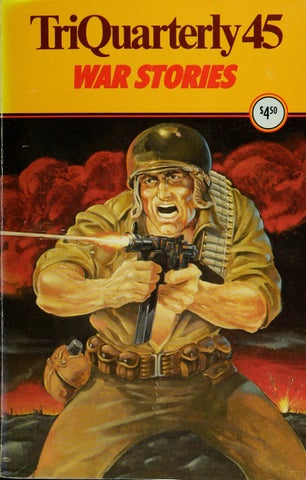

rly4S WARSTOIlIIS

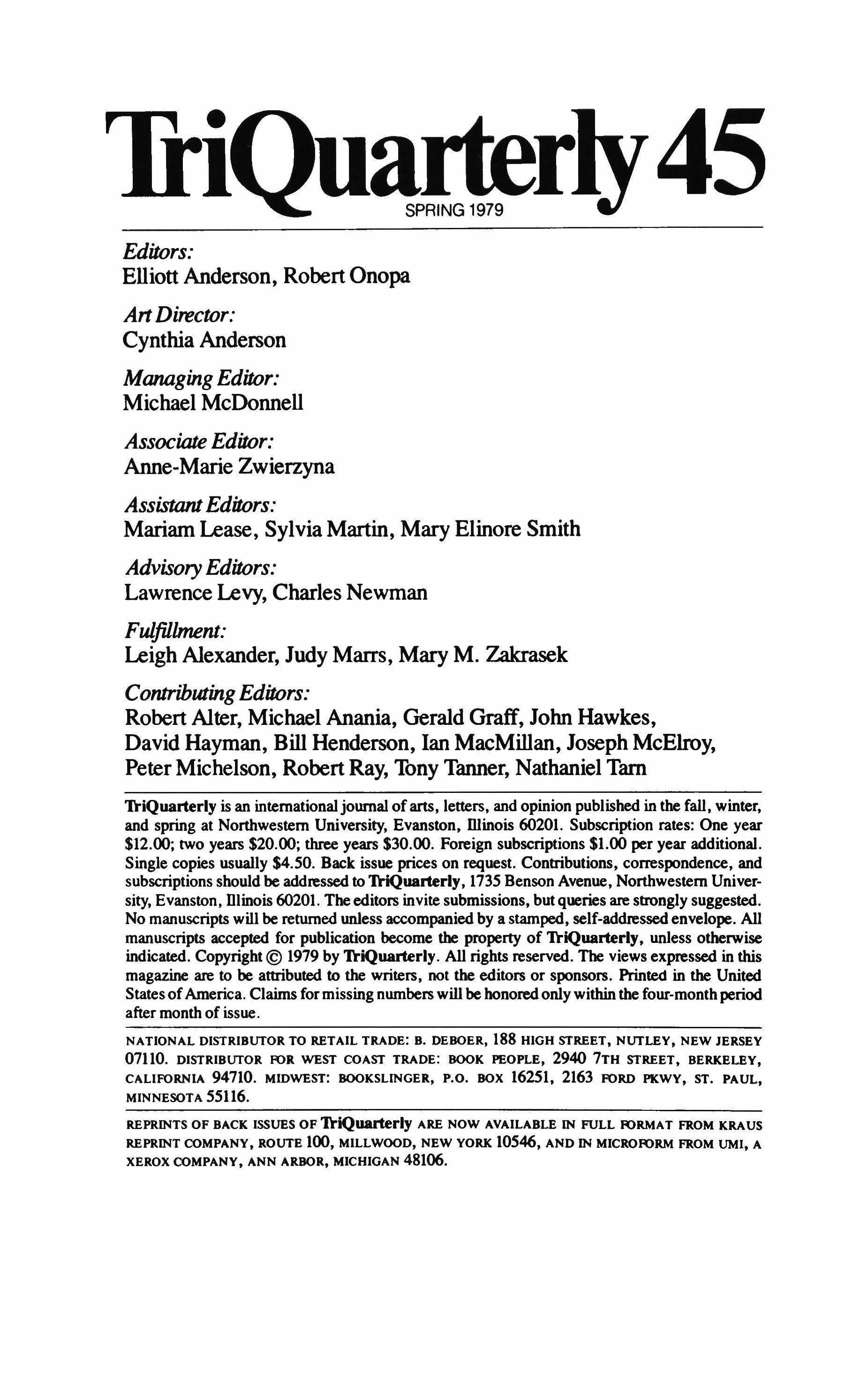

1iiQu��rly45

Editors:

Elliott Anderson, Robert Onopa

AnDirector: Cynthia Anderson

Managing Editor: �ichael�cI)onnell

Associate Editor: Anne-Marie Zwierzyna

AssistantEditors: Mariam Lease, Sylvia Martin, Mary Elinore Smith

AdvisoryEditors: Lawrence Levy, Charles Newman

Fulfillment:

Leigh Alexander, Judy Marrs, Mary M. Zakrasek

Contributing

Editors:

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Gerald Graff, John Hawkes, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Ian �ac�illan, Joseph �cElroy, Peter Michelson, Robert Ray, Tony Tanner, Nathaniel Tarn

TriQuarterly is an internationaljournal ofarts, letters, and opinion published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $12.00; two years $20.00; three years $30.00. Foreign subscriptions $1.00 per year additional. Single copies usually $4.50. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to 'liiQuarterly, 1735 Benson Avenue, Northwestern University, Evanston, Dlinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright© 1979 by TriQuarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States ofAmerica. Claims formissing numbers will be honoredonly within the four-monthperiod after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR WEST COAST TRADE: BOOK PEOPLE, 2940 7TH STREET, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94710. MIDWEST: BOOKSLINGER, P.O. BOX 16251, 2163 FORD PKWY, ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 55116.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF 'liiQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFORM FROM UMI, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

Coverpainting and interior illustrations byRon Villani

Star of David!

Jay Neugeboren

Horses! Horses! Horses! They rear up around me and I slash at their legs with the side of my saber. The family crouches behind me. I hold the boyagainst my side with my left arm. His sister clutches at my leg and weeps inconsolably. I hearwailing and crackling. I see fire leaping around us, in a ring that extends for miles, far beyond the circle of horses. I smell the horses' rankness and feel their warm, sweat-laden bodies. Their flanks are enormous. I fear being crushed. Their veined eyes are crazed with fright. Their enormous lips unfold and they bare their teeth at me. Steam rises from their bodies into the freezing air. They heave and rush about, and I shout at them to go back. Their masters have little control over them. Suddenly I slip

and I am underneath the swollen belly of a horse, and I see that the belly is smeared with blood. With my saber I jab at its thighs and chop at its forefeet. It moves off and I can breathe again. A riderless horse now risesatmy left,its hooves thrashing the air, and I bury the boy beneath me, my body pressed down upon his, and I pray. I glance up and see that the horse's hollow hooves are clotted with mud and snow and dead grass. The horse whinnies and its hooves strike at the snow beside my boots, but miraculously I am not touched.

Do I dream? The horses are taller than the houses. They are wider than the night. I long to slit their bellies and plunge my cold hands in, deep into the steaming blood and entrails. There would I find comfort! In my heart I know the frenzy the Tartars and Cossacks feel when the wild Tarpan horses steal their stores ofhay and entice away their mares. I have seen them kill entire herds of these small-boned and beautiful creatures. I have seen them feast and drink afterward. There is nothing I have not seen.

Now the Jews are leaving Kiev-expelled at midnight by order of the tsar-and I, in myoid soldier's uniform, am among them, a traitor to the army I served for so many years. When the fires began, I took my uniform out ofthe chest next to my bed and I fled from the city, to stand with a cavalry regiment on a small hillside and to watch the lines of weeping Jews, with their nags and their barrows, their broken-down droshkies and their packs, setting westward from the city in the middle of the night. They trudged through snow, wailing and chanting like madmen. The soldiers raced their horses at them now and again, and swung their swords, but more to keep warm than for the pleasures of cruelty. I held back and watched. The sky was bright with fire and falling snowflakes. The night was windless. My own horse was strong and wellrested.

I watched the exodus and it fulfilled my every hope. Jewish backs were bent and Jewish eyes were frightened. At last! How I had hated their devils' eyes! How I had loathed the black pools in those eyes, those pools deep with schemes and lies and tricks! When I approached, in my uniform, they stared at me with such fear-with such frank servility and submissiveness-that I longed to pierce those dark eyes with my dagger, to stab through the veil of fear and suffering to the flesh beneath.

I watched children riding on the backs of their fathers, old men

sitting in the snow and pleading for mercy, young men beating their own fathers with whips and branches to make them rise and go on. Yet all the while I felt nothing but scorn for them. They were dirty and verminous, vile and odorous, a curse on mankind. Wherever they went, they carried with them their plagues and diseases, their books and their lies. How I relished their anguish! Their eyes were phlegm-drenched, their noses large and red and dripping, the men's beards tangled with grease and crumbs and scabs, the women's and children's scalps encrusted with sores. The chosen people, I laughed to myself. The chosen people! They were the ones who chose to be different. They were the ones who declared themselves the anointed of God. Then let them now reap the grim harvest!

Even the rich Jews were bent over, and this satisfied me most of all. What will you do with all your money now? I asked. Tell me that. What will you do with your walls of books and your silk clothing and your gilt-edged furniture and your chests of coins? Now at last you will be real Jews too-now you will feel what I have felt forever. Now you will suffer the way my father suffered and my mother suffered, and the way their fathers and mothers suffered before them. Now you will pay for their suffering! Except, I thought, you will not be as strong and cunning as I have been, and you will not know how to survive your suffering. You will wander as wandering Jews have always wandered, but, set loose in the wilds of Mother Russia, you will not, like me, know how to find and kill animals where no animals can be seen, or to keep warm when you have no heated home, or to stave off disease when you have no doctors.

I saw a family of wealthy Jews walking among a mass of poor Jews. The poor Jews made way for them. The father walked in front, his body almost erect. He wore a hat of gleaming black lamb's wool; a coat with a fur collar. He wore precious eyeglasses, rimmed in gold, and he carried nothing except a single book in a gloved hand. His wife, in black silk and foxfurs, walked three steps behind him, and behind her there walked a man and a womanperhaps a daughter and son, perhaps a husband and wife-carrying bundles in their arms. There were smaller children behind them, dressed luxuriously, like dwarf merchants, and there were servants behind them, pushing barrows and pulling wagons of clothing and furniture and food.

A soldier charged at them, his saber slicing circles in the air

above his head. But the Jew did not bow down. His wife knelt, her hands upon the back of her neck. The children huddled together and screamed. The soldier taunted the Jew but did not kill him. He took the Jew's hat and then he leaned down from his horse and tore the Jew's coat from him. The Jew gave him money and rings. The wife gave the soldier silver candlesticks, a golden menorah. The servants foraged frantically in the wagons, finding more giftsjewelry and silver and spice boxes and pots and silk and dresses and food and coins.

When the soldier returned to our lines, laden down with his spoils, we laughed and cheered him. He carried a woman's undergarment on the tip of his sword. But the rich Jew walked on, bareheaded through the snow, as if he were too proud to even glance back at us and acknowledge what had occurred. How I loathed him then! And how I envied his riches and his family and his pride! I watched him fade into the white landscape, a crown of snow upon his bare head, and I cursed his soul. I thought of the old joke my father had told me when I was a child, a joke I had repeated to my fellow soldiers many times through the years, but which I dared not repeat now. If a rich Jew should ever want to know how he can live forever and gain immortality, my father said, you- must tell him that the secret is to come and settle in our town. Then, before he spokeagain, my father would pause and his eyes would twinkle. No rich Jew ever died here, he would say.

Soon word was given that the bulk of the Jews were gone from Kiev and that the soldiers had permission to return. I returned with them. Their bloodcurdling screams ofjoy brought comfort to my soul. I raced my horse with theirs, even as they cut through the long lines of Jews, knocking them down and trampling upon their ragcovered bodies. Once I pulled my horse to, when I was stopped by an old woman rising from a snowdrift as ifshe had been livingin it. "Bread!" she cried to me, her empty hands trembling in the air. "Children!" she cried. "Bread and children! Bread! Bread! Bread and children!" But what were her losses to me? Her eyes were crazed, her lips seemed to be exploding in small boils. I was furious with her. I dipped my saber down and cut through the snow, to frozen earth. I dislodged some of it, and I flung it at her so that her mouth was filled with it-then my lungs filled with marvelous warmth, and I raced on to the city. Was I dreaming, even then? Had she been there? Was there anyone to whom I could tum to ask if I

had seen and done what I thought I had seen and done? My heart filled with a terriblejoy. "To the city!" Icried. To sack and burn the houses of the rich moneylenders! To take pleasure from strange women! To avenge myself yet once more for what was done t.' me so many years ago

Yet even as I rode on amid the thunder ofother horses, I knew in my soul that it satisfied me but little to pillage and loot the homes of wealthy Jews, or to take my bestial pleasures from their wives and daughters. I had satisfied myself in these ways before, and I knew how deeply I had come to loathe myself for doing so. And yet I knew also that without these opportunities-meager as they seemed to me-to satisfy the rages and desires within me, I would never have survived at all. For these acts of vengeance were to me tastes of the feast to come-they kept my Dream of Vengeance alive-that Dream which spurred me on, that Dream and Hope which were lodged forever in my breast and which sustained me when all else failed. For I had learned this, during all the years that had passed since that dread day when I had been stolen from my village by Jews and sent off to serve in the tsar's army: that the actual taking of revenge for what had been done to me only served to fill up the wells of my bitterness.

In the city the soldiers and the police were beating the Jews with unmerciful cruelty, torturing them without cleverness. I saw a soldier club an aged woman into the snow and drag her into a doorway and lift her black skirts. I saw a man with blood spilling from a hole in his eye. I heard mothers wailing for lost children. I saw a woman appear at a window high above me and tear patches of hair from her head before she shrieked and tumbled to the ground. But I did not hear her fall. I saw a man try to run past soldiers, a Torah in his arms, but the Torah was ripped from him, and the gold and silver ornaments were ripped from the Torah. Jews scurried like rats, trying to flee, trying still to load themselves with possessions. I could smell the fragrant, rich odors of burning flesh. My heart was full.

I abandoned my own horse and left it in the blacksmith's shop, directly outside the Jewish quarter. Then I made my way toward their homes-toward the homes of the wealthy Jews, those whose horses I had shoed, whose droshkies I had repaired, whose iron gates I had built. I knew them well. I knew the favors they could

buy, from the police and from the army and from the government. And I knew in which houses lived the members ofthe Kehilla. Here, as in the village in which I had been born, they were the worms who, in their vanity, believed themselves to be the chosen of the chosen-the most beautiful of God's creatures. But now, their houses in flames, though they would crawl upon their bellies, they were not even cunning serpents. What will befall all Jews, I thought, remembering the old saying, will befall each Jew. Forever and forever and forever! No longer would they prey upon poor Jews, no longer would they live without fear. Their feast was done and I would have my way with them.

But most of their houses were already deserted and in ruins. The soldiers and police had been there before me. I had stayed too long outside the city. Still, I took my pleasures-I smashed windows and goblets, I slashed at furniture and walls, I searched for hidden treasures in floors and ceilings. I drank and grew dizzy. I threw my arms around the shoulders of my fellow soldiers and I kissed them with abandon. We poured marvelous curses on the Jews. Maythey wander forever in the snow with the howling ofwolves in their ears! May their feet and hands freeze and may we be there, in our mercy, to pour boiling water upon their toes and fingers! Maythe mothers live to see their daughters violated by the horses of Turks!

Then I heard the screams of a solitary wealthy Jew, who had not yet fled, and my heart thrilled as I rushed through the door of his house. But three policemen were alreadythere, laughing raucously. The room had been ravaged. Against a wall I saw the back of another policeman, bent over. Underneath him a boy with startled and pained eyes stared to the side, in horror. He was halfdressed. I followed the boy's eyes and I saw that the other policemen were forcing the mother to watch this unnatural act, a knife at her throat. My dull senses were suddenly on fire, and it was not the screaming in the room that had enflamed them, and awakened me.

Rather, it was the sound of gentle breathing which made me tum. An old man sat against a wall, abandoned by the policemen. His daughter lay next to him, her eyes covered with her forearm, in shame. She clutched at her legs, but I saw no blood. The old man stared across the room, his eyes wide and blind-and when I looked into them and he did not look back, it was as if, in the deep pools of those eyes, I could suddenly see myself, and my own father's suffering, when I had been taken from him.

I had seen men couple with other men before. I had seen men kill other men and violate small children. I had seen men in the most abominable acts. I had seen them perform with animals. I had seen men torn apart by wolves, and I had, in the coldest winters, not even turned my eyes away when starving men sustained themselves by the only means possible, when all help was gone and their comrades lay dead and frozen beside them. There was nothing I had not seen during the many years since I was first stolen from my father's house, taken by the Kehilla, and sent away to serve for twenty-five years in the tsar's army.

And suddenly I was that little boy again-the boy who had once been his father's hope and dream. All had been sacrificed so that I might study and become a man of learning, for in me, my father believed, God had planted a special gift. I was my father's jewel. Unlike him, and unlike my brothers and sisters, who were good and hardworking Jews, I had been chosen by God, my father believed, to serve Him with my mind. Myfather dreamed ofseeing me sit one day in the synagogue along the eastern wall, with the other honored and learned men of the community. He dreamed ofseeing me sit at the right hand of our Rebbe, studying Talmud. How cruel his dreams! How vain his hopes! But how wonderful his clear brown eyes when he heard me read and called my brothers and sisters to hear me! Worship was the highest expression of love, he had been taught, and study was the highest form of worship. He held my hands and touched my fingers gently, and he told me that they would always remain pale and fine, like a scholar's-never rough and broken like his own. Never would I be an amoretz like himself! Never! Never

How proud his eyes when the Rebbe of Burshtyn came to our meager dwelling one evening to tell my father that yes, there was a special quality that God had put into my soul which made it incumbent upon the Rebbe to take me as his pupil, without fees. My father counted the Rebbe's words as if they were pearls. The Rebbe praised my father for having borne me into the world and for having protected me until that day. Jews, he said, were like unto a vine of which the grapes represent the scholars and the leaves the simple folk. I hung upon his words and they made their way into my heart and I never forgot them. The leaves of the vine had two important tasks-they were essential to the growth ofthe vine, and they protected the grapes-and therefore they were of greater

importance, since the power of the protector was always greater than the power ofthe protected. In the same way, he went on, as the rabbis had taught, it was better to love than to be beloved

How beautiful my father's eyes when he listened to the Rebbe's words! His eyes were, I thought, the color of the soft earthen bottom of the clearest lake. How full and rich and complete his life would have been had he carried the Rebbe's praise to the grave! How happy he was to sacrifice all so that I might study! Torah was the most precious of wares, he would often say, and a Jew must sell all else to have those wares.

And so I began to fulfill my father's hopes and dreams-I learned to read and to pray, and when I began the study of chumash, my father bought for me a new suit and I was covered with a talis and my mother and sisters showered candy and nuts upon me. But I never even began that real study with which the Rebbe tempted me so lovingly-the study of Talmud. For it was while I was walking to his house one morning, only a few months after his visit to our house, that I was suddenly set upon by three men, who told me that the Rebbe was ill and that they had been sent to take me to the doctor's dwelling, where the Rebbe was waiting to receive me so that he could, should he die, give me his blessing. Their treachery had no bounds, and I followed them without suspicion, for my heart was open in those days.

But then were my father's eyes made blind and his heart cut in two by their evildoing. For they led me straightaway out of our village and to a hovel, wherein I was bound hand and foot and mocked by my kidnappers. They are Jews too they are Jews too, I kept thinking, while they taunted me with terrible stories of the life I would lead in the service of the army of Tsar Nicholas the First. But even their cruel visions turned out to be nothing compared to the life I did come to live. Their imaginations were as meager as their souls.

They counted their money in front of my eyes, ami the name they uttered was that of Toporofsky. They were fearless and shameless, but I told myself even at that very moment that they were only servants doing the master's bidding. I had heard before ofboys like myself being snatched by the khappers-kidnapped and substituted for the sons of the wealthy, whenever the cantonistgzeyrathe evil order-chanced to fall upon a wealthy family. I knew also

that Toporofsky had only one son, the shayne Noah, as he was known in our village-a boy who was already studying with the Rebbe when I had come to him and who was as fair as he was brilliant. Iwas never able to deny it-I had wanted him fora friend. My beloved Noah-my beautiful, talented Noah! I had singled him out as the boy I would have desired to have as my own brother.

But my tender feelings toward Noah were short-lived. Feeling more the hurt my father would soon feel-that helpless rage at not being able to reach me and to bring me back, that passionate loathing he would surely come to direct against himselffor my loss -my heart, rather than breaking in two as I believed my father's would, filled up with bitterness. I vowed, even as I lay on an earthen floor in a hovel in the woods, that some day I would make the father of Noah suffer as he had made my father suffer. If Icould not escape from my fate-and my father with me-yet would I do everything I could to see that I shared that fate with the Jew who had been its instrument.

All this I remembered-and more-as I stood in a strange Jew's house in Kiev and saw a father sit by, helpless and dumb, while his son-a boy the age, I imagined, that I was when I had been stolenbecame the object of a degrading spectacle that would soon become a memory more hated than life itself. God had promised Abraham that one day His Jewish people would be as plentiful as the stars in the heavens and the grains of sand in the sea; yet surely life had shown that it was the bitterness that was forever being held in store for us that was so plentiful. And tasting a portion of that bitterness yet again, I also realized something strange, and for the first time-that surely, by now, my father was dead and buried and that he and I had never, in all the years that had passed, seen one another again.

For when my service oftwenty-five years was done, I had chosen not to return to my village, feeling that to see the animal I had become would have been more painful to my father than to have seen that I was alive. Better to live with a scarred heart, I reasoned, than to make that heart tear again. But I did not fool myself. I knew, even when I made my cowardly decision, that there was something I feared even more than seeing my father again-and that was the fear that if I had returned and we had embraced and he had come to know all that had happened to me during the years we

were apart, he might have forgiven me-and I might have come to forgive myself-and that ifthis had happened I would have'lost the desire to avenge myself, and with it the very dream that I had come to believe was the essence of my being-my true self-and the sustenance of my life.

Almost forty years had passed since the day I did not arrive at the Rebbe's house, and listening now to this other father's quiet breathing, and thinking that my own father had already diednever having seen me or touched me or known me as a grown man -I realized also that I was the age he must have been when he had last seen me and that I had not, with my seed, borne children who would live after me.

He had died without having seen my face again-and imagining in my mind's eye his hungry eyes staring at me from his deathbedhis eyes searching for me and longing to give me his blessingmy heart broke at last. I tore at my hair and I screamed so lustily and with such desperation that the policeman turned to me as if I were the very Angel of Death. In his eyes he already knew-but he did not have a chance. I pulled his head backward by the hair and I slit his throat from one side to the other, in a dark and beautiful crescent of blood. Then, still howling, I made for the others-but they saw my eyes and what I done, and they fled.

I could not utter a single word. My mouth opened, but my tongue was swollen and mute. I turned away so that the family could endure their shame without my eyes upon them. 1 heard the father weeping now. I looked back. The father was down upon his knees before the boy, and they were embracing. 1 wondered how he could have touched his son so soon, without revulsion, and then I wondered how 1 could be so low and loathsome as to doubt the strength of a father's love. I was frightened, as the policemen had had cause to be frightened. 1 stepped toward the family and they moved back from me, and I saw in their faces that they were now wondering if 1 was going to set upon them next.

1 felt as if my life's blood were pouring out of my heart and running in rivulets across myhairychest, flowingthrough the cloth of my cursed uniform, drenching it and weighting me down. 1 felt that they might die of fright if I could not find words with which to save them. I breathed upon them and then I spoke. "I too am a Jew!" I declared, but 1 could say no more. The girl fell forward and

clutched at my leg, uncovering her eyes. The father bowed his head, and, still on his knees, he began to give me his blessing. I stopped him and I spread my arms and they came to me. I would be their protector! I showed them the door, and made signs to them with my hand and with my knife. They understood. We would go out into the streets and make our way, with other Jews, past soldiers and horses and burning buildings, and I would save them. I felt delirious. I bent over the policeman and I removed the jacket of his uniform, so as to cover his face, and when I did I found -may God forgive me as He will surely never forgive him!-that against his bloodstained undergarments he too wore the silver Star of David.

i Thieves' fate

Milovan Djilas

We knew the Germans were tough, but we hoped that at least the Occupation would usher in a kingdom ofthieves. After all, it was a time of anarchy.

And that was the way it almost happened. The police ran off or were killed in air raids, traffic was jammed, and there was a scarcity of just about everything. But apparently a kingdom of thieves was a long way off, if attainable at all.

When the Germans entered the gutted and deserted city, they established a curfew. After dusk they fired at everything that moveddogs, cats, rats. They strangled the night; it ceased to be the golden time of the lover, the thief, the rebel.

Copyright e 1978 Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. All rights reserved.

though. We sneaked through the ruins and crept across backyards and down into sewers.

Just as we got the hang of things, and figured out how to survive under the German evil, the Germans started arresting people.

Rumors circulated that they were sending men off to Germany to work and holding only the Communists. Since I was picked up for no reason at all this time, I was less frightened than during any of my previous arrests.

Jails are jails. This new jail didn't seem too terrible. Just an old army barracks, spacious and rambling, which the Germans used in place of the bombed-out prison.

Also the makeup of the prisoners, though strange, helped allay my fear; thieves, paupers, students, men of wealth, illiterates were all thrown together. You could gamble away your soul, transact business, run rackets, or just loaf. Nobody gave a damn.

The respectable men, "the gentlemen," were mortified to be in jail, especially with thieves. We had a great time feigning pity for them. Sure,jails were for us, the lawbreakers, but what in the world were they in here for?

They sopped up our sympathy and for the first time saw us thieves as human.

The moneybags were certain that the Germans had jailed them to get rid of the competition. We gentlemen of the night couldn't understand why we were there. We could only think that the Germans were dead set on achieving order, and thieves are not overly conducive to that end.

Two men differed widely from the rest of us, and yet more from each other: a bearded professor and a beardless student. Somebody tagged the professor "Apostle," not sci much because of his ascetic appearance, but more because he ranted about repentance and solidarity in the terrible disaster that had befallen Serbs. The student we called "Class." He used that word often and insisted that everyone be judged in terms of the class he belonged to and whose interests he represented. He opposed the professor: misfortune had struck only the Serbian working classes; the Serbian bourgeoisie, no longer able to protect itself, had acquired a new protector in the German invader.

The arguments between Apostle and Class attracted us thieves; in fact, we found them much more amusing than the bloody brawls in the taverns. Although we never made an issue of our identity as

Serbs, we couldn't help feeling like Serbs. And although we didn't belong to the working class, except when we were forced to, we knew we'd never become bourgeois.

Apostle warned us: "They'll exterminate all Serbs. They'll snuff out the Serbian candle." Class objected: "The rich never cared much whether they were Serbs or not. The people are indestructible-they'll take up arms and ensure their survival." We were not intimidated by the doom in Apostle's voice or heartened by Class's pluck. The thieves' worries were mundane: food, tobacco, sex, gambling-and, of course, figuring out ways to escape. But the gentlemen were terrified. They rapidly wilted on their unaccustomed regimen of dry bread and hard beds. They were in absentminded agreement with Apostle. On the other hand, Class, with his confident air, made quite an impression on the students and the workers, who were eager for a fight and for a future.

One thing drove Apostle to despair, while it confirmed Class's suspicions. The same guards and officials who had formerly served the state now served the enemy. The thieves, however, were apt to regard this as auspicious. The masters had changed and life had become different, but jails remained more or less the same.

Another thing worried us all, and that was the fact that no food, messages, or clean clothes got through to us from our women. Not even the educated prisoners could recall reading in their books that such a thing ever happened. We all hoped it was temporary. Nothing, not even the Germans, could stop women from taking care of their men.

We could learn nothing from the guards, not even from the two Ilijas of formertimes-Ilija the Flail, a sergeant, and Ilija the Cake, a detective.

These two Ilijas had been notorious for so long that criminals had heard of them before entering the prison. Injails, only faceless, formless men keep their real names. So the two Ilijas were known to everyone, including the officials, by their nicknames, Flail and Cake. And though Cake was hardly kind, Flail was worse. When he beat a man, a flailing would have felt better.

In his youth, Cake had been a burglar. Today burglars are the aristocracy ofthe underworld, its champions; their work is dangerous and they don't talk. No one ever learned what made Cake tum policeman. There were two versions, both impossible to verify: first, that a girl refused to marry him unless he mended his ways

and, second, that he started loathing himselfwhen he opened a safe and heard the woman of the house moan as ifthe safe had been her child. In any case, he soon became a most dreaded detective. He knew legions of thieves and burglars, and could tell the lawbreaker from the way a job was done. He never hit anyone except when someone resisted or attacked him, at which time a different Cake was released, powerful and cruel. He never forgot or forgave anything, no matter how trivial. He developed an elaborate, evil network of informers, not the usual prostitutes, pickpockets, waiters, and janitors but prisoners and their families. Cake did many favors for those he so diligently sent to prison. He carried messages to their families, brought back clothing and food, and protected the prisoners from Flail and other sadists. He was immune equally to thanks and to curses. In his dark eyes, sheltered by thick brows and long lashes, there was an ever-present sadness. His sadness was for human suffering and human pleasure, both unappeasable, and for immutable human lawlessness-essentially unfathomable.

Flail was a peasant and desperately eager to serve in the army so he could eventually become a policeman. He was a fair-haired, square-headed mountain of a man, with huge hands. To him, men were guilty by virtue oftheir imprisonment, and he felt it his duty to beat them every chance he got, unless someone higher up ordered otherwise. He battered the prisoners passionately, to compensate for his despair at being condemned to a lowlyand mean profession. He pounded them with his fists, punching ribs and kidneys, till he was out of breath. Then he'd really go wild and continue until his victims lost consciousness or spat blood. For them, jail brought back memories of bloody spots on the cobblestones in the prison yard. Flail hated prisoners. He forced them to scrub the concrete floors and polish the tin shit-buckets, bellowing, "If it were up to me there'd be no more jails. No more prisoners. I'd exterminate you like ticks!" When bread was handed out, he'd bark, "Take it, and goto hell! IfI had my way, you'd all be dead, like dogs in the night!"

So God had arranged it: outside, Cake was the scourge; inside, it was Flail.

Strange though it sounds, we expected an explanation from Flail for the senseless arrest of hundreds of men-hundreds in our prison alone. Maybe it wasn't that senseless. Everything had turned upside down, and not even Flail could go on being what he was before the Occupation. His homeland had become part of a

new state, made up of bits and pieces of the old one. The final goal of that state was the extermination of all Serbs within its borders. This was too much even for Flail, because a state's duty had never been to' persecute the innocent. Yet what never was came to pass now, and Serbs were killed indiscriminately-first the innocent, the helpless, the meek. So it came about that we could walk past Flail in peace. We could even shout to each other and smuggle cigarettes and messages, while he just brooded or issued halfhearted warnings. His thumbs hooked into his belt, he would stare forlornly at the flagstones in front of him or sadly eye the rectangle of sky. It was from this new Flail, shaken and subdued, that we expected to find out about the mass arrests.

Even Cake said nothing. He came to work punctual as ever, but now could barely wait to leave. He was withdrawn, as ifembittered by human corruption. He grew listless and flabby. His fierce, dark eyes were empty.

The excitement slowly subsided. We were getting used to our new way of life. The gentlemen were bewildered by their predicament, and we amused ourselves at their expense.

At that time I really started to worry, and all because of llija the Cake. We had known each other since childhood, when we prowled the empty lots at Cubura and hung around the marketplaces, swindling peasants. Though he later went straight and I stayed as God created me, he was still sentimental. For instance, he never expected me to be an informer. Now, not only did he not so much as hint to me the reason forcrammingsuch a crowd into thejail, but he even avoided my eyes. And though I was a veteran prisoner, I was surprised to find no squealers among us. That really flabbergasted me. I never suspected that the Germans had brought with them a new kind of government-they didn't need informers.

The first chance I got, one morning when I was repairing conduits in front of German Commandant Weiss's office, I asked Cake, "What's going on Ilija, my friend? Why all these crazy arrests?" Cake acted as if I had insulted him, and then Weiss appeared, immaculate, smug, a statue come to life. Ilija flattened himself against the wall, German style, and stiffly bowed his head. Weiss acknowledged his salute with absentminded courtesy. It wasn't until the guard had closed the door behind the German that Ilija yelled at me, "Shut up and keep working-unless you want more trouble."

I didn't mind Cake's words too much at the time. Maybe they

were only intended as a warning. Today his words have a different ring, as if he had a premonition of what was awaiting us.

Hardly a week had passed since the incident when Weiss burst into our cell, accompanied by his Serbo-German retinue.

It wasn't dark yet, but the lights were on. It was time for inspection and roll call. There was nothing special, let alone foreboding, about it, except that Weiss was conducting the inspection rather than Schwarz, his. second in command. Anyhow, maybe because Weiss was in charge, we noticed the early lights in that ghostly interval between day and night.

Our cell was on the ground floor, next to the offices, and the first to be inspected. In former times, it housed twelve soldiers, but now over a hundred prisoners were crammed in, packed tight and lying on the floor. We would rise on hearing the key in the lock. To make roll call easier, we formed ranks four deep.

Weiss stopped us with a wave of his hand while a Serbian aide, lively and obese, a former chief of police, pursed his rectangular lips,. stroked his prematurely gray hair, and said, "We'll count later."

They counted us every evening and every morning, as is customary in jail. Though Weiss had waived the head count, he still wanted to know the number. He asked in German, "How many are you?"

The cell foreman was flustered, though he knew that much German. The count was not his responsibility, but that of Schwarz and the former chief of police.

"Idiot!" shouted the former chief ofpolice. "The commandant is asking you how many men are in this cell!" Then he turned to the commander and with an air of deference said, "Sir, according to our list, a hundred and three."

Silence followed. Then Weiss whirled around and addressed his slim, blond second in command, Schwarz, and his Serbian aide: "The simplest procedure would be to take all hundred men from this room, but it would be far more effective to take ten men from each cell."

Schwarz nodded curtly, while the Serbian aide commented with servility, "Exactly, sir. And also, if I may say so, sir, most just." Weiss's face ruled with loathing. To be reminded of justice seemed to him stupid and irrelevant. When the Serbian aide spread out his list of prisoners, Weiss stopped him with a motion: "Just draw circles around the names of those I choose."

Weiss looked us over. It was then I noticed for the first time that his irises were so black they were indistinguishable from his pupils. His eyes devoured us and crushed us. We all tried to look away but felt that there was no way to avoid their glittering darkness-eyes that enveloped each man individually, men's lives in bondage to power.

We never knew how Weiss chose his victims. He endeavored, so we guessed later, to have all classes represented. Even so, there were inconsistencies-four of the rich and four of the intellectuals; one was a contractor, and only one was from the lower classes, a thiefat that. But they were all strong and healthy men, young or middleaged. That's why we thought that they were being sent to Germany to work.

there was a father, as happens in misfortune, who tried to save his son by exchanging places with him, hoping that his son would be safer anywhere but in occupied Serbia.

Weiss noticed the exchange, but surprisingly made no effort to prevent it. He also saw Ilija the Cake whispering to Schwarz and his Serbian aide, pointing out the exchange. The Serbian aide made a face, and Schwarz grinned sardonically.

The Serbian aide circled the numbers of the chosen.

Weiss and his entourage left for the other cells. Two German noncommissioned officers and Cake remained to escort the picked men. Ilija the Cake then ordered the son to go where he belonged and told the father to take his place among the prisoners. At first the Germans didn't understand what was going on, though they didn't much care whether it was the father or the son.

The father implored, even resisted. Ilija the Flail grabbed him by the collar and dragged him along with the rest. They took the whole group out into the prison yard.

We rushed to the windows.

The commotion inside was so great that we could hear nothing from the yard. Since it was forbidden to congregate near the windows, we agreed that only two men should remain at each ofthe three windows and tell us what they saw and heard.

I was nimble and experienced in prison ways, so I found myself hanging by the bars.

The chosen prisoners, tied together in tens, were taken into the prison yard-exactly ten tens, a hundred Serbs. Not long after they were gathered, we heard Weiss delivering a speech or reading something solemn, though we couldn't make out the words. Be-

hind my back, Apostle and Class were arguing quietly; their talk was distracting. Apostle was moaning that they would all be shot, considering that Weiss had selected mostly prominent men. Class contended that the men would be taken to labor camps, having been chosen on the basis of their health and strength. The bourgeois German army was bent on killing only the Serbian proletariat. "No, nol" Apostle insisted bitterly. "It may be a bourgeois army, but it still will kill only Serbs, all Serbs, bourgeois and proletarian alike." "Then all Serbs will become proletarian," Class taunted him. "I hope you are right," lamented Apostle. "Not a chancel Your comrades will provoke the Germans till they kill off all true Serbs," Class goaded him. "Look who serves the Germans -the same people who served your 'true' Serbsl"

The rest of us were silent during Weiss's speech. But the minute he finished there was a commotion, followed by cries in Serbian, commands in German, and a metallic clanking of arms.

The trucks' engines drowned all sound, except for a song coming from the first truck. From our perches on the windows we saw six trucks leave through the prison gate. The last one was uncovered and carried Serbian guards and German soldiers.

That evening we learned nothing. Nor could we come up with any decent explanations for what had happened. Only Apostle and Class continued their interminable argument, conducted in one language but sounding as if it came from the mouths oftwo utterly alien and embattled people.

Not until the next day could we piece it all together. Thejanitors were free to walk the corridors, and the Serbian guards were strangely listless.

Weiss had read the chosen prisoners their sentence. Somewhere in Serbia a. German soldier had been killed; in retaliation, a hundred Serbs were to be shot. It could happen again unless all Serbs forsook their criminal ways and stopped listening to their rebellious leaders.

Why did Weiss read out the sentence to one hundred condemned men when there was no possibility ofappeal?Perhaps the Germans were not yet accustomed to executing crowds of innocent men, so they kept, after their own fashion, to the traditional ritual of execution. An Orthodox priest was even brought to read the scriptures at the execution site.

The men were speechless, struck by the inconceivable horror of

what they had heard. Though Weiss had fervently hoped that everything would pass in silence, a Serb, stronger than he, cried out, "Thank you for the honor of letting us be the very first victims of Kraut bloodsuckers! From our blood

The man was cut short by rifle butts, and commands in German and curses and laments in Serbian. The engines were turned on, and the prisoners ordered to climb into the trucks. The man who had shouted started to sing. Othersjoined him, for the hardest way to die is in silence.

They were taken outside the city limits, to a firing range turned into a place of execution. There they were shot, in bunches of ten, by a German platoon. They were buried by Gypsies, who ransacked the corpses for gold and objects of value for the Germans and filched a little. They would probably meet the same fate. Afraid of rebellion, the Germans had exempted Serbian guards from participating in the shooting, but made them oversee the Gypsies.

The story was confirmed by Schwarz and his Serbian aide during the next day's inspection. Schwarz added, "All Serbs are hostages. You happen to be the first in line." Apostle answered him, "Serbs are forever hostages of death!" "Maybe so," remarked Schwarz dispassionately."But why boast about it?"

After Schwarz and his retinue left, all of us felt a strange relief. Maybe no more Germans would be killed, maybe there would be thousands more arrests, maybe the Allies would give the Germans a hard time and make them sweat to keep their wits together.

Like any other thief, I harbored the idea that flight was the only sure way to salvation. But Class sarcastically pointed out: "First a place is secured against escape; then it becomes a prison. There are bars on the windows and a triple row ofbarbed wire around everything."

At his perch near the window, Apostle hung limply from the bars, his arms long and smooth. He bitterly reminded Class, "They are putting up a wall at night. Using the spotlights. And you know who is building it? Your class!"

Class was taken aback for once, though only for a moment: "Yeah, some ignorant characters

Only the son wailed, the son of the father who had tried the exchange. He tore at his hair and cried, and in vain did we tell him that his father had almost sent him to die in his place. "No, no!" he

sobbed. "He sacrificed himself for me! That's the way my father was tt

We were adjusting to that limbo between life and death. Streams of new prisoners were arriving. They told us of the German attack on Russia. Class exulted: "Now the working class of Europe will rise!" But we thieves wanted to hear what life was like on the outside-whether it was any easier to steal, to hide, to get something to eat, and how our women were managing.

One of the newcomers was Mika the Badger, a famous burglar and the toughest operator in our neighborhood. Badger was also a childhood friend of llija the Cake. I still got along with Cake-I'd warn him of informers and he'd protect me from beatings-but Badger and Cake shunned each other like dog and wolf. Their relationship eventually deteriorated into mutual contempt, Badger calling Cake a dumb cop, Cake calling Badger a stupid thug. Even now, in a German prison, bad blood between the two would not subside. In fact, it became worse at their first confrontation. "So finally you have the masters you deserve!" Badger said to Cake in the yard. Cake was nonplused, but not for long: "A most fitting government for robbers and bums tt

Badger brought us stories ofthe hard life on the outside. Though the Germans had turned on the Reds, cramming them into a special jail, they hadn't lost their appetite for other Serbs, of whatever persuasion. They had already set up local police forces, so that it was harder to steal and the sentences were stiffer-the Germans knew of no sentence more lenient than shooting on the spot.

Our women, even the most irresistible, like Cica the Bolt and Dana the Gypsy, were still prowling around the claws of the German dragon-the noncoms and the truck drivers. The Germans regarded them as whores, though they were not quite that; they lived with anyone they pleased, and they only took money when they needed it to live on.

The Germans would give us no relief. Some ten days after the execution of the first hundred, Weiss came to pick out a second batch.

Again he was heralded by the lights going on earlier than usual. He chose ten men, and the Serbian aide circled their names on his list. The procedure was the same as before, only this time Weiss chose the prosperous and the prominent. After he had left, Class

said to Apostle viciously, "They want to terrorize your class." To which Apostle tearfully replied, "You and your kind will not acknowledge us as men even in death."

In the yard, too, the pattern was repeated. Weiss read the sentence, but the gentlemen didn't sing as they were being carted away.

Only then did it dawn on us that we had gotten used to nothing, and that we had unwittingly convinced ourselves that it was possible to live this way. One's own terror was reflected in the eyes of one's fellow sufferers. We became very close, and the room suddenly grew large as we huddled together on the floor. Even the quarrel between Class and Apostle petered out. Unable to sleep, Badger rose, stretched his arms, and knotted his fists: "How can men die without a murmur, without resistance?" Not a word in reply. Apostle muttered under his breath, "Whatever kept them going died long before they did." Class mumbled, "Consciousness. Consciousness is of ultimate importance."

We were paralyzed with fear. One morning Cake saw me scrubbing the corridor again. He wanted to pass by as if he hadn't noticed me, but I stood up and said to him, "What's going on, Ilija? How much longer do we have to put up with it?" He shrugged, walked past me down the corridor, and then suddenly turned around and said, "Joca, old Fox, not even the Germans know that. Unless being able to do just about anything they please does them in eventually."

Cake had never before addressed me in jail by my nickname, Joca, but always as Jovan, my first name. He had also called me by my other nickname, Fox, as if he was tired of not daring to be anything but a policeman.

On the fifth-or was it the sixth?-day, we were awakened in the middle of the nightby a howling somewhere to the northeast. Trees and houses were flying into the sky, as if trying to escape the tempest, their darkened shapes twisted in fiery convulsions. We decided it had to be the garages by the cemetery. Even though no one said it, we all knew what it meant: the next hundred were to die, and each man saw himself within that number.

The following day new prisoners were brought in. They confirmed what we had suspected-that garages near the cemetery had been set on fire, along with enemy trucks and cisterns. There were no dead among the Germans. But we all sensed that the destruction

of the trucks would be avenged on Serbs,just as ifsoldiers had been killed. Curses were heard against the arsonists, and Apostle wailed loudly, "Serbs have no greater enemies than Serbs! God Almighty can't save us now that we are destroying ourselves." Many looked at Class with fury in their eyes, as if he was personally responsible for the fire. Class said, "This is a struggle without mercy. The Germans have forced us to fight."

The very next day droves of new prisoners were brought in. At the same hour as all previous calls for execution, Weiss marched in with his entourage. "Merchants, businessmen, officials with university degrees, step forward!" he ordered in cold anger.

No one moved. No one wanted to die. "I have issued my orders!" barked Weiss, and the aide ran his finger down a list of names.

The first one to step forward was Apostle. Others followed him like a herd, more than half the cell. We suddenly realized that the thieves and the poor were not a majority, but rather that the prosperous and the educated were a silent and withdrawn bunch.

Weiss picked ten men. The aid called out Apostle and Class, and Schwarz sentenced them: "You two, a nationalist and a Communist, will have the honor of being first."

Class said, "I'd like to be fettered alone, if possible. These men are my class enemies." Apostle said, "I don't want to be tied to him either."

Weiss smiled bitterly and left the cell, walking with a stiff gait. Since he had made no decision one way or the other, Schwarz ordered the two tied together.

The Gypsy gravediggers couldn't tell us how the two had died. In a crowd of condemned men it is hard to single out individuals, even if the Gypsies had not been preoccupied with saving their own skins. Anyway we all knew that they had died without having settled their quarrel, each man unto himself. We mourned them. Some even wiped away a tear. Their absence had turned us into a rootless, hopeless, dying mass.

My memory of those days is confused. I recall, though, that the rich and the Communists were led away to the execution site. By and large, we thieves were left alone. We felt kind ofprivileged. We even thought that the thiefwho was included in the first hundred to be shot was a German mistake. The Germans must have finally concluded that Serbian thieves were no worse or different from their own. What good does it do you to be a Serb if you can't steal

or lie? The Germans would probably send us to forced-labor or reeducation camps, the same as their own criminals, and there we would do all right, or no worse than the rest.

Several times in that period 1 ran into Cake in the corridor. He didn't know what was going on. Once he even made a sour joke: "The time has come for us to envy the thieves. For how long?Only the Germans know that."

Ilija the Flail knew nothing, and we didn't expect anything of him. He was preoccupied with himself, with the same obtuse cruelty he had at one time shown toward the prisoners. He was reluctant to start a conversation but overjoyed to have someone address him. Most thieves felt terror in his presence-theycouldn't forget his cruelty, and they were not at all sure that he wouldn't suddenly revert to his own ways. But 1 ventured to embarrass him from time to time: "How come, sergeant, sir, that you who once zealously performed your duties as guard and jailer in the name of king and country now do the same for the Germans?" Flail would blush and stammer, "That's not for me to say; someone higher up is dealing with that." Another time 1 said to him, "We are both taught, since we were children, to fight the enemy, and now here you are with the enemy, acting as a jailer and a guard even to those who taught you." He answered, "I don't know. All 1 know is that Serbs have lost their minds."

For the next two weeks nothing ofconsequence happened. Once again we plotted and schemed, settling into the old routine.

Then a group of thieves and vagrants was brought in. Among them was Dragi the Prince, a swindler known to police departments throughout Europe.

1 had gotten to know Prince in jail during one of my previous arrests. He was grudgingly respected by the police, and the prisoners idolized him and envied him. Every time he was arrested he promptly received money and parcels and visits from a famous lawyer. He was always allowed to conduct his own defense. He had always, except once, managed to get off the hook. He engaged in intricate swindles, which were difficult to prove, such as seducing rich widows, selling forgeries, peddling fake antiques. He spoke many languages, not fluently but enough to get by. His schooling was by no means extensive, but he appeared well informed, even to scholars, for he knew a bit of everything. His special interest was

history, particularly the lives ofpoliticians and prominent men. He kept his distance from thieves and police alike. He regarded the former as strangers among whom he was thrown by a quirk offate, and the latter as busybodies sticking their noses into his affairs out of sheer ignorance and stupidity. He treated both groups with condescension and compassion. He acted as if he understood that no one could be anything but what God had made him: a thief was a thief, and a cop a cop.

It was not surprising that he arrived impeccably dressed. But it was astonishing that after six weeks his clothes were still clean and pressed.

Prince had an excellent and resourceful memory, which helped him to survive. He recognized me as soon as he had settled down in the cell. He stood there, tall and dark, with bony hands and a trimmed mustache. He addressed me much more cordially than he would have before the Occupation. But then I had done him a favor: I had smuggled a note for him to a diplomat, an antique collector. Maybe that was no special favor, but I felt proud that Prince had recognized me and singled me out among all the rest. He even shook my hand, and said to me in a low voice: "The trouble is, Joca, that not even the Germans know what they want. There just isn't any government. Power and the military, but no government! Rebellions all over Serbia. The Germans now realize that there must be some kind of government; that's why they've formed a new Serbian cabinet. From now on the Germans will carry out executions in an orderly fashion, and only when the need arises."

The news of rebellions made us dizzy with pride. But we felt no reaction to a Serbian collaborationist government, for it would have little or no bearing on our kind of activities. The gentlemen, however, responded very differently: they were overjoyed to have a government, any kind. The Germans would engage in some sort of politics and stop shooting people indiscriminately. Yet they were less than happy to hear about the rebellion, even those among them who understood that without rebellions there would be no need for such a government.

I was curious to hear what was going on in my neighborhood, and what the chances were for thieves, though I assumed that Prince wouldn't know too much about that. But it turned out that Prince knew much more than I dared hope. He had been forced to

leave the bombed-out and strictly policed downtown area and move to the suburbs. He would never have been arrested had he not gone downtown on business in the middle of the day and been caught in a police raid. According to him, there were opportunities galore for all kinds of swindles, but no professional thieves or con men to do the job; swarms of petty chiselers from nearby villages had descended on the city, a sickening bunch that tore out chandeliers and ripped out stoves in exchange for a basket of eggs or a chunk of cheese. They prowled the backyards to snatch a pair of underpants or a pillow case from a clothesline.

Trade and business were still quiet. Everything was, in fact, except for bars and whorehouses. The Golden Barrel was in full swing, and Dana the Gypsy was singing there again.

It was at the Golden Barrel that Prince met Dana. "The Germans thought," said Prince, unexpectedly garrulous, "that Dana was a Gypsy, and they would have sent her to a concentration camp had not a Serbian policeman explained to them that the nickname 'Gypsy' was a term of endearment. Both the nickname and the diminutive Dana were given her by her Serbian admirers. She is now singing German songs and entertaining German noncoms and Serbian policemen and black marketeers. She plays hard to get. Even so, she hasn't gone beyond German lieutenants and Serbian police clerks. The German officers are taken care of by ladies from the upper classes: opera singers, daughters and widows of bankers and real estate operators." A sad story for me to hear, and for Dana's admirers. Her songs had charmed many a scholar, poet, and millionaire; her dark, sparkling eyes and her strong and sultry body had aroused them. Now all that was lost in drunken brawls with German sergeants and their Serbian counterparts, exchanged for worthless German marks.

I was happy to hear that Cica was well and as beautiful as ever, though her situation was no better than Dana's.

Cica was my woman, had been for some time. She was the bestlooking woman in my neighborhood, the most splendid female in the whole world. She was a part-time beautician and a full-time friend. She never participated in burglaries. That wasn't her style. She never told the police anything, no matter how hard they pressed her. Once she was exiled to her hometown to pacify a millionaire whose son had fallen in love with her. She had been arrested many times for helping fugitives and for not registering

her tenants. She despised pickpockets and petty burglars. I think she loved me because my jobs were dangerous and difficult and, above all, not petty. Petty thieves have a petty philosophy, of working some and stealing some, and trusting in God for the rest. But I kept God out of my ventures, trusting instead in my brains, luck, and strength.

Cica accepted money and gifts, but without obligation, and she was always loyal to the man she loved. Oh, she did change lovers, but I always felt I was the only one. Her hair was golden, her breasts warm, her thighs like your mother's womb. I was always afraid that she'd suck in my soul with her upturned lips, and I always passionately wanted her to do so.

Ah, that was my Cica, the only person I could call my own. And now she was running around with a German lieutenant, Prince said. He had not talked to her, but he had seen her in the Golden Barrel and could describe her down to her shoes and a birthmark on her upper lip.

Prison is a place of sufferingand of much bitterness andjealousy of the outside world and the loved ones left there. All I had was Cica. I never knew my father, I hardly remember my mother, and my relatives got rid of me as soon as they could. Cica was all I had, but the trouble was I never had her. No one could ever have her unless she wanted it. She was with the German lieutenant because she liked it that way. There was no point in getting angry. No use tormenting myself. When I get out of prison, I thought, I won't hold it against her. What is there to bitch about? She never promised herself to me. She used to say, with a smile, her cheekbones high and her eyes wide, "I live as I please, and you do whatever you want."

Even so, I was happy when Prince said, "Maybe Cica is trying to save you. YQU know no one has ever been able to resist her. She is a relentless woman. The Germans may think they're seducing her or buying her, but she'll get what she wants and discard them like the rest. The Germans may be her way to you. The only way to get you out."

Ten days after Prince was brought in, the gentlemen started receiving parcels and changes ofclothing. Some even had visitors. And both Weiss and Schwarz turned mellower-Weiss keeping up his dignity and Schwarz holding down his contempt. The Serbian aide fawned less in his dealings with his German superiors.

One day Prince and I were taken to the Serbian aide's office. We found Cake waiting for us there.

While he was opening parcels and examining their contents, I couldn't resist asking, "Is that from Cica? Did she say anything? Is there a message?"

Cake was silent, carefullychecking the clothing and food. Prince gave me a slight smile and a meaningful look.

"Yeah, this is from Cica," said Cake. "She's telling you not to worry unless you've done something the Germans don't like." Then he added contemptuously, "The other parcel is for Prince, from Dana the Gypsy."

"The Germans don't like anything anyone does-these days," Prince said, as if to himself, and took his parcel.

Prince and I were the only criminals to receive parcels. I was so overjoyed, more by Cica's concern than by the parcel itself, that I distributed all my food to my friends. Prince, though not stingy, was more controlled: he shared hisfood withthe sickandthe needy. Then he said, "Now that's something-the Germans letting someone take care of us. The trouble is, once the shooting starts, they don't make much distinction between the well-fed and the hungry."

A couple ofdays after we received our parcels, the lights went on early again-in fact, earlier than usual. Again Weiss selected his gentlemen, this time some real notables.

As soon as Weiss had departed with the men chosen to die, the gentlemen pounced on Prince. "Liar!" they called him. "What government were you talking about? What agreement with the Germans? The only agreement they'll ever make with us Serbs will be when we are all six feet under."

Prince was taken aback. "Well, the Germans," he said, "you know the Germans. They do everything methodically, even insane acts. Something must have gone wrong. Somewhere. They have their rules."

Something indeed had gone wrong, as I found out the next day while I was fixing the basin in the Serbian aide's room. Cake was there, listlessly guarding me, when he said, "An ambush. An ambush of German soldiers. In some godforsaken village, of course. Noone warned the Germans ofthe ambush. Serbia can't be ruled under the best of circumstances, let alone by this wreck of a government. The Germans are taking their revenge on all Serbs. They aren't picky about the class so long as they've got somebody.

Last night another hundred went. Fifty notables and fifty Communists. Maybe there were some big shots among the Communists, but who can tell? They die under assumed names. Nobody knows what's going on."

I could see that Cake was really bothered bysomething. That the burden was not his alone was further demonstrated by a rifle shot that Ilija the Flail fired that same day, around midnight, into his own head.

Flail had been in charge of the sentries that night, under a German noncom, of course. The noncom had gone to sleep after they had made their rounds. Ilija was on duty, and there were thoughts in his head. Heavy, evil thoughts. To kill the thoughts, Ilija had decided to shoot himself. He had taken off his shoe and sock, and had fired the rifle with his big toe right into his chin-the proper way to kill yourself with a rifle. He didn't kill himself in the toilet-the place was unseemly-or in the office-he didn't want his blood to smudge the official chambers-but right smack in the middle of the corridor, because the corridor was a place that had to be swept clean every morning by the prisoners.

The shot made everyone in our room jump awake. There was wild commotion in the corridor.

Early the next day, while we were emptying the shit buckets, we got to know all the details, and we talked of nothing else: when it had happened, how big the pool ofblood was, where in the wall the bullet got caught. We were all anxious to know what Flail looked like dead. The blast had blown away the back of his head and scattered his brains all over wall and floor. His face, the face of a bully, had shrunk beyond recognition, until it looked like the face of a stillborn baby.

No one asked why Flail had killed himself. The night before, the Germans had ordered Serbian guards to shoot the hundred gentlemen and Communists; Ilija the Flail had been in command of the execution squad. He was either too strong or too weak to repeat the performance. So we mourned him as a man who had chosen for himself the fate of Serbs. The Germans didn't give a damn about Flail's suicide. Serbian guards continued executing Serbs allotted to them, and the Germans made sure that everything happened on schedule.

The Germans and their Serbian helpers couldn't imagine an emptyjail. They continued to round up new prisoners of all kinds.

The newcomers confirmed that the Germans had formed a Serbian government, and that the new government, in the interests of law and order, was intent on limiting the executions to participants in the uprising.

The poorer among the prisoners, and that meant us thieves too, were somewhat comforted by the news. So long as they didn't kill at random. As for the rest-who cared? The gentlemen were furious: some government, some law and order, they said; the Germans are still shooting men of prominence, innocence, and honesty.

We started segregating into rich and poor. Until then, the gentlemen had been joined to us by death, and they treated us well and carefully, as if our lives were as valuable as theirs. Now, suddenly, they were estranged from us and telling us that the enemy had more in common with thugs like us than with anyone else, and that we were not fit to die for Serbia. We figured we should lie low before German justice. Power and uprising were not our thing.

Only Prince and Badger were not fooled by the reprieve from execution. Badger said, "The Germans are eyeing Serbs for slaughter; no good can come from them." Prince took Badger and me aside and whispered: "There must be a way around German madness. We can't take up arms, and we can't escape into the woods; we don't have anything worth suffering or sacrificing for. Anywaythe rebels shoot thieves. We've got to convince the Germans that Serbs are worth more to them as slaves than as martyrs. None of those fine gentlemen have managed to do that."

The fine gentlemen didn't think much of this attitude. They had by this time shut themselves offfrom us, and we were more favored than ever. With much dignity and resignation, they continued to join their mortal enemies, the Communists, in common graves.

For leadership we people from the underground turned to Badger and Prince, the only two men who hadn't lost theiridentity in that panic-stricken herd. Curiouslyenough, the two ofthem had never been able to stand each other-Badger had despised Prince, while Prince had taunted Badger-but now they were growing reallyclose. Prince admired Badger's courage, and Badger admired Prince's mind. "If only I had his brains," he'd say. Prince never envied Badger his strength or courage; he thought the human brain more valuable than anything. "Brains always find ways to bend might," he'd say.

For the next few days nothing much happened. Then unexpectedly-I think it was a Monday, and I remember the time-ten o'clock, because Weiss was already in his officethey separated the gentlemen from us. The Germans came into the cell, and the aide called out the gentlemen's .names, and Schwarz ordered them to pick up their belongings. It was clear at once that nothing bad was to happen to them; both the German and the Serbian guards were relaxed and businesslike, not stiffand fierce as when they led men away to be shot. Besides, Weiss said to the group, "Perhaps Serbian leaders will finally sober up, and life will improve for you people."

The gentlemen were moved to the upper-story rooms, and the thieves from those rooms were brought into our cells on the ground floor.

No one had any inkling as to what that move meant. Except maybe Prince: he paced back and forth with his hands behind his back, wrapped in his thoughts, unapproachable. I saw him sitting on his bunk late into the night, smoking.

Several days later, Prince asked to see Schwarz. That seemed strange, even to those of us who had full confidence in him. What business had he with the Germans? What could he offer them? He knew a lot of our tricks and secrets. For us he was one ofthose rare people who break the law and squeal on no one. "H Prince is a squealer," said Badger, "we've all had it." He added, with a hiss, "I'll bash his head in."

Prince came back from Schwarz looking even more distractedso distracted, in fact, that I didn't have the guts to address him until we ran into each other in the washroom. He offered me a halfsmoked cigarette, and that gave me courage to say, "Hey, Prince, what's with you and the Germans?" He looked at me and arched his eyebrows: "There's no way to be on the good side ofthem. Not yet. They only recognize slaves and corpses. We are in serious danger. Couldn't be worse. The gentlemen and the big shots have made a deal with the Germans. What else could explain the separation? It's pretty obvious that relations between them are not as bad as they used to be. And what kind of a deal can we make with them? What can we offer the Germans? They don't give a damn about the tricks of our trade. And they aren't interested in the secrets ofthe prewar Serbian underworld. How do we get out of here alive?"

Then all the pieces fell in place. Not only Weiss and Schwarz, but all the Germans, down to the lowest rank, were sporting some

really fine jewelry which I'd never seen before, while the gentlemen were receiving visits from their wives, who were courteously accompanied across the yard by the German and Serbian guards.

That morning in the corridor I said to Cake, "What's going on? What's going to happen to us? They've separated us from the gentlemen." Cake cut me short: "None of your business. Protect your own skin and don't think!"

I couldn't stop thinking even if I'd wanted to.

That same day, around ten o'clock, Prince was summoned by Weiss personally. Prince didn't stay with him too long, half an hour maybe. After lunch Weiss took him someplace in his car. They came back around dusk, just as the lights were turned on. Prince's return reminded us of Weiss's tours of inspection, when he'd choose the men for execution. The memory sent the fear of God through us. Everyone fell silent. I was the only man in the cell still pretending to be admiring Prince.

Prince was aware of our behavior, but he didn't give a damn. He didn't have much use for the best among humans, let alone the worst.

I was surprised when he asked me and Badger to meet him in the washroom. But Prince was much less generous than we had hoped in our excitement over his confidence in us. "I'll try to get the two of you out ofhere, though I'm not sure I can make it myself. We've got to figure out a way to satisfy their greed or we'll never survive."

That was all that Prince told us. We were left to mull it over. I was satisfied, and Badger grudgingly modified his opinion of Prince's conniving with the Germans.

The next day Prince's forebodings about the agreement between the Germans and the gentlemen came true: we were sentenced, terribly and irrevocably, to be the sole suppliers of Serbs for retaliation-a hundred of us for one German.

This time there were no early lights when the German and Serbian guards arrived. They burst into the cell as the lights went on at the usual hour. Weiss wasn't among them. Schwarz was good enough for us thieves. Nor did Schwarz bother to make the selection. He left that to his Serbian aide. He had no trouble choosing his victims. He knew us well. He looked us over solemnly, pointed his index finger, and ordered the condemned men to step aside. He chose me. My blood ran cold. So I was to die, without resistance, easily, like the rest.

Schwarz kept watch over the whole operation in silence, as if

bored by his own immense self-satisfaction. Our Serbian guards were elated, all of them except Cake, who looked more withdrawn than ever. His eyes avoided mine. He was either unable or not brave enough to help me.

Prince saved me. He went up to Schwarz, whispered something into his ear, and pointed at me. Schwarz motioned me to rejoin the sullen crowd.

The aide substituted a Gypsy for me, a small-time chicken thief.

The Gypsy started to wail from the bottom of his heart. Tears were streaming down his closely cropped mustache. "Why me, dearest sir?" he sobbed. "Who'll feed my six children? Why me, a miserable Gypsy, when you have all these fine Serbs here?"

"Why are you crying? You don't have anything to lose, have you?" the aide said sardonically.

"No Gypsies!" barked Schwarz unexpectedly. "A Serb! I wanta Serb! Only Serbs in exchange for Germans! What's a Gypsydoing here anyway? They and the Jews are under special treatment. Transfer him to the Gypsy quarters and put a Serb in his place!"

Jews and Gypsies were not being exterminated yet. Jews were herded into concentration camps and put to work clearing up bombed-out areas. The Gypsies were confined to their ghettos, where it was hoped they would die of disease and hunger. Maybe the fact that for the moment the Gypsies were treated better than either Serbs or Jews gave the man the courage to say, "You're right, sir. This isn't the place for a Gypsy. Stupid me. I thought I'd be better off trying to pass as a Serb

No one gave a damn about the Gypsy. Schwarz glanced at him with boredom and contempt, while the aide spread his hands in mock horror-"Why do I have to deal with such garbage?" The aide chose a swarthy, stocky young man to replace the Gypsy and bowed slightly to Schwarz, as if congratulating him on his good taste. The young man joined the condemned meekly, in silence, with tears flowing down his face.

Everyone was preoccupied with his own problems. Or duties. The aide located on his list the names of the condemned and carefully circled them.

Then the guards escorted the men out, and we stood paralyzed. No one rushed to the windows to see what was happening. But Badger went stark raving mad. He stood in the middle of the cell and bellowed, "So that's what Serbdom has been reduced to! Let's

at least die like Serbs! Let's shout our battle cries! Let's, my brothers, rush the enemy, with tooth and nail, ifthat's all we've got. That way we'll die happier."

We listened to Badger with fierce, sullen pride, though we knew that was no way to talk. I calmed myselfslowly and deliberately. I helped Badger to simmer down, while Prince sat in his corner as if nothing had happened. That was the way he always acted when he didn't want to be a witness to something.

That same night a group of bold young thieves gathered in the washroom to discuss how best to conduct themselves at the place of execution. They racked their brains late into the night.

The next morning I was doing some chores in the corridor when Dija the Cake came by, acting as if he didn't know me. I followed him into the office on the pretense that I had to fix a lock on a cabinet. "Damn it, Ilija, since when have we thieves become such great Serbs? How come we suddenly count? Thieves and thieving have never brought ruin on anyone. The loot changes owners, that's all. Everything we steal goes right back to the merchants and bankers. The world wouldn't go on without thieves. Life itselfis a form of theft. What would you cops do without us? Even if we were the cause of all evil, we can't be blamed for killing Germans. Our lives may be worth nothing, but our lives have never before been taken for the crimes of others. If we are killed because we've stolen, fine. If we have to die because we are Serbs, okay-as long as we are not the only ones to pay the debt. But to die like this!"

"What the hell do you want from me?" shouted Cake. "You want me to argue with you?" He stood up at the sound of the gate and looked out the window. A dozen of the gentlemen were climbing into coaches, accompanied by their wives, who were crying with joy. Cake continued with his monologue: "What can I tell vou? I am not my own master! I can't leave my job for the same reason that I can'tjoin the rebels. Stay in the back row ifyou can. The ones in the front go first."