�50

lBtJRNETT A COLLIER

STANLEY ELKIN

OAKLEY HALL

�50

Editors':

Elliott Anderson, Robert Onopa

Art Director: Cynthia Anderson

Managing Editor: Michael McDonnell

Associate Editor: Anne-Marie Zwierzyna

Assistant Editors: Mariam Lease, Sylvia Martin, Mary Elinore Smith

Advisory Editors: Lawrence Levy, Charles Newman

Fulfillment:

Leigh Alexander, Judy Marrs, Mary M. Zakrasek

Contributing Editors:

Robert Alter, Michael Anania, Gerald Graff, John Hawkes, David Hayman, Bill Henderson, Joseph McElroy, Peter Michelson, Robert Ray, Tony Tanner, Nathaniel Tarn

TriQuarterly is an international journal of arts, letters, and opinion published in the fall, winter, and spring at Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. Subscription rates: One year $12.00; two years $20.00; three years $30.00. Foreign subscriptions $1.00 per year additional. Single copies usually $4.50. Back issue prices on request. Contributions, correspondence, and subscriptions should be addressed to TriQuarterly, 1735 Benson Avenue, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60201. The editors invite submissions, but queries are strongly suggested. No manuscripts will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped. self-addressed envelope. All manuscripts accepted for publication become the property of TriQuarterly, unless otherwise indicated. Copyright © 1979 by TriQuarterly. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this magazine are to be attributed to the writers, not the editors or sponsors. Printed in the United States of America. Claims for missing numbers will be honored only within the four-month period after month of issue.

NATIONAL DISTRIBUTOR TO RETAIL TRADE: B. DEBOER, 188 HIGH STREET, NUTLEY, NEW JERSEY 07110. DISTRIBUTOR FOR WEST COAST TRADE: BOOK PEOPLE, 2940 7TH STREET, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94710.

REPRINTS OF BACK ISSUES OF TriQuarterly ARE NOW AVAILABLE IN FULL FORMAT FROM KRAUS REPRINT COMPANY, ROUTE 100, MILLWOOD, NEW YORK 10546, AND IN MICROFORM FROM UMI, A XEROX COMPANY, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN 48106.

Oakley Hall is the author of fifteen novels, including Warlock, Corpus of Joe Bailey, Downhill Racer, and most recently, The Bad Lands (Atheneum). "The Kid" is excerpted from a work-in-progress entitled The Spiral Castle. Mr. Hall is also at work on a long novel to be called The Great Journey, about the conquest of Mexico. His short stories have appeared in Antioch Review and Hawaii Review. Mr. Hall teaches at the University of California, Irvine. He lives in Squaw Valley and Balboa.

Peter Collier's The Rockefeller's, An American Dynasty (1976), coauthored with David Horowitz, was nominated for a National Book Award and became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. His first novel, Downriver, was published by Holt, Rinehart and Winston in 1978. Mr. Collier has worked as a free-lance writer and as an editor at Ramparts magazine. He is presently at work on a new book concerning men's liberation. Mr. Collier lives in Oakland, California.

Virgil Burnett has just completed a series of new drawings for a show at the Jacques Baruch Gallery in Chicago. His illustrations for a recent translation of the Exeter Riddle Book (Folio Society of London), and 33 Desseins (Editions l'Oeil de Boeuf) were published in 1978. He has exhibited work in Canada, .Switzerland and France. Mr. Burnett has published two previous stories in TriQuarterly: "Queen Constance" in number 40; and "Picaroon" in number 42. He

lives in Toronto, Canada.

Stanley Elkin is the author of, among other works, a collection of novellas entitled Searches and Seizures which was recently reprinted by David Godine; and The Franchiser, a novel. E. P. Dutton will publish a new collec, tion of novellas, including"The State of the Art" in a volume entitled The Bottom Line in 1979. Mr. Elkin has received grants from the Guggenheim, Longview and Rockefeller Foundations, and has been twice nominated for the National Book Award in fiction. He lives in St. Louis.

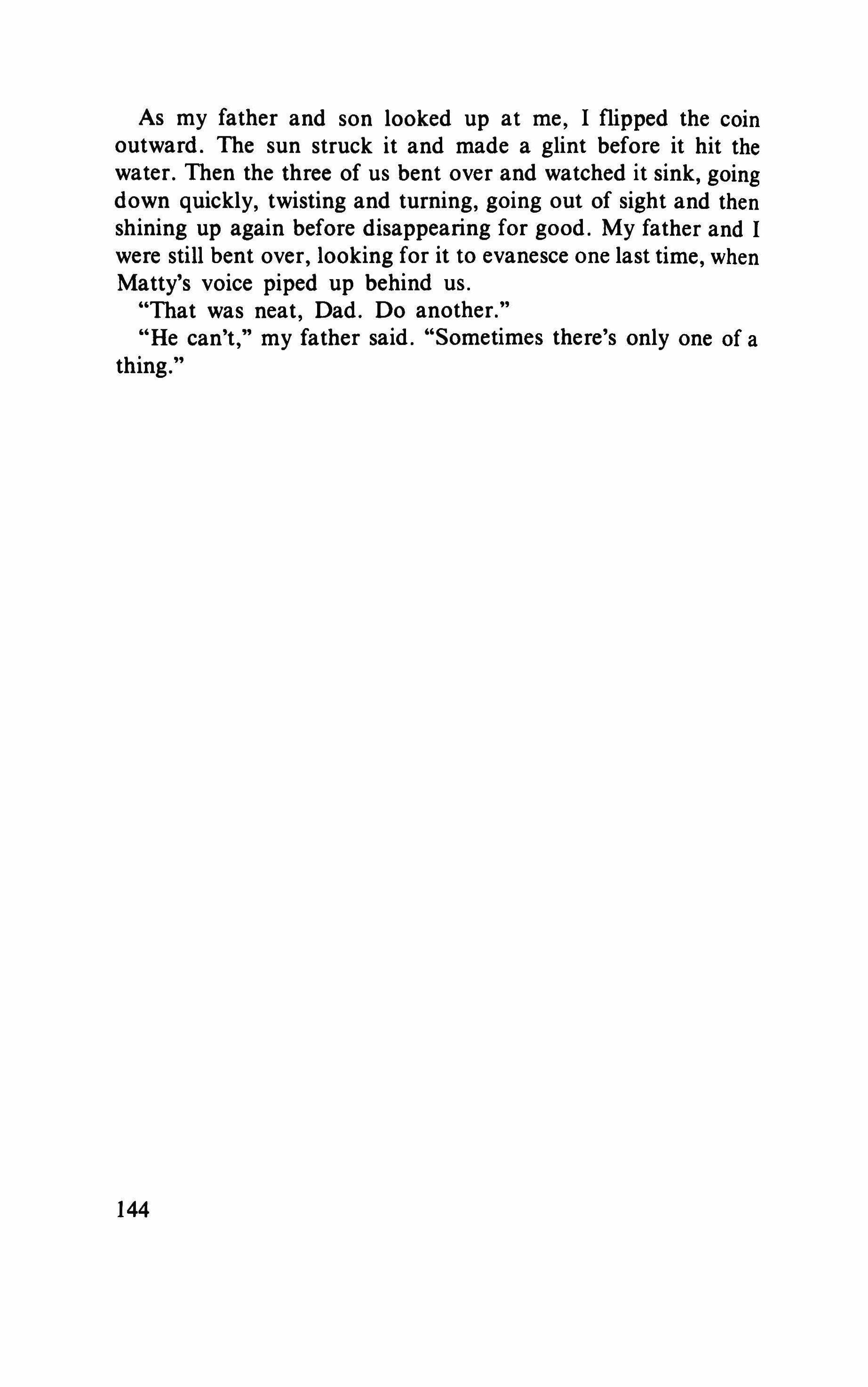

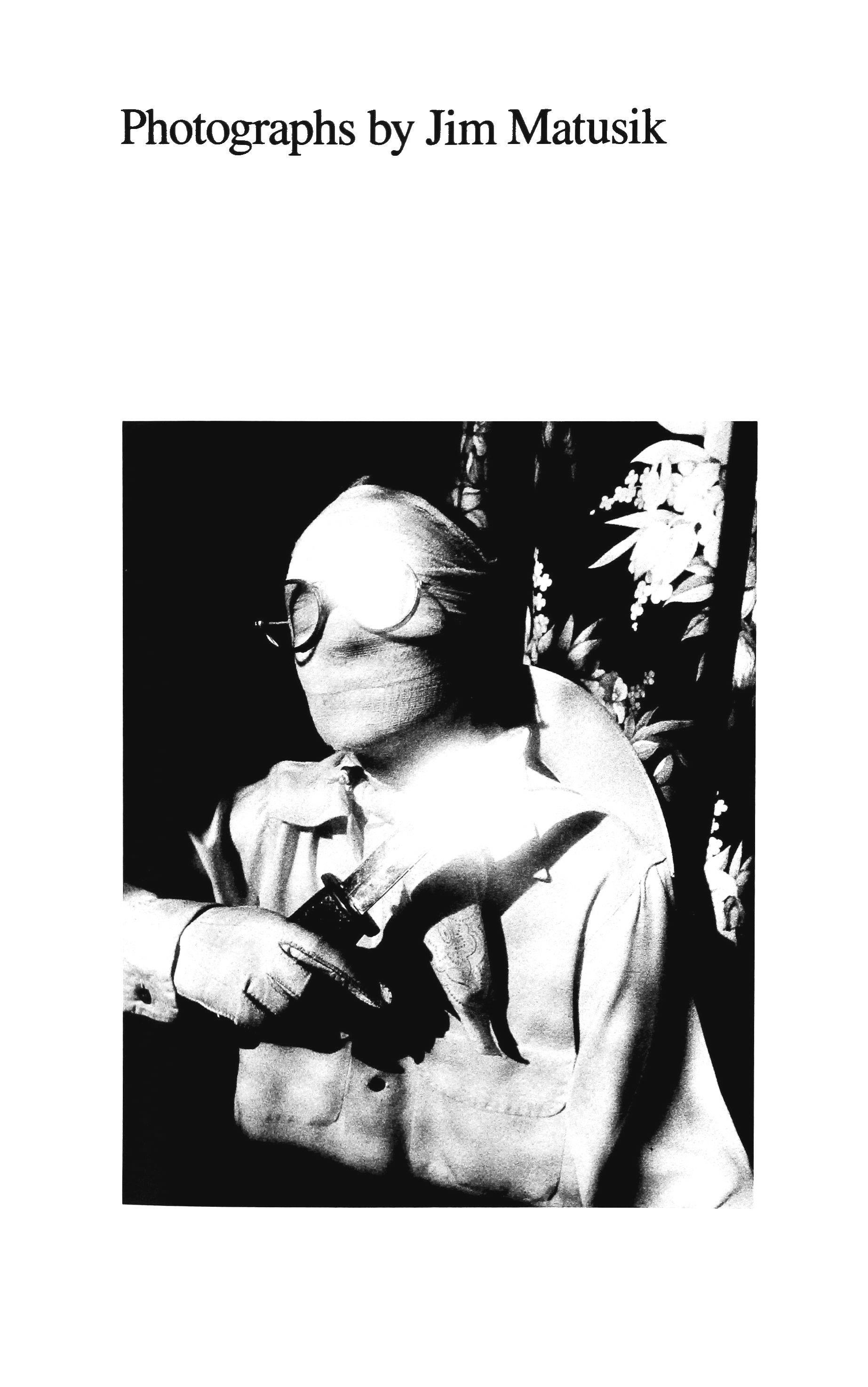

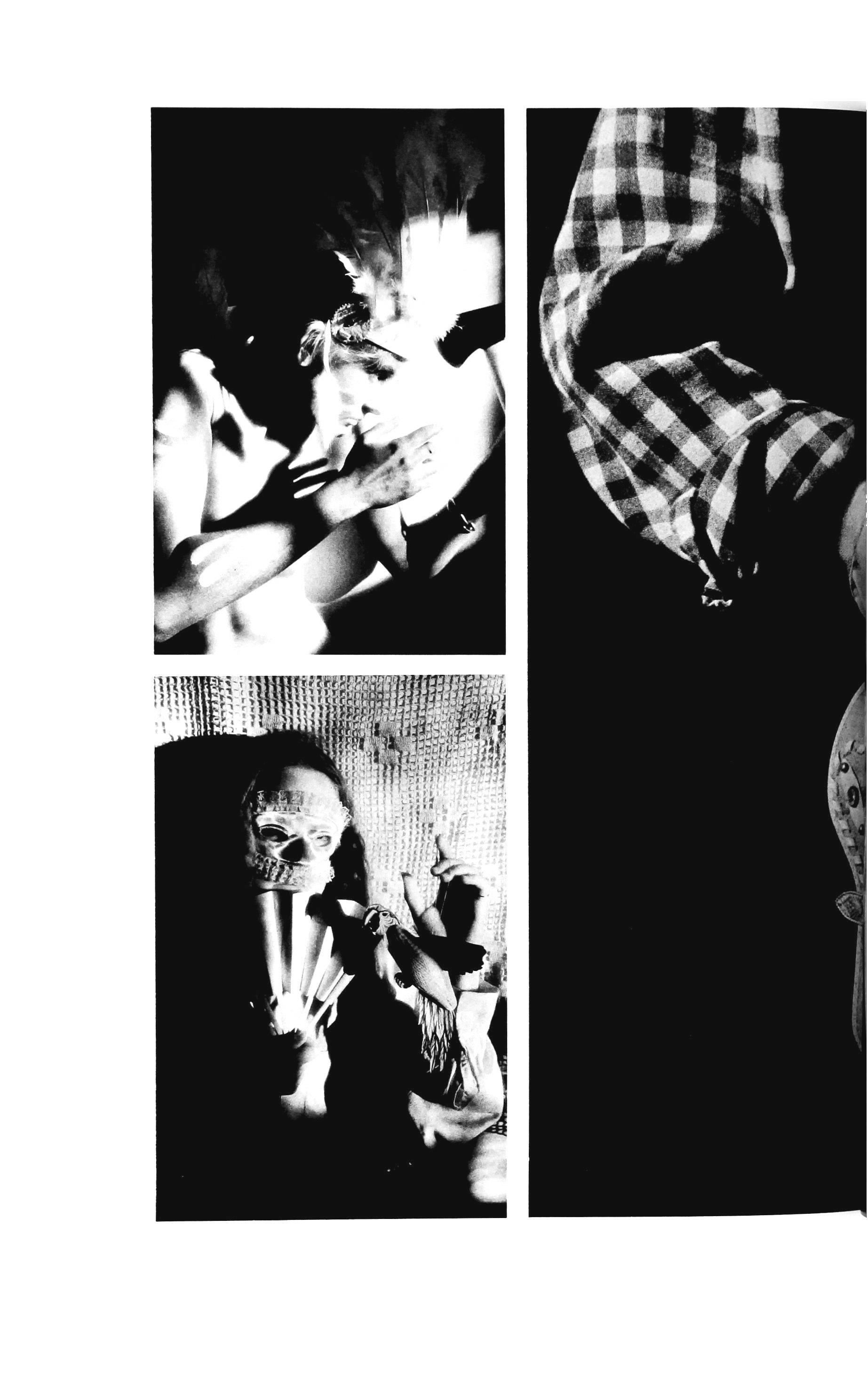

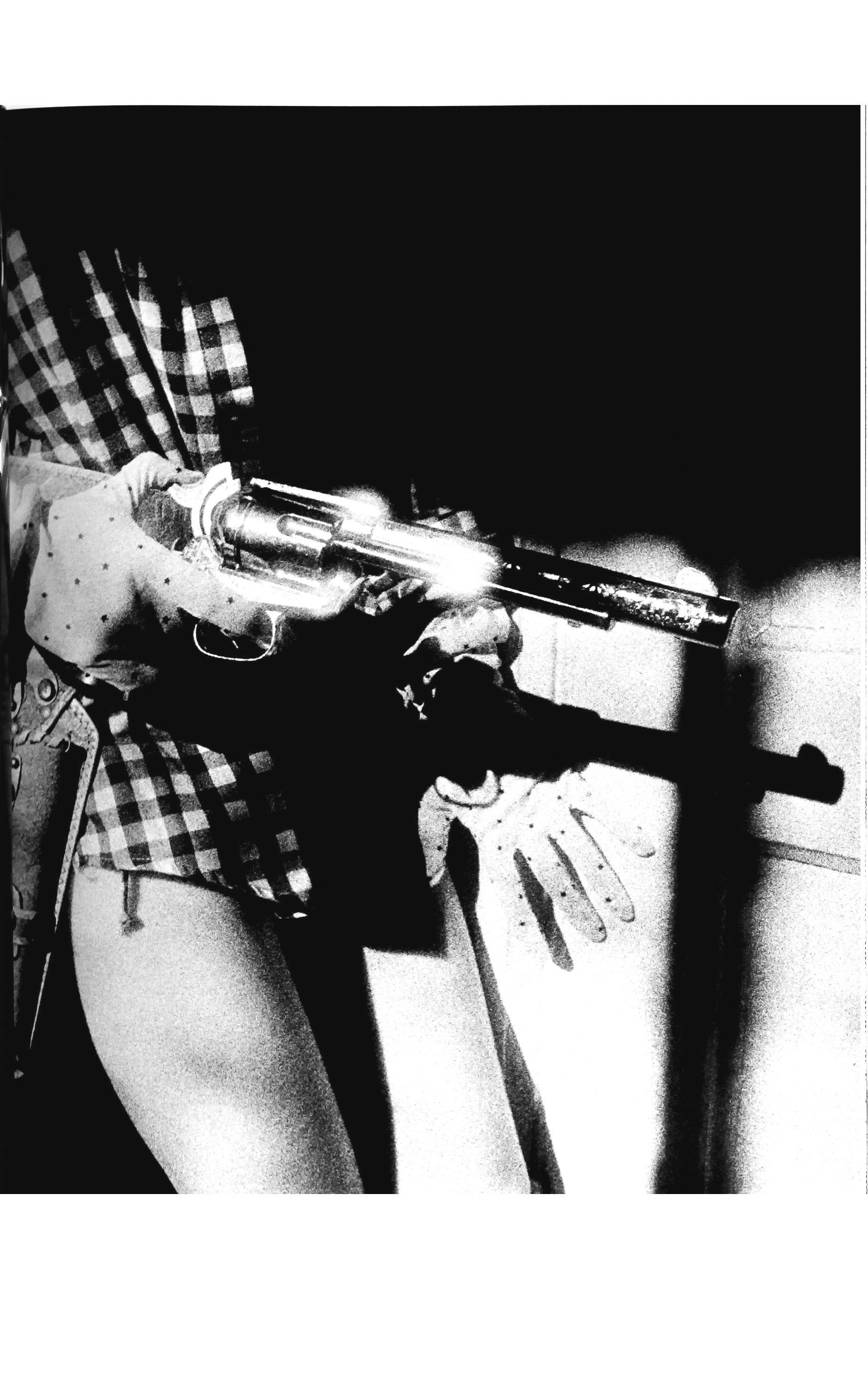

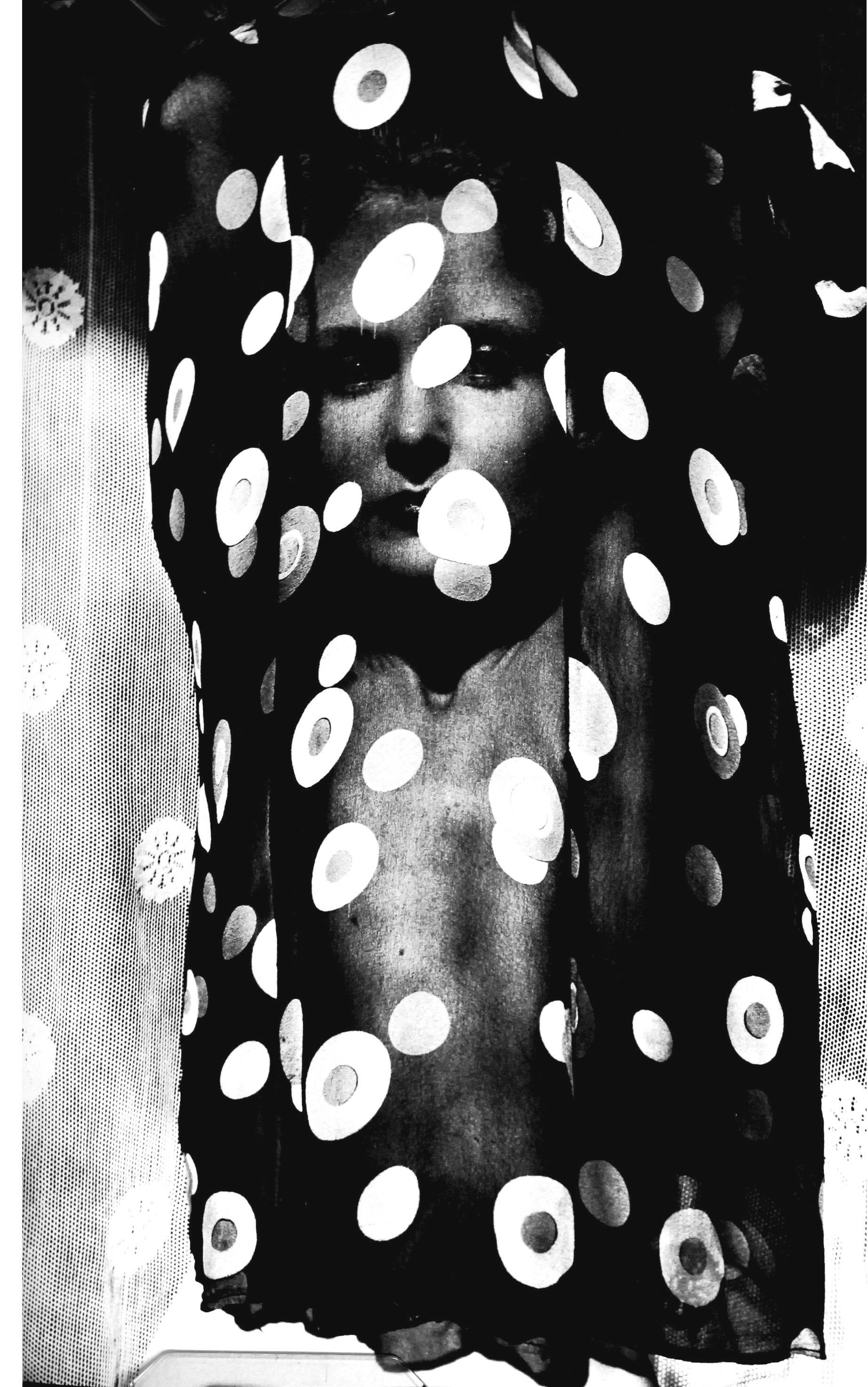

Jim Matusik has been practicing commercial photography in Chicago since 1972. His clients have included Playboy, Oui and Alligator Records, for whom he has provided album covers for several blues anthologies. His photograph of two red shoes suspended from strings illustrates a modular (hinged) shoe box called the "Peditainer" developed by Container Corporation of America. A portfolio of his work appeared in the April, 1978 issue of Zoom magazine.

All the while King Mac and that black gang, ofwhich Moore-Holt was the worst, was growing and spreading out and doing their evil, which when you come to it was the pure destruction of everything decent in the world and even the good world itself-or so it looked like anyway, with their crazy whooping around like a cavalry troop on a charge, and their scratching and diggingfor whatever it is men have always gone crazy scratching and digging after, or maybe only the tearing-things-up badness that lies quiet in everybody until something comes along to rouse it up like June bugs after a storm of rain, or men like those I have mentioned that can galvanize all that meanness and head it in one direction like a stampede of elephants-l say, all the while there's a pure evil, like King Mac and his bunch rousting everything and taking over more and more until it seems there can be no end to it, at the same time, and not too far away, getting his growth, there's a fellow like the Kid who can put an end to it, not by being so infernal clever or stout muscled-though you will never see a man any quicker headed and quicker handed-but just by being himself. Except that it does seem that the like of King Mac is

always a step or two ahead of the Kid, who is forever having to hurry to catch up, and maybe never quite does that, which is why things are like they usually are.

There are different versions of the Kid's birth and kin. Naturally you will hear he was one ofthe general's get, which you can hear ofjust about anybody in the Territory what with the general's reputation in that regard. It is said that the Kid was treated so cruel by a stepfather that he ran away to join the Gypsies, or else he was sold to them forfifteen dollars. That was where he learned the crafts and tricks that served him well later on. These Gypsies traveled up and down putting on shows in mining camps, bull-and-bear fights, knife-throwing exhibitions, fortune-telling, monte games, and such. If the Kid had a special friend among the band it was a big grizzly named the Duke of Cumberland. The Kid tended to him and it was said he couldallbut talk with that big bear.

Those were times when miners were set hard againstforeigners. Fellows with the wrong accent, or color of skin, or slant of eye were being run out ofthe district, some ofthem tar-and-feathered or even strung up if the miners' committees took on strong enough against them. In one place they came like that against the Kid's band of Gypsies-a mob with ropes set on a lynching. But they reckoned without the Kid. He sneaked through the crowd, told the grizzly what was wanted, and let him out of his cage. Well, that was a fine show, with the grizzly chasing miners every which way, and a caterwauling to beat everything. Anyway, the Kid was just a lad when hefirst showed what he was made of and got his friends out of trouble slick as you please.

The other way the Kid might have got his cleverness was being taken in as an orphan to help the cook in a certain establishment where there were women with theirfavorsfor sale, so to speak. It was a high-tone place where the girls wouldfancy-dressfor the parlor of an evening. These women are supposed to have mothered the Kid andfed him, and it was the slant-eye cook that taught him to throw a knife, in return for which he showed the cook how to play monte, having learned that game among the Gypsies. Some have the opinion that the Kid became so swift handed playing a kind offan-tan where you have to snatch up coins veryfast to win. I know the Kid is supposed to be so quick

as to grab a rattlesnake and snap its back like cracking a whip before it can strike, and I have seen him kill a rabbitfor the stew pot by chucking one pebble.

It is my own opinion that the Kid's swiftness came from eating minerslettuce when he was beingfedby the cook and the women in that place. Miners' lettuce is a member ofthe goosefootfamily, with heavy green leaves offgreenish white stalks, that makes a very heartening soup with side meat and carrots cut up into it. It is my understanding that parlor-house women partake of this soup forfemale reasons, and both Chinese and miners favor it too. It is the reason why a Chinaman is so quick at fan-tan and why miners can work such long, hard days underground. And of course it was underground where the Kid was to win through against odds that would have done in a lesser fellow.

There is another story of the Kid's beginnings that has him foundfloating down the river in a tiny coffin, with a ring hung on a chain around his neck. A mine owner's wife adopted him. She already had a daughter, a beautifulfair-haired child named Flora, and the Kid and Flora were brought up as brother and sister. But the mine owner lost his holdings; he and his wife died of the influenza; and the Kid and Flora were orphaned. They were taken in by a man named Jasperson, who ran an orphan school in that place, and was a kind man, though strict. By that time the Kid had given his ring to Flora to wear. It was supposed to have "properties," and it had more than that, as will be seen.

1

When the summons came he was shoveling manure, stacking the dried cakes in the wheelbarrow, and thinking that he was getting tired of his reputation as the fastest hand at cleaning a stable in those parts.

A tickle of dust signified that a horseman was coming down the track from town, and he straightened to lean on his pitchfork, batting flies away from his sweating face.

The horseman appeared at the corral gate-Conroy, stout in his black suit. "Kid, there is a blind fellow up in town looking for you." 7

"What's a blind fellow looking for me with?" the Kid asked. Conroy frowned and scratched his nose. "Got a long stick he jabs around with," he said. "Probably take it to you if you smartanswered him like that."

The Kid laughed and said, "Well, no point changing clothes if he can't see."

"Ought to wash up, though," Conroy said. "Probably he can smell."

The Kid washed and changed his clothes, and strode on up toward town through the fields so as to keep out of the dust of the road. Off to the west flat-bottomed gray clouds hung over the Bucksaws and a little wind was turning the grass to shine in the sun. He took great breaths of the sweet air, and as he tramped along the boardwalks of town he thumped his boot heels down cheerfully, even though it was clear that some he passed were irritated by the noise. He grinned at the men and tipped his cap to the women, which usually mollified them. Eddie Davis called to him from the pharmacy doorway that a blind fellow and a halfbreed were looking for him, waiting in the Last Dollar right now. He turned in through the bat-wing doors, out of the sunshine of the street and into the murk and sour stink of the saloon. Next, it was Ted Masters who told him that the fellow at the table in the corner, with the breed, was looking for him, Whispering behind his hand, "He's blind!"

The blind man was sitting tall in the corner with a play of light from the louvers of the bat-wings catching in his hair, which was curly, fair, and graying. He had a bandage around his head over his eyes, and propped on this was a pair of black spectacles, which seemed a foolish piece of fixing. There was a glass of whiskey before him, and another before the breed, whose gray braids hung from beneath a round-crowned hat, framing a face as wizened as a last winter's apple.

The blind man seemed to know who the Kid was, for he rose out of his seat to say, "Ah, they found you, did they?"

"They did, sir," the Kid said.

"Will you sit down with us? My name is Grace, and this is my guide, Josiah."

The Kid shook hands with Mr. Grace. Josiah, who looked as though he might have died awhile back, grunted. The blind man

remained standing, face pointed down and on the strain, as though trying to make the Kid out through the bandage and the black lenses. "Will you mind if I touch your face? It is my only means of knowing a person's features."

The Kid said he did not mind, and sat stiffly while a light tattoo of fingertips explored his face. When Mr. Grace sat down, his own face looked more at ease. "Will you partake of a glass of whiskey with us?" he asked.

The Kid said he didn't drink whiskey-a promise to his dying mother. At this the blind man pushed his own glass away from him as though it had become distasteful. The breed cupped his drink in his hands. Sometimes little gleams of eyes showed in the dark wrinkles.

"Well, sir, I expect you know why we have come," Mr. Grace said.

"Can't say I do," the Kid said, hugging his arms to his chest as though he had taken a chill.

"It is time for your journey."

"Well, I thought I had a while longer."

Mr. Grace sat there shaking his head.

"I thought I had till-" he started again, but did not go on since they were paying no attention.

"What's his coloring, Jos?" the blind man said, and the breed muttered something. They both sat looking at him with their mouths tucked flat.

The Kid said, "Well, I guess I oughtn't to go off without giving Mr. Collins a couple of weeks' notice. A week, anyhow."

"I've already satisfied Mr. Collins," Mr. Grace said, and the breed lifted his glass and finished the whiskey in it.

Lines of light broke and knit across the table as someone went out and the bat-wings swung. The blind man passed a hand before his spectacles as though he could perceive the change of light.

"I've got to get some stuff from my place, at least."

The blind man rose, very tall and straight in his bearing. He took up a long stick, which he flicked this way and that before stepping boldly around the table. The breed had also risen, not much taller standing than he had been seated.

"Let's go there, then," Mr. Grace said in a deep voice. "There is some need for haste, you see."

At nightfall they hunkered around a camp fire, the breed brazing chunks of meat on the end of a frog-sticker and passing them to him or the blind man. The Kid squatted shivering. He hadn't stopped shivering since the meeting at the Last Dollar, even with his corduroy jacket on and the fire blazing. Mr. Grace leaned back against a tree trunk with his bandaged face raised to the high moon, chewing meat. "Feeling shaky?" he asked in a friendly voice.

"Well, 1 am!" he confessed.

As though understanding that the Kid might wonder how a blind man had perceived that, Mr. Grace said, "When one sense becomes useless, others sharpen out of necessity. Do you know what fear smells like?"

The Kid chewed the gobbet of meat the breed passed him on the knife tip, juice running out the corners of his mouth. Shapes danced yellow in the flames as he considered. "Smells like something going bad, but kind of sour too."

Mr Grace nodded gravely.

"All 1 had to do was take a good whiff of myself," the Kid added, and managed to laugh. The breed made a sound that might have been a chuckle.

"There is no need to ridicule yourself," the blind man said. "Not many are capable of taking a whiff of themselves." Then the blind man asked if he knew what it was all about.

"Well, some of it." He raised a hand to touch the ring that lay inside his shirt on its chain.

Mr. Grace took the bit of meat the breed held out to him. "No one knows all of it, not even the general." He chewed and swallowed and wiped his fingers on his bandanna. "There is great evil abroad in the Territory. It has multiplied faster than the general ever thought possible. Are you aware of the difference between an arithmetical and a geometrical progression?"

The Kid said he hadn't got that far in math at school.

"Let us say it is like locusts multiplying," Mr. Grace said quickly, as though apologetic for having embarrassed him.

The Kid nodded. Then he remembered to speak aloud. "I see, 1 guess."

"Your Companions will be waiting for you," Mr. Grace continued, "with their individual qualities that are of no account without yours."

"Well, I guess I don't know what mine are."

In a severe voice, Mr. Grace said, "The ability to take a whiff of yourself. To shiver with your responsibilities, which you would doubtless be relieved to evade but know you cannot. To focus forces that have been heading in one direction, and head them into another."

"I don't believe I understand that last one," the Kid said, but the blind man seemed sunk in deep thought, and might not have heard.

"Henry Plummer will present a problem," Mr. Grace said, and the breed's face suddenly squinched up. "If he cannot be brought around to our persuasion, you will have to kill him."

"I'm not killing anybody! No sir!"

They both sat looking at him while he shivered like a dog with the pip. Finally he asked who Henry Plummer was.

"A man who was thought to have your qualities once," the blind man said in a tired voice. "But he went wrong. As did others before him and after him."

"Well, what if I go wrong too?"

"Then the last hope is gone," the blind man said, pointing his face toward the moon again.

There was a long silence. Off to the south, coyotes were talking back and forth. The Kid blew his breath out with a rubbery sound, squatting by the fire now, his arms wrapped around his legs. The guide was squinting toward the sound of the coyotes, his face jutted out like a hatchet. "Territory now!" he grunted loudly.

"What he means," the blind man said, "is that from now on every little thing may be of the very greatest consequence."

That night he could not sleep, and at last he slipped out of his bedroll and scrambled up on the sentinel rock that all night had loomed over the coals of the fire like a living presence. Immediately there was a star fall-swift-moving blossoms of fire that arced across the sky until they began to fall, some faster, some more slowly, to be extinguished behind invisible mountains. Shivering in his long-handled underwear and stocking feet, he strained his eyes toward the west, as though trying to penetrate not only the darkness but the future itself.

Josiah had said they were in the Territory now. It was a border famous for its vagueness, a line on a map drawn from this far-off

peak to those unreliable springs, to that disappearing river. All his life he had heard of the dangers there, the rattlers big as your leg that beset the badlands, the fever water of the swamps, the grizzlers and painters of the mountains, the flash floods that burst down out of the canyons of the Bucksaws like express trains when there had been no rain, no sign of a cloud even, and you must always listen for the mutterings of thunder that indicated cloudbursts in the higher peaks; and the savages of the mountains and the deserts beyond, Ki-manches who would sneak in during the moonless part of the night to scalp or capture and torturethough his friend Jimmy Breed had claimed that was a lot of bosh, stories made up by the cavalry who wanted to excuse their own cruelties and who had gone crazy with fear at their own lies.

Bits of gravel augered into his bottom as he hunkered down, listening to the breathing of his companions, to the snorts and hoof stamps from where the horses were tethered. There would be no cockcrow this morning. He started at a scratching and rattling beneath his rock-it was only Josiah poking up the fire.

Presently there were shadings in the darkness. All at once a peak was struck with color. Light poured down a bony mountainside like molten metal. The first range of Bucksaws formed out of the black, beyond it range on range in pit darkness yet; but as Jos chunked wood onto the fire and a scent of ashes prickled in the Kid's nostrils, his eyes were carried up, and up, to those more distant peaks as they loomed grayout of a darker gray, and one last shooting star scratched a phosphorus arc across the sky above them, disappearing at its zenith.

"Oh, my!" he whispered.

"Yes," Mr. Grace replied. He was squatting beside the ring of smoky rocks, teasing last night's fire back to life with a handful of twigs. This morning he wore a bandanna tied over his eyes instead of the bandage, and black-lensed spectacles. In his long underwear he looked bony and starved. Josiah squatted across from him.

"How many days to Bright City, Jos?" the blind man asked. The breed muttered, "Fife. If we keep lucky."

"Don't you fellows worry your heads," the Kid put in from his high rock. "I've always been a lucky one." He slid down to join them, dressing in his striped store pants and justin boots, and

cramming his flannel shirt in all around. The breed nodded approvingly as he strapped on his cartridge belt, drew his revolver, and flipped out the cylinder on its crane to examine the loading.

"Something pretty big moving around in the night. Anybody else hear it?"

"Grizz," Jos said.

"Stock didn't scare."

"No," the blind man said, as Josiah stumped offto stoop down and examine the ground beside the base of the big rock.

"Grizz come to take a look," Jos said.

Joining the breed, the Kid bent to inspect the cluster of scratches and indentations in a patch of damp ground. There were no tracks to be found except this single one, but it looked fresh enough. Jos gruffly ordered him to water the animals until breakfast was ready.

They set out with Josiah in the lead, a bandanna tied over his head like a mammy's. Following him rode the blind man, with his ramrod back and free hand curled on his hipbone, his own bandanna worn like a bandage over his eyes. The Kid brought up the rear, sometimes chirruping to the pack animals trailing behind. In the wake of their little party a tail of reddish dust drifted south.

Their way led down an eroded gully, up a ridge and along it for a way, down again, along the next ridge, in land that tilted down from the soaring peaks with their scarf of clouds. Some of the ravines had been planed to smooth rock by gully-busters.

"Hsti Grizz!" Jos called over his shoulder.

On the third ridge over the grizzly stood motionless, like a fat, fur-coated man with hands held as though poised over revolvers. Then without any apparent movement, he vanished.

They rode on in silence, plodding down a gully and up the next ridge. The peaks seemed no nearer. At noon they halted in a glen of ferns and green brush, where they drank from a run of cold water and ate jerked beef and sweet, pearly pear halves from a can. After lunch they continued to climb more steeply tilted land, with a cold wind flowing into their faces like liquid. Sometimes Jos seemed to be singing in a minor key, like a long moaning, though his tone was not entirely sad.

"Hsst! Looky there!" Jos called out suddenly. This time the bear was behind them, rushing along the gully out

This time the bear was behind them, rushing along the gully out of which they had just climbed, the brush violently and progressively shaken, a great furry ball bouncing over the ridge ahead of them, then vanishing. Minutes later the grizzly reappeared as the fat fur-coated man, standing a quarter of a mile away, forepaws dangling.

"He'll know us when he sees us again," the Kid said. The next time he noticed the grizzly, it was on the other side, about the same distance away, in the same stance.

Jos began singing again. Abruptly the peaks seemed nearer, full of rocky detail in the clear air, almost leaning toward them. There was a rumble of thunder. The breed called a halt, and in a grassy saddle with outcrops of gray rock, like bones protruding from the ground, they made camp among the remains of old camp fires. The Kid helped Jos tend the stock while Mr. Grace squatted, heaping twigs and dried moss into a little pyramid to which he applied a match.

When they joined the blind man at the fire, the breed slapped his holstered revolver and said, "Best friend now. Watch every minute."

"For what, Jos?"

·"Manche. Soldier. Hubychobys. Everything."

"What's hubychobys?"

"That's 'manche for black riders come very fast, go very fast, very bad."Jos's braids jerked in emphasis. "Maybe they watching like big grizz."

"Sure, 1 know," the Kid said, grinning. "I got eyes in the back of my head, too. Two, three of them skulking back there, 1 believe."

"Maybe more," Jos said.

"Perhaps you would help me," Mr. Grace said. He had some loaf sugar wrapped in a cloth, and a brown half-pint of liquor which was to be poured over the sugar. When this was done the blind man sucked the sugar lumps greedily. Jos accepted one also. "Please help yourself," Mr. Grace said.

"I don't partake, thanks. Promise to my mum."

"Yes, of course. As Jos says, we must be very careful from here on. We will all take turns on guard duty tonight."

"I saw those fellows in black sneaking around. You mean they might-"

"Impossible to know what they will do," the blind man interrupted. "And one must never be certain what is to come, for then another thing may take place, to one's surprise. And one must be only careful, never fearful."

"Jos and I can handle guard duty, I expect."

Mr. Grace drew himself up very tall and straight. "Perhaps I am better equipped than either of you for night duty."

The Kid hit his forehead with the palm of his hand. "Sorry. Didn't think."

"Apology accepted," the blind man said, smiling thinly. He warmed his hands over the fire and pressed the heated palms to the bandanna covering his eyes. Jos stumped about with a pan and skillet. There were nervous whickerings from the stock. Jos halted motionless for a moment, and the blind man pointed the knife-blade of his nose toward the sky. When the moment seemed to have passed, Jos grunted.

After supper, when the bedrolls had been laid out and the watches parceled, the Kid ran a rope through a split in the rock outcrop, tied it there, and brought the other end into his bedroll, while Jos, who had the first watch, squatted watching him from beside the dying fire.

He was awakened by a clatter of metal, a cry of warning, and a pounding of hoofs. A rifle cracked and flashed furry red against the dark, and in the flash he saw horsemen bearing down on the blind man and Jos, who were both standing up and firing their revolvers. With a chorus of shouts, the mounted black shapes raced toward them He rolled over, taking the rope around his hip once to pull it taut. As the clot of riders thundered over them, the Kid was jerked so hard he was brought to his feet. After a confused thrashing and a long whinny of pain, the clattering hoofs diminished to silence.

Jos cut the throat ofthe horse, which had a broken leg, but they didn't find the rider until first light. He had crawled beneath a rock, with a revolver in either hand and a rifle across his knees, his face a mess of blood, white bone showing through; one of his legs was twisted half around. He was snoring-asleep or fainted.

Skipping forward under the rock, the Kid snatched away the man's revolvers and kicked the rifle out of reach. The hubychoby stretched after it, and cursed him long and obscenely. He looked

like an Indian, with black greasy hair hanging in short braids, dark, filthy features, and a stubble of black beard. He kept poking his bloody, ugly face forward, like a snake striking, sometimes groaning as he tried to hoist himself into a more comfortable position beneath the shelter of the rock. He wore a rusty black frock coat, like a preacher's coat but torn and stained with dirt and blood, cavalry breeches so old they were faded almost white, and fine black boots.

"Who are you?" the blind man said, standing before him with his arms folded on his chest.

The hubychoby cursed him.

"Name's Cark," los said, to be cursed in turn.

"Who strung that rope?" Cark demanded.

"I did," the Kid said. "Went to a school where the big kids liked to hurrah the little tads' beds at night, scare them sick. They didn't do it any more after we strung ropes a time or two."

Cark examined him with bloodshot eyes, silently. Finally he said, "So you're the Kid, huh? Wouldn't be in your boots."

"Better mine than yours."

Cark began to grunt and groan again, sliding himself forward little by little and trying to reach down as though to straighten his twisted leg, reaching further and further until the blind man cried, "Watch out!" just as a derringer appeared in the wounded man's hand. los jerked up his rifle, but he wasn't going to be in time.

The Kid slapped for his revolver and shot the derringer out of Cark's hand, ventilating him in the process. He had to go and sit by himself for a while. Later they heaped stones over the dead man to save him from the buzzards.

The stock had been scattered, but los recovered one of the pack animals, which they loaded. They started on foot. Luckily the way led downhill now, toward a forest below them, and the wink of a blue lake showing through the trees. Cloud shadows sailed over them as they clambered down the rocks. The Kid noticed that the blind man, who had cut himself a long stick, made as good time as he and los.

All morning they descended the western slopes while clouds gathered. They kept to the ridges as much as they could, but more and more found themselves scrambling down the slick-sided gullies.

Once or twice thunder pealed, and once, looking back, the Kid saw lightning split a black-bellied cloud. At noon they halted to eat bread and jerked beef, Mr. Grace and Jos partaking of the sugar soaked in brandy, and the pack animals cropping grass along the walls of the canyon. They had started on again when the first drops of rain fell, fat and chill.

Jos urged them out of the canyon, and they scrambled up its steep banks as a distant rush of sound grew louder. Jos shouted and beat the packhorse as though he had gone crazy. A wall of white water burst over the ridge above them.

The leaping, frothy-glassy face was filled with branches, boulders, even a tree slowly turning. It peaked, slumped, and peaked high and higher with a roar of sound so vast the Kid could not even hear his own voice shouting. The water slammed down toward them like a gigantic, open hand, plucking up the pack animal and tossing it as though it was a toy horse.

He clutched the blind man's hands and half-carried, halfboosted him over the lip of the bank. Just then he was smashed flat by the great hand, and borne, whirling and gasping for breath, down the canyon at express-train speed. In his last instants of consciousness he had a sensation of calmer water, and of being carried to dry ground in the teeth of what must have been a huge dog, which had saved his life.

2

The Kid wakened in a cave. There was a heavy buzzing sound he could not identify, and a thick, rich smell of cooking that made his stomach heave.

Turning his head, he saw rifles supported on nails driven into cracks in the rock wall. Farther along were painted shields, spears with fringes of eagle feathers just below the points, three long headdresses, a buffalo robe bed. Turning his head the other way, he saw two men sitting at a wooden table, smacking cards down on it. One wore greasy buckskins and a wool hat pulled down to his ears. The other was Jos. The two of them grunted back and forth as they collected the cards again.

Just as it seemed to the Kid that Mr. Grace must have been lost in the flood, the blind man appeared from the direction in which

the light came, his stick flicking right and left before him. He stood over the cardplayers, tall and stiff-backed, silver in his hair.

The smell of cooking meat filled the cave-too thick, too richand the buzzing of insects resounded in his ears. Soon the Kid slept again.

When he came to himself, he was standing buck naked outside the cave. There was a small glade with sun filtering through green leaves, a corral in which half a dozen brown backs showed. Long heads thrown over a rail regarded him curiously. His stomach was empty. He whooped once, "Anybody home?"

No answer. He went inside to inspect the cave, which was a commodious one. Flies and yellow jackets crawled buzzing over long strips of red and yellow meat hung up to dry, and before a fire-blackened wall an iron caldron simmered. The pot contained a soup as dark brown as its smell, which made his empty belly heave again. He went back outside.

A squirrel regarded him from a branch, tail twitching. Carefully he squatted to gather up three round pebbles. He knocked the squirrel off the branch with his second throw. Carrying it inside by its tail, he found a knife with which he gutted and skinned it. He braised the carcass over the coals and ate it down to the bones. Then he lay down to sleep again.

This time he wakened to find three giants standing over him: Jos, Mr. Grace with his bandaged face, and the wool-hatted man, who had yellow animal eyes. Smoke was drifting along the roof of the cave to sweep out through a crack in the roof.

"Hello there," the Kid said.

"Finally come to," Jos said.

"We thought we had lost you," the blind man said, face pointed up to the ceiling.

"You cook meat?" Wool-hat asked. He talked as though he had a harelip, though he hadn't. "You don't like soup?"

"Smells pretty strong for my taste," the Kid said. He sat up, and though his head was spinning, added, "Well, I'm ready to go on."

"Rest one day more, younger," the mountain man said. "Eat soup. Soup make strong."

"Afraid I couldn't keep it down, you see. Always been delicate that way."

This displeased Wool-hat, who stamped away to the wooden table, where Jos presentlyjoined him. Mr. Grace still stood there.

"I thank you for saving my life, sir," he said.

"Did I do that?"

Mr. Grace nodded, and said, "When we leave here we will pass by Greasy Grass. There you will meet Stonepecker, the old chief of the Ki-rnanches. If he likes you he can be of the greatest assistance. "

"We'll get out of here tomorrow, then?" He squinted up at the blind man to see if that might be taken as an order. Mr. Grace nodded. Beyond him Jos and the other were slapping cards down again. He blew out his breath against the smell of the soup and lay back.

In the morning he killed a chipmunk, and cooked and ate it under the fierce disapproval of the mountain man, whose name he had learned was Smith.

As they saddled up in the little corral, Smith stood watching them-wearing a trapper's fur hat, with a long rifle and cartridge belt, and a packsack slung over his shoulder.

"I will join you," he said.

The Kid swung into the saddle. The blind man already sat in his-bandaged eyes and rifle-sight nose pointed toward the sun. Jos had assumed a familiar expression of not understanding the language.

"I guess not," the Kid said firmly. "But I thank you for your hospitality."

The yellow eyeballs seemed to throb, and yellow incisors appeared in the slash of a mouth.

"You have need of me."

The Kid shook his head. The man looked to him to be a masturbator. He swung his reins and clucked, taking the lead. "Wait!" Smith cried in his harelip voice. He jerked off his fur hat to reveal what at first appeared to be a dark brown, curiously shiny skullcap. It was his skull. There was a hairy ridge where the flesh stopped and the bone began. He tipped his head forward and pointed. "Beware of Ki-manche!"

"Thanks," the Kid said, and clucked again.

"'Manche beware of Smith!" the mountain man howled after him, then leaned on his long rifle, still hatless, watching them go.

The Kid waved once more as he led the blind man and los out of the glade. Smith did not return the salute.

After descending through thick growths of pine and fir, they came out of the woods onto a rocky hill. The Indian camp was arrayed below in the narrow meadow called Greasy Grass, and the Kid gasped at the number of white lodges ranked on the green. Smoke rose from many of these, to float in a gauzy layer over the valley. There was a thin yapping of dogs.

They continued downward into cool shade again. A group of mounted braves awaited them as they debouched into the meadow. These seemed friendly, nodding and touching foreheads with their fingers. All wore eagle feathers in their hair. A tall, very dark-skinned brave with a buffalo-horn headdress hailed them: "Welcome, brothers!"

The Kid raised a hand in greeting, and they rode on with their escort. Women in buckskins stood in the open flaps oftepees, and children hurried out to join the procession, along with a yapping pack of dogs, through which the horses waded uneasily.

The brave with the buffalo headdress rode close beside him. He had a nose that looked as though somebody had stepped on it with a hobnail boot. The dogs continued to yap around the horses' hoofs, a spotted one jumping up to nip at his stirrups, whereupon Buffalo-horns raised his spear high, looking into the Kid's face. The Kid put out a hand in restraint, Buffalo-horns lowered his spear, and the spotted dog fled.

"That one's Yellowfinger," los said out of the side of his mouth as they rode on in a close clump of horsemen. "War chief." They passed through the ranks of tepees, with their astrological decorations, and the wooden or smiling faces of the squaws and children. At the foot of the valley rose a conical mountain, gray granite above wooded slopes, surmounted by a cap of snow.

The Kid noticed that the braves performed a curious ritual, each in turn jockeying close to Mr. Grace, to reach out and touch him on the arm or the shoulder while he rode seemingly oblivious to this, bandaged eyes raised as though to the conical peak.

Their guard halted before a lodge larger than the others and more brightly decorated, with lodgepoles poking up and three vertical stakes planted in the ground before the tent flap.

Women's faces appeared in the opening; behind them a stovepipe hat loomed, making its way slowly forward through the crowd of women. The guard dismounted, and the Kid and his companions followed suit. The chief with the stovepipe hat wore pure white buckskins with chest decorations of rainbow porcupine quills. His hands were tucked into his sleeves. He bowed from one to the other of them, his ancient face wreathed in wrinkles and smiles, while his squaws crowded close around him.

"Welcome, my sons," he said in a deep voice.

He embraced Jos, holding him by the upper arms and pressing his cheek to the half-breed's, first one side and then the other. "My son, my son." Next he embraced Mr. Grace in the same way, saying, "The sightless one knows he is always welcome."

"We bring the true son of Two-star, my father," Jos said solemnly.

"So you are the one!" the chief said. He grasped the Kid's arms and pressed his cheeks too, one side and the other; he smelled like clean old leather gloves.

"Welcome, my son, welcome."

"Mighty glad to be here, sir!"

Jos jabbed him with a sharp elbow. "You got some little gift for the chief."

Everything he owned had been lost when the stock had been scattered by the hubychobys, or later in the flash flood, except for the ring on its silver chain that he wore around his neck. He removed his hat to lift the chain over his head and present it to Stonepecker.

When the chief had received the ring, with its white carved stone, into his two hands, he grunted as though he had been struck, raising one of his palms as against a too-bright sun. The women, who had been gathering around the blind man, each touching him in turn and murmuring, fell silent. Stonepecker had bowed his head.

"Thank you, my son, but this must never leave your own breast." His arms rose and he looped the chain back over the Kid's head, his arms remaining raised for a time after he had let it fall back into place.

And he said, "For your generosity I will have a precious gift for you before you leave Greasy Grass."

He shuffled, turning, extending an arm. "Enter!" he said. The Kid and the Companions followed the old chief, the women backing aside before them. The lodge they entered was huge and smoky, with a single slash of light falling from the peak to the circle of cooking stones. Buffalo robe couches were ranked around these. There was milling and whispering among the braves and the women while Stonepecker seated himself with the Kid on his right and Yellowfinger on his left. Mr. Grace and Jos took their places beside the Kid while the braves were arrayed beyond the war chief, their eagle feathers glowing phosphorescently. One of the squaws filled a long pipe with tobacco, lit it with a coal from the fire, and, on her knees, presented it to Stonepecker. He inhaled smoke, groaning with satisfaction. Next the pipe was presented to the Kid, who sucked smoke and felt his head whirling. He remembered to groan appreciatively. The pipe was passed from man to man while the women watched in silence. A crying baby was shushed.

The war chief said, in Ki-manche, "This wapto is very young, great chief."

"But grows older every day," the Kid managed.

The blind man sat up straight as though galvanized, and Stonepecker cried out, "Bah! You speak Ki-manche, my son?"

"There was a half-breed fellow at school that taught me some," he said. "But grows older every day" had been a kind of joke between him and Jimmy Breed, though Jimmy had told him it was a very important saying with the Ki-manches, He repeated the phrase.

"Hear the wisdom of this youth, my people!" Stonepecker said in his deep voice. He bent forward until his forehead was pressed to the buffalo robe on which he sat. Others did the same except for the blind man, whose face was raised to the peak of the tepee. The Kid inhaled the sour-soapy smell of the fleece. There was a chanting murmuring all around.

"It is good!" Stonepecker went on in a churchy voice. "See how each one understands one another here! White and dark. Wapto and Ki-manche. Young and old. For all are the People together in this place!"

The Kid's head went spinning off again from another suck of the cool smoke, but he nodded vigorously to show he agreed with 22

what the chief was saying: "Thy People are in their gravest danger, Great Spirit!" Stonepecker stretched both arms high. "And you have sent us a savior, Spirit!"

The Kid stopped nodding at this, and the chief lowered his arms and for a long time sat hunched in upon himself before continuing:

"What has happened to us, my People? As soon as the wapto has thrust his plowshare under our earth it teems with worms and useless weeds. He increases the population to an unnatural extent. He brings with him whiskey to drown the disappointments which he also brings, and so creates the necessity for prisons to hold his villainies. He spreads over the human face a mask of deception and selfishness, and substitutes the love of wealth and power for the simpleminded honesty, the hospitality, the honor and purity of the natural state that was once the People's.

"In the ancient wisdom it was seen that the wapto were more powerful than the People because the wapto are more numerous. It was also seen that in their greed they would destroy each other as they have destroyed the land and its fruitfulness. As they now destroy the air with the smoke and dust of their vast workings, and the lakes and rivers with their befoulment. Destroying all in their greed, their dissatisfaction, and their villainy.

"And so the golden hoard of the Ancients was to be held so that in the fullness of time the People could purchase back their land from ocean to ocean, that it would become truly theirs. The destroyed land would then be filled over to the height of a man with rich black soil in which grass and trees would grow again, and rivers run, and lakes fill. With buffalo and antelope and ponies for everyone, and beautiful women and strong children to grow to great braves and fruitful squaws. And all the desert despoilment of the wapto would be buried forever, by the People, who had waited so long in their patience and their faith in thee, Great Spirit!

"But the greatest danger has come with the Beaver-man, Spirit! Who scratches and scratches-like a madman, it is said-but digs always deeper and closer, despoiling the earth the more with his very efforts. With his teeming multitudes, and his stinking machinery, and his laboring mules, and his vile hubychoby. Broader and deeper and closer, Spirit, so there is great fear among the People that Beaver-man will discover the hoard!

"But you have sent us your redeemer, Spirit! Who is fair of hair and blue of eye, as has been written. Who possesses the True Ring of the Spiderweb Map, and speaks the tongue of the People, as has been written, and knows the ancient words of wisdom. We thank you with all our hearts, Spirit!"

Stonepecker stretched up his arms once more, then slumped in silence while the pipe was passed. At last he turned and smiled at the Kid.

"Son of Two-star, you are welcome here!"

"Mighty good to be here, sir!"

"You must call me Father, and 1 will call you Son."

"That's fine, Father."

"These Companions of yours for the great task, they are not many. Beaver-man has many warriors. Many. Their evil may not prevail against goodness, but still they are many."

"I expect we'll gather a few more fellows as we go along, sir Father," he added. He'd been trying to keep both eyes open at once, but now he concentrated on squinting through one at a time at the wrinkled, anxious old face. The war chief also looked very worried.

"Turned one down already, didn't like his style," the Kid continued. "All we need's a few good fellows." He tapped his forehead, winking, nodding. "It's all in here."

"Do not underestimate Beaver-man, my son. He also has much in here." Stonepecker tapped his own forehead with a finger like a dried-up bone. Yellowfinger leaned forward to listen to this conversation. His nose was mashed flat except for a perky little peak at the tip, and his nostrils faced straight forward, like a pig's.

"Many braves will wish to accompany you, young wapto," Yellowfinger said in his rasp of a voice. "I suggest twelve braves, the number of the Faultless Ones."

He shook his head, squinting through the smoke. The pipe was passing again, and it would be well if it skipped him this time. Yellowfinger's buffalo horns jerked with anger. "You disdain assistance, wapto!"

Stonepecker said placatingly, "Listen to the reasoning of the son of Two-star, my son."

The Kid held up a forefinger and spoke as the woman on her knees held out the pipe to him. "One," he said loudly. "Just one. The best one!"

He paused, and shook a finger at the pipe squaw, so that she carried the pipe along to Mr. Grace on his right. There was a great waiting silence before he said, "You, Yellowfinger!"

Everyone around him broke into grins. He grinned back. Stonepecker raised an arm for silence.

"And you shall have a thousand warriors when you need them, my son!"

The Kid thanked Stonepecker. The pipe squaw was on her knees before him again. He sucked a little smoke and his head bobbed off into the smoky air like a captive balloon. His body lay back among the buffalo robes for a little nap, to a low murmuring of approbation from all around, like the cooing of pigeons in the corral loft back home.

In the morning he waked to a concatenation of snores and snortings to find himself cocooned in buffalo robes in the big lodge that was even smokier than it had been last night, and stinking of too many people-who, from the look of it, had all fallen asleep on the fly just as he had. Near the tent flap a warrior with a body gleaming with grease and vermilion paint knelt straight-backed holding his spear erect. Before him, on a kind of shelf, was a buffalo-horn helmet, and propped below that a feathered shield. It seemed a strange way for a guard to position himself.

The Kid sat up and immediately groaned and held his head. Now he could see that the kneeling warrior was Yellowfinger. He staggered outside to take a leak. There, tied to one of the upright posts, was the most beautiful horse he had seen in his life, a pale stallion that curved his neck at him and whickered gently while all his hide seemed to flow and weave with motion like mercury, and his mane and tail to lift as though in some little breeze that he kept about him.

"Oh, my!" the Kid said in admiration. He heard a chanted muttering behind him, and looked back inside the lodge to see Stonepecker in his white buckskins standing over the kneeling war chief, making broad gestures with a skeleton hand.

The Kid stood politely by until Stonepecker had finished, then thanked him for his hospitality and said it was time for them to be moving along. Stonepecker gripped his arm and swung him toward the silver stallion.

"My son, this is the mighty horse Muchoby. He can run like the wind, and will be ever faithful to his master. He is yours. He will carry you out of any trouble. Or if you send him back to me, a thousand warriors will come, as I have said. Muchoby, my lovely one, this man is thy master now!"

The silver stallion whickered and tossed his head once, twice. The Kid thanked the old chief and went to stroke the stallion's velvet nose.

They rode out of Stonepecker's encampment on Greasy Grass escorted by warriors with feathered lances and shields, by barking dogs and running boys. The old chief waved from the flap of his lodge-his women grouped about him and the stovepipe hat on his head. Again the blind man seemed oblivious to the horsemen and the boys who came to touch his clothing reverently. Jos jounced pudgily on his pony, glancing back from time to time, while Yellowfinger, his broken-nosed face fierce as a hawk's beneath the buffalo headdress, stared straight ahead, bare chested and fantastically painted, with buckskin trousers on and armed with a rifle, a knife, and a hatchet. At the timberline there were more farewells, more hands outstretched to Mr. Grace, and to the Kid too now. Escort, boys, and dogs turned back except for one spotted mutt that trotted along beside the Kid in the shade of Muchoby, with a lolling tongue and self-satisfied air. The Kid deferred the lead to Yellowfinger, who disappeared into the shadow of the pines. The others followed in single file while the Kid stroked Muchoby's shoulder. The dog squatted close by.

"Better go home, Duke," the Kid said, but the dog paid no attention, trotting alongside as he fell into line.

The trail wound in and out of woods along the edge of a stream, which it crossed from time to time, the horses splashing through the water and clattering up the rocks on the far side. At noon they halted to eat jerked venison and cold sweet potatoes beside a rockbound pool into which clear water poured with a bladder-aching sound. Yellowfinger took tinder, lint, and a bit of steel from one of the pouches strung around his waist and, from another, tobacco and a dried husk. He measured tobacco, twisted the husk, and held it between his teeth while he struck a spark into the tinder, then waved a hand to bring this to a flame and lit his cheroot. He grunted contentedly. The blind man sniffed at

the smoke, face raised to the sun. Jos squatted beside the pool. The spotted dog sat hunched down at the Kid's side, well away from the war chief.

In a moment of silence, Yellowfinger rose and, with a sweeping gesture as though shaping an umbrella that covered them all, said, "My brothers!" Then he passed the cigar from one to another. This time the Kid only pretended to swallow the green-tasting smoke, nodding and saying, "Good! Good!" in Ki-manche, Yellowfinger looked as pleased as his irritated-eagle face could manage.

Soon afterward they started on again; the trail joined another where there were horse turds trampled among innumerable hoofprints in the beaten earth. Yellowfinger dismounted to inspect broken twigs along the trail, and, squatting, poked a finger into one of the turds.

"Many horses," Jos said.

Yellowfinger chopped one hand across the palm of the other. "Half a day, no more. These horses eat corn, not grass." He nodded significantly to the west.

"What color horses?" Mr. Grace enquired.

Yellowfinger prowled the brush along the sides of the trail again. "Some black, some brown."

"Headed which way?" the Kid asked, steadying Muchoby, who nervously curved his silver neck to one side and then the other.

"Both way," Jos said.

Yellowfinger scowled and said, "First to the rising sun, later to the setting sun, only not so many."

By mid-afternoon they had crossed a ridge of high country burnished red-brown in the late sun, terrain of sandstone and scattered boulders. Once they discovered the remains of a cook fire, stones arranged before a blackened boulder. Yellowfinger poked his fingers through the ashes, SCOWling. Here the trail wound steeply downward, and from the clearings enormous distances were visible. A thick band of smoke or haze lay across the horizon, reddening as the red globe of the sun descended and sank into the haze.

"It is the Beaver-man!" Yellowfinger said, pointing. He looked challengingly at the Kid, who did not respond. The spotted dog hunched down beside the silver stallion's forehoofs, tongue lolling.

Presently they joined a wagon road, and at dark came upon a high-sided wagon with a canvas cover. In the glow of a fire, words could be made out painted on the side of the wagon:

DOCTORS!

BALTHAZAR AND PEARL

MEDICINES, SURGERY, HERB CURES

TEETH PULLED $7

FASCINATING EXHIBITS!

Horses whinnied in greeting from a corral among the trees. The dog, Duke, kept close to Muchoby, tail curved between his legs. Against the firelight three men appeared as silhouettes, one incredibly tall and thin between his shorter companions. There was a gleam of rifle barrels. "Just in time for supper, am I right?" a voice called out.

"Please do come and join us, gentlemen," a second voice said. They dismounted to advance into the firelight past the charcoal shadows of the wagon. The tall figure proved to be a cadaverous man with a thatch of white hair. He wore a long gown, and he bowed and backed and beckoned, with an excessive waving of arms. With him was a knickered boy of perhaps nine, with a spoiled, freckled face and red hair. The third man was a dwarf. His short arms swaggered out from his sides as he approached, and shadows caught in the hooked nose and fierce nostrils of his outsize face.

"Greetings, I'm Frank Pearl," he said. "You must be the Kid we've all been hearing about." He shook hands with the Kid, Mr. Grace, and Jos, saying, "Greetings, greetings."

Yellowfinger held up a hand and said, "How, short one!"

"They're still trying to find the pieces of the last fellow called me Shorty," Frank Pearl said, not unpleasantly. "This one is Doctor Balthazar, and-"

"You don't look like much to me," the boy interrupted, staring at the Kid with green eyes hard as stones.

The dwarf swatted him with the back of his hand, and the boy staggered back, to trip and fall. "I'll fix your butt for you, you goddam midget!" he shrieked.

The dwarf started after him, and the boy fled. They could hear him weeping and threatening from the outer dark. Duke cowered beside the Kid.

"Have to apologize for that punk's manners," Frank Pearl said. "Please come and make yourselves comfortable," Balthazar said. "The lad is very disturbed. Abandoned by his mother, fatherless. Still, he's a spunky little fellow."

"Going to get hairs growing out of the palms of his hands being so spunky," the dwarf muttered. They all seated themselves around the fire, where there was a wooden collapsible table and camp chairs. The Kid breathed deeply of the delicious smells emanating from a black pot balanced over the coals.

"You won't mind potluck?" Balthazar asked, rubbing his hands together. "We've lost our cook. Temperamental fellows, these Celestials! However, welcome to our humble hearth!"

"Mighty fine to be here!" the Kid said. The blind man was standing over the fire taking deep breaths. His hair gleamed in the firelight. The dwarf passed a brown bottle and a tin cup.

"Best to fortify before tackling the Doc's stew. Am 1 right, Doc?"

The Kid passed bottle and cup along. "Never touch it, promise to my mum." Yellowfinger, with an expression of ferocious rejection, drew a finger back and forth in front of his face. With one eye squinted half shut he peered into the darkness from where the redheaded boy still occasionally shrilled curses. Duke lay shivering over the Kid's boots.

"The little fellow is certainly upset tonight," Balthazar said to the dwarf. "I do believe it is simple jealousy."

"Thought you said it was spunk," Pearl said. He took the bottle and cup from Mr. Grace, poured and sipped. Balthazar rolled up his loose sleeves to dipper steaming meat, carrots, and potatoes onto tin plates. He passed these around, exclaiming at their heat and blowing on his fingers.

"You are heading toward Bright City?" Mr. Grace enquired.

"Guess we are," Frank Pearl said. "Along with you."

"Such a depressing place now," Balthazar said. "Noisome air, a sense of hopelessness, and yet a kind of fever- Ah, 1 can remember when the Territory was a veritable Eden!"

"General's bad sick," the dwarf said.

"What's his trouble?" the Kid asked. Jos was pushing food into his mouth. Yellowfinger sat peering into the dark with eaglejerks of his head while the blind man sat high-headed and immobile, as though paralyzed by the dwarf's words.

"Just down sick," Pearl said. "He gets down sick and everything goes to hell, or else it's the other way around. Course, King Mac tearing up the pea patch and Moore-Holt racketing aroundanybody'd take to his bed. On your deathbed nobody expects you to do anything." He cackled coarsely.

From the darkness the boy screamed, "Motherbuggers! I'm out here starving to death while you feed your face!"

"I don't know where that little twap learned to talk like that," the dwarf said.

"He must come back and eat his supper," Balthazar said. "He'll make himself sick crying out there like that."

"Come on in and have some chow, slime pot!" Frank Pearl called. In a moment the boy reappeared, sneering, face puffy with tears, hands in his pockets. Duke pressed his belly closer to the Kid's boots.

"Don't just gimme one that's all potatoes," the boy said, as Balthazar heaped meat into a tin bowl, clucking placatingly.

Leaning forward, Yellowfinger caught the boy's hair in his hand, and, while the boy howled, twisted his head from side to side to examine the hair line intently. When released, the boy aimed a kick at the Ki-manche, which the dwarf neatly deflected.

"That peanut-nose nigger better keep his hands offen me!" the boy screamed. Yellowfinger drew his knife and tested it on his thumb. He wiped the blade on his buckskin trouser leg, testing, honing, scowling, and retesting at intervals, while the boy wolfed down his food and glared back at him.

The Kid smuggled a lump of meat to the dog at his feet and encountered the boy's green furious eyes.

"You're supposed to be so almighty good, are you?"

"Opinions differ," he said politely.

"Huh!" the boy said. "Betcha you get laid out!"

"Ki-manche boy not like this," Yellowfinger said, fingering the tip of his knife again.

Balthazar said, "He's a poor motherless child. Fatherless, also. An orphan, in fact."

"Pure son of a bitch, in fact," Pearl said.

The boy had ripped out one word of a curse when the dwarf clouted him so hard on the side of the head that he sprawled in the dirt, spilling his food. He blubbered and cursed, keeping away

from both Yellowfinger and the dwarf while Balthazar filled another bowl for him.

He wiped his nose on the back of his hand and said to the Kid, "I'm the best shooter in the Territory right now, I betcha! You know how many cans I can knock off a fence post at fifty paces? I mean, without a miss?"

"How many is that?"

"Two hundred and fifty-seven. Right, Granddad?"

"I believe that is correct, little fellow."

"Whose paces?" the Kid enquired.

"Yours or mine either!" the boy said, staring at him with the bright green eyes. "I can put you down at fifty paces, yours or mine!"

The blind man cleared his throat and pointed his bandaged eyes at the Kid.

"Don't hold with spraying lead all over the landscape," the Kid said, patting the shivering dog. "Bad for game. I may not be the best you'll ever see, but I am the carefullest."

"Huh!" the boy said. "Carefullest! I bet they lay you out. I betcha I could do it!"

"Better get your growth first," the Kid said.

"I think that will not be," Yellowfinger said, testing his knife on his thumb.

In the morning the Kid was taken on a tour of the little museum inside the wagon. There was a dusty stuffed owl; a two-headed bobcat with both heads snarling, red mouths, white teeth, stiff whiskers; also a stuffed rattlesnake of impressive size. In a huge glass bottle, which glowed from some light source the Kid could not make out, a tiny figure floated in pearly liquid, naked, less than a foot in length, a perfectly formed human adult by the proportions of his body, tiny fingers with shiny flecks of nails. He seemed almost to be swimming in the liquid, rising or sinking slowly, head moving toward them, slit of pink mouth, minute closed eyes, wrinkled cheeks of an old face on a young body.

"Something, isn't he?" Pearl said.

The Kid asked what it was.

"Homunculus. You can tell when there's stormy weather coming by the way he'll sink to the bottom. Like he's doing right now."

"Not alive, is he?"

"Hard to tell. See how it looks like he's swimming? And sometimes you'd swear he's got his eyes open, or he's shaking his head at you. Once I believe I caught him with a hard-on. That was when the brat's mother was still around. She changed her clothes in here, you see."

"He's right on the bottom now," the Kid observed. Indeed, the little man was almost prone on the bottom of his jar, chest a little raised and head raised further, long black hair drifting in invisible current.

"Stormy weather ahead," the dwarf said. "But he don't necessarily just mean weather, you know. See how it looks like he's shaking his head?"

As the Kid moved along to examine displays of obsidian and gold pyrites, where a handwritten card stated, "Reputed to come from the famous Lost Dutchman Mine," Balthazar appeared in his long gown to beckon them into his study, in a second, smaller wagon. Here the walls were lined with leather-bound books and glass jars containing specimens: tarantulas, a nasty-looking little pink and white snake, wasps, an ants' nest. There were three rows of apothecary jars in blue, contents identified in black script. Open on the desk was an enormous volume, one of the exposed pages filled from margin to margin with a tight handwriting as crisp and curly as the doctor's galvanized hair. The second page was two-thirds filled.

"Guess you were up writing last night," the Kid commented. "Saw your light burning late when I was out tending my animal."

Balthazar looked pleased. A pair of wire-rimmed spectacles lay on the table with the book, an inkstand, and a collection of quill pens in a pewter cup. "Very, very late," he said.

"Every night, am I right?" the dwarf growled, and Balthazar nodded solemnly.

"Here I record everything," he said. All at once he appeared taller, more impressive, his face set into noble lines as he pointed a finger at an entry in the open pages. "Your party arrives to join us. Or perhaps you would maintain that it is the other way around? That possibility must also be recorded." He turned to blank pages, the creamy paper glowing. "Here will be recorded your progress and ultimate success. You see, I leave no possibility

for the opposite there." Smiling, he leafed back through page after page, dense with the small, curly script, finally returning to the original pages.

"The work of a lifetime," he said, his eyelids drooping to reveal his exhaustion with his task. Then he perked up to indicate the shelves of leather-bound books, battered journals, boxes containing sheafs of yellowing papers. "My sources. Full of lies, of course. Fantasies. Testaments made up out of whole cloth. But how much, and where? Nuggets of truth must be recognized as such and seized upon by an alert and referential mind." He pulled a volume half out of the shelf of books, only to jam it back contemptuously. "Do I bore you?" he asked.

"Kind of interested, actually," the Kid said.

"Doc's got a tough job on his hands, am I right?" the dwarf said, smothering a yawn. "Well, come on if you've heard enough," he said to the Kid. "We'd better let the doc get on with it."

Outside, clouds had gathered over the peaks of the Bucksaws, but full sun brightened the little glade beside the wagons. The blind man sat beside the camp fire with his face raised to the sun, and the redheaded boy lounged just outside the big wagon, seated on a stone, his hair gleaming like copper. He was whittling, a pile of pale shavings between his boots.

"Hidey!" he called to the Kid. "Been seeing all the spiders and snakes and book junk?" He grinned winsomely to the Kid's nod. In the sun his freckles looked like spots of mold.

"What do you want?" the dwarf asked. "You want something, I know."

"I thought him and me'd go shoot cans off posts. 1 expect you can show me a thing or two at that," he said to the Kid, with the fraudulent grin. "I was just funning last night."

"Well, 1 wasn't," the Kid said, leaning his hands on his cartridge belt. "I hold against throwing lead all over the landscape when there's no necessity."

"It's practice, ain't it?" the boy whined.

"You scout up your shavings when you're through there, you hear me?" the dwarf said. "I'm tired of picking up after you, you little crut."

The boy started to snarl, but then grinned like a chipmunkagain. The Kid asked him if there was any place he could take a wash.

"Fine swimming hole down by the bend of the crick," the boy said, waving an arm. "That's where I always go to wash."

"If you ever washed once on purpose I never heard of it," Pearl said.

The Kid strolled away in the direction the boy had indicated. Down at the bend of the creek, clear water purled over rocks that gleamed black and golden in the sunlight slanting through the pines. There were exposed roots along the cut bank like the limbs of buried men. The Kid folded his clothes on the bank, stuffed his rolled cartridge belt into one boot, which he hid in a snarl of roots, and left his revolver on top of his neatly folded clothing. He eased himself into the creek, splashing water up into his armpits and gasping. He marked the boy's approach by the flicking of the brush tops. The boy appeared on the bank beside the pile of clothing, watching him with arms folded.

"Pretty good hung," he commented. "Though I've seen better."

The Kid thanked him.

"I can tell you how most fellows is hung," the boy confided. "I come down here and watch. Women sure look funny, like somebody smacked them with a ax. Got you a birthmark down there, I see." Grinning, he took up the revolver and aimed it in an exaggerated way.

"Didn't anybody ever tell you not to aim a piece you didn't intend to fire?" the Kid said.

"No," the boy said. "Didn't anybody ever tell me that."

"I'm telling you now."

The hammer clicked sharply.

"You have got a few things to learn, at that," the Kid said. "Apt to break a firing pin snapping dry."

'That so?" the boy said. He snapped the trigger again, aiming the revolver with both hands. Then he pushed the cylinder out on its crane, took a handful of cartridges from his pocket and began inserting them in the cylinder. The Kid whistled.

There was a flash of black and white spots behind the boy. He screamed, leaping out into the water, while the Kid leaned forward to catch the revolver as it fell from his hands. The dog Duke stood on the bank with his teeth bared.

The Kid pulled the boy by the collar, spluttering and cursing, to where he could get his footing. "Bit me!" the boy screamed,

holding his seat. "Motherbuggering stinking mutt bit me! 1'11-" His mouth fell open. Standing there shivering in his drenched clothing he stared at the Kid's chest.

"What's that?" he asked calmly.

"What's what?"

"Hanging from that chain there."

"It's a ring."

"Where'd you get that ring?"

"Fellow gave it to me that 1 saved his life fishing him out of a creek."

"That's my ring you've got on you there, you know it?" the boy said calmly. He wiped his eyes on his soaked sleeve; then he screamed, "That's my mother's ring! You stole that ring from my mother!"

Duke slunk away as the dwarf appeared on the bank. The blind man's tall head approached through the brush. Pearl yelled, "You stop that yelling, hear! You'll deaf everybody within a mile of you, rotface."

"He's got my mother's ring!" the boy screamed. He jerked at his pants and a ridiculously long knife appeared in his hand. The Kid retreated into deeper water with the revolver. "You gimme my mother's ring or I'll cut your privates off!"

"Here!" the dwarf shouted.

"I know you did dirty things to my mother, you buggermothering, dirty-to The boy lunged forward with his knife, and the Kid judiciously retreated again.

The boy screamed curses, he and the dwarf shouting in a kind of concert while Mr. Grace came out on the bank, flicking his long stick ahead of him. Finally the boy waded to the opposite bank and clambered up on it. Pantingthere, he brandished his knife at the Kid.

"I got your number," he said in a calm voice. "You're a sham, that's what you are. Well, I'm heading out of here, but when they lay you low I'll be there."

The dwarf flung a rock at him, which the boy coolly ducked. "I got your number," he said once more. He spat, competently. Suddenly he disappeared. There was a snarling, a shout of pain, and the brush was violently disturbed, progressively receding. The dwarf bent to retrieve his hat, which had fallen off when he had flung the stone.

"Are you all right?" the blind man called out in an anxious voice, his bandaged face jerking from side to side, then bearing straight on the Kid in the water when the Kid replied that he was.

"That's a dangerous boy," Mr. Grace said.

"He's a nasty little piece of work, that's for sure," the dwarf said. The Kid trudged out of the water with his revolver, dressed on the bank, shivering. He whistled. After a time the dogappeared, tongue lolling. The Kid sat beside him, patted and complimented him.

When they returned to camp they found it in a turmoil. The boy had fled, running off all the stock from the corral. Yellowfinger paced like a caged cat before Jos and Doctor Balthazar.

"I will find him!" He jerked a finger along his hair line.

"Please don't think badly of the lad," Balthazar said, standing with his hands concealed in the long sleeves of his gown. "Surely we will recover the animals. The poor child has been badly treated. His mother=-"

"You get that red hair," the dwarf said to the pacing war chief, "and I'll pay you ten dollars for it. But I don't want any boy underneath it."

"Ki-manche care nothing for money!" Yellowfinger said scornfully.

"This rough joking makes me very uncomfortable, gentlemen!" Balthazar said.

"Not as uncomfortable as it's going to make squitpoop," Pearl said. "Am I right, chien"

The blind man laid his hand on the Kid's shoulder. "These also are your Companions," he said. "And there are two more to come. The boy has gone to the other side."

"Is that right?" the Kid said.

There was a sound of hoofs and the silver stallion appeared, with an empty saddle. The Kid moved over to scratch Muchoby's pink nose while the stallion curved his neck from side to side and stamped a hoof nervously.

Presently the other horses appeared, crossing the meadow toward them. Following them was a rider in a tall hat, in dark clothing. There was a moment of tension, Yellowfinger whispering, "Hubychoby!"

"No," Mr. Grace said, as the rider herded the stock closer.

Docilely the horses plodded through the open gate of the little corral. The man accompanying them had a dark brown complexion that looked as much due to whiskey as to sun and wind. His eyeballs were yellow, and his graying mustache drooped on either side of his chin. "My name's Dockerty," he said.

The Kid reached up to shake his hand.

"So you finally come," Dockerty said. "Everybody's been waiting a time."

"Thank you for bringing back our stock," the Kid said.

"Horses are what I'm good at," the other said. He hooked a knee around his saddle horn and sat looking from face to face, as though ticking each one off. "Some bunch," he said, and slipped from a pouch a flat pint bottle half full of whiskey. He tipped this to his lips.

"Come to ride along," he said, wiping his mouth and recorking the bottle.

"You are welcome," the Kid said in a firm voice. "But you will have to take the pledge."

"Surely," Dockerty said. He shied the bottle off into the brush, swung down off his black mare, and began to shake hands all around.

3

At first light the Kid rose. Yawning and scratching, and accompanied by snores from the other bedrolls, he wandered around the side of the wagon to relieve himself in a clump of scrub brush in the gully where they had camped the night. A big man in a uniform appeared and stuck the muzzle of a carbine into his ribs.

"Pull 'em down!" the man snarled. "I want to see what you wear on your belly!"

Wincing on the pebbly ground in his bare feet, the Kid started to unshuck his longhandles. There was a flash of black and white as Duke shot out from under the wagon and fastened his teeth into the big soldier's leg. With a curse the man swung the barrel of his carbine, and Duke dodged and fled, yelping. While the Kid pulled down his underwear, _the soldier continued to curse in a monotone. He was a bulky man with a straggle of graying hair protruding from beneath his forage cap. Stacked yellow chevrons

on his sleeve identified him as a sergeant. He was strung over with harness, cartridge belt and revolver, canteen, and binoculars. He grunted as he examined the ring on its silver chain, and bent to peer at the butterfly birthmark on the Kid's belly. Meanwhile the Kid yawned, stretching to his tiptoes with his hands raised high and locked together.

He slammed these down on the back of the sergeant's neck and the sergeant went down like a dropped trunk. The Kid stepped on the carbine with both feet.

The sergeant rolled over on his back, grimacing with one hand trapped beneath the carbine and the other gripped to the back of his neck. He had a beefy, pockmarked face.

"I'd take it kindly if you'd step off my hand," he said. He added, "General wants to see you, fellow."

The Kid stepped off the rifle, and the other climbed wearily to his feet, brushing the dust from his carbine. He jammed the muzzle into the Kid's solar plexus again. "Let's go!"

"I'll get my clothes on."

They were mounted and a quarter of a mile from the caravan, en route to the fort, when they heard Duke howling behind them. "Ought to brained the critter," the sergeant grumbled.

Before noon they rode through a ruined gate into a weed-grown square, where whitewash had peeled from adobe walls. A flag drooped from the central pole in airless heat. The place was ghostly silent as they dismounted. The sergeant stood before a doorway, beating the soot and dust from his uniform with his cap. The Kid followed suit. When they stepped inside he was blind in the total darkness.

A tongue of flame climbed in a lamp, revealing a desk, a pigeonholed wall, all the slots empty, and a boarded-over broken window. Shadows tilted in sharp-edged slants as the lamp swung, the sergeant lumbering around the room clumsy as a great bear. He was so tall he had to stoop beneath the low ceiling. He banged a bottle down on a desk.

"Nip of whiskey for your dusty throat?"

The Kid said he never touched it, promise to his mother. The sergeant squinted one eye at him, tipped the bottle to his lips, and drank deep. His Adam's apple bounced. When he had put the bottle away, he tapped gently on an inner door, to a muttered response.

They passed into darkness again, and a stink of eucalyptus oil, and again the sergeant lit a lamp so that the room's contents took form out of flickering light. A woman with a shawl drawn across her face sat in a chair against the wall, motionless as a black Buddha. In a bed was a man so slight of frame he hardly disarrayed the coverlet. He had an unkempt white beard and his mouth was open as he snored, his nose pointing toward the ceiling. The sergeant settled the chimney back on the lamp and stepped heavily over to the bed.

The snore broke off. In a small hoarse voice the general said, "Thank you, sergeant major. If you would bring a chair-to "Sir!" The sergeant major lurched to the door again, knocking against the Kid in the process, while the Kid gazed around with interest at objects looming out of the darkness-a gleam of glass cabinet fronts, what appeared to be the varnished foot of a coffin heaped with all kinds of curios and mementos. On one wall was a shadowy painting of cavalry in action against Indians, and on another a naked woman with flesh so white it seemed to illuminate that end of the room. The sergeant major reappeared with a chair, which he slammed down, legs jarring on the floor.

The Kid seated himself and the sergeant major quit the room, leaving the communicating door open. The general snored again. Then a thin, liver-spotted hand appeared from under the coverlet, to slide across his forehead.

"Well, you've finally come," he whispered. "Soon's I could, sir."

Eyelids trembled with effort, but failed to open. "Was your journey a difficult one, my boy?"

"There was a flash flood that was a pretty near thing. Other than that nothing to complain of."