Editors:

Elliott Anderson, Robert Onopa

Executive Editor:

Jonathan Brent

Art Director: Cynthia Anderson

Managing Editor: Michael McDonnell

Associate Editor: Anne-Marie Zwierzyna

Assistant Editors:

Demetra Georgis, Kay Kersch Kirkpatrick, Mary Elinore Smith

Advisory Editors: Lawrence Levy, Charles Newman

Fulfillment:

Leigh Alexander, Judy Marrs

Contributing

Editors:

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Gerald Graff, John Hawkes, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Ian MacMillan, Joseph McElroy, Peter Michelson, Robert Ray, Tony Tanner, Nathaniel Tarn

TriQuarterly is an internationaljoumal ofart and writing published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201.

Subscription rates: One year $12.00; two years $20.00; three years $30.00. Foreign subscriptions $1.00 per year additional. Single copies usually $5.95. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarteriy. 1735 Benson Avenue, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright© 1979 byTriQuarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER. 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY071i0. DISTRIBUTOR FOR WEST COAST TRADE: BOOK PEOPLE, 2940 7TH STREET, BERKE· LEY, CALIFORNIA 94710. MIDWEST: BOOKSLINGER, P.O. BOX 16251,2163 FORD PKWY, ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 55116.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISiUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFILM FROM UMI, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

162

The amorist

Ted Solotaroff

173

We are not in this together

William Kittredge

198

The last Beat story

Eugene Wildman

209

What do I do now?

Nuala Pikowsky

221

Hanson on the bluffs

Kent Anderson

238

Zara Montgomery

Meredith Steinbach

275

The Turning Eilis Dillon

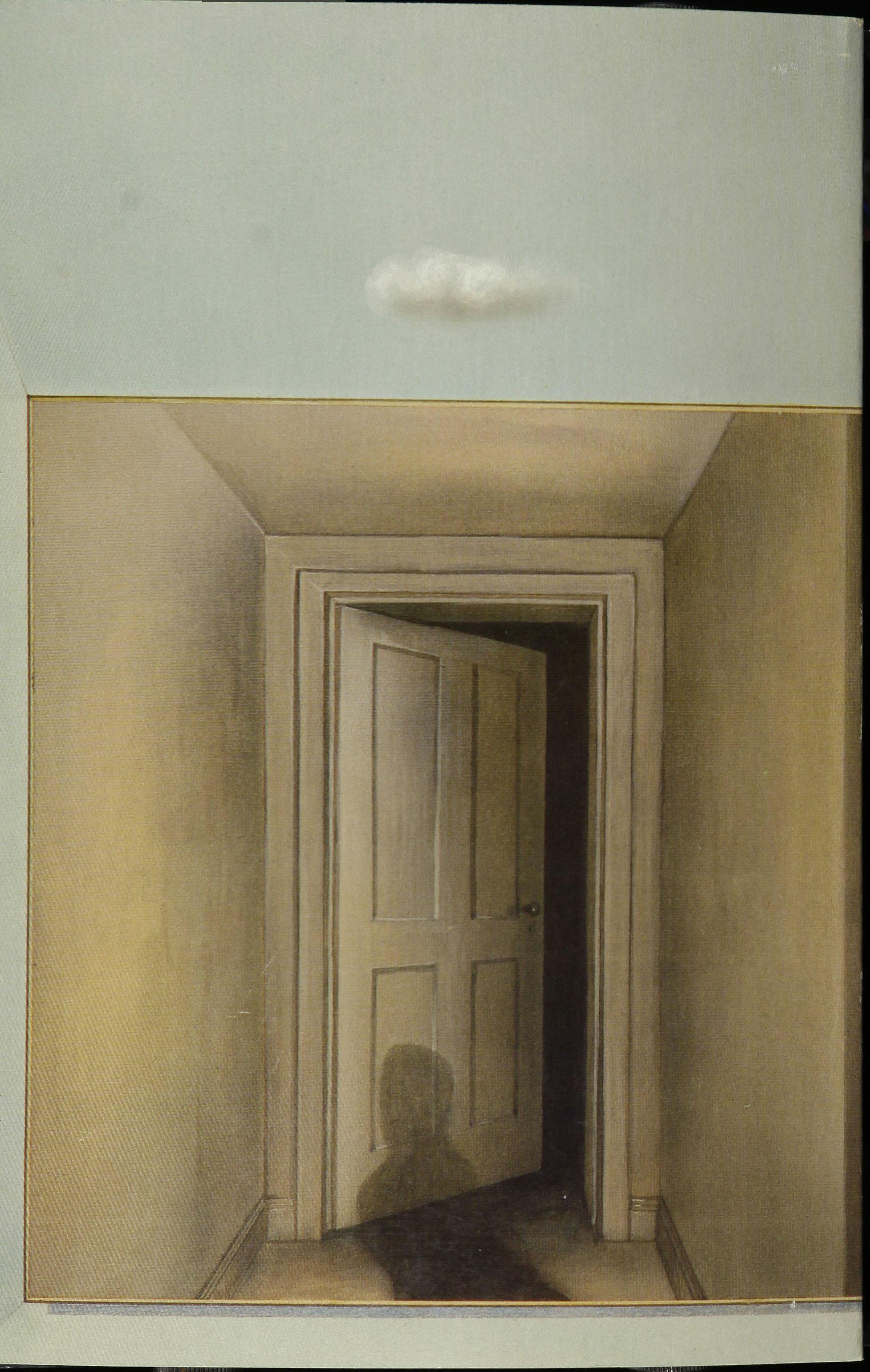

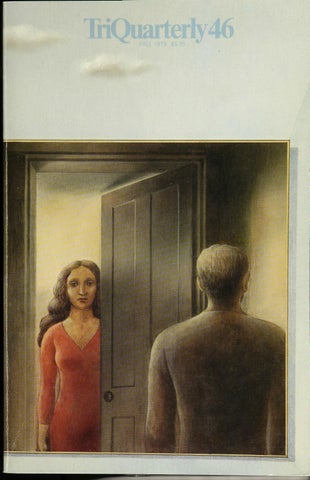

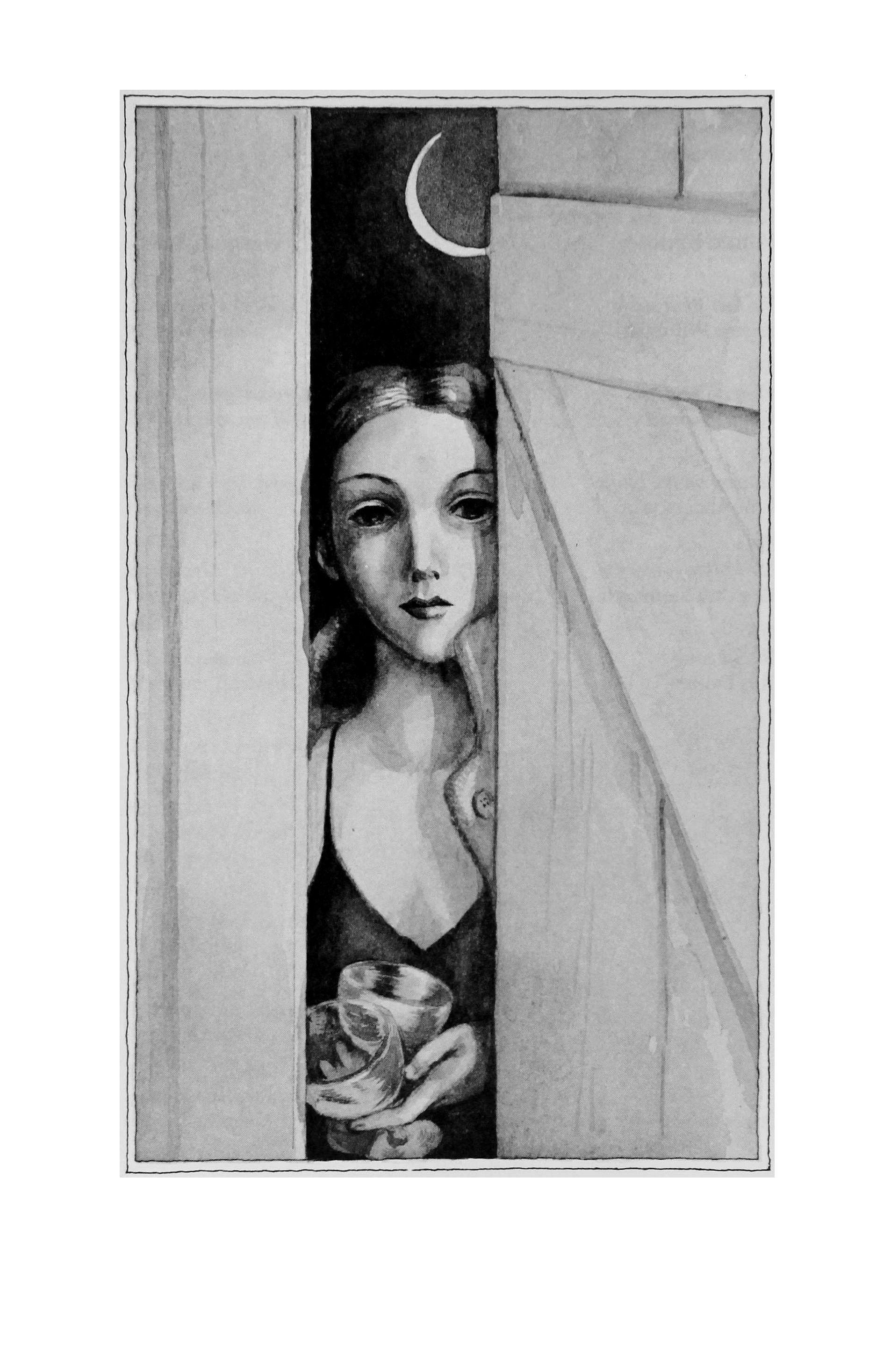

Cover and interior illustrations by Kinuko Craft.

"We are separated," his wife Mary says, the rare times he makes an advance to her.

They are still living in the same house, though he sleeps by himself in a small backyard studio he converted from a coal house, or shed.

"We are separated"-he doesn't know quite how serious she is, and that's why every once in a while he dares make an advance. It might be just a tilt of his head toward her bedroom or an invitation to the shed while she is hanging clothes on the line between it and the house. But she must be quite serious. They haven't slept together since May, when after months apart they spent one night in the same bed in a hotel suite on the sea, in Italy, where they had gone for a month with their children. It's September now. For the past ten years of the twenty they've been married they have been sleeping together more and more rarely. Even during the first ten they slept in separate rooms most of the time. During the last five years he has been away for long periods as artist in residence at universities here and there, every year farther away, the past year in the westernmost part of Texas. This year he applied forjobs even farther-in California, Idaho, Washington-and thought that

some day he would take a flight from which he would never return to settle again in the house; but no university has taken him on, and he's here.

They are in the kitchen now. She's in an armchair. He's sitting on a stool by the table. The two younger children are in bed, the elder is at college. "Come on," he says.

"Why do you ask me? I've told you-we are separated."

"Even divorced people get together sometimes."

"Oh, yes?"

"Yes."

"Well, I'm not."

"Are you going to bed?"

"In a minute. I haven't finished my wine."

She seems to have no urge to have an affair-with anybody. On the other hand, she's not content with her life. She often complains of her dull, repetitious existence, but neither does she make an effort to change it. She often says she's going to look for ajob, but she gives only desultory looks at the want ads in the newspapers. If sexually she leads the life of a nun, he doesn't want to lead that of a friar. He eyes the back door and thinks of the shed. Another trip there. Another lonely night. "Since we are separated," he tells her, "I can take a friend to my studio. 'Hi, Mary,' she'll say on her way over, and you'll hear laughing and music, chamber music. And I'll have parties there. I might even invite you over sometime."

"No, thanks."

She looks quite pretty in her reddish plaid skirt and wine-colored sweater. She ought to be drinking red wine-it would go well with her sweater. Instead she nearly always drinks white.

"And not all the guests will go home. One will stay on and you'll see her in the morning. 'Hi, Mary,' she'll say."

"You live in a fantasy world."

"You just wait."

She goes up to her room.

Why not invite someone over? But even if the person would come, and the chances are that she wouldn't-the studio is awfully close to the house-he's not quite ready. When he makes a telephone call to a girl friend he picks a time when his wife's not around, or he goes to a telephone booth on Main Street. He's still fairly secretive with her, at least about present or very recent

encounters. The past ones he doesn't mind talking about. Her reactions amuse him-she cares so little about them. Interesting her is almost a challenge.

He tells himself, "I should really go away." But there's little money. In Italy, where he was born and grew up, he has some, safe in a bank in her name and in his, in a remote village where he owns a tiny vacant apartment. He could go there. But Italy has become foreign to him. He has few friends left there, and none in the village. And the villagers stare at him and make him feel self-conscious and odd. He tried it two summers ago for a month and didn't have an easy time of it. Here he's on unemployment insurance. He has a feeling that if he leaves home he'll end up on skid row, the Bowery. He can see himself in New York, a gray-haired man on the benches or on the grass of the park. And in winter? The nights already are cold, though it's only early September. Here in this little town he's going to give a few Italian lessons each week. A classic solution. There's that, and the unemployment insurance for which he has to report every other Monday at eight-forty in the morning to a dour clerk two towns away, and there's the dwindling joint savings account, and the infrequent sale of a sketch. Once he was a doctor. He had an office in the center of Rome. He wasn't making much money even then-the making of a lot of money is something which has eluded him always-but by now if he were still there he probably would be quite affluent. Not that he regrets having quit. His had been a very limited practice and rather unpleasanthemorrhoids, rheumatism, varicose veins. So many cases of that sort, so very rarely an interesting case. He remembers a man at the Hassler one night with a high fever and no sign of a germ, no symptoms of an infection whatever. And then he happened to touch the patient's big toe and the man jumped. "You have gout," he told him. "It's one of the few noninfectious diseases that can give you a fever." A dose of colchicine, and the man was well in the morning. A diagnosis like that gave you some satisfaction. But such a sometime thing a case like that was. No, he doesn't regret having left.

Still, there is his future life to consider.

It's September 1978. Each year ending in an eight has brought a big change in his life. But this year, so far, none. He remembers 1928 when he was four years old and his family moved from Rome to a house in Tuscany, and 1938 when they left Italy to go to

England as refugees. In the year 1948 he became a doctor in Rome. In 1958 he got married, left medicine and Italy, and came to America to make his living as an artist. In 1968, with some misgivings, he began teaching. But in 1978 so far nothing very unusual has happened to him, unless it is that he hasn't been able to get a teaching job. But that doesn't seem a sufficiently big change: in 1975 he didn't teach either, though that time he had taken a year off of his own accord. Noris it much ofa change to hear his wife telling him that they are separated-they've been drifting apart for years. And so he waits, superstitious enough to believe that something rather strange will happen to him before the year is over. He is so convinced of this that whenever he goes out with a woman he likes he wonders if perhaps she isn't the one who will bring about the awaited change. In August, at an opening, he met a woman who said she specialized in changing people's lives.

"You are just what I need," he said, half in jest. She took him seriously. She was a management consultant, psychologist, and economist all in one. She phoned him. They met for a drink. The cafe was crowded, and a young man, edging his way past their table, knocked against her shoulder. From her chair she quickly slapped his behind, one sharp spank as if he were a child. Later, in her apartment, she more or less treated him in the same way, and he left disgruntled.

More recently-on Labor Day-he went to a late party in a summer restaurant given by the owners to mark the end of the season. He wasn't invited by them, but a woman friend who was, and whom he saw that afternoon, told him to go-that she was inviting him and that they would meet there. She lived in New York, was in fact leaving for New York the next day, and he wondered if he wouldn't be following her there. They talked, drank and danced, but all without fervor. No-he wouldn't be going to New York. Then another woman talked to him. He knew her a little and would have liked to have known her more than a little, but he had never been alone with her, something which certainly isn't conducive to knowledge. She was a handsome woman with long black hair and the poise of a dancer. She had come to the party with an elderly man with a white beard with whom she lived in a summer cottage they rented. Soon the man left. He watched her dancing with others. Then she came over to him and, hands outstretched, drew him off his chair. "Dance with me," she said. He

danced with her again and again, forgetting the other. What did it matter? The other, too, was dancing, with someone she seemed to like better than him. The music got madder and madder. They danced to one side of the room and, screened by a pillar, they kissed. Later he said something nice about the man she lived with. "It works," she said, "because weekends he lets me do what I like." Still later, she said, "Can you give me a ride home?"

"Sure," he said, and turning to the other, "I'll come for you after."

She shrugged. "Don't bother," she said, about to dance. They left. "I'd like to be with you forever," he said on the way to the car.

"I was thinking the same thing."

He wondered if-no, he was sure-she was going to effect the great change. In the car they were a long time getting started. Driving her to her home, she said, "Come and see me; I'll be here alone next week until Thursday." Did she think it was Sunday? It was Monday, and when he went to see her a week later she was gone, back to the old fellow in Boston.

At the post office a woman who had left her husband the year before said hello. She was quite striking, with masses of curly brown hair and strange, beautiful eyes, eyes that you felt had wept a great deal. He had been introduced to her at a dinner party when she was still married. With a drink in her hand she had come over to him and told him of a teachingexperience she had had in which she couldn't utter a word. Such sympathy and feeling of kinship and intense identification with her had come over him that he had the strongest urge to hug her right there in front of her husband and Mary. Now she told him she was gong to take a trip around the world. For a moment he saw himself leaving with her.

"Are you going alone?"

"Isn't that the only way to travel?"

"Yes," he conceded.

He took her to a coffee shop near his house. "I feel so free," she said, "like a balloon."

"Like a balloon. Then you are a true voyager. Do you know those verses of Baudelaire? 'But the real travelers are only those who leave for the sake of departing. / Lighthearted, like balloons, / Their fate they never avoid, / And, without knowing why, they are always saying, Let's go!'"

"I'm like that," she said, and she seemed already on her way, on a freighter, then on the Trans-Siberian Railroad-she said she never took planes-and he was anchored here, stuck to the house, the backyard, and his shed, which he could see from the coffee shop window.

Sometimes in the shed when the church bell strikes the midnight hour (not twelve but eight bells, as in ships at sea), he thinks of another woman he knows in town. She and her husband own a gallery and have been here almost as long as he has. They, too, have gradually drifted apart, though they continue living under the same roof. He gets along well with both of them but especially well with the wife; in fact he has told her he doesn't think he gets along with anyone as well as with her. At parties or if he meets her on the street, he flirts with her, if only to hear her laugh. She is as buxom as a drop, and warm and protean. With her long hair-blond, amber, or brown, depending-wearingjewelry and an exotic dress, she can look quite beautiful and almost unrecognizable compared with times when, in a more serious mood, she wears her hair bundled up and a plain dun suit. In his shed he thinks of her disheveled. At times she drops in to see them, and when she's about to leave he pretends she's his wife and says, "Well, I guess we'd better go now, hadn't we? We'll see you, Mary." Or if Mary happens to be in the next room when she arrives, he'll say, "Ah, we are all alone." For a moment she looks worried, then laughs. She can't take him seriously. At her house or a friend's, if they are ever alone for a minute, he'll ask her, "So when are you going to come over for a visit?"

"I was over."

"Awl I don't mean that."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean to my studio, upon the stroke of midnight."

"I must say I've thought of it."

"You have?"

"Well, you've asked me so many times. But it's impossible, you know that."

She is probably right. A midnight tryst has consequences, not least the end of the jesting. Better continue pretending. The rest isn't worth it, since they are not in love.

In love he is, with someone far away, in Idaho=-a former

student, twice divorced, whom he met at summer school last year. His wife knows about her.

"I ought to go to Idaho," he says.

"Why don't you?"

"She doesn't love me."

"Why not?"

"Too smart, too beautiful, too young."

Sometimes, rarely now-even that stage has nearly passed, they've done it too often-if she blames him for his poor investments or the sale of his family house in Italy, which he should never have agreed to, they fly into an argument and the word "divorce" comes up. If their elder daughter is at home and present, she takes her mother's side. "Why don't you leave him?" she says.

His younger daughter, a very pretty teenager, is far too involved with a herd of friends to pay them any attention; irritated, she quickly climbs up the stairs to her room, where there's an extension phone. This she and her friends keep busy half the day. Only the little boy, eleven, seems affected. The very word "divorce" brings him to tears. "You never hold hands," he says. "Why can't you be like Lelio and Hannah?" He is talking about his uncle and aunt who, whenever they come for a visit, seem very fond of one another.

His little boy-so wild, so naughty, so hard to take care of-puts him to shame. "He's got more sense than anybody," he says.

September passes, and October and November. Obviously nothing is going to happen to him. Life just drags on. No change this year of 1978, despite the eight. And now it is December.

"What do you want for Christmas?" Mary asks him.

"I don't want anything. Just be nice to me, and tell them to be nice," he says, looking at the children.

"We are nice, aren't we, children? It's you."

"Hm."

The presents come-and her brother from Boston with a large boxful on which they heavily depend.

After supper he always goes to his studio, where it is quiet. For he who has no peace within must have his peace without. He does his best work at night. In the silence of the night, when there is no wind and the traffic on the highway, a thousand or more feet

distant, has died down, if there has been a storm out at sea he can hear the waves crashing on the outer shore four miles away. At infrequent intervals the pounding comes. It sounds something like the trucks on the highway, but they are never as regular as the waves and each sound lasts longer on the road. A faint tap wakes him from his reverie. He doesn't turn to look at the glass panels of the door-the tap has come from nearer. He knows it has been struck at the wall of his own chest, from inside. Another comes, more distinct. He smiles at the unusual visitor. Death knocking? So that is it, the change. A rejuvenating thrill ripples through him. With expert fingers he feels his pulse. He waits in vain for another sign. Hopefully his fingers wait. "Just skipped beats," he says to himself with disappointment, "from too much coffee or something."

There are only six days left until the end of the year. Somehow no one invites them for New Year's Eve. That night he goes to his shed as usual, after supper. A little before midnight he hears someone approaching and Mary appears at the door, laughing. She has an overcoat on, and under it, trailing at her feet, he can see her white lacy nightgown with red embroidery that she got in florence a long time ago. In her hands she has a bottle of champagne and two of their best glasses. "Hi," she says.

He checks out the Velvet Slipper. Can't see shit for a minute in the darkness. Just the jukebox and beer smell and the stink from the men's room door always hanging open. Carl ain't there yet. Must be his methadone day. Carl with his bad feet like he's in slow motion wants to lay them dogs down easy as he can on the hot sidewalk. Little sissy walking on eggs steps pussyfooting up Frankstown to the clinic. Uncle Carl ain't treating to no beer to start the day so he backs out into the brightness of the Avenue, to the early afternoon street quiet after the blast of nigger music and nigger talk.

Ain't nothing to it. Nothing. If he goes left under the trestle and up the stone steps or ducks up the bare path worn through the weeds on the hillside, he can walk along the tracks to the park. Early for the park. The sun everywhere now giving the grass a yellow sheen. If he goes right it's down the Avenue to where the supermarkets and the five and ten used to be. Man, they sure did fuck with this place. What he thinks each time he stares at what was once the heart of the Homewood. Nothing. A parking lot and empty parking stalls with busted meters. Only a fool leave his car next to one of the bent meter poles. Places to park so you can shop

in stores that ain't there no more. Remembers his little Saturday morning wagon hustle when him and all the other kids would lay outside the A&P to haul groceries. Still some white ladies in those days come down from Thomas Boulevard to shop and if you're lucky get one of them and tipped a quarter. Some of them fat black bitches he see in church every Sunday have you pulling ten tons of rice and beans all the way to West Hell and be smiling and yakking all the way and saying what a nice boy you are and l knowed your Mama when she was little and please sonny just set them inside on the table and still be smiling at you with some warm glass of water and a dime after you done hauled their shit halfway round the world.

Hot in the street but nobody didn't like you just coming in and sitting in their air conditioning unless you gonna buy a drink and set it in front of you. The poolroom hot. And too early to be messing with those fools on the corner. Always somebody trying to hustle. Man, when you gonna give me my money, man, [been waiting too long for my money, man, lemme hold this quarter till tonight, man. I'm getting over tonight, man. And the buses climbing the hill and turning the corner by the state store and fools parked in the middle of the street and niggers getting hot honking to get by and niggers paying them no mind like they got important business and just gonna sit there blocking traffic as long as they please and the buses growling and farting those fumes when they struggle around the corner.

Look to the right and to the left but ain't nothing to it, nothing saying move one way or the other. Homewood Avenue a darker gray stripe between the gray sidewalks. Tar patches in the asphalt. Looks like somebody's bad head with the ringworm. Along the curb ground glass sparkles below the broken neck of a Tokay bottle. Just the long neck and shoulders of the bottle intact and a piece of label hanging. Somebody should make a deep ditch out of Homewood Avenue and just go on and push the row houses and boarded storefronts into the hole. Bury it all, like in a movie he had seen a dam burst and the floodwaters ripping through the dry bed of a river till the roaring water overflowed the banks and swept away trees and houses, uprooting everything in its path like a cleansing wind.

He sees Homewood Avenue dipping and twisting at Hamilton. Where Homewood crests at Franktown the heat is a shimmering

curtain above the trolley tracks. No trolleys any more. But the slippery tracks still embedded in the asphalt streets. Somebody forgot to tear out the tracks and pull down the cables. So when it rains or snows some fool always gets caught and the slick tracks flip a car into a telephone pole or upside a hydrant and the carsjust lay there with crumpled fenders and windshields shattered, laying there for no reason just like the tracks and wires are there for no reason now that buses run where the 88 and the 82 Lincoln trolleys used to go.

He remembers running down Lemington Hill because trolleys come only once an hour after midnight and he had heard the clatter of the 82 starting its long glide down Lincoln Avenue. The Dells still working out on "Why Do You Have to Go?" and the tip ofhis dick wet and his balls aching and his finger sticky but he had forgotten all that and forgot the half hour in Sylvia's vestibule because he was flying now, all long strides and pumping arms and his fists opening and closing on the night air as he grappled for balance in a headlong rush down the steep hill. He had heard the trolley coming and wished he was a bird soaring through the black night, a bird with shiny chrome fenders and fishtails and a continental kit. He tried to watch his feet, avoid the cracks and gulleys in the sidewalk. He heard the trolley's bell and crash ofits steel wheels against the tracks. He had been all in Sylvia's drawers and she was wet as a dishrag and moaning her hot breath into his ears and the record player inside the door hiccuping for the thousandth time caught in the groove of gray noise at the end of the disc.

He remembers that night and curses again the empty trolley screaming past him as he had pulled up short half a block from the corner. Hunky driver half sleep in his yellow bubble. As the trolley careened away red sparks had popped above its gimpy antenna. Chick had his nose open and his dick hard but he should have cooled it and split, been out her drawers and down the hill on time. He had fooled around too long. He had missed the trolley and mize well walk. He had to walk and in the darkness over his head the cables had swayed and sung long after the trolley disappeared.

He had to walk cause that's all there was to it. And still no ride of his own so he's still walking. Nothing to it. Either right or left, either up Homewood or down Homewood, walking his hip walk, making something out of the way he is walking since there is nothing else to do, no place to go so he makes something of the

going, lets them see him moving in his own down way, his stylized walk which nobody could walk better even if they had some place to go.

Thinking of a chump shot on the nine ball which he blew and cost him a quarter for the game and his last dollar on a side bet. Of pulling on his checkered bells that morning and the black tank top. How the creases were dead and cherry pop or something on the front and a million wrinkles behind the knees and where his thighs came together. Junky, wino-looking pants he would have rather died than wear just a few years ago before when he was one of the cleanest cats in Westinghouse High School. Sharp and leading the Commodores. Doo Wah Diddy, Wah Diddy bop. Thirty-fivedollar pants when half the cats in the House couldn't spend that much for a suit. It was a bitch in the world. Stone bitch. Feeling like Mister Tooth Decay crawling all sweaty out of the gray sheets. Mom could wash them every day, they still be gray. Like his underclothes. Like every motherfucking thing they had and would ever have. Do Wah Diddy. The rakejerked three or four times through his bush. Left there as decoration and weapon. You could fuck up a cat with those steel teeth. You could get the points sharp as needles. And draw it swift as Billy the Kid.

Thinking it be a bitch out here. Niggers write all over everything don't even know how to spell. Drawing power fists that look like a loaf of bread.

Thinking this whole avenue is like somebody's mouth they let some jive dentist fuck with. All these old houses nothing but rotten teeth and these raggedy pits is where some been dug out or knocked out and ain't nothing left but stumps and snaggleteethjust waiting to go. Thinking, that's right. That's just what it is. Why it stinks around here and why ain't nothing but filth and germs and rot. And what that make me. What it make all these niggers. Thinking yes, yes, that's all it is.

Mr. Strayhorn where he always is down from the corner of Hamilton and Homewood sitting on a folding chair beside his iceball cart. A sweating canvas draped over the front of the cart to keep off the sun. Somebody said the old man a hundred years old, somebody said he was a bad dude in his day. A gambler like his own Granddaddy John French had been. They say Strayhorn whipped three cats half to death try to cheat him in the alley behind Dumperline. Took a knife off one and whipped all three with his

bare hands. Just sits there all summer selling ice-balls. Old and can hardly see. But nobody don't bother him even though he got his pockets full of change every evening.

Shit. One of the young boys will off him one night. Those kids was stone crazy. Kill you for a dime and think nothing of it. Shit. Rep don't mean a thing. They come at you in packs, like wild dogs. Couldn't tell those young boys nothing. He thought he had come up mean. Thought his running buddies be some terrible dudes. Shit. These kids coming up been into more stuffbefore they twelve than most grown men do they whole lives.

Hard out here. He stares into the dead storefronts. Sometime they get in one of them. Take it over till they get run out or set it on fire or it get so filled with shit and niggerpiss don't nobody want to use it no more except for winos and junkies come in at night and could be sleeping on a bed of nails wouldn't make no nevermind to those cats. He peeks without stopping between the wooden slats where the glass used to be. Like he is reading the posters, like there might be something he needed to know on these rain-soaked, sunfaded pieces of cardboard talking about stuff that happened a long time ago.

Self-defense Demonstration Ahmed Jamal. Rummage Sale. Omega Boat Ride. The Dells. Madame Walker's Beauty Products.

A dead bird crushed dry and paper thin in the alley between Albion and Tioga. Like somebody had smeared it with tar and mashed it between the pages of a giant book. If you hadn't seep it in the first place, still plump and bird colored, you'd never recognize it now. Looked now like the lost sole of somebody's shoe. He had watched it happen. Four or five days was all it took. On the third day he thought a cat had dragged it off. But when he passed the corner next afternoon he found the dark shape in the grass at the edge of the cobblestones. The head was gone and the yellow smear of beak but he recognized the rest. By then already looking like the raggedy sole somebody had walked off their shoe.

He was afraid of anything dead. He could look at something dead but no way was he going to touch it. Didn't matter, big or small, he wasn't about to put his hands near nothing dead. His daddy had whipped him when his mother said he sassed her and wouldn't take the dead rat out of the trap. He could whip him again but no way he was gone touch that thing. The dudes come back from Nam talking about puddles of guts and scraping parts of

people into plastic bags. They talk about carrying their own bags so they could get stuffed in if they got wasted. Just knowing what it was for, he would not be able to touch a body bag. Felt funny now pulling out the big green bags you had to put in your garbage can or else the garbage men wouldn't take it. Any kind of plastic sack and he's thinking of machine guns and dudes screaming and grabbing their bellies and rolling around like they do when they're hit in Iwo Jima and Tarawa or the Dirty Dozen or the Magnificent Seven or the High Plains Drifter but the screaming is not in the darkness on a screen it is bright green afternoon and Willie Thompson and them are on patrol. It is a street like Homewood. Quiet like Homewood this time of day and bombed out like Homewood is. Just pieces of buildings standing here and there and fire scars and places ripped and kicked down and cars stripped and dead at the curb. They are moving along in single file and their uniforms are hip and their walks are hip and they are kind of smiling and rubbing their weapons and cats passing a joint fat as a cigar down the line. You can almost hear the music from where Porgy's record shop used to be, like the music so fine it's still there clinging to the boards, the broken glass on the floor, the shelves covered with roach shit and rat shit, a ghost of the music drifting sweet and mellow like the smell of home cooking as the patrol slips on past where Porgy's used to be. Then

Rat tat tat rat tat tat ra ta ta ta ta ta ta

Sudden but almost on the beat. Close enough to the beat so it seems the point man can't take it any longer, can't play this soldier game no longer and he gets happy and the smoke is gone clear to his head so he jumps out almost on the beat, wiggling his hips and throwing up his arms so he can get it all, go on and get down. Like he is exploding to the music. To the beat which pushes him out there all alone, doing it, and it is rat tat tat and we all want to fingerpop behind his twitching hips and his arms flung out but he is screaming and down in the dirty street and the street is exploding all around him in little volcanoes ofdust. And some of the others in the front of the patrol go down with him. No semblance ofrhythm now, just stumbling, or airborne like their feet jerked out from under them. The whole hip procession buckling, shattered as lines of deadly force stitch up and down the avenue.

Hey man, what's to it. Ain't nothing to it man you got it baby hey now where's it at you got it you got it ain't nothing to it something

to it I wouldn't be out here in all this sun you looking good you into something go on man you got it all you know you the Man hey now that was a stone fox you know what I'm talking about you don't be creeping past me yeah nice going you got it all save some for me Mister Clean you seen Ruchell and them yeah you know how that shit is the cat walked right on by like he ain't seen nobody but you know how he is get a little something don't know nobody shit like I tried to tell the cat get straight nigger be yourself before you be by yourself you got a hard head man hard as a stone but he ain't gone listen to me shit no can't nobody do nothing for the cat less he's ready to do for hisself Ruchell yeah man Ruchelland them come by here little while ago yeah baby you got it yeah lemme hold this little something I know you got it you the Man you got to have it lemme hold a little something till this evening I'll put you straight tonight man you know your man do you right I unnerstand yeah that's all that's to it nothing to it Imma see you straight man yeah you fall on by the crib yeah we be into something tonight you fall on by.

Back to the left now. Up Hamilton, past the old man who seems to sleep beside his cart until you get close and then his yellow eyes under the straw hat brim follow you. Cut through the alley past the old grade school. Halfway up the hill the game has already started. You have been hearing the basketball patted against the concrete, the hollow thump of the ball glancing off the metal backboards. The ball players half naked out there under that hot sun, working harder than niggers ever did picking cotton. They shine. Theyglide and leap and fly at each other like their dark bodies are at the ends of invisible strings. This time of day the court is hot as fire. Burn through your shoes. Maybe that's why the niggers play like they do, running and jumping so much because the ground's too hot to stand on. His brother used to play here all day. Up and down all day in the hot sun with the rest of the crazy ball players. Old dudes and young dudes and when people on the side waiting for winners they'd get to arguing and you could hear them bad-mouthing all the way up the hill and cross the tracks in the park. Wolfing like they ready to kill each other.

His oldest brother John came back here to play when he brought his family through in the summer. Here and Mellon and the courts beside the Projects in East Liberty. His brother one of the old dudes now. Still crazy about the game. He sees a dude lose his man and fire ajumperfrom the side. A double pump, a lean, and the ball

arched so it kisses the board and drops through the iron. He could have played the game. Tall and loose. Hands bigger than his brother's. Could palm a ball when he was eleven. Looks at his long fingers. His long feet in raggedy ass sneakers that show the crusty knuckle of his little toe. The sidewalk sloped and split. Little plots of gravel and weeds where whole paving blocks torn away. Past the dry swimming pool. Just a big concrete hole now where people piss and throw bottles like you got two points for shooting them in. Dropping like a rusty spiderweb from tall metal poles, what's left of a backstop and beyond the flaking mesh of the screen the dusty field and beyond that a jungle of sooty trees below the railroad tracks. They called it the Bum's Forest when they were kids and bombed the winos sleeping down there in the shade of the trees. If they walked alongside the tracks all the way to the park they'd have to cross the trestle over Homewood Avenue. Hardly room for trains on the trestle so they always ran and some fool always yelling, Trains coming and everybody else yelling and then its your chest all full and your heart pumping to keep up with the rest. Because the train couldn't kill everybody. It might get the last one, the slow one but it wouldn't run down all the crazy niggers screaming and hauling ass over Homewood Avenue. From the tracks you could look down on the winos curled up under a tree or sitting in a circle sipping from bottles wrapped in brown paper bags. At night they would have fires, hot as it was some summer nights you'd still see their fires from the bleachers while you watched the Legion baseball team kick butt.

From high up on the tracks you could bomb the forest. Stones hissed through the thick leaves. Once in a while a lucky shot shattered a bottle. Some gray, sorry-assed wino motherfucker waking up and shaking his fist and cussing at you and some fool shouts He's coming, he's coming. And not taking the low path for a week because you think he was looking dead in your eyes, spitting blood and pointing at you and you will never go alone the low way along the path because he is behind every bush, gray and bloody mouthed. The raggedy gray clothes flapping like a bird and a bird's feathery, smothering funk covering you as he drags you into the bushes.

He had heard stories about the old days when the men used to hang out in the woods below the tracks. Gambling and drinking wine and telling lies and singing those old time, down home songs.

Hang out there in the summer and when it got cold they'd loaf in the Bucket of Blood, on the corner of Frankstown and Tioga. His granddaddy was in the stories. Old John French one ofthe baddest dudes ever walked these Homewood streets. Old, big-hat John French. They said his granddaddy could sing and nowhisjitterbug father up in the choir of Homewood A.M.E. Zion next to Mrs. Washington who hits those high notes. He was his father's son, people said. Singing all the time and running the streets like his daddy did till his daddy got too old and got saved. Tenor lead of Commodores. Everybody saying the Commodores was the baddest group. If that cat hadn't fucked us over with the record we might have made the big time. Achmet backing us on the conga. Tito on bongos. Tear up the park. Stone tear it up. Little kids and old folks all gone home and ain't nobody in the park but who supposed to be and you got your old lady on the side listening or maybe you singing pretty to pull some new fly bitch catch your eye in the crowd. It all comes down, comes together mellow and fine sometimes. The drums, the smoke, the sun going down and you out there flying and the Commodores steady taking care of business behind your lead.

"You got to go to church. I'm not asking I'm telling. Now you get those shoes shined and I don't want to hear another word out of you, young man." She is ironing his Sunday shirt hot and stiff. She hums along with the gospel songs on the radio. "Don't make me send you to your father." Who is in the bathroom for the half hour he takes doing whatever to get hisself together. Makingeverybody else late. Singing in there while he shaves. You don't want to be the next one after him. "You got five minutes, boy. Five minutes and your teeth better be clean and your hands and face shining." Gagging in the funkybathroom, not wanting to take a breath. How you supposed to brush your teeth, the catjust shit in there. "You're going to church this week and every week. This is my time and don't you try and spoil it, boy. Don't you get no attitude and try to spoil church for me." He is in the park now, sweating in the heat, a man now, but he can hear his mother's voice plain as day, filling up all the empty space around him just as it did in the house on Finance Street. She'd talk them all to church every Sunday. Use her voice like a club to beat everybody out the house. His last time in church was a Thursday. They had the scaffolding

up to clean the ceiling and Deacon Payton's truck was parked outside. Payton's Hauling, Cleaning, and General Repairing. The Young People's Gospel Chorus had practice on Thursday and he knew Adelaide would be there. That chick looked good even in them baggy choir robes. He had seen her on Sunday because his Mom cried and asked him to go to church. Because she knew he stole the money out her purse but he had lied and said he didn't and she knew he was lying and feelingguilty and knew he'd go to church to make up to her. Adelaide up there with the Young People's Gospel Chorus rocking the church. Rocking church and he'd go right on up there, the lead of the Commodores, and sing gospel with them if he could get next to that fine Adelaide. So Thursday he left the poolroom, Where you tipping off to, Man? None ofyour motherfucking business, motherfucker, about seven when she had choir practice and look here Adelaide I been digging you for a long time. Longer and deeper than you'll ever know. Let me tell you something. I know what you're thinking, but don't say it, don't break my heart by saying you heard I was a jive cat and nothing to me and stay away from him he ain't no good and stuff like that I know I got a rep that way but you grown enough now to know how people talk and how you got to find things out for yourself. Don't be putting me down till you let me have a little chance to speak for myself. I ain't gone to lie now. I been out here in the world and into some jive tips. Yeah, I did my time diddy-bopping and trying my wheels out here in the street. I was a devil. I got into everything I was big and bad enough to try. Look here. I could write the book. Pimptime and partytime and jive to stay alive, but I been through all that and that ain't what I want. I want something special, something solid. A woman, not no fingerpopping young girl got her nose open and her behind wagging all the time. That's right. That's right, I ain't talking nasty, I'm talking what I know. I'm talking truth tonight and listen here I been digging you all these years and waiting for you because all that do-wah-diddy ain't nothing, you hear, nothing to it. You grown now and I need just what you got.

Thursday in the vestibule with Adelaide was the last time in Homewood A.M.E. Zion Church. Had to be swift and clean. Swoop down like a hawk and get to her mind. Tuesday she still crying and gripping the elastic of her drawers and saying No. Next

Thursday the only singing she doing is behind some bushes in the park. Oh, Baby. Oh, Baby, it's so good. Tore that pussy up. Don't make no difference. No big thing. She's giving it to somebody else now. All that good stuff still shaking under her robe every second Sunday when the Young People's Gospel Chorus in the loft beside the pulpit. Old man Payton like he guarding the church door asking me did I come around to help clean. "Mr. Payton, I wish I could help but I'm working nights. Matter of fact I'm a little late now. I'm gone be here on my night off, though."

He knew I was lying. Old bald head dude standing there in his coveralls and holding a bucket of Lysol and a scrub brush. Worked all his life and got a piece of truck and a piece of house and still running around yes-sirring and no-mamming the white folks and cleaning their toilets. And he's doing better than most of these chumps. Knew I was lying but smiled his little smile 'cause he knows my Mama and knows she's a good woman and knows Adelaide's grandmother and knows if I ain't here to clean he better guard the door with his soap and rags till I go on about my business.

He can see Ruchell and them over on a bench. Nigger's high already he can tell. Even from this distance as he stands on the little iron bridge over the tracks he knows they been into something. They ain't hardly out there in the sun barbecuing their brains less they been into something already. Niggers be hugging the shade till evening less they been into something.

"Hey now."

"What's to it, Bobby."

"You cats been into something."

"You ain't just talking."

"Ruchell, man, we got that business to take care of."

"Stone business, Bruh. I'm ready to T.e.B., my main man."

"You ain't ready for nothing, nigger."

"Hey man, we're gone to get it together. I'm ready, man. I ain't never been so ready. We gone to score big, Brother Man

They have been walking an hour. The night is cooling. A strong wind has risen and a few pale stars are visible above the yellowpall of the city's lights. Ruchell is talking:

"The reason it's gone to work is the white boy is greedy. He's so

greedy he can't stand for the nigger to have nothing. Did you see Indovina's eyes when we told him we had copped a truckload of color TVs? Shit man. I could hear his mind working. Calculating like. These niggers is dumb. I can rob these niggers. Click. Click. Clickedy. Rob the shit out of these dumb spooks. They been robbing us so long they think that's the way things supposed to be. They so greedy their hands get sweaty they see a nigger with something worth stealing."

"So he said he'd meet us at the car lot."

"That's the deal. I told him we had two vans full."

"And Ricky said he'd let you use his van."

"I already got the keys, man. I told you we were straight with Ricky. He ain't even in town till the weekend."

"I drive up then and you hide in the back."

"Yeah, dude. Just like we done said a hundred times. You go in the office to make the deal and you know how Indovina is. He's gone to send out his nigger Chubby to check the goods."

"And you gonna jump Chubby."

"Be on him like white on rice. Freeze that nigger till you get the money from Indovina."

"You sure Indovina ain't gone to try and follow us."

"What he gonna do that for, man. He'll be happy to see you go."

"With his money."

"Indovina's gone to do whatever you say. Just wave your piece in his face a couple of times. That fat ofay motherfucker ain't got no heart. Chubby is his heart and Ruchell gone take care of Chubby."

"I still think Indovina might go to the cops."

"And say what? He was trying to buy some hot teevees and got ripped off. He ain't hardly saying that. He might just say he got robbed and try to collect insurance. He's slick like that. But if he goes to the cops you can believe he won't be describing us. Naw. The pigs know that greasy dago is a crook. Everybody knows it and won't be no problems. Just score and blow. Score and blow. Leave this motherfucking sorry-ass town. Score and blow."

"When you ain't got nothing you get desperate. You don't care. I mean what you got to be worried about. Your life ain't shit. All you got is a high. Getting high and spending all your time hustling some money so you can get high again. You do anything. Nothing don't

matter. You just take, take, take whatever you can get your hands on. Pretty soon nothing don't matter, John. Youjust got to get that high. And everybody around you the same way. Don't make no difference. You steal a little something. If you get away with it, you try it again. Then something bigger. You get holt to a piece. Other dudes carry a piece. Lots of dudes out there holding something. So you get it and start to carrying it. What's it matter. You ain't nowhere anywhere. Ain't got nothing. Nothing to look forward to but a high. A man needs something. A little money in his pocket. I mean you see people around you and on TV and shit. Man, they got everything. Cars and clothes. They can do something for a woman. They got something. And you look at yourself in the mirror you're going nowhere. Not a penny in your pocket. Your own people disgusted with you. Begging around your family like a little kid or something. Andjail and stealing money from your own mama. You get desperate. You do what you have to do."

The wind is up again that night. September third. At the stoplight Bobby stares at the big sign on the boulevard. A smiling duke emptying a glass of beer. The time and temperature flash beneath the nobleman's uniformed chest. Ricky had installed a tape deck into the dash. A tangle of wires drooped from its guts, but the sound was good. One speaker for the cab, the other for the partitioned-off rear where Ruchell was sitting on the rolls of uncut carpeting. Al Green singing Call Me. Ricky could do things. He made his own tapes; he was customizing the delivery van. Next summer Ricky was driving to California. Fixing up the van so he could live in it. The dude was good with his hands. He had been a mechanic in the war. Government paid him for the shattered knee. Ricky said, Got me a new knee now. Got a four wheeled knee that's gonna ride me away from all this mess. The disability money paid for the van and the customizing and the stereo tape deck. Ricky would always have that limp but the cat was getting hisself together.

Flags were strung across the entrance to the used car lot. The wind made them pop and dance. Rows and rows of cars looking clean and new under the lights. Bobby parked on the street, in the deep shadow at the far end of Indovina's glowing corner.

"Hey, Chubby."

"What's happening now." Chubby's shoulders wide as the door.

He was Indovina's nigger all the way. Had his head laid back so far on his neck it's like he's looking at you through his nose holes instead of his eyes.

"You got the merchandise." Indovina's fingers drum the desk.

"You got the money."

"Ain't your money yet. I thought you said two vans full."

"I can't drive but one at a time. My partner's at a phone booth right now. I got the number here. You show me the bread and he'll bring the rest."

"I want to see them all before I give you a penny."

"Look, Mr. Indovina. This ain't no bullshit tip. We got the stuff, alright. Good stuff like I said. Sony portables. All the same still in the boxes."

"Let's go look."

"I want to see some bread first."

"Give Chubby your key. Chubby, check it out. Count them. Make sure the cartons ain't broke open."

"I want to see some bread."

"Bread. Bread. My cousin DeLuca runs a bakery. I don't deal with bread. I got money. See. That's money in my hand. I got plenty money buy your television sets buy your vans buy you."

"Just trying to do square business, Mr. Indovina."

"Don't forget to check the cartons. Make sure they're sealed."

Somebody must be down. Ruchell or Chubbydown. Bobby had heard two shots. He sees himself in the plate glass window. In a fishbowl and patches of light gliding past. Except where the floodlights are trained, the darkness outside is impenetrable. He cannot see past his image in the glass, past the rushes of light slicing through his body.

"Turn out the goddamn light."

"You kill me you be sorry kill me you be real sorry if one of them dead out there it's just one nigger kill another nigger you kill me you be sorry you killing a white man

Bobby's knee skids on the desk and he slams the gun across the man's fat, sweating face with all the force of his lunge. He is scrambling over the desk, scattering paperandjunk, looking down on Indovina's white shirt, his hairy arms folded over his head. He is thinking of the shots. Thinking that everything is wrong. The shots,

the white man cringing on the floor behind the steel desk. Him atop the desk, his back exposed to anybody coming through the glass door.

Then he is running. Flying into the darkness. He is crouching so low he loses his balance and trips onto all fours. The gun leaps from his hand and skitters toward a wall of tires. He hears the pennants crackling. Hears a motor starting and Ruchell calling his name.

"What you mean you didn't get the money. I done wasted Chubby and you didn't even get the money. Aw shit. Shit. Shit."

He had nearly tripped again over the man's body. Without knowing how he knew, he knew Chubby was dead. Dead as the sole of his shoe. He should stop; he should try to help. But the body was lifeless. He couldn't touch

Ruchell is shuddering and crying. Tears glazing his eyes and he wonders if Ruchell can see where he's going, if Ruchell knows he is driving like a wild man on both sides of the street and weaving in and out the line of traffic. Horns blare after them. Then it's Al Green up again. He didn't know why, when, or who pushed the button but it was Al Green blasting in the cab. Help me help me help me

Jesus is waiting He snatches at the tape deck with both hands to turn it down or off or rip the goddamn cartridge from the machine.

"Slow down, man. Slow down. You gone get us stopped." Rolling down his window. The night air sharp in his face. The whir of tape dying then a hum of silence. The traffic sounds and city sounds pressing again into the cab.

"Nothing. Wasted the dude and we still ain't got nothing."

"They traced the car to Ricky. Ricky said he was out of town. Told them his van stolen when he was out of town. Didn't even know it was gone till they came to his house. Ricky's cool. I know the cat is mad, but he's cool. It's Indovina trying to hang us. He's saying it was a stick-up. Saying Chubby tried to run for help and Ruchell shot him down. His story don't make no sense when you get down to it, but ain't nobody gone to listen to us."

"Then you're going to keep running."

"Ain't no other way. Try to get to the coast. Ruchell knows a guy

there can get us IDs. We was going there anyway. With our stake. We was gone to get jobs and try to get it together. Make a real try. We just needed a little bread to get us started. I don't know why it had to happen the way it did. Ruchell said Chubby tried to go for bad. Said Chubby had a piece down in his pants and Ruchell told him to cool it told the cat don't be no hero and had his gun on him and everything but Chubby had to be a hardhead, had to be John Wayne or some goddamn body. Just called Ruchell a punk and said no punk had the heart to pull the trigger on him. And Ruchell, Ruchell don't play, brother John. Ruchell blew him away when Chubby reached for his piece."

"You don't think you can prove your story."

"I don't know, man. What Indovina is saying don't make no sense, but I heard the cops ain't found Chubby's gun. If they could find that gun. But Indovina, he's a slick old honky. That gun's at the bottom of the Allegheny River if he found it. They found mine. With my prints all over it. Naw. Can't take the chance. It's murder one even though I didn't shoot nobody. That's a long, hard time if they believe Indovina. I can't take the chance."

"Be careful, Bobby. You're a fugitive. Cops out here think they're Wyatt Earp and Marshal Dillon. They shoot first and maybe ask questions later. They still play wild, wild west out here."

"I hear you. But I'd rather take my chances that way. Rather they carry me back in a box than go back to prison. It's hard out there, brother. Real hard. I'm happy you got out. One of us got out anyway."

"Think about it. Take your time. You can stay here as long as you need to. There's plenty of room."

"We gotta go. See Ruchell's cousin in Denver. Get us a little stake, then make our run."

"I'll give you what 1 can if that's what you have to do. But sleep on it. Let's talk again in the morning."

"It's good to see you, man. And the kids and your old lady. At least we had this one evening. Being on the run can drive you crazy."

"Everybody was happy to see you. I knew you'd come. You've been heavy on my mind since yesterday. I wrote a kind of letter to you then. I knew you'd come. But get some sleep now we'll talk in the morning."

"Listen, brother John. I'm sorry, man. I'm really sorry I had to come here like this. You sure your wife ain't mad."

"I'm telling you it's OK. She's as glad to see you as I am. And you can stay both of us want you to stay."

"Running can drive you crazy. From the time I wake in the morning till I go to bed at night, all I can think about is getting away. My head ain't been right since it happened."

"When's the last time you talked to anybody at home."

"It's been a couple weeks. They probably watching people back there. Might even be watching you. That's why I can't stay. Got to keep moving till we get to the coast. I'm sorry, man. I mean nobody was supposed to die. It was easy. We thought we had a perfect plan. Thieves robbing thieves. Just score and blow like Ruchell said. It was our chance and we had to take it. But nobody was supposed to get hurt. I'd be dead now if it was me Chubby pulled on. I couldn'a just looked in somebody's face and blown them away. But Ruchell don't play. And everybody at home I know how they must feel. It was all over TV and the papers. Had our names and where we lived and everything. Goddamn mug shots in the Post-Gazette. Looking like two gorillas. I know it's hurting people. In a way I

wish it had been me. Maybe it would been better. 1 don't really care what happens to me now. Just wish there be some way to get the burden off Mama and everybody. Be easier if I was dead."

"Nobody wants you dead. That's what Mom's most afraid of. Afraid of you coming home in a box."

"I ain't going back to prison. They have to kill me before I go back in prison. Hey, man. Ain't nothing to my crazy talk. You don't want to hear this jive. I'm tired, man. 1 ain't never been so tired Imma sleep talk in the morning, big brother."

He feels his brother squeeze then relax the grip on his shoulder. He has seen his brother cry once before. Doesn't want to see it again. Too many faces in his brother's face. Starting with their mother and going back and going sideways and all of Homewood there if he looked long enough. Notjust faces but streets and voices and rooms and songs.

Bobby listens to the steps. He can hear faintly the squeak of a bed upstairs. Then nothing. Ruchell asleep in another part of the house. Ruchell spent the evening with the kids, playing with their toys. The cat won't even grow up. Still into the Durango Kid, and Whip Wilson and Audie Murphy wasting Japs and shit. Still Saturday afternoon at the Bellmawr show and he is lining up the plastic cowboys against the plastic Indians and boom-booming them down with the kids on the playroom floor. And dressing up the Lone Ranger doll with the mask and guns and cinching the saddle on Silver. Toys like they didn't make when we were coming up. And Christmas morning and so much stuff piled up he'd be crying with exhaustion and bad nerves before half the stuff unwrapped. Christmas morning and they never really went to sleep. Looking out the black windows all night for reindeer and shit. Cheating. Worried that all the gifts will turn to ashes if they get caught cheating, but needing to know, to see if reindeer really can fly.

Childhood friendships are an embarrassment, Elizabeth Murphy thought, in the midst of Pamela and Merrick Stetson's New Year's Day open house in Vermont. I am an embarrassment to Pookie because I am the only one left in the world who calls her that, and I am wearing all the wrong clothes.

Elizabeth was, in fact, dressed in a suede pants suit she had uneasily bought for the occasion at Bonwit's a week ago.

"I would have known you anywhere, Lizzie, you're still so chic," Pookie said after they embraced, and patted the rust-colored suede cloth. "So Wall Street. So New York perfect." The bones, the scent, the smile tilting to the left were identifiably Pookie, transmuted by -what had it been?-twenty years? She was wearing blue jeans and a chamois shirt. Tanned and attractive, Pamela-Pookie at fifty looked tough enough to shoot woodchucks and bury whatever birds the cats mangled.

"Well, you look marvelous. I swear this alternative life style, whatever you're calling it, agrees with you."

"Early to bed and early to rise, we're calling it. And you never see any of the regular guys." They snickered companionably. It had been Pookie's father's favorite line.

Thus Liz was launched. A grizzled and hearty Merrick, his hand cozily under her elbow, guided her to a buffet crowned with his own wines. "One hundred and thirty-five gallons this season," he said, pouring her a glass of the plum. "Come on, I'll show you around."

"I suppose you raise all your own vegetables, too." she said, following him down cellar.

He nodded.

"And can them."

"Mostly we freeze them. Some we keep in the cold roomparsnips and celeriac and beets and so forth."

"Of course." She would not have known celeriac if she had come face to face with it in the market. Parsnips she thought of as pale carrots; why would anyone wittingly grow them?

"Here's our maple syrup, what's left of it. Another six or eight weeks and we'll be tapping again."

"My God, Merrick! Is there anything you don't do?"

"I have a bad knee," he said ruefully. "The whole goddamned kneecap floats around on me. I can't ski any more, or play tennis."

"Poor man," she said, a little unpleasantly.

"Liz, Pam especially wanted to see you again. You ought to know: she isn't well."

"You mean that spleen thing? She looks marvelous. That tan."

"It isn't a tan, it's jaundice."

"What's wrong?"

"Here, take some of these up, will you?" He frowned, sorting wine bottles by label. "It's in her liver."

"What's in her liver, Merrick?"

But a new group of guests had descended the hand-hewn, openriser steps for a guided tour of the sauna, the winery, and the root crops, and she and Merrick were separated.

As if by contractual agreement, neither Liz nor Pookie ever wrote an actual letter. Since grammar school, they had exchanged vacation flurries of postcards crowded with urgent information. Each of these began: A traveler's hello. Early on, the cards ranged no farther than the Statue of Liberty or the Boston Public Gardens. One winter Pookie's view of downtown Indianapolis was followed by one of the Lincoln Memorial from Liz. Then came the covered bridges and scenic vistas of adolescent summers. During their college years-Pookie at Wellesley, Liz at Smith-written communication all but ceased. Occasionally Pookie dispatched an antique valentine and Liz fired back with a hand-tinted view of Mount Greylock. Conventional daughters of their generation, each married the summer after getting her baccalaureate.

Pookie and Merrick crisscrossed Europe before and between children. There was a traveler's hello from the deck of the Cristofaro Columbo; from the steps of the Basilica in Rome; from Piccadilly and Notre Dame; from Cannes and Monte Carlo and the red, red sands of Corsica. Later, a photographic safari in Kenya, another to the Great Barrier Reef. Sequentially, as their three little girls attained a manageable age, they accompanied their parents. That was a period studded with postcards, of energetic, archivable messages. A traveler's hello! Not even Peter Pan crowed more pridefully.

A traveler's hello from Selma and Montgomery. From Memphis and Washington, Boston and Chicago. News of Merrick's arrest at the Pentagon arrived on the back of an aerial view of same. "A traveler's hello from Pig Palace in stitches." Soon thereafter came the decision to move to Vermont. Details about the construction of this house were scanty: "A three-year project, architecturally

incorrect. Experts all say too many wings." With every card, a renewed invitation to Liz to pay a visit.

Liz countered with art reproductions from the Metropolitan gift shop, and views of Wall Street. She kept a dozen of these in her desk, for fast retorts. This year, she vowed, she would go to Vermont.

And then in November a postcard from Pookie from Hanover, a view of Dartmouth College. "A traveler's hello from the northern branch of the Ivy League. I'm here to have my spleen out. Nothing serious, but what will I vent with now?"

Pookie and Liz had been friends since first grade at the Parker School, in suburban Philadelphia. All through grammar school they had been fierce, unabashed best friends, resisting any separation. Pookie had a dollhouse, an exact replica ofthe house she lived in, with nine handsomely proportioned rooms and a portico of white pillars. Behind Pookie's house lay a rose garden of sorts and a lawn for croquet. Liz's house, three blocks away, leaned against a corner grocery and fronted on trolley tracks. The local fire station loomed behind. Pookie's sidewalk was best for roller skating, Liz's third-floor back porch for spying on the firemen through Pookie's father's binoculars.

The social differences, Liz had found herself thinking as she trudged up the serpentine walk to the huge cedar country house with wings-the social differences weren't even noticed until about sixth grade. "Don't envy me," Pookie had warned her once they were in high school, once it was a matter of cars and clothes and leisure-time activities. "I can't bear it if you envy me. None of it is my fault."

But how Pookie had envied the beer-and-pizza kitchen of Liz's brown house, the noisycomings and goings ofuncles no older than Liz's brothers. The all-time sad, singable lyrics on the Stromberg Carlson, causing the bedroom floor above to vibrate with the bass notes. How Pookie had admired the trolleys that squealed and shot blue sparks under the windows all nightlong, theirlighted interiors revealing the solitary, late traveler who excited her imagination. And how, on the frequent weekends she was allowed to stay over, Pookie had adored the shrieking of the fire alarm, the scramble of men and equipment, the terrifying siren that punctured all workaday sounds or, even better, shattered the diminished murmur of

midnight. How she would huddle on the back porch, rubbing her goose bumps, fascinated with the purposeful bustle below.

Purposeful bustle-that was what Pookie had put into her adult life, Liz thought, rounding the last turn and fronting on the house. She had not dared to drive her brother's bulky Pontiac any closer; she would never have been able to park it, she was sure. She carried her house present under her arm: a foot scraper with double brushes guaranteed to remove snow and mud from the ridges of the most elaborately soled hiking boots. Most of the cars parked along the shoulder of the hill were Saabs or Volvos, here and there a Volkswagen or mini-pickup truck. A sprinkling of bumper stickers proclaiming No Nukes and Split Wood, Not Atoms. There was one Recycle Your Grass, Feed a Horse and oneJ'aime Ie Bois. Lucky Pookie, her children all launched, her attitudes in order, her life so meaningful.

Liz had spent the week between Christmas and New Year's in Brattleboro with her youngest brother and his wife. Her brother, who had been in hardware and sheepskin jackets, now owned a chain of shoe stores. Mostly he carried boots with felt liners and hard-wearing leather outdoor shoes. Very little call for high heels, he would say, sprawled in his reclining chair, pulling the tab on his third beer ofthe evening. He and Charlene were enthusiastic snowmobilers; they belonged to a club. Everyone wore quilted jump suits with the club emblem, a wolf, on the breast pocket. Saturday nights, in season, they went out in packs, ten or twelve in a line.

Liz loathed all holidays, Christmas supremely. She could not fake it at Christmas. After the mid-December rush to sell so as to take losses before the year ended, her clients-she was an investment analyst-dropped out of sight until February. The market dozed. The office, at the end of December, was one big poisonous eggnog party. She went to a lot of late-afternoon movies. There was no one she was close to, as she would say, "at the moment." In New York she lived without houseplants hanging in the windows or mung beans sprouting under the sink. She competed for taxis and ate in restaurants three or four times a week, frequently with her ex-husband, Rich, who was now gay. They went dutch and discussed the children, one in prep school in New England, the other a sophomore at Liz's alma mater, Smith. The difference was that Liz, unlike Sally, had been a full-scholarship student. She had

waited on tables six hundred meals a year for four years. During summers, she had assembled weather balloons in a factory. Sally was a dilettante.

There were the usual problems. Mark was failing French. He took his guitar to language lab and played his original folk songs onto the tapes instead of parroting the lessons. Sally, with Liz's connivance, had recently had an abortion. Liz did not tell Sally's father; it would have upset him terribly. He could not, he said, deal with aggressiveness in women. Abortion is an aggressive act, he said frequently.

For the sake of whatever was left in the parenting relationship, and for the sake ofdecencies between them, Liz chose not to argue. Looking back, she could see that she had probably always known Rich was homosexual. She had seen it the minute he got out of uniform. She had seen it each time he reached for the second drink when something loosened and changed direction. He was tender and non-bitchy and she loved in him precisely the qualities that directed the amorous force of his attention away from her. After ten years of leading a double life, he came out of the closet. The children were told in the most considerate way possible why Daddy was leaving. Neither seemed scarred. Rich left Liz the hi-fi, the paired tickets to the Philharmonic, a paid-up year of paddle tennis in Riverdale, and a heavy sense of herself as a dutiful pal.

When they were first married and living in the same city as Pookie and Merrick, Liz remembered that Rich's big word was "hostile." Going to bed early was a hostile act. Merrick-she had agreed with Rich here-had a faintly hostile smile. As couples they had attained only lukewarm friendship. Liz and Pookie did not discuss the gradual erosion of their passionate loyalty; tact got in the way of honesty. Liz had never liked Merrick very much. He was a dogmatic man, intelligent and witty, but suffocatingly insistent on his own point ofview. Daughters, she thought,exactly suited him; he could not have borne the rivalry of sons. She remembered the New Year's Eve they had all gotten drunk together, three couples: Pookie and Merrick; Barby and Rob, now divorced; she and Rich, amiably separated. That night the men had all put their jockey shorts in the refrigerator, she forgot why.

It was mid-afternoon. An expedition was being organizedby the Stetson's middle daughter to hike up to two mysterious domed

rock chambers, presumed to be sacred Indian places. "Go, you'll love it," urged Pookie. "People have been arguing about them for years, whether they'rejust colonial root cellars or pre-Columbian."

Six guests assembled in the entryway. The downstairs windows were now all steamy from animal heat; the living room was chockablock with people and pots full ofavocado trees. All homesprouted, no doubt, Liz thought. At least she had the right boots for tramping in the snow. She was grateful to her brother for the gift. The afternoon was brilliant, the temperature a benevolent 2SO They followed a snowmobile trail for half a mile, then turned to cross a partially frozen brook and climbed along a cut where the footing grew difficult.

Conversation was patchy. "An archaeologist from Yale was here last summer. He said these mounds are clearly Celtic," Ginny said. "Tenth century, most likely." Ginny had one more year to go at Yale. After that, it was to be law school, most likely. The Stetsons' oldest daughter was in medical school at Western Reserve. The youngest grimly expressed no preference as yet.

As they stumbled back down the rock face in the gathering dusk, Liz alternately helped and was helped along by a man with a melancholy mustache. "Madness," he said, falling, and when she too fell, "insane." Then, on the flat, they exchanged biographies. He was no longer married, he worked for a foundation in New York, and he had one son, a high school dropout, and a daughter who swam. "Have you noticed how everybody's children at this party are exceptional?"

"You mean you've noticed, too?" she said.

"Sure. Everybody's children are either in law school or med school or posted to lookout stations to spot forest fires in the Rockies. Isn't anybody else's kid dull normal?"

Liz felt better. "Do spoiled brats count?"

"Friend," he said, "kindred soul. Tell me you don't heat your entire house with wood."

"I don't even grow herbs on the kitchen windowsill."

"Or distill dandelions in the cellar?"

"Listen," she said, "I eat meat. 1 live in a steam-heated duplex in the Village, and, generally speaking, 1 make it a point to avoid ice and snow."

A hundred yards from the house Ginny was waiting for them. "Can I talk to you a minute?" she said to Liz.

Dismissed, the mustache hurried on ahead.

"I don't know if Daddy has spoken to you yet. I think since you're Mommy's oldest friend "

"What's wrong with her, Ginny? I know something's wrong. Is it that spleen thing?"

"It's cancer," the girl said emphatically, giving the syllables equal weight-a word she was learning to thrust into conversations. "It's cancer of the liver, and the doctors say there's nothing more they can do."

Liz repeated "Cancer," but without conviction. The smell of wood smoke drifted to where they were standing. The setting sun had thrown house and hill into knife-edge relief. Cancer was a turkey vulture flapping overhead.

"Right now she's in her denial phase. She feels well, so nothingis happening to her, you know'!'

Liz didn't know. Denial phase-that sounded like something Rich would say. Denial is a hostile act. She reached to take Ginny's hand as a gesture ofcomfort. Suddenly her arms were full of Ginny weeping.

Liz personally felt guilty and reprieved, all in one. Her face flushed hot with guilt. If Pookie was dying ofcancer, then she, Liz, need no longer feel the continual, corrosive, piggish gnawings of envy. Envy is a mortal sin. Envy is for third-raters. Years of it had etched and attenuated their friendship. She had envied Pookie's nose, the slope of her shoulders, her marriage, her loyal dogs. She had envied her clothes, her achieving daughters, her smoothly shaven legs, her convictions, her equanimity and money. She had envied her origins, her dollhouse, her College Board scores. Assaulted by self-blame, still Liz felt marvelous. If Pookie was dying of cancer, then she, Liz, surely was not.

In a little while she and Ginny went back in the house. The man with the mustache was named David Lovejoy. He was waiting with a ravenous expression, not having eaten since breakfast. She was mortified to discover how hungry she was, too. They stuffed themselves with spinach pie and noodle pudding, hot biscuits and avocado salad. No animal had died to furnish this buffet.

Liz put off thinking about Pookie's condition. Everywhere she looked, Pookie was in animated conversation, throwing her shoulders back, arching her pelvis slightly in the gesture of laughter. Pookie embraced arriving and departing guests. Pookie unwrap-

ped a pair of oven mitts, a basket for French bread, the Hammacher Schlemmer boot scraper. Pookie was pouring wine, patting the three dogs, all of them black German shepherds. Pookie with Merrick's arm around her, cozy and doomed.

At the end of the party, Liz and Lovejoy exchanged addresses, telephone numbers. Vague promises were made, the kind she desperately wanted to believe in. For years and years she had been falling through space with an untested parachute. She neither crashed nor pulled the cord.

"Don't come back unless you feel up to it," Merrick said, walking down with her to the hulking Pontiac. He stood there, making small, aimless circles in the dark with his electric torch. As if the decision were his. She and Pookie had had a life before he was even thought of. She made no protest.

Eighteen months after this New Year's Day, Pamela Pookie Stetson lives, first having given up her uterus, then a portion ofher large intestine. She remains cheerful and active after the surgeries, walking with the dogs, vigorously weeding the garden, but she progresses out of denial and into acceptance.

Pookie accepts death the way she had accepted civil disobedience. Then she had learned how to sit hunched over, protecting her kidneys; she had learned how to go limp when arrested, while being carried out of federal buildings and hoisted into paddy wagons. She is doing what she has to do the same way she formed a human chain with other mothers on the cobblestones in front of the Navy buses. Only this time she must do it alone. Even with the whole world waving, she has to set out on her own.

Liz goes weekly to see her, flying up to Burlington, where one or another of the daughters meets her plane. She and Pookie have taken up where they left off, twenty-odd years ago, as if in midsentence. When Pookie is resting, Liz entertains Ginny and the others with details out of their mother's childhood. She describes all the unexceptional entertainments oftheir era, and then remembers the two ten-year-olds spying on the firemen in the adjacent dormitory through Pookie's father's expensive bird-watching binoculars. Grown men, scratching their genitals, blowing their noses, buttoning, unbuttoning. Two little girls, too wicked to be caught.

In Merrick's study, a lovely haphazard welter of books and periodicals, Liz is magnetized by one wall of framed photographs.

Here are the dogs of a lifetime, prick-eared and intelligent on lawns and snowy slopes. Here are the interchangeable little children in snowsuits and shorts. Here is the house going up, and the chimney of massive fieldstones. Here is the family hauling wood together, digging the garden, posing on skis. The central space on the wall is occupied by two glossies of Merrick himself. In one, he is being quick-marched down the Pentagon steps by a grim-faced policeman. In the other, one arm twisted behind his back, he is being led toward the police van. Still, he has turned toward the camera and he is grinning.

"He was knocked unconscious by that guy," Pookie says, breathing behind her. "Knocked cold about ten seconds after I clicked the shutter. That was Chicago."

Liz doesn't answer. She is thinking about the New Jerusalem in which you have your picture taken for posterity while you are being arrested. Along with the flushless toilet and piles of horse manure on the garden, it is the old made new again. The early Christians were masters of civil disobedience. If Merrick had been burned at the stake for his beliefs, she is thinking, Pookie would have been beside him, light meter in hand, recording the moment for posterity.