Spring 1982

Editor

Coeditors, Cage Reader

Associate Editor

Managing Editor

Assistant Editors

Design Director

Editorial Assistants

Advisory Editors

Contributing

Editors

Spring 1982

Editor

Coeditors, Cage Reader

Associate Editor

Managing Editor

Assistant Editors

Design Director

Editorial Assistants

Advisory Editors

Contributing

Editors

Reginald Gibbons

Jonathan Brent, Peter Gena

Bob Perlongo

Molly McQuade

Susan Hahn, Fred Shafer

Gini Kondziolka

Joe LaRusso, Denise Smith, Carol Summerfield, Lenore Zelony

Elliott Anderson, Charles Newman

Michael Anania, Gerald Graff, David Hayman, Bill Henderson

TRIQUARTERLY IS AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ART, WRITING, AND CULTURAL INQUIRY PUBLISHED IN THE FAll, WINTER, AND SPRING AT NORlHWESTERN UNI· VERSITY, EVANSlON, IWNOIS 60201. ISSN:0041·3097.

Subscription rates: one year $14.00; two years $25.00; three years $35.00. Foreign subscripttons $1.00 per year additional. Life subscription$100.00. USA or foreign. Single copies usually $5.95. Baclc: issue prices on request. Correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQparterly. 1735 Benson Avenue. Northwestern University. Evanston. Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions of fiction. poetry. and literary essays. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped. self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the properry of TriQparterly. unless otherwise indicated. Copyright (;11982 by TriQparterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers. not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America.

This publication is made possible in part by grants from the lllinois Arts Council. a state agency, the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines. and the National Endowment for the Arts. Publication oftheJohn Cage Reader was made possible in large part by a generous grant from the Woods Charitable Fund.

National distributor to retail trade: B. Deboer, 113 E. Central Street-Rear. Nutley. New Jersey 07110. Distributor for West Coast trade: Book People. 2940 7th Street. Berkeley. California 94710. Midwest: Bookslinger, 330 East Ninth Street. St. Paul. Minnesota 55101.

Reprints ofback issues ofTriQparterly are now available in full format from Kraus ReprintCompany. Route 100. Millwood. New York 10546. and in microfilm from UMI. a Xerox company. Ann Arbor. Michigan 48106.

We debate the future of fiction and poetry a great deal in literary magazines, in classrooms and bars, at meetings like the American Writers' Congress. If what worries us is the continuation of imaginative writing, then it seems obvious that there will always be those who write, even if it is only for a few hours a week between household chores and child-raising responsibilities, or on scraps of cigarette paper in prison cells. But if we mean, as most of the debaters do, that it is not clear how this work will survive and who will read it, then there are two related questions. Do we have doubts because much poetry and fiction seems undistinguished? Or is it because the reading audience also fails to distinguish itself and does not often honor the work that is most substantial, that speaks to us with the greatest emotional power, quickest sense of the complexity of life, and beauty?

We can reassure ourselves there will always be some readers who cherish imaginative accomplishment, even if they are to be found only among the ranks of fellow writers. But we must also see, each day, that writers need a larger audience, and that the larger audience needs imaginative accomplishments to feed on. Why then is the imagination so often crowded out of our attention?

Loves and births; crimes and outrages; terrors and inhuman force wielded against both innocent and guilty; the triumphs against such force; the pain of divided allegiances in families, courtrooms, nations; any profundity of understanding of our everyday actions: buying a toy, stealing a car, leaving home, loving or hating or hurting or hearing music or frying eggs-all ofthis should be the province of imaginative endeavor, which is simply a part of our way of understanding how we are formed as persons, and what sense our actions may have, what effect they produce on ourselves and on others. But all this is precisely what seems so complicated and almost removed from us at times by the drive in our culture to make all of us into creatures whose lives are defined by quantities and ruled by distant and incomprehensible sources of power. We are left little time by jobs and the media for reflection; and little energy to spare for thinking, even for feeling. As readers most of us are often tired and as undistinguished as the work we read, and this is so partly because of the demands clamoring around us.

I don't mean only the demands of family and work, that must be honored and if we are lucky can be lovingly answered. But so many impersonal, deceitful and alien voices cajole, browbeat, lie, tease, politick, lobby, coax, threaten and flirt around us, at us, with us, that we often find it difficult to give concentrated attention to a story, a drawing or a photograph, a poem, a piece of music. And the newer the imaginative work is, the more it has its own roots in these very same clamoring voices that we want to shut off, and many would rather read Hardy or Keats or listen to Mozart or Brahms (though in their own day they, too, had to fight for the attention of their contemporaries). And, after all, shouldn't we all be glad that anyone wants to read Hardy or listen to Mozart?

What do writers think of this state of affairs? Just "get it into print," a novelist friend told me, when I asked him what was most important to him. "However you can," he said. "I've been lucky, my publishers have always published my work when it was ready, even if the editions were very small." But is this enough, mere preservation for anonymous future readers?

In his Nobel lecture, Czeslaw Milosz spoke of a crisis of memory, a kind of cultural amnesia that cheapens our ability to act responsibly by keeping from us the knowledge of what has gone before; thus our responses as readers are cheapened as well. For without a sense of the history of men and their works, we are prey to both political and artistic manipulation. Milan Kundera's Book of Laughter and Forgetting presents us with a parable of the same crisis, in which an abolished party member, removed by political surgery from Czech history, can be inferred only from the presence of his hat on another man's head in an official photograph. If knowledge of the past is what feeds a writer's sense of his own work, helping him to see what must be done now, out of what has been done before (whether he is concerned with the rhythms in a single line of a poem or the canvas against which he wants to place figures in a war), then a knowledge of the history of imaginative accomplishment gives a reader a place to stand in drawing sustenance from imaginative works, in judging them. We become laughable when our daily lives declare that we don't think there is much at all in the accumulated artistic accomplishment of man that could please us or instruct us. Remembering is a task, a responsibility, as much as it is a pleasure; for many it just takes too much time and trouble.

Our responsibility as readers is clear: diligent attention to new writing, as much of it as we can get hold of, and generous help, when we can give it, and however, to the best work we can find. And there is enormous pleasure in reading good new work, and that is what sustains good readers through the lifelong and wearisome task of keeping up, a task that is the literary editor's consuming responsibility.

"Perhaps the greatest misfortune for a man of letters is not in being the object of his brethren's jealousy, or the victim of conspiracies, or held in contempt by the mighty of this 'world; but in being judged by idiots." That caution is not recent, but came from Voltaire, and the warning is as clear now as then, to an editor, to dispose of biases and peeves as much as possible, to read with eyes and ears open, with expectations that are high but not

categorical. After only a few months as editor of TriQuarterly, I have been chastened already by the way practical realities, too-schedules and money and correspondence with writers, some of them still my friends-erode principles and plans. I have asked myself not only what 1 hope to publish in TriQuarterly, but also what responsibility it is that TriQuarterly or any small literary magazine should bear, in this welter of voices, vices, arguments and despairing cries in which the good works provide a miraculous exhilaration.

If TriQuarterly has a recognizable identity, it arises out of its energy and its range, it seems to me. Its readers respect its devotion to short fiction (a devotion that will remain unchanged), its seriousness (and sometimes its frivolousness), its heft, its handsomeness, and what one would have to call its tone of voice-by turns straightforward, edgy, flashy, testing, theoretical, encyclopedic, heavy, campy, once in a while avant-gardish, scholarly, esoteric. The magazine has been lucky to have the support of Northwestern University, without which it might not have survived (the twentieth anniversary is coming soon). It has won prizes for what it has published and for the way it has presented itself. Its special issues have often been reprinted as hardback books by other publishers. This special and recognizable identity will continue to draw readers, I hope, and more and more writers will send to TriQuarterly the best work they have to offer, as many have done in the past.

The most important work, the best, cannot be categorized or described in advance by anyone. But 1 think it will often look to the world outside the writer, to the culture swirling around his or her solitary labor. Narrow, self, regarding, clever work always has some appeal to the small reader in us, that imp of a reader who doesn't wish to be led out of himself toward others, toward the world, or even toward deeper pleasure or understanding. But there is a larger reader in us, too, who responds to work that is free of self, indulgence; that goes beyond a trivial occasion; that will break, when it needs to, all formal expectations; that has emotional and even philosophical weight; that binds us to others rather than asserting that our solitariness is an interesting state of mind. Or, when we must face our essential solitariness, as the writer does when he or she is writing, then such work explores that state with passion as well as anger, with vision as well as accomplishment and cleverness. The material of such work is anywhere and everywhere, in bed, rooms and newscasts and at racetracks and wakes, and in imaginative flights beyond what is familiar. A fundamental attitude of wonder and delight in seeing what is there-that's the mark that Conrad and Welty and Milosz and many others have found in good writing. It is wonder I find put down this way in a story of William Goyen, "Old Wildwood": "There was so much more to it all, to the life of men and women, than he had known before he came to Galveston just to fish with his grandfather, so much in just a man barefooted on a rock and drinking whiskey in the sun, silent and dangerous and kin to him." And in this sentence, from Goyen's "The White Rooster": "He had a face which, although mischievous lines were scratched upon it and gave it a kind of devilish look, showed that somewhere there was abundant untouched kindness in him, a life which his life had never been able to use." It is much easier to illustrate such vague and eclectic likes and dislikes than

to describe them. In this issue, apart from the celebration ofJohn Cage, which is a fitting continuation of TriQuarterl,'s devotion both to other artistic disciplines and to innovative artistic endeavors, there is Ray Reno's epistolary story, which sets a dramatist's troubles, personal and artistic, against the fall of 1939; Grace Mary Garry's portrayal of adolescent sexual wonder and alarm in the midst of Baptist and Catholic contradictions; Teresa Cadet's personal elegies for public tragedies in the death camps and present-day Poland; and Rush Rankin's tale of romance in our casual land offecklessness and idiosyncrasy. I think Michael Collier's intimate poems, the 1962 interview with Eugenio Montale, and Robert Fagles' translation of a passage from Sophocles offer counterweights of personal loss, the poetic vocation, and the mythic revelations of tragedy, to Jay Wright's remarkable dramatic poem in several voices, a poem that raises issues of race, history, and religious vision.

I hope to find more work that explores the depth of feeling linking domestic horrors with social ones, as Pamela Hadas does in a long poem that will appear in the fall 1982 issue; more work that explicitly addresses the last American war; more work from abroad; more work that considers the shaping of the American artist, like a brief memoir by Michael Harper that will also appear in the fall 1982 issue; more work that can give a shape to the delight in our lives, as well. A good story well-told will always have a place in TriQuarterl,; so will the sort of story that represents a formal conquest, innovative or traditional, of seemingly intractable materials and feelings. The range of poems will also, I hope, be wide.

TriQuarterl,'s reviews will mostly be brief, and will mostly commend to our readers important fiction and poetry that in the din of the crowd is in danger of remaining unheard. There will be more graphic work, more special issues, and more works of unusual nature that have fewer places to roost than the short poem and the short story-novellas, long poems, dramatic forms, whatever.

In short, TriQuarterl, will look for a special sort of engagement arising out of the largest view of the individual life (which is the irreducible material of fiction and poetry) and out of that craftsmanlike and loving awareness of predecessors that both instructs and challenges good writers. Out of that engagement, that intimacy, that remembering, comes the work that is most innovative, that binds us fiercely to others, that lays down a path for future rememberers to trace. These are my preoccupations and hopes as editor. My greatest hope is that TriQuarterl,'s readers will return to the magazine again and again, to see what new voice has for a moment entered the forum, asking to be heard.-Reginald Gibbons

1. There has been talk, even recently, of a "crisis in the novel." Can one speak of an analogous "crisis in poetry"? And if so, in what sense?

Since poetry-like the novel, though on a reduced scale-is becorning an industrial product, it is clear that it too is subject to the oscillations caused by supply and demand, i.e., by the marketplace. Poetry is therefore in crisis no more or less than anything else: a product, if it is not kept current, even by becoming worse, loses its patronage.

But if we wish to consider poetry as a spiritual activity, then it is evident that all great poetry arises from a personal crisis of which the poet may not even be aware. But more than a crisis (the term is suspect nowadays) I would speak of a discontent, of an inner emptiness which the achieved expression temporarily fills. This, however, is the terri, tory out of which every great work of art is born. Your question is marred by the hypothesis that the term poetry must refer to a par, ticular literary genre, which is also true, but not absolutely so. One can imagine a great poetic period that produced nothing of what we ordinarily understand as poetry.

2. The poetry of the postwar period has been characterized by an ideolog, ical "reaction" to henneticism, among other things; what is the status today of this "reaction to henneticism"? And what about henneticism?

I know very little about hermeticism. The term arose in Italy, but did not catch on elsewhere. In Italy it was used in a sense that was not always negative: there was talk of a decadent experimentalism that also included so-called hermeticism, and which was supposed to have "deprovincialized" our literature. At present, if I am not mistaken, the negative use of the term is prevalent; although today the more serious critics are prone to exclude from the field the very poets who are supposed to have given rise to hermeticism. The "herrnetics" are supposedly only their imitators and followers. But this is so with any

school in Italy. Those who come first have certain advantages over those who follow. The opposite can also occur, though rarely: he who follows can gather the fruits of others' experiments that have been left hanging in mid-air. For the moment, this cannot be said of the socalled neo-hermetics, And yet it should be noted how many of the young poets, who according to you are supposed to represent "an ideological reaction to hermeticism," are more obscure than their predecessors and are consequently deprived of a true means of communication. Today there are no poets who communicate in the sense that they are accessible to that abstraction known as "the people"; not even the dialect poets do so. In fact, the return to dialect is one of the surest signs of the "decadent" spirit (still assuming that decadence and hermeticism are labels to be taken seriously).

But then we are not speaking of the call "to an active intellectual awareness of the directions, etc., etc." Who is issuing the invitation? And to whom? Try to name some names and you'll see that it will be hard to keep from laughing. There has never been a period (in the production of so-called poetry) richer in active awareness in every direction, especially in Italy.

Ideological engagement is not a necessary and sufficient condition for the creation of a poetically vital work; nor is it, in itself, a negative condition. Every true poet has been engage in his own way and has not waited for it to be pointed out to him by barely identifiable regulators and guides of production. Naturally, professional poets have often paid tribute to their protectors, princes, and patrons; it is probable that those who are salaried as "poets" in Russia today must run on a prescribed track. These are extreme cases; but the history of poetry is also the history of great, unfettered works. Poetry, whether or not it is engage in the sense demanded by the moment, always finds its response. The error lies in believing that the response must be lightningquick, immediate. There is a place in the world for Holderlin and a place for Brecht. Another error is to believe that the response is measured statistically. Those with the most readers are the most valuable, respond best to the demand of the marketplace. Thus we come back to poetry understood as a commodity to be sold.

3. Many claim that the task ofcontemporary poetry is to develop the new "content" and themes that our time suggests, which also inroZve new problems of communication. Poetry is being called to an active intellectual awareness of the directions in which history moves and is even beingassigned a practical purpose ofclassification and animation, as has occurred in other eras, even long ago. What do :YOU think of this?

(See answer to question 2).

4. Any poetry, or rather any concrete poetry, postulates, explicitly and implicitly, a problem of language, which inoolves a need for innovations and at the same time for a particular relationship with tradition, which is the point from which every poet "innovates." What do you think ofthe linguistic or stylistic experiments of recent poetry? What do you think of neo-expetimentalism? Of the tendency of some currents to reabsorb attitudes and forms of the so-called European or American "aoara-gasde"] What do you think of dialect in recent poetry?

There are no problems of language, experiments, transplants, or derivations from other literatures that have a normative value. Every poet creates the instrument he feels is necessary for himself. What we can see, in any case, is that today in all the arts, technique seems to be understood in the materialistic sense: the collage, the paint in a tube, the noise of the lowered shop shutter, the multilinguistic "cocktail" of words mixed in a shaker "before serving" substitute for the "mediated" expression proper to art. Let's be honest: at this point art is no longer interesting, nor is it in demand anymore. Its failing is that it cannot be produced serially and planned. This does not mean there is no one who practices the profession of artist. The number of artists increases, in fact, in inverse proportion to the decrease in real and true artistic feeling. These supernumerary artists learn and apply the for' mulae: they can be guided, directed, and divided into "currents." If they did not exist, intellectual unemployment would create very serious problems. In fact, with their associates, patrons, and relatives, they make up a totality of economic interests of great significance.

5. Can the irrational moment in poetry, any poetry, be defined? And if so, how can one differentiate the "irrational" in an "engage" poet from the irrational in a "pure" poet? Does the notion ofirrationality coincide with the notion of decadence to the point of a total identification, or is there an irrationality that is necessary, not decadent, i.e., not mythicized as the one possible mode of consciousness?

Does something similar happen in poetry, too? Certainly, though to a much lesser extent, for poetry by its very nature circulates much more slowly. Yet there are beginning to be a considerable number of young poets who have read poets of all times and all kinds and believe they can avail themselves of a very extensive keyboard and try to play it in all directions. Here too they fall into the error ofbelieving that the instrument (the means) is the poetry. I pass over other errors inherent in the fast pace of our time. He who believes he is endowed in terms of poetic technique looks for speedy confirmation, i.e., success, whether within the circle of a small group or in a small review. If the instant consensus of the judges (who write poems themselves) is not forth,

coming, the poet is prepared to change his manner and style; he believes in good faith that he is searching for himself, but in actuality he is only looking for the part that is most acceptable to others, the most salable.

There is a kind of charlatanism, a way of leading people on, which up until a few years ago seemed to be limited to the visual arts and to music: today it has also entered the field of letters and even that very restricted area of literary production which you understand as poetry. Poetry is becoming an art at the very time when art is being challenged and rejected in favor of other human products: the happening, the gesture, the figure, the easily-used cliche. There are no remedies: if the world changed, poetry would change, too; but poetry (or whatever is left of it) cannot change the world. Nor can men of action change it, today; any regime, any social organization whatsoever must come to terms with the absolutely new conditions under which human life is being lived: conditions that are hardly favorable to artistic creation, but endlessly open to every sort of substitute. In this sense a great transformation is under way; and the intellectuals (many of whom are engages) are ready to accept it with enthusiasm. And I don't deny that they must accept it: I only deny that they should claim to be free men.

6. Poetry always seems to be determined by its special contact with prose. What do you think of the relationship between contemporary poetry and contemporary prose, both fiction and nonfiction?

Someone once defined poetry as a dream dreamt in the presence of reason. It was true then, and it is still true today, after Blake, Mallarme, and the Rilke of The Sonnets to Orpheus and the Duino Elegies. There will be a difference between the poet who eliminates some links in a chain of metaphors and the poet who wants to say everything, explain everything; but there will always be the need for reason in these various activities. The use and abuse of reason is present even in those surrealists who claim to immerse themselves in the "gulf stream" of the subconscious.

But here, too, I am not in favor ofrestricting poetry to a certain type of writing in verse or pseudo-verse. I don't think Cervantes or Gogol were more rational than Baudelaire; nor do I think that one can distinguish between decadent rationalism and rationalism of another sort in the realm ofpoetry. One can, however, distinguish between the reason of science and the reason of art: the mechanism may be the same but the intention is different.

The boundaries between prose and verse have been brought much closer: today verse is often an optical illusion. To a certain degree it has always been so; an error in typesetting can ruin a poem;

Ungaretti's Fiumi [Rivers] are incomprehensible without the vertical dripping of their syllables. A large part of modern poetry can only be listened to by those who have seen it.

Verse is always born out of prose and tends to return to it (cf. the frequent "drops in tone" of poets). It is a question of tone and of expressive concentration. The art of the word has many gradations of nuance, many musical possibilities, and does not exhaust them all in one period of history. Certain ages have shown themselves to be more favorable to verse, others to prose. When the necessity for spoken discourse (which can be true poetry) is prevalent, we have a period of prose; when writers appear who are lifted to an intense musical concentration, poetry carries the day. I speak of periods that can be very brief; and of recent periods. In other eras even a long rational discourse in strictly observed metrical verse was possible (e.g., The Divine Comedy); but prose hardly existed then. Today the poem-assumma, the poem-as-machine, is no longer possible in verse-and perhaps no more so in prose. Neither the Cantos nor Ulysses can repeat the miracle of Dante.

7. Poetry, too, constitutes a social "value," whatever place one wishes to assign it in the hierarchy ofvalues of our time. How does poetry in particular fit in with the other forms of expression in art today? What do you think of the place of poetry in our society?

Whatever I have said demonstrates that poetry (in the sense you indicate) already "fits in" very well, too well in fact, with the arts of today. And what about the situation of the poet in contemporary society? In general it is not a happy situation: some are dying of hunger, some live less badly by doing other work, some go into exile, and some disappear without leaving a trace. Where did Babel and Mandelstam go? Or Blok and Mayakovsky, if not to kill themselves? And where did Dino Campana go but to the insane asylum? (I limit myself to the moderns: the list could be much longer.)

But these are illustrious examples in any event: they are the glory of modern poetry. Many others make understandable the discredit into which the modern poetic animal has fallen. And it is not only society's fault: to a large extent it is the fault of the poets.

(This interview was originally published in Nuavi Argomenti.)

Rodney, Indiana April 11, 1939

Dear Tony,

You're right about the second act. It should pick up the note struck by Mrs. Danlever at the end of act one. I've redone the opening and you'll get new dialogue as soon as it comes back from the typist. The snows are gone, and there's a green haze on the yard. Now that spring's here I'm sure I'll start feeling better. Which will be a relief to my long-suffering mother. Poor woman-she couldn't have supposed that a week's visit in January would stretch out to the edge of doom.

Assuming that all goes well, I'll be in New York no later than mid, May.

Give my best to Marcia.

Dear Jack,

PhilRodney, Indiana April 18, 1939

Thanks for your kind inquiry about my health. With the balmy weather we're having, I'm improving rapidly. Plagued with a slight cough and an odd little hearing problem, but otherwise returning to fettle. I had energy enough to completely redo the opening of act two. Sent Tony the material a day or so ago.

Of course I think you'd be a fine Russell. But Tony's the director and I leave the casting to him. I'm only a scribbler and know nothing about the theater.

Still, you have my best wishes.

Warm regards, Phil

Dear Claire,

Rodney, Indiana April 23, 1939

What a fine poem "Two Doors" is! I thought so when you wrote it and am even more impressed seeing it in print. We don't get literary journals in Rodney-The Police Gazette, yes, G,8 and His Battle Aces, yes-but The Niagara Review, no. However, Tony was kind enough to send me a copy a few days back.

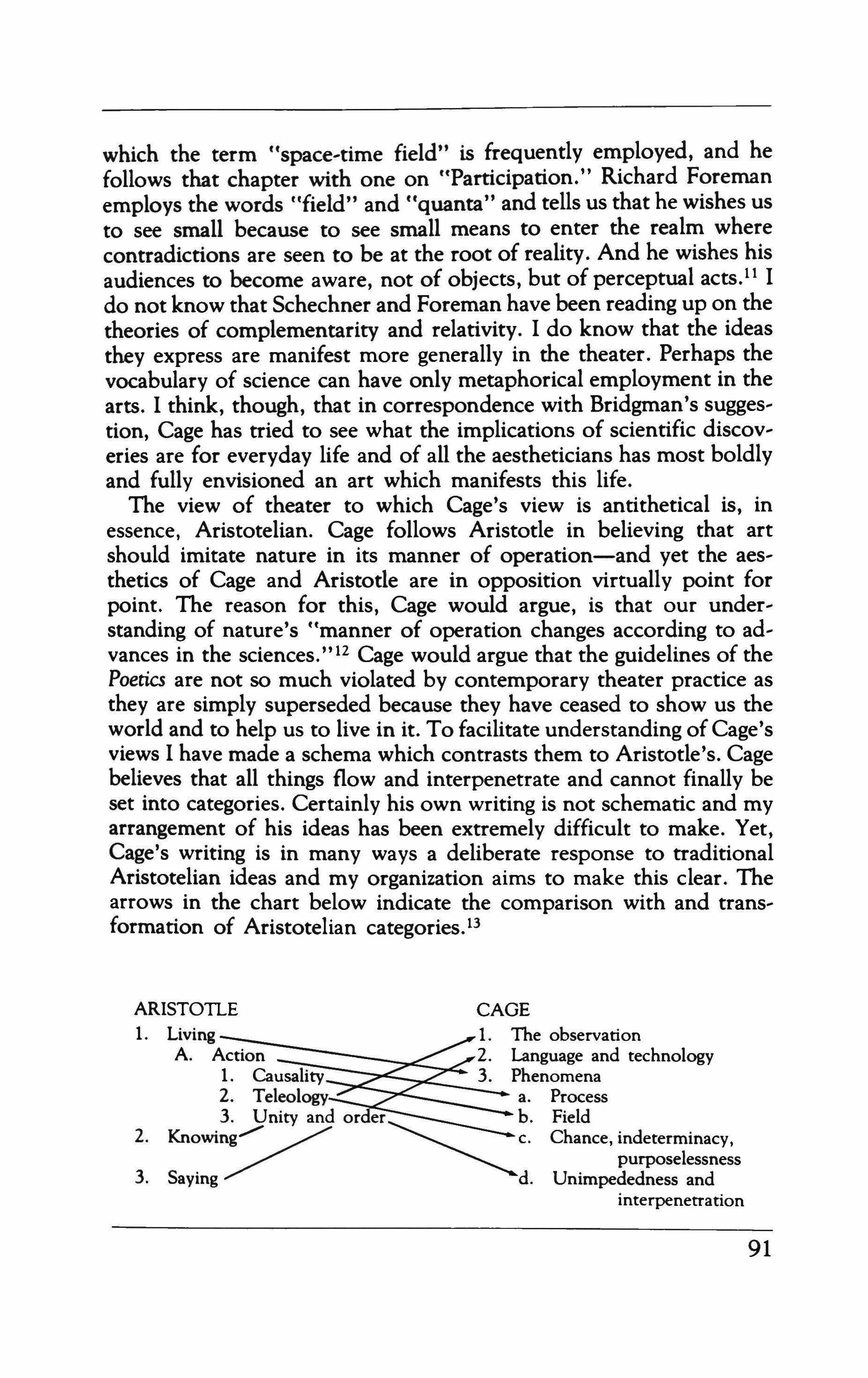

I must confess, though, that it cost me a pang to read it again. I thought of the night you woke me up and read it to me.

Anyway, congratulations. If it doesn't cop some sort of prize, there's no taste left in America.

Love, Phil

Rodney, Indiana April 26, 1939

Dear Tony,

Glad you like the new dialogue. So far as I'm concerned, the play's done. It's in your hands now.

Yet one thing gives me pause. I know I wrote Jack that I thought he could handle Russell, but are you sure you want him in the role? To my mind he relies rather too much on talent and too little on perception. The decision, of course, is yours. Only, if you will, brood on it a bit.

Rain, rain, rain the last three or four days, and, naturally, my cough kicks up, like myoid Plymouth backfiring.

Thanks for sending me Claire's poem-how does she manage so much grace with so much strength? Such a gifted girl I married! And how I miss her.

Yours, Phil

Rodney, Indiana April 29, 1939

Dear Bill,

Your letter disturbed me. Tony's not said a word about the ending. Are you sure his feelings are as strong as your letter suggested? Damn this cough and this intermittent fever-like a bad conscience visiting me at its convenience, not mine. Otherwise I'd be in New York right now.

Do me a favor and sound Tony out. I don't mean that you should throw your weight around-my agent or no. By indirections find

directions out. Assays of bias. You know what I mean. The ending's crucial. I did it in one sitting. Twelve hours at the typewriter and never did anything feel more right.

My best, Phil

May 6, 1939

Dear Claire,

I'm glad you're glad I like the poem even more in print than in typescript. It's a fine piece of work. Was I hitting below the belt to recall your awakening me and reading it to me?

I think you're right to try the book with Leland Press. Gil Roberts has at least an ear, which is more than most editors have. You're including, I hope, "Love Philtres." Not that I wouldn't forgive you for omitting it, but its absence from your first book would give me, I'm afraid, a hollow feeling in the vicinity of my breastbone.

Tony seems pleased with the script. He thought the opening of act two stalled the action, but I revised and he's apparently now satisfied. As you know, action is everything in a play. No matter how striking your characters are-listing port or starboard, idiosyncratic, obsessive, "theatrical" as mountebanks or medieval devils with squibs firing from every orifice-unless the damn thing moves, you've a gallery of waxworks but no play. I think mine moves now, with act two con' tinuing the momentum of act one-which, if I dare say it (or whisper it only to you) is the second best thing I've ever done. The first best is the ending. It's like nothing I've written before, and yet it's what I've always been trying to do. You'll understand, though probably no one else ever will.

Which brings up a problem. Bill Clemons wrote to say that Tony's been talking about wanting the ending changed. I don't know how, but if he does, Donnerwetter, even Stunn und Drang. I knuckled under once, to my regret. So his change brought me some 200 performances! And a maculated play. I don't know. Maybe it's my illness or my age (defunct in my 4Os?), but frankly I don't give a damn about success. What I want is something authentic-a Ming vase or the iron chord that opens the Iliad. So I'd like the play to get at least one clean performance.

I'm morbid, I know, but what else have I to leave behind me? Five plays that brought a now and then flurry of attention and once a shower of shekels, but not a one that will outlive this decade. If I'm going to survive at all, it will be in this play. Otherwise only in a line or two of your poetry, a skewed turn of phrase (I think of your Galatea

poems), will I ever be found, like some dim rubbing from an old coin or tomb-remember Sir John Peyton with his clerk's face and scrub, woman's hips?

Besides, I fear what's happening in Europe. In truth it weighs heavily on me. We're in for a wrackful siege ofbattering days, and damn little will hold out against them. Certainly not my play. Let it have its moment then. Bad cess on those who would plunder it for petty loot-a notice in the Times, the eye of some Hollywood agent. But I've run on too long. Forgive me. All good fortune with the book.

Love, Phil

Rodney, Indiana May 17, 1939

Dear Tony,

The leads seem to be in good hands-Jack as Russell, Delores Sutton as Mrs. Danlever, Bob Thomas as Ted, Joyce Downes as Anne. The others look good too. Only do me a favor, Tony. Don't give Jack and Delores their heads, those vacancies.

The weather's settled down to sultry, but I think the damp and chill of the last weeks have worked into my bones. Despite the stupid fever I'm half the time shivering. If my health were better I'd go somewhere else to get cured-the Mayo Clinic maybe. You've taken good care of my play.

Thanks, Phil

Rodney, Indiana June 12, 1939

Dear Tony,

Sorry to hear about the ruckus Delores is kicking up. But she knew that Mrs. Danlever's in her eighties. What does she want me to dotransmogrify her to a 35,year,0Id belle? And what then will I do with Russell and Ted? Put them in knee pants?

Give her a silver-headed cane and some lace at her throat. My mood is foul. I have to sit with my ear pressed to the radio to hear Gabriel Heatter. And if ever a man had an apt name, he's it. The trump of doom is all he can blow. He sours even the sunshine.

Yours morosely, Phil

Dear Bill,

Rodney, Indiana June 17, 1939

Still nothing from Tony about the ending. When will he drop the damn shoe? I chafe and look around me. Imagine, if you can, a town of twenty-thousand souls under barrage without knowing it. At one end a steel mill, at the other an automobile plant. The mill rolls out great hawsers of black smoke; the plant shivers the streetlights.

But the folk scurry heedless-in pickups, lunchpail sedans, hotrods. Of a Saturday night, with both plants blazing, the downtown streets are choked as if panic had suddenly struck. But no such thing. Merely the jaunting time. Young blades in front of Walgreen's and the Rebob Bar. Waddles ofbobbv-soxers. Farmers and their broods gawking into store windows. On the benches along the courthouse walks sit the old men-relics of the Great War, San Juan Hill, and, a few, even Shiloh and Chancellorsville. They smoke pipes and chew Mail Pouch and spatter the pavement with tobacco juice. Fat blood blisters. Don't they know what's brewing? Sometimes I feel like a visitor approaching Pompeii just in time to catch the first belch and grumble from Vesuvius. And I wonder: What wilderness voice?

All right, all right, I'm glum. But I want out of here. I want to be back in New York.

Phil

Rodney, Indiana June 26, 1939

Dear Tony,

First Delores, now Jack. Tony, my patience is milk thin. Tell the clod that Russell's not the play's hero. He's Augustus Caesar in Antony and Cleopatra, keeping his sword like a dancer at Philippi. His very smallness is his greatness. With an accountant's heart and brain, he totes up chances, finds the main one, and strikes. He will die in his bed, his bladder giving way, a stunned look on his face.

Yet it's a great part. To playa character so shrewd and still so obtuse takes some art. To cast one's glance only a certain distance, as if it ran into a barrier translucent but not transparent-that's a trick for the ages.

But if he doesn't recognize it, dump him. The sonofabitch is not to wreck my play. Tony, I wrote the damn thing with scalpel and cleaver, and I want it done right, at least once.

Phil

Dear Tony,

Rodney, Indiana June 28, 1939

Please forgive my last letter. I'm like a man with the shingles-the smallest things irritate me. And this business in Europe. By all means keep Jack. I'm sure that if you work with him, he'll see what the part involves. And the bastard does have talent. All apologies, Phil

Indiana July 8, 1939

Dear Bill,

Got a letter from Tony ten days or so ago, but only about some troubles Jack Whelan was causing. I'm afraid I replied waspishly, but dogged my letter with an apology. Still no word about the ending.

The more I think about it, the more convinced I am it must remain as it is, as Mrs. Danlever and Ted lived it. How could it be otherwise? She's never believed what stares her in the face. Dead and rotten these fifteen years, her husband still lives; the phone's yet listed in his name. What is unacceptable simply cannot exist. Nor is this just a matter of fantasies; rather she generates hallucinations with the totality of her being-not only desire but will. With that she would reshape the world, undo history. Caesar would not cross the Rubicon So Ted will go in to dinner with her and the others. He will not leave the house, cross to his cottage, pass through the hedge with its strings of rusted trumpet-creepers, follow the slate walk to the door, and then, once inside, go to his bedroom and get from the dresser his Browning target pistol, the one with the custom grips, and blowout his brains. No, this will not happen. Only-Caesar did cross the Rubicon.

Bill, I started this letter three days ago and write now from the County Hospital. I'm not sure what happened. I was writing to you; then it was like looking through a window running with rain. Things wavered. My mother tells me I blundered into a wall. She heard the thud. I don't remember that-only the strange plasticity of things. And awakening here in the hospital. My doctor looks sage, strokes his cheek, but is obviously baffled. Yet, oddly, I feel all right; my fever's subsided and my cough is infrequent. Still, there's this sense ofdisconnection, of translocation.

A moment ago I looked over this letter's opening, and it frightened me. If you glance at my play you'll know what I mean.

Let me tell you something. On the fourth my mother drove me to the park for the festivities. The fireworks were fine, all those carna-

tions blooming and fading in the night sky, and the band struck up a Sousa march. But I merely remembered it. I couldn't actually hear the music. I was sitting at a whitewashed table with ribbed planks, but when I laid my hand on it I couldn't feel the ribbing. I had to dig my nails into a corrugation to register it. Strange. I go home this evening. My doctor, at a loss, strews consoling con, jectures-a momentary attack of vertigo, strain, worry about the play, a sudden gust of this mysterious fever. We'll see. No cause, I suppose, for alarm.

Phil Rodney, Indiana

July 14, 1939

Dear Claire,

I'm writing this with no intention of mailing it. Perhaps when I've assembled a packet, I will. Perhaps not. I came home from the hospital two days ago, after an unsettling experience-not altogether a black, out but a kind of disorientation, displacement, a marine sort of sub, mersion in which things took on a fearful fluidity. My doctor couldn't explain it. Tests revealed nothing. So he sent me home.

On the first night while I never really slept, there was a film of what might have been unconsciousness. The posts at the end of the bed were distinct, the windowsill glittered with moonlight, and, outside, the bole of the apple tree was a solid black shaft. All this was immediately present and yet giving way, or rather admitting something else-another scene, vague shapes of furniture, and three figures dis, solving and reforming, shadows that thinned and thickened but always remained shadows. Yet I thought I recognized Ted's hopeless forlorn mustache, Russell's coinpurse mouth, the sockets of Mrs. Danlever's eyes.

The three figures scrapped over money (early on in act three), Russell arguing that a wooden coffin would be perfectly suitable. Even tasteful. I won't hear of it. Cary's your sister. Ted, reason with her. What do you want me to say-that Dad's bronze coffin and water, proof vault have not preserved him, that only bones and dental work are left? You make me sick. I'm not talking about that sort of thing. I tell you I won't listen to any more ofthis. I don't blame you. I'm going back to my cottage. The port's made me sleepy. That's always your way-go around in a stupor. Yes, it's my way.

I heard none of this and heard it all. Have I told you that I seem to be growing deaf? There were, I knew, cicadas outside, fast little clicks,

like those we made with the tin beetles popular when I was a boy. But I couldn't hear them.

At some point I got out of bed and scraped up a shaving of moonlight. A flavorless ice.

I've tolled the times you clutched me in sleep and said Oh Phil I love you so much. My abacus (no warranty attached) reckons the count at one thousand two hundred twenty. The mind reels. Even in the moonlight, the grass, so green in the sun, is black. With a bad smell.

If Tony thinks I'll change a line, a phrase, a word I've had three bourbons and can't keep my scrawl under control.

So for now, Phil

P.S. I have a strand of Christmas ribbon-but there'll not be another Christmas. It won't snow again. And what happened to the topaz I got you that one Christmas? The size of a man's pocket watch, I recall. Lodged, is it, like a sachet in some drawer? Oh, the ribbon. What I thought was that when I've a number of these letters I'll tie them together with the ribbon, put them in a safety deposit box, and leave them to you in my will. If you want, you can untie and read them, though if I were you, I wouldn't.

I have trouble signing off. Some commentator does it with "thirty." But what does that mean? Everything's so goddamn cryptic. All sorts of codes baffle me, including the protocol of ending a letter that contains a P.S. Does one again subscribe? Well, I will even if I'm damned for it.

Phil

Rodney, Indiana

July 28, 1939

Dear Tony,

I'm sorry, but no. The ending must remain as it is. Trust me. I knew what I was doing when I wrote it.

Yours, Phil

Rodney, Indiana

July 29, 1939

Dear Bill,

The fox has finally left his den. You were right. Tony does want the ending changed. Mrs. Danlever's to be more "sympathetic"; Ted's to be more "sympathetic"; Russell's to be more "sympathetic." And no suicide.

I responded curtly. No changes-not a jot, not a tittle. Ifthat makes the script seem incised on stone I can't help it. I'll endorse no alterations. If he makes them himself, I'll come back and haunt him.

Sympathetic! The word sickens me. What does he think the play's about? A family gathered to bury an only daughter and squabbling over the funeral costs-and Tony wants, like Chamberlain, to dodge and palter in the shifts of lowness.

Damn to be in New York! My cough worsens, my fever mounts, my hearing deteriorates. Padded hammers on a cotton drum. I spend twenty minutes composing a simple declarative sentence. Stead for me, Bill. I need you.

In wormwood, Phil Rodney, Indiana August 1, 1939

Dear Claire,

Another letter for the safety-deposit box. Hitler has renounced his peace treaty with Poland, but Mrs. Danlever says there'll be no war. Won't hear of it. "We'll talk no more," she says at the end of my play. "Now we'll go in to dinner." And that settles that. Except that Ted doesn't go in to dinner.

As I won't change my play to suit Tony'S pandering taste. Once was enough. And what a botch it made, reconciling Warren and Letta when she had soiled things in the first place, confined as she was to her own blinkered experience and unable and unwilling to grant a value to something so fine, though bizarre, as the relationship between Warren and Grant. So I wrote nihil obstat to her judgment and gave it my imprimatur.

Why? For pelf? Would, oh would the motive had been that noble! But in truth I wanted what Tony had promised-the smash hit, the arrival, the triumph. Which I got. PM: "The most powerful, wrenching play ofthe decade." The Times: "Brilliant, original, stunning." Can you wonder that even now the words scorch and smoke?

Yet deeper and more vile, the desire to be understood. They won't understand it, Tony had said, neither the audience nor the critics. They'll be puzzled, then annoyed, then angered. He was right; the event bore him out. Nor could it have been otherwise. Did they not sit there for two hours looking not only through but with Letta's eyes and could they then tolerate having their judgment mocked? And why should I have supposed better of the critics? They too were only playgoers.

Well, they all understood what finally took the boards. No wonder. There was nothing to understand.

But I had my hit, I had my audience, I had my critics. Alum and ashes. And now a green taste to go with the green smell constantly in my nostrils, not the smell of grass or leaves but of the film that covers a stagnant pool such as the one behind the greenhouse on 12th Street. A green membrane, quivering and sightless. A green mist over it like mustard gas on a windless day. Algae grow there and something with a fat pale stalk. The ground stinks. Excrement of flowers.

But you wouldn't remember. Of course you wouldn't. You've never been there. Odd that I should forget that when I recall so much else, the shape of your earlobes, the angularity of your mouth at certain moments in the night, the pulse in your throat.

Outside my window the moon pulses too. Tattered apple tree. I can see the flare from the automobile plant's furnaces but I can't hear the fall of the great hammers. Only voices: She was your sister. You have to come home. Of course. What made you think I wouldn't? But I'll have no bad blood in my house. Mother, I bring no bad blood. I won't have it, you hear?

Now they'll inter Cary a second time. And what will it cost? Ten thousand dollars? Less, of course, much less. But that was what they laid their hands on when they had her committed and got power of attorney over her affairs. Ten thousand dollars! Which, facing lifelong maidenhood, she'd wanted to hang onto. Yet Russell's manipulations paid off, for her as well as for him. Interstate trucking. With the war coming on he'll be a millionaire. Let him. He deserves money.

The issue now is flame-grained oak versus brushed bronze. But it's enough. Murder has been committed for less, even wars fought for less. I think of the tennis balls the Dauphin ofFrance sent to Henry V. And last week at a bar on Broad-Vance's, I think it was-a man knifed another to death over the price of four beers. No bad blood, she had said. But it's all bad, that black surge. With my hatred I've shrivelled enemies like spiders in a flame. And would again when I think of what Tony wants to do to my play. Or when I think of whoever sits across from you in a restaurant and leans forward to light your cigarette, with your fingertips cupping and guiding his hand.

If you ask why I torment myself with such images, I can only answer that there are moments when they alone convict me of living. I can fool my doctor, my mother, even myself. But I can't deny the testimony of my fingernails. They grow at an enormous rate and, brittle, break before I can trim them. I'm surprised to look in the mirror and not find it vacant.

It's a posthumous existence. In front of the house children roller,

skate along the walk. At one place the concrete humps and the children take it with great daring. Not a one of them ever falls. On the porch I sit with the evening paper. Revels in Spiceland, ads for Purina chows and John Deere tractors, columns of homely wisdom from "Soapy" Pearl-e-l'In Rodney, Soapy Sells the Clothes"-tidbits on the local arts, pronouncements from Mayor Herschel "Sammy" Tenbar (ex-used-car salesman, ex-realtor, ex,insurance agent, ex-this-that-andthe-other, but by endowment, inclination, and assiduous practice rhen-now-and-the-dav-after knave, blackguard, and charlatan) on Rodney's glorious future and encomia on Rodney's zealous, forward, looking citizens Eventually the children go home, I check for my obituary, and take the newspaper to the trash can in the back yard. There's a woman named Gail. I knew her years ago, went with her briefly. She's never married and still has her figure. Under her eyes are little puffy lozenges, some sort of hormonal aberration, I suspect. She comes by every couple of weeks. Once we went to the Anchor Room. All very nautical: life-buovs on the walls, great falls ofnetting studded with cork; other such gear along with mounted sailfish and tarpon. We drank, of all things, cuba libres, and she, after several, spoke slurringly of lost chances that might yet be redeemed. I listened, missing much but catching her drift. Yet, after you, what could I do? Adam wandered for two or three hundred years in arid discontent. She's not interested in my play, although she pretends she is and lets me talk about it. Not that I do at any length. A gnomic utterance, an allusion, a near rhyme. All of which you would catch. Do you remernber the language we spoke? Gabotz, notary sojac, nov schmoz kapop. At parties no one could follow our dialogue. And sometimes we didn't need language at all-only a lifted eyebrow or an emanation from the skin. But we would mumble apologies, get our coats, and leave-to have pancakes or waffles at some all-night diner and go home to make love in the morning grayness to the sound of milk trucks in the street below. I look for a word to describe that time and can't find it. Perhaps no word would do, only a collision of words, their chance tumbling into place.

At three in the a.m. and with a fair load of bourbon aboard, my mind goes back to the time we went to Washington for Jack Callaghan's party-wild Jack and his fourth-floor spread at the Willardthe party we'd so looked forward to, such a gang ofold friends. But we took a double room at some motorcourt somewhere and made love first in one room and then in the other and afterwards went out and ate and came back and made love again. (Do you remember the three days at Laura's in Boston? What lions we were! You draped over that low bed with your head on the floor. And how jealous I was of the

faggot you danced with that one night. Maladroit of both feet I sat at the table and slugged myself sodden with gin. But how sweetly you soothed me when later you slid into bed beside me.) In the motor' court, sitting cross-legged on one of the beds, you began to sing in that small sweet voice of yours. The party whirled on without us, memorable we were told, although Jack could not actually recall the details. Something about a girl hanging out a window, all deshabille, and three men pulling her in and then something about a scene in the Emerald Room. And you sang "Fish gotta swim, birds gotta fly and, deaf as I've grown, I still hear the longing in your throat. Once you bent at the waist and kissed me. I've been a husk ever since, a bankrupt, but rich as Pompey home from the East with loot enough to field a modern army. In the morning I shelled out the contents of my wallet, a trivial sum, twenty-five dollars or so, and we drove back to New York with you snoozing in the front seat and I loved you. What now can I settle for?

Again I've gone on too long. Nor do I know how to close this letter. But I must, so I will.

With all my love, Phil

Rodney, Indiana August 5, 1939

Dear Bill,

Et tu, Brute!

Why does a man commit suicide? If I take pains in answering the question, please don't suppose I think you an idiot. My hope is that I'll help you make things clear to Tony.

To the question then. One destroys the self because he has come to see it as both corrupt and hollow. First, Ted's complicity. He stood idly by while Mrs. Danlever and Russell committed Cary to the asylum where she did indeed lose her sanity. That episode in the Palmer House in Chicago: her dogs urinating on her luggage in the lobby and her imperious demands-swathed as she was in a leopard coat-that the bell captain walk them along Randolph. And the in, credible man she picked up in the bar, all Valentino brilliantined hair above that fungus of a face, and three rings on his right hand. Never would she have behaved so before the sanitarium. And what a name for the place! Draining sanity from her as physicians once drained blood from patients anemic to start with. Pathetic when she entered, blighted and mad when she emerged. And he stood by.

The funeral made him take stock. At 47 what did he have? Two failed marriages and a job in a private school in the Bronx teaching the

frippery offspring of theatrical and literary luminaries. And as for his work. Well, you know that before he returned he read through it all, the labor of so many dank nights, and found it-as he had always known-worthless. Verses that scanned and prose that wreathed a python syntax. Nothing else. So he lit a fire (this was in July) and burned it all, published and unpublished.

Then he went home to the old quarrels, the whole flawed and sleety history of greed, cunning, cruelty and coldness. If any hope existed, it lay in Anne. Surely after so many years of marriage to Russell she had come to see him as he was.

And there was hope. All those calls to New York: collect, so Russell wouldn't know of them. Briefadmissions that she missed him, wanted him to know she was thinking ofhim. On the train he remembered the last call, hushed and hurried, Russell due home at any moment: Anne, are you happy? I must be, I guess; I don't think about it

Happy and not think about it? That defied belief. He thought ofhis own life with Becky, and especially ofthat one afternoon in November when he had opened the apartment door to find her, against the late slant of light, floating, buoyant in a flowered gown, across the room to him. They had made love. And afterwards, as if from the shell of her ear, the salt unestranging sound of the sea Happy and not think about it?

From her answer he should have known how withdrawn he would find her. Never would she confess-the terror was too great-that in choosing Russell she had invested unwisely. In the hallway she turned a dry, taut cheek to his kiss. The bowstring snapped.

How, then, can you side with Tony and tell me that Ted must follow his mother into the dining room? No, Bill, that outside door must close with a last audible gasp: not a crash, only a closing.

I wish I could shake the exhaustion I feel over this business in Europe. And to think that Shakespeare gave Bohemia a seacoast and not a tremor was felt anywhere.

Bill, I'm counting on you.

Dear Claire,

Yours, Phil

Rodney, Indiana

August 13, 1939

Jackals from all sides-Tony and now Bill. Snap and another piece of the play gets bolted.

Don't worry. I'll not mail this letter either.

I had a salad today with a large green segmented worm in it. Hal-

lucination? I'm not sure. My mother swore she couldn't see any worm but tossed (ha, ha) the salad out anyway and fixed me another. I couldn't even look at it.

I know I have them-hallucinations, I mean. And sometimes that I'm having them. Combination maybe of medicine and booze. I can't decide whether it's better to go around hallucinating because I'm drunk and coked or because I'm stupefied from insomnia. Or whether it makes a difference. Right now I'm having my fifth bourbon. Naturally, the moon throbs, on a faltering current, and takes the shapes of various faces-Ted's, Russell's, Anne's, Mrs. Danlever's-but always, finally, yours. Did I ever tell you that at certain angles (you below, me above), it was a Medusa face stoning my eyes? No, I never told you. Such words did not come easily. But I remember thinking that no matter who might make love to you he would never see the beauty that I then saw. I ramble, I know, but since you won't read these words (I wouldn't if I were you) they may be easier to forgive. I can manage: ego me absoloo.

Not, however Tony. I do not absolve him. Or Bill. There is such a culpable ignorance, and of that they are guilty. They will not under, stand: it has already happened. Ted has already blown his brains out. There is nothing they can do about it. They might as well try to send the bullet back down the gun barrel. There are ineluctable laws: Caesar has crossed the Rubicon.

All of which strangely cheers me. Let them do what they will, but Ted will still not go in to dinner with his mother. And even ifhe does, the audience will know it's experiencing an illusion and hear, nonetheless, the closing of that outside door.

Now I will switch subjects. On my street lives a postal employee, a former scoutmaster. He has a carved face and a blocky granite body. His hands are stubby, rough as sandpaper. I see him readying for death. Oh, there are no obvious signs. His walk is vigorous, his color burnished. But there is no question that he is tilting towards death. His wife somehow knows. I watch her watching him as he trims his hedge or plants a flower. On her face is a sad awareness, as if she were snapping photographs against the time he will not be there. They've been married for more than thirty years. Like us, they have no children. When she dies, the house will go to strangers; the hedge and the precise tended flowerbeds will become as anonymous as moss. She has a soft, almost bovine face of great compassion and gentleness. Seeing her, I think of the cows we would visit on our late afternoon walks that summer in Pennsylvania, the time we stayed at Roland Childer's farm. Remember what genial girls they were, congregating to greet us but taking care to shoulder away any who wandered too near

the electrified fence? Their protectiveness always touched us, and we would continue our walk hand-in-hand. It was a golden time. I would sit at my Underwood and bang away at my play (my first, and a disaster), and you would sit in the kitchen and write wonderful poems on yellow legal-sized pads-"In Slumber," "The Child Upstairs," "Silences." There was something in that house. We didn't talk when we were working, but we were there and we were together. And our lovemaking was different. So gentle, stroking each other's faces afterward and finally falling asleep crooked into each other, my arms around your waist, your hands gripping my wrists. I don't understand what happened. The globe careened into something.

Perhaps it's my fever or this cough or this frustrating deafness (from the radio nothing but a crackle), but my mood darkens by the day. Even if we survive the coming war, innocence won't. Once, I think we supposed, there was somewhere a jewel of integrity. It's been filched, or it never existed.

I will tell you something. In late spring, to my shame and out of my loneliness, I drove to a brothel in Muncie. The girl wore green silk underthings, had rouged her nipples and painted her face a lead white. Incapacitated, I tipped her outrageously, drove home, and dreamt that night of making love to Yorick's sister.

Do you know that I've lost weight? You'd hardly recognize me.

Love, Phil

Rodney, Indiana August 17, 1939

Dear Tony,

Bear with me. I find it all too easy to snarl these days. The sun melting the asphalt in the streets and no relief at night-just a humid darkness and insects clogging the screens.

Still I will try to answer your last letter dispassionately. The point is this: A play should be concluded in the theater. I don't mean that it's wrong to leave an audience wondering, asking, for instance, what the future of these people will be and so forth. But the central action must conclude by the time the curtain falls. Otherwise the play lacks form. That's why Ted must not go in to dinner with the others. If he does, the central action remains incomplete. And that, more than anything else, leaves lasting dissatisfaction. When a batter steps up to the plate, he must get a hit or a home run or a walk, strike out, get thrown out at base or put out on a caught fly. Any of these events will complete the action-and, whether you root for or against him, you will not feel cheated. So must a play function. In the final analysis it doesn't matter

whether you want the protagonist to fail or succeed. Who wants Othello to murder Desdemona? But tamper with that ending and we will feel defrauded-regardless of how, sitting there, we might cheer some last-minute revelation that would save Desdemona's life.

So think about it, Tony. If the ending is changed, your opening may get rave reviews, but sooner or later the play will spoil and audiences will leave the theater with queasy stomachs. So think about it.

Best, Phil

Rodney, Indiana August 19, 1939

Dear Bill,

I wrote Tony a day or two ago giving him my reasons for keeping the ending as it is. Since you seem in constant touch with him I assume that he's shown you my letter and that I need not repeat my arguments here. So far as I can see, they answer your objections as well as his. My cough worsens, and my energy flags. Right now it suffices only to express my disappointment that you side with Tony. But I do have one question for you as my agent: Have I the right to withdraw my play, to remove it from Tony's hands? I'd appreciate a prompt reply.

Sincerely, Phil

Rodney, Indiana August 20, 1939

Dear Claire,

The news from Leland Press strikes me as encouraging. I don't think Gil would ask to see additional poems if he were not genuinely interested in your work. Perhaps he's right. Fashionable as slender volumes are, yours may be a little emaciated even for verse. Since you've not told me what pieces he has, I can't suggest which ones to add. If you didn't include the Phaedra poem, I think you should send it on. A longish narrative work might be just the thing to fatten the volume. It would also give the book some distinctiveness. No one much writes narrative verse these days.

I'm thinking of trying to get my play back. Tony seems determined to alter (i.e., neuter) the ending, but I want the thing performed at least once as I wrote it-if only in some community playhouse in Duluth, or even Warsaw, Montana.

Let me know how things go at Leland. They'll go well, I'm sure.

Love, Phil

Dear Tony,

Rodney, Indiana August 23, 1939

Since your letter didn't mention the ending, am I to suppose that you've accepted my argument?

About the dialogue between Ted and Anne at the end of act two, I don't understand what you mean by saying it doesn't work. Of course they don't say what they're thinking. What have you got actors for?

I smell a conspiracy. Your letter had an accomplice, a letter from Bob Thomas in the same mail. He too complained about the dialogue. Can't you tell him that an actor sometimes has to play cross-grain to the words? And how can he say he can't perform the ending? It's simply a question of exiting stage right or stage left. What he feels doesn't matter. It's what the audience feels. And if he exits stage right, they'll feel what they're supposed to feel. And you can get him to make that exit, can't you?

Bill's letter, I imagine, will arrive special delivery tonight. Phil

Rodney, Indiana August 23, 1939

Dear Claire,

I know I wrote you only a couple of days ago, but I need someone to talk to.

I'm baffled. None of the people producing my play seems to understand it. Today came letters from Tony and Bob Thomas (he's playing Ted) carping about some dialogue in act two, and Bob insisting that he can't perform the ending. All he has to do is exit stage right. What's there to perform? Beckoned with a banana a chimpanzee could do it. His obtuseness infuriates me. And what is all this rubbish about actors having to feel? Is it beyond them that the writer has felt, the characters feel, the audience feels? The man who throws the switch at the power plant-who cares how he feels so long as he throws the switch?

I wish I could do fiction. I'd be freed of directors and actors, their temperaments, their niggling density.

Do you want to know how I feel? Overwhelmed. Sometimes by the sheer physicality of things. Dog days, acetylene sun, flies so bloated they won't even stir at your approach. There's no energy anywhere. The mailman droops along the walk with the century's woes slung from his shoulder.

Yesterday Chamberlain solemnly averred that England would honor its commitment to Poland. "Honor" must have stuck in his throat. No

matter. The question is whether Hitler believes him and, if he does, whether he'll change his policy. I think not, on both counts.

My mind is parceled out. I think about my play, then about you and our past, then about Europe, then about my illness and doldrums and sargasso seas. There is a crazing, the kind that porcelain sometimes suffers. And there are moments when I don't care. Let things come apart. This lingering has become intolerable.

Do you believe in the coincidence of stars? You left me a week after I finished my play. Three days later the four powers signed the Munich pact. In the late winter I came home for a short visit, fell ill, and have been confined here ever since. It's as if at the axletree ofthe universe a linchpin had worked loose. Of course I don't believe all this, and yet I do. I want some field theory, like original sin. Things might then make sense. They might be as simple as my play. I know what drives Russell and what keeps Ann mortised into her life, but I don't know what tumbles this world along or any life in it, including mine. I don't know why you left me, and I don't know what I'm going to do with the love I still have for you. It's corrosive, eating away at me, like acid, or like a stomach consuming its own lining.

I'm sorry. I know my illness has been talking. When it goes and my hearing returns, my mood will change. I'll bound like the hart. After all, I've much to rejoice in. I've written a good play, and another is already in the vat stage, simmering. In a few months-all this fuss and feathers with Tony and the rest behind me-I'll sit down to start writing it.

There, I feel better already. Mind over matter. Maybe Mrs. Dan' lever has something.

Indiana August 27, 1939

Dear Bill,

It's taken me three days to recover from your letter. Even now my hand trembles. But I'm able, I think, to respond. The sun is setting, and there's a breeze-the first in a week or more. A break at least in the weather.

Ironies spring like tigers. In what I supposed was a bitter joke I speculated in a letter to Tony that, after his and Bob's, your letter was arriving special delivery. So it did, although not that evening. It got here on the 24th.

A memorable and infamous day. Even the Rodney Courier Times bannered the news: "Germany and Russia Sign Non-Aggression Pact!"

Poor Poland. Its only comfort Chamberlain's speech to Parliament that Germany should not nourish the "dangerous delusion" that England and France would not fight. But who else planted the delusion, watered it, and saw that it had the sunlight it needed?

Delusion upon delusion, maggots breeding in a jellied mound. Your sun, once ran the belief, generated your crocodile from the slime of the Nile. That was true, for it warmed the mud where the eggs nested. I'm rambling, you suppose, but images of pathogenesis swarm in my mind. Not long ago you thought my play the best thing I've done"flawless" you called it. What has hatched all these objections?

Four pages of your crabbed coiled handwriting, like trichinosis in a muscle. There's too much exposition in the opening; Russell at times borders on caricature; Anne's motives remain murky; the dialogue between Ted and Anne at the end of act two communicates nothing; Mrs. Danlever's final words sound unnatural; and the ending is all wrong, dead wrong. There's no real reason for Ted to commit suicide, and even if there were, the audience would never know that when he leaves the house he will kill himself. For all they'll be able to tell, he might be leaving to get drunk. In a pique and a sulk. Have I omitted anything?

Reading your letter, I grew more feverish by the moment. The tone was more than critical; it was treasonous.

I never supposed the work "flawless" (your word, not mine). I was insistent-all right, unyielding-on one thing only: Ted must not go in to dinner with his mother and the rest. He must leave, and he must cross to his cottage and commit suicide.

You say the audience won't know he's going to do that. But what else could they possibly suppose? Do you think they actually need to hear the gunshot?

No, on that point you're as wrong as Tony. They'll know, and it's the only ending that can possibly close the play.

But I'll not make a Verdun of everything. If dialogue needs revision here and there, I'll revise it. I'll redo the exchange between Ted and Anne at the end of act two. I'll sharpen Russell's characterization. I'll make Anne's motives more apparent. I'll redistribute the exposition.

But Mrs. Danlever's words must remain as I wrote them. They're precisely what she would say. I know. I know her better than she knows herself. They trigger Ted's leaving and cannot be changed. Still, all things considered, am I not an accommodating fellow?

But I'm hurt. I can't help thinking that you've colluded with Tony to make my play palatable to an audience craving all things sweet and frothy. Cotton candy may look like a bomb burst but melts to a sugary residue. And sells. Is that what you're after-your ten percent? To

save the cost of bronze would you bury your sister in a wooden coffin?

A cruel question, I know. But for some reason-no doubt mad-I don't feel especially benign on this 27th day of August in the Year of Our Lord Nineteen Hundred Thirty-Nine.

In my last letter I asked whether even at this late point I could withdraw my play. Since you gave me no answer I intend to consult an attorney here.

Sincerely,

PhilP.S. Narrative, narrative? What the hell do you mean? The goddamn thing's a play.

Rodney, Indiana

August 28, 1939

Dear Claire,

Three letters in roughly a week. You must wonder at the state of my mind. Not good.

Four days ago I received a brutal letter from Bill. He again harped on the old note-the play's ending-but also went through the script with a magnifying glass and a malevolent eye, finding everywhere blots that were only reflections of his own bleared and-dare I say it?-venal vision. Thinking of his ten percent, he wants a hit. Does he sniff my death and suppose that he must now vulture what he can?

Otherwise I can't account for his criticisms. Some I couldn't even understand. One passage jabbered incoherently about "narrative." I puzzled over it and finally threw up my hands in despair. But even supposing his objections valid, there was no reason to pen them so viciously. I went, I think, into shock.

The letter came on the 24th. There was no sleep that night, and precious little since. The days have passed in a miasma, with things again taking on the undersea shapes they assumed during the curious attack I described earlier this summer. It's as if I had drowned and were visiting the bottom of the monstrous world. Yet it's not unpleasant. Quiet, one drifts at ease on soft currents.

Nor does my fever much bother me. It stays locked at 100-101 degrees and alarms my mother. Today she brought the doctor here. He wanted to hospitalize me. I refused. He argued, but since I could not, for the most part, hear him, he was only making mouths at the event. I nearly laughed.

This morning I got up, dressed, and took a walk before dawn. It was cool, the silence soothing. I wandered aimlessly down one empty street after another. Then I came back and sat on the front stoop and looked at the sleeping houses and the dark watery lawns. Quite at

peace, I thought of the mornings we would leave a late party-the one Ned Parlin threw at the Madison-to find the city filling up with snow. How it would take us by surprise, the hush, the fall of silence. And we would go up to the apartment and have a final drink and a cigarette and watch the flakes rock down past the window. Strangely, even as I was re-experiencing it this morning, I began to think that the serenity we then felt was only a dream. Or perhaps at this stage dreams turn into memories. I remember the corner streetlamp glowing gold through the snow. But did it?

My play too now seems a dream. I've thought of it as historyCaesar crossing the Rubicon-and in part it is: Ted did leave the house and go to his cottage and put the pistol to his temple. And, like the one in my dresser, it was a Browning with custom grips. And he did spray bone and tissue across his bedroom floor. But none of this is actually in the play. It's engraved on history. And the rest? Maybe it is malleable. Maybe Bill is right. I dreamed one thing and wrote another. There is suddenly a great blankness.

If, like Mrs. Danlever, I thought I could create by an act of the will, did I do the same with our life together, endow it with a perfection it never had? I fear I must have. Now I dare not look at my script.

And, good play or bad, what difference does it make? A day or two ago England and Poland signed a mutual assistance pact, and yesterday the German newspapers carried stories of Polish troops massing along the German border and of Poles burning German farmhouses in the corridor. It takes no haruspicy to interpret signs like those.

Still, isn't this precisely when I should hold out? Fix my small imprint on things? I made a drink and, summoning up somehow a spasm of nerve, went through the script. Crystal it may not be, but the flaws Bill discovers are simply not there. What is there is what I willed to be there. Why, at this late date, should I suppose that will is not creative? Merely because we cannot, by willing it, stop Caesar on the far bank? But will can accomplish other things. No one is born a writer; you become one by willing it-by determining that those inchoate shapes struggling inside you will receive form. And by willing, in both exultation and exhaustion, the labor it takes. Can I turn my back on that now? No. I would be like the servant of Caius Gracchus who, learning that the Senate would pay for Gracchus's head with its weight in gold, severed the head from his slain master's body, scooped out the brains, filled the cavity with lead and, taking the thing to the Senate, received his promised reward to the troy ounce. They'll do my playas I wrote it or not at all.

It's taken me all night to come to this point and I'm tired. A moment ago I went out and stood on the lawn. A faint gauze of light

lay along the horizon, but I came in before the sun could ignite it. Now I've lowered the blinds and drawn down the sheet on my bed. I'll have one last bourbon and turn in. My mind is at ease: in a day or two I'll see an attorney about getting my play back. Good night. I love you.

Phil

Rodney, Indiana September 1, 1939

Dear Tony,

This morning Germany invaded Poland. Do what you want with my play. Unheard melodies are sweeter.

Phil

Mary Margaret had never been inside a Baptist church before, and she hadn't meant to be here now. She had said only at the last minute she would come because Mrs. Ross, who had been so nice to her all weekend, had insisted. And Sandra had promised they would see Isaac. The front of the church was crowded, and Mary Margaret sat in the third row, wedged between Sandra and a fat lady she'd never seen before. Mrs. Ross had leaned across Sandra and introduced her to this lady, whose name was Miss Purvey. Miss Purvey had squeezed Mary Margaret's hand and said how nice it was to have her with them on this beautiful morning, but Mary Margaret thought Miss Purvey did not look pleased in spite of what she said. Then Mrs. Ross leaned forward and spoke to a woman in pink, who turned and smiled at Mary Margaret and said how glad she was.

Sandra fidgeted beside her and craned her neck to look around. Sandra was little and cute, with a face not pretty but lively, and she always knew what to say, even to boys. Mary Margaret wished she were little too and thought if she were she would certainly be still so people wouldn't look at her. Mary Margaret was so tall she attracted attention just by being there. She was five feet seven and still growing, the tallest one in the eighth grade except the boys who had failed so many times that they were just waiting to be sixteen so they could quit school for good. The trouble was, Mary Margaret couldn't seem to grow any way but up. At night she would stand sideways before her dresser and look at her outgrown little girl's shape in the mirror. Not like Sandra, who was already nicely rounded.

Mary Margaret balanced her straw purse on her lap and squeezed her bare sunburned arms, hugging herself into a smaller space. Miss Purvey shifted, spreading thick legs under a speckled voile skirt, and Sandra's shoulder nudged her. "I just can't imagine where he is," she said.

Mary Margaret looked at the empty pew two rows in front of her, 34