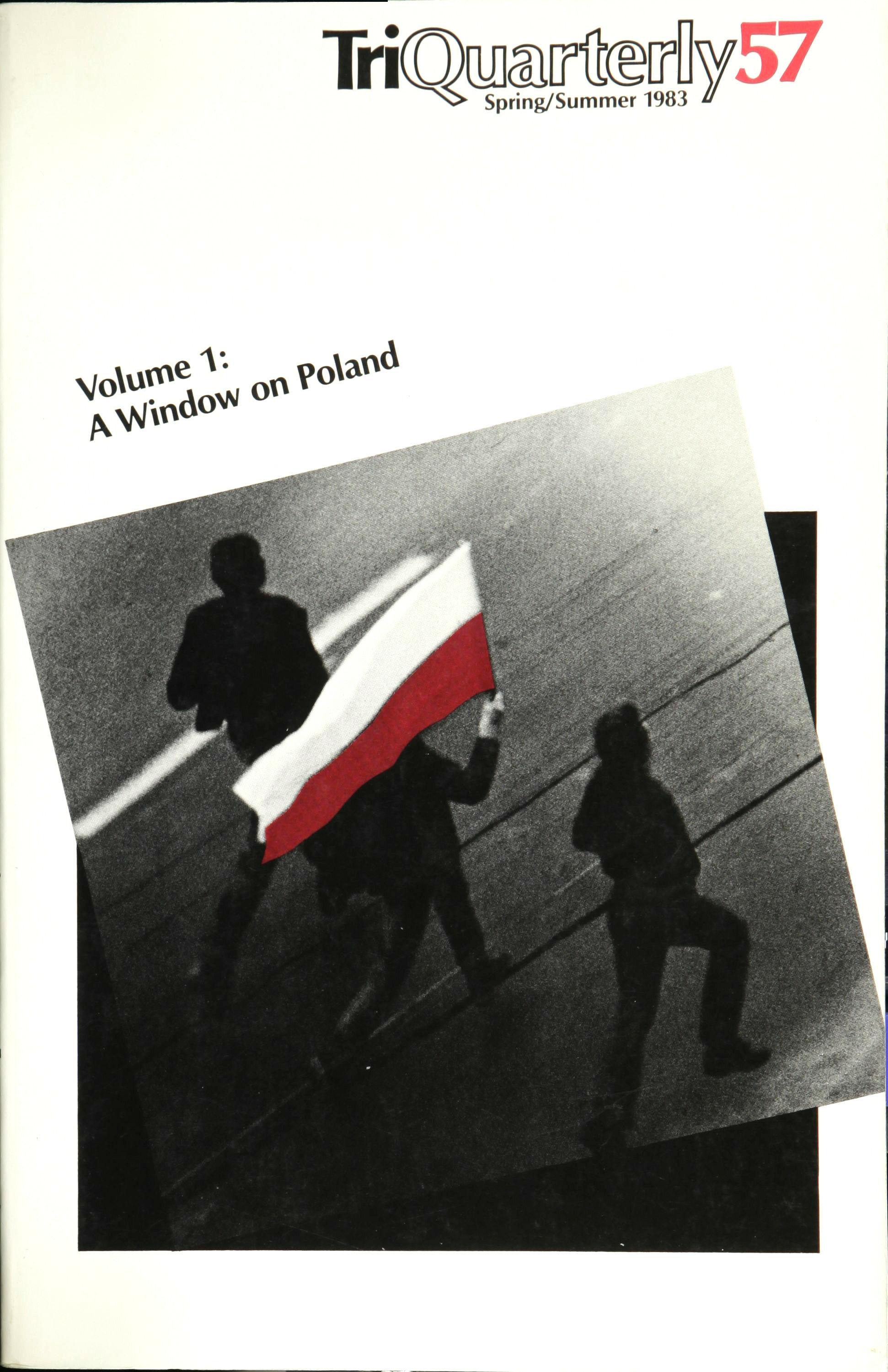

Front cover photograph by Photo Lech.

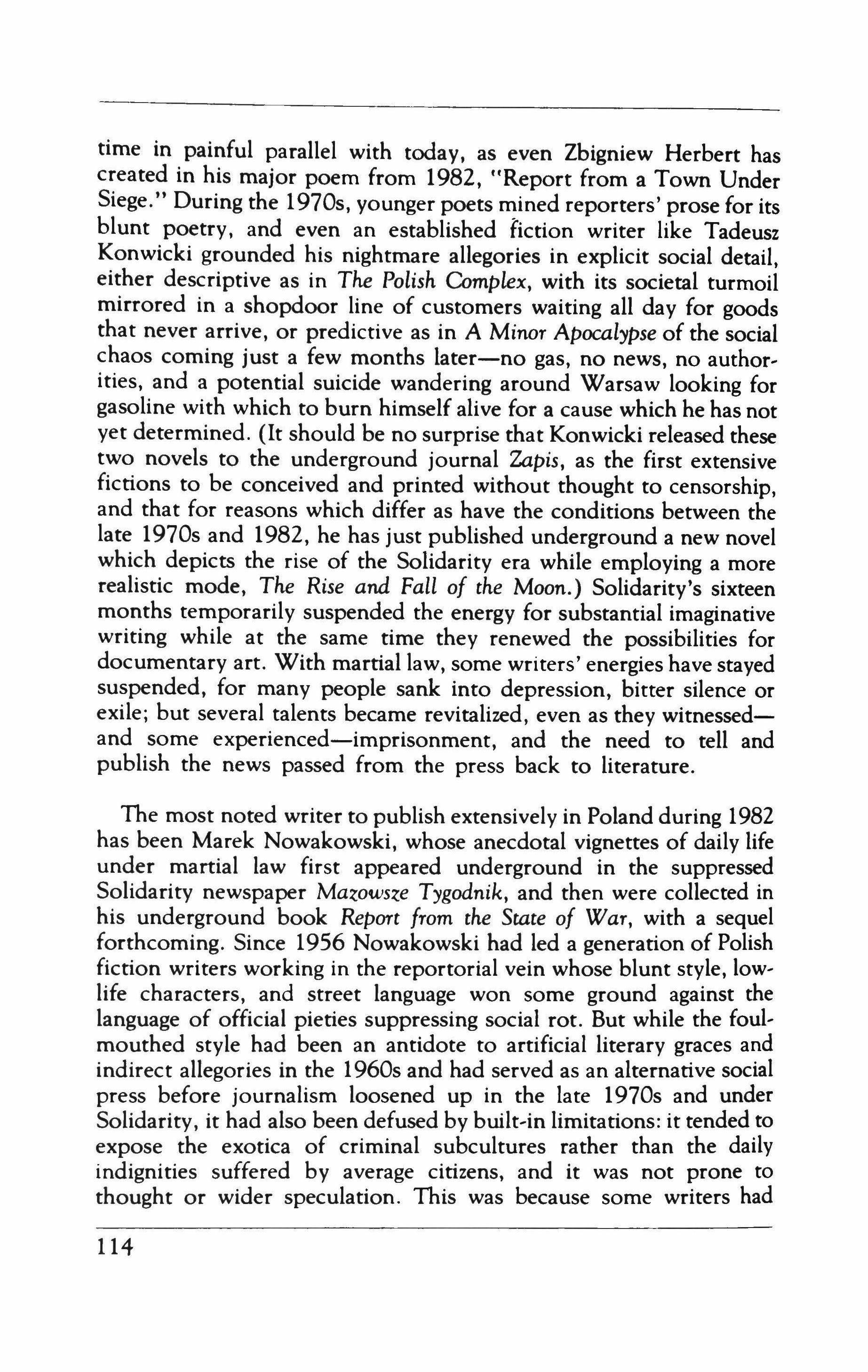

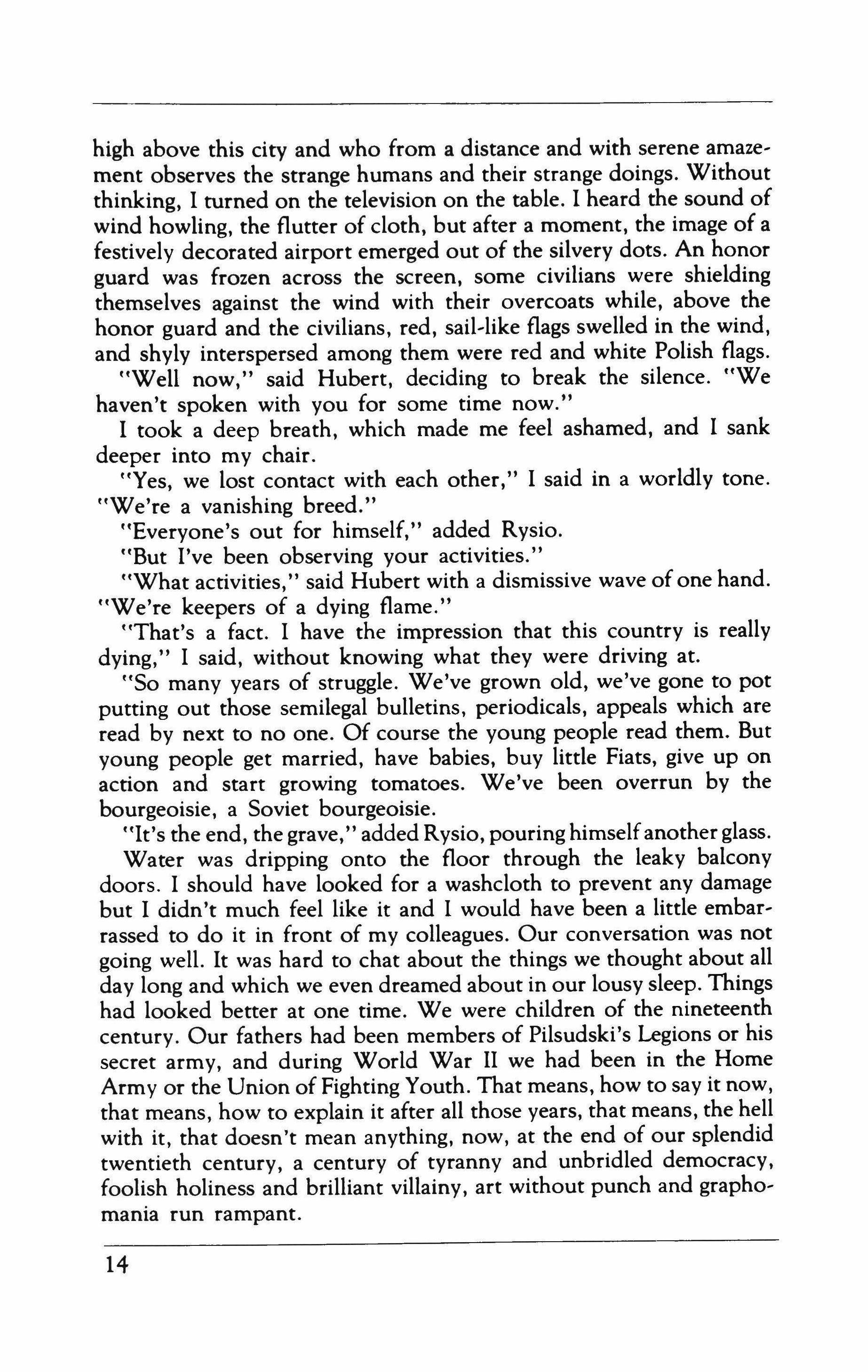

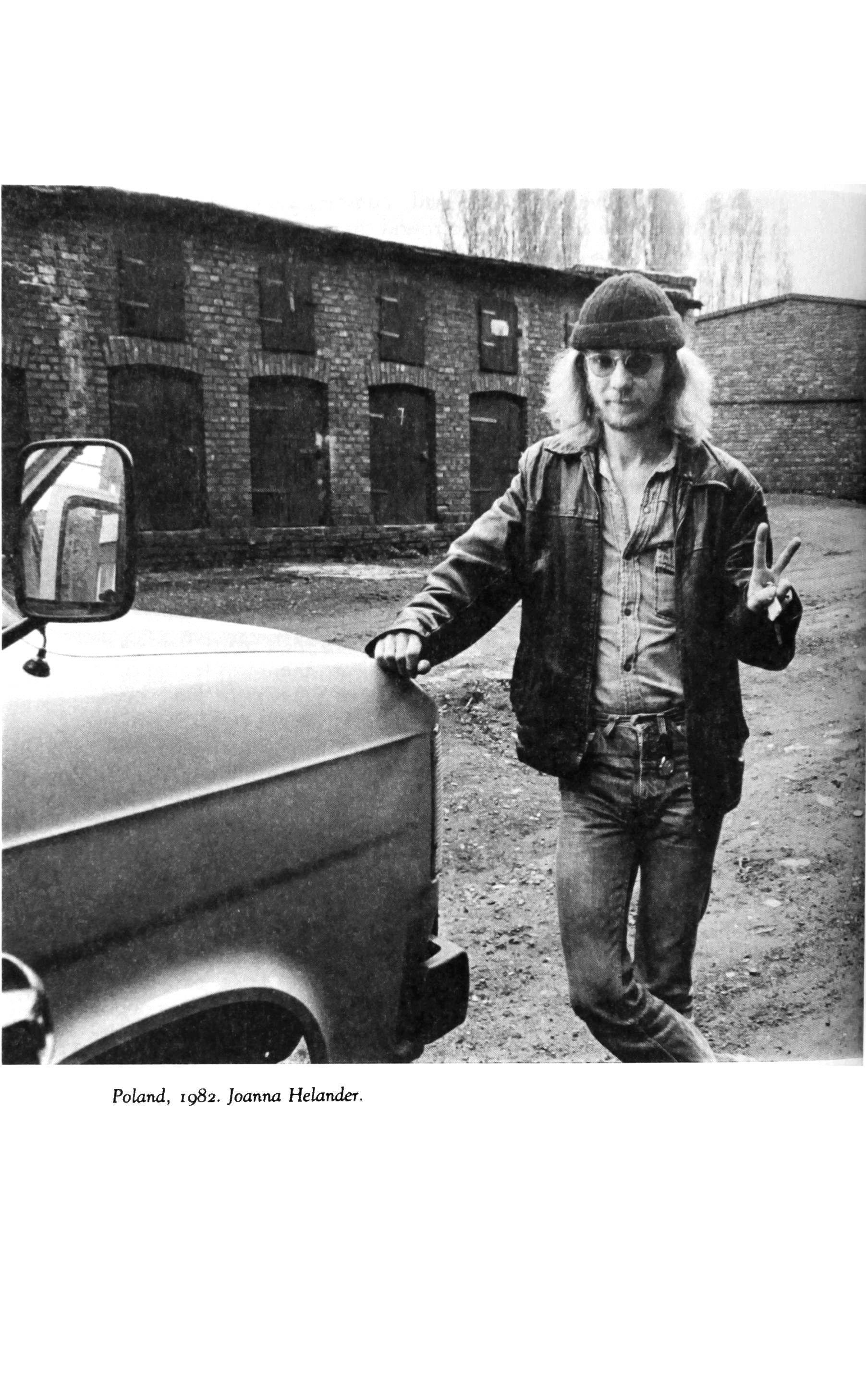

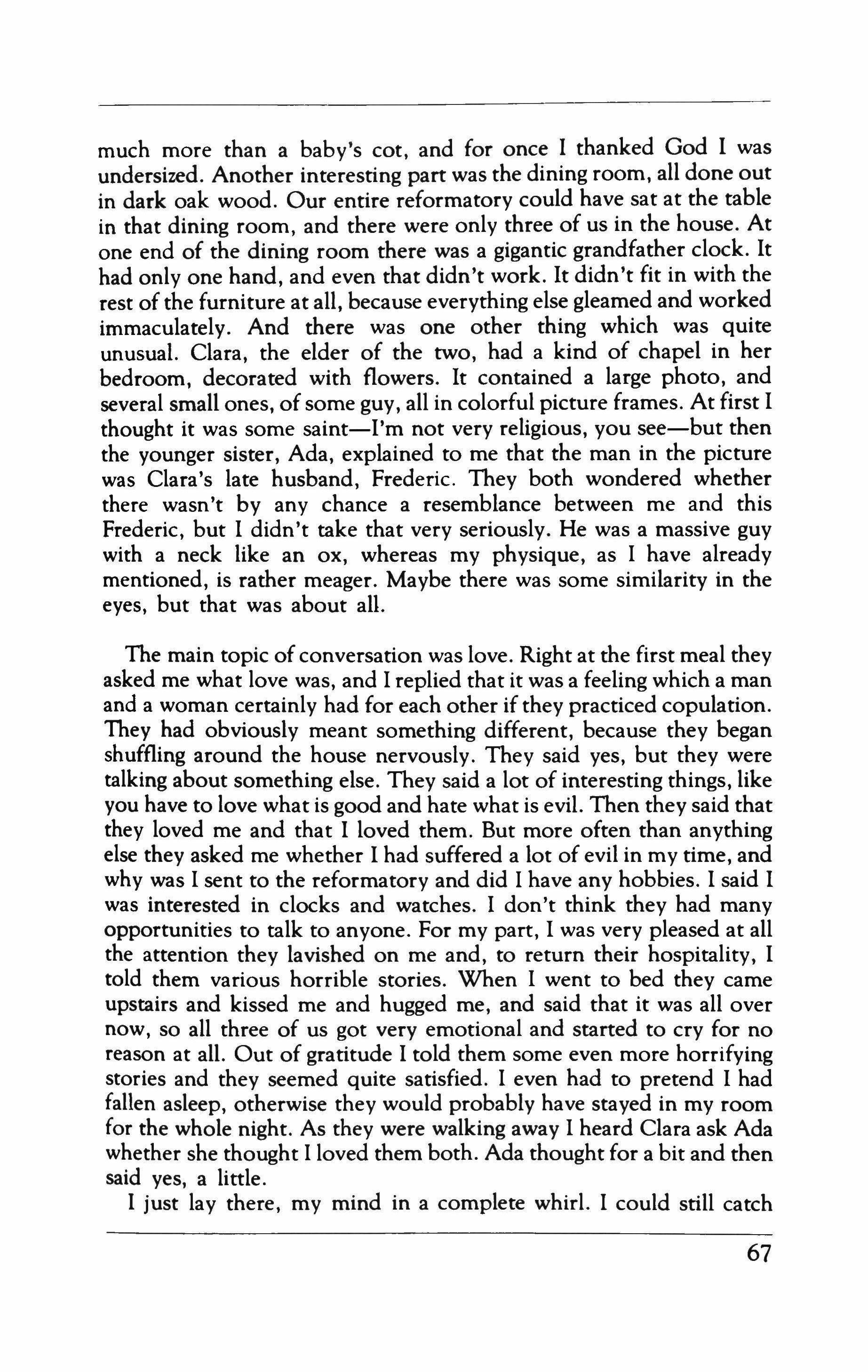

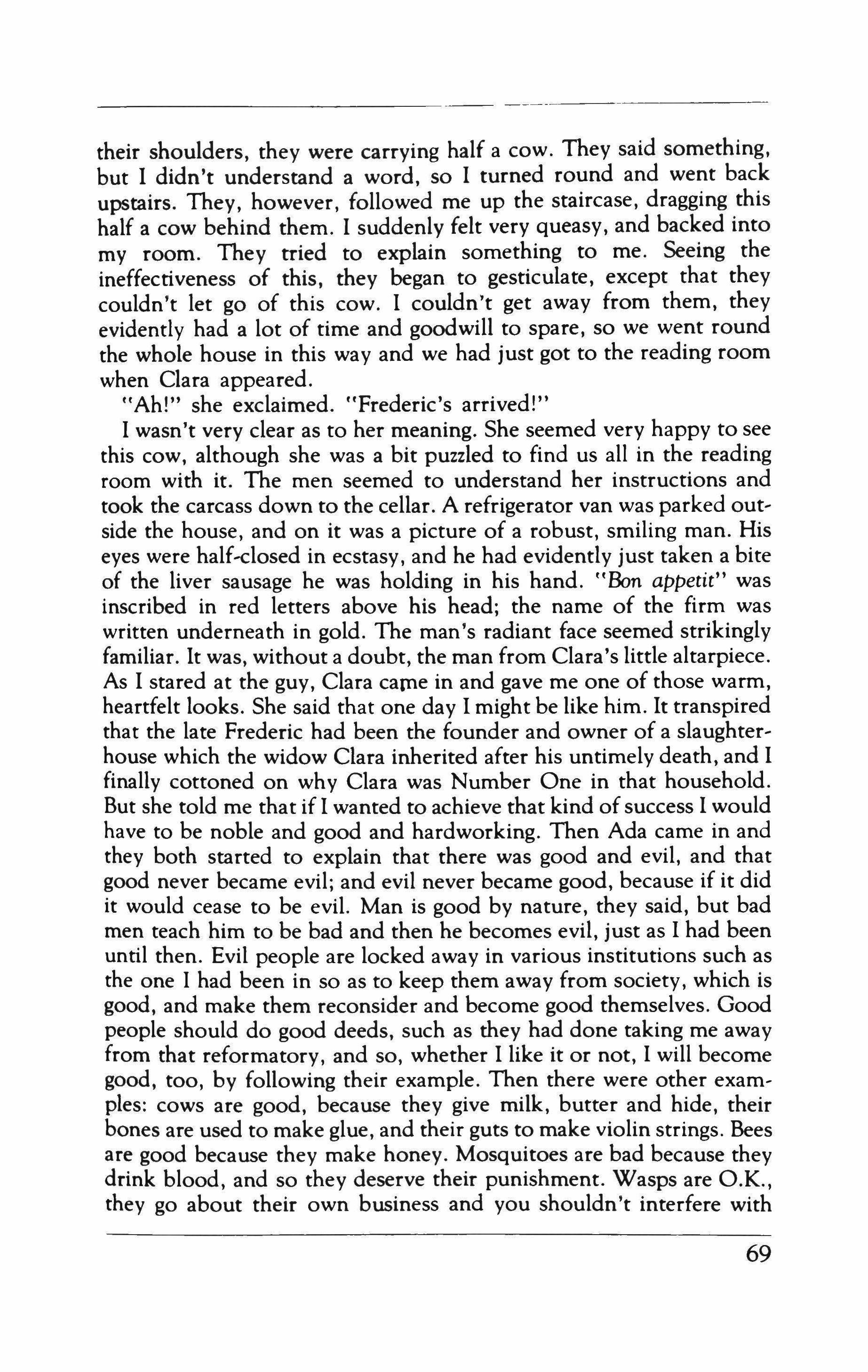

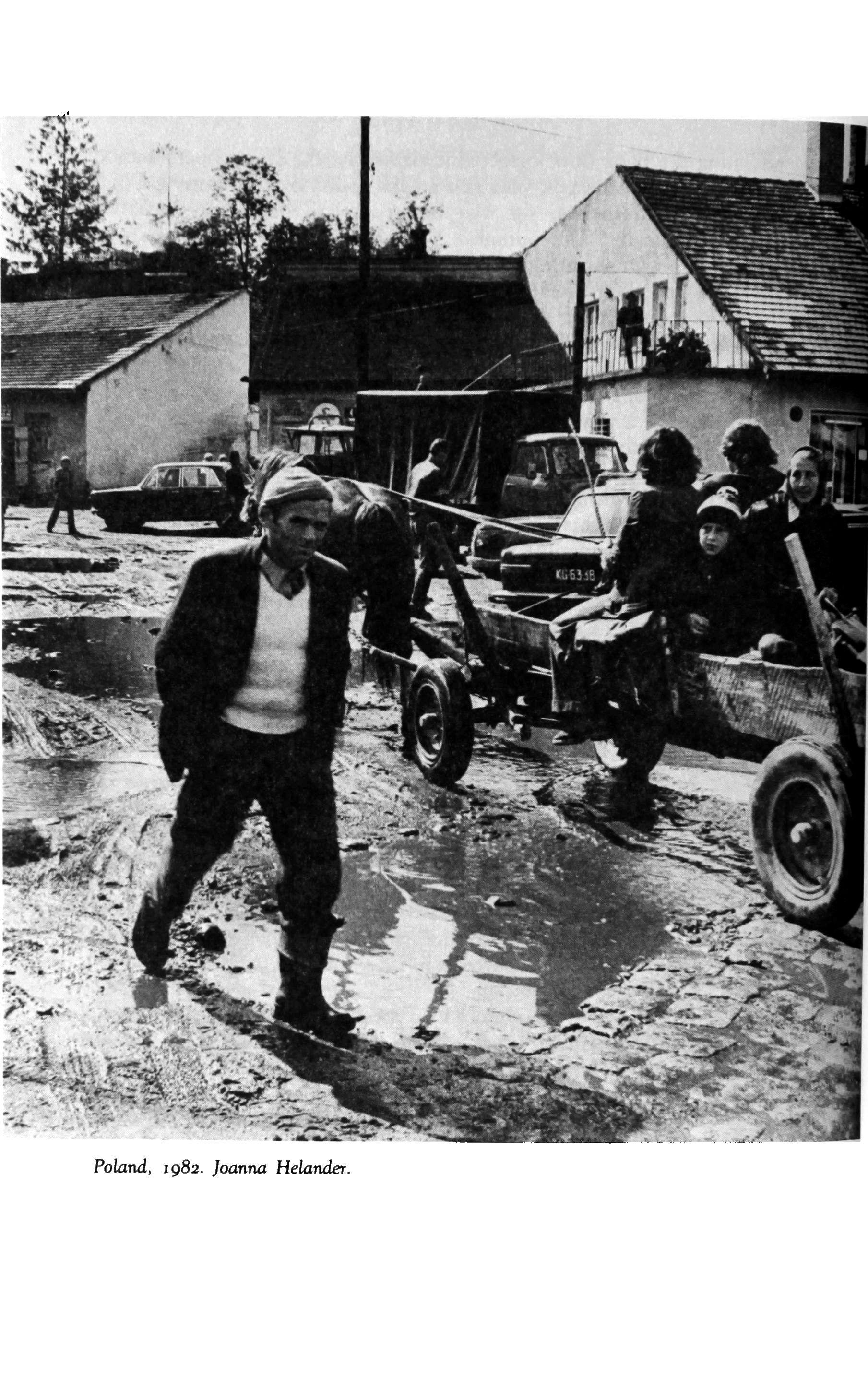

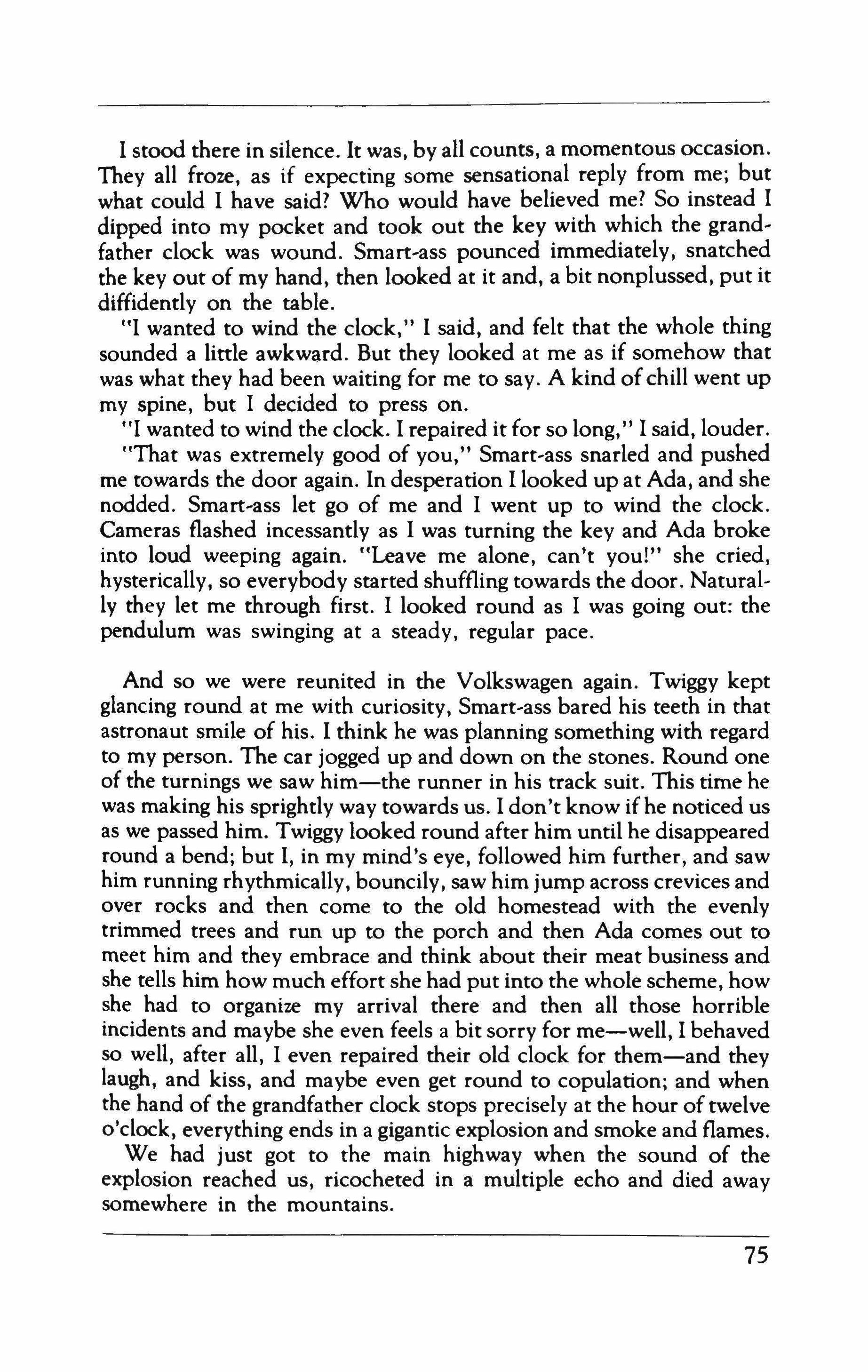

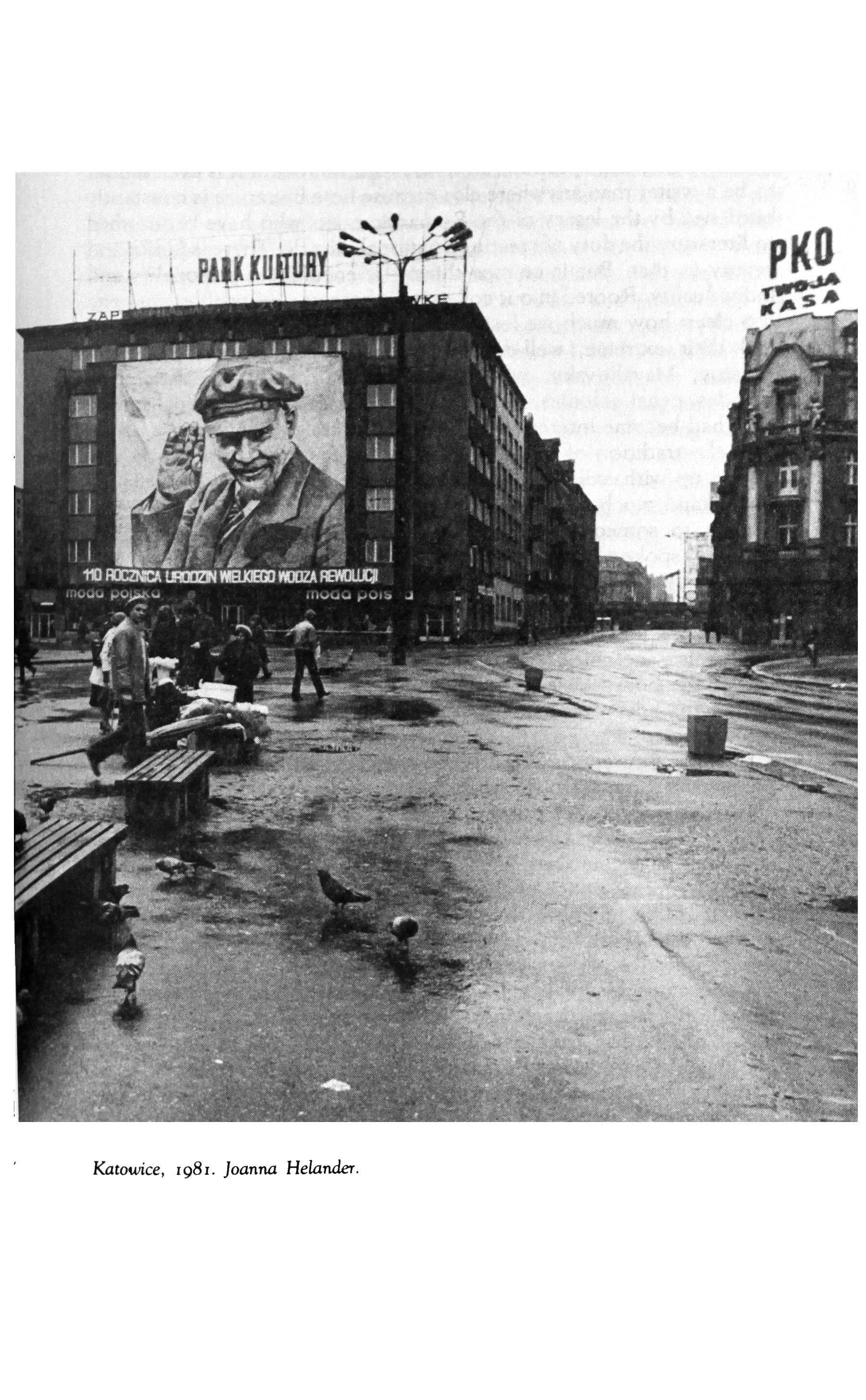

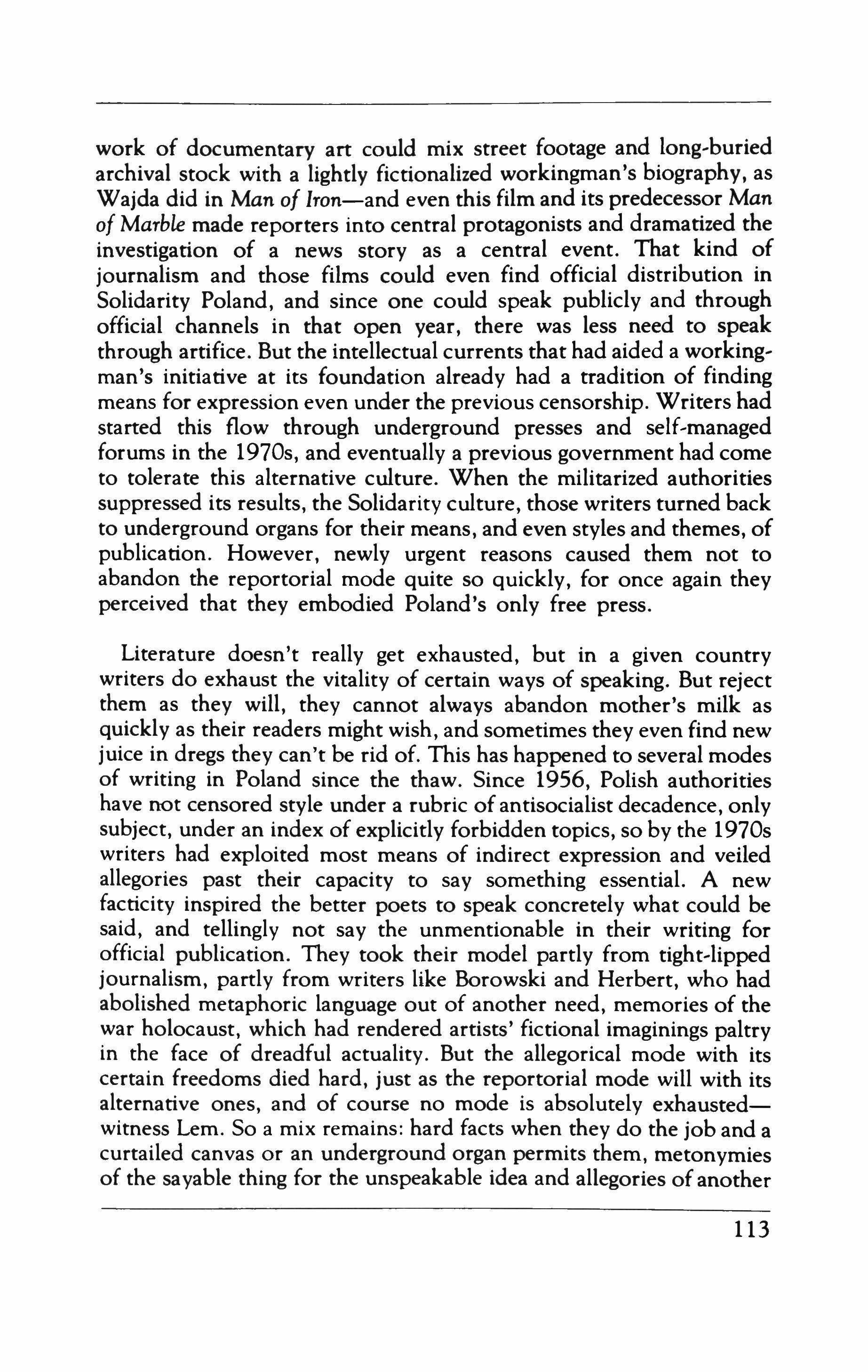

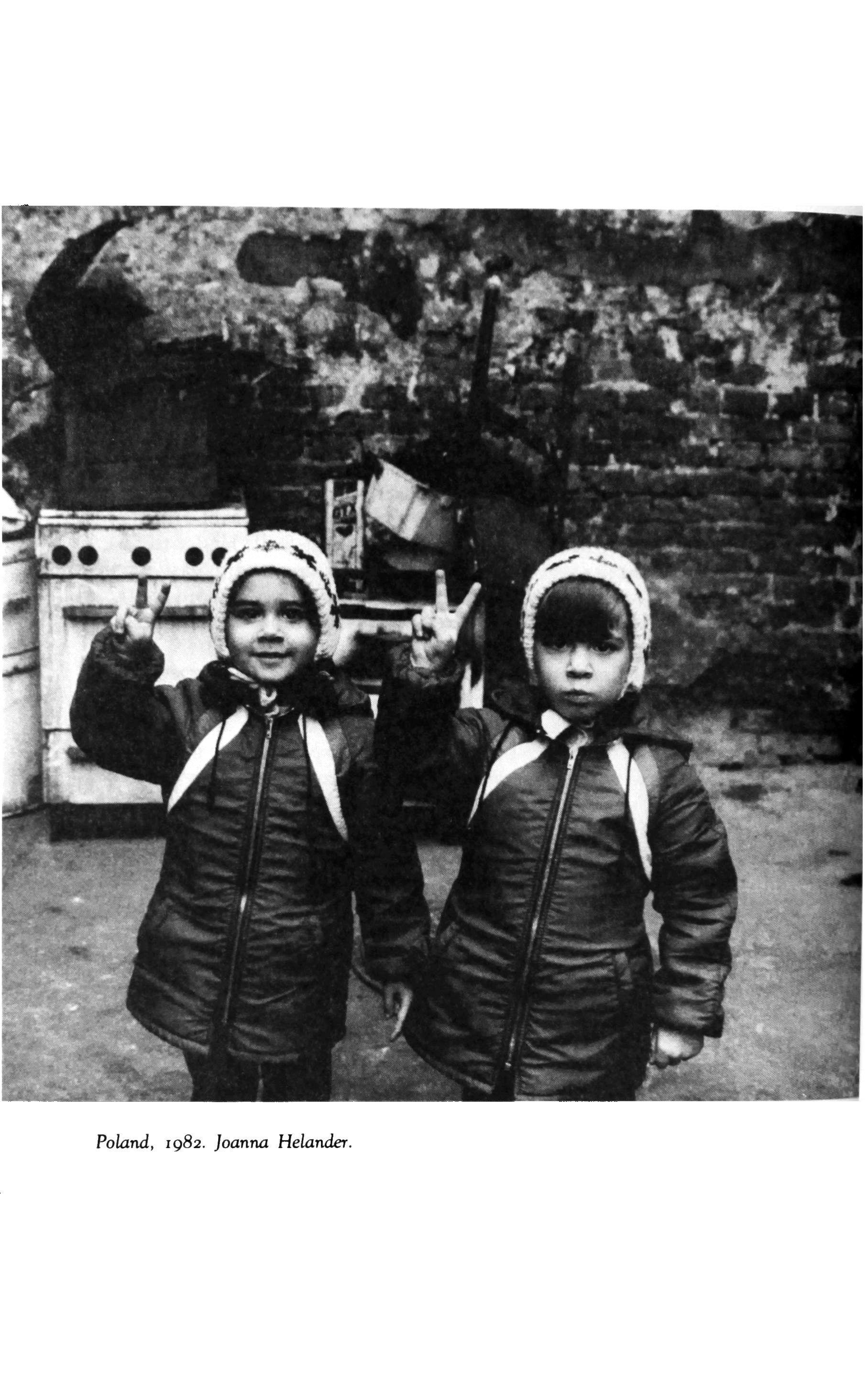

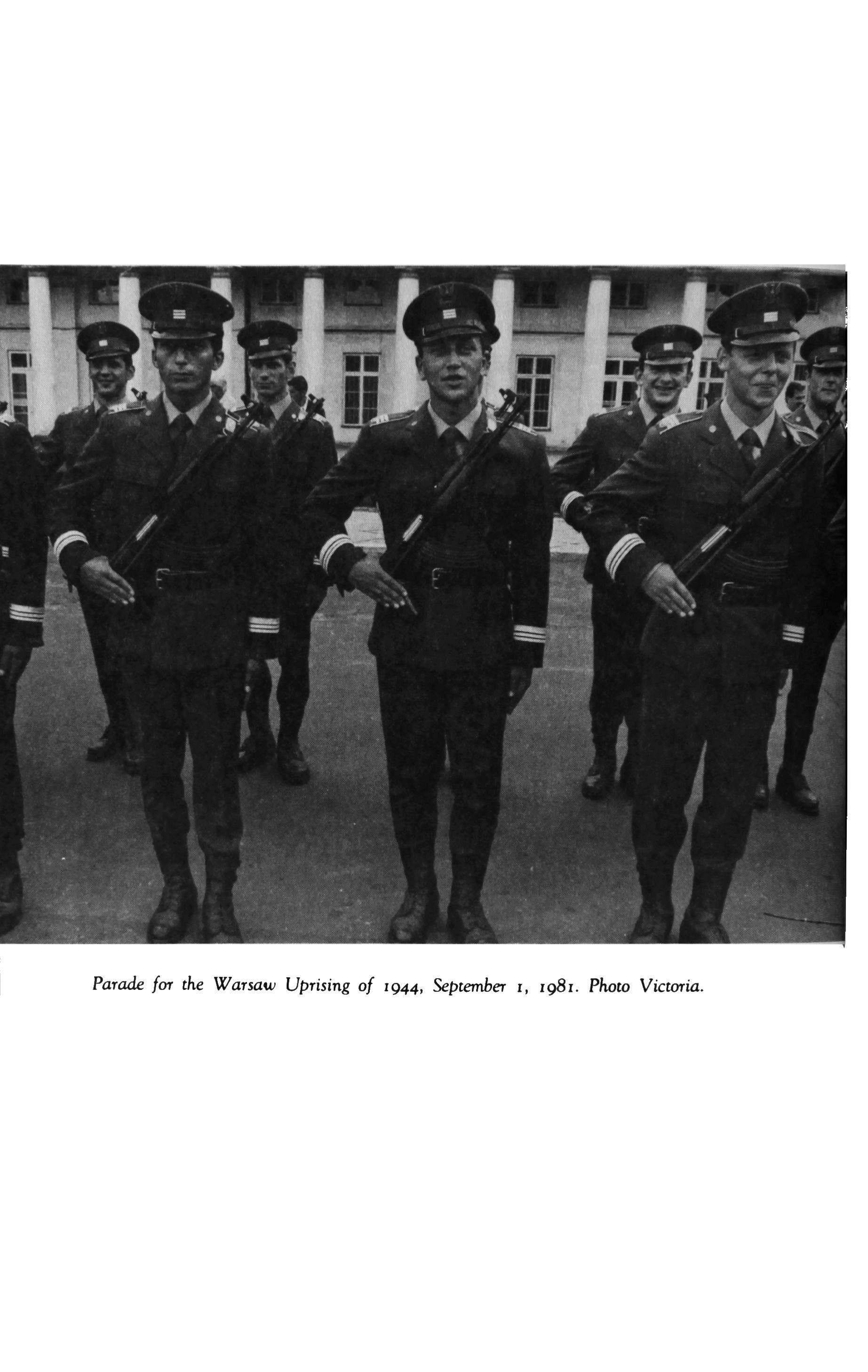

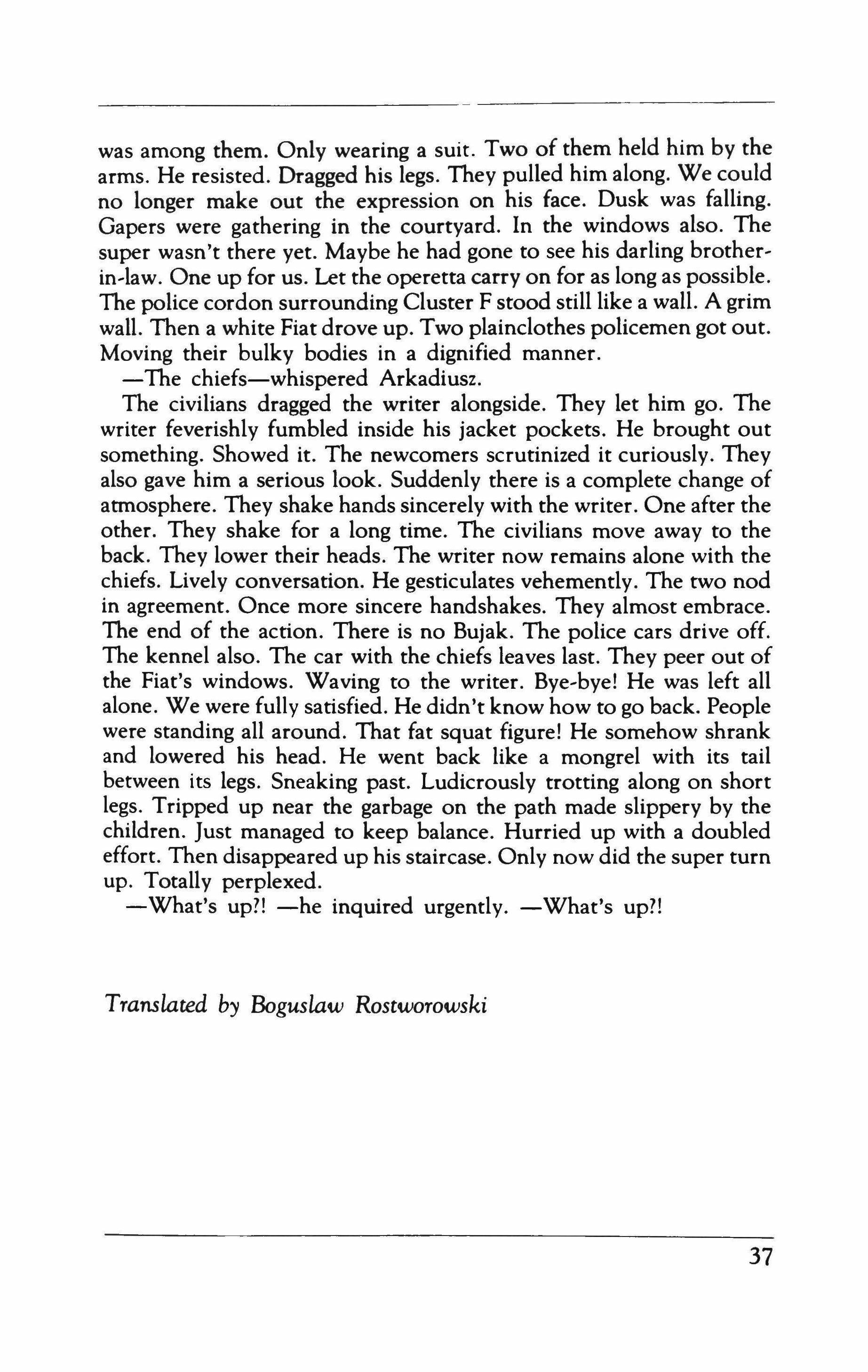

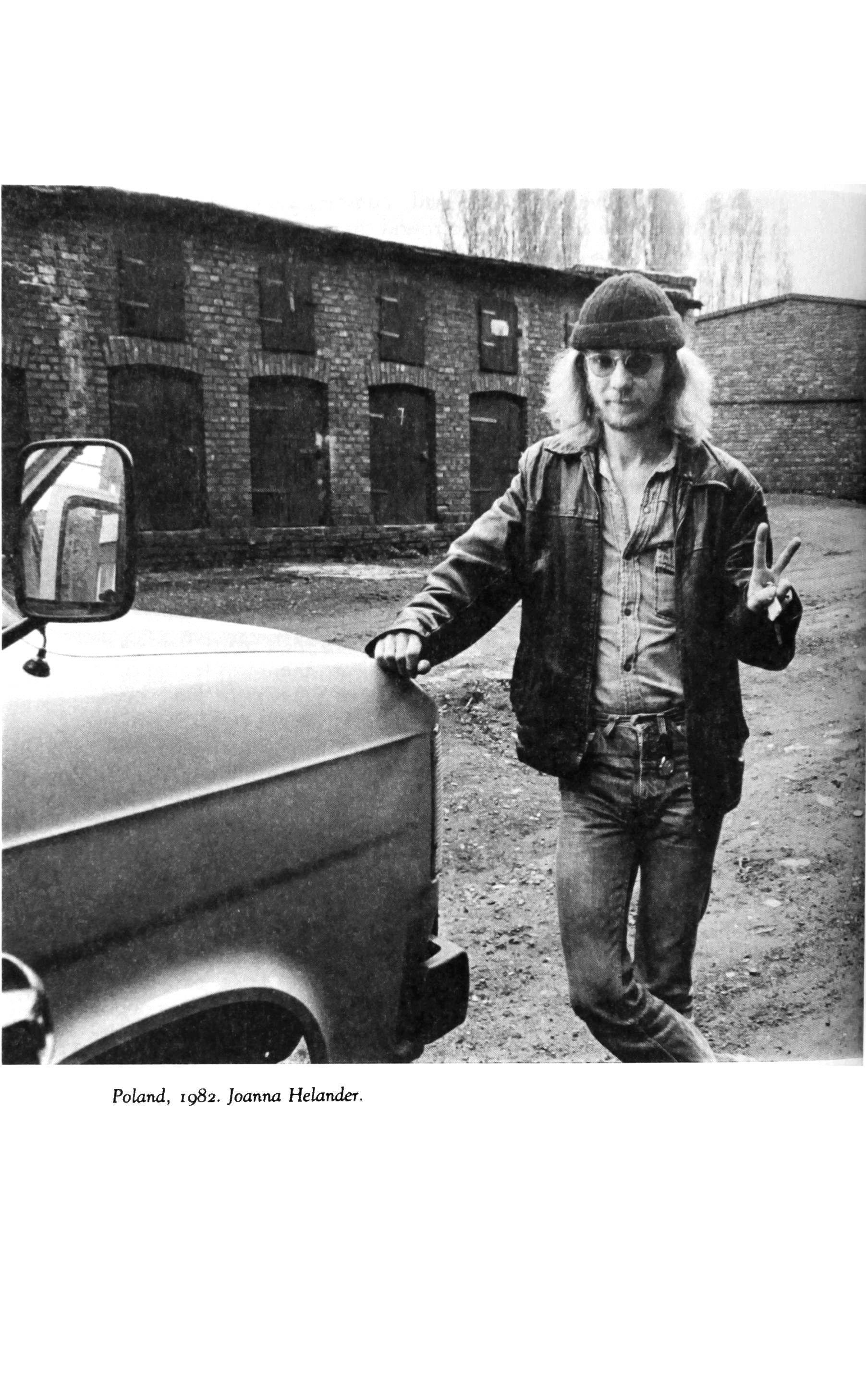

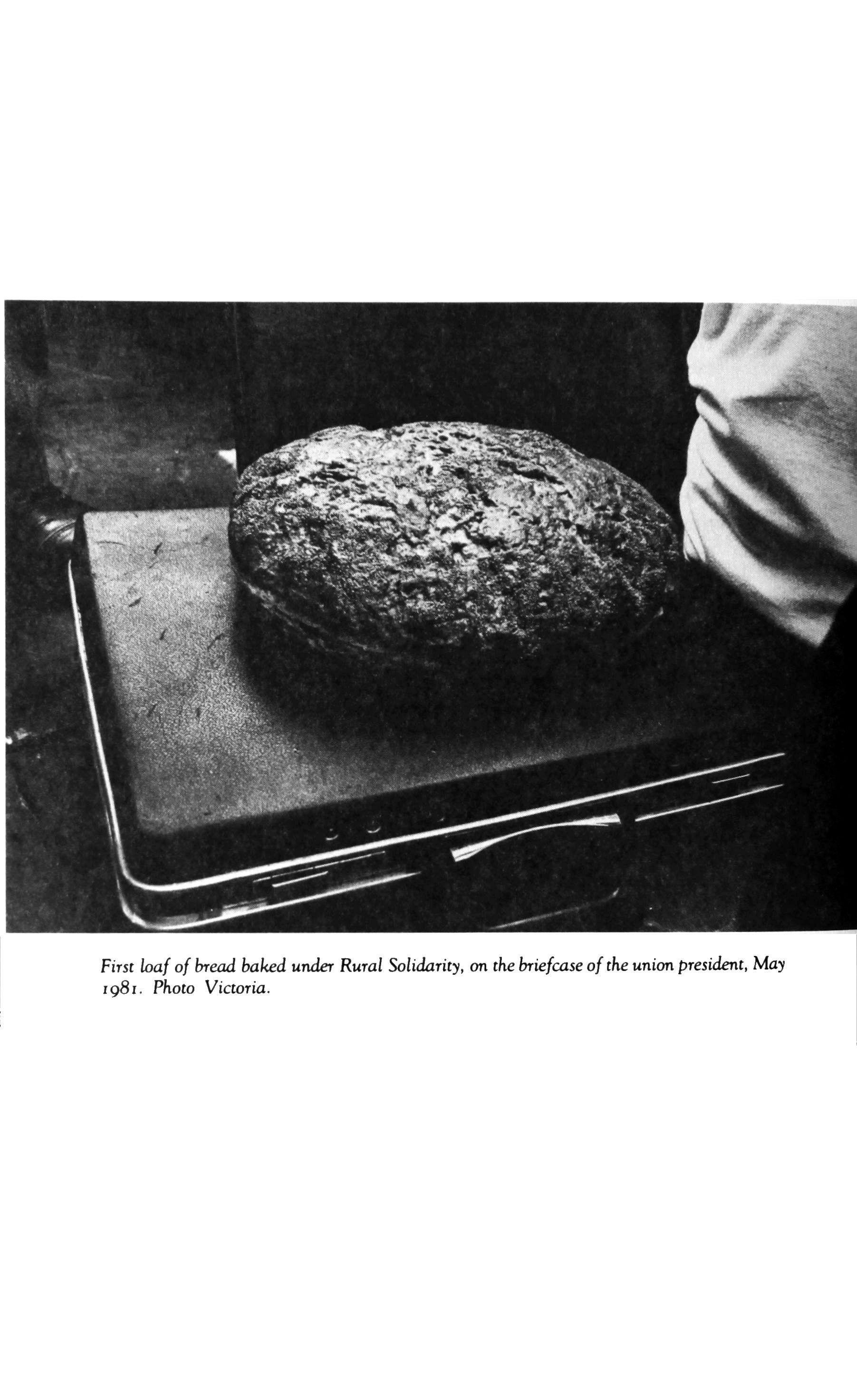

Back cover: anonymous linocut on envelope, from internment camp. Inside photographs by Joanna Helander, Photo Victoria, and Photo Lech.

Linocuts by Leszek Sobocki.

Publication ofthis volume has been made possible in part bygiftsfrom The Legion ofYoung Polish Women ofChicago, founded 1939, and The Polish Arts Club of Chicago.

81

an afterword

94

112

121

4

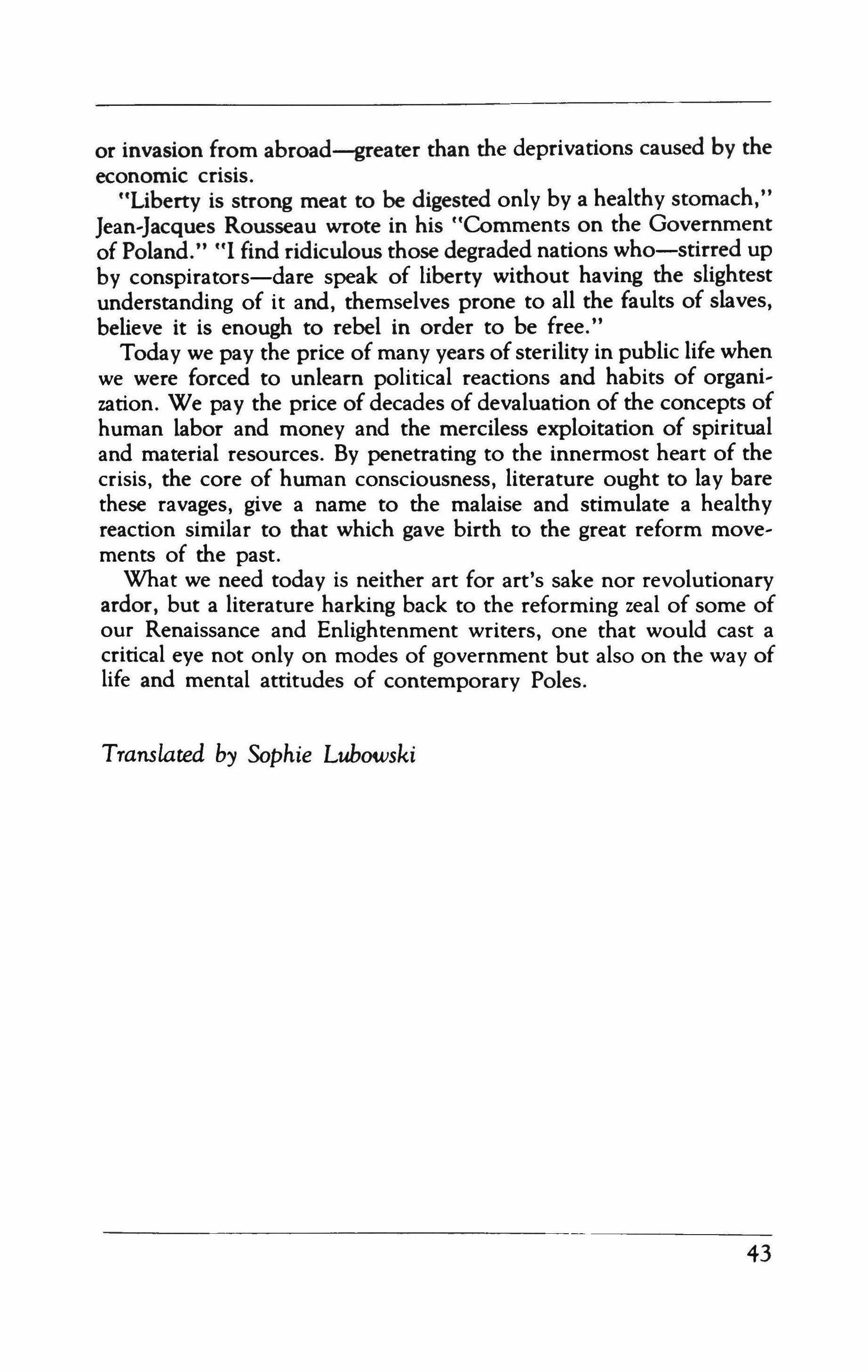

Preface

This volume of TriQuarterly was assembled over the last six months. The work of two of the photographers, and many of the writings, came directly from Poland (the writings having been translated there). Some pieces came to TQ through Richard Lourie, translator of Konwicki and Brandvs, and through Joanna Clark. Timothy Wiles, coeditor, was the principal scout, critic of translations, bagman, and encouraging spirit for the entire volume, writing voluminous guiding letters from Poland, where he was teaching for the year, and making sure that everything found its way to TQ.

Each time a package arrived, usually via Germany or some other circuitous route, I experienced a peculiar thrill at finding it in my hands. The improbable circumstances that had put Polish writers in touch with an American literary magazine were again and again a surprise to me, and the very paper on which the works had been typed-already yellow, flimsy and frail-seemed to show how precarious an enterprise it is to write at all (in Poland or elsewhere) and to hope for readers. The many photos (only a few of which are published here) increased the sense of a privileged moment.

The effect was to make everything, no matter how literary, seem documentary, and to make everything that was simply documentary seem very literary. The ways in which one reads and judges literary works are always influenced mightily by the moment, the context, both experiential and literary; but this simple truth had not been demonstrated to me so forcefully before I began to compile this issue of TQ. It was difficult to make some of the decisions to exclude works. Some pieces were too historically or culturally bound to Poland to be very intelligible to American readers without lots of footnotes; some were too fragmentary. However, I still sense those excluded works, as if they were here by implication, and I wish it were

5

possible to give to readers ofthe following pages my feeling ofbeing as much a witness as I am a reader. For an impression of the atmosphere in Poland in the last few years, when all the work in this volume was written, readers might want to turn first to the Afterword by Timothy Wiles; it comes at the end of the issue only because TQ's emphasis remains on imaginative writing, and so this issue opens with fiction. The fake postmarks and stamps on the back cover and inside the issue are small clandestine linocuts, made by prisoners in internment camps with pieces of ripped-up flooring linoleum. Printed with inks concocted from fruit and vegetable juices, on precious scraps of paper, they have been smuggled out of prisons in great numbers as artistic statements against martial law. The power of the tiny oblique work, in which everything is suggested by means of emblem and a kind of functional irony, is nearly as great in this instance as the power of more direct comment, and certainly shows an enlivening wit and bitter humor. The imagination has taken the normally unremarked evidence and symbol of the state's power to distort reality by means of its orderly and routine functioning, and turned that symbol against the state by unmasking the latent hypocrisy of an apparently innocuous and useful service-certain things cannot be mentioned on the paper inside mailed envelopes, and on the outside, in stamps and postmarks, anti-heroes and nonevents are elevated by the State to heroic and momentous status. It is a fitting twist to this situation that the material in this issue of TQ, which came from writers in Poland, did not come through official Polish mails. And the artistic choice in favor of this means of expression may signal not only the way in which esthetic decisions are enormously influenced by the context in which they are made, but also a need for artistic expression, in addition to a shout through a barred window. It also signals, to my mind, the almost inevitable tendency of many who are not artists to choose artistic expression for their deepest feelings-in this case a complex combination, no doubt, of rage, frustration, bitterness, and injustice. It seems that certain kinds of difficulty make artistic expression more necessary rather than less, and more powerful.

Reginald Gibbons February I9B3

6

From A minor apocalypse

Tadeusz Konwicki

Here comes the end of the world. It's coming, it's drawing closer, or rather, it is the end of my own world which has come creeping up on me. The end of my personal world. But before my universe collapses into rubble, disintegrates into atoms, explodes into the void, one last kilometer of my Golgotha awaits me, one last lap in this marathon, the last few rungs up or down a ladder without meaning. I woke at the gloomy hour at which autumn's hopeless days begin. I lay in bed looking at a window full of rain clouds but it was really filled with one cloud, like a carpet darkened with age. It was the hour for doing life's books, the hour of the daily accounting. Once people did their accounts at midnight before a good night's sleep, now they beat their breasts in the morning, woken by the thuds of their dying hearts.

There was blank paper close at hand, in the bureau. The nitroglycerin of the contemporary writer, the narcotic of the wounded individual. You can immerse yourself in the flat white abyss of the page, hide from yourself and your private universe, which will soon explode and vanish. You can soil that defenseless whiteness with bad blood, furious venom, stinking phlegm, but no one is going to like that, not even the author himself. You can pour the sweetness of artificial harmony, the ambrosia of false courage, the cloying syrup of flattery onto that vacant whiteness and everyone will like it, even the author himself

The first sounds of life could be heard in the building. This building, this great engine, moved slowly into daily life. And so I reached for my first cigarette. The cigarette before breakfast tastes the best. It shortens your life. For many years now I have been laboring at shortening my life. Everybody shortens their existence on the sly.

7

There must be something to all that. Some higher command or perhaps a law of nature in this overpopulated world.

I like the misty dizziness in my head after a deep drag of bitter smoke. I would like to say some suitable farewell to the world. For ever since I was a child I have been departing from this life but I can't finish the job. I loiter at railway crossings, I walk by houses where roof tiles fall, I drink until I drop, I antagonize hooligans. And so I am approaching the finish line. I am in the final turn. I would like to say farewell to you somehow or another. I long to howl in an inhuman voice so that I am heard in the most distant corner of the planet and perhaps even in neighboring constellations or perhaps even in the residence of the Lord God. Is that vanity? Or a duty? Or an instinct which commands us castaways, us cosmic castaways, to shout through the ages into starry space?

We've become intimate with the universe. Every money-hungry poet, foolish humorist, and treacherous journalist wipes his mouth on the cosmos and so why can't I too hold my head up high to where rusted Sputniks and astronaut excrement, frozen bone-hard, go gliding past.

And so I would like to say farewell somehow. I dreamed of teeth all night. I dreamed I was holding a pile of teeth like kernels of corn in my hand. There was even a filling in one, a cheap Warsaw filling from the dental cooperative. To say something complete about myself. Not as a warning, not as knowledge, not even for amusement. Simply to say something which no one else could reveal. Because before falling asleep or perhaps in the first passing cloud of sleep, I begin to understand the meaning of existence, time, and the life beyond this one. I understand that mystery for a fraction of a second, through an instant of distant memories, a brief moment of consolation or fearful foreboding and then plunge immediately into the depths of my bad dreams. In one way or another everyone strains his blood-nourished brain to the breaking point trying to understand. But I'm getting close. I mean, at times I get close. And I would give everything I possess, down to the last scrap but, after all, I don't own anything and so I would be giving a lot of nothing, to see that mystery in all its simplicity, to see it once and then to forget it forever.

I am a biped born not far from the Vistula River of old stock and that means I inherited all its bipedal experience in my genes. I have seen war, that terrible frenzy of mammals murdering each other until they drop in exhaustion. I have observed the birth of life and its end in that act we call death. I have known all the brutality of my species and all its extraordinary angelicalness. I have traveled the thorny path of individual evolution known as fate. I am one of you. I am a perfect,

8

anonymous homo sapiens. So why couldn't a caprice of chance have entrusted me with the secret if it is, in any case, destined to be revealed?

These words have a sort of day-off quality, the luxury of an idler, the twists of a pervert. But after all, all of you who from time to time put the convolutions of your own lazy brains into gear are subject to these same desires and ambitions. The same fears and self-destructive reflexes. The same rebellion and resignation.

Two drunken deliverywomen have knocked over a tall column of crates containing milk bottles. Now, standing stock-still, they are observing the results of the cataclysm, experiencing the complicated and yet at the same time simple process which transforms a mess into some light-minded fun. The transparent rain has caught its wing on our building, which is rotting with age. A Warsaw building built late in the epoch of Stalinism, when Stalinism was decadent and had become Polonized and raggedy.

I have to get up. I have to rise from my bed and perform fifteen acts whose meaning is not to be pondered. An accretion of automatic habits. The blessed cancer of tradition's meaningless routine. But the last war not only took the lives of scores of millions of people. Without intending to, accidentally, the last war shattered the great palace of culture of European morality, aesthetics, and custom. And humankind drove back to the gloomy caverns and the icy caves in their Rolls-Rovces, Mercedes, and Moskviches.

Outside, my city, beneath a cloud the color of an old, blackened carpet. A city to which I was driven by fate from my native city, which I no longer remember and dream of less all the time. Fate only drove me a few hundred kilometers but it separated me from myoid unfulfilled life by an entire eternity of reincarnation. This city is the capital of a people who are evaporating into nothingness. Something needs to be said about that too. But to whom? To those who are no longer with us, who are sailing off into oblivion? Or perhaps to those who devour individuals and whole nations?

The city was beginning to hum like a drive belt. It was stirring from the lethargy of sleep. Moving towards its fate, which I know and which I wish to avoid

I am free. I am one of the few free people in this country of patent slavery. A slavery covered by a sloppy coat of contemporary varnish. I have fought a long and bloodless battle for this pitiable personal freedom. I fought for my freedom against the temptations, ambitions, and appetites which drive everyone blindly on to the slaughterhouse. To

9

the so-called modern slaughterhouse for human dignity, honor, and of something else, too, which we forgot about a long time ago.

I am free and alone. Being alone is a small enough price to pay for this none-too-great luxury of mine. I freed myself on the last lap when the finish line could already be seen by the naked eye. I am a free, anonymous man. My flights and falls occurred while I was wearing a magical cap of invisibility, my successes and sins sailed on in invisible corvettes, and my films and books flew off into the abyss in invisible strongboxes. I am free, anonymous.

And so I'll light up another cigarette. On an empty stomach. Here comes the end of my world. That I know for certain. The untimely end of my world. What will be its harbingers? A sudden, piercing pain in the chest beneath the sternum? The squeal of tires as a car slams on its brakes? An enemy, or perhaps a friend?

Outside, those women were still discussing the catastrophe with the milk. They sat down on the old, dark gray, plastic cases, lit up cigarettes and were watching the watery milk trickle down the catch basin, which was belching steam because, no doubt, hot water from the heat and power plant had again gotten into the water main by mistake. And then I suddenly became aware that no one had delivered milk for years, that I had forgotten the sight of those women workers of indeterminate age pushing carts of milk bottles long ago and in my mind that image was associated with those distant green years when I was young and the world was too.

They're probably making a period film, I told myself, and pressed my forehead against the damp windowpane. But all I saw was an everyday normal street. Small crowds of people hurrying by the buildings on the way to work. As usual when the temperature rises in the morning, a crumbling block of stone facing tore loose from the Palace of Culture and flew crashing down into the jagged gulley of buildings. It was only then that I noticed the eagle on the wall of that great edifice, an eagle on a field of black-that is, on a field of red blackened by rain. Our white eagle is not doing too badly because it is supported from below by a huge globe of the world, which is tightly entwined by a hammer and sickle. The gutter spoke with the bass of an ocarina. Then the wind, perhaps still the summer wind or maybe now a winter wind, came tearing from the Parade Field and turned the poplars' silver sides to the sun, which was confined in wet clouds.

I was out of cigarettes. And when you run out of cigarettes you are suddenly seized by a desire to smoke. And so I opened the next drawer of my treasure chest where I keep outrageous letters and old accounts, broken lighters and tax receipts, photographs from my youth and sleeping powders. And there, among tufts of cotton batting and rolls

10

of bandages from the good old days when it was still worth my while to submit to operations, in those age-encrusted recesses I found a yellowed page from many years ago, a page like a cartouche on a monument or a gravestone, a page where I once began a piece of prose I have not finished yet. I began this work in that wonderful time around New Year's, right after New Year's Eve, with a nice hangover still throbbing healthy in my head. I began on New Year's Day because I had indulged in superstition and wanted to celebrate the new biological and astronomical cycle with some work. Later I realized that my own New Year's begins at the end of summer or the beginning of fall and so that is why I stopped writing and have not written a word since.

And so there was that page, once white, now yellow, for long months, seasons, years, never finished, never completed, with its faded motto which was to bless the wistful scenes, the exalted thoughts, the lovely descriptions of nature. I blew the dust from Warsaw's factories off that waxen corpse of my imagination and read the words, which were the credo of an old Polish magnate in the nineteenth century: "If Russia's interests permit, I would gladly turn my feelings to my original fatherland." What was it I had in mind then? Did I want to read that avowal every morning to my children before breakfast? Or did I intend to copy it out at Christmas to be sent to the magnates of science, literature, and film, my contemporaries? Or was I trying to win the favor of the censor for a piece that had come stillborn from an anemic inspiration?

The windows rattled painfully. Hysterical police sirens leapt from some side street. I glanced at the watch my friend Stanislaw D. had once brought me back from a trip to the Soviet Union. It was going on eight. I knew what that meant. Each day at that hour, an armored refrigerator truck carrying food supplies for the ministers and the Party Secretaries raced through the city escorted by police vans. The cavalcade of vehicles flashed past my building splashing the puddles of milk on the street. The archaic milk deliverers, let out of some old-age home for the day, ground out their butts on the muddy sidewalk, exchanging furtive goodbyes.

Suddenly the gong by my door rang. I froze by the window, not believing my ears, certain that device had not been working for years. But the elegant, xylophone-like sound was repeated, and more insistently this time. Pulling on an old robe, a present from my brother-in-law, Jan L., I moved guardedly toward the door. I opened the door. Hubert and Rvsio, both wearing their Sunday best, suits which reminded me of the carefree middle seventies, were standing at the top of the stairs.

11

Hubert was holding a cane in his right hand and in his left a sinister, looking black briefcase. My heart began beating rapidly, and not without cause, for they came to see me only about twice a year and each of their visits marked a radical change in my life.

"May we come in? It isn't too early?" asked Hubert jovially. I was well acquainted with those artificial smiles of theirs which concealed attacks on my comfort.

Now smiling freely myself, I opened the door hospitably and, as they entered with much ceremony on their part, I instantly divined the purpose of this visit. Thanks to them, I had signed dozens of petitions, memorials, and protests sent over the years to our always tactiturn regime. A few times it cost me some work, and many times I was secretly dispossessed of my civil rights; practically every day I was subjected to some petty, invisible harassments which are even shame, ful to recall but which, adding up over the years, helped estrange me greatly from life. So, we exchanged cordial hugs, smiling all the time like old cronies, but I was already quite tense and my throat had gone dry.

Finally we found ourselves in my living room and we sat down in the wooden armchairs, all in a row as if we were on an airplane flying off to some mysterious and exciting adventure.

"You look good," said Hubert, setting the sinister-looking briefcase down beside him.

"You seem to be holding up too," I said in a friendly tone.

For a moment we looked at each other in embarrassment. Hubert was resting his sinewy hand on his cane. His one blind eye was motionless, the other kept blinking and regarding me with something between affection and irony. Once long ago he had been tortured, perhaps by the anti-Communist underground or perhaps by investigating officers of the Security police and, because of that incident, now long forgotten by everyone, he walked with a cane and was in poor health. Rvsio, whom I remembered as a blond angel, was now balding and had put on weight, the high priest of the plotless allegorical novel without punctuation or dialogue.

We looked good, for old fogeys, that was true. But then the moment of silence lengthened out a bit and something had to be said.

"Would you like a drink?"

"A drink couldn't hurt," said Hubert. "What do you have?"

"Pure vodka. Made from potatoes. Imported potatoes."

"All the more reason not to refuse." Hubert's voice was thunderous, as if he were in some space larger than my cluttered room. While I was getting the bottle and the glasses from the cupboard, they were both looking discreetly about the room. The liquid made

12

from imported potatoes began to gurgle as I cowered at the edge of my chair. A cigarette on an empty stomach is bad for you but a hundred grams of potato vodka is death itself. Or maybe it's better. I raised my glass.

"Good luck."

"Your health." Rysio finally said something, and quickly tossed off the contents of his glass.

Outside, the wind had died down for the moment and the poplars had turned their solid green toward us. My building was, as bad luck would have it, exceptionally quiet and our silence was becoming increasingly louder. But I made a firm decision not to speak and to force them to show their cards.

Hubert set his glass aside with a certain deliberation.

"You're not going out much," he said.

"That's right. Autumn puts me out of sorts."

"A little depression?"

"Something like that."

"Are you writing?"

"I had just started."

He seemed to be looking at me in disbelief. Rysio poured himself another glass.

"What's it going to be?"

"No revelations. I just felt like writing a little nonsense about myself."

"You always wrote about yourself."

"You could be right. But I wanted to write about other people."

"It's high time you did."

"To drown myself out."

The whole thing looked like an examination. And I felt like a high school senior taking his finals. But, after all, I had felt that way my whole life, a student at best.

"Well, Rysio," said Hubert all of a sudden. "Time to get down to business.

Rvsio nodded.

"Something to sign?" I hazarded a guess, squinting accomodatingly over at the black briefcase.

"No, this time it's something else. Perhaps you might begin, Rvsio."

"Go on, go on, since you started," said Rysio eagerly.

A sort of goofy warmth was rising in me. I reached for the bottle automatically, wanting to pour Hubert a glass while I was at it.

"Thanks, that's enough." He stopped me with a somewhat official tone. I took that as a bad sign.

Really I was indifferent. I am a free person who has been suspended

13

high above this city and who from a distance and with serene amazement observes the strange humans and their strange doings. Without thinking, I turned on the television on the table. I heard the sound of wind howling, the flutter of cloth, but after a moment, the image of a festively decorated airport emerged out of the silvery dots. An honor guard was frozen across the screen, some civilians were shielding themselves against the wind with their overcoats while, above the honor guard and the civilians, red, sail-like flags swelled in the wind, and shyly interspersed among them were red and white Polish flags.

"Well now," said Hubert, deciding to break the silence. "We haven't spoken with you for some time now."

I took a deep breath, which made me feel ashamed, and I sank deeper into my chair.

"Yes, we lost contact with each other," I said in a worldly tone. "We're a vanishing breed."

"Everyone's out for himself," added Rysio.

"But I've been observing your activities."

"What activities," said Hubert with a dismissive wave of one hand. "We're keepers of a dying flame."

"That's a fact. I have the impression that this country is really dying," I said, without knowing what they were driving at.

"So many years of struggle. We've grown old, we've gone to pot putting out those semilegal bulletins, periodicals, appeals which are read by next to no one. Of course the young people read them. But young people get married, have babies, buy little Fiats, give up on action and start growing tomatoes. We've been overrun by the bourgeoisie, a Soviet bourgeoisie.

"It's the end, the grave," added Rvsio, pouring himselfanother glass.

Water was dripping onto the floor through the leaky balcony doors. I should have looked for a washcloth to prevent any damage but I didn't much feel like it and I would have been a little embarrassed to do it in front of my colleagues. Our conversation was not going well. It was hard to chat about the things we thought about all day long and which we even dreamed about in our lousy sleep. Things had looked better at one time. We were children of the nineteenth century. Our fathers had been members of Pilsudski's Legions or his secret army, and during World War II we had been in the Home Army or the Union of Fighting Youth. That means, how to say it now, that means, how to explain it after all those years, that means, the hell with it, that doesn't mean anything, now, at the end of our splendid twentieth century, a century of tyranny and unbridled democracy, foolish holiness and brilliant villainy, art without punch and graphomania run rampant.

14

Y&I! �

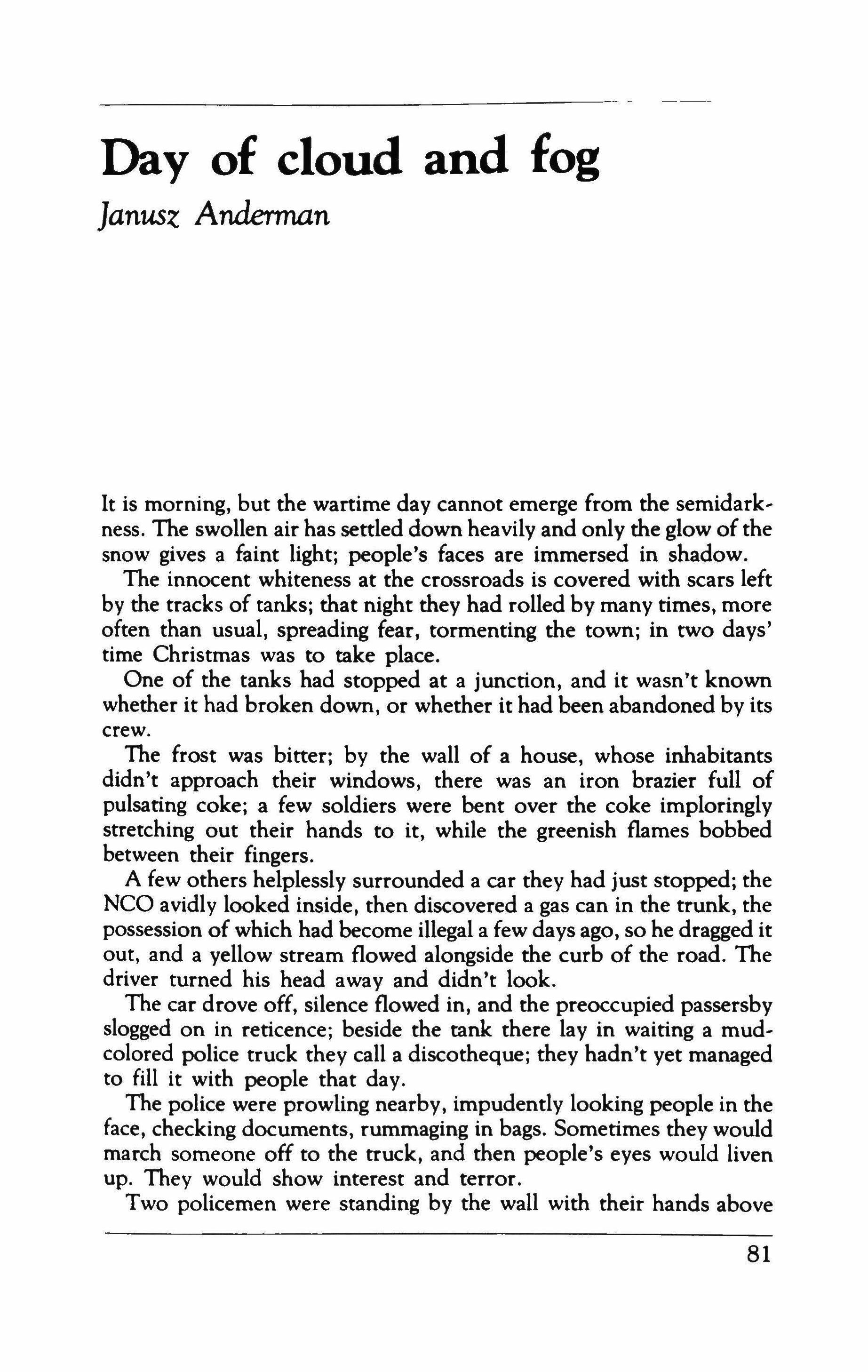

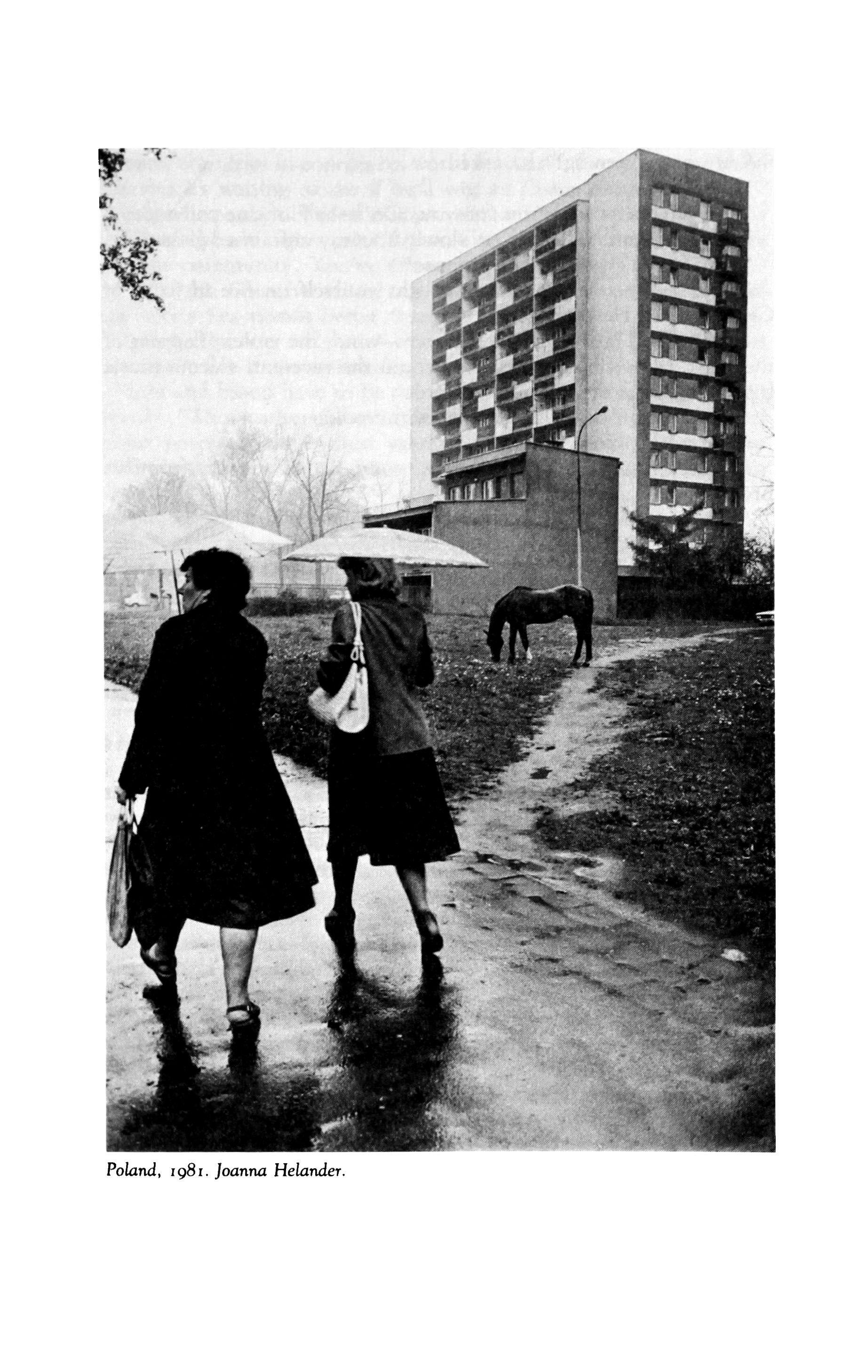

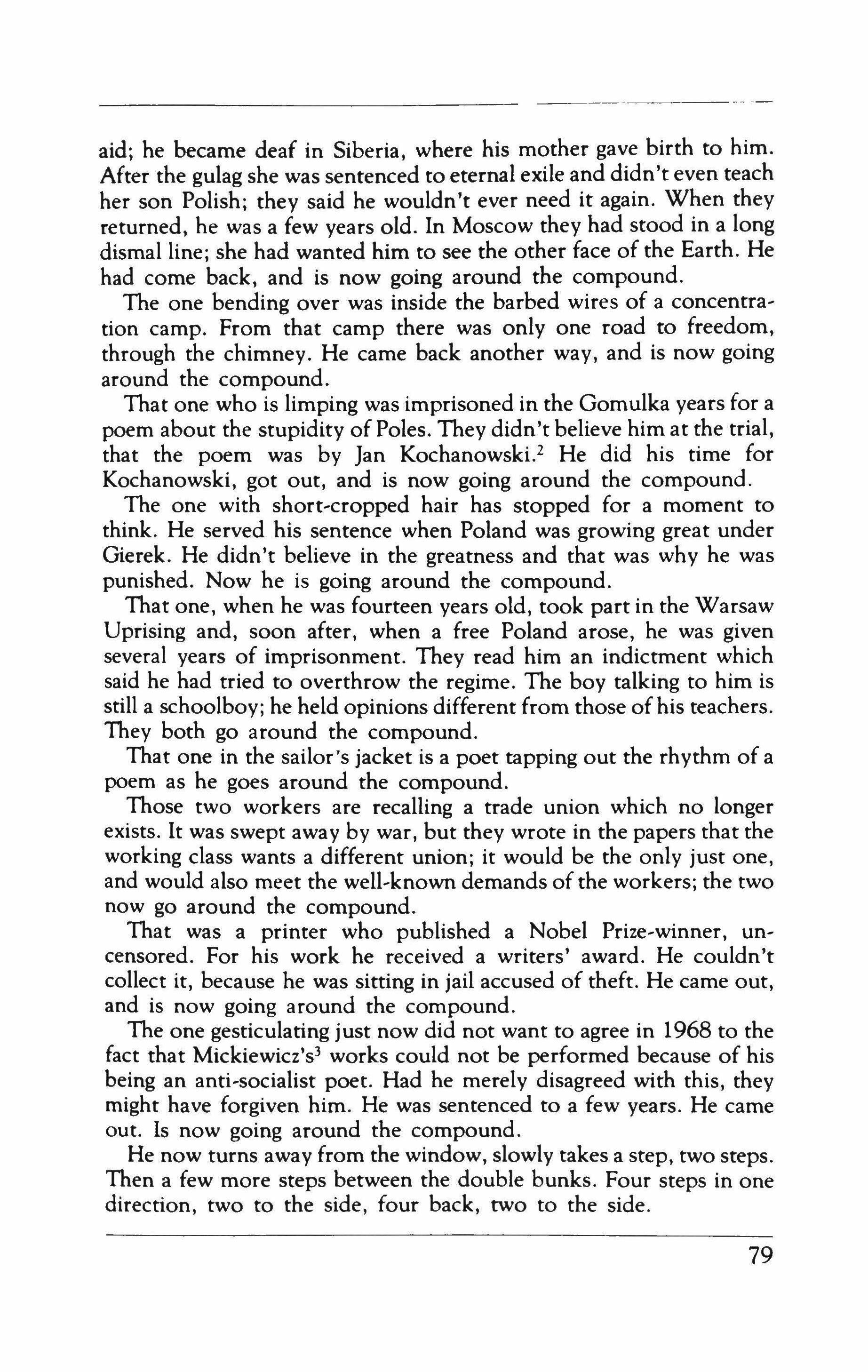

Poland, 1981. Joanna Helander.

1 saw Hubert's good eye fixed on me.

"Are you listening?" he asked.

"Yes, of course."

"We have a proposition for you. On behalf of our colleagues."

My spine went cold and very slowly 1 put my unfinished glass aside.

"What is it you wish to propose?"

"That today at eight p.m. you light yourself on fire in front of Central Party Headquarters."

Nothing had changed on the screen-wind, the violent flapping of the flags, the waiting. Only then could the reverent, solemn music broadcast from the studio be heard.

My throat gulped saliva mixed with vodka.

"Are you joking, Hubert?"

"No, I'm not joking." He wiped some invisible sweat from his brow.

"But why me? Why are you coming to me with this?"

"Who else? Somebody has to do it."

"I understand, I understand everything, I just don't understand why me."

Hubert glanced over at Rysio. "I told you this would happen."

Rysio looked down at the floor.

"Listen," he finally said in some anguish, "we've been discussing this for a long time. We've analyzed all the possible candidates. And it came out you."

My tree of happiness stood by on the windowsill. Only then did I notice how much it had shot up lately and grown thick with young, strong leaves. It was sickly for many years and now, suddenly, without any external cause, it had surged upward, sending out a large number of powerful, knotty branches.

"You see," said Hubert softly, "an act like this can only make sense if it shakes people here in Poland and everywhere abroad. You are known to the Polish readers and you have a bit of a name over there in the West too. Your life story, your personality, are perfect for this situation. Obviously, we can't talk you into it and we won't even tryit's up to you and your conscience. I only wish to pass on an opinion which is not only mine or Rysio's, but that of the entire community which is attempting to put up some resistance. You'll pardon me for my lack of eloquence."

"I doubt whether my death would play the part you expect. I know people whose sacrifice would become a symbol the world over."

They looked at me with curiosity. Hubert rubbed his fingers, which were turning insistently bluish.

"No doubt you're thinking of Jan?" he asked.

16

"Naturally. The whole world knows his films and his books are read in many countries in courses on world literature. Every year we're on tenterhooks waiting to see if he'll win an Oscar or the Nobel."

A barely perceptible smile appeared on Hubert's face.

"That'd be too high a price to pay. Too high a price for the country and our community. You've answered your own question."

"All right. But what about our filmmakers, our composers? I can give you a few names better than mine right off."

"You're the one, old man," said Rysio and reached for the bottle. He clearly felt I was weakening, which gave him heart.

"Life and blood have to be disposed of intelligently," said Hubert wearily. "Those others have a different role to play. Every nugget of genius possesses the highest value in this massacred nation. Their deaths would not enrich us very much and would impoverish us terribly."

"But why not you, or Rysio?"

They glanced at each other with distaste. My blubbering embarrassed them.

"Then why would we have come to you?" asked Hubert. "Let's be frank. Your death will be spectacular, another order up. Don't you see that?"

"You're the one, old man," added Rysio, who was softhearted and was now suffering along with me.

"Listen to me, Hubert. I never interfered in the functioning of our artistic life. I never butted into your affairs, the affairs of a careworn opposition in a country no one cares about. But now I must tell you what I think. You have bred blind, deaf demiurges, who in their marvelous artistic passions create beautiful, universal art but do not notice us crawling in the mud or the daily agonies of our society. They worked hard at guarding the flame of genius that burned in them and gladly exploited the claque of the regime's mass propaganda which boasted of them every day and fed its own complexes with their world renown. You, the emaciated opposition, did not spare them the claques either, anointing them with the charisma of moral approval. They grew fat on our exile, our humiliations, our anonymity. They hopped freely from one sacred grove of national art to another, for we had been driven out of them or had left of our own free will. When you went around pleading with them to sign even the most modest of humanitarian appeals which would displease our team of wanton rulers, they arrogantly sent you packing empty-handed, winking at their coteries to say that you were provocateurs, secret police agents. Their greatness came from our being voluntarily dwarfed. Their genius sprang from our graves as artists. Why shouldn't one of them pay for

17

their decades of solemn, superhuman greatness with a cruel, physical death?"

I turned off the television, where the civilians and soldiers were impatiently waiting for someone. A sudden downpour flew past the balcony, knocking a condom withering on the iron balustrade off into the abyss. Those condoms-bouquets of lillies of the valley, presents to me from my neighbors on the upper floors from their days off.

"We're all racked by envy to one degree or another," said Hubert, somewhat taken aback. He was pale and strenuously rubbing his fingers, which were turning blue. "But let's not talk about that today. Maybe some other time."

"But when are we going to talk if I carry out your command?"

"But, old man, you know," said Rysio, setting his glass aside, "these arguments are indecent."

"I never said anything even though my guts were turning. Hubert, do I need to tell you the names of the people who spent their whole lives walking hand in hand with the government while pretending to go their own way? And their works, which the more clever ones clothed in the garb of universal fashion, world frustration, western melancholy and what is a sort of the neuralgia of the left. And when we became Sovietized to such a degree that a cult of the illicit erupted here, an ambiguous desire for a lick of the forbidden, a pitiful delight in political pornography dressed in the lingerie of allusion, when there arose in Poland that aberration, that scheming contest of selfjustification for all the sins of collaboration, they were the first, greedy for applause, anxious for success, they fastened onto the new state of affairs and littered art with the phony gestures of cunning Rejtans, they muddied our poor art, they stomped out the last of their own conscience in it. Why do you fall down before them when they climb on your crosses looking for the golden apples which feed their pride? Why do you pour admiration on them when their fate is opposed to yours?"

"You chose your own fate. This is not the time for that sort of discussion. Rvsio, isn't it time for us to be going?" Hubert bent forward heavily and drew the black briefcase out from under the table, the briefcase which could contain an appeal for the abolition of the death penalty, a volume of uncensored poetry, or an ordinary homemade bomb.

"Wait a minute, Hubert." I stopped his hand. "Tell me here, in private, man to man, why have you designated me?"

He tore his hand from mine.

"I don't designate. I have the same rights as you do. And the same duties.

18

"But there must be something about me that makes me suitable and others less so."

The rain had hazed the windows over. Nearby a child was playing a melody with one finger, a melody which I remembered from years back, many years back.

"After all, you've always been obsessed with death," whispered Hubert hoarsely. "I never treated your complex as a literary manner' ism. You are the most intimate with death, you shouldn't be afraid of it. You have prepared yourself and us for your death most carefully. What were you thinking about before we arrived?"

"Death."

"You see. It's at your side. All you have to do is reach out."

"Just reach out."

"Yes, that's all."

"Today?"

"Today at eight o'clock in the evening when the party congress is over and the delegates from the entire country are leaving the building.

"What about the others?"

"Who?"

"The people necessary to the nation."

"In sin and holiness, in conformism and rebellion, in betrayal and redemption, they will bear the soul of the nation into eternity."

"You're lying. You're choking on that garbage, your eyes are popping out of their sockets."

Rvsio leapt from his chair, knocking over his glass.

"Leave him alone!" he shouted and began rummaging in Hubert's shirt. Hubert had gone stiff and extended his legs as if he wanted to look at his muddy boots. Rysio began pushing pea-like pills through his lips, which had turned blue. He forced a few drops of water between his clenched teeth. Hubert moved his jaw, closed his eyes then bit one pill in half and tried to swallow it.

Someone rang the bell. I opened the latch with trembling hands. A man, a bit on the drunk side, stood in the doorway, holding onto the doorframe.

"You should run yourself some water because we're going to turn it off," he said, belching a cloud of undigested alcohol.

"I don't need any water."

"I suggest you run your tub and your other faucets. We'll be cutting it off for the whole day."

"Thank you. So did a main burst then?"

"Everything burst. May I sit down here for a minute? I'm dead on my feet."

19

"I'm sorry but my friend isn't feeling well. I have to go fetch an ambulance.

"No one's feeling good these days. I won't bother you then. Stay well."

"The same to you."

He went off to knock on my neighbors' doors. I returned at a run down the hall. Now Hubert was sitting up straight in his chair. He smiled painfully to hide his sudden panic.

"Should I call a doctor?"

"No need to. I'm all right now. Where were we?"

A swath of sunlight moved across the rooftops of the city like a great kite. My friend the sparrow hopped onto one bar of the balustrade and was surprised that I did not greet him.

"Hubert, is there any sense to all this? Do you really believe there is?"

"Now you're asking?"

"Why have you been so unrelenting all your life? In all ways. Is it hormones or some higher force commanding you?"

"Leave him alone, he has to go horne." Rysio pushed me away.

"Isn't it a short way to the party building?"

"Not all deaths are the same, you see," said Hubert in a muffled voice. "We all need the elevated, the majestic, the holy. That is what you can offer us."

"For your sins, old man," added Rysio and attempted a smile. "You have plenty of yours, and ours, on your conscience."

"But they have just as many," I said in despair, affected by the hysteria of that foul autumn day.

"They're not here. You're all alone with God or, if you prefer, with your conscience."

"And where are they?"

"Far away on a small, unhappy planet."

"Hubert, what a stupid joke. Someone put you up to it."

"No, it's not a joke. You know that perfectly well yourself. You've been waiting for us for years. Be honest for once and admit you were waiting."

He looked at me for a long moment with his one good eye and then began searching for his briefcase, which he had kicked under the table during his attack.

"Hubert, answer me-do you believe this is necessary?"

He walked heavily over to me, put his arms around me, and kissed both my cheeks with his cold lips.

"Be at number sixty-three Vistula Street at eleven. Halina and Nadezhda will be waiting for you there. They're in engineering."

20

"The engineering of self-imrnolationl"

"Don't make things more difficult, old man," interjected Rvsio.

A sudden fury seized me. "And what are you supposed to be, just one of the guys? You better start using commas and periods, goddammit. "

At a loss, Rysio began retreating toward the .door.

"The lack of periods bothers you?" he said uncertainly.

"If you used punctuation, then maybe we wouldn't need to show deaths in this country."

A lazy peal of thunder rolled from one end of the city to the other. The wind drove the balcony doors groaning open. I would have closed them but the handle had come off.

"Lend us five thousand for a taxi. It's too much for him to walk home in this weather." Rvsio took Hubert's enchanted briefcase from him and then glanced out into the dark corridor.

I dug a five-thousand-zloty note out of my pocket. They took it without thanking me and started for the front hall. And then we were greeted by a sort of a droning, the high-pitched sound of telephone wires presaging bad weather. They had been making that glassy moan for years now, since the days when the world had still been a calm and normal place.

Hubert stopped before a heap of old slippers which had somehow or other accumulated over the course of a lifetime.

"When did you stop writing? I can't remember anymore," he said, looking askance and unseeing at the junk strewn about the floor.

"But I'm still writing."

"You've started writing again now. You're writing your testament. But I was asking about your fiction."

"I don't recall. Maybe five, maybe seven years ago. That's when I rid myself of two censors in one fell swoop, my own and the state's. I wrote a story for some little underground journal and that was my last piece. After that I was free and impotent."

"You were born to be a slave. Slavery emancipated you, it lent you wings, it made you a provincial classic. And then to punish you, it took everything away like some evil witch."

"Slavery has always perished at the hands of slaves," said Rvsio. "You see what I mean, old man?"

For some reason they loitered when leaving. Hubert began reading my neighbor's calling card tacked beside his bell. They were always a bit curious about my life though good form required contempt for my existence. So he read that card, the shop sign of a Secretary on the Central Committee, without knowing that behind that door an old

21

pensioner had been dying for ten years, had been trying to die day after day but with no success. From above, drops of dirty water dripped from the steps and the edges of the stairs. Our janitor, or as he is to be called these days, the building superintendent, an incorrigible lunatic, was washing the landing. He had already been on television and been written up in the papers and still on he went washing our stairs, the only building superintendent in the country still doing it.

"Don't punk out, old man," said Rysio.

"I have to think it over."

"They're expecting you at eleven, Halina and Nadezhda," added Hubert.

"And if I don't do it?"

"Then you'll go on living the way you've lived till now."

They began down the stairs, supporting each other like two saints, like Cyril and Methodius. And naturally I remembered Rvsio from those years long ago when we both were young. I remember one mad drunken night on some farm near Warsaw, the two of us sleeping side by side on a bed of straw. At that time Rysio was something between a critic and a filmologist. There was a drunken girl lying between us, a girl I never saw again. We were both lying semiconscious on my green poncho which I had obligingly spread out for us. The girl was moaning in her deep, drunken sleep. Rysio was fooling around with her, panting hoarsely with sudden desire and so she turned her back to him. Then she was facing me and I could feel her damp, sleepy breath on my cheek. Rysio did not give up; unconscious but hard at work, he was fumbling at her, tearing at her clothes, slipping under her inert body, breathing wildly. And then, when I was already falling into a delirious fever, Rysio clearly achieved his end, for he suddenly began moaning and pulling himself free on the frantic hay. Unaware of his ecstasies, she breathed her light, calm breath on me. It was only in the morning when, hungover, we were all collecting ourselves on that rustic bed, that I struggled into my raincoat and automatically put my hand in the pocket and to my horror discovered that in the darkness of the night, my pocket had been the victim of Rysio's passion, that he had made love to my pocket with a fierce and youthful love, perhaps even the first of his life.

Now Rvsio wrote unpunctuated, amorphous prose, played adjutant to Hubert, and was a venerable figure in the literary world. I returned to my room to watch them through the window. Just then, by some miracle, an empty taxi happened by, but they missed it and walked off with dignity toward Nowy Swiat. I was curious if they were being followed. But no car pulled away from the curb and no one came running out from the half shadows of any neighboring building.

22

At one point Hubert had hanged himself in his wardrobe; he had been mercilessly baited during one campaign, for at that time, toward the end of the sixties, the regime still had strength enough for cruel spectacles and sinister campaigns. So, Hubert hanged himself, but of course it was the first time he had ever done it and he didn't have the knack yet. The rod broke, the wardrobe turned over, and Hubert survived. Yes, he survived so that years later he could bring me my death sentence.

There was another peal of thunder in the low, cramped sky. I went to the bathroom to wash up. The pipes began gurgling something awful, they hiccupped, but what was left of the water came out. I washed mechanically, wondering if it were right to wash and dress, considering what was in store for me. But, after all, one should take death like communion, neatly dressed and with reverence. But did I have to die? Was someone going to force me off a bridge or douse me with gasoline? The decision was mine, wasn't it? I could die with honor or go on living dishonorably.

The gong resounded again. I thought that Rysio and Hubert had forgotten something or were returning to call off the sentence. Dripping with the little water there was, I ran to the door. An old man with a large, leather bag was sitting on the steps.

"Are you here to see me?" I asked.

"Yes, I am. I've been instructed to turn off the gas."

"But you've already turned it off three times this year."

"What do I know, first they tell me turn it off, then they tell me turn it on. They don't know what they're doing. Every day a house blows up, so to make it look like something's being done about it, they tell me to turn off the gas. It's a lucky thing your apartment's still here because I've got the numbers here of places which are gone." He showed me a dirty slip of paper.

"Well, then why don't you turn off the electricity while you're at it? It doesn't matter to me."

"It doesn't matter to you," said the old man with a sly smirk, and he sprang nimbly into the bathroom. "But it matters to me. I've only got authority for the gas."

And indeed, in a fraction of a second, he had turned the valve, had taken apart the grate on the heater and was already sitting on the edge of the bathtub, lighting up a cigarette that was coming unglued.

"It's nice to take a warm bath, if only to wash your butt, you'll pardon the expression," discoursed the old man, glancing about the bathroom. "But what can you do, orders are orders. Maybe you should have a little talk with the manager, you know what I mean. Speak to his hand."

-

23

"I don't feel like talking with the manager. I'm going to die today."

The old plumber began chuckling merrily.

"Why'd you think that one up for today, isn't there enough going on? That Russian Secretary's coming today. They've got the whole town decked out. There's been bands playing everywhere since this morning. They say there's a sort of festival going on, some big holiday of theirs, maybe it's one of ours too. They've filled up the stands with goods, everywhere, by the Palace of Culture, down by the Vistula, people have been standing in line since early this morning and you're getting set to die."

"I'll be dying to spite them."

The gray-haired tradesman wiped away tears of joy.

"You're a funny man. If we started dying to spite them, there'd be no Poles left. You know what, I'll connect up your gas, but I'll seal up the valve handles. I'll leave it open wide enough so you can use the gas, just you be careful."

"I don't have need for gas. Why don't you take the little heater as a souvenir?"

"You're pretty touchy. If you don't want to, you don't have to. Sign here please."

I accompanied him back to the hall. He took the opportunity to feel my coat, which was hanging by the door.

"Nice wool. Foreign."

"Take it. Wear it in good health."

"What are you talking about? I can pay you. I'll give you fifty thousand.

"I'll give it to you for nothing. The only thing is, when you put it on, give a sigh for my soul, would you?"

"You must be an artist, right? You like a good laugh, right?"

But he rolled the coat up skillfully, packed it in his bag and then was already at my neighbor's door, pressing the doorbell, a severe look on his face.

24

Tortures

Wislawa Szymborska

Nothing has changed.

The body is susceptible to pain, it must eat and breathe air and sleep, it has thin skin and blood right underneath, an adequate stock of teeth and nails, its bones are breakable, its joints are stretchable. In tortures all this is taken into account.

Nothing has changed.

The body shudders as it shuddered before the founding of Rome and after, in the twentieth century before and after Christ. Tortures are as they were, it's just the earth that's grown smaller, and whatever happens seems right on the other side of the wall.

Nothing has changed.

It's just that there are more people, besides the old offenses new ones have appeared, real, imaginary, temporary, and none, but the howl with which the body responds to them, was, is and ever will be a howl of innocence according to the time-honored scale and tonality.

Nothing has changed.

Maybe just the manners, ceremonies, dances. Yet the movement of the hands in protecting the head is the same.

The body writhes, jerks and tries to pull away, its legs give out, it falls, the knees fly up, it turns blue, swells, salivates and bleeds.

25

Nothing has changed. Except for the course of boundaries, the line of forests, coasts, deserts and glaciers. Amid these landscapes traipses the soul, disappears, comes back, draws nearer, moves away, alien to itself, elusive, at times certain, at others uncertain of its own existence, while the body is and is and is and has no place of its own.

Translated by Magnus ]. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire

26

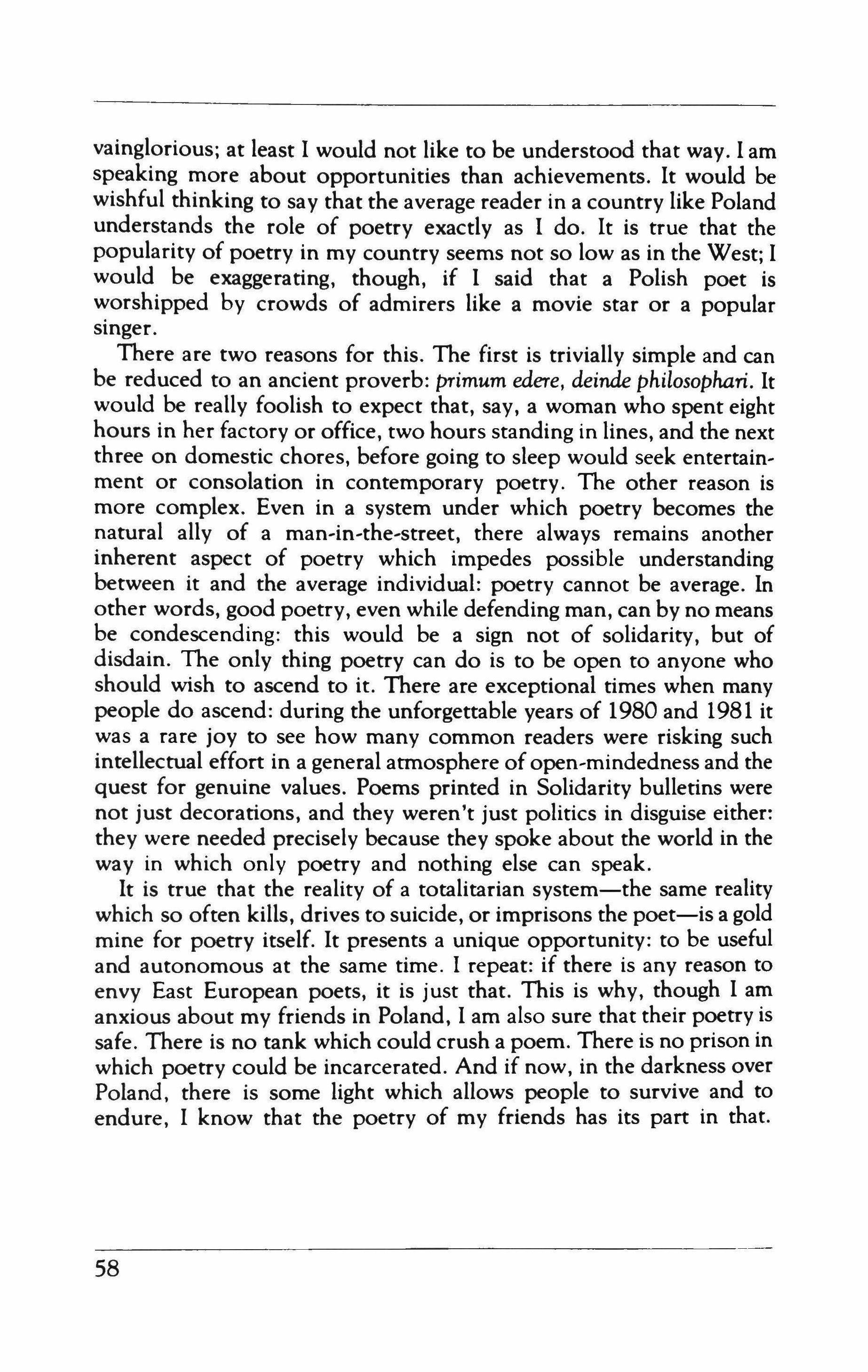

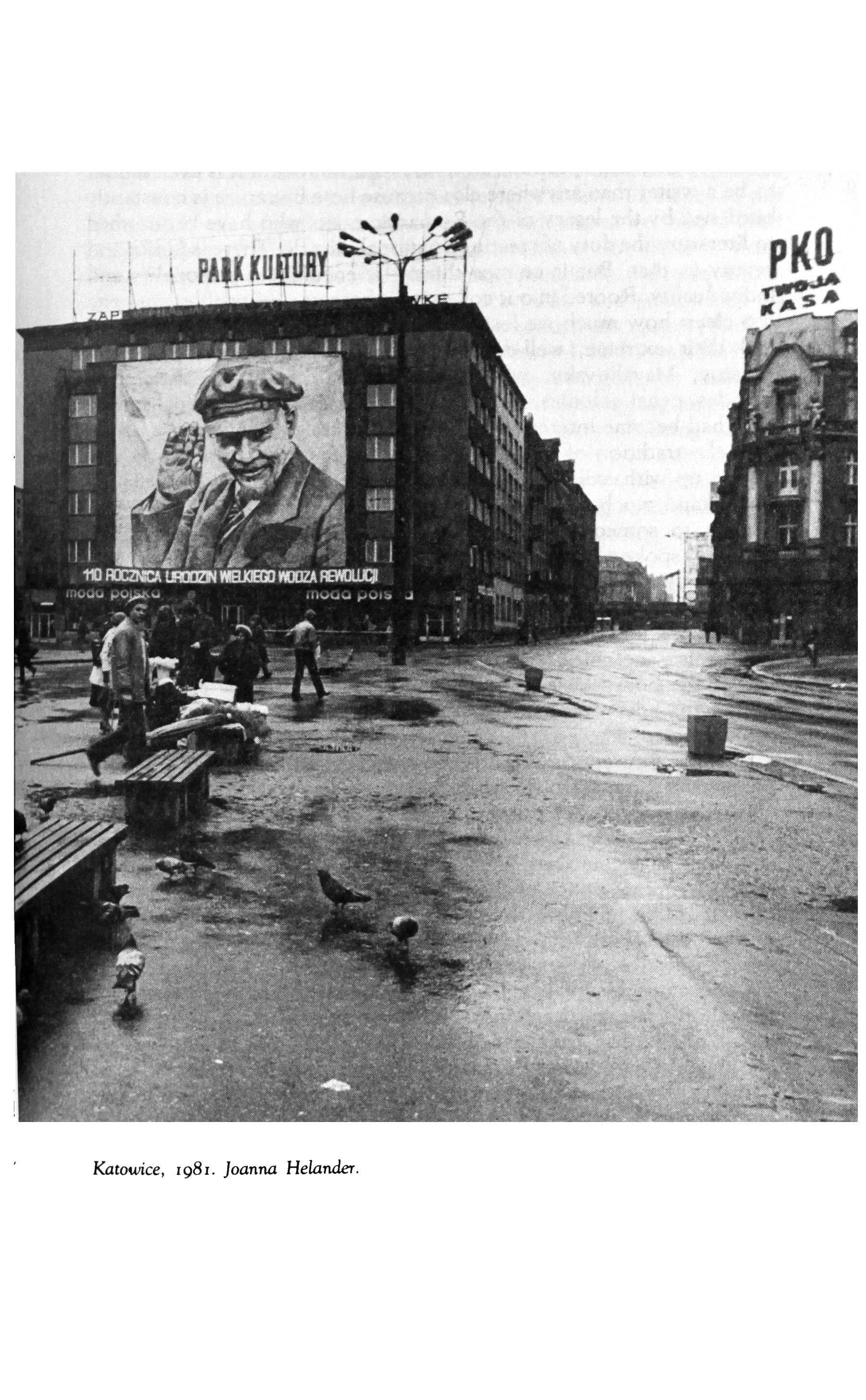

Drawing by Wojtek Wolynski, smuggled from Ostrow internment camp.

Philately

Wiktor Woroszylski

From my childhood

I remember philately Has anyone noticed that philately is no longer the same as it was in our childhood I don't want to be a man of yesterday constantly repeating the words I remember and No Longer is There But what can you do if indeed there are no more of those great searches for adventure those small boys collecting an accident a shimmering slab of ocean the craning neck islands happiness the guttural sound the wonder a piece of the jigsaw puzzle of the world which for each of us arranged itself in different fashion we acquired we exchanged in dark shops for pennies we bought the colorful drug we lay in ambush had to guard our jungle vigilantly The enterprising spirit imagination daydreams all of this created a world wide open for which I am ashamed to yearn uncertain of the motives now that there is a different philately of closed systems to which one buys a ticket of admission Everyone can take out a subscription and within a specified time receive those same specified components of the collection as other subscribers do The bounds are known There is no adventure accident There is organization and specialization those powers

27

of today's world That is total philately Perhaps it confers other satisfactions Of belonging of symmetry of completeness of inclusion among the customers of the philatelic industry of the certainty of receiving the same as others in the chosen area of pasting a surface in a standard way I can't object to that since that's the way things are I can only say that we were concerned with something quite dissimilar that is no more and never will be again

Translated

Translated

by

Magnus ]. Krynski and Robert A. Maguire

28

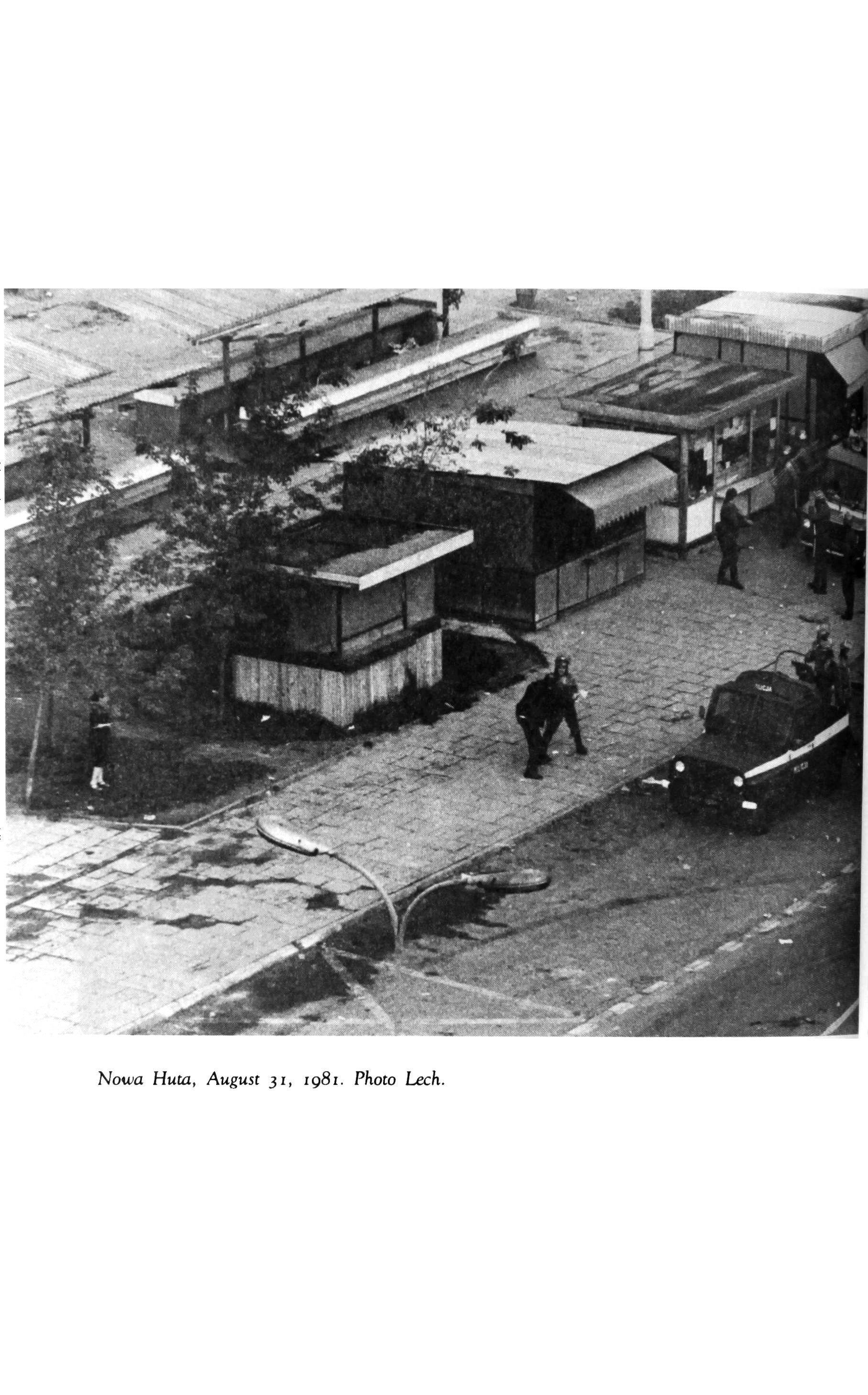

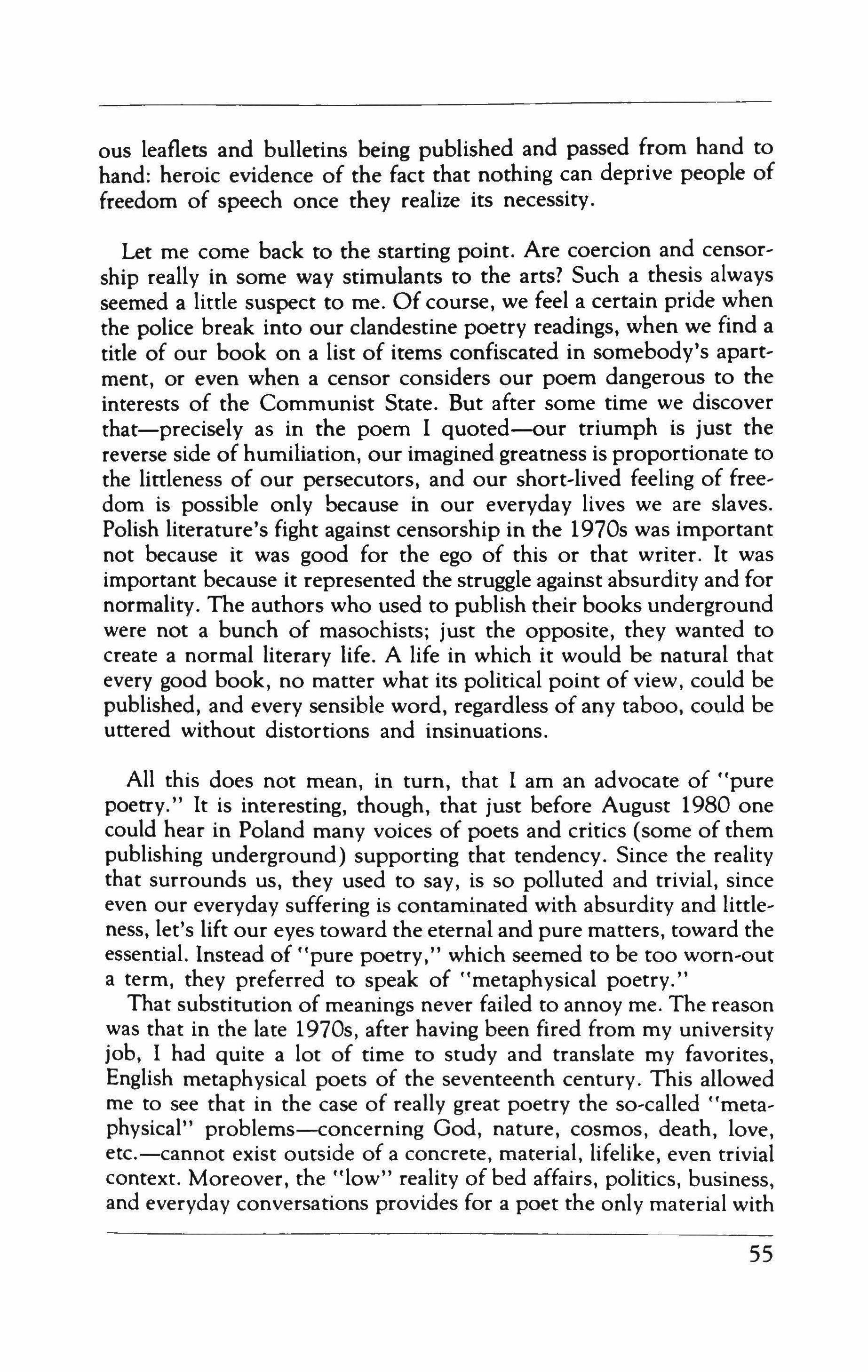

Linocut by Lestek Sobocki.

The peacock

Marek Nowakowski

The railroad station was half-empty. Cashiers sat idly in the few open ticket offices. The handful of travelers was scattered upon benches and alongside walls. They sat sleeping or just gaping ahead. The TV flickered with changing pictures. Some kids were gathered in front of the screen. Silence reigned. A lifeless station. That is the impression it gave. No sign of nervous rushing, elbowing by the ticket offices, quarreling or inquiring about departing trains. Nowhere to be seen were the tramps of both sexes, drunken women of an age difficult to tell, and long-haired, cretinous men typical of station life. Perhaps a few of these figures were lurking in the station's darkest corners. Hounded and uncertain, expecting any moment to be discovered by the omnipresent eye.

Most of all silence struck the ear. So the hard knocking of hobnailed boots against stone slabs jerked up the heads of the few travelers present. The empty space of the station hall was being crossed by a police patrol. Five strapping, well-fed men. They looked around. They woke up a sleeping old man, and checked his documents.

The people soon lowered their heads. They avoided the keen eyes of the police. The patrol went towards the stairs leading to the platforms. Then a sudden din reverberated from the opposite end. It filled the quiet, empty space and drowned the footsteps of the patrol.

The people once again jerked up their heads. They stared in the other direction. In through the electric-eve door came a trunk on wheels. A huge yellow trunk with metal fittings, plastered with hotel and travel-bureau stickers in various languages. It moved on for several meters and stopped. It was followed by a black man. A marvelous tall black man in a white sheepskin coat. His hands glittered with the gold of signets and rings. Lazily walking up to the trunk, he pushed it forward with a strong thrust of his long leg. It sped along on its wheels. Rattling and grinding.

29

The patrol, which was just descending the first steps leading to the platforms, stopped dead. The policemen turned their heads. Their faces were concentrated, their gazes evil. Their hands rested on their machine guns.

The black man was now in the middle of the station hall. The trunk beside him. Once again he set it into motion with the energetic kick of a foot in a soft, shapely, high-heeled shoe. The parted flaps of his white sheepskin coat revealed a bright red sweater and black velvet pants. A peacock! He looked like the embodiment of exuberant, provocative freedom. A freedom impossible to tame.

The people gazed spellbound. Lights of trains, distant journeys That's what filled their eyes.

-Mommy! -whispered a little girl. -Look, a Negro! -she flung out her hand, delighted.

-Well, haven't you ever seen a Negro?! -the mother angrily pulled back her hand. She too avidly eyed that lofty colored figure.

Translated by Boguslaw Rostworowski

Translated by Boguslaw Rostworowski

30

Confidential phone call

Marek Nowakowski

A low sky. Depressing weather. The Rio cafe closed. Where to go? You can't hang around for too long. They'll approach you and check your documents. And back home? The wailing of the old folk: "What are we in for! What are we in for!"

At a distance Blazej was clumsily trotting along. We watched indifferently. He was panting. Fatty-as we called him-was excited.

-You know what, boys! -he called. -They've been questioning the janitor!

We weren't particularly moved. Lots of people were being questioned. But Fatty'S inarticulate account began taking on interesting contours. They're looking for people from Solidarity. The names of Bujak and Janas were mentioned.

Blazej swore on all the saints of this materialistic world that he had seen some civilian showing the photographs to the super. The super had looked carefully, blinking his eyes.

-If I notice anything-he said-I'll report it to you, of course. The super was despicable, and he was sure to report. We didn't like him and he didn't like us either. He would get confused by our sophisticated statements and lose his self-assurance. We were standing in front of the closed Rio cafe and things were no longer the same as they had been a moment ago.

Blazej's story had reacted on our imaginations. Like the prick of a pin. Had some outsider been seen here recently? On the run? We hadn't noticed anyone like that. It was a peaceful white-collar-worker apartment complex. Medium-sized blocks arranged in quadrangles. But we couldn't help thinking about the matter. We had an infinite amount of free time. Flowing in a stream. They hadn't yet opened the schools. Some of us were very pessimistic about the future. They had done away with the Independent Students' Union, and were sure to harass some of us. Ugly times had come about. In the evenings, at

31

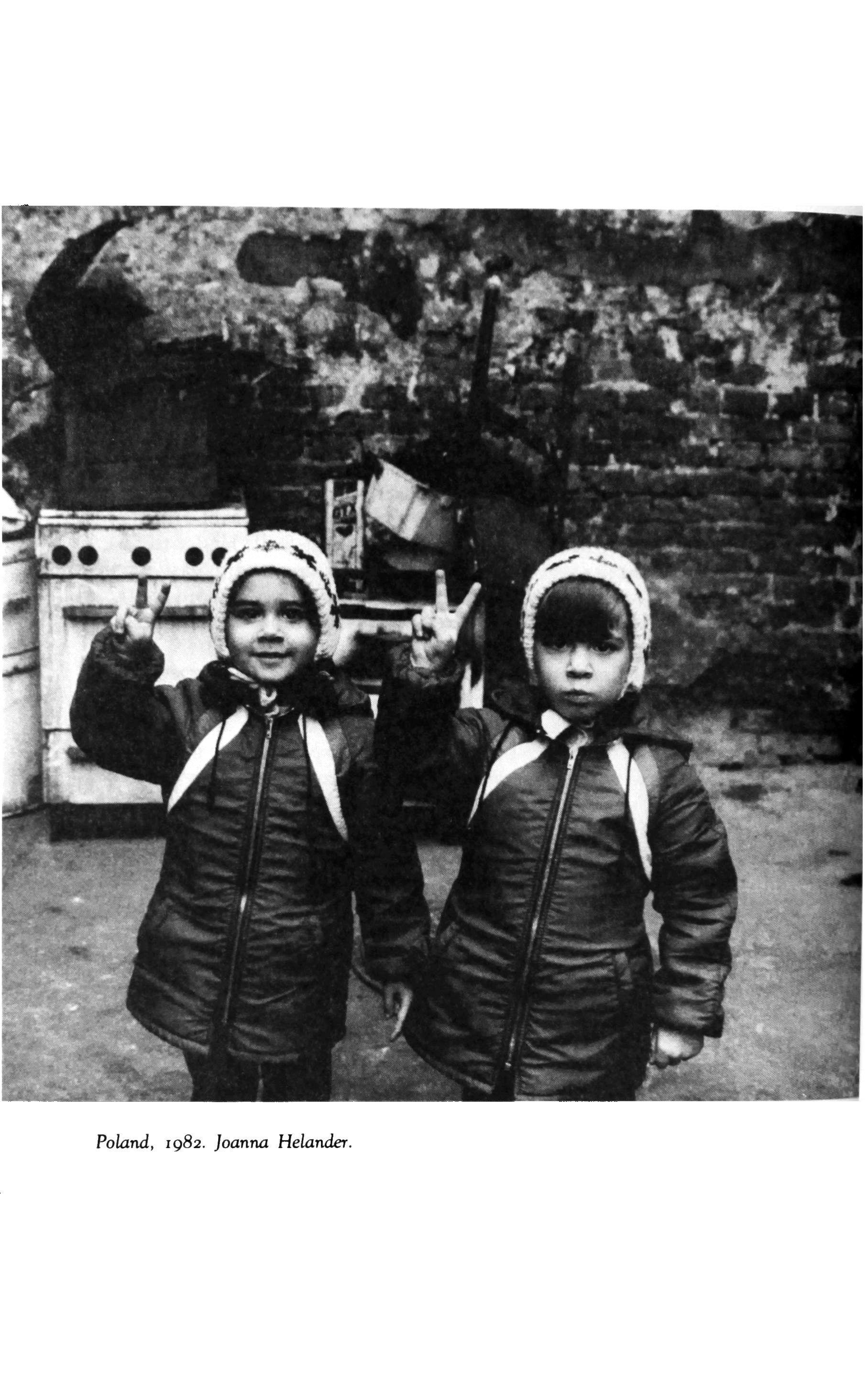

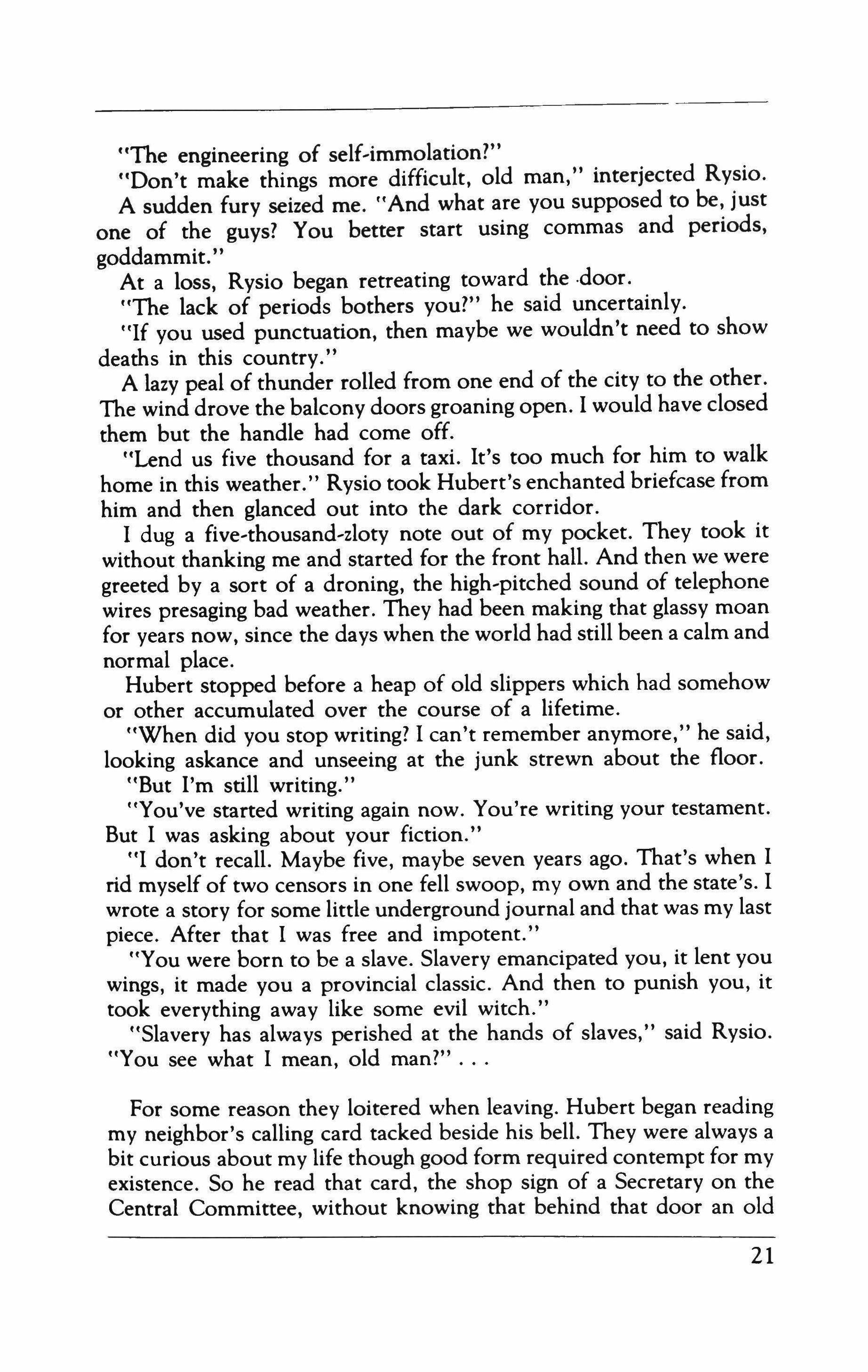

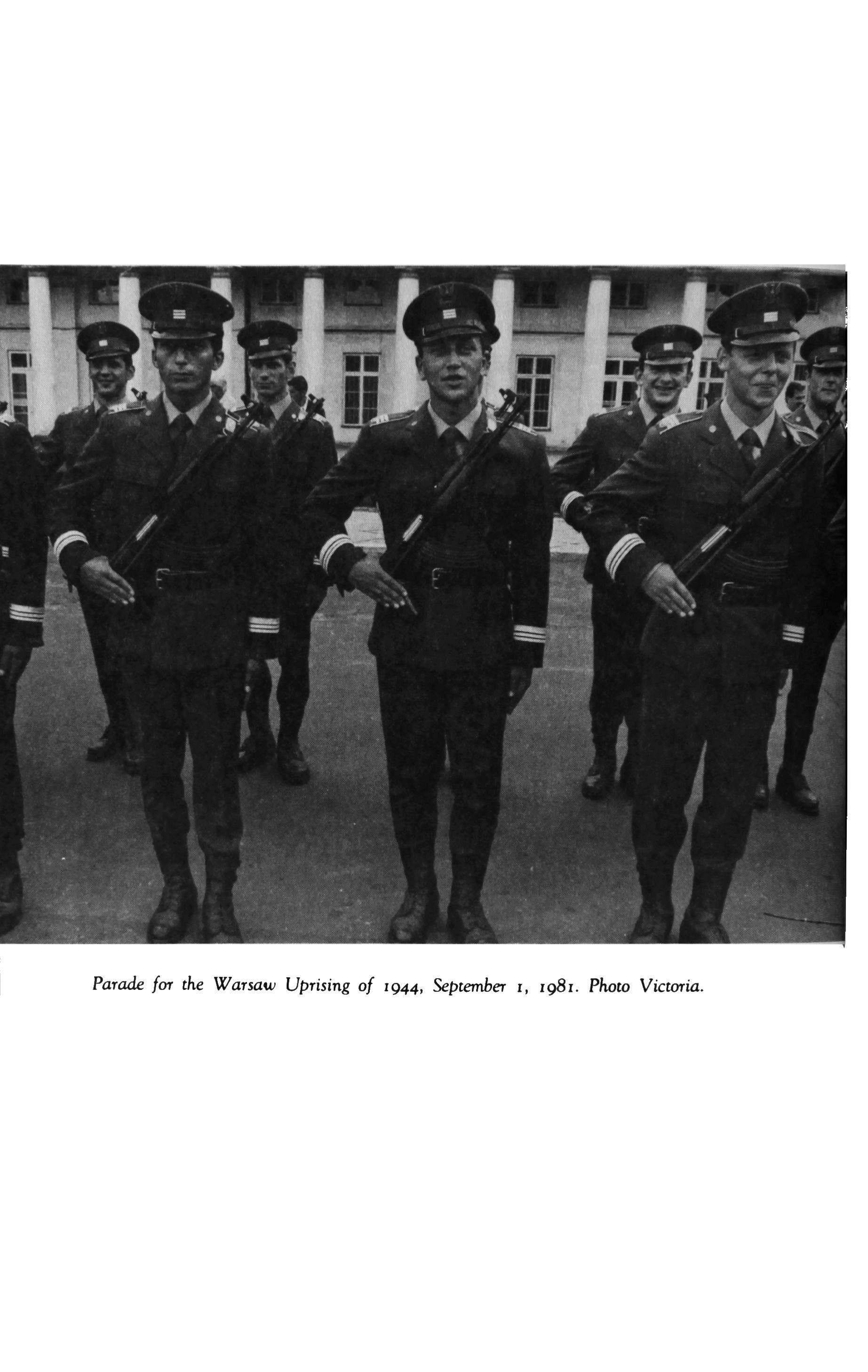

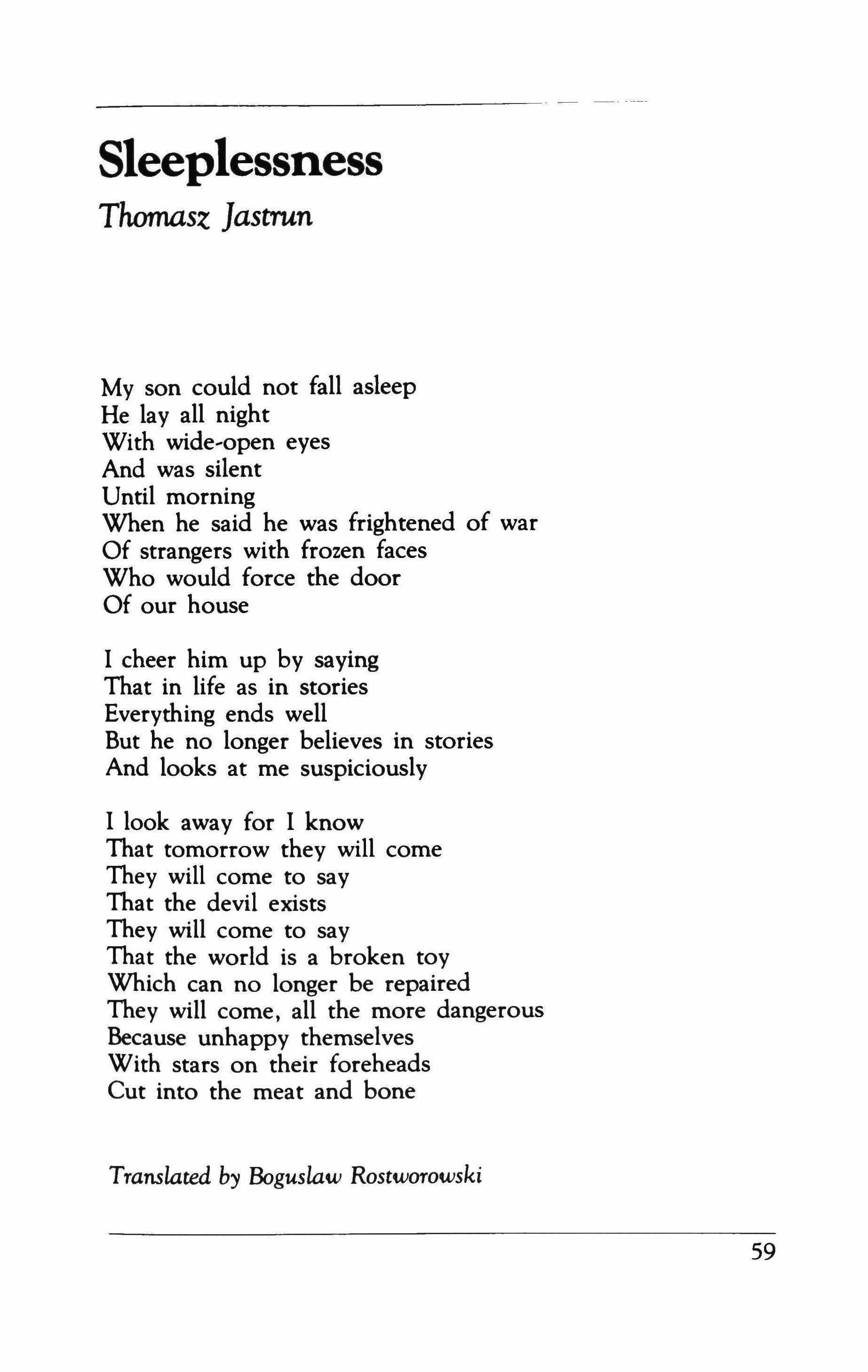

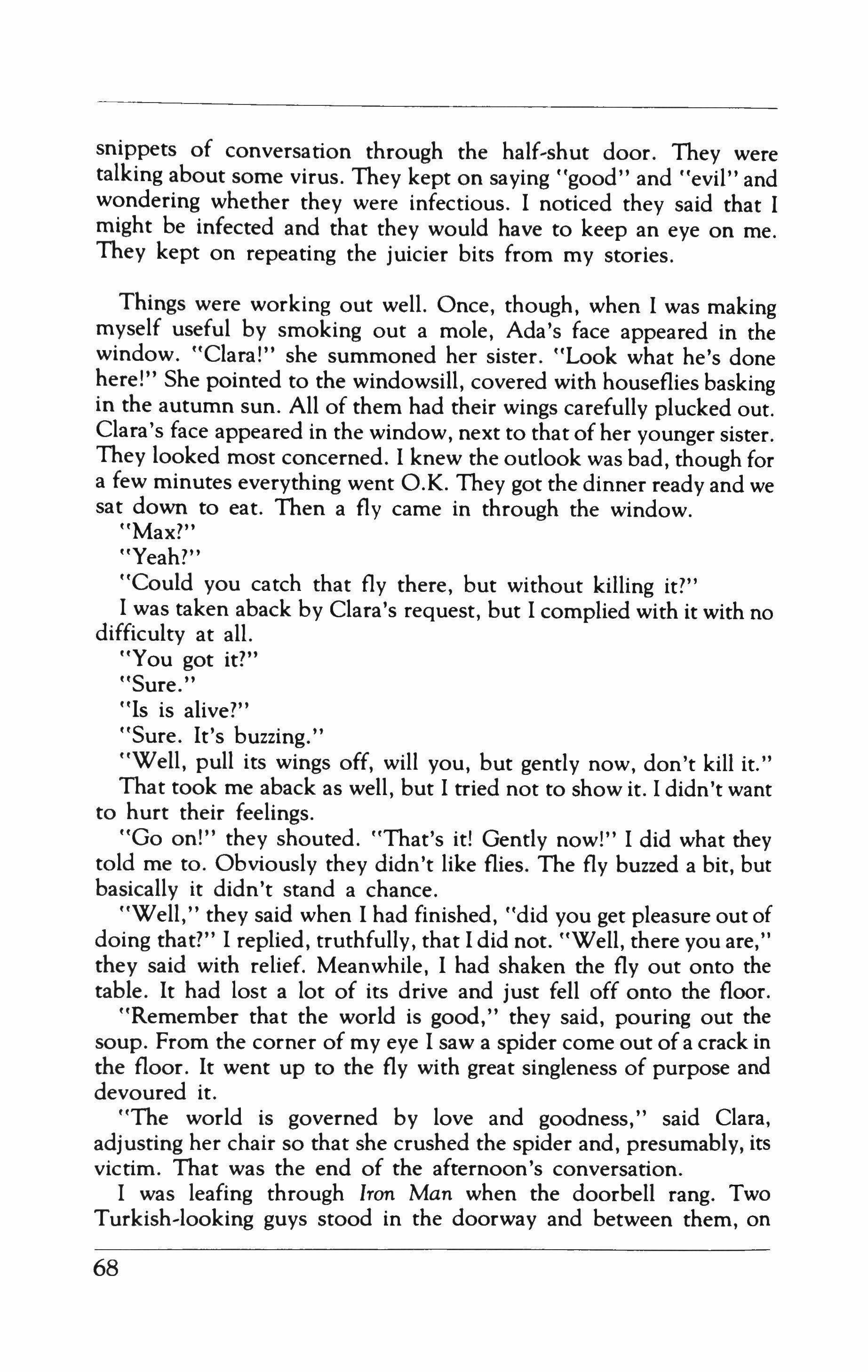

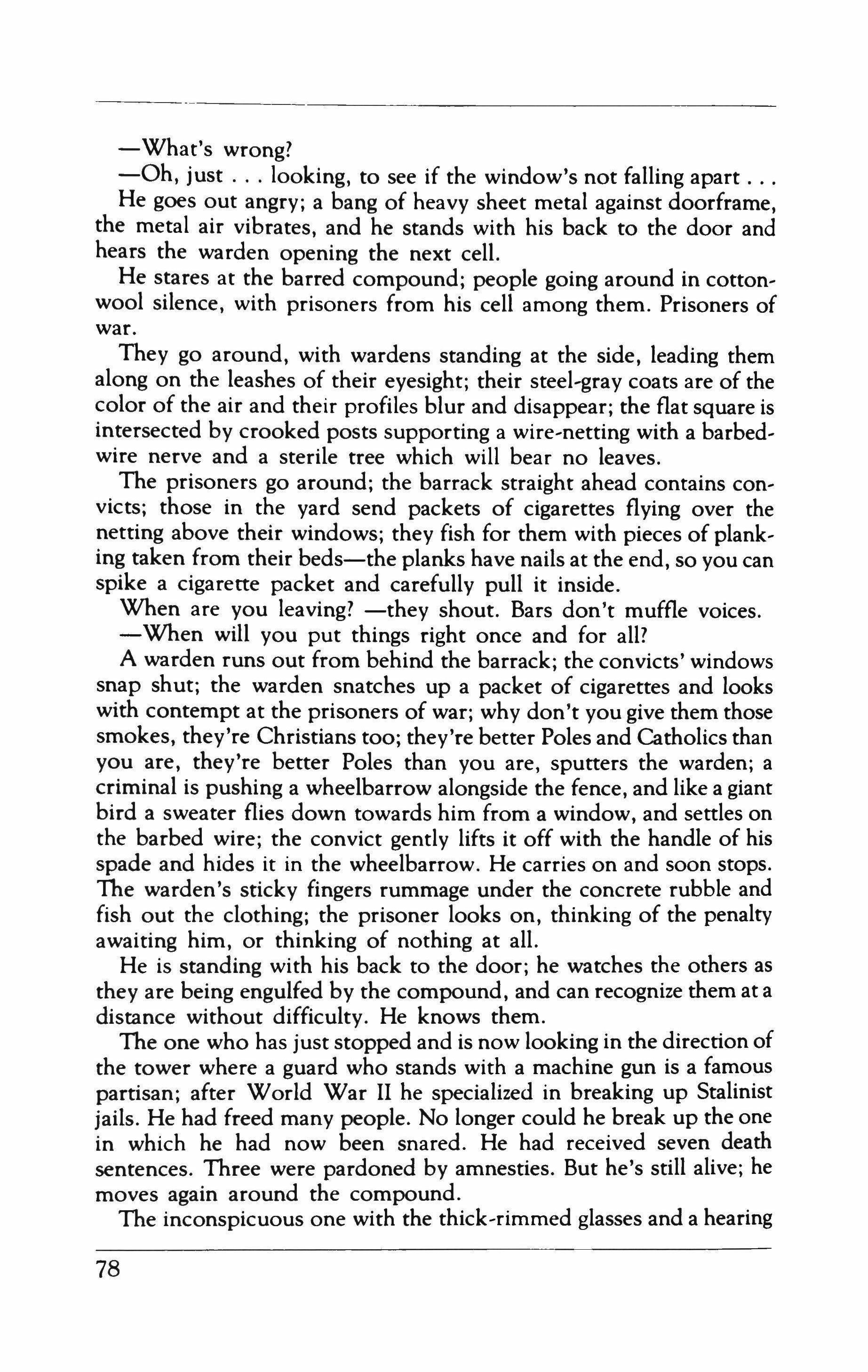

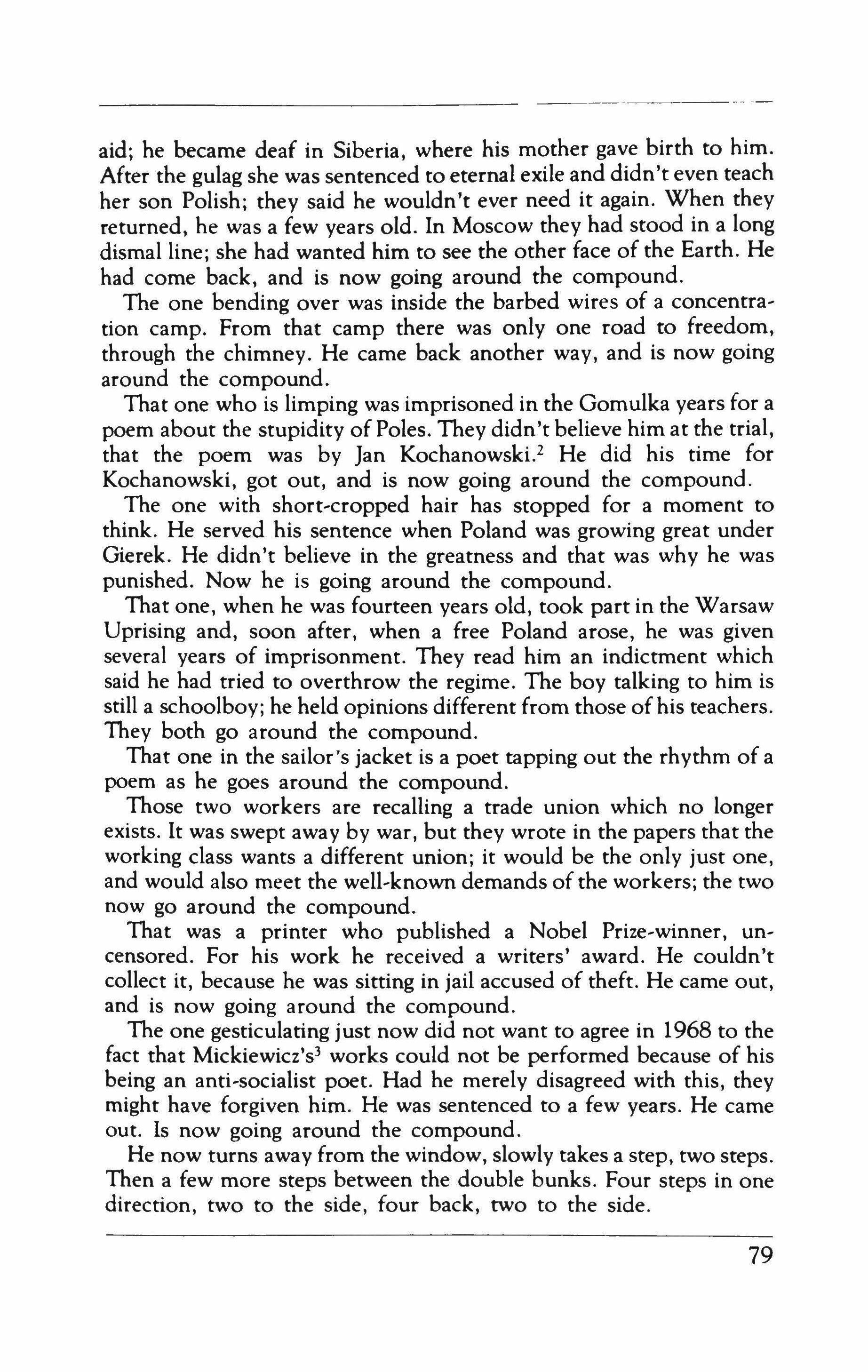

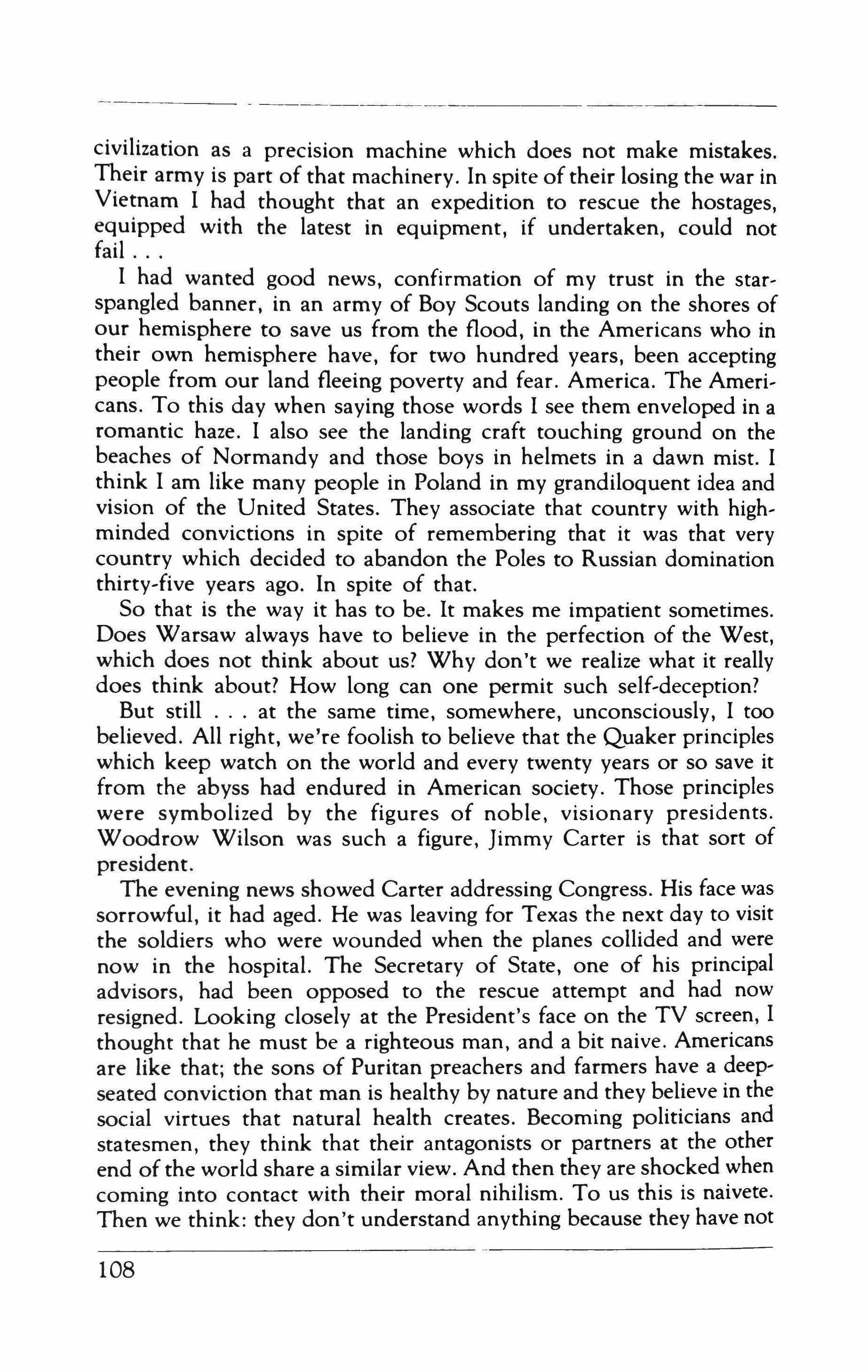

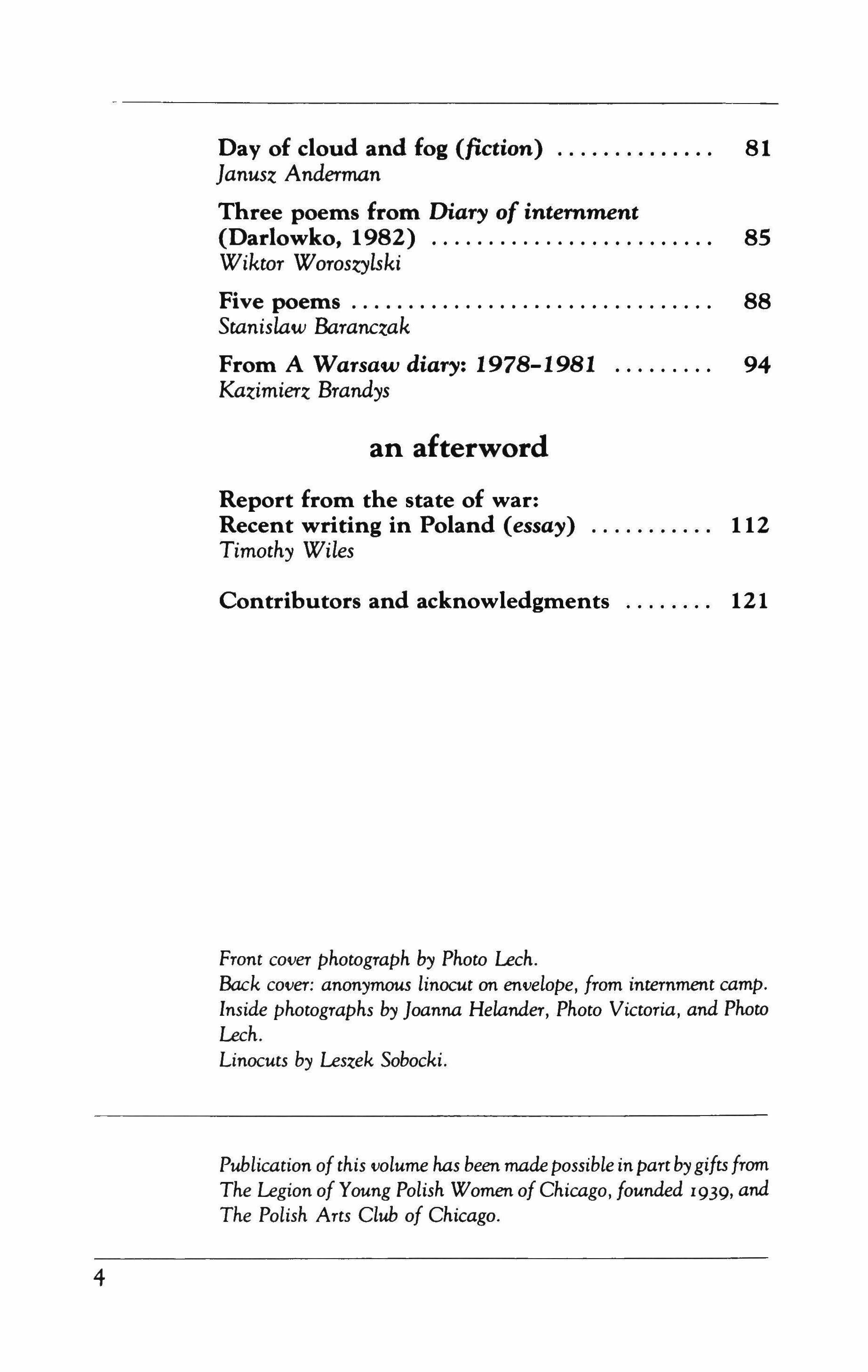

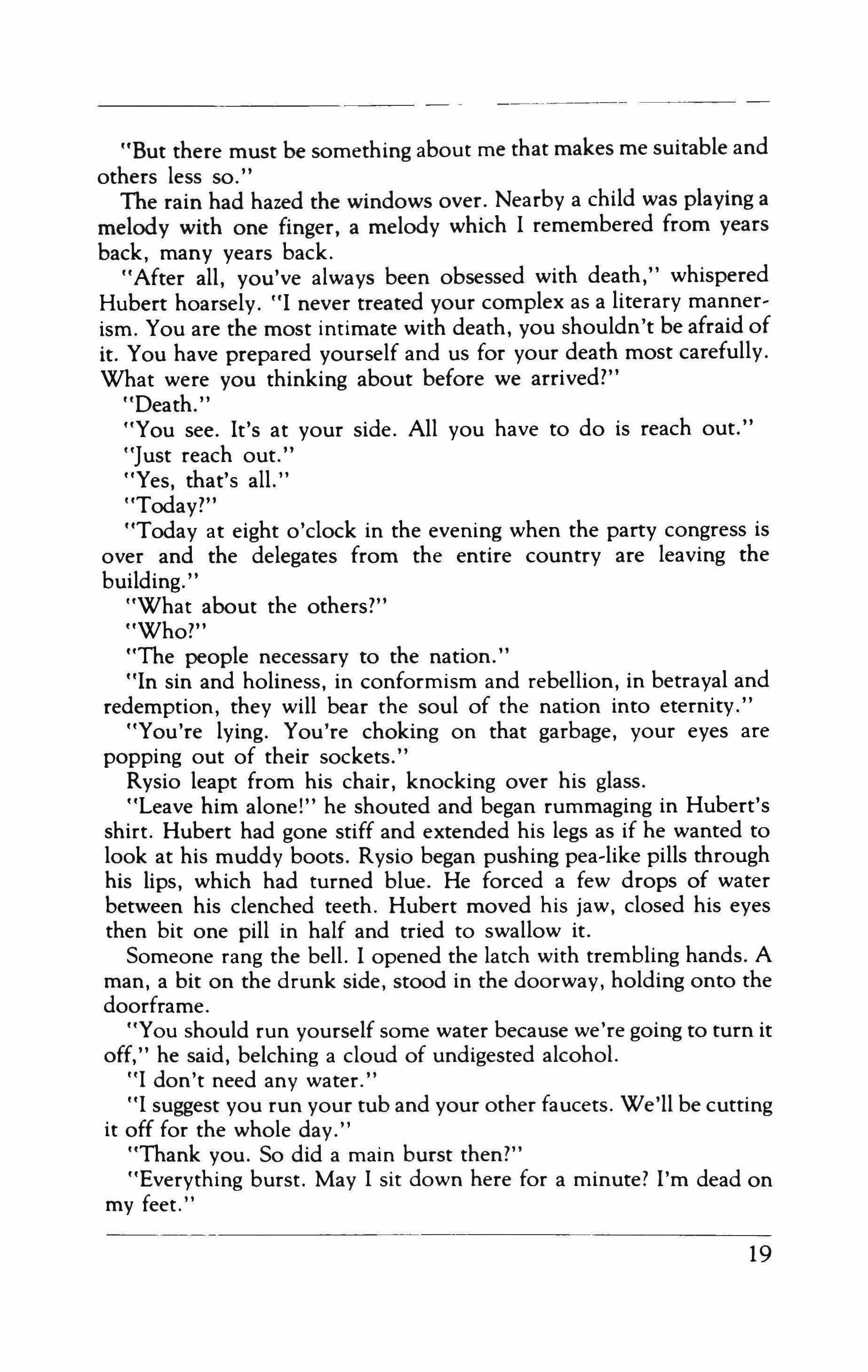

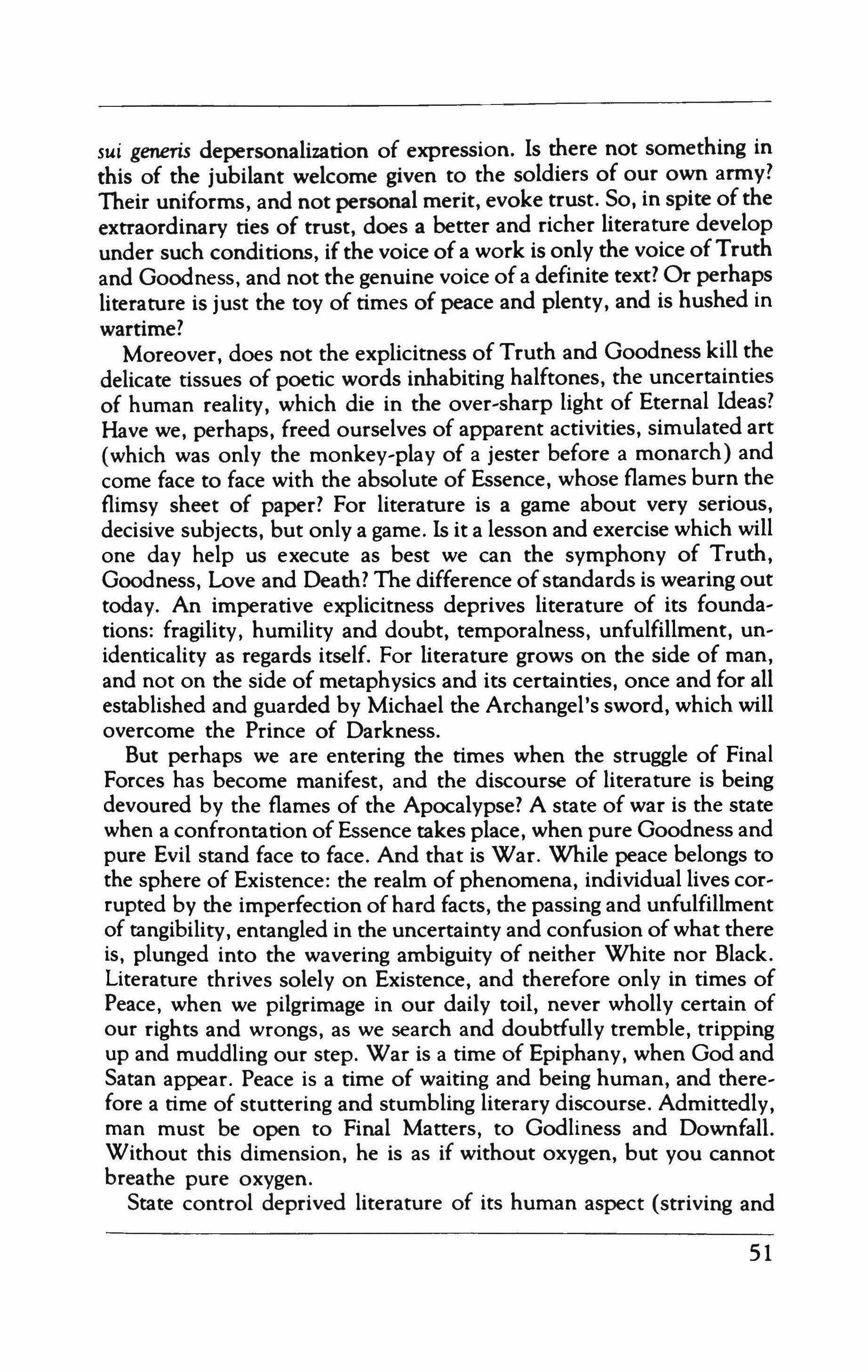

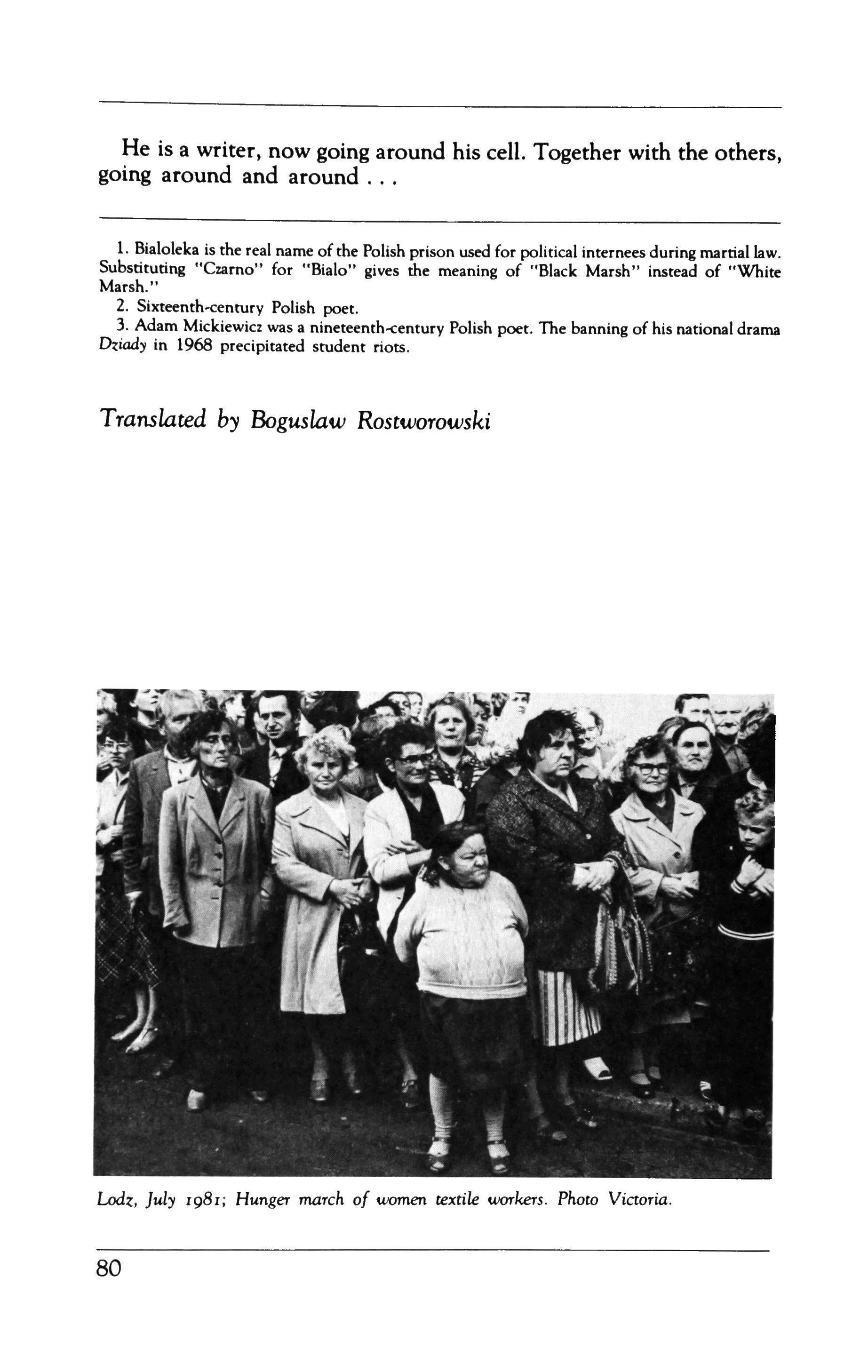

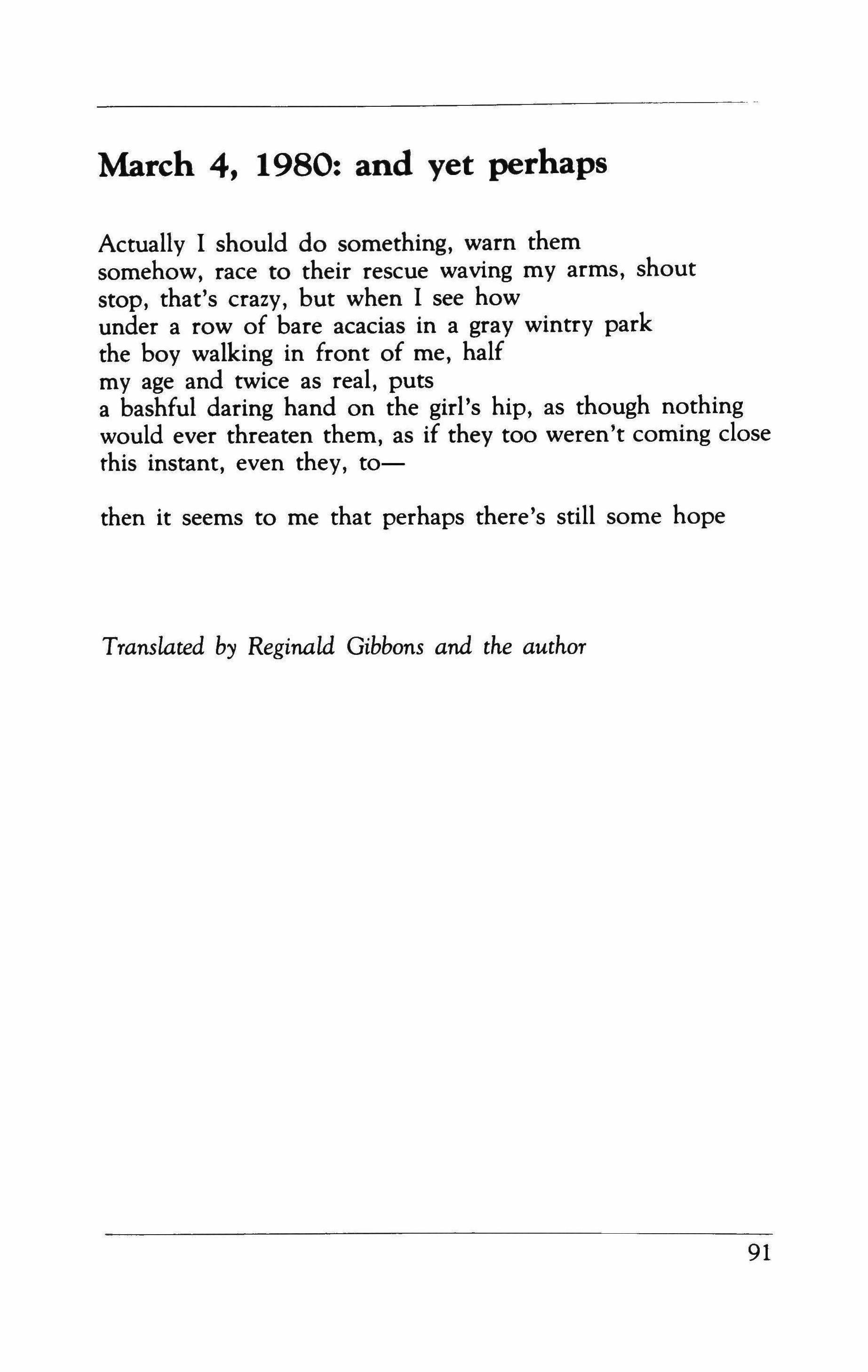

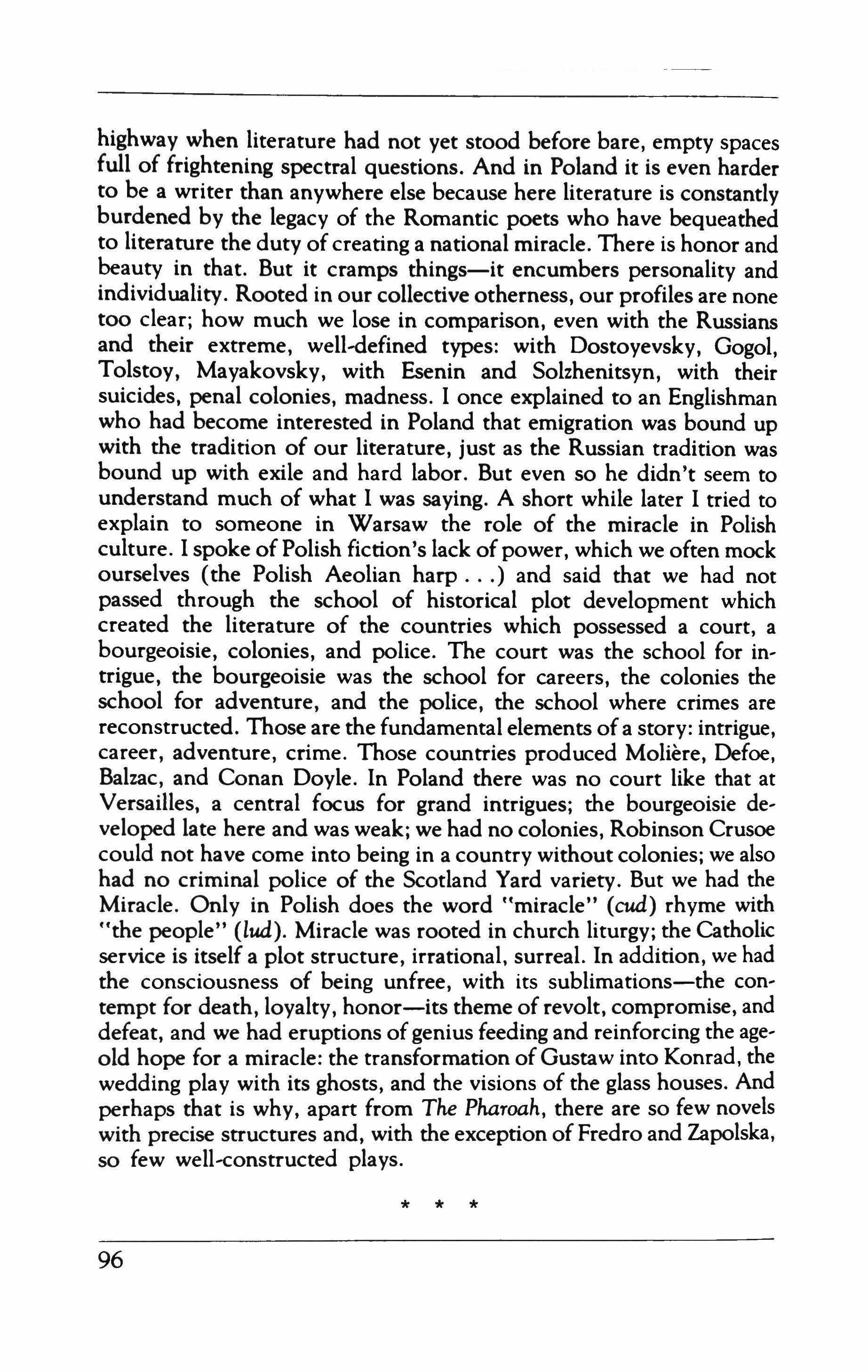

Parade far the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, September I, HXlI. Photo Victaria.

Parade far the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, September I, HXlI. Photo Victaria.

home, we gambled at guessing: what swine would we see in the silver window today? What vermin would deliver a eulogy extolling the state of war and the rosy future awaiting us? What rhetoric would he apply? Would he avoid the reefs, or would he stun us mercilessly? Would it be an oration full of hatred for the latter period? Or would we see someone disguised in the robes of a mentor with painful concern in his face? And so on. They picked those swine perfectly. A natural choice. A whole parade.

-A parade of swindlers-said Wladek.

And for decoration's sake they would throw in a few sclerotic old men who probably had no idea what was happening or what purpose their statements might serve. They were simply pathetic. As Wladek put it: "The grandfather myth has been shattered at last." This was in reference to his family tradition. His father was always telling him about his grandfather. Grandfather was the idol of Wladek's family. But coming back to the swine. Our evenings of masochistic viewing gave birth to an idea. Its author was Babyface, shy and full of erotic complexes, whom we called by that name because as an only child he had been brought up under hothouse conditions, so we often made fun of him.

Didn't one of those glorifiers ofthe state of war live at our complex? However, we hadn't seen him for a week. He's sure to avoid meeting people. Or possibly he's locked himself up in his study to create under the inspiration of the new times.

-He couldn't have got a new villa so quickly-somebody remarked.

He couldn't have got it so quickly. Such a pace is not yet catered to by our national possibilities.

Rysio Pisarski dispelled all doubts. He had seen him yesterday evening. On a walk with his dog. He had an Afghan called Koko.

We concentrated intensely on Babvface's idea. This was a leading swine. A writer by profession. He was the third one on the show. He had had a high rating. We remembered perfectly his television performance. Ordinarily, he was of no interest to us. Dumpy, and always walking with an executive briefcase. In winter he wore a sheepskin coat and a fox hat. He wrote novels which we hadn't read for a long time. We had already acquired a literary taste. We liked good literature and recently we had been delighted with The Tongue Set Free. However, not because of the acclaim caused by the Nobel Prize having been given to this original writer. Earlier on, Auto--da-Fe had been our private discovery. Therefore, in no way could we consider as literature the books by our neighbor from the complex, in which trash, slimy eroticism and simple brute force competed with a false and

33

preconceived picture of reality. In this picture truth was situated exclusively in our part of Europe, and supporting the East was an expression of heroic choice. The writer delicately envelops this East in a mystical mist of secrecy. He suggests outright that a third Rome is situated there, and that we are descended from that cradle. And, also, that humanism is solely our privilege. This in short was the recipe of his vision, philosophy of history and moralizing. This literature did not seem to us worthy of the least interest. It was a waste of time. For years, regardless of times and various upheavals, this writer's books were published in enormous editions. They were rampant everywhere from the bookshop windows to the apartments of the new intelligentsia, where they adorned the shelves of wall-to-wall furniture. He was an unchanging and unimpairable value. After all, we had been brought up in his shadow. For us he was a shadow. He robbed us of light. Pretty soon we became conscious of this, and we didn't drown in the slimy, licentious verbosity, profusely stuffed with descriptions of nature, fodder and horse's sweat, encrusted here and there with the pathos of God and fatherland. That's it! His measure of disgust was overflowing with patriotism and Catholicism. Recently on TV his mouth was full ofjingoistic platitudes. And over the years his face had taken on such a hypocritical look that he could well be used for frightening children as the wolf disguised as Little Red Riding Hood, barely controlling its appetite.

We unleashed our hate, and everyone added his little bit to the portrait of the neighborhood writer, as someone wittily called him. Day after day was burdened by the putrid grandiloquence of those like him, and we had no way of responding. We rubbed hands. Not from the cold however. But enlivened by a hunter's instinct. The hounds were not yet on the chase, but soon

The idea needed detailed planning. Arkadiusz saw to this. He had a cool, precise mind, and did not easily give in to emotions. Why is he studying Oriental philology? He's a born mathematician. Moreover, he has a private interest in Wittgenstein, and often embellishes his statements with the aphorisms of this philosopher. To be honest, he hasn't a match among us. It's just the gregarious instinct of apartmentcomplex life that keeps him among his own age-group.

-I've got it-Arkadiusz drawled. We were burning with curiosity. -Well-he continued-today we ought to ring the police headquarters and give the address where someone resembling Janas or Bujak is hiding out-. Everyone's eyes lit up. An avid silence reigned. We were tasting the morsel. -Let it be Bujak-decided Arkadiusz-. He's first-class bait and should do the trick.

Then we got down to action.

34

Tall Michael went off to reconnoiter. He was to check bearings. He came back delighted.

-He's at home writing-he declared. -I heard the typewriter. We decided for the afternoon. People come back from work. Winter dusk is early. While at the same time visibility is not bad. We wanted to have a show.

-Let's play at confidential telephone calls-. That's what Arkadiusz called the operation.

There was still the snag as to how the telephone informer was to introduce himself. "A well-wisher," or "an ideological informer"? "Ideological" sounds insolent and artificial. Who uses such adjectives these days? Only the papers. We opted for "well-wishing observer." Arkadiusz again asked to be heard.

-Too creative-he drawled. -"Well,wishing observer" sounds as if it were taken straight out of some thriller. We have to base it on living reality. To make the communique plausible. To put it briefly: let it be the super, that is "the director of physical plant." Only in this way will it sound natural and things will turn out according to expectations.

He convinced us. Logic and realism. We had no scruples regarding the super. Often the police would drive up to his place. You should see how he welcomes them! With what hospitality. They leave his home bloated with drink. And then there's the proverbial brother-inlaw. "My brother-in-law's gone to London." "My brother-in-law's in Sweden." A suspicious creature. He would sometimes drive up in his Zastawa car and honk for the super to come out. Super and family would rush out. We felt no scruples. Let it be the super phoning. Bolek decided to play the part. He had a hoarse, somewhat hurried voice. He did a rehearsal on the spot and impressed us. A real honest, to-god informer.

The time separating us from the fixed "zero" hour passed quick as a flash. Absent-mindedness, thoughts a long way away, and lunch at home. We hung around, looked over some books, and time was up! We chose the telephone booth by the supermarket. Bolek went inside. Arkadiusz stood by him like a director. We had left a lookout at the corner. We arranged a signal.

Opposite the third block on Cluster F there was a parallel block, and we took up positions there on the fourth floor in the staircase. We had a perfect view. We could see Bolek through the glass of the booth. He was lifting up the receiver. Now, turning the number on the dial. This is Arkadiusz's description of the event. We had no doubts as to the accuracy and faithfulness of the report.

-The duty officer, please! This is the director of physical plant

35

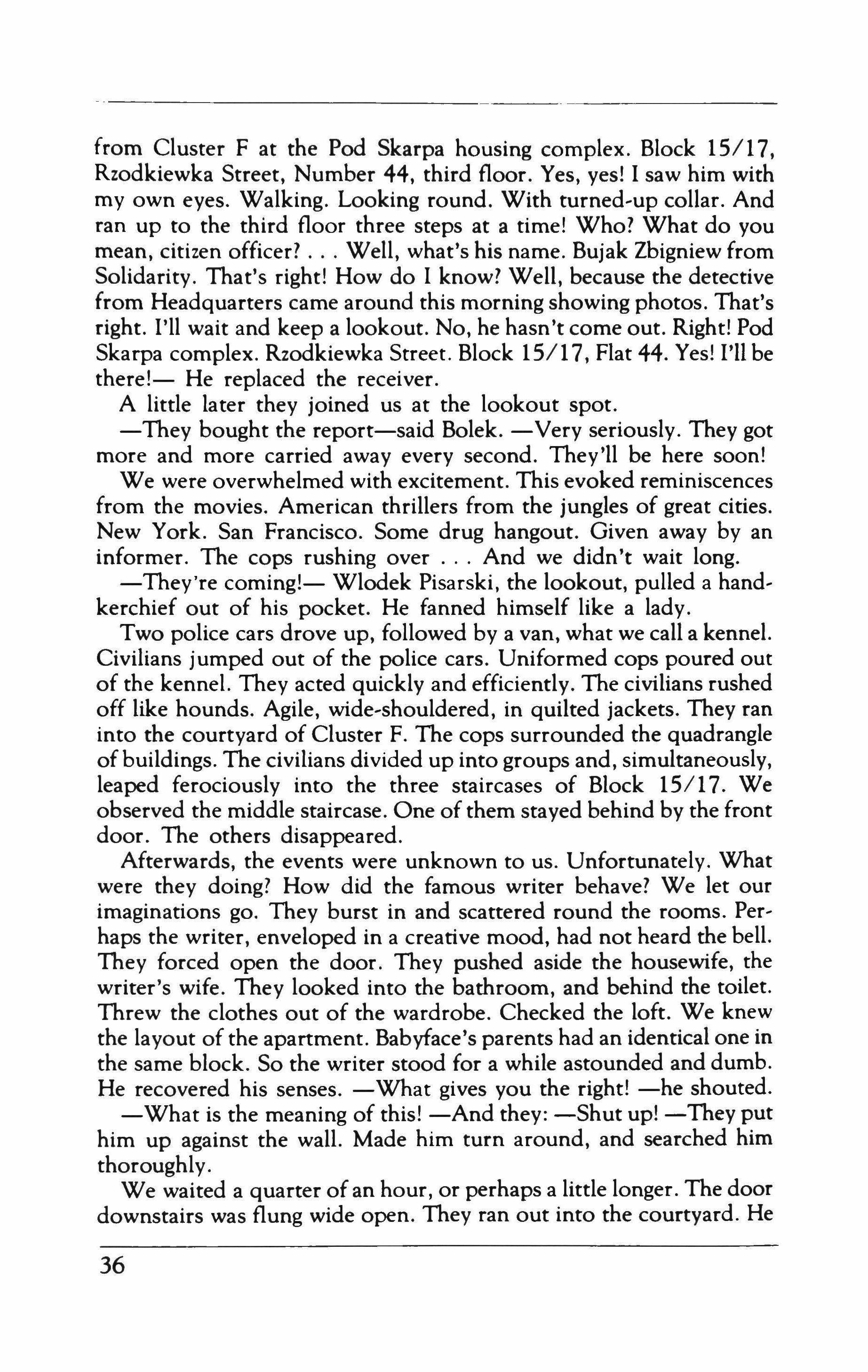

from Cluster F at the Pod Skarpa housing complex. Block 15/17, Rzodkiewka Street, Number 44, third floor. Yes, yes! I saw him with my own eyes. Walking. Looking round. With turned-up collar. And ran up to the third floor three steps at a time! Who? What do you mean, citizen officer? Well, what's his name. Bujak Zbigniew from Solidarity. That's right! How do I know? Well, because the detective from Headquarters came around this morning showing photos. That's right. I'll wait and keep a lookout. No, he hasn't come out. Right! Pod Skarpa complex. Rzodkiewka Street. Block 15/17, Flat 44. Yes! I'll be there!- He replaced the receiver.

A little later they joined us at the lookout spot.

- They bought the report-said Bolek. -Very seriously. They got more and more carried away every second. They'll be here soon!

We were overwhelmed with excitement. This evoked reminiscences from the movies. American thrillers from the jungles of great cities. New York. San Francisco. Some drug hangout. Given away by an informer. The cops rushing over And we didn't wait long.

-They're coming!- Wlodek Pisarski, the lookout, pulled a hand, kerchief out of his pocket. He fanned himself like a lady.

Two police cars drove up, followed by a van, what we call a kennel. Civilians jumped out of the police cars. Uniformed cops poured out of the kennel. They acted quickly and efficiently. The civilians rushed off like hounds. Agile, wide-shouldered, in quilted jackets. They ran into the courtyard of Cluster F. The cops surrounded the quadrangle ofbuildings. The civilians divided up into groups and, simultaneously, leaped ferociously into the three staircases of Block 15/17. We observed the middle staircase. One of them stayed behind by the front door. The others disappeared.

Afterwards, the events were unknown to us. Unfortunately. What were they doing? How did the famous writer behave? We let our imaginations go. They burst in and scattered round the rooms. Per' haps the writer, enveloped in a creative mood, had not heard the bell. They forced open the door. They pushed aside the housewife, the writer's wife. They looked into the bathroom, and behind the toilet. Threw the clothes out of the wardrobe. Checked the loft. We knew the layout of the apartment. Babyface's parents had an identical one in the same block. So the writer stood for a while astounded and dumb. He recovered his senses. -What gives you the right! -he shouted. - What is the meaning of this! -And they: -Shut up! -They put him up against the wall. Made him turn around, and searched him thoroughly.

We waited a quarter of an hour, or perhaps a little longer. The door downstairs was flung wide open. They ran out into the courtyard. He

36

was among them. Only wearing a suit. Two of them held him by the arms. He resisted. Dragged his legs. They pulled him along. We could no longer make out the expression on his face. Dusk was falling. Gapers were gathering in the courtyard. In the windows also. The super wasn't there yet. Maybe he had gone to see his darling brotherin-law. One up for us. Let the operetta carryon for as long as possible. The police cordon surrounding Cluster F stood still like a wall. A grim wall. Then a white Fiat drove up. Two plainclothes policemen got out. Moving their bulky bodies in a dignified manner.

- The chiefs-whispered Arkadiusz.

The civilians dragged the writer alongside. They let him go. The writer feverishly fumbled inside his jacket pockets. He brought out something. Showed it. The newcomers scrutinized it curiously. They also gave him a serious look. Suddenly there is a complete change of atmosphere. They shake hands sincerely with the writer. One after the other. They shake for a long time. The civilians move away to the back. They lower their heads. The writer now remains alone with the chiefs. Lively conversation. He gesticulates vehemently. The two nod in agreement. Once more sincere handshakes. They almost embrace. The end of the action. There is no Bujak. The police cars drive off. The kennel also. The car with the chiefs leaves last. They peer out of the Fiat's windows. Waving to the writer. Bye-bye! He was left all alone. We were fully satisfied. He didn't know how to go back. People were standing all around. That fat squat figure! He somehow shrank and lowered his head. He went back like a mongrel with its tail between its legs. Sneaking past. Ludicrously trotting along on short legs. Tripped up near the garbage on the path made slippery by the children. Just managed to keep balance. Hurried up with a doubled effort. Then disappeared up his staircase. Only now did the super turn up. Totally perplexed.

-What's up?! -he inquired urgently. -What's up?!

Translated by Boguslaw

RostWOTOwski

RostWOTOwski

37

The writer and the state

Andrzej Kijowski

This is a speech delivered publicly during the first independent congress on culture and the arts in modern Poland, December 11-13, 1 <)8 I. The last day of thecongTess «'as canceled because of the declaration of martial law and the internment the previous night of most of the attending luminaries. In Poland, the speech has been published undergTound.

Whatever writers in People's Poland have to say about past successes, the fact is that the audience they have been addressing for the last thirty-five years is the State. Starting in 1945 with the first books brought out by the newly established Czytelnik publishing house, the State bought the writer's work in its entirety. Through its agencies (Czytelnik's cooperative status was a mere fiction) the State made itself responsible for the printing, sales and advertising of this work; through its journals, academic institutions and recommendations circulated to schools and libraries, the State ensured its success, its place in mass culture and in the history of literature (and here, encvclopedias, lexicons and anthologies had their own role to play).

Finally, with the help of prizes, decorations and other marks of approval, the State assigned to the work's author his place in society and determined whether he was to be great, excellent or only distinguished. Or indeed, whether he was to exist at all. In the early postwar years the State's interest in writers was very great since literature was the chief vehicle of propaganda. Later, as new techniques developed and the mass media (movies, television) better fulfilled propaganda needs, interest in literature gradually diminished-a process reflected in the decline of both the subsidies to literature and the caliber of the functionaries and methods used to keep it in line. It is a bureaucratic paradox that the final and most radical act in the takeover of literature by the State-granting writers old-age pensions-took place at a time when official interest in literature had become minimal. The fruits of legislative endeavor ripen slowly and drop from the bough at the most inappropriate moments.

To recap: whatever writers may claim both about their conflicts with the State as addressee, and the affection they succeeded in arousing among their readers (oh, those weary evenings on the lecture

38

circuit with the obligatory carnation wrapped in cellophane, oh, those book fairs with autograph hunters standing in line, oh, those letters from obedient schoolchildren and genuine workers ), whatever might be said on this subject, writers wrote for the State, that is for its bureaucrats and editors. It was the latter's eyes and ears they carried within them like internal screens and microphones. Those who were born flatterers wrote to satisfy this audience, while those who were nonconformist by nature and enjoyed taking risks wrote against the grain, to defeat and savage their mentors. There is nothing new about this: writers have always been divided into those who flirt with their readers and those who are at odds with them. Those are the normal rules of the literary game. In People's Poland this game was played out in a closed circuit embracing writer and State, with the reader as passive witness consuming whatever morsels were thrown to him.

With the economic crisis this system shuddered to a standstill but did not disappear. It had created conditioned reflexes that proved difficult to unlearn. The State will not relinquish its role as the sole or privileged patron of the arts as long as it remains the sole producer and distributor of the means of producing cultural artifacts. Nor is there any good reason why writers should welcome the play of market forces in the book trade, as this would certainly threaten their livelihood. They would like to gain control of the distribution of State subsidies, but have no intention of relinquishing them altogether. The worsening economic situation is a threat which makes it advisable to stick to tried financial supports rather than look for new ones.

So nothing is going to change, except that nothing can stay as it was. For three new factors now have to be taken into account: technology, sociopolitical upheaval and demographic changes.

The technological factor is the entire samizdat movement. Anyone who has discovered how easy it is to print his own books at home and distribute them to his readers from a suitcase will never again stand in line for the official mass-production facilities, particularly when the wait is likely to be a long one.

The sociological factor is the Gdansk Accords, which gave Polish society the chance to transform the systemic tissues of the political setup. So far each single cell of this system guaranteed the survival of the whole and had its own survival guaranteed by the result. The system depended on the specific links between the "lower" and "upper" echelons, or, in other words, on the hierarchic interdependence of functionaries at various levels. Since the Gdansk Accords this system has been shaken up and stimulated into a process of exchanging worse parts for better. In the static universe we had lived in for so many years the principle of alternative choice made its appear-

39

ance-together with a new generation of political activists and (obviously) writers.

As the community replaces the State as the author's public, we shall see the emergence of an audience unaccustomed to State literature-a young audience that will be on the lookout for a new type of creative artist unaccustomed to addressing the State, the kind of artist who had the greatest difficulty in gaining the attention of the big publishing houses and the least difficulty in organizing himself, in making use of all available technical facilities and finding new patrons outside the State network, and-of course-in finding new themes and new modes of expression.

Literature has today gained freedom of action in all the three spheres-stylistic, social, and ideological-fought over throughout the existence of the new State. The earliest and easiest concession was the abandonment of the official aesthetic. The State even showed itself willing to sponsor all kinds of experiments, all varieties of escapism, all sorts of extravaganzas, while at the same time turning the screw on all contemporary themes. But all those aspects of reality suppressed by censorship throughout the years burst into the open in a way that made further secrecy impossible. Today it hardly seems credible that only two years ago any mention of food or drug shortages or of environmental pollution was on the censor's index. In the end the State even gave its stamp of approval to ideological pluralism and in practice abandoned the concept of a protected official ideology.

Today the problem facing literature is not how to extend the range of its freedoms but how to implement, how to use the freedom it has already gained. How to implement it is an organizational and technical problem; how to use it is an artistic problem which each writer must solve in his own way.