UMBER FIVE $1.50 ARCHIVES \ \ .�

THIS AFRICA

Novels by West Africans in English and French by Judith

Illsley Gleason

The first study of African novels as such, This Africa is both a literary history and a survey of the contemporary literary milieu. The author examines the styles and traditions discernible in African novels and discusses, among others, such writers as Chinua Achebe, Cyprian Ekwensi, Mongo Beti, and Camara Laye. The necessary relevant historical, political, and educational factors are treated in scope fully adequate to their importance.

"Mrs. Gleason has written a first-rate study of an important part of the emerging or exploding literary culture of Africa." Lionel Trilling

186 pages

CHRISTIAN MISSIONS IN NIGERIA, 1841-1891

The Making of a New Elite by J. F. Ade Ajayi

In this major contribution to the study of African history, Professor Ajayi surveys the work of missionary groups as one factor initiating great change in Nigeria. He assesses the effects of this change on a new elite, formed as a result of missionary education, that became important in the nationalist movement. In this context, the author makes a detailed study of the Ogboni and Egbo societies as politico-religious institutions.

275 pages

$6.50

MARRIED LIFE IN AN AFRICAN TRIBE

by I.

Schapera

On the basis of observations carried out among the Kgatla of Bechuanaland, the author describes the economic, social, and psychological factors which form their conditions for love and marriage. This classic study in African ethnology has been out of print for some time.

364 pages

$6.50

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY PRESS

$9.50

EVANSTON,

ILLINOIS

POEMS:

AN HANDFUL WITH UIETNESS

What first strikes the reader of these fifty-six poems, now collected for the first time, is their luster and complexity. John Stewart Carter, as poet, writes of the real world: people, places, faces, past and present time. There's a strain of fine wit running through these poems that ensures a felt distance between the poet and his desire. Personality is the prism, memory is the white light it refracts into moods, views, laughter, prejudices poems.

By the author of FULL FATHOM FIVE

1964 winner of The Houghton Mifflin

Literary Fellowship Award

Cloth edition $3.95 Paper edition $1.95

Houghton Mifflin Company Publishers

PREUVES

revul Illensuelle

a publie des textes originaux de

RAYMOND ARON

ALBERT CAMUS

T.S. ELIOT

ALDOUS HUXLEY

ARTHUR KOESTLER

ALBERTO MORAVIA

D. de ROUGEMONT

S.S. SENGHOR

MANES SPERBER

ROGER CAILLOIS

LAWRENCE DURRELL

PIERRE EMMANUEL

KARL JASPERS

HERBERT LUTHY

BORIS PASTERNAK

NATHALIE SARRAUTE

IGNAZIO SILONE

GEORGES VEDEL

Le N°de 96 pages: 0 $ 80 Abonnements

U. B.A.: Un an: $ 8 - Etudiant: $ 5,20 specimen gratuit sur demande

PREUVES-18, Avenue de l'Op�ra-PARIS (ler)

o n ewar ar er

900 NORTH MICHIGAN AVENUE

CHICAGO.

ILLINOIS

Since 1940 this gracious private gallery has offered select paintings, prints, and sculpture, collected from here and abroad sensibly priced and housed in a sp actous apartment.

Gallery open to the public every Friday and Saturday II to 6. Weekdays the gallery is open by appointment DElaware 7-1343. 900 North Michigan is the Jacques Restaurant Building. The doorman at the Delaware entrance will park your car. The gallery is in Apartment 318.

o o 0

WI est selection 0 ua it orne

D o

In addition to , the

now carries

In an rowse

fiction

ISAAC BABEL 7 Maria a play in eight scenes with a foreword by Andrew Field, translated by Denis Caslon.

JONATHAN PENNER 41 The West-Chop Season a chapterfrom a novel in progress

RICHARD BRAUTIGAN 55 Two Stories: Revenge of the lawn, A short history of religion in California

GEORGE P. ELLIOTT 73 In a hole

new african writing

MICHAEL CROWDER 117 Tradition and change in Nigerian literature

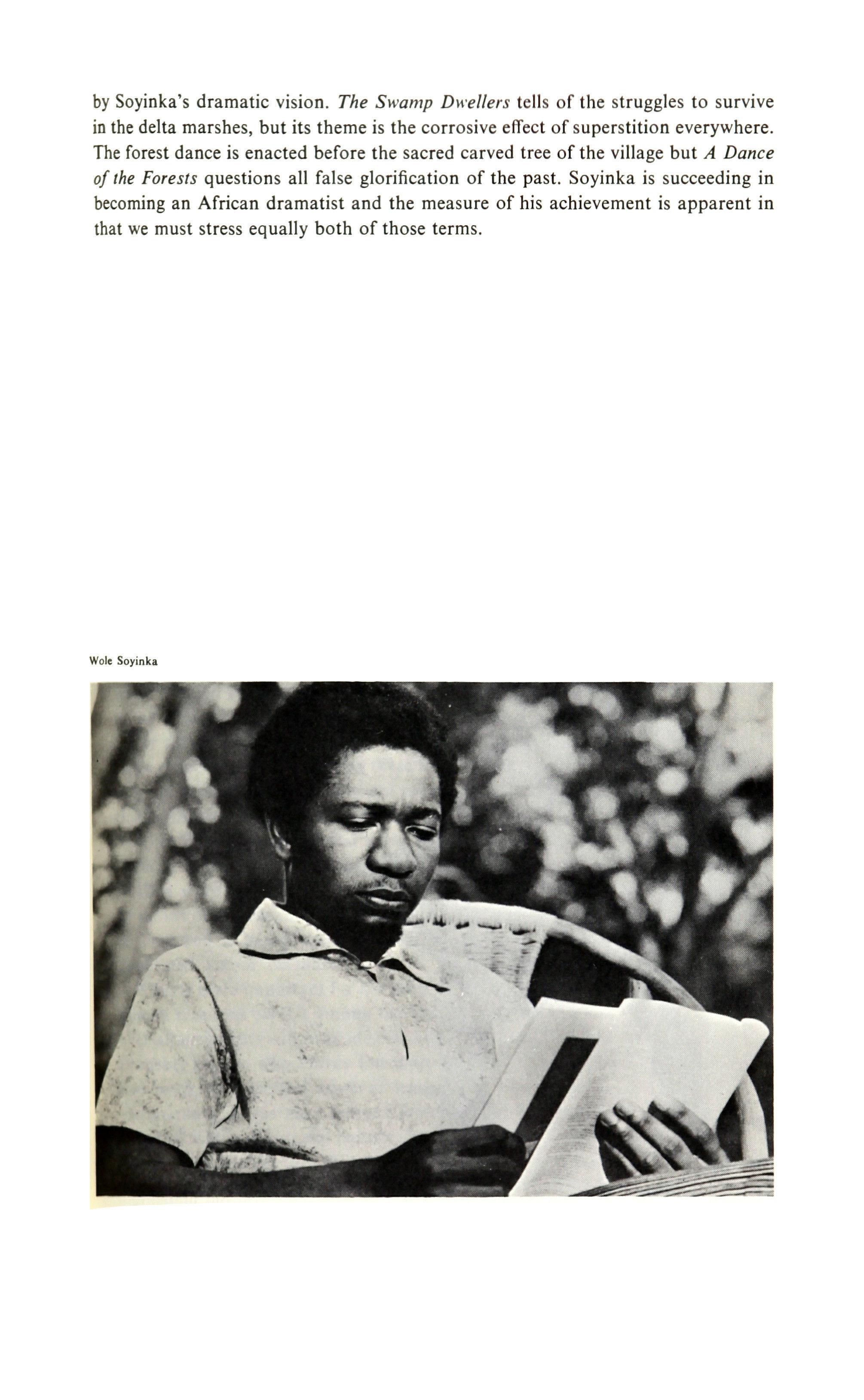

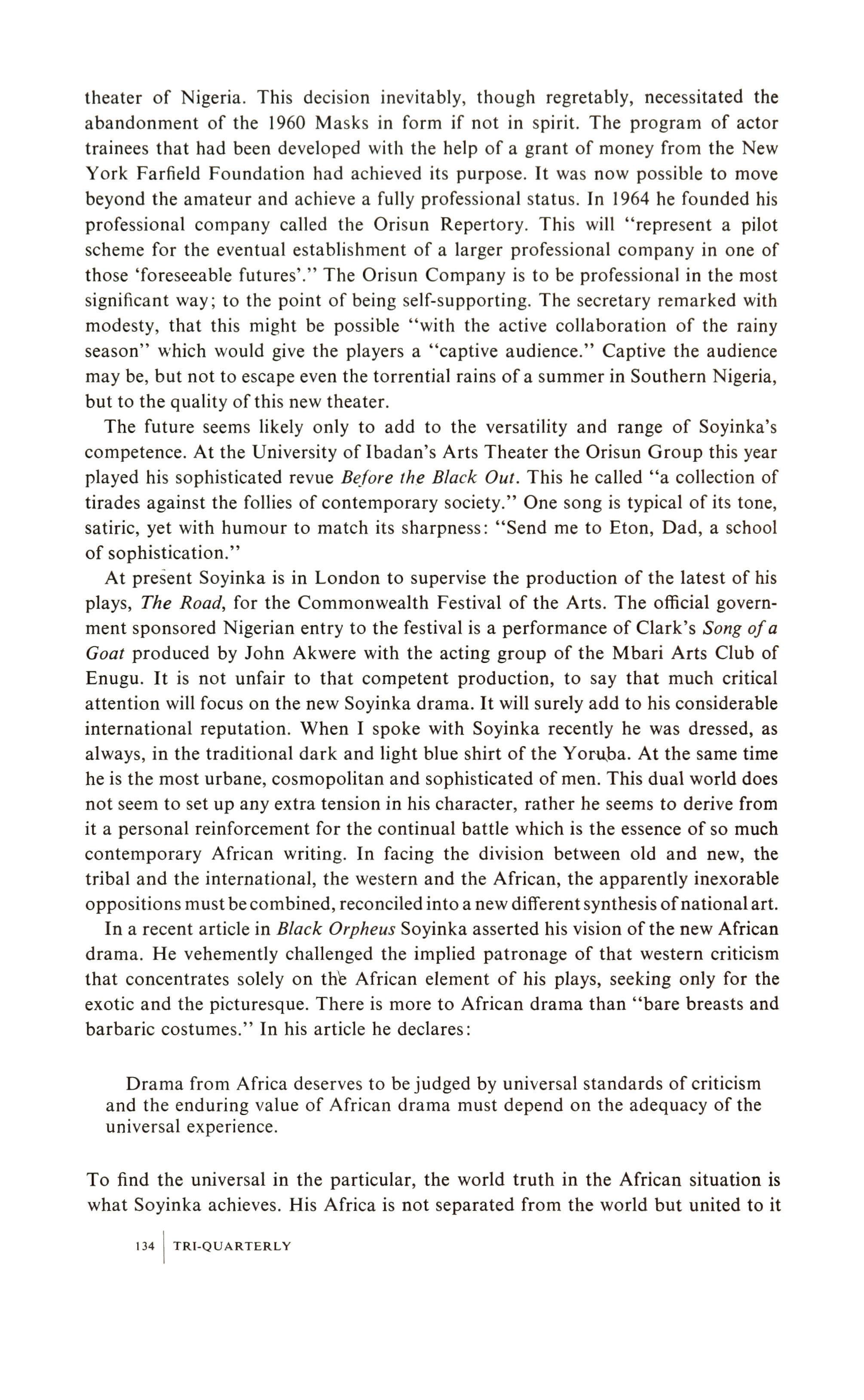

JOHN F. POVEY 129 Wole Soyinka and the Nigerian drama

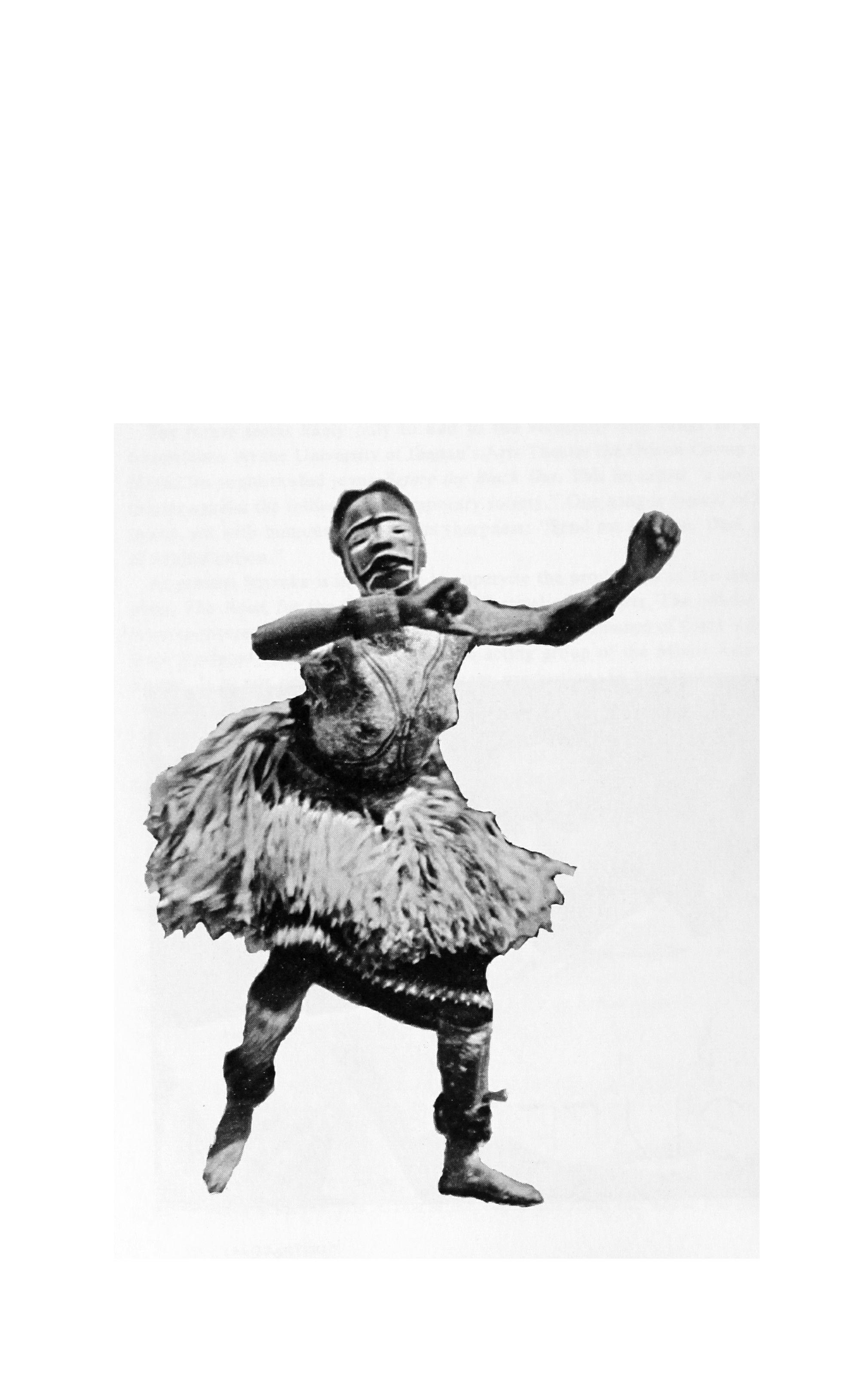

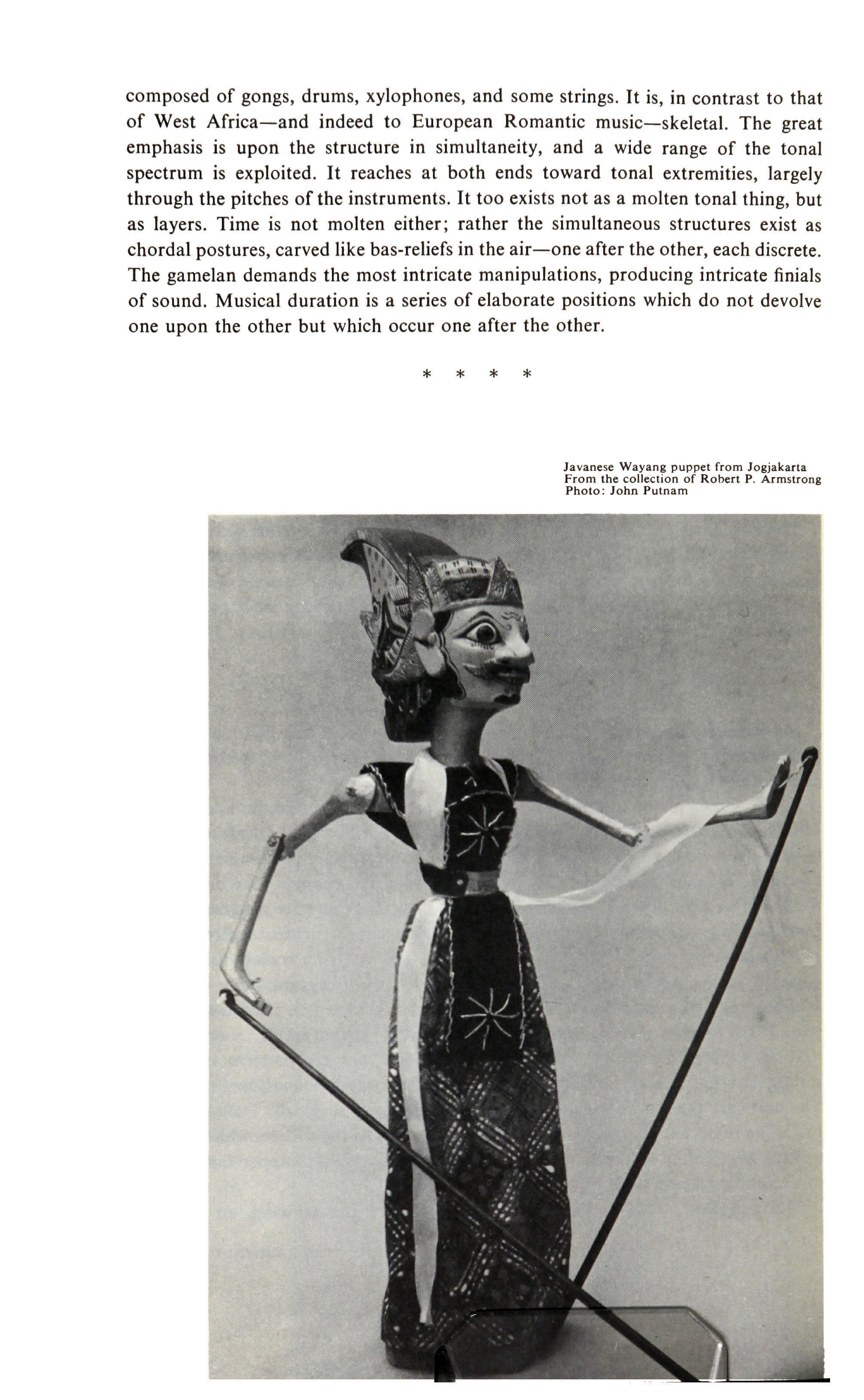

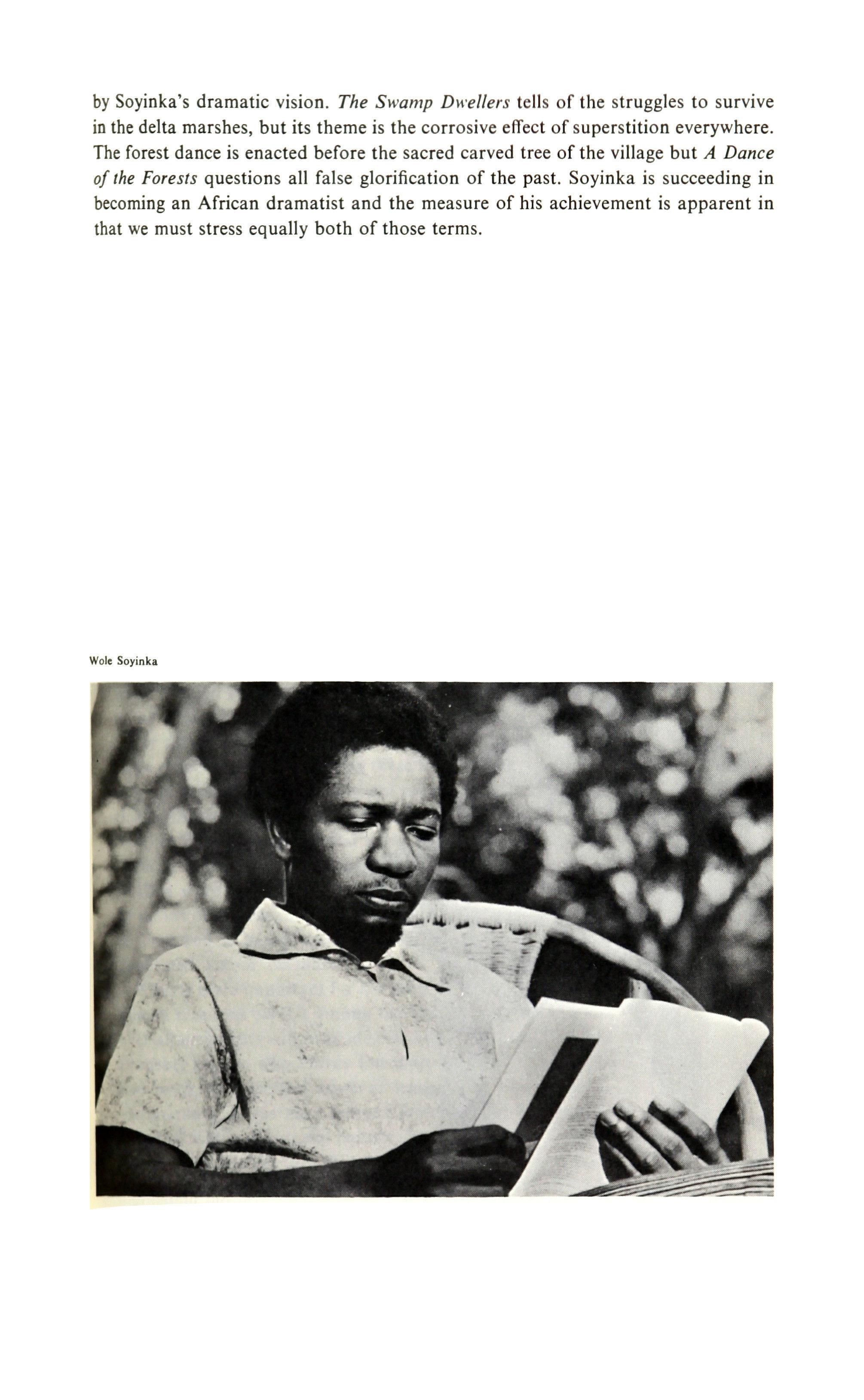

ROBERT PLANT ARMSTRONG 137 Guineaism

art

poetry

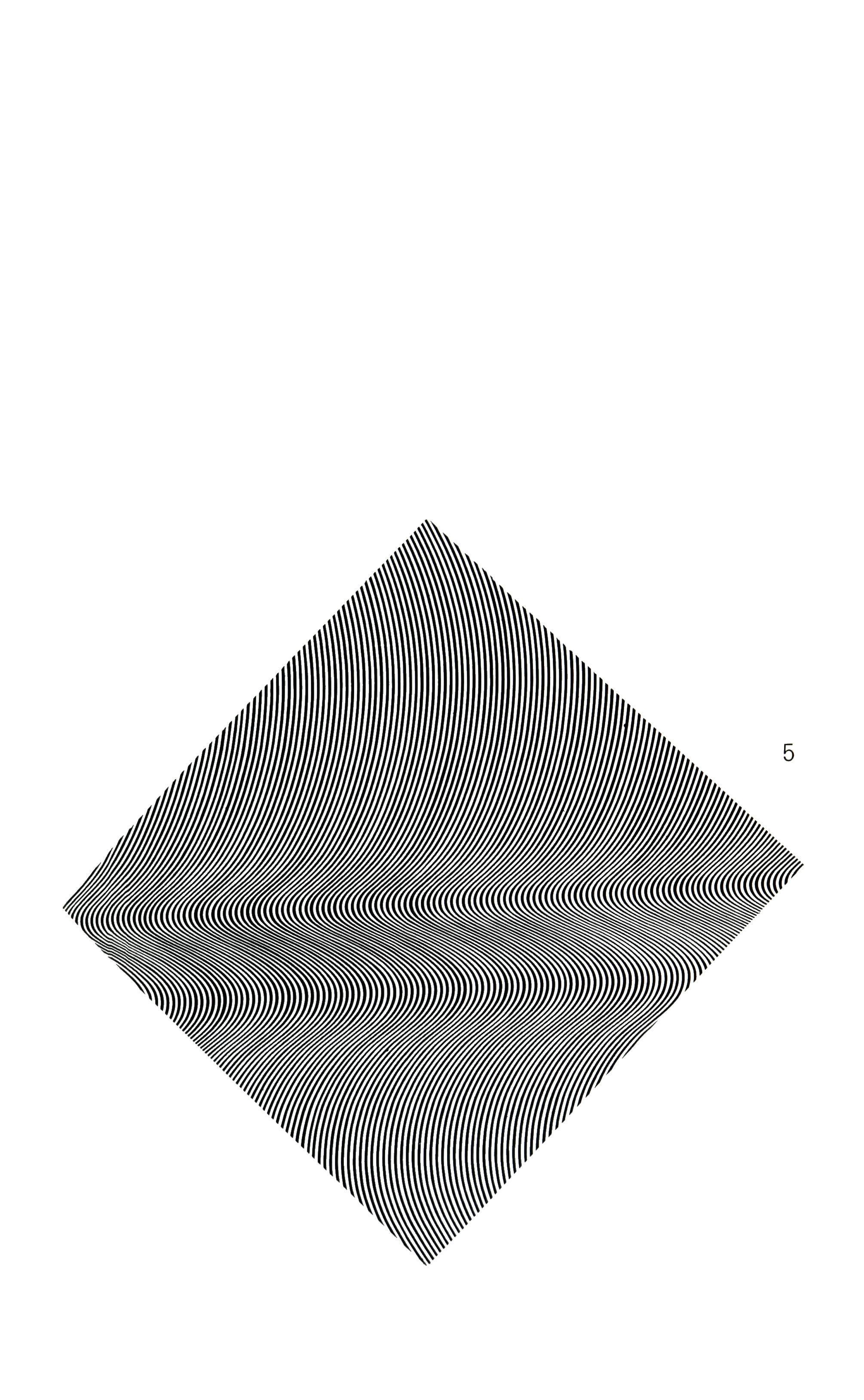

BRIDGET RILEY 60 A portfolio with an introduction by Jack W. Burnham

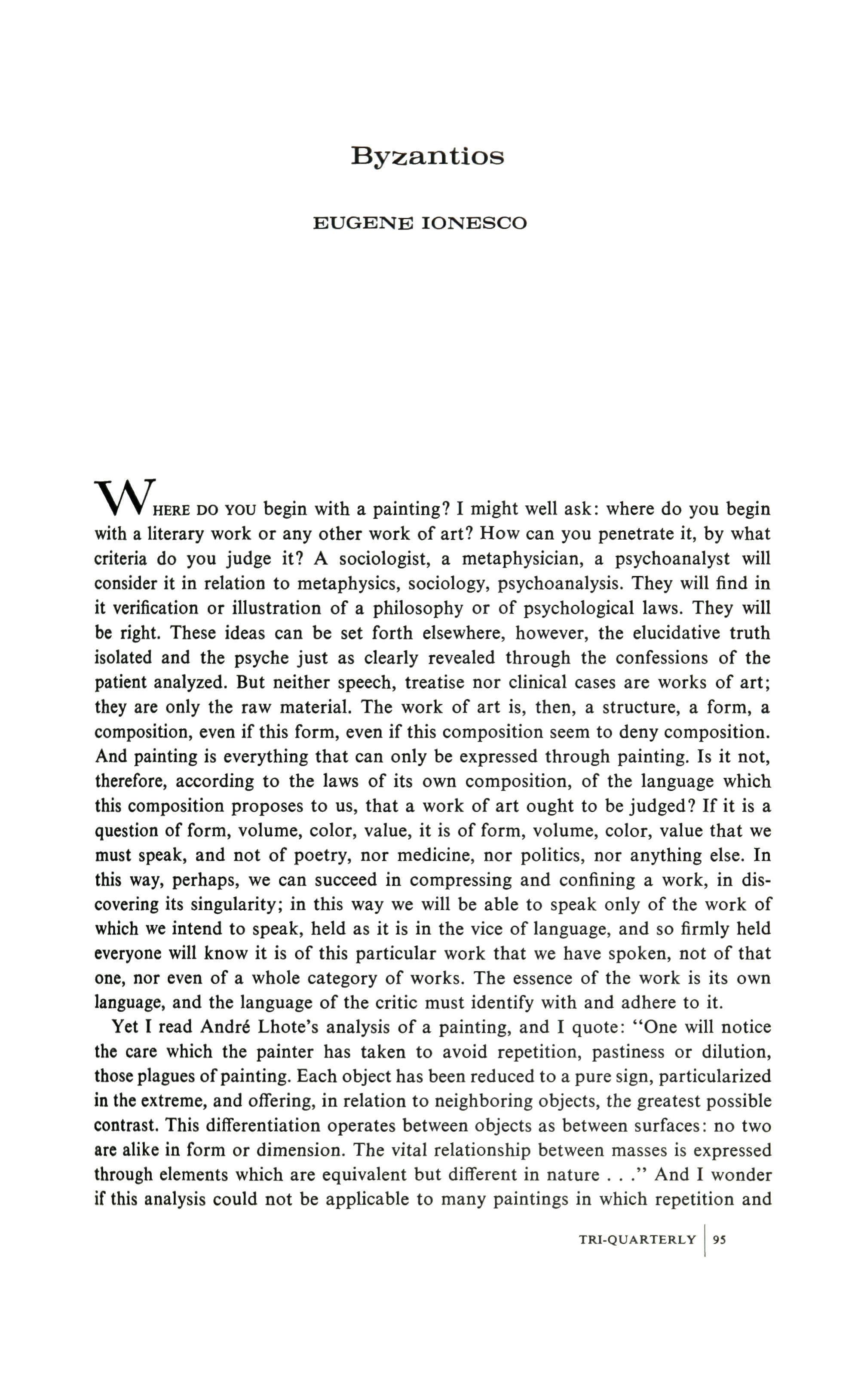

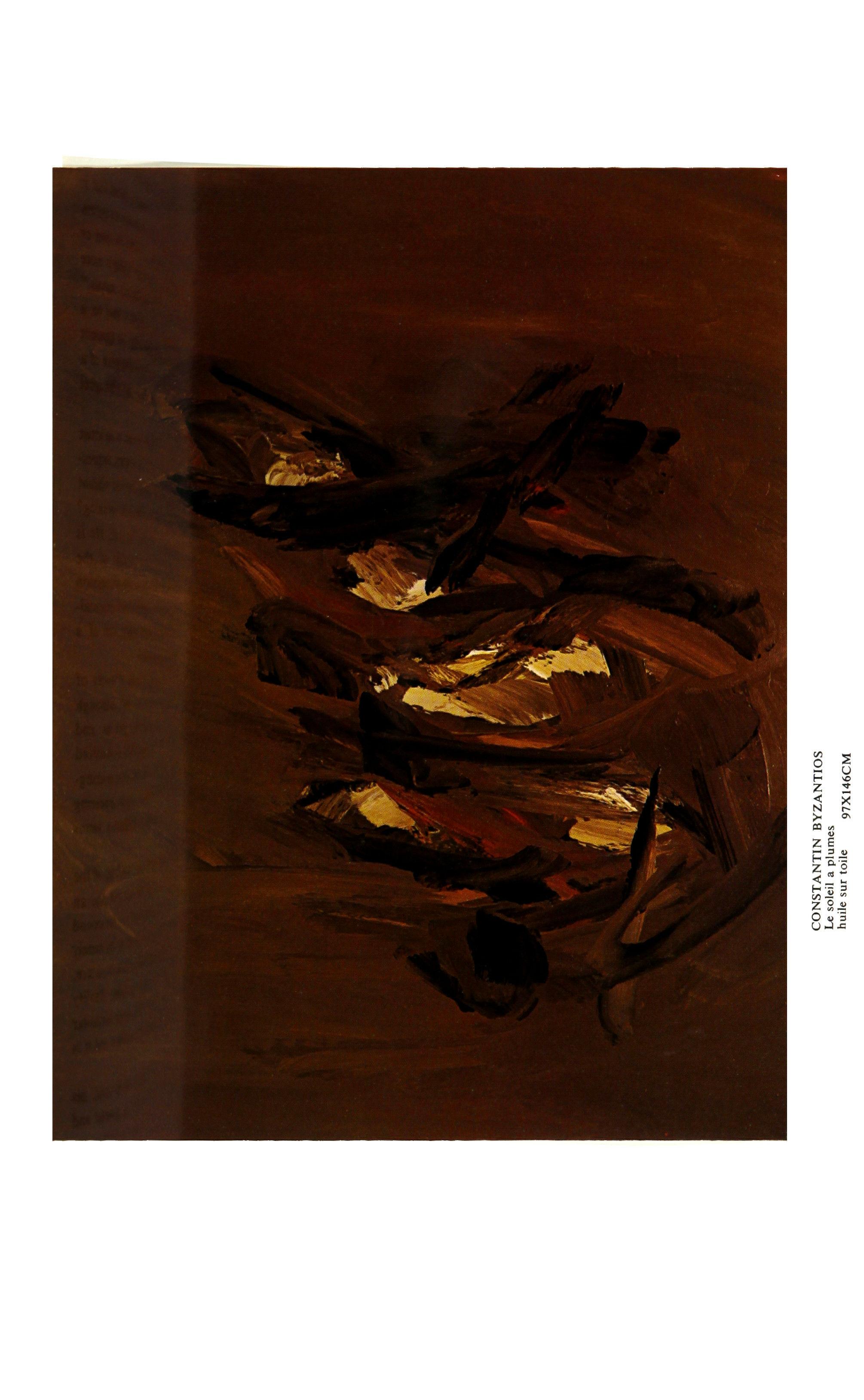

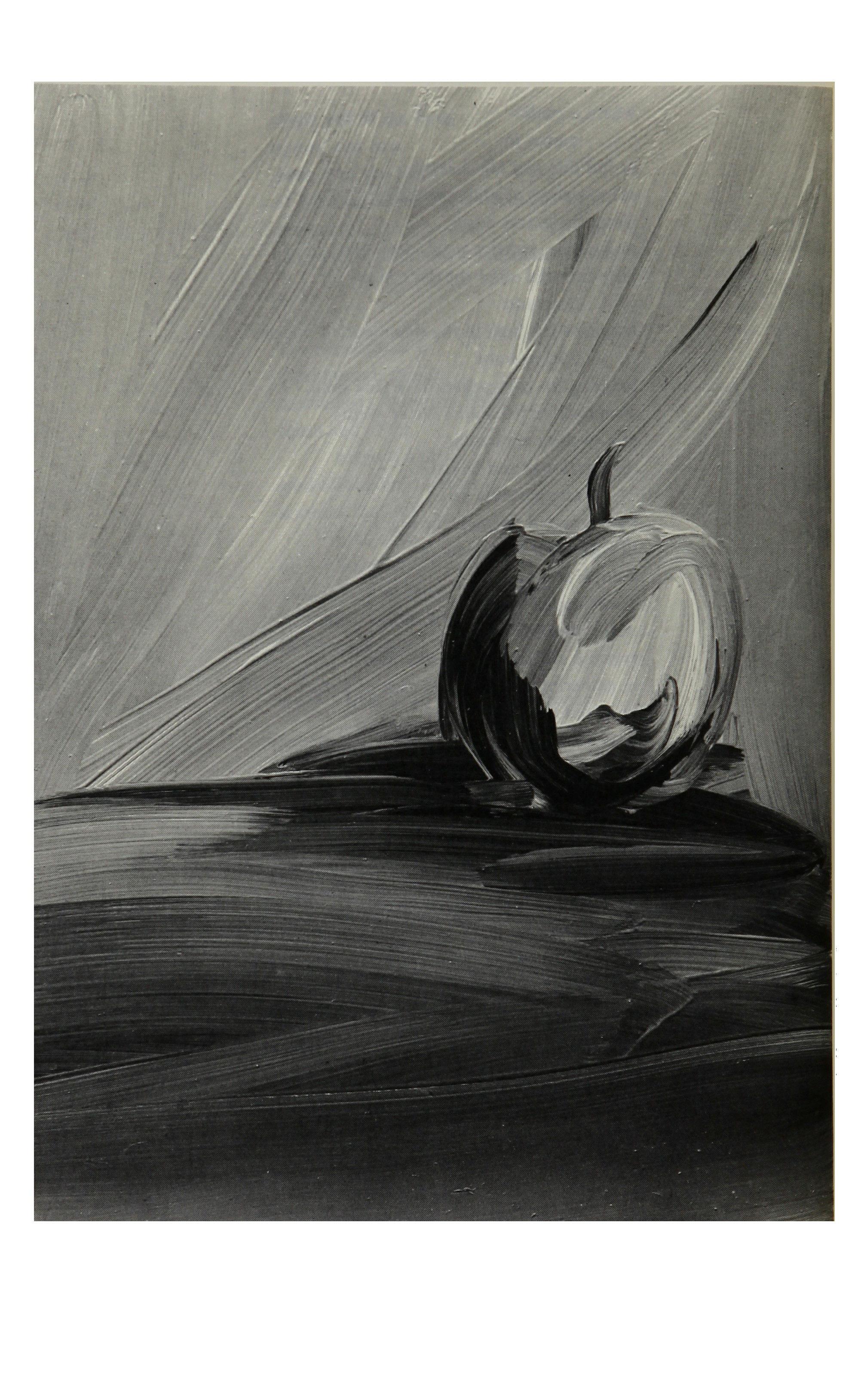

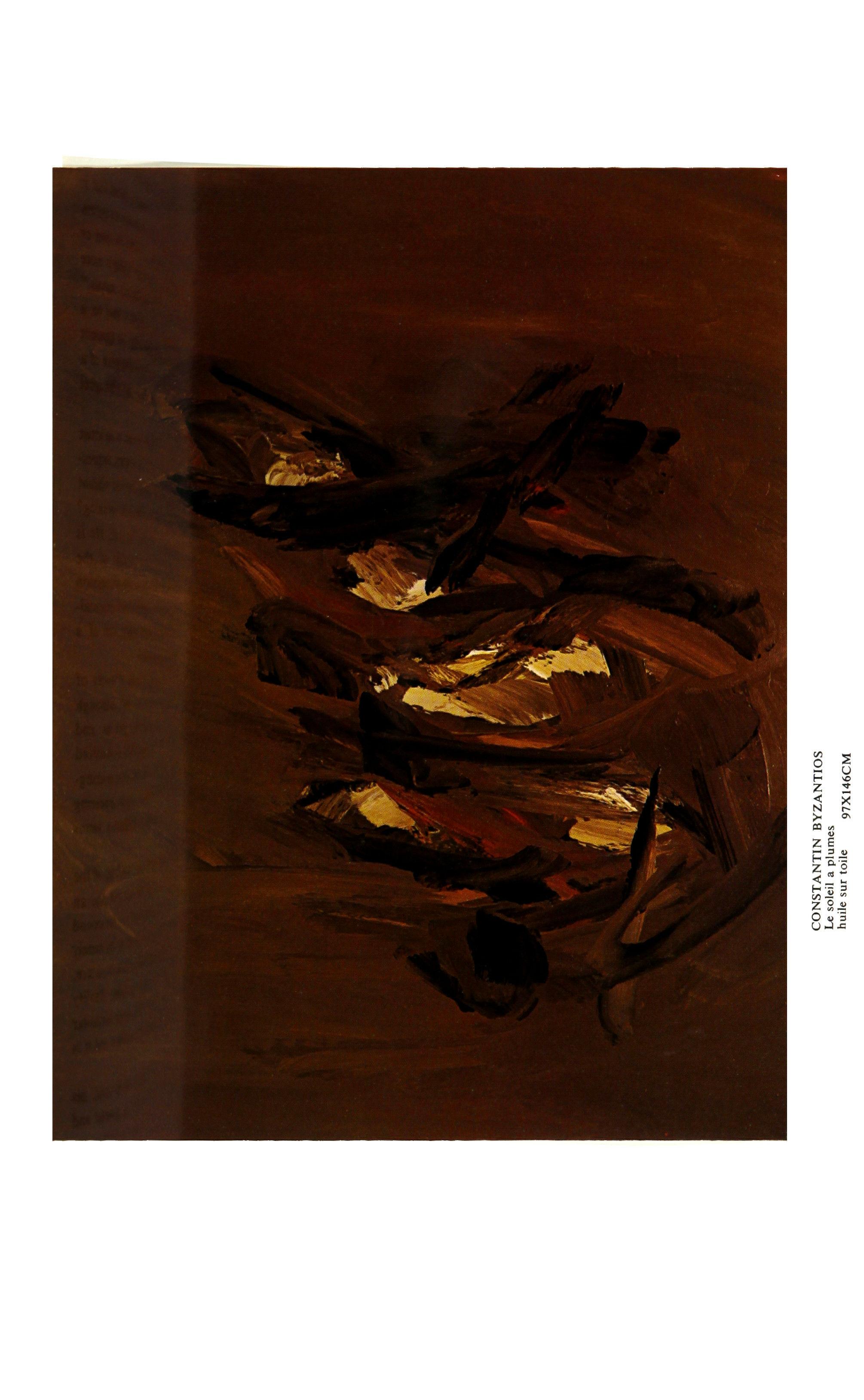

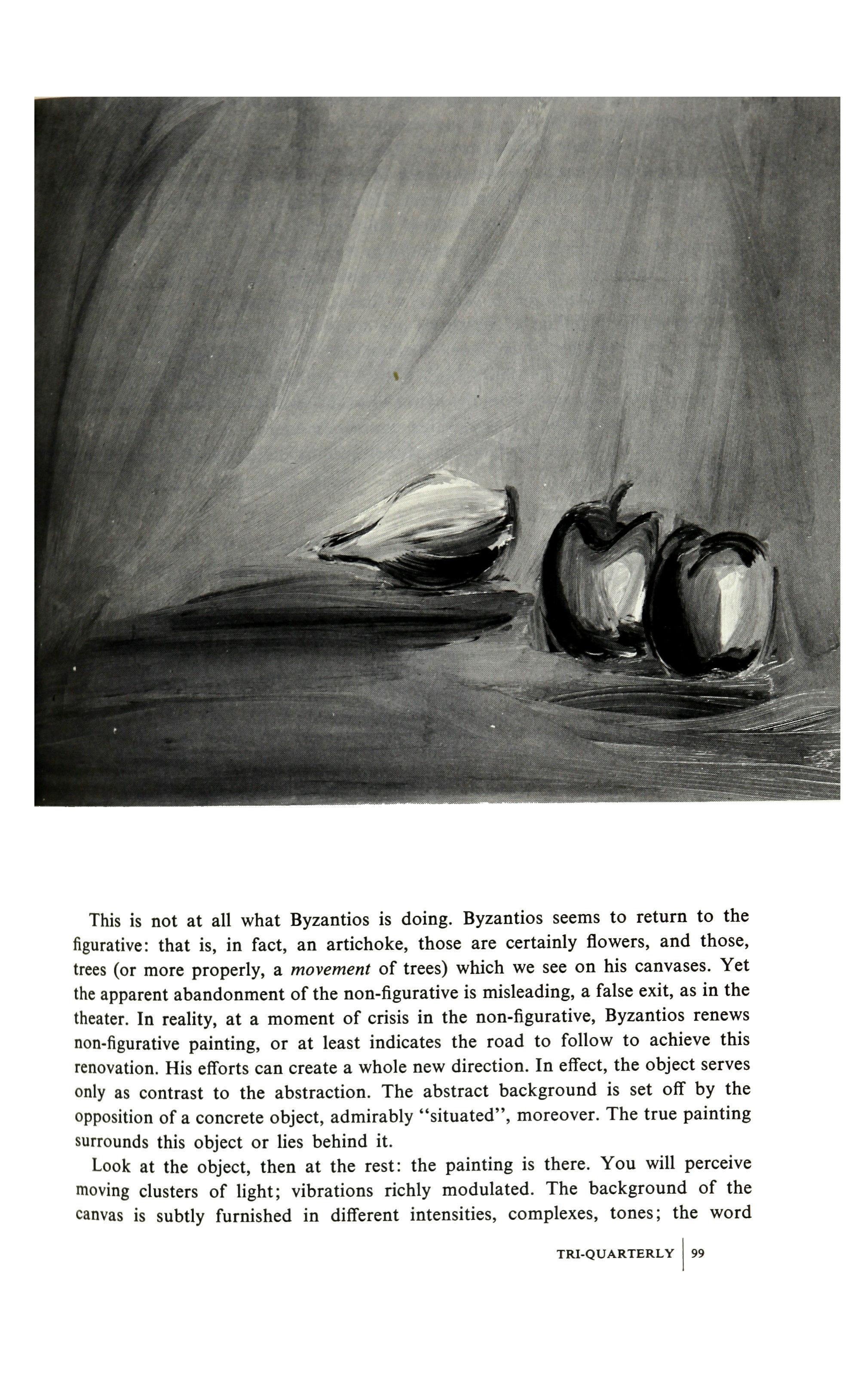

CONSTANTIN BYZANTIOS 95 A portfolio with an introduction by Eugene Ionesco

STANLEY MOSS 37 The red fields, The return

LEONID MARTYNOV 38 Ovidiopolis translated by Babette Deutsch

YEVGENY YEVTUSHENKO 39 The Foreigner translated by Babette Deutsch

MAY SWENSON 40 A basin of eggs

ROBERT HERSHON 53 On horror

LEWIS TURCO 78 My wife of the town

A.R. AMMONS 90 Saliences

GERARD MALANGA 101 A date in Tunis

KLAUS RIFBJERG 102 Kindergarten, Fetus translated by lens Nyholm

RICHARD HOWARD 104 To Aegidus Cantor

JUDSON JEROME 107 St. Thomas, Virgin Islands: May

RONALD TAVEL 108 Mr. John Dryden,

CONTENTS

ROBERT SWARD 109 Idyll, The poet declares for the reader

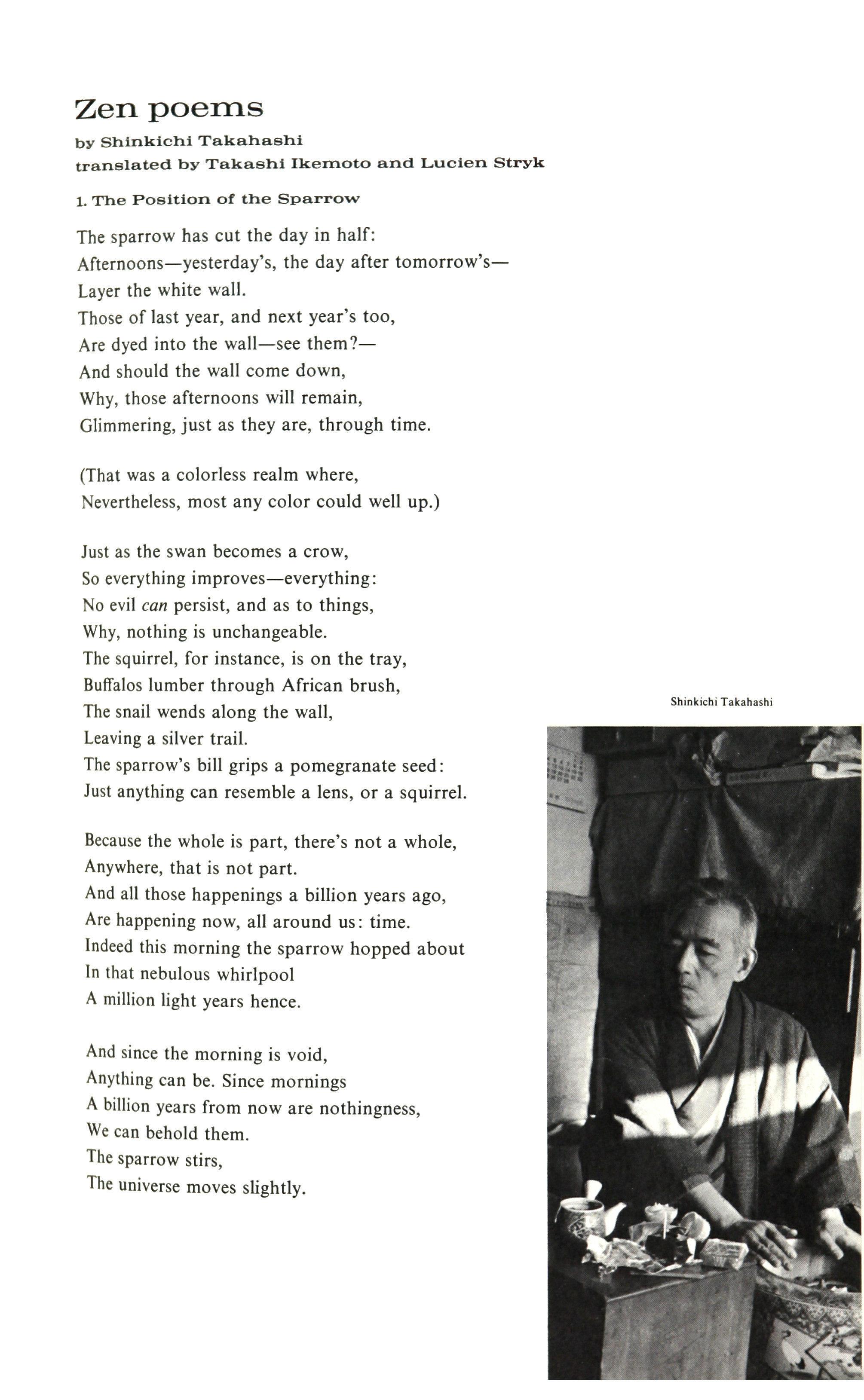

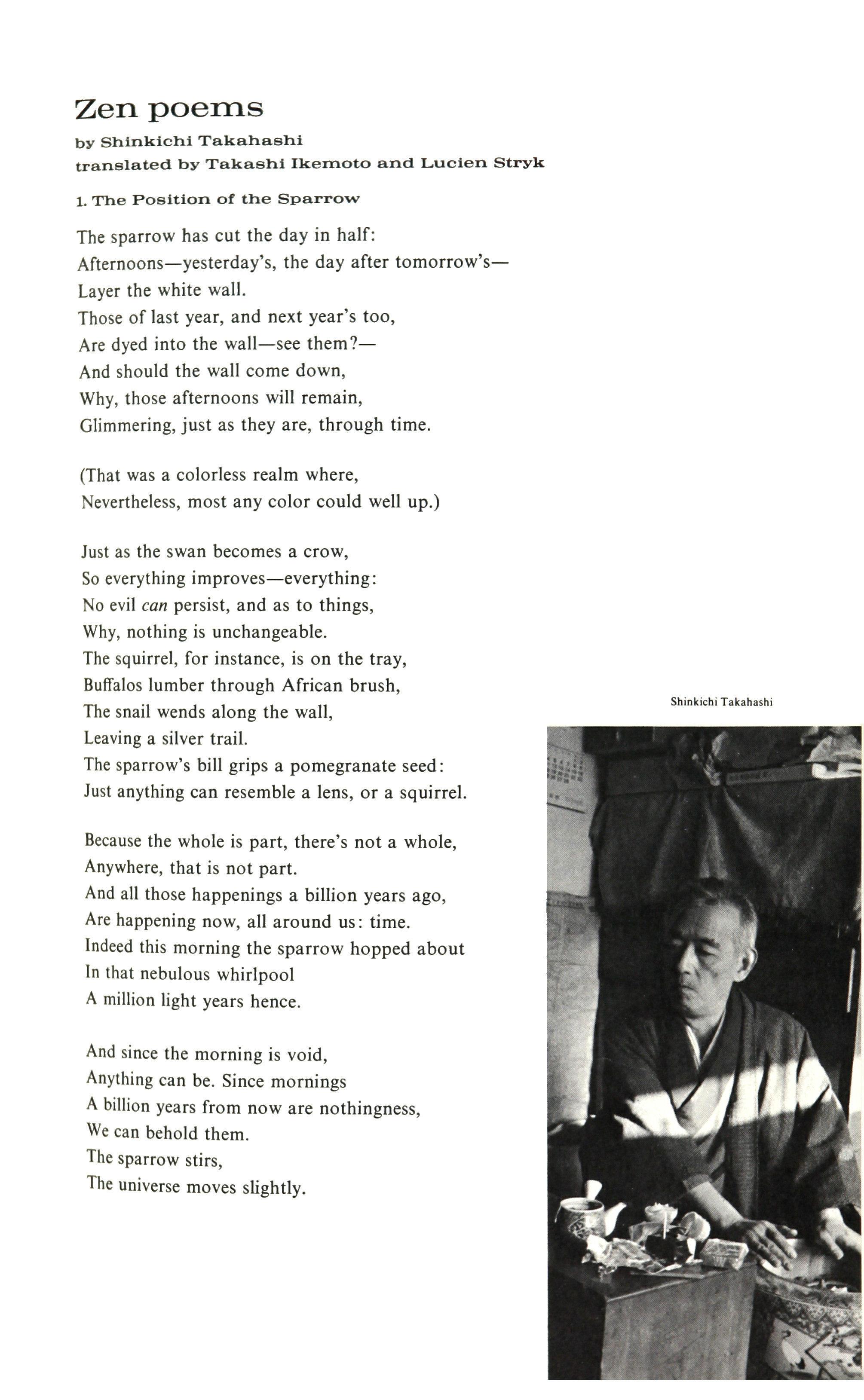

SHINKICHI TAKAHASHI III Zen poems translated by Takashi Ikemoto and Lucien Stryk

EUGENIA MACER 146 Untitled poem

considerations

RICHARD HOWARD 79 A.R. Ammons

PETER MICHELSON 147 The perils of prosody: Configurations of the contemporary voice

RALPH J. MILLS 156 Poems of experience; Midnight in the Century by Maurice English

drama

PETER P. JACOBI 160 Contemporary music and the society it does not belong to

BETAH REEDER 172 The art of tone reproduction

GERALD NELSON 182 Edward Albee and his well made plays

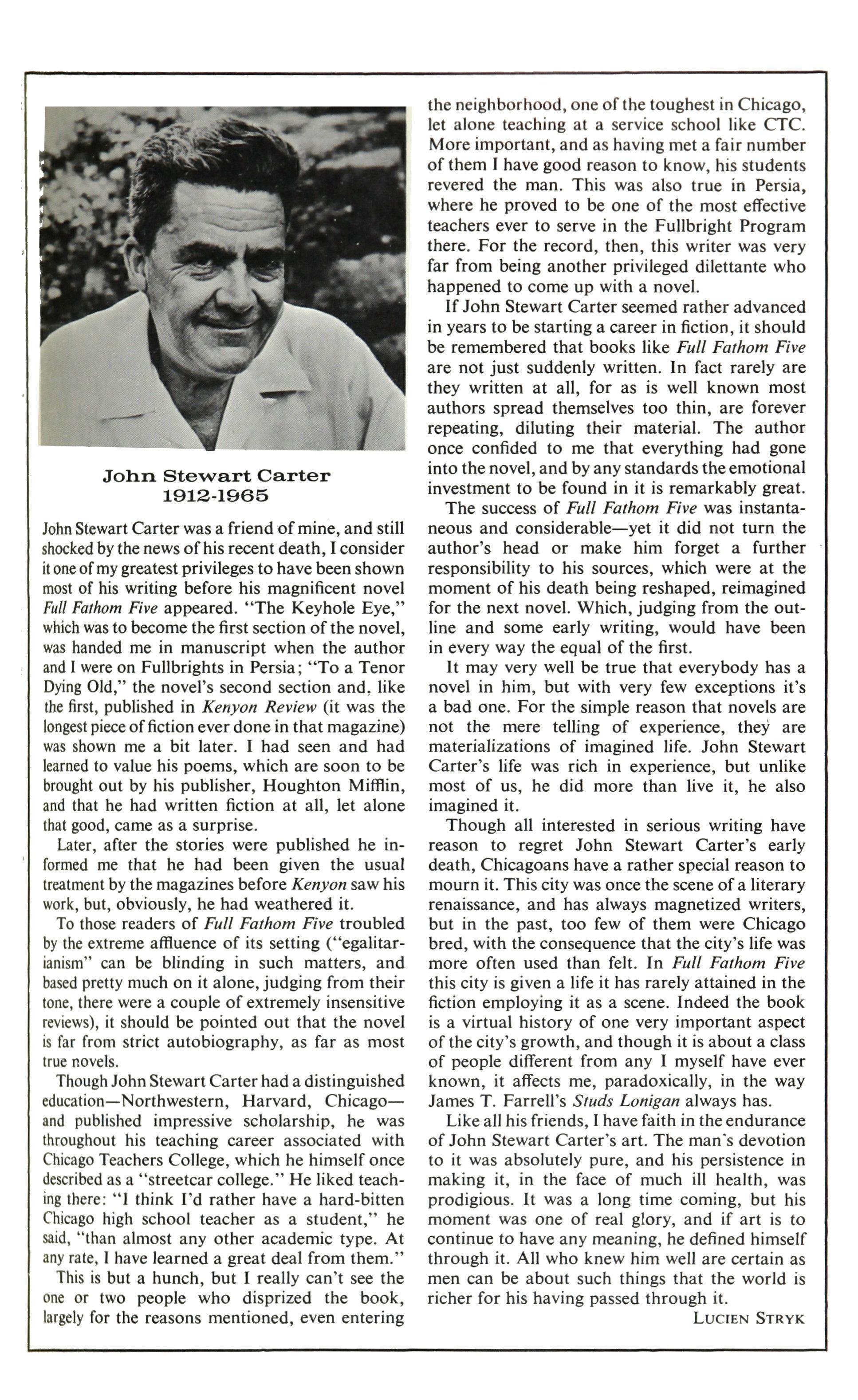

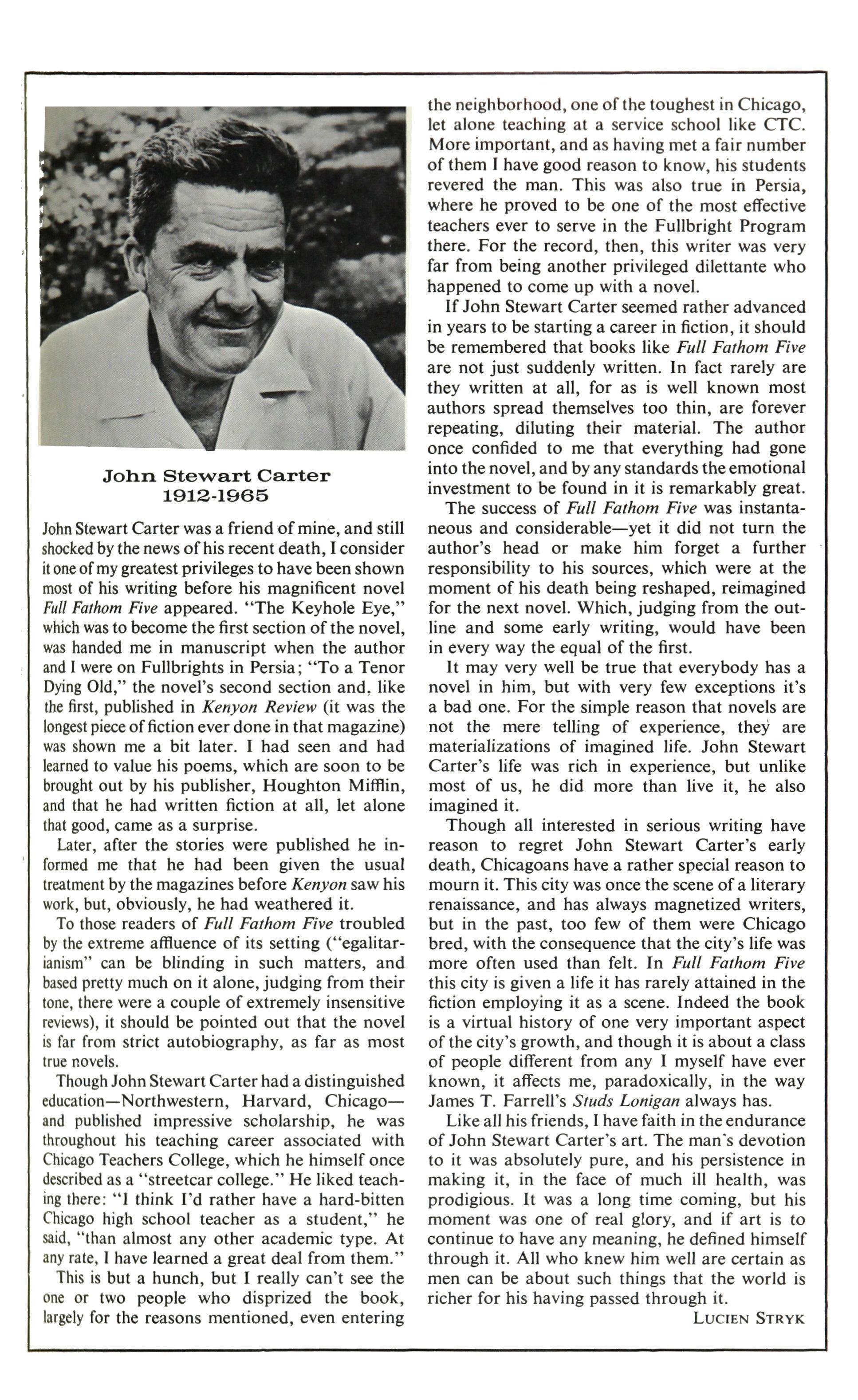

JOHN STEWART CARTER 189 Lucien Stryk 1912-1965

LEONARD BASKIN Cover: Dog in the Meadow

Contributors Back Cover

8DITOR: Charles Newman. ART DIRECTOR: Lawrence Levy. PRODUCTION: Lauretta Akkeron. BUSINESS: Rachel Walther. ADVERTISING: Suzanne Kurman. PHOTOGRAPHY: Gabor Ujvary. ASSOCIATES: C. Colton Johnson. William A. Henkin, Jr. Arthur Francis Gould. STAFF: Joel Pondelik, Hutchins Hapgood, lames Bornemeier, Suzanne Berger.

The TrI·Quarterly is a national journal of arts, letters and opinion, published in the fall, winter and spring quarters at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Subscription rates: $3.00 yearly within the United States; $3.25 Canada and Mexico; $4.00 Foreign. Single copies will be sold for $1.50. Contributions, correspondence and subscriptions should be addressed to Tri-Quarterly, University Hall 101, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. Unsolicited manuscripts are welcome, but will not be returned unless accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. Copyriaht © 1966 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. The views expressed in the magazine, except for editorials, are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW 1ERSEY.

TRI·QUARTERLY

'I'RI-QUAR'l'E:RLY 5

mustc

i I '. I

tranBlated by DeniB CaBlon

Maria

A play in eight BceneB

ISAAC BABEL

Dramatis Personae

MUKOVNIN, Nikolai Vasilyevich

LUDMILA, his daughter

FELZEN, Katerina Vyacheslavovna

DYMSHITS, Isaac Markovich

GOLYTSIN, Sergei Illarionovich, a former prince

NEFEDOVNA, nurse in the house of Mukovnin

EVSTIGNEICH, BISHONKOV, PHILIPPE, disabled war veterans

VISKOVSKY, a former Guards officer

KRAVCHENKO

MADAME DORA

A POLICE INSPECTOR

KALMYKOVA, housemaid of the lodgings at No. 86, Nevsky Prospect

AGASHA, a yard-keeper

ANDREI, KUZMA, floor polishers

SUSHKIN

SAFONOV, a workman

ELENA, his wife

NYUSHKA

A POLICEMAN

A DRUNK, in the police station

A RED SOLDIER, from the front

The action of the play takes place in Petrograd during the thefirst years of the Revolution.

ANDREW FIELD

Babel as playwright

An introductory note

POETIC PROSE and narrative poetry we are on our guard at both these pairings, expecting a creation of ungainly genre, singing parrot or talking meadowlark. It is different, however, with drama: we hear someone speak of a "dramatic poem" or a "dramatic novel" with no sense of incipient dread. (Although it should be noted that the much-esteemed "dramatic novels" of Dostoevsky are weakest in their surfeit of that very virtue.) More than a preference for action over words, the idea of dramatic prose connotates a certain sense of narrative tempo, of action carefully figured with chalk marks, of "scenes" and chapters that end with invisible curtains.

Isaac Babel's miniature stories, for all their power and color, would seem too restricted in scope and too exclusively verbal to warrant meaningful use of the word dramatic, and, in fact, critics and historians of literature have not linked his stories with his dramatic works, which are usually mentioned as an afterthought ("He was also the author of two interesting plays.") in discussions of Babel.

This neglect of the "dramatism" by which I mean the less obvious structural dramatic aspects in Babel's art begins perhaps with a choice of content over device on the part of his critics. Lionel Trilling, for example, has written movingly of Babel's involvement with the Cossackethos as emblematic ofthe "obsessivesignificance that violence has for the intellectual." Trilling speaks further of Babel's "language of force" and quotes his reference to the "army of words" by which art stages its "surprise attack." This reading and it is one towards which we naturally incline internalizes the dramatic elements and makes of them an artist's dialogue or dialectic within himself.

It is in this way that we may overlook the "staging" of the Odessa and Cossack way of life which Babel strove to re-enact in his stories/or its own sake. And when re-reading Babel with this in mind, we are suddenly made aware of the way in which even the stories set in camera contain whole passages that might easily be stage directions. In Babel the plottedness is quite as important as the plot.

It is not really surprising then that, in 1935, Babel writes in a letter: "A strange change has come over me I don't feel like writing in prose. I want to use only the dramatic form." Unlike almost all other major Russian writers before him, Babel did not write plays as a diversion in the course of his artistic career, but rather, he moved steadily towards the form.

Babel's two plays, Sunset (1928) and Maria, written in 1935 and translated here in English for the first time, are both unorthodox in form: by his own testimony Babel "deliberately broke the laws of playwriting" in writing them. Sunset (which has been translated in the collection Noonday 3) is linked to his short stories in that it concerns the Krik family from the Tales 0/ Odessa. The play is, if anything, a more natural and evocative artistic setting for Babel's larger than life Odessans.

The most obvious departure from the traditional in Sunset (as in Maria) is the division of the action. There are no acts; the play is set in eight scenes. The structural models which Babel probably had in mind, I believe, were from the cinema the Russians from the beginning accepted the film as a serious art form, and Babel himself had considerable experience as a scenario writer rather than from Pushkin's Boris Godunov or from Shakespeare.

Nevertheless, the principle characters in Sunset themselves the proud old giant Mendel Krik and his suffering wife Nekhama and their volatile children, Benya, Levka, and Dvoiraare Shakespearean in stature. In Mendel's passion that refuses to be tamed by old age, his inability to grant the just demands that time and one's family conspire to make, he is a pathetically grotesque and colorfully dangerous literary descendant of Lear and Samson. The quarrel of Mendel and Nekhama in bed ("Pullout my teeth, Nekhama, pour Jewish soup

8 TRI·QUARTERLY

in my veins, bend my back "Hot as an oven My God, I'm so ashamed ") is as grand as it is mean. The intermingling of grandeur in mean surroundings and of the biblical with the contemporary which is so notable in Sunset was not peculiar to Babel in this period, but is also to be found in the writings of Leonid Leonov, Vsevolod Ivanov, and several other prominent Soviet writers. Sunset falters as a play because it swerves midway from its promise of tragedy, dissipating the tremendous dramatic energy which had been building up in it.

Maria is a much bolder departure, and it is a greater dramatic achievement, done truly in a wholly new style, though the times were now such that, unlike Sunset, Maria could never reach the boards. Nonetheless, Maria is one of the monuments of Russian drama in this century, and it remains a source of wonder to me that, with all the English anthologies of Russian drama we have, this play has never been included in one.

One may decide that Maria is about the Russian Civil War, but such a conclusion, like much else in the play, has to be by inference. In one of his letters, written in 1934, Babel writes that "the Civil War is out of date as a subject" and has to be approached "from a new angle." It was not merely that the Civil War was "out of date," but also that the subject was so vast and compelling that an oblique or severely limited treatment of it seemed to many Russian writers the most logical artistic approach. To cite but one other famous instance, Mikhail Sholokhov has often been (unfairly) reproached for having reduced the Civil War to the narrow confines ofthe Melekhov family. Maria then, ifyou will, is "only" about the Mukovnin family and the effect that the Civil War has had on it. We do not see the war directly, any more than we see Maria herself who never comes on stage during the play.*

But the axonic leads from the central unit of this one family, disturbed and disintegrating, are many and far-reaching, and Maria as Mary or Mother Russia may well be the incorporeal body of the drama. General Mukovnin, the father, busies himself with his history of Russia past in order not to face the present in which he sells his daughter to the Jew Dymshits. The plainest statement of the truth that is Maria is made early in the play by a minor character, the maid Katya: "An ideal? I don't know. People like us are unfortunate, and that's the way we'll stay. We have been sacrificed, Nikolai Vasilyevich."

The nature and fate of that "ideal" lie somewhere offstage, out of our vision but never out of our consciousness, and this, of course, is one of the reasons why Maria's importance as an "activist" looms so large in the play.

The extraordinary dramatic departure in Maria is the way in which it extends beyond its natural conclusion, Mukovnin's death, and allows a new set of characters "to support the firmament." Not a sunset, but the effusion of a spring day's sunlight, promising that Nyushka's baby will be born in time for a good life. And we recall Aleksandr Blok's lines: Meaningless and dim light.lLive even another quarter century-LAnd all will be like this again. There's no way out." Tragically, both Blok and Babel erred in this The future was neither better, nor the same.

"This feature of the play recalls Vladimir Nabokov's first novel Mashenka (1926) in which the title character, Mashenka, also does not appear. It is commonly thought, based upon several comments quoted in Ilya Ehrenburg's memoirs, that Babel did not have a high opinion of Nabokov as a writer, but an unpublished Babel ms. (to be included in a new Babel anthology to be published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux) mentions Nabokov as one of the most promising writers in Europe. Mashenka is a diminutive form of Maria.

TRI-QUARTERLY 9

Lodgings on the Nevsky Prospect. The room of Dymshits a dirty conglomeration of bags, drawers, andfurniture. Two disabled war veterans, BISHONKOV and EVSTlONEICH, are unpacking provisions. EVSTlONEICH, a big man with a large, redface, has had both legs amputated above the knee. BISHONKOV has one sleeve empty and pinned up. Both men have medals, George crosses, on their chests. DYMSHITS is working out the accounts on an abacus.

EVSTlONEICH: They've tom up the whole road Zandberg was in Vyritsa'. He was helping the people to exist they carted him off.

BISHONKOV: There's too much of this tyranny, Isaac Markovich.

DYMSHITS: Is Korolev still there?

EVSTlGNEICH: How could he be? They've done 'im in. And they've tom up the road good and proper new check-points allover the place.

BISHONKOV: This food business, it's become too difficult, Isaac Markovich. You get used to one check-point, then suddenly it's not there any more. It wouldn't be so bad if they just took away your stuff, but you find yourself staring death in the face.

EVSTlONEICH: You'd not credit it. Every day they find some new way of doing things Take today we're approaching Tsarskoselsky Station shooting breaks out. What's going on? A change of government? No, it's the new way of doing things shoot first, ask questions afterwards.

BISHONKOV: Today they confiscated a whole mass of provisions. "It'll go to children", they say. There's nothing but children in Tsarskoe Selo these days they call it a "colony".

EVSTlONEICH: It's for children all right with beards.

BISHONKOV: But if I'm hungry, I'm going to do something about it, aren't I? Of course I am, if I'm hungry.

DYMSHl'I'S: Where's Philippe? It's Philippe I'm thinking of. Why did you abandon the man?

BISHONKOV: Isaac Markovich, we didn't abandon him. He lost his senses.

EVSTlONEICH: There's someone after him.

BISHONKOV: There's only one word for it tyranny, Isaac Markovich.

EVSTlONEICH: Take this same Philippe, for example: a well-built fellow, the sort you'd notice in a crowd, but no insides, definitely lacking in guts. We're approaching the station the shooting starts people are screaming and falling. I says to him: "Philippe", I says, "we can make it to Suburban Station the back way; the whole gang'll be there". But already he's quite lost his nerve. "I'm scared to go", he says. "All right", I says, "So you're scared. Stay here then. A booze-carrier, he's just a holy fool. They'll only knock you about a bit. What have you got to be afraid of? All you've got on you is a wine-belt". But he'd already fallen flat on the ground. A strong man, strong as a horse, but no guts.

BISHONKOV: We're hoping he'll tum up all right, Isaac Markovich. They haven't got much on him.

DYMSHI'I'S: What was sausage selling at today?

BISHONKOV: Sausage, Isaac Markovich, was selling at 18,000 and it got worse. Doesn't matter where you are these days, it's the same allover.

IVyritsa: a suburb of Petrograd.

10 TRI-QUARTERLY

Scene 1

EVSllGNEICH (opening a secret place in the wall, and transferring to It the provisions): They've levelled our dear Russia to the ground.

DYMSJDTS: What about groats?

BISHONKOV: Groats, Isaac Markovich, was 9,000, and if you say as much as a word they tell you not to buy. They're not the least interested in bargaining. He's just waiting for you to say no. You can't imagine how much these merchants are loving themselves these days.

EVSTlGNEICH (stowing loaves in the wall): Your good wife baked the loaves herself, it was the work of her own hands. She sends her greetings.

DYMSHITS: How are the children, all right?

BISHONKOV: The children are all right, just fine dressed in fur coats, the lucky little things Your wife asks you to come home.

DYMSHITS: Like as if there was nothing else to do. (He continues checking the accounts on his abacus). Bishonkov!

BISHONKOV: Here.

DYMSHITS: I don't see any profit, Bishonkov.

BISHONKOV: It's become too difficult, Isaac Markovich.

DYMSffiTS: I don't see any balance, Bishonkov.

BISHONKOV: There is no balance to see, Isaac Markovich. Evstigneich and I were thinking maybe we should switch to another product. Food's too bulky. Flour is bulky, groats is bulky, calves-foot that's bulky too. We should switch to something else, Isaac Markovich to saccharin or how about precious stones? The diamond is a beautiful thing slip it in the side of your mouth and it's gone.

DYMSffiTS: Philippe is gone. It's Philippe I'm thinking of.

EVSTIGNEICH: Perhaps he's been hurt real bad.

BISHONKOV: There's no two ways about it, in '18 it really meant something to be a disabled veteran, but nowadays

EVSTIGNEICH: You're right, people have become educated. In the old days they couldn't help being conscience-stricken in the presence of disabled veterans, but nowadays they take no notice of them. "What disabled you?", they ask. "A shell took both my legs", says I. "Nothing so very special about that", they say; "You lost them in a flash", they say, "You didn't suffer much". "What do you mean, I didn't suffer?", I ask. "It's a simple fact", they say. "You had chloroform when they levelled off your legs. You never felt a thing. The only thing that bothers you is a bit of trouble with your toes. Your toes seem to tickle and itch, even though they aren't there. That's all the matter is with you". "How can you know such a thing", I ask. "Well", he says, "thanks to the whole bloody mess the people have become educated". And he's obviously become educated if he throws a veteran off a train. "Why", I ask, "do you throw me on to the track? I am a cripple". "Simply because", says he, "we in Russia are fed up with looking at cripples". And he rolls me off like a log of wood Isaac Markovich, I am deeply offended with our people.

(Enter VlSKOVSKY, wearing breeches andjacket, with his shirt unbuttoned).

DYMSHITS: Is it you?

VISKOVSKY: It is.

DYMSHlTS: What about a "how do you do"?2

II.e., a courteous greeting.

TRI-QUARTERLY 11

VISKOYSKY: Ludmila Mukovnina been here, Dymshits?

DYMSHI'I'S: Did it get lost, your "how do you do"? So what if she visited?

YISKOYSKY: You've got the Mukovnins' ring. And I know Maria Nikolaevna would never have given it to you.

DYMSffi'I'S: Well, I didn't get it from the monkeys.

Y1SKOYSKY: How did the ring come into your hands, Dymshits?

DYMSffi'I'S: It was given to me with instructions to sell.

Y1SKOYSKY: Sell it to me.

DYMSffiTS: Why you?

Y1SKOYSKY: Have you ever tried to be a gentleman?

DYMSHITS: I am always a gentleman.

Y1SKOYSKY: Gentlemen don't ask questions.

DYMSffi'I'S: They want foreign currency for the ring.

VISKOYSKY: You owe me fifty pounds.

DYMSHITS: What for?

YISKOYSKY: For the business of the cotton reels.

DYMSffi'I'S: Which you made a mess of.

Y1SKOYSKY: In the Horse Guards they didn't teach us to deal in cotton reels.

DYMSffi'I'S: You made a mess of it because you are a hothead.

Y1SKOYSKY: Give me time, maestro, and I'll learn.

DYMS.ID'1 s: How can you learn if you won't listen? People tell you one thing, you do another. In war you may be a cavalry captain or a count or something I don't know what you are. Perhaps in war you need to be hot-headed, but in business a man must look before he leaps.

Y1SKOYSKY: Yes, sir.

DYMSIDTS: I'm angry with you, Viskovsky, angry for something else again. What sort of trick was that you played with the princess?

Y1SKOYSKY: Well, why not aim high?

DYMSffiTS: You knew she was a virgin.

Y1SKOYSKY: Of superfine quality.

DYMSID'I'S: That sort of superfine quality I can do without. I'm a small man, Mister Cavalry Captain, I don't want this princess coming to me like a Madonna out of an ikon, and looking at me with eyes like silver spoons. What did we agree? I am asking you. We agreed it should be a woman of about thirty or thirty-five, a domestic type of woman, a woman who knows her onions, a woman who would accept my groats and baked bread and 400 grammes of cocoa for her kids, and not say to me afterwards: "You lousy speculator, you've defiled me, you've used me."

YISKOVSKY: Well, there's still the younger Mukovnina.

DYMSHII'S: She's a liar. I don't like a woman when she's a liar. Why didn't you introduce me to the older one?

Y1SKOYSKY: Maria Nikolaevna's gone off into the army.

DYMSHITS: Now there was a woman for you! Maria Nikolaevna quite something to look at, she was, and someone you could talk to. (to Viskovsky) You waited so long, you let her get away.

VISKOVSKY: With the older one it's tricky, Dymshits. It's very tricky.

12 TRI-QUARTERLY

EVmGNEICH: "You", he says, "knew no terror when they got you." "You", he says, "are over the worst already" That's all the comfort I got from him. (The sound ofshooting is heard, distant ot first, but then closer at hand. The shooting intensifies. DYMSm"I� puts out the light andlocks the doors. The green, frosted windowpanes are illuminatedfrom outside).

EVmGNEICH (in a whisper): What a life!

BISHONKOV: Damnation!

EVmGNEICH: The matelots are at it again.

BISHONKOV: It's no kind of a life, Isaac Markovich. (A knock on the door. Silence. VISKOVSKY takes a revolverfrom his pocket and raises the safety catch. A second knock). Who is it?

PIID.IPPE (from the other side of the door): It's me.

EVSTIGNEICH: Let's hear your voice. Who's me?

PIDLIPPE: Open up.

DYMSIflTS: It's Philippe.

(BISHONKOV opens the door. A huge, shapeless being enters the room, leans against the wallfor support, and says nothing. The light is turned on again. HalfofPHILIPPE'S face is deformed with a growth ofproudflesh. His head is slumped on his chest, and his eyes are closed). Did they shoot at you?

PIDLIPPE: No.

EVSTIGNEICH: Are you dead beat, Philippe?

(He and BISHONKOV remove Philippe's sheepskin coat and outer clothing. Then they pullfrom beneath the latter a rubber lining, which they throw on the floor. A sort of armless rubber man, a second Philippe, lies prostrate on the floor. PHILIPPE'S fingers are cut and bleeding.)

They gave 'im the treatment all right And we call ourselves humans.

PHILIPPE (with his head still down on his chest): Tailed he tailed me.

EVSTIGNEICH: He tailed you?

PHILIPPE: Yes.

BVSTIGNEICH: The one in gaiters?

PHILIPPE: Yes.

EVSTIGNEICH: They're really starting to mean business.

DYMSHITS: Did he follow you all the way here?

PHILIPPE (forcing the words out with difficulty): Not all the way shooting started he went there.

(EVSTIGNEICH and BISHONKOV support the injured man and lay him down).

EVSTIONEICH: I said to you, "let's go the back way."

(PHILIPPE groans with pain. Shots are heard in the distance, a burst of machine-gun fire, and then silence). What a life!

BISHONKOV: Damnation!

VISKOVSKY: Where's the ring, maestro?

DYMSHI"!"S: You're so steamed up about that ring, you've got it on the brain.

TRI-QUARTERLY 13

A room in the house of Mukovnin, which serves simultaneously as bedroom, dining-room and study a room typical of the year 1920. Stylish antique furniture,' a small iron stove, with pipes extending right across the room,' beneath the stove, finely-choppedfirewood. Behind a screen LUDMILA NIKOLAEVNA is dressing before going out to the theatre. Hair curling-irons are warming up on a lamp. KATERINA VYACHESLAVOVNA is ironing a dress.

LUDMILA: You're behind the times, madam. At the Mariinsky! nowadays you'll find a very smart crowd. The Krymov sisters, Varya Meyendorf everyone's dressing according to the fashion magazines and living superlatively well, I assure you.

KATYA: Who lives well nowadays? There aren't such people.

LUDMILA: There are plenty. You're behind the times, Katyusha. The gentlemen of the proletariat are developing a taste for the best. They want a woman to be elegant. Do you think your Redko likes you going around looking like nothing on earth? Of course he doesn't like it. Gentlemen of the proletariat are developing a taste for the best, Katyusha.

KATYA: If I were you I wouldn't wear the false eye-lashes, and this sleeveless dress

LUDMILA: You forget, madam. I have an escort.

KATYA: Your escort probably won't notice.

LUDMILA: Nonsense. He too has his own taste, his own temperament.

KATYA: Red-haired men are hot-blooded, that's well known.

LUDMILA: What do you mean, red-haired? My Dymshits, he's chocolate-coloured.

KATYA: And is it true he's got so much money? I think Viskovsky's imagining things.

LUDMILA: Dymshits has six thousand pounds sterling.

KATYA: All made out of cripples?

LUDMILA: None of it made out of cripples. Anyone could have had the same idea. They have their own association, their own profit-sharing pool. Up to now they haven't been searching disabled veterans, so it was easier to get things through.

KATYA: One would have to be a Jew to think of it.

LUDMILA: Come, Katyusha, better to be a Jew than a cocaine-addict like our menfolk. I mean, look at them. One's a cocaine-addict, another got himself shot, a third became a cab-driver, and stands by the Hotel Europe waiting to pick up fares par le temps qui courts the Jews are the most reliable of the lot.

KATYA: You won't find more reliable than Dymshits.

LUDMILA: And, anyway, we're women we're just simple women just like the yardkeeper woman says "I'm fed up with being pushed around". We're no good at being cast adrift on our own it's the truth we don't know how.

KATYA: And will you bear him children?

LUDMILA: Two little redheads.

KATYA: SO it's to be a lawful marriage?

LUDMILA: With the Jews it can't be any other way, Katyusha. They're ever so family-minded. The wife is their counsellor and they make a big fuss over the children. And again, the

3Mariinsky: the Mariinsky Theatre, subsequently to become Leningrad's famous Kirov Theatre. 'Fr. Nowadays.

14 TRI-QUARTERLY

Scene 2

Jew is always grateful to the woman who has been his So it's a truly noble characteristic, their respect for a woman.

KATVA: How is it that you know so much about the Jews?

LUD�nLA: Simply because Papa commanded a corps in Vilna, where there are masses of Jews. Papa had a friend who was a rabbi they're all philosophers, their rabbis.

KATVA (passing the freshly-ironed dress over the screen): After the theatre will it be supper?

LUDWLA: Perhaps.

KATVA: Of course, Ludmila Nikolaevna, a drink: or two an onrush of passion the whole thing'll be lost in a haze.

LUDMU,A: You miss the point entirely, madam. The flirtation will continue for a month, two months. With the Jews it has to be that way. I still haven't decided whether there'll be any kissing.

(MUKOVNIN enters, wearing felt boots and using his scarlet-lined greatcoat as a dressing-gown. He wears two pairs of spectacles.)

MUKOVNIN: (reads) On the 16th of October, 1820, in the reign of the blessed Emperor Alexander, a company of Household troops of the Semenovsky Regiment, forgetting their duty of allegiance and obedience to the military command, did dare to hold an illegal meeting in the late evening hour." (he raises his head) What form did it take, this forgetting of their oath of allegiance? It took the form of the men coming out into the corridor after roll-call and deciding to request the company commander to cancel the next small-group kit inspection in his quarters the company commander actually used to hold such inspections. For this, a so-called meeting, punishment was ordered as follows (he reads) "those lower ranks who were the acknowledged instigators to suffer loss of life. Those men of the First and Second Companies who set an example by creating a disturbance to be hanged. Those private soldiers, referred to in Paragraph No.3 to be flogged through the Battalion six times, as an example to others

LUDWLA: Isn't that terrible?

KATYA: Who can deny that there has been much cruelty in the past?

LUDWLA: I think the Bolsheviks should get hold of Papa's book. It's in their interest to attack the old army.

KATYA: Their demands are always for the immediate moment.

MUKOVNIN: I am breaking down the Semenovsky tragedy into two chapters: first, an investigation of the reasons for the rebellion; second, a description of the mutiny, the tortures, and the banishment to the mines. My story will be a story of barrack life, not a catalogue of peoples, but the fate of those Sidorovs and Proshkas who fell into the clutches of Arakcheevs and were sent off to serve a twenty-year term of military slavery.

LUDMILA: Papa, you must read Katya the chapter on the Emperor Paul. If Tolstoy had been alive, he would have appreciated it, I'm sure.

KATYA: In the papers they demand everything for the immediate moment.

MUKOVNIN: Without knowledge of the past there is no path to the future. The Bolsheviks are fulfilling the work of Ivan Kalita. They are uniting the Russian land. They need us

IArakcheev: Count Arakcheev, Minister of War under Alexander I.

TRI-QUARTERLY IS

regular officers, even if it's only in order to recount our mistakes.

(A bell rings, followed by a noise in the hall. DYMSHITS enters, wearing a fur coat, and carrying packages)

DYMSHITS: Good day to you, Nikolai Vasilyevich! Good day to you, Katerina Vyacheslavna! Is Ludmila Nikolaevna in?

KATYA: She is expecting you.

LUDMILA (from behind the screen): I'm getting dressed

DYMSHITS: Good day to you, Ludmila Nikolaevna! On the street it's such weather you wouldn't put a dog out in it Ippolit drove me here, he wouldn't stop talking, and all nonsense it was too one would have to go a long way to find another like him We will not be late, will we, Ludmila Nikolaevna?

MUKOVNIN: It's broad daylight outside and they're going to the theatre.

KATYA: Nikolai Vasilyevich, the theatres begin at five o'clock in the afternoon nowadays.

MUKOVNIN: Are they saving electricity?

KATYA: Firstly, electricity. Secondly, if you come home late, you'll find yourself stripped bare in the street.

DYMSHITS: A little piece of gammon, Nikolai Vasilyevich. I am not an expert in the matter, but it was sold to me as being corn-fed. As to whether it was really fed on corn or something else I wouldn't know, I wasn't there.

(KATYA has withdrawn to a corner, and is smoking)

MUKOVNIN: Truly Isaac Markovich, you are too kind to us.

DYMSHI'IS: A little crackling

MUKOVNIN (not understanding): I beg your pardon!

DYMSHITS: Not the sort of thing you ate at your father's table, but in Minsk, in Vilyujsk, in Chernobyl, they have a high regard for it. It's little pieces of goose. You must try it and tell me what you think How's the book, Nikolai Vasilyevich?

MUKOVNIN: The book is coming along. I've reached the reign of Alexander Pavlovich.

LUDMILA: It reads like a novel, Isaac Markovich. In my opinion it reminds one of "War and Peace", the part where Tolstoy talks about the soldiers

DYMSHITS: I'm delighted to hear it. Let the shots ring out in the street, Nikolai Vasilyevich, In the street let them beat their heads against brick walls you have your own work to do. Finish the book, we'll have a drink on me. And of the first hundred copies I shall be the buyer A little bit of sausage, Nikolai Vasilyevich: domestic sausage, it came from a German

MUKOVNIN: Truly, Isaac Markovich, I shall become angry.

DYMSHII'S: For me the anger of General Mukovnin would be an honour a divine sausage! This German was quite a prominent professor. Now he's in sausages Ludmila Nikolaevna, I strongly suspect that we shall be late.

LUDMILA (from behind the screen): I am ready.

MUKOVNIN: How much do lowe you, Isaac Markovich?

DYMSHITS: A shoe off the horse that dropped dead today on the Nevsky Prospect.

MUKOVNIN: No, seriously.

DYMSHI'I'S: You want it seriously then two horsehoes off two dead horses.

(LUDMILA NIKOLAEVNA emerges from behind the screen. She is dazzlingly beautiful, slender and rosy-cheeked. She wears a sleeveless black velvet dress, and diamond ear-rings).

16 TRI-QUARTERLY

MUKOVNIN: Is not my daughter a beauty, Isaac Markovich?

DYMSHIlS: I won't say no to that.

KATYA: That's what she is, Isaac Markovich, a Russian beauty.

DYMSHIl": I'm not an expert in the matter, but this is quality merchandise.

MUKOVNIN: I have yet to introduce you to my elder daughter, Masha.

LUDMILA: I warn you, Maria Nikolaevna is the favourite in our family and now the favourite, if you please, has gone off to be a soldier.

MUKOVNIN: What do you mean, soldier, Ludmila? She went into the political. section.

DYMSHIIS: Your Excellency, I can tell you about the political section. They're soldiers, all right.

KATYA (taking LUDMILA to one side): Really. you don't need the ear-rings.

LUDMILA: Don't you think so?

KATYA: Of course not. And afterwards this supper

LUDMILA: You may sleep soundly. madam. You're talking to one who knows. (she kisses Katya) Katyusha, you silly, sweet thing. (to Dymshits) My boots. (turning away, she takes off the ear-rings).

DYMSHIIS (rushing to assist her): Just a moment.

(LUDMILA puts on overshoes, fur coat, and Orenburg scarf DYMSHITS fusses round attentively).

LUDMILA: Every time I put these things on I'm amazed they haven't been sold yet Papa, be good and take your medicine while I'm gone. And don't let him work, Katya.

MUKOVNIN: Katya and I will keep house together.

LUDMILA (kissing her father on the forehead): Do you like my little Papa, Isaac Markovich? Isn't he a father in a million?

DYMSHITS: Nikolai Vasilyevich is so perfect he's superhuman!

LUDMILA: Nobody knows him we're the only ones who do Where did you leave Prince Ippolit?

DYMSHITS: I left him at the gate. His instructions were to wait that's discipline. A moment or so, and we'll be there All the best, Nikolai Vasilyevich!

KATYA: Don't overdo it, now.

DYMSHITS: Not at all we won't, that's guaranteed.

LUDMILA: Goodbye, Daddy.

(MUKOVNIN accompanies his daughter and DYMSHITS out into the hall. Voices off. and laughter, are heard. The general re-enters).

MUKOVNIN: A very kind and worthy Jew.

KATYA (pressing herself into a corner of the divan, and smoking): In my opinion they all lack tact.

MUKOVNIN: Katya, my darling, where should they get tact from? These people used to be allowed to live on one side of the street, and were chased by the police from the other. That's how it was in Kiev on the Bibikovsky Boulevard. Where should they get tact from? One should rather marvel at their energy, their vitality, their resilience.

KATYA: Energy like that has become typical of Russian life, but we're still different. All this IS strange to us.

MUKOVNIN: Fatalism that's certainly not strange to us. Rasputin and the German woman Alice who destroyed a dynasty that's not strange to us. Nothing but good has come of this wonderful race, which gave us Heine. Spinosa, Christ

KATYA: You even praised the Japanese, Nikolai Vasilyevich.

TRI-QUARTERLY 17

MUKOVNIN: Why not? The Japanese are a great people. There is no end to the things we can learn from them.

KATYA: It's easy to see who Maria Nikolaevna takes after You are a Bolshevik, Nikolai Vasilyevich.

MUKOVNIN: I am a Russian officer, Katya, and I ask this question: How is it, gentlemen, and since when is it, that the rules of the game of war have become foreign to you? We have tortured and oppressed these people. They have defended themselves, they have gone over to the attack, and are fighting with resourcefulness, with deliberateness, with desperation,in fact, they are fighting in the name of an ideal, Katya.

KATYA: An ideal? I don't know. People like us are unfortunate, and that's the way we'll stay. We have been sacrificed, Nikolai Vasilyevich,

MUKOVNIN: I'm all for the common people being shaken up. It will be a very good thing. And time's running out, Katya. The only worthwhile Russian emperor, Peter, said: "Delay is death". What a precept! And if it is true, then it is up to you, gentlemen, to have the courage to look at the map, to realize which of your flanks has been turned, where and why defeat has been inflicted upon you To keep my eyes open that is my right, and I will not give it up.

KATYA: Nikolai Vasilyevich, you should take your medicine.

MUKOVNIN: To my brothers in arms, the men with whom I fought side by side, I say: Tirez vos conclusions, delay is death.

(Exit. In the next room someone is playing a Bach fugue on the violoncello. The tone is cool and pure. KATYA listens for a moment, then rises and crosses to the telephone).

KATYA: Give me the District H.Q May I speak to Redko? Redko, is that you? I wanted to say Anyone might think that you were the only one involved in the revolution, you're the only one who won't find time to see someone someone at whose house you spend the night when it suits you (A pause) Redko, take me out for a spin; call for me in a car Oh, all right, if you're busy No, I'm not angry. Why should I be angry?

(She hangs up. The music stops. Enter GOLYTSIN, a long, lean man in a soldier's jacket and puttees, holding a violoncello).

Prince, what was it they said to you at the pub? "Don't playa sad tune"?

GOLYTSIN: "Don't playa sad tune, don't jar our nerves".

KATYA: They need something cheerful, Sergei Illarionovich. People want to forget, to relax

GOLYTSIN: Not everyone. Some people want something sentimental.

KATYA (sitting down at the piano): Your audience what does it consist of?

GOLYTSIN: Dockers from Obvodny.

KATYA: Perhaps you'll end up in the Trade union Do you get your supper thrown in as well?

GOLYTSIN: Yes, I do.

KATYA (playing "Little Apple"6 and singing softly): Through rippled water the steamer steers. We'll feed the fish on volunteers".

6"Little Apple": "Yablochko", a well-known folk tune, to which suitable words were improvised by both sides during the revolution.

7Volunteers, i.e., White soldiers, (who were not conscripted).

18 TRI-QUARTERLY

Why not accompany me? It'd be a good idea if you played them "Little Apple" in the pub. (GOLYTSIN starts to accompany her, strikes a false note, and corrects himself.) Sergei Illarionovich, would it be worth my while to take up shorthand?

GOLYTSIN: Shorthand? I don't know.

KATVA (singing):

"I sit on a barrel, my teardops wet me. Men don't want to wed me, but only to pet me" They need stenographers these days.

GOLYTSIN: I'm afraid I can't advise you. (He picks up the accompaniment to "Little Apple".)

KATYA: Of aU of us Masha is the real woman. She has strength and daring, she is a woman. We sit here sighing, but she is happy in her political section. And apart from happiness, what other law of life have men thought up? There isn't one, there is no other law.

GOLYTSIN: Maria Nikolaevna has always indulged in abrupt changes of direction. That's what makes her so different.

KATVA: She's right. (Sings)

"Ah, little apple, whither art thou rolling?" And then she's having a romance with that Akim Ivanovich.

GOLYTSIN (stops playing): Who is Akim Ivanovich?

KATYA: Their divisional commander, a former blacksmith she mentions him in every letter.

GOLYTSIN: How do you know there is a romance?

KATYA: It's there between the lines. I can tell Or should I go away to Borisoglebsk, to my family? It's home, after all At least you've got the monk you go and visit in the monastery what's his name?

GOLYTSIN: Siony.

KATYA: Siony, What does he teach you?

GOLYTSIN: You were talking about happiness He is teaching me that it is not to be found in a sense of power over people, nor does it lie in that constant greed which we can never satisfy.

KATYA: Come on, Sergei Illarionovich. (Sings)

"Thirsty I sit on a barrel which rolls, Thirsty, with nought in my pocket but holes" Siony that's a pretty name.

Scene 3

LUDMILA and DYMSHITS are in the latter's room. On the table are bottles and the remains of supper. The next room, where BISHONKOV, PHILIPPE and EVSTIGNEICH are playing cards, is partly visible. EVSTIGNEICH, the amputee, has been placed on a chair.

LUDMILA: Felix YUSUpOV8 was as handsome as God, and the champion tennis-player of Russia. But handsome is as handsome does. There was a doll-like quality about him. I met Vladimir Baglei at Felix's house. To the end the Tsar did not appreciate the chivalrous

8Felix Yusopov: one of those involved in the murder of Rasputin.

TRI-QUARTERLY

19

nature of the man. We used to call him "The Teutonic Knight". Frederiks was friendly with Prince Sergei do you know Prince Sergei, who plays the violoncello? Well, at the party there was another item hors de programme, Archbishop Ambrosy. The old man was paying court to me can you imagine it! He was giving me more and more punch, and looking so pious and sly. At first I made no impression on Vladimir, he himself told me: "You were snub-nosed, si demesurement russe, with a blazing colour in your cheeks". At dawn we drove to Tsarskoe, leaving the car in the park, and taking a carriage. He did the driving. "Ludmila Nikolaevna, need I tell you that I have not taken my eyes off you all evening?" "Nina Buturlina noticed it, mon prince". I knew they had been having an affair, or rather a flirtation. "Buturlina c'est Ie passe, Ludmila Nikolaevna" "On revient toujours, ses premiers amours, mon prince", Vladimir did not hold the title of grand duke, coming as he did from a morganatic marriage. The family had not met the Tsarina Vladimir called her an evil genius. And, then well, he was a poet, a boy, he understood nothing of politics We arrived at Tsarskoe. It was dawn. Somewhere down below, over a pond, a nightingale began to sing My companion said again: "Mademoiselle Boutourline c'est le passe", to which I replied, "Mon prince, the past can sometimes catch up with one, and it's so unbearable when it does".

(DYMSHITS puts out the light, lunges at MUKOVNINA and throws her on to the divan. A struggle ensues. She tears herself away and straightens her hair and dress).

BISHONKOV (throwing down a card): Beat that.

PHILIPPE: It's not so easy.

EVSTIGNEICH: SO they took 'im to the fence with 'is hands tied "Well, friend", they said, "turn round". And he says to them, "No need to turn round. I'm a military man, kill me just as I am". Well, the fences there are made of a sort of wattle, half the height of a man it's night, the edge of the village beyond the village the steppe, on the edge of the steppe a ravine

BISHONKOV (making a trick): That makes game.

PHILIPPE: Oh no it doesn't. I've something up my sleeve.

EVSTIGNEICH: So they bring him along Their rifles are at the ready and suddenly he jumps in the air with his hands tied and all, just as if the Good Lord had plucked him from the face of the earth. He flew over the fence and took off, dodging this way and that. They began shooting, but it was night the darkness he ran in circles and loops, and got away.

PHILIPPE (dealing the cards): Good lad!

EVSTIGNEICH: That man's an everlasting hero. He used to be considered a reckless fellow. Half a year on the loose he was, before they got 'im.

PHILIPPE: Did they really finish him off'?

EVSTIGNEICH: Yes, and wrongly, I reckon. The man had had a glimpse of the next world and had jumped back out of the grave. He wasn't meant to be killed.

PHILIPPE: They don't take any notice of things like that these days.

EVSTIGNEICH: I think it's wrong. In every country they have this law: if they haven't killed you, it's your good fortune, so go on living.

PHILIPPE: They'll finish us off all right.

BISHONKOV: That they will.

LUDMILA: Turn on the light. (DYMSHITS does so) I shall have to leave. (She turns, looks at

20 I TRI-QUARTERLY

DYMSHITS, and bursts out laughing). Don't sulk. Come here Tell me, my friend, what were you expecting? I must get used to you first, you know.

DYMSHITS: I am not a shoe that you should have to get used to me.

LUDMILA: I don't deny you arouse in me a feeling of fondness, but this feeling must become stronger. Masha will come out of the army you will meet her. Nothing in our family is done without her. Papa he likes you, but, as you saw, he's quite helpless And then, other things remain to be decided: what about your wife?

DYMSHITS: What does my wife have to do with it?

LUDMILA: 1 know that the Jews are attached to their children.

DYMSHlTS: There's nothing to discuss, really, there's nothing to discuss.

LUDMILA: SO for the time being you must sit quietly beside me, armed with patience.

DYMSHITS: The Jews have been armed with patience ever since they started waiting for the Messiah. Have another drink.

LUDMILA: I've had a lot to drink already.

DYMSHlTS: This wine came to me off a battleship. The Grand Duke had a case of it on board.

LUDMILA: How is it you manage to get hold of everything?

DYMSHITS: I have my sources Drink up this glass.

LUDMILA: Only if you promise to sit here quietly.

DYMSHITS: They sit quietly in the synagogue.

LUDMILA: And look, you've put a frock coat on for the synagogue, of course. The frock coat, Isaac, used to be worn by high-school directors at graduation ceremonies, and by merchants at memorial dinners.

DYMSHITS: I shan't wear a frock coat again.

LUDMILA: And another thing the tickets. Never buy tickets in the front row, my friend. That's what the upstarts do, the nouveaux riches.

DYMSHITS: But that's just what I am, an upstart.

LUDMILA: You have an inner nobility that's something altogether different. Even your name doesn't become you Nowadays one's allowed to put announcements in the newspaper, in "Izvestia" I'd change it to Alexei. Do you like Alexei?

DYMSHI'I'S: Yes, I do. (Again he turns out the light and tries to assault MUKOVNINA.)

EVSTIGNEICH: They're at it again.

PHILIPPE (cocking an ear): Sounds as if our side wins.

BISHONKOV: I like Ludmila Nikolaevna most of all she gives a man a greeting And there are some wild, dishevelled-looking ones running around but she greets me by my patronymic.

(VISKOVSKY enters the veterans' room, stands behind EVSTIGNEICH'S chair, and watches the fall of the cards).

LUDMILA (breakingfree ofDYMSHITs): Call me a driver.

DYMSHITS: At once! There's nothing else for me to do.

LUDMILA: Call me one this instant!

DYMSHITS: It's cold outside thirty degrees of frost. One wouldn't send a mad dog out into it.

LUDMILA: My clothes are all torn. How can 1 go home looking like this?

DYMSHITS: Omelettes aren't made without breaking eggs.

LUDMILA: There we go again Isaac Markovich, you've got the wrong end of the stick.

DYMSHITS: Just my miserable luck.

TRI-QUARTERLY 21

LUDMILA: I tell you, my teeth are hurting, they're hurting unbearably.

DYMSHITS: It doesn't figure What have teeth got to do with it?

LUDMILA: Get me some dental drops. I'm in great pain.

(Exit DYMSHI'I'S. In the next room he bumps into VISKOVSKY.)

VISKOVSKY: God speed, master.

DYMSHITS: Her teeth hurt.

VISKOVSKY: It can happen

DYMSHII'S: It can also happen they don't hurt.

VISKOVSKY: She's lying, Isaac Markovich, she's lying for sure.

PHILIPPE: She's making it up, Isaac Markovich. Her teeth aren't hurting.

LUDMILA (has straightened her hair in front of the mirror, and now walks about the room, stately, cheerful and slightly flushed. She begins to sing):

My love is tall and slender

My love is harsh and tender I feel the sting of his silken cord.

DYMSHITS: I'm not a little boy, Evgeny Alexandrovich I stopped being a little boy a long time ago.

VISKOVSKY: Yes, sir.

LUDMILA (lifts the telephone receiver): 3-75-02 Daddy, is that you? I'm fine Nadya Johansson and her husband were at the theatre. We're having supper at Isaac Markovich's you absolutely must see Spesivtseva", she'll take Pavlova's place Did you take your medicine? You should go to bed Your daughter's a clever girl, Papa, and an awful fibber Katyusha, is that you? Your instructions madam, have been carried out. Le manege continue, j'ai mal aux dents ce soir. (She hangs up, walks around the room singing, and adjusts her hair.)

DYMSHITS: She'll go so far that I won't be at home to her next time she comes.

VISKOVSKY: That's for you to decide.

DYMSHITS: About my wife and children let others ask questions, not her.

VISKOVSKY: Yes, sir.

DYMSHITS: These people aren't worthy to tie my wife's bootlaces, if you want to knownot as much as a single lace.

Scene 4

VISKOVSKY'S room. He is wearing riding breeches and jackboots, but no jacket. The collar of his shirt is open. On the table are bottles, from which a considerable quantity has been drunk.

KRAVCHENKO, a short, ruddy man in military uniform, and MADAME DORA, a skinny woman in black, with a Spanish comb and large, oscillating ear-rings, are reclining on an ottoman.

V1SKOVSKY: One fell swoop, Yashka

I felt the force of a single might, A single passion's fiery bite.

9Spesivtseva: the famous ballerina. 22 TRI-QUARTERLY

KRAVCHENKO: How much do you need?

VISKOVSKY: Ten thousand pounds One fell swoop Did you ever see a pound sterling, Yashka?

KRAVCHENKO: Will you make it all out of cotton-reels?

VISKOVSKY: To hell with cotton-reels. Diamonds. Three-carat diamonds, clear as crystal, pure and without blemish. In Paris those are the only kind they take.

KRAVCHENKO: There can't be any left.

VISKOVSKY: There are diamonds in every house. You just have to know how to get your hands on them. The Rimsky-Korsakovs have some, the Shakhovskoys there are still some diamonds in imperial St. Petersburg.

KRAVCHENKO: You won't make a Red merchant, Evgeny Alexandrovich.

VISKOVSKY: Of course I will! My father was a trader he traded villages for stallions. The old guard gives way, comrade Kravcheoko, but it does not give up.

KRAVCHENKO: You'd better go and call Mukovnina. The woman's fretting out there in the corridor

VISKOVSKY: I shall arrive in Paris in the grand manner.

KRAVCHENKO: This fellow Dymshits where's he disappeared to?

VlSKOVSKY: Either he's sitting it out in the W.C. or he's playing "Sixty Six" with Shapiro and that fellow from Kurlyandia (He opens the door.) Miss, I bid you welcome to our hearth. (He goes out into the corridor.)

DORA (kissing KRAVCHENKO'S hands): Light of my life! My idol! (Enter LUDMILA, with her fur coat on, followed by VISKOVSKY.)

LUDMILA: I don't understand it. We'd made an arrangement

VISKOVSKY: Which is dearer than gold.

LUDMILA: The arrangement was that I should come at eight. Now it's nine forty-five, and he hasn't even left the key. Where on earth has he got to?

VISKOVSKY: He'll do a little speculating and then he'll show up.

LUDMILA: All the same, they're not gentlemen, these people.

VISKOVSKY: Drink some vodka, child.

LUDMILA: Certainly I will I'm frozen but I still can't understand it.

VISKOVSKY: Permit me to present: Ludmila Nikolaevna, Madame Dora, citizen of the French Republic Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite, Among her other talents she possesses a foreign passport.

LUDMILA (offering her hand): Mukovnina.

VISKOVSKY: Yashka Kravchenko you know: an ensign in the war, now a Red artilleryman. He stands by the ten-inch guns of the Kronstadt battery and can aim them in any direction.

KRAVCHENKO: Evgeny Alexandrovich is in good form today.

VISKOVSKY: In any direction Imagine, Yashka, there's no limit to the possibilities. And if they order you to destroy the street where you were born you'll do it. If they order you to shell the orphanage, you'll say "range two-zero-eight", and you'll shell the orphanage. You'll do it, Yashka, as long as they'll allow you to exist, allow you to strum the guitar and sleep with thin women you being fat and liking them thin There's not a thing you won't do, and if they say to you "deny thy mother thrice", you'll do just that. But that's not the point, Yashka. The point is that they'll go further: they won't allow you to drink vodka with the crowd you prefer. They'll make you read boring books, and

TRI-QUARTERLY 23

the songs they'll start making you learn will be boring songs. Then you'll become angry, Red artilleryman, you'll go wild and have a hunted look in your eye. And a couple of citizens will pay you a call: "Let's go, comrade", they'll say. "Shall I bring my things with me or not?", you'll ask. "No need, comrade Kravchenko, it won't take a minute just a few questions nothing important." And they'll put paid to you, Red artilleryman and it'll cost four kopeks. They reckon a bullet from a Colt costs four kopeks, and not a farthing more

DORA: Jacques, take me home

VISKOVSKY: Your health, Yakov! to victorious France, Madame Dora!

LUDMILA (whose glass has been steadily re-filled): I shall go and see whether he's returned

VISKOVSKY: He'll do a little speculating, and then he'll show up marquise, was it your own idea, the lie about your teeth?

LUDMILA: Yes Wasn't it hilarious? (She laughs.) Truly, the other way is quite impossible. The Jews must respect a woman with whom they hope to have a close relationship.

VISKOVSKY: I look at you, Lyuka, and I see a blue-tit. Let's drink, my little blue-tit!

LUDMILA: SO now he's going to start work on me

You've put something in the booze, Viskovsky.

VISKOVSKY: Blue-tit, all the best Mukovnin qualities went into Maria. A row of small teeth was all that was left for you.

LUDMILA: That was a cheap crack, Viskovsky.

VISKOVSKY: And I don't like your flat chest A woman's breast should be handsome, full, and floppy, like a sheep's

KRAVCHENKO: We're going, Evgeny Alexandrovich.

VISKOVSKY: You're not going anywhere Blue-tit, will you marry me?

LUDMILA: No, I'm really much better off with Dymshits. We know what it would be like to marry you: you're drunk now, tomorrow you'll be hung over; then you'll go off God knows where, and after that you'll end up shooting yourself. No, it's Dymshits for us.

KRAVCHENKO: Let us go, Evgeny Alexandrovich, there's a good fellow.

VISKOVSKY: You're not going anywhere A toast! A toast to the woman (to DORA). 'Ibis is Lyuka her sister's called Maria.

KRAVCHENKO: Maria Nikolaevna is in the army, I believe?

LUDMILA: She's on the frontier at the moment.

VISKOVSKY: At the front, Kravchenko, at the front. Their division is commanded by a little nobody.

LUDMILA: That's not true, Viskovsky. He's a metalworker.

VISKOVSKY: The nobody's name is Akim Let's drink to women, Madame Dora! Women love ensigns, waiters, Customs men, Chinamen love is their business it's true, ask a policeman. (He raises his glass.) "To those kind, lovely ladies who have loved us, be it but for a single hour" Of course, sometimes it was for less than an hour. Mere gossamer. Then the gossamer was broken Her sister's name is Maria Imagine, Yashka, that you fell in love with the Tsarina "You are vile" she says to you, "Get 0\1t".

LUDMILA (laughing): That sounds like Maria.

VISKOVSKY: "You are vile, get out" The Horseguards were rejected, and it was decided to go to Furstadtskaya Street, No. 16, Apartment No.4.

LUDMILA: Viskovsky, don't you dare!

24 TRI·QUARTERLY

VISICOVSICV: To the Kronstadt artillery, Yasha! It was decided to go to Furstadtskaya Street. Maria Nikolaevna came out of the house in a grey costume tailleur. She had bought violets at the Troitsky bridge and was wearing them in the buttonhole of her jacket The prince he plays the violoncello the prince had cleaned up his bachelor's quarters, had shoved his dil ty linen under the closet, and had carried his unwashed dishes upstairs to the landing Coffee was laid on at Furstadtskaya Street, and petits fours. They drank the coffee. She had brought Spring and violets with her, and curled her legs up on the divan. He covered her strong, tender legs with a shawl, and was greeted with as" smile, a reassuring, gentle, sad, reassuring smile. She embraced his greying head. "Prince, what about it, Prince?" But the prince's voice turned out to be no deeper than that of a papal choir-boy. Passe, rien ne va plus.

LUDMILA: God, what a malicious creature!

VlSKOVSICV: Imagine it, Yasha, right in front of you the Tsarina takes off her bodice, her stockings, her pantaloons. Perhaps even you'd be scared, Yasha. (LUDMILA Nikolaevna leans back and laughs) So she left No. 16 Furstadtskaya where is her footprint for me to kiss where is her footprint? But Akirn's voice, we trust, has a somewhat deeper ring. What do you think, Ludmila Nikolaevna?

LUDMILA: Viskovsky, you've put something in this vodka I feel dizzy.

VlSKOVSKV: Come here, small fry! (He takes her roughly by the shoulders andpulls her to him.) Dymshits how much did he pay you for the ring?

LUDMILA: What are you talking about?

VlSKOVSKV: The ring isn't yours, it's your sister's. You sold a ring that wasn't yours.

LUDMILA: Let me go !

VlSKOVSKY (pushing her to a side door); Come with me, small fry! (DORA and ICRAVCHENICO are left alone. In the window a searchlight's slow beam is seen. DORA, dishevelled and goggle-eyed, clings to ICRAVCHENICO, kissing his hands, moaning and babbling. PHILIPPE enters on tip-toe, barefooted, and quietly and unhurriedly takes wine, sausage and breadfrom the table.)

P.lfiLIPPE (softly, with his head on one side);Will it be all right,Yakov Ivanovich? (ICRAVCHENICO nods his head, and PHILIPPE goes out, stepping carefully with his bare feet.)

DORA: Light of my life! You're my god, my everything!

(KRAVCHENKO listens attentively, but says nothing. VlSKOVSKY enters and lights a cigarette with trembling hands. The door to the next room is open. Sprawled on a divan, MUKOVNINA weeps).

V1SKOVSKY: Calm yourself, Ludmila Nikolaevna. It'll heal in time.

DORA: Jacques, I want to go back to our room. Take me home, Jacques.

KRAVCHENKO: In just a minute, Dora.

V1SKOVSKY: How about one for the road, citizens?

KRAVCHENKO: Wait a moment, Dora,

VlSKOVSKY: One for the road to the ladies

KRAVCHENlCO: That was not nice, captain.

V1SKOVSKY: To the ladies, Yakov Ivanovich!

KRAVCHENKO: Not nice, captain.

VlSKOVSKY: What's not nice?

KRAVCHENKO: People with gonorrhoea don't sleep with women, Mr. Viskovsky.

TRI-QUAR'IERLY

2S

VISKOVSKY (haughtily): What did you say? (A pause. The crying SlOpS.)

KRAVCHENKO: I said people suffering from gonorrhoea

VISKOVSKY: Take your glasses off, Kravchenko. I'm going to bash your ugly face. (KRAVCHENKO draws a revolver.) All right, if that's what you want. (KRAVCHENKO fires, and the curtain falls. Behind it shots are heard, the sound offalling bodies, and a woman's scream.)

Scene 5

At the MUKOVNINS'. The old nurse is curled up asleep on a chest in a corner. On the table there is a patch oflightfrom a lamp. KATYA reads MUKOVNIN a letter from Maria.

KATYA: At dawn I am woken by the bugle of the staff cavalry squadron. I must be in the political section by 8:00 I do everything there I proof-read articles for the divisional newspaper, I run the literacy classes. Our new reinforcements are Ukrainians, whose language and expressiveness remind me of the Italians. In the course of centuries the old Russian administration oppressed and demeaned their culture. On Millionnaya St. in Petersburg, in our house opposite the Hermitage and Winter Palace, we might just as well have been living in Polynesia not knowing our own people, not even wondering about them. In yesterday's lesson I read from Papa's book the chapter on the murder of Paul. The Emperor so clearly deserved his punishment that nobody gave it a second thought. They asked me and it just goes to show the precise way the ordinary people think all about the disposition of the Regiment and the rooms in the palace, and which company of the Guards had the watch, from among whom the conspirators were recruited, what Paul had done to offend them, etc I go on dreaming of Papa coming here in the summer, if only the Poles will behave themselves you will see, my dearest Papa, a new army, a new military order, entirely different from that of which you tell. By then our park will have blossomed and turned green, the horses will have put on weight at pasture, and the saddles will be ready I have spoken to Akim Ivanovich, and he agrees, so I do hope all will be well with you, my dearest Now it is night. I finished work late and came back to my quarters up steps worn down over four hundred years. I live in the tower, in a vaulted hall which once served as an armoury for the Counts Krasnitsky. The castle is built on a steep hill overlooking a blue river; there is a vast expanse of meadow with a misty wall of forest in the distance. On every level of the castle there are look-out niches, from which they observed the approach of the Tatars and the Russians, and poured boiling oil on the heads of the besiegers. An old woman called Hedwig, housekeeper to the last of the Krasnitskys, cooked my supper and made a fire in the fireplace, which is as deep and dark as a dungeon. In the park below the horses are shifting their feet and slumbering. The Kubanian Cossacks are having their supper round a bonfire and breaking into song. The trees have a snowy overlay, the branches of oaks and chestnuts have become interwoven, the paths and statues are covered with an uneven silver layer of snow. The statues have been preserved: youths throwing the javelin, goddessess, naked and numb, with bent arms, wavy hair and unseeing eyes Hedwig is dozing, and nodding her head, the logs in the fireplace blaze up and fall apart. The centuries have made the bricks ring like glass in this light, as I write, they are golden

26 TRI-QUARTERLY

Alesha's picture is on my table Those same people who did not hesitate to kill him are here. I have just come from them, and have assisted in their liberation Did I do right, Alexei, did I fulfill your last command, to live bravely? I am sure that with that part of him which is immortal he does not reject me It is late, and I cannot sleep for some inexplicable anxiety about you, and for fear of my dreams. In my sleep I see pursuit, torture, and death. I live a strange mixture of proximity to nature and concern for you. Why does Lyuka write so rarely? A few days ago I sent her a piece of paper signed by Akim Ivanovich, to the effect that, as I am a member of the armed forces, they do not have the right to requisition my room. Apart from that, Papa must have a paper to safeguard his library. If it has expired it must be renewed at the Commissariat of Education at the Chernyshev Bridge, room No. 40 I will be happy if Lyuka succeeds in getting married, but the man must visit our house and get to know Papa that's where the heart will tell the truth. And let Nanny get a look at him Katyusha is always complaining about the old woman for not working Katyusha, Nanny's getting on, she's raised two generations of Mukovnins, she has her own thoughts and feelings, she's not a simple person I've always felt that there was very little of the peasant in her, though what did we know ofpeasants in our Polynesia? They say that in Petersburg the food situation has become even worse; and those who are not serving have their rooms and linen requisitioned I am ashamed that we are comfortably off here Akim Ivanovich has taken me hunting twice, I have my own saddle-horse, from the Don (Katya raises her head) There, you see, Nikolai Vasilyevich, everything's fine. (MUKOVNIN covers his eyes with the palm of his hand.) There's no need to cry.

MUKOVNIN: I ask of God for the soul of each of us has its god what did I, a sinful, selfish man, do to earn such children as Masha and Lyuka?

KATYA: But everything's fine, Nikolai Vasilyevich. Why should you weep?

Scene 6

A police station late at night. A drunk is curled up under a bench. He moves his fingers in front ofhis face, as ifhe is trying to convince himselfofsomething. On the bench itself a large, elderly, well-dressed man, in a raccoon coat and tall hat, is dozing. The fur coat hasfallen open, exposing a naked, grey chest. The po/ice inspector is questioning Mukovnina. Her moleskin cap has been knocked sideways, her hair is dishevelled, and her fur coat has been pulled down off one shoulder.

INSPECTOR: Name?

LUDMILA: Let me go.

INSPECTOR: Name?

LUDMILA: Barbara.

INSPECTOR: Patronymic?

LUDMILA: Ivanovna.

INSPECTOR: Where do you work?

LUDMILA: At Laferme's, the tobacco factory.

INSPECTOR: Trade union card?

TRI-QUARTERLY 27

LUDMILA: I don't have it with me.

INSPECTOR: Why are you lying?

LUDMILA: I'm a married woman let me go.

INSPECTOR: Why does it interest you to tell lies? Have you known Brylev long?

LUDMILA: I don't know what you're talking about.

INSPECTOR: Brylev signed authorization for reels of cotton. They went via you to Gutman. Where did you have your depot?

LUDMILA: What are you talking about? What depot?

INSPECTOR: You'll find out presently. (to a policeman) Call Kalrnykova. (thepoliceman brings in Shura KALMYKOVA, the maid at the 86, Nevsky Prospect, lodgings.) You are a lodginghouse servant?

KALMYKOVA: I'm a replacement.

INSPECTOR: Do you know this woman?

KALMYKOVA: I know her ever so well.

INSPECTOR: What can you tell US?

KAUIYKOVA: You ask, I'll answer Their father's a general.

INSPECTOR: Does she do anything?

KALMYKOVA: She makes love that's what she does.

INSPECTOR: Is there a husband?

KALMYKOVA: A wedding in the woods She's got lots of husbands. One of them had to sit in the toilet all evening because of her teeth.

INSPECTOR: What teeth? What's this nonsense?

KALMYKOVA: Ludmila Nikolaevna knows what teeth.

INSPECTOR (to MUKOVNINA): Did you have clients? How many?

LUDMILA: I'm infected I'm ill.

INSPECTOR: We must ascertain how many clients there are.

KALMYKOVA: That I don't know, that I won't say. I won't say what I don't know.

LUDMILA: I'm quite worn out. Let me go.

INSPECTOR: Don't get excited. Look at me.

LUDMILA: I feel faint I shall fall.

INSPECTOR: Look at me!

LUDMILA: My God, why should I look at you?

INSPECTOR (furiously): Because for five whole days and nights I haven't had any sleep. Can you understand that?

LUDMILA: I understand.

INSPECTOR (coming close to her, taking her by the shoulders, and looking into her eyes): How many clients? Speak!

Scene 7

At the MUKOVNINS'. Oil lamps are burning, creating shadows on the walls and ceiling. In front 0/ an illuminated ikon GOLYTSIN is praying. The nurse is asleep on the chest.

GOLYTSIN: Verily, verily I say unto you: Except a com of wheat fall into the ground and

28 TRI-QUARTERLY

die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit. He that loveth his life shall lose it; and he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal. If any man serve me, let him follow me: and where I am, there shall also my servant be: if any man serve me, him shall my Father honour. Now is my soul troubled: and what shall I say? Father, save me from this hour: but for this cause came I unto this hour

KATYA (approaching quietly, standing beside him, and putting her head on his shoulder): My meetings with Redko take place in the H.Q. building, Sergei Illarionovich, in the old ante-room. There's an oilskin divan there. I arrive, Redko locks the door, and then later on it's unlocked again.

OOLYTSIN: I see.

KATYA: I'm going away to Borisoglebsk, Prince.

OOLYTSIN: Well, then, go.

KATYA: Redko teaches me everything who to love, who to hate he says it's the law of the big numbers. Yet I'm a small number or doesn't that count?

GOLYTSIN: It has to count.

KATYA: There! It has to count Look, Nanny, I'm free Wake up. Please wake up. You'll sleep right through the heavenly kingdom.

NEFEDOVNA (raising her head): Where's Lyuka?

KATYA: Lyuka will come soon, Nanny, and I'm going away, so there'll be no one to scold you.

NEFEDOVNA: Why should I be scolded? What's it got to do with me? Nursing is in my blood, I was hired for the children, to raise the children, but there aren't any here. The house is full of women, but there aren't any children. One's gone off to fight, as if they couldn't manage without her the other's dithering around aimlessly What sort of house can it be without children?

KATYA: We'll bear you children by the Holy Ghost.

NEFEDOVNA: You're playing around and don't think I don't know it playing around, and there's no sense to it.

GOLYTSIN: Go off to Borisoglebsk, they need you there. It's a wilderness in Borisoglebsk, Katerina Vyacheslavna, a wilderness in which wild animals devour each other.

NEFEDOVNA: Look at the Molostovs miserable little merchants, but even they managed to get their nurse a pension, fifty rubles a month Make the effort for me, Prince. Why won't they give me a pension?

GOLYTSIN (lighting the stove): They won't listen to me, Nefedovna, I have no influence now.

NEFEDOVNA: But look at them they're just simple tradesmen.

(The door opens. MUKOVNIN backs away from PHll..IPPE, muffled up in rags and hood, huge and shapeless. He is wearingfelt boots.)

MUKOVNIN: Who are you?

PHILIPPE (drawing closer): A friend of Ludmila Nikolaevna.

MUKOVNIN: What do you want?

PHILIPPE: There's been some trouble over there, Your Excellency.

KATYA: Did Isaac Markovich send you?

PIULIPPE: Yes, ma'am. The trouble sort of started out of nothing.

KATYA: And Ludmila Nikolaevna?

PHILIPPE: She was there too, a group of them, there was they overdid it a bit, Your Excellency. Evgeny Alexandrovich said one thing, Yakov Ivanovich sort of contradicted

TRI-QUARTERLY

29

him, and they began squabbling they were both a bit tipsy

OOLYTSIN: Nikolai Vasilyevich, I will have a word with this comrade.

PHILIPPE: Nothing special happened, it was just a misunderstanding, that's all they were both a bit tipsy and had weapons on them.

MUKOVNlN: Where is my daughter?

PHILIPPE: Your Excellency, we don't know where she is.

MUKOVNIN: Where is my daughter? Tell me. You can tell me everything

PHILIPPE (barely audibly): She's been arrested.

MUKOVNIN: I have looked death in the eye. I am a soldier.

PHILIPPE (louder): She's been arrested, Your Excellency.

MUKOVNIN: Arrested what for?

PHILIPPE: The trouble sort of started over an ailment. Yakov Ivanovich, he says, "you've given her the ailment", and Evgeny Alexandrovich well, there was some shooting. They had arms with them, you see well, then they came

MUKOVNIN: Who came? The Secret Police?

PHILIPPE: Some people came and took her away. Who knows who they were? People don't wear uniforms these days, Your Excellency, there's no way of knowing who they are.

MUKOVNIN: I must go to the Smo'ny.w

KATYA: You're not to go anywhere, Nikolai Vasilyevich.

MUKOVNIN: I must go to the Smolny at once.

KATYA: Nikolai Vasilyevich, dearest

MUKOVNIN The fact is, Katya, that my daughter must be returned to me (He goes to the telephone.) Give me Military District H.Q

KATYA: You shouldn't, Nikolai Vasilyevich!

MUKOVNIN: May I speak with comrade Redko? Mukovnin I cannot make my identity any clearer to you, comrade I used to be quartermaster-general of the Sixth Army Is that you, Redko? How do you do, Fedor Nikitich. Mukovnin here. Good day to you. I must apologise if I have dragged you away from your work. The fact is, Fedor Nikitich, that today my daughter Ludmila was taken by armed men from the house at No. 86 Nevsky Prospect. I am not pleading with you, Fedor Nikitich, I know that that is useless in your organization I merely wished to convey to you that I need to see my elder daughter Maria Nikolaevna. The fact is that I have not been well lately, Fedor Nikitich, and I feel the necessity of talking things over with Maria Nikolaevna. We have sent telegrams and express letters; Katerina Vyacheslavna, I know, has gone as far as to bother you with the matter but there has been no reply. My request is that you should put me through to her on a direct line, Fedor Nikitich I might add that I have been summoned to Moscow by General Brusilovu for talks concerning the possibility of my serving You say it was delivered? Delivered on the eighth? I thank you humbly, and wish you every success, Fedor Nikitich. (he hangs up) All is well, they have found Masha, the telegram was delivered on the eighth. She will be in Petersburg tomorrow or the day after, at the latest. You must get Masha's room ready, Nefedovna,

IOSmolny the Smolny Institute Lenin's headquarters and seat of the Bolshevik administration. IIGeneral Brusilov: one of Russia's heroes of World War I, who threw in his lot with the Bolsheviks at an early stage.

30 TRI-QUARTERLY

-g,et up tomorrow at the crack of dawn and get it ready Katyusha is right the place has been neglected. We have neglected everything terribly of late, there's dust everywhere. Do we have some slip-covers, Katyusha?

KATYA: Not for all the furniture, but there are some.

MUKOVNIN (agitatedly pacing the room): Certainly we must put the slip-covers on. It will be nice for Masha to find everything just as she left it. Why not create a cosy atmosphere if one can? Poor Katya doesn't have much fun here with us you have no fun at all, Katyusha, you never go to the theatre, you'll be quite behind the times.

KATYA: I shall leave as soon as Masha returns.

MUKOVNIN (to the veteran): Excuse me, you're name and patronymic?

PIDLIPPE: Philippe Andreevich.

MUKOVNIN: Why don't you take a seat, Philippe Andreevich, we have not thanked you for your trouble we must entertain Philippe Andreevich Nanny, what can we offer our guest? Make yourself at home, Philippe Andreevich, you are warmly welcome, the pleasure is ours. We shall certainly introduce you to Maria Nikolaevna

KATYA: You should rest, Nikolai Vasilyevich, you should lie down.

MUKOVNIN: And if you want to know, I shall not worry about Lyuka for a single moment. This has been a lesson to her a lesson for childishness and inexperience If you want to know, I am content. (He winces with pain, stops, andfalls on to a chair. KATYA rushes to his side.) It's all right, Katya, it's all right

KATYA: What is it?