Editors:

Editors:

Elliott Anderson, Robert Onopa

Executive Editor:

Jonathan Brent

ArtDirector:

Cynthia Anderson

Managing Editor: Michael McDonnell

Associate Editor:

Anne-Marie Zwierzyna

Assistant Editors:

DemetraBowles, LisaJohnson, Kay Kersch Kirkpatrick, Mary Elinore Smith

Advisory Editors: Lawrence Levy, Charles Newman

Fulfillment: Judy Marrs

Contributing

Editors:

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Gerald Graff, John Hawkes, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Ian MacMillan, Joseph McElroy, Peter Michelson, Robert Ray, Tony Tanner, Nathaniel Tarn

TriQuarterly is an international journal of art and writing published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201.

Subscription rates: One year $12.00; two years $20.00; three years $30.00 Foreign subscriptions $1.00 per year additional. Single copies usually $5.95. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, 1735 Benson Avenue, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1980 by TriQuarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 113 E. CENTRE STREET-REAR, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR WEST COAST TRADE: BOOK PEOPLE, 2940 7TH STREET, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94710. MIDWEST: BOOKSLINGER, P.O. BOX 16251, 2163 FORD PKWY, ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 55116.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MlCROFlLM FROM UMI, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

Writers ofthe new west 5

William Kittredge & Steven M. Krauzer

The scalphunters 15

Cormac McCarthy

Gringos 29

Terry McDonell

Swell 40

Ivan Doig

Casus belli 50

Oakley Hall

Streets ofgold 65

Steven M. Krauzer

The price ofgold 80

William Bevis

Tom Fitch and the sparrow bride 98

Dorothy M. Johnson

Nobody's angel 115

Thomas McGuane

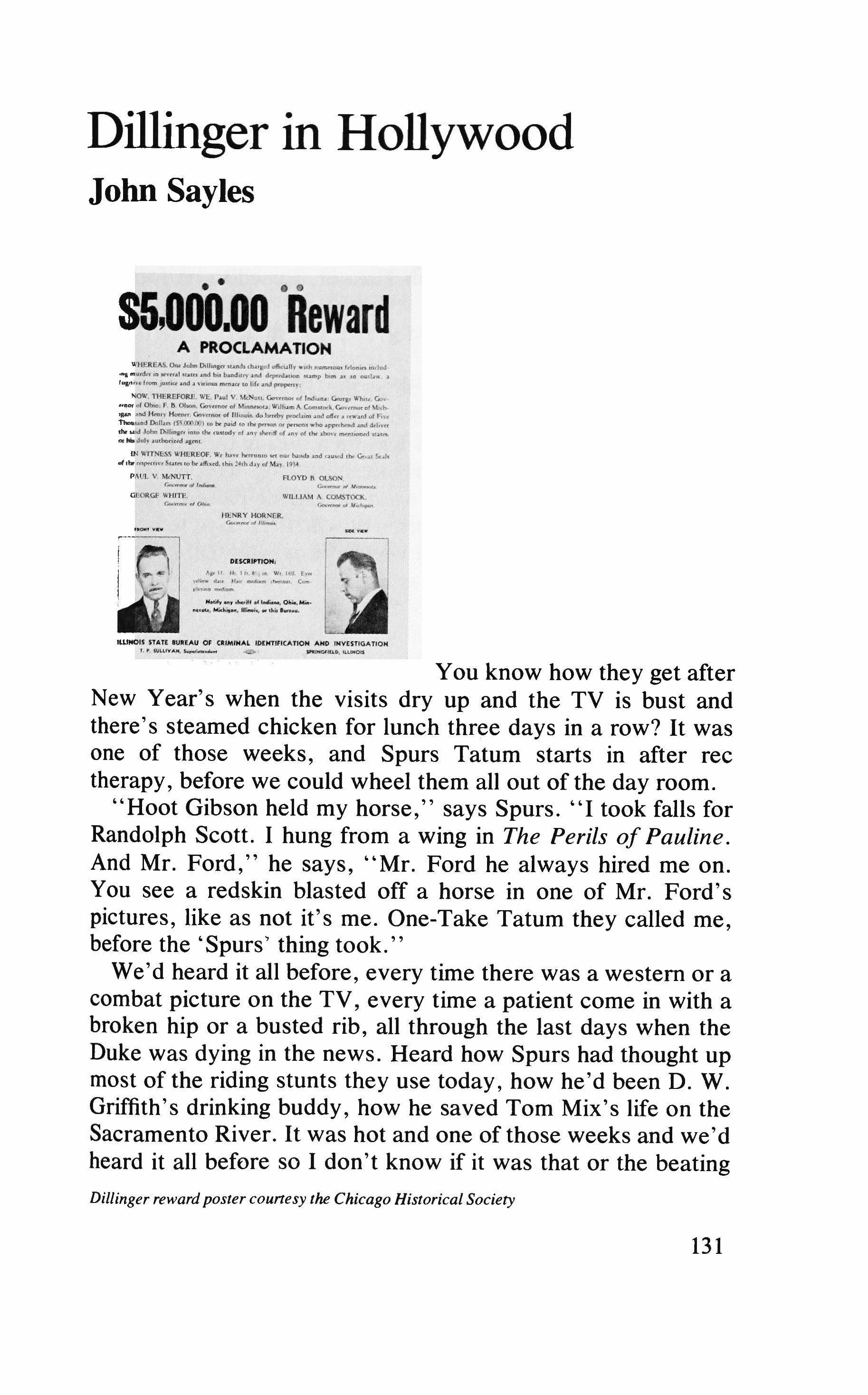

Dillinger in Hollywood 131

John Sayles

Performing arts 144

William Kittredge

Coyote holds afull house in his hand 166

Leslie Marmon Silko

Walking out 175

David Quammen

Where is everyone? 203

Raymond Carver

Snowman 214

Richard Ford

Hunters in the snow 225

Tobias Wolff

Riders 241

Ralph Beer

The basement 257

Cyra McFadden

No rhyme, no reason 265

John Nichols

Good news 273

Edward Abbey

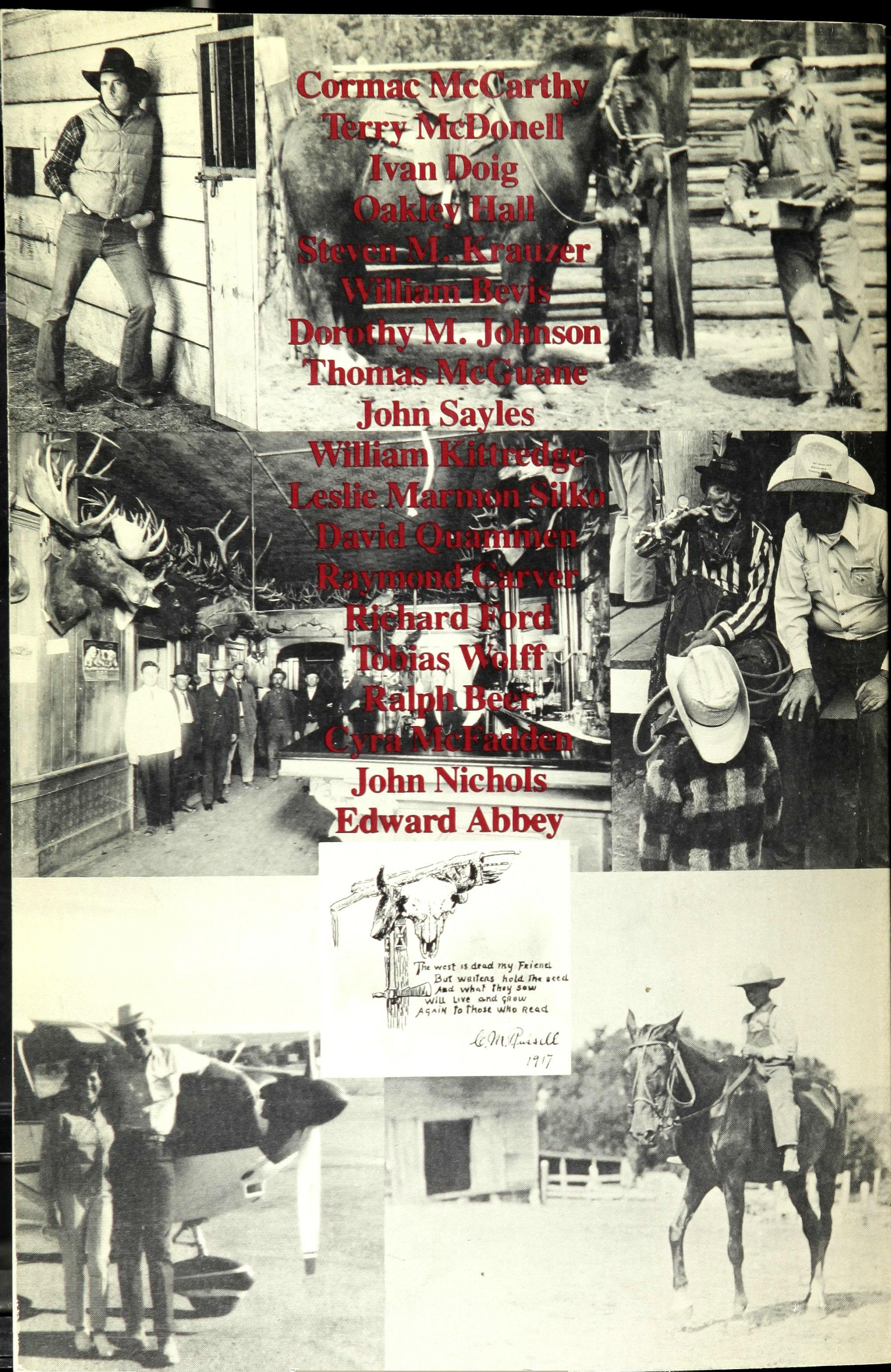

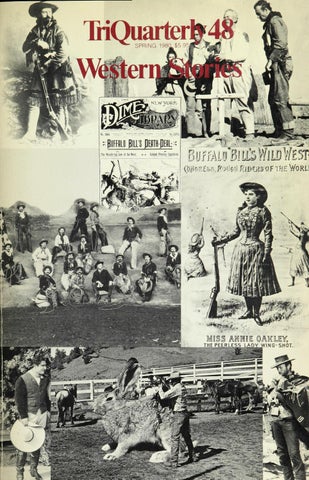

Cover drawings andphotographs courtesy Donna Colvin. Michael Crummett. Thomas McGuane. Ralph Beer, William Kittredge. Margaret Cantlin. Mignon Shanahan. Keith Anderson. Stuart Kaminsky. the C.M. Russell Museum. Great Falls. Montana. the Wyoming State Arrhives. Museums and Historical Department, and the Historical Pictures Service. Inc Chicago.

Several weeks ago, in Billings, Montana, an automobile repair shop was burglarized late in the night. The next morning, a nineteen-year-old mechanic employed at the shop discovered that $8,000 and a 1958 auto were missing, and reported the theft to the county sheriff.

The case has not come to trial yet, so the details are allegations, not substantiated facts. Two nights later at about eleven o'clock, on a Friday, the mechanic and three friends, the youngest seventeen and the oldest twenty-two, sought out a man theybelieved to have committedtheburglary.Theydrove him out into the brush country and beat him with their fists and a tire iron until he wrote out a confession

naming an accomplice. Several of the men fetched the accomplice, and he too was beaten until he signed a confession.

Five hours after picking up the first man, the four delivered the confessions to the sheriff's office. They explained how the confessions had been obtained, and led a deputy to the stolen auto, which had been stripped. The two battered suspects were charged with burglary and auto theft. And the four young men who obtained the confessions were charged with kidnapping, assault, and intimidation.

To those of us who live in the American west, there is a jarring sense of familiarity in this story. In some ways we can see ourselves reflected in this situation as in a mirror. We can imagine the feelings of anger and surprise and confusion and impotence of the four young men, who surely felt, with some justification, that they had served justice in a direct, efficient, and fair way.

Our local newspaper, The Missoulian, used the word "vigilante" in its headline when it reported the incident, a word not bandied about lightly in this part of the world. It conjures up the specter of the gold camps at Bannack and Virginia City in the 1860s, and of Henry Plummer, the road agent who became sheriff. After his election, Plummer went right on with his outlaw ways, and well before his term ran out he and his cohorts were hanged by vigilantes. Law and order had gone wrong, but justice was served by citizen vigilance.

This sometimes bewildering antagonism between rule and right is at the core of the western myth. Myth, according to theorists, is the formal structuring of symbols in an order which defines common social experience. Put differently, a myth is a message from society to its members, suggesting appropriate behavior and response. It seems inarguable that the mythology most commonly associated with the American west is the most enduring and influential message our society has given us in the two hundred years of American social history.

This myth arises from the historical conflict between civilization and wilderness during the centuries of settlement on this continent. It tells us some very simple things: that wilderness is natural and therefore strong, and that civilization is bound by the complex compromises that are law, and therefore weak. It tells us that civilization at times needs to be defended by those

who possess wilderness strengths, and it defines the role of that defender.

Think of the film Shane, where the myth takes classical form. A society of pastoral homesteaders is coming together under the leadership of one of their number, played by Van Heflin. Because of their belief in law and their commitment to family, their civilized weakness, the settlers are unable to answer the violence, essentially warfare, directed toward them by the male society of ranchers who want their land, led by a man named Ryker.

From out of the west, the wilderness, comes a lone rider, a gunfighter named Shane, played by Alan Ladd. The homesteaders include Shane in their lives and their farmer's work, and he considers hanging up his guns to embrace civilization and a settled life. It is a way out of his isolation, his role as a wanderer on the warrior outskirts of society. But in the end he cannot avoid his fate: Shane must join the battle and defend the homesteaders with his terrible skills, defeating the hired gunfighter representative of the mercantilist ranching interests. Then, wounded and alone, forever outside society because his presence is a destructive force, Shane rides away into the wilderness from which he came, into the great shadowy Tetons to the west. The warrior is trapped inside his role. Society needs him in time of peril, and then he must leave because his skills represent lawlessness.

This is the classical form of the myth-and its paradox. The defender of the good society, founded on law, must be one who is himself from the wilderness, who partakes of the savagery necessary to survive in the wild. He is the only one who possesses the skills, the magic quickness of hand, and the willingness to kill. But he must be a good man, acting out of altruism in some form. In Shane, the hired gunfighter also has the skills. But he is acting out of self-interest and posturing arrogance, and as a force of these antisocietal stances, he is defeated.

Those boys back in Billings: they were only being Shane. They had the best interests of society in mind, and they were using direct action to cut through the crap. They were acting out the myth.

What has always been so unique about western mythology is

its inextricable and dialectical involvement with western reality, the two of them woven tight and hard like strands in a sea-grass riata. That they are difficult to separate in any clear way has caused endless consternation, confusion, and sometimes tragedy. Somebody is always trying to be the gunfighter.

Consider Wild Bill Hickok. One of his biographers, James D. Horan, has written, "James Butler Hickok never knew he was a glamorous gunfighter, defender of the helpless, and scourge of evil until he read an article about himself in the February 1867 issue of Harper's New Monthly Magazine." The article describes Hickok's first great gun battle, in which he singlehandedly defended the Rock Creek, Nebraska, stage station against the notorious M'Kandles gang, and was shot and stabbed several times.

The facts are these: In 1861 the twenty-four-year-old Hickok was employed as a wrangler at the station. On July 12 the station's former owner, David McCanles, came to the station with his cousin, his hired man, and his twelve-year-old son to demand an overdue mortgage payment. As McCanles argued with the present owner inside the one-room station house, Hickok shot McCanles from behind a curtain. Hickok then rushed outside and killed the cousin and the hired man. The boy escaped into the cottonwoods along the creek.

Hickok went on to become a lawman, a gambler, a saloon owner, and an actor in western melodramas. Everywhere the myth of his gunman prowess was with him, like a sequined suit he could never take off. In the mirror each morning he shaved the face of a gunfighter. The journalist Henry M. Stanley interviewed him and found him "one of the finest examples of the peculiar class now extant, known as Frontiersman, ranger, hunter, and Indian scout." Colonel Prentiss Ingraham made Hickok the hero of a series he wrote for Beadle's Dime Library.

Myth dogged Hickok to death. On the afternoon ofAugust 2, 1876, as he played poker in Nutthall and Mann's No. 10 Saloon in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, Hickok was shot in the back of the head by a man named Jack McCall.

Killing held no magic for Jack McCall either. He was tried, convicted, and executed. McCall was twenty-five, and had confided to several cronies his ambition to be known as a

famous gunfighter. Hickok was thirty-nine, and had revealed to several friends his constant fear of assassination. An eye disease from which he had suffered for years was rendering him near-blind much of the time.

There is a thread of connection which begins with Hickok. It has something to do with living spuriously. It runs through Buffalo Bill Cody, who began his career as a hunter for the army and the railroad and ended it as a circus impresario who could still wistfully declare, "All my early days I stood between savagery and civilization." The thread touches Tom Mix, the western actor who died while driving a Packard with the horns of a Texas steer mounted on the grill. It ends perhaps with John Wayne, who at the finish was not inauthentic at all, knowing it was over and facing his losses with dignity.

The times change, but the past remains omnipresent here in this territory ofthe spirit, our west. If you are skeptical, stop by a bar in, say, Worland, Wyoming, or Miles City, Montana. Try a Saturday night and stay for more than a couple of drinks. You will see mythology in action, too often worn down into mindless pushing and shoving, counterfeit gunfighter confrontations, or the dark side of warrior individualism, going home alone with a bottle. If you are really skeptical, shoot your mouth off.

There's a good side of it, too. One of the writers in this collection acts plenty proud of the championship belt buckle he won calf roping at the rodeo in Gardiner, Montana. He ought to be. He seems to be working hard to make intimate contact with the true corral-centered way of life of the place he has chosen to inhabit, no doubt with some irony and considerable effort. These things are not given to us. If you are interested in sharing those moments of specific sacredness which adhere to living connected with a place-in this case Montana and that quick bay gelding setting up just as your riata settles--such efforts are required. And they feel good.

Ten minutes from our office in Missoula, up Rattlesnake Creek, there is a trail head which opens onto 60,000 acres of mountain country-yellow tarmac against the evergreens in the fall, and high lakes which seem surfaced with stained glass in the earliest light of morning-all the grand syncopation of wilderness landscape. Some would like to call it innocent, or

use some other loaded term to convert it into a weapon aimed at our supposed latter-day decadence. It's none of those things. Our myth tells us it is to be cherished. Our myth tells us it is from wilderness that we derive our essential strengths.

The myth has also been an insidious trap for those who would write about the west; it can become a box for our imaginations. For a long time it was as if there were only one legitimate story to tell about the west, and that was the mythological story. It was told over and over, first by James Fenimore Cooper and then repeated endlessly in Beadle Nickel-Dime Library thrillers, and Gene Autry B-westerns, and The Virginian, and everywhere else. It was the essential story of America, and it was a great story, and we loved it. But for writers it grew as confining as a celluloid collar.

William Eastlake once told us never to let a publisher put a picture of a horse on the dust jacket of any novel we might happen to publish. "The people who buy it will think it's some goddamned shoot-up," Eastlake said. "And they'll hate it when it isn't."

What Eastlake was talking about were the private stories that all of us who grew up in the west, or came there to live, have to tell about our own experiences, and the difficulty of telling those stories when expected to write from inside the myth. It is a trouble all western writers share to some degree, or at least used to share. It's not so bad any more. Mostly because of the hard labor of a whole group of widely disparate writers, we draw together under the ungainly notion of being antimythological.

The first of such writers worth much mention is Andy Adams. In 1903 he published Log of a Cowboy, detailing a late nineteenth-century cattle drive from northern Mexico, just across the Rio Grande from Brownsville, Texas, to the Blackfeet reservation in northern Montana. It is reasonably accurate and well told, and talks of days in the saddle without drinking water, and dust and cold wind, and putting your saddle in a gunnysack at the drive's end and riding the train home to Texas. It was a life with no room for the lacy-sleeved six-gun exhibitions of Main Street gamblers.

Then, in developing cadence, came Willa Cather, Mari San-

doz, H. L. Davis, John Steinbeck, Wallace Stegner, A. B. Guthrie, Jr., Dorothy M. Johnson; Death Comes for the Archbishop, Old Jules, Honey in the Horn, The Grapes of Wrath, Angle of Repose, The Big Sky, Indian Country. The complete list would fill a book, and all of it, in one way or another, is antimythological. Walter Van Tilburg Clark showed us the dark side of vigilante justice in The Ox-Bow Incident. In The Surrounded, D'Arcy McNickle showed us real Indians from his home country around St. Ignatius on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, suffering the loss of their traditional life in complex and human ways. As writers were cut loose from the mythology, subregional literatures developed: the Pacific Northwest poetry of Theodore Roethke, William Stafford, Richard Hugo; the Texas novels of Larry McMurtry, James Crumley, Max Crawford; the native American voices of N. Scott Momaday, James Welch, Simon Ortiz, Roberta Hill, Ray Young Bear, Leslie Silko. Wallace Stegner continues to be a central figure in this movement. Listen to his voice, this from The Big Rock Candy Mountain:

Things greened beautifully that June. Rains came up out of the southeast, piling up solidly, moving toward them as slowly and surely as the sun moved, and it was fun to watch them come, the three of them standing in the doorway. When they saw the land to the east of them darken under the rain Bo would say, "Well, doesn't look as ifit's going to miss us," and they wouldjump to shut the windows and bring things infrom the yard or clothesline. Then they could stand quietly in the door and watch the good rain come, the front of it like a wall and the wind ahead ofit stirring up dust, until it reached them and drenched the bare packed earth of the yard, and the ground smoked under its feet, and darkened, and ran with little streams, and they heard the swish ofrain on roofand ground and in the air.

Or this, from the story "Carrion Spring," in Wolf Willow:

Three days of chinook had uncovered everything that had been under the snow since November. The yard lay discolored and ugly, grey ash pile, rusted cans, spilled lignite, bones. The clinkers that had given them winter footing for the privy and stable lay in raised grey wafers across the mud; the strung lariats they had usedfor lifelines in blizzard weather had dried out and sagged to the ground. Much was knee-deep down in the corrals by the sod-roofed stable, the whitewashed Logs were yellowed at the corners from dogs lifting their legs against them. Sunken drifts around the hay yard were a reminder ofhow many times

the boys had had to shovel out there to keep the calves from walking into the stacks across the top of the snow. Across the wan and disheveled yard the willows were bare. and beyond them thefloodplain hill was brown. The sky was roiled with grey cloud.

Two experiences, both involving the enormous west and weather-one sacred, one demonic, neither mythological. Both seem to come out of Stegner's childhood, the years from ages six to twelve which he spent growing up around the Cypress Hills of southern Saskatchewan, just over the border from the high plains country of Montana. Those years are detailed in Wolf Willow: the life considered, a personal, and possessed, past.

Lois Hudson, writing in the Spring 1971 issue of the South Dakota Review, says of Stegner that he, like so many of the western writers of his literary generation, was "charged with the double burden of dispelling myth and then building fiction on the fact they must first insist upon." She is saying that western writers have somehow had to prove that the real emotionally possessed life they had grown up inside of, or found when they came to the country-as opposed to the stylized morality play that was supposed to be western experience-was worth writing about. It was a tough battle. Near the end ofOld Jules, just before the old man's death, Mari Sandoz includes this anecdote about herself and her father:

The next day he looked through the papers and found a small item announcing a prize for a short story awarded to Marie. He tore the paper across. ordered pencil and paper brought. wrote her one Line in the old. firm. up-and-down strokes: "You know I consider artists and writers the maggots ofsociety."

Why wouldn't he? Hadn't they told nothing but lies about the strenuous facts of life where he had lived, the endless tum of horizon and the turkey-packed earth where the wash water was flung outside the back door of the ranch house, season after season as the generations passed? That image is suggested by Willa Cather's "The Wagner Matinee"; this is from Old Jules, after the old man's death:

Outside the latefall wind swept over the hard-land country ofthe upper Running Water. tearing at the low sandy knolls that were the knees of the hills. shifting, but not changing, the unalterable sameness of the somnolent land spreading away toward the east.

The east-the direction culture looked, from where culture came. Mark Twain wrote the silliness of Roughing It for an eastern audience, and then migrated as quickly as he could to New York to celebrate his literary triumph. Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show performed before sell-out crowds in Europe, but surely told little of truth or importance. But even early on, some were nettled by the bald artifice. In Wild Bill Hickok's first stage venture, the script called for him to sit beside a crepe camp fire, sip whiskey, and spin yams. On opening night, Hickok took a big swig of what proved to be cold tea, spat it onto the boards, and bellowed, "I ain't telling no lies until I get some real whiskey." Old Jules would have liked that.

Jules could not know that his daughter Mari, like Stegner and the others, was getting ready to write books which would attempt to convey the emotional truth of the various western lives they had come to possess while inhabiting the country. Jules died in 1928, and Old Jules was published in 1935; Honey in the Horn in 1936; The Grapes ofWrath in 1939; The Big Rock Candy Mountain in 1943. A new thing was developing. A whole generation of writers was proving that the west had more stories than gunplay, that the private lives they had lived in the west were worth writing about=just as any life is worth literature if, in seeing it transformed through the eyes of the artist, we come to see our own existence freshly, with renewed sight of what is possible.

We, the writers in this collection, along with others who are for one reason or another missing, are in a real sense their children. Nobody doubts any longer that the west, however it might be defined, is rich material for stories that are honest and faithful and true.

The current status of western writing is similar to that of southern American writing in the early 1930s when a major regional voice, in the persons of such authors as William Faulkner, Robert Penn Warren, Eudora Welty, Andrew Lytle, and Katherine Anne Porter, was beginning to be heard. Just as the old south was gone, the old west is gone. Free ofthe need to write either out ofthe mythology or against it, the writers ofthe new west, responding to the variety and quickness of life in their territory, are experiencing a period of enormous vitality.

We can, all at once, do anything we want, use whatever material we find most compulsively central to express our most private obsessions. The range and quality of material in this collection is proof.-from Raymond Carver's story of alienation in the suburbs to Ivan Doig's ruminations on winter along the Washington seacoast; from Cormac McCarthy's scalp hunters in Old Mexico to David Quammen' s bear hunters in the Crazy Mountains of Montana; from Thomas McGuane's confrontations with the problems of living well on the ranch to William Bevis's meditations on the notion of gold and how it might be sought. Some of us even write novels about making antimythological western movies, or stories about gunfighters that spring right from the heart of the mythology. We can if we want to.

Stegner once wrote, in the introduction to another collection of western writing, that "Nobody has quite made a western yoknapatawpha County, or discovered a historical continuity comparable to that which Faulkner traced from the Chickasaw to the Snopes. Maybe it isn't possible, but I wish someone would try."

It looks like the race is on.

But then-well, the other day some wiseass asked us to name a great writer who dealt with agriculture. How about Tolstoy? Sure, this fellow said, but that was a long time ago and in another country. This made us so impatient we had to shoot him down. Then we had some sprouts.

For the next two weeks they would ride by night, they would make no fire. They had struck the shoes from their horses and filled the nailholes in with clay and those who still had tobacco used their pouches to spit in and they slept in caves and on bare stone. They rode their horses through the tracks of their dismounting and they buried their stool like cats and they hardly spoke at all. Crossing those barren gravel reefs in the night among such unknown coordinates they seemed remote and without substance, like a patrol condemned to ride out some ancient curse. A thing surmised from the blackness by the creak of leather and the chink of metal. Something passing that may have been the wind. They cut the throats of the pack animals and jerked and divided the meat and they traveled under the cape of the wild mountains upon a broad soda plain with dry thunder to the south and rumors of light. Under the gibbous moon horse and rider spanceled to their lean and flickering shadows on the snowblue ground. In the intervals their lunar castings kept

another quarter and these riders seemed invested with a purpose whose origins were antecedent to them, legatees of some order both imperative and remote. Something separate that was yet a blood component.

They crossed the Del Norte and rode south into a land more hostile yet. All day they crouched like owls under the niggard acacia shade and peered out upon that cooking world. Dustdevils stood on the horizon like the smoke of distant fires but of living thing there was none. They eyed the sun in its circus and they rode out upon the cooling plain where the western sky was the color of blood. At a desert well they dismounted and drank jaw to jaw with their horses and remounted and rode on. The little desert wolves yapped in the dusk and Glanton's dog trotted beneath the horse's belly, its footfalls stitched precisely among the hooves.

That night they were visited with a plague of hail out of a faultless sky and the horses shied and moaned and the men dismounted and sat upon the ground with their saddles over their heads while the hail leaped in the sand like small lucent eggs concocted alchemically out of the desert darkness and when they resaddled and rode on they went for miles through cobbled ice while a polar moon rose like a blind eat's eye up over the rim ofthe world. In the night they passed the lights ofa village on the plain but they did not tum.

Toward the morning they saw fires on the horizon. Glanton sent the Delawares. Already the dawnstar burned pale in the east. When they returned they squatted with Glanton and the judge and the Brown brothers and spoke and gestured and then all remounted and all rode on.

Five wagons smoldered on the desert floor and the riders dismounted and moved among the bodies ofthe dead argonauts in silence, those right pilgrims nameless among the stones with their terrible wounds, the viscera spilled from their sides and the naked torsos bristling with arrowshafts. Some by their beards were men but yet bore strange menstrual wounds between their legs and no man's parts for these had been cut away and hung dark and strange from out their grinning mouths. In their wigs of drying blood they lay gazing with ape's eyes up at brother sun now rising in the east.

The wagons were no more than embers armatured with the

blackened shapes of hoopiron and tires, the redhot axles quaking deep within the coals. The riders squatted at the fires and boiled water and drank coffee and roasted meat and they lay down to sleep among the dead.

When the company set forth in the evening they continued south as before. The tracks of the murderers bore on to the west but they were white men who preyed on travelers in that wilderness and disguised their work in this way. The trail ofthe argonauts of course went no further than the ashes they left behind and the intersection ofthese vectors seemed the work of a cynical god, the traces converging blindly in that whited void and the one going on bearing away the souls of the others with them.

The Delawares moved on ahead in the dusk and the Mexican John McGill led the column, dropping from time to time from his horse to lie flat on his belly and skylight the outriders on the desert before them and then remount again without halting his pony or the company which followed. They moved like migrants under a drifting star and their track across the land reflected in its faint arcature the movements of the earth itself. To the west cloudbanks stood above the mountains like the dark warp of the firmament and the starsprent reaches of the galaxies hung in a vast aura above the riders' heads.

Two mornings later the Delawares returned from their dawn reconaissance and reported the Gilefios camped along the shore of a shallow lake less than four hours to the south. They had with them their women and children and dogs and they were many. Glanton when he rose from this council walked out on the desert alone and stood for a long time looking out upon the darkness downcountry.

They saw to their arms, drawing the charges from their pieces and reloading them. They spoke in low voices among themselves although the desert round lay like a great barren plate gently quaking in the heat. In the afternoon a detachment led the horses out to water and led them back again and with dark Glanton and his lieutenants followed the Delawares out to scout the enemy's position.

They had driven a stick into the ground on a rise north of the camp and when the angle of the dipper had swung about to this inclination Toadvine and the Van Diemanlander set the com-

pany in motion and they rode forth south after the others trammeled to chords of rawest destiny, like migratory birds that beat their way by night among the pale or copper stars. They reached the north end of the lake in the cool hours before dawn and turned along the shore. The water was very black and along the beach there lay a wrack of soapy foam and they could hear ducks talking far out on the lake. The embers of the encampment's fires lay below them in a gentle curve like the lights of a distant port. Before them on that lonely strand a solitary rider sat his horse. It was one of the Delawares and he turned his horse without speaking and they followed him up through the brush into the desert.

The party was crouched in a stand of willow a half mile from the fires ofthe enemy. They had muffled the heads ofthe horses and the hooded beasts stood rigid and ceremonial behind them. The new riders dismounted and bound their own horses and they sat upon the ground while Glanton addressed them.

We got a hour, maybe more. When we ride in it's ever man to his own. Dont leave a dog alive if you can help it.

How many is there, John?

Did you learn to whisper in a sawmill? They's enough to go round, said the judge. Dont waste powder and ball on anything that caint shoot back. If we dont kill ever nigger here we need to be whipped and sent home.

This was the extent of their council. The hour that followed was a long hour. They lead the blindfold horses down and stood looking out upon the encampment but they were watching the horizon to the east for the first pale reaches of light. A bird called. Glanton turned to his horse and unhooded it like a falconer at morning. A wind had risen and the horse lifted its head and sniffed the air. The other men followed. The blankets lay where they had fallen. They mounted, pistols in hand, saps of rawhide and riverrock looped about their wrists like the implements of some primitive equestrian game. Glanton looked back at them and then nudged forth his horse.

As they trotted out onto the white salt shore an old man rose from the bushes where he'd been squatting and turned to face them. The dogs that had been waiting on to contest his stool

bolted howling. Ducks began to rise by ones and pairs out on the lake. Someone clubbed the old man down and the riders put rowels to their mounts and lined out for the camp behind the dogs with their clubs whirling and the dogs yapping in terror in a tableau of some hellish hunt, the partisans nineteen in number bearing down upon that encampment where there lay sleeping upward of a thousand souls.

Glanton rode his horse completely through the first wickiup trampling the occupants underfoot. Figures were scrambling out of the low doorways. The raiders went through the village at full gallop and turned and came back. A warrior stepped into their path and leveled a lance at them and Glanton shot him dead. Three others ran and he shot the first two with shots so closely executed that they fell together and the third one seemed to be coming apart as he ran, hit by half a dozen pistol balls.

Within that first minute the slaughter had become general. Women were screaming and naked children and one old man tottered forth waving a pair of white pantaloons. The horsemen moved among them and slew them with clubs or knives. Already a number of the huts were afire and a whole enfilade of refugees had begun streaming along the shore wailing crazily, the riders herding them on and clubbing down the laggards.

When Glanton and his chiefs swung back through the village people were running out under the horses' hooves and the horses were plunging and some of the men were moving among the huts with torches and dragging victims out, slathered and dripping with blood, hacking at the dying and decapitating those who knelt for mercy. There were in the camp a number of Mexican slaves and these ran forth calling out in spanish and were brained or shot and someone swung an infant aloft by its feet and bashed it against a stone metate so that the brains burst forth through the fontanel in a bloody spew and humans on fire came shrieking forth like berserkers and the riders hacked them down with their enormous knives and a woman ran up and embraced the bloodied forefeet of Glanton's warhorse.

By now a small band of warriors had mounted themselves out of the scattered remuda and they advanced upon the village and rattled a drove of arrows among the burning huts. Glanton

drew his rifle from its scabbard and shot the two lead horses and resheathed the rifle and drew his pistol and began to fire between the actual ears of his horse. The mounted indians floundered among the down and kicking horses and they milled and circled and were shot down one by one with rifles until the dozen survivors among them turned and fled up the lake past the groaning column of refugees and disappeared in a drifting wake of soda ash.

Glanton turned his horse. The dead lay awash in the shallows like the victims of some disaster at sea and they were strewn along the salt foreshore in a havoc of blood and entrails. Riders were towing bodies out of the bloody waters of the lake and the froth that rode lightly on the beach was a pale pink in the rising light. They moved among the dead gathering the long black locks with their knives and leaving their victims rawskulled and strange in their bloody cauls. The loosed horses from the remuda came pounding down the reeking strand and disappeared in the smoke and after a while they came pounding back. Men were wading about in the red waters hacking aimlessly at the dead and some lay coupled to the dead or dying bodies of young women. One of the Delawares passed with a collection ofheads like some strange vendor bound for market, the hair twisted about his wrist and the heads dangling and turning together. Glanton knew that every moment on this ground must be contested later in the desert and he rode among the men and urged them on.

McGill came out of the crackling fires and stood staring bleakly at the scene about. He had been skewered through with a lance and he held the stock of it before him. It was fashioned from an aloe stalk and the point of an old cavalry sword bound to the haft curved from out the small of his back. Someone waded out of the water and approached him and the Mexican sat down carefully in the sand.

Get away from him, said Glanton.

McGill turned his head and as he did so Glanton leveled his pistol and shot him through the head. He had the empty rifle clasped upright against the saddle with his knee and now he measured powder down the barrels. Someone shouted to him. The bloody horse trembled and stepped and stepped back and

Glanton spoke to it softly and patched two balls and drove them home. He was watching a rise to the north where a band of mounted Apaches were grouped against the sky. They were perhaps a quarter mile distant, five, six of them, their cries thin and lost. Glanton brought the rifle to the crook of his arm and capped one lock and rotated the barrels and capped the other. He did not take his eyes from the Apaches. Long Webster stepped from his horse and drew his rifle and slid the ramrod from the thimbles and went to one knee, the ramrod upright in the sand, resting the rifle's forestock upon the fist with which he held it. The rifle had set triggers and he cocked the rear one and laid his face against the cheekpiece. He reckoned the drift of the wind and he reckoned against the sun on the side of the silver foresight and he held high and touched off the piece. Glanton sat immobile. The shot was flat and lost in the emptiness and the gray smoke drifted away. The leader of the group on the rise sat his horse. Then he slowly went sideways and pitched to the ground.

Glanton gave a whoop and surged forward. Four men followed. The warriors on the rise had dismounted and were lifting up the fallen man. Glanton turned in the saddle without taking his eyes from the Indians and held out his rifle to the nearest man. This man was Sam Tate and he took the rifle and reined his horse so short he nearly threw it to the ground. Glanton and three rode on and Tate drew the ramrod for a rest and crouched and fired. The horse that carried the wounded chief faltered, ran on. He swiveled the barrels and fired the second charge and it ploughed to the ground. The Apaches reined with shrill cries. Glanton leaned forward and spoke into his horse's ear. The indians raised up their leader to a new mount and riding double they flailed at their horses and set out again. Glanton had drawn his pistol and he gestured with it to the men behind and one pulled up his horse and leaped to the ground and went flat on his belly and drew and cocked his own pistol and pulled down the loading lever and stuck it in the sand and holding it in both hands with his chin buried in the ground he sighted along the barrel. The horses were two hundred yards out and moving fast. With the second shot the pony that bore the leader bucked and a rider alongside reached and took the 21

reins. They were attempting to take the leader off the wounded animal in mid stride when the animal collapsed.

Glanton was first to reach the dying man and he knelt with that alien and barbarous head cradled between his thighs like some reeking outland nurse and dared off the savages with his revolver. They circled on the plain and shook their bows and lofted a few arrows at him and then turned and rode on. Blood bubbled from the man's chest and he turned his lost eyes upward, already glazed, the capillaries breaking up. In those pools there sat each a small and perfect sun.

He rode back to the camp at the fore ofhis small column with the chief's head hanging by its hair from his belt. The men were stringing up the scalps on strips of leather whang and some of the dead lay with broad slices of hide cut from their backs to be used for the making of razorstraps and harness. The dead Mexican McGill had been scalped and the bloody skulls were already blackening in the sun. Most of the wickiups were burned to the ground and because some gold coins had been found a few of the men were kicking through the smoldering ashes. Glanton cursed them on, taking up a lance and mounting the head upon it where it bobbed and leered like a carnival head and riding up and back, calling to them to round up the caballado and move out. When he turned his horse he saw the judge sitting on the ground. The judge had taken off his hat and he was drinking water from a leather bottle. He looked up at Glanton.

That aint him, he said.

What aint.

He nodded. That.

Glanton turned the shaft. The head with its long dark locks swung about to face him.

Who do you think it is if it aint him?

The judge shook his head. I dont know. It aint Gomez. He nodded toward the head. That son of a bitch is sangre puro. Gomez is Mexican.

He aint all Mexican.

You caint be all Mexican. It's like bein all mongrel. But that aint Gomez cause I've seen Gomez and it aint him.

Will it pass for him?

No.

Glanton looked toward the north. He looked down at the judge. You aint seen my dog have ye? he said.

The judge shook his head. You aim to drive that stock? I do. Until I'm made to quit. That might be soon.

That might be.

How long do you think it will take those niggers to regroup?

Glanton spat. It wasnt a question and he didnt answer it. Where's your horse? he said.

Gone.

Well if you aim to ride with us you better be for gettin you one. He looked at the head on the pole. You was some kind ofa goddamned chief, he said.

Within the hour they were mounted and riding south, leaving behind on the scourged shore of the lake a shambles of blood and salt and ashes and driving before them half a thousand horses and mules. The judge rode at the head of the column bearing on the saddle before him a strange dark child covered with ashes. Part of its hair was burned away and it rode mute and stoic watching the land advance before it with huge black eyes like some changeling. The men of that company as they rode turned black in the sun from the blood on their clothes and their faces, paling slowly again in the rising dust until they had assumed once more the color of the land through which they passed.

They rode all day with Glanton bringing up the rear of the column. Toward noon the dog caught them up. His chest was stiff with dried blood and Glanton carried him on the pommel of the saddle until he could recruit himself. In the long afternoon he trotted in the shadow of the horse and in the twilight he trotted far out on the plain where the tall shape of the horse skating over the chaparral eluded him on spider legs.

By now there was a thin line of dust to the north and they rode on into dark and the Delawares dismounted and lay with their ears to the ground and then they mounted up and all rode on again.

When they halted Glanton ordered fires built and the wounded seen to. One ofthe mares had foaled in the desert and this frail form soon hung skewered on a paloverde pole over the raked coals. From a slight rise to the west of the camp the fires

of the enemy were visible ten miles to the north. The company squatted in their bloodstiffened hides and counted the scalps and strung them on poles, the blueblack hair dull and stiff with blood. David Brown went among those haggard butchers as they crouched before the flames but he could find him no surgeon. He carried an arrow in his thigh, fletching and all, that none would touch.

Boys, he said, I'd doctorfy it myself but I caint get no straight grip.

The judge looked up at him and smiled. Will you do her, Holden?

No, Davy, I wont. But I tell you what I will do. What's that.

I'll write a policy on your life against every mishap save the noose.

Damn you.

The judge chuckled. Brown glared about at them. Will none of ye help a man?

None spoke.

Damn all of ye, he said.

He sat and stretched his leg out on the ground and looked at it, he bloodier than most. He gripped the shaft and bore down on it. The sweat stood on his forehead. He held his leg and swore softly. Some watched, some did not. The boy rose. I'll try her, he said.

Good lad, said Brown.

He fetched his saddle to lean against. He turned his leg to the fire for the light and folded his belt and held it and hissed down at the boy kneeling there. Grip her stout, lad. And drive her straight. Then he gripped the belt in his teeth and lay back.

The boy took hold of the shaft close to the man's thigh and pressed forward with his weight. Brown seized the ground on either side of him and his head flew back and his wet teeth shone in the firelight. The boy took a new grip and bore down again. The veins in the man's neck stood like ropes and he cursed the boy's soul. On the fourth essay the point of the arrow came through the flesh of the man's thigh and blood ran over the ground. The boy sat back on his heels and passed the sleeve of his shirt across his brow.

Brown let the belt fall from his teeth. Is it through? he said. It is.

The point? Is it the point? Speak up, man.

The boy drew his knife and cut away the bloody point deftly and handed it up. Brown held it to the firelight and smiled. The point was of hammered copper and it was cocked in its bloodsoaked bindings on the shaft but it had held.

Stout lad, ye'll make a shadetree sawbones yet. Now draw her.

The boy withdrew the shaft from the man's leg smoothly and the man bowed on the ground in a lurid female motion and wheezed raggedly through his teeth. He lay there a moment and then he sat up and took the shaft from the boy and threw it in the fire and rose and went off to make his bed.

When the boy returned to his own blanket the ex-priest Tobin leaned to him and looked about stealthily and hissed at his ear.

Fool, he said. God will not love ye forever.

The boy turned to look at him.

Dont you know he'd oftook you with him? He'd oftook you, boy. Like a bride to the altar.

They rose up and moved on some time after midnight. Glanton had ordered the fires built up and they rode out under flames licking ten feet in the air and lighting all the grounds about where the shadowshapes of the desert brush reeled and shivered on the sands and the riders trod their thin and flaring shadows until they had crossed altogether into the darkness which so well became them.

The horses and mules were ranged far out over the desert and they picked them up for miles to the south and drove them on. The sourceless flare of summer lightning marked out of the night dark mountain ranges at the rim of the world and the half-wild horses on the plain before them trotted in those bluish strobes like horses from a dream evoked out of the absolute void and swallowed up again.

In the smoking dawn the party rode ragged and bloody with their baled peltries less like victors than the harried afterguard of some ruined army retreating across the meridians of chaos and old night, the horses stumbling, the men tottering asleep in 25

the saddles. The broached day discovered the same barren countryside about and the smoke from their fires of the night before stood thin and windless to the north. The pale dust ofthe enemy who were to hound them to the gates of the city seemed no nearer and they shambled on through the rising heat driving the crazed horses before them.

Midmorning they watered at a stagnant pothole that had already been walked through by three hundred animals, the riders hazing them out of the water and dismounting to drink from their hats and then riding on again down the dry bed of the stream and clattering over the stony ground, dry rocks and boulders and then the desert soil again red and sandy and the constant mountains about them thinly grassed and grown with ocotillo and sotol and the secular aloes blooming like phantasmagoria in a fever land. At dusk they sent riders west to build fires on the prairie and the company lay down in the dark and slept while bats crossed silently overhead among the stars. When they rode on in the morning it was still dark and the horses all but fainting. Day found the heathen much advanced upon them. They fought their first stand the dawn following and they fought them running for eight days and nights on the plain and among the rocks in the mountains and from the walls and azoteas of abandoned haciendas and they lost not a man.

On that third night they crouched in the keep of old walls of melted mud with the fires of the enemy not a mile distant on the desert. The judge sat with the Apache boy before the fire and it watched everything with dark berry eyes and some of the men played with it and made it laugh and they gave itjerky and it sat chewing and watching gravely the figures that passed above it. The judge covered it with a blanket and in the morning he was dandling it on one knee while the men saddled their horses.

Toadvine saw him with the child as he passed with his saddle but when he came back ten minutes later the child was dead and the judge had scalped it. Toadvine put the muzzle of his pistol against the great dome of the judge's head.

Goddamn you, Holden.

You either shoot or take that away. Do it now.

Toadvine put the pistol in his belt. The judge smiled and wiped the child's scalp on the leg of his trousers and rose and

turned away. Another ten minutes and they were on the plain again in full flight from the Apaches.

On the afternoon ofthe fifth day they were crossing a dry pan at a walk, driving the horses before them, the indians behind just out of rifle range calling out to them in spanish. From time to time one of the company would dismount with rifle and wiping stick and the indians would flare like quail, pulling their ponies around and standing behind them. To the east trembling in the heat stood the thin white walls of a hacienda and the trees thin and green and rigid rising from it like a scene viewed in a diorama. An hour later they were driving the horses-perhaps now a hundred head-along these walls and down a worn trail toward a spring. A young man rode out on a good bay horse and welcomed them formally in spanish. Noone answered. The young man looked down along the creek where the fields were laid out with acequias and where the workers in their dusty white costumes stood poised with hoes among the new cotton or waist high com. He looked back to the northwest. The Apaches, seventy, eighty ofthem, were just coming past the first of a row ofjacales and defiling along the path and into the shade of the trees.

The peons in the fields saw them at about the same time. They flung their implements from them and began to run, some shrieking, some with their hands atop their heads like prisoners. The young Don looked at the Americans and he looked at the approaching savages again. He said something in spanish. The Americans drove the horses up out of the spring and on through the grove of cottonwoods. The last they saw of him he had drawn a small pistol from his boot and had turned to face the indians.

That evening they led the Apaches directly through the town of Gallego, the street a mud gutter out of which rose swine and wretched hairless dogs. It seemed deserted. The young com in the roadside fields had been washed by recent rains and stood white and luminous, bleached almost transparent by the sun. They rode most of the night and the next day the indians were still there.

They fought them again at Encinillas and they fought them in the dry passes going toward EI Sauz and beyond in the low

foothills from which they could already see the church spires of the city to the south. On the twenty first of July in the year eighteen forty-nine they rode into the city of Chihuahua to a hero's welcome, driving the harlequin horses before them through the dust of the streets in a pandemonium of teeth and whited eyes. Small boys ran among the hooves and the victors in their gory rags smiled through the filth and dust and the caked blood as they bore on poles the desiccated heads of the enemy through that fantasy of music and flowers.

Her mother had planned to call her Melting-Snow-of-Winter

That-Chases-Despair, but it had not worked out. Old T. D. Slant and everybody else around Monterey in 1846 called her Taya. Only Slant knew why. She was a quick, breezy child with rich black hair and eyes that reminded Slant of wet gray stones. And there was a bounce to her, a rhythm in her small tight body that made men notice her. She was sixteen and had been noticing them back for some time.

She passed the customhouse with its Mexican flag snapping in the morning wind and trotted her big Appaloosa across the sandy street, heading up the hill to a place where she could see far out over the Pacific. She liked to sit in a certain little grove of cypress and watch the whales spouting playfully to the south. When there were no whales, she would watch the wide blue flatness for ships. But most of all, she liked to be alone and think about bodies-her body and how other bodies might fit with it. She fell back in the dune grass and swung her feet toward the gray clouds forming over the bay. She turned her ankles in small circles and moved her

hands slowly over her small breasts. Fine. She was fine, if anyone wanted to know.

If she had felt like it she could have turned back down the hill and maybe caught a glimpse of old T. D. leaving the office for his morning drink. Instead she rode down to the beach to dig clams. When she climbed to the top of the hill again, it was late in the afternoon. Still no whales, but looking down into town she saw three men ride up in front of where she lived. They seemed to be arguing over something, pointing over the door at the sign that old T. D. was so proud of. She didn't recognize them but could see that they were dressed like Americans, mostly in skins. She wondered how old they were.

Most of the Americans showing up in Monterey lately were a lot more pleased with old T. D.'s sign and what it told the Mexicans and Californios than they were with old T. D. himself. The sign said that there was an American newspaper in California.

Old T. D. Slant was the founder, editor, and publisher of the California American, had been since he showed up and bought the only printing press in the territory from Vallejo back in 1838, when the Russians were still making everybody nervous. His readers generally believed what they read, but they sure as hell didn't trust Slant personally. The principle of''it takes one to know one" explains why. After all, Slant had wandered west with the rest of them, and they knew who they were. So Slant was said to cheat brilliantly at monte, to have shot three men from ambush, and to be looking for a free lunch. He claimed to be the same age as the century but was lying by twenty years. He was especially vain about the curly auburn beard, which he kept as sweetly perfumed as a French whore's twat. Or so he said.

Why Taya lived with him was a minor local mystery. He told folks that she was his mistress, his child, or both, depending on how he felt like playing it at the time. He was considered shrewd and eccentric.

If anyone wanted to know what had brought him to California, he would snort smugly into his sweet-smelling whiskers and start whispering like a conspirator about spreading civilization. There were some, however, who claimed that on one especially tropical night on the plaza, when he had been lushing up large quantities of mission wine with Fremont's topographi-

cal engineers, he had suddenly blurted out something a good deal closer to the truth.

"I came to California to retire and fuck around," he had shouted.

And in this he was not alone.

The men who Taya saw from the hill were a trinity of bad examples, even for 1846. Galon Burgett, his brother Millard, and Josiah Sewey were three old scoundrels who had been knocking around west ofthe Missouri River since they deserted together from the War of 1812.

Galon was small but well formed, smart as a weasel, and rather handsome. Women usually liked him until they got to know him. His younger brother Millard was smaller yet, barely over five feet tall, and simpleminded. Colicky tufts ofwhite hair sprouted from his empty skull just above each ear, making him appear even dumber than he was-which was difficult. Once when they were kids, one of their rna's cousins made a joke about Millard and the whole family sleeping together in the same bed, and their pa had shot the cousin in the foot. Galon and Millard held hands and giggled while the cousin bled to death. They grew up close. Another time, years later, Galon had used his skinning knife to make a Santa Fe whore give Millard a tongue bath.

Their pal Josiah Sewey had wolf eyes and big scarred hands. He looked like the strong, mean old man that he was. He made a real good bully when he felt like it, which was often. There were even times when he felt like shoving Galon around a little, but for one reason or another he never did. Once Sewey shot one of his own fingers off by accident and was embarrassed about it until Galon made up a story for him to tell. The story went that Sewey had shot it off on purpose, on a bet. Sewey thought the story was perfect and loved to tell it. He liked to hang around with Galon because he admired his mind.

Galon was the idea man, the leader. He pulled a grimy wolf-skin pouch from his saddle and led Millard and Sewey into the office of California's American newspaper. It was the same year that Alexander Cartwright designed the first official baseball diamond and the very same day that the Knicker-

bocker Club in New York held its first bowling tournament. East is east and west is west, as old T. D. Slant was fond of suggesting at the time. Even the sports were different.

"You ever hear of Galon Burgett?"

It was a real sly question, coming as it did from Galon himself. Slant wasn't sure. He snorted ostentatiously into his beard and searched his memory. Yes, he had heard of a Galon Burgett, but he couldn't ferret out just where or how.

"We come about the book," Galon told him.

"A pack of lies," hissed Sewey.

Before Slant could respond, Galon had the evidence out of the pouch. With a flourish, he tossed it on the desk in front of Slant. The coverless, chewed-up volume fell obediently open to the passage Galon wanted. Something about cowardly and unscrupulous dealings with the Shoshone, and a general pettifogging dishonesty on the part of the two varlet brothers named Burgett. The passage went for three pages without a break, ending finally with an explanation of how one Francis Buckdown had been forced on numerous occasions to publicly box the Burgetts' riffraff ears.

Slant noticed that someone, probably Galon Burgett, had been engaging the book in cryptic debates. The words "bullshit" and "goddamn lie" were scrawled here and there in the margins with such bold strokes that the blotches of dried animal blood and other grit covering the pages passed here and there for punctuation.

Slant was not happy. Tentatively, he allowed that he recognized the book as one he might have had something to do with.

"I wouldn't be bragging," Galon told him.

Sewey snarled like a dog.

Millard started to pant.

"Blow it the other way." Slant popped the book shut and insisted that it wasn't his work in any true literary sense. Any fool could see that.

"Oh yeah?" Galon argued. Then what about Hippolyte Weed, who had given him the book and who was also plenty pissed off on account of certain lies about him? And what about

the picture of Indian fighting which was supposed to be on the cover that Weed had traded to Counsel for some rope? Wasn't Slant's name on it? And what about a lot of other things?

Slant chortled self-consciously. So maybe they had never seen the cover. Slant hoped not. That might explain the misunderstanding.

It was getting sticky. Sewey had pulled a nasty-looking knife out of his boot and was waving it in the air, demanding that Slant get to the parts about him. And indeed there were several passages in the book suggesting dark venalities on the part of a certain ticket-of-leave cur named Sewey. Slant finessed Sewey and his knife with an adroit snort and pulled a crisp new copy of the book from the shelf behind him. Galon grabbed it.

The cover depicted a large man, sporting much fringe, in the act of dispatching a pack of obviously wild but rather puny savages. Their dead bodies heaped around him as they fell under his tomahawk and noble purpose. It was Buckdown all right. The Burgetts and Sewey studied the cover, fascinated. It was him for sure, but he never Slant concentrated on Galon, pointing to a line of small type under the title.

"See here," he said. "See here where it says As Written from His Own Dictation by T. D. Slant, Esq. That means I simply wrote down what Buckdown told me. What he told me to write down."

Galon was not impressed. He still insisted that Slant wrote it.

"But not in the pure literary sense," Slant argued.

Thus they were discussing literary sense when Taya walked in with a sack of clams.

4. La Cantina del Futuro Proximo

What a disappointment. Taya's smile dropped to a low curve of disdain as she sized them up. Three smelly old farts. Not at all what she had in mind

Shy," Slant explained as Taya walked past them without a word and disappeared out the door to the patio. Sewey and the Burgetts stared after her, grunting to each other, sizing her up. Young blood?

"Some kind of breed," from Sewey.

"Crow or Shoshone," from Galon. "Pretty," from Millard.

"Yes," said Slant, herding them toward the front door. "My mistress, and not the local worm-eating variety. A princess, in fact, among her own people and developing into a real fine civilized lady here under my wing, shall we say. But to the business at hand. Shall we adjourn to a more appropriate setting?"

Millard thought this meant that they would all go out in the street and have a gunfight, but Slant led them instead to his local cantina.

La Cantina del Futuro Proximo was the most popular cantina in Monterey and thus was usually crowded with mental health problems. Sewey and the Burgetts felt right at home. Slant sat them down at a comer table and went to the bar for a bottle of brandy. At the next table four men and an old woman were playing monte, a game similar to blackjack but easier to cheat at. Millard was captivated. The old woman noticed and winked at him. He didn't understand.

"What's that they're playing?" Millard whispered to Galon.

"Never mind, we got business."

"You can handle it, Galon."

"Millard," Galon scolded, "is that all you care about them lies? You crackbrain!"

Millard hung his head. He was ashamed. He tried to make it up to Galon by squinting as mean as he could at Slant, who was returning to the table with a bottle and four small glasses. But Slant just smiled and dealt out the glasses.

Over the first two drinks Slant conceded that, yes, the boys might have a legitimate grievance. With Buckdown, however, not with him.

"Well," Galon said, "we just want it fixed.

"We want all them books fixed," Sewey added.

Over the third and fourth drinks Slant explained the difficulties. Harper & Brothers back in New York couldn't possibly track down and call back all the copies, even if they could be convinced of such an obligation-which, given the nature ofthe publishing business, was unlikely at best.

"Balls," Sewey grumbled and started fingering the knife in his boot.

"I wouldn't be bragging," said Millard. Galon coughed but didn't speak. He watched Slant like a cat toying with a flower, considering the possibilities.

Over the fifth and sixth drinks Slant insisted that their argument was with Buckdown. After all, it was Buckdown who had initiated the misunderstanding in the first place. Any and all gnawing bones should be picked with him.

"Look here, Slant," Galon said softly. "We don't give a shit about any Harper or how many brothers he's got, and we'll take care of Buckdown after we fix the literature side of it. I've got it all figured out and you don't even have to pay us."

"Yeah," Sewey said, sticking his knife in the table for emphasis. "Counsel says that asshole probably got rich off them lies."

Over the seventh and eighth drinks Slant launched a buoyant explanation of the economics of publishing. Nobody makes any money, etc

"Balls," Sewey growled, now fondling his knife.

Galon was more reasonable. "All you got to do," he told Slant, "is write a book about us."

"About you three?"

Slant's mind churned. A moon-brain scam eclipsed his reason. He reached-slowly for the bottle, and over the ninth and tenth drinks outlined the amount of time and effort such a book would require, and then, after an appropriate pause, snuck in the necessity of a small advance.

"Forget it!"

It was determined that Galon, Millard, and Sewey would give Slant a quick outline of the basic truth and he could fill in around the edges while they saw to other business. Galon had it all worked out.

"Yeah," said Millard, inspired into his first complete sentence of the day. "While we're gone, you can fill in around the edges with literature."

Right. And the bottle was empty.

Back on the patio, Taya sat in the shade shelling clams. She wondered if old T. D. was lying about sleeping with her again. Probably. She wondered if anyone ever believed him. She ate a raw clam. It died going down.

The boys had never been to a barbecue before. All they knew was that they were always eating outside anyway and didn't think it was so hot, especially when they were in civilization. But when Slant explained it as a local custom, they figured what the hell and wound up sitting out on the patio.

The tan ground was raked smooth with clean little rake lines all running in one orderly direction. Pale geraniums, soft magenta and dusty pink, flushed along the whitewashed adobe walls. A spreading cypress, with fading blue and white lupine peeking from its roots, shaded a redwood table set with earthen pots and milky brown platters. The light was soft, dying peacefully and stretching shadows east toward smooth hills bathed in lavender by the sunset. But all was not monotonous pastel. Here and there bright yellow and orange poppies broke loudly through the quiet palette, like the weeds they are.

Galon coughed into the stillness. Then, again and again, he unleashed a jangling chain of spasms from deep in his chest. His noisy fit sent a family of swallows winging from their nest in the cypress. They fluttered in alarmed circles over the patio. "It must be the air," Sewey laughed. "Too much grease in the air."

Galon bent from the waist and rode himself out with a series of convulsive spits at the ground.

The swallows settled back on their branches, but not for long. Millard, who had been carving his initials in the base of the cypress, felt so bad about his brother's cough that he started chucking pieces of bark at the nervous birds.

Slant was inside talking to Taya, telling her to stay out of sight. Naturally she wanted to know. why. Because, Slant explained with an unsteady intensity, the three men on the patio were rather upset with her father and himself. Something about the literature of history. And they were also looking for a free lunch.

Father? Taya was totally unprepared. Not that she wasn't interested. She would often stare into mirrors and dissect her reflection, noting that yes, she might be the daughter of an Indian princess like old T.D. said with his talk of how he had traded for her because she was such a beautiful baby. But she

never got the same story twice and, besides, who ever heard of a Worm Eater with freckles?

Yet she had these feelings, and knew moments when, languishing in the half sleep of rainy mornings, she saw herself on a brave and sensual journey, scouring all manner of terrain, searching out the gene pools and nostalgic tumors of closeted family secrets that would account for her smoky intuitions. She wanted to know if history repeated itself beyond shanks of bone and hanks of hair, but she had never had a clue. Until now.

Old T.D. left her to join the three old farts on the patio. She leaned against the wall in the darkening pantry, sensing the past and the future at the same time. It was traumatic, intoxicating. Father? She hadn't even read the book.

The swallows were still circling when Slant returned to the patio and went to work tossing steaks around on a grilled fire pit. Millard and Sewey were pleased, but Galon kept coughing and spitting into the fire. He ignored the food except to pick now and then at a plate of tiny figs intended as dessert, while Millard and Sewey gnawed at the meat like wolverines and gulped handfuls of fried clams rolled in tortillas. Once they had stuffed themselves, it was on to more brandy and the literary business at hand. Taya listened from the pantry.

The conversation was difficult to follow but about this Buckdown this transgressing double-dealing viper turd this venal captain of falsehoods this polluted forger of truth this dirty rat this liar He should be made to grovel in the pornographic bile of his own sucking counterfeits. Cysts, sties, carbuncles, cavities, slivers, and ingrown horns should come to him as only a partial reward for his salacious frauds. He should be lashed, rib roasted, larruped, pummeled, stomped, drawn and quartered, and creamed. Something to that effect.

Galon seemed to be feeling better. He led Millard and Sewey into a righteous frenzy about how they were going to serve that son-of-a-buck Buckdown right. Slant nodded and made cosmetic notes while the tremors of drunkenness rattling up from

the patio chased off the swallows for good. Suddenly Galon lurched to his feet.

"The big spit," he announced, and staggered off.

Slant grabbed the pause in the conversation and excused himself to go to the pantry for another bottle and his small silver-plated belly gun just in case.

Inside he found Taya loading the gun. Her eyes flashed wet and cold at him, like bullets in a shot glass. He asked her for the gun. She shook her head.

"You're drunk," she said.

Indeed he was, drunk enough to forget himself and blunder through an explanation of how he was just faking it with the Burgetts and Sewey, and how he had no intention of writing down any of their swill.

"Don't you see?" he said, gesturing for the gun. ''I'm just putting them on.

A big mistake and too bad. Framed in the small open window behind them was Galon Burgett, his mouth smeared with vomit, a whip cracking in his bloodshot eyes.

The rape of Melting-Snow-of-Winter-That-Chases-Despair and the castration of Theodosius D'Artagnan Slant took the boys about ten minutes. They accomplished it in what Sewey referred to as southern style. Semi-southern style is closer to the truth, however, since both victims were not conscious throughout, and the idea was always to make each watch what happened to the other. Just ask any Okie.

While Galon held Taya, Millard and Sewey gagged old T.D. and hung him by his wrists from the main redwood ceiling beam. He kicked frantically for a moment, running hopelessly in the still air, getting nowhere. Sewey spun him like a fielddressed animal, and he went limp at the end of the twisting rope as they bent Taya back like a sapling, over the desk. Then an almost isometric quiet, broken only by the sound of fabric being tom from her breasts and crotch. Finally, her one and only scream.

As Sewey and the Burgetts took their turns, Taya strained as if against drowning, counting their thrusts as days, then months. Old T.D. clenched his eyes against the sight of her

finely grained skin glistening under their sweat until he sensed that she had passed out, and he looked with hopeless resignation to see them turn their attention to him.

Sewey said he'd handle it, and he did. Drop his pants for him, he told Millard, and when that was done Sewey grabbed old T.D. by the balls and made a quick swipe with his knife. The scrotum sack and its vein-laced contents came away in his fist.

When she came to, Taya was alone with old T.D., whom the boys had left dangling in shock and bleeding to death over a puddle of blood. She cut him down quickly and, without thinking, began to treat him like a a gelded colt. First she tied off the spermatic artery, then cleaned him out, and packed him with pledgets of tow that she dipped in tincture of muriate of iron. Either he would heal by adhesion or he wouldn't. As she rubbed him dry she wasn't so sure about herself.

His name was James Gilchrist Swan, and I have felt my pull toward him ever since some forgotten frontier pursuit or another landed me into the coastal region of history where he presides, meticulous as a usurer's clerk, diarying and diarying that life of his, four generations and seemingly as many light-years from my own.

This is the 18th day since Swell was shot and there is no offensive smellfrom the corpse. It may be accountedfor in this manner. He was shot through the body and afterwards washed in the breakers, consequently all the blood in him must have run out. He was then rolled up tight in 2 new blankets and put into a new box, nailed up strong.

I know the beach at Crescent Bay where the life of Swell, a chieftain of the Makah tribe, was snapped off. Across on the Canadian shore of the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the lights of modern Victoria now make a spread of white embers atop the burn-dark rim of coastline. But on Swell's final winter night in 1861, only a beach camp fire at Crescent, on our southern shore, flashed bright enough to attract the eye, and Swell

Excerptedfrom Winter Brothers: A Season at the Edge of America by Ivan Doig.

To be published by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. Copyright ©1980 by Ivan Doig. Photograph by Donna Colvin

misread the marker of flame as an encampment of traveling members of his own tribe. Instead, he stepped from his canoe to find that the overnighters were of a neighboring village of Elwha Indians. Among them chanced to be a particular rival of Swell, and his bullet spun the Makah dead into the cold surf.

The killing was less casual than the downtown deaths my morning newspaper brings me three or four times a week-the Elwhas and the Makahs at least had the excuse of lifetimes of quarrel--or deaths that I could go see in aftermath, eligible as I am for all manner of intrusion because of being a writer, were I to accompany the Seattle homicide squad. James G. Swan did go hurrying to be beside Swell's corpse, and there the first of our differences is marked.

Truth told, I find among Swan's words that more than one motive carried him west along the Strait from Port Townsend to the death scene. Swell was his best-regarded friend among the coastal tribes of Washington Territory, a man he had voyaged with, learned legends from. Swan's diary pages show them steadily swapping favors: now Swell is detailing for Swan the Makahs' skill at hunting whales; now Swan is painting for Swell, in red and black, his name and a horse on his canoe sail. Swell said he always went faster in his canoe than the other Indians like a horse, so he wanted to have one painted But solid as the comradeship may have been, so was Swan's Yankee instinct to retrieve the goods which Swell had been consigned to bring home by canoe to another of Swan's coastal acquaintances, a trader situated at the western extent of the Strait. From the merchants of Port Townsend, Swan compiles a list of Swell's cargo, and then, in his small quick hand, sums his resolve: Must therefore lookfor 1 British tea pot, 1 small brass kettle, 1 tin trunk

I ponder this, mulling what it would take to send me off on such an errand-a crate of books, the chance to hear a grand story. But then, this winter, this deliberate season of frontier is itself a fetch of similar sort.

On a morning soon after learning of Swell's death, having traveled with a friendly chieftain of the Clallam band nearest to Port Townsend, Swan strolled into the Elwha village. Charley, the murderer, then got up and made a speech. He said that he shot Swellfor two reasons, one ofwhich was, that the Makahs

had killed two ofthe Elwha's a few months previous, and they were determined to kill a Makah chief to pay for it. And the other reason was, that Swell had taken his squaw away, and would not return either the woman or the fifty blankets he had paidfor her. Swan then haggled out of Charley the potware, several blankets, and a dozen yards of calico. I could not help feeling while standing up alongside this murderer, surrounded by the residents of the village (some 75 persons), that I would gladly give a pull at the rope that should hang him

That day's chastisement was administered with vocal cords rather than hemp, however. When Swan was done, it became the tum of the visiting chieftain to erupt to his Elwha cousins about the paltry compensation Charley was handing over. This talk produced two more blankets which closed the business.

Swan next carried the matter of Swell's death to the federal Indian agent for Washington Territory. Met inconclusion there. Sent a seething letter to the newspaper in the territorial capital of Olympia: an Indian peaceably passing on his way home in his canoe, laden with white men's goods foully murdered agents of our munificent government have not the means at their disposal to defray the expenses of going to arrest the murderer. And at last canoed once more along the Strait to accompany Swell, still nailed up strong, for the hundred miles to the burial site at the Makah village of Neah Bay.

There, Swell's brother Peter came and wished me to go with him and select a suitable spot to bury Swell I did as he desired, marked out the spot and dug out thefirst sand.

And this further: He also brought up the large tomanawas boards-the Makahs' cedar tableaus of magic which would be the grave's monument-ofSwellfor me to paint anew

There, then, is Swan, or at least a shinnying start on him.

In continental outline, the United States rides the map as a galleon carpentered together from the wood yard's leftover slabs: plankish bowsprit ascending at northernmost Maine, line of keel cobbled along Gulf shores and southwest border (Florida an Armada-surplus anchor chain hung fat with seaweed), surprising long, clean amidship-straightness of the

49th parallel across the upper Midwest and West. This patchwork ship of states is, by chance, prowing eastward. Or as I prefer to think of it, forecastle and bow are a-wallow in the Atlantic while great lifting tides gather beneath our Pacific portion of the craft.