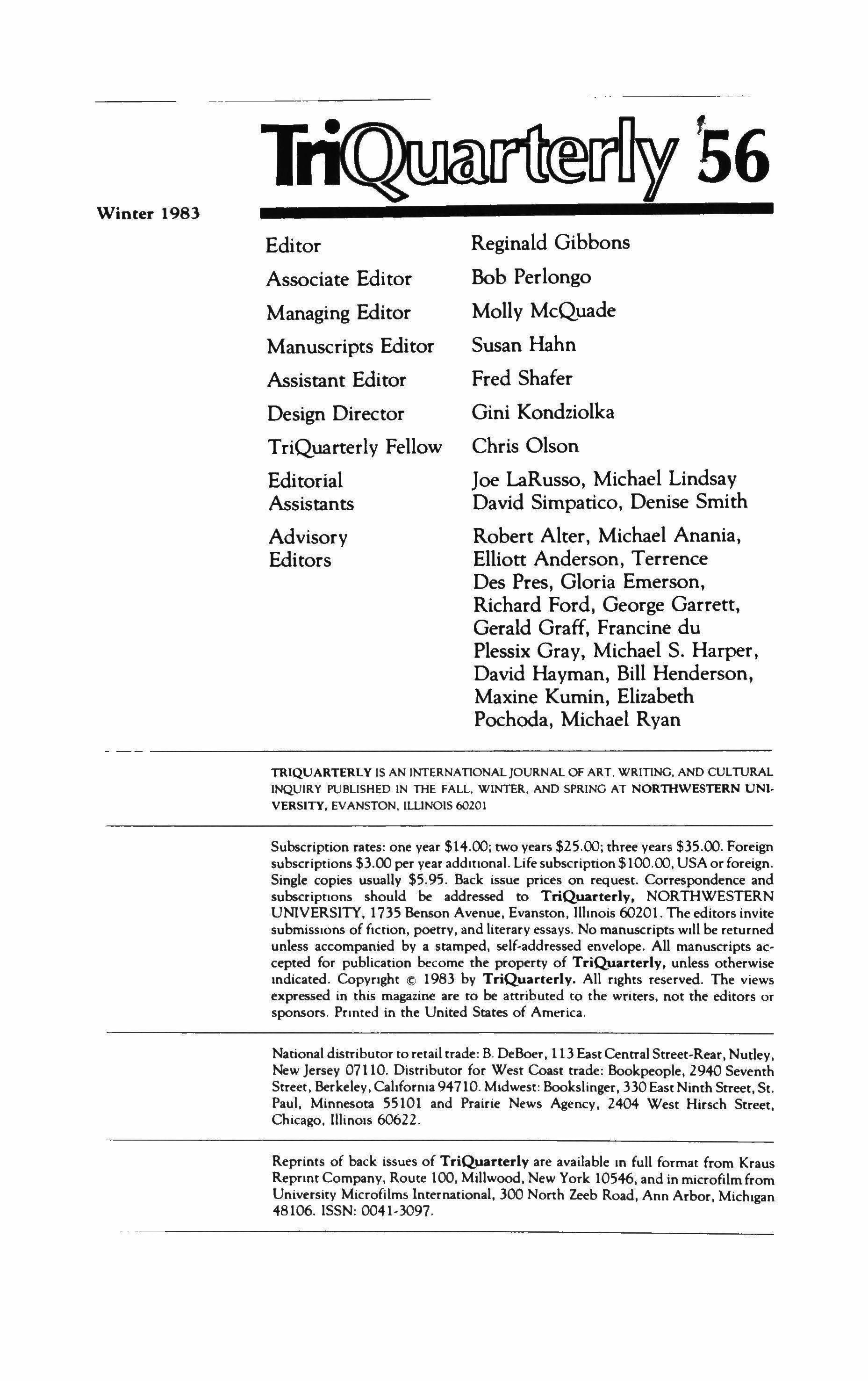

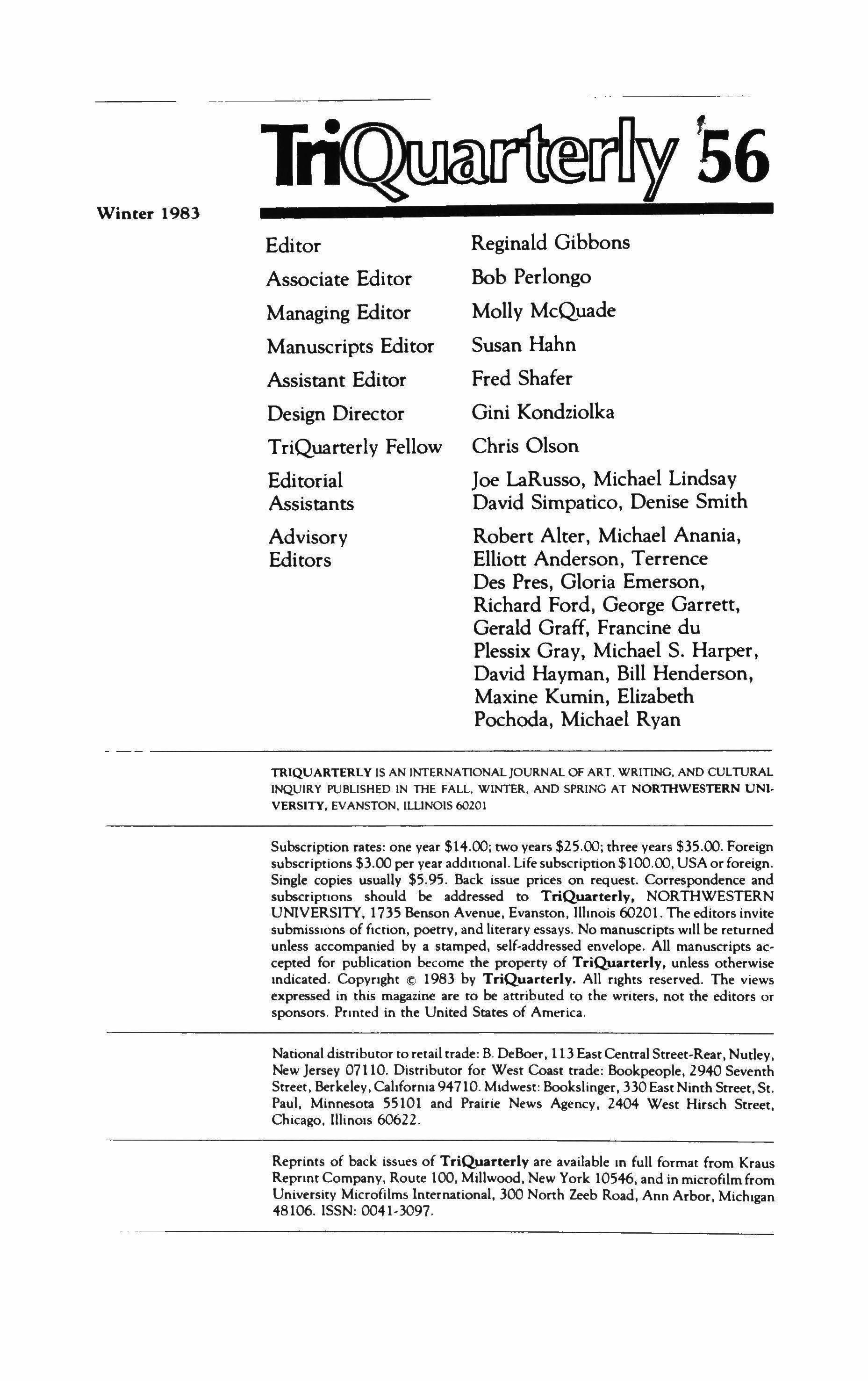

Editor

Associate Editor

Managing Editor

Manuscripts Editor

Assistant Editor

Design Director

TriQuarterly Fellow

Editorial Assistants

Advisory

Editors

Reginald Gibbons

Bob Perlongo

Molly McQuade

Susan Hahn

Fred Shafer

Gini Kondziolka

Chris Olson

Joe laRusso, Michael Lindsay

David Simpatico, Denise Smith

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Elliott Anderson, Terrence

Des Pres, Gloria Emerson, Richard Ford, George Garrett, Gerald Graff, Francine du Plessix Gray, Michael S. Harper, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Maxine Kumin, Elizabeth Pochoda, Michael Ryan

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART. WRITING. AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED IN THE FALL. WINTER. AND SPRING AT NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY. EVANSTON. ILUNOIS 60201

Subscription rates: one year $14.00; two years $25.00; three years $35.00. Foreign subscriptions $3.00 per year addmonal. Life subscription $100.00. USA or foreign. Single copies usually $5.95. Back issue prices on request. Correspondence and subscripnons should be addressed to TriQuarterlv, NORTHWESTERN UNiVERSITY, 1735 Benson Avenue, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite subrnissions of ficnon, poetry, and literary essays. No manuscripts WIll be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterlv, unless otherwise Indicated. Copvnght � 1983 by TriQuarteriv. All nghrs reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Prmted in the United States of America.

National distributor to retail trade: B. DeBoer, 113 East Central Street-Rear, Nutley, New Jersey 07110. Distributor for West Coast trade: Bookpeople, 2940 Seventh Street, Berkeley, Caltfornta 94710. MIdwest: Bookslinger, 330 East Ninth Street, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101 and Prairie News Agency, 2404 West Hirsch Street, Chicago, lllinors 60622.

Reprints of back issues of Tri�rterlv are available In full format from Kraus Reprmr Company, Route 100, Millwood, New York 10546, and in microfilm from University Microfilms International, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106. lSSN: 0041-3097.

Winter 1983

With this issue, TriQuarterly welcomes two new Advisory Editors, Elizabeth Pochoda and Michael Ryan.

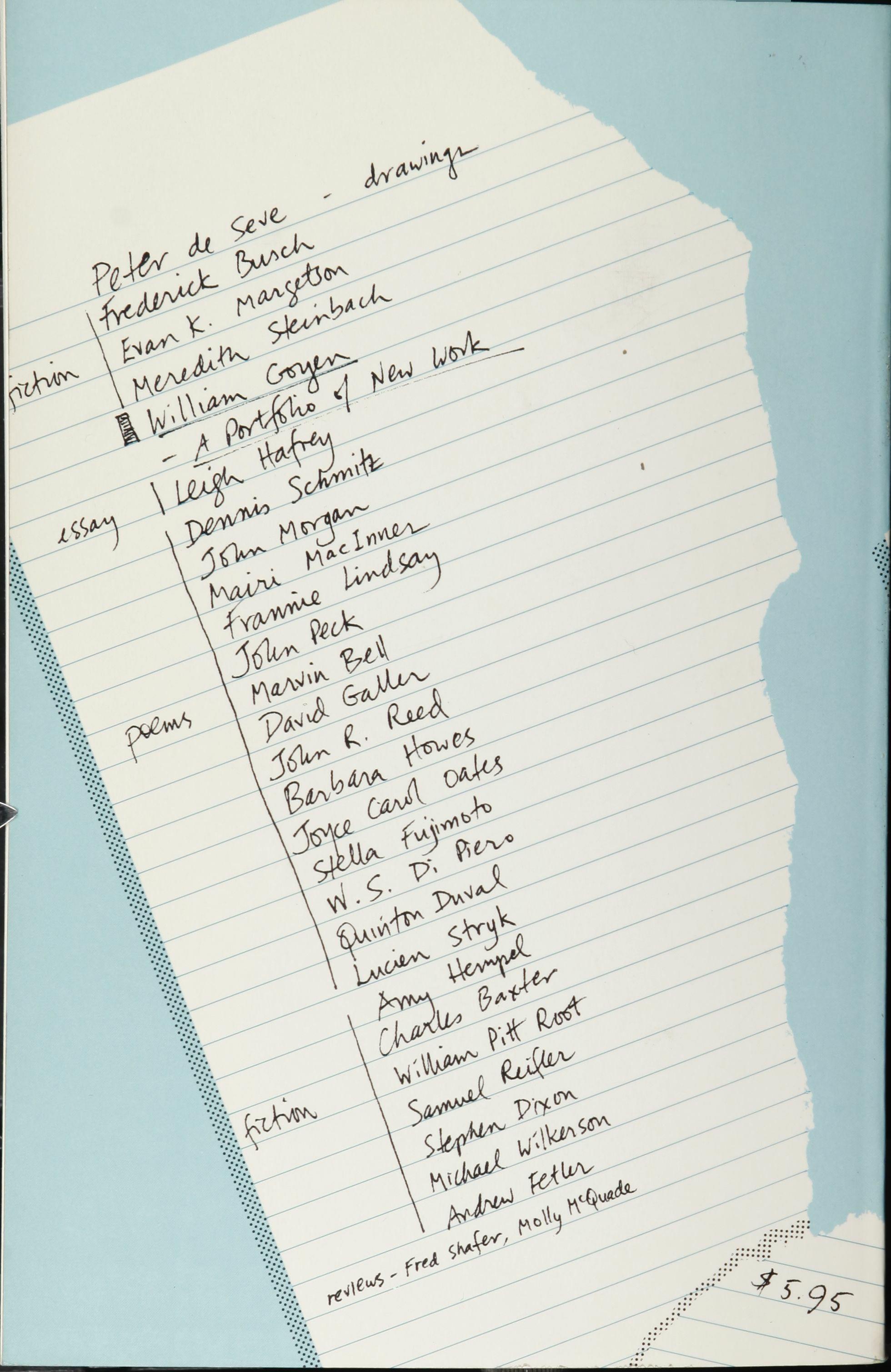

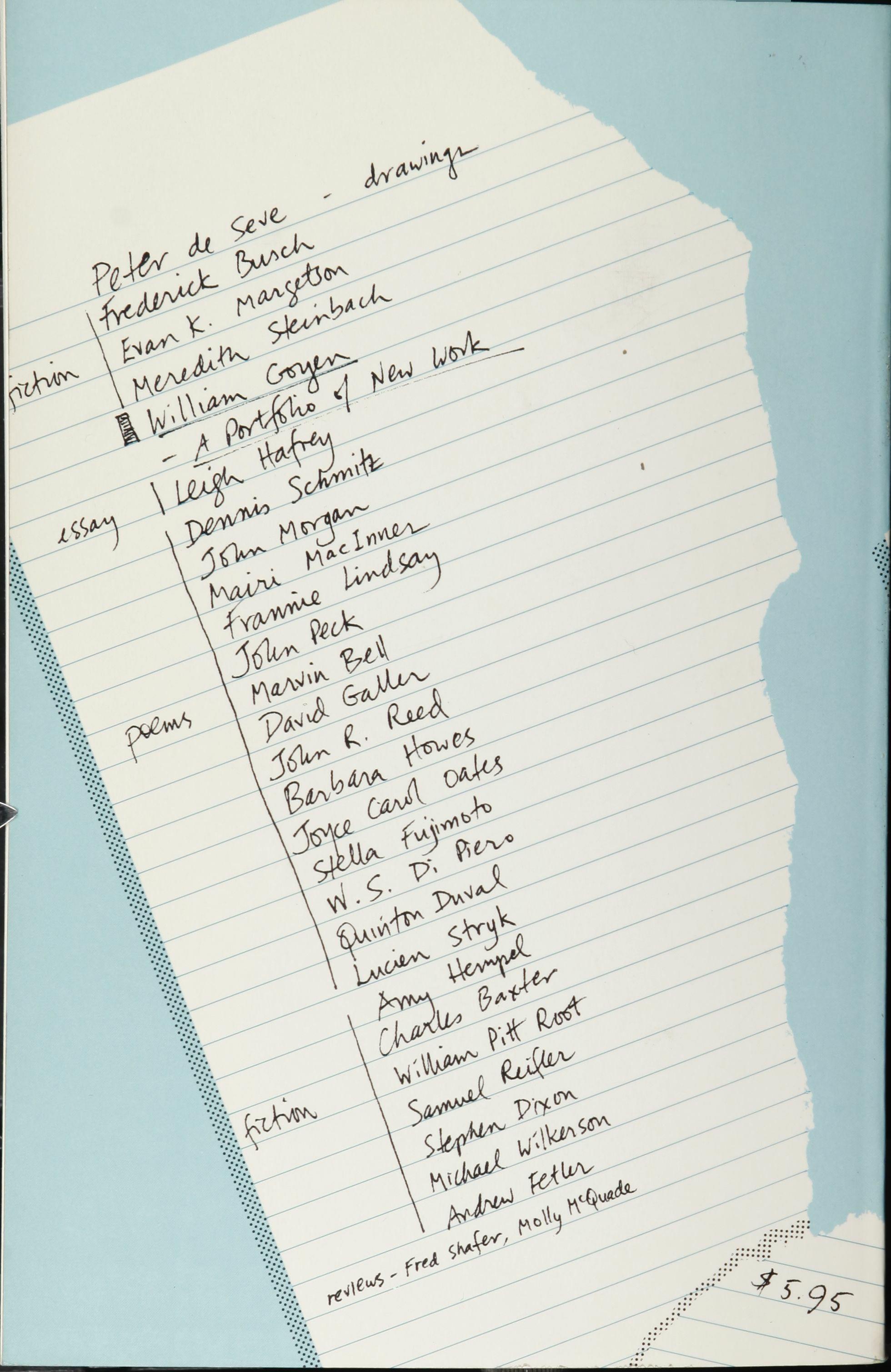

Table of Contents fiction The settlement of Mars Frederick Busch Veterans 14 Evan K. Margetson The very dead 22 Meredith Steinbach 5 New work, work in progress, and an interview 49 William Goyen In the cemetery where AI jolson is buried Amy Hempel 175 Weights 183 Charles &xter Who's to say this isn't love? 197 William Pitt Root Ethnic warp and woof 208 Samuel Rei{Ler Time to go 215 Stephen Dixon At war 228 Michael Wilkerson The third count Andrew Feiler 238 poetry Three poems 137 Dennis Schmitz Ambush 141 John Morgan Three poems 143 Mairi MacInnes 3

Figure by a chimney 147 Frannie Lindsay Two poems John Peck Two poems Marvin Bell Two poems David Galler Trash 158 John R. Reed Super inferno: midway mall 159 Barbara Howes 148 152 155 Two prose poems 161 Joyce Carol Oates Make her wait Stella Fujimoto Three poems 166 W. S. Di Piero 165 Two poems 171 Quinton Duval The great exception Lucien Stryk 173 nonfiction The gilded cage: postmodernism and beyond 126 Leigh Hafrey Reviews: Saint Augustine's Pigeon, Evan S. Connell; The Twofold Vibration, Raymond Federman 260 Contributors 264 Cover by Gini Kondziolka Story illustrations by Peter de Seve 4

The settlement of Mars

Frederick Busch

It began for me in a woman's bed, and my father was there though she wasn't. I was nine years old, and starting to age. "Separate vacations," then, meant only adventure to me. My bespectacled mother would travel west to attend a conference about birds; she would stare through heavy binoculars at what was distant and nameable. My father and I would drive through Massachusetts and New Hampshire into Maine, where he and Bill Brown, a friend from the army, would climb Mount Katahdin and I would stay behind at the Brown family's farm.

And it was adventure-in the days away from New York, and in the drive alone with my father in the light-green '49 Chevrolet, and in my mother's absence. For she seemed to be usually angry at someone, and my father struck me as usually pleased with the world, and surely with me. And though I knew enough to understand that his life was something of a secret he didn't tell me, I also knew enough at nine to accept his silence as a gift: peace, which my mother withheld by offering the truth, in codes I couldn't crack, of her discontent.

I remember the dreamy, slow progress of the car on heat-shimmered highways, and my elbow-this never was permitted when we all drove together on Long Island-permanently stuck from the high window. We slept one night in a motel that smelled like iodine, we ate lobster rolls and hot dogs, I discussed the probable settlement of Mars, and my father nodded gravely toward my knowledge of the future.

He gave me close escapes-the long, gray Hudson which almost hit us, because my father looked only ahead when he drove, never to the side or rear, as we pulled out of a service station; the time we had a flat and the jack collapsed twice, the car crashing onto the wheel hub, my father swearing-"Goddamn it!"-for the first time in my hearing; and the time he let the car drift into a ditch at the side ofthe road, pitching us nose-down, rear left-side wheel in the air, shaken and stranded until a farmer on a high tractor towed us out and sent us smiling together on

5

our way: my father bared his teeth to say, "It's a lucky thing Mother isn't here," while I regretted the decorum I had learned from him-l was not to speak without respect of the woman with binoculars who had journeyed from us.

I thought of those binoculars as we approached the vague shapes of weathered gray buildings, wished that I could stare ahead through them and see what my life, for the next little while, might offer. But the black Zeiss 12 X 50s were thousands of miles from us, and really further than that: they were in my memory of silent bruised field trips, when my father's interest would be in covering ground, and my mother's would be expressed in the spraddle-legged stiffness with which she stared at birds up a slope I knew my father wanted to be climbing.

Bill Brown was short and mild in silver-rimmed glasses. He wore a striped engineer's cap with a long bill, and he smiled at everything my father said. Milly Brown was taller than Bill, and was enormously fat, with wobbling arm flesh and shaking jowls and perpetual streaked flushes on her soft round cheeks. Their daughter, Paula, was fourteen and tall and lean and beautiful. She had breasts. Sweat, such an intimate fact to me, stained the underarms of her sleeveless shirt. She wore dungarees that clung to her buttocks. She rolled the cuffs to just below her knees, and I saw the dusk sun light up golden hairs on her shins. She had been assigned to babysit me for the visit. I could not imagine being babysat by so much of everything I had heard rumored, and was beginning to notice in playgrounds, secrets of the other world.

We ate mashed potatoes and a roast that seemed to heat the kitchen which, like the other rooms in the house, smelled of unwashed bodies and damp earth. I slept that first night on a cot in Paula's room, and I was too tired even to be embarrassed, much less thrilled, by the proximity; I slept in purest fatigue, as if I had journeyed on foot for weeks to another country, in which the air was thin. Next day, we walked the Browns' land-I could not take my eyes from Paula's spiny back and strong thighs as we climbed fences, as she helped me, her child-assignment, up and over and down-and we ate too much hot food, and drank Kool-Aid (forbidden, because too sugary, at home), and we sat around a lot. I rejoiced in such purposelessness, and I suspected that my father enjoyed it too, for our weekend days at home were slanted toward mission; starting each Saturday morning, we tumbled down the long tilted surfaces of the day into weeding and pruning and sweeping and traveling in the silent car to far-offfields to see if something my mother knew to be special was fluttering over marshes in New Jersey or forests in upstate New York.

My father, who made radio advertisements, spoke a little about his

6

work, and Bill Brown said in his pleased soft voice that he had heard my father's ads. But when Bill said, "Where do you get those crazy ideas, Frank?" my father turned the conversation to potato farming, and the moth collection which Bill and Milly kept together, and the maintenance of trucks. I knew that my father understood nothing about engines. He was being generous again, and he was hiding again while someone else talked of nothing that mattered to the private man who had taught me how to throw a baseball, and how to pack a knapsack, and how-I know this now-to shelter inside other people's words. And there was Paula, too, smoking cigarettes without reprimand, swinging beside me on the high-backed wooden bench which was fastened by chains to the ceiling of their porch. I breathed her smoke as now I'd breathe in perfume on smooth, heated skin.

In reply to a question, my father said, "Angie's in Colorado."

"All the way out there," Milly said.

Bill said, "Well."

"Yes, she had a fine opportunity," my father said. "They gave her a scholarship to this conference about bird migration, I guess it is, and she just couldn't say no."

"I'd like to go there some time," Paula said, sighing smoke out.

"Wouldn't you, though?" Milly growled in her rich voice. "Meet some Colorado boys and such, I suspect?"

"Give them a chance to meet a State of Maine girl, don't forget," Paula said. "Uncle Frank, didn't you want to go to Colorado?"

My father's deep voice rumbled softly. "Not when I can meet a State of Maine girl right here, hon. And don't forget, your father and I already spent some time in Colorado."

"Amen that it's over," Bill said.

"I saw your father learn his manners from a mule out there, didn't I, Bill?

"Son of a bitch stepped so hard on my foot, he broke every damned bone inside it. Just squatted there, Frank, you remember? Son of a bitch didn't have the sense to get off once he'd crushed it. It took Frank jumping up and down and kicking him just to make him wake and look down and notice he already done his worst and he could move along. Leisurely, as I remember. He must of been thinking or something. I still get the bowlegged limps in wet weather. I wouldn't cook a mule and eat one if I was starved to death."

"Well, didn't she-" Paula said.

"Angie," I said. I felt my father look at me across the dark porch.

"Didn't Angie want to come up here and meet us?" Paula asked.

Milly said, "Couldn't you think of any personal questions you would like for Frank to answer for you?"

7

"Well, I guess I'm sorry, then."

"That's right," Milly said.

"It was one hell of a basic training," Bill said. He said it in a rush. "They had us with this new mountain division they were starting up. Taught us every goddamned thing you could want to know about carrying howitzers up onto mountains by muleback. How to get killed while skiing. All of it. Then, they take about three hundred of us or so and send us by boat over to some hot jungle they once heard of. Ship all our gear with us too, of course. So we land there in the Philippine Islands with snowshoes, skis, camouflage parkas, light machine guns in white canvas covers, for gosh-sakes, and they ask us if we'd win the war for them."

"It took us a while," my father said.

"Didn't it now?"

Bill went inside and returned with a bottle and glasses. He sat down next to my father, and I heard the gurgle, then a smacking of lips and, from my father, a low groan of pleasure, of uncontrol, which I hadn't heard before. New information was promised by that sound, and I folded my arms across my chest for warmth and settled in to learn, from the invisibility darkness offered, and from the rhythm of the rattle of bottle and glass.

I was jealous that Paula wanted boys in Colorado when I was there, and I was resigned-it was like fighting gravity, I knew-to not bulking sizably enough. Their voices seemed to sink into the cold black air and the smell of Paula's cigarettes, and I heard few whole wordsnothing, surely, about my vanished mother, or about my father and me-and what I knew next was the stubbly friction of my father's cheek as he kissed me goodbye and whispered that he'd see me soon. I thought that we were home and that he was putting me to bed. Then, when I heard the coarse noise of Bill's truck, I opened my eyes and saw that I was on the canvas cot in Paula's room in a bright morning in Maine. I was certain that he was leaving me there to grow up as a farmer, and I almost said aloud the first words that occurred to me: "What about school? Do I go to school here?" School meant breakfast, meant wearing clothes taken from the oak highboy in the room in Stony Brook, Long Island, meant coming downstairs to see my father making coffee while my mother rattled at The Times. The enormity of such stranding drove me in several directions as I came from the cot, "What about school?" still held, like scalding soup, behind my teeth and on my wounded tongue.

Paula, at the doorway, shaking a blouse down over her brassiere-I could not move my eyes from the awful power of her underwearcalled through the cloth, "Don't you be frightened. You fell asleep and

8

you slept deep. Frank and Daddv're climbing, is all. Remember?" Though the cotton finally fell to hide her chest and stomach, I stared there, at strong hidden matters. We ate eggs fried in butter on a woodfired stove while Milly drank coffee and talked about a dull moth which lived on Katahdin and which Bill might bring home. I stared at Paula's lips as they closed around corners of toast and yellow runny yolks.

We shoveled manure into the wheelbarrow Paula let me push, and we fed their dozen cows. One of them she'd named Bobo, and I held straw to Bobo's wet mouth and pretended to enjoy how her nose dripped. I listened to the running-water noises of their stomachs, and I looked at the long stringy muscles in Paula's tanned bare arms. Her face, long like her mother's, but with high cheek bones and wide light eyes, was always in repose, as if she dreamed as she worked while miming for me the nature of her chores and the functions of equipment. I watched the sweat that glistened under her arms and on her broad forehead, and she sounded then like my father, when he took me to his office on a school holiday: I was told about the surfaces of everything I saw, but not of his relation to them, and therefore their relation to me. In Lincoln, Maine, as on East Fifrv-second Street in Manhattan, as in Stony Brook, New York, the world was puzzling and seductive, and I couldn't put my hands on it, and hold.

We went across a blurred meadow that vibrated with black flies and tiny white butterflies which rose and fell like tides. On the crest of a little hill, under gray trees with wide branches and no leaves or fruit, Paula lay flat, groaning as if she were old, and stared up through bugclouds and barren limbs and harsh sun. "Here," she said, patting the sparse fine grass beside her. "Look."

I lay down next to her as tentatively as I might lie now beside a woman whom I'd know I finally couldn't hold. Her arm was almost touching mine, and I thought I could feel its heat. Then the arm rose to point, and I smelled her sweat. "Look," she said again. "He looks like he's resting awhile, but he's hanging onto the air. That's work. He's drifting for food. He'll see a mole from there and strike it too."

Squint as hard as I might, there was nothing for me but bright spots the sun made inside my eyes. I tried to change the focus, as if I looked through my mother's binoculars, but I saw only a branch above us, and it was blurry too. I blinked again; nothing looked right.

"I guess I saw enough birds in my life," I told her.

"That's right, isn't it? Your mother's a bird-watcher. In Colorado, too. I guess there's trouble there."

"They're taking separate vacations this year."

"They sure are. That's what I mean about trouble. Man and wife live

9

together. That's why they get married. They watch birds together, if that's what they do, and they climb up mountains together, and they sleep together in the same bed. Do Frank and Angie sleep in the same bed?"

I was rigid lest our arms touch, and the question made me stiffer. "I don't see your mother climbing any mountains," I said.

"Well, she's too fat, honey. Otherwise she would. And if this wasn't a trip for your father and mine to take alone, a kind of special treat for them, you can bet me and Momma would be there, living out of a little canvas tent and cooking for when Daddy came back down, bug-bit and chewed up by rocks. And you won't find but one bed for the two of them. I still hear them sometimes at night. You know. Do you?"

"Oh, sure. I hear my mom and dad too." That was true: I heard them talking in the living room, or washing dishes after a party, or playing music on the Victrola. "Sure," I said, suspecting that I was soon to learn things terrible and delicious, and worried not only because I was ashamed of what I didn't hear, but because, if I did hear them, I wouldn't know what they meant. The tree limb was blurred, still, and I moved to rub my eyes.

Then that girl of smells-her cigarette smoke layover the odor of the arm she'd raised-and of fleshy swellings and mysterious belly and the awesome mechanics of brassieres, the girl who knew about me and my frights, about my parents and their now-profound deficiencies, said gently, "Come on back to my room. I'll show you something."

When she stood, she took my hand; hers was rough and dry and strong. She pulled me back over field and fences, and I thrilled to the feel of flesh as much as I hated the maternity with which she towed me. But I thought, too, that something alarming was about to be disclosed. I couldn't wait to be told, though I was scared.

Milly was putting clothes through a mangle near the rain barrel, and she waved as we passed. We went through cool shadows into the room Paula had decorated with Dick Powell's picture, and Gable's, and on the far wall a blurred someone with a mustache wore tights and feathered hat and held a sword.

"My library," she said, opening the closet. "Here." And on shelves, stacked, and in shaggy feathering heaps on the closet floor, were little yellowing books and bright comics and magazines which told the truth about the life of Claudette Colbert and Cary Grant. I doubt that she knew what I needed, for she was mostly a teenage kid on a little farm in Maine. She wasn't magical, except to me in her skin, although she was smarter than me about the life I nearly knew I led. But something made her take me from the swarm of sun and insects, the high-hanging

10

invisible bird of prey-that place where, she possibly knew, I sensed how much of my life was a secret to me-and she installed me on the dirty floor of a dirty house, in deepening afternoon, half-inside a closet where, squinting, I fell away from the world and into pictures, words.

I read small glossy-jacketed books, little type on crumbling wartime paper, some line drawings, about Flash Gordon and Ming the Merciless and the plight of the always-kidnapped Dale. I read about death rays and rockets that went to Mars from Venus as quickly as they had to for the sake of mild creatures with six arms who were victimized by Ming's high greed. Dale and the other women had very pointed breasts and often said, "Oh, Flash, do you really think so?"

And there was Captain Marvel, whose curling forelock was so much like Superman's, but whom I preferred because I thought we looked alike and because he never had to bother to change his clothes to get mighty: he said Shazam! and a lightning bolt made him muscular and capable of rescuing women with long legs. I read of Superboy, whose parents in Smallville were so proud of him. Littler worlds, manageable by me, and on my behalf by people who could change, whether in phone booths or storerooms or explosions of light, into what they needed to be: Aqua-Man, Spider Man, the Green Lantern, wide, nostriled Wonder Woman in her glass airplane, and always Flash and Dale, "Oh, Flash, do you really think so?"

For a while, Paula sat behind me, cross-legged on her bed, reading fan magazines and murmuring of Gary Cooper's wardrobe and the number of people Victor Mature could lift into the air. When she went out, she spoke and I answered, but I don't remember what we said. I leaned forward in the darkness, squinting and forgetting to worry that I had to screw my face around my eyes in order to see, and I stayed where I was, which was away.

They had a radio, and we listened to it for a while after dinner, and then Milly showed me, in a room off the kitchen, board after board on which dead moths were stiffly pegged. I squinted at them and said "Wow," and while Paula and Milly sat in sweaters on the porch and talked, I squatted in the closet's mouth, under weak yellow light, and started Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Chessmen of Mars. When Paula entered to change into nightclothes, I was lured from the cruel pursuit of Dejah Thoris by Gahan of Gathol, for the whisper of doth over skin was a new music. But I went back with relief to "The dazzling sun, light of Barsoom clothed Manator in an aureole of splendor as the girl and her captors rode into the city through the Gate of Enemies."

When Paula warned me that the lights were going off, I stumbled toward my cot, and when they were out I undressed and went to sleep,

11

telling myself stories. And next day, after breakfast, and a halfhearted attempt to follow her through chores, I walked over the blurred field to the rank shade of Paula's room, and I sat in the closet doorway, reading of Martian prisons, and heroes who hacked and slew, unaware that I had neither sniffed nor stared at her, and worried only that I might not finish the book and start another before my father and Bill returned. They didn't, and we ate roast beef hash and pulpy carrots, and Milly worked in the shed on the motor of their kitchen blender while Paula listened to "Henry Aldrich" and I attended to rescues performed by the Warlord of Mars.

It was the next afternoon when my father and Bill returned in the truck. They were dirty and tired and beaming, and they smelled like woodsmoke. My father hugged me and kissed me so hard that he hurt me with his unshaved cheeks. He swatted my bottom and rubbed my shoulders with his big hands. Bill presented Milly with a dirty little moth and she clapped her hands and trilled. Paula smoked cigarettes and sat on the porch between Bill and my father, listening, as if she actually cared, to Bill's description of how well my father had done to follow him up Abel's Slide, where the chunks of stone were like steps too high to walk, too short and smooth to climb, and up which you had to spring, my father broke in to say, "Like a goat in a competition. I thought my stomach would burst, following this-this kid. That's you, Bill, part mountain goat and part boy. I don't know how you stayed young for so long. You were the oldest man in the outfit, and what you did was you stayed where you were and I got ancient."

"Nah. Frank, you're in pretty good shape. For someone who makes his living by sitting on his backside. I'll tell you that. You did swell."

"Well, you did better. How's that?"

Bill swallowed beer and nodded. "I'd say that's right."

And they both laughed hard, in a way the rest of us could only smile at and watch.

"Damn," my father said, smiling so wide. "Damn!"

My head felt hot and the skin of my face was too tight for whatever beat beneath it. They were shimmery shapes in the afternoon light, and I rubbed my eyes to make them work in some other way. But what I saw was as through a membrane. Perhaps it was Paula's cool hand on my face that did it, and the surge of smells, the distant mystery of her older skin and knowledge which I suddenly remembered to be mastered by. Perhaps it was the distance my father had traveled over and from which, as I learned from the privacies of his laughter, he still had not returned. Perhaps it was Milly, sitting on the porch steps next to Bill, her hand on his thigh. Or perhaps it was the bird I couldn't see which hung over Lincoln, Maine, drifting to dive. I pushed my face against Paula's hard hand and I rubbed at my eyes and I started to

12

weep long coughing noises which frightened me as much as they must have startled the others.

My father's hobbed climbing boots banged on the porch as he hurried to hold me, but I didn't see him because I knew that if I opened my eyes I would know how far the blindness had progressed. I didn't want to know anything more. He carried me inside while I wailed like an hysterical child-which is what I was, and what I'm sure I felt relieved to be. I listened to their voices when they'd stilled my weeping and asked me questions about pain. I swallowed aspirin with Kool-Aid and heard my father discover the comics and the books I'd read while on my separate vacation. And the relief in his voice, and the smile I heard riding on his breath, served to clench my jaw and lock my hands above my eyes. Because he knew, and they knew, and I still didn't, though I now suspected, because I always trusted him, that I wouldn't die and probably wouldn't go blind.

"Just think of your mother's glasses, love," he whispered while the others walked from the room. He sat on the bed and stroked my face around my fists, which still stayed on my eyes. "Mother has weak eyes, and these things can be passed along-the kids can get them from their parents."

"You mean I caught it from her?"

The bed I was in, Paula's bed-l smelled her on the pillow and the sheets-shook as he nodded and continued to stroke my face. "Like that. Just about, yes. I bet when we go home, and we go to the eye doctor, he'll put a chart up for you to read. Did you have these tests in school? He'll ask you to read the letters, and he'll say you didn't see them too clearly, and he'll tell us to get you some glasses. And that's all. I promise. It isn't meningitis, it isn't polio-" "Polio?" I said. "Polio?"

"No," he said. "No. No, it isn't a sickness. I'm sorry I said that. I was worried for a minute, but now I'm not, I promise. You hear? I'm promising you. Your eyes are weak. Your head'11 feel better from the aspirin-it's just eyestrain, love. It's nothing more."

"Yeah," I said. "Some dumb vacation. I should have gone with Mommy."

I lay in a woman's bed, and in the warmth of her secrets, and in the rich smell of what was coming to me. And my father sat there as his large hands gentled my face. His hands never left me. I dropped my fists, though I kept my eyes closed tight. I felt his strong fingers, roughened by rocks, as they ran along my eyebrows, touched my cheeks, my hairline, my forehead, then eyebrows again, over and over, until, with great gentleness, they dropped upon the locked lids, and he said, "No, no, this is where you should be." So I hid beneath my father's hands, and I rested awhile.

13

Veterans

Evan K. Margetson

The scar that J. G. brought home from 'Nam was not made by a bullet. He got it from a VC prisoner Charlie Company ran a train on in Quang Tri. She had passed out from an overdose of fun but that didn't stop the party. When she woke up J. G. was on top and she took a yank out of his cheek like it was a cheeseburger. He knocked her back out, finished his turn, and then snuffed her with his bayonet. The story of the look on his face when the little beaver woke up was famous on the front. Hell, it was folklore, he had been a star.

Before he got back, J. G. didn't think much about what he would tell people concerning the dent in his face. In the war he had never been anything but proud of it and how he got it. So tonight in the bar, he hadn't been really ready when the woman he was talking to, a bold brown sister with her hair in long braids, just asked him straight out, "Say, brother, how'd you get your beauty mark there?"

The truth suddenly did not seem all that heroic, and in fact would probably have blown his rap.

"I was in 'Nam," he said. "I got this in an ambush."

"Yeah? Who was ambushing who?" she asked.

"I guess we did it to them," J. G. said.

"You had to get close, huh?" she asked.

"One damn near bit my nose off is how I got this," J. G. said. He let her get a better look.

"He gave you the serious Vietnamese facial," she said.

"Yeah, but I gave him the Horrible Harlem nose job with my M� 16," J. G. said.

"You a dangerous man then. I don't know if I should even be talking to you."

14

"Nah, it ain't like that, baby. I'm just patriotic, you know?" J. G. said.

"Hey, it's Mr. Uncle Sambo himself!" she said and leaned back to laugh.

J. G. was snapping along till his look froze on her throat. His scar was burning and itching and he started sweating like he had a fever.

"Hey, brother, are you too high or is there a bug on my neck?" she asked him.

J. G. tried to smile but it carne out mean. He felt like dragging her out by those braids and putting it to her on the hood of a car. He wanted to kiss her.

She stepped back from him. "You scaring me, man," she said.

J. G. refocused his eyes and said, "Don't mean to, baby. I only been back for a few days is all. Ain't no sisters in 'Nam."

"Well, we still here," she said.

"You right," J. G. said, "but I ain't sorry."

"Don't be," she said. "Just don't be looking at me like that cause when I get scared I get mad and you don't know how wild I can be."

"Whoa, lighten up," J. G. said. "It's just that you were looking so fine I had to take a long hard scope to more totally comprehend the magnitude of the star I am having the pleasure of conversing with."

"Now you talking, brother," she said. "C'mon, you still know how to party, right?"

"What?" J. G. said. "Baby, the day I forget how to boogie will be the day I died."

"All right, let's see it then," she said.

J. G. put his hand on her waist and they strolled over to the dance floor.

It was rocking. Thighs were thumping, butts were bumping, sweat was flowing from 'fros and processes alike.

"Work the mad out y'all!" somebody shouted.

"I hear you, brother!"

Jitterbugs and ladybirds were stepping and skating, frowning and grinning, mixing slick mad moves in a soul deep groove.

"Ouch! Too mean, girl!"

"Later for Nixon! He can't stop this jam!"

J. G. was dipping and gyrating to Tandra's slides and motorized spirals. They were getting down so hard that J. G. forgot about his face. All he could see was hers and it was making him feel downright holy.

"I see you stepping, soldier!"

"Got to, baby, to keep up with you!"

16

"Well, look out-I'm just getting started!"

"Won't shake me, lady, I am on the case!"

]. G. pulled a turnaround squat and caught a view from under of Tandra, her eyes slitted and her head laid back to the side. She had a look on her face like the music was making direct hits on her pleasure centers and the ball of mirrors hanging from the ceiling behind her was the fireworks. ]. G. eased up slow, following the curves of her body with his hands, inspecting the goods so close he bumped his nose on a tit and could smell nature under her arms.

The funk was fading out and mellow horns said a slow tune was coming on. All around ]. G. and Tandra bodies were answering that call-to-grind and starting to rub the creases out of each other's clothes. ]. G. shouted "Thank you, brother!" to the D] for his timing, put his arms around those smooth brown shoulders and made heavenly frontal contact. Her sweet hot spot was burning his crotch. He went for a cheek-to-cheek so he could whisper and croon some, but when she felt that cool slick part of his on hers she flinched and drew back. She put her hands on his chest and smiled like she was sorry.

"I'm going to take a little break, sugar, O.K.?" she said.

She tried to slip away but ]. G. wasn't letting go so easy.

"What's the matter," he said, "you don't like this song?"

"It's all right, I just want to take a break I said "

"Hey, I can put my face on the good side so "

"Your face is cool, man. I think it must be the pace-you know?" She pushed against him a little harder.

"We could just stand here and move real slow,"]. G. said and tried to pull her tighter.

"Maybe you not getting the message!" she said, and stamped on his foot.

"Aaaw shit!" ]. G. let go and Tandra sashayed over to the bar. ]. G. shouted out to her back, "If we was in the war, I'd kill you, bitch!"

She stopped, turned around slow and said, "What?! Well, come on then, motherfucker!" She whipped something out of the disco bag she had over her shoulder. "I got something for your ass!" she shouted. It was a small piece but she was coming at]. G.like she knew how to use it. The dance floor had cleared like magic and he was left standing alone under the mirror-ball.

Tandra came right up to]. G. and jabbed the petite firearm in his stomach. "Well? Now what did you say, Mr. So Bad?" she said.

"Back off, brother!" somebody said.

"Shouldn't mess with Tandra!"

"They need to take that outside!"

17

J. G. looked her up and down. He hooked his thumbs under his armpits and cleared his throat. He said into her eyeball, "I'm the killer dick of the DMZ, I'm the one-man train of Charlie Company. I got a grenade for my left nut and a land mine on the right. I got a bazooka in the middle that'll make you holler all night!"

Their faces were so close they could've kissed. On the sidelines folks were enjoying the show.

"Talk yo' way out of it, bro'!"

"Five dollars says she fires him up!"

"She will do it too!"

"Quiet y'all-what's she saying now?"

Tandra dug the piece deeper into J. G.'s ribs. "That ain't what you said. Now I want to hear what you said about ME!"

J. G. looked around but all he could see was shadows in the smoke and no help. He thought about breaking her arm, but he wasn't that mad anymore. He felt like there was a spotlight on his scar. He sucked his teeth like he was bored and looked down at her.

"I said .if we was back in the war .for what you just did to my foot? I would have dusted you!" As he said the last thing he grabbed her hand and jerked it up so she fired into the ceiling. She dropped the iron and J. G. kicked it away.

"Lemme out of here!"

"They ain't playing now!"

Tandra connected with a left hook to J. G.'s eye before he could pin her arms. Her voice was going supersonic in his ear. "Who you think you messing with, nigger? I'll kill your ass!" She was trying to bite and scratch and was shaking her head so that her braids whipped]. G. on his neck. "I'll cut up the other side of your ugly face!"

The bouncers showed up now that the gun was out of the way and pulled J. G. and Tandra apart. One dragged her over to the bar while the other two wrestled]. G. across the floor and out the door with him shouting, "That's right, this is ]. G. from the DMZ, baby-and don't you forget it!"

They took him outside and dropped him on the sidewalk. They stomped on his chest a couple of times for effect. "Yo', man," one of them said. "Don't show around here no more, or you gonna wish you was back at the war, dig? We don't go for that gorilla shit here-so check yourself out. You in civilization now, understand?" The two heroes went back inside.

J. G. pulled himself up on the fender of a car and brushed himself off. Two obvious bulls in a bogus taxi rolled by. He gave them the finger and bopped up the street, trying to figure out how much cash he could get together for a ticket to somewhere.

Up on Broadway he bought a beer in a deli and copped a jay from a

18

no-toothed Puerto Rican outside the porno movie house. After he smoked he felt like the buildings were closing in on him so he crossed to the traffic island separating the up and downtown lanes. There was a bench on it and he sat down to drink his beer. He felt better on the island. He could see people coming from far away and anybody would be able to see him. If they were too scared to pass him by he wouldn't have to see their faces when they made up their minds.

J. G. downed the rest of his brew and threw the bottle so it broke in the street. He wished it were a grenade. "Shirl" He started poking the air like on some unbeliever's chest. "That's right, baby, I'm one dangerous motherfucker, so you better cross the street when you see me coming. My scar is my star and if you stop and stare I say you better be-ware!" The street was quiet like all the buildings were listening close. J. G. stood up to testify better. "I got a M, 16 in my left hand, I got a rocket launcher in my right, I'm a master of camouflage, I'll show up in your bed one night. I'm the runaway train of Charlie Company, I'm the raging blaze of the J. G. stopped.

A little white-haired old white lady was crossing the street right to where J. G. was preaching. She was looking him straight in the eye and came and sat down on the bench. She was wearing a black wool coat even though it was hot out, and she had a red plastic rose pinned to her collar. She was so small her feet were swinging inches off the ground. Her face was so wrinkled that her tiny blue eyes seemed like they were peering out at J. G. from behind some bushes. She was carrying a thermos jug under her arm.

She kept staring at J. G. and it was making him mad. "What you staring at, lady?" he said. "You never see a cold killer before?" He gave her his worst side.

She squinted up at him. "You don't look so bad," she said. "Your eyes are too pinchy, but I think all you need is some good fresh fruit."

"Hey! You got that right," J. G. said. "I'd like to pluck me some right now."

She started to unscrew the thermos.

"What you got there, mama?" J. G. said.

She used the top for a cup and poured something clear into it and took a sip. She passed it to him. "You thirsty, maybe?" she said. J. G. took the cup and smelled what was in it. Straight gin. "You old fox, you," he said. He sat down, wiped some spit offthe cup-edge and tossed back the shot. "That was one on-time taste, grandma." The bench started feeling a little more comfortable.

The old lady poured out another splash. "I don't really need this, you know," she said. "I only drink it for want of something better." She downed her shot.

"Yeah, I hear that," J. G. said. He reached for the thermos. "This

19

good liquor will keep you away from that cheap wine." He took a swig out of the bottle and poured one for the old lady. ]. G. settled back and lit a cigarette.

They looked up the avenue at the traffic lights changing.

"I like the night life," the old lady said. "I often come by here and if by chance someone is sitting and they are friendly, then we can chat. It helps me to sleep."

]. G. was mellow, blowing smoke rings. "Chat on, baby," he said.

"In the daytime all these people want to talk about their operations, but I never had an operation so I don't have anything to say to them." She sipped her drink.

"Must be that fresh fruit keeping the doctor away," ]. G. said.

"That's right!" the old lady said. "And you want to know some, thing?" She gave ]. G. a sly look and waved him closer.

"What's that, mama?"

She whispered in ]. G.'s ear. "I never ever woke up to an alarm clock-but I always got to work on time!"

"Hey, don't let the CIA find out," ]. G. said.

"Oh, I'm not afraid of them." She banged her cup on the bench. "I was never afraid in my whole life!"

]. G. took another hit from the thermos. "We shoulda had you in 'Narn, baby."

She held her glass out for a refill. "I wasn't afraid of my father," she said. "He wanted me to marry one ugly cousin of mine but I wasn't going to have any of that! I got on that boat and came over here all by myself. That's right. And everybody got seasick-but not me. Happy as a lark I was."

"We coulda put you on river patrol," ]. G. said. He flicked his cigarette into a greasy puddle.

"I heard a story once," she said. "There was this epidemic of some disease, influenza I think it was, and two hundred and fifty thousand people died. Well, one brave fellow decided that he would go con, gratulate Death. So he goes on a long journey and finally finds him. And he says to Death, 'Congratulations on your success, sir-the epidemic killed two hundred and fifty thousand people.' And you know what Death said?"

]. O. took a slug of the gin. "I'm ready," he said.

She stared into]. G.'s eyes. "So Death says, Well, I thank you very much but the epidemic only took away one hundred thousand-it was Fear that brought me the rest!'"

]. G. scratched his scar. "Yeah, I guess he will do that," he said.

"Huh? Isn't that a good one?" She jabbed ]. O. in his arm and started laughing till she was coughing and her head was almost on her knees.

20

j. O. patted her on her little cricket's back. "That's one hip story, mama-you all right?"

"I'm fine, fine," she said and doubled over again coughing.

"Don't go dying on me now," j. O. said. He patted her on her shoulders some more. He felt kind of silly and was thinking what did that crazy rap have to do with him? She looked up and had tears in the corners of her eyes.

"I just feel a bit tired is all," she said. "Do you mind if I ?" She laid her head on j. O.'s shoulder. He wanted to pull away but he didn't. He thought her head was about as light as a cigarette ash.

j. O. heard a whistle. Across the street, the dude he had copped the reefer from was making circles with his finger to his ear. "Aw shit," j. O. said.

The old lady's head slipped off his shoulder onto his chest and she started snoring. He wanted another smoke but she was leaning on the pocket where his pack was. A bus groaned by and j. O. watched a ball of paper rolling in the slipstream. He remembered he had been wanting to go somewhere.

21

The very dead

Meredith Steinbach

Teiresias, the boy.

That Europa, Agenor's daughter-skinny and impressionable-had been tantalized by the form the god had taken: the pure white hide of the immense animal, the one black mark of death on his forehead, and the cool pink horns. "Oh, what perfect sport it was, when it started," Teiresias' mother told him. "The small child with the russet hair rushing toward the bull, the one never before among her father's cattle, her father's cattle never before on the beach.

"Up sprang the other girls' warnings as she plucked the bright blue {lowers from the rocky seascape and flung them at the beast. Behind her, the companions' cries-like a lyre.

"Closer she skipped as passively the bull rested, his eyes on Knossos, on the rising tide of the Mediterranean between Tyre and that Island. Her buds pelted the black star, the white nest of fur between his horns; and the bull's mild breath issued from the downy nostrils, moistening the edges of her open bodice and the swellings there. Her little chest was unpainted; she was that young.

"And try, Teiresias. Imagine Europa's surprise: to find the bull so gentle toward her-rubbing its long dewlaps against her shoulder, nuzzling her arms. Then, flaunting her courage before her playmates, Europa mounted the god himself, her skirts hiked up to her thighs, her pink toes spurring his hairy flanks.

"The shore people stand as witnesses-they were the ones who saw

22

it," Teiresias' mother said in answer to her son. Round and round went the brush as Chariklo started at the periphery of one breast, painting toward the center, stopping now and then to change from purple to silver, outlining every segment with a thin black shape. Meticulously she spiraled in on herself until, the young boy saw, she had completed half her morning preparations, she had made a final ring of blue-black specks and at the center one sharp crimson dot. She had chosen the red, she said, because they were going off to meet a friend who had a particular liking for that color although the friend, a god, was not calm enough herself to wear it.

Lightly she oiled the other breast and dusted it with powder. The little boy watched the camel-hair brush dipping into the pallet. The brush had come from Egypt, from Thebes-the other one, Chariklo said, smiling at him with her enormous gray-green eyes in that engaged way that made him think of owls. Teiresias watched her nipple wrinkling like fine cloth, standing out as slowly the brush approached it. "The other Thebes," she blinked. "The one in Egypt." In the window, his back to the courtyard, he felt his little legs swing out, bounce back off the summer currents of the room that meant to him the things he saw, and then he felt the sudden jolt at the heels of his sandals as they struck against the wall beneath him: what he felt. Back and forth he pumped his stumpy legs, hoping she would not again interrupt herself. He waited for the song in his ancestry to rise up, fall again, and soar in the oblivion of his mother's voice.

The child was on the animal, the boy was in the window, the brush moved back and forth: "'Oh, look out!' the little girls shouted after her as they saw Europa's womanhood approaching vaguely now, for the bull had begun to amble, slowly, toward the water. It was then that the great god Zeus, in bull's attire, walked cheerfully into the sea, swimming with his prize astride his back; and it is said that the sudden moisture of her hot wet tears was no less than that of the ocean his underparts were parting then.

"All life's matters are relative things," his mother said, "even for the young and impressionable, and what would seem from afar a terrible or a beautiful fate might have looked quite the opposite to a young girl setting her foot again on solid but confusing ground, or to us thinking of it now in our homes, or from the viewpoint of an old man mending nets on the beach. One old man was said to have witnessed it, but all he would say was a bull, a girl, and an eagle on the wing. Which was wise," his mother said. "It is no small matter to infuriate a god who may at any moment turn himself or a man to a beast.

''It is said that the bull turned his amber eyes halfway around in his

24

head to see the slender girl standing beside him, clinging to his ear. In thought, he pawed the ground beside her scrawny legs, her delicate feet. When Europa looked again, her hand was resting on an eagle's head. Even gods show a little pity now and then.

"And who is to say how Europa felt? She would never answer questions, and it is not for gods to speak of their activities to men. Perhaps when he parted her legs with his bitter talons, feathers were lost in the fray; perhaps that day she drew the ichor of a god with her human hand, and rightly so-some say. Maybe the god folded her in the soft down of his new-formed wings as he took her from behind. And then again, perhaps she stroked his golden beak and welcomed him. After all, young women, too, have their own desires. There are many points of view.

"Needless to say, the thing was done. The penis of a bird entered the body of a woman; and three sons were born.

"But that is a matter faraway from you sitting there in your tunic, with the sun in the window behind your head, from me sitting here each morning painting my breasts, and also from the manner in which this little girl's obsessive brother Kadmos, now our king, determined the fate of Thebes."

From the window he could see a sparrow perched across the way, a sprig of cypress clutched in its beak. Teiresias saw the mottled chest, the dark green twig, the small splayed feet.

"Will you think of it!"

Startled, the bird rose in an are, turned on the wind, and disappeared. Teiresias, too, twisted at the sound; he felt his own little neck turn halfway around to face the center of the room. "When once you set out finally to do something, Teiresias," his mother was saying to him now, the orange-tipped brush pointed his way, "put your goods down in the marketplace. Take your chance. Do not sway in the face of distraction. Above all, keep your head!"

But the boy Teiresias had not at all been tempted toward disloyalties, nor had he been by the little bird. She is painting too fast, he thought; she will stop before Father even gets into the story again. And then it was as if he had had two thoughts at once, and nothing was lost for either one in company. They had borne each other up. He set the image of the bird as in a ring around what his mother said. Wing to wing-eagle to sparrow and eagle again-around the picture of what he heard. His mother smiled at him, poured little drops of paint in a vibrant circle around the board she held up in her hand.

25

"All the sons of Agenor were shipped out of Phoinikia-" she said, "the wife and mother, too-in pursuit of Europa, that sparkle turned cinder in her father's eye. Phoinix, Kilix, Phineus, Thasus-each went his own way in search of the red-black hair, the lost child. Kadmos, that eldest brother, wrapped his young arm around his mother's shoulder and together they set the straight horn of his ship into a polished sea. On that ship it was as if their goals were bound together for the first time in their lives; or so the report came back. Telephassa, the anxious mother, said Europa even in her sleep. In a rocking sea, she woke up crying at the thought of a bull dancing on its two hind feet. "Yes," her son called from the next compartment. "There." Briefly he tossed. "We will." But now we know that Kadmos was saving a word that he would not have uttered aloud. To himself, he said: Escape.

"Now, our king was civilized in his youth-as became all too apparent to his mother, Telephassa, who had brought him up that way. Wherever he went he caused civilization to spring up. It was a storyteller's dream; it was every mother's hope finally realized. No, he could not bear the uncultured life, and everywhere set about rectifying the countryside-while his mother put her face into both her hands and walked about with the little girl's face cupped before her glossy eyes. It has been said that there is a season for each deed, each desire; and this adage Telephassa was forced to emphasize more than once in conversation with her son who was everywhere commanding warriors to engineer instantaneous towns and courts, highways, fountains, and sewage ducts. In her grief, she could not understand that just as some cannot bring themselves to speak to the ill or defamed, the romantic Kadmos could not even think of looking at his sister again.

"It is not often that a mother gives life to two such children, Teiresias, so different from their mother, so like one another. Here was the one completely taken in by the country life, by a bullock with tinted horns-and the other obsessed with engineering mansions, shanties, huts and shacks, central water ducts, walls and ascending ramps. Under stress, the king you've seen being carried through the streets, was in his youth unable to reconcile himself to a hammock slung between two trees. Neither one of the children-the poor mother cried-had a thought for balance in anything! For three years the mother swayed and sighed." His mother stopped.

Again Teiresias looked up to find the source of silence in his mother's voice. Again he felt the two worlds collide: then and now. "Are you tired?" she asked.

"The cow, the snake, the cow," he cried.

26

"All right," she said. She reached out as if to pat him across the distance of that room. The hand went up and down on air and he felt it in his hair. She nodded, and on it went.

"It was in Thrakia that Telephassa, that mother, the Great Aunt of us all, took her stand. She looked out over the Edonian's highway where that road wound through open spaces like a peculiar line on a wrinkled face. Out from the Edonian city it went through rocky ground and unadorned hillsides salted with sheep. It stretched like a ribbon all the way up the farthest incline, and there it stopped. Beyond it there was nothing at all. She saw the warriors clustered together and her son pointing toward it with a stick, sketching buildings, bridges in the air. It was there in Thrakia that Telephassa-that weary mother of Kadmos, Phineus, Thasus, Phoinix, Kilix, and Europa-raised one finger toward her industrious son and died to her own relief.

"It cannot be said that Kadmos did not mourn his mother. Even a rose misses its thorns if somehow they are lost. For years he had lodged his worries in her. His fears about his sister had consolidated themselves in his mother's quavering voice; and he had discounted them like any normal son who was coming of age. But now-just as when the hired mourners pick up their things and leave-the burden fell on Kadmos, and it came in a doubled weight. He could not think of his mother without thinking of his sister; he could not think of Europa without thinking unthinkable thoughts. Carried away by a bull. He had not seen it himself, but he had been told. Zeus, the people had said with the strange smiles on their lips of those who love bad jokes: Zeus, the active god, had taken her. That night after his mother had risen up in the funeral pyre and settled again over the valley in a fine gray dust, an oracle speaking for Athena came to him, or so he said-though if you were to ask now the proper one you would hear quite something else. You would hear that the Athena you know had nothing at all to do with it. You would hear that Kadmos' guilt took on the most simple shape, and that was what he sought. He would take his men and follow a cow until he found his sister and set his mother's dust to rest. Around the country he followed the confused animal, giving way to his old obsessions at every turn. He laid down the foundations of the world wherever that cow lifted up its tail. Yes! The beginnings of our king, no less. And that is the way of all civilizations," Chariclo said, flinging her dark hair back. "They begin in dung and end in dung, and in between: a great flourishing of growth.

"Now then, all men are filled with youthful folly sometime in their lives, as you already know. To most this comes early on, when it is

27

easily forgiven as being the nature of the beast; to others it continues like a scurrilous disease distorting and dementing the activities of those who are so innocent as to venture near the man; to others it comes only late in life. Kadmos had a little bit of each. Such is the making of great men. If he had possessed even slightly more or less than what he had, he would have earned a far less significant place.

"A vision of home came to him one day as he stepped absentmindedly along the road, giving up his chariot for the sake of exercise. His mind was not for once on his work. One of his men had counted it out for him: it was his birthday-his nineteenth year-and he was thinking of his personal history as all people do when an anniversary comes around. Oh! he cried aloud, for he just then remembered his soft Phoinikian bed in which he lay as a boy staring at the cracks that even there traversed the ceiling like glorious viaducts. He had seen the ceramic pots lined up like vats on his window sill and his private bath with its imperturbable new plumbing. He had seen his mother's own plump maids grown now into eagerness for his engineering ways.

"On he strolled, dreaming of his own place in the world, to which he could not return, following almost automatically the receding haunches of the cow which had led him through brambles and thickets, over beds of shale. Now suddenly the distant orange flanks loomed large. For this, Kadmos needed no oracle. He had placed his sandaled foot smack in the middle of the modern world: something steaming, something ghastly, large and warm.

"At his shout, throughout the skeletal town, something stirred again in his men that had not budged for years. They threw down their tools and thought the thoughts of warriors; they catapulted to his side. Here they found our king leaping up and down, shouting into the wind at a small orange speck swatting flies on a distant hill. He had stepped, cried out our leader, in the blasted, ultimate, and last site of his building career! Back and forth he paced on that narrow strip of land that is now the street in front of our own house, dragging one foot deliberately through the weeds and calling for the cow and battleax.

"When his warriors had returned with them, Kadmos set forth his first decree. Musical instruments, he declared, would be strung around each bovine neck. Vaguely his men smiled as they sat at his feet. They scratched their heads, imagining it. They looked a long while into their brass armbands. Henceforth, bells-he clarified-would serve as a warning to all who came after cows in years to come, on earth or in the underworld, to keep always the strictest presence of mind. The tinkle would serve as his personal salute to Athena, who knew always where to step and when.

28

"Bewildered, the men were dismissed to the spring to shovel up water for the sacrifice; and Kadmos was left to curse his authoritarian father, his wayward sister, his domineering mother, his own obsequious life as he tethered a cow: most accursed, brown-eyed, flat-footed thing. He sharpened his ax. It was then that he heard the tune rising up, slowly at first, as if it were merely a part of his self-admonishments, a sort of incantation in the background of his immature distress. He lifted up his head. It was as if all his men were singing together and each one without half his tongue. When Kadmos reached the water, he found them in a bunch, as if they had gathered there with the intention to converse. And there, wrapped entirely round and round their collective waist, was a highly respectable snake-if size alone is reason for respectability, as is so often said.

II How Kadmos killed the snake is of little consequence, as there are many varying reports and you have heard them all: Some say he poked its eyes out with a branch whittled from the poplar tree; others say he tickled it to death with the pinfeather of the native grouse tied to a long stake. Kadmos' own story as he ages is no less variable than the rest.

"When the snake had died, his men fell apart, one from the other, as petals do when even the smallest flower blooms and wilts and casts out parts of itself finally onto the ground. From this ongoing collapse, those few survivors crawled, gasping, away to watch in humility their less fortunate companions fall straight over like felled trees. For Kadmos, very little, as we have seen, has ever been enough. Let us say just this=-wild-eved and unpredictable as a sphinx, the young Kadmos sprang upon the viper's corpse, hacking it into unsavory bits, crying out epithets and yanking from its yellow throat a heap of glittering teeth. Upon this pile of carnage, that youth-who had, even at nineteen, never known the body of man or woman-the man who is now our king, swore an oath and spat.

II From the rock soil and those serpent teeth, by way of Kadmos' finicky watering-and to his bleak astonishment-sprang up spears like young asparagus and with them the forearms of living men, and then the fully clad bodies of an ancestor and several relatives of yours. On each man was the mark that all of us, who have come through that long line from snake to man, now bear. No, it was not a blemish: more of a brand, wine�red and shaped like the head of a spear."

29

The young seer looked toward his mother. It made him dizzy to think of it, to look at her. The one breast spiraled one way; the other spun left until the viewer warmed the fingers of his spirit on the bright red centers of those orbs. "And that," she said, "was the beginning of your father's family and yours." She pulled her coat on and motioned toward the door. "There you have it." But what did he have? What was it in the speech of an eagle, he asked himself, that could determine the fate of the willowy young girl, the fate of his own family, of Knossos and Thebes?

They say that when even the smallest fish jumps, a circle is formed and then another, that its leap is felt on every shore. I have never seen such a thing, but they say it is true. My father took me to hunt turtles once. I suppose in a way it is a similar thing. The turtle, my father said, was the most ancient and therefore the wisest of living beings. Even then, starting on the long road to the sea, I thought-there are many ways of looking at the world. We started out from town on foot. I remember my mother leaning out, half-painted in the early morning, from the window. Her eyes were very large. Which side she had completed in her toiletries escapes me now. Perhaps it was the left. Then again, right is a good enough approach to things.

"It is most important in the hunt-" my father said, clearing his throat as he often did when the need for authority hampered his voice, "to adopt the turtle's every thought." I was only seven then, and this was not hard to do. When my father laid his hand on my back, it was as if a golden carapace had settled there.

In my father's lifelong search for wisdom, he rarely allowed his thoughts to interfere with his stride. On this day there was no exception. He possessed two long, thickly muscled legs bronzed by the sun; and on these he moved along so rapidly that every once in a while, to my great embarrassment, he would turn and find me gone. "Well?" he asked. His stern blue eyes and long blond hair had made him something of a god in our dark community, and as he stared at me I felt my own lank dark hair growing darker still in his view. As I had no answer to his question, finally the moment passed. I kept up with him for a while until slowly I saw again the one blue vein throbbing at the back

30

of his knee, the broad back, his long nearly white hair bounding like a ram between his shoulder blades.

My father must have been deep in thought, and this, I thought, was unfortunate for I had time to run furiously toward him again and again before I was hopelessly lost, before I saw him, grown small with his traveling, turn suddenly in the road. "Well?" he would say when I had caught up with him again. I wished that I had been the pebbles in the road he walked upon.

His eyes are in the sea, the others often said with reverence. You are the son of Sea-Eyes, I had never seen the sea, but I imagined it to be an especially terrifying sight. When I was older I came to think that it was the fear of knowing exactly what they saw in him that made me so slow and disappointing to him that day. On we went, starting and stopping. "Well?" he asked, shifting the bag he carried from one shoulder to the other. What kind of bag it was I do not know. It was as if it had not been on his shoulder until we were halfway there. I only remember that it was blue. Or red.

On our journey there was a moment when we stood side by side. This I remember tenderly-perhaps because we were not in motion then. It is hard to follow after a god. The sun was nearly overhead as we stood there gently watering a rock, I remember. And a snake. "Hmmrn," my father said, looking down at me in the sort of com, munion that fathers often feel when standing next to their sons. "I didn't know you had the mark." For there on my penis at the very tip was the wine-red mark he bore on his own arm. I think now that he would have been more accurate in his response to our common nature if he had sat down right there in the dirt and wept for me. But he did not. "Hmrnrn," he said and rumpled my hair enthusiastically.

We went on again, stammering in our progress. "Well?" he asked while I shuffled my feet in a circle in front of him. When I had dragged myself up alongside him for perhaps the twentieth time, he asked it again. This time I did not turn away. My own sullen eyes met his severe ones. My feet grew into the dirt as he shifted the bag from shoulder to shoulder waiting for my reply. Neither of us looked away. Under his breath he was muttering it again-"Well?" "Well?! Well?! Father! well is a hole with water in the bottom of it!" I cried.

My father, the god, rolled his blue eyes upward toward those of his own kind. In this way we went in search of further wisdom. I do not remember which had the greater effect on me, the turtle or the sea. I have seen turtles since and always I remember my father then. I have never seen the sea again and I have never been able to

31

forget it. "We will be like turtles," my father said, picking me up and plunging me into the waters. "We will wash ourselves before we corne again onto the land." It was true for me then; I could see what the others had said. There standing up to his brown thighs in what they called the sea was my father and in his eyes he carried the waves and at the center of each a turtle was swimming.

When we were on the sand again, my father opened the bag he had carried such a long way and took out a blanket. It was green, I am certain of that. Bright green. Already he had spotted the tracks of the turtle, but he spread out a blanket and took out his cache of food. He had brought along a sack of figs, of which I had a few. I ate some olives, a piece of honey cake, and drank a little wine. We ate these things then because my father said a turtle in its wisdom would not give itself up to a hungry man.

It was late afternoon, and already it was getting a little cooler by the time we set out after the turtle. We had a piece of rope, a stick, and the blanket. I was given the stick to carry. When we carne upon the turtle up the beach a ways, I was disappointed. Oh, it was not the turtle that disappointed me; it was a magnificent turtle: nearly four feet long with a fine shining shell, and in that shell was the red blood, so my father said, of all the living things it had eaten. It was the capturing of the turtle that disappointed me. Yes, it was exciting to hold out the stick and see the monster snap at it, but how quickly and effortlessly my father threw the blanket over its head and wrapped the rope around the cloth-covered neck.

This was the very place where we would lie down to sleep, my father said. We would allow the turtle to collect his thoughts; if we gave him the blanket he would give us our wisdom. During the night I woke shivering with the cold. The sea was pounding against the cliffs down the shore. Here we were without our blanket and my father stretched full-length on the beach, whistling a little in his sleep as I shivered.

As I nestled under the blanket with the turtle. I thought: it's like lying beside a warm rock that slowly cools as the night goes on. Its head was well covered and I felt no danger. Once during the night I woke to find its claws gently scratching along my arm as if to relieve me of some pain. In the morning I woke to find myselfalone, the edges of the blanket neatly tucked around my feet and shoulders. And there on the beach a fire was glowing, and beside it my father crouched next to the bronze ax. The lovely underbelly of the turtle had been split open and my father was roasting its heart on the stick.

How this could have happened, I don't know, since my father was killed, they say, shortly after my conception. I only know that the night before I was to see my friend the potter I fell asleep and when I

32

woke again I had seen my father there and the tortoise turned on its back, its feet and tail still gently moving.

"I have decided to tell you how to comfort people," Chariklo said to the very young Teiresias. "First of all, you must be attentive. There is no greater discouragement to one who is already discouraged than for him to tell his woes, after much welling up and fighting of tears, to a mere lump of a face or to one that is always veering toward the window, toward some more interesting project. You must look the victim in the eyes, even if he does not look at you. When he glances up, your eyes must be there on him. The more they are avoided the more lost, the more victimized. Now here is a young man sitting before you. Can you imagine it? Yes. You are looking into his eyes. He is telling you of the death of his father, or a serious illness he himself has contracted. Now what do you do?"

Teiresias plumped the pillow he was holding. It was red and gold, a peacock embroidered on it, variegated from eye to tail. "I say I'm sorry, I wish it hadn't happened."

"Look at me when you say it."

Teiresias looked up. He stared into her wide eyes. He could see the young man before him, lost, forlorn, without a father. "I'm so sorry. I wish it hadn't happened to you, to him."

"Now say his name," Chariklo said. She did not take her eyes away.

"But I don't know his name."

"Make one up then."

"I'm so sorry, Terry. I wish it hadn't happened."

"That's much better," Chariklo said. "Do you hear the difference?"

"I do. I think I do, that is. I sort of do."

"If a person feels lost, Teiresias, that person feels nameless. Everything has a name, every kingfisher, cuckoo, pigeon, stone. And in each one a spirit. You say Terry's name, already he feels better. He is really there, he knows it now. And you are there and you are listening. Do you understand?"

" Yes," Teiresias nodded.

"Now go on. What do you say next?"

"I say, Tomorrow the sun will shine and we will play ringstick in the yard. You can use my new stick if you want to." Teiresias smiled

33

proudly at himself, at his mother who was named Mother, Chariklo.

«Yes, that's very good," his mother said, leaning forward to pat his knee, to rumple his hair, to squeeze his small arm. "But you don't say that for a while yet. You wait until you've both said other things. Do you know why?"

"He doesn't like to play ringstick, Mother?"

Chariklo threw her head back. She laughed. She squeezed his small, palpable arms.

My mother's house was set at the edge of town near a stand of trees. We who saw the mountains all around us but only saw them from a distance looked upon this thicket in the flatlands as a forest. Forest, we said when directing others to our house. It was only natural that we should live here. My mother was Athena's nymph, and it was said that the goddess frequented that spring which rose up in our woods like encouragement and swelled into a flowered pond. Each morning our maids would receive from the men and women of Thebes the sacrifices to Athena at our front door, and the gifts that supported us. And it was out the back door that I went when I first awoke. I did not know whether it was the overwhelming smell of humus emanating from our backyard that led me out, the embarrassment of being so admired by the celebrants if I should go out the other door, or my growing affection for the dark-haired servant girl who made my bed each morning and who, if asked, would bathe me each and every day, long into my old age. There was nothing better in the world, I thought, than to root among the tender undergrowth in search of sticks and brush for the morning baking, to hear in the distance the sound of birds and my mother's gentle humming as mortal and god lay down together entangled in the far reaches of our backyard. I knew our neighbor to the west would be looking out from her window, her delicate skin as blue as that pond beside which my mother lay in rapture.

It was said that the River Kephissos had embraced this neighbor on its way to Lake Kopais, that it had taken her under its tumultuous surface and made love to her until her flesh had turned blue as the iris of one radiant, staring eye. This humiliation had taken place in Phokis from which Leiriope had then fled, or so people said. Here in Thebes

34

she dwelled on that memory, far away from the place of its occasion, here where people did not falsify the facts in the marketplace and make remarks about love's tumultuous waters practically at the lobe of her tender ear. Often I would see her blue hand rise up in that window overlooking our woods. Each morning her blue hand would wave and then her blue voice would fall gently down upon me in greeting not unlike my own mother's call. Something melancholy would rise up in me then, even as a child, and I could not help the blue tear that sprang each morning out of my eye when Leiriope called my name.

I did not know for some time that Leiriope had a son, for he did not often go out of the house. He was only a bit older than I, but to me age had never made a difference. It was said that the River had fathered him, and his olive skin was smooth as a pebble at the bottom of a stream. His eyes were not blue; they were black as Leiriope's and were said to start the hearts of children and adults (men and women alike) aflame as if those eyes had been pieces of flint for people to strike their bodies against.

It was a custom that no man should take a boy to be his favorite before that boy had sprung his first down from his chin; and yet all the elders and the king, too, it was rumored, had courted him. Little presents they brought him, setting him on their knees and stroking his sleek hair, letting their fingers wander into the hollows of his cheeks, along his child lips. But he would give no response. He sat-not angry, not the slightest irritated, and certainly not in love with them. He was the pebble itself before the persons sitting there. He did not cry out, nor murmur; he sat silent as a chair while his gifts piled up. Often the women would fondle him too, crying out: Tiny Beauty, Perfect Skin. He was nine and I seven when I, too, fell in love with him.

It is true that children in their own ways often fall in love with one another, but my feeling for Narkissos was not the same as that. How does one love another who gives no response? Passionately, I say. More and more-projecting one's own feeling as the sentiments ofthe other, saying that that person must feel as I feel for he will not deny it. It is nothing more than self-love in the end; and what can be more

35

enticing, more destructive than that? There are situations but they are few and terrifying to think about.

One day, inexplicably, Narkissos started coming from his house each day to sit in the woods near where Helen, our maid, and I went to gather kindling. He had, I think, been driven from his own house (even the kitchen, the courtyard, his own room) by the persistence of his suitors. A little arbor had grown up in the woods like a cave and that was how I first saw him-crouched in view of our back door, casting pebbles against a fallen nut-tree. My arms were already full up to my chin with branches which I intended to break down behind our house into more manageable pieces for the hearth, and Helen had gone back to prepare my mother's morning cakes while I continued the search for just one more.

I stopped suddenly before him, staring unkindly. "Whatever has made your hair so silver?" I blurted out. His hair shone out the color of an aging man's, but with luster. His one eye was set in his head just slightly higher than the other. I knew immediately who he was, though later out of politeness I would ask him. No, he was not beautiful as they had said, I thought then. Certainly I was as compelling. I had the same black hair-though mine was not streaked as his was. My skin was soft, too, like a fawn's ears, but my eyes, I knew, did not seem to drift ever so slightly one from the other.

"Well then," I said, watching him looking at me-not with suspicion. No, he was not suspicious. It was as if he did not care what it was that I would say. "If you won't answer my question, will you tell me your name?" I could have said anything and his eyes would have been just as disengaged.

His voice was not unusual; it was neither high nor low; it did not break yet between childhood and manliness. He was about my own age I determined when he said his name, when he said Narkissos. Shyly he said it. Or perhaps I only thought it shyness for I felt it myself as I watched him pitching stones halfheartedly at the nut-tree. Although he did not invite me to sit down with him, I let my bundle of sticks fall with a crash to one side of us. "I live over there," I said, squatting down beside him under the tangled branches. I, too, pitched a stone toward the nut-tree as he looked toward our house and nodded.

"I have silver hair because my father took my mother on a gray day; the sun had just come out from behind a cloud," he said, digging in the dirt for a particular stone. The choice of stones was all-important in pitching. We both knew that; that was unspoken.

"My father is a shade," I said matter-of-facrlv, for he had been so for as long as I could remember-at least when I was awake.

36

"My father is a river," he said. "A god," he said proudly. "When' ever I want I can see my father, whenever someone will take me there. I remember when I was born, too."

"You do?" I said, looking askance at him.

"I do," he said. "I floated up from the river into a hollow cave where I got my silver hair, and then I fell into the world smiling. I was smiling when I was born."

"How do you know you were smiling?" I asked him. We were pitching another round of stones. "Only someone else could have seen that. Maybe you heard someone tell about your smile. Maybe you only thought you remembered it yourself."

"I felt it," he said. "I felt myself smile."

I smiled then off into the open space beyond the thicket where we crouched. I tried to feel it. "Yes," I said. "I see what you mean."

"I haven't smiled since," he said.

"Maybe you should gather wood with Helen and me," I said. "That always makes me smile. I smile, too, when I see your mother in the window. Then I cry."

"I haven't any reason to smile," he said.

"I could make you smile, I make Helen smile when we gather wood, and my mother, too, when I holler in my bath. I could holler. Would that make you smile?"

"No," he said. "Did you know King Kadmos comes to see me?"

"Does he try to make you smile?"

"No. He tries to make himself smile. Everyone wants me for his favorite. Everyone thinks I'm beautiful. My father is a god."